サンク・コスト

Sunk cost, 埋没費用

☆経

済学や経営判断において、サンクコスト(埋没費用、沈没費用あるいは後顧費用とも呼ばれる)とは、既に発生し回収不能な費用を指す。[1][2]

サンクコストは、将来の費用である見込み費用と対比される。見込み費用は、行動を起こせば回避可能な将来の費用である。[3]

つまり、サンクコストとは過去に支払われた金額であり、将来の意思決定にはもはや関係がない。経済学者はサンクコストが将来の合理的な意思決定には無関係

だと主張するが、日常生活では、自動車や家の修理といった状況において、人々は過去の支出をそれらの資産に関する将来の決定に持ち込むことが多い。

| In

economics and business decision-making, a sunk cost (also known as

retrospective cost) is a cost that has already been incurred and cannot

be recovered.[1][2] Sunk costs are contrasted with prospective costs,

which are future costs that may be avoided if action is taken.[3] In

other words, a sunk cost is a sum paid in the past that is no longer

relevant to decisions about the future. Even though economists argue

that sunk costs are no longer relevant to future rational

decision-making, people in everyday life often take previous

expenditures in situations, such as repairing a car or house, into

their future decisions regarding those properties. |

経

済学や経営判断において、サンクコスト(後顧費用とも呼ばれる)とは、既に発生し回収不能な費用を指す。[1][2]

サンクコストは、将来の費用である見込み費用と対比される。見込み費用は、行動を起こせば回避可能な将来の費用である。[3]

つまり、サンクコストとは過去に支払われた金額であり、将来の意思決定にはもはや関係がない。経済学者はサンクコストが将来の合理的な意思決定には無関係

だと主張するが、日常生活では、自動車や家の修理といった状況において、人々は過去の支出をそれらの資産に関する将来の決定に持ち込むことが多い。 |

| Bygones principle According to classical economics and standard microeconomic theory, only prospective (future) costs are relevant to a rational decision.[4] At any moment in time, the best thing to do depends only on current alternatives.[5] The only things that matter are the future consequences.[6] Past mistakes are irrelevant.[5] Any costs incurred prior to making the decision have already been incurred no matter what decision is made. They may be described as "water under the bridge",[7] and making decisions on their basis may be described as "crying over spilt milk".[8] In other words, people should not let sunk costs influence their decisions; sunk costs are irrelevant to rational decisions. Thus, if a new factory was originally projected to cost $100 million, and yield $120 million in value, and after $30 million is spent on it the value projection falls to $65 million, the company should abandon the project rather than spending an additional $70 million to complete it. Conversely, if the value projection falls to $75 million, the company, as a rational actor, should continue the project. This is known as the bygones principle[6][9] or the marginal principle.[10] The bygones principle is grounded in the branch of normative decision theory known as rational choice theory, particularly in expected utility hypothesis. Expected utility theory relies on a property known as cancellation, which says that it is rational in decision-making to disregard (cancel) any state of the world that yields the same outcome regardless of one's choice.[11] Past decisions—including sunk costs—meet that criterion. The bygones principle can also be formalised as the notion of "separability". Separability requires agents to take decisions by comparing the available options in eventualities that can still occur, uninfluenced by how the current situation was reached or by eventualities that are precluded by that history. In the language of decision trees, it requires the agent's choice at a particular choice node to be independent of unreachable parts of the tree. This formulation makes clear how central the principle is to standard economic theory by, for example, founding the folding-back algorithm for individual sequential decisions and game-theoretical concepts such as sub-game perfection.[12] Until a decision-maker irreversibly commits resources, the prospective cost is an avoidable future cost and is properly included in any decision-making process.[9] For instance, if someone is considering pre-ordering movie tickets, but has not actually purchased them yet, the cost remains avoidable. Both retrospective and prospective costs could be either fixed costs (continuous for as long as the business is operating and unaffected by output volume) or variable costs (dependent on volume).[13] However, many economists[who?] consider it a mistake to classify sunk costs as "fixed" or "variable". For example, if a firm sinks $400 million on an enterprise software installation, that cost is "sunk" because it was a one-time expense and cannot be recovered once spent. A "fixed" cost would be monthly payments made as part of a service contract or licensing deal with the company that set up the software. The upfront irretrievable payment for the installation should not be deemed a "fixed" cost, with its cost spread out over time. Sunk costs should be kept separate. The "variable costs" for this project might include data centre power usage, for example. There are cases in which taking sunk costs into account in decision-making, violating the bygones principle, is rational.[14] For example, for a manager who wishes to be perceived as persevering in the face of adversity, or to avoid blame for earlier mistakes, it may be rational to persist with a project for personal reasons even if it is not the benefit of their company. Or, if they hold private information about the undesirability of abandoning a project, it is fully rational to persist with a project that outsiders think displays the fallacy of sunk cost.[15] |

