トマス・モア

Thomas More, 1478-1535

Hans

Holbein, the Younger - Sir Thomas More

☆ トマス・モア卿(Sir Thomas More PC、1478年2月7日 - 1535年7月6日)は、カトリック教会で聖トマス・モアとして崇められ[2]、イギリスの弁護士、裁判官[3]、社会哲学者、作家、政治家、アマチュア 神学者、著名なルネサンス期の人文主義者である[4]。1529年10月から1532年5月までヘンリー8世に仕え、イングランド大法官も務めた[5]。 モアはプロテスタント宗教改革に反対し、マルティン・ルター、フルドリヒ・ツヴィングリ、ウィリアム・ティンデールの神学に対する極論を展開した。ヘン リー8世のカトリック教会からの分離にも反対し、ヘンリーをイングランド国教会の最高首長と認めず、キャサリン・オブ・アラゴンとの結婚を無効とした。覇 者の誓いを拒否した後、彼は偽の証拠だと主張して反逆罪で有罪判決を受け、処刑された。処刑の際、彼はこう言ったと伝えられている: 「私は王の良きしもべ、神の第一のしもべとして死ぬ」と言ったと伝えられている。 教皇ピウス11世は1935年にモアを殉教者として列聖した[7]。教皇ヨハネ・パウロ2世は2000年にモアを政治家と政治家の守護聖人と宣言した [8][9][10]。

| Sir Thomas More PC

(7 February 1478 – 6 July 1535), venerated in the Catholic Church as

Saint Thomas More,[2] was an English lawyer, judge,[3] social

philosopher, author, statesman, amateur theologian, and noted

Renaissance humanist.[4] He also served Henry VIII as Lord High

Chancellor of England from October 1529 to May 1532.[5] He wrote

Utopia, published in 1516, which describes the political system of an

imaginary island state.[6] More opposed the Protestant Reformation, directing polemics against the theology of Martin Luther, Huldrych Zwingli and William Tyndale. More also opposed Henry VIII's separation from the Catholic Church, refusing to acknowledge Henry as supreme head of the Church of England and the annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. After refusing to take the Oath of Supremacy, he was convicted of treason on what he claimed was false evidence, and executed. On his execution, he was reported to have said: "I die the King's good servant, and God's first". Pope Pius XI canonised More in 1935 as a martyr.[7] Pope John Paul II in 2000 declared him the patron saint of statesmen and politicians.[8][9][10] |

トマス・モア卿(Sir Thomas More

PC、1478年2月7日 -

1535年7月6日)は、カトリック教会で聖トマス・モアとして崇められ[2]、イギリスの弁護士、裁判官[3]、社会哲学者、作家、政治家、アマチュア

神学者、著名なルネサンス期の人文主義者である[4]。1529年10月から1532年5月までヘンリー8世に仕え、イングランド大法官も務めた[5]。 モアはプロテスタント宗教改革に反対し、マルティン・ルター、フルドリヒ・ツヴィングリ、ウィリアム・ティンデールの神学に対する極論を展開した。ヘン リー8世のカトリック教会からの分離にも反対し、ヘンリーをイングランド国教会の最高首長と認めず、キャサリン・オブ・アラゴンとの結婚を無効とした。覇 者の誓いを拒否した後、彼は偽の証拠だと主張して反逆罪で有罪判決を受け、処刑された。処刑の際、彼はこう言ったと伝えられている: 「私は王の良きしもべ、神の第一のしもべとして死ぬ」と言ったと伝えられている。 教皇ピウス11世は1935年にモアを殉教者として列聖した[7]。教皇ヨハネ・パウロ2世は2000年にモアを政治家と政治家の守護聖人と宣言した [8][9][10]。 |

| Early life Born on Milk Street in the City of London, on 7 February 1478, Thomas More was the son of Sir John More,[11] a successful lawyer and later a judge,[3][12] and his wife Agnes (née Graunger). He was the second of six children. More was educated at St. Anthony's School, then considered one of London's best schools.[13][14] From 1490 to 1492, More served John Morton, the Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Chancellor of England, as a household page.[15]: xvi Morton enthusiastically supported the "New Learning" (scholarship which was later known as "humanism" or "London humanism"), and thought highly of the young More. Believing that More had great potential, Morton nominated him for a place at the University of Oxford (either in St. Mary Hall or Canterbury College, both now gone).[16]: 38 More began his studies at Oxford in 1492, and received a classical education. Studying under Thomas Linacre and William Grocyn, he became proficient in both Latin and Greek. More left Oxford after only two years—at his father's insistence—to begin legal training in London at New Inn, one of the Inns of Chancery.[15]: xvii [17] In 1496, More became a student at Lincoln's Inn, one of the Inns of Court, where he remained until 1502, when he was called to the Bar.[15]: xvii More could speak and banter in Latin with the same facility as in English. He wrote and translated poetry.[18] He was particularly influenced by Pico della Mirandola and translated the Life of Pico into English.[19] Spiritual life According to his friend, the theologian Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam, More once seriously contemplated abandoning his legal career to become a monk.[20][21] Between 1503 and 1504 More lived near the Carthusian monastery outside the walls of London and joined in the monks' spiritual exercises. Although he deeply admired their piety, More ultimately decided to remain a layman, standing for election to Parliament in 1504 and marrying the following year.[15]: xxi More continued ascetic practices for the rest of his life, such as wearing a hair shirt next to his skin and occasionally engaging in self-flagellation.[15]: xxi A tradition of the Third Order of Saint Francis honours More as a member of that Order on their calendar of saints.[22] Family life  Rowland Lockey after Hans Holbein the Younger, The Family of Sir Thomas More, c. 1594, Nostell Priory More married Joanna "Jane" Colt, the eldest daughter of John Colt of Essex in 1505.[23] In that year he leased a portion of a house known as the Old Barge (originally there had been a wharf nearby serving the Walbrook river) on Bucklersbury, St Stephen Walbrook parish, London. Eight years later he took over the rest of the house and in total he lived there for almost 20 years, until his move to Chelsea in 1525.[16]: 118, 271 [24][25] Erasmus reported that More wanted to give his young wife a better education than she had previously received at home, and tutored her in music and literature.[16]: 119 The couple had four children: Margaret, Elizabeth, Cecily, and John. Jane died in 1511.[16]: 132 Going "against friends' advice and common custom," within 30 days, More had married one of the many eligible women among his wide circle of friends.[26][27] He chose Alice Middleton, a widow, to head his household and care for his small children.[28] The speed of the marriage was so unusual that More had to get a dispensation from the banns of marriage, which, due to his good public reputation, he easily obtained.[26] More had no children from his second marriage, although he raised Alice's daughter from her previous marriage as his own. More also became the guardian of two young girls: Anne Cresacre who would eventually marry his son, John More;[16]: 146 and Margaret Giggs (later Clement) who was the only member of his family to witness his execution (she died on the 35th anniversary of that execution, and her daughter married More's nephew William Rastell). An affectionate father, More wrote letters to his children whenever he was away on legal or government business, and encouraged them to write to him often.[16]: 150 [29]: xiv More insisted upon giving his daughters the same classical education as his son, an unusual attitude at the time.[16]: 146–47 His eldest daughter, Margaret, attracted much admiration for her erudition, especially her fluency in Greek and Latin.[16]: 147 More told his daughter of his pride in her academic accomplishments in September 1522, after he showed the bishop a letter she had written: When he saw from the signature that it was the letter of a lady, his surprise led him to read it more eagerly … he said he would never have believed it to be your work unless I had assured him of the fact, and he began to praise it in the highest terms … for its pure Latinity, its correctness, its erudition, and its expressions of tender affection. He took out at once from his pocket a portague [A Portuguese gold coin] … to send to you as a pledge and token of his good will towards you.[29]: 152 More's decision to educate his daughters set an example for other noble families. Even Erasmus became much more favourable once he witnessed their accomplishments.[16]: 149 A large portrait of More and his extended family, Sir Thomas More and Family, was painted by Holbein; however, it was lost in a fire in the 18th century. More's grandson commissioned a copy, of which two versions survive. The Nostell copy of the portrait shown above also includes the family's two pet dogs and monkey.[note 1] Musical instruments such as a lute and viol feature in the background of the extant copies of Holbein's family portrait. More played the recorder and viol,[30]: 136 and made sure his wives could join in the family consort.[note 2] |

初期の人生 1478年2月7日、ロンドン・シティのミルク・ストリートに生まれたトマス・モアは、弁護士として成功し、後に裁判官となったジョン・モア卿[11] [3][12]とその妻アグネス(旧姓グラウンジャー)の息子である。6人兄弟の2番目だった。1490年から1492年まで、モアはカンタベリー大主教 でイングランド大法官であったジョン・モートンに家政婦として仕えた[15]。 モートンは「新しい学問」(後に「人文主義」または「ロンドン人文主義」として知られる学問)を熱心に支持し、若いモアを高く評価していた。モートンはモ アに大きな可能性があると考え、彼をオックスフォード大学(セント・メアリー・ホールかカンタベリー・カレッジのいずれか、現在はどちらもなくなってい る)に推薦した[16]: 38 モアは1492年にオックスフォード大学で学び始め、古典教育を受けた。トーマス・リナクルとウィリアム・グローシンに師事し、ラテン語とギリシア語の両 方に堪能になった。1496年、モアは法廷裁判所のひとつであるリンカーンズ・イン(Lincoln's Inn)の学生となり、1502年に弁護士に召されるまで在籍した[15]: xvii [17] 。 モアは英語と同じようにラテン語で話し、談笑することができた。特にピコ・デッラ・ミランドラの影響を受け、『ピコの生涯』を英訳した[19]。 精神生活 友人である神学者ロッテルダムのデジデリウス・エラスムスによると、モアは一度、法曹界を捨てて修道士になろうと真剣に考えたことがある[20] [21]。彼らの敬虔さに深く敬服していたが、モアは最終的に平信徒でいることを決意し、1504年に国会議員選挙に立候補し、翌年結婚した[15]: xxi。 モアは残りの人生も禁欲的な修行を続け、毛のシャツを肌身離さず着たり、時には自傷行為に及んだりした[15]: xxi 聖フランシスコ第三修道会の伝統では、モアは同修道会の一員として聖人カレンダーに名を連ねている[22]。 家族生活  ハンス・ホルベインに倣ったローランド・ロック、『トーマス・モア卿の家族』、1594年頃、ノステル修道院。 1505年、モアはエセックスのジョン・コルトの長女ジョアンナ・「ジェーン」・コルトと結婚し[23]、その年、ロンドンのセント・スティーブン・ウォ ルブルック教区バックラーズベリーにあるオールド・バージ(元々は近くにウォルブルック川に通じる埠頭があった)として知られる家の一部を借りた。8年 後、彼はこの家の残りの部分を引き継ぎ、1525年にチェルシーに移るまで、合計約20年間そこに住んだ[16]: 118, 271 [24][25] エラスムスは、モアが若い妻にそれまで家庭で受けていたよりも良い教育を与えたいと考え、音楽や文学の家庭教師をしたと報告している[16]: 119 夫妻には4人の子供がいた: マーガレット、エリザベス、セシリー、ジョンである。ジェーンは1511年に死去した[16]: 132 友人たちの忠告や一般的な慣習に反して」、モアは30日以内に、彼の広い友人たちの中にいた多くの魅力的な女性のうちのひとりと結婚した[26] [27]。 彼は家長となり、小さな子供たちの世話をするために、未亡人のアリス・ミドルトンを選んだ[28]。 この結婚の早さは非常に異例であったため、モアは結婚の前触れの免除を得なければならなかったが、世間での評判が良かったため、彼は簡単にそれを得た [26]。 モアには2度目の結婚による子供はいなかったが、アリスの前の結婚による娘を自分の子供として育てた。モアはまた、2人の少女の後見人となった: アン・クレザックは後に息子のジョン・モアと結婚する[16]: 146とマーガレット・ギグス(後のクレメント)は、モアの処刑に立ち会った唯一の家族 であった(彼女は処刑から35年目に亡くなり、その娘はモアの甥ウィリアム・ラステルと結婚した)。愛情深い父親であったモアは、法律や政府の仕事で留守 にするときはいつも子供たちに手紙を書き、頻繁に手紙を書くように勧めた[16]: 150 [29]: xiv モアは娘たちに息子と同じ古典教育を受けさせることを主張したが、これは当時としては異例のことであった[16]: 146-47 長女マーガレットはその博学さ、特にギリシャ語とラテン語の流暢さで多くの賞賛を集めた[16]: 147 モアは1522年9月、娘の書いた手紙を司教に見せた後、娘の学問的な業績に対する自分の誇りを娘に語った: 署名からそれが女性の手紙であることがわかると、彼は驚いてもっと熱心に読み始めた......私がその事実を断言しなければ、あなたの作品だとは決して 信じなかっただろうと言い、最高の言葉で褒め始めた......その純粋なラテン語らしさ、正確さ、博学さ、そして優しい愛情表現に対して。彼はすぐにポ ケットからポルタグ(ポルトガルの金貨)を取り出し、......あなたへの善意の証として、あなたに送ろうとした[29]: 152 娘を教育するというモアの決断は、他の貴族の模範となった。エラスムスでさえも、彼女たちの功績を目の当たりにすると、好感を抱くようになった[16]: 149 モアとその家族の大きな肖像画『トマス・モア卿と家族』はホルバインによって描かれたが、18世紀に火事で失われた。モアの孫が模写を依頼し、そのうちの2種類が現存している。上に示したノステルの模写には、一家が飼っていた2匹の愛犬と猿も描かれている[注釈 1]。 現存するホルバインの家族肖像画のコピーの背景には、リュートやヴィオールなどの楽器が描かれている。モアはリコーダーとヴィオールを演奏した[30]: 136し、妻たちが家族のコンソートに参加できるようにしていた[注 2]。 |

