スペイン独立戦争から第一共和制の時代まで

From War of Spanish Independence to First Spanish Republic 1808–1874

The Second of May 1808 was the beginning of the popular Spanish resistance against Napoleon.

☆

げんちゃんはこちら(genchan_tetsu.html)

【翻訳用】海豚ワイドモダン(00-Grid-modern.html)

(★ワイドモダンgenD.png)

| War of Spanish Independence and American wars of independence Main article: Contemporary history of Spain See also: History of Spain (1810–73) War of Spanish Independence (1808–1814) Main article: Peninsular War  The Second of May 1808 was the beginning of the popular Spanish resistance against Napoleon. In the late 18th century, Spain had an alliance with France, and therefore did not have to fear a land war. Its only serious enemy was Britain, which had a powerful navy; Spain therefore concentrated its resources on its navy. When the French Revolution overthrew the Bourbons, a land war with France became a threat which the king tried to avoid. The Spanish army was ill-prepared. The officer corps was selected primarily on the basis of royal patronage, rather than merit. About a third of the junior officers had been promoted from the ranks and had few opportunities for promotion or leadership. The rank-and-file were poorly trained peasants. Elite units included foreign regiments of Irishmen, Italians, Swiss, and Walloons, in addition to elite artillery and engineering units. Equipment was old-fashioned and in disrepair. The army lacked its own horses, oxen and mules for transportation, so these auxiliaries were operated by civilians, who might run if conditions looked bad. In combat, small units fought well, but their old-fashioned tactics were hardly of use against the Napoleonic forces, despite repeated desperate efforts at last-minute reform.[113] When war broke out with France in 1808, the army was deeply unpopular. Leading generals were assassinated, and the army proved incompetent to handle command-and-control. Junior officers from peasant families deserted and went over to the insurgents; many units disintegrated. Spain was unable to mobilize its artillery or cavalry. In the war, there was one victory at the Battle of Bailén, and many humiliating defeats. Conditions steadily worsened, as the insurgents increasingly took control of Spain's battle against Napoleon. Napoleon ridiculed the army as "the worst in Europe"; the British who had to work with it agreed.[114] It was not the Army that defeated Napoleon, but the insurgent peasants whom Napoleon ridiculed as packs of "bandits led by monks".[115] By 1812, the army controlled only scattered enclaves, and could only harass the French with occasional raids. The morale of the army had reached a nadir, and reformers stripped the aristocratic officers of most of their legal privileges.[116] Spain initially sided against France in the Napoleonic Wars, but the defeat of her army early in the war led to Charles IV's pragmatic decision to align with the French. Spain was put under a British blockade, and her colonies began to trade independently with Britain, but Britain invaded and was defeated in the British invasions of the Río de la Plata in South America (1806 and 1807) without help from mainland Spain, which emboldened independence and revolutionary hopes in Spain's American colonies. A major Franco-Spanish fleet was lost at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, prompting the king to reconsider his difficult alliance with Napoleon. Spain temporarily broke off from the Continental System, and Napoleon invaded Spain in 1808 and deposed Ferdinand VII, who had been on the throne only forty-eight days after his father's abdication in March 1808. On July 20, 1808, Joseph Bonaparte, eldest brother of Napoleon Bonaparte, entered Madrid and became King of Spain, serving as a surrogate for Napoleon.[117]  The Third of May 1808, Napoleon's troops shoot hostages. Goya Spaniards revolted. Thompson says the Spanish revolt was, "a reaction against new institutions and ideas, a movement for loyalty to the old order: to the hereditary crown of the Most Catholic kings, which Napoleon, an excommunicated enemy of the Pope, had put on the head of a Frenchman; to the Catholic Church persecuted by republicans who had desecrated churches, murdered priests, and enforced a "loi des cultes"; and to local and provincial rights and privileges threatened by an efficiently centralized government.[118] Juntas were formed all across Spain that pronounced themselves in favor of Ferdinand VII. On September 26, 1808, a Central Junta was formed in the town of Aranjuez to coordinate the nationwide struggle against the French. Initially, the Central Junta declared support for Ferdinand VII, and convened a "General and Extraordinary Cortes" for all the kingdoms of the Spanish Monarchy. On February 22 and 23, 1809, a popular insurrection against the French occupation broke out all over Spain.[119] The peninsular campaign was a disaster for France. Napoleon did well when he was in direct command, but that followed severe losses, and when he left in 1809 conditions grew worse for France. Vicious reprisals, famously portrayed by Goya in "The Disasters of War", only made the Spanish guerrillas angrier and more active; the war in Spain proved to be a major, long-term drain on French money, manpower and prestige.[120]  The promulgation of the Constitution of 1812, oil painting by Salvador Viniegra. In March 1812, the Cortes of Cádiz created the first modern Spanish constitution, the Constitution of 1812 (informally named La Pepa). This constitution provided for a separation of the powers of the executive and the legislative branches of government. The Cortes was to be elected by universal suffrage, albeit by an indirect method. Each member of the Cortes was to represent 70,000 people. Members of the Cortes were to meet in annual sessions. The King was prevented from either convening or proroguing the Cortes. Members of the Cortes were to serve single two-year terms. They could not serve consecutive terms; a member could serve a second term only by allowing someone else to serve a single intervening term in office. This attempt at the development of a modern constitutional government lasted from 1808 until 1814.[121] Leaders of the liberals or reformist forces during this revolution were José Moñino, Count of Floridablanca, Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos and Pedro Rodríguez, Conde de Campomanes. Born in 1728, Floridablanca was eighty years of age at the time of the revolutionary outbreak in 1808. He had served as Prime Minister under King Charles III from 1777 until 1792; However, he tended to be suspicious of the popular spontaneity and resisted a revolution.[122] Born in 1744, Jovellanos was somewhat younger than Floridablanco. A writer and follower of the philosophers of the Enlightenment tradition of the previous century, Jovellanos had served as Minister of Justice from 1797 to 1798 and now commanded a substantial and influential group within the Central Junta. However, Jovellanos had been imprisoned by Manuel de Godoy, Duke of Alcudia, who had served as the prime minister, virtually running the country as a dictator from 1792 until 1798 and from 1801 until 1808. Accordingly, even Jovellanos tended to be somewhat overly cautious in his approach to the revolutionary upsurge that was sweeping Spain in 1808.[123] The Spanish army was stretched as it fought Napoleon's forces because of a lack of supplies and too many untrained recruits, but at Bailén in June 1808, the Spanish army inflicted the first major defeat suffered by a Napoleonic army; this resulted in the collapse of French power in Spain. Napoleon took personal charge and with fresh forces, defeating the Spanish and British armies in campaigns of attrition. After this the Spanish armies lost every battle they fought against the French, but were never annihilated; after battles they retreated into the mountains to regroup and launch new attacks and raids. Guerrilla forces sprang up all over Spain and, with the army, tied down huge numbers of Napoleon's troops, making it difficult to sustain concentrated attacks on Spanish forces. The raids became a massive drain on Napoleon's military and economic resources.[124] Spain was aided by the British and Portuguese, led by the Duke of Wellington. The Duke of Wellington fought Napoleon's forces in the Peninsular War, with Joseph Bonaparte playing a minor role as king at Madrid. The brutal war was one of the first guerrilla wars in modern Western history. French supply lines stretching across Spain were mauled repeatedly by the Spanish armies and guerrilla forces; thereafter, Napoleon's armies were never able to control much of the country and ending in French defeat. The war fluctuated, with Wellington spending several years behind his fortresses in Portugal while launching occasional campaigns into Spain.[125] After Napoleon's disastrous 1812 campaign in Russia, Napoleon began to recall his forces for the defence of France against the advancing Russian and other coalition forces, leaving his forces in Spain increasingly undermanned and on the defensive against the advancing Spanish, British and Portuguese armies. At the Battle of Vitoria in 1813, an allied army under the Duke of Wellington decisively defeated the French and in 1814 Ferdinand VII was restored as King of Spain.[126][127] |

