必要のない医療/無駄な医療

Unnecessary health care

☆ 不必要な医療(overutilization、overuse、またはovertreatment)とは、適切な量や費用よりも多く提供される医療のこ とである[1]。医療費がGDPに占める割合が最も高い米国では、過剰使用がその支出の主な要因であり、2012年には医療費の約3分の1(2兆 6,000億ドルのうち7,500億ドル)を占めた[2]。 過剰使用を促進する要因には、保健医療専門家により多くの報酬を支払うこと(fee-for-service)、訴訟から身を守るための防衛医療、消費者 が支払者でない場合における価格感応度からの隔離(患者は商品やサービスを受け取るが、その代金は保険で支払われる(公的保険、民間保険、またはその両 方))などがある。[3] このような要因により、医療制度の多くの関係者(医師、患者、製薬会社、医療機器メーカー)には、医療価格や過剰使用を抑制する十分なインセンティブが与 えられていない[1][4]。このため、国民健康保険制度や米国メディケア・メディケイドサービスセンターなどの支払者は、支払いの条件として医療上の必 要性を重視する。しかし、必要性と必要性の欠如の閾値は、主観的なものであることが多い。 厳密な意味での過剰治療とは、自己限定的な病態の治療(過剰診断)や、限定的な治療しか必要としない病態に対する広範な治療など、不必要な医療介入を指す ことがある。 経済的には過剰医療と結びついている。

| Unnecessary

health

care (overutilization, overuse, or overtreatment) is health care

provided with a higher volume or cost than is appropriate.[1] In the

United States, where health care costs are the highest as a percentage

of GDP, overuse was the predominant factor in its expense, accounting

for about a third of its health care spending ($750 billion out of $2.6

trillion) in 2012.[2] Factors that drive overuse include paying health professionals more to do more (fee-for-service), defensive medicine to protect against litigiousness, and insulation from price sensitivity in instances where the consumer is not the payer—the patient receives goods and services but insurance pays for them (whether public insurance, private, or both).[3] Such factors leave many actors in the system (doctors, patients, pharmaceutical companies, device manufacturers) with inadequate incentive to restrain health care prices or overuse.[1][4] This drives payers, such as national health insurance systems or the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, to focus on medical necessity as a condition for payment. However, the threshold between necessity and lack thereof can often be subjective. Overtreatment, in the strict sense, may refer to unnecessary medical interventions, including treatment of a self-limited condition (overdiagnosis) or to extensive treatment for a condition that requires only limited treatment. It is economically linked with overmedicalization. |

不必要な医療(overutilization、overuse、また

はovertreatment)とは、適切な量や費用よりも多く提供される医療のことである[1]。医療費がGDPに占める割合が最も高い米国では、過剰

使用がその支出の主な要因であり、2012年には医療費の約3分の1(2兆6,000億ドルのうち7,500億ドル)を占めた[2]。 過剰使用を促進する要因には、保健医療専門家により多くの報酬を支払うこと(fee-for-service)、訴訟から身を守るための防衛医療、消費者 が支払者でない場合における価格感応度からの隔離(患者は商品やサービスを受け取るが、その代金は保険で支払われる(公的保険、民間保険、またはその両 方))などがある。[3] このような要因により、医療制度の多くの関係者(医師、患者、製薬会社、医療機器メーカー)には、医療価格や過剰使用を抑制する十分なインセンティブが与 えられていない[1][4]。このため、国民健康保険制度や米国メディケア・メディケイドサービスセンターなどの支払者は、支払いの条件として医療上の必 要性を重視する。しかし、必要性と必要性の欠如の閾値は、主観的なものであることが多い。 厳密な意味での過剰治療とは、自己限定的な病態の治療(過剰診断)や、限定的な治療しか必要としない病態に対する広範な治療など、不必要な医療介入を指す ことがある。 経済的には過剰医療と結びついている。 |

| Definition A forerunner of the term was what Jack Wennberg called unwarranted variation,[5] different rates of treatments based upon where people lived, not clinical rationale. He had discovered that in studies that began in 1967 and were published in the 1970s and the 1980s: "The basic premise – that medicine was driven by science and by physicians capable of making clinical decisions based on well-established fact and theory – was simply incompatible with the data we saw. It was immediately apparent that suppliers were more important in driving demand than had been previously realized."[6] In 2008, US bioethicist Ezekiel J. Emanuel and health economist Victor R. Fuchs defined unnecessary health care as "overutilization", health care provided with a higher volume or cost than is appropriate.[1] Recently, economists have sought to understand unnecessary health care in terms of misconsumption rather than overconsumption.[7] In 2009 two US physicians wrote in an editorial, that unnecessary care was "defined as services which show no demonstrable benefit to patients" and might represent 30% of U.S. medical care.[8] They referred to a 2003 study on regional variations in Medicare spending, which found, "Medicare enrollees in higher-spending regions receive more care than those in lower-spending regions, but do not have better health outcomes or satisfaction with care."[9] In January 2012, the American College of Physicians Ethics, Professionalism, and Human Rights Committee suggested that overtreatment can also be understood in contrast to 'parsimonious care', defined as "care that utilizes the most efficient means to effectively diagnose a condition and treat a patient."[10] In April 2012, Berwick, from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, and Andrew Hackbarth from the RAND Corporation defined overtreatment as "subjecting patients to care that, according to sound science and the patients' own preferences, cannot possibly help them—care rooted in outmoded habits, supply-driven behaviors, and ignoring science." They wrote that trying to do something (treatment or testing) for all patients who might need it inevitably entails doing that same thing for some patients who might not need it." In uncertain situations, "some non-beneficial care was the necessary byproduct of optimal clinical decision making."[11] In October 2015, two pediatricians said that considering "overtreatment as an ethical violation" could help see the conflicting incentives of health care workers for treatment or nontreatment.[12] Low-value health care, for the most part, is administration of tests or treatment, which though useful initially, offer little value if given repeatedly as a part of routine care.[13] |

定義 この用語の前身は、ジャック・ウェンバーグが不当なばらつきと呼んだもので、臨床的根拠ではなく、人々が住んでいる場所に基づいて治療率が異なるというも のであった[5]。彼は、1967年に始まり、1970年代と1980年代に発表された研究の中でそれを発見した: 「医療は科学によって推進され、医師は確立された事実と理論に基づいて臨床判断を下すことができるという大前提は、我々が目にしたデータとは相容れないも のであった。需要を牽引するのは、それまで認識されていた以上に供給者であることがすぐに明らかになった」[6]。 2008年、米国の生命倫理学者であるエゼキエル・J・エマニュエルと保健経済学者であるビクター・R・フックスは、不必要な医療を「過剰利用」、つまり 適切な量やコストよりも高い医療が提供されることと定義した[1]。最近、経済学者は不必要な医療を過剰消費ではなく、誤った消費という観点から理解しよ うとしている[7]。 2009年、2人の米国人医師が論説の中で、不必要な医療とは「患者にとって実証可能な利益を示さないサービス」と定義され、米国の医療の30%を占めて いる可能性があると書いている[8]。彼らは、メディケア支出の地域差に関する2003年の研究に言及し、「支出の多い地域のメディケア加入者は、支出の 少ない地域の加入者よりもより多くの医療を受けているが、保健上のアウトカムや医療に対する満足度が高いわけではない」と述べている[9]。 2012年1月、米国医師会倫理・専門性・人権委員会は、過剰治療は「患者の状態を効果的に診断し、治療するために最も効率的な手段を利用するケア」と定 義される「簡略化されたケア」との対比で理解することもできると示唆した[10]。 2012年4月、Institute for Healthcare ImprovementのBerwickとRAND CorporationのAndrew Hackbarthは、過剰治療とは「健全な科学と患者自身の嗜好によれば、患者を助けることはあり得ないケアを患者に施すこと-時代遅れの習慣、供給主 導の行動、科学無視に根ざしたケア-」であると定義した。彼らは、「治療や検査を必要とする可能性のあるすべての患者に同じことをしようとすると、必然的 にそれを必要としない患者にも同じことをすることになる 」と書いている。不確実な状況では、「有益でない治療も、最適な臨床的意思決定の必要な副産物である」[11]。 2015年10月、2人の小児科医は、「過剰治療を倫理的違反とみなす」ことで、治療や非治療に対する保健医療従事者の相反するインセンティブを見抜くこ とができると述べた[12]。 価値の低い保健医療とは、ほとんどの場合、検査や治療の実施であり、初期には有用であっても、日常診療の一環として繰り返し行われる場合には、ほとんど価 値を提供しないものである[13]。 |