| Personality according to Erasmus Concerning More's personality, Erasmus gave a consistent portrait over a period of thirty five years. Soon after meeting the young lawyer More, who became his best friend[note 3] and invited Erasmus into his household, Erasmus reported in 1500 "Did nature ever invent anything kinder, sweeter or more harmonious than the character of Thomas More?".[31] In 1519, he wrote that More was "born and designed for friendship;[note 4] no one is more open-hearted in making friends or more tenacious in keeping them."[32] In 1535, after More's execution, Erasmus wrote that More "never bore ill-intent towards anyone".[31] "We are 'together, you and I, a crowd'; that is my feeling, and I think I could live happily with you in any wilderness. Farewell, dearest Erasmus, dear as the apple of my eye." — Thomas More to Erasmus, October 31, 1516[33] "When More died I seem to have died myself: because we were a single soul as Pythagoras once said. But such is the flux of human affairs." — Erasmus to Piotr Tomiczki (Bishop of Kraków), August 31, 1535[34] In a 1532 letter, Erasmus wrote "such is the kindliness of his disposition, or rather, to say it better, such is his piety and wisdom, that whatever comes his way that cannot be corrected, he comes to love just as wholeheartedly as if nothing better could have happened to him.[35] In a 1533 letter, Erasmus described More's character as imperiosus – commanding, far-ruling, not at all timid.[36] For his part, "Thomas More was an unflagging apologist for Erasmus for the thirty-six years of their adult lives (1499–1535)."[37] Early political career  Study for a portrait of Thomas More's family, c. 1527, by Hans Holbein the Younger In 1504 More was elected to Parliament to represent Great Yarmouth, and in 1510 began representing London.[38] More first attracted public attention by his conduct in the parliament of 1504, by his daring opposition to the king's demand for money. King Henry VII was entitled, according to feudal laws, to a grant on occasion of his daughter's marriage. But he came to the House of Commons for a much larger sum than he intended to give with his daughter. The members, unwilling as they were to vote the money, were afraid to offend the king, till the silence was broken by More, whose speech is said to have moved the house to reduce the subsidy of three-fifteenths which the Government had demanded to £30,000. One of the chamberlains went and told his master that he had been thwarted by a beardless boy. Henry never forgave the audacity; but, for the moment, the only revenge he could take was upon More's father, whom upon some pretext he threw into the Tower, and he only released him upon payment of a fine of £100. Thomas More even found it advisable to withdraw from public life into obscurity.[23] From 1510, More served as one of the two undersheriffs of the City of London, a position of considerable responsibility in which he earned a reputation as an honest and effective public servant. Interested in public health, he became a Commissioner for Sewers in 1514.[39] More became Master of Requests in 1514,[40] the same year in which he was appointed as a Privy Counsellor.[41] After undertaking a diplomatic mission to the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, accompanying Thomas Wolsey, Cardinal Archbishop of York, to Calais (for the Field of the Cloth of Gold) and Bruges, More was knighted and made under-treasurer of the Exchequer in 1521.[41] As secretary and personal adviser to King Henry VIII, More became increasingly influential: welcoming foreign diplomats, drafting official documents, attending the court of the Star Chamber for his legal prowess but delegated to judge in the under-court for 'poor man's cases'[42]: 491, 492 and serving as a liaison between the King and Lord Chancellor Wolsey. More later served as High Steward for the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge. In 1523 More was elected as knight of the shire (MP) for Middlesex and, on Wolsey's recommendation, the House of Commons elected More its Speaker.[41] In 1525 More became Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, with executive and judicial responsibilities over much of northern England.[41] Chancellorship After Wolsey fell, More succeeded to the office of Lord Chancellor (the chief government minister) in 1529; this was the highest official responsible for equity and common law, including contracts and royal household cases, and some misdemeanour appeals.[43]: 527 He dispatched cases with unprecedented rapidity. In 1532 he was responsible for an anti-pollution act.[39] As Lord Chancellor he was a member (and probably the Presiding Judge at the court when present, who spoke last and cast the deciding vote in case of ties)[44]: 61 of the Court of the Star Chamber, an appeals court on civil and criminal matters, including riot and sedition, that was the final appeal in dissenter's trials.[note 5] Campaign against the Protestant Reformation  Sir Thomas More is commemorated with a sculpture at the late-19th-century Sir Thomas More House, Carey Street, London, opposite the Royal Courts of Justice. More supported the Catholic Church and saw the Protestant Reformation as heresy, a threat to the unity of both church and society. More believed in the theology, argumentation, and ecclesiastical laws of the church, and "heard Luther's call to destroy the Catholic Church as a call to war."[45] Heresy was the single most time-consuming issue Thomas More dealt with in his chancellorship, and probably in the whole of the last ten years of his life. — Richard Rex, More and the heretics: statesman or fanatic? [46]: 107 More wrote a series of books and pamphlets in English and Latin to respond to Protestants, and in his official capacities took action against the illegal book trade, notably fronting a diplomatically-sensitive raid in 1525 of the Hanseatic Merchants in the Steelyard in role as chancellor of the duchy of Lancaster[46]: 106 and given his diplomatic experience negotiating with the Hanse.[47]: 150 Debates with Tyndale More wrote several books against the first edition of Tyndale's English translation of the New Testament:.[48] More wrote the Dialogue concerning Heresies (1529), Tyndale responded with An Answer to Sir T. More's Dialogue (1530), and More replied with his Confutation of Tyndale's Answer (1532).[49] More also wrote or contributed to several other anti-Lutheran books. One of More's criticisms of the initial Tyndale translation was that despite claiming to be in the vernacular, Tyndale had employed numerous neologisms: for example, "Jehovah", "scapegoat", "Passover", "atonement", "mercy seat", "shewbread."[50] More also accused Tyndale of deliberately avoiding common translations in favour of biased words: such as using the emotion "love" instead of the practical action "charity" for Greek agape, using the neologism senior instead of "priest" for the Greek presbyteros[51] (Tyndale changed this to "elder"), and the latinate "congregation" instead of "church".[52] Tyndale's bibles include text other than the scriptures: some of Tyndale's prefaces were direct translations of Martin Luther,[53] and it included marginal glosses which challenged Catholic doctrine.[54] One notable exchange occurred over More's attack on Tyndale's use of congregation. Tyndale pointed out that he was following "your darling" Erasmus' Latin translation of ecclesia by congregatio. More replied that Erasmus needed to coin congregatio because there was no good Latin word, while English had the perfectly fine "church", but that the intent and theology under the words were all important: I have not contended with Erasmus my darling, because I found no such malicious intent with Erasmus my darling, as I find with Tyndale. For had I found with Erasmus my darling the cunning intent and purpose that I find in Tyndale: Erasmus my darling should be no more my darling. But I find in Erasmus my darling that he detests and abhors the errors and heresies that Tyndale plainly teaches and abides by and therefore Erasmus my darling shall be my dear darling still. And surely if Tyndale had either never taught them, or yet had the grace to revoke them: then should Tyndale be my dear darling too. But while he holds such heresies still I cannot take for my darling him that the devil takes for his darling. — Thomas More [37][55] Resignation As the conflict over supremacy between the Papacy and the King reached its peak, More continued to remain steadfast in supporting the supremacy of the Pope as Successor of Peter over that of the King of England. Parliament's reinstatement of the charge of praemunire in 1529 had made it a crime to support in public or office the claim of any authority outside the realm (such as the Papacy) to have a legal jurisdiction superior to the King's.[56] In 1530, More refused to sign a letter by the leading English churchmen and aristocrats asking Pope Clement VII to annul Henry's marriage to Catherine of Aragon, and also quarrelled with Henry VIII over the heresy laws. In 1531, a royal decree required the clergy to take an oath acknowledging the King as Supreme Head of the Church of England. The bishops at the Convocation of Canterbury in 1532 agreed to sign the Oath but only under threat of praemunire and only after these words were added: "as far as the law of Christ allows".[57] This was considered to be the final Submission of the Clergy.[58] Cardinal John Fisher and some other clergy refused to sign. Henry purged most clergy who supported the papal stance from senior positions in the church. More continued to refuse to sign the Oath of Supremacy and did not agree to support the annulment of Henry's marriage to Catherine.[56] However, he did not openly reject the King's actions and kept his opinions private.[59] On 16 May 1532, More resigned from his role as Chancellor but remained in Henry's favour despite his refusal.[60] His decision to resign was caused by the decision of the convocation of the English Church, which was under intense royal threat, on the day before.[61] |

