トルバドゥール

Troubadour

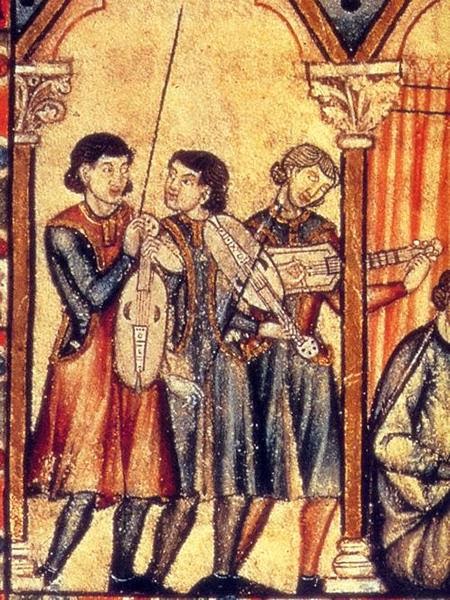

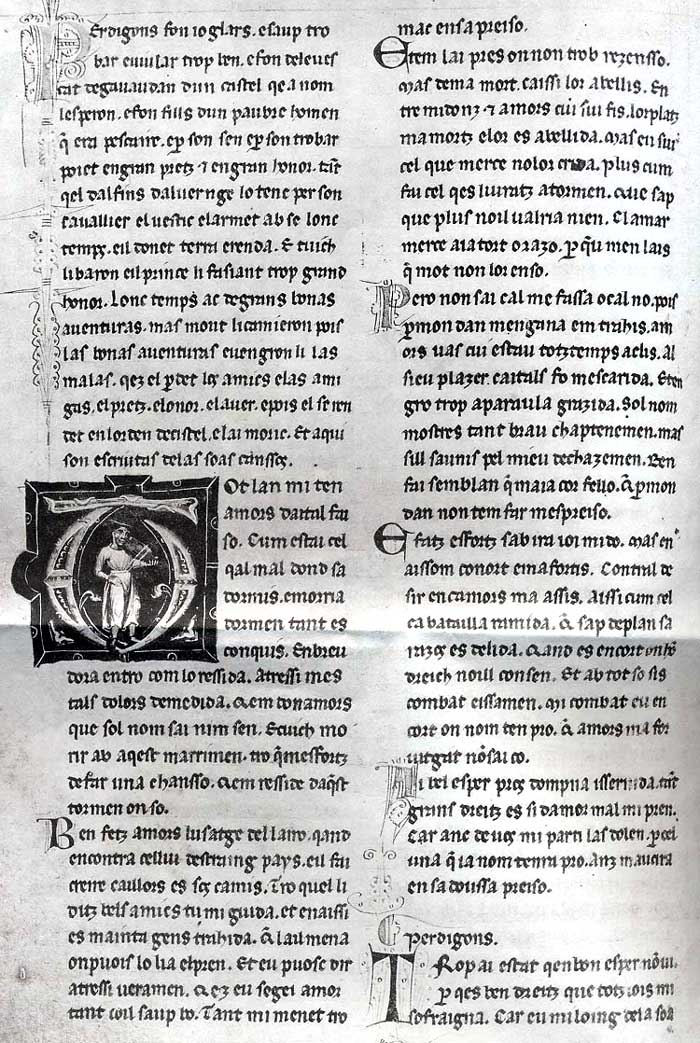

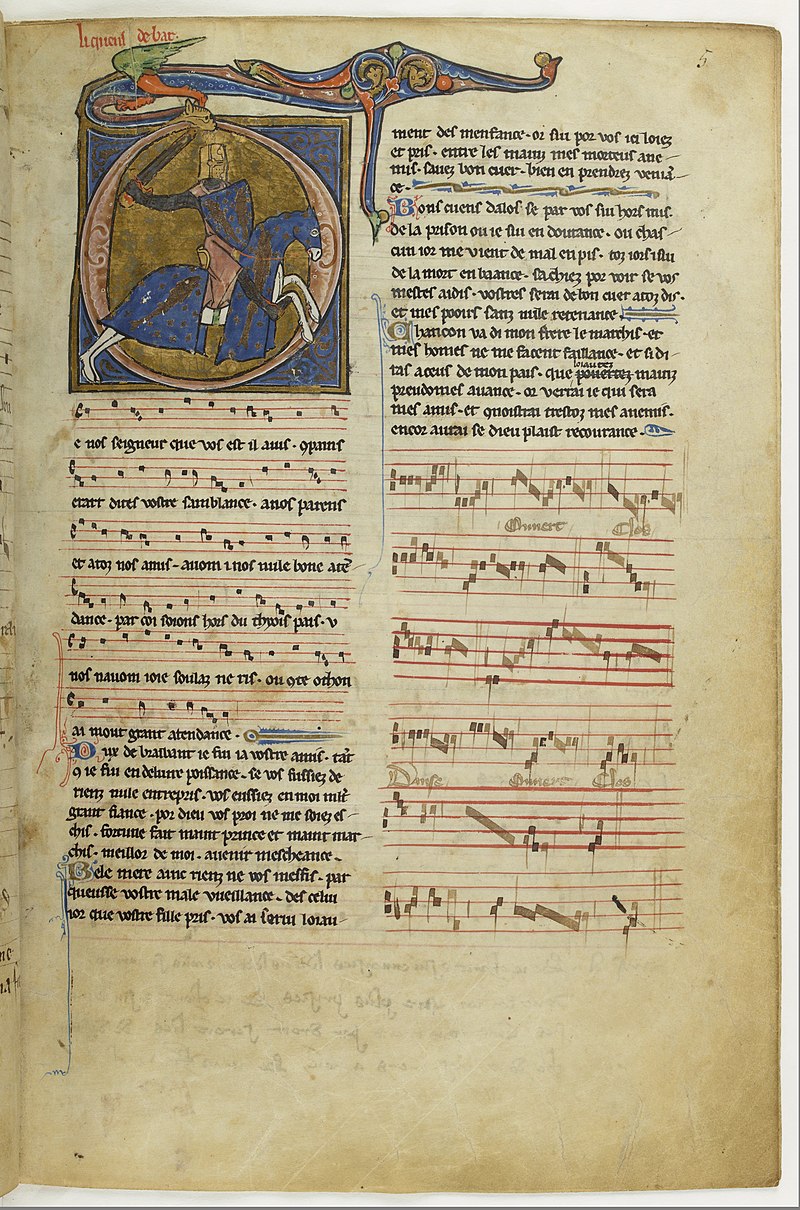

The

troubadour Perdigon

(1190–1220) playing his fiddle.

☆ トルバドゥール(あるいはトルゥバドゥル)(troubadour /ˈtruːbədʊər, -dɔːr/, フランス語: [tʁubaduʁ] ⓘ; オック語: trobador [tɾuβaˈðu] ⓘ)とは、中世盛期(1100年から1350年)にオック語の叙情詩を作詞作曲し、自らも歌った吟遊詩人のことである。トルバドゥールという語は語源的に は男性名詞であるため、同等の女性は通常、トロバイルィッツと呼ばれる。 トルバドゥール派の伝統は11世紀後半にオクシ タニアで始まったが、その後イタリア半島とイベリア半島にも広がった。トルバドゥールの影響を受けて、ドイ ツのミンネザング、ガリシアとポルトガルのトルバドゥリズモ、そしてフランス北部のトルヴェールといった、ヨーロッパ各地で関連する運動が勃興した。ダン テ・アリギエーリは著書『俗語についての演説』の中で、トルバドゥールの歌詞を「修辞的、音楽的、詩的な虚構」と定義した。13世紀初頭の「古典」時代と 世紀半ばの復活を経て、14世紀にトルバドゥールの芸術は衰退し、ペスト(1348年)の頃に消滅した。 トルバドゥールの歌の歌詞は、主に騎士道と宮廷恋愛をテーマとしている。その多くは形而上学的、知的、型にはまったものであった。ユーモアのあるものや下 品な風刺も多かった。作品は3つのスタイルに分類できる。すなわち、トロバール・レウ(軽快)、トロバール・リック(豊か)、トロバール・クルス(閉じ た)である。同様に、多くのジャンルがあり、最も人気があったのはカンソであったが、サーベンテスとテンソスは古典後期に特に人気があった。

| A troubadour

(English: /ˈtruːbədʊər, -dɔːr/, French: [tʁubaduʁ] ⓘ; Occitan: trobador

[tɾuβaˈðu] ⓘ) was a composer and performer of Old Occitan lyric poetry

during the High Middle Ages (1100–1350). Since the word troubadour is

etymologically masculine, a female equivalent is usually called a

trobairitz. The troubadour school or tradition began in the late 11th century in Occitania, but it subsequently spread to the Italian and Iberian Peninsulas. Under the influence of the troubadours, related movements sprang up throughout Europe: the Minnesang in Germany, trovadorismo in Galicia and Portugal, and that of the trouvères in northern France. Dante Alighieri in his De vulgari eloquentia defined the troubadour lyric as fictio rethorica musicaque poita: rhetorical, musical, and poetical fiction. After the "classical" period around the turn of the 13th century and a mid-century resurgence, the art of the troubadours declined in the 14th century and around the time of the Black Death (1348) it died out. The texts of troubadour songs deal mainly with themes of chivalry and courtly love. Most were metaphysical, intellectual, and formulaic. Many were humorous or vulgar satires. Works can be grouped into three styles: the trobar leu (light), trobar ric (rich), and trobar clus (closed). Likewise there were many genres, the most popular being the canso, but sirventes and tensos were especially popular in the post-classical period. |

トルバドゥール(英語: /ˈtruːbədʊər,

-dɔːr/, フランス語: [tʁubaduʁ] ⓘ; オック語: trobador [tɾuβaˈðu]

ⓘ)とは、中世盛期(1100年から1350年)にオック語の叙情詩を作詞作曲し、自らも歌った吟遊詩人のことである。トルバドゥールという語は語源的に

は男性名詞であるため、同等の女性は通常、トロバイルィッツと呼ばれる。 トルバドゥール派の伝統は11世紀後半にオクシタニアで始まったが、その後イタリア半島とイベリア半島にも広がった。トルバドゥールの影響を受けて、ドイ ツのミンネザング、ガリシアとポルトガルのトルバドゥリズモ、そしてフランス北部のトルヴェールといった、ヨーロッパ各地で関連する運動が勃興した。ダン テ・アリギエーリは著書『俗語についての演説』の中で、トルバドゥールの歌詞を「修辞的、音楽的、詩的な虚構」と定義した。13世紀初頭の「古典」時代と 世紀半ばの復活を経て、14世紀にトルバドゥールの芸術は衰退し、ペスト(1348年)の頃に消滅した。 トルバドゥールの歌の歌詞は、主に騎士道と宮廷恋愛をテーマとしている。その多くは形而上学的、知的、型にはまったものであった。ユーモアのあるものや下 品な風刺も多かった。作品は3つのスタイルに分類できる。すなわち、トロバール・レウ(軽快)、トロバール・リック(豊か)、トロバール・クルス(閉じ た)である。同様に、多くのジャンルがあり、最も人気があったのはカンソであったが、サーベンテスとテンソスは古典後期に特に人気があった。 |

| Etymology The English word troubadour was borrowed from the French word first recorded in 1575 in a historical context to mean "langue d'oc poet at the court in the 12th and 13th century" (Jean de Nostredame, Les vies des plus célèbres et anciens Poètes provençaux,[1] p. 14 in Gdf. Compl.).[2] The first use and earliest form of troubador is trobadors, found in a 12th-century Occitan text by Cercamon.[3] The French word itself is borrowed from the Occitan trobador. It is the oblique case of the nominative trobaire "composer", related to trobar "to compose, to discuss, to invent" (Wace, Brut, editions I. Arnold, 3342). Trobar may come, in turn, from the hypothetical Late Latin *tropāre "to compose, to invent a poem" by regular phonetic change. This reconstructed form is based on the Latin root tropus, meaning a trope. In turn, the Latin word derives ultimately from Greek τρόπος (trópos), meaning "turn, manner".[4] Intervocal Latin [p] shifted regularly to [b] in Occitan (cf. Latin sapere → Occitan saber, French savoir "to know"). The Latin suffix -ātor, -ātōris explains the Occitan suffix, according to its declension and accentuation: Gallo-Romance *tropātor[5] → Occitan trobaire (subject case) and *tropātōre[6] → Occitan trobador (oblique case). There is an alternative theory to explain the meaning of trobar as "to compose, to discuss, to invent". It has the support of some historians, specialists of literature, and musicologists to justify the troubadours' origins in Arabic Andalusian musical practices. According to them, the Arabic word ṭaraba "music" (from the triliteral root ṭ–r–b ط ر ب "provoke emotion, excitement, agitation; make music, entertain by singing" as in طرب أندلسي, ṭarab ʾandalusī) could partly be the etymon of the verb trobar.[7][8] Another Arabic root had already been proposed before: ḍ–r–b (ض ر ب) "strike", by extension "play a musical instrument".[9] In archaic and classical troubadour poetry, the word is only used in a mocking sense, having more or less the meaning of "somebody who makes things up". Cercamon writes: Ist trobador, entre ver e mentir, Afollon drutz e molhers et espos, E van dizen qu'Amors vay en biays (These troubadours, between truth and lies/corrupt lovers, women and husbands, / and keep saying that Love proceeds obliquely).[10] Peire d'Alvernha also begins his famous mockery of contemporary authors cantarai d'aquest trobadors,[11] after which he proceeds to explain why none of them is worth anything.[12] When referring to themselves seriously, troubadours almost invariably use the word chantaire ("singer"). |

