ドラッグとの戦争

War on drugs

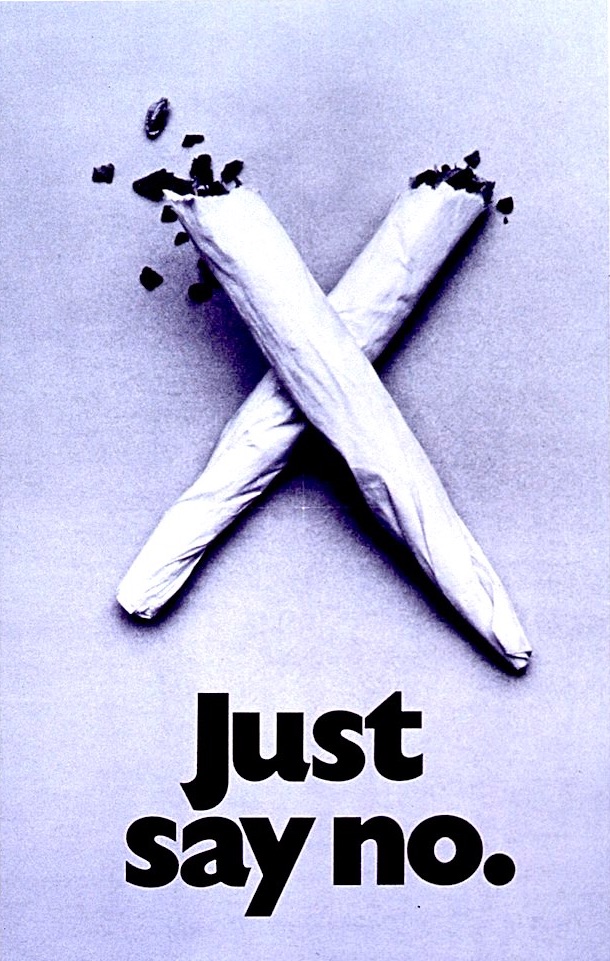

A

U.S. government PSA from the Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health

Administration with a photo image of two marijuana cigarettes and a

"Just Say No" slogan

☆ 麻薬戦争(ドラッグとの戦争、麻薬をめぐる戦争)は、アメリカ合衆国連邦政府が主導する、麻薬禁止、海外援助、軍事介入を内容とする世界的なキャンペーン 政策である。[6][7][8][9] この政策は、アメリカ国内の違法麻薬取引を減少させることを目的としている。この政策には、参加各国政府が国連条約を通じて違法とした向精神薬の生産、流 通、消費を抑制することを目的とした一連の麻薬政策が含まれている。 「麻薬との戦争」という言葉は、1971年6月17日に行われた記者会見の後、メディアによって広められた。この会見でリチャード・ニクソン大統領は麻薬 乱用を「公の敵ナンバーワン」と宣言した。[10] 彼は「この敵と戦い、打ち負かすためには、新たな全面的な攻撃を行う必要がある。...これは世界的な攻撃となる。... 政府全体で取り組む...そして全国的な取り組みとなるだろう」と述べていた。その日、ニクソンは「麻薬乱用防止と取締り」に関する特別メッセージを米連 邦議会に提出しており、その中には「新たな常習者の防止と、常習者の更生」に連邦政府の資源をより多く投入するという内容が含まれていた。この側面は、 「麻薬との戦争」という言葉ほどメディアの注目を集めることはなかった。[11][10][12][13] それ以来、大統領と連邦議会は、一般的に、公衆衛生や治療よりも法の執行と取締りに重点を置くニクソンの当初の政策を維持または拡大してきた。大麻は特別 なケースであり、1930年代に連邦政府の規制の対象となり、1970年以降は乱用される可能性が極めて高く医療的価値のない薬物としてヘロインと同等の 禁止薬物に分類されている。1930年代以降、多数の主流派の研究や調査結果が、このような厳しい分類を推奨していない。1990年代以降、医療用大麻は 38の州で合法化され、また娯楽用大麻も24の州で合法化され、連邦法との間に政策上のギャップが生じ、国連麻薬条約に準拠していない。 2011年6月、薬物政策に関するグローバル委員会は「世界的な薬物との戦いは失敗に終わり、世界中の個人や社会に壊滅的な結果をもたらした」と宣言する 重要な報告書を発表した。[6] 2023年、国連人権高等弁務官は「数十年にわたる処罰的な『薬物との戦い』戦略は、ますます広範囲にわたる物質の生産と消費を防止できなかった」と述べ た。[14] その年、米国連邦政府の麻薬戦争予算は年間390億ドルに達し、1971年からの累積支出は1兆ドルと推定されている。[15] 2024年現在、フェンタニルやその他の合成麻薬に焦点を当てた麻薬戦争が継続している。

★2019年の各地域から米国への違法フェンタニルの流入

| The

war on drugs is the policy of a global campaign,[6] led by the United

States federal government, of drug prohibition, foreign assistance, and

military intervention, with the aim of reducing the illegal drug trade

in the US.[7][8][9] The initiative includes a set of drug policies that

are intended to discourage the production, distribution, and

consumption of psychoactive drugs that the participating governments,

through United Nations treaties, have made illegal. The term "war on drugs" was popularized by the media after a press conference, given on June 17, 1971, during which President Richard Nixon declared drug abuse "public enemy number one".[10] He stated, "In order to fight and defeat this enemy, it is necessary to wage a new, all-out offensive. ... This will be a worldwide offensive. ... It will be government-wide ... and it will be nationwide." Earlier that day, Nixon had presented a special message to the US Congress on "Drug Abuse Prevention and Control", which included text about devoting more federal resources to the "prevention of new addicts, and the rehabilitation of those who are addicted"; that aspect did not receive the same media attention as the term "war on drugs".[11][10][12][13] In the years since, presidential administrations and Congress have generally maintained or expanded Nixon's original initiatives, with the emphasis on law enforcement and interdiction over public health and treatment. Cannabis presents a special case; it came under federal restriction in the 1930s, and since 1970 has been classified as having a high potential for abuse and no medical value, with the same level of prohibition as heroin. Multiple mainstream studies and findings since the 1930s have recommended against such a severe classification. Beginning in the 1990s, cannabis has been legalized for medical use in 38 states, and also for recreational use in 24, creating a policy gap with federal law and non-compliance with the UN drug treaties. In June 2011, the Global Commission on Drug Policy released a critical report, declaring: "The global war on drugs has failed, with devastating consequences for individuals and societies around the world."[6] In 2023, the UN high commissioner for Human Rights stated that "decades of punitive, 'war on drugs' strategies had failed to prevent an increasing range and quantity of substances from being produced and consumed."[14] That year, the annual US federal drug war budget reached $39 billion, with cumulative spending since 1971 estimated at $1 trillion.[15] As of 2024, the war on drugs continues, with a focus on fentanyl and other synthetic drugs. |

麻薬戦争(ドラッグとの戦争、麻薬をめぐる戦争)は、アメリカ合衆国連

邦政府が主導する、麻薬禁止、海外援助、軍事介入を内容とする世界的なキャンペーン政策である。[6][7][8][9]

この政策は、アメリカ国内の違法麻薬取引を減少させることを目的としている。この政策には、参加各国政府が国連条約を通じて違法とした向精神薬の生産、流

通、消費を抑制することを目的とした一連の麻薬政策が含まれている。 「麻薬との戦争」という言葉は、1971年6月17日に行われた記者会見の後、メディアによって広められた。この会見でリチャード・ニクソン大統領は麻薬 乱用を「公の敵ナンバーワン」と宣言した。[10] 彼は「この敵と戦い、打ち負かすためには、新たな全面的な攻撃を行う必要がある。...これは世界的な攻撃となる。... 政府全体で取り組む...そして全国的な取り組みとなるだろう」と述べていた。その日、ニクソンは「麻薬乱用防止と取締り」に関する特別メッセージを米連 邦議会に提出しており、その中には「新たな常習者の防止と、常習者の更生」に連邦政府の資源をより多く投入するという内容が含まれていた。この側面は、 「麻薬との戦争」という言葉ほどメディアの注目を集めることはなかった。[11][10][12][13] それ以来、大統領と連邦議会は、一般的に、公衆衛生や治療よりも法の執行と取締りに重点を置くニクソンの当初の政策を維持または拡大してきた。大麻は特別 なケースであり、1930年代に連邦政府の規制の対象となり、1970年以降は乱用される可能性が極めて高く医療的価値のない薬物としてヘロインと同等の 禁止薬物に分類されている。1930年代以降、多数の主流派の研究や調査結果が、このような厳しい分類を推奨していない。1990年代以降、医療用大麻は 38の州で合法化され、また娯楽用大麻も24の州で合法化され、連邦法との間に政策上のギャップが生じ、国連麻薬条約に準拠していない。 2011年6月、薬物政策に関するグローバル委員会は「世界的な薬物との戦いは失敗に終わり、世界中の個人や社会に壊滅的な結果をもたらした」と宣言する 重要な報告書を発表した。[6] 2023年、国連人権高等弁務官は「数十年にわたる処罰的な『薬物との戦い』戦略は、 ますます広範囲にわたる物質の生産と消費を防止できなかった」と述べた。[14] その年、米国連邦政府の麻薬戦争予算は年間390億ドルに達し、1971年からの累積支出は1兆ドルと推定されている。[15] 2024年現在、フェンタニルやその他の合成麻薬に焦点を当てた麻薬戦争が継続している。 |

