T. S. エリオット

Thomas Stearns Eliot, 1888-1965

★トーマス・スターンズ・エリオット OM(1888年9月26日 - 1965年1月4日)は、詩人、エッセイスト、出版人、劇作家、文芸評論家、編集者。 20世紀の主要詩人の一人とされ、英語圏の近代主義詩における中心人物である

| Thomas

Stearns Eliot OM (26 September 1888 – 4 January 1965) was a poet,

essayist, publisher, playwright, literary critic and editor.[2]

Considered one of the 20th century's major poets, he is a central

figure in English-language Modernist poetry. Born in St. Louis, Missouri, to a prominent Boston Brahmin family, he moved to England in 1914 at the age of 25 and went on to settle, work, and marry there.[3] He became a British citizen in 1927 at the age of 39, subsequently renouncing his American citizenship.[4] Eliot first attracted widespread attention for his poem "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock" in 1915, which, at the time of its publication, was considered outlandish.[5] It was followed by "The Waste Land" (1922), "The Hollow Men" (1925), "Ash Wednesday" (1930), and Four Quartets (1943).[6] He was also known for seven plays, particularly Murder in the Cathedral (1935) and The Cocktail Party (1949). He was awarded the 1948 Nobel Prize in Literature, "for his outstanding, pioneer contribution to present-day poetry".[7][8] |

トーマス・スターンズ・エリオット OM(1888年9月26日 -

1965年1月4日)は、詩人、エッセイスト、出版人、劇作家、文芸評論家、編集者。

20世紀の主要詩人の一人とされ、英語圏の近代主義詩における中心人物である[2]。 1914年、25歳の時にイギリスに渡り、同国に定住、仕事、結婚した[3]。 1927年、39歳の時にイギリス国籍を取得し、その後アメリカ国籍を放棄した[4]。 1915年に発表した詩「J・アルフレッド・プルフロックの恋歌」が広く注目を集め、その後、「荒地」(1922)、「空っぽの男」(1925)、「灰の 水曜日」(1930)、「四つの四重奏」(1943)などが発表された[5]。1948年に「現代の詩に対する卓越した、先駆的な貢献に対して」ノーベル 文学賞を受賞した[7][8]。 |

| Early life and education The Eliots were a Boston Brahmin family, with roots in England and New England. Eliot's paternal grandfather, William Greenleaf Eliot, had moved to St. Louis, Missouri,[6][9] to establish a Unitarian Christian church there. His father, Henry Ware Eliot (1843–1919), was a successful businessman, president and treasurer of the Hydraulic-Press Brick Company in St Louis. His mother, Charlotte Champe Stearns (1843–1929), who wrote poetry, was a social worker, which was a new profession in the U.S. in the early 20th century. Eliot was the last of six surviving children. Known to family and friends as Tom, he was the namesake of his maternal grandfather, Thomas Stearns. Eliot's childhood infatuation with literature can be ascribed to several factors. First, he had to overcome physical limitations as a child. Struggling from a congenital double inguinal hernia, he could not participate in many physical activities and thus was prevented from socialising with his peers. As he was often isolated, his love for literature developed. Once he learned to read, the young boy immediately became obsessed with books, favouring tales of savage life, the Wild West, or Mark Twain's thrill-seeking Tom Sawyer.[10] In his memoir about Eliot, his friend Robert Sencourt comments that the young Eliot "would often curl up in the window-seat behind an enormous book, setting the drug of dreams against the pain of living."[11] Secondly, Eliot credited his hometown with fuelling his literary vision: "It is self-evident that St. Louis affected me more deeply than any other environment has ever done. I feel that there is something in having passed one's childhood beside the big river, which is incommunicable to those people who have not. I consider myself fortunate to have been born here, rather than in Boston, or New York, or London."[12] From 1898 to 1905, Eliot attended Smith Academy, the boys college preparatory division of Washington University, where his studies included Latin, Ancient Greek, French, and German. He began to write poetry when he was 14 under the influence of Edward Fitzgerald's translation of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. He said the results were gloomy and despairing and he destroyed them.[13] His first published poem, "A Fable For Feasters", was written as a school exercise and was published in the Smith Academy Record in February 1905.[14] Also published there in April 1905 was his oldest surviving poem in manuscript, an untitled lyric, later revised and reprinted as "Song" in The Harvard Advocate, Harvard University's student literary magazine.[15] He published three short stories in 1905, "Birds of Prey", "A Tale of a Whale" and "The Man Who Was King". The last mentioned story reflected his exploration of the Igorot Village while visiting the 1904 World's Fair of St. Louis.[16][17][18] His interest in indigenous peoples thus predated his anthropological studies at Harvard.[19] Eliot lived in St. Louis, Missouri for the first 16 years of his life at the house on Locust Street where he was born. After going away to school in 1905, he returned to St. Louis only for vacations and visits. Despite moving away from the city, Eliot wrote to a friend that "Missouri and the Mississippi have made a deeper impression on me than any other part of the world."[20] Following graduation from Smith Academy, Eliot attended Milton Academy in Massachusetts for a preparatory year, where he met Scofield Thayer who later published The Waste Land. He studied at Harvard College from 1906 to 1909, earning a Bachelor of Arts in an elective program similar to comparative literature in 1909 and a Master of Arts in English literature the following year.[2][6] Because of his year at Milton Academy, Eliot was allowed to earn his Bachelor of Arts after three years instead of the usual four.[21] Frank Kermode writes that the most important moment of Eliot's undergraduate career was in 1908 when he discovered Arthur Symons's The Symbolist Movement in Literature. This introduced him to Jules Laforgue, Arthur Rimbaud, and Paul Verlaine. Without Verlaine, Eliot wrote, he might never have heard of Tristan Corbière and his book Les amours jaunes, a work that affected the course of Eliot's life.[22] The Harvard Advocate published some of his poems and he became lifelong friends with Conrad Aiken, the American writer and critic.[23] After working as a philosophy assistant at Harvard from 1909 to 1910, Eliot moved to Paris where, from 1910 to 1911, he studied philosophy at the Sorbonne. He attended lectures by Henri Bergson and read poetry with Henri Alban-Fournier.[6][22] From 1911 to 1914, he was back at Harvard studying Indian philosophy and Sanskrit.[6][24] Whilst a member of the Harvard Graduate School, Eliot met and fell in love with Emily Hale.[25] Eliot was awarded a scholarship to Merton College, Oxford, in 1914. He first visited Marburg, Germany, where he planned to take a summer programme, but when the First World War broke out he went to Oxford instead. At the time so many American students attended Merton that the Junior Common Room proposed a motion "that this society abhors the Americanization of Oxford". It was defeated by two votes after Eliot reminded the students how much they owed American culture.[26] Eliot wrote to Conrad Aiken on New Year's Eve 1914: "I hate university towns and university people, who are the same everywhere, with pregnant wives, sprawling children, many books and hideous pictures on the walls [...] Oxford is very pretty, but I don't like to be dead."[26] Escaping Oxford, Eliot spent much of his time in London. This city had a monumental and life-altering effect on Eliot for several reasons, the most significant of which was his introduction to the influential American literary figure Ezra Pound. A connection through Aiken resulted in an arranged meeting and on 22 September 1914, Eliot paid a visit to Pound's flat. Pound instantly deemed Eliot "worth watching" and was crucial to Eliot's fledgling career as a poet, as he is credited with promoting Eliot through social events and literary gatherings. Thus, according to biographer John Worthen, during his time in England Eliot "was seeing as little of Oxford as possible". He was instead spending long periods of time in London, in the company of Ezra Pound and "some of the modern artists whom the war has so far spared [...] It was Pound who helped most, introducing him everywhere."[27] In the end, Eliot did not settle at Merton and left after a year. In 1915 he taught English at Birkbeck, University of London.[citation needed] In 1916, he completed a doctoral dissertation for Harvard on "Knowledge and Experience in the Philosophy of F. H. Bradley", but he failed to return for the viva voce exam.[6][28] |

