トゥルノ/トゥルニスモ

Turno, turnismo

☆スペイン政治におけるターンイズモ、ターン・パシフィコ、あるいは単にターン[ turnismo, turno pacífico or simply turno](スペイン語で「交代」を意味する)とは、復古王政下の立憲君主制における非公式な二大政党制を指す。これは二つの王朝政党(保守党と自由党)が、選挙を呼びかけた政党が常に勝利することを保証する組織的な選挙不正を通じて政権を交代させる制度であった。[1]

この制度は1879年、復古王政下で初めて実施された選挙から1918年まで続いた。第一次世界大戦中の世論の影響で崩壊し始め、1923年の選挙とミゲル・プリモ・デ・リベラのクーデターを経て、最終的に廃止された。

| In Spanish politics,

the turnismo, turno pacífico or simply turno (Spanish for "turn" or

"shift") refers to an informal two-party system of government within

the constitutional monarchy of the Restoration. It consisted of the

alternation in government of the two dynastic parties (the Conservative

and the Liberal parties) through systematic electoral fraud which

ensured that the party that called the elections always won.[1] The system was in place from 1879, the first elections held under the Restoration, until 1918, when it began to break down in response to public influence during World War I, and was ultimately abandoned after the election of 1923 and coup d'etat of Miguel Primo de Rivera. |

スペイン政治におけるターンイズモ、ターン・パシフィコ、あるいは単に

ターン[ turnismo, turno pacífico or simply turno](スペイン語で「交代」を意味する)とは、復古王政下の立憲君主制における非公式な二大政党制を指す。これは二つの王朝政党(保守党と自由党)が、

選挙を呼びかけた政党が常に勝利することを保証する組織的な選挙不正を通じて政権を交代させる制度であった。[1] この制度は1879年、復古王政下で初めて実施された選挙から1918年まで続いた。第一次世界大戦中の世論の影響で崩壊し始め、1923年の選挙とミゲ ル・プリモ・デ・リベラのクーデターを経て、最終的に廃止された。 |

