西アフリカのヴォドゥン

West African Vodún

A

Vodun shrine in Togoville, Togo in 2017

☆

ヴォドゥン(vodún)またはヴォドゥンシンセン(vodúnsínsen)は、ベナン、トーゴ、ガーナ、ナイジェリアのアジャ(Aja)族、エウェ

(Ewe)族、フォン(Fon)族によって実践されているアフリカの伝統宗教である。修行者は一般にヴォドゥンセントー(vodúnsɛntó)または

ヴォドゥニサン(Vodúnisant)と呼ばれる。

ヴォドゥンは、至高の創造主である神の存在を説き、その下にヴォドゥンと呼ばれるより小さな精霊が存在する。これらの神々の多くは特定の地域と結びついて

いるが、西アフリカ全土で広く崇拝されている神々もいる。キリスト教やヒンドゥー教など、他の宗教に吸収されたものもある。ヴォドゥンは祠に物理的に姿を

現すと信じられており、そこでは通常、動物の犠牲を含む供物が捧げられる。OróやEgúngúnなど、男性だけの秘密結社がいくつかあり、個人がイニシ

エーションを受ける。ヴォドゥンから情報を得るために様々な占いが用いられるが、その中でも最も有名なのがファ(Fá)であり、イニシエイトの社会によっ

て統治されている。

16世紀から19世紀にかけての大西洋奴隷貿易の中で、アメリカ大陸に移送されたアフリカ人奴隷の一人にボドゥンソントがいた。そこで彼らの伝統宗教は、

ハイチのヴォドゥー、ルイジアナのヴードゥー、ブラジルのカンドンブレ・ジェジェといった新宗教の発展に影響を与えた。1990年代以降、外国人観光客に

西アフリカを訪れてもらい、ヴォドゥンへの入信を促す取り組みが活発化している。

多くのヴォドンは、イエス・キリストをヴォドンと解釈するなど、キリスト教と並行して伝統的な宗教を実践している。主に西アフリカで見られる宗教だが、

20世紀後半からは海外にも広がり、さまざまな民族や国民によって信仰されている。

| Vodún or vodúnsínsen

is an African traditional religion practiced by the Aja, Ewe, and Fon

peoples of Benin, Togo, Ghana, and Nigeria. Practitioners are commonly

called vodúnsɛntó or Vodúnisants. Vodún teaches the existence of a supreme creator divinity, under whom are lesser spirits called vodúns. Many of these deities are associated with specific areas, but others are venerated widely throughout West Africa; some have been absorbed from other religions, including Christianity and Hinduism. The vodún are believed to physically manifest in shrines and there are provided with offerings, typically including animal sacrifices. There are several all-male secret societies, including Oró and Egúngún, into which individuals receive initiation. Various forms of divination are used to gain information from the vodún, the most prominent of which is Fá, itself governed by a society of initiates. Amid the Atlantic slave trade of the 16th to the 19th century, vodúnsɛntó were among the enslaved Africans transported to the Americas. There, their traditional religions influenced the development of new religions such as Haitian Vodou, Louisiana Voodoo, and Brazilian Candomblé Jejé. Since the 1990s, there have been growing efforts to encourage foreign tourists to visit West Africa and receive initiation into Vodún. Many vodúnsɛntó practice their traditional religion alongside Christianity, for instance by interpreting Jesus Christ as a vodún. Although primarily found in West Africa, since the late 20th century the religion has also spread abroad and is practised by people of varied ethnicities and nationalities. |

ヴォドゥン(vodún)またはヴォドゥンシンセン

(vodúnsínsen)は、ベナン、トーゴ、ガーナ、ナイジェリアのアジャ(Aja)族、エウェ(Ewe)族、フォン(Fon)族によって実践されて

いるアフリカの伝統宗教である。修行者は一般にヴォドゥンセントー(vodúnsɛntó)またはヴォドゥニサン(Vodúnisant)と呼ばれる。 ヴォドゥンは、至高の創造主である神の存在を説き、その下にヴォドゥンと呼ばれるより小さな精霊が存在する。これらの神々の多くは特定の地域と結びついて いるが、西アフリカ全土で広く崇拝されている神々もいる。キリスト教やヒンドゥー教など、他の宗教に吸収されたものもある。ヴォドゥンは祠に物理的に姿を 現すと信じられており、そこでは通常、動物の犠牲を含む供物が捧げられる。OróやEgúngúnなど、男性だけの秘密結社がいくつかあり、個人がイニシ エーションを受ける。ヴォドゥンから情報を得るために様々な占いが用いられるが、その中でも最も有名なのがファ(Fá)であり、イニシエイトの社会によっ て統治されている。 16世紀から19世紀にかけての大西洋奴隷貿易の中で、アメリカ大陸に移送されたアフリカ人奴隷の一人にボドゥンソントがいた。そこで彼らの伝統宗教は、 ハイチのヴォドゥー、ルイジアナのヴードゥー、ブラジルのカンドンブレ・ジェジェといった新宗教の発展に影響を与えた。1990年代以降、外国人観光客に 西アフリカを訪れてもらい、ヴォドゥンへの入信を促す取り組みが活発化している。 多くのヴォドンは、イエス・キリストをヴォドンと解釈するなど、キリスト教と並行して伝統的な宗教を実践している。主に西アフリカで見られる宗教だが、 20世紀後半からは海外にも広がり、さまざまな民族や国民によって信仰されている。 |

Definition A Vodun priest in Benin photographed in 2018 Vodún is a religion.[1] The anthropologist Timothy R. Landry noted that, although the term Vodún is commonly used, a more accurate name for the religion was vodúnsínsen, meaning "spirit worship".[2] The spelling Vodún is commonly used to distinguish the West African religion from the Haitian religion more usually spelled Vodou;[2] this in turn is often used to differentiate it from Louisiana Voodoo.[3] An alternative spelling sometimes used for the West African religion is Vodu.[4] The religion's adherents are referred to as vodúnsɛntó or, in the French language, Vodúnisants.[2] Vodún is "the predominant religious system" of southern Benin, Togo, and parts of southeast Ghana.[5] The anthropologist Judy Rosenthal noted that "Fon and Ewe forms of Vodu worship are virtually the same".[6] It is part of the same network of religions that include Yoruba religion as well as African diasporic traditions like Haitian Vodou, Cuban Santería, and Brazilian Candomblé.[7] As a result of centuries of interaction between Fon and Yoruba peoples, Landry noted that Vodún and Yoruba religion were "at times, indistinguishable or at least, blurry".[8] Vodún is a fragmented religion divided into "independent small cult units" devoted to particular spirits.[9] As a tradition, Vodún is not doctrinal,[10] with no orthodoxy,[9] and no central text.[10] It is amorphous and flexible,[11] changing and adapting in different situations,[12] and emphasising efficacy over dogma.[13] It is open to ongoing revision,[10] being eclectic and absorbing elements from many cultural backgrounds,[7] including from other parts of Africa but also from Europe, Asia, and the Americas.[14] West African religions commonly absorb elements from elsewhere regardless of their origin;[15] in West Africa, many individuals draw upon African traditional religions, Christianity, and Islam simultaneously to deal with life's issues.[16] In West Africa, vodúnsɛntó sometimes abandon their religion for forms of Christianity like Evangelical Protestantism,[17] although there are also Christians who convert to Vodún.[18] A common approach is for people to practice Christianity while also engaging in Vodún rituals,[19] although there are also vodúnsɛntó who reject Christianity, deeming it incompatible with their tradition.[20] |

定義 2018年に撮影されたベナンのヴォドゥン司祭 ヴォドゥンは宗教のひとつである[1]。人類学者のティモシー・R・ランドリーは、ヴォドゥンという用語は一般的に使用されているが、この宗教のより正確 な名称は「精霊崇拝」を意味するvodúnsínsenであると指摘した[2]。 [2]Vodúnという綴りは、西アフリカの宗教を、より通常Vodouと綴られるハイチの宗教と区別するために一般的に使用されている[2]。 人類学者のジュディ・ローゼンタールは「フォンとエウェのヴォドゥ崇拝の形態は事実上同じである」と述べている。 [6]ヴォドゥは、ヨルバ宗教のほか、ハイチのヴォドゥ、キューバのサンテリア、ブラジルのカンドンブレのようなアフリカのディアスポラ的な伝統を含む宗 教の同じネットワークの一部である[7]。フォンとヨルバの人々の何世紀にもわたる交流の結果、ランドリーはヴォドゥンとヨルバの宗教は「時には区別がつ かなかったり、少なくともぼやけていた」と指摘した[8]。 ヴォドゥンは特定の精霊に捧げられた「独立した小さなカルト単位」に分割された断片的な宗教である[9]。伝統としてのヴォドゥンは教義的ではなく [10]、正統性もなく[9]、中心となるテキストもない。 [10]不定形で柔軟性があり[11]、異なる状況において変化・適応し[12]、教義よりも効能を重視する[13]。現在進行形で改訂が行われており [10]、折衷的であり、アフリカの他の地域だけでなくヨーロッパ、アジア、アメリカ大陸など[7]、多くの文化的背景から要素を吸収している。 [14]西アフリカの宗教は、その起源に関係なく、他の地域からの要素を吸収するのが一般的であり[15]、西アフリカでは、多くの個人が人生の問題に対 処するためにアフリカの伝統宗教、キリスト教、イスラム教を同時に利用している。 [16]西アフリカでは、ヴォドンに改宗するキリスト教徒もいるが[17]、福音主義プロテスタントのようなキリスト教の形態に自分たちの宗教を捨てるこ ともある[18]。一般的なアプローチは、ヴォドンの儀式に参加しながらキリスト教を実践することであるが[19]、自分たちの伝統と相容れないとしてキ リスト教を拒否するヴォドンの人々もいる[20]。 |

