心霊主義運動

Spiritualism movement

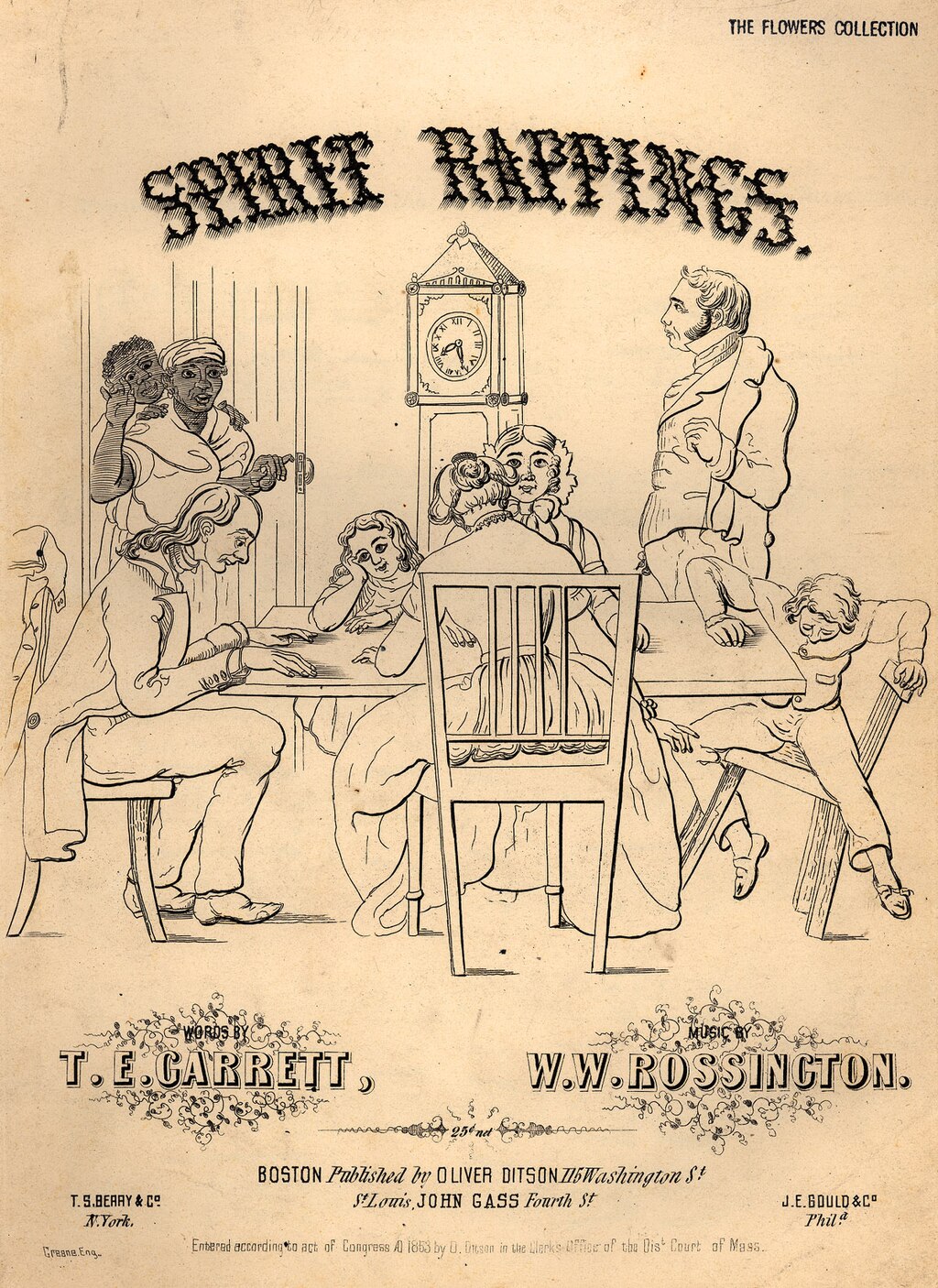

By 1853, when the popular song "Spirit Rappings" was published, spiritualism was an object of intense curiosity.

☆

スピリチュアリズム(Spiritualism)とは、19世紀から20世紀初頭にかけて流行した社会的宗教運動である。これによれば、個人の意識は死後も存続し、生者との接触が可能

とされる[1]。死後の世界、すなわち「霊界」は、スピリチュアリストにとって静的な場所ではなく、霊が相互作用と進化を続ける場と見なされる。霊との接

触が可能であること、そして霊が人間よりも進化しているという二つの信念から、スピリチュアリストは霊が道徳的・倫理的問題や神の本質について生者に助言

できると信じる。一部のスピリチュアリストは「スピリットガイド」——精神的指針を得るために頼る特定の霊——に従う。[2][3]

エマヌエル・スヴェーデンボリはスピリチュアリズムの創始者と称されることがある[4]。この運動は1840年代から1920年代にかけて発展し、特に英

語圏で最大の支持を得た[3][5]。半世紀にわたり、規範となる書物や正式な組織を持たずに繁栄し、定期刊行物、トランス状態の講師による巡回講演、野

外集会、そして熟達した霊媒師たちの布教活動を通じて結束を強めた。多くの著名なスピリチュアリストは女性であり、ほとんどの信奉者と同様に奴隷制廃止や

女性参政権といった運動を支持した[3]。1880年代後半には、霊媒による詐欺行為の告発により非公式な運動の信頼性が低下し、正式なスピリチュアリス

ト組織が出現し始めた[3]。現在、スピリチュアリズムは主に米国、カナダ、英国における様々な宗派のスピリチュアリスト教会を通じて実践されている。

| Spiritualism is a

social religious movement popular in the nineteenth and early twentieth

centuries, according to which an individual's awareness persists after

death and may be contacted by the living.[1] The afterlife, or the

"spirit world", is seen by spiritualists not as a static place, but as

one in which spirits continue to interact and evolve. These two

beliefs—that contact with spirits is possible, and that spirits are

more advanced than humans—lead spiritualists to the belief that spirits

are capable of advising the living on moral and ethical issues and the

nature of God. Some spiritualists follow "spirit guides"—specific

spirits relied upon for spiritual direction.[2][3] Emanuel Swedenborg has some claim to be the father of spiritualism.[4] The movement developed and reached its largest following from the 1840s to the 1920s, especially in English-speaking countries.[3][5] It flourished for a half century without canonical texts or formal organization, attaining cohesion through periodicals, tours by trance lecturers, camp meetings, and the missionary activities of accomplished mediums. Many prominent spiritualists were women, and like most spiritualists, supported causes such as the abolition of slavery and women's suffrage.[3] By the late 1880s the credibility of the informal movement had weakened due to accusations of fraud perpetrated by mediums, and formal spiritualist organizations began to appear.[3] Spiritualism is currently practiced primarily through various denominational spiritualist churches in the U.S., Canada and the United Kingdom. |

スピリチュアリズム(Spiritualism)とは、19世紀から20世紀初頭にかけて流行した社

会的宗教運動である。これによれば、個人の意識は死後も存続し、生者との接触が可能とされる[1]。死後の世界、すなわち「霊界」は、スピリチュアリスト

にとって静的な場所ではなく、霊が相互作用と進化を続ける場と見なされる。霊との接触が可能であること、そして霊が人間よりも進化しているという二つの信

念から、スピリチュアリストは霊が道徳的・倫理的問題や神の本質について生者に助言できると信じる。一部のスピリチュアリストは「スピリットガイド」——

精神的指針を得るために頼る特定の霊——に従う。[2][3] エマヌエル・スヴェーデンボリ(スウェーデンボルグ)はスピリチュアリズムの創始者と称されることがある[4]。この運動は1840年代から1920年代にかけて発展し、特に英 語圏で最大の支持を得た[3][5]。半世紀にわたり、規範となる書物や正式な組織を持たずに繁栄し、定期刊行物、トランス状態の講師による巡回講演、野 外集会、そして熟達した霊媒師たちの布教活動を通じて結束を強めた。多くの著名なスピリチュアリストは女性であり、ほとんどの信奉者と同様に奴隷制廃止や 女性参政権といった運動を支持した[3]。1880年代後半には、霊媒による詐欺行為の告発により非公式な運動の信頼性が低下し、正式なスピリチュアリス ト組織が出現し始めた[3]。現在、スピリチュアリズムは主に米国、カナダ、英国における様々な宗派のスピリチュアリスト教会を通じて実践されている。 |