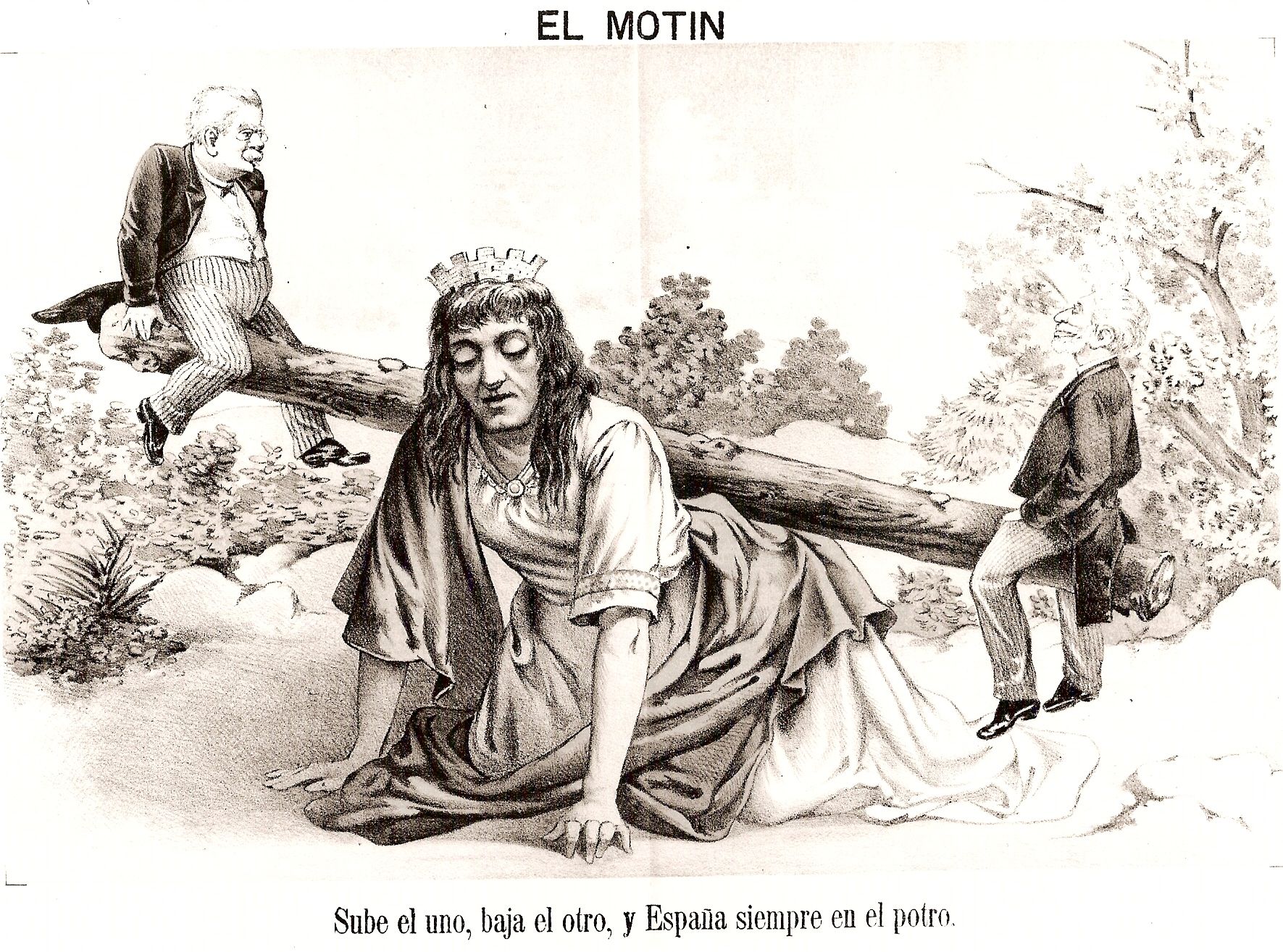

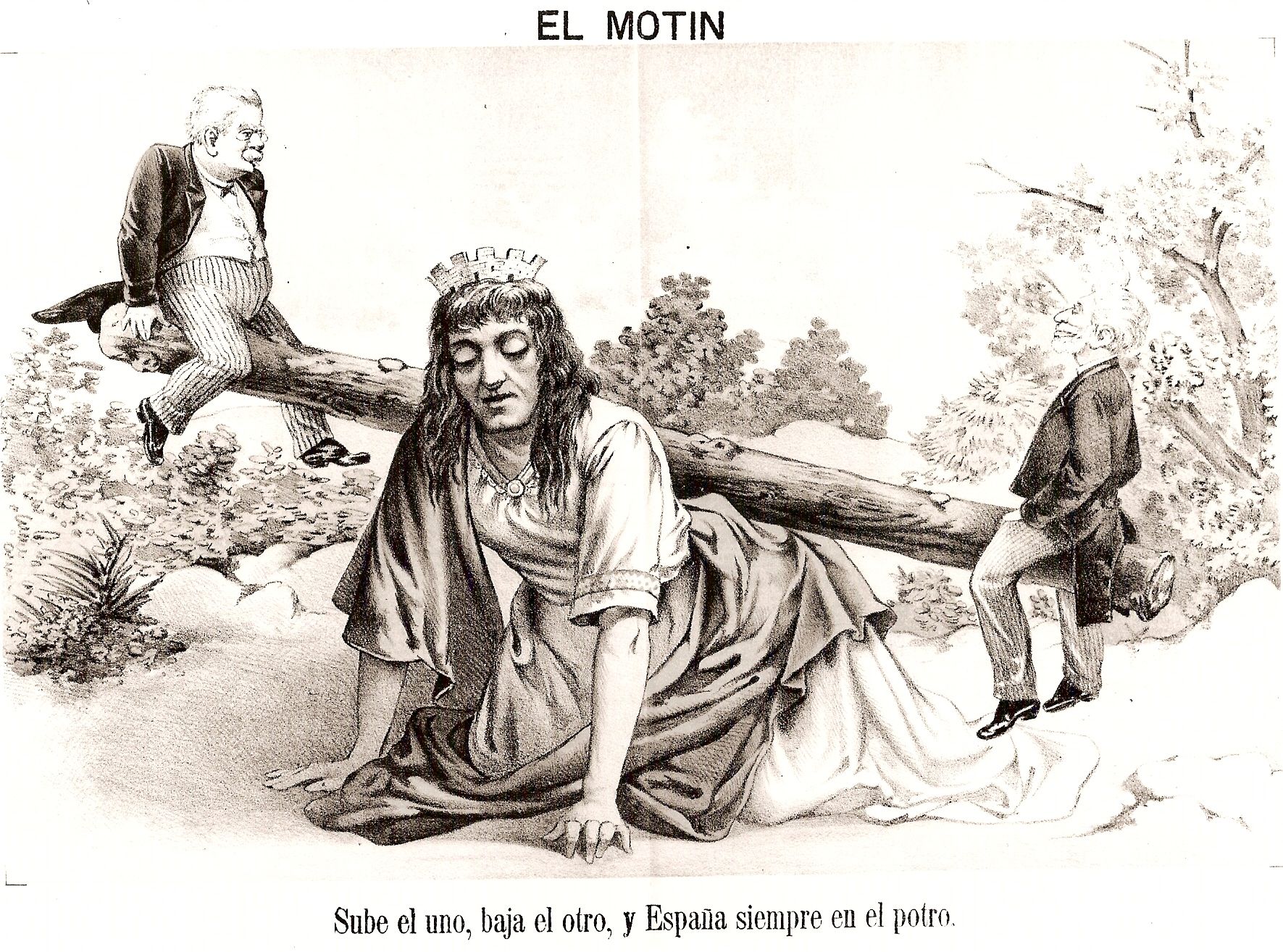

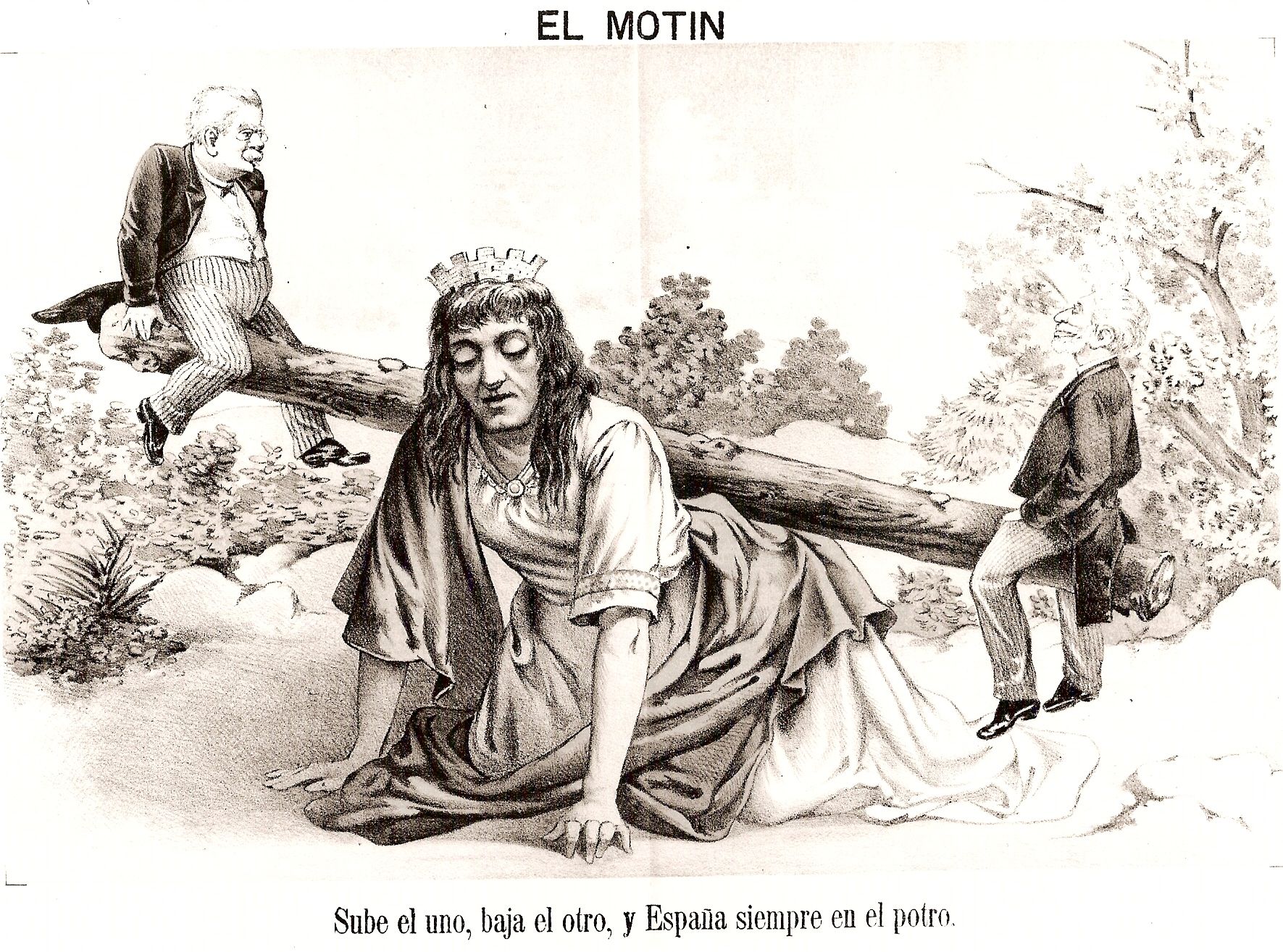

Cartoon in the satirical magazine El Motín depicting Cánovas and Sagasta see-sawing up and down on the back of Spain. |

風刺雑誌『エル・モティン(暴動誌)』の漫画。カノーバスとサガスタがスペインの背中でシーソー遊びをしている様子を描いている。 |

| Background Under the constitutional monarchy of the Bourbon Restoration, government formation required the support of the Crown, and elections were called only in response to a political crisis or the erosion of power of the ruling party. Only two major political parties governed Spain under the Restoration: the Liberal Conservative Party, representing the "right" of the system, and the Liberal Fusionist Party, representing its "left".[2] The Conservative Party was led by Antonio Cánovas del Castillo, the architect of turnismo, and the Liberal Party was led by Práxedes Mateo Sagasta.[3] The two men divided between them all of the political factions which supported the constitutional monarchy, excluding Carlists and republicans, who both rejected the political system, and socialists and anarchists, who rejected the principles of liberty and property on which Spanish bourgeois society was based.[4][5] The first alternation took place in February 1881, when the Liberal Party was called to power after six years of conservative government. In this instance, the transfer of power came at the behest of Alfonso XII, without consultation with Cánovas and against his presumed wishes.[6] According to historian José Ramón Milán García, "its relevance did not escape its protagonists, aware that the monarch's initiative opened the doors to overcoming the entrenched confrontation between left-wing liberalism and the Bourbon dynasty, and therefore the Cainite struggles sustained for decades between the various houses of Spanish liberalism."