邪馬台国

Yamatai

☆ 邪馬台国(やまたいこく、邪馬台国)は、弥生時代後期(紀元前1,000年頃~紀元後300年頃)の倭国(日本)の国名である。中国の『三国志』では、最 初に/*ja-maB-də̂/(邪馬臺)[1]または/*ja-maB-ʔ/(邪馬壹)(東漢の発音を復元したもの)[1][2]と記され、その後に 「国」の字が続く、 卑弥呼(248年頃没)の領地であった。248年頃没)の領地であると記されている。日本の歴史家、言語学者、考古学者の世代は、邪馬台国がどこに位置 し、後の大和国と関係があるかどうかについて議論してきた[3][4][5]。)

| Yamatai or Yamatai-koku (邪

馬台国) (c. 1st century – c. 3rd century) is the Sino-Japanese name of an

ancient country in Wa (Japan) during the late Yayoi period (c. 1,000

BCE – c. 300 CE). The Chinese text Records of the Three Kingdoms first

recorded the name as /*ja-maB-də̂/ (邪馬臺)[1] or /*ja-maB-ʔit/ (邪馬壹)

(using reconstructed Eastern Han Chinese pronunciations)[1][2] followed

by the character 國 for "country", describing the place as the domain of

Priest-Queen Himiko (卑弥呼) (died c. 248 CE). Generations of Japanese

historians, linguists, and archeologists have debated where Yamatai was

located and whether it was related to the later Yamato (大和国).[3][4][5] |

邪

馬台国(やまたいこく、邪馬台国)は、弥生時代後期(紀元前1,000年頃~紀元後300年頃)の倭国(日本)の国名である。中国の『三国志』では、最初

に/*ja-maB-də̂/(邪馬臺)[1]または/*ja-maB-ʔ/(邪馬壹)(東漢の発音を復元したもの)[1][2]と記され、その後に

「国」の字が続く、

卑弥呼(248年頃没)の領地であった。248年頃没)の領地であると記されている。日本の歴史家、言語学者、考古学者の世代は、邪馬台国がどこに位置

し、後の大和国と関係があるかどうかについて議論してきた[3][4][5]。 |

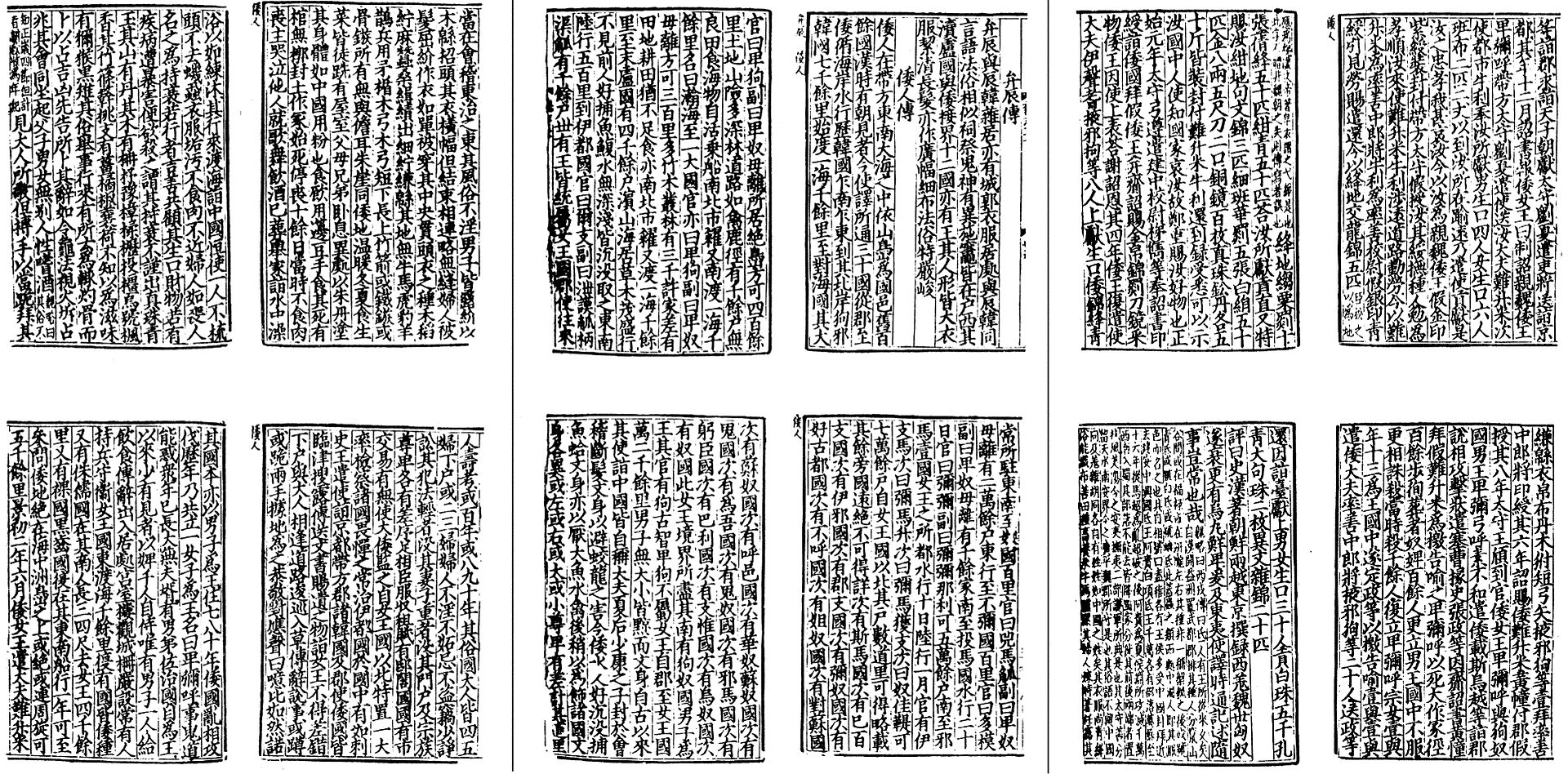

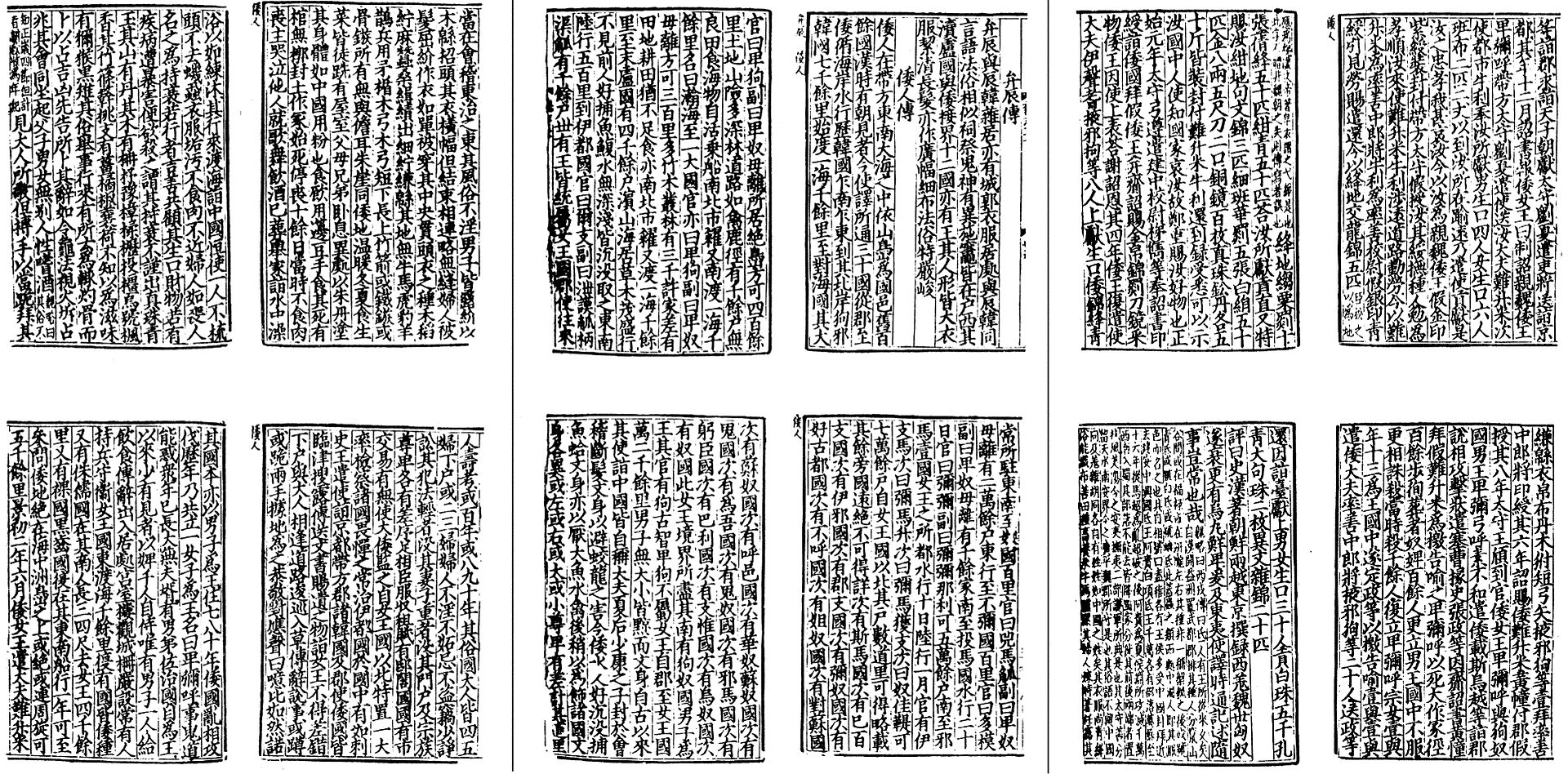

| History Chinese texts  Text of the Wei Zhi (ca. 297) The oldest accounts of Yamatai are found in the official Chinese dynastic Twenty-Four Histories for the 1st- and 2nd-century Eastern Han dynasty, the 3rd-century Wei kingdom, and the 6th-century Sui dynasty. The c. 297 CE Records of Wèi (traditional Chinese: 魏志), which is part of the Records of the Three Kingdoms (三國志), first mentions the country Yamatai, usually spelled as 邪馬臺 (/*ja-maB-də̂/), written instead with the spelling 邪馬壹 (/*ja-maB-ʔit/), or Yamaichi in modern Japanese pronunciation.[3] Most Wei Zhi commentators accept the 邪馬臺 (/*ja-maB-də̂/) transcription in later texts and dismiss this initial spelling using 壹 (/ʔit/) meaning "one" (the anti-fraud character variant for 一 'one') as a miscopy, or perhaps a naming taboo avoidance, of 臺 (/dʌi/) meaning "platform; terrace." This history describes ancient Wa based upon detailed reports of 3rd-century Chinese envoys who traveled throughout the Japanese archipelago: Going south by water for twenty days, one comes to the country of Toma, where the official is called mimi and his lieutenant, miminari. Here there are about fifty thousand households. Then going toward the south, one