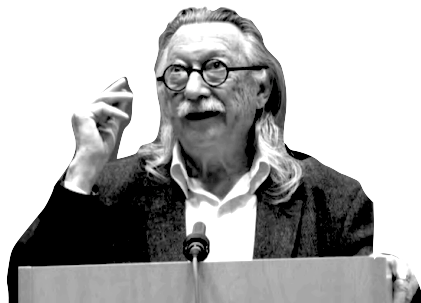

ジョセフ・ワイゼンバウム博士

Joseph Weizenbaum

ジョセフ・ワイゼンバウム博士

Joseph Weizenbaum

ジョセフ・ワイゼンバウム博士(Joseph Weizenbaum, 1923年1月8日 - 2008年3月5日)は、ドイツ出身のユダヤ系アメリカ人のコンピュータ科学者で、マサチューセッツ工科大学の教授であった。

| Joseph

Weizenbaum (8 January 1923 – 5 March 2008) was a German American

computer scientist and a professor at MIT. The Weizenbaum Award is

named after him. He is considered one of the fathers of modern

artificial intelligence. |

ジョ

セフ・ワイゼンバウム博士(Joseph Weizenbaum, 1923年1月8日 -

2008年3月5日)は、ドイツ出身のユダヤ系アメリカ人のコンピュータ科学者で、マサチューセッツ工科大学の教授であった。ワイゼンバウム賞は彼の名前

にちなんでいる。現代の人工知能の父の一人とされる。 |

| Born

in Berlin, Germany to Jewish parents, he escaped Nazi Germany in

January 1936, immigrating with his family to the United States. He

started studying mathematics in 1941 at Wayne State University, in

Detroit, Michigan. In 1942, he interrupted his studies to serve in the

U.S. Army Air Corps as a meteorologist, having been turned down for

cryptology work because of his "enemy alien" status. After the war, in

1946, he returned to Wayne State, obtaining his B.S. in Mathematics in

1948, and his M.S. in 1950.[1][2] Around 1952, as a research assistant at Wayne, Weizenbaum worked on analog computers and helped create a digital computer. In 1956 he worked for General Electric on ERMA, a computer system that introduced the use of the magnetically encoded fonts imprinted on the bottom border of checks, allowing automated check processing via Magnetic Ink Character Recognition (MICR). In 1964 he took a position at MIT. |

ド

イツのベルリンでユダヤ人の両親のもとに生まれ、1936年1月にナチス・ドイツを脱出して、家族とともにアメリカに移住した。1941年、ミシガン州デ

トロイトにあるウェイン州立大学で数学を学び始める。1942年、学業を中断し、アメリカ陸軍航空隊に気象学者として入隊した。「敵性外国人」であること

を理由に暗号解読の仕事を断られたためである。戦後、1946年にウェイン州立大学に戻り、1948年に数学の学士号を、1950年に修士号を取得した

[1][2]。 1952年頃、ウェイン大学の研究助手として、アナログコンピュータの研究に従事し、デジタルコンピュータの作成に貢献した。1956年にはゼネラル・エ レクトリック社のコンピュータシステムERMAに携わり、小切手の下枠に刻印された磁気エンコード・フォントの使用を導入し、磁気インク文字認識 (MICR)により小切手の自動処理を可能にした。 1964年、マサチューセッツ工科大学に着任。 |

| Psychology simulation at MIT In 1966, he published a comparatively simple program called ELIZA, named after the ingenue in George Bernard Shaw's Pygmalion, which performed natural language processing. ELIZA was written in the SLIP programming language of Weizenbaum's own creation. The program applied pattern matching rules to statements to figure out its replies. (Programs like this are now called chatbots.) Driven by a script named DOCTOR, it was capable of engaging humans in a conversation which bore a striking resemblance to one with an empathic psychologist. Weizenbaum modeled its conversational style after Carl Rogers, who introduced the use of open-ended questions to encourage patients to communicate more effectively with therapists. He was shocked that his program was taken seriously by many users, who would open their hearts to it. Famously, when he was observing his secretary using the software - who was aware that it was a simulation - she asked Weizenbaum: "would you mind leaving the room please?".[3] Many hailed the program as a forerunner of thinking machines, a misguided interpretation that Weizenbaum's later writing would attempt to correct.[4] |