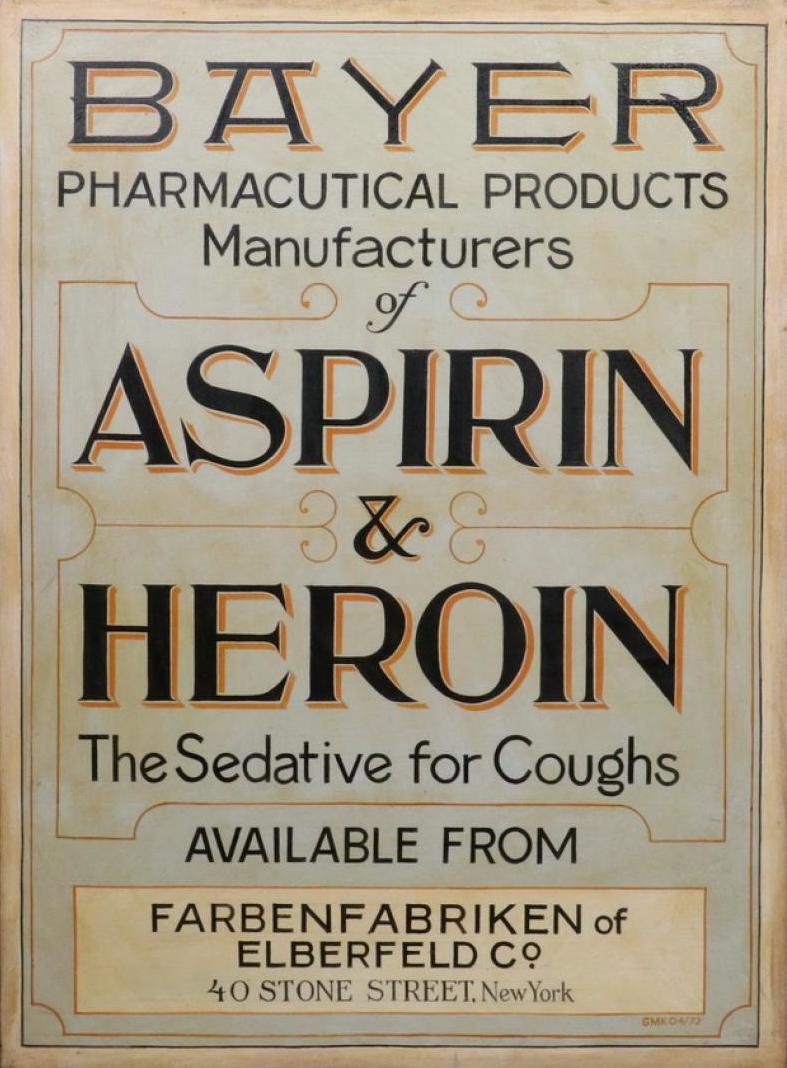

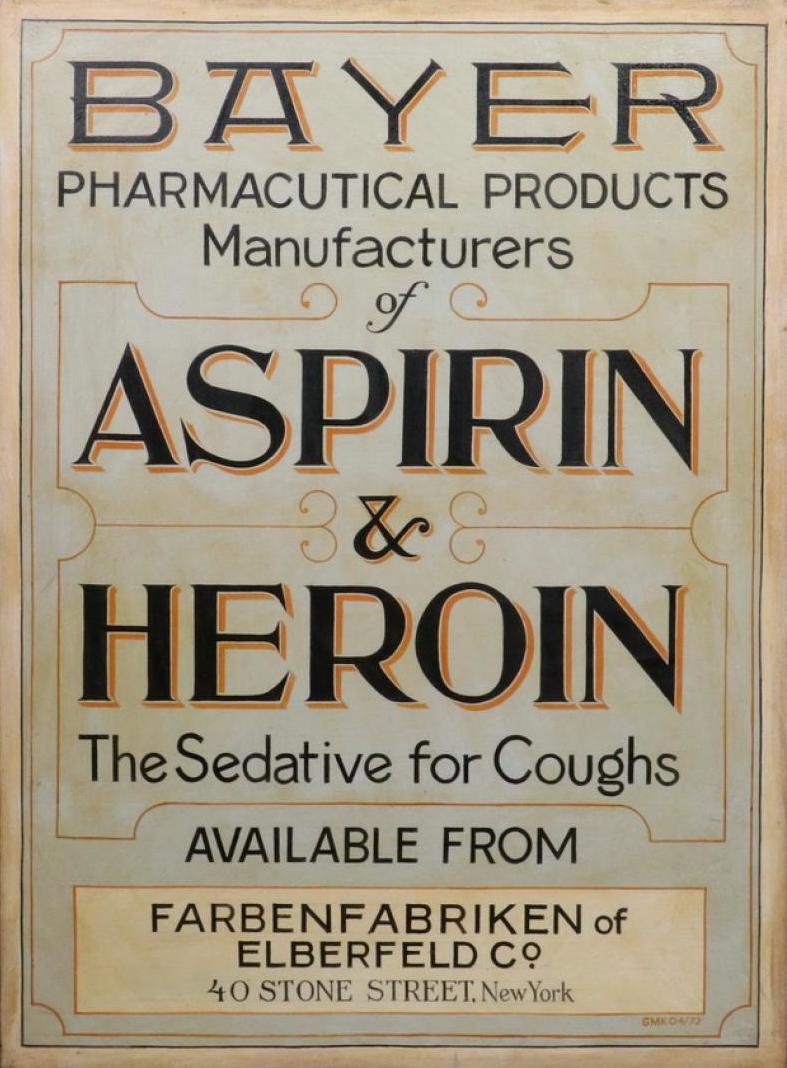

| History See also: History of United States drug prohibition and Legal history of cannabis in the United States Drugs in the US were largely unregulated until the early 20th century. Opium had been used to relieve pain since the Revolutionary War (1775–1783), particularly in the treatment of soldiers during wartime. In the 1800s, the international opium trade was large-scale and lucrative: Britain, and to a lesser degree the other European colonial powers and the US, gained immense profits from selling opium in China and southeast Asia; two opium wars were fought mid-century by Britain against China to ensure the trade continued to serve millions of Chinese opium users.[16] At the same time in America, the use of opiates in the civilian population began to increase dramatically,[17] and cocaine use became prevalent.[18][19] Alcohol consumption steadily grew, as did the temperance movement, well-supported by the middle class, promoting moderation or abstinence.[20][21] The practice of smoking cannabis began to be noticed in the early 1900s.[22] Under the US Constitution, the authority to control dangerous drugs exists separately at both the federal and state level.[23] State and local governments began enacting drug laws in the mid-1800s, while federal drug legislation arrived after the turn of the century. Mid-1800s–1909: Proliferation of unregulated drug use  Advertising sign from Bayer for use in US drug stores, dating from before the federal prohibition of heroin by the Anti-Heroin Act of 1924. The latter half of the 19th century saw a ramping up of opiate use in America. Early in the century, morphine had been isolated from opium, decades later, heroin was created from morphine, each more potent than the previous form.[24][25] With the invention of the hypodermic syringe, introduced in America mid-century, opiates were easily administered and became a preferred medical treatment. During the Civil War (1861–1865), millions of doses of opiates were distributed to sick and wounded soldiers, addicting some;[17] domestic poppy fields were planted in an attempt to meet shortages (the crops proved to be of poor quality).[26] In the civilian population, physicians treated opiates like a wonder drug, prescribing them widely, for chronic pain, irritable babies, asthma, bronchitis, insomnia, "nervous conditions", hysteria, menstrual cramps, morning sickness, gastrointestinal disease, "vapors", and on.[17][27][28] Drugs were also sold over-the-counter as home remedies, and in refreshments. Laudanum, a powdered opium solution, was commonly found in the home medicine cabinet.[27][28] Heroin was available as a cough syrup.[29][30][31] Cocaine was introduced as a surgical anesthetic, and more popularly as a pick-me-up,[18][19] found in soft drinks, cigarettes, blended with wine, in snuff, and other forms.[18][19] Brand names appeared: Coca-Cola contained cocaine until 1903;[32] Bayer created the trademark name "Heroin" for their diamorphine product.[33] In the 1890s, the Sears & Roebuck catalog, distributed to millions of American homes, offered a syringe and a small amount of heroin for $1.50.[31][29][30] America's "first opioid crisis" The 1880s saw opiate addiction surge among among housewives, doctors, and Civil War veterans,[34] creating America's "first opioid crisis."[35][36] By the end of the century, an estimated one in 200 Americans were addicted to opiates, 60% of them women, typically white and middle- to upper-class.[17] Medical journals of the later 1800s were replete with warnings against overprescription. As medical advances like the x-ray, vaccines, and germ theory presented better treatment options, prescribed opiate use began to decline. Meanwhile, opium smoking remained popular among Chinese immigrant laborers, thousands of whom had arrived during the California gold rush; opium dens were established in Chinatowns in cities and towns across America. The public face of opiate use began to change, from affluent white Americans, to "Chinese, gamblers, and prostitutes."[17][37] During this period, states and municipalities began enacting laws banning or regulating certain drugs.[38] In Pennsylvania, an anti-morphine law was passed in 1860.[39] In 1875, San Francisco enacted an anti-opium ordinance, vigorously enforced, imposing stiff fines and jail for visiting opium dens. The rationale held that "many women and young girls, as well as young men of a respectable family, were being induced to visit the Chinese opium-smoking dens, where they were ruined morally and otherwise." The law catered to resentment towards the Chinese laborer population who were being accused of taking jobs; other uses of opiates or other drugs were unaffected. Similar laws were enacted in other states and cities. The federal government became involved, selectively raising the import tariff on the smoking grade of opium. None of these measures proved effective in significantly reducing opium use[40] (the anti-Chinese fervor led to Congress halting Chinese laborer immigration for 10 years with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882[41]). In the following years, opioids, cocaine, and cannabis were associated with various ethnic minorities and targeted in other local jurisdictions.[37][39] In 1906, the Pure Food and Drug Act, also known as the Wiley Act, addressed problems with tainted and adulterated food in the growing industrial food system, and with drug quality, by mandating ingredient labels and prohibiting false or misleading labeling. For drugs, a listing of active ingredients was required; a set of drugs deemed addictive or dangerous, that included opium, morphine, cocaine, caffeine, and cannabis, was specified. Oversight of the act was assigned to the US Department of Agriculture's Bureau of Chemistry, which evolved into the Food and Drug Administration in 1930.[42][43] |

歴史(前史) 参照:米国の麻薬禁止の歴史、米国における大麻の法的な歴史 米国では20世紀初頭まで、麻薬はほとんど規制されていなかった。アヘンは独立戦争(1775年~1783年)以来、特に戦時中の兵士の治療に痛みの緩和 のために使用されていた。1800年代には、国際的なアヘン貿易は大規模かつ利益率の高いものとなっていた。イギリス、そして他のヨーロッパの植民地勢力 やアメリカも、中国や東南アジアでアヘンを販売することで莫大な利益を得ていた。2度のアヘン戦争は、アヘンを常用する数百万人の中国人を確保するため に、イギリスが中国と戦ったものである。[16] アメリカでは、同じ時期に 一般市民の間でアヘンの使用が劇的に増加し始め[17]、コカインの使用も広まった[18][19]。節酒運動も中流階級の支持を受けて盛んになり、節度 ある節酒や禁酒が推奨された。アルコール消費量は着実に増加した。。[22] 米国憲法の下では、危険ドラッグを規制する権限は連邦政府と州政府の両方に存在している。[23] 州および地方自治体は1800年代半ばに薬物関連の法律を制定し始め、連邦政府による薬物関連の法律は世紀が変わってから制定された。 1800年代半ば~1909年:規制されていない薬物の使用の蔓延  1924年のアンチヘロイン法によるヘロインの連邦禁止以前の、米国のドラッグストアで使用されていたバイエル社の広告看板。 19世紀後半、アメリカではアヘン使用が急増した。世紀初頭にはアヘンからモルヒネが単離され、その数十年後にはモルヒネからヘロインが作られた。ヘロイ ンは、それ以前の物質よりもさらに強力な作用を持つものだった。[24][25] 世紀半ばにアメリカで導入された皮下注射器の発明により、アヘン剤は簡単に投与できるようになり、好ましい医療治療法となった。南北戦争(1861年 ~1865年)中には、何百万ものアヘン剤が負傷した兵士たちに配給され、一部の兵士が中毒になった。[17] 国内のケシ畑は不足を補うために植えられたが(作物の品質は低かった)。[26] 一般市民の間では、 医師たちはオピオイドをまるで万能薬のように扱い、慢性的な痛み、疝痛、喘息、気管支炎、不眠症、神経症、ヒステリー、月経痛、つわり、胃腸疾患、気分の 落ち込みなどに対して広く処方していた。 薬は家庭療法やリフレッシュメントとして店頭でも販売されていた。粉末状のアヘン溶液であるラウダナムは家庭の薬箱に常備されていた。[27][28] ヘロインは咳止めシロップとして入手可能であった。[29][30][31] コカインは外科手術用の麻酔薬として導入され、 麻酔薬として導入され、より一般的に気付け薬として用いられた。[18][19] ソフトドリンク、タバコ、ワインに混ぜたり、嗅ぎタバコ、その他の形態で発見された。[18][19] ブランド名が登場した。コカ・コーラは1903年までコカインを含んでいた。[32] バイエルはジアモルヒネ製品に「ヘロイン」という商標名をつけた。[33] 1890年代、何百万ものアメリカ人家庭に配布されたシアーズ・ローバックのカタログでは、1ドル50セントで注射器と少量のヘロインが販売されていた。 [31][29][30] アメリカにおける「最初のオピオイド危機」 1880年代には、主婦、医師、南北戦争の退役軍人らにアヘン中毒者が急増し、アメリカにおける「最初のオピオイド危機」が起こった。そのうち60%は女 性で、その大半は白人の中流階級から上流階級であった。[17] 1800年代後半の医学誌には、処方過多に対する警告が数多く掲載されていた。X線、ワクチン、細菌説などの医学の進歩により、より良い治療法が提示され るようになると、処方されたアヘン使用は減少に向かった。一方、アヘン吸引は、カリフォルニアのゴールドラッシュの際に数千人が移住してきた中国人労働者 の間で依然として人気があり、アヘン窟はアメリカ中の都市や町のチャイナタウンに開設された。アヘン使用の一般的なイメージは、裕福な白人から「中国人、 ギャンブラー、娼婦」へと変化し始めた。[17][37] この時期、州や市町村では特定の薬物の使用を禁止または規制する法律が制定され始めた。[38] ペンシルベニア州では1860年にモルヒネ禁止法が可決された。[39] 1875年にはサンフランシスコがアヘン取り締まり条例を制定し、厳格に施行された。アヘン窟を訪れた者には高額の罰金と投獄が科された。その根拠は、 「多くの女性や少女、そして良家の若い男性までもが、中国人のアヘン吸引のたまり場に足を運ぶよう誘惑され、そこで道徳的にも、その他の面でも堕落させら れている」というものであった。この法律は、職を奪っていると非難されていた中国人労働者に対する憤りを反映したものであり、アヘンやその他の薬物のその 他の使用には影響を与えなかった。同様の法律は他の州や都市でも制定された。連邦政府も関与するようになり、アヘンを喫煙する段階での輸入関税を部分的に 引き上げた。しかし、これらの措置はいずれもアヘンの使用を大幅に減らす効果はなかった[40](反中感情の高まりにより、1882年の中国人排斥法によ り、議会は中国人労働者の移民を10年間停止することになった[41])。その後、オピオイド、コカイン、マリファナはさまざまな少数民族と関連付けら れ、他の地方管轄区域で標的とされた。 1906年、ワイリー法としても知られる純正食品医薬品法が、成長する工業的食品システムにおける汚染や粗悪食品の問題、および医薬品の品質の問題に対処 するために、成分表示を義務付け、虚偽または誤解を招くような表示を禁止した。薬品については、有効成分のリストが義務付けられ、アヘン、モルヒネ、コカ イン、カフェイン、大麻などの中毒性や危険性があるとみなされた薬品が指定された。この法律の監督は米国農務省化学局に委ねられ、同局は1930年に食品 医薬品局へと発展した。[42][43] |

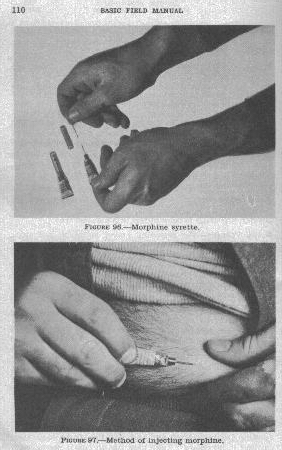

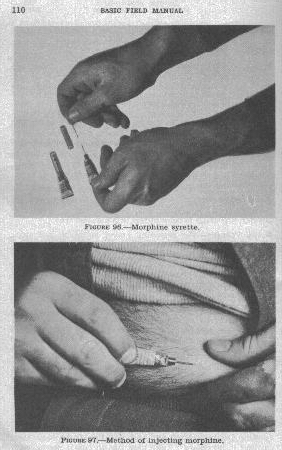

| 1909–1971: Rise of federal drug

prohibition Police destroying illegal drugs in Los Angeles, 1916 On February 9, 1909, the Smoking Opium Exclusion Act, "to prohibit the importation and use of opium for other than medicinal purposes", became the first US federal law to ban the non-medical use of a substance.[38][44][45] This was soon followed by the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914, that regulated and taxed the production, importation, and distribution of opiates and coca products.[46][47] Amending the Smoking Opium Exclusion Act, the Anti-Heroin Act of 1924 specifically outlawed the manufacture, importation and sale of heroin.[24] During World War I (1914–1918), soldiers were commonly treated with morphine, giving rise to addiction among veterans.[48] An international wartime focus on military use of opiates and cocaine for medical treatment and performance enhancement, and concern over potential abuse, lead to the post-war adoption among nations of the 1912 Hague International Opium Convention of 1912, with oversight by the newly established League of Nations. This became the basis of current international drug control policy,[49][50] initially concerned with regulating the free trade of drugs, without affecting production or use. The US, one of the most prohibitionist countries, felt these provisions did not go far enough in restricting drugs.[51] In 1919, the US passed the 18th Amendment, prohibiting the sale, manufacture, and transportation of alcohol, with exceptions for religious and medical use, and the National Prohibition Act, also known as the Volstead Act, to carry out the provisions of the 18th Amendment. By the 1930s, the policy was seen as a failure: production and consumption of alcohol did not decrease, organized crime flourished in the alcohol black market, and tax revenue, particularly needed after the start of the Great Depression in 1929, was lost. Prohibition was repealed by passage of the 21st Amendment in 1933, with President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1933–1945) asking Americans not to abuse "this return to personal freedom."[52] In 1922, the Narcotic Drugs Import and Export Act broadened federal regulation of opiates and coca products by prohibiting import and export for non-medical use,[53] and established the Federal Narcotics Control Board (FNCB) to act as overseer.[54] Anslinger era begins Harry Anslinger discussing cannabis control with Canadian narcotics chief Charles Henry Ludovic Sharman and Assistant Secretary of the Treasury Stephen B. Gibbons (1938)  Anslinger (center) discussing cannabis control with Canadian narcotics chief Charles Henry Ludovic Sharman and Assistant Secretary of the Treasury Stephen B. Gibbons (1938) The Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN) was established as an agency of the US Department of the Treasury by an act of June 14, 1930,[55] with Harry J. Anslinger appointed as commissioner, a position he held for 32 years, until 1962.[56] Anslinger supported Prohibition and the criminalization of all drugs, and spearheaded anti-drug policy campaigns.[57] He did not support a public health and treatment approach, instead urging courts to "jail offenders, then throw away the key." He has been characterized as the first architect of the punitive war on drugs.[58][59][60] According to a report prepared for the Senate of Canada, Anslinger was "utterly devoted to prohibition and the control of drug supplies at the source" and is "widely recognized as having had one of the more powerful impacts on the development of US drug policy, and, by extension, international drug control into the early 1970s."[61] During his three decades heading the FBN, Anslinger zealously and effectively pursued harsh drug penalties, with a particular focus on cannabis. He used his stature as the head of a federal agency to draft legislation, discredit critics, discount medical opinion and scientific findings, and convince lawmakers. Publicly, he used the media and speaking engagements to introduce hyperbolic messages about the evils of drug use.[58][62] In the 1930s, he referred to a collection of news reports of horrific crimes, making unsubstantiated claims attributing them to drugs, particularly cannabis. He announced that youth become "slaves" to cannabis, "continuing addiction until they deteriorate mentally, become insane, turn to violent crime and murder." He promoted a racialized view of drug use, saying that blacks and Latinos were the primary abusers.[58] In Congressional testimony, he declared "of all the offenses committed against the laws of this country, the narcotic addict is the most frequent offender."[63] He was also an effective administrator and diplomat, attending international drug conferences and steadily expanding the FBN's influence.[64] In 1935, the New York Times reported on President Roosevelt's public support of the Uniform State Narcotic Drug Act under the headline, "Roosevelt Asks Narcotic War Aid".[65][66] The Uniform Law Commission developed the act to address the 1914 Harrison Act's lack of state-level enforcement provisions, creating a model law reflecting the Harrison Act that states could adopt to replace the existing patchwork of state laws.[65] Anslinger and the FBN were centrally involved in drafting the act, and in convincing states to adopt it.[67] Cannabis effectively outlawed, prescription drugs With the passage of the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937,[68] federal law reflected state law – by 1936, the non-medical use of cannabis had been banned in every state.[69][70] That year, the first two arrests for tax non-payment under the act, for possession of a quarter-ounce (7g), and trafficking of four pounds (1.8 kg), resulted in sentences of nearly 18 months and four years respectively.[71] The American Medical Association (AMA) had opposed the tax act on grounds that it unduly affected the medical use of cannabis. The AMA's legislative counsel, a physician, testified that the claims about cannabis addiction, violence and overdoses were not supported by evidence.[72][73] Scholars have posited that the act was orchestrated by powerful business interests – Andrew Mellon, Randolph Hearst, and the Du Pont family – to head off cheap competition to pulp and timber and plastics from the hemp industry.[note 2] After the act, cannabis research and medical testing became rare.[88] In 1939, New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, an opponent of the Marihuana Tax Act, formed the LaGuardia Committee to conduct the first US in-depth study of cannabis use. The report, produced by the New York Academy of Medicine and released in 1944, systematically contradicted government claims, finding that cannabis is not physically addictive, and its use does not lead to using other drugs or to crime.[89][90] The FBN's Anslinger branded the study "unscientific", denounced all involved, and disrupted other cannabis studies at the time.[91] In the late 1930s, questions emerged from League of Nations' Opium Advisory Committee concerning the focus on drug prohibition over public health measures such as mental health treatment, drug dispensaries and education. Anslinger, backed by his Canadian counterpart and policy ally, Charles Henry Ludovic Sharman, successfully argued against this view, and kept the focus on increasing global prohibition and supply control measures.[61] While narcotics were under the jurisdiction of the FBN, the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938 required the FDA to ensure that non-narcotic drugs were labeled for safe use. The act determined that certain drugs, including amphetamines, commercialized in the later 1930s, and barbiturates, were unsafe to use without medical supervision and could only be obtained by doctor's prescription. This marked the beginning of the federal distinction between over-the-counter and prescription drugs (clarified in the Durham-Humphrey Amendment of 1951).[92]  WWII US Army first aid manual illustration for injecting morphine using a syrette. "For the relief of severe pain": WWII US Army first aid manual illustrating self-injection of morphine using a syrette. Amphetamines, harsher penalties, international obligations During World War II (1939-1945), in addition to the widespread use of morphine, amphetamines entered military use to combat fatigue and improve morale. In the US, the Benzedrine brand was widely used in the military, and quickly became popular in the public for a variety of medical and recreational applications. Beginning in 1943, American soldiers could buy Benzedrine directly from the army on demand.[93][94] Post-war, amphetamines were promoted as mood elevators and diet pills to great success; by 1945, an estimated 750 million tablets a year were being produced in the US, enough to provide a million people with a daily supply, a trend that grew during the 1950s and 1960s.[95][96] Having failed to preserve world peace, the League of Nations ended post-war, transferring responsibilities to its successor, the United Nations. Anslinger, supported by Sharman, successfully campaigned to ensure that law enforcement and the prohibitionist view remained central to international drug policy. With the 1946 Lake Success Protocol, he helped to make sure that law enforcement was represented on the UN's new drug policy Supervisory Body (today's International Narcotics Control Board), and that it did not fall under a public health-oriented agency like the WHO.[61] In the early 1950s, responding to "white suburban grassroots movements" concerned about dealers preying on teenagers, liberal politicians at state level cracked down on drugs. California, Illinois, and New York passed the first mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses; Congress followed with the Boggs Act of 1951, creating the first federal mandatory minimums for drugs.[97][98] The act unified penalties for the Narcotic Drugs Import and Export Act and the Marihuana Tax Act, effectively criminalizing cannabis. Anslinger testified in favor of the inclusion of cannabis, describing a "stepping-stone" path leading from cannabis to harder drugs and crime.[99] First-offense possession of cannabis carried a 2–10 year minimum and a fine of up to $20,000.[100] This marked a change in Congress's approach to mandatory minimums, increasing their number, severity, and the crimes they covered. According to the United States Sentencing Commission, reporting in 2012: "Before 1951, mandatory minimum penalties typically punished offenses concerning treason, murder, piracy, rape, slave trafficking, internal revenue collection, and counterfeiting. Today, the majority of convictions under statutes carrying mandatory minimum penalties relate to controlled substances, firearms, identity theft, and child sex offenses.".[101] In 1961, the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs became the first of three UN treaties that together form the legal framework for international drug control, and require that domestic drug laws in member countries comply with the conventions.[1] The Single Convention unified existing international drug agreements,[102] and limited possession and use of opiates, cannabis and cocaine to "medicinal and scientific purposes", prohibiting recreational use. Sixty-four countries initially joined; it was ratified and came into force in the US in 1967. The Convention on Psychotropic Substances of 1971 added synthetic, prescription and hallucinogenic drugs. The Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances of 1988 addressed international drug trafficking and "criminalized the entire drug market chain, from cultivation/production to shipment, sale, and possession."[103][1][104][105] In 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson (1963–69) decided that the government needed to make an effort to curtail the social unrest that blanketed the country at the time. He focused on illegal drug use, an approach that was in line with expert opinion on the subject at the time. In the 1960s, it was believed that at least half of the crime in the US was drug-related, and this estimate grew as high as 90% in the next decade.[106] He created the Reorganization Plan of 1968 which merged the Bureau of Narcotics and the Bureau of Drug Abuse Control to form the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs within the Department of Justice.[107] Federal drug schedule system introduced The Richard Nixon presidency (1969–74) incorporated his predecessor's anti-drug initiative in a tough-on-crime platform. In his 1968 presidential nomination acceptance speech, Nixon promised, "Our new Attorney General will ... launch a war against organized crime in this country. ... will be an active belligerent against the loan sharks and the numbers racketeers that rob the urban poor. ... will open a new front against the filth peddlers and the narcotics peddlers who are corrupting the lives of the children of this country."[108][109] In a 1969 special message to Congress, he identified drug abuse as "a serious national threat".[110][111] On October 27, 1970, Nixon signed into law the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970, establishing his approach to drug control. The act largely repealed mandatory minimum sentences:[112] simple possession was reduced from a felony to a misdemeanor, the first offense carried a maximum of one year in prison, and judges had the latitude to assign probation, parole or dismissal. Penalties for trafficking were increased, up to life depending on the quantity and type of drug. Funding was authorized for the Department of Health, Education and Welfare to provide treatment, rehabilitation and education. Additional federal drug agents were provided, and a "no-knock" power was instituted, that allowed entry into homes without warning to prevent evidence from being destroyed. Licensing and stricter reporting and record-keeping for pharmaceutical manufacturers and distributors occurred under the act.[113] Title II of Act, the Controlled Substances Act (CSA), helped align US law with the UN Single Convention, with "many of the provisions of the CSA ... enacted by Congress for the specific purpose of ensuring U.S. compliance with the treaty." The CSA's five drug Schedules, an implementation of the Single Convention's four schedule system, categorized drugs based on medical value and potential for abuse.[114][115] Under the new drug schedules, cannabis was provisionally placed by the administration in the most restrictive Schedule I, "until the completion of certain studies now underway to resolve the issue."[116] As mandated by the CSA, Nixon appointed the National Commission on Marijuana and Drug Abuse, known as the Shafer Commission, to investigate. |

