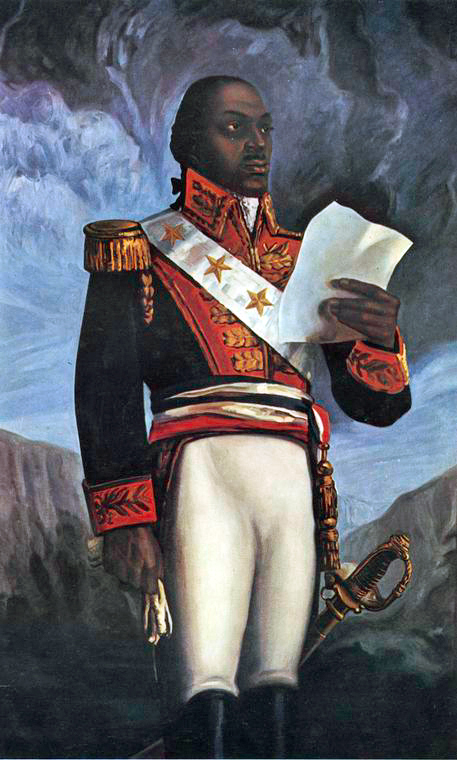

トゥーサン・ルーヴェルチュール

Toussaint Louverture,

1743-1803

Posthumous

1813 painting, A portrait of Toussaint Louverture Oil on Canvas, 65.1 x

54.3 cm. (25.6 x 21.4 in.)

☆フランソワ=ドミニク・トゥーサン・ルーヴェルチュール(フランス語: [fʁɑ̃swa dɔminik tusɛ̃ luvɛʁtyʁ]、英語: /ˌluːvərˈtjʊər/)[2]、別名トゥーサン・ルヴェルチュールまたはトゥーサン・ブレダ(1743年5月20日 - 1803年4月7日)は、ハイチ軍の将軍であり、ハイチ革命の最も著名な指導者であった。生涯において、ルヴェルチュールはまずスペイン軍と戦い、サン= ドマングの王党派と手を組んだ。その後、共和制フランスと手を組み、サン=ドマングの終身総督となった。最後に、ボナパルトの共和制軍と戦った。[3] [4] 革命の指導者として、ルヴェルチュールは軍事的、政治的な才覚を発揮し、初期の奴隷反乱を革命運動へと変えるのに貢献した。ジャン=ジャック・デサリンヌ とともに、トゥーサン・ルーヴェルチュールは現在、「ハイチ建国の父」の一人として知られている。

| François-Dominique

Toussaint Louverture (French: [fʁɑ̃swa dɔminik tusɛ̃ luvɛʁtyʁ],

English: /ˌluːvərˈtjʊər/)[2] also known as Toussaint L'Ouverture or

Toussaint Bréda (20 May 1743 – 7 April 1803), was a Haitian general and

the most prominent leader of the Haitian Revolution. During his life,

Louverture first fought and allied with Spanish forces against

Saint-Domingue Royalists, then joined with Republican France, becoming

Governor-General-for-life of Saint-Domingue, and lastly fought against

Bonaparte's republican troops.[3][4] As a revolutionary leader,

Louverture displayed military and political acumen that helped

transform the fledgling slave rebellion into a revolutionary movement.

Along with Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Louverture is now known as one of

the "Fathers of Haiti".[5][6] Toussaint Louverture was born as a slave in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, now known as Haiti. He was a devout Catholic, and was manumitted as an affranchi (ex-slave) before the French Revolution, identifying as a Creole for the greater part of his life. During his time as an affranchi, he became a salaried employee, an overseer of his former master's plantation, and later became a wealthy slave owner himself; Toussaint Louverture owned several coffee plantations at Petit Cormier, Grande Rivière, and Ennery.[7][8][9] At the start of the Haitian revolution he was nearly 50 years old and began his military career as a lieutenant to Georges Biassou, an early leader of the 1791 War for Freedom in Saint-Domingue.[10] Initially allied with the Spaniards of neighboring Santo Domingo, Louverture switched his allegiance to the French when the new Republican government abolished slavery. Louverture gradually established control over the whole island and used his political and military influence to gain dominance over his rivals.[11] Throughout his years in power, he worked to balance the economy and security of Saint-Domingue. Worried about the economy, which had stalled, he restored the plantation system using paid labor; negotiated trade agreements with the United Kingdom and the United States and maintained a large and well-trained army.[12] Louverture seized power in Saint-Domingue, established his own system of government, and promulgated his own colonial constitution in 1801 that named him as Governor-General for Life, which challenged Napoleon Bonaparte's authority.[13] In 1802, he was invited to a parley by French Divisional General Jean-Baptiste Brunet, but was arrested upon his arrival. He was deported to France and jailed at the Fort de Joux. He died in 1803. Although Louverture died before the final and most violent stage of the Haitian Revolution, his achievements set the grounds for the Haitian army's final victory. Suffering massive losses in multiple battles at the hands of the British and Haitian armies and losing thousands of men to yellow fever, the French capitulated and withdrew permanently from Saint-Domingue the very same year. The Haitian Revolution continued under Louverture's lieutenant, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, who declared independence on 1 January 1804, thereby establishing the sovereign state of Haiti. |

フランソワ=ドミニク・トゥーサ

ン・ルーヴェルチュール(フランス語: [fʁɑ̃swa dɔminik tusɛ̃ luvɛʁtyʁ]、英語:

/ˌluːvərˈtjʊər/)[2]、別名トゥーサン・ルヴェルチュールまたはトゥーサン・ブレダ(1743年5月20日 -

1803年4月7日)は、ハイチ軍の将軍であり、ハイチ革命の最も著名な指導者であった。生涯において、ルヴェルチュールはまずスペイン軍と戦い、サン=

ドマングの王党派と手を組んだ。その後、共和制フランスと手を組み、サン=ドマングの終身総督となった。最後に、ボナパルトの共和制軍と戦った。[3]

[4]

革命の指導者として、ルヴェルチュールは軍事的、政治的な才覚を発揮し、初期の奴隷反乱を革命運動へと変えるのに貢献した。ジャン=ジャック・デサリンヌ

とともに、トゥーサン・ルーヴェルチュールは現在、「ハイチ建国の父」の一人として知られている。[5][6] トゥーサン・ルーヴェルチュールは、現在のハイチにあたるフランス領サン=ドマングの奴隷として生まれた。敬虔なカトリック信者であった彼は、フランス革 命前に自由の身となり、生涯の大半をクレオールとして過ごした。自由の身となってからは、給料をもらう従業員となり、かつての主人のプランテーションの監 督者となり、後に自身も裕福な奴隷所有者となった。トゥーサン・ルーヴェルチュールは、プティ・コルミエ、グランド・リヴィエール、エニーに複数のコー ヒー農園を所有していた。 [7][8][9] ハイチ革命勃発時には50歳近くになっており、1791年のサン・ドマング解放戦争の初期の指導者であったジョルジュ・ビアスーの副官として軍人としての キャリアをスタートさせた。[10] 当初は隣国サント・ドミンゴのスペイン人と手を組んでいたが、新しく樹立された共和制政府が奴隷制度を廃止したため、フランスに忠誠を誓い直した。ルヴェ ルチュールは徐々に島全体を支配下に置き、政治的・軍事的影響力を駆使してライバルたちを圧倒した。 権力を握っていた間、彼はサン=ドマングの経済と治安のバランスを取ることに尽力した。停滞する経済を憂慮した彼は、賃金労働者によるプランテーション制 度を復活させ、イギリスおよびアメリカ合衆国と貿易協定を交渉し、大規模で訓練された軍隊を維持した。[12] ルヴェルチュールはサン=ドマングの権力を掌握し、独自の政治体制を確立し、1801年には自身を終身総督とする植民地憲法を発布し、ナポレオン・ボナパ ルトの権威に異議を唱えた。[13] 1802年、彼はフランス軍のジャン=バティスト・ブリュネ准将に会談に招かれたが、到着後すぐに逮捕された。彼はフランスに送還され、ジュの砦に投獄さ れた。1803年に死去した。ルヴェルチュールはハイチ革命の最終局面で最も激しい戦いが起こる前に死去したが、彼の功績はハイチ軍の最終的な勝利の基礎 を築いた。イギリス軍とハイチ軍との複数の戦闘で甚大な損害を被り、黄熱病で数千人の兵士を失ったフランスは降伏し、その同じ年にサン・ドマングから完全 に撤退した。 ハイチ革命は、ルヴェルチュール将軍の副官ジャン・ジャック・デサリンヌ(Jean-Jacques Dessalines)の下で継続され、1804年1月1日に独立を宣言し、ハイチ共和国が樹立された。 |

| Early life Birth, parentage, and childhood Louverture was born into slavery, the eldest son of Hyppolite, an Allada slave from the slave coast of West Africa, and his second wife Pauline, a slave from the Aja ethnic group, and given the name Toussaint at birth.[11] Louverture's son Issac would later name his great-grandfather, Hyppolite's father, as Gaou Guinou and a son of the King of Allada, although there is little extant evidence of this. The name Gaou possibly originated in the title Deguenon, meaning "old man" or "wise man" in the Allada kingdom, making Gaou Guinou and his son Hyppolite members of the bureaucracy or nobility, but not members of the royal family. In Africa, Hyppolite and his first wife, Catherine, were forced into enslavement due to a series of imperialist wars of expansion by the Kingdom of Dahomey into the Allada territory. In order to remove their political rivals and obtain European trade goods, Dahomean slavers separated the couple and sold them to the crew of the French slave ship Hermione, which then sailed to the French West Indies. The original names of Toussaint's parents are unknown, since the Code Noir mandated that slaves brought to their colonies be made into Catholics, stripped of their African names, and be given more European names in order to assimilate them into the French plantation system. Toussaint's father received the name Hyppolite upon his baptism on Saint-Domingue, as Latin and Greek names were the most fashionable for slaves at this time, followed by French, and Biblical Christian names.[11] Louverture is thought to have been born on the plantation of Bréda at Haut-du-Cap in Saint-Domingue, where his parents were enslaved and where he would spend the majority of his life before the revolution.[14][15] His parents would go on to have several children after him, with five surviving infancy; Marie-Jean, Paul, Pierre, Jean, and Gaou, named for his grandfather. Louverture would grow closest to his younger brother Paul, who along with his other siblings were baptized into the Catholic Church by the local Jesuit Order. Pierre-Baptiste Simon, a carpenter and gatekeeper on the Bréda plantation, is considered to have been Louverture's godfather and went on to become a parental figure to Louverture's family, along with his foster mother Pelage, after the death of Toussaint's parents.[16] Growing up, Toussaint first learned to speak the African Fon language of the Allada slaves on the plantation, then the Creole French of the greater colony, and eventually the Standard French of the elite class (grands blancs) during the revolution. Although he would later become known for his stamina and riding prowess, Louverture earned the nickname Fatras-Bâton ("sickly stick"), in reference to his small thin stature in his youth.[17][18]: 26–27 Toussaint and his siblings were trained to be domestic servants with Louverture being trained as an equestrian and coachmen after showing a talent for handling the horses and oxen on the plantation. This allowed the siblings to work in the manor house and stables, away from the grueling physical labor and deadly corporal punishment meted out in the sugar-cane fields. In spite of this relative privilege, there is evidence that even in his youth Louverture's pride pushed him to engage in fights with members of the Petits-blancs (white commoner) community, who worked on the plantation as hired help. There is a record that Louverture beat a young petit blanc named Ferere, but was able to escape punishment after being protected by the new plantation overseer, François Antoine Bayon de Libertat. De Libertat had become steward of the Bréda property after it was inherited by Pantaléon de Bréda Jr., a grand blanc (white nobleman), and managed by Bréda's nephew the Count of Noah.[19] In spite or perhaps because of this protection, Louverture went on to engage in other fights. On one occasion, he threw the plantation attorney Bergé off a horse belonging to the Bréda plantation, when he attempted to take it outside the bounds of the property without permission.[11] |

