ザ・ニュー・ニグロ

The New Negro

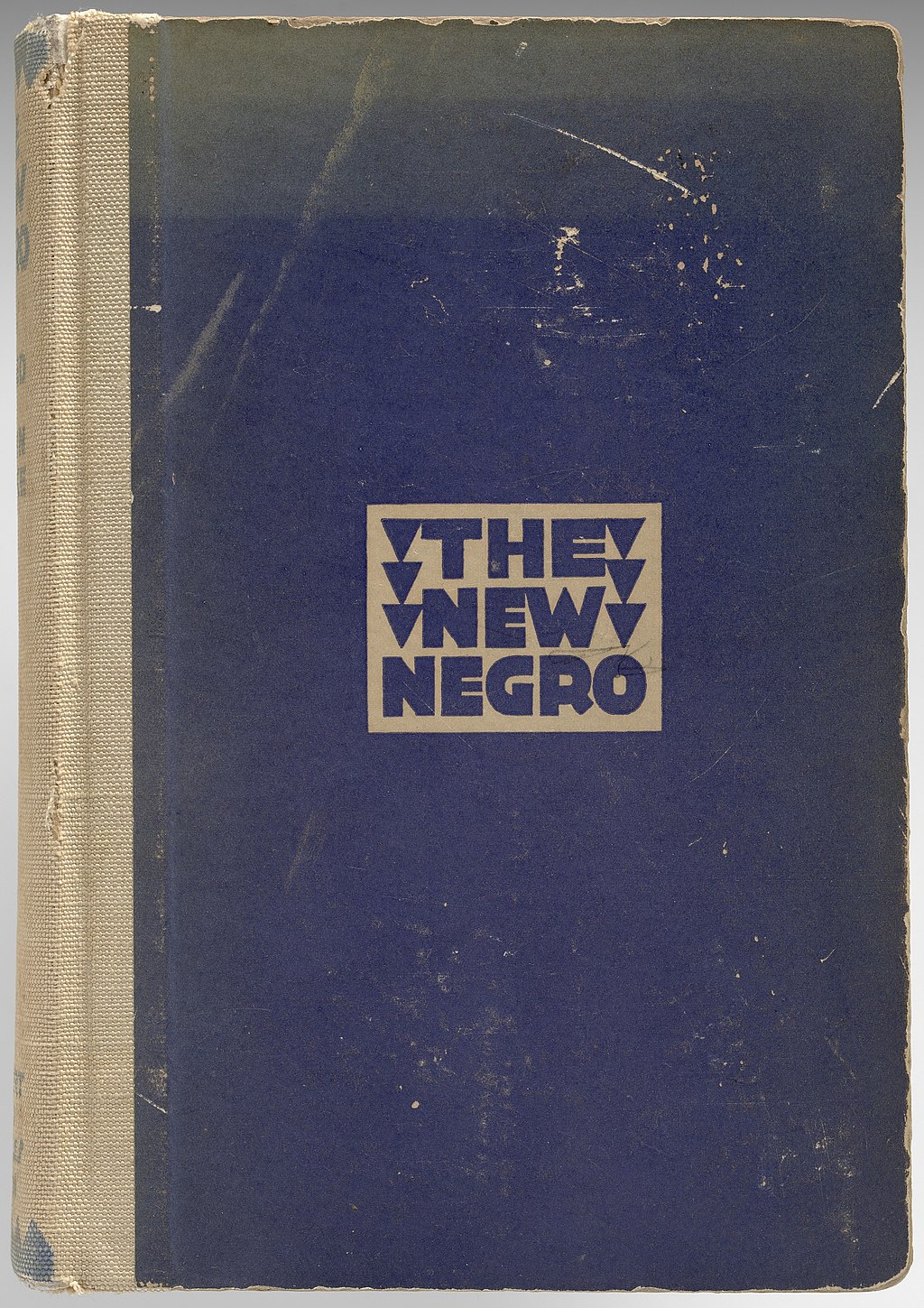

☆『ニュー・ニグロ:解釈』 (1925年)は、ワシントンD.C.在住でハーバード大学で教鞭をとっていたアラン・ロックが編集した、アフリカおよびアフリカ系アメリカ人の芸術と文 学に関する小説、詩、エッセイのアンソロジーである。 。 ニュー・ニグロ運動やハーレム・ルネサンスの盛り上がりから生まれた創造的な努力の結晶として、この本は文学の研究者や批評家たちから、この運動の決定版 とみなされている。[2] 『The New Negro: 「The Negro Renaissance(黒人ルネサンス)」と題された第1部には、ロックの表題論文「The New Negro(新しい黒人)」をはじめ、カウンティー・カレン、ラングストン・ヒューズ、ゾラ・ニール・ハーストン、クロード・マッケイ、ジーン・トゥー マー、エリック・ウォーロンドなどの作家によるノンフィクションのエッセイ、詩、小説が収録されている。 『The New Negro: An Interpretation』では、アフリカ系アメリカ人が社会的、政治的、芸術的な変革をどのように求めていたかが詳しく述べられている。ロックは、 アフリカ系アメリカ人が社会における自分たちの立場を受け入れるのではなく、公民権を擁護し要求していると捉えていた。さらに、このアンソロジーは、単純 化を拒む黒人のアイデンティティの新しいビジョンで、古い固定観念を置き換えることを目指していた。このアンソロジーに収められたエッセイや詩は、現実の 出来事や経験を反映している。 このアンソロジーは、白人の中流階級と同等の市民権を求めた中流階級のアフリカ系アメリカ人市民の声を反映している。しかし、ラングストン・ヒューズなど の作家は、労働者階級の声を代弁しようとした。[3]

| The New Negro: An

Interpretation (1925) is an anthology of fiction, poetry, and essays on

African and African-American art and literature edited by Alain Locke,

who lived in Washington, DC, and taught at Howard University during the

Harlem Renaissance.[1] As a collection of the creative efforts coming

out of the burgeoning New Negro Movement or Harlem Renaissance, the

book is considered by literary scholars and critics to be the

definitive text of the movement.[2] Part 1 of The New Negro: An

Interpretation, titled "The Negro Renaissance", includes Locke's title

essay "The New Negro", as well as nonfiction essays, poetry, and

fiction by writers including Countee Cullen, Langston Hughes, Zora

Neale Hurston, Claude McKay, Jean Toomer, and Eric Walrond. The New Negro: An Interpretation dives into how the African Americans sought social, political, and artistic change. Instead of accepting their position in society, Locke saw the New Negro as championing and demanding civil rights. In addition, his anthology sought to change old stereotypes and replace them with new visions of black identity that resisted simplification. The essays and poems in the anthology mirror real life events and experiences.[3] The anthology reflects the voice of middle-class African-American citizens that wanted to have equal civil rights like their white, middle-class counterparts. However, some writers, such as Langston Hughes, sought to give voice to the lower, working class.[3] |

『ニュー・ニグロ:解釈』(1925年)は、ワシントンD.C.在住で

ハーバード大学で教鞭をとっていたアラン・ロックが編集した、アフリカおよびアフリカ系アメリカ人の芸術と文学に関する小説、詩、エッセイのアンソロジー

である。 。

ニュー・ニグロ運動やハーレム・ルネサンスの盛り上がりから生まれた創造的な努力の結晶として、この本は文学の研究者や批評家たちから、この運動の決定版

とみなされている。[2] 『The New Negro: 「The Negro

Renaissance(黒人ルネサンス)」と題された第1部には、ロックの表題論文「The New

Negro(新しい黒人)」をはじめ、カウンティー・カレン、ラングストン・ヒューズ、ゾラ・ニール・ハーストン、クロード・マッケイ、ジーン・トゥー

マー、エリック・ウォーロンドなどの作家によるノンフィクションのエッセイ、詩、小説が収録されている。 『The New Negro: An Interpretation』では、アフリカ系アメリカ人が社会的、政治的、芸術的な変革をどのように求めていたかが詳しく述べられている。ロックは、 アフリカ系アメリカ人が社会における自分たちの立場を受け入れるのではなく、公民権を擁護し要求していると捉えていた。さらに、このアンソロジーは、単純 化を拒む黒人のアイデンティティの新しいビジョンで、古い固定観念を置き換えることを目指していた。このアンソロジーに収められたエッセイや詩は、現実の 出来事や経験を反映している。 このアンソロジーは、白人の中流階級と同等の市民権を求めた中流階級のアフリカ系アメリカ人市民の声を反映している。しかし、ラングストン・ヒューズなど の作家は、労働者階級の声を代弁しようとした。[3] |

| Structure Part 1: The Negro Renaissance Part 1 contains Locke's title essay "The New Negro", as well as the fiction and poetry sections. One of the poems, "White Houses", represents the African American's struggle to confront and challenge the White House and white America, in order to fight for civil rights. It shows a figure being shut out and left on the street to fend for himself. This is a figure who is not allowed the glory of the inside world, which represents the American ideals of freedom and opportunity. The hypothetical influence on the structure of race and ideology reverberated through "The New Negro."[4] Part 2: The New Negro in a New World "The New Negro in a New World" includes social and political analysis by writers including W. E. B. Du Bois, historian E. Franklin Frazier, Melville J. Herskovits, James Weldon Johnson, Paul U. Kellogg, Elise Johnson McDougald, Kelly Miller, Robert R. Moton, and activist Walter Francis White.[5] The book contains several portraits by Winold Reiss and illustrations by Aaron Douglas. It was published by Albert and Charles Boni, New York, in 1925.[6] |

構成 第1部:黒人ルネサンス 第1部には、ロックの表題論文「ザ・ニュー・ネグロ(The New Negro)」のほか、小説や詩のセクションが含まれている。詩のひとつ「ホワイト・ハウス(White Houses)」は、公民権獲得のためにホワイト・ハウスや白人アメリカ社会に立ち向かい、挑戦しようとするアフリカ系アメリカ人の苦闘を表現している。 この詩は、社会から締め出され、自力で生き延びるために路上に取り残された人物を描いている。これは、アメリカが理想とする自由や機会を内包する世界への 参加を許されない人物である。人種とイデオロギーの構造に及ぼすであろう仮説的な影響は、「ニュー・ネグロ」を通じて反響した。[4] 第2部:新世界におけるニュー・ネグロ 「新世界におけるニュー・ネグロ」には、W. E. B. デュボイス、歴史家のE. フランクリン・フレイジャー、メルヴィル・J・ハーコヴィッツ、ジェームズ・ウェルドン・ジョンソン、ポール・U・ケロッグ、エリス・ジョンソン・マク ドゥーガル、ケリー・ミラー、ロバート・R・モートン、活動家のウォルター・フランシス・ホワイトなどの作家による社会および政治的分析が含まれている。 この本には、ウィノルド・ライスの肖像画が数点と、アーロン・ダグラスのイラストが掲載されている。1925年にニューヨークのアルバート・アンド・チャールズ・ボニ社から出版された。[6] |

| Themes The "Old" vs The "New" Negro Locke commonly draws on the theme of the "Old" vs. the "New Negro". The Old Negro according to Locke was a "creature of moral debate and historical controversy".[7] The Old Negro was restricted by the inhumane conditions of slavery that he was forced to live in; historically traumatized due to events forced upon them and the social perspective of them as a whole. The Old Negro was something to be pushed and moved around and told what to do and worried about.[8] The Old Negro was a product of stereotypes and judgments that were put on them, not ones that they created. They were forced to live in a shadow of themselves and others' actions.[9] The New Negro, according to Locke, refers to Negroes who now have an understanding of themselves. They no longer lack self-respect and self-dependence, which has created a new dynamic and allowed the birth of the New Negro. The Negro spirituals revealed themselves; suppressed for generations under the stereotypes of Wesleyan hymn harmony, secretive, half-ashamed, until the courage of being natural brought them out—and behold, there was folk music.[8] They have become the Negro of today, which is also the changed Negro. Locke speaks about the migration having an effect on the Negro, leveling the playing field and increasing the realm of the Negro because they were moved out of the South and into areas where they could start over. The migration in a sense transformed Negroes and fused them together as they came from all over the world, all walks of life, and all different backgrounds.[10] |

