ホイッグ党

Whigs (British political party) , 1678-1859

☆ホイッグ党(The Whigs)はイングランド、スコットランド、アイルランド、グレートブリテン、イギリスの議会における政党である。1680年代から1850年代にかけて、ホイッグはライバルのトリーと政権を争った。ホイッグ党は1850年代にピール派と急進派と合併して自由党となった。多くのホイッグ党は1886年にアイルランド自治領問題で自由党を離党し、自由ユニオニスト党を結成、1912年に保守党に合併した。 ホイッグ党は絶対王政とカトリック解放に反対し、立憲君主制と議会政治を支持する政治派閥として出発したが、プロテスタント至上主義も支持していた。彼らは1688年の名誉革命で中心的な役割を果たし、ローマ・カトリックのスチュアート王と僭称者の永遠の敵であった。ホイッグ至上主義として知られる時代(1714年~1760年)は、1714年のジョージ1世のハノーヴァー継承と、1715年のジャコバイトの反乱の失敗によって可能となった。ホ イッグは1715年に政府を完全に掌握し、政府、軍隊、英国国教会、法曹界、地方政界のすべての主要役職からトーリーを徹底的に粛清した。ホイッグの最初 の偉大な指導者はロバート・ウォルポールで、1721年から1742年まで政権を掌握し、その子分のヘンリー・ペラムが1743年から1754年まで政権 を率いた。1760年に国王ジョージ3世が即位し、トーリー党の復帰を認めるまで、イギリスはホイッグ党のもとで一党独裁に近い状態を保っていた。しか し、ホイッグ党の権力保持力はその後も長年にわたって強固なままであった。そのため歴史家は、およそ1714年から1783年までの期間を「ホイッグ寡頭 政治の長い期間」と呼んでいる。アメリカ独立戦争中、ホイッグ党はアメリカの独立とアメリカにおける民主主義の創設により同情的な政党であった。 1784年までには、ホイッグとトリーはともに正式な政党となり、チャールズ・ジェームズ・フォックスは、ウィリアム・ピット・ザ・ヤンガーの新トリーに 対抗して再編成されたホイッグ党の党首となった。両党の基盤は、民衆の投票よりも裕福な政治家の支持に依存していた。下院選挙はあったものの、有権者の大 半を支配していたのは少数の人物に過ぎなかった。 両党は18世紀にゆっくりと発展した。当初、ホイッグ党は一般に貴族階級を支持し、カトリック教徒の権利を剥奪し続け、プロテスタント(長老派のような異教徒)を容認する傾向があった。一方、トーリィ党は一般に小貴族や(比較的)小作農の人々を支持し、また強固に確立された英国国教会の正当性を支持した。(いわゆるハイ・トリーは、高教会の英国国教会(アングロ・カトリック)を好んだ。一部の者、特に非純血分裂派の信奉者は、ジャコビティズムとして知られる亡命スチュアート家の王位継承権を公然または秘密裏に支持した)。その後、ホイッグは新興の産業改革派や商人層から支持を集めるようになり、一方、トリーは農民、地主、王党派、(それに関連して)帝国の軍事支出を支持する人々から支持を集めるようになった。 19世紀前半までに、ホイッグのマニフェストは議会の優越性、奴隷制の廃止、選挙権(参政権)の拡大、カトリック教徒の完全な平等権への動きの加速(過激に反カトリックを掲げていた17世紀後半の党の立場からの逆転)を包含するようになっていた。

| The Whigs were a

political party in the Parliaments of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great

Britain and the United Kingdom. Between the 1680s and the 1850s, the

Whigs contested power with their rivals, the Tories. The Whigs became

the Liberal Party when it merged with the Peelites and Radicals in the

1850s. Many Whigs left the Liberal Party in 1886 over the issue of

Irish Home Rule to form the Liberal Unionist Party, which merged into

the Conservative Party in 1912. The Whigs began as a political faction that opposed absolute monarchy and Catholic emancipation, supporting constitutional monarchism and parliamentary government, but also Protestant supremacy. They played a central role in the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and were the standing enemies of the Roman Catholic Stuart kings and pretenders. The period known as the Whig Supremacy (1714–1760) was enabled by the Hanoverian succession of George I in 1714 and the failure of the Jacobite rising of 1715 by Tory rebels. The Whigs took full control of the government in 1715 and thoroughly purged the Tories from all major positions in government, the army, the Church of England, the legal profession, and local political offices. The first great leader of the Whigs was Robert Walpole, who maintained control of the government from 1721 to 1742, and whose protégé, Henry Pelham, led the government from 1743 to 1754. Great Britain approximated a one-party state under the Whigs until King George III came to the throne in 1760 and allowed Tories back in. But the Whig Party's hold on power remained strong for many years thereafter. Thus historians have called the period from roughly 1714 to 1783 the "long period of Whig oligarchy".[13] During the American Revolution, the Whigs were the party more sympathetic to American independence and the creation of a democracy in the United States. By 1784, both the Whigs and Tories had become formal political parties, with Charles James Fox becoming the leader of a reorganized Whig Party arrayed against William Pitt the Younger's new Tories. The foundation of both parties depended more on the support of wealthy politicians than on popular votes. Although there were elections to the House of Commons, only a few men controlled most of the voters. Both parties slowly evolved during the 18th century. In the beginning, the Whig Party generally tended to support the aristocratic families, the continued disenfranchisement of Catholics and toleration of nonconformist Protestants (dissenters such as the Presbyterians), while the Tories generally favoured the minor gentry and people who were (relatively speaking) smallholders; they also supported the legitimacy of a strongly established Church of England. (The so-called High Tories preferred high church Anglicanism, or Anglo-Catholicism. Some, particularly adherents of the non-juring schism, openly or covertly supported the exiled House of Stuart's claim to the throne—a position known as Jacobitism.) Later, the Whigs came to draw support from the emerging industrial reformists and the mercantile class while the Tories came to draw support from farmers, landowners, royalists and (relatedly) those who favoured imperial military spending. By the first half of the 19th century, the Whig manifesto had come to encompass the supremacy of parliament, the abolition of slavery, the expansion of the franchise (suffrage) and an acceleration of the move toward complete equal rights for Catholics (a reversal of the party's late-17th-century position, which had been militantly anti-Catholic).[14] |