語源 英語の「トルバドゥール(troubadour)」という語は、1575年に歴史的文脈の中で初めて記録されたフランス語から借用されたもので、「12世 紀から13世紀にかけての宮廷におけるオック語の詩人」を意味する(ジャン・ド・ノストラダム著『プロヴァンスの最も著名な古代詩人たちの伝記』[1]、 Gdf. Compl. p. 14)。。[2] トルバドゥールという語の最初の使用例および最古の形は、12世紀のオック語のテクストでCercamonによって見られるtrobadorsである。 [3] フランス語の単語自体は、オック語のtrobadorから借用されたものである。これは主格trobaire「作曲家」の斜格であり、「作曲する、論じ る、発明する」という意味のtrobar(Wace, Brut, editions I. Arnold, 3342)に関連している。一方、trobarは、規則的な音韻変化により、仮説上の後期ラテン語*tropāre「作曲する、詩を発明する」から派生し た可能性もある。この再建された形は、ラテン語の語根 tropus(転換)を基にしており、転換を意味する。 また、ラテン語は最終的にはギリシャ語のτρόπος(転換)に由来し、「方向、方法」を意味する。[4] 母音間のラテン語の[p]は、オック語では規則的に[b]に変化した(ラテン語のsapere → オック語のsaber、フランス語のsavoir「知る」を参照)。ラテン語の語尾 -ātor, -ātōris は、語形変化とアクセントから、オック語の語尾を説明できる。ガロ・ロマンス語 *tropātor[5] → オック語 trobaire(主格)および *tropātōre[6] → オック語 trobador(斜格)。 「作曲する、議論する、発明する」という意味の trobar を説明する別の説もある。これは、一部の歴史家や文学専門家、音楽学者が支持している説で、トルバドゥールの起源をアラブのアンダルシア音楽の慣習に求め るものである。彼らによると、アラビア語の「音楽」を表す単語「ṭaraba」(3文字の語根「ṭ–r–b」から派生した「感情、興奮、動揺を引き起こ す、音楽を奏でる、歌で楽しませる」という意味の「طرب أندلسي」、アラビア語で「ʾandalusī」)が、動詞「trobar」の語源の一部である可能性があるという。 アラビア語で「音楽」を意味する単語「タルバ(ṭaraba)」が、動詞「トロバル(trobar)」の語源の一部である可能性がある。[7][8] これに先立ち、別のアラビア語の語根がすでに提案されていた。それは「打つ」を意味する「ドールベ(ḍ–r–b)」で、派生語として「楽器を演奏する」と いう意味もある。[9] 古風な古典的なトルバドゥールの詩では、この単語は嘲笑的な意味でのみ使用され、「でっち上げをする人」という程度の意味合いを持つ。セルカモンは次のよ うに書いている。 私は吟遊詩人、真実と嘘の間で、 愛に溺れた男であり、妻であり、夫である。 そして、人々は言う。愛は曲がりくねって進むと。 [10] ペイレ・ダルベルニャもまた、同時代の作家たちを嘲笑する有名な作品『このトルバドゥールの歌』で始まるが、[11] その後、彼らの作品がどれも価値のないものである理由を説明している。[12] トルバドゥールが自分自身について真剣に言及する際には、ほとんど必ず「シャンテール(歌手)」という言葉を使用する。 |

| Origins The early study of the troubadours focused intensely on their origins. No academic consensus was ever achieved in the area. Today, one can distinguish at least eleven competing theories (the adjectives used below are a blend from the Grove Dictionary of Music and Roger Boase's The Origins and Meaning of Courtly Love): Arabic The sixteenth century Italian historian Giammaria Barbieri[13] was perhaps the first to suggest Arabian (also Arabist or Hispano-Arabic) influences on the music of the troubadours.[14] Later scholars like J.B. Trend have asserted that the poetry of troubadours is connected to Arabic poetry written in the Iberian Peninsula,[15] while others have attempted to find direct evidence of this influence. In examining the works of William IX of Aquitaine, Évariste Lévi-Provençal and other scholars found three lines that they believed were in some form of Arabic, indicating a potential Andalusian origin for his works. The scholars attempted to translate the lines in question, though the medievalist Istvan Frank contended that the lines were not Arabic at all, but instead the result of the rewriting of the original by a later scribe.[16][17] Scholars like Ramón Menéndez Pidal stated that the troubadour tradition was created by William, who had been influenced by Moorish music and poetry while fighting with the Reconquista. However, George T. Beech states that there is only one documented battle that William fought in the Iberian Peninsula, and it occurred towards the end of his life. Beech adds that while the sources of William's inspirations are uncertain, he and his father did have individuals within their extended family with Iberian origins, and he may have been friendly with some Europeans who could speak the Arabic language.[17] Regardless of William's personal involvement in the tradition's creation, Magda Bogin states that Arab poetry was likely one of several influences on European "courtly love poetry", citing Ibn Hazm's "The Ring of the Dove" as an example of a similar Arab tradition.[18] Methods of transmission from Arab Iberia to the rest of Europe did exist, such as the Toledo School of Translators, though it only began translating major romances from Arabic into Latin in the second half of the thirteenth century, with objectionable sexual content removed in deference to the Catholic Church.[19] Bernardine-Marianist According to the Bernardine-Marianist (or Christian) theory, it was the theology espoused by Bernard of Clairvaux and the increasingly important Mariology that most strongly influenced the development of the troubadour genre. Specifically, the emphasis on religious and spiritual love, disinterestedness, mysticism, and devotion to Mary explained "courtly love". The emphasis of the reforming Robert of Arbrissel on "matronage" to achieve his ends can explain the troubadour attitude towards women.[20] Chronologically, however, this hypothesis is hard to sustain, as the forces believed to have given rise to the phenomenon arrived later than it, but the influence of Bernardine and Marian theology can be retained without the origins theory. This theory was advanced early by Eduard Wechssler and further by Dmitri Scheludko (who emphasises the Cluniac Reform) and Guido Errante. Mario Casella and Leo Spitzer have added "Augustinian" influence to it. Celtic or chivalric-matriarchal The survival of pre-Christian sexual mores and warrior codes from matriarchal societies, be they Celtic, Germanic, or Pictish, among the aristocracy of Europe can account for the idea (fusion) of "courtly love". The existence of pre-Christian matriarchy has usually been treated with scepticism as has the persistence of underlying paganism in high medieval Europe, though the Celts and Germanic tribes were certainly less patriarchal than the Greco-Romans. Classical Latin The classical Latin theory emphasises parallels between Ovid, especially his Amores and Ars amatoria, and the lyric of courtly love. The aetas ovidiana that predominated in the 11th century in and around Orléans, the quasi-Ciceronian ideology that held sway in the Imperial court, and the scraps of Plato then available to scholars have all been cited as classical influences on troubadour poetry.[21] Crypto-Cathar According to this thesis, troubadour poetry is a reflection of Cathar religious doctrine. While the theory is supported by the traditional and near-universal account of the decline of the troubadours coinciding with the suppression of Catharism during the Albigensian Crusade (first half of the 13th century), support for it has come in waves. The explicitly Catholic meaning of many early troubadour works also works against the theory. Liturgical The troubadour lyric may be a development of the Christian liturgy and hymnody. The influence of the Song of Songs has even been suggested. There is no preceding Latin poetry resembling that of the troubadours. On those grounds, no theory of the latter's origins in classical or post-classical Latin can be constructed, but that has not deterred some, who believe that a pre-existing Latin corpus must merely be lost to us.[22] That many troubadours received their grammatical training in Latin through the Church (from clerici, clerics) and that many were trained musically by the Church is well-attested. The musical school of Saint Martial's at Limoges has been singled out in this regard.[23] "Para-liturgical" tropes were in use there in the era preceding the troubadours' appearance. Feudal-social This theory or set of related theories has gained ground in the 20th century. It is more a methodological approach to the question than a theory; it asks not from where the content or form of the lyric came but rather in what situation or circumstances did it arise.[24] Under Marxist influence, Erich Köhler, Marc Bloch, and Georges Duby have suggested that the "essential hegemony" in the castle of the lord's wife during his absence was a driving force. The use of feudal terminology in troubadour poems is seen as evidence. This theory has been developed away from sociological towards psychological explanation. Folklore This theory may relate to spring folk rituals. According to María Rosa Menocal, Alfred Jeanroy first suggested that folklore and oral tradition gave rise to troubadour poetry in 1883. According to F. M. Warren, it was Gaston Paris, Jeanroy's reviewer, in 1891 who first located troubadour origins in the festive dances of women hearkening the spring in the Loire Valley. This theory has since been widely discredited, but the discovery of the jarchas raises the question of the extent of literature (oral or written) in the 11th century and earlier.[24] Medieval Latin or Goliardic Hans Spanke analysed the intertextual connexion between vernacular and medieval Latin (such as Goliardic) songs. This theory is supported by Reto Bezzola, Peter Dronke, and musicologist Jacques Chailley. According to them, trobar means "inventing a trope", the trope being a poem where the words are used with a meaning different from their common signification, i.e. metaphor and metonymy. This poem was originally inserted in a serial of modulations ending a liturgic song. Then the trope became an autonomous piece organized in stanza form.[25] The influence of late 11th-century poets of the "Loire school", such as Marbod of Rennes and Hildebert of Lavardin, is stressed in this connexion by Brinkmann.[26] Neoplatonic This theory is one of the more intellectualising. The "ennobling effects of love" in specific have been identified as neoplatonic.[27] It is viewed either as a strength or weakness that this theory requires a second theory about how the neoplatonism was transmitted to the troubadours; perhaps it can be coupled with one of the other origins stories or perhaps it is just peripheral. Käte Axhausen has "exploited" this theory and A. J. Denomy has linked it with the Arabist (through Avicenna) and the Cathar (through John Scotus Eriugena).[28] |