テーマ 「旧」対「新」の黒人 ロックは一般的に「旧」対「新」の黒人というテーマを扱っている。ロックによると、「旧」の黒人は「道徳的議論と歴史的論争の産物」であった。[7] 「旧」の黒人は、奴隷として生きることを強いられた非人道的な状況によって制限されていた。歴史的に、彼らに押し付けられた出来事や、彼ら全体に対する社 会の見方によって心的外傷を負わされていた。年老いた黒人は、押しのけられ、あちこちに移動させられ、何をすべきかを指示され、心配させられる存在であっ た。[8] 老黒人は、彼ら自身が作り出したものではなく、彼らに押し付けられた固定観念や判断の産物であった。彼らは、自分自身や他者の行動の影の中で生きることを 強いられていた。[9] ロックによると、新しい黒人とは、自分自身を理解するようになった黒人のことを指す。彼らはもはや自尊心や自立心を欠くことはなく、それが新たな活力を生 み出し、ニュー・ネグロの誕生を可能にした。 黒人霊歌は、ウェスリアン派の賛美歌調和という固定観念の下で何世代にもわたって抑圧され、秘密主義で、半ば恥じらいを抱いていたが、自然体でいる勇気に よってそれが表に出され、フォークミュージックが誕生した。[8] 彼らは今日の黒人となり、それは変化した黒人でもある。ロックは、南部から離れ、再出発できる地域へと移動したことが、黒人たちに影響を与え、競争の場を 平準化し、黒人の領域を拡大したと述べている。この移動は、ある意味で黒人たちを変容させ、世界中から、あらゆる階層、あらゆる異なる背景を持つ人々が集 まったことで、彼らを融合させたのである。[10] |

| Self-expression One of the themes in Locke's anthology is self-expression. Locke states, "It was rather the necessity for fuller, truer self-expression, the realization of the unwisdom of allowing social discrimination to segregate him mentally, and a counter-attitude to cramp and fetter his own living—and so the 'spite-wall'... has happily been taken down."[8] He explains how it is important to realize that social discrimination can mentally affect you and bring you down. In order to break through that social discrimination, self-expression is needed to show who you truly are, and what you believe in. For Locke, this idea of self-expression is embedded in the poetry, art, and education of the Negro community.[8] Locke includes essays and poems in his anthology that emphasize the theme of self-expression. For example, the poem "Tableau," by Countée Cullen, is about a white boy and a black boy who walk with locked arms while others judge them.[11] It represents that despite the history of racial discrimination from the whites to the blacks, they show what they believe is right in their self-expression, no matter how other people judge them. Their self-expression allows them not to let the judgement make them conform to societal norms with the separation of blacks and whites. Cullen's poem, "Heritage," also shows how one finds self-expression in facing the weight of their own history as African Americans brought from Africa to America as slaves. Langston Hughes' poem, "Youth," puts forth the message that Negro youth have a bright future, and that they should rise together in their self-expression and seek freedom.[12] |

自己表現 ロックのアンソロジーのテーマのひとつは自己表現である。ロックは次のように述べている。「それは、より完全で真実味のある自己表現の必要性であり、社会 的な差別によって精神的に隔離されることの愚かさに気づき、自分の生き方を窮屈に束縛するような態度に反対する姿勢であった。そして、『意地悪な壁』は取 り払われたのだ。」[8] 彼は、社会的な差別が精神的に影響を与え、打ちのめす可能性があることを認識することがいかに重要であるかを説明している。その社会的差別を打ち破るため には、自己表現によって自分が本当はどのような人間で、何を信じているのかを示す必要がある。ロックにとって、自己表現という考え方は、黒人コミュニティ の詩、芸術、教育に組み込まれている。[8] ロックは、自己表現というテーマを強調するエッセイや詩を自身のアンソロジーに収録している。例えば、カウンティー・カレンの詩「タブロー」は、白人少年 と黒人少年が腕を組んで歩いていると、他の人々が彼らを判断するという内容である。[11] これは、白人から黒人への人種差別の歴史があったにもかかわらず、彼らは自己表現において、他人がどう判断しようとも、正しいと信じることを示すという意 味である。彼らの自己表現は、白人と黒人の分離という社会規範に適合させようとする判断をさせないことを可能にする。カレンの詩「遺産」も、アフリカから 奴隷としてアメリカに連れて来られたアフリカ系アメリカ人としての自らの歴史の重みに直面しながら、自己表現を見出す様子を描いている。ラングストン・ ヒューズの詩「青春」は、黒人の若者たちには明るい未来があり、彼らは自己表現において共に立ち上がり、自由を求めるべきだというメッセージを発してい る。[12] |

| Jazz and Blues The publication of Locke's anthology coincided with the rise of the Jazz Age, the Roaring Twenties, and the Lost Generation.[13] Locke's anthology acknowledges how the Jazz Age heavily impacted both individuals and the African-American community collectively, describing it as "a spiritual coming of age"[8] for African-American artists and thinkers, who seized upon their "first chances for group expression and self-determination." Harlem Renaissance poets and artists such as Langston Hughes, Claude McKay, and Georgia Douglas Johnson explored the beauty and pain of black life through jazz and blues and sought to define themselves and their community outside of white stereotypes.[14] Some of the most prominent African-American artists who were greatly influenced by the "New Negro" concept, as reflected in their music and concert works, were William Grant Still and Duke Ellington. Ellington, a renowned jazz artist, began to reflect the "New Negro" in his music, particularly in the jazz suite Black, Brown, and Beige.[15] The Harlem Renaissance prompted a renewed interest in black culture that was even reflected in the work of white artists, the most well known example being George Gershwin's Porgy and Bess.[16] |

ジャズとブルース ロックのアンソロジーの出版は、ジャズエイジ、狂騒の20年代、失われた世代の台頭と時を同じくしていた。[13] ロックのアンソロジーは、ジャズエイジが個人とアフリカ系アメリカ人社会全体に多大な影響を与えたことを認め、アフリカ系アメリカ人の芸術家や思想家に とって「精神的な成熟の時」[8] であったと表現している。彼らは「集団表現と自己決定の最初のチャンス」をつかんだのである。ラングストン・ヒューズ、クロード・マッケイ、ジョージア・ ダグラス・ジョンソンといったハーレム・ルネサンスの詩人や芸術家たちは、ジャズやブルースを通して黒人の生活の美しさと苦悩を探求し、白人によるステレ オタイプから離れて自分自身とコミュニティを定義しようとした。 「ニュー・ニグロ」の概念に強く影響を受けた著名なアフリカ系アメリカ人芸術家には、ウィリアム・グラント・スティルやデューク・エリントンなどがおり、 彼らの音楽やコンサート作品にその影響が反映されている。著名なジャズアーティストであったエリントンは、特にジャズ組曲『Black, Brown, and Beige』において、自身の音楽に「ニュー・ニグロ」の概念を反映し始めた。[15] ハーレム・ルネサンスは、黒人文化への関心を再び呼び起こし、それは白人のアーティストの作品にも反映された。最もよく知られている例は、ジョージ・ガー シュウィンの『ポーギーとベス』である。[16] |

| Reception The release of The New Negro and the writing and philosophy laid out by Locke were met with wide support. However, not everyone agreed with the New Negro movement and its ideas. Some criticized the author's selections, specifically Eric Walrond, who wrote the collection of short stories Tropic Death (1926). He found Locke's selected "contemporary black leaders inadequate or ineffective in dealing with the cultural and political aspirations of black masses".[17] Others, like the African-American academic Harold Cruse, even found the term New Negro "politically naive or overly optimistic". Even some modern late 20th-century authors such as Gilbert Osofsky were concerned that the ideas of the New Negro would go on to stereotype and glamorize black life.[18] Notable black scholar, author, and sociologist W. E. B. DuBois also had a different vision for the type of movement that should have stemmed from the New Negro ideology, hoping that it would go beyond an artistic movement and become more political in nature.[19] The New Negro did eventually influence a movement that went beyond being simply artistic and reshaped the minds of African Americans through political beliefs and promoted a sense of black involvement in the American government, but Locke was adamant about the movement going beyond the United States borders and being a worldwide awakening. Yet, due to the circumstances of the time and the tremendous diversity of opinions about the future of the movement, ideals stemming from the New Negro would not be widely acknowledged again until the civil rights movement (1954–1968).[20] Still, Locke would go on to continue defending the idea of the New Negro.[citation needed][8] |

レセプション 『ザ・ニュー・ニグロ』の発表とロックの著述および哲学は、幅広い支持を集めた。しかし、誰もがニュー・ニグロ運動とその考えに賛同していたわけではな い。著者の選択を批判する者もいた。特に、短編集『トロピック・デス』(1926年)を書いたエリック・ウォーロンドは、 彼は、ロックが選んだ「現代の黒人指導者たち」は「黒人の大衆の文化的、政治的願望に対処するには不適切であり、効果的ではない」と指摘した。[17] また、アフリカ系アメリカ人の学者ハロルド・クルーズのように、「ニュー・ニグロ」という用語を「政治的にナイーブで、楽観的すぎる」と考える者もいた。 ギルバート・オソフスキー(Gilbert Osofsky)のような20世紀後半の現代作家の中にも、ニュー・ニグロの考え方が黒人の生活をステレオタイプ化し、美化するものになるのではないかと 懸念する者もいた。著名な黒人学者、作家、社会学者のW. E. B. デュボイス(W. E. B. DuBois)は、ニュー・ニグロの思想から派生すべき運動のあり方について異なるビジョンを持っていた。芸術運動の域を超え、より政治的な性質を持つこ とを望んでいた。[19] ニュー・ニグロは最終的に、単なる芸術の域を超えた運動に影響を与え、政治的信念を通じてアフリカ系アメリカ人の意識を改革し、黒人のアメリカ政府への関 与意識を促進したが、ロックは、この運動が米国の国境を越え、世界的な覚醒となることを強く主張していた。しかし、当時の状況や運動の将来に関する意見の 多様性により、ニュー・ニグロの理想が再び広く認められることは、公民権運動(1954年~1968年)まで待たなければならなかった。[20] それでも、ロックはニュー・ニグロの考えを擁護し続けた。[要出典][8] |

| Legacy After Locke published The New Negro, the anthology seemed to have served its purpose in trying to demonstrate that African Americans were advancing intellectually, culturally, and socially. This was important in a time like the early 20th century when African Americans were still being looked down upon by most whites. They did not get the same respect as whites did, and that was changing. The publication of The New Negro was able to help many of the authors featured in the anthology get their names and work more widely known. The publication became a rallying cry to other African Americans to try and join the up-and-coming New Negro movement at the time. The New Negro was also instrumental in making strides toward dispelling negative stereotypes associated with African Americans.[21] Locke's legacy sparks a reoccurring interest in examining African culture and art. Not only was his philosophy important during the Harlem Renaissance period, but continuing today, researchers and academia continue to analyze Locke's work. His anthology The New Negro: An Interpretation has endured years of reprinting spanning from 1925 until 2015.[22] It has been reprinted in book form some 35 times since its original publication in 1925[22] by New York publisher Albert and Charles Boni.[23] The most recent reprint was published by Mansfield Center CT: Martino Publishing, 2015.[24] Beyond Locke's work being reprinted, his influences extend to other authors and academics interested in Locke's views and philosophy of African culture and art. Author Anna Pochmara wrote The Making of the New Negro.[25] Journal articles by Leonard Harris, Alain Locke and Community and Identity: Alain Locke's Atavism.[26][27] Essays by John C. Charles, What was Africa to him? : Alain Locke in the book New Voices on the Harlem Renaissance.[28] Locke's influence on the Harlem Renaissance encouraged artists and writers like Zora Neale Hurston to seek inspiration from Africa.[1] Artists Aaron Douglas, William H. Johnson, Archibald Motley, and Horace Pippin created artwork representing the "New Negro Movement" influenced by Locke's anthology.[29] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_New_Negro |

遺産 ロックが『ニュー・ニグロ』を出版した後、このアンソロジーは、アフリカ系アメリカ人が知的、文化的、社会的に進歩していることを示すという目的を果たし たように思われた。これは、20世紀初頭のように、アフリカ系アメリカ人が依然としてほとんどの白人に軽蔑されていた時代には重要なことだった。彼らは白 人が受けていたような尊敬を得ておらず、それは変わりつつあった。『ザ・ニュー・ニグロ』の出版は、このアンソロジーで取り上げられた多くの作家たちが、 その名と作品を広く知られるようになるのに役立った。この出版物は、当時台頭しつつあったニュー・ニグロ運動に参加しようとする他のアフリカ系アメリカ人 たちにとって、結集の掛け声となった。また、『ザ・ニュー・ニグロ』は、アフリカ系アメリカ人に対する否定的な固定観念を払拭する上でも大きな役割を果た した。 ロックの遺産は、アフリカ文化や芸術の研究への関心を再び呼び起こした。彼の哲学はハーレム・ルネサンス期に重要であっただけでなく、今日に至るまで、研 究者や学術界はロックの作品を分析し続けている。彼のアンソロジー『The New Negro: 解釈』は1925年から2015年まで、何年にもわたって再版され続けている。[22] 1925年にニューヨークのアルバート・アンド・チャールズ・ボニー出版社から初版が出版されて以来、書籍として35回ほど再版されている。[23] 最も新しい再版は、コネチカット州マンスフィールドセンターのマルティーノ出版から2015年に出版された。[24] ロックの著作が再版されただけでなく、ロックの作品やアフリカ文化や芸術に関する哲学に興味を持つ他の作家や学者にも影響を与えている。作家のアンナ・ポ チマラは『The Making of the New Negro』を著した。[25] レナード・ハリス、アラン・ロック、コミュニティとアイデンティティ: アラン・ロックの『アタヴィズム』[26][27]。ジョン・C・チャールズ著のエッセイ『彼にとってアフリカとは何だったのか?:アラン・ロック』は、 書籍『ハーレム・ルネサンスに関する新たな視点』に掲載されている[28]。 ハーレム・ルネサンスに対するロックの影響は、ゾラ・ニール・ハリストンなどの芸術家や作家にアフリカからインスピレーションを得るよう促した。[1] 芸術家のアーロン・ダグラス、ウィリアム・H・ジョンソン、アーチボルド・モトリー、ホレス・ピピンは、ロックのアンソロジーに影響を受けた「ニュー・ニ グロ・ムーブメント」を象徴する作品を制作した。[29] |

