テラ・ヌリウス

Terra nullius; テラ・ヌリウス(無主地=むしゅち)

☆ テラ・ヌリウス(ラ テン語: terra nullius、/ˈtɛrə ˈnʌlɪəs/、[1] 複数形: terrae nullius)は、「無主地」を意味するラテン語表現である。[2] 19世紀以降、国際法において、国家による領土占領によって領土が獲得されることを正当化する原則として、時折用いられてきた。[a][4] 現在、テラ・ヌリアスとして時折主張される領土は3つある。ビル・タウィル(エジプトとスーダンの間の細長い土地)、クロアチアとセルビアの国境紛争によ りドナウ川付近に4つの飛び地として存在する土地、そして南極大陸の一部、主にマリー・バード・ランドである。

| Terra nullius

(/ˈtɛrə ˈnʌlɪəs/,[1] plural terrae nullius) is a Latin expression

meaning "nobody's land".[2] Since the nineteenth century it has

occasionally been used in international law as a principle to justify

claims that territory may be acquired by a state's occupation of

it.[a][4] There are currently three territories sometimes claimed to be

terra nullius: Bir Tawil (a strip of land between Egypt and the Sudan),

four pockets of land near the Danube due to the Croatia–Serbia border

dispute, and parts of Antarctica, principally Marie Byrd Land. |

テラ・ヌリウス(ラ

テン語: terra nullius、/ˈtɛrə ˈnʌlɪəs/、[1] 複数形: terrae

nullius)は、「無主地」を意味するラテン語表現である。[2]

19世紀以降、国際法において、国家による領土占領によって領土が獲得されることを正当化する原則として、時折用いられてきた。[a][4]

現在、テラ・ヌリアスとして時折主張される領土は3つある。ビル・タウィル(エジプトとスーダンの間の細長い土地)、クロアチアとセルビアの国境紛争によ

りドナウ川付近に4つの飛び地として存在する土地、そして南極大陸の一部、主にマリー・バード・ランドである。 |

| Doctrine In international law, terra nullius is territory which belongs to no state. Sovereignty over territory which is terra nullius can be acquired by any state by occupation.[5] According to Oppenheim: "The only territory which can be the object of occupation is that which does not already belong to another state, whether it is uninhabited, or inhabited by persons whose community is not considered to be a state; for individuals may live on as territory without forming themselves into a state proper exercising sovereignty over such territory."[6] Occupation of terra nullius is one of several ways in which a state can acquire territory under international law. The other means of acquiring territory are conquest, cession by agreement, accretion through the operations of nature, and prescription through the continuous exercise of sovereignty.[7][8] |

ドクトリン 国際法において、テラ・ヌリウスとはいかなる国家にも属さない領土のことである。オッペンハイムによれば、「占領の対象となりうる唯一の領土は、他の国家 にまだ帰属していない領土であり、無人の領土であろうと、その共同体が国家であるとはみなされない者が居住する領土であろうと、そのような領土に対して主 権を行使する適切な国家を形成することなく、個人が領土として居住することができるからである」[6]。 テラ・ヌリウスの占領は、国際法上、国家が領土を獲得できるいくつかの方法の一つである。領土を獲得する他の手段は、征服、合意による割譲、自然の作用による付加、継続的な主権の行使による時効である[7][8]。 |

| History Although the term terra nullius was not used in international law before the late nineteenth century,[9] some writers have traced the concept to the Roman law term res nullius, meaning nobody's thing. In Roman law, things that were res nullius, such as wild animals (ferae bestiae), lost slaves and abandoned buildings could be taken as property by anyone by seizure. Benton and Straumann, however, state that the derivation of terra nullius from res nullius is "by analogy" only.[10] Sixteenth century writings on res nullius were in the context of European colonisation in the New World and the doctrine of discovery. In 1535, Domingo de Soto argued that Spain had no right to the Americas because the lands had not been res nullius at the time of discovery.[11] Francisco de Vitoria, in 1539, also used the res nullius analogy to argue that the indigenous populations of the Americas, although “barbarians”, had both sovereignty and private ownership over their lands, and that the Spanish had gained no legal right to possession through mere discovery of these lands.[12] Nevertheless, Vitoria stated that the Spanish possibly had a limited right to rule the indigenous Americans because the latter “are unsuited to setting up or administering a commonwealth both legitimate and ordered in human and civil terms.”[13] Alberico Gentili, in his De Jure Belli Libri Tres (1598), drew a distinction between the legitimate occupation of land that was res nullius and illegitimate claims of sovereignty through discovery and occupation of land that was not res nullius, as in the case of the Spanish claim to the Americas.[14] Hugo Grotius, writing in 1625, also stated that discovery does not give a right to sovereignty over inhabited land, “For discovery applies to those things which belong to no one.”[15] By the eighteenth century, however, some writers argued that territorial rights over land could stem from the settlement and cultivation of that land. William Blackstone, in 1765, wrote, “Plantations or colonies, in distant countries, are either such where the lands are claimed by right of occupancy only, by finding them desert and uncultivated, and peopling them from the mother-country; or where, when already cultivated, they have been either gained by conquest, or ceded to us by treaties. And both these rights are founded upon the law of nature, or at least upon that of nations."[16] Borch states that many commentators erroneously interpreted this to mean that any uncultivated lands, whether inhabited or not, could be claimed by a colonising state by right of occupancy.[17] Borch rather argues that before the 19th century, European legal sources tended to justify the extension of European sovereignty over inhabited territory through the concepts of voluntary cession or conquest in a just war.[18] With respect to settlement by Europeans, the defense offered (per theorists such as Locke and Vattel) was that colonized lands were either uninhabited, or were surplus to the needs of the indigenous inhabitants and therefore able to be settled without resulting in dispossession. [19] Borch places the shift towards the view that "uncultivated" but inhabited lands were terra nullius (and could therefore be claimed purely on the basis of being uncultivated) primarily in the 19th century, and argues it was a result of political developments (e.g. the decision to colonize New South Wales despite a large indigenous population) and the rise of new intellectual currents such as Scientific Racism and Legal Positivism.[20] Several years before Blackstone, Emer de Vattel, in his Le droit des gents (1758), drew a distinction between land that was effectively occupied and cultivated, and the unsettled and uncultivated land of nomads which was open to colonisation.[21] The Berlin West Africa Conference of 1884-85 endorsed the principle that sovereignty over an unclaimed territory required effective occupation, and that where native populations had established effective occupation their sovereignty could not be unilaterally overturned by a colonising state.[22]: 10 The term terra nullius was used in 1885 in relation to the dispute between Spain and the United States over Contoy Island. Herman Eduard von Hoist, wrote, “Contoy was not, in an international sense, a desert, that is an abandoned island and hence terra nullius."[23] In 1888, the Institut de Droit International introduced the concept of territorium nullius (nobody’s territory) as a public law equivalent to the private law concept of res nullius.[24] In 1909, the Italian international jurist Camille Piccioni described the island of Spitzbergen in the Arctic Circle as terra nullius. Even though the island was inhabited by the nationals of several European countries, the inhabitants did not live under any formal sovereignty.[25] In subsequent decades, the term terra nullius gradually replaced territorium nullius. Fitzmaurice argues that the two concepts were initially distinct, territorium nullius applying to territory in which the inhabitants might have property rights but had not developed political sovereignty whereas terra nullius referred to an absence of property. Nevertheless, terra nullius also implied an absence of sovereignty because sovereignty required property rights acquired through the exploitation of nature.[26] Michael Connor, however, argues that territorium nullius and terra nullius were the same concept, meaning land without sovereignty, and that property rights and cultivation of land were not part of the concept.[27] The term terra nullius was adopted by the International Court of Justice in its 1975 Western Sahara advisory opinion.[28] The majority wrote, "'Occupation' being legally an original means of peaceably acquiring sovereignty over territory otherwise than by cession or succession, it was a cardinal condition of a valid 'occupation' that the territory should be terra nullius – a territory belonging to no-one – at the time of the act alleged to constitute the 'occupation'."[29] The court found that at the time of Spanish colonisation in 1884, the inhabitants of Western Sahara were nomadic but socially and politically organised in tribes and under chiefs competent to represent them. According to State practice of the time the territory therefore was not terra nullius.[30] |

