音色

Timbre, tone color or

tone quality

☆音楽において音色(timbre)

は、音色や音質(音響心理学から)としても知られ、音符、音、音色の知覚される音質のことである。音色は、合唱の声や楽器の音など、さまざまな種類の音を

区別する。また、同じカテゴリーに属する異なる楽器(例えば、オーボエとクラリネットは同じ木管楽器である)を聴き分けることもできる。

簡単に言えば、音色とは、同じ音を演奏したり歌ったりする場合でも、特定の楽器や人の声が他の楽器と異なる音を持つようにするものである。例えば、同じ音

を同じ音量で演奏するギターとピアノの音の違いである。どちらの楽器も、同じ音を演奏するとき、互いに対して同じようにチューニングされた音を出すことが

できるし、同じ振幅レベルで演奏していても、それぞれの楽器は独自の音色で明瞭に響く。経験豊富な音楽家は、同じ種類の楽器が同じ基本音高とラウドネスで

音を奏でていても、その音色の違いから区別することができる[要出典]。

音色の知覚を決定する音の物理的特性には、周波数スペクトルとエンベロープがある。歌手や楽器演奏者は、異なる歌唱法や演奏法を使うことで、歌っている/

演奏している音楽の音色を変えることができる。例えば、ヴァイオリニストは異なるボウイング・スタイルを使ったり、弦の異なる部分を弾いたりすることで、

異なる音色を得ることができる(例えば、タストを弾くと軽やかで空気感のある音色になり、ポンティチェロを弾くと厳しく均一で攻撃的な音色になる)。エレ

クトリック・ギターやエレクトリック・ピアノでは、エフェクターやグラフィック・イコライザーを使って音色を変えることができる。

| In music, timbre

(/ˈtæmbər, ˈtɪm-, ˈtæ̃-/), also known as tone color or tone quality

(from psychoacoustics), is the perceived sound quality of a musical

note, sound or tone. Timbre distinguishes different types of sound

production, such as choir voices and musical instruments. It also

enables listeners to distinguish different instruments in the same

category (e.g., an oboe and a clarinet, both woodwind instruments). In simple terms, timbre is what makes a particular musical instrument or human voice have a different sound from another, even when they play or sing the same note. For instance, it is the difference in sound between a guitar and a piano playing the same note at the same volume. Both instruments can sound equally tuned in relation to each other as they play the same note, and while playing at the same amplitude level each instrument will still sound distinctively with its own unique tone color. Experienced musicians are able to distinguish between different instruments of the same type based on their varied timbres, even if those instruments are playing notes at the same fundamental pitch and loudness.[citation needed] The physical characteristics of sound that determine the perception of timbre include frequency spectrum and envelope. Singers and instrumental musicians can change the timbre of the music they are singing/playing by using different singing or playing techniques. For example, a violinist can use different bowing styles or play on different parts of the string to obtain different timbres (e.g., playing sul tasto produces a light, airy timbre, whereas playing sul ponticello produces a harsh, even and aggressive tone). On electric guitar and electric piano, performers can change the timbre using effects units and graphic equalizers. |

