スタンリー・カヴェル

Stanley Cavell, 1926-2018

☆ スタンリー・ルイス・キャヴェル(/kəˈvɛl/、1926年9月1日 - 2018年6月19日)は、アメリカの哲学者である。ハーバード大学ウォルター・M・キャボット美学・価値一般論教授を務めた。倫理学、美学、日常言語哲 学の分野で研究を行った。ウィトゲンシュタイン、オースティン、エマーソン、ソロー、ハイデガーに関する影響力のある著作を解釈者として発表した。彼の著 作は会話調で、文学的な参照が頻繁に登場するのが特徴である。

| Stanley Louis Cavell

(/kəˈvɛl/; September 1, 1926 – June 19, 2018) was an American

philosopher. He was the Walter M. Cabot Professor of Aesthetics and the

General Theory of Value at Harvard University. He worked in the fields

of ethics, aesthetics, and ordinary language philosophy. As an

interpreter, he produced influential works on Wittgenstein, Austin,

Emerson, Thoreau, and Heidegger. His work is characterized by its

conversational tone and frequent literary references. |

ス

タンリー・ルイス・キャヴェル(/kəˈvɛl/、1926年9月1日 -

2018年6月19日)は、アメリカの哲学者である。ハーバード大学ウォルター・M・キャボット美学・価値一般論教授を務めた。倫理学、美学、日常言語哲

学の分野で研究を行った。ウィトゲンシュタイン、オースティン、エマーソン、ソロー、ハイデガーに関する影響力のある著作を解釈者として発表した。彼の著

作は会話調で、文学的な参照が頻繁に登場するのが特徴である。 |

| Life Cavell was born as Stanley Louis Goldstein to a Jewish family in Atlanta, Georgia. His mother, a locally renowned pianist, trained him in music from his earliest days.[29] During the Depression, Cavell's parents moved several times between Atlanta and Sacramento, California.[30] As an adolescent, Cavell played lead alto saxophone as the youngest member of a black jazz band in Sacramento.[31] Around this time he changed his name, anglicizing the family's original Polish name, Kavelieruskii (sometimes spelled "Kavelieriskii").[32] He entered the University of California, Berkeley, where, along with his lifelong friend Bob Thompson, he majored in music, studying with, among others, Roger Sessions and Ernest Bloch.[33] After graduation, he studied composition at the Juilliard School of Music in New York City, only to discover that music was not his calling.[34] He entered graduate school in philosophy at UCLA, and then transferred to Harvard University.[35] As a student there he came under the influence of J. L. Austin, whose teaching and methods "knocked him off ... [his] horse."[36] In 1954 he was awarded a Junior Fellowship at the Harvard Society of Fellows. Before completing his Ph.D., he became an Assistant Professor of Philosophy at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1956.[37] Cavell's daughter by his first wife (Marcia Cavell), Rachel Lee Cavell, was born in 1957. In 1962–63 Cavell was a Fellow at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, where he befriended the British philosopher Bernard Williams.[38] Cavell’s marriage to Marcia ended in divorce in 1961. In 1963 he returned to the Harvard Philosophy Department, where he became the Walter M. Cabot Professor of Aesthetics and the General Theory of Value.[39] In the summer of 1964, Cavell joined a group of graduate students, who taught at Tougaloo College, a historically black Protestant college in Mississippi, as part of what became known as the Freedom Summer.[40] He and Cathleen (Cohen) Cavell were married in 1967. In April 1969, during the student protests (chiefly arising from the Vietnam War), Cavell, helped by his colleague John Rawls, worked with a group of African-American students to draft language for a faculty vote to establish Harvard's Department of African and African-American Studies.[41] In 1976, Cavell's first son, Benjamin, was born. In 1979, along with the documentary filmmaker Robert H. Gardner, Cavell helped found the Harvard Film Archive, to preserve and present the history of film.[42] Cavell received a MacArthur Fellowship in 1992.[43] In 1996-97 Cavell was president of the American Philosophical Association (Eastern Division). In 1984, his second son, David, was born.[43] Cavell remained on the Harvard faculty until retiring in 1997. Thereafter, he taught courses at Yale University and the University of Chicago. He also held the Spinoza Chair of Philosophy at the University of Amsterdam in 1998.[44] Cavell died in Boston, Massachusetts of heart failure on June 19, 2018, at the age of 91.[45] He was buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery.[46] |

生涯 キャヴェルは、ジョージア州アトランタのユダヤ人家庭にスタンリー・ルイス・ゴールドスタインとして生まれた。地元で著名なピアニストであった母親は、幼 い頃から彼に音楽を教えた。[29] 大恐慌時代、キャヴェルの両親はアトランタとカリフォルニア州サクラメントの間を何度か引っ越した。[30] 思春期には、キャヴェルはサクラメントの黒人ジャズバンドで最年少メンバーとしてリードアルトサックスを演奏した。[31] この頃、彼は家族のポーランド語の姓であるKavelier (「カヴェリエリスキー」と表記されることもある)[32]。彼はカリフォルニア大学バークレー校に入学し、生涯の友人となるボブ・トンプソンとともに音 楽を専攻し、ロジャー・セッションズやアーネスト・ブロッホらの指導を受けた[33]。卒業後、ニューヨークのジュリアード音楽院で作曲を学んだが、音楽 は自分の天職ではないと気づいた[34]。 カリフォルニア大学ロサンゼルス校(UCLA)の大学院で哲学を学んだ後、ハーバード大学に転校した。[35] ハーバード大学在学中、J. L. オースティンの影響を受け、その教えと手法は「彼を馬から振り落とした」という。[36] 1954年には、ハーバード・フェローシップのジュニア・フェローシップを授与された。博士号取得前に、1956年にカリフォルニア大学バークレー校の哲 学の助教授となった。[37] キャヴェルの最初の妻(マーシャ・キャヴェル)との間の娘、レイチェル・リー・キャヴェルは1957年に生まれた。1962年から63年にかけて、キャ ヴェルはニュージャージー州プリンストンにある高等研究所の研究員となり、そこでイギリスの哲学者バーナード・ウィリアムズと親交を結んだ。[38] キャヴェルとマーシャの結婚は1961年に離婚で終わった。1963年、彼はハーバード大学の哲学部に戻り、ウォルター・M・キャボット美学・価値一般理 論教授となった。[39] 1964年の夏、キャヴェルは、ミシシッピ州にある歴史ある黒人プロテスタント系大学、トゥーガルー・カレッジで教える大学院生グループに加わり、後に 「フリーダム・サマー」として知られることになる活動に参加した。[40] キャスリーン(コーエン)キャヴェルと1967年に結婚した。1969年4月、学生による抗議運動(主にベトナム戦争に反対するもの)のさなか、キャヴェ ルは同僚のジョン・ロウエルズの助力を受け、アフリカ系アメリカ人の学生グループと協力して、ハーバード大学にアフリカ・アフリカ系アメリカ人研究学部を 設立するための教授陣投票の文言を作成した。 1976年、キャヴェルの長男ベンジャミンが誕生した。1979年、ドキュメンタリー映画制作者のロバート・H・ガードナーとともに、映画の歴史を保存し 公開することを目的としたハーバード映画アーカイブの設立に携わった。[42] 1992年、キャヴェルはマッカーサー・フェローシップを受賞した。[43] 1996年から1997年にかけて、キャヴェルはアメリカ哲学協会(東部支部)の会長を務めた。1984年には次男のデイヴィッドが生まれた。キャヴェル は1997年にハーバード大学を定年退職するまで同大学の教員として在職した。その後はイエール大学とシカゴ大学で教鞭をとった。また、1998年にはア ムステルダム大学でスピノザ哲学講座の教授も務めた。 キャヴェルは2018年6月19日、心不全のためマサチューセッツ州ボストンで死去、91歳だった。[45] 彼はマウント・オーバン墓地に埋葬された。[46] |

