三段論法

Syllogism

☆ 三段論法つまりシロギズム(ギリシャ語: συλλογισμός, syllogismos, 「結論、推論」)とは、演繹的推論を適用して、真であると主張または仮定された2つの命題に基づいて結論を導き出す論理的議論の一種である。 その最も初期の形(アリストテレスが紀元前350年の著書『先行分析学』で定義)では、演繹的対義論は、2つの真の前提(命題または声明)が結論、または 論証が伝えようとする主旨を有効に含意するときに生じる[1]。例えば、すべての人間は死すべき存在である(大前提)とソクラテスが人間である(小前提) を知っている場合、我々はソクラテスが死すべき存在であると有効に結論づけることができる。シロジスティック論証は通常、3行の形式で表される: すべての人は死を免れない。 ソクラテスは人である。 したがって、ソクラテスは死すべきものである[2]。 古代においては、2つの対立するシロジスティック理論が存在した:中世以降、定言的三段論法と三段論法は通常同じ意味で使われた。この記事では、この歴史 的な用法についてのみ述べる。この三段論法は、事実が繰り返される観察によって予測される帰納的推論とは対照的に、事実が既存のステートメントを組み合わ せることによって決定される歴史的演繹的推論の中核であった。 学問的な文脈では、ゴットロブ・フレーゲ(Gottlob Frege)、特に彼の『概念スクリプト(Begriffsschrift)』(1879年)の研究により、シロジズムは一階述語論理に取って代わられ た。シロジズムは有効な論理的推論の方法であるため、ほとんどの状況において、また論理学や明晰な思考への一般的な入門書として常に有用である[4] [5]。

A syllogism (Greek:

