トラロック(雨の神)

Tláloc

Tlaloc,

dios de la lluvia. Museo Nacional de Antropología en la Ciudad de México

☆ トラロック(古典ナワトル語:Tláloc [ˈ Ⱖ)[5] はアステカの宗教における雨の神である。地上の豊穣と水の神でもあり[6]、生命と糧を与える神として崇拝されていた。これは多くの儀式と、彼の名におい て行われた生贄のおかげである。彼は雹、雷、稲妻、そして雨さえも支配する力があるとして、悪意はないが恐れられていた。また、彼は洞窟や泉、山、特に彼 が住むと信じられていた聖なる山とも関連している。セロ・トゥラロックは、この神をめぐる儀式がどのように行われたかを理解する上で非常に重要である。彼 の信奉者は古代メキシコで最も古く、最も普遍的な存在だった。 Tlálocにはさまざまな表現があり、Tlálocに捧げられる供物もさまざまである。トラロクはしばしば蝶、ジャガー、蛇の図像で表される[7]。ナ フア族にセンポフアルキソチトルとして知られるメキシコ産のマリーゴールド、タゲテス・ルシダも神の重要なシンボルであり、土着の宗教儀式では儀式用の香 として焚かれた。トラロックの象徴は牙の有無で区別され、同じ大きさの牙が3本か4本か、あるいは2本だけで、伝統的な二股に分かれた舌と対になってい る。常にではないが、多くの場合、トラロックは水の入った何らかの容器も持っている[8]。 Tlálocという名前は特にナワトル語であるが、山頂の祠と生命を与える雨に関連する嵐の神への崇拝は、少なくともテオティワカンと同じくらい古いもの である。それはマヤのチャアク神から採用された可能性が高く、おそらく最終的にはそれ以前のオルメカの前身から派生したものであろう。トラーロクは主にテ オティワカンで崇拝され、大きな儀式はセロ・トラーロクで行われた。テオティワカンの地下にはトラロックの祠が発見されており、この神のために多くの供物 が残されていることがわかる[9]。

| Tláloc (Classical

Nahuatl: Tláloc [ˈtɬaːlok])[5] is the god of rain in Aztec religion. He

was also a deity of earthly fertility and water,[6] worshipped as a

giver of life and sustenance. This came to be due to many rituals, and

sacrifices that were held in his name. He was feared, but not

maliciously, for his power over hail, thunder, lightning, and even

rain. He is also associated with caves, springs, and mountains, most

specifically the sacred mountain where he was believed to reside. Cerro

Tláloc is very important in understanding how rituals surrounding this

deity played out. His followers were one of the oldest and most

universal in ancient Mexico. There are many different representations of Tláloc, and there are many different offerings given to him. Tláloc is often represented through iconography of butterflies, jaguars, and serpents.[7] The Mexican marigold, Tagetes lucida, known to the Nahua as cempohualxochitl, was another important symbol of the god, and was burned as a ritual incense in native religious ceremonies. Representations of Tláloc are distinguished by the presence of fangs, whether that be three or four of the same size, or just two, paired with the traditional bifurcated tongue. Often, but not always, Tláloc will also be carrying some sort of vessel that contains water.[8] Although the name Tláloc is specifically Nahuatl, worship of a storm god, associated with mountaintop shrines and with life-giving rain, is as at least as old as Teotihuacan. It was likely adopted from the Maya god Chaac, perhaps ultimately derived from an earlier Olmec precursor. Tláloc was mainly worshiped at Teotihuacan, while his big rituals were held on Cerro Tláloc. An underground Tláloc shrine has been found at Teotihuacan which shows many offerings left for this deity.[9] |

トラロック(古典ナワトル語:Tláloc [ˈ Ⱖ)[5]

はアステカの宗教における雨の神である。地上の豊穣と水の神でもあり[6]、生命と糧を与える神として崇拝されていた。これは多くの儀式と、彼の名におい

て行われた生贄のおかげである。彼は雹、雷、稲妻、そして雨さえも支配する力があるとして、悪意はないが恐れられていた。また、彼は洞窟や泉、山、特に彼

が住むと信じられていた聖なる山とも関連している。セロ・トゥラロックは、この神をめぐる儀式がどのように行われたかを理解する上で非常に重要である。彼

の信奉者は古代メキシコで最も古く、最も普遍的な存在だった。 Tlálocにはさまざまな表現があり、Tlálocに捧げられる供物もさまざまである。トラロクはしばしば蝶、ジャガー、蛇の図像で表される[7]。ナ フア族にセンポフアルキソチトルとして知られるメキシコ産のマリーゴールド、タゲテス・ルシダも神の重要なシンボルであり、土着の宗教儀式では儀式用の香 として焚かれた。トラロックの象徴は牙の有無で区別され、同じ大きさの牙が3本か4本か、あるいは2本だけで、伝統的な二股に分かれた舌と対になってい る。常にではないが、多くの場合、トラロックは水の入った何らかの容器も持っている[8]。 Tlálocという名前は特にナワトル語であるが、山頂の祠と生命を与える雨に関連する嵐の神への崇拝は、少なくともテオティワカンと同じくらい古いもの である。それはマヤのチャアク神から採用された可能性が高く、おそらく最終的にはそれ以前のオルメカの前身から派生したものであろう。トラーロクは主にテ オティワカンで崇拝され、大きな儀式はセロ・トラーロクで行われた。テオティワカンの地下にはトラロックの祠が発見されており、この神のために多くの供物 が残されていることがわかる[9]。 |

