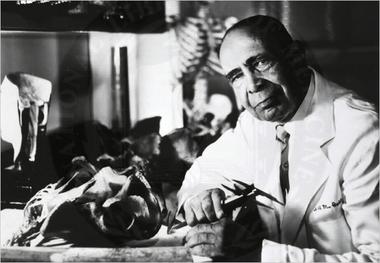

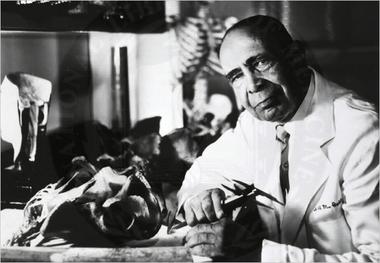

ウィリアム・モンタギュー・コブ

William Montague Cobb, 1904-1990

☆ ウィリアム・モンタギュー・コブ(1904年~1990年)は、アメリカ人医師であり、形質人類学者でもあった[1]。人類学におけるアフリカ系アメリカ 人初の博士号取得者であり、朝鮮戦争後まで唯一の博士号取得者であった[2]コブは、人類学において人種概念とその有色人種コミュニティに与える悪影響の 研究に重点的に取り組んだ。また、全米有色人地位向上協会の初代アフリカ系アメリカ人会長でもあった[3]。医師およびハワード大学の教授としてのキャリ アを通じて、アフリカ系アメリカ人研究者の地位向上に尽力し、公民権運動にも深く関わった[4]。コブは多作で、キャリアを通じて一般向けおよび学術的な 記事の両方を寄稿した。彼の業績は、20世紀前半における生物文化人類学という副次的な学問分野の発展に大きく貢献したとして評価されている[5]。コブ は教育者としても優れており、生涯で5000人以上の学生に社会・健康科学を教えた[6]。

| William Montague Cobb

(1904–1990) was an American board-certified physician and a physical

anthropologist.[1] As the first African-American Ph.D in anthropology,

and the only one until after the Korean War,[2] his main focus in the

anthropological discipline was studying the idea of race and its

negative impact on communities of color. He was also the first

African-American President of the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People.[3] His career both as a physician and a