エラスムスによる人物像 モアの性格について、エラスムスは35年間にわたって一貫した人物像を描いている。 若き弁護士モアと出会ってすぐに親友となり[注釈 3]、エラスムスを家庭に招き入れたエラスムスは、1500年に「トマス・モアの性格ほど優しく、甘美で、調和のとれたものを自然が発明したことがあった だろうか」と報告している[31]。 [31]1519年、彼はモアが「友情のために生まれ、設計された。[注釈 4]友人を作るのにこれほど心を開き、友人を守るのにこれほど粘り強い者はいない」[32]と書いている[31]。 私たちは「一緒にいる、あなたと私は群衆」であり、それが私の気持ちであり、どんな荒野でもあなたとなら幸せに暮らせると思う。さらば、親愛なるエラスムスよ。 - トマス・モアからエラスムスへ、1516年10月31日[33]。 「ピタゴラスがかつて言ったように、私たちはひとつの魂だったのだから。ピタゴラスがかつて言ったように、われわれはひとつの魂だったからだ。 - エラスムスからピョートル・トミツキ(クラクフ司教)へ、1535年8月31日[34]。 1532年の書簡で、エラスムスは「彼の気質の優しさ、いや、もっとよく言えば、彼の信心深さと知恵の深さである。 1533年の手紙の中で、エラスムスはモアの性格をimperiosus(命令的で、遠くまで支配し、まったく臆病ではない)と表現している[36]。 トマス・モアは、二人が成人してからの36年間(1499年-1535年)、エラスムスの弛まぬ弁明者であった」[37]。 初期の政治活動  トマス・モアの家族の肖像画のための下絵、1527年頃、ハンス・ホルベイン作 1504年、モアはグレート・ヤーマスの代表として議会に選出され、1510年からはロンドンの代表となった[38]。 モアが最初に世間の注目を集めたのは、1504年の議会での王の金銭要求に対する大胆な反対行動であった。ヘンリー7世は、封建法に従って、娘の結婚に際 して交付金を受け取る権利があった。しかし彼は、娘と一緒に贈与するつもりだった金額よりもはるかに大きな金額を下院に要求してきた。その沈黙を破ったの がモアで、彼の演説は下院を動かし、政府が要求した15分の3の補助金を30,000ポンドに減額させたと言われている。侍従長の一人が行って、髭のない 少年に邪魔されたと主人に告げた。ヘンリーがこの大胆さを許すことはなかったが、とりあえず彼ができる唯一の復讐は、何らかの口実で塔に投げ込まれたモア の父親に対するもので、100ポンドの罰金を支払うことで釈放された。トマス・モアは、公の生活から身を引き、隠遁することが望ましいとさえ考えた [23]。 1510年以降、モアはロンドン市の2人のアンダーシェリフのうちの1人を務め、その職責は重く、誠実で有能な公僕としての評判を得た。公衆衛生に関心を 持ち、1514年には下水道委員となった[39]。1514年、モアは枢密顧問官に任命されたのと同じ年に、要請の主人となった[40]。神聖ローマ皇帝 シャルル5世への外交使節団を引き受け、ヨーク大司教トマス・ウォルシー枢機卿に同行してカレー(金の布の畑)とブルージュを訪れた後、1521年にモア はナイトの称号を授けられ、大蔵次官となった[41]。 ヘンリー8世の秘書兼個人顧問として、モアはますます影響力を増していった。外国の外交官を迎え入れ、公文書を起草し、その法的手腕で星間法廷に出席した が、「貧乏人の事件」[42]のために下級法廷での裁判を委任された: 491年、492年、国王とウォルジー大法官との連絡役を務めた。その後、モアは オックスフォード大学とケンブリッジ大学の高等執事を務めた。 1523年、モアはミドルセックス州のシャイアー騎士(国会議員)に選出され、ウォルジーの推薦により下院はモアを議長に選出した[41]。1525年、モアはランカスター公国の大法官となり、イングランド北部の大部分を行政・司法面で管轄することになった[41]。 首相職 ウォルジーが失脚すると、モアは1529年に大法官(政府の最高責任者)の職を継承した。大法官は契約や王室の事件、一部の軽犯罪の上訴を含む衡平法・慣 習法を担当する最高官職であった[43]: 527 彼はかつてない速さで事件を処理した。1532年には公害防止法の責任者となった[39]。 大法官として、暴動や反乱を含む民事・刑事に関する控訴裁判所である星の間法廷のメンバー(出席していたときはおそらく裁判長判事であり、最後に発言し、同数の場合は決定票を投じた)[44]: 61であり、反体制派の裁判の最終的な控訴審であった[注釈 5]。 プロテスタント宗教改革反対運動  トマス・モア卿は、19世紀後半に建てられたロンドンのキャリー・ストリート、王立司法裁判所の向かいにあるトマス・モア卿の家に彫刻で記念されている。 モアはカトリック教会を支持し、プロテスタント宗教改革を教会と社会の統一を脅かす異端とみなした。モアは教会の神学、論法、教会法を信じており、「カトリック教会を破壊しようというルターの呼びかけを、戦争への呼びかけとして聞いた」[45]。 異端は、トマス・モアが総長職の中で、そしておそらく彼の生涯の最後の10年間を通して、最も時間をかけて取り組んだ問題であった。 - Richard Rex, More and the heretics: statesman or fanatic? [46]: 107 モアはプロテスタントに対応するために英語とラテン語で一連の書物やパンフレットを執筆し、公的な立場では違法な書籍取引に対して行動を起こし、特に 1525年にはランカスター公国の大法官として、外交的に微妙な立場にあるハンザ商人のスチーリーヤードへの襲撃を指揮した[46]: 106であり、ハ ンザとの外交交渉の経験もある[47]: 150 ティンデールとの論争 モアはティンデールの英語訳新約聖書の初版に反対して数冊の本を書いた[48]。モアは『異端に関する対話』(1529年)を書き、ティンデールは『ティ ンデール卿の対話に対する回答』(1530年)で反論し、モアは『ティンデールの回答に対する反駁』(1532年)で反論した。 モアのティンデール訳に対する批判のひとつは、ティンデールが現地語であると主張しながらも、多くの新語を使用していたことであった。例えば、「エホ バ」、「身代わり」、「過越」、「贖罪」、「慈悲の座」、「シーブレッド」などである。 例えば、「エホバ」、「スケープゴート」、「過越祭」、「贖罪」、「慈悲の座」、「シーフレッド」などである[50]。モアはまた、ティンデールがギリ シャ語のアガペーの実践的行為「慈愛」の代わりに感情「愛」を使ったり、ギリシャ語のプレスビテロス[51]の代わりに「司祭」の代わりに新造語のシニア を使ったり(ティンデールはこれを「長老」に変えた)、「教会」の代わりにラテン語の「集会」を使ったりするなど、偏った言葉を好んで一般的な翻訳を意図 的に避けていると非難した。 [52]ティンデールの聖書には聖典以外のテキストも含まれており、ティンデールの序文の一部はマルティン・ルターの直訳であり[53]、カトリックの教 義に異議を唱えるような注釈も含まれていた[54]。 ティンデールの信徒使用に対するモアの攻撃をめぐって、注目すべきやりとりがあった。ティンデールは、「あなたの愛する」エラスムスがラテン語で ecclesiaをcongregatioと訳したのに倣っていると指摘した。モアは、エラスムスには良いラテン語がなかったからcongregatio という造語を使う必要があったのであり、英語には完璧な 「church 」があった: 私がエラスムスと争わなかったのは、ティンデールに見られるような悪意がエラスムスにはなかったからだ。もし、私の愛するエラスムスに、ティンデールに見 られるような狡猾な意図や目的を見出したとしたら: 私の最愛の人エラスムスは、もはや私の最愛の人ではないはずだ。しかし、私はエラスムスに、ティンデールが明白に教え、遵守している誤りと異端を嫌悪し、 憎んでいることを見出した。そして、もしティンデールがそれらを教えなかったか、あるいは、それらを撤回する恵みをもっていたならば、ティンデールもま た、私の親愛なる最愛の人であるべきである。しかし、彼がそのような異端を持っている間は、悪魔が自分の最愛の人とする彼を、私は最愛の人とすることはで きない。 - トマス・モア [37][55] 辞任 教皇庁と国王の覇権をめぐる対立が頂点に達する中、モアはイングランド王よりもペテロの後継者である教皇の覇権を支持する姿勢を崩さなかった。1529年 に議会がプラエミュニーレ罪を復活させたことで、国王よりも優位な法的管轄権を持つという領域外の権威(教皇庁など)の主張を公的または職権で支持するこ とは犯罪とされた[56]。 1530年、モアはイングランドの主要な教会関係者や貴族たちがヘンリーとキャサリン・オブ・アラゴンの結婚を取り消すようローマ教皇クレメンス7世に求 めた書簡への署名を拒否し、異端に関する法律をめぐってヘンリー8世とも対立した。1531年、勅令は聖職者に対し、国王を英国国教会の最高首長と認める 宣誓をするよう求めた。1532年のカンタベリー総会で司教たちは宣誓書に署名することに同意したが、それは「キリストの法が許す限り」という言葉が付け 加えられた後であり、賛美の脅しを受けてのことであった[57]。 これは聖職者の最終的な服従とみなされた[58]。ジョン・フィッシャー枢機卿をはじめとする聖職者の一部は署名を拒否した。ヘンリーは教皇の姿勢を支持 する聖職者のほとんどを教会の上級職から粛清した。モアは引き続き優越の誓いへの署名を拒否し、ヘンリーとキャサリン妃の結婚の取り消しを支持することに も同意しなかった[56]。しかし、彼は王の行動を公然と拒否することはせず、自分の意見を非公開にした[59]。 1532年5月16日、モアは総長の職を辞したが、拒否していたにもかかわらずヘンリーの寵愛を受け続けた[60]。 彼の辞職の決断は、前日に王室の激しい脅威にさらされていたイギリス教会の召集が決定したことに起因していた[61]。 |

| Controversy on extent of prosecution of heretics There is considerable variation in opinion on the extent and nature of More's prosecution of heretics: witness in recent popular media the difference in portrayals of More in A Man for All Seasons and in Wolf Hall. The English establishment initially regarded Protestants (and Anabaptists) as akin to the Lollards and Hussites whose heresies fed their sedition.[note 6] Ambassador to Charles V Cuthbert Tunstall called Lutheranism the "foster-child" of the Wycliffite heresy[62] that had underpinned Lollardy. Historian Richard Rex wrote:[46]: 106 Thomas More, as lord chancellor [1529–1532], was in effect the first port of call for those arrested in London on suspicion of heresy, and he took the initial decisions about whether to release them, where to imprison them, or to which bishop to send them. He can be connected with police or judicial proceedings against around forty suspected or convicted heretics in the years 1529–33.[note 7] Torture allegations Torture was not officially legal in England, except in pre-trial discovery phase[63]: 62 of kinds of extreme cases that the King had allowed, such as seditious heresy. It was regarded as unsafe for evidence, and was not an allowed punishment. Stories emerged in More's lifetime regarding persecution of the Protestant "heretics" during his time as Lord Chancellor, and he denied them in detail in his Apologia (1533). Many stories were later published by the popular sixteenth-century English Protestant historian John Foxe in his polemical Book of Martyrs. Foxe was instrumental in publicizing accusations of torture, alleging that More had often personally used violence or torture while interrogating heretics.[64] Later Protestant authors such as Brian Moynahan and Michael Farris cite Foxe when repeating these allegations.[65] Biographer Peter Ackroyd also lists claims from Foxe's Book of Martyrs and other post-Reformation sources that More "tied heretics to a tree in his Chelsea garden and whipped them", that "he watched as 'newe men' were put upon the rack in the Tower and tortured until they confessed", and that "he was personally responsible for the burning of several of the 'brethren' in Smithfield."[16]: 305 Historian John Guy commented that "such charges are unsupported by independent proof."[note 8] Modern historian Diarmaid MacCulloch finds no evidence that he was directly involved in torture.[note 9] Richard Marius records a similar claim, which tells about James Bainham, and writes that "the story Foxe told of Bainham's whipping and racking at More's hands is universally doubted today".[note 10] More himself denied these allegations: Stories of a similar nature were current even in More's lifetime and he denied them forcefully. He admitted that he did imprison heretics in his house – 'theyr sure kepynge' – he called it – but he utterly rejected claims of torture and whipping... 'as help me God.'[16]: 298–299 More instead claimed in his "Apology" (1533) that he only applied corporal punishment to two "heretics": a child servant in his household who was caned (the customary punishment for children at that time) for repeating a heresy regarding the Eucharist, and a "feeble-minded" man who was whipped for disrupting the mass by raising women's skirts over their heads at the moment of consecration, More taking the action to prevent a lynching.[66]: 404 Executions Burning at the stake was the standard punishment by the English state for obstinate or relapsed, major seditious or proselytizing heresy, and continued to be used by both Catholics and Protestants during the religious upheaval of the following decades.[67] In England, following the Lollard uprisings, heresy had been linked to sedition (see De heretico comburendo and Suppression of Heresy Act 1414.) Ackroyd and MacCulloch agree that More zealously approved of burning.[16]: 298 Richard Marius maintained that in office More did everything in his power to bring about the extermination of heretics.[68] During More's chancellorship, six people were burned at the stake for heresy, the same rate as under Wolsey: they were Thomas Hitton, Thomas Bilney, Richard Bayfield, John Tewkesbury, Thomas Dusgate, and James Bainham.[16]: 299–306 However, the court of the Star Chamber, of which More as Lord Chancellor was the presiding judge, could not impose the death sentence: it was a kind of appellate supreme court.[69]: 263 More took a personal interest in the three London cases:[46]: 105 John Tewkesbury was a London leather seller found guilty by the Bishop of London John Stokesley[note 11] of harbouring English translated New Testaments; he was sentenced to burning for refusing to recant. More declared: he "burned as there was neuer wretche I wene better worthy."[70] Richard Bayfield was found distributing Tyndale's Bibles, and examined by Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall. More commented that he was "well and worthely burned".[16]: 305 James Bainham was arrested on a warrant of Thomas More as Lord Chancellor and detained at his gatehouse. He was examined by Bishop John Stokesley, abjured, penalized and freed. He subsequently re-canted, and was re-arrested, tried and executed as a relapsed heretic. Popular historian Brian Moynahan alleges that More influenced the eventual execution of William Tyndale in the Duchy of Brabant, as English agents had long pursued Tyndale. He names Henry Phillips, a student at the University of Louvain and follower of Bishop Stokesley, as the man More commissioned to befriend Tyndale and then betray him.[71] This was notwithstanding that the execution took place on 6 October 1536, sixteen months after More himself had been executed, and in a different jurisdiction. Historian Richard Rex argues that linking the execution to More was "bizarre".[46]: 93 Modern treatment Modern commentators have been divided over More's character and actions. Some biographers, including Peter Ackroyd, have taken a relatively tolerant[note 12] or even positive[note 13] view of More's campaign against Protestantism by placing his actions within the turbulent religious climate of the time and the threat of deadly catastrophes such as the German Peasants' Revolt, which More blamed on Luther,[note 14] as did many others, such as Erasmus.[note 15] Others have been more critical, such as writer Richard Marius, an American scholar of the Reformation, believing that such persecutions were a betrayal of More's earlier humanist convictions, including More's zealous and well-documented advocacy of extermination for heretics.[66]: 386–406 This supposed contraction has been called "schizophrenic."[46]: 108 He has been called a "zealous legalist…(with an) itchy finesse of cruelty".[72] Pope John Paul II honoured him by making More patron saint of statesmen and politicians in October 2000, stating: "It can be said that he demonstrated in a singular way the value of a moral conscience ... even if, in his actions against heretics, he reflected the limits of the culture of his time".[8] Australian High Court judge and President of the International Commission of Jurists, Justice Michael Kirby has noted More's resignation as Lord Chancellor demonstrates also a recognition of the fact that, so long as he held office, he was obliged to conform to the King's law. It is often the fact that judges and lawyers must perform acts which they do not particularly like. In Utopia, for example, More had written that he believed capital punishment to be immoral, reprehensible and unjustifiable. Yet as Lord Chancellor and as councillor to the King, he certainly participated in sending hundreds of people to their death, a troubling thought. Doubtless he saw himself, as many judges before and since have done, as a mere instrument of the legal power of the State. — "Thomas More, Martin Luther and the Judiciary today," speech to St Thomas More Society, 1997 |

