スペイン風邪

Spanish flu

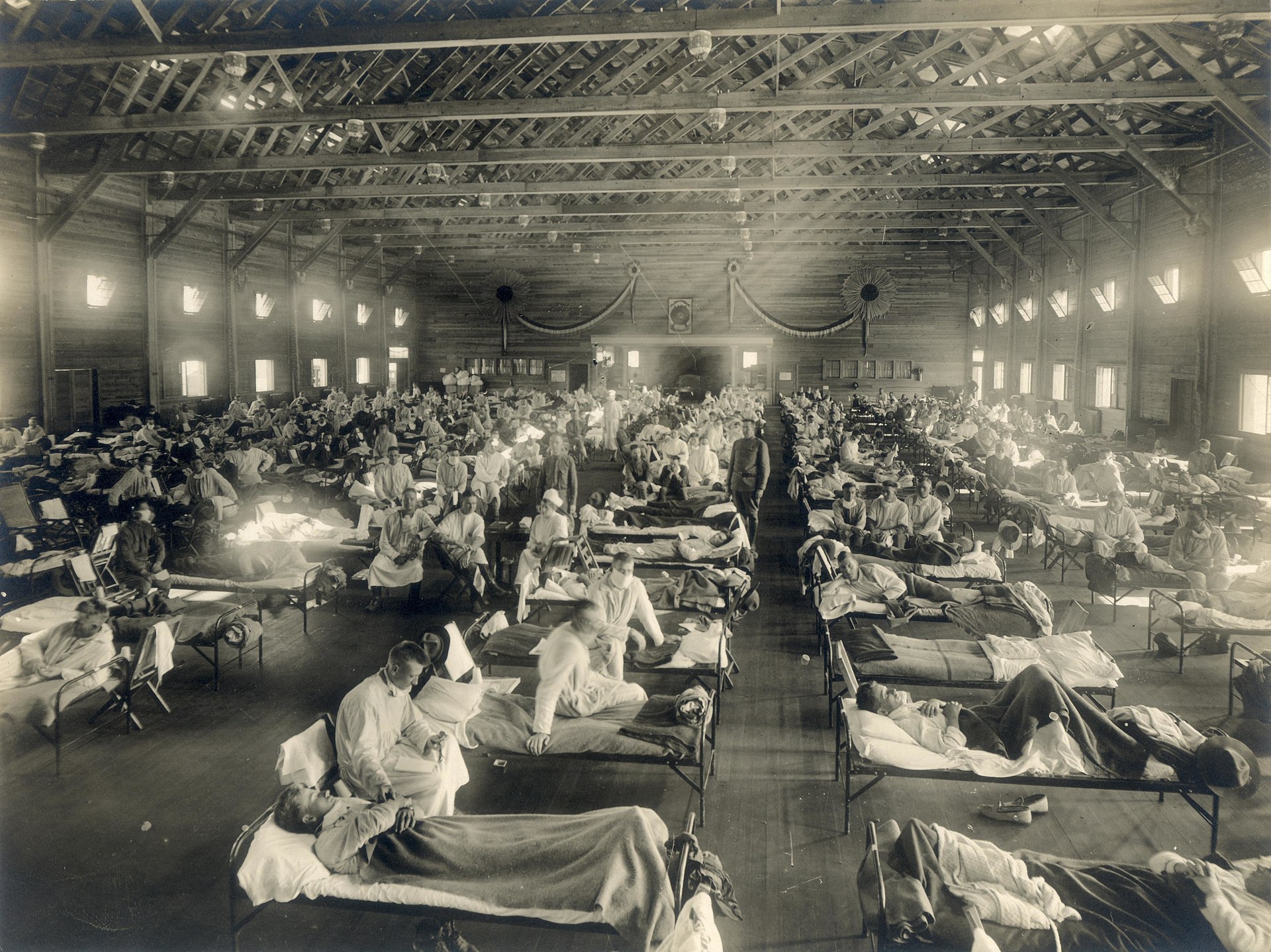

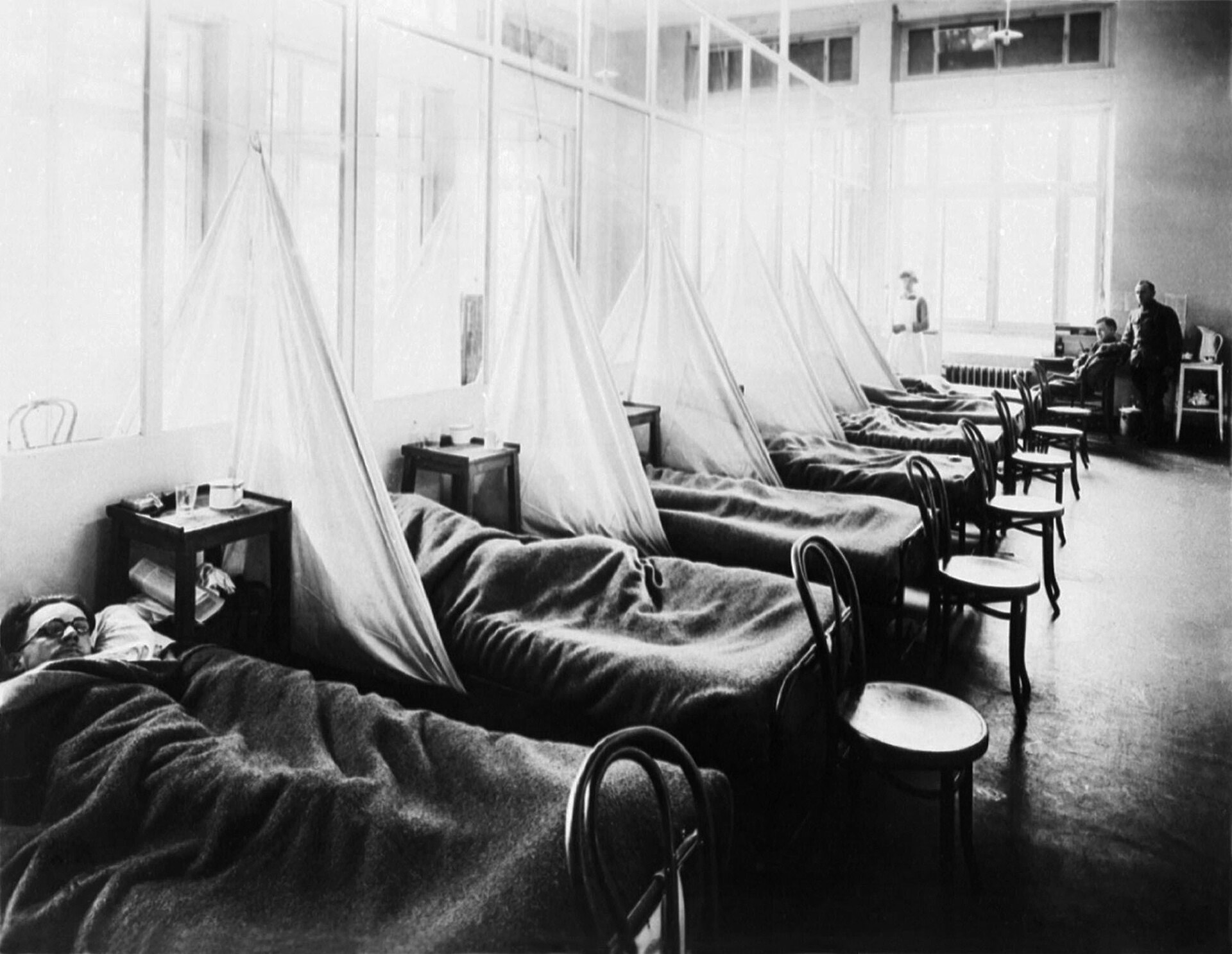

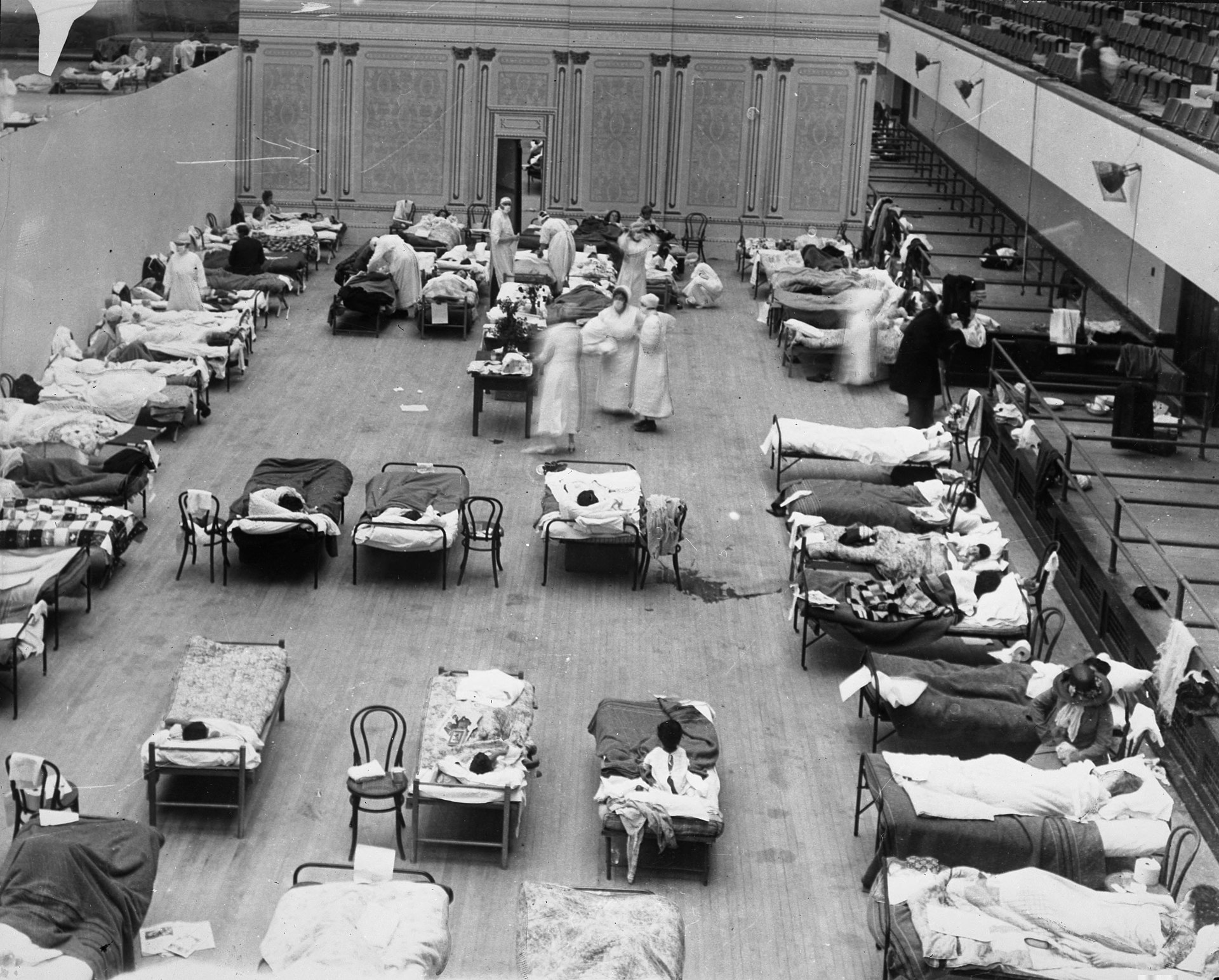

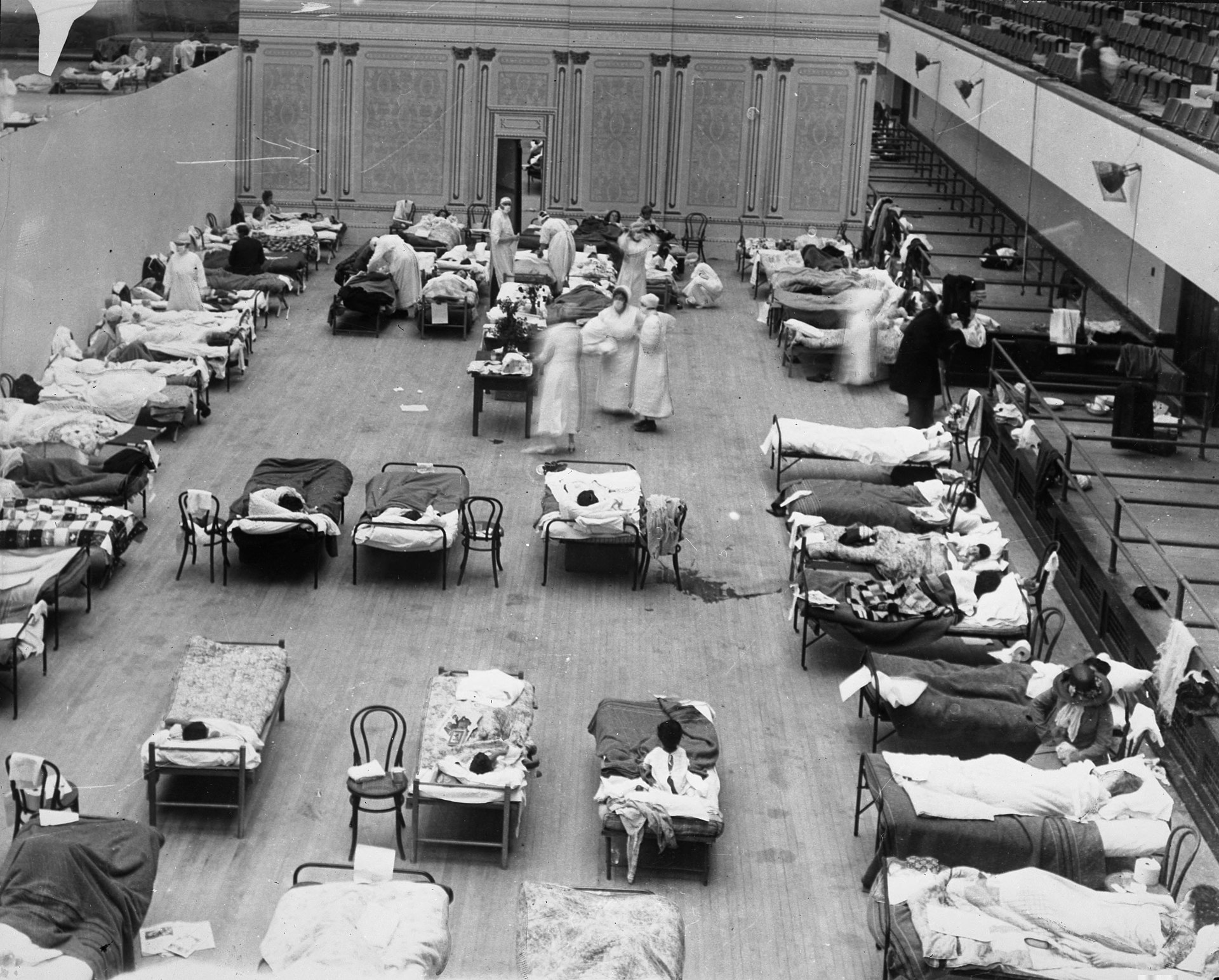

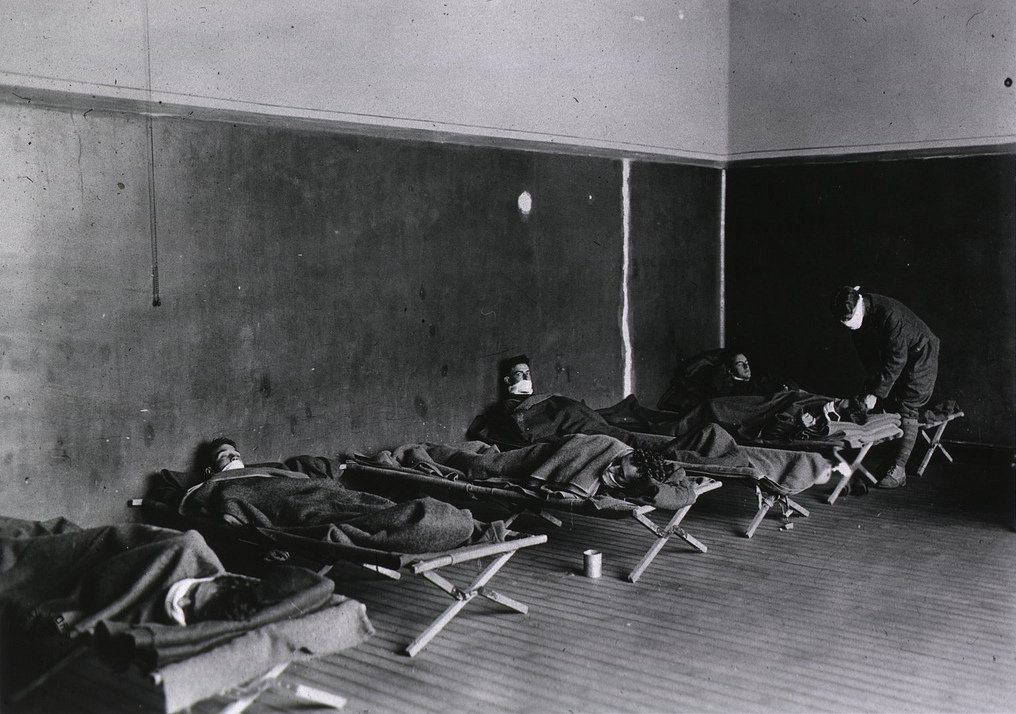

Soldiers sick with Spanish flu at a hospital ward at Camp Funston in Fort Riley, Kansas

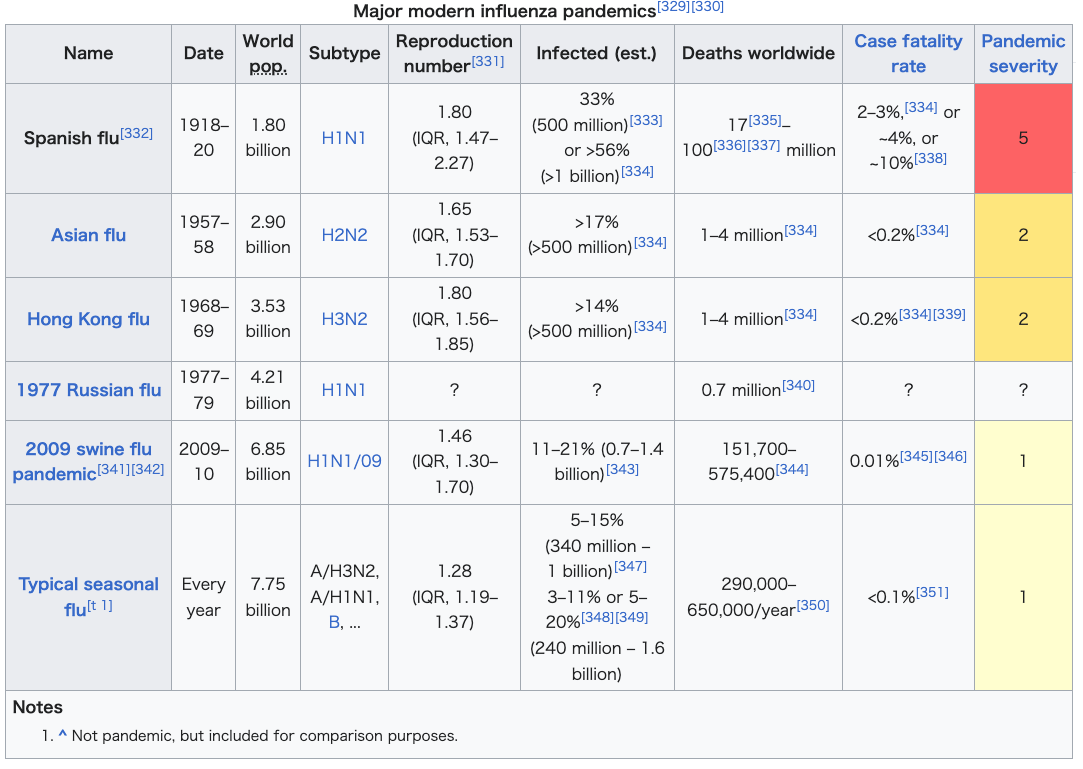

☆1918

年から1920年にかけて発生したインフルエンザの大流行は、スペイン風邪とも呼ばれるが、これはインフルエンザAウイルスのH1N1亜型によって引き起

こされた、きわめて致死率の高い世界的なインフルエンザのパンデミックであった。

記録に残る最初の症例は1918年3月に米国カンザス州で発生し、4月にはフランス、ドイツ、英国でも症例が記録された。2年後には、4つの波にわたって

世界人口のほぼ3分の1にあたる5億人が感染した。

死亡者数は1700万人から5000万人と推定されており[6][7]、1億人に達する可能性もある[8]。

このパンデミックは、第一次世界大戦の終戦間近に勃発した。交戦国では戦時中の検閲官が士気を維持するために悪いニュースを抑制したが、中立国スペインで

は新聞が自由に発生を報道したため、スペインが流行の中心地であるという誤った印象が生まれ、「スペイン風邪」という誤称につながった。[9]

限られた歴史的疫学データにより、パンデミックの地理的発生源は特定できず、初期の感染拡大に関する仮説は競合している。[2]

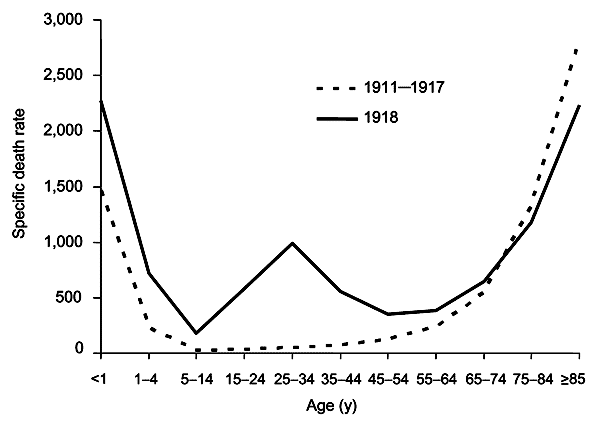

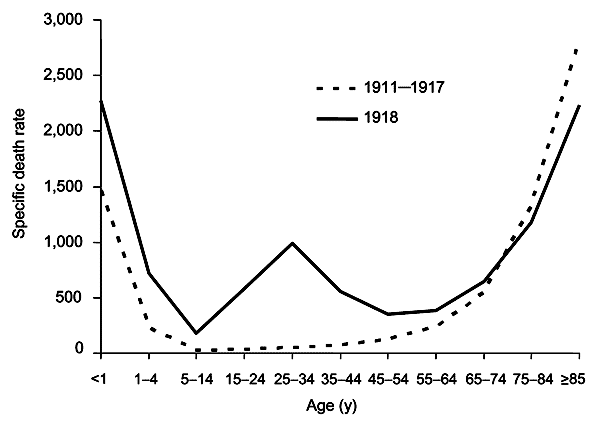

ほとんどのインフルエンザの流行では、若年層と高齢層が不均衡に死亡し、その中間の年齢層では生存率が高いが、このパンデミックでは若い成人層の死亡率が

異常に高かった。[10]

科学者たちは、この高い死亡率について、6年間にわたる気候の異常が、水系感染による拡大の可能性を高め、病気の媒介動物の移動に影響を与えたことなど、

いくつかの説明を提示している。[11] しかし、このパンデミックで若い成人の死亡率が高かったという主張は異論もある。[12]

栄養失調、過密状態の医療キャンプや病院、そして戦争によって悪化した不衛生な環境が細菌の二次感染を促進し、犠牲者のほとんどが典型的な長引く死床の後

に死亡した。[13][14]

1918年のスペイン風邪は、H1N1型インフルエンザウイルスによって引き起こされた3つのインフルエンザ・パンデミックの最初のものだった。他の2つ

は、1977年のロシア風邪と2009年の豚インフルエンザ・パンデミックである。

| The 1918–1920 flu

pandemic, also known as the Great Influenza epidemic or by the common

misnomer Spanish flu, was an exceptionally deadly global influenza

pandemic caused by the H1N1 subtype of the influenza A virus. The

earliest documented case was March 1918 in the state of Kansas in the

United States, with further cases recorded in France, Germany and the

United Kingdom in April. Two years later, nearly a third of the global

population, or an estimated 500 million people, had been infected in

four successive waves. Estimates of deaths range from 17 million to 50

million,[6][7] and possibly as high as 100 million,[8] making it one of

the deadliest pandemics in history. The pandemic broke out near the end of World War I, when wartime censors in the belligerent countries suppressed bad news to maintain morale, but newspapers freely reported the outbreak in neutral Spain, creating a false impression of Spain as the epicenter and leading to the "Spanish flu" misnomer.[9] Limited historical epidemiological data make the pandemic's geographic origin indeterminate, with competing hypotheses on the initial spread.[2] Most influenza outbreaks disproportionately kill the young and old, with a higher survival rate in-between, but this pandemic had unusually high mortality for young adults.[10] Scientists offer several explanations for the high mortality, including a six-year climate anomaly affecting migration of disease vectors with increased likelihood of spread through bodies of water.[11] However, the claim that young adults had a high mortality during the pandemic has been contested.[12] Malnourishment, overcrowded medical camps and hospitals, and poor hygiene, exacerbated by the war, promoted bacterial superinfection, killing most of the victims after a typically prolonged death bed.[13][14] The 1918 Spanish flu was the first of three flu pandemics caused by H1N1 influenza A virus; the others being the 1977 Russian flu and the 2009 Swine flu pandemics.[15][16][17] |