幼少期の生活と教育 エリオット家は、イギリスとニューイングランドにルーツを持つボストンの社会文的エリート(Brahmin)であった。エリオットの父方の祖父であるウィ リアム・グリーンリーフ・エリオットは、ミズーリ州セントルイスに移り住み[6][9]、そこでユニテリアン系のキリスト教会を設立していた。父ヘン リー・ウェア・エリオット(1843-1919)は、セントルイスのハイドロリックプレス・ブリック・カンパニーの社長兼会計責任者として実業家として成 功した。詩を書いた母親のシャーロット・チャンプ・スターンズ(1843-1929)は、20世紀初頭のアメリカでは新しい職業であったソーシャルワー カーであった。エリオットは、6人兄弟の末っ子として生まれた。家族や友人にはトムと呼ばれ、母方の祖父トーマス・スターンズの名前にちなんでいる。 エリオットが幼少期に文学に夢中になったのは、いくつかの要因があると考えられる。まず、幼少期に身体的な制約を乗り越えなければならなかったこと。先天 性の二重鼠径ヘルニアに悩まされ、運動もままならず、同級生との交際もままならなかった。孤立しがちだった彼は、文学を愛するようになった。字が読めるよ うになると、少年はすぐに本に夢中になり、野蛮な生活や西部劇、マーク・トウェインのスリルを求める『トム・ソーヤー』のような物語を好んだ[10]。 エリオットについての回想録の中で、彼の友人ロバート・センコートは、若き日のエリオットが「しばしば窓際の席で巨大な本の後ろに丸まり、生きることの苦 痛に対して夢の薬を設定していた」とコメントしている[11]。第二に、エリオットは故郷が彼の文学的ビジョンを刺激したことを認めている。「セントルイ スが、他のどんな環境よりも私に深い影響を与えたことは自明である。大きな川のそばで子供時代を過ごしたということは、そうでない人には理解できない何か があるような気がする。私は、ボストンやニューヨークやロンドンではなく、ここで生まれたことを幸運だと思っている」[12]。 1898年から1905年まで、エリオットはワシントン大学の男子大学準備部門であるスミス・アカデミーに通い、ラテン語、古代ギリシャ語、フランス語、 ドイツ語などを学んだ。14歳のとき、エドワード・フィッツジェラルドによるオマル・ハイヤームの『ルバイヤート』の翻訳に影響されて詩を書き始める。そ の結果は陰鬱で絶望的なものであり、彼はそれを破棄したという。[13] 彼の最初の出版詩「A Fable For Feasters」は学校の課題として書かれ、1905年2月に『スミスアカデミー記録』誌に掲載された。 [14] また、1905年4月には、現存する最古の詩である無題の抒情詩が掲載され、後に改訂されてハーバード大学の学生文芸誌『ハーバード・アドボケート』に 「ソング」として再掲載された[15] 1905年に「猛禽」「鯨の物語」「王だった人」という三つの短編を発表した。最後に挙げた物語は、1904年のセントルイス万国博覧会を訪れた際にイゴ ロット村を探検したことを反映している[16][17][18]。このように彼の先住民への関心は、ハーバード大学で人類学を学ぶよりも先にあったのであ る[19]。 エリオットは、生まれてから16年間、ミズーリ州セントルイスのローカストストリートの家で暮らした。1905年に進学した後、セントルイスには休暇と訪 問のためだけに戻ってきた。街から離れたにもかかわらず、エリオットは友人に「ミズーリ州とミシシッピ州は世界のどの地域よりも私に深い印象を与えてい る」と書いている[20]。 スミス・アカデミーを卒業後、エリオットはマサチューセッツのミルトン・アカデミーに準備期間として通い、そこで後に『荒地』を出版するスコフィールド・ セイヤーに出会う。1906年から1909年までハーバードカレッジで学び、1909年に比較文学に似た選択科目で学士号を、翌年には英文学の修士号を取 得する。 ミルトン・アカデミーでの1年のおかげで、エリオットは通常の4年の代わりに3年で学士号を取得することができた[21]。フランク・ケルモードは、エリ オットの学部生活において最も重要だったのは1908年に彼がアーサー・シモンズのThe Symbolist Movement in Literatureに出会った時だと記している。この本は、彼にジュール・ラフォルグ、アルチュール・ランボー、ポール・ヴェルレーヌを紹介するもので あった。ヴェルレーヌがいなければ、トリスタン・コルビエールと彼の著書『Les amours jaunes』を知ることはなかったかもしれない、とエリオットは書いている。 1909年から1910年までハーバード大学で哲学の助手を務めた後、エリオットはパリに移り、1910年から1911年にかけてソルボンヌ大学で哲学を 学んだ。1911年から1914年にかけては、ハーバード大学に戻り、インド哲学とサンスクリット語を学ぶ[6][24] ハーバード大学院に在籍中、エミリー・ヘイルと出会い、恋に落ちる[25] 1914年にオックスフォードのマートン大学への奨学金を受ける。彼はまずドイツのマールブルグを訪れ、そこで夏期講習を受ける予定だったが、第一次世界 大戦が勃発すると、代わりにオックスフォードに行くことになった。当時、マートンには多くのアメリカ人学生が通っていたため、ジュニア・コモンルームは 「本会はオックスフォードのアメリカ化を嫌う」という動議を提出した。しかし、エリオットが学生たちにアメリカ文化にどれだけ感謝しているかを思い起こさ せた後、2票差で否決された[26]。 1914年の大晦日、エリオットはコンラッド・エイケンに宛てて手紙を書いた。「私は大学の町も大学人も嫌いだ。妊娠した妻、のびのびとした子供、たくさ んの本、壁には醜い絵、どこも同じだ[...] オックスフォードはとてもきれいだが、私は死ぬのはいやだ」[26] オックスフォードから逃れ、エリオットはロンドンで多くの時間を過ごすことになる。この都市は、いくつかの理由でエリオットに記念碑的で人生を変えるよう な影響を与えたが、その中でも最も重要なのは、影響力のあるアメリカの文学者エズラ・パウンドを紹介したことであった。エイケンの紹介で会うことになった エリオットは、1914年9月22日、パウンドのアパートを訪ねます。パウンドは即座にエリオットを「見るに値する」と判断し、社交行事や文学者の集まり を通じてエリオットを宣伝したとされ、エリオットの詩人としての黎明期には欠かせない存在であった。伝記作家のジョン・ウォーテンによれば、イギリス滞在 中、エリオットは「オックスフォードにはできるだけ顔を出さなかった」という。その代わり、エズラ・パウンドや「戦争が今のところ免れている現代芸術家た ち」と一緒にロンドンで長い時間を過ごしていた[...] 最も助けになったのはパウンドで、彼をあらゆるところに紹介した」[27]。結局、エリオットはマートンに定着せず、1年後に去っている。1915年、ロ ンドン大学バークベック校で英語を教える[citation needed]。 1916年、ハーバード大学の博士論文「F・H・ブラッドレーの哲学における知識と経験」を完成させるが、ビバボイス試験のために戻ってくることができな かった[6][28]。 |

| Marriage Before leaving the US, Eliot had told Emily Hale that he was in love with her. He exchanged letters with her from Oxford during 1914 and 1915, but they did not meet again until 1927.[25][29] In a letter to Aiken late in December 1914, Eliot, aged 26, wrote: "I am very dependent upon women (I mean female society)."[30] Less than four months later, Thayer introduced Eliot to Vivienne Haigh-Wood, a Cambridge governess. They were married at Hampstead Register Office on 26 June 1915.[31] After a short visit, alone, to his family in the United States, Eliot returned to London and took several teaching jobs, such as lecturing at Birkbeck College, University of London. The philosopher Bertrand Russell took an interest in Vivienne while the newlyweds stayed in his flat. Some scholars have suggested that she and Russell had an affair, but the allegations were never confirmed.[32] The marriage seems to have been markedly unhappy, in part because of Vivienne's health problems. In a letter addressed to Ezra Pound, she covers an extensive list of her symptoms, which included a habitually high temperature, fatigue, insomnia, migraines, and colitis.[33] This, coupled with apparent mental instability, meant that she was often sent away by Eliot and her doctors for extended periods of time in the hope of improving her health. As time went on, he became increasingly detached from her. According to witnesses, both Eliots were frequent complainers of illness, physical and mental, while Eliot would drink excessively and Vivienne is said to have developed a liking for opium and ether, drugs prescribed for medical issues. It is claimed that the couple's wearying behaviour caused some visitors to vow never to spend another evening in the company of both together. [34] The couple formally separated in 1933, and in 1938 Vivienne's brother, Maurice, had her committed to a mental hospital, against her will, where she remained until her death of heart disease in 1947. When told via a phone call from the asylum that Vivienne had died unexpectedly during the night, Eliot is said to have buried his face in his hands and cried out ‘Oh God, oh God.’[35] Their relationship became the subject of a 1984 play Tom & Viv, which in 1994 was adapted as a film of the same name. In a private paper written in his sixties, Eliot confessed: "I came to persuade myself that I was in love with Vivienne simply because I wanted to burn my boats and commit myself to staying in England. And she persuaded herself (also under the influence of [Ezra] Pound) that she would save the poet by keeping him in England. To her, the marriage brought no happiness. To me, it brought the state of mind out of which came The Waste Land."[36] |

