ヴィア・ゴードン・チャイルド

Vere Gordon Childe, 1892-1957

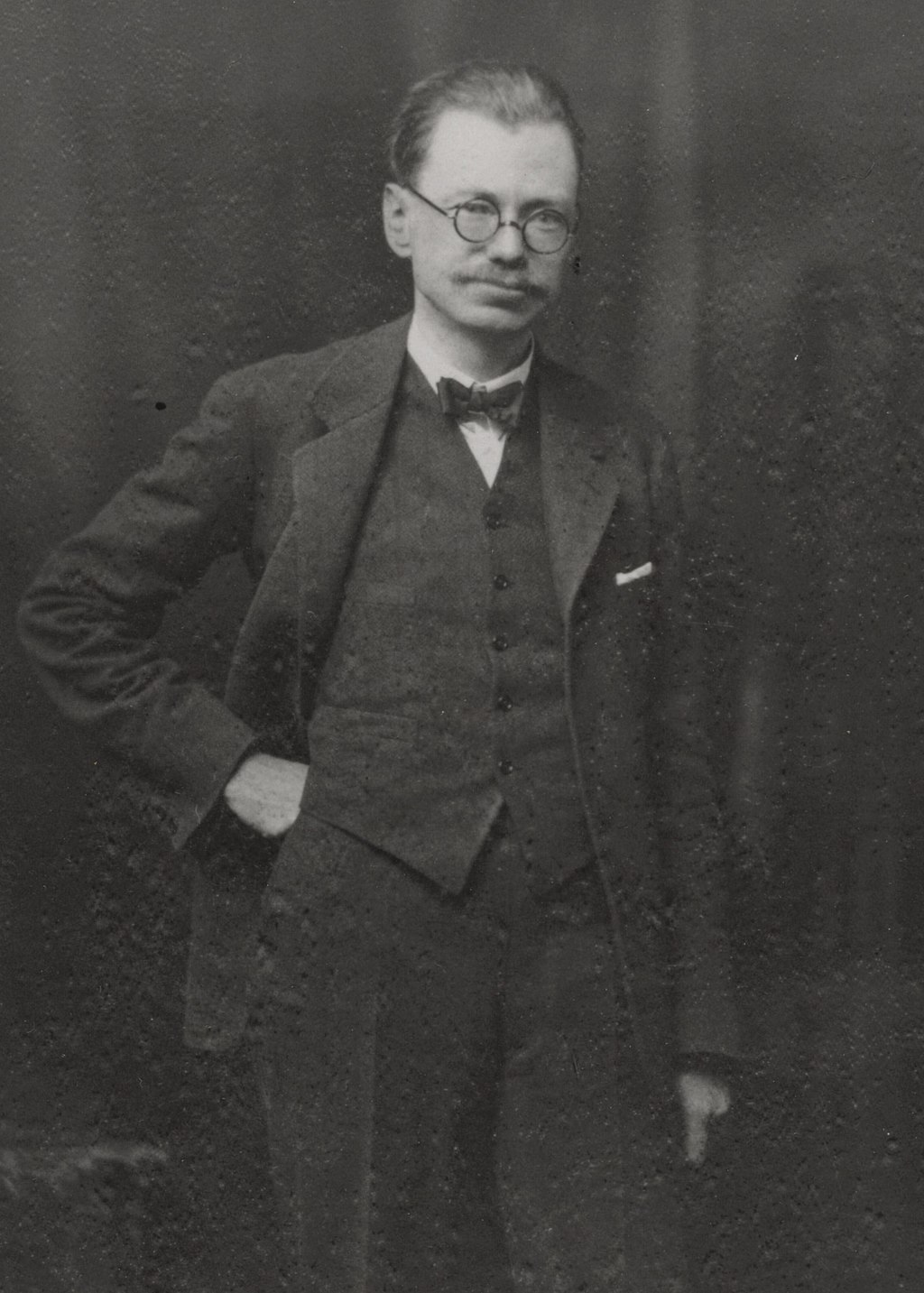

☆ヴィア・ゴードン・チャイルド(Vere Gordon Childe、1892年4月14日 - 1957年10月19日)は、ヨーロッパの先史研究を専門としたオーストラリアの考古学者である。生涯の大半を英国で過ごし、エジンバラ大学、ロンドンの 考古学研究所で研究者として働いた。その間に26冊の著作がある。当初は文化史的考古学の初期の提唱者であったが、後に西欧世界初のマルクス主義的考古学 の提唱者となった。1927年から1946年までエジンバラ大学のアバクロンビー考古学教授を務め、1947年から1957年までロンドン考古学研究所の所長を務めた。この 間、スコットランドと北アイルランドの遺跡発掘を監督し、スカラ・ブレイの集落やメショウェとクオイネスの石室墓の発掘を通じて、新石器時代のオークニー 社会に焦点を当てた。この数十年の間に、彼は発掘報告書、雑誌記事、書籍などを精力的に出版した。スチュアート・ピゴット、グラヘイム・クラークとともに 1934年に先史学会を設立し、初代会長に就任した。熱心な社会主義者であることに変わりはなく、マルクス主義を受け入れ、文化史的アプローチを拒否し て、史的唯物論などのマルクス主義の考え方を考古学的データの解釈の枠組みとして用いた。1956年のハンガリー革命後、ソ連の外交政策に懐疑的になった が、ソ連へのシンパとなり、何度かソ連を訪問した。1956年のハンガリー革命後、ソ連の外交政策に懐疑的になったが、その信条が災いし、講演の招待を何 度も受けたにもかかわらず、アメリカへの入国を法的に禁止された。引退後はオーストラリアのブルーマウンテンズに戻り、そこで自殺した。

| Vere Gordon Childe (14

April 1892 – 19 October 1957) was an Australian archaeologist who

specialised in the study of European prehistory. He spent most of his

life in the United Kingdom, working as an academic for the University

of Edinburgh and then the Institute of Archaeology, London. He wrote

twenty-six books during his career. Initially an early proponent of

culture-historical archaeology, he later became the first exponent of

Marxist archaeology in the Western world. Born in Sydney to a middle-class English migrant family, Childe studied classics at the University of Sydney before moving to England to study classical archaeology at the University of Oxford. There, he embraced the socialist movement and campaigned against the First World War, viewing it as a conflict waged by competing imperialists to the detriment of Europe's working class. Returning to Australia in 1917, he was prevented from working in academia because of his socialist activism. Instead, he worked for the Labor Party as the private secretary of the politician John Storey. Growing critical of Labor, he wrote an analysis of their policies and joined the radical labour organisation Industrial Workers of the World. Emigrating to London in 1921, he became librarian of the Royal Anthropological Institute and journeyed across Europe to pursue his research into the continent's prehistory, publishing his findings in academic papers and books. In doing so, he introduced the continental European concept of an archaeological culture—the idea that a recurring assemblage of artefacts demarcates a distinct cultural group—to the British archaeological community. From 1927 to 1946 he worked as the Abercromby Professor of Archaeology at the University of Edinburgh, and then from 1947 to 1957 as the director of the Institute of Archaeology, London. During this period he oversaw the excavation of archaeological sites in Scotland and Northern Ireland, focusing on the society of Neolithic Orkney by excavating the settlement of Skara Brae and the chambered tombs of Maeshowe and Quoyness. In these decades he published prolifically, producing excavation reports, journal articles, and books. With Stuart Piggott and Grahame Clark he co-founded The Prehistoric Society in 1934, becoming its first president. Remaining a committed socialist, he embraced Marxism, and—rejecting culture-historical approaches—used Marxist ideas such as historical materialism as an interpretative framework for archaeological data. He became a sympathiser with the Soviet Union and visited the country on several occasions, although he grew sceptical of Soviet foreign policy following the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. His beliefs resulted in him being legally barred from entering the United States, despite receiving repeated invitations to lecture there. Upon retirement, he returned to Australia's Blue Mountains, where he committed suicide. One of the best-known and most widely cited archaeologists of the twentieth century, Childe became known as the "great synthesizer" for his work integrating regional research with a broader picture of Near Eastern and European prehistory. He was also renowned for his emphasis on the role of revolutionary technological and economic developments in human society, such as the Neolithic Revolution and the Urban Revolution, reflecting the influence of Marxist ideas concerning societal development. Although many of his interpretations have since been discredited, he remains widely respected among archaeologists. |

ヴィ

ア・ゴードン・チャイルド(Vere Gordon Childe、1892年4月14日 -

1957年10月19日)は、ヨーロッパの先史研究を専門としたオーストラリアの考古学者である。生涯の大半を英国で過ごし、エジンバラ大学、ロンドンの

考古学研究所で研究者として働いた。その間に26冊の著作がある。当初は文化史的考古学の初期の提唱者であったが、後に西欧世界初のマルクス主義的考古学

の提唱者となった。 シドニーでイギリスの中流階級の移民家庭に生まれたチャイルドは、シドニー大学で古典学を学んだ後、イギリスに渡りオックスフォード大学で古典考古学を学 んだ。そこで社会主義運動に傾倒し、第一次世界大戦をヨーロッパの労働者階級に不利益をもたらす帝国主義者の争いだと考えて反対運動を展開した。1917 年にオーストラリアに戻ったが、社会主義活動家であったために学問の世界で働くことはできなかった。代わりに、政治家ジョン・ストーリーの私設秘書として 労働党で働いた。労働党への批判を強め、労働党の政策を分析した論文を執筆し、急進的な労働団体である世界産業別労働者協会に参加した。1921年にロン ドンに移住し、王立人類学研究所の司書となり、ヨーロッパ大陸を旅して大陸先史時代の研究を進め、その成果を学術論文や書籍に発表した。そうすることで、 彼はヨーロッパ大陸の考古学的文化という概念、つまり、繰り返し出土する遺物の集合体が、明確な文化集団を区分するという考え方を、イギリスの考古学コ ミュニティに紹介したのである。 1927年から1946年までエジンバラ大学のアバクロンビー考古学教授を務め、1947年から1957年までロンドン考古学研究所の所長を務めた。この 間、スコットランドと北アイルランドの遺跡発掘を監督し、スカラ・ブレイの集落やメショウェとクオイネスの石室墓の発掘を通じて、新石器時代のオークニー 社会に焦点を当てた。この数十年の間に、彼は発掘報告書、雑誌記事、書籍などを精力的に出版した。スチュアート・ピゴット、グラヘイム・クラークとともに 1934年に先史学会を設立し、初代会長に就任した。熱心な社会主義者であることに変わりはなく、マルクス主義を受け入れ、文化史的アプローチを拒否し て、史的唯物論などのマルクス主義の考え方を考古学的データの解釈の枠組みとして用いた。1956年のハンガリー革命後、ソ連の外交政策に懐疑的になった が、ソ連へのシンパとなり、何度かソ連を訪問した。1956年のハンガリー革命後、ソ連の外交政策に懐疑的になったが、その信条が災いし、講演の招待を何 度も受けたにもかかわらず、アメリカへの入国を法的に禁止された。引退後はオーストラリアのブルーマウンテンズに戻り、そこで自殺した。 20世紀で最もよく知られ、最も広く引用された考古学者の一人であるチャイルドは、地域研究を近東およびヨーロッパ先史の全体像と統合した業績により、 「偉大なる総合者」として知られるようになった。また、新石器革命や都市革命など、人類社会における革命的な技術的・経済的発展の役割を強調したことでも 知られ、社会の発展に関するマルクス主義思想の影響を反映していた。その後、彼の解釈の多くは否定されているが、考古学者の間では広く尊敬されている。 |