1918年から1920年にかけて発生したインフルエンザの大流行は、

スペイン風邪とも呼ばれるが、これはインフルエンザAウイルスのH1N1亜型によって引き起こされた、きわめて致死率の高い世界的なインフルエンザのパン

デミックであった。

記録に残る最初の症例は1918年3月に米国カンザス州で発生し、4月にはフランス、ドイツ、英国でも症例が記録された。2年後には、4つの波にわたって

世界人口のほぼ3分の1にあたる5億人が感染した。

死亡者数は1700万人から5000万人と推定されており[6][7]、1億人に達する可能性もある[8]。 このパンデミックは、第一次世界大戦の終戦間近に勃発した。交戦国では戦時中の検閲官が士気を維持するために悪いニュースを抑制したが、中立国スペインで は新聞が自由に発生を報道したため、スペインが流行の中心地であるという誤った印象が生まれ、「スペイン風邪」という誤称につながった。[9] 限られた歴史的疫学データにより、パンデミックの地理的発生源は特定できず、初期の感染拡大に関する仮説は競合している。[2] ほとんどのインフルエンザの流行では、若年層と高齢層が不均衡に死亡し、その中間の年齢層では生存率が高いが、このパンデミックでは若い成人層の死亡率が 異常に高かった。[10] 科学者たちは、この高い死亡率について、6年間にわたる気候の異常が、水系感染による拡大の可能性を高め、病気の媒介動物の移動に影響を与えたことなど、 いくつかの説明を提示している。[11] しかし、このパンデミックで若い成人の死亡率が高かったという主張は異論もある。[12] 栄養失調、過密状態の医療キャンプや病院、そして戦争によって悪化した不衛生な環境が細菌の二次感染を促進し、犠牲者のほとんどが典型的な長引く死床の後 に死亡した。[13][14] 1918年のスペイン風邪は、H1N1型インフルエンザウイルスによって引き起こされた3つのインフルエンザ・パンデミックの最初のものだった。他の2つ は、1977年のロシア風邪と2009年の豚インフルエンザ・パンデミックである。 |

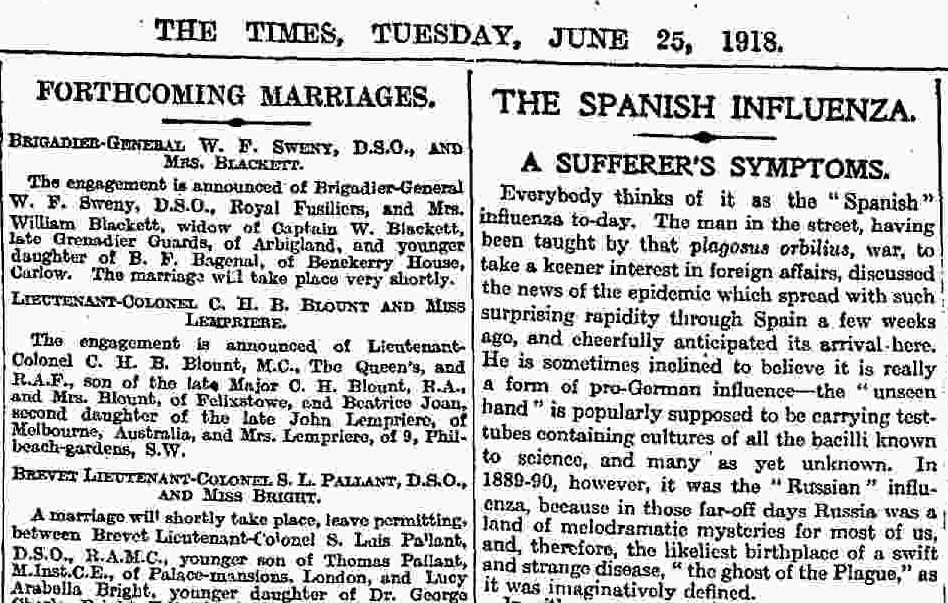

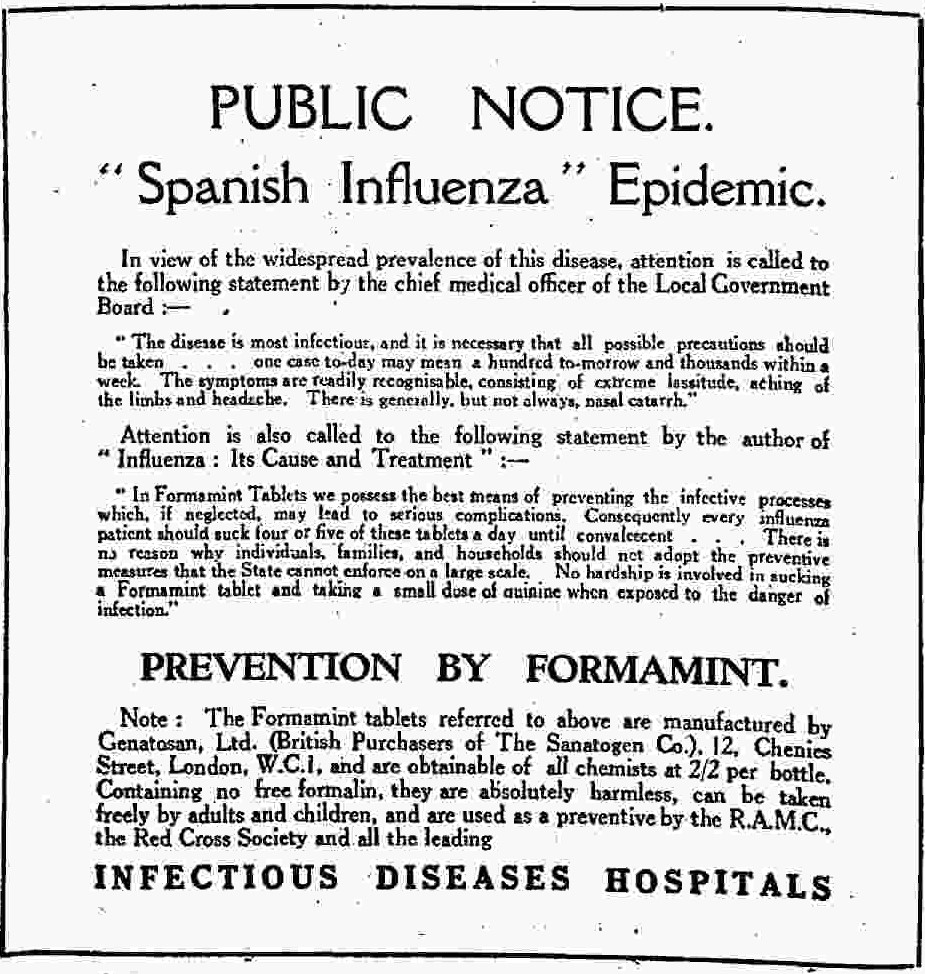

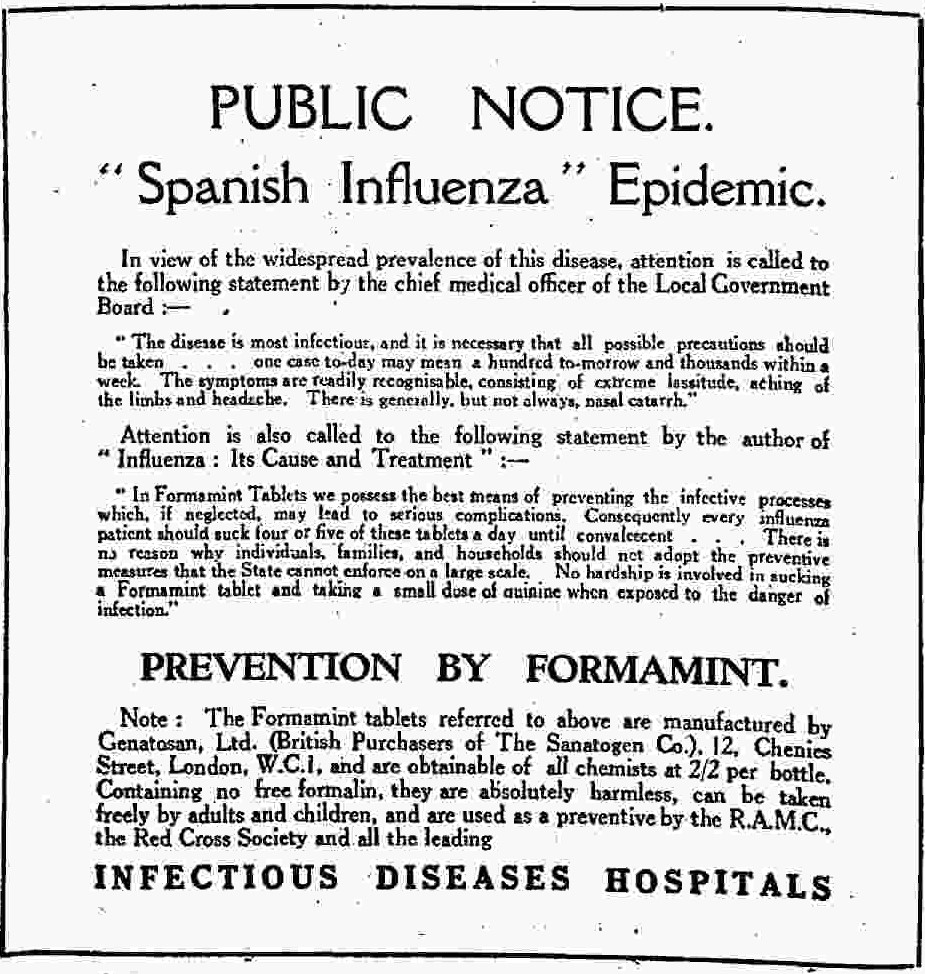

Etymologies El Sol (Madrid), 28 May 1918: "The three-day fever – In Madrid 80,000 Are Infected – H.M. the King is sick" This pandemic was known by many different names—some old, some new—depending on place, time, and context. The etymology of alternative names historicises the scourge and its effects on people who would only learn years later that invisible viruses caused influenza.[18] The lack of scientific answers led the Sierra Leone Weekly News (Freetown) to suggest a biblical framing in July 1918, using an interrogative from Exodus 16 in ancient Hebrew:[a] "One thing is for certain—the doctors are at present flabbergasted; and we suggest that rather than calling the disease influenza they should for the present until they have it in hand, say Man hu—'What is it?'"[20][21][22] Descriptive names Outbreaks of influenza-like illness were documented in 1916–17 at British military hospitals in Étaples, France,[23] and just across the English Channel at Aldershot, England. Clinical indications in common with the 1918 pandemic included rapid symptom progression to a "dusky" heliotrope cyanosis of the face. This characteristic blue-violet cyanosis in expiring patients led to the name 'purple death'.[24][25][26] The Aldershot physicians later wrote in The Lancet, "the influenza pneumococcal purulent bronchitis we and others described in 1916 and 1917 is fundamentally the same condition as the influenza of this present pandemic."[27] This "purulent bronchitis" is not yet linked to the same A/H1N1 virus,[28] but it may be a precursor.[27][29][30] In 1918, 'epidemic influenza' (Italian: influenza, influence),[31] also known at the time as 'the grip' (French: la grippe, grasp),[32] appeared in Kansas in the U.S. during late spring, and early reports from Spain began appearing on 21 May.[33][34] Reports from both places called it 'three-day fever' (fiebre de los tres días).[35][36][37] Associative names  Front page of The Times (London), 25 June 1918: "The Spanish Influenza" Many alternative names are exonyms in the practice of making new infectious diseases seem foreign.[38][39][40] This pattern was observed even before the 1889–1890 pandemic, also known as the 'Russian flu', when the Russians already called epidemic influenza the 'Chinese catarrh', the Germans called it the 'Russian pest', while the Italians in turn called it the 'German disease'.[41][42] These epithets were re-used in the 1918 pandemic, along with new ones.[43] 'Spanish' influenza  Advertisement in The Times, 28 June 1918 for Formamint tablets to prevent "Spanish influenza" Outside Spain, the disease was soon misnamed 'Spanish influenza'.[44][45] In a 2 June 1918 The Times of London dispatch titled, "The Spanish Epidemic," a correspondent in Madrid reported over 100,000 victims of, "The unknown disease…clearly of a gripal character," without referring to "Spanish influenza" directly.[46] Three weeks later The Times reported that, "Everybody thinks of it as the 'Spanish' influenza to-day."[47] Three days after that an advertisement appeared in The Times for Formamint tablets to prevent "Spanish influenza".[48][49] When it reached Moscow, Pravda announced, "Ispánka (the Spanish lady) is in town," making 'the Spanish lady' another common name.[50] The outbreak did not originate in Spain (see below),[51] but reporting did, due to wartime censorship in belligerent nations. Spain was a neutral country unconcerned with appearances of combat readiness, and without a wartime propaganda machine to prop up morale;[52][53] so its newspapers freely reported epidemic effects, including King Alfonso XIII's illness, making Spain the apparent locus of the epidemic.[54] The censorship was so effective that Spain's health officials were unaware its neighboring countries were similarly affected.[55] In an October 1918 "Madrid Letter" to the Journal of the American Medical Association, a Spanish official protested, "we were surprised to learn that the disease was making ravages in other countries, and that people there were calling it the 'Spanish grip'. And wherefore Spanish? …this epidemic was not born in Spain, and this should be recorded as a historic vindication."[56] But before this letter could be published, The Serbian Newspaper (Corfu) said, "Various countries have been assigning the origin of this imposing guest to each other for quite some time, and at one point in time they agreed to assign its origin to the kind and neutral Spain…"[57]  "Spanish influenza," "three-day fever," "the flu." by Rupert Blue, U.S. Surgeon General, 28 September 1918 Other exonyms French press initially used 'American flu', but adopted 'Spanish flu' in lieu of antagonizing an ally.[58] In the spring of 1918, British soldiers called it 'Flanders flu', while German soldiers used 'Flandern-Fieber' (Flemish fever), both after a famous battlefield in Belgium where many soldiers on both sides fell ill.[43][40][59][60] In Senegal it was named 'Brazilian flu', and in Brazil, 'German flu'.[61] In Spain it was also known as the 'French flu' (gripe francesa),[51][9] or the 'Naples Soldier' (Soldado de Nápoles), after a popular song from a zarzuela.[b][58] Spanish flu (gripe española) is now a common name in Spain,[63] but remains controversial there.[64][65] Other names derived from geopolitical borders and social boundaries. In Poland it was the 'Bolshevik disease',[61][66] while the Bolsheviks referred to it as the 'Kirghiz disease'.[60] Some Africans called it a 'white man's sickness', but in South Africa, white men also used the ethnophaulism 'kaffersiekte' (lit. negro disease).[43][67] Japan blamed sumo wrestlers for bringing the disease home from a match in Taiwan by calling it 'sumo flu' (Sumo Kaze), even though three top wrestlers died there.[68][69] World Health Organization 'best practices' first published in 2015 now aim to prevent social stigma by no longer associating culturally significant names with new diseases, listing "Spanish flu" under "examples to be avoided".[70][39][71] Many authors now eschew calling this the Spanish flu,[58] instead using variations of '1918–19/20 flu/influenza pandemic'.[72][73][74] Local names Some language endonyms did not name specific regions or groups of people. Examples specific to this pandemic include: Northern Ndebele: 'Malibuzwe' (let enquiries be made concerning it), Swahili: 'Ugonjo huo kichwa na kukohoa na kiuno' (the disease of head and coughing and spine),[75] Yao: 'chipindupindu' (disease from seeking to make a profit in wartime), Otjiherero: 'kaapitohanga' (disease which passes through like a bullet),[76] and Persian: 'nakhushi-yi bad' (disease of the wind).[77][78] Other names This outbreak was also commonly known as the 'great influenza epidemic',[79][80] after the 'great war', a common name for World War I before World War II.[81] French military doctors originally called it 'disease 11' (maladie onze).[40] German doctors downplayed the severity by calling it 'pseudo influenza' (Latin: pseudo, false), while in Africa, doctors tried to get patients to take it more seriously by calling it 'influenza vera' (Latin: vera, true).[82] A children's song from the 1889–90 flu pandemic[83] was shortened and adapted into a skipping-rope rhyme popular in 1918.[84][85] It is a metaphor for the transmissibility of 'Influenza', where that name was clipped to the apheresis 'Enza':[86][87][88] I had a little bird, its name was Enza. I opened the window, and in-flu-enza. |

語源 1918年5月28日付『エル・ソル』(マドリード)紙:「3日熱 - マドリードで8万人が感染 - 王陛下もご病気」 このパンデミックは、場所や時代、文脈によって、古いものから新しいものまで、さまざまな名称で呼ばれた。 代替名称の語源は、この惨事と、目に見えないウイルスがインフルエンザを引き起こしていることを何年も後に知ることになる人々への影響を歴史的に物語って いる。[18] 科学的な回答が得られないことから、シエラレオネ・ウィークリーニュース(フリータウン)は1918年7月、古代ヘブライ語の『出エジプト記』第16章か らの疑問文を用いて、聖書的な枠組みを提案した 「確かなことはただ一つ、医師たちは今、当惑しているということだ。そして、この病気をインフルエンザと呼ぶよりも、彼らがこの病気を手に負えるようにな るまでは、マンフ(Man hu)『これは何だ?』と呼ぶべきだと我々は提案する」[20][21][22] 記述的な名称 1916年から1917年にかけて、フランス、エタプルのイギリス軍病院[23]、および英仏海峡を隔てたイングランドのアルダショットで、インフルエン ザ様疾患の発生が記録されている。1918年のパンデミックと共通する臨床症状には、急速な症状進行により、顔面が「青みがかった」ヘリオトロープチア ノーゼになることが含まれていた。この特徴的な青紫色のチアノーゼは、死亡する患者にみられ、「紫の死」という名称につながった。[24][25] [26] アルダーショットの医師らは後に『ランセット』誌に「1916年と1917年に我々や他の者たちが記述したインフルエンザ連鎖球菌性化膿性気管支炎は、基 本的に今回のパンデミックのインフルエンザと同じ状態である」と記している。[27] この「化膿性気管支炎」は、まだ同じA/H1N1ウイルスと関連付けられてはいないが、[28] 前兆である可能性はある。[27][29][30] 1918年、当時「流行性感冒」(イタリア語:インフルエンザ、影響)[31]、「流行性感冒」(フランス語:ラ・グリップ、把握)[32]として知られ ていた「流行性感冒」が、 。春の終わり頃にアメリカ合衆国のカンザス州で発生し、5月21日にはスペインからの初期の報告が現れ始めた。[33][34] 両地域からの報告では「3日熱(fiebre de los tres días)」と呼ばれていた。[35][36][37] 関連名称  1918年6月25日付のロンドン・タイムズ紙の第一面:「スペイン風邪」 多くの代替名称は、新しい感染症を外国由来のもののように見せるための外来語である。[38][39][40] このパターンは、1889年から1890年にかけてのパンデミック(「ロシア風邪」とも呼ばれる)以前にも見られた。当時、ロシアではすでに流行性インフ ルエンザを 「中国カタル」と呼び、ドイツ人は「ロシアの疫病」と呼び、イタリア人は「ドイツの病気」と呼んだ。[41][42] これらの異名は、1918年のパンデミックでも、新しい異名とともに再び使用された。[43] 「スペイン風」インフルエンザ  1918年6月28日付のタイムズ紙の広告。「スペイン風」インフルエンザを予防するFormamint錠剤 スペイン国外では、この病気はすぐに「スペイン風邪」と誤って呼ばれるようになった。[44][45] 1918年6月2日付のロンドン・タイムズ紙の「スペインの疫病」と題された記事では、マドリード特派員が「原因不明の病気…明らかに風邪のような症状」 により10万人以上の犠牲者が出ていると報告したが、「スペイン風邪」という言葉は直接には用いられていない。[46] 3週間後、 タイムズ紙は「今日では誰もがそれを『スペイン風』インフルエンザと呼んでいる」と報じた。[47] その3日後には、タイムズ紙に「スペイン風」インフルエンザを予防するFormamint錠の広告が掲載された。[48][49] モスクワに到達した際には、プラウダが「イスパンカ(スペインの女性)が街にいる」と報じ、「スペインの女性」という呼び名も一般的になった。[50] この流行はスペインで発生したものではなかったが(下記参照)[51]、交戦国における戦時中の検閲により、報道は行われた。スペインは中立国であり、戦 闘準備態勢の体裁には関心がなく、戦時下における国民の士気を高揚させるためのプロパガンダの仕組みもなかったため[52][53]、スペインの新聞は流 行病の影響を自由に報道し、アルフォンソ13世の病気も報道したため、スペインが流行病の中心地であるかのように見えた[54]。検閲は非常に効果的であ り、スペインの保健当局は近隣諸国でも同様に流行病が流行していることを知らなかった[55]。 1918年10月、スペインの当局者は、米国医師会誌に寄せた「マドリード便り」の中で、「この病気が他の国々で猛威を振るい、人々がそれを『スペイン風 邪』と呼んでいることを知って驚いた。なぜスペイン風邪なのか?この流行はスペインで発生したものではない。これは歴史的な正当性として記録されるべきで ある」[56] しかし、この手紙が発表される前に、セルビア新聞(コルフ)は次のように伝えている。「この堂々たる来訪者の発生源については、さまざまな国が互いに主張 し合ってきたが、ある時点で、その発生源を親切で中立的なスペインに帰するということで合意した」[57]  「スペイン風邪」、「3日熱」、「インフルエンザ」 1918年9月28日、米国公衆衛生局長官ルパート・ブルー その他の呼称 当初、フランスは「アメリカ風邪」と呼んでいたが、同盟国を刺激しないよう「スペイン風邪」という呼称を採用した。[58] 1918年の春、イギリス兵はこれを「フランダース風邪」と呼び、ドイツ兵は「フランダース熱」(フランドル熱)と呼んだ。これは、両軍の多くの兵士が倒 れたベルギーの有名な戦場にちなんで名付けられたものである。[43][40][59][60] セネガルでは「ブラジル風邪」と呼ばれ 、ブラジルでは「ドイツ風邪」と呼ばれた。[61] スペインでは「フランス風邪」(gripe francesa)[51][9]、またはスペインのサルスエラの人気曲にちなんで「ナポリの兵士」(Soldado de Nápoles)とも呼ばれた。[b][58] スペイン風邪(gripe española)は現在ではスペインでの一般的な名称であるが[63]、スペインでは依然として論争の的となっている。[64][65] 他の名称は、地政学上の境界や社会的な境界から派生した。ポーランドでは「ボルシェビキ病」と呼ばれたが[61][66]、一方、ボルシェビキは「キルギ ス病」と呼んでいた[60]。一部のアフリカ人は「白人の病気」と呼んだが、南アフリカでは白人も民族主義的な用語である 「kaffersiekte」(文字通りには「黒人病」)と呼んでいた。[43][67] 日本では、台湾での試合から持ち帰った病気を「相撲風邪」(Sumo Kaze)と呼び、力士たちを非難した。 2015年に初めて発表された世界保健機関の「ベストプラクティス」は、現在では、文化的に重要な名称を新たな疾患と関連付けることをやめることで社会的 スティグマを防止することを目的としており、「スペイン風邪」を「避けるべき例」として挙げている。[70][3 9][71] 現在では、これをスペイン風邪と呼ぶことを避ける著者が多くなっており、代わりに「1918–19/20年のインフルエンザ/インフルエンザ・パンデミッ ク」のバリエーションが使用されている。[72][73][74] 地域名 言語のエンドネームの中には、特定の地域や人々を指さないものもある。今回のパンデミックに特有の例としては、北ンデベレ語:「Malibuzwe」(問 い合わせをさせてください)、スワヒリ語:「Ugonjo huo kichwa na kukohoa na kiuno」(頭と咳と背骨の病気)[75]、ヤオ語:「chipindupindu (戦時中に利益を得ようとして起こる病気)、オジ・ヘレロ語:『kaapitohanga』(弾丸のように伝播する病気)[76]、ペルシア語: 『nakhushi-yi bad』(風の病気)[77][78]などである。 その他の名称 この流行は、第一次世界大戦を指す「大戦」という通称にちなんで、「大インフルエンザ流行」とも呼ばれた。[79][80] フランス軍の軍医たちは当初、この病気を「11番目の病気」(maladie onze)と呼んでいた。 [40] ドイツの医師たちは「疑似インフルエンザ」(ラテン語:疑似、偽)と呼んでその深刻さを軽視したが、一方でアフリカでは医師たちが「真性インフルエンザ」 (ラテン語:真性、真)と呼んで患者にそれをより深刻に受け止めるよう促していた。[82] 1889年から1890年にかけてのインフルエンザ大流行の際に歌われた子供向けの歌[83]が短縮され、1918年に縄跳びの唄として人気を博した [84][85]。これは「インフルエンザ」の感染力を比喩的に表現したもので、この名称は「エンザ」というアフェレーシスに短縮された[86][87] [88]。 私は小鳥を飼っていた。 その名はエンザ。 窓を開けると、 インフルエンザ。 |