arrives at the country of Yamadai, where a Queen holds her court. [This journey] takes ten days by water and one month by land. Among the officials there are the ikima and, next in rank, the mimasho; then the mimagushi, then the nakato. There are probably more than seventy thousands households. (115, tr. Tsunoda 1951:9) The Wei Zhi also records that in 238 CE, Queen Himiko sent an envoy to the court of Wei emperor Cao Rui, who responded favorably:[3] We confer upon you, therefore, the title 'Queen of Wa Friendly to Wei', together with the decoration of the gold seal with purple ribbon. ...As a special gift, we bestow upon you three pieces of blue brocade with interwoven characters, five pieces of tapestry with delicate floral designs, fifty lengths of white silk, eight taels of gold, two swords five feet long, one hundred bronze mirrors, and fifty catties each of jade and of red beads. (tr. Tsunoda 1951:14-15) The ca. 432 CE Book of the Later Han (traditional Chinese: 後漢書) says the Wa kings lived in the country of Yamatai (邪馬臺國):[4] The Wa dwell on mountainous islands southeast of Han [Korea] in the middle of the ocean, forming more than one hundred communities. From the time of the overthrow of Chaoxian [northern Korea] by Emperor Wu (B.C. 140-87), nearly thirty of these communities have held intercourse with the Han [dynasty] court by envoys or scribes. Each community has its king, whose office is hereditary. The King of Great Wa [Yamato] resides in the country of Yamadai. (tr. Tsunoda 1951:1) The Book of Sui (traditional Chinese: 隋書), finished in 636 CE, records changing the capital's name from the Yamatai recorded in the Book of Wei, to Yamadai (traditional Chinese: 邪靡堆, Middle Chinese: /jia muɑ tuʌi/; interpreted as Yamato (Japanese logographic spelling 大和): Wa is situated in the middle of the great ocean southeast of Baekje and Silla, three thousand li away by water and land. The people dwell on mountainous islands. ...The capital is Yamadai, known in the Wei history as Yamatai. The old records say that it is altogether twelve thousand li distant from the borders of Lelang and Daifang prefectures, and is situated east of Kuaiji and close to Dan'er. (倭國在百濟・新羅東南、水陸三千里、於大海之中、依山島而居。... 都於邪靡堆、則魏志所謂邪馬臺者也。古云、去樂浪郡境及帶方郡並一萬二千里、在會稽之東、與儋耳相近。) (81, tr. Tsunoda 1951:28) The History of the Northern Dynasties, completed 643-659 CE, contains a similar record, but transliterates the name Yamadai using a different character with a similar pronunciation (traditional Chinese: 邪摩堆). |