| Beliefs Mediumship and spirits Spiritualists believe in the possibility of communication with the spirits of dead people, whom they regard as "discarnate humans". They believe that spirit mediums are gifted to carry on such communication, but that anyone may become a medium through study and practice. They believe that spirits are capable of growth and perfection, progressing through higher spheres or planes, and that the afterlife is not a static state, but one in which spirits evolve. The two beliefs—that contact with spirits is possible, and that spirits may dwell on a higher plane—lead to a third belief, that spirits can provide knowledge about moral and ethical issues, as well as about God and the afterlife. Many believers therefore speak of "spirit guides"—specific spirits, often contacted, and relied upon for worldly and spiritual guidance.[2][3] According to spiritualists, anyone may receive spirit messages, but formal communication sessions (séances) are held by mediums, who claim thereby to receive information about the afterlife.[2] Declaration of Principles Spiritualism was equated by some Christians with witchcraft. This 1865 broadsheet, published in the United States, also blamed spiritualism for causing the American Civil War. As an informal movement, spiritualism does not have a defined set of rules, but various spiritualist organizations within the United States have adopted variations on some or all of a "Declaration of Principles" developed between 1899 and 1944. In October 1899, a six article "Declaration of Principles" was adopted by the National Spiritualist Association (NSA) at a convention in Chicago, Illinois.[6] An additional two principles were added by the NSA in October 1909, at a convention in Rochester, New York.[7] Then, in October 1944, a ninth principle was adopted by the National Spiritualist Association of Churches, at a convention in St. Louis, Missouri.[citation needed] In the UK, the main organization representing spiritualism is the Spiritualists' National Union (SNU), whose teachings are based on the Seven Principles.[8] Origins Spiritualism first appeared in the 1840s in the "Burned-over District" of upstate New York, where earlier religious movements such as Millerism and Mormonism had emerged during the Second Great Awakening, although Millerism and Mormonism did not associate themselves with spiritualism. This region of New York State was an environment in which many thought direct communication with God or angels was possible, and that God would not behave harshly—for example, that God would not condemn unbaptised infants to an eternity in Hell.[2] Swedenborg and Mesmer Hypnotic séance. Painting by Swedish artist Richard Bergh, 1887. In this environment, the writings of Emanuel Swedenborg (1688–1772) and the teachings of Franz Mesmer (1734–1815) provided an example for those seeking direct personal knowledge of the afterlife. Swedenborg, who claimed to communicate with spirits while awake, described the structure of the spirit world. Two features of his view particularly resonated with the early spiritualists: first, that there is not a single Hell and a single Heaven, but rather a series of higher and lower heavens and hells; second, that spirits are intermediates between God and humans, so that the divine sometimes uses them as a means of communication.[2] Although Swedenborg warned against seeking out spirit contact, his works seem to have inspired in others the desire to do so. Swedenborg was formerly a highly regarded inventor and scientist, achieving several engineering innovations and studying physiology and anatomy. Then, "in 1741, he also began to have a series of intense mystical experiences, dreams, and visions, claiming that he had been called by God to reform Christianity and introduce a new church."[9] Mesmer did not contribute religious beliefs, but he brought a technique, later known as hypnotism, that it was claimed could induce trances and cause subjects to report contact with supernatural beings. There was a great deal of professional showmanship inherent to demonstrations of Mesmerism, and the practitioners who lectured in mid-19th-century North America sought to entertain their audiences as well as to demonstrate methods for personal contact with the divine.[2] Perhaps the best known of those who combined Swedenborg and Mesmer in a peculiarly North American synthesis was Andrew Jackson Davis, who called his system the "harmonial philosophy". Davis was a practising Mesmerist, faith healer and clairvoyant from Blooming Grove, New York. He was also strongly influenced by the socialist theories of Fourierism.[10] His 1847 book, The Principles of Nature, Her Divine Revelations, and a Voice to Mankind,[11] dictated to a friend while in a trance state, eventually became the nearest thing to a canonical work in a spiritualist movement whose extreme individualism precluded the development of a single coherent worldview.[2][3] |

信念 霊媒と霊魂 スピリチュアリストは、死者の霊魂との交信が可能だと信じている。彼らは死者を「肉体から離れた人間」と見なす。霊媒は生まれつき交信能力を持つが、誰で も学習と訓練によって霊媒になれると考える。霊魂は成長と完成が可能で、より高い領域や次元へと進み、死後の世界は静止した状態ではなく、霊魂が進化する 場だと信じる。霊との接触が可能であること、霊がより高い次元に存在し得るという二つの信念は、第三の信念へとつながる。すなわち霊は、道徳的・倫理的問 題について、また神や死後の世界について知識を提供し得るというものである。多くの信者はこのため「霊的ガイド」について語る。これは特定の霊を指し、し ばしば接触され、世俗的・霊的な導きとして頼りにされる存在である。[2][3] スピリチュアリストによれば、誰でも霊からのメッセージを受け取れるが、正式な交信会(セアンス)は霊媒によって行われ、彼らはそれによって死後の世界に関する情報を受け取ると主張する。[2] 原則宣言 スピリチュアリズムは一部のキリスト教徒によって妖術と同列視された。この1865年にアメリカで発行されたビラは、スピリチュアリズムが南北戦争を引き起こしたとも非難している。 非公式な運動として、スピリチュアリズムには明確な規則集はない。しかし米国内の様々なスピリチュアリズム団体は、1899年から1944年にかけて作成 された「原則宣言」の一部または全部を、様々な形で採用している。1899年10月、全米スピリチュアリズム協会(NSA)はイリノイ州シカゴでの大会 で、6条からなる「原則宣言」を採択した。[6] 1909年10月、ニューヨーク州ロチェスターでの大会でNSAによりさらに2つの原則が追加された。[7] その後1944年10月、ミズーリ州セントルイスでの大会で全国教会スピリチュアリズム協会により第9の原則が採択された。[出典必要] 英国では、スピリチュアリズムを代表する主要組織はスピリチュアリスト全国連合(SNU)であり、その教えは七つの原則に基づいている。[8] 起源 スピリチュアリズムは1840年代、ニューヨーク州北部の「バーンドオーバー地区」で初めて現れた。この地域では第二の大覚醒期にミラー主義やモルモン教といった宗教運動が先に生じていたが、ミラー主義やモルモン教はスピリチュアリズムとは結びついていなかった。 このニューヨーク州の地域は、神や天使との直接的な対話が可能な環境であり、神は厳しく振る舞わないと考えられていた。例えば、洗礼を受けていない幼児を永遠の地獄に落とすようなことは神はしないという考えがあった。[2] スヴェーデンボリとメスマー 催眠降霊会。スウェーデン人画家リチャード・ベルグによる絵画、1887年。 この環境下で、エマヌエル・スヴェーデンボリ(1688–1772)の著作とフランツ・メスマー(1734–1815)の教えは、死後の世界に関する直接 的な個人的知識を求める者たちにとって手本となった。スヴェーデンボリは覚醒状態で霊と交信すると主張し、霊界の構造を記述した。彼の見解のうち、初期ス ピリチュアリストの共感を特に呼んだ二つの特徴がある。第一に、地獄も天国も単一の存在ではなく、高次から低次へと連なる天界と地獄が存在するというこ と。第二に、霊魂は神と人間の中間存在であり、神が時として彼らを伝達手段として用いるということだ[2]。スヴェーデンボリは霊との接触を求めることを 戒めたが、彼の著作は他者にそうした欲求を抱かせるきっかけとなったようだ。 スヴェーデンボリは元々高く評価された発明家・科学者であり、数々の技術革新を達成し、生理学や解剖学を研究していた。その後「1741年、彼は一連の強烈な神秘体験、夢、幻視を経験し始め、神からキリスト教を改革し新たな教会を設立するよう召されたと主張した」[9]。 メスマーは宗教的信念をもたらさなかったが、後に催眠術として知られる技術をもたらした。この技術はトランス状態を誘発し、被験者に超自然的存在との接触 を報告させると主張された。メスマー主義の実演には専門的な見せ物性が内在しており、19世紀中頃の北米で講演した実践者たちは、聴衆を楽しませると同時 に、神との個人的接触の方法を示すことを目指した。[2] スヴェーデンボリとメスマーを特異な北米的統合で組み合わせた人物として最も有名なのは、アンドリュー・ジャクソン・デイヴィスである。彼は自らの体系を 「調和哲学」と呼んだ。デイヴィスはニューヨーク州ブルーミンググローブ出身の、実践的なメスマー主義者、信仰治療師、透視能力者であった。彼はフーリエ 主義の社会主義理論にも強く影響を受けていた[10]。1847年の著書『自然の原理、その神聖なる啓示、そして人類への声』[11]は、トランス状態に ある友人に口述させたもので、極端な個人主義が単一で首尾一貫した世界観の形成を阻んだスピリチュアリズム運動において、最終的に最も正典に近いものと なった[2][3]。 |

| Reform-movement links The Fox sisters Spiritualists often set March 31, 1848, as the beginning of their movement. On that date, Kate and Margaret Fox, of Hydesville, New York, reported that they had made contact with a spirit that was later claimed to be the spirit of a murdered peddler whose body was found in the house, though no record of such a person was ever found. The spirit was said to have communicated through rapping noises, audible to onlookers. The evidence of the senses appealed to practically minded Americans, and the Fox sisters became a sensation. As the first celebrity mediums, the sisters quickly became famous for their public séances in New York.[12] However, in 1888 the Fox sisters admitted that this contact with the spirit was a hoax, though shortly afterward they recanted that admission.[2][3] Amy and Isaac Post, Hicksite Quakers from Rochester, New York, had long been acquainted with the Fox family, and took the two girls into their home in the late spring of 1848. Immediately convinced of the veracity of the sisters' communications, they became early converts and introduced the young mediums to their circle of radical Quaker friends.[13] Cora L. V. Scott Paschal Beverly Randolph Consequently, many early participants in spiritualism were radical Quakers and others involved in the mid-nineteenth-century reforming movement. These reformers were uncomfortable with the more mainstream churches because those churches did little to fight slavery and even less to advance the cause of women's rights.[3] Such links with reform movements, often radically socialist, had already been prepared in the 1840s, as the example of Andrew Jackson Davis shows. After 1848, many socialists became ardent spiritualists or occultists.[14] The most popular trance lecturer prior to the American Civil War was Cora L. V. Scott (1840–1923). Young and beautiful, her appearance on stage fascinated men. Her audiences were struck by the contrast between her physical girlishness and the eloquence with which she spoke of spiritual matters, and found in that contrast support for the notion that spirits were speaking through her. Cora married four times, and on each occasion adopted her husband's last name. During her period of greatest activity, she was known as Cora Hatch.[3] Another spiritualist was Achsa W. Sprague, who was born November 17, 1827, in Plymouth Notch, Vermont. At the age of 20, she became ill with rheumatic fever and credited her eventual recovery to intercession by spirits. An extremely popular trance lecturer, she traveled about the United States until her death in 1861. Sprague was an abolitionist and an advocate of women's rights.[3] Another spiritualist and trance medium prior to the Civil War was Paschal Beverly Randolph (1825–1875), a man of mixed race, who also played a part in the abolitionist movement.[15] Nevertheless, many abolitionists and reformers held themselves aloof from the spiritualist movement; among the skeptics was abolitionist Frederick Douglass.[16] Another social reform movement with significant spiritualist involvement was the effort to improve conditions of Native Americans. Kathryn Troy writes in a study of Indian ghosts in seances: Undoubtedly, on some level spiritualists recognized the Indian spectres that appeared at seances as a symbol of the sins and subsequent guilt of the United States in its dealings with Native Americans. Spiritualists were literally haunted by the presence of Indians. But for many that guilt was not assuaged: rather, in order to confront the haunting and rectify it, they were galvanized into action. The political activism of spiritualists on behalf of Indians was thus the result of combining white guilt and fear of divine judgment with a new sense of purpose and responsibility.[17] |

