スバンテ・ペーボとデニソワ人の関係

Studing

on Between Dr. Svante Pääbo and Denisovan

Svante Pääbo

b.1955/ Denisova 4, a molar

| Svante Pääbo

ForMemRS[Fellow of the Royal Society] (Swedish: [ˈsvânːtɛ̂ ˈpʰɛ̌ːbʊ̂];[3] born 20 April 1955) is a

Swedish geneticist and Nobel Laureate who specialises in the field of

evolutionary genetics.[4] As one of the founders of paleogenetics, he

has worked extensively on the Neanderthal genome.[5][6] In 1997, he

became founding director of the Department of Genetics at the Max

Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig,

Germany.[7][8][9] Since 1999, he has been an honorary professor at

Leipzig University; he currently teaches molecular evolutionary biology

at the university.[10][11] He is also an adjunct professor at Okinawa

Institute of Science and Technology, Japan.[12] In 2022, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine "for his discoveries concerning the genomes of extinct hominins and human evolution".[13][14][15] |

スヴァンテ・ペーボ, 王立協会会員[Fellow of the Royal Society]

(スウェーデン語: [ˈsvânːtɛ̂ ˈpʰɛ̌ːbʊ̂] ; [3] 1955 年 4 月 20 日生まれ)

はスウェーデンの遺伝学者であり、進化遺伝学の分野を専門とするノーベル賞受賞者である。[4]古遺伝学の創始者の一人として、彼はネアンデルタール人のゲ

ノムについて幅広く研究してきました。[5] [6] 1997

年に、ドイツのライプツィヒにあるマックス・プランク進化人類学研究所の遺伝学部の創設所長に就任しました。[7] [8] [9] 1999

年以来、彼は大学の名誉教授を務めている。ライプツィヒ大学; 彼は現在、大学で分子進化生物学を教えています。[10]

[11]彼は、日本の沖縄科学技術大学の非常勤教授でもあります。[12] 2022年、彼は「絶滅した人類のゲノムと人類の進化に関する発見」によりノーベル生理学・医学賞を受賞した。[13] [14] [15] |

| Education and early life Pääbo was born in Stockholm, Sweden, in 1955 and grew up there with his mother,[5] Estonian chemist Karin Pääbo (Estonian: [ˈpæːbo]; 1925–2013), who had escaped from the Soviet invasion in 1944[16] and arrived in Sweden as a refugee during World War II.[17][18] He was born through a extramarital affair[19] of his father, Swedish biochemist Sune Bergström (1916–2004),[5] who, like his son, became a recipient of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (in 1982).[20] Pääbo is his mother's only child; he has via his father's marriage a half-brother (also born in 1955).[21] Pääbo grew up as a native Swedish speaker.[22] In a 2012 interview with the Estonian newspaper Eesti Päevaleht, he said that he self-identifies as a Swede, but has a "special relationship with Estonia".[23] In 1975, Pääbo began studying at Uppsala University, serving one year in the Swedish Defense Forces attached to the School of Interpreters. Pääbo earned his Ph.D. from Uppsala University in 1986 for research investigating how the E19 protein of adenoviruses modulates the immune system.[24] |

教育と幼少期の生活 ペーボは 1955 年にスウェーデンのストックホルムで生まれ、 1944 年のソ連侵攻から逃れてきたエストニア人の化学者カリン・ペーボ (エストニア語: [ˈpæːbo] ; 1925–2013) [ 16 ]の母親とともにそこで育ちました。第二次世界大戦中に難民としてスウェーデンに到着。[17] [18]彼は父親であるスウェーデンの生化学者スネ・バーグストロム(1916-2004) [5]の不倫[ 19]によって生まれ、息子と同様にノーベル生理学・医学賞を受賞した。 (1982年)。[20]ペーボは母親の一人っ子です。彼には父親の結婚により異母兄弟(同じく1955年生まれ)がいる。[21] ペーボはスウェーデン語を母語として育ちました。[22] 2012年のエストニアの新聞Eesti Päevalehtとのインタビューで、彼は自分をスウェーデン人だと自認しているが、「エストニアとは特別な関係」を持っていると述べた。[23] 1975 年にペーボはウプサラ大学で学び始め、通訳学校付属のスウェーデン国防軍に 1 年間勤務しました。ペーボは博士号を取得しました。アデノウイルスのE19タンパク質が免疫系をどのように調節するかを調査する研究で、1986 年にウプサラ大学から博士号を授与されました。[24] |

| Research and career Pääbo at the 2014 Nobel Conference Pääbo is known as one of the founders of paleogenetics, a discipline that uses genetics to study early humans and other ancient species.[25][26] From 1986 to 1987, he did postdoctoral research at the Institute for Molecular Biology II, University of Zurich, Switzerland.[27] As an EMBO Postdoctoral Fellow, Pääbo moved to the United States in 1987, accepting a position as a postdoctoral researcher in biochemistry at the University of California, Berkeley, where he joined Allan Wilson's lab and worked on the genome of extinct mammals.[27][28] In 1990, he returned to Europe to become professor of general biology at the University of Munich, and, in 1997, he became founding director of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany.[28] In 1997, Pääbo and colleagues reported their successful sequencing of Neanderthal mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), originating from a specimen found in Feldhofer grotto in the Neander valley.[29][30] In August 2002, Pääbo's department published findings about the "language gene", FOXP2, which is mutated in some individuals with language disabilities.[31] In 2006, Pääbo announced a plan to reconstruct the entire genome of Neanderthals. In 2007, he was named one of Time magazine's 100 most influential people of the year.[32] In February 2009, at the Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) in Chicago, it was announced that the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology had completed the first draft version of the Neanderthal genome.[33] Over 3 billion base pairs were sequenced in collaboration with the 454 Life Sciences Corporation.[34] In March 2010, Pääbo and his coworkers published a report about the DNA analysis of a finger bone found in the Denisova Cave in Siberia; the results suggest that the bone belonged to an extinct member of the genus Homo that had not yet been recognised, the Denisova hominin.[35] Pääbo first wanted to classify the Denisovans as a species of their own, separate from modern humans and Neanderthals but changed his mind after peer-review.[36][37] Pääbo's doctoral student Viviane Slon was able to successfully map the Denisovan genome, clarifying geographic distribution and admixtures in archaic humans.[38][39] In May 2010, Pääbo and his colleagues published a draft sequence of the Neanderthal genome in the journal Science.[40] He and his team also concluded that there was probably interbreeding between Neanderthals and Eurasian (but not Sub-Saharan African) humans.[41] There is general mainstream support in the scientific community for this theory of interbreeding between archaic and modern humans.[42] This admixture of modern human and Neanderthal genes is estimated to have occurred roughly between 50,000 and 60,000 years ago, in the Middle East.[43] In 2014, he published the book Neanderthal Man: In Search of Lost Genomes where he, in the mixed form of a memoir and popular science, tells the story of the research effort to map the Neanderthal genome combined with his thoughts on human evolution.[20][44] In 2020, Pääbo determined that more severe impacts upon victims of the COVID-19 disease, including the vulnerability to it and the incidence of the necessity of hospitalisation, have been associated via DNA analysis to be expressed in genetic variants at chromosomal region 3, features that are associated with European Neanderthal heritage. That structure imposes greater risks that those affected will develop a more severe form of the disease.[45] The findings are from Pääbo and researchers he leads at the Planck Institute and the Karolinska Institutet.[45] As of October 2022, Pääbo has an h-index of 167 according to Google Scholar[4] and of 133 according to Scopus.[46] |

研究と経歴 2014 年のノーベル会議でのペーボ ペーボは、遺伝学を使用して初期の人類や他の古代種を研究する学問である古遺伝学の創設者の 1 人として知られています。[25] [26] 1986 年から 1987 年まで、スイスのチューリッヒ大学第 2 分子生物学研究所で博士研究員として研究を行いました。[27] EMBO博士研究員として、ペーボは 1987 年に米国に移住し、カリフォルニア大学バークレー校で生化学の博士研究員としての職を受け入れ、そこでアラン・ウィルソンの研究室に加わり、絶滅した哺乳 類のゲノムの研究に取り組みました。[27] [28] 1990 年にヨーロッパに戻り、ミュンヘン大学で一般生物学の教授となり、1997 年にはドイツのライプツィヒにあるマックス・プランク進化人類学研究所の創設所長に就任しました。[28] 1997 年、Pääbo らは、ネアンデル谷のフェルトホーファー洞窟で見つかった標本に由来するネアンデルタール人のミトコンドリア DNA ( mtDNA ) の配列決定に成功したと報告しました。[29] [30] 2002 年 8 月、ペーボの部門は、言語障害のある一部の人で突然変異している「言語遺伝子」FOXP2に関する研究結果を発表しました。[31] 2006年、ペーボはネアンデルタール人の全ゲノムを再構築する計画を発表した。2007 年、彼はタイム誌の今年最も影響力のある 100 人の 1 人に選ばれました。[32] 2009 年 2 月、シカゴで開催された米国科学進歩協会(AAAS)の年次総会で、マックス プランク進化人類学研究所がネアンデルタール人のゲノムの最初の草案を完成したと発表されました。[33] 454 Life Sciences Corporationと協力して、30 億塩基対以上の配列が決定されました。[34] 2010 年 3 月、ペーボと彼の同僚は、シベリアのデニソワ洞窟で発見された指の骨の DNA 分析に関する報告書を発表しました。その結果、この骨はまだ認識されていなかったヒト属の絶滅したメンバーであるデニソワヒト属に属していたことが示唆さ れました。[35]ペーボは当初、デニソワ人を現生人類やネアンデルタール人とは別個の独自の種として分類したいと考えていたが、査読後に考えを変えた。 [36] [37] ペーボの博士課程の学生であるヴィヴィアン・スロンは、デニソワ人ゲノムの地図作成に成功し、旧人類の地理的分布と混合を明らかにすることができた。 [38] [39] 2010 年 5 月、ペーボと彼の同僚は、ネアンデルタール人のゲノムの配列草案をサイエンス誌に発表しました。[40]彼と彼のチームはまた、おそらくネアンデルタール 人とユーラシア人(ただしサハラ以南のアフリカ人ではない)の間に交配があったと結論付けた。[41]科学界では、古代人と現生人類の混血に関するこの理 論に対する一般的な主流の支持が存在します。[42]現生人類とネアンデルタール人の遺伝子のこの混合は、およそ 5 万年から 6 万年前の間に中東で起こったと推定されています。[43] 2014年、彼は著書『ネアンデルタール人:失われたゲノムを求めて』を出版し、回想録と大衆科学を組み合わせた形で、ネアンデルタール人のゲノム地図を 作成する研究活動の物語を、人類の進化についての彼の考えと組み合わせて語った。[20] [44] 2020年、ペーボは、 DNA分析により、新型コロナウイルス感染症に対する脆弱性や入院の必要性の発生など、新型コロナウイルス感染症の犠牲者に対するより深刻な影響が、染色 体領域3の遺伝子変異で発現することに関連していると判断した。ヨーロッパのネアンデルタール人の遺産と関連しています。この構造により、影響を受けた人 がより重篤な病気を発症するリスクが高まります。[45]この発見は、ペーボと、ペーボが率いるプランク研究所とカロリンスカ研究所の研究者らによるもの です。[45] 2022 年 10 月の時点で、Pääbo のh-indexはGoogle Scholar [4]によれば 167 、 Scopusによれば 133 である。[46] |

| Awards and honours In 1992, he received the Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Prize of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, which is the highest honour awarded in German research. Pääbo was elected a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 2000, and in 2004 was elected an international member of the National Academy of Sciences.[47] In 2005, he received the prestigious Louis-Jeantet Prize for Medicine.[1] In 2008, Pääbo was added to the members of the Order Pour le Mérite for Sciences and Arts. In the same year, he received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement.[48] In October 2009, the Foundation For the Future announced that Pääbo had been awarded the 2009 Kistler Prize for his work isolating and sequencing ancient DNA, beginning in 1984 with a 2,400-year-old mummy.[49] In June 2010, the Federation of European Biochemical Societies (FEBS) awarded him the Theodor Bücher Medal for outstanding achievements in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.[50] In 2013, he received Gruber Prize in Genetics for groundbreaking research in evolutionary genetics.[51] In June 2015, he was awarded the degree of DSc (honoris causa) at NUI Galway.[52] He was elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society in 2016,[2] and in 2017, was awarded the Dan David Prize. In 2018, he received the Princess of Asturias Awards in the category of Scientific Research, in 2020 the Japan Prize,[53] in 2021 the Massry Prize[54] and in 2022 the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine[55] for sequencing the first Neanderthal genome.[14] |