ホイッグはイングランド、スコットランド、アイルランド、グレートブリ

テン、イギリスの議会における政党である。1680年代から1850年代にかけて、ホイッグはライバルのトリーと政権を争った。ホイッグ党は1850年代

にピール派と急進派と合併して自由党となった。多くのホイッグ党は1886年にアイルランド自治領問題で自由党を離党し、自由ユニオニスト党を結成、

1912年に保守党に合併した。 ホイッグ党は絶対王政とカトリック解放に反対し、立憲君主制と議会政治を支持する政治派閥として出発したが、プロテスタント至上主義も支持していた。彼ら は1688年の名誉革命で中心的な役割を果たし、ローマ・カトリックのスチュアート王と僭称者の永遠の敵であった。ホイッグ至上主義として知られる時代 (1714年~1760年)は、1714年のジョージ1世のハノーヴァー継承と、1715年のジャコバイトの反乱の失敗によって可能となった。ホイッグは 1715年に政府を完全に掌握し、政府、軍隊、英国国教会、法曹界、地方政界のすべての主要役職からトーリーを徹底的に粛清した。ホイッグの最初の偉大な 指導者はロバート・ウォルポールで、1721年から1742年まで政権を掌握し、その子分のヘンリー・ペラムが1743年から1754年まで政権を率い た。1760年に国王ジョージ3世が即位し、トーリー党の復帰を認めるまで、イギリスはホイッグ党のもとで一党独裁に近い状態を保っていた。しかし、ホ イッグ党の権力保持力はその後も長年にわたって強固なままであった。そのため歴史家は、およそ1714年から1783年までの期間を「ホイッグ寡頭政治の 長い期間」と呼んでいる[13]。アメリカ独立戦争中、ホイッグ党はアメリカの独立とアメリカにおける民主主義の創設により同情的な政党であった。 1784年までには、ホイッグとトリーはともに正式な政党となり、チャールズ・ジェームズ・フォックスは、ウィリアム・ピット・ザ・ヤンガーの新トリーに 対抗して再編成されたホイッグ党の党首となった。両党の基盤は、民衆の投票よりも裕福な政治家の支持に依存していた。下院選挙はあったものの、有権者の大 半を支配していたのは少数の人物に過ぎなかった。 両党は18世紀にゆっくりと発展した。当初、ホイッグ党は一般に貴族階級を支持し、カトリック教徒の権利を剥奪し続け、プロテスタント(長老派のような異 教徒)を容認する傾向があった。一方、トーリィ党は一般に小貴族や(比較的)小作農の人々を支持し、また強固に確立された英国国教会の正当性を支持した。 (いわゆるハイ・トリーは、高教会の英国国教会(アングロ・カトリック)を好んだ。一部の者、特に非純血分裂派の信奉者は、ジャコビティズムとして知られ る亡命スチュアート家の王位継承権を公然または秘密裏に支持した)。その後、ホイッグは新興の産業改革派や商人層から支持を集めるようになり、一方、ト リーは農民、地主、王党派、(それに関連して)帝国の軍事支出を支持する人々から支持を集めるようになった。 19世紀前半までに、ホイッグのマニフェストは議会の優越性、奴隷制の廃止、選挙権(参政権)の拡大、カトリック教徒の完全な平等権への動きの加速(過激 に反カトリックを掲げていた17世紀後半の党の立場からの逆転)を包含するようになっていた[14]。 |

| Name The term Whig began as a short form of whiggamore, a term originally used by people in the north of England to refer to (cattle) drovers from western Scotland who came to Leith to buy corn (the Scottish cattle drivers would call out "Chuig" or "Chuig an bothar"—meaning "away" or "to the road"—this sounded to the English like "Whig", and they came to use the word "Whig" or "Whiggamore" derisively to refer to these people).[15] During the English Civil Wars, when Charles I reigned, the term "Whig" was picked up and used by the English to refer derisively to a radical faction of the Scottish Covenanters who called themselves the Kirk Party (see the Whiggamore Raid). It was later applied to Scottish Presbyterian rebels who were against the king's Episcopalian order in Scotland.[16][17] The word Whig entered English political discourse during the Exclusion Bill crisis of 1679–1681: there was controversy about whether King Charles II's brother, James, Duke of York, should be allowed to succeed to the throne on Charles's death, and Whig became a term of abuse for members of the Country Party, which sought to remove James from the line of succession on the grounds that he was a Roman Catholic (Samuel Johnson, a fervent Tory, often joked that "the first Whig was the Devil".).[18] Eventually, Country Party politicians themselves would start describing their own faction as the "Whigs". In his six-volume history of England, c. 1760, David Hume wrote: The court party reproached their antagonists with their affinity to the fanatical conventiclers in Scotland, who were known by the name of Whigs: The country party found a resemblance between the courtiers and the popish banditti in Ireland, to whom the appellation of Tory was affixed. And after this manner, these foolish terms of reproach came into public and general use; and even at present seem not nearer their end than when they were first invented.[19] |

名称 ウィッグ(Whig)という言葉は、元々はスコットランド西部からトウモロコシを買うためにリース(Leith)にやってきた牛追いの人たちを指す言葉と してイングランド北部の人々が使っていたウィッグガモア(Whiggamore)の短縮形として始まった(スコットランドの牛追いの人たちは「チュイッグ (Chuig)」または「チュイッグ・アン・ボタル(Chuig an bothar)」と呼ぶ-「離れている」または「道へ」という意味-これがイングランド人には「ウィッグ(Whig)」のように聞こえたため、この人たち を揶揄して「ウィッグ(Whig)」または「ウィッグガモア(Whiggamore)」という言葉を使うようになった)。 [15]チャールズ1世が君臨していたイングランドの内戦中、「Whig 」という用語は英国人によって拾われ、自らをカーク党と称するスコットランドのコヴェナント派の急進派を揶揄するのに使われた(ウィッグガモア襲撃事件参 照)。後にスコットランドにおける国王のエピスコパリア教団に反対するスコットランドの長老派の反乱軍にも適用された[16][17]。 チャールズ2世の弟であるヨーク公ジェームズにチャールズの死後王位を継承させるべきかどうかが議論され、ホイッグはジェームズがローマ・カトリック教徒 であることを理由に継承権から排除しようとしたカントリー党のメンバーを罵倒する言葉となった(熱狂的なトーリー党員であったサミュエル・ジョンソンはし ばしば「最初のホイッグは悪魔だ」とジョークを飛ばしていた)[18]。 やがて、カントリー党の政治家たち自身が自分たちの派閥を「ホイッグ」と表現するようになる。 デイヴィッド・ヒュームは1760年頃の6巻からなるイギリス史の中で、次のように書いている: 宮廷党は、ウィッグの名で知られるスコットランドの狂信的な修道院信者と親和性があるとして、敵対勢力を非難した: 田舎党は、宮廷人たちとアイルランドの教皇派の盗賊たちとの間に類似点を見出し、彼らにトーリーという呼称がつけられた。このようにして、これらの愚かな 非難用語は一般に広く使われるようになり、現在でも、それらが最初に考案されたときよりも終わりに近づいていないように思われる[19]。 |

| Origins The parliamentarian faction [icon] This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2024) The precursor to the Whigs was Denzil Holles' parliamentarian faction, which was characterised by its opposition to absolute monarchism. Exclusion Crisis Main articles: Exclusion Crisis and Green Ribbon Club  Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury, painted more than once during his chancellorship in 1672 by John Greenhill Under Lord Shaftesbury's leadership, the Whigs (also known as the Country Party) sought to exclude the Duke of York (who later became King James II) from the throne due to his Roman Catholicism, his favouring of monarchical absolutism, and his connections to France. They believed the heir presumptive, if allowed to inherit the throne, would endanger the Protestant religion, liberty and property.[20] The first Exclusion Bill was supported by a substantial majority on its second reading in May 1679. In response, King Charles prorogued Parliament and then dissolved it, but the subsequent elections in August and September saw the Whigs' strength increase. This new parliament did not meet for thirteen months, because Charles wanted to give passions a chance to die down. When it met in October 1680, an Exclusion Bill was introduced and passed in the Commons without major resistance, but was rejected in the Lords. Charles dissolved Parliament in January 1681, but the Whigs did not suffer serious losses in the ensuing election. The next Parliament first met in March at Oxford, but Charles dissolved it after only a few days, when he made an appeal to the country against the Whigs and determined to rule without Parliament. In February, Charles had made a deal with the French King Louis XIV, who promised to support him against the Whigs. Without Parliament, the Whigs gradually crumbled, mainly due to government repression following the discovery of the Rye House Plot. The Whig peers, the Earl of Melville, the Earl of Leven, and Lord Shaftesbury, and Charles II's illegitimate son the Duke of Monmouth, being implicated, fled to and regrouped in the United Provinces. Algernon Sidney, Sir Thomas Armstrong and William Russell, Lord Russell, were executed for treason. The Earl of Essex committed suicide in the Tower of London over his arrest for treason, whilst Lord Grey of Werke escaped from the Tower.[21] Glorious Revolution  Equestrian portrait of William III by Jan Wyck, commemorating the landing at Brixham, Torbay, 5 November 1688 After the Glorious Revolution of 1688, Queen Mary II and King William III governed with both Whigs and Tories, despite the fact that many of the Tories still supported the deposed Roman Catholic James II.[22] William saw that the Tories were generally friendlier to royal authority than the Whigs and he employed both groups in his government. His early ministry was largely Tory, but gradually the government came to be dominated by the so-called Junto Whigs, a group of younger Whig politicians who led a tightly organised political grouping. The increasing dominance of the Junto led to a split among the Whigs, with the so-called Country Whigs seeing the Junto as betraying their principles for office. The Country Whigs, led by Robert Harley, gradually merged with the Tory opposition in the later 1690s.[23] |