起源 初期のトルバドゥールの研究では、その起源に強い関心が向けられていた。この分野では学術的な合意は一度も達成されていない。今日では、少なくとも11の 競合する説が存在する(以下で使用される形容詞は、Grove Dictionary of MusicとRoger Boase著『The Origins and Meaning of Courtly Love』を組み合わせたものである): アラビア語 16世紀のイタリアの歴史家、ジャンマリア・バルビエリ(Giammaria Barbieri)は、おそらく初めてトルバドゥールの音楽にアラビア(またはアラブ、イスパノ・アラブ)の影響があることを示唆した人物である。 [14] その後、J.B. トレンド(J.B. Trend)などの学者は、トルバドゥールの詩はイベリア半島で書かれたアラビア詩と関連していると主張している。[15] 一方、この影響の直接的な証拠を見つけようとする学者もいる。エヴィラスト・レヴィ=プロヴァンサルをはじめとする学者たちは、ウィリアム9世の作品を調 査した結果、アラビア語の何らかの形であると考えられる3行の詩を見つけ、彼の作品がアンダルシア起源である可能性を示唆した。中世史家のイシュトヴァー ン・フランクは、その3行の詩はアラビア語ではなく、後世の書記が元の文章を書き直した結果であると主張したが、学者たちは問題の詩の翻訳を試みた。 ラモン・メネンデス・ピダルなどの学者は、ムーア人の音楽や詩に影響を受けながらレコンキスタに従事していたウィリアムがトルバドゥールの伝統を生み出し たと主張している。しかし、ジョージ・T・ビーチは、ウィリアムがイベリア半島で戦ったと記録されている戦いは1つだけで、それは彼の人生の終わり頃に起 こったと述べている。 ビーチは、ウィリアムのインスピレーションの源は不明であるが、彼と彼の父親にはイベリア半島に起源を持つ親族がおり、アラビア語を話すヨーロッパ人とも 親交があった可能性があると付け加えている。[17] ウィリアムがこの伝統の創出に個人的に関与していたかどうかに関わらず、 マグダ・ボギンは、ヨーロッパの「宮廷恋愛詩」に影響を与えたもののひとつとして、アラブの詩を挙げている。イブン・ハズムの『鳩の指環』を、同様のアラ ブの伝統の例として挙げている。 アラビア語からラテン語への翻訳は、13世紀後半になってようやく開始されたが、その際、性的な内容についてはカトリック教会の意向を考慮して削除され た。 ベルナルディノ・マリアニスト ベルナルディノ・マリアニスト(またはキリスト教)の説によると、トロバドゥールのジャンルの発展に最も強い影響を与えたのは、ベルナルド・ド・クレル ヴォーが唱えた神学と、次第に重要性を増していったマリア学説であった。具体的には、宗教的・精神的な愛、無私無欲、神秘主義、マリアへの献身が「宮廷の 愛」を説明している。改革者ロベール・ド・アルブシェルの「修道女愛」に重点を置くことで、目的を達成しようとしたことは、トルバドゥールの女性に対する 態度を説明することができる。 しかし年代的に見ると、この仮説は維持するのが難しい。なぜなら、この現象を生み出したと考えられている勢力は、この現象よりも後に登場しているからだ。 しかし、起源説を除けば、ベルナルディン神学とマリア神学の影響は維持できる。この説は、エドゥアルト・ヴェヒトシュラーが早くから唱え、ドミトリー・ シェルドコ(彼はクリュニー修道会の改革を強調している)とグイド・エッランテがさらに発展させた。マリオ・カセッラとレオ・スピッツァーは、これに「ア ウグスティノ会」の影響を加えている。 ケルトまたは騎士道・母系 ヨーロッパの貴族社会における、母系制社会(ケルト、ゲルマン、ピクトなど)から伝わったキリスト教以前の性的道徳や戦士の掟が、「宮廷恋愛」という概念 (融合)の背景にある。キリスト教以前の母系制の存在は、中世ヨーロッパにおける異教の根強い影響と同様に、通常は懐疑的に扱われるが、ケルトやゲルマン 民族は、ギリシャ・ローマ人よりも父系制が弱かったことは確かである。 古典ラテン語 古典ラテン語説は、特に『アモレス』や『アルス・アマトリア』などのオウィディウスと宮廷恋愛の韻文との類似性を強調する。11世紀にオルレアンとその周 辺で優勢だったオウィディウス学派、皇帝の宮廷で支配的だったキケロ主義的なイデオロギー、そして当時学者たちが入手できた断片的なプラトンの著作は、い ずれもトルバドゥール詩に古典的な影響を与えたものとして挙げられている。 秘密のカタリ派 この説によると、トルバドゥールの詩はカタリ派の宗教的教義を反映したものである。この説は、アルビジョワ十字軍(13世紀前半)のカタリ派弾圧と時期を 同じくするトルバドゥールの衰退に関する伝統的かつほぼ普遍的な説明によって裏付けられているが、その支持は波状的に行われてきた。初期のトルバドゥール の作品の多くが明白にカトリック的な意味を持っていることも、この説に反するものである。 典礼 トルバドールの歌詞はキリスト教の典礼や聖歌の発展形である可能性がある。雅歌の影響も示唆されている。トルバドールに似たラテン語の詩はそれ以前には存 在しない。このため、古典ラテン語や後期ラテン語に起源を持つとする説は構築できないが、既存のラテン語のコーパスが失われただけだと考える人もいる。 [22] 多くのトルバドゥールが教会を通じてラテン語の文法教育を受けており(クレリック、聖職者から)、また多くの者が教会で音楽の訓練を受けていたことは、よ く知られている。この点において、リモージュのサン・マルシャルの音楽学校が特に注目されている。[23] トロバドゥールの登場に先立つ時代には、典礼外の「パラ典礼」トロプがすでに用いられていた。 封建的社会 この理論または関連理論は20世紀に支持を集めた。これは理論というよりも、この問題に対する方法論的なアプローチであり、歌詞の内容や形式がどこから来 たのかではなく、どのような状況や環境で生まれたのかを問うものである。[24] マルクス主義の影響下で、エーリッヒ・ケーラー、マルク・ブロック、ジョルジュ・デュビーは、領主の留守中の奥方の「本質的な覇権」が推進力であったと示 唆した。トルバドゥールの詩に封建的な用語が使われていることが、その証拠と見なされている。この説は、社会学的な説明から心理学的説明へと発展してい る。 フォークロア この説は春の民間儀式と関連している可能性がある。マリア・ロサ・メノカルによると、1883年にアルフレッド・ジャンロワが初めてフォークロアと口承が トルバドゥール詩を生み出したと示唆した。F. M. ウォーレンによると、ジャンロワの批評家であるガストン・パリが1891年に初めて、ロワール渓谷で春を祝う女性の祝祭舞踏にトルバドゥール詩の起源を見 出した。この説はその後広く否定されているが、ジャルチャの発見により、11世紀以前の文学(口承または書面)の程度に関する疑問が生じている。[24] 中世ラテン語またはゴリアルド語 ハンス・シュパンケは、俗ラテン語と中世ラテン語(ゴリアルディックなど)の歌の相互関係を分析した。この説はレト・ベッツォラ、ピーター・ドロンク、音 楽学者ジャック・シェイリーによって支持されている。彼らによると、トロバールとは「修辞法を発明する」ことを意味し、修辞法とは、言葉が一般的な意味と は異なる意味で使用される詩、すなわち隠喩や換喩を指す。この詩は、もともと典礼歌の終結部分の転調の連続に挿入されていた。その後、転調は独立した節形 式の作品となった。[25] 11世紀後半のロワール派の詩人、例えばレンヌのマルボやラヴァルディンのイルデベールなどの影響が、この関連性においてブリンクマンによって強調されて いる。[26] 新プラトン主義 この説は、より観念的なもののひとつである。特に「愛の高貴化効果」は新プラトン主義であると特定されている。[27] この説は、新プラトン主義がどのようにしてトルバドゥールたちに伝わったかについて、第二の説を必要とするという点で、長所とも短所とも考えられる。おそ らく、他の起源説のひとつと結びつけることができるかもしれないし、あるいは単に周辺的なものかもしれない。ケーテ・アクスハウゼンはこの説を「利用」 し、A. J. デノミーはこれをアラブ学者(アヴィセンナを通じて)とカタリ派(ジョン・スコトゥス・エリウゲナを通じて)と結びつけた。[28] |

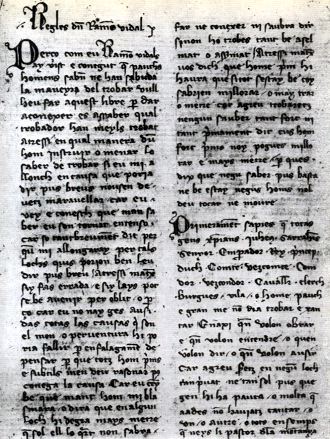

History William IX of Aquitaine portrayed as a knight, who first composed poetry on returning from the Crusade of 1101 Early period The earliest troubadour whose work survives is Guilhèm de Peitieus, better known as Duke William IX of Aquitaine (1071–1126). Peter Dronke, author of The Medieval Lyric, however, believes that "[his] songs represent not the beginnings of a tradition but summits of achievement in that tradition."[29] His name has been preserved because he was the Duke of Aquitaine, but his work plays with already established structures; Eble II of Ventadorn is often credited as a predecessor, though none of his work survives. Orderic Vitalis referred to William composing songs about his experiences on his return from the Crusade of 1101 (c. 1102). This may be the earliest reference to troubadour lyrics. Orderic also provides us (1135) with what may be the first description of a troubadour performance: an eyewitness account of William of Aquitaine. Picauensis uero dux ... miserias captiuitatis suae ... coram regibus et magnatis atque Christianis coetibus multotiens retulit rythmicis uersibus cum facetis modulationibus. (X.21) Then the Poitevin duke ... the miseries of his captivity ... before kings, magnates, and Christian assemblies many times related with rhythmic verses and witty measures.[30] Spread  Trobadours, 14th century The first half of the 12th century saw relatively few recorded troubadours. Only in the last decades of the century did troubadour activity explode. Almost half of all troubadour works that survive are from the period 1180–1220.[31] In total, moreover, there are over 2,500 troubadour lyrics available to be studied as linguistic artifacts (Akehurst, 23). The troubadour tradition seems to have begun in western Aquitaine (Poitou and Saintonge) and Gascony, from there spreading over into eastern Aquitaine (Limousin and Auvergne) and Provence. At its height it had become popular in Languedoc and the regions of Rouergue, Toulouse, and Quercy (c. 1200). Finally, in the early 13th century it began to spread into first Italy and then Catalonia, whence to the rest of modern Spain and then Portugal. This development has been called the rayonnement des troubadours (pronounced [ʁɛjɔnəmɑ̃ de tʁubaduːʁ]).[32] Classical period The classical period of troubadour activity lasted from about 1170 until about 1213. The most famous names among the ranks of troubadours belong to this period. During this period the lyric art of the troubadours reached the height of its popularity and the number of surviving poems is greatest from this period. During this period the canso, or love song, became distinguishable as a genre. The master of the canso and the troubadour who epitomises the classical period is Bernart de Ventadorn. He was highly regarded by his contemporaries, as were Giraut de Bornelh, reputed by his biographer to be the greatest composer of melodies to ever live, and Bertran de Born, the master of the sirventes, or political song, which became increasingly popular in this period. The classical period came to be seen by later generations, especially in the 14th and 15th centuries and outside of Occitania, as representing the high point of lyric poetry and models to be emulated. The language of the classic poets, its grammar and vocabulary, their style and themes, were the ideal to which poets of the troubadour revival in Toulouse (creation of the Consistori del Gay Saber in 1323) and their Catalan and Castilian contemporaries aspired. During the classical period the "rules" of poetic composition had first become standardised and written down, first by Raimon Vidal and then by Uc Faidit. |

歴史 騎士として描かれた、1101年の十字軍遠征から帰還後初めて詩を書いたとされるアキテーヌ王ウィリアム9世 初期 現存する最古の作品を残したトルバドゥールは、アキテーヌ王ウィリアム9世(1071年-1126年)としてよりよく知られるギレーム・ド・ペイトゥスで ある。しかし、『中世の叙情詩』の著者であるピーター・ドロンクは、「彼の歌は伝統の始まりではなく、その伝統における達成の頂点を表している」と考えて いる。[29] 彼の名が残っているのは、彼がアキテーヌ公であったからだが、彼の作品はすでに確立された構造を基にしている。エブレ・デ・ベンタドールは、彼の作品は現 存していないが、しばしば先駆者として挙げられる。オーデリック・ヴィタリスは、1101年の十字軍遠征(1102年頃)からの帰還後に、自身の経験を歌 にしたウィリアムについて言及している。これは、トルバドゥールの歌詞に関する最も古い言及である可能性がある。オーデリックはまた、1135年に、おそ らくはトルバドゥールのパフォーマンスに関する最初の記述である、アクィテーヌのウィリアムの目撃証言を残している。 ピカルディの公爵は...捕虜としての苦難を...国王や有力者、キリスト教徒の同輩たちの前で、変調を伴う韻を踏んだ詩を何度も繰り返し語った。 (X.21) そして、ポワトゥーの公爵は...捕虜としての苦難を...国王、有力者、キリスト教徒の同輩たちの前で、韻を踏んだ詩と機知に富んだ節を何度も繰り返し 語った。[30] 拡散  トルバドゥール、14世紀 12世紀前半には、記録に残るトルバドゥールは比較的少なかった。トルバドゥールの活動が爆発的に増加したのは、世紀の最後の数十年間になってからであ る。現存するトルバドゥールの作品のほぼ半分は、1180年から1220年の間に書かれたものである。さらに、言語学的成果物として研究可能なトルバ ドゥールの歌詞は、全部で2,500以上ある(Akehurst, 23)。トルバドゥールの伝統は、まず西のアキテーヌ(ポワトゥーとサントンジュ)とガスコーニュで始まり、そこから東のアキテーヌ(リムーザンとオー ヴェルニュ)とプロヴァンスに広がったようである。最盛期にはラングドックやルエルグ、トゥールーズ、ケルシー地方でも人気を博した(1200年頃)。そ して13世紀初頭には、まずイタリア、次いでカタルーニャへと広がり、そこから近代スペインの他の地域、そしてポルトガルへと広がっていった。この発展は 「troubadoursのrayonnement(発音:[ʁɛjɔnəmɑ̃ de tʁubaduːʁ])」と呼ばれている。[32] 古典期 トルバドゥールの古典期は、1170年頃から1213年頃まで続いた。トルバドゥールの中でも最も有名な人物は、この時代に活躍した。この時代には、トル バドゥールの叙情芸術は絶頂期を迎え、現存する詩の数も最も多い。この時代には、カンソ(愛の歌)がジャンルとして確立した。カンソの名人であり、古典期 を代表するトルバドゥールはベルナル・ド・ヴェンタドールである。同時代の者たちから非常に高く評価されていたのは、伝記作家が「生きた中で最も優れたメ ロディの作曲家」と評したジロー・ド・ボルネルや、この時代にますます人気が高まったシルヴェンテ(政治歌)の名人ベルトラン・ド・ボルンである。 古典時代は、特に14世紀と15世紀、そしてオクシタニア以外の地域では、叙情詩の頂点であり、見習うべき模範であると見なされるようになった。古典詩人 の言語、その文法や語彙、スタイルやテーマは、トゥールーズで復活したトルバドゥール(1323年にConsistori del Gay Saberが創設)の詩人たちや、彼らの同時代のカタルーニャ人やカスティーリャ人の詩人たちが目指した理想となった。古典時代には、まずレイモン・ヴィ ダルが、次にウク・フェイディットが、詩の構成の「ルール」を初めて標準化し、書き記した。 |