| Philosophy Although trained in the Anglo-American analytic tradition, Cavell frequently interacted with the continental tradition.[47] He includes film and literary study in philosophical inquiry.[47] Cavell wrote extensively on Ludwig Wittgenstein, J. L. Austin, and Martin Heidegger, as well as the American transcendentalists Henry Thoreau[48] and Ralph Waldo Emerson.[49] His work was for a time frequently compared to that of Jacques Derrida, whom he met in 1970. Although their exchange was congenial, Cavell denied the full extent to which deconstruction could undermine the possibility of meaning, instead taking an explicitly ordinary language approach to language and skepticism.[50] He writes about Wittgenstein in a fashion known as the New Wittgenstein, which according to Alice Crary interprets Wittgenstein as putting forward a positive view of philosophy as a therapeutic form.[51] Cavell's work incorporates autobiographical elements concerning how his movement between and within these thinkers' ideas influenced his views in the arts and humanities, beyond the technical study of philosophy. Cavell established his distinct philosophical identity with Must We Mean What We Say? (1969), a collection of essays that addresses topics such as language use, metaphor, skepticism, tragedy, and literary interpretation from the point of view of ordinary language philosophy, of which he is a practitioner and ardent defender. One of the essays discusses Søren Kierkegaard's work on revelation and authority, The Book on Adler, in an effort to help reintroduce the book to modern philosophical readers.[52] In The World Viewed (1971) Cavell looks at photography, film, modernism in art and the nature of media, mentioning the influence of art critic Michael Fried on his work. Cavell is well-known for The Claim of Reason: Wittgenstein, Skepticism, Morality, and Tragedy (1979), which forms the centerpiece of his work and has its origins in his doctoral dissertation. In Pursuits of Happiness (1981), Cavell describes his experience of seven prominent Hollywood comedies: The Lady Eve, It Happened One Night, Bringing Up Baby, The Philadelphia Story, His Girl Friday, Adam’s Rib, and The Awful Truth. Cavell argues that these films, from 1934–1949, form part of what he calls the genre of "The Comedy of Remarriage," and finds in them great philosophical, moral, and political significance. Specifically, Cavell argues that these comedies show that "the achievement of happiness requires not the [...] satisfaction of our needs [...] but the examination and transformation of those needs."[53] According to Cavell, the emphasis these movies place on remarriage draws attention to the fact that, within a relationship, happiness requires "growing up" together with one's partner.[54] In Cities of Words (2004) Cavell traces the history of moral perfectionism, a mode of moral thinking spanning the history of Western philosophy and literature. Having used Emerson to outline the concept, the book suggests ways we might want to understand philosophy, literature, and film as preoccupied with features of perfectionism. In Philosophy the Day After Tomorrow (2005), a collection of essays, Cavell makes the case that J. L. Austin's concept of performative utterance requires the supplementary concept of passionate utterance: "A performative utterance is an offer of participation in the order of law. And perhaps we can say: A passionate utterance is an invitation to improvisation in the disorders of desire."[55] The book also contains extended discussions of Friedrich Nietzsche, Jane Austen, George Eliot, Henry James, and Fred Astaire, as well as familiar Cavellian subjects such as Shakespeare, Emerson, Thoreau, Wittgenstein, and Heidegger. Cavell's final book, Little Did I Know: Excerpts from Memory (2010), is an autobiography written in the form of a diary. In a series of consecutive, dated entries, he inquires about the origins of his philosophy by telling the story of his life. A scholarly journal, Conversations: The Journal of Cavellian Studies, engages with his philosophical work. It is edited by Sérgio Dias Branco and Amir Khan and published by the University of Ottawa. |

哲学 キャヴェルは、英米分析哲学の伝統で訓練を受けたが、大陸哲学の伝統とも頻繁に交流していた。[47] 彼は、映画や文学研究を哲学的な探究に含めている。[47] キャヴェルは、ルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタイン、J.L.オースティン、そしてマーティン・ また、アメリカの超越主義者であるヘンリー・ソローやラルフ・ワルド・エマーソンについても広く論じている。[49] 彼の作品は、1970年に面識のあったジャック・デリダのものと比較されることがしばしばあった。彼らの交流は友好的なものだったが、キャヴェルは脱構築 が意味の可能性を損なう可能性を全面的に否定し、代わりに言語と懐疑論に対しては明白に日常言語のアプローチを取った。[50] 彼は「新ウィトゲンシュタイン」として知られる方法でウィトゲンシュタインについて書いており、アリス・クレイによれば、 ウィトゲンシュタインを、哲学を治療的な形として肯定的に捉えるものとして解釈している。キャヴェルの著作には、これらの思想家の考えの間や内を移動する ことによって、哲学の専門的な研究を超えて、芸術や人文科学における自身の考え方にどのような影響を与えたかに関する自伝的な要素が盛り込まれている。 キャヴェルは、自身の著書『Must We Mean What We Say?』(1969年)で、独自の哲学的なアイデンティティを確立した。この本は、言語の使用、隠喩、懐疑論、悲劇、文学解釈といったトピックを、彼が 実践者であり熱心な擁護者でもある日常言語哲学の観点から論じたエッセイ集である。その中の1つの論文では、セーレン・キルケゴールの啓示と権威に関する 著作『アドラーについての本』を取り上げ、同書を現代の哲学読者に再紹介しようとしている。[52] 『The World Viewed』(1971年)では、キャヴェルは写真、映画、芸術におけるモダニズム、メディアの本質について考察し、美術評論家マイケル・フリードの作 品が自身の作品に与えた影響について言及している。 キャヴェルは、博士論文を基に著した『理性の主張――ウィトゲンシュタイン、懐疑論、道徳性、悲劇』(1979年)でよく知られている。『幸福の追求』 (1981年)では、キャヴェルは7本の著名なハリウッドのコメディ映画―― 『レディ・イヴ』、『或る夜の出来事』、『赤ちゃん教育』、『フィラデルフィア物語』、『彼の女房』、『アダムの肋骨』、『奥様は魔女』の7作品について 述べている。キャヴェルは、1934年から1949年にかけて制作されたこれらの映画は、彼が「再婚喜劇」と呼ぶジャンルの一部を構成しており、これらの 映画には、哲学、道徳、政治の観点から大きな意義があるとしている。具体的には、キャヴェルはこれらのコメディが「幸福の達成には、[...] 私たちのニーズの充足[...]ではなく、それらのニーズの検証と変革が必要である」ことを示していると主張している。[53] キャヴェルによると、これらの映画が再婚に重点を置いていることは、人間関係において、幸福にはパートナーと共に「成長」することが必要であるという事実 を浮き彫りにしている。[54] キャヴェルは著書『言葉の都市』(2004年)で、西洋の哲学と文学の歴史にまたがる道徳的思考様式である道徳的完全主義の歴史をたどっている。エマーソ ンを引用してその概念の概要を示したこの本は、哲学、文学、映画を完全主義の特質に重点を置いて理解する方法を示唆している。エッセイ集『明後日の哲学』 (2005年)では、キャヴェルはJ.L.オースティンのパフォーマティビティ概念には情動的発話という概念の補足が必要であると論じている。「パフォー マティビティとは法の秩序への参加の申し出である。そして、おそらく次のように言えるだろう。情熱的な発話とは、欲望の混乱における即興への招待である」 [55] また、この本には、フリードリヒ・ニーチェ、ジェーン・オースティン、ジョージ・エリオット、ヘンリー・ジェイムズ、フレッド・アステアに関する詳細な議 論も含まれている。また、キャヴェルがよく取り上げる題材である、シェイクスピア、エマーソン、ソロー、ウィトゲンシュタイン、ハイデガーについても言及 されている。キャヴェルの最後の著書『Little Did I Know: 抜粋版(2010年)は、日記形式で書かれた自伝である。日付を入れた連続した一連の項目で、自身の人生の物語を語ることで、自身の哲学の起源について探 求している。 学術誌『カンヴァセーションズ:ザ・ジャーナル・オブ・キャヴェリアン・スタディーズ』は、キャヴェルの哲学的研究を取り上げている。同誌はセルジオ・ディアス・ブランコとアミール・カーンが編集し、オタワ大学から出版されている。 |

