ウィリアム・ブレイク

William Blake, 1757-1827

William Blake by Thomas Phillips (1807)

☆ ウィ リアム・ブレイク(1757年11月28日 - 1827年8月12日)はイギリスの詩人、画家、版画家。生前はほとんど認知されていなかったが、現在ではロマン主義時代の詩と視覚芸術の歴史における重 要人物とみなされている。彼の「予言的作品」と呼ばれる作品は、20世紀の批評家ノースロップ・フライによって「その長所に比例して、英語で最も読まれて いない詩集」と評された。 ブレイクは、その特異な見解から同時代の人々からは狂人扱いされていたが、後の批評家や読者からは、その表現力と創造性、そして作品内の哲学的・神秘主 義的な底流が高く評価されるようになった。彼の絵画と詩はロマン主義運動の一部であり、「プレ・ロマン主義」とも評される。事実、彼は「ロマン主義 とナショナリズムの初期の重要な推進者」と言われている。イングランド国教会(実際には、ほとんどすべての形態の組織化された宗教)に敵対する熱心 なキリスト教徒であったブレイクは、フランス革命とアメリカ革命の理想と野心の影響を受けた。 後に彼はこれらの政治的信条の多くを否定したが、政治活動家トマス・ペインとは友好的な関係を維持した。

| William

Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter,

and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his life, Blake is now

considered a seminal figure in the history of the poetry and visual art

of the Romantic Age. What he called his "prophetic works" were said by

20th-century critic Northrop Frye to form "what is in proportion to its

merits the least read body of poetry in the English language".[2] His

visual artistry led 21st-century critic Jonathan Jones to proclaim him

"far and away the greatest artist Britain has ever produced".[3] In

2002, Blake was placed at number 38 in the BBC's poll of the 100

Greatest Britons.[4] While he lived in London his entire life, except

for three years spent in Felpham,[5] he produced a diverse and

symbolically rich collection of works, which embraced the imagination

as "the body of God"[6] or "human existence itself".[7] Although Blake was considered mad by contemporaries for his idiosyncratic views, he came to be highly regarded by later critics and readers for his expressiveness and creativity, and for the philosophical and mystical undercurrents within his work. His paintings and poetry have been characterised as part of the Romantic movement and as "Pre-Romantic".[8] In fact, he has been said to be "a key early proponent of both Romanticism and Nationalism".[9] A committed Christian who was hostile to the Church of England (indeed, to almost all forms of organised religion), Blake was influenced by the ideals and ambitions of the French and American revolutions.[10][11] Though later he rejected many of these political beliefs, he maintained an amiable relationship with the political activist Thomas Paine; he was also influenced by thinkers such as Emanuel Swedenborg.[12] Despite these known influences, the singularity of Blake's work makes him difficult to classify. The 19th-century scholar William Michael Rossetti characterised him as a "glorious luminary",[13] and "a man not forestalled by predecessors, nor to be classed with contemporaries, nor to be replaced by known or readily surmisable successors".[14] |

ウィ

リアム・ブレイク(1757年11月28日 -

1827年8月12日)はイギリスの詩人、画家、版画家。生前はほとんど認知されていなかったが、現在ではロマン主義時代の詩と視覚芸術の歴史における重

要人物とみなされている。彼の「予言的作品」と呼ばれる作品は、20世紀の批評家ノースロップ・フライによって「その長所に比例して、英語で最も読まれて

いない詩集」と評された[2]。

[2002年、ブレイクはBBCの「最も偉大な英国人100人」の投票で38位に選ばれた[4]。フェルファムで過ごした3年間を除き、生涯ロンドンで暮

らしながら[5]、「神の体」[6]あるいは「人間の存在そのもの」として想像力を取り入れた、多様で象徴的に豊かな作品群を生み出した[7]。 ブレイクは、その特異な見解から同時代の人々からは狂人扱いされていたが、後の批評家や読者からは、その表現力と創造性、そして作品内の哲学的・神秘主 義的な底流が高く評価されるようになった。彼の絵画と詩はロマン主義運動の一部であり、「プレ・ロマン主義」とも評される[8]。事実、彼は「ロマン主義 とナショナリズムの初期の重要な推進者」[9]と言われている。イングランド国教会(実際には、ほとんどすべての形態の組織化された宗教)に敵対する熱心 なキリスト教徒であったブレイクは、フランス革命とアメリカ革命の理想と野心の影響を受けた。 [10][11]後に彼はこれらの政治的信条の多くを否定したが、政治活動家トマス・ペインとは友好的な関係を維持した。19世紀の学者であるウィリア ム・マイケル・ロセッティは、ブレイクを「栄光の光輝」[13]、「先達に追い越されることもなく、同時代人に分類されることもなく、既知の、あるいは容 易に推測できる後継者に取って代わられることもない人物」[14]と評している。 |

