問題含みの「西洋世界」という呼称

Thinking about the problematic designation

of the Western world

Büßender Hieronymus, by Albrecht Dürer

☆

This article is about the grouping of countries with an originally

European shared culture. For other uses, see Western World

(disambiguation). "Western power", "Westerners", and "Western states"

redirect here. For historical politics in Korea, see Westerners (Korean

political faction). For the region of the United States, see Western

United States. For other uses, see Western Power (disambiguation). -

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss

these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these

messages) This article may need to be rewritten to comply with

Wikipedia's quality standards, as neutrality is disputed. (September

2015) This article contains close paraphrasing of non-free copyrighted

sources. (August 2024)

★

この記事は、もともとヨーロッパの共有文化を持つ国々のグループ化についてである。その他の用法については、西洋世界(Western world)を参照のこと。「西洋

の権力」、「西洋人」、および「西洋諸国」は、こちらにリダイレクトされる。韓国の歴史的政治については、西洋人(韓国の政治派閥)を参照のこと。米国の

地域については、米国西部を参照のこと。その他の用法については、西洋の権力(曖昧さ回避)を参照のこと。——

この記事には複数の問題がある。改善にご協力いただくか、または議論に参加してください。(いつ、どのようにしてこれらのメッセージを削除するかについて

はこちらをご覧ください)この記事は、中立性が疑問視されているため、ウィキペディアの品質基準に準拠するために書き直される必要があるかもしれません。

(2015年9月)この記事には、著作権で保護された非フリーのソースの、ほぼ同じ言い換えが含まれています。(2024年8月)

| The Western world,

also known as the West, primarily refers to various nations and states

in Western Europe,[a] Northern America, and Australasia;[b] with some

debate as to whether those in Eastern Europe and Latin America[c] also

constitute the West.[3][4] The Western world likewise is called the

Occident (from Latin occidens 'setting down, sunset, west') in contrast

to the Eastern world known as the Orient (from Latin oriens 'origin,

sunrise, east'). The West is considered an evolving concept; made up of

cultural, political, and economic synergy among diverse groups of

people, and not a rigid region with fixed borders and members.[5]

Definitions of "Western world" vary according to context and

perspectives. Some historians contend that a linear development of the West can be traced from Ancient Greece and Rome,[6] while others argue that such a projection constructs a false genealogy.[7][8] A geographical concept of the West started to take shape in the 4th century CE when Constantine, the first Christian Roman emperor, divided the Roman Empire between the Greek East and Latin West. The East Roman Empire, later called the Byzantine Empire, continued for a millennium, while the West Roman Empire lasted for only about a century and a half. Significant theological and ecclesiastical differences led Western Europeans to consider the Christians in the Byzantine Empire as heretics. In 1054 CE, when the church in Rome excommunicated the patriarch of Byzantium, the politico-religious division between the Western church and Eastern church culminated in the Great Schism or the East–West Schism.[9] Even though friendly relations continued between the two parts of Christendom for some time, the crusades made the schism definitive with hostility.[10] The West during these crusades tried to capture trade routes to the East and failed, it instead discovered the Americas.[11] In the aftermath of the European colonization of the Americas, primarily involving Western European countries, an idea of the "Western" world, as an inheritor of Latin Christendom emerged.[12] According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the earliest reference to the term "Western world" was from 1586, found in the writings of William Warner.[13] The countries that are considered constituents of the West vary according to perspective rather than their geographical location. Countries like Australia and New Zealand, located in the Eastern Hemisphere are included in modern definitions of the Western world, as these regions and others like them have been significantly influenced by the British—derived from colonization, and immigration of Europeans—factors that grounded such countries to the West.[14] Depending on the context and the historical period in question, Russia was sometimes seen as a part of the West, and at other times juxtaposed with it, as well as endorsing anti-Western sentiment.[15][16][17] Running parallel to the rise of the United States as a great power and the development of communication–transportation technologies "shrinking" the distance between both the Atlantic Ocean shores, the US became more prominently featured in the conceptualizations of the West.[15] At some times between the 18th century and the mid-20th century, prominent countries in the West such as the United States, Canada, Brazil, Argentina, Australia, and New Zealand have been envisioned by some as ethnocracies for Whites.[18][19][20] Racism is cited as a contributing factor to European colonization of the New World, which today constitutes much of the "geographical" Western world.[21][22] Starting from the late 1960s, certain parts of the Western world have become notable for their diversity due to immigration.[23][24] The idea of "the West" over the course of time has evolved from a directional concept to a socio-political concept that had been temporalized and rendered as a concept of the future bestowed with notions of progress and modernity.[15] |

西

洋世界(西洋とも呼ばれる)は、主に西ヨーロッパの諸国民および国家[a]、北アメリカ、オセアニア[b]を指す。東ヨーロッパやラテンアメリカ[c]も

西洋に含まれるかどうかについては議論がある。 [3][4]

西洋世界は同様に、オリエント(ラテン語のオリエント「起源、日出、東」)として知られる東洋世界と対比して、オクシデント(ラテン語のオクシデンス「沈

む、日没、西」)とも呼ばれる。西洋は発展する概念とみなされており、多様な人々による文化的、政治的、経済的な相乗効果から成り立っている。固定された

境界線と構成員を持つ硬直した地域ではない。[5] 「西洋」の定義は文脈や視点によって異なる。 古代ギリシャや古代ローマから西洋の直線的な発展をたどることができると主張する歴史家もいるが[6]、そのような見方は系譜を誤って構築していると主張 する歴史家もいる[7][8]。地理的な西洋の概念は、西暦4世紀にコンスタンティヌス帝がローマ帝国をギリシャの東とラテン語圏の西に分割したときに形 成され始めた。東ローマ帝国(後のビザンチン帝国)は千年間存続したが、西ローマ帝国はわずか1世紀半ほどしか続かなかった。西欧諸国とビザンチン帝国の 間には、重大な神学的および教会的な相違があり、西欧諸国はビザンチン帝国のキリスト教徒を異端とみなした。西暦1054年、ローマ教会がビザンティウム の総主教を破門したことにより、西方教会と東方教会の政治的・宗教的な分裂は、大分裂または東西教会大分裂という形で頂点に達した。[9] キリスト教世界の2つの部分の間にはしばらく友好的な関係が続いたが、十字軍遠征により、分裂は敵対的なものとなった。 [10] これらの十字軍遠征の間、西洋は東方への貿易ルートを掌握しようとしたが失敗し、代わりにアメリカ大陸を発見した。 [11] 西ヨーロッパ諸国を中心としたヨーロッパによるアメリカ大陸の植民地化の後、ラテン・キリスト教世界の継承者としての「西洋」という概念が生まれた。 [12] オックスフォード英語辞典によると、「西洋世界」という用語の最も古い使用例は、1586年にウィリアム・ワーナーの著作に見られるものである。 西洋の構成国と見なされる国々は、地理的な位置よりも視点によって異なる。オーストラリアやニュージーランドといった東半球に位置する国々は、植民地化や ヨーロッパからの移民など、英国由来の要因がこれらの地域やその他の国々に大きな影響を与えたため、西洋世界という現代的な定義に含まれている。 [14] 文脈や時代によって、ロシアは時に西洋の一部と見なされ、またある時は西洋と対比され、反西洋感情を煽る存在ともされた。 [15][16][17] 米国が大国として台頭し、大西洋の両岸間の距離を「縮める」通信・交通技術が発展するのに並行して、米国は西洋の概念においてより顕著な存在となった。 18世紀から20世紀半ばにかけてのいくつかの時期には、アメリカ合衆国、カナダ、ブラジル、アルゼンチン、オーストラリア、ニュージーランドといった西 洋の著名な国々は、一部の人々によって白人のための民族主義国家として考えられていた。[18][19][20] 人種主義は、ヨーロッパによる新世界植民地化の要因のひとつとして挙げられており、今日では、この「地理的な」西洋世界の大部分を構成している。。 [21][22] 1960年代後半以降、西洋世界の特定の地域では、移民の流入により多様性が顕著になっている。[23][24] 西洋という概念は、時代とともに、方向性を示す概念から、一時的な社会政治的概念へと進化し、進歩と近代性の概念を付与された未来の概念として表現される ようになった。[15] |