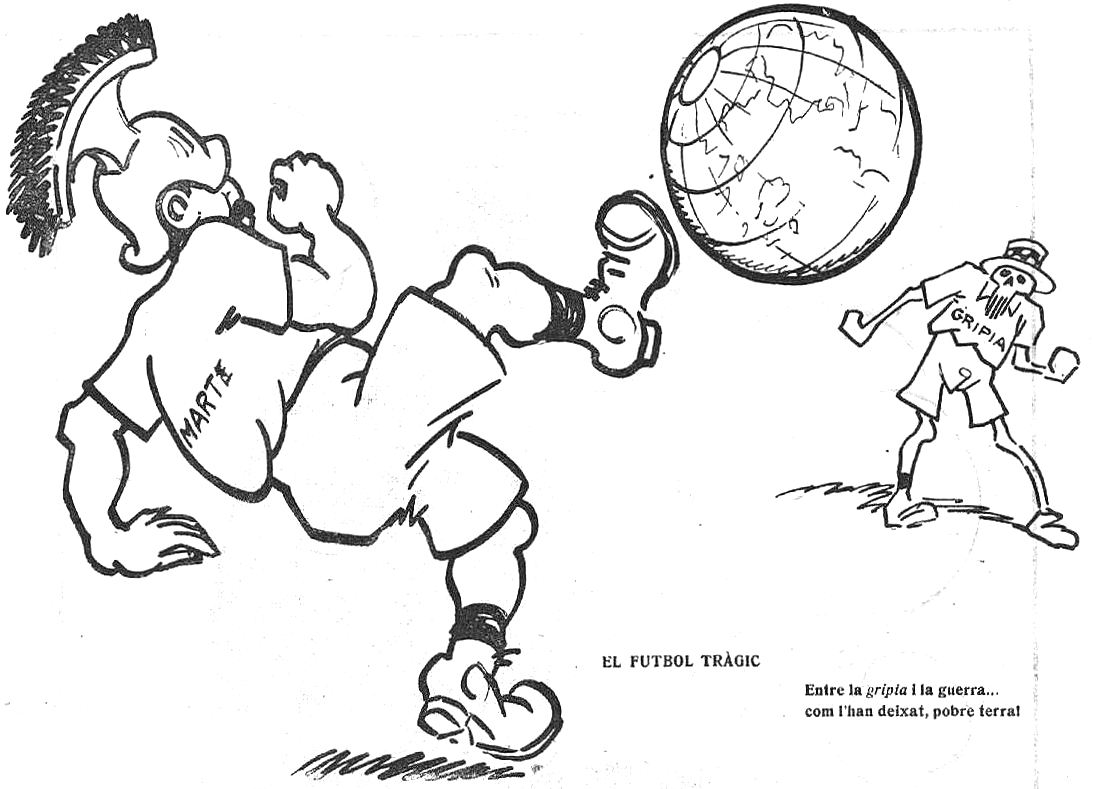

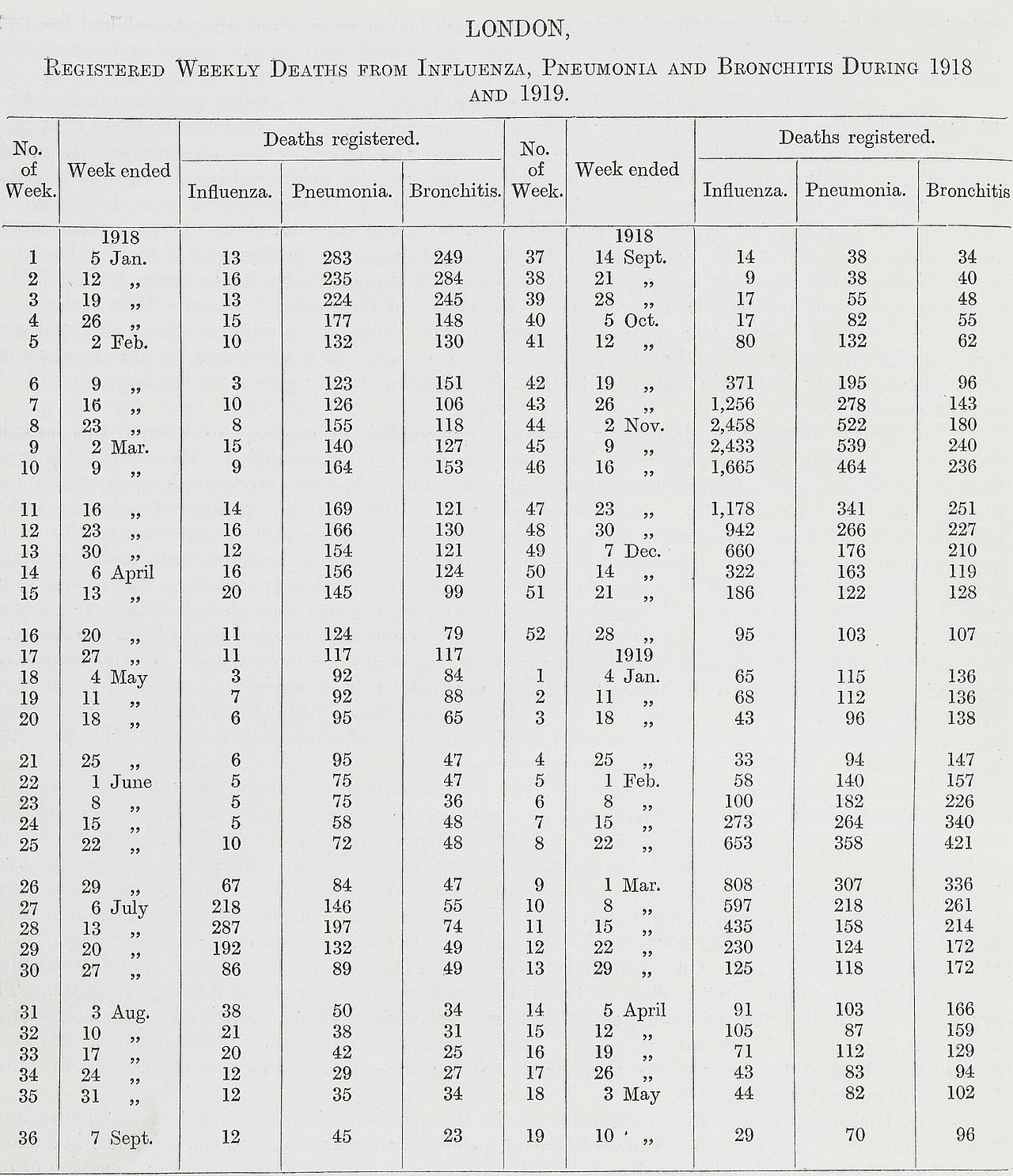

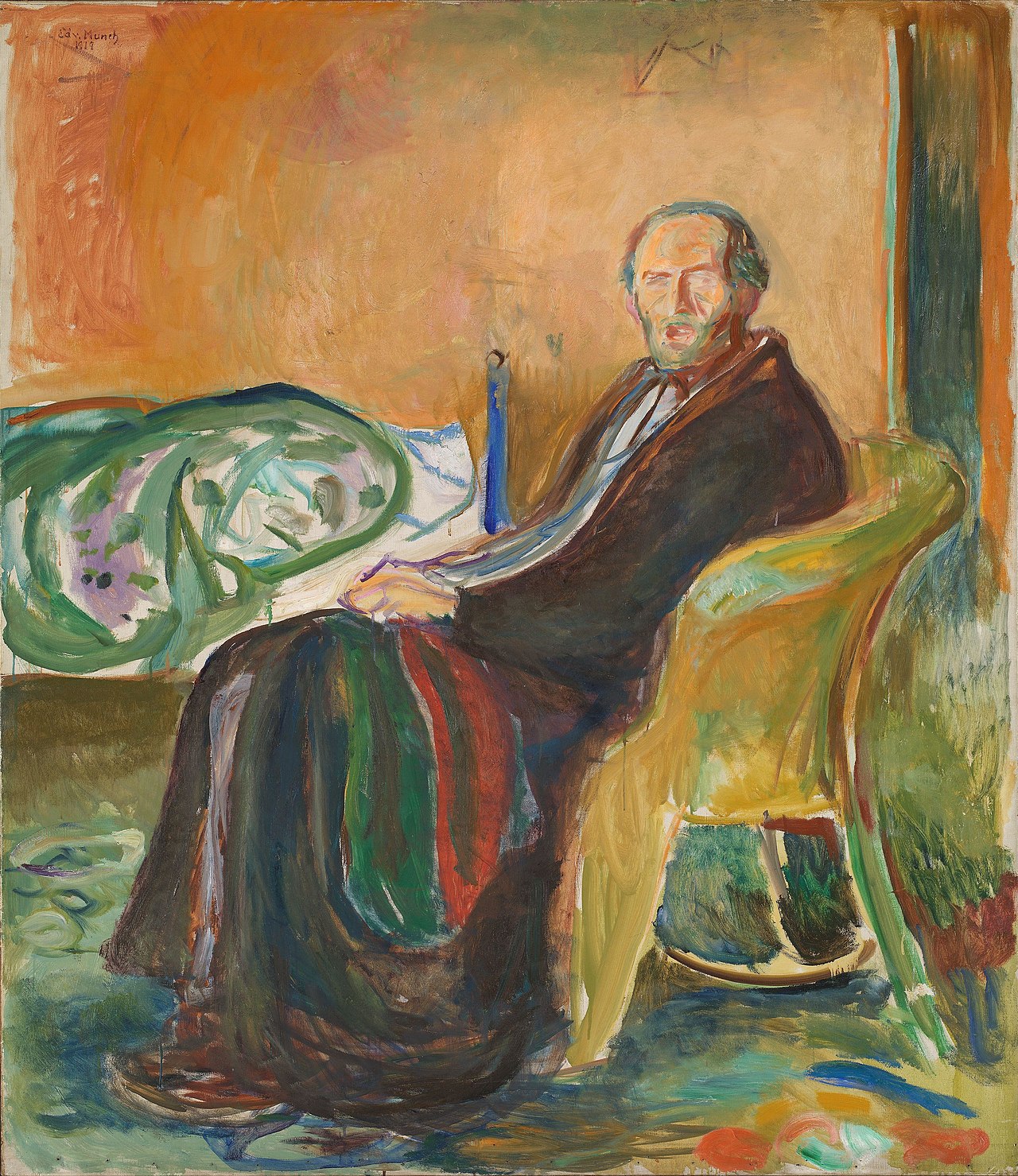

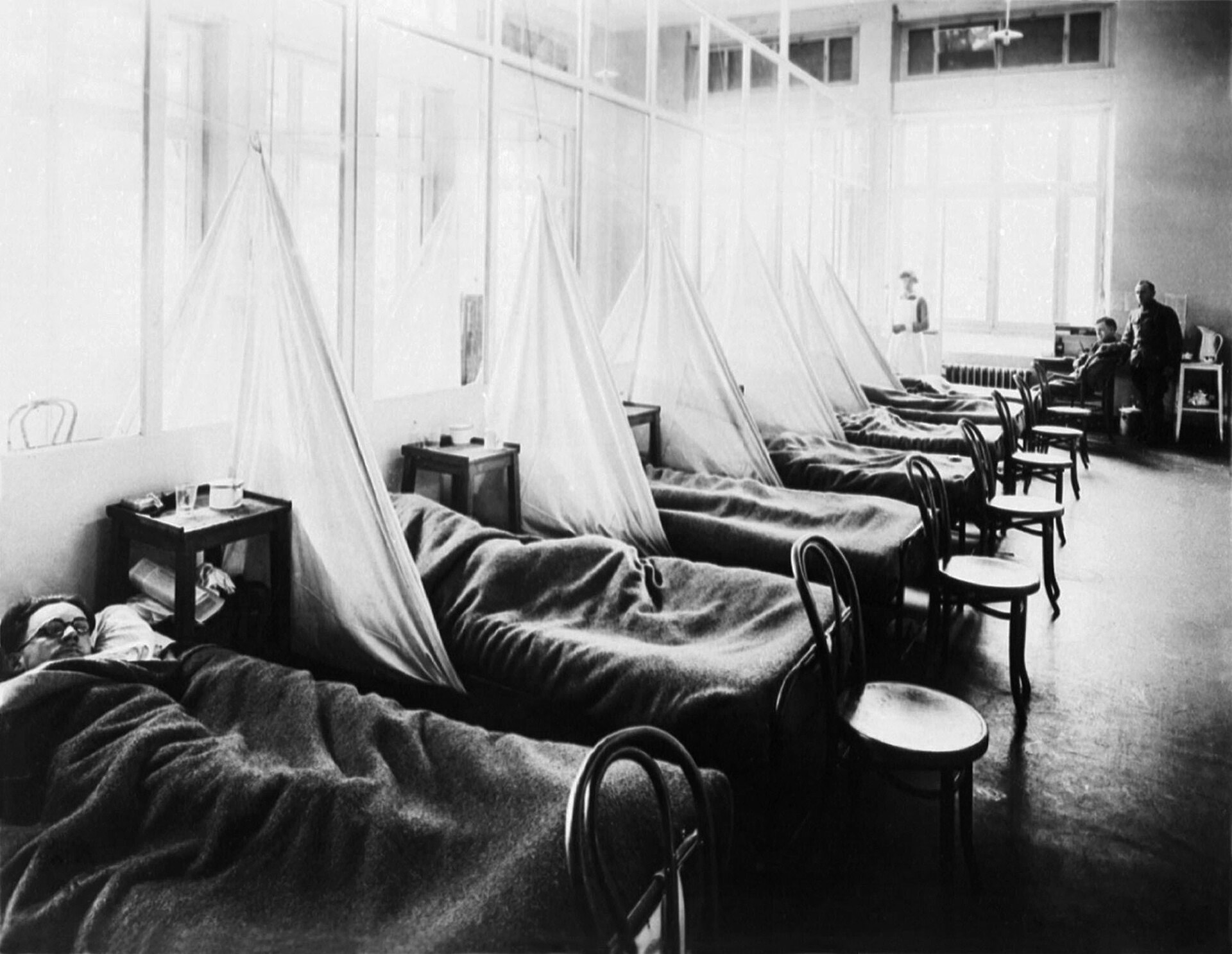

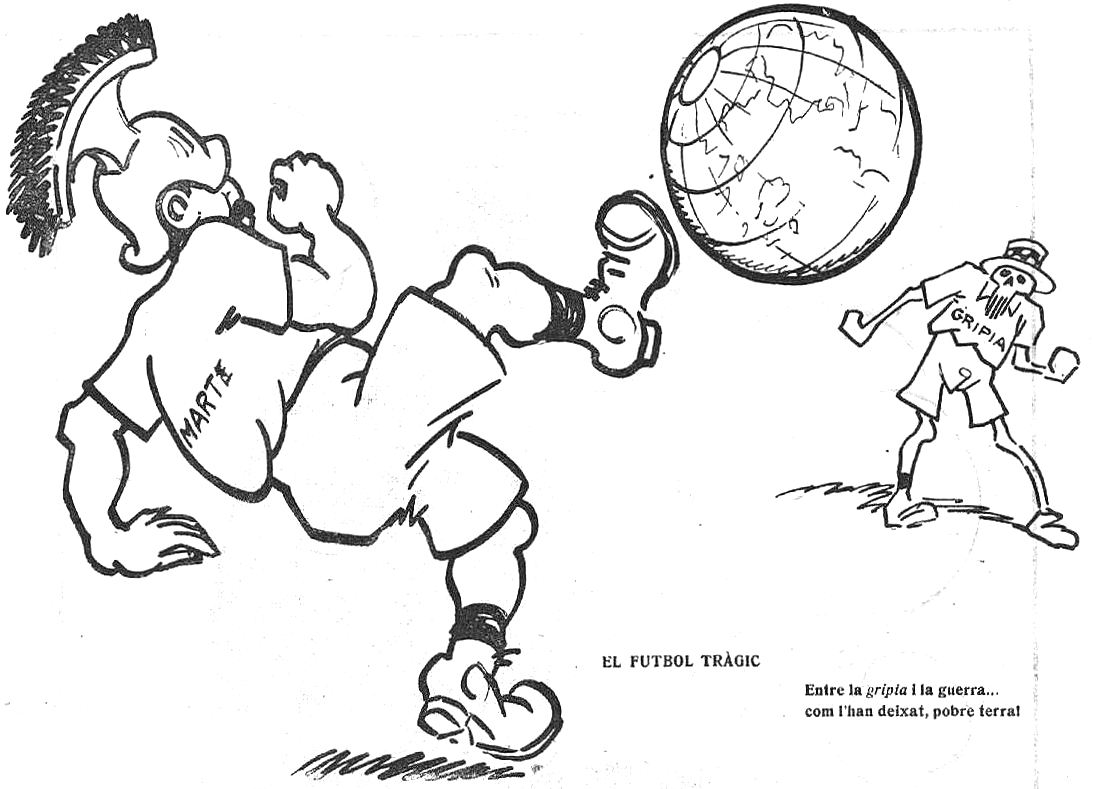

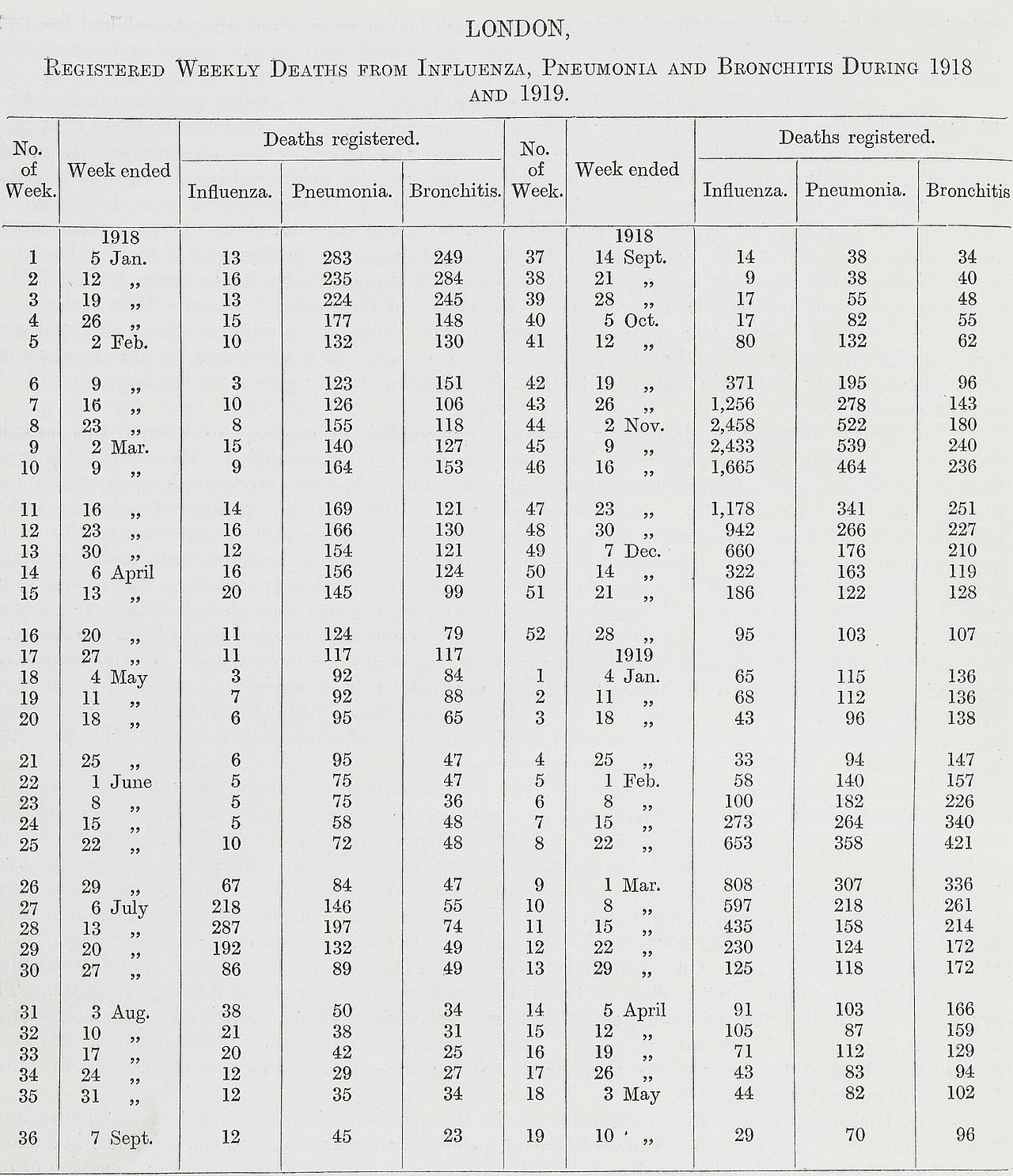

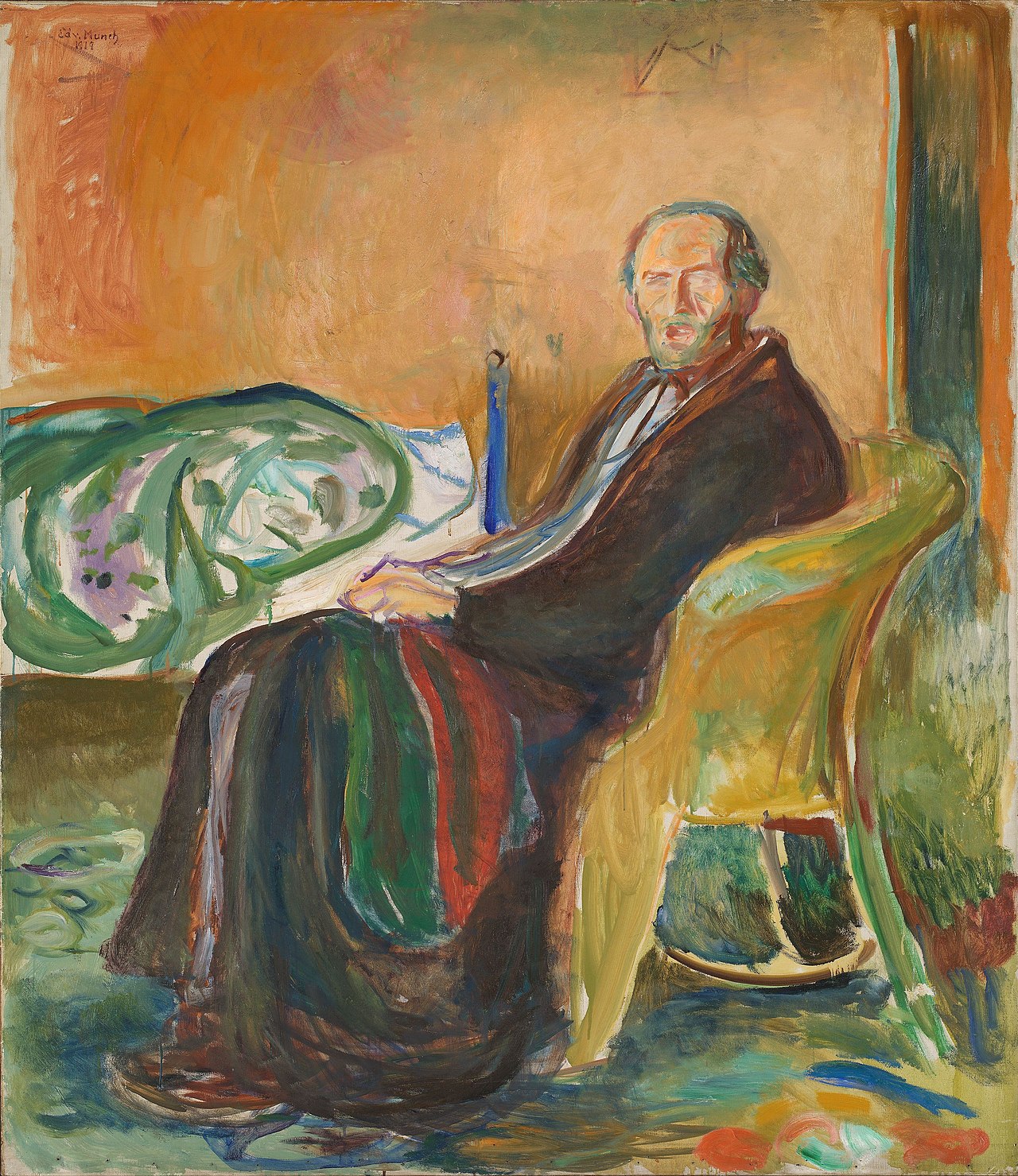

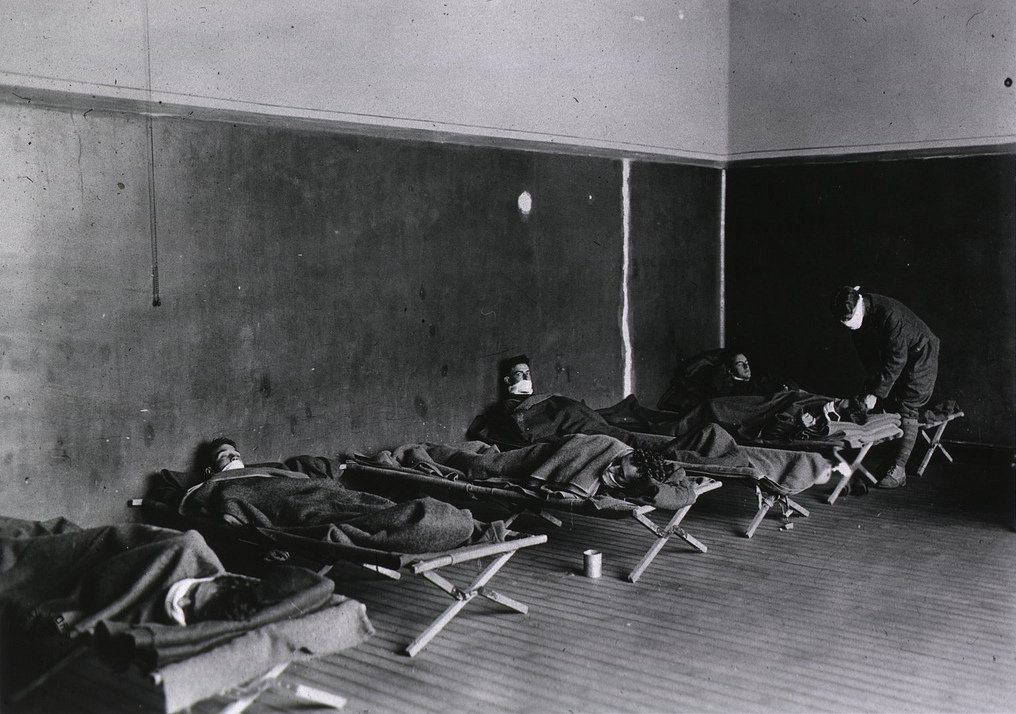

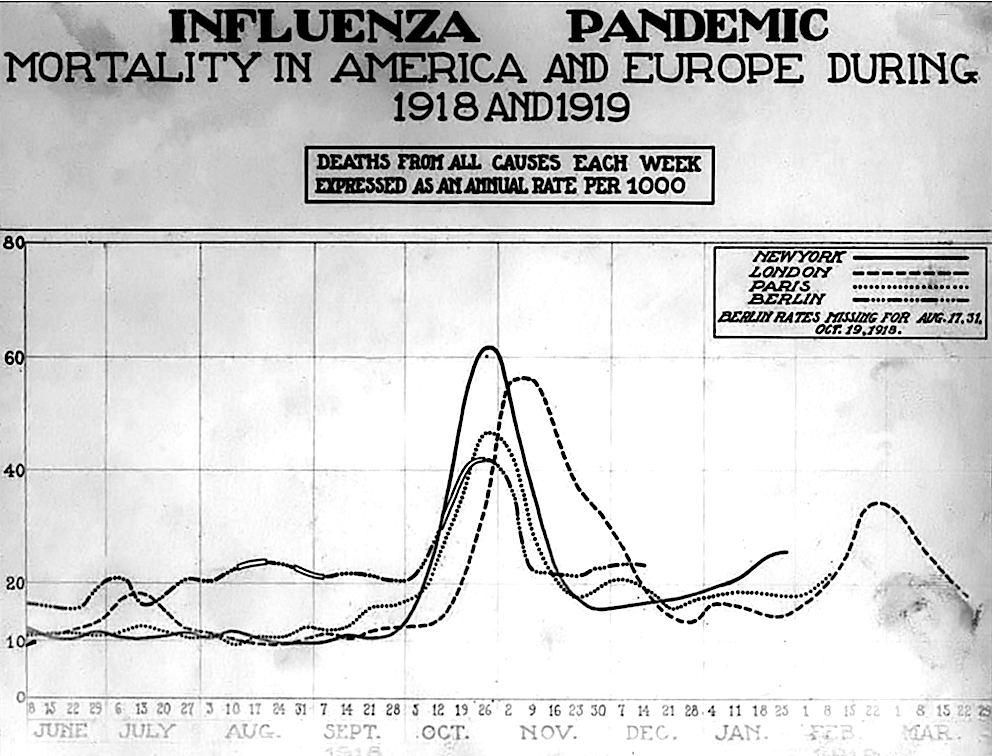

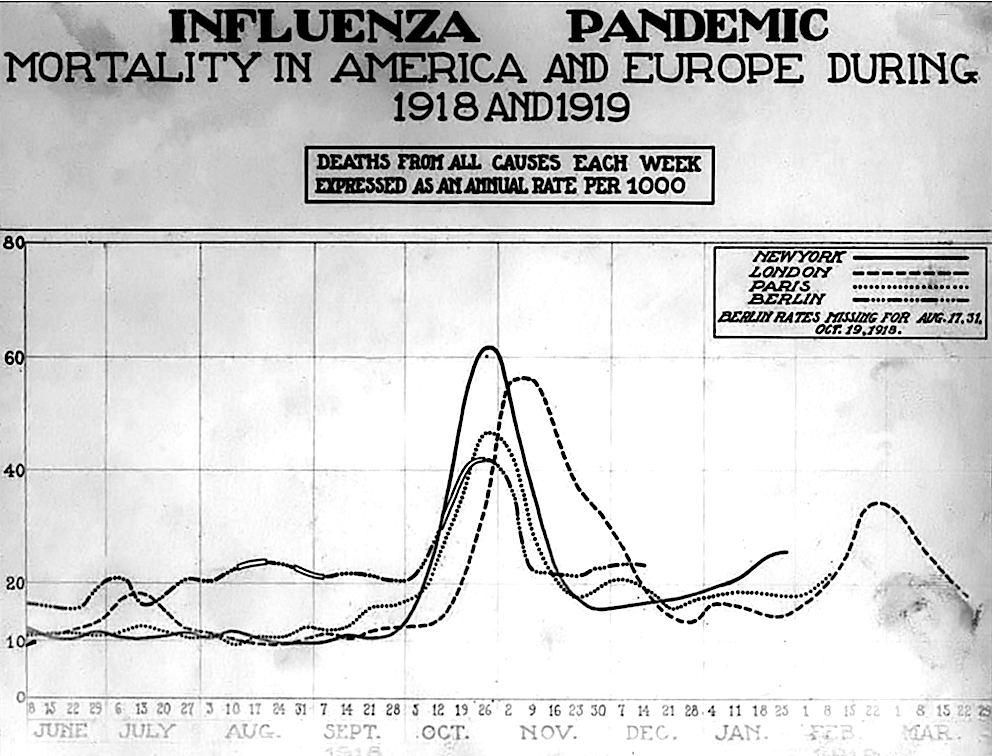

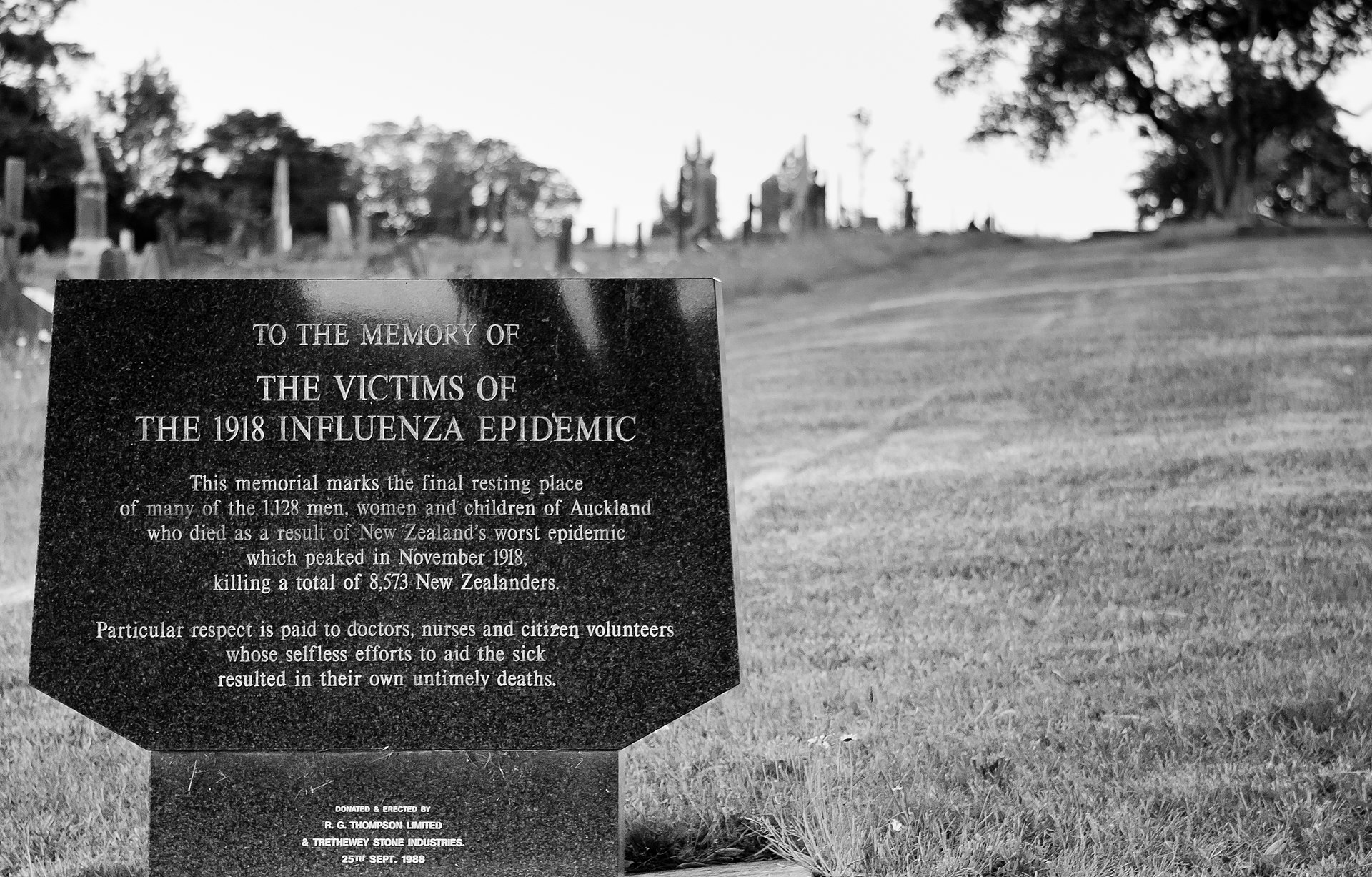

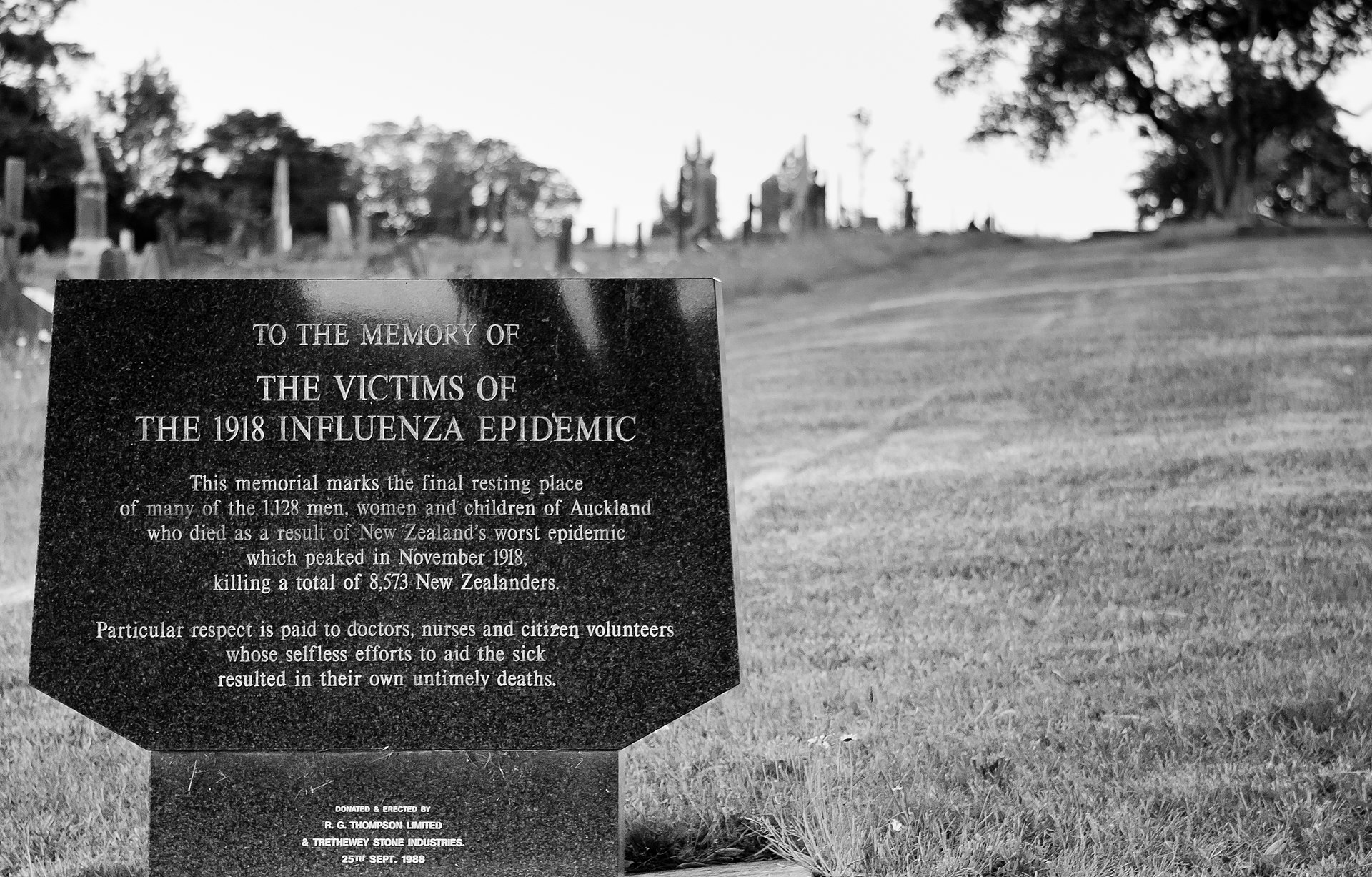

| History Timeline First wave of early 1918  Seattle policemen wearing cloth face masks handed out by the American Red Cross during the Spanish flu pandemic, December 1918 The pandemic is conventionally marked as having begun on 4 March 1918 with the recording of the case of Albert Gitchell, an army cook at Camp Funston in Kansas, United States, despite there having been cases before him.[89] The disease had already been observed 200 miles (320 km) away in Haskell County as early as January 1918, prompting local doctor Loring Miner to warn the editors of the U.S. Public Health Service's academic journal Public Health Reports.[81] Within days of the 4 March first case at Camp Funston, 522 men at the camp had reported sick.[90] By 11 March 1918, the virus had reached Queens, New York.[91] Failure to take preventive measures in March/April was later criticized.[92] As the U.S. had entered World War I, the disease quickly spread from Camp Funston, a major training ground for troops of the American Expeditionary Forces, to other U.S. Army camps and Europe, becoming an epidemic in the Midwest, East Coast, and French ports by April 1918, and reaching the Western Front by the middle of the month.[89] It then quickly spread to the rest of France, Great Britain, Italy, and Spain and in May reached Wrocław and Odessa.[89] After the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (March 1918), Germany started releasing Russian prisoners of war, who then brought the disease to their country.[93] It reached North Africa, India, and Japan in May, and soon after had likely gone around the world as there had been recorded cases in Southeast Asia in April.[94] In June an outbreak was reported in China.[95] After reaching Australia in July, the wave started to recede.[94] The first wave of the flu lasted from the first quarter of 1918 and was relatively mild.[96] Mortality rates were not appreciably above normal;[2] in the United States ~75,000 flu-related deaths were reported in the first six months of 1918, compared to ~63,000 deaths during the same time period in 1915.[97] In Madrid, Spain, fewer than 1,000 people died from influenza between May and June 1918.[98] There were no reported quarantines during the first quarter of 1918. However, the first wave caused a significant disruption in the military operations of World War I, with three-quarters of French troops, half the British forces, and over 900,000 German soldiers sick.[99] Deadly second wave of late 1918  American Expeditionary Force flu patients at U.S. Army Camp Hospital no. 45 in Aix-les-Bains, France, 1918 Spanish satirical cartoon published in November 1918 depicting a "tragic game of football" between Mars, Greek god of war, and the Spanish Flu. There is a short poem as a caption which roughly translates to English as "Between flu and war, look at how they've left her, our poor Earth"  Mars, god of war, plays a "tragic game of football" with a skeleton personification of the Spanish flu, November 1918 The second wave began in the second half of August 1918, probably spreading to Boston, Massachusetts and Freetown, Sierra Leone, by ships from Brest, where it had likely arrived with American troops or French recruits for naval training.[99] From the Boston Navy Yard and Camp Devens (later renamed Fort Devens), about 30 miles west of Boston, other U.S. military sites were soon afflicted, as were troops being transported to Europe.[100] Helped by troop movements, it spread over the next two months to all of North America, and then to Central and South America, also reaching Brazil and the Caribbean on ships.[101] In July 1918, the Ottoman Empire saw its first cases in some soldiers.[102] From Freetown, the pandemic continued to spread through West Africa along the coast, rivers, and the colonial railways, and from railheads to more remote communities, while South Africa received it in September on ships bringing back members of the South African Native Labour Corps returning from France.[101] From there it spread around southern Africa and beyond the Zambezi, reaching Ethiopia in November.[103] On 15 September, New York City saw its first fatality from influenza.[104] The Philadelphia Liberty Loans Parade, held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on 28 September 1918 to promote government bonds for World War I, resulted in 12,000 deaths after a major outbreak of the illness spread among people who had attended the parade.[105] From Europe, the second wave swept through Russia in a southwest–northeast diagonal front, as well as being brought to Arkhangelsk by the North Russia intervention, and then spread throughout Asia following the Russian Civil War and the Trans-Siberian railway, reaching Iran (where it spread through the holy city of Mashhad), and then later India in September, as well as China and Japan in October.[106] The celebrations of the Armistice of 11 November 1918 also caused outbreaks in Lima and Nairobi, but by December the wave was mostly over.[107] The second wave of the 1918 pandemic was much more deadly than the first. The first wave had resembled typical flu epidemics; those most at risk were the sick and elderly, while younger, healthier people recovered easily. October 1918 was the month with the highest fatality rate of the whole pandemic.[108] In the United States, ~292,000 deaths were reported between September–December 1918, compared to ~26,000 during the same time period in 1915.[97] The Netherlands reported over 40,000 deaths from influenza and acute respiratory disease. Bombay reported ~15,000 deaths in a population of 1.1 million.[109] The 1918 flu pandemic in India was especially deadly, with an estimated 12.5–20 million deaths in the last quarter of 1918 alone.[96][page needed] Third wave of 1919  London weekly deaths from influenza during 1918 and 1919 Pandemic activity persisted, in general, into 1919 in many places. This persistence in activity is possibly attributable to climate, specifically in the Northern Hemisphere, where it was winter and thus the usual time for influenza activity.[110][111] The pandemic nonetheless continued into 1919 largely independent of region and climate.[110] Cases began to rise again in some parts of the United States as early as late November 1918,[112] with the Public Health Service issuing its first report of a "recrudescence of the disease" being felt in "widely scattered localities" in early December.[113] This resurgent activity varied across the country, however, possibly on account of differing restrictions.[111] Michigan, for example, experienced a swift resurgence of influenza that reached its peak in December, possibly as a result of the lifting of the ban on public gatherings.[114] Pandemic interventions, such as bans on public gatherings and the closing of schools, were reimposed in many places in an attempt to suppress the spread.[113] There was "a very sudden and very marked rise in general death rate" in most cities in January 1919; nearly all experienced "some degree of recrudescence" of the flu in January and February.[115]: 153–154 Significant outbreaks occurred in cities including Los Angeles,[116] New York City,[1] Memphis, Nashville, San Francisco, and St. Louis.[117] By 21 February, with some local variation, influenza activity was reported to have been declining since mid-January in all parts of the country.[118] Following this "first great epidemic period" that had commenced in October 1918, deaths from pneumonia and influenza were "somewhat below average" in the large cities of the United States between May 1919 and January 1920.[115]: 158 Nonetheless, nearly 160,000 deaths were attributed to these causes in the first six months of 1919.[119] It was not until later in the winter and into the spring that a clearer resurgence appeared in Europe. A significant third wave had developed in England and Wales by mid-February, peaking in early March, though it did not fully subside until May.[120] France also experienced a significant wave that peaked in February, alongside the Netherlands. Norway, Finland, and Switzerland saw recrudescences of pandemic activity in March, and Sweden in April.[121] Much of Spain was affected by "a substantial recrudescent wave" of influenza between January and April 1919.[122] Portugal experienced a resurgence in pandemic activity that lasted from March to September 1919, with the greatest impact being felt on the west coast and in the north of the country; all districts were affected between April and May specifically.[123] Influenza entered Australia for the first time in January 1919 after a strict maritime quarantine had shielded the country through the latter part of 1918.[124] It assumed epidemic proportions first in Melbourne, peaking in mid-February.[125] The flu soon appeared in neighboring New South Wales and South Australia and then spread across the country throughout the year.[124] New South Wales experienced its first wave of infection between mid-March and late May,[126] while a second, more severe wave occurred in Victoria between April and June.[125] Land quarantine measures hindered the spread of the disease, resulting in varied experiences of exposures and outbreaks among the various states. Queensland was not infected until late April; Western Australia avoided the disease until early June, and Tasmania remained free from it until mid-August.[124] Out of the six states, Victoria and New South Wales experienced generally more extensive epidemics. Each experienced another significant wave of illness over the winter. The second epidemic in New South Wales was more severe than the first,[126] while Victoria saw a third wave that was somewhat less extensive than its second, more akin to its first.[125] The disease also reached other parts of the world for the first time in 1919, such as Madagascar, which saw its first cases in April; the outbreak had spread to practically all sections of the island by June.[127] In other parts, influenza recurred in the form of a true "third wave". Hong Kong experienced another outbreak in June,[128] as did South Africa during its fall and winter months in the Southern Hemisphere.[129][130][131] New Zealand also experienced some cases in May.[132] Parts of South America experienced a resurgence of pandemic activity throughout 1919. A third wave hit Brazil between January and June.[110] Between July 1919 and February 1920, Chile, which had been affected for the first time just in October 1918, experienced a severe second wave, with mortality peaking in August 1919.[133] Montevideo similarly experienced a second outbreak between July and September.[134] The third wave particularly affected Spain, Serbia, Mexico and Great Britain, resulting in hundreds of thousands of deaths.[135] It was in general less severe than the second wave but still much more deadly than the initial first wave. Fourth wave of 1920  Public health recommendations from the Illustrated Current News In the Northern Hemisphere, fears of a "recurrence" of the flu grew as fall approached. Experts cited the history of past flu epidemics, such as that of 1889–1890, to predict that such a recurrence a year later was not unlikely,[136][137] though not all agreed.[138] In September 1919, U.S. Surgeon General Rupert Blue said a return of the flu later in the year would "probably, but by no means certainly," occur.[139] France had readied a public information campaign before the end of the summer,[140] and Britain began preparations in the autumn with the manufacture of vaccine.[141] In Japan, the flu broke out again in December and spread rapidly throughout the country, a fact attributed at the time to the coming of cold weather.[142][143] Pandemic-related measures were renewed to check the spread of the outbreak, and health authorities recommended the use of masks.[143] The epidemic intensified in the latter part of December before swiftly peaking in January.