ウィリアム・ウォーカー

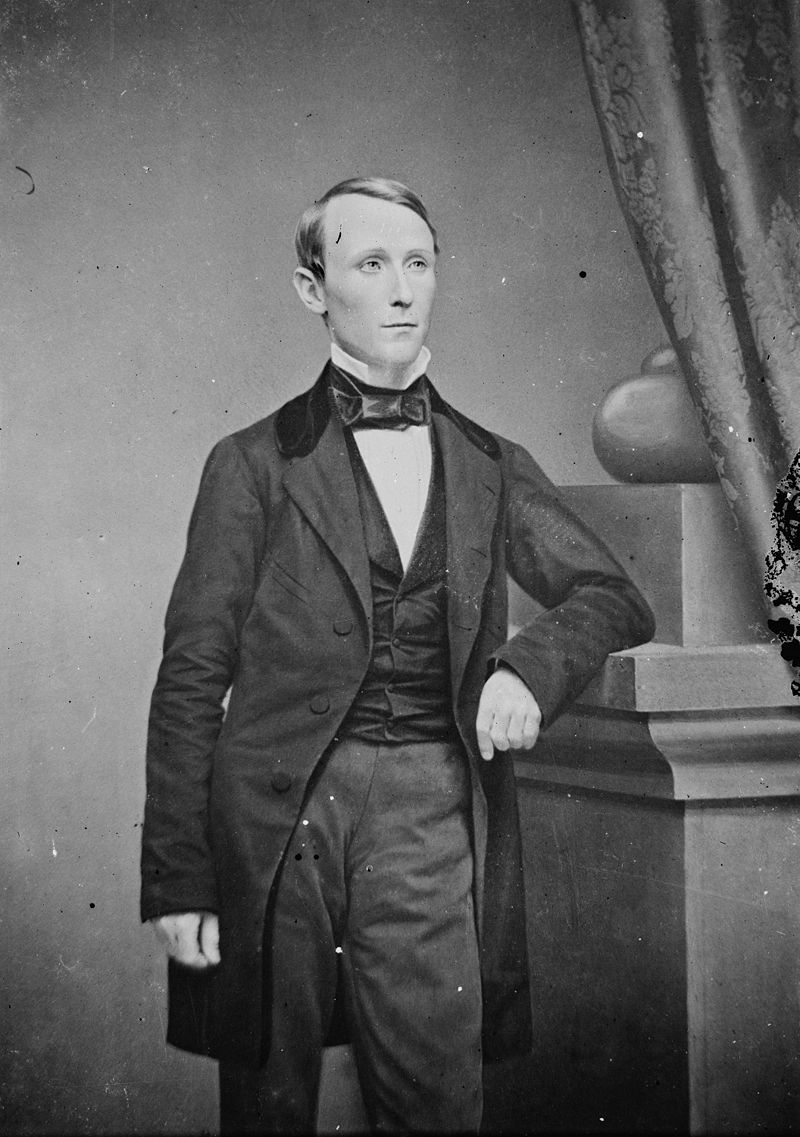

William Walker, May 8, 1824 – September

12, 1860

☆ ウィリアム・ウォーカー(1824年5月8日 - 1860年9月12日)は、アメリカの医師、弁護士、ジャーナリスト、傭兵であった。「明白な使命」という教義に突き動かされたアメリカ合衆国の拡大時代 に、ウォーカーはメキシコと中央アメリカに無許可で軍事遠征を行い、植民地を建設しようとした。このような事業は当時「盗賊/私賊行為(filibustering)」 として知られていた。 カリフォルニアに定住した後、ガストン・ド・ラウゼット=ブールボンの以前の「盗賊行為」プロジェクトに触発されたウォーカーは、1853年から54年に かけてバハ・カリフォルニアとソノラを占領しようとした。彼はそれらの領土をソノラ共和国として独立宣言したが、すぐにメキシコ軍によってカリフォルニア に追い返された。ウォーカーは1855年、ニカラグア民主党が正統派との内戦で雇った傭兵部隊の指揮官としてニカラグアに向かった。彼はニカラグア政府を 掌握し、1856年7月には大統領に就任した。 ウォーカーの政権は、アメリカ大統領フランクリン・ピアースによってニカラグアの合法政府として認められ、当初はニカラグア社会内の一部の有力な層から支 持を得ていた。[2] しかし、ウォーカーは、ニューヨーク市からサンフランシスコへ向かう乗客輸送の主要ルートのひとつを運営していたヴァンダービルトの付属運輸会社を接収し たことで、ウォール街の大物実業家コーネリアス・ヴァンダービルトの反感を買った。大英帝国は、ニカラグア運河の建設の可能性における自国の利益を脅かす 存在としてウォーカーを警戒した。ニカラグアの支配者として、ウォーカーは奴隷制を合法化したが、この措置は一度も施行されることはなく、近隣の中米共和 国の独立を脅かした。コスタリカが主導する軍事同盟がウォーカーを破り、1857年5月1日にニカラグアの大統領を辞任させた。 ウォーカーはその後、再び自らの「盗賊行為」計画を再開しようとし、1860年には著書『ニカラグア戦争』を出版し、中米征服への努力を奴隷制の地理的拡 大と結びつけた。ウォーカーは、南北戦争直前のアメリカ南部の奴隷制推進派から再び支持を得ようとしたのである。同年、ウォーカーは中米に戻ったが、英国 海軍に逮捕され、英国海軍からホンジュラス政府に引き渡され、同国政府によって処刑された。

| William Walker (May

8, 1824 – September 12, 1860) was an American physician, lawyer,

journalist, and mercenary. In the era of the expansion of the United

States, driven by the doctrine of "manifest destiny", Walker organized

unauthorized military expeditions into Mexico and Central America with

the intention of establishing colonies. Such an enterprise was known at

the time as "filibustering". After settling in California, motivated by an earlier filibustering project of Gaston de Raousset-Boulbon, Walker attempted in 1853–54 to take Baja California and Sonora. He declared those territories to be an independent Republic of Sonora, but he was soon driven back to California by the Mexican forces. Walker then went to Nicaragua in 1855 as leader of a mercenary army employed by the Nicaraguan Democratic Party in its civil war against the Legitimists. He took control of the Nicaraguan government and in July 1856 set himself up as the country's president.[1] Walker's regime was recognized as the legitimate government of Nicaragua by US President Franklin Pierce, and it initially enjoyed the support of some important sectors within Nicaraguan society.[2] However, Walker antagonized the powerful Wall Street tycoon Cornelius Vanderbilt by expropriating Vanderbilt's Accessory Transit Company, which operated one of the main routes for the transport of passengers going from New York City to San Francisco. The British Empire saw Walker as a threat to its interests in the possible construction of a Nicaragua Canal. As ruler of Nicaragua, Walker re-legalized slavery, although this measure was never enforced, and threatened the independence of neighboring Central American republics. A military coalition led by Costa Rica defeated Walker and forced him to resign the presidency of Nicaragua on May 1, 1857.[3] Walker then tried to re-launch his filibustering project and in 1860 published a book, The War in Nicaragua, which cast his efforts to conquer Central America as tied to the geographical expansion of slavery. In that way, Walker sought to gain renewed support from pro-slavery forces in the Southern United States on the eve of the American Civil War. The same year, Walker returned to Central America but was arrested by the Royal Navy, who handed him over to the Honduran government, which executed him. |

ウィリアム・ウォーカー(1824年5月8日 -

1860年9月12日)は、アメリカの医師、弁護士、ジャーナリスト、傭兵であった。「明白な使命」という教義に突き動かされたアメリカ合衆国の拡大時代

に、ウォーカーはメキシコと中央アメリカに無許可で軍事遠征を行い、植民地を建設しようとした。このような事業は当時「盗賊行為/私賊行為/フィリバスタリング」として知られていた。 カリフォルニアに定住した後、ガストン・ド・ラウゼット=ブールボンの以前の「盗賊行為」プロジェクトに触発されたウォーカーは、1853年から54年に かけてバハ・カリフォルニアとソノラを占領しようとした。彼はそれらの領土をソノラ共和国として独立宣言したが、すぐにメキシコ軍によってカリフォルニア に追い返された。ウォーカーは1855年、ニカラグア民主党が正統派との内戦で雇った傭兵部隊の指揮官としてニカラグアに向かった。彼はニカラグア政府を 掌握し、1856年7月には大統領に就任した。 ウォーカーの政権は、アメリカ大統領フランクリン・ピアースによってニカラグアの合法政府として認められ、当初はニカラグア社会内の一部の有力な層から支 持を得ていた。[2] しかし、ウォーカーは、ニューヨーク市からサンフランシスコへ向かう乗客輸送の主要ルートのひとつを運営していたヴァンダービルトの付属運輸会社を接収し たことで、ウォール街の大物実業家コーネリアス・ヴァンダービルトの反感を買った。大英帝国は、ニカラグア運河の建設の可能性における自国の利益を脅かす 存在としてウォーカーを警戒した。ニカラグアの支配者として、ウォーカーは奴隷制を合法化したが、この措置は一度も施行されることはなく、近隣の中米共和 国の独立を脅かした。コスタリカが主導する軍事同盟がウォーカーを破り、1857年5月1日にニカラグアの大統領を辞任させた。 ウォーカーはその後、再び自らの「盗賊行為」計画を再開しようとし、1860年には著書『ニカラグア戦争』を出版し、中米征服への努力を奴隷制の地理的拡 大と結びつけた。ウォーカーは、南北戦争直前のアメリカ南部の奴隷制推進派から再び支持を得ようとしたのである。同年、ウォーカーは中米に戻ったが、英国 海軍に逮捕され、英国海軍からホンジュラス政府に引き渡され、同国政府によって処刑された。 |

| Early life William Walker was born in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1824 to James Walker and his wife Mary Norvell. His father was an English settler.[4] His mother was the daughter of Lipscomb Norvell, an American Revolutionary War officer from Virginia.[5] One of Walker's maternal uncles was John Norvell, a U.S. Senator from Michigan and founder of The Philadelphia Inquirer.[6] Walker was engaged to Ellen Martin, but she died of yellow fever before they could be married,[7] and he died without children. Walker graduated summa cum laude from the University of Nashville at the age of 14.[8] In 1843, at the age of 19, he received a medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania.[8] Walker then continued his medical studies at Edinburgh[9] and Heidelberg. He practiced medicine briefly in Philadelphia, but soon moved to New Orleans where he studied law privately.[10] Walker practiced law for a short time, then quit to become co-owner and editor of the New Orleans Crescent newspaper. In 1849, he moved to San Francisco, where he worked as editor of the San Francisco Herald and fought three duels; he was wounded in two of them. Walker then conceived the idea of conquering vast regions of Central America and creating new slave states to join those already part of the Union.[11] These campaigns were known as filibustering, or freebooting, and were supported by the Southern expansionist secret society, the Knights of the Golden Circle.[12][13][14] |

幼少期 ウィリアム・ウォーカーは1824年、テネシー州ナッシュビルでジェームズ・ウォーカーとその妻メアリー・ノーベルの間に生まれた。父親はイギリスからの 入植者であった。[4] 母親はバージニア出身のアメリカ独立戦争の将校リプスコム・ノヴェルの娘であった。[5] ウォーカーの母方の叔父の一人にジョン・ノヴェルがおり、彼はミシガン州選出の上院議員であり、『フィラデルフィア・インクワイラー』の創設者であった。 [6] ウォーカーはエレン・マーティンと婚約していたが、結婚前に彼女は黄熱病で死亡した。[7] ウォーカーは子供をもうけることなく亡くなった。 ウォーカーは14歳でナッシュビル大学を最優秀の成績で卒業した。[8] 1843年、19歳でペンシルベニア大学から医学博士号を取得した。[8] その後、エディンバラ[9]とハイデルベルクで医学の研究を続けた。フィラデルフィアで短期間医療に従事したが、すぐにニューオーリンズに移り、そこで法 律を個人で学んだ。[10] ウォーカーはしばらく弁護士として働いた後、弁護士を辞めてニューオーリンズ・クレセント紙の共同所有者兼編集者となった。1849年、彼はサンフランシ スコに移り、サンフランシスコ・ヘラルド紙の編集者として働き、3回の決闘を経験した。そのうち2回で負傷した。ウォーカーは、中米の広大な地域を征服 し、すでに連邦に加盟している奴隷州に新たな奴隷州を創設するという考えを思い付いた。[11] これらのキャンペーンは、フィリバスター(議事妨害)またはフリーブッティング(略奪行為)として知られ、南部の拡張主義秘密結社であるゴールデン・サー クル騎士団によって支援されていた。[12][13][14] |

| Duel with William Hicks Graham Walker gained national attention by dueling with law clerk William Hicks Graham on January 12, 1851.[15] Walker criticized Graham and his colleagues in the Herald, which angered Graham and prompted him to challenge Walker to a duel.[16] Graham was a notorious gunman, having taken part in a number of duels and shootouts in the Old West. Walker, on the other hand, had experience dueling with single-shot pistols at one time, but his duel with Graham was fought with revolvers.[17] The combatants met at Mission Dolores, where each was given a Colt Dragoon with five shots. They stood face to face at ten paces, and each aimed and fired at the signal of a referee. Graham managed to fire two bullets, hitting Walker in his pantaloons and his thigh, seriously wounding him. Walker tried a number of times to shoot his weapon, but he failed to land even a single shot and Graham was left unscathed. The duel ended when Walker conceded. Graham was arrested but was quickly released. The duel was recorded in The Daily Alta California.[17] |

ウィリアム・ヒックス・グラハムとの決闘 1851年1月12日、ウォーカーは書記官のウィリアム・ヒックス・グラハムと決闘し、国民の注目を集めた。[15] ウォーカーはヘラルド紙でグラハムとその同僚を批判し、グラハムの怒りを買い、決闘を申し込まれることとなった。[16] グラハムは悪名高い銃の名人であり、西部開拓時代には数多くの決闘や銃撃戦に参加していた。一方のウォーカーは、かつては単発式拳銃での決闘の経験があっ たが、グラハムとの決闘ではリボルバーを使用した。 決闘の舞台はミッション・ドロレス教会で、双方に装弾数5発のコルト・ドラグーンが支給された。 10歩の距離で向かい合い、審判の合図で狙いを定めて発砲した。グラハムは2発の銃弾を発射し、ウォーカーのズボンと太ももを撃ち抜いて重傷を負わせた。 ウォーカーは何度も銃を発射しようとしたが、1発も命中させることができず、グラハムは無傷のままだった。ウォーカーが降参したため決闘は終了した。グラ ハムは逮捕されたが、すぐに釈放された。この決闘は『デイリー・アルタ・カリフォルニア』紙に記録された。[17] |

