バリャドリド論争

The Valladolid debate,

1550-1551

☆ バリャドリッド論争(1550-1551年、スペイン語ではLa Junta de ValladolidまたはLa Controversia de Valladolid)は、ヨーロッパの植民者による先住民の権利と処遇について議論した、ヨーロッパ史上初の道徳的論争である。スペインの都市バリャド リッドにあるサン・グレゴリオ大学で開催されたこの討論会は、アメリカ大陸の征服、カトリックへの改宗の正当性、そしてより具体的にはヨーロッパ人入植者 と新大陸の先住民との関係についての道徳的、神学的な討論会であった。それは、原住民がスペイン社会に溶け込む方法、カトリックへの改宗、彼らの権利に関 する多くの反対意見から成っていた。 論争の的となった神学者、ドミニコ会修道士でチアパス司教のバルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスは、アメリカ先住民は人身御供などの習慣があるにもかかわらず、 自然の摂理にかなった自由人であり、植民者と同じ配慮に値すると主張した。 この見解に反対したのは、人文主義者の学者フアン・ヒネス・デ・セプルベダを含む多くの学者や司祭であり、彼らは罪のない人々の人身御供や人肉食、その他 のそのような「自然に対する罪」は容認できず、戦争を含む可能なあらゆる手段によって抑圧されるべきであると主張した。 両者は論争に勝利したと主張したが、どちらの解釈を裏付ける明確な記録はない。この事件は、植民地主義、植民地化された人々の人権、国際関係に関する道徳 的議論の最も初期の例のひとつと考えられている。スペインでは、物議を醸したものの、ラス・カサスをインディオ擁護の第一人者として確立させる役割を果た した。ラス・カサスと他の人々は、エンコミエンダ制度をさらに制限する1542年の新法の成立に貢献した。状況を完全に覆すことはできなかったものの、こ の法律はアメリカ大陸の先住民の扱いにおいてかなりの改善を達成し、それ以前の法律によって認められていた彼らの権利を強化した。

| The Valladolid

debate (1550–1551 in Spanish La Junta de Valladolid or La Controversia

de Valladolid) was the first moral debate in European history to

discuss the rights and treatment of Indigenous people by European

colonizers. Held in the Colegio de San Gregorio, in the Spanish city of

Valladolid, it was a moral and theological debate about the conquest of

the Americas, its justification for the conversion to Catholicism, and

more specifically about the relations between the European settlers and

the natives of the New World. It consisted of a number of opposing

views about the way natives were to be integrated into Spanish society,

their conversion to Catholicism, and their rights. A controversial theologian, Dominican friar and Bishop of Chiapas Bartolomé de las Casas, argued that the Native Americans were free men in the natural order despite their practice of human sacrifices and other such customs, deserving the same consideration as the colonizers.[1] Opposing this view were a number of scholars and priests, including humanist scholar Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda, who argued that the human sacrifice of innocents, cannibalism, and other such "crimes against nature" were unacceptable and should be suppressed by any means possible, including war.[2] Although both sides claimed to have won the disputation, there is no clear record supporting either interpretation. The affair is considered one of the earliest examples of moral debates about colonialism, human rights of colonized peoples, and international relations. In Spain, it served to establish Las Casas as the primary, though controversial defender of the Indians.[3] He and others had contributed to the passing of the New Laws of 1542, which limited the encomienda system further.[4] Though they did not fully reverse the situation, the laws achieved considerable improvement in the treatment of Indigenous people in the Americas and consolidated their rights granted by earlier laws.[4] |

バリャドリッド論争(1550-1551年、スペイン語ではLa

Junta de ValladolidまたはLa Controversia de

Valladolid)は、ヨーロッパの植民者による先住民の権利と処遇について議論した、ヨーロッパ史上初の道徳的論争である。スペインの都市バリャド

リッドにあるサン・グレゴリオ大学で開催されたこの討論会は、アメリカ大陸の征服、カトリックへの改宗の正当性、そしてより具体的にはヨーロッパ人入植者

と新大陸の先住民との関係についての道徳的、神学的な討論会であった。それは、原住民がスペイン社会に溶け込む方法、カトリックへの改宗、彼らの権利に関

する多くの反対意見から成っていた。 論争の的となった神学者、ドミニコ会修道士でチアパス司教のバルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスは、アメリカ先住民は人身御供などの習慣があるにもかかわらず、 自然の摂理にかなった自由人であり、植民者と同じ配慮に値すると主張した。 [1]この見解に反対したのは、人文主義者の学者フアン・ジネス・デ・セプルベダを含む多くの学者や司祭であり、彼らは罪のない人々の人身御供や人肉食、 その他のそのような「自然に対する罪」は容認できず、戦争を含む可能なあらゆる手段によって抑圧されるべきであると主張した[2]。 両者は論争に勝利したと主張したが、どちらの解釈を裏付ける明確な記録はない。この事件は、植民地主義、植民地化された人々の人権、国際関係に関する道徳 的議論の最も初期の例のひとつと考えられている。スペインでは、物議を醸したものの、ラス・カサスをインディオ擁護の第一人者として確立させる役割を果た した[3]。ラス・カサスと他の人々は、アンコミエンダ制度をさらに制限する1542年の新法の成立に貢献した[4]。状況を完全に覆すことはできなかっ たものの、この法律はアメリカ大陸の先住民の扱いにおいてかなりの改善を達成し、それ以前の法律によって認められていた彼らの権利を強化した[4]。 |