συλλογισμός, syllogismos, 'conclusion, inference') is a kind of logical

argument that applies deductive reasoning to arrive at a conclusion

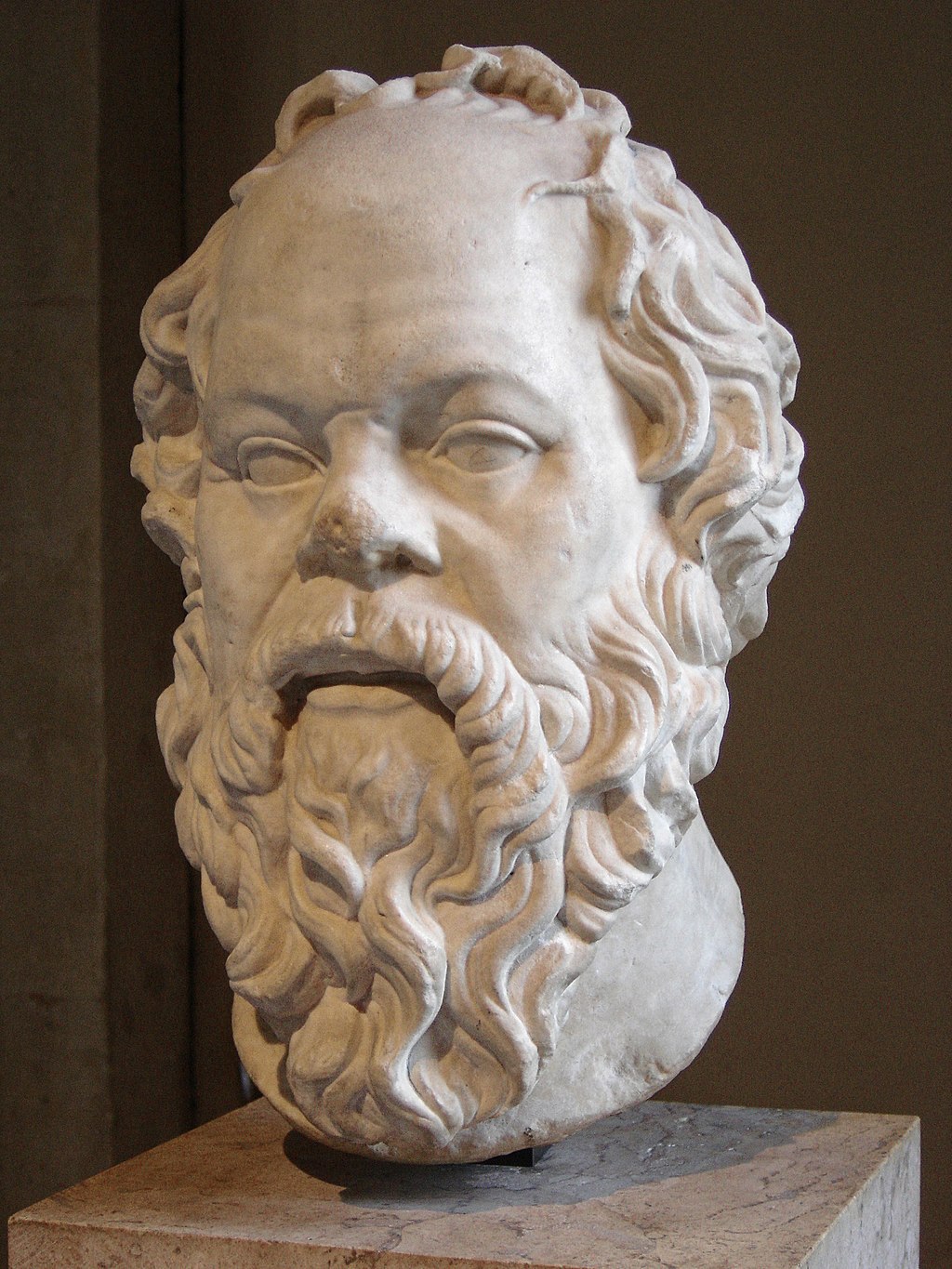

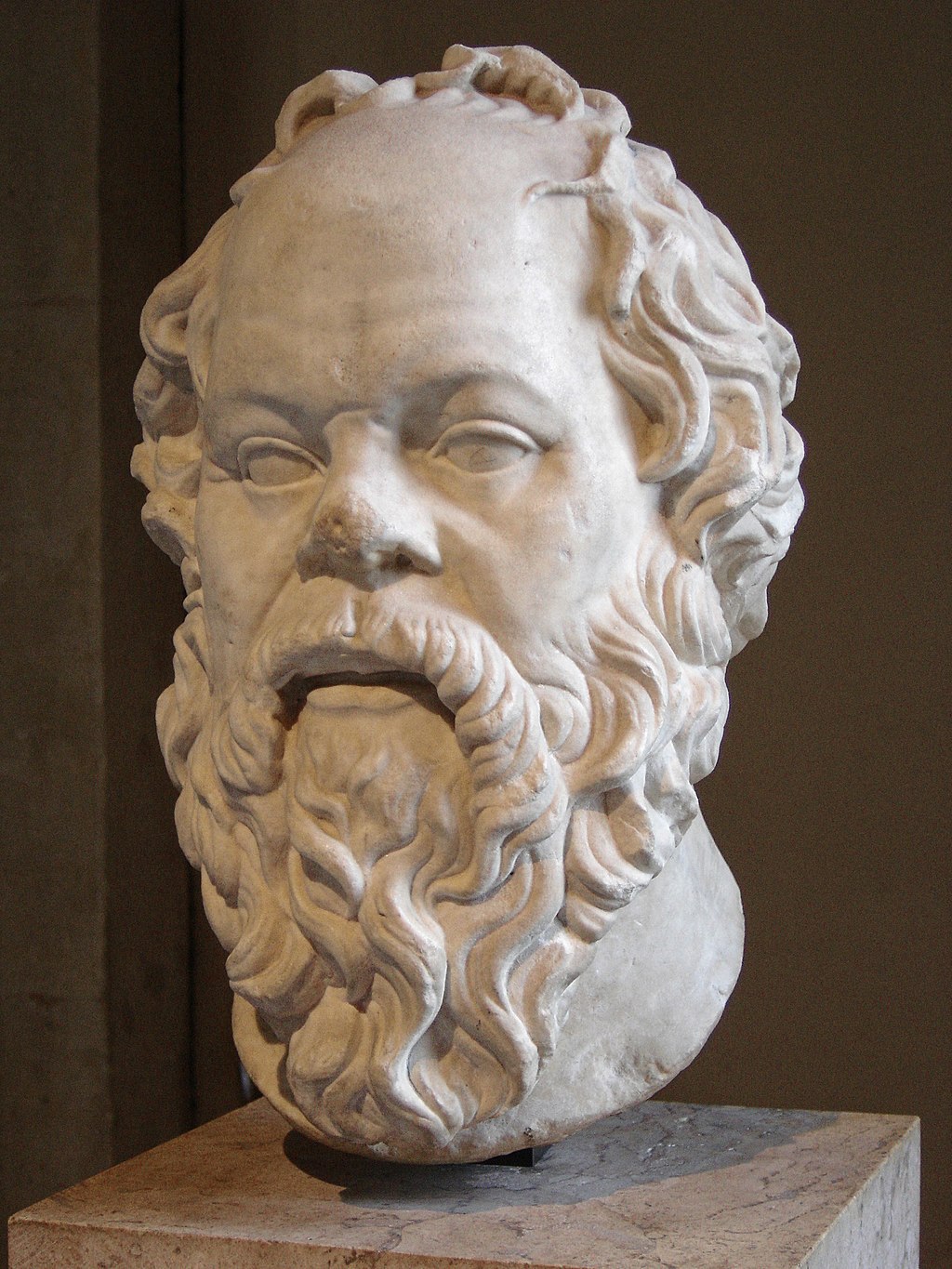

based on two propositions that are asserted or assumed to be true. "Socrates" at the Louvre In its earliest form (defined by Aristotle in his 350 BC book Prior Analytics), a deductive syllogism arises when two true premises (propositions or statements) validly imply a conclusion, or the main point that the argument aims to get across.[1] For example, knowing that all men are mortal (major premise) and that Socrates is a man (minor premise), we may validly conclude that Socrates is mortal. Syllogistic arguments are usually represented in a three-line form: All men are mortal. Socrates is a man. Therefore, Socrates is mortal.