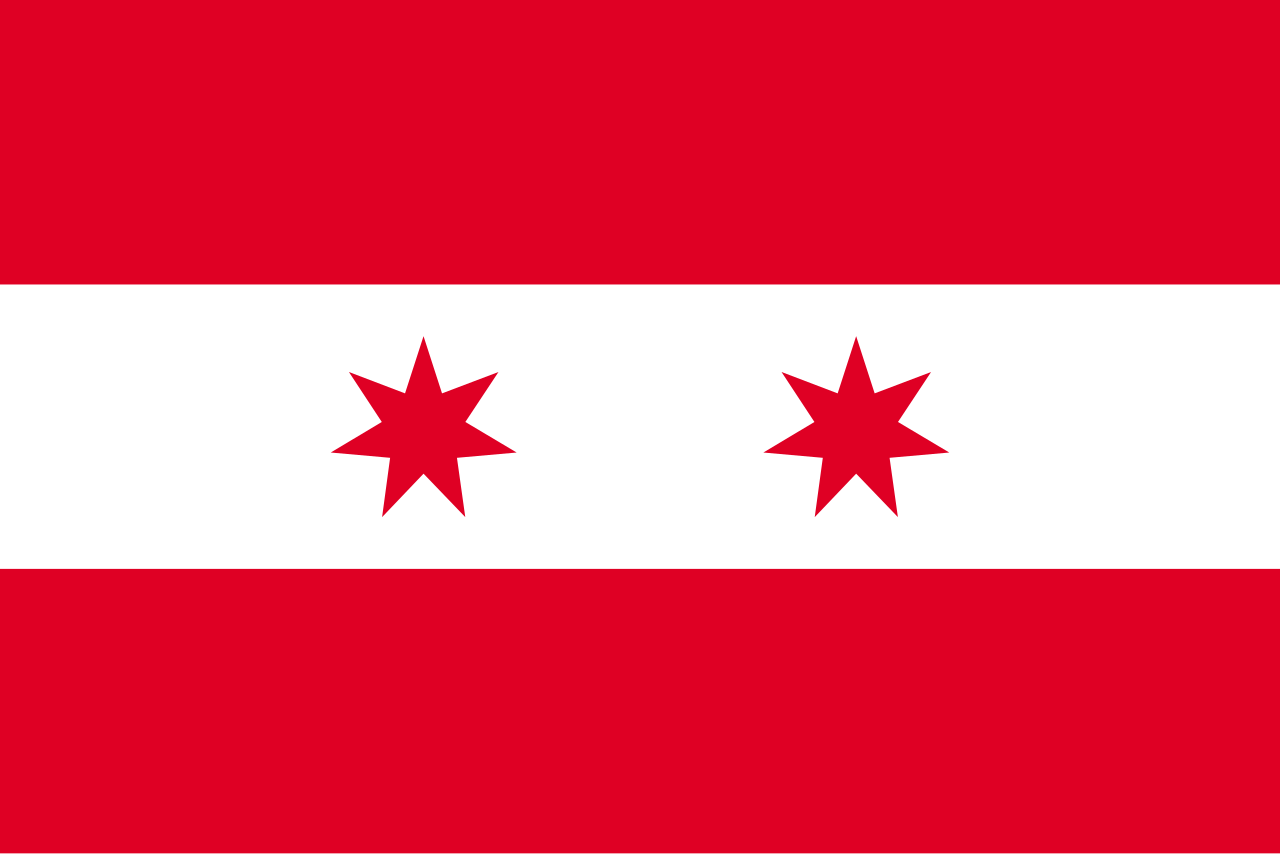

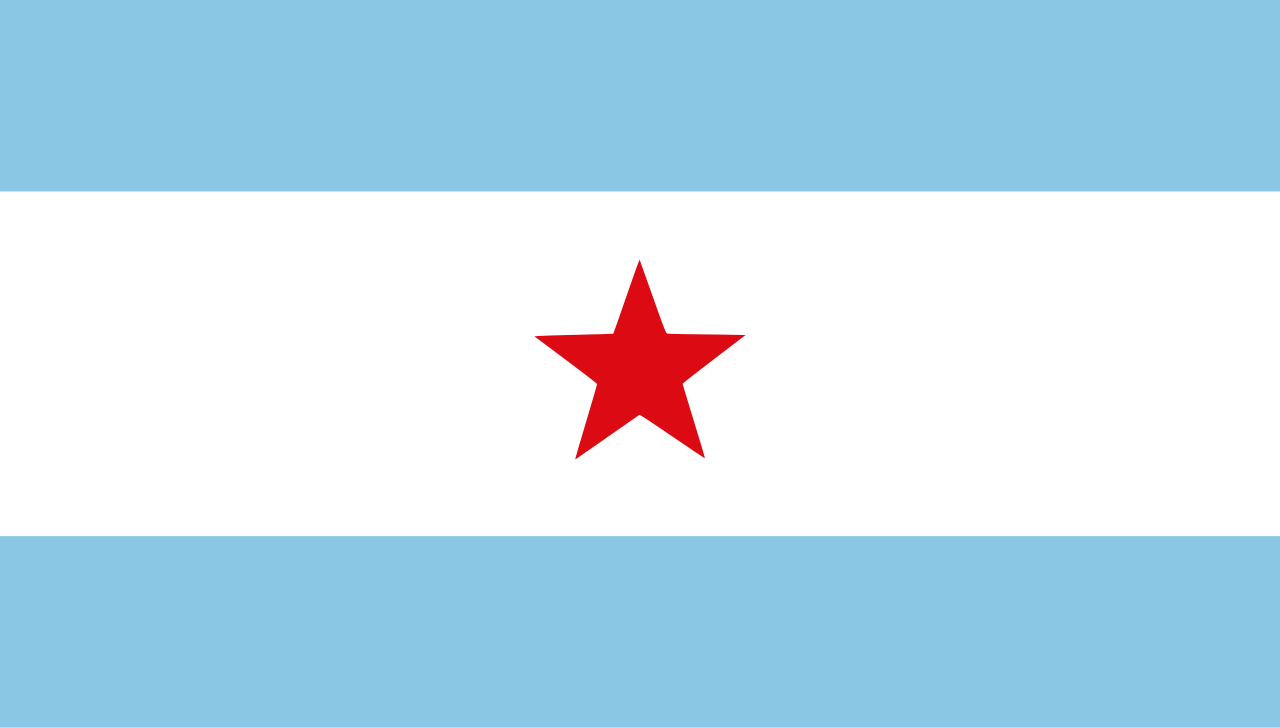

| Invasion of Mexico After a failed attempt to invade the Mexican Province of Sonora from the state of Arizona,[18] In the summer of 1853, Walker traveled to Guaymas in Mexico, seeking a grant from the Mexican government to establish a colony. He proposed that his colony would serve as a fortified frontier, protecting U.S. soil from Indian raids. Mexico refused, and Walker returned to San Francisco determined to obtain his colony regardless of Mexico's position.[19][20] He began recruiting American supporters of slavery and of the Manifest Destiny doctrine, mostly inhabitants of Tennessee and Kentucky. Walker's plans then expanded from forming a buffer colony to establishing an independent Republic of Sonora, which might eventually take its place as a part of the Union (as the Republic of Texas had done in 1845). He funded his project by "selling scrips which were redeemable in lands of Sonora".[10]  Flag of the Republic of Sonora On October 15, 1853, Walker set out with forty-five men to conquer the Mexican territories of Baja California Territory and Sonora State. He succeeded in capturing La Paz, the capital of sparsely populated Baja California, which he declared the capital of a new "Republic of Lower California" (declared November 3, 1853), with himself as president and his former law partner, Henry P. Watkins,[21] as vice president. Walker then put the region under the laws of the American state of Louisiana, which made slavery legal.[21] Whether Walker at this stage intended to tie his filibustering expedition to the cause of slavery is a matter of dispute.[22] Fearful of attacks by Mexico, Walker moved his headquarters twice over the next three months, first to Cabo San Lucas, and then further north to Ensenada to maintain a more secure base of operations. Although he never gained control of Sonora, he pronounced Baja California part of the larger Republic of Sonora.[10] Lack of supplies, severe aridity of Baja California and strong resistance by the Mexican government quickly forced Walker to retreat.[21] Back in California, Walker was indicted by a federal grand jury for waging an illegal war in violation of the Neutrality Act of 1794. However, in the era of Manifest Destiny, Walker's filibustering project had popular support in the southern and western U.S. Walker was tried before Judge I. S. K. Ogier in the US District Court for the Southern District of California. Although two of Walker's associates had already been convicted of similar charges and Judge Ogier summarized the evidence against Walker for the jury, the jury deliberated for only eight minutes before acquitting Walker.[23][24] |

メキシコ侵攻 アリゾナ州からメキシコのソノラ州への侵攻を試みたが失敗した後、[18] 1853年の夏、ウォーカーはメキシコのグアイマスを訪れ、メキシコ政府から入植地設立のための助成金を得ようとした。彼は、自らの入植地が要塞化された 最前線となり、米国本土をインディアンの襲撃から守ることを提案した。メキシコはこれを拒否し、ウォーカーはメキシコの立場に関わらず入植地を手に入れる 決意を固めてサンフランシスコに戻った。[19][20] 彼は奴隷制と明白な使命論の支持者たちを募り、主にテネシー州とケンタッキー州の住民を集めた。ウォーカーの計画は緩衝植民地の形成から、最終的には連邦 の一部となる可能性のある(1845年のテキサス共和国のように)独立したソノラ共和国の樹立へと拡大した。彼は「ソノラの土地と引き換え可能な証書」を 販売することで、そのプロジェクトの資金を調達した。[10]  ソノラ共和国の旗 1853年10月15日、ウォーカーは45人の男たちとともに、メキシコ領バハ・カリフォルニア準州とソノラ州の征服に乗り出した。彼は、人口の少ないバ ハ・カリフォルニアの州都ラパスを占領することに成功し、この地を「下カリフォルニア共和国」の首都(1853年11月3日宣言)と宣言し、自身を大統 領、かつての法律パートナーであったヘンリー・P・ワトキンスを副大統領に任命した。ウォーカーはその後、この地域をアメリカ合衆国のルイジアナ州の法の 下に置き、奴隷制を合法化した。[21] この段階でウォーカーが、彼の盗賊行為を奴隷制の目的に結びつけるつもりだったかどうかは、議論の余地がある。[22] メキシコからの攻撃を恐れたウォーカーは、その後の3か月間に2度、作戦本部を移転した。最初はカボ・サンルーカス、さらに北のエンセナーダへと移り、よ り安全な作戦拠点の確保に努めた。ソノラを制圧することはできなかったが、バハ・カリフォルニアをソノラ共和国の一部であると宣言した。[10] 物資不足、バハ・カリフォルニアの深刻な乾燥、メキシコ政府の強力な抵抗により、ウォーカーはすぐに撤退を余儀なくされた。[21] カリフォルニアに戻ったウォーカーは、1794年の中立法に違反した違法な戦争を遂行したとして、連邦大陪審により起訴された。しかし、明白な使命の時代 において、ウォーカーの盗賊行為計画はアメリカ合衆国南部および西部で人気を博していた。ウォーカーはカリフォルニア南部地区連邦地方裁判所のI. S. K. オジェール判事の元で裁判にかけられた。ウォーカーの2人の仲間がすでに同様の罪で有罪判決を受けており、オジエ判事はウォーカーに対する証拠を陪審員に 要約したが、陪審員はウォーカーを無罪とする前にわずか8分間審議しただけだった。[23][24] |

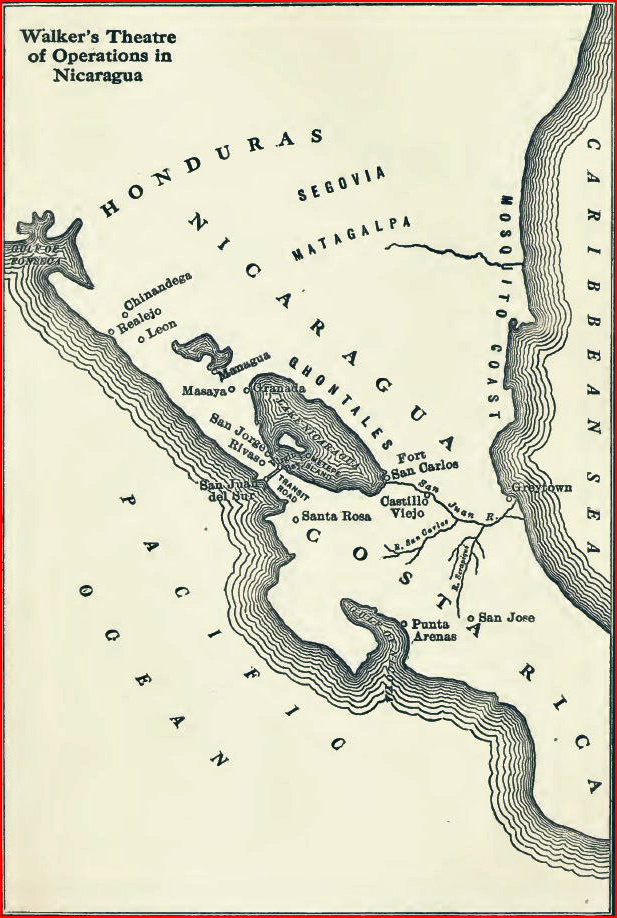

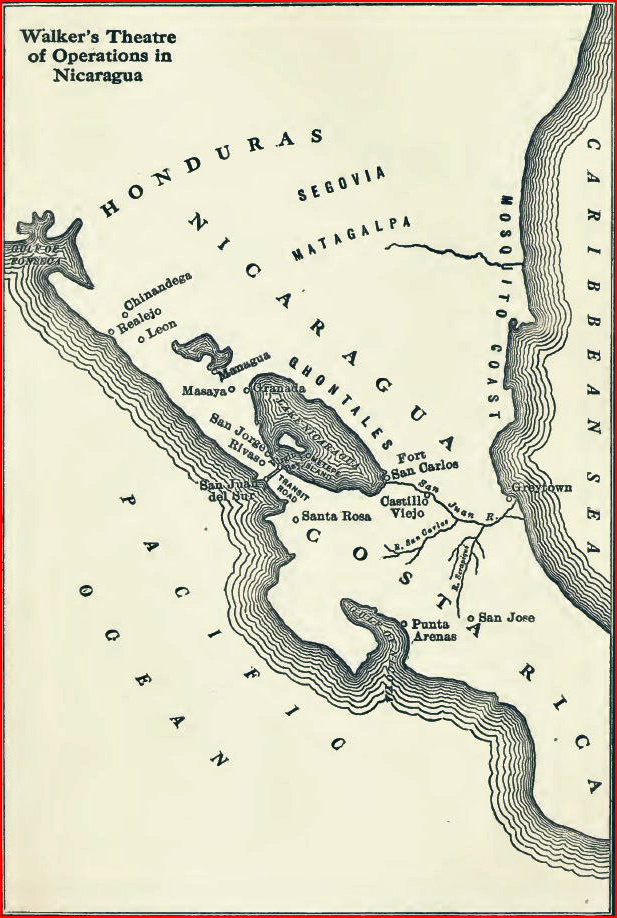

| Invasion of Nicaragua See also: Filibuster War, Nicaragua Canal, and List of participants in the Walker affair  William Walker's Nicaragua map Since there was no inter-oceanic route between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans at the time, and the transcontinental railway did not yet exist, a major trade route between New York City and San Francisco ran through southern Nicaragua. Ships from New York entered the San Juan River from the Atlantic and sailed across Lake Nicaragua. People and goods were then transported by stagecoach across a narrow strip of land near the city of Rivas, before reaching the Pacific and ships to San Francisco. The commercial exploitation of this route had been granted by Nicaragua to the Accessory Transit Company, controlled by shipping magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt.[25] In 1854, a civil war erupted in Nicaragua between the Legitimist Party (also called the Conservative Party), based in the city of Granada, and the Democratic Party (also called the Liberal Party), based in León. The Democratic Party sought military support from Walker who, to circumvent U.S. neutrality laws, obtained a contract from Democratic president Francisco Castellón to bring as many as three hundred "colonists" to Nicaragua. These mercenaries received the right to bear arms in the service of the Democratic government. Walker sailed from San Francisco on May 3, 1855,[26] with approximately sixty men. Upon landing, the force was reinforced by 110 locals.[27][28] With Walker's expeditionary force was the well-known explorer and journalist Charles Wilkins Webber, as well as Belgian-born adventurer Charles Frederick Henningsen, a veteran of the First Carlist War, the Hungarian Revolution, and the war in Circassia.[29] Besides Henningsen, three members of Walker's forces who became Confederate officers were Birkett D. Fry, Robert C. Tyler, and Chatham Roberdeau Wheat. With Castellón's consent, Walker attacked the Legitimists in Rivas, near the trans-isthmian route. He was driven off, but not without inflicting heavy casualties. In this First Battle of Rivas, a schoolteacher called Enmanuel Mongalo y Rubio (1834–1872) burned the Filibuster headquarters. On September 3, during the Battle of La Virgen, Walker defeated the Legitimist army.[27] On October 13, he conquered Granada and took effective control of the country. Initially, as commander of the army, Walker ruled Nicaragua through provisional President Patricio Rivas.[30] U.S. President Franklin Pierce recognized Walker's regime as the legitimate government of Nicaragua on May 20, 1856,[31] and on June 3 the Democratic national convention expressed support of the effort to "regenerate" Nicaragua.[32] However, Walker's first ambassadorial appointment, Colonel Parker H. French, was refused recognition.[33] On September 22, Walker repealed Nicaraguan laws prohibiting slavery, in an attempt to gain support from the Southern states.[32] Walker's actions in the region caused concern in neighboring countries and potential U.S. and European investors who feared he would pursue further military conquests in Central America. C. K. Garrison and Charles Morgan, subordinates of Vanderbilt's Accessory Transit Company, provided financial and logistical support to the Filibusters in exchange for Walker, as ruler of Nicaragua, seizing the company's property (on the pretext of a charter violation) and turning it over to Garrison and Morgan. Outraged, Vanderbilt dispatched two secret agents to the Costa Rican government with plans to fight Walker. They would help regain control of Vanderbilt's steamboats which had become a logistical lifeline for Walker's army.[34] Concerned about Walker's intentions in the region, Costa Rican President Juan Rafael Mora Porras rejected his diplomatic overtures and began preparing the country's military for a potential conflict.[35] Walker organized a battalion of four companies, of which one was composed of Germans, a second of Frenchmen, and the other two of Americans, totaling 240 men placed under the command of Colonel Schlessinger to invade Costa Rica in a preemptive action. This advance force was defeated at the Battle of Santa Rosa on March 20, 1856. The most important strategic defeat of Walker came during the Campaign of 1856–57 when the Costa Rican army, led by Porras, General José Joaquín Mora Porras (the president's brother), and General José María Cañas (1809–1860), defeated the Filibusters in Rivas on April 11, 1856 (the Second Battle of Rivas).[36] It was in this battle that the soldier and drummer Juan Santamaría sacrificed himself by setting the Filibuster stronghold on fire. In parallel with Enmanuel Mongalo y Rubio in Nicaragua, Santamaría would become Costa Rica's national hero. Walker deliberately contaminated the water wells of Rivas with corpses. Later, a cholera epidemic spread to the Costa Rican troops and the civilian population of Rivas. Within a few months nearly 10,000 civilians had died, almost ten percent of the population of Costa Rica.[37]  |