| Cost In the US, the country which spends the most on health care per person globally, patients have fewer doctor visits and fewer days in hospitals than people in other countries do,[14] but prices are high,[15] there is more use of some procedures and new drugs than elsewhere, and doctor salaries are double the levels in other countries.[1] The New York Times reported "no one knows for sure" how much unnecessary care exists in the United States.[16] Overuse of medical care is no longer a large fraction of total health care spending, which was $3.3 trillion in 2016.[17] Researchers in 2014 analyzed many services listed as low value by Choosing Wisely and other sources. They looked at spending in 2008–2009 and found that these services represented 0.6% or 2.7% of Medicare costs[18] and there was no significant pattern of particular types of physicians ordering these low value services.[19] The Institute of Medicine in 2010 gave two estimates of "unnecessary services," using different methodologies: 0.2% or 1% to 5% of health spending,[20] which was US$2.6 trillion.[17] The Institute of Medicine quoted that 2010 report in a 2012 report to support an estimate of 8% ($210 billion) in unnecessary services, without explaining the discrepancy.[21] This IOM 2012 report also said there were $555 billion in other wasted spending, which have an "unknown overlap" with each other and the $210 billion.[21] The United States National Academy of Sciences estimated in 2005, without giving its methods or sources, that "between $.30 and $.40 of every dollar spent on health care is spent on the costs of poor quality," amounting to" slightly more than a half-trillion dollars a year... wasted on overuse, underuse, misuse, duplication, system failures, unnecessary repetition, poor communication, and inefficiency.[22] In 2003 Fisher et al.[23][24] found that there was "no apparent regional health benefit for Medicare recipients from doing more, whether 'more' is expressed as hospitalizations, surgical procedures, or consultations within the hospital."[25] Up to 30% of Medicare spending could be cut in 2003 without harming patients.[24] A study of low-value care in laboratory testing suggested that Medicare may have overspent at least US$1.95 billion on laboratory tests in the year 2019.[26] The study found excessively frequent ordering of Hemoglobin A1c, prostate-specific antigen, vitamin D 25-hydroxy, and lipid panels. When care is overused, patients are put at risk of complications unnecessarily,[27] with documented harm to patients from overuse of surgeries and other treatments.[28] |

費用 世界的に見ても、人民一人当たりの保健医療費が最も多い国である米国では、他国の人々に比べて患者の受診回数や入院日数は少ない[14]が、価格は高く [15]、一部の処置や新薬の使用は他国よりも多く、医師の給与は他国の2倍である[1]。[1] ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙は、米国にどれだけの不必要な医療が存在するのか「確かなことは誰にもわからない」と報じている[16]。 医療の過剰使用は、2016年に3兆3,000億ドルであった総保健医療支出の中で、もはや大きな割合を占めている[17]。 2014年の研究者たちは、Choosing Wiselyや他の情報源によって価値が低いとされた多くのサービスを分析した。彼らは2008年から2009年の支出を調査し、これらのサービスはメ ディケアの費用の0.6%または2.7%を占めており[18]、これらの低価値サービスを注文する医師の個別主義に有意なパターンはなかった[19]。 2010年の医学研究所は、異なる方法論を用いて「不必要なサービス」の2つの推定値を示した: 医学研究所は2012年の報告書の中で、この2010年の報告書を引用し、その食い違いを説明することなく、不必要なサービスの8%(2100億ドル)と いう推計を支持している[17]。[21] この医学研究所の2012年の報告書は、他の無駄な支出も5,550億ドルあるとし、それらは互いに「未知の重複」があり、2,100億ドルであるとして いる。医療に費やされる1ドルのうち40ドルが質の低い医療費に費やされている」とし、「年間5兆ドル強が......過剰使用、過小使用、誤用、重複、 システム障害、不必要な反復、コミュニケーション不足、非効率のために浪費されている」と推定している[22]。[23][24]は、「メディケア受給者 にとって、入院、外科的処置、病院内での診察のいずれを 「多く 」行うことによる地域保健上の利益は明らかではない」[25]とし、2003年には、患者に害を与えることなくメディケア支出の最大30%を削減できる可 能性があることを明らかにした[24]。 臨床検査における低価値医療に関する研究では、メディケアが2019年の臨床検査に少なくとも19億5千万米ドルを過剰に費やしている可能性が示唆された [26]。この研究では、ヘモグロビンA1c、前立腺特異抗原、ビタミンD25水和物、脂質パネルの過剰な頻度の注文が見つかった。 治療が過剰に行われると、患者は不必要に合併症のリスクにさらされることになり[27]、手術やその他の治療の過剰使用による患者への害が記録されている [28]。 |

| Causes Physicians' decisions are the proximate cause of unnecessary care, though the potential incentives and penalties they face can influence their choices.[citation needed] Third-party payers and fee-for-service See also: Fee-for-service When public or private insurance cover expenses and doctors are paid under a fee-for-service (FFS) model, neither has an incentive to consider the cost of treatment, a combination that contributes to waste.[4] Fee-for-service is a large incentive for overuse because health care providers (such as doctors and hospitals) receive revenue from the overtreatment.[1] Atul Gawande investigated Medicare FFS reimbursements in McAllen, Texas, for a 2009 article in the New Yorker.[29][30] In 2006, the town of McAllen was the second-most expensive Medicare market, behind Miami. Costs per beneficiary were almost twice the national average.[31] In 1992, however, McAllen had been almost exactly in line with the Medicare spending average.[31] After looking at other potential explanations such as relatively poorer health or medical malpractice, Gawande concluded the town was a chief example of the overuse of medical services.[32] Gawande concluded that a business culture (physicians viewing their practices as a revenue stream) had established itself there, in contrast to a culture of low-cost high-quality medicine at the Mayo Clinic and in the Grand Junction, Colorado, market.[31][32] Gawande advised: As America struggles to extend healthcare coverage while curbing health care costs, we face a decision that is more important than whether we have a public-insurance option, more important than whether we will have a single-payer system in the long run or a mixture of public and private insurance, as we do now. The decision is whether we are going to reward the leaders who are trying to build a new generation of Mayos and Grand Junctions. If we don't, McAllen won't be an outlier. It will be our future.[31] |

