ユートピア

Utopia

☆ユートピア(utopia)とは、一般的に、その構成員にとって非常に望ましい、あるいはほぼ完璧な性質を持つ架空の共同体や社会を指す。[1]

1516年にトマス・モアが著した『ユートピア』という本で造語された言葉であり、その本では新世界にある架空の島社会が描かれている。仮説上のユートピアは、とりわけ経済、政治、司法などの分野における平等に焦点を当てている。その実現方法や構造は、イデオロギーによって異なる。[2]

リマン・タワー・サージェントは、社会は均質ではなく、相反する欲求を抱えているため、同時に満たすことはできないため、ユートピアの本質は本質的に矛盾

していると主張している。ユートピアの反対語はディストピアである。ユートピア小説やディストピア小説は、人気の文学ジャンルとなっている。空想上のものに対する一般的な表現であ

るにもかかわらず、ユートピアニズムは、建築、ファイル共有、ソーシャルネットワーク、ユニバーサル・ベーシック・インカム、コミューン、国境の開放、さ

らには海賊基地など、現実に基づく分野や概念にインスピレーションを与え、またそれらからもインスピレーションを受けている。

| A utopia

(/juːˈtoʊpiə/ yoo-TOH-pee-ə) typically describes an imaginary community

or society that possesses highly desirable or near-perfect qualities

for its members.[1] It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book

Utopia, which describes a fictional island society in the New World. Hypothetical utopias focus on, among other things, equality in categories such as economics, government and justice, with the method and structure of proposed implementation varying according to ideology.[2] Lyman Tower Sargent argues that the nature of a utopia is inherently contradictory because societies are not homogeneous and have desires which conflict and therefore cannot simultaneously be satisfied. To quote: There are socialist, capitalist, monarchical, democratic, anarchist, ecological, feminist, patriarchal, egalitarian, hierarchical, racist, left-wing, right-wing, reformist, free love, nuclear family, extended family, gay, lesbian and many more utopias [ Naturism, Nude Christians, ...] Utopianism, some argue, is essential for the improvement of the human condition. But if used wrongly, it becomes dangerous. Utopia has an inherent contradictory nature here. — Lyman Tower Sargent, Utopianism: A very short introduction (2010)[3] The opposite of a utopia is a dystopia. Utopian and dystopian fiction has become a popular literary category. Despite being common parlance for something imaginary, utopianism inspired and was inspired by some reality-based fields and concepts such as architecture, file sharing, social networks, universal basic income, communes, open borders and even pirate bases. |

ユートピア

(/juːˈtoʊpiə/

yoo-TOH-pee-ə)とは、一般的に、その構成員にとって非常に望ましい、あるいはほぼ完璧な性質を持つ架空の共同体や社会を指す。[1]

1516年にトマス・モアが著した『ユートピア』という本で造語された言葉であり、その本では新世界にある架空の島社会が描かれている。 仮説上のユートピアは、とりわけ経済、政治、司法などの分野における平等に焦点を当てている。その実現方法や構造は、イデオロギーによって異なる。[2] リマン・タワー・サージェントは、社会は均質ではなく、相反する欲求を抱えているため、同時に満たすことはできないため、ユートピアの本質は本質的に矛盾 していると主張している。引用: 社会には、社会主義、資本主義、君主制、民主主義、無政府主義、エコロジー、フェミニズム、家父長制、平等主義、階層制、人種差別主義、左翼、右翼、改革 主義、自由恋愛、核家族、大家族、ゲイ、レズビアンなど、その他にも多くのユートピアがある。(ナチュリズム、ヌード・クリスチャンなど)ユートピアニズ ムは、人間の状況の改善に不可欠であると主張する者もいる。しかし、誤用すれば危険なものとなる。ユートピアには本質的な矛盾がある。 —ライマン・タワー・サージェント著『ユートピアニズム:ごく短い入門』(2010年)[3] ユートピアの反対語はディストピアである。ユートピア小説やディストピア小説は、人気の文学ジャンルとなっている。空想上のものに対する一般的な表現であ るにもかかわらず、ユートピアニズムは、建築、ファイル共有、ソーシャルネットワーク、ユニバーサル・ベーシック・インカム、コミューン、国境の開放、さ らには海賊基地など、現実に基づく分野や概念にインスピレーションを与え、またそれらからもインスピレーションを受けている。 |

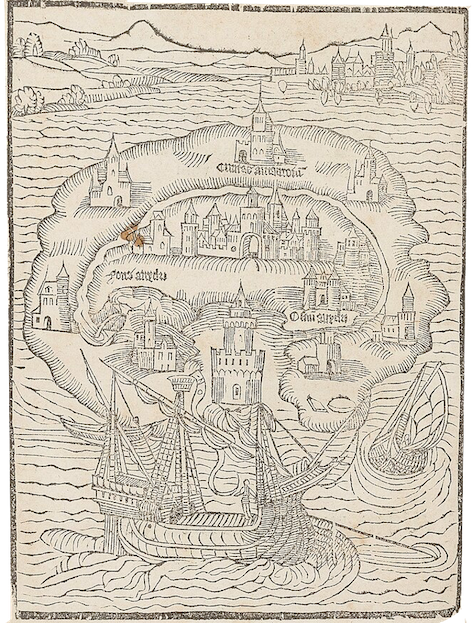

Etymology and history This is the woodcut for Utopia's map as it appears in Thomas More's Utopia printed by Dirk Martens in December 1516 (the first edition). The word utopia was coined in 1516 from Ancient Greek by the Englishman Sir Thomas More for his Latin text Utopia. It literally translates as "no place", coming from the Greek: οὐ ("not") and τόπος ("place"), and meant any non-existent society, when 'described in considerable detail'.[4] However, in standard usage, the word's meaning has shifted and now usually describes a non-existent society that is intended to be viewed as considerably better than contemporary society.[5] In his original work, More carefully pointed out the similarity of the word to eutopia, meaning "good place", from Greek: εὖ ("good" or "well") and τόπος ("place"), which ostensibly would be the more appropriate term for the concept in modern English. The pronunciations of eutopia and utopia in English are identical, which may have given rise to the change in meaning.[5][6] Dystopia, a term meaning "bad place" coined in 1868, draws on this latter meaning. The opposite of a utopia, dystopia is a concept which surpassed utopia in popularity in the fictional literature from the 1950s onwards, chiefly because of the impact of George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four. In 1876, writer Charles Renouvier published a novel called Uchronia (French Uchronie).[7] The neologism, using chronos instead of topos, has since been used to refer to non-existent idealized times in fiction, such as Philip Roth's The Plot Against America (2004),[8] and Philip K. Dick's The Man in the High Castle (1962).[9] According to the Philosophical Dictionary, proto-utopian ideas begin as early as the period of ancient Greece and Rome, medieval heretics, peasant revolts and establish themselves in the period of the early capitalism, reformation and Renaissance (Hus, Müntzer, More, Campanella), democratic revolutions (Meslier, Morelly, Mably, Winstanley, later Babeufists, Blanquists,) and in a period of turbulent development of capitalism that highlighted antagonisms of capitalist society (Saint-Simon, Fourier, Owen, Cabet, Lamennais, Proudhon and their followers).[10] |

語源と歴史 これは、1516年12月にディルク・マルテンスが印刷したトマス・モア著『ユートピア』初版に掲載されたユートピアの地図の木版画である。 ユートピアという語は、1516年に古代ギリシャ語から、トマス・モアのラテン語の著書『ユートピア』のために、イギリス人のトマス・モアによって作られ た造語である。文字通り訳せば「どこでもない場所」となり、ギリシャ語の「οὐ(否定を表す接頭辞)」と「τόπος(場所)」に由来する。「かなり詳細 に記述された」非実在の社会を意味する。[4] しかし、一般的な用法では、この単語の意味は変化し、現在は通常、現代社会よりもかなり良いとされる非実在の社会を指す。[5] モアは、自身の原著作において、この語が「良い場所」を意味するギリシャ語の「eu(良い、または、うまく)」と「topos(場所)」に由来する「ユー トピア」と類似していることを慎重に指摘している。英語では、ユートピアとウトピアの発音は同じであり、これが意味の変化につながった可能性がある。 [5][6] ディストピアという用語は「悪い場所」を意味し、1868年に作られた。この後者の意味に由来する。ユートピアの対義語であるディストピアは、1950年 代以降のフィクション文学において、主にジョージ・オーウェルの『1984年』の影響により、ユートピアよりも人気のある概念となった。 1876年には、作家のシャルル・ルヌヴィエが「Uchronia(フランス語ではUchronie)」という小説を発表している。[7] 「トポス」の代わりに「クロノス」を用いたこの新語は、それ以来、フィクションにおける存在しない理想的な時代を指すために用いられており、例えばフィ リップ・ロスの『アメリカを襲った陰謀』(2004年)[8] やフィリップ・K・ディックの『高い城の男』(1962年)[9] などがある。 『哲学辞典』によると、ユートピア思想の原型は、古代ギリシャ・ローマ時代、中世の異端者、農民の反乱に始まり、初期資本主義、宗教改革、ルネサンスの時 代(フス、ミュンツァー、モア、カンパネッラ)、民主主義革命( メスリー、モレリー、マーベリー、ウィンスタンリー、後のバベウ派、ブランキスト、サン=シモン、フーリエ、オーウェン、カベ、ラメネ、プルードンとその 信奉者など)や、資本主義社会の対立が浮き彫りとなった資本主義の激動的な発展の時代(サン=シモン、フーリエ、オーウェン、カベ、ラメネ、プルードンと その信奉者)に確立された。[10] |

| Definitions and interpretations Famous quotes from writers and characters about utopia: "There is nothing like a dream to create the future. Utopia to-day, flesh and blood tomorrow." —Victor Hugo "It won’t be long until this planet is reborn as 'Utopia'." –Goku Black "A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at, for it leaves out the one country at which Humanity is always landing. And when Humanity lands there, it looks out, and, seeing a better country, sets sail. Progress is the realisation of Utopias." —Oscar Wilde "Utopias are often only premature truths." —Alphonse de Lamartine "None of the abstract concepts comes closer to fulfilled utopia than that of eternal peace." —Theodor W. Adorno "I think that there is always a part of utopia in any romantic relationship." —Pedro Almodovar "In ourselves alone the absolute light keeps shining, a sigillum falsi et sui, mortis et vitae aeternae [false signal and signal of eternal life and death itself], and the fantastic move to it begins: to the external interpretation of the daydream, the cosmic manipulation of a concept that is utopian in principle." —Ernst Bloch "When I die, I want to die in a Utopia that I have helped to build." —Henry Kuttner "A man must be far gone in Utopian speculations who can seriously doubt that if these [United] States should either be wholly disunited, or only united in partial confederacies, the subdivisions into which they might be thrown would have frequent and violent contests with each other." —Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 6. "Most dictionaries associate utopia with ideal commonwealths, which they characterize as an empirical realization of an ideal life in an ideal society. Utopias, especially social utopias, are associated with the idea of social justice." – Lukáš Perný[11] "We are all utopians, so soon as we wish for something different." – Henri Lefebvre[12] "Every daring attempt to make a great change in existing conditions, every lofty vision of new possibilities for the human race, has been labeled Utopian." –Emma Goldman[13] Utopian socialist Étienne Cabet in his utopian book The Voyage to Icaria cited the definition from the contemporary Dictionary of ethical and political sciences: Utopias and other models of government, based on the public good, may be inconceivable because of the disordered human passions which, under the wrong governments, seek to highlight the poorly conceived or selfish interest of the community. But even though we find it impossible, they are ridiculous to sinful people whose sense of self-destruction prevents them from believing. Marx and Engels used the word "utopia" to denote unscientific social theories.[14] Philosopher Slavoj Žižek told about utopia: "Which means that we should reinvent utopia but in what sense. There are two false meanings of utopia one is this old notion of imagining this ideal society we know will never be realized, the other is the capitalist utopia in the sense of new perverse desire that you are not only allowed but even solicited to realize. The true utopia is when the situation is so without issue, without the way to resolve it within the coordinates of the possible that out of the pure urge of survival you have to invent a new space. Utopia is not kind of a free imagination utopia is a matter of inner most urgency, you are forced to imagine it, it is the only way out, and this is what we need today."[15] Philosopher Milan Šimečka said: ...utopism was a common type of thinking at the dawn of human civilization. We find utopian beliefs in the oldest religious imaginations, appear regularly in the neighborhood of ancient, yet pre-philosophical views on the causes and meaning of natural events, the purpose of creation, the path of good and evil, happiness and misfortune, fairy tales and legends later inspired by poetry and philosophy ... the underlying motives on which utopian literature is built are as old as the entire historical epoch of human history. ”[16] Philosopher Richard Stahel said: ...every social organization relies on something that is not realized or feasible, but has the ideal that is somewhere beyond the horizon, a lighthouse to which it may seek to approach if it considers that ideal socially valid and generally accepted."[17] ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Zezek on Utopia ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ ˝Think about the strangeness of today's situation, 30 or 40 years ago we were still debating what the future will be: communist, capitalist, fascist, today nobody even debates these issues, we all silently accept global capitalism is here to stay, on the other hand we are obssessed with cosmic catastrophe, the whole life on earth disintegrating because of some virus, because of an asteroid hitting the earth and so on, so the paradox is that it's much easier to imagine the end of all life on earth than a much more modest radical change in capitalism. Which means that we should reinvent utopia but in what sense. There are two false meanings of utopia one is this old notion of imagining this ideal society we know will never be realized, the other is the capitalist utopia in the sense of new perversed desire that you are not only allowed but even solicited to realize. The true utopia is when the situation is so without issue, without the way to resolve it within the coordinates of the possible that out of the pure urge of survival you have to invent a new space. Utopia is not kind of a free imagination utopia is a matter of inner most urgency, you are forced to imagine it, it is the only way out, and this is what we need today.˝ (http://vimeo.com/7527571) |