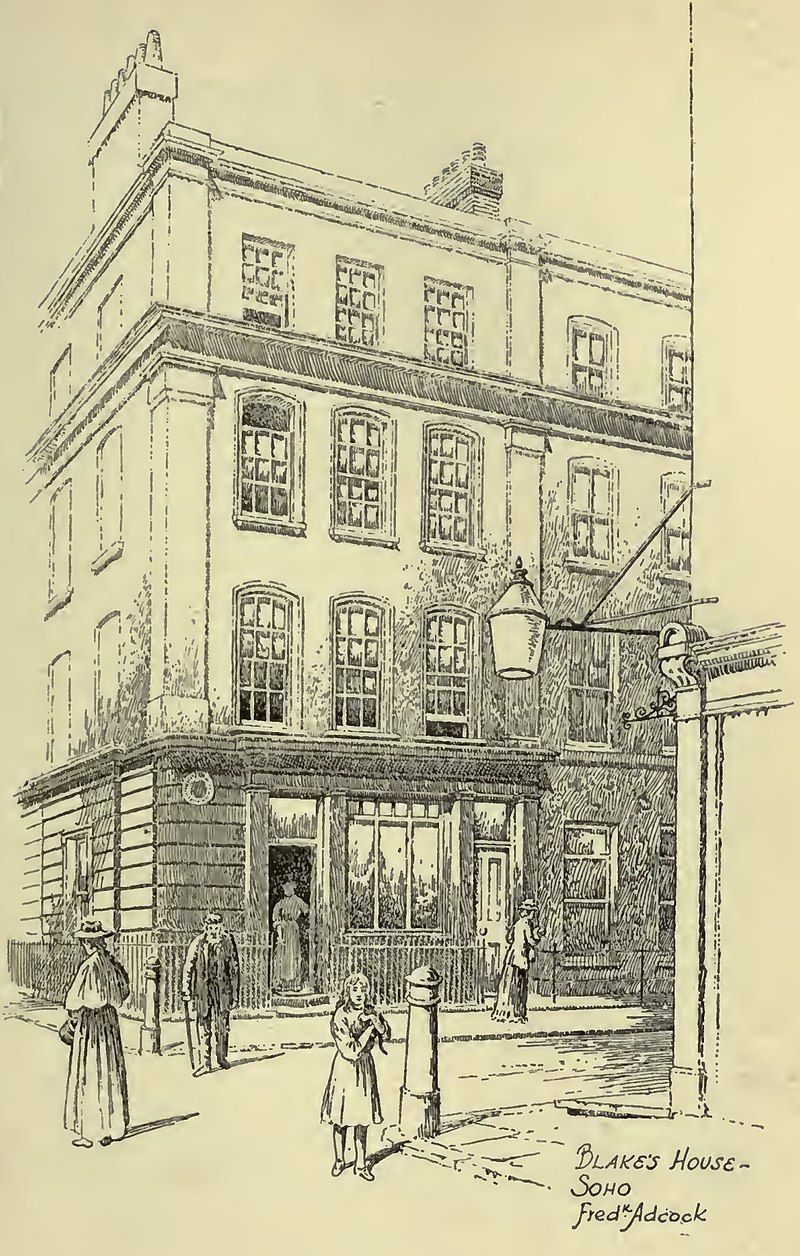

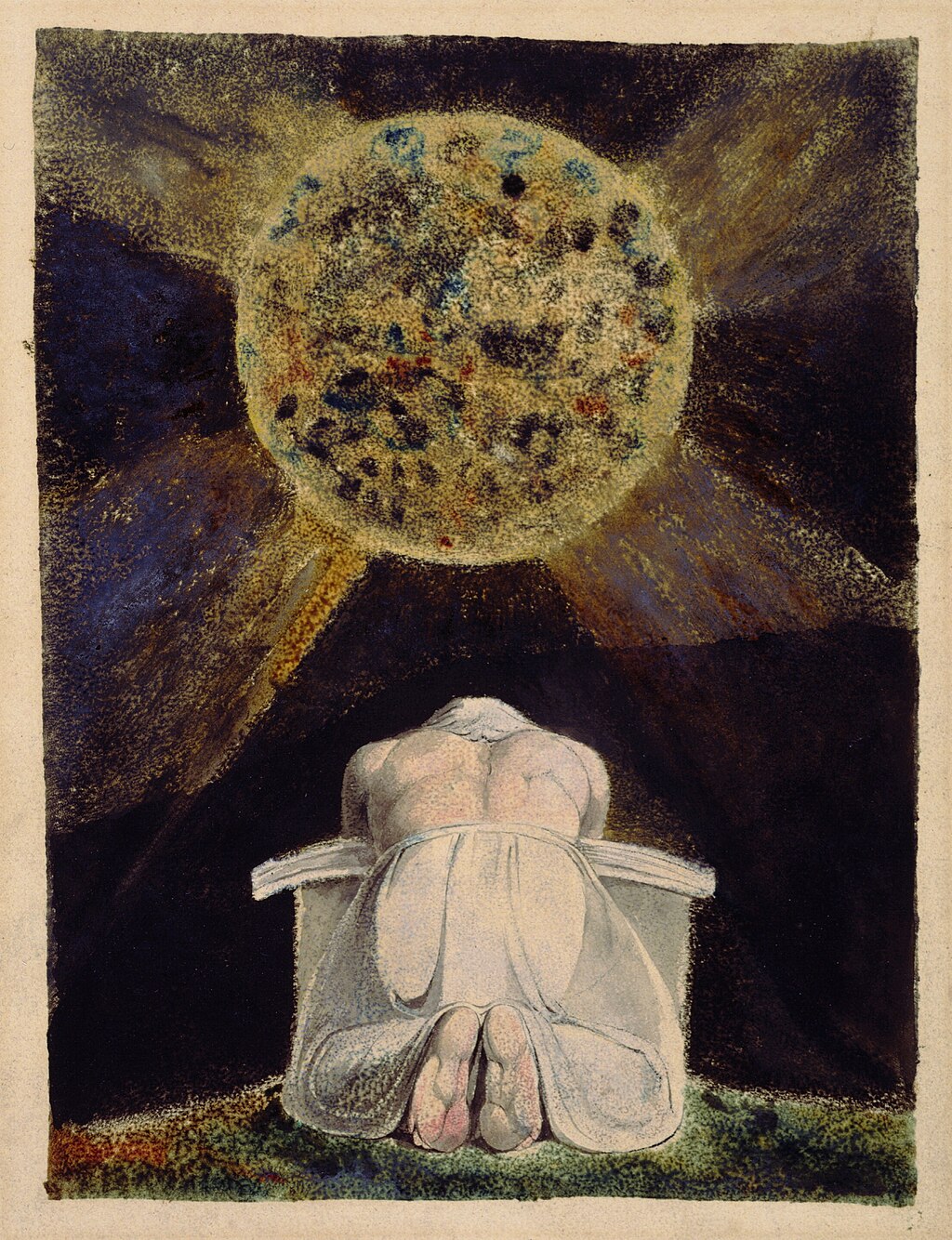

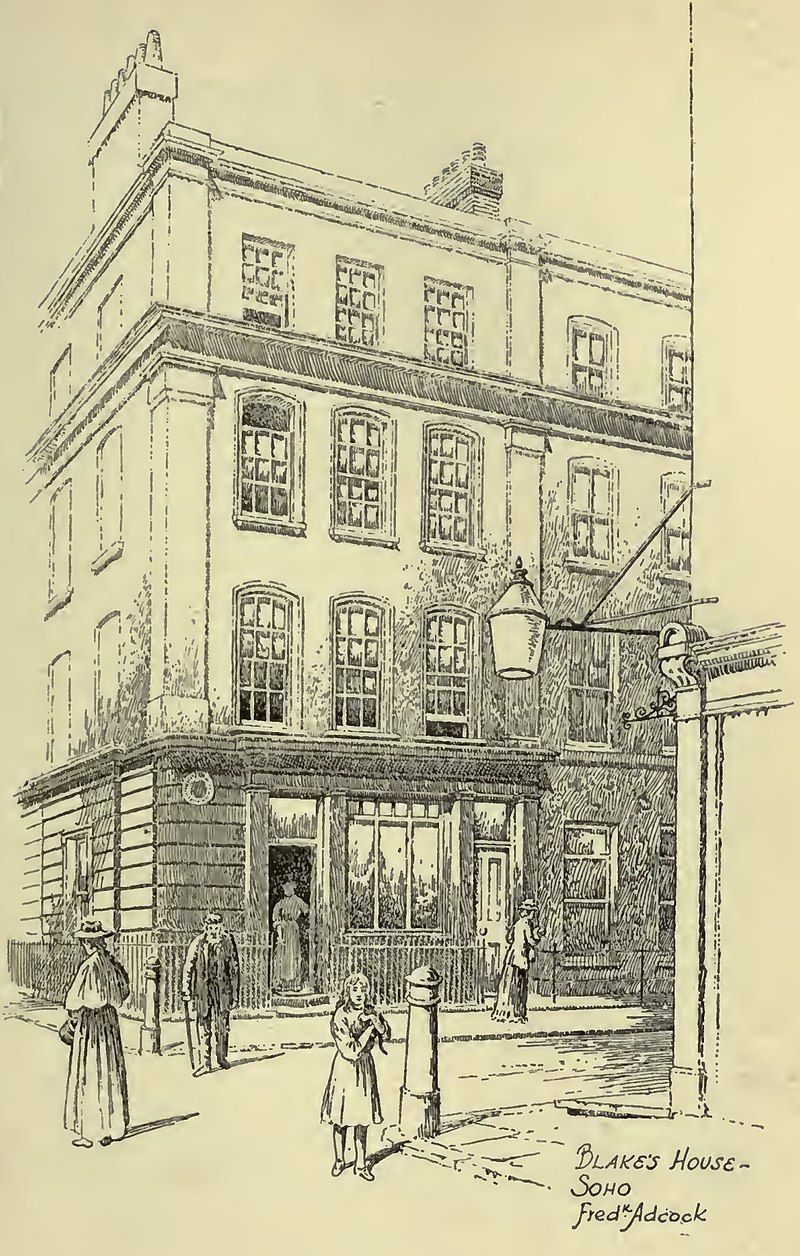

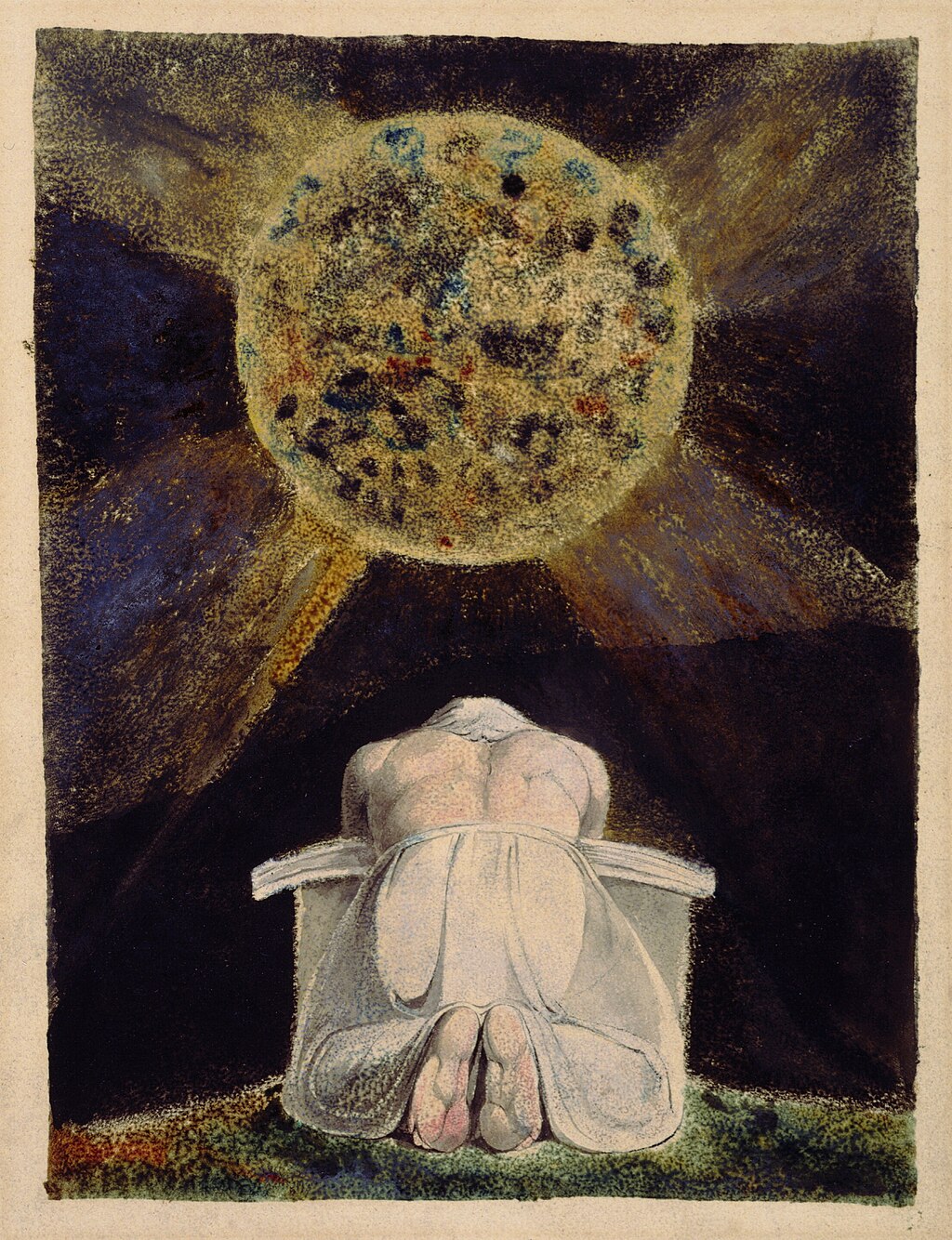

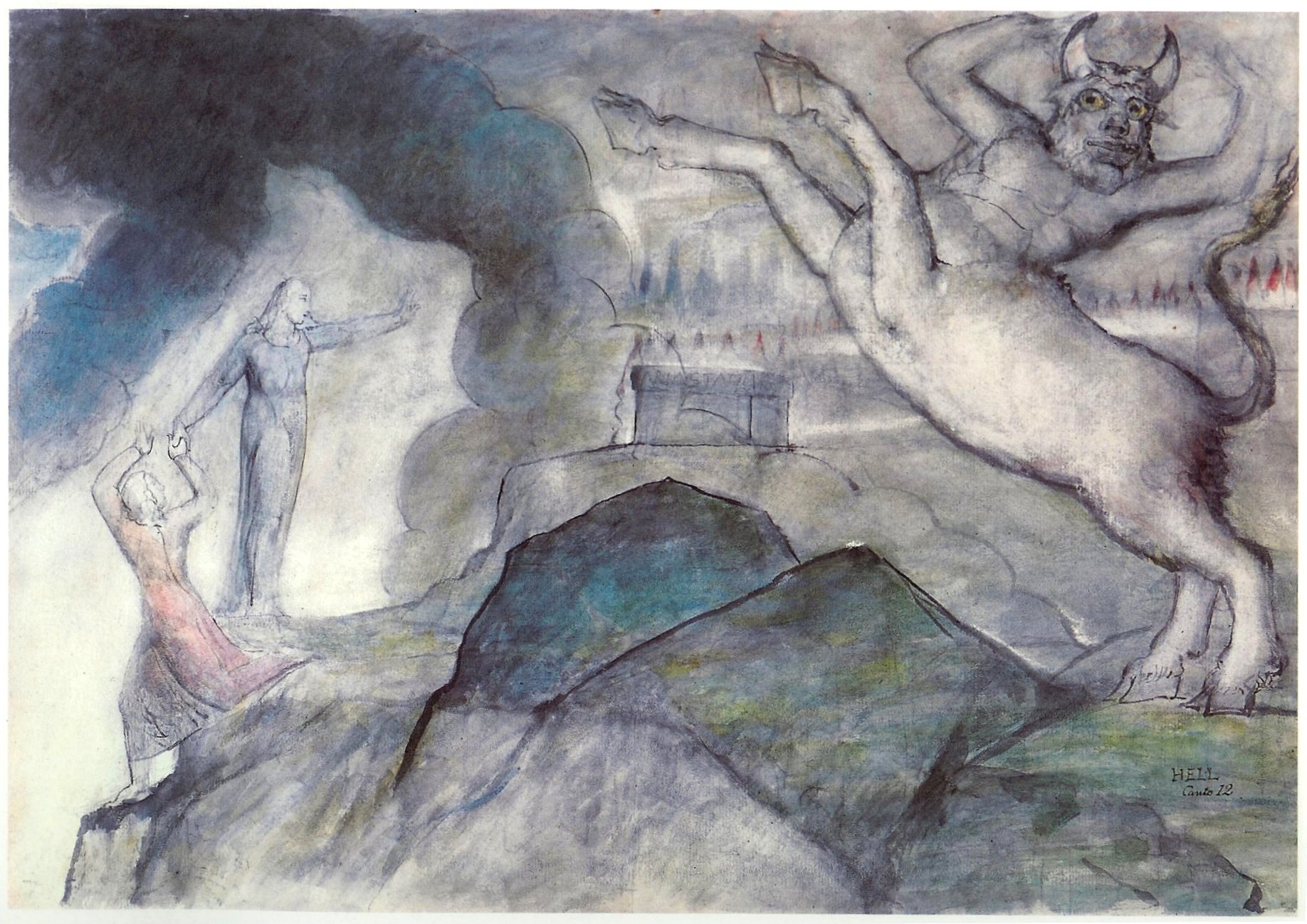

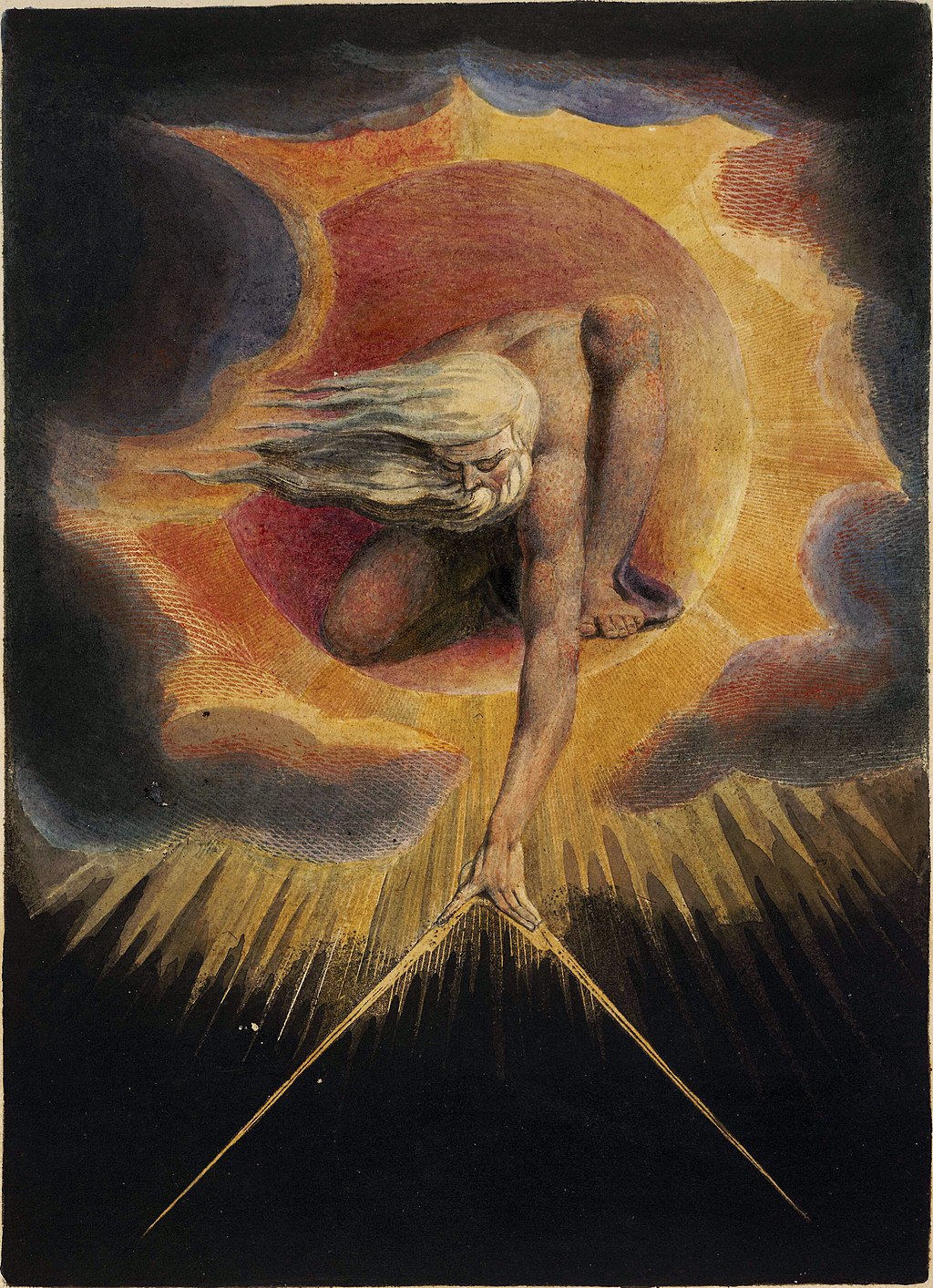

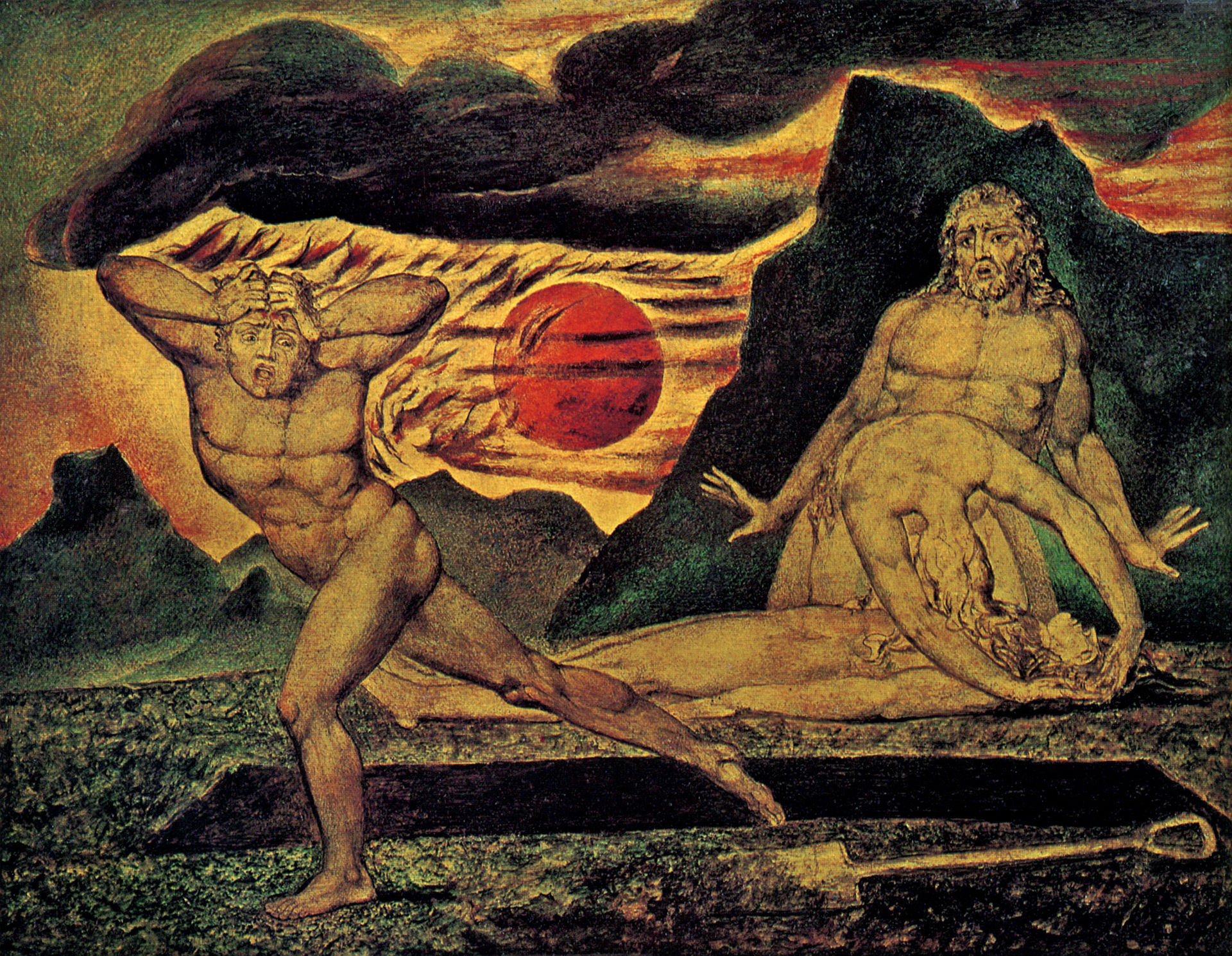

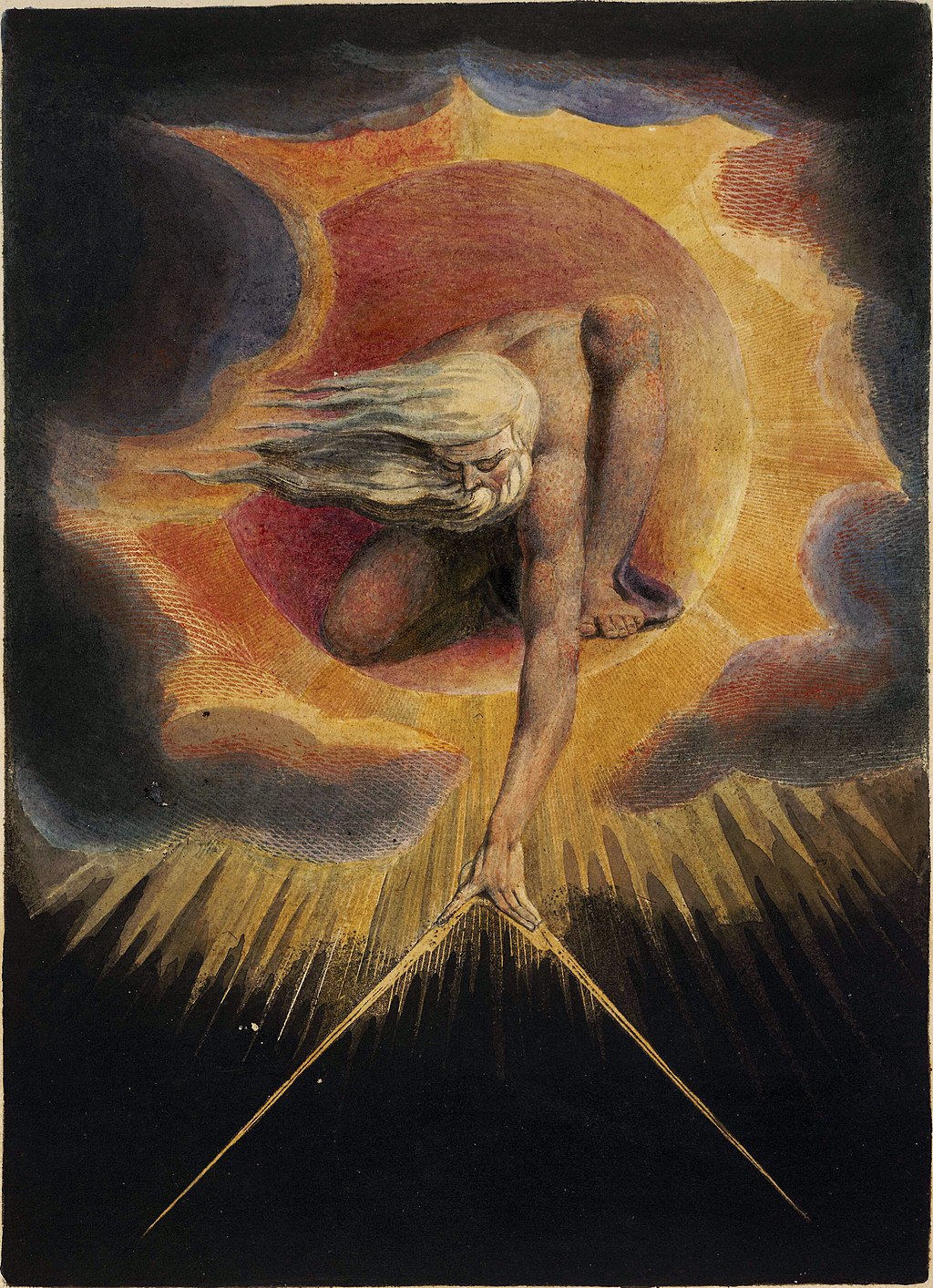

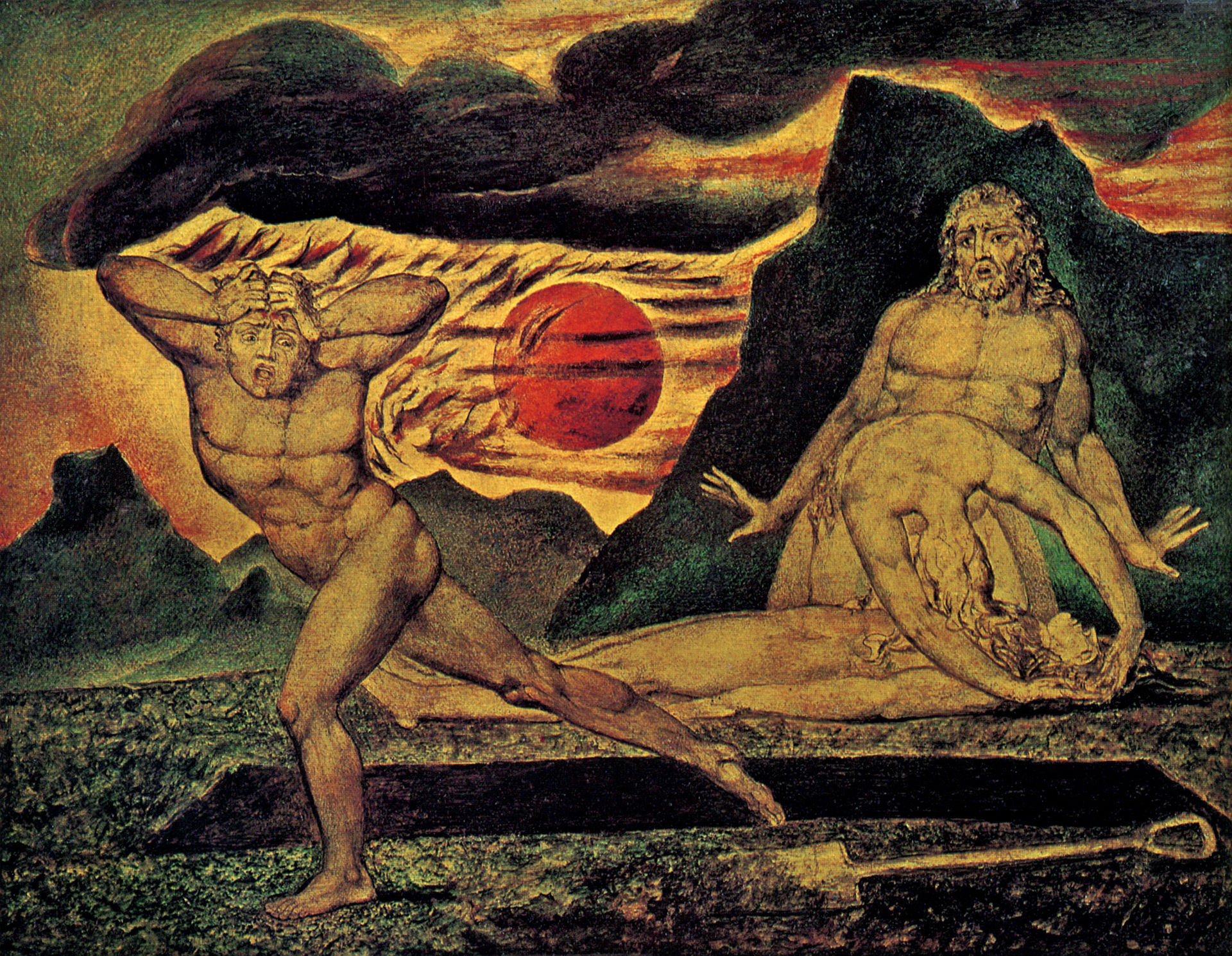

Early life 28 Broad Street (now Broadwick Street) in an illustration of 1912. Blake was born here and lived here until he was 25. The house was demolished in 1965.[15] William Blake was born on 28 November 1757 at 28 Broad Street (now Broadwick St.) in Soho, London. He was the third of seven children,[16][17] two of whom died in infancy. Blake's father, James, was a hosier,[17] who had lived in London.[18] He attended school only long enough to learn reading and writing, leaving at the age of ten, and was otherwise educated at home by his mother Catherine Blake (née Wright).[19] Even though the Blakes were English Dissenters,[20] William was baptised on 11 December at St James's Church, Piccadilly, London.[21] The Bible was an early and profound influence on Blake, and remained a source of inspiration throughout his life. Blake's childhood, according to him, included mystical religious experiences such as "beholding God's face pressed against his window, seeing angels among the haystacks, and being visited by the Old Testament prophet Ezekiel."[22] Blake started engraving copies of drawings of Greek antiquities purchased for him by his father, a practice that was preferred to actual drawing. Within these drawings Blake found his first exposure to classical forms through the work of Raphael, Michelangelo, Maarten van Heemskerck and Albrecht Dürer. The number of prints and bound books that James and Catherine were able to purchase for young William suggests that the Blakes enjoyed, at least for a time, a comfortable wealth.[20] When William was ten years old, his parents knew enough of his headstrong temperament that he was not sent to school but instead enrolled in drawing classes at Henry Pars' drawing school in the Strand.[23] He read avidly on subjects of his own choosing. During this period, Blake made explorations into poetry; his early work displays knowledge of Ben Jonson, Edmund Spenser, and the Psalms. Apprenticeship  The archetype of the Creator is a familiar image in Blake's work. Here, the demiurgic figure Urizen prays before the world he has forged. The Song of Los is the third in a series of illuminated books painted by Blake and his wife, collectively known as the Continental Prophecies. On 4 August 1772, Blake was apprenticed to engraver James Basire of Great Queen Street, at the sum of £52.10, for a term of seven years.[17] At the end of the term, aged 21, he became a professional engraver. No record survives of any serious disagreement or conflict between the two during the period of Blake's apprenticeship, but Peter Ackroyd's biography notes that Blake later added Basire's name to a list of artistic adversaries; and then crossed it out.[24] This aside, Basire's style of line-engraving was of a kind held at the time to be old-fashioned compared to the flashier stipple or mezzotint styles.[25] It has been speculated that Blake's instruction in this outmoded form may have been detrimental to his acquiring of work or recognition in later life.[26] After two years, Basire sent his apprentice to copy images from the Gothic churches in London (perhaps to settle a quarrel between Blake and James Parker, his fellow apprentice). His experiences in Westminster Abbey helped form his artistic style and ideas. The Abbey of his day was decorated with suits of armour, painted funeral effigies and varicoloured waxworks. Ackroyd notes that "...the most immediate [impression] would have been of faded brightness and colour".[27] This close study of the Gothic (which he saw as the "living form") left clear traces in his style.[28] In the long afternoons Blake spent sketching in the Abbey, he was occasionally interrupted by boys from Westminster School, who were allowed in the Abbey. They teased him and one tormented him so much that Blake knocked the boy off a scaffold to the ground, "upon which he fell with terrific Violence".[29] After Blake complained to the Dean, the schoolboys' privilege was withdrawn.[28] Blake claimed that he experienced visions in the Abbey. He saw Christ with his Apostles and a great procession of monks and priests, and heard their chant.[28] Royal Academy On 8 October 1779, Blake became a student at the Royal Academy in Old Somerset House, near the Strand.[30] While the terms of his study required no payment, he was expected to supply his own materials throughout the six-year period. There, he rebelled against what he regarded as the unfinished style of fashionable painters such as Rubens, championed by the school's first president, Joshua Reynolds. Over time, Blake came to detest Reynolds' attitude towards art, especially his pursuit of "general truth" and "general beauty". Reynolds wrote in his Discourses that the "disposition to abstractions, to generalising and classification, is the great glory of the human mind"; Blake responded, in marginalia to his personal copy, that "To Generalize is to be an Idiot; To Particularize is the Alone Distinction of Merit".[31] Blake also disliked Reynolds' apparent humility, which he held to be a form of hypocrisy. Against Reynolds' fashionable oil painting, Blake preferred the Classical precision of his early influences, Michelangelo and Raphael. David Bindman suggests that Blake's antagonism towards Reynolds arose not so much from the president's opinions (like Blake, Reynolds held history painting to be of greater value than landscape and portraiture), but rather "against his hypocrisy in not putting his ideals into practice."[32] Certainly Blake was not averse to exhibiting at the Royal Academy, submitting works on six occasions between 1780 and 1808. Blake became a friend of John Flaxman, Thomas Stothard and George Cumberland during his first year at the Royal Academy. They shared radical views, with Stothard and Cumberland joining the Society for Constitutional Information.[33] Gordon Riots Blake's first biographer, Alexander Gilchrist, records that in June 1780 Blake was walking towards Basire's shop in Great Queen Street when he was swept up by a rampaging mob that stormed Newgate Prison.[34] The mob attacked the prison gates with shovels and pickaxes, set the building ablaze, and released the prisoners inside. Blake was reportedly in the front rank of the mob during the attack. The riots, in response to a parliamentary bill revoking sanctions against Roman Catholicism, became known as the Gordon Riots and provoked a flurry of legislation from the government of George III, and the creation of the first police force. |