幼少期 出生、家柄、幼少期 ルヴェルテュールは奴隷として生まれ、西アフリカの奴隷海岸出身のアラダ族奴隷であったイポリットの第一夫人であるポーリーヌとの間に長男として生まれ た。出生時にトゥーサンと名付けられた。 [11] ルヴェルチュールの息子イサックは、ひ孫にあたるハイポリットの父親をガウ・ギヌーと名付け、アジャ族の王の息子としたが、このことを示す証拠はほとんど 残っていない。おそらく「老人」または「賢者」を意味するアラダ王国の称号「Deguenon」が「Gaou」の語源であり、Gaou Guinouと息子のHyppoliteは官僚または貴族の一員ではあったが、王族の一員ではなかった。アフリカでは、ダホメー王国によるアラダ領への一 連の帝国主義的拡張戦争により、Hyppoliteと最初の妻Catherineは奴隷として強制的に働かされることになった。政治的ライバルを排除し、 ヨーロッパの貿易品を手に入れるため、ダホメーの奴隷商人はこの夫婦を引き離し、フランス領西インド諸島に向かう奴隷船エルミオーヌ号の乗組員に彼らを売 り渡した。 黒人法により、植民地に連れてこられた奴隷はカトリックに改宗させられ、アフリカの名前を剥奪され、フランス式の農園制度に同化させるためにヨーロッパ風 の名前を付けられることになっていたため、トゥーサンの両親の元々の名前は不明である。トゥーサンの父親は、サン・ドマングで洗礼を受けた際にヒッポリッ トという名を受けた。当時、奴隷の間ではラテン語やギリシャ語の名前が最も流行しており、次いでフランス語、聖書に登場するキリスト教の名前が続いた。 ルヴェルチュールは、両親が奴隷として送られたサン・ドマングのオー・デュ・カップにあるブレダ農園で生まれたと考えられており、革命前は人生の大半をそ こで過ごした。[14][15] 両親は彼に続いてさらに数人の子供をもうけ、そのうち5人が幼児期を生き延びた。マリー=ジャン、ポール、ピエール、ジャン、そして祖父にちなんで名づけ られたガウである。ルヴェルチュールは末弟のポールと最も親しくなり、ポールは他の兄弟たちとともに地元のイエズス会によってカトリック教会で洗礼を受け た。ブレダ農園の大工であり門番でもあったピエール=バティスト・シモンは、ルヴェルチュールの名付け親であり、トゥーサンの両親の死後、育ての母ペラー ジュとともにルヴェルチュール一家の保護者的存在となったと考えられている。 [16] 成長するにつれ、トゥーサンはまずプランテーションで奴隷として働いていたアラーダ族のフォン語を学び、その後、より大きな植民地でクレオール・フランス 語を学び、最終的には革命期にエリート層(グラン・ブラン)の標準フランス語を学んだ。 後にスタミナと乗馬の腕前で知られるようになるが、ルヴェルチュールは、若い頃の小柄で痩せた体格から、「病弱な棒」というあだ名で呼ばれていた。 [17][18]:26-27 トゥーサンと兄弟姉妹は、家庭内での使用人となるように訓練された。ルヴェルチュールは、農園で馬や牛を扱う才能を見せ、乗馬と馬車の御者の訓練を受け た。これにより、兄弟は砂糖黍畑での過酷な肉体労働や死を招くほどの体罰から逃れ、邸宅や厩舎で働くことができた。こうした比較的恵まれた環境にもかかわ らず、ルヴェルチュールは若かりし頃、プライドの高さから、砂糖黍畑で雇われ労働者として働いていたプチ・ブラン(白人平民)のコミュニティのメンバーと 喧嘩をしたという証拠がある。ルヴェルテールがフェレールという名の若いプチ・ブランを殴ったという記録があるが、新しい農園監督官フランソワ・アント ワーヌ・バイヨン・ド・リベルタに庇護されたため、処罰を免れた。ド・リベルタは、ブラン(白人の貴族)であるパンタレオン・ド・ブレダ・ジュニアがブレ ダの所有地を相続し、ブレダの甥であるノア伯爵が管理するようになってからは、ブレダの財産の執事を務めていた。[19] こうした庇護にもかかわらず、あるいは、それゆえか、ルヴェルテールは他の喧嘩にも首を突っ込んでいく。あるとき、彼は、ブレダの農園の境界外に無断で馬 を連れ出そうとした農園弁護士ベルジュを、ブレダの農園に属する馬から投げ落とした。[11] |

| First marriage and manumission Until 1938, historians believed that Louverture had been a slave until the start of the revolution.[note 1][citation needed] In the later 20th century, discovery of a personal marriage certificate and baptismal record dated between 1776 and 1777 documented that Louverture was a freeman, meaning that he had been manumitted sometime between 1772 and 1776, the time de Libertat had become overseer. This finding retrospectively clarified a private letter that Louverture sent to the French government in 1797, in which he mentioned he had been free for more than twenty years.[20]: 62 Upon being freed, Toussaint took up the name of Toussaint de Bréda (Toussaint of Bréda), or more simply Toussaint Bréda, in reference to the plantation where he grew up. Toussaint went from being a slave of the Bréda plantation to becoming a member of the greater community of gens de couleur libres (free people of color). This was a diverse group of Affranchis (freed slaves), free blacks of full or majority African ancestry, and Mulattos (mixed-race peoples), which included the children of French planters and their African slaves, as well as distinct multiracial families who had multi-generational mixed ancestries from the varying different populations on the island. The gens de couleur libres strongly identified with Saint-Domingue, with a popular slogan being that while the French felt at home in France, and the slaves felt at home in Africa, they felt at home on the island. Now enjoying a greater degree of relative freedom, Louverture dedicated himself to building wealth and gaining further social mobility through emulating the model of the grands blancs and rich gens de couleur libres by becoming a planter. He began by renting a small coffee plantation, along with its 13 slaves, from his future son-in-law.[21] One of the slaves Louverture owned at this time is believed to have been Jean-Jacques Dessalines, who would go onto become one of Louverture's most loyal lieutenants and a member of his personal guard during the Haitian Revolution.[22] Between 1761 and 1777, Louverture met and married his first wife, Cécile, in a Catholic ceremony. The couple went on to have two sons, Toussaint Jr. and Gabrielle-Toussaint, and a daughter, Marie-Marthe. During this time, Louverture bought several slaves; although this was a means to grow a greater pool of exploitable labor, this was one of the few legal methods available to free the remaining members of a former slave's extended family and social circle. Louverture eventually bought the freedom of Cécile, their children, his sister Marie-Jean, his wife's siblings, and a slave named Jean-Baptist, freeing him so that he could legally marry. Louverture's own marriage, however, soon became strained and eventually broke down, as his coffee plantation failed to make adequate returns. A few years later, the newly freed Cécile left Louverture for a wealthy Creole planter, while Louverture had begun a relationship with a woman named Suzanne, who is believed to have gone on to become his second wife. There is little evidence that any formal divorce occurred, as that was illegal at the time. Louverture, in fact, would go on to completely excise his first marriage from his recollections of his pre-revolutionary life, to the extent that, until recent documents uncovered the marriage, few researchers were aware of the existence of Cécile and her children with Louverture.[11] |

最初の結婚と解放 1938年まで、歴史家たちは、ルヴェルチュールが革命勃発まで奴隷であったと考えていた。 [注1][要出典] 20世紀後半になって、1776年から1777年にかけての日付が記載された個人の結婚証明書と洗礼記録が発見され、ルヴェルテールが自由民であったこと が証明された。つまり、彼が解放されたのは、ド・リベルタが監督官となった1772年から1776年の間のいつかの時点であったことを意味する。この発見 により、1797年にルヴェルテールがフランス政府に送った私的な手紙の内容が後付けで明らかになった。その手紙の中で、彼は20年以上も自由の身であっ たと述べている。[20]:62 解放されたトゥーサンは、自分が育った農園にちなんで、トゥーサン・ド・ブレダ(ブレダのトゥーサン)、あるいはより簡潔にトゥーサン・ブレダと名乗るよ うになった。トゥーサンはブレダ農園の奴隷から、より大きな自由有色人種のコミュニティの一員となった。これは、自由の身となった奴隷(アフリカ系自由 民)、アフリカ系完全自由民、およびムラート(混血の人々)の多様なグループであった。ムラートには、フランス人プランターとアフリカ人奴隷の子供たち、 および島内の異なる異なる人種集団から何世代にもわたって混血した多様な家系を持つ家族が含まれていた。自由有色人種は、サン・ドマングに強い帰属意識を 抱いており、よく使われたスローガンは、「フランス人はフランスに、奴隷たちはアフリカに、自分たちはこの島に、それぞれ居場所がある」というものだっ た。相対的な自由をより多く享受するようになったルヴェルテールは、プランテーション経営者となることで、自由白人や富裕な自由有色人種のモデルを手本と し、富を築き、さらなる社会的地位の向上を目指した。彼はまず、後に自分の娘の婿となる人物から、13人の奴隷とともに小さなコーヒー農園を借り受けた。 [21] ルヴェルテュールが当時所有していた奴隷の一人は、後にルヴェルテュールの最も忠実な副官となり、ハイチ革命時には彼の親衛隊の一員となったジャン= ジャック・デサリンヌであったと考えられている。[22] 1761年から1777年の間、ルヴェルチュールは最初の妻セシルと出会い、カトリックの儀式で結婚した。夫妻の間には、トゥーサン・ジュニアとガブリエ ル・トゥーサンの2人の息子と、マリー・マルスの1人の娘が生まれた。この間、ルヴェルチュールは数人の奴隷を購入した。これは搾取可能な労働力を増やす ための手段であったが、これはかつての奴隷の親族や交友関係の残りのメンバーを解放するために利用できる数少ない合法的な方法のひとつであった。 ルヴェルチュールは最終的に、セシル、彼らの子供たち、彼の姉妹マリー=ジャン、彼の妻の兄弟姉妹、そしてジャン=バティストという名の奴隷の自由を購入 し、彼を解放して合法的に結婚できるようにした。しかし、ルヴェルチュールの結婚生活はすぐに緊張状態となり、最終的には破綻した。彼のコーヒー農園が十 分な利益を上げることができなかったためである。数年後、解放されたばかりのセシルは、裕福なクレオール人農園主のもとへ去り、ルヴェルチュールはスザン ヌという名の女性と関係を持ち始めた。スザンヌは後にルヴェルチュールの2人目の妻になったと考えられている。当時、正式な離婚は違法であったため、正式 な離婚が行われたことを示す証拠はほとんどない。実際、ルヴェルチュールは、革命前の生活の思い出から最初の結婚を完全に消し去り、最近まで、その結婚が 発覚するまで、セシルとルヴェルチュールとの間に生まれた子供たちの存在をほとんどの研究者が知らなかったほどであった。[11] |

| Second marriage In 1782, Louverture married his second wife, Suzanne Simone-Baptiste, who is thought to have been his cousin or the daughter of his godfather Pierre-Baptiste.[20]: 263 Toward the end of his life, Louverture told General Caffarelli that he had fathered at least 16 children, of whom 11 had predeceased him, between his two wives and a series of mistresses.[20]: 264–267 In 1785, Louverture's eldest child, the 24-year-old Toussaint Jr., died from a fever and the family organized a formal Catholic funeral for him. This was officiated by a local priest as a favor for the devout Louverture. Gabrielle-Toussaint disappeared from the historical record at this time and is presumed to have also died, possibly from the same illness that took Toussaint Jr.. Not all of Louverture's children can be identified with certainty, but the three children from his first marriage and his three sons from his second marriage are well known. Suzanne's eldest child, Placide, is generally thought to have been fathered by Seraphim Le Clerc, a Creole planter. In spite of this, Placide was adopted by Louverture and raised as his own. Louverture went on to have at least two sons with Suzanne: Isaac, born in 1784, and Saint-Jean, born in 1791. They would remain enslaved until the start of the revolution, as Louverture spent the 1780s attempting to regain the wealth he had lost with the failure of his coffee plantation in the 1770s.[20]: 264–267 It appears that during this time Louverture returned to play an important role on the Bréda plantation to remain closer to old friends and his family. He remained there until the outbreak of the revolution as a salaried employee and contributed to the daily functions of the plantation.[23] He took up his old responsibilities of looking after the livestock and care of the horses.[24] By 1789, his responsibilities expanded to include acting as a muleteer, master miller, and possibly a slave-driver, charged with organizing the workforce. During this time the Bréda family attempted to divide the plantation and the slaves on it among a new series of four heirs. In an attempt to protect his foster mother, Pelage, Louverture bought a young 22-year-old female slave and traded her to the Brédas to prevent Pelage from being sold to a new owner. By the start of the revolution, Louverture began to accumulate a moderate fortune and was able to buy a small plot of land adjacent to the Bréda property to build a house for his family. He was nearly 48 years old at this time.[21] |

二度目の結婚 1782年、ルヴェルチュールは2人目の妻、スザンヌ・シモーヌ=バティストと結婚した。彼女は従姉妹か、名付け親のピエール=バティストの娘であったと 考えられている。[20]: 263 晩年、ルヴェルチュールはカファレリ将軍に、2人の妻と複数の愛人との間に少なくとも16人の子供をもうけ、そのうち11人は彼より先に亡くなっていたと 語った。 [20]: 264-267 1785年、ルヴェルチュールの長男で24歳のトゥーサン・ジュニアが熱病で死去し、家族は正式なカトリックの葬儀を執り行った。これは敬虔なルヴェル チュールへの好意として、地元の司祭によって執り行われた。ガブリエル=トゥーサンは、この時期から歴史の記録から姿を消し、トゥーサン・ジュニアと同じ 病気で亡くなった可能性が高いと推定されている。 ルヴェルチュールの子供たちのすべてを確実に特定することはできないが、最初の結婚で生まれた3人の子供たちと、2度目の結婚で生まれた3人の息子たちは よく知られている。スザンヌの長男プラシドは、一般的に、クレオール人のプランテーション農場主セラフィム・ルクレールとの間にできた子供であると考えら れている。にもかかわらず、プラシドはルヴェルテールに養子として引き取られ、実の子として育てられた。ルヴェルテールはスザンヌとの間に少なくとも2人 の息子をもうけた。1784年に生まれたアイザックと、1791年に生まれたサン=ジャンである。彼らは革命が始まるまで奴隷のままであり、ルヴェルテー ルは1780年代に1770年代のコーヒー農園の失敗で失った富を取り戻そうとしていた。[20]: 264-267 この間、ルヴェルテールはブレダ農園で重要な役割を担い、旧友や家族とより近い距離で過ごしていたようだ。彼はそこで、革命が勃発するまで給料をもらって 働き続け、プランテーションの日常業務に貢献した。[23] 彼は家畜の世話や馬の世話といった昔の仕事を再び引き受けた。[24] 1789年までに、彼の責任は拡大し、騾馬使いや製粉所の責任者、さらには労働力を組織する奴隷使いとしての役割も担うようになった。この間、ブレダ家は 農園と農園内の奴隷たちを新たな4人の相続人の間で分割しようとした。ペラージュを新しい所有者に売られないように守るため、ルヴェルテールは22歳の若 い女性奴隷を買い、ブレダ家に彼女を売った。革命勃発時には、ルヴェルチュールはかなりの財産を蓄え、ブレダ家の所有地に隣接する小さな土地を購入して家 族のための家を建てることもできた。この時、彼は48歳近くになっていた。[21] |