スペイン独立戦争とアメリカ独立戦争 詳細は「スペイン現代史」を参照 スペイン独立戦争(1808年 - 1814年) スペイン独立戦争(1808年 - 1814年) 詳細は「半島戦争」を参照  1808年5月2日は、スペイン国民によるナポレオンに対する抵抗の始まりとなった。 18世紀後半、スペインはフランスと同盟関係にあったため、陸上での戦争を恐れる必要はなかった。スペインにとって唯一の深刻な敵は、強力な海軍力を有す るイギリスであったため、スペインは海軍に資源を集中させた。フランス革命によりブルボン朝が打倒されると、フランスとの陸上での戦争が現実味を帯び、国 王はこれを回避しようとした。スペイン軍は準備不足であった。士官は主に王の寵愛に基づいて選ばれ、能力は考慮されていなかった。下士官の約3分の1は兵 士から昇進した者で、昇進やリーダーシップの機会はほとんどなかった。一般兵士は訓練不足の農民であった。エリート部隊には、エリート砲兵部隊や工兵部隊 に加え、アイルランド人、イタリア人、スイス人、ワロン人からなる外国人連隊も含まれていた。装備は時代遅れで、老朽化していた。軍隊は輸送用の馬、牛、 ロバを所有していなかったため、これらの補助部隊は民間人によって運営されていたが、状況が悪化すれば彼らも逃げ出す可能性があった。戦闘においては、小 規模な部隊はよく戦ったが、時代遅れの戦術はナポレオン軍に対してほとんど役に立たなかった。1808年にフランスとの戦争が勃発した際、軍隊は国民から 深く嫌われていた。主要な将軍たちは暗殺され、軍隊は指揮統制を執る能力がないことが証明された。農民出身の下士官たちは脱走して反乱軍に加わり、多くの 部隊は崩壊した。スペインは砲兵や騎兵を動員することができなかった。この戦争では、バイレンの戦いで1度勝利を収めたが、屈辱的な敗北を数多く喫した。 反乱軍がスペインのナポレオンに対する戦いを次第に掌握するにつれ、状況は悪化の一途をたどった。ナポレオンはスペイン軍を「ヨーロッパ最悪」と嘲笑し、 共に戦うことを余儀なくされたイギリス人も同意した。[114] ナポレオンを打ち負かしたのはスペイン軍ではなく、ナポレオンが「修道士に率いられた盗賊の一団」と嘲笑した反乱農民たちであった。[115] 1812年までに、スペイン軍が支配していたのは散在する飛び地のみとなり、フランス軍を悩ませることは時折の奇襲のみとなった。軍の士気はどん底に達 し、改革派は貴族出身の士官からほとんどの法的特権を剥奪した。 スペインは当初、ナポレオン戦争においてフランスと敵対していたが、戦争初期に軍が敗北したことにより、カルロス4世はフランスと同盟を結ぶという現実的 な決断を下した。スペインはイギリスの封鎖下に置かれ、スペインの植民地はイギリスと独自に貿易を始めたが、イギリスはスペイン本土からの支援を受けられ ず、南米のリオ・デ・ラ・プラタへの侵攻(1806年と1807年)で敗北した。これにより、スペインのアメリカ植民地では独立と革命への期待が高まっ た。1805年のトラファルガーの海戦でフランス・スペイン連合艦隊の大半が失われ、国王はナポレオンとの困難な同盟関係を見直すこととなった。スペイン は一時的に大陸システムから離脱し、1808年にナポレオンがスペインに侵攻し、1808年3月に父親が退位してからわずか48日間王位にあったフェルナ ンド7世を退位させた。1808年7月20日、ナポレオン・ボナパルトの長兄ジョゼフ・ボナパルトがマドリードに入り、ナポレオンの代理としてスペイン王 となった。[117]  1808年5月3日、ナポレオンの軍隊が人質を銃撃した。ゴヤ スペイン人が反乱を起こしたと述べている。トンプソンはスペイン人の反乱は「新しい制度や考え方に対する反発であり、古い秩序への忠誠を誓う運動であっ た。すなわち、教皇から破門された敵であるナポレオンがフランス人の頭に被らせた、最もカトリック的な王家の世襲による王冠への忠誠、 教会を冒涜し、司祭を殺害し、「宗教法」を強制した共和主義者たちに迫害されたカトリック教会、そして効率的な中央集権政府によって脅かされた地方や地域 の権利と特権に賛同した。[118] スペイン全土でフェルディナンド7世を支持するジュンタが結成された。1808年9月26日、フランスに対する全国的な闘争を調整するために、アラニェス (Aranjuez)の町に中央ジュンタが結成された。中央政府は当初フェルナンド7世を支持すると宣言し、スペイン君主国の全王国を対象に「一般臨時コ ルテス」を召集した。1809年2月22日と23日、フランス占領に対する民衆蜂起がスペイン全土で勃発した。[119] イベリア半島における戦いはフランスにとって惨憺たるものとなった。ナポレオンは自ら指揮を執る際にはうまくやっていたが、それは大きな損失を伴うもので あり、1809年にナポレオンが去ると、スペインにとって状況はさらに悪化した。悪名高い報復は、ゴヤの「戦争の惨禍」に描かれているように、スペインの ゲリラたちをさらに怒らせ、より活発にさせた。スペインにおける戦争は、フランスにとって、長期的に資金、労働力、威信を消耗させる大きな負担となった。  1812年憲法の公布、サルバドール・ビニエグラによる油彩画。 1812年3月、カディス議会はスペイン初の近代憲法である1812年憲法(通称ラ・ペパ)を制定した。この憲法は、行政と立法の権力の分立を規定した。 議会は間接的な方法ではあるが、普通選挙で選出されることになっていた。コルテスの各議員は7万人を代表することになっていた。コルテスの議員は毎年会合 を開くことになっていた。国王はコルテスを召集することも、解散することも禁じられていた。コルテスの議員は2年任期を1期のみ務めることになっていた。 連続して務めることはできず、2期目を務めるには、他の人物が1期の間、議員を務めることを許可しなければならなかった。この近代立憲政治の確立に向けた 試みは、1808年から1814年まで続いた。[121] この革命における自由主義者または改革派の指導者には、ホセ・モニーニョ・デ・フローリダブランカ伯爵、ガスパル・デ・ホベリャーノス、ペドロ・ロドリゲ ス・デ・カンポメネス伯爵らがいた。1728年生まれのフロリダブランカは、1808年の革命勃発時には80歳になっていた。彼は1777年から1792 年までカルロス3世の首相を務めたが、民衆の自発性に対しては疑いを抱きがちで、革命には抵抗を示した。[122] 1744年生まれのホベリャーノスは、フロリダブランカよりもやや年下であった。前世紀の啓蒙主義の哲学者たちの信奉者であり、作家でもあったジョベラノ スは、1797年から1798年まで司法大臣を務め、中央政府内でも影響力のあるグループを率いていた。しかし、ホベリャーノスは、1792年から 1798年、そして1801年から1808年まで首相として事実上独裁者として国を運営していたマヌエル・デ・ゴドイ(アルクーディア公爵)に投獄されて いた。そのため、ホベリャーノスでさえ、1808年にスペインを席巻した革命的興奮に対しては、やや過剰なほど用心深い態度をとる傾向があった。 スペイン軍は、物資不足と訓練不足の兵士が多すぎたために、ナポレオン軍と戦う中で疲弊していたが、1808年6月のバイレンの戦いで、スペイン軍はナポ レオン軍に初めての大きな敗北を与えた。これにより、スペインにおけるフランスの勢力は崩壊した。ナポレオンは自ら指揮を執り、新たな軍勢を率いて、消耗 戦でスペイン軍とイギリス軍を打ち負かした。この後、スペイン軍はフランス軍と戦ったすべての戦いに敗れたが、壊滅することはなかった。戦いの後、スペイ ン軍は山中に退却して再編成し、新たな攻撃や襲撃を仕掛けた。スペイン全土でゲリラ部隊が現れ、軍とともにナポレオンの軍勢の膨大な数を拘束し、スペイン 軍への集中攻撃を維持することを困難にした。襲撃はナポレオンの軍事および経済的資源に大きな打撃を与えた。[124] スペインはウェリントン公爵率いるイギリスとポルトガルの支援を受けた。ウェリントン公爵は半島戦争でナポレオンの軍と戦い、マドリードではジョゼフ・ボ ナパルトが国王として脇役を演じた。この残忍な戦争は、近代西洋史上初のゲリラ戦のひとつであった。スペイン全土に広がるフランス軍の補給路はスペイン軍 とゲリラ部隊によって何度も攻撃され、その後、ナポレオンの軍隊はスペインの大部分を支配することができず、フランスは敗北した。この戦争は変動を繰り返 し、ウェリントンはポルトガルの要塞に数年間籠城しながら、スペインに時折遠征軍を派遣した。 1812年のナポレオンのロシアでの悲惨な作戦の後、ナポレオンはロシア軍およびその他の連合軍の進軍に対してフランスを守るために軍を呼び戻し始め、ス ペインに駐留する軍はますます兵力が不足し、進軍するスペイン軍、イギリス軍、ポルトガル軍に対して防衛的な立場に追い込まれた。1813年のビトリアの 戦いでは、ウェリントン公率いる連合軍がフランス軍を破り、1814年にはフェルディナンド7世がスペイン王に復位した。[126][127] |