[2] In antiquity, two rival syllogistic theories existed: Aristotelian syllogism and Stoic syllogism.[3] From the Middle Ages onwards, categorical syllogism and syllogism were usually used interchangeably. This article is concerned only with this historical use. The syllogism was at the core of historical deductive reasoning, whereby facts are determined by combining existing statements, in contrast to inductive reasoning, in which facts are predicted by repeated observations. Within some academic contexts, syllogism has been superseded by first-order predicate logic following the work of Gottlob Frege, in particular his Begriffsschrift (Concept Script; 1879). Syllogism, being a method of valid logical reasoning, will always be useful in most circumstances and for general-audience introductions to logic and clear-thinking.[4][5] |

三段論法つまりシロギズム(ギリシャ語: συλλογισμός,

syllogismos,

「結論、推論」)とは、演繹的推論を適用して、真であると主張または仮定された2つの命題に基づいて結論を導き出す論理的議論の一種である。 「ルーヴル美術館の「ソクラテス」 その最も初期の形(アリストテレスが紀元前350年の著書『先行分析学』で定義)では、演繹的対義論は、2つの真の前提(命題または声明)が結論、または 論証が伝えようとする主旨を有効に含意するときに生じる[1]。例えば、すべての人間は死すべき存在である(大前提)とソクラテスが人間である(小前提) を知っている場合、我々はソクラテスが死すべき存在であると有効に結論づけることができる。シロジスティック論証は通常、3行の形式で表される: すべての人は死を免れない。 ソクラテスは人である。 したがって、ソクラテスは死すべきものである[2]。 古代においては、2つの対立するシロジスティック理論が存在した: 中世以降、定言的三段論法と三段論法は通常同じ意味で使われた。この記事では、この歴史的な用法についてのみ述べる。この三段論法は、事実が繰り返される 観察によって予測される帰納的推論とは対照的に、事実が既存のステートメントを組み合わせることによって決定される歴史的演繹的推論の中核であった。 学問的な文脈では、ゴットロブ・フレーゲ(Gottlob Frege)、特に彼の『概念スクリプト(Begriffsschrift)』(1879年)の研究により、シロジズムは一階述語論理に取って代わられ た。シロジズムは有効な論理的推論の方法であるため、ほとんどの状況において、また論理学や明晰な思考への一般的な入門書として常に有用である[4] [5]。 |