| Beliefs In Vodún, belief is centred around efficacy rather than Christian notions of faith.[21] Theology  A Vodun altar in Abomey, Benin in 2008 Vodún teaches the existence of a single divine creator being.[5] Below this entity are an uncountable number of spirits who govern different aspects of nature and society.[5] The term vodún comes from the Gbé languages of the Niger-Congo language family.[22] It translates as "spirit", "god", "divinity", or "presence".[7] Among Fon-speaking Yoruba communities, the Fon term vodún is regarded as being synonymous with the Yoruba language term òrìs̩à.[13] The art historian Suzanne Preston Blier called these "mysterious forces or powers that govern the world and the lives of those who reside within it".[23] The religion is continually open to the incorporation of new spirit deities, while those that are already venerated may change and take on new aspects.[24] Some Vodún practitioners for instance refer to Jesus Christ as the vodún of the Christians.[13] A common belief is that the vodún came originally from the sea.[25] The spirits are thought to dwell in Kútmómɛ ("land of the dead"), an invisible world parallel to that of humanity.[26] The vodún spirits have their own individual likes and dislikes;[10] each also has particular songs, dances, and prayers directed to them.[10] These spirits are deemed to manifest within the natural world.[27] When kings introduced new deities to the Fon people, it was often believed that these enhanced the king's power.[28] The cult of each vodún has its own particular beliefs and practices.[29] It may also have its own restrictions on membership, with some groups only willing to initiate family members.[30] People may venerate multiple vodún, sometimes also attending services at a Christian church.[31] Lɛgbà is the spirit of the crossroads who opens up communication between humanity and the spirit world.[32] Sakpatá is the vodún of earth and smallpox,[33] but over time has come to be associated with new diseases like HIV/AIDS.[34] The Dàn spirits are all serpents;[35] Dàn is a serpent vodún associated with riches and cool breezes.[36] Xɛbyosò or Hɛvioso is the spirit of thunder.[37] Gŭ is the spirit of metal and blacksmithing,[38] and in more recent decades has come to be associated with metal vehicles like cars, trains, and planes.[24] Gbădu is the wife of Fá.[39] Tron is the spirit of the kola nut;[40] he was recently introduced to the Vodún pantheon via Ewe speakers from Ghana and Togo.[41] |

信仰 ヴォドーンでは、信仰はキリスト教的な信仰の概念ではなく、効能を中心に据えている[21]。 神学  2008年、ベニンのアボメイにあるヴォドゥンの祭壇 ヴォドゥンとはニジェール・コンゴ語族のグベ諸語に由来する[22]。 [22]「精霊」、「神」、「神性」、「存在」と訳される[7]。フォン語を話すヨルバ族のコミュニティでは、フォン語のvodúnはヨルバ語のòrìs̩àと同義であるとみなされている[13]。 美術史家のスザンヌ・プレストン・ブリエは、これらを「世界とその中に住む人々の生活を支配する神秘的な力や力」と呼んだ[23]。この宗教は、新しい精 霊の神々を取り入れることに絶えず開かれているが、一方で既に崇拝されている神々は変化し、新たな様相を帯びることもある[24]。 一般的な信仰では、ウォドゥンはもともと海からやってきたとされている[25]。ウォドゥンの精霊は、人間と平行した目に見えない世界であるクトゥモーム (Kútmólɛ)(「死者の国」)に住むと考えられている[26]。 [10]これらの精霊は自然界の中に顕現すると考えられている[27]。王がフォン族に新しい神々を導入したとき、それらはしばしば王の権力を高めると信 じられていた[28]。 各ボドゥンの崇拝には独自の信仰と慣習がある[29]。また、入会に独自の制限がある場合もあり、家族のメンバーしか入会を認めないグループもある[30]。 Ll_25Bàは人類と霊界の間のコミュニケーションを開く十字路の霊である[32]。 Sakpatáは大地と天然痘の霊である[33]が、時代とともにHIV/AIDSのような新しい病気と関連付けられるようになった[34]。 [36]XɛbyosòまたはHɛviosoは雷の精霊[37]。Gŭは金属と鍛冶の精霊であり[38]、ここ数十年では自動車、列車、飛行機などの金属 製の乗り物と関連付けられるようになった[24]。GbăduはFáの妻である[39]。Tronはコラナッツの精霊であり[40]、ガーナとトーゴのエ ウェ語を話す人々によって最近ヴォドゥンのパンテオンに導入された[41]。 |

The Temple of the Pythons in Ouidah, centre of Dangbé's worship. Some Beninese acknowledge that certain Yoruba orisa are more powerful than certain vodún.[42] Also part of the Vodun worldview is the azizǎ, a type of forest spirit.[43] Prayers to the vodún usually include requests for financial wealth.[44] Practitioners seek to gain well-being by focusing on the health and remembrance of their families.[45] There may be restrictions on who can venerate the deity; practitioners believe that women must be kept apart from Gbădu's presence, for if they get near her they may be struck barren or die.[39] Devotion to a particular deity may be marked in different ways; devotees of the smallpox spirit Sakpatá for instance scar their bodies to resemble smallpox scars.[34] Patterns of Vodun worship follow various dialects, spirits, practices, songs, and rituals. The divine Creator, called variously Mawu or Mahu, is a female being. She is an elder woman, and usually a mother who is gentle and forgiving. She is also seen as the god who owns all other gods and even if there is no temple made in her name, the people continue to pray to her, especially in times of distress. In one tradition, she bore seven children. Sakpata: Vodun of the Earth, Xêvioso (or Xêbioso): Vodun of Thunder, also associated with divine justice,[46] Agbe: Vodun of the Sea, Gû: Vodun of Iron and War, Agê: Vodun of Agriculture and Forests, Jo: Vodun of Air, and Lêgba: Vodun of the Unpredictable.[47] The Creator embodies a dual cosmogonic principle of which Mawu the moon and Lisa the sun are respectively the female and male aspects, often portrayed as the twin children of the Creator.[48] In other stories, Mawu-Lisa is depicted as a single hermaphroditic person capable of impregnating herself, with two faces rather than being twins.[49] In other branches, the Creator and other vodus are known by different names, such as Sakpo-Disa (Mawu), Aholu (Sakpata), and Anidoho (Da), Gorovodu.[50] The soul Among the Fon, a common belief is that the head is the seat of a person's soul.[34] The head is thus of symbolic importance in Vodún.[34] Some Vodún traditions specifically venerate spirits of deceased humans. The Mama Tchamba tradition for instances honours slaves from the north who are believed to have become ancestors of contemporary Ewe people.[51] Similarly, the Gorovodu tradition also venerates enslaved northerners, who are described as being from the Hausa, Kaybe, Mossi, and Tchamba ethnicities.[31] Acɛ An important concept in Vodún is acɛ, a notion also shared by Yoruba religion and various African diasporic religions influenced by them.[52] Landry defined acɛ as "divine power".[53] It is the acɛ of an object that is deemed to provide it with its power and efficacy.[52] |

ウイダにあるピトン神殿、ダンベ信仰の中心地。 ベナン人の中には、ある種のヨルバのオリサはある種のヴォドゥンよりも強力であると認める者もいる[42]。 また、ヴォドゥンの世界観には森の精霊の一種であるアジザ(azizǎ)も含まれる[43]。 ヴォドゥンへの祈りには通常、金銭的な豊かさを求めるものが含まれる[44]。 [45]神を崇めることができる者に異なる制限がある場合もある。グバドゥに近づくと不妊になったり死んだりする可能性があるため、女性はグバドゥの存在 から遠ざけなければならないと信奉者は信じている[39]。 ヴォドゥン崇拝のパターンは、様々な方言、精霊、慣習、歌、儀式に従っている。神の創造主はマウまたはマフーと呼ばれ、女性の存在である。彼女は年長の女 性で、通常は優しく寛容な母親である。彼女はまた、他のすべての神々を所有する神とみなされ、彼女の名で作られた寺院がなくても、人々は特に苦難の時に彼 女に祈り続ける。ある伝承では、彼女は7人の子供を産んだという。サクパタ 大地のヴォドゥン、ゼヴィオーソ(またはゼビオーソ): 雷のヴォドゥンであり、神の正義とも関連している[46]: 海のヴォドゥン、グー: 鉄と戦争のヴォドゥン、アジェ: アグベ:海のヴォドゥン、グー:鉄と戦争のヴォドゥン、アジェ:農業と森林のヴォドゥン、ジョ:空気のヴォドゥン、レグバ: 予測不能のヴォドゥンである[47]。 創造主は二重の宇宙論的原理を体現しており、月のマウと太陽のリサはそれぞれ女性と男性の側面であり、しばしば創造主の双子の子供として描かれる。 [48]他の説話では、マウ=リサは双子というよりむしろ2つの顔を持つ、自らを孕ませることができる一人の二卵性の人間として描かれている[49]。他 の分派では、創造主や他のヴォドゥスはサクポ=ディサ(マウ)、アホル(サクパタ)、アニドホ(ダ)、ゴロヴォドゥなど異なる名前で知られている [50]。 魂 フォンの間では、頭部は人の魂の座であるという共通の信仰がある[34]。 ヴォドンの伝統の中には、特に亡くなった人間の霊を崇拝するものもある。同様に、ゴロヴォドゥの伝統も奴隷にされた北部の人々を崇拝しており、彼らはハウサ、カイベ、モシ、チャンバの各民族に由来するとされている[31]。 Acɛ ヴォドゥンにおける重要な概念はacl_25であり、この概念はヨルバ宗教や、ヨルバ宗教の影響を受けた様々なアフリカのディアスポラ宗教にも共有されている[52]。 |