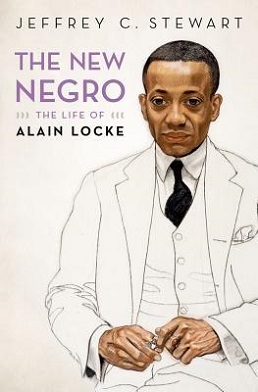

| FIRE!! The New Negro: The Life of Alain Locke Jeffrey C. Stewart  |

火事だ! ニュー・ニグロ:アラン・ロックの生涯 ジェフリー・C・スチュワート  |

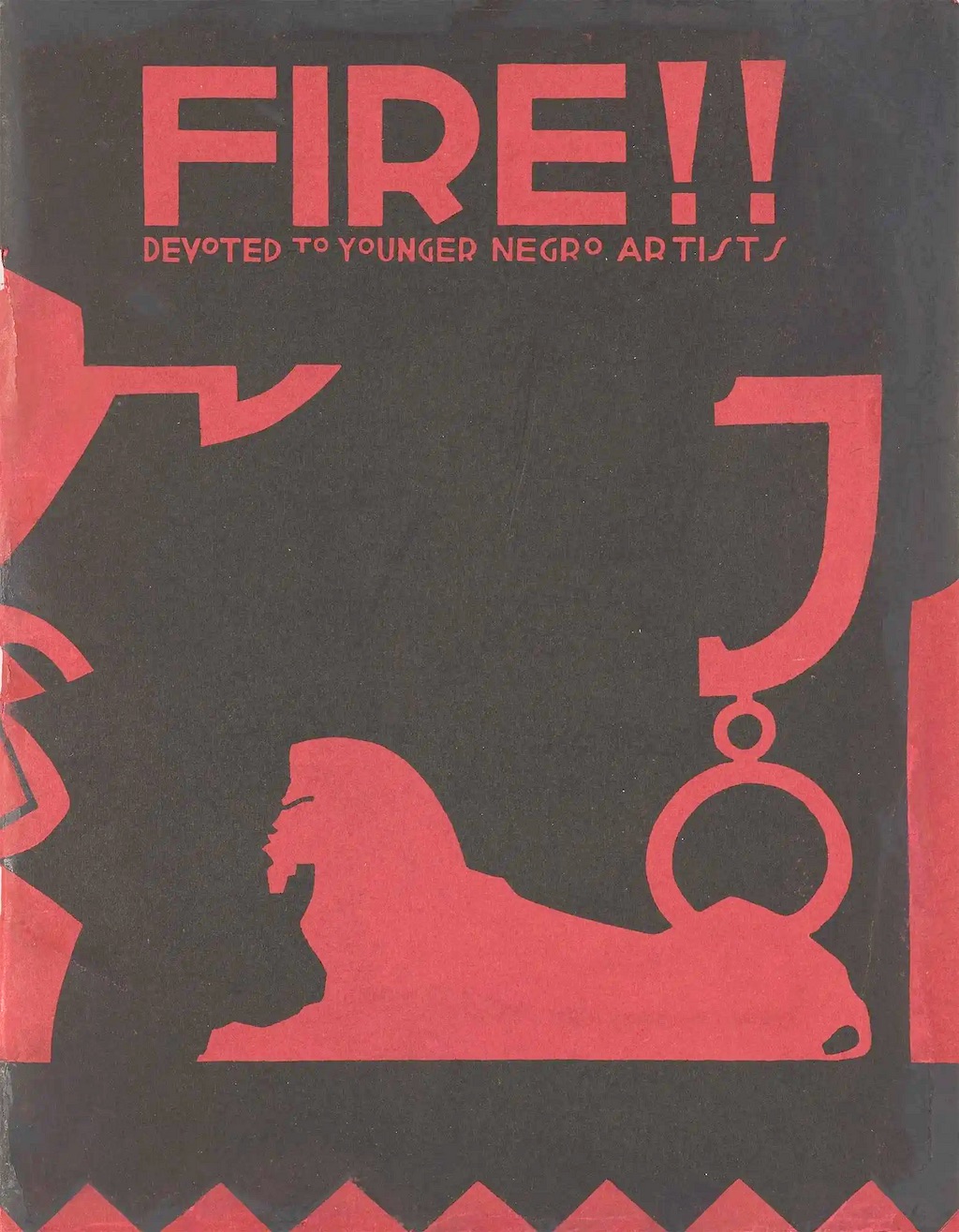

| Fire!! A Quarterly Devoted to the Younger Negro Artists

was an African American literary magazine published in New York City in

1926 during the Harlem Renaissance. The publication was started by

Wallace Thurman, Zora Neale Hurston, Aaron Douglas, John P. Davis,

Richard Bruce Nugent, Gwendolyn Bennett, Lewis Grandison Alexander,

Countee Cullen, and Langston Hughes. The magazine's title referred to

burning up old ideas, and Fire!! challenged the norms of the older

Black generation while featuring younger authors. The publishers

promoted a realistic style, using vernacular language and covering

controversial topics such as homosexuality and prostitution. Many

readers were offended, and some Black leaders denounced the magazine.

The endeavor was plagued by debt, and its quarters burned down, ending

the magazine after just one issue. |

『Fire!!

A Quarterly Devoted to the Younger Negro

Artists』は、1926年のハーレム・ルネサンス期にニューヨークで刊行されたアフリカ系アメリカ人の文学雑誌である。この雑誌は、ウォレス・サー

マン、ゾラ・ニール・ハーストン、アーロン・ダグラス、ジョン・P・デイヴィス、リチャード・ブルース・ニュージェント、グウェンドリン・ベネット、ルイ

ス・グランディソン・アレクサンダー、カウンティ・カレン、ラングストン・ヒューズらによって創刊された。雑誌のタイトルは古い考えを焼き尽くすという意

味で、Fire!!

は若い作家を起用しながら、古い世代の黒人の規範に異議を唱えた。出版社は、口語体を使用し、同性愛や売春などの物議を醸す話題を取り上げるという現実的

なスタイルを推進した。多くの読者は不快に感じ、一部の黒人指導者はこの雑誌を非難した。この試みは負債に悩まされ、その建物は焼失し、わずか1号で廃刊

となった。 |

| History Fire!! was conceived by the self-described Niggerati literary group, to express the African-American experience during the Harlem Renaissance in a modern and realistic fashion, using literature as a vehicle of enlightenment. The magazine's founders wanted to express the changing attitudes of younger African Americans. In Fire!! they explored controversial issues in the Black community, such as homosexuality, bisexuality, interracial relationships, promiscuity, prostitution, and color prejudice.[1] Langston Hughes wrote that the name was intended to symbolize their goal "to burn up a lot of the old, dead conventional Negro-white ideas of the past ... into a realization of the existence of the younger Negro writers and artists, and provide us with an outlet for publication not available in the limited pages of the small Negro magazines then existing."[2] The magazine's headquarters burned to the ground shortly after it published its first issue,[3] ending its operations. |

歴史 Fire!!は、自称ニガラティ文学グループによって構想された。ハーレム・ルネサンス期におけるアフリカ系アメリカ人の経験を、啓発の手段として文学を 用い、現代的なリアリズムで表現することを目的としていた。この雑誌の創刊者たちは、若いアフリカ系アメリカ人の変化する意識を表現しようとしていた。 Fire!!では、同性愛、両性愛、異人種間恋愛、不貞、売春、人種差別など、黒人社会における物議を醸す問題について探求した。 ラングストン・ヒューズは、その誌名は「過去の古い、死んだようなニグロと白人の固定観念を焼き尽くし...若いニグロの作家や芸術家の存在を認識させ、 当時存在していた小さなニグロ雑誌の限られたページ数では不可能だった出版の場を提供すること」を象徴する意図であったと書いている。[2] 雑誌は創刊号を発行した直後に本社が全焼し、[3] 廃刊となった。 |

| Reception Fire!! was plagued by debt and encountered poor sales. It was not well received by the Black public because some felt that the journal did not represent the sophisticated self-image of Blacks in Harlem. Other readers found it offensive for many reasons, and it was denounced by Black leaders such as the Talented Tenth, "who viewed the effort as decadent and vulgar".[4] They disapproved of content relating to prostitution and homosexuality, which they considered degrading to "the race." They also thought many pieces published were a throw-back to old stereotypes, as they were written in the slang and language of the southern vernacular. They felt the "undignified" contents reflected poorly on the Black race. As an example, the critic at the Baltimore Afro-American wrote that he "just tossed the first issue of Fire!! into the fire".[5] Thurman solicited art, poetry, fiction, drama, and essays from his editorial advisers, as well as from such leading figures of the New Negro movement as Countee Cullen and Arna Bontemps. Responses to the magazine ranged from minimal notice in the white press to heated contention among African American critics. Among the latter, the senior rank of intellectuals, such as W.E.B. Du Bois, tended to dismiss it as self-indulgent, while younger figures reacted enthusiastically. But, The Bookman applauded the journal's unique qualities and its personality.[6] Although this magazine had only one issue, "this single issue of Fire!! is considered an event of historical importance."[7] |

レセプション ファイヤー!は負債に苦しみ、販売不振に悩まされていた。この雑誌は、ハーレムに住む黒人の洗練された自己イメージを反映していないと感じる読者もいたた め、黒人読者からはあまり評判が良くなかった。他の読者も、さまざまな理由から不快に感じており、タレンテッド・テンスなどの黒人指導者からは「退廃的で 低俗な試み」として非難された。[4] 彼らは売春や同性愛に関する内容を不適切と考え、それらは「人種」の品位を落とすものだと考えていた。また、南部の俗語や言語で書かれていたため、掲載さ れた多くの記事が古い固定観念への逆戻りであるとも考えていた。彼らは「品位のない」内容が黒人種に悪影響を及ぼすと考えた。例えば、ボルチモア・アフロ アメリカンの批評家は「『ファイア!!』の創刊号を火の中に放り込んだ」と書いた。[5] ターマンは、編集顧問やカウンティー・カレンやアルナ・ボンタンといったニュー・ニグロ運動の指導的人物から、アート、詩、フィクション、ドラマ、エッセ イを募集した。この雑誌に対する反応は、白人系メディアではほとんど注目されなかったが、アフリカ系アメリカ人の批評家たちの間では激しい論争が巻き起 こった。後者の、W.E.B. デュボイスなどの上級知識人層は、それを自己満足的だと切り捨てる傾向にあったが、若い世代は熱狂的に反応した。 しかし、『ブックマン』誌は、この雑誌のユニークな個性と人格を称賛した。[6] この雑誌は1号しか発行されなかったが、「この『ファイア!!』の1号は、歴史的に重要な出来事とみなされている」[7]。 |

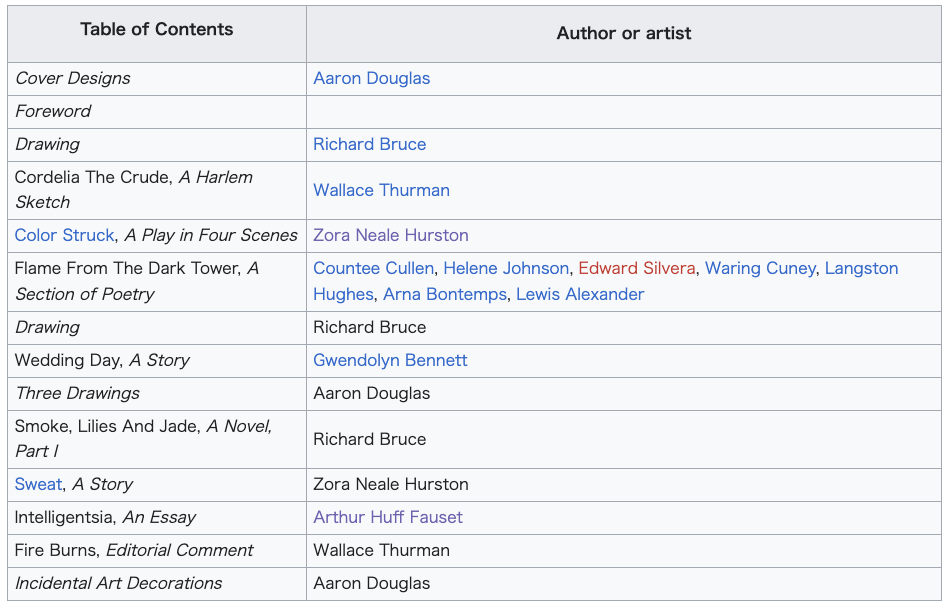

| Features The magazine covered a variety of literary genres: it included a novella, an essay, stories, plays, drawings and illustrations, and poetry.[8]  |