定義と解釈 ユートピアに関する作家や登場人物の有名な引用句: 「未来を創造するのに夢のようなものはない。今日ユートピア、明日は現実のものとなる。」―ヴィクトル・ユーゴー 「この惑星が『ユートピア』として生まれ変わるまで、それほど長くはかからないだろう。」―悟空ブラック 「ユートピアを含まない世界地図は、一瞥する価値もない。なぜなら、そこには人類が常に降り立つことになる国が抜け落ちているからだ。そして人類がそこに 降り立つと、外に目をやり、より良い国があるのを見て、船出するのだ。進歩とはユートピアの実現である。」—オスカー・ワイルド 「ユートピアはしばしば、時期尚早な真実でしかない。」—アルフォンス・ド・ラマルティーヌ 「抽象概念の中で、永遠の平和という概念ほど、実現されたユートピアに近いものはない。」—テオドール・W・アドルノ 「私は、ロマンチックな関係には常にユートピアの要素があると思う。」—ペドロ・アルモドバル 「私たち自身の中だけに、絶対的な光が輝き続けている。偽りの印であり、永遠の生命と死そのものの印である。そして、そこへの素晴らしい動きが始まる。白日夢の外部解釈、原理的にユートピア的な概念の宇宙的操縦へ。」 —エルンスト・ブロッホ 「私が死ぬときは、私が建設を手助けしたユートピアで死にたい」 —ヘンリー・カトナー 「もしこの(合衆国)が完全に分裂するか、あるいは部分的な連合のみで結ばれている場合、その分割された地域間で頻繁かつ激しい争いが起こるだろうと真剣 に疑うような人間は、ユートピア的な思索に深く傾倒しているに違いない」 —アレクサンダー・ハミルトン、『連邦党の論説』第6号 「ほとんどの辞書はユートピアを理想的な共和国と関連づけ、理想的な社会における理想的な生活の実証的な実現として特徴づけている。ユートピア、特に社会的なユートピアは社会正義の概念と関連づけられている。」 - ルカーシュ・ペルニー[11] 「私たちは皆、何か別のものを望む限り、ユートピストである」 - アンリ・ルフェーヴル[12] 「既存の状況に大きな変化をもたらそうとするあらゆる大胆な試み、人類の新たな可能性に対するあらゆる崇高なビジョンは、ユートピア的であるとレッテルを貼られてきた」 - エマ・ゴールドマン[13] ユートピア的社会主義者であるエティエンヌ・カベは、著書『イカリアへの旅』の中で、当時の『倫理的・政治的諸科学辞典』の定義を引用している。 公共の利益に基づくユートピアやその他の政治体制のモデルは、誤った政府の下では、社会の貧弱な構想や利己的な利益を強調しようとする人間の情念の無秩序 さのために、想像できないかもしれない。しかし、たとえそれが不可能だとしても、自己破壊の感覚が信じることを妨げる罪深い人々にとっては、それは滑稽な ことである。 マルクスとエンゲルスは、非科学的社会理論を示すために「ユートピア」という言葉を使用した。 哲学者のスラヴォイ・ジジェクは、ユートピアについて次のように述べている。 「つまり、私たちはユートピアを再発明すべきだが、それはどのような意 味においてなのか、ということだ。ユートピアには2つの誤った意味がある。1つは、私たちが実現不可能だと知っている理想社会を想像するという、この古い 考え方であり、もう1つは、実現することが許されているだけでなく、実現することが求められているという意味での資本主義的ユートピアである。真のユート ピアとは、問題がまったくなく、可能な範囲内で解決する方法もない状況において、生存本能から新しい空間を創り出さなければならないような場合である。 ユートピアとは、自由な想像力によるものではなく、最も切迫した内なる問題である。想像せざるを得ず、それが唯一の解決策であり、そして、それが今日私た ちに必要なことなのである。」[15] 哲学者ミラン・シメチェカは次のように述べている。... ユートピズムは、人類文明の黎明期に共通して見られた思考形態であった。ユートピア思想は、最古の宗教的想像力の中に存在し、自然現象の原因や意味、創造 の目的、善と悪の道、幸福と不幸、後に詩や哲学からインスピレーションを受けたおとぎ話や伝説など、古代の、しかし哲学以前の考え方の周辺に定期的に現れ る。ユートピア文学の根底にある動機は、人類の歴史全体と同じくらい古い。」[16] 哲学者のリチャード・ステールは次のように述べている。 「あらゆる社会組織は、実現不可能な理想を拠り所としている。しかし、その理想は地平線の彼方にある。社会的に妥当で一般的に受け入れられている理想だと考えれば、その理想に近づこうと努力するだろう。」[17] +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ ジジェクの説くユートピア +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ 「今日の状況の奇妙さを考えてみよう。30年も40年も前には、私たちは未来がどうなるのかについてまだ議論していた。共産主義、資本主義、ファシズムな どについてだ。今日では、誰もそのような問題について議論することさえしない。私たちは皆、グローバル資本主義が定着していることを黙って受け入れてい る。その一方で、 宇宙的なカタストロフィに執着し、地球上の生命全体が、何らかのウイルスや地球に衝突する小惑星などによって崩壊するのではないかと不安になっている。つ まり、資本主義がもっと穏やかに急進的に変化するよりも、地球上の生命がすべて絶滅する可能性を想像する方がずっと容易なのだ。つまり、私たちはユートピ アを再発明すべきだが、どのような意味でなのか、ということだ。ユートピアには2つの誤った意味がある。1つは、私たちが実現不可能だと知っている理想社 会を想像するという、この古い概念である。もう1つは、新しい倒錯した欲望という意味での資本主義的ユートピアであり、実現することが許されているだけで なく、むしろ実現することが求められているという意味である。真のユートピアとは、問題がまったくなく、可能な範囲内で解決する方法もない状況において、 生存本能から新しい空間を創り出さなければならないような状況である。ユートピアとは、自由な想像力によるものではなく、切迫した内なる問題である。想像 せざるを得ない状況であり、それが唯一の解決策であり、そして、それが今日、私たちに必要なことなのである」(http://vimeo.com/7527571) |

| Varieties Chronologically, the first recorded Utopian proposal is Plato's Republic.[18] Part conversation, part fictional depiction and part policy proposal, Republic would categorize citizens into a rigid class structure of "golden," "silver," "bronze" and "iron" socioeconomic classes. The golden citizens are trained in a rigorous 50-year-long educational program to be benign oligarchs, the "philosopher-kings." Plato stressed this structure many times in statements, and in his published works, such as the Republic. The wisdom of these rulers will supposedly eliminate poverty and deprivation through fairly distributed resources, though the details on how to do this are unclear. The educational program for the rulers is the central notion of the proposal. It has few laws, no lawyers and rarely sends its citizens to war but hires mercenaries from among its war-prone neighbors. These mercenaries were deliberately sent into dangerous situations in the hope that the more warlike populations of all surrounding countries will be weeded out, leaving peaceful peoples. During the 16th century, Thomas More's book Utopia proposed an ideal society of the same name.[19] Readers, including Utopian socialists, have chosen to accept this imaginary society as the realistic blueprint for a working nation, while others have postulated that Thomas More intended nothing of the sort.[20] It is believed that More's Utopia functions only on the level of a satire, a work intended to reveal more about the England of his time than about an idealistic society.[21] This interpretation is bolstered by the title of the book and nation and its apparent confusion between the Greek for "no place" and "good place": "utopia" is a compound of the syllable ou-, meaning "no" and topos, meaning place. But the homophonic prefix eu-, meaning "good," also resonates in the word, with the implication that the perfectly "good place" is really "no place." |

種類 年代順に見ていくと、ユートピア構想として最初に記録されたものはプラトンの『国家』である。[18] 『国家』は、一部が会話、一部が架空の描写、一部が政策提言となっており、市民を「金」「銀」「銅」「鉄」の4つの社会経済的階級からなる硬直的な階級構 造に分類している。 金の市民は、善良な寡頭制政治者、すなわち「哲人王」となるために、50年間にわたる厳格な教育プログラムで訓練される。プラトンは、この構想を『国家』 などの著作で何度も強調している。支配者たちの知恵によって、公平に分配された資源を通じて、貧困や窮乏が解消されるはずである。ただし、その方法の詳細 については不明である。支配者たちの教育プログラムは、この提案の中心的な概念である。この統治者たちの教育プログラムは、この提案の中心的な概念であ る。この統治者たちは、法律をほとんど持たず、弁護士もおらず、自国民を戦争に送ることはほとんどないが、好戦的な近隣諸国から傭兵を雇う。これらの傭兵 は、意図的に危険な状況に送り込まれ、周辺の好戦的な国々の人口が淘汰され、平和的な人々だけが残ることを期待している。 16世紀には、トマス・モアの著書『ユートピア』が同名の理想社会を提案した。[19] ユートピア社会主義者を含む読者は、この架空の社会を現実的な国家運営の青写真として受け入れることを選択したが、トマス・モアはそのような意図はなかっ たと主張する者もいる。[20] モアの『ユートピア』は風刺のレベルでしか機能せず、理想社会についてよりも、当時のイングランドについて多くを明らかにする作品であると考えられてい る。[21] この解釈は、この本のタイトルと国名、そして「どこでもない場所」を意味するギリシャ語と「良い場所」を意味するギリシャ語の明白な混同によって裏付けら れている。「ユートピア」は「ない」を意味するギリシャ語の「ou-」と「場所」を意味する「topos」の合成語である。しかし、「良い」を意味する同 音の接頭辞「eu-」もこの言葉には響き、完璧な「良い場所」は実際には「ない場所」であるという含みがある。 |