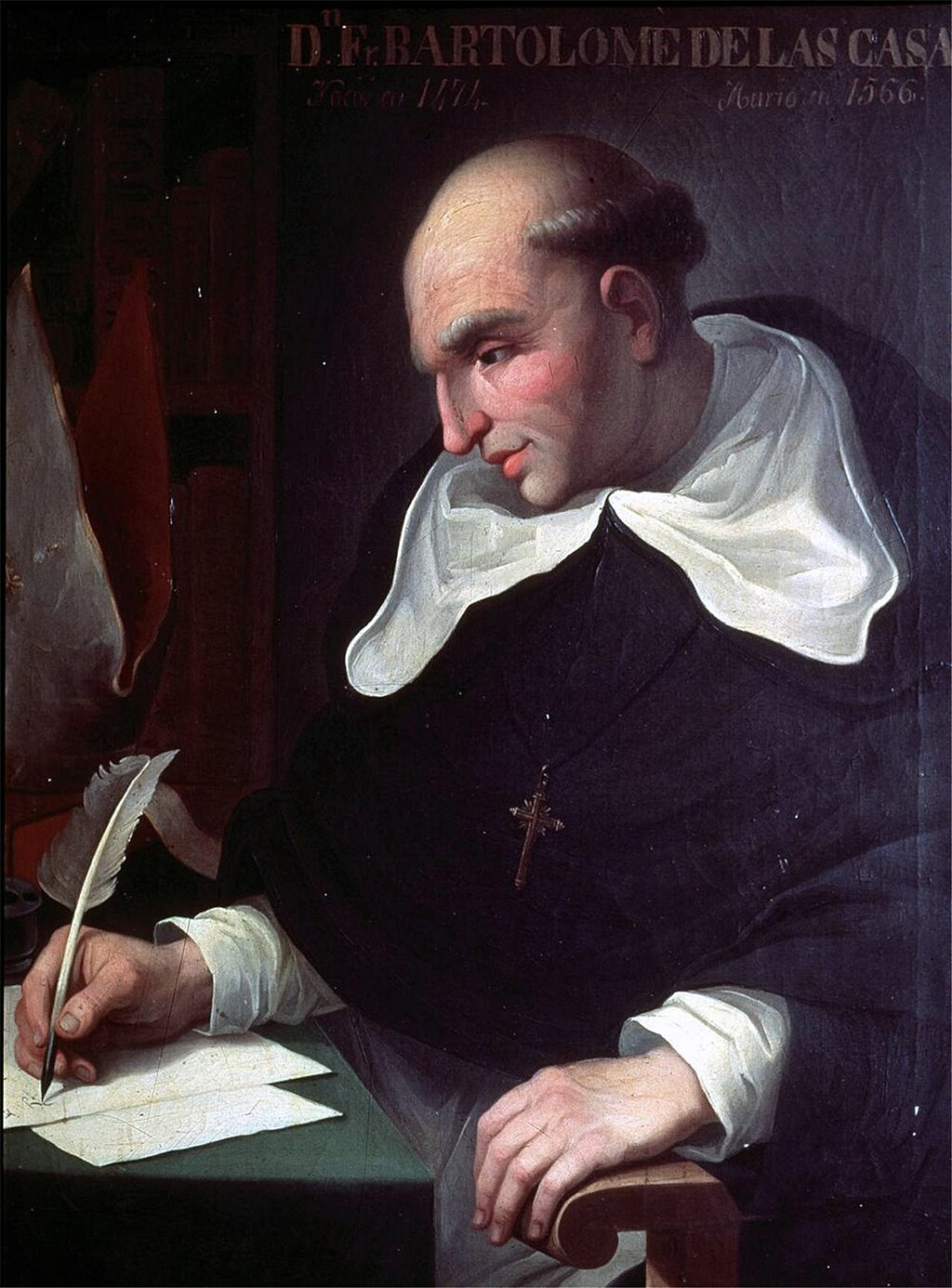

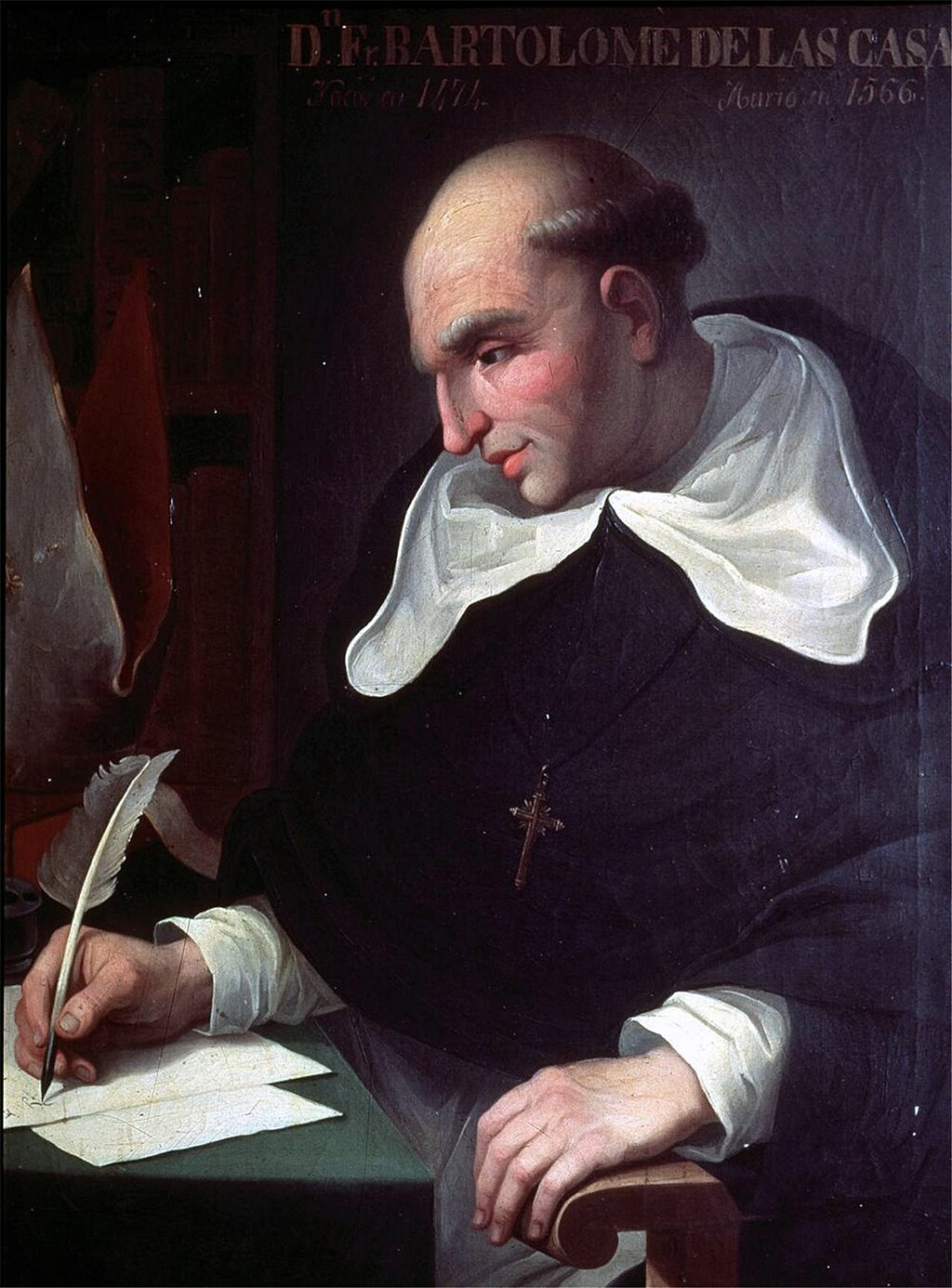

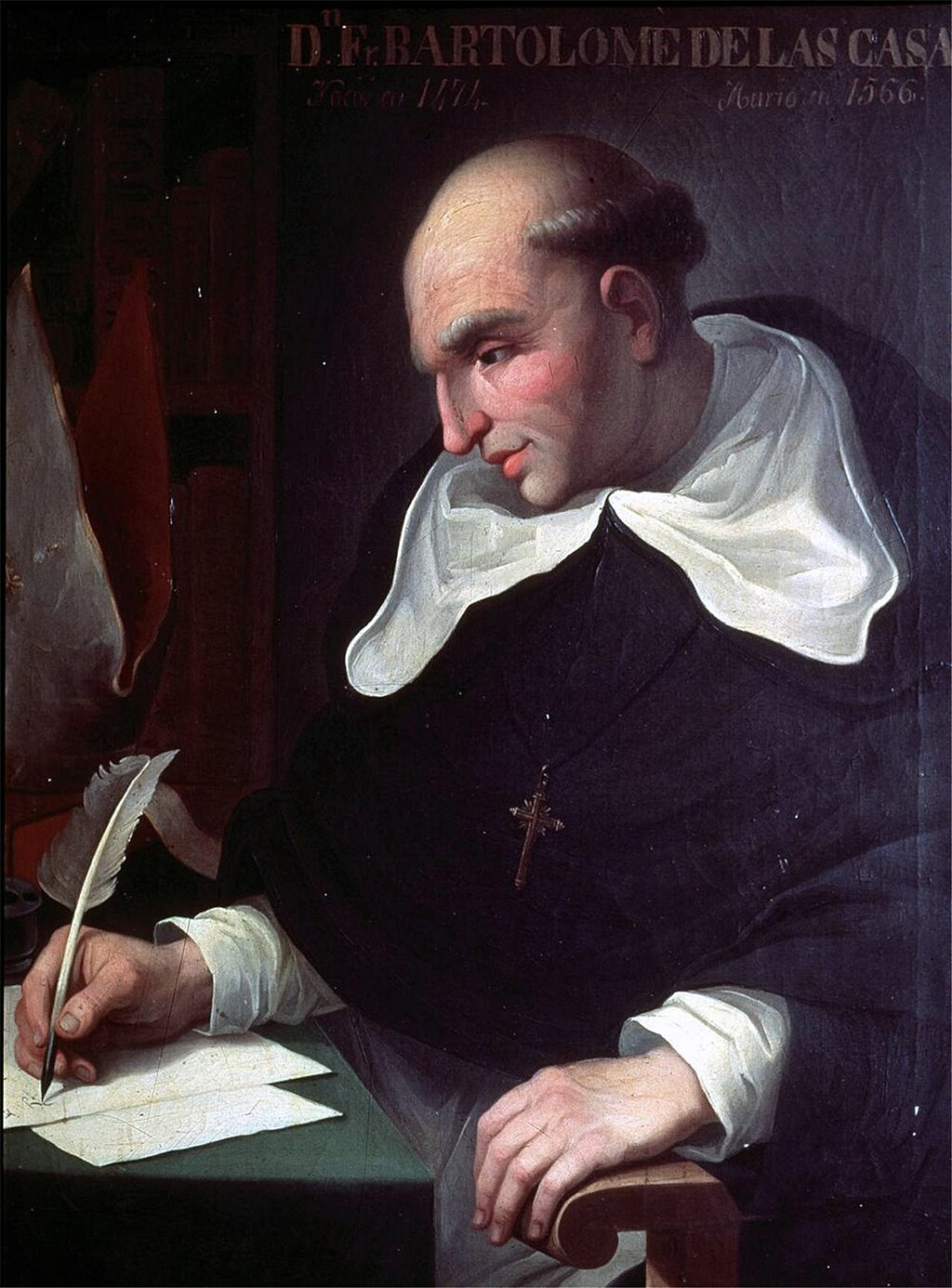

Background Bartolomé de las Casas was the principal defender of the Indians in the Junta of Valladolid Spain's colonization and conquest of the Americas inspired an intellectual debate especially regarding the compulsory Christianization of the Indians. Bartolomé de las Casas, a Dominican friar from the School of Salamanca and member of the growing Christian Humanist movement, worked for years to oppose forced conversions and to expose the treatment of Indigenous people in the encomiendas.[3] His efforts influenced the papal bull Sublimis Deus of 1537 which established the status of the Indigenous people as rational beings. More significantly, Las Casas was instrumental in the passage of the New Laws (the Laws of the Indies) of 1542, which were designed to end the encomienda system.[4] Moved by Las Casas and others, in 1550 the king of Spain Charles I ordered further military expansion to cease until the issue was investigated.[4][5] The king assembled a Junta (Jury) of eminent doctors and theologians to hear both sides and to issue a ruling on the controversy.[1] Las Casas represented one side of the debate. His position found some support from the monarchy, which wanted to control the power of the encomienderos. Representing the other side was Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda, whose arguments were used as support by colonists and landowners who benefited from the system.[6][4] |

背景 バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスは、バリャドリッド憲章におけるインディオの主要な擁護者であった。 スペインによるアメリカ大陸の植民地化と征服は、特にインディオの強制的なキリスト教化に関する知的論争を引き起こした。サラマンカ学派のドミニコ会修道 士であり、成長しつつあったキリスト教ヒューマニズム運動のメンバーであったバルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスは、強制改宗に反対し、エンコミエンダにおける 先住民の扱いを暴露するために長年活動した[3]。さらに重要なことに、ラス・カサスはアンコミエンダ制度を廃止することを目的とした1542年の新法 (インド法)の成立に尽力した[4]。 ラス・カサスらによって動かされたスペイン王シャルル1世は、1550年、この問題が調査されるまでさらなる軍備拡張を停止するよう命じた[4][5]。 彼の立場は、エンコミエンダロの権力をコントロールしたい王政側からも一定の支持を得た。もう一方を代表したのはフアン・ヒネス・デ・セプルベダで、彼の 主張は、この制度から利益を得ていた入植者や地主たちの支持を得た[6][4]。 |

Debate Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda, supporter of the war "jousts" against the Indigenous people Though Las Casas tried to bolster his position by recounting his experiences with the encomienda system's mistreatment of the Indigenous people, the debate remained on largely theoretical grounds. Sepúlveda took a more secular approach than Las Casas, basing his arguments largely on Aristotle and the Humanist tradition to assert that some Indigenous people were subject to enslavement due to their inability to govern themselves, and could be subdued by war if necessary.[1] Las Casas objected, arguing that Aristotle's definition of the barbarian and natural slave did not apply to Indigenous peoples, all of whom were fully capable of reason and should be brought to Christianity without force or coercion.[4] Sepúlveda put forward many of the arguments from his Latin dialogue Democrates Alter Sive de Justi Belli Causis,[7] to assert that what he saw as the barbaric traditions of certain Indigenous peoples justified waging war against them. Civilized peoples, according to Sepúlveda, were obliged to punish such vicious practices as idolatry, sodomy, and cannibalism. Wars had to be waged "in order to uproot crimes that offend nature".[8] Sepúlveda issued four main justifications for just war against certain Indigenous peoples. First, that their natural condition deemed them unable to rule themselves, and it was the responsibility of the Spaniards to act as masters. Second, that Spaniards were entitled to prevent cannibalism as a crime against nature. Third, that the same went for human sacrifice. Fourth, that it was important to convert Indigenous people to Christianity.[9]  Codex Magliabechiano showing in the same drawing the kind of arguments used by both sides, advanced architecture versus brutal killings Las Casas was prepared for part of his opponent's discourse, since he, upon hearing about the existence of Sepúlveda's Democrates Alter, had written in the late 1540s his own Latin work, the Apologia, which aimed at debunking his opponent's theological arguments by arguing that Aristotle's definition of the "barbarian" and the natural slave did not apply to Indigenous people, who were fully capable of reason and should be brought to Christianity without force.[10][11] Las Casas pointed out that every individual was obliged by international law to prevent the innocent from being treated unjustly. He also cited Saint Augustine and Saint John Chrysostom, both of whom had opposed the use of force to bring others to Christian faith. Human sacrifice was wrong, but it would be better to avoid war by any means possible.[12] The arguments presented by Las Casas and Sepúlveda to the junta of Valladolid remained abstract, with both sides clinging to their opposite theories that relied on similar, if not the same, theoretical authorities, which were interpreted to suit their respective arguments.[13] |

ディベート フアン・ヒネス・デ・セプルベダ、先住民に対する戦争「馬上槍試合」の支持者 ラス・カサスは、アンコミエンダ制度による先住民虐待の経験を語ることで、自身の立場を強化しようとしたが、議論は主に理論的な根拠にとどまった。セプル ベダはラス・カサスよりも世俗的なアプローチをとり、主にアリストテレスと人文主義の伝統に基づいて、一部の先住民は自らを統治する能力がないために奴隷 化の対象であり、必要であれば戦争によって征服することができると主張した[1]。ラス・カサスはこれに異議を唱え、アリストテレスの野蛮人と自然奴隷の 定義は先住民には当てはまらず、先住民はみな理性を十分に備えており、武力や強制なしにキリスト教に入信させるべきだと主張した[4]。 セパルベダは、ラテン語の対話集『Democrates Alter Sive de Justi Belli Causis』[7]の多くの論点を提唱し、特定の先住民の野蛮な伝統が彼らに対する戦争を正当化すると主張した。セパルベダによれば、文明人は偶像崇 拝、ソドミー、カニバリズムのような悪習を罰する義務があった。戦争は「自然を冒涜する犯罪を根絶するために」行われなければならなかった[8]。 セパルベダは、特定の先住民族に対する正義の戦争について、主に4つの正当化理由を示した。第一に、先住民の自然的条件から、先住民は自らを支配すること ができないとみなされ、スペイン人が主人として行動する責任があるとした。第二に、スペイン人は自然に対する犯罪としてカニバリズムを防ぐ権利があった。 第三に、人身御供も同様であった。第四に、先住民をキリスト教に改宗させることが重要であるとした[9]。  マリアベッキ写本は、高度な建築と残忍な殺戮という、両陣営が使用した議論の種類を同じ図面で示している。 ラス・カサスは、セパルベダの『デモクラテス・アルテル』の存在を聞いて、1540年代後半に彼自身のラテン語の著作である『アポロギア』を書き、アリス トテレスが定義した「野蛮人」と自然奴隷は先住民には当てはまらず、先住民は理性を十分に備えており、武力を用いずにキリスト教に改宗させるべきだと主張 することで、相手の神学的な議論を論破することを目的としていたからである[10][11]。 ラス・カサスは、すべての個人は国際法によって、罪のない人々が不当に扱われるのを防ぐ義務があると指摘した。彼はまた、聖アウグスティヌスや聖ヨハネ・ クリソストムを引き合いに出し、キリスト教を信仰させるために武力を用いることに反対した。人身御供は間違っているが、どんな手段を使っても戦争は避けた 方がよいというのである[12]。 ラス・カサスとセパルベダがバリャドリッド議会に提出した議論は抽象的なままであり、両者は、同じではないにせよ、似たような理論的権威に依拠し、それぞれの主張に合うように解釈された正反対の理論に固執していた[13]。 |