Apocryphal print of Toussaint reading Abbé Raynal's Histoire des deux Indes before the revolution (1853) Education Louverture gained some education from his godfather Pierre-Baptiste on the Bréda plantation.[25] His extant letters demonstrate a moderate familiarity with Epictetus, the Stoic philosopher who had lived as a slave, while his public speeches showed a familiarity with Machiavelli.[26] Some cite Enlightenment thinker Abbé Raynal, a French critic of slavery, and his publication Histoire des deux Indes predicting a slave revolt in the West Indies as a possible influence.[26][18]: 30–36 [note 2] Louverture received a degree of theological education from the Jesuit and Capuchin missionaries through his church attendance and devout Catholicism. His medical knowledge is attributed to a familiarity with the folk medicine of the African plantation slaves and Creole communities, as well as more formal techniques found in the hospitals founded by the Jesuits and the free people of color.[29] Legal documents signed on Louverture's behalf between 1778 and 1781 suggest that he could not yet write at that time.[30][20]: 61–67 Throughout his military and political career during the revolution, he was known to have verbally dictated his letters to his secretaries, who prepared most of his correspondences. A few surviving documents from the end of his life in his own hand confirm that he eventually learned to write, although his Standard French spelling was "strictly phonetic" and closer to the Creole French he spoke for the majority of his life.[26][31][32] |

革命前(1853年)にトゥーサンがレイナルの著書『ふたつのインド史』を読んでいるという逸話の印刷物 教育 ルヴェルチュールは、名付け親のピエール=バティストからブレッダ農園で教育を受けた。[25] 現存する彼の書簡は、奴隷として生きたストア哲学者エピクテトスの著作に精通していることを示している。一方、彼の公開演説はマキャベリに精通しているこ とを示している。 [26] 啓蒙思想家のレイナル神父を奴隷制度の批判者であるフランスの人物として挙げ、彼の著書『西インド諸島の二つの歴史』が西インド諸島での奴隷の反乱を予言 していたことが影響を与えた可能性があるとする者もいる。[26][18]:30-36[注釈 2] ルーヴェルチュールは、教会への出席と敬虔なカトリック信者として、イエズス会とカプチン会の宣教師から神学の教育を受けていた。彼の医学的知識は、アフ リカ人プランテーション奴隷やクレオール社会の民間療法に精通していたこと、およびイエズス会や自由有色民によって設立された病院で学んだことによるもの である。[29] 1778年から1781年の間にルヴェルチュールが署名した法的文書は、彼が当時まだ文字を書くことができなかったことを示唆している。[30] [20]: 61–67 革命期の軍人および政治家としての経歴を通じて、彼は秘書に口頭で手紙を書き、秘書がその大半を準備していたことで知られている。彼が晩年に自筆で残した 数点の文書が現存しており、最終的には読み書きを習得したことが確認されているが、彼の標準フランス語の綴りは「厳密に音声表記」であり、生涯の大半で話 していたクレオール・フランス語に近いものであった。[26][31][32] |

| Haitian Revolution Main article: Haitian Revolution Beginnings of a rebellion: 1789–1793 Beginning in 1789, the black and mulatto population of Saint-Domingue became inspired by a multitude of factors that converged on the island in the late 1780s and early 1790s leading them to organize a series of rebellions against the central white colonial assembly in Le Cap. In 1789 two mix-race Creole merchants, Vincent Ogé and Julien Raimond, happened to be in France during the early stages of the French Revolution. Here they began lobbying the French National Assembly to expand voting rights and legal protections from the grands blancs to the wealthy slave-owning gens de couleur, such as themselves. Being of majority white descent and with Ogé having been educated in France, the two were incensed that their black African ancestry prevented them from having the same legal rights as their fathers, who were both grand blanc planters. Rebuffed by the assembly they returned to the colony where Ogé met up with Jean-Baptiste Chavannes, a wealthy mixed-race veteran of the American Revolution and an abolitionist. Here the two organized a small scale revolt in 1790 composed of a few hundred gens de couleur, who engaged in several battles against the colonial militias on the island. However, after the movement failed to gain traction Ogé and Chavannes were quickly captured and publicly broken on the wheel in the public square in Le Cap in February 1791. For the slaves on the island worsening conditions due to the neglect of legal protections afforded them by the Code Noir stirred animosities and made a revolt more attractive compared to the continued exploitation by the grands and petits blancs. Then, the political and social disruption caused by the French Revolution's attempt to expand the rights to all men, inspired a series of revolts across several neighbouring French possessions in the Caribbean, which upset much of the established trade among the colonies. Many of the devout Catholic slaves and freedmen, including Toussaint, identified as free Frenchmen and royalists, who desired to protect a series of progressive legal protections afforded to the black citizenry by King Louis XVI and his predecessors.[11] On 14 August 1791, two hundred members of the black and mixed-race population made up of slave foremen, Creoles, and freed slaves gathered in secret at a plantation in Morne-Rouge in the north of Saint-Domingue to plan their revolt. Here prominent early figures of the revolution such as Dutty François Boukman, Jean-François Papillon, Georges Biassou, Jeannot Bullet, and Toussaint gathered to nominate a single leader to guide the revolt. Toussaint, wary of the dangers of taking on such a public role, especially after hearing about what happened to Ogé and Chavannes, went on to nominate Georges Biassou as leader. He would later join his forces as a secretary and lieutenant, and be in command of a small detachment of soldiers.[33][34] During this time, Toussaint took up the name of Monsieur Toussaint, a title that was once been reserved for the white population of Saint-Domingue. Surviving documents show him participating in the leadership of the rebellion, discussing strategy, and negotiating with the Spanish supporters of the rebellion for supplies. Wanting to identify with the royalist cause, Louverture and other rebels wore white cockades upon their sleeves and crosses of St. Louis.[23] A few days after this gathering, a Vodou ceremony at Bois Caïman marked the public start of the major slave rebellion in the north, which had the largest plantations and enslaved population. Louverture did not openly take part in the earliest stages of the rebellion, as he spent the next few weeks sending his family to safety in Santo Domingo and helping his old overseer Bayon de Libertat. Louverture hid him and his family in a nearby wood, and brought them food from a nearby rebel camp. He eventually helped Bayon de Libertat's family escape the island and in the coming years supported them financially as they resettled in the United States and mainland France.[11]  Louverture on a rearing horse Louverture, as depicted in an 1802 French engraving In 1791, Louverture was involved in negotiations between rebel leaders and the French Governor, Blanchelande, for the release of their white prisoners and a return to work, in exchange for a ban on the use of whips, an extra non-working day per week, and the freedom of imprisoned leaders.[35] When the offer was rejected, he was instrumental in preventing the massacre of Biassou's white prisoners.[36] The prisoners were released after further negotiations and escorted to Le Cap by Louverture. He hoped to use the occasion to present the rebellion's demands to the colonial assembly, but they refused to meet.[37] Throughout 1792, as a leader in an increasingly formal alliance between the black rebellion and the Spanish, Louverture ran the fortified post of La Tannerie and maintained the Cordon de l'Ouest, a line of posts between rebel and colonial territory.[38] He gained a reputation for his discipline, training his men in guerrilla tactics and "the European style of war".[39] Louverture emphasized brotherhood and fraternity among his troops and aimed to unify individuals of many populations. He used republican rhetoric to rally the varying groups within Saint-Dominigue and was successful in this effort. His favor of fraternity and strict discipline defined the kind of leader he was.[40] After hard fighting, he lost La Tannerie in January 1793 to the French General Étienne Maynaud de Bizefranc de Laveaux, but it was in these battles that the French first recognized him as a significant military leader.[41] Some time in 1792–1793, Toussaint adopted the surname Louverture, from the French word for "opening" or "the one who opened the way".[42] Although some modern writers spell his adopted surname with an apostrophe, as in "L'Ouverture", he did not. The most common explanation is that it refers to his ability to create openings in battle. The name is sometimes attributed to French commissioner Polverel's exclamation: "That man makes an opening everywhere". Some writers think the name referred to a gap between his front teeth.[43] |

ハイチ革命 詳細は「ハイチ革命」を参照 反乱の始まり:1789年~1793年 1789年、サン=ドマングの黒人と混血の人々は、1780年代後半から1790年代初頭にかけて島に集中したさまざまな要因に触発され、ル・キャップの 中央白人植民地議会に対して一連の反乱を起こすようになった。1789年、2人の混血クレオール商人、ヴィンセント・オジェとジュリアン・レモンは、フラ ンス革命の初期段階にフランスに滞在していた。そこで彼らは、国民議会に働きかけ、自分たちのような富裕な奴隷所有者である有色人種に、グラン・ブランか ら選挙権と法的保護を拡大するよう求めた。白人系が多数派であり、オジェはフランスで教育を受けていたため、2人は自分たちがアフリカ系黒人であるため に、グランド・ブランである自分たちの父親たちと同じ法的権利を持てないことに憤慨していた。議会で拒絶された2人は植民地に戻り、そこでオジェはアメリ カ独立戦争の退役軍人で、奴隷廃止論者でもある富裕な混血人種のジャン=バティスト・シャヴァンヌと出会った。ここで2人は、1790年に数百人の有色人 種の奴隷たちによる小規模な反乱を組織した。反乱軍は、島内の植民地民兵と数回の戦闘を繰り広げた。しかし、この運動が支持を得られなかったため、オジェ とシャヴァンヌはすぐに捕らえられ、1791年2月にル・キャップの広場で公開処刑された。黒人奴隷たちにとって、黒人奴隷法による法的保護の怠慢により 状況が悪化することは、憎悪を煽り、グラン・ブランやプティ・ブランによる搾取の継続よりも反乱が魅力的に思えるようになった。 そして、フランス革命による権利拡大の試みによる政治的・社会的混乱は、カリブ海のフランス領のいくつかで一連の反乱を引き起こし、植民地間の確立された 貿易の多くを混乱させた。トゥーサンを含む敬虔なカトリック教徒の奴隷や解放奴隷の多くは、ルイ16世とその前任者によって黒人市民に与えられた一連の進 歩的な法的保護を保護したいと望む自由の身のフランス人および王党派であった。 1791年8月14日、奴隷の監督者、クレオール、解放された奴隷など、黒人と混血の人種からなる200人の住民が、サン・ドマングの北部にあるモーン・ ルージュの農園に秘密裏に集まり、反乱計画を練った。ここで、デュティ・フランソワ・ブークマン、ジャン=フランソワ・パピヨン、ジョルジュ・ビアスー、 ジャンノ・ビュレット、トゥーサンといった革命初期の著名な人物が集まり、蜂起を指揮する単独の指導者を指名した。トゥーサンは、特にオジェとシャヴァン ヌに起こったことを耳にしてから、そのような公的な役割を引き受けることの危険性を警戒し、ジョルジュ・ビアスーを指導者に指名した。後に彼は書記と副官 としてトゥーサンに従い、小規模な兵士部隊の指揮を執ることになる。[33][34] この時期、トゥーサンはかつてサン・ドマングの白人のみが使用していた「ムッシュー・トゥーサン」という称号を使用するようになった。現存する文書には、 彼が反乱軍の指導者として戦略を練り、反乱軍を支援するスペイン人たちと物資の調達について交渉している様子が描かれている。王党派の運動に共感したル ヴェルチュールと他の反乱軍は、白いコカードを袖に付け、聖ルイの十字架を身に着けていた。 この集会の数日後、奴隷の反乱が最も多く、奴隷人口も最も多かった北部で、ボア・カイマン島でのヴードゥー教の儀式が、奴隷反乱の公式な開始を告げるもの となった。ルヴェルトゥールは、最初の反乱の段階では公然と参加することはなく、その後の数週間を家族をサント・ドミンゴの安全な場所に送り届けたり、か つての上司バイヨン・ド・リベルタの支援に費やした。ルヴェルチュールは彼と彼の家族を近くの森に隠し、近くの反乱軍キャンプから食料を運んだ。最終的に 彼はバイヨン・ド・リベルタの家族を島からの脱出を手助けし、彼らがアメリカ合衆国とフランス本土に移住するまでの数年間、経済的に支援した。[11]  馬に乗るルヴェルチュール 1802年のフランス版画に描かれたルヴェルチュール 1791年、ルヴェルテールは反乱軍の指導者たちとフランス総督ブランシュランとの間で、白人の捕虜の解放と労働への復帰を条件に、鞭打ちの禁止、週に1 日の追加の休日、投獄されている指導者の解放を求める交渉に関与した。 [35] この申し出が拒否された際には、ビアスーの白人の捕虜の虐殺を防ぐのに尽力した。[36] 捕虜はさらなる交渉の後に解放され、ルヴェルチュールによってル・キャップまで護送された。彼はこの機会を利用して、反乱軍の要求を植民地議会に提出しよ うとしたが、彼らは会合を拒否した。[37] 1792年を通して、黒人反乱軍とスペインの同盟が次第に公式なものとなる中、ルヴェルチュールはラ・タネリー要塞を指揮し、反乱軍と植民地領土の間の防 衛線であるコルドン・ド・ロエストを維持した。[38] 彼は規律を重んじ、ゲリラ戦術と「ヨーロッパ式の戦争」を兵士たちに訓練させたことで評判を得た。 [39] ルヴェルチュールは、自らの軍隊における同胞愛と友愛を強調し、多くの民族の個々人を統合することを目指した。彼はサン・ドマング内のさまざまな集団をま とめ上げるために共和制のレトリックを用い、この努力は成功した。同胞愛と厳格な規律を重んじる姿勢が、彼がどのような指導者であるかを明確に示してい た。[40] 激しい戦いの後、1793年1月にラ・タネリーをフランス軍のエティエンヌ・メイノー・ド・ビゼフラン・ド・ラヴォー将軍に奪われたが、これらの戦いでフ ランス軍は初めて彼を重要な軍事指導者として認識した。[41] 1792年から1793年の間のある時期、トゥーサンは「開く」あるいは「道を開いた者」を意味するフランス語に由来する「ルヴェルチュール」という姓を 名乗った。[42] 現代の作家の中には、彼の姓を「ルヴェルチュール」とアポストロフィ付きで表記する者もいるが、トゥーサンはそうしなかった。最も一般的な説明は、戦場で 突破口を開く能力に由来するというものである。この名前は、フランス人委員ポルヴェレルの「あの男はどこでも突破口を作る」という叫びから来ているという 説もある。一部の作家は、この名前は前歯の間の隙間を指していると考えている。[43] |

