トリスタン・ツァラ

Tristan Tzara, 1896-1963

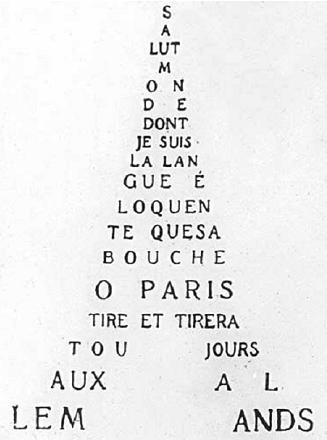

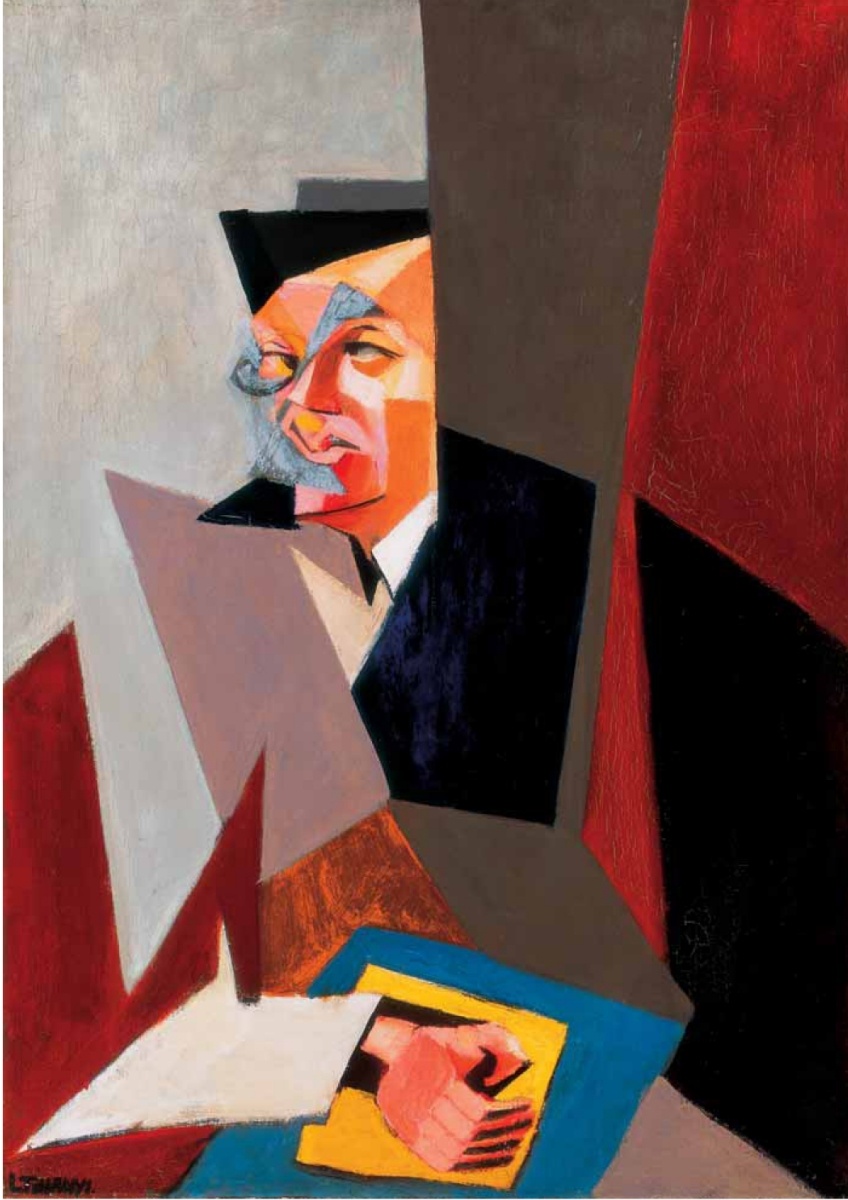

Portrait

of Tristan Tzara, by Robert Delaunay (1923)

☆ トリスタン・ツァラ(Tristan Tzara: [tʁistɑ̃ dzaʁa]、ルーマニア語: [trisˈtan ˈt͡sara]、本名サミュエルまたはサミー・ローゼンシュトック、S. Samyroとしても知られる、1896年4月28日[旧暦4月16日] - 1963年12月25日)は、ルーマニアの前衛詩人、エッセイスト、パフォーマンスアーティストである。ジャーナリスト、劇作家、文学・美術評論家、作曲 家、映画監督としても活躍し、反体制的なダダイズム運動の創始者の一人であり中心人物であったことで最もよく知られている。アドリアン・マニウの影響を受 け、思春期のツァラは象徴主義に興味を抱くようになり、イオーン・ヴィネア(彼とは実験的な詩も共作した)と画家マルセル・ヤンコとともに雑誌『シンボ ル』を創刊した。 第一次世界大戦中、ヴィネアの『Chemarea』に短期間協力した後、ツァラはジャンコとともにスイスへ移住した。 ツァラがキャバレー・ヴォルテールやツンフトハウス・ツア・ヴァークで発表した作品や、詩や芸術に関するマニフェストは、初期ダダイズムの主要な特徴と なった。 彼の作品は、ヒューゴ・ボールが好んだ穏健なアプローチとは対照的に、ダダイズムのニヒルな側面を代表するものとなった。 1919年にパリに移住したツァラは、当時「ダダイズムの代表者」の一人となり、雑誌『リテレチュール』のスタッフに加わった。これは、運動がシュールレ アリスムへと進化する第一歩となった。彼は、ダダイズムの分裂につながる主要な論争に関与し、アンドレ・ブルトンやフランシス・ピカビアに対しては自身の 主義を擁護し、ルーマニアではヴィネアとジャンコの折衷的なモダニズムに対しては反対した。この芸術に対する個人的な見解は、彼のダダイストの戯曲『ガ ス・ハート』(1921年)と『雲のハンカチ』(1924年)を定義づけた。自動書記の技法の先駆者であったツァラは、最終的にはブルトンのシュールレア リスムに同調し、その影響を受けて、有名なユートピア詩『近似の人』を書いた。 晩年には、ツァラはヒューマニストおよび反ファシストの視点と共産主義のビジョンを融合させ、スペイン内戦では共和党員として、第二次世界大戦中はフラン ス抵抗運動に参加し、国民議会で議員を務めた。1956年の革命の直前にハンガリー人民共和国の自由化を支持する演説を行ったため、それまで所属していた フランス共産党から距離を置くようになった。1960年には、アルジェリア戦争におけるフランスの行動に抗議した知識人の一人であった。 トリスタン・ツァラは、影響力のある作家でありパフォーマーであり、キュビスムや未来派からビート・ジェネレーション、シチュアシオニスト、ロック音楽の さまざまな潮流へとつながりを生み出したことで知られている。多くのモダニストたちと交友があり、コラボレーションを行っていた彼は、若い頃にはダンサー のマヤ・クルシェックと恋仲になり、その後スウェーデンのアーティストであり詩人であるグレタ・クヌートソンと結婚した。

| Tristan Tzara

(French: [tʁistɑ̃ dzaʁa]; Romanian: [trisˈtan ˈt͡sara]; born Samuel or

Samy Rosenstock, also known as S. Samyro; 28 April [O.S. 16 April]

1896[1] – 25 December 1963) was a Romanian avant-garde poet, essayist

and performance artist. Also active as a journalist, playwright,

literary and art critic, composer and film director, he was known best

for being one of the founders and central figures of the

anti-establishment Dada movement. Under the influence of Adrian Maniu,

the adolescent Tzara became interested in Symbolism and co-founded the

magazine Simbolul with Ion Vinea (with whom he also wrote experimental

poetry) and painter Marcel Janco. During World War I, after briefly collaborating on Vinea's Chemarea, he joined Janco in Switzerland. There, Tzara's shows at the Cabaret Voltaire and Zunfthaus zur Waag, as well as his poetry and art manifestos, became a main feature of early Dadaism. His work represented Dada's nihilistic side, in contrast with the more moderate approach favored by Hugo Ball. After moving to Paris in 1919, Tzara, by then one of the "presidents of Dada", joined the staff of Littérature magazine, which marked the first step in the movement's evolution toward Surrealism. He was involved in the major polemics which led to Dada's split, defending his principles against André Breton and Francis Picabia, and, in Romania, against the eclectic modernism of Vinea and Janco. This personal vision on art defined his Dadaist plays The Gas Heart (1921) and Handkerchief of Clouds (1924). A forerunner of automatist techniques, Tzara eventually aligned himself with Breton's Surrealism, and under its influence wrote his celebrated utopian poem "The Approximate Man". During the final part of his career, Tzara combined his humanist and anti-fascist perspective with a communist vision, joining the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War and the French Resistance during World War II, and serving a term in the National Assembly. Having spoken in favor of liberalization in the People's Republic of Hungary just before the Revolution of 1956, he distanced himself from the French Communist Party, of which he was by then a member. In 1960, he was among the intellectuals who protested against French actions in the Algerian War. Tristan Tzara was an influential author and performer, whose contribution is credited with having created a connection from Cubism and Futurism to the Beat Generation, Situationism and various currents in rock music. The friend and collaborator of many modernist figures, he was the lover of dancer Maja Kruscek in his early youth and was later married to Swedish artist and poet Greta Knutson. |

トリスタン・ツァラ(フランス語: [tʁistɑ̃

dzaʁa]、ルーマニア語: [trisˈtan ˈt͡sara]、本名サミュエルまたはサミー・ローゼンシュトック、S.

Samyroとしても知られる、1896年4月28日[旧暦4月16日] -

1963年12月25日)は、ルーマニアの前衛詩人、エッセイスト、パフォーマンスアーティストである。ジャーナリスト、劇作家、文学・美術評論家、作曲

家、映画監督としても活躍し、反体制的なダダイズム運動の創始者の一人であり中心人物であったことで最もよく知られている。アドリアン・マニウの影響を受

け、思春期のツァラは象徴主義に興味を抱くようになり、イオーン・ヴィネア(彼とは実験的な詩も共作した)と画家マルセル・ヤンコとともに雑誌『シンボ

ル』を創刊した。 第一次世界大戦中、ヴィネアの『Chemarea』に短期間協力した後、ツァラはジャンコとともにスイスへ移住した。 ツァラがキャバレー・ヴォルテールやツンフトハウス・ツア・ヴァークで発表した作品や、詩や芸術に関するマニフェストは、初期ダダイズムの主要な特徴と なった。 彼の作品は、ヒューゴ・ボールが好んだ穏健なアプローチとは対照的に、ダダイズムのニヒルな側面を代表するものとなった。 1919年にパリに移住したツァラは、当時「ダダイズムの代表者」の一人となり、雑誌『リテレチュール』のスタッフに加わった。これは、運動がシュールレ アリスムへと進化する第一歩となった。彼は、ダダイズムの分裂につながる主要な論争に関与し、アンドレ・ブルトンやフランシス・ピカビアに対しては自身の 主義を擁護し、ルーマニアではヴィネアとジャンコの折衷的なモダニズムに対しては反対した。この芸術に対する個人的な見解は、彼のダダイストの戯曲『ガ ス・ハート』(1921年)と『雲のハンカチ』(1924年)を定義づけた。自動書記の技法の先駆者であったツァラは、最終的にはブルトンのシュールレア リスムに同調し、その影響を受けて、有名なユートピア詩『近似の人』を書いた。 晩年には、ツァラはヒューマニストおよび反ファシストの視点と共産主義のビジョンを融合させ、スペイン内戦では共和党員として、第二次世界大戦中はフラン ス抵抗運動に参加し、国民議会で議員を務めた。1956年の革命の直前にハンガリー人民共和国の自由化を支持する演説を行ったため、それまで所属していた フランス共産党から距離を置くようになった。1960年には、アルジェリア戦争におけるフランスの行動に抗議した知識人の一人であった。 トリスタン・ツァラは、影響力のある作家でありパフォーマーであり、キュビスムや未来派からビート・ジェネレーション、シチュアシオニスト、ロック音楽の さまざまな潮流へとつながりを生み出したことで知られている。多くのモダニストたちと交友があり、コラボレーションを行っていた彼は、若い頃にはダンサー のマヤ・クルシェックと恋仲になり、その後スウェーデンのアーティストであり詩人であるグレタ・クヌートソンと結婚した。 |

| Name S. Samyro, a partial anagram of Samy Rosenstock, was used by Tzara from his debut and throughout the early 1910s.[2] A number of undated writings, which he probably authored as early as 1913, bear the signature Tristan Ruia, and, in summer of 1915, he was signing his pieces with the name Tristan.[3][4] In the 1960s, Rosenstock's collaborator and later rival Ion Vinea claimed that he was responsible for coining the Tzara part of his pseudonym in 1915.[3] Vinea also stated that Tzara wanted to keep Tristan as his adopted first name, and that this choice had later attracted him the "infamous pun" Triste Âne Tzara (French for "Sad Donkey Tzara").[3] This version of events is uncertain, as manuscripts show that the writer may have already been using the full name, as well as the variations Tristan Țara and Tr. Tzara, in 1913–1914 (although there is a possibility that he was signing his texts long after committing them to paper).[5] In 1972, art historian Serge Fauchereau, based on information received from Colomba, the wife of avant-garde poet Ilarie Voronca, recounted that Tzara had explained his chosen name was a pun in Romanian, trist în țară, meaning "sad in the country"; Colomba Voronca was also dismissing rumors that Tzara had selected Tristan as a tribute to poet Tristan Corbière or to Richard Wagner's Tristan und Isolde opera.[6] Samy Rosenstock legally adopted his new name in 1925, after filing a request with Romania's Ministry of the Interior.[6] The French pronunciation of his name has become commonplace in Romania, where it replaces its more natural reading as țara ("the land", Romanian pronunciation: [ˈt͡sara]).[7] |