professor at Howard University was dedicated to the advancement of

African-American researchers and he was heavily involved in civil

rights activism.[4] Cobb wrote prolifically and contributed both

popular and scholarly articles during the course of his career. His

work has been noted as a significant contribution to the development of

the sub-discipline of biocultural anthropology during the first half of

the 20th century.[5] Cobb was also an accomplished educator and taught

over 5000 students in the social and health sciences during his

lifetime.[6] |

ウィリア

ム・モンタギュー・コブ(1904年~1990年)は、アメリカ人医師であり、形質人類学者でもあった[1]。人類学におけるアフリカ系アメリカ人初の博

士号取得者であり、朝鮮戦争後まで唯一の博士号取得者であった[2]コブは、人類学において人種概念とその有色人種コミュニティに与える悪影響の研究に重

点的に取り組んだ。また、全米有色人地位向上協会の初代アフリカ系アメリカ人会長でもあった[3]。医師およびハワード大学の教授としてのキャリアを通じ

て、アフリカ系アメリカ人研究者の地位向上に尽力し、公民権運動にも深く関わった[4]。コブは多作で、キャリアを通じて一般向けおよび学術的な記事の両

方を寄稿した。彼の業績は、20世紀前半における生物文化人類学という副次的な学問分野の発展に大きく貢献したとして評価されている[5]。コブは教育者

としても優れており、生涯で5000人以上の学生に社会・健康科学を教えた[6]。 |

| Early and personal life Cobb was born on October 12, 1904, in Washington DC. His mother, Alexizne Montague Cobb, grew up in Massachusetts and was partly of Native American descent. His father, William Elmer Cobb, grew up in Selma, Alabama. His parents met in Washington DC when his father started his own printing business for the African-American community. The tipping point for Cobb's initial interest in anthropology came from a book of the animal kingdom that his grandfather owned. In this book, there were illustrations of human beings separated by race, but were illustrated with what Cobb called "equal dignity." This led to an interest in the concept of race, as the same type of "equal dignity" was not granted in the society that surrounded Cobb's life.[2] Cobb attended Dunbar High School, a highly esteemed Washington, DC. African-American high school in 1917.[4] He was a successful student and athlete, and went on to win championships in cross-country as well as lightweight and welterweight boxing during his high school and collegiate years.[6] He married Hilda B. Smith, Ruth Smith Lloyd's sister, and they had two children.[7][8] Cobb died of pneumonia on November 20, 1990, at the age of 86.[4] |

生い立ち コブは1904年10月12日、ワシントンD.C.で生まれた。母親のアレクシスネ・モンタギュー・コブはマサチューセッツ州で育ち、一部がネイティブア メリカンである。父親のウィリアム・エルマー・コブはアラバマ州セルマで育った。両親は、父親がアフリカ系アメリカ人コミュニティ向けに印刷業を立ち上げ た際にワシントンD.C.で出会った。 コブが人類学に興味を持つきっかけとなったのは、祖父が所有していた動物図鑑だった。この本には、人種別に分けられた人間のイラストが掲載されていたが、 コブが「平等な尊厳」と呼ぶようなイラストだった。これが人種という概念への興味につながった。コブが生活していた社会では、同じ「平等な尊厳」が与えら れていなかったからだ[2]。 コブは、1917年にワシントンD.C.で非常に評価の高いアフリカ系アメリカ人高校、ダンバー高校に入学した[4]。1917年、アフリカ系アメリカ人 の高校に入学した[4]。彼は優秀な生徒であり、スポーツ選手でもあった。高校と大学時代には、クロスカントリー、ライト級およびウェルター級のボクシン グで優勝した[6]。彼はルース・スミス・ロイドの妹であるヒルダ・B・スミスと結婚し、2人の子どもに恵まれた[7][8]。コブは1990年11月 20日、肺炎のため86歳で死去した[4]。 |

| Education Following his graduation from Dunbar High School in 1921, Cobb earned his Bachelor of Arts from Amherst College in 1925. Following completion of his baccalaureate degree, he received a Blodgett Scholarship for proficiency in biology which allowed him to pursue research in embryology at Woods Hole Marine Biology Laboratory.[4] He earned his MD (Doctor of Medicine) in 1929 from the Howard University Medical School. He worked jobs throughout his time in medical school.[1] Cobb then accepted a position at Howard University which he was offered prior to his graduation.[4] Numa P. G. Adams, who was the Dean of Howard University at the time, was assigned the task of organizing a new faculty of African-American physicians to help advance the school in the medical field. Cobb, in turn had the aspirations of creating a laboratory of anatomy and physical anthropology at Howard University that would have the resources for African-American scholars to contribute to debates in racial biology. As a part of Dean Adams' efforts, Cobb was sent to study under biological anthropologist T. Wingate Todd at Case Western Reserve University.[2] Cobb's dissertation work was an expansive survey of the Hamann-Todd Skeletal Collection, a large skeletal population now housed at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History which is associated with Case Western Reserve University.[4] He earned his Ph.D in Anthropology in 1932 and his dissertation was published under the title Human Archives the following year.[4] |