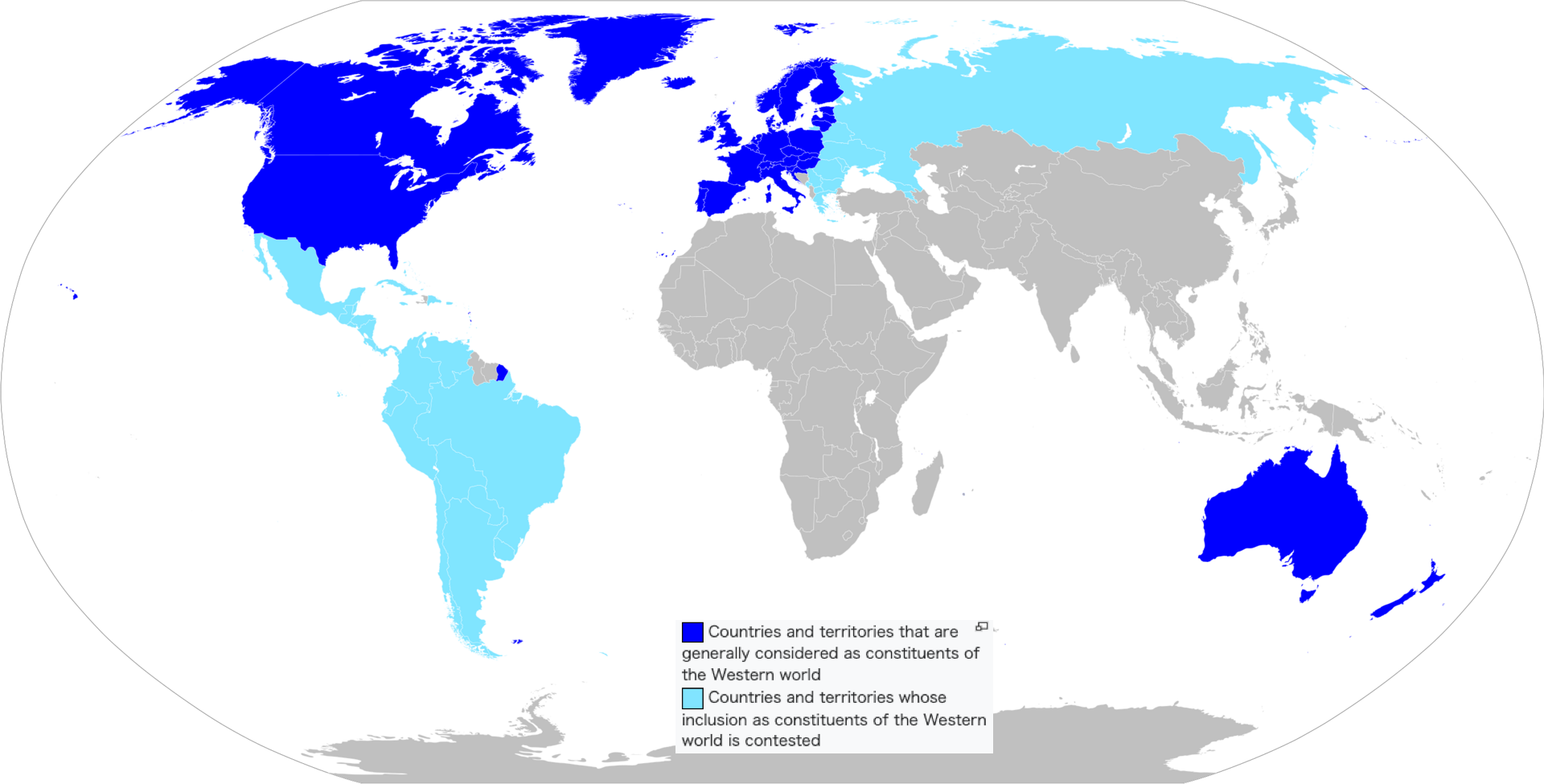

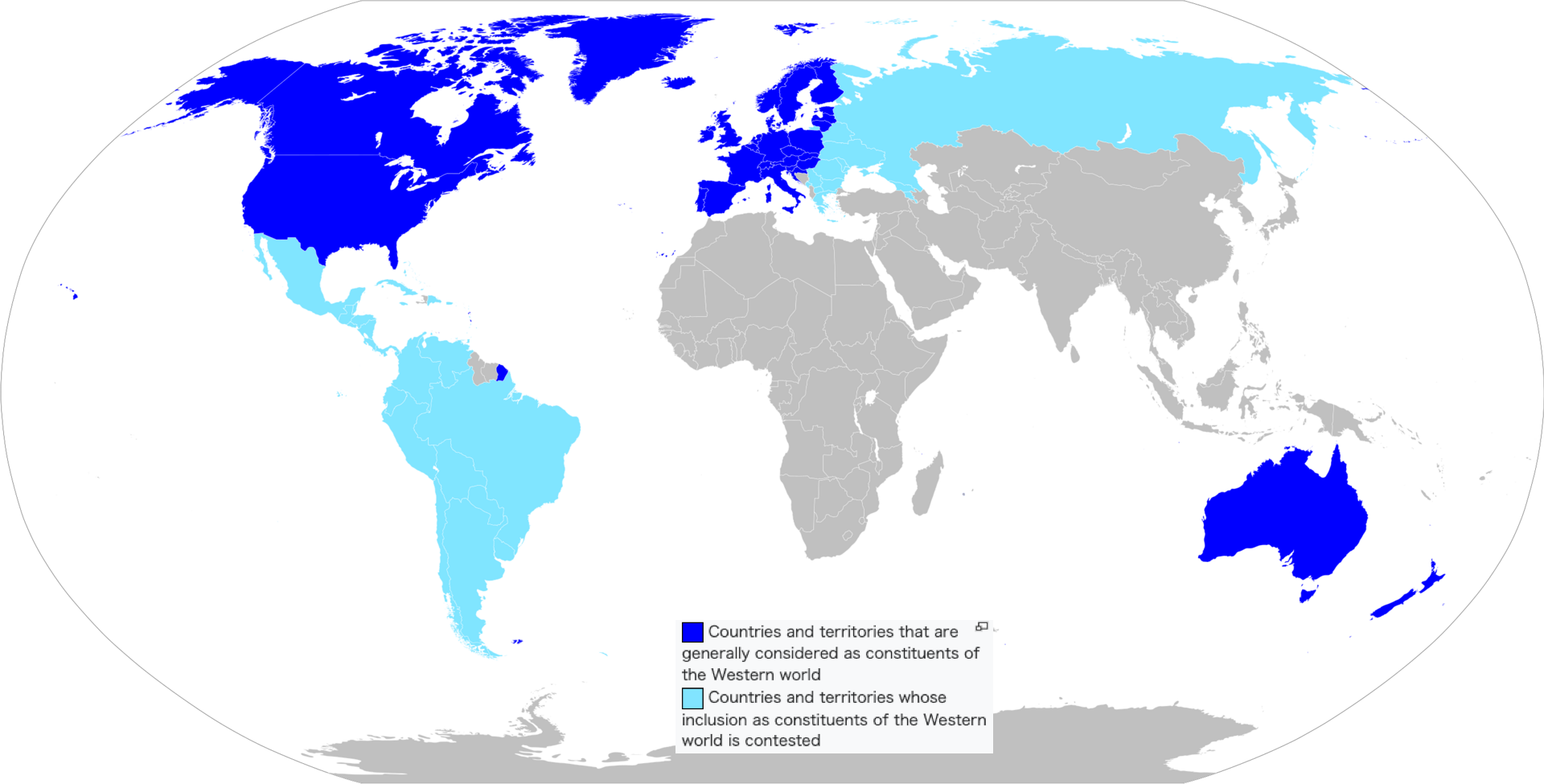

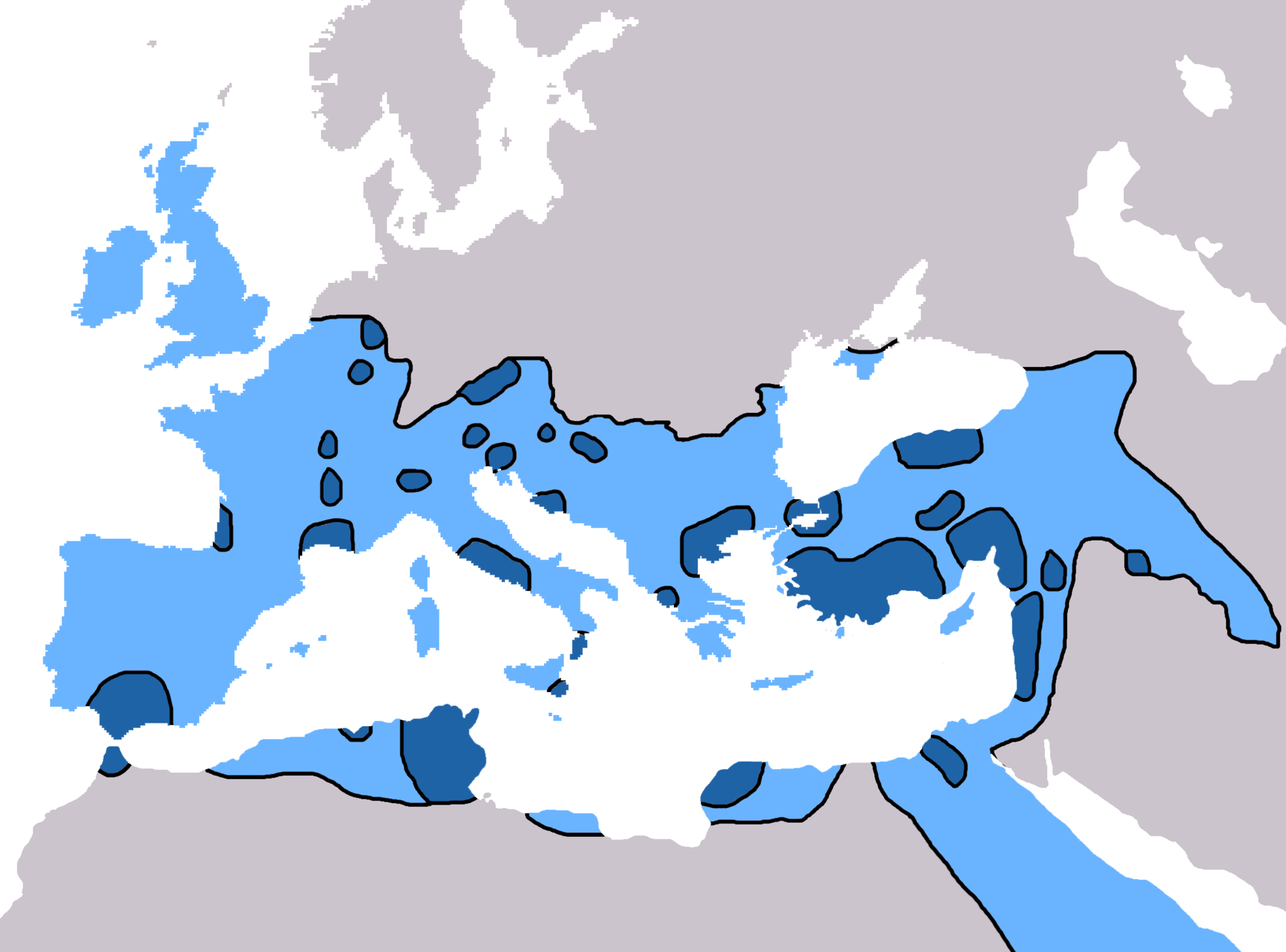

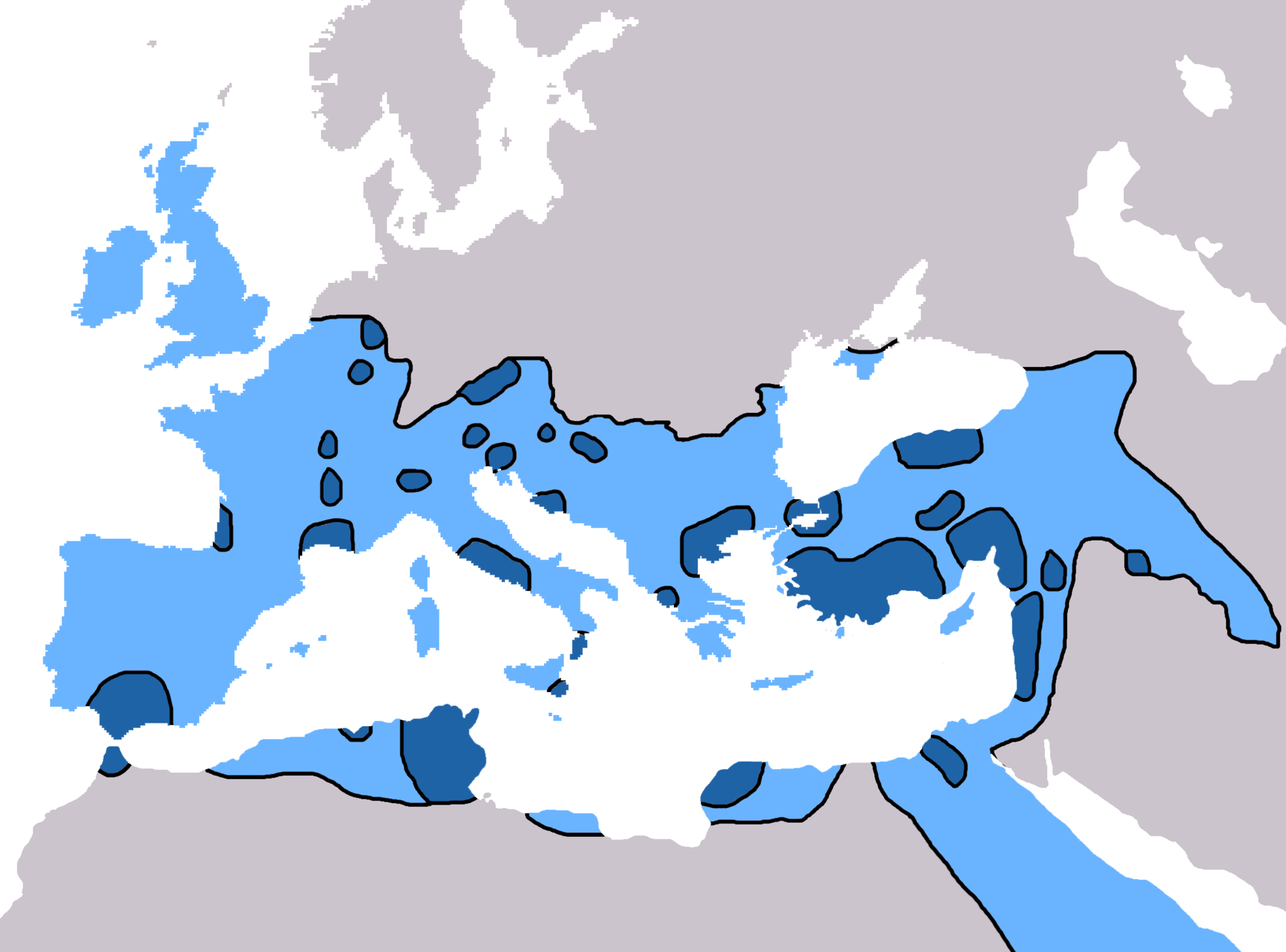

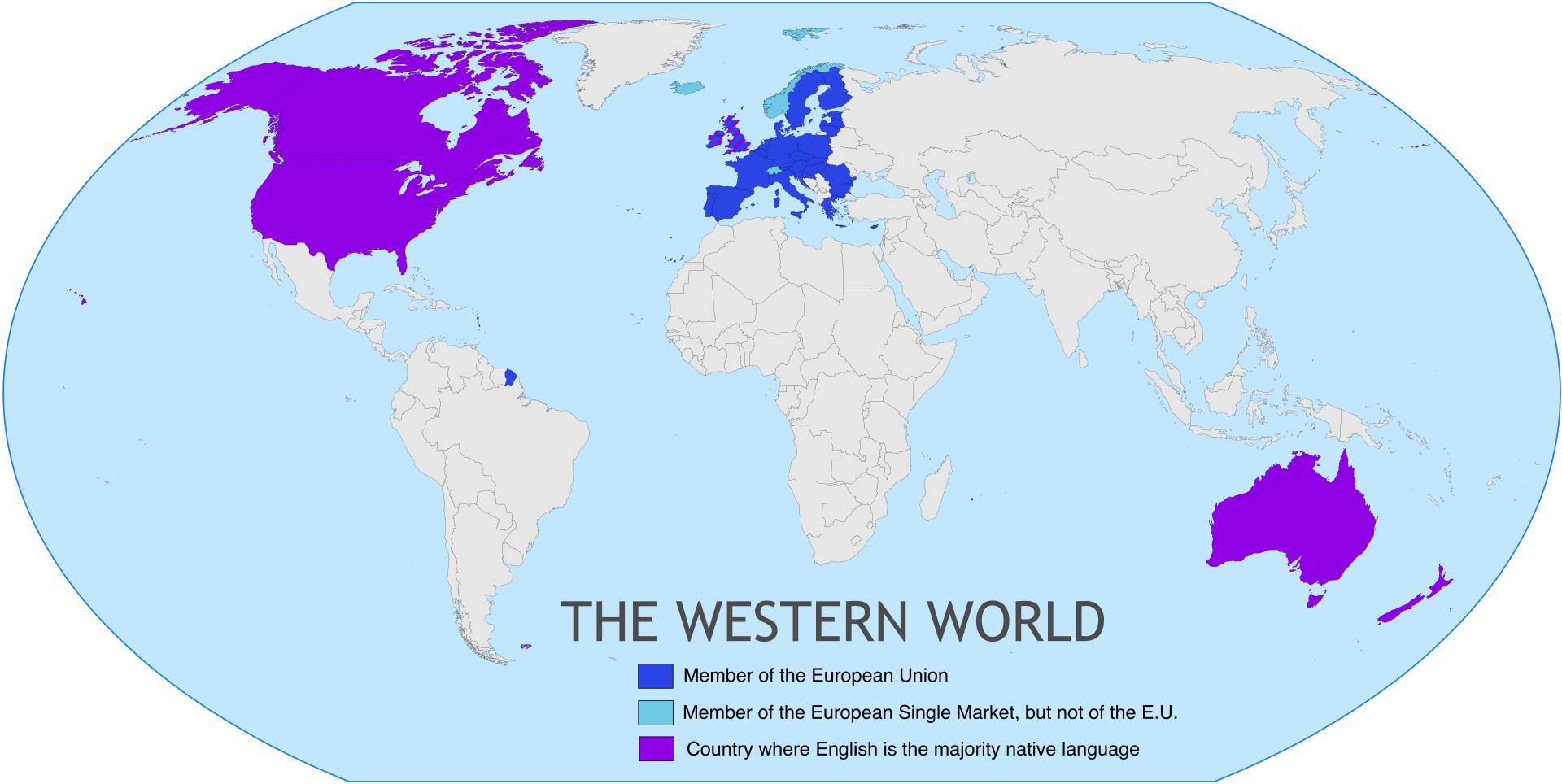

| 【青】Countries and territories that are generally considered as constituents of the Western world 【水色】Countries and territories whose inclusion as constituents of the Western world is contested  |

【青】一般的に西洋の一部と見なされている国および地域 【水色】西洋の一部と見なすことに対して異論のある国および地域  |

| Introduction The origins of Western civilization can be traced back to the ancient Mediterranean world. Ancient Greece[d] and Ancient Rome[e] are generally considered to be the birthplaces of Western civilization—Greece having heavily influenced Rome—the former due to its impact on philosophy, democracy, science, aesthetics, as well as building designs and proportions and architecture; the latter due to its influence on art, law, warfare, governance, republicanism, engineering and religion. Western Civilization is also closely associated with Christianity,[43] the dominant religion in the West, with roots in Greco-Roman and Jewish thought. Christian ethics, drawing from the ethical and moral principles of its historical roots in Judaism, has played a pivotal role in shaping the foundational framework of Western societies.[44][45][46] Earlier civilizations, such as the ancient Egyptians and Mesopotamians, had also significantly influenced Western civilization through their advancements in writing, law codes, and societal structures.[43] The convergence of Greek-Roman and Judeo-Christian influences in shaping Western civilization has led certain scholars to characterize it as emerging from the legacies of Athens and Jerusalem,[47][48][49] or Athens, Jerusalem and Rome.[50] In ancient Greece and Rome, individuals identified primarily as subjects of states, city-states, or empires, rather than as members of Western civilization. The distinct identification of Western civilization began to crystallize with the rise of Christianity during the Late Roman Empire. In this period, peoples in Europe started to perceive themselves as part of a unique civilization, differentiating from others like Islam, giving rise to the concept of Western civilization. By the 15th century, Renaissance intellectuals solidified this concept, associating Western civilization not only with Christianity but also with the intellectual and political achievements of the ancient Greeks and Romans.[43] Historians, such as Carroll Quigley in "The Evolution of Civilizations",[51] contend that Western civilization was born around AD 500, after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, leaving a vacuum for new ideas to flourish that were impossible in Classical societies. In either view, between the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the Renaissance, the West (or those regions that would later become the heartland of the culturally "western sphere") experienced a period of decline, and then readaptation, reorientation and considerable renewed material, technological and political development.[52] Classical culture of the ancient Western world was partly preserved during this period due to the survival of the Eastern Roman Empire and the introduction of the Catholic Church; it was also greatly expanded by the Arab importation[53][54] of both the Ancient Greco-Roman and new technology through the Arabs from India and China to Europe.[55][56] |

はじめに 西洋文明の起源は古代地中海世界にまで遡ることができる。古代ギリシャ[d]と古代ローマ[e]は一般的に西洋文明の発祥地と考えられている。ギリシャは 哲学、民主主義、科学、美学、建築デザインやプロポーション、建築に多大な影響を与えた。一方、ローマは芸術、法律、戦争、統治、共和制、工学、宗教に影 響を与えた。西洋文明は、西洋で支配的な宗教であるキリスト教とも密接に関連している。キリスト教は、ギリシャ・ローマ思想やユダヤ教思想をルーツとす る。キリスト教の倫理は、その歴史的ルーツであるユダヤ教の倫理・道徳原則から引き出されたものであり、西洋社会の基礎的枠組みを形成する上で重要な役割 を果たしてきた。[44][45][46] 古代エジプト人やメソポタミア人などの初期文明も、文字、法典、社会構造の進歩を通じて西洋文明に大きな影響を与えてきた。 ギリシャ・ローマ文明とユダヤ・キリスト教文明の影響が西洋文明の形成に集約されたことにより、一部の学者は、西洋文明はアテネとエルサレムの遺産から生 まれたと特徴づけている。 古代ギリシャや古代ローマでは、個人は西洋文明の構成員というよりも、主として国家、都市国家、あるいは帝国の臣民として認識されていた。西洋文明という 明確な概念は、ローマ帝国末期のキリスト教の興隆とともに形成され始めた。この時代に、ヨーロッパの人々は自分たちを独自の文明の一部として認識し始め、 イスラム教など他の文明と区別するようになった。これが西洋文明という概念の起源である。15世紀までに、ルネサンス期の知識人たちは、西洋文明をキリス ト教だけでなく、古代ギリシアや古代ローマの知的・政治的業績とも関連付けることで、この概念を確固たるものにした。 キャロル・クィグリー著『文明の進化』などの歴史家は、西洋文明は西ローマ帝国滅亡後の西暦500年頃に誕生したと主張している。古典的社会では不可能 だった新しいアイデアが花開くための空白期間が生まれたのである。いずれの見解にせよ、西ローマ帝国の滅亡からルネサンスまでの間、西洋(あるいは後に文 化的に「西洋圏」の中心地となる地域)は衰退の時期を経験し、その後、再適応、再方向付け、そして物質的、技術的、政治的な発展が大幅に再開された。 古代西洋の古典文化は、東ローマ帝国の存続とカトリック教会の導入により、この期間の一部が保存された。また、アラブ人を通じて古代ギリシャ・ローマ文明 とインドや中国からヨーロッパへの新しい技術が導入されたことにより、大きく拡大した。 |

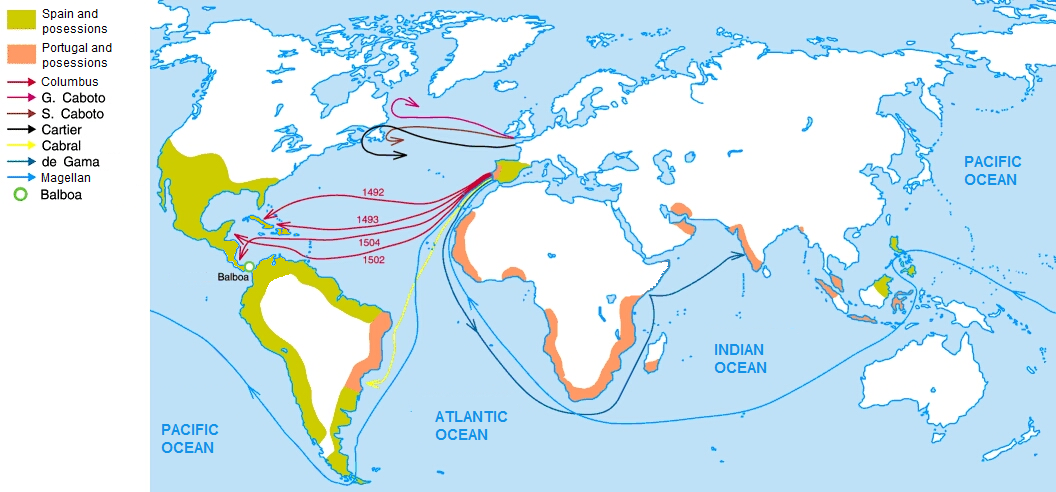

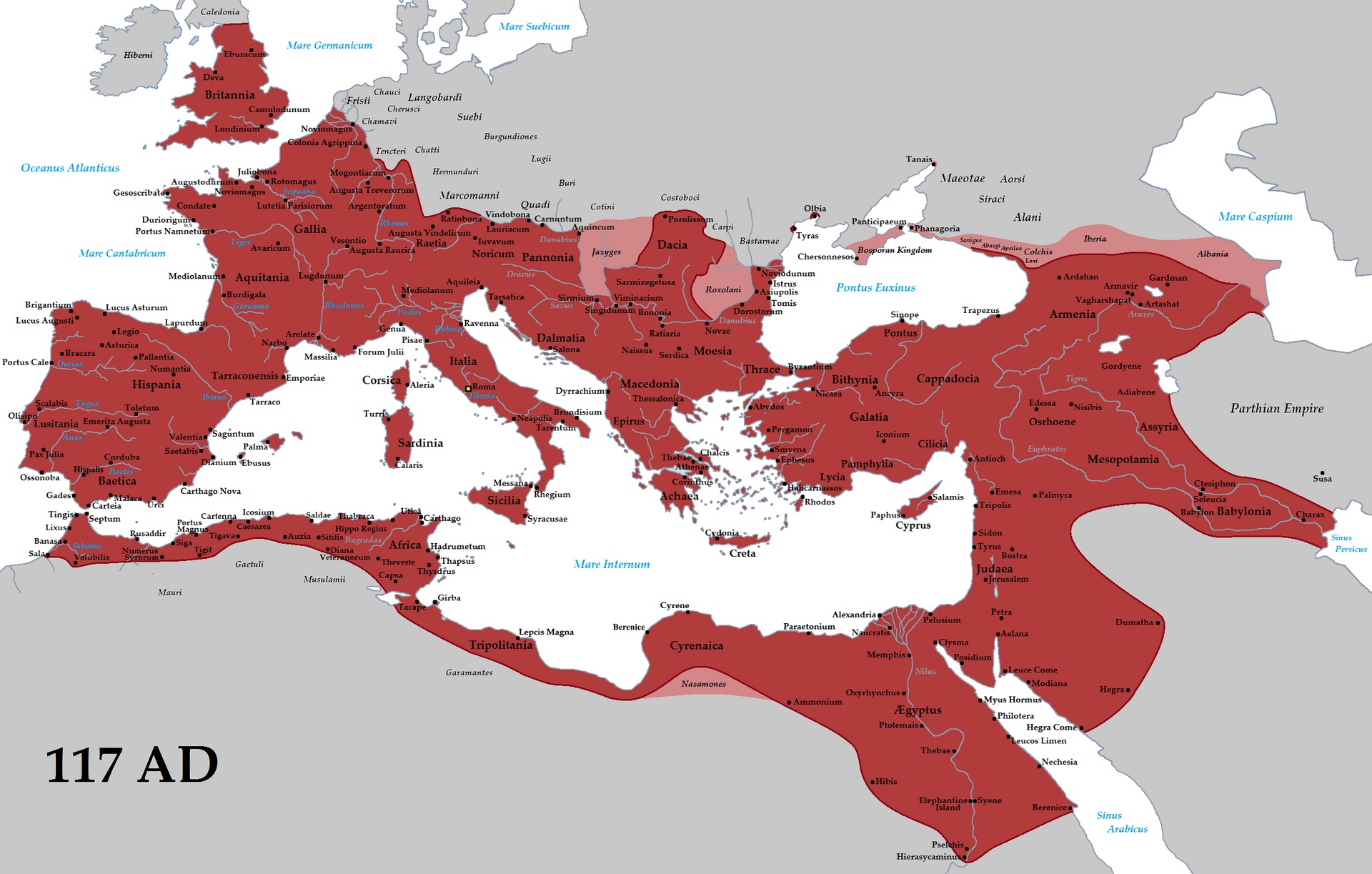

Christopher Columbus arrives at the New World. Since the Renaissance, the West evolved beyond the influence of the ancient Greeks and Romans and the Islamic world, due to the successful Second Agricultural, Commercial,[57] Scientific,[58] and Industrial[59] revolutions (propellers of modern banking concepts). The West rose further with the 18th century's Age of Enlightenment and through the Age of Exploration's expansion of peoples of European empires in the 18th and 19th centuries, particularly the globe-spanning colonial empires of Western Europe.[60] Numerous times, this expansion was accompanied by Catholic missionaries, who attempted to proselytize Christianity. In the modern era, Western culture has undergone further transformation through the Renaissance, Ages of Discovery and Enlightenment, and the Industrial and Scientific Revolutions.[61][62] The widespread influence of Western culture extended globally through imperialism, colonialism, and Christianization by Western powers from the 15th to 20th centuries. This influence persists through the exportation of mass culture, a phenomenon often referred to as Westernization.[63] There was debate among some in the 1960s as to whether Latin America as a whole is in a category of its own.[64] [64] Arnold J. Toynbee, Change and Habit. The challenge of our time (Oxford 1966, 1969) at 153–56; also, Toynbee, A Study of History (10 volumes, 2 supplements). |

クリストファー・コロンブスが新大陸に到着する。 ルネサンス以降、西洋は古代ギリシャ・ローマやイスラム世界の影響を越えて発展し、農業革命、商業革命[57]、科学革命[58]、産業革命[59](近 代的銀行概念の推進力)を成功させた。西洋は、18世紀の啓蒙時代を経てさらに発展し、18世紀から19世紀にかけての探検時代には、ヨーロッパ諸国の帝 国主義による拡大、特に西欧による地球規模の植民地帝国主義が展開された。[60] この拡大は、キリスト教の布教を試みるカトリック宣教師たちを伴うことが多かった。 近代においては、西洋文化はルネサンス、大航海時代、啓蒙時代、産業革命、科学革命などを経て、さらなる変容を遂げた。[61][62] 西洋文化の広範な影響力は、15世紀から20世紀にかけての西洋諸国の帝国主義、植民地主義、キリスト教化を通じて世界中に広がった。この影響力は、大衆 文化の輸出を通じて現在も持続しており、この現象はしばしば西洋化(ウェスタンライゼーション)と呼ばれる。[63] 1960年代には、ラテンアメリカ全体が独自のカテゴリーに属するかどうかについて、一部で議論があった。[64] [64] Arnold J. Toynbee, Change and Habit. The challenge of our time (Oxford 1966, 1969) at 153–56; also, Toynbee, A Study of History (10 volumes, 2 supplements). |