[7] Historian Carlos Dardé noted that the 1881 election made clear "that the ultimate interpreter of the state of affairs, and the one who had the power to make decisions―over and above the parliamentary majorities and the president of the government―was the monarch."[8] In response to the 1881 transfer of power, Cánovas formulated a system of rules "that both parties would have to respect in order to avoid falling again into the danger of royal whims. [...] The first thing he saw clearly was the need to control the royal prerogative, to standardize it and give it fixed criteria, far from personal criteria; to achieve a balance between royal and parliamentary power, for which party leaders were going to be the arbiters." In November 1885, following the death of the king and during the brief regency of the pregnant queen Maria Christina of Austria, Cánovas resigned as prime minister and advised Maria Christina to appoint Sagasta as prime minister. Cánovas then met with Sagasta and General Arsenio Martínez Campos to communicate his decision. At the meeting, Cánovas and Sagasta informally agreed to alternate power automatically over the following years, an agreement which has become commonly known as the "Pact of El Pardo".[4] The new system departed from the traditional Spanish custom from the time of Isabella II, in which moderates and conservatives held a monopoly on parliamentary power, leaving progressives only the pronunciamiento to achieve power through force. According to Ángeles Lario, the Pact of El Pardo "turned the two major parties into the true directors of political life, consensually controlling the royal prerogative upwards and the construction of the necessary parliamentary majorities downward [through electoral fraud], thus defining the life of this important period of [Spanish] liberalism and at the same time being the origin of its most serious limitations."[9] |