| Aftermath At the conclusion of the debates, the judges argued amongst themselves and then scattered without any definite decision. For several years the Council of the Indies pressed the participants to issue an opinion. Apparently, most of the judges wrote their own statements, but these have never been recovered, with the exception of one by the Doctor Anaya, who approved of the conquests in order to spread Christianity and stop certain Indigenous activities viewed as sinful, but added the caveat that the conquests must be undertaken "for the good of the Indians and not for gold." The junta never issued a collective decision.[14] In the end, while both parties declared that they had won the debate, neither received the outcome they desired. Las Casas did not see the end to Spanish wars of conquest in the New World, and Sepúlveda did not see the New Laws' restrictions on the power of the encomienda system overturned. The debate cemented Las Casas's position as the lead defender of the Indigenous peoples in the Spanish Empire,[3] and further weakened the encomienda system. However, it did not substantially alter Spanish treatment of the Indigenous people in its developing colonies.[4] Both Sepúlveda and Las Casas maintained their positions long after the end of the debate, but their arguments became less significant when the Spanish presence in the New World became permanent.[15] Sepúlveda's arguments contributed to the policy of "war by fire and blood" that the Third Mexican Provincial Council implemented in 1585 during the Chichimeca War.[16] According to Lewis Hanke, while Sepúlveda became the hero of the conquistadors, his success was short-lived, and his works were never published in Spain again during his lifetime.[17] Las Casas's ideas had a more lasting impact on the decisions of the king, Philip II, as well as on history and human rights.[18] Las Casas's criticism of the encomienda system contributed to its replacement with reducciones.[19] His testimonies on the peaceful nature of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas also encouraged nonviolent policies concerning the religious conversions of the Indigenous peoples in New Spain and Peru. It also helped convince more missionaries to come to the Americas to study the indigenous people, such as Bernardino de Sahagún, who learned the native languages to discover more about their cultures and civilizations.[20] Ultimately, however, the impact of Las Casas's doctrine was also limited. In 1550, the king had ordered that the conquest should cease, because the Valladolid debate was to decide whether the war was just or not. But the government's orders were hardly respected: conquistadors such as Pedro de Valdivia went on to wage war in Chile during the first half of the 1550s. Expanding Spanish territory in the New World was allowed again in May 1556, and a decade later, Spain began its conquest of the Philippines.[18] Modern reception In recent years, the Valladolid debate has been noted for its role (albeit marginal) in the conception of international politics in the sixteenth-century.[21] Las Casas's ethical arguments offer a reflection on the question of jurisdiction, asking whether law can be applied internationally, especially in so-called 'rogue states'.[22] The debate also holds a place in contemporary just war theory, as scholars aim to expand jus ad bellum within war studies.[22] |

余波 討論が終わると、審判団は互いに議論し、明確な決定を下すことなく散り散りになった。数年間、印度評議会は参加者たちに意見を出すよう迫った。アナヤ医師 は、キリスト教を広め、罪深いとされる先住民の活動を阻止するための征服を承認したが、征服は 「インディオの利益のためであり、金のためではない 」という注意書きを付け加えた。盟約者団は集団的な決定を下すことはなかった[14]。 結局、両党は論争に勝利したと宣言したものの、どちらも望んだ結果を得ることはできなかった。ラス・カサスはスペインの新大陸征服戦争の終結を見ることは なく、セパルベダは新法によるアンコミエンダ制度の権力制限が覆されることを見ることはなかった。この論争は、スペイン帝国における先住民擁護の第一人者 としてのラス・カサスの地位を確固たるものとし[3]、アンコミエンダ制度をさらに弱体化させた。しかし、発展途上の植民地における先住民に対するスペイ ンの扱いが大きく変わることはなかった[4]。 セプルベダとラス・カサスは論争が終わった後もその立場を維持したが、新大陸におけるスペインの存在が恒久的なものになると、彼らの主張はあまり重要ではなくなった[15]。 ルイス・ハンケによれば、セプルベダは征服者たちの英雄となったが、その成功は長くは続かず、彼の著作がスペインで出版されることは生涯なかった[17]。 ラス・カサスの思想は、歴史や人権だけでなく、国王フィリップ2世の決断により永続的な影響を与えた[18]。ラス・カサスのアンコミエンダ制度への批判 は、レドゥッチョネスへの置き換えに貢献した[19]。 アメリカ大陸の先住民の平和的な性質に関する彼の証言は、ニュースペインとペルーの先住民の宗教的改宗に関する非暴力的な政策をも促した。また、先住民の 文化や文明についてより深く知るために先住民の言語を学んだベルナルディーノ・デ・サハグンのように、先住民を研究するためにアメリカ大陸にやってくる宣 教師をより多く説得するのにも役立った[20]。 しかし、結局のところ、ラス・カサスの教義の影響も限定的なものであった。1550年、国王は征服の中止を命じた。バリャドリッドの討論会で戦争の是非が 決定されることになっていたからである。しかし、政府の命令はほとんど尊重されなかった。ペドロ・デ・バルディビアなどの征服者たちは、1550年代前半 にチリで戦争を起こした。1556年5月には新大陸でのスペイン領土の拡大が再び許可され、その10年後にはスペインはフィリピンの征服を開始した [18]。 現代の受容 近年、バリャドリッド論争は、16世紀における国際政治の概念において(わずかではあったが)その役割を果たしたとして注目されている[21]。ラス・カ サスの倫理的な議論は、特にいわゆる「ならず者国家」において国際的に法を適用することができるのかという、裁判権の問題についての考察を提供している [22]。 また、この議論は現代の正義の戦争論においても重要な位置を占めており、学者たちは戦争研究においてユス・アド・ベラムを拡大することを目指している[22]。 |

| Reflection in art In 1938 the story of the German writer Reinhold Schneider Las Casas and Charles V (Las Casas vor Karl V. [de]) was published. In 1992 the Valladolid debate became an inspiration source for Jean-Claude Carrière who published the novel La Controverse de Valladolid (Dispute in Valladolid). The novel was filmed in French for television under the same name.[23] The director was Jean-Danielle Veren, with Jean-Pierre Marielle playing Las Casas and Jean-Louis Trintignant acting as Sepúlveda. Carrière's work was later was staged as a play in 1999 at the Theatre de l'Atelier in Paris.[24] It was later translated into English, and performed at The Public Theater in New York City in 2005,[1] and in Spokane, Washington in 2019.[25] |

芸術における反射 1938年、ドイツの作家ラインホルト・シュナイダー・ラス・カサスとシャルル5世の物語(Las Casas vor Karl V. [de])が出版された。 1992年、バリャドリッドの論争がジャン=クロード・カリエールのインスピレーションの源となり、小説『La Controverse de Valladolid(バリャドリッドの論争)』が出版された。監督はジャン=ダニエル・ヴェレンで、ラス・カサス役をジャン=ピエール・マリエール、セ パルベダ役をジャン=ルイ・トランティニャンが演じた。 キャリエールの作品はその後、1999年にパリのアトリエ劇場で演劇として上演された[24]。 その後英語に翻訳され、2005年にニューヨークのパブリック・シアターで上演され[1]、2019年にはワシントン州スポケーンで上演された[25]。 |

| Catholic Church and the Age of Discovery Sublimis Deus |

カトリック教会と大航海時代 神の昇華 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Valladolid_debate |

|

"Wild Men" depicted on the facade of the Colegio de San Gregorio |

Church of San Pablo, adjacent to Colegio de San Gregorio. |

| References Byun, Chang-Uk. "The Valladolid Debate between Las Casas and Sepúlveda of 1550" (PDF). Korea Presbyterian Journal of Theology. 42: 257–276. Castilla Urbano, Francisco. "Chapter 9 The Debate of Valladolid (1550–1551)". A Companion to Early Modern Spanish Imperial Political and Social Thought. Brill. doi:10.1163/9789004421882_011. S2CID 219139505. Comas, Juan (1971). "Historical Reality and the Detractors of Father Las Casas". In Friede, Juan; Keen, Benjamin (eds.). Bartolomé de las Casas in history : toward an understanding of the man and his work. Internet Archive. DeKalb : Northern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-0-87580-025-7. Crow, John A. (1992). The Epic of Latin America, 4th ed. University of California Press, Berkeley Hanke, Lewis (1949). The Spanish Struggle for Justice in the Conquest of America. University of Pennsylvania Press. Hernandez, Bonar Ludwig (2001). "The Las Casas-Sepúlveda Controversy: 1550-1551". Ex Post Facto. 10. San Francisco State University: 95–105. Losada, Ángel (1971). "Controversy between Sepúlveda and Las Casas". In Juan Friede; Benjamin Keen (eds.). Bartolomé de las Casas in History: Toward an Understanding of the Man and his Work. Collection spéciale: CER. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press. pp. 279–309. ISBN 0-87580-025-4. OCLC 421424974. Minahane, J. (2014)” The controversy at Valladolid, 1550- 1551”. Church and State. Nu.116.Valladolid index Poole, S. (1965). "War by Fire and Blood" the Church and the Chichimecas 1585. The Americas, 22(2), 115-137. doi:10.2307/979237 French Benoit, Jean Louis. (2013) “L’évangélisation des Indiens d’Amérique Autour de la « légende noire »”, Amerika [Online], 8 | 2013. L’évangélisation des Indiens d’Amérique Casas, B., & Llorente, J. (1822). Oeuvres de don barthélemi de las casas, évêque de chiapa, défenseur de la liberté des naturels de l'amérique : Précédées de sa vie, et accompagnées de notes historiques, additions, développemens, etc., etc., avec portrait. Paris etc.: Alexis Eymery etc. |

参考文献 Byun, Chang-Uk. 「1550年のラス・カサスとセプルベダによるバリャドリッド論争」 (PDF). 韓国長老教会神学雑誌. 42: 257–276. カスティージャ・ウルバノ, フランシスコ. 「第9章 バルセロナ論争(1550–1551)」. 近代スペイン帝国政治・社会思想の伴奏. Brill. doi:10.1163/9789004421882_011. S2CID 219139505. コマス、フアン (1971). 「歴史的現実とラス・カサス神父の批判者たち」. フリーデ、フアン; キーン、ベンジャミン (編). バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサス史: 人物と業績の理解に向けて. インターネットアーカイブ. デカルブ: ノーザン・イリノイ大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-87580-025-7. Crow, John A. (1992). 『ラテンアメリカの叙事詩』第 4 版。カリフォルニア大学出版、バークレー Hanke, Lewis (1949). 『アメリカ征服におけるスペインの正義の闘争』。ペンシルベニア大学出版。 ヘルナンデス、ボナー・ルードヴィヒ(2001)。「ラス・カサスとセプルベダの論争:1550-1551」。Ex Post Facto。10。サンフランシスコ州立大学:95–105。 ロサダ、アンヘル(1971)。「セプルベダとラス・カサスの論争」。フアン・フリーデ、ベンジャミン・キーン(編). 『バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサス史:人物と業績の理解 towards』. 特別コレクション:CER. デカルブ:ノーザン・イリノイ大学出版局. pp. 279–309. ISBN 0-87580-025-4. OCLC 421424974. ミナハネ, J. (2014)「1550-1551年のバジャドリードの論争」『教会と国家』第116号.バジャドリード索引 プール, S. (1965). 「火と血の戦争」教会とチチメカ族 1585. 『アメリカ大陸』22(2), 115-137. doi:10.2307/979237 フランス語 Benoit, Jean Louis. (2013) 「L’évangélisation des Indiens d’Amérique Autour de la « légende noire »」, Amerika [オンライン], 8 | 2013. L’évangélisation des Indiens d’Amérique カサス, B., & ジョルディ, J. (1822). ドン・バルテレミ・デ・ラス・カサス、チアパ司教、アメリカ先住民の自由の擁護者の著作:その生涯、歴史的注釈、追加、展開など、肖像画付き。パリなど:アレクシス・エメリなど。 |