名前 S. Samyroは、Samy Rosenstockの部分的アナグラムであり、ツァラはデビュー時から1910年代の初期にかけてこの名前を使用していた。[2] 1913年にはすでに書いたと思われる日付の記載のない文章のいくつかには、Tristan Ruiaという署名があり、1915年の夏には、作品にTristanという名前で署名していた。[3][4] 1960年代、ローゼンシュトックの協力者であり、後にライバルとなったイオン・ヴィネアは、1915年にツァラという偽名の部分を考案したのは彼である と主張した。[3] ヴィネアはまた、ツァラはトリスタンを養子として名乗る最初の名前として残しておきたかったとし、 後に「悪名高い駄洒落」である「悲しきロバ・ツァラ(フランス語で「悲しきロバ・ツァラ」)」という名前を気に入ったという。[3] この出来事の経緯については、作家がすでに1913年から1914年には、フルネーム、および「トリスタン・ツァラ」や「トリ・ツァラ」というバリエー ションを使用していたことを示す原稿があるため、不確かである。(ただし、紙に書き留めてからかなり経ってから署名していた可能性もある)[5]。 1972年、前衛詩人イラリエ・ヴォロンカの妻コロンバから得た情報に基づき、美術史家のセルジュ・フォシュローは、ツァラが自ら選んだ名前はルーマニア 語で「田舎で悲しい」という意味の「trist în țară」という言葉遊びであると説明したと述べた。コロンバ・ヴォロンカは、ツァラがトリスタンという名前を選んだのは、詩人トリスタン・コルビエール へのオマージュのため、あるいはリヒャルト・ワーグナーのオペラ『トリスタンとイゾルデ』へのオマージュのためだという噂を否定した。詩人トリスタン・コ ルビエールへのオマージュ、あるいはリヒャルト・ワーグナーのオペラ『トリスタンとイゾルデ』から取ったという噂を否定した。[6] サミー・ローゼンストックは1925年にルーマニア内務省に申請し、正式に新しい名前を名乗るようになった。[6] 彼の名前のフランス語発音はルーマニアでは一般的になり、本来の読み方であるțara(「土地」、ルーマニア語発音: [ˈt͡sara])に取って代わっている。[7] |