ニカラグア侵攻 関連項目: ニカラグア運河、ウォーカー事件の関係者一覧、ニカラグア侵攻  ウィリアム・ウォーカーのニカラグア地図 当時、大西洋と太平洋の間には大洋間航路が存在せず、また大陸横断鉄道もまだ存在していなかったため、ニューヨーク市とサンフランシスコ間の主要な貿易 ルートはニカラグア南部を通っていた。ニューヨークからの船は大西洋からサンファン川に入り、ニカラグア湖を航行した。人々や商品は、リバス市の近くの狭 い土地を馬車が走り、太平洋とサンフランシスコ行きの船に到着する前に運ばれた。この航路の商業利用は、海運王コーネリアス・ヴァンダービルトが支配する アクセス・トランジット・カンパニーにニカラグアが許可したものである。 1854年、ニカラグアでは、グラナダ市を拠点とする正統党(保守党とも呼ばれる)と、レオン市を拠点とする民主党(自由党とも呼ばれる)との間で内戦が 勃発した。民主党はウォーカーに軍事的支援を求め、ウォーカーは米国の中立法を回避するために、民主党の大統領フランシスコ・カステリョンから、300人 もの「入植者」をニカラグアに連れてくる契約を取り付けた。これらの傭兵は、民主党政府に仕える権利として武器の携帯を許可された。ウォーカーは1855 年5月3日、約60人の男たちとともにサンフランシスコから出航した。上陸後、現地人110人がこの部隊に加わった。[27][28] ウォーカーの遠征部隊には、著名な探検家でありジャーナリストでもあったチャールズ・ウィルキンス・ウェバー、そしてベルギー生まれの冒険家で、第一次カ ルリスタ戦争、ハンガリー革命、そしてチェルケス戦争のベテランであるチャールズ・フレデリック・ヘニングセンがいた。 [29] ヘニングセンの他に、連合国軍の将校となったウォーカー軍の3人のメンバーは、バーケット・D・フライ、ロバート・C・タイラー、チャタム・ロベルドー・ ウィートであった。 カスティーリャの同意を得て、ウォーカーはリバスで正統派を攻撃した。彼は追い払われたが、多大な犠牲を強いることなくというわけにはいかなかった。この リバスでの最初の戦いにおいて、エンマヌエル・モンガロ・イ・ルビオ(1834年-1872年)という名の教師が、盗賊団の本部を焼き払った。9月3日、 ラ・ビルヘンでの戦いにおいて、ウォーカーは正統派軍を打ち破った。[27] 10月13日、彼はグラナダを征服し、事実上、国の支配権を握った。当初、軍司令官として、ウォーカーは臨時大統領パトリシオ・リバスを通じてニカラグア を統治した。[30] 1856年5月20日、アメリカ大統領フランクリン・ピアースはウォーカー政権をニカラグアの合法政府として承認し、[31] 6月3日には民主党全国大会がニカラグアの「再生」に向けた取り組みへの支持を表明した。[32] しかし、ウォーカーが最初に任命した駐在大使、パーカー・H・フレンチ大佐は フランス大佐の任命は拒否された。[33] 9月22日、ウォーカーは南部諸州からの支持を得るために、奴隷制を禁止するニカラグアの法律を廃止した。 ウォーカーのこの地域での行動は、近隣諸国や潜在的な米国および欧州の投資家たちに懸念を抱かせた。彼らはウォーカーがさらに軍事的な征服を中米で進める のではないかと恐れたのだ。C. K. ギャリソンとチャールズ・モーガンは、ヴァンダービルトの従属会社であるアクセスリー・トランジット社の部下であり、ニカラグアの支配者であるウォーカー が同社の財産を(憲章違反を理由に)差し押さえ、ギャリソンとモーガンに引き渡すことを条件に、フィリバスターズに財政的および後方支援を提供した。怒り を露わにしたヴァンダービルトは、ウォーカーと戦う計画を携えて2人の秘密工作員をコスタリカ政府に派遣した。彼らはウォーカーの軍隊にとって物流の生命 線となっていたヴァンダービルトの蒸気船の支配権を取り戻す手助けをする予定であった。 ウォーカーの地域における意図を懸念したコスタリカ大統領フアン・ラファエル・モラ・ポラスは、彼の外交的申し入れを拒絶し、潜在的な紛争に備えて軍の準 備を開始した。[35] ウォーカーは、ドイツ人、フランス人、アメリカ人の各1社で構成される4社からなる大隊を編成し、総勢240人の部隊をシュレシンジャー大佐の指揮下に置 き、先制攻撃としてコスタリカに侵攻させた。この先遣隊は1856年3月20日のサンタ・ローザの戦いで敗北した。 ウォーカーにとって最も重要な戦略的敗北は、1856年から1857年にかけてのキャンペーン中、ポラス将軍、ホセ・ホアキン・モラ・ポラス将軍(大統領 の弟)、ホセ・マリア・カニャス将軍(1809年~1860年)が率いるコスタリカ軍が、1856年4月11日にリバスでフィラデルフィア軍を打ち負かし たとき(第二次リバス会戦)であった。 [36] この戦いで、兵士で太鼓奏者のフアン・サンタマリアが、盗賊の砦に火を放って自らの命を犠牲にした。 ニカラグアのエマニュエル・モンガロ・イ・ルビオと並んで、サンタマリアは、コスタリカの国民的英雄となった。 ウォーカーは意図的にリバス市の井戸に死体を投げ込んで汚染させた。 その後、コレラがコスタリカ軍とリバス市の一般市民の間で流行した。数ヶ月の間に、およそ1万人の民間人が死亡し、これはコスタリカの人口のほぼ10パー セントに相当した。[37]  |

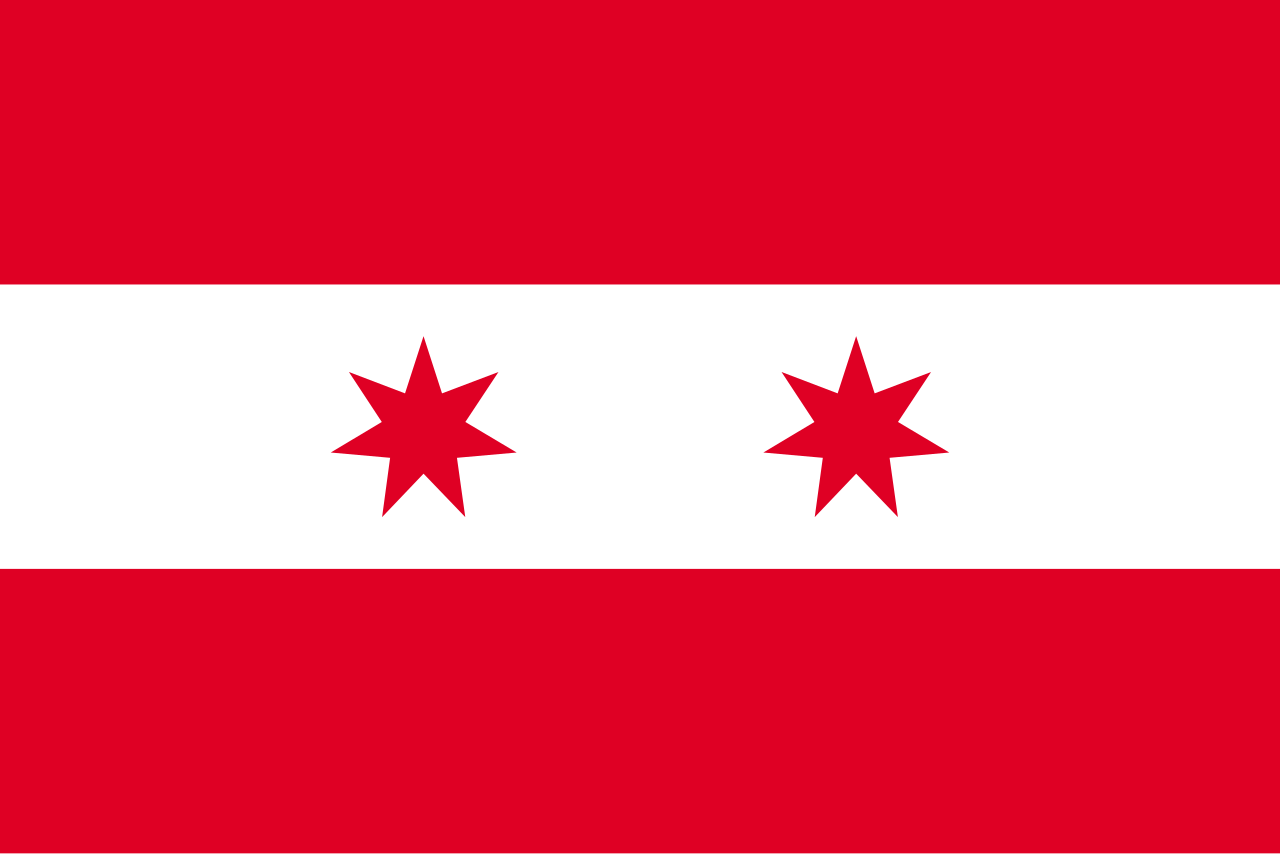

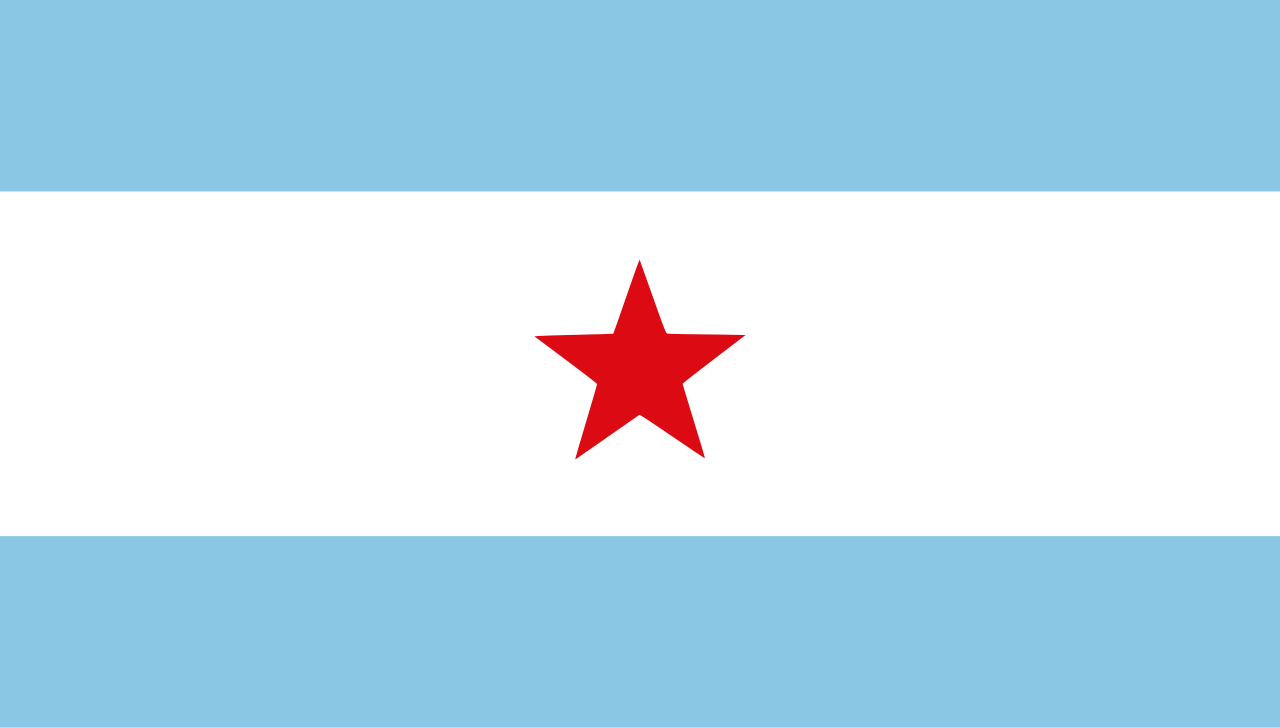

Flag of Nicaragua under Walker From the north, President José Santos Guardiola sent Honduran troops under the leadership of the Xatruch brothers, who joined Salvadoran troops to fight Walker.[citation needed] Florencio Xatruch led his troops against Walker and the filibusters in la Puebla, Rivas. Later, because of the opposition of other Central American armies, José Joaquín Mora Porras was made Commandant General-in-Chief of the Allied Armies of Central America in the Third Battle of Rivas (April 1857).[38] During this civil war, Honduras and El Salvador recognized Xatruch as brigade and division general. On June 12, 1857, after Walker surrendered, Xatruch made a triumphant entrance to Comayagua, which was then the capital of Honduras. Both the nickname by which Hondurans are known today, Catracho, and the more infamous nickname for Salvadorans, "Salvatrucho", are derived from Xatruch's figure and successful campaign as leader of the allied armies of Central America, as the troops of El Salvador and Honduras were national heroes, fighting side by side as Central American brothers against William Walker's troops.[39] As the general and his soldiers returned from battle, some Nicaraguans affectionately yelled out "¡Vienen los xatruches!" ("Here come Xatruch's boys!") However, Nicaraguans had trouble pronouncing the general's Catalan name, so they altered the phrase to "los catruches" and ultimately to "los catrachos".[40] A key role was played by the Costa Rican Army in unifying the other Central American armies to fight against Filibusters. The "Campaign of the Transit" (1857) is the name given by Costa Rican historians to the groups of several battles fought by the Costa Rican Army, supervised by Colonel Salvador Mora, and led by Colonel Blanco and Colonel Salazar at the San Juan River. By establishing control of this bi-national river at its border with Nicaragua, Costa Rica prevented military reinforcements from reaching Walker and his Filibuster troops via the Caribbean Sea. Also, Costa Rican diplomacy neutralized U.S. official support for Walker by taking advantage of the dispute between the magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt and William Walker.[41] |

ウォーカー政権下のニカラグア国旗 北部からは、ホセ・サントス・グアルディオラ大統領が、ハトルク兄弟の指揮下にあるホンジュラス軍を派遣した。この部隊は、ウォーカーと戦うためにエルサ ルバドル軍に加わった。[要出典] フロレンシオ・ハトルクは、プエブラ、リバスでウォーカーとニカラグアの海賊たちに対して軍を率いた。その後、他の中米諸国の軍の反対により、ホセ・ホア キン・モラ・ポラスが1857年4月の第三次リバス戦役で中米連合軍総司令官となった。 この内戦中、ホンジュラスとエルサルバドルは、チャトルクを旅団長および師団長として承認した。1857年6月12日、ウォーカーが降伏した後、チャトル クはホンジュラスの首都であったコマイアガに凱旋した。今日、ホンジュラス人が呼ばれる愛称「カタラチョ」と、エルサルバドル人の悪名高い愛称「サルバト ルチョ」は、いずれも中米連合軍のリーダーとして活躍したサトルッチの姿と成功したキャンペーンに由来する。エルサルバドルとホンジュラスの軍隊は、ウィ リアム・ウォーカーの軍隊と戦う中米の兄弟として肩を並べて戦った国民的英雄であった。 将軍と兵士たちが戦場から戻ってくると、一部のニカラグア人は「チャトルの男たちがやってきた!」と愛情を込めて叫んだ。しかし、ニカラグア人は将軍のカ タロニア語名を発音するのが難しかったため、「チャトル」を「ロス・カトルチェス(los catruches)」、最終的には「ロス・カトラチョス(los catrachos)」と発音するようになった。 コスタリカ軍は、他の中米諸国の軍隊を統合して、フィリスブスターと戦う上で重要な役割を果たした。「通過作戦」(1857年)とは、コスタリカの歴史家 が、サルバドール・モーラ大佐の指揮下、ブランコ大佐とサラサール大佐が率いたコスタリカ軍がサンファン川で戦った一連の戦いを指す名称である。このニカ ラグアとの国境にある二国間の川を制圧することで、コスタリカは、ウォーカーと彼のフィリバスター軍にカリブ海経由で軍事増援が届くのを阻止した。また、 コスタリカの外交は、大富豪コーネリアス・ヴァンダービルトとウィリアム・ウォーカーの間の紛争を利用することで、ウォーカーに対する米国政府の公式支援 を無効化した。[41] |