歴史 テラ・ヌリウスという用語は19世紀後半以前には国際法では使われていなかったが[9]、この概念をローマ法のres nullius(誰のものでもない)という用語になぞらえた作家もいる。ローマ法では、野生の動物(ferae bestiae)、失われた奴隷、放棄された建物など、res nulliusであるものは、差し押さえによって誰でも所有物として奪うことができた。しかし、ベントンとストラウマンは、res nulliusからterra nulliusが派生したのは「類推による」だけであると述べている[10]。 16世紀のres nulliusに関する著作は、新大陸におけるヨーロッパ人の植民地化と発見の教義の文脈で書かれたものであった。1535年、ドミンゴ・デ・ソトは、ス ペインはアメリカ大陸に対する権利を持たないと主張した。1539年、フランシスコ・デ・ビトリアもまた、レス・ヌリウスの類推を用いて、アメリカ大陸の 先住民は「野蛮人」であったとはいえ、その土地に対する主権と私的所有権の両方を持っており、スペインはこれらの土地の単なる発見によって所有権に対する 法的権利を得たわけではないと主張した[11]。 [12]にもかかわらず、ヴィトーリアは、スペイン人がアメリカ原住民を支配する権利は限定的なものである可能性があると述べていた。なぜならアメリカ原 住民は「人間的、市民的な観点から見て、合法的で秩序ある連邦を設立したり、管理したりするのに適していないからである」[13]。 アルベリコ・ジェンティリは『De Jure Belli Libri Tres』(1598年)の中で、レス・ヌリウスである土地の合法的な占領と、スペインのアメリカ大陸に対する主張の場合のように、レス・ヌリウスではな い土地の発見と占領による非合法的な主権の主張とを区別していた[14]。 ヒューゴ・グロティウスも1625年に執筆しており、「発見は誰のものでもないものに適用されるからである」[15]と述べている。 しかし、18世紀になると、土地に対する領有権は、その土地の定住と耕作から生じ得ると主張する作家も現れた。1765年、ウィリアム・ブラックストーン は、「遠い国のプランテーションや植民地は、その土地が砂漠で未開の地であることを発見し、母国から入植することによって、占有権のみを主張する場合と、 すでに耕作されている場合、征服によって獲得された場合と、条約によって我々に割譲された場合とがある。そして、これらの権利はいずれも自然法則、あるい は少なくとも国民法則に基づいている」[16]。 ボルヒによれば、多くの論者はこれを誤って解釈し、人が住んでいるか否かにかかわらず、耕作されていない土地は占領権によって植民地化する国家が請求でき ると解釈していた[17]。ボルヒはむしろ、19世紀以前のヨーロッパの法源は、正当な戦争における自発的な割譲または征服という概念を通じて、人が住む 領土に対するヨーロッパの主権の拡張を正当化する傾向があったと論じている。 [18]ヨーロッパ人による入植に関しては、(ロックやヴァッテルといった理論家によって)植民地化された土地は無人であるか、あるいは先住民の必要を満 たす余剰地であり、それゆえ土地収奪を招くことなく入植することができるという弁明が提示されていた。[19]。ボルヒは、「耕作されていない」が人が居 住している土地はテラ・ヌリウスである(したがって、純粋に耕作されていないという理由だけで権利を主張することができる)という見解への転換は主に19 世紀に起こったとし、それは政治的発展(例えば、先住民が多く居住しているにもかかわらずニュー・サウス・ウェールズを植民地化するという決定)と科学的 人種主義や法実証主義といった新たな知的潮流の台頭の結果であったと論じている[20]。 ブラックストーンの数年前、エマール・ド・ヴァッテルは『紳士の権利』(Le droit des gents、1758年)の中で、効果的に占領され耕作されている土地と、植民地化の余地がある遊牧民の未開拓地とを区別していた[21]。 1884年から1885年にかけてのベルリン西アフリカ会議では、未開拓地に対する主権には効果的な占領が必要であり、先住民が効果的な占領を確立してい る場合には、その主権を植民地化する国家が一方的に覆すことはできないという原則が支持されていた[22]: 10 テラ・ヌリウスという用語は、1885年にスペインとアメリカの間で起こったコントイ島をめぐる紛争に関連して使われた。ヘルマン・エドゥアルド・フォ ン・ホイストは、「コントイ島は国際的な意味では砂漠ではなく、放棄された島であり、したがってテラ・ヌリウスであった」と書いている[23]。1888 年、国際法研究所は、テリトリアム・ヌリウス(誰の領土でもない)という概念を、私法上のレス・ヌリウスの概念に相当する公法上の概念として導入した [24]。 1909年、イタリアの国際法学者カミーユ・ピッチョーニは、北極圏にあるスピッツベルゲン島をテラ・ヌリウスと表現した。この島にはヨーロッパのいくつかの国の国民が居住していたが、住民は正式な主権のもとで生活していなかった[25]。 その後数十年の間に、テラ・ヌリウスという言葉は次第にテリトリアム・ヌリウスに取って代わられた。フィッツマウリスは、この2つの概念は当初は別個のも のであり、テッラ・ヌリウスが所有権のない領土を指すのに対し、テッラ・ヌリウスは所有権のない領土を指すと主張している。しかしながら、マイケル・コ ナーは、テリトリウム・ヌリウスとテラ・ヌリウスは同じ概念であり、主権のない土地を意味し、土地の所有権や耕作はその概念には含まれないと主張している [27]。 テラ・ヌリウスという用語は、国際司法裁判所が1975年に発表した西サハラの勧告的意見[28]で採用されたものであり、その多数派は、「『占領』は、 割譲や継承以外の方法で領土に対する主権を平和的に獲得する本来の手段であり、『占領』を構成すると主張される行為の時点で、その領土がテラ・ヌリウス (誰のものでもない領土)であることが、有効な『占領』の基本的条件であった。 「裁判所は、1884年のスペインの植民地化当時、西サハラの住民は遊牧民であったが、社会的、政治的には部族に組織され、部族を代表する首長の下にいた ことを明らかにした。当時の国家慣習によれば、それゆえ領土は無地ではなかった[30]。 |