MITの心理学シミュレーション 1966年、ジョージ・バーナード・ショーの『ピグマリオン』に登場する純情娘にちなんで名付けられた、自然言語処理を行う比較的単純なプログラム 「ELIZA」を発表した。ELIZAは、ワイゼンバウムが独自に開発したプログラミング言語「SLIP」で書かれていた。このプログラムは、文にパター ンマッチングのルールを適用して、返事を考えるものだった。(DOCTORというスクリプトで動かすと、まるで共感心理学者と会話しているかのように、人 間と会話することができる。ワイゼンバウムは、患者がセラピストとより効果的にコミュニケーションできるよう、自由形式の質問を導入したカール・ロジャー ズをモデルに、その会話スタイルを考案した。彼は、自分のプログラムが多くのユーザーに真剣に受け止められ、心を開いてもらえることに衝撃を受けた。有名 なのは、彼が秘書がこのソフトウェアを使うのを観察していたとき、秘書はそれがシミュレーションであることを承知で、ワイゼンバウムに「部屋を出ていただ けますか」と尋ねたことである[3]。多くの人がこのプログラムを思考機械の先駆けとして歓迎したが、ワイゼンバウムの後の著作でその誤った解釈を正そう とすることになった[4]。 |

| Apprehensions about Artificial Intelligence He started to think philosophically about the implications of artificial intelligence and later became one of its leading critics.[5] In an interview with MIT's The Tech, Weizenbaum elaborated on his fears, expanding them beyond the realm of mere artificial intelligence, explaining that his fears for society and the future of society were largely because of the computer itself. His belief was that the computer, at its most base level, is a fundamentally conservative force and that despite being a technological innovation, it would end up hindering social progress. Weizenbaum used his experience working with Bank of America as justification for his reasoning, saying that the computer allowed banks to deal with an ever-expanding number of checks in play that otherwise would have forced drastic changes to banking organization such as decentralization. As such, although the computer allowed the industry to become more efficient, it prevented a fundamental re-haul of the system.[6] Despite working so closely with computers for many years, Weizenbaum frequently worried about the negative effects they would have on the world, particularly with regards to the military, calling the computer "a child of the military." When asked about the belief that a computer science professional would more often than not end up working with defense, Weizenbaum detailed his position on rhetoric, specifically euphemism, with regards to its effect on societal viewpoints. He believed that the terms "the military" and "defense" did not accurately represent the organizations and their actions. He made it clear that he did not think of himself as a pacifist, believing that there are certainly times where arms are necessary, but by referring to defense as killings and bombings, humanity as a whole would be less inclined to embrace violent reactions so quickly.[6] |

人工知能への不安 ワイゼンバウムは、人工知能の意味について哲学的に考えるようになり、後に人工知能の主要な批判者の一人となった[5]。 MITのThe Techとのインタビューで、ワイゼンバウムは自分の恐怖を詳しく説明し、それを単なる人工知能の領域を超えて広げ、社会と社会の未来に対する彼の恐怖 は、主にコンピュータそのものに起因すると説明している。コンピューターは、その最も基本的な部分で、根本的に保守的な力を持っており、技術革新であるに もかかわらず、結局は社会の進歩を妨げることになるというのが、彼の信念であった。ワイゼンバウムは、バンク・オブ・アメリカでの勤務経験を根拠に、コン ピュータのおかげで、銀行は増え続ける小切手の処理に対応できるようになり、さもなければ、分散化など銀行組織の抜本的な変更を余儀なくされただろう、と 述べた。このように、コンピュータは業界の効率化を可能にしたものの、システムの根本的な見直しは防いだのである[6]。 長年コンピュータと密接に仕事をしてきたにもかかわらず、ワイゼンバウムは、コンピュータが世の中に与える悪影響、特に軍事への影響をたびたび心配し、コ ンピュータを "軍人の子供 "と呼んでいた。コンピュータ・サイエンスの専門家が国防に携わることになることが多いという考えについて尋ねると、ワイゼンバウムは、レトリック、特に 婉曲表現が社会的視点に与える影響について、自分の立場を詳しく説明した。彼は、「軍隊」や「防衛」という言葉は、組織やその行動を正確に代表することが できないと考えていた。彼は自分が平和主義者だとは思っていないことを明らかにし、確かに武器が必要な時もあるが、防衛を殺害や爆撃と呼ぶことで、人類全 体が暴力的な反応をすぐに受け入れてしまうことはないだろうと考えている[6]。 |