歴史 中国のテキスト  『魏志』(297年頃)のテキスト 邪馬台国に関する最古の記述は、1、2世紀の東漢、3世紀の魏、6世紀の隋の各王朝の正史『二十四史』に見られる。 紀元297年頃の『魏志倭人伝』には、「魏志倭人伝」と「魏志倭人伝」がある。297年の『魏志倭人伝』である: 三国志の一部である『魏志』には、邪馬台国が初めて登場する、 通常、邪馬臺(/*ja-maB-də↪Mn_302/)と表記されるが、代わりに邪馬壹(/*ja-maB-ʔit/)と表記される。 [3] 魏志倭人伝の解説者の多くは、後世の書物では邪馬臺(/*ja-maB-də̂/)の表記を受け入れ、「一」を意味する壹(/ʔit/)(一の「一」に対 する不正防止のための異体字)を用いたこの最初の表記を、「台;テラス」を意味する臺(/dʌ/)の誤写、あるいはおそらく命名のタブー回避として退けて いる。この歴史は、日本列島を旅した3世紀の遣唐使の詳細な報告に基づいて、古代の「和」を記述している: 水路で20日間南下すると、當麻(とうま)の国に着く。ここには約5万世帯がある。そして南へ向かうと、女王が宮廷を開いているヤマダイの国に着く。[こ の旅は)水路で10日、陸路で1ヶ月かかる。役人には、イキマ、次にミマショ、次にミマグシ、次にナカトがいる。世帯数はおそらく7万以上であろう。 (115、角田訳1951:9)。 また『魏志』には、238年に卑弥呼女王が魏の皇帝曹瑞の宮廷に使者を送り、曹瑞が好意的な返事をしたことが記されている[3]。 ...特別な贈り物として、文字が織り込まれた青錦3枚、繊細な花模様のタペストリー5枚、白絹50丈、金8テール、長さ5尺の剣2本、銅鏡100枚、玉と紅玉各50顆を贈る。(角田1951:14-15)。 432年頃の後漢書である。432年頃の『後漢書』によると、和王は邪馬台国に住んでいた[4]。 和人は漢の東南にある山がちな島々に住み、百以上の集落を形成している。武帝による朝鮮(朝鮮半島北部)打倒(B.C.140-87)の時から、これらの 共同体のうち30近くが、使節や書記によって漢(王朝)の宮廷と交流してきた。それぞれの共同体には王がおり、その地位は世襲制である。大倭の王は邪馬台 国に住んでいる」(角田訳 1951:1 紀元636年に完成した『隋書』には、都の名前を『魏書』に記された邪馬台国から邪馬台国に変更したことが記されている: /jia muɑ tuʌ/)に変更されたことが記録されている: 倭は百済と新羅の東南の大海の真ん中に位置し、水と陸で3000里離れている。人々は山がちな島々に住んでいる。...首都は邪馬台国であり、魏志倭人伝 では邪馬台国として知られている。古い記録によると、楽浪県と大方県の境から全部で一万二千里離れており、杭州の東に位置し、段爾に近い。(倭國在百濟・ 新羅東南、水陸三千里、於大海之中、依山島而居。都於邪靡堆、則魏志所謂邪馬臺者也。古云、去樂浪郡境及帶方郡並一萬二千里、在會稽之東、與儋耳相近。 643-659年に完成した『北朝史』にも同様の記録があるが、ヤマダイという名前は発音が似ている別の文字(繁体字:邪摩堆)を使って音訳されている。 |

| Japanese texts The first Japanese books, such as the Kojiki or Nihon Shoki, were mainly written in a variant of Classical Chinese called kanbun. The first texts actually in the Japanese language used Chinese characters, called kanji in Japanese, for their phonetic values. This usage is first seen in the 400s or 500s to spell out Japanese names, as on the Eta Funayama Sword or the Inariyama Sword. This gradually formalized over the 600s and 700s into the Man'yōgana system, a rebus-like transcription that uses specific kanji to represent Japanese phonemes. For instance, man'yōgana spells the Japanese mora ka using (among others) the character 加, which means "to add", and was pronounced as /kˠa/ in Middle Chinese and adopted into Japanese with the pronunciation ka. Irregularities within this awkward system led Japanese scribes to develop phonetically regular syllabaries. The new kana were graphic simplifications of Chinese characters. For instance, ka is written か in hiragana and カ in katakana, both of which derive from the Man'yōgana 加 character (hiragana from the cursive form of the kanji, and katakana from a simplification of the kanji). The c. 712 Kojiki (古事記, "Records of Ancient Matters") is the oldest extant book written in Japan. The "Birth of the Eight Islands" section phonetically transcribes Yamato as 夜麻登, pronounced in Middle Chinese as /jiaH mˠa təŋ/ and used to represent the Old Japanese morae ya ma to2 (see also Man'yōgana#chartable). The Kojiki records the Shintoist creation myth that the god Izanagi and the goddess Izanami gave birth to the Ōyashima (大八州, "Eight Great Islands") of Japan, the last of which was Yamato: Next they gave birth to Great-Yamato-the-Luxuriant-Island-of-the-Dragon-Fly, another name for which is Heavenly-August-Sky-Luxuriant-Dragon-Fly-Lord-Youth. The name of "Land-of-the-Eight-Great-Islands" therefore originated in these eight islands having been born first. (tr. Chamberlain 1919:23) Chamberlain (1919:27) notes this poetic name "Island of the Dragon-fly" is associated with legendary Emperor Jimmu, whose honorific name includes "Yamato", as Kamu-yamato Iware-biko. The 720 Nihon Shoki (日本書紀, "Chronicles of Japan") transcribes Yamato with the Chinese characters 耶麻騰, pronounced in Middle Chinese as /jia mˠa dəŋ/ and in Old Japanese as ya ma to2 or ya ma do2. In this version of the Eight Great Islands myth, Yamato is born second instead of eighth: Now when the time of birth arrived, first of all the island of Ahaji was reckoned as the placenta, and their minds took no pleasure in it. Therefore it received the name of Ahaji no Shima. Next there was produced the island of Oho-yamato no Toyo-aki-tsu-shima. (tr. Aston 1924 1:13) The translator Aston notes a literal meaning for the epithet of Toyo-aki-tsu-shima of "rich harvest's" (or "rich autumn's") "island" (i.e. "Island of Bountiful Harvests" or "Island of Bountiful Autumn"). The c. 600-759 Man'yōshū (万葉集, "Myriad Leaves Collection") transcribes various pieces of text using not the phonetic man'yōgana spellings, but rather a logographic style of spelling, based on the pronunciation of the kanji using the native Japanese vocabulary of the same meaning. For instance, the name Yamato is sometimes spelled as 山 (yama, "mountain") + 蹟 (ato, "footprint; track; trace"). Old Japanese pronunciation rules caused the sound yama ato to contract to just yamato. |