特徴 この雑誌は、小説、エッセイ、物語、戯曲、絵画、イラスト、詩など、さまざまな文学ジャンルをカバーしていた。[8]  |

| Representation in other media The story of the rise and fall of Fire!! is showcased in the 2004 movie Brother to Brother. It features a gay African-American college student named Perry Williams. He befriends an elderly gay African American named Bruce Nugent. Williams learns that Nugent was a writer and co-founder of Fire!!, and associated with other notable writers and artists of the Harlem Renaissance. "Fire!!" is heavily mentioned in the play Smoke, Lilies, and Jade by Carl Hancock Rux, first developed at the Joseph Papp Public Theater under the direction of George C. Wolfe and later produced at the California Institute of the Arts Center for New Performance, as well as in the play FIRE! written by Jenifer Nii. The play premiered in 2010 at Salt Lake City, Utah's Plan B Theatre Company. The 45-minute play covers Wallace Thurman's life, with a focus on the production of "Fire!!" and the writing he did following it. |

他のメディアでの表現 Fire!! の盛衰の物語は、2004年の映画『Brother to Brother』で描かれている。この映画は、ゲイの黒人大学生ペリー・ウィリアムズを主人公としている。彼は、ブルース・ニュージェントという名の年配 のゲイの黒人と親しくなる。ウィリアムズは、ニュージェントが作家であり、Fire!! の共同創設者であったこと、そしてハーレム・ルネッサンスの著名な作家や芸術家たちと交流があったことを知る。 「Fire!!」は、ジョセフ・パップ・パブリック・シアターでジョージ・C・ウルフの演出により初演され、その後カリフォルニア芸術センターのニューパ フォーマンスセンターで再演されたカール・ハンコック・ラックスの戯曲『スモーク、リリーズ、アンド・ジェイド』でも大きく取り上げられている。また、 ジェニファー・ニーによる戯曲『FIRE!』でも取り上げられている。この戯曲は2010年にユタ州ソルトレイクシティのプランBシアターカンパニーで初 演された。45分間のこの作品は、ウォレス・サーマンの生涯を、「ファイアー!!」の制作とそれに続く執筆活動に焦点を当てて描いている。 |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fire!! |

|

| Alain LeRoy Locke (September 13,

1885 – June 9, 1954) was an American writer, philosopher, and educator.

Distinguished in 1907 as the first African American Rhodes Scholar,

Locke became known as the philosophical architect—the acknowledged

"Dean"—of the Harlem Renaissance.[2] He is frequently included in

listings of influential African Americans. On March 19, 1968, the Rev.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. proclaimed: "We're going to let our children

know that the only philosophers that lived were not Plato and

Aristotle, but W. E. B. Du Bois and Alain Locke came through the

universe."[3] |

アラン・ルロイ・ロック(1885年9月13日 -

1954年6月9日)は、アメリカの作家、哲学者、教育者である。1907年にアフリカ系アメリカ人として初めてローズ奨学生に選ばれたことで知られる

ロックは、ハーレム・ルネサンスの哲学的指導者、すなわち「ディーン」として知られるようになった。彼は影響力のあるアフリカ系アメリカ人のリストに頻繁

に挙げられている。1968年3月19日、キング牧師は次のように宣言した。「私たちは子供たちに、生きた哲学者はプラトンやアリストテレスではなく、

W. E. B. デュボイスとアラン・ロックがいたことを知らしめるつもりだ」[3] |

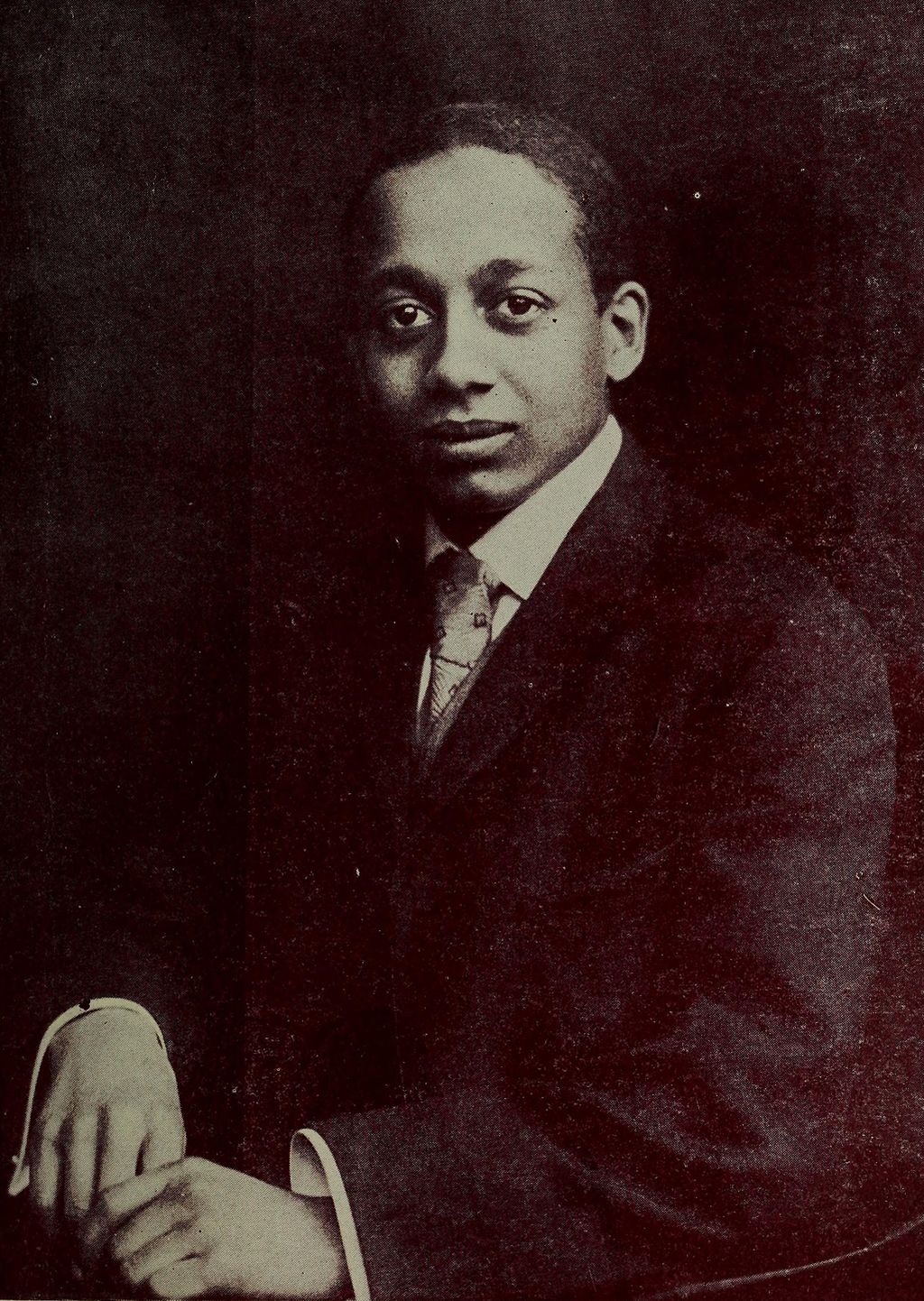

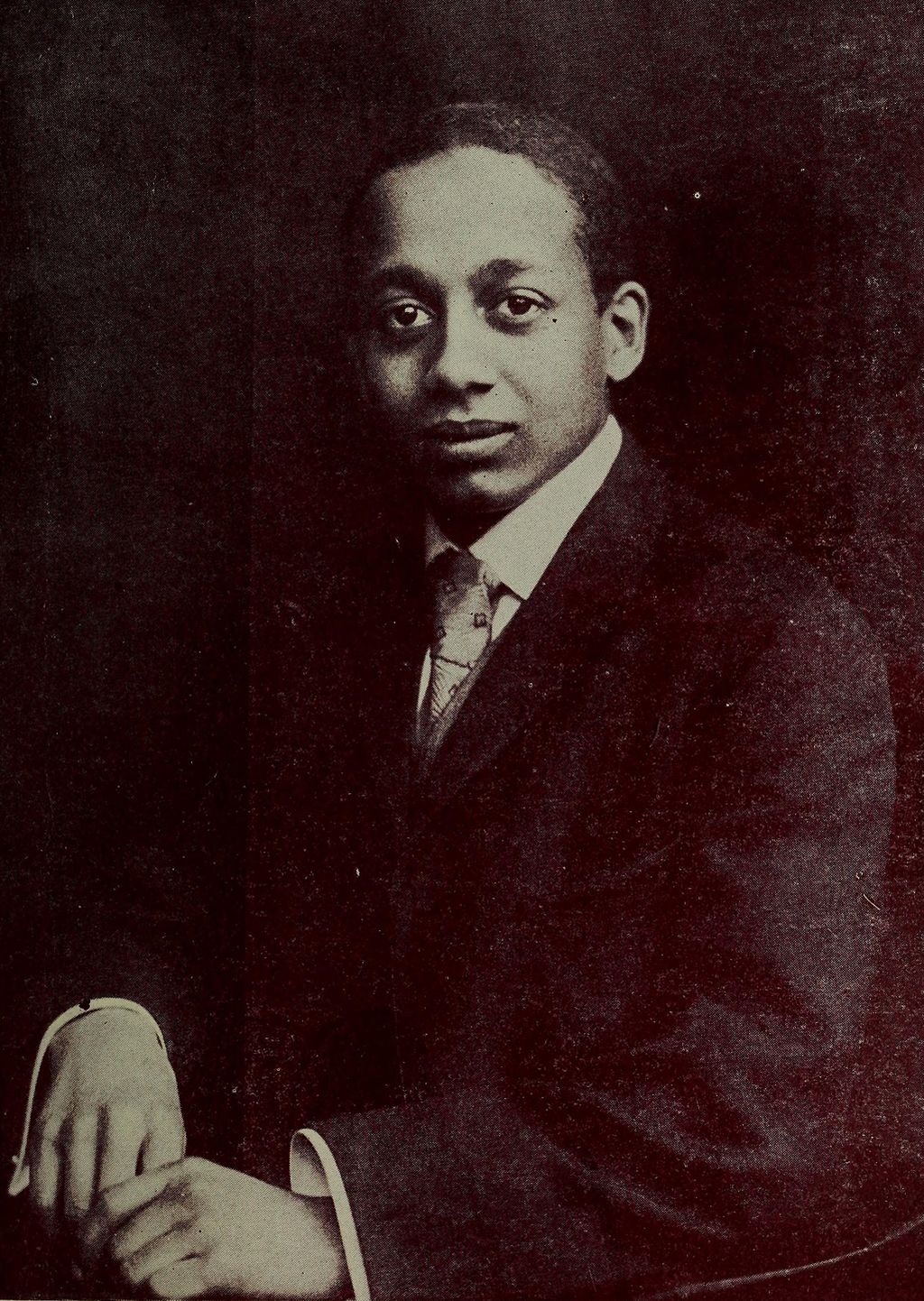

Early life and education Alain LeRoy Locke, c.1907 He was born Arthur Leroy Locke in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on September 13, 1885,[4] to parents Pliny Ishmael Locke (1850–1892) and Mary (née Hawkins) Locke (1853–1922), both of whom were descended from prominent families of free blacks. Called "Roy" as a boy, he was their only child. His father was one of the first black employees of the U.S. Postal Service, and his paternal grandfather taught at Philadelphia's Institute for Colored Youth. His mother Mary was a teacher and inspired Locke's passion for education and literature. Mary's grandfather, Charles Shorter, fought as a soldier and was a hero in the War of 1812.[2][1] At the age of 16, Locke chose to use the first name of "Alain".[4] In 1902, Locke graduated from Central High School in Philadelphia, second in his 107th class in the academic institution. He also attended Philadelphia School of Pedagogy.[5] In 1907, Locke graduated from Harvard University with degrees in English and philosophy; he was honored as a member of the Phi Beta Kappa Society and recipient of the Bowdoin prize.[6] That year he was the first African American to be selected as a Rhodes Scholar to the University of Oxford (and the last to be selected until 1963, when John Edgar Wideman and John Stanley Sanders, a future notable writer and politician, respectively, were selected). In the early 20th century, Rhodes selectors did not meet candidates in person, but there is evidence that at least some selectors knew that Locke was African-American.[7] On arriving at Oxford, Locke was denied admission to several colleges. Several American Rhodes Scholars from the South refused to live in the same college or attend events with Locke.[6][7] He was finally admitted to Hertford College, where he studied literature, philosophy, Greek, and Latin, from 1907 to 1910. Alongside his friend and fellow student Pixley ka Isaka Seme, he was part of the Oxford Cosmopolitan Club, contributing to its first publication.[8] In 1910, he attended the University of Berlin, where he studied philosophy. Locke wrote from Oxford in 1910 that the "primary aim and obligation" of a Rhodes Scholar "is to acquire at Oxford and abroad generally a liberal education, and to continue subsequently the Rhodes mission [of international understanding] throughout life and in his own country. If once more it should prove impossible for nations to understand one another as nations, then, as Goethe said, they must learn to tolerate each other as individuals".[9][10][11] |