学歴 1921年にダンバー高校を卒業後、コブは1925年にアマースト大学で文学士号を取得した。学士号取得後、彼は生物学における優れた能力が認められ、 ウッドホール海洋生物学研究所で発生学の研究を行うためのブロジェット奨学金を受けた[4]。1929年にはハワード大学医学部で医学博士号を取得した。 彼は医学部の在学中、さまざまな仕事をしていた[1]。卒業前にオファーされていたハワード大学のポジションをコブは受け入れた[4]。当時ハワード大学 の学部長であったヌマ・P・G・アダムスは、医学分野における同大学の進歩を支援するために、アフリカ系アメリカ人医師の新しい学部組織化という任務を任 されていた。コブは、ハワード大学に解剖学と人類学の実験室を設立し、アフリカ系アメリカ人研究者が人種生物学に関する議論に貢献できる環境を整えること を目指していた。ディーン・アダムス学長の取り組みの一環として、コブはケース・ウェスタン・リザーブ大学で生物人類学者のT.ウィングート・トッドに師 事することになった[2]。コブの博士論文は、ケース・ウェスタン・リザーブ大学と提携関係にあるクリーブランド自然史博物館に現在収蔵されている大規模 な このコレクションは、現在、ケース・ウェスタン・リザーブ大学と提携関係にあるクリーブランド自然史博物館に保管されている。[4] 1932年に人類学の博士号を取得し、翌年に『Human Archives』というタイトルで博士論文が発表された。[4] |

| Career Following the conferral of his doctorate, Cobb remained at Case Western Reserve University as a fellow, where he continued work on the Hamman-Todd Collection with a focus on cranial suture closure. His 1940 publication "Cranio-Facial Union in Man" produced as a result of this work established his expertise as a functional anatomist and is one of his most widely cited works to date.[5] During this period, Cobb also worked with physical anthropologist Aleš Hrdlička on a survey of the skeletal collection at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC.[4] He returned to the Howard University Medical School in 1930 where he taught for the majority of his career and established the W. Montague Cobb Skeletal Collection.[6] He became the university's first distinguished professor in 1969 and became professor emeritus in 1973.[4] In addition to his work at Howard, Cobb also taught at Stanford University, the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, the University of Washington, the University of Maryland, West Virginia University, Harvard Medical School, the Medical College of Wisconsin at Milwaukee, and the Catholic University of America during his lifetime.[6] Cobb was heavily involved with a number of anthropological and medical organizations during his career. He was an active member of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists since its second meeting in 1930 and served on its board on multiple occasions, both as its vice president (1948–50 and 1954–56) and president (1957–59). He also held leadership roles with the Anthropological Society of Washington, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the American Eugenics Society, and the Medico-Chirurgical Society of the District of Columbia. He also served as chairman on the Council of Medical Education and Hospitals for two terms (1948–63).[4] Throughout his lifetime Cobb pursued work aimed at furthering the opportunities of African Americans both within society in general and within the health sciences. He was an active member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and served as its president from 1976 to 1982.[4] He created the Imhotep Conferences on Hospital Integration in 1957 as a part of the NAACP, an annual conference seeking to end hospital and medical school segregation that continued until 1964.[9] He was an active member of the National Medical Association, an organization dedicated to the advancement of African-American physicians and other health professionals.[4][10] He was a longtime contributor to its journal, the Journal of the National Medical Association, of which he served as editor from 1944 to his death in 1990. He also served as the organization's president from 1964 to 1965.[4] In addition to his involvement in both African-American and European American-led professional organizations and journals, Cobb was active in community outreach through work on race and health published in popular African-American magazines such as Negro Digest, Pittsburgh Courier, and Ebony.[4] |