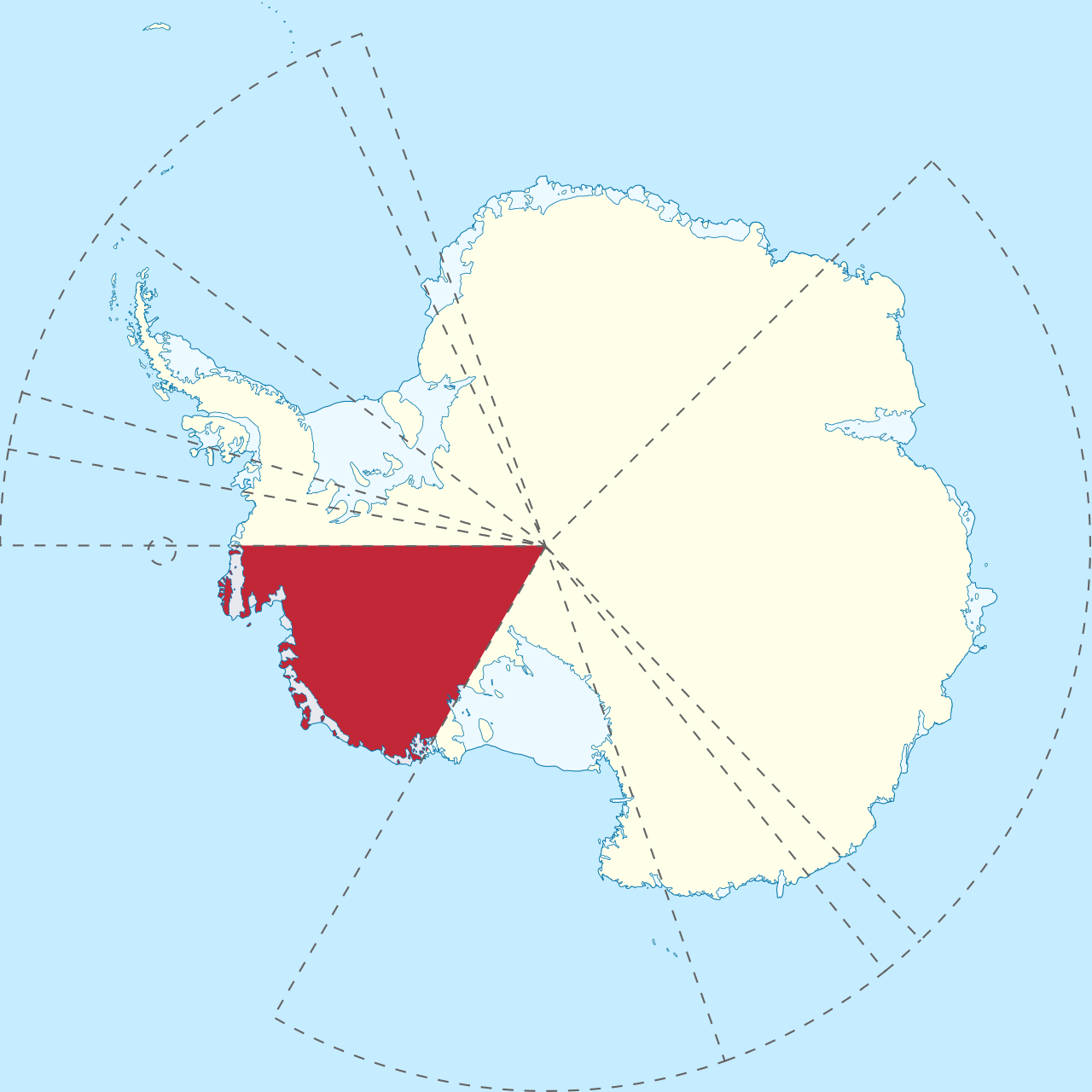

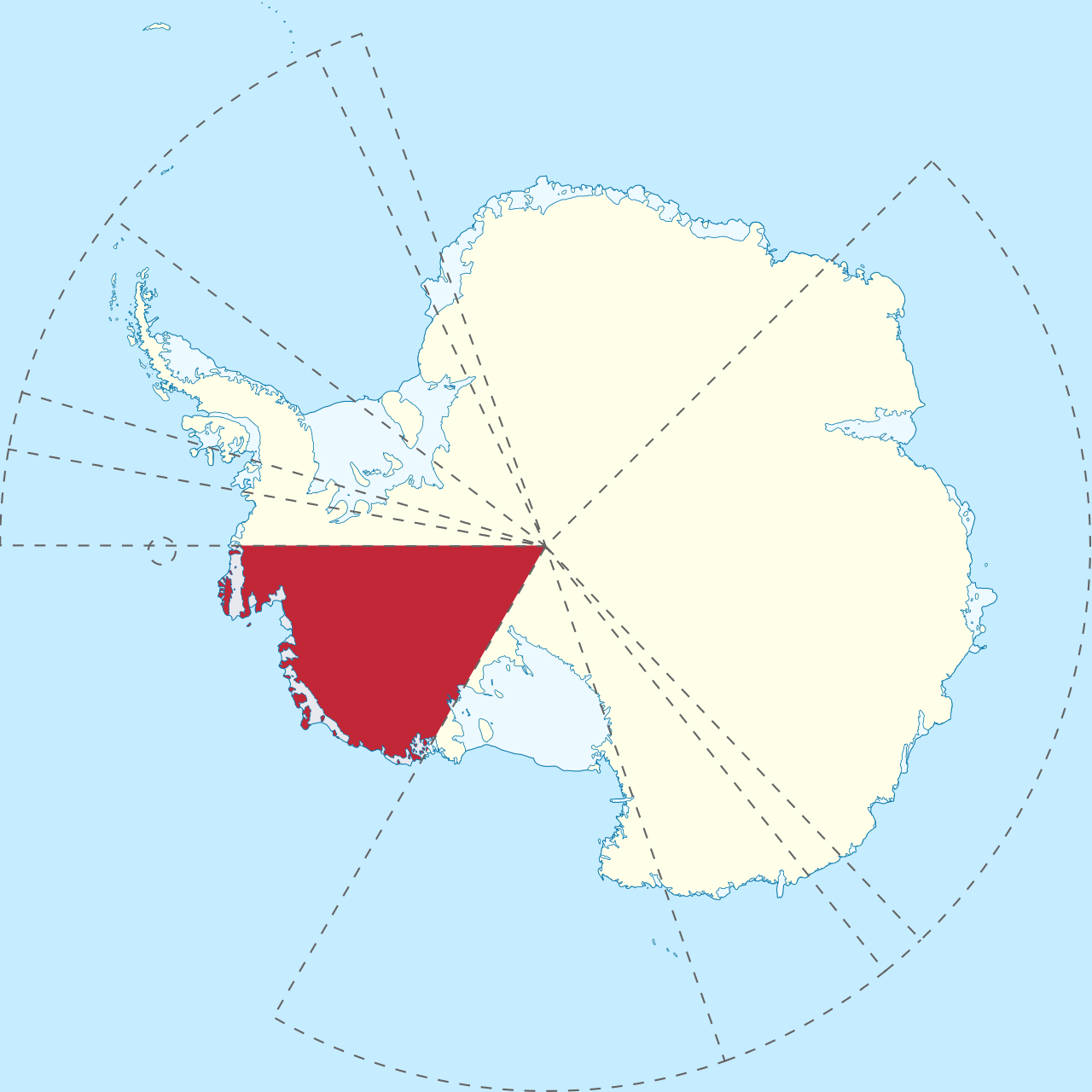

Current claims of terra nullius Simplified map showing Egypt's territory (yellow), the Sudan's territory (blue), the disputed Halaib Triangle (light green) and Wadi Halfa Salient (dark green), and the unclaimed Bir Tawil (white). There are three instances where land is sometimes claimed to be terra nullius: Bir Tawil bordering Egypt and the Sudan, four small areas along the Croatia–Serbia border, and Marie Byrd Land in Antarctica. Bir Tawil Main article: Bir Tawil Further information: Egypt–Sudan border Between Egypt and the Sudan is the 2,060 km2 (800 sq mi) landlocked territory of Bir Tawil, which was created by a discrepancy between borders drawn in 1899 and 1902. One border placed Bir Tawil under the Sudan's control and the Halaib Triangle under Egypt's; the other border did the reverse. Each country asserts the border that would give it the much larger Halaib Triangle, to the east, which is adjacent to the Red Sea, with the side effect that Bir Tawil is unclaimed by either country (each claims the other owns it). Bir Tawil has no settled population, but the land is used by Bedouins who roam the area.[b] Gornja Siga and other pockets Main article: Croatia–Serbia border dispute  The Croatia–Serbia border dispute in the Bačka and Baranja area. The Croatian claim corresponds to the red line, while the Serbian claim corresponds to the course of the Danube. Under Serbian control, claimed by Croatia Under de facto Croatian control, although not claimed by either Croatia or Serbia Croatia and Serbia dispute several small areas on the east bank of the Danube. However, four pockets on the western river bank, of which Gornja Siga is the largest, are not claimed by either country. Serbia makes no claims on the land while Croatia states that the land belongs to Serbia.[34] Croatia states that the disputed area is not terra nullius and they are negotiating with Serbia to settle the border.