日本の書物 古事記』や『日本書紀』のような日本の最初の書物は、主に漢文と呼ばれる古典中国語の変形で書かれていた。実際に日本語で書かれた最初のテキストは、日本 語では漢字と呼ばれる漢字を音価に使っていた。この使い方は、400年代から500年代にかけて、エタ船山刀や稲荷山刀のように、日本人の名前を綴るため に初めて見られる。これは、600年代から700年代にかけて徐々に正式になり、特定の漢字を使って日本語の音素を表す「万葉仮名」へと変化した。例え ば、万葉仮名は「加」の字を使って「モラ・カ」と表記する。「加」は「加える」という意味で、中国語では「kˠ」と発音され、日本語では「カ」と発音され た。この不規則なシステムは、日本の書記たちに音韻的に規則正しい音節を開発させた。新仮名は漢字を簡略化したものである。例えば、「か」はひらがなで 「か」、カタカナで「カ」と表記されるが、どちらも万葉仮名の加文字に由来する(ひらがなは漢字の草書体、カタカナは漢字を簡略化したもの)。 712年頃の『古事記』は、現存する日本最古の書物である。八島誕生」の項では、ヤマトを夜麻登と音写し、中文では/jiaH mˠa tə↪Ll/ と発音し、古語のモラエ・ヤ・マ・ト2(万葉仮名#図表も参照)を表している。古事記』には、イザナギの神とイザナミの女神が大八島を生み、その最後の島 が大和であったという神話が記されている: その最後の島が大和である。次に、彼らは大八洲龍神島を生み、その別名は天八洲龍神島である。したがって、「八大大陸 」という名前は、この八つの島が最初に生まれたことに由来する。(チェンバレン1919:23)。 Chamberlain(1919:27)は、この詩的な名前 「龍の飛ぶ島 」は、神武大和磐余彦として、「大和 」を敬称に含む伝説的な神武天皇に関連していると指摘している。 720年の『日本書紀』では、大和を漢字の耶麻騰と表記しており、中文では/jia ma dəl_14/ と、古文では ya ma to2 または ya ma do2 と発音する。この八大島神話のバージョンでは、ヤマトは8番目ではなく2番目に生まれている: さて、誕生の時が来たとき、まずアハジ島は胎盤とみなされ、彼らの心はそれを喜ばなかった。そのため、アハジの島と名付けられた。次に、オホヤマトノトヨアキツシマが生まれた。(アストン1924 1:13訳)。 翻訳者アストンは、豊秋津島の 「豊」(または 「豊秋」)の 「島」(すなわち 「豊穣の島 」または 「豊穣の秋の島」)の文字通りの意味を指摘している。 600~759年頃の『万葉集』には、万葉仮名表記ではなく、漢字の発音に基づき、同じ意味の語彙を用いた対訳的な表記で様々な文章が書き写されている。 例えば、大和という名前は、山(yama、「山」)+蹟(ato、「足跡、跡」)と表記されることがある。古い日本語の発音規則により、yama atoという音はyamatoだけに収縮した。 |

| Government According to the Chinese record Twenty-Four Histories, Yamatai was originally ruled by the shamaness Queen Himiko. The other officials of the country were also ranked under the queen, with the highest position called ikima, followed by mimasho, then mimagushi, and the lowest-ranking position of nakato. According to the legends, Himiko lived in a palace with 1,000 female handmaidens and one male servant who would feed her. This palace was most likely located at the site of Makimuku in Nara prefecture. She ruled for most of the known history of Yamatai. After Queen Himiko died, an unknown king became ruler of the country for a short period, and then Queen Toyo reigned before Yamatai disappears from historical records. |

政府 中国の『二十四史』によれば、邪馬台国はもともと巫女の卑弥呼女王によって統治されていた。他の官吏も女王の下に位置づけられ、最高位は「イキマ」、次い で「ミマショウ」、「ミマグシ」、最下位は「ナカト」と呼ばれた。伝説によれば、卑弥呼は1,000人の侍女と、彼女を養う1人の召使とともに宮殿に住ん でいた。この宮殿は奈良県の巻向の地にあった可能性が高い。卑弥呼は邪馬台国の歴史の大半を支配した。 卑弥呼女王が亡くなった後、無名の王が短期間この国の支配者となり、その後、トヨ女王が統治した後、ヤマタイは歴史的記録から姿を消した。 |