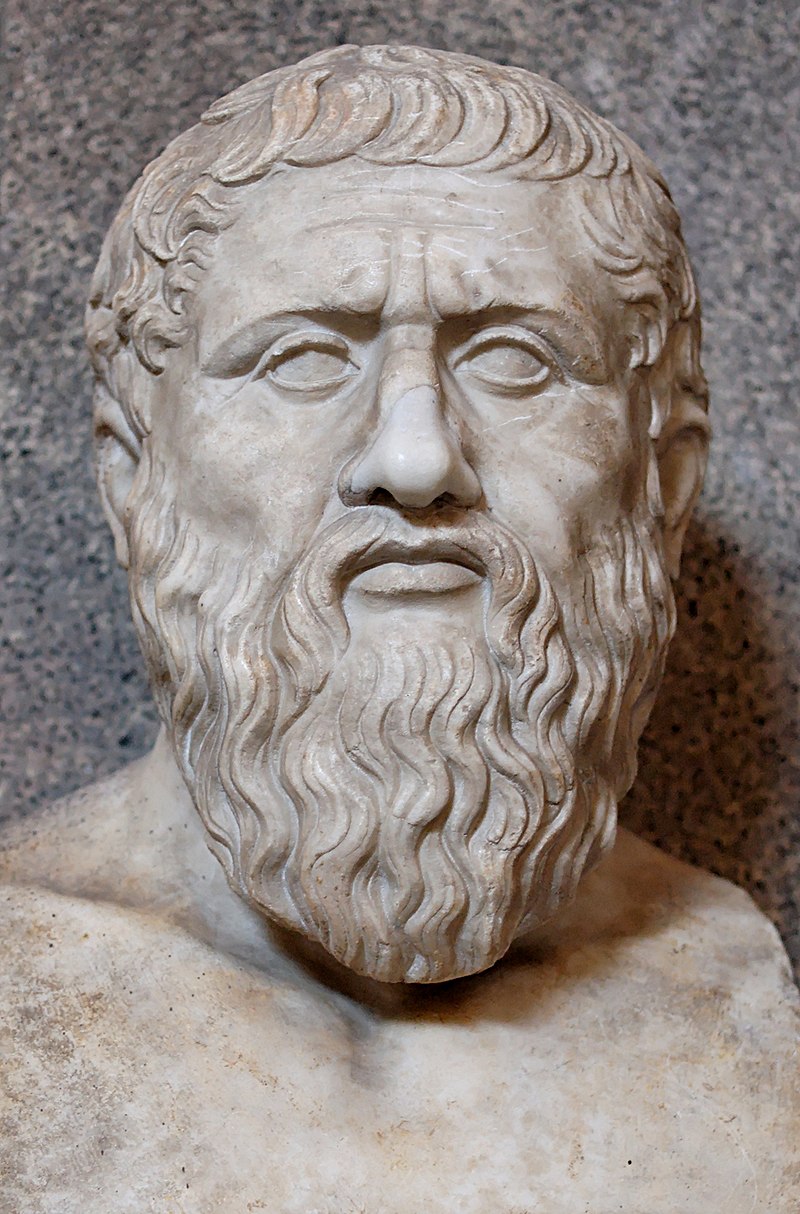

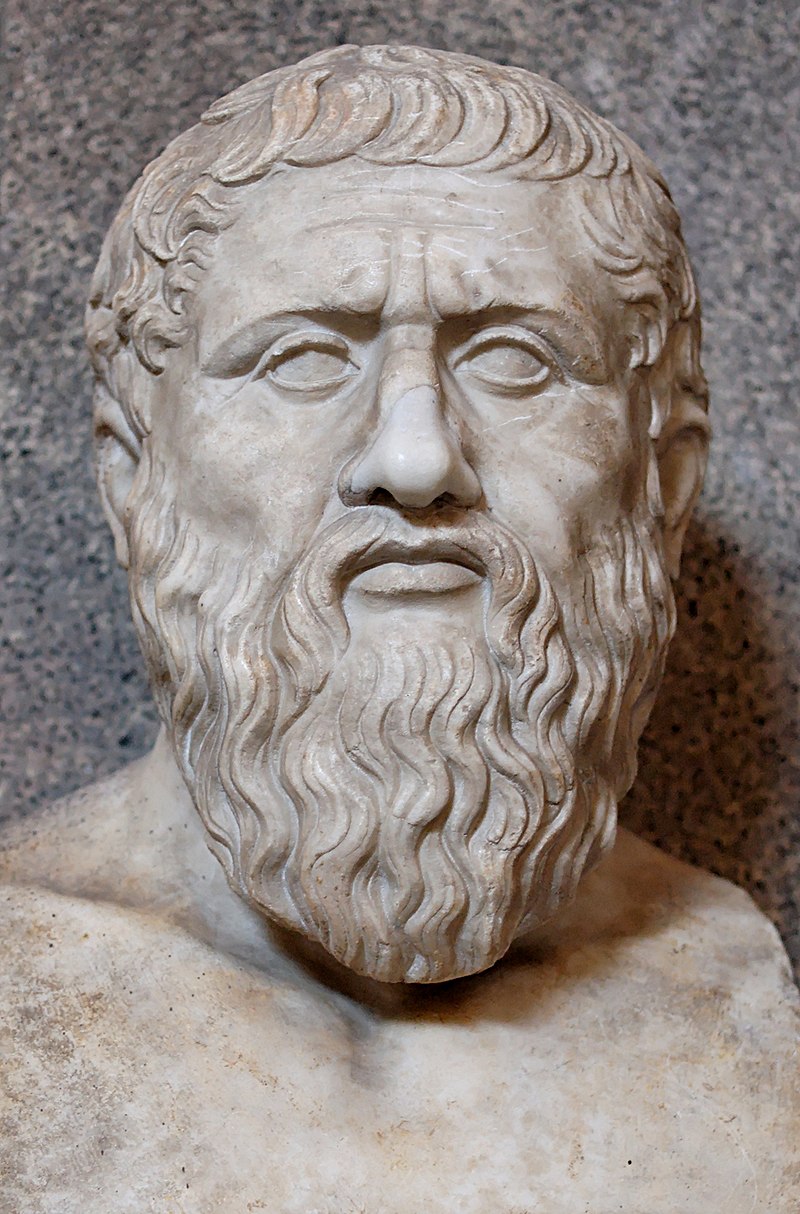

| Culture This section is an excerpt from Western culture.[edit]  Plato, arguably the most influential figure in early Western philosophy. Western culture, also known as Western civilization, European civilization, Occidental culture, Western society, or simply the West, refers to the internally diverse culture of the Western world. The term "Western" encompasses the social norms, ethical values, traditional customs, belief systems, political systems, artifacts and technologies primarily rooted in European and Mediterranean histories. A broad concept, "Western culture" does not relate to a region with fixed members or geographical confines. It generally refers to the classical era cultures of Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome that expanded across the Mediterranean basin and Europe, and later circulated around the world predominantly through colonization and globalization.[65] Historically, scholars have closely associated the idea of Western culture with the classical era of Greco-Roman antiquity.[66][67] However, scholars also acknowledge that other cultures, like Ancient Egypt, the Phoenician city-states, and several Near-Eastern cultures stimulated and influenced it.[68][69][70] The Hellenistic period also promoted syncretism, blending Greek, Roman, and Jewish cultures. Major advances in literature, engineering, and science shaped the Hellenistic Jewish culture from which the earliest Christians and the Greek New Testament emerged.[71][72][73] The eventual Christianization of Europe in late-antiquity would ensure that Christianity, particularly the Catholic Church, remained a dominant force in Western culture for many centuries to follow.[74][75][76] Western culture continued to develop during the Middle Ages as reforms triggered by the medieval renaissances, the influence of the Islamic world via Al-Andalus and Sicily (including the transfer of technology from the East, and Latin translations of Arabic texts on science and philosophy by Greek and Hellenic-influenced Islamic philosophers),[77][78][79] and the Italian Renaissance as Greek scholars fleeing the fall of Constantinople brought ancient Greek and Roman texts back to central and western Europe.[80] Medieval Christianity is credited with creating the modern university,[81][82] the modern hospital system,[83] scientific economics,[84][85] and natural law (which would later influence the creation of international law).[86] European culture developed a complex range of philosophy, medieval scholasticism, mysticism and Christian and secular humanism, setting the stage for the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century, which fundamentally altered religious and political life. Led by figures like Martin Luther, Protestantism challenged the authority of the Catholic Church and promoted ideas of individual freedom and religious reform, paving the way for modern notions of personal responsibility and governance.[87][88][89][90] The Enlightenment in the 17th and 18th centuries shifted focus to reason, science, and individual rights, influencing revolutions across Europe and the Americas and the development of modern democratic institutions. Enlightenment thinkers advanced ideals of political pluralism and empirical inquiry, which, together with the Industrial Revolution, transformed Western society. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the influence of Enlightenment rationalism continued with the rise of secularism and liberal democracy, while the Industrial Revolution fueled economic and technological growth. The expansion of rights movements and the decline of religious authority marked significant cultural shifts. Tendencies that have come to define modern Western societies include the concept of political pluralism, individualism, prominent subcultures or countercultures, and increasing cultural syncretism resulting from globalization and immigration. |

文化 このセクションは西洋文化からの抜粋である。[編集]  プラトンは、初期の西洋哲学において最も影響力を持った人物である。 西洋文化は、西洋文明、ヨーロッパ文明、西洋文化、西洋社会、または単に西洋とも呼ばれ、西洋世界の内部的に多様な文化を指す。「西洋」という用語は、主 にヨーロッパと地中海の歴史に根ざした社会規範、倫理観、伝統的慣習、信念体系、政治体制、人工物、技術などを包含する。広義の概念である「西洋文化」 は、固定されたメンバーや地理的な境界を持つ地域とは関係がない。一般的に、地中海沿岸地域とヨーロッパに広がった古代ギリシャと古代ローマの古典時代の 文化を指し、その後、主に植民地化とグローバル化を通じて世界中に広がった。 歴史的に、学者たちは西洋文化の概念をギリシャ・ローマ時代の古典時代と密接に関連付けている。[66][67] しかし、学者たちは古代エジプト、フェニキア都市国家、およびいくつかの近東文化のような他の文化も西洋文化に刺激を与え、影響を与えたことを認めてい る。[68][69][70] ヘレニズム時代もまた、ギリシャ、ローマ、ユダヤの文化を融合するシンクレティズムを推進した。文学、工学、科学の分野における大きな進歩はヘレニズム的 ユダヤ文化を形成し、そこから初期キリスト教とギリシア語新約聖書が生まれた。[71][72][73] 古代末期におけるヨーロッパのキリスト教化は、キリスト教、特にカトリック教会が西洋文化において支配的な勢力であり続けることを確実にした。[74] [75][76] 西洋文化は中世においても、中世ルネサンス、アル・アンダルスやシチリア島を経由したイスラム世界の影響(東方からの技術移転や、ギリシャやヘレニズムの 影響を受けたイスラムの哲学者による科学や哲学に関するアラビア語文献のラテン語訳を含む) [77][78][79] また、コンスタンティノープルの陥落から逃れたギリシャの学者たちが古代ギリシャ・ローマの文献を西欧にもたらしたことにより、イタリア・ルネサンスが起 こった。[80] 中世のキリスト教は、近代的な大学[81][82]、近代的な病院システム[83]、科学的な経済学[84][85]、自然法(後に国際法の制定に影響を 与えることになる)の創出に貢献したとされている。 [86] ヨーロッパ文化は、哲学、中世スコラ学、神秘主義、キリスト教ヒューマニズム、世俗ヒューマニズムなど、複雑な思想体系を発展させ、16世紀の宗教改革の 舞台を整えた。宗教改革は、宗教と政治生活を根本的に変えた。マルティン・ルターのような人物に導かれたプロテスタントは、カトリック教会の権威に異議を 唱え、個人の自由と宗教改革の理念を推進し、個人の責任と統治に関する近代的概念への道筋をつけた。[87][88][89][90] 17世紀と18世紀の啓蒙主義は、理性、科学、個人の権利に焦点を移し、ヨーロッパとアメリカ大陸の革命や近代的な民主的機関の発展に影響を与えた。啓蒙 思想家たちは政治的多元主義と経験的調査の理想を推進し、産業革命とともに西洋社会を変革した。19世紀から20世紀にかけては、啓蒙思想の合理主義の影 響は世俗主義や自由民主主義の台頭とともに続き、一方で産業革命は経済と技術の成長を促した。権利運動の拡大と宗教的権威の衰退は、文化の大きな転換を象 徴するものであった。現代の西洋社会を特徴づける傾向には、政治的多元主義の概念、個人主義、著名なサブカルチャーやカウンターカルチャー、そしてグロー バル化や移民による文化的シンクレティズムの増加などがある。 |

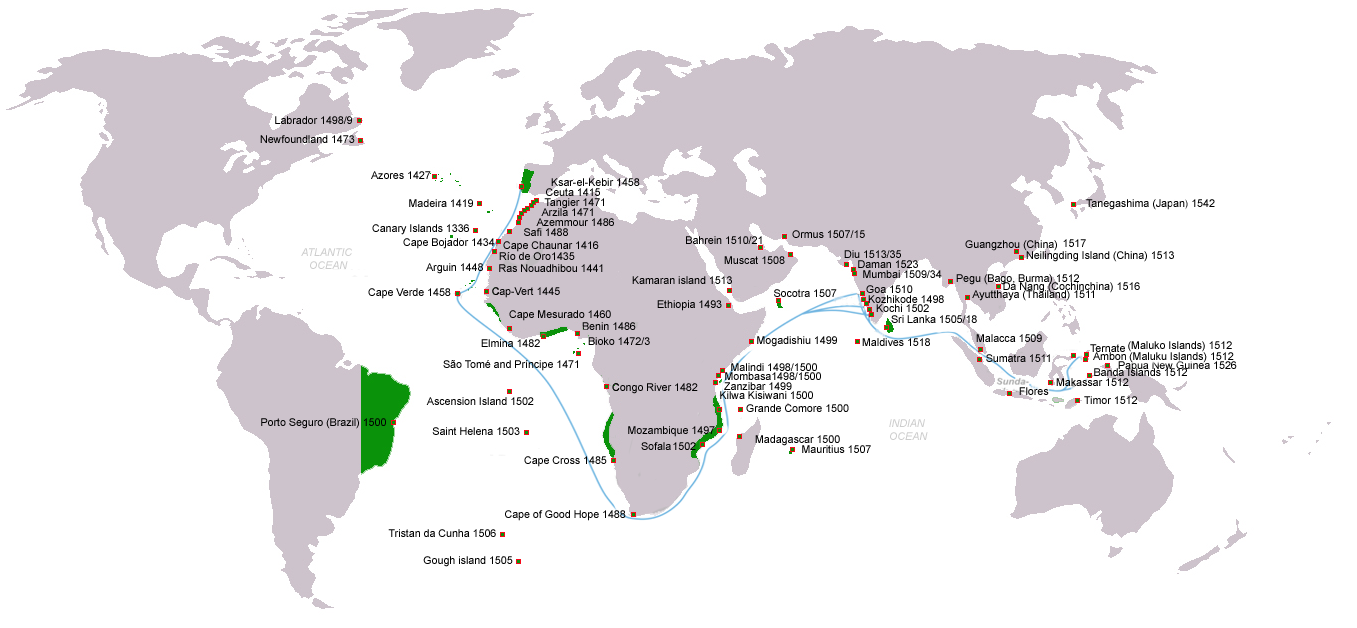

| Historical divisions See also: History of Western civilization This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (July 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this message) The west of the Mediterranean region during Antiquity The geopolitical divisions in Europe that created a concept of East and West originated in the ancient tyrannical and imperialistic Graeco-Roman times.[91] The Eastern Mediterranean was home to the highly urbanized cultures that had Greek as their common language (owing to the older empire of Alexander the Great and of the Hellenistic successors), whereas the West was much more rural in its character and more readily adopted Latin as its common language. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the beginning of medieval times (or Middle Ages), Western and Central Europe were substantially cut off from the East, where Byzantine Greek culture and Eastern Christianity became founding influences in the Eastern European world such as the East and South Slavic peoples.[citation needed]  The main travels of the Age of Discovery (began in 15th century) Roman Catholic Western and Central Europe thus maintained a distinct identity, particularly as it began to redevelop during the Renaissance. Even following the Protestant Reformation, Protestant Europe continued to see itself as more tied to Roman Catholic Europe than other parts of the perceived "civilized world". Use of the term West as a specific cultural and geopolitical term developed over the course of the Age of Exploration as Europe spread its culture to other parts of the world. Roman Catholics were the first major religious group to migrate to the New World, as settlers in the colonies of Spain and Portugal (and later, France) belonged to that faith. English and Dutch colonies, on the other hand, tended to be more religiously diverse. Settlers to these colonies included Anglicans, Dutch Calvinists, English Puritans and other nonconformists, English Catholics, Scottish Presbyterians, French Huguenots, German and Swedish Lutherans, as well as Quakers, Mennonites, Amish, and Moravians.[citation needed] |

歴史的な区分 関連項目:西洋文明の歴史 この節では検証可能な参考文献や出典が全く示されていないか、不十分です。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。 出典の無い内容は疑問視される可能性があり、削除される場合があります。 (2018年7月) (Learn how and when to remove this message) 古代における地中海地域の西側 ヨーロッパにおける地政学的な区分は、古代の暴君的かつ帝国主義的なギリシア・ローマ時代に端を発し、東と西という概念を生み出した。[91] 東地中海は、ギリシア語を共通語とする高度に都市化された文化圏であった(これは、アレクサンダー大王とそのヘレニズム後継者たちの古い帝国によるもので ある)。一方、西はより農村的な性格であり、ラテン語を共通語としてより容易に採用した。西ローマ帝国の滅亡と中世(または中世)の始まり後、西ヨーロッ パと中央ヨーロッパは東側から実質的に隔離され、ビザンティン・ギリシャ文化と東方キリスト教が東スラブ民族や南スラブ民族などの東ヨーロッパ世界に影響 を与えるようになった。  大航海時代(15世紀に始まる)の主な旅行 ローマ・カトリックの西ヨーロッパおよび中央ヨーロッパは、ルネサンス期に再発展を始めたことで、特に独自性を維持した。 プロテスタント革命の後も、プロテスタントのヨーロッパは、認識されていた「文明世界」の他の地域よりもローマ・カトリックのヨーロッパとより結びついて いると見なしていた。 ヨーロッパがその文化を世界の他の地域に広めた大航海時代を通じて、特定の文化および地政学用語としての「西洋」という用語の使用が発展した。スペインや ポルトガル(後にフランス)の植民地に入植した人々はローマ・カトリック信者であったため、ローマ・カトリックは新大陸に移住した最初の主要な宗教集団と なった。一方、イギリスとオランダの植民地では、宗教はより多様であった。これらの植民地への入植者には、英国国教会、オランダのカルビン派、英国の ピューリタンやその他の非国教派、英国のカトリック、スコットランドの長老派、フランスのユグノー、ドイツとスウェーデンのルーテル派、さらにはクエー カー教徒、メノナイト、アーミッシュ、モラビア派などがいた。 |