1909年~1971年:連邦麻薬禁止令の施行 1916年、ロサンゼルスで違法薬物を破壊する警察 1909年2月9日、「医療目的以外のアヘンの輸入および使用を禁止する」ことを目的とした「喫煙アヘン排除法」が、非医療目的の物質使用を禁止する初の 連邦法となった。[38][44][45] これに続いて、1914年には「ハリソン麻薬税法」が制定され 1914年のハリソン麻薬税法により、アヘンおよびコカ製品の生産、輸入、流通が規制され課税されることとなった。[46][47] 喫煙阿片排除法を改正した1924年の反ヘロイン法は、ヘロインの製造、輸入、販売を明確に違法とした。[24] 第一次世界大戦(1914年 - 1918年)中、兵士たちはモルヒネを投与されることが一般的であり、退役軍人の中には中毒になる者もいた。[48] 戦時中、医療やパフォーマンスの向上を目的としたアヘンやコカインの軍事利用に国際的な注目が集まり、乱用の可能性に対する懸念が高まった。その結果、戦 後、新たに設立された国際連盟による監督の下、1912年のハーグ国際アヘン会議(1912年)が各国によって採択されることとなった。これが現在の国際 的な麻薬規制政策の基礎となり、当初は麻薬の自由貿易の規制に重点が置かれ、生産や使用には影響を与えなかった。最も厳格な麻薬禁止政策をとる国のひとつ であるアメリカ合衆国は、これらの規定では麻薬を十分に規制できないと感じていた。 1919年、米国は宗教および医療目的での使用を例外としてアルコールの販売、製造、輸送を禁止する憲法修正第18条と、同修正条項の施行を目的とした禁 酒法(別名ボルステッド法)を可決した。1930年代には、この政策は失敗と見なされていた。アルコールの生産と消費は減らず、アルコールの闇市場では組 織犯罪が横行し、特に1929年の世界恐慌以降は必要とされていた税収が失われた。1933年に21条修正案が可決され、禁酒法は廃止された。フランクリ ン・D・ルーズベルト大統領(1933年~1945年)は、アメリカ国民に「個人の自由への回帰」を悪用しないよう求めた。[52] 1922年には麻薬取締法(Narcotic Drugs Import and Export Act)が制定され、医療目的以外での輸入と輸出が禁止され、アヘンやコカ製品の連邦規制が強化された。また、連邦麻薬取締局(FNCB)が監督機関とし て設立された。 アンスリンガー時代が始まる ハリー・アンスリンガーがカナダ麻薬取締局長官チャールズ・ヘンリー・ルドヴィック・シャーマンおよび財務次官補スティーブン・B・ギボンズと大麻取締に ついて協議(1938年)  アンスリンガー(中央)がカナダ麻薬取締局長官チャールズ・ヘンリー・ルドヴィック・シャーマンおよび財務次官補スティーブン・B・ギボンズと大麻取締に ついて協議(1938年) 連邦麻薬局(FBN)は、1930年6月14日の法律により米国財務省の機関として設立され、ハリー・J・アンスリンガーが初代局長に任命された。彼は 1962年まで32年間その職を務めた 1962年までその職にあった。[56] アンスリンガーは、麻薬の禁止と犯罪化を支持し、麻薬対策キャンペーンの先頭に立った。[57] 彼は公衆衛生や治療のアプローチを支持せず、代わりに裁判所に対して「犯罪者を刑務所に入れて、鍵を捨てる」よう強く求めた。彼は、薬物に対する処罰的な 戦争の最初の立案者と評されている。[58][59][60] カナダ上院のために作成された報告書によると、アンシラーは「薬物の禁止と供給源の管理に完全に専念」し、「米国の薬物政策の展開に最も強い影響を与えた 人物の一人であり、ひいては1970年代初頭までの国際的な薬物規制にも影響を与えた人物として広く認識されている」とされる。[61] FBNのトップとして30年間在任中、アンシグラーは特に大麻に焦点を当て、厳格な麻薬処罰を熱心かつ効果的に追求した。彼は連邦機関のトップとしての地 位を活かし、法案の起草、批判者の信用失墜、医学的見解や科学的発見の軽視、そして議員への説得を行った。公の場では、メディアや講演の機会を利用して、 薬物使用の害について誇張したメッセージを伝えた。[58][62] 1930年代には、恐ろしい犯罪に関する一連の報道に言及し、それらの犯罪を薬物、特に大麻のせいにする裏付けのない主張を行った。彼は、若者たちは大麻 の「奴隷」となり、「精神が衰え、正気を失い、暴力犯罪や殺人に走るまで中毒が続く」と発表した。彼は、黒人とラテン系住民が麻薬乱用者の主なグループで あると述べ、人種差別的な麻薬使用観を広めた。[58] 議会証言では、「この国の法律に違反して犯された犯罪のすべてにおいて、麻薬中毒者が最も頻繁に犯罪を犯している」と宣言した。[63] 彼はまた、有能な行政官および外交官でもあり、国際麻薬会議に出席し、FBNの影響力を着実に拡大した。[64] 1935年、ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙は、「ルーズベルト大統領、麻薬戦争への支援を要請」という見出しで、大統領が麻薬統一法を支持していることを報道 した。[65][66] 統一法委員会は、1914年のハリソン法の州レベルでの施行規定の欠如に対処するために同法を策定し 1914年のハリソン法に州レベルでの施行規定が欠けていたことを受け、ハリソン法を反映したモデル法を策定し、州が既存の州法の寄せ集めを置き換えるた めに採用できるようにした。[65] アンスリンガーとFBNは、この法律の草案作成に中心的に関与し、州にこの法律を採用させるよう説得した。[67] 大麻は事実上非合法化され処方薬化される 1937年のマリファナ税法の成立により、連邦法が州法を反映するようになった。1936年までに、医療目的以外での大麻の使用は全州で禁止されていた。 この年、25グラム(0.7オンス)の所持と4ポンド(1.8キログラム)の売買により、それぞれ約18ヶ月と4年の実刑判決が下された。[71] アメリカ医学会(AMA)は、この税法が医療用大麻の使用に不当な影響を与えるとして反対していた。AMAの立法顧問である医師は、大麻の中毒、暴力、過 剰摂取に関する主張は証拠によって裏付けられていないと証言した。[72][73] 学者たちは、この法律は強力な企業利益(アンドリュー・メロン、ランドルフ・ハースト、デュポン家)によって画策されたものであり、 アンドリュー・メロン、ランドルフ・ハースト、デュポン家といった有力な企業利益が、麻業界からのパルプや木材、プラスチックへの安価な競争を阻止するた めに、この法律を策定したという仮説が学者たちによって立てられている。[注2] この法律が制定された後、大麻の研究や医療試験はまれなものとなった。[88] 1939年、マリファナ税法に反対していたニューヨーク市長フィオレロ・ラガーディアは、大麻使用に関する米国初の徹底的な研究を行うラガーディア委員会 を結成した。ニューヨーク医学アカデミーが作成し、1944年に発表されたこの報告書は、政府の主張に系統的に反論し、大麻には身体的依存性はなく、大麻 の使用が他の薬物の使用や犯罪につながることもないと結論づけた。[89][90] FBNのアンスリンガーは、この研究を「非科学的」と決めつけ、関係者を非難し、当時行われていた他の大麻研究を妨害した。[91] 1930年代後半には、国際連盟のアヘン諮問委員会から、精神衛生治療、薬局、教育といった公衆衛生対策よりも薬物の禁止に重点が置かれていることへの疑 問が提起された。アンシグラーは、カナダの同僚であり政策同盟者であるチャールズ・ヘンリー・ルドヴィック・シャーマンに支援され、この見解に反対する主 張を成功させ、世界的な禁止と供給管理措置の強化に重点を置いた。 麻薬が連邦麻薬局の管轄下にあった間、1938年の食品・医薬品・化粧品法は、麻薬以外の医薬品については安全な使用法のラベル表示を義務付けるよう FDAに求めた。この法律では、1930年代後半に商品化されたアンフェタミンやバルビツール酸塩などの特定の薬物は、医師の監督なしに使用するには危険 であり、医師の処方箋なしには入手できないと定められた。これが、市販薬と処方薬の区別を連邦政府が明確にした始まりである(1951年のダーラム・ハン フリー修正法で明確化された)[92]。  WWII 米軍救急マニュアルのイラスト。シレットを使用したモルヒネの注射。 「激しい痛みの緩和」:WWII 米軍救急マニュアルのイラスト。シレットを使用したモルヒネの自己注射。 アンフェタミン、より厳しい処罰、国際的な義務 第二次世界大戦中(1939年~1945年)、モルヒネが広く使用されていたことに加え、疲労と士気向上対策としてアンフェタミンが軍で使用されるように なった。米国では、軍で広く使用されていた「ベンゼドリン」ブランドが、医療や娯楽の様々な用途で一般市民の間でも急速に普及した。1943年以降、米軍 兵士は必要に応じて軍から直接ベンゼドリンを購入することができた。[93][94] 戦後、アンフェタミンは気分を高揚させ、ダイエット効果のある薬として宣伝され、大成功を収めた。1945年までに、 米国では年間推定7億5千万錠が生産され、100万人が毎日摂取できる量であった。この傾向は1950年代と1960年代に拡大した。[95][96] 世界平和の維持に失敗した国際連盟は、戦後、その責任を後継機関である国際連合に移管して解散した。アンスリンガーはシャーマンの支援を受け、法の執行と 禁止論が国際的な麻薬政策の中心であり続けるよう、キャンペーンを展開した。1946年のレイクサクセス議定書により、彼は法の執行が国連の新しい麻薬政 策監督機関(現在の国際麻薬統制委員会)に代表されるよう尽力し、法の執行が世界保健機関(WHO)のような公衆衛生を目的とした機関の管轄下に入らない よう図った。 1950年代初頭、ティーンエイジャーを狙う売人たちを懸念する「郊外の白人の草の根運動」に応える形で、州レベルのリベラル派政治家たちが麻薬取締に乗 り出した。カリフォルニア州、イリノイ州、ニューヨーク州では、薬物犯罪に対する初の最低刑が制定された。連邦議会はこれに続き、1951年にボッグス法 を制定し、薬物に対する初の連邦最低刑を定めた。[97][98] この法律は麻薬輸入・輸出法と大麻税法の刑罰を統一し、事実上、大麻を犯罪化した。アンシグラーは大麻を犯罪化することに賛成の立場をとり、大麻からより 強力な麻薬や犯罪へとつながる「踏み石」のような道筋について証言した。[99] 大麻の初犯所持には最低2年から10年の懲役と最高2万ドルの罰金が科せられた。[100] これは連邦議会が義務的最低刑に取組む姿勢の変化を意味し、その数、厳格さ、対象犯罪のすべてが増大した。米国量刑委員会の2012年の報告によると、 「1951年以前は、通常、強制最低刑は反逆罪、殺人、海賊行為、強姦、奴隷売買、国内歳入徴収、偽造に関する犯罪を処罰するものであった。今日、強制最 低刑を規定する法律に基づく有罪判決の大多数は、規制薬物、銃器、ID窃盗、児童に対する性犯罪に関するものである」[101]。 1961年、麻薬に関する単一条約が、国際的な麻薬規制の法的枠組みを構成する3つの国連条約の最初のものとなり、加盟国の国内麻薬法が条約に準拠するこ とが義務付けられた。[1] 単一条約は、それまでの国際的な麻薬協定を統一し、[102] アヘン、大麻、コカインの所持と使用を「医療および科学目的」に限定し、娯楽目的の使用を禁止した。当初は64カ国が加盟し、1967年にアメリカで批准 され発効した。1971年の向精神薬に関する条約では、合成薬、処方薬、幻覚剤が追加された。1988年の麻薬及び向精神薬の不正取引の防止に関する条約 では、国際的な麻薬密売に対処し、「栽培・生産から出荷、販売、所持に至る麻薬市場の全連鎖を犯罪化した」[103][1][104][105] 1968年、リンドン・B・ジョンソン大統領(1963年~1969年在任)は、当時国内を覆っていた社会不安を抑制するために政府が努力する必要がある と判断した。彼は違法薬物使用に焦点を当てたが、これは当時この問題に関する専門家の意見に沿ったアプローチであった。1960年代には、米国の犯罪の少 なくとも半分は薬物関連であると考えられており、その推定値は次の10年間で90%にまで上昇した。[106] 彼は1968年の再編計画を作成し、麻薬取締局と麻薬乱用取締局を統合して司法省内に麻薬・危険ドラッグ取締局を設立した。[107] 連邦麻薬スケジュール制度が導入された リチャード・ニクソン大統領(1969年~1974年)は、犯罪に厳格に対処するという政策に、前任者の反麻薬イニシアティブを盛り込んだ。1968年の 大統領指名受諾演説で、ニクソンは「我々の新しい司法長官は...この国における組織犯罪との戦いを開始する。都市部の貧困層から金を巻き上げる高利貸し や賭博屋に対しては、積極的に戦うつもりだ。この国の子供たちの生活を蝕む悪徳業者や麻薬密売業者に対しては、新たな戦線を展開するつもりだ」[108] [109] 1969年の議会への特別メッセージで、彼は薬物乱用を「深刻な国民の脅威」と位置づけた。[110][111] 1970年10月27日、ニクソンは「1970年包括的麻薬乱用防止・取締法」に署名し、麻薬取締に対する自身の考え方を確立した。この法律は、最低刑の 義務付けをほぼ廃止した。単純所持は重罪から軽罪に格下げされ、初犯の場合は最大1年の禁固刑となり、裁判官は保護観察、仮釈放、または不起訴処分を決定 する裁量権を持つことになった。麻薬取引に対する罰則は強化され、麻薬の量や種類によっては終身刑が科される場合もあった。保健教育福祉省が治療、リハビ リ、教育を提供するための資金が承認された。連邦麻薬取締官が追加で配置され、証拠隠滅を防ぐために警告なしに家宅捜索を行う「ノックなし」権限が制定さ れた。この法律に基づき、医薬品製造業者および販売業者に対する認可や、より厳格な報告および記録管理が行われた。[113] 同法の第2条である規制物質法(CSA)は、米国の法律を国連単一条約に整合させるのに役立ち、「CSAの規定の多くは...米国が条約を遵守することを 確実にするという特定の目的のために議会によって制定された」ものである。単一条約の4段階のスケジュール制度を導入したCSAの5段階の薬物スケジュー ルは、薬物を医療上の価値と乱用の可能性に基づいて分類した。[114][115] 新しい薬物分類では、大麻は「この問題を解決するための現在進行中の特定の研究が完了するまで」という条件付きで、政権により最も制限の厳しいスケジュー ルIに暫定的に分類された。[116] CSAの規定に従い、ニクソン大統領は大麻と薬物乱用に関する国家委員会(通称シェーファー委員会)を任命し、調査を命じた。 |