結婚 アメリカを離れる前に、エリオットはエミリー・ヘイルに恋をしていることを告げていた。1914年から1915年にかけてオックスフォードから彼女と手紙 を交換したが、1927年まで再会することはなかった[25][29]。1914年12月末、26歳のエリオットはエイケンへの手紙で、「私は女性(つま り女性社会)にとても依存している」と書いている[30]。4ヶ月もしないうちにセイヤーはエリオットにケンブリッジの家庭教師ヴィヴィアン・ヘイウッド (Vivienne Haigh-Wood )を紹介している。二人は1915年6月26日にハムステッド登記所で結婚した[31]。 アメリカの家族のもとを一人で短期間訪れた後、エリオットはロンドンに戻り、ロンドン大学バークベック・カレッジで講義をするなど、いくつかの教職に就い た。哲学者のバートランド・ラッセルは、新婚の二人が彼のアパートに滞在している間、ヴィヴィアンに関心を寄せていた。一部の学者は彼女とラッセルが不倫 関係にあったことを示唆したが、その疑惑は確認されなかった[32]。 ヴィヴィアンの健康問題などもあり、結婚生活は著しく不幸なものであったようだ。エズラ・パウンドに宛てた手紙には、常習的な高熱、疲労、不眠、偏頭痛、 大腸炎などの症状が網羅されている[33]。 このことは、明らかに精神的に不安定であることと相まって、エリオットと医師によって、健康を改善するためにしばしば長期間の留守番をさせられることを意 味した。時間が経つにつれて、彼はますます彼女から離れるようになった。目撃者によると、エリオット夫妻は身体的、精神的な病気を頻繁に訴え、エリオット は過度の飲酒をし、ヴィヴィアンは医療問題で処方されるアヘンやエーテルを好むようになったと言われている。この夫婦の疲れるような振る舞いを見て、もう 二度と二人と一緒の夜は過ごさないと誓う訪問者もいたと言われている[34]。[1933年に夫婦は正式に別居し、1938年にはヴィヴィアンの兄モーリ スが彼女の意思に反して彼女を精神病院に入院させ、1947年に心臓病で死亡するまでそこに留まった。ヴィヴィアンが夜中に突然亡くなったことを精神病院 からの電話で知らされたとき、エリオットは両手で顔を埋め、「ああ、神様、神様」と泣いたと言われている[35]。 二人の関係は1984年の戯曲『トムとヴィヴ』の題材となり、1994年に同名の映画として映像化された。 60代に書かれた私的な論文の中で、エリオットは告白している。「私がヴィヴィアンに恋をしていたのは、船を燃やして英国に留まることを約束したかったか らだ。そして彼女は、(エズラ)パウンドの影響もあって、詩人を英国にとどめておけば救われると自分自身に言い聞かせていたのです。彼女にとって、この結 婚は何の幸せももたらさなかった。私にとっては、『荒地』が生まれるような心の状態をもたらした」[36]。 |

| Teaching, banking, and publishing After leaving Merton, Eliot worked as a schoolteacher, most notably at Highgate School in London, where he taught French and Latin: his students included John Betjeman.[6] He subsequently taught at the Royal Grammar School, High Wycombe in Buckinghamshire. To earn extra money, he wrote book reviews and lectured at evening extension courses at University College London and Oxford. In 1917, he took a position at Lloyds Bank in London, working on foreign accounts. On a trip to Paris in August 1920 with the artist Wyndham Lewis, he met the writer James Joyce. Eliot said he found Joyce arrogant, and Joyce doubted Eliot's ability as a poet at the time, but the two writers soon became friends, with Eliot visiting Joyce whenever he was in Paris.[37] Eliot and Wyndham Lewis also maintained a close friendship, leading to Lewis's later making his well-known portrait painting of Eliot in 1938. Charles Whibley recommended T.S. Eliot to Geoffrey Faber.[38] In 1925 Eliot left Lloyds to become a director in the publishing firm Faber and Gwyer (later Faber and Faber), where he remained for the rest of his career.[39][40] At Faber and Faber, he was responsible for publishing distinguished English poets, including W. H. Auden, Stephen Spender, Charles Madge and Ted Hughes.[41] |

教師、銀行、出版 マートン校を卒業後、エリオットは教師として働き、特にロンドンのハイゲート校ではフランス語とラテン語を教え、生徒にはジョン・ベッチェマンもいた [6]。副収入を得るため、書評を書いたり、ロンドン大学やオックスフォード大学の夜間公開講座で講義をしたりした。1917年、ロンドンのロイズ銀行に 就職し、外国為替を担当する。1920年8月、画家のウィンダム・ルイスとパリに旅行した際、作家のジェームズ・ジョイスに出会った。エリオットはジョイ スを傲慢だと感じ、ジョイスは当時エリオットの詩人としての能力を疑っていたというが、二人の作家はすぐに友人となり、エリオットはパリにいるときはジョ イスのもとを訪れるようになった[37]。 エリオットとウィンダム・ルイスも親交を持ち、後にルイスが1938年にエリオットの有名なポートレートを描くきっかけとなっている[38]。 1925年、エリオットはロイズを離れ、出版社フェイバー・アンド・グワイヤー(後のフェイバー・アンド・フェイバー)の取締役となり、そこで残りのキャ リアを過ごした[39][40]。 フェイバー・アンド・フェイバーでは、W・H・オーデン、スティーブン・スペンサー、チャールズ・マッジ、テッド・ヒューズなどの著名イギリス詩人の出版 の責任者であった[41]。 |

| Conversion to Anglicanism and

British citizenship On 29 June 1927, Eliot converted from Unitarianism to Anglicanism, and in November that year he took British citizenship, thereby renouncing his United States citizenship in the event he had not officially done so previously.[42] He became a churchwarden of his parish church, St Stephen's, Gloucester Road, London, and a life member of the Society of King Charles the Martyr.[43][44] He specifically identified as Anglo-Catholic, proclaiming himself "classicist in literature, royalist in politics, and anglo-catholic [sic] in religion".[45][46] About 30 years later Eliot commented on his religious views that he combined "a Catholic cast of mind, a Calvinist heritage, and a Puritanical temperament".[47] He also had wider spiritual interests, commenting that "I see the path of progress for modern man in his occupation with his own self, with his inner being" and citing Goethe and Rudolf Steiner as exemplars of such a direction.[48] One of Eliot's biographers, Peter Ackroyd, commented that "the purposes of [Eliot's conversion] were two-fold. One: the Church of England offered Eliot some hope for himself, and I think Eliot needed some resting place. But secondly, it attached Eliot to the English community and English culture."[41] |

英国国教会への改宗とイギリス国籍の取得 1927年6月29日、エリオットはユニテリアン主義から英国国教会に改宗し、同年11月にはイギリス国籍を取得した(それまで正式に取得していなかった アメリカ合衆国の市民権を放棄した)[42]。 [42] 彼は教区教会であるロンドンのグロスター・ロードのセント・スティーブンの教会長になり、殉教者チャールズ王の協会の終身会員となった[43][44]。 彼は特にアングロ・カトリックであると認識し、自分自身を「文学における古典主義者、政治における王党派、宗教におけるアングロ・カトリック(sic)」 と宣言している[45][46]。 約30年後、エリオットは彼の宗教観について、「カトリックの精神構造、カルヴァン主義の遺産、清教徒的気質」を兼ね備えているとコメントしている [47]。 彼はまた幅広い精神的関心を持っており、「私は現代人の進歩の道を、彼自身の自己、彼の内面との関わりに見る」とコメントし、ゲーテやルドルフシュタイ ナーをそうした方向の例として引用していた[48]。 エリオットの伝記作家の一人であるピーター・アクロイドは、「(エリオットの転向の)目的は2つあった」とコメントしている。一つは、英国国教会がエリ オット自身に希望を与え、エリオットは安息の場所を必要としていたと思う。しかし第二に、それはエリオットをイギリスのコミュニティとイギリス文化に結び つけるものであった」[41]。 |