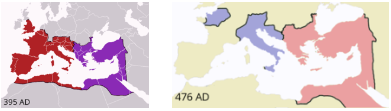

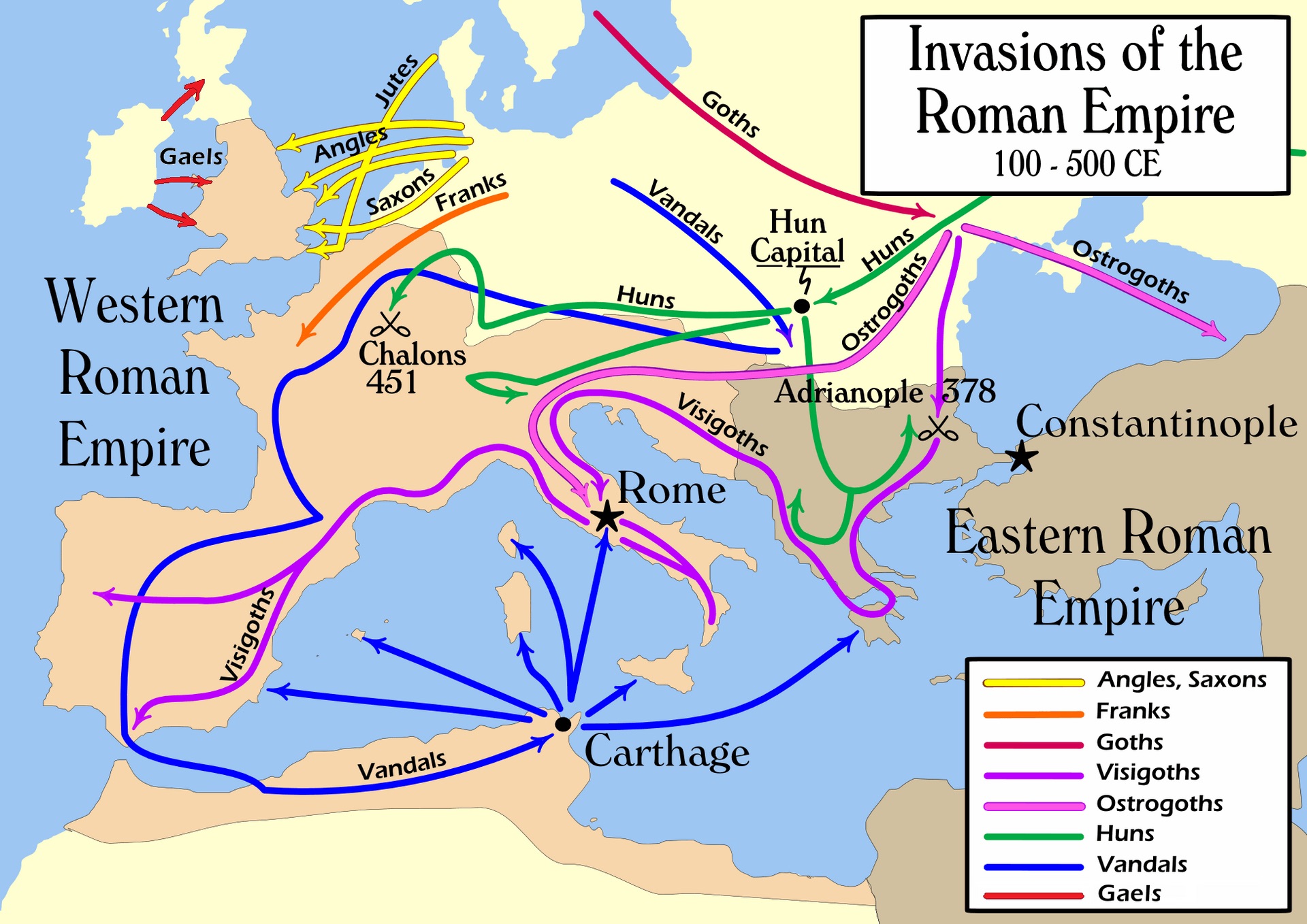

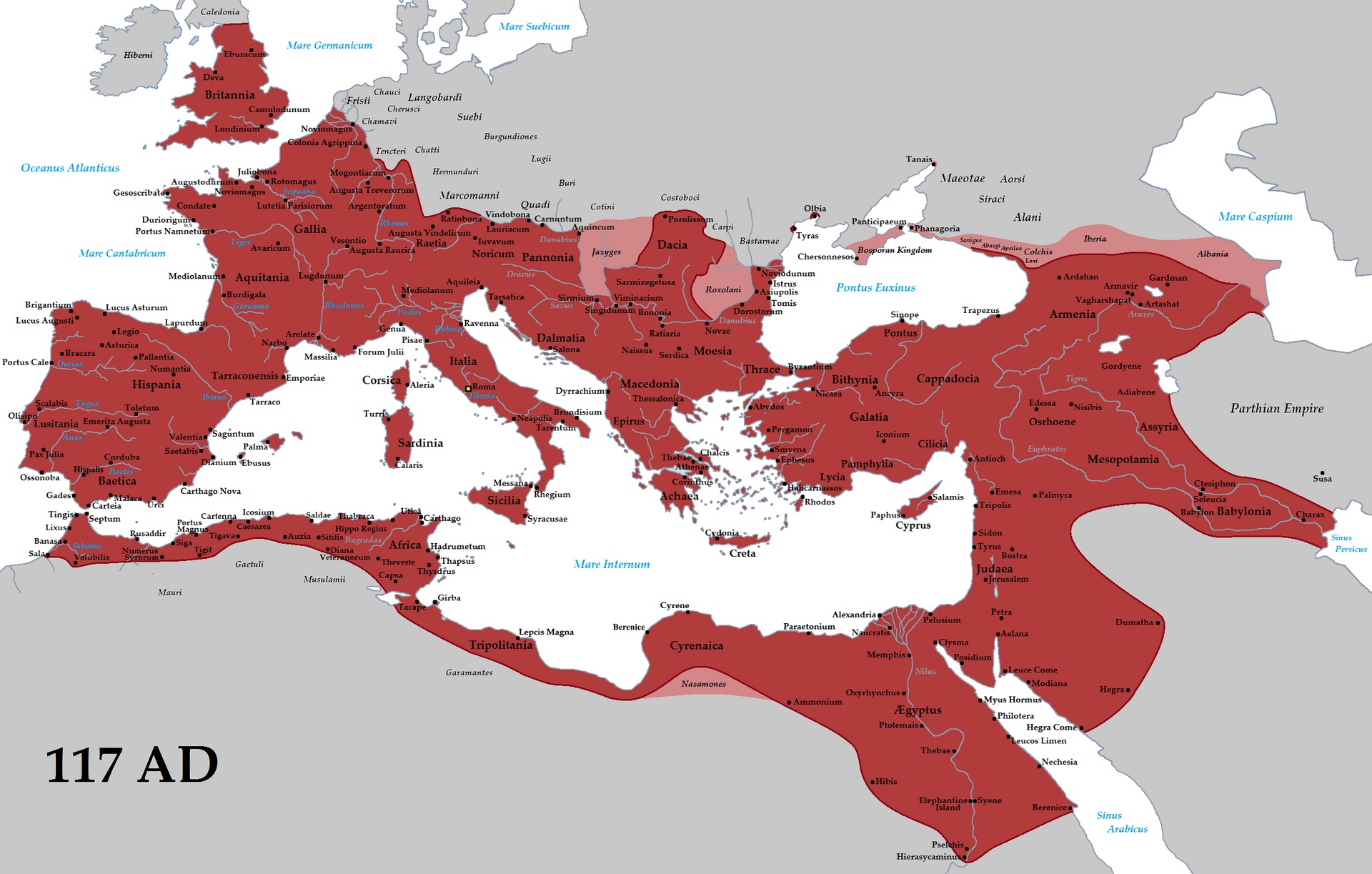

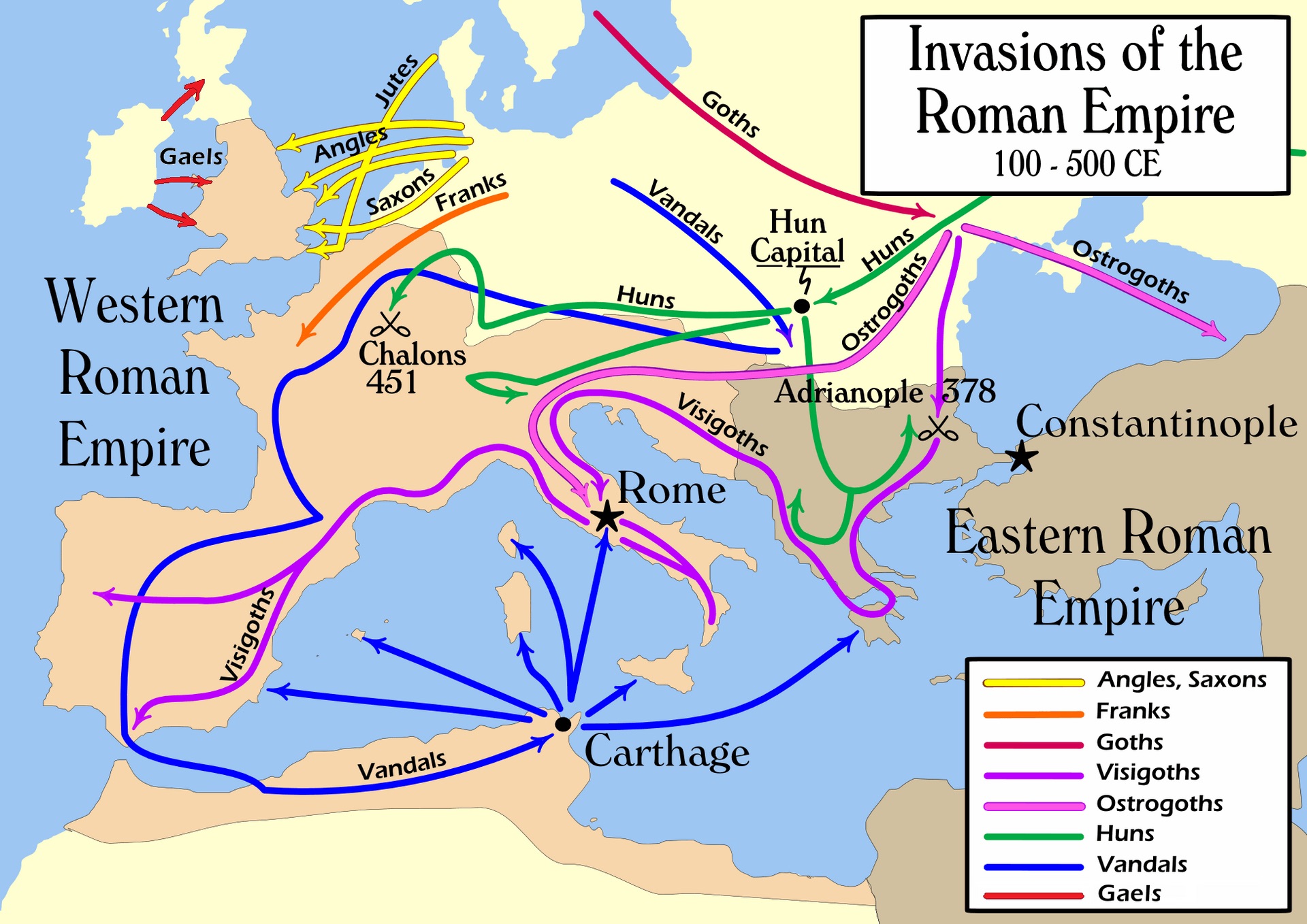

| Ancient Roman world (6th century BC – AD 395–476) Main articles: Roman Republic, Roman Empire, and Fall of the Western Roman Empire This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (April 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  The Roman Republic in 218 BC after having managed the conquest of most of the Italian Peninsula, on the eve of its most successful and deadliest war with the Carthaginians  Graphical map of post-AD 395 Roman Empire highlighting differences between western Roman Catholic and eastern Greek Orthodox parts, on the eve of the death of last emperor to rule on both the western and eastern halves. The concept of "East-West" originated in the cultural division between Christian Churches.[91] Western and Eastern Roman Empires on the eve of Western collapse in September of AD 476.  The Roman Empire in AD 117. During 350 years the Roman Republic turned into an Empire expanding up to twenty-five times its area. Ancient Rome (6th century BC – AD 476) is a term to describe the ancient Roman society that conquered Central Italy assimilating the Italian Etruscan culture, growing from the Latium region since about the 8th century BC, to a massive empire straddling the Mediterranean Sea. In its 10-centuries territorial expansion, Roman civilization shifted from a small monarchy (753–509 BC), to a republic (509–27 BC), into an autocratic empire (27 BC – AD 476). Its Empire came to dominate Western, Central and Southeastern Europe, Northern Africa and, becoming an autocratic Empire a vast Middle Eastern area, when it ended. Conquest was enforced using the Roman legions and then through cultural assimilation by eventual recognition of some form of Roman citizenship's privileges. Nonetheless, despite its great legacy, a number of factors led to the eventual decline and ultimately fall of the Roman Empire.[citation needed] The Roman Empire succeeded the approximately 500-year-old Roman Republic (c. 510–30 BC). In 350 years, from the successful and deadliest war with the Phoenicians which began in 218 BC to the rule of Emperor Hadrian by AD 117, ancient Rome expanded up to twenty-five times its area. The same time passed again before its fall in AD 476. Rome had expanded long before the empire reached its zenith with the conquest of Dacia in AD 106 (modern-day Romania) under Emperor Trajan. During its territorial peak, the Roman Empire controlled about 5,000,000 square kilometres (1,900,000 sq mi) of land surface and had a population of 100 million. From the time of Caesar (100–44 BC) to the Fall of the Western Roman Empire, Rome dominated Southern Europe, the Mediterranean coast of Northern Africa and the Levant, including the ancient trade routes with population living outside. Ancient Rome has contributed greatly to the development of law, war, art, literature, architecture, technology and language in the Western world, and its history continues to have a major influence on the world today. The Latin language has been the base from which Romance languages evolved and it has been the official language of the Catholic Church and all Catholic religious ceremonies all over Europe until 1967, as well as one of, or the official language of countries such as Italy and Poland (9th–18th centuries).[92][citation needed]  Ending invasions on Roman Empire since the 2nd and throughout the 5th centuries establishing mostly Germanic kingdoms in its place In AD 395, a few decades before its Western collapse, the Roman Empire formally split into a Western and an Eastern one, each with their own emperors, capitals, and governments, although ostensibly they still belonged to one formal Empire. The Western Roman Empire provinces eventually were replaced by Northern European Germanic ruled kingdoms in the 5th century due to civil wars, corruption, and devastating Germanic invasions from such tribes as the Huns, Goths, the Franks and the Vandals by their late expansion throughout Europe. The three-day Visigoths's AD 410 sack of Rome who had been raiding Greece not long before, a shocking time for Greco-Romans, was the first time after almost 800 years that Rome had fallen to a foreign enemy, and St. Jerome, living in Bethlehem at the time, wrote that "The City which had taken the whole world was itself taken."[93] There followed the sack of AD 455 lasting 14 days, this time conducted by the Vandals, retaining Rome's eternal spirit through the Holy See of Rome (the Latin Church) for centuries to come.[94][95] The ancient Barbarian tribes, often composed of well-trained Roman soldiers paid by Rome to guard the extensive borders, had become militarily sophisticated "Romanized barbarians", and mercilessly slaughtered the Romans conquering their Western territories while looting their possessions.[96] The Roman Empire is where the idea of "the West" began to emerge.[f] The Eastern Roman Empire, governed from Constantinople, is usually referred to as the Byzantine Empire after AD 476, the traditional date for the fall of the Roman Empire and beginning of the Early Middle Ages. The survival of the Eastern Roman Empire protected Roman legal and cultural traditions, combining them with Greek and Christian elements, for another thousand years. The name Byzantine Empire was first used centuries later, after the Byzantine Empire ended. The dissolution of the Western half, nominally ended in AD 476, but in truth a long process that ended by the rise of Catholic Gaul (modern-day France) ruling from around the year AD 800, left only the Eastern Roman Empire alive. The Eastern half continued to think of itself as the Eastern Roman Empire until AD 610–800, when Latin ceased to be the official language of the empire. The inhabitants called themselves Romans because the term "Roman" was meant to signify all Christians. The Pope crowned Charlemagne as Emperor of the Romans of the newly established Holy Roman Empire, and the West began thinking in terms of Western Latins living in the old Western Empire, and Eastern Greeks (those inside the Roman remnant of the old Eastern Empire).[97] |

古代ローマ世界(紀元前6世紀 - 西暦395年 - 476年) 主な記事:ローマ共和国、ローマ帝国、西ローマ帝国の滅亡 この節は検証可能な参考文献や出典が全く示されていないか、不十分です。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。 出典の記載がない内容は、異議申し立てにより削除される場合があります。 (2018年4月) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  イタリア半島の大部分を征服した後の紀元前218年のローマ共和国、カルタゴ人との最も成功し、最も犠牲の多い戦争の前夜  西ローマ・カトリックと東ギリシャ正教の異なる部分を強調した、西暦395年以降のローマ帝国の地図。西半分と東半分を統治した最後の皇帝の死の前夜。 「東西」という概念は、キリスト教会の文化的な分裂に由来する。[91] 西ローマ帝国が崩壊する前夜の西暦476年9月における西ローマ帝国と東ローマ帝国。  西暦117年のローマ帝国。350年の間にローマ共和国は、その面積が25倍にまで拡大する帝国へと変貌した。 古代ローマ(紀元前6世紀 - 476年)とは、イタリア中部を征服し、エトルリア文化を同化させ、紀元前8世紀頃からラティウム地方から始まった古代ローマ社会が、地中海をまたぐ巨大 な帝国へと成長したことを指す用語である。10世紀にわたる領土拡大の過程で、ローマ文明は小規模な君主制(紀元前753年~509年)から共和制(紀元 前509年~紀元前27年)を経て、専制的な帝国(紀元前27年~西暦476年)へと変遷した。ローマ帝国は、西ヨーロッパ、中央ヨーロッパ、南東ヨー ロッパ、北アフリカを支配し、専制的な帝国として広大な中東地域をも支配下に置いたが、その支配は終焉を迎えた。ローマ軍団による征服が強制され、その 後、ローマ市民権の特権の何らかの形態を最終的に承認することで、文化的同化が図られた。 しかし、その偉大な遺産にもかかわらず、いくつかの要因がローマ帝国の衰退と最終的な崩壊につながった。 ローマ帝国は、約500年の歴史を持つローマ共和国(紀元前510年頃~30年頃)の後を継いだ。紀元前218年に始まったフェニキア人との最も成功し、 かつ最も犠牲の多い戦争から、西暦117年にハドリアヌス帝が統治するまでの350年間で、古代ローマは面積を25倍にまで拡大した。西暦476年に滅亡 するまで、同じだけの年月が経過した。ローマ帝国が絶頂期を迎えるはるか以前、トラヤヌス帝の治世下の西暦106年(現在のルーマニア)のダキア征服に よってローマは拡大していた。領土のピーク時には、ローマ帝国は地表の約5,000,000平方キロメートル(1,900,000平方マイル)を支配し、 人口は1億人に達した。シーザー(紀元前100年~44年)の時代から西ローマ帝国滅亡までの間、ローマは南ヨーロッパ、北アフリカの地中海沿岸、レバン ト地方を支配し、古代の交易路を含め、その外に住む人々にも影響を与えた。古代ローマは西洋世界の法律、戦争、芸術、文学、建築、技術、言語の発展に多大 な貢献を果たし、その歴史は今日の世界にも大きな影響を与え続けている。ラテン語はロマンス諸語の基盤となり、1967年まではヨーロッパ全域のカトリッ ク教会およびカトリックの宗教儀式の公用語であった。また、イタリアやポーランド(9世紀から18世紀)などの国々では、公用語または国語の一つであっ た。[92][要出典]  2世紀以降、5世紀にかけてローマ帝国への侵略が続き、その代わりに主にゲルマン人の王国が設立された 西ローマ帝国が崩壊する数十年前の西暦395年、ローマ帝国は公式に西ローマ帝国と東ローマ帝国に分裂し、それぞれ独自の皇帝、首都、政府を有したが、表 向きには依然として一つの帝国に属していた。西ローマ帝国の属州は、内戦や腐敗、フン族、ゴート族、フランク族、ヴァンダル族といった部族によるヨーロッ パ全域にわたる後期の侵略による壊滅的なゲルマン人の侵略により、5世紀には北ヨーロッパのゲルマン人が支配する王国に置き換えられた。ギリシャを略奪し ていた西ゴート族が西暦410年にローマを3日間略奪したことは、ギリシャ・ローマ人にとって衝撃的な出来事であった。これは、ローマがほぼ800年ぶり に外国の敵に陥落した出来事であり、当時ベツレヘムに住んでいた聖ヒエロニムスは、「全世界を征服した都市が、今や征服された」と記している。 [93] その後、西暦455年にヴァンダル族による14日間にわたる略奪が起こった。ローマの永遠の精神は、ローマ教皇庁(ラテン教会)を通じて、何世紀にもわ たって保たれた。 [94][95] 古代の蛮族は、ローマから報酬を得て広大な国境を守るために訓練されたローマ兵で構成されることが多く、軍事的に洗練された「ローマ化された蛮族」とな り、ローマ人が西の領土を征服するのを容赦なく虐殺し、彼らの所有物を略奪した。 ローマ帝国は、「西洋」という概念が誕生し始めた場所である。[f] コンスタンティノープルから統治された東ローマ帝国は、通常、西暦476年をローマ帝国滅亡の年、初期中世の始まりの年とする伝統的な見解に従い、ビザン チン帝国と呼ばれる。東ローマ帝国が存続したことにより、ローマの法や文化の伝統はギリシャやキリスト教の要素と融合し、さらに1000年にわたって保護 された。ビザンチン帝国という名称が初めて使われたのは、ビザンチン帝国が滅亡した後、数世紀を経てからのことだった。西ローマ帝国の崩壊は、名目上は西 暦476年に終わったが、実際には西暦800年頃にカトリックのガリア(現在のフランス)が台頭するまでの長い過程を経て、東ローマ帝国のみが生き残っ た。東ローマ帝国は、西暦610年から800年まで、帝国の公用語がラテン語でなくなった時まで、自らを東ローマ帝国であると考えていた。住民たちは自ら をローマ人と呼んだ。なぜなら、「ローマ人」という言葉はすべてのキリスト教徒を意味していたからである。教皇は、新たに建国された神聖ローマ帝国の皇帝 としてシャルルマーニュを戴冠させた。そして、西側では、旧西側帝国に住む西側のラテン人と、東側では、旧東側帝国のローマ人残党内部に住む東側のギリシ ア人という考え方が始まった。[97] |