| Independence of Spanish America Main article: Spanish American wars of independence The pro-independence forces delivered a crushing defeat to the royalists and secured the independence of Peru in the 1824 battle of Ayacucho. Spain lost all of its North and South American territories, except Cuba and Puerto Rico, in a complex series of revolts 1808–26.[128] Spain was at war with Britain 1798–1808, and the British blockade cut Spain's ties to the overseas empire. Trade was handled by American and Dutch traders. The colonies thus had achieved economic independence from Spain, and set up temporary governments or juntas which were generally out of touch with Spain. After 1814, as Napoleon was defeated and Ferdinand VII was back on the throne, the king sent armies to regain control and reimpose autocratic rule. In the next phase 1809–16, Spain defeated all the uprising. A second round 1816–25 was successful and drove the Spanish out of all of its mainland holdings. Spain had no help from European powers. Indeed, Britain (and the United States) worked against it. When they were cut off from Spain, the colonies saw a struggle for power between Spaniards who were born in Spain (called "peninsulares") and those of Spanish descent born in New Spain (called "creoles"). The creoles were the activists for independence. Multiple revolutions enabled the colonies to break free of the mother country. In 1824 the armies of generals José de San Martín of Argentina and Simón Bolívar of Venezuela defeated the last Spanish forces; the final defeat came at the Battle of Ayacucho in southern Peru. After that Spain played a minor role in international affairs. Business and trade in the ex-colonies were under British control. Spain kept only Cuba and Puerto Rico in the New World.[129] |