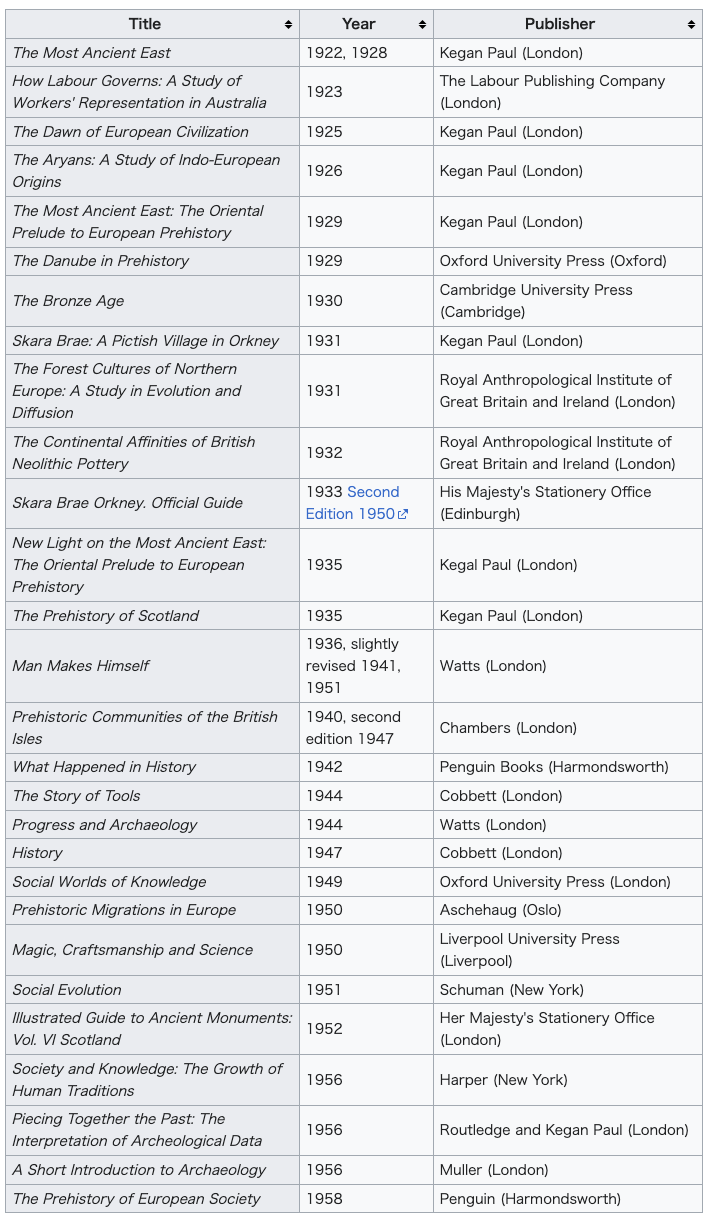

| Early life Childhood: 1892–1910 Childe was born on 14 April 1892 in Sydney.[1] He was the only surviving child of the Reverend Stephen Henry Childe (1844–1923) and Harriet Eliza Childe, née Gordon (1853–1910), a middle-class couple of English descent.[2] The son of an Anglican priest, Stephen Childe was ordained into the Church of England in 1867 after gaining a BA from the University of Cambridge. Becoming a teacher, in 1871 he married Mary Ellen Latchford, with whom he had five children.[3] They moved to Australia in 1878, where Mary died. On 22 November 1886 Stephen married Harriet Gordon, an Englishwoman from a wealthy background who had moved to Australia as a child.[4] Her father was Alexander Gordon.[5] Gordon Childe was raised alongside five half-siblings at his father's palatial country house, the Chalet Fontenelle, in the township of Wentworth Falls in the Blue Mountains, west of Sydney.[6] Rev. Childe worked as the minister for St. Thomas' Parish, but proved unpopular, arguing with his congregation and taking unscheduled holidays.[6] A sickly child, Gordon Childe was educated at home for several years, before receiving a private-school education in North Sydney.[7] In 1907, he began attending Sydney Church of England Grammar School, gaining his Junior Matriculation in 1909 and Senior Matriculation in 1910. At school he studied ancient history, French, Greek, Latin, geometry, algebra, and trigonometry, achieving good marks in all subjects, but he was bullied because of his physical appearance and unathletic physique.[8] In July 1910 his mother died; his father soon remarried.[9] Childe's relationship with his father was strained, particularly following his mother's death, and they disagreed on religion and politics: the Reverend was a devout Christian and conservative while his son was an atheist and socialist.[9] University in Sydney and Oxford: 1911–1917 Childe studied for a degree in classics at the University of Sydney in 1911; although focusing on written sources, he first came across classical archaeology through the work of the archaeologists Heinrich Schliemann and Arthur Evans.[10] At university, he became an active member of the debating society, at one point arguing that "socialism is desirable." Increasingly interested in socialism, he read the works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, as well as those of the philosopher G. W. F. Hegel, whose dialectics heavily influenced Marxist theory.[11] At university, he became a great friend of fellow undergraduate and future judge and politician Herbert Vere Evatt, with whom he remained in lifelong contact.[12] Ending his studies in 1913, Childe graduated the following year with various honours and prizes, including Professor Francis Anderson's prize for philosophy.[13] "My Oxford training was in the Classical tradition to which bronzes, terracottas and pottery (at least if painted) were respectable while stone and bone tools were banausic." — Gordon Childe, 1957.[14] Wishing to continue his education, he gained a £200 Cooper Graduate Scholarship in Classics, allowing him to pay the tuition fees at Queen's College, part of the University of Oxford, England. He set sail for Britain aboard the SS Orsova in August 1914, shortly after the outbreak of World War I.[15] At Queen's, Childe was entered for a diploma in classical archaeology followed by a Literae Humaniores degree, although he never completed the former.[16] While there, he studied under John Beazley and Arthur Evans, the latter being Childe's supervisor.[17] In 1915, he published his first academic paper, "On the Date and Origin of Minyan Ware", in the Journal of Hellenic Studies, and the following year produced his B.Litt. thesis, "The Influence of Indo-Europeans in Prehistoric Greece", displaying his interest in combining philological and archaeological evidence.[18] At Oxford he became actively involved with the socialist movement, antagonising the conservative university authorities. Becoming a noted member of the left-wing reformist Oxford University Fabian Society, he was there in 1915 when it changed its name to the Oxford University Socialist Society, following a split from the Fabian Society.[19] His best friend and flatmate was Rajani Palme Dutt, a fervent socialist and Marxist. The pair often got drunk and tested each other's knowledge about classical history late at night.[20] With Britain in the midst of World War I, many British-based socialists refused to enlist in the military despite the government-mandated conscription. They believed the ruling classes of Europe's imperialist nations were waging the war for their own interests at the expense of the working classes; these socialists thought class war was the only conflict they should be concerned with. Dutt was imprisoned for refusing to fight, and Childe campaigned for the release of both him and other socialists and pacifist conscientious objectors. Childe was never required to enlist in the military, most likely due to his poor health and eyesight.[21] His anti-war sentiments concerned the authorities; the intelligence agency MI5 opening a file on him, his mail was intercepted, and he was kept under observation.[22] Early career in Australia: 1918–1921  From 1919 to 1921, Childe worked for the leftist politician John Storey as his personal assistant. Childe returned to Australia in August 1917.[23] As a known socialist agitator, he was placed under surveillance by the security services, who intercepted his mail.[24] In 1918 he became senior resident tutor at St Andrew's College, Sydney University, joining Sydney's socialist and anti-conscription movement. In Easter 1918 he spoke at the Third Inter-State Peace Conference, an event organised by the Australian Union of Democratic Control for the Avoidance of War, a group opposed to Prime Minister Billy Hughes's plans to introduce conscription. The conference had a prominent socialist emphasis; its report argued that the best hope to end international war was the "abolition of the Capitalist System". News of Childe's participation reached the Principal of St Andrew's College, who forced Childe to resign despite much opposition from staff.[25] Staff members secured him work as a tutor in ancient history in the Department of Tutorial Classes, but the university chancellor William Cullen feared that he would promote socialism to students and fired him.[26] The leftist community condemned this as an infringement of Childe's civil rights, and the centre-left politicians William McKell and T.J. Smith raised the issue in the Parliament of Australia.[27] Moving to Maryborough, Queensland, in October 1918, Childe took up employment teaching Latin at the Maryborough Boys Grammar School, where his students included P. R. Stephensen. Here, too, his political affiliations became known, and he was subject to an opposition campaign from local conservative groups and the Maryborough Chronicle, resulting in abuse from some pupils. He soon resigned.[28] Realising he would be barred from an academic career by the university authorities, Childe sought employment within the leftist movement. In August 1919, he became private secretary and speech writer to the politician John Storey, a prominent member of the centre-left Labor Party then in opposition to New South Wales' Nationalist Party government. Representing the Sydney suburb of Balmain on the New South Wales Legislative Assembly, Storey became state premier in 1920 when Labor achieved electoral victory.[29] Working within the Labor Party allowed Childe greater insight into its workings; the deeper his involvement, the more he became critical of Labor, believing that once in political office they betrayed their socialist ideals and moved to a centrist, pro-capitalist stance.[30] He joined the radical leftist Industrial Workers of the World, which at the time was banned in Australia.[30] In 1921 Storey sent Childe to London to keep the British press updated about developments in New South Wales, but Storey died in December and an ensuing New South Wales election restored a Nationalist government under George Fuller's premiership. Fuller thought Childe's job unnecessary, and in early 1922 terminated his employment.[31] London and early books: 1922–1926 Unable to find an academic job in Australia, Childe remained in Britain, renting a room in Bloomsbury, Central London, and spending much time studying at the British Museum and the Royal Anthropological Institute library.[32] An active member of London's socialist movement, he associated with leftists at the 1917 Club in Gerrard Street, Soho. He befriended members of the Marxist Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) and contributed to their publication, Labour Monthly, but had not yet openly embraced Marxism.[33] Having earned a good reputation as a prehistorian, he was invited to other parts of Europe to study prehistoric artefacts. In 1922 he travelled to Vienna to examine unpublished material about the painted Neolithic pottery from Schipenitz, Bukovina, held in the Prehistoric Department of the Natural History Museum; he published his findings in the 1923 volume of the Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute.[34][35] Childe used this excursion to visit museums in Czechoslovakia and Hungary, bringing them to the attention of British archaeologists in a 1922 article in Man.[36] After returning to London, in 1922 Childe became a private secretary for three Members of Parliament, including John Hope Simpson and Frank Gray, both members of the centre-left Liberal Party.[37] Supplementing this income, Childe worked as a translator for the publishers Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. and occasionally lectured in prehistory at the London School of Economics.[38] "As the [Australian] Labour Party, starting with a band of inspired Socialists, degenerated into a vast machine for capturing political power, but did not know how to use that political power except for the profit of individuals; so the [One Big Union] will, in all likelihood, become just a gigantic apparatus for the glorification of a few bosses. Such is the history of all Labour organizations in Australia, and that is not because they are Australian, but because they are Labour." — Gordon Childe, How Labour Governs, 1923.[39] In 1923 the London Labour Company published his first book, How Labour Governs. Examining the Australian Labor Party and its connections to the Australian labour movement, it reflects Childe's disillusionment with the party, arguing that once elected, its politicians abandoned their socialist ideals in favour of personal comfort.[40] Childe's biographer Sally Green noted that How Labour Governs was of particular significance at the time because it was published just as the British Labour Party was emerging as a major player in British politics, threatening the two-party dominance of the Conservatives and Liberals; in 1923 Labour formed their first government.[41] Childe planned a sequel expanding on his ideas, but it was never published.[42] In May 1923 he visited the museums in Lausanne, Bern, and Zürich to study their prehistoric artefact collections; that year he became a member of the Royal Anthropological Institute. In 1925, he became the institute's librarian, one of the only archaeological jobs available in Britain, through which he began cementing connections with scholars across Europe.[43] His job made him well known in Britain's small archaeological community; he developed a great friendship with O. G. S. Crawford, the archaeological officer to the Ordnance Survey, influencing Crawford's move toward socialism and Marxism.[44] In 1925, Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co published Childe's second book, The Dawn of European Civilisation, in which he synthesised the data about European prehistory that he had been exploring for several years. An important work, it was released when there were few professional archaeologists across Europe and most museums focused on their locality; The Dawn was a rare example that looked at the larger picture across the continent. Its importance was also due to the fact that it introduced the concept of the archaeological culture into Britain from continental scholarship, thereby aiding in the development of culture-historical archaeology.[45] Childe later said the book "aimed at distilling from archaeological remains a preliterate substitute for the conventional politico-military history with cultures, instead of statesmen, as actors, and migrations in place of battles".[46] In 1926 he published a successor, The Aryans: A Study of Indo-European Origins, exploring the theory that civilisation diffused northward and westward into Europe from the Near East via an Indo-European linguistic group known as the Aryans; with the ensuing racial use of the term "Aryan" by the German Nazi Party, Childe avoided mention of the book.[47] In these works, Childe accepted a moderate version of diffusionism, the idea that cultural developments diffuse from one place to others, rather than being independently developed in many places. In contrast to the hyper-diffusionism of Grafton Elliot Smith, Childe suggested that although most cultural traits spread from one society to another, it was possible for the same traits to develop independently in different places.[48] |