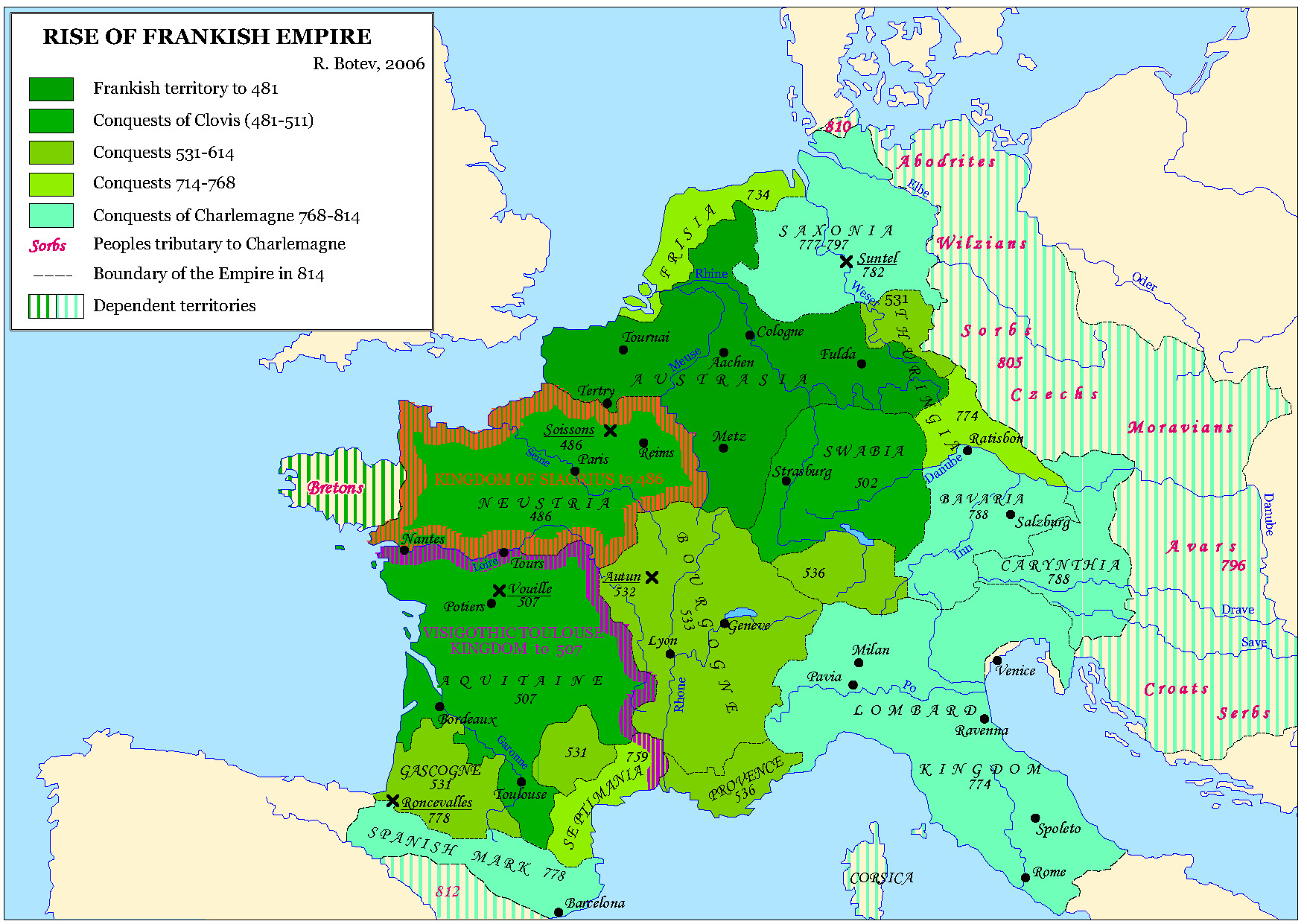

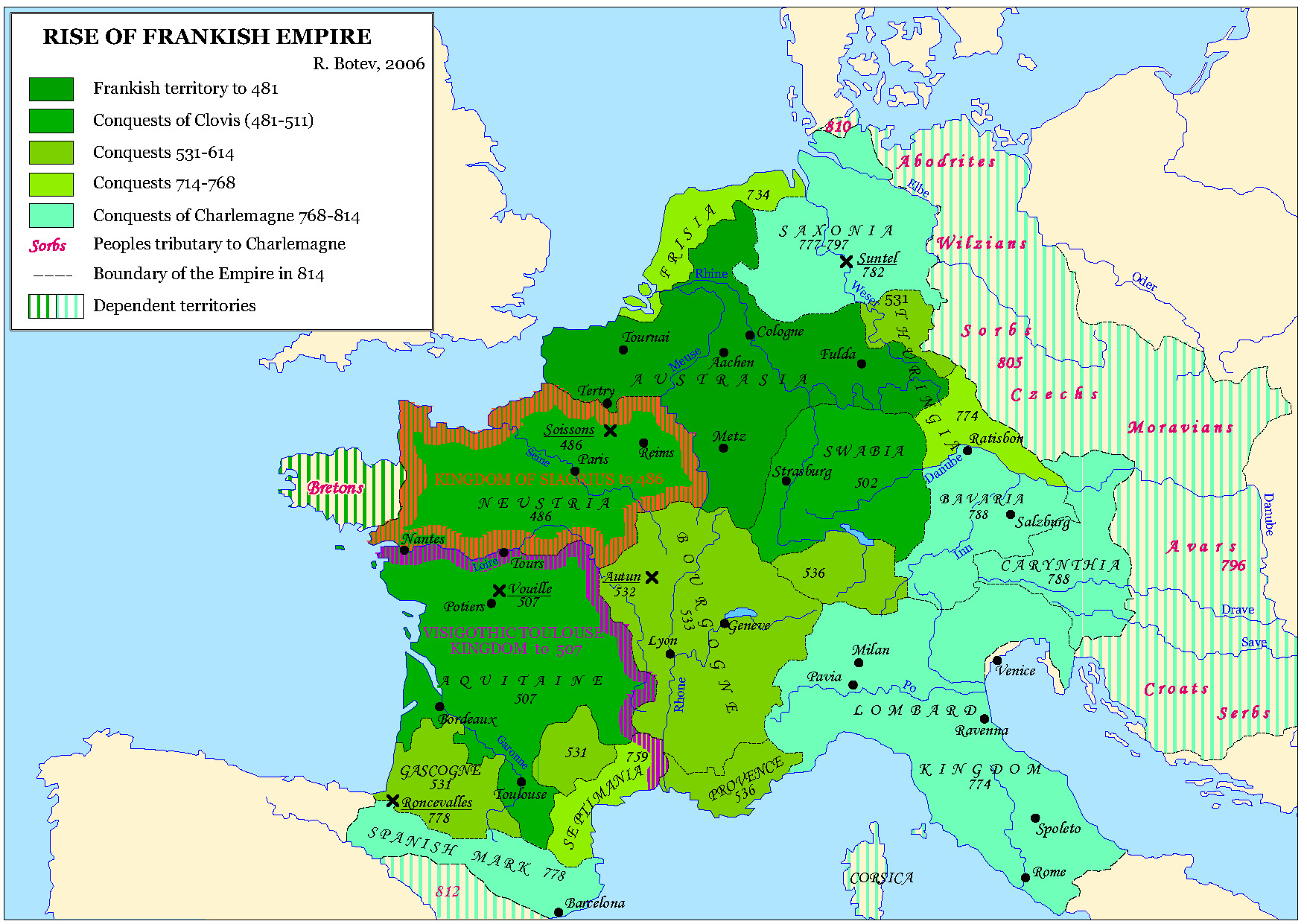

| The birth of the European West during the Middle Ages Main articles: Byzantine Empire, Holy Roman Empire, East–West Schism, and Reformation Further information: Christendom, Greek scholars in the Renaissance, and Peace of Westphalia This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  Apex of Byzantine Empire's conquests (AD 527–565) In the early 4th century, the central focus of power was on two separate imperial legacies within the Roman Empire: the older Aegean Sea Greek heritage (of Classical Greece) in the Eastern Mediterranean, and the newer most successful Tyrrhenian Sea Latin heritage (of Ancient Latium and Tuscany) in the Western Mediterranean. A turning point was Constantine the Great's decision to establish the city of Constantinople (today's Istanbul) in modern-day Turkey as the "New Rome" when he picked it as capital of his Empire (later called "Byzantine Empire" by modern historians) in AD 330.  The Byzantine Empire in AD 1025 before Christian East-West Schism This internal conflict of legacies had possibly emerged since the assassination of Julius Caesar three centuries earlier, when Roman imperialism had just been born with the Roman Republic becoming "Roman Empire", but reached its zenith during 3rd century's many internal civil wars. This is the time when the Huns (part of the ancient Eastern European tribes named barbarians by the Romans) from modern-day Hungary penetrated into the Dalmatian (modern-day Croatia) region then originating in the following 150 years in the Roman Empire officially splitting in two halves. Also the time of the formal acceptance of Christianity as Empire's religious policy, when the Emperors began actively banning and fighting previous pagan religions.  History of the spread of Christianity: in AD 325 (dark blue) and AD 600 (blue) following Western Roman Empire's collapse under Germanic migrations. The Eastern Roman Empire included lands south-west of the Black Sea and bordering on the Eastern Mediterranean and parts of the Adriatic Sea. This division into Eastern and Western Roman Empires was later reflected in the administration of the Roman Catholic and Eastern Greek Orthodox churches, with Rome and Constantinople debating over whether either city was the capital of Western religion.[citation needed] As the Eastern (Orthodox) and Western (Catholic) churches spread their influence, the line between Eastern and Western Christianity was moving. Its movement was affected by the influence of the Byzantine empire and the fluctuating power and influence of the Catholic church in Rome. The geographic line of religious division approximately followed a line of cultural divide.[citation needed]  Rise of the Germanic Frankish Empire before Charlemagne's coronation in Rome In AD 800 under Charlemagne, the Early Medieval Franks established an empire that was recognized by the Pope in Rome as the Holy Roman Empire (Latin Christian revival of the ancient Roman Empire, under perpetual Germanic rule from AD 962) inheriting ancient Roman Empire's prestige but offending the Eastern Roman Emperor in Constantinople, and leading to the Crusades and the East–West Schism. The crowning of the Emperor by the Pope led to the assumption that the highest power was the papal hierarchy, quintessential Roman Empire's spiritual heritage authority, establishing then, until the Protestant Reformation, the civilization of Western Christendom.[citation needed] The earliest concept of Europe as a cultural sphere (instead of simple geographic term) is believed to have been formed by Alcuin of York during the Carolingian Renaissance of the 9th century, but was limited to the territories that practised Western Christianity at the time.[98] The Latin Church of western and central Europe split with the eastern Greek patriarchates in the Christian East–West Schism, also known as the "Great Schism", during the Gregorian Reforms (calling for a more central status of the Roman Catholic Church Institution), three months after Pope Leo IX's death in April 1054.[99] Following the 1054 Great Schism, both the Western Church and Eastern Church continued to consider themselves uniquely orthodox and catholic. Augustine wrote in On True Religion: "Religion is to be sought... only among those who are called Catholic or orthodox Christians, that is, guardians of truth and followers of right."[100] Over time, the Western Christianity gradually identified with the "Catholic" label, and people of Western Europe gradually associated the "Orthodox" label with Eastern Christianity (although in some languages the "Catholic" label is not necessarily identified with the Western Church). This was in note of the fact that both Catholic and Orthodox were in use as ecclesiastical adjectives as early as the 2nd and 4th centuries respectively. Meanwhile, the extent of both Christendoms expanded, as Germanic peoples, Bohemia, Poland, Hungary, Scandinavia, Finnic peoples, Baltic peoples, British Isles and the other non-Christian lands of the northwest were converted by the Western Church, while Eastern Slavic peoples, Bulgaria, Serbia, Montenegro, Russian territories, Vlachs and Georgia were converted by the Eastern Orthodox Church.[citation needed] |

中世におけるヨーロッパ西部の誕生 主な記事:ビザンティン帝国、神聖ローマ帝国、東西教会の分裂、宗教改革 さらに詳しい情報:キリスト教、ルネサンス期のギリシア学者、ヴェストファーレン和約 この節は検証可能な参考文献や出典が全く示されていないか、不十分です。この記事を改善するために、この節に参考文献や出典を追加してください。 出典の記載がない資料は、異議申し立てを受けた上で削除される場合があります。 (2021年11月) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  ビザンティン帝国の征服の頂点(西暦527年から565年) 4世紀初頭、ローマ帝国内の2つの別々の帝国の遺産に権力の中心が置かれていた。すなわち、東地中海におけるより古いエーゲ海のギリシャの遺産(古典ギリ シャの)と、西地中海におけるより新しい最も成功したティレニア海のラテン人の遺産(古代ラティウムとトスカーナの)である。転換期となったのは、コンス タンティヌス大帝が西暦330年に、自らの帝国(後の歴史家たちによって「ビザンチン帝国」と呼ばれる)の首都として、現在のトルコに「新ローマ」として コンスタンティノープル(現在のイスタンブール)を建設することを決定したことである。  キリスト教の東西分裂前の西暦1025年のビザンチン帝国 この遺産の内部対立は、おそらく3世紀前のジュリアス・シーザー暗殺以来、ローマ帝国がローマ共和国から「ローマ帝国」へと生まれ変わったときに生じたも ので、3世紀の多くの内戦の間に頂点に達した。この時代に、現在のハンガリーからフン族(ローマ人によって野蛮人と名付けられた古代東ヨーロッパ部族の一 部)がダルマチア(現在のクロアチア)地域に侵入し、その後150年にわたってローマ帝国が公式に2つに分裂することとなった。また、キリスト教が帝国の 宗教政策として正式に受け入れられ、皇帝たちがそれまでの異教の宗教を積極的に禁止し、戦うようになった時代でもある。  キリスト教の広がりの歴史:西暦325年(濃い青)と西暦600年(青)は、ゲルマン民族の移動による西ローマ帝国の崩壊後。 東ローマ帝国は黒海の南西の土地を含み、東地中海とアドリア海の一部に接していた。この東西ローマ帝国への分割は、後にローマ・カトリック教会と東方正教会の運営に反映され、ローマとコンスタンティノープルはどちらが西方の宗教の首都であるかをめぐって論争した。 東方教会(正教会)と西方教会(カトリック教会)が影響力を広げるにつれ、東方キリスト教と西方キリスト教の境界線は移動した。その移動はビザンティン帝 国の影響と、ローマのカトリック教会の変動する権力と影響力によって影響を受けた。宗教的な境界線の地理的な線は、おおよそ文化的な境界線の線に沿ってい た。  ローマにおけるシャルルマーニュの戴冠式前のゲルマン・フランク王国の勃興 西暦800年、カール大帝のもとで初期中世フランク王国はローマ教皇によって神聖ローマ帝国として認められた(古代ローマ帝国のラテン・キリスト教復興、 西暦962年からの永遠のゲルマン支配下)。古代ローマ帝国の威信を受け継いだが、コンスタンティノープルの東ローマ皇帝を怒らせ、十字軍と東西教会の分 裂につながった。教皇による皇帝の戴冠は、最高の権力はローマ帝国の精神的な遺産の権威の典型である教皇のヒエラルキーにあるという考えにつながり、プロ テスタント革命が起こるまで、西ヨーロッパのキリスト教文明を確立した。 ヨーロッパを文化圏として捉えるという概念(単なる地理的概念ではなく)は、9世紀のカロリング朝ルネサンスの時代にアルクイン・オブ・ヨークによって形成されたと考えられているが、当時、西ヨーロッパのキリスト教が実践されていた地域に限られていた。 西ヨーロッパおよび中央ヨーロッパのラテン教会は、グレゴリウス改革(ローマ・カトリック教会の機関のより中央集権的な地位を求める)の3か月後、 1054年4月にレオ9世が死去したことにより、キリスト教東西教会分裂(「大分裂」とも呼ばれる)で東部のギリシャ総主教庁と分裂した。 [99] 1054年の大分裂の後も、西方教会と東方教会はそれぞれが唯一の正統かつ普遍的な教会であると主張し続けた。アウグスティヌスは『真の宗教』の中で、 「宗教は... カトリックまたは正統派キリスト教徒と呼ばれる人々、すなわち、真理の守護者であり、正義の信奉者である人々の中でしか見出せない」と書いている。 [100] 時が経つにつれ、西方のキリスト教は次第に「カトリック」というラベルと同一視されるようになり、西ヨーロッパの人々は「正統派」というラベルを東方のキ リスト教と関連付けるようになった(ただし、一部の言語では「カトリック」というラベルは必ずしも西方教会と同一視されるわけではない)。これは、カト リックと正教会という名称がそれぞれ2世紀と4世紀にはすでに教会を表す形容詞として使用されていたという事実によるものである。一方、西教会によってゲ ルマン民族、ボヘミア、ポーランド、ハンガリー、スカンジナビア、フィンランド民族、バルト民族、ブリテン諸島、および北西の他の非キリスト教国が改宗し た一方で、東スラブ民族、ブルガリア、セルビア、モンテネグロ、ロシア領、ワラキア人、グルジアは東方正教会によって改宗した。[要出典] |

The Byzantine Empire in AD 1180 before Latin Fourth Crusade In 1071, the Byzantine army was defeated by the Muslim Turco-Persians of medieval Asia, resulting in the loss of most of Asia Minor. The situation was a serious threat to the future of the Eastern Orthodox Byzantine Empire. The Emperor sent a plea to the Pope in Rome to send military aid to restore the lost territories to Christian rule. The result was a series of western European military campaigns into the eastern Mediterranean, known as the Crusades. Unfortunately for the Byzantines, the crusaders (belonging to the members of nobility from France, German territories, the Low countries, England and Italy) had no allegiance to the Byzantine Emperor and established their own states in the conquered regions, including the heart of the Byzantine Empire. The Holy Roman Empire would dissolve on 6 August 1806, after the French Revolution and the creation of the Confederation of the Rhine by Napoleon.  The Greek Byzantine Empire split by a newly established Latin Crusader State after the Fourth Crusade (shown partly in Greece and partly in Turkey) The decline of the Byzantine Empire (13th–15th centuries) began with the Latin Christian Fourth Crusade in AD 1202–04, considered to be one of the most important events, solidifying the schism between the Christian churches of Greek Byzantine Rite and Latin Roman Rite. An anti-Western riot in 1182 broke out in Constantinople targeting Latins. The extremely wealthy (after previous Crusades) Venetians in particular made a successful attempt to maintain control over the coast of Catholic present-day Croatia (specifically the Dalmatia, a region of interest to the maritime medieval Venetian Republic moneylenders and its rivals, such as the Republic of Genoa) rebelling against the Venetian economic domination.[101] What followed dealt an irrevocable blow to the already weakened Byzantine Empire with the Crusader army's sack of Constantinople in April 1204, capital of the Greek Christian-controlled Byzantine Empire, described as one of the most profitable and disgraceful sacks of a city in history.[102] This paved the way for Muslim conquests in present-day Turkey and the Balkans in the coming centuries (only a handful of the Crusaders followed to the stated destination thereafter, the Holy Land). The geographical identity of the Balkans is historically known as a crossroads of cultures, a juncture between the Latin and Greek bodies of the Roman Empire, the destination of a massive influx of pagans (meaning "non-Christians") Bulgars and Slavs, an area where Catholic and Orthodox Christianity met,[103] as well as the meeting point between Islam and Christianity. The Papal Inquisition was established in AD 1229 on a permanent basis, run largely by clergymen in Rome,[104] and abolished six centuries later. Before AD 1100, the Catholic Church suppressed what they believed to be heresy, usually through a system of ecclesiastical proscription or imprisonment, but without using torture,[105] and seldom resorting to executions.[106][107][108][109] |

ラテン第4回十字軍遠征前の西暦1180年のビザンチン帝国 1071年、ビザンチン帝国軍は中世アジアのイスラム教徒トルコ・ペルシア軍に敗北し、小アジアの大半を失う結果となった。この事態は、東方正教のビザン チン帝国の将来にとって深刻な脅威であった。皇帝はローマ教皇に嘆願書を送り、キリスト教の支配下に失われた領土を回復するための軍事支援を要請した。そ の結果、十字軍として知られる一連の西ヨーロッパによる東地中海への軍事行動が引き起こされた。ビザンチン帝国にとって不幸なことに、十字軍(フランス、 ドイツ領、ネーデルラント、イングランド、イタリアの貴族階級に属する者たち)はビザンチン皇帝に忠誠を誓うことはなく、征服した地域に自分たちの国家を 樹立し、その中にはビザンチン帝国の中心地も含まれていた。 神聖ローマ帝国は、フランス革命とナポレオンによるライン同盟の創設を経て、1806年8月6日に消滅した。  ギリシャのビザンチン帝国は、第4回十字軍遠征後に新たに建国されたラテン十字軍国家によって分裂した(ギリシャとトルコにまたがる地域)。 ビザンチン帝国の衰退(13世紀から15世紀)は、西暦1202年から1204年にかけてのラテン・キリスト教徒による第4回十字軍から始まった。これ は、ギリシャ・ビザンチン式とラテン・ローマ式のキリスト教会の分裂を固める上で最も重要な出来事のひとつと考えられている。1182年には、コンスタン ティノープルでラテン人を標的とした反西欧暴動が勃発した。特に、それまでの十字軍遠征で非常に裕福になったヴェネツィア人は、ヴェネツィアの経済支配に 反発したカトリックの現在のクロアチア(特に、ヴェネツィア共和国の海洋中世貸し手とそのライバルであるジェノヴァ共和国にとって関心の高い地域であるダ ルマチア)の海岸の支配を維持しようと試みた。 [101] 1204年4月、十字軍がギリシャ正教徒が支配するビザンチン帝国の首都コンスタンティノープルを略奪したことにより、すでに弱体化していたビザンチン帝 国に決定的な打撃が与えられた。この略奪は、歴史上最も利益をもたらし、かつ不名誉な略奪のひとつとされている。 [102] これにより、数世紀後の現在のトルコおよびバルカン半島におけるイスラム教徒の征服への道が開かれた(十字軍の戦士のうち、その後の目的地である聖地を目 指した者はほんの一握りであった)。バルカン半島の地理的な特徴は、歴史的に文化の交差点として知られており、ローマ帝国のラテン人とギリシア人の境界、 異教徒(「非キリスト教徒」を意味する)ブルガール人とスラヴ人の大規模な流入先、カトリックと正教のキリスト教が交わる地域[103]、そしてイスラム 教とキリスト教の交差点でもあった。ローマ教皇による異端審問は西暦1229年に常設され、主にローマの聖職者によって運営され[104]、6世紀後に廃 止された。西暦1100年以前には、カトリック教会は異端と見なしたものを、通常は教会による破門や投獄という制度を通じて弾圧していたが、拷問は用い ず、死刑にすることはまれであった。 |