過ぎ去ったことは水に流す原則 古典派経済学と標準的なミクロ経済理論によれば、合理的な意思決定に関連するコストは将来のコストのみである。[4] どの時点においても、最善の行動は現在の選択肢のみに依存する。[5] 重要なのは将来の結果だけだ。[6] 過去の過ちは無関係である。[5] 意思決定以前に発生した費用は、どのような決定がなされようとも既に発生済みである。これらは「過ぎ去ったことは水に流す」[7] と表現され、それらに基づいて意思決定を行うことは「こぼれたミルクを嘆く」[8] と言える。つまり、人はサンクコストに意思決定を左右されるべきではない。サンクコストは合理的な意思決定には無関係である。したがって、新工場の当初計 画コストが1億ドルで、1億2000万ドルの価値を生み出すと予測されていた場合、3000万ドルを費やした後に価値予測が6500万ドルに低下したな ら、会社は追加の7000万ドルを投じて完成させるよりも、プロジェクトを放棄すべきである。逆に、価値予測が7500万ドルに低下した場合、会社は合理 的な主体としてプロジェクトを継続すべきである。これは「過ぎ去った事実は考慮しない原則」[6][9] あるいは「境界原則」[10] として知られる。 過ぎ去った事実は考慮しない原則は、規範的意思決定理論の一分野である合理的選択理論、特に期待効用仮説に根ざしている。期待効用理論は「相殺」と呼ばれ る性質に依存しており、これは意思決定において、自らの選択に関わらず同じ結果をもたらす世界の状態を無視(相殺)することが合理的であると述べる。 [11] 過去の決定——サンクコストを含む——はこの基準を満たす。 過去不問の原則は「分離可能性」の概念として形式化することもできる。分離可能性は、エージェントが現在の状況に至った経緯や、その経緯によって排除され た事象の影響を受けず、依然として発生し得る事象における選択肢を比較して決定を下すことを要求する。決定木の用語で言えば、特定の選択ノードにおける主 体選択が、到達不可能な木の部分から独立していることを要求する。この定式化は、例えば個々の連続的決定のための折り畳みアルゴリズムや、サブゲーム完全 性といったゲーム理論的概念の基盤を成すことで、この原理が標準的な経済理論においていかに中心的な位置を占めるかを明らかにする。[12] 意思決定者が資源を不可逆的に投入するまでは、見込みコストは回避可能な将来のコストであり、あらゆる意思決定プロセスに適切に含まれるべきである。 [9] 例えば、映画チケットの事前予約を検討しているが、まだ実際に購入していない場合、そのコストは回避可能なままである。 過去費用と将来費用の双方は、固定費(事業継続中ずっと継続し、生産量に影響されない)または変動費(生産量に依存する)のいずれかとなり得る。[13] しかし多くの経済学者[誰?]は、サンクコストを「固定」または「変動」に分類することを誤りと見なしている。例えば、企業がエンタープライズソフトウェ アの導入に4億ドルを投じた場合、その費用は「サンクコスト」である。なぜなら、これは一度限りの支出であり、一度使えば回収できないからだ。一方、「固 定」費用とは、ソフトウェアを導入した企業とのサービス契約やライセンス契約に基づく月々の支払いを指す。導入時の前払い不可回収費用を、時間をかけて費 用を分散させる「固定費」と見なすべきではない。沈没費用は区別すべきである。このプロジェクトの「変動費」には、例えばデータセンターの電力使用量など が含まれる。 意思決定においてサンクコスト(埋没費用)を考慮し、過ぎ去った原則に反する行為が合理的となる場合がある。[14] 例えば、逆境に耐える姿勢を周囲に示したい管理者や、過去の過失の責任を回避したい管理者は、たとえ会社にとって利益とならなくても、個人的な理由でプロ ジェクトを継続することが合理的である場合がある。あるいは、プロジェクト放棄の非現実性に関する内部情報を保持している場合、外部から見てサンクコスト の誤謬を示すプロジェクトを継続することは完全に合理的である。[15] |

| Fallacy effect See also: fail fast (business), escalation of commitment, and the captain goes down with the ship The bygones principle does not always accord with real-world behavior. Sunk costs often influence people's decisions,[7][14] with people believing that investments (i.e., sunk costs) justify further expenditures.[16] People demonstrate "a greater tendency to continue an endeavor once an investment in money, effort, or time has been made".[17][18] This is the sunk cost fallacy, and such behavior may be described as "throwing good money after bad",[19][14] while refusing to succumb to what may be described as "cutting one's losses".[14] People can remain in failing relationships because they "have already invested too much to leave". Other people are swayed by arguments that a war must continue because lives will have been sacrificed in vain unless victory is achieved. Individuals caught up in psychologically manipulative scams will continue investing time, money and emotional energy into the project, despite doubts or suspicions that something is not right.[20] These types of behaviour do not seem to accord with rational choice theory and are often classified as behavioural errors.[21] Rego, Arantes, and Magalhães point out that the sunk cost effect exists in committed relationships. They devised two experiments, one of which showed that people in a relationship which they had invested money and effort in were more likely to keep that relationship going than end it; and in the second experiment, while people are in a relationship which they had invested enough time in, they tended to devote more time to the relationship.[22] It also means people fall into the sunk cost fallacy. However, people should ignore sunk costs and make rational decisions when planning for the future; time, money, and effort often make people continue to maintain this relationship, which is equivalent to investing in failed projects. According to evidence reported by De Bondt and Makhija (1988), managers of many utility companies in the United States have been overly reluctant to terminate economically unviable nuclear plant projects.[23] In the 1960s, the nuclear power industry promised "energy too cheap to meter". Nuclear power lost public support in the 1970s and 1980s, when public service commissions nationwide ordered prudency reviews. From these reviews, De Bondt and Makhija find evidence that the commissions denied many utility companies even partial recovery of nuclear construction costs on the grounds that they had been mismanaging the nuclear construction projects in ways consistent with throwing good money after bad.[24]  The sunk cost fallacy has also been called the "Concorde fallacy": the British and French governments took their past expenses on the costly supersonic jet as a rationale for continuing the project, as opposed to "cutting their losses". There is also evidence of government representatives failing to ignore sunk costs.[21] The term "Concorde fallacy"[25] derives from the fact that the British and French governments continued to fund the joint development of the costly Concorde supersonic airplane even after it became apparent that there was no longer an economic case for the aircraft. The British government privately regarded the project as a commercial disaster that should never have been started. Political and legal issues made it impossible for either government to pull out.[9] The idea of sunk costs is often employed when analyzing business decisions. A common example of a sunk cost for a business is the promotion of a brand name. This type of marketing incurs costs that cannot normally be recovered.[citation needed] It is not typically possible to later "demote" one's brand names in exchange for cash.[citation needed] A second example is research and development (R&D) costs. Once spent, such costs are sunk and should not affect future pricing decisions.[citation needed] A pharmaceutical company's attempt to justify high prices because of the need to recoup R&D expenses would be fallacious.[citation needed] The company would charge a high price whether R&D cost one dollar or one million.[citation needed] R&D costs and the ability to recoup those costs are a factor in deciding whether to spend the money on R&D in the first place.[26] Dijkstra and Hong proposed that part of a person's behavior is influenced by a person's current emotions. Their experiments showed that emotional responses benefit from the sunk cost fallacy. Negative influences lead to the sunk cost fallacy. For example, anxious people face the stress brought about by the sunk cost fallacy. When stressed, they are more motivated to invest in failed projects rather than take additional approaches. Their report shows that the sunk cost fallacy will have a greater impact on people under high load conditions, and people's psychological state and external environment will be the key influencing factors.[27] The sunk cost effect may cause cost overrun. In business, an example of sunk costs may be an investment into a factory or research that now has a lower value or none. For example, $20 million has been spent on building a power plant; the value now is zero because it is incomplete (and no sale or recovery is feasible). The plant can be completed for an additional $10 million or abandoned, and a different but equally valuable facility built for $5 million. Abandonment and construction of the alternative facility is the more rational decision, even though it represents a total loss of the original expenditure—the original sum invested is a sunk cost. If decision-makers are irrational or have the "wrong" (different) incentives, the completion of the project may be chosen. For example, politicians or managers may have more incentive to avoid the appearance of a total loss. In practice, there is considerable ambiguity and uncertainty in such cases, and decisions may, in retrospect, appear irrational that were, at the time, reasonable to the economic actors involved and in the context of their incentives. A decision-maker might make rational decisions according to their incentives, outside of efficiency or profitability. This is considered an incentive problem and is distinct from a sunk cost problem. Some research has also noted circumstances where the sunk cost effect is reversed, where individuals appear irrationally eager to write off earlier investments to take up a new endeavor.[28] |