改革運動の関連事項 フォックス姉妹 スピリチュアリズム運動の始まりは、しばしば1848年3月31日とされる。この日、ニューヨーク州ハイドズビルのケイトとマーガレット・フォックス姉妹 は、霊と接触したと報告した。後にその霊は、殺害された行商人の霊だと主張された。その遺体は家の中で発見されたが、そのような人格の記録は一切見つかっ ていない。その霊は、傍観者にも聞こえるノック音を通じて意思疎通を図ったと言われる。感覚的な証拠は現実的なアメリカ人の心を捉え、フォックス姉妹はセ ンセーションを巻き起こした。最初の有名霊媒師として、姉妹はニューヨークでの公開降霊会で瞬く間に名声を得た[12]。しかし1888年、フォックス姉 妹はこの霊との接触が偽装だったと認めたが、間もなくその告白を撤回した[2]。[3] ニューヨーク州ロチェスター出身のヒックス派クエーカー教徒、エイミーとアイザック・ポスト夫妻は、フォックス家と長年親交があった。夫妻は1848年春 の終わりに二人の少女を自宅に迎え入れた。夫妻は姉妹の霊媒能力の真実性を即座に確信し、初期の信者となった。そして若い霊媒師たちを、急進的なクエー カー教徒の友人たちの輪に紹介した。[13] コーラ・L・V・スコット パスカル・ベバリー・ランドルフ 結果として、スピリチュアリズムの初期参加者には急進的クエーカー教徒や19世紀中頃の改革運動に関わった者たちが多かった。これらの改革者たちは主流派 教会に違和感を抱いていた。なぜならそれらの教会は奴隷制との闘いにほとんど取り組まず、女性の権利推進にはなおさら無関心だったからだ。[3] こうした改革運動(しばしば急進的社会主義的)との結びつきは、アンドリュー・ジャクソン・デイヴィスの例が示すように、1840年代に既に準備されていた。1848年以降、多くの社会主義者が熱心なスピリチュアリストやオカルティストとなった。[14] 南北戦争前の最も人気のあるトランス・レクチャー講師は、コーラ・L・V・スコット(1840–1923)であった。若く美しい彼女の舞台上の姿は男性を 魅了した。聴衆は、彼女の少女のような肉体と霊的事柄について語る雄弁さの対比に衝撃を受け、その対比こそが霊が彼女を通して語っているという考えを裏付 けるものと見なした。コーラは四度結婚し、その度に夫の姓を名乗った。最も活動的な時期にはコーラ・ハッチとして知られていた。[3] もう一人のスピリチュアリストは、1827年11月17日にバーモント州プリマスノッチで生まれたアックスァ・W・スプレイグである。20歳の時、彼女は リウマチ熱に罹患したが、最終的に回復したのは霊の取り次ぎによるものだと主張した。非常に人気の高いトランス・レクチャー講師として、1861年に亡く なるまでアメリカ各地を巡った。スプレイグは奴隷制度廃止論者であり、女性の権利擁護者でもあった。[3] 南北戦争以前のもう一人のスピリチュアリストでトランス・メディアは、混血の男性パシュカル・ベバリー・ランドルフ(1825–1875)であった。彼も また奴隷制度廃止運動に関与した[15]。しかしながら、多くの奴隷制度廃止論者や改革派はスピリチュアリズム運動から距離を置いていた。懐疑派の中には 奴隷制度廃止論者フレデリック・ダグラスも含まれていた。[16] スピリチュアリストが深く関与したもう一つの社会改革運動は、先住民の生活改善運動であった。キャスリン・トロイは霊媒術におけるインディアン亡霊に関する研究でこう記している: 疑いなく、あるレベルではスピリチュアリストたちは、霊媒術の場で現れるインディアン亡霊を、アメリカ合衆国が先住民に対して犯した罪とその後の罪悪感の 象徴として認識していた。スピリチュアリストたちは文字通り、インディアンの存在に悩まされていた。しかし多くの人々にとって、その罪悪感は和らぐことは なかった。むしろ、その悩まされる存在と向き合い、是正するために、彼らは行動を起こすよう奮い立たされたのである。インディアンのためにスピリチュアリ ストたちが政治活動を行ったのは、白人の罪悪感と神の裁きへの恐れが、新たな目的意識と責任感と結びついた結果であった。[17] |

| Believers and skeptics In the years following the sensation that greeted the Fox sisters, demonstrations of mediumship (séances and automatic writing, for example) proved to be a profitable venture, and soon became popular forms of entertainment and spiritual catharsis. The Fox sisters earned a living this way and others followed their lead.[2][3] Showmanship became an increasingly important part of spiritualism, and the visible, audible, and tangible evidence of spirits escalated as mediums competed for paying audiences. As independent investigating commissions repeatedly established, most notably the 1887 report of the Seybert Commission,[18] fraud was widespread, and some of these cases were prosecuted in the courts.[19] Despite numerous instances of chicanery, the appeal of spiritualism was strong. Prominent in the ranks of its adherents were those grieving the death of a loved one. Many families during the time of the American Civil War had seen their men go off and never return, and images of the battlefield, produced through the new medium of photography, demonstrated that their loved ones had not only died in overwhelmingly huge numbers, but horribly as well. One well known case is that of Mary Todd Lincoln who, grieving the loss of her son, organized séances in the White House which were attended by her husband, President Abraham Lincoln.[16] The surge of Spiritualism during this time, and later during World War I, was a direct response to those massive battlefield casualties.[20] In addition, the movement appealed to reformers, who fortuitously found that the spirits favoured such causes du jour as abolition of slavery, and equal rights for women.[3] It also appealed to some who had a materialist orientation and rejected organized religion. In 1854 the utopian socialist Robert Owen was converted to spiritualism after "sittings" with the American medium Maria B. Hayden (credited with introducing spiritualism to England); Owen made a public profession of his new faith in his publication The Rational Quarterly Review and later wrote a pamphlet, "The future of the Human race; or great glorious and future revolution to be effected through the agency of departed spirits of good and superior men and women".[21] |

信者と懐疑者 フォックス姉妹がセンセーションを巻き起こした後の数年間、霊媒術の実演(例えば降霊会や自動書記)は儲かる商売となり、すぐに娯楽や精神的カタルシスの 人気形態となった。フォックス姉妹はこの方法で生計を立て、他の者たちも彼女たちの後を追った[2][3]。霊媒術においてショーマンシップはますます重 要な要素となり、霊媒師たちが有料観客を獲得するために競い合う中で、霊の存在を示す可視的・可聴的・触知的な証拠はエスカレートしていった。独立した調 査委員会が繰り返し立証したように、特に1887年のセイバート委員会報告書[18]が示す通り、詐欺は広く蔓延しており、これらの事例の一部は法廷で訴 追された。[19] 数々の不正行為が明らかになったにもかかわらず、スピリチュアリズムの魅力は衰えなかった。信奉者の中でも特に目立ったのは、愛する人の死を悲しむ者たち であった。南北戦争の時代、多くの家族は男性が戦場へ赴き、二度と戻らないのを目の当たりにした。写真という新たな媒体によって生み出された戦場の光景 は、愛する人々が膨大な数で、しかも恐ろしい死を遂げたことを示していた。よく知られた事例として、息子を失った悲しみから、メアリー・トッド・リンカー ンがホワイトハウスで降霊会を主催し、夫であるエイブラハム・リンカーン大統領も参加したことが挙げられる[16]。この時期、そして後に第一次世界大戦 中にスピリチュアリズムが急増したのは、まさにこうした戦場の大量死傷者への直接的な反応であった。[20] さらにこの運動は改革派にも訴求した。彼らは偶然にも、霊が奴隷制廃止や女性の平等権といった当時の重要課題に賛同していることを発見したのである。 [3] また、唯物論的傾向を持ち組織化された宗教を拒む者たちにも訴えかけた。1854年、ユートピア社会主義者ロバート・オーウェンは、アメリカの霊媒マリ ア・B・ヘイデン(スピリチュアリズムを英国に紹介したとされる人物)との「交霊会」を経てスピリチュアリズムに改宗した。オーウェンは自身の刊行物『理 性季刊評論』で新たな信仰を公に表明し、後に小冊子『人類の未来、あるいは善き優れた男女の亡霊の働きかけによって実現される偉大で輝かしい未来の革命』 を著した。[21] |

| A

number of scientists who investigated the phenomenon also became

converts. They included chemist and physicist William Crookes

(1832–1919),[citation needed] evolutionary biologist Alfred Russel

Wallace (1823–1913)[22][independent source needed] and physicist Sir

Oliver Lodge.[citation needed] Nobel laureate Pierre Curie was

impressed by the mediumistic performances of Eusapia Palladino and

advocated their scientific study.[23] Other prominent adherents

included journalist and pacifist William T. Stead (1849–1912)[24] and

physician and author Arthur Conan Doyle (1859–1930).[20] Doyle, who lost his son Kingsley in World War I, was also a member of the Ghost Club. Founded in London in 1862, its focus was the scientific study of alleged paranormal activities in order to prove (or refute) the existence of paranormal phenomena. Members of the club included Charles Dickens, Sir William Crookes, Sir William F. Barrett, and Harry Price.[25] The Paris séances of Eusapia Palladino were attended by an enthusiastic Pierre Curie and a dubious Marie Curie. Thomas Edison wanted to develop a "spirit phone", an ethereal device that would summon to the living the voices of the dead and record them for posterity.[26] The claims of spiritualists and others as to the reality of spirits were investigated by the Society for Psychical Research, founded in London in 1882. The society set up a Committee on Haunted Houses.[27] Prominent investigators who exposed cases of fraud came from a variety of backgrounds, including professional researchers such as Frank Podmore of the Society for Psychical Research and Harry Price of the National Laboratory of Psychical Research, and professional conjurers such as John Nevil Maskelyne. Maskelyne exposed the Davenport brothers by appearing in the audience during their shows and explaining how the trick was done. Houdini exposed the tricks of "mediums" The psychical researcher Hereward Carrington exposed fraudulent mediums' tricks, such as those used in slate-writing, table-turning, trumpet mediumship, materializations, sealed-letter reading, and spirit photography.[28] The skeptic Joseph McCabe, in his book Is Spiritualism Based on Fraud? (1920), documented many fraudulent mediums and their tricks.[29] Magicians and writers on magic have a long history of exposing the fraudulent methods of mediumship. During the 1920s, professional magician Harry Houdini undertook a well-publicised campaign to expose fraudulent mediums; he was adamant that "Up to the present time everything that I have investigated has been the result of deluded brains."[30] Other magician or magic-author debunkers of spiritualist mediumship have included Chung Ling Soo,[31] Henry Evans,[32] Julien Proskauer,[33] Fulton Oursler,[34] Joseph Dunninger,[35] and Joseph Rinn.[36] In February 1921 Thomas Lynn Bradford, in an experiment designed to ascertain the existence of an afterlife, committed suicide in his apartment by blowing out the pilot light on his heater and turning on the gas. After that date, no further communication from him was received by an associate whom he had recruited for the purpose.[37] |