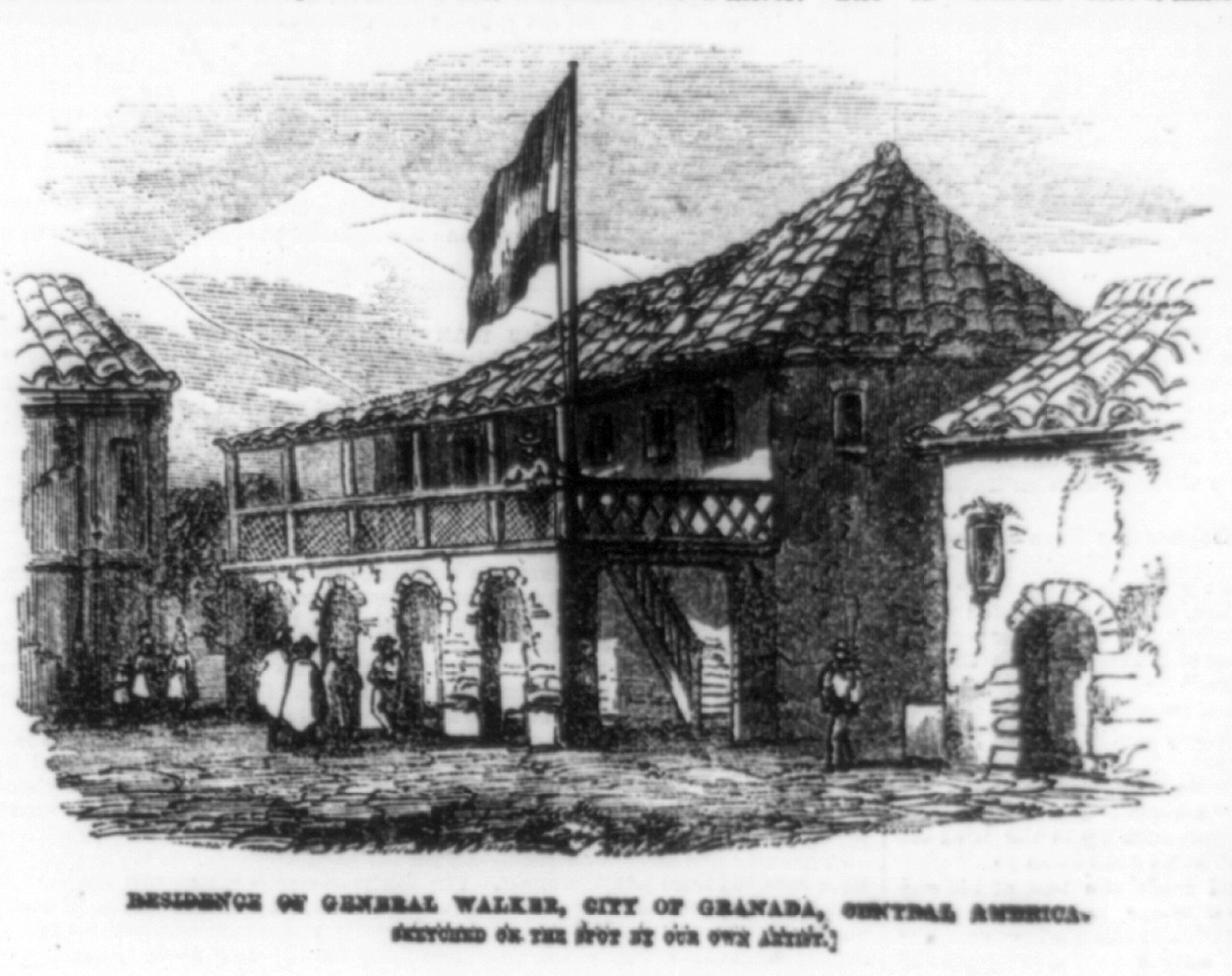

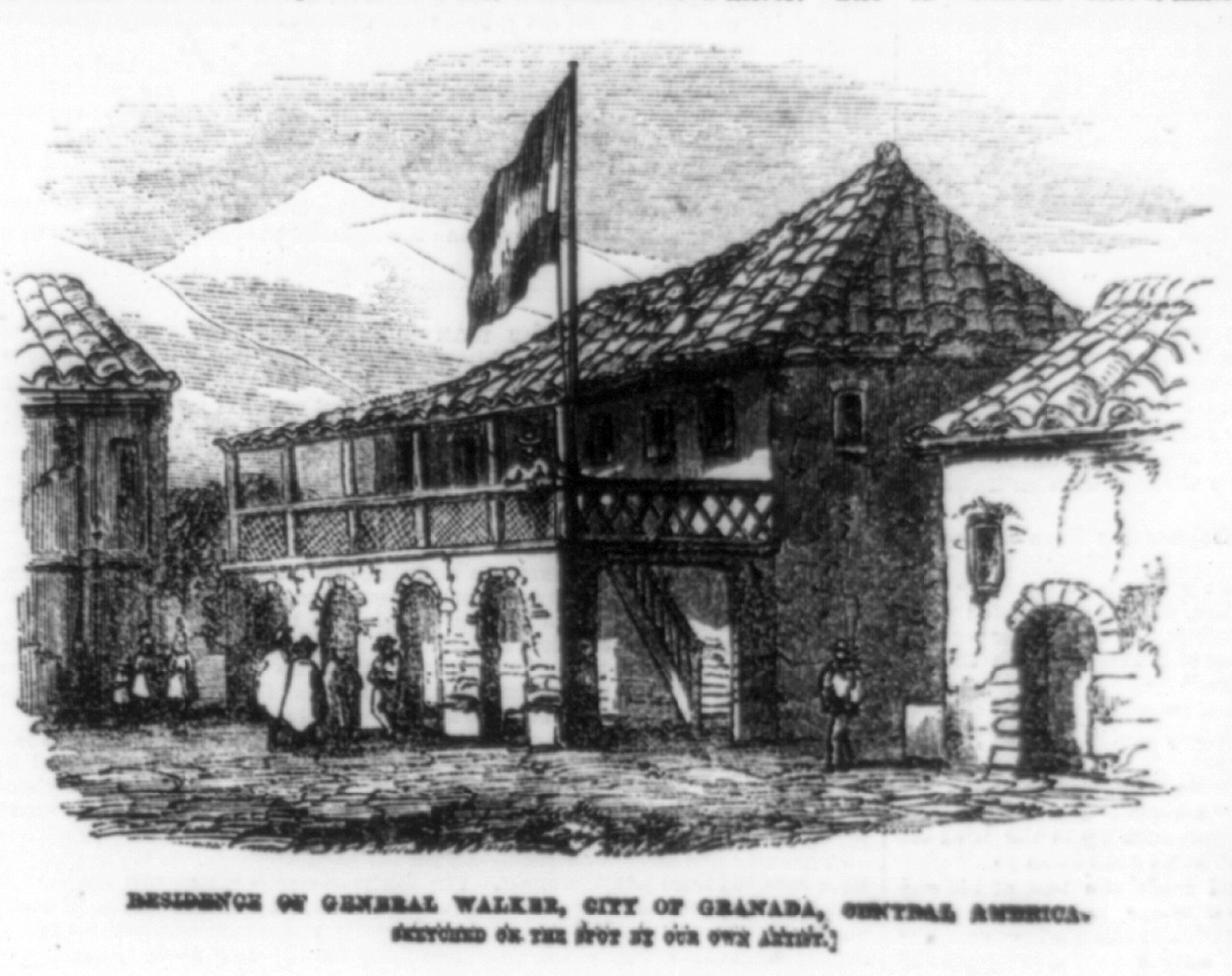

President Walker's house in Granada, Nicaragua. On October 12, 1856, during the siege of Granada, Guatemalan officer José Víctor Zavala ran under heavy fire to capture Walker's flag and bring it back to the Central American coalition army trenches shouting "Filibuster bullets don't kill!". Zavala survived this adventure unscathed.[42] Walker took up residence in Granada and set himself up as President of Nicaragua, after conducting a fraudulent election. He was inaugurated on July 12, 1856, and soon launched an Americanization program, reinstating slavery, declaring English an official language, and reorganizing currency and fiscal policy to encourage emigration from the United States.[43] Realizing that his position was becoming precarious, he sought support from the Southerners in the U.S. by recasting his campaign as a fight to spread the institution of black slavery, which was the basis of the Southern agrarian economy. With this in mind, Walker revoked Nicaragua's emancipation edict of 1821.[44] This move increased Walker's popularity among Southern whites and attracted the attention of Pierre Soulé, an influential New Orleans politician, who campaigned to raise support for Walker's war. Nevertheless, Walker's army was weakened by massive defections and an epidemic of cholera and was finally defeated by the Central American coalition led by Costa Rican President Juan Rafael Mora Porras (1814–1860). On October 12, 1856, Guatemalan Colonel José Víctor Zavala crossed the square of the city to the house where Walker's soldiers took shelter. Under heavy fire, he reached the enemy's flag and carried it back with him, shouting to his men that the Filibuster bullets did not kill.[42] On December 14, 1856, as Granada was surrounded by 4,000 troops from Costa Rica, Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala, along with independent Nicaraguan allies, Charles Frederick Henningsen, one of Walker's generals, ordered his men to set the city ablaze before escaping and fighting their way to Lake Nicaragua. When retreating from Granada, the oldest Spanish colonial city in Nicaragua, he left a detachment with orders to level it in order to instill, as he put it, "a salutary dread of American justice". It took them over two weeks to smash, burn and flatten the city; all that remained were inscriptions on the ruins that read "Aqui Fue Granada" ("Here was Granada").[45] On May 1, 1857, Walker surrendered to Commander Charles Henry Davis of the United States Navy under the pressure of Costa Rica and the Central American armies and was repatriated. Upon disembarking in New York City, he was greeted as a hero, but he alienated public opinion when he blamed his defeat on the U.S. Navy. Within six months, he set off on another expedition, but he was arrested by the U.S. Navy Home Squadron under the command of Commodore Hiram Paulding and once again returned to the U.S. amid considerable public controversy over the legality of the navy's actions.[46] |

ニカラグアのグラナダにあるウォーカー大統領の邸宅。1856年10月12日、グラナダ包囲戦のさなか、グアテマラ軍のホセ・ビクトル・サバラ大佐は、激 しい銃撃の中を走り抜け、ウォーカーの国旗を奪取して中米連合軍の塹壕まで持ち帰り、「盗賊の銃弾は殺さない!」と叫んだ。サバラは無傷でこの冒険を生き 延びた。 ウォーカーはグラナダに居を構え、不正選挙を行った後、ニカラグアの大統領に就任した。1856年7月12日に就任し、すぐにアメリカ化政策を開始し、奴 隷制を復活させ、英語を公用語とし、米国からの移民を奨励するために通貨と財政政策を再編した。 [43] 自身の立場が不安定になりつつあることを悟った彼は、南部の農耕経済の基盤である黒人奴隷制度の普及を掲げることで、米国南部からの支持を求めようとし た。この考えに基づき、ウォーカーは1821年のニカラグアの解放令を破棄した。[44] この動きにより、南部の白人層の間でウォーカーの人気が高まり、ニューオーリンズの有力政治家ピエール・スーレの注目を集めた。スーレはウォーカーの戦争 への支持を高めるためのキャンペーンを行った。しかし、大規模な離反とコレラの流行により、ウォーカーの軍隊は弱体化し、最終的には、コスタリカ大統領フ アン・ラファエル・モラ・ポラス(1814年~1860年)が率いる中米連合軍によって敗北した。 1856年10月12日、グアテマラの大佐ホセ・ビクトル・サバラは、市内の広場からウォーカーの兵士たちが避難している家屋まで進軍した。激しい銃撃を受けながらも敵の旗に到達し、部下たちに「盗賊の弾丸は殺さない」と叫びながら旗を奪い返した。 1856年12月14日、コスタリカ、ホンジュラス、エルサルバドル、グアテマラの4,000人の軍勢とニカラグアの独立同盟軍に包囲されたグラナダで、 ウォーカーの将軍の一人であるチャールズ・フレデリック・ヘニングセンは、部下たちにグラナダを放火してからニカラグア湖まで撤退し戦うよう命じた。ニカ ラグアで最も古いスペイン植民都市であるグラナダから撤退する際、彼は「アメリカ正義の恐ろしいまでの威圧感」を植え付けるために、都市を破壊するよう命 令を下した部隊を残した。都市を破壊し、焼き払い、更地にするのに2週間以上を要した。残ったのは「Aqui Fue Granada」(「ここにグラナダがあった」)と書かれた廃墟だけだった。 1857年5月1日、ウォーカーは、コスタリカと中米諸国の軍隊の圧力により、アメリカ海軍のチャールズ・ヘンリー・デイヴィス司令官に降伏し、本国送還 された。ニューヨークに上陸したウォーカーは英雄として迎えられたが、敗因をアメリカ海軍のせいだと非難したことで世論の反感を買った。それから6か月も 経たないうちに、ウォーカーは再び遠征に出発したが、ヒラム・パウリング提督指揮下のアメリカ海軍ホーム艦隊に逮捕され、海軍の行動の合法性をめぐって世 論が大きく揺れる中、再びアメリカに送還された。[46] |

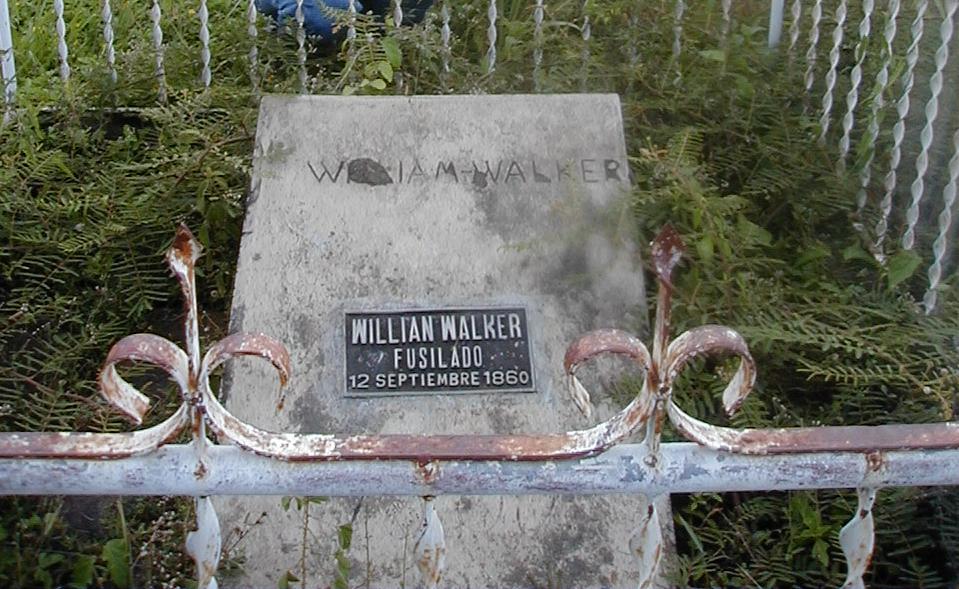

Conviction and execution William Walker's grave in the Old Trujillo Cemetery, Trujillo, Colón, Honduras After writing an account of his Central American campaign (published in 1860 as War in Nicaragua), Walker once again returned to the region. British colonists in Roatán, Bay Islands, fearing that the Honduran government would move to assert its control over them, approached Walker with an offer to help him in establishing an independent, English-speaking administration over the islands. Walker disembarked in the port city of Trujillo but was arrested by Royal Navy officer Nowell Salmon. The British controlled the neighboring regions of Honduras and the Mosquito Coast and had considerable strategic and economic interest in the construction of an inter-oceanic canal through Central America; Britain therefore regarded Walker as a menace to its own affairs in the region.[47] Rather than return him to the U.S., for reasons that remain unclear, Salmon sailed to Trujillo and handed Walker over to the Honduran government along with his chief of staff, Colonel A. F. Rudler. Both men were tried by a military court on charges of piracy and "filibusterism". In his defense, Walker argued that piracy could not be committed on land and "filibusterism" wasn't a word.[48] Rudler was sentenced to four years of hard labor in Honduran mines, but Walker was sentenced to death, and executed by firing squad, near the site of the present-day hospital, on September 12, 1860.[49] William Walker was 36 years old. He is buried in the "Old Cemetery", Trujillo, Colón, Honduras. |