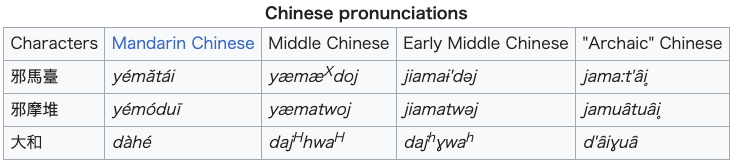

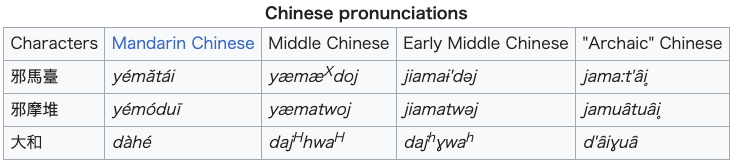

| Pronunciations Modern Japanese Yamato (大和) descends from Old Japanese Yamatö or Yamato2, which has been associated with Yamatai. The latter umlaut or subscript diacritics distinguish two vocalic types within the proposed eight vowels of Nara period (710-794) Old Japanese (a, i, ï, u, e, ë, o, and ö, see Jōdai Tokushu Kanazukai), which merged into the five modern vowels (a, i, u, e, and o). During the Kofun period (250-538) when kanji were first used in Japan, Yamatö was written with the ateji 倭 for Wa, the name given to "Japan" by Chinese writers using a character meaning "docile, submissive". During the Asuka period (538-710) when Japanese place names were standardized into two-character compounds, the spelling of Yamato was changed to 大倭, adding the prefix 大 ("big; great"). Following the ca. 757 graphic substitution of 和 ("peaceful") for 倭 ("docile"), the name Yamato was spelled 大和 ("great harmony"), using the Classical Chinese expression 大和 (pronounced in Middle Chinese as /dɑH ɦuɑ/, as used in Yijing 1, tr. Wilhelm 1967:371: "each thing receives its true nature and destiny and comes into permanent accord with the Great Harmony.") The early Japanese texts above give three spellings of Yamato in kanji: 夜麻登 (Kojiki), 耶麻騰 (Nihon Shoki), and 山蹟 (Man'yōshū). The Kojiki and Nihon Shoki use Sino-Japanese on'yomi readings of ya 夜 "night" or ya or ja 耶 (an interrogative sentence-final particle in Chinese), ma 麻 "hemp", and to 登 "rise; mount" or do 騰 "fly; gallop". In contrast, the Man'yōshū uses Japanese kun'yomi readings of yama 山 "mountain" and ato 跡 "track; trace". As noted further above, Old Japanese pronunciation rules caused yama ato to contract to yamato. The early Chinese histories above give three transcriptions of Yamatai: 邪馬壹 (Wei Zhi), 邪馬臺 (Hou Han Shu), and 邪摩堆 (Sui Shu). The first syllable is consistently written with 邪 "a place name", which was used as a jiajie graphic-loan character for 耶, an interrogative sentence-final particle, and for 邪 "evil; depraved". The second syllable is written with 馬 "horse" or 摩 "rub; friction". The third syllable of Yamatai is written in one variant with 壹 "faithful, committed", which is also financial form of 一, "one", and more commonly using 臺 "platform; terrace" (cf. Taiwan 臺灣) or 堆 "pile; heap". Concerning the transcriptional difference between the 邪馬壹 spelling in the Wei Zhi and the 邪馬臺 in the Hou Han Shu, Hong (1994:248-9) cites Furuta Takehiko [ja] that 邪馬壹 was correct. Chen Shou, author of the ca. 297 Wei Zhi, was writing about recent history based on personal observations; Fan Ye, author of the ca. 432 Hou Han Shu, was writing about earlier events based on written sources. Hong says the San Guo Zhi uses 壹 ("one") 86 times and 臺 ("platform") 56 times, without confusing them. During the Wei period, 臺 was one of their most sacred words, implying a religious-political sanctuary or the emperor's palace. The characters 邪 and 馬 mean "evil; depraved" and "horse", reflecting the contempt Chinese felt for a barbarian country, and it is most unlikely that Chen Shou would have used a sacred word after these two characters. It is equally unlikely that a copyist could have confused the characters, because in their old form they do not look nearly as similar as in their modern printed form. Yamadai was Fan Yeh's creation. (1994:249) He additionally cites Furuta that the Wei Zhi, Hou Han Shu, and Xin Tang Shu histories use at least 10 Chinese characters to transcribe Japanese to, but 臺 is not one of them. In historical Chinese phonology, the Modern Chinese pronunciations differ considerably from the original 3rd-7th century transcriptions from a transitional period between Archaic or Old Chinese and Ancient or Middle Chinese. The table below contrasts Modern pronunciations (in Pinyin) with differing reconstructions of Early Middle Chinese (Edwin G. Pulleyblank 1991), "Archaic" Chinese (Bernhard Karlgren 1957), and Middle Chinese (William H. Baxter 1992). Note that Karlgren's "Archaic" is equivalent with "Middle" Chinese, and his "yod" palatal approximant i̯ (which some browsers cannot display) is replaced with the customary IPA j. |

発音 現代日本語のヤマト(大和)は、古語のヤマト(Yamatö)またはヤマト2(Yamato2)から派生したもので、ヤマタイ(Yamatai)と関連付 けられてきた。奈良時代(710~794年)の8つの母音(a、i、ï、u、e、ë、o、ö、『上代特殊奏法会』参照)は、現代の5つの母音(a、i、 u、e、o)に統合された。 日本で初めて漢字が使われた古墳時代(250~538年)には、ヤマトは「倭」のアテ字で書かれた。飛鳥時代(538~710年)に日本の地名が二字熟語に統一されると、「大和」は「大倭」と表記されるようになり、接頭辞の「大」が付けられた。 757年頃、大和は「大倭」と表記されるようになった。757年頃、和(「平和な」)が倭(「従順な」)に置き換えられると、大和という地名は大和(「大 調和」)と表記されるようになり、中国古典の表現である大和(中国中文では/dɑH ↪Lu_251/ と発音される: 「各事物はその本性と運命を受け取り、大いなる調和と永久に一致するようになる」)。 上記の日本語の初期のテキストには、大和の漢字表記が3つある:夜麻登(古事記)、耶麻騰(日本書紀)、山蹟(万葉集)。古事記』と『日本書紀』では、耶 「夜」または耶「耶」または耶「耶」(中国語の疑問詞の終助詞)、麻「麻」、登「登」または登「翔」または登「翔」または登「翔」または登「翔」(中国語 の疑問詞の終助詞)を漢音読みしている。一方、『万葉集』では、山(yama)と跡(ato)を訓読みしている。さらに前述したように、旧日本語の発音規 則によって、ヤマ・アトはヤマトに収縮した。 上記の初期の中国史では、邪馬壹(魏志)、邪馬臺(后漢書)、邪堆(隋書)の3つの読み方がある。最初の音節は一貫して邪「地名」で表記され、これは疑問 文の終助詞である耶と邪「悪;堕落」の字形貸字として使われた。第二音節は馬または摩と書く。ヤマタイの第3音節は、壹「忠実な、献身的な」で表記される バリエーションがあるが、これは一「一」の金融形でもあり、より一般的には臺「台、テラス」(台湾の臺灣を参照)または堆「山、山積み」で表記される。魏 志』の邪馬壹と『后漢書』の邪馬臺の表記の違いについて、洪(1994:248-9)は邪馬壹が正しいとする古田武彦[ja]の意見を引用している。陳寿 は『魏志』(297年頃)の著者である。297年の『魏志』の著者陳寿は、個人的な観察に基づいて最近の歴史について書いている。432年ごろの『后漢 書』の著者である范曄は、文献資料に基づいてそれ以前の出来事について書いている。洪氏によれば、『三国志』では壹(「一」)が86回、臺(「台」)が 56回、混同されることなく使われている。 魏の時代、臺は最も神聖な言葉のひとつで、宗教的・政治的な聖域や皇帝の宮殿を意味していた。邪」と「馬」は「邪悪な、堕落した」と「馬」を意味し、中国 人が野蛮な国を軽蔑していたことを反映しており、陳寿がこの2文字の後に神聖な言葉を使ったとは考えにくい。陳寿がこの2つの文字の後に神聖な言葉を使っ たとは考えにくいし、書写者がこの2つの文字を混同したとも考えにくい。山代は范逸の創作である。(1994:249) さらに古田氏は、『魏志』『後漢書』『新唐書』には少なくとも10字の漢字が使われているが、「臺」はその中には含まれていないと述べている。 歴史的な中国語の音韻論において、現代中国語の発音は、アルカイックまたはオールド・チャイニーズと古代またはミドル・チャイニーズの間の過渡期に作られ た3~7世紀のオリジナルの音写とはかなり異なっている。以下の表は、現代中国語の発音(ピンイン)と、中国語中期の初期(Edwin G. Pulleyblank 1991)、「アルカイック」中国語(Bernhard Karlgren 1957)、および中国語中期の異なる復元(William H. Baxter 1992)を対比したものである。Karlgrenの 「Archaic 」は 「Middle 」中国語と同等であり、彼の 「yod 」口蓋近似音i̯(一部のブラウザでは表示できない)は慣用的なIPA jに置き換えられていることに注意されたい。 |

