妖 術

Witchcraft

☆

妖術(witchcraft

)とは、妖術師(witch)と呼ばれる人格による呪術的使用のことである。伝統的に「妖術」とは、超自然的な危害や災難を他者に与えるために呪術を用い

ることを意味し、これが最も一般的で広く普及している意味である[1]。

ブリタニカ百科事典によれば、「このように定義された妖術は、より想像力の中に存在する」ものであるが、「多くの文化にとって、世界の悪の実行可能な説明

として構成されてきた」[2]。これらの社会のほとんどは、妖術に対して保護呪術的または対抗呪術を用い、魔女と疑われるものを敬遠、追放、投獄、体罰、

または殺害してきた。人類学者は、異なる文化における有害なオカルト的実践に関する類似した信念に対して「妖術」という用語を使用しており、これらの社会

は英語で話すときにしばしばこの用語を使用する[3][4][5]。

妖術を悪意ある呪術として信じることは古代メソポタミアから証明されており、ヨーロッパでは魔女への信仰は古典古代にまでさかのぼる。中世と近世のヨー

ロッパでは、告発された妖術師はたいてい女性であり[6]、自分たちの共同体に対して密かに黒魔術(maleficium)を使ったと信じられていた。通

常、妖術の告発は告発された妖術師の隣人によってなされ、社会的緊張から続いた。妖術師は悪魔や悪魔と交信していると言われることもあったが、人類学者の

ジャン・ラ・フォンテーヌは、そのような告発は主に「教会の敵」とみなされる人々に対してなされたと指摘している[7]。妖術師と疑われた者は、有罪とさ

れた場合、あるいは単に有罪と思われた場合、しばしば訴追され、処罰された。近世のヨーロッパの魔女狩りや魔女裁判では、何万人もの処刑が行われた。呪術

的なヒーラーや助産婦が妖術で告発されることもあったが[8][4][9][10]、告発された者の中では少数派であった。ヨーロッパにおける妖術信仰

は、啓蒙主義の時代以降、徐々に減少していった。

妖術の概念を含む多くの先住民の信仰体系も同様に魔女を悪意あるものと定義し、妖術を退けたり解いたりする治療者(メディスンピープルや妖術師など)を求

めている[11][12]。

アフリカやメラネシアの人々の中には、魔女は自分の中にある邪悪な精神や物質によって動かされると信じている者もいる。現代の妖術師狩りはアフリカとアジ

アの一部で行われている。

1930年代以降、ある種の現代的な異教の信奉者たちは妖術師を自認し、ネオ・ペイガンの信念と実践の一部として「妖術」という用語を再定義している

[13][14][15]。他のネオ・ペイガンはその否定的な意味合いからこの用語を避けている[16]。

★ 用語法:witchcraftは古くは「魔術」、witchは「魔女」と翻訳されてきたものである。しかしながら魔術と訳すると magic (呪術)とwitchcraft の区別がつきにくくなり、またwitchには、男性のものも含まれるので「魔女」はジェンダー論的に正しい翻訳とは言えない。女性を悪魔的に存在として排除してきた西洋のジェンダー・イデオロギーの産物が「魔女=ウイッチ」という単語である。そのために、私のDeepL 翻訳辞書には、witchcraftは「妖術」、witchは「妖術師」と翻訳する。しかし、DeepLは、しばしば、混乱をおこし、せっかく学習させた 語彙の翻訳をそのまま訳さず、以前の慣習的な翻訳をすることがあるので、注意をされたい。

| Witchcraft is the

use of magic by a person called a witch. Traditionally, "witchcraft"

means the use of magic to inflict supernatural harm or misfortune on

others, and this remains the most common and widespread meaning.[1]

According to Encyclopedia Britannica, "Witchcraft thus defined exists

more in the imagination", but it "has constituted for many cultures a

viable explanation of evil in the world".[2] The belief in witches has

been found throughout history in a great number of societies worldwide.

Most of these societies have used protective magic or counter-magic

against witchcraft, and have shunned, banished, imprisoned, physically

punished or killed alleged witches. Anthropologists use the term

"witchcraft" for similar beliefs about harmful occult practices in

different cultures, and these societies often use the term when

speaking in English.[3][4][5] Belief in witchcraft as malevolent magic is attested from ancient Mesopotamia, and in Europe, belief in witches traces back to classical antiquity. In medieval and early modern Europe, accused witches were usually women[6] who were believed to have secretly used black magic (maleficium) against their own community. Usually, accusations of witchcraft were made by neighbors of accused witches, and followed from social tensions. Witches were sometimes said to have communed with demons or with the Devil, though anthropologist Jean La Fontaine notes that such accusations were mainly made against perceived "enemies of the Church".[7] It was thought witchcraft could be thwarted by white magic, provided by 'cunning folk' or 'wise people'. Suspected witches were often prosecuted and punished, if found guilty or simply believed to be guilty. European witch-hunts and witch trials in the early modern period led to tens of thousands of executions. While magical healers and midwives were sometimes accused of witchcraft themselves,[8][4][9][10] they made up a minority of those accused. European belief in witchcraft gradually dwindled during and after the Age of Enlightenment. Many indigenous belief systems that include the concept of witchcraft likewise define witches as malevolent, and seek healers (such as medicine people and witch doctors) to ward-off and undo bewitchment.[11][12] Some African and Melanesian peoples believe witches are driven by an evil spirit or substance inside them. Modern witch-hunting takes place in parts of Africa and Asia. Since the 1930s, followers of certain kinds of modern paganism identify as witches and redefine the term "witchcraft" as part of their neopagan beliefs and practices.[13][14][15] Other neo-pagans avoid the term due to its negative connotations.[16] |

妖術(witchcraft

)とは、妖術師(witch)と呼ばれる人格による呪術的使用のことである。伝統的

に「妖術」とは、超自然的な危害や災難を他者に与えるために呪術を用いることを意味し、これが最も一般的で広く普及している意味である[1]。

ブリタニカ百科事典によれば、「このように定義された妖術は、より想像力の中に存在する」ものであるが、「多くの文化にとって、世界の悪の実行可能な説明

として構成されてきた」[2]。これらの社会のほとんどは、妖術に対して保護呪術的または対抗呪術を用い、魔女と疑われるものを敬遠、追放、投獄、体罰、

または殺害してきた。人類学者は、異なる文化における有害なオカルト的実践に関する類似した信念に対して「妖術」という用語を使用しており、これらの社会

は英語で話すときにしばしばこの用語を使用する[3][4][5]。 妖術を悪意ある呪術として信じることは古代メソポタミアから証明されており、ヨーロッパでは魔女への信仰は古典古代にまでさかのぼる。中世と近世のヨー ロッパでは、告発された妖術師はたいてい女性であり[6]、自分たちの共同体に対して密かに黒魔術(maleficium)を使ったと信じられていた。通 常、妖術の告発は告発された妖術師の隣人によってなされ、社会的緊張から続いた。妖術師は悪魔や悪魔と交信していると言われることもあったが、人類学者の ジャン・ラ・フォンテーヌは、そのような告発は主に「教会の敵」とみなされる人々に対してなされたと指摘している[7]。妖術師と疑われた者は、有罪とさ れた場合、あるいは単に有罪と思われた場合、しばしば訴追され、処罰された。近世のヨーロッパの魔女狩りや魔女裁判では、何万人もの処刑が行われた。呪術 的なヒーラーや助産婦が妖術で告発されることもあったが[8][4][9][10]、告発された者の中では少数派であった。ヨーロッパにおける妖術信仰 は、啓蒙主義の時代以降、徐々に減少していった。 妖術の概念を含む多くの先住民の信仰体系も同様に魔女を悪意あるものと定義し、妖術を退けたり解いたりする治療者(メディスンピープルや妖術師など)を求 めている[11][12]。 アフリカやメラネシアの人々の中には、魔女は自分の中にある邪悪な精神や物質によって動かされると信じている者もいる。現代の妖術師狩りはアフリカとアジ アの一部で行われている。 1930年代以降、ある種の現代的な異教の信奉者たちは妖術師を自認し、ネオ・ペイガンの信念と実践の一部として「妖術」という用語を再定義している [13][14][15]。他のネオ・ペイガンはその否定的な意味合いからこの用語を避けている[16]。 |

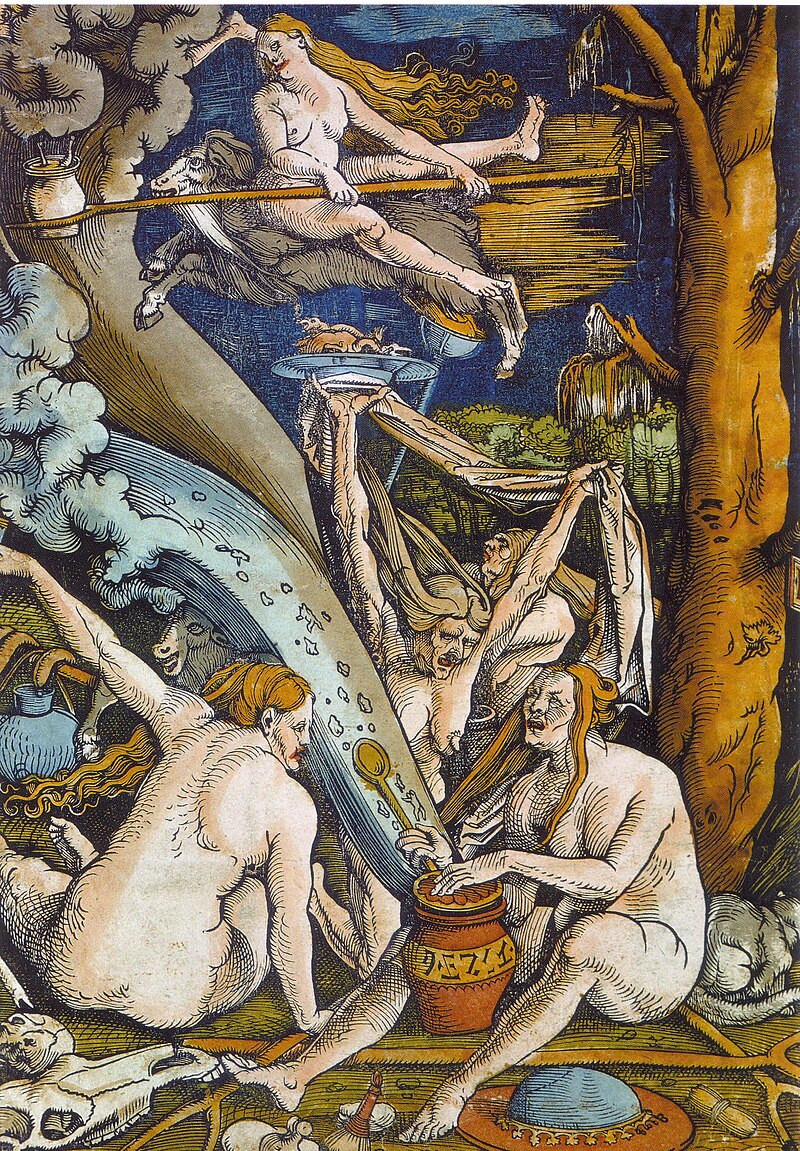

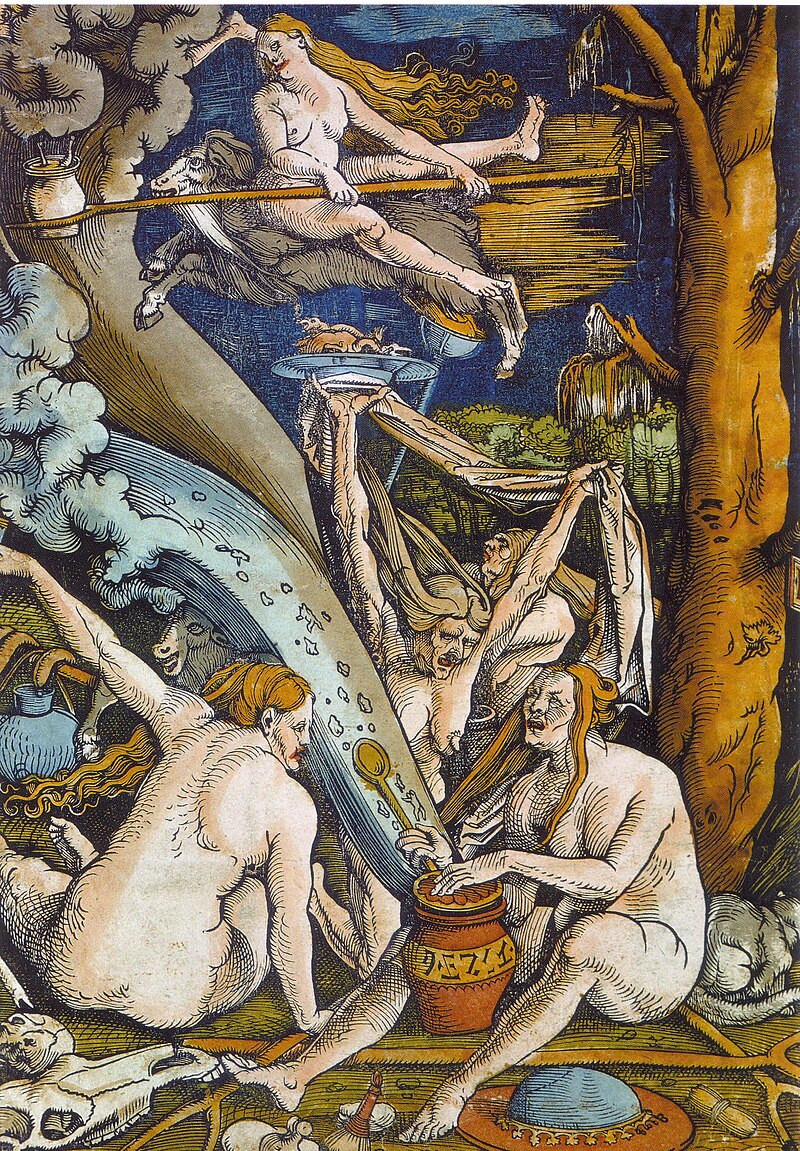

Concept The Witches by Hans Baldung (woodcut), 1508 The most common meaning of "witchcraft" worldwide is the use of harmful magic.[17] Belief in malevolent magic and the concept of witchcraft has lasted throughout recorded history and has been found in cultures worldwide, regardless of development.[3][18] Most societies have feared an ability by some individuals to cause supernatural harm and misfortune to others. This may come from mankind's tendency "to want to assign occurrences of remarkable good or bad luck to agency, either human or superhuman".[19] Historians and anthropologists see the concept of "witchcraft" as one of the ways humans have tried to explain strange misfortune.[19][20] Some cultures have feared witchcraft much less than others, because they tend to have other explanations for strange misfortune.[19] For example, the Gaels of Ireland and the Scottish Highlands historically held a strong belief in fairy folk, who could cause supernatural harm, and witch-hunting was very rare in these regions compared to other regions of the British Isles.[21] Historian Ronald Hutton outlined five key characteristics ascribed to witches and witchcraft by most cultures that believe in this concept: the use of magic to cause harm or misfortune to others; it was used by the witch against their own community; powers of witchcraft were believed to have been acquired through inheritance or initiation; it was seen as immoral and often thought to involve communion with evil beings; and witchcraft could be thwarted by defensive magic, persuasion, intimidation or physical punishment of the alleged witch.[17] A common belief worldwide is that witches use objects, words, and gestures to cause supernatural harm, or that they simply have an innate power to do so. Hutton notes that both kinds of practitioners are often believed to exist in the same culture and that the two often overlap, in that someone with an inborn power could wield that power through material objects.[22] One of the most influential works on witchcraft and concepts of magic was E. E. Evans-Pritchard's Witchcraft, Oracles and Magic Among the Azande, a study of Azande witchcraft beliefs published in 1937. This provided definitions for witchcraft which became a convention in anthropology.[20] However, some researchers argue that the general adoption of Evans-Pritchard's definitions constrained discussion of witchcraft beliefs, and even broader discussion of magic and religion, in ways that his work does not support.[23] Evans-Pritchard reserved the term "witchcraft" for the actions of those who inflict harm by their inborn power and used "sorcery" for those who needed tools to do so.[24] Historians found these definitions difficult to apply to European witchcraft, where witches were believed to use physical techniques, as well as some who were believed to cause harm by thought alone.[25][26] The distinction "has now largely been abandoned, although some anthropologists still sometimes find it relevant to the particular societies with which they are concerned".[22] |

概念 ハンス・バルドゥングの『魔女たち』(木版画)、1508年 「妖術」という用語は、世界中で最も一般的な意味として、有害な呪術の使用を指す[17]。悪意のある呪術や妖術の概念は、記録された歴史を通じて存続 し、その発展の程度に関わらず、世界中の文化に見られる[3][18]。ほとんどの社会は、他者に超自然的な害や不幸をもたらす能力を持つ個人を恐れてき た。これは、「顕著な幸運や不運の出来事を、人間または超人的な存在の作用によるものと見なしたい」という人類の傾向に由来しているかもしれない。 [19] 歴史学者や人類学者は、「妖術」という概念を、人間が奇妙な不幸を説明しようとした方法のひとつと捉えている。[19][20] 一部の文化では、奇妙な不幸について他の説明がある傾向があるため、他の文化よりも妖術をそれほど恐れていない。[19] 例えば、アイルランドのゲール族やスコットランドの高地では、超自然的な害をもたらす妖精を信じる強い信仰が歴史的にあり、これらの地域では、イギリス諸 島の他の地域に比べて魔女狩りはほとんど行われていなかった。[21] 歴史家のロナルド・ハットンは、この概念を信じるほとんどの文化が魔女や妖術に与える 5 つの重要な特徴を次のように要約している。他者に害や不幸をもたらすために呪術を使うこと。それは、魔女が自分のコミュニティに対して使うものだった。妖 術の力は、相続や入信によって得られるものと信じられていた。それは不道徳とみなされ、多くの場合、悪の存在との交わりが関係していると考えられていた。 そして、妖術は、防御的な呪術、説得、威嚇、あるいは容疑者に対する体罰によって阻止することができるとされていた。 世界中で広く信じられているのは、妖術師は物、言葉、身振りを使って超自然的な害をもたらす、あるいは単にそうする生来の力を持っているという説だ。ハッ トンは、どちらのタイプの術者も同じ文化の中に存在し、生来の力を持つ者がその力を物質的な物を通して発揮する場合もあり、2 つはしばしば重なる、と指摘している。[22] 妖 術と呪術の概念に関する最も影響力のある著作のひとつは、1937年に出版された、アザンデの妖術の信仰に関する研究『アザンデの妖術、神託、呪術』であ る。この著作は、人類学における慣例となった妖術の定義を提示した。[20] しかし、一部の研究者は、エヴァンズ=プリチャードの定義が一般的に採用されたことで、彼の著作が支持していない方法で、妖術の信念に関する議論、さらに は呪術や宗教に関するより広範な議論が制限されたと主張している。[23] エヴァンズ=プリチャードは、「妖術」という用語を、生来の力で害を及ぼす者の行為にのみ使用し、その行為を行うために道具を必要とする者については「魔 術」という用語を使用した。[24] 歴史家たちは、この定義をヨーロッパの妖術には適用することが難しいと判断した。ヨーロッパでは、妖術師は物理的な技術を使うだけでなく、思考だけで害を 与えると信じられていた者もいたからだ。[25][26] この区別は「現在ではほとんど廃れているが、一部の人類学者は、研究対象とする特定の社会には依然として関連性があると考える場合もある」[22]。 |

| While

most cultures believe witchcraft to be something willful, some

Indigenous peoples in Africa and Melanesia believe witches have a

substance or an evil spirit in their bodies that drives them to do

harm.[22] Such substances may be believed to act on their own while the

witch is sleeping or unaware.[23] The Dobu people believe women work

harmful magic in their sleep while men work it while awake.[27]