[35]  Marie Byrd Land Main article: Marie Byrd Land See also: Territorial claims in Antarctica marie Marie Byrd Land While several countries made claims to parts of Antarctica in the first half of the 20th century, the remainder, including most of Marie Byrd Land (the portion east from 150°W to 90°W), has not been claimed by any sovereign state. Signatories to the Antarctic Treaty of 1959 agreed not to make such claims, except the Soviet Union and the United States, who reserved the right to make a claim. An undefined area from 20°W to 45°E was historically considered potentially unclaimed; the Norwegian claim in Queen Maud Land was interpreted as covering the coastal regions, but not continuing all the way to the South Pole. In 2015, the claim was extended to reach as far as 90°S.[36] |

テラ・ヌリウスの現在の主張 エジプトの領土(黄色)、スーダンの領土(青色)、係争中のハライブ・トライアングル(薄緑色)とワディ・ハルファ・サリエント(濃緑色)、未申請のビル・タウィル(白色)を示す簡略地図。 このうち、3つの土地は無領土であると主張されることがある: エジプトとスーダンに隣接するビル・タウィル、クロアチアとセルビアの国境に沿った4つの小さな地域、そして南極大陸のマリー・バード・ランドである。 ビル・タウィル 主な記事 ビル・タウィル さらに詳しい情報 エジプトとスーダンの国境 エジプトとスーダンの間には、2,060 km2 (800 sq mi)の内陸領土であるビル・タウィルがあり、1899年と1902年に引かれた国境線の不一致によって生まれた。一方の国境線はビル・タウィルをスーダ ンの支配下に置き、ハライブ・トライアングルをエジプトの支配下に置いたが、もう一方の国境線はその逆であった。各国は、紅海に隣接する東側のハライブ・ トライアングルを領有する国境線を主張しているが、その副作用として、ビル・タウィルはどちらの国にも領有されていない(それぞれが相手の領有権を主張し ている)。ビル・タウィルには定住人口はいないが、ベドウィンがこの地域を歩き回っている[b]。 ゴルニャ・シガとその他のポケット 主な記事 クロアチア・セルビア国境紛争  バチュカとバランジャ地域におけるクロアチアとセルビアの国境紛争。クロアチアの主張は赤線に対応し、セルビアの主張はドナウ川の流路に対応している。 セルビアの支配下にあり、クロアチアが領有権を主張している。 事実上クロアチアの支配下にあるが、クロアチアもセルビアも領有権を主張していない。 クロアチアとセルビアはドナウ川東岸のいくつかの小さな地域を争っている。しかし、ゴルニャ・シガを最大とする西岸の4つの小地域は、両国とも領有権を主 張していない。クロアチアは、紛争地域はテラ・ヌリアスではなく、国境を解決するためにセルビアと交渉していると述べている[34]。  マリー・バード・ランド 主な記事 マリー・バード・ランド こちらも参照のこと: 南極大陸の領有権主張 マリー マリー・バード・ランド 20世紀前半にいくつかの国が南極大陸の一部の領有権を主張したが、マリー・バード・ランドの大部分(西経150度から東経90度までの部分)を含む残り の部分は、どの主権国家も領有権を主張していない。1959年に締結された南極条約では、ソビエト連邦とアメリカが領有権を留保した以外は、領有権を主張 しないことに合意している。 クィーン・モード・ランドにおけるノルウェーの領有権主張は、沿岸地域をカバーすると解釈されていたが、南極点まで続いているわけではなかった。2015年、請求権は南緯90度まで拡大された[36]。 |