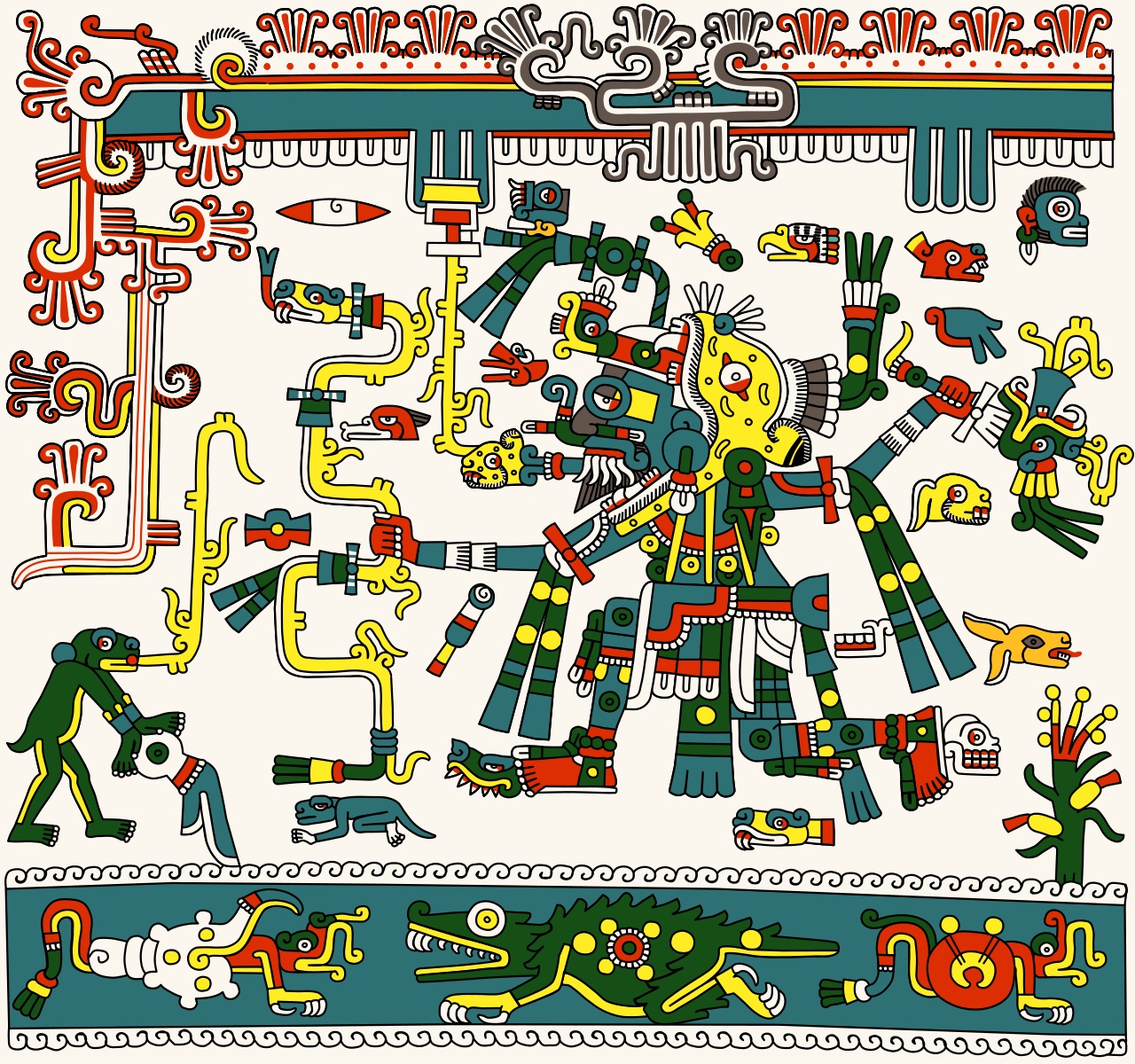

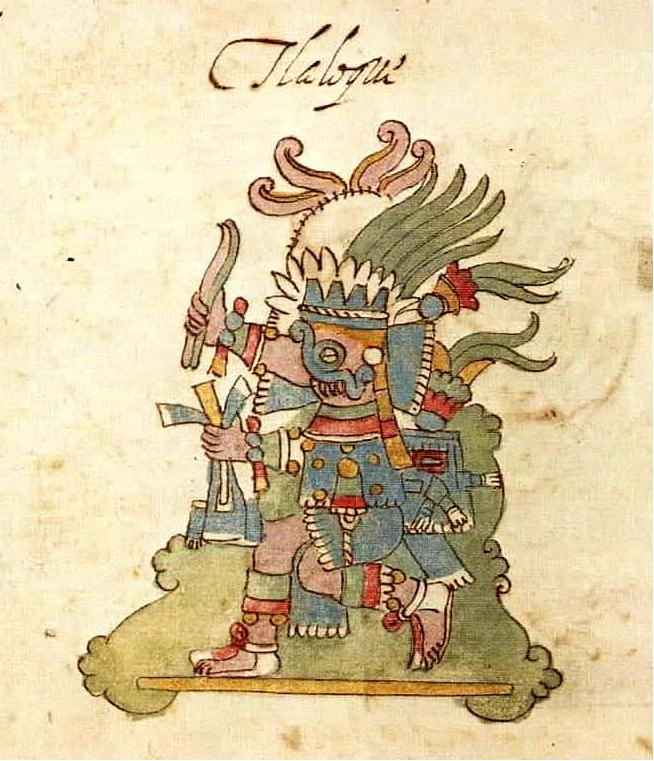

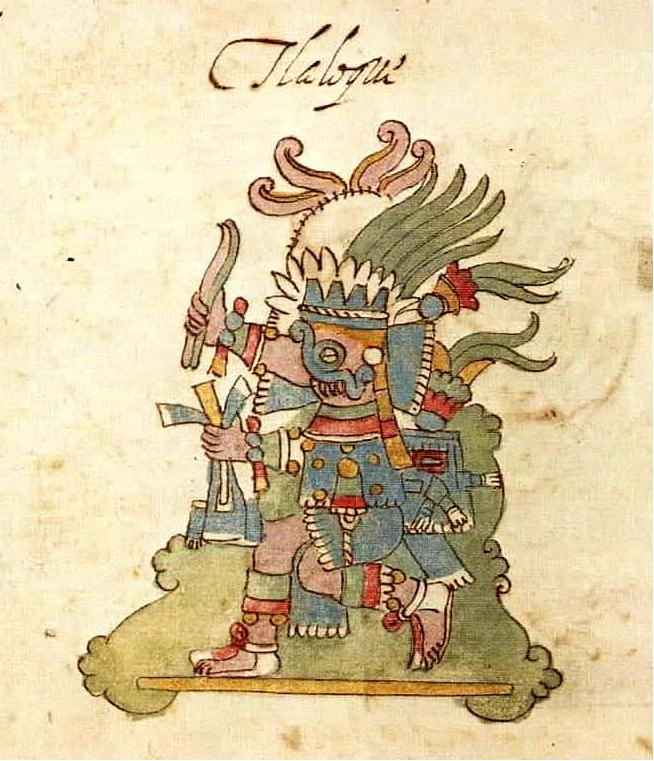

| Deity iconography In Aztec iconography, many different sculptures, and pieces of work have been mislabeled or mistaken as Tláloc. For a while, anything that was abstract and on the scarier side was labelled as Tláloc. However, in reality, Tláloc's two main identifiers are fangs, along with ringed eyes.[8] Furthermore, his lips are a very defining feature – they are shaped like a mustache. He is most often coupled with lightning, maize, and water in visual representations and artwork.[10] Other forms of Tláloc include a variety of elements or symbols: jaguar, serpent, owl, water lily, bifurcated tongue, quetzal, butterfly, shell, spider, eye-of-the-reptile symbol, cross Venus / symbol. The number of different symbols associated with Tláloc stem from past, widespread confusion on the deity's appearance, along with the old, widespread worship of this deity.[7] Offerings dedicated to Tláloc in Tenochtitlan were known to include several jaguar skulls and even a complete jaguar skeleton. The Mexica held Jaguars to a very high standard, associated with the underworld, Jaguars were considered the ultimate sacrificial animal due to their value, which the Mexica decided was high.[10] Tláloc's impersonators often wore the distinctive mask and heron-feather headdress, usually carrying a cornstalk or a symbolic lightning bolt wand; another symbol was a ritual water jar. Along with this, Tláloc is manifested in the form of boulders at shrine-sites, and in the Valley of Mexico the primary shrine of this deity was located atop Cerro Tláloc.[9] Cerro Tláloc was where human sacrifice was held, in the name of the water deity. In Coatlinchan, a colossal statue weighing 168 tons was found that was thought to represent Tláloc. However, one scholar believes that the statue may not have been Tláloc at all but his sister or some other female deity. This is a classic confusion as nobody could seem to figure out what was Tláloc, and what was not. This statue was relocated to the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City in 1964.[11] While pre-Hispanic cultures are thought to have become extinct once the Spanish had completed the colonization of Mexico, aspects of pre-Hispanic cultures continue to influence Mexican culture. Accordingly, Tláloc has continued to be represented in Mexican culture even after the Spanish were thought to have completed evangelizing in Mexico. In fact, even as the Spanish were beginning to proselytize in Mexico, religious syncretism was occurring.[12] Analyses of evangelization plays put on by the Spanish, in order to convert the indigenous peoples to Christianity, suggests that the Spanish might have unknowingly created connections between Christianity and indigenous religious figures, such as Tláloc.[12] Indigenous Mexicans viewing these plays might have made connections between the sacrifice Abraham was willing to make of Isaac, to the sacrifices that were made to Tláloc and other deities.[12] These connections may have allowed indigenous peoples to retain ideas about sacrifice even as they were being forcibly converted to Christianity. Early syncretism between indigenous religions and Christianity, also included more direct connections to Tláloc. Some churches built during the sixteenth century, such as the Santiago Tlatelolco church had stones depicting Tláloc within the interior of the church.[13] Even as the Roman Catholic Church sought to eradicate indigenous religious traditions, depiction of Tláloc still remained within worship spaces, suggesting that Tláloc would still have been worshipped after Spanish colonization.[13] It is clear that Tláloc would have continued to have played a role in Mexican cultures immediately after colonization. Despite the fact that it has been half a millennium since the conquest of Mexico, Tláloc still plays a role in shaping Mexican culture. At Coatlinchan, a giant statue of Tláloc continues to play a key role in shaping local culture, even after the statue was relocated to Mexico City.[14] In Coatlinchan, people still celebrate the statue of Tláloc, so much so that some local residents still seek to worship him, while the local municipality has also erected a reproduction of the original statue.[14] This makes sense as Tláloc is one of the most renowned deities, who has to this day many believers and followers. Many residents of Coatlinchan, relate to the statue of Tláloc in the way that they might associate themselves with a patron saint, linking their identity as a resident of the town with the image of Tláloc.[14] While Tláloc plays an especially important role in the lives of the people of Coatlinchan, the god also plays an important role in shaping the Mexican identity. Images of Tláloc are found throughout Mexico from Tijuana to the Yucatán, and images of the statue of Tláloc found at Coatlinchan are deployed as a symbol of the Mexican nation.[14] Tláloc and other pre-Hispanic features are critical to creating a common Mexican identity that unites people throughout Mexico. Due to the fact that many scholars believe that Tláloc also has Mayan roots, this widespread appreciation is common in Mesoamerica.[15] Accordingly, people throughout Mexico, and especially in Coatlinchan, refer to Tláloc in very anthropomorphized ways, referring to Tláloc as a person, as the Mexica did with many deities.[15] Furthermore, people continue to observe superstitions about Tláloc.[15] Despite centuries of colonial erasure, Tláloc continues to be represented in American culture. |