| 1971–present: The "War on Drugs" On May 27, 1971, after a trip to Vietnam, two congressmen, Morgan F. Murphy (Democrat) and Robert H. Steele (Republican), released a report describing a "rapid increase in heroin addiction within the United States military forces in South Vietnam". They estimated that "as many as 10 to 15 percent of our servicemen are addicted to heroin in one form or another."[117][115][118][119] On June 6, a New York Times article, "It's Always A Dead End on 'Scag Alley'", cited the Murphy-Steele report in a discussion of heroin addiction. The article stated that, in the US, "the number of addicts is estimated at 200,000 to 250,000, only about one‐tenth of 1 per cent of the population but troublesome out of all proportion." It also noted, "Heroin is not the only drug problem in the United States. 'Speed' pills – among them, amphetamines – are another problem, and not least in the suburbs where they are taken by the housewife (to cure her of the daily 'blues') and by her husband (to keep his weight down)."[120] On June 17, 1971, Nixon presented to Congress a plan for expanded anti-drug abuse measures. He painted a dire picture: "Present efforts to control drug abuse are not sufficient in themselves. The problem has assumed the dimensions of a national emergency. ... If we cannot destroy the drug menace in America, then it will surely in time destroy us." His strategy involved both treatment and interdiction: "I am proposing the appropriation of additional funds to meet the cost of rehabilitating drug users, and I will ask for additional funds to increase our enforcement efforts to further tighten the noose around the necks of drug peddlers, and thereby loosen the noose around the necks of drug users." He singled out heroin and broadened the scope beyond the US: "To wage an effective war against heroin addiction, we must have international cooperation. In order to secure such cooperation, I am initiating a worldwide escalation in our existing programs for the control of narcotics traffic."[121] Later the same day, Nixon held a news conference at the White House, where he described drug abuse as "America's public enemy number one." He announced, "In order to fight and defeat this enemy, it is necessary to wage a new, all-out offensive. ... This will be a worldwide offensive dealing with the problems of sources of supply ... It will be government wide, pulling together the nine different fragmented areas within the government in which this problem is now being handled, and it will be nationwide in terms of a new educational program." Nixon also stated that the problem wouldn't end with the addiction of soldiers in the Vietnam War.[122] He pledged to ask Congress for a minimum of $350 million for the anti-drug effort (when he took office in 1969, the federal drug budget was $81 million).[123] The news media focused on Nixon's militaristic tone, describing his announcement with variations of the phrase "war on drugs". The day after Nixon's press conference, the Chicago Tribune proclaimed, "Nixon Declares War on Narcotics Use in US". In England, The Guardian headlined, "Nixon declares war on drug addicts." The US anti-drug campaign came to be commonly referred to as the war on drugs;[124] the term also became used to refer to any government's prosecution of a US-style prohibition-based drug policy.[125] Facing reelection, with drug control as a campaign centerpiece, Nixon formed the Office of Drug Abuse Law Enforcement (ODALE) in late 1971. ODALE, armed with new federal enforcement powers, began orchestrating drug raids nationwide to improve the administration's watchdog reputation. In a private conversation while helicoptering over Brooklyn, Nixon was reported to have commented, "You and I care about treatment. But those people down there, they want those criminals off the streets." From 1972 to 1973, ODALE performed 6,000 drug arrests in 18 months, the majority of the arrested black.[126] In 1972, the Shafer Commission released its report, "Marihuana: A Signal of Misunderstanding", comprising a review of the medical literature and a national drug survey. It recommended decriminalization for personal possession and use of small amounts of cannabis, and prohibition only of supply. The conclusion was not acted on by Nixon or by Congress.[127][128] Citing the Shafer report, a lobbying campaign from 1973 to 1978, spearheaded by the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML), convinced 11 states to decriminalize cannabis for personal use.[129] In 1973, Nixon created the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) by an executive order accepted by Congress, to "establish a single unified command to combat an all-out global war on the drug menace."[130] The agency was charged with enforcing US controlled substances laws and regulations nationally and internationally, coordinating with federal, state and local agencies and foreign governments, and overseeing legally-produced controlled substances.[131] The DEA absorbed the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs, ODALE, and other drug-related federal agencies or personnel from them.[115] Nixon's role reviewed Decades later, a controversial quote attributed to John Ehrlichman, Nixon's domestic policy advisor, claimed that the war on drugs was fabricated to undermine the anti-war movement and African-Americans. In a 2016 Harper's cover story, Ehrlichman, who died in 1999,[132] was quoted from journalist Dan Baum's 1994 interview notes: "... by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did."[133][134][135][136] The veracity of the quote was challenged by Ehrlichman's children,[137] and Nixon-era officials.[138] In the end, the increasingly punitive reshaping of US drug policy by later administrations was most responsible for creating some of the conditions Ehrlichman described.[139] In a 2011 commentary, Robert DuPont, Nixon's drug czar, argued that the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Act had represented a degree of drug reform. He noted that the act had rolled back mandatory minimum sentencing and balanced the "long-dominant law enforcement approach to drug policy, known as 'supply reduction'" with an "entirely new and massive commitment to prevention, intervention and treatment, known as 'demand reduction'". Thus, Nixon was not in fact the originator of what came to be called the "war on drugs".[140] During Nixon's term, some 70% of federal anti-drug money was spent on demand-side public health measures, and 30% on supply-side interdiction and punishment, a funding ratio not repeated under subsequent administrations.[141][142] The war on drugs under the next two presidents, Gerald Ford (1974–77) and Jimmy Carter (1977–81), was essentially a continuation of their predecessors' policies. Carter's campaign platform included decriminalization of cannabis and an end to federal penalties for possession of up to one ounce.[110] In a 1977 "Drug Abuse Message to the Congress", Carter stated, "Penalties against possession of a drug should not be more damaging to an individual than the use of the drug itself." None of his advocacy was translated into law.[143][144] Reagan escalation, militarization, and "Just Say No" The presidency of Ronald Reagan (1981–89) saw an increase in federal focus on interdiction and prosecution. Shortly after his inauguration, Reagan announced, "We're taking down the surrender flag that has flown over so many drug efforts; we're running up a battle flag."[145] From 1980 to 1984, the annual budget of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) drug enforcement units went from $8 million to $95 million.[146][147] In 1982, Vice President George H. W. Bush and his aides began pushing for the involvement of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the US military in drug interdiction efforts.[148] Early in the Reagan term, First Lady Nancy Reagan, with the help of an advertising agency, began her youth-oriented "Just Say No" anti-drug campaign. Propelled by the First Lady's tireless promotional efforts through the 1980s, "Just Say No" entered the American vernacular. Later research found that the campaign had little or no impact on youth drug use.[149][150][151] One striking change attributed to the effort: public perception of drug abuse as America's most serious problem, in the 2-6% range in 1985, rose to 64% in 1989.[152] In January 1982, Reagan established the South Florida Task Force, chaired by Bush, targeting a surge of cocaine and cannabis entering through the Miami region, and the sharp rise in related crime. The project involved the DEA, the Customs Service, the FBI and other agencies, and Armed Forces ships and planes. It was called the "most ambitious and expensive drug enforcement operation" in US history; critics called it an election year political stunt. By 1986, the task force had made over 15,000 arrests and seized over six million pounds of cannabis and 100,000 pounds of cocaine, doubling cocaine seizures annually – administration officials called it Reagan's biggest drug enforcement success. However, law enforcement agents at the time said their impact was minimal; cocaine imports had increased by 10%, to an estimated 75-80% of America's supply. According to the head of the task force's investigative unit, "Law enforcement just can't stop the drugs from coming in." A Bush spokesperson emphasized disrupting smuggling routes rather than seizure quantities as the measure of success."[153][154][155] In 1984, Reagan signed the Comprehensive Crime Control Act, which included harsher penalties for cannabis cultivation, possession, and distribution. It also established equitable sharing, a new civil asset forfeiture program that allowed state and local law enforcement to share the proceeds from asset seizures made in collaboration with federal agencies.[156][157] Under the controversial program, up to 80% of seizure proceeds can go to local law enforcement, expanding their budgets. By 2019, $36.5 billion worth of assets had been seized, much of it drug-related, much of it distributed to state and local agencies.[158] Crackdown on crack As the media focused on the emergence of crack cocaine in the early 1980s, the Reagan administration shored up negative public opinion, encouraging the DEA to emphasize the harmful effects of the drug. Stories of "crack whores" and "crack babies" became commonplace.[159] In the summer of 1986, crack dominated the news. Time declared crack the issue of the year.[159] Newsweek compared the magnitude of the crack story to Vietnam and Watergate.[160] The cocaine overdose deaths of rising basketball star Len Bias, and young NFL football player Don Rogers,[161] both in June, received wide coverage.[160] Riding the wave of public fervor, that October Reagan signed into law much harsher sentencing for crack through the Anti-Drug Abuse Act, commonly known as the Len Bias law.[160][162] According to historian Elizabeth Hinton, "[Reagan] led Congress in criminalizing drug users, especially African American drug users, by concentrating and stiffening penalties for the possession of the crystalline rock form of cocaine, known as 'crack', rather than the crystallized methamphetamine that White House officials recognized was as much of a problem among low-income white Americans".[163] The Anti-Drug Abuse Act appropriated an additional $1.7 billion to drug war funding, and established 29 new mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses (until then, the American legal system had seen 55 minimum sentences in total).[164] Of particular note, the act made sentences for larger amounts of cocaine 100 times more severe for crack than for the powder form.[165] With the 100:1 ratio, conviction in federal court for possession of 5 grams of crack would receive the same 5-year mandatory minimum as possession of 500 grams of powder cocaine.[166][167] Debate at the time considered whether crack, generally used by blacks, was more addictive than the powder form, generally used by whites,[159] comparing the effects of snorting powder cocaine with the briefer, more intense high from smoking crack;[168] pharmacologically, there is no difference between the two.[169] According to the DEA, at first crack "was not fully appreciated as a major threat because it was primarily being consumed by middle class users who were not associated with cocaine addicts ... However, partly because crack sold for as little as $5 a rock, it ultimately spread to less affluent neighborhoods."[170] Support for Reagan's drug crime legislation was bipartisan. According to historian Hinton, Democrats supported drug legislation as they had since the Johnson administration,[163] though Reagan was a Republican. Internationally, the Reagan term saw a huge increase in US military anti-drug activity in other countries. The Department of Defense budget for interdiction increased from $4.9 million in 1982 to $397 million by 1987. The DEA also expanded its foreign presence. Countries were encouraged to adopt the same type of punitive drug approach that was in place in the US, with the threat of economic sanctions for non-compliance. The UN Single Convention provided a legal framework, and in 1988, the Convention against Illicit Traffic expanded that framework, working the US-style punitive approach into international law.[171] By the end of Reagan's presidency in 1989, illicit drugs were more readily available and cheaper than at the start of his first term in 1981.[172] |