音楽において音色(/ˈtæmbər,

ˈtæm-、ˈtɪ-/)は、音色や音質(音響心理学から)としても知られ、音符、音、音色の知覚される音質のことである。音色は、合唱の声や楽器の音な

ど、さまざまな種類の音を区別する。また、同じカテゴリーに属する異なる楽器(例えば、オーボエとクラリネットは同じ木管楽器である)を聴き分けることも

できる。 簡単に言えば、音色とは、同じ音を演奏したり歌ったりする場合でも、特定の楽器や人の声が他の楽器と異なる音を持つようにするものである。例えば、同じ音 を同じ音量で演奏するギターとピアノの音の違いである。どちらの楽器も、同じ音を演奏するとき、互いに対して同じようにチューニングされた音を出すことが できるし、同じ振幅レベルで演奏していても、それぞれの楽器は独自の音色で明瞭に響く。経験豊富な音楽家は、同じ種類の楽器が同じ基本音高とラウドネスで 音を奏でていても、その音色の違いから区別することができる[要出典]。 音色の知覚を決定する音の物理的特性には、周波数スペクトルとエンベロープがある。歌手や楽器演奏者は、異なる歌唱法や演奏法を使うことで、歌っている/ 演奏している音楽の音色を変えることができる。例えば、ヴァイオリニストは異なるボウイング・スタイルを使ったり、弦の異なる部分を弾いたりすることで、 異なる音色を得ることができる(例えば、タストを弾くと軽やかで空気感のある音色になり、ポンティチェロを弾くと厳しく均一で攻撃的な音色になる)。エレ クトリック・ギターやエレクトリック・ピアノでは、エフェクターやグラフィック・イコライザーを使って音色を変えることができる。 |

| Synonyms Tone quality and tone color are synonyms for timbre, as well as the "texture attributed to a single instrument". However, the word texture can also refer to the type of music, such as multiple, interweaving melody lines versus a singable melody accompanied by subordinate chords. Hermann von Helmholtz used the German Klangfarbe (tone color), and John Tyndall proposed an English translation, clangtint, but both terms were disapproved of by Alexander Ellis, who also discredits register and color for their pre-existing English meanings.[1] Determined by its frequency composition, the sound of a musical instrument may be described with words such as bright, dark, warm, harsh, and other terms. There are also colors of noise, such as pink and white. In visual representations of sound, timbre corresponds to the shape of the image,[2] while loudness corresponds to brightness; pitch corresponds to the y-shift of the spectrogram. |

類義語 音質や音色は、音色と同義語であり、「単一の楽器に帰属する質感」でもある。しかし、テクスチャーという言葉は、複数の旋律線が織り成す旋律と、従属和音 を伴う歌える旋律など、音楽の種類を指すこともある。ヘルマン・フォン・ヘルムホルツはドイツ語のKlangfarbe(音色)を使い、ジョン・ティンダ ルは英語のclangtintという訳語を提案したが、この2つの用語はアレクサンダー・エリスによって否定された。また、ピンクや白といったノイズの色 もある。音の視覚的表現では、音色は画像の形に対応し[2]、ラウドネスは明るさに対応し、ピッチはスペクトログラムのYシフトに対応する。 |

| ASA definition The Acoustical Society of America (ASA) Acoustical Terminology definition 12.09 of timbre describes it as "that attribute of auditory sensation which enables a listener to judge that two nonidentical sounds, similarly presented and having the same loudness and pitch, are dissimilar", adding, "Timbre depends primarily upon the frequency spectrum, although it also depends upon the sound pressure and the temporal characteristics of the sound".[3] |

ASAの定義 アメリカ音響学会(ASA)のAcoustical Terminology定義12.09では、音色について「同じように提示され、同じラウドネスとピッチを持つ2つの同一でない音を、リスナーが異質であ ると判断することを可能にする聴覚感覚の属性」と説明し、「音色は主に周波数スペクトルに依存するが、音圧や音の時間的特性にも依存する」と付け加えてい る[3]。 |

| Attributes Many commentators have attempted to decompose timbre into component attributes. For example, J. F. Schouten (1968, 42) describes the "elusive attributes of timbre" as "determined by at least five major acoustic parameters", which Robert Erickson finds, "scaled to the concerns of much contemporary music":[4] Range between tonal and noiselike character Spectral envelope Time envelope in terms of rise, duration, and decay (ADSR, which stands for "attack, decay, sustain, release") Changes both of spectral envelope (formant-glide) and fundamental frequency (micro-intonation) Prefix, or onset of a sound, quite dissimilar to the ensuing lasting vibration An example of a tonal sound is a musical sound that has a definite pitch, such as pressing a key on a piano; a sound with a noiselike character would be white noise, the sound similar to that produced when a radio is not tuned to a station. Erickson gives a table of subjective experiences and related physical phenomena based on Schouten's five attributes:[5] Subjective ++++++++++ Tonal character, usually pitched Noisy, with or without some tonal character, including rustle noise Coloration Beginning/ending Coloration glide or formant glide Microintonation Vibrato Tremolo Attack Final sound Objective ++++++++++ Periodic sound Noise, including random pulses characterized by the rustle time (the mean interval between pulses) Spectral envelope Physical rise and decay time Change of spectral envelope Small change (one up and down) in frequency Frequency modulation Amplitude modulation Prefix Suffix See also Psychoacoustic evidence below. |