神々の図像 アステカの図像学では、さまざまな彫刻や作品がトラロックと誤記されたり、間違えられたりしてきた。しばらくの間、抽象的で恐ろしげなものはすべてトラ ロックのラベルが貼られていた。しかし実際には、トラロックの2大特徴は牙であり、環状の目である[8]。さらに、彼の唇は口ひげのような形をしており、 非常に特徴的である。トラロックの他の形態には、ジャガー、蛇、フクロウ、睡蓮、二又に分かれた舌、ケツァール、蝶、貝殻、蜘蛛、爬虫類の目のシンボル、 十字架の金星/シンボルなど、様々な要素やシンボルがある。トラーロクにまつわるさまざまなシンボルの数は、この神への古くからの広範な崇拝とともに、神 の外見に関する過去の広範な混乱に由来している[7]。 テノチティトランのトラロックに捧げられた供物には、数体のジャガーの頭蓋骨や完全なジャガーの骨格まで含まれていたことが知られている。メキシカ人は ジャガーを非常に高い基準で崇拝しており、冥界と関連していた。ジャガーはその価値が高いとメキシカ人が判断したため、究極の生贄動物と考えられていた [10]。 トラロックのなりすましは、しばしば特徴的なマスクとサギの羽の頭飾りを身につけ、通常はトウモロコシの茎や象徴的な稲妻の杖を持っていた。これととも に、トラロックは祠の岩の形をして現れ、メキシコの谷では、この神の主な祠はセロ・トラロックの頂上にあった[9]。セロ・トラロックでは、水の神の名に おいて人身御供が行われていた。 コアトリンチャンでは、Tlálocを表すと思われる重さ168トンの巨像が発見された。しかし、ある学者は、この彫像はトラロックではなく、彼の妹か他 の女性の神だったのではないかと考えている。これは典型的な混乱であり、何がトラロックで何がトラロックでないのか、誰にもわからなかったようだ。この像 は1964年にメキシコシティの国立人類学博物館に移された[11]。 スペイン人がメキシコの植民地化を完了すると、先スペイン文化は消滅したと考えられているが、先スペイン文化の側面はメキシコ文化に影響を与え続けてい る。したがって、スペイン人がメキシコでの布教を完了したと考えられている後も、トラロックはメキシコ文化の中で表現され続けている。スペイン人が先住民 をキリスト教に改宗させるために行った伝道劇の分析によると、スペイン人は知らず知らずのうちに、キリスト教とトラロックのような先住民の宗教的人物を結 びつけていた可能性がある[12]。 [12] これらの劇を観たメキシコ先住民は、アブラハムがイサクを犠牲にすることを厭わなかったことと、トラロックや他の神々に捧げられた生贄との間につながりを 持ったかもしれない。先住民の宗教とキリスト教との初期のシンクレティズムには、トラロックとの直接的なつながりも含まれていた。16世紀に建てられたサ ンティアゴ・トラテロルコ教会のようないくつかの教会には、教会内部にトラロクが描かれた石があった[13]。ローマ・カトリック教会が先住民の宗教的伝 統を根絶しようとしたときでさえ、トラロクの描写は礼拝空間に残っており、スペインの植民地化後もトラロクが崇拝されていたことを示唆している[13]。 トラロクが植民地化直後のメキシコ文化において役割を果たし続けていたことは明らかである。 メキシコ征服から半世紀が経過しているにもかかわらず、トラルクはメキシコ文化を形成する役割を果たしている。コアトリンチャンでは、巨大なトラーロク像 がメキシコシティに移された後も、地元文化を形成する上で重要な役割を果たし続けている[14]。コアトリンチャンでは、今でもトラーロク像を崇拝しよう とする地元住民がいるほど、人々はトラーロク像を祝福しており、地元自治体もオリジナルの像の複製を建立している[14]。トラーロクは、今日に至るまで 多くの信奉者と信者を持つ、最も有名な神々の一人であるため、これは理にかなっている。コアトリンチャンの住民の多くは、守護聖人と自分を結びつけるよう に、町の住民としてのアイデンティティとトラロックの像を結びつけてトラロックの像と関わっている[14]。トラロックはコアトリンチャンの人々の生活に おいて特に重要な役割を果たしているが、この神はメキシコのアイデンティティを形成する上でも重要な役割を果たしている。ティフアナからユカタンまでメキ シコ全土にトラーロクの像があり、コアトリンチャンで発見されたトラーロクの像はメキシコ国民の象徴として配備されている[14]。トラーロクやその他の 先スペイン的な特徴は、メキシコ全土の人々を結びつけるメキシコ人共通のアイデンティティを形成する上で非常に重要である。多くの学者がトラロックのルー ツはマヤにもあると信じていることから、このような広範な評価はメソアメリカで一般的である[15]。したがって、メキシコ全土、特にコアトリンチャンの 人々はトラロックを非常に擬人化した方法で呼び、メキシカが多くの神々に対して行ったように、トラロックを人として呼んでいる。 |