経歴 博士号取得後も、コブはケース・ウェスタン・リザーブ大学で研究員として働き続け、頭蓋縫合閉鎖に焦点を当てたハマン・トッド・コレクションの研究を続け た。1940年に発表された「Cranio-Facial Union in Man」は、この研究から生まれたもので、機能解剖学者としてのコブの専門性を確立し、今日まで最も多く引用された著作のひとつとなった[5]。この期 間、コブは、ワシントンD.C.のスミソニアン博物館の骨格コレクションの調査で、人類学者のアレス・フルディチュカとも協力していた[4]。ワシントン D.C.のスミソニアン博物館の骨格コレクションの調査に、物理人類学者のAleš Hrdličkaとともに携わった[4]。1930年にハワード大学医学部に戻り、そこで大半のキャリアを過ごし、W. Montague Cobb Skeletal Collectionを設立した[6]。1969年に同大学の初代特別教授となり、1973年に名誉教授となった[4]。ハワード大学での仕事に加え、コ ブはスタンフォード大学、アーカンソー大学リトルロック校、ワシントン大学、メリーランド大学、ウェストバージニア大学、ハーバード大学医学部、ミル ウォーキーのウィスコンシン医科大学、カトリック大学でも教鞭を執った[6]。 コブは、そのキャリアを通じて多くの人類学および医学関連団体と深く関わっていた。彼は1930年の第2回会議以来、アメリカ人類身体学者協会の活発なメ ンバーであり、副会長(1948年~50年、1954年~56年)および会長(1957年~59年)として、何度も理事会のメンバーを務めた。また、ワシ ントン人類学会、アメリカ科学振興協会、アメリカ優生学会、コロンビア特別区医学会でも指導的役割を果たした。さらに、医学教育・病院評議会の議長を2期 (1948年~1963年)務めた[4]。 生涯を通じて、コブはアフリカ系アメリカ人の社会進出と健康科学分野での活躍を目指して研究に取り組んだ。彼は全米有色人地位向上協会(NAACP)の活 発なメンバーであり、1976年から1982年まで会長を務めた[4]。1957年にはNAACPの一部としてイムホテプ病院統合会議を創設し、1964 年まで続いた病院と医学部の人種隔離の撤廃を目指した年次会議を開催した 1964年まで続いた[9]。彼は全米医師会(National Medical Association)の活発なメンバーであり、この組織はアフリカ系アメリカ人医師やその他の医療従事者の地位向上を目的としていた[4][10]。 彼はその機関誌『全米医師会ジャーナル』(Journal of the National Medical Association)に長年寄稿しており、1944年から1990年に亡くなるまで編集者を務めた。また、1964年から1965年にかけては、同団 体の会長も務めた[4]。アフリカ系アメリカ人とヨーロッパ系アメリカ人が主導する専門組織や専門誌に関与する一方で、コブは『ネグロ・ダイジェスト』、 『ピッツバーグ・クーリエ』、『エボニー』といったアフリカ系アメリカ人向けの人気雑誌で人種と健康に関する記事を発表するなど、地域社会への貢献活動に も積極的に取り組んでいた[4]。 |

| Scholarship Throughout his career, Cobb applied his technical expertise in functional anatomy and medicine to a variety of topics, including the issues of African-American health, child development, and disproving scientific justifications for racism. His approach has been characterized as a form of applied anthropology and activist scholarship.[4] His work explicitly critiqued hierarchical understandings of human variation, and he often subverted racist evolutionary arguments through highlighting the resiliency of African Americans. He took as an example the experience of the Transatlantic slave trade which he argued acted as a selective pressure and would have led to a genetically stronger population relative to European Americans who did not experience this population bottleneck.[5] Cobb often used his expertise in anatomy and biology in order to combat racist explanations for perceived differences between African Americans and European Americans. One of the most widely cited studies in this effort was Cobb's "Race and Runners," published in 1936. In this work, Cobb took the case of Jesse Owens to dispel the idea that his success as a quadruple gold medal winner could be explained by his " African-American genes," an argument that stemmed from the idea that Black people were stronger and more athletic than whites at the cost of decreased intelligence.[5] Proponents of this idea often pointed to the supposed existence of extra musculature or differences in nerve thicknesses that allowed African-American athletes to excel relative to European Americans. Cobb addressed this question by surveying the anatomical characteristics of Owens as well as other prominent African Americans in different sports. Cobb demonstrated that not only could their successes not be explained by a shared racial trait, the physiology that would make a superior athlete in one sport would be very different from another. Instead, Cobb accounted for the achievements of African-American athletes relative to European Americans in sports as due to "training and incentive" rather than any "special physical endowment".[11] During the latter years of his career, Cobb took a more philosophical approach to his anatomical perspective of humanity. He often used biological metaphors to point to key issues within society. Cobb's most prominent philosophical contribution was arguably his 1975 publication, "An anatomist's view of human relations. Homo sanguinis versus Homo sapiens--mankind's present dilemma".[4] This work focused primarily on the fundamental conflict in human nature he described as being between the civilized people suggested by our binomial designation Homo sapiens ("Man the Wise") and the much older and violent organism he described via his coined term Homo sanguinus ("Man the bloody").[12] Cobb described the recent "adaptations" of civilization and ethics as similar to recently evolved anatomical traits like bipedalism, a key human trait which has nonetheless resulted in a host of health conditions due to our lineage's adaptations for quadrupedal locomotion. Cobb argued that man the wise is up against the ancient evolutionary tradition of man as a "bloody, predatory primate" and that this history of violence and hatred will thus be difficult to overcome.[12] Cobb's final presented publication in 1988, "Human Variation: Informing the Public," applied his Homo sanguinus more closely to the rapid cultural change of the late 20th century.[4] Cobb saw this period of rapid development as both a key opportunity for continued progress against racism and other forms of inequality and a potential for such issues to become more firmly embedded within the system of the society: "Just as an embryological defect cannot be corrected, so our mammoth construction programs can be wrong, which is not obvious until it is too late."[13] |