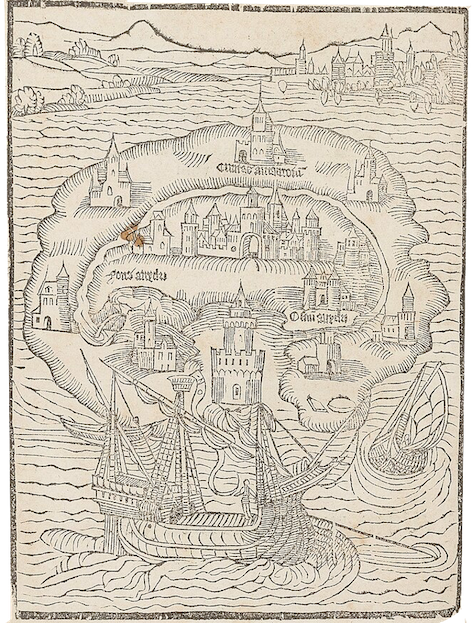

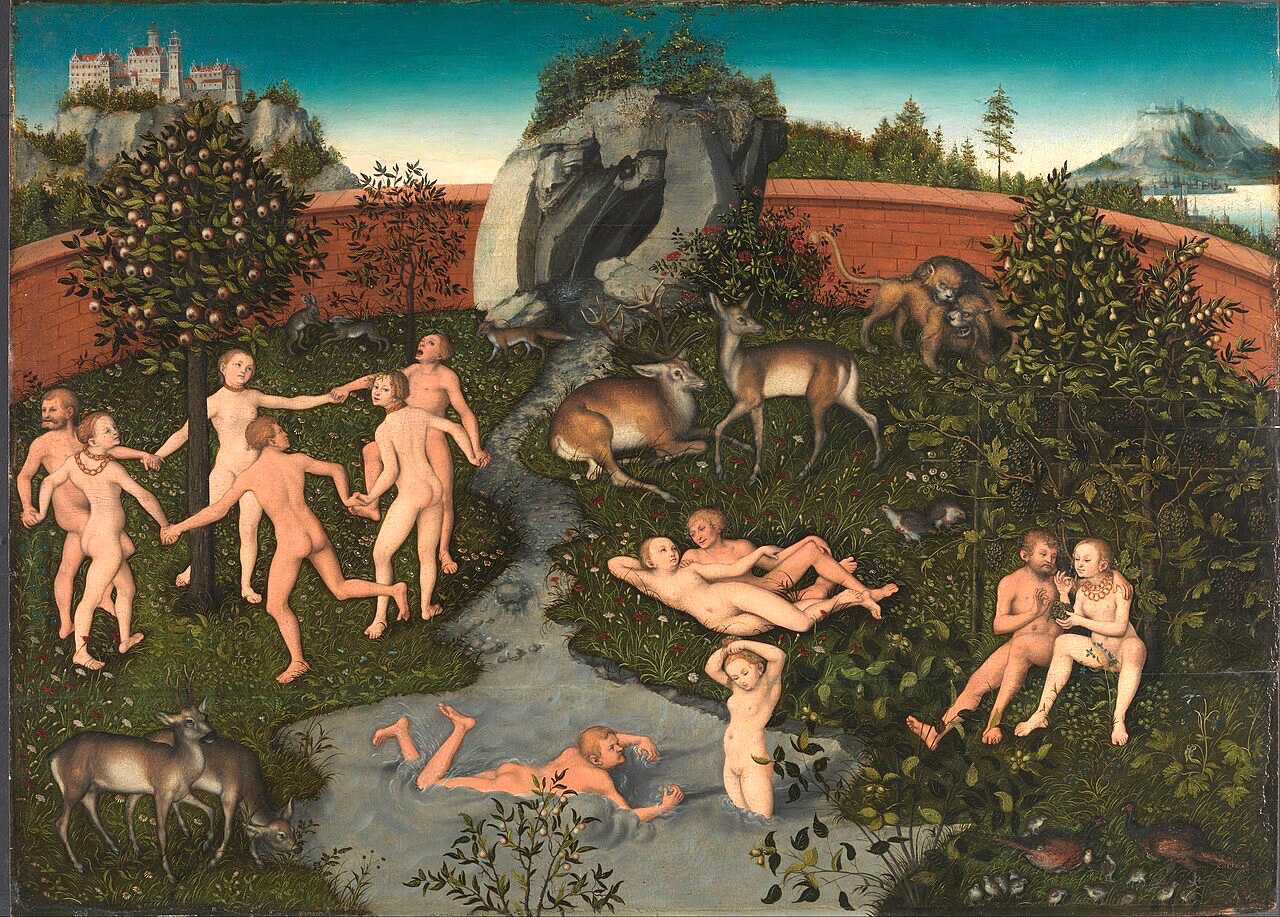

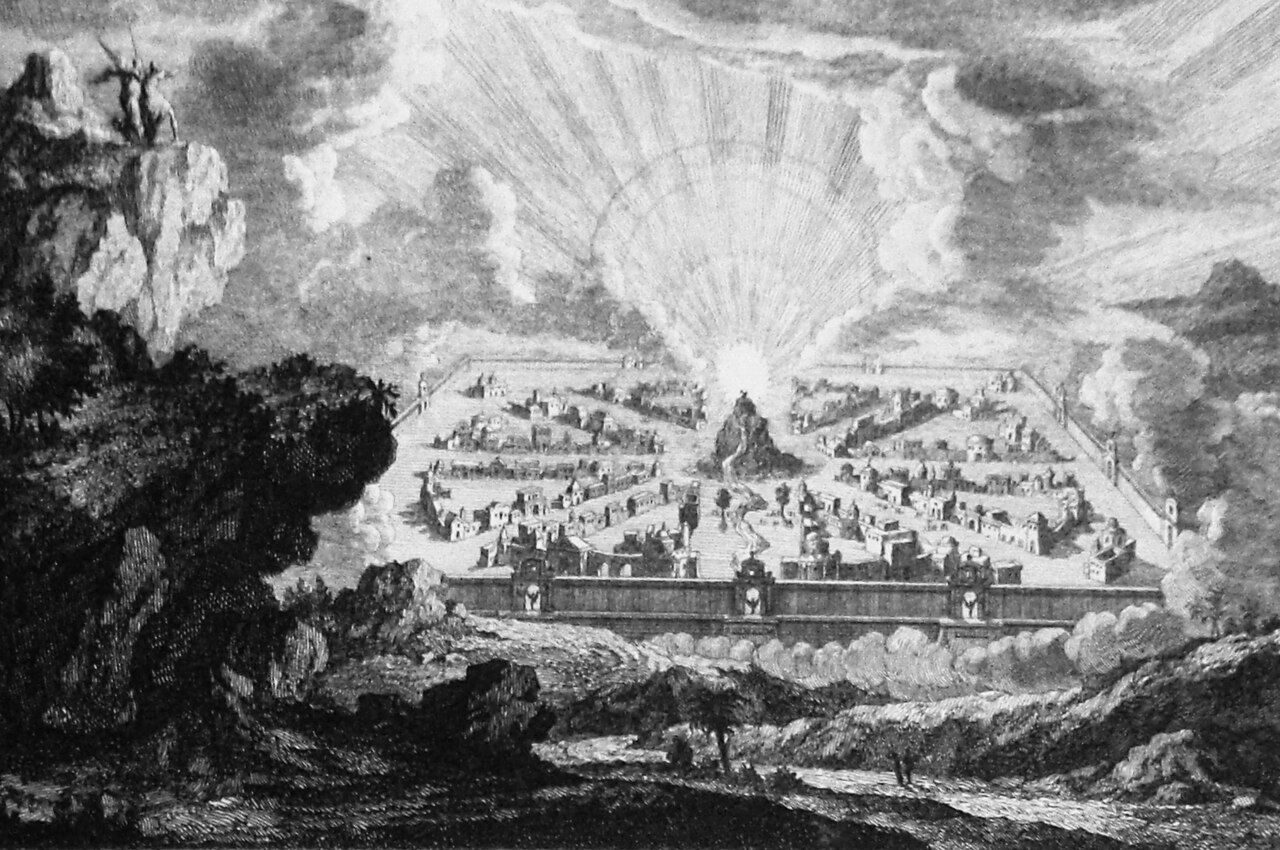

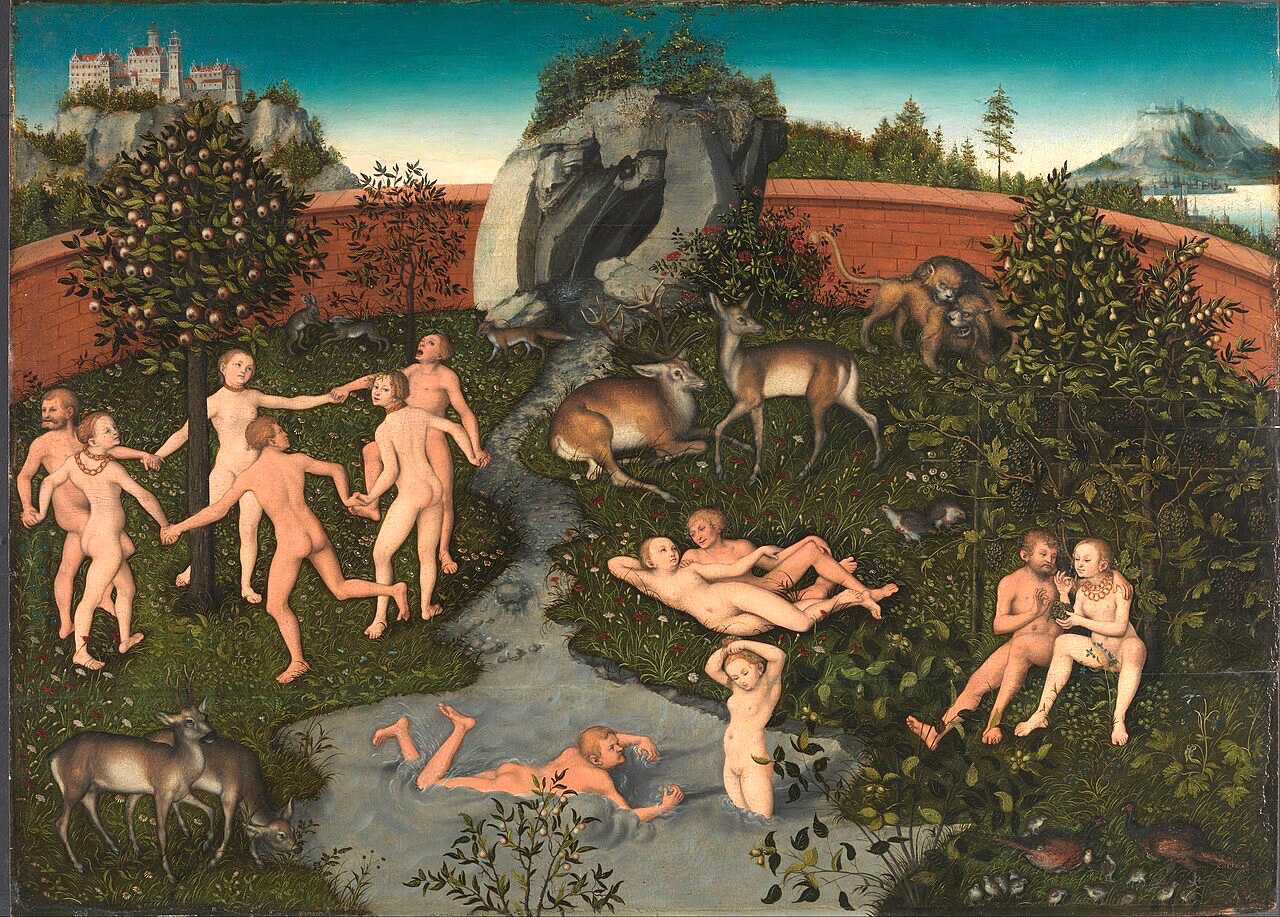

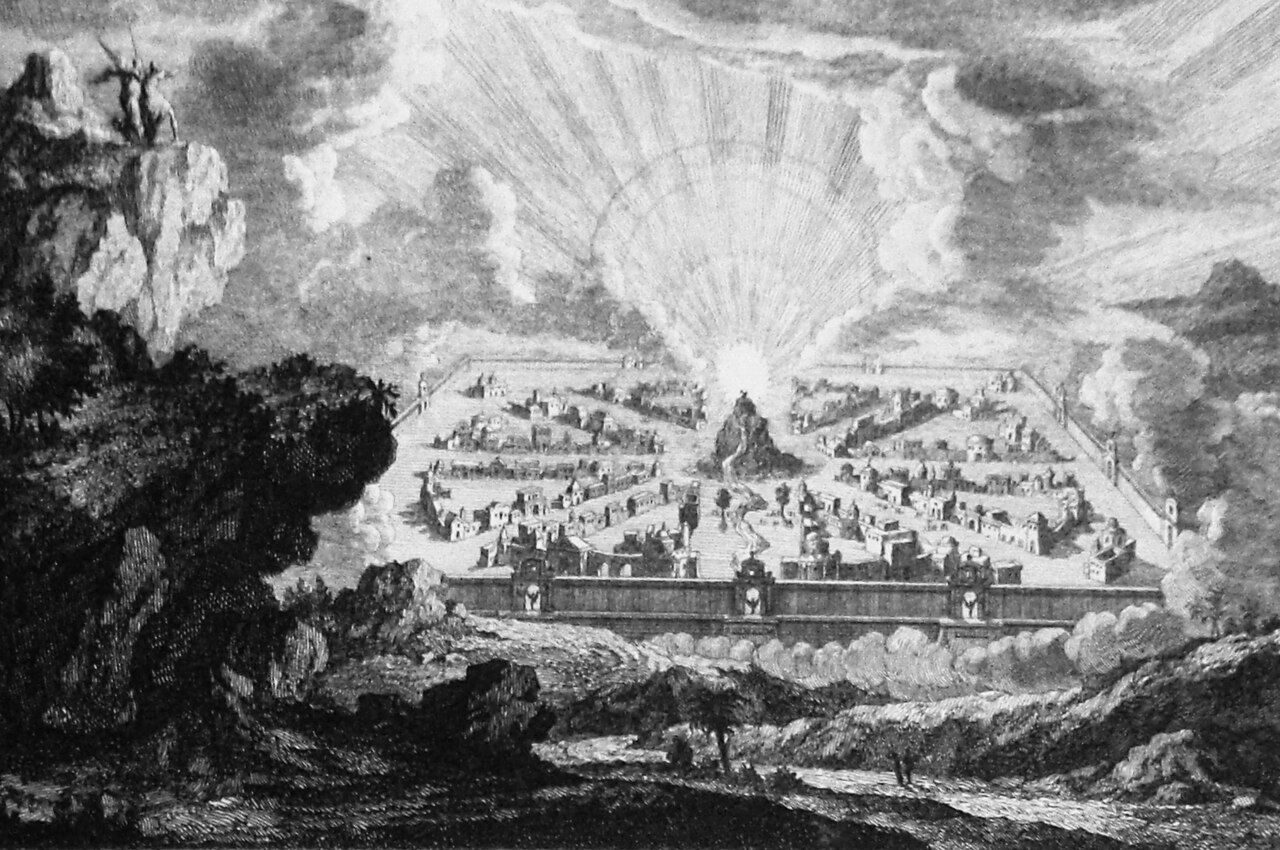

| Mythical and religious utopias Further information: Palingenesis and Apocatastasis  The Earthly Paradise – Garden of Eden, the left panel from Hieronymus Bosch's The Garden of Earthly Delights In many cultures, societies, and religions, there is some myth or memory of a distant past when humankind lived in a primitive and simple state but at the same time one of perfect happiness and fulfillment. In those days, the various myths tell us, there was an instinctive harmony between humanity and nature. People's needs were few and their desires limited. Both were easily satisfied by the abundance provided by nature. Accordingly, there were no motives whatsoever for war or oppression. Nor was there any need for hard and painful work. Humans were simple and pious and felt themselves close to their God or gods. According to one anthropological theory, hunter-gatherers were the original affluent society. These mythical or religious archetypes are inscribed in many cultures and resurge with special vitality when people are in difficult and critical times. However, in utopias, the projection of the myth does not take place towards the remote past but either towards the future or towards distant and fictional places, imagining that at some time in the future, at some point in space, or beyond death, there must exist the possibility of living happily. In the United States and Europe, during the Second Great Awakening (ca. 1790–1840) and thereafter, many radical religious groups formed utopian societies in which faith could govern all aspects of members' lives. These utopian societies included the Shakers, who originated in England in the 18th century and arrived in America in 1774. A number of religious utopian societies from Europe came to the United States in the 18th and 19th centuries, including the Society of the Woman in the Wilderness (led by Johannes Kelpius (1667–1708), the Ephrata Cloister (established in 1732) and the Harmony Society, among others. The Harmony Society was a Christian theosophy and pietist group founded in Iptingen, Germany, in 1785. Due to religious persecution by the Lutheran Church and the government in Württemberg,[22] the society moved to the United States on October 7, 1803, settling in Pennsylvania. On February 15, 1805, about 400 followers formally organized the Harmony Society, placing all their goods in common. The group lasted until 1905, making it one of the longest-running financially successful communes in American history. The Oneida Community, founded by John Humphrey Noyes in Oneida, New York, was a utopian religious commune that lasted from 1848 to 1881. Although this utopian experiment has become better known today for its manufacture of Oneida silverware, it was one of the longest-running communes in American history. The Amana Colonies were communal settlements in Iowa, started by radical German pietists, which lasted from 1855 to 1932. The Amana Corporation, manufacturer of refrigerators and household appliances, was originally started by the group. Other examples are Fountain Grove (founded in 1875), Riker's Holy City and other Californian utopian colonies between 1855 and 1955 (Hine), as well as Sointula[23] in British Columbia, Canada. The Amish and Hutterites can also be considered an attempt towards religious utopia. A wide variety of intentional communities with some type of faith-based ideas have also started across the world. Anthropologist Richard Sosis examined 200 communes in the 19th-century United States, both religious and secular (mostly utopian socialist). 39 percent of the religious communes were still functioning 20 years after their founding while only 6 percent of the secular communes were.[24] The number of costly sacrifices that a religious commune demanded from its members had a linear effect on its longevity, while in secular communes demands for costly sacrifices did not correlate with longevity and the majority of the secular communes failed within 8 years. Sosis cites anthropologist Roy Rappaport in arguing that rituals and laws are more effective when sacralized.[25] Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt cites Sosis's research in his 2012 book The Righteous Mind as the best evidence that religion is an adaptive solution to the free-rider problem by enabling cooperation without kinship.[26] Evolutionary medicine researcher Randolph M. Nesse and theoretical biologist Mary Jane West-Eberhard have argued instead that because humans with altruistic tendencies are preferred as social partners they receive fitness advantages by social selection,[list 1] with Nesse arguing further that social selection enabled humans as a species to become extraordinarily cooperative and capable of creating culture.[31] The Book of Revelation in the Christian Bible depicts an eschatological time with the defeat of Satan, of Evil and of Sin. The main difference compared to the Old Testament promises is that such a defeat also has an ontological value: "Then I saw 'a new heaven and a new earth,' for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and there was no longer any sea...'He will wipe every tear from their eyes. There will be no more death' or mourning or crying or pain, for the old order of things has passed away"[32] and no longer just gnosiological (Isaiah: "See, I will create/new heavens and a new earth./The former things will not be remembered,/nor will they come to mind".[33][34][35] Narrow interpretation of the text depicts Heaven on Earth or a Heaven brought to Earth without sin. Daily and mundane details of this new Earth, where God and Jesus rule, remain unclear, although it is implied to be similar to the biblical Garden of Eden. Some theological philosophers believe that heaven will not be a physical realm but instead an incorporeal place for souls.[36]  The Golden Age by Lucas Cranach the Elder Golden Age The Greek poet Hesiod, around the 8th century BC, in his compilation of the mythological tradition (the poem Works and Days), explained that, prior to the present era, there were four other progressively less perfect ones, the oldest of which was the Golden Age. Scheria Perhaps the oldest Utopia of which we know, as pointed out many years ago by Moses Finley,[37] is Homer's Scheria, island of the Phaeacians.