1971年~現在:「麻薬との戦争」 1971年5月27日、ベトナムへの訪問後、民主党のモーガン・F・マーフィー(Morgan F. Murphy)と共和党のロバート・H・スティール(Robert H. Steele)の2人の下院議員が、「南ベトナムの米軍部隊におけるヘロイン中毒の急速な増加」について述べた報告書を公表した。彼らは「米軍兵士の 10~15パーセントが何らかの形でヘロイン中毒である」と推定した。[117][115][118][119] 6月6日付のニューヨーク・タイムズ紙の記事「『スキャッグ・アレイ』は常に袋小路」は、ヘロイン中毒に関する議論の中で、マーフィー=スティール報告書 に言及した。記事では、米国における「麻薬常用者の数は20万人から25万人と推定され、これは人口のわずか0.1%にすぎないが、その影響は計り知れな い」と述べている。また、「ヘロインは米国における唯一の麻薬問題ではない。スピード・ピル(覚醒剤など)もまた問題であり、特に郊外では、主婦が(日々 の憂鬱を紛らわすために)摂取し、また、夫が(体重を維持するために)摂取している」とも指摘している。[120] 1971年6月17日、ニクソン大統領は議会に薬物乱用対策の拡大計画を提出した。彼は次のように深刻な現状を説明した。「薬物乱用を抑制するための現在 の取り組みだけでは十分ではない。この問題は、国民の緊急事態という規模にまで拡大している。もしアメリカで薬物の脅威を根絶できないのであれば、いずれ は確実に我々自身が滅びることになるだろう。」彼の戦略は、治療と阻止の両方を伴うものであった。「私は麻薬常用者の更生にかかる費用を賄うための追加予 算を提案する。また、麻薬密売人の首にさらにきつく縄をかけ、麻薬常用者の首に掛かる縄を緩めるために、取締りの強化に充てる追加予算を要求するつもり だ。」彼はヘロインを特に取り上げ、その範囲を米国以外にも広げた。「ヘロイン中毒との効果的な戦いを展開するには、国際協力が必要である。そのような協 力を確保するために、麻薬密売取締りのための現行プログラムを世界規模で強化するつもりである」[121] 同日、ニクソンはホワイトハウスで記者会見を開き、そこで麻薬乱用を「アメリカ合衆国の公敵ナンバーワン」と表現した。「この敵と戦い、打ち負かすために は、新たな全面的な攻勢をかける必要がある。... これは、供給源の問題に対処する世界的な攻勢となるだろう... 政府全体で取り組むことになる。現在この問題に対処している政府内の9つの異なる断片的な分野を統合し、新たな教育プログラムの観点から全国的な取り組み となるだろう」と発表した。また、ニクソンは、ベトナム戦争に従軍した兵士たちの薬物中毒問題が、この問題の終結を意味するものではないと述べた。 [122] 彼は、反薬物運動のために最低でも3億5000万ドルを議会に要求すると誓った(1969年の就任時、連邦政府の薬物対策予算は8100万ドルであっ た)。[123] 報道機関は、ニクソンの軍事的表現に焦点を当て、彼の発表を「薬物との戦争」という表現で報じた。ニクソン大統領の記者会見の翌日、シカゴ・トリビューン 紙は「ニクソン大統領、米国内の麻薬使用に宣戦布告」と報じた。イギリスでは、ガーディアン紙が「ニクソン大統領、麻薬中毒者に宣戦布告」と見出しを付け た。米国の反麻薬キャンペーンは一般的に「麻薬との戦争」と呼ばれるようになり、[124] この用語は、米国式の禁止に基づく麻薬政策を推進する政府を指す場合にも用いられるようになった。[125] 再選を目指し、薬物対策を選挙の目玉に掲げたニクソンは、1971年後半に麻薬乱用取締局(ODALE)を設立した。 ODALEは、新たな連邦取締権限を武器に、政権の監視役としての評判を高めるために、全米規模の麻薬捜索を指揮し始めた。 ブルックリン上空をヘリコプターで飛行中、ニクソンは「あなたと私は治療を重視している。しかし、街にいる人々は、犯罪者を街から追い出したいと思ってい る」と述べたと伝えられている。1972年から1973年にかけて、ODALEは18ヶ月間で6,000人の麻薬犯罪者を逮捕したが、その大半は黒人で あった。 1972年、シャファー委員会は「マリファナ:誤解の兆候」と題する報告書を公表した。この報告書は、医学文献のレビューと国民薬物調査から構成されてい た。この報告書は、少量の大麻の個人所有と使用の非犯罪化を推奨し、供給のみを禁止することを提言した。この結論はニクソン大統領や連邦議会によって実行 されることはなかった。[127][128] 1973年から1978年にかけて行われたロビー活動キャンペーンでは、マリファナ法改革全国機構(NORML)が主導し、シェイファー報告書を引用し て、11の州で大麻の非犯罪化を実現した。[129] 1973年、ニクソン大統領は「薬物の脅威に対する全面的な世界戦争に対抗するための、単一の統一司令部の設立」を目的として、議会が承認した大統領令に より麻薬取締局(DEA)を設立した。[130] この機関は、 連邦、州、地方の各機関および外国政府と調整を図り、合法的に生産された規制薬物を監督する任務を負っていた。[131] DEAは麻薬取締局(ODALE)やその他の麻薬関連の連邦機関またはその職員を吸収した。[115] ニクソンの役割を検証 数十年後、ジョン・エリックマン(ジョン・エリックマン)の物議を醸した発言が、ニクソンの国内政策顧問に帰せられ、薬物戦争は反戦運動とアフリカ系アメ リカ人を弱体化させるためにでっちあげられたと主張した。2016年の『ハーパーズ』誌の表紙記事で、1999年に死去したエリックマンについて、ジャー ナリストのダン・バウム(ダン・バウム)が1994年のインタビューメモから引用した。「...ヒッピーをマリファナと結びつけ、黒人をヘロインと結びつ けることで、両者を厳しく犯罪化し、それらのコミュニティを混乱させることができる。彼らのリーダーを逮捕し、家宅捜索を行い、集会を解散させ、毎晩の ニュースで彼らを悪者として扱うことができる。我々は薬物について嘘をついていると知っていたのか?もちろん、私たちは知っていた」[133][134] [135][136] この発言の真実性については、エリックマンの子供たち[137]やニクソン政権の政府高官たち[138]から疑問が呈された。結局、その後の政権による米 国の薬物政策の厳罰化が進むにつれ、エリックマンが述べた状況のいくつかが生み出されることになった。 2011年の論評で、ニクソン政権下の麻薬問題担当長官であったロバート・デュポンは、包括薬物乱用防止法は一定の薬物改革を象徴するものであったと主張 した。同法は、最低刑の義務付けを廃止し、「『供給削減』として知られる、薬物政策に対する長年にわたって支配的であった法執行アプローチ」と、「『需要 削減』として知られる、予防、介入、治療に対するまったく新しい大規模な取り組み」とをバランスさせた、と指摘した。したがって、ニクソンは後に「麻薬戦 争」と呼ばれるようになった政策の創始者ではなかったのである。[140] ニクソンの任期中、連邦政府の麻薬対策費の約70%は需要側対策としての公衆衛生対策に、30%は供給側対策としての取り締まりと処罰に費やされたが、こ の資金配分比率はその後、どの政権下でも繰り返されることはなかった。[141][142] 次の2人の大統領、ジェラルド・フォード(1974年~1977年)とジミー・カーター(1977年~1981年)の下での麻薬戦争は、本質的には前任者 の政策の継続であった。カーターの選挙公約には、大麻の非犯罪化と1オンスまでの所持に対する連邦刑罰の廃止が含まれていた。[110] 1977年の「議会への薬物乱用に関するメッセージ」で、カーターは「薬物の所持に対する刑罰は、薬物使用そのものよりも個人に大きなダメージを与えるべ きではない」と述べた。しかし、彼の主張はどれも法律化されることはなかった。[143][144] レーガンによるエスカレーション、軍事化、そして「ノーと言うだけ」 ロナルド・レーガン大統領(1981年~1989年)の時代には、連邦政府による取り締まりと起訴への重点が強化された。就任直後、レーガンは「これまで 麻薬対策の多くで掲げられてきた降参の旗を降ろし、戦いの旗を掲げる」と宣言した。[145] 1980年から1984年にかけて、連邦捜査局(FBI)の麻薬取締部門の年間予算は 麻薬取締部門の年間予算は800万ドルから9500万ドルに増加した。[146][147] 1982年、ジョージ・H・W・ブッシュ副大統領と側近たちは、麻薬阻止活動への中央情報局(CIA)と米軍の関与を推進し始めた。[148] レーガン政権初期、ナンシー・レーガン大統領夫人は広告代理店の協力を得て、若者向けの「薬物にノーと言おう」という反薬物キャンペーンを開始した。 1980年代を通じて、大統領夫人のたゆまぬキャンペーン活動により、「薬物にノーと言おう」というフレーズはアメリカ俗語として定着した。その後の調査 では、このキャンペーンが若者の薬物使用にほとんど、あるいはまったく影響を与えなかったことが判明した。[149][150][151] その努力がもたらした顕著な変化のひとつとして、1985年には2~6%台であったアメリカで最も深刻な問題としての薬物乱用に対する国民の認識が、 1989年には64%に上昇したことが挙げられる。[152] 1982年1月、レーガン大統領はマイアミ地域へのコカインとマリファナの流入の急増と、関連犯罪の急増に対処するため、ブッシュを議長とする南フロリダ 対策本部を設置した。このプロジェクトには麻薬取締局、税関、FBI、その他の機関、および軍の船舶と航空機が関与した。これは米国史上「最も野心的で費 用のかかる麻薬取締作戦」と呼ばれたが、批判派はこれを選挙年の政治的パフォーマンスと評した。1986年までに、この対策本部は15,000人以上を逮 捕し、600万ポンド以上の大麻と10万ポンド以上のコカインを押収した。これは、コカインの押収量が毎年倍増していたことを意味し、政府高官はこれを レーガン大統領の麻薬取締における最大の成功と呼んだ。しかし、当時の法執行官たちはその影響は限定的だったと述べている。コカインの輸入量は10%増加 し、アメリカの供給量の75~80%を占めるまでになっていた。対策本部の捜査部門の責任者は、「法執行だけでは麻薬の流入を食い止めることはできない」 と述べた。ブッシュ大統領の報道官は、成功の尺度として押収量よりも密輸ルートの遮断を強調した。[153][154][155] 1984年、レーガン大統領は大麻の栽培、所持、販売に対する厳罰を盛り込んだ包括犯罪取締法に署名した。この法律はまた、公平な分配、すなわち連邦機関 と協力して資産を押収した場合に、州および地方の法執行機関がその収益を分配できるという新しい民事資産没収プログラムを確立した。[156][157] 物議を醸したこのプログラムでは、押収品の収益の最大80%を地方の法執行機関に分配することができ、その予算を拡大できる。2019年までに、365億 ドル相当の資産が押収され、その多くは麻薬関連のもので、その多くは州および地方の機関に分配された。 クラックに対する取り締まり 1980年代初頭にクラック・コカインが出現したことにメディアが注目する中、レーガン政権は世論の否定的な反応を後押しし、麻薬取締局(DEA)にこの 麻薬の有害性を強調するよう促した。「クラック・ホーレス(クラック中毒の売春婦)」や「クラック・ベイビー(クラック中毒の新生児)」といった話が一般 的になった。[159] 1986年夏には、クラックがニュースを独占した。タイム誌は、その年の問題はコカインだと宣言した。[159] ニューズウィーク誌は、コカインに関するニュースの大きさをベトナム戦争やウォーターゲート事件と比較した。[160] 6月にバスケットボール界の新星レナード・バイアスとNFLの若手フットボール選手ドン・ロジャースがコカインの過剰摂取により死亡した事件は、大きな注 目を集めた。[160] 世論の高まりを受けて、10月にレーガン大統領は麻薬乱用防止法を改正し、コカインに対する刑罰を大幅に強化する法律に署名した。一般に「レン・バイアス 法」として知られている。歴史家のエリザベス・ヒントンによると、「(レーガンは)コカインの結晶状形態である『クラック』の所持に対する処罰を集中させ 厳格化することで、特にアフリカ系アメリカ人の麻薬使用者を犯罪者として扱うよう議会を主導した。ホワイトハウスの高官が、低所得の白人アメリカ人にも同 程度の問題があると認識していた結晶状のメタンフェタミンではなく」[163]。 麻薬乱用防止法は麻薬戦争の資金としてさらに17億ドルを計上し、麻薬犯罪に対する29の新たな最低刑を義務付けた(それまでは、アメリカの法制度では合 計55の最低刑が定められていた)。[164] 特に注目すべきは、この法律により、コカインの量が多い場合の刑期が、粉末状のコカインよりもクラック・コカインの方が100倍重くなったことである。 165] 100対1の比率により、連邦裁判所で5グラムのクラック所持で有罪判決を受けると、粉末コカイン500グラム所持と同じ5年の最低刑が科されることにな る。[166][167] 当時の議論では、一般的に黒人が使用するクラックが、一般的に白人が使用する粉末状のものよりも中毒性が高いかどうかについて検討された。[ 159] 粉末コカインを鼻から吸引した場合と、より短時間で強烈なハイになるクラックを吸引した場合の効果を比較した。[168] 薬理学的に見ると、両者には違いはない。[169] DEAによると、当初クラックは「コカイン中毒者とは関連のない中流階級のユーザーが主に消費していたため、大きな脅威とはみなされていなかった... しかし、1個5ドルという安さもあって、最終的には低所得者層が住む地域にも広がった」[170] レーガンの麻薬犯罪取締法への支持は党派を超えていた。歴史家のヒントンによると、レーガンは共和党員であったが、民主党はジョンソン政権以来、麻薬取締 法を支持していたという。 国際的には、レーガン政権下で、米国の軍事力による他国での麻薬対策活動が大幅に増加した。麻薬取締のための国防総省の予算は、1982年の490万ドル から1987年には3億9700万ドルに増加した。麻薬取締局(DEA)も海外での活動を拡大した。各国には、米国で実施されているのと同様の厳罰主義的 な麻薬対策を採用することが奨励され、これに従わない場合は経済制裁の脅威が与えられた。国連単一条約が法的枠組みを提供し、1988年には不正取引条約 がその枠組みを拡大し、米国式の懲罰的アプローチを国際法に取り入れた。 1989年のレーガン大統領の任期終了までに、違法薬物は1981年の大統領就任当初よりも入手しやすく、価格も安くなっていた。 |