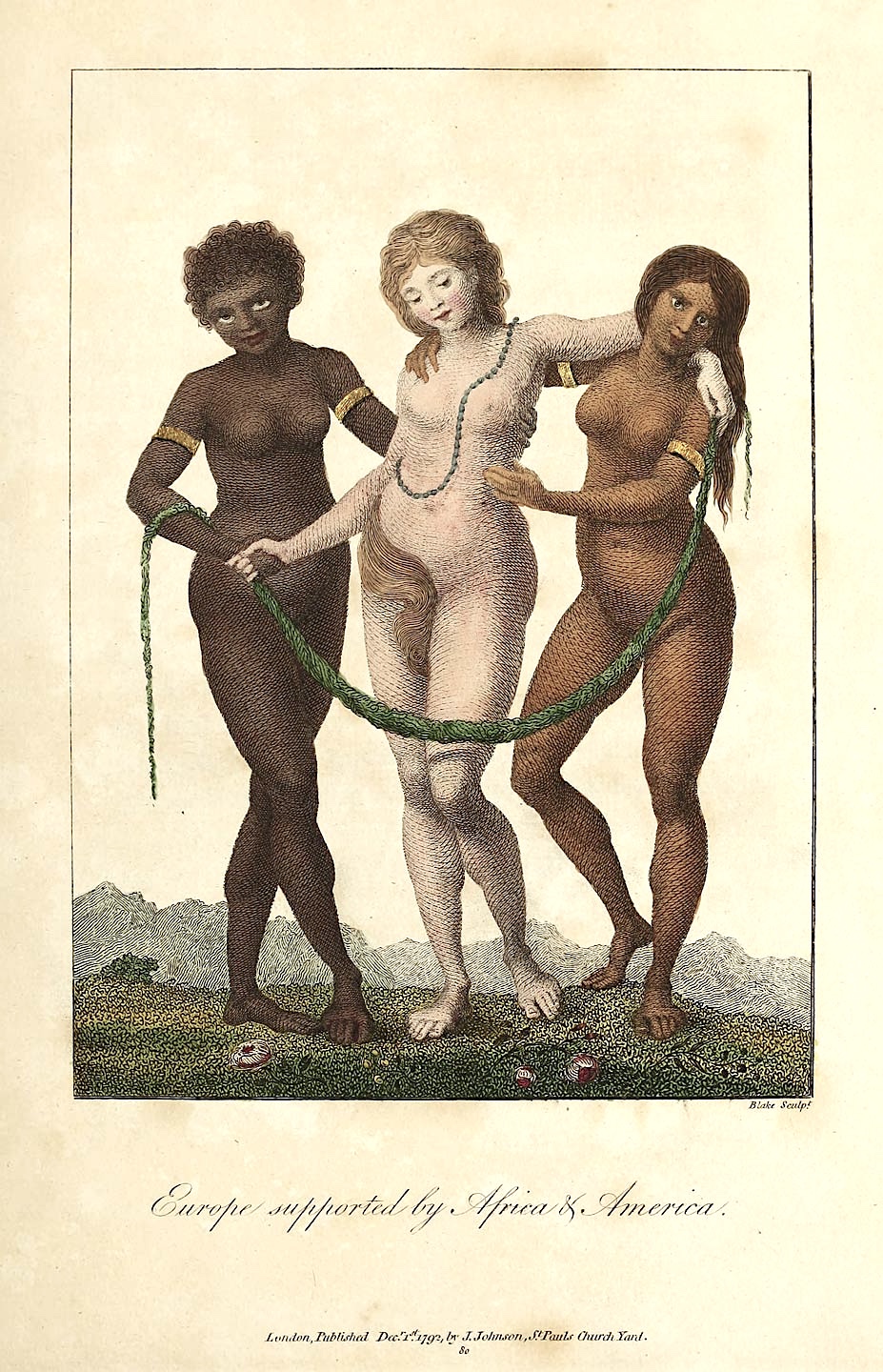

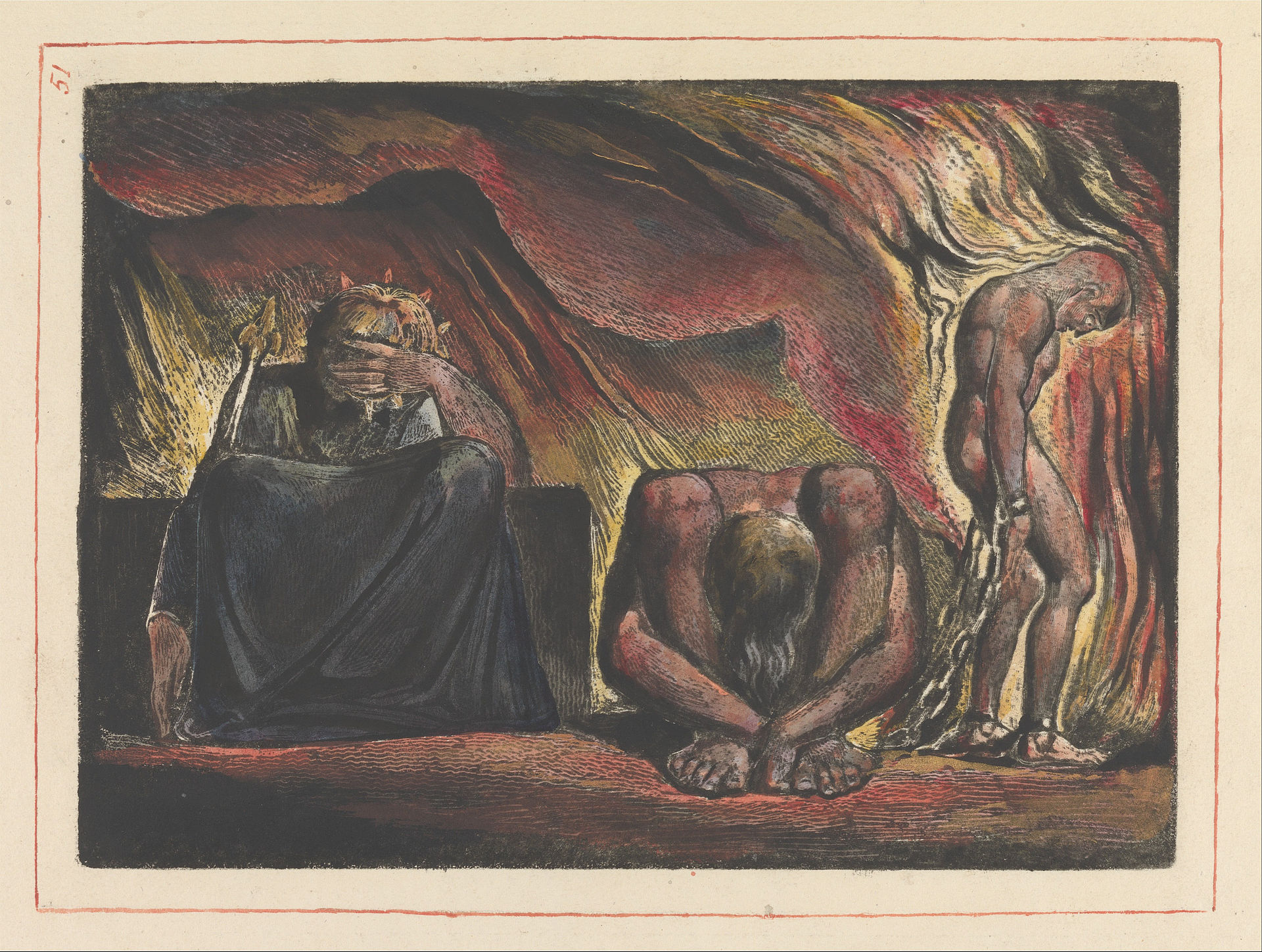

初期の生活 1912年のイラストに描かれたブロード・ストリート28番地(現在のブロードウィック・ストリート)。ブレイクはここで生まれ、25歳まで住んでいた。この家は1965年に取り壊された[15]。 ウィリアム・ブレイクは1757年11月28日、ロンドンのソーホーにあるブロード・ストリート28番地(現在のブロードウィック・ストリート)で生まれ た。7人兄弟の3番目で[16][17]、うち2人は幼児期に死亡。ブレイクの父ジェームズはロンドンに住んでいた掃除屋であった[17]。 [19]ブレイク一家はイギリスの異教徒であったが[20]、ウィリアムは12月11日にロンドンのピカデリーにあるセント・ジェームズ教会で洗礼を受け た[21]。彼によれば、ブレイクの幼少期には、「窓に押し付けられた神の顔を見たり、干し草の山の中で天使を見たり、旧約聖書の預言者エゼキエルの訪問 を受けたり」といった神秘的な宗教体験があった[22]。 ブレイクは、父親が買ってくれたギリシア古美術の素描の複製を彫り始めた。これらの素描の中でブレイクは、ラファエロ、ミケランジェロ、マールテン・ファ ン・ヘームスケルク、アルブレヒト・デューラーの作品を通して、古典的な形態に初めて触れることになる。ジェームズとキャサリンが幼いウィリアムのために 購入することができた版画や装丁本の数は、ブレイク夫妻が少なくとも一時期はゆとりある富を享受していたことを示唆している[20]。ウィリアムが10歳 のとき、両親は彼の強情な気質を十分に理解していたため、学校には行かせず、ストランドにあるヘンリー・パーズのデッサン教室に入学させた[23]。初期 の作品にはベン・ジョンソン、エドモンド・スペンサー、詩篇の知識が見られる。 徒弟制度  創造主の原型は、ブレイクの作品ではおなじみのイメージである。ここでは、悪魔のような人物ウリゼンが、自分が作り上げた世界の前で祈りを捧げている。ロスの歌』は、ブレイクとその妻によって描かれた、「大陸の予言」と総称される一連の挿絵本の第3作目である。 1772年8月4日、ブレイクはグレート・クイーン・ストリートの彫版師ジェームズ・バジールに52.10ポンドで7年間弟子入りした[17]。しかし、 ピーター・アクロイドの伝記によれば、ブレイクは後にバジールの名前を芸術上の敵対者リストに加え、その後、その名前を消している。 [24] このことはさておき、バジールの線刻画のスタイルは、当時、派手なスティプルやメゾチントのスタイルに比べ、古風なものであった[25]。 2年後、バジールは弟子をロンドンのゴシック教会の画像を模写させた(おそらくブレイクと弟子仲間のジェームズ・パーカーとの喧嘩を解決するため)。ウェ ストミンスター寺院での経験は、彼の芸術的スタイルとアイデアの形成に役立った。当時のウェストミンスター寺院は、鎧兜、彩色された葬儀用の肖像画、色と りどりの蝋人形で飾られていた。アクロイドは、「......最も直接的な印象は、色あせた明るさと色彩であったろう」[27]と記している。このゴシッ ク(ブレイクはゴシックを「生きている形」と見ていた)の綿密な研究は、ブレイクの作風に明確な痕跡を残した。彼らはブレイクをからかい、ある少年はブレ イクを苦しめたので、ブレイクはその少年を足場から地面に叩き落とし、「その上にものすごい暴力で倒れた」[29]。ブレイクが学長に苦情を申し立てた 後、少年たちの特権は撤回された[28]。キリストと使徒たち、修道士や司祭の大行列を見、聖歌を聞いたという[28]。 ロイヤル・アカデミー 1779年10月8日、ブレイクはストランド近くのオールド・サマーセット・ハウスにあるロイヤル・アカデミーの学生となる[30]。そこで彼は、同校の 初代学長ジョシュア・レイノルズが提唱したルーベンスなどの流行の画家の未完成なスタイルに反発した。やがてブレイクは、レイノルズの芸術に対する姿勢、 特に「一般的な真理」と「一般的な美」を追求する姿勢を嫌悪するようになった。レノルズは『論考』の中で、「抽象化、一般化、分類を好む性質は、人間の心 の偉大な栄光である」と書いているが、ブレイクは私的複製につけた余白で、「一般化することは馬鹿であることであり、特定化することは唯一の功利の区別で ある」と反論している[31]。ブレイクはまた、レノルズの見かけの謙虚さを嫌い、それは偽善の一形態であるとした。レノルズの流行の油絵に対して、ブレ イクは初期に影響を受けたミケランジェロやラファエロの古典的な精密さを好んだ。 デイヴィッド・ビンドマンは、ブレイクのレイノルズに対する反感は、会長の意見(ブレイクと同様、レイノルズは歴史画の方が風景画や肖像画よりも価値があ るとした)からというよりも、むしろ「自分の理想を実践しないという偽善に対するもの」[32]であったと指摘する。確かにブレイクはロイヤル・アカデ ミーへの出品を嫌っていたわけではなく、1780年から1808年にかけて6回作品を提出している。 ブレイクはロイヤル・アカデミーでの最初の年に、ジョン・フラックスマン、トーマス・ストサード、ジョージ・カンバーランドの友人となった。彼らは急進的な意見を共有し、ストサードとカンバーランドは憲法情報協会に参加した[33]。 ゴードン暴動 ブレイクの最初の伝記作者アレクサンダー・ギルクリストは、1780年6月、ブレイクがグレート・クイーン・ストリートのバジールの店に向かって歩いてい たところ、ニューゲート刑務所を襲撃した暴徒に巻き込まれたと記録している[34]。ブレイクはこの暴動の最前列にいたと伝えられている。この暴動は、 ローマ・カトリックに対する制裁を撤廃する議会法案に反発したもので、ゴードン暴動として知られるようになり、ジョージ3世政府による立法が活発化し、最 初の警察が創設された。 |