| Early history Main article: History of logic In antiquity, two rival syllogistic theories existed: Aristotelian syllogism and Stoic syllogism.[3] Aristotle Main article: Term logic Aristotle defines the syllogism as "a discourse in which certain (specific) things having been supposed, something different from the things supposed results of necessity because these things are so."[6] Despite this very general definition, in Prior Analytics Aristotle limits himself to categorical syllogisms that consist of three categorical propositions, including categorical modal syllogisms.[7] The use of syllogisms as a tool for understanding can be dated back to the logical reasoning discussions of Aristotle. Before the mid-12th century, medieval logicians were only familiar with a portion of Aristotle's works, including such titles as Categories and On Interpretation, works that contributed heavily to the prevailing Old Logic, or logica vetus. The onset of a New Logic, or logica nova, arose alongside the reappearance of Prior Analytics, the work in which Aristotle developed his theory of the syllogism. Prior Analytics, upon rediscovery, was instantly regarded by logicians as "a closed and complete body of doctrine", leaving very little for thinkers of the day to debate and reorganize. Aristotle's theory on the syllogism for assertoric sentences was considered especially remarkable, with only small systematic changes occurring to the concept over time. This theory of the syllogism would not enter the context of the more comprehensive logic of consequence until logic began to be reworked in general in the mid-14th century by the likes of John Buridan. Aristotle's Prior Analytics did not, however, incorporate such a comprehensive theory on the modal syllogism—a syllogism that has at least one modalized premise, that is, a premise containing the modal words necessarily, possibly, or contingently. Aristotle's terminology in this aspect of his theory was deemed vague and in many cases unclear, even contradicting some of his statements from On Interpretation. His original assertions on this specific component of the theory were left up to a considerable amount of conversation, resulting in a wide array of solutions put forth by commentators of the day. The system for modal syllogisms laid forth by Aristotle would ultimately be deemed unfit for practical use and would be replaced by new distinctions and new theories altogether. Medieval syllogism Boethius Boethius (c. 475–526) contributed an effort to make the ancient Aristotelian logic more accessible. While his Latin translation of Prior Analytics went primarily unused before the 12th century, his textbooks on the categorical syllogism were central to expanding the syllogistic discussion. Rather than in any additions that he personally made to the field, Boethius' logical legacy lies in his effective transmission of prior theories to later logicians, as well as his clear and primarily accurate presentations of Aristotle's contributions. Peter Abelard Another of medieval logic's first contributors from the Latin West, Peter Abelard (1079–1142), gave his own thorough evaluation of the syllogism concept and accompanying theory in the Dialectica—a discussion of logic based on Boethius' commentaries and monographs. His perspective on syllogisms can be found in other works as well, such as Logica Ingredientibus. With the help of Abelard's distinction between de dicto modal sentences and de re modal sentences, medieval logicians began to shape a more coherent concept of Aristotle's modal syllogism model. Jean Buridan The French philosopher Jean Buridan (c. 1300 – 1361), whom some consider the foremost logician of the later Middle Ages, contributed two significant works: Treatise on Consequence and Summulae de Dialectica, in which he discussed the concept of the syllogism, its components and distinctions, and ways to use the tool to expand its logical capability. For 200 years after Buridan's discussions, little was said about syllogistic logic. Historians of logic have assessed that the primary changes in the post-Middle Age era were changes in respect to the public's awareness of original sources, a lessening of appreciation for the logic's sophistication and complexity, and an increase in logical ignorance—so that logicians of the early 20th century came to view the whole system as ridiculous.[8] |