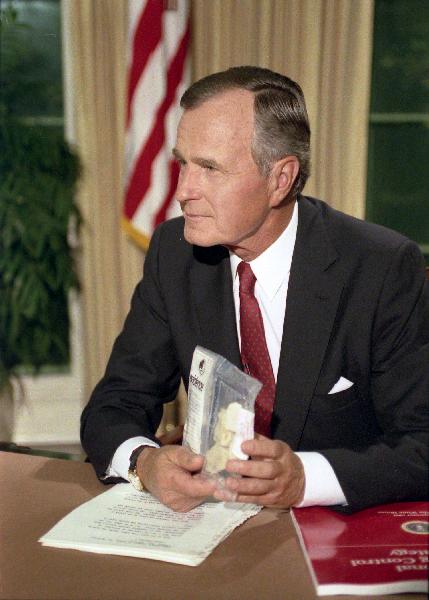

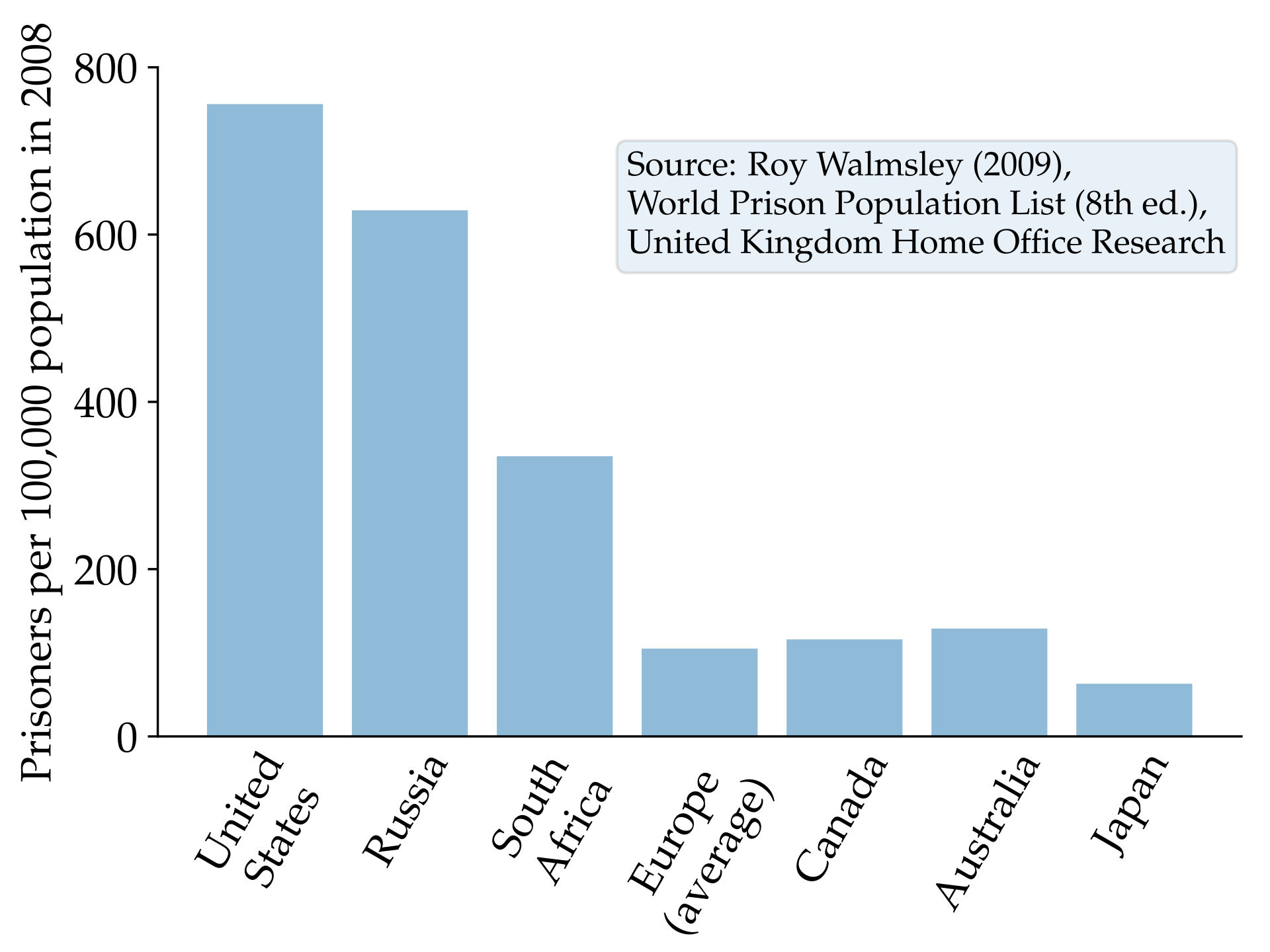

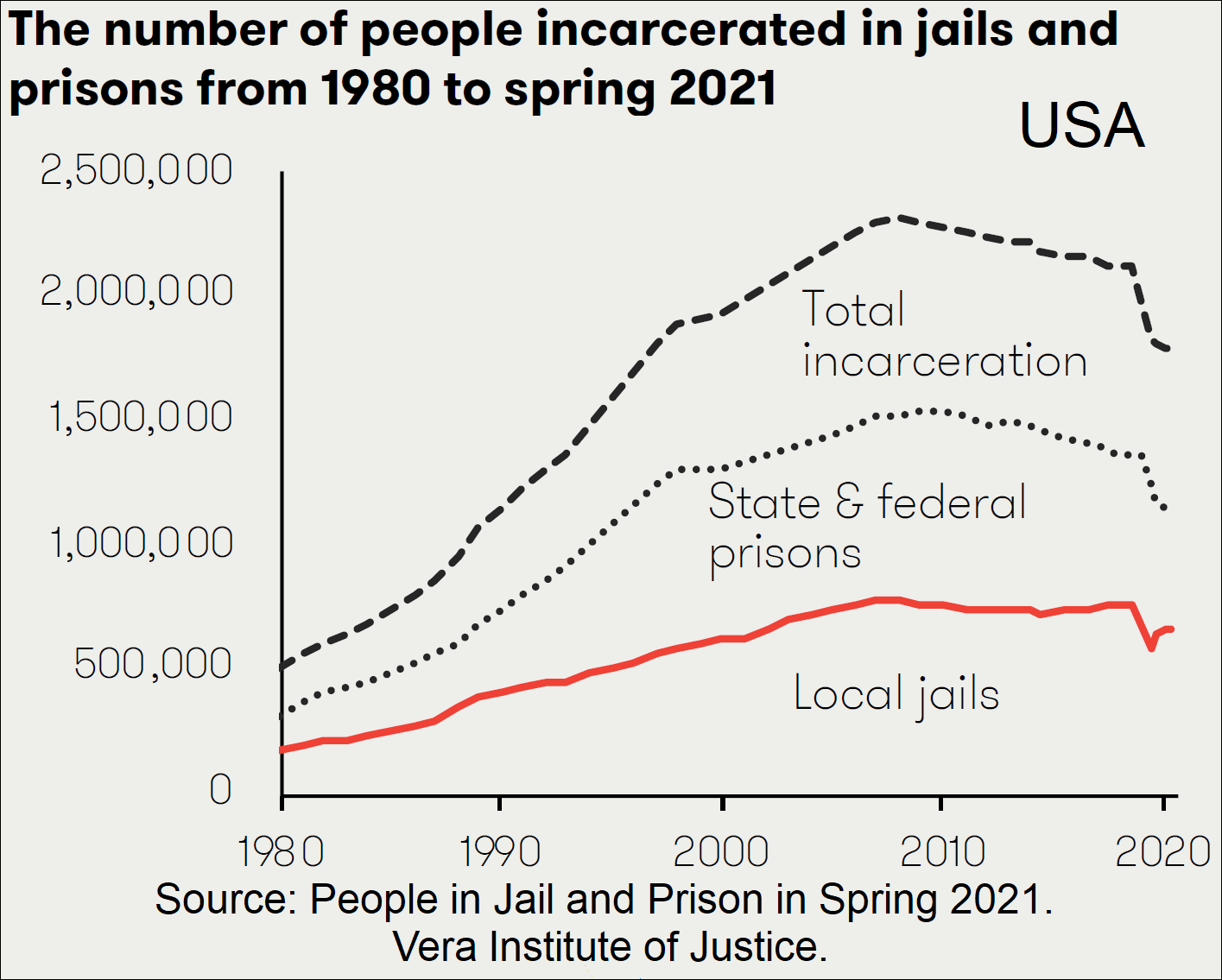

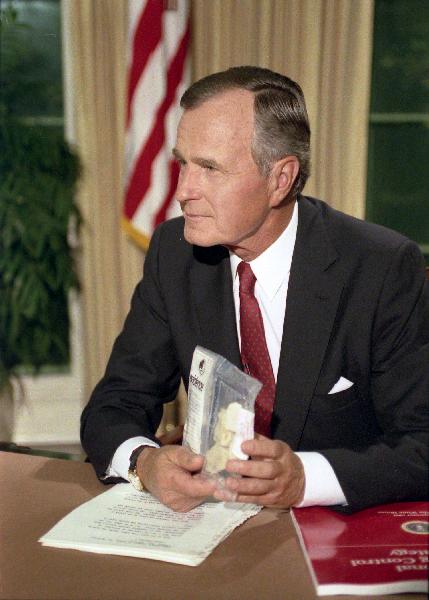

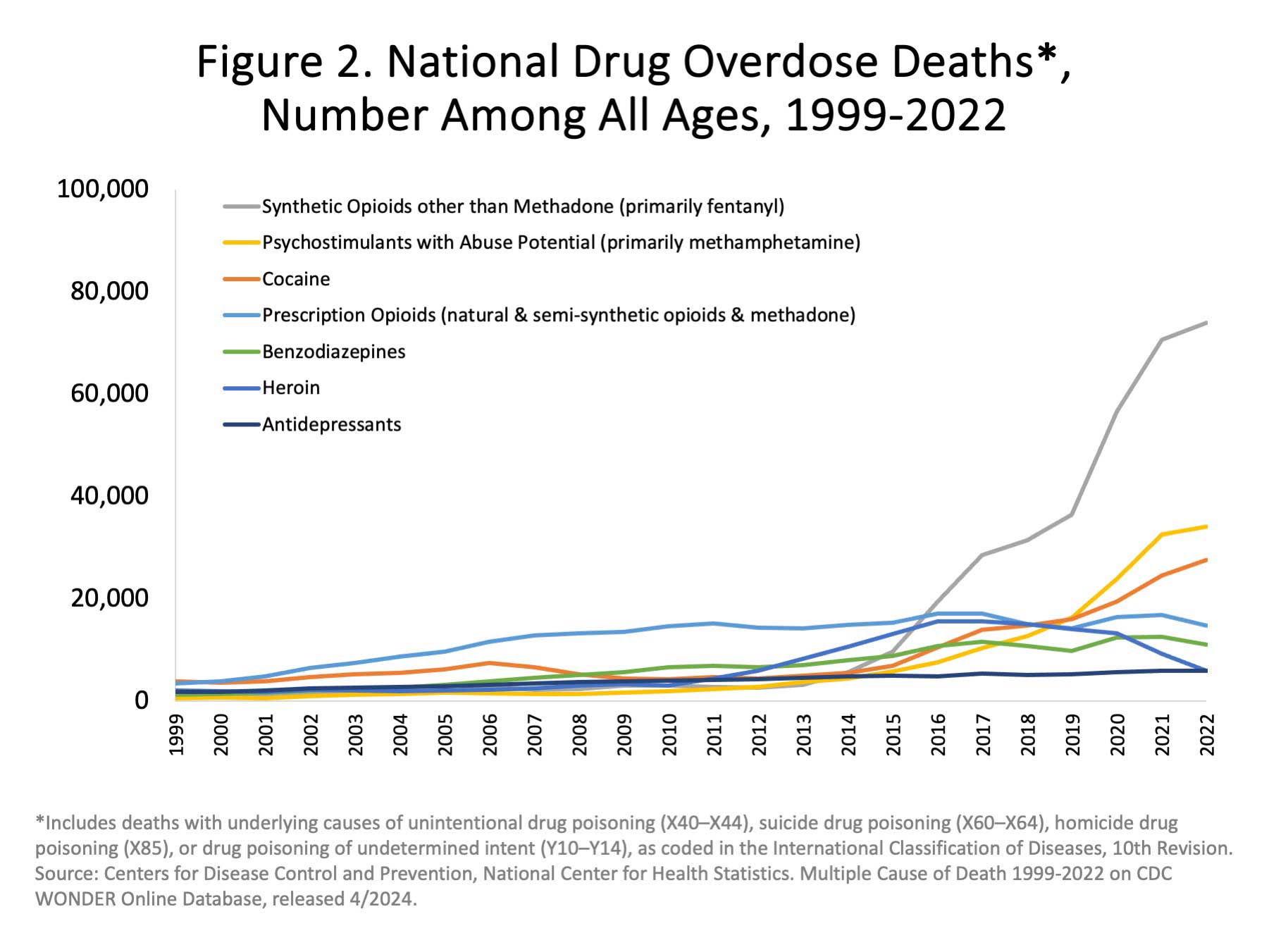

Hard line maintained and a new

opioid crisis President George H. W. Bush holds up a bag of crack cocaine during his Address to the Nation on National Drug Control Strategy on September 5, 1989. Next to occupy the Oval Office, Reagan protégé and former VP George H. W. Bush (1989–93) maintained the hard line drawn by his predecessor and former boss. In his first prime-time address to the nation, Bush held up a plastic bag of crack "seized a few days ago in a park across the street from the White House" (turned out that DEA agents had to lure the seller to Lafayette Park to make the requested arrest).[173] The administration increased narcotics regulation in the first National Drug Control Strategy, issued by the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) in 1989.[174] The director of ONDCP became commonly known as the US drug czar.[115] In the National Defense Authorization Act for 1990–91, Congress included Section 1208 – the 1208 Program, expanded into the 1033 Program in 1996 – authorizing the Department of Defense to transfer surplus military equipment that the DoD determined to be "suitable for use in counter-drug activities", to local law enforcement agencies.[175] As president, Bill Clinton (1993–2001), seeking to reposition the Democratic Party as tough on crime,[176] dramatically raised the stakes for drug felonies with his signing of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994. The act introduced the federal "three-strikes" provision that mandated life imprisonment for violent offenders with two prior convictions for violent crimes or drugs, and provided billions of dollars in funding for states to expand their prison systems and increase law enforcement.[177] During this period, state and local governments initiated controversial drug policies that demonstrated racial biases, such as the stop-and-frisk police practice in New York City, and state-level "three strikes" felony laws, which began with California in 1994.[178] During the 1990s, opioid use in the US dramatically rose, leading to the ongoing situation commonly called the opioid epidemic. A loose consensus of observers describe three main phases to date: overprescription of legal opioids beginning in the early to mid-1990s; a rise in heroin use in the later 2000s as prescription opioids became more difficult to obtain; and the rise of more powerful fentanyl and other synthetic opioids around the mid-2010s.[179][180][181] Prior to 1990s, the use of opioids to treat chronic pain in the US was limited; some scholars suggest there was hesitation to prescribe opioids due to historical problems with addiction dating back to the 1800s. A critical point in the development of the epidemic is often seen as the release in 1996 of OxyContin (oxicodone) by Purdue Pharma, and the subsequent aggressive and deceptive opioid marketing efforts by Purdue and other pharma companies, conducted without sufficient official oversight.[182] Thus the problem emerged from within the healthcare system: the DEA initially targeted doctors, pharmacists, pill mills, and pharmaceutical companies. As law enforcement cracked down on the pharmaceutical supply, illicit drug trafficking in opioids grew to meet demand.[183] The George W. Bush (2001–2009) administration maintained the hard line approach.[184] In a TV interview in February 2001, Bush's new attorney general, John Ashcroft, said about the war on drugs, "I want to renew it. I want to refresh it, relaunch it if you will."[185] In 2001, after 9/11 and the Patriot Act, the DEA began highlighting the tie between drug trafficking and international terrorism, gaining the agency expanded funding to increase its global presence.[186] Growing dissent  The US incarceration rate peaked in 2008. The US rate was the highest in the world in 2008. Chart is for prisoners per 100,000 population of all ages.[187][188]  US timeline graphs of number of people incarcerated in jails and prisons[189]  Holding up signs at an anti-war on drugs protest in Los Angeles, 2011. Anti-war on drugs protest in Los Angeles, 2011. In the summer of 2001, a report by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), "The Drug War is the New Jim Crow", tied the vastly disproportionate rate of African American incarceration to the range of rights lost once convicted. It stated that, while "whites and blacks use drugs at almost exactly the same rates ... African-Americans are admitted to state prisons at a rate that is 13.4 times greater than whites, a disparity driven largely by the grossly racial targeting of drug laws." Between federal and state laws, those convicted of even simple possession could lose the right to vote, eligibility for educational assistance including loans and work-study programs, custody of their children, and personal property including homes. The report concluded that the cumulative effect of the war on drugs amounted to "the US apartheid, the new Jim Crow".[185] This view was further developed by lawyer and civil rights advocate Michelle Alexander in her 2010 book, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness.[190] In the year 2000, the US drug-control budget reached $18.4 billion,[191] nearly half of which was spent financing law enforcement while only one-sixth was spent on treatment. In the year 2003, 53% of the requested drug control budget was for enforcement, 29% for treatment, and 18% for prevention.[192] During his presidency, Barack Obama (2009-2017) implemented his "tough but smart" approach to the war on drugs. While he claimed that his method differed from those of previous presidents, in reality, his practices were similar.[193] In May 2009, Gil Kerlikowske, Director of the ONDCP – Obama's drug czar – indicated that the Obama administration did not plan to significantly alter drug enforcement policy, but that it would not use the term "war on drugs", considering it to be "counter-productive".[194] In August 2010, Obama signed the Fair Sentencing Act into law, reducing the 100:1 sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine to 18:1 for pending and future cases.[165][195][196] In 2013, Obama's Justice Department issued a policy memorandum known as the Cole Memo, stating that it would defer to state laws that authorize the production, distribution and possession of cannabis, "based on assurances that those states will impose an appropriately strict regulatory system."[197][198] In 2011, the Global Commission on Drug Policy, an international non-governmental group composed primarily of former heads of state and government, and leaders from various sectors, released a report that stated, "The global war on drugs has failed." It recommended a paradigm shift, to a public health focus, with decriminalization for possession and personal use.[199] Obama's ONDCP did not support the report, stating: "Drug addiction is a disease that can be successfully prevented and treated. Making drugs more available ... will make it harder to keep our communities healthy and safe."[140] International divisions, state-level changes  California Attorney General Kamala Harris visiting the U.S.–Mexico border on March 24, 2011, to discuss strategies to combat drug cartels In May 2012, the ONDCP published "Principles of Modern Drug Policy", broadly focusing on public health, human rights, and criminal justice reform, while targeting drug traffickers.[200] According to ONDCP director Kerlikowske, drug legalization is not the "silver bullet" solution to drug control, and success is not measured by the number of arrests made or prisons built.[201] That month, a joint statement, "For a humane and balanced drug policy", was signed by Italy, Russia, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the US, promoting a combination of "enforcement to restrict the supply of drugs, with efforts to reduce demand and build recovery."[202] Meanwhile, at the state level, 2012 saw Colorado and Washington become the first two states to legalize the recreational use of cannabis with the passage of Amendment 64 and Initiative 502 respectively.[203] A 2013 ACLU report declared the anti-marijuana crusade a "war on people of color". The report found that "African Americans [were] 3.73 times more likely than whites to be apprehended despite nearly identical usage rates, and marijuana violations accounting for more than half of drug arrests nationwide during the previous decade". Under Obama's policies, nonwhite drug offenders received less excessive criminal sanctions, but by examining criminals as strictly violent or nonviolent, mass incarceration persisted.[193] In March 2016, the International Narcotics Control Board stated that the UN's international drug treaties do not mandate a "war on drugs" and that the choice is not between "'militarized' drug law enforcement on one hand and the legalization of non-medical use of drugs on the other", health and welfare should be the focus of drug policy.[204] That April, the UN General Assembly Special Session (UNGASS) on the "World Drug Problem" was held.[205] The Wall Street Journal assessed the attendees' positions as "somewhat" in two camps: "Some European and South American countries as well as the U.S. favored softer approaches. Eastern countries such as China and Russia and most Muslim nations like Iran, Indonesia and Pakistan remained staunchly opposed."[206] The outcome document recommended treatment, prevention and other public health measures, and committed to "intensifying our efforts to prevent and counter" drug production and trafficking, through, "inter alia, more effective drug-related crime prevention and law enforcement measures."[207][208] Under President Donald Trump (2017-2021), Attorney General Jeff Sessions reversed the previous Justice Department's cannabis policies, rescinding the Cole Memo that deferred federal enforcement in states where cannabis had been legalized[197][209] He instructed federal prosecutors to "charge and pursue the most serious, readily provable offense" in drug cases, regardless of whether mandatory minimum sentences applied, which could trigger mandatory minimums for lower-level charges.[210][211][212] With cannabis legalized to some degree in over 30 states, Sessions' directive was seen by both Democrats and Republicans as a rogue throwback action, and there was a bipartisan outcry. Trump fired Sessions in 2018 over other issues.[213] |