賞と栄誉 1992 年に、ドイツ研究協会のゴットフリート ヴィルヘルム ライプニッツ賞を受賞しました。この賞は、ドイツの研究分野で最高の栄誉とされています。ペーボは 2000 年にスウェーデン王立科学アカデミーの会員に選出され、2004 年には国立科学アカデミーの国際会員に選出されました。[47] 2005 年に、彼は名誉あるルイ・ジャンテ医学賞を受賞しました。[1] 2008 年、ペーボは科学と芸術のためのプール・ル・メリット勲章の会員に加えられました。同年、米国功績アカデミーのゴールデン プレート賞を受賞しました。[48]2009年10月、未来財団は、1984年に2,400年前のミイラから始まった古代DNAの単離と配列決定の業績に より、ペーボ氏が2009年のキスラー賞を受賞したと発表した。[49] 2010年6月、欧州生化学協会連盟(FEBS)は生化学と分子生物学における顕著な功績を称えて彼にテオドール・ビューヒャーメダルを授与した。 [50] 2013 年、進化遺伝学の画期的な研究により、グルーバー賞遺伝学賞を受賞しました。[51] 2015年6月、ゴールウェイNUIで博士号(名誉勲章)を授与された。[52]彼は2016 年に王立協会の外国人会員に選出され[2] 、2017 年にはダン・デイビッド賞を受賞しました。2018年に科学研究部門でアストゥリアス王女賞、2020年に日本賞、[53]、 2021年にマスリー賞[54]、2022年にノーベル生理学・医学賞[55]を配列決定により受賞した。最初のネアンデルタール人のゲノム。[14] |

| Personal life Pääbo wrote in his 2014 book Neanderthal Man: In Search of Lost Genomes that he is bisexual. He assumed he was gay until he met Linda Vigilant, an American primatologist and geneticist whose "boyish charms" attracted him. They have co-authored many papers, are married and raising a son and a daughter together in Leipzig.[56][6] |

私生活 ペーボは、2014 年の著書『ネアンデルタール人: 失われたゲノムを求めて』の中で、自分はバイセクシュアルであると書いています。アメリカの霊長類学者で遺伝学者のリンダ・ヴィジラントに出会うまで、彼 は自分が同性愛者であると思い込んでいたが、その「少年のような魅力」に惹かれたという。彼らは多くの論文を共著しており、結婚してライプツィヒで息子と 娘を一緒に育てています。[56] [6] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Svante_P%C3%A4%C3%A4bo |

Google translator |

The Denisovans or

Denisova hominins ( /dɪˈniːsəvə/ di-NEE-sə-və) are an extinct species

or subspecies of archaic human that ranged across Asia during the Lower

and Middle Paleolithic. Denisovans are known from few physical remains;

consequently, most of what is known about them comes from DNA evidence.

No formal species name has been established pending more complete

fossil material. The Denisovans or

Denisova hominins ( /dɪˈniːsəvə/ di-NEE-sə-və) are an extinct species

or subspecies of archaic human that ranged across Asia during the Lower

and Middle Paleolithic. Denisovans are known from few physical remains;

consequently, most of what is known about them comes from DNA evidence.

No formal species name has been established pending more complete

fossil material.The first identification of a Denisovan individual occurred in 2010, based on mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) extracted from a juvenile female finger bone excavated from the Siberian Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains in 2008.[1] Nuclear DNA indicates close affinities with Neanderthals. The cave was also periodically inhabited by Neanderthals, but it is unclear whether Neanderthals and Denisovans ever cohabited in the cave. Additional specimens from Denisova Cave were subsequently identified, as was a single specimen from the Baishiya Karst Cave on the Tibetan Plateau, and Cobra Cave in the Annamite Mountains of Laos. DNA evidence suggests they had dark skin, eyes, and hair, and had a Neanderthal-like build and facial features. However, they had larger molars which are reminiscent of Middle to Late Pleistocene archaic humans and australopithecines. Denisovans apparently interbred with modern humans, with the highest percentages (roughly 5%) occurring in Melanesians, Aboriginal Australians, and Filipino Negritos. This distribution suggests that there were Denisovan populations across Asia, the Philippines, and New Guinea and/or Australia, but this is unconfirmable. Introgression into modern humans may have occurred as recently as 30,000 years ago in New Guinea, which, if correct, might indicate this population persisted as late as 14,500 years ago. There is also evidence of interbreeding with the Altai Neanderthal population, with about 17% of the Denisovan genome from Denisova Cave deriving from them. A first-generation hybrid nicknamed "Denny" was discovered with a Denisovan father and a Neanderthal mother. Additionally, 4% of the Denisovan genome comes from an unknown archaic human species which diverged from modern humans over one million years ago. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Denisovan |

デニソワ人(デニソワじん、Denisova

hominin)は、前期・中期旧石器時代にアジア全域に分布していた旧人類の絶滅種、または亜種である。デニソワ人の遺骨は少なく、その結果、DNAの

証拠から判明することがほとんどである。正式な種名は、化石資料がより完全なものになるまで確立されない。 デニソワ人(デニソワじん、Denisova

hominin)は、前期・中期旧石器時代にアジア全域に分布していた旧人類の絶滅種、または亜種である。デニソワ人の遺骨は少なく、その結果、DNAの

証拠から判明することがほとんどである。正式な種名は、化石資料がより完全なものになるまで確立されない。2008年にアルタイ山脈のシベリア・デニソワ洞窟[1]から出土した女性の指の骨から抽出したミトコンドリアDNA(mtDNA)に基づいて、2010 年にデニソワ人の個体が初めて特定された。核DNAからはネアンデルタール人との近親性が示されている。この洞窟には定期的にネアンデルタール人も住んで いたが、ネアンデルタール人とデニソワ人が同居したことがあるかどうかは不明である。デニソワ洞窟の標本は、その後、中国のチベット高原にあるバイシヤ・ カルスト洞窟の標本と同様に、追加で同定された。DNAの証拠から、彼らは黒い肌、目、髪を持ち、ネアンデルタール人のような体格と顔立ちをしていたこと がわかった。しかし、彼らはより大きな大臼歯を持っており、中期更新世から後期更新世にかけての古人やアウストラロピテクスを思わせる。 デニソワ人は現代人と交配したとされ、その割合はメラネシア人、オース トラリアのアボリジニ、フィリピンのネグリトに最も多く(およそ5%)見られる。この分布は、ユーラシア、フィリピン、ニューギニア、オーストラリアにデ ニソワ人の集団がいたことを示唆しているが、これは未確認である。現代人への遺伝子移入はニューギニアで3万年前に起こった可能性があり、もしそれが正し ければ、この集団は14,500年前まで存続していたことになるかもしれない。また、アルタイに住むネアンデルタール人との交雑の証拠もあり、デニソワ洞 窟のデニソワ人ゲノムの約17%は彼らに由来するものである。デニソワ人の父とネアンデルタール人の母を持つ「デニー」というニックネームの一代雑種が発 見された。さらに、デニスバン・ゲノムの4%は、100万年以上前に現代人と分岐した未知の古人種に由来するものである。出典:https://x.gd/etb7T |

| 発見史 2008年にロシアの西シベリアのアルタイ山脈にあるデニソワ洞窟で子供の骨の断片が発見され、放射性炭素年代測定により約4万1千年前のものと推定され た。また、同じ場所で、大人の巨大な臼歯も発見されている[2]。 2010年3月25日付のイギリスの科学雑誌『ネイチャー』において、マックス・プランク進化人類学研究所の研究チームは、発見された骨のミトコンドリア DNAの解析結果から、デニソワ人は100万年ほど前に現生人類から分岐した、未知の新系統の人類だったと発表した[3][4]。DNAのみに基づいて新 種の人類が発見されたのは、科学史上初めての事である[5]。 2019年4月11日付で学術誌『Cell』に発表された論文によると、デニソワ人には独立した3つのグループが存在し、このグループの内の1つは、ネア ンデルタール人とデニソワ人との違いと同じぐらいに、他の2グループのデニソワ人と異なっていることが示唆されている[6]。 名称 上述の通り、化石資料の不足から正式な種名については確立されていないが、一部の研究者からはホモ・デニソワ(H. denisova)[7] やホモ・アルタイエンシス(H. altaiensis)[8]などの学名が提案されている。出典:https://x.gd/etb7T |

他の人類との遺伝的関係 2010年12月23日、マックス・プランク進化人類学研究所などの国際研究チームにより『ネイチャー』に論文が掲載された。見つかった骨の一部は5 - 7歳の少女の小指の骨であり[2]、細胞核のDNAの解析の結果、デニソワ人はネアンデルタール人と近縁なグループで、80万4千年前に現生人類であるホ モ・サピエンスとの共通祖先からネアンデルタール人・デニソワ人の祖先が分岐し、64万年前にネアンデルタール人から分岐した人類であることが推定された [9]。デニソワ洞窟は、ネアンデルタール人化石発見地のうち最も近いイラク北部シャニダール遺跡から、約4000 kmの距離を隔てている。メラネシア人のゲノムの4-6%がデニソワ人固有のものと一致することから[10]、現在のメラネシア人にデニソワ人の遺伝情報 の一部が伝えられている可能性が高いことが判明した[9]。この他、中国南部の住人の遺伝子構造の約1%が、デニソワ人由来という研究発表も、スウェーデ ンのウプサラ大学の研究チームより出されている[11]。ネアンデルタール人と分岐した年数も、35万年ほど前との説も浮上している[2]。ジョージ・ワ シントン大学の古人類学者のブライアン・リッチモンドは、デニソワ洞窟で見つかった巨大臼歯からデニソワ人は体格はネアンデルタール人と同じか、それより も大きいとみている[2]。 ネアンデルタール人やデニソワ人はその後絶滅してしまったが、アフリカ土着のネグロイドを除く現在の現生人類遺伝子のうち数%はネアンデルタール人由来で ある。中東での現生人類祖先とネアンデルタール人との交雑を示す研究成果は2010年5月に発表されているが、2010年12月にアジア内陸部におけるデ ニソワ人とも現生人類祖先は交雑したとする研究結果が出たことから、この結果が正しければ、過去には異種の人類祖先同士の交雑・共存は通常のことだった可 能性が出てきた[12]。 なお、アジア内陸部でデニソワ人と交雑した現生人類祖先は、その後、長い期間をかけてメラネシアなどに南下していったと考えられる[要出典]。また、中国 方面に移住したグループは漢民族となり、高地に移住したグループはチベット人となったともされる[13]。 発見された化石が少ないことから、現生人類との関連などは今後の研究により変更される可能性もある。デニソワ人の体格などの外形、生活様式、人口などはこ れからの研究が待たれる点である。ただ、巨大臼歯からはがっしりした顎を持っていたことが推定されている[14]。 2018年8月22日、古遺伝学者のビビアン・スロンは2012年にロシアで発見された10代の少女の化石が母がネアンデルタール人、父がデニソワ人で あったと科学誌「ネイチャー」で発表した[15][16][17]。 2019年9月、ヘブライ大学やスタンフォード大学で研究をしているデビッド・ゴクマンにより、DNAのメチル化を調べて骨格に関する32の特徴を抽出 し、デニソワ人の骨格を提案するという研究結果が発表された[18][19]。この研究によると、デニソワ人の外見は、狭い額やがっしりした顎などを持 ち、ネアンデルタール人によく似た特徴を持っていた可能性がある。一方、頭頂骨の幅が広いなど、ネアンデルタール人とも異なる特徴も、見て取れるという [5]。 出典:https://x.gd/etb7T |