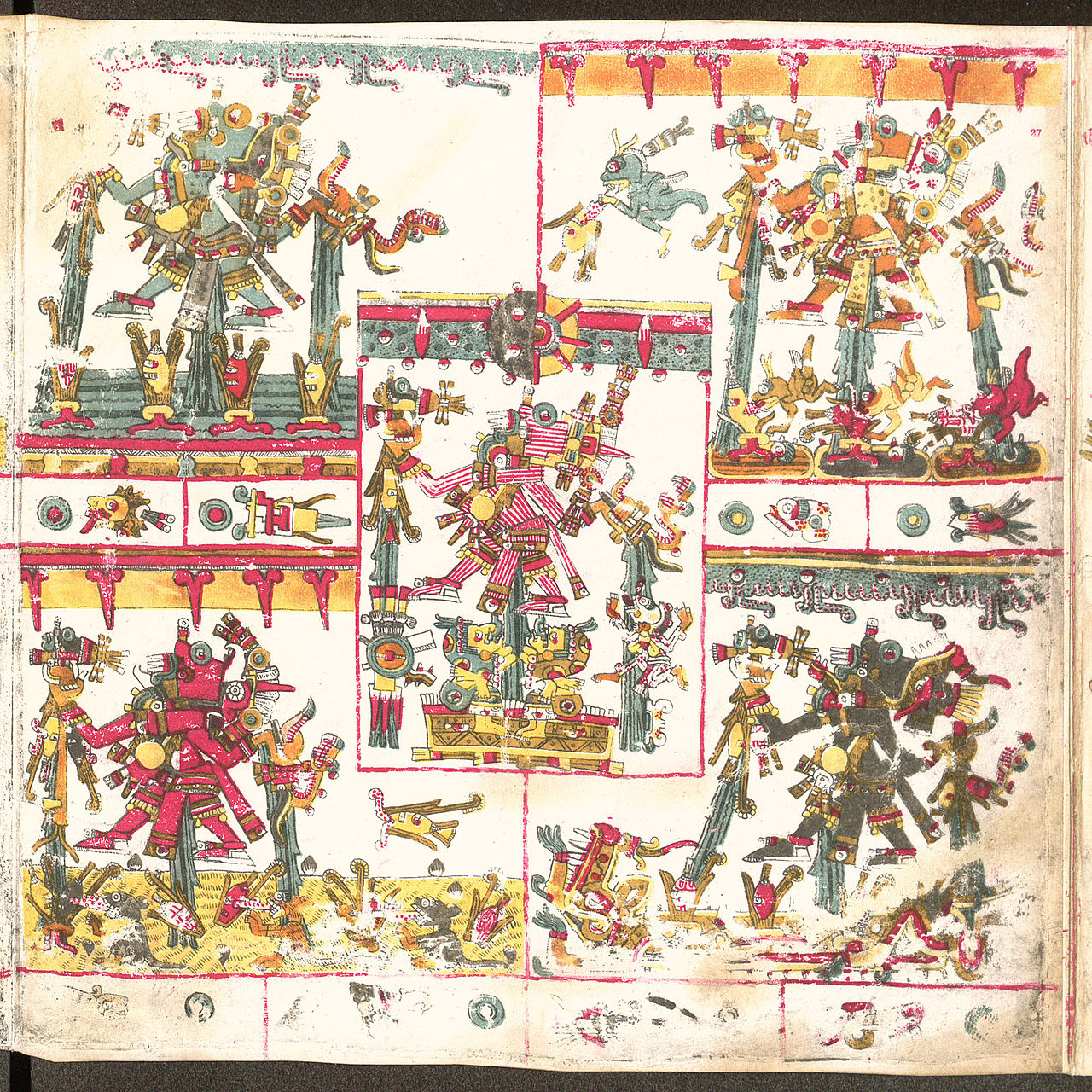

Tláloc in the Codex Borgia |

Tláloc in the Codex Laud |

Mesoamerican representations A brazier depicting Tláloc from Ozuluama, Classic Veracruz culture. Evidence suggests that Tláloc was represented in many other Mesoamerican cultures and religions. Tláloc is thought to be one of the most commonly worshipped deities at Teotihuacan and it is specifically here, in Teotihuacan, that representations of Tláloc often show him having jaguar teeth and features. This differs from the Maya version of Tláloc, as the Maya representation depicts no specific relation to jaguars. The inhabitants of Teotihuacan thought of thunder as the rumblings of the jaguar and associated thunder with Tláloc as well. It is likely that this god was given these associations because he is also known as "the provider" among the Aztecs.[16] A chacmool excavated from the Maya site of Chichén Itzá in the Yucatán by Augustus Le Plongeon possesses imagery associated with Tláloc.[17] This chacmool is similar to others found at the Templo Mayor in Tenochtitlán.[17] The chacmool found at Chichén Itzá appears to have been used for sacrificial purposes, as the chacmool is shaped like a captive who has been bound.[17] Likewise, two of the chacmools that have been found at Templo Mayor make clear reference to Tláloc. The first chacmool portrays Tláloc three times. Once on the vessel for collecting the blood and heart of sacrificed victims, once on the underpart of the chacmool with aquatic motifs related to Tláloc, and the actual figure of the chacmool itself is of Tláloc as the figure portrays the iconic goggle eyes and large fangs. The other chacmool was found at the Tláloc half of the double pyramid-temple complex and clearly represents Tláloc for the same reasons. In addition to the chacmools, human corpses were found in close proximity to the Tlálocan half of Templo Mayor, which were likely war captives. These archaeological findings could explain why the Maya tended to associate their version of Tláloc, Chaac, with the bloodiness of war and sacrifice, because they adopted it from the Aztecs, who used Maya captives for sacrifice to Tláloc.[18] Furthermore, Tláloc can be seen in many examples of Maya war imagery and war-time decoration, such as appearing on “shields, masks, and headdresses of warriors.”[19] This evidence affirms the Maya triple connection between war-time, sacrifice, and the rain deity as they likely adopted the rain deity from the Aztecs, but blurred the line between sacrifice and captive capture, and religion.[17] Tláloc was also associated with the earth, and it is believed this is also a reason why sacrifices may have been made to him.[17] Sacrifices to Tláloc were not solely a Maya phenomenon, and it is known that the Aztecs also made sacrifices to Tláloc. Just as the Maya had also worshipped their own version of Tláloc, so did the Mixtec people of Oaxaca, who were known to worship a rain god that is extremely similar to other manifestations of Tláloc.[20] |

メソアメリカの表現 古典期ベラクルス文化のオズルアマから出土したトラロックの火鉢。 その証拠に、トラロックはメソアメリカの他の多くの文化や宗教でも表現されている。トラルクはテオティワカンで最も一般的に崇拝された神々の一人と考えら れており、特にこのテオティワカンでは、トラルクの表現にしばしばジャガーの歯と特徴が見られる。これはマヤのトラロックの表現とは異なり、マヤの表現で はジャガーとの特別な関係は描かれていない。テオティワカンの住民は、雷をジャガーの鳴き声と考え、雷をトラロックとも関連付けていた。この神はアステカ 人の間で「供給者」としても知られているため、このような関連付けがなされたのだろう[16]。 オーガスタス・ル・プロンジョンによってユカタン州のチチェン・イッツァのマヤ遺跡から発掘されたチャクモールは、トラーロクに関連するイメージを持って いる[17]。このチャクモールは、テノチティトランのテンプロ・マヨールで発見された他のチャクモールと類似している。 [17] チチェン・イッツァで発見されたチャクモールは、縛られた捕虜のような形をしていることから、生け贄の目的で使用されたようである[17]。同様に、テン プロ・マヨールで発見されたチャクモールのうち2つは、明らかにトラロックに言及している。最初のチャクモールは、トラロックを3回描いている。一度目は 生け贄の犠牲者の血液と心臓を採取する容器に、一度目はチャクモールの下部にトラロックに関連する水生生物のモチーフが描かれており、チャクモールの実際 の姿は象徴的なギョロ目と大きな牙が描かれていることからトラロックの姿である。もう一つのチャクモールは、二重ピラミッドと神殿の複合体のトラロックの 半分で発見され、同じ理由で明らかにトラロックを表している。チャックムールに加えて、人間の死体がテンプロ・マヨールのトラロック半神殿のすぐ近くで発 見されたが、これは戦争で捕虜になったものであろう。 これらの考古学的発見から、マヤが自分たちのトラロックのバージョンであるチャアクを戦争や生け贄の血なまぐさいものと結びつける傾向があったのは、マヤ の捕虜をトラロックの生け贄としていたアステカからチャアクを取り入れたからだと説明することができる[18]。 [18]さらに、Tlálocは「戦士の盾、仮面、頭飾り」[19]に見られるなど、マヤの戦争のイメージや戦時中の装飾の多くの例で見ることができる。 この証拠は、マヤが戦時、生贄、雨の神の間の三重のつながりを確証するものであり、彼らはおそらくアステカから雨の神を取り入れたが、生贄と捕虜の捕獲、 そして宗教の間の境界線を曖昧にしたものである。 Tlálocは大地とも関連しており、これも生贄がTlálocに捧げられた理由であると考えられている[17]。マヤが独自のトラロックのバージョンを 崇拝していたように、オアハカのミクステカ族もトラロックの他の顕現と極めて類似した雨の神を崇拝していたことが知られている[20]。 |