| Separation and remarriage By 1932, Eliot had been contemplating a separation from his wife for some time. When Harvard offered him the Charles Eliot Norton professorship for the 1932–1933 academic year, he accepted and left Vivienne in England. Upon his return, he arranged for a formal separation from her, avoiding all but one meeting with her between his leaving for America in 1932 and her death in 1947. Vivienne was committed to the Northumberland House mental hospital in Woodberry Down, Manor House, London, in 1938, and remained there until she died. Although Eliot was still legally her husband, he never visited her.[49] From 1933 to 1946 Eliot had a close emotional relationship with Emily Hale. Eliot later destroyed Hale's letters to him, but Hale donated Eliot's to Princeton University Library where they were sealed, following Eliot's and Hale's wishes, for 50 years after both had died, until 2020.[50] When Eliot heard of the donation he deposited his own account of their relationship with Harvard University to be opened whenever the Princeton letters were.[25] From 1938 to 1957 Eliot's public companion was Mary Trevelyan of London University, who wanted to marry him and left a detailed memoir.[51][52][53] From 1946 to 1957, Eliot shared a flat at 19 Carlyle Mansions, Chelsea, with his friend John Davy Hayward, who collected and managed Eliot's papers, styling himself "Keeper of the Eliot Archive".[54][55] Hayward also collected Eliot's pre-Prufrock verse, commercially published after Eliot's death as Poems Written in Early Youth. When Eliot and Hayward separated their household in 1957, Hayward retained his collection of Eliot's papers, which he bequeathed to King's College, Cambridge, in 1965. On 10 January 1957, at the age of 68, Eliot married Esmé Valerie Fletcher, who was 30. In contrast to his first marriage, Eliot knew Fletcher well, as she had been his secretary at Faber and Faber since August 1949. They kept their wedding secret; the ceremony was held in St. Barnabas' Church, Kensington, London,[56] at 6:15 am with virtually no one in attendance other than his wife's parents. Eliot had no children with either of his wives. In the early 1960s, by then in failing health, Eliot worked as an editor for the Wesleyan University Press, seeking new poets in Europe for publication. After Eliot's death, Valerie dedicated her time to preserving his legacy, by editing and annotating The Letters of T. S. Eliot and a facsimile of the draft of The Waste Land.[57] Valerie Eliot died on 9 November 2012 at her home in London.[58] |

別居と再婚 1932年になると、エリオットは妻との別居をしばらく考えていた。1932年から1933年にかけて、ハーバード大学が彼にチャールズ・エリオット・ ノートン教授の職を与えると、彼はそれを受け、ヴィヴィアンを英国に残した。1932年に渡米してから1947年に亡くなるまで、一度だけ会うことを許し たが、その後、正式に別れることになった。ヴィヴィアンは1938年にロンドンのマナーハウス、ウッドベリーダウンにあるノーサンバーランド・ハウスとい う精神病院に収容され、死ぬまでそこにいた。1933年から1946年まで、エリオットはエミリー・ヘイルと親密な関係にあった。エリオットは後にヘイル の手紙を破棄したが、ヘイルはエリオットの手紙をプリンストン大学図書館に寄贈し、エリオットとヘイルの希望に従って、両者の死後50年間、2020年ま で封印された[50]。寄贈を聞いたエリオットは、プリンストンの手紙が開封されるたびに、ハーバード大学に自分たちの関係の記録を寄託している [25]。 1938年から1957年までエリオットの公の伴侶はロンドン大学のメアリー・トレヴェリアンであり、彼女は彼との結婚を望み、詳細な回顧録を残している [51][52][53]。 1946年から1957年まで、エリオットはチェルシーのカーライル・マンション19番地にあるアパートを友人のジョン・デイヴィ・ヘイワードとシェア し、彼はエリオットの書類を収集・管理し、自らを「エリオットのアーカイブの管理人」と称した[54][55]。ヘイワードはまたエリオットのプルフロッ ク以前の詩を集め、エリオットの死後に「初期青年時代に書いた詩」として商業出版されることになった。1957年にエリオットとヘイワードが別居したと き、ヘイワードはエリオットの論文コレクションを保持し、1965年にケンブリッジのキングス・カレッジに遺贈した。 1957年1月10日、68歳になったエリオットは、30歳だったエスメ・ヴァレリー・フレッチャーと結婚した。最初の結婚とは対照的に、エリオットはフ レッチャーをよく知っていた。彼女は1949年8月からフェイバー・アンド・フェイバー社で彼の秘書をしていたからだ。結婚式は、ロンドンのケンジントン にあるセント・バルナバ教会で、午前6時15分に、妻の両親以外にはほとんど誰も出席することなく行われた[56]。エリオットにはどちらの妻との間にも 子供はいなかった。1960年代初頭、健康を害したエリオットは、ウェスリアン大学出版局の編集者として、ヨーロッパで新しい詩人の出版を模索する仕事を した。エリオットの死後、ヴァレリーは『T. S. エリオットの手紙』や『荒地』の草稿のファクシミリを編集し、彼の遺産の保存に時間を費やした[57]。 ヴァレリー・エリオットは2012年11月9日にロンドンの自宅で死去した[58]。 |

| Death and honours Eliot died of emphysema at his home in Kensington in London, on 4 January 1965,[59] and was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium.[60] In accordance with his wishes, his ashes were taken to St Michael and All Angels' Church, East Coker, the village in Somerset from which his Eliot ancestors had emigrated to America.[61] A wall plaque in the church commemorates him with a quotation from his poem East Coker: "In my beginning is my end. In my end is my beginning."[62] In 1967, on the second anniversary of his death, Eliot was commemorated by the placement of a large stone in the floor of Poets' Corner in London's Westminster Abbey. The stone, cut by designer Reynolds Stone, is inscribed with his life dates, his Order of Merit, and a quotation from his poem Little Gidding, "the communication / of the dead is tongued with fire beyond / the language of the living."[63] In 1986, a blue plaque was placed on the apartment block - No. 3 Kensington Court Gardens - where he lived and died.[64] |

死と栄誉 1965年1月4日、ロンドンのケンジントンの自宅で肺気腫のため死去し[59]、ゴルダーズ・グリーン斎場で火葬された[60]。彼の希望で、遺灰はエ リオットの祖先がアメリカに移住したサマセットの村、イースト・コーカーにある聖マイケル&オールエンジェル教会に運ばれた[61]。 教会の壁に、彼の詩イースト・コカーからの引用で記念するプレートがある。「私の始まりは、私の終わり。私の終わりは私の始まりである」[62]。 1967年、エリオットの二周忌に、ロンドンのウェストミンスター寺院の詩人たちのコーナーの床に大きな石が置かれ、エリオットを記念することになった。 デザイナー、レイノルズ・ストーンの手によるこの石には、彼の生年月日、勲章、そして彼の詩『リトル・ギディング』からの引用「死者のコミュニケーション は/生者の言葉を超えて/火で舌を打つ」が刻まれている[63]。 1986年には、彼が住み、亡くなったアパートメントブロック - No.3 Kensington Court Gardens - に青いプレートが設置された[64]。 |

| Poetry For a poet of his stature, Eliot produced relatively few poems. He was aware of this even early in his career; he wrote to J.H. Woods, one of his former Harvard professors, "My reputation in London is built upon one small volume of verse, and is kept up by printing two or three more poems in a year. The only thing that matters is that these should be perfect in their kind, so that each should be an event."[65] Typically, Eliot first published his poems individually in periodicals or in small books or pamphlets and then collected them in books. His first collection was Prufrock and Other Observations (1917). In 1920, he published more poems in Ara Vos Prec (London) and Poems: 1920 (New York). These had the same poems (in a different order) except that "Ode" in the British edition was replaced with "Hysteria" in the American edition. In 1925, he collected The Waste Land and the poems in Prufrock and Poems into one volume and added The Hollow Men to form Poems: 1909–1925. From then on, he updated this work as Collected Poems. Exceptions are Old Possum's Book of Practical Cats (1939), a collection of light verse; Poems Written in Early Youth, posthumously published in 1967 and consisting mainly of poems published between 1907 and 1910 in The Harvard Advocate, and Inventions of the March Hare: Poems 1909–1917, material Eliot never intended to have published, which appeared posthumously in 1997.[66] During an interview in 1959, Eliot said of his nationality and its role in his work: "I'd say that my poetry has obviously more in common with my distinguished contemporaries in America than with anything written in my generation in England. That I'm sure of. ... It wouldn't be what it is, and I imagine it wouldn't be so good; putting it as modestly as I can, it wouldn't be what it is if I'd been born in England, and it wouldn't be what it is if I'd stayed in America. It's a combination of things. But in its sources, in its emotional springs, it comes from America."[67] Cleo McNelly Kearns notes in her biography that Eliot was deeply influenced by Indic traditions, notably the Upanishads. From the Sanskrit ending of The Waste Land to the "What Krishna meant" section of Four Quartets shows how much Indic religions and more specifically Hinduism made up his philosophical basic for his thought process.[68] It must also be acknowledged, as Chinmoy Guha showed in his book Where the Dreams Cross: T S Eliot and French Poetry (Macmillan, 2011) that he was deeply influenced by French poets from Baudelaire to Paul Valéry. He himself wrote in his 1940 essay on W.B. Yeats: "The kind of poetry that I needed to teach me the use of my own voice did not exist in English at all; it was only to be found in French." ("Yeats", On Poetry and Poets, 1948). |