[144] Between October 1919 and 23 January 1920, 780,000 cases were reported across the country, with at least 20,000 deaths recorded by that date. This apparently reflected "a condition of severity three times greater than for the corresponding period of" 1918–1919, during Japan's first epidemic.[144] Nonetheless, the disease was regarded as being milder than it had been the year before, albeit more infectious.[145] Despite its rapid peak at the beginning of the year, the outbreak persisted throughout the winter, before subsiding in the spring.[146] In the United States, there were "almost continuously isolated or solitary cases" of flu throughout the spring and summer months of 1919.[147] An increase in scattered cases became apparent as early as September,[148] but Chicago experienced one of the first major outbreaks of the flu beginning in the middle of January.[149] The Public Health Service announced it would take steps to "localize the epidemic",[150] but the disease was already causing a simultaneous outbreak in Kansas City and quickly spread outward from the center of the country in no clear direction.[147] A few days after its first announcement, PHS issued another assuring that the disease was under the control of state health authorities and that an outbreak of epidemic proportions was not expected.[151] It became apparent within days of the start of Chicago's explosive growth in cases that the flu was spreading in the city at an even faster rate than in winter 1919, though fewer were dying.[152] Within a week, new cases in the city had surpassed its peak during the 1919 wave.[153] Around the same time, New York City began to see its own sudden increase in cases,[154] and other cities around the country were soon to follow.[155] Certain pandemic restrictions, such as the closing of schools and theaters and the staggering of business hours to avoid congestion, were reimposed in cities like Chicago,[156] Memphis,[157] and New York City.[158] As they had during the epidemic in fall 1918, schools in New York City remained open,[158] while those in Memphis were shuttered as part of more general restrictions on public gatherings.[157]  American Red Cross nurses tend to flu patients in temporary wards set up inside the Oakland Municipal Auditorium The fourth wave in the United States subsided as swiftly as it had appeared, reaching a peak in early February.[159] "An epidemic of considerable proportions marked the early months of 1920", the U.S. Mortality Statistics would later note; according to data at this time, the epidemic resulted in one third as many deaths as the 1918–1919 experience.[160] New York City alone reported 6,374 deaths between December 1919 and April 1920, almost twice the number of the first wave in spring 1918.[1] Other U.S. cities including Detroit, Milwaukee, Kansas City, Minneapolis, and St. Louis were hit particularly hard, with death rates higher than all of 1918.[117] The Territory of Hawaii experienced its peak of the pandemic in early 1920, recording 1,489 deaths from flu-related causes, compared with 615 in 1918 and 796 in 1919.[161] Poland experienced a devastating outbreak during the winter months, with its capital Warsaw reaching a peak of 158 deaths in a single week, compared to the peak of 92 reached in December 1918; however, the 1920 epidemic passed in a matter of weeks, while the 1918–1919 wave had developed over the entire second half of 1918.[162] By contrast, the outbreak in western Europe was considered "benign", with the age distribution of deaths beginning to take on that of seasonal flu.[163] Five countries in Europe (Spain, Denmark, Finland, Germany and Switzerland) recorded a late peak between January–April 1920.[121] Mexico experienced a fourth wave between February and March. In South America, Peru experienced "asynchronous recrudescent waves" throughout the year. A severe third wave hit Lima, the capital city, between January and March, resulting in an all-cause excess mortality rate approximately four times greater than that of the 1918–1919 wave. Ica similarly experienced another severe pandemic wave in 1920, between July and October.[164] A fourth wave also occurred in Brazil, in February.[110] Korea and Taiwan, both colonies of Japan at this time, also experienced pronounced outbreaks in late 1919 and early 1920.[165][166] Post-pandemic By mid-1920, the pandemic was largely considered to be "over" by the public as well as governments.[167] Though parts of Chile experienced a third, milder wave between November 1920 and March 1921,[133] the flu seemed to be mostly absent through the winter of 1920–1921.[115]: 167 In the United States, for example, deaths from pneumonia and influenza were "very much lower than for many years".[115]: 167 Seasonal Influenza after the end of the pandemic, began to be reported again from many places in 1921.[115]: 168 Influenza continued to be felt in Chile, where a post pandemic fourth wave affected seven of its 24 provinces between June and December 1921.[133] The winter of 1921–1922 was the first major reappearance of seasonal influenza in the Northern Hemisphere after the pandemic ended, in many parts its most significant occurrence since the main pandemic in late 1918. Northwestern Europe was particularly affected. All-cause mortality in the Netherlands approximately doubled in January 1922 alone.[115]: 168 In Helsinki, a major epidemic (the fifth since 1918) prevailed between November and December 1921.[168] The flu was also widespread in the United States, its prevalence in California reportedly greater in early March 1922 than at any point since the pandemic ended in 1920.[115]: 172 In the years after 1920, the disease, a novel one in 1918, assumed a more familiar nature, coming to represent at least one form of the "seasonal flu". The virus, H1N1, remained endemic, occasionally causing more severe or otherwise notable outbreaks as it gradually evolved over the years.[169] The period since its initial appearance in 1918 has been termed a "pandemic era", in which all flu pandemics since its emergence have been caused by its own descendants.[170] Following the first of these post-1918 pandemics, in 1957, the virus was totally displaced by the novel H2N2, the reassortant product of the human H1N1 and an avian influenza virus, which thereafter became the active influenza A virus in humans.[169] In 1977, an influenza virus bearing a very close resemblance to the seasonal H1N1, which had not been seen since the 1950s, appeared in Russia and subsequently initiated a "technical" pandemic that principally affected those 26 years of age and younger.[171][172] While some natural explanations, such as the virus remaining in some frozen state for 20 years,[172] have been proposed to explain this unprecedented[173] phenomenon, the nature of influenza itself has been cited in favor of human involvement of some kind, such as an accidental leak from a lab where the old virus had been preserved for research purposes.[172] Following this miniature pandemic, the reemerged H1N1 became endemic once again but did not displace the other active influenza A virus, H3N2 (which itself had displaced H2N2 through a pandemic in 1968).[171][169] For the first time, two influenza A viruses were observed in cocirculation.[174] This state of affairs has persisted even after 2009, when a novel H1N1 virus emerged, sparked a pandemic, and thereafter took the place of the seasonal H1N1 to circulate alongside H3N2.[174] Potential origins Despite its name, historical and epidemiological data cannot identify the geographic origin of the Spanish flu.[2] However, several theories have been proposed. United States The first confirmed cases originated in the United States. Historian Alfred W. Crosby stated in 2003 that the flu originated in Kansas,[175] and author John M. Barry described a January 1918 outbreak in Haskell County, Kansas, as the point of origin in his 2004 article.[81] A 2018 study of tissue slides and medical reports led by evolutionary biology professor Michael Worobey found evidence against the disease originating from Kansas, as those cases were milder and had fewer deaths compared to the infections in New York City in the same period. The study did find evidence through phylogenetic analyses that the virus likely had a North American origin, though it was not conclusive. In addition, the haemagglutinin glycoproteins of the virus suggest that it originated long before 1918, and other studies suggest that the reassortment of the H1N1 virus likely occurred in or around 1915.[176] Europe  Edvard Munch (1863–1944), Self-Portrait with the Spanish Flu (1919)  Egon Schiele (1890–1918), Die Familie, painted a few days before his death and just after the death of his wife Edith from the Spanish flu[177] The major U.K. troop staging and hospital camp in Étaples in France has been theorized by virologist John Oxford as being at the center of the Spanish flu.[178] His study found that in late 1916 the Étaples camp was hit by the onset of a new disease with high mortality that caused symptoms similar to the flu.[179][178] According to Oxford, a similar outbreak occurred in March 1917 at army barracks in Aldershot,[180] and military pathologists later recognized these early outbreaks as the same disease as the Spanish flu.[181][178] The overcrowded camp and hospital at Étaples was an ideal environment for the spread of a respiratory virus. The hospital treated thousands of victims of poison gas attacks, and other casualties of war, and 100,000 soldiers passed through the camp every day. It also was home to a piggery and poultry was regularly brought in from surrounding villages to feed the camp. Oxford and his team postulated that a precursor virus, harbored in birds, mutated and then migrated to pigs kept near the front.[180][181] A report published in 2016 in the Journal of the Chinese Medical Association found evidence that the 1918 virus had been circulating in the European armies for months and possibly years before the 1918 pandemic.[182] Political scientist Andrew Price-Smith published data from the Austrian archives suggesting the influenza began in Austria in early 1917.[183] A 2009 study in Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses found that Spanish flu mortality simultaneously peaked within the two-month period of October and November 1918 in all fourteen European countries analyzed, which is inconsistent with the pattern that researchers would expect if the virus had originated somewhere in Europe and then spread outwards.[121] China In 1993, Claude Hannoun, the leading expert on the Spanish flu at the Pasteur Institute, asserted the precursor virus was likely to have come from China and then mutated in the United States near Boston and from there spread to Brest, France, Europe's battlefields, the rest of Europe, and the rest of the world, with Allied soldiers and sailors as the main disseminators.[184] Hannoun considered several alternative hypotheses of origin, such as Spain, Kansas, and Brest, as being possible, but not likely.[184] In 2014, historian Mark Humphries argued that the mobilization of 96,000 Chinese laborers to work behind the British and French lines might have been the source of the pandemic. Humphries, of the Memorial University of Newfoundland in St. John's, based his conclusions on newly unearthed records. He found archival evidence that a respiratory illness that struck northern China (where the laborers came from) in November 1917 was identified a year later by Chinese health officials as identical to the Spanish flu.[185][186] Unfortunately, no tissue samples have survived for modern comparison.[187] Nevertheless, there were some reports of respiratory illness on parts of the path the laborers took to get to Europe, which also passed through North America.[187] China was one of the few regions of the world seemingly less affected by the Spanish flu pandemic, where several studies have documented a comparatively mild flu season in 1918.[188][189][190] (Although this is disputed due to lack of data during the Warlord Period, see Around the globe.) This has led to speculation that the Spanish flu pandemic originated in China,[190][191] as the lower rates of flu mortality may be explained by the Chinese population's previously acquired immunity to the flu virus.[174][190] In the Guangdong Province it was reported that early outbreaks of influenza in 1918 disproportionately impacted young men. The June outbreak infected children and adolescents between 11 and 20 years of age, while the October outbreak was most common in those aged 11 to 15.[192] A report published in 2016 in the Journal of the Chinese Medical Association found no evidence that the 1918 virus was imported to Europe via Chinese and Southeast Asian soldiers and workers and instead found evidence of its circulation in Europe before the pandemic.[182] The 2016 study found that the low flu mortality rate (an estimated one in a thousand) recorded among the Chinese and Southeast Asian workers in Europe suggests that the Asian units were not different from other Allied military units in France at the end of 1918 and, thus, were not a likely source of a new lethal virus.[182] Further evidence against the disease being spread by Chinese workers was that workers entered Europe through other routes that did not result in a detectable spread, making them unlikely to have been the original hosts.[176] |