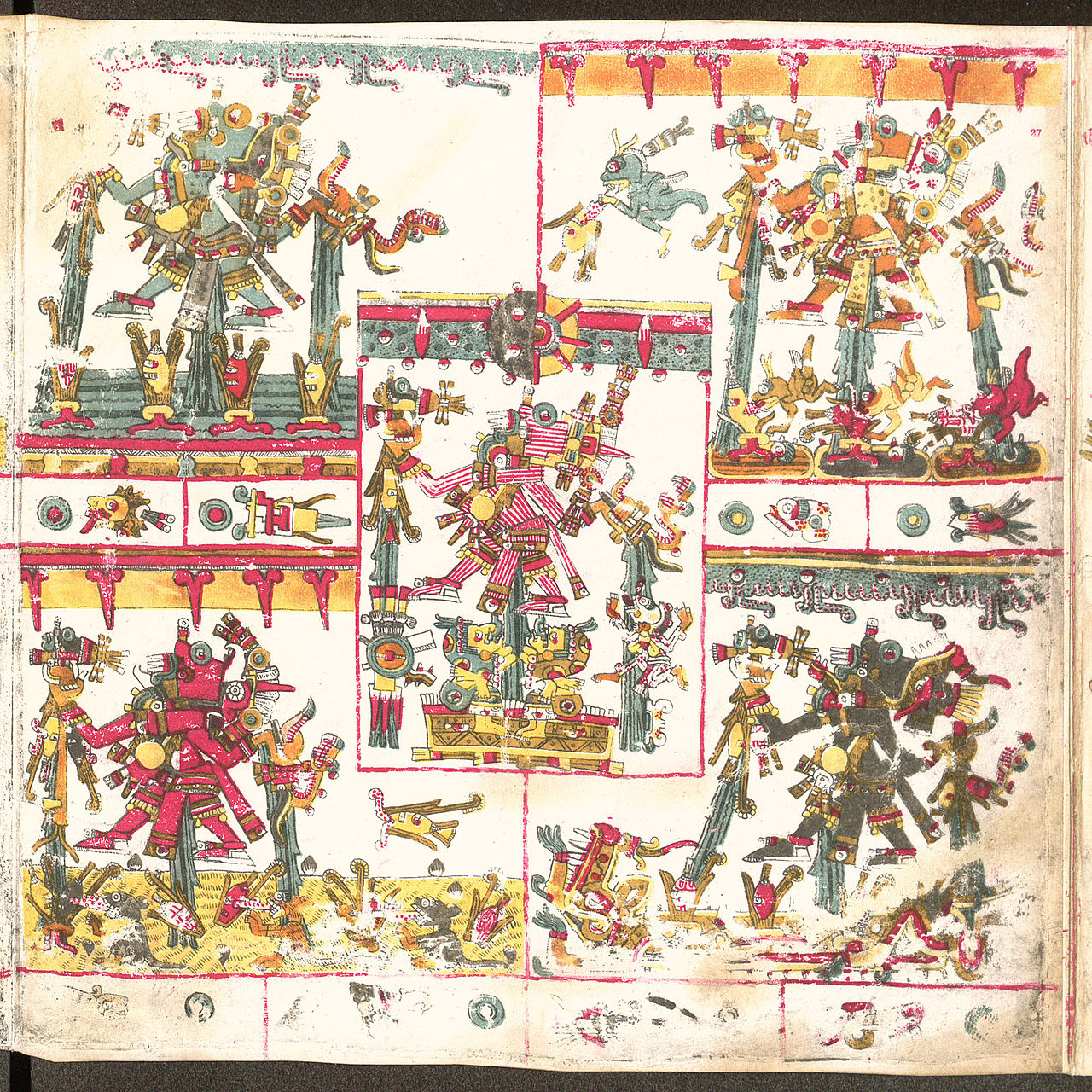

| Historical cosmology See also: Aztec mythology Depiction of Patterns of War, Tláloc (bottom right) In Aztec cosmology, the four corners of the universe are marked by "the four Tlálocs" (Classical Nahuatl: Tlālōquê [tɬaːˈloːkeʔ]) which both hold up the sky and function as the frame for the passing of time. Tláloc was the patron of the Calendar day Mazātl. In Aztec mythology, Tláloc was the lord of the third sun which was destroyed by fire. On page 28 of the Codex Borgia, the Five Tlaloque are pictured watering maize fields. Each Tláloc is pictured watering the maize with differing types of rains, of which only one was beneficial. The rain that was beneficial to the land was burnished with jade crystals and likely represented the type of rain that would make a bountiful harvest. The other forms of rain were depicted as destroyers of crops, “fiery rain, fungus rain, wind rain, and flint blade rain”. This depiction shows the power that Tláloc had over the Central American crop supply. Also, the high ratio of damaging rains to beneficial rains likely symbolizes the ratio of the likelihood that crops are destroyed to them being nourished. This would explain why so much effort and resources were put forth by the Central Americans in order to appease the Gods.[21] Additionally, Tláloc is thought to be one of the patron deities of the trecena of 1 Quiahuitl (along with Chicomecoatl). Trecenas are the thirteen-day periods into which the 260-day calendar is divided. The first day of each trecena dictates the augury, or omen, and the patron deity or deities associated with the trecena.[16] In Aztec mythic cosmography, Tláloc ruled the fourth layer of the upper world, or heavens, which is called Tlálocan ("place of Tláloc") in several Aztec codices, such as the Vaticanus A and Florentine codices. Described as a place of unending springtime and a paradise of green plants, Tlálocan was the destination in the afterlife for those who died violently from phenomena associated with water, such as by lightning, drowning, and water-borne diseases.[16] These violent deaths also included leprosy, venereal disease, sores, dropsy, scabies, gout, and child sacrifices.[10] The Nahua believed that Huitzilopochtli could provide them with fair weather for their crops and they placed an image of Tláloc, who was the rain-god, near him so that if necessary, the war god could compel the rain maker to exert his powers.[22] |

歴史的宇宙論 こちらも参照のこと: アステカ神話 戦争のパターン、トラーロクの描写(右下) アステカの宇宙論では、宇宙の四隅は「4つのトラロック」(古典ナワトル語: Tlālōquê [tɬaː ˈ ʔ [tɬ])によって示されている。Tlálocは暦日Mazātlの守護神であった。アステカ神話では、トラルクは火によって破壊された第三の太陽の主で あった。 ボルジア写本の28ページには、5人のトラロックがトウモロコシ畑に水を撒いている絵が描かれている。それぞれのトラロックは異なる種類の雨でトウモロコ シに水を与えているが、そのうち有益な雨はひとつだけである。土地に有益な雨は翡翠の結晶で焼かれており、豊作をもたらす雨の種類を表しているのだろう。 他の雨の形は作物を破壊するものとして描かれており、「火の雨、菌の雨、風の雨、火打ち刃の雨」となっている。この描写は、トラロックが中米の作物供給に 対して力を持っていたことを示している。また、有害な雨と有益な雨の比率が高いのは、農作物が破壊される可能性と養われる可能性の比率を象徴しているのだ ろう。このことは、神々を鎮めるために中央アメリカ人が多くの努力と資源を投入した理由を説明することになる[21]。 さらに、トラロックはキアフイトル1世のトレセナの守護神の一人であると考えられている(チコメコアトルとともに)。トレセナとは、260日の暦を13日 の期間に分割したものである。各トレセナの最初の日は、オーギュリー(前兆)、およびトレセナに関連する守護神または神々を指示する[16]。 アステカ神話の宇宙誌では、トラーロックは天界の第4層を支配しており、バチカヌスA写本やフィレンツェ写本などのいくつかのアステカ写本ではトラーロカ ン(「トラーロックの場所」)と呼ばれている。終わりのない春の場所、緑の植物が生い茂る楽園として描写されたトラーロカンは、雷、溺死、水を媒介とする 病気など、水に関連する現象によって激しく死んだ人々の死後の世界における目的地であった[16]。これらの激しい死には、ハンセン病、性病、ただれ、水 腫、疥癬、痛風、子供の生贄なども含まれていた[10]。 ナワ族はフイツィロポクトリが農作物のために好天をもたらすと信じており、必要であれば軍神が雨乞いの力を発揮させることができるように、雨の神であるトラロックの像をフイツィロポクトリの近くに置いた[22]。 |