原因 医師が直面する潜在的なインセンティブや罰則がその選択に影響を与えることはあるが、医師の決断が不必要な医療の近因である[要出典]。 第三者支払機関とフィー・フォー・サービス こちらも参照のこと: フィー・フォー・サービス 公的または民間の保険が費用を負担し、医師がフィー・フォー・サービス(FFS)モデルで支払われる場合、どちらも治療費を考慮するインセンティブを持た ず、この組み合わせが無駄を助長する[4]。フィー・フォー・サービスは、過剰治療から医療提供者(医師や病院など)が収入を得るため、過剰使用の大きな インセンティブとなる[1]。 アトゥル・ガワンデは、2009年に『ニューヨーカー』誌に寄稿するため、テキサス州マッカレンのメディケアFFS診療報酬を調査した[29][30]。 2006年、マッカレン市はマイアミに次いで2番目に高額なメディケア市場であった。受給者一人当たりの費用は国民平均のほぼ2倍であった[31]。 しかし1992年には、マッカレンはメディケア支出平均とほぼ一致していた[31]。比較的保健状態が悪かったり、医療過誤があったりといった他の潜在的 な説明も検討した結果、ガワンデは、この町は医療サービスの過剰利用の主要な例であると結論づけた[32]。 ガワンデは、メイヨークリニックやコロラド州グランドジャンクション市場の低コストの質の高い医療文化とは対照的に、ビジネス文化(医師は診療を収入源と みなす)がそこに定着していると結論づけた[31][32]。ガワンデはこう助言している: 米国が保健医療費を抑制しながら医療保険の適用範囲を拡大しようと奮闘しているとき、われわれは、公的保険という選択肢を持つかどうかよりも、長期的に単 一保険制度にするか、現在のように公的保険と民間保険の混合にするかどうかよりも重要な決断に直面している。その決断とは、新世代のマイヨスとグランド・ ジャンクションを築こうとしている指導者たちに報いるのかどうかということだ。そうしなければ、マッカレンは異常な存在ではなくなってしまう。それが私た ちの未来なのだ[31]。 |

| Medical malpractice laws and

defensive medicine See also: Medical malpractice To protect themselves from legal prosecution U.S. physicians have an incentive to order clinically unnecessary tests or tests of little potential value.[1] While defensive medicine is a favored explanation for high medical costs by physicians, Gawande estimated in 2010 it only contributed to 2.4% of the total $2.3 trillion of U.S. health care spending in 2008.[25][33] Direct-to-consumer advertising Direct-to-consumer advertising can encourage patients to ask for drugs, devices, diagnostics, or procedures. Sometimes service providers will simply give these treatments or services rather than attempting the potentially more unpleasant task of convincing the patient what they have requested is not needed, or is likely to cause more harm than good.[1] Physician predispositions Dartmouth Medical School professor Gilbert Welch argued 2016 that certain predispositions by physicians and the general public may lead to unnecessary health care, including:[34][35] Attempting to mitigate a risk without considering how small or unlikely the potential benefit is Attempting to fix an underlying problem, instead of using a less-risky monitoring or coping strategy Acting too quickly, when waiting for more information might be wiser Acting without considering the benefits of doing nothing Discounting downsides of diagnostic testing Preferring newer over older treatments without considering the cost of new treatments or the effectiveness of older ones Treating patients with terminal illness to maximize life span over quality of life, without probing a patient's preferences |

医療過誤法と防衛医療 こちらも参照のこと: 医療過誤 法的訴追から身を守るために、米国の医師は臨床的に不必要な検査や潜在的価値の低い検査を指示する動機がある[1]。防衛医療は医師による高医療費の説明 として好まれているが、Gawandeは2010年に、2008年の米国の保健医療費総額2兆3,000億ドルの2.4%にしか寄与していないと推定して いる[25][33]。 消費者直接広告 消費者向け直接広告は、患者に医薬品、機器、診断、処置を求めるよう促すことができる。時には、サービス提供者は、患者が要求したものが不要である、ある いは善いことよりも害をもたらす可能性が高いことを説得するという、より不愉快になりうる作業を試みるよりも、単にこれらの治療やサービスを提供すること もある[1]。 医師の素質 ダートマス医科大学のギルバート・ウェルチ教授は2016年、以下のような医師や一般市民のある種の素因が不必要な保健医療につながる可能性があると主張 した[34][35]。 潜在的な利益がどれほど小さいか、あるいは可能性が低いかを考慮せずにリスクを軽減しようとする。 よりリスクの低いモニタリングや対処法を用いず、根本的な問題を解決しようとする。 より多くの情報を待つ方が賢明であるにもかかわらず、あまりにも迅速に行動する。 何もしないことの利点を考えずに行動する 診断検査のマイナス面を軽視する。 新しい治療法の費用や古い治療法の有効性を考慮せずに、古い治療法よりも新しい治療法を優先する。 終末期の患者に対して、QOL(生活の質)よりも寿命を格律するような治療をする。 |

| Examples Imaging Overuse of diagnostic imaging, such as X-rays and CT scans, is defined as any application unlikely to improve patient care.[36] Factors that contribute to overuse include "self-referral, patient wishes, inappropriate financially motivated factors, health system factors, industry, media, lack of awareness" and defensive medicine.[36] Respected organizations—such as the American College of Radiology (ACR), Royal College of Radiologists (RCR) and the World Health Organization (WHO)—have developed "appropriateness criteria".[36] The Canadian Association of Radiologists estimated in 2009 that 30% of imaging was unnecessary in the Canadian health care system.[37] 2008 Medicare claims showed overuse with chest CT's.[38] Financial incentives have also been shown to have a significant impact on dental X-ray use with dentists who are paid a separate fee for each X-ray providing more X-rays.[39] Overuse of imaging can lead to a diagnosis of a condition that would have otherwise remained irrelevant (overdiagnosis).[40] Physician self-referral Main article: Physician self-referral One type of overuse can be physician self-referral.[41] Multiple studies have replicated the finding that when non-radiologists have an ownership interest in the fees generated by radiology equipment—and can self-refer—their use of imaging is unnecessarily higher.[41] The majority of U.S. growth in imaging use (the fastest-growing physician service) comes from self-referring nonradiologists.[41] In 2004, this overuse was estimated to contribute to $16 billion of annual U.S. health care costs.[41] As of a 2018 review evidence of overtreatment overmedicalization, and overdiagnosis in Pediatrics have been use of commercial rehydration solution, antidepressants, and parenteral nutrition; overmedicalization with planned early deliveries, immobilization of ankle injuries, use of hydrolyzed infant formula; and overdiagnosis of hypoxemia among children recovering from bronchiolitis.[42] Others Hospitalizations[43] for those with chronic conditions who could be treated as outpatients[44] Surgeries in Medicare patients in their last year of life; regions with high levels had higher death rates[45][46] Antibiotic use for viral or self-limiting infections[1][47] (an overmedication that can promote antibiotic resistance) Opiate prescriptions[48] carry the risk of addiction. In some cases, the number of pills prescribed might exceed what is actually needed for pain relief from a given condition, or a different pain management technique or medication would be effective but less risky. Many blood transfusions in the U.S. are given without checking to see if they are needed after a previous transfusion, or are given in cases where monitoring, recovering the patient's own blood, or iron therapy would be effective and reduce the risk of complications[49] An estimated one in eight coronary stents (used in $20,000 procedures) with nonacute indications (U.S.)[50][51] Stents performed by the formal chair of cardiology, Mark Midei, at St. Joseph Medical Center of Towson, Maryland[52][53][54][55] Heart bypass surgeries at Redding Medical Center which resulted in an FBI raid[56][57][58] Screening patients with advanced cancer for other cancers[59] Annual cervical cancer screening in women with medical histories of normal pap smear and HPV test results[60][61] |