属性 多くの論者が、音色を構成する属性に分解することを試みてきた。例えば、J. F. Schouten (1968, 42)は「音色のとらえどころのない属性」を「少なくとも5つの主要な音響パラメータによって決定される」と表現しており、Robert Ericksonは「多くの現代音楽の関心事に合わせてスケーリングされている」と見なしている[4]。 音調とノイズのような性格の幅 スペクトル包絡線 立ち上がり、持続時間、減衰の時間エンベロープ(ADSR、「アタック、ディケイ、サステイン、リリース」の略) スペクトル・エンベロープ(フォルマント・グライド)と基本周波数の変化(マイクロ・イントネーション)。 音の前置詞、つまり音の始まりは、その後に続く持続的な振動とはまったく異なる。 調性音の例は、ピアノの鍵盤を押すような、明確な音程を持つ楽音である。ノイズのような性質を持つ音はホワイトノイズで、ラジオのチューニングが合っていないときに発生する音に似ている。 エリクソンは、シューテンの5つの属性に基づく主観的体験と関連する物理現象の表を示している[5]。 主観的 ++++++++++ 音色の特徴、通常は音程がある ノイズ(ざわめきノイズを含む) 音色のあるなしを問わない。 色調 開始/終了 発色グライドまたはフォルマントグライド マイクロイントネーション ビブラート トレモロ アタック 最終音 客観的 ++++++++++ 周期的な音 ざわめき時間(パルス間の平均間隔)で特徴づけられるランダムパルスを含むノイズ スペクトルエンベロープ 物理的な立ち上がりと減衰の時間 スペクトル包絡線の変化 周波数の小さな変化(上下1回ずつ) 周波数変調 振幅変調 接頭辞 接尾辞 下記の音響心理学的証拠も参照のこと。 |