スペイン領アメリカ独立 詳細は「スペイン領アメリカ独立戦争」を参照 独立派は1824年のアヤクチョの戦いで王党派に壊滅的な敗北を与え、ペルーの独立を確実にした。 スペインは1808年から1826年にかけての複雑な一連の反乱により、キューバとプエルトリコを除く北米と南米の領土をすべて失った。[128] スペインは1798年から1808年にかけてイギリスと戦争状態にあり、イギリスの海上封鎖によりスペインの海外帝国とのつながりは断たれた。貿易はアメ リカとオランダの商人によって行われた。こうして植民地はスペインから経済的に自立し、スペインとほとんど接触のない臨時政府や軍事会議を樹立した。 1814年以降、ナポレオンが敗北しフェルディナンド7世が王位に復帰すると、国王は軍隊を派遣して支配権を取り戻し、専制政治を再び敷いた。次の段階で ある1809年から1816年にかけて、スペインはすべての蜂起を鎮圧した。1816年から1825年にかけての第2次ラウンドは成功し、スペインは本土 のすべての領土を失った。スペインはヨーロッパ列強の支援を得ることができなかった。実際、イギリス(およびアメリカ)はスペインに反対していた。スペイ ンから孤立すると、植民地ではスペイン本土生まれのスペイン人(「ペニンスラレス」と呼ばれる)と、新スペイン生まれのスペイン系の人々(「クリオール」 と呼ばれる)の間で権力闘争が起こった。クレオール派は独立運動の推進派であった。 幾度もの革命を経て、植民地は母国から独立を果たした。 1824年、アルゼンチンのホセ・デ・サン・マルティン将軍とベネズエラのシモン・ボリバル将軍の軍隊が最後のスペイン軍を打ち破った。 最終的な敗北はペルー南部のアイアクトゥーの戦いで決まった。 その後、スペインは国際情勢において、より小さな役割を担うようになった。旧植民地におけるビジネスと貿易は英国の管理下に置かれた。スペインが新世界で 維持したのはキューバとプエルトリコのみであった。[129] |