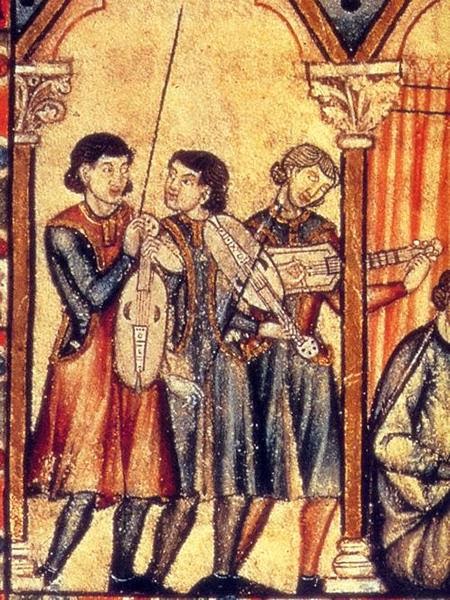

| Lives See also: List of troubadours and trobairitz, Minstrel, Vida (Occitan literary form), Razo, Consistori del Gay Saber, and Consistori de Barcelona The 450 or so troubadours known to historians came from a variety of backgrounds. They made their living in a variety of ways, lived, and travelled in many different places, and were actors in many types of social context. The troubadours were not wandering entertainers. Typically, they stayed in one place for a lengthy period of time under the patronage of a wealthy nobleman or woman. Many did travel extensively, however, sojourning at one court and then another. Status The earliest known troubadour, the Duke of Aquitaine, came from the high nobility. He was followed immediately by two poets of unknown origins, known only by their sobriquets, Cercamon and Marcabru, and by a member of the princely class, Jaufre Rudel. Many troubadours are described in their vidas as poor knights. It was one of the most common descriptors of status. Berenguier de Palazol, Gausbert Amiel, Guilhem Ademar, Guiraudo lo Ros, Marcabru, Peire de Maensac, Peirol, Raimon de Miraval, Rigaut de Berbezilh, and Uc de Pena are all so described. Albertet de Sestaro is described as the son of a noble jongleur, presumably a petty noble lineage. Later troubadours especially could belong to lower classes, ranging from the middle class of merchants and "burgers" (persons of urban standing) to tradesmen and others who worked with their hands. Salh d'Escola and Elias de Barjols were described as the sons of merchants and Elias Fonsalada was the son of a burger and jongleur. Perdigon was the son of a "poor fisherman" and Elias Cairel of a blacksmith. Arnaut de Mareuil is specified in his vida as coming from a poor family, but whether this family was poor by noble standards or materially is not apparent. Many troubadours also possessed a clerical education. For some this was their springboard to composition, since their clerical education equipped them with an understanding of musical and poetic forms as well as vocal training. The vidas of the following troubadours note their clerical status: Aimeric de Belenoi, Folquet de Marselha (who became a bishop), Gui d'Ussel, Guillem Ramon de Gironella, Jofre de Foixà (who became an abbot), Peire de Bussignac, Peire Rogier, Raimon de Cornet, Uc Brunet, and Uc de Saint Circ. Trobadors and joglars  Musicians in the time of the Cantigas de Santa Maria. These were in the court of the king, two vielle players and one citoler. The Occitan words trobador and trobaire are relatively rare compared with the verb trobar (compose, invent), which was usually applied to the writing of poetry. It signified that a poem was original to an author (trobador) and was not merely sung or played by one. The term was used mostly for poetry only and in more careful works, like the vidas, is not generally applied to the composition of music or to singing, though the troubadour's poetry itself is not so careful. Sometime in the middle of the 12th century, however, a distinction was definitely being made between an inventor of original verse and the performers of others'. The latter were called joglars in both Occitan and Catalan, from the Latin ioculatores, giving rise also to the French jongleur, Castilian juglar, and English juggler, which has come to refer to a more specific breed of performer. The medieval jongleur/joglar is really a minstrel. At the height of troubadour poetry (the "classical period"), troubadours are often found attacking jongleurs and at least two small genres arose around the theme: the ensenhamen joglaresc and the sirventes joglaresc. These terms are debated, however, since the adjective joglaresc seems to imply "in the manner of the jongleurs". Inevitably, however, pieces of these genres are verbal attacks at jongleurs, in general and in specific, with named individuals being called out. It is clear, for example from the poetry of Bertran de Born, that jongleurs were performers who did not usually compose. They often performed the troubadours' songs: singing, playing instruments, dancing, and even doing acrobatics.[33] In the late 13th century Guiraut Riquier bemoaned the inexactness of his contemporaries and wrote a letter to Alfonso X of Castile, a noted patron of literature and learning of all kinds, for clarification on the proper reference of the terms trobador and joglar. According to Riquier, every vocation deserved a name of its own and the sloppy usage of joglar assured that it covered a multitude of activities, some, no doubt, with which Riquier did not wish to be associated. In the end Riquier argued—and Alfonso X seems to agree, though his "response" was probably penned by Riquier—that a joglar was a courtly entertainer (as opposed to popular or low-class one) and a troubadour was a poet and composer. Despite the distinctions noted, many troubadours were also known as jongleurs, either before they began composing or alongside. Aimeric de Belenoi, Aimeric de Sarlat, Albertet Cailla, Arnaut de Mareuil, Elias de Barjols, Elias Fonsalada, Falquet de Romans, Guillem Magret, Guiraut de Calanso, Nicoletto da Torino, Peire Raimon de Tolosa, Peire Rogier, Peire de Valeira, Peirol, Pistoleta, Perdigon, Salh d'Escola, Uc de la Bacalaria, Uc Brunet, and Uc de Saint Circ were jongleur-troubadours. Vidas and razos A vida is a brief prose biography, written in Occitan, of a troubadour. The word vida means "life" in Occitan. In the chansonniers, the manuscript collections of medieval troubadour poetry, the works of a particular author are often accompanied by a short prose biography. The vidas are important early works of vernacular prose nonfiction.[34] Nevertheless, it appears that many of them derive their facts from literal readings of their objects' poems, which leaves their historical reliability in doubt. Most of the vidas were composed in Italy in the 1220s, many by Uc de Saint Circ. A razo (from Occitan for "reason") was a similar short piece of Occitan prose detailing the circumstances of a particular composition. A razo normally introduced the poem it explained; it might, however, share some of the characteristics of a vida. The razos suffer from the same problems as the vidas in terms of reliability. Many are likewise the work of Uc de Saint Circ.  Late 16th-century Italian cursive on paper, recording a song of Perceval Doria Podestà-troubadours A phenomenon arose in Italy, recognised around the turn of the 20th century by Giulio Bertoni, of men serving in several cities as podestàs on behalf of either the Guelph or Ghibelline party and writing political verse in Occitan rhyme. These figures generally came from the urban middle class. They aspired to high culture and though, unlike the nobility, they were not patrons of literature, they were its disseminators and its readers. The first podestà-troubadour was Rambertino Buvalelli, possibly the first troubadour native to the Italian Peninsula, who was podestà of Genoa between 1218 and 1221. Rambertino, a Guelph, served at one time or another as podestà of Brescia, Milan, Parma, Mantua, and Verona. It was probably during his three-year tenure there that he introduced Occitan lyric poetry to the city, which was later to develop a flourishing Occitan literary culture. Among the podestà-troubadours to follow Rambertino, four were from Genoa: the Guelphs Luca Grimaldi, who also served in Florence, Milan, and Ventimiglia, and Luchetto Gattilusio, who served in Milan, Cremona, and Bologna, and the Ghibellines Perceval Doria, who served in Arles, Avignon, Asti, and Parma, and Simon Doria, sometime podestà of Savona and Albenga. Among the non-Genoese podestà-troubadours was Alberico da Romano, a nobleman of high rank who governed Vicenza and Treviso as variously a Ghibelline and a Guelph. He was a patron as well as a composer of Occitan lyric. Mention should be made of the Provençal troubadour Isnart d'Entrevenas, who was podestà of Arles in 1220, though he does not fit the phenomenon Giulio Bertoni first identified in Italy. Trobairitz Main article: Trobairitz The trobairitz were the female troubadours, the first female composers of secular music in the Western tradition. The word trobairitz was first used in the 13th-century Romance of Flamenca and its derivation is the same as that of trobaire but in feminine form. There were also female counterparts to the joglars: the joglaresas. The number of trobairitz varies between sources: there were twenty or twenty-one named trobairitz, plus an additional poet known only as Domna H. There are several anonymous texts ascribed to women; the total number of trobairitz texts varies from twenty-two (Schultz-Gora),[35] twenty-five (Bec), thirty-six (Bruckner, Shepard, and White),[36] and forty-six (Rieger).[37] Only one melody composed by a trobairitz (the Comtessa de Dia) survives. Out of a total of about 450 troubadours and 2,500 troubadour works, the trobairitz and their corpus form a minor but interesting and informative portion. They are, therefore, quite well studied.  Castelloza The trobairitz were in most respects as varied a lot as their male counterparts, with the general exceptions of their poetic style and their provenance. They wrote predominantly cansos and tensos; only one sirventes by a named woman, Gormonda de Monpeslier, survives (though two anonymous ones are attributed to women). One salut d'amor, by a woman (Azalais d'Altier) to a woman (Clara d'Anduza) is also extant and one anonymous planh is usually assigned a female authorship. They wrote almost entirely within the trobar leu style; only two poems, one by Lombarda and another Alais, Yselda, and Carenza, are usually considered to belong to the more demanding trobar clus. None of the trobairitz were prolific, or if they were their work has not survived. Only two have left us more than one piece: the Comtessa de Dia, with four, and Castelloza, with three or four. One of the known trobairitz, Gaudairença, wrote a song entitled Coblas e dansas, which has not survived; no other piece of hers has either. The trobairitz came almost to a woman from Occitania. There are representatives from the Auvergne, Provence, Languedoc, the Dauphiné, Toulousain, and the Limousin. One trobairitz, Ysabella, may have been born in Périgord, Northern Italy, Greece, or Palestine. All the trobairitz whose families we know were high-born ladies; only one, Lombarda, was probably of the merchant class. All the trobairitz known by name lived around the same time: the late 12th and the early 13th century (c. 1170 – c. 1260). The earliest was probably Tibors de Sarenom, who was active in the 1150s (the date of her known composition is uncertain). The latest was either Garsenda of Forcalquier, who died in 1242, though her period of poetic patronage and composition probably occurred a quarter century earlier, or Guilleuma de Rosers, who composed a tenso with Lanfranc Cigala, known between 1235 and 1257. There exist brief prose biographies—vidas—for eight trobairitz: Almucs de Castelnau (actually a razo), Azalais de Porcairagues, the Comtessa de Dia, Castelloza, Iseut de Capio (also a razo), Lombarda, Maria de Ventadorn, and Tibors de Sarenom. |