詩 エリオットの詩は、彼のような偉大な詩人としては、比較的少ないものであった。ロンドンでの私の評判は、一冊の小さな詩集の上に築かれ、一年に二、三編を 印刷することによって維持されている。重要なのは、これらがその種類において完璧であること、つまりそれぞれが出来事であるべきだということだ」 [65]。 典型的には、エリオットはまず定期刊行物や小さな本やパンフレットで個別に詩を発表し、その後それらを本に集めた。最初の作品集は『Prufrock and Other Observations』(1917年)である。1920年、彼はさらに詩をAra Vos Prec (London)とPoems: 1920年(ニューヨーク)。これらは、イギリス版の「オード」がアメリカ版の「ヒステリー」に置き換えられた以外は、同じ詩(順序は異なる)が掲載され ていた。1925年には『荒地』と『プルフロック』『詩集』の詩を一冊にまとめ、『ホロウ・メン』を加えて『詩集』とした。1909-1925. 以後、Collected Poemsとして更新している。例外として、軽妙な詩を集めたOld Possum's Book of Practical Cats(1939年)、1907年から1910年にかけて『ハーバード・アドボケート』誌に発表した詩を中心に、1967年に死後出版したPoems Written in Early Youth、Inventions of the March Hareがある。詩集1909-1917』は、エリオットが出版するつもりのなかった資料で、1997年に死後に出版された[66]。 1959年のインタビューで、エリオットは自分の国籍とそれが自分の作品に果たす役割についてこう語っている。「私の詩は、イギリスの私の世代に書かれた ものよりも、アメリカの優れた同時代の作家たちと明らかに多くの共通点を持っていると言えるでしょう。それは確かだ。... できるだけ控えめに言えば、もし私がイギリスで生まれていたら、今のようなものにはならなかったでしょうし、アメリカにとどまっていたら、今のようなもの にはならなかったでしょう。いろいろなことが重なり合っているのです。しかし、その源、その感情の泉はアメリカから来ている」[67]。 クレオ・マクネリー・カーンズは、エリオットがインドの伝統、特にウパニシャッドから深い影響を受けていたことを伝記で述べている。荒地』のサンスクリッ ト語の終わりから『四重唱』の「クリシュナの意味するところ」の部分まで、インド宗教、特にヒンドゥー教が彼の思考プロセスの哲学的基礎をどれだけ構成し ているかを示している[68]。またチンモイ・グハが彼の著書Where the Dreams Crossで示したように、このことは認めなければならないだろう。またチンモイ・グハが著書Where Dreams Cross: T S Eliot and French Poetry (Macmillan, 2011)で示したように、彼がボードレールからポール・ヴァレリーまでのフランスの詩人に深く影響を受けていたことを認めなければならない。彼自身、 1940年のW.B.イェイツに関するエッセイでこう書いている。「私が自分の声の使い方を教えるのに必要な種類の詩は、英語にはまったく存在せず、フラ ンス語にしかなかった」。(「イェイツ」『詩と詩人について』1948年)と述べている。 |

| "The Love Song of J. Alfred

Prufrock" In 1915, Ezra Pound, overseas editor of Poetry magazine, recommended to Harriet Monroe, the magazine's founder, that she should publish "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock".[69] Although the character Prufrock seems to be middle-aged, Eliot wrote most of the poem when he was only twenty-two. Its now-famous opening lines, comparing the evening sky to "a patient etherised upon a table", were considered shocking and offensive, especially at a time when Georgian Poetry was hailed for its derivations of the nineteenth century Romantic Poets.[70] The poem's structure was heavily influenced by Eliot's extensive reading of Dante and refers to a number of literary works, including Hamlet and those of the French Symbolists. Its reception in London can be gauged from an unsigned review in The Times Literary Supplement on 21 June 1917. "The fact that these things occurred to the mind of Mr. Eliot is surely of the very smallest importance to anyone, even to himself. They certainly have no relation to poetry."[71] |

"The Love Song of J. Alfred

Prufrock" (J・アルフレッド・プルフロックの愛の歌 1915年、ポエトリー誌の海外編集者エズラ・パウンドは、同誌の創刊者ハリエット・モンローに「The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock」の出版を勧めた[69]。登場するプルフロックは中年のようだが、エリオットはまだ22歳の時にこの詩の大部分を執筆している。夕方の 空を「テーブルの上でエーテル漬けにされた患者」に例えたその有名な冒頭の行は、特にジョージアンポエジーが19世紀のロマン派詩人からの派生で賞賛され ていた時代には、衝撃的で不快なものと見なされていた[70]。 この詩の構造は、エリオットのダンテの幅広い読書から大きな影響を受け、ハムレットやフランスの象徴主義者の作品など、多くの文学作品に言及している [70]。ロンドンでの受容は、1917年6月21日の『タイムズ・リテラリー・サプリメント』誌の無署名の批評から知ることができる[70]。「これら のことがエリオット氏の心に浮かんだという事実は、誰にとっても、彼自身にとっても、きわめて小さな重要なことであることは確かだ。それらは確かに詩とは 何の関係もない」[71]。 |

| "The Waste Land" In October 1922, Eliot published "The Waste Land" in The Criterion. Eliot's dedication to il miglior fabbro ('the better craftsman') refers to Ezra Pound's significant hand in editing and reshaping the poem from a longer Eliot manuscript, to the shortened version that appears in publication.[72] It was composed during a period of personal difficulty for Eliot—his marriage was failing, and both he and Vivienne were suffering from nervous disorders. Before the poem's publication as a book in December 1922, Eliot distanced himself from its vision of despair. On 15 November 1922, he wrote to Richard Aldington, saying, "As for The Waste Land, that is a thing of the past so far as I am concerned and I am now feeling toward a new form and style."[73] The poem is often read as a representation of the disillusionment of the post-war generation. Dismissing this view, Eliot commented in 1931, "When I wrote a poem called The Waste Land, some of the more approving critics said that I had expressed 'the disillusion of a generation', which is nonsense. I may have expressed for them their own illusion of being disillusioned, but that did not form part of my intention."[74] The poem is known for its obscure nature—its slippage between satire and prophecy; its abrupt changes of speaker, location, and time. This structural complexity is one of the reasons why the poem has become a touchstone of modern literature, a poetic counterpart to a novel published in the same year, James Joyce's Ulysses.[75] Among its best-known phrases are "April is the cruellest month", "I will show you fear in a handful of dust" and "Shantih shantih shantih"—the Sanskrit mantra which ends the poem. |