| Selected special lectureships Patricia Wise Lecture, American Film Institute, 1982 Mrs. William Beckman Lectures, University of California, Berkeley, 1983 Tanner Lecture, Stanford University, April 1986 Carus Lectures, American Philosophical Association, 1988 Plenary Address, Shakespeare World Congress, Los Angeles, 1996 Presidential Address, American Philosophical Association, Atlanta, 1996 Howison Lectures, University of California, Berkeley, February, 2002 Bibliography Must We Mean What We Say? (1969) The Senses of Walden (1972) Expanded edition San Francisco: North Point Press, 1981. The World Viewed: Reflections on the Ontology of Film (1971); 2nd enlarged edn. (1979) The Claim of Reason: Wittgenstein, Skepticism, Morality, and Tragedy (1979) New York: Oxford University Press. Pursuits of Happiness: The Hollywood Comedy of Remarriage (1981) ISBN 978-0-674-73906-2 Themes Out of School: Effects and Causes (1984) Disowning Knowledge: In Six Plays of Shakespeare (1987); 2nd edn.: Disowning Knowledge: In Seven Plays of Shakespeare (2003) In Quest of the Ordinary: Lines of Scepticism and Romanticism (1988) Chicago: Chicago University Press. This New Yet Unapproachable America: Lectures after Emerson after Wittgenstein (1988) Conditions Handsome and Unhandsome: The Constitution of Emersonian Perfectionism (1990) A Pitch of Philosophy: Autobiographical Exercises (1994) Philosophical Passages: Wittgenstein, Emerson, Austin, Derrida (1995) Contesting Tears: The Melodrama of the Unknown Woman (1996) Emerson's Transcendental Etudes (2003) Cavell on Film (2005) Cities of Words: Pedagogical Letters on a Register of the Moral Life (2004) Philosophy the Day after Tomorrow (2005) Little Did I Know: Excerpts from Memory (2010) Here and There: Sites of Philosophy (2022) |

特別講義 パトリシア・ワイズ講義、アメリカン・フィルム・インスティチュート、1982年 ウィリアム・ベックマン夫人講義、カリフォルニア大学バークレー校、1983年 タナー講義、スタンフォード大学、1986年4月 カルス講義、アメリカ哲学協会、1988年 全体会議講演、ロサンゼルス・シェイクスピア世界会議、1996年 大統領講演、アメリカ哲学協会、アトランタ、1996年 2002年2月、カリフォルニア大学バークレー校、ハウソン・レクチャー 主要業績 言ったことは本当に意味しているのか?(1969年 ウォールデンにおける感覚(1972年) 増補版 サンフランシスコ:ノースポイントプレス、1981年 世界の見方:映画の存在論についての考察(1971年) 第2版増補版(1979年) 『理性の主張:ウィトゲンシュタイン、懐疑論、道徳、そして悲劇』(1979年)ニューヨーク:オックスフォード大学出版。 『幸福の追求:ハリウッドの再婚コメディ』(1981年)ISBN 978-0-674-73906-2 『学校外のテーマ:影響と原因』(1984年) 知識の放棄:シェイクスピアの6つの劇において(1987年)第2版:知識の放棄:シェイクスピアの7つの劇において(2003年) 日常の探究:懐疑論とロマン主義の系譜(1988年)シカゴ大学出版。 この新しい、しかし近づきがたいアメリカ:エマーソンに続くウィトゲンシュタインの講義(1988年) 美しい条件と醜い条件:エマーソンの完璧主義の構造(1990年) 哲学のピッチ:自伝的演習(1994年) 哲学的パッセージ:ウィトゲンシュタイン、エマーソン、オースティン、デリダ(1995年) 涙をめぐる論争:無名女性のメロドラマ(1996年) エマーソンの超越論的エチュード(2003年) キャヴェル映画論(2005年) 言葉の都市:道徳的生活のレヴェルにおける教育的な手紙(2004年) 明後日の哲学(2005年) ほとんど知らなかった:記憶からの抜粋(2010年) ここかしこ:哲学の現場(2022年) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stanley_Cavell |

|

| 哲学の「声」 : デリダのオースティン批判論駁 / スタンリー・カヴェル著 ; 中川雄一訳, 春秋社 , 2008 - A pitch of philosophy : autobiographical exercises. ウィトゲンシュタイン新解釈の立役者にして、その特異な手法ゆえに孤高を保つ哲学の巨人カヴェル。音楽も映画も演劇も、ユダヤ移民の子としての人生も、す べてが哲学の論点と呼応しあい響きあって織りなされる彼の重層的な万華鏡世界が、デリタ‐オースティン論争を中心に展開。デリタの予断を正し、“声”の抑 圧を暴く。 第1章 哲学と“声”の横領 第2章 反哲学と“声”の質入れ ・形而上学的な声 ・異なる哲学をもつ世界 ・破壊幻想 ・デリタのオースティンと実証主義の賭け金 ・弁解の理論の排除—悲劇について ・「不真面目なもの」の理論を排除する ・懐疑論と真面目さ ・コミュニケーションあるいは譲渡をめぐる二つの描像 ・何が(どのような物)が伝送されるのか?オースティンが動く ・世界とかかわる言語についての二つの描像 ・私が私の言葉に貼りつく—署名についての三つの描像 第3章 オペラと“声”の貸借 |

|

| In ethics and value theory, perfectionism

is the persistence of will in obtaining the optimal quality of

spiritual, mental, physical, and material being. Thomas Hurka describes

perfectionism as follows: This moral theory starts from an account of the good life, or the intrinsically desirable life. And it characterizes this life in a distinctive way. Certain properties, it says, constitute human nature or are definitive of humanity—they make humans human. The good life, it then says, develops these properties to a high degree or realizes what is central to human nature. Different versions of the theory may disagree about what the relevant properties are and so disagree about the content of the good life. But they share the foundational idea that what is good, ultimately, is the development of human nature.[1] |