歴史 年表 1918年初頭の最初の波  スペイン風邪のパンデミック時にアメリカ赤十字社から支給された布製マスクを着用したシアトルの警察官、1918年12月 パンデミックは、それ以前にも患者はいたものの、1918年3月4日にカンザス州のキャンプ・ファンストンの軍用炊事係アルバート・ギッチェルの症例が記 録されたことから始まったとされている。[89] しかし、この病気は1918年1月には早くも200マイル(320キロ)離れたハスケル郡でも確認されており、地元の医師ローリング・マイナーは 米国公衆衛生局の学術誌『Public Health Reports』の編集者に警告を発した。[81] 3月4日にキャンプ・ファンストンで最初の症例が確認されてから数日のうちに、キャンプの522人の兵士が体調不良を訴えた。[90] 1918年3月11日までに、ウイルスはニューヨーク州クイーンズにまで到達した。[91] 3月と4月に予防措置を取らなかったことは、後に批判された。[92] 米国が第一次世界大戦に参戦すると、この病気は、アメリカ遠征軍の主要な訓練場であるキャンプ・ファンストンから、他の米国陸軍のキャンプやヨーロッパへ と急速に広がり、1918年4月までに米国中西部、東海岸、フランスの港で流行となり、 。その後、急速にフランス、イギリス、イタリア、スペインの他の地域にも広がり、5月にはヴロツワフとオデッサに到達した。[89] ブレスト・リトフスク条約(1918年3月)の締結後、ドイツはロシア人捕虜の解放を開始し、解放された捕虜が その病気は自国にも持ち込まれた。[93] 5月には北アフリカ、インド、日本に到達し、4月には東南アジアでの感染例が記録されていることから、その後まもなく世界中に広がった可能性が高い。 [94] 6月には中国での発生が報告された。[95] 7月にオーストラリアに到達した後、流行は収まり始めた。[94] インフルエンザの最初の流行は1918年第1四半期から始まり、比較的軽症であった。死亡率は通常より著しく高いということはなく、米国では1918年の 最初の6か月間で約7万5千人のインフルエンザ関連死が報告されたが、 1915年の同時期には約3,000人の死者が出ていた。[97] スペインのマドリードでは、1918年5月から6月にかけてインフルエンザによる死亡者は1,000人以下であった。[98] 1918年第1四半期には隔離の報告はなかった。しかし、第一次波は第一次世界大戦の軍事作戦に大きな混乱をもたらし、フランス軍の4分の3、イギリス軍 の半数、そして90万人以上のドイツ兵が感染した。 1918年後半の致命的な第二次波  1918年、フランス、エグ・レ・バンの米陸軍第45野戦病院のアメリカ遠征軍のインフルエンザ患者 1918年11月に発表されたスペイン風刺漫画。ギリシャ神話の戦争の神マルスとスペイン風邪による「悲劇的なサッカーの試合」を描いている。キャプショ ンには短い詩が添えられており、英語に訳すと「インフルエンザと戦争の間、地球がどれほどひどい状態になっているか見てみろ」となる  戦争の神マルスがスペイン風邪の骸骨と「悲劇的なサッカーの試合」をしている。1918年11月 1918年8月後半に第2波が始まり、おそらくブレストからボストン、マサチューセッツ州、フリータウン、シエラレオネに、アメリカ軍または海軍訓練のた めのフランス人志願兵とともに到着した船舶によって広がった。[99] ボストン海軍造船所とキャンプ・デベンズ(後にフォート・デベンズと改名)から、ボストンから西に約30マイル離れた他の米軍 軍事施設も被害を受け、ヨーロッパに輸送される部隊も被害を受けた。[100] 軍の移動により、このウイルスは2か月間で北米全土に広がり、その後は中央アメリカと南アメリカにも広がった。ブラジルとカリブ海地域にも船舶を通じて到 達した。[101] 1918年7月、オスマン帝国では兵士の一部に最初の症例が見られた。[102] フリータウンから、西アフリカの沿岸部、河川、植民地鉄道に沿ってパンデミックは拡大し、鉄道の終着駅からさらに離れた地域にも広がった。一方、南アフリ カでは、9月にフランスから帰還した南アフリカ先住民労働部隊の兵士を乗せた船によって、ウイルスが持ち込まれた。[101] そこからウイルスはアフリカ南部に広がり、11月にはザンベジ川を越えてエチオピアに到達した。[103] 9月15日、ニューヨーク市でインフルエンザによる初の死者が出た。[104] 1918年9月28日にペンシルベニア州フィラデルフィアで開催された第一次世界大戦のための公債を促進するためのフィラデルフィア・リバティー・ロー ン・パレードでは、パレードに参加した人々の間でインフルエンザが大流行し、12,000人が死亡した。[105] ヨーロッパから始まった第二波は、ロシアを南西から北東に向かう対角線状に襲い、北ロシア介入によってアルハンゲリスクにも到達した。その後、ロシア内戦 とシベリア横断鉄道に沿ってアジア全域に広がり、イラン(聖地マシュハドに広がった)に到達し、 マシュハドの聖地に広がった)後、9月にはインド、10月には中国と日本にも広がった。[106] 1918年11月11日の休戦協定の祝賀会もリマとナイロビでの発生の原因となったが、12月にはその流行はほぼ終息した。[107] 1918年のパンデミックの第2波は、第1波よりもはるかに致死率が高かった。第1波は典型的なインフルエンザの流行に似ており、最もリスクが高いのは病 人や高齢者で、若く健康な人々は容易に回復した。1918年10月は、パンデミック全体で最も死亡率が高かった月であった。[108] 米国では、1918年9月から12月の間に約29万2000人の死亡が報告されたが、1915年の同じ時期では約2万6000人であった。[97] オランダでは、インフルエンザと急性呼吸器疾患による死亡が4万人を超えたと報告された。ボンベイでは、人口110万人のうち約1万5000人が死亡した と報告されている。[109] インドにおける1918年のインフルエンザのパンデミックは特に致命的であり、1918年の最後の四半期だけで推定1250万~2000万人が死亡した。 [96][要出典] 1919年の第3波  1918年から1919年のロンドンにおけるインフルエンザによる週ごとの死亡者数 パンデミックの活動は、多くの場所で概ね1919年まで続いた。この活動の持続は、おそらく気候、特に北半球の冬の時期で、インフルエンザの活動が活発に なる時期であったことによるものと考えられる。[110][111] しかし、パンデミックは地域や気候とはほとんど関係なく1919年も続いた。[110] 1918年11月下旬には早くも、米国の一部地域で再び患者数が増加し始め[112]、12月初旬には「広範囲にわたる地域」で「病気の再流行」が感じら れるという公衆衛生局による最初の報告書が発表された[113]。しかし、この再流行は国によって異なり、おそらくは 。ミシガン州では、おそらく集会禁止令が解除されたことが原因で、12月にインフルエンザが急速に再流行し、ピークに達した。[114] パンデミック対策として、集会禁止令や学校閉鎖が多くの地域で再び実施され、感染拡大の抑制が試みられた。[113] 1919年1月には、ほとんどの都市で「死亡率が非常に急激かつ顕著に上昇」し、1月と2月にはほぼすべての都市でインフルエンザの「ある程度の再流行」 が見られた。[115]:153–154 ロサンゼルス、[116] ニューヨーク市、[ 1] メンフィス、ナッシュビル、サンフランシスコ、セントルイスでも発生した。[117] 2月21日までに、地域差はあるものの、1月中旬以降、全米各地でインフルエンザの活動が減少していることが報告された。[118] 1918年10月に始まったこの「最初の大きな流行期」の後、 1919年5月から1920年1月までの間、米国の大都市における肺炎およびインフルエンザによる死亡者数は「平均よりやや下回る程度」であった。 [115]:158 それにもかかわらず、1919年の最初の6か月間で、これらの原因による死亡者数は16万人近くに上った。[119] ヨーロッパで明確な回復傾向が見られるようになったのは、冬が終わり春を迎えてからであった。2月中旬にはイングランドとウェールズで第3の大きな波が発 生し、3月初旬にピークに達したが、完全に沈静化するのは5月になってからであった。[120] フランスでもオランダと同様に、2月に大きな波が発生した。ノルウェー、フィンランド、スイスでは3月に、スウェーデンでは4月にパンデミックの再流行が 見られた。[121] スペインの大部分は、1919年1月から4月にかけて「大幅な再流行の波」に襲われた。[122] ポルトガルでは、1919年3月から9月にかけてパンデミックの活動が再燃し、その影響は西海岸と北部で最も大きかった。特に4月から5月にかけては、す べての地域で影響が見られた。[123] 厳格な海上検疫により1918年後半のオーストラリアは守られていたが、1919年1月に初めてインフルエンザがオーストラリアに上陸した。[124] メルボルンで最初に流行し、2月中旬にピークに達した。[125] インフルエンザはすぐに 隣接するニュー・サウス・ウェールズ州と南オーストラリア州にもすぐに広がり、その後、1年を通じて全国に広がった。[124] ニュー・サウス・ウェールズ州では3月中旬から5月下旬にかけて最初の感染の波が起こり、[126] ビクトリア州では4月から6月にかけて2度目の、より深刻な感染の波が起こった。[125] 検疫措置により感染の拡大は妨げられ、州によって感染や流行の状況は様々であった。クイーンズランド州では4月下旬まで感染が確認されず、西オーストラリ ア州では6月初旬まで、タスマニア州では8月中旬まで感染が確認されなかった。6つの州のうち、ビクトリア州とニューサウスウェールズ州では、より広範囲 にわたる流行が確認された。冬には、それぞれにさらに大きな流行の波が到来した。ニューサウスウェールズ州では2度目の流行が1度目よりも深刻であった が、ビクトリア州では3度目の流行は2度目よりも規模が小さく、1度目により似たものとなった。 1919年には、マダガスカルなど、初めて世界中の他の地域にも感染が拡大した。同国では4月に最初の感染者が確認され、6月にはほぼ全土に広がった。 [127] その他の地域では、インフルエンザが「第3波」として再び発生した。香港では6月に新たな流行が発生し[128]、南半球の南アフリカでも秋から冬にかけ て流行した[129][130][131]。ニュージーランドでも5月にいくつかの症例が確認された[132]。 南米の一部地域では、1919年を通してパンデミックの活動が再燃した。第3波は1月から6月にかけてブラジルを襲った。[110] 1919年7月から1920年2月にかけて、1918年10月に初めて感染が確認されたチリでは、1919年8月に死亡率がピークに達する深刻な第2波が 発生した。[133] モンテビデオでも同様に、7月から9月にかけて第2の流行が発生した。[134] 第3波は特にスペイン、セルビア、メキシコ、イギリスに大きな影響を与え、数十万人の死者を出した。[135] 第2波ほど深刻ではなかったが、それでも第1波の最初の感染拡大よりもはるかに多くの死者を出した。 1920年の第4波  イラストレイテッド・カレント・ニュースによる公衆衛生勧告 北半球では、秋が近づくにつれ、インフルエンザの「再流行」への懸念が高まった。専門家は、1889年から1890年にかけての流行など過去のインフルエ ンザの流行の歴史を挙げ、1年後の再流行の可能性は低くないと予測したが、全員が同意したわけではなかった。1919年9月、米国の 米国公衆衛生局長官ルパート・ブルーは、その年の後半にインフルエンザが再流行する可能性は「おそらく、しかし確実に」あると述べた。[139] フランスは夏が終わる前に広報キャンペーンの準備を整え[140]、イギリスは秋にワクチン製造の準備を開始した。[141] 日本では12月に再びインフルエンザが流行し、急速に全国に広がった。この事実は、当時、寒さが到来したことによるものとされた。[142][143] パンデミック関連の対策が再び実施され、流行の拡大を食い止めるため、保健当局はマスクの使用を推奨した。[143] 12月後半に流行が激化し、1月に急速にピークに達した。[144] 1919年10月から1920年1月23日までの間に、全国で780,000件の症例が報告され、少なくとも20,000人の死亡が記録された。これは、 日本における最初の流行の1918年から1919年の同時期と比較して「3倍の深刻な状況」を反映しているように思われた。[144] それでも、この病気は、感染力は強かったものの、前年よりも症状は軽いとみなされていた。[145] 年初めに急速にピークに達したものの、流行は冬の間中続き、春になってようやく沈静化した。[146] 米国では、1919年の春から夏にかけて「ほぼ絶え間なく」インフルエンザの「孤立した、あるいは単独の症例」が報告された。[147] 9月には早くも散発的な症例の増加が明らかになったが、[148] シカゴでは1月半ばからインフルエンザの最初の大きな流行のひとつが発生した。[149] 公衆衛生局は「 「流行を局所化する」ための措置を取ると発表したが[150]、この病気はすでにカンザスシティで同時多発的な発生を引き起こしており、その後は明確な方 向性もなく、米国の中心部から急速に広がっていった。[147] 最初の発表から数日後、PHSは再度、この病気は州の保健当局の管理下にあり、流行規模の発生は予想されないという確約を発表した。[151] シカゴでの感染が爆発的に増加し始めた数日後には、1919年の冬よりもさらに速いペースでインフルエンザが蔓延していることが明らかになったが、死亡者 数は少なかった。[152] 1週間も経たないうちに、シカゴでの新たな感染者数は1919年の流行時のピークを上回った。[ 153] ほぼ同時期に、ニューヨーク市でも急激な感染者数の増加が見られ始め[154]、やがて全米の他の都市でも同様の事態となった[155]。学校や劇場を閉 鎖し、混雑を避けるために営業時間をずらすなど、パンデミック対策として実施されていた一定の制限が、 シカゴ[156]、メンフィス[157]、ニューヨーク市[158]などでは、学校や劇場を閉鎖し、混雑を避けるために営業時間をずらすといったパンデ ミック対策が再び実施された。  オークランド市公会堂内に設置された臨時病棟で、アメリカ赤十字社の看護師がインフルエンザ患者の看護にあたる 米国における第4の流行は、発生から急速に沈静化し、2月初旬にピークに達した。[159] 米国死亡率統計は後に、「1920年の初期には、相当な規模の流行がみられた」と記している。この時期のデータによると、この流行による死亡者数は、 1918年から1919年の流行による死亡者数の3分の1であった 。ニューヨーク市だけで1919年12月から1920年4月までの間に6,374人の死亡が報告され、1918年春の最初の流行のほぼ2倍に上った。 [1] デトロイト、ミルウォーキー、カンザスシティ、ミネアポリス、セントルイスを含む他の米国の都市は特に大きな打撃を受け 死亡率は1918年全体よりも高かった。[117] ハワイ準州では1920年初頭にパンデミックのピークを迎え、インフルエンザ関連死は1,489人に達した。1918年には615人、1919年には 796人が死亡している。[161] ポーランドでは冬の間に壊滅的な流行が発生し、首都ワルシャワでは1918年12月の92人のピークと比較して、1週間で158人の死者が出るピークに達 した。しかし、1920年の流行は数週間で終息したのに対し、1918年から1919年の流行は 1918年の後半全体にわたって広がっていた。[162] これとは対照的に、西ヨーロッパでの流行は「穏やか」で、死亡者の年齢分布は季節性インフルエンザのそれと似ていた。[163] ヨーロッパの5か国(スペイン、デンマーク、フィンランド、ドイツ、スイス)では、1920年1月から4月の間に後期のピークが記録された。[121] メキシコでは2月から3月にかけて第4波が発生した。南米ではペルーで「非同期再流行波」が1年を通じて発生した。1月から3月にかけてはリマ(首都)に 深刻な第3波が襲来し、あらゆる原因による死亡率は1918年から1919年の波の約4倍に達した。イカでも同様に、1920年の7月から10月にかけ て、別の深刻なパンデミックの波が到来した。[164] ブラジルでは2月に第4の波が発生した。[110] 当時日本の植民地であった韓国と台湾でも、1919年後半から1920年前半にかけて、顕著な流行が発生した。[165][166] パンデミック後 1920年半ばには、パンデミックは一般市民だけでなく政府も「終息した」とほぼ認識していた。[167] チリの一部では1920年11月から1921年3月にかけて3度目の、より穏やかな流行がみられたが、[133] 1920年から1921年の冬の間は、ほとんど流行しなかったようである。[115]:167 米国では、例えば、肺炎とインフルエンザによる死亡者数は「ここ何年もの間と比較して非常に少なかった」[115]:167 パンデミックの終息後、季節性インフルエンザは1921年から各地で再び報告され始めた。[115]:168 チリではパンデミック後の第4波が1921年6月から12月の間に24州のうち7州に影響を与えた。。1921年から1922年の冬は、パンデミック終息 後の北半球における季節性インフルエンザの最初の大きな再流行となり、多くの地域で1918年後半のパンデミック以来最も深刻な事態となった。特に北西 ヨーロッパが大きな影響を受けた。オランダでは、1922年1月だけで全死因による死亡率が約2倍に増加した。[115]: 168 ヘルシンキでは、1918年以来5度目となる大流行が1921年11月から12月にかけて発生した 。[168] インフルエンザは米国でも流行し、1922年3月初旬にはカリフォルニア州での感染率が1920年のパンデミック以来最も高くなったと報告されている。 [115]: 172 1920年以降、1918年に新型であったこの病気は、より身近な存在となり、少なくとも「季節性インフルエンザ」の一形態を代表するようになった。 H1N1型ウイルスはその後も流行を続け、時折、より深刻な、あるいは注目に値する流行を引き起こしながら、徐々に変異していった。[169] 1918年の初登場以来のこの期間は「パンデミック時代」と呼ばれ、それ以降のインフルエンザ・パンデミックはすべて、このウイルスの子孫によって引き起 こされている。[17 1918年以降の最初のパンデミックの後、1957年には、ヒトのH1N1と鳥インフルエンザウイルスの再集合体である新型H2N2が完全に主流となり、 その後、新型H2N2はヒトの間で活発なインフルエンザAウイルスとなった。 1977年には、1950年代以来目撃されていなかった季節性H1N1と非常に類似したインフルエンザウイルスがロシアで出現し、その後、主に26歳以下 の年齢層に影響を与えた「技術的」パンデミックが始まった。[171][172] ウイルスが20年間凍結状態のままであったというような、いくつかの自然現象による説明が提案されているが、[172] この前例のない現象[173] を説明するために、いくつかの自然現象が提案されているが、インフルエンザの性質そのものが、研究目的で古いウイルスを保存していた研究所からの偶発的な 漏出など、何らかの人為的な関与を支持する根拠として挙げられている。[172] このミニパンデミックの後、再出現したH1N1は再び常在化したが、他の活動中のインフルエンザAウイルスであるH3N2(これは1968年のパンデミッ クでH2N 1968年のパンデミックによりH2N2を駆逐した)H3N2が主流となった。[171][169] 初めて、2種類のインフルエンザAウイルスが同時に存在する状態が観察された。[174] この状態は、新型H1N1ウイルスが現れ、パンデミックを引き起こし、その後季節性H1N1に取って代わり、H3N2とともに流行した2009年以降も続 いている。[174] 起源の可能性 その名称にもかかわらず、歴史的および疫学的なデータではスペイン風邪の地理的な起源を特定することはできない。[2] しかし、いくつかの説が提唱されている。 米国 最初の確認された症例は米国で発生した。歴史学者のアルフレッド・W・クロスビーは2003年に、インフルエンザはカンザス州で発生したと述べている [175]。また、作家のジョン・M・バリーは、2004年の論文で、1918年1月にカンザス州ハスケル郡で発生したアウトブレイクを発生源として説明 している[81]。 2018年、進化生物学教授マイケル・ウォロベイが主導した組織スライドと医療報告書の研究では、カンザス州が発症地であるという証拠は見つからなかっ た。その理由は、同時期のニューヨーク市の感染症と比較すると、カンザス州での症例は症状が軽く、死亡者も少なかったからである。この研究では、系統発生 学分析により、ウイルスが北米で発生した可能性が高いという証拠は発見されたが、決定的なものではなかった。さらに、ウイルスのヘマグルチニン糖タンパク 質は、1918年よりもずっと以前に起源があったことを示唆しており、他の研究では、H1N1ウイルスの再集合は1915年頃に起こった可能性が高いこと が示唆されている。[176] ヨーロッパ  エドヴァルド・ムンク(1863年-1944年)『スペイン風邪とともに自画像』(1919年)  エゴン・シーレ(1890年-1918年)は、スペイン風邪で妻のエディトが死亡した直後に、死の数日前の『家族』を描いた。 フランス、エタプルにあったイギリス軍の主要な兵站基地および病院キャンプが、スペイン風邪の中心地であったという説がウイルス学者ジョン・オックス フォードによって提唱されている。[178] 彼の研究によると、1916年後半にエタプルキャンプが、インフルエンザに似た症状を引き起こす死亡率の高い新しい病気の発生に襲われたことが分かった。 [179][ オックスフォードによると、同様の集団発生は1917年3月にアルダショットの陸軍兵舎でも発生しており[180]、軍の病理学者は後にこれらの初期の集 団発生をスペイン風邪と同じ病気であると認識した[181][178]。エタプルの過密な収容所と病院は、呼吸器ウイルスの蔓延に理想的な環境であった。 病院では数千人の毒ガス攻撃の犠牲者やその他の戦争の犠牲者が治療を受け、毎日10万人の兵士が収容所を通過した。また、養豚場もあり、収容所の食料とし て、周辺の村から定期的に家禽が持ち込まれていた。オックスフォードと彼のチームは、鳥類に宿る前駆体ウイルスが変異し、戦線近くで飼育されている豚に移 動したと仮定した。[180][181] 2016年に『中国医学協会誌』で発表された報告書では、1918年のパンデミックの数ヶ月、あるいは数年前から、1918年のウイルスがヨーロッパの軍 隊で流行していた証拠が発見されたと報告している。[182] 政治学者のアンドリュー・プライス=スミスは、オーストリアの公文書館のデータから、インフルエンザは1917年初頭にオーストリアで始まった可能性を示 唆している。[183] 2009年の『インフルエンザおよびその他の呼吸器ウイルス』誌に掲載された研究では、分析対象となったヨーロッパの14か国すべてにおいて、1918年 10月と11月の2か月間にスペイン風邪による死亡率が同時にピークに達していたことが判明した。これは、ウイルスがヨーロッパのどこかで発生し、その 後、外部に広がっていったとすれば、研究者が予想するパターンと一致しない。 中国 1993年、パスツール研究所のスペイン風邪研究の第一人者であるクロード・ハヌーンは、前駆体ウイルスは中国からやって来て、米国ボストン近郊で変異 し、そこからフランスのブレスト、ヨーロッパの戦場 、連合軍の兵士や船員が主な感染者となり、ヨーロッパの戦場、ヨーロッパのその他の地域、そして世界のその他の地域へと広がっていったと主張した。 [184] ハヌンは、スペイン、カンザス、ブレストなど、いくつかの起源に関する代替仮説を可能性はあるが、可能性は低いとみなした。[184] 2014年、歴史家のマーク・ハンフリーズは、9万6000人の中国人労働者が英仏軍の後方で働くために動員されたことが、パンデミックの源となった可能 性があると主張した。ハンフリーズは、セントジョンズにあるニューファンドランド記念大学の教授であり、その結論は新たに発見された記録に基づいている。 彼は、1917年11月に中国北部(出稼ぎ労働者の出身地)を襲った呼吸器疾患が、1年後に中国の保健当局によってスペイン風邪と同一のものと特定された という記録を発見した。[185][186] 残念ながら、現代のものと比較できる組織サンプルは残っていない。[187] それでも、出稼ぎ労働者がヨーロッパに向かう際に通った航路の一部では呼吸器疾患の報告があり、その航路は北米も通っていた。[187] 中国は、スペイン風邪の世界的大流行の影響が比較的少なかった数少ない地域のひとつであり、複数の研究が1918年のインフルエンザの流行は比較的軽度で あったことを記録している。(ただし、軍閥時代に関するデータの不足により、この点については異論もある。世界全体を参照のこと。) このため、スペイン風邪のパンデミックは中国で発生したのではないかという推測がなされている。[190][191] インフルエンザによる死亡率が低かったのは、中国人口が以前にインフルエンザウイルスに対する免疫を獲得していたためである可能性がある。[174] [190] 広東省では、1918年のインフルエンザの初期の流行は若い男性に不均衡な影響を与えたと報告されている。6月の流行では11歳から20歳までの子供や若 者が感染し、10月の流行では11歳から15歳までの年齢層に最も多く見られた。[192] 2016年に『中国医学協会誌』で発表された報告書では、1918年のウイルスが中国人および東南アジアの兵士や労働者によってヨーロッパに持ち込まれた という証拠は見つからず、むしろ、パンデミック以前にヨーロッパでウイルスが循環していた証拠が見つかった。2016年の研究では、ヨーロッパで中国人お よび東南アジアの労働者たちに記録されたインフルエンザの死亡率の低さ(推定で1000人に1人)から、 1918年末のフランスにおける他の連合軍部隊とアジア部隊に違いは見られず、したがって、アジア部隊が新型の致死性ウイルスの感染源である可能性は低い ことを示唆している。[182] 中国人労働者によって新型ウイルスが蔓延したという説に反するさらなる証拠として、労働者は他のルートでヨーロッパに入国しており、そのルートではウイル スが蔓延した形跡は見られなかったため、彼らが最初の感染者である可能性は低い。[176] |