| Reign of Ferdinand VII (1813–1833) Aftermath of the Napoleonic wars Main article: History of Spain (1810–73) The Napoleonic wars had severe negative effects on Spain's long-term economic development. The Peninsular war ravaged towns and countryside alike, and the demographic impact was the worst of any Spanish war, with a sharp decline in population in many areas caused by casualties, outmigration, and disruption of family life. The marauding armies seized farmers' crops, and more importantly, farmers lost much of their livestock, their main capital asset. Severe poverty became widespread, reducing market demand, while the disruption of local and international trade, and the shortages of critical inputs, seriously hurt industry and services. The loss of a vast colonial empire reduced Spain's overall wealth, and by 1820 it had become one of Europe's poorest and least-developed societies; three-fourths of the people were illiterate. There was little industry beyond the production of textiles in Catalonia. Natural resources, such as coal and iron, were available for exploitation, but the transportation system was rudimentary, with few canals or navigable rivers, and road travel was slow and expensive. British railroad builders were pessimistic and did not invest. Eventually a small railway system was built, radiating from Madrid and bypassing the natural resources. The government relied on high tariffs, especially on grain, which further slowed economic development. For example, eastern Spain was unable to import inexpensive Italian wheat, and had to rely on expensive homegrown products carted in over poor roads. The export market collapsed apart from some agricultural products. Catalonia had some industry, but Castile remained the political and cultural center, and was not interested in promoting industry.[130] Although the juntas, that had forced the French to leave Spain, had sworn by the liberal Constitution of 1812, Ferdinand VII had the support of conservatives and he rejected it.[131] He ruled in the authoritarian fashion of his forebears.[132] The government, nearly bankrupt, was unable to pay its soldiers. There were few settlers or soldiers in Florida, so it was sold to the United States for $5 million. In 1820, an expedition intended for the colonies revolted in Cadiz. When armies throughout Spain pronounced themselves in sympathy with the revolters, led by Rafael del Riego, Ferdinand was forced to accept the liberal Constitution of 1812. This was the start of the second bourgeois revolution in Spain, the trienio liberal which lasted from 1820 to 1823.[127] Ferdinand was placed under effective house arrest for the duration of the liberal experiment. |

フェルナンド7世の治世(1813年~1833年) ナポレオン戦争の余波 詳細は「スペインの歴史 (1810年~1873年)」を参照 ナポレオン戦争はスペインの長期的な経済発展に深刻な悪影響を及ぼした。半島戦争は都市部も農村部も荒廃させ、人口動態への影響はスペインの戦争の中でも 最悪のもので、多くの地域で死傷者、国外移住、家庭崩壊により人口が急激に減少した。略奪軍は農民の作物を奪い、さらに重要なことには、農民は家畜の多く を失い、家畜は彼らの主な資本資産であった。深刻な貧困が広まり、市場の需要が減退する一方で、地域内および国際貿易の混乱と、重要な投入物の不足によ り、産業とサービスは深刻な打撃を受けた。広大な植民地帝国を失ったことでスペインの総体的な富は減少し、1820年にはヨーロッパで最も貧しく、最も発 展の遅れた社会の一つとなった。 カタルーニャ地方では、織物生産以外にはほとんど産業がなかった。石炭や鉄などの天然資源は採掘可能であったが、運輸システムは未発達で、運河や航行可能 な河川はほとんどなく、道路での移動は遅く費用もかかった。英国の鉄道建設業者は悲観的で投資を行わなかった。結局、小さな鉄道システムが建設され、マド リードから放射状に伸び、天然資源を迂回する形となった。政府は高い関税、特に穀物に頼っていたが、これは経済発展をさらに遅らせた。例えば、スペイン東 部では安価なイタリア産の小麦を輸入できず、悪路を走って運ばれてくる高価な国産品に頼らざるを得なかった。輸出市場は、一部の農産物を除いて崩壊した。 カタルーニャには産業があったが、カスティーリャは依然として政治と文化の中心であり、産業振興には関心がなかった。 フランス軍のスペイン撤退を強行した軍事委員会は、1812年の自由主義的な憲法に誓いを立てていたが、フェルナンド7世は保守派の支持を受けており、それを拒否した。[131] 彼は先祖代々の権威主義的なやり方で統治した。[132] ほぼ破産状態にあった政府は、兵士たちに給与を支払うことができなかった。フロリダには入植者も兵士もほとんどいなかったため、500万ドルでアメリカ合 衆国に売却された。1820年、植民地を目的とした遠征隊がカディスで反乱を起こした。スペイン全土の軍隊がラファエル・デル・リエゴ率いる反乱軍に同調 したため、フェルナンドは1812年の自由主義憲法を受け入れざるを得なかった。これがスペインにおける2度目のブルジョワ革命、自由主義的3か年 (1820年から1823年)の始まりであった。[127] フェルナンドは自由主義的実験の期間中、事実上の軟禁状態に置かれた。 |

| Trienio liberal (1820–23) Main article: Trienio liberal The tumultuous three years of liberal rule that followed (1820–23) were marked by various absolutist conspiracies. The liberal government was viewed with hostility by the Congress of Verona in 1822, and France was authorized to intervene. France crushed the liberal government with massive force in the so-called "Hundred Thousand Sons of Saint Louis" expedition, and Ferdinand was restored as absolute monarch in 1823. In Spain proper, this marked the end of the second Spanish bourgeois revolution. |

自由主義の3年間(1820年~1823年) 詳細は「自由主義の3年間」を参照 自由主義者による波乱に満ちた3年間の統治(1820年~1823年)は、さまざまな絶対主義者の陰謀によって特徴づけられた。1822年、自由主義政府 はヴェローナ議会から敵対的に見なされ、フランスが介入することを承認された。フランスは「サン・ルイの10万の息子たち」遠征と呼ばれる遠征で、圧倒的 な武力で自由主義政府を打ち砕き、1823年にはフェルディナンドが絶対王政の君主として復権した。スペイン本国では、これが第二スペイン市民革命の終結 を意味した。 |