異端者訴追の範囲に関する論争 モアによる異端者訴追の範囲と性質については、意見がかなり分かれている。最近の一般的なメディアでは、『万能の男』と『ウルフ・ホール』におけるモアの 描写の違いが目撃されている。チャールズ5世の大使カスバート・タンストールは、ルーテル派をロラーディーを支えていたウィクリフ派の異端[62]の「里 子」と呼んだ。 歴史家のリチャード・レックスは次のように書いている[46]: 106 トマス・モアは大法官[1529-1532]として、異端の疑いでロンドンで逮捕された人々の実質的な最初の窓口であり、彼らを釈放するかどうか、どこに 投獄するか、どの司教のもとに送るかについての最初の決定を下した。彼は1529年から33年にかけて、異端と疑われた、あるいは有罪判決を受けた約40 人の警察や司法手続きに関わることができる[注釈 7]。 拷問疑惑 イングランドでは、公判前の発見段階[63]を除き、拷問は公式には合法ではなかった。拷問は証拠としては危険とみなされ、刑罰としては認められていなかった。 モアが大法官であった時代に、プロテスタントの「異端者」に対する迫害に関する話が生前に浮上し、彼は『弁明』(1533年)の中でそれらを詳細に否定した。 後に、16世紀イギリスのプロテスタント史家ジョン・フォクシーが、その極論的な『殉教者の書』の中で、多くのエピソードを発表した。フォクセは、モアが 異端者を尋問する際にしばしば個人的に暴力や拷問を行ったと主張し、拷問の告発を公にすることに貢献した[64]。 ブライアン・モイナハンやマイケル・ファリスといった後のプロテスタントの著者は、これらの主張を繰り返す際にフォクセを引用している。 [65]伝記作家のピーター・アクロイドも、フォクセの『殉教者の書』や宗教改革後の他の資料から、モアは「異端者をチェルシーの庭の木に縛り付けて鞭で 打った」、「『新教徒』が塔の中で獄門にかけられ、自白するまで拷問されるのを見ていた」、「スミスフィールドで何人かの『兄弟たち』を焼き殺したのはモ ア個人の責任である」という主張を挙げている[16]: 305 歴史家ジョン・ガイは、「このような告発は独立した証拠に裏付けられていない」とコメントしている[注釈 8] 近代史家ディアメイド・マッカロクは、モアが拷問に直接関与したという証拠はないと見なしている[注釈 9] リチャード・マリウスは、ジェームズ・ベイナムについて語った同様の主張を記録しており、「フォクシーが語った、モアの手によるベイナムの鞭打ちと鞭打ち の話は、今日では誰もが疑っている」と書いている[注釈 10]。 モア自身はこれらの疑惑を否定している: 同じような話はモアの存命中にもあり、彼はそれを強く否定した。彼は異端者を自分の家に監禁したことは認めたが、拷問や鞭打ちの主張は完全に否定した。神よ、お助けください」[16]: 298-299 その代わりにモアは『弁明』(1533年)の中で、自分が体罰を加えたのは2人の「異端者」だけであったと主張している。聖体に関する異端を繰り返したた めに杖で打たれた(当時の子供に対する慣例であった)自分の家の使用人の子供と、奉献の瞬間に女性のスカートを頭上にあげてミサを妨害したために鞭で打た れた「気の弱い」男であり、モアはリンチを防ぐためにそのような行動をとったのであった[66]: 404 処刑 火あぶりは、頑固な異端、再発した異端、主要な扇動的異端、布教的異端に対するイングランド国家による標準的な刑罰であり、その後数十年の宗教的動乱の 間、カトリックとプロテスタントの両方によって使われ続けた[67]。イングランドでは、ロラードの反乱の後、異端は扇動と結びつけられていた(De heretico comburendoとSuppression of Heresy Act 1414を参照)。 アクロイドとマッカロックは、モアが火刑を熱心に承認していたことに同意している[16]:298 リチャード・マリウスは、モアは在任中、異端者を絶滅させるために全力を尽くしたと主張している[68]。 モアの大法官在任中、異端の罪で火あぶりの刑に処されたのは、ウォルジーの時代と同じ割合で、トマス・ヒットン、トマス・ビルニー、リチャード・ベイ フィールド、ジョン・テュークスベリー、トマス・ダスゲート、ジェームズ・ベイナムの6人であった[16]: 299-306 しかし、大法官であったモアが裁判長を務めた星法廷は、死刑判決を下すことはできなかった。 モアはロンドンの3つの事件に個人的な関心を寄せていた[46]: 105 ジョン・テュークスベリーはロンドンの皮革販売業者で、ロンドン司教ジョン・ストークスリー[注釈 11]によって英語訳の新約聖書を所持しているとして有罪判決を受けた。モアは、「私がこれほどふさわしい惨事はないとして火刑に処した」と宣言した[70]。 リチャード・ベイフィールドはティンデールの聖書を配布しているところを発見され、カスバート・タンストール司教に尋問された。モアは、彼は「よくよく焼かれた」とコメントした[16]: 305 ジェームズ・ベイナムは大法官トマス・モアの令状で逮捕され、彼の門衛所に拘留された。彼はジョン・ストークスリー司教の尋問を受け、棄教し、刑罰を受け、釈放された。その後、彼は再び棄教し、再び異端者として逮捕され、裁判にかけられ、処刑された。 人気のある歴史家ブライアン・モイナハンは、モアがブラバント公国でのウィリアム・ティンデールの処刑に影響を与えたと主張している。彼は、ルーヴァン大 学の学生でストークスリー司教の信奉者であったヘンリー・フィリップスを、モアがティンデールと親しくなり、彼を裏切るように依頼した人物として挙げてい る[71]。これは、処刑が1536年10月6日に行われたにもかかわらず、モア自身が処刑された16ヵ月後であり、別の司法管轄区で行われた。歴史家の リチャード・レックスは、この処刑とモアを結びつけるのは「奇妙」であると論じている[46]: 93。 現代の扱い 現代の論者たちはモアの性格や行動をめぐって意見が分かれている。 ピーター・アクロイドを含む一部の伝記作家は、モアの行動を当時の激動する宗教情勢や、モアがルターのせいにしたドイツ農民反乱のような致命的な大災害の 脅威[注釈 14]の中に位置づけることによって、モアのプロテスタント反対運動を比較的寛容に[注釈 12]、あるいは肯定的に[注釈 13]捉えており、エラスムスのような他の多くの人々と同様である[注釈 15]。 また、宗教改革に関するアメリカの研究者である作家のリチャード・マリウスのように、このような迫害はモアのそれまでの人文主義的信念を裏切るものであ り、モアが異端者の抹殺を熱心に提唱していたことはよく知られている[66]: 386-406 このような収縮は「分裂病」と呼ばれている[46]: 108 彼は「熱心な合法主義者...(かゆいところに手が届くような残酷な技巧を持つ)」と呼ばれている[72]。 教皇ヨハネ・パウロ二世は、2000年10月、政治家と政治家の守護聖人として彼を称え、次のように述べた: 「たとえ異端者に対する行動において、当時の文化の限界を反映していたとしても......」[8]。 オーストラリア高等法院判事で国際法律家委員会会長のマイケル・カービー判事は、次のように述べている。 モアの大法官辞任は、彼が大法官である限り、国王の法に従わざるを得なかったという事実の認識でもあった。裁判官や弁護士が、自分たちが特に好まない行為 を行わなければならないことはよくあることである。例えば、モアは『ユートピア』の中で、死刑は不道徳であり、非難されるべきものであり、正当化できない と信じていると書いている。しかし、彼は大法官として、また国王の顧問官として、何百人もの人々を死に追いやることに関与した。それ以前も以後も、多くの 判事がそうであるように、彼も自分自身を国家の法的権力の単なる道具としか考えていなかったに違いない。 - トマス・モア、マルティン・ルター、そして今日の司法」、聖トマスモア協会でのスピーチ、1997年 |

| Indictment, trial and execution In 1533, More refused to attend the coronation of Anne Boleyn as Queen of England. Technically, this was not an act of treason, as More had written to Henry seemingly acknowledging Anne's queenship and expressing his desire for the King's happiness and the new Queen's health.[note 16] Despite this, his refusal to attend was widely interpreted as a snub against Anne, and Henry took action against him. Shortly thereafter, More was charged with accepting bribes, but the charges had to be dismissed for lack of any evidence. In early 1534, More was accused by Thomas Cromwell of having given advice and counsel to the "Holy Maid of Kent," Elizabeth Barton, a nun who had prophesied that the king had ruined his soul and would come to a quick end for having divorced Queen Catherine. This was a month after Barton had confessed, which was possibly done under royal pressure,[73][74] and was said to be concealment of treason.[75] Though it was dangerous for anyone to have anything to do with Barton, More had indeed met her, and was impressed by her fervour. But More was prudent and told her not to interfere with state matters. More was called before a committee of the Privy Council to answer these charges of treason, and after his respectful answers the matter seemed to have been dropped.[76] On 13 April 1534, More was asked to appear before a commission and swear his allegiance to the parliamentary Act of Succession.[note 17] More accepted Parliament's right to declare Anne Boleyn the legitimate Queen of England, though he refused "the spiritual validity of the king's second marriage",[77] and, holding fast to the teaching of papal supremacy, he steadfastly refused to take the oath of supremacy of the Crown in the relationship between the kingdom and the church in England. More furthermore publicly refused to uphold Henry's annulment from Catherine. John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, refused the oath along with More. The oath reads in part:[78] ...By reason whereof the Bishop of Rome and See Apostolic, contrary to the great and inviolable grants of jurisdictions given by God immediately to emperors, kings and princes in succession to their heirs, hath presumed in times past to invest who should please them to inherit in other men's kingdoms and dominions, which thing we your most humble subjects, both spiritual and temporal, do most abhor and detest... In addition to refusing to support the King's annulment or supremacy, More refused to sign the 1534 Oath of Succession confirming Anne's role as queen and the rights of their children to succession. More's fate was sealed.[79][80] While he had no argument with the basic concept of succession as stated in the Act, the preamble of the Oath repudiated the authority of the Pope.[59][81][82] Indictment His enemies had enough evidence to have the King arrest him on treason. Four days later, Henry had More imprisoned in the Tower of London. There More prepared a devotional Dialogue of Comfort against Tribulation. While More was imprisoned in the Tower, Thomas Cromwell made several visits, urging More to take the oath, which he continued to refuse. In his unfinished History of the Passion, written in the Tower to his daughter Meg, he wrote of feeling favoured by God: "For methinketh God maketh me a wanton, and setteth me on his lap and dandleth me."[83]  The site of the scaffold at Tower Hill where More was executed by decapitation A commemorative plaque at the site of the ancient scaffold at Tower Hill, with Sir Thomas More listed among other notables executed at the site The charges of high treason related to More's violating the statutes as to the King's supremacy (malicious silence) and conspiring with Bishop John Fisher in this respect (malicious conspiracy) and, according to some sources, included asserting that Parliament did not have the right to proclaim the King's Supremacy over the English Church. One group of scholars believes that the judges dismissed the first two charges (malicious acts) and tried More only on the final one, but others strongly disagree.[56] Regardless of the specific charges, the indictment related to violation of the Treasons Act 1534 which declared it treason to speak against the King's Supremacy:[84] If any person or persons, after the first day of February next coming, do maliciously wish, will or desire, by words or writing, or by craft imagine, invent, practise, or attempt any bodily harm to be done or committed to the king's most royal person, the queen's, or their heirs apparent, or to deprive them or any of them of their dignity, title, or name of their royal estates … That then every such person and persons so offending … shall have and suffer such pains of death and other penalties, as is limited and accustomed in cases of high treason.[85] Trial The trial was held on 1 July 1535, before a panel of judges that included the new Lord Chancellor, Sir Thomas Audley, as well as Anne Boleyn's uncle, Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, her father Thomas Boleyn and her brother George Boleyn. Norfolk offered More the chance of the king's "gracious pardon" should he "reform his [...] obstinate opinion". More responded that, although he had not taken the oath, he had never spoken out against it either and that his silence could be accepted as his "ratification and confirmation" of the new statutes.[86] Thus More was relying upon legal precedent and the maxim "qui tacet consentire videtur" ("one who keeps silent seems to consent"[87]), understanding that he could not be convicted as long as he did not explicitly deny that the King was Supreme Head of the Church, and he therefore refused to answer all questions regarding his opinions on the subject.[88] William Frederick Yeames, The meeting of Sir Thomas More with his daughter after his sentence of death, 1872 Thomas Cromwell, at the time the most powerful of the King's advisors, brought forth Solicitor General Richard Rich to testify that More had, in his presence, denied that the King was the legitimate head of the Church. This testimony was characterised by More as being extremely dubious. Witnesses Richard Southwell and Mr. Palmer (a servant to Southwell) were also present and both denied having heard the details of the reported conversation.[89] As More himself pointed out: Can it therefore seem likely to your Lordships, that I should in so weighty an Affair as this, act so unadvisedly, as to trust Mr. Rich, a Man I had always so mean an Opinion of, in reference to his Truth and Honesty, … that I should only impart to Mr. Rich the Secrets of my Conscience in respect to the King's Supremacy, the particular Secrets, and only Point about which I have been so long pressed to explain my self? which I never did, nor never would reveal; when the Act was once made, either to the King himself, or any of his Privy Councillors, as is well known to your Honours, who have been sent upon no other account at several times by his Majesty to me in the Tower. I refer it to your Judgments, my Lords, whether this can seem credible to any of your Lordships.[90] Beheading of Thomas More, 1870 illustration The jury took only fifteen minutes, however, to find More guilty. After the jury's verdict was delivered and before his sentencing, More spoke freely of his belief that "no temporal man may be the head of the spirituality" (take over the role of the Pope). According to William Roper's account, More was pleading that the Statute of Supremacy was contrary to Magna Carta, to Church laws and to the laws of England, attempting to void the entire indictment against him.[56] He was sentenced to be hanged, drawn, and quartered (the usual punishment for traitors who were not the nobility), but the King commuted this to execution by decapitation.[note 18] Execution The execution took place on 6 July 1535 at Tower Hill. When he came to mount the steps to the scaffold, its frame seeming so weak that it might collapse,[91][92] More is widely quoted as saying (to one of the officials): "I pray you, master Lieutenant, see me safe up and [for] my coming down, let me shift for my self";[93] while on the scaffold he declared "that he died the king's good servant, and God's first." Theologian Scott W. Hahn notes that the misquoted "but God's first" is a line from Robert Bolt's stage play A Man For All Seasons, which differs from his actual words.[94][note 19] After More had finished reciting the Miserere while kneeling,[95][96] the executioner reportedly begged his pardon, then More rose up, kissed him and forgave him.[97][98][99][100] Relics Thomas More's grave, St Peter ad Vincula Sir Thomas More family's vault Another comment More is believed to have made to the executioner is that his beard was completely innocent of any crime, and did not deserve the axe; he then positioned his beard so that it would not be harmed.[101] More asked that his adopted daughter Margaret Clement (née Giggs) be given his headless corpse to bury.[102] She was the only member of his family to witness his execution. He was buried at the Tower of London, in the chapel of St Peter ad Vincula in an unmarked grave. His head was fixed upon a pike over London Bridge for a month, according to the normal custom for traitors. More's daughter Margaret Roper (née More) later rescued the severed head.[103] It is believed to rest in the Roper Vault of St Dunstan's Church, Canterbury,[104] perhaps with the remains of Margaret and her husband's family.[105] Some have claimed that the head is buried within the tomb erected for More in Chelsea Old Church.[106] Among other surviving relics is his hair shirt, presented for safe keeping by Margaret Clement.[107] This was long in the custody of the community of Augustinian canonesses who until 1983 lived at the convent at Abbotskerswell Priory, Devon. Some sources, including one from 2004, claimed that the shirt, made of goat hair was then at the Martyr's church on the Weld family's estate in Chideock, Dorset.[108][109] It is now preserved at Buckfast Abbey, near Buckfastleigh in Devon.[110][111] Epitaph In 1533, More wrote to Erasmus and included what he intended should be the epitaph on his family tomb: Within this tomb Jane, wife of More, reclines; This More for Alice and himself designs. The first, dear object of my youthful vow, Gave me three daughters and a son to know; The next—ah! virtue in a stepdame rare!— Nursed my sweet infants with a mother’s care. With both my years so happily have past, Which most my love, I know not—first or last. Oh! had religion destiny allowed, How smoothly mixed had our three fortunes flowed! But, be we in the tomb, in heaven allied, So kinder death shall grant what life denied.[112] |