[38] A mythical place, often equated with classical Corcyra, (modern Corfu/Kerkyra), where Odysseus was washed ashore after 10 years of storm-tossed wandering and escorted to the King's palace by his daughter Nausicaa. With stout walls, a stone temple and good harbours, it is perhaps the 'ideal' Greek colony, a model for those founded from the middle of the 8th C onward. A land of plenty, home to expert mariners (with the self-navigating ships), and skilled craftswomen who live in peace under their king's rule and fear no strangers. Plutarch, the Greek historian and biographer of the 1st century, dealt with the blissful and mythic past of humanity. Arcadia From Sir Philip Sidney's prose romance The Old Arcadia (1580), originally a region in the Peloponnesus, Arcadia became a synonym for any rural area that serves as a pastoral setting, a locus amoenus ("delightful place"). The Biblical Garden of Eden  A new heaven and new earth,[39] Mortier's Bible, Phillip Medhurst Collection The Biblical Garden of Eden as depicted in the Old Testament Bible's Book of Genesis 2 (Authorized Version of 1611): And the Lord God planted a garden eastward in Eden; and there he put the man whom he had formed. Out of the ground made the Lord God to grow every tree that is pleasant to the sight and good for food; the tree of life also in the midst of the garden and the tree of knowledge of good and evil. [...] And the Lord God took the man and put him into the garden of Eden to dress it and to keep it. And the Lord God commanded the man, saying, Of every tree of the garden thou mayest freely eat: but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, thou shalt not eat of it: for in the day that thou eatest thereof thou shalt surely die. [...] And the Lord God said, It is not good that the man should be alone; [...] And the Lord God caused a deep sleep to fall upon Adam and he slept: and he took one of his ribs and closed up the flesh instead thereof and the rib, which the Lord God had taken from man, made he a woman and brought her unto the man. According to the exegesis that the biblical theologian Herbert Haag proposes in the book Is original sin in Scripture?,[40] published soon after the Second Vatican Council, Genesis 2:25 would indicate that Adam and Eve were created from the beginning naked of the divine grace, an originary grace that, then, they would never have had and even less would have lost due to the subsequent events narrated.[41] On the other hand, while supporting a continuity in the Bible about the absence of preternatural gifts (Latin: dona praeternaturalia)[42] with regard to the ophitic event, Haag never makes any reference to the discontinuity of the loss of access to the tree of life. The Land of Cockaigne The Land of Cockaigne (also Cockaygne, Cokaygne), was an imaginary land of idleness and luxury, famous in medieval stories and the subject of several poems, one of which, an early translation of a 13th-century French work, is given in George Ellis' Specimens of Early English Poets. In this, "the houses were made of barley sugar and cakes, the streets were paved with pastry and the shops supplied goods for nothing." London has been so called (see Cockney) but Boileau applies the same to Paris.[43] Schlaraffenland is an analogous German tradition. All these myths also express some hope that the idyllic state of affairs they describe is not irretrievably and irrevocably lost to mankind, that it can be regained in some way or other. One way might be a quest for an "earthly paradise" – a place like Shangri-La, hidden in the Tibetan mountains and described by James Hilton in his utopian novel Lost Horizon (1933). Christopher Columbus followed directly in this tradition in his belief that he had found the Garden of Eden when, towards the end of the 15th century, he first encountered the New World and its indigenous inhabitants.[citation needed] The Peach Blossom Spring The Peach Blossom Spring (桃花源), a prose piece written by the Chinese poet Tao Yuanming, describes a utopian place.[44][45] The narrative goes that a fisherman from Wuling sailed upstream a river and came across a beautiful blossoming peach grove and lush green fields covered with blossom petals.[46] Entranced by the beauty, he continued upstream and stumbled onto a small grotto when he reached the end of the river.[46] Though narrow at first, he was able to squeeze through the passage and discovered an ethereal utopia, where the people led an ideal existence in harmony with nature.[47] He saw a vast expanse of fertile lands, clear ponds, mulberry trees, bamboo groves and the like with a community of people of all ages and houses in neat rows.[47] The people explained that their ancestors escaped to this place during the civil unrest of the Qin dynasty and they themselves had not left since or had contact with anyone from the outside.[48] They had not even heard of the later dynasties of bygone times or the then-current Jin dynasty.[48] In the story, the community was secluded and unaffected by the troubles of the outside world.[48] The sense of timelessness was predominant in the story as a perfect utopian community remains unchanged, that is, it had no decline nor the need to improve.[48] Eventually, the Chinese term Peach Blossom Spring came to be synonymous for the concept of utopia.[49] Datong Datong is a traditional Chinese Utopia. The main description of it is found in the Chinese Classic of Rites, in the chapter called "Li Yun" (禮運). Later, Datong and its ideal of 'The World Belongs to Everyone/The World is Held in Common' 'Tianxia weigong/天下爲公' 'influenced modern Chinese reformers and revolutionaries, such as Kang Youwei. Ketumati It is said, once Maitreya is reborn into the future kingdom of Ketumati, a utopian age will commence.[50] The city is described in Buddhism as a domain filled with palaces made of gems and surrounded by Kalpavriksha trees producing goods. During its years, none of the inhabitants of Jambudvipa will need to take part in cultivation and hunger will no longer exist.[51] |