生い立ち 子供時代:1892年~1910年 チャイルドは1892年4月14日にシドニーで生まれた[1]。イギリス系の中流階級の夫婦であったスティーヴン・ヘンリー・チャイルド牧師(1844- 1923)とハリエット・イライザ・チャイルド、旧姓ゴードン(1853-1910)の間に生まれた唯一の子供であった[2]。英国国教会の司祭の息子で あったスティーヴン・チャイルドは、ケンブリッジ大学で学士号を取得した後、1867年に英国国教会に叙階された。教師となった1871年にメアリー・エ レン・ラッチフォードと結婚し、5人の子供をもうけた[3]。1886年11月22日、スティーヴンはハリエット・ゴードンと結婚した。ゴードンの父親は アレクサンダー・ゴードンだった[4]。 [5] ゴードン・チルドは、シドニーの西、ブルー・マウンテンズのウェントワース・フォールズにある父親の豪邸、シャレー・フォンテネルで5人の異母兄妹ととも に育てられた[6]。チルド牧師はセント・トーマス教区の牧師として働いたが、信徒と口論したり、予定外の休暇を取ったりして不人気だった[6]。 1907年、シドニー・チャーチ・オブ・イングランド・グラマー・スクールに通い始め、1909年にジュニア・マトリシペーションを、1910年にシニ ア・マトリシペーションを取得した[7]。学校では古代史、フランス語、ギリシア語、ラテン語、幾何学、代数学、三角法を学び、すべての科目で良い成績を 収めたが、外見と運動不足の体格のせいでいじめられた[8]。1910年7月に母親が亡くなり、父親はすぐに再婚した。 [特に母の死後、父との関係はぎくしゃくし、宗教と政治について意見が対立した。牧師は敬虔なクリスチャンで保守的であったが、息子は無神論者で社会主義 者であった[9]。 シドニーとオックスフォードの大学:1911-1917年 1911年、チャイルドはシドニー大学で古典学の学位を取得するために学ぶ。文字資料が中心であったが、考古学者ハインリッヒ・シュリーマンとアーサー・ エヴァンスの研究を通じて、古典考古学に初めて触れた[10]。社会主義への関心が高まり、カール・マルクスやフリードリッヒ・エンゲルスの著作、哲学者 G・W・F・ヘーゲルの著作を読む。 「私のオックスフォードでの訓練は、ブロンズ像、テラコッタ、陶器(少なくとも絵が描かれていれば)が立派なものである一方、石器や骨董品は無作法なものであるという古典主義の伝統の中で行われた。」 - ゴードン・チャイルド、1957年[14]。 学業を続けたい彼は、200ポンドのクーパー大学院奨学金を得て、イギリスのオックスフォード大学のクイーンズ・カレッジの授業料を支払うことができた。 第一次世界大戦が勃発した直後の1914年8月、彼はSSオルソヴァ号でイギリスに向けて出航した[15]。クイーンズ・カレッジでは、古典考古学のディ プロマと、それに続くリテラエ・フマニオーレスの学位取得を目指したが、前者を取得することはなかった[16]。 [1915年、『Journal of Hellenic Studies』誌に最初の学術論文「ミニヤン焼の年代と起源について」を発表し、翌年には文学士論文「The Influence of Indo-Europeans in Prehistoric Greece」を発表し、文献学と考古学の証拠を組み合わせることに関心を示した[18]。 オックスフォードでは社会主義運動に積極的に参加し、保守的な大学当局と対立した。左翼改革派のオックスフォード大学フェビアン協会の名物会員となり、 1915年に同協会がフェビアン協会との分裂を経てオックスフォード大学社会主義協会に名称を変更した際も、彼はそこにいた[19]。彼の親友で同居人 は、熱烈な社会主義者でマルクス主義者のラジャニ・パルメ・ダットだった。イギリスが第一次世界大戦の真っ只中にあった頃、イギリスを拠点とする社会主義 者の多くは、政府が徴兵制を義務付けていたにもかかわらず、軍隊に入隊することを拒否した。彼らは、ヨーロッパの帝国主義諸国の支配階級が、労働者階級を 犠牲にして自分たちの利益のために戦争を仕掛けていると考えていた。これらの社会主義者は、階級闘争だけが自分たちが関心を持つべき争いだと考えていた。 ダットは戦闘を拒否したために投獄され、チルダは彼や他の社会主義者、平和主義者の良心的兵役拒否者の釈放を求める運動を行った。チャイルドは入隊する必 要はなかったが、その理由はおそらく健康と視力が悪かったからであろう[21]。チャイルドの反戦感情は当局に懸念され、諜報機関MI5はチャイルドの ファイルを作成し、郵便物は傍受され、チャイルドは監視下に置かれた[22]。 オーストラリアでの初期のキャリア: 1918-1921  1919年から1921年まで、チャイルドは左翼政治家ジョン・ストーリーの個人秘書として働く。 1917年8月、チャイルドはオーストラリアに戻る。社会主義者の扇動家として知られたチャイルドは、治安当局の監視下に置かれ、郵便物を傍受された [24]。1918年、チャイルドはシドニー大学セント・アンドリューズ・カレッジの上級講師となり、シドニーの社会主義・反徴兵運動に加わる。1918 年の復活祭には、ビリー・ヒューズ首相の徴兵制導入計画に反対する団体「戦争回避のためのオーストラリア民主統制連合」が主催した第3回州間講和会議で演 説した。この会議は社会主義を強調したもので、その報告書は、国際戦争を終わらせる最善の望みは「資本主義体制の廃止」であると主張した。チャイルドが参 加したというニュースはセント・アンドリューズ・カレッジの校長にも届き、校長はスタッフの多くの反対にもかかわらずチャイルドに辞職を強要した [25]。 職員はチュートリアルクラス部で古代史の講師として仕事を確保したが、大学総長のウィリアム・カレンは、彼が学生に社会主義を広めることを恐れ、彼を解雇 した[26]。 左翼社会はこれをチャイルドの公民権の侵害として非難し、中道左派の政治家ウィリアム・マッケルとT. チャイルドは1918年10月にクイーンズランド州メリーボローに移り、メリーボロー・ボーイズ・グラマー・スクールでラテン語を教えることになった。こ こでも彼の政治的所属が知られるようになり、地元の保守派グループやメリーボロ・クロニクル紙から反対運動を受け、一部の生徒から罵声を浴びることになっ た。彼はすぐに辞職した[28]。 大学当局から学者としてのキャリアを禁じられることを悟ったチャイルドは、左翼運動に就職先を求めた。1919年8月、当時ニューサウスウェールズ州国民 党政権と対立していた中道左派労働党の有力メンバーであった政治家ジョン・ストーリーの私設秘書兼スピーチ・ライターになった。ストーリーはシドニー郊外 のバルメインを代表するニュー・サウス・ウェールズ州議会議員であり、労働党が選挙で勝利した1920年には州首相となった[29]。労働党内で働くこと で、チャイルドは労働党の活動をより深く理解することができた。 [1921 年、ストーリーはチャイルドをロンドンに派遣し、ニューサウスウェールズ州の動向について英国の報道機関に最新情報を提供させたが、ストーリーは12月に 死去し、続くニューサウスウェールズ州選挙でジョージ・フラーが首相を務める国民党政権が復活した。フラーはチャイルドの仕事を不要と考え、1922年初 めにチャイルドの雇用を打ち切った[31]。 ロンドンと初期の著書 1922-1926 オーストラリアで学問的な仕事を見つけることができなかったチャイルドはイギリスに留まり、ロンドン中心部のブルームズベリーに部屋を借りて、大英博物館 や王立人類学研究所の図書館で多くの時間を勉強に費やした[32]。ロンドンの社会主義運動の活動的なメンバーであったチャイルドは、ソーホーのジェラー ド・ストリートにあった1917クラブで左翼主義者たちと交流した。マルクス主義のイギリス共産党(CPGB)のメンバーと親しくなり、彼らの出版物 『Labour Monthly』に寄稿したが、まだ公然とマルクス主義を受け入れていたわけではなかった[33]。先史学者として高い評価を得ていた彼は、先史時代の遺 物を研究するためにヨーロッパ各地に招かれた。1922年にはウィーンを訪れ、自然史博物館の先史学部門に所蔵されていたブコヴィナ州シペニッツの新石器 時代の彩色土器に関する未発表の資料を調査し、その成果を1923年の『王立人類学研究所紀要』(Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute)に発表した[34][35]。 [36] ロンドンに戻ったチルダは1922年、中道左派自由党のジョン・ホープ・シンプソンやフランク・グレイら3人の国会議員の私設秘書となった[37]。この 収入を補うため、チルダは出版社ケガン・ポール・トレンチ・トリューブナー社で翻訳者として働き、ロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクスで先史学の講義 をすることもあった[38]。 「オーストラリアの)労働党が、触発された社会主義者の一団から出発して、政治権力を獲得するための巨大な機械に堕落したが、その政治権力を個人の利益の ため以外にどのように使うかを知らなかったように、[ワン・ビッグ・ユニオン]は、おそらく、少数のボスを美化するための巨大な装置にすぎないだろう。こ のような歴史は、オーストラリアにおけるすべての労働組合の歴史であり、それは彼らがオーストラリア人だからではなく、労働者だからである。" - ゴードン・チルド『労働はいかに統治するか』1923 年[39]。 1923年、ロンドン労働社は彼の最初の著書『How Labour Governs』を出版した。オーストラリア労働党とオーストラリアの労働運動とのつながりを検証したこの本は、チャイルドの同党への幻滅を反映してお り、同党の政治家たちはいったん当選すると、個人的な安楽を優先して社会主義的理想を放棄してしまうと主張している[40]。 [40]チャイルドの伝記作家サリー・グリーンは、『労働者の統治法(How Labour Governs)』が当時特に重要な意味をもっていたのは、英国労働党が英国政治の主要な担い手として台頭し、保守党と自由党の二大政党支配を脅かすよう になった矢先に出版されたからだと述べている。チャイルドは彼の考えを発展させた続編を計画したが、出版されることはなかった[42]。 1923年5月、ローザンヌ、ベルン、チューリッヒの博物館を訪れ、先史時代の遺物コレクションを研究した。1925年、彼は英国で唯一の考古学の仕事のひとつである研究所の司書となり、その仕事を通じてヨーロッパ中の学者とのつながりを築き始めた[43]。 1925年、Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Coはチャイルドの2冊目の著書『ヨーロッパ文明の夜明け』を出版した。この重要な著作は、ヨーロッパ全土に専門の考古学者がほとんどおらず、ほとんどの 博物館がそれぞれの地域に焦点を当てていた時代に発表された。その重要性は、大陸の学問から考古学的文化という概念をイギリスに導入し、文化史的考古学の 発展を助けたという事実にも起因している[45]。後にチルドは、この本は「政治家ではなく文化をアクターとし、戦いの代わりに移住を伴う、従来の政治・ 軍事史に代わる前文書的なものを考古学的遺跡から抽出することを目指した」と述べている[46]: アーリア人として知られるインド・ヨーロッパ語族を経由して、文明は近東からヨーロッパへと北上し、西へと拡散していったという説を探求している。グラフ トン・エリオット・スミスの超拡散主義とは対照的に、チャイルドはほとんどの文化的特質はある社会から別の社会へと広がっていくが、同じ特質が異なる場所 で独立して発展することは可能であると示唆していた[48]。 |