誤謬効果 関連項目:迅速な失敗(ビジネス)、コミットメントのエスカレーション、船長は船と共に沈む 過ぎ去った事象の原則は、必ずしも現実世界の行動と一致しない。サンクコストはしばしば人々の意思決定に影響を与える[7][14]。人々は投資(すなわ ちサンクコスト)がさらなる支出を正当化すると信じている[16]。人々は「金銭、労力、時間の投資がなされた後、その取り組みを継続する傾向が強くな る」ことを示す。[17][18] これがサンクコストの誤謬であり、このような行動は「無駄な出費にさらに金を投じる」[19][14] と表現され得る一方で、「損失を確定させる」[14] ことに屈することを拒む。人々は「既に去るには多すぎる投資をした」という理由で、失敗した関係に留まり続けることがある。また、戦争は勝利を収めなけれ ば犠牲になった命が無駄になるから継続すべきだという主張に、人々は影響を受ける。心理的操作を伴う詐欺に巻き込まれた個人は、何かがおかしいという疑念 や不安を抱えながらも、時間や金銭、感情的なエネルギーをその計画に注ぎ続ける[20]。こうした行動は合理的選択理論と一致せず、しばしば行動上の誤り と分類される[21]。 レゴ、アランテス、マガリャンイスは、サンクコスト効果が恋愛関係にも存在すると指摘している。彼らが設計した二つの実験のうち、一つでは金銭と労力を投 資した関係にある人々が、その関係を終わらせるよりも継続する傾向が強いことが示された。二つ目の実験では、十分な時間を投資した関係にある人々は、その 関係にさらに多くの時間を割く傾向があった。[22] これは人々がサンクコストの誤謬に陥ることも意味する。しかし将来計画を立てる際には、人々はサンクコストを無視し合理的な判断を下すべきだ。時間・金 銭・労力が関係維持を継続させる要因となり、それは失敗したプロジェクトへの投資と同等である。 デ・ボンドとマキジャ(1988)が報告した証拠によれば、米国の多くの公益事業会社の経営者は、経済的に採算の取れない原子力発電所プロジェクトを中止 することに過度に消極的であった[23]。1960年代、原子力産業は「計量不能なほど安価なエネルギー」を約束した。1970年代から80年代にかけ て、全米の公益事業委員会が慎重性審査を命じたことで、原子力発電は国民の支持を失った。デ・ボンドとマキジャはこれらの審査から、委員会が多くの公益事 業会社に対し、原子力建設プロジェクトを「無駄遣いを続ける」形で誤管理していたことを理由に、建設費用の一部すら回収させなかった証拠を発見している。 [24]  サンクコストの誤謬は「コンコルドの誤謬」とも呼ばれる。英国とフランス政府は、高コストの超音速ジェット機への過去の支出を、損失を確定させる「損切り」ではなく、プロジェクト継続の根拠としたのである。 政府関係者がサンクコストを無視できなかった証拠もある[21]。「コンコルドの誤謬」[25]という用語は、英仏両政府が、経済的根拠が失われた後も、 高コストなコンコルド超音速旅客機の共同開発への資金提供を継続した事実から由来する。英国政府は非公式に、このプロジェクトを商業的失敗であり、開始す べきではなかったと認識していた。政治的・法的な問題により、いずれの政府も撤退が不可能となった。[9] サンクコストの概念は、ビジネス判断の分析で頻繁に用いられる。企業における典型的なサンクコストの例はブランド名のプロモーションである。この種のマー ケティングは通常回収不可能な費用を伴う。[出典必要] 後からブランド名を「降格」させて現金化することは通常不可能だ。[出典が必要] 第二の例は研究開発費(R&D)である。いったん支出されたこうした費用はサンクコストとなり、将来の価格決定に影響を与えるべきではない。[出 典が必要] 製薬会社が研究開発費を回収する必要性を理由に高価格を正当化しようとする試みは誤りである。[出典が必要] その企業は、研究開発費が1ドルであろうと100万ドルであろうと、高価格を設定するだろう。[出典が必要] 研究開発費とその回収可能性は、そもそも研究開発に資金を投じるかどうかの判断要素である。[26] ダイクストラとホンは、人格の一部が現在の感情に影響されると提唱した。彼らの実験は、感情的反応がサンクコストの誤謬から利益を得ることを示した。負の 影響がサンクコストの誤謬を招く。例えば不安を抱える人々は、サンクコストの誤謬がもたらすストレスに直面する。ストレス下では、新たなアプローチを取る よりも失敗したプロジェクトへの投資を続ける動機が強まる。彼らの報告によれば、サンクコストの誤謬は負荷の高い状況下で人々に大きな影響を与え、個人の 心理状態と外部環境が主要な影響要因となる。[27] サンクコスト効果はコスト超過を引き起こす可能性がある。ビジネスにおけるサンクコストの例としては、現在価値が低下した、あるいは無価値となった工場や 研究への投資が挙げられる。例えば、発電所建設に2000万ドルを費やしたが、未完成のため現在価値はゼロである(売却や回収は不可能)。この発電所は追 加1000万ドルで完成させるか、放棄して500万ドルで同等の価値を持つ別の施設を建設するかの選択肢がある。放棄と代替施設の建設がより合理的な判断 だ。たとえ当初の支出が完全に損失となるとしても、当初投資した金額はサンクコストだからだ。意思決定者が非合理的だったり「誤った」(異なる)インセン ティブを持っていたりすると、プロジェクトの完成が選択される可能性がある。例えば政治家や経営者は、完全な損失という印象を避けるインセンティブが強い 場合がある。実際、こうした事例にはかなりの曖昧さと不確実性が伴い、当時の経済主体とそのインセンティブの文脈では合理的だった決定が、後から見れば非 合理的に見えることもある。意思決定者は、効率性や収益性とは別に、自身のインセンティブに基づいて合理的な決定を下すことがある。これはインセンティブ 問題と見なされ、サンクコスト問題とは区別される。一部の研究では、サンクコスト効果が逆転する状況も指摘されている。つまり、個人が新たな取り組みを始 めるために、過去の投資を非合理的に熱心に帳消しにしようとする場合だ。[28] |