背景 ブルボン復古王政下の立憲君主制では、政権樹立には王室の支持が必要であり、選挙は政治危機や与党の権力衰退に応じてのみ実施された。復古王政下のスペイ ンを統治した主要政党は二つだけだった。体制の「右」を代表する自由保守党と、「左」を代表する自由融合党である。[2] 保守党はターン主義の設計者アントニオ・カノバス・デル・カスティーヨが率い、自由党はプラクセデス・マテオ・サガスタが率いた。[3] この二人は、立憲君主制を支持する全ての政治派閥を分け合った。ただし、政治体制を拒否したカルリスタと共和主義者、そしてスペインのブルジョワ社会が基 盤とする自由と財産の原則を拒否した社会主義者とアナキストは除外された。[4] [5] 最初の政権交代は1881年2月に起こった。6年間の保守党政権の後、自由党が政権に招かれたのである。この場合、権力の移譲はアルフォンソ12世の指示 によるもので、カノーバスとの協議もなく、彼の予想される意思に反して行われた。[6] 歴史家ホセ・ラモン・ミラン・ガルシアによれば、「その重要性は当事者たちにも理解されていた。彼らは、国王の主導が左派自由主義とブルボン王朝との根深 い対立を克服する道を開き、それによってスペイン自由主義諸派の間で数十年にわたり続いたカイン的な争いを終結させることを認識していた」 [7] 歴史家カルロス・ダルデは、1881年の選挙が「議会多数派や政府首相を超えて、国家の状況を最終的に解釈し、決定権を持つのは君主である」ことを明らか にしたと指摘している。[8] 1881年の権力移譲を受けて、カノバスは「両党が王の気まぐれによる危険に再び陥らないために遵守すべき」規則体系を策定した。[...] 彼がまず明確に認識したのは、王権を統制し、個人的基準から離れた固定基準で標準化する必要性だった。王権と議会権力の均衡を図るため、政党指導者が仲裁 者となるべきだと考えたのである。」 1885年11月、国王の死後、妊娠中のオーストリアのクリスティーナ王妃による短期間の摂政期間中、カノーバスは首相を辞任し、クリスティーナ王妃にサ ガスタを首相に任命するよう助言した。カノーバスはその後、サガスタとアルセニオ・マルティネス・カンポス将軍と会談し、自身の決定を伝えた。この会合で カノーバスとサガスタは、今後数年間にわたり自動的に政権を交代させることで非公式に合意した。この合意は一般に「エル・パルド協定」として知られるよう になった[4]。この新体制は、イサベラ2世の時代から続くスペインの伝統的慣習から脱却した。それまでは穏健派と保守派が議会権力を独占し、進歩派は武 力によるクーデター(プロンシニアメント)でしか権力を掌握できなかったのである。 アンヘレス・ラリオによれば、エル・パルド協定は「二大政党を政治生活の真の支配者へと変貌させた。合意によって上層部では王権を掌握し、下層部では(選 挙不正を通じて)必要な議会多数派の構築を支配した。これにより[スペイン]自由主義の重要な時代の様相が定められたと同時に、その最も深刻な限界の起源 ともなった」[9]。 |