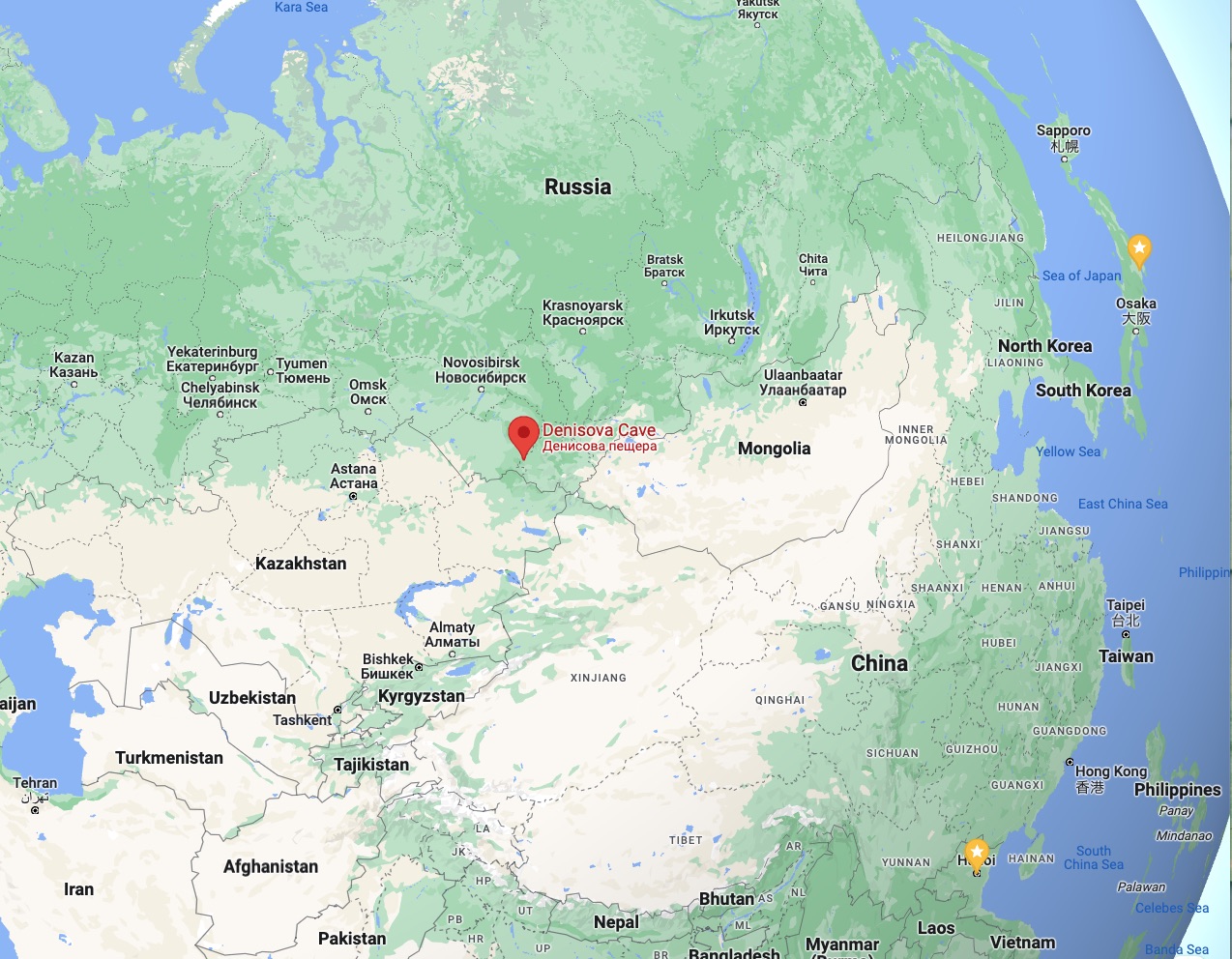

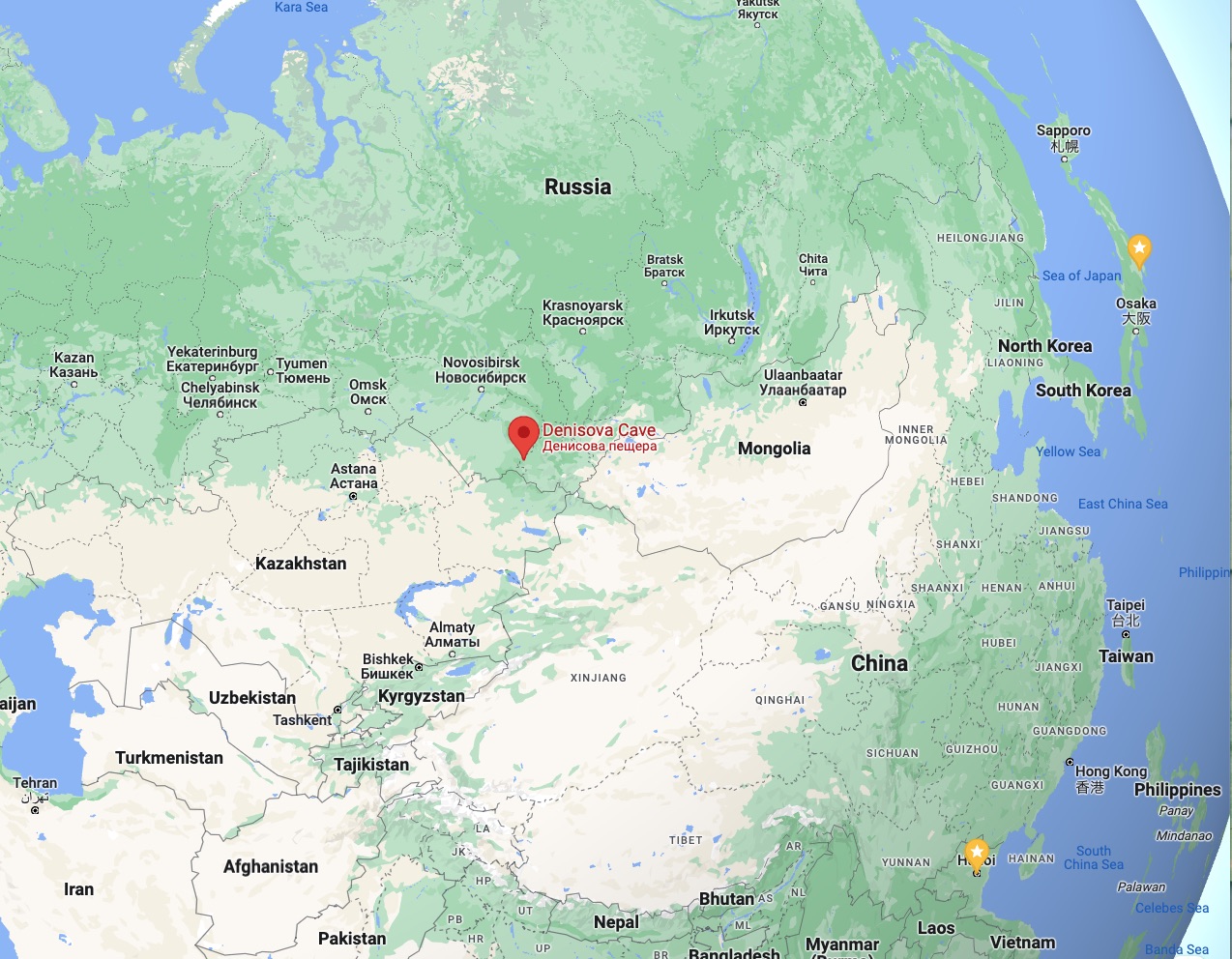

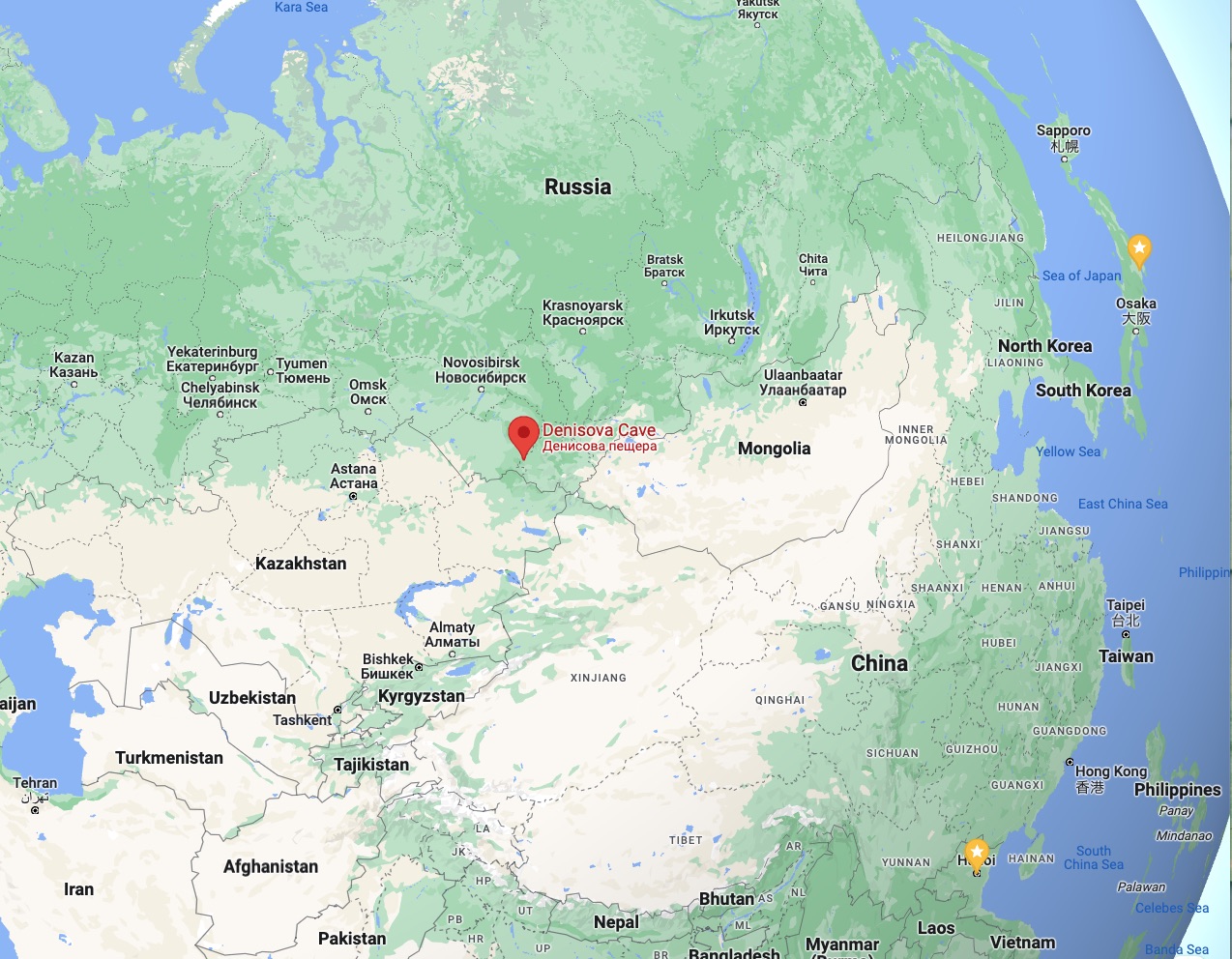

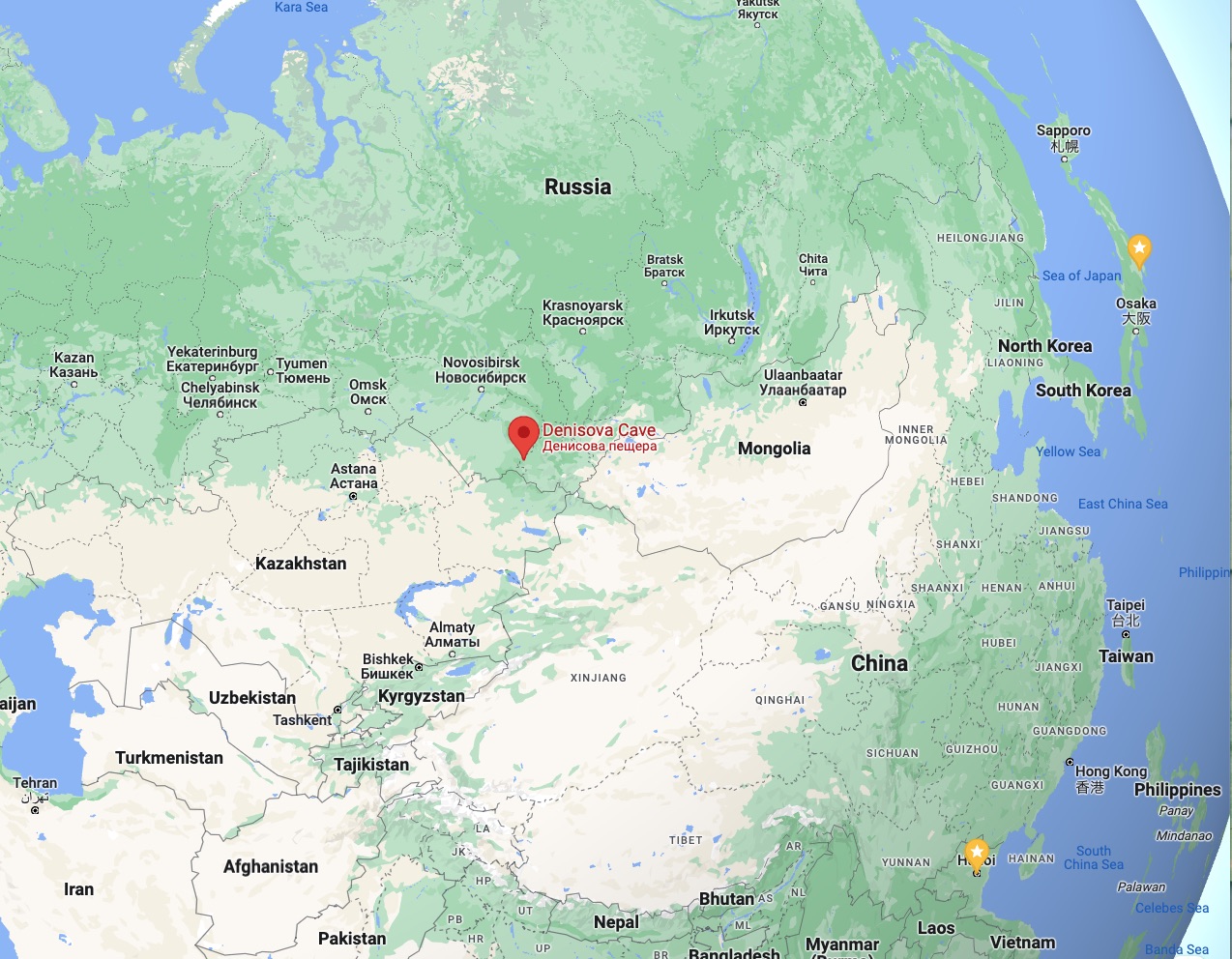

| Taxonomy Denisovans may represent a new species of Homo or an archaic subspecies of Homo sapiens (modern humans), but there are too few fossils to erect a proper taxon. Proactively proposed species names for Denisovans are H. denisova[2] or H. altaiensis.[3] Discovery Denisovan is located in AsiaDenisova CaveDenisova CaveBaishiya Karst CaveBaishiya Karst CaveTam Ngu Hao 2 CaveTam Ngu Hao 2 Cave Locations of paleoarchaeological finds linked to Denisovans: Denisova Cave (blue) in the Altai Mountains of Siberia; Baishiya Karst Cave (yellow) on the Tibetan Plateau; and Tam Ngu Hao 2 Cave (grey) in northern Laos The Denisova Cave, where the first reported Denisovans were found Denisova Cave is in south-central Siberia, Russia, in the Altai Mountains near the border with Kazakhstan, China and Mongolia. It is named after Denis (Dyonisiy), a Russian hermit who lived there in the 18th century. The cave was first inspected for fossils in the 1970s by Russian paleontologist Nikolai Ovodov, who was looking for remains of canids.[4] In 2008, Michael Shunkov from the Russian Academy of Sciences and other Russian archaeologists from the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences in Novosibirsk Akademgorodok investigated the cave and found the finger bone of a juvenile female hominin originally dated to 50–30,000 years ago.[1][5] The estimate has changed to 76,200–51,600 years ago.[6] The specimen was originally named X-woman because matrilineal mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) extracted from the bone demonstrated it to belong to a novel ancient hominin, genetically distinct both from contemporary modern humans and from Neanderthals.[1] In 2019, Greek archaeologist Katerina Douka and colleagues radiocarbon dated specimens from Denisova Cave, and estimated that Denisova 2 (the oldest specimen) lived 195,000–122,700 years ago.[6] Older Denisovan DNA collected from sediments in the East Chamber dates to 217,000 years ago. Based on artifacts also discovered in the cave, hominin occupation (most likely by Denisovans) began 287±41 or 203±14 ka. Neanderthals were also present 193±12 ka and 97±11 ka, possibly concurrently with Denisovans.[7] Specimens The fossils of five distinct Denisovan individuals from Denisova Cave have been identified through their ancient DNA (aDNA): Denisova 2, 3, 4, 8, and 11. An mtDNA-based phylogenetic analysis of these individuals suggests that Denisova 2 is the oldest, followed by Denisova 8, while Denisova 3 and Denisova 4 were roughly contemporaneous.[8] During DNA sequencing, a low proportion of the Denisova 2, Denisova 4 and Denisova 8 genomes were found to have survived, but a high proportion of the Denisova 3 genome was intact.[8][9] The Denisova 3 sample was cut into two, and the initial DNA sequencing of one fragment was later independently confirmed by sequencing the mtDNA from the second.[10] These specimens remained the only known examples of Denisovans until 2019, when a research group led by Fahu Chen, Dongju Zhang and Jean-Jacques Hublin described a partial mandible discovered in 1980 by a Buddhist monk in the Baishiya Karst Cave on the Tibetan Plateau in China. Known as the Xiahe mandible, the fossil became part of the collection of Lanzhou University, where it remained unstudied until 2010.[11] It was determined by ancient protein analysis to contain collagen that by sequence was found to have close affiliation to that of the Denisovans from Denisova Cave, while uranium decay dating of the carbonate crust enshrouding the specimen indicated it was more than 160,000 years old.[12] The identity of this population was later confirmed through study of environmental DNA, which found Denisovan mtDNA in sediment layers ranging in date from 100,000 to 60,000 years before present, and perhaps more recent.