起源 議会派閥 [アイコン] このセクションは拡張が必要だ。追加することで手助けができる。(2024年1月) ホイッグスの前身はデンジル・ホレスの議会派で、絶対君主制への反対を特徴としていた。 排外主義の危機 主な記事 排斥危機とグリーンリボンクラブ  アンソニー・アシュレイ・クーパー、第1代シャフツベリー伯爵(1672年、ジョン・グリーンヒルにより首相在任中に複数回描かれる シャフツベリー卿の指導の下、ホイッグ党(別名カントリー党)は、ヨーク公(後のジェームズ2世)がローマ・カトリックを信仰し、君主絶対主義を支持し、 フランスとつながりがあったことから、ヨーク公を王位から排除しようとした。彼らは、推定相続人が王位を継承することを許せば、プロテスタントの宗教、自 由、財産が危険にさらされると考えていた[20]。 最初の排斥法案は、1679年5月の第二読会で、かなりの賛成多数で支持された。これを受けてチャールズ王は議会を一時休会とし、その後解散したが、8月 と9月に行われた選挙でホイッグ派の勢力が拡大した。この新しい議会は13ヶ月間開かれなかったが、これはチャールズ王が激情が収まるのを待つためであっ た。1680年10月に開かれた議会では、排斥法案が提出され、コモンズでは大きな抵抗もなく可決されたが、貴族院では否決された。チャールズは1681 年1月に議会を解散したが、続く選挙でホイッグ党は大きな敗北を喫することはなかった。次の議会は3月にオックスフォードで初めて開かれたが、チャールズ はわずか数日で解散し、ホイッグ教徒に対する国民へのアピールを行い、議会なしで統治することを決定した。2月、シャルルはフランス王ルイ14世と取引 し、ホイッグ教徒に対する支援を約束していた。議会なきホイッグ家は、ライ・ハウス陰謀事件発覚後の政府の弾圧などにより、徐々に崩壊していった。メル ヴィル伯爵、レーヴェン伯爵、シャフツベリー卿、チャールズ2世の嫡子モンマス公といったホイッグ党の貴族たちは、この陰謀に巻き込まれ、連合諸州に逃れ て再編成された。アルジャーノン・シドニー、トーマス・アームストロング卿、ラッセル公ウィリアム・ラッセルは反逆罪で処刑された。エセックス伯爵は反逆 罪で逮捕されたことを苦にロンドン塔で自殺し、ヴェルケ公グレイは塔から脱出した[21]。 名誉革命(Glorious Revolution)  1688年11月5日、トーベイのブリックスハムへの上陸を記念したヤン・ウィック作のウィリアム3世の騎馬肖像。 1688年の栄光革命後、女王メアリー2世と国王ウィリアム3世は、ホイッグ派とトーリー派の両方とともに政治を行った。初期の政権はトーリ派が中心で あったが、次第に若手のホイッグ政治家グループ、いわゆるジュント・ウィッグが政権を支配するようになり、彼らは緊密に組織化された政治グループを率いて いた。ジュント派の支配が強まるにつれ、いわゆるカントリー・ウィッグ派はジュント派が自分たちの主義主張を裏切って政権に就いたと見なし、ウィッグ派の 分裂を招いた。ロバート・ハーレーに率いられたカントリー・ウィッグスは、1690年代後半になると次第にトーリー派の反対派と合併した[23]。 |