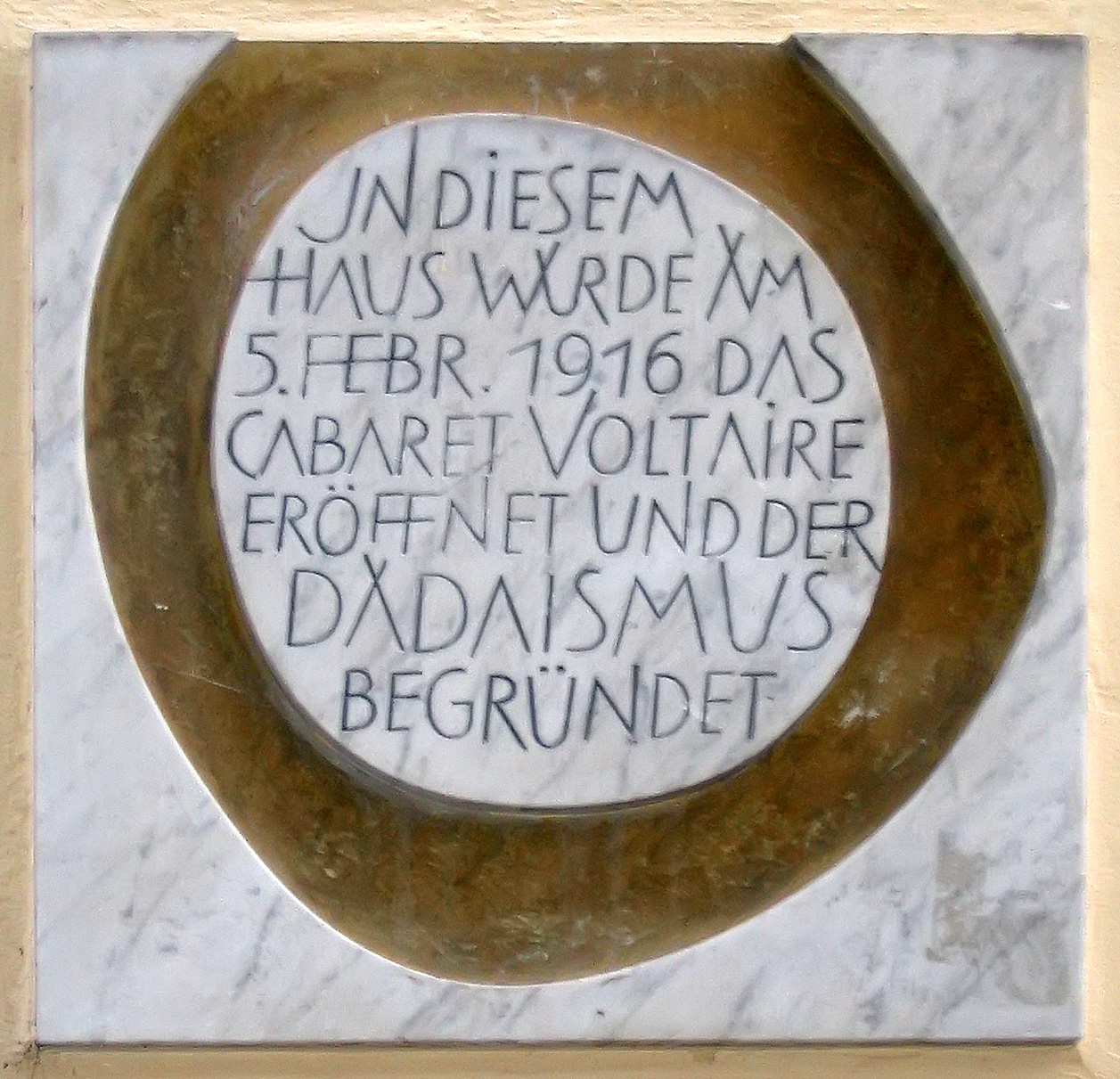

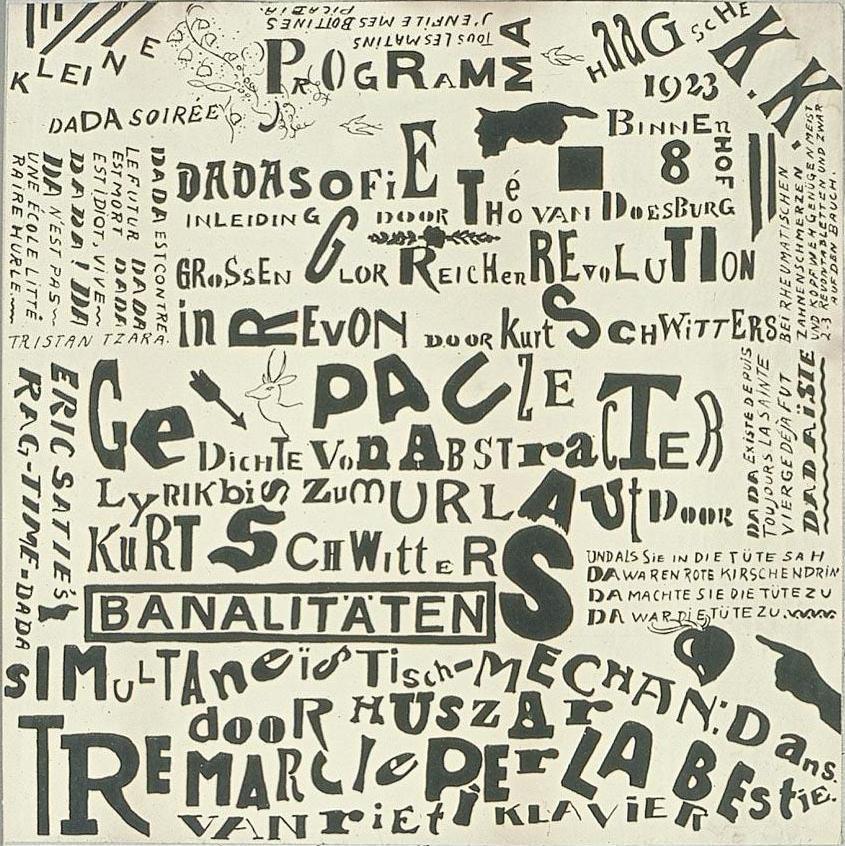

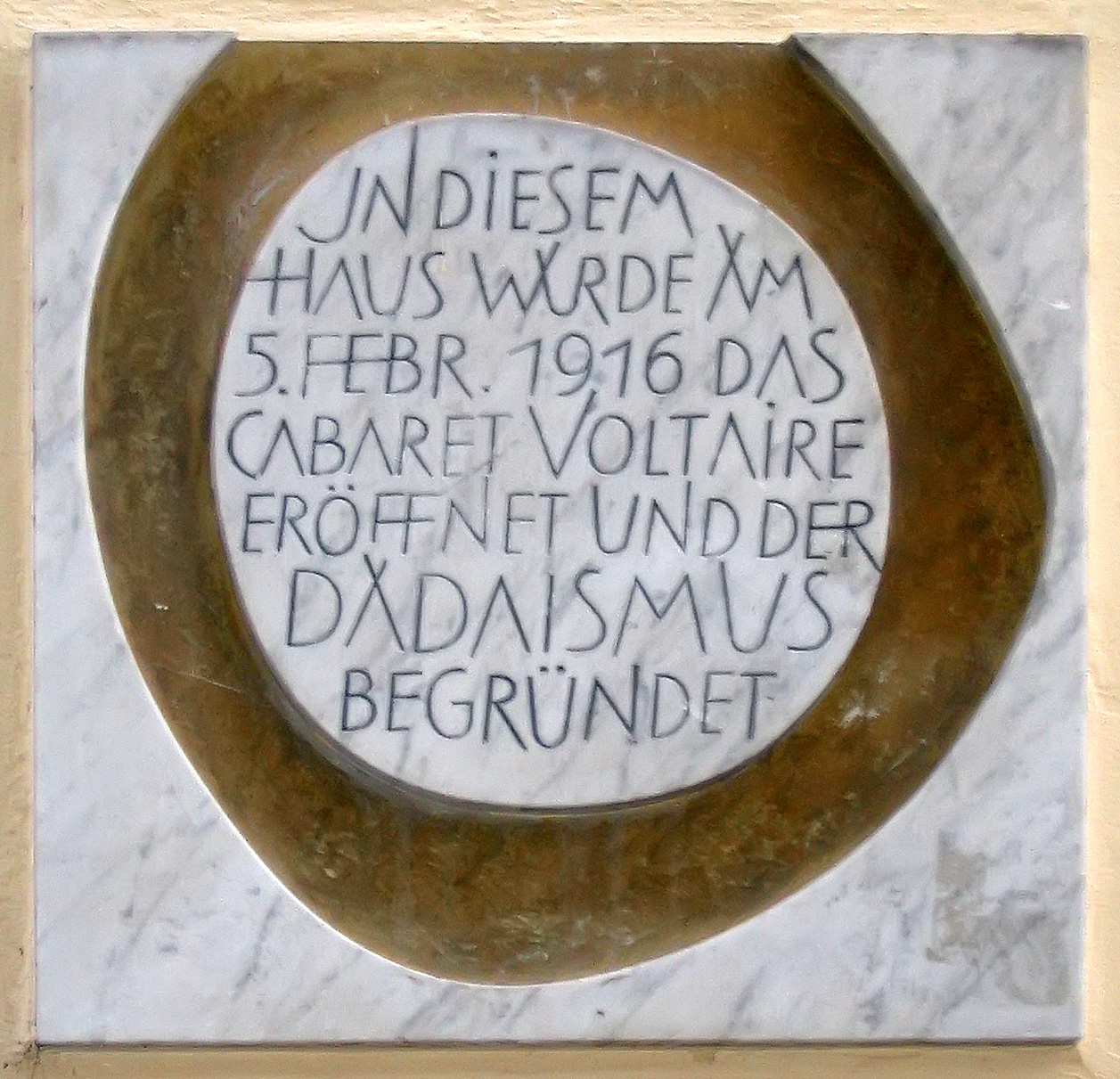

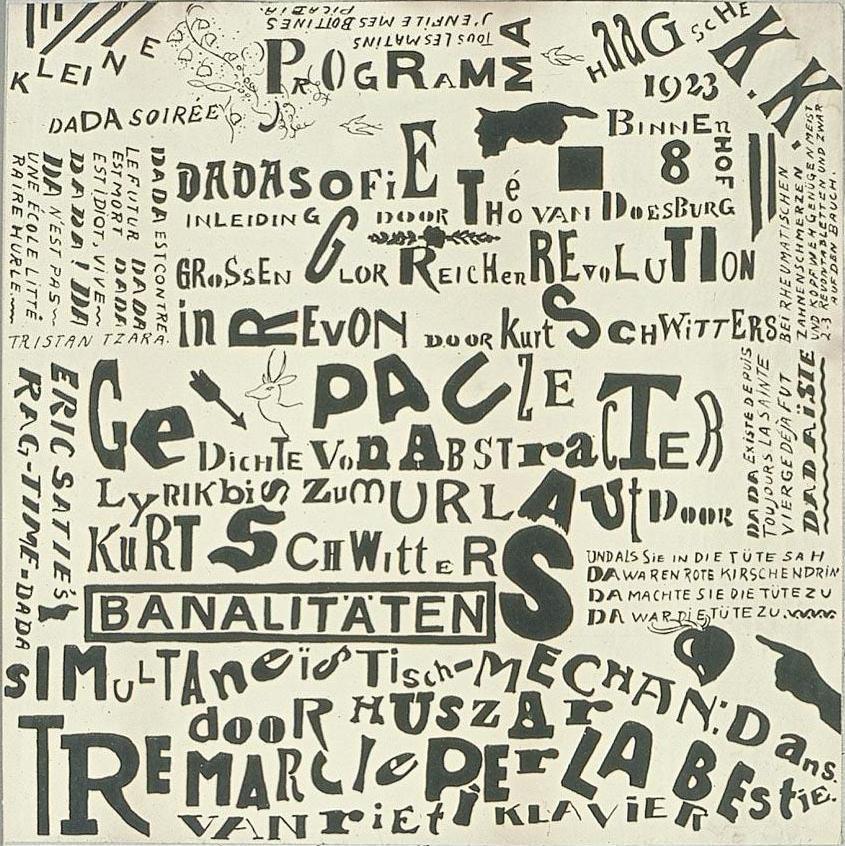

| Biography Early life and Simbolul years Tzara was born in Moinești, Bacău County, in the historical region of Western Moldavia. His parents were Jewish Romanians who reportedly spoke Yiddish as their first language;[8] his father Filip and grandfather Ilie were entrepreneurs in the forestry business.[9][10] Tzara's mother was Emilia Rosenstock (née Zibalis).[10] Owing to the Romanian Kingdom's discrimination laws, the Rosenstocks were not emancipated, and thus Tzara was not a full citizen of the country until after 1918.[9] He moved to Bucharest at the age of eleven, and attended the Schemitz-Tierin boarding school.[9] It is believed that the young Tzara completed his secondary education at a state-run high school, which is identified as the Saint Sava National College[9] or as the Sfântul Gheorghe High School.[11] In October 1912, when Tzara was aged sixteen, he joined his friends Vinea and Marcel Janco in editing Simbolul. Reputedly, Janco and Vinea provided the funds.[12] Like Vinea, Tzara was also close to their young colleague Jacques G. Costin, who was later his self-declared promoter and admirer.[13] Despite their young age, the three editors were able to attract collaborations from established Symbolist authors, active within Romania's own Symbolist movement. Alongside their close friend and mentor Adrian Maniu (an Imagist who had been Vinea's tutor),[14] they included N. Davidescu, Alfred Hefter-Hidalgo, Emil Isac, Claudia Millian, Ion Minulescu, I. M. Rașcu, Eugeniu Sperantia, Al. T. Stamatiad, Eugeniu Ștefănescu-Est, and Constantin T. Stoika, as well as journalist and lawyer Poldi Chapier.[15] In its inaugural issue, the journal even printed a poem by one of the leading figures in Romanian Symbolism, Alexandru Macedonski.[15] Simbolul also featured illustrations by Maniu, Millian and Iosif Iser.[16]  The Chemarea circle in 1915. From left: Tzara, M. H. Maxy, Ion Vinea, and Jacques G. Costin Although the magazine ceased print in December 1912, it played an important part in shaping Romanian literature of the period. Literary historian Paul Cernat sees Simbolul as a main stage in Romania's modernism, and credits it with having brought about the first changes from Symbolism to the radical avant-garde.[17] Also according to Cernat, the collaboration between Samyro, Vinea and Janco was an early instance of literature becoming "an interface between arts", which had for its contemporary equivalent the collaboration between Iser and writers such as Ion Minulescu and Tudor Arghezi.[18] Although Maniu parted with the group and sought a change in style which brought him closer to traditionalist tenets, Tzara, Janco and Vinea continued their collaboration. Between 1913 and 1915, they were frequently vacationing together, either on the Black Sea coast or at the Rosenstock family property in Gârceni, Vaslui County; during this time, Vinea and Samyro wrote poems with similar themes and alluding to one another.[19] Chemarea and 1915 departure Tzara's career changed course between 1914 and 1916, during a period when the Romanian Kingdom kept out of World War I. In autumn 1915, as founder and editor of the short-lived journal Chemarea, Vinea published two poems by his friend, the first printed works to bear the signature Tristan Tzara.[20] At the time, the young poet and many of his friends were adherents of an anti-war and anti-nationalist current, which progressively accommodated anti-establishment messages.[21] Chemarea, which was a platform for this agenda and again attracted collaborations from Chapier, may also have been financed by Tzara and Vinea.[12] According to Romanian avant-garde writer Claude Sernet, the journal was "totally different from everything that had been printed in Romania before that moment."[22] During the period, Tzara's works were sporadically published in Hefter-Hidalgo's Versuri și Proză, and, in June 1915, Constantin Rădulescu-Motru's Noua Revistă Română published Samyro's known poem Verișoară, fată de pension ("Little Cousin, Boarding School Girl").[2] Tzara had enrolled at the University of Bucharest in 1914, studying mathematics and philosophy, but did not graduate.[9][23] In autumn 1915, he left Romania for Zürich, in neutral Switzerland. Janco, together with his brother Jules Janco, had settled there a few months before, and was later joined by his other brother, Georges Janco.[24] Tzara, who may have applied to the Faculty of Philosophy at the local university,[9][25] shared lodging with Marcel Janco, who was a student at the Technische Hochschule, in the Altinger Guest House[26] (by 1918, Tzara had moved to the Limmatquai Hotel).[27] His departure from Romania, like that of the Janco brothers, may have been in part a pacifist political statement.[28] After settling in Switzerland, the young poet almost completely discarded Romanian as his language of expression, writing most of his subsequent works in French.[23][29] The poems he had written before, which were the result of poetic dialogues between him and his friend, were left in Vinea's care.[30] Most of these pieces were first printed only in the interwar period.[23][31] It was in Zürich that the Romanian group met with the German Hugo Ball, an anarchist poet and pianist, and his young wife Emmy Hennings, a music hall performer. In February 1916, Ball had rented the Cabaret Voltaire from its owner, Jan Ephraim, and intended to use the venue for performance art and exhibits.[32] Hugo Ball recorded this period, noting that Tzara and Marcel Janco, like Hans Arp, Arthur Segal, Otto van Rees, and Max Oppenheimer "readily agreed to take part in the cabaret".[33] According to Ball, among the performances of songs mimicking or taking inspiration from various national folklores, "Herr Tristan Tzara recited Rumanian poetry."[34] In late March, Ball recounted, the group was joined by German writer and drummer Richard Huelsenbeck.[33] He was soon after involved in Tzara's "simultaneist verse" performance, "the first in Zürich and in the world", also including renditions of poems by two promoters of Cubism, Fernand Divoire and Henri Barzun.[35] Birth of Dada  Cabaret Voltaire plaque commemorating the birth of Dada It was in this milieu that Dada was born, at some point before May 1916, when a publication of the same name first saw print. The story of its establishment was the subject of a disagreement between Tzara and his fellow writers. Cernat believes that the first Dadaist performance took place as early as February, when the nineteen-year-old Tzara, wearing a monocle, entered the Cabaret Voltaire stage singing sentimental melodies and handing paper wads to his "scandalized spectators", leaving the stage to allow room for masked actors on stilts, and returning in clown attire.[36] The same type of performances took place at the Zunfthaus zur Waag beginning in summer 1916, after the Cabaret Voltaire was forced to close down.[37] According to music historian Bernard Gendron, for as long as it lasted, "the Cabaret Voltaire was dada. There was no alternative institution or site that could disentangle 'pure' dada from its mere accompaniment [...] nor was any such site desired."[38] Other opinions link Dada's beginnings with much earlier events, including the experiments of Alfred Jarry, André Gide, Christian Morgenstern, Jean-Pierre Brisset, Guillaume Apollinaire, Jacques Vaché, Marcel Duchamp, and Francis Picabia.[39] In the first of the movement's manifestos, Ball wrote: "[The booklet] is intended to present to the Public the activities and interests of the Cabaret Voltaire, which has as its sole purpose to draw attention, across the barriers of war and nationalism, to the few independent spirits who live for other ideals. The next objective of the artists who are assembled here is to publish a revue internationale [French for 'international magazine']."[40] Ball completed his message in French, and the paragraph translates as: "The magazine shall be published in Zürich and shall carry the name 'Dada' ('Dada'). Dada Dada Dada Dada."[40] The view according to which Ball had created the movement was notably supported by writer Walter Serner, who directly accused Tzara of having abused Ball's initiative.[41] A secondary point of contention between the founders of Dada regarded the paternity for the movement's name, which, according to visual artist and essayist Hans Richter, was first adopted in print in June 1916.[42] Ball, who claimed authorship and stated that he picked the word randomly from a dictionary, indicated that it stood for both the French-language equivalent of "hobby horse" and a German-language term reflecting the joy of children being rocked to sleep.[43] Tzara himself declined interest in the matter, but Marcel Janco credited him with having coined the term.[44] Dada manifestos, written or co-authored by Tzara, record that the name shares its form with various other terms, including a word used in the Kru languages of West Africa to designate the tail of a sacred cow; a toy and the name for "mother" in an unspecified Italian dialect; and the double affirmative in Romanian and in various Slavic languages.[45] Dadaist promoter Before the end of the war, Tzara had assumed a position as Dada's main promoter and manager, helping the Swiss group establish branches in other European countries.[25][46] This period also saw the first conflict within the group: citing irreconcilable differences with Tzara, Ball left the group.[47] With his departure, Gendron argues, Tzara was able to move Dada vaudeville-like performances into more of "an incendiary and yet jocularly provocative theater."[48] He is often credited with having inspired many young modernist authors from outside Switzerland to affiliate with the group, in particular the Frenchmen Louis Aragon, André Breton, Paul Éluard, Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes and Philippe Soupault.[4][49] Richter, who also came into contact with Dada at this stage in its history, notes that these intellectuals often had a "very cool and distant attitude to this new movement" before being approached by the Romanian author.[49] In June 1916, he began editing and managing the periodical Dada as a successor of the short-lived magazine Cabaret Voltaire—Richter describes his "energy, passion and talent for the job", which he claims satisfied all Dadaists.[50] He was at the time the lover of Maja Kruscek, who was a student of Rudolf Laban; in Richter's account, their relationship was always tottering.[51] As early as 1916, Tristan Tzara took distance from the Italian Futurists, rejecting the militarist and proto-fascist stance of their leader Filippo Tommaso Marinetti.[52] Richter notes that, by then, Dada had replaced Futurism as the leader of modernism, while continuing to build on its influence: "we had swallowed Futurism—bones, feathers and all. It is true that in the process of digestion all sorts of bones and feathers had been regurgitated."[49] Despite this and the fact that Dada did not make any gains in Italy, Tzara could count poets Giuseppe Ungaretti and Alberto Savinio, painters Gino Cantarelli and Aldo Fiozzi, as well as a few other Italian Futurists, among the Dadaists.[53] Among the Italian authors supporting Dadaist manifestos and rallying with the Dada group was the poet, painter and in the future a fascist racial theorist Julius Evola, who became a personal friend of Tzara.[54] The next year, Tzara and Ball opened the Galerie Dada permanent exhibit, through which they set contacts with the independent Italian visual artist Giorgio de Chirico and with the German Expressionist journal Der Sturm, all of whom were described as "fathers of Dada".[55] During the same months, and probably owing to Tzara's intervention, the Dada group organized a performance of Sphinx and Strawman, a puppet play by the Austro-Hungarian Expressionist Oskar Kokoschka, whom he advertised as an example of "Dada theater".[56] He was also in touch with Nord-Sud, the magazine of French poet Pierre Reverdy (who sought to unify all avant-garde trends),[4] and contributed articles on African art to both Nord-Sud and Pierre Albert-Birot's SIC magazine.[57] In early 1918, through Huelsenbeck, Zürich Dadaists established contacts with their more explicitly left-wing disciples in the German Empire — George Grosz, John Heartfield, Johannes Baader, Kurt Schwitters, Walter Mehring, Raoul Hausmann, Carl Einstein, Franz Jung, and Heartfield's brother Wieland Herzfelde.[58] With Breton, Soupault and Aragon, Tzara traveled Cologne, where he became familiarized with the elaborate collage works of Schwitters and Max Ernst, which he showed to his colleagues in Switzerland.[59] Huelsenbeck nonetheless declined to Schwitters membership in Berlin Dada.[60] As a result of his campaigning, Tzara created a list of so-called "Dada presidents", who represented various regions of Europe. According to Hans Richter, it included, alongside Tzara, figures ranging from Ernst, Arp, Baader, Breton and Aragon to Kruscek, Evola, Rafael Lasso de la Vega, Igor Stravinsky, Vicente Huidobro, Francesco Meriano and Théodore Fraenkel.[61] Richter notes: "I'm not sure if all the names who appear here would agree with the description."[62] End of World War I The shows Tzara staged in Zürich often turned into scandals or riots, and he was in permanent conflict with the Swiss law enforcers.[63] Hans Richter speaks of a "pleasure of letting fly at the bourgeois, which in Tristan Tzara took the form of coldly (or hotly) calculated insolence" (see Épater la bourgeoisie).[64] In one instance, as part of a series of events in which Dadaists mocked established authors, Tzara and Arp falsely publicized that they were going to fight a duel in Rehalp, near Zürich, and that they were going to have the popular novelist Jakob Christoph Heer for their witness.[65] Richter also reports that his Romanian colleague profited from Swiss neutrality to play the Allies and Central Powers against each other, obtaining art works and funds from both, making use of their need to stimulate their respective propaganda efforts.[66] While active as a promoter, Tzara also published his first volume of collected poetry, the 1918 Vingt-cinq poèmes ("Twenty-five Poems").