初期の歴史 主な記事 論理学の歴史 古代において、2つの対立する音韻論が存在した: アリストテレス的音韻論とストア的音韻論である[3]。 アリストテレス アリストテレス 論理学用語 アリストテレスはシロジズムを「ある(特定の)物事が想定されたとき、これらの物事がそうであるために、必然的に想定された物事とは異なる何かが生じる言 説」と定義している[6]。この非常に一般的な定義にもかかわらず、『先行分析学』においてアリストテレスは、カテゴリー的様相シロジズムを含む、3つの カテゴリー的命題からなるカテゴリー的シロジズムに限定している[7]。 理解のための道具としての対句の使用は、アリストテレスの論理的推論の議論にまで遡ることができる。12世紀半ば以前、中世の論理学者たちは『カテゴ リー』や『解釈について』といったアリストテレスの著作の一部しか知らなかった。新論理学(ロジカ・ノーヴァ)の勃興は、アリストテレスがシロジズム理論 を展開した『先行分析学』の再登場とともに起こった。 再発見された『先行分析学』は、論理学者たちから即座に「閉ざされた完全な教義体系」と見なされ、当時の思想家たちが議論したり再編成したりする余地はほ とんど残されていなかった。アリストテレスが主張文に対するシロジズムの理論を確立したことは特に注目に値する。このシロジズムの理論が、より包括的な帰 結の論理学の文脈に入るのは、14世紀半ばにジョン・ブリダンのような人物によって論理学全般が再編成され始めてからである。 しかし、アリストテレスの『先行分析学』には、このような包括的な理論は盛り込まれていなかった。すなわち、少なくとも一つの様相化された前提、すなわ ち、必然的、可能性的、偶発的という様相語を含む前提を持つ三段論法に関する理論である。アリストテレスのこの理論における用語は曖昧で、多くの場合不明 瞭であり、『解釈論』での彼の発言と矛盾するものさえあった。この理論の特定の要素に関する彼の当初の主張は、かなりの量の議論に委ねられ、その結果、当 時の論者たちによってさまざまな解決策が提示された。アリストテレスが提唱した様相的三段論法は、最終的には実用に適さないと判断され、新しい区別と新し い理論に取って代わられることになる。 中世の三段論法 ボエティウス ボエティウス(475頃-526)は、古代のアリストテレス論理学をより身近なものにする努力をした。彼がラテン語訳した『先行論理学』は12世紀以前に はほとんど使われることはなかったが、定言命法に関する彼の教科書は、対論的議論を拡大する上で中心的な役割を果たした。ボエティウスの論理学的遺産は、 彼自身がこの分野に加えたというよりもむしろ、先行理論を後世の論理学者に効果的に伝えたことと、アリストテレスの貢献を明確かつ主に正確に提示したこと にある。 ピーター・アベラール もう一人の中世論理学の最初の貢献者であるラテン西方出身のピーター・アベラール(1079-1142)は、ボエティウスの注釈書や単行本に基づく論理学 の論考である『弁証法』の中で、シロジズムの概念とそれに付随する理論について独自の徹底的な評価を下している。シロジズムに関する彼の視点は、 Logica Ingredientibusなどの他の著作にも見られる。アベラールによるde dicto様相文とde re様相文の区別の助けを借りて、中世の論理学者たちはアリストテレスの様相シロジズム・モデルのより首尾一貫した概念を形成し始めた。 ジャン・ビュリダン フランスの哲学者ジャン・ビュリダン(1300年頃-1361年)は、中世後期の最も優れた論理学者と見なされており、2つの重要な著作を残している: その中で彼は、シロジズムの概念、その構成要素と区別、論理的能力を拡張するための道具の使用方法について論じた。ビュリダンの議論から200年間、シロ ジスティック・ロジックについて語られることはほとんどなかった。論理学の歴史家は、中世以降の時代における主な変化は、原典に対する一般の認識に関する 変化、論理学の洗練さと複雑さに対する評価の低下、論理的無知の増加であり、20世紀初頭の論理学者はシステム全体を滑稽なものとみなすようになったと評 価している[8]。 |