| Precedentes La Junta de Valladolid también fue parte de la más extensa polémica sobre los justos títulos del dominio de la Corona de Castilla sobre América, que se remonta a finales del siglo xv, con las Bulas Alejandrinas y el Tratado de Tordesillas acordado con el Reino de Portugal, y a los recelos con que ambos documentos fueron recibidos en otras cortes europeas. Se dice que el rey Francisco I de Francia pidió retóricamente que le mostraran la cláusula del testamento de Adán en que tales documentos se basaban y que diera derecho a repartir el mundo entre castellanos y portugueses. La consideración necesaria de los estudios y de una reflexión pública efectuada por esta Junta fue excepcional, en comparación con cualquier otro proceso histórico de formación de un imperio y estuvo en sintonía con la preocupación y la gran importancia que, desde el comienzo mismo del descubrimiento de América, la Monarquía Católica sintió siempre de mantener bajo un control paternalista a los naturales y que produjo y siguió produciendo el gran corpus legislativo de las Leyes de Indias. El precedente en la generación anterior a la Junta de Valladolid fue la Junta de Burgos de 1512, que había asentado jurídicamente el derecho a hacer la guerra a los indígenas que se resistieran a la evangelización (para garantizarlo se estableció la lectura de un famoso Requerimiento), buscando un equilibrio entre el predominio social de los colonizadores españoles y la protección al indio, que se quiso conseguir con la encomienda. Resultado de todo ello fueron las Leyes de Burgos de 1512. Hacia 1550 se suscitó en Valladolid, España, una intensa polémica en torno a los siguientes temas: los derechos naturales de los habitantes del Nuevo Mundo, las justas causas para hacer la guerra a los indios y la legitimidad de la conquista. Esta polémica estaba inserta en el marco de una larga controversia entre los que, por un lado, eran partidarios de la libertad absoluta de los indios y de una entrada pacífica en las nuevas tierras y los que, por otro lado, apoyaban el mantenimiento de la esclavitud y el dominio despótico y propiciaban el empleo de la fuerza contra los indios del Nuevo Mundo. Si se analiza desde una perspectiva antropológico-filosófica, se advierte que lo que estaba en tela de juicio era la dignidad humana de los habitantes del Nuevo Mundo. Fray Bartolomé de las Casas y Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda son los representantes de las dos posturas que disputaron por la humanidad del indio. |

先例 バリャドリッド会議は、15世紀末にさかのぼる、カスティーリャ王冠のアメリカに対する支配権の正当性に関する大規模な論争の一部でもありました。この論 争は、アレクサンドリア勅書とポルトガル王国との間で締結されたトルデシージャス条約、およびこれらの文書が他のヨーロッパ諸国によって受け止められた不 審感から生じました。フランス国王フランソワ1世は、これらの文書が根拠としているアダムの遺言の条項、すなわちカスティーリャとポルトガルに世界分割の 権利を与える条項を提示するよう、修辞的に要求したと言われています。 この会議(フンタ)による研究と公の考察は、 他の帝国形成の歴史的過程と比較しても例を見ないものであり、アメリカ大陸の発見当初から、カトリック王政が先住民を父権的に支配し続けることを常に重視 し、インディアス法という膨大な法体系を制定し、その制定を継続してきたこととも一致していた。 バジャドリード会議(フンタ)の前の世代における先例は、1512年のブルゴス会議(フンタ)で、これは、伝道に抵抗する先住民に対して戦争を行う権利を 法的に確立し(これを保証するために、有名な「要求書」の朗読が義務付けられた)、スペインの植民者たちの社会的優位と、エンコミエンダによって達成しよ うとした先住民たちの保護とのバランスを追求したものだった。その成果が、1512年のブルゴス法だ。1550年頃、スペインのバリャドリッドで、新大陸 の住民の自然権、インディオに対して戦争を行う正当な理由、征服の正当性といった問題をめぐって激しい論争が巻き起こった。この論争は、一方ではインディ オの絶対的な自由と新大陸への平和的な入植を支持する者たち、他方では奴隷制と専制的な支配の維持を支持し、新大陸のインディオたちに対する武力行使を擁 護する者たちとの間の長年の論争の枠組みの中で起こった。人類学的・哲学的な観点から分析すると、問題となっていたのは新大陸の住民の人間としての尊厳 だったことがわかる。 バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスとフアン・ヒネス・デ・セプルベダは、インディオの人間性をめぐる論争の双方の立場を代表する人物だ。 |

| Planteamiento del debate En la Junta de Valladolid la discusión partió de bases teológicas, consideradas superiores en ese contexto a las de cualquier otro saber (philosophia est ancilla theologiae). No discurrió en torno a si los indígenas de América eran seres humanos con alma o salvajes susceptibles de ser domesticados como animales. Tal cosa hubiera sido considerada herética y ya estaba resuelta por la bula Sublimis Deus, de Paulo III (1537). Esta bula fue una contundente respuesta del papado a opiniones que ponían en entredicho la humanidad de los naturales. La bula, incitada por dos dominicos españoles, no pretendió definir la racionalidad del indígena sino que, suponiendo dicha racionalidad en cuanto que los indios son hombres, declaró su derecho a la libertad y a la propiedad y el derecho a abrazar el cristianismo, que se les debía predicar pacíficamente. El propósito declarado de la discusión en la Junta de Valladolid era ofrecer una base teológica y de derecho para decidir cómo debía procederse en los descubrimientos, las conquistas y la población de las Indias. |

議論の展開 バリャドリッドの会議では、議論は、その文脈では他のあらゆる知識よりも優れているとみなされていた神学的な根拠(philosophia est ancilla theologiae)から始まった。 アメリカ先住民は魂を持つ人間なのか、それとも動物のように飼いならすことのできる野蛮人なのかという議論は展開されなかった。そのような議論は異端とみ なされ、パウロ3世の教皇勅書「Sublimis Deus」(1537年)によってすでに解決されていた。この教皇勅書は、先住民の人間性を疑問視する意見に対する教皇の断固たる回答だった。2人のスペ イン人ドミニコ会修道士によって促されたこの教皇勅書は、先住民の合理性を定義しようとしたものではなく、先住民も人間である以上、その合理性を前提とし て、先住民の自由と財産、そしてキリスト教を受け入れる権利を平和的に説教すべきであると宣言したものだった。 バリャドリッド会議での議論の目的は、インディアスの発見、征服、および人口増加について、どのように対処すべきかを決定するための神学的および法的根拠を提供することだった。 |

| Participantes En la Junta de Valladolid de 1550 los principales contendientes dialécticos fueron fray Bartolomé de las Casas y Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda. El representante papal, el cardenal Salvatore Roncieri, presidía la discusión. Participaron, entre otros, Domingo de Soto, Bartolomé de Carranza y Melchor Cano (que para la segunda parte del debate tuvo que ser sustituido por Pedro de la Gasca, pues partió al Concilio de Trento). No es casualidad que todos ellos fueran dominicos: la Orden de Predicadores controlaba las universidades españolas a través de las cátedras y los colegios. Varios en esa Junta (como Soto y Cano) eran discípulos de Francisco de Vitoria, muerto cuatro años antes, en 1546. Vitoria encabezó la escuela de Salamanca (por desarrollarse en la Universidad de Salamanca). Carranza enseñaba en el mismo Valladolid, y Sepúlveda, que había estudiado en Alcalá de Henares y en Bolonia y se había destacado por su antierasmismo, no era docente universitario, sino preceptor del propio príncipe Felipe. Fue su oposición a las Leyes Nuevas de Indias de 1542 (cuya revocación habían conseguido los encomenderos en los distintos virreinatos) lo que había provocado la vuelta a España de Bartolomé de las Casas, que era Obispo de Chiapas. Comenzó una polémica intelectual entre los dos: Sepúlveda publicó su De justis belli causis apud indios y Las Casas replicó con sus Treinta proposiciones muy jurídicas. La Junta debía resolver el conflicto. Sepúlveda aportaba un trabajo titulado Democrates alter, en el que sostenía que los indios, considerados como seres inferiores, debían quedar sometidos a los españoles y lo completó con más argumentación escrita en el mismo sentido. La Apologética de las Casas fue el texto clave en las discusiones. Los trabajos se desarrollaron entre los meses de agosto y septiembre de 1550. La Junta quedó inconclusa y por ello volvió a convocarse el año siguiente. En la disputa no hubo resolución final. Los dos exponentes se consideraron vencedores. |

参加者 1550年のバリャドリッド会議では、主な論争者は、バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサス修道士とフアン・ヒネス・デ・セプルベダだった。教皇の代表であるサルヴァトーレ・ロンチェリ枢機卿が議論の議長を務めた。 その他、ドミンゴ・デ・ソト、バルトロメ・デ・カランサ、メルチョール・カノ(議論の後半はトレント公会議に出席するため、ペドロ・デ・ラ・ガスカに代わって参加)などが参加した。 彼ら全員がドミニコ会修道士であったことは偶然ではない。説教者修道会は、教授職や大学を通じてスペインの大学を支配していたからだ。 この会議(フンタ)の参加者の中には、4年前に亡くなったフランシスコ・デ・ヴィトリアの弟子たち(ソトやカノなど)もいた。ヴィトリアは、サラマンカ大学(サラマンカ大学)で発展したサラマンカ学派の指導者として知られている。 カランサは同じバリャドリッドで教鞭を執っており、アルカラ・デ・エナレスとボローニャで学び、反エラスムス主義で知られていたセプルベダは、大学教授で はなく、フェリペ王子自身の家庭教師だった。1542年のインディアス新法(さまざまな副王領のエンコミエンデロスによって廃止された)に反対したことか ら、チアパス司教だったバルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスがスペインに戻った。2人の間で知的論争が始まった。セプルベダは『De justis belli causis apud indios』を出版し、ラス・カサスはその反論として『30の法的な提案』を発表した。会議(フンタ)がこの紛争を解決することになった。 セプルベダは Democrates alter という著作を提出し、インディオは劣った存在であり、スペイン人に服従すべきだと主張し、同じ趣旨の議論をさらに書き加えた。ラス・カサスが書いた Apologética は、この議論の重要なテキストとなった。議論は 1550 年 8 月から 9 月にかけて行われ、会議(フンタ)は結論に至らず、翌年も再開された。この論争には最終的な解決は得られず、双方の主張は勝利とみなされた。 |

| Enfrentamiento de posturas Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda estaba a favor de la guerra justa contra los indios, a quienes creía seres humanos, y que era causada por sus pecados y su idolatría. De no haberlos creído seres humanos, tampoco podrían pecar y malamente podrían los españoles tener el deber de evangelización. También defendió su inferioridad, que obligaba a los españoles a tutelarlos. Correspondió a Bartolomé de las Casas el esfuerzo de demostrar que los americanos eran seres humanos iguales a los europeos. La contribución de Domingo de Soto a esta postura fue fundamental. En el mismo sentido que estos últimos, el espíritu intelectual que animaba el debate, aun no estando presente, era el de Francisco de Vitoria, que se había cuestionado si, desde un principio, era lícita la conquista americana. Los asistentes a la Junta pudieron tenerlo presente en sus reflexiones sobre la naturaleza de los indígenas. |