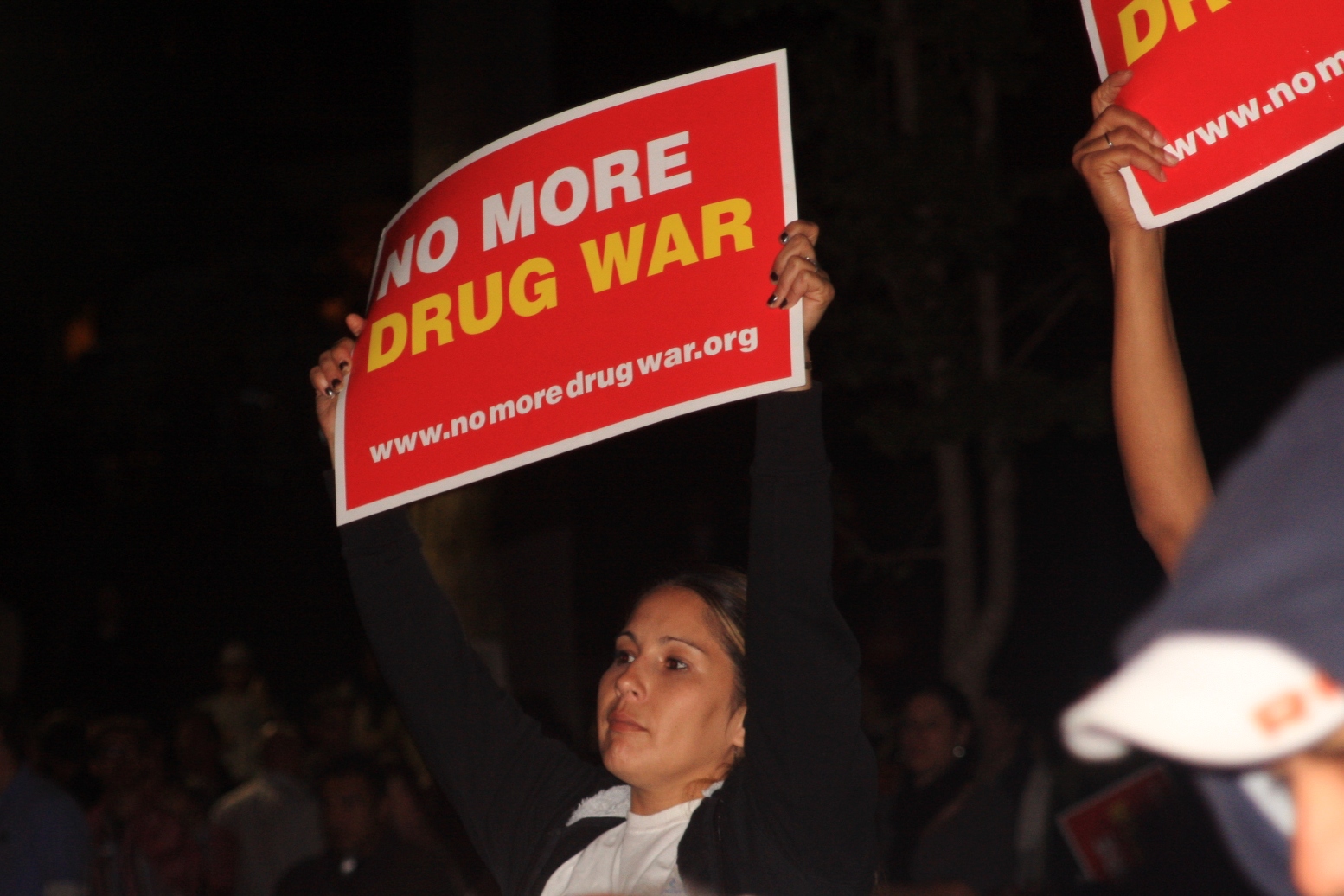

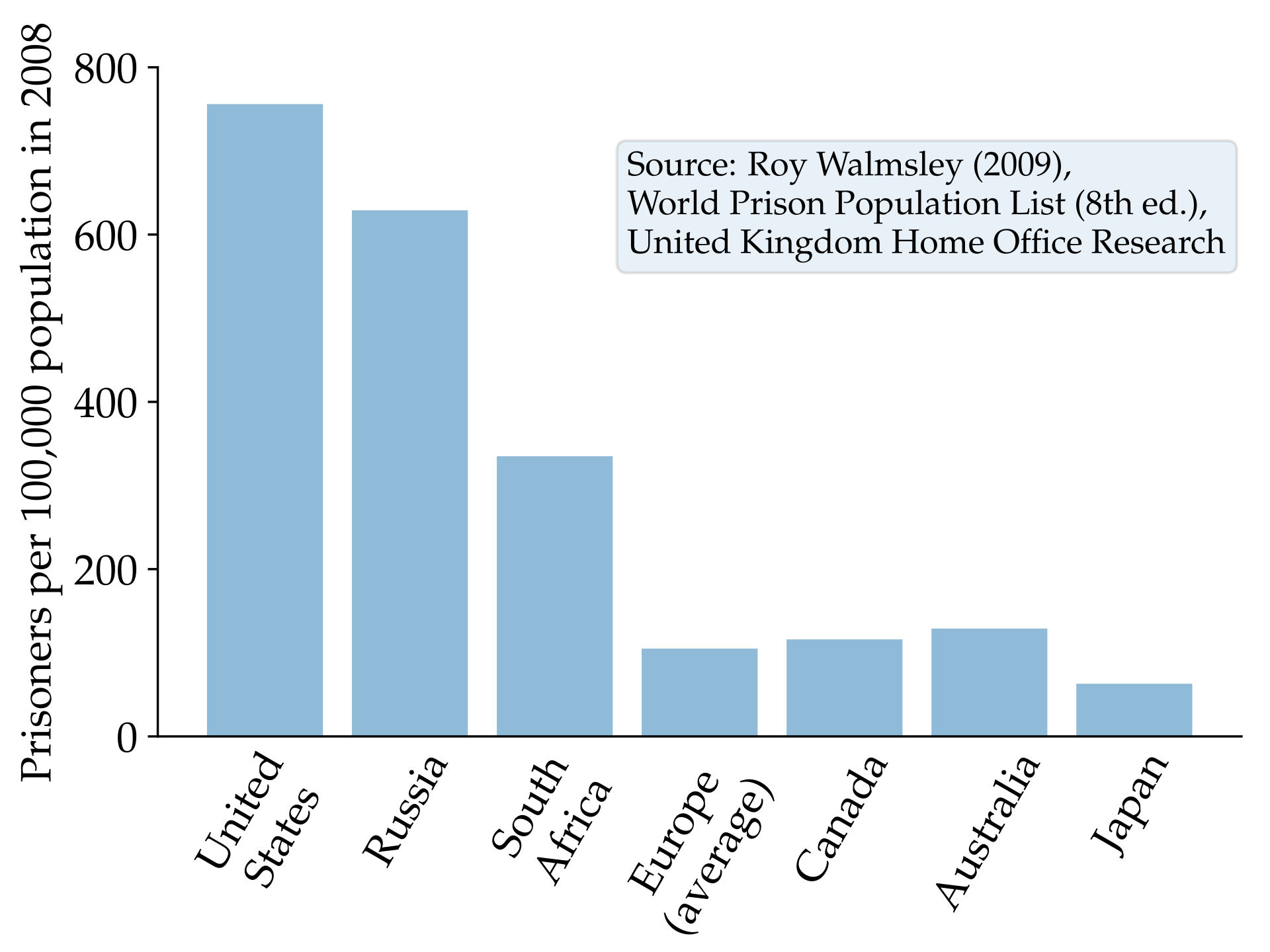

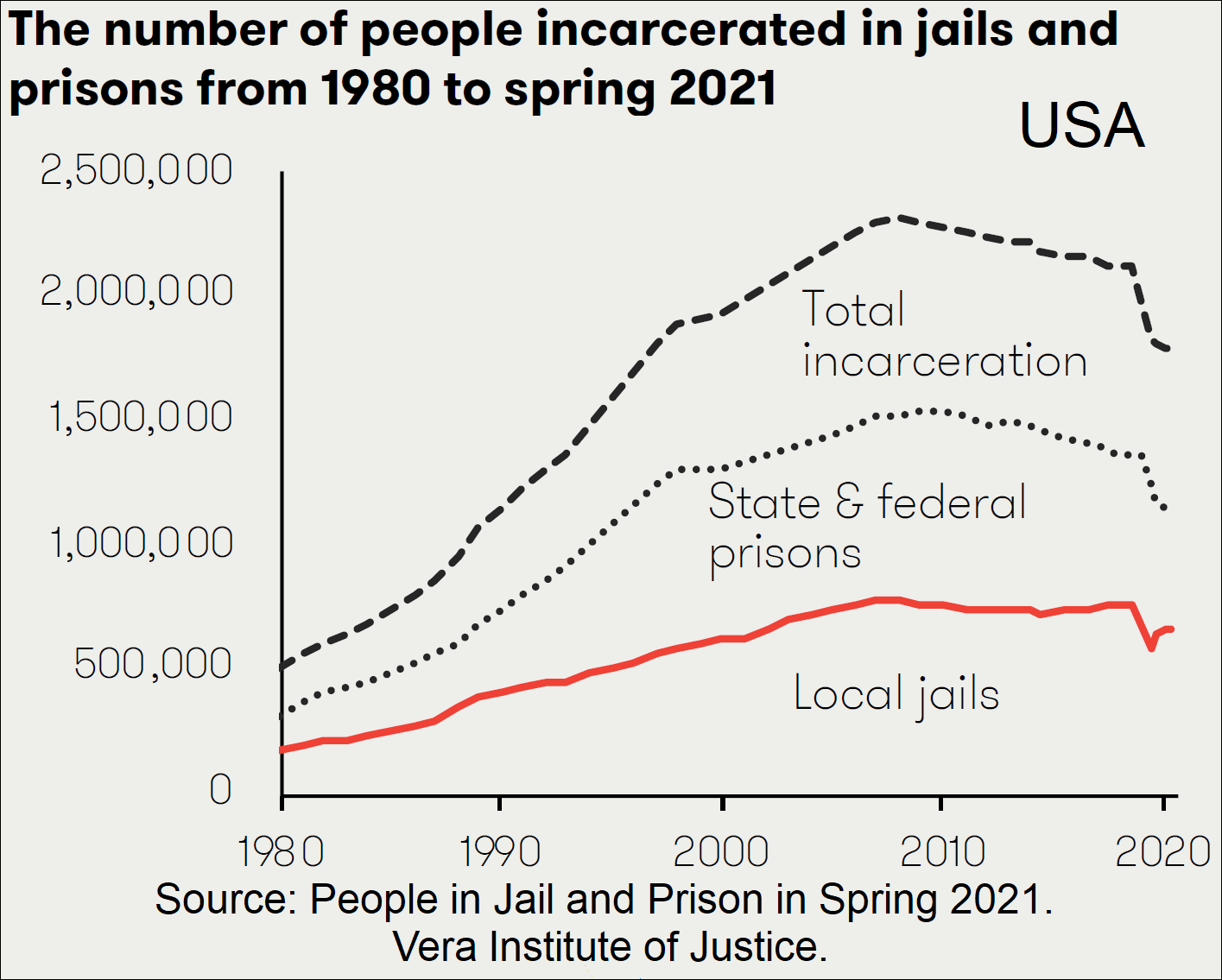

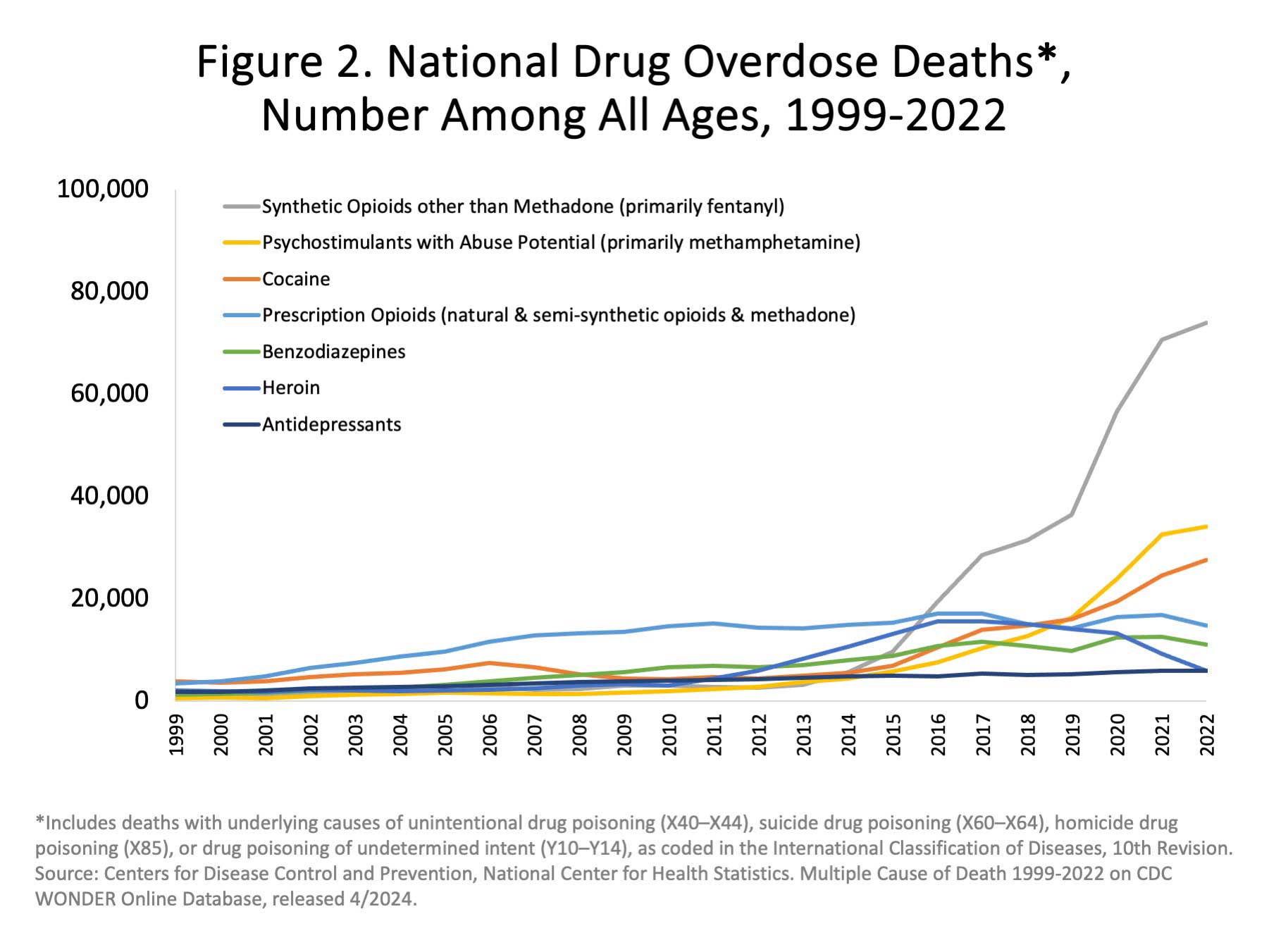

強硬路線を維持し、新たなオピオイド危機を招く 1989年9月5日、ジョージ・H・W・ブッシュ大統領は、国家麻薬対策戦略に関する国民への演説の中で、クラックコカインの袋を掲げた。 次に大統領執務室(オーバル・オフィス)に入ったレーガン大統領の腹心であり、元副大統領のジョージ・H・W・ブッシュ(在任:1989年~1993年) は、前任者であり元上司が敷いた強硬路線を維持した。初めてのゴールデンタイムの国民向け演説で、ブッシュは「数日前にホワイトハウスの向かいの公園で押 収した」と、プラスチック袋に入ったクラックコカインを掲げた(麻薬取締局の捜査官が売人をラファイエット公園までおびき寄せて逮捕したことが判明し た)。[173] 政権は 1989年に国家麻薬対策政策室(ONDCP)が発表した「第一次国家麻薬対策戦略」において、麻薬規制を強化した。[174] ONDCPの局長は、一般的に「麻薬問題担当長官」と呼ばれるようになった。[115] 1990年から1991年の国防権限法において、議会は 第1208条(1996年に1033条に拡大された1208プログラム)を盛り込み、国防総省が「麻薬対策に適している」と判断した余剰軍事装備を地元の 法執行機関に譲渡することを認めた。 ビル・クリントン大統領(1993-2001)は、民主党を犯罪に厳しい政党として再構築しようとし、1994年の暴力犯罪取締法に署名したことにより、 薬物犯罪の刑罰を大幅に強化した。この法律は、暴力的犯罪または麻薬犯罪で2件の有罪判決を受けた暴力的犯罪者に対して終身刑を義務付ける連邦法「スリー ストライク」を導入し、刑務所システムの拡張と法執行の強化のために州に数十億ドルの資金を提供した。[177] この期間中、 州および地方自治体は、人種的偏見を示す物議を醸した薬物政策を開始した。例えば、ニューヨーク市における警察の職務質問や、1994年にカリフォルニア 州で始まった州レベルの「スリーストライク」重罪犯法などである。 1990年代には、米国におけるオピオイドの使用が劇的に増加し、現在一般的に「オピオイド危機」と呼ばれる事態を招いた。 観察者の間では、おおむね次の3つの段階を経て現在に至っているという見方が一般的である。すなわち、1990年代前半から半ばにかけての合法オピオイド の過剰処方、処方オピオイドの入手が困難になった2000年代後半のヘロイン使用の増加、そして2010年代半ば頃からのより強力なフェンタニルやその他 の合成オピオイドの増加である 。1990年代以前は、米国における慢性疼痛の治療におけるオピオイドの使用は限られていた。一部の学者は、1800年代にまで遡る中毒に関する歴史的な 問題により、オピオイドの処方にためらいがあったと指摘している。この流行の重要な転換点は、1996年にパデュー・ファルマ社がオキシコンチン(オキシ コドン)を発売し、その後、パデュー社や他の製薬会社が積極的かつ欺瞞的なオピオイドのマーケティング活動を展開したことであると見られている。この活動 は、十分な公式監督なしに行われた。[182] このように、この問題は医療制度内部から発生した。麻薬取締局(DEA)は当初、医師、薬剤師、薬局、製薬会社を標的にした。法執行機関が医薬品供給を厳 しく取り締まるにつれ、需要を満たすためにオピオイド系鎮痛薬の不正取引が増加した。 ジョージ・W・ブッシュ(2001年~2009年)政権は強硬路線を維持した。2001年2月のテレビインタビューで、ブッシュ大統領の司法長官に就任し たジョン・アシュクロフトは、麻薬との戦いについて「私はそれを再開したい。刷新し、再出発させたい」と述べた。[185] 2001年、9月11日の同時多発テロと愛国者法の成立後、麻薬取締局(DEA)は麻薬密売と国際テロリズムの関連性を強調し始め、世界的な存在感を高め るために、同局の予算は拡大した。[186] 高まる反対意見  米国の投獄率は2008年にピークに達した。2008年には米国の投獄率は世界で最も高かった。グラフは全年齢人口10万人当たりの受刑者数を示す。 [187][188]  米国の刑務所および拘置所に収監されている人数の年表グラフ[189]  2011年、ロサンゼルスでの反麻薬戦争抗議デモでプラカードを掲げる人々。 2011年、ロサンゼルスでの薬物戦争反対デモ。 2001年夏、アメリカ自由人権協会(ACLU)の報告書「薬物戦争は新たなジム・クロウ法である」は、アフリカ系アメリカ人の著しく不均衡な投獄率と、 有罪判決を受けた後に失われる権利の範囲を関連付けた。報告書は、「白人および黒人の薬物使用率はほぼ同じであるが... アフリカ系アメリカ人が州立刑務所に収監される割合は、白人の13.4倍であり、この格差は主に薬物関連法が人種を露骨に標的にしていることによって生じ ている」と述べた。連邦法と州法の間で、単純所持で有罪となった者は、選挙権を失い、ローンやワーク・スタディ・プログラムなどの教育支援の対象から外さ れ、子供の親権や住宅などの個人資産を失う可能性がある。報告書は、麻薬戦争の累積的影響は「米国のアパルトヘイト、新たなジム・クロウ」に等しいと結論 づけた。[185] この見解は、弁護士で公民権運動家のミシェル・アレクサンダーが2010年に出版した著書『The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness』でさらに発展させた。[190] 2000年には、米国の麻薬対策予算は184億ドルに達し、[191] そのほぼ半分が法執行の資金に充てられ、治療には6分の1しか使われなかった。2003年には、麻薬対策予算の要求額の53%が取締り、29%が治療、 18%が予防に充てられた。[192] バラク・オバマ(2009年~2017年)は、大統領在任中、麻薬戦争に対して「厳格だが賢明な」アプローチを実施した。彼は、自らの手法は歴代の大統領 のそれとは異なると主張したが、実際には、その実践は類似していた。[193] 2009年5月、オバマ政権の麻薬問題担当長官であるギル・ケリーコウスキーは、オバマ政権は麻薬取締政策を大幅に変更するつもりはないが、「 「麻薬との戦争」という用語は「非生産的」であるとして使用しないと表明した。[194] 2010年8月、オバマ大統領はフェア・センテンシング法に署名し、コカインの粉末とクラックのコカインの量刑格差を100対1から18対1に縮小し、係 属中および将来の事件に適用されることとなった。[165][19 5][196] 2013年、オバマ政権の司法省は、コロメモとして知られる政策覚書を発行し、大麻の生産、流通、所持を認める州法を尊重する方針を表明した。ただし、 「それらの州が適切に厳格な規制システムを導入することを確約している場合」に限るとしている。[197][198] 2011年、元国家元首や政府高官、各界のリーダーを中心とした国際的非政府組織である「薬物政策グローバル・コミッション」は、「世界的な薬物との戦い は失敗した」とする報告書を公表した。所持と個人使用の非犯罪化を伴う公衆衛生への重点化というパラダイムシフトを提言した。[199] オバマ政権の麻薬問題担当長官は、この報告書を支持せず、次のように述べた。「薬物中毒は予防と治療が可能な病気である。薬物の入手を容易にすれば、地域 社会の健康と安全を維持することが難しくなるだろう」と述べた。[140] 国際的な分裂、州レベルでの変化  2011年3月24日、カリフォルニア州司法長官のカマラ・ハリスが、麻薬カルテル対策の戦略について話し合うために、米国とメキシコの国境を訪問した 2012年5月、ONDCPは「現代の薬物政策の原則」を発表し、薬物密売人を標的にしながらも、公衆衛生、人権、刑事司法改革に広く焦点を当てた。 ONDCPのケリコウスキー局長によると、薬物の合法化は薬物対策の「特効薬」ではなく 。成功は逮捕者数や刑務所の建設数で測られるものではないと述べた。[201] その月、イタリア、ロシア、スウェーデン、イギリス、アメリカによる共同声明「人道的なバランスのとれた薬物政策のために」が署名され、「 需要削減と回復支援の取り組みと組み合わせた薬物の供給制限」を推進した。[202] 一方、州レベルでは、2012年にコロラド州とワシントン州が、それぞれ修正第64条とイニシアティブ502号の可決により、娯楽用マリファナ使用を合法 化した最初の2つの州となった。 2013年のACLUの報告書は、反マリファナ運動を「有色人種に対する戦争」と宣言した。報告書は、「アフリカ系アメリカ人は、使用率がほぼ同じにもか かわらず、白人の3.73倍の確率で逮捕されており、過去10年間で全国的に薬物関連逮捕の半分以上がマリファナ違反によるものだった」と指摘している。 オバマ大統領の政策の下、非白人の薬物犯罪者は過剰な刑事制裁をあまり受けなくなったが、犯罪者を厳格に暴力的か非暴力的かで分類することによって、大量 収監は依然として続いている。 2016年3月、国際麻薬統制委員会は、国連の国際麻薬協定は「麻薬との戦争」を義務づけておらず、選択肢は「『軍事化』された麻薬取締法の執行と、非医 療目的の麻薬使用の合法化」のどちらかではないと述べ、保健と福祉が麻薬政策の中心となるべきだと主張した 。[204] その4月には、「世界的な麻薬問題」に関する国連総会特別セッション(UNGASS)が開催された。[205] ウォールストリート・ジャーナルは、参加者の立場を「やや」2つの陣営に分かれると評価した。「一部のヨーロッパ諸国や南米諸国、そして米国は、より穏や かなアプローチを支持した。中国やロシアなどの東欧諸国、そしてイラン、インドネシア、パキスタンなどのイスラム諸国のほとんどは、断固として反対の姿勢 を崩さなかった」と評価した。[206] 成果文書では、薬物の治療、予防、その他の公衆衛生対策が推奨され、「特に、より効果的な薬物関連犯罪の防止と法執行措置を通じて」薬物の生産と密売を 「防止し、対抗するための努力を強化する」ことが約束された。[207][208] ドナルド・トランプ大統領(2017年~2021年)の下で、司法長官のジェフ・セッションズは、大麻が合法化された州における連邦法の執行を延期する コールメモを撤回し、前司法省の大麻政策を覆した[197][209]。彼は、連邦検察官に対し、薬物事件では「最も深刻で、容易に立証できる犯罪容疑で 起訴し、追及する」よう指示した 最低刑が適用されるかどうかに関わらず、薬物事件では「最も深刻で立証が容易な犯罪で起訴し、追及する」よう連邦検察官に指示した。これにより、より軽微 な罪状に対する最低刑が適用される可能性がある。[210][211][212] 30以上の州で大麻が一定の範囲で合法化されている中、セッションズ長官の指示は民主党・共和党の両方から悪辣な逆行行為と見なされ、超党派で抗議の声が 上がった。トランプ大統領は2018年、他の問題を理由にセッションズ長官を解任した。[213] |

| Some policy reversal attempts

and successes In 2018, Trump signed into law the First Step Act which, among other federal prison reforms, made the 2010 Fair Sentencing Act retroactive. A US Supreme Court decision in 2021 determined that retroactivity applied to cases where mandatory minimum penalties had been imposed.[214] In 2020, both the ACLU and The New York Times reported that Republicans and Democrats were in agreement that it was time to end the war on drugs. While on the presidential campaign trail, President Joe Biden (2021–present) stated that he would take the steps to alleviate the war on drugs and end the opioid epidemic.[215][216] On December 4, 2020, during the Trump administration, the House of Representatives passed the Marijuana Opportunity Reinvestment and Expungement Act (MORE Act), which would decriminalize cannabis at the federal level by removing it from the list of scheduled substances, expunge past convictions and arrests, and tax cannabis to "reinvest in communities targeted by the war on drugs".[215][217] The MORE Act was received in the Senate in December 2020 where it remained.[218] In April 2022, the act was again passed by the House, and awaits Senate action.