| Modern history The Aristotelian syllogism dominated Western philosophical thought for many centuries. Syllogism itself is about drawing valid conclusions from assumptions (axioms), rather than about verifying the assumptions. However, people over time focused on the logic aspect, forgetting the importance of verifying the assumptions. In the 17th century, Francis Bacon emphasized that experimental verification of axioms must be carried out rigorously, and cannot take syllogism itself as the best way to draw conclusions in nature.[9] Bacon proposed a more inductive approach to the observation of nature, which involves experimentation and leads to discovering and building on axioms to create a more general conclusion.[9] Yet, a full method of drawing conclusions in nature is not the scope of logic or syllogism, and the inductive method was covered in Aristotle's subsequent treatise, the Posterior Analytics. In the 19th century, modifications to syllogism were incorporated to deal with disjunctive ("A or B") and conditional ("if A then B") statements. Immanuel Kant famously claimed, in Logic (1800), that logic was the one completed science, and that Aristotelian logic more or less included everything about logic that there was to know. (This work is not necessarily representative of Kant's mature philosophy, which is often regarded as an innovation to logic itself.) Kant's opinion stood unchallenged in the West until 1879, when Gottlob Frege published his Begriffsschrift (Concept Script). This introduced a calculus, a method of representing categorical statements (and statements that are not provided for in syllogism as well) by the use of quantifiers and variables. A noteworthy exception is the logic developed in Bernard Bolzano's work Wissenschaftslehre (Theory of Science, 1837), the principles of which were applied as a direct critique of Kant, in the posthumously published work New Anti-Kant (1850). The work of Bolzano had been largely overlooked until the late 20th century, among other reasons, because of the intellectual environment at the time in Bohemia, which was then part of the Austrian Empire. In the last 20 years, Bolzano's work has resurfaced and become subject of both translation and contemporary study. This led to the rapid development of sentential logic and first-order predicate logic, subsuming syllogistic reasoning, which was, therefore, after 2000 years, suddenly considered obsolete by many.[original research?] The Aristotelian system is explicated in modern fora of academia primarily in introductory material and historical study. One notable exception to this modern relegation is the continued application of Aristotelian logic by officials of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, and the Apostolic Tribunal of the Roman Rota, which still requires that any arguments crafted by Advocates be presented in syllogistic format. Boole's acceptance of Aristotle George Boole's unwavering acceptance of Aristotle's logic is emphasized by the historian of logic John Corcoran in an accessible introduction to Laws of Thought.[10][11] Corcoran also wrote a point-by-point comparison of Prior Analytics and Laws of Thought.[12] According to Corcoran, Boole fully accepted and endorsed Aristotle's logic. Boole's goals were "to go under, over, and beyond" Aristotle's logic by:[12] providing it with mathematical foundations involving equations; extending the class of problems it could treat, as solving equations was added to assessing validity; and expanding the range of applications it could handle, such as expanding propositions of only two terms to those having arbitrarily many. More specifically, Boole agreed with what Aristotle said; Boole's 'disagreements', if they might be called that, concern what Aristotle did not say. First, in the realm of foundations, Boole reduced Aristotle's four propositional forms to one form, the form of equations, which by itself was a revolutionary idea. Second, in the realm of logic's problems, Boole's addition of equation solving to logic—another revolutionary idea—involved Boole's doctrine that Aristotle's rules of inference (the "perfect syllogisms") must be supplemented by rules for equation solving. Third, in the realm of applications, Boole's system could handle multi-term propositions and arguments, whereas Aristotle could handle only two-termed subject-predicate propositions and arguments. For example, Aristotle's system could not deduce: "No quadrangle that is a square is a rectangle that is a rhombus" from "No square that is a quadrangle is a rhombus that is a rectangle" or from "No rhombus that is a rectangle is a square that is a quadrangle." Basic structure A categorical syllogism consists of three parts: Major premise Minor premise Conclusion/Consequent Each part is a categorical proposition, and each categorical proposition contains two categorical terms.[13] In Aristotle, each of the premises is in the form "All S are P," "Some S are P", "No S are P" or "Some S are not P", where "S" is the subject-term and "P" is the predicate-term: "All S are P," and "No S are P" are termed universal propositions; "Some S are P" and "Some S are not P" are termed particular propositions. More modern logicians allow some variation. Each of the premises has one term in common with the conclusion: in a major premise, this is the major term (i.e., the predicate of the conclusion); in a minor premise, this is the minor term (i.e., the subject of the conclusion). For example: Major premise: All humans are mortal. Minor premise: All Greeks are humans. Conclusion/Consequent: All Greeks are mortal. Each of the three distinct terms represents a category. From the example above, humans, mortal, and Greeks: mortal is the major term, and Greeks the minor term. The premises also have one term in common with each other, which is known as the middle term; in this example, humans. Both of the premises are universal, as is the conclusion. Major premise: All mortals die. Minor premise: All men are mortals. Conclusion/Consequent: All men die. Here, the major term is die, the minor term is men, and the middle term is mortals. Again, both premises are universal, hence so is the conclusion. Polysyllogism Main article: Polysyllogism A polysyllogism, or a sorites, is a form of argument in which a series of incomplete syllogisms is so arranged that the predicate of each premise forms the subject of the next until the subject of the first is joined with the predicate of the last in the conclusion. For example, one might argue that all lions are big cats, all big cats are predators, and all predators are carnivores. To conclude that therefore all lions are carnivores is to construct a sorites argument. |