This

very profitable Central European Fourth Crusade had prompted the 14th

century Renaissance (translated as 'Rebirth') of Italian city-states

including the Papal States, on eve of the Protestant Reformation and

Counter-Reformation (which established the Roman Inquisition to succeed

the Medieval Inquisition). There followed the discovery of the American

continent, and consequent dissolution of West Christendom as even a

theoretical unitary political body, later resulting in the religious

Eighty Years War (1568–1648) and Thirty Years War (1618–1648) between

various Protestant and Catholic states of the Holy Roman Empire (and

emergence of religiously diverse confessions). In this context, the

Protestant Reformation (1517) may be viewed as a schism within the

Catholic Church. German monk Martin Luther, in the wake of precursors,

broke with the pope and with the emperor by the Catholic Church's

abusive commercialization of indulgences in the Late Medieval Period,

backed by many of the German princes and helped by the development of

the printing press, in an attempt to reform corruption within the

church.[110][111][112] Both these religious wars ended with the Peace of Westphalia (1648), which enshrined the concept of the nation-state, and the principle of absolute national sovereignty in international law. As European influence spread across the globe, these Westphalian principles, especially the concept of sovereign states, became central to international law and to the prevailing world order.[113] |

こ

の非常に有益な中央ヨーロッパ第4回十字軍は、プロテスタント革命と対抗宗教改革(中世の異端審問に代わるローマ異端審問を確立した)の直前に、教皇領を

含むイタリア都市国家の14世紀ルネサンス(「再生」の意)を促した。その後、アメリカ大陸が発見され、西キリスト教世界は理論上の単一政治体としての存

在意義を失い、後に神聖ローマ帝国のさまざまなプロテスタントおよびカトリック国家間で宗教的な八十年戦争(1568年~1648年)および三十年戦争

(1618年~1648年)が勃発した(そして、宗教的に多様な宗派が現れた)。この文脈において、プロテスタントの宗教改革(1517年)は、カトリッ

ク教会内の分裂と見なすことができる。ドイツの修道士マルティン・ルターは、先行する者たちに続いて、カトリック教会が中世後期に免罪符を乱用して商業化

したことに対して、ドイツ諸侯の多くから支持を受け、印刷機の開発に助けられながら、ローマ教皇と神聖ローマ皇帝と決別した。教会内の腐敗を改革しようと

したのである。[110][111][112] これらの宗教戦争は、いずれもウェストファリア条約(1648年)によって終結した。この条約は国民国家の概念を確立し、国際法における国家の主権の原則 を定めた。ヨーロッパの影響力が世界中に広がるにつれ、ウェストファリアの原則、特に主権国家の概念は、国際法と世界秩序の中心となった。[113] |

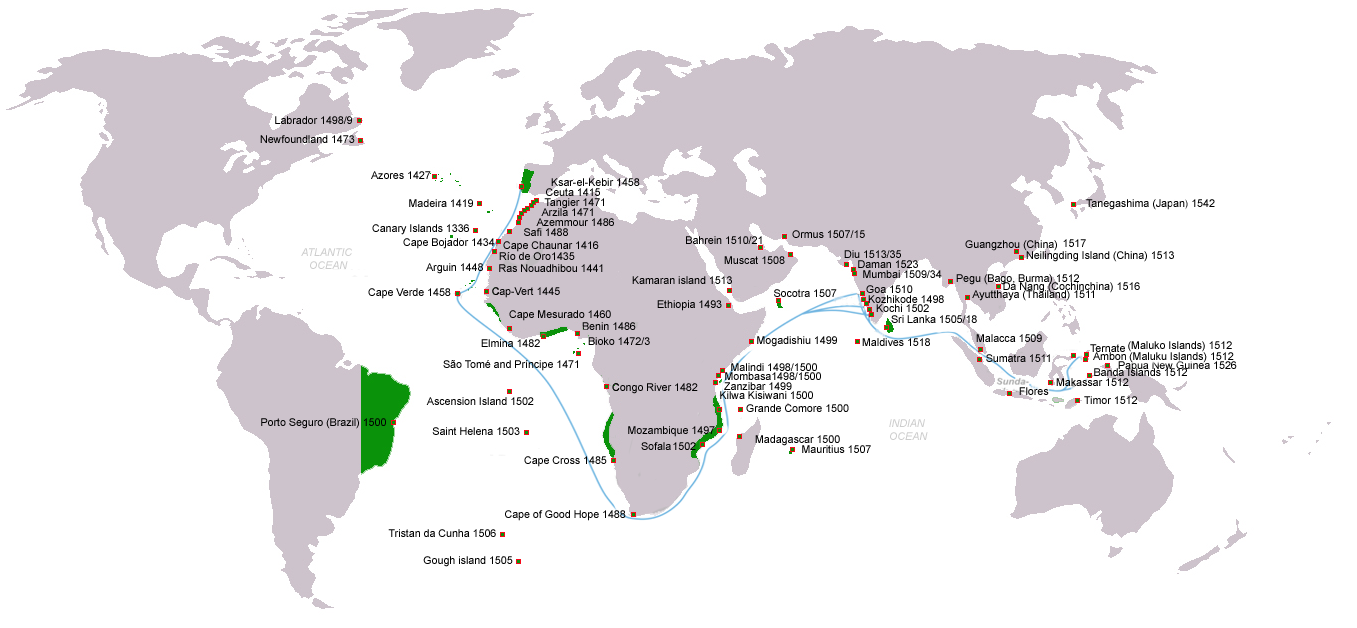

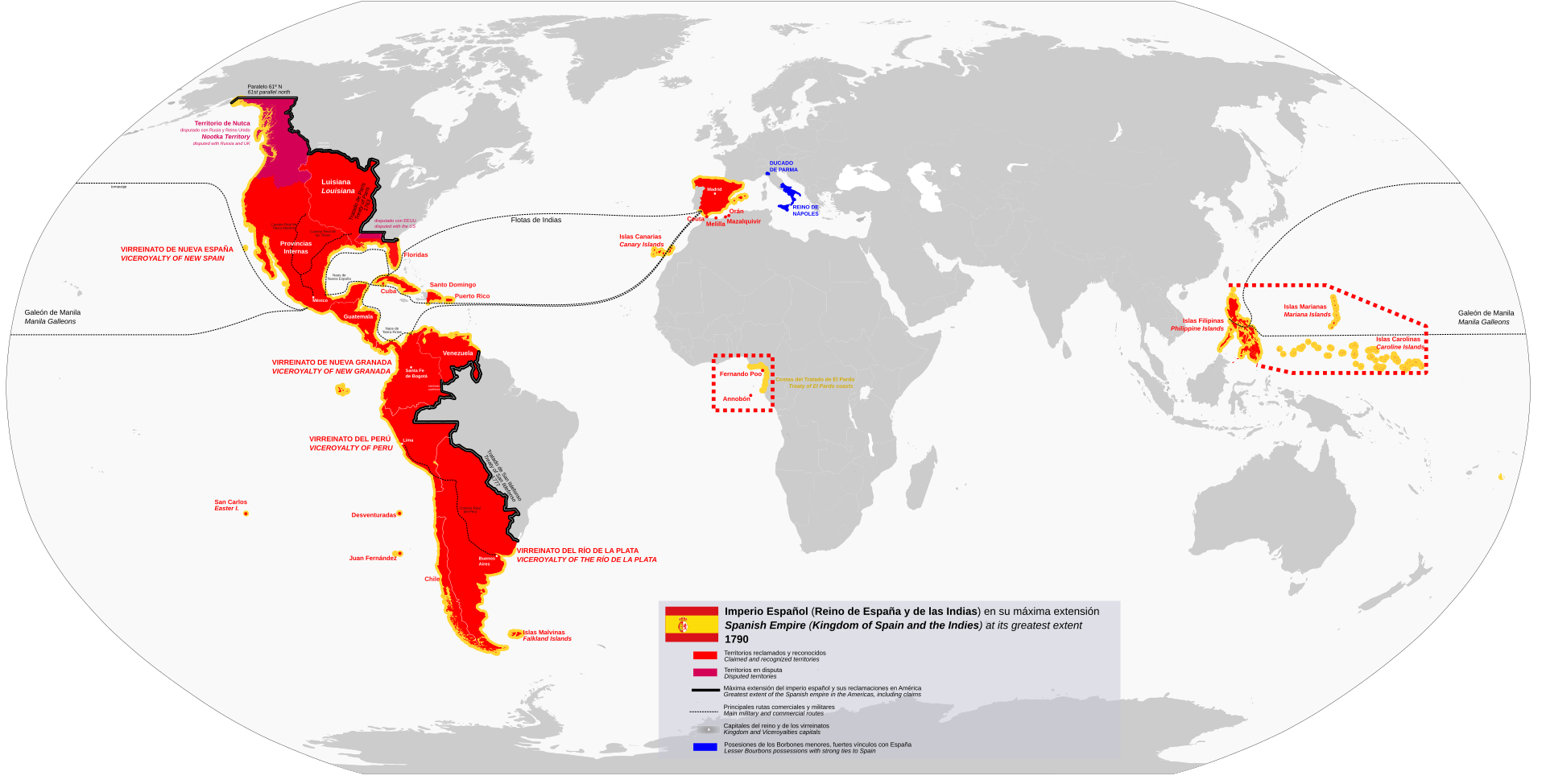

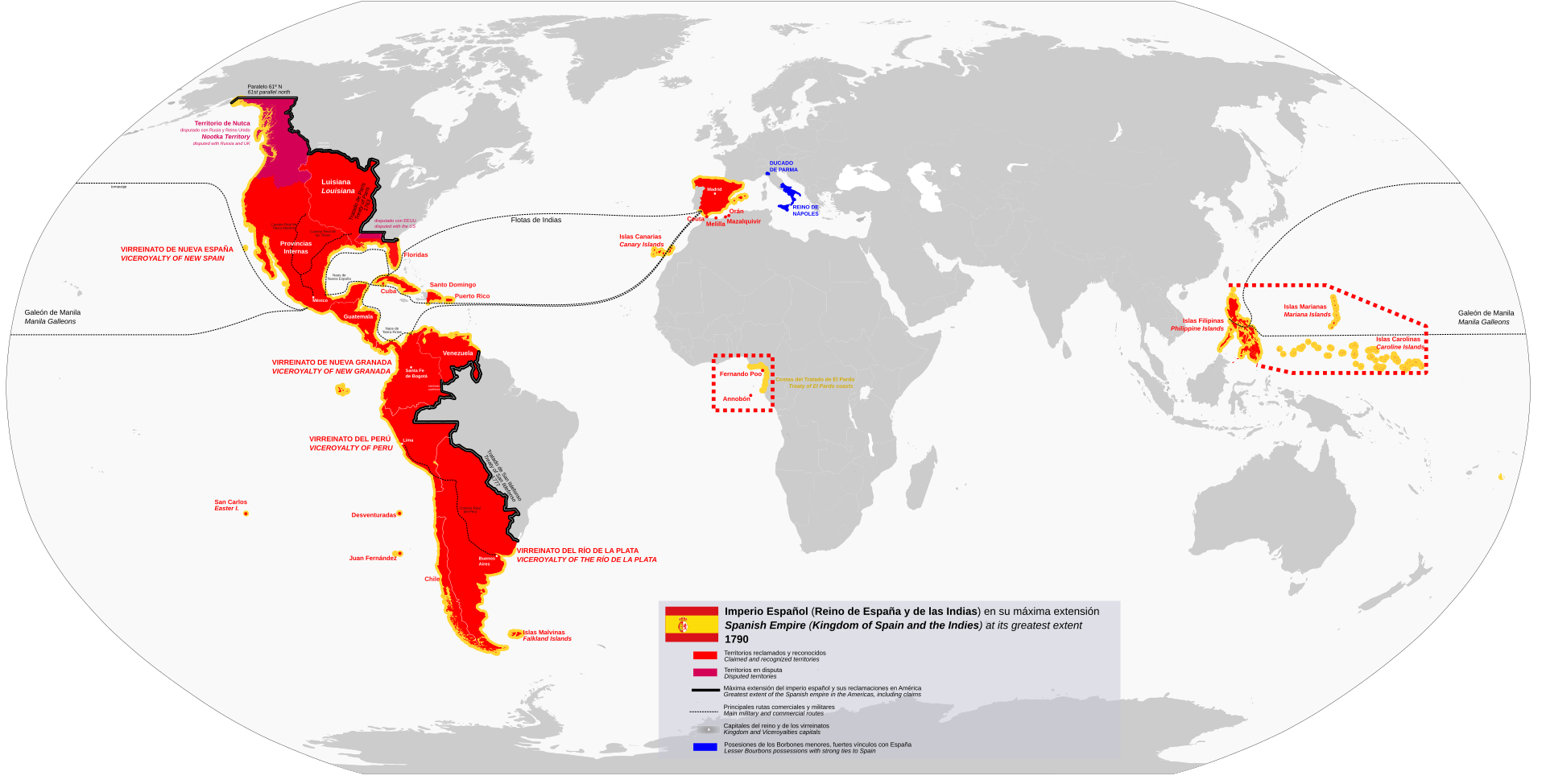

| Expansion of the West: the Era of Colonialism (15th–20th centuries) Main articles: New World, Analysis of Western European colonialism and colonization, Mercantilism, and Imperialism This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  Portuguese discoveries and explorations since 1336: first arrival places and dates; main Portuguese spice trade routes in the Indian Ocean (blue); territories claimed by King John III of Portugal (c. 1536) (green)  Apex of Spanish Empire in 1790 In the 13th and 14th centuries, a number of European travelers, many of them Christian missionaries, had sought to cultivate trading with Asia and Africa. With the Crusades came the relative contraction of the Orthodox Byzantine's large silk industry in favor of Catholic Western Europe and the rise of Western Papacy. The most famous of these merchant travelers pursuing East–west trade was Venetian Marco Polo. But these journeys had little permanent effect on east–west trade because of a series of political developments in Asia in the last decades of the 14th century, which put an end to further European exploration of Asia: namely the new Ming rulers were found to be unreceptive of religious proselytism by European missionaries and merchants. Meanwhile, the Ottoman Turks consolidated control over the eastern Mediterranean, closing off key overland trade routes.[citation needed] The Portuguese spearheaded the drive to find oceanic routes that would provide cheaper and easier access to South and East Asian goods, by advancements in maritime technology such as the caravel ship introduced in the mid-1400s. The charting of oceanic routes between East and West began with the unprecedented voyages of Portuguese and Spanish sea captains. In 1492, European colonialism expanded across the globe with the exploring voyage of merchant, navigator, and Hispano-Italian colonizer Christopher Columbus. Such voyages were influenced by medieval European adventurers after the European spice trade with Asia, who had journeyed overland to the Far East contributing to geographical knowledge of parts of the Asian continent. They are of enormous significance in Western history as they marked the beginning of the European exploration, colonization and exploitation of the American continents and their native inhabitants.[g][h] The European colonization of the Americas led to the Atlantic slave trade between the 1490s and the 1800s, which also contributed to the development of African intertribal warfare and racist ideology. Before the abolition of its slave trade in 1807, the British Empire alone (which had started colonial efforts in 1578, almost a century after Portuguese and Spanish empires) was responsible for the transportation of 3.5 million African slaves to the Americas, a third of all slaves transported across the Atlantic.[115] The Holy Roman Empire was dissolved in 1806 by the French Revolutionary Wars; abolition of the Roman Catholic Inquisition followed.[citation needed] Due to the reach of these empires, Western institutions expanded throughout the world. This process of influence (and imposition) began with the voyages of discovery, colonization, conquest, and exploitation of Portugal enforced as well by papal bulls in 1450s (by the fall of the Byzantine Empire), granting Portugal navigation, war and trade monopoly for any newly discovered lands,[116] and competing Spanish navigators. It continued with the rise of the Dutch East India Company by the destabilizing Spanish discovery of the New World, and the creation and expansion of the English and French colonial empires, and others.[citation needed] Even after demands for self-determination from subject peoples within Western empires were met with decolonization, these institutions persisted. One specific example was the requirement that post-colonial societies were made to form nation-states (in the Western tradition), which often created arbitrary boundaries and borders that did not necessarily represent a whole nation, people, or culture (as in much of Africa), and are often the cause of international conflicts and friction even to this day. Although not part of Western colonization process proper, following the Middle Ages Western culture in fact entered other global-spanning cultures during the colonial 15th–20th centuries.[citation needed] Historically colonialism had been justified with the values of individualism and enlightenment.[117] The concepts of a world of nation-states born by the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, coupled with the ideologies of the Enlightenment, the coming of modernity, the Scientific Revolution[118] and the Industrial Revolution,[119] would produce powerful social transformations, political and economic institutions that have come to influence (or been imposed upon) most nations of the world today. Historians agree that the Industrial Revolution has been one of the most important events in history.[120] The course of three centuries since Christopher Columbus' late 15th century's voyages, of deportation of slaves from Africa and British dominant northern-Atlantic location, later developed into modern-day United States of America, evolving from the ratification of the Constitution of the United States by thirteen States on the North American East Coast before end of the 18th century. |

西洋の拡大:植民地主義の時代(15世紀~20世紀) 主な記事:新世界、西欧の植民地主義と植民地化の分析、重商主義、帝国主義 この節は検証可能な参考文献や出典が全く示されていないか、不十分です。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。 出典の記載がない項目は、削除される場合があります。 (2021年11月) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  1336年以降のポルトガルによる発見と探検:最初の到着地と日付;ポルトガルによるインディアン・オーシャン(青)の主な香辛料貿易ルート;ポルトガルのジョアン3世王(1536年頃)が領有権を主張した領土(緑)  1790年のスペイン帝国の最盛期 13世紀と14世紀には、多くのキリスト教宣教師を含むヨーロッパの旅行者たちが、アジアやアフリカとの貿易を模索していた。十字軍の遠征により、正教ビ ザンチン帝国の大きな絹産業は相対的に縮小し、カトリックの西ヨーロッパと西方のローマ教皇庁が優勢となった。東西貿易に従事した商人旅行者として最も有 名なのはヴェネツィア人のマルコ・ポーロである。しかし、14世紀の最後の数十年間にアジアで次々と政治的な動きがあったため、これらの旅は東西貿易にほ とんど恒久的な影響を及ぼさなかった。すなわち、ヨーロッパの宣教師や商人による宗教改宗活動に新明の支配者が非協力的であることが判明したのである。一 方、オスマン・トルコは東地中海の支配を固め、主要な陸上貿易ルートを遮断した。 ポルトガルは、1400年代半ばに登場したキャラベル船などの海洋技術の進歩により、南アジアや東アジアの品物をより安く、より簡単に手に入れることがで きる海洋航路の発見を先導した。東西間の海洋航路の地図作成は、ポルトガルとスペインの船長たちによる前例のない航海から始まった。1492年、商人であ り航海者であり、またスペイン系イタリア人の植民者でもあったクリストファー・コロンブスの探検航海により、ヨーロッパの植民地主義は世界中に拡大した。 このような航海は、アジアとのヨーロッパの香辛料貿易の後、極東まで陸路を旅し、アジア大陸の一部の地理的知識に貢献した中世ヨーロッパの冒険家たちに影 響を受けた。彼らは西洋の歴史において、ヨーロッパによるアメリカ大陸の探検、植民地化、先住民の搾取の始まりを象徴する存在であり、非常に重要な意味を 持っている。[g][h] ヨーロッパによるアメリカ大陸の植民地化は、1490年代から1800年代にかけて大西洋奴隷貿易につながり、それはまた、アフリカの部族間戦争と人種差 別的イデオロギーの発展にも寄与した。1807年に奴隷貿易が廃止されるまで、大英帝国(ポルトガル帝国やスペイン帝国より約1世紀遅い1578年に植民 地化の努力を開始)だけでも、350万人のアフリカ人奴隷をアメリカ大陸に送った。これは大西洋を渡った奴隷の3分の1にあたる。[115] 神聖ローマ帝国はフランス革命戦争により1806年に解体され、ローマ・カトリックの異端審問も廃止された。 [要出典] これらの帝国の勢力範囲の拡大により、西洋の制度が世界中に広がった。この影響(および押し付け)のプロセスは、1450年代に教皇勅書によって強制され たポルトガルの発見、植民地化、征服、搾取の航海から始まった。この航海により、ポルトガルは、新たに発見された土地での航海、戦争、貿易の独占権を獲得 した。それは、スペインによる新大陸発見が不安定化をもたらしたことによるオランダ東インド会社の台頭、およびイギリスやフランスの植民地帝国の創設と拡 大などによっても継続した。[要出典] 西洋の帝国の被支配民族による自決要求が植民地独立という形で実現した後も、これらの制度は存続した。その一例として、植民地後の社会が国民国家(西洋の 伝統)を形成することが求められたことが挙げられる。これは、必ずしも国民全体、国民、文化を代表するとは限らない恣意的な境界や国境を生み出すことが多 く(アフリカの多くの地域のように)、今日に至るまで国際紛争や摩擦の原因となっている。西洋による植民地化の過程とは直接関係しないが、中世以降、15 世紀から20世紀にかけての植民地時代に、西洋文化は事実上、世界に広がる他の文化圏に浸透した。[要出典] 歴史的に、植民地主義は個人主義と啓蒙主義の価値観によって正当化されてきた。[117] 1648年のウェストファリア条約によって誕生した国民国家の世界という概念は、啓蒙思想、近代化、科学革命[118]、産業革命[119]といった思想 と結びつき、強力な社会変革を生み出し、政治・経済制度を生み出した。この制度は、今日の世界のほとんどの国々に影響を与え(あるいは押し付けられ)てい る。歴史家たちは、産業革命が歴史上最も重要な出来事のひとつであったことに同意している。 15世紀後半のクリストファー・コロンブスの航海から3世紀にわたる歴史の中で、アフリカからの奴隷の強制連行や、北大西洋地域における英国の支配を経て、18世紀末までに北米東海岸の13州による米国憲法批准へとつながり、現代の米国が誕生した。 |

| Enlightenment (17th–18th centuries) Main articles: Age of Enlightenment and Scientific Revolution Eric Voegelin described the 18th-century as one where "the sentiment grows that one age has come to its close and that a new age of Western civilization is about to be born". According to Voeglin the Enlightenment (also called the Age of Reason) represents the "atrophy of Christian transcendental experiences and [seeks] to enthrone the Newtonian method of science as the only valid method of arriving at truth".[121] Its precursors were John Milton and Baruch Spinoza.[122] Meeting Galileo in 1638 left an enduring impact on John Milton and influenced Milton's great work Areopagitica, where he warns that, without free speech, inquisitorial forces will impose "an undeserved thraldom upon learning".[123] The achievements of the 17th century included the invention of the telescope and acceptance of heliocentrism. 18th century scholars continued to refine Newton's theory of gravitation, notably Leonhard Euler, Pierre Louis Maupertuis, Alexis-Claude Clairaut, Jean Le Rond d'Alembert, Joseph-Louis Lagrange, Pierre-Simon de Laplace. Laplace's five-volume Treatise on Celestial Mechanics is one of the great works of 18th-century Newtonianism. Astronomy gained in prestige as new observatories were funded by governments and more powerful telescopes developed, leading to the discovery of new planets, asteroids, nebulae and comets, and paving the way for improvements in navigation and cartography. Astronomy became the second most popular scientific profession, after medicine.[124] A common metanarrative of the Enlightenment is the "secularization theory". Modernity, as understood within the framework, means a total break with the past. Innovation and science are the good, representing the modern values of rationalism, while faith is ruled by superstition and traditionalism.[125] Inspired by the Scientific Revolution, the Enlightenment embodied the ideals of improvement and progress. Descartes and Isaac Newton were regarded as exemplars of human intellectual achievement. Condorcet wrote about the progress of humanity in the Sketch of the Progress of the Human Mind (1794), from primitive society to agrarianism, the invention of writing, the later invention of the printing press and the advancement to "the Period when the Sciences and Philosophy threw off the Yoke of Authority".[126] French writer Pierre Bayle denounced Spinoza as a pantheist (thereby accusing him of atheism). Bayle's criticisms garnered much attention for Spinoza. The pantheism controversy in the late 18th century saw Gotthold Lessing attacked by Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi over support for Spinoza's pantheism. Lessing was defended by Moses Mendelssohn, although Mendelssohn diverged from pantheism to follow Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz in arguing that God and the world were not of the same substance (equivalency). Spinoza was excommunicated from the Dutch Sephardic community, but for Jews who sought out Jewish sources to guide their own path to secularism, Spinoza was as important as Voltaire and Kant.[127] |