[219] Over time, states in the US have approached drug liberalization at a varying pace. Initially, in the 1930s, the states were ahead of the federal government in prohibiting cannabis; in recent decades, the trend has reversed. Beginning with cannabis for medical use in California in 1996, states began to legalize cannabis. As of 2023, 38 states, four US territories, and the District of Columbia (DC) had legalized cannabis for medical use;[220] for non-medical use, 24 of the states, three territories, and DC, had legalized it, and seven states decriminalized.[221] Decriminalization in this context usually refers to first-time offenses and small quantities, such as, in the case of cannabis, under an ounce (28g).[222] In November 2020, Oregon became the first state to decriminalize a number of drugs, including heroin, methamphetamine, PCP, LSD and oxycodone, shifting from a criminal approach to a public health approach;[223][224][215] portions of that policy were reversed in April 2024.[225] In 2022, Biden signed into law the Medical Marijuana and Cannabidiol Research Expansion Act, to allow cannabis to be more easily researched for medical purposes. It is the first standalone cannabis reform bill enacted at the federal level.[226][227][228] That October, Biden stated on social media, "We classify marijuana at the same level as heroin – and more serious than fentanyl. It makes no sense," and pledged to start a review by the Attorney General on how cannabis is classified.[229] On October 6, he pardoned all those with federal convictions for simple cannabis possession (to a degree symbolic, as none of those affected were imprisoned at the time), and urged the states, where the large majority of convictions rest, to do the same. His action affected 6,500 people convicted from 1992 to 2021, and thousands convicted in the District of Columbia.[230] The War continues, focus on fentanyl In 2023, the US State Department announced plans to launch a "global coalition to address synthetic drug threats", with more than 80 countries expected to join.[231][232][233] That April, Anne Milgram, head of the DEA since 2021, stated to Congress that two Mexican drug cartels posed "the greatest criminal threat the United States has ever faced." Supporting a DEA budget request of $3.7 billion for 2024, Milgram cited fentanyl in the "most devastating drug crisis in our nation's history."[234][235] In January 2024, the DEA confirmed that it was reviewing the classification of cannabis as a Schedule I narcotic. Days later, documents were released from the Department of Health and Human Services stating that cannabis has "a currently accepted medical use" in the US and a "potential for abuse less than the drugs or other substances in Schedules I and II."[229] On April 30, indicating a DEA decision, the Justice Department announced, "Today, the Attorney General circulated a proposal to reclassify marijuana from Schedule I to Schedule III. Once published by the Federal Register, it will initiate a formal rulemaking process as prescribed by Congress in the Controlled Substances Act."[236] Schedule III drugs, considered to have moderate to low potential for dependence, include ketamine, anabolic steroids, testosterone, and Tylenol with codeine.[237] In the DEA's "National Drug Threat Assessment 2024", director Milgram outlined the "most dangerous and deadly crisis", involving synthetic drugs including fentanyl and methamphetamine. She singled out the Sinaloa and Jalisco cartels in Mexico, which manufacture the synthetics in Mexican labs supplied with precursor chemicals and machinery from China, sell through "vast distribution networks" in the US, and use Chinese money laundering operations to return the proceeds to Mexico. Milgram states, "As the lead law enforcement agency in the Administration's whole-of-government response to defeat the Cartels and combat the drug poisoning epidemic in our communities, DEA will continue to collaborate on strategic counterdrug initiatives with our law enforcement partners across the United States and the world."[238] |

政策転換の試みと成功例 2018年、トランプ大統領は、連邦刑務所の改革の一環として、2010年の公正量刑法を遡及適用する内容の「第一歩法」に署名し、法律化した。2021 年の米国最高裁判所の判決では、強制最低刑が科された事件に遡及適用が適用されると判断した。[214] 2020年、ACLUとニューヨーク・タイムズ紙は、共和党と民主党が麻薬戦争を終わらせる時が来たという点で一致していると報じた。ジョー・バイデン大 統領(2021年~現在)は大統領選の遊説中、麻薬戦争を緩和し、オピオイドの流行を終息させるための措置を取るつもりだと述べた。[215][216] 2020年12月4日、トランプ政権下において、連邦議会下院は、大麻をスケジュール物質リストから削除することで連邦レベルで大麻を非犯罪化し、過去の 有罪判決と逮捕歴を抹消し、大麻に課税して「 。[215][217] MORE法は2020年12月に上院に提出されたが、そのままとなっている。[218] 2022年4月、この法案は再び下院で可決され、上院の対応を待っている。[219] 時が経つにつれ、米国の各州はさまざまなペースで薬物の自由化に近づいてきた。当初、1930年代には、連邦政府よりも州が先に大麻を禁止していたが、こ こ数十年でその傾向は逆転した。1996年のカリフォルニア州における医療用大麻に始まり、各州は大麻の合法化に乗り出した。2023年現在、医療用大麻 は38州、4つの米領土、コロンビア特別区(DC)で合法化されている。[220] 非医療用大麻については、24州、3つの領土、コロンビア特別区(DC)で合法化されており、7つの州では非犯罪化されている。[221] この文脈における非犯罪化は通常、初犯や少量の場合を指し、例えば、大麻の場合 オンス(28グラム)以下などである。[222] 2020年11月、オレゴン州はヘロイン、メタンフェタミン、PCP、LSD、オキシコドンを含む多数の薬物を非犯罪化し、刑事罰アプローチから公衆衛生 アプローチへと転換した初の州となった。[223][224][215] その政策の一部は2024年4月に撤回された。[225] 2022年、バイデンは医療用大麻の研究をより容易にすることを目的とした医療用マリファナおよびカンナビジオール研究拡大法に署名し、同法は成立した。 これは連邦レベルで成立した初の単独の大麻改革法案である。[226][227][228] 同年10月、バイデンはソーシャルメディア上で「我々はマリファナをヘロインと同じレベルに分類している。フェンタニルよりも深刻だ。それは理にかなって いない」と述べ、大麻の分類方法について司法長官による見直しを開始すると約束した。[229] 10月6日、彼は単純所持で連邦有罪判決を受けた者全員に恩赦を与えた(当時、影響を受けた者の誰もが収監されていなかったため、象徴的な意味合いが強 い)。また、有罪判決の大半が下されている州にも同様の措置を取るよう促した。彼の行動は、1992年から2021年の間に有罪判決を受けた6,500 人、およびコロンビア特別区で有罪判決を受けた数千人の人々に影響を与えた。[230] 戦争は続く、フェンタニルに焦点を当てる 2023年、米国国務省は「合成麻薬の脅威に対処するための世界連合」を発足させる計画を発表し、80カ国以上が参加すると予想された。[231] [232][233] 同年4月、2021年よりDEAのトップを務めるアン・ミルグラムは、メキシコの麻薬カルテル2つが「米国がこれまで直面した中で最大の犯罪上の脅威」を もたらしていると議会で述べた。2024年度のDEA予算として37億ドルを要求したミルグラムは、フェンタニルを「わが国の歴史上最も壊滅的な薬物危 機」を引き起こしていると述べた。[234][235] 2024年1月、DEAは大麻をスケジュールI麻薬に分類することを見直していることを確認した。数日後、米国では大麻には「現在認められている医療用 途」があり、「スケジュールIおよびIIの薬物やその他の物質よりも乱用の可能性が低い」という内容の文書が保健福祉省から発表された。[229] 4月30日、DEAの決定を受けて司法省は「本日、司法長官は大麻をスケジュールIからスケジュールIIIに再分類する提案を回覧した。連邦官報で公表さ れれば、連邦規制物質法で規定されている正式な規則制定プロセスが開始される」と発表した。[236] 依存性の中程度から低いとされるスケジュールIIIの薬物には、ケタミン、蛋白同化ステロイド、テストステロン、およびコデインを含むタイレノールが含ま れる。[237] DEAの「2024年の国家麻薬脅威評価」において、ミルグラム局長はフェンタニルやメタンフェタミンなどの合成麻薬が関わる「最も危険で致命的な危機」 について概説した。 彼女は、中国から前駆物質や機械を調達したメキシコの研究所で合成麻薬を製造し、米国の「広大な流通網」を通じて販売し、中国マネーロンダリング事業を利 用して収益をメキシコに還流させているメキシコのシナロア・カルテルとハリスコ・カルテルを特に取り上げた。ミルグラムは、「麻薬カルテルを壊滅し、地域 社会における麻薬汚染の蔓延と戦うために、政府全体で取り組む行政の主導的な法執行機関として、DEAは、米国および世界中の法執行機関のパートナーと、 戦略的な麻薬対策イニシアティブにおいて引き続き協力していく」と述べている。[238] |