近代史 アリストテレス的な三段論法は、何世紀にもわたって西洋の哲学思想を支配してきた。対論自体は、仮定(公理)から妥当な結論を導き出すことであり、仮定を検証することではない。しかし、時代とともに人々は論理の側面に注目し、仮定を検証することの重要性を忘れてしまった。 17世紀、フランシス・ベーコンは、公理の実験的検証は厳密に行われなければならないことを強調し、自然界において結論を導き出す最良の方法として、シロ ジズムそのものを取り上げることはできないとした[9]。ベーコンは、実験を伴う自然観察に対して、より帰納的なアプローチを提案し、公理を発見し、それ を積み重ねて、より一般的な結論を導き出すようにした[9]。しかし、自然界において結論を導き出す完全な方法は、論理学やシロジズムの範囲ではなく、帰 納的な方法は、アリストテレスのその後の論考である『事後分析学』で取り上げられている。 19世紀には、接続詞(「AまたはB」)や条件文(「もしAならばB」)を扱うために、シロジズムに改良が加えられた。イマヌエル・カントは有名な『論理 学』(1800年)の中で、論理学は一つの完成された科学であり、アリストテレス論理学には論理学に関するあらゆることが多かれ少なかれ含まれていると主 張した。(この著作は必ずしもカントの成熟した哲学を代表するものではなく、論理学そのものに対する革新とみなされることが多い)。1879年、ゴットロ ブ・フレーゲが『概念字典』を出版するまで、カントの意見は西洋では揺るがなかった。これは微積分を導入したもので、量化詞と変数を用いることによって、 範疇的な文(そして対義語に規定されていない文も同様に)を表現する方法である。 特筆すべき例外は、ベルナルド・ボルツァーノの著作『科学論』(Wissenschaftslehre、1837年)で展開された論理学であり、その原理 は、死後に出版された著作『新反カント』(New Anti-Kant, 1850年)において、カントに対する直接的な批判として応用された。ボルツァーノの業績は、当時オーストリア帝国の一部であったボヘミアの知的環境など の理由から、20世紀後半までほとんど見過ごされていた。この20年間で、ボルツァーノの作品は再浮上し、翻訳や現代研究の対象となった。 その結果、文言論理学と一階述語論理学が急速に発展し、シロジスティック推論は2000年の時を経て、突如として多くの人々から時代遅れとみなされるようになった。 この現代的な降格に対する一つの顕著な例外は、教義修道会およびローマ教皇庁の職員がアリストテレス論理学を適用し続けていることである。 ブールのアリストテレス受容 ジョージ・ブールがアリストテレスの論理学を揺るぎなく受け入れていたことは、論理学の歴史家であるジョン・コーコランが『思考の法則』のわかりやすい入 門書の中で強調している[10][11]。コーコランはまた、『先行分析学』と『思考の法則』のポイントごとの比較も書いている[12]。コーコランによ れば、ブールはアリストテレスの論理学を完全に受け入れ、支持していた。ブールの目標は、アリストテレスの論理学を「下にも、上にも、超える」ことであっ た[12]。 論理学に方程式を含む数学的基礎を与える; 方程式の解法が妥当性の評価に追加されたことで、論理学が扱うことのできる問題のクラスが拡張された。 2項しかない命題を任意に多数の項を持つ命題に拡張するなど、扱うことのできる応用範囲を拡大した。 より具体的に言えば、ブールはアリストテレスが述べたことに同意していた。ブールの「不同意」とでも言うべき点は、アリストテレスが述べなかったことに関 係している。第一に、基礎の領域では、ブールはアリストテレスの4つの命題形式を1つの形式、方程式の形式に縮小した。第二に、論理学の問題領域におい て、ブールは論理学に方程式の解法を加えたが、これも革命的なアイデアであり、アリストテレスの推論規則(「完全な五段論法」)を方程式の解法規則で補わ なければならないというブールの教義を含んでいた。第三に、応用の領域において、アリストテレスが二項主語-述語の命題と論証しか扱えなかったのに対し、 ブールのシステムは多項の命題と論証を扱うことができた。例えば、アリストテレスのシステムは推論することができなかった: 例えば、アリストテレスのシステムは、「四角形である正方形はひし形である長方形ではない」から「四角形である正方形はひし形である長方形ではない」、あ るいは「長方形であるひし形は四角形である正方形ではない」を推論することができなかった。 基本構造 定言的三段論法は3つの部分からなる: 大前提 小前提 結論/結果 アリストテレスでは、各前提は「すべてのSはPである」、「あるSはPである」、「ないSはPである」、「あるSはPではない」という形式であり、「S」は主語項、「P」は述語項である: 「すべてのSはPである」と「SはPではない」は普遍命題と呼ばれる; 「あるSはPである」と「あるSはPではない」は特定命題と呼ばれる。 より現代的な論理学者は、いくつかのバリエーションを認めている。大前提の場合、これは大項目(すなわち結論の述語)であり、小前提の場合、これは小項目(すなわち結論の主語)である。例えば 大前提: すべての人間は死を免れない。 小前提:ギリシャ人はすべて人間である。 結論/結果: すべてのギリシャ人は死ぬべきである。 3つの明瞭な言葉のそれぞれは部門を表す。上記の例から、人間、死すべき、ギリシャ人:死すべきは主要な用語であり、ギリシャ人はマイナーな用語である。 また、前提は、中間の用語として知られている互いに共通の 1 つの用語を持っている;この例では、人間。前提はどちらも普遍的であり、結論も同様である。 大前提:すべての人間は死ぬ。 小前提:すべての人間は死を免れない。 結論/結果: すべての人間は死ぬ。 ここで、大項はdie、小項はmen、中項はmortalsである。ここでも、両前提は普遍的であり、したがって結論も普遍的である。 多義語 主な記事 多義語 多項対立論法(sorites)とは、一連の不完全なシロジズムを、最初の前提の述語が最後の前提の述語と結合して結論に至るまで、各前提の述語が次の前 提の述語を形成するように配置した論法のことである。たとえば、ライオンはすべて大型ネコ科動物であり、大型ネコ科動物はすべて肉食動物であり、肉食動物 はすべて肉食動物であると主張することができる。したがって、すべてのライオンは肉食動物であると結論づけることは、ソーライト論法を構築することであ る。 |

| Types https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Syllogism |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