[67] A major event took place in autumn 1918, when Francis Picabia, who was then publisher of 391 magazine and a distant Dada affiliate, visited Zürich and introduced his colleagues there to his nihilistic views on art and reason.[68] In the United States, Picabia, Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp had earlier set up their own version of Dada. This circle, based in New York City, sought affiliation with Tzara's only in 1921, when they jokingly asked him to grant them permission to use "Dada" as their own name (to which Tzara replied: "Dada belongs to everybody").[69] The visit was credited by Richter with boosting the Romanian author's status, but also with making Tzara himself "switch suddenly from a position of balance between art and anti-art into the stratospheric regions of pure and joyful nothingness."[70] The movement subsequently organized its last major Swiss show, held at the Saal zur Kaufleutern, with choreography by Susanne Perrottet, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, and with the participation of Käthe Wulff, Hans Heusser, Tzara, Hans Richter and Walter Serner.[71] It was there that Serner read from his 1918 essay, whose very title advocated Letzte Lockerung ("Final Dissolution"): this part is believed to have caused the subsequent mêlée, during which the public attacked the performers and succeeded in interrupting, but not canceling, the show.[72] Following the November 1918 Armistice with Germany, Dada's evolution was marked by political developments. In October 1919, Tzara, Arp and Otto Flake began publishing Der Zeltweg, a journal aimed at further popularizing Dada in a post-war world were the borders were again accessible.[73] Richter, who admits that the magazine was "rather tame", also notes that Tzara and his colleagues were dealing with the impact of communist revolutions, in particular the October Revolution and the German revolts of 1918, which "had stirred men's minds, divided men's interests and diverted energies in the direction of political change."[73] The same commentator, however, dismisses those accounts which, he believes, led readers to believe that Der Zeltweg was "an association of revolutionary artists."[73] According to one account rendered by historian Robert Levy, Tzara shared company with a group of Romanian communist students, and, as such, may have met with Ana Pauker, who was later one of the Romanian Communist Party's most prominent activists.[74] Arp and Janco drifted away from the movement ca. 1919, when they created the Constructivist-inspired workshop Das Neue Leben.[75] In Romania, Dada was awarded an ambiguous reception from Tzara's former associate Vinea. Although he was sympathetic to its goals, treasured Hugo Ball and Hennings and promised to adapt his own writings to its requirements, Vinea cautioned Tzara and the Jancos in favor of lucidity.[76] When Vinea submitted his poem Doleanțe ("Grievances") to be published by Tzara and his associates, he was turned down, an incident which critics attribute to a contrast between the reserved tone of the piece and the revolutionary tenets of Dada.[77] Paris Dada  Tzara (second from right) in the 1920s, with Margaret C. Anderson, Jane Heap, and John Rodker  Tzara reading L'Action Française, French nationalist newspaper in the 1920s, archives Charmet. In late 1919, Tristan Tzara left Switzerland to join Breton, Soupault and Claude Rivière in editing the Paris-based magazine Littérature.[25][78] Already a mentor for the French avant-garde, he was, according to Hans Richter, perceived as an "Anti-Messiah" and a "prophet".[79] Reportedly, Dada mythology had it that he entered the French capital in a snow-white or lilac-colored car, passing down Boulevard Raspail through a triumphal arch made from his own pamphlets, being greeted by cheering crowds and a fireworks display.[79] Richter dismisses this account, indicating that Tzara actually walked from Gare de l'Est to Picabia's home, without anyone expecting him to arrive.[79] He is often described as the main figure in the Littérature circle, and credited with having more firmly set its artistic principles in the line of Dada.[25][80] When Picabia began publishing a new series of 391 in Paris, Tzara seconded him and, Richter says, produced issues of the magazine "decked out [...] in all the colors of Dada."[57] He was also issuing his Dada magazine, printed in Paris but using the same format, renaming it Bulletin Dada and later Dadaphone.[81] At around that time, he met American author Gertrude Stein, who wrote about him in The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas,[82] and the artist couple Robert and Sonia Delaunay (with whom he worked in tandem for "poem-dresses" and other simultaneist literary pieces).[83] Tzara became involved in a number of Dada experiments, on which he collaborated with Breton, Aragon, Soupault, Picabia or Paul Éluard.[4][84][85] Other authors who came into contact with Dada at that stage were Jean Cocteau, Paul Dermée and Raymond Radiguet.[86] The performances staged by Dada were often meant to popularize its principles, and Dada continued to draw attention on itself by hoaxes and false advertising, announcing that the Hollywood film star Charlie Chaplin was going to appear on stage at its show,[48] or that its members were going to have their heads shaved or their hair cut off on stage.[87] In another instance, Tzara and his associates lectured at the Université populaire in front of industrial workers, who were reportedly less than impressed.[88] Richter believes that, ideologically, Tzara was still in tribute to Picabia's nihilistic and anarchic views (which made the Dadaists attack all political and cultural ideologies), but that this also implied a measure of sympathy for the working class.[88] Dada activities in Paris culminated in the March 1920 variety show at the Théâtre de l'Œuvre, which featured readings from Breton, Picabia, Dermée and Tzara's earlier work, La Première aventure céleste de M. Antipyrine ("The First Heavenly Adventure of Mr. Antipyrine").[89] Tzara's melody, Vaseline symphonique ("Symphonic Vaseline"), which required ten or twenty people to shout "cra" and "cri" on a rising scale, was also performed.[90] A scandal erupted when Breton read Picabia's Manifeste cannibale ("Cannibal Manifesto"), lashing out at the audience and mocking them, to which they answered by aiming rotten fruit at the stage.[91] The Dada phenomenon was only noticed in Romania beginning in 1920, and its overall reception was negative. Traditionalist historian Nicolae Iorga, Symbolist promoter Ovid Densusianu, the more reserved modernists Camil Petrescu and Benjamin Fondane all refused to accept it as a valid artistic manifestation.[92] Although he rallied with tradition, Vinea defended the subversive current in front of more serious criticism, and rejected the widespread rumor that Tzara had acted as an agent of influence for the Central Powers during the war.[93] Eugen Lovinescu, editor of Sburătorul and one of Vinea's rivals on the modernist scene, acknowledged the influence exercised by Tzara on the younger avant-garde authors, but analyzed his work only briefly, using as an example one of his pre-Dada poems, and depicting him as an advocate of literary "extremism".[94] Dada stagnation  Saint-Julien-le-Pauvre, site of the 1921 "Dada excursion" By 1921, Tzara had become involved in conflicts with other figures in the movement, whom he claimed had parted with the spirit of Dada.[95] He was targeted by the Berlin-based Dadaists, in particular by Huelsenbeck and Serner, the former of whom was also involved in a conflict with Raoul Hausmann over leadership status.[41] According to Richter, tensions between Breton and Tzara had surfaced in 1920, when Breton first made known his wish to do away with musical performances altogether and alleged that the Romanian was merely repeating himself.[96] The Dada shows themselves were by then such common occurrences that audiences expected to be insulted by the performers.[67] A more serious crisis occurred in May, when Dada organized a mock trial of Maurice Barrès, whose early affiliation with the Symbolists had been shadowed by his antisemitism and reactionary stance: Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes was the prosecutor, Aragon and Soupault the defense attorneys, with Tzara, Ungaretti, Benjamin Péret and others as witnesses (a mannequin stood in for Barrès).[97] Péret immediately upset Picabia and Tzara by refusing to make the trial an absurd one, and by introducing a political subtext with which Breton nevertheless agreed.[98] In June, Tzara and Picabia clashed with each other, after Tzara expressed an opinion that his former mentor was becoming too radical.[99] During the same season, Breton, Arp, Ernst, Maja Kruschek and Tzara were in Austria, at Imst, where they published their last manifesto as a group, Dada au grand air ("Dada in the Open Air") or Der Sängerkrieg in Tirol ("The Battle of the Singers in Tyrol").[100] Tzara also visited Czechoslovakia, where he reportedly hoped to gain adherents to his cause.[101] Also in 1921, Ion Vinea wrote an article for the Romanian newspaper Adevărul, arguing that the movement had exhausted itself (although, in his letters to Tzara, he continued to ask his friend to return home and spread his message there).[102] After July 1922, Marcel Janco rallied with Vinea in editing Contimporanul, which published some of Tzara's earliest poems but never offered space to any Dadaist manifesto.[103] Reportedly, the conflict between Tzara and Janco had a personal note: Janco later mentioned "some dramatic quarrels" between his colleague and him.[104] They avoided each other for the rest of their lives and Tzara even struck out the dedications to Janco from his early poems.[105] Julius Evola also grew disappointed by the movement's total rejection of tradition and began his personal search for an alternative, pursuing a path which later led him to esotericism and fascism.[54] Evening of the Bearded Heart  Theo van Doesburg's poster for a Dada soirée (ca.1923) Tzara was openly attacked by Breton in a February 1922 article for Le Journal de Peuple, where the Romanian writer was denounced as "an impostor" avid for "publicity".[106] In March, Breton initiated the Congress for the Determination and Defense of the Modern Spirit. The French writer used the occasion to strike out Tzara's name from among the Dadaists, citing in his support Dada's Huelsenbeck, Serner, and Christian Schad.[107] Basing his statement on a note supposedly authored by Huelsenbeck, Breton also accused Tzara of opportunism, claiming that he had planned wartime editions of Dada works in such a manner as not to upset actors on the political stage, making sure that German Dadaists were not made available to the public in countries subject to the Supreme War Council.[107] Tzara, who attended the Congress only as a means to subvert it,[108] responded to the accusations the same month, arguing that Huelsenbeck's note was fabricated and that Schad had not been one of the original Dadaists.[107] Rumors reported much later by American writer Brion Gysin had it that Breton's claims also depicted Tzara as an informer for the Prefecture of Police.[109] In May 1922, Dada staged its own funeral.[110] According to Hans Richter, the main part of this took place in Weimar, where the Dadaists attended a festival of the Bauhaus art school, during which Tzara proclaimed the elusive nature of his art: "Dada is useless, like everything else in life. [...] Dada is a virgin microbe which penetrates with the insistence of air into all those spaces that reason has failed to fill with words and conventions."[111] In "The Bearded Heart" manifesto a number of artists backed the marginalization of Breton in support of Tzara. Alongside Cocteau, Arp, Ribemont-Dessaignes, and Éluard, the pro-Tzara faction included Erik Satie, Theo van Doesburg, Serge Charchoune, Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Marcel Duchamp, Ossip Zadkine, Jean Metzinger, Ilia Zdanevich, and Man Ray.[112] During an associated soirée, Evening of the Bearded Heart, which began on 6 July 1923, Tzara presented a re-staging of his play The Gas Heart (which had been first performed two years earlier to howls of derision from its audience), for which Sonia Delaunay designed the costumes.[83] Breton interrupted its performance and reportedly fought with several of his former associates and broke furniture, prompting a theatre riot that only the intervention of the police halted.[113] Dada's vaudeville declined in importance and disappeared altogether after that date.[114] Picabia took Breton's side against Tzara,[115] and replaced the staff of his 391, enlisting collaborations from Clément Pansaers and Ezra Pound.[116] Breton marked the end of Dada in 1924, when he issued the first Surrealist Manifesto. Richter suggests that "Surrealism devoured and digested Dada."[110] Tzara distanced himself from the new trend, disagreeing with its methods and, increasingly, with its politics.[25][67][84][117] In 1923, he and a few other former Dadaists collaborated with Richter and the Constructivist artist El Lissitzky on the magazine G,[118] and, the following year, he wrote pieces for the Yugoslav-Slovenian magazine Tank (edited by Ferdinand Delak).[119] Transition to Surrealism  Maison Tzara, designed by Adolf Loos Tzara continued to write, becoming more seriously interested in the theater. In 1924, he published and staged the play Handkerchief of Clouds, which was soon included in the repertoire of Serge Diaghilev's Ballets Russes.[120] He also collected his earlier Dada texts as the Seven Dada Manifestos. Marxist thinker Henri Lefebvre reviewed them enthusiastically; he later became one of the author's friends.[121] In Romania, Tzara's work was partly recuperated by Contimporanul, which notably staged public readings of his works during the international art exhibit it organized in 1924, and again during the "new art demonstration" of 1925.[122] In parallel, the short-lived magazine Integral, where Ilarie Voronca and Ion Călugăru were the main animators, took significant interest in Tzara's work.[123] In a 1927 interview with the publication, he voiced his opposition to the Surrealist group's adoption of communism, indicating that such politics could only result in a "new bourgeoisie" being created, and explaining that he had opted for a personal "permanent revolution", which would preserve "the holiness of the ego".