対立する立場 フアン・ヒネス・デ・セプルベダは、インディオたちを人間であると信じ、彼らの罪と偶像崇拝が戦争の原因であるとして、インディオたちに対する正当な戦争 を支持していました。インディオたちを人間だと信じなかったならば、彼らは罪を犯すこともなく、スペイン人が彼らを改宗させる義務もなかったでしょう。ま た、インディオたちの劣等性を主張し、スペイン人が彼らを保護する義務があると主張しました。 バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスはその反対立場を主張し、アメリカ人はヨーロッパ人と同等の存在であることを証明する努力をした。ドミンゴ・デ・ソトのこの立場への貢献は決定的だった。 彼らと同じ意味で、この議論を活気づけた知的精神は、その場にはいなかったものの、アメリカ大陸の征服が最初から合法であったかどうかを疑問視していたフ ランシスコ・デ・ヴィトリアのものだった。会議(フンタ)の出席者は、先住民の本質について考察する際に、このことを念頭に置いていたかもしれない。 |

| Tesis de Ginés de Sepúlveda Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda, partidario de la guerra justa contra los indios. Sepúlveda en Democrates secundus o de las justas causas de la guerra contra los indios siguió argumentos aristotélicos y humanistas que obtuvo de Palacios Rubios y Poliziano. Propuso cuatro "justos títulos" a fin de justificar la conquista: El derecho de tutela de los indios, que implicaba su sometimiento al gobierno de los cristianos en el convencimiento que por su propio bien sujetarse a los españoles, ya que son incapaces de gobernarse a sí mismos. Ello no significaba que se los deba reducir a servidumbre o esclavitud, sino a que, por así decirlo, fueran considerados siempre menores de edad. La necesidad de impedir, incluso por la fuerza, el canibalismo y otras conductas antinaturales que practican los indígenas. La obligación de salvar a las futuras víctimas inocentes que serían sacrificadas a los dioses falsos. El mandato de evangelización que Cristo dio a los apóstoles y el papa al Rey Católico. Hacer la guerra facilitaría la prédica de la fe. El conjunto de argumentos que utilizó es complejo. Los desarrolló en varias obras más y pueden englobarse en argumentos de razón y de derecho natural y argumentos teológicos.[1] Los planteamientos que Sepúlveda utilizó para argumentar que la conquista española era justificada, los escribió en sus publicaciones Demócrates Alter o Diálogo de las justas causas de la guerra; la apología pro libro de Justis Belli Causis o Defensa de las justas causas de la guerra; su defensa ante la junta de Valladolid y dos cartas a Melchor Cano, donde afirmó su doctrina tergiversada. De estos escritos se desprendieron sus respectivos argumentos, que Sepúlveda explicó, por un lado los que atentaban contra la razón y el derecho natural, como la supuesta barbarie de los indios y el derecho a civilizarlos, por medio de la sumisión, se mencionaba como “servidumbre natural”, sus continuos pecados contra la ley natural que daba derecho a corregirlos y evitar sus barbaries, y por último la defensa de las víctimas que creaban los indígenas como producto de sus barbaries; y por otro lado los argumentos teológicos, que era la autorización pontificia para combatir los pecados contra la supuesta ley natural y eliminar las barreras que ponían los indios a la predicación del evangelio. Argumentos de razón y derecho natural: Sepúlveda explicó que el indio no era intrínsecamente malo sino que lo que le pervirtió fue su cultura, su entorno, por ende dijo que la "barbarie" que autorizaba la conquista tenía una connotación fundamentalmente moral. Sepúlveda dijo ...Digo que los bárbaros, se entiende como los que no viven conforme a la razón natural y tienen costumbres malas públicamente entre ellos aprobadas....ora les venga por falta de religión, donde los hombres se crían brutales, ora por malas costumbres y falta de buena doctrina y castigo... con esto aseveró que el fin de la conquista era la civilización y bien de los bárbaros, ya que con leyes justas y conformes a la ley natural, hacía de la vida de los indios una inserción a una vida mejor y más suave, agregando que si se rehusaba al imperio puede ser obligado por las armas, y esa guerra sería justa en virtud del derecho natural. Dentro de la misma temática con respecto a la servidumbre natural, Sepúlveda se basó en las sagradas escrituras y dijo ...Porque escrito esta en el libro de los proverbios “El que es necio servirá al sabio” tales son las gentes bárbaras e inhumanas, ajenas a la vida civil y a las costumbres pacíficas, y será siempre justo y conforme al derecho natural que tales gentes se sometan al imperio de príncipe y naciones más cultas y humanas, para que merced a sus virtudes y a la prudencia de sus leyes, depongan la barbarie y se reduzcan a vida más humana y al culto de la virtud. Sepúlveda describió aspectos de los indígenas, los cuales calificó de acciones bárbaras, como que no poseían ciencia y que eran iletrados, que no tuvieran leyes escritas, que eran caníbales, cobardes y carecían de propiedad privada, entre otros. Sin dejar de lado que eran solo connotaciones morales, el indio podía ser civilizado ya que la condición de bárbaro fue, en el pensamiento de Sepúlveda, un estado accidental superable y no una naturaleza humana distinta y por ende la posición de servidumbre del indio no fue en sí misma un estado de esclavitud sino un sometimiento político del cual podían evolucionar intelectual y moralmente si eran gobernados por una nación civilizada. Así mismo, la barbarie, entendida como estado de atraso cultural y moral que redundaba en costumbres condenadas "por la naturaleza" y en una supuesta ineptitud para gobernarse humanamente, autorizaba a cualquier pueblo civilizado que estuviera en condiciones de seguir a los bárbaros en conformidad con la "ley natural", de sacarlos de su estado inhumano para someterlos a su dominio político. Incluso por las armas, si no había otro remedio. Esta conclusión en que el hombre dependía de su propia razón, que le permitía autodirigirse y autodiscernir, pero si el hombre era carente del uso de la razón no era dueño de sí y debía servir a quien sea capaz de regirlo y por ende que si la finalidad de la guerra era la civilización de los bárbaros, era entonces un supuesto bien para estos. Sepúlveda justificó la dominación política pero rechazó la dominación civil, o sea la esclavitud y la privación de sus bienes. Sostuvo No digo que a estos bárbaros se les haya de despojar de sus posesiones y bienes, ni que se les haya de reducir a servidumbre, sino que se debe someter al imperio de los cristianos... Es importante destacar que Sepúlveda defendió la sujeción política, pero no su esclavitud pues la creencia vulgar confunde ambas cosas, y lo hace partidario de la esclavitud. Con respecto a los "pecados contra la ley natural", Sepúlveda, basándose en el hecho de que los indios ofrecían sacrificios humanos en gran número a sus dioses falsos, y otros actos similares, dijo: ...y ha de entenderse que estas naciones de los indios, quebrantan la ley natural, no porque en ellas se cometan estos pecados, simplemente, sino porque en ellas tales pecados son oficialmente aprobados....y no los castigase en sus leyes o en sus costumbres, o no impusiese penas levísimas a los más graves y especialmente a aquellos que la naturaleza detesta más, de esa nación se diría con toda justicia y propiedad, que no observa la ley natural, y podrían con pleno derecho los cristianos, si rehusaba someterse a su imperio, destruirlas por sus nefastos delitos y barbarie e inhumanidad.... Sepúlveda trató de proteger a las víctimas de las barbaries humanas señalando: A todos los hombres, les está mandado por ley divina y natural, el defender a los inocentes de ser matados cruelmente, con una muerte indigna, si pueden hacerlo sin gran incomodo suyo y puso como hombres rectos y salvaguardadores de las víctimas a los cristianos. Argumentos teológicos: Con respecto a la autorización pontificia para combatir los graves delitos contra la supuesta ley natural, Sepúlveda dijo que la potestad del papa Si bien se aplica propiamente a aquellas cosas que pertenecen a la salvación del alma, y a los bienes espirituales, sin embargo, no está excluida de las cosas temporales en cuanto se ordenan a las espirituales por ello el papa podía obligar a las naciones a que resguarden la ley natural. Sepúlveda indicó, además, que a nadie se podía obligar a abrazar la fe católica La razón de lo cual es porque aquella violencia sería inútil, pues nadie, repugnando su voluntad, que no es posible coaccionar, puede ser hecho creyente. De modo que debe usarse la enseñanza y de las persecuciones pero a pesar de ello los cristianos podían inducir por medios racionales a los bárbaros a civilizarse, ya que era su obligación. Si el primer intento no resultaba, Sepúlveda mencionaba Si no se puede proveer de otro modo el asunto de la religión, es licito a los españoles, ocupar sus tierras y provincias, y establecer nuevos señores y destituir a los antiguos. |

ヒネス・デ・セプルベダの論文 フアン・ヒネス・デ・セプルベダ、インディオに対する正当な戦争の支持者。 セプルベダは『Democrates secundus o de las justas causas de la guerra contra los indios(インディオに対する戦争の正当な理由)』において、パラシオス・ルビオスとポリツィアーノから得たアリストテレスとヒューマニストの主張に 従いました。彼は征服を正当化するために 4 つの「正当な権利」を提案しました。 インディオの保護権。これは、インディオは自らを統治することができないため、彼ら自身の利益のためにスペイン人に服従すべきであるという信念に基づくも ので、インディオを服従させることを意味していた。これは、インディオを奴隷や奴隷として扱わなければならないという意味ではなく、いわば、インディオを 常に未成年者とみなすことを意味していた。 先住民が実践する人食いやその他の反自然的な行為を、武力によってでも阻止する必要性。 偽りの神々に生贄として捧げられるであろう、将来の無実の犠牲者を救う義務。 キリストが使徒たちに、そして教皇がカトリック王に与えた伝道の使命。 戦争を行うことは、信仰の布教を容易にする。 彼が用いた一連の論拠は複雑だ。彼はこれらの論拠を他のいくつかの著作で展開しており、それらは理性と自然法に基づく論拠、および神学的な論拠に分類することができる。[1] セプルベダが、スペインの征服は正当であると主張するために用いた考え方は、彼の著作『デモクラテス・アルテル』または『戦争の正当な理由に関する対 話』、Justis Belli Causis または『戦争の正当な理由の擁護』という著作、バリャドリッドの会議(フンタ)での弁論、そしてメルチョール・カノ宛ての 2 通の手紙に記されている。これらの著作から、セプルベダが説明したそれぞれの主張が導き出された。一方では、インディオの野蛮さと彼らを服従させて文明化 するという権利など、理性と自然法に反する主張があり、これは「自然の奴隷状態」と表現された。また、自然法に対する彼らの絶え間ない罪は、彼らを矯正 し、その野蛮さを防ぐ権利を与えるとされた。そして最後に、インディオたちの野蛮さによって生じた犠牲者を擁護する。一方、神学的な主張は、自然法に反す る罪と闘い、インディオたちが福音の説教の妨げとなっている障壁を取り除くことを教皇が承認したものだった。 理性と自然法の議論:セプルベダは、インディオは本質的に悪ではなく、彼らの文化や環境によって堕落したと説明し、したがって、征服を正当化する「野蛮さ」には、基本的に道徳的な意味合いがあると述べた。セプルベダは ...私は、野蛮人とは、自然の理にかなった生活を送っておらず、公に認められた悪習を持っている者たちだと考える...それは、宗教の欠如によって、人間が残虐に育つ場合もあれば、悪習や良き教義や罰の欠如による場合もある... これにより、征服の目的は野蛮人の文明化と幸福にあると主張し、公正で自然法に則った法律によって、インディオたちの生活はより良く、より穏やかなものに なると付け加えた。また、帝国への服従を拒否した場合は、武力によって服従させることができ、その戦争は自然法によって正当なものとなる、と述べた。 同じテーマである自然の奴隷制について、セプルベダは聖書に基づいて次のように述べている。 ...箴言に「愚かな者は賢者に仕える」と書かれているように、野蛮で非人間的な人々は、市民生活や平和的な習慣から遠く離れている。そのような人々が、 より教養があり人間的な君主や国家の支配に従うことは、常に正当であり、自然法に合致する。そうすることで、彼らの美徳と賢明な法律のおかげで、彼らは野 蛮さを捨て、より人間的な生活と美徳の崇拝に身を委ねることができるからだ。 セプルベダは、先住民の特徴を「野蛮な行為」と表現し、科学を持たない、文盲である、成文法がない、人食いである、臆病である、私有財産がない、などと いった点を挙げた。これらはあくまで道徳的な意味合いであり、セプルベダは、野蛮という状態は、克服可能な一時的なものであり、人間の本質ではないと考え ていた。したがって、インディオの奴隷的な立場は、それ自体が奴隷状態ではなく、文明国によって統治されれば、知的、道徳的に進化できる政治的服従の状態 であると見なしていた。同様に、文化・道徳の遅れた状態であり、「自然」によって非難される慣習や、人間らしい統治を行う能力の欠如をもたらす「野蛮」 は、野蛮人を「自然法」に従って追放し、非人間的な状態から解放して、政治的支配下に置くことを、あらゆる文明人に正当化していた。他の手段がない場合 は、武力によってでも。この結論は、人間は自らの理性によって自己を支配し、自己を判断することができるが、理性を欠く人間は自己の主人ではなく、自分を 支配できる者に仕えるべきであり、したがって、戦争の目的が野蛮人の文明化であるならば、それは野蛮人にとって善である、というものであった。セプルベダ は政治的支配を正当化したが、市民的支配、つまり奴隷制や財産の剥奪は拒否した。彼は次のように主張した 私は、これらの野蛮人たちから財産や所有物を奪い、奴隷にすべきだと言っているのではない。ただ、彼らをキリスト教徒の支配下に置くべきだと言っているだけだ... セプルベダは、政治的服従は擁護したが、奴隷制は擁護しなかったことを強調しておくことが重要だ。なぜなら、一般的な考えでは、この 2 つは混同され、奴隷制を支持する立場とみなされるからだ。 「自然法に反する罪」に関しては、セプルベダは、インディオたちが偽りの神々に大量の人身御供を捧げていたことなど、同様の行為に基づいて、次のように述べている。 ...そして、これらのインディオの民族は、単にこれらの罪を犯しているからではなく、そのような罪が公式に容認されているという理由で、自然法に違反し ていると理解すべきだ...。そして、その法律や慣習でそれらを罰せず、最も重大な罪、特に自然が最も嫌悪する罪に対してごく軽い罰しか科さない場合、そ の民族は、自然法を守っていないと正当かつ適切に言われ、キリスト教徒は、その支配に従わない場合、その民族の凶悪な犯罪と野蛮さと非人道性のために、そ の民族を滅ぼす権利を有すると考えられる……。 セプルベダは、人間の残虐行為の犠牲者を保護しようとして、次のように指摘した。 すべての人間は、神聖かつ自然の法によって、無実の者を残酷に、不名誉な死から守る義務がある。 そして、キリスト教徒を、正義の人であり、犠牲者を守る者であると位置付けた。 神学的な論拠:自然法に反する重大な犯罪と戦うための教皇の権限について、セプルベダは、教皇の権限は は、本来は魂の救済と霊的な財産に属する事柄に適用されるが、霊的な事柄に秩序を与える限り、一時的な事柄からも除外されるものではない 。したがって、教皇は各国に自然法を保護するよう強制することができる。 セプルベダはさらに、誰にもカトリックの信仰を受け入れることを強制することはできないと述べた その理由は、そのような暴力は無駄だからだ。なぜなら、強制することは不可能な意志に反して、誰かを信者にすることはできないからだ。したがって、教育と迫害を用いるべきだ しかし、それにもかかわらず、キリスト教徒は、野蛮人を文明化するために合理的な手段を用いて誘導することができた。なぜなら、それは彼らの義務だったからだ。最初の試みが失敗した場合、セプルベダは次のように述べた 宗教の問題を他の方法で解決できない場合、スペイン人は彼らの土地と領土を占領し、新しい領主を任命し、旧領主を罷免することは合法である。 |