事例 画像診断 X線検査やCT検査などの画像診断の過剰使用は、患者ケアを改善する見込みのない適用と定義されている[36]。過剰使用の要因としては、「自己紹介、患 者の希望、不適切な金銭的動機による要因、保健システム要因、産業界、メディア、認識不足」、防衛医療などが挙げられる[36]。米国放射線学会 (ACR)、王立放射線科学会(RCR)、世界保健機関(WHO)などの権威ある団体は、「適切性基準」を策定している。[36] Canadian Association of Radiologistsは、2009年にカナダの保健医療システムにおいて、画像診断の30%が不必要であると推定している [37] 。 画像診断の過剰使用は、そうでなければ無関係のままであった病態の診断(過剰診断)につながる可能性がある[40]。 医師の自己紹介 主な記事 医師の自己紹介 過剰使用の一種に医師の自己紹介がある[41]。複数の研究により、放射線科医以外の医師が放射線機器から発生する料金の所有権を持ち、自己紹介ができる 場合、画像診断の利用が不必要に高くなるという知見が再現されている[41]。米国における画像診断の利用増加(最も急速に成長している医師サービス)の 大部分は、放射線科医以外の医師の自己紹介によるものである[41]。2004年、この過剰使用は、米国の年間保健医療費の160億ドルに寄与していると 推定された[41]。 2018年のレビューでは、小児科における過剰治療の過剰医療化、過剰診断の証拠としては、市販の補水液、抗うつ薬、非経口栄養剤の使用、計画的早期分 娩、足首の怪我の固定、加水分解乳児用調製粉乳の使用による過剰医療化、気管支炎から回復した小児における低酸素血症の過剰診断などが挙げられている [42]。 その他 外来患者として治療が可能であった慢性疾患患者の入院[43][44]。 メディケア患者における人生最後の年の手術;高水準の地域では死亡率が高かった[45][46]。 ウイルス感染や自己限定的感染に対する抗生物質の使用[1][47](抗生物質耐性を促進しうる過剰投薬)。 アヘン剤の処方[48]には中毒のリスクがある。場合によっては、処方された錠剤の数が、ある症状の鎮痛に実際に必要な数を超えていたり、異なる疼痛管理 法や薬剤の方が有効だがリスクが少なかったりすることもある。 米国では、輸血が必要であるかどうかを確認することなく輸血が行われたり、モニタリングや患者自身の血液の回収、鉄剤療法が有効で合併症のリスクを減らせ るような場合に輸血が行われることが多い[49]。 非急性期適応の冠動脈ステント(20,000ドルの手技で使用)の推定8本に1本(米国)[50][51]。 メリーランド州タウソンのセント・ジョセフ・メディカル・センターで、心臓病学の正式なチェアマンであるマーク・ミデイが行ったステント[52][53] [54][55]。 レディング・メディカル・センターでの心臓バイパス手術はFBIの手入れを受ける結果となった[56][57][58]。 進行がん患者の他のがんに対するスクリーニング[59]。 パップスメアやHPV検査の結果が正常であった病歴を持つ女性における年1回の子宮頸がんスクリーニング[60][61]。 |

| Reduction efforts Utilization management (utilization review) has evolved over decades among both public and private payers in an attempt to reduce overuse.[62] In this effort, insurers employ physicians to review the actions of other physicians and detect overuse. Utilization review has a poor reputation among most clinicians as a corrupted system in which utilization reviewers have their own perverse incentives (i.e., find ways to deny coverage no matter what) and in some cases are not practicing physicians, lacking real-world clinical insight or wisdom. Results of a recent systematic review found that many studies focused more on reductions in utilization than in improving clinically meaningful measures.[63] The 2010 U.S. health care reform, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, did not contain serious strategies to reduce overuse; "the public has made it clear that it does not want to be told what medical care it can and cannot have."[16] Uwe Reinhardt, a health economist at Princeton, said "the minute you attack overutilization, you will be called a Nazi before the day is out".[16] Professional societies and other groups have begun to push for policy changes that would encourage clinicians to avoid providing unnecessary care. Most physicians accept that laboratory tests are overused, but "it remains difficult to persuade them to consider the possibility that they, too, might be overutilizing laboratory tests."[64] In November 2011, the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation began the Choosing Wisely campaign, which aims to raise awareness of overtreatment and change physician behavior by publicizing lists of tests and treatments that are often overused, and which doctors and patients should try to avoid.[65] The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) issued a 2017 guideline, "Developing and Managing a Medical Laboratory (Test) Utilization Program (GP49)", to help laboratories establish stewardship programs.[66] Clinical decision support tools can help decrease unnecessary laboratory testing.[67] The PLUGS initiative (Patient-Centered Laboratory Utilization Guidance Services) aims to formalize laboratory stewardship practices.[68] The TRUU-Lab (Test Renaming for Understanding and Utilization in the Laboratory) initiative is a cooperative effort of CDC, CMS, FDA, and CAP. The project aims to standardize the names of laboratory tests to limit errant test ordering.[69][70] Genetic testing stewardship programs have been established to streamline molecular diagnostic ordering patterns.[71] The Joint Commission offers accreditation in patient blood management in conjunction with AABB. To become accredited, participating hospitals may distribute guidelines for appropriateness of blood transfusion, form a committee to audit blood utilization, identify areas for improvement, and monitor compliance.[72] In the UK, 2011, online platform AskMyGP was launched to decrease the amount of unnecessary medical appointments. In the app patients are given a questionnaire about their symptoms, which then assesses the patient's need for medical care. The program was a success, and as of January 2018 has managed over 29,000 patient episodes. The Royal College of Pathologists issued 2021 guidelines for the minimum time that should elapse before a given laboratory test is repeated in a specific clinical scenario.[73] In April 2012, the Lown Institute and the New America Foundation Health Policy Program convened the 'Avoiding Avoidable Care'[74] conference. It was the first major medical conference to focus entirely on overuse, and it included presentations from speakers including Bernard Lown, Don Berwick, Christine Cassel, Amitabh Chandra, JudyAnn Bigby, and Julio Frenk.[75] A second meeting was planned for December 2013.[76] Since the meeting, the Lown Institute has focused its work on deepening the understanding of overuse and generating public discussion of the ethical and cultural drivers of overuse, especially on the role of the hidden curriculum in medical school and residency.[citation needed] Patient safety committees, which are charged with reviewing the quality of care, can view overutilization as adverse event.[77] |