生活 参照:トルバドゥールとトロバイルの一覧、吟遊詩人、オック語文学の形式であるヴィダ、ラゾ、ゲイ・サベール審議会、バルセロナ審議会 歴史家が知る450人ほどのトルバドゥールは、さまざまな背景を持っていた。彼らはさまざまな方法で生計を立て、さまざまな場所に住み、旅をし、さまざま な社会的文脈の中で活動していた。トルバドゥールは放浪の芸能人ではなかった。通常、彼らは富裕な貴族の庇護を受け、ひとつの場所に長期間滞在した。しか し、多くの者はあちこちの宮廷を転々としていた。 地位 最も初期に知られるようになったトルバドゥール、アキテーヌ公爵は、高貴な家柄の出身であった。 彼に続いて、出自不明で、あだ名でしか知られていない2人の詩人、セルカモンとマルカブリュ、そして王子階級のメンバー、ジャウフレ・ルデルが続いた。 多くのトルバドゥールは、その伝記の中で貧しい騎士として描写されている。 それは、最も一般的な地位の描写のひとつであった。ベレンゲル・デ・パラス、ゴスベル・アミエル、ギレム・アデマール、ギラウド・ロ・ロス、マルカブル、 ペイレ・ド・メナサック、ペイロール、ライモン・ド・ミラヴァル、リゴー・ド・ベルベシル、ウク・ド・ペナは、すべてそう描写されている。アルベレット・ ド・セスタロは、おそらくは小貴族の血筋である高貴なジョングルール(曲芸師)の息子として描写されている。 後のトルバドゥールは特に、商人や「バーガー」(都市の地位を持つ人々)の中流階級から、職人や肉体労働者などの下層階級に属する者もいた。サル・デスコ ラとエリアス・ド・バルジョルは商人の息子とされ、エリアス・フォンサラダはバーガーでジョングルール(曲芸師)の息子であった。ペルディゴンは「貧しい 漁師」の息子であり、エリアス・カイレルは鍛冶屋の息子であった。アルノー・ド・マリュイは、自身のヴィーダの中で、自分が貧しい家柄の出身であると明記 しているが、この家が貴族の基準で貧しかったのか、物質的に貧しかったのかは明らかではない。 多くのトルバドゥールは、聖職者の教育も受けていた。聖職者の教育は、音楽や詩の形式、声楽の訓練に対する理解を彼らに与えたため、一部の者にとっては、 これが作曲への足がかりとなった。以下のトルバドゥールのヴィーダには、彼らの聖職者としての地位が記載されている。Aimeric de Belenoi、Folquet de Marselha(後に司教となる)、Gui d'Ussel、Guillem Ramon de Gironella、Jofre de Foixà(後に修道院長となる)、Peire de Bussignac、Peire Rogier、Raimon de Cornet、Uc Brunet、Uc de Saint Circ。 トルバドゥールとジョグラー  サンタ・マリアの歌(Cantigas de Santa Maria)の時代の音楽家たち。 これらは王の宮廷にいた、2人のヴィエル奏者と1人のシトール奏者である。 オック語の「トロバドール(trobador)」と「トロバドゥール(trobaire)」という言葉は、動詞の「トロバール(trobar)」(作曲す る、発明する)と比較すると、比較的珍しい。 これは、詩が作者(トロバドール)のオリジナルであり、単に歌ったり演奏されたりするものではないことを意味していた。この用語は主に詩のみに使用され、 ヴィーダスのようなより入念な作品では、音楽の作曲や歌には一般的に適用されないが、トルバドゥールの詩自体はそれほど入念ではない。しかし、12世紀の 中頃には、オリジナルの詩の作者と他人の詩を歌うパフォーマーとの間に明確な区別が確立されていた。後者は、ラテン語の ioculatores に由来するオック語とカタロニア語の両方で joglars と呼ばれ、フランス語の jongleur、カスティーリャ語の juglar、英語の juggler へと派生し、より特定のジャンルのパフォーマーを指すようになった。中世の jongleur/joglar は、実際には吟遊詩人である。 トルバドゥール詩の全盛期(「古典期」)には、トルバドゥールがしばしばジョングルールを攻撃する場面が見られ、少なくとも2つの小ジャンルがテーマとし て生まれた。enshenamen joglarescとsirventes joglarescである。ただし、形容詞のjoglarescは「ジョングルールのやり方」を意味するようであるため、これらの用語については議論があ る。しかし、必然的に、これらのジャンルの作品は、一般的に、また特定の人物を名指して、曲芸師を言葉で攻撃するものとなっている。例えば、ベルトラン・ ド・ボーンの詩から、曲芸師は通常作曲を行わないパフォーマーであったことが明らかである。彼らはしばしばトルバドゥールの歌を演奏し、歌い、楽器を演奏 し、踊り、さらには曲芸も披露した。 13世紀後半、ギロー・リキエは同時代の不誠実さを嘆き、文学や学問のパトロンとして知られたカスティーリャ王アルフォンソ10世に手紙を書き、トルバ ドゥールとジョングラーという用語の適切な参照先について明確化を求めた。リキエールによれば、あらゆる職業にはそれぞれ固有の名称があるべきであり、 ジョングラーのいい加減な用法は、それが多数の活動をカバーすることを保証するものであり、その中にはリキエールが関わりたくない活動も含まれていること は間違いない。結局、リキエは、ジョングラーは宮廷のエンターテイナー(大衆向けや低級なエンターテイナーとは対照的)であり、トルバドゥールは詩人であ り作曲家であると主張した。アルフォンソ10世も同意見のようだが、おそらく「回答」はリキエが書いたものだろう。 このように区別されていたにもかかわらず、多くのトルバドゥールは作曲を始める前、あるいは作曲と並行して、ジョングルールとしても知られていた。アイメ リック・ド・ベレヌー、アイメリック・ド・サラルタ、アルベルテ・カイヤ、アルノー・ド・マリュイユ、エリアス・ド・バルジョルス、エリアス・フォンサ ラーダ、ファルケ・ド・ロマンス、ギレム・マグレ、ギラウ・ド・カランソ、ニコレット・ダ・トリノ 、ペイレ・ロジェ、ペイレ・ド・ヴァレイラ、ペイロール、ピストレタ、ペルディゴン、サル・デスコラ、ウク・ド・ラ・バカラリア、ウク・ブリュネ、ウク・ ド・サン・シルクは、ジョングルール・トルバドゥールであった。 ヴィーダとラゾー ヴィーダとは、オック語で書かれたトルバドゥールの簡潔な散文伝記である。ヴィーダという語はオック語で「人生」を意味する。中世のトルバドゥール詩の原 稿コレクションであるシャンソニエでは、特定の作者の作品には短い散文伝記が添えられていることが多い。ヴィーダは、土地言葉による散文のノンフィクショ ンの初期の重要な作品である。[34] しかし、それらの多くは、対象となる詩の字義通りの解釈から事実を導き出しているように見えるため、歴史的な信頼性には疑問が残る。ヴィーダのほとんどは 1220年代にイタリアで書かれたもので、その多くはユック・ド・サン・シルクによるものである。 ラゾ(オック語で「理由」の意)は、オック語の散文による同様の短い作品で、特定の作品の背景を詳しく説明するものである。ラゾは通常、説明の対象となる 詩を紹介するもので、しかし、ビダのいくつかの特徴を共有している可能性もある。ラゾは、信頼性の面でビダと同じ問題を抱えている。多くは同様に、ウク・ ド・サン・シルクの作品である。  16世紀後半のイタリアの紙上の草書体で、ペルセヴァル・ドリアの歌を記録したもの ポデスタ・トルバドゥール イタリアでは、20世紀初頭にジュリオ・ベルトリによって認識された現象が起こった。それは、複数の都市で、グェルフィ派またはギベッリーニ派の代表とし てポデスタを務め、オック語韻律で政治的な詩を書く男性たちである。これらの人物は一般的に都市の中流階級出身であった。彼らは高い文化を志し、貴族とは 異なり文学のパトロンではなかったが、文学の普及者であり、読者であった。 最初のポデスタ・トルバドゥールは、おそらくイタリア半島出身の最初のトルバドゥールであるランベルトゥーノ・ブヴァレッリ(Rambertino Buvalelli)で、1218年から1221年の間、ジェノヴァのポデスタを務めた。ランベルトゥーノはグエルフィ派で、ブレシア、ミラノ、パルマ、 マントヴァ、ヴェローナのポデスタを歴任した。おそらく、彼が3年間その地でポデスタを務めていた間に、オック語の叙情詩をこの街に紹介し、後にオック語 の文学文化が栄えるようになったのだろう。 ランベルトゥーノに続くポデスタ・トルバドゥールの中には、ジェノヴァ出身者が4人いた。グエルフィ派のルカ・グリマルディはフィレンツェ、ミラノ、ヴェ ンティミリアでもポデスタを務め、ルッケット・ガッティルージオは ミラノ、クレモナ、ボローニャで仕えたルッケット・ガッティルージオ、そしてアルル、アヴィニョン、アスティ、パルマで仕えたギベリン派のパーシヴァル・ ドリア、サヴォーナとアルベンガのポデスタを務めたこともあるシモン・ドリアなどがいた。ジェノヴァ人以外のポデスタ・トルバドゥールとしては、アルベリ コ・ダ・ラマーノがいた。彼は貴族階級の高位にあり、ヴィチェンツァとトレヴィーゾを支配し、ギベリン派とグエルフィ派の間で立場を変えていた。彼は後援 者であると同時に、オック語の叙情詩の作曲家でもあった。 1220年にアルルのポデスタを務めたプロヴァンスのトルバドゥール、イスナール・ダン・トランヴェーナスについても言及すべきであるが、彼はジュリオ・ ベルトンが最初にイタリアで特定した現象には当てはまらない。 トロバイル 詳細は「トロバイル」を参照 トロバイルは女性トルバドゥールであり、西洋の伝統における世俗音楽の最初の女性作曲家である。トロバイルという語は13世紀の『フラメンカのロマンス』 で初めて使用され、語源はトロバイルと同じだが女性形である。ジョグラールには女性版のジョグラレスも存在した。トロバイルの人数については資料によって 異なり、20人または21人の名前が挙げられたトロバイルに加え、ドムナ・Hとして知られる詩人が1人いる。女性に帰せられる匿名のテキストもいくつか存 在し、トロバイルのテキストの総数は22(シュルツ=ゴラ)[35]、25(ベック)、36(ブルックナー、シェパード、ホワイト)[36]、46(リー ガー)[37]と異なる。 Gora)[35]、25(Bec)、36(Bruckner、Shepard、White)[36]、46(Rieger)[37]など、諸説ある。ト ロバアドゥスによって作曲されたメロディは1曲のみ(ディア伯爵夫人)が現存している。総計約450人のトルバドゥールと2,500曲のトルバドゥール作 品のうち、トルバドゥール女性とその作品群は、マイナーではあるが興味深く、また有益な部分を構成している。そのため、彼女たちについてはかなり詳しく研 究されている。  Castelloza トロバイルは、詩のスタイルと出身地を除いては、ほとんどの点で男性の同業者と同様に多様であった。彼らは主にカンソとテンスを書いた。女性として名前が 残っているゴルモンダ・ド・モンペリエが書いたシルヴェンテスは1つだけ現存している(ただし、匿名のものが2つあるが、これらは女性によるものとされて いる)。女性(アザライ・ダルティエ)が女性(クララ・ダンデュサ)に宛てた1編のサルート・ダモール(頌愛の歌)も現存しており、また、1編の匿名のプ ラングは通常、女性の作品とされている。彼女たちはほぼすべてトロバル・レウのスタイルで詩を書いており、ロンバルダとアライスの2人の作品のみが、より 高度なトロバル・クルスのスタイルに属すると考えられている。トロバイルの女性たちは多作であったわけではなく、また、多作であったとしても、その作品は 現存していない。2人だけが1つ以上の作品を残している。ディア伯爵夫人は4つ、カステロザは3つか4つの作品を残している。トロバイルの女性として知ら れている人物の1人、ガウダレンサは、Coblas e dansasという題名の歌を書いたが、現存していない。彼女の他の作品も現存していない。 トロバアイレスはほぼオクシタニア出身の女性であった。オーヴェルニュ、プロヴァンス、ラングドック、ドーフィネ、トゥールーズ、リムーザン出身の代表者 もいる。トロバアイレスの一人、イサベラは、ペリゴール、北イタリア、ギリシャ、パレスチナのいずれかで生まれたのかもしれない。家柄が判明しているトロ バアイレスはすべて高貴な生まれの女性であり、おそらく商人階級出身と思われるのはロンバルダただ一人である。名前が知られているトロバイルはすべて、ほ ぼ同時代に生きた。12世紀後半から13世紀初頭(1170年頃~1260年頃)である。最も早い時期に活躍したのは、おそらく1150年代に活躍した ティボ・ド・サレノム(Tibors de Sarenom)であろう(彼女の作曲の年代は不明である)。最も遅く活躍したのは、1242年に亡くなったフォルカルキエのガルセンダであるが、彼女が 詩の庇護者として活躍し、詩作を行っていたのはおそらくその四半世紀前であったと考えられる。あるいは、1235年から1257年の間に活躍したランフラ ンク・シガーラとテンソを作詞したギヨマ・ド・ロゼールである。トロバイル(trobairitz)の8人、アルムクス・デ・カステルノー(Almucs de Castelnau)(実際にはラゾ(razo))、アザライ・デ・ポルカイラグ(Azalais de Porcairagues)、ディア伯爵夫人(Comtessa de Dia)、カステロザ(Castelloza)、イゾット・ド・カピオ(Iseut de Capio)(同じくラゾ)、ロンバルダ(Lombarda)、マリア・デ・ベンタドールン(Maria de Ventadorn)、ティボル・デ・サレノム(Tibors de Sarenom)については、簡潔な散文による伝記(vidas)が残されている。 |