神話的・宗教的なユートピア さらに詳しい情報: 再生とアポカタスタシス  地上の楽園 - エデンの園、ヒエロニムス・ボスの『快楽の園』の左側のパネル 多くの文化、社会、宗教において、人類が原始的でシンプルな状態で暮らしながら、同時に完全な幸福と充足感に満ちていた遠い過去の神話や記憶がある。当時 の人々は、人間と自然との間に本能的な調和があったと、さまざまな神話が伝えている。人々のニーズは少なく、欲望も限られていた。どちらも自然がもたらす 豊富な恵みによって容易に満たされていた。したがって、戦争や抑圧の動機はまったく存在しなかった。また、辛く苦しい労働の必要性もなかった。人間は素朴 で敬虔であり、神や神々との距離が近いと感じていた。ある人類学説によると、狩猟採集民こそが、本来の裕福な社会であったという。 こうした神話や宗教的な原型は多くの文化に刻み込まれており、人々が困難な時代や危機的な時代に直面したときに、特別な活力をもって再び浮上する。しか し、ユートピアにおいては、神話の投影は遠い過去ではなく、未来や遠く離れた架空の場所に向けられる。つまり、未来のある時点、あるいは宇宙のある地点、 あるいは死後の世界において、幸福に暮らす可能性が存在するはずだという考え方である。 米国とヨーロッパでは、第2の大覚醒(1790年頃~1840年)とその後の時代に、多くの急進的な宗教団体が、信仰が団員の生活のあらゆる側面を支配す るユートピア社会を形成した。こうしたユートピア社会には、18世紀に英国で誕生し、1774年にアメリカに到着したシェーカー教団も含まれる。18世紀 から19世紀にかけて、ヨーロッパから多数の宗教的ユートピア社会がアメリカに渡ってきた。その中には、荒野の女(Society of the Woman in the Wilderness)(ヨハネス・ケルピウス(Johannes Kelpius、1667年-1708年)が指導)、エフラタ隠修士団(Ephrata Cloister)(1732年設立)、ハーモニー協会(Harmony Society)などがある。ハーモニー協会は、1785年にドイツのイプティンゲンで設立されたキリスト教神智学と敬虔主義のグループである。 ヴュルテンベルクのルター派教会と政府による宗教迫害のため、[22] 1803年10月7日にアメリカ合衆国に移住し、ペンシルベニア州に定住した。 1805年2月15日、約400人の信奉者がハーモニー協会を正式に結成し、すべての財産を共有した。このグループは1905年まで存続し、アメリカ史 上、財政的に最も成功した共同体の一つとなった。 ニューヨーク州オナイダでジョン・ハンフリー・ノイレスが創設したオナイダ共同体は、1848年から1881年まで存続したユートピア的宗教共同体であっ た。このユートピア的実験は、現在ではオナイダ銀器の製造でよく知られているが、アメリカ史上最も長く存続した共同体のひとつであった。アイオワ州のアマ ナ・コロニーは、急進的なドイツ敬虔主義者たちによって始められた共同社会であり、1855年から1932年まで続いた。冷蔵庫や家庭用電化製品のメー カーであるアマナ・コーポレーションは、もともとこのグループによって設立された。その他の例としては、ファウンテン・グローブ(1875年創設)、ライ カーズ・ホーリー・シティ、および1855年から1955年の間にカリフォルニアに作られた他のユートピア的コロニー(Hine)、そしてカナダのブリ ティッシュコロンビア州にあるソイントゥーラ[23]がある。アーミッシュやフッター派も、宗教的ユートピアの試みとみなすことができる。信仰に基づく考 え方を持つさまざまな意図的な共同体も、世界中で誕生している。 人類学者のリチャード・ソシスは、19世紀のアメリカ合衆国における200のコミューンを調査した。その中には宗教系と世俗系(主にユートピア社会主義) の両方が含まれていた。宗教的なコミューンの39パーセントは設立から20年後も存続していたが、世俗的なコミューンでは6パーセントのみであった。 [24] 宗教的なコミューンがそのメンバーに要求する犠牲の数は、その存続期間に直線的な影響を与えたが、一方で、世俗的なコミューンでは、犠牲の要求は存続期間 と相関せず、その大半は8年以内に失敗した。ソシスは、儀式や法は神聖化されるとより効果的になるという主張を、人類学者ロイ・ラパポートを引き合いに出 して述べている。社会心理学者ジョナサン・ヘイトは、2012年の著書『The Righteous Mind』の中で、ソシスの研究を引用し、宗教は親族関係がなくても協力を可能にするため、フリーライダー問題に対する適応的な解決策であるという最良の 証拠であると述べている。 。進化医学の研究者ランドルフ・M・ネスと理論生物学者メアリー・ジェーン・ウェスト=エバーハートは、利他的傾向を持つ人間が社会的なパートナーとして 好まれるため、社会淘汰によって適応上の優位性を得るという主張をしている[一覧1]。ネスはさらに、社会淘汰によって人類という種が非常に協力的にな り、文化を生み出す能力を得ることが可能になったと主張している[31]。 キリスト教の聖書におけるヨハネの黙示録は、終末論的な時代を、サタン、悪、罪の敗北として描いている。旧約聖書の約束と比較した際の主な違いは、このよ うな敗北には存在論的な価値もあるということである。「私はまた、『新しい天と新しい地』を見た。最初の天と最初の地は過ぎ去り、もはや海はなくなった。 もはや死もなく、悲しみも叫びも痛みもない。先のものは過ぎ去ったからだ」[32]とあり、もはや単なる認識論的なものではない(イザヤ書:「見よ、私は 新しい天と新しい地を創造する。先のものは思い起こされることもなく、心に浮かぶこともない」[33][34][35])。テキストを狭義に解釈すると、 地上の天国、あるいは罪のない天国がもたらされると描写される。神とイエスが支配するこの新しい地球の日常的なありふれた詳細については、聖書のエデンの 園に似ていることが暗示されているものの、依然として不明である。一部の神学哲学者は、天国は物理的な領域ではなく、魂のための無形の場所であると信じて いる。  ルーカス・クラナッハ(父)による『黄金時代 黄金時代 ギリシャの詩人ヘシオドスは、紀元前8世紀頃、神話の伝統をまとめた著作(詩『仕事と日々』)の中で、現在の時代以前には、より完全性が低い4つの時代が存在し、その中で最も古い時代は黄金時代であったと説明している。 シェリア おそらく、我々が知る最も古いユートピアは、モーゼス・フィンリーが何年も前に指摘したように、ホメーロスの『シェリア』、すなわちフェアクイア人の島で ある。古典時代のコルフ島(現在のコルフ島/ケルキラ島)と同一視されることも多いこの場所は、10年間にわたる嵐に翻弄された放浪の末にオデュッセウス が流れ着き、王女ナウシカアに導かれて王宮に辿り着いた場所である。頑丈な城壁、石造りの神殿、良港を備えたこの理想郷は、おそらくギリシャの植民都市の 「理想型」であり、8世紀半ば以降に建設された植民都市の模範となった。豊かな土地であり、熟練した船乗り(自動操縦の船とともに)や、王の支配下で平和 に暮らし、よそ者を恐れない熟練した職人たちが暮らす土地である。 1世紀のギリシャの歴史家であり伝記作家であるプルタルコスは、人類の幸福で神話的な過去について扱った。 アルカディア フィリップ・シドニー卿の散文ロマンス『古きアルカディア』(1580年)に登場するアルカディアは、もともとペロポネソス半島の一地域であったが、牧歌的な舞台となる田園地帯の代名詞、すなわち「快い場所」となった。 聖書のエデンの園  新しい天と新しい地[39]、モルティエの聖書、フィリップ・メドハースト・コレクション 旧約聖書の創世記2章(1611年の欽定訳)に描かれた聖書のエデンの園: 主なる神は、エデンの園の東に園を設け、そこに、その形に造った人を置かれた。 主なる神は、土地のちりで、見るからに好ましく、食べても良い木をすべて育てるため、地から木を育てるようになされた。 命の木も園の中央に、善悪の知識の木もあった。 主なる神は人を連れて行ってエデンの園に住まわせ、その園を耕させ、またそこを守らせた。 主なる神は人に命じて言われた、「あなたは、園のどの木からでも思いのまま食べてよい。しかし、善悪の知識の木からは取って食べてはならない。それを取っ て食べる日には、あなたは必ず死ぬ」。 主なる神は言われた。「人がひとりでいるのは良くない。」主なる神は、アダムを深い眠りに落とし、眠った時に、彼のあばら骨の一つを取り、その代わりに肉をふさがれた。主なる神が人から取ったあばら骨で、ひとりの女を造り、人のところへ連れて来られた。 聖書神学者ハーバート・ハーグが第二バチカン公会議の直後に出版した著書『聖書における原罪はあるのか?』で提示した解釈によると、創世記2章25節は、 アダムとエバは神の恩寵を最初から受けずに創造されたことを示しており、その恩寵は、彼らが決して持たなかったものであり、 と主張している。[41] 一方、ヘーグは、蛇の誘惑に関する出来事について、超自然的賜物(ラテン語:dona praeternaturalia)の不在に関する聖書の連続性を支持しているが、生命の木へのアクセスを失うという非連続性については一切言及していな い。 コッカイヌの地 コッカイネの地(またはコッカイグネ、コッカイグネ)は、怠惰と贅沢の空想上の地であり、中世の物語で有名であり、いくつかの詩の主題となっている。その うちの1つは、13世紀のフランス作品の初期の翻訳であり、ジョージ・エリスの『初期英国詩人選集』に収録されている。この詩では、「家々は麦芽糖とケー キでできており、通りはペストリーで舗装され、店は無料で品物を供給していた」とある。ロンドンは「コックニー」という名称で呼ばれているが(参照)、ボ ワローは同じことをパリにも適用している。[43] シュララッフェンランドは類似したドイツの伝統である。これらの神話はすべて、楽園のような状態が人類から永遠に失われたわけではなく、何らかの方法で再 び取り戻せるのではないかという希望も表現している。 その一つの方法は、「地上の楽園」を求めることである。それは、ジェームズ・ヒルトンがユートピア小説『失われた地平線』(1933年)で描いた、チベッ トの山中に隠されたシャングリラのような場所である。クリストファー・コロンブスは、15世紀末に新世界とその先住民と初めて遭遇した際に、エデンの園を 発見したと信じていたが、これはまさにこの伝統を踏襲したものである。 桃花源 桃花源(とうかしん)は、中国の詩人陶淵明が書いた散文で、理想郷を描いている。[44][45] 武陵の漁師が川をさかのぼって行くと、美しい桃の花が咲き乱れる林と、花びらで覆われた緑豊かな野原に出くわしたという話である。[46] その美しさに魅了された漁師はさらに川をさかのぼり、 。最初は狭かったが、彼はその通路をくぐり抜け、自然と調和した理想的な生活を送る人々がいる、この世のものとは思えないような理想郷を発見した。 [47] 彼は肥沃な土地、澄んだ池、桑の木、竹林など、あらゆる年齢の人々からなる共同体と整然と並ぶ家々を目にした。[4 7] その人々は、自分たちの祖先が秦の時代の国内紛争のさなかにこの場所に逃げ延び、自分たちもそれ以来一度もそこを離れず、外部の人々と接触したこともない のだと説明した。[48] 彼らは、過去の時代の後の王朝や、当時存在していた晋の王朝のことも聞いたことがなかった。[48] 物語では、その共同体は外界の混乱とは無縁で孤立していた。[48] 完璧なユートピア社会は変化しない、つまり、衰退も改善の必要性もないという意味で、この物語には永遠の感覚が支配的であった。[48] やがて、桃源郷という言葉はユートピアの概念と同義語となった。[49] 大同 大同は伝統的な中国のユートピアである。その主な記述は、中国の古典『礼記』の「礼運」という章に見られる。その後、大同とその理想である「天下は公のもの」という考え方は、康有為などの近代中国の改革者や革命家に影響を与えた。 ケトゥマティ 未来にケトゥマティ王国に弥勒が生まれ変わると、理想郷の時代が始まると言われている。[50] その都市は仏教では、宝石でできた宮殿が立ち並び、カルパヴリクシャの木々が実を結ぶ理想郷として描かれている。その時代には、ジャンブードヴィパの住民 は誰も耕作に従事する必要がなくなり、飢餓はもはや存在しなくなる。[51] |