[13] In 2018, a team of Laotian, French, and American anthropologists, who had been excavating caves in the Laotian jungle of the Annamite Mountains since 2008, was directed by local children to the site Tam Ngu Hao 2 ("Cobra Cave") where they recovered a human tooth. The tooth (catalogue number TNH2-1) developmentally matches a 3.5 to 8.5 year old, and a lack of amelogenin (a protein on the Y chromosome) suggests it belonged to a girl barring extreme degradation of the protein over a long period of time. Dental proteome analysis was inconclusive for this specimen, but the team found it anatomically comparable with the Xiahe mandible, and so tentatively categorized it as a Denisovan, although they could not rule out it being Neanderthal. The tooth probably dates to 164,000 to 131,000 years ago.[14] Some older findings may or may not belong to the Denisovan line, but Asia is not well mapped in regards to human evolution. Such findings include the Dali skull,[15] the Xujiayao hominin,[16] Maba Man, the Jinniushan hominin, and the Narmada hominin.[17] The Xiahe mandible shows morphological similarities to some later East Asian fossils such as Penghu 1,[12][18] but also to Chinese H. erectus.[10] In 2021, Chinese palaeoanthropologist Qiang Ji suggested his newly erected species, H. longi, may represent the Denisovans based on the similarity between the type specimen's molar and that of the Xiahe mandible.[19] |

分類 デニソワ人は、ホモの新種、またはホモ・サピエンス(現生人類)の古亜種に相当する可能性がありますが、適切な分類群を確立するには化石が少なすぎます。 デニソワ人に対して積極的に提案されている種名は、H. denisova [2]またはH. altaiensisです。[3] 発見 デニソワ人はアジアにありますデニソワ洞窟デニソワ洞窟バイシヤカルスト洞窟バイシヤカルスト洞窟タムグーハオ 2 洞窟タムグーハオ 2 洞窟 デニソワ人に関連する古考古学的発見の場所:シベリアのアルタイ山脈のデニソワ洞窟 (青) 。チベット高原のバイシヤカルスト洞窟(黄色)。ラオス北部のタムグーハオ 2 洞窟(灰色) デニソワ洞窟、最初に報告されたデニソワ人が発見された場所 デニソワ洞窟は、ロシアのシベリア中南部、カザフスタン、中国、モンゴルとの国境近くのアルタイ山脈にあります。この名前は、 18 世紀にそこに住んでいたロシアの隠者デニス (デュニシイ) にちなんで名付けられました。この洞窟は、1970 年代にイヌ科動物の化石を探していたロシアの古生物学者ニコライ・オヴォドフによって初めて化石検査が行われました。[4] 2008年、ロシア科学アカデミーのマイケル・シュンコフ氏と、ノボシビルスク・アカデムゴロドクにあるロシア科学アカデミーシベリア支部考古学・民族学 研究所の他のロシア考古学者らが洞窟を調査し、当初の年代が特定された若い女性のヒト族の指の骨を発見した。 5万年から3万年前まで。[1] [5]この推定は 76,200 ~ 51,600 年前に変更されました。[6]この標本はもともと母系ミトコンドリア DNAから X-ウーマンと名付けられました。 骨から抽出された (mtDNA) は、それが現代の現生人類ともネアンデルタール人の両方とも遺伝的に異なる、新規の古代人類に属していることを示しました。[1] 2019年、ギリシャの考古学者カテリーナ・ドゥカ氏らはデニソワ洞窟の標本を放射性炭素年代測定し、デニソワ2(最古の標本)は19万5000~12万 2700年前に生息していたと推定した。[6]東部屋の堆積物から収集された古いデニソワ人の DNA は 217,000 年前に遡ります。同様に洞窟内で発見された遺物に基づくと、人類の占領(おそらくデニソワ人による)は 287±41 年または 203±14 kaに始まりました。ネアンデルタール人も 193±12 ka と 97±11 ka に存在し、おそらくデニソワ人と同時に存在しました。[7] 標本 デニソワ洞窟から出土した 5 人の異なるデニソワ人の化石が、古代 DNA (aDNA)によって特定されました: デニソワ 2、3、4、8、および11。これらの個体の mtDNA ベースの系統解析では、デニソバ 2 が最も古く、次にデニソバ 8 が続き、デニソバ 3 とデニソバ 4 はほぼ同時代であることが示唆されています。[8] DNA 配列決定中に、デニソバ 2、デニソバ 4、およびデニソバ 8 ゲノムの低い割合が生き残っていることが判明しましたが、デニソバ 3 ゲノムの大部分は無傷であったことが判明しました。[8] [9]デニソバ 3 サンプルは 2 つに切断され、1 つの断片の最初の DNA 配列は、後に 2 番目の断片の mtDNA を配列することによって独立して確認されました。[10] これらの標本は、2019年にファーフ・チェン氏、ドンジュ・チャン氏、ジャン・ジャック・ハブリン氏率いる研究グループが1980年に中国のチベット高 原にあるバイシヤ・カルスト洞窟で僧侶によって発見された部分的な下顎骨について報告するまで、デニソワ人の唯一知られている例であった。 。夏河下顎骨として知られるこの化石は、蘭州大学のコレクションの一部となり、2010年まで研究されませんでした。[11]古代のタンパク質分析によ り、コラーゲンが含まれていることが判明しました。配列により、デニソワ洞窟のデニソワ人と密接な関係があることが判明し、標本を覆っている炭酸塩地殻の ウラン崩壊年代測定により、それが16万年以上前のものであることが示されました。[12]この集団の正体は後に環境 DNAの研究によって確認され、堆積物層から現在より 10 万年から 6 万年前、おそらくはより最近の年代のデニソワ人の mtDNA が発見されました。[13] 2018年、2008年以来アンナマイト山脈のラオスのジャングルで洞窟を発掘していたラオス人、フランス人、アメリカ人の人類学者のチームは、地元の子 供たちにタムグーハオ2(「コブラの洞窟」)の場所に案内されました。人間の歯を取り戻した。この歯 (カタログ番号 TNH2-1) は発育上 3.5 ~ 8.5 歳の年齢に一致しており、アメロゲニン( Y 染色体上のタンパク質)が欠如しています。) 長期間にわたるタンパク質の極端な分解を除けば、それが少女のものであることを示唆しています。この標本の歯のプロテオーム分析は決定的ではなかったが、 研究チームはそれが解剖学的に夏河の下顎骨と同等であることを発見し、暫定的にデニソワ人として分類したが、ネアンデルタール人の可能性も排除できなかっ た。この歯はおそらく 164,000 年から 131,000 年前のものと考えられます。[14] 古い発見の中にはデニソワ人の系統に属するものとそうでないものもありますが、人類の進化に関してアジアは十分に地図化されていません。このような発見に は、ダリの頭蓋骨、[15]徐家屋原人、[16] マバ人、金牛山原人、およびナルマダ原人が含まれます。[17]夏河の下顎骨は、澎湖 1、[12] [18]などの一部の後期東アジアの化石と形態学的類似性を示しますが、中国のH. エレクトスとも形態学的類似性を示します。[10] 2021 年、中国の古人類学者 Qiang Ji は、新たに設立された種であるH.longiを示唆しました。、タイプ標本の臼歯と夏河の下顎骨の類似性に基づいて、デニソワ人を表している可能性があり ます。[19] |