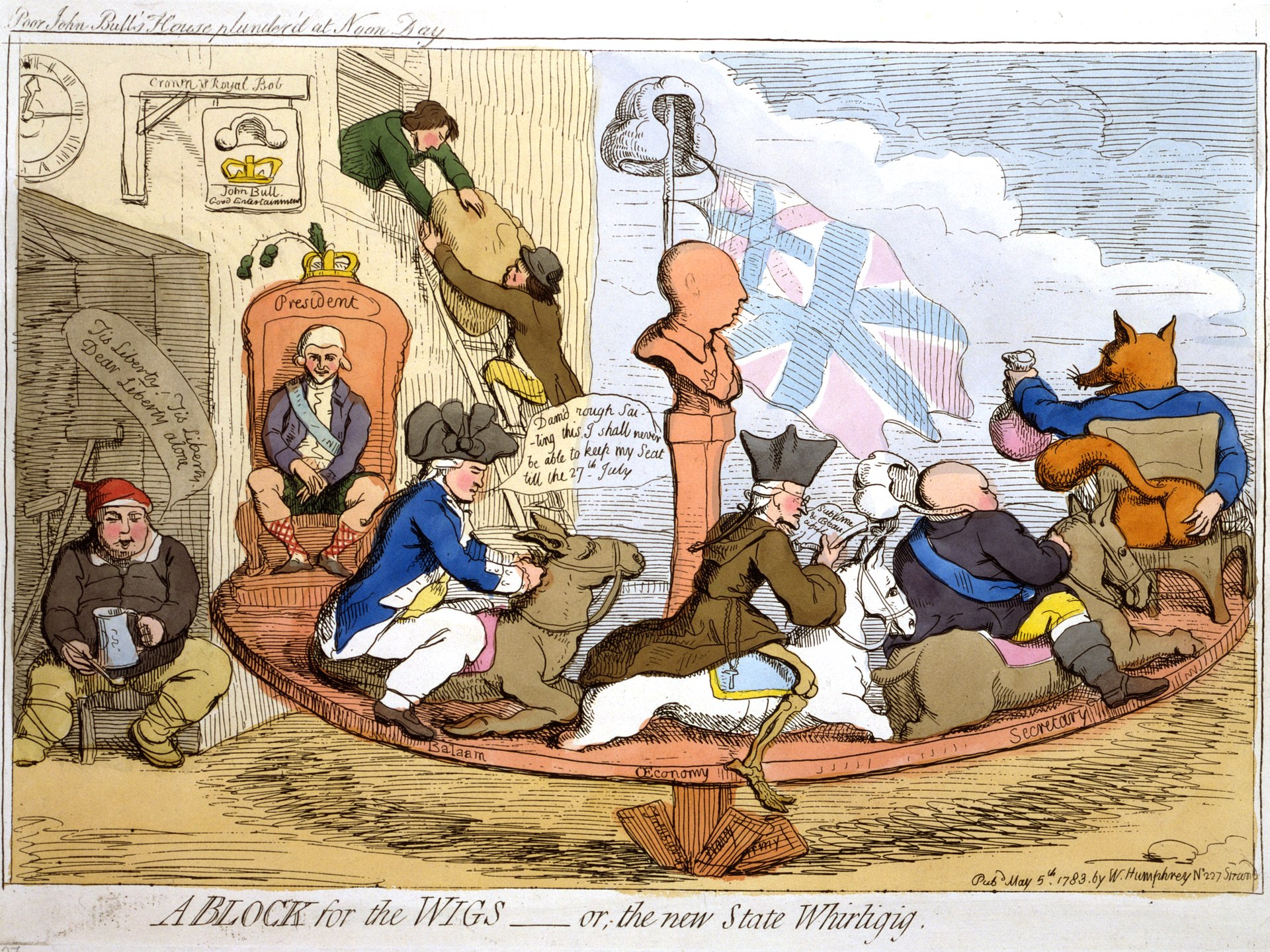

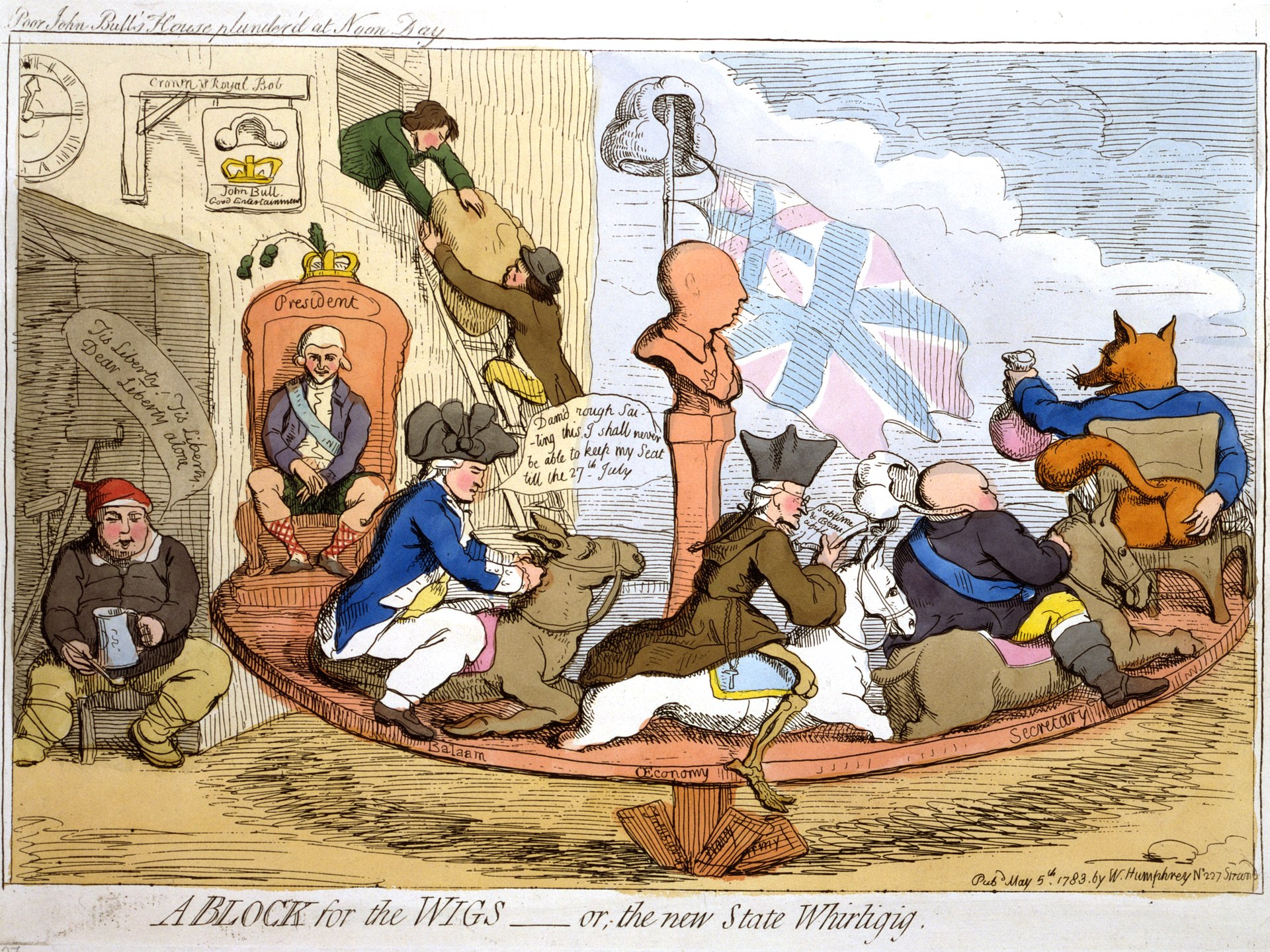

| History 18th century Although William's successor Anne had considerable Tory sympathies and excluded the Junto Whigs from power, after a brief and unsuccessful experiment with an exclusively Tory government she generally continued William's policy of balancing the parties, supported by her moderate Tory ministers, the Duke of Marlborough and Lord Godolphin. However, as the War of the Spanish Succession went on and became less and less popular with the Tories, Marlborough and Godolphin were forced to rely more and more on the Junto Whigs, so that by 1708 they headed an administration of the Parliament of Great Britain dominated by the Junto. Anne herself grew increasingly uncomfortable with this dependence on the Whigs, especially as her personal relationship with the Duchess of Marlborough deteriorated. This situation also became increasingly uncomfortable to many of the non-Junto Whigs, led by the Duke of Somerset and the Duke of Shrewsbury, who began to intrigue with Robert Harley's Tories. In the spring of 1710, Anne dismissed Godolphin and the Junto ministers, replacing them with Tories.[23] The Whigs now moved into opposition and particularly decried the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, which they attempted to block through their majority in the House of Lords. The Tory administration led by Harley and the Viscount Bolingbroke persuaded the Queen to create twelve new Tory peers to force the treaty through.[24] Liberal ideals Main article: Whiggism The Whigs primarily advocated the supremacy of Parliament, while calling for toleration for Protestant dissenters. They adamantly opposed a Catholic as king.[25] They opposed the Catholic Church because they saw it as a threat to liberty, or as Pitt the Elder stated: "The errors of Rome are rank idolatry, a subversion of all civil as well as religious liberty, and the utter disgrace of reason and of human nature".[26] Ashcraft and Goldsmith (1983) have traced in detail, in the period 1689 to 1710, the major influence of the liberal political ideas of John Locke on Whig political values, as expressed in widely cited manifestos such as "Political Aphorisms: or, the True Maxims of Government Displayed", an anonymous pamphlet that appeared in 1690 and was widely cited by Whigs.[27] The 18th-century Whigs borrowed the concepts and language of universal rights employed by political theorists Locke and Algernon Sidney (1622–1682).[28] By the 1770s the ideas of Adam Smith, a founder of classical liberalism became important. As Wilson and Reill (2004) note: "Adam Smith's theory melded nicely with the liberal political stance of the Whig Party and its middle-class constituents".[29] Samuel Johnson (1709–1784), a leading London intellectual, repeatedly denigrated the "vile"[30] Whigs and praised the Tories, even during times of Whig political supremacy. In his great Dictionary (1755), Johnson defined a Tory as "one who adheres to the ancient Constitution of the state and the apostolical hierarchy of the Church of England, opposed to a Whig". He linked 18th-century Whiggism with 17th-century revolutionary Puritanism, arguing that the Whigs of his day were similarly inimical to the established order of church and state. Johnson recommended that strict uniformity in religious externals was the best antidote to the objectionable religious traits that he linked to Whiggism.[31] Protectionism At their inception, the Whigs were protectionist in economic policy, with free trade policies being advocated by Tories.[32] The Whigs were opposed to the pro-French policies of the Stuart kings Charles II and James II as they believed that such an alliance with the Catholic absolute monarchy of France endangered liberty and Protestantism. The Whigs claimed that trade with France was bad for England and developed an economic theory of overbalance, that is a deficit of trade with France was bad because it would enrich France at England's expense.[33] In 1678, the Whigs passed the Prohibition of 1678 that banned certain French goods from being imported into England. The economic historian William Ashley claimed that this Act witnessed the "real starting-point in the history of Whig policy in the matter of trade".[34] It was repealed upon the accession of James II by a Tory-dominated House of Commons but upon the accession of William III in 1688 a new Act was passed that prohibited the importation of French goods.[35] In 1704, the Whigs passed the Trade with France Act that renewed protectionism against France. In 1710, Queen Anne appointed the predominantly Tory Harley Ministry, which favoured free trade. When the Tory minister Lord Bolingbroke proposed a commercial treaty with France in 1713 that would have led to freer trade, the Whigs were vehemently against it and it had to be abandoned.[36] In 1786, Pitt's government negotiated the Eden Agreement, a commercial treaty with France which led to freer trade between the two countries. All of the Whig leaders attacked this on traditional Whig anti-French and protectionist grounds. Fox claimed that France was England's natural enemy and that it was only at Britain's expense that she could grow. Edmund Burke, Richard Sheridan, William Windham and Charles Grey all spoke out against the trade agreement on the same grounds.[37] Ashley claimed that "[t]he traditional policy of the Whig party from before the Revolution [of 1688] down to the time of Fox was an extreme form of Protectionism".[38] The Whigs' protectionism of this period is today increasingly cited with approval by heterodox economists such as Ha-Joon Chang, who wish to challenge contemporary prevailing free trade orthodoxies via precedents from the past.[39] Later on, several members from the Whig party came to oppose the protectionism of the Corn Laws, but trade restrictions were not repealed even after the Whigs returned to power in the 1830s.[40] Whig Supremacy  A c. 1705 portrait of John Somers, 1st Baron Somers by Godfrey Kneller. With the succession of Elector George Louis of Hanover as king in 1714, the Whigs returned to government with the support of some Hanoverian Tories. The Jacobite rising of 1715 discredited much of the Tory party as treasonous Jacobites, and the Septennial Act ensured that the Whigs became the dominant party, establishing the Whig oligarchy. Between 1717 and 1720 the Whig Split led to a division in the party. Government Whigs led by the former soldier James Stanhope were opposed by Robert Walpole and his allies. While Stanhope was backed by George I, Walpole and his supporters were closer to the Prince of Wales. Following his success in defeating the government over the Peerage Bill in 1719, Walpole was invited back into government the following year. He was able to defend the government in the Commons when the South Sea Bubble collapsed. When Stanhope died unexpectedly in 1721, Walpole replaced him as leader of the government and became known as the first Prime Minister. In the 1722 general election the Whigs swept to a decisive victory. Between 1714 and 1760, the Tories struggled as an active political force, but always retained a considerable presence in the House of Commons. The governments of Walpole, Henry Pelham and his older brother the Duke of Newcastle dominated between 1721 and 1757 (with a brief break during the also-Whig Carteret ministry). The leading entities in these governments consistently referred to themselves as "Whigs".[41] George III's accession This arrangement changed during the reign of George III, who hoped to restore his own power by freeing himself from the great Whig magnates. Thus George promoted his old tutor Lord Bute to power and broke with the old Whig leadership surrounding the Duke of Newcastle. After a decade of factional chaos, with distinct Bedfordite, Chathamite, Grenvillite and Rockinghamite factions successively in power and all referring to themselves as "Whigs", a new system emerged with two separate opposition groups. The Rockingham Whigs claimed the mantle of Old Whigs as the purported successors of the party of the Pelhams and the great Whig families. With such noted intellectuals as Edmund Burke behind them, the Rockingham Whigs laid out a philosophy which for the first time extolled the virtues of faction, or at least their faction. The other group were the followers of Lord Chatham, who as the great political hero of the Seven Years' War generally took a stance of opposition to party and faction.[42] The Whigs were opposed by the government of Lord North which they accused of being a Tory administration. While it largely consisted of individuals previously associated with the Whigs, many old Pelhamites as well as the Bedfordite Whig faction formerly led by the Duke of Bedford and elements of that which had been led by George Grenville, it also contained elements of the Kings' Men, the group formerly associated with Lord Bute and which was generally seen as Tory-leaning.[43] American impact The association of Toryism with Lord North's government was also influential in the American colonies and writings of British political commentators known as the Radical Whigs did much to stimulate colonial republican sentiment. Early activists in the colonies called themselves Whigs,[example needed] seeing themselves as in alliance with the political opposition in Britain, until they turned to independence and started emphasising the label Patriots.[citation needed] In contrast, the American Loyalists, who supported the monarchy, were consistently also referred to as Tories. Later, the United States Whig Party was founded in 1833 on the basis of opposition to a strong presidency, initially the presidency of Andrew Jackson, analogous to the British Whig opposition to a strong monarchy.