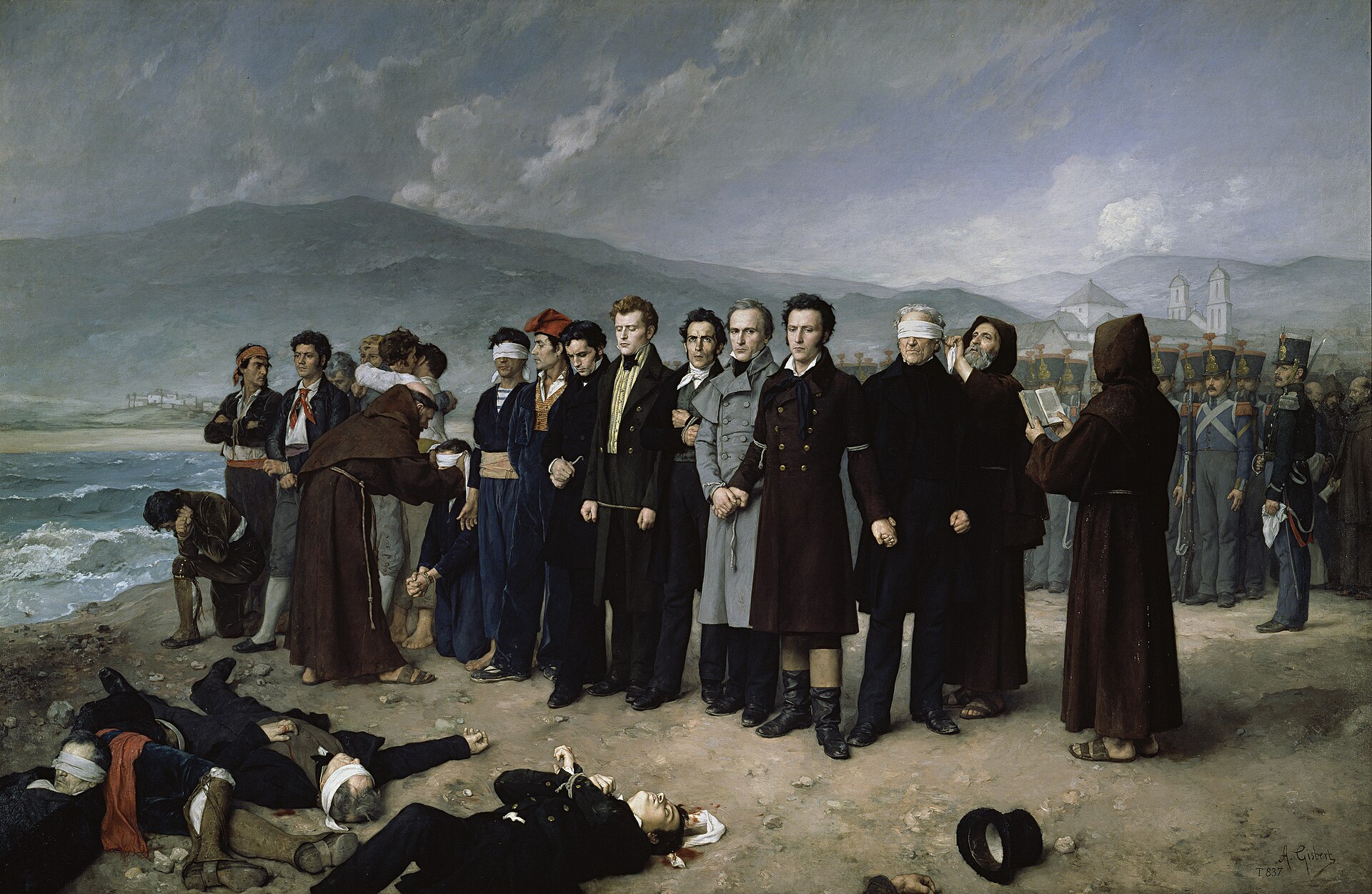

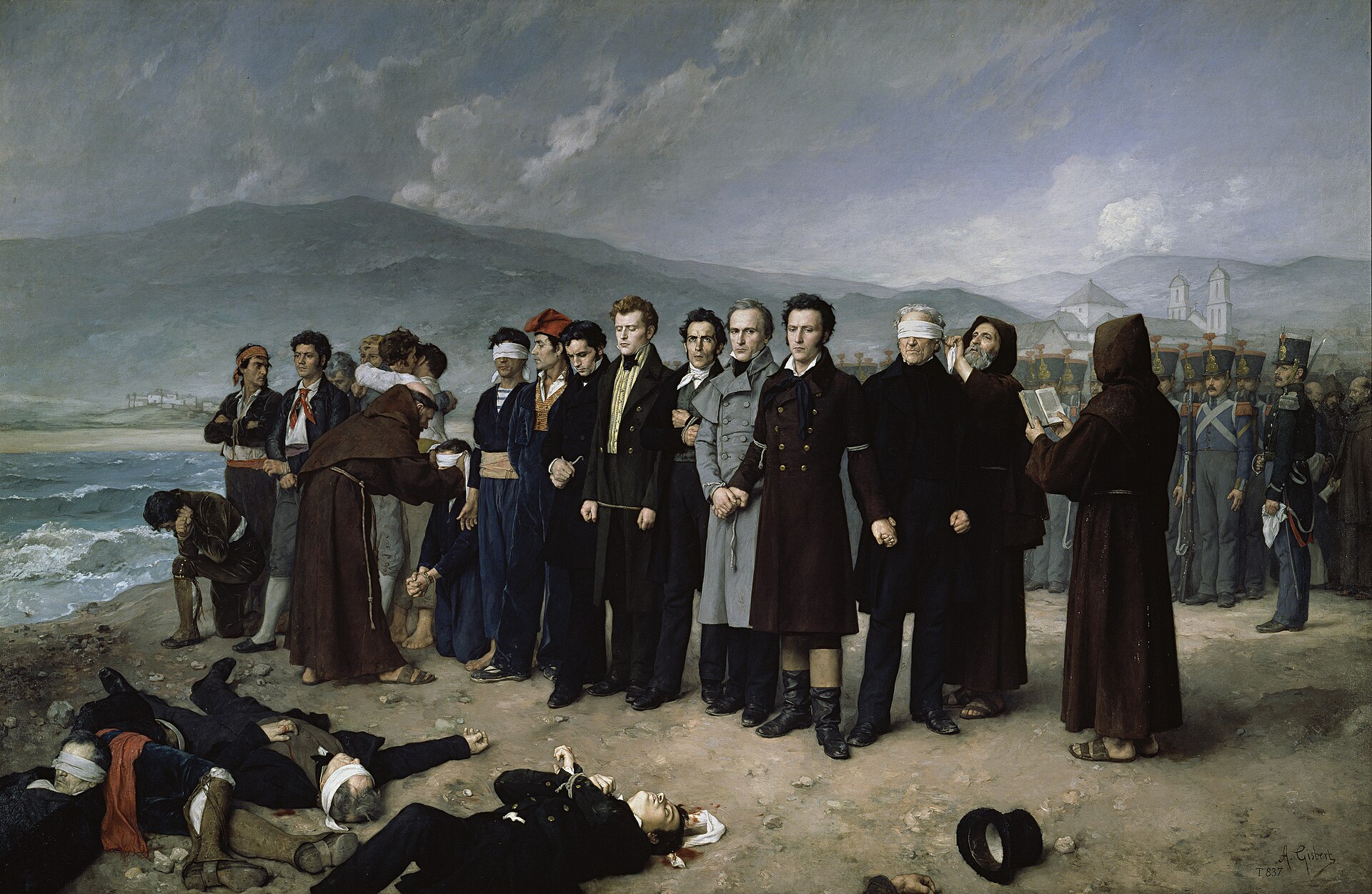

| "Ominous Decade" (1823–1833) Main article: Ominous Decade  Execution of Torrijos and his men in 1831. Ferdinand VII took repressive measures against the liberal forces in his country.  Battle of the First Carlist War, by Francisco de Paula Van Halen In Spain, the failure of the second bourgeois revolution was followed by uneasy peace for the next decade. Having borne only a female heir presumptive, it appeared that Ferdinand would be succeeded by his brother, Infante Carlos. While Ferdinand aligned with the conservatives, fearing another national insurrection, he did not view Carlos's reactionary policies as a viable option. Ferdinand – resisting the wishes of his brother – decreed the Pragmatic Sanction of 1830, enabling his daughter Isabella to become Queen. Carlos, who made known his intent to resist the sanction, fled to Portugal. |

「不吉な10年」(1823年~1833年) 詳細は「不吉な10年」を参照  1831年のトリホスとその部下たちの処刑。フェルナンド7世は自国の自由主義勢力に対して弾圧政策をとった。  フランシスコ・デ・パウラ・ファン・アレンによる第一次カルリスタ戦争の戦い スペインでは、第二ブルジョワ革命の失敗後、不安定な平和が10年間続いた。フェルナンドには女性しか推定相続人がいなかったため、彼の跡継ぎは弟のカル ロス王子となるはずであった。フェルナンドは保守派と手を組み、国民の反乱を恐れていたが、カルロスの反動的な政策を支持するつもりはなかった。フェル ディナンドは、兄の意向に抵抗し、1830年のプラクティカ・サンクション(暫定承認)を公布し、自身の娘イザベラが女王となることを可能にした。カルロ スは、この承認に抵抗する意向を明らかにし、ポルトガルに逃亡した。 |