幼少期と教育 アラン・ロリー・ロック、1907年頃 彼は1885年9月13日、ペンシルベニア州フィラデルフィアでアーサー・リロイ・ロックとして生まれた。両親はプリニー・イシュマエル・ロック (1850年-1892年)とメアリー(旧姓ホーキンス)・ロック(1853年-1922年)で、両者とも自由黒人の著名な家系の出身であった。少年時代 は「ロイ」と呼ばれていた彼は、両親にとって唯一の子供であった。父親は米国郵便局の黒人職員の一人であり、父方の祖父はフィラデルフィアの有色人青年協 会で教鞭をとっていた。母親のメアリーは教師であり、ロックの教育と文学への情熱に影響を与えた。メアリーの祖父チャールズ・ショーターは兵士として戦 い、1812年の戦争では英雄となった。[2][1] 16歳のとき、ロックは「アラン」というファーストネームを使うことを選んだ。[4] 1902年、ロックはフィラデルフィアのセントラル高校を卒業した。彼は107番目のクラスで2番目の成績だった。また、フィラデルフィア教育大学にも通った。[5] 1907年、ロックはハーバード大学を英文学と哲学の学位を取得して卒業した。彼はファイ・ベータ・カッパ会員に選ばれ、ボウディン賞を受賞した。[6] その年、彼はアフリカ系アメリカ人として初めてオックスフォード大学のローズ奨学生に選ばれた(1963年にジョン・エドガー・ウィドマンとジョン・スタ ンリー・サンダース(のちに著名な作家および政治家となる)が選ばれるまで、最後の選出となった)。20世紀初頭、ローズ奨学生選考委員会は候補者と直接 会うことはなかったが、少なくとも一部の選考委員はロックがアフリカ系アメリカ人であることを知っていたという証拠がある。[7] オックスフォードに到着したロックは、いくつかのカレッジへの入学を拒否された。南部出身の数人のアメリカ人ローズ奨学生は、ロックと同じ大学で生活する ことや、ロックとイベントに参加することを拒否した。[6][7] 最終的にロックはハートフォード・カレッジに入学を許可され、1907年から1910年まで、そこで文学、哲学、ギリシャ語、ラテン語を学んだ。友人で同 級生のピクスリー・カ・イサカ・セミとともに、ロックはオックスフォード・コスモポリタン・クラブのメンバーとなり、その最初の出版に貢献した。[8] 1910年にはベルリン大学に進学し、そこで哲学を学んだ。 ロックは1910年にオックスフォードから、ローズ奨学生の「第一の目的と義務」は 「オックスフォードおよび広く海外でリベラルアーツを習得し、その後生涯にわたって、また自国において、ローズ奨学生としての使命(国際理解)を継続する こと」であると述べた。もし再び、国民として国民を理解することが不可能であると証明された場合、ゲーテが言ったように、お互いを個人として寛容に受け入 れることを学ばなければならない」と述べた。[9][10][11] |

| Teaching and scholarship Locke received an assistant professorship in English at Howard University in 1912.[12] While at Howard, he became a member of Phi Beta Sigma fraternity. Locke returned to Harvard in 1916 to work on his doctoral dissertation, The Problem of Classification in the Theory of Value. In his thesis, he discusses the causes of opinions and social biases, and that these are not objectively true or false, and therefore not universal. Locke received his PhD in philosophy in 1918. Locke returned to Howard University as the chair of the department of philosophy. During this period, he began teaching the first classes on race relations. After working to gain equal pay for African-American and white faculty at the university, he was dismissed in 1925.[13] Following the appointment in 1926 of Mordecai W. Johnson, the first African-American president of Howard, Locke was reinstated in 1928 at the university. Beginning in 1935, he returned to philosophy as a topic of his writing.[14] He continued to teach generations of students at Howard until he retired in 1953. Locke Hall, on the Howard campus, is named in his honor. Among his prominent former students is actor Ossie Davis, who said that Locke encouraged him to go to Harlem because of his interest in theatre. And he did. In addition to teaching philosophy, Locke promoted African-American artists, writers, and musicians. He encouraged them to explore Africa and its many cultures as inspiration for their works. He encouraged them to depict African and African-American subjects, and to draw on their history for subject material. The library resources built up by Dorothy B. Porter to support these studies included materials which he donated from his travels and contacts.[15] |

教育と研究 1912年、ロックはハワード大学で英語学の助教授職を得た。[12] ハワード大学在学中に、ロックはファイ・ベータ・シグマ友愛会の会員となった。 ロックは1916年にハーバード大学に戻り、博士論文『価値論における分類の問題』の執筆に取り組んだ。論文の中で、彼は意見や社会的な偏見の原因につい て論じ、それらは客観的に真実でも偽りでもないため、普遍的ではないと論じた。ロックは1918年に哲学博士号を取得した。 ロックはハワード大学の哲学部の主任教授として復職した。この期間に、人種関係に関する最初の授業を担当し始めた。同大学でアフリカ系アメリカ人と白人の教職員の給与を平等にするよう働きかけた後、1925年に解雇された。 1926年にハワード大学初の黒人学長モルデカイ・W・ジョンソンが就任すると、ロックは1928年に同大学に復職した。1935年からは、執筆テーマと して哲学に戻った。[14] 1953年に引退するまで、ロックはハワード大学で何世代もの学生たちに教え続けた。ハワード大学のキャンパス内にあるロック・ホールは、彼の功績を称え て名付けられた。著名な元学生には俳優のオジー・デイヴィスがおり、ロックが演劇に興味を持っていた彼にハーレムに行くよう勧めたという。そして、彼は ハーレムに行った。 ロックは、哲学を教えるだけでなく、アフリカ系アメリカ人の芸術家、作家、音楽家を支援した。彼らにアフリカとその多様な文化を探究し、作品のインスピ レーションとするよう奨励した。アフリカやアフリカ系アメリカ人を題材とし、彼らの歴史を題材とするよう奨励した。これらの研究を支援するためにドロ シー・B・ポーターが構築した図書館リソースには、彼が旅行や人脈から寄贈した資料も含まれていた。[15] |

| Harlem Renaissance and the "New Negro" Locke was the guest editor of the March 1925 issue of the periodical Survey Graphic, for a special edition titled "Harlem, Mecca of the New Negro": about Harlem and the Harlem Renaissance, which helped educate white readers about its flourishing culture.[16] In December of that year, he expanded the issue into The New Negro, a collection of writings by him and other African Americans, which would become one of his best-known works. A landmark in black literature (later acclaimed as the "first national book" of African America),[17] it was an instant success. Locke contributed five essays: the "Foreword", "The New Negro", "Negro Youth Speaks", "The Negro Spirituals", and "The Legacy of Ancestral Arts". This book established his reputation as "a leading African-American literary critic and aesthete."[14] Locke's philosophy of the New Negro was grounded in the concept of race-building; that race is not merely an issue of heredity but is more an issue of society and culture.[18] He raised overall awareness of potential black equality; he said that no longer would blacks allow themselves to adjust or comply with unreasonable white requests. This idea was based on self-confidence and political awareness. Although in the past the laws regarding equality had been ignored without consequence by white America, Locke's philosophical idea of The New Negro allowed for fair treatment. Because this was an idea and not a law, people held its power. If they wanted this idea to flourish, they were the ones who would need to "enforce" it through their actions and overall points of view. While his own writing was sophisticated philosophy, and therefore not popularly accessible, he mentored other writers in the movement who would become more broadly known, such as Zora Neale Hurston.[7] The "philosophical basis" of the Renaissance has since been widely recognized to originate from Locke.[19] |

ハーレム・ルネサンスと「ニュー・ニグロ」 ロックは、1925年3月に発行された定期刊行誌『サーベイ・グラフィック』の「ハーレム、ニュー・ニグロのメッカ」と題された特別号のゲスト編集者を務 めた。ハーレムとハーレム・ルネサンスに関する特集で、活気のあるハーレム文化について白人読者の理解を深めるのに役立った。[16] 同年12月には、この特集を『ニュー・ニグロ』という本にまとめ、自身や他のアフリカ系アメリカ人の文章をまとめた。この本は、ロックの最も有名な作品の ひとつとなった。黒人文学における画期的な作品(後にアフリカ系アメリカ人の「最初の国民的著作」と称賛される)[17]であり、たちまち成功を収めた。 ロックは「序文」、「ニュー・ニグロ」、「ニグロ・ユース・スピークス」、「ニグロ・スピリチュアルズ」、「先祖伝来の芸術の遺産」の5つのエッセイを寄 稿した。この本により、彼は「アフリカ系アメリカ人の一流の文学評論家、審美家」としての名声を確立した。 ロックの『ニュー・ニグロ』の哲学は、人種形成という概念に基づいている。すなわち、人種とは単に遺伝の問題ではなく、むしろ社会や文化の問題であるとい う考え方である。[18] 彼は、黒人が平等になる可能性について全般的な認識を高めた。彼は、黒人はもはや理不尽な白人の要求に適応したり従ったりすることは許さないだろうと述べ た。この考えは、自信と政治意識に基づいている。過去において、平等に関する法律は白人のアメリカ人によって無視されてきたが、ロックの『ニュー・ニグ ロ』の哲学的な考え方は公平な待遇を可能にした。これは法律ではなく考え方であるため、人々はそれに力を感じた。この考え方を広めたいのであれば、人々は 自らの行動や全体的な視点を通してそれを「強制」する必要がある。 彼の著作は洗練された哲学であり、一般にはあまり受け入れられなかったが、彼は運動に参加する他の作家たちを指導し、ゾラ・ニール・ハーストン(Zora Neale Hurston)など、広く知られるようになる作家を育てた。ルネサンスの「哲学的な基礎」は、ロックに由来するものであると広く認識されるようになっ た。 |

| Feud with Albert C. Barnes One author whose work Locke edited for both Survey Graphic as well as The New Negro was art collector, critic, and theorist Albert Barnes. Barnes and Locke were connected in their shared views on the importance of Negro art in America.[20] Barnes promulgated notions of the superiority of black art in terms of spirituality and emotion, owing to the collective suffering from which black artists draw to create their work.[20] Locke argued for the primacy of craft objects and the visual tradition as being the greatest contributor of black art to the American canon.[21] The commonalities between the two men's stance on black art led Barnes to believe Locke was stealing his ideas, creating a rift between the two men.[20] Locke touches on his feud with Barnes in his book The Negro in Art.[21] |

アルバート・C・バーンズとの確執 ロックが『サーベイ・グラフィック』と『ザ・ニュー・ニグロ』の両誌のために編集した作品の著者である美術収集家、批評家、理論家のアルバート・バーン ズ。バーンズとロックは、アメリカにおけるニグロ芸術の重要性に関する共通の考え方でつながっていた。[20] バーンズは、黒人芸術家たちが作品を生み出す際に描く集団的な苦悩から、精神性と感情の観点で黒人芸術の優位性を唱えた。[20] ロックは、工芸品と視覚的伝統が 黒人芸術がアメリカ美術の正統な流れに加わる最大の貢献者であると主張した。[21] 黒人芸術に対する2人の姿勢の共通点から、バーンズはロックが自分のアイデアを盗用していると考え、2人の間に亀裂が生じた。[20] ロックは著書『The Negro in Art』の中で、バーンズとの確執について触れている。[21] |

| Religious beliefs Painting by Betsy Graves Reyneau Locke identified himself as a Baháʼí throughout the last half of his life (1918–1954).[22] He declared his belief in Baháʼu'lláh in the year 1918. Due to the lack of an official enrollment system for the religion, the date when Locke converted to that faith is unverified.[23] However, the National Baháʼí Archives discovered a "Baháʼí Historical Record" card that Locke completed in 1935 for a Baháʼí census from the National Spiritual Assembly.[23] He was one of seven African-American members from the Washington, D.C. Baháʼí movement to complete the card.[23] On the card, Locke wrote the year 1918 as the year he was accepted into the Baháʼí Faith, and wrote Washington, D.C., as the place he was accepted.[23] It was common to write to ʻAbdu'l-Bahá to declare one's new faith, and Locke received a letter, or "tablet", from ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in return. When ʻAbdu'l-Bahá died in 1921, Locke enjoyed a close relationship with Shoghi Effendi, then head of the Baháʼí Faith. Shoghi Effendi is reported to have said to Locke, "People as you, Mr. Gregory, Dr. Esslemont and some other dear souls are as rare as diamond."[6] He is among some 40 African Americans known to have joined the religion during the ministry of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá before the leader's death in later 1921.[24] |