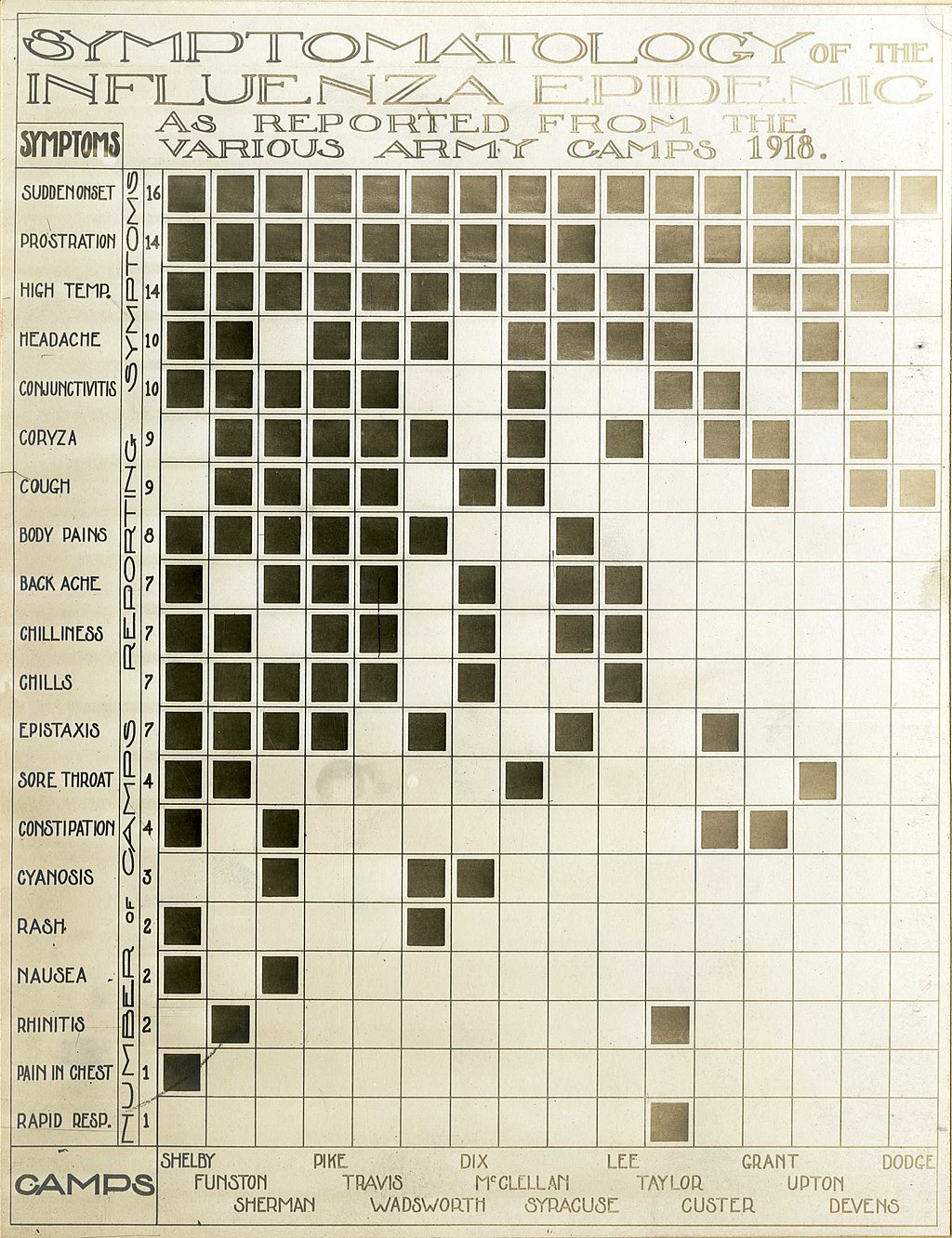

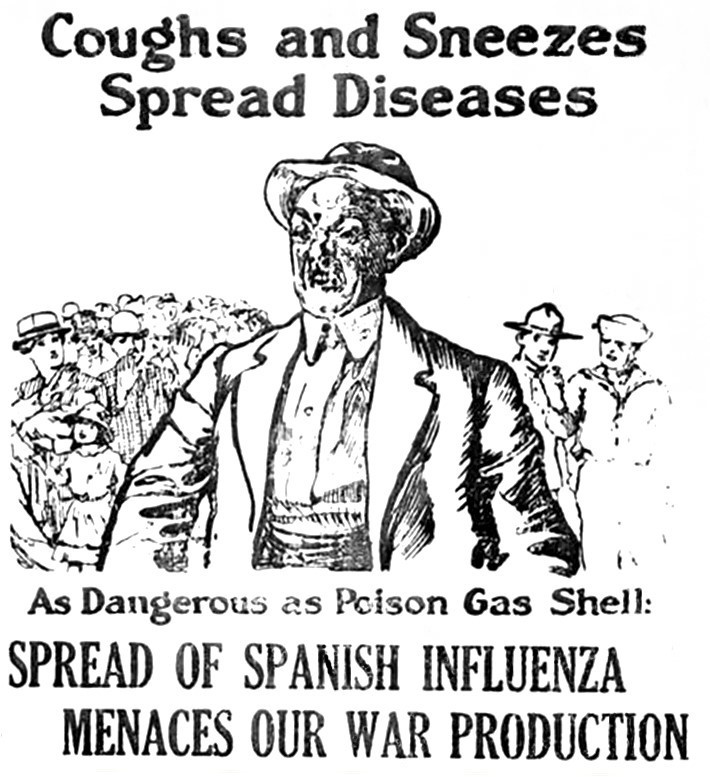

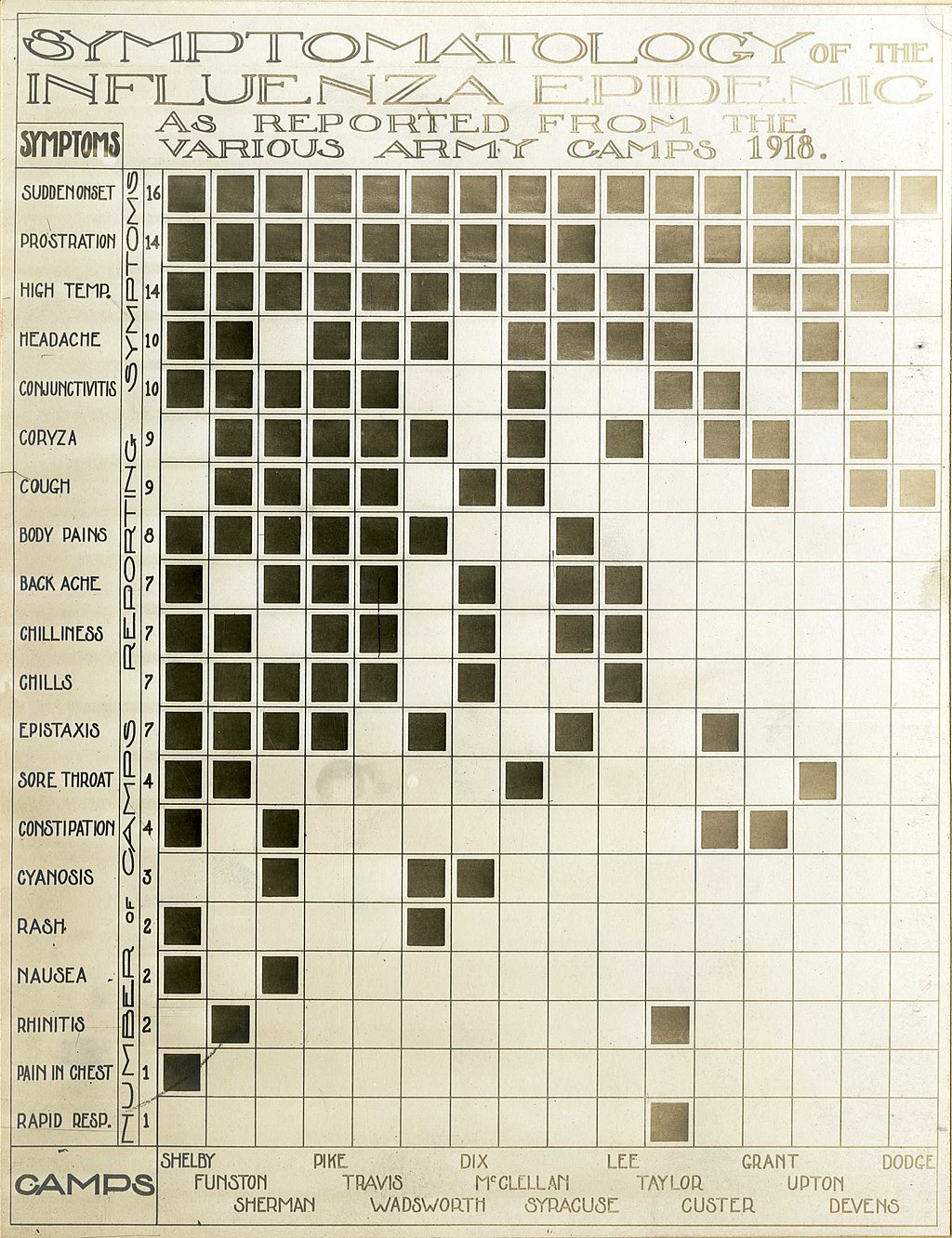

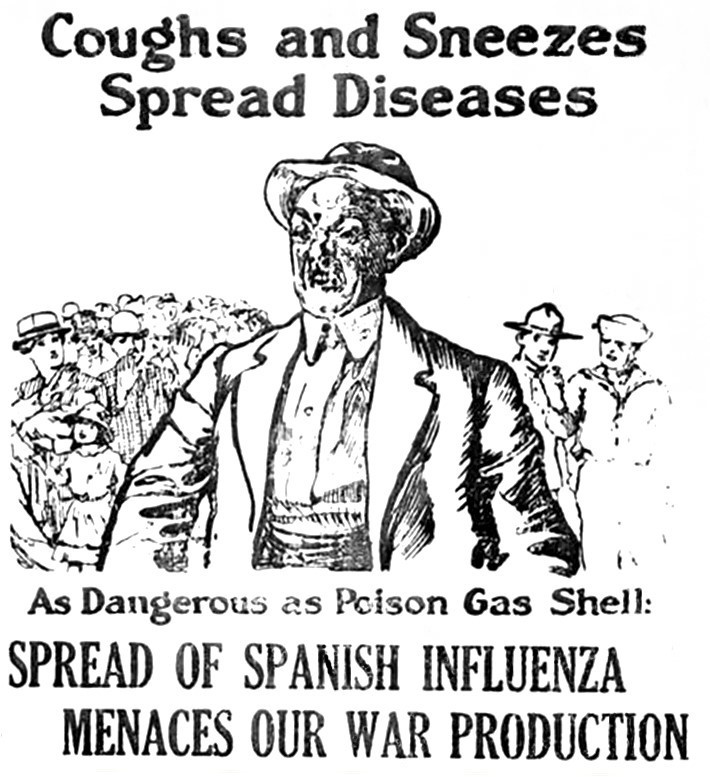

| Epidemiology and pathology Transmission and mutation  U.S. Army flu patients at Field Hospital No. 29 near Hollerich, Luxembourg 1918. As U.S. troops deployed en masse for the war effort in Europe, they carried the Spanish flu with them. The basic reproduction number of the virus was between 2 and 3.[193] The close quarters and massive troop movements of World War I hastened the pandemic, and probably both increased transmission and augmented mutation. The war may also have reduced people's resistance to the virus. Some speculate the soldiers' immune systems were weakened by malnourishment, as well as the stresses of combat and chemical attacks, increasing their susceptibility.[194][195] A large factor in the worldwide occurrence of the flu was increased travel. Modern transportation systems made it easier for soldiers, sailors, and civilian travelers to spread the disease.[196] Another was lies and denial by governments, leaving the population ill-prepared to handle the outbreaks.[197] The severity of the second wave has been attributed to the circumstances of the First World War.[198] In civilian life, natural selection favors a mild strain. Those who get very ill stay home, and those mildly ill continue with their lives, preferentially spreading the mild strain. In the trenches, natural selection was reversed. Soldiers with a mild strain stayed where they were, while the severely ill were sent on crowded trains to crowded field hospitals, spreading the deadlier virus. The second wave began, and the flu quickly spread around the world again. Consequently, during modern pandemics, health officials look for deadlier strains of a virus when it reaches places with social upheaval.[199] The fact that most of those who recovered from first-wave infections had become immune showed that it must have been the same strain of flu. This was most dramatically illustrated in Copenhagen, which escaped with a combined mortality rate of just 0.29% (0.02% in the first wave and 0.27% in the second wave) because of exposure to the less-lethal first wave.[200] For the rest of the population, the second wave was far more deadly; the most vulnerable people were those like the soldiers in the trenches – adults who were young and fit.[201] After the lethal second wave struck in late 1918, new cases dropped abruptly. In Philadelphia, for example, 4,597 people died in the week ending 16 October, but by 11 November, influenza had almost disappeared from the city. One explanation for the rapid decline in the lethality of the disease is that doctors became more effective in the prevention and treatment of pneumonia that developed after the victims had contracted the virus. However, John Barry stated in his 2004 book The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague In History that researchers have found no evidence to support this position.[81] Another theory holds that the 1918 virus mutated extremely rapidly to a less lethal strain. Such evolution of influenza is a common occurrence: there is a tendency for pathogenic viruses to become less lethal with time, as the hosts of more dangerous strains tend to die out.[81] Fatal cases did continue into 1919, however. One notable example was that of ice hockey player Joe Hall, who, while playing for the Montreal Canadiens, fell victim to the flu in April after an outbreak that resulted in the cancellation of the 1919 Stanley Cup Finals.[202] Signs and symptoms  US Army symptomology of the flu The majority of the infected experienced only the typical flu symptoms of sore throat, headache, and fever, especially during the first wave.[203] However, during the second wave, the disease was much more serious, often complicated by bacterial pneumonia, which was often the cause of death.[203] This more serious type would cause heliotrope cyanosis to develop, whereby the skin would first develop two mahogany spots over the cheekbones which would then over a few hours spread to color the entire face blue, followed by black coloration first in the extremities and then further spreading to the limbs and the torso.[203] After this, death would follow within hours or days due to the lungs being filled with fluids.[203] Other signs and symptoms reported included spontaneous mouth and nosebleeds, miscarriages for pregnant women, a peculiar smell, teeth and hair falling out, delirium, dizziness, insomnia, loss of hearing or smell, and impaired vision.[203] One observer wrote, "One of the most striking of the complications was hemorrhage from mucous membranes, especially from the nose, stomach, and intestine. Bleeding from the ears and petechial hemorrhages in the skin also occurred".[204] The majority of deaths were from bacterial pneumonia,[205][206][207] a common secondary infection associated with influenza. This pneumonia was itself caused by common upper respiratory-tract bacteria, which were able to get into the lungs via the damaged bronchial tubes of the victims.[208] The virus also killed people directly by causing massive hemorrhages and edema in the lungs.[207] Modern analysis has shown the virus to be particularly deadly because in animal trials it triggers an overreaction of the body's immune system (sometimes referred to as a cytokine storm).[81] The strong immune reactions of young adults were postulated to have ravaged the body, whereas the weaker immune reactions of children and middle-aged adults resulted in fewer deaths among those groups.[209] Misdiagnosis Because the virus that caused the disease was too small to be seen under a microscope at the time, there were problems with correctly diagnosing it.[210] The bacterium Haemophilus influenzae was instead mistakenly thought to be the cause, as it was big enough to be seen and was present in many, though not all, patients.[210] For this reason, a vaccine that was used against that bacillus did not make an infection rarer but did decrease the death rate.[211] During the deadly second wave there were also fears that it was in fact plague, dengue fever, or cholera.[212] Another common misdiagnosis was typhus, which was common in circumstances of social upheaval, and was therefore also affecting Russia in the aftermath of the October Revolution.[212] In Chile, the view of the country's elite was that the nation was in severe decline, and therefore doctors assumed that the disease was typhus caused by poor hygiene, and not an infectious one, causing a mismanaged response which did not ban mass gatherings.[212] The role of climate conditions  Poster with the slogan: "Coughs and sneezes spread diseases" Studies have shown that the immune system of Spanish flu victims could have been weakened by adverse climate conditions which were particularly unseasonably cold and wet for extended periods of time during the duration of the pandemic. This affected especially WWI troops exposed to incessant rains and lower-than-average temperatures for the duration of the conflict, and especially during the second wave of the pandemic. Ultra-high-resolution climate data combined with highly detailed mortality records analyzed at Harvard University and the Climate Change Institute at the University of Maine identified a severe climate anomaly that impacted Europe from 1914 to 1919, with several environmental indicators directly influencing the severity and spread of the Spanish flu pandemic.[11] Specifically, a significant increase in precipitation affected all of Europe during the second wave of the pandemic, from September to December 1918. Mortality figures follow closely the concurrent increase in precipitation and decrease in temperatures. Several explanations have been proposed for this, including the fact that lower temperatures and increased precipitation provided ideal conditions for virus replication and transmission, while also negatively affecting the immune systems of soldiers and other people exposed to the inclement weather, a factor proven to increase likelihood of infection by both viruses and pneumococcal co-morbid infections documented to have affected a large percentage of pandemic victims (one fifth of them, with a 36% mortality rate).[213][214][215][216][217] A six-year climate anomaly (1914–1919) brought cold, marine air to Europe, drastically changing its weather, as documented by eyewitness accounts and instrumental records, reaching as far as the Gallipoli campaign, in Turkey, where ANZAC troops suffered extremely cold temperatures despite the normally Mediterranean climate of the region. The climate anomaly likely influenced the migration of H1N1 avian vectors which contaminate bodies of water with their droppings, reaching 60% infection rates in autumn.[218][219][220] The climate anomaly has been associated with an anthropogenic increase in atmospheric dust, due to the incessant bombardment; increased nucleation due to dust particles (cloud condensation nuclei) contributed to increased precipitation.[221][222][223] |

疫学と病理学 感染と変異  1918年、ルクセンブルクのホレリッヒ近郊の第29野戦病院における米軍のインフルエンザ患者。米軍がヨーロッパでの戦争に大規模に展開する中、スペイン風邪もまた持ち込まれた。 このウイルスの基本再生産数は2から3の間であった。[193] 第1次世界大戦における密集した状況と大規模な軍隊の移動は、パンデミックを早め、おそらくは感染の拡大と変異の増大を加速させた。また、戦争は人々のウ イルスに対する抵抗力を低下させた可能性もある。兵士たちの免疫システムは栄養失調や戦闘や化学攻撃のストレスによって弱まり、感染しやすくなったという 説もある。[194][195] 世界的なインフルエンザの発生の大きな要因は、旅行の増加であった。近代的な交通システムにより、兵士や水兵、民間人の旅行者が病気を広げやすくなった。 [196] もう一つの要因は、政府による嘘と否定であり、それによって人々は発生に対処する準備ができていなかった。[197] 第2波の深刻さは、第一次世界大戦の状況に起因している。[198] 一般市民の生活においては、自然淘汰は穏やかな株を好む。重篤な症状を呈する者は自宅に留まり、軽症の者は生活を続け、軽症株を優先的に広める。塹壕で は、自然淘汰は逆転した。軽症株の兵士はそのまま留まり、重篤な症状を呈する者は混雑した列車で混雑した野戦病院に送られ、より致死性の高いウイルスを広 めることになった。第2波が始まり、インフルエンザは再び急速に世界中に広がった。そのため、現代のパンデミックにおいては、社会が混乱している地域にウ イルスが到達した際には、保健当局はより致死率の高いウイルス株を捜し求めるようになった。[199] 第1波の感染から回復した人のほとんどが免疫を獲得していたという事実は、同じインフルエンザの株であったに違いないことを示している。これはコペンハー ゲンで最も劇的に示された。コペンハーゲンでは、致死性の低い第1波に感染したことで、死亡率は合計0.29%(第1波では0.02%、第2波では 0.27%)で済んだのである。[200] それ以外の地域では、第2波の致死率ははるかに高かった。最も感染しやすい人々は、塹壕にいる兵士のような人々、つまり若くて健康な成人であった。 [201] 致死率の高い第2波が1918年後半に襲った後、新たな感染者は急激に減少した。例えばフィラデルフィアでは、10月16日までの1週間で4,597人が 死亡したが、11月11日にはインフルエンザはほぼ市内から姿を消した。致死率の急速な低下の理由のひとつとして、ウイルスに感染した後に発症する肺炎の 予防と治療に医師がより効果的になったことが挙げられる。しかし、ジョン・バリーは2004年の著書『The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague In History』の中で、この説を裏付ける証拠は見つかっていないと述べている。[81] 別の説では、1918年のウイルスが致死性の低い株へと急速に変異したというものがある。このようなインフルエンザの進化はよくあることである。病原性ウ イルスは時が経つにつれ致死率が低下する傾向があり、より危険な株の宿主は絶滅する傾向にある。[81] しかし、1919年にも致死例は続いた。注目すべき例としては、モントリオール・カナディアンズでプレーしていたアイスホッケー選手のジョー・ホールが、 1919年のスタンレー・カップ決勝が中止となるほどの流行が発生した後の4月にインフルエンザの犠牲となったことが挙げられる。 兆候と症状  米国陸軍によるインフルエンザの症状学 感染者の大半は、特に最初の流行期には、喉の痛み、頭痛、発熱といった典型的なインフルエンザの症状のみを経験した。[203] しかし、2回目の流行期には、この病気ははるかに深刻になり、細菌性肺炎を併発することが多く、これが死因となることも多かった。[203] このより深刻なタイプでは、ヘリオトロープチアノーゼが発症し、 まず頬骨の上に2つのマホガニー色の斑点が生じ、数時間のうちに顔全体が青く変色し、その後、四肢に黒い色調が現れ、さらに四肢と胴体に広がる。 [203] その後、肺が体液で満たされるため、数時間から数日のうちに死に至る。[203] その他の兆候や 報告されたその他の兆候や症状には、自然に起こる口や鼻からの出血、妊娠中の女性の流産、独特の臭い、歯や髪の抜け落ち、錯乱、めまい、不眠、聴力や嗅覚 の喪失、視力の低下などがあった。ある観察者は、「最も顕著な合併症のひとつは、粘膜、特に鼻、胃、腸からの出血であった。耳からの出血や皮膚の点状出血 も発生した」とある。[204] 死因の大半は細菌性肺炎によるものであった。[205][206][207] これはインフルエンザに付随する一般的な二次感染である。この肺炎は、被害者の損傷した気管支を通って肺に侵入した一般的な上気道細菌によって引き起こさ れた。[208] また、ウイルスは肺に大量出血や浮腫を引き起こすことによっても直接的に人を死に至らしめた。[207] 現代の分析では、ウイルスが特に致死性が高いのは、 動物実験では、このウイルスが免疫システムの過剰反応(サイトカインストームと呼ばれることもある)を引き起こすことが分かっている。[81] 若い成人の強い免疫反応が体を破壊したのに対し、子供や中高年層の弱い免疫反応は、そのグループでの死亡者数の減少につながったと推測されている。 [209] 誤診 当時、この病気を引き起こすウイルスは顕微鏡でも見えないほど小さかったため、正確な診断を下すことが困難であった。目に見えるほど大きく、患者の多くに 存在していたため、インフルエンザ菌が原因であると誤って考えられていた。[210] このため、その細菌に対して使用されていたワクチンは感染を稀にするものではなく、死亡率を低下させるものであった。[211] 致命的な第2波の間には、実際にはペスト、デング熱、コレラではないかという懸念もあった。[212] もう一つの一般的な誤診は発疹チフスであった。これは社会が混乱した状況でよく見られるもので、10月革命後のロシアでも影響を及ぼしていた。[2 12]チリでは、エリート層の間では国民が深刻な衰退状態にあるという見方が一般的であったため、医師たちはこの病気が不衛生が原因のチフスであり、感染 性のものではないと想定し、大規模な集会を禁止しないという不適切な対応をとった。 気候条件の役割  「咳やくしゃみで病気が広がる」というスローガンが書かれたポスター 研究によると、スペイン風邪の犠牲者の免疫システムは、特にパンデミックの期間中に長期間にわたって季節外れの寒さと雨に見舞われた悪条件の気候によって 弱められていた可能性がある。これは、特に第一次世界大戦中の兵士たちに影響を与えた。彼らは、戦時中、特にパンデミックの第2波の間、絶え間ない雨と平 均気温を下回る気温にさらされていた。ハーバード大学とメイン大学気候変動研究所で分析された超高解像度の気候データと詳細な死亡記録を組み合わせたとこ ろ、1914年から1919年にかけてヨーロッパに影響を与えた深刻な気候異常が特定され、いくつかの環境指標がスペイン風邪のパンデミックの深刻さと広 がりに直接影響を与えたことが明らかになった。[11] 具体的には、1918年9月から12月にかけてのパンデミックの第2波の期間に、ヨーロッパ全土で降水量が大幅に増加した。死亡率は、降水量の増加と気温 の低下にほぼ一致して増加した。これにはいくつかの説明が提案されているが、その中には、気温の低下と降水量の増加がウイルスの複製と感染に理想的な条件 をもたらした一方で、悪天候にさらされた兵士やその他の人々の免疫システムに悪影響を与えたという事実も含まれている。この要因は、ウイルスと肺炎球菌の 併発感染の両方による感染の可能性を高めることが証明されており、パンデミックの犠牲者の大半(5分の1、死亡率36%)に影響を与えたことが記録されて いる。[ 213][214][215][216][217] 6年間にわたる気候の異常(1914年~1919年)により、ヨーロッパには冷たく湿った空気が流れ込み、気象が劇的に変化した。これは、目撃者の証言や 機器による記録によって証明されており、トルコのガリポリ戦線にまで及んだ。この地域は通常は地中海性気候であるにもかかわらず、アンザック軍は極度の寒 さに苦しんだ。この気候の異常は、糞によって水場を汚染し、秋には感染率が60%に達したH1N1鳥インフルエンザの媒介生物の移動に影響を与えた可能性 が高い。[218][219][220] この気候の 異常は、絶え間ない砲撃による人為的な大気中の塵の増加と関連している。塵の粒子(雲凝縮核)による核生成の増加が、降水量の増加に寄与した。[221] [222][223] |