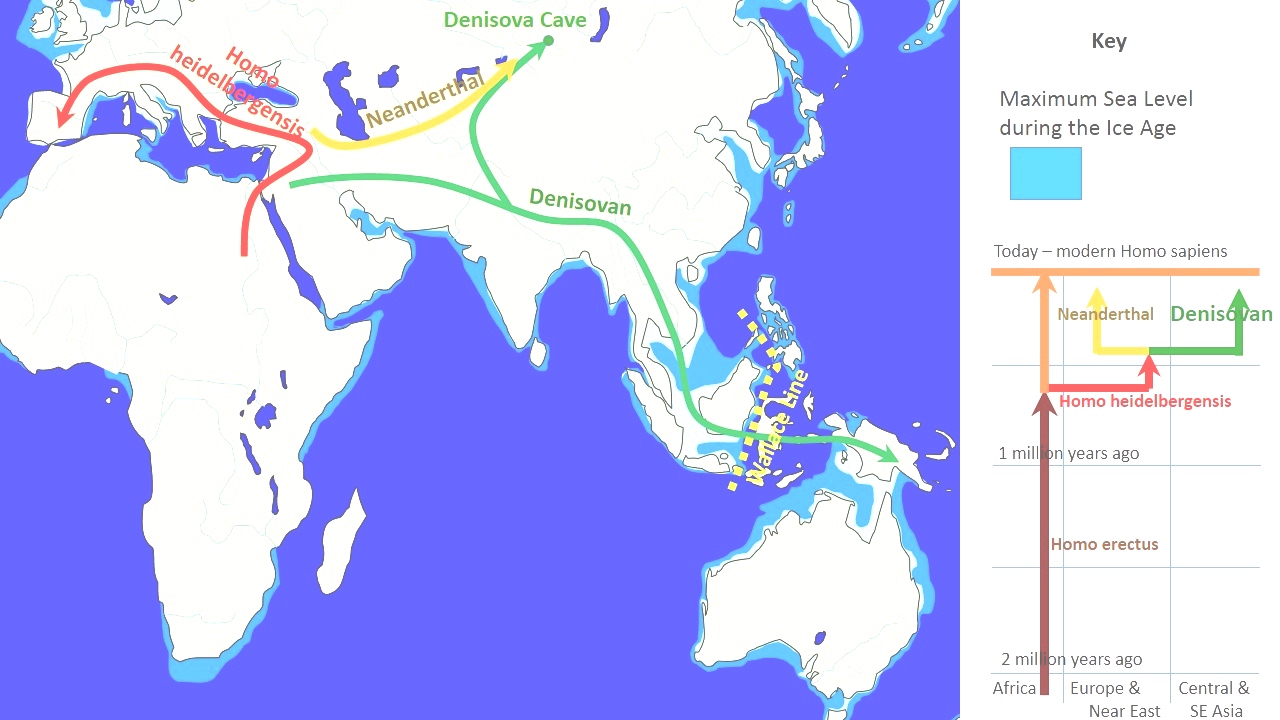

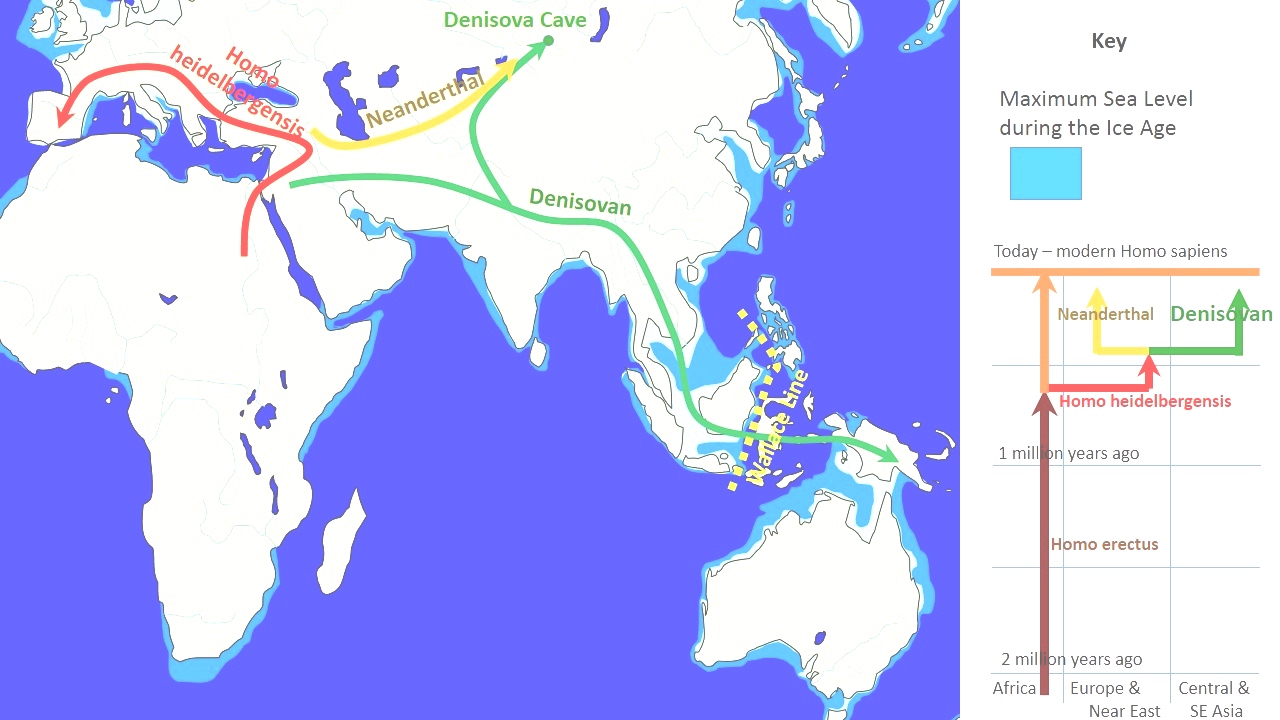

Evolution EvolutionSequenced mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), preserved by the cool climate of the cave (average temperature is at freezing point), was extracted from Denisova 3 by a team of scientists led by Johannes Krause and Svante Pääbo from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany. Denisova 3's mtDNA differs from that of modern humans by 385 bases (nucleotides) out of approximately 16,500, whereas the difference between modern humans and Neanderthals is around 202 bases. In comparison, the difference between chimpanzees and modern humans is approximately 1,462 mtDNA base pairs. This suggested that Denisovan mtDNA diverged from that of modern humans and Neanderthals about 1,313,500–779,300 years ago; whereas modern human and Neanderthal mtDNA diverged 618,000–321,200 years ago. Krause and colleagues then concluded that Denisovans were the descendants of an earlier migration of H. erectus out of Africa, completely distinct from modern humans and Neanderthals.[1] However, according to the nuclear DNA (nDNA) of Denisova 3—which had an unusual degree of DNA preservation with only low-level contamination—Denisovans and Neanderthals were more closely related to each other than they were to modern humans. Using the percent distance from human–chimpanzee last common ancestor, Denisovans/Neanderthals split from modern humans about 804,000 years ago, and from each other 640,000 years ago.[20] Using a mutation rate of 1×10−9 or 0.5×10−9 per base pair (bp) per year, the Neanderthal/Denisovan split occurred around either 236–190,000 or 473–381,000 years ago respectively.[23] Using 1.1×10−8 per generation with a new generation every 29 years, the time is 744,000 years ago. Using 5×10−10 nucleotide site per year, it is 616,000 years ago. Using the latter dates, the split had likely already occurred by the time hominins spread out across Europe.[24] H. heidelbergensis is typically considered to have been the direct ancestor of Denisovans and Neanderthals, and sometimes also modern humans.[25] Due to the strong divergence in dental anatomy, they may have split before characteristic Neanderthal dentition evolved about 300,000 years ago.[20] The more divergent Denisovan mtDNA has been interpreted as evidence of admixture between Denisovans and an unknown archaic human population,[26] possibly a relict H. erectus or H. erectus-like population about 53,000 years ago.[23] Alternatively, divergent mtDNA could have also resulted from the persistence of an ancient mtDNA lineage which only went extinct in modern humans and Neanderthals through genetic drift.[20] Modern humans contributed mtDNA to the Neanderthal lineage, but not to the Denisovan mitochondrial genomes yet sequenced.[27][28][29][30] The mtDNA sequence from the femur of a 400,000-year-old H. heidelbergensis from the Sima de los Huesos Cave in Spain was found to be related to those of Neanderthals and Denisovans, but closer to Denisovans,[31][32] and the authors posited that this mtDNA represents an archaic sequence which was subsequently lost in Neanderthals due to replacement by a modern-human-related sequence.[33] |