起訴、裁判、処刑 1533年、モアはアン・ブーリンのイングランド女王としての戴冠式への出席を拒否した。厳密には、モアはヘンリー宛にアンの王妃就任を認め、王の幸福と 新王妃の健康を願うような手紙を送っていたため、これは反逆行為ではなかった[注釈 16] にもかかわらず、出席拒否はアンに対するねたみと広く解釈され、ヘンリーは彼に対して行動を起こした。その直後、モアは賄賂を受け取った罪で起訴された が、証拠がないという理由で告訴は棄却された。 1534年初頭、モアはトーマス・クロムウェルによって、「ケントの聖なる乙女」エリザベス・バートンに助言と助言を与えたとして告発された。エリザベス は、キャサリン妃と離婚したことで王の魂が破滅し、すぐに最期を迎えるだろうと予言した修道女であった。これはバートンが告白した1ヵ月後のことであり、 おそらく王室の圧力によって行われたものであり[73][74]、謀反の隠蔽であったと言われている[75]。バートンと関わることは誰にとっても危険で あったが、モアは実際に彼女に会ったことがあり、その熱心さに感銘を受けた。しかしモアは思慮深く、彼女に国家の問題に干渉しないように言った。モアはこ れらの反逆罪に答えるために枢密院の委員会に呼ばれ、彼の丁重な答えの後、この問題は取り下げられたようであった[76]。 1534年4月13日、モアは委員会に出頭し、議会の継承法に忠誠を誓うよう求められた[註 17]。モアはアン・ブーリンをイングランドの正統な女王と宣言する議会の権利を受け入れたが、「王の再婚の精神的有効性」は拒否し[77]、教皇至上主 義の教えを堅持し、イングランドにおける王国と教会の関係において王室至上主義の宣誓を行うことを断固として拒否した。さらに、ヘンリーのキャサリン妃と の婚約破棄を支持することも公に拒否した。ロチェスター司教ジョン・フィッシャーもモアとともに宣誓を拒否した。宣誓の内容は以下の通りである[78]。 ...ローマ司教と使徒座は、神が皇帝、王、王侯に即座に与え、その相続人に継承させるという、偉大で侵すべからざる司法権の付与に反して、過去におい て、自分たちの意に沿う者に、他人の王国と領地を相続させるということを行ってきたのであり、このようなことを、私たち最も謙虚な臣民は、霊的にも時間的 にも、最も忌み嫌い、嫌悪する... モアは、国王の廃位や覇権を支持することを拒否したことに加え、アンの王妃としての役割とその子供たちの継承権を確認する1534年の「継承の誓い」に署 名することも拒否した。モアの運命は封印された[79][80]。モアは、法に記された継承の基本的概念には異論がなかったが、誓いの前文は教皇の権威を 否定していた[59][81][82]。 告発 彼の敵は、国王に反逆罪で彼を逮捕させるに十分な証拠を持っていた。4日後、ヘンリーはモアをロンドン塔に投獄した。そこでモアは『苦難に対する慰めの対 話』という献身的な文書を作成した。モアが塔に幽閉されている間、トマス・クロムウェルは何度も面会に訪れ、モアに宣誓をするよう促したが、彼は拒否し続 けた。 未完の『受難史』は、塔の中で娘のメグに宛てて書かれたもので、彼は神の恩恵を感じていると書いている: 「神は私を淫らな女にして、膝の上に置き、撫で回されたと思う」[83]。  モアが断頭台で処刑されたタワー・ヒルの足場跡 タワー・ヒルの古代の足場跡にある記念プレート。この場所で処刑された他の著名人の中にトマス・モア卿の名前が挙げられている。 大逆罪の容疑は、モアが国王の優越性に関する法令に違反したこと(悪意のある沈黙)と、この点で司教ジョン・フィッシャーと共謀したこと(悪意のある共 謀)に関連しており、いくつかの資料によれば、議会には英国教会に対する国王の優越を宣言する権利はないと主張したことも含まれていた。ある学者のグルー プは、裁判官は最初の2つの罪状(悪意ある行為)を却下し、最後の罪状のみでモアを裁いたと考えているが、他の学者たちは強く反対している[56]。 具体的な罪状にかかわらず、起訴状は1534年の反逆罪法違反に関連しており、それは国王の至上権に反対する発言を反逆罪とするものであった[84]。 次の2月1日以降、ある者またはある者が、悪意を持って、言葉や書面によって、または工作によって、国王の最も王らしい人物、王妃、またはそれらの相続人 らに対して、身体的危害を加えることを望み、意志し、欲し、または想像し、考案し、実践し、もしくは試み、またはそれらもしくはそれらの者から、その威 厳、称号、または王家の遺産の名称を奪おうとしたならば、.... その場合、このような犯罪を犯した者はすべて、大逆罪の場合に限定され慣例となっているように、死刑およびその他の刑罰を受けなければならない。 [85] 裁判 裁判は1535年7月1日、新しい大法官であるトーマス・オードリー卿、アン・ブーリンの叔父である第3代ノーフォーク公トーマス・ハワード、父トーマ ス・ブーリン、弟ジョージ・ブーリンを含む裁判官団の前で行われた。ノーフォークはモアに、「頑固な意見を改める」のであれば、王の「寛大な恩赦」の機会 を与えることを申し出た。これに対してモアは、自分は宣誓はしていないものの、それに反対する発言もしたことがなく、自分の沈黙は新しい法令に対する「批 准と確認」として受け入れられると答えた[86]。 このように、モアは判例と「qui tacet consentire videtur」(「沈黙を守る者は同意したように見える」[87])という格言に依拠し、国王が教会の最高責任者であることを明確に否定しない限り有罪 になることはないと理解していたため、この問題に関する自分の意見に関するすべての質問に答えることを拒否していた[88]。 ウィリアム・フレデリック・イェームス『死刑判決後のトマス・モア卿と娘との面会』1872年 トマス・クロムウェルは当時、国王の最も有力な助言者であったが、リチャード・リッチ法務総監を呼び寄せ、モアが彼の面前で、国王が教会の正当な元首であ ることを否定したと証言させた。この証言は極めて疑わしいものであるとモアは評した。目撃者のリチャード・サウスウェルとパーマー氏(サウスウェルの使用 人)も同席していたが、二人とも報告された会話の詳細を聞いていないと否定した[89]: それゆえ、私がこのような重大な事件において、真実と正直さに関して私が常に過小評価していたリッチ氏を信頼するような不用意な行動をとることが、諸君に とってあり得ると思われるであろうか......私がリッチ氏に伝えるべきは、王の覇権に関する私の良心の秘密であり、私が長い間釈明を迫られてきた特定 の秘密であり、唯一の点である。この法律が制定されたとき、国王自身にも、その枢密顧問官たちにも、私は決して明かさなかったし、明かそうともしなかっ た。諸君の判断に委ねるが、このことが諸君の誰かにとって信憑性があると思われるかどうか[90]。 トマス・モアの斬首、1870年のイラスト しかし、陪審員はわずか15分でモアを有罪とした。 陪審の評決が下された後、判決を受けるまでの間、モアは「いかなる現世の人間も精神性の長となることはできない」(ローマ教皇の役割を引き継ぐ)という信 念を自由に語った。ウィリアム・ローパーの記述によれば、モアは至上憲章がマグナ・カルタ、教会法、イングランド法に反していることを訴え、自分に対する 起訴全体を無効にしようとしていた[56]。 彼は絞首刑、引き分け、四つ裂きの刑(貴族以外の反逆者に対する通常の刑罰)を宣告されたが、国王はこれを断頭刑に減刑した[注釈 18]。 処刑 処刑は1535年7月6日にタワー・ヒルで行われた。足場の骨組みは崩れそうなほど弱く[91][92]、モアが足場の階段に登ろうとしたとき、(役人の 一人に向かって)こう言ったと広く引用されている: 「中尉殿、お願いです、私が安全に上がるのを見届けてください、そして(私が)降りるときは、自分のために交代させてください」[93]。神学者のスコッ ト・W・ハーンは、誤引用された 「but God's first 」はロバート・ボルトの舞台劇『A Man For All Seasons』の台詞であり、実際の彼の言葉とは異なると指摘している[94][注釈 19] モアがひざまずきながらミゼレーレを唱え終わった後[95][96]、処刑人は彼に許しを請い、その後モアは立ち上がり、彼に接吻し、彼を許したと伝えら れている[97][98][99][100]。 聖遺物 トマス・モアの墓、セント・ピーター・アド・ヴィンクラ トマス・モア卿一家の丸天井 モアが処刑人に言ったとされるもう一つの言葉は、彼の髭には何の罪もなく、斧に値しないというものであった。モアは、養女のマーガレット・クレメント(旧 姓ギグス)に彼の首のない死体を埋葬するよう求めた[102]。彼はロンドン塔の聖ピーター・アド・ヴィンクラ礼拝堂に無名の墓に埋葬された。彼の首は、 裏切り者に対する通常の慣習に従って、1ヶ月間ロンドン橋の上に杭で固定された。 後にモアの娘マーガレット・ローパー(旧姓モア)が切断された頭部を救出した[103]。おそらくマーガレットと彼女の夫の家族の遺骨とともに、カンタベリーの聖ダンスタン教会のローパー・ヴォールトに眠っていると考えられている[104]。 現存する他の遺物の中には、マーガレット・クレメントが保管のために贈ったモアのヘアシャツがある[107]。これは、1983年までデヴォンのアボッツ カースウェル修道院に住んでいたアウグスティノ会のカノネス修道女の共同体に長く保管されていた。2004年のものを含むいくつかの資料では、山羊の毛で 作られたこのシャツは当時、ドーセット州チドックにあるウェルド家の領地にある殉教者の教会にあったとされている[108][109]。現在ではデヴォン 州バックファストリーに近いバックファスト修道院に保存されている[110][111]。 墓碑銘 1533年、モアはエラスムスに手紙を書き、彼の家族の墓の墓碑銘として意図したものを添えた: この墓の中に、モアの妻ジェーンが横たわっている; このモアはアリスと自分のためにデザインした。 このモアはアリスと彼自身のためにデザインした、 三人の娘と一人の息子を授かった; その次は......ああ!継母の美徳は稀有なものだ。 私の可愛い乳飲み子を、母のように大切に育ててくれた。 私の歳月はこのように幸福に過ぎ去った、 私の愛は、最初か最後かわからない。 ああ、宗教が運命を許していたなら、 私たちの3つの運勢は、どれほどスムーズに混ざり合って流れていたことだろう! しかし、私たちは墓の中で、天国で同盟している、 [112]。 |