| Alliance with the Spanish: 1793–1794 Despite adhering to royalist views, Louverture began to use the language of freedom and equality associated with the French Revolution.[44] From being willing to bargain for better conditions of slavery late in 1791, he had become committed to its complete abolition.[45][46] After an offer of land, privileges, and recognizing the freedom of slave soldiers and their families, Jean-François and Biassou formally allied with the Spanish in May 1793; Louverture likely did so in early June. He had made covert overtures to General Laveaux prior but was rebuffed as Louverture's conditions for alliance were deemed unacceptable. At this time the republicans were yet to make any formal offer to the slaves in arms and conditions for the blacks under the Spanish looked better than that of the French.[47] In response to the civil commissioners' radical 20 June proclamation (not a general emancipation, but an offer of freedom to male slaves who agreed to fight for them) Louverture stated that "the blacks wanted to serve under a king and the Spanish king offered his protection."[48] On 29 August 1793, he made his famous declaration of Camp Turel to the black population of St. Domingue: Brothers and friends, I am Toussaint Louverture; perhaps my name has made itself known to you. I have undertaken vengeance. I want Liberty and Equality to reign in St. Domingue. I am working to make that happen. Unite yourselves to us, brothers and fight with us for the same cause.[27] On the same day, the beleaguered French commissioner, Léger-Félicité Sonthonax, proclaimed emancipation for all slaves in French Saint-Domingue,[49] hoping to bring the black troops over to his side.[50] Initially, this failed, perhaps because Louverture and the other leaders knew that Sonthonax was exceeding his authority.[51] However, on 4 February 1794, the French revolutionary government in France proclaimed the abolition of slavery.[52] For months, Louverture had been in diplomatic contact with the French general Étienne Maynaud de Bizefranc de Laveaux. During this time, his competition with the other rebel leaders was growing, and the Spanish had started to look with disfavor on his near-autonomous control of a large and strategically important region.[53] Louverture's auxiliary force was employed to great success, with his army responsible for half of all Spanish gains north of the Artibonite in the West in addition to capturing the port town of Gonaïves in December 1793.[54] However, tensions had emerged between Louverture and the Spanish higher-ups. His superior with whom he enjoyed good relations, Matías de Armona, was replaced with Juan de Lleonart – who was disliked by the black auxiliaries. Lleonart failed to support Louverture in March 1794 during his feud with Biassou, who had been stealing supplies for Louverture's men and selling their families as slaves. Unlike Jean-François and Bissaou, Louverture refused to round up enslaved women and children to sell to the Spanish. This feud also emphasized Louverture's inferior position in the trio of black generals in the minds of the Spanish – a check upon any ambitions for further promotion.[55] On 29 April 1794, the Spanish garrison at Gonaïves was suddenly attacked by black troops fighting in the name of "the King of the French", who demanded that the garrison surrender. Approximately 150 men were killed and much of the populace forced to flee. White guardsmen in the surrounding area had been murdered, and Spanish patrols sent into the area never returned.[56] Louverture is suspected to have been behind this attack, although was not present. He wrote to the Spanish 5 May protesting his innocence – supported by the Spanish commander of the Gonaïves garrison, who noted that his signature was absent from the rebels' ultimatum. It was not until 18 May that Louverture would claim responsibility for the attack, when he was fighting under the banner of the French.[57] The events at Gonaïves made Lleonart increasingly suspicious of Louverture. When they had met at his camp 23 April, the black general had shown up with 150 armed and mounted men, as opposed to the usual 25, choosing not to announce his arrival or waiting for permission to enter. Lleonart found him lacking his usual modesty or submission, and after accepting an invitation to dinner 29 April, Louverture afterward failed to show. The limp that had confined him to his bed during the Gonaïves attack was thought to be feigned and Lleonart suspected him of treachery.[58] Remaining distrustful of the black commander, Lleonart housed his wife and children whilst Louverture led an attack on Dondon in early May, an act which Lleonart later believed confirmed Louverture's decision to turn against the Spanish.[59] |

スペインとの同盟:1793年~1794年 王党派の考えに固執していたにもかかわらず、ルヴェルテールはフランス革命に関連する自由と平等の概念を使い始めた。[44] 1791年の後半には奴隷の待遇改善を求めて交渉する姿勢を見せていたが、彼は奴隷制度の完全廃止に尽力するようになった。 [45][46] 土地と特権の提供、そして奴隷兵とその家族の自由を認めるという申し出を受け、ジャン=フランソワとビアスーは1793年5月にスペインと正式に同盟を結 んだ。ルヴェルテュールも6月初旬に同様の行動に出たと思われる。ルヴェルテュールはそれ以前にラヴォー将軍に秘密裏に接触を試みていたが、ルヴェル テュールの同盟条件が受け入れられないと判断され、拒絶されていた。この時点では、共和派はまだ武器を取る奴隷たちに正式な申し出を行っておらず、スペイ ン支配下の黒人たちの条件の方がフランス支配下のそれよりも良いように見えた。[47] 6月20日の市民委員による急進的な宣言(完全な解放ではなく、戦うことを承諾した男性奴隷に自由を与えるというもの)に対して、ルヴェルテュールは「黒 人たちは王の下で仕えたいと望んでおり、スペイン王は彼らに保護を約束した」と述べた。[48] 1793年8月29日、彼はサン・ドマングの黒人住民に向けて、有名なカン・チュレルの宣言を行った。 同胞の皆さん、私はトウサン・ルーヴェルチュールである。私の名は、おそらく皆さんにも知れ渡っていることだろう。私は復讐を誓った。私は、サン・ドマン グに自由と平等が君臨することを望んでいる。私はそれを実現するために働いている。同胞の皆さん、私たちと団結し、同じ大義のために共に戦おうではない か。 同じ日、苦境に立たされたフランス人総督レジェ=フェリシテ・ソンソナックスは、フランス領サン・ドマングのすべての奴隷の解放を宣言し、黒人兵士たちを 味方につけようとした。[50] 当初は失敗したが、おそらくそれは、ルヴェルチュールと他の指導者たちが、ソンソナックスが権限を越えていることを知っていたからである。[51] しかし、1794年2月4日、フランス革命政府は奴隷制度の廃止を宣言した。数ヶ月間、ルヴェルチュールはフランス軍の将軍エティエンヌ・メイノー・ド・ ビゼフラン・ド・ラヴォーと外交上の接触を持っていた。この間、他の反乱軍指導者たちとの競争が激化し、スペインは、広大で戦略的に重要な地域をほぼ独力 で支配するルヴェルチュールを快く思わなくなっていた。 ルヴェルチュールの支援部隊は大きな成功を収め、彼の軍隊は1793年12月にゴナイーヴの港町を占領したことに加え、西のアルティボニット川の北側でス ペイン軍が獲得した戦利品の半分を占めた。[54] しかし、ルヴェルチュールとスペインの上層部との間に緊張が生じた。彼と良好な関係にあった上官マティアス・デ・アルモナは、フアン・デ・レオナールに交 代させられたが、レオナールは黒人補助兵たちから嫌われていた。レオナールは、1794年3月にビヤスーとの確執のさなか、ビヤスーがルヴェルテュの部下 たちの物資を盗み、彼らの家族を奴隷として売っていたにもかかわらず、ルヴェルテュを支援しなかった。ジャン=フランソワやビサウとは異なり、ルヴェル テュールはスペイン人たちに奴隷の女性や子供たちを捕らえて売り渡すことを拒否した。この確執により、スペイン人たちの心の中で、黒人将軍3人組の中でル ヴェルテュールが劣勢であることが強調された。これは、さらなる昇進を目指す野望に対する歯止めとなった。 1794年4月29日、ゴナイーブのスペイン軍駐屯地は突如、「フランス王」の名のもとに戦う黒人軍勢に襲撃され、駐屯地に降伏を要求した。およそ150 人の男たちが殺され、多くの住民が逃亡を余儀なくされた。周辺の白人の守備兵は殺害され、この地域に派遣されたスペインのパトロール隊は戻ってくることは なかった。[56] ルヴェルチュールは、この攻撃の背後にいたと疑われているが、現場にはいなかった。彼は5月5日にスペイン人に対して無実を訴える手紙を書き、ゴナイーブ 駐屯地のスペイン人司令官が、反乱軍の最後通牒には彼の署名がなかったことを指摘した。ルヴェルチュールがこの襲撃の責任を認めるのは、フランス軍の旗の 下で戦っていた5月18日のことだった。 ゴナイブでの出来事により、レオナルトはルヴェルチュールに対してますます疑いを抱くようになった。4月23日に彼が野営地で会ったとき、黒人将軍はいつ もの25人ではなく、武装した騎兵150人を従えて現れた。レオナルトは、彼がいつもの謙虚さや従順さを欠いていると感じ、4月29日に夕食への招待を受 け入れた後、ルヴェルチュールは姿を見せなかった。ゴナイーブ襲撃の際、彼をベッドに拘束した足の故障は偽装されたものと考えられ、ルレオナルトは彼が裏 切ったのではないかと疑った。[58] ルレオナルトは黒人指揮官に対して依然として不信感を抱いており、5月初旬にルヴェルテールがドンドンへの攻撃を指揮している間、ルレオナルトは彼の妻と 子供たちをかくまった。この行為は、後にルレオナルトがルヴェルテールがスペインに反旗を翻す決意をしたことを確信させるものとなった。[59] |

Alliance with the French: 1794–1796 Louverture surveying his troops The timing of and motivation behind Louverture's volte-face against Spain remains debated among historians. C. L. R. James claimed that upon learning of the emancipation decree in May 1794, Louverture decided to join the French in June.[60] It is argued by Beaubrun Ardouin that Toussaint was indifferent toward black freedom, concerned primarily for his own safety and resentful over his treatment by the Spanish – leading him to officially join the French on 4 May 1794 when he raised the republican flag over Gonaïves.[61] Thomas Ott sees Louverture as "both a power-seeker and sincere abolitionist" who was working with Laveaux since January 1794 and switched sides on 6 May.[62] Louverture claimed to have switched sides after emancipation was proclaimed and the commissioners Sonthonax and Polverel had returned to France in June 1794. However, a letter from Toussaint to General Laveaux confirms that he was already fighting officially on the behalf of the French by 18 May 1794.[63] In the first weeks, Louverture eradicated all Spanish supporters from the Cordon de l'Ouest, which he had held on their behalf.[64] He faced attack from multiple sides. His former colleagues in the slave rebellion were now fighting against him for the Spanish. As a French commander, he was faced with British troops who had landed on Saint-Domingue in September, as the British hoped to take advantage of the ongoing instability to capture the prosperous island.[65] Henry Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville, who was Secretary of State for War for British prime minister William Pitt the Younger, instructed Sir Adam Williamson, the lieutenant-governor of Jamaica, to sign an agreement with representatives of the French colonists that promised to restore the ancien regime, slavery and discrimination against mixed-race colonists, a move that drew criticism from abolitionists William Wilberforce and Thomas Clarkson.[66][67] On the other hand, Louverture was able to pool his 4,000 men with Laveaux's troops in joint actions.[68] By now his officers included men who were to remain important throughout the revolution: his brother Paul, his nephew Moïse Hyacinthe, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, and Henri Christophe.[69] Before long, Louverture had put an end to the Spanish threat to French Saint-Domingue. In any case, the Treaty of Basel of July 1795 marked a formal end to hostilities between the two countries. Black leaders Jean-François and Biassou continued to fight against Louverture until November, when they left for Spain and Florida, respectively. At that point, most of their men joined Louverture's forces.[70] Louverture also made inroads against the British presence, but was unable to oust them from Saint-Marc. He contained them by resorting to guerilla tactics.[71] Throughout 1795 and 1796, Louverture was also concerned with re-establishing agriculture and exports, and keeping the peace in areas under his control. In speeches and policy he revealed his belief that the long-term freedom of the people of Saint-Domingue depended on the economic viability of the colony.[72] He was held in general respect, and resorted to a mixture of diplomacy and force to return the field hands to the plantations as emancipated and paid workers.[73] Workers regularly staged small rebellions, protesting poor working conditions, their lack of real freedom, or their fear of a return to slavery. They wanted to establish their own small holdings and work for themselves, rather than on plantations.[74] Another of Louverture's concerns was to manage potential rivals for power within the French part of the colony. The most serious of these was the mulatto commander Jean-Louis Villatte, based in Cap-Français. Louverture and Villate had competed over the command of some sections of troops and territory since 1794. Villatte was thought to be somewhat racist toward black soldiers such as Louverture and planned to ally with André Rigaud, a free man of color, after overthrowing French General Étienne Laveaux.[75] In 1796 Villate drummed up popular support by accusing the French authorities of plotting a return to slavery. On 20 March, he succeeded in capturing the French Governor Laveaux, and appointed himself Governor. Louverture's troops soon arrived at Cap-Français to rescue the captured governor and to drive Villatte out of town. Louverture was noted for opening the warehouses to the public, proving that they were empty of the chains that residents feared had been imported to prepare for a return to slavery. He was promoted to commander of the West Province two months later, and in 1797 was appointed as Saint-Domingue's top-ranking officer.[76] Laveaux proclaimed Louverture as Lieutenant Governor, announcing at the same time that he would do nothing without his approval, to which Louverture replied: "After God, Laveaux."[77] |