信念と実行 ホンジュラス、コロン県トルヒーヨ、トルヒーヨ旧墓地にあるウィリアム・ウォーカーの墓 中米遠征の記録を著した後(1860年に『ニカラグア戦争』として出版)、ウォーカーは再びこの地域に戻ってきた。 ベイ諸島のロアタン島にいた英国人入植者たちは、ホンジュラス政府が自分たちに対して支配権を主張してくるのではないかと恐れ、ウォーカーに、島々を独立 した英語圏の行政区域として確立するのを支援するよう持ちかけた。ウォーカーはトリニダードの港町に上陸したが、英国海軍士官のノウェル・サーモンに逮捕 された。英国はホンジュラスとモスキート海岸の近隣地域を支配しており、中央アメリカを通る太平洋と大西洋を結ぶ運河の建設には、戦略的にも経済的にも大 きな関心を持っていた。そのため、英国はウォーカーをこの地域の自国の問題にとっての脅威とみなした。 ウォーカーを米国に引き渡さなかった理由については不明であるが、サーモンはトリニダードに向かい、ウォーカーと参謀長のアレクサンダー・フレデリック・ ラドラー大佐をホンジュラス政府に引き渡した。両名は海賊行為と「フィリスベリザム(議事妨害)」の容疑で軍事法廷にかけられた。ウォーカーは、海賊行為 は陸上では成立しないと主張し、「フィリバスター」という言葉は存在しないと弁明した。[48] ラドラーは4年の重労働を命じられ、ホンジュラスの鉱山で服役したが、ウォーカーには死刑が宣告され、1860年9月12日に現在の病院の近くで銃殺刑に 処された。[49] ウィリアム・ウォーカーは36歳だった。彼はホンジュラス、コロン州トルヒーヨの「オールド・セメタリー」に埋葬されている。 |

| Influence and reputation William Walker convinced many Southerners of the desirability of creating a slave-holding empire in tropical Latin America. In 1861, when U.S. Senator John J. Crittenden proposed that the 36°30' parallel north be declared as a line of demarcation between free and slave territories, some Republicans denounced such an arrangement, with New York congressman Roscoe Conkling saying that it "would amount to a perpetual covenant of war against every people, tribe, and State owning a foot of land between here and Tierra del Fuego".[50][51]  The Costa Rica National Monument represents the five united Central American nations carrying weapons and William Walker fleeing. Before the end of the American Civil War, Walker's memory enjoyed great popularity in the southern and western United States, where he was known as "General Walker"[52] and as the "gray-eyed man of destiny".[8] Northerners, on the other hand, generally regarded him as a pirate. Despite his intelligence and personal charm, Walker consistently proved to be a limited military and political leader. Unlike men of similar ambition, such as Cecil Rhodes, Walker's grandiose scheming ultimately failed. In Central American countries, the successful military campaign of 1856–1857 against William Walker became a source of national pride and identity,[53] and it was later promoted by local historians and politicians as substitute for the war of independence that Central America had not experienced. April 11 is a Costa Rican national holiday in memory of Walker's defeat at Rivas. Juan Santamaría, who played a key role in that battle, is honored as one of two Costa Rican national heroes, the other one being Juan Rafael Mora himself. The main airport serving San José (in Alajuela) is named in Santamaría's honor. To this day, a sense of Central American "coalition" among the nations of Costa Rica, Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala, along with independent Nicaraguan allies, is remembered and celebrated as a unifying shared history. |

影響力と評判 ウィリアム・ウォーカーは、熱帯のラテンアメリカに奴隷制帝国を築くことの望ましい点を多くの南部人に納得させた。1861年、 ジョン・J・クリッテンデン上院議員が北緯36度30分線を自由州と奴隷州の境界線とすることを提案した際には、共和党員の中にはそのような取り決めを非 難する者もおり、ニューヨーク選出の下院議員ロスコー・コンクリングは「ここからティエラ・デル・フエゴまでの土地を所有するあらゆる民族、部族、国家に 対して永遠に戦争を続けることを誓うに等しい」と述べた。[50][51]  コスタリカの国立記念碑は、武器を手にした5つの中央アメリカ諸国民と、逃亡するウィリアム・ウォーカーを表している。 南北戦争が終結する前、ウォーカーの記憶はアメリカ合衆国南部と西部で人気を博し、彼は「ウォーカー将軍」[52]、「運命の灰色の目の男」[8]として 知られていた。一方、北部の人々は、彼を海賊とみなしていた。ウォーカーは、知性と人格的魅力を備えていたにもかかわらず、一貫して限られた軍事的・政治 的指導者であることが証明された。セシル・ローズのような同様の野望を持つ人物とは異なり、ウォーカーの壮大な計画は最終的に失敗した。 中米諸国では、1856年から1857年にかけてのウィリアム・ウォーカーに対する軍事作戦の成功は、国民の誇りとアイデンティティの源となった [53]。また、それは後に、中米が経験したことのない独立戦争の代替物として、地元の歴史家や政治家によって宣伝された。4月11日は、リバスでの ウォーカーの敗北を記念するコスタリカの祝日である。この戦いで重要な役割を果たしたフアン・サンタマリアは、コスタリカの国民的英雄の2人のうちの1人 として称えられている。もう1人はフアン・ラファエル・モラである。サンホセ(アラフエラ)の主要空港は、サンタマリアの名誉を称えて名づけられた。 今日に至るまで、コスタリカ、ホンジュラス、エルサルバドル、グアテマラの国民の間には、中米における「連合」という意識が根強くあり、独立したニカラグアの同盟国とともに、統一された共有の歴史として記憶され、祝われている。 |

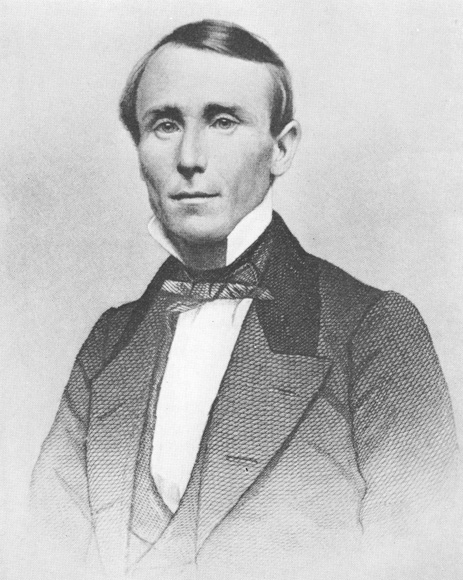

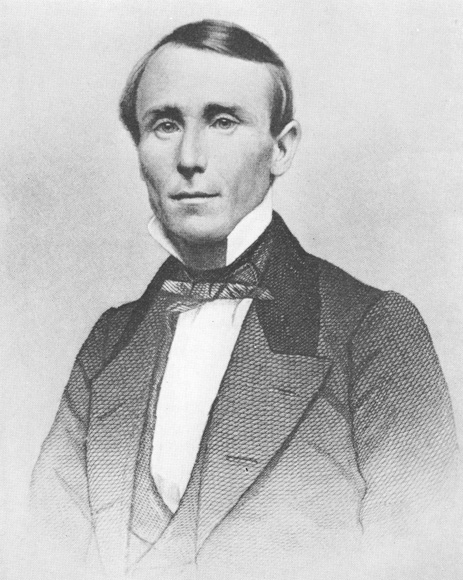

Cultural legacy Portrait by George Dury Walker's campaigns in Lower California and Nicaragua are the subject of a historical novel by Alfred Neumann, published in German as Der Pakt (1949), and translated in English as Strange Conquest (a previous UK edition was published as Look Upon This Man).[54] Walker's campaign in Nicaragua has inspired two films, both of which take considerable liberties with his story: Burn! (1969) directed by Gillo Pontecorvo, starring Marlon Brando, and Walker (1987) directed by Alex Cox, starring Ed Harris. Walker's name is used for the main character in Burn!, though the character is not meant to represent the historical William Walker and is portrayed as British.[55] On the other hand, Alex Cox's Walker incorporates into its surrealist narrative many of the signposts of William Walker's life and exploits, including his original excursions into northern Mexico to his trial and acquittal on breaking the neutrality act to the triumph of his assault on Nicaragua and his execution.[56] In Part Five, Chapter 48, of Gone with the Wind, Margaret Mitchell cites William Walker, "and how he died against a wall in Truxillo", as a topic of conversation between Rhett Butler and his filibustering acquaintances, while Rhett and Scarlett O'Hara are on honeymoon in New Orleans.[57] A poem written by Nicaraguan Catholic priest and minister of culture from 1979 to 1987 during the Sandinista period Ernesto Cardenal, Con Walker En Nicaragua, translated as With Walker in Nicaragua,[58] gives a historical treatment of the affair from the Nicaraguan perspective. The villain of the Nantucket series, by science fiction writer S. M. Stirling, is a 20th-century American mercenary named William Walker, who is time-displaced from 1998 CE to 1250 BCE. Walker demonstrates a similar personality to his historical namesake, leading a filibuster force to Mycenaean Greece and initiating a version of the Trojan War with firearms. John Neal's 1859 novel True Womanhood includes a character who travels from the US to Nicaragua. When he returns, it turns out he has been involved in Walker's campaign there.[59] This may be based on his son James or his friend's son, Appleton Oaksmith, both of whom made the trip and were involved with Walker in that country.[60] |

文化遺産 ジョージ・デュリーによる肖像画 アルフレッド・ノイマンによる歴史小説『Der Pakt』(1949年、ドイツ語)の主題となっている。英語版は『Strange Conquest』(以前の英国版は『Look Upon This Man』として出版)である。[54] ウォーカーのニカラグアでのキャンペーンは、2本の映画のインスピレーションとなった。どちらの映画もウォーカーのストーリーをかなり脚色している。 (1969年)は、監督がジッロ・ポンテコーヴァ、主演がマーロン・ブランド、ウォーカー(1987年)は、監督がアレックス・コックス、主演がエド・ハ リスである。ウォーカーの名前は『バーン!』の主人公の名前として使われているが、この人物は史実のウィリアム・ウォーカーを象徴するものではなく、英国 人として描かれている。[55] 一方、アレックス・コックス監督の『ウォーカー』では、ウィリアム・ウォーカーの人生と功績の指標となる多くの出来事が、シュールレアリスム的な物語の中 に組み込まれている。これには、メキシコ北部への最初の遠征、中立法違反の裁判と無罪判決、ニカラグア侵攻の勝利と処刑などが含まれる。 [56] 『風と共に去りぬ』の第5部第48章で、マーガレット・ミッチェルは、ウィリアム・ウォーカーについて、「そして、彼がトルヒージョの壁でどのように死ん だか」を、レット・バトラーと彼の盗賊仲間との会話の話題として挙げている。レットとスカーレット・オハラがニューオーリンズで新婚旅行中である。 [57] ニカラグアのカトリック司祭であり、1979年から1987年のサンディニスタ時代に文化大臣を務めたエルネスト・カルデナルが書いた詩『ニカラグアでのウォーカーとの日々』は、ニカラグアの視点からこの情事を歴史的に扱っている。 SF作家S・M・スターリングの小説『ナンタケット・シリーズ』の悪役は、20世紀のアメリカ人傭兵ウィリアム・ウォーカーであり、西暦1998年から紀 元前1250年にタイムスリップする。ウォーカーは歴史上の同名人物と類似した人格を示し、ミケーネ時代のギリシャに盗賊軍を率いて侵入し、銃器を用いた トロイ戦争の一幕を始める。 ジョン・ニールの1859年の小説『真の女らしさ』には、米国からニカラグアに渡った人物が登場する。彼が帰国すると、ウォーカーのニカラグアでのキャン ペーンに関与していたことが判明する。[59] これは、ウォーカーの息子のジェームズか、友人の息子のアップルトン・オークスミスがモデルである可能性がある。この2人はその国を訪れ、ウォーカーと関 わっていた。[60] |

| Walker, William. The War in Nicaragua. New York (NY): S.H. Goetzel, 1860.[61] |

|

| Gaston de Raousset-Boulbon Knights of the Golden Circle, a secret society interested in annexing territories in Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean to be added to the United States as slave states Nicaragua Canal Panama Canal Florencio Xatruch Granada, Nicaragua, the colonial city that William Walker destroyed |

ガストン・ド・ラウゼット=ブールボン ゴールデン・サークル騎士団、メキシコ、中米、カリブ海地域を併合して奴隷州としてアメリカ合衆国に加えようとした秘密結社 ニカラグア運河 パナマ運河 フロレンシオ・シャトルチ ニカラグアのグラナダ、ウィリアム・ウォーカーが破壊した植民都市 |

| References Secondary sources Carr, Albert Z. The World and William Walker, 1963. Dando-Collins, Stephen. Tycoon's War: How Cornelius Vanderbilt Invaded a Country to Overthrow America's Most Famous Military Adventurer (2008) excerpt and text search Richard Harding Davis (1906), Real Soldiers of Fortune, "General William Walker, the King of the Filibusters" (Chapter 5). Dueñas Van Severen, J. Ricardo (2006). La invasión filibustera de Nicaragua y la Guerra Nacional (PDF) (in Spanish). Secretaría General del Sistema de la Integración Centroamericana SG-SICA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 October 2009. Gobat, Michel. Empire by Invitation: William Walker and Manifest Destiny in Central America (Harvard UP, 2018) roundtable evaluation by scholars at H-Diplo Juda, Fanny. California Filibusters: A History of their Expeditions into Hispanic America McPherson, James M. (1988). Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 909. ISBN 0195038630. May, Robert E. (2002). Manifest Destiny's Underworld: Filibustering in Antebellum America. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0807855812. May, Robert E. (2002). The Southern Dream of a Caribbean Empire. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0813025124. Martelle, Scott (2018). William Walker's Wars. Chicago: Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1613737293. Moore, J. Preston. "Pierre Soule: Southern Expansionist and Promoter," Journal of Southern History 21:2 (May, 1955), 208 & 214. Norvell, John Edward, "How Tennessee Adventurer William Walker became Dictator of Nicaragua in 1857: The Norvell Family origins of the Grey Eyed Man of Destiny," The Middle Tennessee Journal of Genealogy and History, Vol XXV, No. 4, Spring 2012 "1855: American Conquistador," American Heritage, October 2005. Recko, Corey. "Murder on the White Sands." University of North Texas Press. 2007 Scroggs, William O. (1916). Filibusters and Financiers; the story of William Walker and his associates. New York: The Macmillan Company. "William Walker" Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 28 Oct. 2008. Primary sources Doubleday, C.W. Reminiscences of the Filibuster War in Nicaragua. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1886. Jamison, James Carson. With Walker in Nicaragua: Reminiscences of an Officer of the American Phalanx. Columbia, MO: E.W. Stephens, 1909. Wight, Samuel F. Adventures in California and Nicaragua: a Truthful Epic. Boston: Alfred Mudge & Son, 1860. Fayssoux Collection. Tulane University. Latin American Library. United States Magazine. Sept., 1856. Vol III No. 3. pp. 266–72 "Filibustering", Putnam's Monthly Magazine (New York), April 1857, 425–35. "Walker's Reverses in Nicaragua," Anti-Slavery Bugle, November 17, 1856. "The Lesson" National Era, June 4, 1857, 90. "The Administration and Commodore Paulding," National Era, January 7, 1858. "Wanted – A Few Filibusters," Harper's Weekly, January 10, 1857. "Reception of Gen. Walker," New Orleans Picayune, May 28, 1857. "Arrival of Walker," New Orleans Picayune, May 28, 1857. "Our Influence in the Isthmus," New Orleans Picayune, February 17, 1856. New Orleans Sunday Delta, June 27, 1856. "Nicaragua and President Walker," Louisville Times, December 13, 1856. "Le Nicaragua et les Filibustiers," Opelousas Courier, May 10, 1856. "What is to Become of Nicaragua?," Harper's Weekly, June 6, 1857. "The Late General Walker," Harper's Weekly, October 13, 1860. "What General Walker is Like," Harper's Weekly, September, 1856. "Message of the President to the Senate in Reference to the Late Arrest of Gen. Walker," Louisville Courier, January 12, 1858. "The Central American Question – What Walker May Do," New York Times, January 1, 1856. "A Serious Farce," New York Times, December 14, 1853. 1856–57 New York Herald Horace Greeley editorials. Further reading Harrison, Brady. William Walker and the Imperial Self in American Literature. Athens, Ga.: University of Georgia Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0820325446. Cabrera Geserick, Marco. "The Legacy of the Filibuster War: National Identity and Collective Memory in Central America." Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books, 2019. ISBN 978-1-498559812. Deville, Patrick, Pura Vida: Vie et mort de William Walker, Seuil, Paris, 2004 [ISBN missing] Scroggs, William O., Ph.D., Professor of Economics and Sociology in Louisiana State University. Filibusters and Financiers: the Story of William Walker and his Associates. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1916. |