| Later life Abercromby Professor of Archaeology: 1927–1946 "Because the early Hindus and Persians did really call themselves Aryans, this term was adopted by some nineteenth-century philologists to designate the speakers of the 'parent tongue'. It is now applied scientifically only to the Hindus, Iranian peoples and the rulers of Mitanni whose linguistic ancestors spoke closely related dialects and even worshipped common deities. As used by Nazis and anti-semites generally, the term 'Aryan' means as little as the words 'Bolshie' and 'Red' in the mouths of crusted tories." — Gordon Childe criticising the Nazi conception of an Aryan race, What Happened in History, 1942.[49] In 1927, the University of Edinburgh offered Childe the post of Abercromby Professor of Archaeology, a new position established in the bequest of the prehistorian Lord Abercromby. Although sad to leave London, Childe took the job, moving to Edinburgh in September 1927.[50] Aged 35, Childe became the "only academic prehistorian in a teaching post in Scotland". Many Scottish archaeologists disliked Childe, regarding him as an outsider with no specialism in Scottish prehistory; he wrote to a friend that "I live here in an atmosphere of hatred and envy."[51] He nevertheless made friends in Edinburgh, including archaeologists like W. Lindsay Scott, Alexander Curle, J. G. Callender, and Walter Grant, as well as non-archaeologists like the physicist Charles Galton Darwin, becoming godfather to Darwin's youngest son.[52] Initially lodging at Liberton, he moved into the semi-residential Hotel de Vere on Eglinton Crescent.[53] At Edinburgh University, Childe focused on research rather than teaching. He was reportedly kind to his students but had difficulty talking to large audiences; many students were confused that his BSc degree course in archaeology was structured counter-chronologically, dealing with the more recent Iron Age first before progressing backward to the Palaeolithic.[54] Founding the Edinburgh League of Prehistorians, he took his more enthusiastic students on excavations and invited guest lecturers to visit.[55] An early proponent of experimental archaeology, he involved his students in his experiments; in 1937 he used this method to investigate the vitrification process evident at several Iron Age forts in northern Britain.[56] Childe regularly travelled to London to visit friends, among whom was Stuart Piggott, another influential British archaeologist who succeeded Childe as Edinburgh's Abercromby Professor.[57] Another friend was Grahame Clark, whom Childe befriended and encouraged in his research.[58] The trio were elected onto the committee of the Prehistoric Society of East Anglia. At Clark's suggestion, in 1935 they used their influence to convert it into a nationwide organisation, the Prehistoric Society, of which Childe was elected president.[59] Membership of the group grew rapidly; in 1935 it had 353 members and by 1938 it had 668.[60] Childe spent much time in continental Europe and attended many conferences there, having learned several European languages. In 1935, he first visited the Soviet Union, spending 12 days in Leningrad and Moscow; impressed with the socialist state, he was particularly interested in the social role of Soviet archaeology. Returning to Britain, he became a vocal Soviet sympathiser and avidly read the CPGB's Daily Worker, although was heavily critical of certain Soviet policies, particularly the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact with Nazi Germany.[61] His socialist convictions led to an early denunciation of European fascism, and he was outraged by the Nazi co-option of prehistoric archaeology to glorify their own conceptions of an Aryan racial heritage.[62] Supportive of the British government's decision to fight the fascist powers in the Second World War, he thought it probable that he was on a Nazi blacklist and made the decision to drown himself in a canal should the Nazis conquer Britain.[63] Though opposing fascist Germany and Italy, he also criticised the imperialist, capitalist governments of the United Kingdom and United States: he repeatedly described the latter as being full of "loathsome fascist hyenas".[64] This did not prevent him from visiting the U.S. In 1936 he addressed a Conference of Arts and Sciences marking the tercentenary of Harvard University; there, the university awarded him an honorary Doctor of Letters degree.[65] He returned in 1939, lecturing at Harvard, the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of Pennsylvania.[66] Excavations  Neolithic dwellings at Skara Brae in Orkney, the site excavated by Childe 1927–30 Childe's university position meant he was obliged to undertake archaeological excavations, something he loathed and believed he did poorly.[67] Students agreed, but recognised his "genius for interpreting evidence".[68] Unlike many contemporaries, he was scrupulous with writing up and publishing his findings, producing almost annual reports for the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland and, unusually, ensuring that he acknowledged the help of every digger.[55] His best-known excavation was undertaken from 1928 to 1930 at Skara Brae in the Orkney Islands. Having uncovered a well-preserved Neolithic village, in 1931 he published the excavation results in a book titled Skara Brae. He made an error of interpretation, erroneously attributing the site to the Iron Age.[69] During the excavation, Childe got on particularly well with the locals; for them, he was "every inch the professor" because of his eccentric appearance and habits.[70] In 1932, Childe, collaborating with the anthropologist C. Daryll Forde, excavated two Iron Age hillforts at Earn's Hugh on the Berwickshire coast,[71] while in June 1935 he excavated a promontory fort at Larriban near to Knocksoghey in Northern Ireland.[72] Together with Wallace Thorneycroft, another Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, Childe excavated two vitrified Iron Age forts in Scotland, at Finavon, Angus (1933–34) and at Rahoy, Argyllshire (1936–37).[73] In 1938, he and Walter Grant oversaw excavations at the Neolithic settlement of Rinyo; their investigation ceased during the Second World War, but resumed in 1946.[74] Publications Childe continued writing and publishing books on archaeology, beginning with a series of works following on from The Dawn of European Civilisation and The Aryans by compiling and synthesising data from across Europe. First was The Most Ancient Near East (1928), which assembled information from across Mesopotamia and India, setting a background from which the spread of farming and other technologies into Europe could be understood.[75] This was followed by The Danube in Prehistory (1929) which examined the archaeology along the Danube river, recognising it as the natural boundary dividing the Near East from Europe; Childe believed it was via the Danube that new technologies travelled westward. Although Childe had used culture-historical approaches in earlier publications, The Danube in Prehistory was his first publication to provide a specific definition of the concept of an archaeological culture, revolutionising the theoretical approach of British archaeology.[76] "We find certain types of remains—pots, implements, ornaments, burial rites, house forms—constantly recurring together. Such a complex of regularly associated traits we shall term a 'cultural group' or just a 'culture'. We assume that such a complex is the material expression of what today would be called a people." — Gordon Childe, The Danube in Prehistory, 1929.[77] Childe's next book, The Bronze Age (1930), dealt with the Bronze Age in Europe, and displayed his increasing adoption of Marxist theory as a means of understanding how society functioned and changed. He believed metal was the first indispensable article of commerce, and that metal-smiths were therefore full-time professionals who lived off the social surplus.[78] In 1933, Childe travelled to Asia, visiting Iraq—a place he thought "great fun"—and India, which he felt was "detestable" due to the hot weather and extreme poverty. Touring archaeological sites in the two countries, he opined that much of what he had written in The Most Ancient Near East was outdated, going on to produce New Light on the Most Ancient Near East (1935), in which he applied his Marxist-influenced ideas about the economy to his conclusions.[79] After publishing Prehistory of Scotland (1935), Childe produced one of the defining books of his career, Man Makes Himself (1936). Influenced by Marxist views of history, Childe argued that the usual distinction between (pre-literate) prehistory and (literate) history was a false dichotomy and human society has progressed through a series of technological, economic, and social revolutions. These included the Neolithic Revolution, when hunter-gatherers began settling in permanent farming communities, through to the Urban Revolution, when society moved from small towns to the first cities, and up to more recent times, when the Industrial Revolution changed the nature of production.[80] After the outbreak of the Second World War, Childe was unable to travel across Europe, instead focusing on writing Prehistoric Communities of the British Isles (1940).[81] Childe's pessimism regarding the war's outcome led him to believe that "European civilization—capitalist and Stalinist alike—was irrevocably headed for a Dark Age."[82] In this state of mind he produced a sequel to Man Makes Himself titled What Happened in History (1942), an account of human history from the Palaeolithic through to the fall of the Roman Empire. Although Oxford University Press offered to publish the work, he released it through Penguin Books because they could sell it at a cheaper price, something he believed pivotal in providing knowledge for those he called "the masses".[83] This was followed by two short works, Progress and Archaeology (1944) and The Story of Tools (1944), the latter an explicitly Marxist text written for the Young Communist League.[84] Institute of Archaeology, London: 1946–1956  The Neolithic passage tomb of Maes Howe on Mainland, Orkney, excavated by Childe 1954–55 In 1946, Childe left Edinburgh to take up the position as director and professor of European prehistory at the Institute of Archaeology (IOA) in London. Anxious to return to London, he had kept silent over his disapproval of government policies so he would not be prevented from getting the job.[85] He took up residence in the Isokon building near to Hampstead.[86] Located in St John's Lodge in the Inner Circle of Regent's Park, the IOA was founded in 1937, largely by the archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler, but until 1946 relied primarily on volunteer lecturers.[87] Childe's relationship with the conservative Wheeler was strained, for their personalities were very different; Wheeler was an extrovert who pursued the limelight, was an efficient administrator, and was intolerant of others' shortcomings, while Childe lacked administrative skill, and was tolerant of others.[88] Childe was popular among the institute's students, who saw him as a kindly eccentric; they commissioned a bust of Childe from Marjorie Maitland Howard. His lecturing was nevertheless considered poor, as he often mumbled and walked into an adjacent room to find something while continuing to talk. He further confused his students by referring to the socialist states of eastern Europe by their full official titles, and by referring to towns by their Slavonic names rather than the names with which they were better known in English.[89] He was deemed better at giving tutorials and seminars, where he devoted more time to interacting with his students.[90] As Director, Childe was not obliged to excavate, though he did undertake projects at the Orkney Neolithic burial tombs of Quoyness (1951) and Maes Howe (1954–55).[91] In 1949 he and Crawford resigned as fellows of the Society of Antiquaries. They did so to protest the selection of James Mann—keeper of the Tower of London's armouries—as the society's president, believing Wheeler (a professional archaeologist) was a better choice.[92] Childe joined the editorial board of the periodical Past & Present, founded by Marxist historians in 1952.[93] During the early 1950s, he also became a board member for The Modern Quarterly—later The Marxist Quarterly—working alongside the board's chairman Rajani Palme Dutt, his best friend and flatmate from his Oxford days.[94] He authored occasional articles for Palme Dutt's socialist journal, the Labour Monthly, but disagreed with him over the Hungarian Revolution of 1956; Palme Dutt defended the Soviet Union's decision to quash the revolution using military force, but Childe, like many Western socialists, strongly opposed it. The event made Childe abandon faith in the Soviet leadership, but not in socialism or Marxism.[95] He retained a love of the Soviet Union, having visiting on multiple occasions; he was also involved with a CPGB satellite body, the Society for Cultural Relations with the USSR, and served as president of its National History and Archaeology Section from the early 1950s until his death.[96] In April 1956, Childe was awarded the Gold Medal of the Society of Antiquaries for his services to archaeology.[97] He was invited to lecture in the United States on multiple occasions, by Robert Braidwood, William Duncan Strong, and Leslie White, but the U.S. State Department barred him from entering the country due to his Marxist beliefs.[98] Whilst working at the institute, Childe continued writing and publishing books dealing with archaeology. History (1947) promoted a Marxist view of the past and reaffirmed Childe's belief that prehistory and literate history must be viewed together, whilst Prehistoric Migrations (1950) displayed his views on moderate diffusionism.[99] In 1946 he also published a paper in the Southwestern Journal of Anthropology. This was "Archaeology and Anthropology", which argued that the disciplines of archaeology and anthropology should be used in tandem, an approach that would be widely accepted in the decades following his death.[100] Retirement and death: 1956–1957 In mid-1956, Childe retired as IOA director a year prematurely. European archaeology had rapidly expanded during the 1950s, leading to increasing specialisation and making the synthesising that Childe was known for increasingly difficult.[101] That year, the institute was moving to Gordon Square, Bloomsbury, and Childe wanted to give his successor, W.F. Grimes, a fresh start in the new surroundings.[102] To commemorate his achievements, the Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society published a Festschrift edition on the last day of his directorship containing contributions from friends and colleagues all over the world, something that touched Childe deeply.[102] Upon his retirement, he told many friends he planned to return to Australia, visit his relatives, and commit suicide; he was terrified of becoming old, senile, and a burden on society, and suspected he had cancer.[103] Subsequent commentators suggested that a core reason for his suicidal desires was a loss of faith in Marxism following the Hungarian Revolution and Nikita Khrushchev's denouncement of Joseph Stalin,[104] although Bruce Trigger dismissed this explanation, noting that while Childe was critical of Soviet foreign policy, he never saw the state and Marxism as synonymous.[105]  A view of Grose Valley from Govetts Leap, the site where Childe chose to end his life Sorting out his affairs, Childe donated most of his library and all of his estate to the institute.[106] After a February 1957 holiday visiting archaeological sites in Gibraltar and Spain, he sailed to Australia, reaching Sydney on his 65th birthday. Here, the University of Sydney, which had once barred him from working there, awarded him an honorary degree.[107] He travelled around the country for six months, visiting family members and old friends, but was unimpressed by Australian society, believing it reactionary, increasingly suburban, and poorly educated.[108] Looking into Australian prehistory, he found it a profitable field for research,[109] and lectured to archaeological and leftist groups on this and other topics, taking to Australian radio to criticise academic racism towards Indigenous Australians.[110] Writing personal letters to many friends,[111] he sent one to Grimes, requesting that it not be opened until 1968. In it, he described how he feared old age and stated his intention to take his own life, remarking that "life ends best when one is happy and strong."[112] On 19 October 1957, Childe went to the area of Govett's Leap in Blackheath, an area of the Blue Mountains where he had grown up. Leaving his hat, spectacles, compass, pipe, and Mackintosh raincoat on the cliffs, he fell 1000 feet (300 m) to his death.[113] A coroner ruled his death as accidental, but his death was recognised as suicide when his letter to Grimes was published in the 1980s.[114] His remains were cremated at the Northern Suburbs Crematorium, and his name added to a small family plaque in the Crematorium Gardens.[115] Following his death, an "unprecedented" level of tributes and memorials were issued by the archaeological community,[116] all, according to Ruth Tringham, testifying to his status as Europe's "greatest prehistorian and a wonderful human being".[117] |