啓蒙主義(17世紀~18世紀) 主な記事:啓蒙時代と科学革命 エリック・ヴォーゲリンは、18世紀を「一つの時代が終わりを迎え、西洋文明の新たな時代が誕生しようとしているという感情が高まる」時代であったと表現 している。ヴォーゲリンによれば、啓蒙主義(理性の時代とも呼ばれる)は、「キリスト教の超越的体験の衰退」を表し、「真理に到達するための唯一の有効な 方法として、ニュートン流の科学的手法を王座に就かせよう」とするものである。 [121] その先駆者としては、ジョン・ミルトンやバールーフ・スピノザが挙げられる。[122] 1638年にガリレオと会ったことはジョン・ミルトンに永続的な影響を与え、ミルトンの代表作『アレオパギタ』にも影響を与えた。ミルトンは、言論の自由 がなければ、審問官の勢力が「学問に不当な束縛を課す」と警告している。[123] 17世紀の功績には、望遠鏡の発明と地動説の受容が含まれる。18世紀の学者たちは、特にレオンハルト・オイラー、ピエール・ルイ・マペルチュイ、アレク シス=クロード・クレロー、ジャン・ル・ロン・ダランベール、ジョゼフ=ルイ・ラグランジュ、ピエール=シモン・ド・ラプラスのように、ニュートンの万有 引力の理論をさらに洗練させていった。ラプラスの『天体力学論』全5巻は、18世紀のニュートン主義の偉大な業績のひとつである。政府による新しい天文台 の建設やより高性能な望遠鏡の開発により、天文学の威信が高まり、新しい惑星、小惑星、星雲、彗星の発見につながり、航海術や地図作成の改善への道筋をつ けた。天文学は医学に次いで2番目に人気の高い科学分野となった。 啓蒙主義の一般的なメタナラティブは「世俗化理論」である。この枠組みで理解される近代とは、過去との完全な決別を意味する。革新と科学は善であり、合理 主義という近代的価値観を体現するものである。一方、信仰は迷信と伝統主義に支配されている。[125] 科学革命に触発された啓蒙主義は、改善と進歩の理想を体現した。デカルトとアイザック・ニュートンは、人間の知的達成の模範とみなされた。コンドルセは 『人間精神の進歩のスケッチ』(1794年)で、原始社会から農耕社会、文字の発明、そして印刷機の発明を経て、「科学と哲学が権威のくびきを脱する時 代」へと進歩する人類について書いた。 フランスの作家ピエール・ベールはスピノザを汎神論者として非難した(それによってスピノザを無神論者として非難した)。ベールの批判はスピノザにとって 大きな注目を集めるものとなった。18世紀後半の汎神論論争では、ゴットホルト・レッシングがフリードリヒ・ハインリヒ・ヤコービからスピノザの汎神論を 支持したことで攻撃された。メンデルスゾーンは汎神論から離れ、ゴットフリート・ヴィルヘルム・ライプニッツに従って、神と世界は同一の物質(同等)では ないと主張したが、レスリングはモーゼス・メンデルスゾーンに擁護された。スピノザはオランダのセファルディム社会から破門されたが、世俗主義への道を導 くユダヤの源を求めたユダヤ人にとって、スピノザはヴォルテールやカントと同様に重要であった。[127] |

| 19th century In the early 19th century, the systematic urbanization process (migration from villages in search of jobs in manufacturing centers) had begun, and the concentration of labor into factories led to the rise in the population of the towns. World population had been rising as well. It is estimated to have first reached one billion in 1804.[128] Also, the new philosophical movement later known as Romanticism originated, in the wake of the previous Age of Reason of the 1600s and the Enlightenment of 1700s. These are seen as fostering the 19th century Western world's sustained economic development.[129] Before the urbanization and industrialization of the 1800s, demand for oriental goods such as porcelain, silk, spices and tea remained the driving force behind European imperialism in Asia, and (with the important exception of British East India Company rule in India) the European stake in Asia remained confined largely to trading stations and strategic outposts necessary to protect trade.[130] Industrialization, however, dramatically increased European demand for Asian raw materials; and the severe Long Depression of the 1870s provoked a scramble for new markets for European industrial products and financial services in Africa, the Americas, Eastern Europe, and especially in Asia (Western powers exploited their advantages in China for example by the Opium Wars).[131] This resulted in the "New Imperialism", which saw a shift in focus from trade and indirect rule to formal colonial control of vast overseas territories ruled as political extensions of their mother countries.[i] The later years of the 19th century saw the transition from "informal imperialism" (hegemony)[j] by military influence and economic dominance, to direct rule (a revival of colonial imperialism) in the African continent and Middle East.[135] During the socioeconomically optimistic and innovative decades of the Second Industrial Revolution between the 1870s and 1914, also known as the "Beautiful Era", the established colonial powers in Asia (United Kingdom, France, Netherlands) added to their empires also vast expanses of territory in the Indian Subcontinent and Southeast Asia. Japan was involved primarily during the Meiji period (1868–1912), though earlier contacts with the Portuguese, Spaniards and Dutch were also present in the Japanese Empire's recognition of the strategic importance of European nations. Traditional Japanese society became an industrial and militarist power like the Western British Empire and the French Third Republic, and similar to the German Empire.[verification needed][citation needed] At the close of the Spanish–American War in 1898 the Philippines, Puerto Rico, Guam and Cuba were ceded to the United States under the terms of the Treaty of Paris. The US quickly emerged as the new imperial power in East Asia and in the Pacific Ocean area. The Philippines continued to fight against colonial rule in the Philippine–American War.[136] By 1913, the British Empire held sway over 412 million people, 23% of the world population at the time,[137] and by 1920, it covered 35,500,000 km2 (13,700,000 sq mi),[138] 24% of the Earth's total land area.[139] At its apex, the phrase "the empire on which the sun never sets" described the British Empire, because its expanse around the globe meant that the sun always shone on at least one of its territories.[140] As a result, its political, legal, linguistic and cultural legacy is widespread throughout the Western world.[citation needed] In the aftermath of the Second World War, decolonizing efforts were employed by all Western powers under United Nations (ex-League of Nations) international directives.[citation needed] Most of colonized nations received independence by 1960. Great Britain showed ongoing responsibility for the welfare of its former colonies as member states of the Commonwealth of Nations. But the end of Western colonial imperialism saw the rise of Western neocolonialism or economic imperialism. Multinational corporations came to offer "a dramatic refinement of the traditional business enterprise", through "issues as far ranging as national sovereignty, ownership of the means of production, environmental protection, consumerism, and policies toward organized labor." Though the overt colonial era had passed, Western nations, as comparatively rich, well-armed, and culturally powerful states, wielded a large degree of influence throughout the world, and with little or no sense of responsibility toward the peoples impacted by its multinational corporations in their exploitation of minerals and markets.[141][142] The dictum of Alfred Thayer Mahan is shown to have lasting relevance, that whoever controls the seas controls the world.[143] |

19世紀 19世紀初頭には、組織的な都市化プロセス(製造業の中心地での職を求めての村からの移住)が始まり、労働力の工場への集中が都市人口の増加につながっ た。世界の人口も増加していた。1804年に初めて10億人に達したと推定されている。[128] また、1600年代の啓蒙時代と1700年代の啓蒙主義を経て、後にロマン主義として知られることになる新しい哲学運動が起こった。これらは19世紀の西 洋世界の持続的な経済発展を促進したと見られている。[129] 1800年代の都市化と工業化以前は、陶磁器、絹、香辛料、茶などの東洋の産物に対する需要が、ヨーロッパによるアジアの帝国主義の推進力であり続け、 (インドにおけるイギリス東インド会社の支配という重要な例外はあるものの)ヨーロッパのアジアにおける利害関係は、貿易を保護するために必要な貿易拠点 や戦略的前哨基地にほぼ限定されていた。 しかし、産業化によりヨーロッパのアジアの原材料に対する需要は劇的に増加した。1870年代の深刻な世界恐慌は、ヨーロッパの工業製品や金融サービスの 新たな市場を求めて、アフリカ、アメリカ、東ヨーロッパ、そして特にアジアで市場争奪戦を引き起こした(西欧諸国は、例えばアヘン戦争によって中国での優 位性を確保した)。 [131] これが「新帝国主義」へとつながり、貿易や間接統治から、広大な海外領土を本国政治の延長として正式に植民地支配する方向へと転換した。[i] 19世紀後半には、軍事的影響力や経済的支配による「非公式な帝国主義」(覇権)[j]から、アフリカ大陸や中東における直接統治(植民地帝国主義の復 活)へと移行した。 [135] 1870年代から1914年までの第二産業革命の時代は、社会経済的に楽観的で革新的な数十年間であり、「美しい時代」とも呼ばれた。この時代にアジアの 既成の植民地大国(イギリス、フランス、オランダ)は、インディアン亜大陸と東南アジアの広大な領土も自らの帝国に加えた。日本は主に明治時代(1868 年~1912年)にこれに関与したが、それ以前にもポルトガル人、スペイン人、オランダ人との接触があり、ヨーロッパ諸国の戦略的重要性を認識していた。 伝統的な日本社会は、西洋の英国帝国やフランス第三共和政のような産業・軍国主義国家となり、ドイツ帝国にも似ていた。 1898年の米西戦争の終結により、パリ条約の条項に基づき、フィリピン、プエルトリコ、グアム、キューバがアメリカ合衆国に割譲された。アメリカは急速 に東アジアおよび太平洋地域における新たな帝国勢力として台頭した。フィリピンは、米比戦争で植民地支配に抵抗し続けた。 1913年までに、大英帝国は当時世界人口の23%にあたる4億1200万人を支配下に置き[137]、1920年には35,500,000km2 (13,700,000平方マイル)[138]、地球上の陸地の総面積の24%を占めるようになった。 [139] その最盛期には、「日没することのない帝国」という表現が大英帝国を形容していた。なぜなら、大英帝国は地球上の至る所に領土を広げていたため、常に少な くともその領土の1つには太陽が照っていたからである。[140] その結果、その政治、法律、言語、文化の遺産は西洋世界全体に広がっている。 [要出典]第二次世界大戦後、国連(旧国際連盟)の国際指令の下、すべての西側諸国が植民地解放の努力を行った。[要出典]1960年までに、ほとんどの 植民地国が独立を果たした。イギリスは、英連邦の加盟国として、かつての植民地の福祉に対して継続的な責任を示した。しかし、西側諸国の植民地帝国主義の 終焉は、西側諸国の新植民地主義または経済的帝国主義の台頭を招いた。多国籍企業は、「国家主権、生産手段の所有、環境保護、消費者主義、組織労働者に対 する政策など、幅広い問題」を通じて、「従来の企業経営を劇的に洗練」するようになった。植民地支配の時代は終わったものの、相対的に裕福で、軍備も充実 し、文化的に強力な国家として、欧米諸国は世界中に大きな影響力を持ち、鉱物資源や市場の搾取において、多国籍企業が影響を及ぼした人々に対しては、ほと んど、あるいはまったく責任を感じていなかった。[141][142] アルフレッド・セイヤー・マハンの言葉は、今なお妥当性を持ち続けている。「海を支配する者が世界を支配する」という言葉である。[143] |

| Cold War (1947–1991) Main article: Cold War This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (April 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) During the Cold War, a new definition emerged. Earth was divided into three "worlds". The First World, analogous in this context to what was called the West, was composed of NATO members and other countries aligned with the United States. The Second World was the Eastern bloc in the Soviet sphere of influence, including the Soviet Union (15 republics including the then occupied but now independent Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania) and Warsaw Pact countries like Poland, Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania, East Germany (now united with West Germany), and Czechoslovakia (now split into the Czech Republic and Slovakia). The Third World consisted of countries, many of which were unaligned with either the west or the east; important members included India, Yugoslavia, Finland (Finlandization) and Switzerland (Swiss Neutrality); some include the People's Republic of China, though this is disputed, since the People's Republic of China, as communist, had friendly relations—at certain times—with the Soviet bloc, and had a significant degree of importance in global geopolitics. Some Third World countries aligned themselves with either the US-led West or the Soviet-led Eastern bloc. A number of countries did not fit comfortably into this neat definition of partition, including Switzerland, Sweden, Austria, and Ireland, which chose to be neutral. Finland was under the Soviet Union's military sphere of influence (see FCMA treaty) but remained neutral and was not communist, nor was it a member of the Warsaw Pact or Comecon but a member of the EFTA from 1986, and was west of the Iron Curtain. In 1955, when Austria again became a fully independent republic, it did so under the condition that it remain neutral; but as a country to the west of the Iron Curtain, it was in the United States' sphere of influence. Spain did not join NATO until 1982, seven years after the death of the authoritarian Franco. The 1980s advent of Mikhail Gorbachev led to the end of the Cold War following the dissolution of the Soviet Union. |

冷戦(1947年 - 1991年) 詳細は「冷戦」を参照 この節には出典が全く示されていない。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。出典のない項目は、異議申し立てにより削除される場合があります。 (2021年4月) (Learn how and when to remove this message) 冷戦中、新たな定義が生まれた。地球は3つの「世界」に分けられた。第1世界は、この文脈では西側諸国と呼ばれたものと類似しており、NATO加盟国とアメリカ合衆国と同盟を結ぶその他の国々で構成されていた。 第二世界は、ソビエト連邦の影響下にある東欧圏で、ソビエト連邦(当時占領下にあったが、現在は独立したエストニア、ラトビア、リトアニアを含む15の共 和国)、ポーランド、ブルガリア、ハンガリー、ルーマニア、東ドイツ(現在は西ドイツと統一)、チェコスロバキア(現在はチェコ共和国とスロバキアに分 裂)などのワルシャワ条約機構加盟国が含まれる。 第三世界は、西側にも東側にも属さない国々で構成されていた。重要なメンバーには、インド、ユーゴスラビア、フィンランド(フィンランド化)、スイス(ス イスの中立)などが含まれる。一部には中華人民共和国も含まれるが、これは議論の余地がある。中華人民共和国は共産主義国家として、ソ連圏と友好関係に あった時期があり、また世界的な地政学上も重要な国であったからだ。一部の第三世界諸国は、米国を中心とする西側陣営またはソ連を中心とする東側陣営のい ずれかに加担した。 スイス、スウェーデン、オーストリア、アイルランドなど、中立の立場を選んだ国々を含め、多くの国々がこの明確な区分にうまく当てはまらない。フィンラン ドはソビエト連邦の軍事的な影響下にあったが(フィンランド条約を参照)、中立の立場を維持し、共産主義でもワルシャワ条約機構やコメコンの加盟国でもな く、1986年からは欧州自由貿易連合(EFTA)の加盟国となり、鉄のカーテンの西側に位置していた。1955年、オーストリアが再び完全な独立共和国 となった際には、中立の立場を維持することが条件とされた。しかし、鉄のカーテンの西側に位置する国として、米国の影響下にあった。スペインは、独裁者フ ランコの死から7年後の1982年になってようやくNATOに加盟した。 1980年代に登場したミハイル・ゴルバチョフは、ソビエト連邦の崩壊を経て、冷戦の終結をもたらした。 |

Modern definitions Asia (as the "Eastern world"), the Arab world, and Africa The exact scope of the Western world is somewhat subjective in nature, depending on whether cultural, economic, spiritual or political criteria are employed. It is a generally accepted Western view to recognize the existence of at least three "major worlds" (or "cultures", or "civilizations"), broadly in contrast with the Western: the Eastern world, the Arab and the African worlds, with no clearly specified boundaries. Additionally, Latin American and Orthodox European worlds are sometimes either a sub-civilization within Western civilization or separately considered "akin" to the West.  Latin America and Orthodox worlds[image reference needed] Many anthropologists, sociologists and historians oppose "the West and the Rest" in a categorical manner.[144] The same has been done by Malthusian demographers with a sharp distinction between European and non-European family systems. Among anthropologists, this includes Durkheim, Dumont, and Lévi-Strauss.[144] |

現代的な定義では、 アジア(「東洋」)、アラブ世界、アフリカ 西洋に含まれる。西洋の範囲は、文化、経済、精神、政治のどの基準を用いるかによって、ある程度主観的なものとなる。西洋と対比される「主要な世界」(ま たは「文化」、「文明」)として、明確な境界線が定められていない「東洋世界」、「アラブ世界」、「アフリカ世界」の少なくとも3つが存在するという見方 は、西洋では一般的に受け入れられている。さらに、ラテンアメリカ世界と正教ヨーロッパ世界は、西洋文明内の亜文明であるか、または西洋と「同類」である とみなされることもある。  ラテンアメリカと正教世界[画像参照] 多くの人類学者、社会学者、歴史家は、「西洋とその他」という区分に断固として反対している。[144] マルサスの人口統計学者も、ヨーロッパと非ヨーロッパの家族制度を明確に区別している。人類学者の中では、デュルケーム、デュモン、レヴィ=ストロースな どがこれに該当する。[144] |

| Cultural definition Further information: Western culture, Culture of Europe, and Culture of the United States The Oxford English dictionary noted that the earliest use of the term "Western world" in the English language was in 1586, found in the writings of William Warner.[13] In modern usage, Western world refers to Europe and to areas whose populations largely originate from Europe, through the Age of Discovery's imperialism.[145][146][147] In the 20th century, Christianity declined in influence in many Western countries, mostly in the European Union where some member states have experienced falling church attendance and membership in recent years,[148] and also elsewhere. Secularism (separating religion from politics and science) increased. However, while church attendance is in decline, in some Western countries (i.e. Italy, Poland, and Portugal), more than half of the people state that religion is important,[149] and most Westerners nominally identify themselves as Christians (e.g. 59% in the United Kingdom) and attend church on major occasions, such as Christmas and Easter. In the Americas, Christianity continues to play an important societal role, though in areas such as Canada, a low level of religiosity is common due to a European-type secularization. The official religions of the United Kingdom and some Nordic countries are forms of Christianity, while the majority of European countries have no official religion. Despite this, Christianity, in its different forms, remains the largest faith in most Western countries.[150] Christianity remains the dominant religion in the Western world, where 70% are Christians.[151] A 2011 Pew Research Center survey found that 76.2% of Europeans, 73.3% in Oceania, and about 86.0% in the Americas (90% in Latin America and the Caribbean and 77.4% in Northern America) described themselves as Christians.[151][152] Since the mid-twentieth century, the west became known for its irreligious sentiments, following the Age of Enlightenment and the French Revolution, inquisitions were abolished in the 19th and 20th centuries, this hastened the separation of church and state, and secularization of the Western world where unchurched spirituality is gaining more prominence over organized religion.[153] Certain parts of the Western world have become notable for their diversity since the late 1960s.[23][24] Earlier, between the eighteenth century to mid-twentieth century, prominent western countries like the United States, Canada, Brazil, Argentina, Australia, and New Zealand have been once envisioned as homelands for whites.[18][19][20] Racism has been noted as a contributing factor to Westerners' colonization of the New World, which makes up much of the geographical West today.[21][22] Countries in the Western world are also the most keen on digital and televisual media technologies, as they were in the postwar period on television and radio: from 2000 to 2014, the Internet's market penetration in the West was twice that in non-Western regions.[154] |