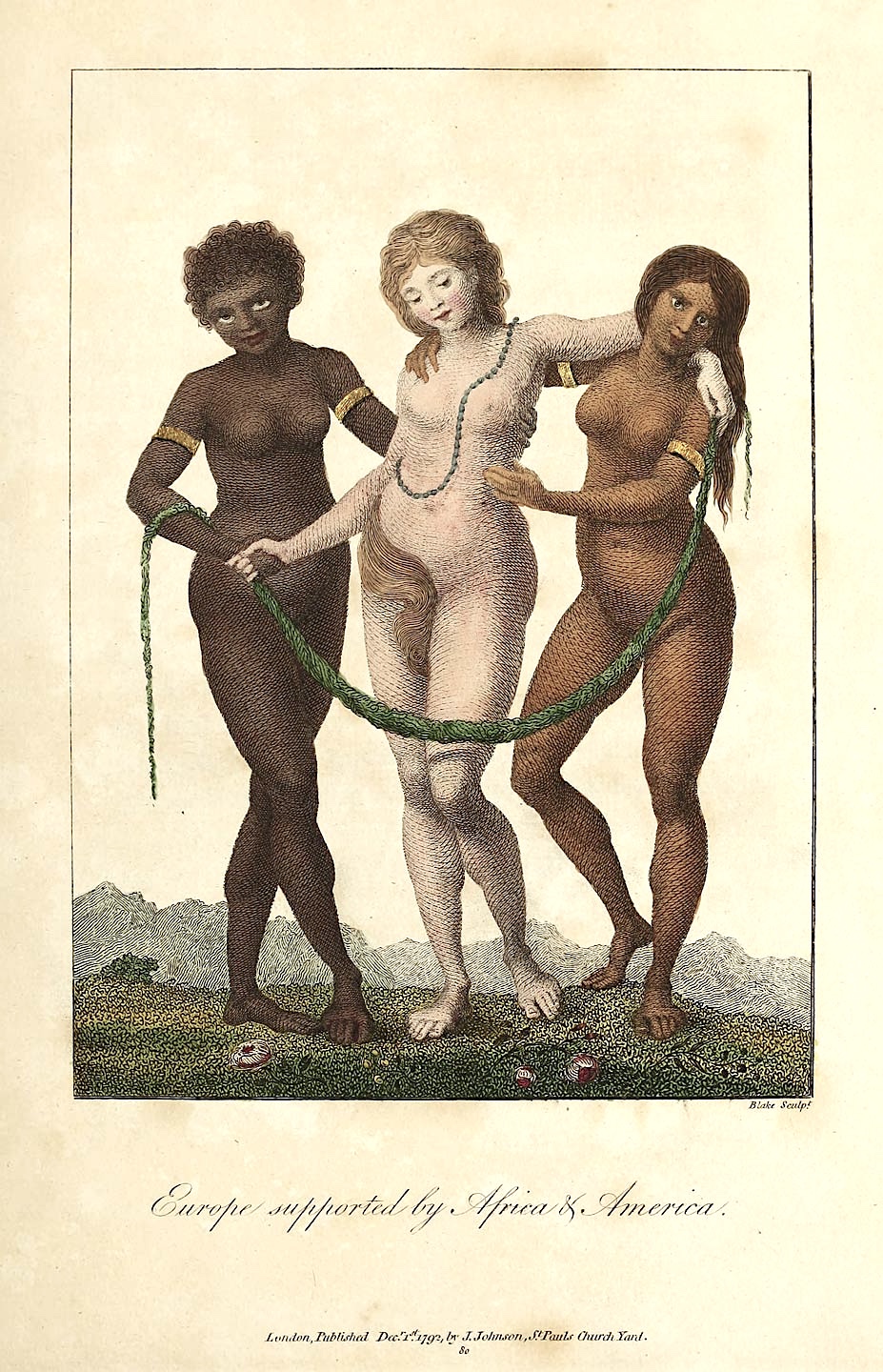

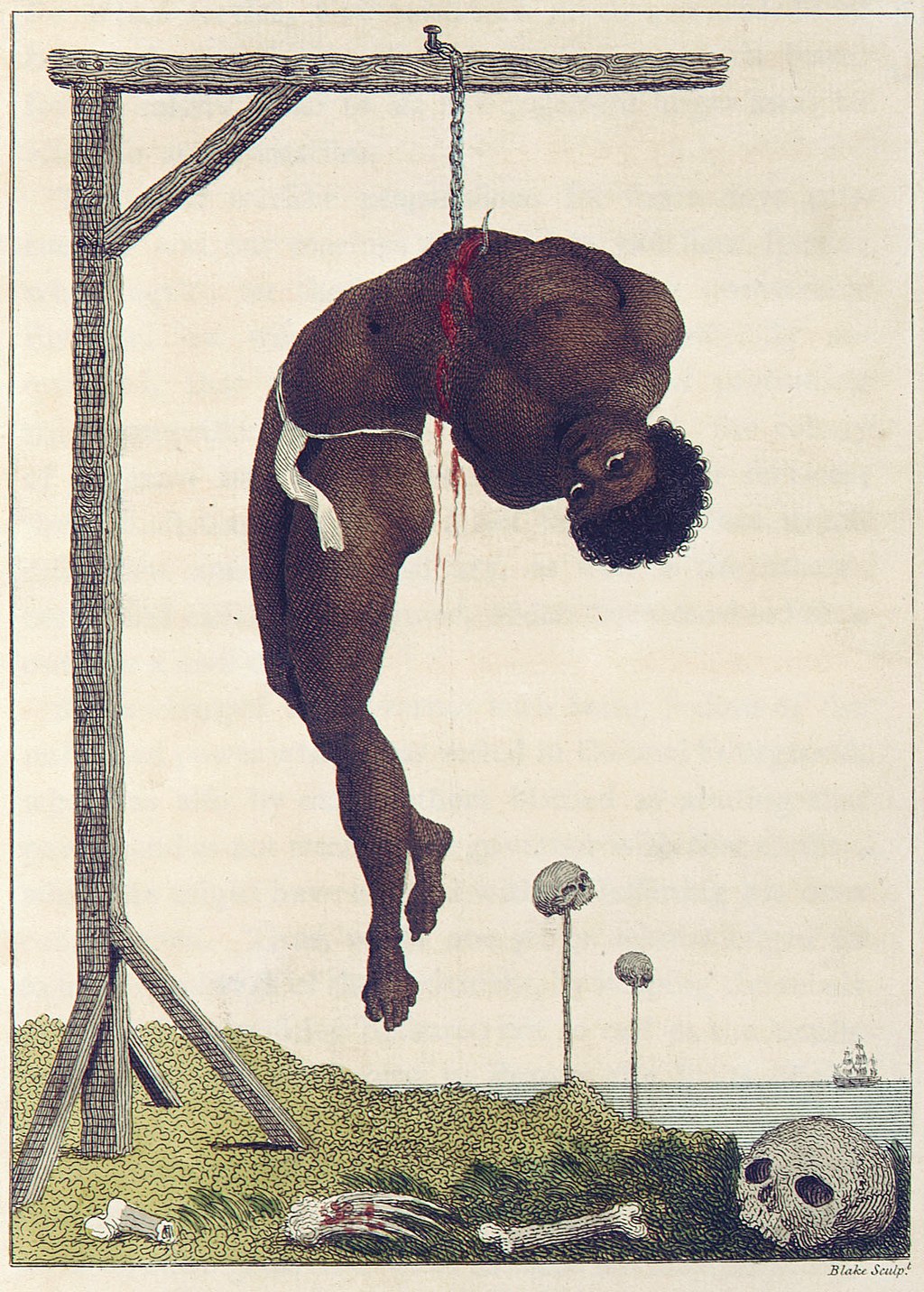

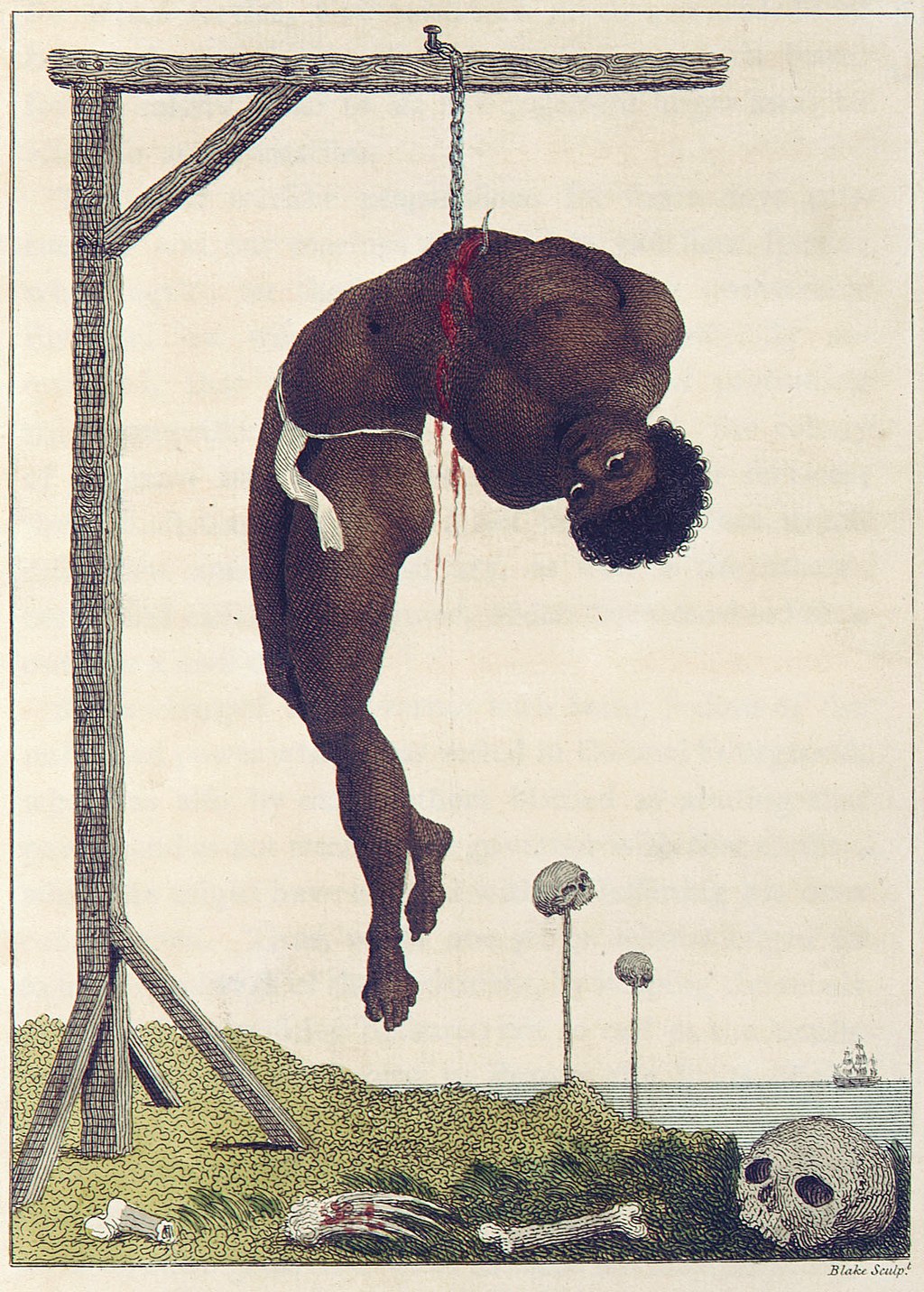

| Marriage In 1781 Blake met Catherine Boucher[35] when he was recovering from a relationship that had culminated in a refusal of his marriage proposal. He recounted the story of his heartbreak for Catherine and her parents, after which he asked Catherine: "Do you pity me?" When she responded affirmatively, he declared: "Then I love you". Blake married Catherine, who was five years his junior, on 18 August 1782 in St Mary's Church, Battersea. Illiterate, Catherine signed her wedding contract with an X. The original wedding certificate may be viewed at the church, where a commemorative stained-glass window was installed between 1976 and 1982.[36] Later,[when?] in addition to teaching Catherine to read and write, Blake trained her as an engraver. Throughout his life she proved a valuable aid, helping to print his illuminated works and maintaining his spirits throughout numerous misfortunes.[citation needed] Career  Oberon, Titania and Puck with Fairies Dancing (1786) Around 1783, Blake's first collection of poems, Poetical Sketches, was printed.[37] In 1784, after his father's death, Blake and former fellow apprentice James Parker opened a print shop. They began working with radical publisher Joseph Johnson.[38] Johnson's house was a meeting-place for some leading English intellectual dissidents of the time: theologian and scientist Joseph Priestley; philosopher Richard Price; artist John Henry Fuseli;[39] early feminist Mary Wollstonecraft; and English-American revolutionary Thomas Paine. Along with William Wordsworth and William Godwin, Blake had great hopes for the French and American revolutions and wore a Phrygian cap in solidarity with the French revolutionaries, but despaired with the rise of Robespierre and the Reign of Terror in France. That same year, Blake composed his unfinished manuscript An Island in the Moon (1784).[citation needed] Blake illustrated Original Stories from Real Life (2nd edition, 1791) by Mary Wollstonecraft. Although they seem to have shared some views on sexual equality and the institution of marriage, no evidence is known that would prove that they had met. In Visions of the Daughters of Albion (1793), Blake condemned the cruel absurdity of enforced chastity and marriage without love and defended the right of women to complete self-fulfillment.[citation needed] From 1790 to 1800, William Blake lived in North Lambeth, London, at 13 Hercules Buildings, Hercules Road.[40] The property was demolished in 1918, but the site is now marked with a plaque.[41] A series of 70 mosaics commemorates Blake in the nearby railway tunnels of Waterloo Station.[42][43][44] The mosaics largely reproduce illustrations from Blake's illuminated books, The Songs of Innocence and of Experience, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, and the prophetic books.[44] Relief etching In 1788, aged 31, Blake experimented with relief etching, a method he used to produce most of his books, paintings, pamphlets and poems. The process is also referred to as illuminated printing, and the finished products as illuminated books or prints. Illuminated printing involved writing the text of the poems on copper plates with pens and brushes, using an acid-resistant medium. Illustrations could appear alongside words in the manner of earlier illuminated manuscripts. He then etched the plates in acid to dissolve the untreated copper and leave the design standing in relief (hence the name). This is a reversal of the usual method of etching, where the lines of the design are exposed to the acid, and the plate printed by the intaglio method. Relief etching (which Blake referred to as "stereotype" in The Ghost of Abel) was intended as a means for producing his illuminated books more quickly than via intaglio. Stereotype, a process invented in 1725, consisted of making a metal cast from a wood engraving, but Blake's innovation was, as described above, very different. The pages printed from these plates were hand-coloured in watercolours and stitched together to form a volume. Blake used illuminated printing for most of his well-known works, including Songs of Innocence and of Experience, The Book of Thel, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell and Jerusalem.[45] Engravings  Europe Supported by Africa and America engraving by William Blake Although Blake has become better known for his relief etching, his commercial work largely consisted of intaglio engraving, the standard process of engraving in the 18th century in which the artist incised an image into the copper plate, a complex and laborious process, with plates taking months or years to complete, but as Blake's contemporary, John Boydell, realised, such engraving offered a "missing link with commerce", enabling artists to connect with a mass audience and became an immensely important activity by the end of the 18th century.[46] Europe Supported by Africa and America is an engraving by Blake held in the collection of the University of Arizona Museum of Art. The engraving was for a book written by Blake's friend John Gabriel Stedman called The Narrative of a Five Years Expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam (1796).[47] It depicts three women embracing one another. Black Africa and White Europe hold hands in a gesture of equality, as the barren earth blooms beneath their feet. Europe wears a string of pearls, while her sisters Africa and America are depicted wearing slave bracelets.[48] Some scholars have speculated that the bracelets represent the "historical fact" of slavery in Africa and the Americas while the handclasp refer to Stedman's "ardent wish": "we only differ in color, but are certainly all created by the same Hand."[48] Others have said it "expresses the climate of opinion in which the questions of color and slavery were, at that time, being considered, and which Blake's writings reflect".[49] Blake employed intaglio engraving in his own work, such as for his Illustrations of the Book of Job, completed just before his death. Most critical work has concentrated on Blake's relief etching as a technique because it is the most innovative aspect of his art, but a 2009 study drew attention to Blake's surviving plates, including those for the Book of Job: they demonstrate that he made frequent use of a technique known as "repoussage", a means of obliterating mistakes by hammering them out by hitting the back of the plate. Such techniques, typical of engraving work of the time, are very different from the much faster and fluid way of drawing on a plate that Blake employed for his relief etching, and indicates why the engravings took so long to complete.[50] |

結婚 1781年、ブレイクはプロポーズを断られた恋愛から立ち直っていた頃、キャサリン・ブーシェ[35]と出会う。彼はキャサリンと彼女の両親のために失恋 のエピソードを語り、その後キャサリンに尋ねた: 「君は僕を憐れんでくれるかい?彼女が肯定的な返事をすると、彼は宣言した: 「と訊ねた。ブレイクは1782年8月18日、5歳年下のキャサリンとバタシーのセント・メアリー教会で結婚した。結婚証明書の原本は教会で見ることがで き、1976年から1982年にかけて記念のステンドグラスが設置された[36]。 その後[いつ?]、ブレイクはキャサリンに読み書きを教えることに加えて、彼女を彫金師として訓練した。彼女はブレイクの生涯を通じて貴重な助力者となり、彼の照明作品の印刷を手伝い、数々の不運に見舞われながらも彼の精神を支えた[要出典]。 経歴  オベロン、ティターニア、パックと妖精たちの踊り (1786) 1783年頃、ブレイクの最初の詩集『Poetical Sketches』が印刷された[37]。 1784年、父の死後、ブレイクは元弟子仲間のジェームズ・パーカーとともに印刷所を開いた。ジョンソンの家は、神学者・科学者のジョセフ・プリースト リー、哲学者のリチャード・プライス、芸術家のジョン・ヘンリー・フーセリ、[39]初期のフェミニスト、メアリー・ウルストンクラフト、英米の革命家ト マス・ペインなど、当時のイギリスを代表する知識人反体制派が集う場所であった。ウィリアム・ワーズワースやウィリアム・ゴドウィンとともに、ブレイクは フランス革命やアメリカ革命に大きな希望を抱き、フランス革命派と連帯するためにフリジア帽をかぶったが、ロベスピエールの台頭とフランスにおける恐怖政 治に絶望した。同年、ブレイクは未完の稿『月の島』(1784年)を執筆した[要出典]。 ブレイクはメアリー・ウルストンクラフトの『Original Stories from Real Life』(第2版、1791年)の挿絵を描いた。二人は性の平等と結婚制度についていくつかの見解を共有していたようだが、二人が会っていたことを証明 するような証拠は知られていない。ブレイクは『アルビオンの娘たちの幻影』(1793年)の中で、強制的な貞操や愛のない結婚の残酷な不条理を非難し、女 性の完全な自己実現の権利を擁護した[要出典]。 1790年から1800年まで、ウィリアム・ブレイクはロンドンのノース・ランベスのヘラクレス・ロードにあるヘラクレス・ビルディング13番地に住んで いた[40]。この建物は1918年に取り壊されたが、現在その場所にはプレートが掲げられている[41]。 [42][43][44]モザイク画の大部分は、ブレイクの照明本『無垢と経験の歌』、『天国と地獄の結婚』、予言書の挿絵を再現したものである [44]。 レリーフ・エッチング 1788年、31歳のブレイクはレリーフ・エッチングの実験を行った。この技法はイルミネーテッド・プリンティングとも呼ばれ、完成品はイルミネーテッ ド・ブックまたは版画と呼ばれる。イルミネーテッド・プリンティングでは、耐酸性のメディウムを使い、ペンや筆で銅版に詩のテキストを書き込んだ。挿絵 は、以前のイルミネーテッド写本のように、文字と一緒に表示することができた。その後、銅版を酸でエッチングし、未処理の銅を溶かし、浮き彫りにしたデザ インを残した(これが名前の由来である)。 これは通常のエッチングの方法とは逆で、デザインの線は酸にさらされ、版は凹版法で印刷される。レリーフ・エッチング(ブレイクは『アベルの幽霊』の中で 「ステレオタイプ」と呼んでいる)は、凹版よりも早くイルミネーテッド・ブックを制作するための手段として考案された。ステレオタイプは1725年に発明 された製法で、木版画から金属の鋳型を作るというものだったが、ブレイクの革新は上述のようにまったく異なるものだった。これらの版から印刷されたページ は、水彩絵の具で手彩色され、一冊に綴じ合わされた。ブレイクは、『無垢と経験の歌』、『テルの書』、『天国と地獄の結婚』、『エルサレム』など、有名な 作品のほとんどに照光印刷を用いた[45]。 エングレーヴィング  「アフリカとアメリカに支えられたヨーロッパ」 ウィリアム・ブレイク作 ブレイクはレリーフ・エッチングでよく知られるようになったが、彼の商業作品の大部分はインタリオ・エングレーヴィングで構成されていた。インタリオ・エ ングレーヴィングは、18世紀におけるエングレーヴィングの標準的なプロセスで、アーティストが銅版にイメージを刻み込むというもの。 アフリカとアメリカに支えられたヨーロッパ』は、アリゾナ大学美術館が所蔵するブレイクのエングレーヴィングである。このエングレーヴィングは、ブレイク の友人ジョン・ガブリエル・ステッドマンが書いた『スリナムの反乱した黒人に対する5年間の遠征の物語』(1796年)という本のために描かれた。アフリ カの黒人とヨーロッパの白人は、不毛の大地が彼女たちの足元に花を咲かせる中、平等を示すジェスチャーで手を取り合っている。ヨーロッパは真珠の紐をつ け、姉妹のアフリカとアメリカは奴隷のブレスレットをつけて描かれている[48]。一部の学者は、ブレスレットはアフリカとアメリカ大陸における奴隷制の 「歴史的事実」を表し、合掌はステッドマンの「熱烈な願い」を指していると推測している: 「私たちは色が違うだけで、確かにすべて同じ手によって創造された」[48]。また、「当時、色と奴隷制の問題が検討され、ブレイクの著作が反映していた 意見の風潮を表現している」と言う人もいる[49]。 ブレイクは、死の直前に完成した『ヨブ記の挿絵』など、自身の作品に凹版画を用いた。批評の大半は、ブレイクの技法としての浮き彫りエッチングに集中して いるが、2009年の研究では、ヨブ記の挿絵を含むブレイクの現存する版に注目した。このような技法は、当時のエングレーヴィングの典型的なものであり、 ブレイクがレリーフ・エッチングに用いた、版に素早く流れるように描く方法とは大きく異なり、エングレーヴィングの完成に時間がかかった理由を示している [50]。 |