| 主観的 |

客観的 |

| 音色の特徴、通常は音程がある |

周期的な音 |

| ノイズ(ざわめきノイズを含む) 音色のあるなしを問わない。 |

ざわめき時間(パルス間の平均間隔)で特徴づけられるランダムパルスを含むノイズ |

| 色調 |

スペクトルエンベロープ |

| 開始/終了 |

物理的な立ち上がりと減衰の時間 |

| 発色グライドまたはフォルマントグライド |

スペクトル包絡線の変化 |

| マイクロイントネーション |

周波数の小さな変化(上下1回ずつ) |

| ビブラート |

周波数変調 |

| トレモロ | 振幅変調 |

| アタック | 接頭辞 |

| 最終音 | 接尾辞 |

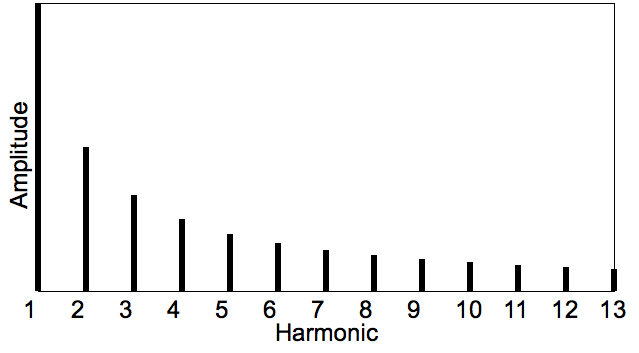

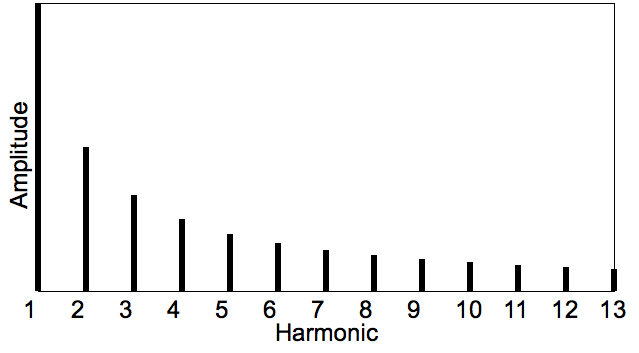

| Harmonics Further information: Fourier transform  Harmonic spectrum The richness of a sound or note a musical instrument produces is sometimes described in terms of a sum of a number of distinct frequencies. The lowest frequency is called the fundamental frequency, and the pitch it produces is used to name the note, but the fundamental frequency is not always the dominant frequency. The dominant frequency is the frequency that is most heard, and it is always a multiple of the fundamental frequency. For example, the dominant frequency for the transverse flute is double the fundamental frequency. Other significant frequencies are called overtones of the fundamental frequency, which may include harmonics and partials. Harmonics are whole number multiples of the fundamental frequency, such as ×2, ×3, ×4, etc. Partials are other overtones. There are also sometimes subharmonics at whole number divisions of the fundamental frequency. Most instruments produce harmonic sounds, but many instruments produce partials and inharmonic tones, such as cymbals and other indefinite-pitched instruments. When the tuning note in an orchestra or concert band is played, the sound is a combination of 440 Hz, 880 Hz, 1320 Hz, 1760 Hz and so on. Each instrument in the orchestra or concert band produces a different combination of these frequencies, as well as harmonics and overtones. The sound waves of the different frequencies overlap and combine, and the balance of these amplitudes is a major factor in the characteristic sound of each instrument. William Sethares wrote that just intonation and the western equal tempered scale are related to the harmonic spectra/timbre of many western instruments in an analogous way that the inharmonic timbre of the Thai renat (a xylophone-like instrument) is related to the seven-tone near-equal tempered pelog scale in which they are tuned. Similarly, the inharmonic spectra of Balinese metallophones combined with harmonic instruments such as the stringed rebab or the voice, are related to the five-note near-equal tempered slendro scale commonly found in Indonesian gamelan music.[6] |

ハーモニクス さらに詳しい情報 フーリエ変換  倍音スペクトル 楽器が出す音や音の豊かさは、いくつかの異なる周波数の和で表されることがある。最も低い周波数は基本周波数と呼ばれ、その周波数が生み出す音高が音名の 由来となるが、基本周波数が必ずしも支配的な周波数とは限らない。支配周波数とは、最もよく聞こえる周波数のことで、常に基本周波数の倍数である。例え ば、横笛の支配周波数は基本周波数の2倍である。その他の重要な周波数は基本周波数の倍音と呼ばれ、倍音や部分音が含まれる。倍音は基本周波数の整数倍 で、例えば2倍、3倍、4倍などである。部分音は他の倍音である。また、基本周波数の整数倍のサブハーモニクスが存在することもある。ほとんどの楽器は倍 音を出すが、シンバルやその他の不定音の楽器など、部分倍音や非倍音を出す楽器も多い。 オーケストラやコンサート・バンドのチューニング・ノートが演奏されるとき、その音は440Hz、880Hz、1320Hz、1760Hzなどの組み合わ せとなる。オーケストラやコンサートバンドの各楽器は、これらの周波数の異なる組み合わせと、倍音や倍音を出す。異なる周波数の音波が重なり合い、組み合 わさることで、これらの振幅のバランスが各楽器の特徴的なサウンドの大きな要因となる。 ウィリアム・セザレスは、ジャストイントネーションと西洋の平均律音階は、タイのレナート(木琴のような楽器)の非調和的な音色が、それらが調律される7 音に近い平均律ペローグ音階と関係しているのと同じように、多くの西洋楽器の倍音スペクトル/ティンブルと関係していると書いている。同様に、弦楽器のレ バブや声楽のような和声楽器と組み合わされたバリのメタロフォンの非調和的なスペクトルは、インドネシアのガムラン音楽でよく見られる5音からなる等和音 に近いスレンドロ音階と関連している[6]。 |