Further, in cultures where substances within the body are believed to

grant supernatural powers, the substance may be good, bad, or morally

neutral.[28][29] Hutton draws a distinction between those who

unwittingly cast the evil eye and those who deliberately do so,

describing only the latter as witches.[19] The universal or cross-cultural validity of the terms "witch" and "witchcraft" are debated.[20] Hutton states: [Malevolent magic] is, however, only one current usage of the word. In fact, Anglo-American senses of it now take at least four different forms, although the one discussed above seems still to be the most widespread and frequent. The others define the witch figure as any person who uses magic ... or as the practitioner of nature-based Pagan religion; or as a symbol of independent female authority and resistance to male domination. All have validity in the present.[19] According to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions there is "difficulty of defining 'witches' and 'witchcraft' across cultures—terms that, quite apart from their connotations in popular culture, may include an array of traditional or faith healing practices".[30] Anthropologist Fiona Bowie notes that the terms "witchcraft" and "witch" are used differently by scholars and the general public in at least four ways.[20] Neopagan writer Isaac Bonewits proposed dividing witches into even more distinct types including, but not limited to: Neopagan, Feminist, Neogothic, Neoclassical, Classical, Family Traditions, Immigrant Traditions, and Ethnic.[31] |

ほ

とんどの文化では、妖術は故意の行為であると信じられているが、アフリカやメラネシアの一部の先住民は、妖術師は自分の体内に有害な物質や悪霊を宿してお

り、それが彼らに悪行をさせるのだと信じている[22]。このような物質は、妖術師が眠っている間や意識がない間に、自動的に作用すると考えられている。

[23] ドブ族は、女性は睡眠中に有害な呪術を行い、男性は覚醒中にそれを行うと信じている。[27]

さらに、体内の物質が超自然的な力を与えると信じられている文化では、その物質は良いもの、悪いもの、あるいは道徳的に中立なものなど、さまざまな性質を

持つことがある。[28][29] ハットンは、無意識に邪眼をかける人と、意図的にそうする人を区別し、後者だけを「魔女」と表現している。[19] 「魔女(妖術師)」や「妖術」という用語の普遍性や文化間の妥当性については議論がある。[20] ハットンは次のように述べている。 しかし、[悪意のある呪術] は、この言葉の現在の用法の一つにすぎない。実際、英米でのこの言葉の意味は、現在では少なくとも 4 つの異なる形をとっているが、上で述べたものが依然として最も広く、頻繁に使用されているようだ。他の意味では、魔女とは、呪術を使う人物、あるいは自然 を信仰する異教の宗教の信者、あるいは独立した女性の権威と男性支配に対する抵抗の象徴と定義されている。これらはすべて、現在でも有効だ。[19] 国連超法規的、即決、または恣意的な処刑に関する特別報告者によると、「文化を超えて『妖術師』や『妖術』を定義することは困難である。これらの用語は、 大衆文化における意味合いとはまったく異なり、さまざまな伝統的または信仰的な治療行為を含む場合がある」とされている。[30] 人類学者フィオナ・ボウイは、「妖術」と「妖術師」という用語は、学者と一般の人々によって、少なくとも 4 つの点で異なる意味で使用されていると指摘している。[20]新異教の作家アイザック・ボネウィッツは、魔女を、新異教、フェミニスト、ネオゴシック、新 古典主義、古典的、家族の伝統、移民の伝統、民族など、さらに明確な種類に分類することを提案した。[31] |

| Etymology Further information: Witch (word) The word "witchcraft" is over a thousand years old: Old English formed the compound wiccecræft from wicce ('witch') and cræft ('craft').[32] The masculine form was wicca ('male sorcerer').[33] According to the Oxford English Dictionary, wicce and wicca were probably derived from the Old English verb wiccian, meaning 'to practice witchcraft'.[34] Wiccian has a cognate in Middle Low German wicken (attested from the 13th century). The further etymology of this word is problematic. It has no clear cognates in other Germanic languages outside of English and Low German, and there are numerous possibilities for the Indo-European root from which it may have derived. Another Old English word for 'witch' was hægtes or hægtesse, which became the modern English word "hag" and is linked to the word "hex". In most other Germanic languages, their word for 'witch' comes from the same root as these; for example German Hexe and Dutch heks.[35] In colloquial modern English, the word witch is particularly used for women.[36] A male practitioner of magic or witchcraft is more commonly called a 'wizard', or sometimes, 'warlock'. When the word witch is used to refer to a member of a neo-pagan tradition or religion (such as Wicca), it can refer to a person of any gender.[37] |

語源 詳細情報:妖術師(魔女) (単語) 「witchcraft(妖術)」という言葉は 1000 年以上の歴史がある。古英語では、「wicce(魔女)」と「cræft(技術)」を組み合わせて「wiccecræft」という複合語が形成されていた [32]。男性形は「wicca(男性の邪術師)」だった[33]。 オックスフォード英語辞典によると、wicce と wicca は、おそらく「妖術を使う」という意味の古英語動詞 wiccian から派生したものだ。[34] Wiccian には、中低ドイツ語の wicken(13 世紀から確認されている)に同源語がある。この単語のさらに深い語源は問題が多い。英語と低地ドイツ語以外のゲルマン語には明確な同源語がなく、インド・ ヨーロッパ語族の語源についても複数の可能性が考えられる。 「妖術師」を表す別の古英語は「hægtes」または「hægtesse」で、これは現代英語の「hag」となり、「hex」という言葉と関連している。 他のほとんどのゲルマン語では、「魔女」を表す単語はこれらと同じ語源から派生している。例えば、ドイツ語の「Hexe」やオランダ語の「heks」など だ。[35] 口語的な現代英語では、「妖術師(魔女)」という単語は特に女性に対して使用される。[36] 呪術や妖術を行う男性は、より一般的には「wizard」または「warlock」と呼ばれる。「witch」という単語が、新異教の伝統や宗教(ウィッ カなど)の信者を指す場合、それはあらゆる性別の者を指すことがある。[37] |

Beliefs about practices Preparation for the Witches' Sabbath by David Teniers the Younger. It shows a witch brewing a potion overlooked by her familiar spirit or a demon; items on the floor for casting a spell; and another witch reading from a grimoire while anointing the buttocks of a young witch about to fly upon an inverted besom. Witches are commonly believed to cast curses; a spell or set of magical words and gestures intended to inflict supernatural harm.[38] Cursing could also involve inscribing runes or sigils on an object to give that object magical powers; burning or binding a wax or clay image (a poppet) of a person to affect them magically; or using herbs, animal parts and other substances to make potions or poisons.[39][40][41][22] Witchcraft has been blamed for many kinds of misfortune. In Europe, by far the most common kind of harm attributed to witchcraft was illness or death suffered by adults, their children, or their animals. "Certain ailments, like impotence in men, infertility in women, and lack of milk in cows, were particularly associated with witchcraft". Illnesses that were poorly understood were more likely to be blamed on witchcraft. Edward Bever writes: "Witchcraft was particularly likely to be suspected when a disease came on unusually swiftly, lingered unusually long, could not be diagnosed clearly, or presented some other unusual symptoms".[42] A common belief in cultures worldwide is that witches tend to use something from their target's body to work magic against them; for example hair, nail clippings, clothing, or bodily waste.[22] Such beliefs are found in Europe, Africa, South Asia, Polynesia, Melanesia, and North America.[22] Another widespread belief among Indigenous peoples in Africa and North America is that witches cause harm by introducing cursed magical objects into their victim's body; such as small bones or ashes.[22] James George Frazer described this kind of magic as imitative.[a] In some cultures, witches are believed to use human body parts in magic,[22] and they are commonly believed to murder children for this purpose. In Europe, "cases in which women did undoubtedly kill their children, because of what today would be called postpartum psychosis, were often interpreted as yielding to diabolical temptation".[44] Witches are believed to work in secret, sometimes alone and sometimes with other witches. Hutton writes: "Across most of the world, witches have been thought to gather at night, when normal humans are inactive, and also at their most vulnerable in sleep".[22] In most cultures, witches at these gatherings are thought to transgress social norms by engaging in cannibalism, incest and open nudity.[22] Witches around the world commonly have associations with animals.[45] Rodney Needham identified this as a defining feature of the witch archetype.[46] In some parts of the world, it is believed witches can shapeshift into animals,[47] or that the witch's spirit travels apart from their body and takes an animal form, an activity often associated with shamanism.[47] Another widespread belief is that witches have an animal helper.[47] In English these are often called "familiars", and meant an evil spirit or demon that had taken an animal form.[47] As researchers examined traditions in other regions, they widened the term to servant spirit-animals which are described as a part of the witch's own soul.[48] Necromancy is the practice of conjuring the spirits of the dead for divination or prophecy, although the term has also been applied to raising the dead for other purposes. The biblical Witch of Endor performed it (1 Samuel 28th chapter), and it is among the witchcraft practices condemned by Ælfric of Eynsham:[49][50][51] "Witches still go to cross-roads and to heathen burials with their delusive magic and call to the devil; and he comes to them in the likeness of the man that is buried there, as if he arises from death."[52] |

慣習に関する信念 デヴィッド・テニールス・ザ・ヤングによる「魔女の安息日の準備」。妖術師が、使い魔や悪魔に見守られながら薬を調合している様子、呪文を唱えるために床 に置かれた道具、そして、逆さまに立てたほうきに乗って飛び立とうとしている若い妖術師の臀部に油を塗りながら、魔術書を読む別の妖術師が描かれている。 妖術師は、超自然的な害を与えることを目的とした呪文や一連の呪術的な言葉や身振りを使って呪いをかけるものと一般に信じられている[38]。呪いには、 ある物体にルーン文字や印を刻んでその物体に呪術的な力を与える、人物の蝋人形や粘土人形(ポペット)を燃やしたり縛ったりしてその人物に呪術的な影響を 与える、あるいはハーブや動物の部位、その他の物質を使って薬や毒を作るといった行為も含まれる。[39][40][41][22] 妖術は、さまざまな不幸の原因とされてきた。ヨーロッパでは、妖術による害として最もよく見られたのは、大人、子供、または家畜が苦しむ病気や死だった。 「男性の不妊、女性の不妊、牛の乳の出ない病気などの特定の病気は、特に妖術と関連していた」。よく理解されていない病気は、妖術のせいにされる傾向が強 かった。エドワード・ベバーは、「妖術は、病気が異常に早く発症したり、異常に長く続いたり、明確に診断できなかったり、その他の異常な症状が見られた場 合に、特に疑われる傾向があった」と書いている。[42] 世界中の文化に共通する信念として、妖術師は、その対象者の体から何か(例えば、髪の毛、爪の切り屑、衣服、排泄物など)を使って呪術を行う傾向があると いうものがある。[22] このような信念は、ヨーロッパ、アフリカ、南アジア、ポリネシア、メラネシア、北米で見られる。[22] アフリカと北アメリカの先住民の間で広く信じられているもう一つの信念は、妖術師は、小さな骨や灰などの呪われた呪術的な物を被害者の体内に導入すること で害を与えるというものです。[22] ジェームズ・ジョージ・フレイザーは、この種の呪術を模倣的であると表現しています。[a] 一部の文化では、妖術師は呪術に人間の身体の一部を使用すると考えられており[22]、この目的のために子供たちを殺害すると一般に信じられている。ヨー ロッパでは、「今日では産後精神病と呼ばれるような症状のために、女性が間違いなく自分の子供たちを殺害したケースも、悪魔の誘惑に屈したものと解釈され ることが多かった」[44]。 妖術師は、時には単独で、時には他の妖術師たちと協力して、秘密裏に活動していると信じられている。ハットンは、「世界のほとんどの地域では、妖術師たち は、普通の人間が活動していない夜、そして最も無防備な睡眠中に集まるものと信じられている」と書いている。[22] ほとんどの文化では、こうした集会に参加する妖術師たちは、人食いや近親相姦、公然と裸になるなど、社会規範に違反する行為を行っていると考えられてい る。[22] 世界中の妖術師は、一般的に動物と関連付けられている。[45] ロドニー・ニーダムは、これを妖術師の原型を特徴づける要素として特定した。[46] 世界の一部の地域では、妖術師は動物に変身できると信じられている。[47] あるいは、妖術師の魂は身体から分離して動物の形をとる、と信じられている。これは、シャーマニズムと関連付けられることが多い活動だ。[47] もう一つの広く信じられている説は、妖術師には動物の助手がいるというものです。[47] 英語では、これらはしばしば「ファミリア」と呼ばれ、動物の姿をした悪霊や悪魔を意味します。[47] 研究者たちは他の地域の伝統を調査するうちに、この用語を、妖術師自身の魂の一部として記述される、使用人の霊獣にまで拡大しました。[48] ネクロマンシーは、占いや予言のために死者の霊を召喚する行為を指すが、この用語は他の目的で死者を蘇らせる行為にも適用されることがある。聖書のエンド アの魔女がこれを行った(サムエル記上 28 章)とされており、これは、アインシャムのエルフリックが非難した妖術の慣習のひとつでもある[49][50][51]。「妖術師たちは、今でも、その欺 く呪術を駆使して、十字路や異教徒の埋葬地へ行き、悪魔を呼び出す。すると、悪魔は、そこに埋葬されている人間の姿で、まるで死から蘇ったかのように彼ら の前に現れる。[52] |

| Witchcraft and folk healers Main article: Cunning folk  Diorama of a cunning woman or wise woman in the Museum of Witchcraft and Magic Most societies that have believed in harmful or black magic have also believed in helpful or white magic.[53] Where belief in harmful magic is common, it is typically forbidden by law as well as hated and feared by the general populace, while helpful or apotropaic (protective) magic is tolerated or accepted by the population, even if the orthodox establishment opposes it.[54] In these societies, practitioners of helpful magic provide (or provided) services such as breaking the effects of witchcraft, healing, divination, finding lost or stolen goods, and love magic.[55] In Britain, and some other parts of Europe, they were commonly known as 'cunning folk' or 'wise people'.[55] Alan Macfarlane wrote that while cunning folk is the usual name, some are also known as 'blessers' or 'wizards', but might also be known as 'white', 'good', or 'unbinding witches'.[56] Historian Owen Davies says the term "white witch" was rarely used before the 20th century.[57] Ronald Hutton uses the general term "service magicians".[55] Often these people were involved in identifying alleged witches.[53] Such helpful magic-workers "were normally contrasted with the witch who practiced maleficium—that is, magic used for harmful ends".[58] In the early years of the European witch hunts "the cunning folk were widely tolerated by church, state and general populace".[58] Some of the more hostile churchmen and secular authorities tried to smear folk-healers and magic-workers by falsely branding them 'witches' and associating them with harmful 'witchcraft',[55] but generally the masses did not accept this and continued to make use of their services.[59] The English MP and skeptic Reginald Scot sought to disprove magic and witchcraft altogether, writing in The Discoverie of Witchcraft (1584), "At this day, it is indifferent to say in the English tongue, 'she is a witch' or 'she is a wise woman'".[60] Historian Keith Thomas adds "Nevertheless, it is possible to isolate that kind of 'witchcraft' which involved the employment (or presumed employment) of some occult means of doing harm to other people in a way which was generally disapproved of. In this sense the belief in witchcraft can be defined as the attribution of misfortune to occult human agency".[4] Emma Wilby says folk magicians in Europe were viewed ambivalently by communities, and were considered as capable of harming as of healing,[61] which could lead to their being accused as malevolent witches. She suggests some English "witches" convicted of consorting with demons may have been cunning folk whose supposed fairy familiars had been demonised.[62] Hutton says that magical healers "were sometimes denounced as witches, but seem to have made up a minority of the accused in any area studied".[53] Likewise, Davies says "relatively few cunning-folk were prosecuted under secular statutes for witchcraft" and were dealt with more leniently than alleged witches. The Constitutio Criminalis Carolina (1532) of the Holy Roman Empire, and the Danish Witchcraft Act of 1617, stated that workers of folk magic should be dealt with differently from witches.[63] It was suggested by Richard Horsley that 'diviner-healers' (devins-guerisseurs) made up a significant proportion of those tried for witchcraft in France and Switzerland, but more recent surveys conclude that they made up less than 2% of the accused.[64] However, Éva Pócs says that half the accused witches in Hungary seem to have been healers,[65] and Kathleen Stokker says the "vast majority" of Norway's accused witches were folk healers.[66] |