[124] In 1925, Tristan Tzara was in Stockholm, where he married Greta Knutson, with whom he had a son, Christophe (born 1927).[4] A former student of painter André Lhote, she was known for her interest in phenomenology and abstract art.[125] Around the same period, with funds from Knutson's inheritance, Tzara commissioned Austrian architect Adolf Loos, a former representative of the Vienna Secession whom he had met in Zürich, to build him a house in Paris.[4] The rigidly functionalist Maison Tristan Tzara, built in Montmartre, was designed following Tzara's specific requirements and decorated with samples of African art.[4] It was Loos' only major contribution in his Parisian years.[4] In 1929, he reconciled with Breton, and sporadically attended the Surrealists' meetings in Paris.[67][84] The same year, he issued the poetry book De nos oiseaux ("Of Our Birds").[67] This period saw the publication of The Approximate Man (1931), alongside the volumes L'Arbre des voyageurs ("The Travelers' Tree", 1930), Où boivent les loups ("Where Wolves Drink", 1932), L'Antitête ("The Antihead", 1933) and Grains et issues ("Seed and Bran", 1935).[84] By then, it was also announced that Tzara had started work on a screenplay.[126] In 1930, he directed and produced a cinematic version of Le Cœur à barbe, starring Breton and other leading Surrealists.[127] Five years later, he signed his name to The Testimony against Gertrude Stein, published by Eugene Jolas's magazine transition in reply to Stein's memoir The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, in which he accused his former friend of being a megalomaniac.[128] The poet became involved in further developing Surrealist techniques, and, together with Breton and Valentine Hugo, drew one of the better-known examples of "exquisite corpses".[129] Tzara also prefaced a 1934 collection of Surrealist poems by his friend René Char, and the following year he and Greta Knutson visited Char in L'Isle-sur-la-Sorgue.[130] Tzara's wife was also affiliated with the Surrealist group at around the same time.[4][125] This association ended when she parted with Tzara late in the 1930s.[4][125] At home, Tzara's works were collected and edited by the Surrealist promoter Sașa Pană, who corresponded with him over several years.[131] The first such edition saw print in 1934, and featured the 1913–1915 poems Tzara had left in Vinea's care.[30] In 1928–1929, Tzara exchanged letters with his friend Jacques G. Costin, a Contimporanul affiliate who did not share all of Vinea's views on literature, who offered to organize his visit to Romania and asked him to translate his work into French.[132] Affiliation with communism and Spanish Civil War Alarmed by the establishment of Adolf Hitler's Nazi regime, which also signified the end of Berlin's avant-garde, he merged his activities as an art promoter with the cause of anti-fascism, and was close to the French Communist Party (PCF). In 1936, Richter recalled, he published a series of photographs secretly taken by Kurt Schwitters in Hanover, works which documented the destruction of Nazi propaganda by the locals, ration stamp with reduced quantities of food, and other hidden aspects of Hitler's rule.[133] After the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, he briefly left France and joined the Republican forces.[84][134] Alongside Soviet reporter Ilya Ehrenburg, Tzara visited Madrid, which was besieged by the Nationalists (see Siege of Madrid).[135] Upon his return, he published the collection of poems Midis gagnés ("Conquered Southern Regions").[84] Some of them had previously been printed in the brochure Les poètes du monde défendent le peuple espagnol ("The Poets of the World Defend the Spanish People", 1937), which was edited by two prominent authors and activists, Nancy Cunard and the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda.[136] Tzara had also signed Cunard's June 1937 call to intervention against Francisco Franco.[137] Reportedly, he and Nancy Cunard were romantically involved.[138] Although the poet was moving away from Surrealism,[67] his adherence to strict Marxism-Leninism was reportedly questioned by both the PCF and the Soviet Union.[139] Semiotician Philip Beitchman places their attitude in connection with Tzara's own vision of Utopia, which combined communist messages with Freudo-Marxist psychoanalysis and made use of particularly violent imagery.[140] Reportedly, Tzara refused to be enlisted in supporting the party line, maintaining his independence and refusing to take the forefront at public rallies.[141] However, others note that the former Dadaist leader would often show himself a follower of political guidelines. As early as 1934, Tzara, together with Breton, Éluard and communist writer René Crevel, organized an informal trial of independent-minded Surrealist Salvador Dalí, who was at the time a confessed admirer of Hitler, and whose portrait of William Tell had alarmed them because it shared likeness with Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin.[142] Historian Irina Livezeanu notes that Tzara, who agreed with Stalinism and shunned Trotskyism, submitted to the PCF cultural demands during the writers' congress of 1935, even when his friend Crevel committed suicide to protest the adoption of socialist realism.[143] At a later stage, Livezeanu remarks, Tzara reinterpreted Dada and Surrealism as revolutionary currents, and presented them as such to the public.[144] This stance she contrasts with that of Breton, who was more reserved in his attitudes.[143] World War II and Resistance During World War II, Tzara took refuge from the German occupation forces, moving to the southern areas, controlled by the Vichy regime.[4][84] On one occasion, the antisemitic and collaborationist publication Je Suis Partout made his whereabouts known to the Gestapo.[145] After having secure his book collection and african art collection, Tzara fled in 1940 towards south of France, and hide first in a village called Sanary, then after being expelled by the police, in Saint-Tropez. In 1941, he is arrested but he managed to escape thanks to the complancency of a policeman.[146] Tzara joined the French Resistance, rallying with the Maquis. A contributor to magazines published by the Resistance, Tzara also took charge of the cultural broadcast for the Free French Forces clandestine radio station.[4][84] He lived in Aix-en-Provence, then in Souillac, and ultimately in Toulouse.[4] His son Cristophe was at the time a Resistant in northern France, having joined the Francs-Tireurs et Partisans.[145] In Axis-allied and antisemitic Romania (see Romania during World War II), the regime of Ion Antonescu ordered bookstores not to sell works by Tzara and 44 other Jewish-Romanian authors.[147] In 1942, with the generalization of antisemitic measures, Tzara was also stripped of his Romanian citizenship rights.[148] In December 1944, five months after the Liberation of Paris, he was contributing to L'Éternelle Revue, a pro-communist newspaper edited by philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, through which Sartre was publicizing the heroic image of a France united in resistance, as opposed to the perception that it had passively accepted German control.[149] Other contributors included writers Aragon, Char, Éluard, Elsa Triolet, Eugène Guillevic, Raymond Queneau, Francis Ponge, Jacques Prévert and painter Pablo Picasso.[149] Upon the end of the war and the restoration of French independence, Tzara was naturalized a French citizen.[84] During 1945, under the Provisional Government of the French Republic, he was a representative of the Sud-Ouest region to the National Assembly.[135] According to Livezeanu, he "helped reclaim the South from the cultural figures who had associated themselves to Vichy [France]."[143] In April 1946, his early poems, alongside similar pieces by Breton, Éluard, Aragon and Dalí, were the subject of a midnight broadcast on Parisian Radio.[150] In 1947, he became a full member of the PCF[67] (according to some sources, he had been one since 1934).[84] International leftism Over the following decade, Tzara lent his support to political causes. Pursuing his interest in primitivism, he became a critic of the Fourth Republic's colonial policy, and joined his voice to those who supported decolonization.[141] Nevertheless, he was appointed cultural ambassador of the Republic by the Paul Ramadier cabinet.[151] He also participated in the PCF-organized Congress of Writers, but, unlike Éluard and Aragon, again avoided adapting his style to socialist realism.[145] He returned to Romania on an official visit in late 1946-early 1947,[152][153] as part of a tour of the emerging Eastern Bloc during which he also stopped in Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia.[153] The speeches he and Sașa Pană gave on the occasion, published by Orizont journal, were noted for condoning official positions of the PCF and the Romanian Communist Party, and are credited by Irina Livezeanu with causing a rift between Tzara and young Romanian avant-gardists such as Victor Brauner and Gherasim Luca (who rejected communism and were alarmed by the Iron Curtain having fallen over Europe).[154] In September of the same year, he was present at the conference of the pro-communist International Union of Students (where he was a guest of the French-based Union of Communist Students, and met with similar organizations from Romania and other countries).[155] In 1949–1950, Tzara answered Aragon's call and become active in the international campaign to liberate Nazım Hikmet, a Turkish poet whose 1938 arrest for communist activities had created a cause célèbre for the pro-Soviet public opinion.[156][157] Tzara chaired the Committee for the Liberation of Nazım Hikmet, which issued petitions to national governments[157][158] and commissioned works in honor of Hikmet (including musical pieces by Louis Durey and Serge Nigg).[157] Hikmet was eventually released in July 1950, and publicly thanked Tzara during his subsequent visit to Paris.[159] His works of the period include, among others: Le Signe de vie ("Sign of Life", 1946), Terre sur terre ("Earth on Earth", 1946), Sans coup férir ("Without a Need to Fight", 1949), De mémoire d'homme ("From a Man's Memory", 1950), Parler seul ("Speaking Alone", 1950), and La Face intérieure ("The Inner Face", 1953), followed in 1955 by À haute flamme ("Flame out Loud") and Le Temps naissant ("The Nascent Time"), and the 1956 Le Fruit permis ("The Permitted Fruit").[84][160] Tzara continued to be an active promoter of modernist culture. Around 1949, having read Irish author Samuel Beckett's manuscript of Waiting for Godot, Tzara facilitated the play's staging by approaching producer Roger Blin.[161] He also translated into French some poems by Hikmet[162] and the Hungarian author Attila József.[153] In 1949, he introduced Picasso to art dealer Heinz Berggruen (thus helping start their lifelong partnership),[163] and, in 1951, wrote the catalog for an exhibit of works by his friend Max Ernst; the text celebrated the artist's "free use of stimuli" and "his discovery of a new kind of humor."[164] 1956 protest and final years  Tzara's grave in the Cimetière du Montparnasse In October 1956, Tzara visited the People's Republic of Hungary, where the government of Imre Nagy was coming into conflict with the Soviet Union.[145][153] This followed an invitation on the part of Hungarian writer Gyula Illyés, who wanted his colleague to be present at ceremonies marking the rehabilitation of László Rajk (a local communist leader whose prosecution had been ordered by Joseph Stalin).[153] Tzara was receptive of the Hungarians' demand for liberalization,[145][153] contacted the anti-Stalinist and former Dadaist Lajos Kassák, and deemed the anti-Soviet movement "revolutionary".[153] However, unlike much of Hungarian public opinion, the poet did not recommend emancipation from Soviet control, and described the independence demanded by local writers as "an abstract notion".[153] The statement he issued, widely quoted in the Hungarian and international press, forced a reaction from the PCF: through Aragon's reply, the party deplored the fact that one of its members was being used in support of "anti-communist and anti-Soviet campaigns."[153] His return to France coincided with the outbreak of the Hungarian Revolution, which ended with a Soviet military intervention. On 24 October, Tzara was ordered to a PCF meeting, where activist Laurent Casanova reportedly ordered him to keep silent, which Tzara did.[153] Tzara's apparent dissidence and the crisis he helped provoke within the Communist Party were celebrated by Breton, who had adopted a pro-Hungarian stance, and who defined his friend and rival as "the first spokesman of the Hungarian demand."[153] He was thereafter mostly withdrawn from public life, dedicating himself to researching the work of 15th-century poet François Villon,[141] and, like his fellow Surrealist Michel Leiris, to promoting primitive and African art, which he had been collecting for years.[145] In early 1957, Tzara attended a Dada retrospective on the Rive Gauche, which ended in a riot caused by the rival avant-garde Mouvement Jariviste, an outcome which reportedly pleased him.[165] In August 1960, one year after the Fifth Republic had been established by President Charles de Gaulle, French forces were confronting the Algerian rebels (see Algerian War). Together with Simone de Beauvoir, Marguerite Duras, Jérôme Lindon, Alain Robbe-Grillet and other intellectuals, he addressed Premier Michel Debré a letter of protest, concerning France's refusal to grant Algeria its independence.[166] As a result, Minister of Culture André Malraux announced that his cabinet would not subsidize any films to which Tzara and the others might contribute, and the signatories could no longer appear on stations managed by the state-owned French Broadcasting Service.[166] In 1961, as recognition for his work as a poet, Tzara was awarded the prestigious Taormina Prize.[84] One of his final public activities took place in 1962, when he attended the International Congress on African Culture, organized by English curator Frank McEwen and held at the National Gallery in Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia.[167] He died one year later in his Paris home, and was buried at the Cimetière du Montparnasse.[4] |