奨学金 コブは、アフリカ系アメリカ人の健康問題、子どもの発達、人種差別に対する科学的根拠の否定など、さまざまなテーマに機能解剖学と医学の専門知識を応用し てきた。彼のアプローチは応用人類学と活動家としての学問の一形態として特徴づけられてきた[4]。彼の研究は、人間の多様性に対する階層的な理解を明確 に批判し、アフリカ系アメリカ人の回復力を強調することで人種差別的な進化論的議論をしばしば覆した。彼は大西洋横断奴隷貿易の経験を引き合いに出し、こ の人口のボトルネックを経験しなかったヨーロッパ系アメリカ人に対して、遺伝的に強い集団を生み出す選択圧として働いたと主張した[5]。 コブは、アフリカ系アメリカ人とヨーロッパ系アメリカ人の違いに対する人種差別的な説明に対抗するために、解剖学と生物学における専門知識をしばしば利用 した。この取り組みの中で最も広く引用された研究のひとつが、1936年に発表されたコブの「Race and Runners」である。この研究の中で、コブはジェシー・オーウェンズの事例を取り上げ、彼が4つの金メダルを獲得した成功は「アフリカ系アメリカ人の 遺伝子」によるものであるという説を否定した。この説は、黒人は白人よりも強くて運動神経が優れているが、その代償として知能指数が低いという考え方から 生まれたものである。そして、知性は低下するものの、白人よりも黒人の方がより強く、より運動神経に優れているという考え方から生じた議論である[5]。 この考えを支持する人々は、アフリカ系アメリカ人アスリートがヨーロッパ系アメリカ人アスリートよりも優れた成績を収めることを可能にする、余分な筋肉の 存在や神経の太さの違いをしばしば指摘していた。コブは、オーエンスや他の著名なアフリカ系アメリカ人スポーツ選手の解剖学的特徴を調査することで、この 疑問に答えた。 コブは、彼らの成功が人種的特徴によって説明できるものではないばかりか、あるスポーツで優れたアスリートとなる生理機能は、他のスポーツでは大きく異な ることを証明した。その代わりに、コブはアフリカ系アメリカ人アスリートのスポーツにおける功績を、ヨーロッパ系アメリカ人アスリートのそれと比較して、 「特別な身体的素質」ではなく「トレーニングと動機付け」によるものと説明した[11]。 コブはキャリアの後期において、人類に対する解剖学的見地についてより哲学的なアプローチをとった。彼はしばしば生物学的な比喩を用いて、社会における重 要な問題点を指摘した。コブの最も顕著な哲学的貢献は、1975年に出版された『An anatomist's view of human relations. 「ホモ・サピエンス対ホモ・サングィニス―人類の現在のジレンマ」[4]。この著作は、主に彼が文明人と称するホモ・サピエンス(「賢い人間」)と、彼が ホモ・サングィニス(「血にまみれた人間」)という造語で表現した、はるかに古く暴力的である生物との間の、人間の本質的な対立に焦点を当てている [12]。 [12] コブは、文明と倫理の最近の「適応」を、二足歩行のような最近進化した解剖学的特徴に類似していると説明している。二足歩行は人間の重要な特徴であるが、 四足歩行への適応により、さまざまな健康問題を引き起こしている。コブは、賢明な人間は「血に飢えた肉食霊長類」としての人間の古代の進化の伝統に立ち向 かっているとし、暴力と憎しみの歴史は克服するのが難しいと論じた[12]。1988年に発表されたコブの最後の著書『Human Variation: 「Human Variation: Informing the Public」は、20世紀後半の急激な文化変化に、コブの「ホモ・サングイヌス」をより密接に適用したものである[4]。コブは、この急速な発展の時代 を、人種差別やその他の不平等に対する継続的な進歩のための重要な機会であると同時に、そのような問題が社会のシステムにさらに深く根付く可能性があると 捉えていた。「発生上の欠陥は修正できないのと同じように、私たちの巨大建設計画も間違っている可能性がある。しかし、それが明らかになるのは手遅れに なってからなのだ。」[13] |