妖術と民間治療師 主な記事:狡猾な民間治療師  魔女と魔法の博物館にある、狡猾な女性または賢い女性のジオラマ 有害な魔法や黒魔術を信じるほとんどの社会は、有益な魔法や白魔術も信じています。[53] 有害な魔法の信仰が一般的な地域では、通常、その魔法は法律で禁止されているだけでなく、一般大衆からも嫌われ、恐れられています。一方、有益な魔法や魔 除け(保護)の魔法は、正統派が反対しても、大衆からは容認または受け入れられています。[54] これらの社会では、有益な魔法の術者は、妖術の効果を打ち破る、治療、占い、紛失物や盗品の捜索、恋愛の魔法などのサービスを提供している(または提供し ていた)。[55] 英国やヨーロッパの一部の地域では、彼らは「狡猾な民」または「賢者」として広く知られていた。[55] アラン・マクファーレンは、狡猾な民衆は一般的な名称であるが、一部は「祝福者」や「魔法使い」としても知られているが、「白い」、「良い」、「束縛を解 く魔女」としても知られていると書いている。[56] 歴史家のオーウェン・デービスは、「白い魔女」という用語は 20 世紀以前はほとんど使用されていなかったと述べています。[57] ロナルド・ハットンは、一般的な用語として「サービスマジシャン」を使用しています。[55] 多くの場合、これらの人々は、妖術師と疑われる人物の特定に関わっていた[53]。 このような有益な呪術師は、「通常、有害な目的のために呪術、すなわち有害な呪術を行う妖術師とは対照的だった」[58]。ヨーロッパの魔女狩りが始まっ た当初、「狡猾な民衆は、教会、国家、そして一般大衆から広く容認されていた」[59]。[58] より敵対的な教会関係者や世俗当局者は、民間治療師や呪術師たちを「魔女」と偽って烙印を押し、有害な「妖術」と関連付けて中傷しようとしたが[55]、 一般大衆はこれを認めず、彼らのサービスを利用し続けた。[59] 英国の議員で懐疑論者のレジナルド・スコットは、呪術と妖術を完全に否定しようとし、『The Discoverie of Witchcraft』(1584年)の中で、「今日では、英語では『彼女は魔女だ』と『彼女は賢い女性だ』と言うことは同じ意味だ」と書いている。 [60] 歴史家のキース・トーマスは、「それにもかかわらず、一般的に非難されるような方法で他の人々に害を与えるための何らかのオカルト的な手段の使用(または その使用の推定)を伴う、そのような「妖術」を分離することは可能だ。この意味で、妖術の信仰は、オカルト的な人間の行為に不幸の原因を求めるものと定義 することができる」と付け加えている。[4] エマ・ウィルビーは、ヨーロッパの民俗魔術師は、コミュニティから両義的に見られ、癒す能力と同じくらい害を与える能力もあるとみなされていた[61]た め、悪意のある魔女として告発される可能性があったと述べています。彼女は、悪魔と交わると有罪判決を受けた一部の英国の「魔女」は、妖精の使い魔が悪魔 化されていた、狡猾な民俗魔術師であった可能性があると指摘しています[62]。 ハットンは、呪術師は「時には魔女として非難されたが、調査したどの地域でも、被告人の少数派だったようだ」と述べています。[53]同様に、デービス は、「世俗法に基づいて妖術で起訴された狡猾な民衆は比較的少なく、魔女とされた者よりも寛大な処分を受けた」と述べています。神聖ローマ帝国の「犯罪憲 法」(1532年)および1617年のデンマークの妖術法では、民間呪術師は妖術師とは異なって扱われるべきであると規定されていた。[63] リチャード・ホースリーは、「占い師・治療師」 (devins-guerisseurs)が、フランスとスイスで妖術師として裁判にかけられた人々のかなりの割合を占めていたと主張しているが、最近の 調査では、その割合は被告人の 2% 未満であると結論付けられている。[64] しかし、エヴァ・ポックスは、ハンガリーで妖術師として告発された人々の半数は治療師であったようだと述べ、[65] キャスリーン・ストッカーは、ノルウェーで告発された妖術師の大半は民間治療師であったと述べている。[66] |

| Witch-hunts and thwarting witchcraft The examples and perspective in this section may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. You may improve this section, discuss the issue on the talk page, or create a new section, as appropriate. (August 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  A witch bottle, used as counter-magic against witchcraft Societies that believe (or believed) in witchcraft may also believe that it can be thwarted in various ways. One common way is to use protective magic or counter-magic, often with the help of magical healers such as cunning folk or witch-doctors.[53] This includes performing rituals, reciting charms, or the use of talismans, amulets, anti-witch marks, witch bottles, witch balls, and burying objects such as horse skulls inside the walls of buildings.[67] Another believed cure for bewitchment is to persuade or force the alleged witch to lift their spell.[53] Often, people have attempted to thwart the witchcraft by physically punishing the alleged witch, such as by banishing, wounding, torturing or killing them. Hutton wrote that "In most societies, however, a formal and legal remedy was preferred to this sort of private action", whereby the alleged witch would be prosecuted and then formally punished if found guilty.[53] |

魔女狩りと妖術の阻止 このセクションの例や見解は、このテーマに関する世界的な見解を必ずしも反映しているわけではない。このセクションを改善したり、トークページで議論した り、必要に応じて新しいセクションを作成したりすることができる。(2023年8月) (このメッセージの削除方法と時期についてはこちらをご覧ください)  妖術に対する呪術として使われる呪薬瓶 妖術を信じる(または信じていた)社会では、妖術はさまざまな方法で阻止できると信じられている場合もある。一般的な方法としては、保護呪術や対抗呪術を 使用することが挙げられ、多くの場合、狡猾な民間治療師や呪術師などの呪術師の助けを借りる。[53] これには、儀式を行う、呪文を唱える、お守り、護符、妖術師対策の印、妖術師瓶、妖術師玉を使用したり、馬の頭蓋骨などの物を建物の壁の中に埋めることな どが含まれる。[67] 妖術のもう一つの治療法は、妖術師とされる人物に呪いを解くよう説得または強制することだ。[53] 多くの場合、人々は、妖術師とされる人物を追放、負傷、拷問、殺害するなど、身体的な罰を与えることで妖術を阻止しようとしてきた。ハットンは、「しか し、ほとんどの社会では、この種の私的行為よりも、正式な法的措置が好まれた」と書いており、それにより、妖術師と疑われた者は起訴され、有罪判決を受け た場合は正式に罰せられた。[53] |

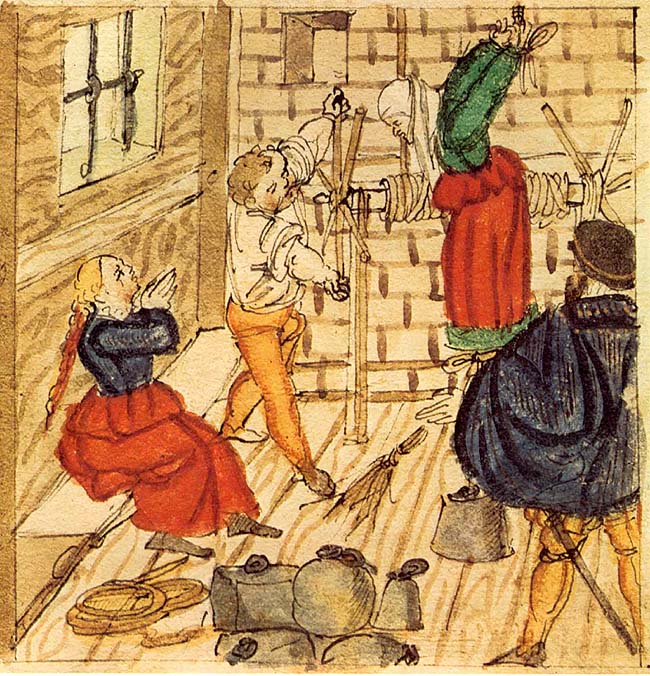

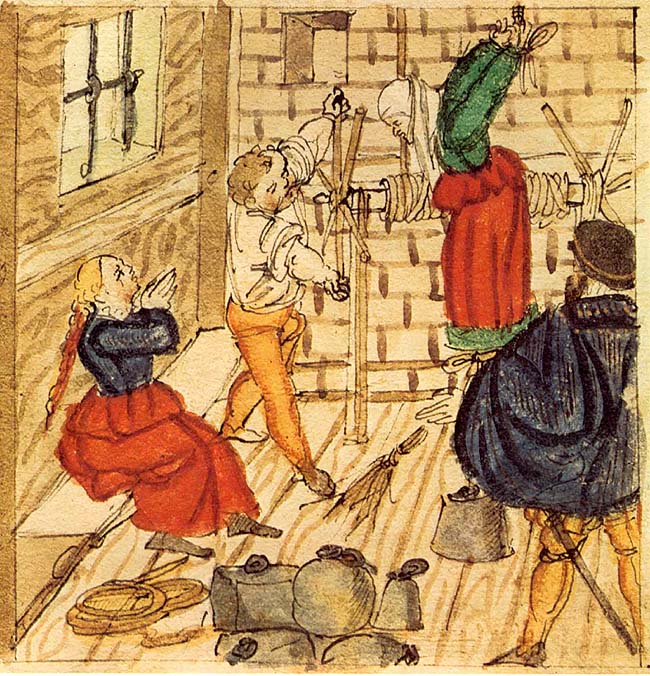

Accusations of witchcraft The torture used against accused witches, 1577 Throughout the world, accusations of witchcraft are often linked to social and economic tensions. Females are most often accused, but in some cultures it is mostly males, such as in Iceland.[68] In many societies, accusations are directed mainly against the elderly, but in others age is not a factor, and in some cultures it is mainly adolescents who are accused.[69] Éva Pócs writes that reasons for accusations of witchcraft fall into four general categories. The first three of which were proposed by Richard Kieckhefer, and the fourth added by Christina Larner:[70] 1. A person was caught in the act of positive or negative sorcery 2. A well-meaning sorcerer or healer lost their clients' or the authorities' trust 3. A person did nothing more than gain the enmity of their neighbors 4. A person was reputed to be a witch and surrounded with an aura of witch-beliefs or occultism. |

妖術の告発 1577年に妖術師と非難された者たちに対する拷問 世界中で、妖術の告発はしばしば社会的、経済的緊張と関連している。告発されるのはほとんどの場合女性だが、アイスランドなど一部の文化では主に男性が告 発される[68]。多くの社会では、告発は主に高齢者を対象としているが、年齢は要因とならない社会もあり、一部の文化では主に青少年が告発される [69]。 エヴァ・ポックスは、妖術の告発理由は 4 つの大分類に分類できると述べています。最初の 3 つはリチャード・キークヘファーが提案したもので、4 つ目はクリスティーナ・ラーナーが追加したものです[70]。 1. ポジティブまたはネガティブな妖術の行為で捕まった 2. 善意の邪術師や治療師が、顧客や当局の信頼を失った 3. ある人物が、隣人の敵意を買うような行為をした 4. ある人物が、妖術師であると評判になり、妖術師やオカルトの信奉者たちに取り囲まれた。 |

| Modern witch-hunts Main articles: Witch-hunt, Witch trials in the early modern period, and Modern witch-hunts Witch-hunts, scapegoating, and the shunning or murder of suspected witches still occurs.[71] Many cultures worldwide continue to have a belief in the concept of "witchcraft" or malevolent magic.[72] Apart from extrajudicial violence, state-sanctioned execution also occurs in some jurisdictions. For instance, in Saudi Arabia practicing witchcraft and sorcery is a crime punishable by death and the country has executed people for this crime as recently as 2014.[73][74][75] Witchcraft-related violence is often discussed as a serious issue in the broader context of violence against women.[76][77][78][79][80] In Tanzania, an estimated 500 older women are murdered each year following accusations of witchcraft or accusations of being a witch, according to a 2014 World Health Organization report.[81] Children who live in some regions of the world, such as parts of Africa, are also vulnerable to violence stemming from witchcraft accusations.[82][83][84][85] Such incidents have also occurred in immigrant communities in Britain, including the much publicized case of the murder of Victoria Climbié.[86][87] |

現代のウイッチハント 主な記事:ウイッチハント、近世における魔女裁判、現代のウイッチハント 魔女狩り、スケープゴート、魔女容疑者の追放や殺害は、今でも起こっている。[71] 世界中の多くの文化では、「妖術」や悪意のある魔法という概念が今でも信じられている。[72] 超法規的暴力とは別に、一部の法域では国家が認可した死刑も執行されている。例えば、サウジアラビアでは、妖術や魔術を実践することは死刑に処せられる犯罪であり、2014 年にもこの犯罪で人々が処刑されている。[73][74][75] 妖術に関連する暴力は、女性に対する暴力というより広い文脈の中で深刻な問題としてしばしば議論されている。[76][77][78][79][80] 2014年の世界保健機関(WHO)の報告によると、タンザニアでは、妖術の容疑または妖術師であるとの非難を受けて、毎年推定 500 人の高齢女性が殺害されている。[81] アフリカの一部など、世界の一部の地域に住む子供たちも、妖術の容疑による暴力にさらされている。[82][83][84][85] このような事件は、ビクトリア・クリムビーの殺害事件など、英国の移民コミュニティでも発生している。[86][87] |

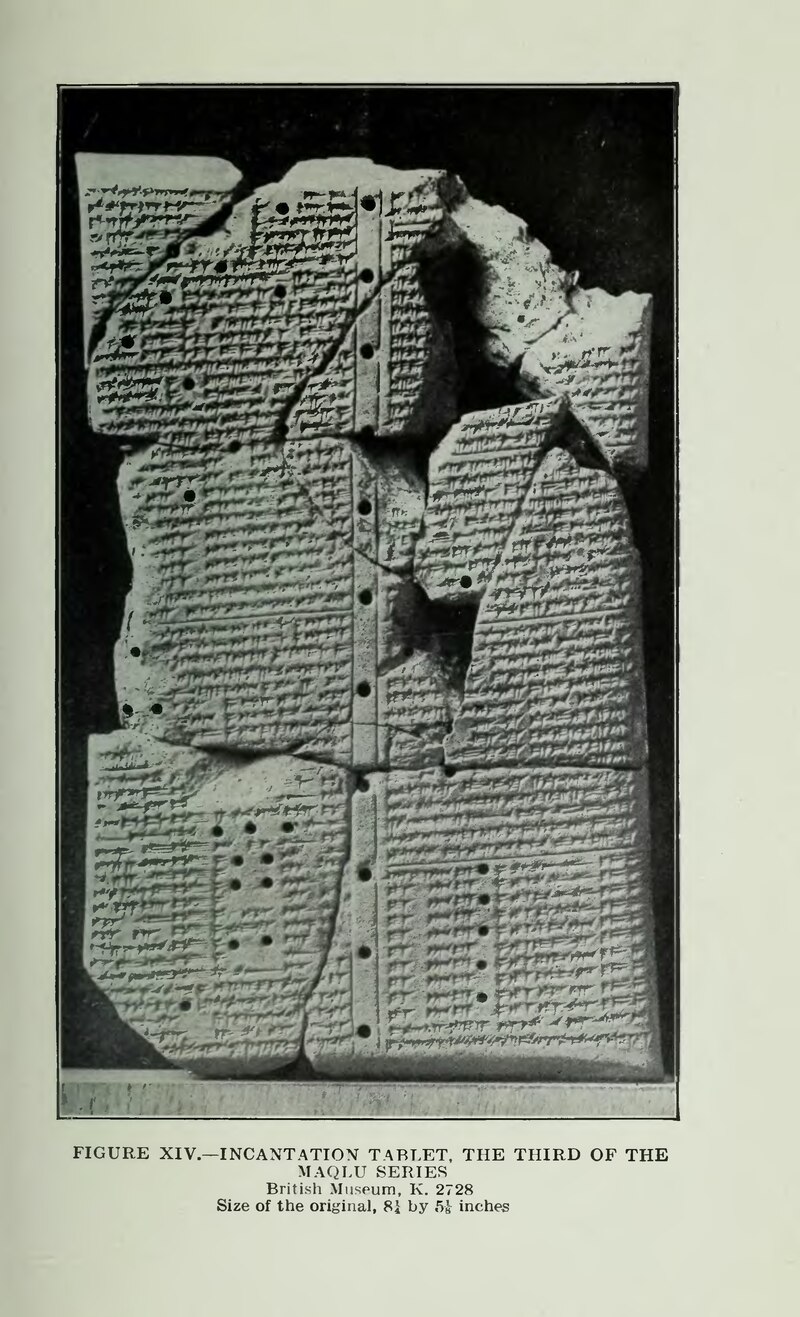

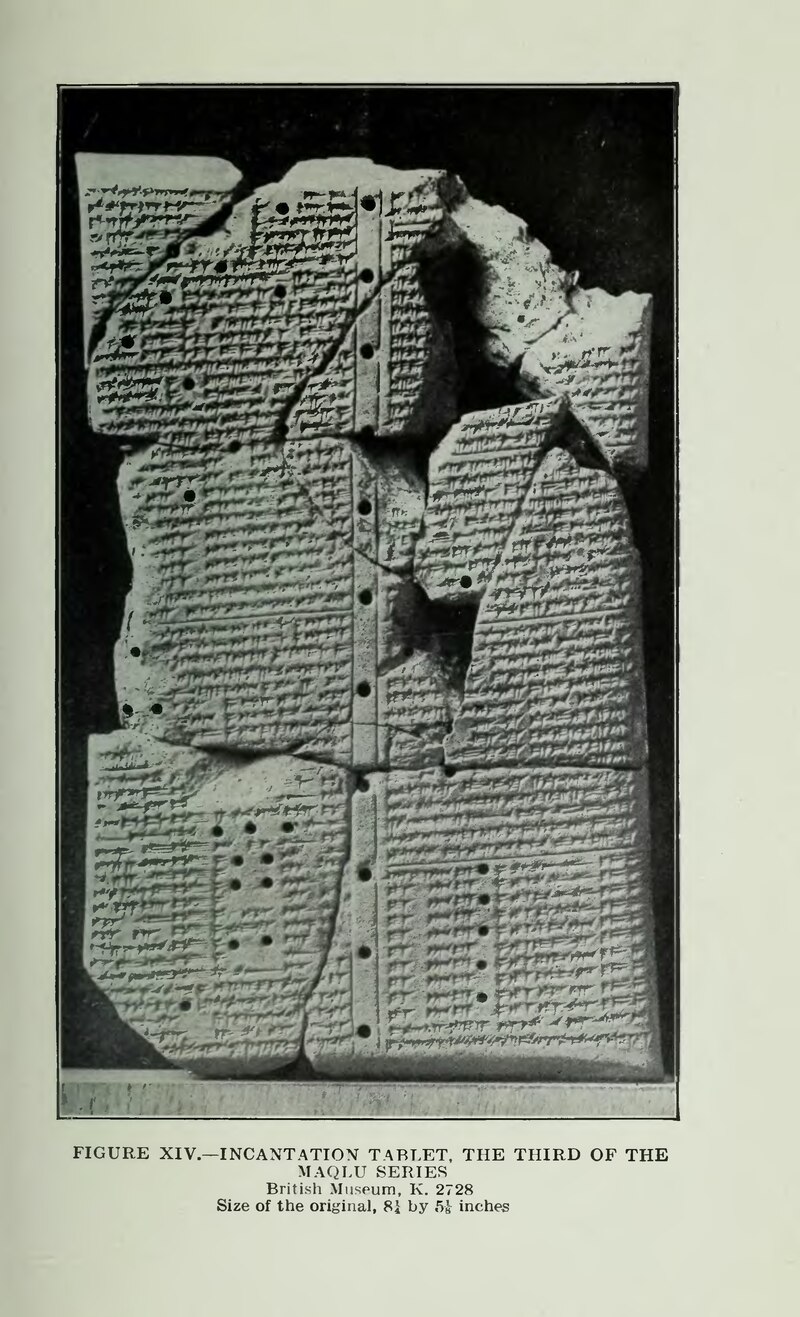

| Religious perspectives Ancient Mesopotamian religion  A clay tablet from the Maqlû, outlining an ancient Akkadian anti-witchcraft ritual. Main article: Witchcraft in the Middle East Magic was an important part of ancient Mesopotamian religion and society, which distinguished between 'good' (helpful) and 'bad' (harmful) rites.[88] In ancient Mesopotamia, they mainly used counter-magic against witchcraft (kišpū[89]), but the law codes also prescribed the death penalty for those found guilty of witchcraft.[88] According to Tzvi Abusch, ancient Mesopotamian ideas about witches and witchcraft shifted over time, and the early stages were "comparable to the archaic shamanistic stage of European witchcraft".[90] In this early stage, witches were not necessarily considered evil, but took 'white' and 'black' forms, could help others using magic and medical knowledge, generally lived in rural areas and sometimes exhibited ecstatic behavior.[90] In ancient Mesopotamia, a witch (m. kaššāpu, f. kaššāptu, from kašāpu ['to bewitch'][89]) was "usually regarded as an anti-social and illegitimate practitioner of destructive magic ... whose activities were motivated by malice and evil intent and who was opposed by the ašipu, an exorcist or incantation-priest".[90] These ašipu were predominantly male representatives of the state religion, whose main role was to work magic against harmful supernatural forces such as demons.[90] The stereotypical witch mentioned in the sources tended to be those of low status who were weak or otherwise marginalized, including women, foreigners, actors, and peddlers.[88] The Law Code of Hammurabi (18th century BCE) allowed someone accused of witchcraft (harmful magic) to undergo trial by ordeal, by jumping into a holy river. If they drowned, they were deemed guilty and the accuser inherited the guilty person's estate. If they survived, the accuser's estate was handed over instead.[88] The Maqlû ("burning") is an ancient Akkadian text, written early in the first millennium BCE, which sets out a Mesopotamian anti-witchcraft ritual.[91] This lengthy ritual includes invoking various gods, burning an effigy of the witch, then dousing and disposing of the remains.[92] |