| Plan continuation bias A related phenomenon is plan continuation bias,[29][30][31][32][33] which is recognised as a subtle cognitive bias that tends to force the continuation of a plan or course of action even in the face of changing conditions. In the field of aerospace, it has been recognised as a significant causal factor in accidents, with a 2004 NASA study finding that in 9 out of the 19 accidents studied, aircrew exhibited this behavioural bias.[29] This is a hazard for ships' captains or aircraft pilots who may stick to a planned course even when it is leading to a fatal disaster, and they should abort instead. A famous example is the Torrey Canyon oil spill in which a tanker ran aground when its captain persisted with a risky course rather than accepting a delay.[34] It has been a factor in numerous air crashes and an analysis of 279 approach and landing accidents (ALAs) found that it was the fourth most common cause, occurring in 11% of cases.[35] Another analysis of 76 accidents found that it was a contributory factor in 42% of cases.[36] There are also two predominant factors that characterise the bias. The first is an overly optimistic estimate of the probability of success, possibly to reduce cognitive dissonance making a decision. The second is that of personal responsibility: when you are personally accountable, it is difficult for you to admit that you were wrong.[29] Projects often suffer cost overruns and delays due to the planning fallacy and related factors, including excessive optimism, an unwillingness to admit failure, groupthink, and aversion to loss of sunk costs.[37] |

計画継続バイアス 関連する現象として計画継続バイアスがある[29][30][31][32][33]。これは状況が変化しても計画や行動方針の継続を強いる傾向にある、 微妙な認知バイアスとして認識されている。航空宇宙分野では、事故の重要な原因因子として認識されており、2004年のNASA研究では調査対象19件の 事故のうち9件で乗務員がこの行動バイアスを示していたことが判明している[29]。 これは船舶の船長や航空機のパイロットにとって危険であり、致命的な災害につながる場合でも計画された航路に固執し、中止すべき時に中止しない可能性があ る。有名な事例として、タンカー船長が遅延を受け入れず危険な航路を強行した結果座礁したトーリー・キャニオン油流出事故がある[34]。このバイアスは 数多くの航空事故に関与しており、279件の着陸事故分析では11%の事例で発生し、4番目に多い原因とされた。[35] 別の76件の事故分析では、42%の事例でこの傾向が寄与要因となっていた。[36] このバイアスを特徴づける主な要因は二つある。第一に、意思決定に伴う認知的不協和を軽減するためか、成功確率を過度に楽観的に見積もることだ。第二に、個人的な責任問題である。自ら責任を負う立場では、誤りを認めることが困難になる。[29] 計画の誤謬や関連要因(過度な楽観主義、失敗を認めない姿勢、集団思考、サンクコストの損失回避など)により、プロジェクトはしばしばコスト超過や遅延を苦悩する。[37] |