こ

の現象を調査した科学者の多くもまた、その信奉者となった。化学者兼物理学者ウィリアム・クルックス(1832–1919)、[出典必要]進化生物学者ア

ルフレッド・ラッセル・ウォレス(1823–1913)[22][独立した出典が必要]、物理学者サー・オリバー・ロッジらが含まれる。ノーベル賞受賞者

ピエール・キュリーは、霊媒エウサピア・パラディーノの霊媒行為に感銘を受け、その科学的調査を提唱した。他の著名な支持者には、ジャーナリストで平和主

義者のウィリアム・T・ステッド(1849–1912)や、医師で作家アーサー・コナン・ドイル(1859–1930)がいた。[20] 第一次世界大戦で息子キングズリーを失ったドイルもゴーストクラブの会員だった。1862年にロンドンで設立されたこのクラブは、超常現象の存在を証明 (あるいは反証)するため、超常現象とされる活動の科学的研究を目的としていた。クラブのメンバーにはチャールズ・ディケンズ、ウィリアム・クルックス 卿、ウィリアム・F・バレット卿、ハリー・プライスらが名を連ねた[25]。ユーサピア・パラディーノのパリでの降霊会には、熱心なピエール・キュリーと 懐疑的なマリー・キュリーが出席した。トーマス・エジソンは「霊電話」の開発を望んでいた。これは死者の声を現世に呼び寄せ、後世のために記録する幽玄な 装置である。[26] 霊魂の実在性に関するスピリチュアリストらの主張は、1882年にロンドンで設立された心霊研究協会によって調査された。同協会は心霊現象調査委員会を設置した。[27] 詐欺事件を暴いた著名な調査者たちは様々な経歴を持っていた。心霊研究協会のフランク・ポッドモアや国民心霊研究所のハリー・プライスといった専門研究者 から、ジョン・ネヴィル・マスクリンのようなプロの魔術師までいた。マスクリンはダベンポート兄弟のショーに観客として現れ、手口の解説を行うことで彼ら の詐欺を暴いた。 フーディーニは「霊媒師」のトリックを暴いた 心霊研究家のヘレワード・キャリントンは、スレート書き、テーブル回転、トランペット霊媒、物質化現象、封印書簡解読、霊写真など、詐欺的霊媒師のトリッ クを暴露した。[28] 懐疑論者ジョセフ・マッケイブは著書『スピリチュアリズムは詐欺か?』(1920年)で、多くの詐欺的霊媒師とその手口を記録した。[29] 呪術師や呪術に関する著述家たちは、霊媒の詐欺的手法を暴く長い歴史を持つ。1920年代、プロの呪術師ハリー・フーディーニは詐欺的霊媒を暴露する大々 的なキャンペーンを展開した。彼は「これまで私が調査したものは全て、錯覚に陥った脳みその産物だ」と断言した。[30] 霊媒術を暴いた他の魔術師や呪術的著作家には、チョン・リン・スー[31]、ヘンリー・エヴァンス[32]、ジュリアン・プロスカウアー[33]、フルト ン・アースラー[34]、ジョセフ・ダニンジャー[35]、ジョセフ・リンらがいる。[36] 1921年2月、トーマス・リン・ブラッドフォードは死後の世界の存在を確認する実験として、自宅アパートで暖房器具のパイロットランプを消しガスを開放して自殺した。その後、彼がこの目的のために勧誘した協力者からは、彼からの連絡は一切届かなかった。[37] |

| Unorganized movement Middle-class Chicago women discuss spiritualism (1906) The movement quickly spread throughout the world; though only in the United Kingdom did it become as widespread as in the United States.[5] Spiritualist organizations were formed in America and Europe, such as the London Spiritualist Alliance, which published a newspaper called The Light, featuring articles such as "Evenings at Home in Spiritual Séance", "Ghosts in Africa" and "Chronicles of Spirit Photography", advertisements for "mesmerists" and patent medicines, and letters from readers about personal contact with ghosts.[38] In Britain, by 1853, invitations to tea among the prosperous and fashionable often included table-turning, a type of séance in which spirits were said to communicate with people seated around a table by tilting and rotating the table. By 1897, spiritualism was said to have more than eight million followers in the United States and Europe,[39] mostly drawn from the middle and upper classes. Spiritualism was mainly a middle- and upper-class movement, and especially popular with women. American spiritualists would meet in private homes for séances, at lecture halls for trance lectures, at state or national conventions, and at summer camps attended by thousands. Among the most significant of the camp meetings were Camp Etna, in Etna, Maine; Onset Bay Grove, in Onset, Massachusetts; Lily Dale, in western New York State;[40] Camp Chesterfield, in Indiana; the Wonewoc Spiritualist Camp, in Wonewoc, Wisconsin; and Lake Pleasant, in Montague, Massachusetts. In founding camp meetings, the spiritualists appropriated a form developed by U.S. Protestant denominations in the early nineteenth century. Spiritualist camp meetings were located most densely in New England, but were also established across the upper Midwest. Cassadaga, Florida, is the most notable spiritualist camp meeting in the southern states.[2][3][41] A number of spiritualist periodicals appeared in the nineteenth century, and these did much to hold the movement together. Among the most important were the weeklies the Banner of Light (Boston), the Religio-Philosophical Journal (Chicago), Mind and Matter (Philadelphia), the Spiritualist (London), and the Medium (London). Other influential periodicals were the Revue Spirite (France), Le Messager (Belgium), Annali dello Spiritismo (Italy), El Criterio Espiritista (Spain), and the Harbinger of Light (Australia). By 1880, there were about three dozen monthly spiritualist periodicals published around the world.[42] These periodicals differed a great deal from one another, reflecting the great differences among spiritualists. Some, such as the British Spiritual Magazine were Christian and conservative, openly rejecting the reform currents so strong within spiritualism. Others, such as Human Nature, were pointedly non-Christian and supportive of socialism and reform efforts. Still others, such as the Spiritualist, attempted to view spiritualist phenomena from a scientific perspective, eschewing discussion on both theological and reform issues.[43] Books on the supernatural were published for the growing middle class, such as 1852's Mysteries, by Charles Elliott, which contains "sketches of spirits and spiritual things", including accounts of the Salem witch trials, the Lane ghost, and the Rochester rappings.[44] The Night Side of Nature, by Catherine Crowe, published in 1853, provided definitions and accounts of wraiths, doppelgängers, apparitions and haunted houses.[45] Mainstream newspapers treated stories of ghosts and haunting as they would any other news story. An account in the Chicago Daily Tribune in 1891, "sufficiently bloody to suit the most fastidious taste", tells of a house believed to be haunted by the ghosts of three murder victims seeking revenge against their killer's son, who was eventually driven insane. Many families, "having no faith in ghosts", thereafter moved into the house, but all soon moved out again.[46] In the 1920s many "psychic" books were published of varied quality. Such books were often based on excursions initiated by the use of Ouija boards. A few of these popular books displayed unorganized spiritualism, though most were less insightful.[47] The movement was extremely individualistic, with each person relying on his or her own experiences and reading to discern the nature of the afterlife. Organisation was therefore slow to appear, and when it did it was resisted by mediums and trance lecturers. Most members were content to attend Christian churches, and particularly universalist churches harboured many spiritualists. As the spiritualism movement began to fade, partly through the publicity of fraud accusations and partly through the appeal of religious movements such as Christian science, the Spiritualist Church was organised. This church can claim to be the main vestige of the movement left today in the United States.[2][3] |