Modern utopias New Harmony, Indiana, a utopian attempt, depicted as proposed by Robert Owen  Sointula, a Finnish utopian settlement in British Columbia, Canada In the 21st century, discussions around utopia for some authors include post-scarcity economics, late capitalism, and universal basic income; for example, the "human capitalism" utopia envisioned in Utopia for Realists (Rutger Bregman 2016) includes a universal basic income and a 15-hour workweek, along with open borders.[52] Scandinavian nations, which as of 2019 ranked at the top of the World Happiness Report, are sometimes cited as modern utopias, although British author Michael Booth has called that a myth and wrote a 2014 book about the Nordic countries.[53] Economics Main articles: Utopian socialism, Fourierism, Icarians, and Owenism Particularly in the early 19th century, several utopian ideas arose, often in response to the belief that social disruption was created and caused by the development of commercialism and capitalism. These ideas are often grouped in a greater "utopian socialist" movement, due to their shared characteristics. A once common characteristic is an egalitarian distribution of goods, frequently with the total abolition of money. Citizens only do work which they enjoy and which is for the common good, leaving them with ample time for the cultivation of the arts and sciences. One classic example of such a utopia appears in Edward Bellamy's 1888 novel Looking Backward. William Morris depicts another socialist utopia in his 1890 novel News from Nowhere, written partially in response to the top-down (bureaucratic) nature of Bellamy's utopia, which Morris criticized. However, as the socialist movement developed, it moved away from utopianism; Marx in particular became a harsh critic of earlier socialism which he described as "utopian". (For more information, see the History of Socialism article.) In a materialist utopian society, the economy is perfect; there is no inflation and only perfect social and financial equality exists. Edward Gibbon Wakefield's utopian theorizing on systematic colonial settlement policy in the early-19th century also centred on economic considerations, but with a view to preserving class distinctions;[54] Wakefield influenced several colonies founded in New Zealand and Australia in the 1830s, 1840s and 1850s. In 1905, H. G. Wells published A Modern Utopia, which was widely read and admired and provoked much discussion. Also consider Eric Frank Russell's book The Great Explosion (1963), the last section of which details an economic and social utopia. This forms the first mention of the idea of Local Exchange Trading Systems (LETS). During the "Khrushchev Thaw" period,[55] the Soviet writer Ivan Efremov produced the science-fiction utopia Andromeda (1957) in which a major cultural thaw took place: humanity communicates with a galaxy-wide Great Circle and develops its technology and culture within a social framework characterized by vigorous competition between alternative philosophies. The English political philosopher James Harrington (1611–1677), author of the utopian work The Commonwealth of Oceana, published in 1656, inspired English country-party republicanism (1680s to 1740s) and became influential in the design of three American colonies. His theories ultimately contributed to the idealistic principles of the American Founders. The colonies of Carolina (founded in 1670), Pennsylvania (founded in 1681), and Georgia (founded in 1733) were the only three English colonies in America that were planned as utopian societies with an integrated physical, economic and social design. At the heart of the plan for Georgia was a concept of "agrarian equality" in which land was allocated equally and additional land acquisition through purchase or inheritance was prohibited; the plan was an early step toward the yeoman republic later envisioned by Thomas Jefferson.[56][57][58] The communes of the 1960s in the United States often represented an attempt to greatly improve the way humans live together in communities. The back-to-the-land movements and hippies inspired many to try to live in peace and harmony on farms or in remote areas and to set up new types of governance.[59] Communes like Kaliflower, which existed between 1967 and 1973, attempted to live outside of society's norms and to create their own ideal communalist society.[60][61] People all over the world organized and built intentional communities with the hope of developing a better way of living together. Many of these intentional communities are relatively small. Many intentional communities have a population close to 100, with many possibly exceeding this number.[62] While this may seem large, it is pretty small in comparison to the rest of society. From the small populations, it is apparent that people do not prefer this kind of living[citation needed]. While many of these new small communities failed, some continue to grow, such as the religion-based Twelve Tribes, which started in the United States in 1972. Since its inception, it has grown into many groups around the world. Similarly, a commune called Brook Farm established itself in 1841. Founded by Charles Fourier's visions of Utopia, they attempted to recreate his idea of a central building in society called the Phalanx.[63] Unfortunately, this commune could not sustain itself and failed after only six years of operation. They wanted to stay open for longer, but they could not afford it. Their goal, however, was very similar to that of Utopia: to lead a more wholesome and simpler life than the atmosphere of pressure surrounding society at the time.[63] It is clear that despite ambition, it is difficult for communes to stay in operation for very long. Science and technology  Utopian flying machines, France, 1890–1900 (chromolithograph trading card) Though Francis Bacon's New Atlantis is imbued with a scientific spirit, scientific and technological utopias tend to be based in the future, when it is believed that advanced science and technology will allow utopian living standards; for example, the absence of death and suffering; changes in human nature and the human condition. Technology has affected the way humans have lived to such an extent that normal functions, like sleep, eating or even reproduction, have been replaced by artificial means. Other examples include a society where humans have struck a balance with technology and it is merely used to enhance the human living condition (e.g. Star Trek). In place of the static perfection of a utopia, libertarian transhumanists envision an "extropia", an open, evolving society allowing individuals and voluntary groupings to form the institutions and social forms they prefer. Mariah Utsawa presented a theoretical basis for technological utopianism and set out to develop a variety of technologies ranging from maps to designs for cars and houses which might lead to the development of such a utopia. In his book Deep Utopia: Life and Meaning in a Solved World, philosopher Nick Bostrom explores what to do in a "solved world", assuming that human civilization safely builds machine superintelligence and manages to solve its political, coordination and fairness problems. He outlines some technologies considered physically possible at technological maturity, such as cognitive enhancement, reversal of aging, self-replicating spacecrafts, arbitrary sensory inputs (taste, sound...), or the precise control of motivation, mood, well-being and personality.[64] One notable example of a technological and libertarian socialist utopia is Scottish author Iain Banks' Culture. Opposing this optimistic perspective are scenarios where advanced science and technology will, through deliberate misuse or accident, cause environmental damage or even humanity's extinction. Critics, such as Jacques Ellul and Timothy Mitchell advocate precautions against the premature embrace of new technologies. Both raise questions about changing responsibility and freedom brought by division of labour. Authors such as John Zerzan and Derrick Jensen consider that modern technology is progressively depriving humans of their autonomy and advocate the collapse of the industrial civilization, in favor of small-scale organization, as a necessary path to avoid the threat of technology on human freedom and sustainability. There are many examples of techno-dystopias portrayed in mainstream culture, such as the classics Brave New World and Nineteen Eighty-Four, often published as "1984", which have explored some of these topics. Ecological  Ecotopia 1990. Yoga class Ecological utopian society describes new ways in which society should relate to nature. Ecotopia: The Notebooks and Reports of William Weston from 1975 by Ernest Callenbach was one of the first influential ecological utopian novels.[65] Richard Grove's book Green Imperialism: Colonial Expansion, Tropical Island Edens and the Origins of Environmentalism 1600–1860 from 1995 suggested the roots of ecological utopian thinking.[66] Grove's book sees early environmentalism as a result of the impact of utopian tropical islands on European data-driven scientists.[67] The works on ecological eutopia perceive a widening gap between the modern Western way of living that destroys nature[68] and a more traditional way of living before industrialization.[69] Ecological utopias may advocate a society that is more sustainable. According to the Dutch philosopher Marius de Geus, ecological utopias could be inspirational sources for movements involving green politics.[70] Feminism See also: Utopian and dystopian fiction § Feminist utopias Utopias have been used to explore the ramifications of genders being either a societal construct or a biologically "hard-wired" imperative or some mix of the two.[71] Socialist and economic utopias have tended to take the "woman question" seriously and often to offer some form of equality between the sexes as part and parcel of their vision, whether this be by addressing misogyny, reorganizing society along separatist lines, creating a certain kind of androgynous equality that ignores gender or in some other manner. For example, Edward Bellamy's Looking Backward (1887) responded, progressively for his day, to the contemporary women's suffrage and women's rights movements. Bellamy supported these movements by incorporating the equality of women and men into his utopian world's structure, albeit by consigning women to a separate sphere of light industrial activity (due to women's lesser physical strength) and making various exceptions for them in order to make room for (and to praise) motherhood. One of the earlier feminist utopias that imagines complete separatism is Charlotte Perkins Gilman's Herland (1915).[citation needed] In science fiction and technological speculation, gender can be challenged on the biological as well as the social level. Marge Piercy's Woman on the Edge of Time portrays equality between the genders and complete equality in sexuality (regardless of the gender of the lovers). Birth-giving, often felt as the divider that cannot be avoided in discussions of women's rights and roles, has been shifted onto elaborate biological machinery that functions to offer an enriched embryonic experience. When a child is born, it spends most of its time in the children's ward with peers. Three "mothers" per child are the norm and they are chosen in a gender neutral way (men as well as women may become "mothers") on the basis of their experience and ability. Technological advances also make possible the freeing of women from childbearing in Shulamith Firestone's The Dialectic of Sex. The fictional aliens in Mary Gentle's Golden Witchbreed start out as gender-neutral children and do not develop into men and women until puberty and gender has no bearing on social roles. In contrast, Doris Lessing's The Marriages Between Zones Three, Four and Five (1980) suggests that men's and women's values are inherent to the sexes and cannot be changed, making a compromise between them essential. In My Own Utopia (1961) by Elizabeth Mann Borghese, gender exists but is dependent upon age rather than sex – genderless children mature into women, some of whom eventually become men.[71] "William Marston's Wonder Woman comics of the 1940s featured Paradise Island, also known as Themyscira, a matriarchal all-female community of peace, loving submission, bondage and giant space kangaroos."[72] Utopian single-gender worlds or single-sex societies have long been one of the primary ways to explore implications of gender and gender-differences.[73] In speculative fiction, female-only worlds have been imagined to come about by the action of disease that wipes out men, along with the development of technological or mystical method that allow female parthenogenic reproduction. Charlotte Perkins Gilman's 1915 novel approaches this type of separate society. Many feminist utopias pondering separatism were written in the 1970s, as a response to the Lesbian separatist movement;[73][74][75] examples include Joanna Russ's The Female Man and Suzy McKee Charnas's Walk to the End of the World and Motherlines.[75] Utopias imagined by male authors have often included equality between sexes, rather than separation, although as noted Bellamy's strategy includes a certain amount of "separate but equal".[76] The use of female-only worlds allows the exploration of female independence and freedom from patriarchy. The societies may be lesbian, such as Daughters of a Coral Dawn by Katherine V. Forrest or not, and may not be sexual at all – a famous early sexless example being Herland (1915) by Charlotte Perkins Gilman.[74] Charlene Ball writes in Women's Studies Encyclopedia that use of speculative fiction to explore gender roles in future societies has been more common in the United States compared to Europe and elsewhere,[71] although such efforts as Gerd Brantenberg's Egalia's Daughters and Christa Wolf's portrayal of the land of Colchis in her Medea: Voices are certainly as influential and famous as any of the American feminist utopias. Urban Design Walter Elias Disney's original EPCOT (concept) (Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow), Paolo Soleri's Arcosanti, and Saudi Prince Mohammed bin Salman's Neom are examples of Utopian city design. |