倫理および価値理論において、完璧主義とは、精神、心、身体、物質のそれぞれにおいて最適な質を追求する意志の持続である。トーマス・ハーカは完璧主義を次のように説明している。 この道徳理論は、善き人生、すなわち本質的に望ましい人生についての説明から始まる。そして、この人生を独特な方法で特徴づける。特定の性質が人間性を構 成し、あるいは人間性を決定づける、つまり人間を人間たらしめている、とこの理論は言う。そして、善き人生とは、これらの特性を高度に発達させること、あ るいは人間の本質の中核をなすものを実現することであると説く。この理論の異なるバージョンでは、関連する特性について意見が分かれる可能性があり、善き 人生の内容についても意見が分かれる可能性がある。しかし、善きものとは究極的には人間性を発達させることであるという基本的な考え方は共通している。 [1] |

| History Perfectionism, as a moral theory, has a long history and has been addressed by influential philosophers. Aristotle stated his conception of the good life (eudaimonia). He taught that politics and political structures should promote the good life among individuals; because the polis can best promote the good life, it should be adopted over other forms of social organization. The philosopher Stanley Cavell develops the concept of moral perfectionism as the idea that there is an unattained but attainable self that one ought to strive to reach. Moral perfectionists believe that the ancient questions such as "Am I living as I am supposed to?" make all the difference in the world and they describe the commitment we ought to have in ways that seem, but are not, impossibly demanding. We do so because it is only in the keeping such an "impossible" view in mind that one can strive for one's "unattained but attainable self." In his book Cities of Words: Pedagogical Letters on a Register of the Moral Life (2005),[2] based on a lecture course called "Moral Perfectionism" that he first gave at Harvard University in the 1980s, Stanley Cavell characterizes moral perfectionism in general, and what he calls "Emersonian perfectionism," the form of moral perfectionism he embraces and defends, not as a theory of moral philosophy comparable to Immanuel Kant’s deontological view that there is a universal moral law (the categorical imperative) by which we can rationally determine whether an action is right or wrong, or John Stuart Mill’s utilitarian view that the good action is that which will cause the least harm, or the greatest good for the greatest number. For Cavell, moral perfectionism is an outlook or register of thought, a way of thinking about morality expressed thematically in certain works of philosophy, literature and film. As William Rothman summarizes Cavell's idea, "takes it to be our primary task as human beings—at once our deepest wish, whether or not we know this about ourselves, and our moral obligation—to become more fully human, to realize our humanity in our lives in the world, which always requires the simultaneous acknowledgment of the humanity of others (our acknowledgment of them, and theirs of us)."[3] Cities of Words pairs chapters on major philosophers in the Western tradition, such as Plato, Aristotle, Immanuel Kant, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Friedrich Nietzsche, John Stuart Mill, Sigmund Freud and John Rawls, endorsing Cavell's understanding of moral perfectionism and such artists as William Shakespeare, Henry James, Henrik Ibsen and George Bernard Shaw, with chapters on a film, all but one (A Tale of Winter (1992) by Eric Rohmer) a member of the classical Hollywood genres; what he called "the comedy of remarriage" and "the melodrama of the unknown woman". Cavell's argument is that these films are illustrative of moral perfectionism (and, more specifically, Emersonian perfectionism).The moral questions couples in remarriage comedies like It Happened One Night, The Awful Truth and The Philadelphia Story address in their witty give- and-take, for example, are, as Cavell puts it, "formulated less well by questions concerning what they ought to do, what it would be best or right for them to do, than by the question how they shall live their lives, what kind of persons they aspire to be."[4]7 |

歴史 道徳理論としての完璧主義は長い歴史があり、影響力のある哲学者たちによって論じられてきた。アリストテレスは、善き人生(eudaimonia)につい ての自身の考えを述べた。彼は、政治と政治体制は個人の善き人生を促進すべきであると教えた。なぜなら、ポリス(都市国家)は善き人生を最も促進できるた め、他の社会組織の形態よりもポリスを採用すべきである。 哲学者のスタンリー・キャヴェルは、到達できていないが到達可能な自己があり、その自己に到達するために努力すべきであるという考えとして、道徳的完璧主 義の概念を展開している。道徳的完璧主義者は、「自分は本来あるべきように生きているだろうか」といった古代からの問いが、世界に大きな違いをもたらすと 考えている。また、私たちが持つべき責任について、不可能なほど厳しく、しかし不可能ではない方法で説明している。なぜなら、そのような「不可能」な見方 を維持することだけが、「達成されていないが達成可能な自己」を目指して努力することにつながるからだ。 スタンリー・キャヴェルは、1980年代にハーバード大学で初めて行った講義「道徳的完全主義」を基に著した著書『言葉の都市:道徳的生活のレヴェルにお ける教育的な手紙』(2005年)[2]の中で、道徳的完全主義を一般的に特徴づけ、また彼が支持し擁護する道徳的完全主義の形である「エマーソン的完全 主義」を 、カントの義務論的な見解に匹敵する道徳哲学の理論、すなわち、普遍的な道徳律(カテゴリー的命令)によって、ある行為が正しいか間違っているかを合理的 に判断できるとする見解、あるいは、ミルの功利主義的な見解、すなわち、善き行為とは、最小限の害を引き起こす行為、あるいは、最大多数にとって最大の善 をもたらす行為であるとする見解とは異なる。キャヴェルにとって、道徳的完全主義とは、思想の展望や思考様式であり、特定の哲学、文学、映画作品において テーマ的に表現される道徳についての考え方である。ウィリアム・ロスマンはキャヴェルの考えを次のように要約している。「人間として、より完全に人間にな ること、つまり、この世界で生きる中で人間性を実現することは、人間としての最も重要な課題であり、同時に、それが自分自身について知っているかどうかに 関わらず、人間としての最も深い願いであり、道徳的な義務でもある。(私たちが彼らを認め、彼らが私たちを認める)」ことを常に必要とする。」[3] 『言葉の都市』は、西洋の伝統における主要な哲学者たち、例えばプラトン、アリストテレス、イマニュエル・カント、ラルフ・ウォルドー・エマーソン、フ リードリヒ・ニーチェ、ジョン・スチュアート・ミル、ジークムント・フロイト、ジョン・ロールズなどの章をペアで組み合わせており、キャヴェルの道徳的完 全主義の理解を支持し、 ウィリアム・シェイクスピア、ヘンリー・ジェイムズ、ヘンリック・イプセン、ジョージ・バーナード・ショーといった芸術家たち、そしてハリウッド古典派の ジャンルの1つである映画(エリック・ロメール監督の『冬物語』(1992年)を除く)についての章で構成されている。キャヴェルは、これらの映画を「再 婚の喜劇」と「未知の女性のメロドラマ」と呼んでいる。キャヴェルの主張は、これらの映画は道徳的完全主義(より具体的にはエマーソンの完全主義)を体現 しているというものである。『或る夜の出来事』、『奥様は魔女』、『フィラデルフィア物語』といった再婚コメディでカップルがウィットに富んだ応酬の中で 扱う道徳的な問題は、例えば、 例えば、カヴェルが言うように、「彼らが何をすべきか、彼らにとって何が最善か、何が正しいかという問いよりも、彼らがどのように人生を生きるか、彼らが どのような人間になりたいかという問いによって、よりうまく表現されている」[4]7 |