進化 進化ネアンデルタール人、ホモ・ハイデルベルゲンシス、ホモ・エレクトスと比較したデニソワ人の進化と地理的広がり 洞窟の冷涼な気候(平均気温は氷点下)によって保存された配列決定された ミトコンドリア DNA (mtDNA) は、マックス・プランク進化人類学研究所のヨハネス・クラウスとスヴァンテ・ペーボ率いる科学者チームによってデニソワ 3 から抽出されました。ライプツィヒ、ドイツ。デニソワ 3 号の mtDNA は、現生人類の mtDNA とは約 16,500 塩基中 385 塩基 (ヌクレオチド)異なりますが、現生人類とネアンデルタール人との違いは約 202 塩基です。それに比べてチンパンジーとの違いはそして現生人類は約 1,462 mtDNA 塩基対です。これは、デニソワ人の mtDNA が、約 1,313,500 ~ 779,300 年前に現生人類およびネアンデルタール人の mtDNA から分岐したことを示唆しています。一方、現生人類とネアンデルタール人の mtDNA は 618,000 ~ 321,200 年前に分岐しました。その後、クラウスらは、デニソワ人はアフリカから初期に移住したホモ・エレクトスの子孫であり、現生人類やネアンデルタール人とは完 全に異なると結論づけた。[1] しかし、デニソワ 3 号の核 DNA (nDNA)によると、DNA の保存状態は低レベルであり、デニソワ人とネアンデルタール人は現生人類よりも近縁でした。人類とチンパンジーの最後の共通祖先からの距離のパーセントを 使用すると、デニソワ人/ネアンデルタール人は約 80 万 4,000 年前に現生人類から分かれ、64 万年前に相互に分かれました。[20]の突然変異率を使用します。1 × 10 -9または年間0.5 × 10 -9塩基対( bp) 当たり、ネアンデルタール人とデニソワ人の分裂はそれぞれ約 236 ~ 190,000 年前または 473 ~ 381,000 年前に起こりました。[23]使用する世代あたり1.1 × 10 -8で、29 年ごとに新しい世代が発生します。その時は 744,000 年前です。使用する 1 年あたり5 × 10 -10ヌクレオチド部位、それは 616,000 年前です。後者の日付を使用すると、ヒト族がヨーロッパ全土に広がった時点で分裂はすでに起こっていた可能性が高い。[24] H. ハイデルベルゲンシスは通常、デニソワ人やネアンデルタール人の直接の祖先であり、場合によっては現生人類の直接の祖先であると考えられています。 [25]歯の解剖学的構造には大きな分岐があるため、約 30 万年前に特徴的なネアンデルタール人の歯列が進化する前に分裂した可能性があります。[20] より分岐したデニソワ人の mtDNA は、デニソワ人と未知の古代人類集団[26] 、おそらくは約 53,000 年前の遺存した H. エレクトスまたはH. エレクトスに似た集団との混合の証拠であると解釈されている。[23]あるいは、分岐した mtDNA は、現生人類とネアンデルタール人で遺伝的浮動によってのみ絶滅した古代の mtDNA 系統の存続から生じた可能性もあります。[20]現生人類はネアンデルタール人の系統に mtDNA を提供しましたが、デニソワ人のミトコンドリア ゲノムにはまだ配列されていませんでした。[27] [28] [29] [30]スペインのシマ・デ・ロス・ウエソス洞窟から出土した40万年前のH.ハイデルベルゲンシスの大腿骨のmtDNA配列は、ネアンデルタール人とデ ニソワ人のものと関連していることが判明したが、デニソワ人により近いものであった[31] [32]。著者らは、この mtDNA は古代の配列を表しており、その後ネアンデルタール人では現生人類に関連する配列に置き換わったために失われたと主張した。[33] |

Demographics DemographicsDenisovans are known to have lived in Siberia, Tibet, and Laos.[14] The Xiahe mandible is the earliest recorded human presence on the Tibetan Plateau.[12] Though their remains have been identified in only these three locations, traces of Denisovan DNA in modern humans suggest they ranged across East Asia,[34][35] and potentially western Eurasia.[36] In 2019, geneticist Guy Jacobs and colleagues identified three distinct populations of Denisovans responsible for the introgression into modern populations now native to, respectively: Siberia and East Asia; New Guinea and nearby islands; and Oceania and, to a lesser extent, across Asia. Using coalescent modeling, the Denisova Cave Denisovans split from the second population about 283,000 years ago; and from the third population about 363,000 years ago. This indicates that there was considerable reproductive isolation between Denisovan populations.[37] Based on the high percentages of Denisovan DNA in modern Papuans and Australians, Denisovans may have crossed the Wallace Line into these regions (with little back-migration west), the second known human species to do so,[17] along with earlier Homo floresiensis. By this logic, they may have also entered the Philippines, living alongside H. luzonensis which, if this is the case, may represent the same or a closely related species.[38] These Denisovans may have needed to cross large bodies of water.[37] Alternately, high Denisovan DNA admixture in modern Papuan populations may simply represent higher mixing among the original ancestors of Papuans prior to crossing the Wallace line. Icelanders also have an anomalously high Denisovan heritage, which could have stemmed from a Denisovan population far west of the Altai mountains. Genetic data suggests Neanderthals were frequently making long crossings between Europe and the Altai mountains especially towards the date of their extinction.[36] Using exponential distribution analysis on haplotype lengths, Jacobs calculated introgression into modern humans occurred about 29,900 years ago with the Denisovan population ancestral to New Guineans; and 45,700 years ago with the population ancestral to both New Guineans and Oceanians. Such a late date for the New Guinean group could indicate Denisovan survival as late as 14,500 years ago, which would make them the latest surviving archaic human species. A third wave appears to have introgressed into East Asia, but there is not enough DNA evidence to pinpoint a solid timeframe.[37] The mtDNA from Denisova 4 bore a high similarity to that of Denisova 3, indicating that they belonged to the same population.[20] The genetic diversity among the Denisovans from Denisova Cave is on the lower range of what is seen in modern humans, and is comparable to that of Neanderthals. However, it is possible that the inhabitants of Denisova Cave were more or less reproductively isolated from other Denisovans, and that, across their entire range, Denisovan genetic diversity may have been much higher.[8] Denisova Cave, over time of habitation, continually swung from a fairly warm and moderately humid pine and birch forest to tundra or forest-tundra landscape.[7] Conversely, Baishiya Karst Cave is situated at a high elevation, an area characterized by low temperature, low oxygen, and poor resource availability. Colonization of high-altitude regions, due to such harsh conditions, was previously assumed to have only been accomplished by modern humans.[12] Denisovans seem to have also inhabited the jungles of Southeast Asia.[35] The Tam Ngu Hao 2 site might have been a closed forest environment.[14] |

人口 人口デニソワ人はシベリア、チベット、ラオスに住んでいたことが知られています。[14]夏河の下顎骨は、チベット高原における人類の存在が記録された最古の ものである。[12]彼らの遺体はこれら 3 か所でしか確認されていないが、現生人類のデニソワ人 DNA の痕跡は、彼らが東アジア全域、[34] [35]、そしておそらく西ユーラシア全域に広がっていたことを示唆している。[36] 2019年、遺伝学者のガイ・ジェイコブズらは、現在原住民となっている現代集団への遺伝子移入の原因となっているデニソワ人の3つの異なる集団をそれぞ れ特定した。ニューギニアと近隣の島々。オセアニア、そして程度は低いですがアジア全域です。使用する合体モデリング、デニソワ洞窟デニソワ人は約 283,000 年前に 2 番目の集団から分かれました。そして約363,000年前の3番目の集団から。これは、デニソワ人の集団間にかなりの生殖的隔離があったことを示していま す。[37] 現代のパプア人やオーストラリア人におけるデニソワ人 DNA の割合が高いことから、デニソワ人はウォーレス線を越えてこれらの地域に(西方への逆移住はほとんどない)、初期のホモ・フロレシエンシスと並んで、そう することが知られている人類で 2 番目の種となった可能性がある[17]。。この論理によれば、彼らはフィリピンにも侵入し、H. ルゾネンシスと共存している可能性があり、これが事実であれば、同じ種または近縁種である可能性があります。[38]これらのデニソワ人は大きな水域を渡 る必要があった可能性がある。[37]あるいは、現代のパプア人集団におけるデニソワ人 DNA の混合率が高いということは、ウォレス線を越える前のパプア人の元の祖先間での混合率が高かったことを単に表しているのかもしれない。アイスランド人はま た、アルタイ山脈のはるか西にあるデニソワ人の人口に由来する可能性がある、異常に高いデニソワ人の血統を持っています。遺伝的データは、ネアンデルター ル人が、特に絶滅の日に向けて、ヨーロッパとアルタイ山脈の間を頻繁に長距離横断していたことを示唆しています。[36] ジェイコブズは、ハプロタイプの長さに関する指数分布分析を使用して、現生人類への遺伝子移入が約 29,900 年前にニューギニア人の祖先であるデニソワ人集団で起こったと計算しました。そして45,700年前にはニューギニア人とオセアニア人の両方の祖先を持つ 人々がいた。ニューギニア人グループのこのような遅い年代は、デニソワ人が 14,500 年前まで生存していたことを示している可能性があり、これは彼らが現存する最も古い旧人類種となることになる。第3波は東アジアに侵入したようだが、確実 な時期を特定するのに十分なDNA証拠はない。[37] デニソバ 4 の mtDNA はデニソバ 3 の mtDNA と高い類似性を示し、これらが同じ集団に属していることを示しています。[20]デニソワ洞窟のデニソワ人の遺伝的多様性は、現生人類に見られるものより も低い範囲にあり、ネアンデルタール人のそれに匹敵します。しかし、デニソワ洞窟の住民は多かれ少なかれ生殖面で他のデニソワ人から隔離されていた可能性 があり、生息範囲全体でデニソワ人の遺伝的多様性ははるかに高かった可能性があります。[8] デニソワ洞窟は、居住期間の経過とともに、かなり暖かく適度に湿度の高い松や白樺の森からツンドラまたは森林とツンドラの風景へと変化し続けました。 [7]逆に、バイシヤ カルスト洞窟は標高が高く、低温、低酸素、資源の入手困難が特徴の地域にあります。このような過酷な条件のため、高地への植民地化は、これまで現生人類の みが成し遂げたと考えられていた。[12]デニソワ人は東南アジアのジャングルにも住んでいたようです。[35]タムグーハオ 2 の遺跡は閉鎖された森林環境だった可能性があります。[14] |

| Anatomy Little is known of the precise anatomical features of the Denisovans since the only physical remains discovered so far are a finger bone, four teeth, long bone fragments, a partial jawbone,[11][14] and a parietal bone skull fragment.[22] The finger bone is within the modern human range of variation for women,[10] which is in contrast to the large, robust molars which are more similar to those of Middle to Late Pleistocene archaic humans. The third molar is outside the range of any Homo species except H. habilis and H. rudolfensis, and is more like those of australopithecines. The second molar is larger than those of modern humans and Neanderthals, and is more similar to those of H. erectus and H. habilis.[20] Like Neanderthals, the mandible had a gap behind the molars, and the front teeth were flattened; but Denisovans lacked a high mandibular body, and the mandibular symphysis at the midline of the jaw was more receding.[12][18] The parietal is reminiscent of that of H. erectus.[39] A facial reconstruction has been generated by comparing methylation at individual genetic loci associated with facial structure.[40] This analysis suggested that Denisovans, much like Neanderthals, had a long, broad, and projecting face; large nose; sloping forehead; protruding jaw; elongated and flattened skull; and wide chest and hips. The Denisovan tooth row was longer than that of Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans.[41] Middle-to-Late Pleistocene East Asian archaic human skullcaps typically share features with Neanderthals. The skullcaps from Xuchang feature prominent brow ridges like Neanderthals, though the nuchal and angular tori near the base of the skull are either reduced or absent, and the back of the skull is rounded off like in early modern humans. Xuchang 1 had a large brain volume of approximately 1800 cc, on the high end for Neanderthals and early modern humans, and well beyond the present-day human average.[42] The Denisovan genome from Denisova Cave has variants of genes which, in modern humans, are associated with dark skin, brown hair, and brown eyes.[43] The Denisovan genome also contains a variant region around the EPAS1 gene that in Tibetans assists with adaptation to low oxygen levels at high elevation,[44][12] and in a region containing the WARS2 and TBX15 loci which affect body-fat distribution in the Inuit.[45] In Papuans, introgressed Neanderthal alleles are highest in frequency in genes expressed in the brain, whereas Denisovan alleles have highest frequency in genes expressed in bones and other tissue.[46] |