組織化されていない運動 シカゴの中流階級の女性たちがスピリチュアリズムについて議論する(1906年) この運動は瞬く間に世界中に広がった。ただし、アメリカほど広く普及したのはイギリスだけだった。[5] アメリカやヨーロッパではスピリチュアリズム団体が結成された。例えばロンドン・スピリチュアリズム同盟は『ザ・ライト』という新聞を発行し、「霊媒セッ ションの家庭での夕べ」「アフリカの幽霊」「霊写真記録」といった記事、「催眠術師」や特許医薬品の広告、読者からの幽霊との個人的な人格接触に関する手 紙などを掲載した。[38] 1853年までに英国では、富裕層や上流階級の間で茶会に招かれる際、テーブルターニングがしばしば行われた。これはテーブルを傾け回転させることで、周 囲に座る人民と霊が交信すると言われる霊媒術の一種である。1897年までに、スピリチュアリズムは米国と欧州で800万人以上の信者を獲得したと言われ る[39]。その大半は中産階級と上流階級から集まった。 スピリチュアリズムは主に中流・上流階級の運動であり、特に女性に人気があった。アメリカのスピリチュアリストたちは、霊媒会のためには私邸で、トランス 状態の講義のためには講堂で、州や国民規模の大会では会場で、そして数千人が参加するサマーキャンプで集まった。最も重要なキャンプ集会には、メイン州エ トナの「キャンプ・エトナ」、マサチューセッツ州オンセットの「オンセット・ベイ・グローブ」、ニューヨーク州西部の「リリー・デイル」、インディアナ州 の「キャンプ・チェスターフィールド」、ウィスコンシン州ウォネウォックの「ウォネウォック・スピリチュアリズム・キャンプ」、マサチューセッツ州モンタ ギューの「レイク・プレザント」があった。キャンプ集会を創設するにあたり、スピリチュアリストたちは19世紀初頭に米国プロテスタント諸派が発展させた 形式を流用した。スピリチュアリストのキャンプ集会はニューイングランド地方に最も密集して存在したが、中西部北部全域にも設立された。フロリダ州カサダ ガは南部諸州における最も著名なスピリチュアリストのキャンプ集会である[2][3]。[41] 19世紀には数多くのスピリチュアリズム系定期刊行物が登場し、これらは運動の結束に大きく寄与した。最も重要な週刊誌としては、『光の旗』(ボスト ン)、『宗教哲学ジャーナル』(シカゴ)、『心と物質』(フィラデルフィア)、『スピリチュアリスト』(ロンドン)、『メディアム』(ロンドン)が挙げら れる。その他の影響力のある定期刊行物には、『霊学レビュー』(フランス)、『メッサジェ』(ベルギー)、『スピリチュアリズム年鑑』(イタリア)、『ス ピリチュアリズムの基準』(スペイン)、『光の先駆者』(オーストラリア)があった。1880年までに、世界中で約30種類の月刊スピリチュアリズム誌が 発行されていた。[42] これらの雑誌は互いに大きく異なり、スピリチュアリスト間の大きな差異を反映していた。例えば『ブリティッシュ・スピリチュアル・マガジン』のようなもの はキリスト教的で保守的であり、スピリチュアリズム内に強い改革潮流を公然と拒絶した。一方『ヒューマン・ネイチャー』のようなものは明らかに非キリスト 教的で、社会主義や改革運動を支持した。さらに『スピリチュアリスト』のようなものは、神学的議論や改革問題の議論を避けつつ、科学的視点からスピリチュ アリズム現象を捉えようとした。[43] 超自然現象に関する書籍は、成長する中産階級向けに刊行された。例えば1852年のチャールズ・エリオット著『神秘』には「霊と霊的な事象のスケッチ」が 収録され、セイラム妖術師裁判、レーン家の幽霊、ロチェスターのノック現象などの記録が含まれている。[44] キャサリン・クロウの『自然の暗黒面』(1853年刊)は、亡霊、ドッペルゲンガー、幻影、幽霊屋敷の定義と事例を提供した。[45] 主流紙は幽霊や心霊現象の話を、他のニュース記事と同様に扱った。1891年のシカゴ・デイリー・トリビューン紙の記事は「最も気難しい趣味にも合うほど 血なまぐさい」内容で、殺人被害者3人の亡霊が復讐を求めて現れるとされる家について記している。被害者の亡霊は殺害者の息子を追い詰め、最終的にその息 子を狂気に追い込んだという。 その後「幽霊を信じない」多くの家族がその家に引っ越したが、皆すぐにまた出て行った。[46] 1920年代には質が様々だった「超能力」本が多数出版された。こうした本はしばしばウィジャボードを使った探索を基にしていた。人気本の中にはまとまりのないスピリチュアリズムを示すものもあったが、大半は洞察に欠けていた。[47] この運動は極めて個人主義的であり、各人格が自身の経験と読書に依拠して死後の世界の性質を見極めていた。そのため組織化は遅く、実現した際には霊媒師や トランス状態の講師たちから抵抗を受けた。大多数の信者はキリスト教教会に通うことに満足しており、特にユニヴァーサリスト教会には多くのスピリチュアリ ストが身を寄せていた。 スピリチュアリズム運動が衰退し始めたのは、詐欺疑惑の公表やキリスト教科学などの宗教運動の台頭が要因だった。そうした中でスピリチュアリズム教会が組織化された。この教会は、今日アメリカに残る同運動の主要な遺構と言えるだろう。[2][3] |

| Other mediums Emma Hardinge Britten London-born Emma Hardinge Britten (1823–99) moved to the United States in 1855 and was active in spiritualist circles as a trance lecturer and organiser. She is best known as a chronicler of the movement's spread, especially in her 1884 Nineteenth Century Miracles: Spirits and Their Work in Every Country of the Earth, and her 1870 Modern American Spiritualism, a detailed account of claims and investigations of mediumship beginning with the earliest days of the movement. William Stainton Moses (1839–92) was an Anglican clergyman who, in the period from 1872 to 1883, filled 24 notebooks with automatic writing, much of which was said to describe conditions in the spirit world. However, Frank Podmore was skeptical of his alleged ability to communicate with spirits and Joseph McCabe described Moses as a "deliberate impostor", suggesting his apports and all of his feats were the result of trickery.[48][49] Eusapia Palladino (1854–1918) was an Italian spiritualist medium from the slums of Naples who made a career touring Italy, France, Germany, Britain, the United States, Russia and Poland. Palladino was said by believers to perform spiritualist phenomena in the dark: levitating tables, producing apports, and materializing spirits. On investigation, all these things were found to be products of trickery.[50][51] The British medium William Eglinton (1857–1933) claimed to perform spiritualist phenomena such as movement of objects and materializations. All of his feats were exposed as tricks.[52][53] The Bangs Sisters, Mary "May" E. Bangs (1862–1917) and Elizabeth "Lizzie" Snow Bangs (1859–1920), were two spiritualist mediums based in Chicago, who made a career out of painting the dead or "spirit portraits". Mina Crandon (1888–1941), a spiritualist medium in the 1920s, was known for producing an ectoplasm hand during her séances. The hand was later exposed as a trick when biologists found it to be made from a piece of carved animal liver.[54] In 1934, the psychical researcher Walter Franklin Prince described the Crandon case as "the most ingenious, persistent, and fantastic complex of fraud in the history of psychic research."[55] Helen Duncan The American voice medium Etta Wriedt (1859–1942) was exposed as a fraud by the physicist Kristian Birkeland when he discovered that the noises produced by her trumpet were caused by chemical explosions induced by potassium and water and in other cases by lycopodium powder.[56] Another well-known medium was the Scottish materialization medium Helen Duncan (1897–1956). In 1928 photographer Harvey Metcalfe attended a series of séances at Duncan's house and took flash photographs of Duncan and her alleged "materialization" spirits, including her spirit guide "Peggy".[57] The photographs revealed the "spirits" to have been fraudulently produced, using dolls made from painted papier-mâché masks, draped in old sheets.[58] Duncan was later tested by Harry Price at the National Laboratory of Psychical Research; photographs revealed Duncan's ectoplasm to be made from cheesecloth, rubber gloves, and cut-out heads from magazine covers.[59][60] |

その他の霊媒師 エマ・ハーディンジ・ブリテン ロンドン生まれのエマ・ハーディンジ・ブリテン(1823–99)は1855年にアメリカへ移住し、トランス状態の講演者および組織者としてスピリチュア リズム界で活動した。彼女は特に1884年の『19世紀の奇跡:地球上のあらゆる国における霊とその働き』や、1870年の『現代アメリカ霊媒術』におい て、この運動の広がりを記録した人物として最もよく知られている。後者は運動の初期段階から始まる霊媒能力の主張と調査の詳細な記録である。 ウィリアム・ステイントン・モーゼス(1839–92)は英国国教会の聖職者で、1872年から1883年にかけて24冊のノートに自動筆記を記した。そ の多くは霊界の状況を記述したものとされた。しかしフランク・ポッドモアは彼の霊との交信能力を疑い、ジョセフ・マッケイブはモーゼスを「熟議な詐欺師」 と評し、彼のアポート現象や全ての能力は手品によるものだと示唆した。 エウサピア・パラディーノ(1854–1918)はナポリのスラム出身のイタリア人スピリチュアリスト霊媒師で、イタリア、フランス、ドイツ、イギリス、 アメリカ、ロシア、ポーランドを巡業して生計を立てた。信奉者によれば、パラディーノは暗闇の中で霊現象を起こしたと言われる:テーブルの浮遊、アポート の出現、霊体の物質化などだ。調査の結果、これら全てが手品の産物であることが判明した。[50][51] 英国の霊媒師ウィリアム・エグリントン(1857–1933)は、物体の移動や物質化といったスピリチュアリズム現象を実演すると主張した。彼の業は全て手品として暴かれた。[52][53] バングス姉妹、すなわちメアリー・「メイ」・E・バングス(1862–1917)とエリザベス・「リジー」・スノー・バングス(1859–1920)は、 シカゴを拠点とした二人のスピリチュアリズム霊媒師であり、死者の肖像画、すなわち「霊の肖像画」を描くことで生計を立てていた。 ミナ・クランドン(1888–1941)は1920年代の霊媒師で、降霊会中にエクトプラズムの手を出現させることで知られていた。この手は後に、生物学 者によって動物の肝臓を彫刻した偽造品であることが暴かれた[54]。1934年、超心理学者ウォルター・フランクリン・プリンスはクランドン事件を「超 心理研究史上最も巧妙で執拗かつ幻想的な詐欺の複合体」と評した[55]。 ヘレン・ダンカン アメリカの音声霊媒エッタ・ヴリート(1859–1942)は、物理学者クリスチャン・ビルケランドによって詐欺師と暴かれた。ビルケランドは、彼女のト ランペットから発せられる音が、カリウムと水による化学爆発、あるいはリコポディウム粉末によって引き起こされていることを発見したのである。[56] もう一人の有名な霊媒師は、スコットランドの物質化霊媒師ヘレン・ダンカン(1897–1956)である。1928年、写真家ハーヴェイ・メトカーフはダ ンカンの自宅で行われた一連の降霊会に参加し、ダンカンと彼女の「物質化」した霊たち、そして彼女の霊的ガイド「ペギー」のフラッシュ写真を撮影した。 [57] 写真からは、これらの「霊」が偽造されたものであることが明らかになった。それは、ペイントを施した紙粘土の仮面で作られた人形に、古いシーツをまとわせ ていたのである。[58] ダンカンは後に、ハリー・プライスによって国民超心理研究所で検証された。写真からは、ダンカンのエクトプラズムが、チーズクロス、ゴム手袋、雑誌の表紙 から切り抜いた頭部で作られていたことが判明した。[59][60] |