| Happiness Perfection means more than—or something different from—happiness or pleasure, and perfectionism is distinct from utilitarianism in all its forms. A society devoted to perfectionist principles may not produce happy citizens—far from it. Kant regarded such a society as government paternalism, which he denied for the sake of a "patriotic" state (imperium non paternale, sed patrioticum). While the individual is responsible for living a virtuous life, the state should be limited to the regulation of human coexistence.[5] Alfred Naquet was of the view that there are no universal parameters of perfection. Individuals and cultures choose those values that, for them, represent the ideal of perfection. For example, one individual may view education as leading perfection, while to another beauty is the highest ideal. He wrote in this regard: The true role of collective existence ... is to learn, to discover, to know. Eating, drinking, sleeping, living, in a word, is a mere accessory. In this respect, we are not distinguished from the brute. Knowledge is the goal. If I were condemned to choose between a humanity materially happy, glutted after the manner of a flock of sheep in a field, and a humanity existing in misery, but from which emanated, here and there, some eternal truth, it is on the latter my choice would fall.[6] From a critical perspective, similar sentiments were expressed by Matthew Arnold in his Culture and Anarchy essays. According to the view he advanced in the 1869 publication, "Culture [...] is a study of perfection". He further wrote that: "[Culture] seeks to do away with classes; to make the best that has been thought and known in the world current everywhere; to make all men live in an atmosphere of sweetness and light [...]".[7] Moreover, in the preface of that text, he wrote: The whole scope of the essay is to recommend culture as the great help out of our present difficulties; culture being a pursuit of our total perfection by means of getting to know, on all the matters which most concern us, the best which has been thought and said in the world, and, through this knowledge, turning a stream of fresh and free thought upon our stock notions and habits, which we now follow staunchly but mechanically, vainly imagining that there is a virtue in following them staunchly which makes up for the mischief of following them mechanically. |

幸福 完全性は幸福や快楽よりも多くを意味し、また幸福や快楽とは異なるものであり、完全主義はあらゆる形態の功利主義とは異なるものである。完全主義の原則に 専心する社会は、幸福な市民を生み出すとは限らない。カントは、そのような社会を「政府による父権主義」とみなしたが、それは「愛国的な」国家 (imperium non paternale, sed patrioticum)のために否定されるべきであるとした。個人が徳のある生活を送る責任を負う一方で、国家は人間同士の共存を規制することに限定さ れるべきである。 アルフレッド・ナケは、完璧さの普遍的な基準は存在しないという見解を持っていた。個人や文化は、その個人や文化にとって完璧さの理想を表す価値観を選 ぶ。例えば、ある個人は教育が完璧さにつながると考えるかもしれないが、別の個人は美が最高の理想であると考えるかもしれない。 彼はこの点について次のように書いている。 集合的存在の真の役割は...学ぶこと、発見すること、知ることである。食べる、飲む、眠る、生きる、一言で言えば、それは単なる付属物にすぎない。この 点において、我々は獣と何ら変わるところはない。知識こそが目的である。もし私が、物質的に幸せで、羊の群れのように飽食する人間性と、悲惨な状況にあり ながらも、そこから時折、永遠の真理が発せられる人間性とのどちらかを選ばなければならないとしたら、私は後者を選ぶだろう。 批判的な観点から見ると、マシュー・アーノルドは『文化と無政府状態』のエッセイで同様の考えを述べている。1869年の出版で彼が示した見解によると、 「文化とは...完全性の研究である」という。さらに彼は次のように書いている。「文化は階級をなくし、世界で考えられ、知られている最善のものをどこで も通用するようにし、すべての人を甘美で明るい雰囲気の中で生活させることを目指している...」[7] さらに、そのテキストの序文で、彼は次のように書いている。 このエッセイの目的は、文化を、私たちが現在抱える困難を乗り越えるための大きな助けとして推奨することである。文化とは、私たちにとって最も関心のある あらゆる事柄について、世界で考えられ、語られた最善のものに触れることで、私たちの完全性を追求することである。そして、この知識を通じて、今では機械 的に固執しているが、機械的に固執することには悪影響があるものの、固執することには美徳があると思い込み、固執している弊害を補うことができると無駄な 期待を抱いている、私たちの固定観念や習慣に、新鮮で自由な思考の流れを向けることである。 |

| Transhumanism Philosopher Mark Alan Walker argues that rational perfectionism is, or should be, the ethical imperative behind transhumanism.[citation needed] |

トランスヒューマニズム 哲学者のマーク・アラン・ウォーカーは、トランスヒューマニズムの背後にある倫理的義務は合理的完璧主義である、またはそうあるべきだと主張している。[要出典] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perfectionism_(philosophy) |

|

| First published in 1982, Kripke's

Wittgenstein on Rules and Private Language contends that the central

argument of Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations centers on a

devastating rule-following paradox that undermines the possibility of

our ever following rules in our use of language. Kripke writes that

this paradox is "the most radical and original skeptical problem that

philosophy has seen to date", and that Wittgenstein does not reject the

argument that leads to the rule-following paradox, but accepts it and

offers a "skeptical solution" to ameliorate the paradox's destructive

effects. Most commentators accept that Philosophical Investigations contains the rule-following paradox as Kripke presents it, but few have agreed with his attributing a skeptical solution to Wittgenstein. Kripke himself expresses doubts in Wittgenstein on Rules and Private Language as to whether Wittgenstein would endorse his interpretation of Philosophical Investigations. He says that the work should not be read as an attempt to give an accurate statement of Wittgenstein's views, but rather as an account of Wittgenstein's argument "as it struck Kripke, as it presented a problem for him". The portmanteau "Kripkenstein" has been coined for Kripke's interpretation of Philosophical Investigations. Kripkenstein's main significance was a clear statement of a new kind of skepticism, dubbed "meaning skepticism": the idea that for isolated individuals there is no fact in virtue of which they mean one thing rather than another by the use of a word. Kripke's "skeptical solution" to meaning skepticism is to ground meaning in the behavior of a community. Kripke's book generated a large secondary literature, divided between those who find his skeptical problem interesting and perceptive, and others, such as Gordon Baker, Peter Hacker, and Colin McGinn, who argue that his meaning skepticism is a pseudo-problem that stems from a confused, selective reading of Wittgenstein. Kripke's position has been defended against these and other attacks by the Cambridge philosopher Martin Kusch, and Wittgenstein scholar David G. Stern considers Kripke's book "the most influential and widely discussed" work on Wittgenstein since the 1980s.[29] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saul_Kripke |