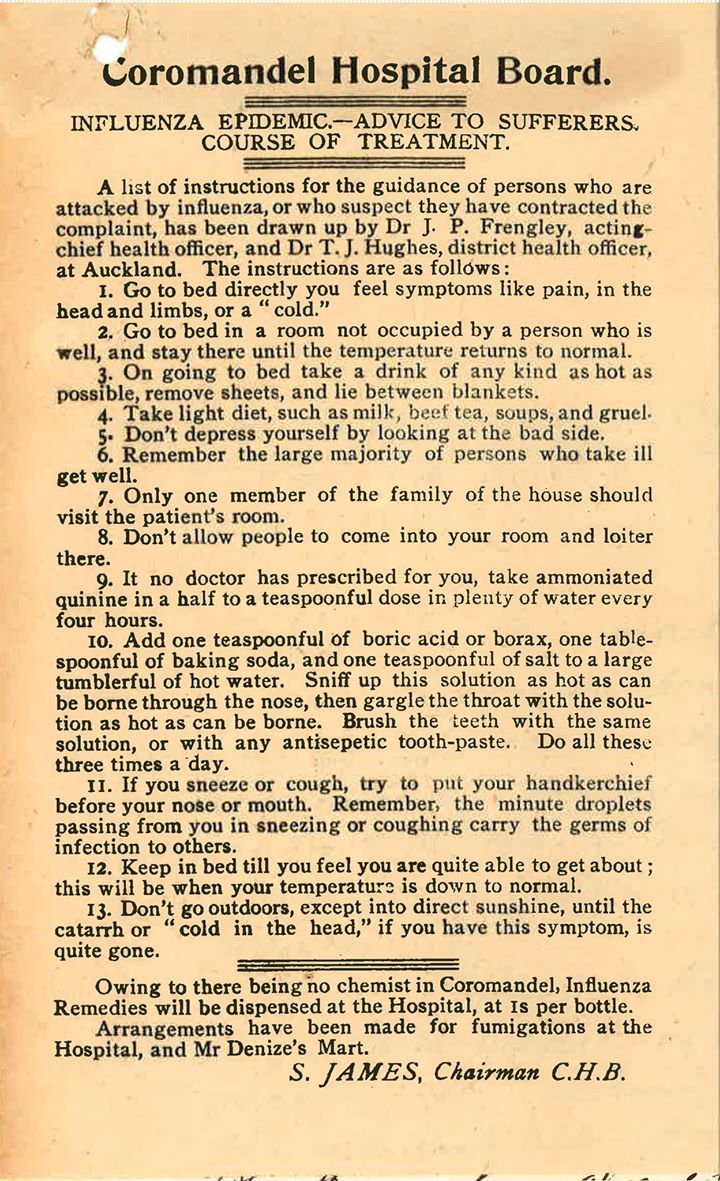

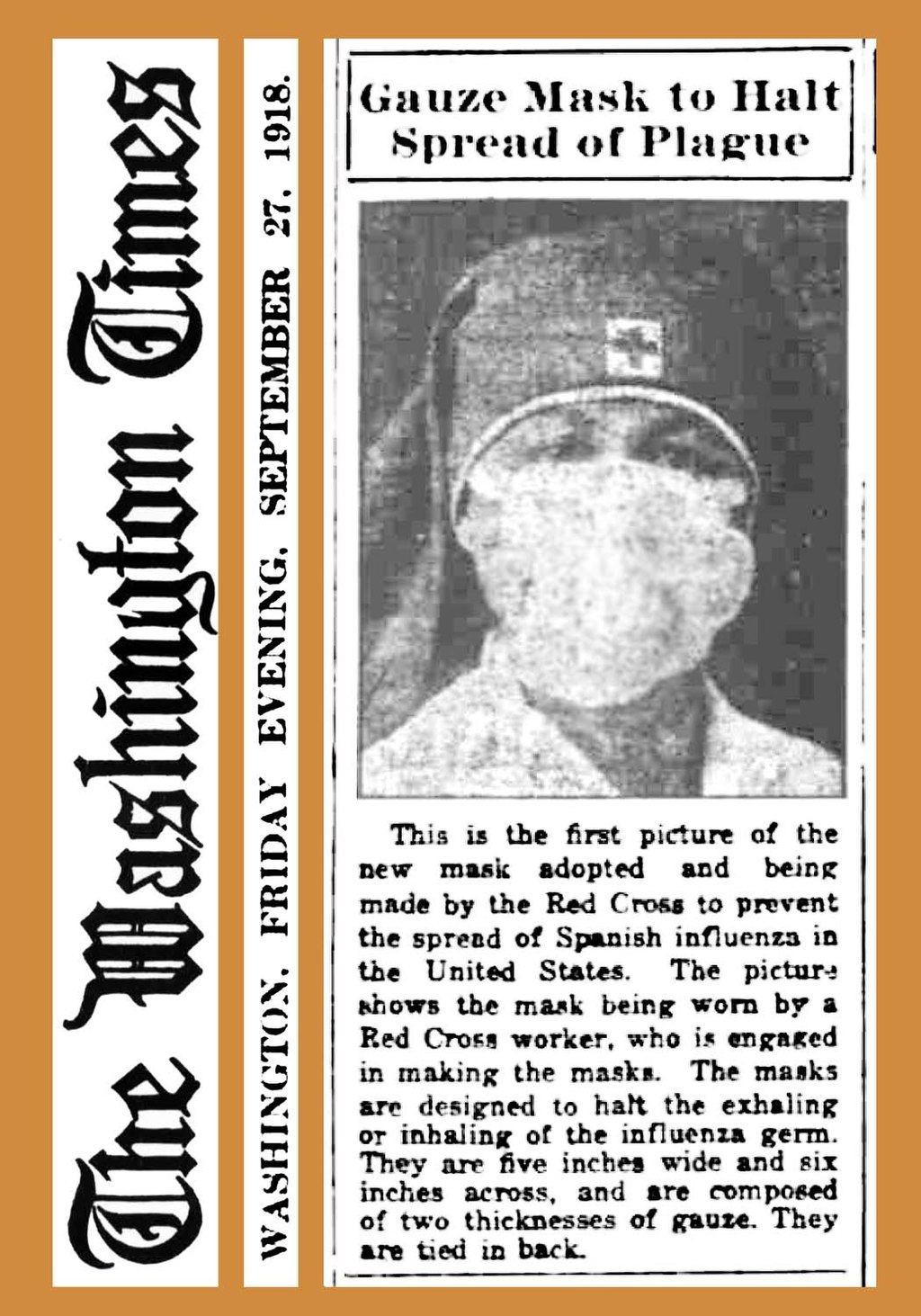

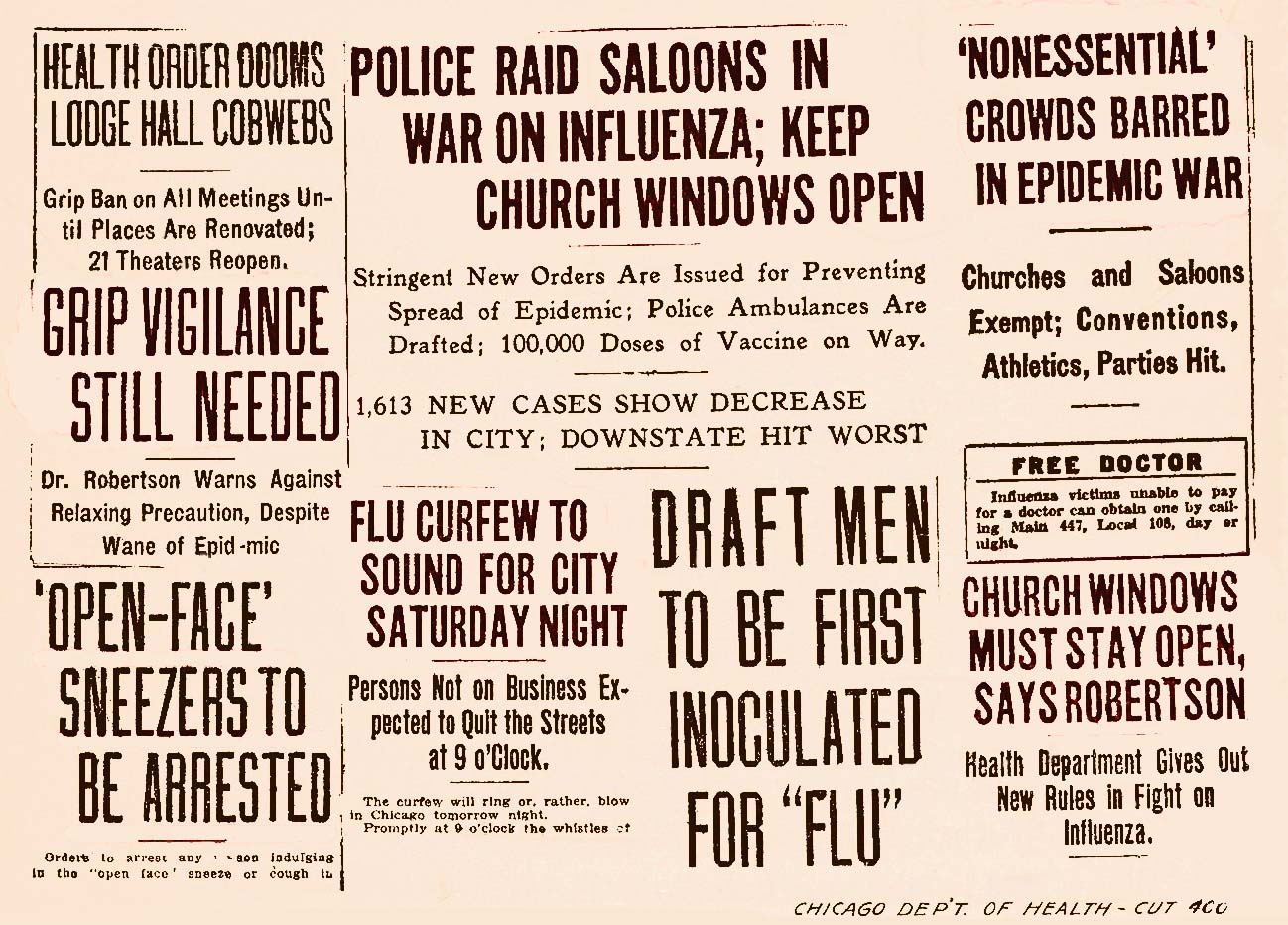

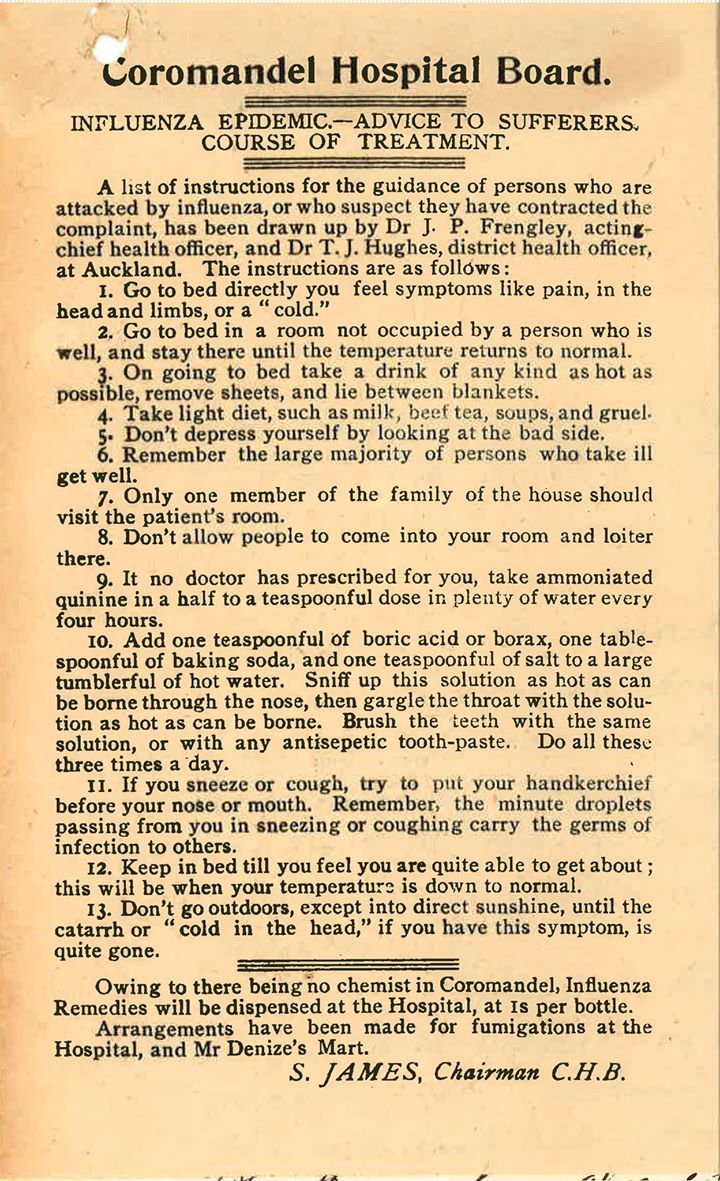

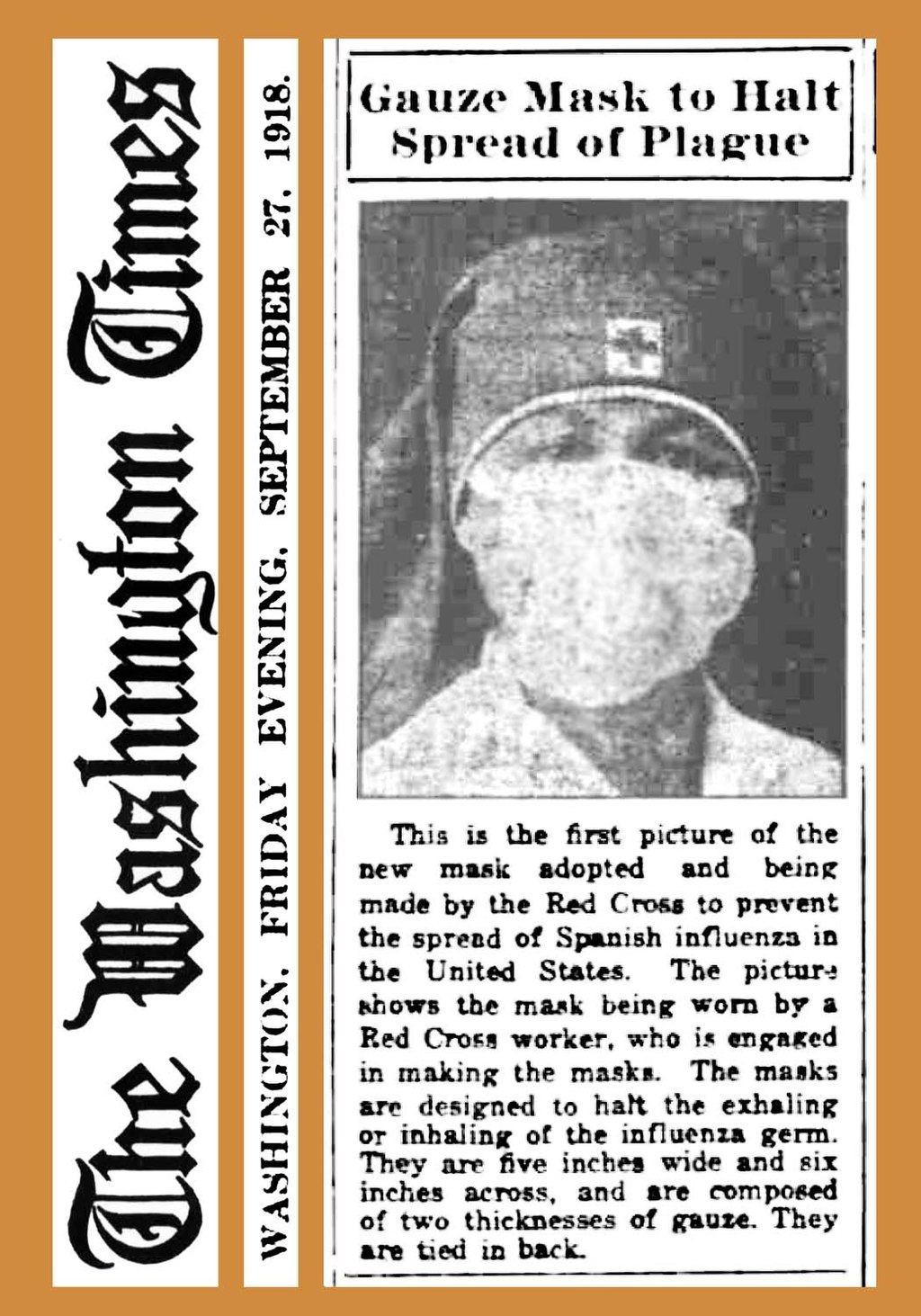

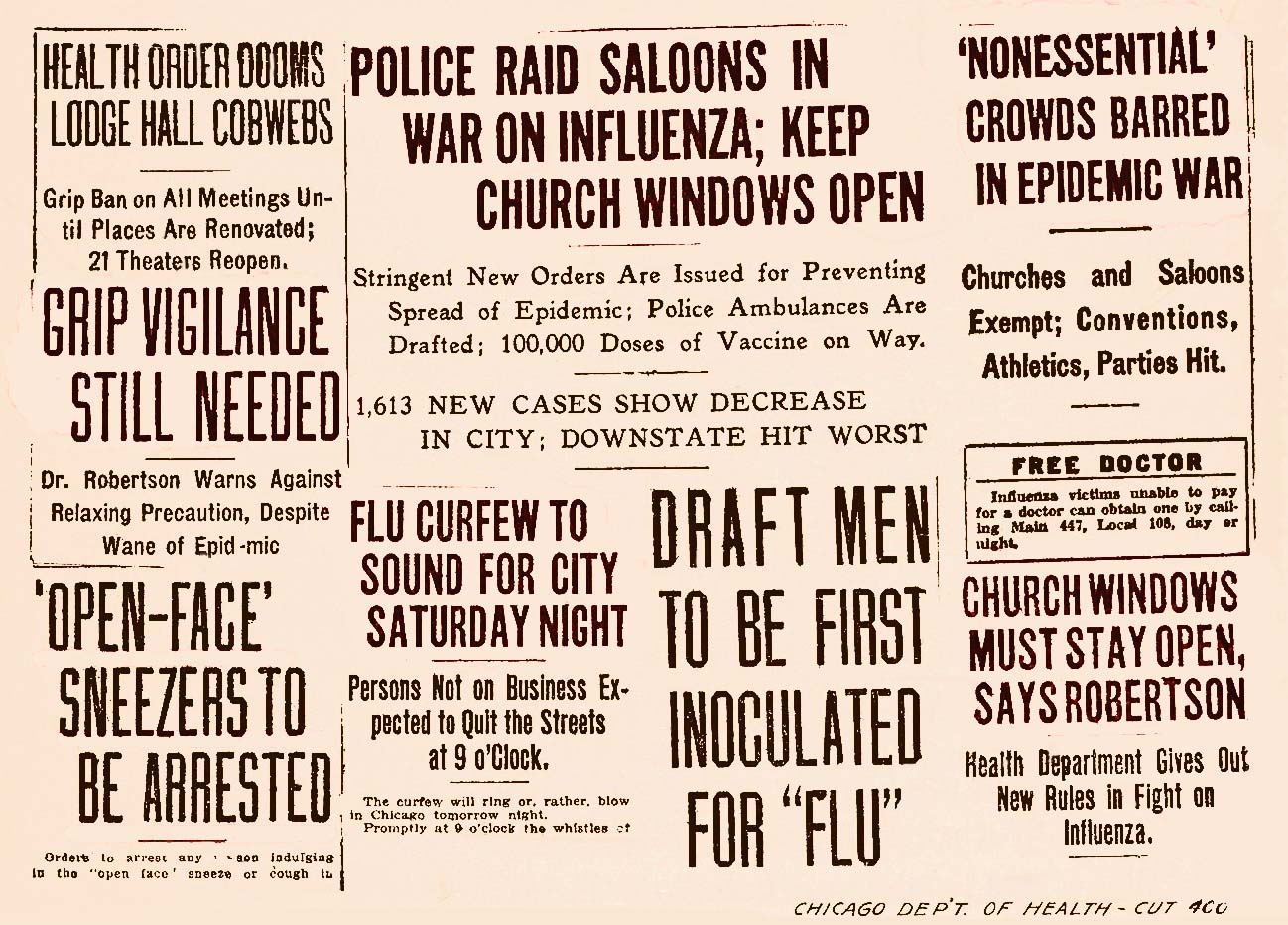

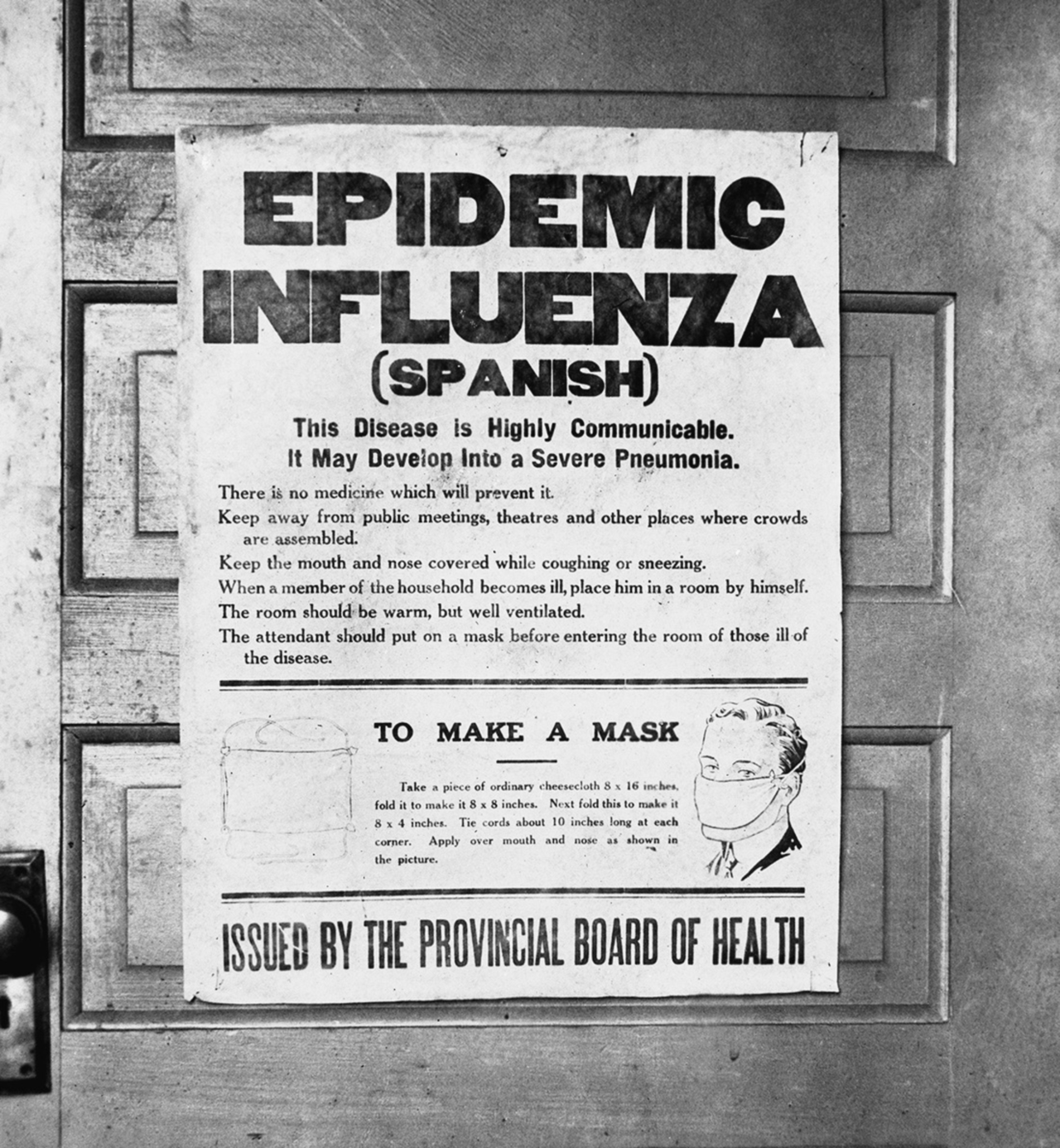

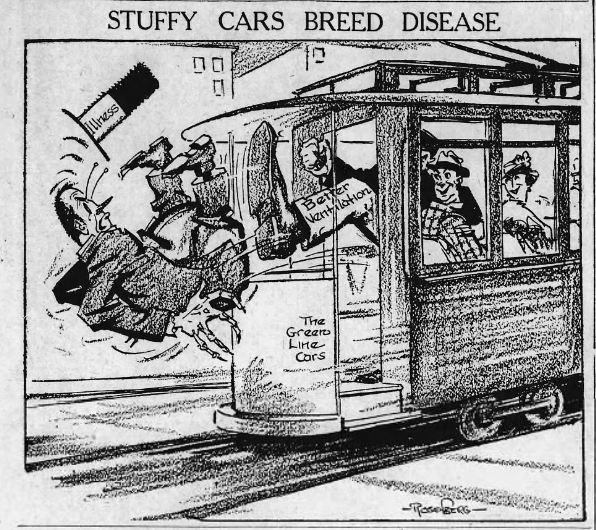

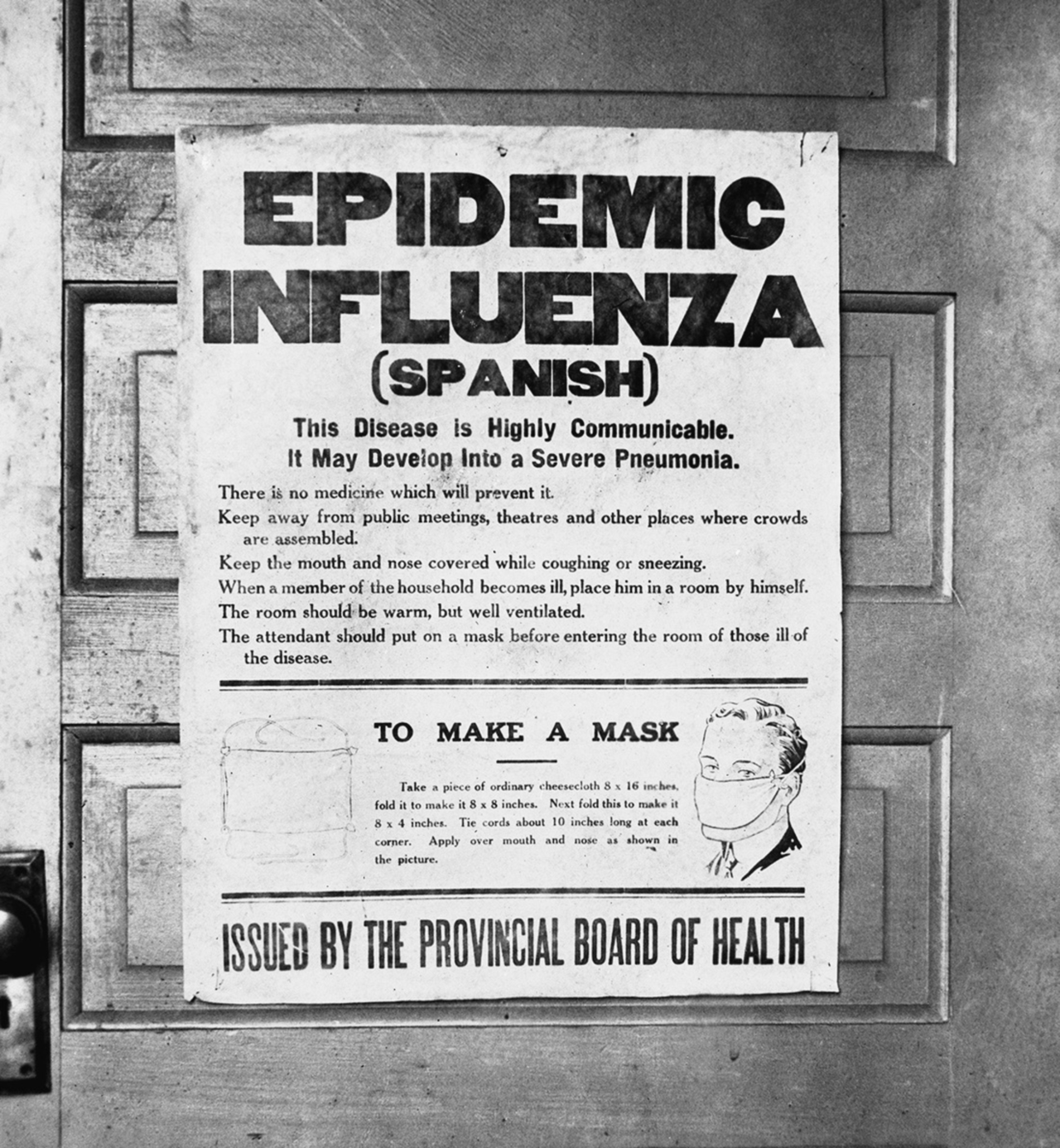

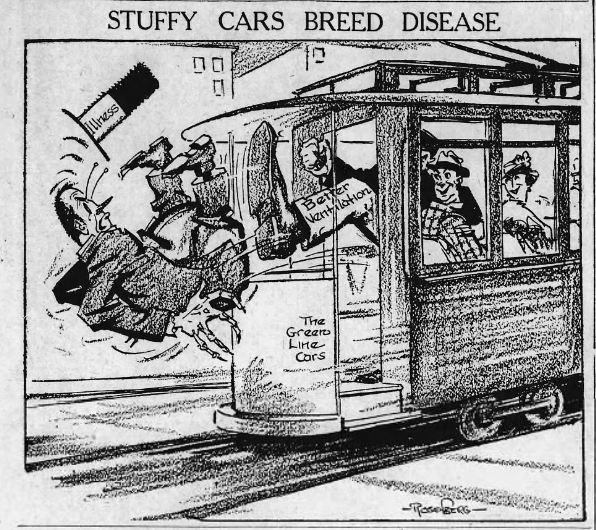

| Responses Public health management  Coromandel Hospital Board (New Zealand) advice to influenza sufferers (1918)  In September 1918, the Red Cross recommended two-layer gauze masks to halt the spread of "plague".[224]  1918 Chicago newspaper headlines reflect mitigation strategies such as increased ventilation, arrests for not wearing face masks, sequenced inoculations, limitations on crowd size, selective closing of businesses, curfews, and lockdowns.[225] After October's strict containment measures showed some success, Armistice Day celebrations in November and relaxed attitudes by Thanksgiving caused a resurgence.[225] While systems for alerting public health authorities of infectious spread did exist in 1918, they did not generally include influenza, leading to a delayed response.[226] Nevertheless, actions were taken. Maritime quarantines were declared on islands such as Iceland, Australia, and American Samoa, saving many lives.[226] Social distancing measures were introduced, for example closing schools, theatres, and places of worship, limiting public transportation, and banning mass gatherings.[227] Wearing face masks became common in some places, such as Japan, though there were debates over their efficacy.[227][228] There was also some resistance to their use, as exemplified by the Anti-Mask League of San Francisco. Vaccines were also developed, but as these were based on bacteria and not the actual virus, they could only help with secondary infections.[227] The actual enforcement of various restrictions varied.[229] To a large extent, the New York City health commissioner ordered businesses to open and close on staggered shifts to avoid overcrowding on the subways.[230] A later study found that measures such as banning mass gatherings and requiring the wearing of face masks could cut the death rate up to 50 percent, but this was dependent on their being imposed early in the outbreak and not being lifted prematurely.