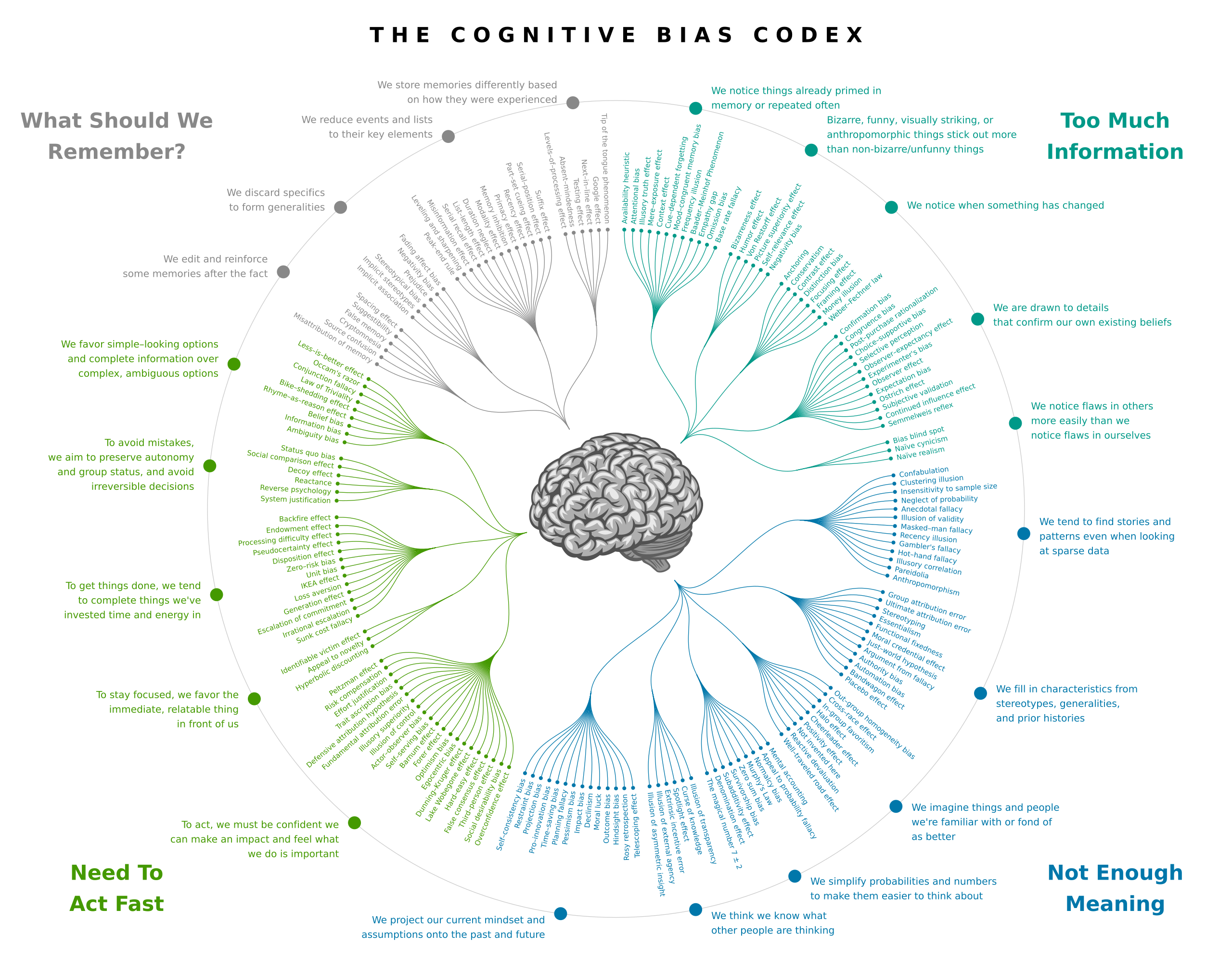

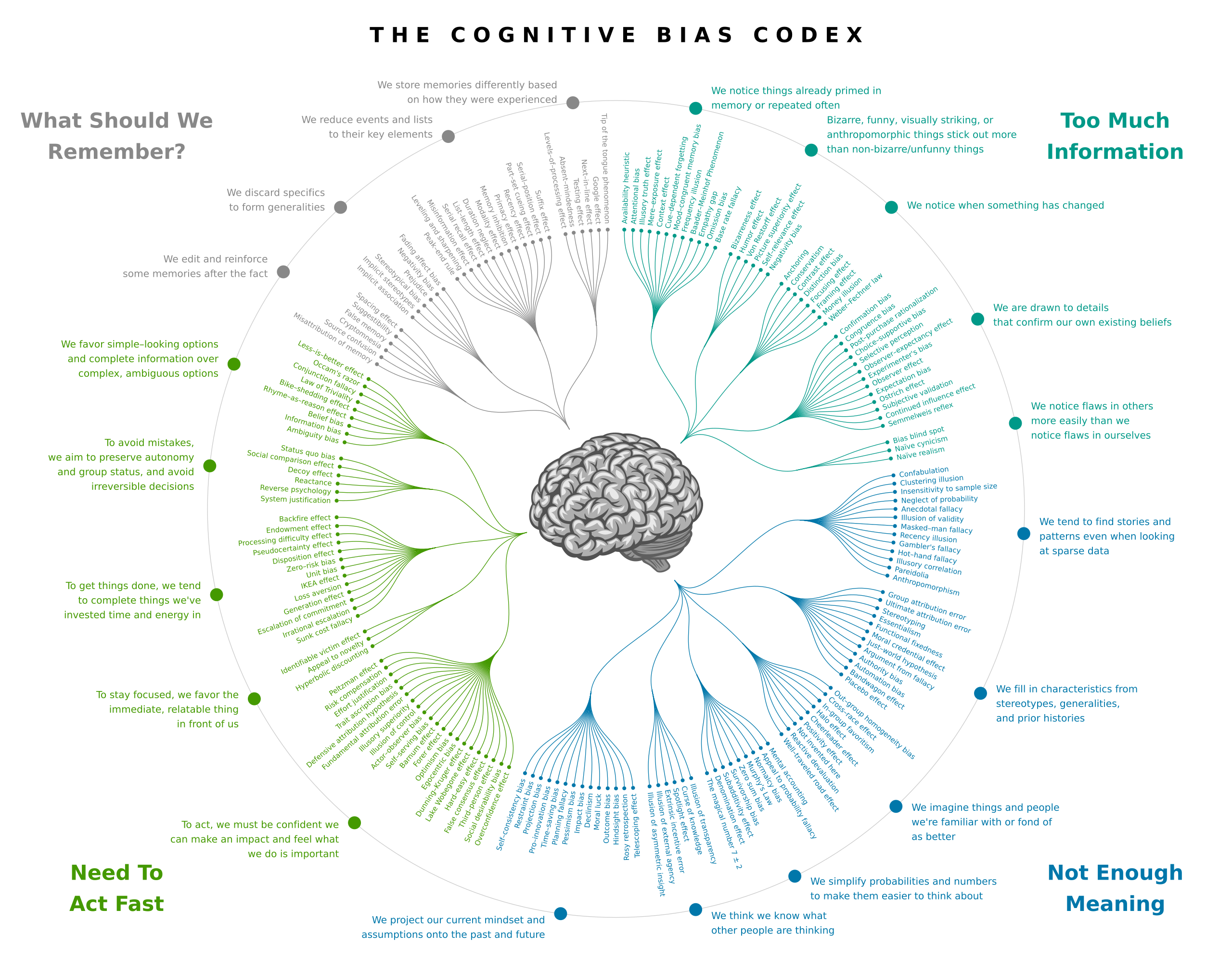

Psychological factors The psychology of the cognitive bias offers a set of "need to act fast" biases (light green) that affect rationality in economics. [click twice to browse]. Evidence from behavioral economics suggests that there are at least four specific psychological factors underlying the sunk cost effect: Framing effects, a cognitive bias where people decide on options based on whether the options are presented with positive or negative connotations; e.g. as a loss or as a gain.[38] People tend to avoid risk when a positive frame is presented but seek risks when a negative frame is presented.[39] An overoptimistic probability bias, whereby after an investment the evaluation of one's investment-reaping dividends is increased.[citation needed] The requisite of personal responsibility. Sunk cost appears to operate chiefly in those who feel a personal responsibility for the investments that are to be viewed as a sunk cost.[citation needed] The desire not to appear wasteful—"One reason why people may wish to throw good money after bad is that to stop investing would constitute an admission that the prior money was wasted."[18] Taken together, these results suggest that the sunk cost effect may reflect non-standard measures of utility, which is ultimately subjective and unique to the individual. Framing effect The framing effect which underlies the sunk cost effect builds upon the concept of extensionality where the outcome is the same regardless of how the information is framed. This is in contradiction to the concept of intentionality, which is concerned with whether the presentation of information changes the situation in question. Take two mathematical functions: f(x) = 2x + 10 f(x) = 2 · (x + 5) While these functions are framed differently, regardless of the input "x", the outcome is analytically equivalent. Therefore, if a rational decision maker were to choose between these two functions, the likelihood of each function being chosen should be the same. However, a framing effect places unequal biases towards preferences that are otherwise equal. The most common type of framing effect was theorised in Kahneman & Tversky, 1979 in the form of valence framing effects.