| Historical claims of terra nullius Several territories have been claimed to be terra nullius. In a minority of those claims, international and domestic courts have ruled on whether the territory is or was terra nullius or not. Africa Burkina Faso and the Niger A narrow strip of land adjacent to two territorial markers along the Burkina Faso–Niger border was claimed by neither country until the International Court of Justice settled a more extensive territorial dispute in 2013. The former unclaimed territory was awarded to the Niger.[37] Western Sahara Main article: Advisory opinion on Western Sahara At the request of Morocco, the International Court of Justice in 1975 addressed whether Western Sahara was terra nullius at the time of Spanish colonization in 1885. The court found in its advisory opinion that Western Sahara was not terra nullius at that time. Asia Pinnacle Islands (Diaoyu Islands/Senkaku Islands) A disputed archipelago in the East China Sea, the uninhabited Pinnacle Islands, were claimed by Japan to have become part of its territory as terra nullius in January 1895, following the Japanese victory in the First Sino-Japanese War. However, this interpretation is not accepted by the People's Republic of China (PRC) and the Republic of China (Taiwan), both of whom claim sovereignty over the islands. Saudi–Iraqi neutral zone Saudi Arabian–Iraqi neutral zone Saudi–Kuwaiti neutral zone Saudi Arabian–Kuwaiti neutral zone Scarborough Shoal (South China Sea) The People's Republic of China, the Republic of China (Taiwan) and the Philippines claim the Scarborough Shoal or Panatag Shoal or Huangyan Island (simplified Chinese: 黄岩岛; traditional Chinese: 黃巖島; pinyin: Huángyán Dǎo), nearest land being the island of Luzon at 220 km (119 nmi), located in the South China Sea. The Philippines claims it under the principles of terra nullius and EEZ (exclusive economic zone), while both China and Taiwan continue claiming the shoal continuing from their predecessor, who claimed the shoal based on historical records that Chinese fishermen had discovered and mapped the shoal since the 13th century. Previously, the shoal was administered as part of Municipality of Masinloc, Province of Zambales for the Philippines. Since the Scarborough Shoal standoff in 2012, the shoal is administered as part of Xisha District, Sansha City, Hainan Province for the People's Republic of China. Taiwan places the shoal under the administration of Cijin District, Kaohsiung City, but do not hold effective control of the shoal.[38][39] The Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) denied the lawfulness of China's claim in 2016[40][41][42][43][44] , where China have rejected the ruling, calling it "ill-founded".[45] In 2019, Taiwan also rejected the ruling and have continued sending more naval vassals to the area.[46] [47] It has been speculated that Scarborough Shoal is a prime location for the construction of an artificial island [citation needed] and Chinese ships have been seen in the vicinity of the shoal. Analysis of photos has concluded that the ships lack dredging equipment and therefore represent no imminent threat of reclamation work.[48] Europe Ireland The term terra nullius has been applied by some modern academics in discussing the English colonisation of Ireland, although the term is not used in the international law sense and is often used as an analogy. Griffen and Cogliano state that the English viewed Ireland as a terra nullius.[49] In The Irish Difference: A Tumultuous History of Ireland’s Breakup With Britain, Fergal Tobin writes that "Ireland had no tradition of unified statehood and no culturally unified establishment. Indeed, it had never known any kind of political unity until a version of it was imposed by Cromwell's sword […] So the English Protestant interest […] came to regard Ireland as a kind of terra nullius."[50] Similarly, Bruce McLeod writes in The Geography of Empire in English Literature, 1580-1745 that "although the English were familiar with Ireland and its geography in comparison to North America, they treated Ireland as though it were terra nullius and thus easily and geometrically subdivided into territorial units."[51] Rolston and McVeigh trace this attitude back to Gerald of Wales (13th century), who wrote "This people despises work on the land, has little use for the money-making of towns, contemns the rights and privileges of citizenship, and desires neither to abandon, nor lose respect for, the life which it has been accustomed to lead in the woods and countryside." The semi-nomadism of the native Irish meant that some English judged them not to be productive users of land. However, Rolston and McVeigh state that Gerald made it clear that Ireland was acquired by conquest and not through the occupation of terra nullius.[52] Rockall According to Ian Mitchell, Rockall was terra nullius until it was claimed by the United Kingdom in 1955. It was formally annexed in 1972.[53][54][55] Sealand In 1967, Paddy Roy Bates claimed an abandoned British anti-aircraft gun tower in the North Sea as the "Principality of Sealand". The structure is now within British territorial waters and no country recognises Sealand.[56] Svalbard Denmark–Norway, the Dutch Republic, the Kingdom of Great Britain, and the Kingdom of Scotland all claimed sovereignty over the archipelago of Svalbard in the seventeenth century, but none permanently occupied it. Expeditions from each of these polities visited Svalbard principally during the summer for whaling, with the first two sending a few wintering parties in the 1620s and 1630s.[57] During the 19th century, both Norway and Russia made strong claims to the archipelago. In 1909, Italian jurist Camille Piccioni described Spitzbergen, as it was then known, as terra nullius: The issue would have been simpler if Spitzbergen, until now terra nullius, could have been attributed to a single state, for reasons of neighbouring or earlier occupation. But this is not the case and several powers can, for different reasons, make their claims to this territory which still has no master.[58] The territorial dispute was eventually resolved by the Svalbard Treaty of 9 February 1920 which recognized Norwegian sovereignty over the islands. North America Canada Joseph Trutch, the first Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia, insisted that First Nations had never owned land, and thus their land claims could safely be ignored. It is for this reason that most of British Columbia remains unceded land.[59] In Guerin v. The Queen, a Canadian Supreme Court decision of 1984 on aboriginal rights, the Court stated that the government has a fiduciary duty toward the First Nations of Canada and established aboriginal title to be a sui generis right. Since then there has been a more complicated debate and a general narrowing of the definition of "fiduciary duty".[citation needed] Eastern Greenland Norway occupied and claimed parts of (then uninhabited) eastern Greenland in 1931, claiming that it constituted terra nullius and calling the territory Erik the Red's Land.[60] The Permanent Court of International Justice ruled against the Norwegian claim. The Norwegians accepted the ruling and withdrew their claim. United States A similar concept of "uncultivated land" was employed by John Quincy Adams to identify supposedly unclaimed wilderness.[61] Guano Islands The Guano Islands Act of 18 August 1856 enabled citizens of the U.S. to take possession of islands containing guano deposits. The islands can be located anywhere, so long as they are not occupied and not within the jurisdiction of other governments. It also empowers the President of the United States to use the military to protect such interests, and establishes the criminal jurisdiction of the United States. Oceania Australia Further information: Indigenous land rights in Australia The British penal colony of New South Wales, which included more than half of mainland Australia, was proclaimed by Governor Captain Arthur Phillip at Sydney in February 1788.[62] At the time of British colonisation, Aboriginal Australians had occupied Australia for at least 50,000 years. They were complex hunter-gatherers with diverse economies and societies and about 250 different language groups.[63][64] The Aboriginal population of the Sydney area was an estimated 4,000 to 8,000 people who were organised in clans which occupied land with traditional boundaries.[65][66] There is debate over whether Australia was colonised by the British from 1788 on the basis that the land was terra nullius. Frost, Attwood and others argue that even though the term terra nullius was not used in the eighteenth century, there was widespread acceptance of the concept that a state could acquire territory through occupation of land that was not already under sovereignty and was uninhabited or inhabited by peoples who had not developed permanent settlements, agriculture, property rights or political organisation recognised by European states.[67] Borch, however, states that, "it seems much more likely that there was no legal doctrine maintaining that inhabited land could be regarded as ownerless, nor was this the basis of official policy, in the eighteenth century or before. Rather it seems to have developed as a legal theory in the nineteenth century.”[68] In Mabo v Queensland (No 2) (1992), Justice Dawson stated, "Upon any account, the policy which was implemented and the laws which were passed in New South Wales make it plain that, from the inception of the colony, the Crown treated all land in the colony as unoccupied and afforded no recognition to any form of native interest in the land."[69] Stuart Banner states that the first known Australian legal use of the concept (although not the term) terra nullius was in 1819 in a tax dispute between Barron Field and the Governor of New South Wales Lachlan Macquarie. The matter was referred to British Attorney General Samuel Shepherd and Solicitor General Robert Gifford who advised that New South Wales had not been acquired by conquest or cession, but by possession as "desert and uninhabited".[70][71] In 1835, a Proclamation by Governor Bourke stated that British subjects could not obtain title over vacant Crown land directly from Aboriginal Australians.[72] In R v Murrell (1836) Justice Burton of the Supreme Court of New South Wales stated, "although it might be granted that on the first taking possession of the Colony, the aborigines were entitled to be recognised as free and independent, yet they were not in such a position with regard to strength as to be considered free and independent tribes. They had no sovereignty."[73] In the Privy Council case Cooper v Stuart (1889), Lord Watson stated that New South Wales was, "a tract of territory practically unoccupied, without settled inhabitants or settled law, at the time when it was peacefully annexed to the British dominions."[74] In the Mabo Case (1992), the High Court of Australia considered the question of whether Australia had been colonised by Britain on the basis that it was terra nullius. The court did not consider the legality of the initial colonisation as this was a matter of international law and, "The acquisition of territory by a sovereign state for the first time is an act of state which cannot be challenged, controlled or interfered with by the courts of that state."[75] The questions for decision included the implications of the initial colonisation for the transmission of the common law to New South Wales and whether the common law recognised that the Indigenous inhabitants had any form of native title to land. Dismissing a number of previous authorities, the court rejected the "enlarged notion of terra nullius", by which lands inhabited by Indigenous peoples could be considered desert and uninhabited for the purposes of Australian municipal law.[76] The court found that the common law of Australia recognised a form of native title held by the Indigenous peoples of Australia and that this title persisted unless extinguished by a valid exercise of sovereign power inconsistent with the continued right to enjoy native title.[77] Clipperton Island The sovereignty of Clipperton Island was settled by arbitration between France and Mexico. King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy rendered a decision in 1931 that the sovereignty of Clipperton Island belongs to France from the date of November 17, 1858. The Mexican claim was rejected for lack of proof of prior Spanish discovery and, in any event, no effective occupation by Mexico before 1858, when the island was therefore territorium nullius, and the French occupation then was sufficient and legally continuing.[78] South Island of New Zealand In 1840, the newly appointed Lieutenant-Governor of New Zealand, Captain William Hobson of the Royal Navy, following instructions from the British government, declared the Middle Island of New Zealand (later known as the "South Island") as terra nullius,[citation needed] and therefore fit for occupation by European settlers. Hobson's decision was also influenced by a small party of French settlers heading towards Akaroa on Banks Peninsula to settle in 1840.[79][need quotation to verify] South America Patagonia Patagonia was according to some considerations regarded a terra nullius in the 19th century. This notion ignored the Spanish Crown's recognition of indigenous Mapuche sovereignty and is considered by scholars Nahuelpán and Antimil to have set the stage for an era of Chilean "republican colonialism".[80] |