参考文献 二次資料 Carr, Albert Z. 『世界とウィリアム・ウォーカー』、1963年。 Dando-Collins, Stephen. 『タイクーンの戦争:コーネリアス・ヴァンダービルトがアメリカを転覆させるために国を侵略した方法』(2008年)抜粋とテキスト検索 リチャード・ハーディング・デイヴィス著『実在の幸運の兵士たち』(1906年)第5章「フィリスターの王、ウィリアム・ウォーカー将軍」 ドゥエニャス・ヴァン・セヴェレン著『ニカラグアへのフィリスターの侵略と国家戦争』(PDF) (スペイン語) 中央アメリカ統合機構事務局(SG-SICA) オリジナル(PDF)のアーカイブ 2009年10月7日 ゴバット、ミシェル著。『帝国の招待状:ウィリアム・ウォーカーと中央アメリカにおける明白な運命』(ハーバード大学出版、2018年)H-Diploの学者による円卓会議評価 ジュダ、ファニー著。『カリフォルニアの盗賊:ヒスパニック系アメリカへの遠征の歴史 マクファーソン、ジェームズ・M. (1988年). 『自由の叫び: 南北戦争時代』. ニューヨーク: オックスフォード大学出版. p. 909. ISBN 0195038630. メイ、ロバート・E. (2002年). 『マニフェスト・デスティニーの地下世界:南北戦争前のアメリカにおける盗賊行為』. ノースカロライナ大学出版. ISBN 978-0807855812. メイ、ロバート・E. (2002年). 『カリブ帝国という南部の夢』. ゲインズビル: フロリダ大学出版. ISBN 978-0813025124. Martelle, Scott (2018). William Walker's Wars. Chicago: Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1613737293. Moore, J. Preston. 「Pierre Soule: Southern Expansionist and Promoter,」 Journal of Southern History 21:2 (May, 1955), 208 & 214. ノベル、ジョン・エドワード著「1857年、テネシーの冒険家ウィリアム・ウォーカーがニカラグアの独裁者となった経緯:運命の灰色の目の男のノベル家系」『ミドルテネシー系図・歴史ジャーナル』第25巻第4号、2012年春号 「1855年:アメリカのコンキスタドール」『アメリカン・ヘリテージ』2005年10月号 レコ、コリー著「ホワイトサンズでの殺人事件」 ノーステキサス大学出版 2007年 スクロッグス、ウィリアム・O著(1916年)『フィリスブスターとフィナンシェ:ウィリアム・ウォーカーと仲間たちの物語』ニューヨーク:マクミラン社 「ウィリアム・ウォーカー」『ブリタニカ百科事典』2008年。ブリタニカ百科事典オンライン。2008年10月28日。 一次資料 Doubleday, C.W. 『ニカラグアの盗賊戦争の回想録』。ニューヨーク:G.P. Putnam's Sons、1886年。 Jamison, James Carson. 『ニカラグアにおけるウォーカー:アメリカン・ファランクスの将校の回想録』。コロンビア、ミズーリ州:E.W. Stephens、1909年。 ライト、サミュエル・F. 『カリフォルニアとニカラグアでの冒険:真実の叙事詩』ボストン:アルフレッド・マッジ&サン、1860年。 フェソス・コレクション。 チューレン大学。 ラテンアメリカ図書館。 米国マガジン。 1856年9月。 第3巻第3号。 266-72ページ 「フィリバスター(議事妨害)」、『パトナム・マンスリー・マガジン』(ニューヨーク)、1857年4月、425-35ページ。 「ニカラグアにおけるウォーカーの敗北」、『反奴隷制のラッパ』、1856年11月17日。 「教訓」、『ナショナル・エラ』、1857年6月4日、90ページ。 「行政とポールディング提督」『ナショナル・エラ』1858年1月7日。 「求む、少数のフィリバスター」『ハーパーズ・ウィークリー』1857年1月10日。 「ウォーカー将軍の歓迎」『ニューオーリンズ・ピカユーン』1857年5月28日。 「ウォーカーの到着」、ニューオーリンズ・ピカユーン、1857年5月28日。 「地峡における我々の影響力」、ニューオーリンズ・ピカユーン、1856年2月17日。 ニューオーリンズ・サンデー・デルタ、1856年6月27日。 「ニカラグアとウォーカー大統領」、ルイビル・タイムズ、1856年12月13日。 「ニカラグアとフィリバスティアーズ」『オペルーサ・クーリエ』、1856年5月10日。 「ニカラグアはどうなるのか?」『ハーパーズ・ウィークリー』、1857年6月6日。 「故ウォーカー将軍」『ハーパーズ・ウィークリー』、1860年10月13日。 「ウォーカー将軍とはどんな人物か」『ハーパーズ・ウィークリー』、1856年9月。 「ウォーカー将軍の逮捕に関する大統領の声明」、ルイビル・クーリエ、1858年1月12日。 「中米問題 - ウォーカーが何をし得るか」、ニューヨーク・タイムズ、1856年1月1日。 「深刻な茶番劇」、ニューヨーク・タイムズ、1853年12月14日。 1856年~1857年 『ニューヨーク・ヘラルド』のホレス・グリーリーによる社説。 参考文献 Harrison, Brady. William Walker and the Imperial Self in American Literature. Athens, Ga.: University of Georgia Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0820325446. Cabrera Geserick, Marco. 「フィリスター戦争の遺産:中米における国民のアイデンティティと集合的記憶」ランハム、メリーランド州:レキシントンブックス、2019年。ISBN 978-1-498559812。 Deville, Patrick, Pura Vida: Vie et mort de William Walker, Seuil, Paris, 2004 [ISBN 欠落] スロッグス、ウィリアム・O・博士、ルイジアナ州立大学経済学・社会学教授。『フィリバスターズ・アンド・フィナンシャーズ:ウィリアム・ウォーカーと仲間たちの物語』ニューヨーク:マクミラン社、1916年。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Walker_(filibuster) |

**

| UN DÍA COMO HOY: LOS

INDÍGENAS FUERON A LA GUERRA DE 1856 Recordemos que el 20 de marzo de 1856, en la Hacienda Santa Rosa, el ejército costarricense libró su primera batalla contra los filibusteros. Posteriormente se dio la batalla de Rivas y la rendición de William Walker el 1 de mayo de 1857. Según Ibarra (1992), en noviembre de 1856, indígenas huetares de Pacaca (hoy Ciudad Colón), envían una carta al presidente Juan Mora Porras, donde indican que: “cooperamos con nuestra pequeñez a la grande obra de nuestra independencia con las cantidades siguientes…”, seguido de una lista de bienes entre las que hay reses gordas o algunos pesos. La misma fuente menciona que 50 indígenas de Tucurrique y Orosi se enlistaron como cargueros. En una lista de soldados indígenas muertos y heridos, realizados por Hoffman y Calvo, aparecen como provenientes de Aserrí, Cot, Barva, Curridabat, Pacaca, Orosi y Tucurrique. Don Manuel de Jesús Jiménez, en Noticias de Antaño, describe que “al final de la guerra se hizo un gran Baile de Palacio el 24 de mayo de 1857, al que los indios y otros soldados no fueron invitados”. Fotomontaje de ex combatientes frente a la Casona de Santa Rosa. |

今日のような日:1856年、先住民は戦争

を始めた 1856年3月20日、アシエンダ・サンタ・ロサで、コスタリカ軍はフィリバスターと最初の戦闘を行った。その後、リバスの戦いが続き、1857年5月1 日にウィリアム・ウォーカーが降伏した。 Ibarra(1992)によると、1856年11月、パカカ(現在のシウダー・コロン)のフエタル・インディアンは、フアン・モラ・ポラス大統領に書簡 を送り、「われわれは独立という偉大な仕事に以下の金額でささやかながら協力する」と述べ、太った牛と数ペソを含む物資のリストを添えた。 同じ資料には、トゥクリケとオロシのインディオ50人がカルゲーロとして入隊したことが記されている。ホフマンとカルボが作成した先住民兵士の死傷者リス トには、アセリ、コット、バルバ、クリダバット、パカカ、オロシ、トゥクリケの出身と記されている。 ドン・マヌエル・デ・ヘスス・ヒメネス(Don Manuel de Jesús Jiménez)は、『Noticias de Antaño』の中で、「戦争末期の1857年5月24日、インディアスや他の兵士は招待されなかったが、盛大な宮廷舞踏会が開かれた」と記述している。 カソナ・デ・サンタ・ロサ前の元戦闘員のフォトモンタージュ。 |

|

|

| A filibuster

(from the Spanish filibustero), also known as a freebooter, is someone

who engages in an unauthorized military expedition into a foreign

country or territory to foster or support a political revolution or

secession. The term is usually applied to United States American

citizens who incited rebellions/insurrections across Latin America with

its recently independent but unstable nations freed from royal control

of the Kingdom of Spain and its Spanish Empire in the 1810s and 1820s.

Particularly in the mid-19th century, usually with the goal of

establishing an American-loyal regime that could later be annexed into

the North American Union as territories or free states, serving the

interests of the United States. Probably the most notable example is

the Filibuster War initiated by William Walker (1824–1860), in the

1850s in Nicaragua and Central America. Filibusters are irregular soldiers who act without official authorization from their own government, and are generally motivated by financial gain, political ideology, or the thrill of adventure. Unlike mercenaries, filibusters are independently motivated and work for themselves, while a mercenary leader operates on behalf of others.[1] The freewheeling actions of the filibusters of the 1850s led to the name being applied figuratively later in the North American English language political idiom of the political and legislative delaying act of filibustering in the United States Congress, especially in the upper chamber of the U.S. Senate.[2] |

フィ

リバスター(スペイン語の「filibustero」に由来)は、フリーブーターとも呼ばれ、政治革命や分離独立を促進または支援するために、外国または

他国の領土に無許可で軍事遠征を行う人物である。この用語は通常、1810年代から1820年代にかけてスペイン王国およびスペイン帝国の王政支配から解

放されたばかりで不安定な状態にあった、スペインから独立したばかりの中南米諸国で反乱や暴動を扇動した米国市民に対して用いられる。特に19世紀半ばに

は、通常、アメリカに忠誠を誓う政権を樹立し、後に北米連合に併合して領土または自由州とすることを目的としていた。おそらく最も有名な例は、1850年

代にニカラグアおよび中米でウィリアム・ウォーカー(1824年~1860年)が始めた「フィリスバスター戦争」であろう。 フィリーバスターとは、自国政府の正式な許可なく行動する非正規兵のことで、一般的には金銭的利益、政治的イデオロギー、あるいは冒険のスリルを動機とし ている。傭兵とは異なり、フィリーバスターは個人的な動機に基づいて行動し、自分自身のために働くが、傭兵のリーダーは他者のために行動する。[1] 1850年代のフィリーバスターの自由奔放な行動は、後に北米英語の政治用語として、米国議会、特に上院における政治的・立法的引き延ばし戦術を意味する 「フィリーバスター」という比喩的な名称が適用されるようになった。上院で使用されるようになった。[2] |

History A Jolly Roger used by filibusters during a land engagement in Mexico in 1688, described as a "red flag with a death’s head at the center and two crossed bones below the head, in white, in the middle of the red"[3]  Battle of San Jacinto in Nicaragua in 1856 The English term "filibuster" derives from the Spanish filibustero, itself deriving originally from the Dutch vrijbuiter, 'privateer, pirate, robber' (also the root of English freebooter).[4] The Spanish form entered the English language in the 1850s, as applied to military adventurers from the United States then operating in Central America and the Spanish West Indies.[5] The Spanish language term was first applied to persons raiding Spanish colonies and merchant ships of the Kingdom of Spain and its Spanish Empire in the Americas, in the West Indies islands of the Caribbean Sea, the most famous of whom was the Englishman naval hero and captain, Sir Francis Drake (c. 1540 – 1596) of the beginning Royal Navy of the Kingdom of England, with his June 1572 sea campaign and infamous raid and sacking of the town on Nombre de Dios of (Colon Province in modern Panama in Central America). With the end of the era of Caribbean / West Indies piracy in the early 18th century, the term of reference "filibuster" fell out of general currency for a while.[6] The term was revived in the following mid-19th century to describe the actions of adventurers who tried to take control of various Caribbean / West Indies islands, Mexican, and Central American territories by force of arms. In 1806, the general Francisco de Miranda launched an unsuccessful expedition to liberate Venezuela from Royal Spanish rule with volunteers from the north in the United States recruited in New York City. The three most prominent filibusters of that era were Narciso López (1797–1851) and John Quitman (1798–1858), both in Cuba along with William Walker (1824–1860), with the Walker affair in Baja California, Sonora of northern Mexico; along with further south to Costa Rica and lastly Nicaragua in Central America. The term returned to North American English language parlance to refer to López's 1851 Cuban expedition.[7][8] Other filibusters include the Americans Aaron Burr (former Vice President of the United States, about the Louisiana Purchase / Louisiana Territory and old Southwest Territory), William Blount (old Southwest Territory / West Florida / Florida), Augustus W. Magee (Texas / Republic of Texas), George Mathews (East Florida / Florida), George Rogers Clark (Louisiana Purchase / Louisiana Territory and old Southwest Territory / Mississippi Territory), William S. Smith (Venezuela), Ira Allen (Canada), William A. Chanler (Cuba and Venezuela), Samuel Brannan (Kingdom of Hawaii / Hawaii), Joseph C. Morehead and Henry Alexander Crabb (Sonora, northern Mexico) and James Long (Texas / Republic of Texas).[7][9] Non-American filibusters include French Marquis Charles de Pindray and Count Gaston de Raousset-Boulbon (Sonora, northern Mexico), the Venezuelan Narciso López (Cuba) and Gregor MacGregor (Florida, Central America, and South America). Although the American public often enjoyed reading about the thrilling adventures of mercenary filibusters, those Americans involved in filibustering expeditions were usually in violation of the first Neutrality Act of 1794 that made it illegal for a citizen to wage war against another country at peace with the United States. For example, the journalist John L. O'Sullivan (1813–1895), who coined the related phrase "manifest destiny" for the movement of American westward expansion, was put on trial for raising money in America for López's failed southern filibustering expedition in Cuba. The second Neutrality Act of 1818 became of great frustration for American filibusters. Article 6 stated anyone engaged in filibustering could receive a maximum three years imprisonment and three thousand dollars in fines. However, it was not uncommon for in the early Republic of late 18th and early 19th century politicians to "overlook" and sometimes "assist" some filibuster missions in the hopes to add to U.S. territory.[10] This conflict meant the U.S. Army was reluctant to arrest filibusters who broke the terms of this legislation. Officers were worried that without permission from the American federal courts, such as the United States District Court to make these arrests, they could face arrest themselves.[10] |