その後の人生 アバクロンビー考古学教授:1927-1946年 初期のヒンズー教徒とペルシア人は自分たちのことをアーリア人と呼んでいたので、この言葉は19世紀の言語学者たちによって 「親語 」の話者を指す言葉として採用された。現在では、ヒンズー教徒、イラン人、ミタンニの支配者のうち、言語的祖先が密接に関連した方言を話し、共通の神々を 崇拝していた人々だけに科学的に適用されている。ナチスや反ユダヤ主義者一般が使う 「アーリア人 」という言葉は、「ボリシー 」や 「レッド 」という言葉と同じように、「カサカサした東欧人 」の口にはほとんど意味をなさない」。 - ゴードン・チャイルドは、ナチスのアーリア民族の概念を批判している、『歴史の中で起こったこと』、1942年[49]。 1927年、エディンバラ大学は、先史学者アバクロンビー卿の遺贈によって新設されたアバクロンビー考古学教授のポストをチルドに与えた。ロンドンを離れ ることを惜しみつつも、チャイルドはその職を引き受け、1927年9月にエジンバラに移った[50]。35歳のチャイルドは、「スコットランドで教壇に立 つ唯一のアカデミックな先史学者」となった。スコットランドの考古学者の多くはチルドをスコットランド先史学を専門としない部外者とみなして嫌っており、 彼は友人に「私はここで憎悪と嫉妬に満ちた雰囲気の中で暮らしている」と書き送っている[51]。当初はリバートンに下宿していたが、エグリントン・クレ セントにある半居住用のホテル・ド・ヴィアに移り住んだ[53]。 エディンバラ大学では、チャイルドは教えることよりも研究に専念した。多くの学生は、考古学の学士号取得コースが、旧石器時代に遡る前にまず最近の鉄器時 代を扱うという逆時系列的な構成になっていたことに困惑していた。 [54]エディンバラ先史学連盟を設立し、熱心な学生を発掘調査に連れて行ったり、ゲスト講師を招いたりした[55]。実験考古学を早くから提唱し、学生 を実験に参加させた。1937年にはこの方法を用いて、イギリス北部のいくつかの鉄器時代の砦で見られるガラス固化の過程を調査した[56]。 チャイルドは定期的にロンドンを訪れ、友人を訪ねた。その中には、チャイルドの後任としてエディンバラのアバクロンビー教授に就任した、同じく影響力のあ るイギリスの考古学者スチュアート・ピゴットもいた[57]。もう一人の友人はグラヘイム・クラークで、チャイルドは彼と親しくなり、彼の研究を奨励した [58]。クラークの提案により、1935年、彼らは影響力を行使してこの協会を全国的な組織である先史学会へと改組させ、チャイルドはその会長に選出さ れた[59]。同団体の会員数は急速に増加し、1935年には353名、1938年には668名となった[60]。 チャイルドはヨーロッパ大陸で多くの時間を過ごし、ヨーロッパの言語をいくつか習得し、多くの会議に出席した。1935年、彼は初めてソビエト連邦を訪 れ、レニングラードとモスクワで12日間を過ごした。社会主義国家に感銘を受けた彼は、ソビエト考古学の社会的役割に特に興味を持った。英国に戻ると、彼 は声高なソ連シンパとなり、CPGBの『デイリー・ワーカー』を熱心に読むようになったが、特定のソ連の政策、特にナチス・ドイツとのモロトフ=リッベン トロップ協定には激しく批判的だった[61]。彼の社会主義的信念は早くからヨーロッパのファシズムを非難することにつながり、ナチスがアーリア人種の遺 産という独自の概念を美化するために先史考古学を利用したことに憤慨した。 [62] 第二次世界大戦でファシスト勢力と戦うというイギリス政府の決定を支持したが、ナチスのブラックリストに載る可能性が高いと考え、ナチスがイギリスを征服 した場合は運河で溺死する決意をした。 [63] ファシズムのドイツとイタリアに反対しながらも、イギリスとアメリカの帝国主義的で資本主義的な政府も批判した。1936年には、ハーバード大学の創立 100周年を記念する芸術科学会議で演説を行い、同大学から名誉文学博士号を授与された[65]。1939年には再び訪米し、ハーバード大学、カリフォル ニア大学バークレー校、ペンシルベニア大学で講義を行った[66]。 発掘  1927年から30年にかけてチャイルドによって発掘されたオークニーのスカラ・ブレイの新石器時代の住居。 チャイルドは大学での立場上、考古学的な発掘調査を行うことを義務づけられていたが、それは彼にとって大嫌いなことであり、自分は下手なことをしたと考えていた[67]。学生たちもそれに同意していたが、彼の「証拠を解釈する天才」[68]を認めていた。 彼の最も有名な発掘調査は、1928年から1930年にかけてオークニー諸島のスカラ・ブレイで行われたものである。保存状態のよい新石器時代の村を発見 した彼は、1931年に発掘結果を『スカラ・ブレイ』という本にして出版した。発掘中、チャイルドは地元の人々と特に仲良くなった。風変わりな風貌と習慣 のため、地元の人々にとってチャイルドは「いかにも教授」であった[70]。 1932年、チルドは人類学者のC・ダリル・フォードと共同で、バーウィックシャー海岸のアーンズ・ヒューで2つの鉄器時代の丘砦を発掘し[71]、 1935年6月には北アイルランドのノックソヒーに近いラリバン(Larriban)で岬の砦を発掘した[72]。 [1938年には、ウォルター・グラントとともに新石器時代の集落であるリニョの発掘を監督した。 出版物 チャイルドは考古学に関する本の執筆と出版を続け、『ヨーロッパ文明の夜明け』と『アーリア人』に続く一連の著作で、ヨーロッパ全土のデータを編集・統合 した。最初の著作は『最も古代の近東』(The Most Ancient Near East、1928年)であり、メソポタミアとインド全域からの情報を収集し、農耕やその他の技術がヨーロッパに伝播した背景を明らかにした[75]。チ ルダはそれ以前の出版物でも文化史的アプローチを用いていたが、『先史時代のドナウ』は考古学的文化という概念の具体的な定義を提示した最初の出版物であ り、イギリス考古学の理論的アプローチに革命をもたらした[76]。 「われわれは、ある種の遺物-壺、道具、装飾品、埋葬儀礼、住居形態-が常に一緒に繰り返されていることを発見する。このような規則的に関連した形質の複 合体を、われわれは『文化集団』あるいは単に『文化』と呼ぶことにする。このような複合体は、今日では民族と呼ばれるものの物質的表現であると仮定す る」。 - ゴードン・チルド『先史時代のドナウ』1929年[77]。 チャイルドの次の著書である『青銅器時代』(1930年)はヨーロッパの青銅器時代を扱っており、社会がどのように機能し、変化していったかを理解する手 段として、マルクス主義理論を採用するようになっていた。1933年、チルダはアジアを旅行し、イラクを訪れたが、イラクは彼にとって「とても楽しい」場 所であり、インドは暑い気候と極度の貧困のために「嫌悪すべき」場所であった。この2カ国の考古学的遺跡を巡り、彼は『最も古代の近東』で書いたことの多 くが時代遅れであると意見し、『最も古代の近東に関する新しい光』(New Light on the Most Ancient Near East, 1935)を出版した。 スコットランドの先史』(Prehistory of Scotland、1935年)を出版した後、チャイルドは彼のキャリアを決定づけた書物のひとつである『Man Makes Himself』(Man Makes Himself、1936年)を出版した。マルクス主義の歴史観の影響を受けたチャイルドは、(文字のない)先史時代と(文字のある)歴史時代という通常 の区別は誤った二分法であり、人間社会は一連の技術的、経済的、社会的革命を経て進歩してきたと主張した。これには、狩猟採集民が永続的な農耕共同体に定 住し始めた新石器革命から、社会が小さな町から最初の都市へと移行した都市革命、そして産業革命によって生産の性質が変化した最近の時代までが含まれる [80]。 第二次世界大戦勃発後、チャイルドはヨーロッパを横断することができず、代わりに『Prehistoric Communities of the British Isles(イギリス諸島の先史時代の共同体)』(1940年)の執筆に集中した[81]。 このような心境で、彼は『What Happened in History』(1942年)というタイトルの、旧石器時代からローマ帝国の滅亡に至る人類の歴史を描いた『What Happened in History』の続編を執筆した[82]。この著作はオックスフォード大学出版局から出版を申し込まれたものの、彼はペンギン・ブックスから発売した。 ペンギン・ブックスの方が安い値段で売ることができたからであり、彼が「大衆」と呼ぶ人々に知識を提供する上で極めて重要なことだと考えていた[83]。 ロンドン考古学研究所:1946年-1956年  1954-55年にチャイルドによって発掘されたオークニー、メインランドのメース・ハウの新石器時代の通路墓 1946年、チャイルドはエディンバラを離れ、ロンドンの考古学研究所(IOA)の所長兼ヨーロッパ先史学教授に就任した。ロンドンに戻りたがっていた彼 は、政府の政策に反対していたため、その職に就くことを妨げられないように沈黙を守っていた[85]。彼はハムステッドに近いイソコンビルに住居を構えた [86]。 リージェンツ・パークのインナーサークルにあるセント・ジョンズ・ロッジに位置するIOAは、1937年に主に考古学者のモーティマー・ウィーラーによっ て設立されたが、1946年までは主にボランティアの講師に頼っていた。 [ホイラーは脚光を浴びることを追い求める外向的な性格で、効率的な管理者であり、他人の欠点に寛容であった。それにもかかわらず、彼の講義は稚拙であっ たと考えられている。というのも、彼はしばしばぶつぶつ言いながら隣の部屋に行き、何かを探しながら話を続けたからである。彼はさらに、東ヨーロッパの社 会主義国家を正式名称で呼んだり、町を英語でよく知られている名前ではなくスラヴ名で呼んだりして、学生たちを混乱させた[89]。 [チャイルドは、チュートリアルやセミナーで学生との交流により多くの時間を割いていた[90]。チャイルドはディレクターとして、クオイネス(1951 年)とメイス・ハウ(1954-55年)のオークニー新石器時代墳墓でのプロジェクトを引き受けたものの、発掘をする義務はなかった[91]。 1949年、彼とクロフォードは古物協会のフェローを辞任した。1952年にマルクス主義の歴史家たちによって創刊された定期刊行物『Past & Present』の編集委員会に加わった[93]。 1950年代初頭には『The Modern Quarterly』(後の『The Marxist Quarterly』)の理事にも就任し、オックスフォード時代からの親友であり同居人であった同誌のラジャニ・パルメ・ダット会長とともに働いた。 [パルメ・ダットの社会主義雑誌『労働月報』に時折記事を寄稿していたが、1956年のハンガリー革命をめぐってパルメ・ダットと意見が対立した。パル メ・ダットは、軍事力を行使して革命を鎮圧するというソビエト連邦の決定を擁護したが、チルダは多くの西欧の社会主義者と同様、それに強く反対した。この 出来事によって、チルダはソ連の指導者への信頼は捨てたが、社会主義やマルクス主義への信頼は捨てなかった[95]。彼はソ連への愛情を持ち続け、何度も ソ連を訪れた。彼はまた、CPGBの衛星組織である対ソ文化関係協会にも関わり、1950年代初頭から亡くなるまで、同協会の国家史・考古学部門の会長を 務めた[96]。 1956年4月、チャイルドは考古学への貢献が認められ、古美術学会のゴールド・メダルを授与された[97]。 ロバート・ブレイドウッド、ウィリアム・ダンカン・ストロング、レスリー・ホワイトから何度もアメリカでの講演に招かれたが、マルクス主義の信条を理由に アメリカ国務省から入国を禁じられた[98]。History』(1947年)はマルクス主義的な過去観を促進し、先史時代と文字史は一緒に見なければな らないというチルドの信念を再確認するものであり、『Prehistoric Migrations』(1950年)は穏健な拡散主義に対する彼の見解を示すものであった[99]。これは「考古学と人類学」(Archaeology and Anthropology)であり、考古学と人類学の学問を並行して用いるべきであると主張したもので、このアプローチは彼の死後数十年で広く受け入れら れることになる[100]。 引退と死: 1956-1957 1956年半ば、チャイルドはIOA理事を1年早く退任した。その年、研究所はブルームズベリーのゴードン・スクエアに移転しており、チャイルドは後任の W.F.グライムスに新しい環境で新たなスタートを切らせたかったのである[102]。チャイルドの功績を記念して、Proceedings of the Prehistoric Societyは所長職の最終日に、世界中の友人や同僚からの寄稿を収録したフェストシュラフト版を出版した。 [引退後、彼は多くの友人に、オーストラリアに戻り、親戚を訪ね、自殺するつもりだと話した。老齢になり、老衰し、社会の重荷になることを恐れ、癌の疑い があった。 [その後の論者たちは、彼の自殺願望の核心的な理由は、ハンガリー革命とニキータ・フルシチョフによるヨシフ・スターリンの糾弾を受けてマルクス主義への 信頼を失ったことであると示唆したが[104]、ブルース・トリガーはこの説明を否定し、チルドはソ連の外交政策に批判的であったが、国家とマルクス主義 を同義語として見たことはなかったと指摘した[105]。  チャイルドが人生の終焉を選んだ場所、ゴヴェッツリープからグロース渓谷を望む。 1957年2月の休暇でジブラルタルとスペインの遺跡を訪れた後、オーストラリアに渡り、65歳の誕生日にシドニーに到着した。シドニーでは、かつて彼の 研究を禁じていたシドニー大学から名誉学位が授与された[107]。6ヶ月間オーストラリア国内を旅行し、家族や旧友を訪ねたが、オーストラリア社会には 感銘を受けず、反動的で、郊外化が進み、教育水準が低いと考えた[108]。 多くの友人に個人的な手紙を書いたが[111]、そのうちの一通をグライムスに送り、1968年まで開封しないよう要請した。1957年10月19日、 チャイルドは自分が育ったブルー・マウンテンズのブラックヒースのゴヴェッツ・リープに向かった。帽子、眼鏡、コンパス、パイプ、マッキントッシュのレイ ンコートを崖の上に置き去りにしたまま、彼は300メートル(1000フィート)落下して死亡した。 [114] 彼の遺体はノーザン・サバーブズ火葬場で荼毘に付され、火葬場の庭園にある小さな家族用のプレートに彼の名前が加えられた[115]。 彼の死後、考古学コミュニティから「前例のない」レベルの賛辞と追悼文が発表され[116]、ルース・トリンガムによれば、そのすべてが彼の「ヨーロッパ で最も偉大な先史学者であり、素晴らしい人間」としての地位を証言するものであった[117]。 |