| Respuesta de las Casas Fray Bartolomé de las Casas fue el principal defensor de los indios en la Junta de Valladolid. Las Casas, que no le va a la zaga en aristotelismo, demostró la racionalidad de los indios a través de su civilización: la arquitectura de los aztecas rebatió la comparación con las abejas que había hecho Sepúlveda. No encontró en las costumbres de los indígenas americanos una mayor crueldad que la que pudiera encontrarse en las civilizaciones del Viejo Mundo o en el pasado de España: "Menor razón hay para que los defectos y costumbres incultas y no moderadas que en estas nuestras indianas gentes halláremos nos maravillen y, por ellas, las menospreciemos, pues no solamente muchas y aun todas las repúblicas fueron muy más perversas, irracionales y en prabidad más estragadas, y en muchas virtudes y bienes morales muy menos morigeradas y ordenadas. Pero nosotros mismos, en nuestros antecesores, fuimos muy peores, así en la irracionalidad y confusa policía como en vicios y costumbres brutales por toda la redondez desta nuestra España"[2] Frente a los "justos títulos" que defendía Sepúlveda, las Casas se valió de los argumentos del fallecido Francisco de Vitoria quien había expuesto una lista de "títulos injustos" y otros "justos títulos": En sus títulos injustos, Vitoria fue el primero que se atrevió a negar que la bulas de Alejandro VI, conocidas en conjunto como las Bulas Alejandrinas o Bulas de Donación Papal, fuesen un título válido de dominio de las tierras descubiertas. Tampoco eran aceptables el primado universal del emperador, la autoridad del papa (que carecía de poder temporal) ni un sometimiento o conversión obligatorios de los indios. No se les podía considerar pecadores o poco inteligentes, sino que eran libres por naturaleza y dueños legítimos de sus propiedades. Cuando los españoles llegaron a América no portaban ningún título legítimo para ocupar aquellas tierras que ya tenían dueño. Las Bulas de donación papal y el Requerimiento que se leía a los indígenas para justificar su sometimiento eran títulos menos seguros que los que daba la aplicación del derecho de comunicación, que si era negado por los indígenas permitía a los españoles obtenerlo a la fuerza. Negó el derecho de ocupación por la pura aplicación de la fuerza, pero defendió la libertad de transitar por los mares, argumento muy polémico también defendido por Hugo Grocio, y que no convenía al monopolio colonial del comercio con las Indias. La evangelización no era una obligación de los españoles, pero sí un derecho de los indígenas.[3] |

レスポンス・デ・ラス・カサス フアン・バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスは、バリャドリッド会議(フンタ)でインディオの主な擁護者だった。 アリストテレス主義に劣らないラス・カサス氏は、インディオの文明を通じてその合理性を証明した。アステカの建築は、セプルベダ氏が例に挙げたミツバチと の比較を反駁した。ラス・カサス氏は、アメリカ先住民の習慣に、旧世界やスペインの過去に見られるような残酷さ以上のものは見出せなかった。 「これらの私たちのインドの民に見られる欠点や無教養で節度のない習慣に驚嘆し、それによって彼らを軽蔑する理由はほとんどない。なぜなら、多くの、ある いはすべての共和国は、はるかに邪悪で、非合理的で、道徳的に堕落しており、多くの美徳や道徳的善において、はるかに節度と秩序に欠けていたからだ。しか し、私たち自身、私たちの先祖は、非合理で混乱した政治、そしてこのスペイン全土に蔓延する悪徳や野蛮な習慣において、彼らよりもはるかに悪かったのだ」 [2] セプルベダが擁護した「正当な称号」に対して、ラス・カサスはその死後、フランシスコ・デ・ヴィトリアが「不当な称号」と「正当な称号」のリストを提示した議論を引用した。 不公正な権利において、ヴィトリアは、アレクサンドル6世の教皇勅書(アレクサンドル教皇勅書または教皇の寄進勅書として知られる)が、発見された土地の 支配権に関する有効な権利ではないことを、初めて否定した人物だ。また、皇帝の普遍的優位性、教皇の権威(教皇には世俗的権力がない)、インディオの強制 的な服従や改宗も容認できなかった。インディオは罪人であり、知性に欠ける存在ではなく、本来は自由であり、自分たちの財産の正当な所有者だった。スペイ ン人がアメリカ大陸に到着したとき、彼らはすでに所有者がいたその土地を占領する正当な権利を持っていなかった。 教皇の寄進状と、先住民に服従を正当化するために読み上げられた要求書は、コミュニケーションの権利の適用によって得られる権利よりも不安定な権利だった。コミュニケーションの権利は、先住民が拒否した場合、スペイン人が武力によって獲得することができた。 彼は、純粋な武力による占領の権利を否定したが、海を航行する自由は擁護した。これは、ヒューゴ・グロティウスも主張した、非常に論争の的となった主張であり、インディアスとの貿易の植民地独占には都合の悪いものだった。 伝道活動はスペイン人の義務ではなかったが、先住民にはその権利があった。 |