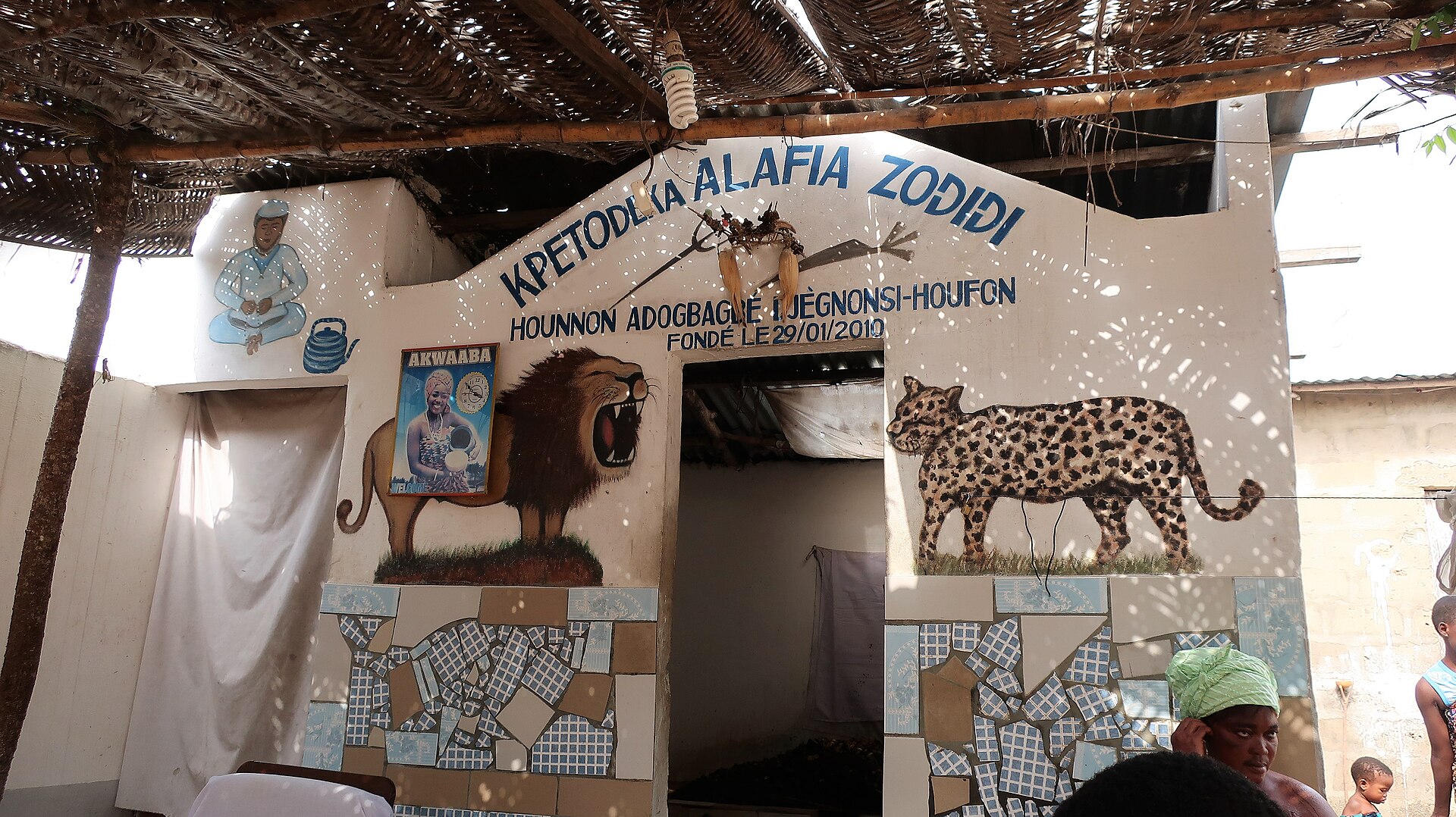

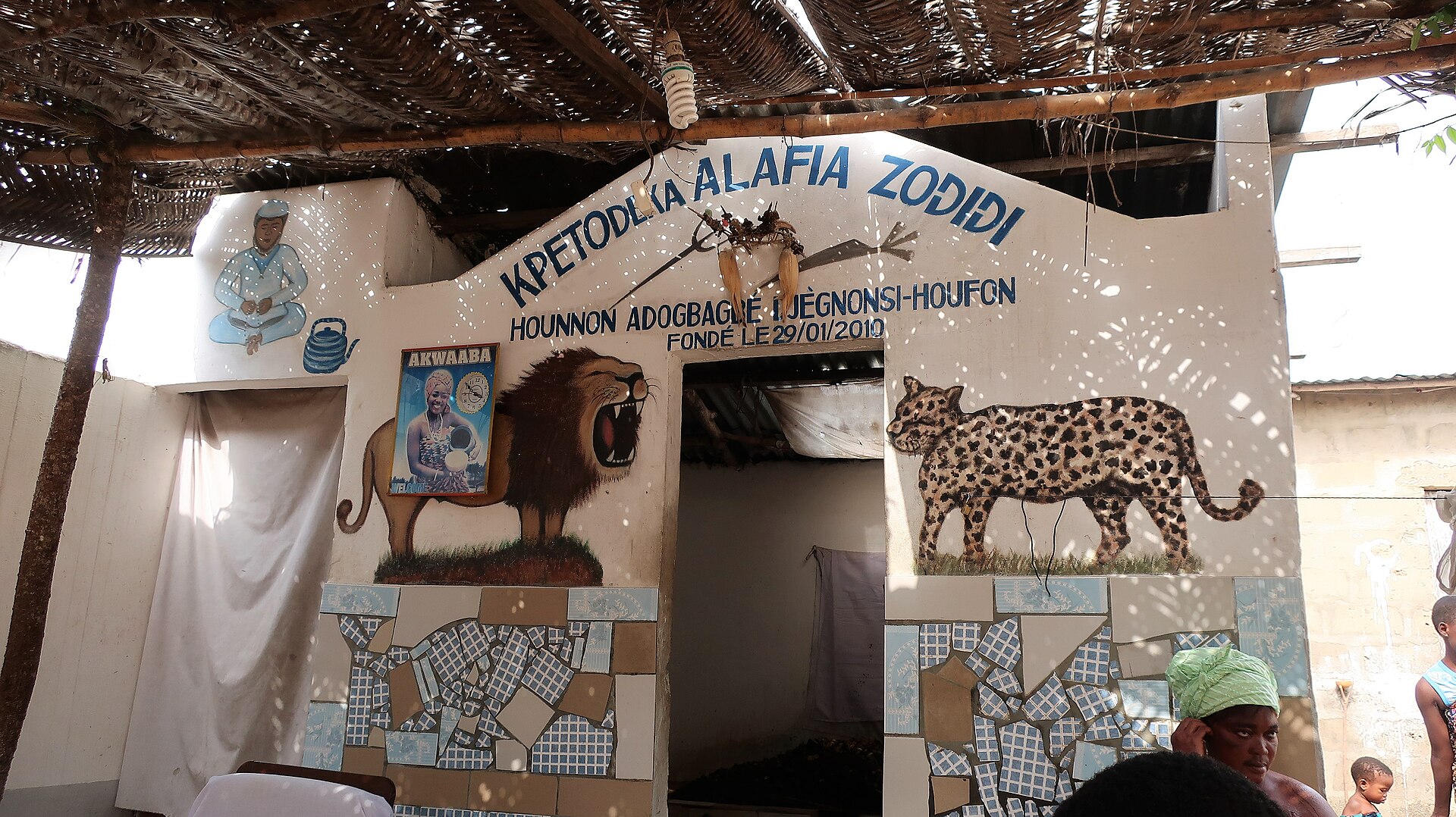

Practice A Vodun temple in Grand-Popo, Benin, in 2018 The anthropologist Dana Rush noted that Vodun "permeates virtually all aspects of life for its participants".[5] As a tradition, it prioritises action and getting things done.[10] Rosenthal found that, among members of the Gorovodu tradition, people stated that they followed the religion because it helped to heal their children when the latter fell sick.[54] Financial transactions play an important role, with both the vodún and their priests typically expecting payment for their services.[55] Landry described the religion as being "deeply esoteric".[56] A male priest may be referred to with the Fon word hùngán.[55] These practitioners may advertise their ritual services using radio, television, billboard adverts, and the internet.[57] There are individuals who claim the title of the "supreme child of Vodún in Benin", however there are competing claimants to the title and it is little recognised outside Ouidah.[58]  A priest in Abomey caring for a shrine The forest is a major symbol in Vodún.[13] Vodun practitioners believe that many natural materials contain supernatural powers, including leaves, meteorites, kaolin, soil from the crossroads, the feathers of African grey parrots, turtle shells, and dried chameleons.[59] Landry stated that a connection to the natural environment was "a dominant theme" in the religion.[59] The forest in particular is important in Vodun cosmology, and learning the power of the forest and of particular leaves that can be found there is a recurring theme among practitioners.[60] Leaves, according to Landry, are "building blocks for the spirits' power and material presence on earth".[59] Leaves will often be immersed in water to create vodùnsin (vodun water), which is used to wash both new shrines and new initiates.[61] |

練習風景 2018年、ベニンのグランポポにあるヴォドゥン寺院 人類学者のダナ・ラッシュは、ヴォードゥンは「その参加者にとって生活の事実上すべての側面に浸透している」と指摘している[5]。 伝統として、ヴォードゥンは行動と物事を成し遂げることを優先する[10]。 ローゼンタールは、ゴロヴォドゥの伝統のメンバーの中で、人々がこの宗教を信仰しているのは、自分の子供が病気になったときに病気を治すのに役立ったから だと述べていることを発見した[54]。金銭的な取引が重要な役割を果たし、ヴォードゥンとその司祭の両方が通常、彼らのサービスに対する支払いを期待し ている[55]。 ランドリーはこの宗教を「深く秘教的」であると評した[56]。男性司祭はフォン語のフンガン(hùngán)で呼ばれることがある[55]。これらの修行者はラジオ、テレビ、看板広告、インターネットを使って儀式のサービスを宣伝することがある[57]。  祠の手入れをするアボメイの司祭 森はヴォドゥンにおける主要なシンボルである[13]。ヴォドゥンの修行者たちは、葉、隕石、カオリン、十字路の土、アフリカオウムの羽毛、亀の甲羅、乾 燥したカメレオンなど、多くの自然素材に超自然的な力が宿っていると信じている[59]。ランドリーは、自然環境とのつながりがこの宗教における「支配的 なテーマ」であると述べている。 [59]特に森はヴォドゥンのコスモロジーにおいて重要であり、森とそこで見つけることができる特定の葉の力を学ぶことは、修行者の間で繰り返されるテー マである[60]。ランドリーによれば、葉は「精霊の力と地上における物質的存在のための構成要素」である[59]。 |