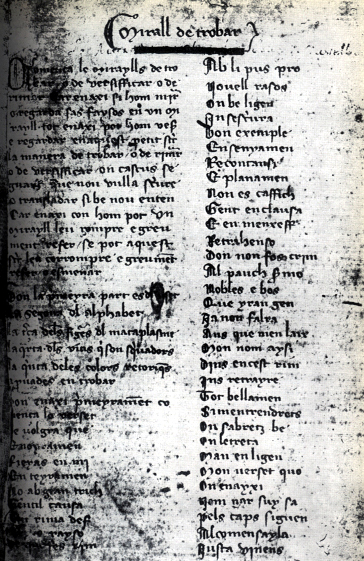

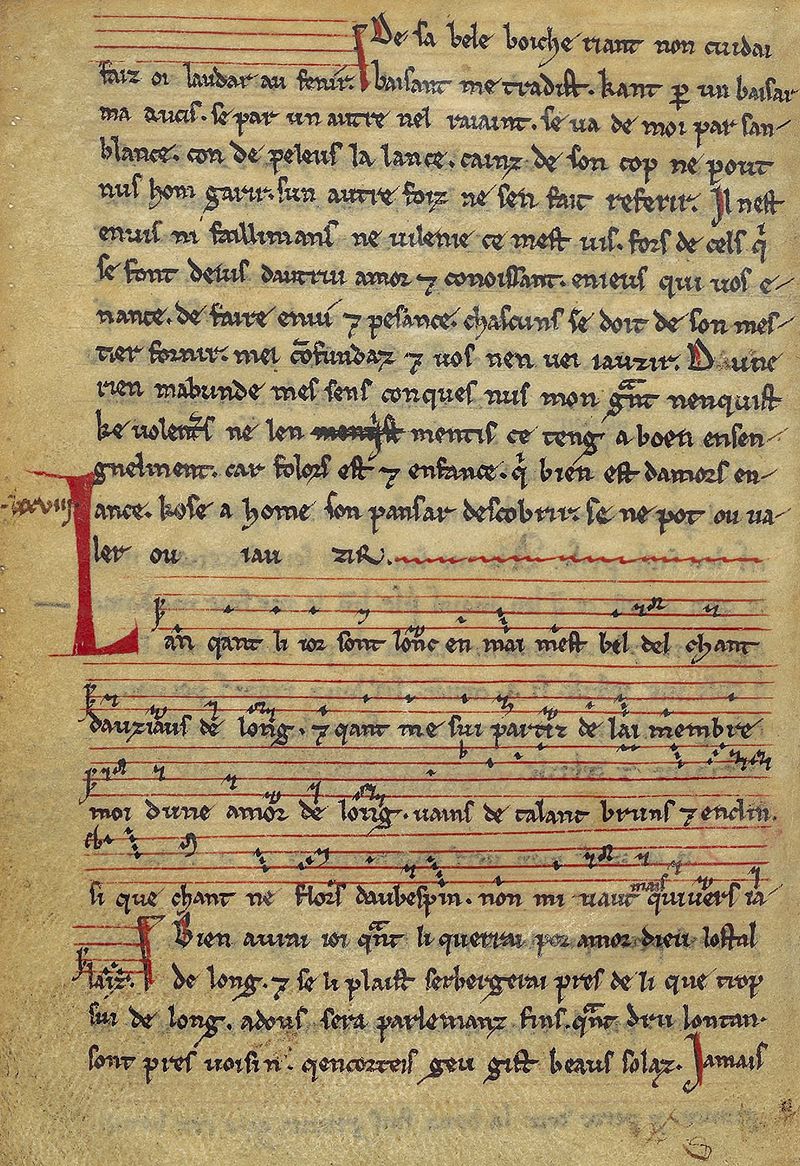

| Works Schools and styles Three main styles of Occitan lyric poetry have been identified: the trobar leu (light), trobar ric (rich), and trobar clus (closed, hermetic). The first was by far the most common: the wording is straightforward and relatively simple compared to the ric and literary devices are less common than in the clus. This style was the most accessible and it was immensely popular. The most famous poet of the trobar leu was Bernart de Ventadorn. The trobar clus regularly escapes modern scholarly interpretation. Words are commonly used metaphorically and symbolically and what a poem appears to be about on its surface is rarely what is intended by the poet or understood by audiences "in the know". The clus style was invented early by Marcabru but only favoured by a few masters thereafter. The trobar ric style is not as opaque as the clus, rather it employs a rich vocabulary, using many words, rare words, invented words, and unusual, colourful wordings. Modern scholars recognise several "schools" in the troubadour tradition. Among the earliest is a school of followers of Marcabru, sometimes called the "Marcabrunian school": Bernart Marti, Bernart de Venzac, Gavaudan, and Peire d'Alvernhe. These poets favoured the trobar clus or ric or a hybrid of the two. They were often moralising in tone and critical of contemporary courtly society. Another early school, whose style seems to have fallen out of favour, was the "Gascon school" of Cercamon, Peire de Valeira, and Guiraut de Calanso. Cercamon was said by his biographer to have composed in the "old style" (la uzansa antiga) and Guiraut's songs were d'aquella saison ("of that time"). This style of poetry seems to be attached to early troubadours from Gascony and was characterised by references to nature: leaves, flowers, birds, and their songs. This Gascon "literary fad" was unpopular in Provence in the early 13th century, harming the reputation of the poets associated with it. In the late 13th century a school arose at Béziers, once the centre of pre-Albigensian Languedoc and of the Trencavel lordships, in the 1260s–80s. Four poets epitomise this "school": Bernart d'Auriac, Joan Esteve, Joan Miralhas, and Raimon Gaucelm. The latter three were natives of Béziers and all four lived there. All were members of the urban middle class and no courtesans: Miralhas was possibly a potter and Bernart was a mayestre (teacher). All wrote in Occitan but were supporters of the French king Louis IX and the French aristocracy against the native Occitan nobility. They have been described as "Gallicised". Raimon Gaucelm supported the Eighth Crusade and even wrote a planh, the only known one of its kind, to a burgher of Béziers. Joan Esteve and Bernart both composed in support of the French in the Aragonese Crusade. The Béziers poets are a shining example of the transformation of Occitania in the aftermath of the Albigensian Crusade, but also of the ability of troubadours to survive it.[38] Genres Troubadours, at least after their style became established, usually followed some set of "rules", like those of the Leys d'amors (compiled between 1328 and 1337). Initially all troubadour verses were called simply vers, yet this soon came to be reserved for only love songs and was later replaced by canso, though the term lived on as an antique expression for the troubadours' early works and was even employed with a more technically meaning by the last generation of troubadours (mid-14th century), when it was thought to derive from the Latin word verus (truth) and was thus used to describe moralising or didactic pieces. The early troubadours developed many genres and these only proliferated as rules of composition came to be put in writing. The known genres are: Alba (morning song) – the song of a lover as dawn approaches, often with a watchman warning of the approach of a lady's jealous husband Arlabecca – a song defined by poetic metre, but perhaps once related to the rebec Canso, originally vers, also chanso or canço – the love song, usually consisting of five or six stanzas with an envoi Cobla esparsa – a stand-alone stanza Comiat – a song renouncing a lover Crusade song (canso de crozada) – a song about the Crusades, usually encouraging them Dansa or balada – a lively dance song with a refrain Descort – a song heavily discordant in verse form and/or feeling Desdansa – a dance designed for sad occasions Devinalh – a riddle or cryptogram Ensenhamen – a long didactic poem, usually not divided into stanzas, teaching a moral or practical lesson Enuig – a poem expressing indignation or feelings of insult Escondig – a lover's apology Estampida – a dance-like song Gap – a boasting song, often presented as a challenge, often similar to modern sports chants Maldit – a song complaining about a lady's behaviour and character Partimen – a poetical exchange between two or more poets in which one is presented with a dilemma by another and responds Pastorela – the tale of the love request of a knight to a shepherdess Planh – a lament, especially on the death of some important figure Plazer – a poem expressing pleasure Salut d'amor – a love letter addressed to another, not always one's lover Serena – the song of a lover waiting impatiently for the evening (to consummate his love) Sestina – highly structured verse form Sirventes – a political poem or satire, originally put in the mouth of a paid soldier (sirvens) Sonnet (sonet) – an Italian genre imported into Occitan verse in the 13th century Tenso – a poetical debate which was usually an exchange between two poets, but could be fictional Torneyamen – a poetical debate between three or more persons, often with a judge (like a tournament) Viadeira – a traveller's complaint All these genres were highly fluid. A cross between a sirventes and a canso was a meg-sirventes (half-sirventes).[39] A tenso could be "invented" by a single poet; an alba or canso could be written with religious significance, addressed to God or the Virgin; and a sirventes may be nothing more than a political attack. The maldit and the comiat were often connected as a maldit-comiat and they could be used to attack and renounce a figure other than a lady or a lover, like a commanding officer (when combined, in a way, with the sirventes). Peire Bremon Ricas Novas uses the term mieja chanso (half song) and Cerverí de Girona uses a similar phrase, miga canço, both to refer to a short canso and not a mixture of genres as sometimes supposed. Cerverí's mig (or meig) vers e miga canço was a vers in the new sense (a moralising song) that was also highly critical and thus combined the canso and the sirventes. Among the more than one hundred works of Cerverí de Girona are many songs with unique labels, which may correspond more to "titles" than "genres", but that is debatable: peguesca (nonsense), espingadura (flageolet song), libel (legal petition), esdemessa (leap), somni (dream), acuyndamen (challenge), desirança (nostalgia), aniversari (anniversary), serena (serene).[40] Most "Crusading songs" are classified either as cansos or sirventes but sometimes separately. Some styles became popular in other languages and in other literary or musical traditions. In French, the alba became the aubade, the pastorela the pastourelle, and the partimen the jeu parti. The sestina became popular in Italian literature. The troubadours were not averse to borrowing either. The planh developed out of the Latin planctus and the sonnet was stolen from the Sicilian School. The basse danse (bassa dansa) was first mentioned in the troubadour tradition (c. 1324), but only as being performed by jongleurs. The Monge de Montaudon receiving a sparrow hawk as a prize for his performance in a contest Performance Troubadours performed their own songs. Jongleurs (performers) and cantaires (singers) also performed troubadours' songs. They could work from chansonniers, many of which have survived, or possibly from more rudimentary (and temporary) songbooks, none of which have survived, if they even existed. Some troubadours, like Arnaut de Maruelh, had their own jongleurs who were dedicated to singing their patron's work. Arnaut's joglar et cantaire, probably both a singer and a messenger, who carried his love songs to his lady, was Pistoleta. The messenger was commonplace in troubadour poetry; many songs reference a messenger who will bring it to its intended ear. A troubadour often stayed with a noble patron of his own and entertained his court with his songs. Court songs could be used not only as entertainment but also as propaganda, praising the patron, mocking his enemies, encouraging his wars, teaching ethics and etiquette, and maintaining religious unity. The court was not the only venue for troubadour performance. Competitions were held from an early date. According to the vida of the Monge de Montaudon, he received a sparrow hawk, a prized hunting bird, for his poetry from the cour du Puy, some sort of poetry society associated with the court of Alfonso II of Aragon. The most famous contests were held in the twilight of the troubadours in the 14th and 15th centuries. The jocs florals held by the Consistori del Gay Saber at Toulouse, by Peter IV of Aragon at Lleida, and the Consistori de la Gaya Sciència at Barcelona awarded floral prizes to the best poetry in various categories, judging it by its accordance with a code called the Leys d'amors. Troubadour songs are still performed and recorded today, albeit rarely. A chantar m'er Duration: 1 minute and 11 seconds.1:11 The only existing song by a trobairitz which survives with music. Problems playing this file? See media help. Music Troubadour songs were usually monophonic. Fewer than 300 melodies out of an estimated 2500 survive.[41] Most were composed by the troubadours themselves. Some were set to pre-existing pieces of music. Raimbaut de Vaqueyras wrote his Kalenda maya ("The Calends of May") to music composed by jongleurs at Montferrat. Grammars and dictionaries Beginning in the early 13th century, the spread of Occitan verse demanded grammars and dictionaries, especially for those whose native tongue was not Occitan, such as the Catalan and Italian troubadours, and their imitators. The production of such works only increased with the academisation of the troubadour lyric in the 14th century.  |