| Archaeological theory "By far the most important source [of Childe's thinking], especially in the early stages of his career, was the highly developed western European archaeology, which had been established as a scientific discipline for over a century. His research and publications took the form mainly of contributions to the development of that tradition. His thinking was also influenced, however, by ideas derived from Soviet archaeology and American anthropology as well as from more remote disciplines. He had a subsidiary interest in philosophy and politics, and was more concerned than were most archaeologists of his time with justifying the social value of archaeology." — Bruce Trigger, 1980.[118] The biographer Sally Green noted that Childe's beliefs were "never dogmatic, always idiosyncratic" and "continually changing throughout his life".[119] His theoretical approach blended together Marxism, diffusionism, and functionalism.[120] Childe was critical of the evolutionary archaeology dominant during the nineteenth century. He believed archaeologists who adhered to it placed a greater emphasis on artefacts than on the humans who had made them.[121] Like most archaeologists in Western Europe and the United States at the time, Childe did not regard humans as naturally inventive or inclined to change; thus, he tended to perceive social change in terms of diffusion and migration rather than internal development or cultural evolution.[122] During the decades in which Childe was working, most archaeologists adhered to the three-age system first developed by the Danish antiquarian Christian Jürgensen Thomsen. This system rested upon an evolutionary chronology that divided prehistory into the Stone Age, Bronze Age, and Iron Age, but Childe highlighted that many of the world's societies were still effectively Stone Age in their technology.[123] He nevertheless saw it as a useful model for analysing socio-economic development when combined with a Marxist framework.[124] He therefore used technological criteria for dividing up prehistory into three ages, but instead used economic criteria for sub-dividing the Stone Age into the Palaeolithic and Neolithic, rejecting the concept of the Mesolithic as useless.[125] Informally, he adopted the division of past societies into the framework of "savagery", "barbarism", and "civilisation" that Engels had employed.[122] Culture-historical archaeology In the early part of his career, Childe was a proponent of the culture-historical approach to archaeology, coming to be seen as one of its "founders and chief exponents".[126] Culture-historical archaeology revolved around the concept of "culture", which it had adopted from anthropology. This was "a major turning point in the history of the discipline", allowing archaeologists to look at the past through a spatial dynamic rather than a temporal one.[127] Childe adopted the concept of "culture" from the German philologist and archaeologist Gustaf Kossinna, although this influence might have been mediated through Leon Kozłowski, a Polish archaeologist who had adopted Kossina's ideas and who had a close association with Childe.[128] Trigger expressed the view that while adopting Kossina's basic concept, Childe displayed "no awareness" of the "racist connotations" Kossina had given it.[128] Childe's adherence to the culture-historical model is apparent in three of his books—The Dawn of European Civilisation (1925), The Aryans (1926) and The Most Ancient East (1928)—but in none of these does he define what he means by "culture".[129] Only later, in The Danube in Prehistory (1929), did Childe give "culture" a specifically archaeological definition.[130] In this book, he defined a "culture" as a set of "regularly associated traits" in the material culture—i.e. "pots, implements, ornaments, burial rites, house forms"—that recur across a given area. He said that in this respect a "culture" was the archaeological equivalent of a "people". Childe's use of the term was non-racial; he considered a "people" to be a social grouping, not a biological race.[131] He opposed the equation of archaeological cultures with biological races—as various nationalists across Europe were doing at the time—and vociferously criticised Nazi uses of archaeology, arguing that the Jewish people were not a distinct biological race but a socio-cultural grouping.[132] In 1935, he suggested that culture worked as a "living functioning organism" and emphasised the adaptive potential of material culture; in this he was influenced by anthropological functionalism.[133] Childe accepted that archaeologists defined "cultures" based on a subjective selection of material criteria; this view was later widely adopted by archaeologists like Colin Renfrew.[134] Later in his career, Childe tired of culture-historical archaeology.[122] By the late 1940s he was questioning the utility of "culture" as an archaeological concept and thus the basic validity of the culture-historical approach.[135] McNairn suggested that this was because the term "culture" had become popular across the social sciences in reference to all learned modes of behaviour, and not just material culture as Childe had done.[136] By the 1940s, Childe was doubtful as to whether a certain archaeological assemblage or "culture" really reflected a social group who had other unifying traits, such as a shared language.[137] In the 1950s, Childe was comparing the role culture-historical archaeology had among prehistorians to the place of the traditional politico-military approach among historians.[122] Marxist archaeology "To me Marxism means effectively a way of approach to and a methodological device for the interpretation of historical and archaeological material and I accept it because and in so far as it works. To the average communist and anti-communist alike ... Marxism means a set of dogmas—the words of the master from which as among mediaeval schoolmen, one must deduce truths which the scientist hopes to infer from experiment and observation." — Gordon Childe, in letter to Rajani Palme Dutt, 1938.[138] Childe has typically been seen as a Marxist archaeologist, being the first archaeologist in the West to use Marxist theory in his work.[139] Marxist archaeology emerged in the Soviet Union in 1929, when the archaeologist Vladislav I. Ravdonikas published a report titled "For a Soviet History of Material Culture". Criticising the archaeological discipline as inherently bourgeois and therefore anti-socialist, Ravdonikas's report called for a pro-socialist, Marxist approach to archaeology as part of the academic reforms instituted under Joseph Stalin's rule.[140] It was during the mid-1930s, around the time of his first visit to the Soviet Union, that Childe began to make explicit reference to Marxism in his work.[141] Many archaeologists have been profoundly influenced by Marxism's socio-political ideas.[142] As a materialist philosophy, Marxism emphasises the idea that material things are more important than ideas, and that the social conditions of a given period are the result of the existing material conditions, or mode of production.[143] Thus, a Marxist interpretation foregrounds the social context of any technological development or change.[144] Marxist ideas also emphasise the biased nature of scholarship, each scholar having their own entrenched beliefs and class loyalties;[145] Marxism thus argues that intellectuals cannot divorce their scholarly thinking from political action.[146] Green said that Childe accepted "Marxist views on a model of the past" because they offer "a structural analysis of culture in terms of economy, sociology and ideology, and a principle for cultural change through economy".[119] McNairn noted that Marxism was "a major intellectual force in Childe's thought",[147] while Trigger said Childe identified with Marx's theories "both emotionally and intellectually".[148] Childe said he used Marxist ideas when interpreting the past "because and in so far as it works"; he criticised many fellow Marxists for treating the socio-political theory as a set of dogmas.[138] Childe's Marxism often differed from the Marxism of his contemporaries, both because he made reference to the original texts of Hegel, Marx, and Engels rather than later interpretations and because he was selective in using their writings.[119] McNairn considered Childe's Marxism "an individual interpretation" that differed from "popular or orthodox" Marxism;[149] Trigger called him a "a creative Marxist thinker";[150] Gathercole thought that while Childe's "debt to Marx was quite evident", his "attitude to Marxism was at times ambivalent".[151] The Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm later described Childe as "the most original English Marxist writer from the days of my youth".[152] Aware that in the context of the Cold War his affiliation with Marxism could prove dangerous for him, Childe sought to make his Marxist ideas more palatable to his readership.[153] In his archaeological writings, he sparingly made direct reference to Marx.[141] There is a distinction in his published works from the latter part of his life between those that are explicitly Marxist and those in which Marxist ideas and influences are less obvious.[153] Many of Childe's fellow British archaeologists did not take his adherence to Marxism seriously, regarding it as something which he did for shock value.[154] "The Marxist view of history and prehistory is admittedly material determinist and materialist. But its determinism does not mean mechanism. The Marxist account is in fact termed 'dialectical materialism'. It is deterministic in as much as it assumes that the historical process is not a mere succession of inexplicable or miraculous happenings, but that all the constituent events are interrelated and form an intelligible pattern." — Gordon Childe, 1979 [1949].[155] Childe was influenced by Soviet archaeology but remained critical of it, disapproving of how the Soviet government encouraged the country's archaeologists to assume their conclusions before analysing their data.[156] He was also critical of what he saw as the sloppy approach to typology in Soviet archaeology.[157] As a moderate diffusionist, Childe was heavily critical of the "Marrist" trend in Soviet archaeology, based on the theories of the Georgian philologist Nicholas Marr, which rejected diffusionism in favour of unilinear evolutionism.[158] In his view, it "cannot be un-Marxian" to understand the spread of domesticated plants, animals, and ideas through diffusionism.[157] Childe did not publicly air these criticisms of his Soviet colleagues, perhaps so as not to offend communist friends or to provide ammunition for right-wing archaeologists.[159] Instead, he publicly praised the Soviet system of archaeology and heritage management, contrasting it favourably with Britain's because it encouraged collaboration rather than competition between archaeologists.[160] After first visiting the country in 1935, he returned in 1945, 1953, and 1956, befriending many Soviet archaeologists, but shortly before his suicide sent a letter to the Soviet archaeological community saying he was "extremely disappointed" they had methodologically fallen behind Western Europe and North America.[161] Other Marxists—such as George Derwent Thomson[162] and Neil Faulkner[163]—argued that Childe's archaeological work was not truly Marxist because he failed to take into account class struggle as an instrument of social change, a core tenet of Marxist thought.[164] While class struggle was not a factor Childe considered in his archaeological work, he accepted that historians and archaeologists typically interpreted the past through their own class interests, arguing that most of his contemporaries produced studies with an innate bourgeois agenda.[165] Childe further diverged from orthodox Marxism by not employing dialectics in his methodology.[166] He also denied Marxism's ability to predict the future development of human society, and—unlike many other Marxists—did not consider humanity's progress into pure communism inevitable, instead opining that society could fossilize or become extinct.[167] Neolithic and Urban Revolutions Influenced by Marxism, Childe argued that society experienced widescale changes in relatively short periods of time,[168] citing the Industrial Revolution as a modern example.[169] This idea was absent from his earliest work; in studies like The Dawn of European Civilisation he talked of societal change as "transition" rather than "revolution".[170] In writings from the early 1930s, such as New Light on the Most Ancient East, he began to describe social change using the term "revolution", although had yet to fully develop these ideas.[171] At this point, the term "revolution" had gained Marxist associations due to Russia's October Revolution of 1917.[172] Childe introduced his ideas about "revolutions" in a 1935 presidential address to the Prehistoric Society. Presenting this concept as part of his functional-economic interpretation of the three-age system, he argued that a "Neolithic Revolution" initiated the Neolithic era, and that other revolutions marked the start of the Bronze and Iron Ages.[173] The following year, in Man Makes Himself, he combined these Bronze and Iron Age Revolutions into a singular "Urban Revolution", which corresponded largely to the anthropologist Lewis H. Morgan's concept of "civilization".[174] For Childe, the Neolithic Revolution was a period of radical change, in which humans—who were then hunter-gatherers—began cultivating plants and breeding animals for food, allowing for greater control of the food supply and population growth.[175] He believed the Urban Revolution was largely caused by the development of bronze metallurgy, and in a 1950 paper proposed ten traits that he believed were present in the oldest cities: they were larger than earlier settlements, they contained full-time craft specialists, the surplus was collected together and given to a god or king, they witnessed monumental architecture, there was an unequal distribution of social surplus, writing was invented, the sciences developed, naturalistic art developed, trade with foreign areas increased, and the state organisation was based on residence rather than kinship.[176] Childe believed the Urban Revolution had a negative side, in that it led to increased social stratification into classes and oppression of the majority by a power elite.[177] Not all archaeologists adopted Childe's framework of understanding human societal development as a series of transformational "revolutions"; many believed the term "revolution" was misleading because the processes of agricultural and urban development were gradual transformations.[178] Influence on processual and post-processual archaeology Through his work, Childe contributed to two of the major theoretical movements in Anglo-American archaeology that developed in the decades after his death, processualism and post-processualism. The former emerged in the late 1950s, emphasised the idea that archaeology should be a branch of anthropology, sought the discovery of universal laws about society, and believed that archaeology could ascertain objective information about the past. The latter emerged as a reaction to processualism in the late 1970s, rejecting the idea that archaeology had access to objective information about the past and emphasising the subjectivity of all interpretation.[179] The processual archaeologist Colin Renfrew described Childe as "one of the fathers of processual thought" due to his "development of economic and social themes in prehistory",[180] an idea echoed by Faulkner.[181] Trigger argued that Childe's work foreshadowed processual thought in two ways: by emphasising the role of change in societal development, and by adhering to a strictly materialist view of the past. Both of these arose from Childe's Marxism.[182] Despite this connection, most American processualists ignored Childe's work, seeing him as a particularist who was irrelevant to their search for generalised laws of societal behaviour.[183] In keeping with Marxist thought, Childe did not agree that such generalised laws exist, believing behaviour is not universal but conditioned by socio-economic factors.[184] Peter Ucko, one of Childe's successors as director of the Institute of Archaeology, highlighted that Childe accepted the subjectivity of archaeological interpretation, something in stark contrast to the processualists' insistence that archaeological interpretation could be objective.[185] As a result, Trigger thought Childe to be a "prototypical post-processual archaeologist".[179] |