Shrines A Vodun shrine in Tegbi, in the Volta region of Ghana, in 2021 The spirit temple is often referred to as the vodúnxɔ or the hunxɔ.[62] This may be located inside a practitioner's home, in a publicly accessible communal area, or hidden in a part of the forest accessible only to initiates.[63] Its location impacts who uses it; some are used only be a household, others by a village, and certain shrines attract international pilgrims.[64] For adherents, these shrines are deemed to be physical incarnations of the spirits,[65] and not simply images or representations of them.[66] Rosenthal called these shrines "god-objects".[67] A wooden carved statue is referred to as a bòcyɔ.[68] Particular objects are selected for use in building a shrine based on intrinsic qualities they are believed to possess.[52] The constituent parts of the shrine are dependent on the identity of the spirit being enshrined there. Fá for instance is enshrined in 16 palm nuts, while Xɛbyosò's shrines require sò kpɛn ("thunderstones') believed to have been created where lightning struck the earth.[69] Gbǎdù, as the "mother of creation," often requires that her shrines incorporate a vagina, either of a deceased family matriarch or of an animal, along with camwood, charcoal, kaolin, and mud.[70] Lɛgbà, meanwhile, is represented by mounds of soil,[71] typically covering leaves and other objects buried within it.[36] There may also be some experimentation in the ingredients used in constructing the shrine, as practitioners hope to make the manifested spirit as efficacious as possible.[56]  A shrine to Lɛgbà Plant material is often used in building shrines,[60] with specific leaves being important in the process.[61] Offerings may be given to a tree from which material is harvested.[72] Shrines may also include material from endangered species, including leopard hides, bird eggs, parrot feathers, insects, and elephant ivory.[73] Various foreign initiates, while trying to leave West Africa, have found material intended for their shrines confiscated at airport customs.[74] In a ritual that typically incorporates divination, sacrifices, and leaf baths for both the objects and the practitioner, the spirit is installed within these shrines.[73] It is the objects added, and the rituals performed while adding them, that are deemed to give the spirit its earthly power.[63] An animal will usually be sacrificed to ensure the spirit manifests within the shrine;[75] it is believed that the animal charges the spirit's acɛ, which gives the shrine life.[26] For shrines to Lɛgbà, for instance, a rooster force-fed red palm oil will often by buried alive at the spot where the shrine is to be built.[26] When praying at a shrine, it is customary for a worshipper to leave a gift of money for the spirits.[76] There are often also pots around it in which offerings may be placed.[36] Wooden stakes may be impaled into the floor around the shrine as part of an individual's petition.[77] In this material form, the spirits must be maintained, fed, and cared for.[78] Offerings and prayers will be directed towards the shrine as a means of revitalising its power.[52] At many shrines, years of dried blood and palm oil have left a patina across the shrine and offering vessels.[36] Some have been maintained for hundreds of years.[27] Shrines may also be adorned and embellished with new objects gifted by devotees.[79] Shrines of Yalódè for instance may be adorned in brass bracelets, and those of Xɛbyosò with carved wooden axes.[64] Although these objects are not seen as part of the spirit's material body itself, they are thought to carry the deity's divine essence.[80] |

神社 2021年、ガーナのボルタ地方にあるテグビのヴォドゥン祠。 精霊の神殿はしばしばvodúnxɔまたはhunxɔと呼ばれる[62]。これは修行者の家の中にあったり、公にアクセス可能な共同区域にあったり、イニシエートのみがアクセス可能な森の一部に隠されていたりする[63]。その場所は誰が使用するかに影響する。 信者にとって、これらの祠は精霊の物理的な化身であり[65]、精霊の単なる像や表象ではないと考えられている[66]。 ローゼンタールはこれらの祠を「神像」と呼んだ[67]。 祠の構成要素は、そこに祀られる精霊のアイデンティティに依存している[52]。例えば、ファーは16個の椰子の実の中に祀られ、スビョーソーの祠には雷 が大地に落ちてできたとされる「雷石」(sò kp%)が必要である[69]。グバドゥ(Gbǎdù)は「創造の母」として、彼女の祠にはしばしば、亡くなった家長や動物の膣と、クスノキ、木炭、カオ リン、泥が必要である[70]。 [70]一方、Ll_25Bàは土の塚によって表され[71]、一般的にはその中に葉や他の物を埋める。[36]また、祠を建てる際に使用される材料に は、可能な限り顕現した霊を効能のあるものにしたいという修行者の願いから、多少の実験が行われることもある[56]。  Lɛgbàを祀る祠 祠を建てる際には植物の材料が使われることが多く[60]、その中でも特定の葉が重要である[61]。 材料が収穫された木に供物が捧げられることもある[72]。祠には、ヒョウの皮、鳥の卵、オウムの羽、昆虫、象牙など、絶滅危惧種の材料が含まれることもある[73]。 通常、占い、生贄、物体と修行者の両方のための葉浴を組み込んだ儀式において、霊はこれらの祠の中に設置される[73]。霊に地上の力を与えると考えられているのは、追加される物体と、それらを追加する間に行われる儀式である[63]。 霊が祠の中に現れるようにするために、通常、動物が犠牲にされる[75]。動物が霊のacɛを充電し、それが祠に生命を与えると信じられている[26]。 [26]祠で祈りを捧げるとき、参拝者は精霊のために賽銭を置くのが通例である[76]。 また、祠の周囲にはしばしば壺があり、そこに供物を入れることができる[36]。個人の請願の一環として、祠の周囲の床に木の杭を突き刺すことがある [77]。 この物質的な形において、精霊は維持され、養われ、世話されなければならない[78]。供え物や祈りは、その力を活性化させる手段として祠に向けられる [52]。多くの祠では、乾燥した血やパーム油の年月が祠や供え物の器全体にパティナを残している[36]。 [27]祠はまた、信者から贈られた新しいもので飾られたり装飾されたりすることもある[79]。例えばヤロデの祠は真鍮の腕輪で飾られ、シュルビョソの 祠は木彫りの斧で飾られる[64]。これらの物は霊魂の物質的な肉体の一部とは見なされないが、神の神聖なエッセンスが宿っていると考えられている [80]。 |

| Oró and Egúngún The Oró and Egúngún groups are all-male secret societies.[81] In Beninese society, these groups command respect through fear.[82] In contemporary Benin, it is common for a young man to be initiated into both societies on the same day.[82] A culture of secrecy surrounds the Egúngún society.[83] Once initiated, a man will be expected to have his own Egúngún mask made;[84] these masks are viewed as embodiments of the ancestors.[85] Some people also make these masks, but do not consecrate or use them, for sale on the international art market, but other members of the society disapprove of this practice.[86] Possession Possession is part of most Vodún cults.[58] Rosenthal noted, from her ethnographic research in Togo, that females were more often possessed than males.[67] Her research also found children as young as 10 being possessed, although most were over 15.[67] In some vodún groups, priests will rarely go into possession trance as they are responsible for overseeing the broader ceremony.[67] The possessed person is often referred to as the vodún itself.[87] Once the person has received the spirit, they will often be dressed in attire suitable for that possessing entity.[88] The possessed will address other attendees, offering them advice on illnesses, conduct, and making promises.[89] When a person is possessed, they may be cared for by another individual.[67] Those possessed often enjoy the prestige of having hosted their deities.[90] |

オロとエグングン オロとエグングンは男性だけの秘密結社である[81]。 ベニンの社会では、これらの結社は恐怖によって尊敬を集めている[82]。現代のベナンでは、若い男性が同じ日に両方の結社に入門することが一般的である[82]。 エグングン社会を取り巻く秘密の文化[83]。 入門すると、男性は自分自身のエグングンの仮面を作ることが期待される[84]。これらの仮面は祖先の具現と見なされている[85]。一部の人々は国際的 な芸術市場で販売するために、これらの仮面を作るが、聖別したり使用したりはしないが、社会の他のメンバーはこの習慣を否定している[86]。 憑依 ローゼンタールはトーゴでのエスノグラファー調査から、男性よりも女性の方が憑依されることが多いと述べている[58]。彼女の調査では、10歳の子供が憑依されていることも発見されたが、ほとんどは15歳以上であった[67]。 憑依された者はしばしばヴォドゥンそのものと呼ばれる[87]。一旦霊を受け取った者は、しばしばその憑依している存在に適した服装をする[88]。 |

Offerings and animal sacrifice An animal sacrifice at a shrine in Abomey, Benin in 2004 Vodun involves animal sacrifices to both ancestors and other spirits,[26] a practice called vɔ in Fon.[36] Animal species commonly used for sacrifice include birds, dogs, cats, goats, rams, and bulls.[91] There is ample evidence that in parts of West Africa, human sacrifice was also performed prior to European colonisation, such as in the Dahomey kingdom during the Annual Customs of Dahomey.[92] Typically, a message to the spirits will be spoken into the animal's ear and its throat will then be cut.[93] The shrine itself will be covered in the victim's blood.[94] This is done to feed the spirit by nourishing its acɛ.[95] Practitioners believe that this act maintains the relationship between humans and the spirits.[26] The meat will be cooked and consumed by the attendees,[96] something believed to bestow blessing from the vodún for the person eating it.[89] The individual who killed the animal will often take ritual precautions to pacify their victim and discourage their spirit from taking vengeance upon them.[97] Among followers in the United States, where butchery skills are far rarer, it is less common for practitioners to eat the meat.[98] Also present in the U.S. are practitioners who have rejected the role of animal sacrifice in Vodun, deeming it barbaric.[99] |