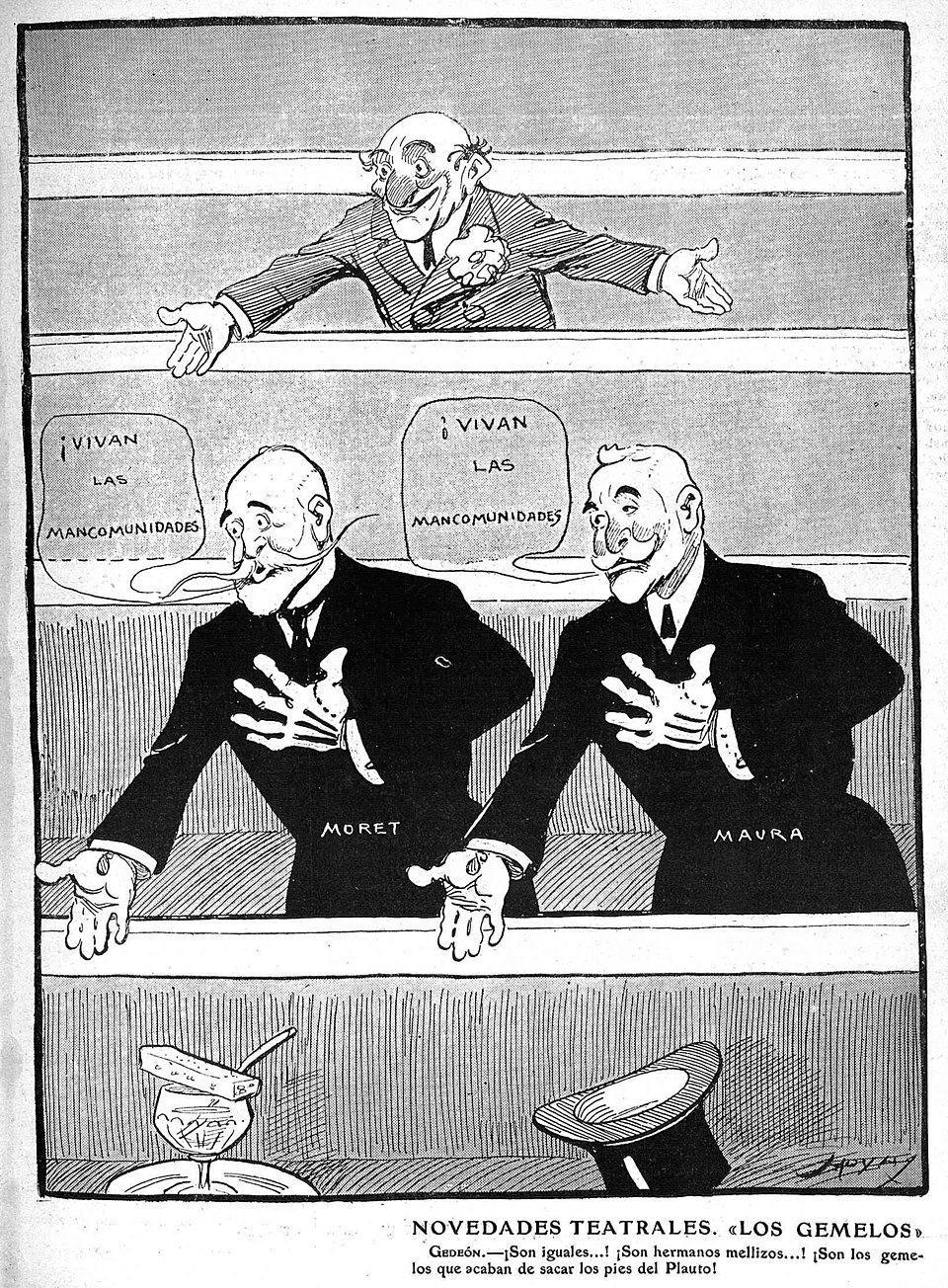

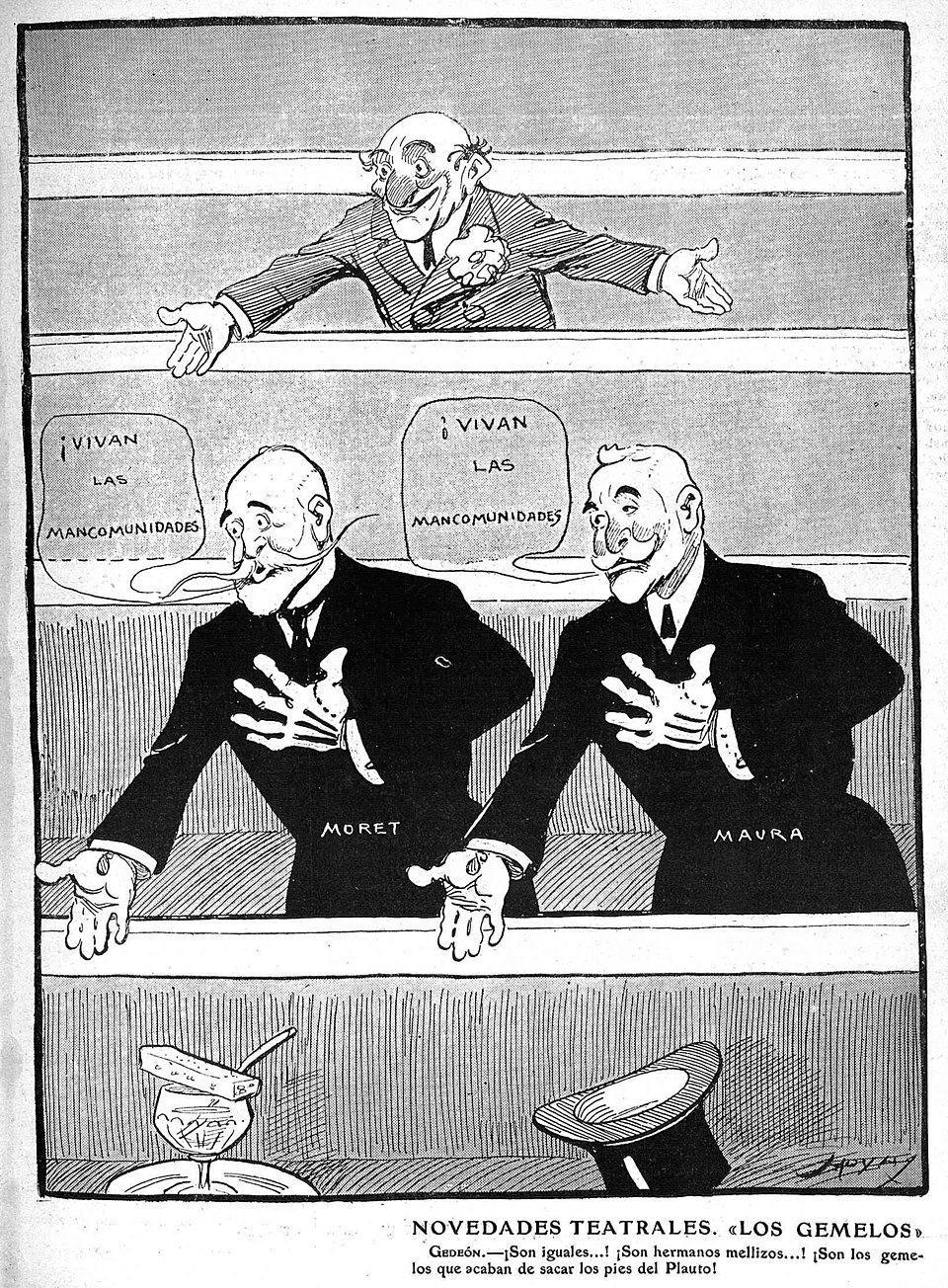

New Theatre "The Twins" from the Spanish magazine Gedeón, 1909. |

スペインの雑誌『ゲデオン』1909年掲載の新劇「双子」。 |

| Operation See also: Caciquism The turno followed a series of steps: The Crown called one of the two major parties to govern. If the Liberal Party was in power, the Crown called the Conservative Party, and vice versa. In other words, the first step was to secure the Crown's support. Because the Restoration regime was premised on a parliamentary system, it was essential that the new government have the support of the Cortes Generales. To achieve this, the Crown dissolved the Cortes and called new elections. The new elections were manipulated through encasillado and the caciquismo system, by which the minister of the interior, provincial civil governors, and local bosses would instruct their clients to vote to ensure that the party which had entered power would obtain a majority. Thus, changes of government occurred before elections, and no government lost an election it called. |