1982年に初めて出版されたクリプケ著『ルールと私的言語に関するウィトゲンシュタイン』は、ウィトゲンシュタインの『哲学探究』の中心的な論点は、言語の使用において私たちがルールに従う可能性を損なう、破壊的なルール順守のパラドックスにあると主張している。クリプケは、このパラドックスは「哲学が今日まで見てきた中で最も急進的かつ独創的な懐疑的な問題」であり、ウィトゲンシュタインは規則遵守のパラドックスにつながる議論を否定するのではなく、それを認め、その破壊的な影響を改善するための「懐疑的な解決策」を提示していると書いている。 ほとんどの論者は、『哲学探究』にクリプケが提示した通りの規則遵守のパラドックスが含まれていることを認めているが、クリプケが懐疑的な解決策をウィトゲンシュタインに帰属させていることには同意していない。 クリプケ自身も、『規則と私的言語』におけるウィトゲンシュタインが『哲学探究』の解釈を支持するかどうかについては疑問を呈している。同氏は、この作品 はウィトゲンシュタインの考えを正確に述べようとした試みとして読むべきではなく、むしろ「クリプケが感じたように、クリプケにとって問題となった」ウィ トゲンシュタインの議論の説明として読むべきであると述べている。 「クリプケンシュタイン」という造語は、クリプケによる『哲学探究』の解釈を指す。クリプケンシュタインの主な意義は、新しい種類の懐疑論を明確に述べた ことである。この懐疑論は「意味の懐疑論」と呼ばれ、孤立した個人にとって、言葉を使うことで一方のことを意味し、他方を意味しないという事実はないとい う考え方である。意味に対する懐疑論に対するクリプケの「懐疑的解決」は、意味をコミュニティの行動に根ざすというものである。 クリプケの著書は多くの二次文献を生み出したが、その中には、クリプケの懐疑的な問題提起を興味深く洞察力に富むものと考える者と、ゴードン・ベイカー、 ピーター・ハッカー、コリン・マギンといった、クリプケの意味に対する懐疑論はウィトゲンシュタインの混乱した選択的な読解に由来する偽りの問題であると 主張する者とに分かれている。クリプケの立場は、ケンブリッジ大学の哲学者マーティン・クッシュ(Martin Kusch)によって、これらの批判やその他の批判に対して擁護されている。ウィトゲンシュタイン学者のデヴィッド・G・スターン(David G. Stern)は、クリプケの著書を「1980年代以降のウィトゲンシュタイン研究において最も影響力があり、広く議論されている」著作であると考えてい る。[29] |

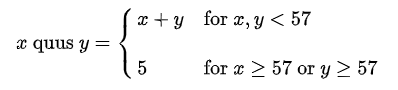

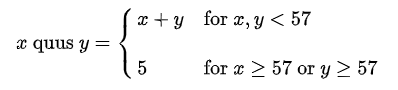

| Wittgenstein on Rules and Private Language

is a 1982 book by philosopher of language Saul Kripke in which he

contends that the central argument of Ludwig Wittgenstein's

Philosophical Investigations centers on a skeptical rule-following

paradox that undermines the possibility of our ever following rules in

our use of language. Kripke writes that this paradox is "the most

radical and original skeptical problem that philosophy has seen to

date" (p. 60). He argues that Wittgenstein does not reject the argument

that leads to the rule-following paradox, but accepts it and offers a

"skeptical solution" to alleviate the paradox's destructive effects. Kripkenstein: Kripke's skeptical Wittgenstein While most commentators accept that the Philosophical Investigations contains the rule-following paradox as Kripke presents it, few have concurred in attributing Kripke's skeptical solution to Wittgenstein. Kripke expresses doubts in Wittgenstein on Rules and Private Language as to whether Wittgenstein would endorse his interpretation of the Philosophical Investigations. He says that his book should not be read as an attempt to give an accurate summary of Wittgenstein's views, but rather as an account of Wittgenstein's argument "as it struck Kripke, as it presented a problem for him" (p. 5). The portmanteau "Kripkenstein" has been coined as a term for a fictional person who holds the views expressed by Kripke's reading of the Philosophical Investigations; in this way, it is convenient to speak of Kripke's own views, Wittgenstein's views (as generally understood), and Kripkenstein's views. Wittgenstein scholar David G. Stern considers Kripke's book the most influential and widely discussed work on Wittgenstein since the 1980s.[1] The rule-following paradox In Philosophical Investigations §201a Wittgenstein states the rule-following paradox: "This was our paradox: no course of action could be determined by a rule, because any course of action can be made out to accord with the rule". Kripke gives a mathematical example to illustrate the reasoning that leads to this conclusion. Suppose that you have never added numbers greater than or equal to 57 before. Further, suppose that you are asked to perform the computation 68 + 57. Our natural inclination is that you will apply the addition function as you have before, and calculate that the correct answer is 125. But now imagine that a bizarre skeptic comes along and argues: That there is no fact about your past usage of the addition function that determines 125 as the right answer. That nothing justifies you in giving this answer rather than another. After all, the skeptic reasons, by hypothesis you have never added numbers 57 or greater before. It is perfectly consistent with your previous use of "plus" that you actually meant "quus", defined as:  Thus under the quus function, if either of the two numbers added is 57 or greater, the sum is 5. The skeptic argues that there is no fact that determines that you ought to answer 125 rather than 5, as all your prior addition is compatible with the quus function instead of the plus function, for you have never added a number greater than or equal to 57 before. Further, your past usage of the addition function is susceptible to an infinite number of different quus-like interpretations. It appears that every new application of "plus", rather than being governed by a strict, unambiguous rule, is actually a leap in the dark. Similar skeptical reasoning can be applied to the meaning of any word of any human language. The power of Kripke's example is that in mathematics the rules for the use of expressions appear to be defined clearly for an infinite number of cases. Kripke doesn't question the mathematical validity of the "+" function, but rather the meta-linguistic usage of "plus": what fact can we point to that shows that "plus" refers to the mathematical function "+"? If we assume for the sake of argument that "plus" refers to the function "+", the skeptical problem simply resurfaces at a higher level. The addition algorithm itself will contain terms susceptible to different and incompatible interpretations. In short, rules for interpreting rules provide no help, because they themselves can be interpreted in different ways. Or, as Wittgenstein puts it, "any interpretation still hangs in the air along with what it interprets, and cannot give it any support. Interpretations by themselves do not determine meaning" (Philosophical Investigations §198a). The skeptical solution Following David Hume, Kripke distinguishes between two types of solution to skeptical paradoxes. Straight solutions dissolve paradoxes by rejecting one (or more) of the premises that lead to them. Skeptical solutions accept the truth of the paradox, but argue that it does not undermine our ordinary beliefs and practices in the way it seems to. Because Kripke thinks that Wittgenstein endorses the skeptical paradox, he is committed to the view that Wittgenstein offers a skeptical, and not a straight, solution.[2] The rule-following paradox threatens our ordinary beliefs and practices concerning meaning because it implies that there is no such thing as meaning something by an expression or sentence. John McDowell explains this as follows. We are inclined to think of meaning in contractual terms: that is, that meanings commit or oblige us to use words in a certain way. When you grasp the meaning of the word "dog", for example, you know that you ought to use that word to refer to dogs, and not cats. But if there cannot be rules governing the uses of words, as the rule-following paradox apparently shows, this intuitive notion of meaning is utterly undermined. Kripke holds that other commentators on Philosophical Investigations have believed that the private language argument is presented in sections occurring after §243.[3] Kripke reacts against this view, noting that the conclusion to the argument is explicitly stated by §202, which reads “Hence it is not possible to obey a rule ‘privately’: otherwise thinking one was obeying a rule would be the same as obeying it.” Further, in this introductory section, Kripke identifies Wittgenstein's interests in the philosophy of mind as related to his interests in the foundations of mathematics, in that both subjects require considerations about rules and rule-following.[4] Kripke's skeptical solution is this: A language-user's following a rule correctly is not justified by any fact that obtains about the relationship between their candidate application of a rule in a particular case and the putative rule itself (as for Hume the causal link between two events a and b is not determined by any particular fact obtaining between them taken in isolation); rather, the assertion that the rule that is being followed is justified by the fact that the behaviors surrounding the candidate instance of rule-following (by the candidate rule-follower) meet other language users' expectations. That the solution is not based on a fact about a particular instance of putative rule-following—as it would be if it were based on some mental state of meaning, interpretation, or intention—shows that this solution is skeptical in the sense Kripke specifies. |