Etymology Tláloc, as shown in the late 16th century Codex Ríos. Tláloc was also associated with the world of the dead and with the earth. His name is thought to be derived from the Nahuatl word tlālli "earth", and its meaning has been interpreted as "path beneath the earth," "long cave," "he who is made of earth",[23] as well as "he who is the embodiment of the earth".[24] J. Richard Andrews interprets it as "one that lies on the land," identifying Tláloc as a cloud resting on the mountaintops.[25] Other names of Tláloc were Tlamacazqui ("Giver")[26] and Xoxouhqui ("Green One");[27] and (among the contemporary Nahua of Veracruz), Chaneco.[28] |

語源 16世紀末のリオス写本に描かれたトラロック。 Tlálocは死者の世界や大地とも関連していた。彼の名前はナワトル語のtlālli「大地」に由来すると考えられており、その意味は「大地の下の道」 「長い洞窟」「大地でできた者」[23]、また「大地の体現者」と解釈されている[24]。リチャード・アンドリュースはこれを「大地に横たわる者」と解 釈し、トラーロクを山頂で休息する雲と見なしている[25]。トラーロクの他の名前はトラマカズキ(「与える者」)[26]とソクソウキ(「緑の者」) [27]であり、(ベラクルスの現代ナワ族の間では)シャネコであった[28]。 |

| Child sacrifice and rituals In the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan, one of the two shrines on top of the Great Temple was dedicated to Tláloc. The high priest who was in charge of the Tláloc shrine was called "Quetzalcoatl Tláloc Tlamacazqui." It was the northernmost side of this temple that was dedicated to Tláloc, the god of rain and agricultural fertility. In this area, a bowl was kept in which sacrificial hearts were placed on certain occasions, as offerings to the rain gods.[29] Although the Great Temple had its northern section dedicated to Tláloc, the most important site of worship of the rain god was on the peak of Cerro Tláloc, a 4,100 metres (13,500 ft) mountain on the eastern rim of the Valley of Mexico. Here the Aztec ruler would come and conduct important ceremonies annually. Additionally, throughout the year, pilgrims came to the mountain and offered precious stones and figures at the shrine. Many of the offerings found here also related to water and the sea.[16] The Tlálocan-bound dead were not cremated as was customary, but instead they were buried in the earth with seeds planted in their faces and blue paint covering their foreheads.[30] Their bodies were dressed in paper and accompanied by a digging stick for planting put in their hands.[31]  Tláloc, Collection E. Eug. Goupil, 17th century The second shrine on top of the main pyramid at Tenochtitlan was dedicated to Tláloc. Both his shrine, and Huitzilopochtli's next to it, faced west. Sacrifices and rites took place in these temples. The Aztecs believed Tláloc resided in mountain caves, thus his shrine in Tenochtitlan's pyramid was called "mountain abode." Many rich offerings were regularly placed before it, especially those linked to water, such as shells, jade, and sand. Cerro Tláloc was situated directly east of the pyramid, which is very in-line with classic Aztec architecture. The Mexica did and designed everything with cosmological direction. It was forty-four miles away, with a long road connecting the two places of worship. On Cerro Tláloc, there was a shrine containing stone images of the mountain itself and other neighboring peaks. The shrine was called Tlálocan, in reference to the paradise. Also, the shrine contained four pitchers containing water. Each pitcher would produce a different fate if used on crops: the first would bring forth a good harvest, the second would cause the harvest to fail and rot, the third would dry the harvest out, and the final one would freeze it. Sacrifices that took place on Cerro Tláloc were thought to favor early rains. The Atlcahualo festivals was celebrated from 12 February until 3 March. Dedicated to the Tlaloque, this veintena involved the sacrifice of children on sacred mountaintops, like Cerro Tláloc. This form of human sacrifice was not only specific, but necessary in the eyes of the Aztecs. The children were beautifully adorned, dressed in the style of Tláloc and the Tlaloque. The children were "chosen" by the community, and although this selection came with honor, being selected came with great responsibility. Furthermore, these children were not usually of high social class. The children to be sacrificed were carried to Cerro Tláloc on litters strewn with flowers and feathers, while also being surrounded by dancers. Once the children reached the peak, they would have to stay overnight with the priests at the vigil. The priests were not allowed to leave this site, or else they would be considered "mocauhque", meaning they who are abandoned. Then, at the shrine, the children's hearts would be pulled out by Aztec priests. If, on the way to the shrine, these children cried, their tears were viewed as positive signs of imminent and abundant rains. Every Atlcahualo festival, seven children were sacrificed in and around Lake Texcoco in the Aztec capital. The children were either slaves or the second-born children of noblepeople, or pīpiltin.[32] If the children did not cry, it meant a bad year for their whole system of living - agriculture. To signify when the rains were about to end, the Aztecs relied on the call from a bird known as the "cuitlacochin". This would also signify a switch to soft rain rolling in. The festival of Tozoztontli (24 March – 12 April) similarly involved child sacrifice. During this festival, the children were sacrificed in caves. The flayed skins of sacrificial victims that had been worn by priests for the last twenty days were taken off and placed in these dark caverns. The winter veintena of Atemoztli (9 December – 28 December) was also dedicated to the Tlaloque. This period preceded an important rainy season, so statues were made out of amaranth dough. Their teeth were pumpkin seeds and their eyes, beans. Once these statues were offered copal, fine scents, and other food items, while they were also prayed to and adorned with finery. Afterwards, their doughy chests were opened, their "hearts" taken out, before their bodies were cut up and eaten. The ornaments with which they had been adorned were taken and burned in peoples’ patios. On the final day of the "veintena," people celebrated and held banquets.[33] Tláloc was also worshipped during the Huey Tozotli festival, which was celebrated annually.[34] Evidence from the Codex Borbonicus suggests that Huey Tozotli was a commemoration of Centeotl, the god of maize. While Tláloc is not normally associated with Huey Tozotli, evidence from the Codex Borbonicus indicates that Tláloc was worshipped during this festival.[34] Additional evidence from the Book of Gods and Rites suggest rulers from the Aztec Empire and other states would make a pilgrimage to Cerro Tláloc during the Huey Tozotli festival in order to present offerings to Tláloc.[34] The Book of Gods and Rites also suggests that a child was sacrificed as a part of this pilgrimage as well, although this could simply be the result of colonial sensationalism on the part of the Spanish authors.[34] It is argued that Tláloc was incorporated into celebrations of Huey Tozotli because of his role as the god of rain.[34] Huey Tozotli was a celebration of the maize harvest, and it would make sense that worshippers might want to celebrate Tláloc during this festival as his powers of the rain would be critical to having a successful harvest of maize.[34] Tláloc was linked to the regenerative capacity of weather, and, as such, he was worshipped at Cerro Tláloc because much of the rain in Central Mexico is formed over range of which Cerro Tláloc is a part.[35] Tláloc was worshipped on Cerro Tláloc during the Etzalcualiztli festival, in which rulers from across Central Mexico performed rituals to Tláloc in order to ask for rain, and to celebrate fertility and the change of the seasons.[35] An important part of these pilgrimages to Cerro Tláloc during Etzalcualitztli was the sacrifice of both adults and children to Tláloc.[35] |