略歴 幼少期とシンボル時代 ツァラは、歴史的な地域である西モルダヴィアのバカル県モイネシュティで生まれた。両親はユダヤ系ルーマニア人で、イディッシュ語を第一言語として話して いたと伝えられている。父フィリップと祖父イリエは林業の事業家であった。ツァラの母はエミリア・ローゼンストック(旧姓ジバリス)であった。 ibalis)であった。[10] ルーマニア王国の差別法により、ローゼンストック家は解放されず、ツァラは1918年まで同国の完全な市民権を持たなかった。[9] 彼は11歳の時にブカレストに移り、シェミッツ・ティリン寄宿学校に通った。[9] 若いツァラは公立高校で中等教育を修了したと考えられており、その高校は聖サヴァ国立大学 。1912年10月、ツァラが16歳になったとき、彼は友人であるヴィネアとマルセル・ヤンコとともに『シンボル』誌の編集に加わった。伝えられるところ によると、ジャンコとヴィネアが資金を提供したという。[12] ヴィネアと同様、ツァラも若い同僚のジャック・G・コスティンと親しく、後にツァラは彼を自分のプロモーターであり、また崇拝者であると公言した。 [13] 3人の編集者は、若いながらも、ルーマニア独自の象徴主義運動で活躍する著名な象徴主義作家たちから協力を取り付けることができた。彼らの親しい友人であ り師でもあったアドリアン・マニウ(ヴィネアの指導者であったイマジズムの作家)とともに、N.ダヴィデスク、アルフレッド・ヘフター=イダルゴ、エミー ル・イサック、クラウディア・ミリアン、イオン・ムヌレスク、I.M.ラスク、エウゲニウ・スペランティア、Al. T. スタマティアデ、オイゲニウ・ステファネスク=エスト、コンスタンティン・T・ストイカ、そしてジャーナリスト兼弁護士のポルディ・チャピエールである。 [15] 創刊号には、ルーマニア象徴主義の主要人物の一人であるアレクサンドル・マケドンスキの詩も掲載された。[15] 『シンボル』誌には、マニウ、ミリアン、イオシフ・イゼールによるイラストも掲載された。[16]  1915年の「Chemarea」サークル。左から:ツァラ、M. H. マクシー、イオン・ヴィネア、ジャック・G・コスティン 雑誌は1912年12月に印刷を中止したが、当時のルーマニア文学の形成に重要な役割を果たした。文学史家のポール・チェルナットは、『シンボルル』を ルーマニアのモダニズムの主要な舞台と見なし、象徴主義から急進的前衛への最初の変化をもたらしたと評価している。[17] またチェルナットによると、サミロ、ヴィネア、ジャンコの共同作業は、文学が 「芸術のインターフェース」となるというもので、同時代の同等のものとしては、イゼルとイオン・ミヌレスクやトゥドール・アルゲージといった作家とのコラ ボレーションが挙げられる。[18] マニウはグループを離れ、伝統主義の信条により近いスタイルの変化を求めたが、ツァラ、ジャンコ、ヴィネアは共同作業を続けた。1913年から1915年 の間、彼らは黒海沿岸やヴァスルイ県のガルチェニにあるローゼンストック家の土地で、しばしば一緒に休暇を過ごした。この間、ヴィネアとサミロは、互いに 影響を受けながら、類似したテーマの詩を書いた。[19] 「Chemarea」と1915年の旅立ち ツァラのキャリアは、第一次世界大戦にルーマニア王国が参戦しなかった1914年から1916年の間に方向転換した。1915年秋、ヴィネアは短命に終 わった雑誌『Chemarea』の創刊者兼編集者として、友人の詩を2編発表した。この2編は、トリスタン・ツァラの署名が掲載された最初の印刷物であっ た。[20] 当時、若い詩人とその友人の多くは、 反戦・反国家主義の潮流を支持し、反体制的なメッセージを徐々に広めていった。[21] この運動のプラットフォームであった『Chemarea』は、チャピエールとのコラボレーションを再び呼び込み、ツァラとヴィネアによって資金提供されて いた可能性もある。[12] ルーマニアの前衛作家クロード・スネルによると、この雑誌は「それ以前にルーマニアで出版されたものとは全く異なっていた」という。[22] この時期、ツァラの作品は、ヘフテル=イダルゴの『Versuri și Proză』に断続的に掲載され、1915年6月にはコンスタンティン・ラドゥレスク=モトルの『Noua Revistă Română』にサミロの有名な詩「Verișoară, fată de pension(寄宿学校に通う少女、いとこ)」が掲載された。 ツァラは1914年にブカレスト大学に入学し、数学と哲学を学んでいたが、卒業はしていない。[9][23] 1915年秋、彼はルーマニアを離れ、中立国スイスにあるチューリッヒへと向かった。ジャンコは、弟のジュール・ジャンコとともに数ヶ月前にそこに定住し ており、後に他の弟のジョルジュ・ジャンコも合流した。[24] ツァラは地元の大学の哲学部に願書を提出した可能性があるが、[9][25] チューリッヒ工科大学の学生であったマルセル・ジャンコと宿舎を共有していた。アルティンガー・ゲストハウス(Altinger Guest House)に滞在していた。(1918年までにツァラはリマットクアイ・ホテル(Limmatquai Hotel)に移っている。)[27] ルーマニアからの出国は、ジャンコ兄弟の場合と同様に、平和主義的な政治的声明であった可能性もある。[28] スイスに落ち着いた後、若い詩人はルーマニア語をほぼ完全に捨て去り 表現言語としてほとんど使わなくなり、その後の作品のほとんどをフランス語で書いた。[23][29] それ以前に書いた詩は、友人との詩の対話の成果であり、ヴィーネアに託された。[30] これらの作品のほとんどは、戦間期になって初めて印刷された。[23][31] チューリッヒで、ルーマニア人グループはドイツ人の詩人でピアニストのヒューゴ・ボールと、彼の若い妻でミュージックホールのパフォーマーであるエミー・ ヘニングスと出会った。1916年2月、Ballはキャバレー・ヴォルテールをオーナーのJan Ephraimから借り受け、パフォーマンスアートや展示の会場として使用するつもりであった。[32] Hugo Ballはこの時期を記録しており、TzaraとMarcel JancoがHans Arp、Arthur Segal、Otto van Rees、Max Oppenheimerらとともに 「キャバレーへの参加を快諾した」と記録している。[33] ボールによると、さまざまな民族のフォークロアを模倣したり、そこから着想を得た歌のパフォーマンスの中で、「ツァラ氏はルーマニアの詩を朗読した」とい う。[34] 3月下旬、ボールは、このグループに ドイツ人作家でドラマーのRichard Huelsenbeckが加わった。[33] 彼は間もなくツァラの「同時詩」パフォーマンスに参加した。これは「チューリッヒで、そして世界で初めて」のもので、キュビズムの推進者である Fernand DivoireとHenri Barzunの詩の朗読も含まれていた。 ダダの誕生  ダダの誕生を記念するキャバレー・ヴォルテール内のプレート このような環境の中で、1916年5月以前のある時点で、同名の出版物として初めて印刷されたダダが誕生した。ダダイズムの誕生については、ツァラと彼の 仲間たちとの間で意見の相違があった。セルナットは、最初のダダイストのパフォーマンスは早くも2月に行われたと信じており、19歳のツァラがモノクルを かけ、感傷的なメロディーを歌いながらキャバレー・ヴォルテールのステージに登場し、「スキャンダルに酔いしれる観客」たちに紙塊を渡し、 仮面をつけた長身の俳優たちに場所を譲り、道化の衣装を身にまとって戻ってきた。[36] 同じようなパフォーマンスは、キャバレー・ヴォルテールが閉鎖に追い込まれた後、1916年夏からツンフトハウス・ツァ・ヴァークでも行われた。[37] 音楽史家のベルナール・ジェンドロンによると、キャバレー・ヴォルテールが存続していた限り、「キャバレー・ヴォルテールはダダイズムだった。純粋な」ダ ダを単なる付随物から切り離すことのできる代替の機関や場所は存在せず、またそのような場所が望まれることもなかった」[38] 他の意見では、ダダの始まりはもっと以前の出来事、アルフレッド・ジャリ、アンドレ・ジイド、クリスチャン・モルゲンシュテルン、ジャン=ピエール・ブリ セ、ギヨーム・アポリネール、ジャック・ヴァシェ、マルセル・デュシャン、フランシス・ピカビアらの実験と関連づけている。 運動の最初の宣言文で、ボールは次のように書いている。「この小冊子は、戦争や国家主義の障壁を越えて、他の理想のために生きる少数の独立した精神に注目 を集めることを唯一の目的とするキャバレー・ヴォルテールの活動と関心を一般の人々に紹介することを意図している。次に、ここに集まった芸術家たちが目指 すのは、国際的な雑誌(仏語で「国際誌」)を発行することである。」[40] ボールはメッセージをフランス語で書き上げ、その段落は次のように訳される。「雑誌はチューリッヒで発行され、その名は『ダダ』(『Dada』)とする。 ダダ、ダダ、ダダ、ダダ」[40] バルがこの運動を創始したという見解は、作家のヴァルター・ゼルンが特に支持しており、ツァラがバルのイニシアティブを悪用したと直接非難した。[41] ダダイズムの創始者たちの間で論争となったもう一つの論点は、この運動の名称の生みの親が誰であるかという点であった。視覚芸術家でありエッセイストでも あったハンス・リヒターによると、この名称が最初に印刷物で使用されたのは1916年6月であったという。[42] ボールは、この名称の生みの親であると主張し、辞書からランダムに選んだと述べたが、 それはフランス語の「hobby horse」と、揺りかごで眠る子供の喜びを表すドイツ語の用語の両方を意味していると述べた。[43] ツァラ自身はこの件に関心を示さなかったが、マルセル・ヤンコは彼がこの用語を造語したと主張した。[44] ツァラが単独で、または共同執筆したダダイズム宣言では、 ツァラが単独または共同で執筆したダダイズム宣言では、この名称は、西アフリカのクルー諸語で神聖な牛の尾を意味する語、特定のイタリア方言における「母 親」を意味する玩具や名称、ルーマニア語やスラブ諸語における二重の肯定語など、さまざまな他の用語と形態を共有していることが記録されている。 ダダイストのプロモーター ツァラは、終戦前にダダイズムの主要なプロモーター兼マネージャーとしての地位を確立し、スイスのグループが他のヨーロッパ諸国に支部を設立するのを支援 した。[25][46] この時期には、グループ内での最初の対立も生じた。ツァラとの相容れない相違を理由に、ボールはグループを去った。[47] 彼の離脱により、ジェンドロンは、ツァラはダダイズムのボードビル的なパフォーマンスを「扇動的でありながら、冗談めかして挑発的な演劇」へと発展させる ことができたと主張している。[48] 彼は、スイス国外の多くの若いモダニズム作家たちにグループへの参加を促した人物としてよく知られており、特にフランス人のルイ・アラゴン、アンドレ・ブ ルトン、ポール・エリュアール、ジョルジュ・リブモン=デサイーニュ、フィリップ・スーポーが挙げられる。[4][49] 同じくこの時期にダダと接触したリヒターは、ルーマニア人作家に接触される前、これらの知識人たちは「この新しい運動に対して非常にクールで距離を置いた 態度」を取っていたと指摘している。[ 1916年6月、彼は短命に終わった雑誌『キャバレー・ヴォルテール』の後継誌として、定期刊行物『ダダ』の編集と管理を始めた。リヒターは、この仕事に 対する「エネルギー、情熱、才能」を称賛し、それがすべてのダダイストを満足させたとしている。[50] 彼は当時、ルドルフ・ラバンの生徒であったマヤ・クルシェツキの恋人であった。リヒターの説明によると、2人の関係は常に不安定であった。[51] 1916年には早くも、トリスタン・ツァラはイタリア未来派から距離を置き、その指導者であったフィリッポ・トマーゾ・マリネッティの軍国主義的でファシ ズムの先駆的な姿勢を拒絶した。[52] リヒターは、ダダがその影響力を拡大し続けながら、当時すでに未来派に取って代わってモダニズムのリーダーとなっていたことを指摘している。「我々は未来 派を骨も羽も残さず飲み込んでしまった。消化の過程で、骨や羽根のすべてが吐き出されたのは事実である。」[49] このような経緯があり、またダダがイタリアで成功を収めることはなかったにもかかわらず、ツァラは詩人のジュゼッペ・ウンガレッティやアルベルト・サ ヴィーニオ、画家のジーノ・カンタレッリやアルド・フィオッツィ、 また、少数の他のイタリア未来派の芸術家たちもダダイストの仲間となった。[53] ダダイストのマニフェストを支持し、ダダイストグループに合流したイタリア人作家の中には、詩人であり画家であり、後にファシストの民族理論家となった ジュリオ・エヴォラがおり、彼はツァラの個人的な友人となった。[54] 翌年、ツァラとボールはギャラリー・ダダの常設展示を開始し、そこでイタリアの独立系視覚芸術家ジョルジョ・デ・キリコやドイツ表現主義の雑誌『デア・ シュトゥルム』と接触した。彼らはみな「ダダイズムの父」と称された。[55] 同じ時期、おそらくツァラの介入により、ダダイストたちは 「ダダイズム演劇」の例として宣伝した、オーストリア=ハンガリー表現主義のオスカー・ココシュカによる人形劇『スフィンクスとストローマン』の公演を企 画した。[56] また、彼はフランスの詩人ピエール・レヴェルディの雑誌『Nord-Sud』とも交流があり(レヴェルディはあらゆる前衛的傾向の統合を目指していた)、 [4] Nord-Sudとピエール・アルベール・ビロのSIC誌の両方にアフリカ美術に関する記事を寄稿した。[57] 1918年初頭、チューリッヒ・ダダイストたちはヒュルゼンベックを通じて、ドイツ帝国のより明確な左翼の弟子たちと接触した。ジョージ・グロス、ジョ ン・ハートフィールド、ヨハネス・バーダー、クルト・シュヴィッタース、ヴァルター・メーリング、ラウル・ハウスマン、カール・アインシュタイン 、フランツ・ユング、ハートフィールドの弟ヴィーラント・ヘルツォルフェなどと接触した。[58] ツァラはブルトン、スーポー、アラゴンとともにケルンを訪れ、シュヴィッタースとマックス・エルンストの精巧なコラージュ作品に親しんだ。そして、その作 品をスイスにいる同僚たちに見せた。[59] しかし、フュルステンベックはシュヴィッタースのベルリン・ダダへの参加を拒否した。[60] ツァラは、自身のキャンペーン活動の結果、ヨーロッパのさまざまな地域を代表する、いわゆる「ダダイズムの指導者」のリストを作成した。ハンス・リヒター によると、このリストにはツァラのほか、エルンスト、アルプ、バーダー、ブルトン、アラゴンからクルシェク、エボラ、ラファエル・ラッソ・デ・ラ・ベガ、 イーゴリ・ストラヴィンスキー、ビセンテ・ウイドボロ、フランチェスコ・メリアーノ、テオドール・フラエンケルまで、さまざまな人物が含まれていたとい う。「ここに挙げられたすべての人物が、この説明に同意するかどうかはわからない」とリヒターは述べている。 第一次世界大戦の終結 チューリッヒでツァラが企画したショーはしばしばスキャンダルや暴動に発展し、彼はスイスの法執行機関と常に衝突していた。ハンス・リヒターは「ブルジョ ワをからかう喜び」について語っており、トリスタン・ツァラの場合は、冷たく(あるいは熱く)計算された無礼という形を取っていた(『ブルジョワを驚かせ る』を参照)。 4] あるとき、ダダイストたちが既存の作家たちをあざける一連のイベントの一環として、ツァラとアルプは、チューリッヒ近郊のレハルプで決闘を行うつもりであ り、人気小説家のヤコブ・クリストフ・ヘールを証人に立てるつもりであると偽って公表した。