文化の定義 さらに詳しい情報:西洋文化、ヨーロッパ文化、アメリカ文化 オックスフォード英語辞典によると、英語で「西洋世界」という用語が最初に使用されたのは1586年で、ウィリアム・ワーナーの著作に見られるという。 現代の用法では、「西洋世界」はヨーロッパと、大航海時代の帝国主義を通じてヨーロッパから人口の多くが派生した地域を指す。 20世紀には、多くの西洋諸国でキリスト教の影響力が低下した。特に欧州連合(EU)では、近年、一部の加盟国で教会への出席者数や会員数が減少してい る。世俗主義(宗教と政治、科学を分離する)が強まった。しかし、教会への出席率が低下している一方で、一部の西側諸国(イタリア、ポーランド、ポルトガ ルなど)では、国民の半数以上が宗教を重要視していると回答しており[149]、ほとんどの西側諸国の人々は名目上はキリスト教徒と自認しており(例え ば、英国では59%)、クリスマスやイースターなどの主要な行事には教会に出席している。アメリカ大陸では、キリスト教は依然として重要な社会的役割を果 たしているが、カナダなどの地域では、ヨーロッパ型の世俗化により、宗教心の低さが一般的である。イギリスや北欧諸国の一部では、キリスト教が国教とされ ているが、ヨーロッパ諸国の大部分には国教はない。にもかかわらず、キリスト教は、その異なる形態で、ほとんどの西側諸国で最大の信仰であり続けている。 キリスト教は西洋世界では依然として支配的な宗教であり、70%がキリスト教徒である。[151] 2011年のピュー・リサーチ・センターの調査では、ヨーロッパ人の76.2%、オセアニアの73.3%、アメリカ大陸の約86.0%(ラテンアメリカお よびカリブ海地域の90%、北アメリカ大陸の77.4%)がキリスト教徒であると回答している。 [151][152] 20世紀半ば以降、西洋は無宗教の感情で知られるようになった。啓蒙時代やフランス革命を経て、19世紀と20世紀には異端審問が廃止され、これが教会と 国家の分離を早め、西洋世界の世俗化が進んだ。その結果、組織化された宗教よりも無宗教の精神性がより注目されるようになった。 1960年代後半以降、西洋世界の特定の地域では、その多様性が際立っている。[23][24] それ以前の18世紀から20世紀半ばにかけては、アメリカ合衆国、カナダ、ブラジル、アルゼンチン、オーストラリア、ニュージーランドといった著名な西洋 諸国は、白人たちの故郷として考えられていた。 [18][19][20] 人種主義は、西洋人が現在の地理的な西半球の大部分を占める新大陸を植民地化した要因のひとつであると指摘されている。 西洋諸国は、テレビやラジオが戦後にそうであったように、デジタルおよびテレビメディア技術にも最も熱心に取り組んでいる。2000年から2014年にかけて、西洋におけるインターネットの市場浸透率は、非西洋地域における浸透率の2倍であった。[154] |

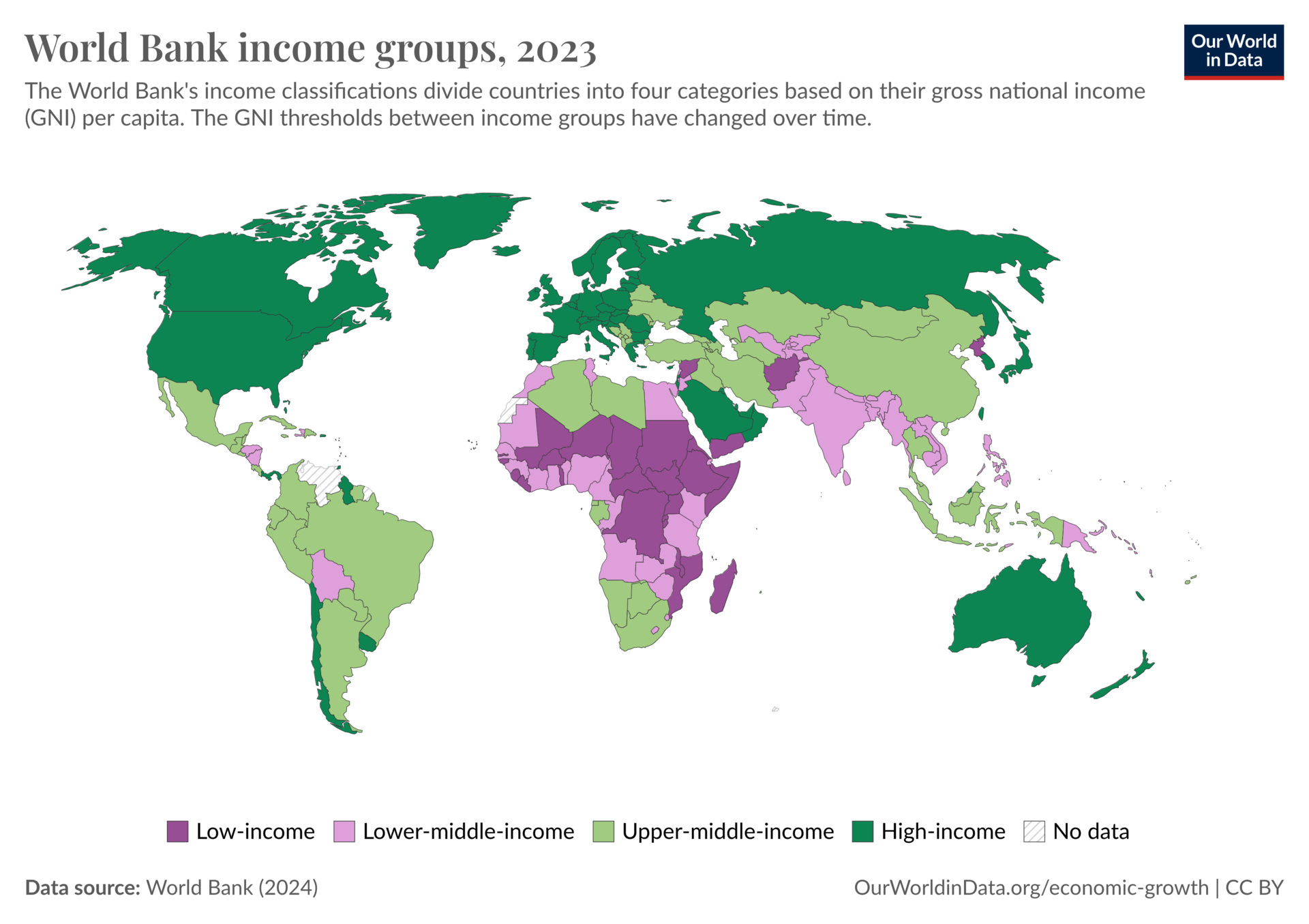

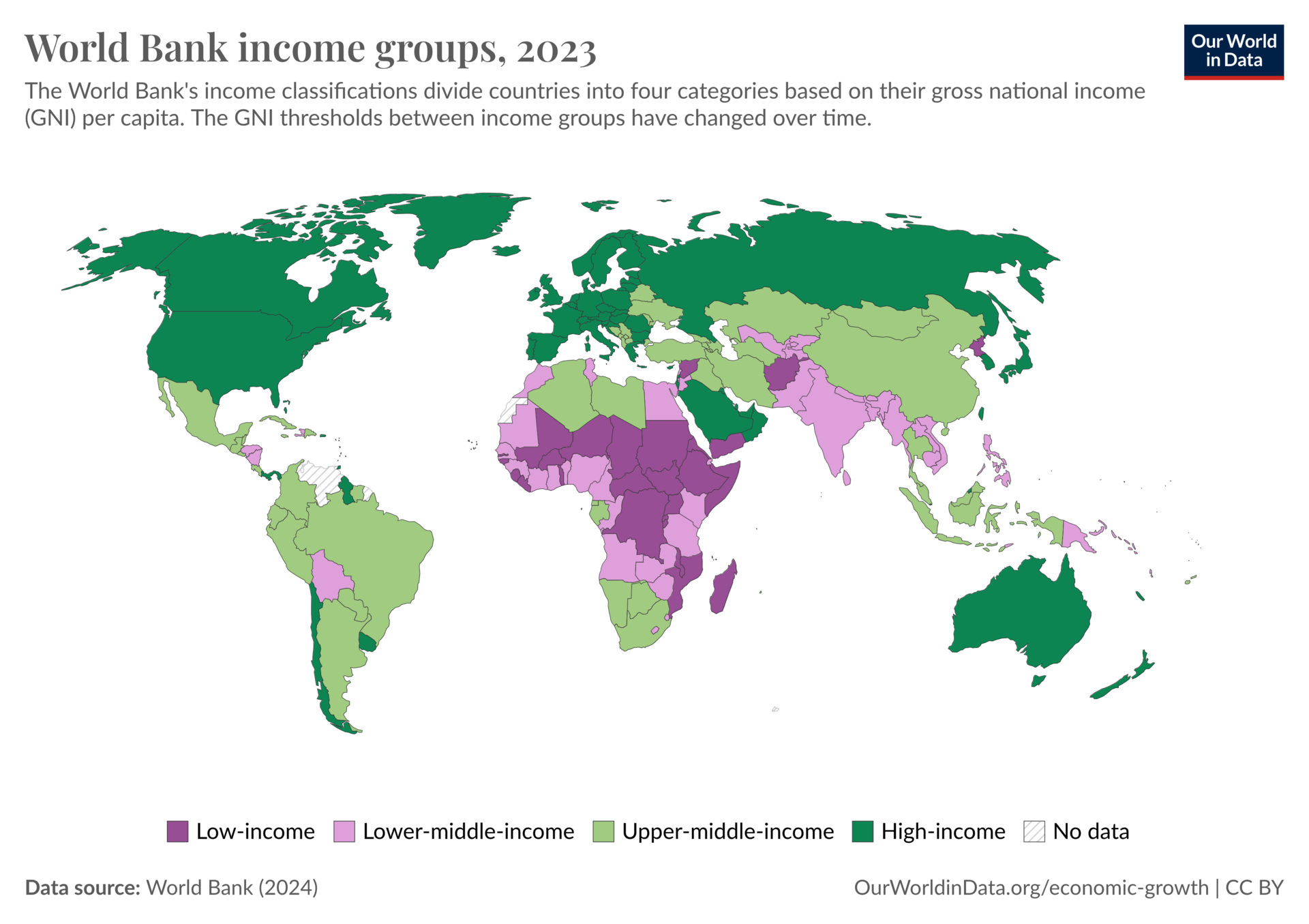

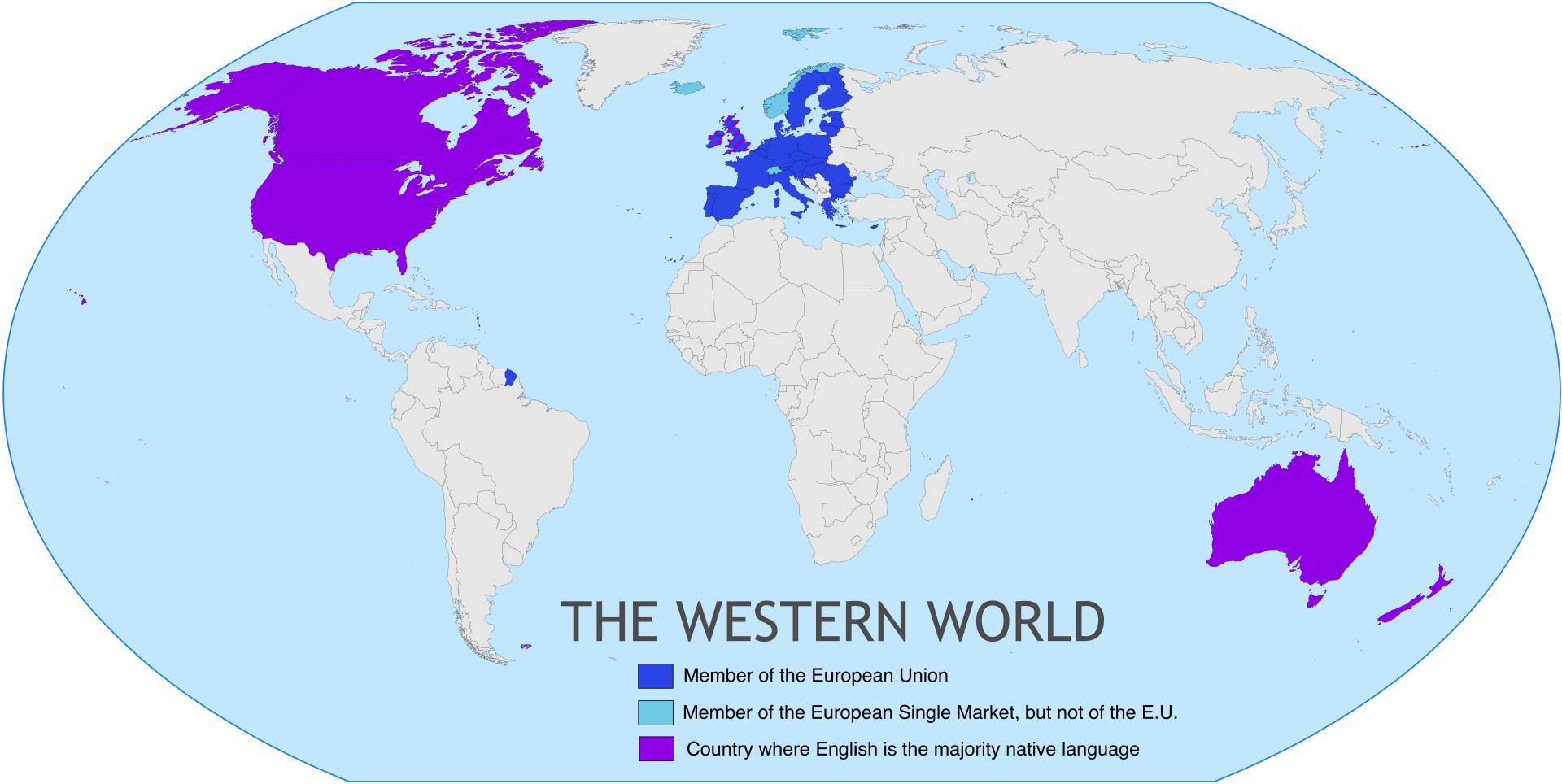

Economic definition Countries by income group  Map of the Western world consisting of the anglosphere (as defined by James Bennett), the European Union and European Single Market members, 2017 The term "Western world" is sometimes interchangeably used with the term First World or developed countries, stressing the difference between First World and the Third World or developing countries. This usage occurs despite the fact that many countries that may be culturally Western are developing countries – in fact, a significant percentage of the Americas are developing countries. It is also used despite many developed countries or regions not being culturally Western (e.g. Japan, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macao). Privatization policies (involving government enterprises and public services) and multinational corporations are often considered a visible sign of Western nations' economic presence, especially in Third World countries, and represent a common institutional environment for powerful politicians, enterprises, trade unions and firms, bankers and thinkers of the Western world.[155][156][157][158][159] |

経済的な定義 所得グループ別の国々  ジェームズ・ベネットが定義したアングロサクソンの世界、欧州連合および欧州単一市場の加盟国からなる西側諸国の地図、2017年 「西洋世界」という用語は、第1世界または先進国という用語と置き換えて使用されることがあり、第1世界と第3世界または発展途上国との間の相違を強調す る。この用法は、文化的に西洋的であると考えられる多くの国々が発展途上国であるという事実にもかかわらず使用される。実際、アメリカ大陸の相当な割合が 発展途上国である。また、多くの先進国や地域が文化的に西洋的ではないにもかかわらず使用される(例えば、 日本、シンガポール、韓国、台湾、香港、マカオなど)。 民営化政策(政府系企業や公共サービスを含む)や多国籍企業は、特に第三世界の国々において、西洋諸国の経済的影響力の目に見える兆候であると見なされる ことが多く、西洋世界の強力な政治家、企業、労働組合、企業、銀行家、思想家にとって共通の制度的環境を表している。[155][156][157] [158][159] |

| Other views A series of scholars of civilization, including Arnold J. Toynbee, Alfred Kroeber and Carroll Quigley have identified and analyzed "Western civilization" as one of the civilizations that have historically existed and still exist today. Toynbee entered into quite an expansive mode, including as candidates those countries or cultures who became so heavily influenced by the West as to adopt these borrowings into their very self-identity. Carried to its limit, this would in practice include almost everyone within the West, in one way or another. In particular, Toynbee refers to the intelligentsia formed among the educated elite of countries impacted by the European expansion of centuries past. While often pointedly nationalist, these cultural and political leaders interacted within the West to such an extent as to change both themselves and the West.[64] The theologian and paleontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin conceived of the West as the set of civilizations descended from the Nile Valley Civilization of Egypt.[160] Palestinian-American literary critic Edward Said uses the term "Occident" in his discussion of Orientalism. According to his binary, the West, or Occident, created a romanticized vision of the East, or Orient, to justify colonial and imperialist intentions. This Occident-Orient binary focuses on the Western vision of the East instead of any truths about the East. His theories are rooted in Hegel's master-slave dialectic: The Occident would not exist without the Orient and vice versa.[citation needed] Further, Western writers created this irrational, feminine, weak "Other" to contrast with the rational, masculine, strong West because of a need to create a difference between the two that would justify imperialist ambitions, according to the Said-influenced Indian-American theorist Homi K. Bhabha.[citation needed] The idea of "the West" over the course of time has evolved from a directional concept to a sociopolitical concept, and has been temporalized and rendered as a concept of the future bestowed with notions of progress and modernity.[15] |

その他の見解 アーノルド・J・トインビー、アルフレッド・クロバー、キャロル・クィグリーなど、文明論の学者たちは、「西洋文明」を歴史的に存在し、現在も存在する文 明の一つとして特定し、分析している。トインビーは、西洋の影響を非常に強く受け、その影響を自己同一性の一部として取り入れた国や文化を候補として含め るなど、かなり広義の定義を提示している。極端に言えば、これは事実上、西洋のほぼすべての人々を何らかの形で含むことになる。特にトインビーは、過去数 世紀にわたるヨーロッパの拡大の影響を受けた国の教育を受けたエリート層から形成された知識階級について言及している。これらの文化および政治のリーダー たちは、しばしば顕著なナショナリストであったが、西洋内部で相互に影響し合い、西洋と彼ら自身の両方を変えるほどの影響力を持っていた。 神学者であり古生物学者でもあったピエール・テイヤール・ド・シャルダンは、西洋をエジプトのナイル渓谷文明に由来する一連の文明として捉えていた。 パレスチナ系アメリカ人の文学評論家エドワード・サイードは、オリエンタリズムの議論の中で「西洋」という用語を使用している。彼の二元論によると、西 洋、すなわち西洋は、植民地主義や帝国主義の意図を正当化するために、東洋、すなわち東をロマンチックに描いたビジョンを作り出した。この西洋と東洋の二 元論は、東洋に関する真実ではなく、西洋の東洋観に焦点を当てている。彼の理論はヘーゲルの主従弁証法に根ざしている。西洋は東洋なしには存在せず、その 逆もまた真である。[要出典] さらに、西洋の作家たちは、帝国主義的野望を正当化するために、西洋と異なるものを作り出す必要があったため、この非合理的で女性的で弱い「他者」を作り 出した。これは、サイードの影響を受けたインディアン・アメリカ人の理論家ホミ・K・バハーによると、西洋の理論家たちによるものだという。[要出典] 「西洋」という概念は、時代とともに方向性を示す概念から社会政治的な概念へと発展し、時間軸が加えられ、進歩と近代性の概念を備えた未来の概念として描かれるようになった。[15] |

| Americas Anti-Western sentiment Atlanticism East–West dichotomy Far West Global Northwest Global North and Global South Monroe Doctrine Western Hemisphere Western Culture Greater Europe |

アメリカ大陸 反西洋感情 大西洋主義 東西二元論 極西部 グローバル北西部 グローバル北とグローバル南 モンロー主義 西半球 西洋文化 大ヨーロッパ |