[40] This form of framing signifies types of framing. The first type can be considered positive where the "sure thing" option highlights the positivity whereas if it is negative, the "sure thing" option highlights the negativity, while both being analytically identical. For example, saving 200 people from a sinking ship of 600 is equivalent to letting 400 people drown. The former framing type is positive and the latter is negative. Ellingsen, Johannesson, Möllerström and Munkammar[41] have categorised framing effects in a social and economic orientation into three broad classes of theories. Firstly, the framing of options presented can affect internalised social norms or social preferences - this is called variable sociality hypothesis. Secondly, the social image hypothesis suggests that the frame in which the options are presented will affect the way the decision maker is viewed and will in turn affect their behaviour. Lastly, the frame may affect the expectations that people have about each other's behaviour and will in turn affect their own behaviour. |

心理的要因 認知バイアスの心理学は、経済学における合理性に影響を与える「迅速な行動の必要性」バイアス群(薄緑)を提供する。[クリックして閲覧]。 行動経済学の証拠によれば、サンクコスト効果の背景には少なくとも4つの特定の心理的要因が存在する: フレーミング効果:選択肢が肯定的または否定的なニュアンス(例:損失か利益か)で提示されるかによって判断が左右される認知バイアス。[38] 肯定的枠組みではリスク回避傾向が強まり、否定的枠組みではリスク追求傾向が強まる。[39] 過度に楽観的な確率バイアス。投資後、自身の投資がもたらす利益の評価が過大になる傾向。[出典必要] 個人的責任感の必要性。サンクコストは、主に、サンクコストと見なされる投資に対して個人的な責任を感じる人々に作用するようだ。[出典必要] 無駄遣いと思われたくないという欲求——「人々が損失を追う投資を続ける理由の一つは、投資を止めることがこれまでの資金が無駄だったと認めることになるからだ」[18] これらの結果を総合すると、サンクコスト効果は非標準的な効用測定を反映している可能性があり、それは究極的には主体的で個人に固有のものだと言える。 フレーミング効果 サンクコスト効果の根底にあるフレーミング効果は、情報の提示方法にかかわらず結果が同じであるという拡張性の概念に基づいている。これは、情報の提示方法が状況を変えるかどうかを扱う意図主義とは対立する。 二つの数学的関数を考えてみよう: f(x) = 2x + 10 f(x) = 2 · (x + 5) これらの関数は表現が異なるが、入力「x」に関わらず結果は解析的に同等である。したがって、合理的な意思決定者がこれら二つの関数から選択する場合、各関数が選ばれる確率は同じであるべきだ。しかし、フレーミング効果は本来同等の選好に対して不均等な偏りを生じさせる。 最も一般的なフレーミング効果は、カーネマンとトヴェルスキー(1979)によって価数フレーミング効果として理論化された[40]。この形式はフレーミ ングの類型を示す。第一の類型は「確実な選択肢」が肯定性を強調する「ポジティブ」とみなせる。逆に否定的な場合、「確実な選択肢」が否定性を強調する が、両者は分析的に同一である。例えば、600人が乗った沈みゆく船から200人を救うことは、400人を溺死させることに等しい。前者のフレーミングは 肯定的、後者は否定的である。 Ellingsen, Johannesson, Möllerström and Munkammar[41]は、社会的・経済的指向におけるフレーミング効果を三つの広範な理論分類に分類した。第一に、提示される選択肢のフレーミング は、内面化された社会的規範や社会的選好に影響を与える。これは可変的社会性仮説と呼ばれる。第二に、社会的イメージ仮説は、選択肢が提示される枠組みが 意思決定者の見られ方に影響を与え、それが行動に影響すると示唆する。最後に、枠組みは人々が互いの行動に対して抱く期待に影響を与え、それが自身の行動 に影響する。 |