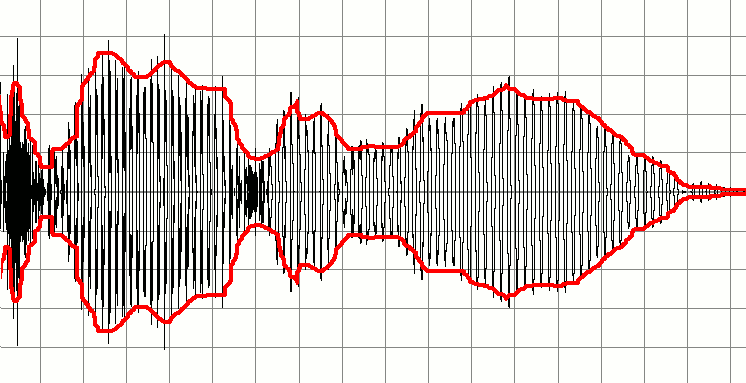

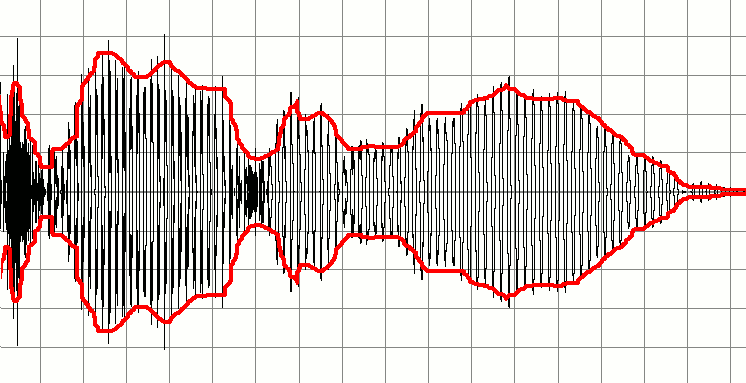

Envelope A signal and its envelope marked with red The timbre of a sound is also greatly affected by the following aspects of its envelope: attack time and characteristics, decay, sustain, release (ADSR envelope) and transients. Thus these are all common controls on professional synthesizers. For instance, if one takes away the attack from the sound of a piano or trumpet, it becomes more difficult to identify the sound correctly, since the sound of the hammer hitting the strings or the first blast of the player's lips on the trumpet mouthpiece are highly characteristic of those instruments. The envelope is the overall amplitude structure of a sound. |

エンベロープ 赤で示した信号とそのエンベロープ サウンドの音色は、エンベロープの次の側面にも大きく影響される:アタック・タイムと特性、ディケイ、サステイン、リリース(ADSRエンベロープ)、そ してトランジェント。したがって、これらはすべてプロ用シンセサイザーに共通するコントロールだ。例えば、ピアノやトランペットの音からアタックを取り除 いてしまうと、音を正しく識別することが難しくなる。なぜなら、ハンマーが弦を叩く音や、トランペットのマウスピースに奏者が唇を当てた最初の一吹きは、 それらの楽器に非常に特徴的だからだ。エンベロープとは、音の全体的な振幅構造のことである。 |