[44] The True Whig Party, which for a century dominated Liberia, was named for the American party rather than directly for the British one. Two-party system  In A Block for the Wigs (1783), caricaturist James Gillray caricatured Charles James Fox's return to power in a coalition with Frederick North, Lord North (George III is the blockhead in the centre) Dickinson reports the following: All historians are agreed that the Tory party declined sharply in the late 1740s and 1750s and that it ceased to be an organized party by 1760. The research of Sir Lewis Namier and his disciples [...] has convinced all historians that there were no organized political parties in Parliament between the late 1750s and the early 1780s. Even the Whigs ceased to be an identifiable party, and Parliament was dominated by competing political connections, which all proclaimed Whiggish political views, or by independent backbenchers unattached to any particular group.[45] The North administration left power in March 1782 following the American Revolution and a coalition of the Rockingham Whigs and the former Chathamites, now led by the Earl of Shelburne, took its place. After Rockingham's unexpected death in July 1782, this uneasy coalition fell apart, with Charles James Fox, Rockingham's successor as faction leader, quarrelling with Shelburne and withdrawing his supporters from the government. The following Shelburne administration was short-lived and Fox returned to power in April 1783, this time in an unexpected coalition with his old enemy Lord North. Although this pairing seemed unnatural to many at the time, it was to last beyond the demise of the coalition in December 1783. The coalition's untimely fall was brought about by George III in league with the House of Lords and the King now brought in Chatham's son William Pitt the Younger as his prime minister. It was only now that a genuine two-party system can be seen to emerge, with Pitt and the government on the one side, and the ousted Fox-North coalition on the other. On 17 December 1783, Fox stated in the House of Commons that "[i]f [...] a change must take place, and a new ministry is to be formed and supported, not by the confidence of this House or the public, but the sole authority of the Crown, I, for one, shall not envy that hon. gentleman his situation. From that moment I put in my claim for a monopoly of Whig principles".[46] Although Pitt is often referred to as a Tory and Fox as a Whig, Pitt always considered himself to be an independent Whig and generally opposed the development of a strict partisan political system. Fox's supporters saw themselves as legitimate heirs of the Whig tradition and they strongly opposed Pitt in his early years in office, notably during the regency crisis revolving around the King's temporary insanity in 1788–1789, when Fox and his allies supported full powers as regent for their ally, the Prince of Wales. The opposition Whigs were split by the onset of the French Revolution. While Fox and some younger members of the party such as Charles Grey and Richard Brinsley Sheridan were sympathetic to the French revolutionaries, others led by Edmund Burke were strongly opposed. Although Burke himself was largely alone in defecting to Pitt in 1791, much of the rest of the party, including the influential House of Lords leader the Duke of Portland, Rockingham's nephew Lord Fitzwilliam and William Windham, were increasingly uncomfortable with the flirtations of Fox and his allies with radicalism and the French Revolution. They split in early 1793 with Fox over the question of support for the war with France and by the end of the year they had openly broken with Fox. By the summer of the next year, large portions of the opposition had defected and joined Pitt's government. 19th century Many of the Whigs who had joined with Pitt would eventually return to the fold, joining again with Fox in the Ministry of All the Talents following Pitt's death in 1806. The followers of Pitt—led until 1809 by Fox's old colleague the Duke of Portland—rejected the label of Tories and preferred to call themselves The Friends of Mr. Pitt. After the fall of the Talents ministry in 1807, the Foxite Whigs remained out of power for the better part of 25 years. The accession of Fox's old ally, the Prince of Wales, to the regency in 1811 did not change the situation, as the Prince had broken entirely with his old Foxite Whig companions. The members of the government of Lord Liverpool from 1812 to 1827 called themselves Whigs.[47] Structure and appeal By 1815, the Whigs were still far from being a "party" in the modern sense. They had no definite programme or policy and were by no means even united. Generally, they stood for reducing crown patronage, sympathy towards nonconformists, support for the interests of merchants and bankers and a leaning towards the idea of a limited reform of the voting system.[48] Most Whig leaders, such as Lord Grey, Lord Grenville, Lord Althorp, William Lamb (later Lord Melbourne) and Lord John Russell, were still rich landowners. The most prominent exception was Henry Brougham, the talented lawyer, who had a relatively modest background.[49] Hay argues that Whig leaders welcomed the increasing political participation of the English middle classes in the two decades after the defeat of Napoleon in 1815. The fresh support strengthened their position in Parliament. Whigs rejected the Tory appeals to governmental authority and social discipline and extended political discussion beyond Parliament. Whigs used a national network of newspapers and magazines as well as local clubs to deliver their message. The press organised petitions and debates and reported to the public on government policy, while leaders such as Henry Brougham (1778–1868) built alliances with men who lacked direct representation. This new approach to the grass roots helped to define Whiggism and opened the way for later success. Whigs thereby forced the government to recognise the role of public opinion in parliamentary debate and influenced views of representation and reform throughout the 19th century.[50] Return to power  Portrait of Lord Melbourne by John Partridge. Melbourne was twice Prime Minister during the 1830s. Whigs restored their unity by supporting moral reforms, especially the abolition of slavery. They triumphed in 1830 as champions of Parliamentary reform. They made Lord Grey prime minister 1830–1834 and the Reform Act 1832 championed by Grey became their signature measure. It broadened the franchise and ended the system of "rotten and pocket boroughs" (where elections were controlled by powerful families) and instead redistributed power on the basis of population. It added 217,000 voters to an electorate of 435,000 in England and Wales. Only the upper and middle classes voted, so this shifted power away from the landed aristocracy to the urban middle classes. In 1832, the party abolished enslavement in the British Empire with the Slavery Abolition Act 1833. It purchased and freed the slaves, especially those in the Caribbean sugar islands. After parliamentary investigations demonstrated the horrors of child labour, limited reforms were passed in 1833. The Whigs also passed the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 that reformed the administration of relief to the poor[51] and the Marriage Act 1836 that allowed civil marriages. It was around this time that the great Whig historian Thomas Babington Macaulay began to promulgate what would later be coined the Whig view of history, in which all of English history was seen as leading up to the culminating moment of the passage of Lord Grey's reform bill. This view led to serious distortions in later portrayals of 17th-century and 18th-century history, as Macaulay and his followers attempted to fit the complex and changing factional politics of the Restoration into the neat categories of 19th-century political divisions. In 1836, a private gentleman's Club was constructed in Pall Mall, Piccadilly as a consequence of the successful Reform Act 1832. The Reform Club was founded by Edward Ellice Sr., MP for Coventry and Whig Whip, whose riches came from the Hudson's Bay Company but whose zeal was chiefly devoted to securing the passage of the Reform Act 1832. This new club, for members of both Houses of Parliament, was intended to be a forum for the radical ideas which the First Reform Bill represented: a bastion of liberal and progressive thought that became closely associated with the Liberal Party, who largely succeeded the Whigs in the second half of the 19th century. Until the decline of the Liberal Party in the early 20th century, it was de rigueur for Liberal MPs and peers to be members of the Reform Club, being regarded as an unofficial party headquarters. However, in 1882 the National Liberal Club was established under William Ewart Gladstone's chairmanship, designed to be more "inclusive" towards Liberal grandees and activists throughout the United Kingdom. Transition to the Liberal Party The Liberal Party (the term was first used officially in 1868, but had been used colloquially for decades beforehand) arose from a coalition of Whigs, free trade Tory followers of Robert Peel and free trade Radicals, first created, tenuously under the Peelite Earl of Aberdeen in 1852 and put together more permanently under the former Canningite Tory Lord Palmerston in 1859. Although the Whigs at first formed the most important part of the coalition, the Whiggish elements of the new party progressively lost influence during the long leadership of former Peelite William Ewart Gladstone. Subsequently, the majority of the old Whig aristocracy broke from the party over the issue of Irish home rule in 1886 to help form the Liberal Unionist Party, which in turn would merge with the Conservative Party by 1912.[52] However, the Unionist support for trade protection in the early twentieth century under Joseph Chamberlain (probably the least Whiggish character in the Liberal Unionist party) further alienated the more orthodox Whigs. By the early twentieth century "Whiggery" was largely irrelevant and without a natural political home. One of the last active politicians to celebrate his Whiggish roots was the Liberal Unionist statesman Henry James.[53] |