|

|

| Roy Andrew Miller describes the phonological gap between these Middle Chinese reconstructions and the Old Japanese Yamatö. The Wei chih account of the Wo people is chiefly concerned with a kingdom which it calls Yeh-ma-t'ai, Middle Chinese i̯a-ma-t'ḁ̂i, which inevitably seems to be a transcription of some early linguistic form allied with the word Yamato. The phonology of this identification raises problems which after generations of study have yet to be settled. The final -ḁ̂i of the Middle Chinese form seems to be a transcription of some early form not otherwise recorded for the final -ö of Yamato. (1967:17-18) While most scholars interpret 邪馬臺 as a transcription of pre-Old Japanese yamatai, Miyake (2003:41) cites Alexander Vovin that Late Old Chinese ʑ(h)a maaʳq dhəə 邪馬臺 represents a pre-Old Japanese form of Old Japanese yamato2 (*yamatə). Tōdō Akiyasu reconstructs two pronunciations for 䑓 – dai < Middle dǝi < Old *dǝg and yi < yiei < *d̥iǝg – and reads 邪馬臺 as Yamai.[citation needed] The etymology of Yamato, like those of many Japanese words, remains uncertain. While scholars generally agree that Yama- signifies Japan's numerous yama 山 "mountains", they disagree whether -to < -tö signifies 跡 "track; trace", 門 "gate; door", 戸 "door", 都 "city; capital", or perhaps 所 "place". Bentley (2008) reconstructs underlying Wa's endonym *yama-tǝ(ɨ) as underlying the transcription 邪馬臺's pronunciation *ja-maˀ-dǝ > *-dǝɨ.[6] |

ロイ・アンドリュー・ミラーは、これらの中国語中文の復元と日本語の古語ヤマトとの間の音韻論的なギャップについて述べている。 魏志倭人伝は倭人について、主にイエ・マ・タイと呼ばれる王国について記述しているが、この王国は中国語でイ̪ア̫マ̂イと呼ばれ、必然的にヤマトという 言葉と結びついた初期の言語形式の転写であると考えられる。この識別の音韻論は、何世代にもわたる研究にもかかわらず、まだ決着のついていない問題を提起 している。中国語中文の末尾の-ḁ̂イは、ヤマトの末尾の-öについて他に記録されていない何らかの初期の形の音写であると思われる。 ほとんどの学者が邪馬臺を旧日本語以前のyamataiの音写と解釈しているのに対し、三宅(2003:41)はAlexander Vovinを引用して、後期旧漢語ʑ(h)a maaʳq dhə 邪馬臺は旧日本語以前のyamato2 (*yamatə)の音写であると述べている。東堂安芸守は䑓の発音をdai < Middle dǝi < Old *dǝg と yi < yiei < *d̥iǝg の2つに再構成し、邪馬臺をヤマイと読んでいる[要出典]。 大和の語源は、多くの日本語の語源と同様、不確かなままである。学者たちは一般的に、「山」が日本の多くの「山」を意味することに同意しているが、-to < -töが「軌跡」、「門」、「扉」、「都」、あるいは「場所」を意味するのかどうかについては意見が分かれている。Bentley(2008)は、和語の 語源である*yama-tǝ(ɨ)を、邪馬臺の発音*ja-maˀ-dǝ > *-dǝɨの根底にあるものとして再構築している[6]。 |