| Overoptimistic probability bias In 1968, Knox and Inkster[42] approached 141 horse bettors: 72 of the people had just finished placing a $2.00 bet within the past 30 seconds, and 69 people were about to place a $2.00 bet in the next 30 seconds. Their hypothesis was that people who had just committed themselves to a course of action (betting $2.00) would reduce post-decision dissonance by believing more strongly than ever that they had picked a winner. Knox and Inkster asked the bettors to rate their horse's chances of winning on a 7-point scale. What they found was that people who were about to place a bet rated the chance that their horse would win at an average of 3.48 which corresponded to a "fair chance of winning" whereas people who had just finished betting gave an average rating of 4.81 which corresponded to a "good chance of winning". Their hypothesis was confirmed: after making a $2.00 commitment, people became more confident their bet would pay off. Knox and Inkster performed an ancillary test on the patrons of the horses themselves and managed (after normalization) to repeat their finding almost identically. Other researchers have also found evidence of inflated probability estimations.[43][44] Sense of personal responsibility In a study of 96 business students, Staw and Fox[45] gave the subjects a choice between making an R&D investment either in an underperforming company department, or in other sections of the hypothetical company. Staw and Fox divided the participants into two groups: a low responsibility condition and a high responsibility condition. In the high responsibility condition, the participants were told that they, as manager, had made an earlier, disappointing R&D investment. In the low responsibility condition, subjects were told that a former manager had made a previous R&D investment in the underperforming division and were given the same profit data as the other group. In both cases, subjects were then asked to make a new $20 million investment. There was a significant interaction between assumed responsibility and average investment, with the high responsibility condition averaging $12.97 million and the low condition averaging $9.43 million. Similar results have been obtained in other studies.[46][43][47] |

過度に楽観的な確率バイアス 1968年、ノックスとインクスター[42]は141人の競馬賭け客に接触した。そのうち72人は直近30秒以内に2ドルの賭けを終えたばかりで、69人 は次の30秒以内に2ドルの賭けをしようとしていた。彼らの仮説は、行動(2ドルの賭け)を直前に決定した人々は、勝者を選んだという確信をこれまで以上 に強く持つことで、決定後の不協和を軽減するだろうというものだった。ノックスとインクスターは賭け手に、自分の馬の勝率を7段階評価で評価するよう求め た。その結果、賭けをしようとしている人々は、自分の馬が勝つ確率を平均3.48と評価した。これは「勝つ可能性はそこそこある」に相当する。一方、賭け を終えたばかりの人々は平均4.81と評価し、これは「勝つ可能性は高い」に相当した。彼らの仮説は裏付けられた。2ドルを賭けるというコミットメントを した後、人々は自分の賭けが報われるとより確信するようになったのだ。ノックスとインクスターは馬券購入者自身を対象に追加実験を行い、正規化処理後ほぼ 同一の結果を再現した。他の研究者も確率過大評価の証拠を確認している[43]。[44] 個人的責任感 96名の経営学学生を対象とした研究で、スタウとフォックス[45]は被験者に、業績不振の部門か、架空企業の他の部門のいずれかに研究開発投資を行う選 択肢を与えた。彼らは被験者を「低責任条件」と「高責任条件」の2群に分け、前者は「経営者として以前行った研究開発投資が期待外れだった」と説明し、後 者は「以前の経営者が行った研究開発投資が期待外れだった」と説明した。高責任条件では、参加者は自身(管理者)が以前、期待外れの研究開発投資を行った と伝えられた。低責任条件では、以前の管理者が業績不振部門に研究開発投資を行ったと伝えられ、他グループと同じ利益データが提示された。いずれの場合 も、参加者は新たに2000万ドルの投資を行うよう求められた。想定責任と平均投資額の間には有意な交互作用が認められ、高責任条件では平均1297万ド ル、低責任条件では平均943万ドルであった。同様の結果は他の研究でも得られている。[46][43][47] |

| Desire not to appear wasteful icon This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (April 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) A ticket buyer who purchases a ticket in advance to an event they eventually turn out not to enjoy makes a semi-public commitment to watching it. To leave early is to make this lapse of judgment manifest to strangers, an appearance they might otherwise choose to avoid.[48] As well, the person may not want to leave the event because they have already paid, so they may feel that leaving would waste their expenditure.[49] Alternatively, they may take a sense of pride in having recognised the opportunity cost of the alternative use of time. |

無駄遣いと思われたくないという気持ち icon この節は出典を一切示していない。信頼できる出典を引用してこの節を改善してほしい。出典のない記述は削除される可能性がある。(2024年4月)(このメッセージの削除方法と時期について) 事前に購入したチケットの行事を結局楽しめなかった場合、その観覧は半ば公的な約束となる。途中で退出することは、この判断の誤りを見知らぬ人々に露呈さ せる行為であり、本来なら避けたいと思うような印象を与えることになる。[48] また、既に代金を支払っているため、退出することで支出が無駄になると感じるかもしれない。[49] あるいは、時間の代替的な活用による機会費用を認識したことに誇りを感じる人格もある。 |

| Neuroeconomics and neuroscience approaches In recent years, there has been a resurgence in studies of how the brain processes information with respect to sunk costs. Measuring sensitivity to sunk costs in laboratory studies can be challenging, as it is often difficult to disentangle the influence of sunk costs from future returns on investment. In a cross-species study in humans, rats, and mice, Sweis et al[50] discovered a conserved evolutionary history to sensitivity to sunk costs across species. This has opened up more questions as to what might the evolutionary drivers be behind why the brain is capable of processing information in this way, what utility, if any, sensitivity to sunk costs may confer, and how might distinct circuits in the brain[51] give rise to this sort of valuation depending on the framing of the question, circumstances of the environment, or state of the individual.[52][53][54] Ongoing work is characterizing how neurons encode sensitivity to sunk costs, how sunk costs appear only after certain types of choices, and how sunk costs could contribute to mood burden. |