[65] リヒターはまた、ルーマニア人の同僚が スイスの中立性を悪用して連合国と中央同盟国を互いに争わせ、両者から美術品や資金を入手し、それぞれのプロパガンダ活動を活発化させる必要性をうまく利 用したとリヒターは報告している。[66] プロモーターとして活動する一方で、ツァラは最初の詩集『25の詩』(1918年)も出版した。[67] 1918年秋には、当時『391』誌の発行者であり、ダダイズムと遠くない関係にあったフランシス・ピカビアがチューリッヒを訪れ、芸術と理性に対する彼 のニヒルな見解を同僚たちに紹介した。ニューヨークを拠点とするこのグループは、ツァラとの提携を模索し始めたのは1921年になってからで、冗談半分に 「Dada」という名称を自分たちの名前として使用する許可を求めた(これに対してツァラは「Dadaはみんなのものだ」と答えた)[69]。リヒター は、この訪問がルーマニア人作家の地位向上につながったと評価しているが、同時に ツァラ自身が「芸術と反芸術のバランスを保っていた立場から、突如として純粋で喜びに満ちた無の境地へと移行した」とリヒターは述べている。[70] その後、この運動はスイスで最後の主要な展覧会を企画し、ザール・ツア・カウフレウテルンで開催された。この展覧会では、スザンヌ・ペロテ、ソフィー・ト イバー=アルプが振り付けを担当し、ケーテ・ウルフ、ハンス・ ヘルツァー、ツァラ、ハンス・リヒター、そしてヴァルター・ゼルンが参加した。[71] そこで、ゼルンは1918年のエッセイを朗読した。そのタイトルは『最後の弛緩(ファイナル・ディソリューション)』であった。この部分が原因で、観客が パフォーマーを攻撃し、ショーを中断させることに成功したが、中止させることはできなかった。[72] 1918年11月のドイツとの休戦協定に続いて、ダダの進化は政治的な展開によって特徴づけられた。1919年10月、ツァラ、アルプ、オットー・フレー クは、国境が再び行き来できるようになった戦後の世界でダダをさらに普及させることを目的とした雑誌『Der Zeltweg』の発行を開始した。[73] リヒターは、この雑誌は「かなりおとなしい」と認めているが、ツァラと彼の同僚たちは 共産主義革命、特に1918年の十月革命とドイツの反乱が「人々の心を揺さぶり、人々の関心を分断し、エネルギーを政治的変化の方向にそらした」ことの影 響に対処していたと指摘している。[73] しかし、同じ評論家は、読者が 『ツェルトヴェーク』が「革命的な芸術家の集まり」であると信じ込ませたという説を退けている。[73] 歴史家のロバート・レヴィーによる説明によると、ツァラはルーマニアの共産主義学生グループと交流があり、後にルーマニア共産党の最も著名な活動家の一人 となるアナ・パウカーと会った可能性がある。[74] アルプとヤンコは、1919年頃に運動から離れていった。1919年頃、構成主義に影響を受けたワークショップ「Das Neue Leben」を創設したためである。[75] ルーマニアでは、ツァラの元仲間であるヴィネアはダダに対して曖昧な反応を示した。ヴィネアはダダの目標に共感し、ヒューゴ・ボールやヘニングスを尊敬 し、自身の著作をダダの要求に合わせることを約束したが、ヴィネアはツァラとジャンコたちに明晰性を求めた。[76] ヴィネアが詩「D ツァラとその仲間たちに出版を依頼したところ、断られた。この事件は、作品の控えめなトーンとダダの革命的な主義との対照に起因するものだと批評家は考え ている。 1920年代のパリ・ダダの  メンバー(右から2番目がツァラ)、マーガレット・C・アンダーソン、ジェーン・ヒープ、ジョン・ロドカーと。  1920年代のフランスのナショナリスト新聞『L'Action Française』を読むツァラ。シャルメ文書館所蔵。 1919年の終わり頃、トリスタン・ツァラはスイスを離れ、ブルトン、スーポー、クロード・リヴィエールとともにパリを拠点とする雑誌『リテレール』の編 集に加わった。[25][78] すでにフランス前衛派の指導者であった彼は、ハンス・リヒターによると、「反救世主」であり「預言者」として認識されていた。[79] 伝えられるところによると、ダダイズムの神話では、 彼は雪のように白い、あるいはライラック色の車でフランス首都に入り、ラスパイユ大通りの自身のパンフレットでできた凱旋門を通り、歓声と花火で迎えられ たというダダイズムの神話がある。[79] リヒターは、この説明を否定し、ツァラは実際には誰も彼が来るとは思っていなかったにもかかわらず、東駅(Gare de l'Est)からピカビアの家まで歩いたと指摘している。[79] 彼はリテレクションの中心人物とみなされることが多く、ダダイズムの芸術的原則をより強固に定着させた功績を認められている。[25][80] ピカビアがパリで391の新しいシリーズの出版を始めたとき、ツァラは彼を支持し、リヒターによると、雑誌の各号を「ダダイズムのあらゆる色で飾り立て た」という。[57] 彼はまた、ダダイズムの雑誌も発行していた 雑誌を発行しており、パリで印刷されていたが、同じフォーマットを使用し、タイトルを『ダダ通信』、後に『ダダフォン』と改名した。[81] ほぼ同時期に、彼はアメリカの作家ガートルード・スタインと出会い、彼女は『アリス・B・トクラスの自伝』の中で彼について書いた。[82] また、芸術家夫婦のロベールとソニア・ドローネー(彼らは「詩のドレス」やその他の同時進行主義の文学作品で共同作業を行った)とも知り合った。[83] ツァラはダダの実験に数多く関わり、ブルトン、アラゴン、スーポー、ピカビア、ポール・エリュアールらと協力した。[4][84][85] その段階でダダと接触した他の作家には、ジャン・コクトー、ポール・デルメー、レイモン・ラディゲなどがいる。[86] ダダが上演したパフォーマンスは、しばしば その主義を広めることを目的としたものであり、ダダイストたちはハリウッド映画スターのチャールズ・チャップリンがダダのショーに登場すると発表したり [48]、メンバーたちがステージ上で丸刈りにされる、あるいは髪を切られると発表したりするなど、デマや虚偽の広告によって注目を集め続けた[87]。 また、ツァラと仲間たちは 一般大衆大学で産業労働者の前で講義を行ったが、労働者たちはあまり感銘を受けなかったと伝えられている。[88] リヒターは、イデオロギー的には、ツァラはピカビアのニヒルで無政府的な見解(ダダイストがすべての政治的・文化的イデオロギーを攻撃する理由となった) に依然として敬意を表していたが、それは労働者階級に対するある程度の共感を意味していたと考えている。[88] パリのダダイストたちの活動は、1920年3月にテアトル・ド・ロップで行われたバラエティショーで頂点に達した。このショーでは、ブルトン、ピカビア、 デルメー、ツァラの初期の作品『アンチピリン氏の最初の天体冒険』の朗読が行われた。[89] ツァラのメロディ『ヴァセリン交響曲』では、 10人から20人が「クラ」「クリ」と叫びながら音程を上げていく「ヴァセリン交響曲(Vaseline symphonique)」も演奏された。[90] ピカビアの「人食い人種宣言(Manifeste cannibale)」をブルトンが朗読し、聴衆を攻撃し嘲笑したことでスキャンダルが勃発し、聴衆は腐った果物を舞台に投げつけた。[91] ルーマニアでダダイズムが注目されるようになったのは1920年になってからで、その全体的な評価は否定的なものであった。伝統主義者の歴史家ニコラエ・ ヨルガ、象徴主義の推進者オヴィディウス・デスヌシアヌ、より控えめなモダニストのカミル・プレスクとベンジャミン・フォンダネは、ダダイズムを芸術的表 現として正当に評価することは拒否した。[92] ヴィネアは伝統に忠実でありながらも、より深刻な批判を前にしては破壊的な潮流を擁護し、ツァラが戦時中に中央同盟国の影響力を行使していたという広範に 流布した噂を否定した 。『スブラトルル』の編集者で、ヴィネアのモダニズムのライバルの一人であったオイゲン・ロヴィネスクは、ツァラが若い前衛作家たちに与えた影響を認めた が、彼の作品を分析したのはダダイズム以前の詩を一例として挙げただけで、文学的「過激主義」の提唱者として描いたに過ぎなかった。 ダダイズムの停滞  サン・ジュリアン・ル・ポーヴル、1921年の「ダダイズム遠足」の開催地 1921年までに、ツァラはダダイズム運動の他の人物たちと対立するようになっていた。ツァラは、彼らをダダイズムの精神から離れてしまったと主張してい た。[95] 彼はベルリンを拠点とするダダイストたち、特にヒュルゼンベックとザーナーに狙われていた。ヒュルゼンベックは、指導的地位を巡ってラウル・ハウスマンと も対立していた 。リヒターによると、ブルトンとツァラの間の緊張は1920年に表面化し、ブルトンが初めて音楽パフォーマンスを完全に廃止したいという希望を明らかに し、ルーマニア人が単に同じことを繰り返しているだけだと主張した。 さらに深刻な危機は5月に起こった。ダダイストたちは、初期に象徴主義者たちと関わりを持っていたものの、反ユダヤ主義と反動的な姿勢がその評価を損ねて いたモーリス・バレスの模擬裁判を行った。ジョルジュ・リボーモン=デセーニュが検察官、アラゴンとスーポーが弁護人、ツァラ、ウンガレッティ、ベンジャ ミン・ペレ、その他の証人(マネキンがバレスの代わりを務めた)が出席した。[97] ペレは、この裁判を馬鹿げたものにしないよう、また、 しかし、その政治的な含意については、ブルトンも同意していた。[98] 6月、ツァラがかつての師が急進的になりすぎているという意見を述べたことで、ツァラとピカビアは衝突した。[99] 同じ時期、ブルトン、アルプ、エルンスト、マーヤ・クルシェック、ツァラはオーストリアのインストに滞在し、 彼らはグループとしての最後のマニフェスト『Dada au grand air(「戸外におけるダダ」)または『Der Sängerkrieg in Tirol(「チロルの歌合戦」)』を発表した。[100] ツァラはチェコスロバキアも訪れ、そこで自身の主義への支持者を獲得しようとしたと伝えられている。[101] また、1921年には、イオン・ヴィネアがルーマニアの新聞『アデヴァル』に、ダダイズム運動はすでにその力を尽くしたと主張する記事を書いた(ただし、 ツァラに宛てた手紙では、彼は友人に対して、故郷に戻ってそこで自身のメッセージを広めるよう、引き続き呼びかけた)。[102] 1922年7月以降、マルセル・ヤンコは ツァラの初期の詩をいくつか掲載したが、ダダイストのマニフェストを掲載することはなかった。[103] 伝えられるところによると、ツァラとジャンコの対立には個人的な背景があった。ジャンコは後に、同僚との「劇的な口論」について言及している。[104] 彼らは その後生涯にわたって互いを避け、ツァラは初期の詩からヤンコへの献辞を削除したほどであった。[105] ジュリオ・エヴォラもまた、運動が伝統を完全に拒絶していることに失望し、代替となるものを個人的に探し始め、後に秘教とファシズムへとつながる道を歩み 始めた。[54] 髭の心臓の夜  テオ・ファン・ドースブルフによるダダイズムの夜会のポスター(1923年頃) ツァラは1922年2月のル・ジュルナル・ド・ピュプル誌の記事でブルトンから公然と攻撃された。ルーマニア人作家は「宣伝」に熱心な「詐欺師」と非難さ れた。[106] 3月にはブルトンが「現代精神の決定と防衛のための会議」を始めた。フランスの作家は、この機会を利用して、ダダイストの中からツァラの名前を除外し、ダ ダイストのヒュルゼンベック、ザーナー、クリスチャン・シャドを支持した。[107] ブルトンは、ヒュルゼンベックが書いたとされるメモに基づいて、ツァラを日和見主義者であると非難し、 政治舞台のアクターたちを動揺させないようにダダイズムの作品の戦時中の版を計画し、最高戦争評議会が管轄する国々ではドイツのダダイストの作品が一般に 公開されないようにしたと主張した。[107] ツァラは、この会議を妨害する目的で出席しただけであったが、[108] 同月、ツァラは非難に対して、ヒュルゼンベックのメモは捏造であり、シャドは本来のダダイストの一人ではなかったと反論した。[107] アメリカの作家ブライオン・ギシンがかなり後に伝えた噂によると、ブルトンの主張はツァラを警察庁の情報提供者として描いていたという。[109] 1922年5月、ダダは自分たちの葬儀を行った。ハンス・リヒターによると、その葬儀の主な部分はワイマールで行われ、ダダイストたちはバウハウス美術学 校の祭典に出席した。その際、ツァラは自身の芸術の捉えどころのない性質を宣言した。「ダダは役に立たない。人生における他のあらゆるものと同じよう に。... ダダは、理性が言葉や慣習で満たすことができなかったあらゆる空間へと、空気の如く執拗に浸透する処女微生物である」[111] 「髭の心臓」宣言では、多くの芸術家たちがブルトンを疎外しツァラを支持した。 コクトー、アルプ、リブモン=デザンジュ、エリュアールらツァラ派には、エリック・サティ、テオ・ファン・ドースブルフ、セルゲイ・シャルチューン、ル イ・フェルディナン・セリーヌ、マルセル・デュシャン、オシップ・ザッキン、ジャン・メッツィンガー、イリヤ・ザダネヴィッチ、マン・レイらがいた 、マン・レイなどがいた。[112] 1923年7月6日に始まった関連イベント「髭の心臓の夕べ」で、ツァラは、2年前に観客の嘲笑を浴びて初演された自身の戯曲『ガス・ハート』の再演を 行った。ソニア・ドローネーが衣装をデザインした。[83] ブルトンは公演を中断し、かつての仲間数人と喧嘩し、家具を壊したと伝えられている。これにより劇場での暴動が起こり、警察が介入してようやく収まった。 [113] ダダイズムのボードビルはその後、重要性を失い、完全に消滅した。[114] ピカビアはツァラに対してブルトンの味方につき、[115] 391のスタッフを入れ替え、クレマン・パンセールやエズラ・パウンドと協力した。[116] ブルトンは1924年に最初のシュールレアリスム宣言を発表し、ダダイズムの終焉を宣言した。リヒターは「シュールレアリスムはダダイズムを吸収し消化し た」と示唆している[110]。ツァラは新しい潮流から距離を置き、その手法に反対し、次第にその政治にも反対するようになった[25][67][84] [117]。1923年、 ツァラはリヒターや構成主義の芸術家エル・リシツキーらと協力し、雑誌『G』を制作した。[118] 翌年には、彼はユーゴスラビア・スロベニアの雑誌『タンク』(編集:フェルディナンド・デラック)に寄稿した。[119] シュールレアリスムへの移行  アドルフ・ロース設計のツァラ邸 ツァラは執筆活動を続け、演劇にもより真剣な関心を寄せるようになった。1924年には『雲のハンカチ』という戯曲を出版し、上演した。この作品はすぐに セルゲイ・ディアギレフ率いるロシア・バレエ・リュスのレパートリーに加えられた。[120] また、それ以前のダダイズムのテキストを『ダダイズム7つの宣言』としてまとめた。マルクス主義思想家のアンリ・ルフェーヴルは、この作品を熱狂的に評価 し、後にツァラの友人となった。[121] ルーマニアでは、ツァラの作品は『コンティンポラヌル』誌によって部分的に再評価された。同誌は1924年に主催した国際美術展でツァラの作品の朗読会を 催し、1925年の「新しい芸術のデモンストレーション」でも再び朗読会を行った。[122] 並行して、イラリエ・ヴォロンカとイオン・カルガルが中心となって短期間発行されていた雑誌『インテグラル』は、 、ツァラの作品に大きな関心を寄せていた。