"荒地" 1922年10月、エリオットは「The Criterion」誌に "The Waste Land "を発表した。エリオットがil miglior fabbro(「優れた職人」)に捧げた言葉は、エズラ・パウンドがこの詩を編集し、長いエリオットの原稿から出版に現れる短縮版へと形を変えた重要な手 腕に言及する[72]。 この詩は、エリオットにとって個人的に困難な時期に作曲された。彼の結婚は失敗し、彼とヴィヴィアンの両方が神経障害に苦しんでいたのである。1922年 12月にこの詩が本として出版される前に、エリオットはその絶望のビジョンから距離を置いた。1922年11月15日、彼はリチャード・オルディントンに 宛てて、「『荒地』に関しては、私に関する限り過去のものであり、私は今、新しい形式とスタイルに向かって気持ちを向けている」と書いている[73]。こ の詩はしばしば、戦後世代の幻滅を表現したものとして読まれることがある。この見方を否定して、エリオットは1931年に次のようにコメントしている。 「私が『荒地』という詩を書いたとき、より肯定的な批評家の中には、私が『ある世代の幻滅』を表現したと言った人がいたが、それはナンセンスなことだ。私 は彼らのために、彼ら自身の幻滅しているという幻想を表現したのかもしれないが、それは私の意図の一部を形成するものではなかった」[74]。 この詩は、風刺と予言の間のずれ、話者、場所、時間の突然の変化など、その不明瞭な性質で知られている。この構造の複雑さが、この詩が現代文学の試金石と なった理由の一つであり、同じ年に出版された小説、ジェームズ・ジョイスの『ユリシーズ』と詩的に対をなすものである[75]。 4月は最も残酷な月」、「一握りの塵で恐怖を見せてやる」、「Shantih shantih shantih」(詩の最後にあるサンスクリット語のマントラ)などがよく知られている。 |

| "The Hollow Men" "The Hollow Men" appeared in 1925. For the critic Edmund Wilson, it marked "The nadir of the phase of despair and desolation given such effective expression in 'The Waste Land'."[76] It is Eliot's major poem of the late 1920s. Similar to Eliot's other works, its themes are overlapping and fragmentary. Post-war Europe under the Treaty of Versailles (which Eliot despised), the difficulty of hope and religious conversion, Eliot's failed marriage.[77] Allen Tate perceived a shift in Eliot's method, writing, "The mythologies disappear altogether in 'The Hollow Men'." This is a striking claim for a poem as indebted to Dante as anything else in Eliot's early work, to say little of the modern English mythology—the "Old Guy Fawkes" of the Gunpowder Plot—or the colonial and agrarian mythos of Joseph Conrad and James George Frazer, which, at least for reasons of textual history, echo in The Waste Land.[78] The "continuous parallel between contemporaneity and antiquity" that is so characteristic of his mythical method remained in fine form.[79] "The Hollow Men" contains some of Eliot's most famous lines, notably its conclusion: This is the way the world ends Not with a bang but a whimper. |

"ホロウ・メン" "The Hollow Men "は1925年に登場した。批評家エドモンド・ウィルソンによれば、「『荒地』で効果的に表現された絶望と荒廃の段階の底を示すもの」[76]であり、 1920年代後半のエリオットの主要詩である。エリオットの他の作品と同様、そのテーマは重なり合い、断片的である。エリオットが軽蔑したヴェルサイユ条 約下の戦後のヨーロッパ、希望と宗教的転換の困難さ、エリオットの結婚の失敗[77]。 アレン・テイトはエリオットの手法の変化を感じ取り、「『ホロウ・メン』では神話が完全に消滅している」と書いている[77]。これは、エリオットの初期 の作品の中でもダンテに負うところが大きい詩であり、近代イギリスの神話-火薬陰謀事件の「ガイ・フォークス爺さん」-や、ジョセフ・コンラッドやジェー ムズ・ジョージ・フレイザーの植民地・農耕地の神話は言うまでもないが、少なくともテキスト史上の理由で『荒地』に反響している-に対する印象深い主張で ある[78]。 [また、エリオットの神話的手法の特徴である「現代と古代の間の連続的な並行関係」は、素晴らしい形で残っていた[79]。「The Hollow Men」には、特にその結論において、エリオットの最も有名なセリフがいくつか含まれている。 これが世界の終わり方だ。 このようにして世界は終わるのだ。 |

| "Ash-Wednesday" "Ash-Wednesday" is the first long poem written by Eliot, after his 1927 conversion to Anglicanism. Published in 1930, it deals with the struggle that ensues when a person who has lacked faith acquires it. Sometimes referred to as Eliot's "conversion poem", it is richly but ambiguously allusive, and deals with the aspiration to move from spiritual barrenness to hope for human salvation. Eliot's style of writing in "Ash-Wednesday" showed a marked shift from the poetry he had written prior to his 1927 conversion, and his post-conversion style continued in a similar vein. His style became less ironic, and the poems were no longer populated by multiple characters in dialogue. Eliot's subject matter also became more focused on his spiritual concerns and his Christian faith.[80] Many critics were particularly enthusiastic about "Ash-Wednesday". Edwin Muir maintained that it is one of the most moving poems Eliot wrote, and perhaps the "most perfect", though it was not well received by everyone. The poem's groundwork of orthodox Christianity discomfited many of the more secular literati.[6][81] |

"灰の水曜日" "Ash-Wednesday "は、エリオットが1927年に英国国教会に改宗した後、初めて書いた長編詩である。1930年に発表されたこの詩は、信仰を持たなかった人が信仰を持つ ようになったときに起こる葛藤を扱っている。エリオットの「回心の詩」とも呼ばれるこの作品は、豊かでありながら曖昧な言い回しで、精神の不毛から人間の 救済への希望へと向かう願望を扱っている。灰の水曜日」でのエリオットの文体は、1927年の改宗前の詩から著しく変化しており、改宗後の文体も同様の傾 向が続いている。また、改宗後の作風も同様で、皮肉が少なくなり、複数の登場人物が対話するような詩は見られなくなった。エリオットの主題はまた、彼の精 神的な懸念と彼のキリスト教の信仰に焦点を当てるようになった[80]。 多くの批評家は特に「灰の水曜日」に熱狂的であった。エドウィン・ミュアは、この詩はエリオットが書いた最も感動的な詩の一つであり、おそらく「最も完璧 な」詩であると主張したが、すべての人に受け入れられたわけではなかった。この詩は正統派キリスト教を下敷きにしており、世俗的な文学者の多くを落胆させ た[6][81]。 |

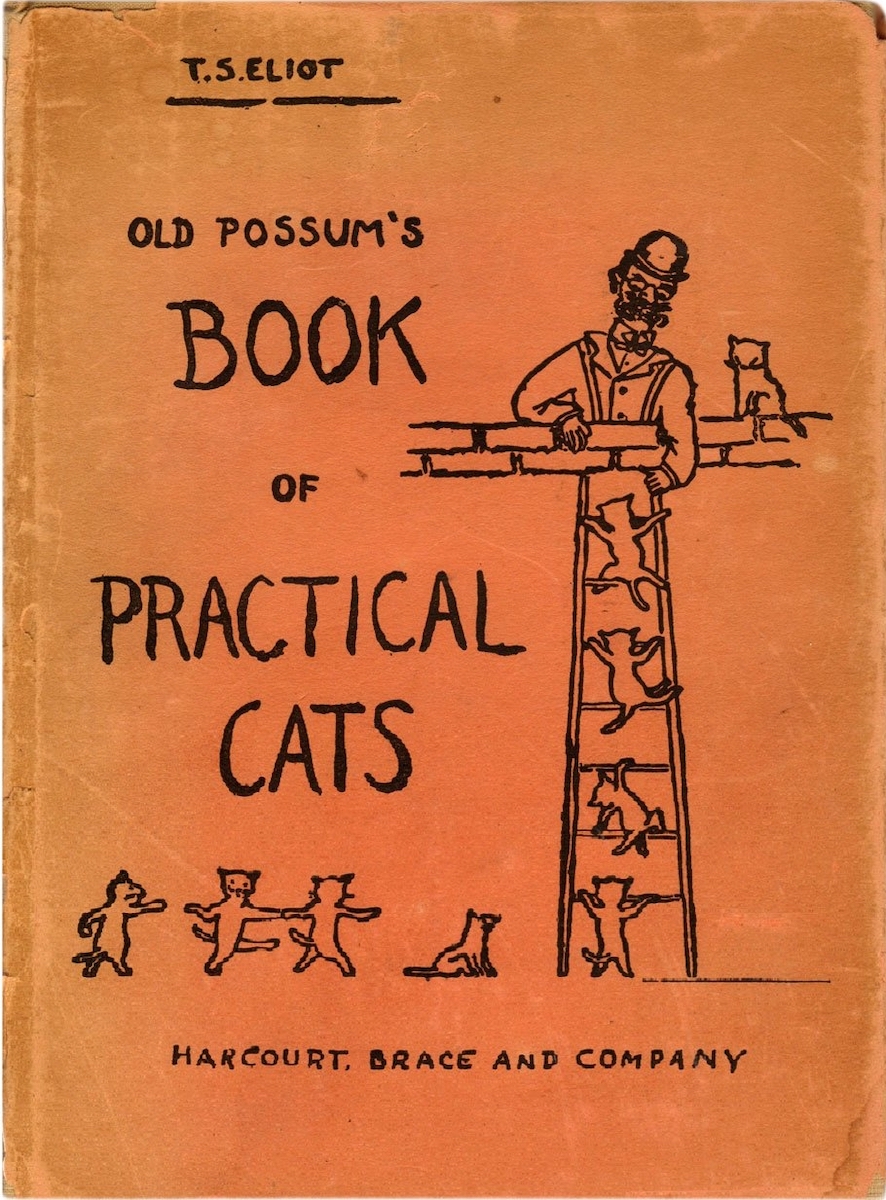

| Old Possum's

Book of Practical Cats In 1939, Eliot published a book of light verse, Old Possum's Book of Practical Cats. ("Old Possum" was Ezra Pound's friendly nickname for Eliot.) The first edition had an illustration of the author on the cover. In 1954, the composer Alan Rawsthorne set six of the poems for speaker and orchestra in a work titled Practical Cats. After Eliot's death, the book was the basis of the musical Cats by Andrew Lloyd Webber, first produced in London's West End in 1981 and opening on Broadway the following year.[82] |