神経経済学と神経科学のアプローチ 近年、脳がサンクコストに関して情報を処理する仕組みに関する研究が再興している。実験室での研究においてサンクコストへの感受性を測定することは困難で ある。なぜなら、サンクコストの影響と将来の投資収益率の影響を分離することがしばしば難しいからである。ヒト、ラット、マウスを対象とした種横断研究に おいて、Sweisら[50]は、サンクコストへの感受性に関して種を超えて保存された進化の歴史を発見した。 これにより、脳がこのような情報処理能力を持つ進化的な要因は何か、サンクコストへの感受性がもたらす効用(もしあるならば)は何か、そして脳内の異なる 回路[51]が、問題の設定方法、環境状況、個人の状態に応じて、この種の評価をどのように生み出すのかといった新たな疑問が提起された。[52] [53][54] 進行中の研究では、ニューロンがサンクコストへの感受性をどのように符号化するか、サンクコストが特定の選択後にのみ現れるメカニズム、そしてサンクコス トが気分負担にどのように寄与しうるかが解明されつつある。 |

| Disposition effect Endowment effect Escalation of commitment Region-beta paradox Foot-in-the-door technique Prospect theory Psychology of previous investment Stop-loss order Thinking, Fast and Slow |

処分効果 所有効果 コミットメントのエスカレーション 地域ベータのパラドックス 足がかりテクニック プロスペクト理論 先行投資の心理 損切り注文 ファスト&スロー |

| References |

|

| Amankwah-Amoah, J. (2014). "A

unified framework of explanations for strategic persistence in the wake

of others' failures". Journal of Strategy and Management. 7 (4):

422–444. doi:10.1108/JSMA-01-2014-0009. Arkes, H.R.; Ayton, P. (1999). "The Sunk Cost and Concorde effects: are humans less rational than lower animals?". Psychological Bulletin. 125 (5): 591–600. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.125.5.591. S2CID 10296273. Bade, Robin; and Michael Parkin. Foundations of Microeconomics. Addison Wesley Paperback 1st Edition: 2001. Bernheim, D. and Whinston, M. "Microeconomics". McGraw-Hill Irwin, New York, NY, 2008. ISBN 978-0-07-290027-9. Doody, Ryan (2020). "The Sunk Cost 'Fallacy' Is Not a Fallacy" (PDF). Ergo: An Open Access Journal of Philosophy. 6 (40): 1153–1190. doi:10.3998/ergo.12405314.0006.040. Kahneman, D. (2011) Thinking, Fast and Slow, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, ISBN 978-0374275631. (Reviewed by Freeman Dyson in New York Review of Books, 22 December 2011, pp. 40–44.) Klein, G. and Bauman, Y. The Cartoon Introduction to Economics Volume One: Microeconomics Hill and Wang 2010 ISBN 978-0-8090-9481-3. Samuelson, Paul; and Nordhaus, William. Economics. McGraw-Hill International Editions: 1989. Sutton, J. Sunk Costs and Market Structure. The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1991 ISBN 0-262-19305-1. Varian, Hal R. Intermediate Microeconomics: A Modern Approach. Fifth Ed. New York, 1999 ISBN 0-393-97830-3. |

Amankwah-Amoah, J. (2014).

「他者の失敗後の戦略的持続性に関する統一的な説明枠組み」. Journal of Strategy and Management. 7

(4): 422–444. doi:10.1108/JSMA-01-2014-0009. Arkes, H.R.; エイトン、P.(1999)。「サンクコストとコンコルド効果:人間は下等動物より非合理的か?」。『心理学的レビュー』125巻5号:591–600 頁。doi:10.1037/0033-2909.125.5.591。S2CID 10296273。 ベイド、ロビン;マイケル・パーキン共著。『ミクロ経済学の基礎』。アディソン・ウェズリーペーパーバック第1版:2001年。 バーンハイム、D.;ウィンストン、M.共著。「ミクロ経済学」。マグロウヒル・アーウィン、ニューヨーク、NY、2008年。ISBN 978-0-07-290027-9。 Doody, Ryan (2020). 「サンクコストの『誤謬』は誤謬ではない」 (PDF). Ergo: An Open Access Journal of Philosophy. 6 (40): 1153–1190. doi:10.3998/ergo.12405314.0006.040. カーネマン, D. (2011) 『ファスト&スロー』ファラー・ストラウス・アンド・ジルー社 ISBN 978-0374275631. (フリーマン・ダイソンによる書評が『ニューヨーク・レビュー・オブ・ブックス』2011年12月22日号 pp. 40–44 に掲載された。) クライン, G. と ボーマン, Y. 『漫画でわかる経済学 第1巻:ミクロ経済学』ヒル・アンド・ワン社 2010年 ISBN 978-0-8090-9481-3. サミュエルソン, ポール; 及び ノードハウス, ウィリアム. 『経済学』. マクグローヒル・インターナショナル版: 1989年. サットン、J. 『サンクコストと市場構造』MITプレス、マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ、1991年 ISBN 0-262-19305-1。 バリアン、ハル・R. 『中級ミクロ経済学:現代的アプローチ』第5版、ニューヨーク、1999年 ISBN 0-393-97830-3。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sunk_cost |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099