削減努力 利用管理(利用審査)は、過剰利用を減らすために、公的・私的支払者の間で数十年にわたり発展してきた。利用審査は、多くの臨床医の間では、利用審査担当 者が独自の逆インセンティブを持ち(すなわち、何があっても保険適用を拒否する方法を見つける)、場合によっては実地医家ではなく、実臨床の見識や知恵に 欠ける腐敗したシステムであるとして評判が悪い。最近のシステマティックレビューの結果では、多くの研究が臨床的に意味のある尺度の改善よりも利用率の削 減に重点を置いていることがわかった [63] 。 プリンストン大学の保健経済学者であるウーヴェ・ラインハルトは、「過剰利用を攻撃した途端、その日のうちにナチス呼ばわりされるだろう」と述べている [16]。 専門家協会やその他の団体は、臨床医が不必要な医療を提供しないように促すような政策変更を推し進め始めている。ほとんどの医師は臨床検査が過剰に使用さ れていることを認めているが、「自分も臨床検査を過剰に使用している可能性を考慮するよう説得することは依然として困難である」[64]。2011年11 月、米国内科学会財団はChoosing Wiselyキャンペーンを開始した。このキャンペーンは、過剰に使用されることが多く、医師や患者が避けるよう努めるべき検査や治療のリストを公表する ことで、過剰治療に対する認識を高め、医師の行動を変えることを目的としている[65]。 臨床検査標準化機構(Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute:CLSI)は、検査室がスチュワードシッププログラムを確立するのを支援するために、2017年にガイドライン「医療検査(検査)利 用プログラムの開発と管理(GP49)」を発行した[66]。 臨床判断支援ツールは不必要な臨床検査を減らすのに役立つ[67]。 PLUGSイニシアチブ(Patient-Centered Laboratory Utilization Guidance Services)は、検査室スチュワードシップの実践を公式化することを目的としている[68]。 TRUU-Lab(Test Renaming for Understanding and Utilization in the Laboratory)イニシアチブは、CDC、CMS、FDA、CAPの共同作業である。このプロジェクトは、検査室検査の名称を標準化し、誤った検査 オーダーを制限することを目的としている[69][70]。分子診断のオーダーパターンを合理化するために、遺伝子検査スチュワードシッププログラムが設 立されている[71]。 合同委員会は、AABBと共同で患者の血液管理に関する認定を行っている。認定を受けるために、参加病院は輸血の適切性に関するガイドラインを配布し、血 液利用を監査する委員会を結成し、改善点を特定し、コンプライアンスを監視することができる[72]。 英国では2011年、不必要な医療予約を減らすために、オンラインプラットフォームAskMyGPが開始された。このアプリでは、患者は自分の症状に関す る質問票を渡され、その後、患者の医療の必要性が評価される。このプログラムは成功し、2018年1月現在、29,000件以上の患者エピソードを管理し ている。 英国王立病理学会(Royal College of Pathologists)は、特定の臨床シナリオにおいて所定の臨床検査が繰り返されるまでに経過すべき最小時間に関する2021年のガイドラインを発 表した[73]。 2012年4月、Lown InstituteとNew America Foundation Health Policy Programは『Avoiding Avoidable Care』[74]会議を開催した。これは過剰使用に完全に焦点を当てた最初の主要な医学会議であり、バーナード・ラウン、ドン・バーウィック、クリス ティン・カッセル、アミタブ・チャンドラ、ジュディ・アン・ビグビー、フリオ・フレンクなどの講演者によるプレゼンテーションが行われた[75]。 この会議以降、Lown Instituteは、過剰使用に対する理解を深め、過剰使用の倫理的・文化的要因、特に医学部や研修医における隠れたカリキュラムの役割について、一般 市民の議論を喚起することにその活動の重点を置いている[要出典]。 医療の質を審査する役割を担う患者安全委員会は、過剰使用を有害事象とみなすことができる [77] 。 |

| Medicare fraud – Claiming of

Medicare health care reimbursement to which the claimant is not entitled Moral hazard – Increases in the exposure to risk when insured, or when another bears the cost Antibiotic misuse – Improper use of antibiotic medications Antibiotic stewardship – Efforts to promote antimicrobial agents Choosing Wisely – U.S.-based educational campaign Clinical decision support – Health information technology Overmedicalization – Categorization of human problems as medical Overdiagnosis – Diagnosis of disease that will never cause symptoms or death during a patient's lifetime Overdose – Use of an excessive amount of a drug Patient blood management – Set of medical practices |

メディケア詐欺 - 権利のないメディケアの保健報酬を請求すること。 モラルハザード-保険に加入している場合、あるいは他の人が費用を負担している場合に、危険にさらされる機会が増えること。 抗生物質の誤用 - 抗生物質製剤の不適切な使用。 Antibiotic stewardship(抗生物質スチュワードシップ) - 抗菌薬の普及に努める。 Choosing Wisely - 米国を拠点とした教育キャンペーン Clinical decision support(臨床意思決定支援) - 保健情報技術 過剰医療 - 人間の問題を医療として分類すること 過剰診断 - 患者が生きている間に症状や死亡を引き起こすことのない病気を診断すること。 過剰投与 - 薬物を過剰に使用すること。 患者血液管理 - 一連の医療行為 |

| Brownlee, Shannon (2007).

Overtreated: Why too much medicine is making us sicker and poorer.

London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-58234-580-2. Gawande, Atul (May 11, 2015). "America's Epidemic of Unnecessary Care". newyorker.com. Retrieved May 4, 2015. Hendee WR, Becker GJ, Borgstede JP, et al. (October 2010). "Addressing overutilization in medical imaging". Radiology. 257 (1): 240–5. doi:10.1148/radiol.10100063. PMID 20736333. R. E. Malone (October 1998). "Whither the almshouse? Overutilization and the role of the emergency department". Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 23 (5): 795–832. doi:10.1215/03616878-23-5-795. PMID 9803363. S2CID 10081763. Sana M. Al-Khatib, Anne Hellkamp, Jeptha Curtis, Daniel Mark, Eric Peterson, Gillian D. Sanders, Paul A. Heidenreich, Adrian F. Hernandez, Lesley H. Curtis & Stephen Hammill (January 2011). "Non-evidence-based ICD implantations in the United States". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 305 (1): 43–49. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.1915. PMC 3432303. PMID 21205965. David B. Larson, Lara W. Johnson, Beverly M. Schnell, Shelia R. Salisbury & Howard P. Forman (January 2011). "National trends in CT use in the emergency department: 1995–2007". Radiology. 258 (1): 164–173. doi:10.1148/radiol.10100640. PMID 21115875. – a story on the study Gawande, Atul A.; Colla, Carrie H.; Halpern, Scott D.; Landon, Bruce E. (April 3, 2014). "Avoiding Low-Value Care". New England Journal of Medicine. 370 (14): e21. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1401245. PMID 24693918. |

Brownlee, Shannon (2007). 過剰治療:

なぜ薬が増えすぎると、私たちは病気になり、貧しくなるのか?London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-58234-580-2. Gawande, Atul (May 11, 2015). 「America's Epidemic of Unnecessary Care」. newyorker.com. 2015年5月4日取得。 Hendee WR, Becker GJ, Borgstede JP, et al. (October 2010). 「医療画像診断における過剰利用に対処する」。Radiology. 257 (1): 240–5. doi:10.1148/radiol.10100063. PMID 20736333. R. E. Malone (October 1998). 「病院はどこへ行くのか?Overutilization and the role of the emergency department". Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 23 (5): 795–832. doi:10.1215/03616878-23-5-795. PMID 9803363. S2CID 10081763. Sana M. Al-Khatib, Anne Hellkamp, Jeptha Curtis, Daniel Mark, Eric Peterson, Gillian D. Sanders, Paul A. Heidenreich, Adrian F. Hernandez, Lesley H. Curtis & Stephen Hammill (January 2011). 「米国におけるエビデンスに基づかないICD植込み」。JAMA:米国医師会雑誌。305 (1): 43–49. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.1915. PMC 3432303. PMID 21205965. David B. Larson, Lara W. Johnson, Beverly M. Schnell, Shelia R. Salisbury & Howard P. Forman (January 2011). 「救急部におけるCT使用の国民的傾向: 1995-2007". Radiology. 258 (1): 164–173. doi:10.1148/radiol.10100640. PMID 21115875. - この研究に関する記事 Gawande, Atul A.; Colla, Carrie H.; Halpern, Scott D.; Landon, Bruce E. (April 3, 2014). 「Avoiding Low-Value Care」. ニューイングランド医学ジャーナル。370 (14): e21. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1401245. PMID 24693918. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unnecessary_health_care |

|

★ 無駄な医療(日本語ウィキペディア)