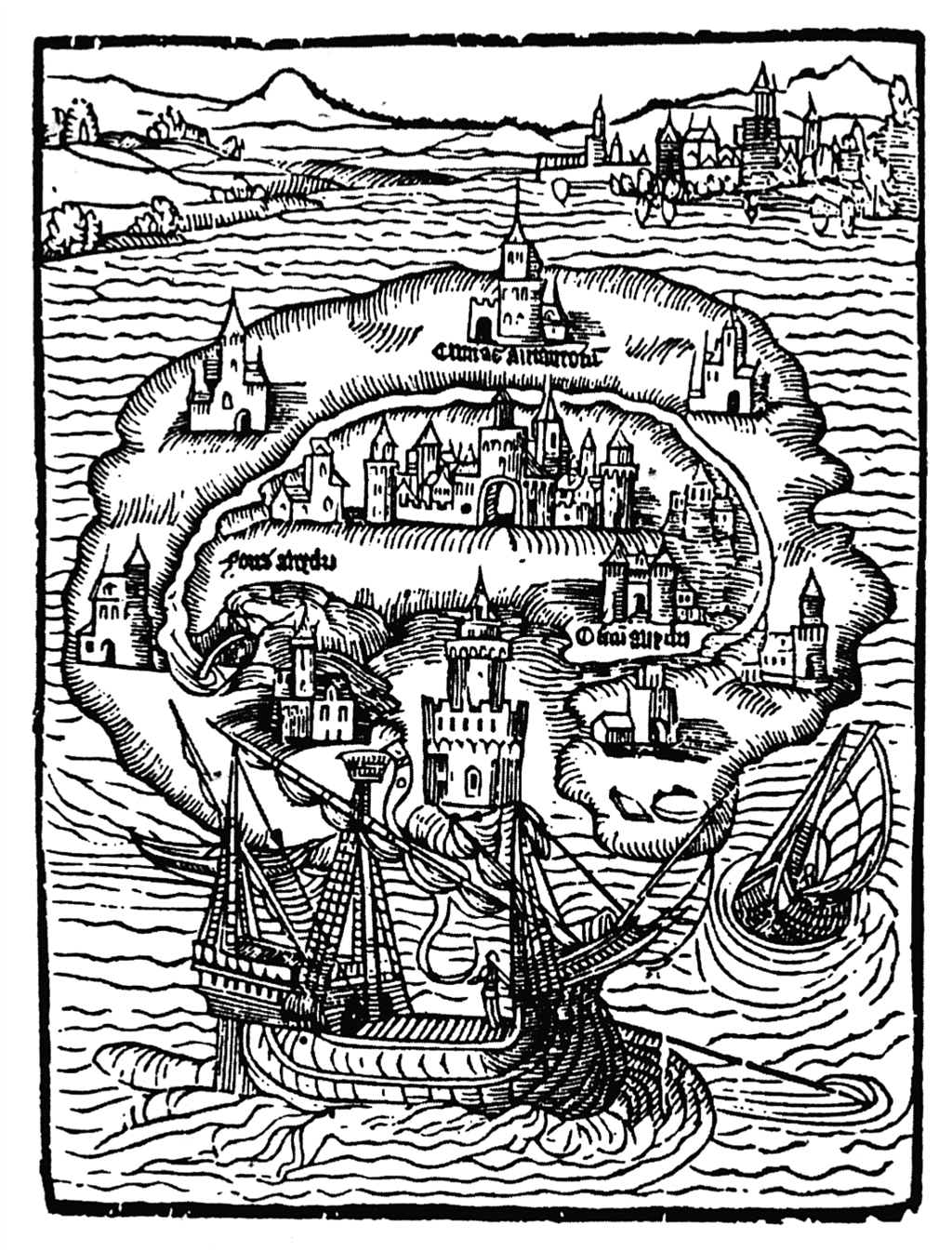

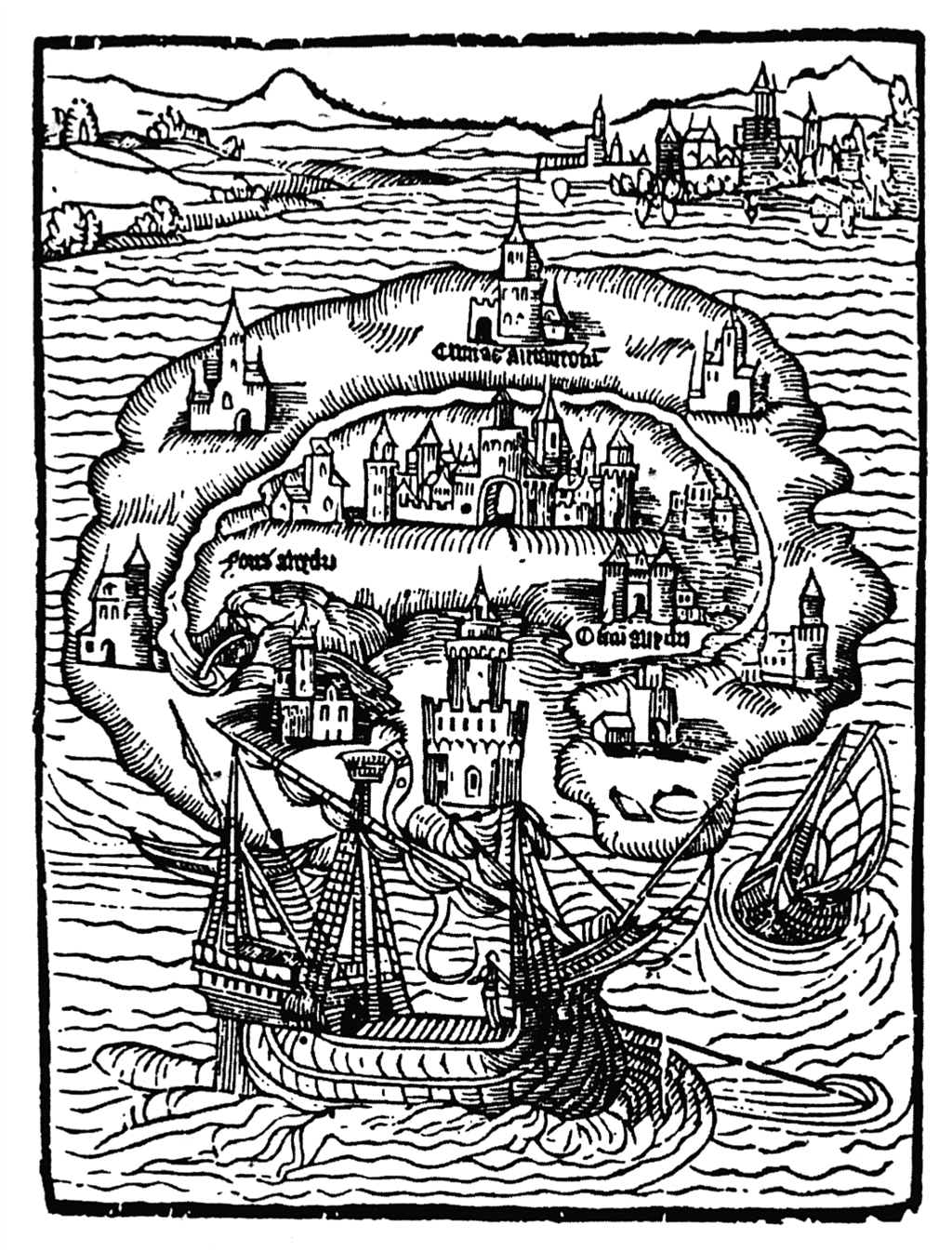

| Scholarly and literary work History of King Richard III Between 1512 and 1519 More worked on a History of King Richard III, which he never finished but which was published after his death. The History is a Renaissance biography, remarkable more for its literary skill and adherence to classical precepts than for its historical accuracy.[113] Some consider it an attack on royal tyranny, rather than on Richard III himself or the House of York.[114] More uses a more dramatic writing style than had been typical in medieval chronicles; Richard III is limned as an outstanding, archetypal tyrant—however, More was only seven years old when Richard III was killed at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485, so he had no first-hand, in-depth knowledge of him. The History of King Richard III was written and published in both English and Latin, each written separately, and with information deleted from the Latin edition to suit a European readership.[115] It greatly influenced William Shakespeare's play Richard III. Modern historians attribute the unflattering portraits of Richard III in both works to both authors' allegiance to the reigning Tudor dynasty that wrested the throne from Richard III in the Wars of the Roses.[115][116] According to Caroline Barron, Archbishop John Morton, in whose household More had served as a page (see above), had joined the 1483 Buckingham rebellion against Richard III, and Morton was probably one of those who influenced More's hostility towards the defeated king.[117][118] Clements Markham asserts that the actual author of the chronicle was, in large part, Archbishop Morton himself and that More was simply copying, or perhaps translating, Morton's original material.[119][120] Utopia Main article: Utopia (More book)  A 1516 illustration of Utopia More's best known and most controversial work, Utopia, is a frame narrative written in Latin.[121] More completed the book, and theologian Erasmus published it in Leuven in 1516. It was only translated into English and published in his native land in 1551 (16 years after his execution), and the 1684 translation became the most commonly cited. More (who is also a character in the book) and the narrator/traveller, Raphael Hythlodaeus (whose name alludes both to the healer archangel Raphael, and 'speaker of nonsense', the surname's Greek meaning), discuss modern ills in Antwerp, as well as describe the political arrangements of the imaginary island country of Utopia (a Greek pun on 'ou-topos' [no place] and 'eu-topos' [good place]) among themselves as well as to Pieter Gillis and Hieronymus van Busleyden.[122] Utopia's original edition included a symmetrical "Utopian alphabet" omitted by later editions, but which may have been an early attempt or precursor of shorthand. Utopia is structured into two parts, both with much irony: Book I has conversations between friends on various European political issues: the treatment of criminals, the enclosure movement, etc.; Book II is a remembered discourse by Raphael Hythlodaeus on his supposed travels, in which the earlier issues are revisited in fantastical but concrete forms that has been called mythical idealism. For example, the proposition in the Book I "no republic can be prosperous or justly governed where there is private property and money is the measure of everything."[123] Utopia contrasts the contentious social life of European states with the perfectly orderly, reasonable social arrangements of Utopia and its environs (Tallstoria, Nolandia, and Aircastle). In Utopia, there are no lawyers because of the laws' simplicity and because social gatherings are in public view (encouraging participants to behave well), communal ownership supplants private property, men and women are educated alike, and there is almost complete religious toleration (except for atheists, who are allowed but despised). More may have used monastic communalism as his model, although other concepts he presents such as legalising euthanasia remain far outside Church doctrine. Hythlodaeus asserts that a man who refuses to believe in a god or an afterlife could never be trusted, because he would not acknowledge any authority or principle outside himself. A scholar has suggested that More is most interested in the type of citizen Utopia produces.[123] Some take the novel's principal message to be the social need for order and discipline rather than liberty. Ironically, Hythlodaeus, who believes philosophers should not get involved in politics, addresses More's ultimate conflict between his humanistic beliefs and courtly duties as the King's servant, pointing out that one day those morals will come into conflict with the political reality. Utopia gave rise to a literary genre, Utopian and dystopian fiction, which features ideal societies or perfect cities, or their opposite. Works influenced by Utopia included New Atlantis by Francis Bacon, Erewhon by Samuel Butler, and Candide by Voltaire. Although Utopianism combined classical concepts of perfect societies (Plato and Aristotle) with Roman rhetorical finesse (cf. Cicero, Quintilian, epideictic oratory), the Renaissance genre continued into the Age of Enlightenment and survives in modern science fiction. Religious polemics In 1520 the reformer Martin Luther published three works in quick succession: An Appeal to the Christian Nobility of the German Nation (Aug.), Concerning the Babylonish Captivity of the Church (Oct.), and On the Liberty of a Christian Man (Nov.).[16]: 225 In these books, Luther set out his doctrine of salvation through faith alone, rejected certain Catholic practices, and attacked abuses and excesses within the Catholic Church.[16]: 225–6 In 1521, Henry VIII formally responded to Luther's criticisms with the Assertio, written with More's assistance.[124] Pope Leo X rewarded the English king with the title "Fidei defensor" ("Defender of the Faith") for his work combating Luther's heresies.[16]: 226–7 Martin Luther then attacked Henry VIII in print, calling him a "pig, dolt, and liar".[16]: 227 At the king's request, More composed a rebuttal: the Responsio ad Lutherum was published at the end of 1523. In the Responsio, More defended papal supremacy, the sacraments, and other Church traditions. More, though considered "a much steadier personality",[125] described Luther as an "ape", a "drunkard", and a "lousy little friar" amongst other epithets.[16]: 230 Writing under the pseudonym of Gulielmus Rosseus,[41] More tells Luther that: for as long as your reverend paternity will be determined to tell these shameless lies, others will be permitted, on behalf of his English majesty, to throw back into your paternity's shitty mouth, truly the shit-pool of all shit, all the muck and shit which your damnable rottenness has vomited up, and to empty out all the sewers and privies onto your crown divested of the dignity of the priestly crown, against which no less than the kingly crown you have determined to play the buffoon.[126] His saying is followed with a kind of apology to his readers, while Luther possibly never apologized for his sayings.[126] Stephen Greenblatt argues, "More speaks for his ruler and in his opponent's idiom; Luther speaks for himself, and his scatological imagery far exceeds in quantity, intensity, and inventiveness anything that More could muster. If for More scatology normally expresses a communal disapproval, for Luther, it expresses a deep personal rage."