作戦 関連項目:カシキズム ターノは一連の手順に従って進められた: 王室は二大政党のいずれかを政権に招いた。自由党が政権を握っている場合、王室は保守党を招き、その逆も同様であった。つまり、最初のステップは王室の支持を確保することだった。 復古王政体制は議会制を前提としていたため、新政府がコルテス・ジェネラレスの支持を得ることが不可欠であった。これを達成するため、王室はコルテスを解散し、新たな選挙を実施した。 新たな選挙は、エンカシジャードとカシキズム制度によって操作された。内務大臣、地方行政長官、地元ボスらが支持者に投票指示を出し、政権与党が過半数を獲得するよう仕向けたのである。こうして政権交代は選挙前に発生し、自ら招いた選挙で敗北する政権は存在しなかった。 |

Election results under turnismo |

ターンイズモ下での選挙結果 |

| Cessation Despite being modelled on the United Kingdom system of parliamentary democracy, the Spanish system under turismo lacked responsiveness to popular opinion. Growing opposition to the system was first apparent after Spain's defeat in the Spanish–American War, and a period of grave instability began in 1918 and 1919. Between 1920 and 1923, a serious attempt was made to reconstruct the turno, but it was brought to an end by the military coup d'état of Miguel Primo de Rivera in September 1923.[10] |

終結 スペインのターン制政治は、英国の議会制民主主義をモデルにしていたにもかかわらず、国民の意見に対する反応性が欠けていた。この体制への反対が高まった のは、米西戦争でのスペイン敗北後が最初であり、1918年から1919年にかけて深刻な不安定期が始まった。1920年から1923年にかけて、トゥル ノ体制の再構築が真剣に試みられたが、1923年9月のミゲル・プリモ・デ・リベラの軍事クーデターによって終焉を迎えた。[10] |

| Duopoly Rotativismo [pt], a similar system in operation in Portugal Two-party system |