定 義

無 駄な医療(むだないりょう、英語: Unnecessary health care)、過剰利用(かじょうりよう、英語: over utilization)、濃厚診療(のうこうしんりょう)とは、適切な量や費用を超えている医療をさす[1]。過剰医療を招く原因には、医療機関への診 療報酬を出来高払い制とし、かつ医療費が公的・民間医療保険により補償されるという事情が関係している[2]。このような制度の下では、医師と患者は、医 療費や受診を抑えるという動機は働かない[1][3]。ただし「どこからが無駄か」「どの程度からが過剰か」を判断することは別途の課題である。 似たものに過剰治療(かじょうちりょう、英語: over treatments)があり、不必要な医学的介入(治療)を指す。過剰治療は、それを行っても症状にほとんど改善は現れない。また過剰診断とは、患者に とって症状がなく無害な状態に病名診断を下すことであり、これにより過剰治療がまねかれる。 2011年よりアメリカ合衆国では、不要であるばかりか有害である治療介入の一覧を示すChoosing Wisely(賢い選択)キャンペーンが始まったり[4]、2013年のG8認知症サミットでは、イギリスが国家戦略として、死亡の増加につながる不要な 抗精神病薬の使用を低減してきたことを報告し[5]、日本でも、不要であるのに処方されている風邪薬を保険適用から外すことを検討するなど、無駄な医療へ の関心が集まっている[6]。

背景

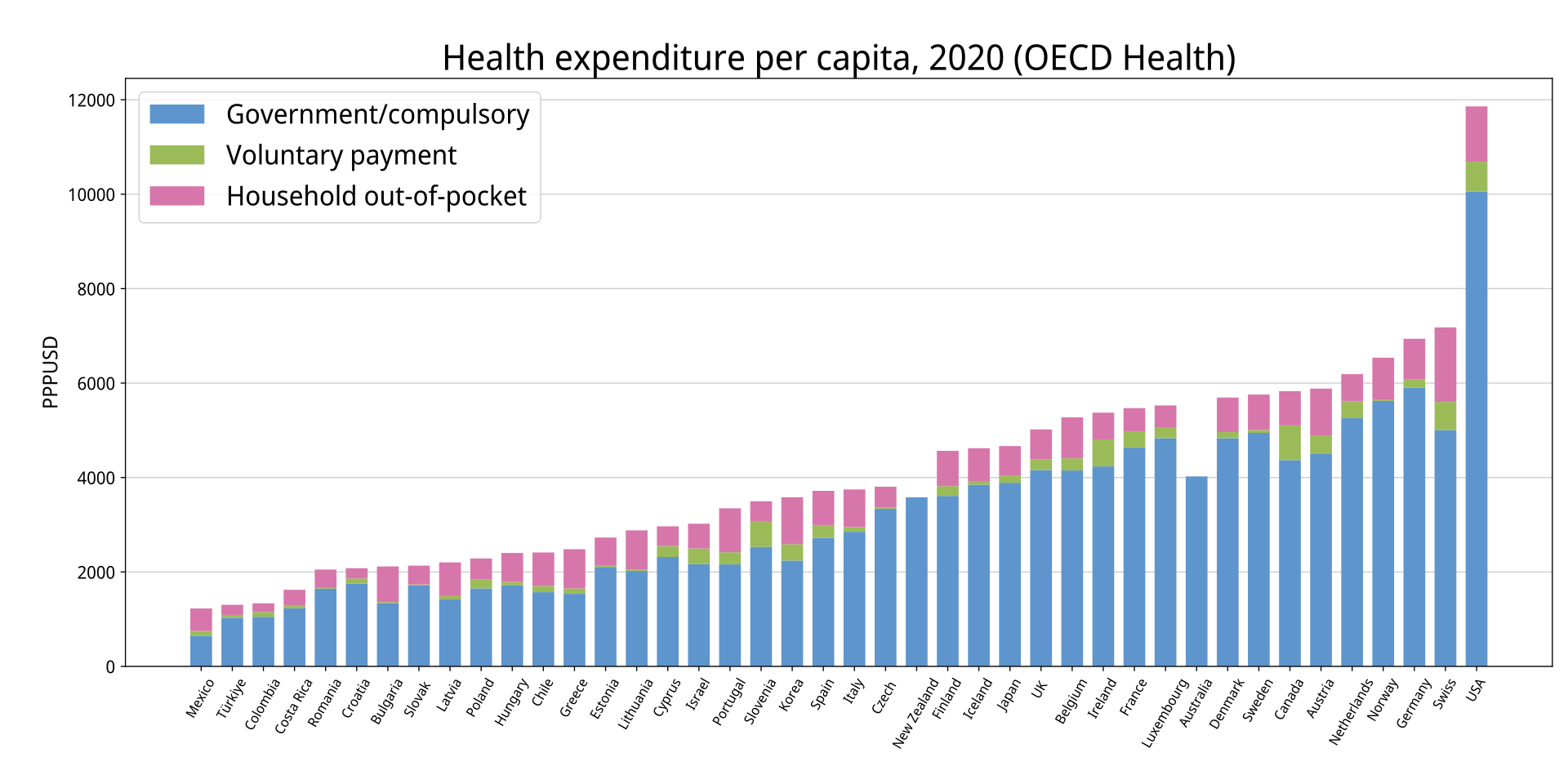

OECD各国の一人あたり保健支出(青は公的、赤は私的) [7]

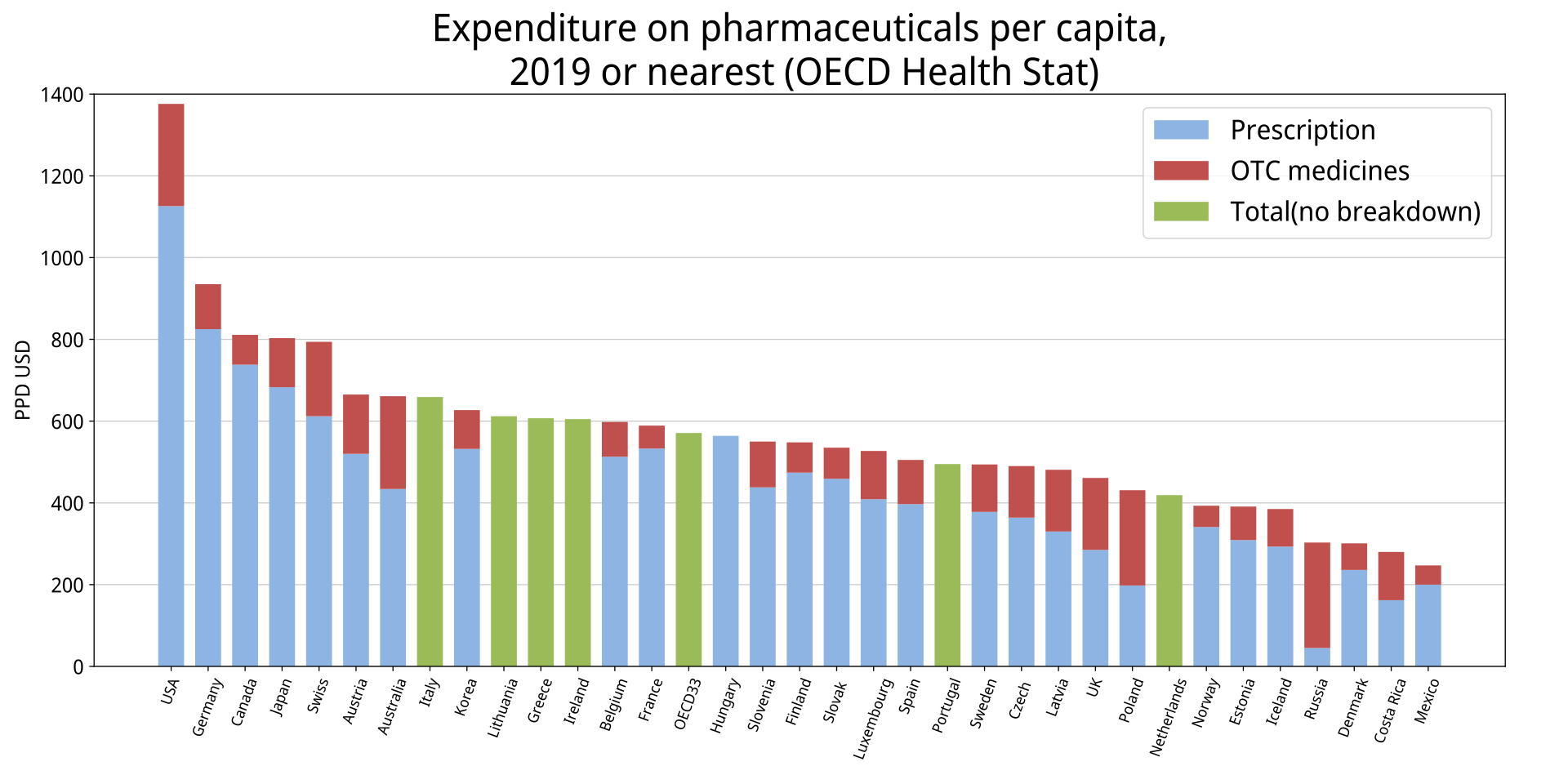

OECD各国の人口あたり医薬品消費額 [7]