[231] Medical treatment As there were no antiviral drugs to treat the virus, and no antibiotics to treat the secondary bacterial infections, doctors would rely on a random assortment of medicines with varying degrees of effectiveness, such as aspirin, quinine, arsenics, digitalis, strychnine, epsom salts, castor oil, and iodine.[232] Treatments of traditional medicine, such as bloodletting, ayurveda, and kampo were also applied.[233] Information dissemination Due to World War I, many countries engaged in wartime censorship, and suppressed reporting of the pandemic.[234] For example, the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera was prohibited from reporting daily death tolls.[235] The newspapers of the time were also generally paternalistic and worried about mass panic.[235] Misinformation also spread along with the disease. In Ireland there was a belief that noxious gases were rising from the mass graves of Flanders Fields and being "blown all over the world by winds".[236] There were also rumors that the Germans were behind it, for example by poisoning the aspirin manufactured by Bayer, or by releasing poison gas from U-boats.[237] |

対応 公衆衛生管理  コロマンデル病院委員会(ニュージーランド)によるインフルエンザ患者への助言(1918年)  1918年9月、赤十字社は「ペスト」の蔓延を食い止めるために2層構造のガーゼマスクを推奨した。[224]  1918年のシカゴの新聞の見出しは、換気量の増加、マスク未着用者の逮捕、順番に予防接種、群衆の人数制限、一部の事業所の閉鎖、夜間外出禁止令、封鎖 といった緩和策を反映している。[225] 10月の厳格な封じ込め策が一定の成果を上げた後、11月の休戦記念日の祝賀と感謝祭による態度の緩和により、再び流行が起こった。[225] 1918年には、感染拡大を公衆衛生当局に警告するシステムは存在していたものの、インフルエンザは一般的に含まれていなかったため、対応が遅れた。 [226] それでも、対策は講じられた。アイスランド、オーストラリア、アメリカ領サモアなどの島々では海上検疫が宣言され、多くの命が救われた。[226] 社会的距離を保つための措置が導入され、例えば、学校、劇場、礼拝所の閉鎖、公共交通機関の利用制限、大規模集会の禁止などが行われた。[2 27] フェイスマスクの着用は、日本など一部の地域では一般的になったが、その有効性については議論があった。[227][228] サンフランシスコのアンチマスクリーグに代表されるように、その使用には抵抗もあった。ワクチンも開発されたが、これらは細菌を基にしており実際のウイル スを基にしたものではなかったため、二次感染の予防にしか役立たなかった。[227] 実際に行われた様々な制限の施行は様々であった。[229] ニューヨーク市の保健局長は、地下鉄の過密を避けるため、企業に対して時差出勤制の導入を命じた。[230] その後の研究では、大規模な集会の禁止やマスクの着用義務などの措置により、死亡率を最大50%削減できる可能性があることが分かったが、これは発生初期にそれらの措置がとられ、早期に解除されなかった場合に限られる。 医療措置 ウイルスを治療する抗ウイルス薬も、二次的な細菌感染を治療する抗生物質もなかったため、医師たちはアスピリン、キニーネ、ヒ素、ジギタリス、ストリキ ニーネ、エプソム塩、ヒマシ油、ヨウ素など、効果の程度が異なるさまざまな薬品を適当に用いた。[232] また、瀉血、アーユルヴェーダ、漢方などの伝統医学による治療も行われた。[233] 情報伝達 第一次世界大戦のため、多くの国が戦時検閲を行い、パンデミックに関する報道を抑制した。[234] 例えば、イタリアの新聞『コリエーレ・デラ・セラ』は、毎日の死者数の報道を禁じられた。[235] 当時の新聞は概して温情主義であり、大衆のパニックを懸念していた。[235] 誤った情報もまた、病気の流行とともに広まった。アイルランドでは、フランダース・フィールドの集団墓地から有毒ガスが立ち上り、「風に乗って世界中に吹 き荒れている」という考えがあった。[236] また、例えばドイツ軍がバイエル社製の頭痛薬アスピリンに毒を混入したり、Uボートから毒ガスを放出したりしているという噂もあった。[237] |