宗教的見解 古代メソポタミアの宗教  マクルから出土した粘土板。古代アッカドの妖術対策の儀式が記されている。 主な記事:中東の妖術 呪術は、古代メソポタミアの宗教および社会において重要な役割を果たしており、「良い」(有益な)儀式と「悪い」(有害な)儀式が区別されていた [88]。古代メソポタミアでは、主に妖術に対する対抗呪術(kišpū[89])が用いられていたが、法典では、妖術の罪で有罪となった者には死刑が科 せられることも規定されていた。[88] Tzvi Abusch によると、妖術師や妖術に関する古代メソポタミアの考え方は、時間の経過とともに変化し、初期の段階は「ヨーロッパの妖術の古風なシャーマニズムの段階に 匹敵する」ものでした。[90] この初期の段階では、妖術師は必ずしも悪とみなされていたわけではなく、「白」と「黒」の2つの形態を取り、呪術や医学の知識を使って他人を助け、一般的 には農村部に住み、時には恍惚状態になるような行動を見せた。[90] 古代メソポタミアでは、魔女(m. kaššāpu、f. kaššāptu、kašāpu [「魅惑する」] から)は、「通常、破壊的な魔法を使う反社会的で非合法な術者...その活動は悪意と邪悪な意図によって動機付けられ、アシュピ、つまり悪魔祓い師や呪術 師によって反対されていた」とみなされていた。[90] これらのアシュピは、主に国家宗教の代表である男性で、悪魔などの有害な超自然的な力に対して呪術を行うことを主な役割としていた[90]。資料に言及さ れている典型的な妖術師は、女性、外国人、俳優、行商人など、弱者または社会から疎外された低地位の人たちだった[88]。 ハンムラビ法典(紀元前 18 世紀)では、妖術(有害な呪術)で告発された者は、聖なる川に飛び込む試練による裁判を受けることが認められていた。溺死した者は有罪とみなされ、告発者は有罪者の財産を相続した。生き残った場合は、告発者の財産が譲渡された。[88] Maqlû(「燃焼」)は、紀元前 1000 年代初頭に書かれた古代アッカド語の文書で、メソポタミアの妖術対策の儀式について記している。[91] この長い儀式には、さまざまな神々の召喚、妖術師の像の焼却、その遺体の水浸しと処分などが含まれる。[92] |

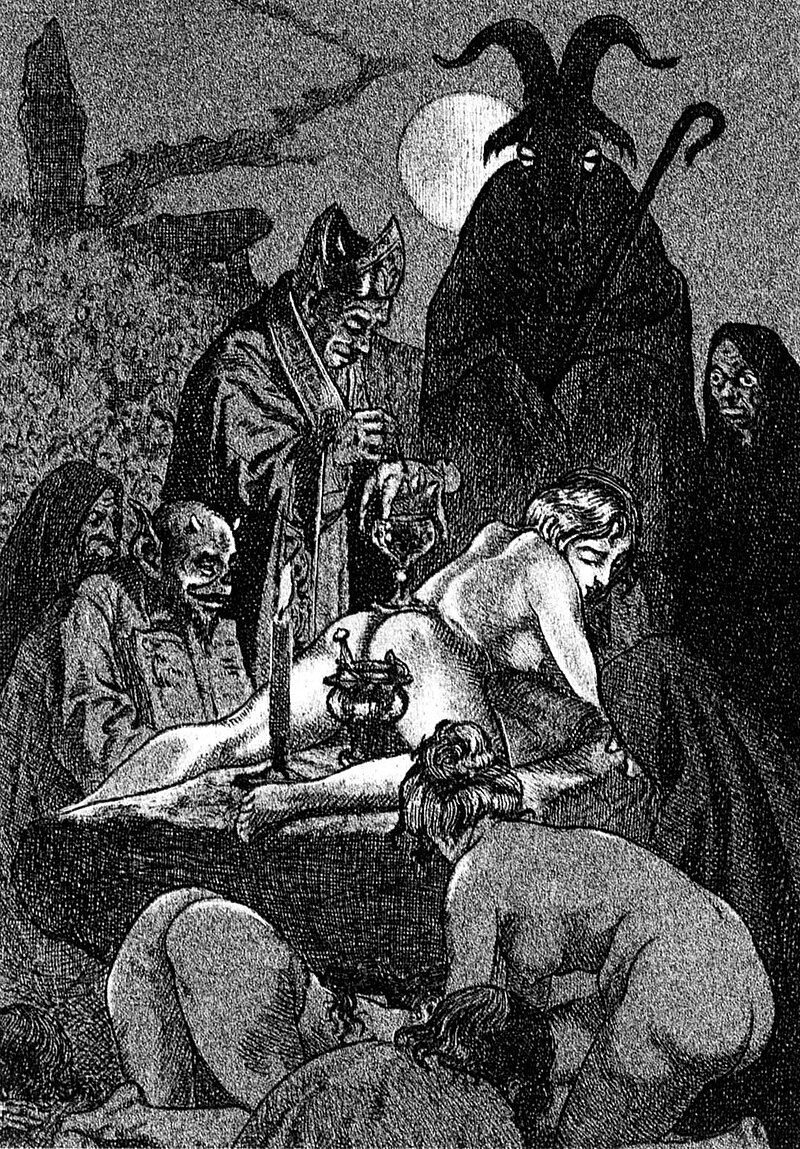

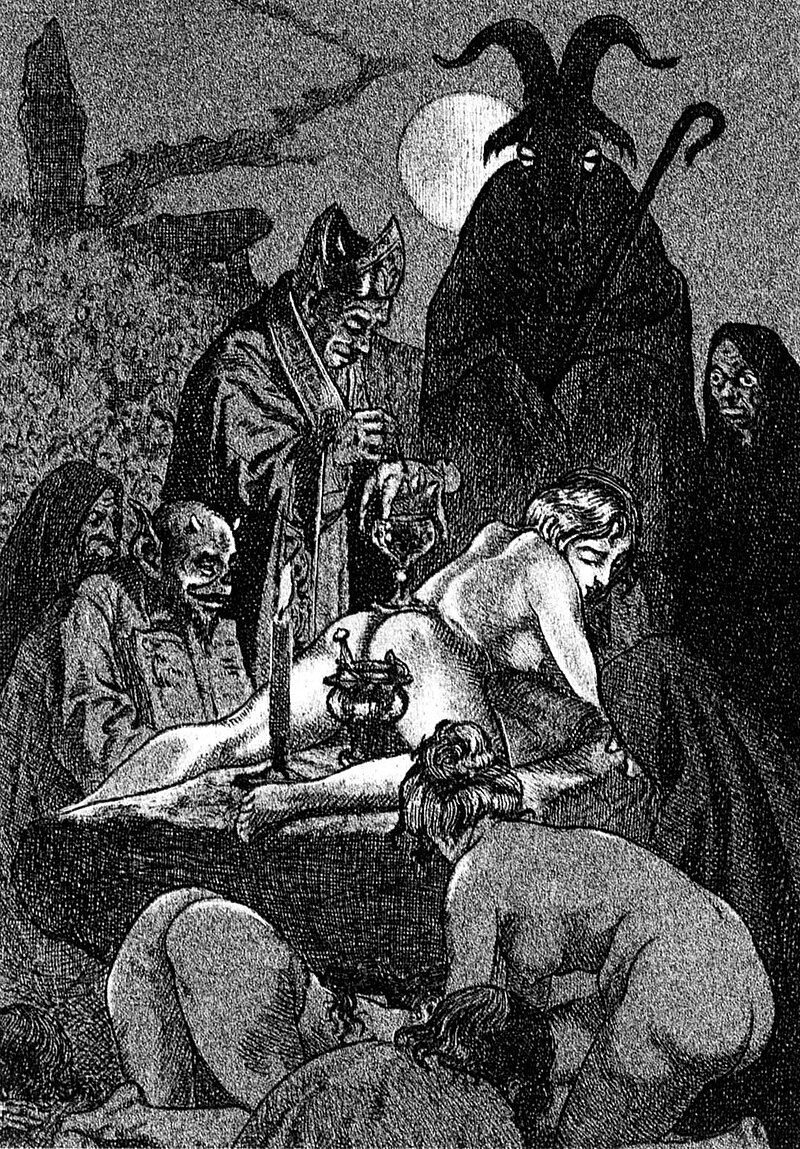

| Abrahamic religions Witchcraft's historical evolution in the Middle East reveals a multi-phase journey influenced by culture, spirituality, and societal norms. Ancient witchcraft in the Near East intertwined mysticism with nature through rituals and incantations aligned with local beliefs. In ancient Judaism, magic had a complex relationship, with some forms accepted due to mysticism[93] while others were considered heretical.[94] The medieval Middle East experienced shifting perceptions of witchcraft under Islamic and Christian influences, sometimes revered for healing and other times condemned as heresy. Jewish See also: Witchcraft and divination in the Hebrew Bible Jewish attitudes toward witchcraft were rooted in its association with idolatry and necromancy, and some rabbis even practiced certain forms of magic themselves.[95][96] References to witchcraft in the Tanakh, or Hebrew Bible, highlighted strong condemnations rooted in the "abomination" of magical belief. Christianity similarly condemned witchcraft, considering it an abomination and even citing specific verses to justify witch-hunting during the early modern period. Christian  Illustration by Martin van Maële of a Witches' Sabbath and Black Mass overseen by a horned Devil, in the 1911 edition of La Sorcière, by Jules Michelet Main article: Christian views on magic Historically, the Christian concept of witchcraft derives from Old Testament laws against it. In medieval and early modern Europe, many Christians believed in magic. As opposed to the helpful magic of the cunning folk, witchcraft was seen as evil and associated with Satan and Devil worship. This often resulted in deaths, torture and scapegoating (casting blame for misfortune),[97][98] and many years of large scale witch-trials and witch hunts, especially in Protestant Europe, before largely ending during the Age of Enlightenment. Christian views in the modern day are diverse, ranging from intense belief and opposition (especially by Christian fundamentalists) to non-belief. During the Age of Colonialism, many cultures were exposed to the Western world via colonialism, usually accompanied by intensive Christian missionary activity (see Christianization). In these cultures, beliefs about witchcraft were partly influenced by the prevailing Western concepts of the time. In Christianity, sorcery came to be associated with heresy and apostasy and to be viewed as evil. Among Catholics, Protestants, and the secular leadership of late medieval/early modern Europe, fears about witchcraft rose to fever pitch and sometimes led to large-scale witch-hunts. The fifteenth century saw a dramatic rise in awareness and terror of witchcraft. Tens of thousands of people were executed, and others were imprisoned, tortured, banished, and had lands and possessions confiscated. The majority of those accused were women, though in some regions the majority were men.[99][100]: 23 In Scots, the word warlock came to be used as the male equivalent of witch (which can be male or female, but is used predominantly for females).[101][102] The Malleus Maleficarum (Latin for 'Hammer of The Witches') was a witch-hunting manual written in 1486 by two German monks, Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger. It was used by both Catholics and Protestants[103] for several hundred years, outlining how to identify a witch, what makes a woman more likely than a man to be a witch, how to put a witch on trial, and how to punish a witch. The book defines a witch as evil and typically female. It became the handbook for secular courts throughout Europe, but was not used by the Inquisition, which even cautioned against relying on it.[104] It was the most sold book in Europe for over 100 years, after the Bible.[105] Islamic Main article: Islam and magic Islamic perspectives on magic encompass a wide range of practices,[106] with belief in black magic and the evil eye coexisting alongside strict prohibitions against its practice.[107] The Quran acknowledges the existence of magic and seeks protection from its harm. Islam's stance is against the practice of magic, considering it forbidden, and emphasizes divine miracles rather than magic or witchcraft.[108] The historical continuity of witchcraft in the Middle East underlines the complex interaction between spiritual beliefs and societal norms across different cultures and epochs. |

アブラハムの宗教 中東における妖術の歴史的進化は、文化、精神性、社会規範の影響を受けた多段階の過程を明らかにしている。近東の古代の妖術は、地元の信仰に合わせた儀式 や呪文を通じて、神秘主義と自然を絡み合わせていた。古代ユダヤ教では、呪術は複雑な関係にあり、神秘主義のために受け入れられるもの[93] もあれば、異端とみなされるもの[94] もありました。中世の中東では、イスラム教とキリスト教の影響を受けて、妖術に対する認識が変化し、時には癒しの力として崇められ、時には異端として非難 されました。 ユダヤ教 参照:ヘブライ語聖書における妖術と占術 ユダヤ教の妖術に対する態度は、偶像崇拝や降霊術との関連に根ざしており、一部のラビは、ある種の呪術を自ら実践していた[95][96]。タナク(ヘブ ライ語聖書)における妖術に関する言及は、呪術的信念の「忌まわしい行為」に根ざした強い非難を強調している。キリスト教も同様に妖術を忌まわしい行為と 非難し、近世初期には、ウイッチハントを正当化するために特定の聖句を引用した。 キリスト教  1911年版のジュール・ミシュレの『La Sorcière』に掲載された、角のある悪魔が監督する魔女たちの安息日と黒ミサを描いたマーティン・ヴァン・マエレのイラスト 主な記事:キリスト教の呪術観 歴史的に、キリスト教の妖術の概念は、それを禁じる旧約聖書の法律に由来している。中世および近世ヨーロッパでは、多くのキリスト教徒が呪術を信じてい た。狡猾な民衆の役立つ魔法とは対照的に、妖術は悪とみなされ、悪魔や悪魔崇拝と関連付けられていた。これはしばしば、死、拷問、スケープゴート(不幸の 責任を転嫁すること)につながり[97][98]、特にプロテスタントのヨーロッパでは、啓蒙時代までにほぼ終焉を迎えるまで、長年にわたる大規模な魔女 裁判やウイッチハントが行われた。現代のキリスト教徒の見方は、強い信念や反対(特にキリスト教原理主義者によるもの)から、まったく信じないものまでさ まざまです。植民地時代、多くの文化は植民地主義によって西洋の世界に接触し、その多くは、激しいキリスト教の布教活動(キリスト教化を参照)を伴いまし た。これらの文化では、妖術に関する信念は、当時の西洋の一般的な概念に一部影響を受けていました。 キリスト教では、魔術は異端や背教と関連付けられ、悪とみなされるようになった。カトリック教徒、プロテスタント、そして中世後期から近世初期のヨーロッ パの世俗的指導者たちの間で、妖術に対する恐怖が最高潮に達し、時には大規模なウイッチハントにつながった。15 世紀には、妖術に対する認識と恐怖が劇的に高まった。何万人もの人々が処刑され、その他多くの人々が投獄、拷問、追放され、土地や財産を没収された。告発 された者の大半は女性だったが、一部の地域では男性が過半数を占めていた[99][100]: 23 。スコットランド語では、warlock という単語が、魔女(男性でも女性でも使えるが、主に女性に対して使われる)の男性形として使われるようになった[101][102]。 『魔女狩り』は、1486 年にドイツの 2 人の修道士、ハインリッヒ・クラマーとヤコブ・スプレンガーによって書かれた、魔女狩りの手引書だ。この本は、カトリック教徒とプロテスタントの両方に よって[103] 数百年にわたって使用され、魔女を見分ける方法、女性が男性よりも魔女になりやすい理由、魔女を裁判にかける方法、魔女を罰する方法などが記載されていま した。この本は、魔女を邪悪で、通常は女性であると定義している。この本は、ヨーロッパ全土の世俗裁判所の手引書となったが、異端審問では使用されず、こ の本に頼ることを警告する声さえあった[104]。この本は、聖書に次いで 100 年以上にわたり、ヨーロッパで最も売れた本だった[105]。 イスラム 主な記事:イスラム教と魔法 イスラム教の呪術に対する見方は、幅広い慣習を網羅しており[106]、黒魔術や邪眼の信仰が、その実践の厳格な禁止と共存している[107]。コーラン は呪術の存在を認め、その害からの保護を求めている。イスラム教は、呪術の実践を禁じ、呪術や妖術よりも神の奇跡を強調する立場をとっている[108]。 中東における妖術の歴史的連続性は、異なる文化や時代における精神的な信念と社会規範との複雑な相互作用を強調している。 |

Modern paganism The sorceress Ceridwen of Welsh mythology is considered a Goddess in Modern paganism and Wicca.[109] Main articles: Neopagan witchcraft and Semitic neopaganism During the 20th century, interest in witchcraft rose in English-speaking and European countries. From the 1920s, Margaret Murray popularized the 'witch-cult hypothesis': the idea that those persecuted as 'witches' in early modern Europe were followers of a benevolent pagan religion that had survived the Christianization of Europe. This has been discredited by further historical research.[110][111][112][113][114] From the 1930s, occult neopagan groups began to emerge who called their religion a kind of 'witchcraft'. They were initiatory secret societies inspired by Murray's 'witch cult' theory, ceremonial magic, Aleister Crowley's Thelema, and historical paganism.[115][116][117] The biggest religious movement to emerge from this is Wicca. Today, some Wiccans and members of related traditions self-identify as "witches" and use the term "witchcraft" for their magico-religious beliefs and practices, primarily in Western anglophone countries.[13] |