過剰医療の研究は、1970-80年代のJack Wennbergによる研究unwarranted variation が先駆けである。彼は受給できる医療が、臨床的必要性ではなく市民の居住地域に関係すると報告した[8]。

過剰医療により、患者は無用な合併症リスクに晒されることとなるが(医原病)[9]、しかし医療提供者(医師や医療機関)は、出来高払い制度であれば過剰治療により更なる収入を得ることができる[1]。出来高払い制度は過剰医療を行うことに大きな動機を与える[1]。

米国の医療は1人あたり医療支出が世界で最も高く[7]、医療支出が高額となる最たる理由に過剰医療が挙げられている[1]。『ニューヨーク・タイムズ』

は「米国は慢性的な過剰医療の国である」と述べている[10]。米国における医療の30%は、患者に明確な利益をもたらさない不要な医療であると推定され

ている[11]。

殆どの医師は、臨床検査が行われすぎていることを認識しているが、しかし「臨床検査が過剰に行われている可能性について、その検討を説得するのは依然として困難である」とされている[12]。

こうした背景にて、Choosing

Wisely(賢い選択)キャンペーンが2011年には始まったが、これはアメリカ内科医学委員会(英語版)が創設したABIM財団(英語版)によるもの

である[4]。60以上のアメリカの専門機関が、不要で無駄であるばかりでなく、有害でさえありえるような治療介入を、2014年末までに一覧にする

[4]。

2009年にもイギリス政府は、年間約14万人の認知症患者が不要な抗精神病薬を処方され、毎年約1800人の死亡につながっているという報告をもとに、

その使用の削減を国家戦略としており、2006年の約17%の使用率を、5年後の2011年には約7%まで減らしてきたことを認知症G8サミットにて報告

している[5]。

日本でも、2010年に厚生労働省が、うつ病などに対して安易に大量処方を行う薬漬け医療や、それによっておこる過量服薬事故に対する対策を開始している

[13]。こうした問題はたびたび報道されてきた[14]。2014年6月に発売されたChoosing

Wiselyを紹介している『絶対に受けたくない無駄な医療』という書籍が1か月で3刷りとなり、7月の社会保障制度改革推進会議では、風邪薬を保険適用

から外すことを検討するなど、無駄な医療へと関心が集まっている[6]。日本の242の急性期病院において、33種類の無駄な医療を調査した2022年の

報告では、入院・外来あわせた患者1000人あたり、年間115〜219回の無駄な医療が提供され、その医療費は57〜129億円と推計されている

[15]。

2014年にBMJ(英国医学雑誌)でも、「医師たちは世界中の有害な医療の過剰使用を減らせるか?」といった記事にて、各国の取り組みを紹介している

[4]。オランダはアメリカと同様のキャンペーンを持ち、イギリスは英国国立医療技術評価機構(NICE)が治療の費用と効果の根拠を精査しているし、イ

タリアでは国家による「スロー医学」の取り組みの一環として「より多くは、良いということではない」キャンペーンを実施し、ドイツや日本ではまだ計画段階

である[4]。

要因

過剰医療をまねく理由には、医師側の便益、患者側の希望、不適切な経済的要因、医療制度、ビジネス的の圧力、マスメディア、意識の欠如、防衛医療などが挙げられる[16]。

保険制度および出来高払い制度

→「社会的入院」、「医薬分業」、「薬価差益」、および「多剤併用問題」も参照

患者の医療費が公的・民間医療保険で担われ、かつ医師の診療報酬が出来高払い制度である場合、治療費用を検討する動機が医師にも患者にも働かないため、無駄な医療を行うことに貢献することとなる[3]。

画像診断

→「医療被曝」も参照

画像診断の過剰使用は、重要でない事象を病気と診断する過剰診断につながるとされる[17]。X線やCTといった画像診断の過剰使用によって、患者への医

療が向上することはほとんどない[16]。カナダ放射線医師協会(英語版)は、カナダの医療における画像診断の30%は不要なものであると推定している

[18]。米国放射線医学会(ACR)、王立放射線医学会(RCR)、WHOなどの団体は「妥当な基準」を策定している[16]。

日本の医療においてはCTおよびMRIの設置台数の多さが指摘されており、人口あたりの台数は共にOECD各国中1位であった[19]。ランセットには、日本は世界で最も年間の医療被曝が多いとする論文が掲載された[20]。

医師自身への受診紹介

過剰医療をまねく理由の一つに、医師自身への受診紹介があるとされる[21]。

複数の研究では、非放射線科医は、放射線設備の使用から収入が得られ、かつ自己への受診紹介が可能な場合、彼らは不必要な画像診断をより行う傾向にあると

された[21]。米国における画像診断増加の主な要因は、非放射線科医による自己参照行為に起因するとされる[21]。米国ではこのような行為により、

2004年で160億米ドルの年間医療費を発生させていると推定されている[21]。

その他

救急部門受診の12-56%は不適切なものである[22]。

入院措置[23]。外来診療で十分な慢性疾患者を入院させる[24]。社会的入院。

死亡率の高いグループや、末期の患者に対しても手術を行う[25][26]。

不適切な抗生物質の投与[27][1][28][29]。抗生物質処方の50%以上は不適切である[27]。

消費者へのマーケティングの影響[1]。病気喧伝。

オピオイド処方[30]。

米国における輸血行為[31]。

米国では、ステント術(費用は$20,000ドル)の8例に1例が非急性患者に対しての施術であった[32][33]。

米国Redding Medical Centerにおける冠動脈バイパス術は、FBI捜査に発展した[34][35][36]

2008年には、メディケア患者は胸部CT撮影の頻度が通常の二倍であった[37]。

進行がん患者に対しては、他の癌患者よりも頻繁に検査が行われていた[38]。

パップテストやヒトパピローマウイルス検査歴のある女性について、年間の子宮頸癌検査[39][40]。

防衛医療

→「防衛医療」も参照

医師は自身を医療訴訟から守るため、臨床的には不必要・有益性が少ない検査を実施する傾向がある[1]。防衛医療の拡大は医療費を増加させ、2008年の米国医療費(2.3兆米ドル)の2.8%を占めると試算された[41][42]。

削減方法

医師に、この処置や検査は必要か、その副作用などのリスクは何か、他の簡単なまた安全な方法はあるか、未処置ではどうなるか、費用はどれくらいになるかを質問するという「5つの質問」ポスター[43]は、すでにアメリカの一部の診療所に貼られている[4]。