供え物と生け贄 2004年、ベナンのアボメイの祠における動物の生け贄 ヴォドゥンでは、祖先と他の精霊の両方[26]に対する動物の生け贄が行われ、フォン語ではvɔと呼ばれる習慣がある[36]。 典型的には、精霊へのメッセージが動物の耳元で語られ、その喉が切られる[93]。 [26]肉は調理され、参列者によって食される[96]が、食する者にヴォドゥンからの祝福が授けられると信じられている[89]。動物を殺した者は、犠 牲者をなだめ、その霊が復讐するのを思いとどまらせるために儀式的な予防措置をとることが多い[97]。 また、ヴォドゥンにおける動物の生贄の役割を野蛮であるとみなして否定する修行者もアメリカに存在する[99]。 |

Initiation Animal heads and other body parts, sold for ritual uses, at the Akodessawa Market in Lomé, Togo in 2015 Initiation bestows a person with the power of a vodún.[42] It results in long-term obligations to the spirits that a person has received; that person is expected to honour their spirits with praise, to feed them, and to supply them with money, while in turn the spirit offers benefits to the initiate, giving them promises of protection, abundance, long-life, and a large family.[73] The typical age of a person being initiated varies between spirit cults; in some cases children are preferred.[92] The process of initiation can last from a few months to a few years.[10] It differs among spirit cults; in Benin, Fá initiation usually takes less than a week, whereas initiations into the cults of other vodún may take several weeks or months.[100] Initiation is expensive;[101] especially high sums are generally charged for foreigners seeking initiation or training.[102] Practitioners believe that some spirits embody powers that are too intense for non-initiates.[42] Being initiated is described as "to find the spirit's depths".[103] Animal sacrifice is a typical feature of initiation.[26] Trainees will often be expected to learn many different types of leaves and respective qualities.[43] |

イニシエーション 2015年、トーゴのロメにあるアコデサワ・マーケットで、儀式用に売られている動物の頭や体の一部。 イニシエーションは、人にヴォドゥンの力を授ける[42]。その結果、人が受け取った精霊に対して長期的な義務を負うことになる。その人は精霊を賞賛して 敬い、食事を与え、金銭を供給することが期待され、その一方で精霊はイニシエイトに利益を提供し、保護、豊かさ、長寿、大家族を約束する[73]。 イニシエーションを受ける人の典型的な年齢は霊のカルトによって異なり、子供が好まれる場合もある[92]。イニシエーションのプロセスは数ヶ月から数年 続く[10]。 [100]イニシエーションは高価であり、[101]特にイニシエーションやトレーニングを求める外国人には一般的に高額な費用が請求される[102]。 イニシエーションを受けることは「霊の深淵を見出すこと」と表現される[42]。 |

| Divination Divination plays an important role in Vodún.[29] Different vodún groups often utilise different divinatory methods; the priestesses of Mamíwátá for instance employ mirror gazing, while the priests of Tron use kola nut divination.[29] Across Vodún's practitioners, Fá is often deemed the best form of divination.[104] Its initiates claim that it is the only system that has sufficient acɛ to be consistently accurate.[104] This is a system adopted from the Yoruba.[105] Fá diviners typically believe that the priests of other spirits do not have the right to read the sacred signs of Fá.[42] A consultation with an initiate is termed a fákínan.[106] In Vodun, a diviner is called a bokónó.[107] A successful diviner is expected to provide solutions to their client's problem, for instance selling them charms, spiritual baths, or ceremonies to alleviate their issue.[108] The fee charged will often vary depending on the client, with the diviner charging a reduced rate for family members and a more expensive rate to either tourists or to middle and upper-class Beninese.[108] Diviners will often recommend that their client seeks initiation.[109] |

占い 占いはヴォドゥンにおいて重要な役割を果たす[29]。異なるヴォドゥン集団はしばしば異なる占術を用いる。例えばマミワタの巫女は鏡の視線を用い、トロンの司祭はコラの実の占いを用いる[29]。 これはヨルバから採用されたシステムである[105]。ファの占い師は通常、他の精霊の司祭にはファの神聖な印を読む権利はないと信じている[42]。 ヴォドゥンでは、占い師はボコノー(bokónó)と呼ばれる[107]。成功した占い師は、クライアントの問題に対する解決策を提供することが期待され、例えば、クライアントの問題を軽減するために、チャーム、スピリチュアルバス、儀式を販売する[108]。 |

Healing and bǒ A Ewe bǒciɔ made in the latter half of the 20th century, on display in Strasbourg. Healing is a central element of Vodún.[16] The Fon term bǒ can be translated into English as "charm"; many Francophone Beninese refer to them as gris gris.[110] These are amulets made from zoological and botanical material that is then activated using secret incantations,[111] the latter called bǒgbé ("bǒ's language").[112] Families or individuals often keep their recipes for creating bǒ a closely guarded secret;[113] there is a widespread belief that if someone else discovers the precise ingredients they will have power over its maker.[114] Bǒ are often sold;[115] tourists for instance often buy them to aid in attracting love, wealth, or protection while travelling.[116] Bǒ designed for specific functions may have particular names; a zǐn bǒ is alleged to offer invisibility while a fifó bǒ provides the power of translocation.[113] Anthropomorphic figurines produced especially in the Fon and Ayizo area of southern Benin are commonly called bǒciɔ ("bǒ cadaver").[117] These bǒciɔ are often kept within a shrine or house—sometimes concealed in the rafters or under a bed—although in some places have also been situated outside, in public spaces.[118] Although bǒciɔ are not intended as representations of vodún,[119] early European travellers who encountered these objects labelled them "idols" and "fetishes".[120] |

癒しとbǒ ストラスブールに展示されている20世紀後半に制作されたエウェのbǒciɔ。 癒しはヴォドゥンの中心的な要素である[16]。 フォンの用語bǒは英語に訳すと「お守り」であり、多くのフランス語圏のベナン人はbǒをグリグリと呼ぶ[110]。 [112]家族または個人はしばしばBǒを作るためのレシピを厳重に秘密にしている。[113]誰かが正確な材料を発見した場合、彼らはその製作者に対し て力を持つことになるという信仰が広まっている[114]。 zǐn bǒは透明をもたらすとされ、fifó bǒは転移の力をもたらすとされる[113]。特にベナン南部のフォンとアイゾ地域で作られる擬人化された置物は、一般的にbǒciɔ(「bǒの死体」) と呼ばれる[117]。 [117]これらのbǒciɔはしばしば祠や家の中に保管され、時には垂木の中やベッドの下に隠されることもあるが、場所によっては屋外の公共スペースに 置かれることもある[118]。bǒciɔはウォドゥンの表象として意図されたものではないが[119]、これらのオブジェに遭遇した初期のヨーロッパ人 旅行者は「偶像」や「フェティッシュ」と呼んだ[120]。 |

| Azě Another belief in Vodún is in azě, a universal and invisible power,[121] and one which many practitioners regard as the most powerful spiritual force available.[41] In English, azě has sometimes been translated as "witchcraft".[41] Several vodún, such as Kɛnnɛsi, Mǐnɔna, and Gbădu, are thought to draw their power from azě.[121] Many practitioners draw a distinction between azě wiwi, the destructive and harmful side of this power, and azě wèwé, its protective and benevolent side.[122] People who claim to use this power call themselves azětɔ and typically insist that they employ azě wèwé to protect their families from azě wiwi.[123] In Vodún lore, becoming an azětɔ comes at a cost, for the azě gives the practitioner a propensity for illness and shortens their life.[110] According to Vodún belief, azěto wiwi are capable of transforming into animals and flying.[113] To become an azěto wiwi, an individual must use azě to kill someone, commonly a relative.[110] In the tradition, practitioners of azě wiwi send their soul out at night, where they gather with other practitioners to plot how they will devour other people's souls, ultimately killing them.[16] Owls, black cats, and vultures are all regarded as dangerous agents of azě.[121] Many people fear that their success will attract the envy of malevolent azětɔ within their family or neighbourhood.[121] The identity of the azěto wiwi, many practitioners believe, can be ascertained through divination.[124] Landry found that everyone he encountered in Benin believed in azě to various degrees,[125] whereas many non-Africans arriving for initiation were more sceptical of its existence.[126] |

アジェ ヴォドゥンにおけるもう一つの信仰はアジエ(azě)であり、普遍的で目に見えない力[121]であり、多くの修行者が最も強力な霊力とみなしている [41]。英語ではアジエは「魔術」と訳されることもある[41]。 [121]多くの修行者は、この力の破壊的で有害な側面であるアジエ・ウィウィと、保護的で善良な側面であるアジエ・ウェウェを区別している。 [122]この力を使うと主張する人々は自らをazětɔと呼び、一般的には家族をazě wiwiから守るためにazě wèwéを使うと主張する[123]。ヴォドゥンの伝承では、azětɔになるには代償が必要であり、azěは修行者に病気の傾向を与え、寿命を縮める [110]。 ヴォドゥンの信仰によれば、アジエト・ウィウィウィは動物に変身して空を飛ぶことができる[113]。アジエト・ウィウィになるためには、アジエを使って 誰か(一般的には親族)を殺さなければならない[110]。伝承では、アジエト・ウィウィの修行者は夜になると魂を外に送り出し、そこで他の修行者と集 まって他人の魂をどのように貪り、最終的に殺すかを企む。 [121]多くの人々は、自分の成功が家族や近隣の悪意あるazětɔの嫉妬を集めることを恐れている[121]。多くの修行者は、azěto wiwiの正体は占いによって知ることができると信じている[124]。 |