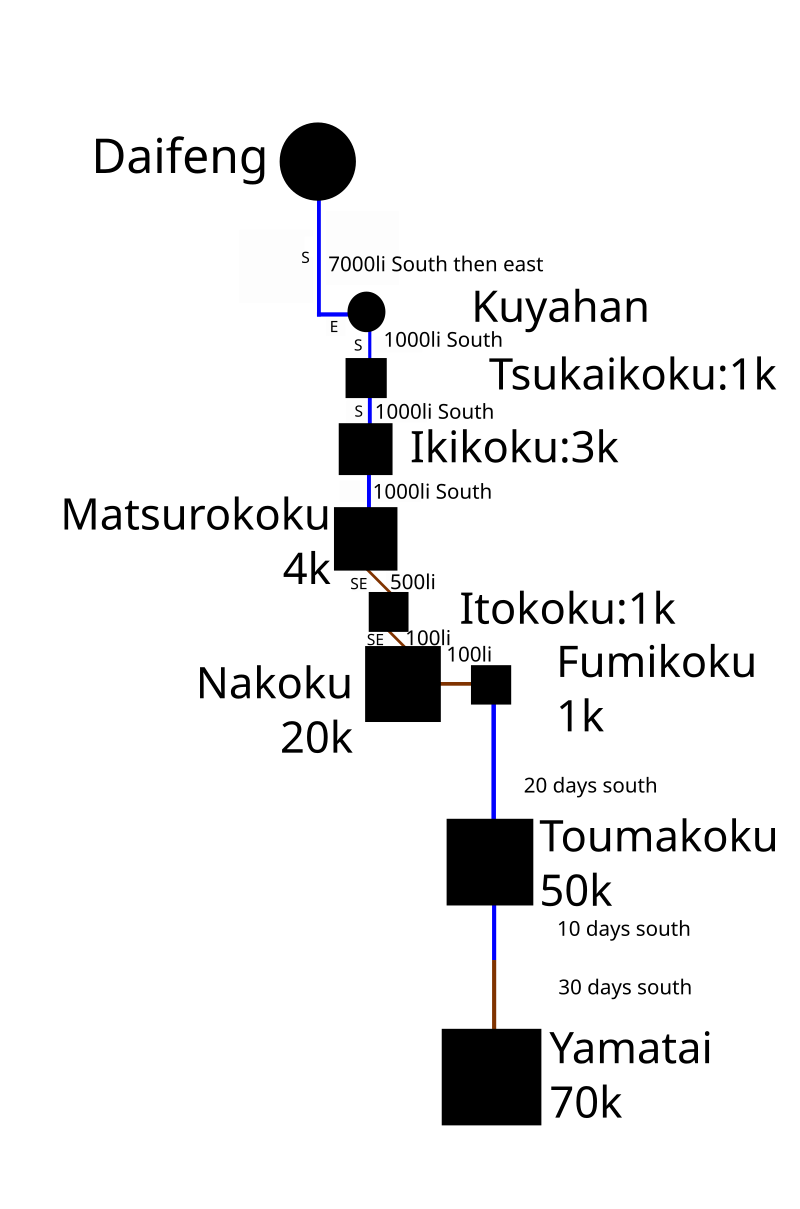

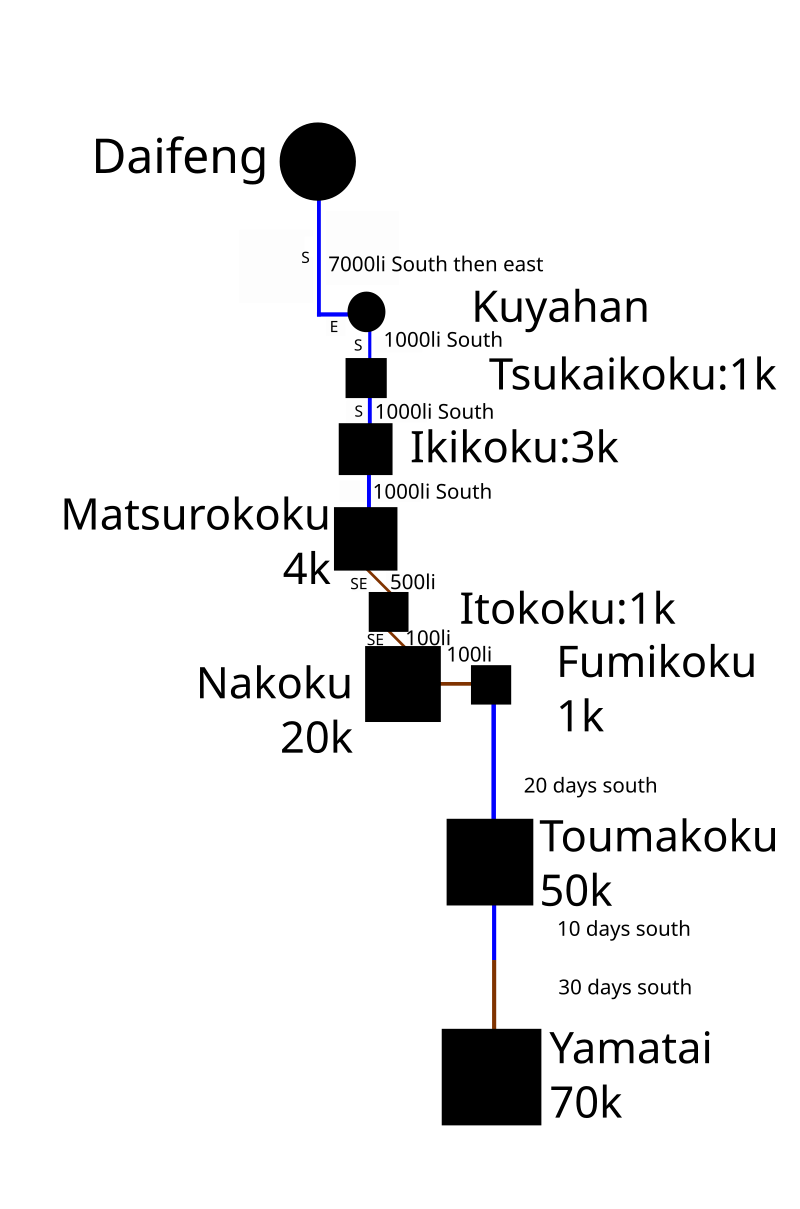

Location Map illustrating the path from the Daifeng commandery to Yamatai, and its distances in the Wajinden. The location of Yamatai-koku is one of the most contentious topics in Japanese history. Generations of historians have debated "the Yamatai controversy" and have hypothesized numerous localities, some of which are fanciful like Okinawa (Farris 1998:245). General consensus centers around two likely locations of Yamatai, either northern Kyūshū or Yamato Province in the Kinki region of central Honshū. Imamura describes the controversy. The question of whether the Yamatai Kingdom was located in northern Kyushu or central Kinki prompted the greatest debate over the ancient history of Japan. This debate originated from a puzzling account of the itinerary from Korea to Yamatai in Wei-shu. The northern Kyushu theory doubts the description of distance and the central Kinki theory the direction. This has been a continuing debate over the past 200 years, involving not only professional historians, archeologists and ethnologists, but also many amateurs, and thousands of books and papers have been published. (1996:188) Imamura. Keiji. 1996. Prehistoric Japan: New Perspectives on Insular East Asia. University of Hawaiʻi Press. The location of ancient Yamatai-koku and its relation with the subsequent Kofun-era Yamato polity remains uncertain. In 1989, archeologists discovered a giant Yayoi-era complex at the Yoshinogari site in Saga Prefecture, which was thought to be a possible candidate for the location of Yamatai. While some scholars, most notably Seijo University historian Takehiko Yoshida, interpret Yoshinogari as evidence for the Kyūshū Theory, many others support the Kinki Theory based on Yoshinogari clay vessels and the early development of Kofun (Saeki 2006). The recent archeological discovery of a large stilt house suggests that Yamatai-koku was located near Makimuku in Sakurai, Nara (Anno. 2009). Makimuku has also revealed wooden tools such as masks and a shield fragment. A large amount of pollen that would have been used to dye clothes was also found at the site of Makimuku. Clay pots and vases were also found at the site of Makimuku similar to ones found in other prefectures of Japan. Another site at Makimuku supporting the theory that Yamatai once existed there is, the possible burial site of Queen Himiko at the Hashihaka burial mound. Himiko was the ruler of Yamatai from c. 180 C.E.- c. 248 C.E. |