テラ・ヌリウスの歴史的主張 いくつかの領土がテラ・デュ・ルリアスであると主張されてきた。これらの主張のうち少数派ではあるが、国際裁判所や国内裁判所が、その領土がテラ・ヌリアスであるか否か、あるいはテラ・ヌリアスであったか否かについて判決を下している。 アフリカ ブルキナファソとニジェール ブルキナファソとニジェールの国境沿いの2つの領土標識に隣接する狭い土地は、2013年に国際司法裁判所がより広範な領土紛争に決着をつけるまで、どちらの国も領有権を主張していなかった。かつての未申請領土はニジェールに与えられた[37]。 西サハラ 主な記事 西サハラに関する勧告的意見 モロッコの要請を受けた国際司法裁判所は1975年、西サハラが1885年にスペインが植民地化した時点ではテラ・ヌリアスであったかどうかを扱った。裁判所は勧告的意見の中で、西サハラは当時テラ・ヌリウスではなかったと判断した。 アジア ピナクル諸島(釣魚島/尖閣諸島) 東シナ海に浮かぶ群島で、無人島である尖閣諸島は、日清戦争での日本の勝利後、1895年1月に日本の領土になったと主張した。しかし、この解釈は中華人民共和国(PRC)と中華民国(台湾)には受け入れられておらず、両者とも島の領有権を主張している。 サウジアラビア・イラク中立地帯 サウジアラビア・イラク中立地帯 サウジ・クウェート中立地帯 サウジアラビア・クウェート中立地帯 スカボロー浅瀬(南シナ海) 中華人民共和国、中華民国(台湾)およびフィリピンは、南シナ海にあるスカボロー諸島またはパナタグ諸島または黄岩島(簡体字:黄岩岛、繁体字:黃巖島、 ピンイン:Huángyán Dǎo)の領有権を主張している。中国と台湾は、13世紀以来、中国の漁民が浅瀬を発見し、地図を作成したという歴史的記録に基づいて浅瀬の領有権を主張 してきた先代から引き続き、浅瀬の領有権を主張している。 以前、この浅瀬はフィリピンのザンバレス州マシンロック市の一部として管理されていた。2012年のスカボロー諸島の対立以降は、中華人民共和国の海南省 三沙市西沙区の一部として管理されている。台湾は同魚礁を高雄市旗津区の管理下に置いているが、実効支配はしていない[38][39]。 常設仲裁裁判所(PCA)は2016年に中国の主張の合法性を否定しており[40][41][42][43][44]、中国は「根拠がない」として判決を拒否している[45]。 2019年、台湾も判決を拒否し、さらに海軍の臣下を送り続けている[46][47]。 スカボロー浅瀬は人工島建設の一等地であると推測されており[要出典]、中国船は浅瀬付近で目撃されている。写真を分析した結果、これらの船には浚渫装置がないため、埋め立て工事の差し迫った脅威にはならないと結論付けられている[48]。 ヨーロッパ アイルランド テラ・ヌリウスという用語は、イギリスによるアイルランドの植民地化を論じる際に、一部の現代学者によって適用されているが、この用語は国際法の意味では 使われておらず、類推として使われることが多い。グリフェンとコリアーノは、イギリス人はアイルランドをテラ・ヌリウスと見なしていたと述べている [49]: ファーガル・トビンは『The Irish Difference: A Tumultuous History of Ireland's Breakup With Britain』の中で、「アイルランドには統一国家の伝統も文化的に統一された体制もなかった。実際、クロムウェルの剣によって政治的統一が押しつけら れるまで、アイルランドはいかなる政治的統一も知らなかった[中略]そのため、イギリスのプロテスタントの関心は[中略]アイルランドを一種のテラ・ヌリ ウスとみなすようになった」[50]と同様に、ブルース・マクラウドは『The Geography of Empire in English Literature, 1580-1745』のなかで、「イギリス人はアイルランドとその地理を北米と比較して熟知していたにもかかわらず、アイルランドをテラ・ヌリウスである かのように扱い、そのため領土単位に容易かつ幾何学的に細分化した」と書いている。 「51] ロルストンとマクヴェイは、この態度をウェールズのジェラルド(13世紀)まで遡り、彼は「この民族は土地での労働を軽蔑し、町での金儲けをほとんど利用 せず、市民権の権利と特権を軽んじ、森や田園地帯で送ることに慣れてきた生活を放棄することも、尊敬を失うことも望まない」と書いている。アイルランド先 住民の半遊牧民的な生活から、イングランド人の中には彼らを土地の生産的な利用者ではないと判断する者もいた。しかし、ロルストンとマクヴェイは、ジェラ ルドがアイルランドは征服によって獲得したものであり、テラ・ヌリウスの占領によって獲得したものではないことを明確にしたと述べている[52]。 ロッコール イアン・ミッチェルによれば、ロックオールは1955年にイギリスが領有権を主張するまでテラ・ヌリアスであった。1972年に正式に併合された[53][54][55]。 シーランド 1967年、パディ・ロイ・ベイツは北海にあるイギリスの廃墟となった高射砲塔を「シーランド公国」と主張した。この建造物は現在イギリスの領海内にあり、シーランドを承認している国はない[56]。 スヴァールバル デンマーク・ノルウェー、オランダ共和国、グレートブリテン王国、スコットランド王国はいずれも17世紀にスヴァールバル諸島の領有権を主張したが、永久 に占領した国はなかった。これらの国の探検隊は、主に捕鯨のために夏季にスヴァールバル諸島を訪れ、最初の2カ国は1620年代と1630年代に少数の越 冬隊を派遣した[57]。 19世紀には、ノルウェーとロシアがスバールバル諸島の領有権を強く主張した。1909年、イタリアの法学者カミーユ・ピッチョーニは、当時知られていたスピッツベルゲンをテラ・ヌリウスと表現した: もしスピッツベルゲンがテラ・ヌリウスであったとしても、隣国や以前からの占領という理由で単一の国家に帰属していれば、問題はもっと単純だっただろう。 しかし、そうではなく、複数の国家がさまざまな理由で、いまだに主がいないこの領土に対する領有権を主張することができるのである[58]。 領土問題は最終的に1920年2月9日のスヴァールバル条約によって解決され、島々に対するノルウェーの主権が認められた。 北米 カナダ ブリティッシュ・コロンビア州の初代副知事ジョセフ・トラッチは、ファースト・ネーションズは土地を所有したことがないため、彼らの土地主張は無視しても問題ないと主張した。ブリティッシュコロンビア州の大半が未譲渡地であるのはこのためである[59]。 先住民の権利に関する1984年のカナダ最高裁判決であるGuerin v. The Queenでは、政府はカナダの先住民に対して信認義務を負うとし、先住民の所有権は特別な権利であるとした。