『オールド・ポッサムの実用ネコの本』(Old Possum's

Book of Practical Cats) 1939年、エリオットは軽妙な詩の本『オールド・ポッサムの実用ネコの本』を出版した。(初版の表紙には著者のイラストが描かれていた。1954年、作 曲家アラン・ローストホーンは、この詩のうち6篇をスピーカーとオーケストラのために作曲し、『Practical Cats』と題する作品を発表している。エリオットの死後、この本はアンドリュー・ロイド・ウェバーによるミュージカル『キャッツ』の原作となり、 1981年にロンドンのウエストエンドで初演、翌年にはブロードウェイで開幕した[82]。 |

| Macavity's a Mystery Cat: he's

called the Hidden Paw— For he's the master criminal who can defy the Law. He's the bafflement of Scotland Yard, the Flying Squad's despair: For when they reach the scene of crime—Macavity's not there! Macavity, Macavity, there's no one like Macavity, He's broken every human law, he breaks the law of gravity. His powers of levitation would make a fakir stare, And when you reach the scene of crime—Macavity's not there! You may seek him in the basement, you may look up in the air— But I tell you once and once again, Macavity's not there! Macavity's a ginger cat, he's very tall and thin; You would know him if you saw him, for his eyes are sunken in. His brow is deeply lined with thought, his head is highly domed; His coat is dusty from neglect, his whiskers are uncombed. He sways his head from side to side, with movements like a snake; And when you think he's half asleep, he's always wide awake. Macavity, Macavity, there's no one like Macavity, For he's a fiend in feline shape, a monster of depravity. You may meet him in a by-street, you may see him in the square— But when a crime's discovered, then Macavity's not there! He's outwardly respectable. (They say he cheats at cards.) And his footprints are not found in any file of Scotland Yard's And when the larder's looted, or the jewel-case is rifled, Or when the milk is missing, or another Peke's been stifled, Or the greenhouse glass is broken, and the trellis past repair Ay, there's the wonder of the thing! Macavity's not there! And when the Foreign Office find a Treaty's gone astray, Or the Admiralty lose some plans and drawings by the way, There may be a scrap of paper in the hall or on the stair— But it's useless to investigate—Macavity's not there! And when the loss has been disclosed, the Secret Service say: It must have been Macavity!'—but he's a mile away. You'll be sure to find him resting, or a-licking of his thumb; Or engaged in doing complicated long division sums. Macavity, Macavity, there's no one like Macavity, There never was a Cat of such deceitfulness and suavity. He always has an alibi, and one or two to spare: At whatever time the deed took place—MACAVITY WASN'T THERE ! And they say that all the Cats whose wicked deeds are widely known (I might mention Mungojerrie, I might mention Griddlebone) Are nothing more than agents for the Cat who all the time Just controls their operations: the Napoleon of Crime! |

Macavity's a Mystery Cat:

彼はHidden Pawと呼ばれています。 法を破ることのできる名犯罪者だからだ。 ロンドン警視庁は困惑し、 飛行部隊は絶望する。 犯罪現場に到着しても マキャヴィティはいない! マカビティ、マカビティ、マカビティのような人はいない。 人間の掟を破り 重力の掟も破った 彼の空中浮遊の力は、狂信者を凝視させるだろう。 犯行現場に行くとそこにはいない! 地下で探してもいいし、空を見上げてもいい。 だが、何度でも言う。マカビティはそこにはいない。 マカビティはジンジャー・キャットで 背が高くて細いんだ 彼の目はくぼんでいて、見ればわかる。 彼の眉は深く考え事をしていて、彼の頭は高く窪んでいる。 毛は放置されて埃だらけ、ひげは梳かれていない。 頭を左右に振って、蛇のような動きをする。 半分眠ったかと思うと、いつも目を覚ましている。 マカビティ、マカビティ、マカビティのような人はいない。 ネコの形をした悪魔で、堕落の怪物だからだ。 街角で会ってもいいし、広場で会ってもいい。 だが犯罪が発見された時 マキャヴィティの姿はない! 彼は外見上では立派だが (カードでイカサマをすると言われている) ロンドン警視庁の書類にも 彼の足跡はない 食料庫が略奪され宝石箱が荒らされ 牛乳がなくなったり、ペケが窒息死したり 温室のガラスが割れたり、棚の修理が遅れたりしても そうだ 驚くべきことがある マカヴィティがいないんだ 外務省が条約に迷いがあることに気づいたり 提督が設計図や図面を紛失しても 廊下や階段に紙切れがあるかもしれない... しかし、調査しても無駄です。 そして、紛失が明らかになったとき、シークレットサービスは言う。 マカビティの仕業に違いない!」と言うが、彼は1マイルも離れている。 しかし、彼は1マイル離れたところにいるのです。 あるいは複雑な割り算に夢中になっている。 マカビティ、マカビティ、マカビティのような人はいない。 これほど欺瞞に満ち溢れた猫はいない。 彼は常にアリバイがあり、一つや二つは余裕を持っている。 犯行がいつであれ マキャヴィティはそこにいなかった! そして、悪い行いが広く知れ渡っている猫たちは皆、こう言うのです。 (マンゴジェリーやグリドルボーンを挙げるかもしれない) いつも支配している猫の代理人にすぎない。 犯罪のナポレオンと呼ばれる。 |

| Four Quartets Eliot regarded Four Quartets as his masterpiece, and it is the work that most of all led him to being awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.[6] It consists of four long poems, each first published separately: "Burnt Norton" (1936), "East Coker" (1940), "The Dry Salvages" (1941) and "Little Gidding" (1942). Each has five sections. Although they resist easy characterisation, each poem includes meditations on the nature of time in some important respect—theological, historical, physical—and its relation to the human condition. Each poem is associated with one of the four classical elements, respectively: air, earth, water, and fire. "Burnt Norton" is a meditative poem that begins with the narrator trying to focus on the present moment while walking through a garden, focusing on images and sounds such as the bird, the roses, clouds and an empty pool. The meditation leads the narrator to reach "the still point" in which there is no attempt to get anywhere or to experience place and/or time, instead experiencing "a grace of sense". In the final section, the narrator contemplates the arts ("words" and "music") as they relate to time. The narrator focuses particularly on the poet's art of manipulating "Words [which] strain, / Crack and sometimes break, under the burden [of time], under the tension, slip, slide, perish, decay with imprecision, [and] will not stay in place, / Will not stay still." By comparison, the narrator concludes that "Love is itself unmoving, / Only the cause and end of movement, / Timeless, and undesiring." "East Coker" continues the examination of time and meaning, focusing in a famous passage on the nature of language and poetry. Out of darkness, Eliot offers a solution: "I said to my soul, be still, and wait without hope." "The Dry Salvages" treats the element of water, via images of river and sea. It strives to contain opposites: "The past and future / Are conquered, and reconciled." "Little Gidding" (the element of fire) is the most anthologised of the Quartets.[83] Eliot's experiences as an air raid warden in the Blitz power the poem, and he imagines meeting Dante during the German bombing. The beginning of the Quartets ("Houses / Are removed, destroyed") had become a violent everyday experience; this creates an animation, where for the first time he talks of love as the driving force behind all experience. From this background, the Quartets end with an affirmation of Julian of Norwich: "All shall be well and / All manner of thing shall be well."[84] The Four Quartets draws upon Christian theology, art, symbolism and language of such figures as Dante, and mystics St. John of the Cross and Julian of Norwich.[84] |