フランスとの同盟:1794年~1796年 ルヴェルチュールが兵士たちを視察 ルヴェルチュールがスペインに対して急転回した時期とその動機については、歴史家の間で議論が続いている。C. L. C. L. R. ジェームズは、1794年5月の奴隷解放令の発表を受けて、ルヴェルチュールは6月にフランス側につくことを決めたと主張している。[60] ボーブラン・アルドゥアンは、トゥーサンは黒人の自由には関心がなく、自身の安全を第一に考え、スペイン人による仕打ちに憤っていたため、1794年5月 4日にゴナイーブで共和制の旗を掲げたときにフランス側に正式に合流したと主張している。 [61] トーマス・オットは、ルヴェルチュールを「権力志向であり、かつ真摯な奴隷解放論者」と見なし、1794年1月からラヴォーと協力していたが、5月6日に 寝返ったと見ている。[62] ルヴェルテールは、解放が宣言され、1794年6月に特使のソンソナックスとポルヴェレルがフランスに戻った後に寝返ったと主張した。しかし、トゥーサン からラヴォー将軍宛ての手紙には、1794年5月18日までにすでに公式にフランス側の戦いに参加していたことが確認されている。 最初の数週間で、ルヴェルチュールはスペインの支持者たちを、彼らのために確保していたコルドン・ド・ロエストから一掃した。[64] 彼は多方面からの攻撃に直面した。奴隷反乱の元仲間たちは今ではスペインのために彼と戦っていた。フランス軍司令官として、彼は9月にサン・ドマング島に 上陸したイギリス軍と対峙した。イギリスは、この不安定な状況を好機と捉え、繁栄するこの島を占領しようとしていた。 [65] ヘンリー・ダンダス初代メルヴィル子爵は、イギリス首相ウィリアム・ピット・ザ・ヤンガーの国務大臣(国防大臣)であり、ジャマイカ副総督のアダム・ウィ リアムソン卿に、旧体制、奴隷制、混血植民民に対する差別を復活させることを約束するフランス人入植者の代表者との協定に署名するよう指示した。この動き は、奴隷廃止論者のウィリアム・ウィルバーフォースとトーマス・クラークソンから批判を招いた。[66][67] 一方、ルヴェルチュールは4,000人の兵士をラヴォーの軍と統合し、共同行動を取ることができた。[68] その頃には、彼の部下の中には、革命を通じて重要な役割を果たすことになる人物がいた。すなわち、彼の兄弟ポール、甥のモイーズ・ハイアンス、ジャン= ジャック・デサリン、アンリ・クリストフである。[69] 間もなく、ルヴェルチュールはスペインによるフランス領サン・ドマングへの脅威を排除した。いずれにせよ、1795年7月のバーゼル条約によって、両国間 の戦闘は正式に終結した。黒人指導者ジャン=フランソワとビアスーは、11月までルヴェルチュールと戦い続けたが、その後、それぞれスペインとフロリダへ と去った。この時点で、彼らのほとんどがルヴェルチュールの軍に加わった。[70] ルヴェルチュールはイギリス軍に対しても進撃したが、サン=マルクから追い出すことはできなかった。彼はゲリラ戦術を用いてイギリス軍を封じ込めた。 [71] 1795年から1796年にかけて、ルヴェルチュールは農業と輸出の再建、および支配地域における治安維持にも力を注いだ。演説や政策において、彼はサ ン・ドマングの人々の長期的な自由は植民地の経済的存続にかかっているという信念を明らかにした。 彼は一般的に尊敬を集めており、解放された賃金労働者として農場に戻すために、外交と武力の混合手段に訴えた。[73] 労働者は劣悪な労働条件や、自由がほとんどないこと、奴隷制への回帰への恐怖を理由に、定期的に小規模な反乱を起こした。彼らは農場ではなく、自分たちの 小規模な農場を所有し、自分たちで働きたいと考えていた。[74] ルヴェルチュールが懸念していたことのひとつに、植民地内のフランス領内で権力を争う可能性のあるライバルたちを管理することがあった。 その中でも最も深刻な問題は、カップ・フランセを拠点とする混血の司令官ジャン=ルイ・ヴィアテであった。ルヴェルチュールとヴィラテは、1794年以 来、いくつかの部隊と領土の指揮権を巡って争っていた。ヴィラテはルヴェルチュールのような黒人兵士に対して人種差別的な傾向があり、フランス人将軍エ ティエンヌ・ラヴォーを打倒した後、自由身分の混血であるアンドレ・リゴーと手を組むつもりであったと考えられている。[75] 1796年、ヴィラテはフランス当局が奴隷制への回帰を企てていると非難し、民衆の支持を集めた。 3月20日、ヴィヤテはフランス総督ラヴォーを捕らえることに成功し、自らを総督に任命した。 ルヴェルチュールの軍隊はすぐにカップ・フランセに到着し、捕らえられた総督を救出するとともに、ヴィヤテを町から追い出した。 ルヴェルチュールは、住民が奴隷制への回帰に備えて輸入されたのではないかと恐れていた鎖が倉庫にないことを証明するために、倉庫を一般公開したことで知 られている。彼はその2ヶ月後に西州の司令官に昇進し、1797年にはサン・ドマングの最高位の将校に任命された。[76] ラヴォーはルヴェルトゥールを副知事と宣言し、同時に、ルヴェルトゥールは「神に次いで、ラヴォー」と答えた。[77] |

| Third Commission: 1796–1797 A few weeks after Louverture's triumph over the Villate insurrection, France's representatives of the third commission arrived in Saint-Domingue. Among them was Sonthonax, the commissioner who had previously declared abolition of slavery on the same day as Louverture's proclamation of Camp Turel.[78] At first the relationship between the two men was positive. Sonthonax promoted Louverture to general and arranged for his sons, Placide and Isaac, who were eleven and fourteen respectively to attend a school in mainland France for the children of colonial officials .[79] This was done to provide them with a formal education in the French language and culture, one that Louverture highly desired for his children, but to also use them as political hostages against Louverture should he act against the will of the central French authority in Paris. In spite of this Placide and Isaac ran away enough times from the school that they were moved to the Collège de la Marche, a division of the old University of Paris. Here in Paris they would regularly dine with members of the French nobility such as Joséphine de Beauharnais, who would go on to become Empress of France as the wife of Napoleon Bonaparte. In September 1796, elections were held to choose colonial representatives for the French national assembly. Louverture's letters show that he encouraged Laveaux to stand, and historians have speculated as to whether he was seeking to place a firm supporter in France or to remove a rival in power.[80] Sonthonax was also elected, either at Louverture's instigation or on his own initiative. While Laveaux left Saint-Domingue in October, Sonthonax remained.[81][82] Sonthonax, a fervent revolutionary and fierce supporter of racial equality, soon rivaled Louverture in popularity. Although their goals were similar, they had several points of conflict.[83][84] While Louverture was quoted as saying that "I am black, but I have the soul of a white man" in reference to his self-identification as a Frenchman, loyalty to the French nation, and Catholicism. Sonthonax, who had married a free black woman by this time, countered with "I am white, but I have the soul of a black man" in reference to his strong abolitionist and secular republican sentiments.[11] They strongly disagreed about accepting the return of the white planters who had fled Saint-Domingue at the start of the revolution. To the ideologically motivated Sonthonax, they were potential counter-revolutionaries who had fled the liberating force of the French Revolution and were forbidden from returning to the colony under pain of death. Louverture on the other hand saw them as wealth generators who could restore the commercial viability of the colony. The planters political and familial connections to Metropolitan France could also foster better diplomatic and economic ties to Europe.[85][11] In summer 1797, Louverture authorized the return of Bayon de Libertat, the former overseer of the Bréda plantation, with whom he had shared a close relationship ever since he was enslaved. Sonthonax wrote to Louverture threatening him with prosecution and ordering him to get de Libertat off the island. Louverture went over his head and wrote to the French Directoire directly for permission for de Libertat to stay.[86] Only a few weeks later, he began arranging for Sonthonax's return to France that summer.[76] Louverture had several reasons to want to get rid of Sonthonax; officially he said that Sonthonax had tried to involve him in a plot to make Saint-Domingue independent, starting with a massacre of the whites of the island.[87] The accusation played on Sonthonax's political radicalism and known hatred of the aristocratic grands blancs, but historians have varied as to how credible they consider it.[88][89] On reaching France, Sonthonax countered by accusing Louverture of royalist, counter-revolutionary, and pro-independence tendencies.[90] Louverture knew that he had asserted his authority to such an extent that the French government might well suspect him of seeking independence.[91] At the same time, the French Directoire government was considerably less revolutionary than it had been. Suspicions began to brew that it might reconsider the abolition of slavery.[92] In November 1797, Louverture wrote again to the Directoire, assuring them of his loyalty, but reminding them firmly that abolition must be maintained.[93] |

第3委員会:1796年~1797年 ルヴェルチュールがヴィラテの反乱を鎮圧してから数週間後、第3委員会のフランス代表団がサン・ドマングに到着した。その中には、以前にルヴェルチュール がトゥーレル砦で宣言したのと同じ日に奴隷制度の廃止を宣言したソンソナックス委員がいた。[78] 当初、両者の関係は良好だった。ソントノラックスはルヴェルチュールを将軍に昇進させ、当時それぞれ11歳と14歳だった息子たち、プラシドとイサックを 植民地役人の子供たちが通うフランス本土の学校へ入学させた。[79] これは、ルヴェルチュールが子供たちに強く望んでいたフランス語とフランス文化の正式な教育を与えるためであったが、同時に、ルヴェルチュールがパリの中 央フランス当局の意向に反する行動を取った場合に、彼らを政治的な人質として利用するためでもあった。このような事情があったにもかかわらず、プラシドと アイザックは学校から何度も逃げ出し、パリ旧大学の付属機関であるコレージュ・ド・ラ・マルシュに移された。パリでは、後にナポレオン・ボナパルトの妻と してフランス皇后となるジョゼフィーヌ・ド・ボアルネなど、フランス貴族のメンバーと定期的に食事を共にしていた。 1796年9月、植民地の代表者を選出する選挙が実施され、国民議会に送る代表者を選出した。 ルーヴェルチュールの書簡によると、彼はラヴォーに立候補するよう勧めたことが分かっている。 歴史家たちは、彼がフランスに強力な支援者を置くことを目指していたのか、それとも権力におけるライバルを排除しようとしていたのかについて推測してい る。[80] ソンソナックスもまた、ルーヴェルチュールの働きかけによるものか、あるいは彼自身の主導によるものかは不明だが、選出された。ラヴォーが10月にサン・ ドマングを去った一方で、ソンソナックスは残った。[81][82] 熱烈な革命家であり、人種平等を強く支持するソンソナックスは、すぐにルヴェルチュールと肩を並べるほどの人気者となった。彼らの目標は似ていたが、いく つかの点で対立していた。[83][84] ルヴェルチュールは「私は黒人だが、白人の魂を持っている」と述べたと伝えられている。これは、彼がフランス人としての自己認識、フランス国民への忠誠、 カトリック信仰について言及したものである。この時点で自由の身となった黒人女性と結婚していたソンソナックスは、奴隷制度廃止論者であり世俗共和主義者 であったことから、「私は白人だが、黒人の魂を持っている」と反論した。[11] 彼らは、革命勃発時にサン・ドマングから逃亡した白人のプランテーション農場主たちの帰還を認めることについて強く意見が対立した。思想的に動機付けられ たソンソナックスにとって、彼らはフランス革命の解放勢力から逃亡した潜在的な反革命家であり、死を覚悟してでも植民地への帰還を禁じられるべきであっ た。一方、ルヴェルチュールは彼らを植民地の商業的価値を回復させる富の創出者とみなしていた。プランテーション経営者たちの本国フランスとの政治的およ び家族的なつながりは、ヨーロッパとのより良い外交および経済関係を促進することも可能であった。 1797年夏、ルヴェルチュールは奴隷時代から親交のあったブレッド農園の元監督官バイヨン・ド・リベルタの帰国を許可した。ソントノックスはルヴェル チュールに告訴すると脅し、リベルタを島から出すよう命じた。ルヴェルチュールは、その命令を無視して、直接フランス政府にデ・リベルタの滞在許可を求め る手紙を書いた。[86] それからわずか数週間後、彼はその夏にソントノラックスをフランスに帰国させる手配を始めた。 [76] ルヴェルテールがソントノーを追い出したいと考えた理由はいくつかあった。公式には、ソントノーは彼をサン・ドマング独立の陰謀に関与させようとし、その ためにまず島の白人の虐殺を企てた、と彼は述べた。[87] この告発はソントノーの政治的急進主義と、貴族階級であるグラン・ブランに対する彼の知られた憎悪を煽ったが、歴史家たちはこの告発の信憑性をどう考える かについては意見が分かれている。[88][89] フランスに到着したソンソナックスは、ルヴェルチュールが王党派であり、反革命派であり、独立派であると非難した。[90] ルヴェルチュールは、自分がフランス政府に独立を求めているのではないかと疑われるほど、自分の権威を主張していることを知っていた。[91] 同時に、フランス政府はそれまでよりも革命色が薄れていた。奴隷制度廃止の見直しを検討するのではないかという疑念が持ち上がった。[92] 1797年11月、ルヴェルテュールは再び執筆し、ディレクトワールに忠誠を誓うことを確約したが、同時に奴隷制度廃止は維持されなければならないと強く 主張した。[93] |