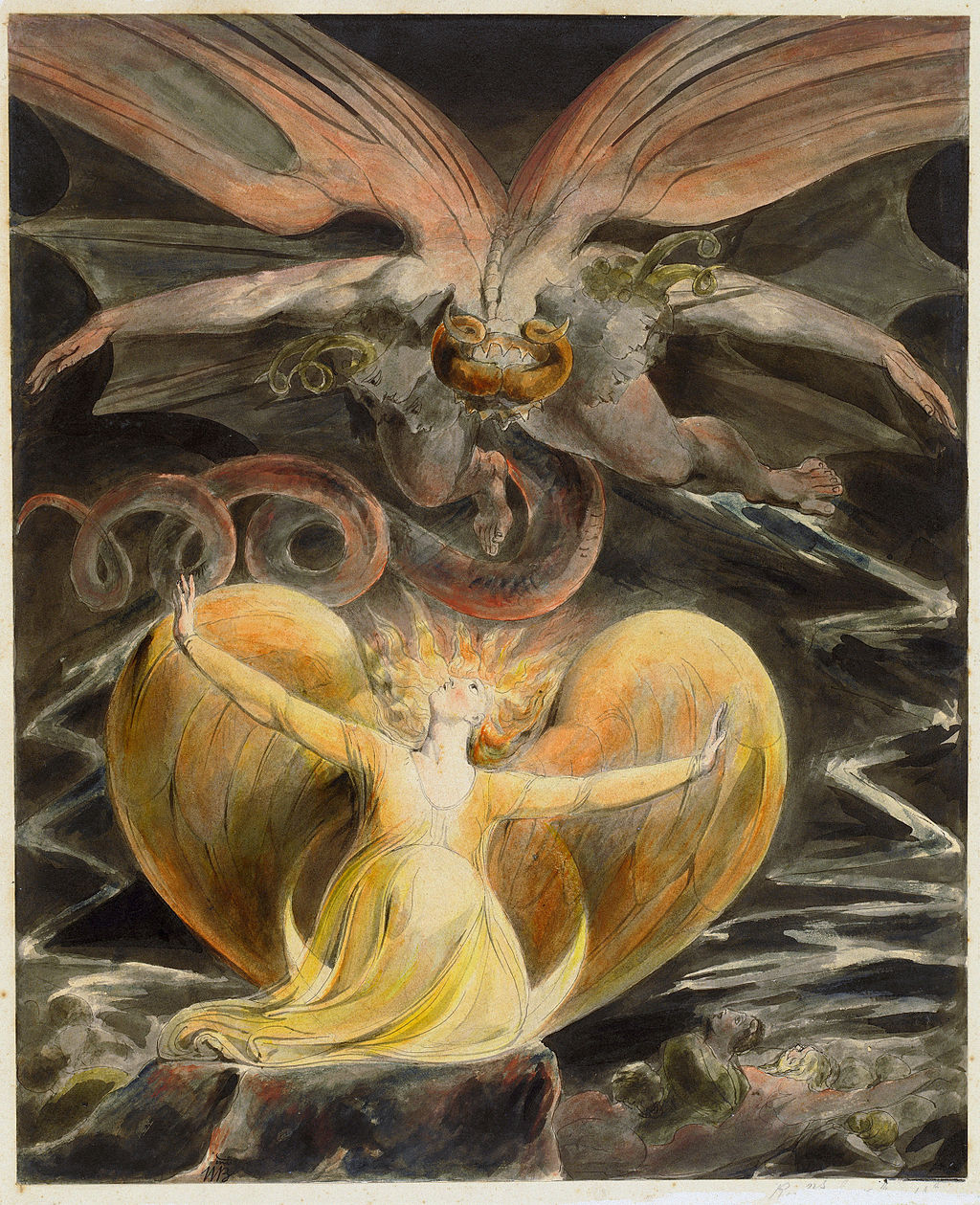

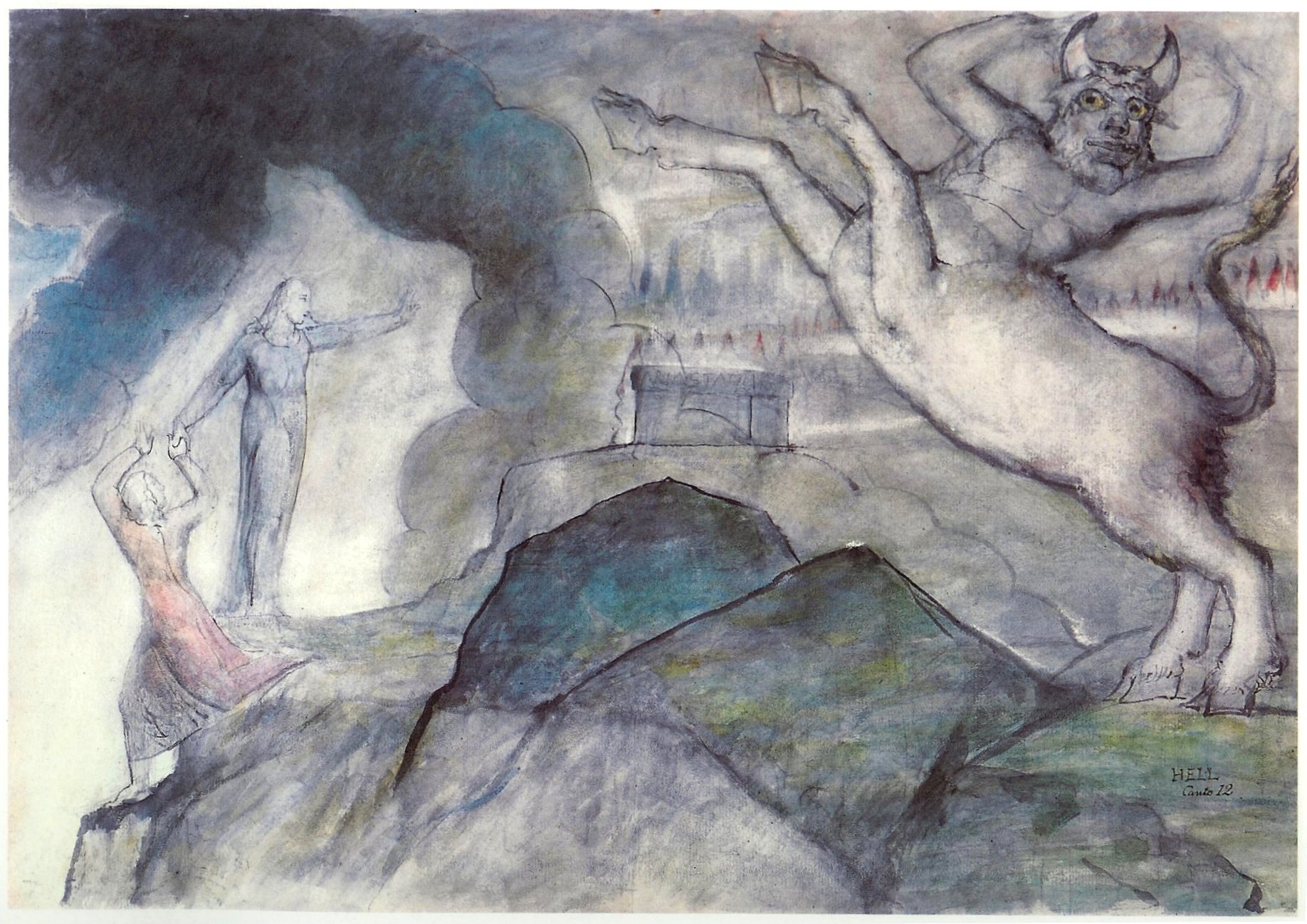

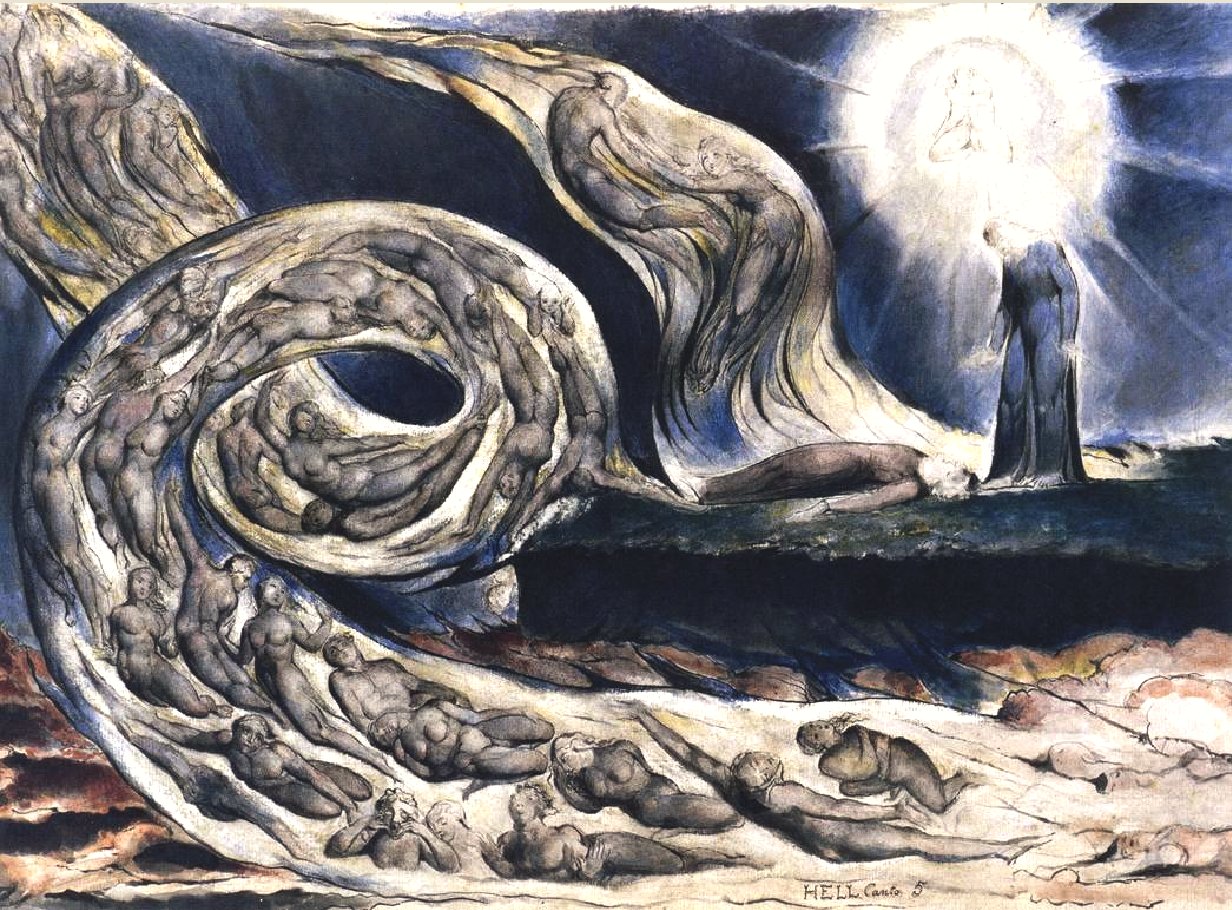

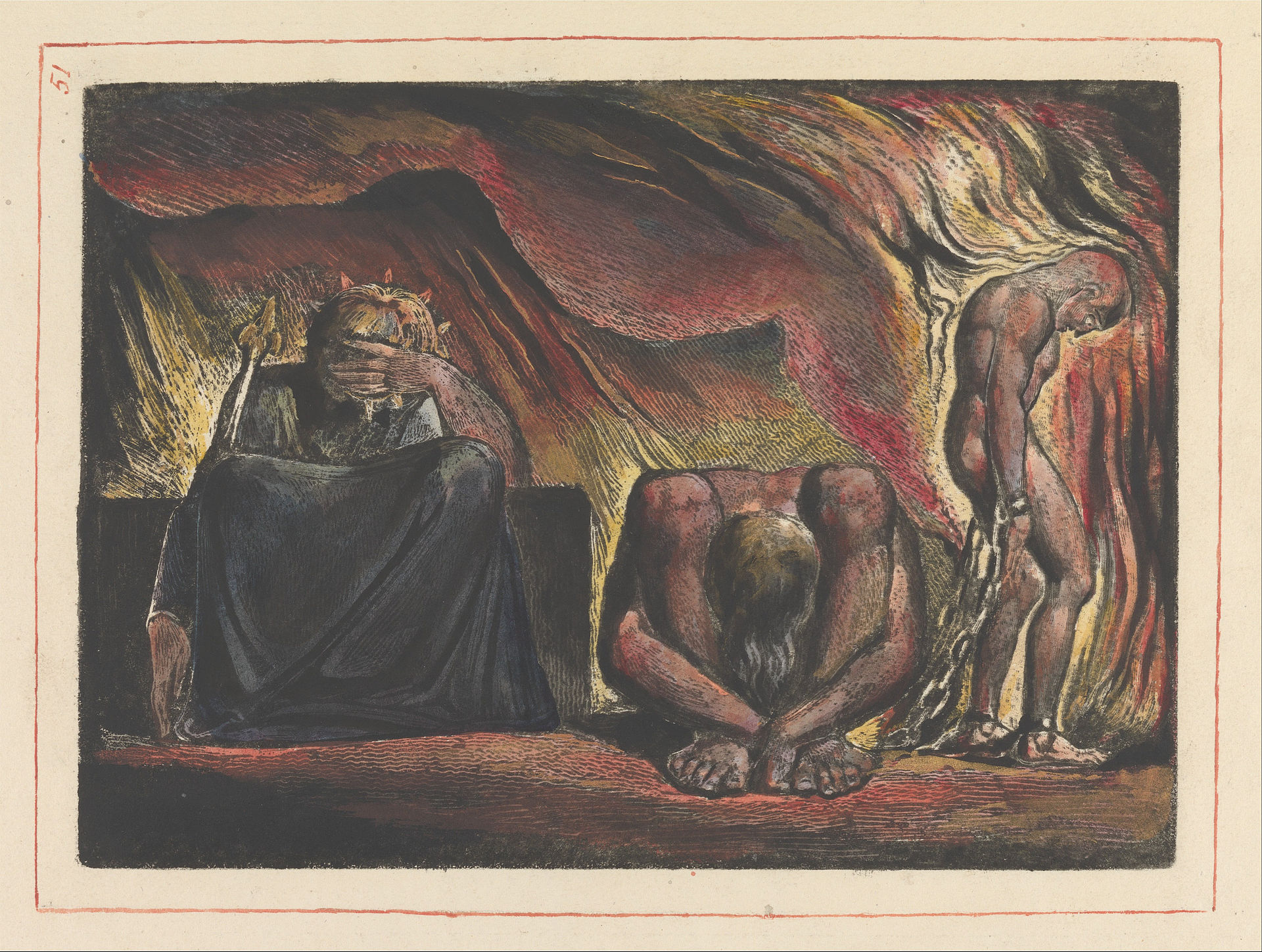

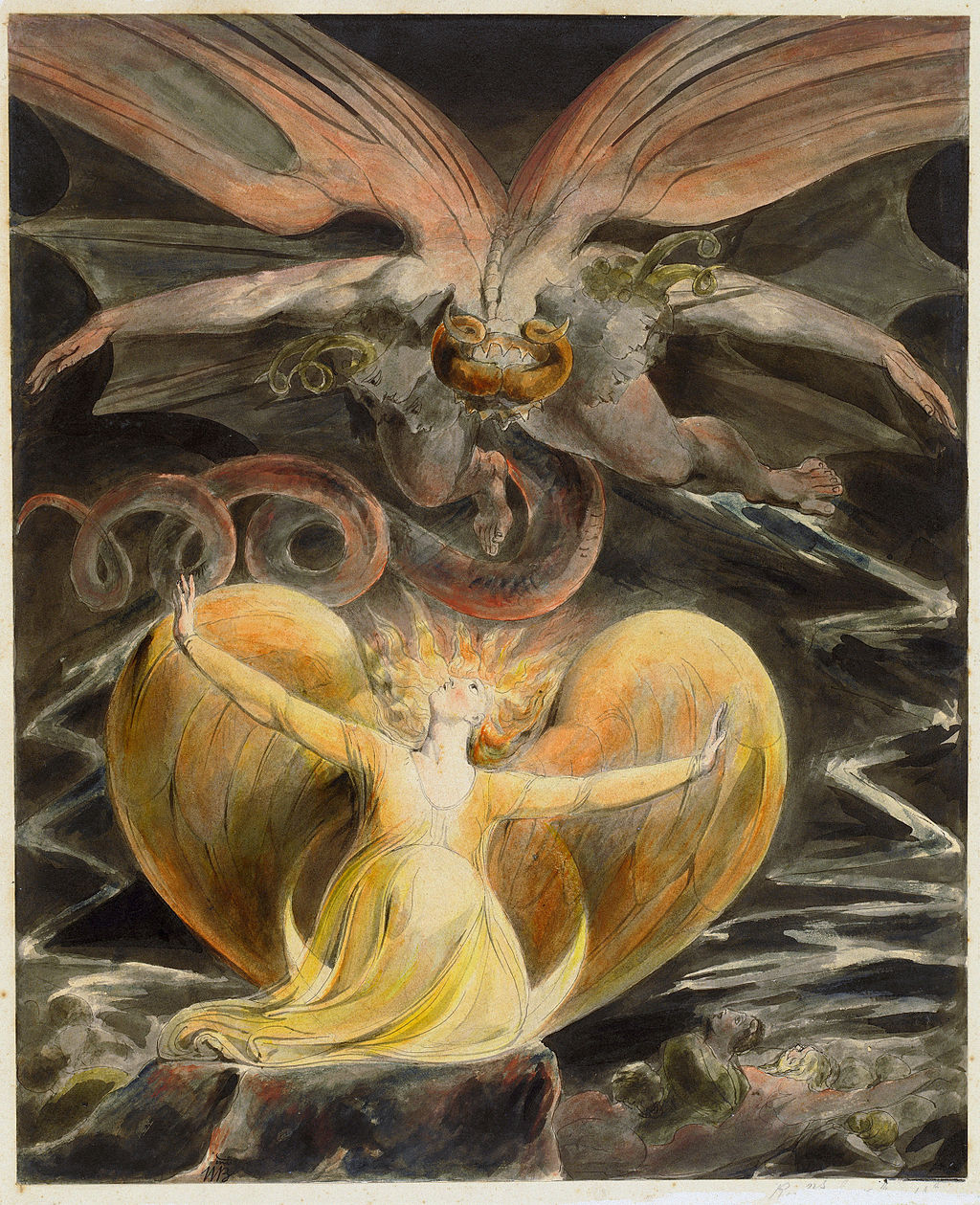

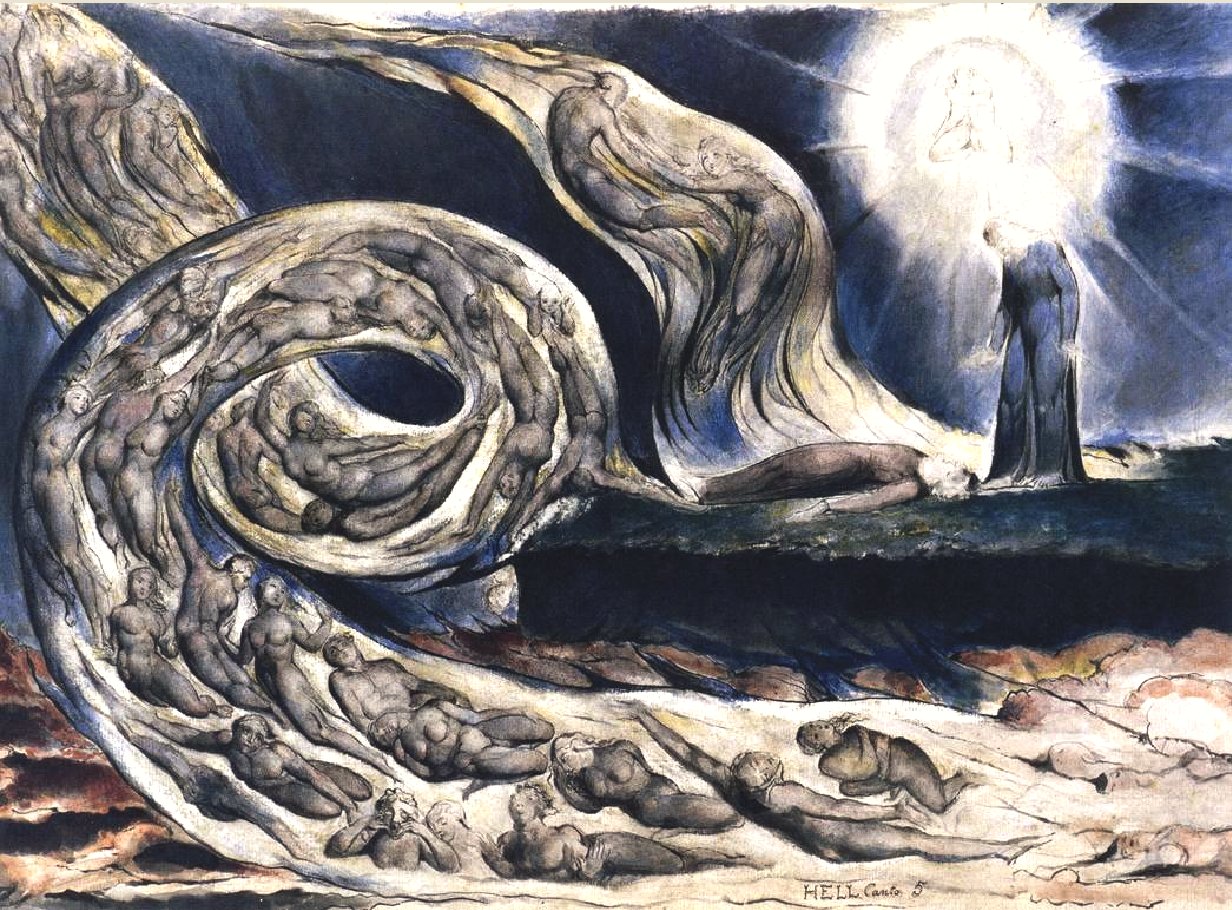

| Later life The cottage in Felpham, now Blake’s Cottage, where Blake lived from 1800 until 1803 Blake's marriage to Catherine was close and devoted until his death. Blake taught Catherine to write, and she helped him colour his printed poems.[51] Gilchrist refers to "stormy times" in the early years of the marriage.[52] Some biographers have suggested that Blake tried to bring a concubine into the marriage bed in accordance with the beliefs of the more radical branches of the Swedenborgian Society,[53] but other scholars have dismissed these theories as conjecture.[54] In his Dictionary, Samuel Foster Damon suggests that Catherine may have had a stillborn daughter for which The Book of Thel is an elegy. That is how he rationalizes the Book's unusual ending, but notes that he is speculating.[55] Felpham In 1800, Blake moved to a cottage at Felpham, in Sussex (now West Sussex), to take up a job illustrating the works of William Hayley, a minor poet. It was in this cottage that Blake began Milton (the title page is dated 1804, but Blake continued to work on it until 1808). The preface to this work includes a poem beginning "And did those feet in ancient time", which became the words for the anthem "Jerusalem". Over time, Blake began to resent his new patron, believing that Hayley was uninterested in true artistry, and preoccupied with "the meer drudgery of business" (E724). Blake's disenchantment with Hayley has been speculated to have influenced Milton: a Poem, in which Blake wrote that "Corporeal Friends are Spiritual Enemies". (4:26, E98)  'Skofeld' wearing "mind forged manacles" in Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Giant Albion, Plate 51 Blake's trouble with authority came to a head in August 1803, when he was involved in a physical altercation with a soldier, John Schofield.[56] Blake was charged not only with assault, but with uttering seditious and treasonable expressions against the king. Schofield claimed that Blake had exclaimed "Damn the king. The soldiers are all slaves."[57] Blake was cleared in the Chichester assizes of the charges. According to a report in the Sussex county paper, "[T]he invented character of [the evidence] was ... so obvious that an acquittal resulted".[58] Schofield was later depicted wearing "mind forged manacles" in an illustration to Jerusalem The Emanation of the Giant Albion.[59] Return to London Sketch of Blake from, circa 1804, by John Flaxman Blake returned to London in 1804 and began to write and illustrate Jerusalem (1804–20), his most ambitious work. Having conceived the idea of portraying the characters in Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, Blake approached the dealer Robert Cromek, with a view to marketing an engraving. Knowing Blake was too eccentric to produce a popular work, Cromek promptly commissioned Blake's friend Thomas Stothard to execute the concept. When Blake learned he had been cheated, he broke off contact with Stothard. He set up an independent exhibition in his brother's haberdashery shop at 27 Broad Street in Soho. The exhibition was designed to market his own version of the Canterbury illustration (titled The Canterbury Pilgrims), along with other works. As a result, he wrote his Descriptive Catalogue (1809), which contains what Anthony Blunt called a "brilliant analysis" of Chaucer and is regularly anthologised as a classic of Chaucer criticism.[60] It also contained detailed explanations of his other paintings. The exhibition was very poorly attended, selling none of the temperas or watercolours. Its only review, in The Examiner, was hostile.[61]  Blake's The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed with Sun (1805) is one of a series of illustrations of Revelation 12. Also around this time (circa 1808), Blake gave vigorous expression of his views on art in an extensive series of polemical annotations to the Discourses of Sir Joshua Reynolds, denouncing the Royal Academy as a fraud and proclaiming, "To Generalize is to be an Idiot".[62] In 1818, he was introduced by George Cumberland's son to a young artist named John Linnell.[63] A blue plaque commemorates Blake and Linnell at Old Wyldes' at North End, Hampstead.[64] Through Linnell he met Samuel Palmer, who belonged to a group of artists who called themselves the Shoreham Ancients. The group shared Blake's rejection of modern trends and his belief in a spiritual and artistic New Age. Aged 65, Blake began work on illustrations for the Book of Job, later admired by Ruskin, who compared Blake favourably to Rembrandt, and by Vaughan Williams, who based his ballet Job: A Masque for Dancing on a selection of the illustrations. In later life Blake began to sell a great number of his works, particularly his Bible illustrations, to Thomas Butts, a patron who saw Blake more as a friend than a man whose work held artistic merit; this was typical of the opinions held of Blake throughout his life.  William Blake's image of the Minotaur to illustrate Inferno, Canto XII, 12–28, The Minotaur XII The commission for Dante's Divine Comedy came to Blake in 1826 through Linnell, with the aim of producing a series of engravings. Blake's death in 1827 cut short the enterprise, and only a handful of watercolours were completed, with only seven of the engravings arriving at proof form. Even so, they have earned praise: [T]he Dante watercolours are among Blake's richest achievements, engaging fully with the problem of illustrating a poem of this complexity. The mastery of watercolour has reached an even higher level than before, and is used to extraordinary effect in differentiating the atmosphere of the three states of being in the poem.[65]  Blake's The Lovers' Whirlwind illustrates Hell in Canto V of Dante's Inferno. Blake's illustrations of the poem are not merely accompanying works, but rather seem to critically revise, or furnish commentary on, certain spiritual or moral aspects of the text. Because the project was never completed, Blake's intent may be obscured. Some indicators bolster the impression that Blake's illustrations in their totality would take issue with the text they accompany: in the margin of Homer Bearing the Sword and His Companions, Blake notes, "Every thing in Dantes Comedia shews That for Tyrannical Purposes he has made This World the Foundation of All & the Goddess Nature & not the Holy Ghost." Blake seems to dissent from Dante's admiration of the poetic works of ancient Greece, and from the apparent glee with which Dante allots punishments in Hell (as evidenced by the grim humour of the cantos). At the same time, Blake shared Dante's distrust of materialism and the corruptive nature of power, and clearly relished the opportunity to represent the atmosphere and imagery of Dante's work pictorially. Even as he seemed to be near death, Blake's central preoccupation was his feverish work on the illustrations to Dante's Inferno; he is said to have spent one of the last shillings he possessed on a pencil to continue sketching.[66] Final years "Head of William Blake" by James De Ville. Life mask taken in plaster cast in September 1823, Fitzwilliam Museum. Headstone in Bunhill Fields, London, erected on Blake's grave in 1927 and moved to its present location in 1964–65 Ledger stone on Blake's grave, unveiled in 2018 Blake's last years were spent at Fountain Court off the Strand (the property was demolished in the 1880s, when the Savoy Hotel was built).[1] On the day of his death (12 August 1827), Blake worked relentlessly on his Dante series. Eventually, it is reported, he ceased working and turned to his wife, who was in tears by his bedside. Beholding her, Blake is said to have cried, "Stay Kate! Keep just as you are – I will draw your portrait – for you have ever been an angel to me." Having completed this portrait (now lost), Blake laid down his tools and began to sing hymns and verses.[67] At six that evening, after promising his wife that he would be with her always, Blake died. Gilchrist reports that a female lodger in the house, present at his expiration, said, "I have been at the death, not of a man, but of a blessed angel."[68] George Richmond gives the following account of Blake's death in a letter to Samuel Palmer: He died ... in a most glorious manner. He said He was going to that Country he had all His life wished to see & expressed Himself Happy, hoping for Salvation through Jesus Christ – Just before he died His Countenance became fair. His eyes Brighten'd and he burst out Singing of the things he saw in Heaven.[69] Catherine paid for Blake's funeral with money lent to her by Linnell. Blake's body was buried in a plot shared with others, five days after his death – on the eve of his 45th wedding anniversary – at the Dissenter's burial ground in Bunhill Fields, in what is today the London Borough of Islington.[70][44] His parents' bodies were buried in the same graveyard. Present at the ceremonies were Catherine, Edward Calvert, George Richmond, Frederick Tatham and John Linnell. Following Blake's death, Catherine moved into Tatham's house as a housekeeper. She believed she was regularly visited by Blake's spirit. She continued selling his illuminated works and paintings, but entertained no business transaction without first "consulting Mr. Blake".[71] On the day of her death, in October 1831, she was as calm and cheerful as her husband, and called out to him "as if he were only in the next room, to say she was coming to him, and it would not be long now".[72] On her death, longtime acquaintance Frederick Tatham took possession of Blake's works and continued selling them. Tatham later joined the fundamentalist Irvingite church and under the influence of conservative members of that church burned manuscripts that he deemed heretical.[73] The exact number of destroyed manuscripts is unknown, but shortly before his death Blake told a friend he had written "twenty tragedies as long as Macbeth", none of which survive.[74] Another acquaintance, William Michael Rossetti, also burned works by Blake that he considered lacking in quality,[75] and John Linnell erased sexual imagery from a number of Blake's drawings.[76] At the same time, some works not intended for publication were preserved by friends, such as his notebook and An Island in the Moon. Blake's grave is commemorated by two stones. The first was a stone that reads "Near by lie the remains of the poet-painter William Blake 1757–1827 and his wife Catherine Sophia 1762–1831". The memorial stone is situated approximately 20 metres (66 ft) away from the actual grave, which was not marked until 12 August 2018.[44] For years since 1965, the exact location of William Blake's grave had been lost and forgotten. The area had been damaged in the Second World War; gravestones were removed and a garden was created. The memorial stone, indicating that the burial sites are "nearby", was listed as a Grade II listed structure in 2011.[77][78] A Portuguese couple, Carol and Luís Garrido, rediscovered the exact burial location after 14 years of investigatory work, and the Blake Society organised a permanent memorial slab, which was unveiled at a public ceremony at the site on 12 August 2018.[44][78][79][80] The new stone is inscribed "Here lies William Blake 1757–1827 Poet Artist Prophet" above a verse from his poem Jerusalem. The Blake Prize for Religious Art was established in his honour in Australia in 1949. In 1957 a memorial to Blake and his wife was erected in Westminster Abbey.[81] Another memorial lies in St James's Church, Piccadilly, where he was baptised. A memorial to William Blake in St James's Church, Piccadilly At the time of Blake's death, he had sold fewer than 30 copies of Songs of Innocence and of Experience.[82] |