| Legacy Cobb distinguished himself by representing the pursuit of social responsibility in the field of anthropology, as well as by being an activist scholar who often applied anthropological methods to issues of racism and inequality.[4] He undertook studies within the scope of his expertise in anatomy that aimed at disproving racist explanations for social difference. He believed that scholars must take responsibility "not only for their own thoughts and actions but also for their own society" because the values that are expressed in scientific work, whether subtly or overtly, are key in the shaping of culture and society.[2] He was one of the first anthropologist to undertake a demographic analysis that illustrated the consequences of segregation and racism on the African-American population, and he wanted to create the resources so he would not be the last.[4] One of Cobb's greatest contributions to this end is the expansive skeletal collection he curated during his time at Howard University which is now housed at the university's W. Montague Cobb Research Laboratory, a research laboratory led by biological anthropologist Fatimah Jackson that also houses the New York African Burial Ground collection.[1] Cobb was long involved in African descendants' struggle for freedom, justice, and equality. He assumed a number of roles in African-American-led organizations, including the National Urban League and the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, and he was a longtime editor of the first African-American medical journal, the Journal of the National Medical Association.[14] He was a member of the board of directors for the NAACP from 1949 until his death and president from 1976 to 1982.[4] Cobb played a key role in efforts to expand access to medical care through his active leadership in the National Medical Association, and this activism led to his testimony to congress during the hearings leading up to the passage of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965. He was present at the signing of this bill into law by invitation of President Lyndon B. Johnson.[15][16] During his lifetime, Cobb was honored by more than 100 organizations for his efforts as a scholar and as an activist, including the American Association for Anatomy's highest award, the Henry Gray Award, which he received for his outstanding contributions in the field in 1980.[4] He was also the recipient of the U.S. Navy's Distinguished Public Service Award and received honorary doctorates from several institutions, including the Medical College of Wisconsin, Georgetown University, the University of the Witwatersrand, Morgan State University, Howard University, and Amherst College.[6] The American Association for Anatomy named the W.M. Cobb Award in Morphological Sciences after Cobb to honor his legacy with its first recipient in 2020.[17] |