二大政党制 ポルトガルで運用されている類似の制度である輪番制 二大政党制 |

| References 1. Romero Salvador 2021, p. 27; 30-31; Fernández Sarasola 2006, p. 82 2. Dardé 1996, p. 17 3. Dardé 1996, p. 17 4. Francisco J. Romero Salvado (2012). Spain 1914-1918: Between War and Revolution. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-61449-3. For the following four decades two monarchist or 'dynastic' parties rotated in office: the Conservatives, headed by Cánovas himself, and the Liberals, led by Práxedes Mateo Sagasta. The succession in government of these two groups was so systematic that the Canovite order was known as Turno Pacífico (Peaceful Rotation). The governing class was formed by the representatives of the dominant landowning oligarchies of Castilian wheat growers and Andalusian wine and olive oil producers. As the years went by, the group also included large financial interests such as banks, state companies and big concerns like railways. Thus liberal democracy in Spain, as in most European countries at the time, was a sham and a way to disguise the supremacy of these privileged groups in society. It perpetuated the co-existence of modern liberal institutions with a semi-feudal socio-economic order. […] The ruling system avoided confrontation and instead sought compromise and stability. The party in power at election time respected the strongholds of the dynastic opposition and even the most important seats of such enemies as the Republicans on the Left and the Carlists on the Right. 5. Villares 2009, p. 58-59 6. Dardé 2021, pp. 174, 179«Los “obstáculos tradicionales” que, en frase de Salustiano Olózaga, se oponían a que gobernaran los progresistas, habían desaparecido».Milán García 2003, p. 103«Don Alfonso supo apreciar el indudable cambio experimentado por una oposición liberal que, aunque mantenía aún pulsiones revolucionarias heredadas del viejo progresismo, se había mostrado capaz de admitir entre sus filas a elementos de fidelidad dinástica probada y había arriado algunos de sus leit motivs históricos [como la soberanía nacional], por lo que a principios de 1881 envió mensajes claros a Cánovas de que debía dejar el paso franco a los liberales, lo que forzó la consiguiente crisis de gobierno que terminó con el encargo a Sagasta de formar un nuevo gabinete. […] Culminaba así el complicado aprendizaje de paciencia, lealtad y moderación que los constitucionales se habían visto precisados a realizar en este período y llegaba el momento de empezar a disfrutar sus réditos».Varela Ortega 2001, p. 178Suárez Cortina 2006, p. 108; 113 7. Milán García 2003, p. 104 8. Dardé 2021, pp. 178 9. Lario 2003, p. 38 10. Angel Smith, Historical Dictionary of Spain, p. 624. |

参考文献 1. ロメロ・サルバドール 2021, p. 27; 30-31; フェルナンデス・サラソラ 2006, p. 82 2. ダルデ 1996, p. 17 3. ダルデ 1996, p. 17 4. フランシスコ・J・ロメロ・サルバド (2012). 『スペイン1914-1918:戦争と革命の間』. ラウトレッジ. ISBN 978-1-134-61449-3. その後40年間、二つの王党派あるいは「王朝派」政党が政権を交代で掌握した。カノバス自身が率いる保守党と、プラクセデス・マテオ・サガスタが率いる自 由党である。この二つの勢力の政権交代は極めて体系的であったため、カノバス派の体制は「平和的交代(Turno Pacífico)」として知られた。支配階級は、カスティーリャの小麦生産者やアンダルシアのワイン・オリーブ油生産者といった、有力な土地所有寡頭勢 力の代表者たちで構成されていた。時が経つにつれ、このグループには銀行や国営企業、鉄道のような大企業といった大規模な金融資本も加わった。こうしてス ペインの自由民主主義は、当時のほとんどのヨーロッパ諸国と同様、見せかけのものであり、社会におけるこれらの特権階級の優越性を隠す手段となった。この 体制は近代的自由主義制度と半封建的経済社会秩序の共存を永続させた。[…] 支配システムは対立を避け、代わりに妥協と安定を追求した。選挙時に与党となった政党は、王朝的野党の牙城を尊重し、左派の共和派や右派のカルリストと いった敵対勢力の重要議席さえも守った。 5. Villares 2009, p. 58-59 6. Dardé 2021, pp. 174, 179「サリュスティアーノ・オロサガの言葉によれば、進歩派の政権樹立を阻んでいた『伝統的な障害』は消滅していた」 ミラン・ガルシア 2003, p. 103「ドン・アルフォンソは、自由主義野党が確かに変化したことを評価した。彼らは旧進歩主義から受け継いだ革命的衝動をまだ保持していたが、王室への 忠誠心が証明された要素を自らの陣営に受け入れる能力を示し、歴史的な主眼(例えば国家主権)の一部を放棄したのである。それゆえ1881年初頭、彼はカ ノバスに対し、自由主義者に道を譲るべきだという明確なメッセージを送った。これが政府危機を招き、サガスタに新内閣の組閣を委ねる結果となった。[…] こうして憲法派がこの期間に迫られた忍耐、忠誠、節度という複雑な修練は頂点に達し、その成果を享受し始める時が来たのである」。Varela Ortega 2001, p. 178Suárez Cortina 2006, p. 108; 113 7. ミラン・ガルシア 2003, p. 104 8. ダルデ 2021, pp. 178 9. ラリオ 2003, p. 38 10. アンヘル・スミス『スペイン歴史辞典』p. 624. |