現代のユートピア インディアナ州ニューハーモニーは、ロバート・オーウェンが提唱したとされるユートピアの試みである  カナダのブリティッシュコロンビア州にあるフィンランドのユートピア的入植地 21世紀において、一部の著者の描くユートピアに関する議論には、ポスト・サクシティー経済、後期資本主義、ユニバーサル・ベーシック・インカムなどが含 まれる。例えば、『リアリストのためのユートピア』(2016年、Rutger Bregman著)で描かれる「ヒューマン・キャピタリズム」のユートピアには、ユニバーサル・ベーシック・インカムと週15時間労働制、そして国境の開 放が含まれている。 2019年時点で『世界幸福度報告書』で上位にランクインしているスカンディナヴィア諸国は、現代のユートピアとして挙げられることがあるが、イギリスの作家マイケル・ブースはそれを神話と呼び、北欧諸国について2014年に本を書いている。 経済 詳細は「ユートピアン社会主義」、「フーリエ主義」、「イカロス」、および「オーウェニズム」を参照 特に19世紀初頭には、しばしば商業主義や資本主義の発展によって社会が混乱し、それが原因で生じたという信念に呼応するかたちで、いくつかのユートピア 思想が生まれた。これらの思想は、その共通点から、より大きな「ユートピアン社会主義」運動としてまとめられることが多い。かつて一般的であった特徴のひ とつは、貨幣の完全廃止を伴う平等主義的な財の分配である。市民は、自分たちが楽しむことのできる仕事や公益のための仕事のみを行い、芸術や科学の育成に 十分な時間を割く。このようなユートピアの典型的な例としては、エドワード・ベラミーの1888年の小説『後ろ向きに歩く』が挙げられる。ウィリアム・モ リスは、1890年に発表した小説『ニュース・フロム・ノーウェア』で、別の社会主義的ユートピアを描いている。この小説は、ベラミーのユートピアのトッ プダウン型(官僚的)な性質に批判的な部分があり、ベラミーのユートピアへの回答として書かれたものだった。しかし、社会主義運動が発展するにつれ、ユー トピアニズムから離れていった。特にマルクスは、それ以前の社会主義を「ユートピアン」と表現し、厳しく批判した。(詳細は「社会主義の歴史」を参照)唯 物論的社会主義のユートピア社会では、経済は完璧であり、インフレは存在せず、社会と経済の面で完璧な平等が実現している。 19世紀初頭の体系的な植民地入植政策に関するエドワード・ギボン・ウェイクフィールドのユートピア論も経済的考察を中心に据えていたが、階級の区別を維 持する見解であった。[54] ウェイクフィールドは、1830年代、1840年代、1850年代にニュージーランドとオーストラリアに設立された複数の植民地に影響を与えた。 1905年にはH.G.ウェルズが『近代ユートピア』を出版し、広く読まれ賞賛され、多くの議論を巻き起こした。また、エリック・フランク・ラッセルの著 書『大爆発』(1963年)の最後の章では、経済的・社会的ユートピアが詳細に描かれている。これは、地域交換取引システム(LETS)のアイデアが初め て言及されたものである。 フルシチョフの雪解け」の時代に、ソビエトの作家イワン・エフレモフは、主要な文化の雪解けが起こるSFユートピア小説『アンドロメダ』(1957年)を 執筆した。この小説では、人類は銀河全体で大圏航路を使ってコミュニケーションを行い、代替となる哲学間の活発な競争によって特徴づけられる社会的な枠組 みの中で、技術と文化を発展させる。 1656年に発表されたユートピア作品『オシアナの共同体』の著者である英国の政治哲学者ジェームズ・ハリントン(1611年~1677年)は、英国の国 政政党共和主義(1680年代~1740年代)に影響を与え、アメリカの3つの植民地の設計に影響力を及ぼした。彼の理論は最終的に、アメリカ建国者の理 想主義的原則に貢献した。カロライナ植民地(1670年設立)、ペンシルベニア植民地(1681年設立)、ジョージア植民地(1733年設立)は、アメリ カにおける3つのイギリス植民地で、物理的、経済的、社会的統合を目的としたユートピア社会として計画された唯一の植民地であった。ジョージアの計画の中 心には、「農地平等」という概念があった。土地は平等に分配され、購入や相続による追加の土地取得は禁止された。この計画は、後にトーマス・ジェファーソ ンが構想した「農民共和国」への初期段階であった。[56][57][58] 1960年代のアメリカのコミューンは、しばしば人間がコミュニティで共に暮らす方法を大幅に改善しようとする試みを表していた。土地回帰運動やヒッピー は、多くの人々を刺激し、農場や辺境で平和と調和のうちに暮らすことを試みさせ、新しいタイプの統治形態を打ち立てさせた。[59] 1967年から1973年にかけて存在したカリフラワーのような共同体は、社会の規範から離れて独自の理想的な共産主義社会を築こうとした。[60] [61] 世界中の人々が、より良い共同生活のあり方を模索して、意図的なコミュニティを組織し、建設した。これらの意図的なコミュニティの多くは比較的小規模であ る。多くの意図的なコミュニティの人口は100人前後であり、この数字を超えるコミュニティも多い。[62] これは一見すると大規模に見えるが、社会全体から見るとかなり小規模である。人口の少なさから、人々はこのような生活を好んでいないことが明らかである [要出典]。多くの新しい小規模コミュニティは失敗したが、1972年にアメリカで始まった宗教に基づくTwelve Tribesのように、成長を続けているものもある。発足以来、世界中に多くのグループに成長している。同様に、1841年にブルック・ファームと呼ばれ るコミューンが設立された。シャルル・フーリエの理想郷構想を基に設立されたこのコミューンは、社会における中央の建物であるファランクスを再構築しよう とした。[63] 残念ながら、このコミューンは6年間の運営期間を経て、維持できなくなり、失敗に終わった。彼らはより長く存続したかったが、それはできなかった。しか し、彼らの目標はユートピアのそれと非常に似ており、当時の社会を取り巻く重苦しい雰囲気よりも、より健全でシンプルな生活を送ることを目指していた。 [63] 野心はあったものの、共同体が長期間にわたって存続することは困難であることは明らかである。 科学と技術  空想上の飛行機械、フランス、1890年~1900年(石版画のトレーディングカード) フランシス・ベーコンの『ニュー・アトランティス』は科学的要素に満ちているが、科学技術に関するユートピアは、高度な科学技術がユートピア的な生活水 準、すなわち死や苦痛のない生活、人間性や人間の状態の変化を可能にする未来を基盤としている傾向がある。テクノロジーは、人間が生活する方法に多大な影 響を与え、睡眠や食事、さらには生殖といった通常の機能が人工的な手段に置き換えられるようになった。その他の例としては、人間がテクノロジーとバランス を保ち、人間生活の向上のためにテクノロジーが利用されている社会(例えば『スタートレック』)が挙げられる。ユートピアの静的な完璧さの代わりに、リバ タリアン・トランスヒューマニストは「エクストロピア」を構想している。エクストロピアは、個人や任意のグループが、自分たちが望む制度や社会形態を形成 できる、開放的で進化する社会である。 マライア・ウツワは、技術的ユートピア主義の理論的根拠を示し、そのようなユートピアの実現につながる可能性のある、地図から自動車や住宅の設計に至るま で、さまざまな技術の開発に着手した。 著書『ディープ・ユートピア:解決された世界における生命と意味』の中で、哲学者のニック・ボストロムは、人類文明が機械の超知性を安全に構築し、政治、 調整、公平性の問題を解決できたと仮定して、「解決された世界」で何をすべきかを考察している。彼は、技術的成熟の段階で物理的に可能であると考えられる いくつかの技術について概説している。例えば、認知機能の向上、老化の逆行、自己複製宇宙船、任意の感覚入力(味覚、聴覚など)、あるいは動機、気分、幸 福、性格の精密な制御などである。 技術的自由主義的社会主義のユートピアの顕著な例としては、スコットランドの作家イアン・バンクスの『カルチャー』がある。 こうした楽観的な見解に反対するものとしては、高度な科学技術が故意の悪用や事故によって環境破壊や人類の絶滅さえも引き起こすというシナリオがある。 ジャック・エリュールやティモシー・ミッチェルといった批評家は、新しい技術を早急に受け入れることに対する警戒を唱えている。両者とも、分業化によって 生じる責任と自由の変化について疑問を投げかけている。ジョン・ザーザンやデリック・ジェンセンなどの著述家は、現代のテクノロジーが人間から自律性を徐 々に奪っているとみなし、テクノロジーが人間の自由や持続可能性を脅かすのを回避するための必要不可欠な道として、産業文明の崩壊と小規模な組織化を提唱 している。 テクノディストピアの例は、主流文化の中で数多く描かれており、例えば古典の『すばらしい新世界』や『一九八四年』は、しばしば「1984」として出版されているが、これらのトピックの一部を掘り下げている。 エコロジカル  エコトピア 1990年 ヨガクラス エコロジカルなユートピア社会は、社会が自然と関わる新しい方法を描写している。エコトピア:アーネスト・カレンバックによる1975年のウィリアム・ ウェストンのノートとレポートは、影響力のあるエコロジカルなユートピア小説の最初のものである。リチャード・グローブの著書『グリーン・インペリアリズ ム: 1995年の著書『植民地拡大、熱帯の楽園と環境保護主義の起源 1600年~1860年』では、エコロジカルなユートピア思想のルーツを示唆している。[66] グローヴの著書では、初期の環境保護主義は、ユートピア的な熱帯の島が 。エコロジカル・ユートピアに関する作品では、自然を破壊する近代西欧の生活様式[68]と、産業化以前のより伝統的な生活様式[69]との間に広がる ギャップが認識されている。エコロジカル・ユートピアは、より持続可能な社会を提唱している可能性がある。オランダの哲学者マリウス・デ・グースによれ ば、エコロジカル・ユートピアは、環境保護政策を伴う運動のインスピレーションの源となりうるという。 フェミニズム 参照:ユートピアおよびディストピア小説 § フェミニスト・ユートピア ユートピアは、ジェンダーが社会構築物であるか、生物学的に「生得的な」必然であるか、あるいはその両方の混合であるか、といった問題を探究するために用 いられてきた。[71] 社会主義的および経済的なユートピアは、「女性問題」を真剣に受け止め、 女性嫌悪への対処、分離主義に沿った社会の再編、ジェンダーを無視したある種の男女両性具有的な平等、あるいはその他の方法など、そのビジョンには、ジェ ンダー間の平等を何らかの形で提供することがしばしば含まれていた。例えば、エドワード・ベラミーの『後ろ向きに振り返って』(1887年)は、当時の時 代としては先進的な内容で、当時の女性参政権や女性権利運動に呼応していた。ベラミーは、女性と男性の平等を彼の理想郷の構造に組み込むことで、これらの 運動を支持した。ただし、女性を軽工業活動という別の領域に閉じ込め(女性の体力が劣っているため)、母性を尊重し賞賛するために、女性に対してさまざま な例外を設けた。完全な分離主義を想定した初期のフェミニストのユートピアのひとつに、シャーロット・パーキンス・ギルマンの『ヘールランド』(1915 年)がある。 SFや科学技術の推測においては、ジェンダーは生物学的なレベルだけでなく、社会的なレベルでも問われる。マーガレット・ピアシーの『時の果ての女』で は、男女間の平等と、性別に関係なく性的な面でも完全な平等が描かれている。出産は、女性の権利や役割を論じる際に避けては通れない問題であると捉えられ ることが多いが、この作品では、出産は精巧な生物学的機械に委ねられ、より豊かな胎児体験を提供するという機能を持つものへと変化している。子供が生まれ ると、そのほとんどの時間を同年代の子供たちとともに小児病棟で過ごす。子供一人につき3人の「母親」が付き添うのが普通であり、性別に関係なく経験と能 力に基づいて選ばれる(「母親」には男性もなる)。技術の進歩により、シュラミス・ファイアストーンの『性の弁証法』で描かれたように、女性が出産から解 放されることも可能になった。メアリー・ジェントル(Mary Gentle)の『ゴールデン・ウィッチブリード』(Golden Witchbreed)に登場する架空の宇宙人は、性別を問わない子供として生まれ、思春期を迎えるまで男女に成長せず、社会的役割も性別とは関係がな い。これに対し、ドリス・レッシング(Doris Lessing)の『ゾーン3、4、5の間の結婚』(The Marriages Between Zones Three, Four and Five)(1980年)では、男女の価値観は性別に内在し、変えることはできないため、両者の妥協が不可欠であると示唆している。エリザベス・マン・ボ ルゲセの『マイ・オウン・ユートピア』(1961年)では、性別は存在するが、それは性別よりも年齢に依存している。性別のない子供は女性へと成長し、そ の中には最終的に男性になる者もいる。[71] 「ウィリアム・マーストンの 1940年代のウィリアム・マーストンの『ワンダーウーマン』のコミックでは、パラダイス・アイランド(別名テミスキュラ)が描かれている。そこは平和 で、愛に満ちた服従、緊縛、そして巨大な宇宙カンガルーのいる、母系制の女性だけの共同体である。」[72] 理想郷のような単一性の世界や単一性の社会は、ジェンダーやジェンダーの違いが持つ意味を探究する主要な方法のひとつとして長い間存在してきた。[73] 空想科学小説では、女性のみの世界は、男性を根絶する病気の作用によって、あるいは女性が単為生殖を行うことを可能にする技術的または神秘的な方法の発展 によってもたらされると想像されてきた。シャーロット・パーキンス・ギルマンの1915年の小説は、この種の分離社会にアプローチしている。分離主義を考 察した多くのフェミニストのユートピアは、レズビアン分離主義運動への反応として1970年代に書かれた。[73][74][75] 例としては、ジョアンナ・ラス(Joanna Russ)の『The Female Man』やスージー・マッキー・チャナス(Suzy McKee Charnas)の『Walk to the End of the World』や『 男性作家によるユートピアは、男女の分離ではなく、男女平等を想定していることが多いが、ベラミーの戦略には「分離しても平等」という考え方が含まれてい る。[76] 女性だけの世界を描くことで、家父長制からの女性の独立と自由を探究することができる。その社会は、キャサリン・V・フォレストの『サンゴの夜明けの娘た ち』のようにレズビアン社会である場合もあれば、そうでない場合もあり、性的な要素が全くない場合もある。初期の無性の作品として有名なのはシャーロッ ト・パーキンス・ギルマンの『ヘラルド』(1915年)である。シャーリーン・ボールは『女性学事典』の中で、 未来社会におけるジェンダーの役割を探求する思索的なフィクションの使用は、ヨーロッパやその他の地域と比較して、アメリカ合衆国ではより一般的であると 述べている。[71] ゲルド・ブラントンバーグの『エガリアの娘たち』や、クリスタ・ウォルフが『メデア:声』で描いたコルキス国の描写などは、確かにアメリカにおけるフェミ ニストのユートピア小説と同様に影響力があり、有名である。 都市設計 ウォルター・エリアス・ディズニーのオリジナルEPCOT(コンセプト)(Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow)、パオロ・ソレリのアルコサンティ、サウジアラビアのムハンマド・ビン・サルマン王子のネオムは、ユートピア都市設計の例である。 |

| Critical Utopia Critical utopia is a theory conceptualised by literary theorist Tom Moylan.[77] In contrast with utopianism, critical utopia rejects utopia. The idea is highly self-referential and uses the idea of utopia to advance society while critiquing it simultaneously. A problem with utopianism is identified: it has limitations since the imagined utopia is significantly distant from current society. Utopia also fails to acknowledge the differences between people that result in differences in experience.[77] Moylan explains that "[critical utopias] ultimately refer to something other than a predictable alternative paradigm, for at their core they identify self-critical utopian discourse itself as a process that can tear apart the dominant ideological web. Here, then, critical utopian discourse becomes a seditious expression of social change and popular sovereignty carried on in a permanently open process of envisioning what is not yet."[78] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Utopia |

批判的ユートピア 批判的ユートピアは、文学理論家トム・モイランが概念化した理論である。[77] ユートピアニズムとは対照的に、批判的ユートピアはユートピアを否定する。その考え方はきわめて自己言及的であり、ユートピアの考え方を用いて社会を発展 させながら、同時にそれを批判する。ユートピアニズムの問題点が指摘されている。想像上のユートピアは現在の社会から著しくかけ離れているため、限界があ る。また、ユートピアは、人々の経験の違いを生み出す人々の間の相違を認識できないという欠点もある。[77] モイランは、「批判的ユートピアは、究極的には、予測可能な代替パラダイム以外の何かに言及する。なぜなら、その核心において、自己批判的なユートピア的 言説自体を、支配的なイデオロギーの網を切り裂くことのできるプロセスとして特定しているからだ。したがって、批判的ユートピア論は、社会変革と人民主権 の反逆的な表現となり、まだ見ぬものを構想する永遠に開かれたプロセスの中で継続されるのである」[78]。 |

| List of utopian literature New world order (Bahá'í) Nutopia Utopia (disambiguation) Utopia for Realists Utopian and dystopian fiction |