[127] Confronting Luther confirmed More's theological conservatism. He thereafter avoided any hint of criticism of Church authority.[16]: 230 In 1528, More published another religious polemic, A Dialogue Concerning Heresies, that asserted the Catholic Church was the one true church, established by Christ and the Apostles, and affirmed the validity of its authority, traditions and practices.[16]: 279–81 In 1529, the circulation of Simon Fish's Supplication for the Beggars prompted More to respond with the Supplycatyon of Soulys. In 1531, a year after More's father died, William Tyndale published An Answer unto Sir Thomas More's Dialogue in response to More's Dialogue Concerning Heresies. More responded with a half million words: the Confutation of Tyndale's Answer. The Confutation is an imaginary dialogue between More and Tyndale, with More addressing each of Tyndale's criticisms of Catholic rites and doctrines.[16]: 307–9 More, who valued structure, tradition and order in society as safeguards against tyranny and error, vehemently believed that Lutheranism and the Protestant Reformation in general were dangerous, not only to the Catholic faith but to the stability of society as a whole.[16]: 307–9 Correspondence Most major humanists were prolific letter writers, and Thomas More was no exception. As in the case of his friend Erasmus of Rotterdam, however, only a small portion of his correspondence (about 280 letters) survived. These include everything from personal letters to official government correspondence (mostly in English), letters to fellow humanist scholars (in Latin), several epistolary tracts, verse epistles, prefatory letters (some fictional) to several of More's own works, letters to More's children and their tutors (in Latin), and the so-called "prison-letters" (in English) which he exchanged with his oldest daughter Margaret while he was imprisoned in the Tower of London awaiting execution.[45] More also engaged in controversies, most notably with the French poet Germain de Brie, which culminated in the publication of de Brie's Antimorus (1519). Erasmus intervened, however, and ended the dispute.[54] More also wrote about more spiritual matters. They include: A Treatise on the Passion (a.k.a. Treatise on the Passion of Christ), A Treatise to Receive the Blessed Body (a.k.a. Holy Body Treaty), and De Tristitia Christi (a.k.a. The Agony of Christ). More handwrote the last in the Tower of London while awaiting his execution. This last manuscript, saved from the confiscation decreed by Henry VIII, passed by the will of his daughter Margaret to Spanish hands through Fray Pedro de Soto, confessor of Emperor Charles V. More's friend Luis Vives received it in Valencia, where it remains in the collection of Real Colegio Seminario del Corpus Christi museum. |

学術・文学作品 リチャード3世の歴史 1512年から1519年にかけて、モアは『リチャード3世史』の執筆に取り組んだ。この『リチャード三世史』はルネサンス期の伝記であり、歴史的な正確 さよりも、その文学的な技巧と古典的な戒律への忠実さが際立っている[113]。リチャード三世自身やヨーク家に対するというよりも、王家の専制政治に対 する攻撃であるという見方もある[114]。モアは、中世の年代記によく見られるような劇的な文体を用いており、リチャード三世は傑出した典型的な暴君と して描かれている。 リチャード3世の歴史』は英語とラテン語の両方で書かれ、それぞれ別々に出版された。現代史家は、両作品におけるリチャード3世の肖像が不評なのは、両著 者が薔薇戦争でリチャード3世から王位を奪ったテューダー朝に忠誠を誓っていたためであるとしている[115][116]。 キャロライン・バロンによれば、モアがページとして仕えていたジョン・モートン大司教(上記参照)は、リチャード3世に対する1483年のバッキンガムの 反乱に加わっており、モートンは敗れた王に対するモアの敵意に影響を与えた人物の一人であったと思われる。 [117][118]クレメンツ・マーカムは、この年代記の実際の著者の大部分はモートン大司教自身であり、モアはモートンの原典を単にコピー、あるいは 翻訳したに過ぎないと主張している[119][120]。 ユートピア 主な記事 ユートピア (モアの本)  1516年の『ユートピア』の挿絵 モアの最もよく知られ、最も物議を醸した作品である『ユートピア』はラテン語で書かれた枠物語である[121]。モアはこの本を完成させ、神学者エラスム スが1516年にルーヴェンで出版した。モアが英訳され、母国で出版されたのは1551年(処刑から16年後)で、1684年の翻訳が最もよく引用される ようになった。モア(この本の登場人物でもある)と語り手であり旅行者でもあるラファエル・ヒュトロダイオス(その名前は、癒しの大天使ラファエルと、苗 字のギリシャ語の意味である「無意味なことを話す人」の両方を暗示している)は、アントワープにおける現代の病について論じている、 ユートピア』(ギリシャ語で 「ou-topos」[no place]と 「eu-topos」[good place]をもじったダジャレ)の架空の島国ユートピアの政治的取り決めについて、自分たちだけでなく、ピーテル・ギリスやヒエロニムス・ファン・ブス レーデンに説明した。 [122] 『ユートピア』の初版には、後の版では省略された左右対称の「ユートピア・アルファベット」が含まれていたが、これは速記法の初期の試みあるいは先駆けで あったかもしれない。 ユートピア』は2部構成になっており、どちらも皮肉が効いている。第1巻は、ヨーロッパのさまざまな政治問題(犯罪者の処遇、囲い込み運動など)に関する 友人同士の会話、第2巻は、ラファエル・ヒュトロダイオスが旅先で語ったとされる思い出の談話であり、そこでは、神話的観念論と呼ばれるような、空想的だ が具体的な形で以前の問題が再検討されている。例えば、第一書の命題「私有財産があり、貨幣がすべての尺度であるような共和国は、繁栄することも、公正に 統治されることもありえない」[123]。 ユートピア』は、ヨーロッパ諸国の争いの絶えない社会生活と、ユートピアとその周辺(タルストリア、ノーランディア、エアキャッスル)の完全に秩序だった 合理的な社会体制を対比させている。ユートピアでは、法律が簡素であるため弁護士も存在せず、社交の場が人目にさらされるため(参加者に善良な振る舞いを 促す)、共同所有が私有財産に取って代わり、男女は同じように教育され、宗教はほぼ完全に寛容である(無神論者は認められているが軽蔑されている)。 モアは修道院の共同体主義を手本にしたのかもしれないが、安楽死の合法化など、彼が提示した他の概念は、教会の教義からは大きく外れている。ヒスロダイオ スは、神や死後の世界を信じることを拒否する人間は、自分以外の権威や原理を認めないため、決して信用できないと主張している。ある学者は、モアが最も関 心を寄せているのは『ユートピア』が生み出す市民のタイプであると示唆している[123]。 この小説の主要なメッセージは、自由よりもむしろ秩序と規律の社会的必要性であると考える者もいる。皮肉なことに、哲学者は政治に関与すべきではないと考 えるヒスロダイオスは、モアの人文主義的信念と王の下僕としての宮廷的義務との間の究極的な葛藤を取り上げ、そうした道徳観はいつか政治的現実と衝突する ことになると指摘している。 ユートピアは、理想社会や完璧な都市、あるいはその対極を描くユートピア小説やディストピア小説という文学ジャンルを生み出した。ユートピアの影響を受け た作品には、フランシス・ベーコンの『ニュー・アトランティス』、サミュエル・バトラーの『エレホン』、ヴォルテールの『キャンディード』などがある。 ユートピア主義は、古典的な完全社会の概念(プラトンやアリストテレス)とローマ時代の修辞学的技巧(キケロ、キンティリアヌス、叙事詩的演説など)を組 み合わせたものだが、ルネサンス期のジャンルは啓蒙主義の時代まで続き、現代のSFにも生き残っている。 宗教論争 1520年、改革者マルティン・ルターは3つの著作を立て続けに出版した: ルターはこれらの著作の中で、信仰のみによる救済の教義を示し、ある種のカトリックの慣習を否定し、カトリック教会内の乱用や行き過ぎを攻撃した [16]: 225。 [16]: 225-6 1521年、ヘンリー8世はルターの批判に対し、モアの助力を得て書かれた『アセルティオ』で正式に反論した[124]。教皇レオ10世は、ルターの異端 と闘った功績を称え、イギリス王に「信仰の擁護者」の称号を与えた[16]: 226-7 その後、マルティン・ルターは印刷物でヘンリー8世を攻撃し、彼を「豚、間抜け、嘘つき」と呼んだ[16]: 227 王の要請を受けたモアは反論を作成し、1523年末に『Responsio ad Lutherum』が出版された。レスポンシオの中でモアは、教皇至上主義、秘跡、その他の教会の伝統を擁護した。モアは、「より安定した人格」 [125]と考えられていたが、ルターのことを「猿」、「酒飲み」、「最低の修道士」などと評した[16]: 230 グリエルムス・ロッセウスというペンネームで書いた[41]モアは、ルターに次のように言う: あなたの敬虔な父系がこのような恥知らずな嘘をつくと決心している限り、他の人々は、英国陛下に代わって、あなたの父系の糞のような口、まさに糞の中の糞 のような口に、あなたの忌まわしい腐敗が吐き出したすべての泥と糞を投げ戻し、すべての下水道と便所を、あなたが道化役を演じると決心した王冠に劣らず、 司祭の冠の威厳を奪われたあなたの王冠の上に空っぽにすることを許されるだろう」[126]。 ルターが自分の発言について謝罪したことはなかったかもしれないが[126]。スティーヴン・グリーンブラットは、「モアは自分の支配者のために、相手の 慣用句で語っている。モアにとってのスカトロジーが通常、共同体的な不評を表すとすれば、ルターにとってのそれは、個人的な深い怒りを表すのである」 [127]。 ルターとの対決は、モアの神学的保守主義を確認した。1528年、モアはもうひとつの宗教論争書『異端についての対話』(A Dialogue Concerning Heresies)を出版し、カトリック教会がキリストと使徒たちによって設立された唯一の真の教会であると主張し、その権威、伝統、実践の正当性を肯定 した[16]: 279-81 1529年、シモン・フィッシュの『乞食のための祈り』(Supplication for the Beggars)が流布したことで、モアは『スーリズの補給』(Supplycatyon of Soulys)で対抗した。 1531年、モアの父が亡くなった翌年、ウィリアム・ティンデールは、モアの『異端についての対話』(Dialogue Concerning Heresies)に対して、『トマス・モア卿の対話への回答』(An Answer unto Sir Thomas More's Dialogue)を出版した。これに対してモアは、50万語に及ぶ「ティンデールの回答に対する反駁」で反論した。駁論はモアとティンデールの架空の対 話であり、モアはカトリックの儀式や教義に対するティンデールの批判をそれぞれ取り上げている[16]: 307-9 モアは、暴政や誤りに対する安全装置として、社会の構造、伝統、秩序を重んじたが、ルター派とプロテスタント宗教改革一般は、カトリックの信仰だけでな く、社会全体の安定にとっても危険であると激しく信じていた[16]: 307-9 文通 ほとんどの主要な人文主義者は多量の手紙を書いたが、トマス・モアも例外ではなかった。しかし、友人であったロッテルダムのエラスムスの場合と同様に、彼 の書簡はごく一部(約280通)しか残っていない。その中には、個人的な書簡から政府の公式文書(ほとんどが英語)、人文主義者仲間の学者への書簡(ラテ ン語)、いくつかの書簡集、詩の書簡、モア自身のいくつかの著作への序文(架空のものもある)、モアの子供たちとその家庭教師への書簡(ラテン語)、ロン ドン塔に幽閉され処刑を待つ間に長女マーガレットと交わしたいわゆる「獄中書簡」(英語)など、あらゆるものが含まれている。 [45]モアはまた、特にフランスの詩人ジェルマン・ド・ブリエと論争を繰り広げ、ド・ブリエの『アンチモルス』(1519年)の出版に至った。しかし、 エラスムスが介入し、論争は終結した[54]。 モアはまた、より精神的な事柄についても書いている。その中には以下のようなものがある: 受難論』(別名『キリストの受難に関する論考』)、『祝福された肉体を受けるための論考』(別名『聖体論』)、『キリストの苦悩』(別名『キリストの苦 悩』)などである。モアは処刑を待つ間、ロンドン塔で最後の原稿を手書きした。この最後の写本は、ヘンリー8世の没収令から救われ、娘マーガレットの遺言 により、皇帝シャルル5世の告解師フレイ・ペドロ・デ・ソトを通じてスペインの手に渡り、モアの友人ルイス・ヴィヴェスがバレンシアで受け取り、レアル・ コレヒオ・セミナリオ・デル・コルプス・クリスティ博物館に所蔵されている。 |