| Bibliography Dardé, Carlos (1996). "La Restauración, 1875-1902. Alfonso XII y la regencia de María Cristina". Historia 16-Temas de Hoy. Madrid. ISBN 84-7679-317-0. — (2021). Alfonso XII. Un rey liberal. Biografía breve. Madrid: Ediciones 19. ISBN 978-84-17280-70-3. Fernández Sarasola, Ignacio (2006). "La idea de partido político en la España del siglo XX". Revista Española de Derecho Constitucional (77): 77–107. ISSN 0211-5743. Jover, José María (1981). "La época de la Restauración. Panorama político-social, 1875-1902". Revolución burguesa, oligarquía y constitucionalismo (1834-1923). Vol. VIII de la Historia de España, dirigida por Manuel Tuñón de Lara. Barcelona: Labor. pp. 269-406. ISBN 84-335-9428-1. Lario, Ángeles (2003). "Alfonso XII. El rey que quiso ser constitucional" (PDF). Ayer (52). Dossier: ‘’La política en el reinado de Alfonso XII’’, Carlos Dardé, editor: 15–38. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2024-10-10. Retrieved 2025-09-21. Milán García, José Ramón (2000). "La revolución entra en palacio. El liberalismo dinástico de Sagasta (1875-1903)". Berceo (139): 93–122. ISSN 0210-8550. — (2003). Los liberales en el reinado de Alfonso XII: el difícil arte de aprender de los fracasos (PDF). Dossier: ‘’La política en el reinado de Alfonso XII’’, Carlos Dardé, editor. Ayer. pp. 91–116. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2023-02-10. Retrieved 2025-09-21. Romero Salvador, Carmelo (2021). Caciques y caciquismo en España (1834-2020). Prólogo de Ramón Villares. Madrid: Los books de la Catarata. ISBN 978-84-1352-212-8. Suárez Cortina, Manuel (2006). La España Liberal (1868-1917). Política y sociedad. Vol. 27 de la Historia de España 3er. Milenio, dirigida por Elena Hernández Sandoica. Madrid: Síntesis. ISBN 84-9756-415-4. Varela Ortega, José (2001). Los amigos políticos. Partidos, elecciones y caciquismo en la Restauración (1875-1900). Prólogo de Raymond Carr. Madrid: Marcial Pons. ISBN 84-7846-993-1. Villares, Ramón (2009). "Alfonso XII y Regencia. 1875-1902". In Ramón Villares; Javier Moreno Luzón (eds.). Restauración y Dictadura. Vol. 7 de la Historia de España, dirigida por Josep Fontana y Ramón Villares. Barcelona-Madrid: Crítica/Marcial Pons. |

参考文献 Dardé, Carlos (1996). 「復古王政、1875-1902。アルフォンソ12世とマリア・クリスティーナ摂政」『Historia 16-Temas de Hoy』マドリード。ISBN 84-7679-317-0。 — (2021). 『アルフォンソ12世。自由主義の王』 略歴。マドリード:エディシオネス19。ISBN 978-84-17280-70-3。 フェルナンデス・サラスラ、イグナシオ(2006)。「20世紀スペインにおける政党の概念」。スペイン憲法法雑誌(77):77–107。ISSN 0211-5743。 ホベル、ホセ・マリア (1981). 「復古王政時代。政治・社会情勢、1875-1902」. ブルジョア革命、寡頭政治、立憲主義 (1834-1923). スペイン史第 VIII 巻、マヌエル・トゥニョン・デ・ララ編. バルセロナ: ラボル. pp. 269-406. ISBN 84-335-9428-1。 Lario, Ángeles (2003). 「アルフォンソ12世。憲法を望んだ王」 (PDF). Ayer (52). 特集:「アルフォンソ12世の治世における政治」、Carlos Dardé 編集:15–38。2024年10月10日にオリジナル(PDF)からアーカイブ。2025年9月21日に取得。 ミラン・ガルシア、ホセ・ラモン(2000)。「革命が宮殿に侵入。サガスタの王朝自由主義(1875-1903)」。ベルセオ(139):93-122。ISSN 0210-8550。 — (2003). アルフォンソ12世の治世における自由主義者たち:失敗から学ぶという難しい技術 (PDF). 特集:『』アルフォンソ12世の治世における政治『』、カルロス・ダルデ、編集者。Ayer。91–116ページ。2023年2月10日にオリジナル (PDF)からアーカイブ。2025年9月21日に取得。 ロメロ・サルバドール、カルメロ(2021)。スペインの首長と首長政治(1834-2020)。ラモン・ビジャレスによる序文。マドリード:ロス・ブックス・デ・ラ・カタラタ。ISBN 978-84-1352-212-8。 スアレス・コルティナ、マヌエル(2006)。『自由主義のスペイン(1868-1917)』。政治と社会。スペインの歴史 第 27 巻、第 3 千年紀、エレナ・エルナンデス・サンドイカ監修。マドリード:シンテシス。ISBN 84-9756-415-4。 バレラ・オルテガ、ホセ(2001)。『政治的な友人たち。復古期(1875-1900)における政党、選挙、地方政治の支配』。レイモンド・カーによる序文。マドリード:マルシャル・ポンス。ISBN 84-7846-993-1。 ビジャレス、ラモン(2009)。「アルフォンソ12世と摂政。1875-1902」。ラモン・ビジャレス、ハビエル・モレノ・ルゾン(編)。『復古王政 と独裁政権』。ジョセップ・フォンタナ、ラモン・ビジャレス編『スペインの歴史』第7巻。バルセロナ・マドリード:クリティカ/マルシャル・ポンス。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turno |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099