それ以来、より複雑な議論が行われ、「信認 義務」の定義が一般的に狭められている[要出典]。 東グリーンランド ノルウェーは1931年にグリーンランド東部(当時は無人)の一部を占領し、領有権を主張し、その領土をエリック・ザ・レッズ・ランドと呼んだ[60]。 国際司法裁判所はノルウェーの主張を退ける判決を下した。ノルウェー側は判決を受け入れ、主張を撤回した。 アメリカ合衆国 ジョン・クインシー・アダムズは、未開拓の原野を特定するために「未開拓地」という同様の概念を用いた[61]。 グアノ諸島 1856年8月18日に制定されたグアノ諸島法により、アメリカ市民はグアノが堆積している島を所有できるようになった。島は、占領されておらず、他国政 府の管轄下にない限り、どこにあってもよい。また、合衆国大統領にそのような権益を保護するために軍隊を使用する権限を与え、合衆国の刑事裁判権を確立し ている。 オセアニア オーストラリア さらに詳しい情報 オーストラリアの先住民の土地の権利 オーストラリア本土の半分以上を含むイギリスの流刑地ニューサウスウェールズは、1788年2月にシドニーでアーサー・フィリップ総督によって宣言された [62]。イギリスの植民地化当時、オーストラリア先住民は少なくとも5万年前からオーストラリアに居住していた。彼らは多様な経済と社会を持ち、約 250の異なる言語グループを持つ複雑な狩猟採集民であった[63][64]。シドニー地域のアボリジニの人口は推定4,000~8,000人で、伝統的 な境界線を持つ土地を占有する氏族で組織されていた[65][66]。 オーストラリアが1788年からイギリスによって植民地化された土地であるかどうかについては、議論がある。フロスト、アッ トウッドらは、18世紀にはテラ・ヌリウスという言葉は使われていなかったにもかかわらず、国家がすでに 主権の下になく、永住地、農業、財産権、政治組織などをヨーロッパ国家が認めていない民族が居住してい ない土地を占領して領土を獲得することができるという概念が広く受け入れられていたと主張してい る[67]。 [しかし、ボルヒは、「18世紀以前には、人が居住する土地は所有者のいない土地とみなすことができるとする法理は存在しなかったし、これが公式政策の基 礎となることもなかった。むしろそれは19世紀に法理論として発展したようである」[68]。 Mabo v. Queensland (No 2) (1992)において、ドーソン判事は、「どのように考えても、ニュー・サウス・ウェールズで実施された政策と成立した法律は、植民地の設立当初から、王 室が植民地内のすべての土地を無所有地として扱い、土地に対するいかなる形態の先住民の利益も認めなかったことを明白にしている」と述べている[69]。 スチュアート・バナーによれば、テラ・ヌリウスという概念(用語ではないが)がオーストラリアで初めて法的に使用されたのは、1819年、バロン・フィー ルドとニュー・サウス・ウェールズ州知事ラクラン・マッコーリーとの間の課税紛争であった。この問題はイギリスの司法長官サミュエル・シェパードと司法長 官ロバート・ギフォードに付託され、彼らはニュー・サウス・ウェールズは征服や割譲によって獲得されたものではなく、「砂漠で無人」であったとして領有さ れたものであると助言した[70][71]。 1835年、バーク総督による布告は、英国臣民は空き地の国有地の所有権をオーストラリア先住民から直接取得することはできないとした[72]。 ニュー・サウス・ウェールズ州最高裁判所のR v Murrell判事(1836年)において、バートン判事は、「植民地を最初に領有した時点で、アボリジニは自由で独立した部族として認められる権利が あったことは認められるかもしれないが、しかし、彼らは自由で独立した部族とみなされるほど、力に関して有利な立場にあったわけではない。彼らには主権が なかった」[73]。 枢密院のクーパー対スチュアート事件(1889年)において、ワトソン卿はニュー・サウス・ウェールズが「平和的にイギリス領に併合された時点では、定住者も定住法もない、実質的に未占領の領土であった」と述べている[74]。 マボ事件(1992年)において、オーストラリア高等法院は、オーストラリアがテラ・ヌリウスであることを根拠に、イギリスによって植民地化されたかどう かという問題を検討した。裁判所は、最初の植民地化の合法性は国際法の問題であり、「主権国家が初めて領土を獲得することは国家の行為であり、その国家の 裁判所が異議を唱えたり、管理したり、干渉したりすることはできない」[75]として、最初の植民地化がニュー・サウス・ウェールズ州へのコモンローの継 承に与える影響や、コモンローが先住民の土地に対する何らかの形の土着権原を認めているかどうかなどを判断の対象とした。裁判所は、多くの過去の判例を退 けて、先住民が居住していた土地はオーストラリアの自治体法の目的上、砂漠で無人であるとみなすことができるという「テラ・ヌリウスの拡大概念」を否定し た[76]。裁判所は、オーストラリアのコモンローは、オーストラリアの先住民が所有していた土着の所有権を認めており、土着の所有権を享受し続ける権利 と矛盾する主権権力の有効な行使によって消滅しない限り、この所有権は存続すると判断した[77]。 クリッパートン島 クリッパートン島の領有権は、フランスとメキシコの仲裁によって決着した。イタリア国王ビクトル・エマニュエル3世は1931年、クリッパートン島の主権 は1858年11月17日からフランスに帰属するという決定を下した。メキシコの主張は、スペインによる先行発見の証拠がなく、いずれにせよ、1858年 以前にメキシコによる有効な占領が行われておらず、そのため島は領有権(territorium nullius)であったため、当時のフランスの占領は十分であり、法的に継続するものであったとして却下された[78]。 ニュージーランド南島 1840年、新たにニュージーランド副知事に任命されたイギリス海軍のウィリアム・ホブソン大尉は、イギリス政府の指示に従い、ニュージーランド中島(後 に「南島」として知られる)をテラ・ヌリウスと宣言した[要出典]。ホブソンの決定は、1840年にバンクス半島のアカロアに向かって入植を目指したフラ ンス人入植者の小集団にも影響を与えた[79][要検証]。 南米 パタゴニア パタゴニアは19世紀には無領土と見なされていた。この考え方はスペイン王室による先住民マプーチェの主権の承認を無視したものであり、学者のナウエルパンやアンティミルによってチリの「共和制植民地主義」の時代を築いたと考えられている[80]。 |