現代異教 ウェールズ神話の魔女セリドウェンは、現代異教やウィッカでは女神とみなされている[109]。 主な記事:新異教の妖術、セム新異教 20 世紀、英語圏やヨーロッパ諸国では、妖術への関心が高まった。1920年代から、マーガレット・マレーは「妖術師カルト説」を普及させた。これは、近世 ヨーロッパで「妖術師」として迫害された人々は、ヨーロッパのキリスト教化後も生き残った慈悲深い異教の信者たちだったという説だ。この説は、その後の歴 史研究によって否定されている。 1930年代から、自分たちの宗教を「妖術」の一種と呼ぶオカルト的な新異教主義者グループが出現し始めた。彼らは、マレーの「魔女カルト」説、儀式魔 術、アレイスター・クロウリーの「テレマ」や歴史的な異教主義に触発された、入会の儀式を行う秘密結社だった。[115][116][117] この動きから生まれた最大の宗教運動は、ウィッカだ。今日、一部のウィッカ教徒や関連する伝統の信者は、主に英語圏の西洋諸国において、自らを「魔女」と 認識し、その魔法的・宗教的信念や慣習を「妖術」と呼んでいる。[13] |

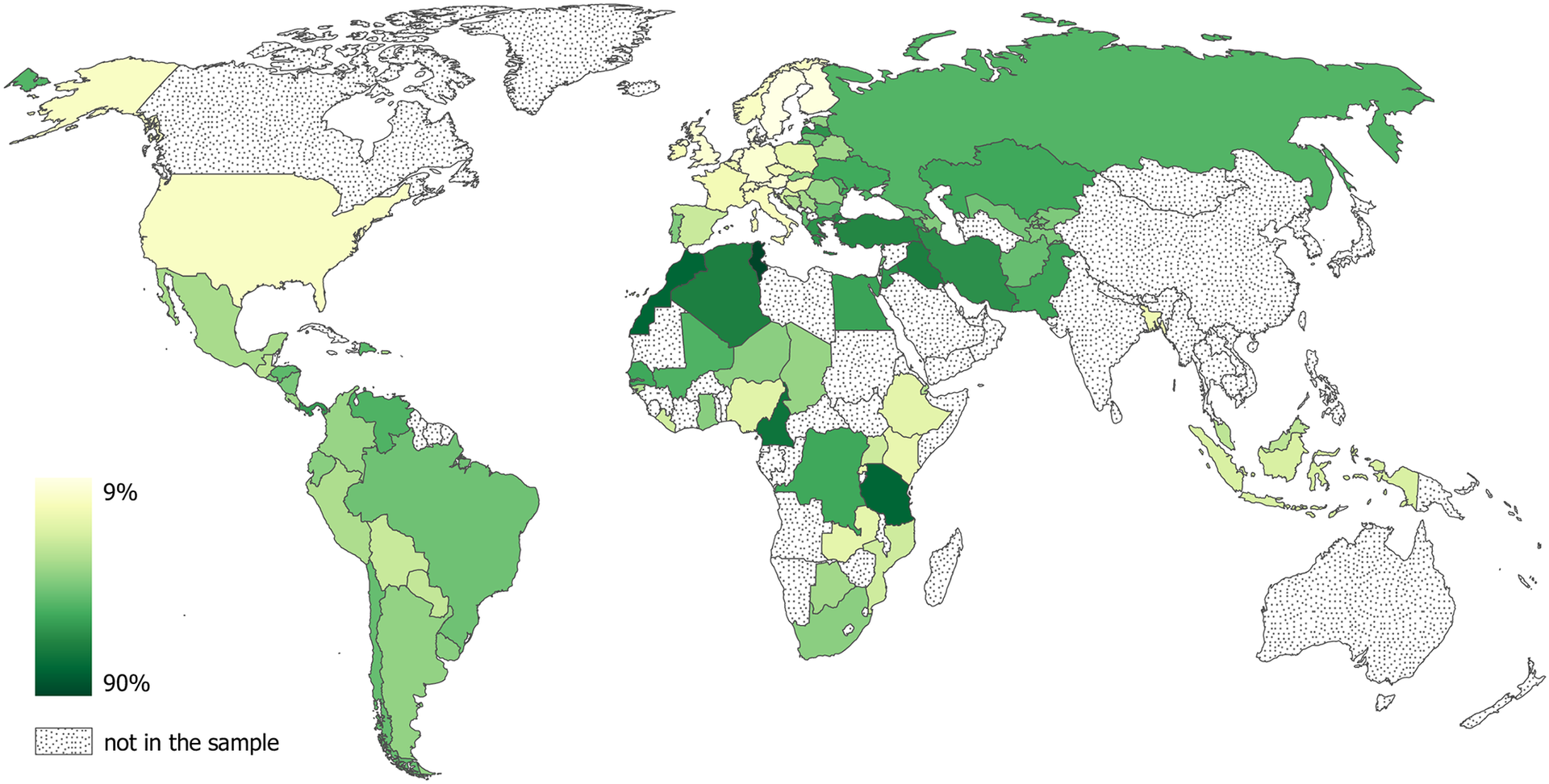

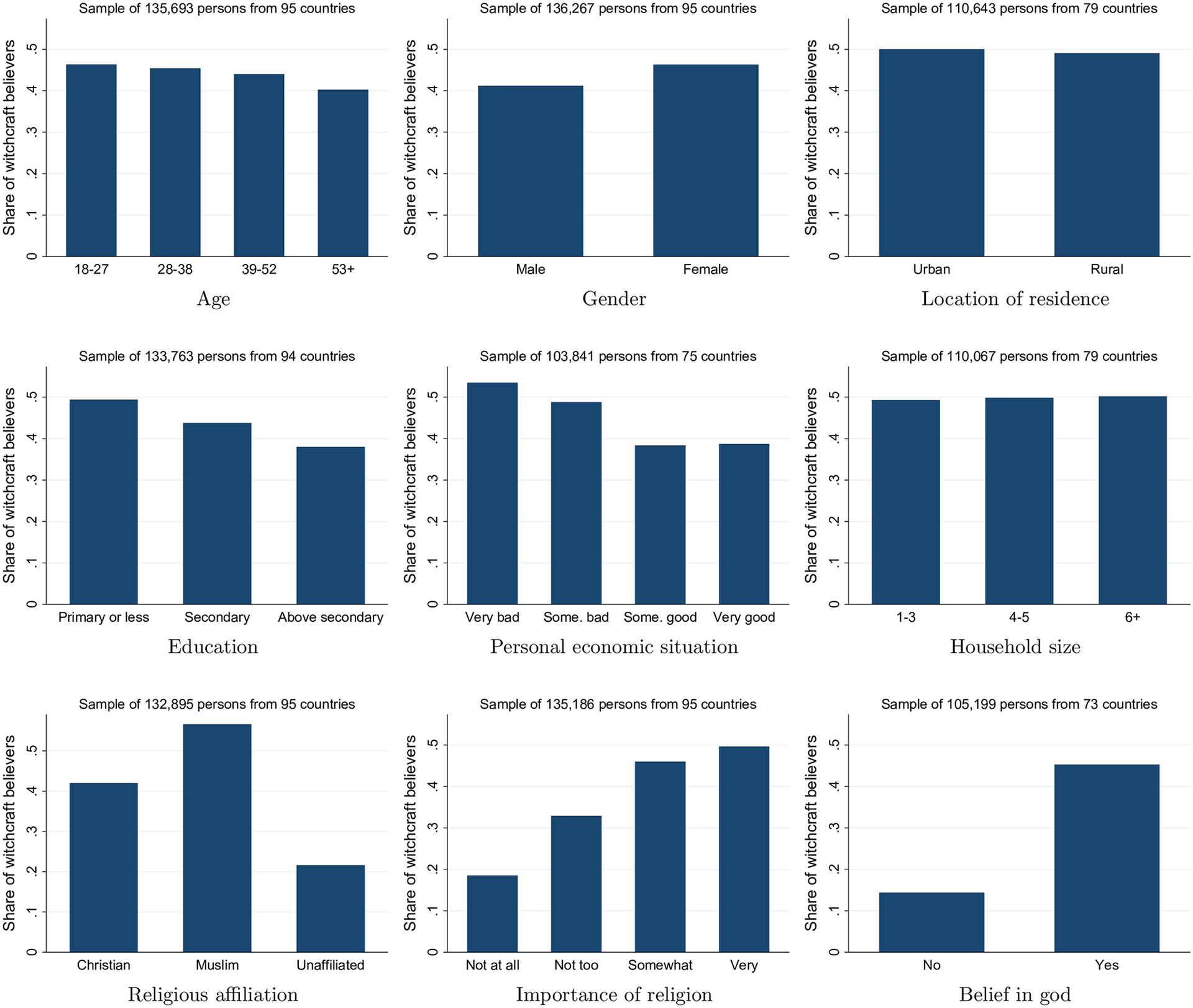

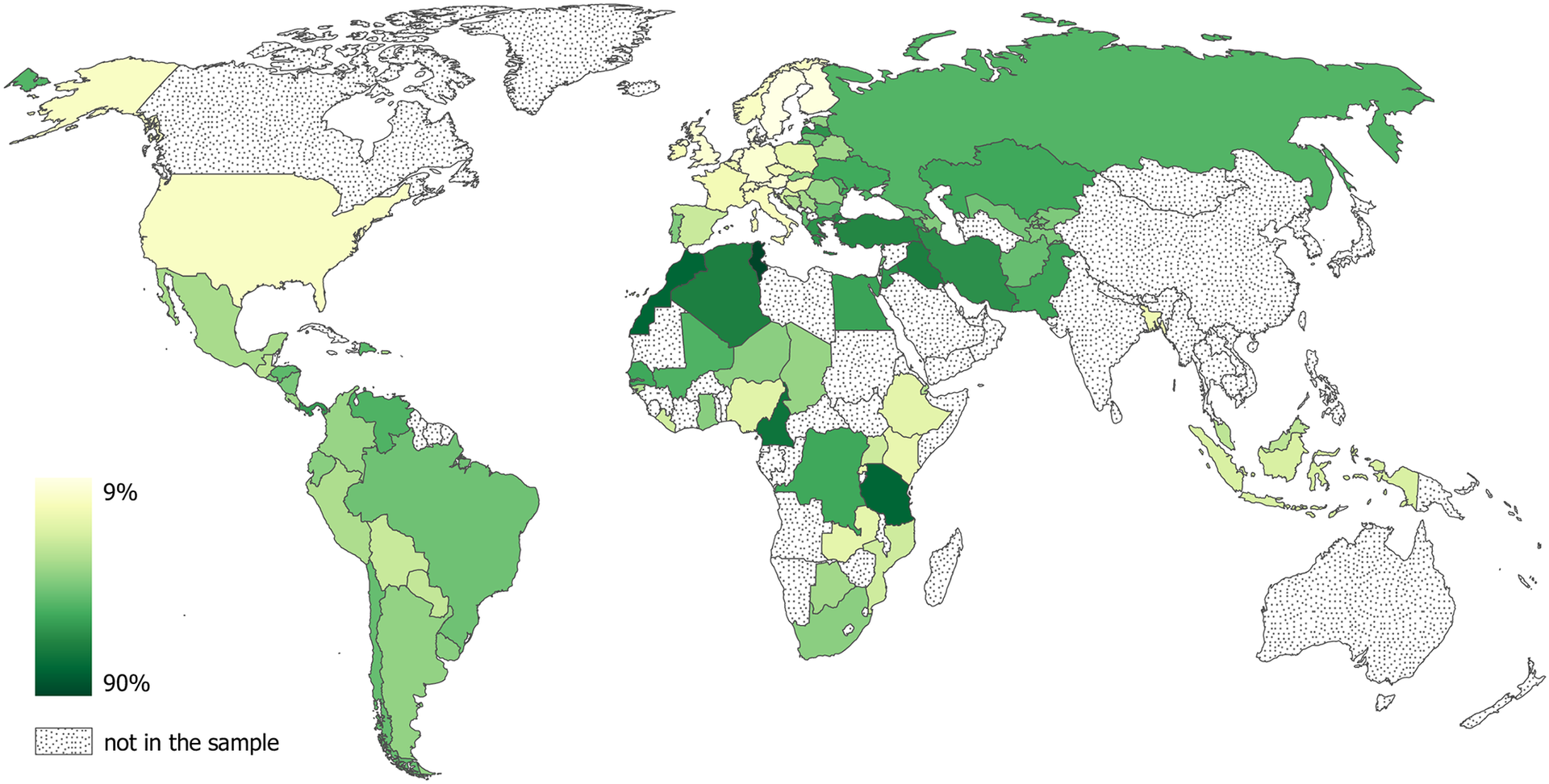

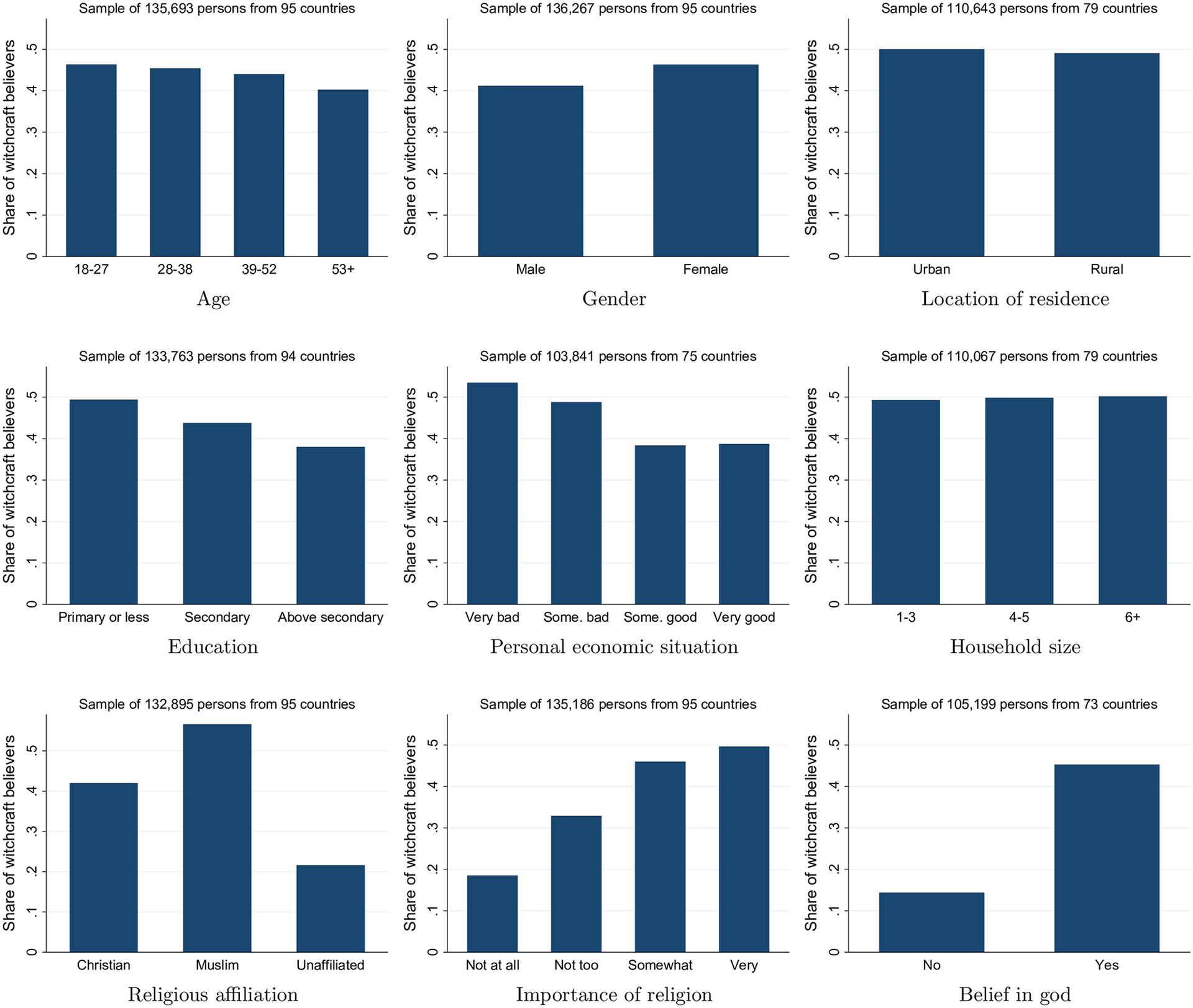

Regional perspectives Prevalence of belief in witchcraft by country[118]  Socio-demographic correlates of witchcraft beliefs[118] A 2022 study found that belief in witchcraft, as in the use of malevolent magic or powers, is still widespread in some parts of the world. It found that belief in witchcraft varied from 9% of people in some countries to 90% in others, and was linked to cultural and socioeconomic factors. Stronger belief in witchcraft correlated with poorer economic development, weak institutions, lower levels of education, lower life expectancy, lower life satisfaction, and high religiosity.[119][118] It contrasted two hypotheses about future changes in witchcraft belief:[118] witchcraft beliefs should decline "in the process of development due to improved security and health, lower exposure to shocks, spread of education and scientific approach to explaining life events" according to standard modernization theory "some aspects of development, namely rising inequality, globalization, technological change, and migration, may instead revive witchcraft beliefs by disrupting established social order" according to literature largely inspired by observations from Sub-Saharan Africa. |