解剖学 これまでに発見された物理的遺物は指の骨、4本の歯、長骨の破片、顎の部分[11] [14]、および頭頂骨の頭蓋骨の破片だけであるため、デニソワ人の正確な解剖学的特徴についてはほとんど知られていない。[22]指の骨は女性の現生人 類の変動範囲内にあり[10]、これは中期から後期更新世の旧人類のものに似た大きくて頑丈な臼歯とは対照的である。第三大臼歯は、ホモ・ハビリスとホ モ・ルドルフェンシスを除くヒト属の範囲外にあり、アウストラロピテクス類のそれに似ています。。第二大臼歯は現生人類やネアンデルタール人のものより大 きく、ホモ・エレクトスやホモ・ハビリスのものにより似ています。[20]ネアンデルタール人のように、下顎には臼歯の後ろに隙間があり、前歯は平らに なっていました。しかし、デニソワ人には高い下顎体がなく、顎の正中線の下顎結合はさらに後退していました。[12] [18]頭頂骨はH. エレクトスのものを彷彿とさせます。[39] 顔の再構築は、顔の構造に関連する個々の遺伝子座のメチル化を比較することによって生成されました。[40]この分析は、デニソワ人がネアンデルタール人 とよく似て、長く、幅が広く、突き出た顔を持っていたことを示唆しました。大きな鼻。傾斜した額。突き出た顎。細長く平らな頭蓋骨。そして広い胸と腰。デ ニソワ人の歯列は、ネアンデルタール人や解剖学的現生人類の歯列よりも長かった。[41] 更新世中期から後期にかけての東アジアの古風な人間の頭蓋骨は、通常、ネアンデルタール人と共通の特徴を持っています。許昌の頭蓋骨は、ネアンデルタール 人のような顕著な眉の隆起を特徴としていますが、頭蓋骨の基部近くの項部と角のある環は減少しているか欠如しており、頭蓋骨の後部は初期の現生人類のよう に丸くなっています。許昌 1 号の脳容積は約 1800 cc と、ネアンデルタール人や初期現代人としては最高レベルであり、現生人類の平均をはるかに上回っていました。[42] デニソワ洞窟のデニソワ人のゲノムには、現生人類の褐色の肌、茶色の髪、茶色の目に関連する遺伝子の変異体が含まれています。[43]デニソワ人のゲノム には、チベット人において高地での低酸素レベルへの適応を助けるEPAS1遺伝子の周囲の変異領域も含まれており[44] [12] 、体脂肪に影響を与えるWARS2およびTBX15遺伝子座を含む領域にも含まれています。イヌイットに分布。[45]パプア人では、遺伝子移入されたネ アンデルタール人の対立遺伝子が脳で発現する遺伝子の頻度が最も高いのに対し、デニソワ人の対立遺伝子は骨やその他の組織で発現する遺伝子の頻度が最も高 い。[46] |

| Culture Denisova Cave Early Middle Paleolithic stone tools from Denisova Cave were characterized by discoidal (disk-like) cores and Kombewa cores, but Levallois cores and flakes were also present. There were scrapers, denticulate tools, and notched tools, deposited about 287±41 thousand years ago in the Main Chamber of the cave; and about 269±97 thousand years ago in the South Chamber; up to 170±19 thousand and 187±14 thousand years ago in the Main and East Chambers, respectively.[7] Middle Paleolithic assemblages were dominated by flat, discoidal, and Levallois cores, and there were some isolated sub-prismatic cores. There were predominantly side scrapers (a scraper with only the sides used to scrape), but also notched-denticulate tools, end-scrapers (a scraper with only the ends used to scrape), burins, chisel-like tools, and truncated flakes. These dated to 156±15 thousand years ago in the Main Chamber, 58±6 thousand years ago in the East Chamber, and 136±26–47±8 thousand years ago in the South Chamber.[7] Early Upper Paleolithic artefacts date to 44±5 thousand years ago in the Main Chamber, 63±6 thousand years ago in the East Chamber, and 47±8 thousand years ago in the South Chamber, though some layers of the East Chamber seem to have been disturbed. There was blade production and Levallois production, but scrapers were again predominant. A well-developed, Upper Paleolithic stone bladelet technology distinct from the previous scrapers began accumulating in the Main Chamber around 36±4 thousand years ago.[7] In the Upper Paleolithic layers, there were also several bone tools and ornaments: a marble ring, an ivory ring, an ivory pendant, a red deer tooth pendant, an elk tooth pendant, a chloritolite bracelet, and a bone needle. However, Denisovans are only confirmed to have inhabited the cave until 55 ka; the dating of Upper Paleolithic artefacts overlaps with modern human migration into Siberia (though there are no occurrences in the Altai region); and the DNA of the only specimen in the cave dating to the time interval (Denisova 14) is too degraded to confirm species identity, so the attribution of these artefacts is unclear.[47][7] Tibet In 1998, five child hand- and footprint impressions were discovered in a travertine unit near the Quesang hot springs in Tibet, which in 2021 were dated to 226 to 169 thousand years ago using uranium decay dating. This is the oldest evidence of human occupation of the Tibetan Plateau, and given the Xiahe mandible is the oldest human fossil from the region (albeit, younger than the Quesang impressions), these may have been made by Denisovan children. The impressions were printed onto a small panel of space, and there is little overlap between all the prints, so they seem to have been taking care to make new imprints in unused space. If considered art, they are the oldest known examples of rock art. Similar hand stencils and impressions do not appear again in the archeological record until roughly 40,000 years ago.[48] The footprints comprise four right impressions and one left superimposed on one of the rights. They were probably left by two individuals. The tracks of the individual who superimposed their left onto their right may have scrunched up their toes and wiggled them in the mud, or dug their finger into the toe prints. The footprints average 192.3 mm (7.57 in) long, which roughly equates to a 7 or 8 year old child by modern human growth rates. There are two sets of handprints (from a left and right hand), which may have been created by an older child unless one of the former two individuals had long fingers. The handprints average 161.1 mm (6.34 in), which roughly equates with a 12 year old modern human child, and the middle finger length agrees with a 17 year old modern human. One of the handprints shows an impression of the forearm, and the individual was wiggling their thumb through the mud.[48] |

文化 デニソワ洞窟 デニソワ洞窟から出土した中期前期旧石器は、円盤状(円盤状)コアとコンベワコアが特徴でしたが、ルヴァロワコアやフレークも存在しました。洞窟の主室に は、約 287 ± 41,000 年前に堆積したスクレーパー、歯状の道具、およびギザギザのある道具がありました。そして約26万9±9万7千年前の南の部屋。メインチャンバーと東チャ ンバーではそれぞれ最大17万±1万9千年前と18万7±1万4千年前まで。[7] 中期旧石器時代の集合体は、平らな、円盤状、およびルヴァロア核が大半を占めており、孤立した準角柱状の核もいくつかありました。主にサイド スクレーパー (側面のみをこするためのスクレーパー) がありましたが、ノッチ付きの歯状のツール、エンド スクレーパー (こするために使用される端のみを備えたスクレーパー)、ビュリン、のみのようなツール、および切頭フレークもありました。これらは、主室では 156 ± 15 千年前、東室では 58 ± 6 千年前、南室では 136 ± 26 ~ 47 ± 8 千年前に遡ります。[7] 前期上部旧石器時代の遺物は、主室で 44 ± 5 千年前、東室で 63 ± 6 千年前、南室で 47 ± 8 千年前に遡りますが、東室のいくつかの層は、邪魔された。ブレードの生産とルヴァロアの生産がありましたが、やはりスクレーパーが主流でした。以前のスク レーパーとは異なる、よく発達した後期旧石器時代の石の小刀技術が、約 36 ± 4,000 年前に主室に蓄積され始めました。[7] 上部旧石器時代の層には、大理石の指輪、象牙の指輪、象牙のペンダント、アカシカの歯のペンダント、ヘラジカの歯のペンダント、緑泥石のブレスレット、骨 の針など、いくつかの骨の道具や装飾品もありました。しかし、デニソワ人が洞窟に住んでいたことが確認されているのは55万年前までである。後期旧石器時 代の遺物の年代測定は、現代人のシベリア移住と重なっています(ただし、アルタイ地域ではそのような事例はありません)。そして、この期間(デニソワ14 年)に遡る洞窟内の唯一の標本のDNAは、種の同一性を確認するには劣化しすぎているため、これらの遺物の帰属は不明である。[47] [7] チベット 1998年、チベットのケサン温泉近くのトラバーチン で5つの子供の手形と足形の印象が発見され、2021年にはウラン崩壊年代測定により22万6千年から16万9千年前のものであると判明した。これはチ ベット高原に人類が居住したことを示す最古の証拠であり、夏河の下顎骨がこの地域で発見された最古の人類化石であることを考えると(ケサンの印象よりも若 いとはいえ)、これらはデニソワ人の子供たちによって作られた可能性があります。印象は小さなパネルに印刷されており、すべての版の間の重複はほとんどな いため、未使用のスペースに新しい版を作成することに注意を払っているようです。芸術とみなされるなら、それらは知られている中で最も古いロックアートの 例です。同様の手書きのステンシルや印象は、およそ 40,000 年前まで考古学的記録に再び現れません。[48] 足跡は 4 つの右側の印象と、右側の 1 つに重ねられた 1 つの左側の印象で構成されます。おそらく二人が残したものと思われます。左足と右足を重ね合わせた人の足跡は、足の指を縮めて泥の中で小刻みに動いたり、 足の指の跡に指を食い込んだりした可能性があります。足跡の長さは平均 192.3 mm (7.57 インチ) で、現代の人間の成長率からすると 7 歳または 8 歳の子供にほぼ相当します。手形は 2 セット (左手と右手) あり、前の 2 人のどちらかが長い指を持っていない限り、年長の子供によって作成された可能性があります。手形の平均の長さは 161.1 mm (6.34 インチ) で、これは現生人類の 12 歳の子供にほぼ相当し、中指の長さは現生人類の 17 歳と一致します。手形の 1 つは前腕の印象を示しており、[48] |

| Interbreeding See also: Interbreeding between archaic and modern humans Analyses of the modern human genomes indicate past interbreeding with at least two groups of archaic humans, Neanderthals[49] and Denisovans,[20][50] and that such interbreeding events occurred on multiple occasions. Comparisons of the Denisovan, Neanderthal, and modern human genomes have revealed evidence of a complex web of interbreeding among these lineages.[49] Archaic humans As much as 17% of the Denisovan genome from Denisova Cave represents DNA from the local Neanderthal population.[49] Denisova 11 was an F1 (first generation) Denisovan/Neanderthal hybrid; the fact that such an individual was found may indicate interbreeding was a common occurrence here.[51] The Denisovan genome shares more derived alleles with the Altai Neanderthal genome from Siberia than with the Vindija Cave Neanderthal genome from Croatia or the Mezmaiskaya cave Neanderthal genome from the Caucasus, suggesting that the gene flow came from a population that was more closely related to the local Altai Neanderthals.[52] However, Denny's Denisovan father had the typical Altai Neanderthal introgression, while her Neanderthal mother represented a population more closely related to Vindija Neanderthals.[53] About 4% of the Denisovan genome derives from an unidentified archaic hominin,[49] perhaps the source of the anomalous ancient mtDNA, indicating this species diverged from Neanderthals and humans over a million years ago. The only identified Homo species of Late Pleistocene Asia are H. erectus and H. heidelbergensis,[52][54] though in 2021, specimens allocated to the latter species were reclassified as H. longi and H. daliensis.[55] Before splitting from Neanderthals, their ancestors ("Neandersovans") migrating out of Africa into Europe apparently interbred with an unidentified "superarchaic" human species who were already present there; these superarchaics were the descendants of a very early migration out of Africa around 1.9 mya.[56] |