『ウィトゲンシュタインの規則と言語哲学』は、言語哲学者ソール・クリ

プケが1982年に発表した著書であり、同書の中でクリプケは、ルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタインの『哲学探究』の中心的な論点は、言語使用における規

則遵守の可能性を損なう懐疑的な規則遵守のパラドックスであると主張している。クリプケは、このパラドックスは「哲学が今日まで見てきた中で最も急進的か

つ独創的な懐疑的な問題」であると書いている(60ページ)。彼は、ウィトゲンシュタインは規則遵守のパラドックスにつながる議論を否定しているのではな

く、その議論を受け入れ、その破壊的な影響を緩和する「懐疑的な解決策」を提示していると主張している。 「クリプケンシュタイン」クリプケの懐疑的なウィトゲンシュタイン ほとんどの論者は、クリプケが提示した通りに『哲学探究』に規則遵守のパラドックスが含まれていることを認めているが、クリプケの懐疑的な解決策をウィト ゲンシュタインに帰する意見には同意する者はほとんどいない。クリプケは『ルールと私的言語』におけるウィトゲンシュタインが『探究』の解釈を支持するか どうかについて疑問を呈している。彼は、著書はウィトゲンシュタインの考えを正確に要約しようとする試みではなく、むしろクリプケが「クリプケに衝撃を与 え、クリプケに問題を提起した」ウィトゲンシュタインの議論の説明であると述べる(p. 5)。「クリプケンシュタイン」という造語は、クリプケの『哲学探究』の解釈で示された見解を持つ架空の人物を表す用語として作られた。このように、クリ プケ自身の見解、ウィトゲンシュタインの見解(一般的に理解されているもの)、クリプケンシュタインの見解について話すのは便利である。ウィトゲンシュタ イン学者のデイヴィッド・G・スターンは、クリプケの著書を1980年代以降のウィトゲンシュタイン研究において最も影響力があり、広く議論された著作で あると評価している。[1] 規則遵守のパラドックス 『哲学探究』第201a項において、ウィトゲンシュタインは「これが我々のパラドックスであった。行動の選択はすべて規則に適合するように見せることができるため、行動の選択を規則によって決定することはできない」と述べている。 クリプケは、この結論に至る論理を説明する数学的な例を挙げている。 57以上の数字を足したことが一度もないと仮定しよう。 さらに、68 + 57の計算を行うように頼まれたとしよう。 私たちは、これまでと同じように足し算の機能を使い、答えは125だと計算するだろう。 しかし、ここで奇妙な懐疑論者が現れ、次のように主張したと想像してみよう。 あなたのこれまでの「足し算」の使用法について、125が正解であると決定づけるような事実は存在しない。 この答えを出すことに正当性を与えるものは何もない。 結局のところ、懐疑論者はこう推論する。仮説として、あなたはこれまで57以上の数字を足したことがない。あなたが実際に意味したのは「クウス」であり、それは次のように定義される。  したがって、quus機能では、加算された2つの数値のいずれかが57以上であれば、合計は5となる。懐疑論者は、これまでの加算はすべてプラス機能では なくquus機能と互換性があるため、5ではなく125と答えるべきだという事実はないと主張する。なぜなら、57以上の数値を加算したことは一度もない からだ。 さらに、あなたのこれまでの加算機能の使用法は、無限の異なるクウス的な解釈を受けやすい。「プラス」の新しい使用法は、厳格で明確な規則に支配されるのではなく、実際には暗中模索であるように見える。 同様の懐疑的な推論は、あらゆる人間の言語の単語の意味にも適用できる。クリプケの例の強みは、数学では表現の使用に関するルールが無限のケースに対して 明確に定義されているように見えることである。クリプケは「+」の数学的な正当性を疑っているのではなく、「プラス」のメタ言語的な使用法を疑っている。 「プラス」が数学関数「+」を指していることを示す事実とは何だろうか? 仮に「プラス」が「+」という数学的関数を指していると仮定したとしても、疑念はより高いレベルで再び浮上する。加算アルゴリズム自体が、異なる解釈や互 換性のない解釈を受けやすい用語を含んでいるからだ。つまり、規則を解釈する規則は役に立たない。なぜなら、それ自体が異なる解釈を受けうるからだ。ある いは、ヴィトゲンシュタインの言葉を借りれば、「あらゆる解釈は、解釈対象とともに宙に浮いたままであり、それを裏付けることはできない。解釈それ自体は 意味を決定しない」(『哲学探究』§198a)。 懐疑論的解決策 デイヴィッド・ヒュームにならって、クリプケは懐疑論的パラドックスに対する解決策を2種類に区別している。 直接的な解決策は、パラドックスを引き起こす前提条件の1つ(または複数)を否定することでパラドックスを解消する。 懐疑論的解決策は、パラドックスの真実性を認めるが、パラドックスが私たちの通常の信念や慣習を損なうことはない、と主張する。クリプケは、ウィトゲン シュタインが懐疑的パラドックスを支持していると考えているため、ウィトゲンシュタインは懐疑的な解決策を提示しており、単純な解決策ではないという見解 に固執している。 規則に従うことのパラドックスは、表現や文章によって意味を伝えるということがありえないことを暗示しているため、意味に関する我々の通常の信念や慣習を 脅かす。ジョン・マクダウェルはこれを次のように説明している。私たちは意味を契約上の用語で考える傾向がある。つまり、意味は私たちに特定の方法で言葉 を使うことを強制する、あるいは義務づけるという考え方である。例えば、「dog」という単語の意味を理解すると、その単語は犬を指すために使うべきであ り、猫を指すために使うべきではないと分かる。しかし、言葉の使用を規定する規則が存在し得ない場合、規則に従うことのパラドックスが明らかに示すよう に、この意味に関する直感的な概念は完全に損なわれる。 クリプケは、『哲学探究』の他の論評者たちが、私的言語論証は§243以降のセクションで提示されていると信じていると主張している。[3] クリプケは、この見解に反対し、論証の結論は§202で明確に述べられていると指摘している。「したがって、ルールを『私的に』遵守することは不可能であ る。そうでなければ、ルールを遵守していると考えていることは、ルールを遵守していることと同じである。」 さらに、この序論の章で、クリプケは、心の哲学におけるウィトゲンシュタインの関心は、数学の基礎における関心と関連していると指摘している。なぜなら、 両方の主題において、規則と規則の順守に関する考察が必要とされるからである。[4] クリプケの懐疑論的な解決策は次の通りである。言語使用者が規則を正しく守っていることは、特定の事例における規則の候補となる適用と想定される規則自体 との関係について得られる事実によって正当化されるものではない(ヒュームにとって、2つの出来事aとbの因果関係は、 むしろ、そのルールに従っているという主張は、ルールに従っている候補者(ルールに従う候補者)によるルールに従う候補事例を取り巻く行動が、他の言語使 用者の期待に応えるという事実によって正当化される。その解決策が、仮定された規則遵守の特定の事例に関する事実に基づいているわけではないという点(そ れが意味、解釈、意図といった何らかの心的状態に基づいている場合のように)は、この解決策がクリプケが特定する意味で懐疑的であることを示している。 |