地域的視点 国別の妖術の信仰の普及率[118]  妖術の信仰と社会人口統計学的相関[118] 2022年の研究では、悪意のある呪術や力の使用といった妖術の信仰が、世界の一部の地域では依然として広く浸透していることが明らかになった。この調査 では、妖術の信仰は、国によって 9% から 90% まで幅があり、文化的および社会経済的要因と関連していることが明らかになった。妖術の信仰が強いほど、経済発展が遅れ、制度が脆弱で、教育水準が低く、 平均寿命が短く、生活満足度が低く、宗教的傾向が強いという相関関係が見られた。[119][118] この調査では、妖術の信仰の将来の変化について 2 つの仮説が対比されている。[118] 標準的な近代化理論によれば、妖術の信仰は「治安と保健の改善、衝撃への曝露の減少、教育の普及、および人生における出来事を説明する科学的アプローチの普及による発展の過程で」衰退するはずである。 サハラ以南のアフリカでの観察結果に大きく影響を受けた文献によれば、「開発の一部の側面、すなわち、格差の拡大、グローバル化、技術変化、および移住は、確立された社会秩序を混乱させることによって、妖術の信仰を復活させる可能性がある」とのことです。 |

| Africa Main article: Witchcraft in Africa African witchcraft encompasses various beliefs and practices. These beliefs often play a significant role in shaping social dynamics and can influence how communities address challenges and seek spiritual assistance. Much of what "witchcraft" represents in Africa has been susceptible to misunderstandings and confusion, due to a tendency among western scholars to approach the subject through a comparative lens vis-a-vis European witchcraft.[120] For example, the Maka people of Cameroon believe in an occult force known as djambe, that dwells inside a person. It is often translated as "witchcraft" or "sorcery", but it has a broader meaning that encompasses supernatural harm, healing and shapeshifting; this highlights the problem of using European terms for African concepts.[121] While some 19th–20th century European colonialists tried to stamp out witch-hunting in Africa by introducing laws banning accusations of witchcraft, some former African colonies introduced laws banning witchcraft after they gained independence. This has produced an environment that encourages persecution of suspected witches.[122] In the Central African Republic, hundreds of people are convicted of witchcraft yearly, with reports of violence against accused women.[123] The Democratic Republic of the Congo witnessed a disturbing trend of child witchcraft accusations in Kinshasa, leading to abuse and exorcisms supervised by self-styled pastors.[124] In Ghana, there are several "witch camps", where women accused of witchcraft can seek refuge, though the government plans to close them.[125] In west Kenya, there have been cases of accused witches being burned to death in their homes by mobs.[126] Malawi faces a similar issue of child witchcraft accusations, with traditional healers and some Christian counterparts involved in exorcisms, causing abandonment and abuse of children.[127] In Nigeria, Pentecostal pastors have intertwined Christianity with witchcraft beliefs for profit, leading to the torture and killing of accused children.[128] Sierra Leone's Mende people see witchcraft convictions as beneficial, as the accused receive support and care from the community.[129] Lastly, in Zulu culture, healers known as sangomas protect people from witchcraft and evil spirits through divination, rituals and mediumship.[130] However, concerns arise regarding the training and authenticity of some sangomas. In parts of Africa, beliefs about illness being caused by witchcraft continue to fuel suspicion of modern medicine, with serious healthcare consequences. HIV/AIDS[131] and Ebola[132] are two examples of often-lethal infectious disease epidemics whose medical care and containment has been severely hampered by regional beliefs in witchcraft. Other severe medical conditions whose treatment is hampered in this way include tuberculosis, leprosy, epilepsy and the common severe bacterial Buruli ulcer.[133][134] |

アフリカ 主な記事:アフリカの妖術 アフリカの妖術には、さまざまな信仰や慣習がある。これらの信仰は、社会動態の形成に重要な役割を果たすことが多く、コミュニティが課題に対処したり、霊 的な助けを求めたりする方法に影響を与えることがある。アフリカの「妖術」の多くは、西洋の学者たちがヨーロッパの妖術と比較しながらこのテーマに取り組 む傾向があるため、誤解や混乱を招きやすい。例えば、カメルーンのマカ族は、人間の中に宿る「ジャンベ」というオカルトの力を信じている。これは「妖術」 や「魔術」と訳されることが多いが、超自然的な害、治癒、変身などを含むより広い意味を持っている。これは、アフリカの概念にヨーロッパの用語を使用する ことの問題点を浮き彫りにしている[121]。 19 世紀から 20 世紀にかけて、一部のヨーロッパの植民地主義者は、妖術の告発を禁止する法律を導入してアフリカでのウイッチハントを根絶しようとしたが、一部のアフリカ の旧植民地では、独立後に妖術を禁止する法律が導入された。これにより、妖術師と疑われる人々に対する迫害を助長する環境が生まれている。[122] 中央アフリカ共和国では、毎年何百人もの人々が妖術師として有罪判決を受け、被告人の女性に対する暴力も報告されている。[123] コンゴ民主共和国では、キンシャサで子供たちが妖術師と非難されるという不穏な傾向が見られ、自称牧師による虐待や悪魔祓いが横行している。[124] ガーナには、妖術師と非難された女性が避難できる「妖術師キャンプ」がいくつかあるが、政府はこれらのキャンプを閉鎖する計画だ。[125] ケニア西部では、妖術師と非難された人々が、暴徒によって自宅で焼殺される事件が発生している[126]。マラウイも、子供たちに対する妖術師の告発とい う同様の問題を抱えており、伝統的治療師や一部のキリスト教徒が、悪魔祓いに関与し、子供たちの遺棄や虐待を引き起こしている[127]。ナイジェリアで は、ペンテコステ派の牧師たちが、利益のためにキリスト教と妖術の信仰を絡み合わせ、告発された子供たちに対する拷問や殺害につながっている。[128] シエラレオネのメンデ族は、魔女として有罪判決を受けた者はコミュニティから支援とケアを受けるため、魔女裁判は有益だと考えている。[129] 最後に、ズールー族の文化では、サンゴマと呼ばれる治療師が、占いや儀式、霊媒術によって人々を妖術や悪霊から守っている。[130] しかし、一部のサンゴマの訓練や信頼性については懸念が寄せられている。 アフリカの一部地域では、病気は妖術によって引き起こされるという信念が、現代医療に対する疑念を煽り続け、深刻な医療上の問題を引き起こしている。 HIV/AIDS[131] やエボラ[132] は、地域における妖術の信念によって医療や感染の封じ込めが著しく妨げられている、しばしば死に至る感染症の流行の 2 つの例だ。同様の理由で治療が妨げられている他の重篤な医療状態には、結核、ハンセン病、てんかん、および一般的な重度の細菌性ブルリ潰瘍が含まれる。 [133][134] |

| Americas North America Main article: Witchcraft in North America North America hosts a diverse array of beliefs about witchcraft, some of which have evolved through interactions between cultures.[135][136] Native American peoples such as the Cherokee,[137] Hopi,[138] the Navajo[5] among others,[139] believed in malevolent "witch" figures who could harm their communities by supernatural means; this was often punished harshly, including by execution.[140] In these communities, medicine people were healers and protectors against witchcraft.[137][138] The term "witchcraft" arrived with European colonists, along with European views on witchcraft.[135] This term would be adopted by many Indigenous communities for their own beliefs about harmful magic and harmful supernatural powers. Witch hunts took place among Christian European settlers in colonial America and the United States, most infamously the Salem witch trials in Massachusetts. These trials led to the execution of numerous individuals accused of practicing witchcraft. Despite changes in laws and perspectives over time, accusations of witchcraft persisted into the 19th century in some regions, such as Tennessee, where prosecutions occurred as late as 1833. Some North American witchcraft beliefs were influenced by beliefs about witchcraft in Latin America, and by African witchcraft beliefs through the slave trade.[141][142][136] Native American cultures adopted the term for their own witchcraft beliefs.[143] Neopagan witchcraft practices such as Wicca then emerged in the mid-20th century.[135][136] |

アメリカ 北アメリカ 主な記事:北アメリカの妖術 北アメリカには、妖術に関するさまざまな信仰があり、そのうちのいくつかは文化間の交流を通じて発展してきた。[135][136] チェロキー族[137]、ホピ族[138]、ナバホ族[5] などのネイティブアメリカンは、超自然的な力でコミュニティに害を及ぼす悪意のある「妖術師」の存在を信じていた。妖術師は、多くの場合、死刑を含む厳し い罰を受けた。これらのコミュニティでは、薬師は妖術師から人々を守る治療者であり、守護者だった。 「妖術」という用語は、ヨーロッパの植民者たちとともに、ヨーロッパの妖術に関する見解とともに伝わった[135]。この用語は、有害な呪術や有害な超自 然的な力に関する独自の信念を持つ多くの先住民コミュニティによって採用された。ウイッチハントは、植民地時代のアメリカおよびアメリカ合衆国のキリスト 教徒の入植者たちの間で起こり、最も悪名高いのはマサチューセッツ州でのセーラム魔女裁判だ。これらの裁判は、妖術を実践したとして告発された多くの人々 の処刑につながった。時間の経過とともに法律や見方が変化したにもかかわらず、テネシー州など一部の地域では 19 世紀まで妖術の告発が続き、1833 年まで起訴が行われていました。 北米の妖術の信仰の一部は、ラテンアメリカの妖術の信仰や、奴隷貿易を通じて伝わったアフリカの妖術の信仰の影響を受けています。[141][142] [136] ネイティブアメリカンの文化は、自分たちの妖術の信仰にこの用語を採用しました。[143] その後、20 世紀半ばには、ウィッカなどの新異教の妖術の慣習が登場しました。[135][136] |

| Latin America Main article: Witchcraft in Latin America Witchcraft beliefs in Latin America are influenced by Spanish Catholic, Indigenous, and African beliefs. In Colonial Mexico, the Mexican Inquisition showed little concern for witchcraft; the Spanish Inquisitors treated witchcraft accusations as a "religious problem that could be resolved through confession and absolution". Anthropologist Ruth Behar writes that Mexican Inquisition cases "hint at a fascinating conjecture of sexuality, witchcraft, and religion, in which Spanish, indigenous, and African cultures converged".[144] There are cases where European women and Indigenous women were accused of collaborating to work "love magic" or "sexual witchcraft" against men in colonial Mexico.[145] According to anthropology professor Laura Lewis, "witchcraft" in colonial Mexico represented an "affirmation of hegemony" for women and especially Indigenous women over their white male counterparts in the casta system.[146] Belief in witchcraft is a constant in the history of colonial Brazil, for example the several denunciations and confessions given to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith of Bahia (1591–1593), Pernambuco and Paraíba (1593–1595).[147] Brujería, often called a Latin American form of witchcraft, is a syncretic Afro-Caribbean tradition that combines Indigenous religious and magical practices from the Caribbean, together with Catholicism, and European witchcraft.[148] The tradition and terminology is considered to encompass both helpful and harmful practices.[149] A male practitioner is called a brujo, a female practitioner, a bruja.[149] Healers may be further distinguished by the terms kurioso or kuradó, a man or woman who performs trabou chikí ("little works") and trabou grandi ("large treatments") to promote or restore health, bring fortune or misfortune, deal with unrequited love, and more serious concerns. Sorcery usually involves reference to an entity referred to as the almasola or homber chiki.[150] |

ラテンアメリカ 主な記事:ラテンアメリカの妖術 ラテンアメリカの妖術の信仰は、スペインのカトリック、先住民、アフリカの信仰の影響を受けています。植民地時代のメキシコでは、メキシコ異端審問は妖術 にほとんど関心を示さず、スペインの異端審問官は妖術の告発を「告白と赦免によって解決できる宗教上の問題」として扱っていました。人類学者のルース・ベ ハーは、メキシコ異端審問の事件は「スペイン、先住民、アフリカの文化が融合した、セクシュアリティ、妖術、宗教に関する興味深い推測をほのめかしてい る」と述べています。[144] 植民地時代のメキシコでは、ヨーロッパの女性と先住民の女性が、男性に対して「愛の呪術」や「性的妖術」を行うために共謀したとして告発されたケースがあ る[145]。人類学教授のローラ・ルイスによると、植民地時代のメキシコにおける「妖術」は、カスタ制度における白人男性に対する女性、特に先住民の女 性たちの「ヘゲモニーの肯定」を表していた[146]。 妖術の信仰は、植民地時代のブラジルの歴史において常に存在していた。例えば、バイア(1591年~1593年)、ペルナンブコ、パライバ(1593年~1595年)の信仰教義審問所に対して、複数の告発や自白が提出されている。[147] ブルヘリア(Brujería)は、しばしばラテンアメリカの妖術と呼ばれ、カリブ海の先住民による宗教的・呪術的慣習と、カトリック、ヨーロッパの妖術 が融合した、アフリカとカリブ海諸国の伝統である。[148] この伝統と用語は、有益な慣習と有害な慣習の両方を網羅すると考えられている。[149] 男性の術者はブルホ、女性の術者はブルハと呼ばれる。[149] ヒーラーは、さらに「kurioso」または「kuradó」という用語で区別される場合があり、これは、健康の促進や回復、幸運や不運の招来、片思いの 解決、より深刻な問題に対処するために、「trabou chikí」(「小さな仕事」)や「trabou grandi」(「大きな治療」)を行う男性または女性を指す。魔術は通常、アルマソラまたはホンバー・チキと呼ばれる存在への言及を伴う。[150] |

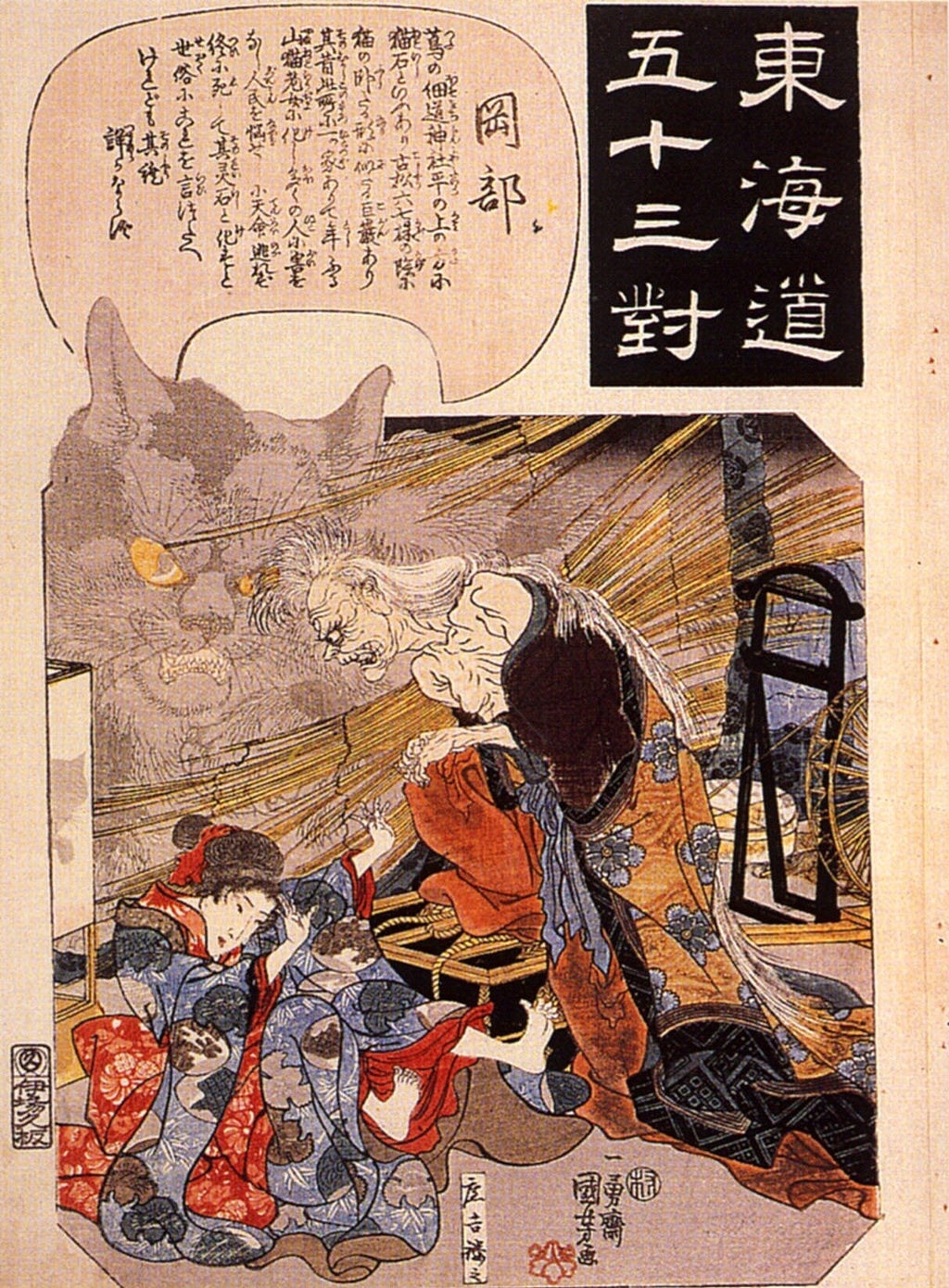

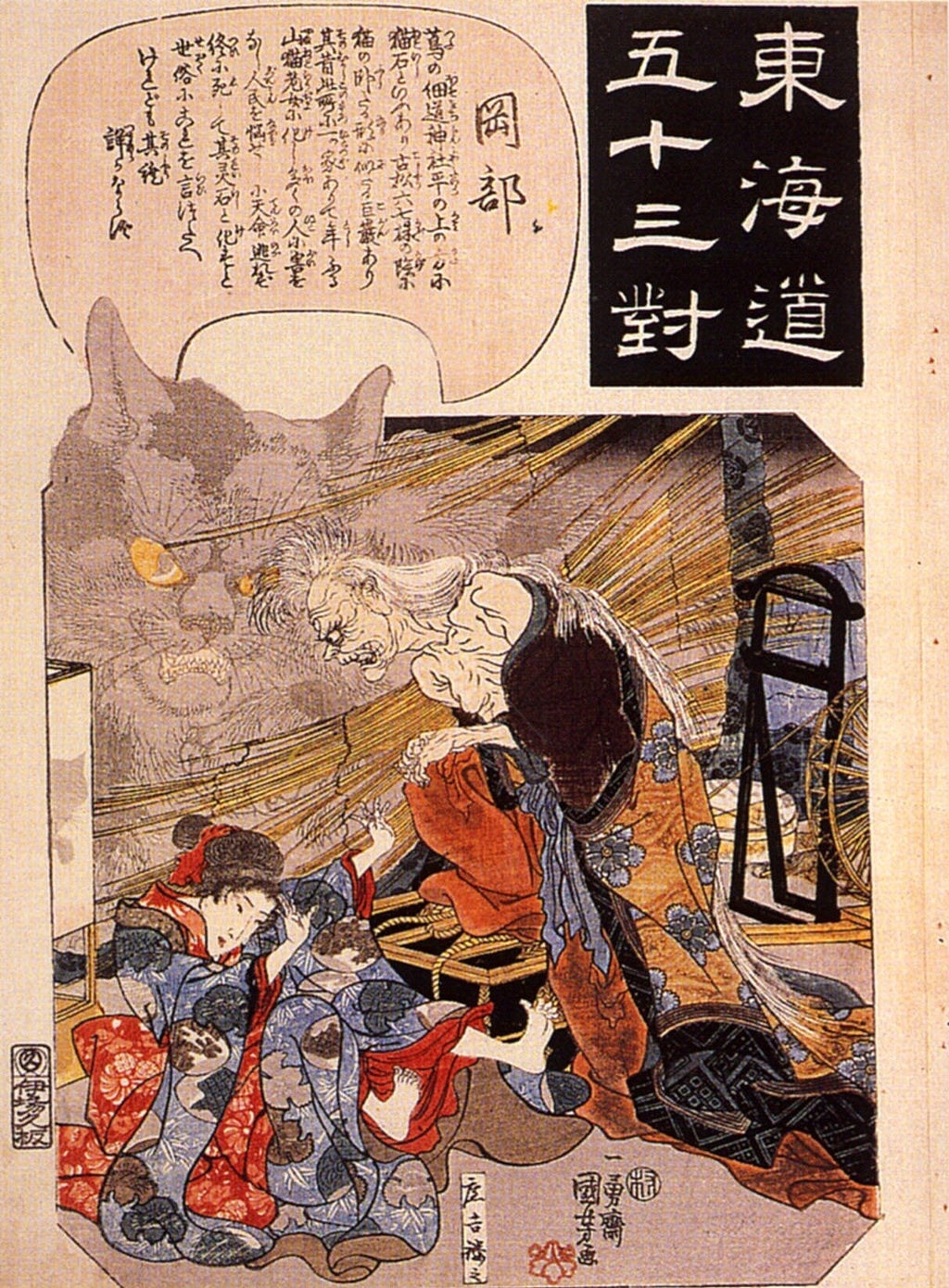

| Asia Main article: Asian witchcraft  Okabe – The cat witch, by Utagawa Kuniyoshi East Asia In Chinese culture, the practice of Gong Tau involves black magic for purposes such as revenge and financial assistance.[citation needed] Japanese folklore features witch figures who employ foxes as familiars. Korean history includes instances of individuals being condemned for using spells. The Philippines has its own tradition of Philippine witches, distinct from Western portrayals, with their practices often countered by indigenous Philippine shamans.[citation needed] |