その後の生活 1800年から1803年までブレイクが住んでいたフェルファムのコテージ(現在のブレイクス・コテージ ブレイクとキャサリンの結婚は、ブレイクが亡くなるまで親密で献身的なものだった。ブレイクはキャサリンに書くことを教え、キャサリンは彼が印刷した詩に 色を塗るのを手伝った[51]。 [52]伝記作家の中には、ブレイクがスウェーデンボルグ協会のより急進的な支部の信条に従って、妾を婚姻の場に連れ込もうとしたと示唆する者もいるが [53]、他の学者たちはこれらの説を憶測として退けている[54]。 サミュエル・フォスター・デイモンは『辞典』の中で、キャサリンには死産した娘がいた可能性があり、『テルの書』はそのためのエレジーであると示唆してい る。それが『テルの書』の特異な結末を合理化する方法であるが、彼は憶測であると指摘している[55]。 フェルファム 1800年、ブレイクはサセックス州(現ウェスト・サセックス州)のフェルファムのコテージに移り住み、小詩人ウィリアム・ヘイリーの作品の挿絵の仕事を 引き受けた。ブレイクはこのコテージで『ミルトン』に着手した(タイトルページの日付は1804年だが、ブレイクは1808年までこの作品に取り組み続け た)。この作品の序文には、アンセム「エルサレム」の歌詞となった「そして太古の昔にその足は」で始まる詩が含まれている。やがてブレイクは、ヘイリーが 真の芸術性には関心がなく、「ビジネスの単なる雑務」(E724)に夢中になっていると考え、新しいパトロンに腹を立てるようになった。ブレイクのヘイ リーに対する幻滅は、ミルトンに影響を与えたと推測されている:その詩の中で、ブレイクは「肉体の友は精神の敵である」と書いている。(4:26, E98)  エルサレムで「マインド・フォージド・マナクル」を身につけた「スコフェルド」: 巨人アルビオンの発露』、プレート51 1803年8月、ブレイクは兵士のジョン・スコフィールドと肉体的な口論になり、権力との闘争に発展した[56]。ブレイクは暴行だけでなく、国王に対す る扇動的で反逆的な表現を口にした罪でも告発された。スコフィールドは、ブレイクが「クソ王め。兵士はみな奴隷だ」[57]と叫んだと主張していた。サ セックス郡紙の報道によれば、「(証拠の)捏造された性格は......非常に明白であったため、結果として無罪となった」[58]。スコフィールドは後 に、『巨人アルビオンの発露』(Jerusalem The Emanation of the Giant Albion)の挿絵で「偽造された手枷」をはめた姿で描かれた[59]。 ロンドンへの帰還 1804年頃のブレイクのスケッチ(ジョン・フラックスマン作) ブレイクは1804年にロンドンに戻り、彼の最も野心的な作品である『エルサレム』(1804-20)の執筆と挿絵を始めた。チョーサーの『カンタベリー 物語』の登場人物を描くことを思いついたブレイクは、版画を売り込もうと画商のロバート・クロメックに持ちかけた。クロメックは、ブレイクがあまりに風変 わりで、大衆受けするような作品を作れないことを知っていたので、すぐにブレイクの友人であるトーマス・ストサードにこの構想を実行するよう依頼した。騙 されたと知ったブレイクは、ストサードと連絡を絶った。彼は、ソーホーのブロード・ストリート27番地にある弟の小間物店で、独立した展覧会を開いた。こ の展覧会は、カンタベリーの挿絵の自作版(『カンタベリーの巡礼者たち』と題された)を他の作品とともに売り出すためのものだった。その結果、彼はアンソ ニー・ブラントがチョーサーを「見事な分析」と呼んだ、チョーサー批評の古典として定期的にアンソロジスト化される『説明的カタログ』(1809年)を執 筆した[60]。この展覧会の来場者は非常に少なく、テンペラ画や水彩画はまったく売れなかった。唯一の批評は『エグザミナー』誌で、敵意むき出しのもの だった[61]。  ブレイクの『大いなる赤い竜と太陽をまとった女』(1805年)は、ヨハネの黙示録12章の一連の挿絵のひとつである。 またこの頃(1808年頃)、ブレイクは『ジョシュア・レイノルズ卿の談話』への広範で極論的な注釈のシリーズで、芸術に関する自身の見解を精力的に表明し、王立アカデミーを詐欺だと非難し、「一般化することは愚か者であることだ」と宣言した[62]。 1818年、ジョージ・カンバーランドの息子から、ジョン・リンネルという若い画家を紹介される[63]。 ブレイクとリンネルを記念する青いプレートが、ハムステッドのノース・エンドにあるオールド・ウィルデス邸に掲げられている[64]。このグループは、ブ レイクが現代の流行を拒絶し、精神的で芸術的なニューエイジを信奉していることに共感していた。後にラスキンはブレイクをレンブラントと比較して賞賛し、 ヴォーン・ウィリアムズはバレエ『ヨブ記』を題材にした: ヴォーン・ウィリアムズは、この挿絵をもとにバレエ『ヨブ記:仮面舞踏会』を創作した。 後年、ブレイクは多くの作品、特に聖書の挿絵をトーマス・バッツに売るようになるが、バッツはブレイクを芸術的価値のある人物というよりも友人として見ていたパトロンであった。  ウィリアム・ブレイクが『インフェルノ』の挿絵のために描いたミノタウロスの像。 ダンテの『神曲』の依頼は、1826年にリネルを通じてブレイクにもたらされた。1827年にブレイクが死去したため、この事業は中断され、完成したのはわずかな水彩画と、校正刷りの7点のみとなった。それでも、これらの作品は賞賛を得た: [ダンテの水彩画は、ブレイクの最も豊かな業績のひとつであり、この複雑な詩の挿絵という問題に完全に取り組んでいる。水彩画の技巧は以前よりもさらに高いレベルに達しており、詩の中の3つの存在の状態の雰囲気を描き分けるのに、並外れた効果を発揮している[65]。  ブレイクの『恋人たちのつむじ風』は、ダンテの『地獄篇』のカントVの地獄を描いている。 ブレイクが描いた詩の挿絵は、単なる添え物ではなく、むしろ詩の精神的あるいは道徳的な側面を批判的に改訂したり、解説を加えたりしているように見える。 このプロジェクトは完成しなかったため、ブレイクの意図は不明瞭かもしれない。剣を持つホメロスとその仲間たち』の余白に、ブレイクはこう記している。" ダンテス・コメディアのあらゆることが、暴虐な目的のために、彼がこの世をすべての基礎とし、女神の自然と聖霊ではなくしたことを物語っている"。ブレイ クは、ダンテが古代ギリシアの詩的作品を賞賛していることや、ダンテが地獄で罰を与えることに喜びを感じているように見えること(カントスの厳しいユーモ アが物語っている)に異論を唱えているようだ。 同時に、ブレイクはダンテの物質主義や権力の堕落に対する不信感を共有しており、ダンテの作品の雰囲気やイメージを絵画的に表現する機会を喜んでいたこと は明らかである。死期が迫っているように見えても、ブレイクの中心的な関心事は、ダンテの『地獄篇』の挿絵を描くことに熱中していた。 晩年 ジェームズ・デ・ヴィル作「ウィリアム・ブレイクの頭部」。1823年9月に石膏像で撮影された生前のマスク、フィッツウィリアム博物館。 ロンドンのバンヒル・フィールズにある墓石。1927年にブレイクの墓に建立され、1964-65年に現在の場所に移された。 2018年に除幕されたブレイクの墓の台石 ブレイクの晩年は、ストランド沖のファウンテンコートで過ごした(この建物は1880年代にサヴォイ・ホテルの建設に伴い取り壊された)[1] 。やがてブレイクは作業を中断し、枕元で涙を流していた妻の方を向いたと伝えられている。その妻を見て、ブレイクはこう叫んだと言われている!ケイト!今 のままでいてくれ。君の肖像画を描いてあげよう。この肖像画が完成すると(現在は失われている)、ブレイクは道具を置き、賛美歌と詩を歌い始めた [67]。その晩6時、妻にいつも一緒にいると約束した後、ブレイクは息を引き取った。ギルクリストによれば、彼の死に立ち会った家の下宿人の女性は、 「私は人の死に立ち会ったのではなく、祝福された天使の死に立ち会ったのです」と言ったという[68]。 ジョージ・リッチモンドはサミュエル・パーマーに宛てた手紙の中で、ブレイクの死について次のように語っている: 彼は......とても輝かしい死に方をしました。彼は生涯ずっと見たいと思っていたあの国に行くと言い、イエス・キリストによる救いを望み、幸せであることを表明した。彼の目は輝き、天国で見たことを歌い出した[69]。 キャサリンはリネルから貸与された金でブレイクの葬儀代を支払った。ブレイクの遺体は、死後5日目、つまり45回目の結婚記念日の前夜に、現在のロンド ン、イズリントン区のバンヒル・フィールズにあるディセンダントの埋葬地に、他の人々と共同で埋葬された[70][44]。式にはキャサリン、エドワー ド・カルヴァート、ジョージ・リッチモンド、フレデリック・テイサム、ジョン・リンネルが参列した。ブレイクの死後、キャサリンは家政婦としてテイサムの 家に移り住んだ。彼女はブレイクの霊が定期的に訪ねてくると信じていた。1831年10月、死の当日、キャサリンは夫と同じように穏やかで明るく、「まる で夫が隣の部屋にいるかのように」夫に呼びかけ、「今、彼のところに行くから、もう長くはかからないと」言った[72]。 彼女の死後、長年の知人であったフレデリック・タサムがブレイクの作品を所有し、販売を続けた。破壊された原稿の正確な数は不明だが、死の直前、ブレイク は友人に「『マクベス』ほどの長さの悲劇を20本書いた」と語ったが、現存するものはひとつもなかった[73]。 [74] 別の知人であるウィリアム・マイケル・ロセッティもまた、質が低いと考えたブレイクの作品を焼却し[75]、ジョン・リンネルはブレイクの多くの絵から性 的なイメージを消した[76]。 ブレイクの墓は2つの石碑によって記念されている。ひとつは、「Near by lie the remains of the poet-painter William Blake 1757-1827 and his wife Catherine Sophia 1762-1831」と書かれた石である。この記念石は、2018年8月12日まで標示されていなかった実際の墓から約20メートル(66フィート)離れ た場所にある[44]。1965年以来何年もの間、ウィリアム・ブレイクの墓の正確な場所は失われ、忘れられていた。この地域は第二次世界大戦で被害を受 け、墓石が撤去され、庭園が造成された。埋葬地が「近くにある」ことを示す記念石は、2011年にグレードⅡの登録建造物に指定された[77][78]。 ポルトガル人夫婦のキャロルとルイス・ガリードは、14年にわたる調査作業の末に正確な埋葬地を再発見し、ブレイク協会は恒久的な記念板を組織し、 2018年8月12日に現地で行われた公開式典で除幕された。 [44][78][79][80]新しい石には、彼の詩「エルサレム」の一節の上に「ここにウィリアム・ブレイクは眠る 1757-1827 詩人 芸術家 預言者」と刻まれている。 1949年、ブレイクを記念してオーストラリアに宗教芸術のためのブレイク賞が設立された。1957年、ウェストミンスター寺院にブレイク夫妻の記念碑が建立された[81]。また、ブレイクが洗礼を受けたピカデリーのセント・ジェームズ教会にも記念碑がある。 ピカデリーのセント・ジェームズ教会にあるウィリアム・ブレイクの記念碑 ブレイクが亡くなった時、『Songs of Innocence and of Experience』の売り上げは30部に満たなかった[82]。 |

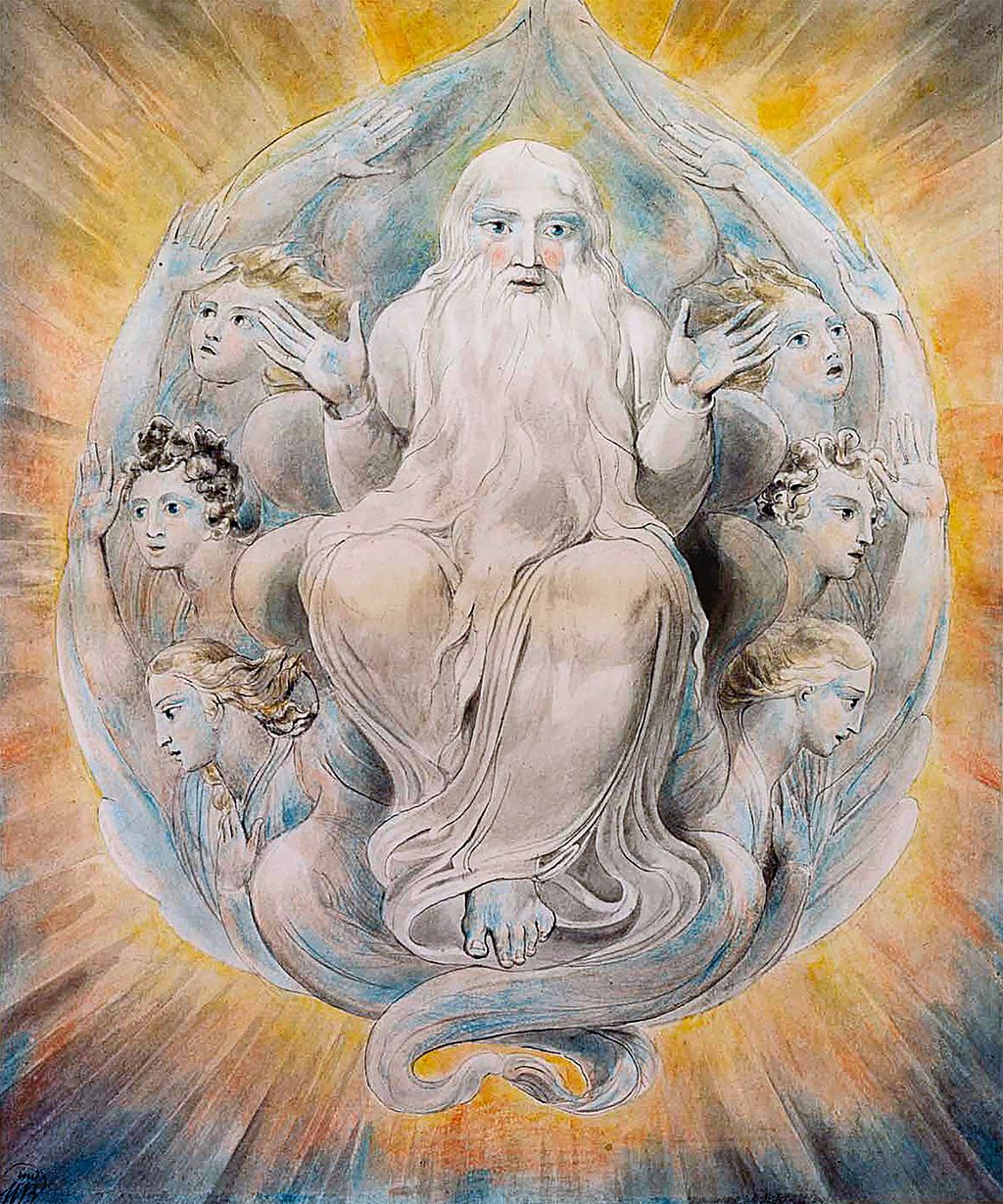

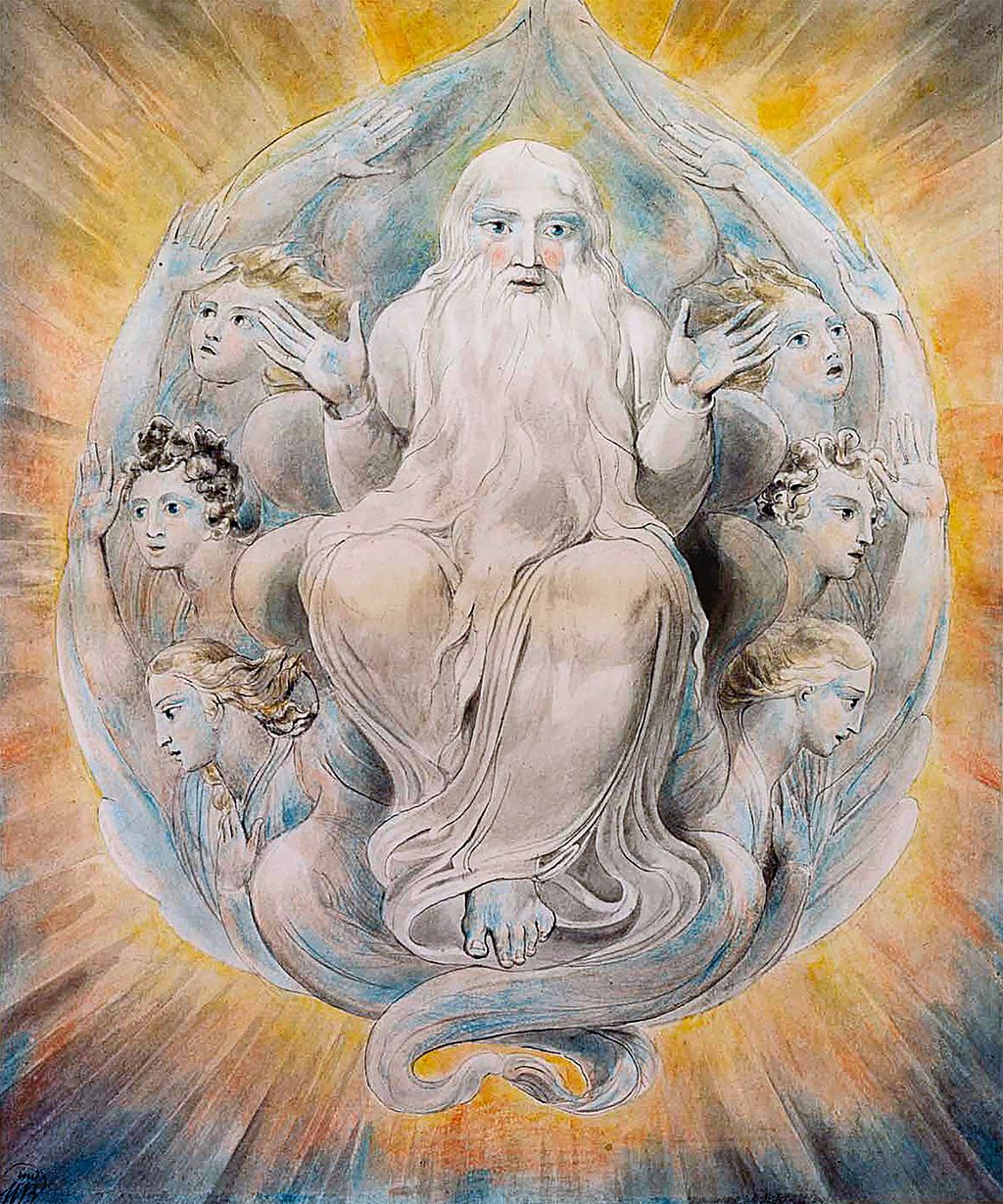

| Opinions Politics Blake was not active in any well-established political party. His poetry consistently embodies an attitude of rebellion against the abuse of class power as documented in David Erdman's major study Blake: Prophet Against Empire: A Poet's Interpretation of the History of His Own Times (1954). Blake was concerned about senseless wars and the blighting effects of the Industrial Revolution. Much of his poetry recounts in symbolic allegory the effects of the French and American revolutions. Erdman claims Blake was disillusioned with the political outcomes of the conflicts, believing they had simply replaced monarchy with irresponsible mercantilism. Erdman also notes Blake was deeply opposed to slavery and believes some of his poems, read primarily as championing "free love", had their anti-slavery implications short-changed.[83] A more recent study, William Blake: Visionary Anarchist by Peter Marshall (1988), classified Blake and his contemporary William Godwin as forerunners of modern anarchism.[84] British Marxist historian E. P. Thompson's last finished work, Witness Against the Beast: William Blake and the Moral Law (1993), claims to show how far he was inspired by dissident religious ideas rooted in the thinking of the most radical opponents of the monarchy during the English Civil War. Development of views  God blessing the seventh day, 1805 watercolour Because Blake's later poetry contains a private mythology with complex symbolism, his late work has been less published than his earlier more accessible work. The Vintage anthology of Blake edited by Patti Smith focuses heavily on the earlier work, as do many critical studies such as William Blake by D. G. Gillham. The earlier work is primarily rebellious in character and can be seen as a protest against dogmatic religion especially notable in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, in which the figure represented by the "Devil" is virtually a hero rebelling against an imposter authoritarian deity. In later works, such as Milton and Jerusalem, Blake carves a distinctive vision of a humanity redeemed by self-sacrifice and forgiveness, while retaining his earlier negative attitude towards what he felt was the rigid and morbid authoritarianism of traditional religion. Not all readers of Blake agree upon how much continuity exists between Blake's earlier and later works. Psychoanalyst June Singer has written that Blake's late work displayed a development of the ideas first introduced in his earlier works, namely, the humanitarian goal of achieving personal wholeness of body and spirit. The final section of the expanded edition of her Blake study The Unholy Bible suggests the later works are the "Bible of Hell" promised in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. Regarding Blake's final poem, Jerusalem, she writes: "The promise of the divine in man, made in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, is at last fulfilled."[85] John Middleton Murry notes discontinuity between Marriage and the late works, in that while the early Blake focused on a "sheer negative opposition between Energy and Reason", the later Blake emphasised the notions of self-sacrifice and forgiveness as the road to interior wholeness. This renunciation of the sharper dualism of Marriage of Heaven and Hell is evidenced in particular by the humanisation of the character of Urizen in the later works. Murry characterises the later Blake as having found "mutual understanding" and "mutual forgiveness".[86] Religious views  Urizen − from Blake's Ancient of Days, 1794. The "Ancient of Days" is described in Chapter 7 of the Book of Daniel. This image depicts Copy D of the illustration currently held at the British Museum.[87] Regarding conventional religion, Blake was a satirist and ironist in his viewpoints which are illustrated and summarized in his poem Vala, or The Four Zoas, one of his uncompleted prophetic books begun in 1797. The demi-mythological and demi-religious main characters of the book are the Four Zoas (Urthona, Urizen, Luvah and Tharmas), who were created by the fall of Albion in Blake's mythology. It consists of nine books, referred to as "nights". These outline the interactions of the Zoas, their fallen forms and their Emanations. Blake intended the book to be a summation of his mythic universe. Blake's Four Zoas, which represent four aspects of the Almighty God and Vala is the first work to mention them.[88] In particular, Blake's God/Man union is broken down into the bodily components of Urizen (head), Urthona (loins), Luvah (heart), and Tharmas (unity of the body) with paired Emanations being Ahania (wisdom, from the head), Enitharmon (what can't be attained in nature, from the loins), Vala (nature, from the heart), and Enion (earth mother, from the separation of unity).[89] As connected to Blake's understanding of the divine, the Zoas are the God the Father (Tharmas, sense), the Son of God (Luvah, love), the Holy Ghost (Urthona, imagination), and Satan who was originally of the divine substance (Urizen, reason) and their Emanations represent Sexual Urges (Enion), Nature (Vala), Inspiration (Enitharmon), and Pleasure (Ahania).[90] Blake believed that each person had a twofold identity with one half being good and the other evil. In Vala, both the character Orc and The Eternal Man discuss their selves as divided. By the time he was working on his later works, including Vala, Blake felt that he was able to overcome his inner battle but he was concerned about losing his artistic abilities. These thoughts carried over into Vala as the character Los (imagination) is connected to the image of Christ, and he added a Christian element to his mythic world. In the revised version of Vala, Blake added Christian and Hebrew images and describes how Los experiences a vision of the Lamb of God that regenerates Los's spirit. In opposition to Christ is Urizen and the Synagogue of Satan, who later crucifies Christ. It is from them that Deism is born.[91]  The Body of Abel Found by Adam and Eve, c. 1825. Watercolour on wood. Blake did not subscribe to the notion of a body distinct from the soul that must submit to the rule of the soul, but sees the body as an extension of the soul, derived from the "discernment" of the senses. Thus, the emphasis orthodoxy places upon the denial of bodily urges is a dualistic error born of misapprehension of the relationship between body and soul. Elsewhere, he describes Satan as the "state of error", and as beyond salvation.[92] Blake opposed the sophistry of theological thought that excuses pain, admits evil and apologises for injustice. He abhorred self-denial,[93] which he associated with religious repression and particularly sexual repression:[94] Prudence is a rich ugly old maid courted by Incapacity. He who desires but acts not breeds pestilence. (7.4–5, E35) He saw the concept of "sin" as a trap to bind men's desires (the briars of Garden of Love), and believed that restraint in obedience to a moral code imposed from the outside was against the spirit of life: Abstinence sows sand all over The ruddy limbs & flaming hair But Desire Gratified Plants fruits & beauty there. (E474) He did not hold with the doctrine of God as Lord, an entity separate from and superior to mankind;[95] this is shown clearly in his words about Jesus Christ: "He is the only God ... and so am I, and so are you." A telling phrase in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell is "men forgot that All deities reside in the human breast". |