宗教的信念 ベッツィ・グレイブス・レイノーによる絵画 ロックは、人生の後半(1918年から1954年)を通じてバハーイー教徒であると名乗っていた。[22] 彼は1918年にバハーイー教のバハーウッラーへの信仰を宣言した。この宗教には公式な登録制度がなかったため、ロックが改宗した正確な日付は不明であ る。[23] しかし、ナショナル・バハーイ・アーカイブスは、ロックが1935年にナショナル・スピリチュアル・アセンブリによるバハーイの国勢調査のために記入した 「バハーイ歴史記録」カードを発見した。[23] ロックは、ワシントンD.C.のバハーイ運動から7人のアフリカ系アメリカ人のメンバーの1人として、このカードを記入した。。ロックは、バハーイ信仰に 受け入れられた年として1918年を、受け入れられた場所としてワシントンD.C.をカードに記入した。[23] 自分の新しい信仰を表明するためにアブドゥルバハに手紙を書くことは一般的であり、ロックはアブドゥルバハから返事として手紙、すなわち「石板」を受け 取った。 1921年にアブドゥルバハが亡くなると、ロックはバハーイー教の指導者であったショーギ・エフェンディと親密な関係を築いた。ショーギ・エフェンディは ロックに対して「あなたのような人々、グレゴリーさん、エッスルモント博士、そして他の何人かの親愛なる人々は、ダイヤモンドのように貴重な存在です」と 語ったと言われている。[6] 彼は、1921年後半に指導者が死去する前に、アブドゥル・バハの在任中にこの宗教に入信したことが知られている約40人のアフリカ系アメリカ人のうちの 一人である。[24] |

| Sexual orientation Locke was homosexual, and may have encouraged and supported other gay African Americans who were part of the Harlem Renaissance.[25] Given the discriminatory laws against it, he was not fully open about his orientation.[7] He referred to it as a point of "vulnerable/invulnerability", representing an area of both risk and strength.[6] |

性的指向 ロックは同性愛者であり、ハーレム・ルネサンスに参加していた他のゲイの黒人たちを励まし、支援していた可能性がある。[25] 差別的な法律を考慮すると、彼は自身の性的指向について完全にオープンではなかった。[7] 彼はそれを「脆弱性/無敵」のポイントと呼び、リスクと強さの両方の領域を表していると表現した。[6] |

| Death, influence and legacy After his retirement from Howard University in 1953, Locke moved to New York City.[26] He had heart disease.[26] Following a six-week illness, he died at Mount Sinai Hospital on June 9, 1954.[27] During his illness, he was cared for by his friend and protégée, Margaret Just Butcher.[28][29] Butcher used notes from Locke's unfinished work to write The Negro in American Culture (1956).[30] Journey of ashes Locke was cremated, and his remains given to Dr. Arthur Fauset, Locke's close friend and executor of his estate. He was an anthropologist who was a major figure in the Harlem Renaissance. After Fauset died in 1983, and the remains were given to his friend, Reverend Sadie Mitchell, who ministered at African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas in Philadelphia. Mitchell retained the ashes until the mid-1990s, when she asked Dr. J. Weldon Norris, a professor of music at Howard University, to take the ashes to the university. The ashes were held at Howard University's Moorland–Spingarn Research Center until 2007. That year they were discovered when two former Rhodes scholars were working on the Centennial of Locke's selection as a Rhodes Scholar. Concerned that the human remains were not properly cared for, the university transferred them to its W. Montague Cobb Research Laboratory, which had extensive experience handling human remains (and had worked on those from the African Burying Ground in New York). Locke's ashes, which had been stored in a plain paper bag in a simple round metal container, were transferred to a small funerary urn and locked in a safe.[7] Howard University officials initially considered having Locke's ashes buried in a niche at Locke Hall on the Howard campus, as the ashes of Langston Hughes had been interred in 1991 at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York City. But Kurt Schmoke, the university's legal counsel, was concerned about setting a precedent that might lead to too many people trying to gain burials at the university. After reviewing legal issues, university officials decided to bury the remains off-site. They thought to bury Locke beside his mother, Mary Hawkins Locke. However, Howard officials quickly discovered a problem: she had been interred at Columbian Harmony Cemetery in Washington, D.C., but that cemetery closed in 1959. Her remains and others from that cemetery were transferred to National Harmony Memorial Park. (She and 37,000 other unclaimed remains from Columbian Harmony were buried in a mass grave, with no markers.)[7] University officials eventually decided to bury Alain Locke's remains at historic Congressional Cemetery in Washington, DC. Former African-American Rhodes Scholars raised $8,000 to purchase a burial plot there. Locke was interred at Congressional Cemetery on September 13, 2014. His tombstone reads: 1885–1954 Herald of the Harlem Renaissance Exponent of Cultural Pluralism On the back of the headstone is a nine-pointed Baháʼí star (representing Locke's religious beliefs); a Zimbabwe Bird, emblem of the nation Locke adopted as a Rhodes Scholar; a lambda, symbol of the gay rights movement; and the logo of Phi Beta Sigma, the fraternity Locke joined. In the center of these four symbols is an Art Deco representation of an African woman's face set against the rays of the sun. This image is a simplified version of the bookplate that Harlem Renaissance painter Aaron Douglas designed for Locke. Below the bookplate image are the words "Teneo te, Africa" ("I hold you, my Africa"). This represented Locke's belief that African Americans needed to study African culture to enlarge their sense of self.[7] |

死、影響、そして遺産 1953年にハワード大学を退職した後、ロックはニューヨーク市に移住した。[26] 彼は心臓病を患っていた。[26] 6週間の闘病生活の後、1954年6月9日にマウント・サイナイ病院で死去した。[27] 闘病中、彼は友人であり弟子であったマーガレット・ジャスト・ブッチャーに世話をされていた。[28][29] ブッチャーは、ロックの未完の作品のメモを基に『アメリカ文化におけるニグロ』(1956年)を執筆した。 灰の旅 ロックは火葬され、遺灰は親友であり遺言執行人であった人類学者のアーサー・フォーセット博士に引き渡された。彼は人類学者であり、ハーレム・ルネサンス の主要人物であった。1983年にファウセットが死去すると、遺灰は彼の友人でフィラデルフィアのアフリカ聖公会聖トマス教会の牧師であったセディ・ミッ チェル牧師に引き継がれた。ミッチェルは1990年代半ばまで遺灰を保管し、その後、遺灰をハワード大学の音楽学部の教授であったJ. ウェルドン・ノリス博士に託した。 遺灰は2007年までハワード大学のムーアランド=スプリンガーン研究センターで保管されていた。その年、2人の元ローズ奨学生がロックのローズ奨学生と しての選出100周年記念事業に取り組んでいる際に、遺灰が発見された。遺骨が適切に保管されていないことを懸念した大学は、遺骨の取り扱い経験が豊富な W.モンタギュー・コブ研究施設(ニューヨークのアフリカ人墓地の遺骨の取り扱い経験もある)に遺灰を移した。紙袋に入れられたシンプルな丸い金属容器に 保管されていたロックの遺灰は、小さな骨壷に移され、金庫に保管された。 ハワード大学の関係者は当初、ロックの遺灰をハワード大学のキャンパス内にあるロック・ホールの壁龕に埋葬することを検討していた。ラングストン・ヒュー ズの遺灰は1991年にニューヨーク市の黒人文化研究ショーンバーグ・センターに埋葬されている。しかし、同大学の顧問弁護士であるカート・シュモーク氏 は、この先例が大学への埋葬を望む人々があとを絶たない事態につながることを懸念した。法的問題を検討した結果、大学当局は遺骨を学外に埋葬することを決 定した。ロウクの遺骨は、母親のメアリー・ホーキンス・ロウクの隣に埋葬することを考えた。しかし、ハワード当局はすぐに問題を発見した。彼女はワシント ンD.C.のコロンビアン・ハーモニー墓地に埋葬されていたが、その墓地は1959年に閉鎖されていた。彼女の遺体と他の遺体はナショナル・ハーモニー記 念公園に移された。(彼女とコロンビアン・ハーモニーの37,000体以上の引き取り手のいない遺体は、墓標のない共同墓地に埋葬された)[7] 最終的にワシントンD.C.の歴史ある連邦議会議事堂墓地にアラン・ロックの遺骨を埋葬することが大学当局によって決定された。元アフリカ系アメリカ人 ローズ奨学生たちは、同墓地の埋葬区画を購入するために8,000ドルを集めた。ロックは2014年9月13日に連邦議会議事堂墓地に埋葬された。彼の墓 石には次のように刻まれている。 1885–1954 ハーレム・ルネサンスの旗手 文化多元主義の提唱者 墓石の裏面には、バハーイ教の9つの突起を持つ星(ロックの宗教的信念を表す)、ロックがローズ奨学生として選ばれた際に選んだ国民の象徴であるジンバブ エの鳥、ゲイの権利運動のシンボルであるラムダ、そしてロックが参加した友愛団体であるファイ・ベータ・シグマのロゴが刻まれている。これらの4つのシン ボルの中央には、太陽の光に照らされたアール・デコ調のアフリカ人女性の顔が描かれている。この図は、ハーレム・ルネサンスの画家アーロン・ダグラスが ロックのためにデザインした蔵書票の簡略版である。蔵書票の図の下には「Teneo te, Africa(アフリカよ、私はあなたを支える)」という言葉が書かれている。これは、アフリカ系アメリカ人が自己の感覚を広げるためにはアフリカ文化を 学ぶ必要があるというロックの信念を表している。[7] |

| Influence, legacy and honors At Howard University, the main building for the College of Arts and Sciences is dedicated to his legacy, and was named "Alain Locke Hall".[31] His personal and literary papers are held within the manuscript department in the university's Moorland-Spingarn Research Center. Locke's former residence on R Street NW in Washington's Logan Circle neighborhood is marked with a historical plaque.[32] In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed Locke among his 100 Greatest African Americans.[33] Similarly, Columbus Salley's book, The Black 100, included Locke, ranking him as the 36th most influential African-American.[13] In 2019, Jeffrey Stewart won a Pulitzer Prize in Biography for The New Negro: the Life of Alain Locke.[34] In 2020, Rhodes Scholar and attorney Dr. Ann Olivarius wrote a guest column in The Financial Times suggesting that statues of Locke and Zambian civil-rights activist Lucy Banda-Sichone replace the statue of Cecil Rhodes at Oriel College, Oxford University.[35] Schools named after Locke include: Alain L. Locke Elementary School PS 208 in South Harlem The Locke High School in Los Angeles, California The Alain Locke Public School, an elementary school in West Philadelphia Alain Locke Charter Academy in Chicago. Illinois Alain Locke Elementary School in Gary, Indiana |

影響、遺産、栄誉 ハワード大学では、人文科学部のメインビルディングは彼の遺産に捧げられ、「アラン・ロック・ホール」と名付けられた。[31] 彼の個人的な文書や文学的な原稿は、同大学のムーアランド・スプリンガーン研究センターの原稿部門に保管されている。 ワシントンDCのローガンサークル地区にあるロックの旧居は、歴史を示す銘板が掲げられている。[32] 2002年には、学者モレフィ・ケテ・アサンテが著書『100 Greatest African Americans』でロックをその1人に挙げた。[33] 同様に、コロンバス・サリー著『The Black 100』でもロックが取り上げられ、最も影響力のあるアフリカ系アメリカ人の36位にランクインした。[13] 2019年には、ジェフリー・スチュワートが著書『The New Negro: the Life of Alain Locke』でピューリッツァー賞伝記部門を受賞した。[34] 2020年には、ローズ奨学生で弁護士のアン・オリヴァリウス博士が、オックスフォード大学オリエル・カレッジにあるセシル・ローズの銅像を、ロックとザ ンビアの公民権運動家ルーシー・バンダ=シチョーンの銅像に置き換えるべきだと提案するコラムをフィナンシャル・タイムズ紙に寄稿した。 ロックにちなんで名付けられた学校には以下がある。 サウスハーレムのアラン・L・ロック小学校 PS 208 カリフォルニア州ロサンゼルスのロック高校 フィラデルフィア西部のアラン・ロック公立小学校 イリノイ州シカゴのアラン・ロック・チャーター・アカデミー インディアナ州ゲリーのアラン・ロック小学校 |