歴史 1688年のメキシコにおける陸上戦闘で、海賊行為を行う者たちが使用したジョリー・ロジャーは、「赤地に白で、中央に死の頭部、その下に2本の交差した骨」と描写されている。  1856年のニカラグアにおけるサン・ジャシントの戦い 英語の「filibuster」という用語は、スペイン語の「filibustero」に由来し、さらにその語源はオランダ語の「vrijbuiter」 (「私掠船、海賊、強盗」)である(英語の「freebooter」の語源でもある)。[4] スペイン語の「filibustero」は、1850年代に英語に入り、当時中米およびスペイン領西インド諸島で活動していた米国の軍人冒険家に適用され た。[5] スペイン語の用語は、スペイン領やスペイン帝国のアメリカ大陸、カリブ海の西インド諸島の商船を襲撃した人格に初めて適用された。最も有名な人物は、イン グランド王国初期の王立海軍の海軍英雄であり船長であったサー・フランシス・ドレーク(c. 1540 – 1596)である。1572年6月の海戦と、中米のパナマにあるコロン州のノムブレ・デ・ディオス(スペイン語で「神の数」の意)の町への悪名高い襲撃と 略奪を行った。18世紀初頭にカリブ海・西インド諸島の海賊時代が終焉を迎えると、しばらくの間、「フィリスバスター」という用語は一般的ではなくなっ た。 この用語は、19世紀半ばに復活し、カリブ海や西インド諸島の諸島、メキシコ、中米の領土を武力によって支配しようとした冒険家の行動を表現するように なった。1806年、フランシスコ・デ・ミランダ将軍は、ニューヨークで募集したアメリカ北部の志願者とともに、スペイン王政下のベネズエラを解放するた めの遠征を敢行したが、失敗に終わった。この時代における最も著名な3人の海賊は、ナルシソ・ロペス(1797年-1851年)とジョン・クィットマン (1798年-1858年)で、2人ともキューバにいた。また、ウィリアム・ウォーカー(1824年-1860年)は、メキシコ北部のソノラ州バハ・カリ フォルニアでウォーカー事件を起こした。さらに南下してコスタリカ、最後に中米のニカラグアでも事件を起こした。この用語は、1851年のロペスのキュー バ遠征を指す北米英語の俗語として復活した。[7][8] その他の海賊には、アメリカ人のアーロン・バー(ルイジアナ購入/ルイジアナ領土および旧南西領土)、ウィリアム・ブラウント(旧南西領土/西フロリダ/ フロリダ)、オーガスタス・W・マギー(テキサス/テキサス共和国)、ジョージ・マシューズ(東フロリダ/フロリダ)、ジョージ・ロジャース・クラーク (ルイジアナ購入/ルイジアナ領土および旧南西領土/ミシシッピ領土)、ウィリアム・S・スミス(ベネズエラ)、アイラ・アレン(カナダ)、ウィリアム・ A・チャンラー(キューバおよびベネズエラ)、サミュエル・ブラナン(ハワイ王国/ハワイ)、ジョセフ・C・モアヘッドおよびヘン スミス(ベネズエラ)、アイラ・アレン(カナダ)、ウィリアム・A・チャンラー(キューバおよびベネズエラ)、サミュエル・ブラナン(ハワイ王国/ハワ イ)、ジョセフ・C・モアヘッドおよびヘンリー・アレクサンダー・クラブ(ソノラ、メキシコ北部)、ジェームズ・ロング(テキサス/テキサス共和国)であ る。[7][9] アメリカ人以外のフィリバスターとしては、フランスのシャルル・ド・パンドラ侯爵とガストン・ド・ラウセット=ブールボン伯爵(メキシコ北部ソノラ)、ベネズエラのナルシソ・ロペス(キューバ)、グレゴール・マクグレガー(フロリダ、中米、南米)などがいる。 アメリカ国民は傭兵によるスリリングな冒険談を好んで読んでいたが、実際には、これらのアメリカ人が関与した冒険は、通常、1794年の第一次中立法に違 反していた。この法律は、アメリカと平和条約を結んでいる国に対して、自国民が戦争を仕掛けることを違法とするものだった。例えば、アメリカ西部への拡大 運動に関連して「明白な使命(manifest destiny)」という表現を考案したジャーナリストのジョン・L・オサリバン(1813年~1895年)は、キューバでのロペスの南側での失敗に終 わった海上での武力威嚇作戦のためにアメリカ国内で資金を集めたとして裁判にかけられた。 1818年の第二次中立法は、アメリカの海上での武力威嚇作戦にとって大きな不満の種となった。第6条では、海賊行為に関与した者は最高3年の禁固刑と 3,000ドルの罰金に処せられると定められていた。しかし、18世紀後半から19世紀初頭の初期の共和国では、米国の領土を拡大することを期待して、一 部の海賊行為を「見逃す」ことや、時には「支援」することも珍しくなかった。[10] この対立により、 この法律の条件を破った盗賊を逮捕することに、米軍は消極的であった。連邦裁判所、例えば米国連邦地方裁判所の許可なしにこうした逮捕を行うことは、自分 たち自身が逮捕される可能性があると、将校たちは心配していた。[10] |

| Filibusters and the press There was widespread support in the press for filibusters' missions. A number of journalists were sympathetic towards filibusters, such as John O'Sullivan and Moses S. Beach at the famous New York Sun and L. J. Sigur of the New Orleans Daily Delta. All supported Narciso López's missions to Cuba. John S. Thrasher contributed articles for the annexation of Cuba in the New Orleans Picayune. Some enterprising enthused journalists also enlisted themselves to fight for filibustering missions, such as Richardson Hardy and John McCann of the Cincinnati Nonpareil.[11] The poet Theodore O'Hara was a member of William Walker's expedition to Nicaragua. He worked on the Kentucky Yeoman and the Democratic Rally newspapers. After this, he served in the Confederate States Army in the American Civil War (1861–1865).[12] However, filibustering was not universally praised in the press. Papers backing the Republican party's position of being anti-filibuster would use the term to denounce not just actors such as William Walker but also the abolitionist filibuster John Brown, who led a failed mission into Virginia with the aim of causing a slave revolt. Knowing it would harm their campaign, Republicans identified the actions of Brown as originating in the same lawless ideology as the Democrat endorsed Walker or the pro slavery factions operating in the Bleeding Kansas period, and hence inherently denounced his raid.[13] Samuel Brannan's filibustering mission to Hawaii was identified by contemporary newspapers as being little more than a colonising scheme, although they refrained from passing moral judgement and the Daily Evening Picayune revised their opinion to the tamer 'emigrating company'.[14] Catholic newspapers had varying opinions on filibustering, but broadly denounced these missions for cultural hubris and violence. Despite criticisms of a 'mad spirit of aggression abroad', Catholic commentators often had more issue with the perceived moral decay domestically that filibusters represented, and could see potential in a Spanish Catholic revival abroad, even if it came as a consequence of violence.[15] |

フィリバスターと報道機関 フィリバスターの使命は、報道機関から広く支持されていた。 ニューヨーク・サン紙のジョン・オサリバンやモーゼス・S・ビーチ、ニューオーリンズ・デイリー・デルタ紙のL.J.シガーなど、多くのジャーナリストが フィリバスターに共感していた。 彼らは皆、ナルシソ・ロペスのキューバ遠征を支持していた。 ジョン・S・スレイサーは、ニューオーリンズ・ピカユーン紙にキューバ併合に関する記事を寄稿していた。また、リチャードソン・ハーディやジョン・マッカ ンなど、進取の気性に富んだジャーナリストの中には、シンシナティ・ノンパレルの紙上で、フィリバスター活動に身を投じる者もいた。[11] 詩人のセオドア・オハラは、ウィリアム・ウォーカーのニカラグア遠征隊の一員であった。彼はケンタッキー・ヨーマン紙と民主党ラリー紙で働いていた。その 後、南北戦争(1861年~1865年)ではアメリカ連合国軍に従軍した。[12] しかし、新聞では、議事妨害行為は必ずしも賞賛されてはいなかった。共和党の立場を支持する新聞は、ウィリアム・ウォーカーのような人物だけでなく、奴隷 制廃止論者の議事妨害者ジョン・ブラウンも非難するためにこの用語を使用した。ブラウンは、バージニア州への失敗した襲撃作戦を指揮し、奴隷の反乱を引き 起こそうとした。共和党は、ブラウンによる行動が、民主党が支援するウォーカーや、カンザス州で奴隷制推進派として活動していた人々と同じ無法なイデオロ ギーに由来するものだと考え、したがって、ブラウンによる襲撃は本質的に非難されるべきものだと主張した。 [13] サミュエル・ブラナンによるハワイへの盗賊行為のようなミッションは、当時の新聞では植民地化計画以外の何者でもないとして認識されていたが、道徳的な判 断を下すことは控え、デイリー・イブニング・ピカユーン紙は「おとなしい移住会社」というより穏やかな表現に意見を修正した。[14] カトリック系新聞は、フィリバスターに対する意見は様々であったが、概してこれらのミッションを文化的な傲慢さと暴力を理由に非難した。海外への狂気じみ た侵略精神」という批判にもかかわらず、カトリックの論説家は、フィリバスターが象徴する国内の道徳的腐敗をより問題視することが多く、たとえそれが暴力 の結果であったとしても、海外におけるスペイン系カトリックの復活に可能性を見出していた。[15] |

| Antebellum United States Connection to slavery The mid-nineteenth century (1848–1860) saw Southern planters raise private armies for expeditions to Mexico, the Caribbean, Central and South America to acquire territories that could be annexed to the Union as slave states. Despite not being authorized by their government, Southern elites often held considerable sway over U.S. foreign policy and national politics. Despite widespread opposition from Northerners, filibustering thrust slavery into American foreign policy.[16] Historians have noted that filibustering was not a common practice and was carried out by "the most radical proslavery expansionists". Hardline defenders of slavery saw its preservation as their "top priority", leading to support for filibusters and their campaigns abroad. At the height of filibustering, pro-slavery politicians wanted to expand the United States further into Latin America, as far as Paraguay and Peru. However, these attempts were quickly withdrawn when military and diplomatic retaliation was pursued.[17] The author and filibuster Horace Bell observed that it could be unpopular to be opposed to filibusterism, as being so "was to be opposed to African slavery".[18] On the abolitionist side, John Brown was accused by both Catholic and pro Republican newspapers of being a filibuster after leaving New York and heading to Virginia to lead the raid on Harpers Ferry.[15] Comparisons were drawn between his actions and those of Walker, notably how both aimed to use violence to change the status of slavery (with Walker wanting to introduce slavery and Brown wanting to destroy it).[13] Many future Confederate officers and soldiers, such as Chatham Roberdeau Wheat, of the Louisiana Tigers, obtained valuable military experience from filibuster expeditions. |

南北戦争前のアメリカ 奴隷制とのつながり 19世紀半ば(1848年~1860年)には、南部の農園主たちが、奴隷州として連邦に併合できる領土を獲得するために、メキシコ、カリブ海地域、中南米 への遠征のための私設軍隊を組織した。政府の承認を受けていないにもかかわらず、南部のエリート層はしばしば米国の外交政策や国内政治に大きな影響力を及 ぼした。北部からの広範な反対にもかかわらず、フィリバスターは奴隷制をアメリカの外交政策に押し込んだ。 歴史家は、フィリバスターは一般的ではなく、「最も急進的な奴隷制拡張論者」によって行われたと指摘している。奴隷制の強硬派は、奴隷制の維持を「最優先 事項」と見なし、フィリバスターとその海外キャンペーンを支持するに至った。フィビュステリアが最盛期を迎えていた頃、奴隷制賛成派の政治家たちは、米国 をラテンアメリカにさらに拡大し、パラグアイやペルーにまで手を伸ばそうとしていた。しかし、軍事的・外交的報復措置が取られると、こうした試みはすぐに 撤回された。[17] フィビュステリアの支持者であり作家のホレス・ベルは、フィビュステリアに反対することは「アフリカの奴隷制に反対すること」であり、不人気であると指摘した。[18] 奴隷制度廃止論者側では、ジョン・ブラウンがニューヨークを離れ、バージニア州に向かい、ハーパーズ・フェリーの襲撃を指揮したことで、カトリック系と共 和党系の両方の新聞から、議事妨害行為を行ったと非難された。[15] 彼の行動とウォーカーの行動は比較され、特に、両者が暴力を用いて奴隷制度の現状を変えようとした点(ウォーカーは奴隷制を導入しようとし、ブラウンはそ れを破壊しようとした)が注目された。[13] ルイジアナ・タイガースのチャタム・ロベルドー・ウィートなど、多くの南軍の将校や兵士が、議事妨害の遠征から貴重な軍事経験を得た。 |

William Walker William Walker is a famous filibuster, having failed at multiple attempts to invade Latin American countries and establish a pro-slavery, American regime. In the 1850s, American adventurer William Walker launched several filibustering campaigns leading a private mercenary army. In 1853, he declared a short-lived republic in the Mexican states of Sonora and Baja California. Later, when a path through Lake Nicaragua was being considered as the possible site of a canal through Central America (see Nicaragua canal), he was hired as a mercenary by one of the factions in a civil war in Nicaragua. He declared himself commander of the country's army in 1856; and soon afterward President of the Republic. Walker received no form of direct military or financial aid from the US government but in 1856 his government did receive official recognition from Democratic President Franklin Pierce. In June of the same year Walker was endorsed as an agent of Central America's regeneration by the Democratic National Convention's party platform. This support for Walker was later publicly retracted due to allegations of corruption but ‘Walker's movement to many Democrats, represented a natural outgrowth of the U.S. annexation of Texas, the Mexican-American War.[19] After attempting to take control of the rest of Central America he was defeated by the four other Central American nations he tried to invade and eventually executed in 1860 by the local Honduran authorities he had tried to overthrow.[20] The author Horace Bell served as a major with Walker in Nicaragua in 1856. Colonel Parker H. French served as Minister of Hacienda and was appointed as Minister Plenipotentiary to Washington in 1855, but Pierce refused to recognise his credentials and did not meet with him. Rather than return to Nicaragua, French spent several months spending his spoils, enjoying a lavish lifestyle that included staying in luxury hotel suites and entertaining the press and politicians with cigars and champagne. Eventually French ran into legal troubles connected to recruiting volunteers for the Walker regime and he hastily returned to Nicaragua in March 1856.[21][22] In the traditional historiography in both the United States and Latin America, Walker's filibustering represented the high tide of antebellum American imperialism. His brief seizure of Nicaragua in 1855 is typically called a representative expression of manifest destiny with the added factor of trying to expand slavery into Central America. Historian Michel Gobat, however, presents a strongly revisionist interpretation. He argues that Walker was invited in by Nicaraguan liberals who were trying to force economic modernization and political liberalism, and that thus it was not an attempted projection of American power.[23] |

ウィリアム・ウォーカー ウィリアム・ウォーカーは有名な海賊であり、ラテンアメリカ諸国への侵攻と奴隷制支持のアメリカ政権樹立を試みたが、何度も失敗している。 1850年代、アメリカの冒険家ウィリアム・ウォーカーは、私設傭兵軍を率いて、いくつかの海賊行為キャンペーンを展開した。1853年、彼はメキシコの ソノラ州とバハ・カリフォルニア州で短命に終わった共和国を宣言した。その後、ニカラグア湖を通る航路が、中米を通る運河の建設候補地として検討された際 (ニカラグア運河を参照)、彼はニカラグアの内戦中の派閥の1つに傭兵として雇われた。1856年には自らが国民軍の司令官であると宣言し、その後まもな くして共和国の大統領となった。ウォーカーは米国政府から軍事的、財政的な直接支援は一切受けなかったが、1856年には民主党のフランクリン・ピアース 大統領から公式に承認された。同年6月、民主党全国大会の党綱領でウォーカーは中米再生の代理人として支持された。ウォーカーへの支持は、後に汚職疑惑に より撤回されたが、「ウォーカーの運動は多くの民主党員にとって、テキサス併合や米墨戦争の自然な帰結であった。 [19] その後、中央アメリカ諸国の支配を試みたが、侵略を試みた他の4つの中央アメリカ諸国に敗北し、最終的には1860年に、打倒を試みたホンジュラス当局に よって処刑された。[20] 著者のホレス・ベルは、1856年にニカラグアでウォーカーの少佐を務めた。パーカー・H・フレンチ大佐はハシエンダ大臣を務め、1855年にワシントン に全権大使として任命されたが、ピアースは信任状を認めず、彼と会うことも拒否した。フレンチはニカラグアに戻る代わりに、数か月間戦利品を費やし、高級 ホテルのスイートルームに滞在したり、葉巻やシャンパンで報道関係者や政治家をもてなすなど、贅沢な生活を満喫した。結局、フレンチはウォーカー政権のた めに志願兵を募ったことに関連した法的な問題に巻き込まれ、1856年3月に急遽ニカラグアに戻った。[21][22] 米国とラテンアメリカにおける従来の歴史学では、ウォーカーの盗賊行為は南北戦争前のアメリカ帝国主義の絶頂期を象徴するものとされている。1855年の ニカラグアの短期間の占領は、奴隷制を中央アメリカに拡大しようとしたという要素を加えた、明白な使命の典型的な表現であると一般的に呼ばれている。しか し、歴史家のミシェル・ゴバは、ウォーカーのニカラグア侵攻について、強い修正主義的な解釈を示している。ウォーカーは、経済の近代化と政治的自由主義を 強制しようとしていたニカラグアのリベラル派によって招き入れられたのであり、したがって、それはアメリカの力の誇示を試みたものではなかったと主張して いる。[23] |

| Masculinity and filibustering Historians such as Gail Bederman and Amy Greenburg have noted the influence of masculinity of filibustering, particularly the form of "martial manhood" that many filibusterers adopted during the period.[24] Many men in antebellum America sought a return to the type of masculinity displayed on the frontier – one supposedly of strength, violence and self reliance. Greenburg uses primary sources to examine the appeal to masculinity in the recruitment campaigns of filibuster missions, focusing on how the deteriorating working class conditions enabled locations such as Nicaragua to be advertised as a space for men to celebrate their strength.[24] Bederman, meanwhile, emphasises the importance of nostalgia for the American frontier, and draws together notions of race, masculinity and gender to display how people felt insecure in their identities so reverted back to the typical ideal of what it meant to be a white man.[25] |