子供の犠牲と儀式 アステカの首都テノチティトランでは、大神殿の上にある2つの祠のうちの1つがトラロックに捧げられていた。トラロックの祠を管理していた大祭司は、「ケ ツァルコアトル・トラロック・トラマカスキ 」と呼ばれていた。雨と農業の豊穣の神であるトラロクに捧げられたのは、この神殿の一番北側だった。大神殿の北側はトラロックに捧げられていたが、雨の神 を祀る最も重要な場所は、メキシコ渓谷の東の縁にある標高4,100メートルの山、セロ・トラロックの頂上にあった。アステカの支配者は毎年ここに来て重 要な儀式を行っていた。さらに、一年を通して巡礼者たちがこの山を訪れ、祠に宝石や人形を捧げた。ここで見られる供物の多くは、水と海にも関連していた [16]。 トラロカン族に縛られた死者は慣習的に火葬されず、顔に種を植えられ、額に青いペンキを塗られて土に埋められた[30]。 死体は紙で着飾られ、手に植物を植えるための掘り棒が添えられた[31]。  トラロック、E. Eug. Goupil、17世紀 テノチティトランの主ピラミッドの頂上にある第二の祠堂は、トラロックに捧げられていた。彼の祠とその隣にあるフイツィロポチュトリの祠は、どちらも西を 向いていた。これらの神殿では生贄と儀式が行われた。アステカ人はトラルクが山の洞窟に住んでいると信じていたため、テノチティトランのピラミッドにある 彼の祠は「山の住まい」と呼ばれていた。その祠の前には、貝殻、ヒスイ、砂など、特に水に関連する多くの豊かな供物が定期的に捧げられた。セロ・トゥラ ロックはピラミッドの真東に位置しており、これは古典的なアステカ建築の流れを汲んでいる。メキシカ人は、宇宙論的な方向性を持ってあらゆることを行い、 設計した。セロ・トゥラロクからピラミッドまでは44マイルも離れており、2つの礼拝所を結ぶ長い道があった。セロ・トゥラロックには、山そのものと近隣 の峰の石像を納めた祠があった。祠は楽園にちなんでトラロカンと呼ばれていた。また、祠には水の入った4つの水差しがあった。1つ目は豊作をもたらし、2 つ目は収穫を失敗させ腐らせ、3つ目は収穫を乾燥させ、最後の1つは収穫を凍らせる。セロ・トゥラロックで行われた生贄は、早期の雨をもたらすと考えられ ていた。 2月12日から3月3日まで、アトラカワロの祭りが祝われた。トラロケに捧げられたこのヴェインテナでは、セロ・トゥラロックのような神聖な山頂で子供た ちが生贄として捧げられた。このような人身御供は、アステカの人々の目には特殊であると同時に必要なものであった。子供たちは美しく飾られ、トラロックと トラロケのスタイルに身を包んだ。子供たちは共同体から「選ばれた」のであり、この選出には名誉が伴うが、選ばれることには大きな責任が伴う。さらに、こ れらの子供たちは通常、社会的地位が高いわけではなかった。生け贄となる子供たちは、花や羽が散らばった駕籠に乗せられてセロ・トゥラロックに運ばれ、踊 り子たちに取り囲まれた。子供たちは山頂に着くと、神父のもとで一晩寝かされる。神父たちはこの場所を離れることは許されず、さもなければ「モカウケ」、 つまり見捨てられた者とみなされた。そうしないと、神官たちは 「モカウケ」(捨てられた者)とみなされるからである。祠に向かう途中、この子供たちが泣いた場合、その涙は差し迫った豊かな雨の前兆と見なされた。アト ルカワロの祭りのたびに、アステカの首都にあるテクスココ湖とその周辺で、7人の子供たちが生贄として捧げられた。子供たちは奴隷か貴族の二番目の子供、 ピピルティン(pīpiltin)であった[32]。子供たちが泣かなかった場合、彼らの生活システム全体、つまり農業にとって厄年を意味した。アステカ 族は、雨がいつ終わるかを知らせるために、「クイトラコチン」と呼ばれる鳥の鳴き声を頼りにしていた。この鳴き声は、柔らかい雨に切り替わる合図でもあっ た。 Tozoztontliの祭り(3月24日~4月12日)も同様に、子供の生け贄を伴うものだった。この祭りの間、子供たちは洞窟で生贄として捧げられた。この20日間、祭司たちが身に着けていた犠牲者の皮が剥がされ、暗い洞窟に置かれた。 アテモズトリの冬のヴェインテナ(12月9日~12月28日)もトラロケに捧げられた。この期間は重要な雨季の前であったため、像はアマランサスの生地で 作られた。歯はカボチャの種、目は豆だった。これらの彫像は、コパルや上質な香り、その他の食物を捧げられ、また祈りを捧げられ、装飾品で飾られた。その 後、生地で覆われた胸が開けられ、「心臓」が取り出され、胴体は切り刻まれて食べられた。飾られた装飾品は持ち去られ、人々のパティオで燃やされた。ヴェ インテナ」の最終日には、人々は祝宴を開いた[33]。 ボルボニクスの写本から、フエ・トゾトリはトウモロコシの神センテオトルの記念祭であったことが示唆されている[34]。34]『神々と儀式の書』からの 追加的な証拠は、アステカ帝国や他の国家の支配者たちがフエ・トゾトリ祭りの期間中にセロ・トゥラロクに巡礼し、トゥラロクに供物を捧げていたことを示唆 している。 [34]『神々と儀式の書』では、この巡礼の一環として子供が生贄として捧げられたことも示唆されているが、これは単にスペイン人著者による植民地時代の センセーショナリズムの結果かもしれない[34]。 [34]フエイ・トゾトリはトウモロコシの収穫を祝う祭りであり、トウモロコシの収穫を成功させるためには彼の雨の力が不可欠であるため、この祭りにト ラーロクを祝おうとするのは理にかなっている[34]。 トラロクは天候の再生能力と結びついており、中央メキシコの雨の多くはセロ・トラロクが含まれる山脈で形成されるため、セロ・トラロクで崇拝された。 [35]トラロクはエツァルクアリツリ祭の間、セロ・トゥラロクに祀られた。エツァルクアリツリ祭の間、中央メキシコの支配者たちはトラロクに雨乞いの儀 式を行い、豊穣と季節の移り変わりを祝った[35]。エツァルクアリツリ祭の間のセロ・トゥラロクへの巡礼の重要な部分は、トラロクへの大人と子供の犠牲 であった[35]。 |

Related deities Five Tlaloquê depicted in the Codex Borgia. Archaeological evidence indicates Tláloc was worshipped in Mesoamerica before the Aztecs even settled there in the 13th century AD. He was a prominent god in Teotihuacan at least 800 years before the Aztecs.[33] This has led to Meso-American goggle-eyed rain gods being referred to generically as "Tláloc," although in some cases it is unknown what they were called in these cultures, and in other cases we know that he was called by a different name, e.g., the Maya version was known as Chaac and the Zapotec deity as Cocijo. Chalchiuhtlicue, or "she of the jade skirt" in Nahuatl, was the deity connected with the worship of ground water. Therefore, her shrines were by springs, streams, irrigation ditches, or aqueducts, the most important of these shrines being at Pantitlan, in the center of Lake Texcoco. Sometimes described as Tláloc's sister, Chalchiuhtlicue was impersonated by ritual performers wearing the green skirt that was associated with Chalchiuhtlicue. Like that of Tláloc, her cult was linked to the earth, fertility and nature's regeneration.[9] Tláloc was first married to the goddess of flowers, Xochiquetzal, which literally translates to "Flower Quetzal." Xochiquetzal personifies pleasure, flowers, and young female sexuality. In doing so, she is associated with pregnancies and childbirths and was believed to act as a guardian figure for new mothers. Unlike many other female deities, Xochiquetzal maintains her youthful appearance and is often depicted in opulent attire and gold adornments.[16] Tláloc was the father of Tecciztecatl, possibly with Chalchiuhtlicue. Tláloc had an older sister named Huixtocihuatl. |