Treaties with Britain and the United States: 1798 British commander Thomas Maitland meeting with Louverture to negotiate For months, Louverture was in sole command of French Saint-Domingue, except for a semi-autonomous state in the south, where general André Rigaud had rejected the authority of the third commission.[94] Both generals continued harassing the British, whose position on Saint-Domingue was increasingly weak.[95] Louverture was negotiating their withdrawal when France's latest commissioner, Gabriel Hédouville, arrived in March 1798, with orders to undermine his authority.[96] Nearing the end of the revolution Louverture grew substantially wealthy; owning numerous slaves at Ennery, obtaining thirty-one properties, and earning almost 300,000 colonial livre per year from these properties.[97] As leader of the revolution, this accumulated wealth made Louverture the richest person on Saint-Domingue. Louverture's actions evoked a collective sense of worry among the European powers and the US, who feared that the success of the revolution would inspire slave revolts across the Caribbean, the South American colonies, and the southern United States.[98] On 30 April 1798, Louverture signed a treaty with British Army officer Thomas Maitland, exchanging the withdrawal of British troops from western Saint-Domingue in return for a general amnesty for the French counter-revolutionaries in those areas. In May, Port-au-Prince was returned to French rule in an atmosphere of order and celebration.[99] In July, Louverture and Rigaud met commissioner Hédouville together. Hoping to create a rivalry that would diminish Louverture's power, Hédouville displayed a strong preference for Rigaud, and an aversion to Louverture.[100] However, General Maitland was also playing on French rivalries and evaded Hédouville's authority to deal with Louverture directly.[101] In August, Louverture and Maitland signed treaties for the evacuation of all remaining British troops in Saint-Dominigue. On 31 August, they signed a secret treaty that lifted the British Royal Navy's blockade on Saint-Domingue in exchange for a promise that Louverture would not attempt to cause unrest in the British West Indies.[102] As Louverture's relationship with Hédouville reached the breaking point, an uprising began among the troops of his adopted nephew, Hyacinthe Moïse. Attempts by Hédouville to manage the situation made matters worse and Louverture declined to help him. As the rebellion grew to a full-scale insurrection, Hédouville prepared to leave the island, while Louverture and Dessalines threatened to arrest him as a troublemaker.[103] Hédouville sailed for France in October 1798, nominally transferring his authority to Rigaud. Louverture decided instead to work with Phillipe Roume, a member of the third commission who had been posted to the Spanish parts of the colony.[104] Although Louverture continued to protest his loyalty to the French government, he had expelled a second government representative from the territory and was about to negotiate another autonomous agreement with one of France's enemies.[105] The United States had suspended trade with France in 1798 because of increasing tensions between the American and French governments over the issue of privateering. The two countries entered into the so-called "Quasi"-War, but trade between Saint-Domingue and the United States was desirable to both Louverture and the United States. With Hédouville gone, Louverture sent diplomat Joseph Bunel, a grand blanc former planter married to a Black Haitian wife, to negotiate with the administration of John Adams. Adams as a New Englander who was openly hostile to slavery was much more sympathetic to the Haitian cause than the Washington administration before and Jefferson after, both of whom came from Southern slave-owning planter backgrounds. The terms of the treaty were similar to those already established with the British, but Louverture continually rebuffed suggestions from either power that he should declare independence.[106] As long as France maintained the abolition of slavery, he appeared to be content to have the colony remain French, at least in name.[107] |

イギリスおよびアメリカとの条約:1798年 イギリス軍司令官トーマス・メイタンがルヴェルチュールと会談し、交渉を行う 数ヶ月間、ルヴェルチュールはフランス領サン=ドマングの唯一の司令官であったが、南部の半自治地域では、アンドレ・リゴー将軍が第3委員会の権限を拒否 していた。[94] 両将軍はイギリスを悩ませ続け、サン=ドマングにおけるイギリスの立場はますます弱体化した。 [95] ルヴェルチュールは彼らの撤退について交渉中であったが、1798年3月、フランスから派遣された最新の総督ガブリエル・エドゥヴィルが、彼の権威を弱体 化させる命令を携えて到着した。[96] 革命の終わりが近づくにつれ、ルヴェルチュールは大幅に裕福になった。エニーに多数の奴隷を所有し、31の不動産を手に入れ、それらの不動産から年間30 万リーヴル近くの収益を得ていた。 [97] 革命の指導者として、この蓄積された富により、ルヴェルチュールはサン・ドマング島で最も裕福な人格となった。ルヴェルチュールの行動は、ヨーロッパ列強 およびアメリカ合衆国に不安を呼び起こした。革命の成功がカリブ海、南米の植民地、およびアメリカ南部で奴隷の反乱を誘発することを恐れたのである。 1798年4月30日、ルヴェルチュールはイギリス陸軍士官トーマス・メイランドと条約を結び、サン・ドマング西部からのイギリス軍撤退と引き換えに、そ の地域におけるフランス反革命派に対する恩赦を約束させた。5月には、秩序と祝賀ムードの中で、ポルトープランスは再びフランスの支配下に戻った。 7月、ルヴェルチュールとリゴーはヘドゥヴィル委員と会談した。ルヴェルチュールの力を削ぐためにライバル関係を作り出そうと考えたヘドゥヴィルは、リ ゴーに強い好意を示し、ルヴェルチュールに対して嫌悪感を示した。 [100] しかし、メイランド将軍もまたフランスの対立感情を利用し、ヘドゥヴィルの権限を回避して、ルヴェルトゥールと直接交渉を行った。[101] 8月、ルヴェルトゥールとメイランドは、サン・ドマングに残るすべての英国軍の撤退に関する条約に署名した。8月31日、彼らはイギリス王立海軍によるサ ン・ドマングへの封鎖を解除する代わりに、ルヴェルチュールがイギリス領西インド諸島で動乱を起こさないことを約束するという秘密条約に署名した。 ルヴェルチュールとエドゥヴィルの関係が限界に達すると、養子の甥であるハイチンテ・モイーズの軍隊の間で反乱が始まった。ヘドゥヴィルが事態の収拾を図 ろうとしたことで事態はさらに悪化し、ルヴェルチュールはヘドゥヴィルを助けることを拒否した。反乱が本格的な蜂起へと拡大する中、ヘドゥヴィルは島を去 る準備をし、一方、ルヴェルチュールとデサリンはヘドゥヴィルを反乱分子として逮捕すると脅した。[103] ヘドゥヴィルは1798年10月にフランスに向けて出帆し、名目上はリゴーに権限を委譲した。ルヴェルチュールは、代わりにスペイン領に赴任していた第3 委員会の委員フィリップ・ルーメと協力することを決めた。[104] ルヴェルチュールはフランス政府への忠誠を訴え続けたが、領土から2人目の政府代表を追放し、フランスの敵対国の一つと新たな自治協定の交渉を行おうとし ていた。[105] アメリカとフランスの間で私掠船問題をめぐり緊張が高まっていたため、アメリカは1798年にフランスとの貿易を停止していた。両国は「準戦争」と呼ばれ る状態に突入したが、サン・ドマングとアメリカ間の貿易は、ルヴェルチュールとアメリカ双方にとって望ましいものであった。エドゥヴィルが去った後、ル ヴェルチュールは、黒人のハイチ人女性と結婚した元プランテーション経営者の外交官ジョセフ・ブネルを、ジョン・アダムズ政権との交渉に派遣した。奴隷制 に公然と敵対するニューイングランド人であったアダムズは、南部の奴隷所有プランテーションの出身であるワシントン政権以前、そしてジェファーソン政権以 後よりも、ハイチの主張に共感していた。条約の条件はすでにイギリスと締結されていたものと同様であったが、ルヴェルチュールはどちらの国からも独立を宣 言するよう促す提案を断り続けた。[106] フランスが奴隷制度の廃止を維持する限り、彼は植民地が少なくとも名目上はフランス領であり続けることに満足しているようであった。[107] |

| Expansion of territory: 1799–1801 Further information: War of the South  Louverture accused André Rigaud (pictured) of trying to assassinate him. In 1799, the tensions between Louverture and Rigaud came to a head. Louverture accused Rigaud of trying to assassinate him to gain power over Saint-Domingue. Rigaud claimed Louverture was conspiring with the British to restore slavery.[108] The conflict was complicated by racial overtones that escalated tensions between full blacks and mulattoes.[109][110] Louverture had other political reasons for eliminating Rigaud; only by controlling every port could he hope to prevent a landing of French troops if necessary.[111] After Rigaud sent troops to seize the border towns of Petit-Goave and Grand-Goave in June 1799, Louverture persuaded Roume to declare Rigaud a traitor and attacked the southern state.[112] The resulting civil war, known as the War of the South, lasted more than a year, with the defeated Rigaud fleeing to Guadeloupe, then France, in August 1800.[113] Louverture delegated most of the campaign to his lieutenant, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, who became infamous, during and after the war, for massacring mulatto captives and civilians.[114] The number of deaths is contested: the contemporary French general François Joseph Pamphile de Lacroix suggested 10,000 deaths, while the 20th-century Trinidadian historian C. L. R. James claimed there were only a few hundred deaths.[26][115] In November 1799, during the civil war, Napoleon Bonaparte gained power in France and passed a new constitution declaring that French colonies would be subject to special laws.[116] Although many Black people in the colonies suspected this meant the re-introduction of slavery, Napoleon began by confirming Louverture's position and promising to maintain existing anti-slavery laws.[117] But he also forbade Louverture to invade Spanish Santo Domingo, an action that would put Louverture in a powerful defensive position.[118] Louverture was determined to proceed anyway and coerced Roume into supplying the necessary permission.[119] At the same time, in order to improve his political relationships with other European powers, Louverture tooks steps to stabilize the political landscape of the Caribbean, which included limiting his anti-slavery sentiments in the interest of realpolitik.[11] When Isaac Yeshurun Sasportas, a Sephardic Jewish merchant from Saint-Dominigue, attempted to travel to the British colony of Jamaica to foment a slave rebellion there, Louverture initially supported him; however, as he decided he needed Britain's support, Louverture subsequently leaked Sasportas' intentions to the British authorities in Jamaica, who arrested and hung him in Kingston on December 23, 1799.[11][120][121] In January 1801, Louverture and his nephew, General Hyacinthe Moïse invaded the Spanish territory, taking possession of it from the governor, Don Garcia, with few difficulties. The area had been less developed and populated than the French section. Louverture brought it under French law, abolishing slavery and embarking on a program of modernization. He now controlled the entire island.[122] |

領土の拡大:1799年~1801年 詳細情報:サウス戦争  ルヴェルチュールはアンドレ・リゴー(写真)が自分を暗殺しようとしていると非難した。 1799年、ルヴェルチュールとリゴーの間の緊張は頂点に達した。ルヴェルチュールは、リゴーがサン=ドマングの権力を握るために自分を暗殺しようとして いると非難した。リゴーは、ルヴェルトゥールがイギリスと共謀して奴隷制を復活させようとしていると主張した。[108] この対立は、純粋な黒人と混血の人々との間の緊張をエスカレートさせた人種的な背景によって複雑化していた。[109][110] ルヴェルトゥールがリゴーを排除しようとしたのには、政治的な理由もあった。すべての港を支配することによってのみ、必要であればフランス軍の上陸を阻止 できると期待していたのだ。[111] 1799年6月にリゴーが軍を派遣して国境の町プチ・ゴアヴとグラン・ゴアヴを占領した後、ルヴェルチュールはルメを説得してリゴーを反逆者と宣言させ、 南部の州を攻撃した。[112] その結果起きた内戦は南部戦争として知られ、1年以上続き、敗れたリゴーは1800年8月にグアドループ島、そしてフランスへと逃亡した。 [113] ルヴェルチュールは、ほとんどの戦役を副官のジャン=ジャック・デサリンに委任したが、デサリンは戦争中および戦争後に、混血の捕虜や民間人を虐殺したこ とで悪名高い人物となった。[114] 死亡者数については異論があり、同時代のフランス人将軍フランソワ=ジョゼフ・パンフィル・ド・ラクロワは1万人と推定したが、20世紀のトリニダード・ トバゴ人歴史家C.L.R.ジェームズは C. L. R. ジェームズは、死者は数百人だったと主張している。 1799年11月、内戦中、ナポレオン・ボナパルトがフランスで権力を握り、フランス植民地は特別な法律に従うべきであると宣言する新憲法を制定した。植 民地に住む多くの黒人たちは、これは奴隷制の再導入を意味するのではないかと疑ったが、ナポレオンはまず、ルヴェルチュールの立場を確認し、現行の反奴隷 制法を維持することを約束した。 [117] しかし、ナポレオンはルヴェルテュールがスペイン領サント・ドミンゴを侵略することを禁じた。これはルヴェルテュールを強力な防衛的立場に置く行為であっ た。[118] ルヴェルテュールはそれでも進める決意を固め、ルーメに強制して必要な許可を得た。[119] 同時に、他のヨーロッパ列強との政治的な関係を改善するために、ルーヴェルチュールはカリブ海地域の政治情勢を安定させるための措置を講じた。その中に は、現実主義の利益のために奴隷制度廃止の主張を制限することも含まれていた。 [11] サン・ドマング出身のセファルディ系ユダヤ人商人アイザック・イェシュルーン・サスポータスが、ジャマイカのイギリス植民地で奴隷の反乱を煽動しようとし た際、ルヴェルテールは当初彼を支援した。しかし、イギリスの支援が必要だと判断したルヴェルテールは、その後サスポータスの意図をジャマイカのイギリス 当局にリークした。サスポータスは1799年12月23日にキングストンで逮捕され、絞首刑にされた。 [11][120][121] 1801年1月、ルヴェルチュールと甥のハイアサント・モイーズ将軍はスペイン領に侵攻し、総督のドン・ガルシアから領土を奪った。この地域はフランス領 よりも開発が進んでおらず、人口も少なかった。ルヴェルチュールはフランス法を適用し、奴隷制度を廃止して近代化計画に着手した。これにより、彼は島全体 を支配下に置いた。[122] |