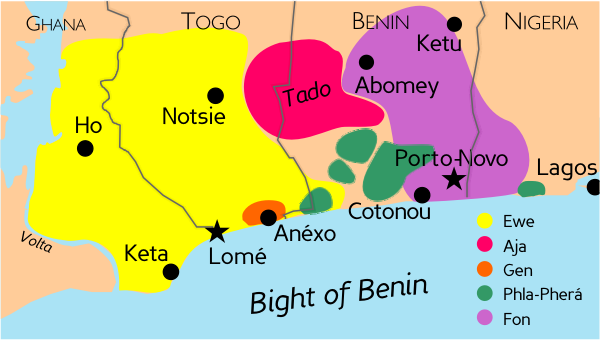

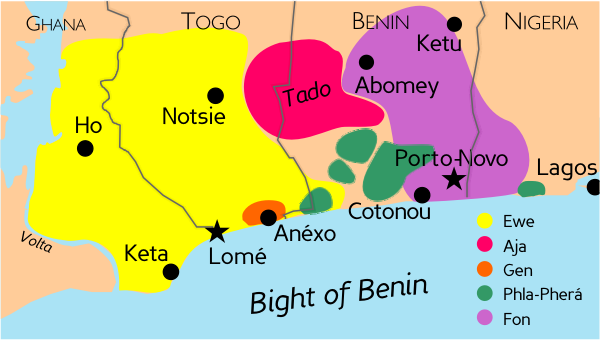

| History Pre-colonial history  Area of Vodún practice encompassing Ewe and Fon populations Landry noted that prior to European colonialism, Vodún was not identified as "a monolithic religion" but was "a social system made of countless spirit and ancestor cults that existed without religious boundaries."[7] Many of these cults were closely interwoven with political structures, sometimes representing something akin to state religions.[127] From the early 16th century, waves of Adja and related peoples migrated eastward, establishing close ties with each other and forming the basis for the emergent Fon people.[128] The Fon made contact with Portuguese sailors in the 16th century and subsequently also the French, British, Dutch, and Danish in the 17th and 18th centuries.[128] The 17th century saw the rise of the Dahomey state in this area of West Africa.[119] This generated religious change; early in the 17th century, Dahomey's king Agaja conquered the Xwedá kingdom (in what is now southern Benin) and the Xwedá's serpent vodún came to be widely adopted by the Fon.[35] From circa 1727 to 1823, Dahomey was a vassal state of Oyo, the Yoruba-led kingdom to the east, with this period seeing considerable religious exchange between the two.[129] Fon peoples adopted the Fá, Oró, and Egúngún cults from the Yoruba.[129] Fá was for instance present among the Fon by the reign of Dahomey's fifth ruler, Tegbesu (r.1732-74) and by the reign of Gezo (r.1818-58) had become well established in the Dahomean royal palace.[129] As a result of the Atlantic slave trade, practitioners of Vodún were enslaved and transported to the Americas, where their practices influenced those of developing African diasporic traditions.[130] Coupled with the religion of the Kongo people from Central Africa, the Vodún religion of the Fon became one of the two main influences on Haitian Vodou.[131] Like the name Vodou itself, many of the terms used in this creolised Haitian religion derive from the Fon language;[132] including the names of many deities, which in Haiti are called lwa.[133] In Brazil, the dominant African diasporic religion became Candomblé and this was divided into various traditions called nacoes ("nations"). Of these nacoes, the Jeje tradition uses terms borrowed from Ewe and Fon languages,[134] for instance referring to its spirit deities as vodun.[135] |

歴史 植民地以前の歴史  エウェ族とフォン族を含むヴォドゥン信仰地域 ランドリーによれば、ヨーロッパの植民地支配以前、ヴォドゥンは「一枚岩の宗教」ではなく、「無数の精霊崇拝や祖先崇拝が宗教的な境界を越えて存在する社 会システム」であった[7]。 [127]16世紀初頭から、アジャと関連する民族の波が東へと移動し、互いに密接な関係を築き、新興のフォン族の基礎を形成した[128]。フォン族は 16世紀にポルトガルの船乗りと接触し、その後17世紀から18世紀にかけてフランス、イギリス、オランダ、デンマークとも接触した[128]。 17世紀には西アフリカのこの地域でダホメー国家が勃興した[119]。これは宗教的な変化をもたらし、17世紀初頭にはダホメーのアガジャ王がスウェダ 王国(現在のベナン南部)を征服し、スウェダ王国の蛇のヴォドゥンがフォン族に広く採用されるようになった。 [1727年頃から1823年頃まで、ダホメイは東に位置するヨルバ主導の王国オヨの属国であり、この時期には両者の間でかなりの宗教的交流があった [129]。フォン族はヨルバからファー、オロ、エグングンのカルトを取り入れた[129]。 1818-58)の治世にはダホメイの王宮に定着していた[129]。 大西洋奴隷貿易の結果、ヴォドゥンの実践者は奴隷となりアメリカ大陸に運ばれ、彼らの実践は発展途上のアフリカ系ディアスポラ伝統の実践に影響を与えた [130]。中央アフリカのコンゴ人の宗教と結合し、フォンのヴォドゥン宗教はハイチのヴォドゥーに影響を与えた2つの主要な宗教の1つとなった。 [131]ヴォドゥという名前自体がそうであるように、このクレオール化されたハイチの宗教で使用される用語の多くはフォン語に由来している[132]。 これらのナコエのうち、ジェジェの伝統はエウェ語やフォン語から借用した用語を使用しており[134]、例えばその精霊の神々をヴォドゥンと呼んでいる [135]。 |