関連する神々 ボルジア写本に描かれた5体のトラロケ。 考古学的証拠によれば、トラロックはアステカ人が西暦13世紀にメソアメリカに定住する以前から崇拝されていた。このことから、メソアメリカのゴーグルア イの雨の神は一般的に「Tláloc」と呼ばれるようになったが、これらの文化圏でどのように呼ばれていたのか不明な場合もあれば、マヤのものは Chaac、サポテカのものはCocijoと呼ばれるなど、別の名前で呼ばれていたことがわかっている場合もある。 ナワトル語で 「翡翠のスカートの女 」と呼ばれるチャルチウトリクエは、地下水の崇拝に関係する神であった。そのため、彼女の祠は泉、小川、灌漑用水路、水路橋のそばにあり、最も重要な祠は テスココ湖の中央にあるパンティトランにあった。トラロックの妹と表現されることもあるチャルチウトリクエは、チャルチウトリクエにちなんだ緑色のスカー トをはいたパフォーマティによって儀式に登場した。トラロックと同様に、彼女の崇拝は大地、豊穣、自然の再生と結びついていた[9]。 Tlálocは最初に花の女神であるXochiquetzalと結婚した。ソチケツァルは快楽、花、若い女性の性を擬人化している。そうすることで、彼女 は妊娠と出産に関連付けられ、新しい母親の守護神として働くと信じられていた。他の多くの女性神々とは異なり、キソチケツァルは若々しい容姿を保ち、豪華 な衣装と金の装飾品で描かれることが多い[16]。 TlálocはTecciztecatlの父であり、おそらくChalchiuhtlicueとの間に生まれた。TlálocにはHuixtocihuatlという姉がいた。 |

Cerro Tláloc Tláloc effigy vessel; 1440–1469; painted earthenware; height: 35 cm (13⁄4 in.); Museo del Templo Mayor (Mexico City). One side of the Aztecs' great temple, the Templo Mayor, was dedicated to the storm god Tláloc, the pyramid-temple symbolizing his mountain-cave abode. This jar, covered with stucco and painted blue, is adorned with the visage of Tláloc, identified by his coloration, ringed eyes and jaguar teeth; the Aztecs likened the rumble of thunder to the feline's growl  Archeological site atop Cerro Tláloc There is a sanctuary found atop Cerro Tláloc, dedicated to the god, Tláloc; it is thought that the location of this sanctuary in relation to other temples surrounding it may have been a way for the Aztecs to mark the time of year and keep track of important ceremonial dates.[36] Research has shown that different orientations linked to Cerro Tláloc revealed a grouping of dates at the end of April and beginning of May associated with certain astronomical and meteorological events. Archaeological, ethnohistoric, and ethnographic data indicate that these phenomena coincide with the sowing of maize in dry lands associated with agricultural sites.[37] The precinct on the summit of the mountain contains 5 stones which are thought to represent Tláloc and his four Tlaloque, who are responsible for providing rain for the land. It also features a structure that housed a statue of Tláloc in addition to idols of many different religious regions, such as the other sacred mountains.[38] Geographical setting Cerro Tláloc is the highest peak of the part of the Sierra Nevada called Sierra del Rio Frio that separates the valleys of Mexico and Puebla. It rises over two different ecological zones: alpine meadows and subalpine forests. The rainy season starts in May and lasts until October. The highest annual temperature occurs in April, the onset of the rainy season, and the lowest in December–January. Some 500 years ago weather conditions were slightly more severe, but the best time to climb the mountain was practically the same as today: October through December, and February until the beginning of May. The date of the feast of Huey Tozotli celebrated atop Cerro Tláloc coincided with a period of the highest annual temperature, shortly before dangerous thunderstorms might block access to the summit.[39] Archaeological evidence The first detailed account of Cerro Tláloc by Jim Rickards in 1929 was followed by visits or descriptions by other scholars. In 1953 Wicke and Horcasitas carried out preliminary archaeological investigations at the site; their conclusions were repeated by Parsons in 1971. Archaeo-astronomical research began in 1984, some of which remains unpublished. In 1989 excavation was undertaken at the site by Solis and Townsend.[40] The current damage that is present at the top of Cerro Tláloc is thought to be likely of human destruction, rather than natural forces. There also appears to have been a construction of a modern shrine that was built in the 1970s, which suggests that there was a recent/present attempt to conduct rituals on the mountain top.[38] |

セロ(山の)・トラロック(トラロック山) 1440-1469年、彩色土器、高さ35cm、テンプロ・マヨール博物館(メキシコ・シティ)。アステカの大神殿であるテンプロ・マヨールの片側は嵐の 神トラロックに捧げられ、ピラミッド神殿は彼の山の洞窟の住処を象徴していた。漆喰で覆われ、青く塗られたこの壷には、色彩、輪状の目、ジャガーの歯に よって識別されるトラロックの顔が描かれている。  セロトラロックの考古学遺跡 セロ・トゥラロクの頂上には、神トラロクに捧げられた聖域がある。この聖域とそれを取り囲む他の神殿との位置関係は、アステカ人が1年の時間を示し、重要 な儀式の日付を把握するための方法であった可能性があると考えられている[36]。調査によると、セロ・トゥラロクに関連するさまざまな方角から、特定の 天文学的・気象学的イベントに関連する4月末と5月初めの日付のグループが明らかになった。考古学的、民族史学的、民族学的データによると、これらの現象 は、農業用地に関連する乾燥した土地でのトウモロコシの種蒔きと一致している[37]。山頂の境内には5つの石があり、これはトラロックと、土地に雨を降 らせる役割を担う4人のトラロックを表していると考えられている。また、他の聖山など様々な宗教的地域の偶像に加え、トラロックの像を納めた建造物もある [38]。 地理的設定 セロ・トゥラロックは、メキシコとプエブラの谷を隔てるシエラ・デル・リオ・フリオと呼ばれるシエラネバダ山脈の最高峰である。高山草原と亜高山帯の森林 という2つの異なる生態系の上にそびえる。雨季は5月から10月まで続く。年間最高気温は雨季に入る4月で、最低気温は12月から1月である。約500年 前の気象条件はもう少し厳しかったが、登山のベストシーズンは実質的に現在と同じだった: 10月から12月、2月から5月初旬までである。セロ・トゥラロク山頂で祝われるフエ・トゾトリの祝祭の日は、年間気温が最も高くなる時期と重なり、危険 な雷雨が山頂へのアクセスを遮断する少し前であった[39]。 考古学的証拠 1929年、ジム・リカードがセロ・トゥラロクについて初めて詳細に記述し、その後、他の学者たちによる訪問や記述が続いた。1953年、ウィッケとホル カシタスはこの遺跡の考古学的予備調査を行い、その結論は1971年にパーソンズによって繰り返された。1984年に考古学的・天文学的調査が開始され、 その一部は未発表のままである。1989年には、ソリスとタウンゼントによって発掘調査が行われた[40]。セロ・トゥラロクの頂上に存在する現在の損傷 は、自然の力ではなく、人為的な破壊によるものと考えられている。また、1970年代に建てられた近代的な祠の建設もあったようで、山頂で儀式を行おうと する試みが最近/現在も行われていたことを示唆している[38]。 |

| Aktzin Cocijo Chaac Cerro Tláloc Tlaloque(この項目) |

アクツィン コシホ チャアク トラロックの丘 トラロック |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tl%C3%A1loc |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