| Evolution Spiritualists reacted with an uncertainty to the theories of evolution in the late 19th and early 20th century. Broadly speaking the concept of evolution fitted the spiritualist thought of the progressive development of humanity. At the same time, however, the belief in the animal origins of humanity threatened the foundation of the immortality of the spirit, for if humans had not been created by God, it was scarcely plausible that they would be specially endowed with spirits. This led to spiritualists embracing spiritual evolution.[61] The spiritualists' view of evolution did not stop at death. Spiritualism taught that after death spirits progressed to spiritual states in new spheres of existence. According to spiritualists, evolution occurred in the spirit world "at a rate more rapid and under conditions more favourable to growth" than encountered on earth.[62] In a talk at the London Spiritualist Alliance, John Page Hopps (1834–1911) supported both evolution and spiritualism. Hopps claimed humanity had started off imperfect "out of the animal's darkness" but would rise into the "angel's marvellous light". Hopps claimed humans were not fallen but rising creatures and that after death they would evolve on a number of spheres of existence to perfection.[62] Theosophy is in opposition to the spiritualist interpretation of evolution. Theosophy teaches a metaphysical theory of evolution mixed with human devolution. Spiritualists do not accept the devolution of the theosophists. To theosophy, humanity starts in a state of perfection (see Golden age) and falls into a process of progressive materialization (devolution), developing the mind and losing the spiritual consciousness. After the gathering of experience and growth through repeated reincarnations humanity will regain the original spiritual state, which is now one of self-conscious perfection. Theosophy and spiritualism were both very popular metaphysical schools of thought especially in the early 20th century and thus were always clashing in their different beliefs. Madame Blavatsky was critical of spiritualism; she distanced theosophy from spiritualism as far as she could and allied herself with eastern occultism.[63] Gerald Massey One medium who rejected evolution was Cora L. V. Scott; she dismissed evolution in her lectures and instead supported a type of pantheistic spiritualism.[64] The spiritualist Gerald Massey wrote that Darwin's theory of evolution was incomplete.[65] Alfred Russel Wallace believed qualitative novelties could arise through the process of spiritual evolution, in particular the phenomena of life and mind. Wallace attributed these novelties to a supernatural agency.[66] Later in his life, Wallace was an advocate of spiritualism and believed in an immaterial origin for the higher mental faculties of humans; he believed that evolution suggested that the universe had a purpose, and that certain aspects of living organisms are not explainable in terms of purely materialistic processes, in a 1909 magazine article entitled "The World of Life", which he later expanded into a book of the same name.[67] Wallace argued in his 1911 book World of Life for a spiritual approach to evolution and described evolution as "creative power, directive mind and ultimate purpose". Wallace believed natural selection could not explain intelligence or morality in the human being so suggested that non-material spiritual forces accounted for these. Wallace believed the spiritual nature of humanity could not have come about by natural selection alone, the origins of the spiritual nature must originate "in the unseen universe of spirit".[68][69] Oliver Lodge also promoted a version of spiritual evolution in his books Man and the Universe (1908), Making of Man (1924) and Evolution and Creation (1926). The spiritualist element in the synthesis was most prominent in Lodge's 1916 book Raymond, or Life and Death which revived a large interest for the public in the paranormal.[70] Allan Kardec promoted a version of spiritualism, Spiritism, which combined spiritual evolution with reincarnation, popularized by French romantic socialists.[71][72] Spiritism also established a peculiar relationship with the philosophy of Positivism.[73] While Positivism rejected theological and metaphysical explanations, valuing only empirical and scientific knowledge, Kardec sought to integrate this vision with the belief in the existence of the spirit and in communication with the dead.[72] Thus, Spiritism presented itself as a "Positive Faith", attempting to reconcile the rational and investigative method of Positivism with the belief in the immortality of the soul and in reincarnation.[74] Kardec appropriated the scientific language of the time to give legitimacy to his doctrine, structuring it as a kind of "spiritual science" that offered evidence of life after death and promoted a reforming morality in a context of social and religious crisis in the 19th century.[75] After the 1920s Main articles: Spiritualist Church, Spiritualists' National Union, Survivalism (life after death), and Spiritualist Association of Great Britain After the 1920s, spiritualism evolved in three different directions, all of which exist today. |

進化論 19世紀末から20世紀初頭にかけて、スピリチュアリストたちは進化論に対して不確かな反応を示した。大まかに言えば、進化の概念は人類の漸進的発展とい うスピリチュアリストの思想に合致していた。しかし同時に、人類が動物に起源を持つという信念は、霊の不滅という基盤を脅かすものであった。なぜなら、も し人間が神によって創造されなかったならば、彼らが特別に霊を授けられているとは到底考えられないからである。このためスピリチュアリストたちは霊的進化 論を受け入れたのである。[61] スピリチュアリストの進化観は死で終わらなかった。スピリチュアリズムは、死後、霊魂が新たな存在領域において霊的状態へと進化すると教えた。スピリチュアリストによれば、霊界における進化は「地上よりも速い速度で、かつ成長に有利な条件下で」起こるという。[62] ロンドン・スピリチュアリズム同盟での講演で、ジョン・ページ・ホップス(1834–1911)は進化論とスピリチュアリズムの両方を支持した。ホップス は人類が「動物の闇」から不完全な状態で始まったが、「天使の驚くべき光」へと昇華すると主張した。ホップスは人間は堕落した存在ではなく上昇する存在で あり、死後、複数の存在領域で進化を遂げて完全なる境地に至ると述べた。[62] 神智学はスピリチュアリズムの進化解釈とは対立する。神智学は人間の退化を伴う形而上学的進化論を教える(ミヘ)。スピリチュアリストは神智学者の退化説 を受け入れない。神智学によれば、人類は完全な状態(黄金時代参照)から始まり、次第に物質化(退化)する過程に陥り、知性を発達させつつ霊的意識を失っ ていく。繰り返される転生を通じて経験を集積し成長した後、人類は本来の霊的状態、すなわち自己意識的な完全性を取り戻すのだ。 神智学とスピリチュアリズムは、特に20世紀初頭に非常に人気のある形而上学的な思想流派であり、異なる信念ゆえに常に対立していた。ブラヴァツキー夫人 はスピリチュアリズムを批判し、可能な限り神智学をスピリチュアリズムから距離を置き、東洋のオカルティズムと結びついた[63]。 ジェラルド・マッセイ 進化論を拒否した霊媒の一人がコーラ・L・V・スコットである。彼女は講演で進化論を退け、代わりに一種の汎神論的スピリチュアリズムを支持した[64]。スピリチュアリストのジェラルド・マッセイは、ダーウィンの進化論は不完全だと記している[65]。 アルフレッド・ラッセル・ウォレスは、特に生命と精神の現象において、質的な新奇性が精神的進化の過程を通じて生じ得ると信じていた。ウォレスはこれらの 新奇性を超自然的な作用に帰した。[66] ウォレスは晩年、スピリチュアリズムの提唱者となり、人間の高度な精神能力は非物質的な起源を持つと信じた。彼は進化論が宇宙に目的があることを示唆し、 生物の特定の側面は純粋に物質的な過程では説明できないと考えた。これは1909年の雑誌記事「生命の世界」で述べられ、後に同名の書籍に発展した。 [67] ウォレスは1911年の著書『生命の世界』で、進化に対する精神的アプローチを主張し、進化を「創造力、指導的知性、究極の目的」と表現した。ウォレスは 自然淘汰では人間の知性や道徳性を説明できないと考え、これらは非物質的な精神的力によって説明されるべきだと示唆した。ウォレスは、人類の精神的性質は 自然淘汰だけでは生じ得ず、その起源は「目に見えない精神の宇宙」に由来すると信じていた。[68][69] オリバー・ロッジも著書『人間と宇宙』(1908年)、『人間の形成』(1924年)、『進化と創造』(1926年)において、一種の精神的進化論を提唱 した。この統合理論におけるスピリチュアリズム的要素は、1916年の著書『レイモンド、あるいは生と死』で最も顕著であり、超常現象に対する大衆の関心 を再び喚起した。[70] アラン・カルデックはスピリチュアリズムの一形態であるスピリチュアリズムを提唱した。これは霊的進化と輪廻転生を組み合わせたもので、フランスのロマン 主義的社会主義者によって普及した。[71][72] スピリチュアリズムは実証主義の哲学とも特異な関係を築いた。[73] 実証主義が神学的・形而上学的説明を排し、経験的・科学的知識のみを重視する一方で、カルデックはこの思想と霊の存在・死者との交信を信じる信念を統合し ようとした。[72] こうしてスピリチュアリズムは「実証的信仰」を標榜し、実証主義の合理的・探究的方法と、魂の不滅や輪廻転生への信仰との調和を図ったのである。[74] カルデックは当時の科学的言語を借用して自らの教義に正当性を与え、19世紀の社会的・宗教的危機の文脈において死後の生命の証拠を提供し、改革的な道徳 を推進する一種の「霊的科学」として体系化した。[75] 1920年代以降 主な記事:スピリチュアリズム教会、スピリチュアリズム全国連合、サバイバル主義(死後の生命)、英国スピリチュアリズム協会 1920年代以降、スピリチュアリズムは三つの異なる方向へ進化し、いずれも今日まで存続している。 |

| Syncretism The first of these continued the tradition of individual practitioners, organised in circles centered on a medium and clients, without any hierarchy or dogma. Already by the late 19th century spiritualism had become increasingly syncretic, a natural development in a movement without central authority or dogma.[3] Today, among these unorganised circles, spiritualism is similar to the new age movement. However, theosophy, with its inclusion of Eastern religion, astrology, ritual magic and reincarnation, is an example of a closer precursor of the 20th-century new age movement.[76] Today's syncretic spiritualists are quite heterogeneous in their beliefs regarding issues such as reincarnation or the existence of God. Some appropriate new age and neo-pagan beliefs, while others call themselves "Christian spiritualists", continuing with the tradition of cautiously incorporating spiritualist experiences into their Christian faith. Spiritualist art Main article: Spiritualist art Spiritualism also influenced art, having a pervasive influence on artistic consciousness, with spiritualist art having a huge impact on what became modernism and therefore art today.[77] Spiritualism also inspired the pioneering abstract art of Vasily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, Kasimir Malevich, Hilma af Klint, Georgiana Houghton,[78] and František Kupka.[79] Spiritualist church Main articles: Spiritualist church, Spiritualists' National Union, Spiritualist Association of Great Britain, and Spiritual church movement The second direction taken has been to adopt formal organization, patterned after Christian denominations, with established liturgies and a set of seven principles, and training requirements for mediums. In the United States the spiritualist churches are primarily affiliated either with the National Spiritualist Association of Churches or the loosely allied group of denominations known as the spiritual church movement; in the U.K. the predominant organization is the Spiritualists' National Union, founded in 1890.[citation needed] Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes Formal education in spiritualist practice emerged in 1920s, with organizations like the William T. Stead Center in Chicago, Illinois, and continue today with the Arthur Findlay College at Stansted Hall in England, and the Morris Pratt Institute in Wisconsin, United States.[citation needed] Diversity of belief among organized spiritualists has led to a few schisms, the most notable occurring in the U.K. in 1957 between those who held the movement to be a religion sui generis (of its own with unique characteristics), and a minority who held it to be a denomination within Christianity. In the United States, this distinction can be seen between the less Christian organization, the National Spiritualist Association of Churches, and the more Christian spiritual church movement.[citation needed] The practice of organized spiritualism today resembles that of any other religion, having discarded most showmanship, particularly those elements resembling the conjurer's art. There is thus a much greater emphasis on "mental" mediumship and an almost complete avoidance of the apparently miraculous "materializing" mediumship that so fascinated early believers such as Arthur Conan Doyle.[80] Psychical research Main article: Parapsychology Already as early as 1882, with the founding of the Society for Psychical Research (SPR), parapsychologists emerged to investigate spiritualist claims.[81] The SPR's investigations into spiritualism exposed many fraudulent mediums which contributed to the decline of interest in physical mediumship.[82] Recognition Spiritualism and its belief system were affirmed as covered by the Employment Equality Regulations 2003 at the United Kingdom Employment Appeal Tribunal in 2009.[83] |