オピニオン 政治 ブレイクは既成の政党には所属していなかった。彼の詩は一貫して、階級権力の濫用に対する反抗の態度を体現している: Prophet Against Empire: A Poet's Interpretation of the History of His Own Times (1954)に記されている。ブレイクは無分別な戦争と産業革命の害悪を憂慮していた。彼の詩の多くは、フランス革命とアメリカ革命の影響を象徴的な寓話 として語っている。エドマンによれば、ブレイクはこれらの紛争がもたらした政治的結果に幻滅し、単に王制が無責任な重商主義に取って代わられただけだと考 えたという。エドマンはまた、ブレイクが奴隷制に深く反対していたことを指摘し、彼の詩のいくつかは主に「自由恋愛」を擁護するものとして読まれており、 反奴隷制の意味合いが端折られていると考えている[83]: ピーター・マーシャルによる『William Blake: Visionary Anarchist』(1988年)は、ブレイクと同時代のウィリアム・ゴドウィンを近代アナーキズムの先駆者として分類している: William Blake and the Moral Law (1993)は、彼がイギリス内戦中の最も急進的な君主制反対派の考え方に根ざした反体制的な宗教的思想にどこまで触発されていたかを示していると主張し ている。 見解の展開  7日目を祝福する神、1805年の水彩画 ブレイクの晩年の詩には、複雑な象徴主義を伴う私的な神話が含まれているため、初期の親しみやすい作品に比べ、晩年の作品はあまり出版されてこなかった。 パティ・スミスが編集したブレイクのヴィンテージ・アンソロジーは、D.G.ギラムのウィリアム・ブレイクなど多くの批評的研究と同様、初期の作品に重点 を置いている。 初期の作品は主に反抗的な性格を持ち、独断的な宗教に対する抗議として見ることができる。特に『天国と地獄の結婚』では顕著で、「悪魔」に代表される人物 は事実上、偽者の権威主義的な神に反抗する英雄である。ミルトン』や『エルサレム』といった後期の作品において、ブレイクは、伝統的な宗教の厳格で病的な 権威主義だと感じていたものに対する初期の否定的な態度を保ちつつも、自己犠牲と赦しによって救済される人間性という独特のヴィジョンを描き出している。 ブレイクの初期作品と後期作品の間にどれほどの連続性が存在するかについては、ブレイクを読むすべての人が同意しているわけではない。 精神分析学者のジューン・シンガーは、ブレイクの後期の作品には、初期の作品で最初に紹介された思想、すなわち、個人の身体と精神の完全性を達成するとい う人道的な目標が発展していると書いている。彼女のブレイク研究書『The Unholy Bible』の増補版の最終章は、後期の作品が『天国と地獄の結婚』で約束された「地獄の聖書」であることを示唆している。ブレイクの最後の詩『エルサレ ム』について、彼女は「『天国と地獄の結婚』でなされた、人間の中の神的なものという約束は、ついに成就した」と書いている[85]。 ジョン・ミドルトン・マリーは、初期のブレイクが「エネルギーと理性との間の全く否定的な対立」に焦点を当てていたのに対して、後期のブレイクは内的全体 性への道として自己犠牲と赦しという概念を強調しているという点で、『結婚』と後期の作品との間の不連続性を指摘している。天国と地獄の結婚』のような鋭 利な二元論を放棄したことは、特に後期の作品におけるウリゼンの性格の人間化によって証明されている。ミュリーは後期のブレイクを「相互理解」と「相互赦 し」を見出したと評している[86]。 宗教観  ウリゼン - ブレイクの『Ancient of Days』(1794年)より。日の昔」はダニエル書第7章に記述されている。この画像は、現在大英博物館に所蔵されている挿絵のコピーDを描いたものである[87]。 従来の宗教に関して、ブレイクは風刺主義者であり、アイロニストであった。その視点は、1797年に着手された未完の予言書のひとつである詩『ヴァラ、あ るいは四つの象』に描かれ、要約されている。この詩集の主人公は、ブレイクの神話に登場するアルビオンの滅亡によって生まれた四人のゾア(ウルトナ、ウリ ゼン、ルヴァ、タルマス)である。夜」と呼ばれる9冊の本から成る。ゾア族、その堕落した姿、そして彼らのエマネイションの相互作用について概説してい る。ブレイクはこの本を、彼の神話世界の総括とするつもりだった。ブレイクの4つのゾアは、全能の神とヴァラの4つの側面を表しており、それらに言及した 最初の作品である。 [88]特に、ブレイクの神と人間の結合は、ウリゼン(頭)、ウルトナ(腰)、ルヴァ(心)、タルマス(身体の統一)の身体的構成要素に分解され、対にな るエマネイションは、アハニア(知恵、頭から)、エニサルモン(自然では到達できないもの、腰から)、ヴァラ(自然、心から)、エニオン(大地母、統一の 分離から)である。 [89]神についてのブレイクの理解と関連しているように、ゾーアは父なる神(タルマス、感覚)、神の子(ルヴァ、愛)、聖霊(ウルトナ、想像力)、そし てもともと神の物質であったサタン(ウリゼン、理性)であり、それらのエマネイションは性的衝動(エニオン)、自然(ヴァラ)、インスピレーション(エニ サルモン)、快楽(アハニア)を表している[90]。 ブレイクは各人が二重のアイデンティティを持ち、一方は善であり、他方は悪であると信じていた。ヴァラ』では、登場人物のオークと『永遠の人』の両方が、 自己が分裂していると論じている。ヴァラ』を含む晩年の作品に取り組む頃には、ブレイクは内なる戦いを克服できたと感じていたが、芸術的能力を失うことを 懸念していた。ロス(想像力)というキャラクターがキリストのイメージと結びついていることから、こうした思いは『ヴァラ』にも引き継がれ、彼は神話の世 界にキリスト教的な要素を加えた。ヴァラ』の改訂版では、ブレイクはキリスト教とヘブライ語のイメージを加え、ロスが神の子羊の幻視を体験してロスの精神 を再生させる様子を描いている。キリストと対立するのは、後にキリストを十字架につけるウリゼンとサタンのシナゴーグである。彼らから神道が生まれるので ある[91]。  『アダムとイヴが見つけたアベルの遺体』1825年頃。木に水彩。 ブレイクは、魂の支配に従わなければならない魂とは別個の身体という概念には与せず、身体は魂の延長であり、感覚の「識別」に由来するものだと考えてい る。従って、正統派が肉体的衝動の否定に重きを置くのは、肉体と魂の関係についての誤った理解から生まれた二元論的誤りなのである。他の箇所では、彼はサ タンを「誤りの状態」であり、救いを超えた存在であると表現している[92]。 ブレイクは、苦痛を言い訳にし、悪を認め、不正を謝罪する神学思想の詭弁に反対した。彼は自己否定を忌み嫌い[93]、それは宗教的抑圧、特に性的抑圧と結びついていた[94]。 プルーデンス(思慮深さ)は、インキャパシティ(無能力)に求愛される豊かで醜い老女房である。 欲しても行動しない者は疫病を生む。(7.4-5, E35) 彼は「罪」という概念を、人の欲望を縛る罠(『愛の園』の荊)とみなし、外から押し付けられた道徳規範に従う自制は、生命の精神に反すると考えた: 禁欲は砂をまき散らす 赤らんだ手足と燃えるような髪 しかし欲望は満たされる 果実と美をそこに植える。(E474) このことは、イエス・キリストについての彼の言葉にはっきりと示されている[95]: 「彼は唯一の神であり......私もそうであり、あなたもそうである」。天国と地獄の結婚』の中で、「人間は、すべての神が人間の胸に宿っていることを忘れている」という言葉がある。 |

| Enlightenment philosophy Blake had a complex relationship with Enlightenment philosophy. His championing of the imagination as the most important element of human existence ran contrary to Enlightenment ideals of rationalism and empiricism.[96] Due to his visionary religious beliefs, he opposed the Newtonian view of the universe. This mindset is reflected in an excerpt from Blake's Jerusalem:  Blake's Newton (1795) demonstrates his opposition to the "single-vision" of scientific materialism: Newton fixes his eye on a compass (recalling Proverbs 8:27,[97] an important passage for Milton)[98] to write upon a scroll that seems to project from his own head.[99] I turn my eyes to the Schools & Universities of Europe And there behold the Loom of Locke whose Woof rages dire Washd by the Water-wheels of Newton. black the cloth In heavy wreathes folds over every Nation; cruel Works Of many Wheels I view, wheel without wheel, with cogs tyrannic Moving by compulsion each other: not as those in Eden: which Wheel within Wheel in freedom revolve in harmony & peace. (15.14–20, E159) Blake believed the paintings of Sir Joshua Reynolds, which depict the naturalistic fall of light upon objects, were products entirely of the "vegetative eye", and he saw Locke and Newton as "the true progenitors of Sir Joshua Reynolds' aesthetic".[100] The popular taste in the England of that time for such paintings was satisfied with mezzotints, prints produced by a process that created an image from thousands of tiny dots upon the page. Blake saw an analogy between this and Newton's particle theory of light.[101] Accordingly, Blake never used the technique, opting rather to develop a method of engraving purely in fluid line, insisting that: a Line or Lineament is not formed by Chance a Line is a Line in its Minutest Subdivision[s] Strait or Crooked It is Itself & Not Intermeasurable with or by any Thing Else Such is Job. (E784) It has been supposed that, despite his opposition to Enlightenment principles, Blake arrived at a linear aesthetic that was in many ways more similar to the Neoclassical engravings of John Flaxman than to the works of the Romantics, with whom he is often classified.[102] However, Blake's relationship with Flaxman seems to have grown more distant after Blake's return from Felpham, and there are surviving letters between Flaxman and Hayley wherein Flaxman speaks ill of Blake's theories of art.[103] Blake further criticized Flaxman's styles and theories of art in his responses to criticism made against his print of Chaucer's Caunterbury Pilgrims in 1810.[104] |

啓蒙思想 ブレイクは啓蒙思想と複雑な関係にあった。人間存在の最も重要な要素として想像力を擁護する彼の姿勢は、合理主義と経験主義という啓蒙主義の理想とは相反 するものであった[96]。先見の明のある宗教的信念から、彼はニュートン的宇宙観に反対した。この考え方は、ブレイクの『エルサレム』からの抜粋に反映 されている:  ブレイクの『ニュートン』(1795年)は、科学的唯物論の「単一視」に対する彼の反対を示している: ニュートンはコンパス(ミルトンにとって重要な一節である箴言8:27[97]を想起させる)[98]に目を固定し、自分の頭から突き出たような巻物に文 字を書き込んでいる[99]。 私はヨーロッパの学校と大学に目を向ける。 そしてそこでロックの織機を見る。 ニュートンの水車によって洗われる。 重苦しい花輪があらゆる国の上に折り重なる。 多くの歯車、歯車なき歯車、専制的な歯車。 互いに強制されて動いている。 自由な車輪の中の車輪が、調和と平和のうちに回転している。(15.14-20, E159) ブレイクは、自然主義的な光の物体への落差を描いたジョシュア・レイノルズ卿の絵画は、完全に「植物的な目」の産物だと考えており、ロックとニュートンを 「ジョシュア・レイノルズ卿の美学の真の祖先」と見なしていた[100]。当時のイギリスでは、このような絵画に対する大衆の嗜好は、メゾチント(ページ に描かれた何千もの小さな点からイメージを作り出す製法で作られた版画)で満たされていた。ブレイクはこの技法とニュートンの光の粒子理論との間に類似性 を見出していた[101]。したがって、ブレイクはこの技法を使うことはなく、むしろ純粋に流動的な線で彫る方法を開発することを選び、次のように主張し た: 線またはリニアメントは偶然によって形成されるものではない 線はその最も微細な部分において線であり、まっすぐであるか、曲がっているか、それ自体であり、他のいかなるものとも、あるいは他のいかなるものによっても相互測定不可能である。(E784) 啓蒙主義に反対していたにもかかわらず、ブレイクが到達した直線的な美学は、多くの点で、彼がしばしば分類されるロマン派の作品よりも、ジョン・フラック スマンの新古典主義の版画に類似していたと考えられている[102]。 [しかし、ブレイクとフラックスマンの関係は、ブレイクがフェルファムから戻った後、より疎遠になったようであり、フラックスマンとヘイリーの間には、ブ レイクの芸術理論を悪く言うフラックスマンの手紙が残っている[103]。 ブレイクは、1810年にチョーサーの『コウンタベリーの巡礼者たち』の版画に対してなされた批判に対する回答の中で、フラックスマンの様式や芸術理論を さらに批判した[104]。 |

Sexuality Blake's Lot and His Daughters, Huntington Library, c. 1800 "Free Love" Since his death, Blake has been claimed by those of various movements who apply his complex and often elusive use of symbolism and allegory to the issues that concern them.[105] In particular, Blake is sometimes considered (along with Mary Wollstonecraft and her husband William Godwin) a forerunner of the 19th-century "free love" movement, a broad reform tradition starting in the 1820s that held that marriage is slavery, and advocated the removal of all state restrictions on sexual activity such as homosexuality, prostitution, and adultery, culminating in the birth control movement of the early 20th century. Blake scholarship was more focused on this theme in the earlier 20th century than today, although it is still mentioned notably by the Blake scholar Magnus Ankarsjö who moderately challenges this interpretation. The 19th-century "free love" movement was not particularly focused on the idea of multiple partners, but did agree with Wollstonecraft that state-sanctioned marriage was "legal prostitution" and monopolistic in character. It has somewhat more in common with early feminist movements[106] (particularly with regard to the writings of Mary Wollstonecraft, whom Blake admired). Blake was critical of the marriage laws of his day, and generally railed against traditional Christian notions of chastity as a virtue.[107] At a time of tremendous strain in his marriage, in part due to Catherine's apparent inability to bear children, he directly advocated bringing a second wife into the house.[108] His poetry suggests that external demands for marital fidelity reduce love to mere duty rather than authentic affection, and decries jealousy and egotism as a motive for marriage laws. Poems such as "Why should I be bound to thee, O my lovely Myrtle-tree?" and "Earth's Answer" seem to advocate multiple sexual partners. In his poem "London" he speaks of "the Marriage-Hearse" plagued by "the youthful Harlot's curse", the result alternately of false Prudence and/or Harlotry. Visions of the Daughters of Albion is widely (though not universally) read as a tribute to free love since the relationship between Bromion and Oothoon is held together only by laws and not by love. For Blake, law and love are opposed, and he castigates the "frozen marriage-bed". In Visions, Blake writes: Till she who burns with youth, and knows no fixed lot, is bound In spells of law to one she loathes? and must she drag the chain Of life in weary lust? (5.21-3, E49) In the 19th century, poet and free love advocate Algernon Charles Swinburne wrote a book on Blake drawing attention to the above motifs in which Blake praises "sacred natural love" that is not bound by another's possessive jealousy, the latter characterised by Blake as a "creeping skeleton".[109] Swinburne notes how Blake's Marriage of Heaven and Hell condemns the hypocrisy of the "pale religious letchery" of advocates of traditional norms.[110] Another 19th-century free love advocate, Edward Carpenter (1844–1929), was influenced by Blake's mystical emphasis on energy free from external restrictions.[111] In the early 20th century, Pierre Berger described how Blake's views echo Mary Wollstonecraft's celebration of joyful authentic love rather than love born of duty,[112] the former being the true measure of purity.[113] Irene Langridge notes that "in Blake's mysterious and unorthodox creed the doctrine of free love was something Blake wanted for the edification of 'the soul'."[114] Michael Davis' 1977 book William Blake a New Kind of Man suggests that Blake thought jealousy separates man from the divine unity, condemning him to a frozen death.[115] As a theological writer, Blake has a sense of human "fallenness". S. Foster Damon noted that for Blake the major impediments to a free love society were corrupt human nature, not merely the intolerance of society and the jealousy of men, but the inauthentic hypocritical nature of human communication.[116] Thomas Wright's 1928 book Life of William Blake (entirely devoted to Blake's doctrine of free love) notes that Blake thinks marriage should in practice afford the joy of love, but notes that in reality it often does not,[117] as a couple's knowledge of being chained often diminishes their joy. Pierre Berger also analyses Blake's early mythological poems such as Ahania as declaring marriage laws to be a consequence of the fallenness of humanity, as these are born from pride and jealousy.[118] Some scholars have noted that Blake's views on "free love" are both qualified and may have undergone shifts and modifications in his late years. Some poems from this period warn of dangers of predatory sexuality such as The Sick Rose. Magnus Ankarsjö notes that while the hero of Visions of the Daughters of Albion is a strong advocate of free love, by the end of the poem she has become more circumspect as her awareness of the dark side of sexuality has grown, crying "Can this be love which drinks another as a sponge drinks water?"[119] Ankarsjö also notes that a major inspiration to Blake, Mary Wollstonecraft, similarly developed more circumspect views of sexual freedom late in life. In light of Blake's aforementioned sense of human 'fallenness' Ankarsjö thinks Blake does not fully approve of sensual indulgence merely in defiance of law as exemplified by the female character of Leutha,[120] since in the fallen world of experience all love is enchained.[121] Ankarsjö records Blake as having supported a commune with some sharing of partners, though David Worrall read The Book of Thel as a rejection of the proposal to take concubines espoused by some members of the Swedenborgian church.[122] Blake's later writings show a renewed interest in Christianity, and although he radically reinterprets Christian morality in a way that embraces sensual pleasure, there is little of the emphasis on sexual libertarianism found in several of his early poems, and there is advocacy of "self-denial", though such abnegation must be inspired by love rather than through authoritarian compulsion.[123] Berger (more so than Swinburne) is especially sensitive to a shift in sensibility between the early Blake and the later Blake. Berger believes the young Blake placed too much emphasis on following impulses,[124] and that the older Blake had a better formed ideal of a true love that sacrifices self. Some celebration of mystical sensuality remains in the late poems (most notably in Blake's denial of the virginity of Jesus's mother). However, the late poems also place a greater emphasis on forgiveness, redemption, and emotional authenticity as a foundation for relationships. |