[123] 1927年の同誌とのインタビューで、彼はシュールレアリスムグループの共産主義の採用に反対の意を表明し、そのような政治は「新しいブルジョワ階級」を 生み出す結果にしかならないと指摘し、また「自我の神聖さ」を維持する個人的な「永遠の革命」を選んだと説明した。[124] 1925年、トリスタン・ツァラはストックホルムに滞在し、グレタ・クヌーソンと結婚した。彼女との間に息子のクリストフ(1927年生まれ)がいる。 [4] 画家のアンドレ・ロート(André Lhote)の元生徒であったグレタは、現象学と抽象芸術への関心で知られていた。[125] 。ほぼ同時期、クヌッソンが相続した財産を資金源として、ツァラはチューリッヒで知り合ったウィーン分離派の元代表者であるオーストリア人建築家アドル フ・ロースに、パリの自宅の建築を依頼した。モンマルトルに建てられた厳格な機能主義建築の「メゾン・トリスタン・ツァラ」は、ツァラの特別な要望に従っ て設計され、アフリカ美術のサンプルで装飾された。 1929年、彼はブルトンと和解し、パリで時折開催されるシュールレアリストの会合に出席するようになった。[67][84] 同年、詩集『De nos oiseaux(我らの鳥)』を出版した。[67] この時期には、『The Approximate Man(おおよその人間)』(1931年)のほか、『L'Arbre des voyageurs(旅人の樹)』(1 1932年)『狼が飲むところ』(1932年)、『アンティテート』(1933年)、『粒と問題』(1935年)が出版された。[84] その頃、ツァラが脚本の執筆を始めたことも発表された。[126] 1930年、彼は ブルトンや他の主要なシュルレアリストたちが出演する『髭のある心臓』の映画版を監督・制作した。[127] 5年後、彼はユージン・ジョラスが発行する雑誌『transition』に掲載された、スタインの回顧録『アリス・B・トクラスの自伝』への返答として 『ガートルード・スタインに対する証言』に署名し、かつての友人を誇大妄想狂であると非難した。[128] 詩人はシュルレアリスムの技法をさらに発展させ、ブルトンとヴァランティーヌ・ユゴーとともに「絶妙な死体」のよく知られた例のひとつを描いた。 [129] ツァラは1934年に友人ルネ・シャールのシュルレアリスム詩集の序文を書き、翌年にはグレタ・ガットソンとともにシャールを訪ねた。 ツァラの妻もほぼ同時期にシュルレアリスムのグループと関わりを持っていた。[4][125] この関係は、彼女が1930年代後半にツァラと別れたときに終わった。[4][125] ツァラの作品は、自宅で収集・編集された。シュールレアリスムの推進者サシャ・パナがツァラと数年にわたって文通し、1934年に最初の版が印刷された。 この版には、ツァラがヴィネアに預けていた1913年から1915年の詩が収録されていた [30] 1928年から1929年にかけて、ツァラは友人で『コンティンポラヌル』の関係者であったジャック・G・コスティンと手紙のやりとりをした。コスティン はヴィーニャの文学観のすべてに賛同していたわけではなかったが、ルーマニア訪問の手配を申し出て、ツァラの作品をフランス語に翻訳するよう依頼した。 共産主義とスペイン内戦との関わり アドルフ・ヒトラーのナチス政権樹立に危機感を覚え、それはベルリンの前衛芸術の終焉をも意味していたため、彼は芸術プロモーターとしての活動を反ファシ ズム運動と融合させ、フランス共産党(PCF)と親交を深めた。1936年、リヒターは、クルト・シュヴィッタースがハノーファーで密かに撮影した写真シ リーズを出版した。その作品には、地元住民によるナチス・プロパガンダの破壊、配給切手の食料の減量、ヒトラーの支配の隠された側面などが記録されてい た。[133]スペイン内戦勃発後、彼はフランスを一時離れ、共和軍に参加した。[84][134 ソビエト連邦の記者イリヤ・エレンブルクとともにツァラは、ナショナリストに包囲されていたマドリードを訪問した(マドリード包囲戦を参照)。[135] 帰国後、詩集『Midis gagnés(征服された南の地域)』を出版した。[84] そのうちのいくつかは、以前にパンフレット『Les poètes du monde défendent le peuple espagnol(世界の詩人たちはスペイン国民を守る)』に掲載されていた。1937年)は、著名な作家であり活動家でもあったナンシー・クナールとチ リの詩人パブロ・ネルーダの2人によって編集されていた。ツァラは、1937年6月のクナールによるフランシスコ・フランコに対する介入要請にも署名して いた。[137] 伝えられるところによると、ツァラとナンシー・クナールは恋愛関係にあったという。[138] 詩人はシュールレアリスムから離れていたが[67]、厳格なマルクス・レーニン主義への固執は、フランス共産党とソビエト連邦の両方から疑問視されていた と伝えられている[139]。記号論学者フィリップ・ベッチマンは、彼らの態度をツァラ自身のユートピア像と関連づけている 共産主義のメッセージとフロイト・マルクス主義精神分析を組み合わせ、特に暴力的なイメージを用いたツァラ自身のユートピアのビジョンと関連づけている。 伝えられるところによると、ツァラは党の路線を支持するよう勧誘されることを拒み、独立性を維持し、公の集会で前面に出ることを拒んだという。 しかし、他の人々は、元ダダイストのリーダーはしばしば政治的指針の信奉者であることを示していたと指摘している。1934年には早くも、ツァラはブルト ン、エリュアール、共産主義者の作家ルネ・クレヴェルとともに、ヒトラーの熱烈な崇拝者であったと告白していた、独立心の強いシュールレアリストのサルバ ドール・ダリの非公式な裁判を組織した。ウィリアム・テルの肖像画が、 。歴史家のイリーナ・リヴゼアヌは、スターリン主義に賛成しトロツキズムを避けていたツァラが、1935年の作家会議において、友人のクレーヴェルが社会 主義リアリズムの採用に抗議して自殺したにもかかわらず、PCFの文化的要求を受け入れたと指摘している 。後年、リヴゼアヌはツァラがダダイズムとシュールレアリスムを革命的な潮流として再解釈し、それを公衆に提示したと指摘している。 第二次世界大戦とレジスタンス 第二次世界大戦中、ツァラはドイツ占領軍から逃れ、ヴィシー政権が支配する南部地域へと移った。[4][84] ある時、反ユダヤ主義と協力主義の出版物『Je Suis Partout』がゲシュタポにツァラの居場所を知らせた。[145] 蔵書とアフリカ美術のコレクションを安全な場所に確保したツァラは、1940年に南仏へ逃亡し、まずサナリという村に身を隠し、その後警察に追われてサン =トロペに身を寄せた。1941年には逮捕されたが、警察官の寛大さにより脱出に成功した。ツァラはフランス抵抗運動に参加し、マキに合流した。レジスタ ンスが発行する雑誌に寄稿したツァラは、自由フランス軍の秘密ラジオ局の文化放送も担当した。[4][84] 彼はエクス=アン=プロヴァンス、そしてスーリヤックに住み、最終的にはトゥールーズに住んだ。[4] 息子のクリストフは当時、フランスの北部でレジスタンスとして活動しており、フラン・ティレール・エ・パルティザンに参加していた。[145] 5]枢軸国側で反ユダヤ主義のルーマニア(第二次世界大戦中のルーマニアを参照)では、イオン・アントネスク政権がツァラと他の44人のユダヤ系ルーマニ ア人作家の作品を販売しないよう書店に命じた。[147]1942年、反ユダヤ主義政策が一般化すると、ツァラはルーマニアの市民権も剥奪された。 [148] 1944年12月、パリ解放から5か月後、彼は哲学者ジャン=ポール・サルトルが編集する親共産主義の新聞『エテルネル・ルヴュ』に寄稿していた。サルト ルは、この新聞を通じて、ドイツの支配を受動的に受け入れたという認識とは対照的に、抵抗で団結したフランスの英雄的なイメージを宣伝していた ドイツの支配を受動的に受け入れたという認識に反対する形で、抵抗に団結したフランスの英雄的なイメージを広めていた。[149] 他の寄稿者には、作家のアラゴン、シャル、エリュアール、エルザ・トリオレ、ユージン・ユイヴィック、レイモン・クノー、フランシス・ポンジュ、ジャッ ク・プレヴェール、画家のパブロ・ピカソなどがいた。[149] 戦争が終わり、フランスの独立が回復すると、ツァラはフランスに帰化された。[84] 1945年、フランス共和国臨時政府のもと、彼は国民議会における南西地域圏の代表となった。[135] リヴェゼアヌによると、彼は「ヴィシー政権(フランス)と関係を持った文化人たちから南を奪還するのに貢献した」という。 [143] 1946年4月には、彼の初期の詩が、ブルトン、エリュアール、アラゴン、ダリなどの同時代の詩人たちの作品とともに、パリのラジオ局で深夜放送のテーマ となった。[150] 1947年には、彼はフランス共産党(PCF)の正式党員となった。[67](一部の情報源によると、1934年から党員であったという説もある。) [84] 国際左翼 その後10年間、ツァラは政治的な大義に支援の手を差し伸べた。プリミティヴィスムへの関心を追求し、第四共和制の植民地政策の批判者となり、非植民地化 を支持する人々の声に加わった。[141] それにもかかわらず、彼はポール・ラマディエ内閣によって共和国の文化大使に任命された。[151] また、PCFが主催する作家会議にも参加したが、エリュアールやアラゴンとは異なり、社会主義リアリズムに自身のスタイルを適応させることは再び避けた。 [145] 彼は1946年末から1947年初頭にかけて公式訪問でルーマニアに戻ったが、[152][153] その際には、勃興しつつあった東側諸国を歴訪する一環として、チェコスロバキア、ハンガリー、ユーゴスラビア連邦人民共和国にも立ち寄った。[153] 彼とサシャ・パナが ツァラと若いルーマニアの前衛芸術家たち(ヴィクトル・ブラウネルやゲラシム・ルカなど)との間に亀裂を生じさせた。ルカは 共産主義を拒絶し、ヨーロッパに鉄のカーテンが敷かれたことに警戒感を抱いていた)[154]同年9月、彼は親共産主義の国際学生連盟の会議に出席した (フランスを拠点とする共産主義学生同盟の招待客として出席し、ルーマニアやその他の国々の同様の組織と会合した)[155] 1949年から1950年にかけて、ツァラはアラゴンの呼びかけに応え、トルコの詩人ナズィム・ヒクメトの解放を求める国際キャンペーンに積極的に参加し た。ヒクメトは1938年に共産主義活動により逮捕され、親ソ連派の世論にセンセーションを巻き起こした人物である。[156][157] ツァラはナズィム・ヒクメト解放委員会の委員長を務め、 ナジム・ヒクメト解放委員会の委員長を務め、各国政府に嘆願書を提出し[157][158]、ヒクメトを称える作品(ルイ・デュレイやセルジュ・ニッグに よる楽曲など)を委嘱した。[157] ヒクメトは最終的に1950年7月に釈放され、その後のパリ訪問の際にはツァラに公に感謝の意を表した。[159] この時期の彼の作品には、以下のようなものがある。『生命の兆候』(1946年)、『大地の上の大地』(1946年)、『戦うことなく』(1949年)、 『人間の記憶から』(1950年)、『一人で語る』(1950年)、『 1955年には『ア・オート・フランム』(『炎の声』)と『ル・タン・ネザン』(『誕生する時』)、1956年には『ル・フリュイ・ペルミ』(『許された 果実』)が続いた。[84][160] ツァラは、モダニズム文化の積極的な推進者であり続けた。1949年頃、アイルランド人作家サミュエル・ベケットの『ゴドーを待ちながら』の原稿を読んだ ツァラは、プロデューサーのロジェ・ブランクに働きかけて、この劇の上演を実現させた。[161] また、ヒクメト[162]やハンガリー人作家アティッラ・ヨージェフ[153]の詩をフランス語に翻訳した。194 彼は美術商ハインツ・ベルグリーンにピカソを紹介し(こうして彼らの生涯にわたる協力関係が始まった)、[163] 1951年には友人のマックス・エルンストの作品の展覧会のカタログを執筆した。その文章は、芸術家の「刺激の自由な使用」と「新しい種類のユーモアの発 見」を称賛した。[164] 1956年の抗議と晩年  モンパルナス墓地にあるツァラの墓 1956年10月、ツァラはハンガリー人民共和国を訪れた。同国では、イムレ・ナジ(Imre Nagy)政権がソビエト連邦と対立しつつあった。[145][153] ハンガリーの作家ジュラ・イリエシュ(Gyula Illyés)からの招待に応じたもので、彼は同僚にラースロー・ライク(László Rajk)の名誉回復式典に出席してほしかった。ライクは地元の共産主義指導者であり、 起訴はヨシフ・スターリンによって命じられた)。[153] ツァラはハンガリー人の自由化要求を受け入れ[145][153]、反スターリニストで元ダダイストのラヨシュ・カーシャークと接触し、反ソビエト運動を 「革命的」とみなした。[153] しかし、ハンガリーの世論の多くとは異なり、詩人はソビエト支配からの解放を推奨せず ソ連支配からの解放を推奨せず、地元の作家たちが求めた独立を「抽象的な概念」と表現した。[153] 彼が発表した声明はハンガリーおよび国際的な報道機関で広く引用され、PCFから反発を招いた。アラゴンの返答を通じて、党は党員が「反共産主義および反 ソビエトキャンペーン」の支援に利用されているという事実を嘆いた。[153] 彼のフランスへの帰国はハンガリー動乱の勃発と重なり、ソビエト軍の介入により終結した。10月24日、ツァラはPCFの会合に出席するよう命じられ、そ こで活動家のローラン・カサノヴァがツァラに沈黙を守るよう命じたと伝えられている。ツァラはそれに従った。[153] ツァラの明らかな反対意見と、彼が共産党内部で引き起こした危機は、ハンガリー支持の立場を取っていたブルトンに歓迎され、彼は友人でありライバルであっ たツァラを「ハンガリーの要求の最初の代弁者」と定義した。[153] その後は公の場からほとんど姿を消し、15世紀の詩人フランソワ・ヴィヨンの作品の研究に専念し[141]、また、同じシュールレアリストのミシェル・レ リスと同様に、長年収集していた原始美術やアフリカ美術の普及に努めた[145]。1957年初頭、ツァラは 左岸で開かれたダダイズム回顧展に出席したが、この展覧会は、ライバルの前衛芸術運動であるジャリヴィスム運動による暴動によって幕を閉じた。この結果に 彼は満足したと伝えられている。[165] 1960年8月、シャルル・ド・ゴール大統領によって第五共和制が樹立されてから1年後、フランス軍はアルジェリアの反乱軍と対峙していた(アルジェリア 戦争を参照)。シモーヌ・ド・ボーヴォワール、マルグリット・デュラス、ジェローム・リンドン、アラン・ロブ=グリエら他の知識人とともに、彼はミシェ ル・ドブレ首相に抗議文を提出し、フランスがアルジェリアの独立を認めないことについて抗議した。 その結果、アンドレ・マルロー文化大臣は、ツァラや他の署名者たちが関与する映画には一切の助成を行わないと発表し、署名者たちはフランス国営放送局の運 営する放送局に登場することができなくなった。 1961年、詩人としての業績が認められ、ツァラは権威あるタオルミナ賞を受賞した。[84] 彼が最後に公の場に姿を見せたのは1962年で、 。1962年、彼は、イギリスの学芸員フランク・マキューエンが主催し、南ローデシアのソールズベリーにあるナショナル・ギャラリーで開催されたアフリカ 文化に関する国際会議に出席した。[167] 彼はその1年後にパリの自宅で死去し、モンパルナス墓地に埋葬された。[4] |