作品 楽派と様式 オック語のリリック詩には主に3つの様式があることが確認されている。すなわち、トロバール・レウ(軽快)、トロバール・リック(豊か)、トロバール・ク ルス(閉鎖的、難解)である。最も一般的なのはトロバール・レウであった。表現は直接的で比較的単純であり、リックに比べ文学的技法はあまり用いられな い。この様式は最も親しみやすく、絶大な人気を博した。トロバール・レウの最も有名な詩人はベルナル・ド・ヴェンタドールである。トロバール・クルスは、 現代の学者による解釈からは通常除外される。言葉は一般的に隠喩や象徴として用いられ、詩の表面的なテーマは、詩人が意図したものや、事情通の聴衆が理解 するものとは異なることが多い。クルースのスタイルはマルカブルーによって早くから発明されたが、その後はごく一部の名人たちによってのみ好まれた。トロ バール・リックのスタイルはクルースほど難解ではなく、むしろ豊富な語彙が用いられ、多くの単語、珍しい単語、造語、そして独特で多彩な表現が使われる。 現代の学者たちは、トルバドゥール伝統の中にいくつかの「流派」を認めている。最も初期のものはマルカブリュの信奉者たちの流派であり、これは時に「マル カブリュ派」とも呼ばれる。ベルナル・マルティ、ベルナル・ド・ヴェンザック、ガヴォダン、ペイレ・ダルベルニュなどがこれに属する。これらの詩人たち は、トルバドゥール・クルースまたはリック、あるいはその2つのハイブリッドを好んだ。彼らは道徳的な調子で、同時代の宮廷社会を批判することが多かっ た。 もう一つの初期の流派は、セルカモン、ペイレ・ド・ヴァレイラ、ギロー・ド・カランソの「ガスコーニュ派」であるが、そのスタイルは人気を失ったようであ る。セルカモンは伝記作家によって「古いスタイル(la uzansa antiga)」で作曲したと言われ、ギローの歌は「その時代のもの(d'aquella saison)」であった。この詩のスタイルは、ガスクーニャ地方の初期のトルバドゥールたちに愛好され、自然、すなわち葉、花、鳥、そしてそれらの歌を 題材とするのが特徴であった。このガスクーニャ地方の「文学的流行」は、13世紀初頭のプロヴァンス地方では不評であり、それに関わった詩人たちの評判を 落とすこととなった。 13世紀後半、かつてアルビジョア十字軍以前のラングドックの中心地であり、1260年代から1280年代にかけてトランカヴェル領主の拠点でもあったベ ジエに、ひとつの学派が生まれた。この「学派」を代表する詩人として、ベルナール・ダウリアック、ジョアン・エステーヴ、ジョアン・ミララス、そしてライ モン・ガウセルムの4人が挙げられる。後者の3人はベジエの出身であり、4人ともベジエに住んでいた。彼らは皆、都市の中流階級に属し、娼婦ではなく、ミ ララスはおそらく陶芸家であり、ベルナールは教師(mayestre)であった。彼らは皆、オック語で詩を書いたが、地元のオック語貴族に対して、フラン ス王ルイ9世とフランス貴族の支持者であった。彼らは「ガリア化」したと表現されている。ライモン・ガウセルムは第8回十字軍を支援し、ベジエの市民を題 材としたプラン(planh)という形式の詩を書いた唯一の人物である。ジョアン・エステベとベルナールは、アラゴン十字軍におけるフランス軍を支援する 詩を書いた。ベジエの詩人たちは、アルビジョア十字軍の余波によるオクシタニアの変容の輝かしい例であると同時に、その変容を生き延びたトルバドゥールの 能力の例でもある。 ジャンル トルバドゥールたちは、少なくとも彼らのスタイルが確立された後は、通常、レイ・ダムール(1328年から1337年の間に編纂された)のような「ルー ル」のいくつかに従っていた。当初、トルバドゥールの詩はすべて単に「vers(ヴェール)」と呼ばれていたが、やがてそれは愛の歌だけに限定されるよう になり、後に「canso(カンソ)」に取って代わられた。しかし、この言葉はトルバドゥールの初期の作品を表す古風な表現として生き残り、トルバドゥー ルの最後の世代(14世紀半ば)には、より技術的な意味で用いられるようになった。初期のトルバドゥールたちは多くのジャンルを開発したが、作曲のルール が文書化されるようになると、それらのジャンルはさらに増えていった。 知られているジャンルは以下の通りである。 アルバ(朝の歌) - 夜明けが近づく中、恋人が歌う歌。 しばしば、嫉妬深い夫が近づいていることを警告する番人が登場する アルラベッカ - 詩脚によって定義される歌。 かつては、レベック(中世の弾き語り楽器)に関連していた可能性もある カンソ(Canso)は、もともとはヴェルス(vers)で、シャンソ(chanso)またはカンソ(cancio)とも呼ばれ、通常5~6節からなり、 アンヴォイ(envoi)で終わる愛の歌である コブラ・エスパーサ(Cobla esparsa)は、独立した節である コミアト(Comiat)は、恋人をあきらめる歌である 十字軍歌(canso de crozada)は、十字軍を題材にした歌で、通常は十字軍を鼓舞する内容である ダンスまたはバラダ(Dansa ou balada)は、リフレインのある活気のあるダンスの歌である Descort – 韻律や感情において不協和音を多用した歌 Desdansa – 悲しい場面で踊られるダンス Devinalh – なぞなぞまたは暗号文 Ensenhamen – 道徳や実践的な教訓を教える長い教訓詩で、通常はスタンザに分けられていない Enuig – 憤りや侮辱された感情を表現する詩 Escondig – 恋人の謝罪 Estampida – ダンスのような歌 Gap – 自慢の歌、しばしば挑戦として提示され、現代のスポーツの応援歌に似ていることが多い Maldit – 女性の行動や性格を非難する歌 Partimen – 2人以上の詩人による詩のやりとりで、一方がもう一方にジレンマを提示し、それに対してもう一方が返答する Pastorela – 騎士が羊飼いの女性に愛を求める物語 プラン(Plagh) - 特に重要な人物の死を悼む嘆き プレゼ(Plazer) - 喜びを表現する詩 サル・ダムール(Salut d'amor) - 必ずしも恋人とは限らない相手に宛てたラブレター セレナ(Serena) - 夜(愛を成就させる)を待ち焦がれる恋人の歌 セスティナ(Sestina) - 高度に構造化された詩の形式 シルヴェンテス(Sirventes) - 政治的な詩または風刺、もともとは有給の兵士(シルヴェンテ)の口から発せられたもの ソネット(sonet) - 13世紀にイタリアのジャンルがオック語の詩に輸入された テンソ(tenso) - 通常は2人の詩人による詩の討論だが、架空の人物による場合もある トーネヤメン(torneyamen) - 3人以上の人物による詩の討論で、審判役が参加する場合もある(トーナメントのようなもの ヴィアデイラ(viadeira) - 旅行者の苦情 これらのジャンルはすべて、非常に流動的であった。シルヴェンテスとカンソの折衷形は、メグ・シルヴェンテス(ハーフ・シルヴェンテス)であった。 [39] テンソは一人の詩人によって「発明」されることもあり、アルバやカンソは神や聖母マリアに捧げられた宗教的な意味を持つこともあった。また、シルヴェンテ スは政治的な攻撃に過ぎない場合もあった。また、マルディットとコミアットはマルディット・コミアットとして結び付けられることが多く、女性や恋人以外の 人物、例えば上官などを攻撃したり、非難したりするために用いられることもあった(マルディットと組み合わさる場合もある)。 ペイレ・ブレモン・リカス・ノヴァスはmieja chanso(半歌)という用語を使用しており、セルベリ・デ・ジローナはmiga cançoという同様の表現を使用している。どちらも短いカンソを指しており、時折考えられているような、ジャンルの混合ではない。セルベーリ作のmig (またはmeig)vers e miga cançoは、新しい意味でのvers(道徳的な歌)であり、非常に批判的であったため、cansoとsirventesを組み合わせたものとなった。セ ルベリ・デ・ジローナの100を超える作品の中には、独特なラベルが付けられた歌も多く、これらは「ジャンル」というよりも「タイトル」に該当するかもし れないが、議論の余地がある。ペグエスカ(ナンセンス)、エスピングアドラ(フラジェットの歌)、 オレットの歌)、libel(訴状)、esdemessa(飛躍)、somni(夢)、acuyndamen(挑戦)、desirança(郷愁)、 aniversari(記念日)、serena(穏やか)などがある。[40] ほとんどの「十字軍歌」はカンソまたはシルヴェンテに分類されるが、時には個別に分類されることもある。いくつかのスタイルは、他の言語や文学・音楽の伝 統において人気を博した。フランス語では、アルバはオーバードとなり、パストレラはパストゥレル、パルティマンはジュ・パルティとなった。セスティナはイ タリア文学で人気を博した。トルバドゥールたちも、他者からの借用を嫌うことはなかった。プランはラテン語のプランクトゥスから発展し、ソネットはシチリ ア派から盗まれた。バスダンス(basse danse)は、トルバドゥールたちの伝統の中で初めて言及された(1324年頃)が、それはあくまでも、道化師たちによって演奏されたものとしてであっ た。 モンジュ・ド・モントードンがコンテストでのパフォーマンスの賞品としてスズメバチを受け取る パフォーマンス トルバドゥールは自作の歌を披露した。 ジョングル(パフォーマー)やカンタイユ(歌手)もトルバドゥールの歌を披露した。 彼らはシャンソニエ(楽譜)を元にパフォーマンスを行ったが、シャンソニエの多くは現存している。あるいは、より初歩的(かつ一時的な)歌集を元にパ フォーマンスを行った可能性もあるが、そのような歌集は現存していない。アルノー・ド・マルユール(Arnaut de Maruelh)のようなトルバドゥールには、パトロンの作品を歌う専属のジョングルールがいた。アルノーのジョングルール兼カンタール (cantaire)であるピストレット(Pistoleta)は、おそらく歌手であり、またメッセンジャーでもあった。メッセンジャーはトルバドゥール の詩では一般的であり、多くの歌が、意中の人の耳に歌を届けるメッセンジャーについて言及している。トルバドゥールは、しばしば自身のパトロンの貴族のも とに滞在し、歌で宮廷を楽しませた。宮廷の歌は、娯楽としてだけでなく、パトロンを称え、敵をあざけり、戦争を鼓舞し、倫理や礼儀作法を教え、宗教的団結 を維持するプロパガンダとしても使われた。 宮廷はトルバドゥールのパフォーマンスの唯一の場ではなかった。 早い時期からコンテストも開催されていた。 モンジュ・ド・モントードンの伝記によると、彼はピュイの宮廷から、狩猟用の鳥として珍重されていたハヤブサを詩の褒美として受け取ったという。これはア ラゴン王アルフォンソ2世の宮廷に関連する詩の協会のようなものだった。最も有名なコンテストは、14世紀から15世紀にかけてのトルバドゥールの黄昏期 に開催された。トゥールーズの「賢きゲイの審議会」、アラゴン王ペドロ4世の主催によるリェイダのコンテスト、そしてバルセロナの「ゲイ・サエンシア審議 会」が主催したジョック・フローラルでは、愛の規範と呼ばれる「レイス・ダムール」に準拠しているかどうかを基準に、さまざまなカテゴリーにおける最優秀 詩にフローラル賞が授与された。 トルバドゥールの歌は、現在でも稀にではあるが、演奏や録音されている。 A chantar m'er 再生時間: 1分11秒 トルバイルリッツの歌で、楽譜が現存している唯一の歌。 このファイルの再生に問題がありますか? メディアヘルプをご覧ください。 音楽 トルバドゥールの歌は通常モノフォニックであった。推定2500曲のうち、300曲未満が現存している。[41] そのほとんどはトルバドゥール自身によって作曲された。中には既存の楽曲にメロディをつけたものもある。Raimbaut de Vaqueyrasは、モンフェッラートの道化師が作曲した楽曲に「Kalenda maya(5月の初め)」を付けた。 文法と辞書 13世紀初頭から、オック語の詩が広まるにつれ、文法や辞書が必要とされるようになった。特に、カタルーニャ人やイタリア人のトルバドゥール、および彼ら の模倣者など、母国語がオック語でない人々にとっては必要不可欠であった。14世紀にトルバドゥールの歌詞がアカデミックなものになっていくにつれ、この ような作品の制作はさらに増加した。 |

| Image

Title Translation of title

Author Date, place Character |

画像 タイトル タイトル訳 著者 日付、場所 キャラクター |

Razos de trobar "Explanations of composition" Raimon Vidal c. 1210 Prose guide to poetic composition that defends the superiority of Occitan over other vernaculars. Occitan–Italian dictionary. |

韻文の断片 「構成の説明」 ライモン・ヴィダル 1210年頃 オック語が他の土地言葉よりも優れていることを擁護する詩作の散文ガイド。 オック語-イタリア語辞書。 |

Lo breviari d'amors "Breviary of love" Matfre Ermengau begun 1288 A pious encyclopedia, the last section of which, "Perilhos tractatz d'amor de donas, seguon qu'en han tractat li antic trobador en lurs cansos", is an Occitan grammar. |

愛の書簡集 「愛の書簡集」 マフレ・エルメンガウ 1288年開始

敬虔な百科事典で、最後の章「ペリリョス・トラタッツ・ダモン・デ・ドナス、セグオン・クエン・エン・ハン・トラタッツ・リ・アンティク・トロバドール・

エン・ルルス・カンソス」は、オック語の文法である。 |

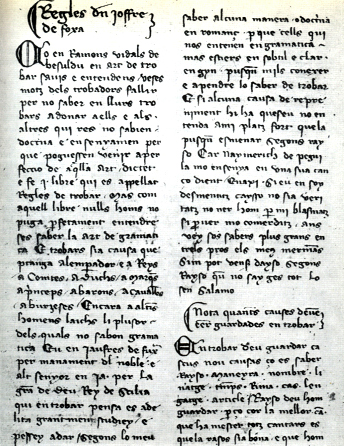

Regles de trobar[43] "Rules of composition" Jaufre de Foixa 1289–91, Sicily Contains many examples of troubadour verse, designed to augment the Razos de trobar. |

レグルス・ド・トロバール[43] 「作曲のルール」

ジャウフレ・ド・フォイヤ 1289年-91年、シチリア 多くのトルバドゥールの詩の例を含み、レグルス・ド・トロバールを補完する目的で書かれた。 |

Mirall de trobar "Mirror of composition" Berenguer d'Anoia early 14th century Mainly covers rhetoric and errors, and is littered with examples of troubadour verse. |

Mirall de trobar(ミラー・デ・トロバール)

「作曲の鏡」 Berenguer d'Anoia(ベレンゲール・ダノイア) 14世紀初頭

主として修辞学と誤りを扱っており、トルバドゥールの詩の例が散りばめられている。 |

Leys d'amors[44] "Laws of love" Guilhem Molinier 1328–37, Toulouse First commissioned in 1323. Prose rules governing the Consistori del Gay Saber and the Consistori de Barcelona. |