歴史 18世紀 ウィリアムの後継者であるアンは、トリーのシンパシーをかなり持っており、純党ウィッグを政権から排除していたが、トーリーだけの政権を短期間試みたもの の失敗に終わった後、穏健なトリーの閣僚であるマールバラ公爵とゴドルフィン卿に支えられ、ウィリアムの政策を引き継いだ。しかし、スペイン継承戦争が進 行し、トリーの人気が低下するにつれ、マールバラとゴドルフィンは純党ウィッグにますます頼らざるを得なくなり、1708年には純党が支配する英国議会の 政権を率いることになった。特にマールバラ公爵夫人との個人的な関係が悪化するにつれて、アン自身はホイッグ派への依存をますます不快に思うようになっ た。この状況は、サマセット公爵やシュルーズベリー公爵を筆頭とするジュント以外のホイッグの多くにとっても不快感を募らせるものであった。1710年 春、アンはゴドルフィンと純党の閣僚を解任し、トリーと交代させた[23]。 ホイッグ派は今度は反対派に転じ、特に1713年のユトレヒト条約を非難し、貴族院での多数派を通じてこれを阻止しようとした。ハーレーとボリングブロー ク子爵に率いられたトーリー政権は、女王を説得し、条約を強行成立させるために新たに12人のトーリー貴族を創設させた[24]。 自由主義の理想 主な記事 ホイッグ主義 ホイッグは主に議会の優越を主張する一方で、プロテスタントの異教徒に対する寛容を求めた。彼らはカトリック教会を自由への脅威とみなし、ピット長老が述 べたようにカトリック教会に反対した: 「ローマの誤りは偶像崇拝であり、宗教的自由だけでなくあらゆる市民的自由の破壊であり、理性と人間性の完全な恥辱である」[26]。 AshcraftとGoldsmith(1983)は、1689年から1710年にかけて、ジョン・ロックのリベラルな政治思想がホイッグの政治的価値観 に大きな影響を与えたことを詳細に追跡している。 [18世紀のホイッグは、政治理論家のロックやアルジャーノン・シドニー(1622-1682)が採用した普遍的権利の概念や言葉を借用した[28]。 WilsonとReill (2004)は、「アダム・スミスの理論は、ホイッグ党とその中産階級の有権者のリベラルな政治姿勢とうまく融合した」と述べている[29]。 ロンドンを代表する知識人であったサミュエル・ジョンソン(1709-1784)は、ホイッグ党が政治的に優位に立っていた時期でさえも、「下劣な」 [30]ホイッグ党を繰り返し非難し、トーリー党を賞賛していた。ジョンソンはその偉大な『辞典』(1755年)の中で、トーリーとは「ホイッグと対立す る、国家の古代憲法と英国国教会の使徒的ヒエラルキーを堅持する者」と定義している。彼は18世紀のホイッグ主義を17世紀の革命的ピューリタニズムと結 びつけ、当時のホイッグも同様に既成の教会と国家の秩序に敵対していたと主張した。ジョンソンは、宗教的外見上の厳格な統一こそが、ホイッグ主義と結びつ けた好ましくない宗教的特質に対する最善の解毒剤であると提言した[31]。 保護主義 ホイッグは、フランスのカトリック絶対王政との同盟が自由とプロテスタンティズムを危うくすると考え、スチュアート朝のチャールズ2世とジェームズ2世の 親フランス政策に反対していた。ホイッグスはフランスとの貿易はイングランドにとって悪いことだと主張し、フランスとの貿易赤字はイングランドの犠牲の上 にフランスを富ませることになるため悪いことだというオーバーバランスという経済理論を展開した[33]。 1678年、ホイッグ党は1678年禁酒法を可決し、特定のフランス製品をイングランドに輸入することを禁止した。経済史家のウィリアム・アシュレイは、 この法律が「貿易に関するホイッグ政策の歴史における真の出発点」であったと主張している[34]。トーリーが支配する下院によってジェームズ2世が即位 するとこの法律は廃止されたが、1688年にウィリアム3世が即位すると、フランス製品の輸入を禁止する新たな法律が成立した[35]。1710年、アン 女王は自由貿易を支持するトーリー派の多いハーレー省を任命した。1713年、トーリー派のボリングブローク卿がフランスとの自由貿易につながる通商条約 を提案したが、ホイッグ派は猛反対し、断念せざるを得なかった[36]。 1786年、ピット政権はフランスとの商業条約であるエデン協定を交渉し、両国間の自由貿易を実現した。ホイッグの指導者たちは皆、伝統的なホイッグの反 フランス、保護主義を理由にこれを攻撃した。フォックスは、フランスはイギリスの天敵であり、イギリスの犠牲の上にこそイギリスは成長できると主張した。 エドモンド・バーク、リチャード・シェリダン、ウィリアム・ウィンダム、チャールズ・グレイも同じ理由で貿易協定に反対を表明した[37]。 アシュレイは、「(1688年の)革命前からフォックスの時代までのホイッグ党の伝統的な政策は、極端な形の保護主義であった」と主張している[38]。 この時期のホイッグ党の保護主義は、今日、過去の判例を通じて現代の一般的な自由貿易の正統性に異議を唱えようとするハ・ジュン・チャンのようなヘテロ ドックスな経済学者たちによって肯定的に引用されることが多くなっている[39]。 その後、ホイッグ党の何人かはコーン法の保護主義に反対するようになったが、1830年代にホイッグ党が政権に復帰した後も貿易制限は撤廃されなかった[40]。 ホイッグの優位  1705年頃、ゴッドフリー・ケネラー作のソマーズ男爵の肖像画。 1714年、ハノーファー選帝侯ジョージ・ルイが国王に即位すると、ホイッグはハノーファー派の一部のトリーの支持を得て政権に復帰した。1715年の ジャコバイトの蜂起により、トーリー党の多くはジャコバイトの反逆者として信用を失い、9年法によってホイッグ党が優勢となり、ホイッグ寡頭政治が確立し た。1717年から1720年にかけてホイッグ分裂が起こり、党内が分裂した。元軍人のジェームズ・スタンホープ率いる政府ウィッグは、ロバート・ウォル ポールとその同盟勢力に反対された。スタンホープがジョージ1世の支持を受けていたのに対し、ウォルポールとその支持者はプリンス・オブ・ウェールズに近 かった。1719年に貴族院法案で政府を破ったウォルポールは、翌年再び政府に招かれた。南海バブルが崩壊した際には、下院で政府を擁護することができ た。1721年にスタンホープが急死すると、ウォルポールが後任の政府首班となり、初代首相として知られるようになった。1722年の総選挙ではホイッグ 党が圧勝した。 1714年から1760年までの間、トーリーは活発な政治勢力として苦戦を強いられたが、常に下院でかなりの存在感を示していた。1721年から1757 年にかけては、ウォルポール、ヘンリー・ペラム、そしてその兄のニューカッスル公爵の政権が支配的だった(同じくホイッグのカータレット政権の間は一時中 断)。これらの政権の主要人物は一貫して自らを「ホイッグ」と称していた[41]。 ジョージ3世の即位 この体制はジョージ3世の治世に変化し、ジョージはホイッグの大物たちから自らを解放することで自らの権力を回復することを望んだ。こうしてジョージは古 くからの家庭教師であったビュート卿を政権に登用し、ニューカッスル公を取り巻く古いホイッグの指導層と決別した。ベッドフォード派、チャタミ派、グレン ヴィル派、ロッキンガム派が相次いで政権を握り、全員が自らを「ホイッグ」と呼ぶという派閥の混乱が10年間続いた後、2つの反対派からなる新体制が誕生 した。ロッキンガム派のウィッグは、ペラム家とウィッグの名家の党の後継者として、オールド・ウィッグのマントを主張した。エドマンド・バークなどの著名 な知識人を後ろ盾に、ロッキンガム・ウィッグは初めて派閥、少なくとも自分たちの派閥の美徳を称揚する哲学を打ち出した。もうひとつのグループはチャタム 卿の支持者たちであり、チャタム卿は七年戦争の偉大な政治的英雄として、党派や派閥に反対する立場をとっていた[42]。 ホイッグ派は、彼らがトーリー政権であると非難したノース卿の政権に反対していた。ノース公は、かつてホイッグ党に属していた人物、多くの旧ペラム派、か つてベッドフォード公が率いていたベッドフォード派ホイッグ、ジョージ・グレンヴィルが率いていたホイッグの要素で構成されていたが、かつてビュート公が 率いていたキングス・メンの要素も含んでおり、一般的にはトーリー派と見られていた[43]。 アメリカへの影響 急進派ホイッグとして知られるイギリスの政治評論家の著作は、植民地の共和主義的感情を大いに刺激した。植民地の初期の活動家は自らをホイッグと呼び[要 出典]、イギリスの政治的反対勢力と同盟関係にあるとみなしていたが、彼らが独立に転じ、パトリオットというレッテルを強調し始めるまではそうであった [要出典]。対照的に、王政を支持するアメリカのロイヤリストは一貫してトーリーとも呼ばれていた。 その後、1833年に強力な大統領制(当初はアンドリュー・ジャクソンの大統領制)に反対することを基礎として、強力な王政に反対するイギリスのホイッグ 党に類似したアメリカ合衆国のホイッグ党が設立された[44]。