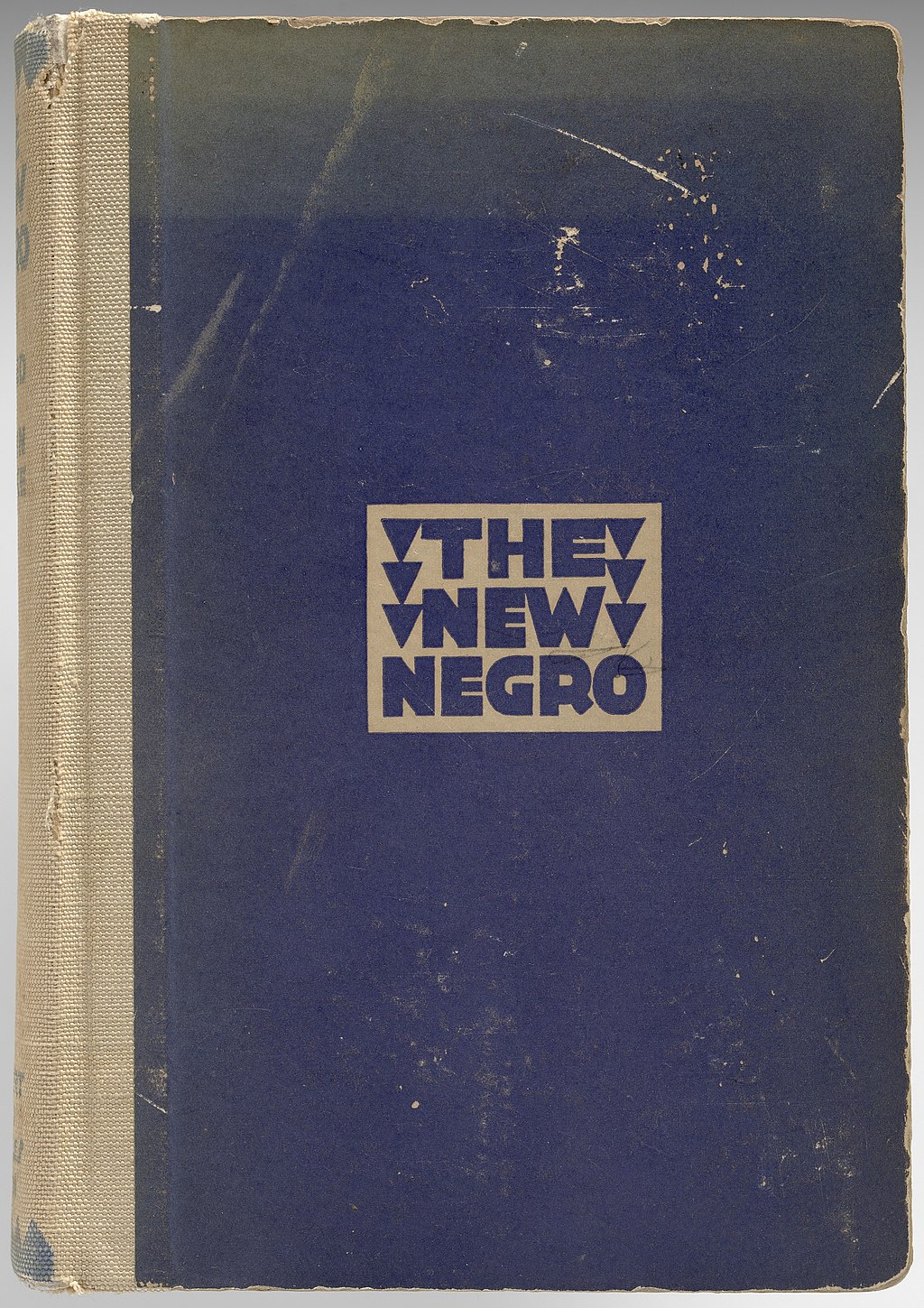

Major works First edition of The New Negro (1925) In addition to the books listed below, Locke edited the "Bronze Booklet" series, a set of eight volumes published in the 1930s by Associates in Negro Folk Education. He regularly published reviews of poetry and literature by African Americans in journals such as Opportunity and Phylon. His works include: The New Negro: An Interpretation. New York: Albert and Charles Boni, 1925. Harlem: Mecca of the New Negro. Survey Graphic 6.6 (March 1, 1925).[36] When Peoples Meet: A Study of Race and Culture Contacts. Alain Locke and Bernhard J. Stern (eds). New York: Committee on Workshops, Progressive Education Association, 1942. The Philosophy of Alain Locke: Harlem Renaissance and Beyond. Edited by Leonard Harris. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1989. Race Contacts and Interracial Relations: Lectures of the Theory and Practice of Race. Washington, D.C.: Howard University Press, 1916. Reprinted, edited by Jeffery C. Stewart. Washington: Howard University Press, 1992. Negro Art Past and Present. Washington: Associates in Negro Folk Education, 1936 (Bronze Booklet No. 3). The Negro and His Music. Washington: Associates in Negro Folk Education, 1936 (Bronze Booklet No. 2). "The Negro in the Three Americas". Journal of Negro Education 14 (Winter 1944): 7–18. "Negro Spirituals". Freedom: A Concert in Celebration of the 75th Anniversary of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States (1940). Compact disc. New York: Bridge, 2002. Audio (1:14). "Spirituals" (1940). The Critical Temper of Alain Locke: A Selection of His Essays on Art and Culture. Edited by Jeffrey C. Stewart. New York and London: Garland, 1983, pp. 123–26. The New Negro: An Interpretation. New York: Arno Press, 1925. Four Negro Poets. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1927. Plays of Negro Life: a Source-Book of Native American Drama. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1927. A Decade of Negro Self-Expression. Charlottesville, Virginia, 1928. The Negro in America. Chicago: American Library Association, 1933. Negro Art – Past and Present. Washington, D.C.: Associates in Negro Folk Education, 1936. The Negro and His Music. Washington, D.C.: Associates in Negro Folk Education, 1936; also New York: Kennikat Press, 1936. The Negro in Art: A Pictorial Record of the Negro Artist and of the Negro Theme in Art. Washington, D.C.: Associates in Negro Folk Education, 1940; also New York: Hacker Art Books, 1940. "A Collection of Congo Art". Arts 2 (February 1927): 60–70. "Harlem: Dark Weather-vane". Survey Graphic 25 (August 1936): 457–462, 493–495. "The Negro and the American Stage". Theatre Arts Monthly 10 (February 1926): 112–120. "The Negro in Art". Christian Education 13 (November 1931): 210–220. "Negro Speaks for Himself". The Survey 52 (April 15, 1924): 71–72. "The Negro's Contribution to American Art and Literature". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 140 (November 1928): 234–247. "The Negro's Contribution to American Culture". Journal of Negro Education 8 (July 1939): 521–529. "A Note on African Art". Opportunity 2 (May 1924): 134–138. "Our Little Renaissance". Ebony and Topaz, edited by Charles S. Johnson. New York: National Urban League, 1927. "Steps Towards the Negro Theatre". Crisis 25 (December 1922): 66–68. The Problem of Classification in the Theory of Value: or an Outline of a Genetic System of Values. PhD dissertation: Harvard, 1917. "Locke, Alain". [Autobiographical sketch.] Twentieth Century Authors. Edited by Stanley Kunitz and Howard Haycroft. New York: 1942, p. 837. "The Negro Group". Group Relations and Group Antagonisms. Edited by Robert M. MacIver. New York: Institute for Religious Studies, 1943. World View on Race and Democracy: A Study Guide in Human Group Relations. Chicago: American Library Association, 1943. Le Rôle du nègre dans la culture des Amériques. Port-au-Prince: Haiti Imprimerie de l'état, 1943. "Values and Imperatives". In Sidney Hook and Horace M. Kallen (eds), American Philosophy, Today and Tomorrow. New York: Lee Furman, 1935, pp. 312–33. Reprinted: Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1968; Harris, The Philosophy of Alain Locke, 31–50. "Pluralism and Ideological Peace". In Milton R. Konvitz and Sidney Hook (eds), Freedom and Experience: Essays Presented to Horace M. Kallen. Ithaca: New School for Research and Cornell University Press, 1947, pp. 63–69. "Cultural Relativism and Ideological Peace". In Lyman Bryson, Louis Finfelstein, and R. M. MacIver (eds), Approaches to World Peace. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1944, pp. 609–618. Reprinted in The Philosophy of Alain Locke, 67–78. "Pluralism and Intellectual Democracy". Conference on Science, Philosophy and Religion, Second Symposium. New York: Conference on Science, Philosophy and Religion, 1942, pp. 196–212. Reprinted in The Philosophy of Alain Locke, 51–66. "The Unfinished Business of Democracy". Survey Graphic 31 (November 1942): 455–61. "Democracy Faces a World Order". Harvard Educational Review 12.2 (March 1942): 121–28. "The Moral Imperatives for World Order". Summary of Proceedings, Institute of International Relations, Mills College, Oakland, CA, June 18–28, 1944, 19–20. Reprinted in The Philosophy of Alain Locke, 143, 151–152. "Major Prophet of Democracy". Review of Race and Democratic Society by Franz Boas. Journal of Negro Education 15.2 (Spring 1946): 191–92. "Ballad for Democracy". Opportunity: Journal of Negro Life 18:8 (August 1940): 228–29. Three Corollaries of Cultural Relativism. Proceedings of the Second Conference on the Scientific and the Democratic Faith. New York, 1941. "Reason and Race". Phylon 8:1 (1947): 17–27. Reprinted in Jeffrey C. Stewart, ed. The Critical Temper of Alain Locke: A Selection of His Essays on Art and Culture. New York and London: Garland, 1983, pp. 319–27. "Values That Matter". Review of The Realms of Value, by Ralph Barton Perry. Key Reporter 19.3 (1954): 4. "Is There a Basis for Spiritual Unity in the World Today?" Town Meeting: Bulletin of America's Town Meeting on the Air 8.5 (June 1, 1942): 3–12. "Unity through Diversity: A Bahá'í Principle". The Baháʼí World: A Biennial International Record, Vol. IV, 1930–1932. Wilmette: Baháʼí Publishing Trust, 1989 [1933]. Reprinted in Locke 1989, 133–138. Note: Leonard Harris's reference (Locke 1989, 133 n.) should be amended to read, Volume IV, 1930–1932 (not "V, 1932–1934"). "Lessons in World Crisis". The Baháʼí World: A Biennial International Record, Vol. IX, 1940–1944. Wilmette: Baháʼí Publishing Trust, 1945. Reprint, Wilmette: Baháʼí Publishing Trust, 1980 [1945]. "The Orientation of Hope". The Baháʼí World: A Biennial International Record, Vol. V, 1932–1934. Wilmette: Baháʼí Publishing Trust, 1936. Reprint in Locke 1989, 129–132. Note: Leonard Harris's reference (Locke 1989, 129 n.) should be amended to read, "Volume V, 1932–1934" (not "Volume IV, 1930–1932"). "A Baháʼí Inter-Racial Conference". The Baháʼí Magazine (Star of the West), 18.10 (January 1928): 315–16. "Educator and Publicist", Star of the West 22.8 (November 1931), 254–55. Obituary of George William Cook [Baha'i], 1855–1931. "Impressions of Haifa". [Appreciation of Baha'i leader, Shoghi Effendi, whom Locke met during his first of two Baha'i pilgrimages to Haifa, Palestine (now Israel)]. Star of the West 15.1 (1924): 13–14; Alaine [sic] Locke, "Impressions of Haifa", in Baháʼí Year Book, Vol. One, April 1925 – April 1926, comp. National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of the United States and Canada (New York: Baháʼí Publishing Committee, 1926), 81, 83; Alaine [sic] Locke, "Impressions of Haifa", in The Baháʼí World: A Biennial International Record, Vol. II, April 1926 – April 1928, comp. National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of the United States and Canada (New York: Bahá'í Publishing Committee, 1928; reprint, Wilmette: Baháʼí Publishing Trust, 1980), 125, 127; Alain Locke, "Impressions of Haifa", in The Bahá'í World: A Biennial International Record, Vol. III, April 1928 – April 1930, comp. National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of the United States and Canada (New York: Baháʼí Publishing Committee, 1930; reprint, Wilmette: Baháʼí Publishing Trust, 1980), 280, 282. "Minorities and the Social Mind". Progressive Education 12 (March 1935): 141–50. The High Cost of Prejudice. Forum 78 (December 1927). The Negro Poets of the United States. Anthology of Magazine Verse 1926 and Yearbook of American Poetry. Sesquicentennial edition. Ed. William S. Braithwaite. Boston: B.J. Brimmer, 1926, pp. 143–151. The Critical Temper of Alain Locke: A Selection of His Essays on Art and Culture. Edited by Jeffrey C. Stewart. New York and London: Garland, 1983, pp. 43–45. Plays of Negro Life: A Source-Book of Native American Drama. Alain Locke and Montgomery Davis (eds). New York and Evanston: Harper and Row, 1927. "Decorations and Illustrations by Aaron Douglas". "Impressions of Luxor". The Howard Alumnus 2.4 (May 1924): 74–78. |