四つの四重奏曲 エリオットは『四つの四重奏曲』を自らの代表作と位置づけ、彼をノーベル文学賞受賞に導いた最大の作品である[6]。「バーント・ノートン』(1936 年)、『イースト・コーカー』(1940年)、『ドライ・サルベージ』(1941年)、『リトル・ギディング』(1942年)である。それぞれ5つのセク ションで構成されている。それぞれの詩は、神学的、歴史的、物理的な時間の性質や、人間の状態との関係といった重要な点についての瞑想を含んでおり、簡単 に性格づけることはできませんが、そのような詩が多いのも事実です。それぞれの詩は、古典的な四大元素の一つである空気、土、水、火にそれぞれ関連付けら れている。 "Burnt Norton "は瞑想的な詩で、語り手が庭を歩きながら、鳥、バラ、雲、空のプールなどのイメージや音に注目し、今この瞬間に集中しようとするところから始まる。瞑想 の結果、語り手は「静止点」に到達する。そこでは、どこにも行こうとせず、場所や時間を経験しようとせず、代わりに「感覚の恵み」を経験するのである。最 後のセクションでは、語り手は芸術(「言葉」と「音楽」)を時間に関連させながら熟考する。語り手は特に詩人の芸術である "Words [which] strain, / Crack and sometimes break, under the burden [of time], under the tension, slip, slide, perish, decay with imprecision, [and] will not stay in place, / Will not stay still." を操ることに着目している。それに比べて語り手は、"愛そのものは動かない、/ただ動きの原因と終わり、/時間を超越し、欲望を持たない "と結論付けているのである。 "East Coker "では、時間と意味の考察を続け、言語と詩の性質に焦点を当てた有名な一節がある。暗闇の中から、エリオットは解決策を提示する。"私は魂に言った"" じっと待て""望みはない" "The Dry Salvages "では、川や海のイメージを通じて、水の要素を扱っています。過去と未来が征服され、和解する」。 「エリオットは、電撃戦の空襲監視員としての経験がこの詩の力となっており、ドイツの爆撃中にダンテに会うことを想像している[83]。四重奏曲の冒頭 (「家々は/撤去され、破壊された」)は暴力的な日常体験となっていた。このことがアニメーションを生み出し、そこで初めて彼はすべての経験の原動力とし ての愛について語るのである。このような背景から、「四重奏曲」はジュリアン・オブ・ノリッジの断言で終わっている。「すべてはうまくいくだろうし、/あ らゆることがうまくいくだろう」[84]。 四重奏曲』は、ダンテや神秘主義者の十字架の聖ヨハネ、ノリッチのジュリアンといった人物のキリスト教神学、芸術、象徴主義、言語などを用いている [84]。 |

| Plays |

脚本(省略) |

| Literary criticism Eliot also made significant contributions to the field of literary criticism, and strongly influenced the school of New Criticism. He was somewhat self-deprecating and minimising of his work and once said his criticism was merely a "by-product" of his "private poetry-workshop". But the critic William Empson once said, "I do not know for certain how much of my own mind [Eliot] invented, let alone how much of it is a reaction against him or indeed a consequence of misreading him. He is a very penetrating influence, perhaps not unlike the east wind."[89] In his critical essay "Tradition and the Individual Talent", Eliot argues that art must be understood not in a vacuum, but in the context of previous pieces of art. "In a peculiar sense [an artist or poet] ... must inevitably be judged by the standards of the past."[90] This essay was an important influence over the New Criticism by introducing the idea that the value of a work of art must be viewed in the context of the artist's previous works, a "simultaneous order" of works (i.e., "tradition"). Eliot himself employed this concept on many of his works, especially on his long-poem The Waste Land.[91] Also important to New Criticism was the idea—as articulated in Eliot's essay "Hamlet and His Problems"—of an "objective correlative", which posits a connection among the words of the text and events, states of mind, and experiences.[92] This notion concedes that a poem means what it says, but suggests that there can be a non-subjective judgment based on different readers' different—but perhaps corollary—interpretations of a work. More generally, New Critics took a cue from Eliot in regard to his "'classical' ideals and his religious thought; his attention to the poetry and drama of the early seventeenth century; his deprecation of the Romantics, especially Shelley; his proposition that good poems constitute 'not a turning loose of emotion but an escape from emotion'; and his insistence that 'poets... at present must be difficult'."[93] Eliot's essays were a major factor in the revival of interest in the metaphysical poets. Eliot particularly praised the metaphysical poets' ability to show experience as both psychological and sensual, while at the same time infusing this portrayal with—in Eliot's view—wit and uniqueness. Eliot's essay "The Metaphysical Poets", along with giving new significance and attention to metaphysical poetry, introduced his now well-known definition of "unified sensibility", which is considered by some to mean the same thing as the term "metaphysical".[94][95] His 1922 poem The Waste Land[96] also can be better understood in light of his work as a critic. He had argued that a poet must write "programmatic criticism", that is, a poet should write to advance his own interests rather than to advance "historical scholarship". Viewed from Eliot's critical lens, The Waste Land likely shows his personal despair about World War I rather than an objective historical understanding of it.[97] Late in his career, Eliot focused much of his creative energy on writing for the theatre; some of his earlier critical writing, in essays such as "Poetry and Drama",[98] "Hamlet and his Problems",[92] and "The Possibility of a Poetic Drama",[99] focused on the aesthetics of writing drama in verse. |

文芸批評 エリオットは文芸批評の分野でも大きな貢献をし、新批評派に強い影響を与えた。彼は自分の作品についてやや自虐的であり、批評は「私的な詩のワークショッ プ」の「副産物」に過ぎないと述べたこともある。しかし、批評家ウィリアム・エンプソンはかつて、「私自身が(エリオットを)どれだけ発明したのか、まし てやどれだけ彼に対する反応なのか、あるいは実際に彼を誤読した結果なのか、確かなことはわからない」と述べている。彼は非常に浸透力のある影響力を持 ち、おそらく東風に似ていなくもない」[89]。 批評的エッセイ「伝統と個人の才能」において、エリオットは芸術が真空の中で理解されるのではなく、以前の芸術作品の文脈の中で理解されなければならない と論じている[89]。「このエッセイは、芸術作品の価値は芸術家の過去の作品、すなわち作品の「同時的な秩序」(すなわち「伝統」)の文脈で見なければ ならないという考えを導入し、新批評主義に重要な影響を与えた[90]。エリオット自身、多くの作品、特に長編詩『荒地』においてこの概念を採用している [91]。 また新批評主義にとって重要だったのは、エリオットのエッセイ「ハムレットとその問題」において明確にされた、テキストの言葉と出来事、心の状態、経験の 間につながりを仮定する「客観的相関関係」の考え方であった[92]。この概念は、詩はそれが言うことを意味していると認めるが、異なる読者の作品に対す る異なる-おそらく相関する解釈に基づいて主観的ではない判断もできると示唆するものであった。 より一般的には、新批評家たちは彼の「『古典的な』理想と彼の宗教思想、17世紀初頭の詩と演劇への注目、ロマン派、特にシェリーへの軽蔑、優れた詩は 『感情の解放ではなく、感情からの逃避』であるという彼の提案、そして『詩人は...現在、困難でなければならない』という彼の主張」についてエリオット から手がかりを得ている」[93]。 エリオットのエッセイは形而上学的詩人に対する関心を復活させる大きな要因であった。エリオットは特に、形而上学的詩人たちが経験を心理的かつ感覚的なも のとして示すと同時に、この描写にエリオットの見解では知恵と独自性を吹き込むことができると賞賛している。エリオットのエッセイ「形而上学的詩人たち」 は、形而上学的な詩に新しい意義と注意を与えるとともに、今ではよく知られた「統一された感性」の定義を紹介し、これは「形而上学的」という用語と同じ意 味だと考える者もいる[94][95]。 彼の1922年の詩『荒地』[96]もまた、批評家としての彼の仕事に照らしてより良く理解することができる。彼は詩人が「プログラム批評」、つまり「歴 史的学問」を進めるためではなく、自身の利益を進めるために書くべきであると主張していた。エリオットの批評レンズから見ると、『荒地』は第一次世界大戦 に対する客観的な歴史的理解よりもむしろ彼の個人的な絶望を示していると思われる[97]。 エリオットのキャリアの後半では、演劇のために書くことに創作エネルギーの多くを注いだ。「詩とドラマ」[98]、「ハムレットとその問題」[92]、 「詩的ドラマの可能性」[99]といったエッセイの中の彼の初期のいくつかの評論は、詩でドラマを書くことの美学に焦点を当てたものである。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/T._S._Eliot |

|

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

++

☆

☆

☆