男らしさと私賊行為 ゲイル・ベダーマンやエイミー・グリーンバーグなどの歴史家は、私賊行為における男らしさの影響、特にその時代に多くの私賊行為者が採用した「武勇の男ら しさ」の形について指摘している。[24] 南北戦争前のアメリカでは、多くの男性が、開拓時代に見られた男らしさ、すなわち、強さ、暴力、自立を求めるようになっていた。グリーンバーグは一次資料 を基に、私賊行為の宣伝活動における男らしさへの訴えを検証し、労働者階級の状況が悪化する中で、ニカラグアのような場所が男性の力を讃える場として宣伝 されるようになった経緯に焦点を当てている。 一方、ベダーマンは、アメリカ開拓時代への郷愁の重要性を強調し、人種、男らしさ、ジェンダーの概念をまとめ、人々がアイデンティティに不安を感じ、白人男性であることの典型的な理想像に立ち返ったことを示している。[25] |

| Filibustering outside of the Americas While typically associated with Latin America, South America and the Caribbean, historians such as Dominic Alessio have proposed examples of filibustering elsewhere. Emphasising the centrality of unauthorised individuals in filibustering, the actions of Gabriel D'Annuzio in Fiume, Adel Aubert du Petit-Thouars in Tahiti and Giuseppe Garibaldi in Italy were suggested as non-American filibusters.[26] Indeed, some contemporary American newspapers styled the actions of Garibaldi and his insurgents in pre-unification Italy as filibustering.[15] It ought to be emphasised, however, that filibustering was predominantly used to refer to mid 19th century missions contained within the Americas, and that applying the term outside of this context risks being anachronistic. |

アメリカ大陸以外の私賊行為 私賊行為は一般的にラテンアメリカ、南アメリカ、カリブ海地域と関連付けられているが、ドミニク・アレッシオなどの歴史家は、それ以外の地域での私賊行為 の例を挙げている。私賊行為における無許可の個人の中心的役割を強調し、フィウメのガブリエル・ダヌンツィオ、タヒチのアドル・オーベール・デュ・プ ティ・トワール、イタリアのジュゼッペ・ガリバルディの行動が、非アメリカの私賊行為として提案された。[26] 実際、当時のアメリカの新聞の中には、統一前のイタリアにおけるガリバルディと彼の反乱軍の行動を私賊行為と表現したものもあった。[15] ただし、強調すべきは、私賊行為という言葉は主に19世紀半ばの南北アメリカ大陸における作戦を指して使われていたことであり、この文脈以外でこの用語を適用することは時代錯誤となる危険性があるということだ。 |

| Women's involvement with filibustering Women often participated in filibustering, taking active roles such as planning, propaganda, participation, and popularization. Women also composed songs, arranged balls and concerts on behalf of the filibusters. Most of the interest came from women in the Gulf and Mid-Atlantic states as they were closer to the events. Correspondingly those in the Northern states tended not to take much interest in what was going on further south. Many women attended the filibuster expeditions as settlers, to help with casualties and to aid the expeditions in any way they could. Many women were at the front line experiencing first hand the armed engagements. A few even took up arms and used them to defend their men and property. Jane McManus Storm Cazneau had an important role in negotiating between filibusters and U.S. politicians. She persuaded Moses S. Beach to promote lectures about William Walker and his group. All of these women embraced the idea of expansionism to spread American slavery in Central and South America. John Quitman's daughter Louisa used anti-Spanish rhetoric as she saw fit so that the Spanish deserved to be punished for what they had done to Narciso López and his men after they had been taken prisoner.[27] |

女性と私賊行為 女性は私賊行為にしばしば参加し、計画、宣伝、参加、普及など、積極的な役割を担った。女性は歌を作ったり、私賊行為の代行として舞踏会やコンサートを企 画したりもした。関心の大半は、事件現場に近かったメキシコ湾岸州や中部大西洋州の女性から寄せられた。それに対し、北部の州の女性は、南部で起こってい ることに対してあまり関心を示さなかった。多くの女性が、負傷者の手当てを手伝ったり、できる限りの支援をしたりするために、入植者として私賊行為遠征に 参加した。多くの女性が最前線に立ち、武力衝突を直接体験した。中には武器を手に取り、男性や財産を守るためにそれを使った者もいた。 ジェーン・マクマナス・ストーム・カズノーは、私賊行為者と米国の政治家との交渉において重要な役割を果たした。彼女は、モーゼス・S・ビーチにウィリア ム・ウォーカーとその一味に関する講演を推進するよう説得した。これらの女性たちはみな、アメリカの中南米における奴隷制拡大という考えを受け入れてい た。ジョン・クィットマンの娘ルイーザは、スペインがナルシソ・ロペスとその部下たちを捕虜にした後、彼らに対して行った仕打ちに値する罰を与えるべきだ と、好んで反スペイン的な暴言を吐いた。[27] |

| Filibusters and freemasonry Several well-known figures in filibusterism were also Freemasons and this organization played a major role within the hierarchy of the filibusters. Narciso López and José Gonzales of the Cuban expedition were both Freemasons. Other Freemasons who took part in filibustering came from Louisiana and were involved with the 1810 incursion into West Florida. Later in 1836 Freemasons were involved in the Texas Revolution. These included Stephen F. Austin, Mirabeau Buonaparte Lamar, and David Crockett among others. Freemasons from New Orleans had helped in planning the conquest of Texas. Several lodges were an important element of the filibusters, contributing many men to the cause of expansionism. Part of the Masonic emphasis was that members should support their country's freedoms. During the period when Narciso López was planning his expedition to Cuba the Havana Club, founded in 1848 by Cuban Freemasons, had endorsed the idea of inviting a filibuster expedition to Cuba to overthrow the colonial Spanish and free the island. The flag that López and others designed for their expedition had masonic emblems built into it. These included representations of the Mason's triangular apron. The Star of Texas was included to represent the five points of the fellowship of the Masons.[citation needed] This flag was adopted as the Cuban national flag fifty-two years after López's failed adventure. Other filibustering Freemasons of note included Chatham Roberdeau Wheat and Theodore O'Hara the poet. They came from an extensive network of lodges in the Southern U.S. such as Soloman's Lodge No. 20 in Jacksonville and Marion Lodge No. 19 in Ocala. The reach of the Masons was wide and helpful. On arriving at John Hardee Dilworth's estate, Jose Gonzales used Freemasonry symbols, which prevented him from being arrested as Dilworth was also a Mason and had been told by presidential order to arrest Gonzales.[28] |

フィリバスターとフリーメイソン フィリバスターの著名な人物の何人かはフリーメイソンでもあり、この組織はフィリバスターのヒエラルキーの中で主要な役割を果たしていた。キューバ遠征の ナルシソ・ロペスとホセ・ゴンザレスは、ともにフリーメイソンであった。私賊行為に参加した他のフリーメイソンはルイジアナ出身で、1810年の西フロリ ダ侵攻に関与していた。その後、1836年のテキサス革命にもフリーメイソンが関与した。これにはスティーブン・F・オースティン、ミラボー・ボナパル ト・ラマー、デイビッド・クロケットなどが含まれる。ニューオーリンズのフリーメイソンはテキサス征服の計画に協力した。いくつかのロッジは私賊行為の重 要な要素であり、拡張主義の目的のために多くの人員を派遣した。フリーメイソンが特に強調していたのは、会員は自国の自由を支援すべきであるという点で あった。 ナルシソ・ロペスがキューバ遠征を計画していた時期、1848年にキューバのフリーメイソンによって設立されたハバナ・クラブは、キューバに私賊行為の遠 征隊を招き入れ、植民地支配するスペインを打倒し、島を解放するというアイデアを支持していた。ロペスと他の人々が遠征のためにデザインした旗には、フ リーメイソンのシンボルが組み込まれていた。これには、メイソンの三角エプロンの表現も含まれていた。テキサスの星は、メイソンの友愛の5つの点を表すた めに含まれていた。[要出典] この旗は、ロペスの失敗に終わった冒険から52年後にキューバの国旗として採用された。 その他の著名なフリーメイソンによる私賊行為としては、チャタム・ロバードア・ウィートや詩人のセオドア・オハラなどが挙げられる。彼らは、ジャクソンビ ルにあるソロモンズ・ロッジ第20号やオカラにあるマリオン・ロッジ第19号など、米国南部の広範なロッジのネットワークからやって来た。フリーメイソン の影響力は広く、また有益でもあった。ジョン・ハーディー・ディルワースの屋敷に到着した際、ホセ・ゴンザレスはフリーメイソンのシンボルを使用した。こ れにより、ディルワースもメイソンであったため、ゴンザレスを逮捕するよう大統領命令を受けていたにもかかわらず、ゴンザレスは逮捕を免れた。[28] |

| "Major F. P. Hann" hoax The Frank Hann letters were a series of hoax letters published in 1895, purported to be written by a "Major F. P. Hann", who claimed to be an American filibuster fighting against the Spanish colonial rule of Cuba. Hann wrote a fake account of his supposed experiences in the Cuban War of Independence, detailing accounts of battles and operations that took place as well as commenting on the political situation within the country. The real Frank Hann, a twenty-year-old man who lived in Gainesville, Florida, used the pseudonym "Anderfer" to release the letters he forged, acting as a medium for the letters written by "Major Hann". He used the hoax to raise his own profile in the U.S. as a war hero, while also attempting to garner support for filibuster missions in Cuba. The episode draws attention to the influence of the media and yellow journalism on American sentiment towards foreign affairs during the period.[29] |

「F. P. ハン少佐」のデマ フランク・ハンによる手紙は、1895年に発表された一連の偽の手紙であり、「F. P. ハン少佐」が書いたとされるもので、スペインのキューバ植民地支配に抵抗するアメリカ人私賊行為の戦士であると主張していた。ハンは、キューバ独立戦争に おける自身の経験をでっちあげ、戦闘や作戦の詳細、さらには国内の政治情勢についてのコメントを記した。 フロリダ州ゲインズビルに住む20歳の青年、フランク・ハーンは、「アンダーファー」という偽名を使い、偽造した手紙を公表し、「ハーン少佐」が書いた手 紙の仲介役を務めた。彼は、この偽のニュースで、米国における自身の知名度を上げ、戦争の英雄として名乗りを上げるとともに、キューバでの私賊行為作戦へ の支援を集めようとした。 この事件は、この時期におけるアメリカ人の対外情勢に対する見方に対するメディアとイエロージャーナリズムの影響に注目を集めた。[29] |

| Depiction in popular media William Walker's filibusters are the subject of a poem by Ernesto Cardenal.[30] John Neal's 1859 novel True Womanhood includes a character who travels from the US to Nicaragua to aid Walker's campaign.[31] Other media portrayals of filibustering include: Richard Harding Davis novels, the 1987 film Walker by Alex Cox, Blood Meridian by Cormac McCarthy, Ned Buntline's novels The B'hoys of New York and The Mysteries and Miseries of New Orleans, and Lucy Petway Holcombe's The Free Flag of Cuba.[citation needed] Season 1 episode 8 of The High Chaparral is titled "The Filibusteros" and depicts a fictional group of post–Civil War Confederate soldiers in Mexico. Historians such as Aims McGuinness promote the view that Filibustering catalysed an opposition discourse, that Manifest destiny had spawned.[32] In doing so this discourse in addition to the trauma and collective memory of the Filibuster War (caused by events such as the burning of Granada) is theorised to have created the original sense of widespread Latin American identity and Costa-Rican national identity.[33] |

大衆メディアにおける描写 ウィリアム・ウォーカーの議事妨害は、エルネスト・カルデナルの詩の主題となっている。[30] ジョン・ニールの1859年の小説『真の女らしさ』には、ウォーカーのキャンペーンを手助けするために米国からニカラグアに渡る登場人物が登場する。 [31] 私賊行為を題材としたその他のメディア作品には、 リチャード・ハーディング・デイヴィスの小説、1987年のアレックス・コックス監督の映画『ウォーカー』、コーマック・マッカーシーの『ブラッド・メリ ディアン』、ネッド・バンラインの小説『ニューヨークの悪ガキたち』と『ニューオーリンズの謎と悲劇』、ルーシー・ペットウェイ・ホルコムの『キューバの 自由の旗』などがある。 [要出典] 『ハイ・チャパラル』のシーズン1第8話は「The Filibusteros」というタイトルで、南北戦争後のメキシコにおける南軍兵士たちの架空のグループを描いている。 Aims McGuinnessなどの歴史家は、私賊行為が反対派の議論を促進し、明白な使命が生まれたという見解を支持している。[32] そうすることで、この議論は、グラナダの焼失などの出来事によって引き起こされたフィバスター戦争のトラウマと集合的記憶に加えて、ラテンアメリカ全体の アイデンティティとコスタリカ国民のアイデンティティの原初の感覚を生み出したと理論化されている。[33] |

| British Legions Burr conspiracy El filibusterismo Foreign Enlistment Act 1870 (UK) Heimosodat Hunters' Lodges Kingdom of Sedang Knights of the Golden Circle Little green men (Russo-Ukrainian War) Raj of Sarawak Vikings |

英国軍団 バー陰謀 フィリバスター 外国人入隊法(1870年、英国) ヘイモスダット ハンターズ・ロッジ セダン王国 黄金の円騎士団 リトル・グリーン・メン(ロシア・ウクライナ戦争) サラワクのラジ バイキング |

| Further reading Brown, Charles H. Agents of Manifest Destiny: The Lives and Times of the Filibusters. University of North Carolina Press, 1980. ISBN 0-8078-1361-3. Karp, Matthew (2016). This Vast Southern Empire: Slaveholders at the Helm of the American Foreign Policy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-73725-9. Lipski, John M. "Filibustero: origin and development." Journal of Hispanic Philology 6, 1982, pp. 213–238. ISSN 0147-5460. May, Robert E. "Manifest Destiny's Filibusters" in Sam W. Haynes and Christopher Morris, eds. Manifest Destiny and Empire: American Antebellum Expansionism. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-89096-756-3. May, Robert E. Manifest Destiny's Underworld: Filibustering in Antebellum America. University of North Carolina Press, 2002. ISBN 0-8078-2703-7. Roche, James Jeffrey. The story of the Filibusters. T. F. Unwin, 1891. Schreckengost, Gary. The First Louisiana Special Battalion: Wheat's Tigers in the Civil War. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland and Company, Inc., Publishers, 2008. ISBN 978-0-7864-3202-8. |

さらに読む ブラウン、チャールズ・H. 『明白な使命の代理人:私賊行為者の生涯と時代』。ノースカロライナ大学出版、1980年。ISBN 0-8078-1361-3。 カープ、マシュー(2016年)。『この広大な南部帝国:奴隷所有者が主導するアメリカの外交政策』。ケンブリッジ、マサチューセッツ州:ハーバード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-674-73725-9。 Lipski, John M. 「フィリバスター:起源と発展」『ヒスパニック文献学ジャーナル』6、1982年、213-238ページ。ISSN 0147-5460。 メイ、ロバート E. 「マニフェスト・デスティニーの私賊行為」 サム W. ヘインズ、クリストファー・モリス編 『マニフェスト・デスティニーと帝国:南北戦争前のアメリカ拡張主義』 テキサス州カレッジステーション:テキサスA&M大学出版、1997年。ISBN 0-89096-756-3. メイ、ロバート E. 『マニフェスト・デスティニーの裏側:南北戦争前のアメリカにおける私賊行為』。ノースカロライナ大学出版、2002年。ISBN 0-8078-2703-7。 ロシュ、ジェイムズ・ジェフリー著『私賊行為の物語』T. F. アンウィン、1891年。 シュレケンゴスト、ゲイリー著『ルイジアナ第1特別大隊:南北戦争におけるウィートタイガース』ノースカロライナ州ジェファーソン:マクファーランド・アンド・カンパニー、2008年。ISBN 978-0-7864-3202-8。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Filibuster_(military) |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