アジア 主な記事:アジアの妖術  岡部 – 猫の魔女、歌川国芳作 東アジア 中国文化では、復讐や金銭の援助などの目的で黒魔術を使う「ゴンタウ」という呪術がある。日本の民話には、狐を使い魔とする妖術師が登場する。韓国の歴史 には、呪術を使ったことで非難された人物がいる。フィリピンには、西洋の描写とはまったく異なる、フィリピン独自の「フィリピン魔女」という伝統があり、 その呪術は、多くの場合、フィリピン先住民のシャーマンによって打ち消される。 |

| Middle East Main article: Witchcraft in the Middle East Witchcraft beliefs in the Middle East have a long history, and magic was a part of the ancient cultures and religions of the region.[151] In ancient Mesopotamia (Sumeria, Assyria, Babylonia), a witch (m. kaššāpu, f. kaššāptu) was "usually regarded as an anti-social and illegitimate practitioner of destructive magic ... motivated by malice and evil intent".[90] Ancient Mesopotamian societies mainly used counter-magic against witchcraft (kišpū), but the law codes also prescribed the death penalty for those found guilty of witchcraft.[88] For the ancient Hittites, magic could only be sanctioned by the state, and accusations of witchcraft were often used to control political enemies.[152] As the ancient Hebrews focused on their worship on Yahweh, Judaism clearly distinguished between forms of magic and mystical practices which were accepted, and those which were viewed as forbidden or heretical, and thus "witchcraft".[153] In the medieval Middle East, under Islamic and Christian influences, witchcraft's perception fluctuated between healing and heresy, revered by some and condemned by others.[citation needed] In the present day diverse witchcraft communities have emerged.[citation needed] |

中東 主な記事:中東の妖術 中東の妖術の信仰は長い歴史があり、呪術はこの地域の古代文化や宗教の一部だった[151]。 古代メソポタミア(シュメール、アッシリア、バビロニア)では、妖術師(男性:kaššāpu、女性:kaššāptu)は「通常、悪意や邪悪な意図に駆 られて破壊的な呪術を行う反社会的で非合法な者」とみなされていました。[90] 古代メソポタミア社会では、主に妖術(kišpū)に対する対抗呪術が用いられていたが、法典では、妖術の罪で有罪となった者には死刑が科せられることも 規定されていた。[88] 古代ヒッタイト人にとって、呪術は国家によってのみ認可され、妖術の告発はしばしば政敵を支配するために利用された[152]。 古代ヘブライ人はヤハウェの崇拝に重点を置いていたため、ユダヤ教は、容認される呪術や神秘的な行為と、禁じられたり異端とみなされる「妖術」とを明確に区別していた[153]。 中世の中東では、イスラム教とキリスト教の影響を受けて、妖術の認識は、癒しと異端の間で揺れ動き、一部の人々に崇拝され、他の人々からは非難された。[要出典] 現在、さまざまな妖術のコミュニティが出現している。[要出典] |

| Europe Main article: European witchcraft Ancient Roman world Main article: European witchcraft § Antiquity  Caius Furius Cressinus Accused of Sorcery, Jean-Pierre Saint-Ours, 1792 European belief in witchcraft can be traced back to classical antiquity, when concepts of magic and religion were closely related. During the pagan era of ancient Rome, there were laws against harmful magic.[154] According to Pliny, the 5th century BCE laws of the Twelve Tables laid down penalties for uttering harmful incantations and for stealing the fruitfulness of someone else's crops by magic.[154] The only recorded trial involving this law was that of Gaius Furius Cresimus.[154] The Classical Latin word veneficium meant both poisoning and causing harm by magic (such as magic potions), although ancient people would not have distinguished between the two.[155] In 331 BCE, a deadly epidemic hit Rome and at least 170 women were executed for causing it by veneficium. In 184–180 BCE, another epidemic hit Italy, and about 5,000 were executed for veneficium.[155] If the reports are accurate, writes Hutton, "then the Republican Romans hunted witches on a scale unknown anywhere else in the ancient world".[155] Under the Lex Cornelia de sicariis et veneficis of 81 BCE, killing by veneficium carried the death penalty. During the early Imperial era, the Lex Cornelia began to be used more broadly against other kinds of magic,[155] including sacrifices made for evil purposes. The magicians were to be burnt at the stake.[154] Witch characters—women who work powerful evil magic—appear in ancient Roman literature from the first century BCE onward. They are typically hags who chant harmful incantations; make poisonous potions from herbs and the body parts of animals and humans; sacrifice children; raise the dead; can control the natural world; can shapeshift themselves and others into animals; and invoke underworld deities and spirits. They include Lucan's Erichtho, Horace's Canidia, Ovid's Dipsas, and Apuleius's Meroe.[155] |

ヨーロッパ 主な記事:ヨーロッパの妖術 古代ローマ世界 主な記事:ヨーロッパの妖術 § 古代  邪術の罪で告発されたガイウス・フリウス・クレシヌス、ジャン=ピエール・サン・ウル、1792年 ヨーロッパの妖術の信仰は、呪術と宗教の概念が密接に関連していた古代にさかのぼることができます。古代ローマの異教時代には、有害な呪術を禁止する法律 があった[154]。プリニウスによると、紀元前 5 世紀の十二表法では、有害な呪文を唱えたり、呪術によって他人の作物の収穫を盗んだりした場合の罰則が定められていた[154]。この法律が適用された唯 一の裁判は、ガイウス・フリウス・クレシヌスの裁判だった[154]。 古典ラテン語の「veneficium」は、毒殺と呪術(魔法の薬など)による危害の両方を意味していたが、古代の人々は 2 つを区別していなかっただろう[155]。紀元前 331 年、ローマで致命的な疫病が流行し、その原因として少なくとも 170 人の女性が veneficium で処刑された。紀元前 184 年から 180 年にかけて、イタリアを再び疫病が襲い、約 5,000 人がヴェネフィキウムの罪で処刑された[155]。この報告が正確であれば、ハットンは「共和政ローマ人は、古代世界でも他に例を見ない規模で妖術師を 狩った」と記している[155]。 紀元前 81 年の Lex Cornelia de sicariis et veneficis(暗殺者および毒殺者に関する法律)では、毒殺は死刑とされた。帝政初期、Lex Cornelia は、悪意のある目的のための生贄など、他の種類の呪術に対してもより広く適用されるようになった[155]。魔術師たちは火刑に処された[154]。 強力な邪悪な呪術を使う女性である妖術師は、紀元前 1 世紀以降の古代ローマ文学に登場する。彼らは通常、有害な呪文を唱える老婆であり、ハーブや動物や人間の体の一部を使って毒薬を作り、子供たちを犠牲に し、死者を蘇らせ、自然界を支配し、自分自身や他人を動物に変身させ、冥界の神々や精霊を呼び出す。その例としては、ルカヌスのエリクト、ホラティウスの カニディア、オウィディウスのディプサス、アプルレイウスのメロエなどが挙げられる。 |

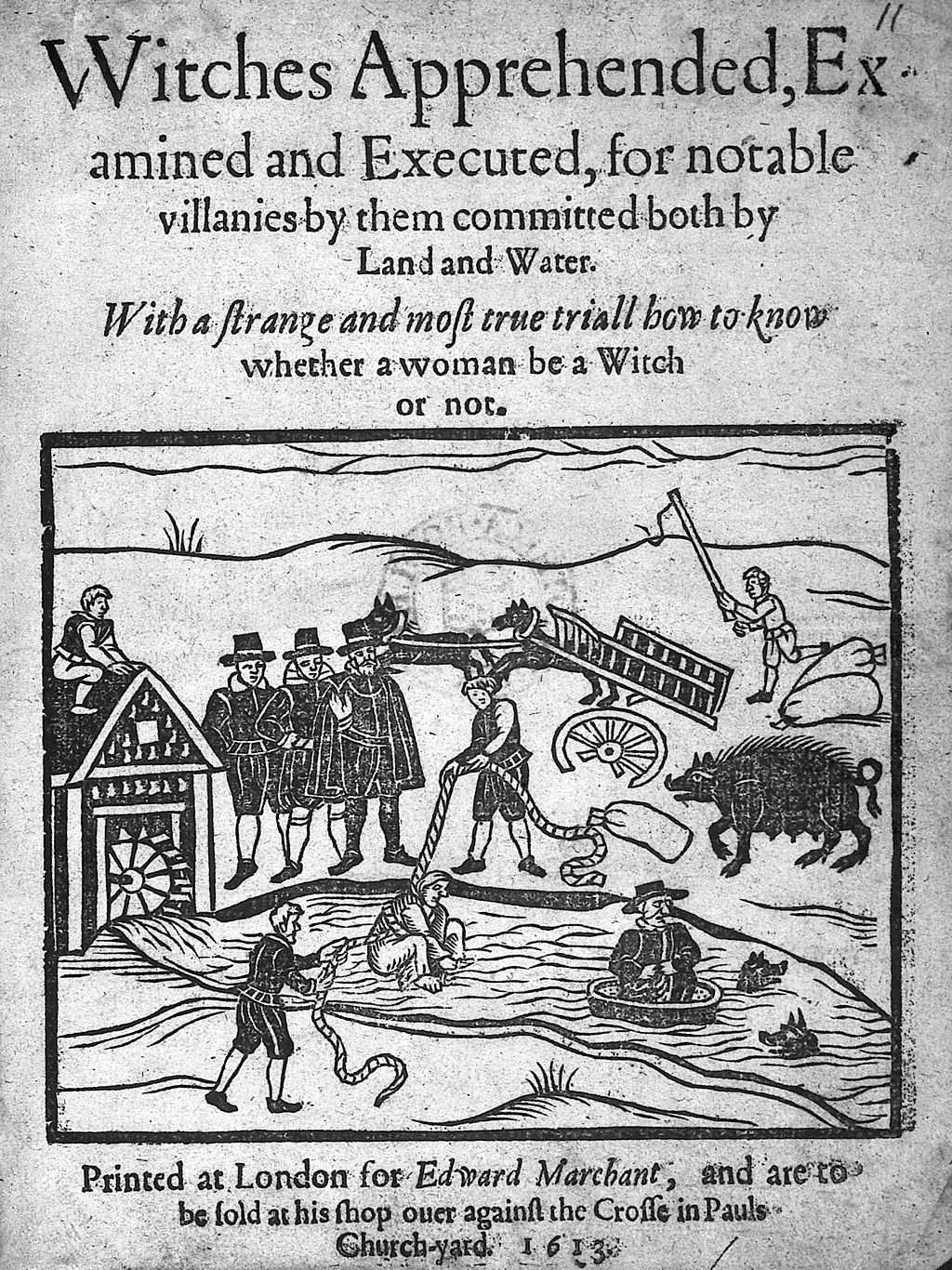

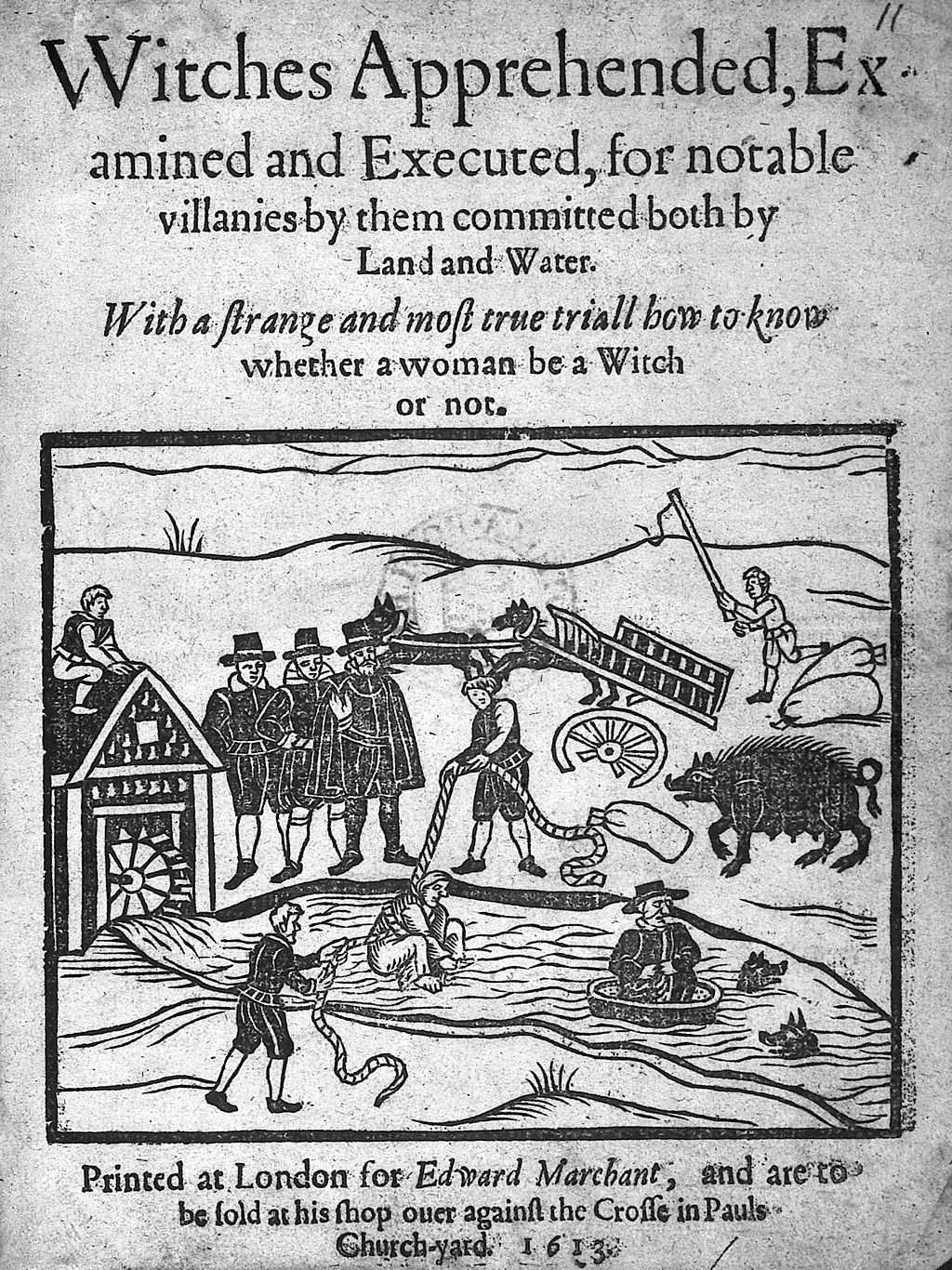

Early modern and contemporary Europe A 1613 English pamphlet showing "Witches apprehended, examined and executed" This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) By the early modern period, major witch hunts and witch trials began to take place in Europe, partly fueled by religious tensions, societal anxieties, and economic upheaval. One influential text was the Malleus Maleficarum, a 1486 treatise that provided a framework for identifying, prosecuting, and punishing witches. Witches were typically seen as people who caused harm or misfortune through black magic, and were sometimes believed to have made a pact with the Devil.[156] Usually, accusations of witchcraft were made by neighbors and followed from social tensions. Accusations were often made against marginalized individuals, women, the elderly, and those who did not conform to societal norms. Women made accusations as often as men. The common people believed that magical healers (called 'cunning folk' or 'wise people') could undo bewitchment. Hutton says that magical healers were sometimes denounced as witches themselves, "but seem to have made up a minority of the accused in any area studied".[53] The witch-craze reached its peak between the 16th and 17th centuries, resulting in the execution of tens of thousands of people. This dark period of history reflects the confluence of superstition, fear, and authority, as well as the societal tendency to find scapegoats for complex problems. A feminist interpretation of the witch trials is that misogynist views led to the association of women and malevolent witchcraft.[156] During the 16th century and mid 18th century Scotland had 4000-6000 prosecutions against accused witches, a much higher rate then the European average.[157][158] Russia also experienced its own iteration of witchcraft trials during the 17th century. Witches were often accused of sorcery and engaging in supernatural activities, leading to their excommunication and execution. The blending of ecclesiastical and secular jurisdictions in Russia's approach to witchcraft trials highlighted the intertwined nature of religious and political power during that time. As the 17th century progressed, the fear of witches shifted from mere superstition to a tool for political manipulation, with accusations used to target individuals who posed threats to the ruling elite.[159] Since the 1940s, neopagan witchcraft movements have emerged in Europe, seeking to revive and reinterpret ancient pagan and mystical practices. Wicca, pioneered by Gerald Gardner, is the most influential. Drawing inspiration from ceremonial magic, historical paganism, and the now-discredited witch-cult theory, Wicca emphasizes a connection to nature, the divine, and personal growth. Similarly, Stregheria in Italy reflects a desire to reconnect with the country's pagan past. Many of these neopagans self-identify as "witches". Neopagan witchcraft in Europe encompasses a wide range of traditions.[citation needed] |