1世紀にわたってリベリアを支配した真のホイッグ党は、イギリスの党に直接由来するのでは なく、アメリカの党にちなんで命名された。 二大政党制  風刺画家のジェームズ・ギレイは、『かつらのためのブロック』(1783年)の中で、チャールズ・ジェームズ・フォックスがフレデリック・ノース卿と連立を組んで政権に復帰する様子を風刺画に描いている(中央のブロックヘッドはジョージ3世)。 ディキンソンは次のように報告している: トーリー党が1740年代後半から1750年代にかけて急激に衰退し、1760年までに組織された党ではなくなったことは、どの歴史家も認めている。ルイ ス・ナミエ卿とその弟子たちの研究[...]は、1750年代後半から1780年代前半にかけて議会には組織政党が存在しなかったことをすべての歴史家に 確信させた。ホイッグ党でさえも識別可能な政党ではなくなっており、議会は、全員がホイッグ的な政治的見解を表明する競合する政治的コネクションか、特定 のグループに属さない独立した後方支援者によって支配されていた[45]。 アメリカ独立戦争後の1782年3月、ノース政権は政権を去り、ロッキンガム・ウィッグとシェルバーン伯爵が率いる旧チャタム派の連合がその座に就いた。 1782年7月にロッキンガムが不慮の死を遂げると、この不穏な連合は崩壊し、ロッキンガムの後継者として派閥を率いたチャールズ・ジェームズ・フォック スはシェルバーンと対立し、政府から支持者を離脱させた。続くシェルバーン政権は短命に終わり、フォックスは1783年4月、今度は宿敵ノース公との予想 外の連立で政権に返り咲いた。このコンビは当時多くの人々には不自然に思われたが、1783年12月の連立解消後も続いた。ジョージ3世が貴族院と手を組 んだために連立は早々に崩壊し、国王はチャタムの息子ウィリアム・ピットを首相に迎えた。 ピットと政府、そして追放されたフォックスとノースの連合という、正真正銘の二大政党制が誕生したのである。1783年12月17日、フォックスは下院で 次のように述べた。「もし(...)変化を余儀なくされ、新しい省が設立され、本院や国民の信任ではなく、王室の唯一の権威によって支持されるのであれ ば、私はその紳士をうらやましいとは思わない。その瞬間から、私はホイッグの原則の独占を主張するようになった」[46]。ピットはしばしばトーリーと呼 ばれ、フォックスはホイッグと呼ばれるが、ピットは常に自らを独立したホイッグであると考え、厳格な党派政治体制の発展に反対していた。フォックスの支持 者たちは、自分たちをホイッグの伝統の正当な継承者だと考えており、ピットの就任初期、特に1788年から1789年にかけての国王の一時的な発狂に端を 発する摂政危機の際には強く反発した。 反対派のホイッグ党はフランス革命の勃発によって分裂した。フォックスやチャールズ・グレイ、リチャード・ブリンズレー・シェリダンら一部の若手党員はフ ランス革命派に同調したが、エドマンド・バークを筆頭とする他の党員は強く反対した。バーク自身は1791年にほぼ一人でピットに離反したが、有力な貴族 院指導者であったポートランド公爵、ロッキンガムの甥フィッツウィリアム卿、ウィリアム・ウィンダムなど党の残りのメンバーの多くは、フォックスとその同 盟者たちが急進主義やフランス革命に傾倒することに次第に不快感を抱くようになった。彼らは1793年初頭、対仏戦争支持の是非をめぐってフォックスと対 立し、年末には公然とフォックスと決別した。翌年の夏までに、反対派の大部分は離反してピット政権に参加した。 19世紀 ピット側についたホイッグの多くはやがて復党し、1806年のピットの死後、フォックスとともに再び万能省に加わった。1809年までフォックスの古くか らの同僚であったポートランド公爵が率いていたピットの支持者たちは、トーリーのレッテルを拒否し、自分たちをピット氏の友人と呼ぶことを好んだ。 1807年にタレンツ政権が崩壊した後、フォックス派のホイッグは25年もの間、政権から遠ざかっていた。1811年にフォックスの古くからの盟友である プリンス・オブ・ウェールズが摂政に就任したが、プリンスはフォックス派ホイッグの古くからの仲間と完全に決別していたため、状況は変わらなかった。 1812年から1827年までのリバプール公政権のメンバーは自らをホイッグと称した[47]。 構造とアピール 1815年まで、ホイッグは近代的な意味での「政党」にはまだほど遠かった。彼らは明確な綱領や政策を持たず、決して団結さえしていなかった。グレイ卿、 グレンヴィル卿、アルソープ卿、ウィリアム・ラム(後のメルボルン卿)、ジョン・ラッセル卿など、ホイッグの指導者たちのほとんどは、まだ裕福な地主で あった。最も著名な例外は、有能な弁護士であったヘンリー・ブロアムで、彼は比較的質素な生い立ちであった[49]。 ヘイによれば、ホイッグの指導者たちは、1815年にナポレオンが敗北してからの20年間、イギリスの中産階級の政治参加の高まりを歓迎していた。新鮮な 支持は議会における彼らの立場を強化した。ホイッグ党は、政府の権威と社会規律を訴えるトーリー党を否定し、政治的議論を議会の枠を超えて拡大した。ホ イッグは新聞や雑誌の国民的ネットワークや地元のクラブを利用してメッセージを伝えた。新聞は請願や討論会を組織し、政府の政策について国民に報告した。 ヘンリー・ブローム(1778-1868)のような指導者は、直接の代表権を持たない人々と同盟関係を築いた。草の根に対するこの新しいアプローチは、ホ イッグ主義を定義づけるのに役立ち、後の成功への道を開いた。これによりホイッグは、議会審議における世論の役割を政府に認識させ、19世紀を通じて代表 制と改革に関する見解に影響を与えた[50]。 政権への復帰  ジョン・パートリッジによるメルボルン卿の肖像画。メルボルンは1830年代に2度首相を務めた。 ホイッグは道徳改革、特に奴隷制廃止を支持し、結束を回復した。彼らは1830年に議会改革の擁護者として勝利を収めた。彼らはグレイ卿を1830年から 1834年にかけて首相とし、グレイが提唱した改革法1832は彼らの代表的な政策となった。この改革法は選挙権を拡大し、「腐敗したポケット行政区」 (選挙が有力な一族によって支配されていた)制度を廃止し、代わりに人口に基づいて権力を再配分した。これにより、イングランドとウェールズの有権者43 万5,000人に21万7,000人が加わった。上流階級と中流階級のみが投票したため、土地貴族から都市の中流階級に権力が移った。1832年、党は奴 隷制度廃止法1833によって大英帝国の奴隷制度を廃止した。特にカリブ海の砂糖諸島の奴隷を買い取り、解放した。議会の調査によって児童労働の恐ろしさ が実証された後、1833年に限定的な改革が可決された。ホイッグ党はまた、1834年に貧民救済行政を改革する貧民法改正法[51]を、1836年には 市民結婚を認める結婚法を可決した。 この頃、偉大なホイッグ派の歴史家トーマス・バビントン・マコーレーが、後にホイッグ史観と呼ばれることになる、イギリス史のすべてがグレイ卿の改革法案 成立という頂点に至るものとみなす歴史観を広め始めた。マコーレーとその支持者たちは、王政復古期の複雑で変化する派閥政治を、19世紀の政治区分のきれ いなカテゴリーに当てはめようとしたためである。 1836年、1832年の改革法の成功を受けて、ピカデリーのポールモールに私設紳士クラブが建設された。改革派クラブは、コヴェントリーの国会議員でホ イッグ・ウィップだったエドワード・エリス・シニアによって設立された。彼はハドソンズ・ベイ・カンパニーで富を築いたが、1832年改革法の成立に熱意 を注いだ。議会両院の議員を対象としたこの新しいクラブは、第一次改革法案に代表される急進的な思想のフォーラムとなることを意図したもので、リベラルで 進歩的な思想の砦であり、19世紀後半にホイッグの後を大きく引き継いだ自由党と密接な関係を持つようになった。 20世紀初頭に自由党が衰退するまで、自由党の議員や貴族は改革クラブの会員であることが当然であり、非公式な党本部とみなされていた。しかし1882 年、ウィリアム・ユワート・グラッドストンが会長を務める国民リベラル・クラブが設立され、イギリス全土のリベラル派の大物や活動家をより「包括的」に受 け入れるようになった。 自由党への移行 自由党(この言葉は1868年に初めて公式に使用されたが、それ以前から数十年にわたって口語で使用されていた)は、ホイッグ、ロバート・ピールの自由貿 易主義者、自由貿易急進派の連合から生まれた。当初はホイッグ党が連立の最も重要な部分を形成していたが、元ピール派のウィリアム・ユワート・グラッドス トンが長期にわたって党首を務めた間に、新党のホイッグ党的要素は次第に影響力を失っていった。その後、旧ウィッグ貴族の大多数は1886年にアイルラン ドの自治権問題で党を離党し、自由統一党の結成に協力した。20世紀初頭には、「ホイッグ」はほとんど無用の存在となり、本来の政治的居場所を失ってい た。ホイッグ的なルーツを讃える最後の現役政治家のひとりが、自由統一派の政治家ヘンリー・ジェイムズであった[53]。 |