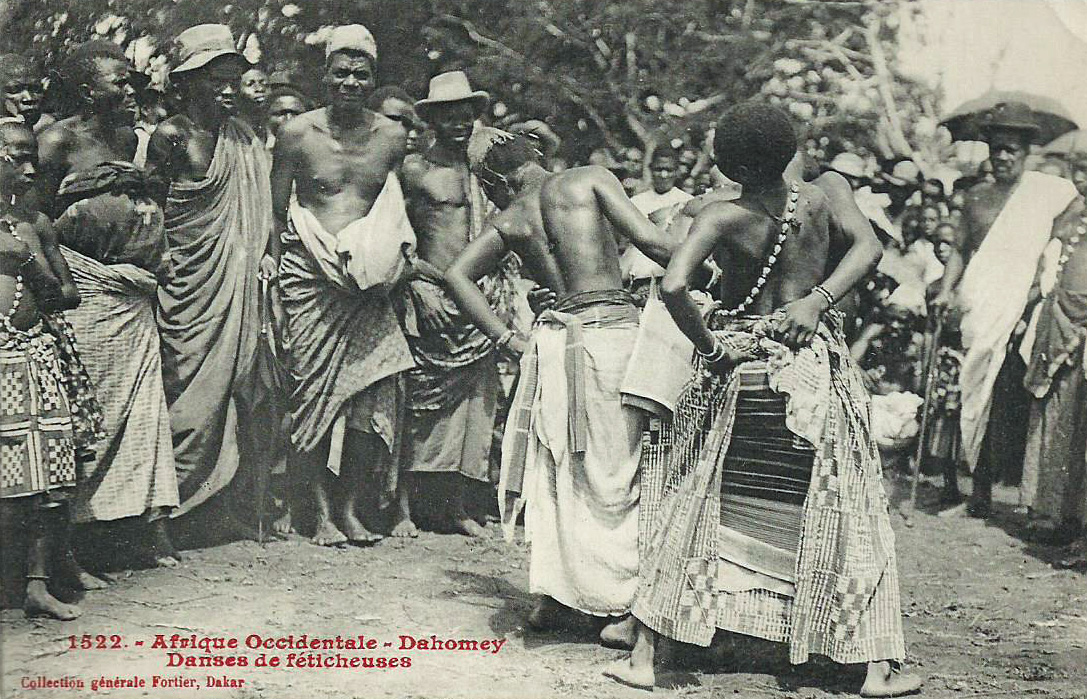

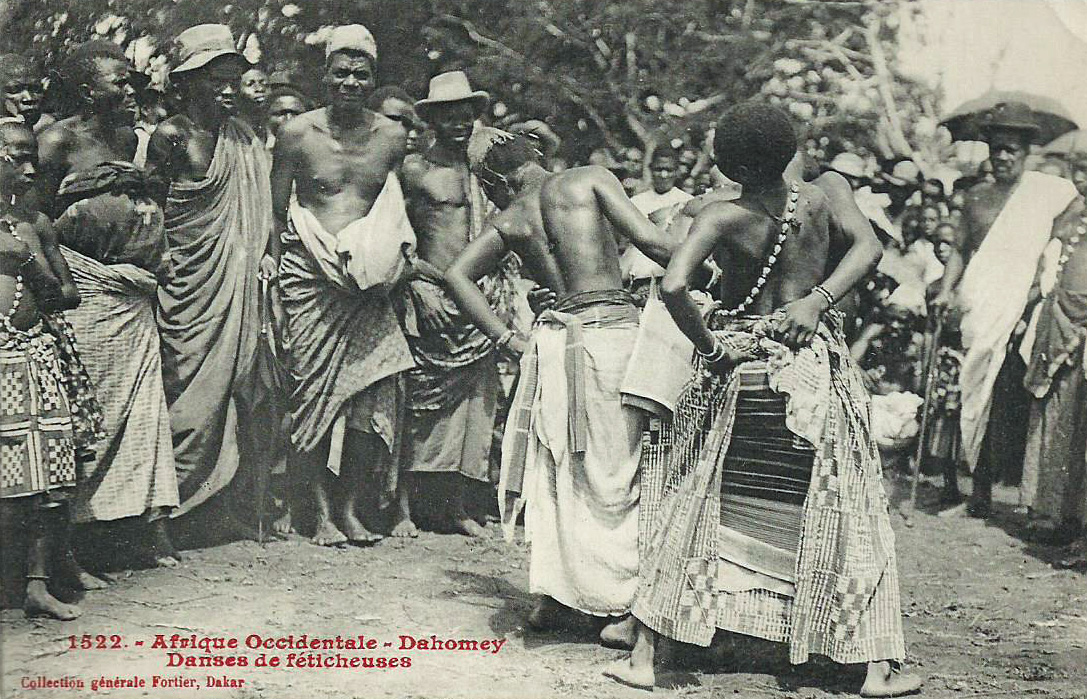

Colonialism and Christianity A ritual dance in Dahomey photographed in the 1920s In 1890, France invaded Dahomey and dethroned its king, Béhanzin.[136] In 1894, it became a French protectorate under a puppet king, Agoli-agbo, but in 1900 the French ousted him and abolished the Kingdom of Dahomey.[136] To the west, the area that became Togo became a German protectorate in 1884. Germany maintained control until 1919 when, following their defeat in the First World War, the eastern portion became part of the British Gold Coast and the western part became French territory.[137] Christian missionaries were active in this part of West Africa from the 18th century. A German Presbyterian mission had established in the Gold Coast in 1737 before spreading their efforts into the Slave Coast in the 19th century. These Presbyterians attempted to break adherence to Vodún in the southern and plateau regions.[20] The 19th century also saw conversion efforts launched by Roman Catholic, Anglican, and Methodist missionaries.[20] Although proving less of an influence than Christianity, Islam also impacted Vodún, reflected in the occasional use of Islamic script in the construction of Vodún charms.[138] |

植民地主義とキリスト教 1920年代に撮影されたダホメイの儀式ダンス 1890年、フランスはダホメーを侵略し、その王ベハンジンを失脚させた[136]。1894年、アゴリ=アグボという傀儡王の下でフランスの保護領と なったが、1900年、フランスはアゴリ=アグボを追放し、ダホメー王国を廃止した[136]。西のトーゴとなった地域は、1884年にドイツの保護領と なった。ドイツは1919年まで支配を維持し、第一次世界大戦での敗戦後、東部はイギリスのゴールドコーストの一部となり、西部はフランス領となった [137]。 キリスト教の宣教師は18世紀から西アフリカのこの地域で活動していた。ドイツ長老派の宣教師が1737年にゴールドコーストに設立され、19世紀には奴 隷海岸にもその活動を広めた。これらの長老派は南部や高原地帯のヴォドゥン信仰を断ち切ろうとした[20]。19世紀にはローマ・カトリック、聖公会、メ ソジストの宣教師たちによる改宗活動も始まった[20]。 キリスト教ほどではないが、イスラム教もヴォドンに影響を与えており、ヴォドンのお守りを作る際にイスラム教の文字が使われることがある[138]。 |

| Post-colonial history In 1960, Dahomey became an independent state,[139] as did Togo.[140] In 1972, Mathieu Kérékou seized power of Dahomey in a military coup and subsequently transformed it into a Marxist-Leninist state, the People's Republic of Benin.[141] Kérékou believed that Vodún wasted time, money, and resources that were better spent on economic development.[142] In 1973 he banned Vodún ceremonies during the rainy season, with further measures to suppress the religion following throughout the 1970s.[143] Under Kérékou's rule, Vodun priests had to perform new initiations in secret, and the duration of the initiatory process was often shortened from a period of years to one of months, weeks, or days.[144] In 1989, Benin transitioned to democratic governance.[145] After becoming prime minister in 1991, Nicéphore Soglo lifted many anti-Vodún laws.[145] The Beninese government planned "Ouidah '92: The First International Festival of Vodun Arts and Cultures," which took place in 1993;[146] among the special guests invited were Pierre Verger and Mama Lola, reflecting attempts to build links across the African diaspora.[127] It also established 10 January as "National Vodún Day."[145] From the 1990s, the Beninese government increasingly made a concerted effort to encourage Vodún-themed tourism, hoping that many foreigners would come seeking initiation.[147] By the late 1960s, some American black nationalists were travelling to West Africa to gain initiation into Vodún or Yoruba religion.[148] By the late 1980s, some white middle-class Americans began arriving for the same reason.[148] Some initiates of Haitian Vodou or Santería still go to West Africa for initiation as they believe that it is there that the "real secrets" or "true spiritual power" can be found;[149] the majority of arrivals seek initiation into Fá.[58] West Africans have also taken the religion to the U.S., where it has interacted and blended with diasporic religions like Vodou and Santería.[150] Many West African practitioners have seen the international promotion of Vodún as a means of healing the world and countering hate and violence,[151] as well as a means of promoting their own ritual abilities to an international audience, which will potentially attract new clients.[152] |

植民地支配後の歴史 1960年、ダホメーはトーゴと同様に独立国家となった[139]。1972年、マチュー・ケレコウが軍事クーデターによってダホメーの権力を掌握し、マ ルクス・レーニン主義国家であるベナン人民共和国へと変貌させた[141]。 [142]1973年、彼は雨季のヴォドゥン儀式を禁止し、1970年代を通してヴォドゥン宗教を弾圧するための更なる措置が続いた[143]。ケレコウ の支配下で、ヴォドゥンの司祭は秘密裏に新たなイニシエーションを行わなければならず、イニシエーションの期間はしばしば数年から数ヶ月、数週間、数日に 短縮された[144]。 1989年、ベナンは民主的な統治に移行した[145]。1991年に首相に就任したニセフォール・ソグロは多くの反ヴォドゥン法を解除した[145]。 ベナン政府は1993年に開催された「ウイダー'92:ヴォドゥン芸術と文化の第1回国際フェスティバル」を企画した[146]。 [また、1月10日を「ナショナリズムの日」と制定した[145]。1990年代以降、ベナン政府は、多くの外国人が入門を求めて訪れることを期待して、 ヴォドゥンをテーマとした観光を奨励する努力を強めていった[147]。 1960年代後半には、アメリカの黒人ナショナリストの何人かがヴォドゥンやヨルバの宗教に入信するために西アフリカを訪れていた[148]。 1980年代後半には、白人の中流階級のアメリカ人の何人かが同じ理由で西アフリカを訪れるようになった。 [148]ハイチのヴォドゥやサンテリアの入信者の中には、「本当の秘密」や「真のスピリチュアル・パワー」がそこにあると信じているため、今でも入信の ために西アフリカに行く者もいる[149]、 多くの西アフリカの修行者たちは、ヴォドゥンの国際的な普及を、世界を癒し、憎しみや暴力に対抗する手段[151]、また自分たちの儀式の能力を国際的な 聴衆に広める手段であると見なしており、それは潜在的に新たな顧客を惹きつけることになる[152]。 |

Demographics A Vodun altar in Grand-Popo, Benin photographed in 2018 About 17% of the population of Benin, some 1.6 million people, follow Vodun. (This does not count other traditional religions in Benin.) In addition, many of the 41.5% of the population that refer to themselves as "Christian" practice a syncretized religion, not dissimilar from Haitian Vodou or Brazilian Candomblé; indeed, many of them are descended from freed Brazilian slaves who settled on the coast near Ouidah.[153] In Togo, about half the population practices indigenous religions, of which Vodun is by far the largest, with some 2.5 million followers; there may be another million Vodunists among the Ewe of Ghana, as a 13% of the total Ghana population of 20 million are Ewe and 38% of Ghanaians practice traditional religion. According to census data, about 14 million people practice traditional religion in Nigeria, most of whom are Yoruba practicing Ifá, but no specific breakdown is available.[153] Although initially present only among West Africans, Vodún is not followed by people of many races, ethnicities, nationalities, and classes.[154] Foreigners who come for initiation are predominantly from the United States;[155] many of them have already explored African diasporic traditions like Haitian Vodou, Santería, or Candomblé, or alternatively Western esoteric religions such as Wicca.[156] Many of the spiritual tourists who arrived in West Africa had little or no Fon or French, nor an understanding of the region's cultural and social norms.[157] Some of these foreigners seek initiation so that they can initiate others as a source of revenue.[158] |

人口統計 2018年に撮影されたベナン、グランポポのヴォドゥンの祭壇 ベナンの人口の約17%、約160万人がヴォドゥンを信仰している。(さらに、人口の41.5%のうち「キリスト教徒」と称する人々の多くは、ハイチの ヴォドゥーやブラジルのカンドンブレに似ていなくもない、シンクレタイズされた宗教を実践している。実際、彼らの多くは、ウイダ近くの海岸に定住した解放 されたブラジル人奴隷の子孫である[153]。 トーゴでは、人口の約半数が土着の宗教を信仰しており、その中でもヴォドゥンは250万人の信者を抱える最大の宗教である。ガーナの総人口2,000万人 のうち13%がエウェ人であり、ガーナ人の38%が伝統的な宗教を信仰していることから、ガーナのエウェ人の中にもさらに100万人のヴォドゥニストがい る可能性がある。国勢調査のデータによると、ナイジェリアでは約1,400万人が伝統的な宗教を信仰しており、そのほとんどはイファを信仰するヨルバ人で あるが、具体的な内訳は不明である[153]。 当初は西アフリカ人の間にのみ存在していたが、ヴォドゥンは多くの人種、民族、ナショナリズム、階級の人々によって信奉されている[154]。 [156]西アフリカに到着したスピリチュアルな観光客の多くは、フォン語やフランス語、またこの地域の文化的・社会的規範をほとんど、あるいは全く理解 していなかった[157]。 これらの外国人の中には、収入源として他者をイニシエートできるようにイニシエーションを求める者もいる[158]。 |

Reception and influence A shrine in Abomey, Benin In the view of some foreign observers, Vodún is Satanism and demon worship.[159] Although seeing its deities as malevolent demons, many West African Christians still regard Vodún as being effective and powerful.[160] Some Beninese regard Christianity as "less worrisome and less expensive" than Vodún;[106] many individuals converted to Christianity to deal with bewitchment, believing that Jesus could heal and protect them for free, whereas any vodún offering to counter witches would extract a substantial price.[161] |