| Trascendencia Sacrificio azteca, Códice Mendoza. Argumentos para ambas partes del debate: costumbres antinaturales y arquitectura civilizada. El debate de Valladolid sirvió para actualizar las Leyes de Indias y crear la figura del "protector de indios". Las conquistas se frenaron, regulándose de tal forma que, en teoría, solo a los religiosos les estaba permitido avanzar en territorios vírgenes. Una vez que hubieran convenido con la población indígena las bases del asentamiento, se adentrarían más tarde las fuerzas militares, seguidas por los civiles. Las ordenanzas de Felipe II (1573) llegaron a prohibir hacer nuevas "conquistas". Se ha destacado lo históricamente inusual que son tales escrúpulos en la concepción de un Imperio. Don Phelipe, etc. A los Virreyes presidentes Audiençias y gouernadores de las nuestras Indias del mar oceano y a todas las otras personas a quien lo infrascripto toca y atañe y puede tocar y atañer en qualquier manera saued que para que los descubrimientos nueuas poblagiones y pacificaçiones de las tierras y prouincias que en las Indias estan por descubrir poblar y paçificar se hagan con más façilidad y como conuiene al seruicio de dios y nuestro y bien de los naturales entre otras cossas hemos mandado hazer las ordenanças siguientes (...) Los descubridores por mar o tierra no se empachen en guerra ni conquista en ninguna manera ni ayudar a vnos indios contra otros ni se rebuelban en quistiones ni contiendas con los de la tierra por ninguna caussa ni razon que sea ni les hagan dagno ni mal. alguno ni les tomen contra su voluntad cossa suya sino fuese por rescate o dandoselo ellos de su voluntad... Ordenanzas de descubrimiento, nueva población y pacificación de las Indias dadas por Felipe II, el 13 de julio de 1573, en el bosque de Segovia. El orden que se ha de thener en descubrir y poblar.[4] Surgió de esta disputa el moderno derecho de gentes (ius gentium). Veamos cómo lo resume el profesor Claudio Finzi,[5] en el contexto del debate respecto a a comparación entre las colonizaciones española, inglesa y francesa (lo que explica la mención en el texto, por ejemplo, a expresiones como "aberraciones demoniacas papistas", propias de esa polémica): Si pasamos a la América española, en el campo de la historia de las ideas encontramos diferencias relevantes con cuanto hemos dicho hasta ahora. En efecto, es intensa a finales de los primeros tiempos la actividad misionera con acentos milenarios. Además, para todo el siglo XVI y las primeras décadas del siglo XVII, se desarrolla un intenso debate político sobre la nueva tierra, sobre los indígenas, los motivos que pueden justificar la conquista española. Es un debate del cual participaron las mejores inteligencias españolas de la época, teólogos, juristas, políticos. Nada similar podemos encontrar en otro lugar. También por los motivos circunstanciales: ni los franceses ni los ingleses ni los portugueses se encontraron con organismos políticos desarrollados y organizados en Estados, como los reinos azteca e inca que encontraron los españoles. En España, gracias también a la decisión tomada de posiciones papales, se supera rápido el problema de la naturaleza del indio. Pablo III con la célebre bula Sublimis Deus de 1537, declara a los indígenas hombres con todos los efectos y capacidades de cristianos. Es cierto que esto no parece suficiente porque quedaba en vigor el requerimiento y la bula Inter caetera promulgada por Alejandro VI en 1493, sobre la cual Juan López de Palacios Rubios y Matías de Paz de 1512 fundaban jurídicamente la ocupación de América. Lo que se quiere notar aquí es que siempre en los treinta años del 1500 dos teólogos dominicanos de la celebérrima Universidad de Salamanca, Francisco de Vitoria y Domingo de Soto, enfrentaron el problema de los principados indígenas americanos. Colocados en el camino que conduce a la más moderna teoría del estado, construyeron un camino paralelo a aquel de Maquiavelo y de Jean Bodin, los dos, pero sobre todo el primero con la fuerza de la novedad y gran vigor polémico, que era de los eclesiásticos (por esto propia fuerza) corría lentamente la discusión de lo religioso a lo político y declararon la legitimidad política de las regiones y de los soberanos indígenas americanos. Ellos no eran ni paganos ni pecadores para sacarles la soberanía india y la legitimidad de sus gobernantes, ya que la sociedad y el poder están fundados sobre la naturaleza y no sobre la gracia, como decía santo Tomás de Aquino (los dos son dominicanos y Victoria introduce como libro de texto la Suma Teológica de santo Tomás en Salamanca). La legitimidad del poder no depende por lo tanto del hecho que el gobernante sea o no cristiano, como habían sostenido primero algunos herejes para los cuales era después un poder pagano legítimo y la afirmación de nuestros dos españoles, si nunca lo han conocido, sólo podían estar en las aberraciones demoníacas papistas. Pero hay más. Para demostrar la racionalidad de los indios americanos, Francisco se Vitoria recurre a lo político. Demuestra que eran razonables y que podían tener una vida política, fundándose en abundante noticias que llegaban de América a su convento de San Esteban, afirma que había vida social y política y por lo tanto son racionales. De esta manera va más allá de lo que afirmó Pablo III en su bula de 1537, cuando era la racionalidad el reconocimiento de la naturaleza humana de los indios. Para Victoria la existencia de una vida asociada, con leyes, con comercio, instituciones, gobierno, es lo que cuenta. De un lado, por lo tanto, Vitoria y Soto reconocen la legitimidad de los príncipes americanos; por el otro niegan la existencia de poderes universales: ni el Papa ni el emperador son los señores del mundo. No hay entonces valor político alguno en la bula Inter coetera con la que en 1493 el papa Alejandro VI había dividido el mundo en meridional para los españoles y portugueses. Vitoria y Soto deben preguntarse después cuál es o puede ser el motivo legítimo que permite estar a España en América. Vitoria dará una larga lista de motivos, muchos ilegítimos y puestos premeditadamente, otros legítimos, por lo que la presencia española en América queda a salvo, pero lo que aquí interesa es el reconocimiento a la política americana y de los estados americanos. Las razones que en él aduce para justificar la legitimidad de la presencia española en América son motivos que también se dan en Europa, por ejemplo entre franceses y españoles. No es casual, en efecto, que Carlos V permanezca desconcertado de las dos relectiones de Indis que Vitoria escribe al sacerdote del convento de San Esteban, donde Vitoria vivía, para prohibir los debates posteriores a su argumentación. Sin peros (es significativo) saca su favor a Vitoria que años después quisiera enviar a Trento como teólogo imperial. Esta fue por años y decenios la línea vigente. No faltó también en el mundo hispano negadores radicales de la humanidad del indio o de su posibilidad de civilización; mucho menos faltó quien explotó a los indios en su propio interés. Pero el plan de debate de aquellas ideas que declaraba el derecho hispánico a la sumisión de los indios por su naturaleza inferior, fueron voces minoritarias y perdedoras. De este punto de vista me parece que se puede decir que resulta en cambio cuanto insatisfactoria la posición de Bartolomé de Las Casas, el dominicano defensor de los indios, que muchos trabajos han estado y se han aprovechado de la polémica sobre la colonización española y católica. En sus ideas, en sus posiciones intelectuales y políticas hay algo que grita y contrasta con el mundo que está naciendo. Se enfrentaban sus ideas con las de Vitoria y Soto, paradojalmente, Las Casas aparece más cerca de Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda, el célebre autor de grandes textos políticos y filosóficos donde se sostenía, casi solo entre los teóricos políticos y contrario a la autoridad de Carlos V, pero como buen aristotélico, la esclavitud natural de los indios americanos. El gran amigo de los indios, Las Casas, y el gran enemigo de los indios, Sepúlveda, tuvieron también un durísimo encuentro público en Valladolid ante una comisión de estudiosos, teólogos, juristas, encargados de evaluar las respectivas posiciones. No obstante, los dos adversarios pensaban del mismo modo ambos de nuevo a esquemas políticos de tipo medieval, legados de la vieja concepción de la teocracia pontificia, aquella que siguiendo la bula de Alejandro VI constituía título legítimo de infundamento y de dominio político. En la práctica, las dos posiciones que se confrontaron en la Junta justificaban el dominio castellano aunque con acciones muy diferenciadas entre sí. Ambas motivaciones, así como el ambiente intelectual generado por la Junta de Valladolid y la polémica, inspiraron nuevas Leyes de Indias a añadir a las anteriores. La sincera preocupación de Bartolomé de las Casas por la suerte de los indios que tan crudamente describió en su obra Brevísima Relación de la Destrucción de las Indias le llevó a una notable propuesta que permitió entender su concepción del indígena: Le parecía admisible una buena idea que salvó a muchos lugares de América de la despoblación, sobre todo a las islas Antillas, la importación de esclavos negros, naturalmente más inclinados al trabajo que los débiles indios. Un buen argumento aristotélico, sin duda, pero floja defensa de los derechos humanos modernos, del que más pocos años más tarde, en 1559 o 1560 se desdijo: Antiguamente, antes que hobiese ingenios, teníamos por opinión en esta isla [la Española], que si al negro no acaecía ahorcalle, nunca moría, porque nunca habíamos visto negro de su enfermedad muerto... pero después que los metieron en los ingenios, por los grandes trabajos que padecían y por los brebajes que de las mieles de cañas hacen y beben, hallaron su muerte y pestilencia, y así muchos dellos cada día mueren.[6] El hispanista John Elliott afirma que a pesar de las posibles limitaciones de las medidas, estas constrastan con las de otros imperios por el esfuerzo llevado a cabo para garantizar los derechos de la población indígena: Las ordenanzas llegaron tarde y la «pacificación» de nuevo cuño a menudo resultó ser no mucho más que un eufemismo para la antigua «conquista». Con todo, tanto la convocatoria de la discusión de Valladolid como la legislación que siguió a continuación constituyen un testimonio del compromiso de la corona por garantizar la «justicia» para sus poblaciones de súbditos indígenas, un empeño para el que no es fácil encontrar paralelos por su constancia y vigor en la historia de otros imperios coloniales.[7] |

重要性 アステカの生贄、メンドーサ写本。議論の両陣営の主張:反自然的な慣習と文明的な建築。 バリャドリッドの議論は、インディアス法(植民地法)の改正と「インディオの保護者」という役職の創設につながった。 征服は抑制され、理論上は宗教者だけが未開の領土に進出することが認められた。先住民と入植の基盤について合意に達した後、軍隊が先に入植し、その後民間 人が続くことになった。フェリペ2世の勅令(1573年)は、新たな「征服」を禁止するまでになった。このような帝国建設の構想における良心の呵責は、歴 史的に見ても非常に珍しいことだと指摘されている。 ドン・フェリペ、など。大西洋のインディアス諸島の副王、審問官、総督、および以下に記載する事項に関係する、あるいは何らかの形で関係する可能性のある すべての人々に、以下の通り命じる。インディアス諸島の未発見の土地および州の発見、開拓、平和化については、より迅速かつ、神の奉仕および我々の利益、 そして先住民の福祉にふさわしい方法で実施されるよう、以下の条例を制定する。、神と我らの奉仕、および先住民の福祉にふさわしい方法で行われるよう、以 下の法令を制定することを命じた。海や陸で発見した者は、いかなる戦争や征服にも関与してはならず、あるインディオを他のインディオに対して援助してはな らず、いかなる理由や理由があっても、その土地の住民と争いや争議を起こしてはならず、彼らに危害や損害を与えてはならない。彼らの意志に反して、彼らの 所有物を奪ってはならない。ただし、身代金として、あるいは彼らの意志で渡されたものはこの限りではない... 1573年7月13日、セゴビアの森でフェリペ2世が公布した、インディアスの発見、新植民地化、平和に関する法令。発見と植民地化に関する規則。[4] この論争から、現代の国際法(ius gentium)が生まれた。クラウディオ・フィンツィ教授[5]が、スペイン、イギリス、フランスの植民地化に関する議論の文脈で、これをどのように要 約しているかを見てみよう(この文脈では、例えば、この論争に特徴的な「悪魔的な教皇主義の異常」といった表現が引用されている)。 スペインのアメリカ大陸に移ると、思想史の分野では、これまで述べてきたこととは大きな違いが見られる。実際、初期には、千年にも及ぶ伝統を重んじる宣教 活動が活発だった。さらに、16 世紀から 17 世紀初頭にかけて、新しい土地、先住民、スペインの征服を正当化する理由について、激しい政治的議論が繰り広げられた。この議論には、当時のスペインの最 も優れた知識人、神学者、法学者、政治家たちが参加した。このようなことは、他の場所では見られない。その理由は、状況的なものもある。フランス人、イギ リス人、ポルトガル人は、スペイン人が出会ったアステカ王国やインカ王国のような、国家として発展し組織化された政治体制に遭遇しなかったからだ。スペイ ンでは、教皇の決定も一因となり、インディオの性質に関する問題はすぐに解決された。1537年、教皇パウロ3世は、有名な教皇勅書「Sublimis Deus」で、インディオをキリスト教徒としてのすべての権利と能力を有する人間であると宣言した。確かに、これは十分ではないように見える。なぜなら、 1493年にアレハンドロ6世が公布した要求と教皇勅書「Inter caetera」が依然として有効であり、1512年にフアン・ロペス・デ・パラシオス・ルビオスとマティアス・デ・パズは、この教皇勅書に基づいてアメ リカ占領の法的根拠を確立したからだ。ここで注目すべきは、1500年代の30年間、サラマンカ大学の著名なドミニコ会神学者フランシスコ・デ・ヴィトリ アとドミンゴ・デ・ソトが、アメリカ先住民の諸公国問題に取り組んだことだ。彼らは、最も近代的な国家理論へと至る道筋を築き、マキャヴェッリとジャン・ ボダンと並行する道を歩んだ。しかし、特に前者には、教会関係者特有の革新性と激しい論争の力があり、宗教的な議論を政治的な議論へと徐々に移行させ、ア メリカ先住民の地域と支配者の政治的正当性を宣言した。彼らは、インディアンたちの主権と支配者の正当性を奪うような異教徒でも罪人でもなかった。なぜな ら、社会と権力は、聖トマス・アクィナスが述べたように、恵みではなく、自然に基づいて成立しているからだ(2人はドミニコ会修道士であり、ビクトリア は、サラマンカで聖トマスの『神学大全』を教科書として採用している)。したがって、権力の正当性は、統治者がキリスト教徒であるかどうかによって決まる ものではない。これは、当初、異端者たちが主張していたことであり、彼らにとっては、それは後に異教の権力の正当性となった。しかし、この2人のスペイン 人が、それを知らなかったとしたら、彼らの主張は、悪魔的な教皇主義の狂気によるものしかあり得ない。しかし、それだけではない。アメリカ先住民たちの合 理性を示すために、フランシスコ・デ・ヴィトリアは政治に言及している。彼は、彼らが合理的であり、政治的な生活を送ることができたことを、サン・エステ バン修道院にアメリカから届いた豊富な情報に基づいて証明し、彼らには社会生活と政治があったため、彼らは合理的であると主張している。このように、彼 は、インディオの人間の本質を合理性として認めた、1537年の教皇パウロ3世の勅書よりもさらに一歩進んだ主張をしている。ビクトリアにとって、法律、 商業、制度、政府を備えた共同体の存在こそが重要なのだ。したがって、ビクトリアとソトは、一方ではアメリカ大陸の君主の正当性を認め、他方では普遍的な 権力の存在を否定している。教皇も皇帝も、世界の支配者ではないのだ。したがって、1493年に教皇アレクサンドル6世がスペインとポルトガルに世界を分 割した教皇勅書「Inter coetera」には、いかなる政治的価値もない。ヴィトリアとソトは、スペインがアメリカ大陸に存在することを正当化する理由は何であるか、あるいは何 であるべきかを問わなければならない。ヴィトリアは、多くの不正で意図的に挙げた理由と、正当な理由の長いリストを挙げ、スペインのアメリカ大陸での存在 を正当化したが、ここで重要なのは、アメリカ大陸の政治とアメリカ大陸の国家の承認だ。ヴィトリアがスペインのアメリカ大陸での存在の正当性を主張するた めに挙げた理由は、ヨーロッパ、例えばフランスとスペインの間でも見られる理由だ。実際、カルロス5世が、ビトリアが住んでいたサン・エステバン修道院の 司祭に、彼の主張に対するその後の議論を禁止するために書いた2通の手紙に困惑していることは偶然ではない。しかし(これは重要なことだが)、彼は、数年 後に帝国神学者としてトレントに派遣したいと考えていたビトリアを支持している。これが、何十年にもわたって主流の立場だった。スペイン語圏にも、イン ディオの人間性や文明化の可能性を徹底的に否定する人々がいたことは言うまでもない。ましてや、自らの利益のためにインディオを搾取した人々もいた。しか し、インディオは本質的に劣っているため、スペインの支配に従うべきだと主張した議論は、少数派の意見であり、敗北に終わった。この観点から、スペインと カトリックによる植民地化に関する論争を題材にした多くの著作が、インディオの擁護者であったドミニコ会のバルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサス (Bartolomé de Las Casas)の立場は、むしろ不満足なものだったといえると思う。彼の思想、知的・政治的立場には、誕生しつつある世界と対照的な、何か叫びのようなもの がある。彼の考えは、パラドックス的に、ビトリアやソトの考えと対立しており、ラス・カサス氏は、政治・哲学の偉大な著作の著者であり、政治理論家の中で ほぼ唯一、カルロス 5 世の権威に反対し、良きアリストテレス主義者として、アメリカ先住民の奴隷制を当然のものとして主張したフアン・ヒネス・デ・セプルベダ氏に近い立場に 立っていた。インディオたちの偉大な友人であるラス・カサスと、インディオたちの偉大な敵であるセプルベダは、バジャドリードで、それぞれの立場を評価す る学者、神学者、法学者からなる委員会面前で、激しい公開討論を交わした。しかし、2人の敵対者は、どちらも中世的な政治体制、すなわち、アレクサンドル 6世の教皇勅書に従って、植民地化と政治的支配の正当な根拠となっていた、教皇の権威による神権政治という古い考え方に立ち返っていた。 実際には、会議(フンタ)で対立した2つの立場は、その行動は大きく異なっていたものの、カスティージャの支配を正当化していた。 この 2 つの動機、そしてバジャドリードの会議(フンタ)と論争によって生み出された知的風潮は、それまでの法律に追加される新しいインディアス法(Leyes de Indias)の制定につながった。バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスが、その著作『インディアスの破壊に関する極短報告』で、インディオたちの運命について 率直に懸念を表明したことは、彼のインディオに対する考え方を理解する上で重要なヒントとなる。彼は、アメリカ大陸の多くの地域、特にアンティル諸島の人 口減少を救った、黒人奴隷の輸入は良い考えだと考えていた。黒人は、体力の弱いインディオよりも当然、労働に熱心だったからだ。これは確かにアリストテレ ス的な良い議論だけど、現代の人権観からは見劣りする弱い弁明であり、彼はその数年後、1559年か1560年にこの見解を撤回している。 「昔、砂糖工場ができる前は、この島(エスパニョーラ島)では、黒人は絞首刑に処せられない限り決して死なない、と信じられていた。なぜなら、病気で死ん だ黒人を見たことがなかったからだ。しかし、彼らを砂糖工場に送り込んだ後、過酷な労働と、サトウキビの蜜から作った飲み物を飲まされたため、彼らは死と 疫病に見舞われ、毎日多くの者が死んでいる。[6] スペイン史研究家のジョン・エリオットは、その措置には限界があったかもしれないが、先住民の人権を保障するための努力は、他の帝国とは対照的だったと主張している。 条例は遅すぎ、新たな「平和化」は、多くの場合、かつての「征服」を美化したにすぎなかった。しかし、バジャドリードでの議論の招集と、それに続く立法 は、先住民臣民に対する「正義」の保障に対する王室のコミットメントの証であり、その持続性と力強さは、他の植民地帝国史において類例を見いだすのが難し い。[7] |