| Veneration Catholic Church Pope Leo XIII beatified Thomas More, John Fisher, and 52 other English Martyrs on 29 December 1886. Pope Pius XI canonised More and Fisher on 19 May 1935, and More's feast day was established as 9 July.[128] Since 1970 the General Roman Calendar has celebrated More with St John Fisher on 22 June (the date of Fisher's execution). On 31 October 2000 Pope John Paul II declared More "the heavenly Patron of Statesmen and Politicians".[8] More is the patron of the German Catholic youth organisation Katholische Junge Gemeinde.[129] It is reported that the canonization ceremony was greeted with a "minimal and hostile" treatment by the British press, and officially boycotted by the parliament and universities.[130] Anglican Communion In 1980, despite their staunch opposition to the English Reformation, More and Fisher were added as martyrs of the reformation to the Church of England's calendar of "Saints and Heroes of the Christian Church", to be commemorated every 6 July (the date of More's execution) as "Thomas More, scholar, and John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, Reformation Martyrs, 1535".[10][131] The annual remembrance of 6 July, is recognized by all Anglican Churches in communion with Canterbury, including Australia, Brazil, Canada, and South Africa.[132] In an essay examining the events around the addition to the Anglican calendar, Scholar William Sheils links the reasoning for More's recognition to a "long-standing tradition hinted at in Rose Macaulay's ironic debating point of 1935 about More's status as an 'unschismed Anglican', a tradition also recalled in the annual memorial lecture held at St. Dunstan's Church in Canterbury, where More's head is said to be buried."[132] Sheils also noted the influence of the 1960s popular play and film A Man for All Seasons which gave More a "reputation as a defender of the right of conscience".[132] Thanks to the play's depiction, this "brought his life to a broader and more popular audience" with the film "extending its impact worldwide following the Oscar triumphs".[132] Around this time the atheist Oxford historian and public intellectual, Hugh Trevor-Roper held More up as "the first great Englishman whom we feel that we know, the most saintly of Humanists...the universal man of our cool northern Renaissance."[132] By 1978, the quincentenary of More's birth Trevor-Roper wrote an essay putting More in the Renaissance Platonist tradition, and claim his reputation was "quite independent of his Catholicism."[132] (Only, later on, did a more critical view arise in academia, led by Professor Sir Geoffrey Elton, which "challenged More's reputation for saintliness by focusing on his dealings with heretics, the ferocity of which, in fairness to him, More did not deny. In this research, More's role as a prosecutor, or persecutor, of dissidents has been at the center of the debate.")[132] Legacy  Statue of More at the Ateneo Law School chapel, Makati, Philippines The steadfastness and courage with which More maintained his religious convictions, and his dignity during his imprisonment, trial, and execution, contributed much to More's posthumous reputation, particularly among Roman Catholics. His friend Erasmus defended More's character as "more pure than any snow" and described his genius as "such as England never had and never again will have."[133] Upon learning of More's execution, Emperor Charles V said: "Had we been master of such a servant, we would rather have lost the best city of our dominions than such a worthy councillor."[134] G. K. Chesterton, a Roman Catholic convert from the Church of England, predicted More "may come to be counted the greatest Englishman, or at least the greatest historical character in English history."[135] He wrote "the mind of More was like a diamond that a tyrant threw away into a ditch, because he could not break it."[136] Historian Hugh Trevor-Roper called More "the first great Englishman whom we feel that we know, the most saintly of humanists, the most human of saints, the universal man of our cool northern renaissance."[137] Jonathan Swift, an Anglican, wrote that More was "a person of the greatest virtue this kingdom ever produced".[138][139][140] Some consider this quote to be of Samuel Johnson, although it is not found in Johnson's writings.[141][142] Swift put More in the company of Socrates, Brutus, Epaminondas and Junius.[143] The metaphysical poet John Donne, also honoured in their calendar by Anglicans,[144] was More's great-great-nephew.[145] US Senator Eugene McCarthy had a portrait of More in his office.[146] Marxist theoreticians such as Karl Kautsky considered the book a critique of economic and social exploitation in pre-modern Europe and More is claimed to have influenced the development of socialist ideas.[147] In 1963, Moreana, an academic journal focusing on analysis of More and his writings, was founded.[148] In 2002, More was placed at number 37 in the BBC's poll of the 100 Greatest Britons.[149] Legal More debated Christopher St Germain through various books: while agreeing on various issues on equity, More disagreed with secret witnesses, the admissibility of hearsay, and found St Germain's criticism of religious courts superficial or ignorant.[150] More and St Germain's views on equity owed in part to the 15th Century humanist theologian, Jean Gerson, who taught that consideration of the individual circumstances should be the norm not the exception.[151] Before More, English Lord Chancellors tended to be clerics (with a role as Keeper of the King's Conscience); from More on, they tended to be lawyers.[152] A 1999 poll of legal British professionals nominated More as the person who most embodies the virtues of the law needed at the close of the millennium. The virtues were More's views on the primacy of conscience and his role in the practical establishment of the principle of equity in English secular law through the Court of Chancery.[153] In literature and popular culture William Roper's biography of More (his father-in-law) was one of the first biographies in Modern English. Sir Thomas More is a play written circa 1592 in collaboration between Henry Chettle, Anthony Munday, William Shakespeare, and others. In it More is portrayed as a wise and honest statesman. The original manuscript has survived as a handwritten text that shows many revisions by its several authors, as well as the censorious influence of Edmund Tylney, Master of the Revels in the government of Queen Elizabeth I. The script has since been published and has had several productions.[154][155] In 1941, the 20th-century British author Elizabeth Goudge (1900–1984) wrote a short story, "The King's Servant", based on the last few years of Thomas More's life, seen through his family, and especially his adopted daughter, Anne Cresacre More.[156] The 20th-century agnostic playwright Robert Bolt portrayed Thomas More as the tragic hero of his 1960 play A Man for All Seasons. The title is drawn from what Robert Whittington in 1520 wrote of More: More is a man of an angel's wit and singular learning. I know not his fellow. For where is the man of that gentleness, lowliness and affability? And, as time requireth, a man of marvelous mirth and pastimes, and sometime of as sad gravity. A man for all seasons.[137] In 1966, the play A Man for All Seasons was adapted into a film with the same title. It was directed by Fred Zinnemann and adapted for the screen by the playwright. It stars Paul Scofield, a noted British actor, who said that the part of Sir Thomas More was "the most difficult part I played."[157] The film won the Academy Award for Best Picture and Scofield won the Best Actor Oscar. In 1988 Charlton Heston starred in and directed a made-for-television film that restored the character of "the common man" that had been cut from the 1966 film. In the 1969 film Anne of the Thousand Days, More is portrayed by actor William Squire. Catholic science fiction writer R. A. Lafferty wrote his novel Past Master as a modern equivalent to More's Utopia, which he saw as a satire. In this novel, Thomas More travels through time to the year 2535, where he is made king of the world "Astrobe", only to be beheaded after ruling for a mere nine days. One character compares More favourably to almost every other major historical figure: "He had one completely honest moment right at the end. I cannot think of anyone else who ever had one." Karl Zuchardt's novel, Stirb du Narr! ("Die you fool!"), about More's struggle with King Henry, portrays More as an idealist bound to fail in the power struggle with a ruthless ruler and an unjust world. In her 2009 novel Wolf Hall, its 2012 sequel Bring Up the Bodies, and the final book of the trilogy, her 2020 The Mirror and the Light, the novelist Hilary Mantel portrays More (from the perspective of a sympathetically portrayed Thomas Cromwell) as an unsympathetic persecutor of Protestants and an ally of the Habsburg empire. Literary critic James Wood in his book The Broken Estate, a collection of essays, is critical of More and refers to him as "cruel in punishment, evasive in argument, lusty for power, and repressive in politics".[158] Aaron S. Zelman's non-fiction book The State Versus the People includes a comparison of Utopia with Plato's Republic. Zelman is undecided as to whether More was being ironic in his book or was genuinely advocating a police state. Zelman comments, "More is the only Christian saint to be honoured with a statue at the Kremlin."[citation needed] By this Zelman implies that Utopia influenced Vladimir Lenin's Bolsheviks, despite their brutal repression of religion. Other biographers, such as Peter Ackroyd, have offered a more sympathetic picture of More as both a sophisticated philosopher and man of letters, as well as a zealous Catholic who believed in the authority of the Holy See over Christendom. The protagonist of Walker Percy's novels, Love in the Ruins and The Thanatos Syndrome, is "Dr Thomas More", a reluctant Catholic and descendant of More. More is the focus of the Al Stewart song "A Man For All Seasons" from the 1978 album Time Passages, and of the Far song "Sir", featured on the limited editions and 2008 re-release of their 1994 album Quick. In addition, the song "So Says I" by indie rock outfit The Shins alludes to the socialist interpretation of More's Utopia. Jeremy Northam depicts More in the television series The Tudors as a peaceful man, as well as a devout Roman Catholic and loving family patriarch.[159] In David Starkey's 2009 documentary series Henry VIII: The Mind of a Tyrant, More is depicted by Ryan Kiggell. More is depicted by Andrew Buchan in the television series The Spanish Princess.[160] In the years 1968–2007 the University of San Francisco's Gleeson Library Associates awarded the annual Sir Thomas More Medal for Book Collecting to private book collectors of note,[161] including Elmer Belt,[162] Otto Schaefer,[163] Albert Sperisen, John S. Mayfield and Lord Wardington.[164] Institutions named after More Main article: List of institutions named after Thomas More Communism, socialism and anti-communism Having been praised "as a Communist hero by Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, and Karl Kautsky" because of the Communist attitude to property in his Utopia,[6] under Soviet Communism the name of Thomas More was in ninth position from the top of Moscow's Stele of Freedom (also known as the Obelisk of Revolutionary Thinkers),[165] as one of the most influential thinkers "who promoted the liberation of humankind from oppression, arbitrariness, and exploitation."[note 20] This monument was erected in 1918 in Aleksandrovsky Garden near the Kremlin at Lenin's suggestion.[6][166][note 20] The Great Soviet Encyclopedia's English translation (1979) described More as "the founder of Utopian socialism", the first person "to describe a society in which private property ... had been abolished" (a society in which the family was "a cell for the communist way of life"), and a thinker who "did not believe that the ideal society would be achieved through revolution", but who "greatly influenced reformers of subsequent centuries, especially Morelly, G. Babeuf, Saint-Simon, C. Fourier, E. Cabet, and other representatives of Utopian socialism."[note 21] Utopia also inspired socialists such as William Morris.[note 22] Many see More's communism or socialism as purely satirical.[note 22] In 1888, while praising More's communism, Karl Kautsky pointed out that "perplexed" historians and economists often saw the name Utopia (which means "no place") as "a subtle hint by More that he himself regarded his communism as an impracticable dream".[147] Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, the Russian Nobel Prize-winning, anti-Communist author of The Gulag Archipelago, argued that Soviet communism needed enslavement and forced labour to survive, and that this had been " ...foreseen as far back as Thomas More, the great-grandfather of socialism, in his Utopia".[note 23] In 2008, More was portrayed on stage in Hong Kong as an allegorical symbol of the pan-democracy camp resisting the Chinese Communist Party in a translated and modified version of Robert Bolt's play A Man for All Seasons.[167] |