考古学理論 「チャイルドの思想の)最も重要な源泉は、特にそのキャリアの初期においては、一世紀以上にわたって科学的な学問分野として確立されていた、高度に発展し た西欧の考古学であった。彼の研究や出版物は、主にその伝統の発展への貢献という形をとっていた。しかし、彼の思考は、ソビエト考古学やアメリカ人類学、 さらに遠く離れた学問分野からも影響を受けていた。彼は哲学と政治に副次的な関心を持っており、考古学の社会的価値を正当化することに、当時の考古学者の 多くよりも関心を持っていた。" - ブルース・トリガー、1980年[118]。 伝記作家のサリー・グリーンは、チルドの信念は「決して独断的ではなく、常に特異」であり、「生涯を通じて絶えず変化していた」と述べている[119]。 チルドの理論的アプローチは、マルクス主義、拡散主義、機能主義を融合させたものであった[120]。当時の西ヨーロッパやアメリカのほとんどの考古学者 と同様に、チャイルドは人間が生まれながらにして発明的であったり、変化を好むとは考えていなかった。そのため、チャイルドは社会の変化を内部的な発展や 文化の進化ではなく、拡散や移動という観点から捉える傾向があった[122]。 チルドが活動していた数十年間、ほとんどの考古学者はデンマークの古文書学者クリスチャン・ユルゲンセン・トムセンによって最初に開発された三時代制を信 奉していた。このシステムは、先史時代を石器時代、青銅器時代、鉄器時代に分割する進化年代学に基づいていたが、チャイルドは世界の多くの社会がその技術 においてまだ実質的に石器時代であることを強調した[123]。それにもかかわらず、彼はマルクス主義の枠組みと組み合わせることで、社会経済的発展を分 析するための有用なモデルとなると考えた。 [124]そのため彼は、先史時代を3つの時代に分割するために技術的な基準を用いたが、その代わりに石器時代を旧石器時代と新石器時代に細分化するため に経済的な基準を用い、中石器時代の概念は役に立たないとして否定した[125]。非公式には、エンゲルスが採用した「野蛮」、「野蛮」、「文明」という 枠組みへの過去の社会の分割を採用した[122]。 文化史的考古学 そのキャリアの初期において、チャイルドは考古学における文化史的アプローチの提唱者であり、その「創始者であり主要な提唱者」の一人と見なされるように なった[126]。文化史的考古学は、人類学から取り入れた「文化」という概念を中心に展開していた。これは「この学問の歴史における大きな転換点」であ り、考古学者たちが時間的なものではなく空間的なダイナミズムを通して過去を見ることを可能にした[127]。 [127]チルダはドイツの言語学者であり考古学者でもあったグスタフ・コシナから「文化」の概念を採用したが、この影響はコシナの思想を採用し、チルダ と親密な関係にあったポーランドの考古学者レオン・コズウォフスキを通じて媒介されたのかもしれない[128]。トリガーは、コシナの基本概念を採用しな がらも、チルダはコシナが与えた「人種差別的な意味合い」については「まったく認識していなかった」という見解を示している[128]。 チャイルドが文化史的モデルに固執していることは、彼の著作のうち『ヨーロッパ文明の夜明け』(1925年)、『アーリア人』(1926年)、『最も古代 の東方』(1928年)の3冊において明らかであるが、これらのどれにおいても彼は「文化」とは何を意味するのかを定義していない[129]。 [129]後に『先史時代のドナウ』(1929年)で初めて、チャイルドは「文化」に考古学的な定義を与えた[130]。この本で彼は「文化」を、物質文 化における「規則的に関連づけられた形質」、すなわち「壺、道具、装飾品、埋葬儀礼、住居形態」の集合であり、ある地域全体で反復しているものと定義し た。彼はこの点で、「文化」は考古学的に「民族」に相当すると述べた。チャイルドのこの用語の使用は非人種的なものであり、彼は「民族」を生物学的な人種 ではなく、社会的な集団であると考えていた[131]。彼は、当時ヨーロッパ中の様々な民族主義者が行っていたように、考古学的な文化を生物学的な人種と 同一視することに反対し、ナチスの考古学の利用を激しく批判し、ユダヤ民族は明確な生物学的な人種ではなく、社会文化的な集団であると主張した [132]。 [1935年、彼は文化が「生きた機能する有機体」として機能することを示唆し、物質文化の適応的な可能性を強調した。 1940年代後半になると、彼は考古学的概念としての「文化」の有用性、ひいては文化史的アプローチの基本的妥当性に疑問を呈していた[135]。マクネ アンは、「文化」という用語が、チルドのように物質文化だけでなく、すべての学習された行動様式を指すものとして社会科学全体に普及していたためだと指摘 している[136]。 [136]1940年代までに、チャイルドはある考古学的な集合体や「文化」が、共有された言語など他の統一的な特徴を持つ社会集団を本当に反映している のかどうかについて疑念を抱いていた[137]。 1950年代には、チャイルドは先史学者の間で文化史的考古学が担っていた役割を、歴史学者の間で伝統的な政治・軍事的アプローチが担っていた役割と比較 していた[122]。 マルクス主義の考古学 「私にとってマルクス主義とは、事実上、歴史学的・考古学的資料の解釈のためのアプローチ方法であり、方法論的装置である。共産主義者も反共産主義者も同 じである。マルクス主義とは、中世の学徒たちのように、科学者が実験と観察から推論することを望む真理を、そこから推論しなければならない一連の教義、つ まり師匠の言葉を意味する」。 - ゴードン・チャイルド、ラジャニ・パルメ・ダットに宛てた手紙、1938年[138]。 チルダは一般的にマルクス主義的な考古学者と見なされており、西側で初めてマルクス主義的な理論を用いた考古学者であった[139]。 マルクス主義的な考古学がソビエト連邦で登場したのは、1929年に考古学者ウラディスラフ・I・ラブドニカスが『ソビエトの物質文化史のために』と題す る報告書を発表した時である。ラヴドニカスの報告書は、考古学の学問分野が本質的にブルジョア的であり、それゆえ反社会主義的であると批判し、ヨシフ・ス ターリンの支配下で制定された学問改革の一環として、考古学に親社会主義的でマルクス主義的なアプローチを求めた[140]。チルドが自身の著作の中でマ ルクス主義について明確に言及し始めたのは、1930年代半ば、彼が初めてソ連を訪れた頃であった[141]。 多くの考古学者がマルクス主義の社会政治的思想に大きな影響を受けている[142]。 唯物論的な哲学であるマルクス主義は、物質的なものは思想よりも重要であり、ある時代の社会状況は既存の物質的条件、すなわち生産様式の結果であるという 考えを強調している[143]。したがって、マルクス主義的な解釈は、あらゆる技術開発や変化の社会的背景を前景化している。 [144] マルクス主義の思想はまた学問の偏った性質を強調しており、それぞれの学者が自身の凝り固まった信念や階級的忠誠心を持っている。 [146]グリーンは、チルドが「過去のモデルに関するマルクス主義の見解」を受け入れたのは、それが「経済、社会学、イデオロギーの観点から文化を構造 的に分析し、経済を通じて文化を変化させる原理」を提供しているからだと述べている[119]。 マクネアンは、マルクス主義が「チルドの思想における主要な知的力」であったと指摘し[147]、トリガーは、チルドがマルクスの理論に「感情的にも知的 にも」共感していたと述べている[148]。 チャイルドは過去を解釈する際にマルクス主義の思想を「それが機能するからであり、機能する限りにおいて」使用したと述べていた。チャイルドのマルクス主 義はしばしば同時代の人々のマルクス主義とは異なっていたが、それはチャイルドがヘーゲル、マルクス、エンゲルスの原典を後世の解釈ではなく参照したため であり、また彼らの著作を選択的に使用したためでもあった[138]。 [119]マクナイアンはチャイルドのマルクス主義を「大衆的な、あるいは正統的な」マルクス主義とは異なる「個人的な解釈」とみなし[149]、トリ ガーは彼を「創造的なマルクス主義の思想家」と呼んだ[150]。ガザコールは、チャイルドの「マルクスへの恩義は非常に明白」であったが、彼の「マルク ス主義に対する態度は時に両義的」であったと考えていた。 [151]マルクス主義の歴史家エリック・ホブズボームは後にチャイルドを「私の青春時代から最も独創的なイギリスのマルクス主義作家」と評している [152]。冷戦の状況においてマルクス主義との提携が彼にとって危険なものとなりうることを認識していたチャイルドは、マルクス主義の思想を読者にとっ てより受け入れやすいものにしようと努めた[153]。 彼の考古学的著作において、マルクスへの直接的な言及は控えめであった。 [141]晩年に出版された彼の著作には、明確にマルクス主義的なものと、マルクス主義的な思想や影響があまり明らかでないものとが区別されている [153]。 チャイルドの同僚のイギリス人考古学者の多くは、彼がマルクス主義に固執していることを真剣に受け止めておらず、それは彼が衝撃的な価値を得るために行っ ていることだと考えていた[154]。 「歴史と先史に対するマルクス主義の見方は、たしかに物質決定論的で唯物論的である。しかし、その決定論はメカニズムを意味しない。マルクス主義の説明は 実際、『弁証法的唯物論』と呼ばれている。歴史的過程は、不可解な出来事や奇跡的な出来事の単なる連続ではなく、すべての構成要素が相互に関連しあい、理 解可能なパターンを形成していると仮定している点で、決定論的なのである。" - ゴードン・チルド、1979年[1949年][155]。 チャイルドはソビエトの考古学に影響を受けたが、ソビエト政府に批判的であり、ソビエトの考古学者がデータを分析する前に結論を決めつけることを推奨して いたことを不服としていた[156]。また、ソビエトの考古学における類型論への杜撰なアプローチを批判していた[157]。 [157]穏健な拡散主義者であったチャイルドは、グルジアの言語学者ニコラス・マールの理論に基づくソ連の考古学における「マリスト」的傾向を激しく批 判していた。 [157]チルドは、共産主義者の友人を怒らせないように、あるいは右派の考古学者に弾みをつけないようにするためか、ソ連の同僚に対するこうした批判を 公言しなかった[159]。その代わりに、ソ連の考古学と遺産管理のシステムを公に賞賛し、考古学者間の競争よりもむしろ協力が奨励されているという点 で、イギリスと好対照をなしていた。 [160] 1935年に初めてソビエトを訪れた後、1945年、1953年、1956年に再訪し、多くのソビエトの考古学者と親交を深めたが、自殺する直前にソビエ トの考古学コミュニティに書簡を送り、彼らが方法論的に西欧や北米に遅れをとっていることに「非常に失望している」と述べた[161]。 ジョージ・ダーウェント・トムソン[162]やニール・フォークナー[163]のような他のマルクス主義者は、チャイルドの考古学的研究は真にマルクス主 義的なものではなかったと主張していた。 階級闘争はチルドが考古学的研究において考慮した要素ではなかったが、彼は歴史家や考古学者が一般的に自らの階級的利害を通じて過去を解釈することを認め ており、同時代の研究者のほとんどが生来のブルジョア的な意図をもって研究を進めていたと主張していた[164]。 [165]チルドはさらに、自身の方法論に弁証法を用いないことによって、正統的なマルクス主義から乖離していた[166]。彼はまた、人類社会の将来の 発展を予測するマルクス主義の能力を否定し、他の多くのマルクス主義者とは異なり、人類が純粋な共産主義へと進歩することが不可避であるとは考えておら ず、その代わりに社会が化石化したり絶滅したりする可能性があると意見していた[167]。 新石器革命と都市革命 マルクス主義の影響を受けたチャイルドは、近代的な例として産業革命を挙げながら、社会は比較的短期間で大規模な変化を経験すると主張していた [168]。 [この時点で、「革命」という用語は1917年のロシアの十月革命によってマルクス主義的な関連性を獲得していた[172]。翌年、彼は『人間は自らを創 る』(Man Makes Himself)において、これらの青銅器時代と鉄器時代の革命を単一の「都市革命」に統合しており、これは人類学者ルイス・H・モーガンの「文明」の概 念にほぼ対応していた[174]。 チルドにとって新石器革命とは、当時狩猟採集民であった人類が、食料供給の管理と人口増加を可能にするために、植物を栽培し、食料のために動物を繁殖させ るようになった急激な変化の時期であった。 [チャイルドは、都市革命は青銅器冶金の発展が主な原因であると考え、1950年の論文で、最古の都市に存在すると考えられる10の特徴を提唱した。 [176]チルドは、都市革命が階級への社会階層の拡大と権力エリートによる多数派への抑圧をもたらしたという負の側面も持っていると考えていた [177]。すべての考古学者が、人類社会の発展を一連の変革的な「革命」として理解するというチルドの枠組みを採用していたわけではなく、農業や都市の 発展過程は段階的な変革であったため、「革命」という言葉は誤解を招くと考える考古学者も多かった[178]。 プロセス考古学とポストプロセス考古学への影響 チャイルドはその研究を通じて、彼の死後数十年の間に発展した英米考古学における2つの主要な理論運動、プロセス主義とポスト・プロセッショナル主義に貢 献した。前者は1950年代後半に登場し、考古学は人類学の一分野であるべきだという考えを強調し、社会に関する普遍的な法則の発見を求め、考古学は過去 に関する客観的な情報を確認できると信じていた。後者は1970年代後半にプロセス主義への反動として登場し、考古学が過去に関する客観的な情報を入手で きるという考えを否定し、すべての解釈の主観性を強調した[179]。 プロセス的な考古学者であるコリン・レンフルーは、「先史時代における経済的・社会的テーマの発展」[180]によって、チルドを「プロセス的思想の父の 一人」であると評し、この考えはフォークナーも同様である[181]。トリガーは、チルドの仕事は、社会の発展における変化の役割を強調することと、過去 についての厳格な唯物論的見解を堅持することの2点において、プロセス的思想の予兆であると主張した。これらはいずれもチャイルドのマルクス主義から生じ たものであった[182]。このような関係にもかかわらず、アメリカの過程主義者のほとんどはチャイルドの研究を無視し、チャイルドを社会的行動の一般化 された法則の探求とは無関係な特殊主義者とみなしていた[183]。マルクス主義思想と同様に、チャイルドはそのような一般化された法則が存在することに 同意しておらず、行動は普遍的なものではなく、社会経済的要因によって条件づけられるものであると考えていた。 [184]チャイルドの後継者の一人であるピーター・ウッコは、チャイルドが考古学的解釈の主観性を受け入れていたことを強調しており、考古学的解釈は客 観的でありうるというプロセス主義者の主張とは対照的であった[185]。その結果、トリガーはチャイルドを「典型的なポスト・プロセッショナルな考古学 者」であると考えていた[179]。 |