| Recreaciones fílmicas Existe, por un lado, un telefilm francés que recrea este episodio con el título de La Controverse de Valladolid del año 1992, dirigido por Jean-Daniel Verhaeghe, con guion de Jean-Claude Carrière, y que cuenta como actores con Jean-Louis Trintignant (Sepúlveda), Jean-Pierre Marielle (Las Casas) y Jean Carmet (Legado del papa). No obstante, en él se hacen aseveraciones no contrastadas y llamativas que podrían tacharse de propaganda, y se enfoca la Junta como un concilio para decidir si los indígenas eran hombres con alma o no, lo cual ya había sido previamente establecido por la bula Sublimis Deus, de Pablo III (1537).[8] Por otro lado, en 2023, se filmó en Valladolid, el documental "La Controversia de Valladolid. El amanecer de los derechos humanos", dirigido por Juan Rodríguez-Briso. El documental está basado en una investigación histórica realizada en los archivos de Simancas, de Sevilla y la Biblioteca Nacional. El largometraje destaca la relevancia de la Junta de Valladolid, como discusión predecesora sobre los derechos humanos. Un grupo de especialistas en historia, teología y derecho, -encarnados por Noemí Morante, Carlos Pinedo, Carlos Tapia, Mercedes Asenjo-, se reúnen en un programa de radio para reflexionar, indagar, cuestionar y debatir sobre la Junta de Valladolid. El film muestra diferentes momentos históricos, que darán lugar al debate entre Bartolomé de las Casas y Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda entre 1550 y 1551. Hace hincapié en este hito, como un proceso histórico que ocupa los primeros 50 años del siglo xvi. El documental, -que cuenta con la participación de Televisión Española-, contempla otros hechos precedentes como las implicancias del testamento de Isabel La Católica, en cuanto a la figura legal de los indígenas, el Sermón de Montesinos de 1511, como primera protesta sobre los tratos abusivos hacia los nativos por parte de los adelantados; las clases impartidas por Francisco de Vitoria en la Universidad de Salamanca, donde se cuestiona la legitimidad de la conquista. Estos y otros sucesos, desembocaran en la Junta de Valladolid de 1550 – 1551. Javier Bermejo (Antonio de Montesinos) Agustín Ustarroz (Sepúlveda), Ales Furundarena (Las Casas), Alfonso Mendiguchía (Hernán Cortés) Isabel La Católica (Lucía Bravo) Pablo Viñas (Francisco de Vitoria) y Miguel Sánchez González (Carlos V) dan vida a personajes históricos relevantes en el documental. Fue filmando en Valladolid, en el propio Colegio San Gregorio, donde se produjo originalmente el debate. |

映画化 一方、このエピソードを再現したフランスのテレビ映画『ラ・コントロヴェール・ド・ヴァラドリード』(1992年)がある。監督はジャン=ダニエル・ヴェ ルヘーグ、脚本はジャン=クロード・キャリエール、主演はジャン=ルイ・トランティニャン(セプルベダ)、ジャン=ピエール・マリエル(ラス・カサス)、 ジャン・カルメ(教皇の使節)だ。しかし、この作品では、検証されていない、宣伝と受け取られるような主張が数多くあり、会議(フンタ)は、先住民が魂を 持つ人間であるかどうかを判断するための公会議として描かれている。しかし、この問題は、パウルス3世の教皇勅書「Sublimis Deus」(1537年)によって、すでに決定されていた。[8] 一方、2023年には、フアン・ロドリゲス・ブリソ監督によるドキュメンタリー映画「バリャドリッドの論争。人権の夜明け」がバリャドリッドで撮影され た。このドキュメンタリーは、セビリアのシマンカス公文書館および国立図書館の公文書を調査して制作された。この長編映画は、人権に関する先駆的な議論の 場として、バリャドリッド会議の重要性を強調している。歴史、神学、法律の専門家たち(ノエミ・モランテ、カルロス・ピネド、カルロス・タピア、メルセデ ス・アセンホ)がラジオ番組に集まり、バジャドリード会議について考察、調査、疑問、議論を行う。この映画は、1550年から1551年にかけて、バルト ロメ・デ・ラス・カサスとフアン・ヒネス・デ・セプルベダの間で繰り広げられた議論のきっかけとなった、さまざまな歴史的瞬間を描いている。この画期的な 出来事を、16世紀前半の50年間にわたる歴史的プロセスとして強調している。このドキュメンタリーは、テレヴィシオン・エスパニョーラも参加しており、 イサベル・ラ・カタリナの遺言が先住民の法的地位に与えた影響、1511年のモンテシノスの説教(先住民に対する虐待的な扱いを非難した最初の抗議)、 サラマンカ大学でのフランシスコ・デ・ヴィトリアによる、征服の正当性を疑問視する講義など、他の出来事とも関連している。これらの出来事は、1550年 から1551年にかけてのバリャドリッド会議(フンタ)へとつながった。ハビエル・ベルメホ(アントニオ・デ・モンテシノス)、アグスティン・ウスタロッ ツ(セプルベダ)、アレス・フルンダレナ(ラス・カサス)、アルフォンソ・メンディグチア(エルナン・コルテス)、イサベル・ラ・カタリナ(ルシア・ブラ ボ)、パブロ・ヴィニャス(フランシスコ・デ・ビトリア)、ミゲル・サンチェス・ゴンサレス(カルロス5世)が、このドキュメンタリーで重要な歴史上の人 物を演じています。撮影は、議論が実際に開催されたバジャドリードのサン・グレゴリオ学院で行われた。 |

| Bibliografía adicional Alfredo Gomez Muller, La cuestion de la legitimidad de la conquista de América: Las Casas y Sepulveda, Ideas y Valores, 1991 ISSN 0120-0062, n° 85-86, p. 3-18 (Universidad Nacional de Colombia). Marcel Bataillon, El padre las Casas y la defensa de los indios, Globus, 1994 ISBN 978-84-88424-47-1 (or. 1971), con A. Saint-Lu. Jean Dumont (2009). El amanecer de los derechos del hombre. La controversia de Valladolid. Ediciones Encuentro. ISBN 9788474909982. Ana Manero Salvador, La controversia de Valladolid: España y el análisis de la legitimidad de la conquista de América, Revistra Electrónica Iberoamericana, Vol 3, N.º 2, 2009, Centro de Estudios de Iberoamérica, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid (España) disponible en http://e-archivo.uc3m.es/handle/10016/7733#preview |

追加文献 アルフレド・ゴメス・ムラー、『アメリカ征服の正当性問題:ラス・カサスとセプルベダ』、Ideas y Valores、1991年、ISSN 0120-0062、第85-86号、3-18ページ(コロンビア国立大学)。 マルセル・バタイヨン、エル・パдре・ラス・カサスとインディオの擁護、Globus、1994年 ISBN 978-84-88424-47-1(1971年)、A. Saint-Lu との共著。 ジャン・デュモン(2009)。『人権の夜明け。バリャドリッドの論争』。エディシオンズ・エンクエントロ。ISBN 9788474909982。 アナ・マネロ・サルバドール、『バリャドリッドの論争:スペインとアメリカ征服の正当性の分析』、Revistra Electrónica Iberoamericana、第3巻、第2号、2009年、イベロアメリカ研究センター、カルロス3世大学(スペイン)、http://e- archivo.uc3m.es/handle/10016/7733#preview で閲覧可能。 |

| https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Junta_de_Valladolid |

★

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