Constitution of 1801 An engraving of Louverture Napoleon had informed the inhabitants of Saint-Domingue that France would draw up a new constitution for its colonies, in which they would be subjected to special laws.[123] Despite his protestations to the contrary, the former slaves feared that he might restore slavery. In March 1801, Louverture appointed a constitutional assembly, composed chiefly of white planters, to draft a constitution for Saint-Domingue. He promulgated the Constitution on 7 July 1801, officially establishing his authority over the entire island of Hispaniola. It made him governor-general for life with near absolute powers and the possibility of choosing his successor. However, Louverture had not explicitly declared Saint-Domingue's independence, acknowledging in Article 1 that it was a single colony of the French Empire.[124] Article 3 of the constitution states: "There cannot exist slaves [in Saint-Domingue], servitude is therein forever abolished. All men are born, live and die free and French."[125] The constitution guaranteed equal opportunity and equal treatment under the law for all races, but confirmed Louverture's policies of forced labor and the importation of workers through the slave trade.[126] Identifying as a loyal Christian Frenchman, Louverture was not willing to compromise Catholicism for Vodou, the dominant faith among former slaves. Article 6 states that "the Catholic, Apostolic, Roman faith shall be the only publicly professed faith."[127] This strong preference for Catholicism went hand in hand with Louverture's self-identification of being a Frenchman, and his movement away from associating with Vodou and its origins in the practices of the plantation slaves from Africa.[128] Louverture charged Colonel Charles Humbert Marie Vincent, who personally opposed the drafted constitution, with the task of delivering it to Napoleon. Several aspects of the constitution were damaging to France: the absence of provision for French government officials, the lack of trade advantages, and Louverture's breach of protocol in publishing the constitution before submitting it to the French government. Despite his disapproval, Vincent attempted to submit the constitution to Napoleon but was briefly exiled to the Mediterranean island of Elba for his pains.[129][note 3] Louverture identified as a Frenchman and strove to convince Bonaparte of his loyalty. He wrote to Napoleon, but received no reply.[131] Napoleon eventually decided to send an expedition of 20,000 men to Saint-Domingue to restore French authority, and possibly, to restore slavery as well.[132] Given the fact that France had signed a temporary truce with Great Britain in the Treaty of Amiens, Napoleon was able to plan this operation without the risk of his ships being intercepted by the Royal Navy. |

1801年憲法 ルヴェルチュール作の版画 ナポレオンは、フランスが植民地のために新しい憲法を起草し、その中で彼らが特別な法律の対象となることを、サン・ドマングの住民に伝えていた。 [123] 彼がそうではないと抗議したにもかかわらず、元奴隷たちは、彼が奴隷制を復活させるのではないかと恐れた。1801年3月、ルヴェルチュールは、主に白人 の農場主で構成される憲法制定議会を任命し、サン・ドマングの憲法草案の作成を委ねた。そして1801年7月7日、憲法を公布し、イスパニオラ島全体に対 する自らの権限を正式に確立した。これにより、彼は終身の総督となり、ほぼ絶対的な権力を持ち、後継者を選ぶことも可能となった。しかし、ルヴェルチュー ルはサン=ドマングの独立を明確に宣言しておらず、憲法第1条では、それがフランス帝国の単一植民地であることを認めていた。[124] 憲法第3条には、「(サン=ドマングに)奴隷は存在しえない。永遠に隷属は廃止される。すべての人は生まれ、生き、死ぬまで自由であり、フランス人であ る」と定められた。[125] この憲法は、すべての人の人種を問わず、機会均等と法の下の平等を保証したが、ルヴェルチュールの強制労働と奴隷貿易による労働者の輸入政策を追認した。 [126] 忠実なキリスト教徒であるフランス人であると自認するルヴェルチュールは、元奴隷たちの間で主流の信仰であったヴードゥー教のためにカトリックを妥協する つもりはなかった。第6条では、「カトリック、使徒、ローマの信仰は唯一の公に表明される信仰である」と規定している。[127] このカトリックへの強い偏愛は、ルヴェルチュールが自らをフランス人であると認識していたことと一致しており、また、ヴードゥーやアフリカからのプラン テーション奴隷の慣習に由来するものから離れていくこととも一致していた。[128] ルヴェルテールは、起草された憲法に個人的に反対していたシャルル・ウンベルト・マリー・ヴィンセント大佐に、憲法草案をナポレオンに提出するよう命じ た。憲法にはフランスにとって不利な点がいくつかあった。フランス政府役人に関する規定がないこと、貿易上の利点がないこと、そしてルヴェルテールが憲法 をフランス政府に提出する前に公表したことである。ヴィンセントは不賛成であったものの、憲法をナポレオンに提出しようとしたが、そのために地中海のエル バ島に短期間追放された。[129][注釈 3] ルヴェルテールはフランス人であると名乗り、ボナパルトに忠誠を誓うことを説得しようとした。彼はナポレオンに手紙を書いたが、返事はなかった。 [131] ナポレオンは最終的に、フランスによる支配を回復するため、またおそらく奴隷制をも回復するために、2万人の遠征隊をサン・ドマング島に派遣することを決 めた。[132] フランスがアミアンの和約でイギリスと一時休戦を結んでいたことを考えると、ナポレオンはイギリス海軍に船団を妨害される危険なしにこの作戦を計画するこ とができた。 |

Leclerc's campaign: 1801–1802 Napoleon dispatched General Charles Emmanuel Leclerc (pictured) to seize control of the island. Napoleon's troops, under the command of his brother-in-law, General Charles Emmanuel Leclerc, were directed to seize control of the island by diplomatic means, proclaiming peaceful intentions, and keep secret his orders to deport all black officers.[133] Meanwhile, Louverture was preparing for defense and ensuring discipline. This may have contributed to a rebellion against forced labor led by his nephew and top general, Moïse, in October 1801. Because the activism was violently repressed, when the French ships arrived, not all of Saint-Domingue supported Louverture.[134] In late January 1802, while Leclerc sought permission to land at Cap-Français and Christophe held him off, the Vicomte de Rochambeau suddenly attacked Fort-Liberté, effectively quashing the diplomatic option.[135] Christophe had written to Leclerc: "you will only enter the city of Cap, after having watched it reduced to ashes. And even upon these ashes, I will fight you." Louverture's plan in case of war was to burn the coastal cities and as much of the plains as possible, retreat with his troops into the inaccessible mountains, and wait for yellow fever to decimate the French.[136] The biggest impediment to this plan proved to be difficulty in internal communications. Christophe burned Cap-Français and retreated, but Paul Louverture was tricked by a false letter into allowing the French to occupy Santo Domingo. Other officers believed Napoleon's diplomatic proclamation, while some attempted resistance instead of burning and retreating.[137] With both sides shocked by the violence of the initial fighting, Leclerc tried belatedly to revert to the diplomatic solution. Louverture's sons and their tutor had been sent from France to accompany the expedition with this end in mind and were now sent to present Napoleon's proclamation to Louverture.[138] When these talks broke down, months of inconclusive fighting followed. This ended when Christophe, ostensibly convinced that Leclerc would not re-institute slavery, switched sides in return for retaining his generalship in the French military. General Jean-Jacques Dessalines did the same shortly later. On 6 May 1802, Louverture rode into Cap-Français and negotiated an acknowledgement of Leclerc's authority in return for an amnesty for him and his remaining generals. Louverture was then forced to capitulate and placed under house arrest on his property in Ennery.[139] |

レクレールの作戦:1801年~1802年 ナポレオンは、シャルル・エマニュエル・レクレール将軍(写真)を派遣し、島の支配権を掌握した。 ナポレオンの義弟であるシャルル・エマニュエル・レクレール将軍の指揮下にあるナポレオンの軍隊は、外交手段によって島を掌握し、平和的な意図を表明し、 黒人将校全員を追放するという命令を秘密裏に遂行するよう指示されていた。[133] 一方、ルヴェルチュールは防衛の準備と規律の徹底を図っていた。これが、1801年10月に甥であり最高司令官のモイーズが主導した強制労働に対する反乱 の一因となった可能性がある。この反乱は激しく鎮圧されたため、フランス艦隊が到着した際には、サン・ドマングのすべての人々がルヴェルチュールを支持し ていたわけではなかった。[134] 1802年1月下旬、レクレールがカップ・フランセに上陸する許可を求め、クリストフがそれを阻止している間、ロシャンボー子爵が突如としてフォート・リ ベルテを攻撃し、外交手段は事実上頓挫した。[135] クリストフはレクレールに次のような手紙を書いていた。「君がカップの町に入ることができるのは、その町が灰燼に帰したあとだ。そして、その灰燼の上で も、私は君と戦うだろう」と。 戦争になった場合のルヴェルチュールの計画は、沿岸の町と平野をできるだけ多く焼き払い、部隊を率いて近づきがたい山岳地帯に撤退し、黄熱病でフランス軍 が壊滅するのを待つというものだった。[136] この計画の最大の障害は、国内の通信の難しさであった。クリストフはカップ・フランスを焼き払い撤退したが、ポール・ルヴェルチュールは偽の手紙に騙さ れ、フランス軍にサントドミンゴを占領することを認めてしまった。他の将校たちはナポレオンの外交的宣言を信じたが、中には焼き払いと撤退ではなく抵抗を 試みた者もいた。 初期の戦闘の激しさに双方が衝撃を受けたため、レクレールは遅ればせながら外交的解決に戻ろうとした。ルヴェルチュールの息子たちとその家庭教師がフラン スから派遣され、この目的のために遠征に同行していた。そして、彼らは今、ナポレオンの宣言をルヴェルチュールに伝えるために派遣された。[138] これらの話し合いが決裂すると、数か月にわたる決着のつかない戦闘が続いた。 クリストフが、表向きには、レクレールが再び奴隷制を復活させることはないと確信し、フランス軍の将軍職を維持することを条件に寝返ったことで、この戦闘 は終結した。ジャン=ジャック・デサリネ将軍もまもなく同じ行動に出た。1802年5月6日、ルヴェルチュールはカップ・フランセに入り、ルクレールと残 りの将軍たちに恩赦を与えることを条件に、ルクレールの権威を認めるよう交渉した。ルヴェルチュールは降伏を余儀なくされ、エニーの所有地で軟禁された。 [139] |