主要作品 『ニュー・ニグロ』初版(1925年) 以下に挙げる書籍に加え、ロックは「ブロンズ・ブックレット」シリーズの編集も手がけた。これは、1930年代に「アソシエーツ・イン・ニグロ・フォー ク・エデュケーション」から出版された全8巻のシリーズである。ロックは、雑誌『オポチュニティ』や『ファイロン』に、アフリカ系アメリカ人の詩や文学の 批評を定期的に寄稿していた。彼の作品には以下のようなものがある。 『ニュー・ニグロ:解釈』。ニューヨーク:アルバート・アンド・チャールズ・ボニ、1925年。 『ハーレム:ニュー・ニグロのメッカ』。『サーベイ・グラフィック』6.6(1925年3月1日)。[36] 『人々が会うとき:人種と文化の接触に関する研究』。アラン・ロックとバーナード・J・スターン(編)。ニューヨーク:進歩的教育協会ワークショップ委員会、1942年。 アラン・ロックの哲学:ハーレム・ルネサンスとその先。レナード・ハリス編。フィラデルフィア:テンプル大学出版、1989年。 人種間の接触と異人種間関係:人種理論と実践の講義。ワシントンD.C.:ハワード大学出版、1916年。ジェフリー・C・スチュワート編、ワシントン:ハワード大学出版、1992年。 『ニグロ芸術の過去と現在』ワシントン:ニグロ民族教育協会、1936年(ブロンズ・ブックレット第3号)。 『ニグロとニグロ音楽』ワシントン:ニグロ民族教育協会、1936年(ブロンズ・ブックレット第2号)。 「3つのアメリカにおけるニグロ」『ニグロ教育ジャーナル』14(1944年冬):7-18。 「ニグロ・スピリチュアルズ」『自由:合衆国憲法修正第13条75周年記念コンサート』(1940年)。コンパクトディスク。ニューヨーク:ブリッジ、2002年。音声(1:14)。 「スピリチュアルズ」(1940年)。 アラン・ロックの批評的気質:芸術と文化に関する彼のエッセイの抜粋。 ジェフリー・C・スチュワート編。 ニューヨークおよびロンドン:ガーラード、1983年、123-26ページ。 ニュー・ニグロ:解釈。 ニューヨーク:アーノ・プレス、1925年。 4人のニグロ詩人。 ニューヨーク:サイモン・アンド・シュスター、1927年。 ニグロの人生劇:ネイティブ・アメリカン演劇のソースブック。ニューヨーク:Harper and Brothers、1927年。 ニグロの自己表現の10年。バージニア州シャーロッツビル、1928年。 アメリカにおけるニグロ。シカゴ:アメリカ図書館協会、1933年。 ニグロ芸術の過去と現在。ワシントンD.C.:ニグロ民族教育協会、1936年。 The Negro and His Music. ワシントンD.C.: Associates in Negro Folk Education, 1936; また、ニューヨーク: Kennikat Press, 1936. The Negro in Art: A Pictorial Record of the Negro Artist and of the Negro Theme in Art. ワシントンD.C.: Associates in Negro Folk Education, 1940; また、ニューヨーク: Hacker Art Books, 1940. 「コンゴ美術のコレクション」『Arts』2(1927年2月):60-70。 「ハーレム:暗い風見鶏」『Survey Graphic』25(1936年8月):457-462、493-495。 「ニグロとアメリカの舞台」『Theatre Arts Monthly』10(1926年2月):112-120。 「芸術におけるニグロ」『クリスチャン・エデュケーション』13(1931年11月):210-220。 「ニグロは自らを語る」『ザ・サーベイ』52(1924年4月15日):71-72。 「ニグロのアメリカ芸術と文学への貢献」『アメリカ政治社会学会紀要』140号(1928年11月):234-247ページ。 「ニグロのアメリカ文化への貢献」『ニグロ教育ジャーナル』8号(1939年7月):521-529ページ。 「アフリカ美術についての覚書」。『オポチュニティ』2 (1924年5月): 134-138。 「私たちの小さなルネサンス」。チャールズ・S・ジョンソン編『エボニー・アンド・トパーズ』。ニューヨーク: ナショナル・アーバン・リーグ、1927年。 「ニグロ・シアターへの歩み」。『クライシス』25 (1922年12月): 66-68。 価値論における分類の問題:または価値の生成システムの概略。 博士論文:ハーバード大学、1917年。 「ロック、アラン」。 [自伝的スケッチ] 20世紀の作家たち。 スタンリー・クニッツとハワード・ヘイクロフト編。 ニューヨーク:1942年、837ページ。 「ニグロ・グループ」。『グループ関係とグループ対立』。ロバート・M・マクイヴァー編。ニューヨーク:Institute for Religious Studies、1943年。 『人種と民主主義に関する世界観:人間集団関係の研究ガイド』。シカゴ:アメリカ図書館協会、1943年。 『アメリカ大陸文化におけるニグロの役割』。ポルトープランス:Haiti Imprimerie de l'état、1943年。 「価値と要請」。シドニー・フックとホレス・M・カレン(編)『アメリカ哲学、今日と明日』ニューヨーク:リー・ファーマン、1935年、312-33 ページ。再版:ニューヨーク州フリーポート:Books for Libraries Press、1968年;ハリス著『アラン・ロックの哲学』31-50ページ。 「多元主義とイデオロギー的平和」。ミルトン・R・コンヴィッツとシドニー・フック編『自由と経験:ホレス・M・カレンに捧げる論文集』イサカ:ニュー・スクール・フォー・リサーチ・アンド・コーネル・ユニバーシティ・プレス、1947年、63-69ページ。 「文化的相対主義とイデオロギー的平和」。ライマン・ブライソン、ルイス・フィンフェルスタイン、R. M. マクイベア編『世界平和へのアプローチ』ニューヨーク:Harper & Brothers、1944年、609-618ページ。アラン・ロックの哲学』67-78ページにも再掲。 「多元主義と知的な民主主義」。科学・哲学・宗教に関する会議、第2回シンポジウム。ニューヨーク:科学・哲学・宗教に関する会議、1942年、196-212ページ。アラン・ロックの哲学、51-66ページに再掲。 「民主主義の未解決問題」。Survey Graphic 31(1942年11月):455-61。 「民主主義は世界秩序に直面する」『ハーバード教育評論』12.2(1942年3月):121-28。 「世界秩序のための道徳的義務」『会議の要約、ミルズ・カレッジ国際関係研究所、カリフォルニア州オークランド、1944年6月18日~28日、19-20。アラン・ロックの哲学』143、151-152ページに再掲。 「民主主義の主要な預言者」。フランツ・ボアズ著『人種と民主的社会』の書評。『Journal of Negro Education』15.2(1946年春):191-192。 「民主主義のためのバラード」『Opportunity: Journal of Negro Life』18:8(1940年8月):228-29。 文化相対主義の3つの帰結。『科学的民主主義信仰に関する第2回会議議事録』ニューヨーク、1941年。 「理性と人種」『Phylon』8:1(1947):17-27。ジェフリー・C・スチュワート編『アラン・ロックの批判的精神:芸術と文化に関する論文集』ニューヨークおよびロンドン:ガーランド、1983年、319-27ページに再録。 「重要な価値観」ラルフ・バートン・ペリー著『価値の領域』書評。キー・レポーター19.3(1954年):4。 「今日の世の中に精神的な統一の基盤はあるのか?」『タウンミーティング:放送によるアメリカのタウンミーティング会報』8.5(1942年6月1日):3-12。 「多様性による統一:バハーイーの原則」『バハーイー・ワールド:2年毎の国際記録』第4巻、1930-1932年。ウィルメット: バハーイ出版トラスト、1989年 [1933年]。Locke 1989, 133–138 に再掲。注:レナード・ハリスによる参照(Locke 1989, 133 n.)は、第4巻、1930–1932年(「第5巻、1932–1934年」ではない)と訂正すべきである。 「世界危機における教訓」。『バハーイ世界:2年に1度の国際記録』第9巻、1940年~1944年。ウィルメット:バハーイ出版トラスト、1945年。再版、ウィルメット:バハーイ出版トラスト、1980年[1945年]。 「希望の方向性」『バハーイ世界:2年に1度の国際記録』第5巻、1932年~1934年。ウィルメット:バハーイ出版トラスト、1936年。ロック 1989年、129~132ページに再録。注:レナード・ハリスが参照した文献(Locke 1989, 129 n.)は、「第4巻、1930年~1932年」ではなく、「第5巻、1932年~1934年」と訂正すべきである。 「バハーイー人種間会議」。バハーイ誌(スター・オブ・ザ・ウェスト)、18.10(1928年1月):315-16。 「教育者および広報担当者」、スター・オブ・ザ・ウェスト22.8(1931年11月)、254-55。ジョージ・ウィリアム・クック[バハーイ]、1855-1931の死亡記事。 「ハイファの印象」。[パレスチナ(現イスラエル)のハイファへの2度にわたるバハーイ巡礼の最初の際にロックが会ったバハーイ指導者ショーギ・エフェン ディへの感謝の意]。『スター・オブ・ザ・ウェスト』15.1(1924年):13-14;アライン・ロウク、「ハイファの印象」、『バハーイ・イヤー・ ブック』第1巻、1925年4月~1926年4月、編者 米国およびカナダのバハーイー教徒国民精神議会編(ニューヨーク:バハーイー出版委員会、1926年)、81、83ページ;アレイン・ロック著「ハイファ の印象」、『バハーイー世界:2年ごとの国際記録』第2巻、1926年4月~1928年4月、編者 米国およびカナダのバハーイー教徒国民精神協議会編(ニューヨーク:バハーイー出版委員会、1928年;再版、ウィルメット:バハーイー出版トラスト、 1980年)、125、127;アラン・ロック著「ハイファの印象」、『バハーイー世界: 第3巻、1928年4月~1930年4月、編集:米国およびカナダのバハーイー教徒国民精神議会(ニューヨーク:バハーイー出版委員会、1930年;再 版、ウィルメット:バハーイー出版トラスト、1980年)、280、282。 「マイノリティと社会心理」。Progressive Education 12(1935年3月):141-50。 偏見の代償。Forum 78(1927年12月)。 米国のニグロ詩人たち。雑誌詩アンソロジー1926および米国詩年鑑。150周年記念版。編集:ウィリアム・S・ブレイトヘイ。ボストン:B.J. Brimmer、1926年、143~151ページ。 アラン・ロックの批評的傾向:芸術と文化に関する彼のエッセイの抜粋。ジェフリー・C・スチュワート編。ニューヨークおよびロンドン:Garland、1983年、43~45ページ。 『ニグロの生活劇:ネイティブ・アメリカン演劇の資料集』 アラン・ロック、モンゴメリー・デイヴィス(編) ニューヨーク、エバンストン:ハーパー・アンド・ロー、1927年 「アーロン・ダグラスによる装飾と挿絵」 「ルクソールの印象」『ハワード・アルムナス』2.4(1924年5月):74-78 |

| Posthumous works Alain Locke's previously unpublished, posthumous works include: Locke, Alain. "The Moon Maiden" and "Alain Locke in His Own Words: Three Essays". World Order 36.3 (2005): 37–48. Edited, introduced and annotated by Christopher Buck and Betty J. Fisher. Four previously unpublished works by Alain Locke: "The Moon Maiden" (37) [a love poem for a white woman who left him]; "The Gospel for the Twentieth Century" (39–42); "Peace between Black and White in the United States" (42–45); "Five Phases of Democracy" (45–48). Locke, Alain. "Alain Locke: Four Talks Redefining Democracy, Education, and World Citizenship". Edited, introduced and annotated by Christopher Buck and Betty J. Fisher. World Order 38.3 (2006/2007): 21–41. Four previously unpublished speeches/essays by Alain Locke: "The Preservation of the Democratic Ideal" (1938 or 1939); "Stretching Our Social Mind" (1944); "On Becoming World Citizens" (1946); "Creative Democracy" (1946 or 1947). |

死後発表された作品 アラン・ロックの死後発表された未発表作品には以下がある。 ロック、アラン。「The Moon Maiden」および「アラン・ロック自身の言葉:3つのエッセイ」。World Order 36.3 (2005): 37–48。編集、紹介、注釈:クリストファー・バックおよびベティ・J・フィッシャー。 アラン・ロックによる未発表作品4点: 「The Moon Maiden」(37)[彼のもとを去った白人女性へのラブポエム]、 「The Gospel for the Twentieth Century」(39-42)、 「Peace between Black and White in the United States」(42-45)、 「Five Phases of Democracy」(45-48)。 ロック、アラン。「アラン・ロック:民主主義、教育、世界市民権を再定義する4つの講演」。編集、紹介、注釈:クリストファー・バック、ベティ・J・フィッシャー。『世界秩序』38.3(2006/2007):21-41。 アラン・ロックによる未発表の4つの講演/エッセイ: 「民主主義的理想の保存」(1938年または1939年)、 「社会的な視野を広げる」(1944年)、 「世界市民になることについて」(1946年)、 「創造的民主主義」(1946年または1947年)。 |

| Harlem Renaissance American philosophy List of American philosophers Leonard Harris Jeffrey C. Stewart The New Negro: The Life of Alain Locke |

ハーレム・ルネサンス アメリカ哲学 アメリカ哲学者一覧 レナード・ハリス ジェフリー・C・スチュワート 新ニグロ:アラン・ロックの生涯 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alain_LeRoy_Locke |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