受容と影響 ベナン、アボメイの祠 一部の外国人からは、ヴォドゥンは悪魔崇拝であると見られている。西アフリカのキリスト教徒の多くは、ヴォドゥンの神々を邪悪な悪魔と見なしているが、そ れでもヴォドゥンは効果的で強力だと考えている。ベナン人の中には、キリスト教はヴォドゥンよりも「心配が少なく、お金もかからない」と考えている人もい る。魔女に対抗するためにヴォドゥンを捧げれば相当な代償を払わされるのに対し、イエスなら無料で癒し、守ってくれると信じて、妖術に対処するためにキリ スト教に改宗した人も多い。 |

| Sources Álvarez López, Laura; Edfeldt, Chatarina (2007). "The Role of Language in the Construction of Gender and Ethnic-Religious Identities in Brazilian-Candomblé Communities". In Allyson Jule (ed.). Language and Religious Identity: Women in Discourse. Oxford: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 149–171. ISBN 978-0230517295. Bellegarde-Smith, Patrick; Michel, Claudine (2006). "Introduction". In Bellegarde-Smith, Patrick; Michel, Claudine (eds.). Haitian Vodou: Spirit, Myth and Reality. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. xvii–xxvii. ISBN 978-0-253-21853-7. Blier, Suzanne Preston (1995a). African Vodun: Art, Psychology, and Power. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226058603. Blier, Suzanne Preston (1995b). "Vodun: West African Roots of Vodou". In Donald J., Cosentino (ed.). Sacred Arts of Haitian Vodou. Los Angeles: UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History. pp. 61–87. ISBN 0-930741-47-1. Capone, Stefania (2010). Searching for Africa in Brazil: Power and Tradition in Candomblé. Translated by Lucy Lyall Grant. Durham and London: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-4636-4. Cosentino, Donald J. (1995). "Imagine Heaven". In Donald J., Cosentino (ed.). Sacred Arts of Haitian Vodou. Los Angeles: UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History. pp. 25–55. ISBN 0-930741-47-1. Fandrich, Ina J. (2007). "Yorùbá Influences on Haitian Vodou and New Orleans Voodoo". Journal of Black Studies. 37 (5): 775–791. doi:10.1177/0021934705280410. JSTOR 40034365. S2CID 144192532. Forte, Jung Ran (2010a). "Vodun Ancestry, Diaspora Homecoming, and the Ambiguities of Transnational Belongings in the Republic of Benin". In Percy C. Hintzen; Jean Muteba Rahier; Felipe Smith (eds.). Global Circuits of Blackness: Interrogating the African Diaspora. University of Illinois Press. pp. 174–200. ISBN 978-0252077531. Landry, Timothy R. (2015). "Vodún, Globalisation, and the Creative Layering of Belief in Southern Benin". Journal of Religion in Africa. 45 (2): 170–199. Landry, Timothy R. (2016). "Incarnating Spirits, Composing Shrines, and Cooking Divine Power in Vodún". Material Religion. 12: 50–73. doi:10.1080/17432200.2015.1120086. S2CID 148063421. Landry, Timothy R. (2019). Vodún: Secrecy and the Search for Divine Power. Contemporary Ethnography. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0812250749. Long, Carolyn Morrow (2002). "Perceptions of New Orleans Voodoo: Sin, Fraud, Entertainment, and Religion". Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions. 6 (1): 86–101. doi:10.1525/nr.2002.6.1.86. JSTOR 10.1525/nr.2002.6.1.86. Métraux, Alfred (1972) [1959]. Voodoo in Haiti. Translated by Hugo Charteris. New York: Schocken Books. Rosenthal, Judy (1998). Possession, Ecstasy and Law in Ewe Voodoo. Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0813918044. Rush, Diana (2017) [2013]. Vodun in Coastal Bénin: Unfinished, Open-Ended, Global. Critical Investigations of the African Diaspora. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press. ISBN 978-0826519085. Wafer, Jim (1991). The Taste of Blood: Spirit Possession in Brazilian Candomblé. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-1341-6. |

情報源 Álvarez López, Laura; Edfeldt, Chatarina (2007). 「ブラジルのカンドンブレ・コミュニティにおけるジェンダーと民族・宗教的アイデンティティの構築における言語の役割」. In Allyson Jule (ed.). 言語と宗教的アイデンティティ: Women in Discourse. Oxford: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0230517295. Bellegarde-Smith, Patrick; Michel, Claudine (2006). 「はじめに」. Bellegarde-Smith, Patrick; Michel, Claudine (eds.). Haitian Vodou: Spirit, Myth and Reality. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-21853-7. Blier, Suzanne Preston (1995a). African Vodun: Art, Psychology, and Power. Chicago and London: Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226058603. Blier, Suzanne Preston (1995b). 「ヴォドゥン:西アフリカのヴォドゥのルーツ」. In Donald J., Cosentino (ed.). Sacred Arts of Haitian Vodou. Los Angeles: UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History. ISBN 0-930741-47-1. Capone, Stefania (2010). Searching for Africa in Brazil: Power and Tradition in Candomblé. ルーシー・ライアル・グラント訳。Durham and London: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-4636-4. Cosentino, Donald J. (1995). 「天国を想像する」. Donald J., Cosentino編. Sacred Arts of Haitian Vodou. Los Angeles: UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History. ISBN 0-930741-47-1. Fandrich, Ina J. (2007). 「Yorùbá Influences on Haitian Vodou and New Orleans Voodoo」. Journal of Black Studies. 37 (5): 775–791. doi:10.1177/0021934705280410. jstor 40034365. s2cid 144192532. Forte, Jung Ran (2010a). 「Vodun Ancestry, Diaspora Homecoming, and the Ambiguities of Transnational Belongings in the Republic of Benin」. Percy C. Hintzen; Jean Muteba Rahier; Felipe Smith (eds.). Global Circuits of Blackness: アフリカン・ディアスポラを問う。イリノイ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0252077531. Landry, Timothy R. (2015). 「Vodún, Globalisation, and the Creative Layering of Belief in Southern Benin」. Journal of Religion in Africa. 45 (2): 170-199. Landry, Timothy R. (2016). 「ヴォドゥンにおける精霊の化身、祠の構成、神力の調理」。Material Religion. 12: 50-73. doi:10.1080/17432200.2015.1120086. s2cid 148063421. Landry, Timothy R. (2019). Vodún: Secrecy and the Search for Divine Power. 現代民族誌。Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0812250749. Long, Carolyn Morrow (2002). 「ニューオーリンズ・ブードゥー教の認識: 罪、詐欺、娯楽、宗教」. Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions. 6 (1): 86–101. doi:10.1525/nr.2002.6.1.86. JSTOR 10.1525/nr.2002.6.1.86. Métraux, Alfred (1972) [1959]. ハイチのブードゥー教 Hugo Charteris訳。ニューヨーク: Schocken Books. Rosenthal, Judy (1998). Ewe Voodooにおける所有、エクスタシー、法。Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0813918044. Rush, Diana (2017) [2013]. Vodun in Coastal Bénin: Unfinished, Open-Ended, Global. Critical Investigations of the African Diaspora. ナッシュビル: Vanderbilt University Press. ISBN 978-0826519085. Wafer, Jim (1991). The Taste of Blood: The Taste of Blood: The Spirit Possession in Brazilian Candomblé. Philadelphia: Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-1341-6. |

| Further reading Aronson, Lisa (2007). "Ewe Ceramics as the Visualisation of Vodun". African Arts. 40 (1): 80–85. Bay, Edna (2008). Asen, Ancestors, and Vodun: Tracing Change in African Art. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. Falen, Douglas J. (2007). "Good and Bad Witches: The Transformation of Witchcraft in Bénin". West Africa Review. 10 (1): 1–27. Falen, Douglas J. (2018). African Science: Witchcraft, Vodun, and Healing in Southern Benin. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0299318901. Forte, Jung Ran (2010). "Black Gods, White Bodies: Westerners' Initiations in Contemporary Benin". Transforming Anthropology. 18 (2): 129–145. Meyer, Birgit (1999). Translating the Devil: Religion and Modernity among the Ewe in Ghana. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. Montgomery, Eric; Vannier, Christian (2017). An Ethnography of a Vodu Shrine in Southern Togo: Of Spirit, Slave and Sea. Studies of Religion in Africa. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-34108-1. Strandsberg, Camilla (2000). "Kérékou, God of the Ancestors: Religion and the Conception of Political Power in Benin". African Affairs. 99 (396): 395–414. |

さらに読む Aronson, Lisa (2007). 「ヴォドゥンの視覚化としてのエウェの陶芸」. African Arts. 40 (1): 80-85. Bay, Edna (2008). Asen, Ancestors, and Vodun: Tracing Change in African Art. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. Falen, Douglas J. (2007). 「良い魔女と悪い魔女: The Transformation of Witchcraft in Bénin」. West Africa Review. 10 (1): 1-27. Falen, Douglas J. (2018). アフリカの科学: Witchcraft, Vodun, and Healing in Southern Benin. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0299318901. Forte, Jung Ran (2010). "Black Gods, White Bodies: 現代ベナンにおける西洋人のイニシエーション」. Transforming Anthropology. 18 (2): 129-145. Meyer, Birgit (1999). Translating the Devil: Religion and Modernity among the Ewe in Ghana. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. Montgomery, Eric; Vannier, Christian (2017). An Ethnography of a Vodu Shrine in Southern Togo: Of Spirit, Slave and Sea. Studies of Religion in Africa. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-34108-1. Strandsberg, Camilla (2000). 「先祖の神ケレコウ: ベナンにおける宗教と政治権力の概念」. African Affairs. 99 (396): 395-414. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/West_African_Vod%C3%BAn |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆ ☆

☆