近世および現代ヨーロッパ 1613年に発行された、妖術師が逮捕、尋問、処刑される様子を描いた英国のパンフレット この節は、検証のための出典が不足しています。信頼できる出典をこの節に追加して、この記事を改善してください。出典が記載されていない情報は、削除される可能性があります。(2023年10月) (このメッセージの削除方法についてはこちらをご覧ください) 近世になると、宗教的緊張、社会的不安、経済混乱などを背景に、ヨーロッパで大規模な魔女狩りや魔女裁判が始まった。影響力のあった文献としては、 1486年に著された『魔女狩り』がある。この著書は、魔女を特定、起訴、処罰するための枠組みを定めた。妖術師は、通常、黒魔術によって害や不幸をもた らす人物と見なされ、悪魔と契約を結んだと信じられることもあった[156]。通常、妖術師の告発は隣人によって行われ、社会的な緊張から生じていた。告 発は、社会から疎外された個人、女性、高齢者、社会規範に従わない者に対してよく行われた。女性も男性と同じくらい頻繁に告発を行った。一般の人々は、呪 術師(「狡猾な者」や「賢者」と呼ばれた)が呪術を解くことができると信じていた。ハットンは、呪術師も魔女として告発されることがあったが、「調査した どの地域でも、被告人の少数派だったようだ」と述べている[53]。魔女狩りは 16 世紀から 17 世紀にかけて最盛期を迎え、何万人もの人々が処刑された。この暗い歴史は、迷信、恐怖、権威が融合し、複雑な問題のスケープゴートを探すという社会の傾向 を反映している。魔女裁判のフェミニスト的な解釈では、女性嫌悪の考え方が、女性と悪意のある妖術との関連付けにつながったとされている[156]。 16 世紀から 18 世紀半ばにかけて、スコットランドでは 4000 件から 6000 件の魔女裁判が行われ、その数はヨーロッパ平均をはるかに上回った。[157][158] ロシアも 17 世紀に独自の魔女裁判を経験した。妖術師たちはしばしば邪術や超自然的な行為を行ったとして告発され、破門や処刑に処された。ロシアの魔女裁判における教 会と世俗の司法権の融合は、当時の宗教的権力と政治的権力の絡み合った性質を浮き彫りにした。17 世紀が進むにつれて、魔女に対する恐怖は単なる迷信から政治的な操作の道具へと変化し、支配層にとって脅威となる個人を標的にした告発が利用されるように なった[159]。 1940年代以降、ヨーロッパでは、古代の異教や神秘的な慣習を復活させ、再解釈しようとする新異教の妖術運動が台頭してきた。ジェラルド・ガードナーが 先駆者となったウィッカは、最も影響力のある運動だ。儀式魔術、歴史的な異教、そして現在では信用を失った魔女崇拝説から着想を得たウィッカは、自然、 神、そして個人の成長とのつながりを重視している。同様に、イタリアのストレゲリアは、この国の異教の過去とのつながりを再構築したいという願望を反映し ている。これらの新異教徒の多くは、自らを「魔女」と認識している。ヨーロッパの新異教の妖術は、幅広い伝統を網羅している。 |

| Oceania [icon] This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. Find sources: "Pacific Witchcraft" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (October 2023) Beliefs in witchcraft and sorcery are widespread across Oceania, where traditional spiritual systems often coexist with introduced religions such as Christianity. In many societies, witchcraft serves as an explanation for illness, death, or misfortune, and may be associated with social tensions or unresolved conflicts. In the Cook Islands, the Māori term for black magic is purepure.[160] Practitioners known as taʻunga historically served as priests, healers, and spiritual advisors. They were believed to possess sacred knowledge and were responsible for conducting rituals, healing the sick, and maintaining spiritual balance within the community.[161] In Papua New Guinea, belief in witchcraft—often referred to locally as sanguma—remains deeply ingrained in many communities, particularly in the Highlands region. Sorcery is commonly blamed for unexplained deaths, illness, crop failure, or other misfortunes. It is estimated that 50 to 150 people are killed each year in the country as a result of witchcraft accusations.[162] In 2008, reports indicated that more than fifty individuals were killed in two Highlands provinces alone for allegedly practicing sorcery.[163] Victims are often women, and attacks may involve torture, public shaming, or execution. Although the government repealed the Sorcery Act in 2013, which previously allowed sorcery as a defense in murder cases, enforcement of protective laws remains inconsistent, and community-led violence continues. In Milne Bay Province, including the Samarai Islands, witchcraft beliefs persist, but violence against the accused is significantly lower compared to the Highlands. Anthropological research suggests that local interpretations of witchcraft in these areas are less associated with malevolence and more integrated into broader spiritual and cultural practices. This has been linked to greater social standing for women and fewer gender-based witchcraft accusations.[164] Other parts of Oceania, including Fiji, Tonga, and Samoa, also maintain traditions involving spiritual power and magical influence. In Fiji, for example, concepts such as valavala vakalou (spiritual acts) and traditional healing practices are still recognized in some rural areas. However, the influence of Christianity and formal legal systems has reduced the prevalence of witchcraft-related violence. In many Pacific Island societies today, witchcraft is viewed through a cultural or religious lens rather than a criminal one, and cases involving supernatural claims are more likely to be addressed through customary dispute resolution or church-based mediation. |

オセアニア [アイコン このセクションは拡張が必要です。追加してご支援ください。 出典: 「太平洋の妖術」 – ニュース · 新聞 · 書籍 · 学術誌 · JSTOR (2023年10月) 妖術や邪術の信仰は、伝統的な精神体系がキリスト教などの外来宗教と共存することが多いオセアニア全域に広く見られます。多くの社会では、妖術は病気、死、不運の説明として用いられ、社会的緊張や未解決の紛争と関連している場合があります。 クック諸島では、黒魔術を意味するマオリ語は「purepure」だ。[160] taʻunga として知られる術者は、歴史的に司祭、治療者、精神的な助言者としての役割を果たしてきた。彼らは神聖な知識を有すると信じられ、儀式を行い、病人を癒 し、コミュニティ内の精神的なバランスを維持する責任があった。[161] パプアニューギニアでは、妖術(現地では sanguma とよく呼ばれる)の信仰が、多くのコミュニティ、特に高地地域において深く根付いている。邪術は、原因不明の死、病気、作物の不作、その他の不幸の原因と してよく非難される。この国では、妖術の容疑で毎年 50 人から 150 人が殺害されていると推定されている[162]。2008 年、ハイランド地方 2 州だけで、妖術を行った容疑で 50 人以上が殺害されたとの報告がある[163]。被害者は多くの場合女性であり、拷問、公の場で恥をかかせたり、処刑されるなどの攻撃を受けることがある。 政府は、殺人事件で邪術を弁護理由として認めていた 2013 年に邪術法を廃止したが、保護法の施行は依然として一貫しておらず、コミュニティ主導の暴力は続いている。 サマライ諸島を含むミルンベイ州では、妖術の信仰が根強く残っているが、ハイランド地方に比べ、被告に対する暴力は著しく少ない。人類学的研究によると、 これらの地域における妖術の解釈は、悪意と関連性が低く、より広範な精神的・文化的慣習に統合されているようです。これは、女性の社会的地位の向上と、性 別に基づく妖術の告発の減少と関連していると考えられています[164]。 フィジー、トンガ、サモアなど、オセアニアの他の地域でも、霊力や呪術の影響に関する伝統が維持されています。例えばフィジーでは、ヴァラヴァラ・ヴァカ ル(霊的な行為)や伝統的な治療行為などの概念が、一部の農村地域では今でも認識されている。しかし、キリスト教や正式な法制度の影響により、妖術に関連 する暴力は減少している。今日の多くの太平洋諸島社会では、妖術は犯罪ではなく文化や宗教の観点から捉えられており、超自然的な主張を含む事件は、慣習的 な紛争解決や教会による調停によって解決される場合が多い。 |

| Witches in art and literature Further information: Witch (archetype) § In art and literature, and List of fictional witches  Albrecht Dürer c. 1500: Witch riding backwards on a goat Witches have a long history of being depicted in art, although most of their earliest artistic depictions seem to originate in Early Modern Europe, particularly the Medieval and Renaissance periods. Many scholars attribute their manifestation in art as inspired by texts such as Canon Episcopi, a demonology-centered work of literature, and Malleus Maleficarum, a "witch-craze" manual published in 1487, by Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger.[165] Witches in fiction span a wide array of characterizations. They are typically, but not always, female, and generally depicted as either villains or heroines.[166] |

芸術や文学における妖術師たち 詳細情報:魔女=妖術師 (アーキタイプ) § 芸術や文学、および架空の人物である妖術師の一覧  アルブレヒト・デューラー、1500年頃:山羊に逆向きに乗った妖術師 妖術師は、芸術作品に長く描かれてきたが、その最も初期の芸術的描写の多くは、近世ヨーロッパ、特に中世およびルネサンス時代に起源があると思われる。多 くの学者は、芸術における妖術師の表現は、悪魔学を中心とした文学作品『カノン・エピスコピ』や、1487 年にハインリッヒ・クラマーとヤコブ・スプレンガーによって出版された「魔女狩り」の教本『魔女狩り』などの著作から着想を得たものと見なしている。 [165] フィクションに登場する妖術師は、さまざまな特徴を持っている。彼らは通常、女性であるが、必ずしもそうではなく、一般的に悪役またはヒロインとして描か れる。[166] |

| Aradia, or the Gospel of the Witches – 1899 book by Charles Godfrey Leland Feminist interpretations of witch trials in the early modern period Flying ointment – Hallucinogenic salve used in the practice of witchcraft History of goetia – Magical practice involving evocation of spirits Kitchen witch – Witch doll Witches' Sabbath – Gathering of those believed to practice witchcraft |

アラディア、あるいは魔女たちの福音書 – 1899年にチャールズ・ゴッドフリー・リーランドが著した本 近世における魔女裁判のフェミニスト的解釈 飛行軟膏 – 妖術の儀式で使用される幻覚作用のある軟膏 ゴエティアの歴史 – 霊を呼び出す呪術 キッチンウィッチ – 魔女の人形 魔女の Sabbath – 妖術を信じる者たちの集会 |

| Works cited Abusch, Tzvi (2002). Mesopotamian Witchcraft: Toward a History and Understanding of Babylonian Witchcraft Beliefs and Literature. Brill Styx. ISBN 978-90-04-12387-8. Adler, Margot (2006). Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshippers, and Other Pagans in America Today. New York: Penguin Books. OCLC 515560. Ankarloo, Bengt; Clark, Stuart (2001). Witchcraft and Magic in Europe: Biblical and Pagan Societies. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Philadelphia Press. ISBN 978-0-8264-8606-6. Buse, Jasper (1995). Cook Islands Maori Dictionary. Cook Islands Ministry of Education. ISBN 978-0-7286-0230-4. Cusack, Carole M. (2009). "The Return of the Goddess: Mythology, Witchcraft and Feminist Spirituality". In Pizza, Murphy; Lewis, James (eds.). Handbook of Contemporary Paganism. Brill. ISBN 978-9004163737. Davies, Owen (2003). Cunning-Folk: Popular Magic in English History. London: Hambledon Continuum. ISBN 978-1-85285-297-9. Ehrenreich, Barbara; English, Deirdre (2010). Witches, Midwives & Nurses: A History of Women Healers (2nd ed.). New York: Feminist Press at CUNY. ISBN 978-1-55861-690-5. Herrera-Sobek, María (2012). Celebrating Latino Folklore: An Encyclopedia of Cultural Traditions. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-34339-1. Hutton, Ronald (1999). The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820744-3. Hutton, Ronald (2017). The Witch: A History of Fear, from Ancient Times to the Present. Yale University Press. Levack, Brian (2013). The Oxford Handbook of Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe and Colonial America. Oxford University Press. Pócs, É. (1999). Between the Living and the Dead: A Perspective on Witches and Seers in the Early Modern Age. Hungary: Central European University Press. ISBN 978-963-9116-19-1. Reiner, E. (1995). Astral Magic in Babylonia. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. ISBN 978-0-87169-854-4. Thomas, Keith (1997). Religion and the Decline of Magic. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0297002208. Wilby, Emma (2005). Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits: Shamanistic Visionary Traditions in Early Modern British Witchcraft and Magic. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-84519-079-8. Willis, Deborah (2018). Malevolent Nurture: Witch-Hunting and Maternal Power in Early Modern England. Cornell University Press. |

引用文献 Abusch, Tzvi (2002). メソポタミアの妖術:バビロニアの妖術の信仰と文学の歴史と理解に向けて。ブリル・スティックス。ISBN 978-90-04-12387-8。 Adler, Margot (2006). 月を引き下げる: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshippers, and Other Pagans in America Today. New York: Penguin Books. OCLC 515560. Ankarloo, Bengt; Clark, Stuart (2001). Witchcraft and Magic in Europe: Biblical and Pagan Societies. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Philadelphia Press. ISBN 978-0-8264-8606-6. ブーズ、ジャスパー (1995)。クック諸島マオリ語辞典。クック諸島教育省。ISBN 978-0-7286-0230-4。 Cusack, Carole M. (2009). 「女神の復活:神話、妖術、フェミニストの精神性」 Pizza, Murphy; Lewis, James (eds.). Handbook of Contemporary Paganism. ブリル。ISBN 978-9004163737。 デービス、オーウェン (2003)。 Cunning-Folk: Popular Magic in English History. ロンドン: ハンブルドン・コンティニュアム。ISBN 978-1-85285-297-9。 エーレンライク、バーバラ; イングリッシュ、ディアドラ (2010)。 Witches, Midwives & Nurses: 女性治療者の歴史(第 2 版)。ニューヨーク:CUNY フェミニスト・プレス。ISBN 978-1-55861-690-5。 Herrera-Sobek, María (2012). Celebrating Latino Folklore: An Encyclopedia of Cultural Traditions. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-34339-1. ハットン、ロナルド (1999)。月の勝利:現代異教の妖術の歴史。オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-820744-3。 ハットン、ロナルド (2017)。魔女:古代から現代までの恐怖の歴史。エール大学出版局。 レヴァック、ブライアン (2013)。『オックスフォード・ハンドブック 初期近代ヨーロッパと植民地アメリカにおける妖術』 オックスフォード大学出版局。 ポクス、É. (1999)。『生者と死者の間:初期近代における魔女と予言者に関する考察』 ハンガリー:中央ヨーロッパ大学出版局。ISBN 978-963-9116-19-1。 ライナー、E.(1995)。『バビロニアの星占術』 フィラデルフィア:アメリカ哲学協会。ISBN 978-0-87169-854-4。 トーマス、キース(1997)。『宗教と呪術の衰退』 英国オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0297002208。 ウィルビー、エマ(2005)。『狡猾な民と親しい精霊たち:近世英国の妖術と魔術におけるシャーマニズムの幻想的伝統』。サセックス・アカデミック・プレス。ISBN 978-1-84519-079-8。 ウィリス、デボラ(2018)。『悪意に満ちた養育:近世英国のウイッチハントと母親の権力』。コーネル大学出版局。 |

| Bailey, M. D. (2010). Battling

Demons: Witchcraft, Heresy, and Reform in the Late Middle Ages.

Pennsylvania State University Press. Bosworth, Joseph (1991) [1882]. Toller, T. Northcote (ed.). An Anglo-Saxon dictionary, based on the manuscript collections of the late Joseph Bosworth. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Chardonnens, László Sándor (2007). Anglo-Saxon Prognostics, 900–1100: Study and Texts. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-9004158290. Epstein, I. (2008). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Children's Issues Worldwide. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-05559-1. Ginzburg, Carlo (1983) [1966]. The Night Battles: Witchcraft and Agrarian Cults in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. Translated by Tedeschi, John; Tedeschi, Anne. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0801843860. Ginzburg, Carlo (2004) [1989]. Ecstasies: Deciphering the Witches' Sabbath. Translated by Raymond Rosenthal. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-29693-7. Gill, William Wyatt (1892). "Wizards". The South Pacific and New Guinea, Past and Present. Sydney: Charles Potter, Government Printer. Hutton, R. (2006). Witches, Druids and King Arthur. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-85285-555-0. Kent, Elizabeth (2005). "Masculinity and Male Witches in Old and New England". History Workshop. 60: 69–92. doi:10.1093/hwj/dbi034. Lima, R. (2005). Stages of Evil: Occultism in Western Theater and Drama. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2362-2. Lühr, R. (1988). Expressivität und Lautgesetz im Germanischen (in German). Heidelberg: Winter. ISBN 978-3533038641. North, Richard (1997). Heathen Gods in Old English Literature. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Rasbold, K. (2019). Crossroads of Conjure: The Roots and Practices of Granny Magic, Hoodoo, Brujería, and Curanderismo. Llewellyn Worldwide. ISBN 978-0-7387-5824-4. Ruickbie, Leo (2004). Witchcraft out of the Shadows: A History. London: Robert Hale. ISBN 978-0-7090-7567-7. Williams, Howard (1865). The Superstitions of Witchcraft. London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, & Green – via Project Gutenberg. |

ベイリー、M. D. (2010). 悪魔との戦い:中世後期における妖術、異端、そして改革。ペンシルベニア州立大学出版局。 ボスワース、ジョセフ (1991) [1882]. トラー、T. ノースコート (編). 故ジョセフ・ボスワースの写本コレクションに基づくアングロサクソン語辞典。オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局。 シャルドネン、ラースロー・サンドール (2007)。『アングロサクソン予言、900-1100:研究とテキスト』。ライデン:ブリル。ISBN 978-9004158290。 エプスタイン、I. (2008)。『グリーンウッド世界子供問題事典』。グリーンウッドプレス。ISBN 978-0-313-05559-1。 Ginzburg, Carlo (1983) [1966]. The Night Battles: Witchcraft and Agrarian Cults in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. 翻訳:Tedeschi, John; Tedeschi, Anne. ボルチモア:ジョンズ・ホプキンズ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0801843860。 Ginzburg, Carlo (2004) [1989]. エクスタシー:妖術師の安息日を解読する。レイモンド・ローゼンタール訳。シカゴ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-226-29693-7。 ギル、ウィリアム・ワイアット (1892)。「ウィザード」。『南太平洋とニューギニア、過去と現在』。シドニー:チャールズ・ポッター、政府印刷局。 ハットン、R. (2006)。『妖術師、ドルイド、アーサー王』。ブルームズベリー・アカデミック。ISBN 978-1-85285-555-0。 ケント、エリザベス (2005)。「オールド・イングランドとニュー・イングランドの男らしさと男性妖術師」。歴史ワークショップ。60: 69–92. doi:10.1093/hwj/dbi034。 リマ, R. (2005). 悪の段階: 西洋演劇とドラマにおけるオカルティズム. ケンタッキー大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-8131-2362-2. リュール, R. (1988). 表現性と音韻法則のゲルマン語における研究 (ドイツ語). ハイデルベルク: ウィンター. ISBN 978-3533038641. ノース、リチャード (1997)。古英語文学における異教の神々。英国ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。 ラスボルト、K. (2019)。呪術の岐路:おばあちゃんの魔法、フードゥー、ブルヘリア、およびキュランデリスモのルーツと実践。ルウェリン・ワールドワイド。ISBN 978-0-7387-5824-4。 Ruickbie, Leo (2004). 影から現れた妖術:その歴史。ロンドン:ロバート・ヘイル。ISBN 978-0-7090-7567-7。 Williams, Howard (1865). 妖術の迷信。ロンドン:ロングマン、グリーン、ロングマン、ロバーツ、グリーン – プロジェクト・グーテンベルク経由。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Witchcraft |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