セクシュアリティ ブレイクの「ロットとその娘たち」、ハンティントン・ライブラリー、1800年頃 "自由な愛" ブレイクの死後、ブレイクはさまざまな運動の人々によって主張されてきた。彼らは、彼の複雑で、しばしばとらえどころのない象徴主義や寓意の使い方を、自 分たちに関わる問題に適用してきた。 [特に、ブレイクは(メアリ・ウルストンクラフトとその夫ウィリアム・ゴドウィンとともに)19世紀の「自由恋愛」運動の先駆者とみなされることがある。 この運動は、結婚は奴隷制度であるとし、同性愛、売春、不倫などの性行為に対するあらゆる国家的制限の撤廃を提唱した1820年代に始まる広範な改革運動 であり、20世紀初頭の避妊運動へと結実した。20世紀初頭のブレイク研究では、今日よりもこのテーマに焦点が当てられていたが、ブレイク研究者のマグナ ス・アンカーショは、この解釈に適度に異議を唱えている。19世紀の "自由恋愛 "運動は、複数のパートナーという考え方に特に焦点を当てていたわけではなかったが、国家が公認する結婚は "合法的売春 "であり独占的な性格を持つというウルストンクラフトに同意していた。この運動は、初期のフェミニズム運動[106](特にブレイクが敬愛したメアリー・ ウルストンクラフトの著作に関して)とやや共通点がある。 ブレイクは当時の結婚法に批判的であり、一般的に貞操を美徳とする伝統的なキリスト教の概念に憤慨していた[107]。キャサリンが明らかに子供を産めな いこともあり、結婚生活に多大な緊張を強いられていた時期に、彼は直接的に2人目の妻を家に迎えることを提唱した[108]。愛しいマートルの木よ、なぜ 私はあなたと結ばれなければならないのか」、「地球の答え」などの詩は、複数の性的パートナーを推奨しているように見える。また、「ロンドン」の詩では、 「若い娼婦の呪い」に悩まされる「結婚恐怖症」について語っている。アルビオンの娘たちの幻影』は、ブロミオンとウートゥーンの関係が愛ではなく法によっ てのみ保たれていることから、自由な愛への賛辞として広く(普遍的ではないが)読まれている。ブレイクにとって法と愛は対立するものであり、彼は「凍りつ いた結婚ベッド」を非難している。ブレイクは『幻影』の中でこう書いている: 若さに燃え、定まった境遇を知らない彼女が 掟の呪縛に縛られ、大嫌いな人と結ばれるのか? 疲れ果てた欲望の中で人生の鎖を引きずらなければならないのか? 19世紀、詩人であり自由恋愛の提唱者であったアルジャーノン・チャールズ・スウィンバーンは、ブレイクに関する著書の中で、ブレイクが「忍び寄る骸骨」 と形容した、他人の独占的な嫉妬に縛られない「神聖な自然な愛」を賞賛している上記のモチーフに注目している[109]。 [スウィンバーンは、ブレイクの『天国と地獄の結婚』が、伝統的な規範の擁護者たちの「青白い宗教的嗜虐」の偽善を非難していることを指摘している [110]。もう一人の19世紀の自由恋愛の擁護者であるエドワード・カーペンター(1844-1929)は、外的な制約から解放されたエネルギーに対す るブレイクの神秘主義的な強調に影響を受けていた[111]。 20世紀初頭、ピエール・ベルジェは、ブレイクの見解がメアリー・ウルストンクラフトの、義務から生まれた愛よりもむしろ喜びに満ちた本物の愛を讃えるこ とに共鳴しており[112]、前者が純粋さの真の尺度であると述べている。 [アイリーン・ラングリッジは「ブレイクの神秘的で異端的な信条において、自由な愛の教義はブレイクが『魂』を教育するために望んだものであった」と指摘 している[114]。 マイケル・デイヴィスの1977年の著書『ウィリアム・ブレイク a New Kind of Man』は、ブレイクが嫉妬は人間を神の統一体から引き離し、凍死させると考えていたことを示唆している[115]。 神学的な作家として、ブレイクは人間の「堕落」を感じている。S.フォスター・デイモンは、ブレイクにとって自由恋愛社会に対する主要な障害は堕落した人 間性であり、単に社会の不寛容や人間の嫉妬だけでなく、人間のコミュニケーションの不真面目な偽善性であると指摘した[116]。 [116] トーマス・ライトの1928年の著書『Life of William Blake』(ブレイクの自由恋愛の教義に完全に捧げられた)は、ブレイクは結婚が実際には愛の喜びを与えるはずだと考えているが、現実にはそうならない ことが多いと指摘している[117]。ピエール・バーガーもまた、『アハニア』のようなブレイクの初期の神話詩は、結婚法が高慢と嫉妬から生まれたもので あり、人類の堕落の結果であると宣言していると分析している[118]。 自由恋愛」に対するブレイクの見解は修飾的であり、晩年には変化や修正が加えられている可能性があると指摘する学者もいる。この時期の詩の中には、『病め る薔薇』のように略奪的な性愛の危険性を警告するものもある。マグナス・アンカーショー(Magnus Ankarsjö)は、『アルビオンの娘たちの幻影(Visions of the Daughters of Albion)』の主人公が自由恋愛の強い支持者である一方で、詩の終わりには性の暗黒面に対する意識が高まり、「スポンジが水を飲むように他人を飲むこ れが愛だろうか」と叫びながら、より慎重になっていると指摘している[119]。前述したブレイクの人間の「堕落性」に対する感覚に照らして、アンカー ショは、ブレイクがリュータの女性キャラクターに例示されるような、単に法に背くだけの官能的な耽溺を完全には認めていないと考えている[120]。 [121]アンカーショは、ブレイクがパートナーをある程度共有するコミューンを支持していたと記録しているが、デイヴィッド・ウォーラルは『テルの書』 をスウェーデンボルグ教会の一部のメンバーによって支持された妾を娶るという提案の拒絶として読んでいる[122]。 ブレイクの後期の著作はキリスト教への新たな関心を示しており、官能的な快楽を受け入れる形でキリスト教道徳を根本的に解釈し直しているが、初期の詩のい くつかで見られた性的自由主義の強調はほとんど見られず、「自己否定」の擁護が見られるが、そのような無欲は権威主義的な強制ではなく、むしろ愛によって 鼓舞されなければならない[123]。 バーガーは(スウィンバーンよりも)初期のブレイクと後期のブレイクとの間の感性の変化に特に敏感である。ベルガーは、若いブレイクは衝動に従うことに重 きを置きすぎており[124]、年老いたブレイクは自己を犠牲にする真の愛という理想をよりよく形成していたと考えている。神秘的な官能性の賛美は後期の 詩にも残っている(最も顕著なのは、ブレイクがイエスの母の処女性を否定したことである)。しかし、後期の詩はまた、人間関係の基礎として、赦し、贖罪、 感情的な信頼性をより重視している。 |

| Legacy Creativity Northrop Frye, commenting on Blake's consistency in strongly held views, notes Blake "himself says that his notes on [Joshua] Reynolds, written at fifty, are 'exactly Similar' to those on Locke and Bacon, written when he was 'very Young'. Even phrases and lines of verse will reappear as much as forty years later. Consistency in maintaining what he believed to be true was itself one of his leading principles ... Consistency, then, foolish or otherwise, is one of Blake's chief preoccupations, just as 'self-contradiction' is always one of his most contemptuous comments".[125]  Blake's A Negro Hung Alive by the Ribs to a Gallows, an illustration to J. G. Stedman's Narrative, of a Five Years' Expedition, against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam (1796) Blake abhorred slavery,[126] and believed in racial and sexual equality.[citation needed] Several of his poems and paintings express a notion of universal humanity: "As all men are alike (tho' infinitely various)". In one poem, narrated by a black child, white and black bodies alike are described as shaded groves or clouds, which exist only until one learns "to bear the beams of love": When I from black and he from white cloud free, And round the tent of God like lambs we joy: Ill shade him from the heat till he can bear, To lean in joy upon our fathers knee. And then I'll stand and stroke his silver hair, And be like him and he will then love me. (23-8, E9) Blake retained an active interest in social and political events throughout his life, and social and political statements are often present in his mystical symbolism. His views on what he saw as oppression and restriction of rightful freedom extended to the Church. His spiritual beliefs are evident in Songs of Experience (1794), in which he distinguishes between the Old Testament God, whose restrictions he rejected, and the New Testament God whom he saw as a positive influence. Visions From a young age, William Blake claimed to have seen visions. The first may have occurred as early as the age of four when, according to one anecdote, the young artist "saw God" when God "put his head to the window", causing Blake to break into screaming.[127] At the age of eight or ten in Peckham Rye, London, Blake claimed to have seen "a tree filled with angels, bright angelic wings bespangling every bough like stars."[127] According to Blake's Victorian biographer Gilchrist, he returned home and reported the vision and only escaped being thrashed by his father for telling a lie through the intervention of his mother. Though all evidence suggests that his parents were largely supportive, his mother seems to have been especially so, and several of Blake's early drawings and poems decorated the walls of her chamber.[128] On another occasion, Blake watched haymakers at work, and thought he saw angelic figures walking among them.[127]  The Ghost of a Flea, 1819–1820. Having informed painter-astrologer John Varley of his visions of apparitions, Blake was subsequently persuaded to paint one of them.[129] Varley's anecdote of Blake and his vision of the flea's ghost became well-known.[129] Blake claimed to experience visions throughout his life. They were often associated with beautiful religious themes and imagery, and may have inspired him further with spiritual works and pursuits. Certainly, religious concepts and imagery figure centrally in Blake's works. God and Christianity constituted the intellectual centre of his writings, from which he drew inspiration. Blake believed he was personally instructed and encouraged by Archangels to create his artistic works, which he claimed were actively read and enjoyed by the same Archangels. In a letter of condolence to William Hayley, dated 6 May 1800, four days after the death of Hayley's son,[130] Blake wrote: I know that our deceased friends are more really with us than when they were apparent to our mortal part. Thirteen years ago I lost a brother, and with his spirit I converse daily and hourly in the spirit, and see him in my remembrance, in the region of my imagination. I hear his advice, and even now write from his dictate. In a letter to John Flaxman, dated 21 September 1800, Blake wrote: [The town of] Felpham is a sweet place for Study, because it is more spiritual than London. Heaven opens here on all sides her golden Gates; her windows are not obstructed by vapours; voices of Celestial inhabitants are more distinctly heard, & their forms more distinctly seen; & my Cottage is also a Shadow of their houses. My Wife & Sister are both well, courting Neptune for an embrace... I am more famed in Heaven for my works than I could well conceive. In my Brain are studies & Chambers filled with books & pictures of old, which I wrote & painted in ages of Eternity before my mortal life; & those works are the delight & Study of Archangels. (E710) In a letter to Thomas Butts, dated 25 April 1803, Blake wrote: Now I may say to you, what perhaps I should not dare to say to anyone else: That I can alone carry on my visionary studies in London unannoy'd, & that I may converse with my friends in Eternity, See Visions, Dream Dreams & prophecy & speak Parables unobserv'd & at liberty from the Doubts of other Mortals; perhaps Doubts proceeding from Kindness, but Doubts are always pernicious, Especially when we Doubt our Friends. In A Vision of the Last Judgement Blake wrote: Error is Created Truth is Eternal Error or Creation will be Burned Up & then & not till then Truth or Eternity will appear It is Burnt up the Moment Men cease to behold it I assert for My self that I do not behold the Outward Creation & that to me it is hindrance & not Action it is as the Dirt upon my feet No part of Me. What it will be Questiond When the Sun rises do you not see a round Disk of fire somewhat like a Guinea O no no I see an Innumerable company of the Heavenly host crying Holy Holy Holy is the Lord God Almighty I question not my Corporeal or Vegetative Eye any more than I would Question a Window concerning a Sight I look thro it & not with it. (E565-6) Despite seeing angels and God, Blake has also claimed to see Satan on the staircase of his South Molton Street home in London.[82] Aware of Blake's visions, William Wordsworth commented, "There was no doubt that this poor man was mad, but there is something in the madness of this man which interests me more than the sanity of Lord Byron and Walter Scott."[131] In a more deferential vein, John William Cousins wrote in A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature that Blake was "a truly pious and loving soul, neglected and misunderstood by the world, but appreciated by an elect few", who "led a cheerful and contented life of poverty illumined by visions and celestial inspirations".[132] Blake's sanity was called into question as recently as the publication of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica, whose entry on Blake comments that "the question whether Blake was or was not mad seems likely to remain in dispute, but there can be no doubt whatever that he was at different periods of his life under the influence of illusions for which there are no outward facts to account, and that much of what he wrote is so far wanting in the quality of sanity as to be without a logical coherence". Cultural influence Main article: William Blake in popular culture William Blake's portrait in profile, by John Linnell. This larger version was painted to be engraved as the frontispiece of Alexander Gilchrist's Life of Blake (1863). Blake's work was neglected for a generation after his death and almost forgotten by the time Alexander Gilchrist began work on his biography in the 1860s. The publication of the Life of William Blake rapidly transformed Blake's reputation, in particular as he was taken up by Pre-Raphaelites and associated figures, in particular Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Algernon Charles Swinburne. In the 20th century, however, Blake's work was fully appreciated and his influence increased. Important early and mid-20th-century scholars involved in enhancing Blake's standing in literary and artistic circles included S. Foster Damon, Geoffrey Keynes, Northrop Frye and David V. Erdman. While Blake had a significant role in the art and poetry of figures such as Rossetti, it was during the Modernist period that this work began to influence a wider set of writers and artists. William Butler Yeats, who edited an edition of Blake's collected works in 1893, drew on him for poetic and philosophical ideas,[133] while British surrealist art in particular drew on Blake's conceptions of non-mimetic, visionary practice in the painting of artists such as Paul Nash and Graham Sutherland.[134] His poetry came into use by a number of British classical composers such as Benjamin Britten and Ralph Vaughan Williams, who set his works. Modern British composer John Tavener set several of Blake's poems, including The Lamb (as the 1982 work "The Lamb") and The Tyger. Many such as June Singer have argued that Blake's thoughts on human nature greatly anticipate and parallel the thinking of the psychoanalyst Carl Jung. In Jung's own words: "Blake [is] a tantalizing study, since he compiled a lot of half or undigested knowledge in his fantasies. According to my ideas they are an artistic production rather than an authentic representation of unconscious processes."[135][136] Similarly, Diana Hume George claimed that Blake can be seen as a precursor to the ideas of Sigmund Freud.[137] Blake had an enormous influence on the beat poets of the 1950s and the counterculture of the 1960s, frequently being cited by such seminal figures as beat poet Allen Ginsberg, songwriters Bob Dylan, Jim Morrison,[138] Van Morrison,[139][140] and English writer Aldous Huxley. The Pulitzer-winning composer William Bolcom set Songs of Innocence and of Experience to music,[141] with different poems set to different styles of music, "from modern techniques to Broadway to Country/Western" and reggae.[142] Much of the central conceit of Philip Pullman's fantasy trilogy His Dark Materials is rooted in the world of Blake's The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. Blake also features as a relatively significant character in Brian Catling's fantasy novel The Erstwhile, where his visions of angelic beings are figured into the story. Canadian music composer Kathleen Yearwood is one of many contemporary musicians that have set Blake's poems to music. After World War II, Blake's role in popular culture came to the fore in a variety of areas such as popular music, film, and the graphic novel, leading Edward Larrissy to assert that "Blake is the Romantic writer who has exerted the most powerful influence on the twentieth century."[143] |

レガシー 創造性 ノースロップ・フライは、ブレイクが強く抱いている見解の一貫性についてコメントし、ブレイクが「50歳のときに書いた(ジョシュア・)レイノルズについ てのノートは、『非常に若い』ときに書いたロックやベーコンについてのノートと『まったく似ている』」と述べていることを紹介している。詩のフレーズや行 でさえ、40年も経ってから再び登場する。彼が真実であると信じたことを維持する一貫性は、それ自体が彼の主要な原則の一つであった。自己矛盾』が常に彼 の最も軽蔑的なコメントのひとつであるように、一貫性は、愚かであろうとなかろうと、ブレイクの最大の関心事のひとつなのだ」[125]。  ブレイクの『絞首台に生きたまま吊るされた黒人』(J.G.ステッドマンの『スリナムの反乱した黒人に対する5年間の遠征の物語』(1796年)の挿絵)。 ブレイクは奴隷制度を忌み嫌い[126]、人種と性の平等を信じていた: 「すべての人が同じであるように(しかし無限に様々である)」。黒人の子供が語るある詩では、白人と黒人の身体は、「愛の光線に耐える」ことを学ぶまでし か存在しない、日陰の木立や雲のように表現されている: 私が黒から、彼が白から自由になるとき、 子羊のように神の天幕を囲み、喜び合おう: 彼が耐えられるようになるまで、彼を暑さから守ろう、 父祖の膝の上に、喜びのうちに寄りかかろう。 そして私は立って、彼の銀の髪を撫でる、 そして彼のようになり、彼は私を愛するだろう。(23-8, E9) ブレイクは生涯を通じて社会的、政治的な出来事に積極的な関心を持ち続け、社会的、政治的な主張はしばしば彼の神秘主義的象徴の中に見られる。彼が抑圧と 見なし、正当な自由を制限するものに対する彼の見解は、教会にまで及んでいる。彼の精神的な信念は『経験の歌』(1794年)に顕著に表れており、その中 で彼は旧約聖書の神を否定し、新約聖書の神を肯定的な影響力を持つものとして区別している。 ヴィジョン 若い頃からウィリアム・ブレイクは幻視を見たと主張していた。ある逸話によれば、最初の幻視は4歳のときに起こったとされ、神が「窓に頭を近づけた」とき に、若い画家は「神を見た」。 「ブレイクのヴィクトリア朝時代の伝記作家ギルクリストによれば、ブレイクは家に戻ってその幻視を報告し、母親の介入によって、嘘をついたとして父親に殴 打されることだけは免れたという。あらゆる証拠から、彼の両親はおおむね協力的であったと考えられるが、彼の母親は特に協力的であったようで、ブレイクの 初期の絵や詩のいくつかが彼女の部屋の壁に飾られていた[128]。別の機会に、ブレイクは干し草職人が働いているのを見て、天使のような人影がその中を 歩いているのを見たと思った[127]。  『ノミの幽霊』1819-1820年。画家で占星術師のジョン・ヴァーリーに幻視のことを伝えたブレイクは、その後、その幻視のひとつを描くよう説得された[129]。ヴァーリーのブレイクとノミの幽霊の幻視に関する逸話は有名になった[129]。 ブレイクは生涯を通じて幻視を経験したと主張した。それらはしばしば美しい宗教的なテーマやイメージと結びついており、精神的な作品や追求によって彼をさ らに奮い立たせたのかもしれない。確かに、宗教的な概念やイメージはブレイクの作品の中心に描かれている。神とキリスト教は彼の著作の知的中心を構成し、 そこからインスピレーションを引き出した。ブレイクは、芸術作品を創作するために大天使たちから個人的に指導を受け、励まされていると信じていたが、その 大天使たちが積極的に作品を読み、楽しんでいたと主張している。1800年5月6日、ヘイリーの息子の死の4日後にウィリアム・ヘイリーに宛てた哀悼の手 紙の中で、ブレイクはこう書いている[130]: 私は、亡くなった友人たちが、私たちの死すべき部分に顕現していたときよりも、本当に私たちとともにいることを知っています。13年前、私は兄弟を亡くし たが、彼の霊とは毎日、毎時間、霊の中で会話を交わし、私の想像力の領域で、彼を想起している。私は彼の忠告を聞き、今でも彼の口述筆記によって手紙を書 いている。 1800年9月21日付のジョン・フラックスマン宛ての手紙の中で、ブレイクはこう書いている: [フェルファムの町は、ロンドンよりも精神的な場所なので、勉強するのに最適な場所です。天は黄金の門を四方に開き、窓は蒸気に邪魔されず、天界の住人の 声はより明瞭に聞こえ、その姿はより明瞭に見える。私の妻と妹は二人とも元気で、ネプチューンに抱擁を求めている...。私は自分の作品について、想像以 上に天上で名声を得ている。私の脳内には書斎と部屋があり、私が生前の永遠の時代に書き、描いた古い書物や絵で満たされている。(E710) 1803年4月25日付のトーマス・バッツへの手紙の中で、ブレイクはこう書いている: 今、私は、おそらく他の誰にもあえて言うべきでないことを、あなたに言うことができる。私は一人で、ロンドンで幻視の研究を誰にも迷惑をかけずに続けることができ、永遠の友と語り合い、幻視を見、夢を見、予言し、たとえ話をすることができる。 ブレイクは『最後の審判の幻影』の中でこう書いている: 誤りは創造され、真理は永遠である 誤りや創造は焼き尽くされ、真理や永遠が現れるのは、人がそれを見なくなった瞬間である。太陽が昇るとき、あなたはギニアのような丸い火の円盤を見ないのか。(E565-6) 天使と神を見たにもかかわらず、ブレイクはロンドンのサウス・モルトン・ストリートの自宅の階段でサタンを見たとも主張している[82]。 ブレイクの幻視を知っていたウィリアム・ワーズワースは、「この哀れな男が狂っていることは疑いないが、この男の狂気には、バイロン卿やウォルター・ス コットの正気よりも興味をそそられるものがある」とコメントした[131]。 131]また、ジョン・ウィリアム・カズンズは『A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature』の中で、ブレイクは「真に敬虔で愛に満ちた魂であり、世間からは軽視され誤解されているが、ごく少数の選ばれた人々には評価されて いる」、「幻影と天からのインスピレーションに照らされた、陽気で満足な清貧生活を送っていた」と書いている[132]。 [132] ブレイクの正気性については、1911年にブリタニカ百科事典が出版されたときにも疑問が呈され、そのブレイクの項目には「ブレイクが狂人であったか、狂 人でなかったかについては、今後も論争が続きそうであるが、彼が人生のさまざまな時期において、外見上の事実が説明できない幻想の影響下にあったこと、そ して彼の書いたものの多くが、論理的な一貫性を欠くほど正気の質を欠くものであったことに疑いの余地はない」とコメントされている。 文化的影響 主な記事 大衆文化におけるウィリアム・ブレイク ジョン・リンネルによるウィリアム・ブレイクの横顔の肖像画。この拡大版は、アレクサンダー・ギルクリストの『ブレイクの生涯』(1863年)の扉絵として描かれた。 ブレイクの作品は、彼の死後何世代にもわたって顧みられることなく、1860年代にアレクサンダー・ギルクリストが伝記の執筆を始める頃にはほとんど忘れ 去られていた。特に、ダンテ・ガブリエル・ロセッティやアルジャーノン・チャールズ・スウィンバーンをはじめとするラファエル前派の人々によって取り上げ られた。しかし20世紀になると、ブレイクの作品は十分に評価されるようになり、その影響力も増大した。20世紀初頭から半ばにかけて、S.フォスター・ デイモン、ジェフリー・ケインズ、ノースロップ・フライ、デイヴィッド・V.エドマンといった重要な学者たちが、文学界や芸術界におけるブレイクの地位向 上に貢献した。 ブレイクはロセッティのような人物の芸術や詩に重要な役割を果たしたが、この作品がより幅広い作家や芸術家に影響を与え始めたのはモダニズムの時代であっ た。1893年にブレイクの作品集を編集したウィリアム・バトラー・イェイツは、詩的で哲学的なアイデアを得るためにブレイクを利用し[133]、イギリ スのシュルレアリスム芸術は特に、ポール・ナッシュやグレアム・サザーランドのような芸術家の絵画において、非模倣的で幻視的な実践というブレイクの概念 を利用した[134]。現代のイギリスの作曲家ジョン・タヴナーは、1982年の作品『The Lamb』や『The Tyger』など、ブレイクの詩をいくつか作曲している。 ジューン・シンガーのような多くの人は、ブレイクの人間性に関する思考は、精神分析学者カール・ユングの思考を大きく先取りし、それと並行していると主張 している。ユング自身の言葉を借りれば 「ブレイクは(中途半端な、あるいは未消化の知識を)空想の中にたくさん詰め込んでいるので、興味深い研究対象である。同様に、ダイアナ・ヒューム・ ジョージは、ブレイクはジークムント・フロイトの思想の先駆けとして見ることができると主張している[137]。 ブレイクは1950年代のビート詩人や1960年代のカウンターカルチャーに多大な影響を与え、ビート詩人のアレン・ギンズバーグ、ソングライターのボ ブ・ディラン、ジム・モリソン、ヴァン・モリソン[138]、[139][140]、イギリスの作家オルダス・ハクスリーなどの重要人物によって頻繁に引 用されている。ピューリッツァー賞を受賞した作曲家ウィリアム・ボルコムは、『Songs of Innocence and of Experience』を音楽化し[141]、異なる詩を「モダン・テクニックからブロードウェイ、カントリー/ウェスタン」、レゲエといった異なるスタ イルの音楽に合わせた[142]。 フィリップ・プルマンのファンタジー三部作『ヒズ・ダーク・マテリアルズ』の中心的な構想の多くは、ブレイクの『天国と地獄の結婚』の世界に根ざしてい る。ブレイクはまた、ブライアン・キャトリングのファンタジー小説『The Erstwhile』でも比較的重要なキャラクターとして登場し、彼の見た天使のような存在が物語に組み込まれている。カナダの作曲家キャスリーン・イ ヤーウッドは、ブレイクの詩を音楽化した多くの現代音楽家の一人である。第二次世界大戦後、大衆文化におけるブレイクの役割は、ポピュラー音楽、映画、グ ラフィック・ノベルなど様々な分野で前面に押し出されるようになり、エドワード・ラリシーは「ブレイクは20世紀に最も強い影響を及ぼしたロマン派の作家 である」と断言するに至った[143]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Blake |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆ ☆

☆