| Reign of Isabella II (1833–1868) Main articles: Minority of Isabella II of Spain, Isabella II of Spain, and History of Spain (1810–73) Ferdinand's death in 1833 and the accession of Isabella II sparked the First Carlist War (1833–39). Isabella was only three years old at the time so her mother, Maria Cristina of Bourbon-Two Sicilies governed as regent. Carlos invaded the Basque country in the north of Spain and attracted support from absolutist reactionaries and conservatives, known as the "Carlist" forces. The supporters of reform and of limitations on the absolutist rule of the Spanish throne rallied behind Isabella and the regent, Maria Cristina; these reformists were called "Christinos." Though Christino resistance to the insurrection seemed to have been overcome by the end of 1833, Maria Cristina's forces suddenly drove the Carlist armies from most of the Basque country. Carlos then appointed the Basque general Tomás de Zumalacárregui as his commander-in-chief. Zumalacárregui resuscitated the Carlist cause, and by 1835 had driven the Christino armies to the Ebro River and transformed the Carlist army from a demoralized band into a professional army of 30,000 of superior quality to the government forces. Zumalacárregui's death in 1835 changed the Carlists' fortunes. The Christinos found a capable general in Baldomero Espartero. His victory at the Battle of Luchana (1836) turned the tide of the war, and in 1839, the Convention of Vergara put an end to the first Carlist insurrection.[133] The progressive General Espartero, exploiting his popularity as a war hero and his sobriquet "Pacifier of Spain", demanded liberal reforms from Maria Cristina. The Queen Regent preferred to resign and let Espartero become regent instead in 1840. Espartero's liberal reforms were then opposed by moderates, and the former general's heavy-handedness caused a series of sporadic uprisings throughout the country from various quarters, all of which were bloodily suppressed. He was overthrown as regent in 1843 by Ramón María Narváez, a moderate, who was in turn perceived as too reactionary. Another Carlist uprising, the Matiners' War, was launched in 1846 in Catalonia, but it was poorly organized and suppressed by 1849.  Episode of the 1854 Spanish Revolution in the Puerta del Sol, by Eugenio Lucas Velázquez. Isabella II took a more active role in government after coming of age, but she was unpopular throughout her reign (1833–68). There was another pronunciamiento in 1854 led General Leopoldo O'Donnell, intending to topple the discredited rule of the Count of San Luis. A popular insurrection followed the coup and the Progressive Party obtained widespread support in Spain and came to government in 1854.[134] After 1856, O'Donnell, who had already marched on Madrid that year and ousted another Espartero ministry, attempted to form the Liberal Union, his own political project. Following attacks on Ceuta by tribesmen based in Morocco, a war against the latter country was successfully waged by generals O'Donnell and Juan Prim. The later part of Isabella's reign saw also the Spanish retake of Santo Domingo (1861–1865), and the fruitless Chincha Islands War (1864–1866) against Peru and Chile. |

イサベル2世の治世(1833年 - 1868年) 主な記事:スペイン王女イサベル2世の少数派、スペイン王女イサベル2世、スペインの歴史(1810年 - 1873年) 1833年のフェルナンドの死とイサベル2世の即位により、第一次カルリスタ戦争(1833年 - 1839年)が勃発した。当時、イザベラはわずか3歳であったため、母親のマリア・クリスティーナ・デ・ブルボン=シシリアが摂政として統治した。カルロ スはスペイン北部のバスク地方に侵攻し、絶対王政派の反動主義者や保守派の支持を集めた。絶対王政のスペイン王位に制限を設ける改革派は、イザベラと摂政 のマリア・クリスティーナを支持し、これらの改革派は「クリスティーノ」と呼ばれた。1833年末には、反乱に対するクリスティーノの抵抗は克服されたか に見えたが、マリア・クリスティーナの軍勢は突如としてカトリック軍をバスク地方の大部分から追い払った。カルロスはその後、バスク人将軍トマス・デ・ス マラカルレギを司令官に任命した。スマラカルレギはカルリスタ運動を復活させ、1835年までにクリスティーノ軍をエブロ川まで追いやり、士気の低下した 一団から政府軍に匹敵する質の高い3万人のプロフェッショナルな軍隊へと変貌させた。1835年のスマラカルレギの死はカルリスタの運命を変えた。クリス ティーノ派はバルドメロ・エスパーテーロという有能な将軍を得た。 1836年のルチャナの戦いでの勝利により戦況が変わり、1839年にはベルガラ協定により、第一次カルリスタ戦争は終結した。 進歩的なエスパーテーロ将軍は、戦争の英雄としての人気と「スペインの乳母」というあだ名を活かし、マリア・クリスティーナに自由主義的改革を要求した。 摂政女王は辞任し、1840年にはエスパルテーロが摂政となることを望んだ。エスパルテーロの自由主義的改革は穏健派に反対され、元将軍の強引なやり方 は、国内のさまざまな地域から一連の散発的な反乱を引き起こしたが、それらはすべて血なまぐさい弾圧を受けた。彼は1843年に穏健派のラモン・マリア・ ナルバエスによって摂政の地位から追われたが、今度は彼が反動的すぎるとみなされた。1846年にはカタルーニャで新たなカルリスタ蜂起、マティネーレス 戦争が勃発したが、組織が不十分であったため、1849年には鎮圧された。  1854年のスペイン革命のエピソードを描いた、エウヘニオ・ルーカス・ベラスケスの作品『プエルタ・デル・ソル』。 イサベル2世は成人後、より積極的な政治的役割を担ったが、彼女の治世(1833年~1868年)は不人気であった。1854年には、レオポルド・オドン ネル将軍が主導する新たな発動宣言が起こり、サン・ルイス伯爵の失脚を狙った。このクーデターに続き、民衆蜂起が起こり、進歩党がスペイン全土で広範な支 持を得て、1854年に政権を握った。[134] 1856年以降、すでにその年にマドリードに進軍し、エスパーテーロ内閣を退陣させていたオドンネルは、自由連合という自身の政治プロジェクトを結成しよ うとした。モロッコを拠点とする部族によるセウタへの攻撃を受けて、オドンネル将軍とフアン・プリム将軍はモロッコとの戦争を成功させた。イサベル女王の 治世の後半には、スペインがサント・ドミンゴを再占領(1861年~1865年)し、ペルーとチリとの間で実りのないチンチャ諸島戦争(1864年 ~1866年)が起こった。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