| Aboriginal title Australian history wars Henry A. Reynolds Native title in Australia Mabo v Queensland Wik Peoples v Queensland Allodial title Antarctic Treaty System Common heritage of humanity Discovery doctrine Extraterrestrial real estate Frontier Frontier thesis Indigenous land rights International waters International zones Land claim Manifest destiny No man's land Res nullius (original and broader formulation in law) Space colonization Space law Uncontacted peoples Wilderness Appropriation concepts Adverse possession Homestead principle Original appropriation Pedis possessio Seasteading Usucaption Uti possidetis |

アボリジニの称号 オーストラリア史戦争 ヘンリー・A・レイノルズ オーストラリアにおける先住民の権利 マボ対クイーンズランド州 ウィック・ピープルズ対クイーンズランド州 アローディアル・タイトル 南極条約制度 人類共通の遺産 ディスカバリー・ドクトリン 地球外不動産 フロンティア フロンティアテーゼ 先住民の土地の権利 国際水域 国際水域 土地の主張 マニフェスト・デスティニー 無人の土地 レス・ヌリウス(法における原初的かつ広範な定式化) 宇宙植民地化 宇宙法 未接触民族 原生地域 収用の概念 不利な占有 ホームステッドの原則 原初的帰属 所有権 シースティード 使用許諾 ウティ・ポシデティス |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Terra_nullius |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