保険制度改革

→「包括払い制度」および「日本の医療 § 請求審査機能の強化」も参照

医療技術評価

→「医療技術評価」、「根拠に基づく医療」、および「臨床ガイドライン」も参照

医療技術評価においては、治療手法について「医学的効果」と「経済的費用」の両面から評価が行われる。

自己負担額の設定

→詳細は「生活保護問題 § 医療扶助の不適切受給問題」を参照

日本の医療扶助制度は、公費負担医療でありながら出来高払い制度を取っているため、過剰医療が指摘されている。

Choosing Wisely キャンペーン

Logo for the campaign

→詳細は「en:Choosing Wisely」を参照

Choosing

Wisely(賢い選択)キャンペーンは、アメリカ内科医学委員会(英語版)が創設したABIM財団(英語版)により2011年から展開された運動であ

る。患者と医師に対して過剰医療についての情報を提供することで、医師と患者との関係を密にし、患者中心医療の推進を目的としている[44]。

このキャンペーンにおいて、ABIM財団はそれぞれの分野学会に対し、各分野において過剰医療を行わないための推奨事項を5項目挙げるよう依頼した。各学

会よりもたらされた勧告「Five Things Physicians and Patients Should

Question(医師と患者が問い直すべき5つの項目)」の一覧はABIM財団のサイトに掲載されている[45][46][47][48]。

またカナダにおいてはChoosing Wisely Canadaとして、カナダ医師会が主導している[49]。

アメリカ家庭医学会(英語版)[50]。

危険な徴候のない腰痛に対し、発症から6週間未満はX線撮影を行う必要はない[51]。

副鼻腔炎に対し、症状が6日以降も続く場合や初診時より症状が悪化している場合を除き、機械的に抗生物質を処方すべきではない。

自覚症状のない低リスクの患者に対し、毎年のように心電図検査やその他の心臓検査を行う必要はない。

アメリカ一般内科学会(英語版)[52]

インスリン投与を行っていない2型糖尿病患者は、指グルコース試験を毎日家で実施する必要はない。

自覚症状のない成人に対し、定期的な健康診断は不要である。

低リスクの外科手術であれば、術前の所定の検査は不要である。

平均余命10年以下の成人に対しては、がん検診は不要である。

患者や医療従事者の利便性のために、CVカテーテルを設けたり、また挿入したままにしてはならない。

アメリカ小児科学会 [53]

ウイルス性呼吸器疾患(副鼻腔炎、咽頭炎、気管支炎)と思われる場合は、抗菌薬を投与すべきではない。

4歳以下の子供の呼吸器疾患に対し、風邪薬や鎮咳剤を投与したり推奨してはならない。

頭部の軽い外傷に対し、CT撮影は不要である。

子供の単純な熱性けいれんに対し、CTやMRIなどの神経画像撮影は不要である。

日常的な腹痛の訴えに対し、CT撮影は不要である。

アメリカ老年医学会(英語版)[54]、カナダ老年医学会(Canadian Geriatrics Society)[55]

進行性の認知症には経管栄養法を推奨できない。代わりに経口摂取の援助を提案する。

認知症による行動と心理の徴候について、抗精神病薬を第一選択とすべきではない。

65歳以上に対し、HbA1cの7.5%未満達成のために薬物療法を行なうべきではない。ほとんどの場合は中程度の管理でよい。

高齢者の不眠症・興奮・譫妄に対して、ベンゾジアゼピンや他の鎮静催眠剤を第一選択とすべきではない。

無症候であれば、高齢者の細菌尿症に抗菌薬を用いるべきではない。

アメリカ外科学会(英語版)[56]

軽微・単箇所の外傷に対して全身CT撮影は不要である。

平均余命10年未満であり、家族や本人に大腸腫瘍の病歴が無い患者については、自覚症状が無ければ大腸癌検査は不要である。

病歴や健康診断結果において目立った特徴のない外来患者に対し、入院時や手術前の胸部X線撮影は不要である。

アメリカ麻酔科学会(英語版)[57]

癌が原因ではない慢性痛に対しては、オピオイド系鎮痛剤を第一選択としてはならない。

患者に薬物依存症を含めたリスクを説明して話し合うまで、オピオイド系鎮痛剤による長期の薬物療法を行ってはならない。

癌が原因ではない慢性痛には、大きなリスクや費用になる不可逆的となるような治療は行わない。

アメリカ神経学会(英語版)[58]

頭痛に対し、脳波測定は不要である。

単純な失神に対し、他の神経学的症状がないのなら頸動脈造影は不要である。

片頭痛に対してのオピオイドやButalbital(英語版)の処方は、最終手段である場合を除いてすべきでない。

アメリカ耳鼻咽喉・頭頸部外科学会(英語版)[59]

突発性難聴に対し、頭部CTは不要である。

中耳腔換気用チューブ留置後の耳漏に対し、合併症が無いのであれば経口抗生物質を処方すべきではない。

急性外耳炎に対し、合併症が無いのであれば経口抗生物質を処方すべきではない。

急性副鼻腔炎に対し、合併症が無いのであれば画像撮影は不要である。

主訴が嗄声である患者に対し、前喉頭検査をせずにCTやMRIをすべきではない。

アメリカ精神医学会(APA)[60]

適切な初期評価および経過観察が行われていない患者に対し、抗精神病薬を処方してはならない。

二種類以上の抗精神病薬を継続的に投与してはならない。

認知症による行動と心理的な症状の治療として、抗精神病薬を第一選択としてはならない。

成人の不眠症に対し、最初の治療介入として抗精神病薬を継続的に処方してはならない。

児童と青年に対して精神障害でないのならば、最初の治療介入として抗精神病薬を継続的に処方してはならない。

アメリカ頭痛学会(英語版)[61]

片頭痛の基準を満たすが容態が安定している患者に対し、神経画像研究は不要である。

頭痛に対し、MRI撮影が可能な状況であれば、緊急時を除いてCT撮影は不要である

臨床試験でないのであれば、片頭痛トリガーポイントへの外科的非活性化処置は推奨しない。

再発性の頭痛に対して、オピオイドやブタルビタールの処方は、最終手段である場合を除いて行わない。

頭痛に対し、OTC鎮痛薬を長期・頻繁に用いることは推奨できない(薬物乱用頭痛)。

アメリカ腎臓学会(英語版)[62]

徴候や症状のない平均余命の少ない患者に対し、ルーチン的がん検査は不要である。

高血圧・心臓病・慢性腎臓病(CKD, 糖尿病を含む)の患者に対し、NSAIDsの処方は避けるべきである[63]。

アメリカ睡眠学会(英語版)[64]

合併型の睡眠障害でないのなら、慢性不眠患者への睡眠ポリフラフ検査は避けるべきである。

成人の慢性不眠症に対して睡眠薬使用を中心とした治療は避けるべきである。代わりに認知行動療法を勧め、必要なら補助療法を検討する。

児童の不眠に対し医薬品を処方してはならない。たいてい親子関係が理由であるため、行動療法的に介入する。

むずむず脚症候群の診断に対し睡眠ポリグラフ検査をしてはならない。病歴があいまいであり、周期的な脚の動きがあることを文章記録する必要がある場合は例外とする。

体重が安定した睡眠時無呼吸患者に対し、無症候性、接着性であるならば、陽圧気道療法の滴定研究を行ってはならない。

米国カイロプラクティック協会(英語版)[65]

レッドフラッグがない発症から6週間以内の急性腰痛患者に脊椎画像の検査は行わない。

患者の改善を観察するために繰り返し画像検査は行わない。

能動的治療の目標設定なしに、腰痛障害に対して受動的もしくは軽減目的の物理療法機器の長期的な使用を避ける。

心理社会的スクリーニングもしくは評価なしに長期的な疼痛マネジメントを提供しない。

長期治療や腰痛予防を目的に腰痛サポーターやベルトを処方しない。

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