遺産 コブは、人類学の分野における社会的責任の追求を体現し、また人種差別や不平等といった問題に対して人類学の手法を応用する活動家学者としても知られてい た[4]。彼は、人種差別的な社会格差の説明を否定することを目的とした、解剖学における専門分野の研究に取り組んだ。彼は、科学的な研究に表現される価 値観は、それが表面的であろうと、あるいは隠されているであろうと、文化や社会を形成する上で重要な鍵を握っているため、学者には「自らの思想や行動だけ でなく、自らの社会に対しても責任を持つ」必要があると信じていた[2]。彼は、アフリカ系アメリカ人社会における人種差別や隔離がもたらす結果を明らか にする人口統計学的分析に着手した最初の人類学者の一人であり、自分が 最後の一人にならないようにしたかったのだ[4]。この目的においてコブが果たした最も大きな貢献の一つは、ハワード大学に在籍していた間に彼がキュレー ションした膨大な骨格コレクションであり、現在は同大学のW.モンタギュー・コブ研究ラボに保管されている。この研究ラボは生物人類学者のファティマ・ ジャクソンが率いており、ニューヨーク・アフリカン・バーリアル・グラウンド・コレクションも保管されている[1]。 コブはアフリカ系アメリカ人の子孫が自由、正義、平等を求めて闘うことに長い間携わっていた。彼は、全米都市同盟や黒人生活史研究協会など、アフリカ系ア メリカ人が主導する組織でさまざまな役職を務め、また、アフリカ系アメリカ人初の医学雑誌『全米医師会雑誌』の編集者を長年務めた[14]。19 1949年から亡くなるまでNAACPの理事を務め、1976年から1982年まで会長を務めた[4]。コブは全米医師会の積極的なリーダーシップを通じ て医療へのアクセス拡大に重要な役割を果たし、この活動により、1965年のメディケアとメディケイドの成立に向けた公聴会において議会で証言することと なった。彼はリンドン・B・ジョンソン大統領の招待により、この法案の署名式に出席した[15][16]。 コブは生涯を通じて、学者および活動家としての功績を称えられ、100以上の団体から表彰された。その中には、1980年に解剖学分野における顕著な貢献 に対して贈られた、アメリカ解剖学会の最高賞であるヘンリー・グレイ賞も含まれる[4]。また、 米国海軍の功労賞も受賞し、ウィスコンシン医科大学、ジョージタウン大学、ウィットウォータースランド大学、モーガン州立大学、ハワード大学、アマースト 大学など、複数の教育機関から名誉博士号を授与された[6]。米国解剖学会は、コブの業績を称え、2020年に最初の受賞者にコブの名を冠した形態科学の W.M.コブ賞を創設した[17]。 |

| Selected publications "Human Archives" – 1932. "Race and Runners" –1936. "Cranio Facial Union of Man" – 1940. "The Cranio-Facial Union and the Maxillary Tuber in Mammals" – 1943. "Medical Care and the Plight of the Negro in Medicine" – 1947. "An anatomist's view of human relations. Homo sanguinis versus Homo sapiens--mankind's present dilemma" – 1975. "Human Rights—A New Fight in Cultural Evolution" – 1978. "The Black American in Medicine" – 1981. "Human Variation: Informing the Public" – 1988. In addition those listed above, Cobb had more than 1100 publications on various topics.[5] |

主な著作 「Human Archives」 - 1932年 「Race and Runners」 - 1936年 「Cranio Facial Union of Man」 - 1940年 「The Cranio-Facial Union and the Maxillary Tuber in Mammals」 - 1943年 「Medical Care and the Plight of the Negro in Medicine」 - 1947年 「An anatomist's view of human relations. 「ホモサングイニス対ホモサピエンス―人類の現在のジレンマ」1975年 「人権―文化進化における新たな戦い」1978年 「医学における黒人アメリカ人」1981年 「ヒトの多様性:一般市民への情報提供」1988年 上記のリストに加え、コブはさまざまなテーマについて1100以上の論文を発表している[5]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Montague_Cobb |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