Leys d'amors[44] 「愛の掟」 ギレム・モリニエ

1328年-1337年 トゥールーズ 1323年に初めて委託された。 Consistori del Gay SaberとConsistori

de Barcelonaを規定する散文の規則。 |

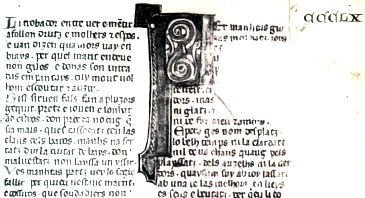

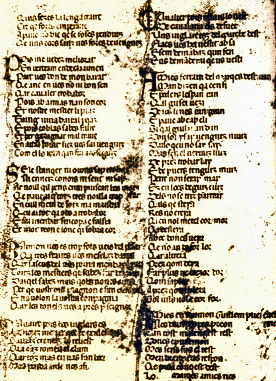

| Legacy Main article: Occitan literature Transmission Some 2,600 poems or fragments of poems have survived from around 450 identifiable troubadours. They are largely preserved in songbooks called chansonniers made for wealthy patrons. Troubadour songs are generally referred to by their incipits, that is, their opening lines. If this is long, or after it has already been mentioned, an abbreviation of the incipit may be used for convenience. A few troubadour songs are known by "nicknames", thus D'un sirventes far by Guilhem Figueira is commonly called the Sirventes contra Roma. When a writer seeks to avoid using unglossed Occitan, the incipit of the song may be given in translation instead or a title may even be invented to reflect the theme of the work. Especially in translations designed for a popular audience, such as Ezra Pound's, English titles are commonly invented by the translator/editor. There are examples, however, of troubadour songs given Occitan titles in the manuscripts, such as an anonymous pastorela that begins Mentre per una ribeira, which is entitled Porquieira. Table of chansonniers The number of Occitan parchment chansonniers given as extant varies between authors, depending on how they treat fragmentary and multilingual manuscripts. Conventionally, fragments are classified as fragments of the surviving chansonnier they most closely resemble and not as chansonniers in their own right. Some chansonniers have received both Occitan and French letters: troubadour D is trouvère H, W is M and X is U. The lettering (siglas) was introduced by Karl Bartsch, who placed sources he considered more reliable higher in the alphabet. This system is imperfect, however, since many of the chansonniers produced for an Italian audience are heavily edited and do not necessarily more closely resemble the original compositions. While parchment chansonniers are more durable, paper ones also exist and have received lower-case siglas.[46][47] |

伝統 詳細は「オック語文学」を参照 伝承 およそ450人の特定されたトルバドゥールから、2,600編ほどの詩または詩の断片が現存している。それらは主に、裕福なパトロンのために作られたシャ ンソニエと呼ばれる歌集に保存されている。 トルバドゥールの歌は一般的に冒頭の行、すなわちその歌の最初の数行によって言及される。これが長い場合、またはすでに言及されている場合は、便宜上冒頭 の行の省略形が使用されることもある。トルバドゥールの歌には「愛称」で知られているものもあり、例えばギレム・フィゲイラによる『D'un sirventes』は一般的に『Sirventes contra Roma』と呼ばれている。著者が未翻訳のオック語を使用しないようにする場合、その歌の冒頭は翻訳で示されるか、作品のテーマを反映したタイトルが新た に考案されることもある。特にエズラ・パウンドのような一般読者向けの翻訳では、翻訳者や編集者が英語のタイトルを新たに考案することが一般的である。し かし、写本では、トルバドゥールの歌にオック語のタイトルが付けられている例もある。例えば、匿名のパストレーラ(牧歌)の歌「Mentre per una ribeira」は、「Porquieira」というタイトルで知られている。 シャンソニエの表 現存するオック語の羊皮紙シャンソニエの数は、断片的な多言語の写本をどのように扱うかによって、著者によって異なる。通常、断片は、現存するシャンソニ エに最もよく似た断片として分類され、それ自体がシャンソニエとして分類されることはない。シャンソニエの中には、オック語とフランス語の両方の文字が使 われているものもある。例えば、トルバドゥールDはtrouvère H、WはM、XはUである。文字表記(シグラ)はカール・バルシュが導入したもので、彼がより信頼性が高いと判断した資料をアルファベットの上位に配置し た。しかし、このシステムは不完全である。なぜなら、イタリアの聴衆向けに制作されたシャンソニエの多くは大幅に編集されており、必ずしもオリジナルの楽 曲により近いとは限らないからだ。羊皮紙のシャンソニエはより耐久性があるが、紙のシャンソニエも存在し、小文字のシグラスが使用されている。[46] [47] |

| Image

Troubadour manuscript letter (sigla) Provenance

(place of origin, date) Location (library,

city) Shelfmark (with external link to digitization, where available) Notes |

画像 トルバドゥール写本の手紙(シグラ) 由来(原産地、日付)

所蔵先(図書館、都市) 請求記号 (デジタル化への外部リンク、可能な場合) 注釈 |

A Lombardy, 13th century Biblioteca Vaticana, Rome Latin 5232 |

A ロンバルディア、 13世紀 ヴァチカン図書館、 ローマ ラテン語 5232 |

|

C Occitania, 14th century Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris BN f.f. 856 |

|

D Lombardy, 12 August 1254 Biblioteca Estense, Modena α.R.4.4 = Kg.4.MS2 = E.45 The Poetarum Provinciali. |

|

G Lombardy or

Venetia, late 13th century Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan R 71 sup. Contains troubadour music. |

|

I Lombardy, 13th century Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris BN f.f. 854 |

|

K Lombardy, 13th century Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris BN f.f. 12473 |

|

P Lombardy, 1310 Biblioteca Laurenziana, Florence Plut.XLI.42 |

|

R Toulousain

or Rouergue, 14th century Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris BN f.f. 22543 Contains more troubadour music than any other manuscript. Perhaps produced for Henry II of Rodez. |

|

S Lombardy, 13th century Bodleian Library, Oxford Douce 269 |

|

Sg Catalonia, 14th century Biblioteca de Catalunya, Barcelona 146 The famous Cançoner Gil. Called Z in the reassignment of letter names by François Zufferey. |

|

U Lombardy, 14th century Biblioteca Laurenziana, Florence Plut.XLI.43 |

|

W perhaps

Artois, 1254–c. 1280 Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris BN f.f. 844 Also trouvère manuscript M. Contains the chansonnier du roi of Theobald I of Navarre. Possibly produced for Charles I of Naples. Contains troubadour music. |

|

X Lorraine, 13th century Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris BN f.f. 20050 Chansonnier de Saint-Germain-des-Prés. Also trouvère manuscript U and therefore has marks of French influence. Contains troubadour music. Owned by Saint-Germain-des-Prés in the 18th century. |

| Ashik Bard Bhāts Filí Griot Minstrels Skald Dziady (wandering beggars) Lirnyk |

Ashik Bard Bhāts Filí Griot Minstrels Skald Dziady (放浪の乞食) Lirnyk |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Troubadour |

|

Perdigon or Perdigo

(fl. 1190–1220[2]) was a troubadour from Lespéron in the Gévaudan.[3]

Fourteen of his works survive, including three cansos with melodies.[4]

He was respected and admired by contemporaries, judging by the

widespread inclusion of his work in chansonniers and in citations by

other troubadours.[4] Perdigon or Perdigo

(fl. 1190–1220[2]) was a troubadour from Lespéron in the Gévaudan.[3]

Fourteen of his works survive, including three cansos with melodies.[4]

He was respected and admired by contemporaries, judging by the

widespread inclusion of his work in chansonniers and in citations by

other troubadours.[4]Though his biography is made confounding by contradicting statements in his vida and allusions in his and others' poems, Perdigon's status as a jongleur from youth and an accomplished fiddler is well-attested in contemporary works (by him and others) and manuscript illustrations depicting him with his fiddle.[2] Perdigon travelled widely and was patronised by Dalfi d'Alvernha, the House of Baux,[a] Peter II of Aragon, and Barral of Marseille.[2] His service to the latter provides an early definite date for his career, as Barral died in 1192 and Perdigon composed a canso—which survives with music—for him.[2] According to his vida, Perdigon was the son of a poor fisherman who excelled through his "wit and inventiveness" to honour and fame, was clothed and eventually armed, knighted, and granted land and rent by Dalfi d'Alvernha.[3] After this period of his life, which is said to have lasted a long time, the manuscripts of his vida diverge. According to one version, death deprived him of his friends, male and female, and so he lost his position and entered a Cistercian monastery, where he died.[3][4] That he entered a Cistercian monastery has never been proven, but has received some support from two of his works.[3]  Perdigon, with his famous fiddle. According to another version of his vida, he became a strong opponent of Catharism—a sect suppressed by the Catholic Church as heretical—and supported the Albigensian Crusade against them.[4] He is said to have accompanied Guillem des Baux, Folquet de Marselha, and the Abbot of Cîteaux to Rome to oppose Raymond VI of Toulouse after the latter's excommunication in 1208. The author of the vida blames Perdigon for "[bringing] about and [arranging] all these deeds."[5] The biographer further claims that Perdigon sang to the populace to encourage the Crusade and even boasted of humiliating Peter II of Aragon who opposed the Crusades and died at the Battle of Muret fighting against the Crusaders.[5] For this reason he became despised by those in favor of Catharism, and due to the war lost all his friends who fought in it: Simon de Montfort, Guillem des Baux,[b] and many others.[5] In the end, the son of Dalfi d'Alvernha, abandoned him, confiscated his land, and sent him away. The biographer claims that he went to Lambert de Monteil and begged to be entered into the Cistercian monastery of "Silvabela", but the author incorrectly believes Lambert to be the son-in-law of Guillem des Baux, and the monastery Silvabela ("beautiful forest") never existed.[5] His vidas are questionable. Among Perdigon's surviving songs is a torneyamen with Raimbaut de Vaqueiras and Ademar de Peiteus.[6] Unusually for the period, Perdigon, along with Aimeric de Peguilhan, through-composed his melodies.[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perdigon |

ペルディゴンまたはペルディゴ(1190年頃

-1220年頃)は、ジェヴォーダンのレスペロン出身のトルバドゥールであった。[3]

彼の作品は14編が現存しており、その中には旋律付きのカンソが3編含まれている。[4]

彼の作品がシャンソニエで広く取り上げられ、他のトルバドゥールたちによって引用されていたことから、同時代の人々から尊敬と賞賛を集めていたことがわか

る。[4] ペルディゴンまたはペルディゴ(1190年頃

-1220年頃)は、ジェヴォーダンのレスペロン出身のトルバドゥールであった。[3]

彼の作品は14編が現存しており、その中には旋律付きのカンソが3編含まれている。[4]

彼の作品がシャンソニエで広く取り上げられ、他のトルバドゥールたちによって引用されていたことから、同時代の人々から尊敬と賞賛を集めていたことがわか

る。[4]彼の伝記は、彼のヴィーダ(vida)における矛盾する記述や、彼や他の詩人の詩における暗示によって混乱しているが、ペルディゴンが若き日からジョング ルール(jongleur)として活躍し、熟練したヴァイオリニストであったことは、同時代の作品(彼自身や他の人々による)や、彼と彼のヴァイオリンを 描いた写本の挿絵によって証明されている。ペルディゴンは広く旅をし、 ダルフィ・ダルベルニャ、ボー家、アラゴン王ペドロ2世、マルセイユのバラルに庇護されていた。[2] バラルが1192年に死去し、ペルディゴンがカンソ(音楽が残っている)を作曲したことから、ペルディゴンのキャリアの初期の明確な日付がわかる。[2] 彼の伝記によると、ペルディゴンは貧しい漁師の息子であったが、「機知と創意」によって名誉と名声を得て、衣服を身にまとい、最終的には武器を手にし、騎 士の称号を受け、ダルフィ・ダルヴェルニャから土地と地代を授けられたという。[3] 長い期間続いたと言われる彼の人生のこの期間の後、彼の伝記の原稿は分岐する。あるバージョンによると、死によって男女の友を失った彼は地位を失い、シ トー会の修道院に入り、そこで亡くなったという。[3][4] 彼がシトー会の修道院に入ったことは証明されていないが、彼の作品2点からある程度の裏付けがある。[3]  ペルディゴン、彼の有名なヴァイオリンとともに。 彼の伝記の別のバージョンによると、ペルディゴンはカトリック教会によって異端として弾圧されたカタル派の強力な反対者となり、アルビジョワ十字軍を支援 したという。[4] 1208年にトゥールーズのレイモン6世が破門された後、ペルディゴンはギレム・デ・ボー、フォルケット・ド・マルセイユ、シトー修道院長らとともにロー マに赴き、レイモン6世に反対したと言われている。伝記の著者はペルディゴンを非難し、「これらの行為のすべてを引き起こし、計画した」と述べている。 [5] 伝記作家はさらに、ペルディゴンが民衆に十字軍を奨励する歌を歌い、 。このため、ペルディゴンはカタリ派の支持者たちから軽蔑されるようになり、戦争によって戦った友人たちをすべて失った。シモン・ド・モンフォール、ギレ ム・デ・ボー、その他多くの者たちである。[5] 結局、ダルフィ・ダルベルニャの息子は彼を見捨て、彼の土地を没収し、彼を追放した。伝記作家は、彼はランベール・ド・モンテイユのもとへ行き、シトー修 道会の「シルヴァベーラ」修道院への入門を懇願したと主張しているが、著者はランベールをギレム・デ・ボーの娘婿であると誤って信じており、シルヴァベー ラ修道院(「美しい森」)は実在しなかったと主張している。[5] 彼のヴィーダスは疑わしい。 ペルディゴンの現存する歌の中には、レイモン・ド・ヴァケラスとアデマール・ド・ペイトゥスとの間のトルネヤマンがある。[6] ペルディゴンは、ペギルアン・ド・エメリックとともに、その時代としては珍しく、メロディを最初から最後まで作曲した。[7] |

Music

of the Troubadours 1: Tant m'abelis

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