シンクレティズム これらのうち最初のものは、個人実践者の伝統を継承し、霊媒と依頼者を中心としたサークルで組織され、いかなる階層構造や教義も持たなかった。19世紀後 半にはすでにスピリチュアリズムはますます折衷的になっており、中央権威や教義を持たない運動における自然な発展であった。[3] 今日、こうした非組織的なサークルにおけるスピリチュアリズムはニューエイジ運動に類似している。しかし、東洋宗教・占星術・儀礼呪術・輪廻転生を取り込 んだ神智学は、20世紀のニューエイジ運動より近い先駆例と言える。[76] 現代の折衷的スピリチュアリストは、輪廻転生や神の存在といった問題に関する信念が極めて多様である。ニューエイジやネオ・ペイガニズムの思想を取り入れ る者もいれば、「キリスト教スピリチュアリスト」を名乗り、スピリチュアリズムの体験を慎重にキリスト教信仰に取り入れる伝統を継承する者もいる。 スピリチュアリスト芸術 詳細記事: スピリチュアリスト芸術 スピリチュアリズムは芸術にも影響を与え、芸術的意識に広範な影響を及ぼした。スピリチュアリスト芸術は、後にモダニズムとなり、今日の芸術へと発展する過程に多大な影響を与えたのである。[77] スピリチュアリズムはまた、ワシリー・カンディンスキー、ピート・モンドリアン、カジミール・マレーヴィチ、ヒルマ・アフ・クリント、ジョージアナ・ホートン[78]、フランティシェク・クプカ[79]といった先駆的な抽象芸術にも影響を与えた。 スピリチュアリズム教会 主な記事:スピリチュアリズム教会、スピリチュアリズム国民連合、英国スピリチュアリズム協会、スピリチュアル教会運動 第二の方向性は、キリスト教の宗派を模した正式な組織化を採用するもので、確立された典礼と七つの原則、霊媒師の養成要件を備えている。アメリカではスピ リチュアリズム教会は主に、全国スピリチュアリズム教会協会か、スピリチュアル教会運動として知られる緩やかな宗派連合のいずれかに所属している。英国で は1890年に設立されたスピリチュアリズム国民連合が主要組織である。[出典が必要] シャーロック・ホームズの作者、アーサー・コナン・ドイル スピリチュアリズム実践の正式な教育は1920年代に現れ、イリノイ州シカゴのウィリアム・T・ステッド・センターなどの組織が設立された。現在もイング ランドのスタンステッド・ホールにあるアーサー・フィンドレイ・カレッジや、アメリカ合衆国ウィスコンシン州のモリス・プラット・インスティテュートで継 続されている。[出典が必要] 組織化されたスピリチュアリスト間の信仰の多様性は、いくつかの分裂を引き起こした。最も顕著なのは1957年に英国で起きた分裂で、運動を独自の特性を 持つ宗教(宗教として独自の性質を持つ)と考える派と、キリスト教内の宗派と考える少数派との対立であった。アメリカでは、この区別が、キリスト教的色彩 の薄い組織である国民スピリチュアリズム教会協会と、よりキリスト教色の強いスピリチュアル教会運動との間に見られる。[出典が必要] 今日の組織化されたスピリチュアリズムの実践は、他の宗教と同様の様相を呈している。特に手品師の技に似た要素を含む、大げさな見せ物はほとんど廃れた。 したがって「精神的」な霊媒能力への重視が格段に高まり、アーサー・コナン・ドイルら初期信者を魅了した「物質化」霊媒能力のような奇跡的現象はほぼ完全 に回避されている。[80] 心霊研究 詳細記事: 超心理学 早くも1882年、心霊研究協会(SPR)の設立と共に、超心理学者がスピリチュアリズムの主張を検証するために登場した。[81] SPRによるスピリチュアリズム調査は多くの詐欺的霊媒を暴き、物質的霊媒術への関心の衰退に寄与した。[82] 法的承認 スピリチュアリズムとその信仰体系は、2009年に英国雇用上訴裁判所において、2003年雇用平等規則の適用対象として認められた。[83] |

| Dowsing List of channelers List of spiritualist organizations New religious movement Spiritualism in fiction |

Dowsing List of channelers List of spiritualist organizations New religious movement Spiritualism in fiction |

| Works cited Albanese, Catherine L. (2007). A Republic of Mind and Spirit: A Cultural History of American Metaphysical Religion. New Haven/London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300136159. Alvarado, Carlos S.; Biondi, Massimo; Kramer, Wim (2006). "Historical Notes on Psychic Phenomena in Specialised Journals". European Journal of Parapsychology. 21 (1): 58–87. Bassett, J. (1990). 100 Years of National Spiritualism. The Headquarters Publishing Co.[ISBN missing] Braude, Ann (2001). Radical Spirits: Spiritualism and Women's Rights in Nineteenth-Century America (2nd ed.). Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0253215024. OCLC 47785582. Britten, Emma Hardinge (1884). Nineteenth Century Miracles: Spirits and Their Work in Every Country of the Earth. New York: William Britten. ISBN 978-0766162907. Butt, G. Baseden (2013) [1925]. Madame Blavatsky. Literary Licensing. ISBN 978-1494069407. Campbell, Geo.; Hardy, Thomas; Milmokre, Jas. (June 6, 1900). "Baer-Spiritualistic Challenge". Nanaimo Free Press. Vol. 27, no. 44. Nanaimo, Canada: Geo. Norris. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com. Carroll, Bret E. (1997). Spiritualism in Antebellum America. Religion in North America. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0253333155. Clodd, Edward (1917). The Question: A Brief History and Examination of Modern Spiritualism. London: Grant Richards. Davis, Andrew Jackson (1852) [1847]. Fishbough, William (ed.). The Principles of Nature, Her Divine Revelations, and a Voice to Mankind. New York: S. S. Lyon and W. Fishbough – via University of Michigan. Deveney, John Patrick (1997). Paschal Beverly Randolph: A Nineteenth-Century Black American Spiritualist, Rosicrucian, and Sex Magician. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0791431207. Doyle, Arthur Conan (1926). The History of Spiritualism, volume 1. New York: G.H. Doran. ISBN 978-1410102430. Doyle, Arthur Conan (1926). The History of Spiritualism, volume 2. New York: G.H. Doran. ISBN 978-1410102430. Guthrie, John J. Jr.; Lucas, Phillip Charles; Monroe, Gary, eds. (2000). Cassadaga: the South's Oldest Spiritualist Community. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0813017433. Harrison, W. H. (1880). Psychic Facts: A Selection from Various Authors. London: Ballantyne Press. Hess, David (1987). Spiritism and Science in Brazil (PhD dissertation). Dept. of Anthropology, Cornell University. Kurtz, Paul, ed. (1985). A Skeptic's Handbook of Parapsychology. Prometheus Books. ISBN 0879753005. Lawton, George (1932). The Drama of Life After Death: A Study of the Spiritualist Religion. Henry Holt and Company. OCLC 936427452. Mann, Walter (1919). The Follies and Frauds of Spiritualism. London: Watts & Co. McCabe, Joseph (1920). Is Spiritualism Based on Fraud?. London: Watts & Co. Melton, J. Gordon, ed. (2001). Encyclopedia of Occultism & Parapsychology. Vol. 2 (5th ed.). Gale Group. ISBN 0810394898. PBS (October 19, 1994). Telegrams from the Dead (television documentary). American Experience. Podmore, Frank (2011) [1902, Methuen & Company]. Modern Spiritualism: A History and a Criticism. Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1108072588. Rinn, Joseph (1950). Sixty Years Of Psychical Research: Houdini and I Among the Spiritualists. Truth Seeker. Spence, Lewis (2003). Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology. Kessinger Publishing Company. Strube, Julian (2016). "Socialist Religion and the Emergence of Occultism: A Genealogical Approach to Socialism and Secularization in 19th-Century France". Religion. 46 (3): 359–388. doi:10.1080/0048721X.2016.1146926. S2CID 147626697. Troy, Kathryn (2017). The Specter of the Indian: Race, Gender, and Ghosts in American Séances, 1848-1890. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-1438466095. Urban, Hugh B. (2015). New Age, Neopagan and New Religious Movements. Oakland: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520281189. Wallace, Alfred Russel (1866). The Scientific Aspect of the Supernatural. London: F. Farrah – via wku.edu. Weisberg, Barbara (2004). Talking to the Dead (1st ed.). San Francisco: Harper. ISBN 978-0060566678. OCLC 54939577. Wicker, Christine (2004). Lily Dale: the True Story of the Town that talks to the Dead. San Francisco: Harper. |