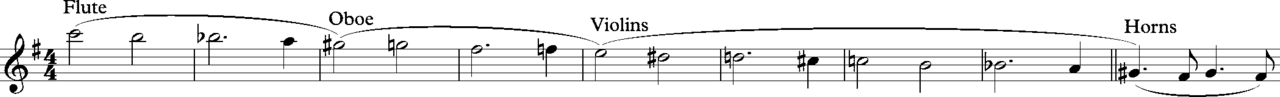

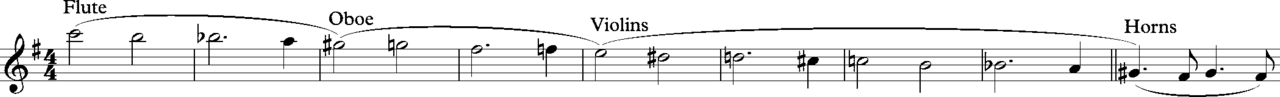

| In music history Instrumental timbre played an increasing role in the practice of orchestration during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Berlioz[7] and Wagner[8] made significant contributions to its development during the nineteenth century. For example, Wagner's "Sleep motif" from Act 3 of his opera Die Walküre, features a descending chromatic scale that passes through a gamut of orchestral timbres. First the woodwind (flute, followed by oboe), then the massed sound of strings with the violins carrying the melody, and finally the brass (French horns). Duration: 27 seconds.0:27 Wagner Sleep music from Act 3 of Die Walküre  Wagner Sleep music from Act 3 of Die Walküre Debussy, who composed during the last decades of the nineteenth and the first decades of the twentieth centuries, has been credited with elevating further the role of timbre: "To a marked degree the music of Debussy elevates timbre to an unprecedented structural status; already in Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune the color of flute and harp functions referentially".[9] Mahler's approach to orchestration illustrates the increasing role of differentiated timbres in music of the early twentieth century. Norman Del Mar describes the following passage from the Scherzo movement of his Sixth Symphony, as "a seven-bar link to the trio consisting of an extension in diminuendo of the repeated As ... though now rising in a succession of piled octaves which moreover leap-frog with Cs added to the As.[10] The lower octaves then drop away and only the Cs remain so as to dovetail with the first oboe phrase of the trio." During these bars, Mahler passes the repeated notes through a gamut of instrumental colors, mixed and single: starting with horns and pizzicato strings, progressing through trumpet, clarinet, flute, piccolo and finally, oboe: Duration: 21 seconds.0:21 Mahler, Symphony No. 6, Scherzo, Figure 55, bars 5–12  Mahler, Symphony No. 6, Scherzo, Figure 55, bars 5–12 (See also Klangfarbenmelodie.) In rock music from the late 1960s to the 2000s, the timbre of specific sounds is important to a song. For example, in heavy metal music, the sonic impact of the heavily amplified, heavily distorted power chord played on electric guitar through very loud guitar amplifiers and rows of speaker cabinets is an essential part of the style's musical identity. |

音楽史において 楽器の音色は、18世紀から19世紀にかけて、オーケストレーションの実践においてますます大きな役割を果たすようになった。19世紀には、ベルリオーズ [7]とワーグナー[8]がその発展に大きく貢献した。例えば、ワーグナーのオペラ『ワルキューレ』第3幕の「眠りのモチーフ」は、半音階を下降させなが らオーケストラの様々な音色を通過していく。まず木管(フルート、次いでオーボエ)、次にヴァイオリンが旋律を担う弦楽器の重厚な響き、そして最後に金管 (フレンチホルン)である。 演奏時間:27秒0:27 ワーグナー『ワルキューレ』第3幕より 眠りの音楽  ワーグナー『ワルキューレ』第3幕より眠りの音楽 19世紀末から20世紀初頭にかけて作曲したドビュッシーは、音色の役割をさらに高めたと評価されている。「ドビュッシーの音楽は、顕著な程度に、音色を 前例のない構造的な地位に高めている。ノーマン・デルマーは、交響曲第6番のスケルツォ楽章の次のような一節をこう表現している。 「繰り返されるAsのディミヌエンドの延長からなるトリオへの7小節のつながり......しかし、今度はAsにCsが加わって跳躍するオクターヴの積み 重ねの連続で上昇する[10]......その後、低いオクターヴは下がり、Csだけが残り、トリオの最初のオーボエのフレーズと重なる」 ホルンとピチカート弦楽器から始まり、トランペット、クラリネット、フルート、ピッコロ、そして最後にオーボエが演奏される: 演奏時間:21秒 0:21 マーラー、交響曲第6番、スケルツォ、第55図、5-12小節  マーラー、交響曲第6番、スケルツォ、第55図、5-12小節 (Klangfarbenmelodieも参照のこと)。 1960年代後半から2000年代までのロック音楽では、特定の音の音色が曲にとって重要である。例えば、ヘヴィ・メタル音楽では、大音量のギター・アン プと何列ものスピーカー・キャビネットを通してエレキ・ギターで演奏される、重く増幅され、重く歪んだパワー・コードの音のインパクトが、このスタイルの 音楽的アイデンティティの重要な部分となっている。 |

| Psychoacoustic evidence Often, listeners can identify an instrument, even at different pitches and loudness, in different environments, and with different players. In the case of the clarinet, acoustic analysis shows waveforms irregular enough to suggest three instruments rather than one. David Luce suggests that this implies that "[C]ertain strong regularities in the acoustic waveform of the above instruments must exist which are invariant with respect to the above variables".[11] However, Robert Erickson argues that there are few regularities and they do not explain our "...powers of recognition and identification." He suggests borrowing the concept of subjective constancy from studies of vision and visual perception.[12] Psychoacoustic experiments from the 1960s onwards tried to elucidate the nature of timbre. One method involves playing pairs of sounds to listeners, then using a multidimensional scaling algorithm to aggregate their dissimilarity judgments into a timbre space. The most consistent outcomes from such experiments are that brightness or spectral energy distribution,[13] and the bite, or rate and synchronicity[14] and rise time,[15] of the attack are important factors. |