| The "straight" solution In contrast to the kind of solution offered by Kripke (above) and Crispin Wright (elsewhere), McDowell interprets Wittgenstein as correctly (by McDowell's lights) offering a "straight solution".[5] McDowell argues that Wittgenstein does present the paradox (as Kripke argues), but he argues further that Wittgenstein rejects the paradox on the grounds that it assimilates understanding and interpretation. In order to understand something, we must have an interpretation. That is, to understand what is meant by "plus", we must first have an interpretation of what "plus" means. This leads one to either skepticism—how do you know your interpretation is the correct interpretation?—or relativity, whereby our understandings, and thus interpretations, are only so determined insofar as we have used them. On this latter view, endorsed by Wittgenstein in Wright's readings, there are no facts about numerical addition that we have so far not discovered, so when we come upon such situations, we can flesh out our interpretations further. According to McDowell, both of these alternatives are rather unsatisfying, the latter because we want to say that there are facts about numbers that have not yet been added. McDowell further writes that to understand rule-following we should understand it as resulting from inculcation into a custom or practice. Thus, to understand addition is simply to have been inculcated into a practice of adding. This position is often called "anti-antirealism", meaning that he argues that the result of sceptical arguments, like that of the rule-following paradox, is to tempt philosophical theory into realism, thereby making bold metaphysical claims. Since McDowell offers a straight solution, making the rule-following paradox compatible with realism would be missing Wittgenstein's basic point that the meaning can often be said to be the use. This is in line with quietism, the view that philosophical theory results only in dichotomies and that the notion of a theory of meaning is pointless. Semantic realism and Kripkenstein George M. Wilson argues that there is a way to lay out Kripkenstein as a philosophical position compatible with semantic realism:[6] by differentiating between two sorts of conclusions resulting from the rule-following paradox, illustrated by a speaker S using a term T: BSC (Basic Sceptical Conclusion): There are no facts about S that fix any set of properties as the standard of correctness for S's use of T. RSC (Radical Sceptical Conclusion): No one ever means anything by any term. Wilson argues that Kripke's sceptic is indeed committed to RSC, but that Kripke reads Wittgenstein as embracing BSC but refuting RSC. This, Wilson argues, is done with the concept of familiarity. When S uses T, its correctness is determined neither by a fact about S (hereby accepting the rule-following paradox) nor a correspondence between T and the object termed (hereby denying the idea of correspondence theory), but the irreducible fact that T is grounded in familiarity, being used to predicate other similar objects. This familiarity is independent of and, in some sense, external to S, making familiarity the grounding for semantic realism. Still, Wilson's suggested realism is minimal, partly accepting McDowell's critique. |

「単純な」解決策 クリプケ(上記)やクリスピン・ライト(別所)が提示した解決策とは対照的に、マクダウェルはウィトゲンシュタインを正しく解釈しており(マクダウェルに よれば)、「単純な解決策」を提供している。[5] マクダウェルは、クリプケが主張するように、ウィトゲンシュタインはパラドックスを提示していると主張しているが、さらに、ウィトゲンシュタインは、パラ ドックスが理解と解釈を同一視しているという理由で、それを否定していると主張している。何かを理解するためには、解釈が必要である。つまり、「プラス」 が何を意味するかを理解するためには、まず「プラス」が何を意味するかの解釈が必要である。このことは、懐疑論(自分の解釈が正しい解釈であるとどうして わかるのか?)か相対論(つまり、理解、ひいては解釈は、それを使用する限りにおいてのみ決定される)のどちらかに導く。ライトの解釈でウィトゲンシュタ インが支持したこの後者の見解では、これまで発見されていない数の加算に関する事実はないため、そのような状況に遭遇した際には、解釈をさらに深めること ができる。マクダウェルによると、この2つの選択肢はどちらもあまり満足のいくものではない。後者は、まだ加算されていない数の事実があると言いたいから だ。 マクダウェルはさらに、規則に従うことを理解するには、それが習慣や慣行に植え付けられた結果であると理解すべきだと書いている。したがって、足し算を理 解するとは、足し算の慣行に植え付けられた結果であると理解することに他ならない。この立場はしばしば「反アンチ・リアリズム」と呼ばれ、規則に従うパラ ドックスのような懐疑論的議論の結果は、哲学理論をリアリズムに傾倒させ、大胆な形而上学的主張を生み出すという意味である。マクダウェルは単純な解決策 を提示しているため、規則に従うパラドックスを実在論と両立させることは、意味はしばしば用法であると言えるというウィトゲンシュタインの基本的な主張を 見失うことになる。これは静寂主義に沿ったものであり、哲学理論は二分法に帰結するのみであり、意味の理論という概念は無意味であるという見解である。 意味論的実在論とクリプケ主義 ジョージ・M・ウィルソンは、クリプケ主義を意味論的実在論と両立する哲学的立場として位置づける方法があると主張している。[6] 話し手Sが用語Tを使用することによって生じる、規則順守のパラドックスから生じる2種類の結論を区別することによって、 BSC(基本的な懐疑的結論):SのTの使用について、Sの性質を確定する事実はない。 RSC(根本的懐疑的結論):誰も用語によって何かを意味することはない。 ウィルソンは、クリプケの懐疑論は確かにRSCに傾倒しているが、クリプケはウィトゲンシュタインをBSCを支持しRSCを否定するものとして解釈してい ると論じている。ウィルソンは、これは「馴染み」という概念によって行われていると論じている。SがTを使用する場合、その正しさはSに関する事実(これ により規則順守のパラドックスを受け入れる)でも、Tと(対応関係理論の考えを否定する)呼称された対象との対応関係でも決定されるのではなく、Tが他の 類似した対象を述語として使用されることで、親しみによって根拠付けられているという不可分の事実によって決定される。この親しみはSとは独立しており、 ある意味ではSの外にあるため、親しみが意味論的リアリズムの根拠となる。 それでも、ウィルソンが示唆するリアリズムは最小限のものであり、マクダウェルの批判を部分的に受け入れている。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wittgenstein_on_Rules_and_Private_Language |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