引用文献 アルバーネーゼ、キャサリン・L.(2007)。『心と精神の共和国:アメリカ形而上学宗教の文化史』。ニューヘイブン/ロンドン:イェール大学出版局。ISBN 978-0300136159。 アルバラード、カルロス・S.;ビオンディ、マッシモ;クレイマー、ウィム(2006)。「専門誌における超常現象の歴史的考察」。『ヨーロッパ超心理学ジャーナル』。21巻1号:58–87頁。 バセット、J.(1990)。『全米スピリチュアリズム100年史』。ザ・ヘッドクォーターズ出版。[ISBN欠落] ブラウド、アン(2001)。『急進的な霊魂たち:19世紀アメリカにおけるスピリチュアリズムと女性の権利』(第2版)。ブルーミントン:インディアナ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0253215024。OCLC 47785582。 ブリテン、エマ・ハーディンジ(1884)。『19世紀の奇跡:地球上のあらゆる国における霊とその働き』。ニューヨーク:ウィリアム・ブリテン。ISBN 978-0766162907。 バット、G. ベースデン(2013)[1925]。『ブラヴァツキー夫人』。リテラリー・ライセンシング。ISBN 978-1494069407. キャンベル、ジオー;ハーディ、トーマス;ミルモークレ、ジャス(1900年6月6日)。「ベア霊媒術への挑戦」。『ナナイモ・フリー・プレス』第27巻第44号。カナダ・ナナイモ:ジオー・ノリス。p. 2 – Newspapers.com経由。 キャロル、ブレット・E.(1997)。『南北戦争前のアメリカにおけるスピリチュアリズム』。北米の宗教。ブルーミントン:インディアナ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0253333155。 クロッド、エドワード(1917)。『問題:現代スピリチュアリズムの簡史と検証』。ロンドン:グラント・リチャーズ。 デイヴィス、アンドリュー・ジャクソン(1852) [1847年]. フィッシュボウ、ウィリアム(編)。『自然の原理、その神聖なる啓示、そして人類への声』。ニューヨーク:S. S. ライオンとW. フィッシュボウ – ミシガン大学経由。 デヴェニー、ジョン・パトリック(1997年)。『パスカル・ベバリー・ランドルフ:19世紀の黒人アメリカ人スピリチュアリスト、薔薇十字会会員、そして性魔術師』。オールバニ:ニューヨーク州立大学出版局。ISBN 978-0791431207。 ドイル、アーサー・コナン(1926)。『スピリチュアリズムの歴史』第1巻。ニューヨーク:G.H.ドーラン。ISBN 978-1410102430。 ドイル、アーサー・コナン(1926)。『スピリチュアリズムの歴史』第2巻。ニューヨーク:G.H.ドーラン。ISBN 978-1410102430。 ガスリー、ジョン・J・ジュニア;ルカーチ、フィリップ・チャールズ;モンロー、ゲイリー編(2000)。『カサダガ:南部最古のスピリチュアリズム共同体』。フロリダ州ゲインズビル:フロリダ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0813017433。 ハリソン、W・H(1880)。『超心理的事実:諸著作者からの選集』。ロンドン:バランタイン出版社。 ヘス、デイヴィッド(1987)。『ブラジルにおけるスピリチュアリズムと科学』(博士論文)。コーネル大学人類学部。 クルツ、ポール編(1985)。『懐疑論者のための超心理学ハンドブック』。プロメテウス・ブックス。ISBN 0879753005。 ロートン、ジョージ(1932)。『死後の生命のドラマ:スピリチュアリズム宗教の研究』。ヘンリー・ホルト・アンド・カンパニー。OCLC 936427452。 マン、ウォルター(1919)。『スピリチュアリズムの愚行と詐欺』。ロンドン:ワッツ社。 マッケイブ、ジョセフ(1920)。『スピリチュアリズムは詐欺に基づくか?』。ロンドン:ワッツ社。 メルトン、J・ゴードン編(2001)。『オカルトと超心理学事典』。第2巻(第5版)。ゲイル・グループ。ISBN 0810394898。 PBS(1994年10月19日)。『死者からの電報』(テレビドキュメンタリー)。『アメリカン・エクスペリエンス』。 ポッドモア、フランク(2011年)[1902年、メシューン社]。『現代スピリチュアリズム:その歴史と批判』。第2巻。ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 978-1108072588。 リン、ジョセフ(1950)。『心霊研究の60年:スピリチュアリストたちの中のフーディーニと私』。トゥルース・シーカー。 スペンス、ルイス(2003)。『オカルティズムと超心理学事典』。ケシンジャー出版。 ストルーベ、ジュリアン(2016)。「社会主義宗教とオカルティズムの出現:19世紀フランスにおける社会主義と世俗化の系譜学的アプローチ」『宗教』 46巻3号:359–388頁。doi:10.1080/0048721X.2016.1146926。S2CID 147626697. トロイ、キャスリン(2017)。『インディアン、亡霊:1848-1890年アメリカ霊媒術における人種、性別、そして幽霊』ニューヨーク州立大学出版局。ISBN 978-1438466095。 アーバン、ヒュー・B.(2015)。『ニューエイジ、ネオペイガン、そして新宗教運動』。オークランド:カリフォルニア大学出版局。ISBN 978-0520281189。 ウォレス、アルフレッド・ラッセル(1866)。『超自然現象の科学的側面』。ロンドン:F. ファラー – wku.edu経由。 ワイズバーグ、バーバラ(2004)。『死者との対話』(初版)。サンフランシスコ:ハーパー。ISBN 978-0060566678。OCLC 54939577。 ウィッカー、クリスティーン(2004)。『リリー・デイル:死者と話す町の真実の物語』。サンフランシスコ:ハーパー。 |

| Further reading Brandon, Ruth (1983). The Spiritualists: The Passion for the Occult in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. Brown, Slater (1970). The Heyday of Spiritualism. New York: Hawthorn Books. Buescher, John B. (2003). The Other Side of Salvation: Spiritualism and the Nineteenth-Century Religious Experience. Boston: Skinner House Books. ISBN 978-1558964488. Chapin, David (2004). Exploring Other Worlds: Margaret Fox, Elisha Kent Kane, and the Antebellum Culture of Curiosity. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. Doyle, Arthur Conan (1975). The History of Spiritualism. New York: Arno Press. ISBN 978-0405070259. Lehman, Amy (2009). Victorian Women and the Theatre of Trance: Mediums, Spiritualists and Mesmerists in Performance. McFarland. ISBN 978-0786434794. Lindgren, Carl Edwin (January 1994). "Spiritualism: Innocent Beliefs to Scientific Curiosity". Journal of Religion and Psychical Research. 17 (1): 8–15. ISSN 2168-8621. Archived from the original on 2013-12-02. Lindgren, Carl Edwin (March 1994). "Scientific investigation and Religious Uncertainty 1880–1900". Journal of Religion and Psychical Research. 17 (2): 83–91. ISSN 2168-8621. Archived from the original on 2013-12-03. Moore, William D. (1997). "'To Hold Communion with Nature and the Spirit-World:' New England's Spiritualist Camp Meetings, 1865–1910". In Annmarie Adams; Sally MacMurray (eds.). Exploring Everyday Landscapes: Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture, VII. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-0870499838. Moreman, Christopher M. (2013). The Spiritualist Movement: Speaking with the Dead in America and around the World 3 Vols. Praeger. ISBN 978-0-313-39947-3. National Spiritualist Association (1934) [1911]. Spiritualist Manual (5 ed.). Chicago, Illinois: Printing Products Corporation. Natale, Simone (2016). Supernatural Entertainments: Victorian Spiritualism and the Rise of Modern Media Culture. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-07104-6. Stoddart, Jane (1919). The case against spiritualism. United Kingdom: Hodder & Stoughton. |

参考文献 ブランドン、ルース(1983)。『スピリチュアリストたち:19世紀と20世紀におけるオカルトへの情熱』。ニューヨーク:アルフレッド・A・クノップ。 ブラウン、スレイター(1970)。『スピリチュアリズムの全盛期』。ニューヨーク:ホーソーン・ブックス。 ビューシャー、ジョン・B.(2003)。救済の向こう側:スピリチュアリズムと19世紀の宗教体験。ボストン:スキナー・ハウス・ブックス。ISBN 978-1558964488。 チャピン、デイヴィッド(2004)。『異世界を探る:マーガレット・フォックス、エリシャ・ケント・ケイン、そして南北戦争前の好奇心の文化』。アマースト:マサチューセッツ大学出版局。 ドイル、アーサー・コナン(1975)。『スピリチュアリズムの歴史』。ニューヨーク:アーノ・プレス。ISBN 978-0405070259。 レーマン、エイミー(2009)。『ヴィクトリア朝の女性とトランス劇場:パフォーマンストランスにおける霊媒、スピリチュアリスト、そして催眠術師』。マクファーランド。ISBN 978-0786434794。 リンドグレン、カール・エドウィン(1994年1月)。「スピリチュアリズム:無邪気な信仰から科学的関心へ」。『宗教と超心理研究ジャーナル』。17巻1号:8–15頁。ISSN 2168-8621。2013年12月2日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。 リンドグレン、カール・エドウィン(1994年3月)。「科学的調査と宗教的不確実性 1880–1900」『宗教と心霊研究ジャーナル』17(2): 83–91. ISSN 2168-8621. 2013-12-03にオリジナルからアーカイブ. ムーア、ウィリアム・D. (1997). 「『自然と霊界との交わりを持つために』:ニューイングランドのスピリチュアリズム野外集会、1865–1910年」. アンマリー・アダムズ、サリー・マクマレー(編)『日常の風景を探る:民家建築の視点 VII』所収. ノックスビル:テネシー大学出版局. ISBN 978-0870499838. モアマン、クリストファー・M. (2013). 『スピリチュアリズム運動:アメリカと世界における死者との対話』全3巻. プレガー. ISBN 978-0-313-39947-3. 国民スピリチュアリズム協会 (1934) [1911]. 『スピリチュアリズム手引書』 (第5版). イリノイ州シカゴ: プリンティング・プロダクツ社. ナターレ、シモーネ(2016)。『超自然的娯楽:ヴィクトリア朝スピリチュアリズムと近代メディア文化の台頭』。ユニバーシティ・パーク:ペンシルベニア州立大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-271-07104-6。 ストッダード、ジェーン(1919)。『スピリチュアリズムに対する反論』。イギリス:ホッダー・アンド・ストゥートン。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spiritualism_(movement) |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099