異種交配 現生人類のゲノムの分析では、ネアンデルタール人[49]とデニソワ人[20] [50]という少なくとも 2 つの旧人類グループとの過去の交雑が示されており、そのような交雑事象が複数回発生したことが示されている。デニソワ人、ネアンデルタール人、現生人類の ゲノムを比較すると、これらの系統間に複雑な交雑の網があった証拠が明らかになった。[49] 古風な人間 デニソワ洞窟のデニソワ人ゲノムの 17% は、地元のネアンデルタール人集団の DNA を表しています。[49]デニソワ 11 号はF1 (第一世代) デニソワ人とネアンデルタール人のハイブリッドでした。そのような個体が発見されたという事実は、ここでは異種交配が一般的に起こっていたことを示してい る可能性がある。[51]デニソワ人のゲノムは、クロアチアのヴィンディヤ洞窟のネアンデルタール人ゲノムやコーカサスのメズマイスカヤ洞窟のネアンデル タール人ゲノムよりも、シベリアのアルタイ人ネアンデルタール人のゲノムとより多くの派生対立遺伝子を共有しており、遺伝子の流れがより近縁な集団から来 たことを示唆している地元のアルタイのネアンデルタール人に。[52]しかし、デニーのデニソワ人の父親は典型的なアルタイ人のネアンデルタール人の遺伝 子移入を持っていましたが、彼女のネアンデルタール人の母親はヴィンディジャ・ネアンデルタール人とより近縁な集団を表していました。[53] デニソワ人のゲノムの約 4% は未確認の古人族に由来しており[49]おそらく異常な古代 mtDNA の源であり、この種が 100 万年以上前にネアンデルタール人と人類から分岐したことを示しています。更新世後期アジアで確認されているヒト属種はH. エレクトスとH. ハイデルベルゲンシスだけである[52] [54]が、2021 年に後者の種に割り当てられた標本はH. ロンギとH. ダリエンシスに再分類された。[55] ネアンデルタール人から分かれる前に、アフリカからヨーロッパに移住した彼らの祖先(「ネアンデルソワ人」)は、明らかにそこにすでに存在していた未確認 の「超古」人類種と交雑したようです。これらの超古人は、約190万年前にアフリカから出た非常に初期の移住者の子孫でした。[56] |

| Modern Humans A 2011 study found that Denisovan DNA is prevalent in Aboriginal Australians, Near Oceanians, Polynesians, Fijians, Eastern Indonesians and Mamanwans (from the Philippines); but not in East Asians, western Indonesians, Jahai people (from Malaysia) or Onge (from the Andaman Islands). This means that Denisovan introgression occurred within the Pacific region rather than on the Asian mainland, and that ancestors of the latter groups were not present in Southeast Asia at the time, which in turn means that eastern Asia was settled by modern humans in two distinct migrations.[35] In the Melanesian genome, about 4–6%[20] or 1.9–3.4% derives from Denisovan introgression.[57] It was reported that New Guineans and Australian Aborigines have the most introgressed DNA,[17] but Australians have less than New Guineans,[58] until a 2021 study discovered 30 to 40% more Denisovan ancestry in Filipino Negritos than in Papuans, by their estimates roughly 5% of the genome. The Aeta in Luzon have the highest proportion of Denisovan ancestry of any population in the world.[38] In Papuans, less Denisovan ancestry is seen in the X chromosome than autosomes, and some autosomes (such as chromosome 11) also have less Denisovan ancestry, which could indicate hybrid incompatibility. The former observation could also be explained by less female Denisovan introgression into modern humans, or more female modern human immigrants who diluted Denisovan X chromosome ancestry.[43] In contrast, 0.2% derives from Denisovan ancestry in mainland Asians and Native Americans.[59] South Asians were found to have levels of Denisovan admixture similar to that seen in East Asians.[60] The discovery of the 40,000-year-old Chinese modern human Tianyuan Man lacking Denisovan DNA significantly different from the levels in modern-day East Asians discounts the hypothesis that immigrating modern humans simply diluted Denisovan ancestry whereas Melanesians lived in reproductive isolation.[61][17] A 2018 study of Han Chinese, Japanese, and Dai genomes showed that modern East Asians have DNA from two different Denisovan populations: one similar to the Denisovan DNA found in Papuan genomes, and a second that is closer to the Denisovan genome from Denisova Cave. This could indicate two separate introgression events involving two different Denisovan populations. In South Asian genomes, DNA only came from the same single Denisovan introgression seen in Papuans.[60] A 2019 study found a third wave of Denisovans which introgressed into East Asians. Introgression, also, may not have immediately occurred when modern humans immigrated into the region.[37] The timing of introgression into Oceanian populations likely occurred after Eurasians and Oceanians split roughly 58,000 years ago, and before Papuan and Aboriginal Australians split from each other roughly 37,000 years ago. Given the present day distribution of Denisovan DNA, this may have taken place in Wallacea, though the discovery of a 7,200 year old Toalean girl (closely related to Papuans and Aboriginal Australians) from Sulawesi carrying Denisovan DNA makes Sundaland another potential candidate. Other early Sunda hunter gatherers so far sequenced carry very little Denisovan DNA, which either means the introgression event did not take place in Sundaland, or Denisovan ancestry was diluted with gene flow from the mainland Asian Hòabìnhian culture and subsequent Neolithic cultures.[62] In other regions of the world, archaic introgression into humans stems from a group of Neanderthals related to those which inhabited Vindija Cave, Croatia, as opposed to archaics related to Siberian Neanderthals and Denisovans. However, about 3.3% of the archaic DNA in the modern Icelandic genome descends from the Denisovans, and such a high percentage could indicate a western Eurasian population of Denisovans which introgressed into either Vindija-related Neanderthals or immigrating modern humans.[36] Denisovan genes may have helped early modern humans migrating out of Africa to acclimatize[citation needed]. Although not present in the sequenced Denisovan genome, the distribution pattern and divergence of HLA-B*73 from other HLA alleles (involved in the immune system's natural killer cell receptors) has led to the suggestion that it introgressed from Denisovans into modern humans in West Asia. In a 2011 study, half of the HLA alleles of modern Eurasians were shown to represent archaic HLA haplotypes, and were inferred to be of Denisovan or Neanderthal origin.[63] A haplotype of EPAS1 in modern Tibetans, which allows them to live at high elevations in a low-oxygen environment, likely came from Denisovans.[44][12] Genes related to phospholipid transporters (which are involved in fat metabolism) and to trace amine-associated receptors (involved in smelling) are more active in people with more Denisovan ancestry.[64] Denisovan genes may have conferred a degree of immunity against the G614 mutation of SARS-CoV-2.[65] |

現生人類 2011年の研究では、デニソワ人のDNAがオーストラリア先住民、近オセアニア人、ポリネシア人、フィジー人、東部インドネシア人、およびママンワン人 (フィリピン出身)に蔓延していることが判明した。しかし、東アジア人、インドネシア西部人、ジャハイ人(マレーシア出身)、オンゲ人(アンダマン諸島出 身)ではそうではありません。これは、デニソワ人の侵入はアジア本土ではなく太平洋地域内で発生し、後者のグループの祖先は当時の東南アジアには存在して いなかったことを意味し、ひいては東アジアには現生人類が2回の異なる移住で定住したことを意味する。[35]メラネシア人のゲノムでは、約 4 ~ 6% [20]または 1.9 ~ 3.4% がデニソワ人の遺伝子移入に由来します。[57]ニューギニア人とオーストラリアのアボリジニが最も遺伝子移入された DNA を持っていると報告されている[17]が、オーストラリア人はニューギニア人よりも遺伝子移入度が低い[58] が、2021 年の研究でフィリピンのネグリト人はパプア人よりもデニソワ人の祖先が 30 ~ 40% 多いことが判明するまで[58] 、彼らの推定によれば、ゲノムのおよそ 5% です。ルソン島のアエタ族は、世界のどの人口よりもデニソワ人祖先の割合が最も高い人々です。[38]パプア人では、 X 染色体に見られるデニソワ人の祖先はパプア人より常染色体、および一部の常染色体 ( 11 番染色体など) もデニソワ人の祖先が少なく、これは雑種の不適合性を示している可能性があります。前者の観察は、現生人類へのデニソワ人の女性の遺伝子移入が少ないこ と、またはデニソワ人 X 染色体の祖先を薄めた女性の現生人類移民が多いことによっても説明できるかもしれない。[43] 対照的に、0.2%はアジア本土およびアメリカ先住民のデニソワ人の祖先に由来しています。[59] 南アジア人には、東アジア人に見られるものと同様のレベルのデニソワ人混合物が存在することが判明した。[60] 4万年前の中国現生人類天元人の発見は、現代の東アジア人とは大きく異なるデニソワ人のDNAを欠いており、メラネシア人は生殖隔離の中で生きていたのに 対し、現生人類の移民は単にデニソワ人の祖先を希薄化させただけであるという仮説を軽視した。[61] [17]漢民族、日本語、ダイ族に関する 2018 年の研究ゲノム解析の結果、現代の東アジア人は2つの異なるデニソワ人集団由来のDNAを持っていることが示された。1つはパプアのゲノムで見つかったデ ニソワ人のDNAに似ており、もう1つはデニソワ洞窟のデニソワ人のゲノムに近い。これは、2 つの異なるデニソワ人集団が関与した 2 つの別々の遺伝子移入事象を示している可能性があります。南アジアのゲノムでは、DNA はパプア人に見られるのと同じ単一のデニソワ人の遺伝子移入にのみ由来していました。[60] 2019年の研究では、東アジア人に侵入したデニソワ人の第3波が判明した。また、現生人類がこの地域に移住したときに、すぐに遺伝子移入が起こったわけ ではないかもしれない。[37] オセアニア人集団への遺伝子移入のタイミングは、約5万8千年前にユーラシア人とオセアニア人が分かれた後、そして約3万7千年前にパプア人とオーストラ リア先住民が分かれる前に起こったと考えられる。現在のデニソワ人 DNA の分布を考慮すると、これはウォラセアで起こった可能性がありますが、デニソワ人 DNA を持つスラウェシ島出身の 7,200 歳のトアレ人の少女 (パプア人やオーストラリア先住民と密接な関係) が発見されたことにより、スンダランドも別の候補地となっています。これまでに配列決定されている他の初期スンダ狩猟採集民は、デニソワ人の DNA をほとんど持っていない。これは、スンダランドで遺伝子移入事象が起こらなかったか、あるいはデニソワ人の祖先がアジア本土のホビアン文化とその後の遺伝 子の流れによって薄められたことを意味する。新石器時代の文化。[62] 世界の他の地域では、シベリアのネアンデルタール人やデニソワ人に関連する古遺物とは対照的に、人類への古風な遺伝子移入は、クロアチアのヴィンディヤ洞 窟に生息していた人々に関連するネアンデルタール人のグループに由来しています。しかし、現代のアイスランド人のゲノムに含まれる古期DNAの約3.3% はデニソワ人に由来しており、このような高い割合は、西ユーラシアのデニソワ人集団がヴィンディージャ関連のネアンデルタール人または移住した現生人類の いずれかに遺伝子移入したことを示している可能性がある。[36] デニソワ人の遺伝子は、アフリカから移住してきた初期の現生人類が順応するのに役立った可能性がある[要出典]。配列決定されたデニソワ人のゲノムには存 在しませんが、HLA-B*73 の分布パターンと他のHLA対立遺伝子 (免疫系のナチュラルキラー細胞受容体に関与) からの分岐により、HLA-B*73 がデニソワ人から現生人類に遺伝子移入したという示唆につながりました。西アジアで。2011年の研究では、現生ユーラシア人のHLA対立遺伝子の半分が 古風なHLAハプロタイプを表すことが示され、デニソワ人またはネアンデルタール人起源であると推測された。[63]現代のチベット人が低酸素環境の高地 で暮らすことを可能にするEPAS1のハプロタイプは、おそらくデニソワ人由来のものである。[44] [12]リン脂質トランスポーター(脂肪代謝に関与)およびトレースアミン関連受容体(嗅覚に関与)に関連する遺伝子は、デニソワ人の祖先が多い人々でよ り活性が高い。[64]デニソワ人遺伝子は、 SARS-CoV-2の G614 変異に対するある程度の免疫を与えた可能性がある。[65] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Denisovan |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099