Personal life The bronze bust of Childe by Marjorie Maitland Howard[186] has been kept in the library of the Institute of Archaeology since 1958.[187] Childe thought it made him look like a Neanderthal.[188] Childe's biographer Sally Green found no evidence that Childe ever had a serious intimate relationship; she assumed he was heterosexual because she found no evidence of same-sex attraction.[189] Conversely, his student Don Brothwell thought him to be homosexual.[190] He had many friends of both sexes, although he remained "awkward and uncouth, without any social graces".[189] Despite his difficulties in relating to others, he enjoyed interacting and socialising with his students, often inviting them to dine with him.[191] He was shy and often hid his personal feelings.[192] Brothwell suggested that these personality traits may reflect undiagnosed Asperger syndrome.[190] Childe believed the study of the past could offer guidance for how humans should act in the present and future.[193] He was known for his radical left-wing views,[154] being a socialist from his undergraduate days.[194] He sat on the committees of several left-wing groups, although avoided involvement in Marxist intellectual arguments within the Communist Party and—with the exception of How Labour Governs—did not commit his non-archaeological opinions to print.[195] Many of his political views are therefore evident only through comments made in private correspondence.[195] Renfrew noted that Childe was liberal-minded on social issues, but thought that—although Childe deplored racism—he did not entirely escape the pervasive nineteenth-century view on distinct differences between different races.[196] Trigger similarly observed racist elements in some of Childe's culture-historical writings, including the suggestion that Nordic peoples had a "superiority in physique", although Childe later disavowed these ideas.[197] In a private letter Childe wrote to the archaeologist Christopher Hawkes, he said he disliked Jews.[198] Childe was an atheist and critic of religion, viewing it as a false consciousness based in superstition that served the interests of dominant elites.[199] In History (1947) he commented that "magic is a way of making people believe they are going to get what they want, whereas religion is a system for persuading them that they ought to want what they get."[200] He nevertheless regarded Christianity as being superior over (what he regarded as) primitive religion, commenting that "Christianity as a religion of love surpasses all others in stimulating positive virtue."[201] In a letter written during the 1930s, he said that "only in days of exceptional bad temper do I desire to hurt people's religious convictions."[202] Childe was fond of driving cars, enjoying the "feeling of power" he got from them.[203] He often told a story about how he had raced at high speed down Piccadilly, London, at three in the morning for the sheer enjoyment of it, only to be pulled over by a policeman.[204] He loved practical jokes, and allegedly kept a halfpenny in his pocket to trick pickpockets. On one occasion he played a joke on the delegates at a Prehistoric Society conference by lecturing them on a theory that the Neolithic monument of Woodhenge had been constructed as an imitation of Stonehenge by a nouveau riche chieftain. Some audience members failed to realise he was being tongue in cheek.[205] He could speak several European languages, having taught himself in early life when he was travelling across the continent.[206] Childe's other hobbies included walking in the British hillsides, attending classical music concerts, and playing the card game contract bridge.[204] He was fond of poetry; his favourite poet was John Keats, and his favourite poems were William Wordsworth's "Ode to Duty" and Robert Browning's "A Grammarian's Funeral".[204] He was not particularly interested in reading novels, but his favourite was D. H. Lawrence's Kangaroo (1923), a book echoing many of Childe's own feelings about Australia.[204] He was a fan of good quality food and drink, and frequented restaurants.[207] Known for his battered, tatty attire, Childe always wore his wide-brimmed black hat—purchased from a hatter in Jermyn Street, central London—as well as a tie, which was usually red, a colour chosen to symbolise his socialist beliefs. He regularly wore a black Mackintosh raincoat, often carrying it over his arm or draped over his shoulders like a cape. In summer he frequently wore shorts with socks, sock suspenders, and large boots.[208] |

私生活 マージョリー・メイトランド・ハワードによるチャイルドのブロンズ胸像[186]は、1958年以来、考古学研究所の図書館に保管されている[187]。チャイルドはこの胸像をネアンデルタール人のように見えると考えていた[188]。 チャイルドの伝記作家であるサリー・グリーンは、チャイルドが真剣な親密な交際をした証拠がないことを発見した。 [189]他人と関わることが苦手であったにもかかわらず、彼は学生たちとの交流や社交を楽しんでおり、しばしば学生たちを食事に招いていた[191]。 チャイルドは、過去の研究が現在と未来において人間がどのように行動すべきかの指針を与えることができると信じていた[193]。 彼は急進的な左翼的見解で知られており[154]、学部時代から社会主義者であった[194]。 彼はいくつかの左翼団体の委員会に参加していたが、共産党内のマルクス主義的な知的論争への関与は避けており、『労働者の統治方法』を除いては、考古学以 外の意見を活字にすることはなかった[195]。 195]レンフルーは、チャイルドが社会問題に関してリベラルな考えを持っていたことを指摘しながらも、チャイルドは人種差別を非難していたとはいえ、異 なる人種間の明確な差異に関する19世紀に蔓延した見解から完全に逃れることはできなかったと考えていた[196]。 [196]トリガーも同様に、チャイルドの文化史的著作のいくつかには人種差別的な要素が見受けられ、その中には北欧の民族は「体格において優れている」 という示唆も含まれていたが、チャイルドは後にこうした考えを否定している[197]。 チャイルドは無神論者であり、宗教を支配的なエリートの利益に奉仕する迷信に基づく誤った意識とみなして批判していた[199]。『歴史』(1947年) の中で、彼は「魔術は人々に自分が望むものを手に入れることができると信じさせる方法であり、宗教は人々が手に入れるものを欲しがるべきだと説得するため のシステムである」とコメントしている[200]。 「それにもかかわらず、彼はキリスト教を(彼が原始的な宗教とみなすものよりも)優れているとみなしており、「愛の宗教としてのキリスト教は、積極的な美 徳を刺激するという点で、他のすべての宗教を凌駕している」とコメントしている[201]。1930年代に書かれた手紙の中で、彼は「例外的に機嫌が悪い 日に限って、私は人々の宗教的信念を傷つけたいと思う」と述べている[202]。 チャイルドは車の運転が好きで、車から得られる「力感」を楽しんでいた[203]。彼はよく、それを楽しむためにロンドンのピカデリーを夜中の3時に猛ス ピードで駆け抜けたが、警官に止められたという話をしていた[204]。あるとき彼は、先史学会の会議で、新石器時代の遺跡ウッドヘンジは、裕福な酋長に よってストーンヘンジの模倣として建てられたという説を講義し、参加者にジョークを飛ばした。聴衆のなかには、チャイルドが毒舌を吐いていることに気づか ない者もいた[205]。 チャイルドはヨーロッパのいくつかの言語を話すことができたが、それは若い頃に大陸を旅していたときに独学で習得したものだった[206]。 チャイルドのその他の趣味は、イギリスの丘陵地帯を散歩すること、クラシック音楽のコンサートに出席すること、カードゲームのコントラクト・ブリッジをプ レイすることであった[204]。 彼は詩が好きで、好きな詩人はジョン・キーツであり、ウィリアム・ワーズワースの「義務頌」とロバート・ブラウニングの「文法家の葬式」がお気に入りで あった[204]。ローレンスの『カンガルー』(1923年)は、チルド自身のオーストラリアに対する思いの多くを反映した本であった[204]。黒い マッキントッシュのレインコートを腕にかけたり、マントのように肩にかけたりした。夏にはソックス付きのショートパンツ、ソックス・サスペンダー、大きな ブーツをよく履いていた[208]。 |