ユートピア文学の一覧 新世界秩序(バハーイ) ヌートピア ユートピア(曖昧さ回避) 現実主義者のためのユートピア ユートピアとディストピア小説 |

| This

is a list of utopian literature. A utopia is a community or society

possessing highly desirable or perfect qualities. It is a common

literary theme, especially in speculative fiction and science fiction. Pre-16th century The word "utopia" was coined in Greek language by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book Utopia, but the genre has roots dating back to antiquity. Assemblywomen (391 BC) by Aristophanes - Early piece of utopian satire. Aristophanes's play mocks Athenian democracy's excesses through the story of the Athenian women taking control of the government and instituting a proto-communist utopia.[1] The Republic (ca. 370-360 BC) a Socratic dialogue by Plato which eventually arrives at a thought experiment of Kallipolis, the "Beautiful City" - One of the earliest conceptions of a utopia.[2][3] Laws (360 BC) by Plato[4] The Republic (ca. 300 BC) by Zeno of Citium, an ideal society based on the principles of Stoicism. Sacred History (ca. 300 BC) by Euhemerus – Describes the rational island paradise of Panchaea[5] Islands of the Sun (ca. 165–50 BC) by Iambulus – Utopian novel describing the features and inhabitants of the title Islands[6] Life of Lycurgus (ca. 100 CE) by Plutarch[3] The Peach Blossom Spring (Tao Hua Yuan) (421 CE) by Tao Yuanming[7] The Virtuous City (Al-Madina al-Fadila) by Al-Farabi (874–950) – A story of Medina as an ideal society ruled by Muhammad[8] The Book of the City of Ladies (1404) by Christine de Pizan – the earliest European work on women's history by a woman,[9] and about a utopian city constructed exclusively by women's histories. 16th–17th centuries Utopia (1516) by Thomas More[3][10] which coined the modern term, referring to a "Nowhere Place". Wolfaria (1521) by Johann Eberlin von Günzburg – a Lutheran utopia which levied harsh punishments on sinners[11] La Città felice (1553) by Francesco Patrizi[12] A Work touching the Good Ordering of a Common Weal (1559) by Joannes Ferrarius Montanus[11] Siuqila: Too Good to be True (1580) by Thomas Lupton[13] Repubblica immaginaria (1580s) by Ludovico Agostini The City of the Sun (later published as Civitas solis) (1602) by Tommaso Campanella[13] Il Belluzzi, o vero della citta felice (1615) by Lodovico Zuccolo[13] Histoire du grand et admirable royaume d'Antangil (1616) attributed to Jean de Moncy – detailed description of the ordering of the island of Antangil, with a classical republic and multiple checks on power[11][14] Christianopolis (Reipublicae Christianopolitanae descriptio) (1619) by Johann Valentin Andreae[3][13] The City of the Sun (1623) by Tommaso Campanella – Depicts a theocratic and egalitarian society.[3] La Repubblica d'Evandria (1625) by Lodovico Zuccolo[13] New Atlantis (1627) by Sir Francis Bacon[13][15] The Man in the Moone (1638) by Francis Godwin[3][13] A Description of the Famous Kingdom of Macaria (1641) by Samuel Hartlib[3] Marcaria (1641) by Gabriel Plattes[13] Nova Solyma (1648) by Samuel Gott[3] The Law of Freedom in a Platform (1652) by Gerrard Winstanley – a radical communist vision of an ideal state[3][13] Gargantua and Pantagruel (ca. 1653–1694) by François Rabelais[3][13] The Commonwealth of Oceana (1656) by James Harrington – a constitutionalist utopian republic in which a balanced allocation of land ensured a balanced government[3][13] Comical History of the States and Empires of the Moon (Histoire Comique Contenant les Etats et Empires de la Lune) (1657) by Cyrano de Bergerac[3] The Blazing World (1666) by Margaret Cavendish – Describes a utopian society in a story mixing science-fiction, adventure, and autobiography.[3] The Isle of Pines (1668) by Henry Neville – Five people are shipwrecked on an idyllic island in the Southern Hemisphere.[16] The History of the Sevarites or Sevarambi (1675) by Denis Vairasse[3] The Southern Land Known (La Terre Australe connue) (1676) by Gabriel de Foigny[3] Sinapia (1682)[11][17] The Adventures of Telemachus (1699) by Francois de Salignac de la Mothe Fenelon[3] 18th century Robinson Crusoe (1719) by Daniel Defoe[3][18] Gulliver's Travels (1726) by Jonathan Swift[3] The Adventures of Sig. Gaudentio di Lucca (1737) by Simon Berington[3] The Life and Adventures of Peter Wilkins (1751) by Robert Paltock[3] A General Idea of the College of Mirania (1753) by William Smith – Describes a Eutopian educational system. This is the earliest known utopia published in the United States.[19] A Vindication of Natural Society (1756) by Edmund Burke[3] Candide, ou l'Optimisme (1759) by Voltaire Rasselas (1759) by Samuel Johnson[3] Millenium Hall (1762) by Sarah Scott[3] An Account of the First Settlement ... of the Cessares (1764) by James Burgh[3] Memoirs of the Year Two Thousand Five Hundred (original title: L'An 2440, rêve s'il en fut jamais, which translates literally to The Year 2440: A Dream If Ever There Was One) (1771) by Louis-Sébastien Mercier[3] Supplément au voyage de Bougainville (1772) by Denis Diderot – A set of philosophical dialogues written by Denis Diderot, inspired by Louis Antoine de Bougainville's Voyage autour du monde. Diderot presents Bougainville's descriptions of Tahiti as a utopia, standing in contrast to European culture.[20] The Adventures of Mr. Nicholas Wisdom (original title: Mikołaja Doświadczyńskiego przypadki) (1776) by Ignacy Krasicki[21] Enquiry Concerning Political Justice (1793) by William Godwin[3] Description of Spensonia (1795) by Thomas Spence[3] 19th century Theory of the Four Movements (1808) by Charles Fourier[3] The Empire of the Nairs (1811) by James Henry Lawrence[3] The Voyage to Icaria (1842) by Étienne Cabet – Inspired the Icarian movement[22][23] Sibling Life or Brothers and Sisters (Swedish: Syskonlif; 1848) by Fredrika Bremer[24] Hunt, John Hale (1862). The Honest Man's Book of Finance and Politics: Showing the Cause and Cure of Artificial Poverty, Dearth of Employment, and Dullness of Trade. New York City: John Windt.Open access icon[25] Vril, the Power of the Coming Race (1871) by Edward Bulwer-Lytton is an utopian novel with a superior subterranean cooperative society.[3] Erewhon (1872) by Samuel Butler – Satirical utopian novel with dystopian elements set in the Southern Alps, New Zealand.[citation needed] Mizora, (1880–81) by Mary E. Bradley Lane[citation needed] A Crystal Age, by W.H. Hudson (1906 edition cover) A Crystal Age (1887), by W.H. Hudson – An amateur ornithologist and botanist falls down a crevice, and wakes up centuries later, in a world where humans live in families, in harmony with each other and animals; but, where reproduction, emotions, and secondary sexual characteristics are repressed, except for the Alpha males and females.[26] Looking Backward (1888) by Edward Bellamy[27] Freeland (1890) by Theodor Hertzka Gloriana, or the Revolution of 1900 (1890) by Lady Florence Dixie – The female protagonist poses as a man, Hector l'Estrange, is elected to the House of Commons, and wins women the vote. The book ends in the year 1999, with a description of a prosperous and peaceful Britain governed by women.[28] News from Nowhere (1892) by William Morris – "Nowhere" is a place without politics, a future society based on common ownership and democratic control of the means of production.[29][citation needed] 2894, or The Fossil Man (A Midwinter Night's Dream) (1894) by Walter Browne A Traveler from Altruria (1894) by William Dean Howells Equality (1897) by Edward Bellamy The Future State: Production and Consumption in the Socialist State. (Der Zukunftsstaat: Produktion und Konsum im Sozialstaat.) (1898) by Kārlis Balodis – he adopted the pseudonym Ballod-Atlanticus from Bacon's book Nova Atlantis (1627) The God of Civilization: A Romance (1890) by Minnie A. Weeks Pittock 20th-21st centuries NEQUA or The Problem of the Ages by Jack Adams – A feminist utopian science fiction novel printed in Topeka, Kansas in 1900. Sultana's Dream (1905) by Begum Rokeya – A Bengali feminist Utopian story about Lady-Land. A Modern Utopia (1905) by H. G. Wells – An imaginary, progressive utopia on a planetary scale in which the social and technological environment are in continuous improvement, a world state owns all land and power sources, positive compulsion and physical labor have been all but eliminated, general freedom is assured, and an open, voluntary order of "samurai" rules.[30] Beatrice the Sixteenth by Irene Clyde – A time traveller discovers a lost world, which is an egalitarian utopian postgender society.[31] Red Star (novel) (1908) Red Star (Russian: Красная звезда) is Alexander Bogdanov's 1908 science fiction novel about a communist society on Mars. The first edition was published in St. Petersburg in 1908, before eventually being republished in Moscow and Petrograd in 1918, and then again in Moscow in 1922. The Millennium: A Comedy of the Year 2000 by Upton Sinclair. A novel in which capitalism finds its zenith with the construction of The Pleasure Palace. During the grand opening of this, an explosion kills everybody in the world except eleven of the people at the Pleasure Palace. The survivors struggle to rebuild their lives by creating a capitalistic society. After that fails, they create a successful utopian society "The Cooperative Commonwealth," and live happily forever after.[32] Herland (1915) by Charlotte Perkins Gilman – An isolated society of women who reproduce asexually has established an ideal state that reveres education and is free of war and domination. The New Moon: A Romance of Reconstruction (1918) by Oliver Onions[33] The Islands of Wisdom (1922) by Alexander Moszkowski – In the novel various utopian and dystopian islands that embody social-political ideas of European philosophy are explored. The philosophies are taken to their extremes for their absurdities when they are put into practice. It also features an "island of technology" which anticipates mobile telephones, nuclear energy, a concentrated brief-language that saves discussion time and a thorough mechanization of life. Men Like Gods (1923) by H. G. Wells – Men and women in an alternative universe without world government in a perfected state of anarchy ("Our education is our government," a Utopian named Lion says;[34]) sectarian religion, like politics, has died away, and advanced scientific research flourishes; life is governed by "the Five Principles of Liberty," which are privacy, freedom of movement, unlimited knowledge, truthfulness, and freedom of discussion and criticism.[citation needed] Lost Horizon (1933) by James Hilton - The mythical community of Shangri-La For Us, The Living: A Comedy of Customs (1938, published in 2003) by Robert A. Heinlein – A futuristic utopian novel explaining practical views on love, freedom, drive, government and economics.[citation needed] Islandia (1942) by Austin Tappan Wright – An imaginary island in the Southern Hemisphere, a utopia containing many Arcadian elements, including a policy of isolation from the outside world and a rejection of industrialism.[citation needed] Walden Two (1948) by B. F. Skinner – A community in which every aspect of living is put to rigorous scientific testing. A professor and his colleagues question the effectiveness of the community started by an eccentric man named T.E. Frazier.[citation needed] The Noon Universe (1961-1985). The Strugatsky Brothers have been argued to have created their own utopian ideology based on the primacy of science.[35] Ther series starts as a "socialist utopia" in which the humanity has survived its crises but still has problems to solve, and in which the conflict is between "the good and the better."[36] In the later books this utopia gets gradually deconstructed.[37] Island (1962) by Aldous Huxley – Follows the story of Will Farnaby, a cynical journalist, who shipwrecks on the fictional island of Pala and experiences their unique culture and traditions which create a utopian society.[citation needed] Eutopia (1967) by Poul Anderson The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia (1974) by Ursula K. Le Guin - Is set between a pair of planets: one that like Earth today is dominated by private property, nation states, gender hierarchy, and war, and the other an anarchist society without private property. Ecotopia: The Notebooks and Reports of William Weston (1975) by Ernest Callenbach – Ecological utopia in which the Pacific Northwest has seceded from the union to set up a new society.[38] Woman on the Edge of Time (1976) by Marge Piercy – The story of a middle-aged Hispanic woman who has visions of two alternative futures, one utopian and the other dystopian.[39] The Probability Broach (1980) by L. Neil Smith – A libertarian or anarchic utopia[40] Voyage from Yesteryear (1982) by James P. Hogan – A post-scarcity economy where money and material possessions are meaningless.[41] Bolo'Bolo (1983) by Hans Widmer published under his pseudonym P.M. – An anarchist utopian world organised in communities of around 500 people Always Coming Home (1985) by Ursula K. Le Guin – A combination of fiction and fictional anthropology about a society in California in the distant future.[citation needed] Pacific Edge (1990) by Kim Stanley Robinson – Set in El Modena, California in 2065, the story describes a transformation process from the late twentieth century to an ecologically sane future.[42] The Fifth Sacred Thing (1993) by Starhawk – A post-apocalyptic novel depicting two societies, one a sustainable economy based on social justice, and its neighbor, a militaristic and intolerant theocracy.[citation needed] The Giver (1993) by Lois Lowry – Story set in a society which at first appears to be a utopia free of violence and severe forms of hate but actually turns out to be a dystopia with features such as euthanasia of the old and young. 3001: The Final Odyssey (1997) by Arthur C. Clarke – Describes human society in 3001 as seen by an astronaut who was frozen for a thousand years. Aria (2001–2008) by Kozue Amano – A manga and anime series set on terraformed version of the planet Mars in the 24th century. The main character, Akari, is a trainee gondolier working in the city of Neo-Venezia, based on modern-day Venice.[citation needed] Manna (2003) by Marshall Brain – Essay that explores several issues in modern information technology and user interfaces, including some around transhumanism. Some of its predictions, like the proliferation of automation and AI in the fast food industry, are becoming true years later. Second half of the book describes perfect Utopian society.[43] Uniorder: Build Yourself Paradise (2014), by Joe Oliver. Essay on how to build the Utopia of Thomas More by using computers.[44] The Culture series by Iain M. Banks – A science fiction series released from 1987 through 2012. The stories centre on The Culture, a utopian, post-scarcity space society of humanoid aliens, and advanced superintelligent artificial intelligences living in artificial habitats. The main theme is of the dilemmas that an idealistic, more-advanced civilization faces in dealing with smaller, less-advanced civilizations that do not share its ideals, and whose behaviour it sometimes finds barbaric. In some of the stories action takes place mainly in non-Culture environments, and the leading characters are often on the fringes of (or non-members of) the Culture. Terra Ignota by Ada Palmer – A science fiction series released from 2016 to 2021 drawing from renaissance humanism, the enlightenment, and the rationalist movement. Takes place in the year 2454, when the nation-state system has given way to a system of globe-spanning voluntary cultural collectives known as hives, each with their own set of laws and values. |