| In popular culture The colours of the Whig Party (blue and buff, a yellow-brown colour named after buff leather) were particularly associated with Charles James Fox.[54] Poet Robert Burns in "Here's a health to them that's awa" wrote: It's guid to support Caledonia's cause And bide by the Buff and the Blue. "The British Whig March" for piano was written by Oscar Telgmann in Kingston, Ontario, c. 1900.[55] Punk band The Men That Will Not Be Blamed for Nothing have a song named "Doing It for the Whigs". |

大衆文化 ホイッグ党の色(青とバフ、バフ革にちなんで名付けられた黄褐色)は、特にチャールズ・ジェームズ・フォックスと関連していた[54]。 詩人ロバート・バーンズは 「Here's a health to them that's awa 」の中でこう書いている: カレドニアの大義を支持するのは良いことだ。 カレドニアの大義を支持するのは良いことだ。 ピアノのための 「The British Whig March 」は、1900年頃にオンタリオ州キングストンでオスカー・テルグマンによって書かれた[55]。 パンク・バンド、ザ・メン・ザット・ウィル・ノット・ビー・ブラック・フォー・ナッシング(The Men That Will Not Be Blamed for Nothing)に「Doing It for the Whigs」という曲がある。 |

| Electoral performance |

(省略) |

| Early-18th-century Whig plots Foxite King of Clubs (Whig club) Kingdom of Great Britain List of United Kingdom Whig and allied party leaders (1801–1859) Patriot Whigs Whig government Whig Party (United States) |

18世紀初頭のホイッグの陰謀 フォックス派 キング・オブ・クラブ(ホイッグ・クラブ) グレートブリテン王国 イギリスのホイッグ党と連合党の指導者リスト(1801年-1859年) パトリオット・ウィッグ ホイッグ政府 ホイッグ党(アメリカ合衆国) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Whigs_(British_political_party) |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