| Difference between Deciding and Choosing His influential 1976 book Computer Power and Human Reason displays his ambivalence towards computer technology and lays out his case: the possibility of programming computers to perform one task or another that humans also perform (i.e., whether Artificial Intelligence is achievable or not) is irrelevant to the question of whether computers can be put to a given task. Instead, Weizenbaum asserts that the definition of tasks and the selection of criteria for their completion is a creative act that relies on human values, which cannot come from computers. Weizenbaum makes the crucial distinction between deciding and choosing. Deciding is a computational activity, something that can ultimately be programmed. Choice, however, is the product of judgment, not calculation. In deploying computers to make decisions that humans once made, the agent doing so has made a choice based on their values that will have particular, non-neutral consequences for the subjects who will experience the outcomes of the computerized decisions that the agent has instituted. |

決定する」と「選択する」の違い ワイゼンバウムは、1976年に出版した『コンピュータの力と人間の理性』において、コンピュータ技術に対する彼の両義性を示し、「人間も行うある作業や 別の作業をコンピュータにプログラムすることが可能かどうか(すなわち、人工知能が実現できるかどうか)は、コンピュータにある作業をさせることができる かという問題とは無関係である」という主張を展開している。むしろ、課題の定義やその達成基準の選定は、人間の価値に依拠した創造的行為であり、コン ピュータからは得られないとワイゼンバウムは主張している。ワイゼンバウムは、「決定」と「選択」を決定的に区別している。決定することは、計算機的な活 動であり、最終的にはプログラムすることができるものである。しかし、選択は計算ではなく、判断の産物である。かつて人間が行った決定をコンピュータで行 う場合、それを行うエージェントは自分の価値観に基づいて選択を行うが、そのエージェントの行ったコンピュータによる決定の結果を経験する主体には、特別 で中立的でない結果をもたらすことになる。 |

| Returning to roots In 1996, Weizenbaum moved to Berlin and lived in the vicinity of his childhood neighborhood.[2][7] A German documentary film on Weizenbaum, "Weizenbaum. Rebel at Work.", was released in 2007 and later dubbed in English.[8] The documentary film Plug & Pray on Weizenbaum and the ethics of artificial intelligence was released in 2010.[9] Until his death he was Chairman of the Scientific Council at the Institute of Electronic Business in Berlin. In addition to working at MIT, Weizenbaum held academic appointments at Harvard, Stanford, the University of Bremen, and other universities. Weizenbaum was buried at the Weißensee Jewish cemetery in Berlin.[10] A memorial service was held in Berlin on 18 March 2008. |

ルーツへの回帰 1996年、ヴァイツェンバウムはベルリンに移り住み、幼少期に住んでいた地域の近辺に住んでいた[2][7]。 ヴァイツェンバウムのドイツ語のドキュメンタリー映画「Weizenbaum. Rebel at Work. "が2007年に公開され、後に英語にも吹き替えられた[8]。 2010年にはワイゼンバウムと人工知能の倫理を描いたドキュメンタリー映画『Plug & Pray』が公開された[9]。 亡くなるまでベルリンの電子ビジネス研究所の科学評議会議長を務めた。MITでの勤務に加え、ハーバード大学、スタンフォード大学、ブレーメン大学などでも教鞭をとった。 2008年3月18日、ベルリンで追悼式が行われた[10]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Weizenbaum. |

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報