音響心理学的証拠 異なる音程や音量、異なる環境、異なる奏者であっても、聴き手が楽器を識別できることはよくある。クラリネットの場合、音響分析では、1つの楽器ではなく 3つの楽器を示唆するほど不規則な波形が見られる。デイヴィッド・ルースは、このことは次のことを示唆していると指摘する。 「上記の楽器の音響波形には、上記の変数に対して不変な、ある種の強い規則性が存在するはずだ」[11]。 しかし、ロバート・エリクソンは、規則性はほとんどなく、それらは私たちの「...認識と識別の力」を説明するものではないと主張している。彼は主観的不変性の概念を視覚と視覚知覚の研究から借りることを提案している[12]。 1960年代以降の音響心理学実験は、音色の性質を解明しようと試みた。その1つの方法は、リスナーに2つの音のペアを聴かせ、多次元スケーリングアルゴ リズムを使って、その非類似性判断を音色空間に集約させるというものである。このような実験から得られた最も一貫性のある結果は、明るさまたはスペクトル のエネルギー分布[13]と、アタックのバイト、またはレートとシンクロニシティ[14]、立ち上がり時間[15]が重要な要因であるということである。 |

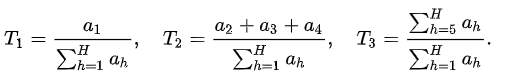

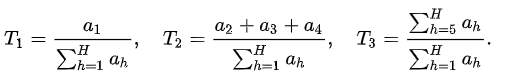

| Tristimulus timbre model The concept of tristimulus originates in the world of color, describing the way three primary colors can be mixed together to create a given color. By analogy, the musical tristimulus measures the mixture of harmonics in a given sound, grouped into three sections. It is basically a proposal of reducing a huge number of sound partials, which can amount to dozens or hundreds in some cases, down to only three values. The first tristimulus measures the relative weight of the first harmonic; the second tristimulus measures the relative weight of the second, third, and fourth harmonics taken together; and the third tristimulus measures the relative weight of all the remaining harmonics:[16][17][page needed]  However, more evidence, studies and applications would be needed regarding this type of representation, in order to validate it. |

三刺激音色モデル 三刺激(tristimulus)の概念は色の世界に由来し、3つの原色をミックスしてある色を作り出す方法を表している。それになぞらえて、音楽の三刺 激音は、与えられた音に含まれる倍音の混合を測定し、3つのセクションにグループ化する。これは基本的に、場合によっては数十から数百にもなる膨大な数の 音の部分音を、たった3つの値に減らす提案である。最初の三刺激子は第一倍音の相対的な重みを測定し、第二の三刺激子は第二、第三、第四倍音を合わせた相 対的な重みを測定し、第三の三刺激子は残りのすべての倍音の相対的な重みを測定する:[16][17][要ページ]。  しかし、この種の表現を検証するためには、より多くの証拠、研究、応用が必要だろう。 |

| Brightness The term "brightness" is also used in discussions of sound timbres, in a rough analogy with visual brightness. Timbre researchers consider brightness to be one of the perceptually strongest distinctions between sounds[14] and formalize it acoustically as an indication of the amount of high-frequency content in a sound, using a measure such as the spectral centroid. |

Brightness The term "brightness" is also used in discussions of sound timbres, in a rough analogy with visual brightness. Timbre researchers consider brightness to be one of the perceptually strongest distinctions between sounds[14] and formalize it acoustically as an indication of the amount of high-frequency content in a sound, using a measure such as the spectral centroid. |

| Formant |

フォルマント |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timbre |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099