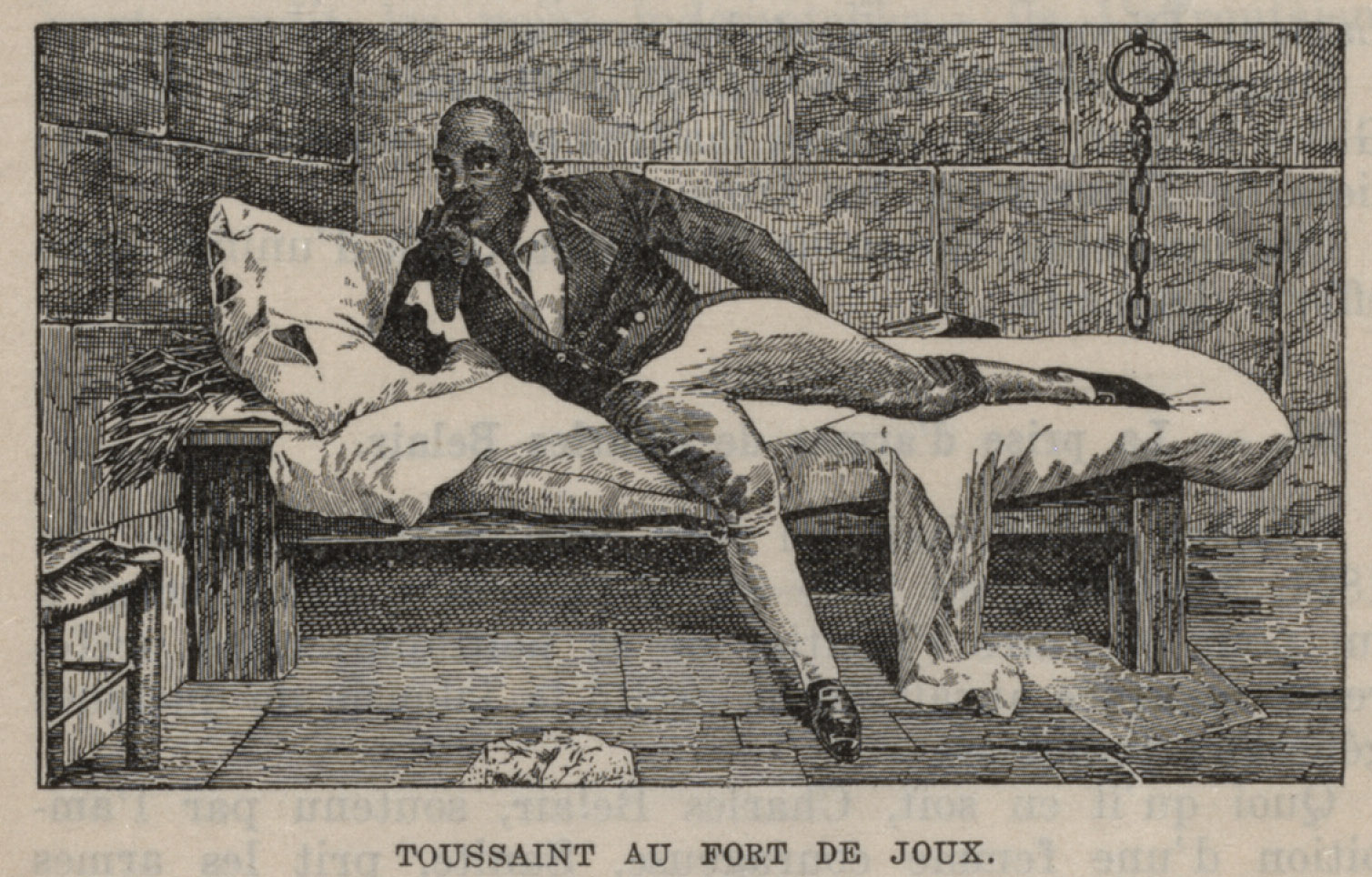

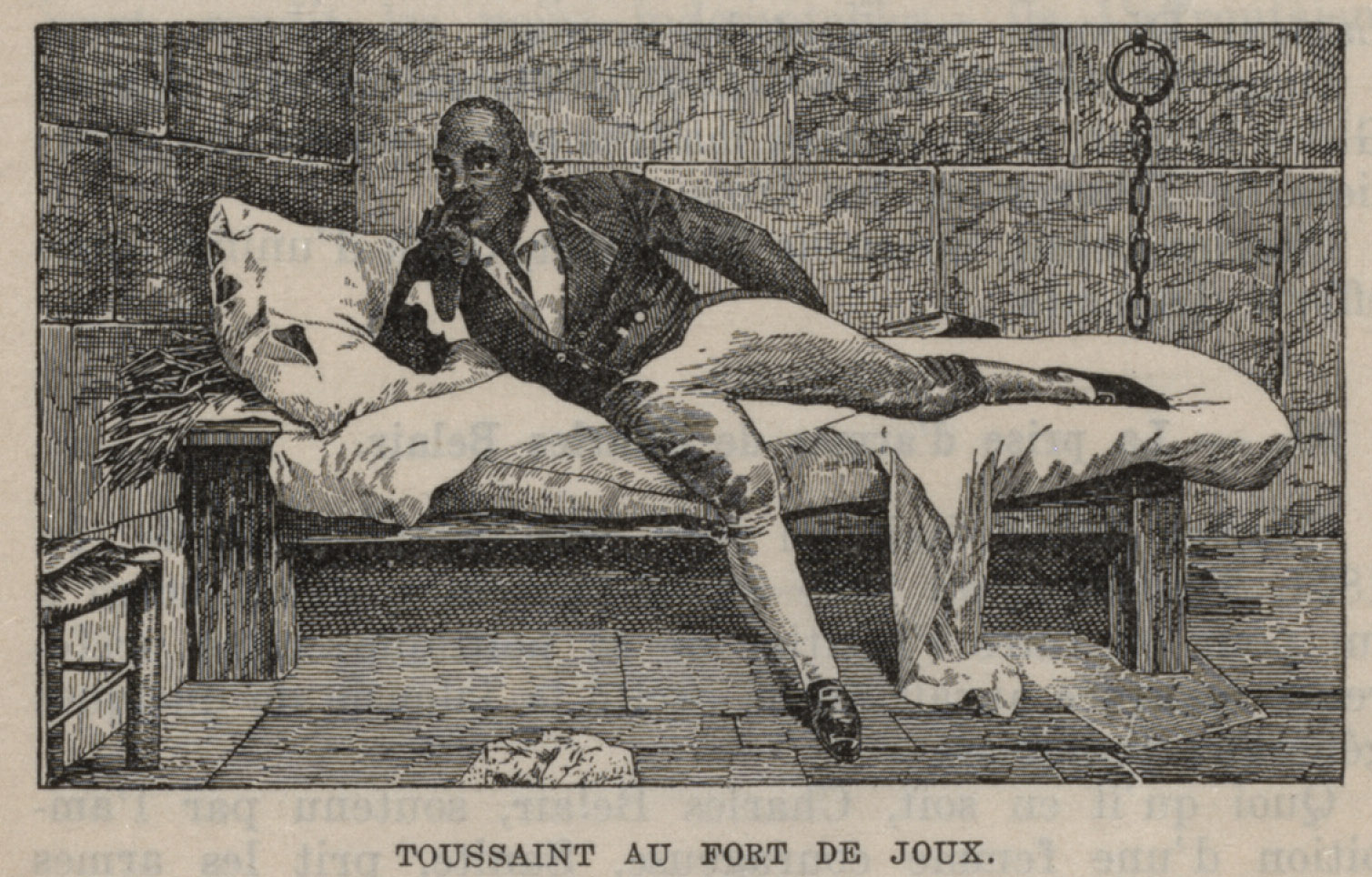

Arrest, imprisonment, and death: 1802–1803 Illustration of Louverture imprisoned at the Fort-de-Joux in France, where he died in 1803 Jean-Jacques Dessalines was at least partially responsible for Louverture's arrest, as asserted by several authors, including Louverture's son, Isaac. On 22 May 1802, after Dessalines learned that Louverture had failed to instruct a local rebel leader to lay down his arms per the recent ceasefire agreement, he immediately wrote to Leclerc to denounce Louverture's conduct as "extraordinary". For this action, Dessalines and his spouse received gifts from Jean Baptiste Brunet.[140] Leclerc originally asked Dessalines to arrest Louverture, but he declined. Jean Baptiste Brunet was ordered to do so, but accounts differ as to how he accomplished this. One version said that Brunet pretended that he planned to settle in Saint-Domingue and was asking Louverture's advice about plantation management. Louverture's memoirs, however, suggest that Brunet's troops had been provocative, leading Louverture to seek a discussion with him. Either way, Louverture had a letter, in which Brunet described himself as a "sincere friend", to take with him to France. Embarrassed about his trickery, Brunet absented himself during the arrest.[141][142] Finally on June 7, 1802, despite the promises made in exchange for his surrender, Toussaint Louverture – as well as a hundred members of his inner circle – were captured and deported to France. Brunet transported Louverture and his companions on the frigate Créole and the 74-gun Héros, claiming that he suspected the former leader of plotting another uprising. Upon boarding Créole, Toussaint Louverture warned his captors that the rebels would not repeat his mistake, saying that, "In overthrowing me you have cut down in Saint Domingue only the trunk of the tree of liberty; it will spring up again from the roots, for they are numerous and they are deep."[143]  Death of General Toussaint Louverture in the prison of Fort de Joux in France, on 7 April 1803 The ships reached France on 2 July 1802 and, on 25 August, Louverture was imprisoned at Fort-de-Joux in Doubs.[citation needed] During this time, Louverture wrote a memoir.[144] He died in prison on 7 April 1803 at the age of 59. Suggested causes of death include exhaustion, malnutrition, apoplexy, pneumonia, and possibly tuberculosis.[145][146] |

逮捕、投獄、死:1802年~1803年 フランスにあるフォール・ド・ジュの要塞に投獄され、1803年に死亡したルヴェルチュールの挿絵 ジャン=ジャック・デサリンは、ルヴェルチュールの逮捕に少なくとも部分的責任があった。これは、ルヴェルチュールの息子であるアイザックを含む複数の著 者が主張していることである。1802年5月22日、デサリンは、ルヴェルチュールが最近締結された停戦協定に従って地元の反乱軍指導者に武器を置くよう 指示しなかったことを知ると、すぐにルクレールに手紙を書き、ルヴェルチュールの行動を「異常」と非難した。この行動により、デサリンズとその配偶者は ジャン・バティスト・ブリュネから贈り物を受け取った。 レクレールは当初、デサリンズにルヴェルチュールを逮捕するよう要請したが、デサリンズはこれを断った。ジャン・バティスト・ブリュネに逮捕を命じたが、 ブリュネがどのようにしてこれを成し遂げたかについては、異なる説明がある。一説によると、ブリュネはサン・ドマングに定住するつもりであると偽り、農園 経営についてルヴェルチュールの助言を求めたという。しかし、ルヴェルチュールの回顧録によると、ブルネットの軍隊が挑発的であったため、ルヴェルチュー ルは彼と話し合いを持つことになったという。いずれにしても、ルヴェルチュールは、ブルネットが自分を「誠実な友人」と表現した手紙をフランスに持って行 くことになっていた。策略を弄したことに気恥ずかしくなったブルネットは、逮捕の場には姿を見せなかった。 1802年6月7日、ついに降伏の条件として交わされた約束にもかかわらず、トゥーサン・ルーヴェルチュールと側近の100名が捕らえられ、フランスに送 還された。ブリュネは、ルーヴェルチュールと仲間たちをフリゲート艦クレオールと74門艦ヘロス号に乗せ、前リーダーが新たな蜂起を企てているのではない かと疑っていると主張した。クレオール号に乗り込む際、トゥーサン・ルーヴェルチュールは捕虜たちに、反乱軍は自分の過ちを繰り返さないだろうと警告し、 「私を倒したところで、サン・ドマングの自由の木は幹だけを切り倒したようなものだ。根は数多く深く張っているのだから、また芽を出すだろう」と述べた。 [143]  1803年4月7日、フランス、フォール・ド・ジュの監獄にて、トゥーサン・ルーヴェルチュール将軍が死去 船団は1802年7月2日にフランスに到着し、8月25日にはルヴェルチュールはドゥー県のフォール・ド・ジュの要塞に投獄された。この間、ルヴェル チュールは回顧録を執筆した。[144] 彼は1803年4月7日に59歳で獄死した。死因として考えられているのは、衰弱、栄養失調、脳卒中、肺炎、おそらく結核である。[145][146] |

| Views and stances Religion and spirituality Throughout his life, Louverture was known as a devout Roman Catholic.[147] Having been baptized into the church as a slave by the Jesuits, Louverture would go on to be one of the few slaves on the Bréda plantation to be labeled devout. He celebrated Mass every day when possible, regularly served as godfather at multiple slave baptisms, and constantly quizzed others on the catechism of the church. In 1763 the Jesuits were expelled for spreading Catholicism among the slaves and undermining planter propaganda that slaves were mentally inferior. Toussaint would grow closer to the Capuchin Order that succeeded them in 1768, especially as they did not own plantations like the Jesuits. Louverture would also go on to have two formal Catholic weddings to both of his wives once freed. In his memoirs he fondly recounted the weekly ritual his family had on Sundays of going to church and enjoying a communal meal.[11] Although spending most of his life as a member of the Catholic faith, Louverture's early life included aspects of the Vodou religion. Vodou was common among slaves in Saint-Dominque as it was passed down through black communities of Allada origin. Characteristics of the Vodou belief include a link between spirits and herbs used for medicine. Historian and author Sudhir Hazareesingh writes: "Toussaint undoubtably made this connection, and drew upon the magical recipes of sorcerers in his practice of natural medicine".[148] Louverture was regarded as a doctor for some time during his travels across the colony which aided in his process of generating a following among those in Saint-Dominque in the earlier years of Louverture's adult life. After defeating forces led by André Rigaud in the War of the South, Louverture consolidated his power by decreeing a new constitution for the colony in 1801. It established Catholicism as the official religion.[127] Although Vodou was generally practiced on Saint-Domingue in combination with Catholicism, little is known for certain if Louverture had any connection with it. Officially as ruler of Saint-Domingue, he discouraged its practice and eventually persecuted its followers.[149] Historians have suggested that he was a member of high degree of the Masonic Lodge of Saint-Domingue, mostly based on a Masonic symbol he used in his signature. The memberships of several free blacks and white men close to him have been confirmed.[150] |

見解と立場 宗教と精神性 生涯を通じて、ルヴェルテュールは敬虔なローマ・カトリック教徒として知られていた。[147] イエズス会によって奴隷として洗礼を受けたルヴェルテュールは、ブレッド農園の数少ない敬虔な奴隷の一人となった。可能な限り毎日ミサを祝し、複数の奴隷 の洗礼式で定期的に名付け親を務め、教会の教理問答を絶えず他人に質問していた。1763年、イエズス会は奴隷たちにカトリックを広め、奴隷は精神的に 劣っているというプランテーション主たちの宣伝を弱体化させたとして追放された。トゥーサンは、1768年にイエズス会に代わって彼らを引き継いだカプチ ン修道会と特に親しくなり、 ルヴェルチュールもまた、解放後に2度、妻たちと正式なカトリックの結婚式を挙げた。彼は回顧録の中で、日曜日に家族で教会に行き、皆で食事を楽しむとい う毎週の儀式を愛情を込めて語っている。 生涯の大半をカトリック信者として過ごしたルヴェルチュールであったが、その初期の人生にはヴードゥー教の要素も含まれていた。ヴードゥー教は、アラダ族 の黒人コミュニティに受け継がれてきたもので、サン・ドマングの奴隷の間では一般的であった。ヴードゥー教の信仰の特徴には、薬として用いられる霊と薬草 とのつながりがある。歴史家で作家のSudhir Hazareesinghは、「トゥーサンは間違いなくこのつながりを意識し、自然療法の実践において魔術師の呪術的処方を利用していた」と書いている。 [148] ルヴェルチュールは、植民地を旅していた時期には医師として活動していた時期があり、それがルヴェルチュールが成人してからの早い時期に、サン・ドマング の人々から支持を集めるのに役立った。 南部戦争でアンドレ・リゴー率いる軍を打ち破った後、1801年に植民地に新しい憲法を制定し、ルヴェルチュールは自らの権力を強化した。この憲法は、カ トリックを公式の宗教として定めた。[127] ヴードゥーは一般的にカトリックと組み合わせてサン=ドマング島で信仰されていたが、ルヴェルチュールがヴードゥーと関係があったかどうかはほとんど知ら れていない。公式にはサン・ドマングの統治者として、彼はその信仰を禁じ、最終的にはその信者たちを迫害した。 歴史家たちは、彼がサン・ドマングのフリーメイソンのロッジの高位会員であった可能性が高いと示唆している。その根拠は主に、彼が署名に使用したフリーメイソンのシンボルにある。彼と親しい自由黒人や白人男性の数人が会員であったことが確認されている。 |