地図 大豊司令部から邪馬台国までの道筋と、その距離を和人伝で示した地図。 邪馬台国の位置は、日本史の中で最も論争が多いテーマの一つである。何世代もの歴史家たちが「邪馬台国論争」を繰り広げ、沖縄のような架空の地名も含め、 多くの仮説を立ててきた(Farris 1998:245)。一般的なコンセンサスは、邪馬台国が九州北部か、本州中部の近畿地方にある大和国の2つの可能性が高いという点に集中している。今村 氏はこの論争についてこう述べている。 邪馬台国が九州北部か近畿中部かという問題は、日本の古代史をめぐる最 大の論争を引き起こした。この論争は、朝鮮から魏志倭人伝の邪馬台国への旅程に関する不可解な記述に端を発している。九州北部説は距離の記述に疑問を呈 し、近畿中部説は方角の記述に疑問を呈した。この論争は、プロの歴史学者、考古学者、民俗学者だけでなく、多くのアマチュアも巻き込んで、過去200年に わたって続けられており、何千冊もの本や論文が出版されている。(1996:188) Imamura. Keiji. 1996. Prehistoric Japan: New Perspectives on Insular East Asia. University of Hawaiʻi Press. 古代の邪馬台国の位置と、その後の古墳時代のヤマト政権との関係は、いまだ不確かなままである。1989年、考古学者が佐賀県の吉野ヶ里遺跡で弥生時代の 巨大複合施設を発見し、邪馬台国の場所の候補と考えられた。成城大学の歴史学者である吉田武彦氏を筆頭に、吉野ヶ里を九州説の証拠と解釈する学者がいる一 方で、吉野ヶ里の土器や古墳の早期発達を根拠に近畿説を支持する学者も多い(佐伯氏 2006年)。 最近、考古学的に大きな高床式住居が発見されたことから、邪馬台国は奈良県桜井市の牧椋の近くにあったと考えられている(安野. 2009)。牧椋からは、仮面や盾片などの木器も出土している。牧椋遺跡からは、衣服の染色に使われたと思われる花粉も大量に発見された。他県で発見され たものと同様の土器や壷も牧椋遺跡から発見された。邪馬台国がかつて存在したという説を裏付ける牧椋遺跡のもう一つの遺跡は、女王卑弥呼が埋葬された可能 性のある箸墓古墳である。卑弥呼は西暦180年頃から248年頃まで邪馬台国の支配者であった。 |

| In popular culture Yamatai, depicted as an isolated island somewhere in the Pacific, is the setting of the 2013 video game Tomb Raider and its 2018 film adaptation. Queen Himiko is a key part of the plot.[7] Yamatai appears as historic setting 1990's video game, Legend of Himiko. Yamatai and its queen Himiko are the main villains in the Steel Jeeg anime series. Yamtaikoku is the setting of the 2020/22 limited time event of the mobile game Fate/Grand Order, prominently featuring Queen Himiko.[8] Queen Himiko and the Yamatai Kingdom are the subjects of the song "Himiko" by Japanese EDM group Wednesday Campanella.[9] |

ポピュラーカルチャー 太平洋の孤島として描かれるヤマタイは、2013年のビデオゲーム『トゥームレイダー』と2018年の映画化の舞台である。女王卑弥呼はプロットの重要な部分である[7]。 ヤマタイは1990年代のビデオゲーム『卑弥呼伝説』の歴史的舞台として登場する。 邪馬台国とその女王卑弥呼はアニメ『鋼鉄ジーグ』シリーズの主な悪役である。 邪馬台国はモバイルゲーム『Fate/Grand Order』の2020年・22年の期間限定イベントの舞台であり、女王卑弥呼が大きくフィーチャーされている[8]。 卑弥呼女王と邪馬台国は、日本のEDMグループ、水曜日のカンパネラの曲「卑弥呼」の題材となっている[9]。 |

| References Schuessler, Axel (2014). "Phonological Notes on Hàn Period Transcriptions of Foreign Names and Words" in Studies in Chinese and Sino-Tibetan Linguistics: Dialect, Phonology, Transcription and Text. Series: Language and Linguistics Monograph Series. 53 Ed. VanNess Simmons, Richard & Van Auken, Newell Ann. Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan. p. 255, 286 Schuessler, Axel (2009). Minimal Old Chinese and Later Han Chinese. University of Hawaii Press. p. 298, 299 Sansom, George Bailey (1958). A history of Japan to 1334. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. pp. 14–16. ISBN 0-8047-0522-4. OCLC 36820223. Delmer M. Brown, ed. (1988–1999). The Cambridge history of Japan. Vol. 1. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 22. ISBN 0-521-22352-0. OCLC 17483588. Huffman, James L. (2010). Japan in world history. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 6–11. ISBN 978-0-19-536808-6. OCLC 323161049. Bentley, John (2008). "The Search for the Language of Yamatai" in Japanese Language and Literature , 42.1, p. 11 of pp. 1-43. Pinchefsky, Carol (March 12, 2013). "A Feminist Reviews Tomb Raider's Lara Croft". Forbes. "Super Ancient Shinsengumi History GUDAGUDA Yamataikoku 2022". "Wednesday Campanella has released the music video for "Himiko," in which Utaha becomes a weather caster and predicts heavy rain". |

参考文献 Schuessler, Axel (2014). 「Phonological Notes on Hàn Period Transcriptions of Foreign Names and Words" in Studies in Chinese and Sino-Tibetan Linguistics: Dialect, Phonology, Transcription and Text. シリーズ: 言語学モノグラフシリーズ。53 Ed. ヴァネス・シモンズ、リチャード&ヴァン・オーケン、ニューウェル・アン。Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan. Schuessler, Axel (2009). 最小古漢語と後漢語. ハワイ大学出版局。 Sansom, George Bailey (1958). A history of Japan to 1334. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0522-4. OCLC 36820223. Delmer M. Brown, ed. (1988-1999). ケンブリッジ日本史. 第1巻。ケンブリッジ大学出版局. ISBN 0-521-22352-0. OCLC 17483588. Huffman, James L. (2010). 世界史の中の日本. オックスフォード: オックスフォード大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-19-536808-6. OCLC 323161049. Bentley, John (2008). 「邪馬台国の言語の探求" in Japanese Language and Literature , 42.1, p. 11 of pp. Pinchefsky, Carol (March 12, 2013). 「A Feminist Reviews Tomb Raider's Lara Croft」. Forbes. 「Super Ancient Shinsengumi History GUDAGUDA Yamataikoku 2022」. 「水曜日のカンパネラが「卑弥呼」のミュージックビデオを公開した。 |

| Sources "Remains of what appears to be Queen Himiko's palace found in Nara", The Japan Times, Nov 11, 2009. Aston, William G, tr. 1924. Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to AD 697. 2 vols. Charles E Tuttle reprint 1972. Baxter, William H. 1992. A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology. Mouton de Gruyter. Chamberlain, Basil Hall, tr. 1919. The Kojiki, Records of Ancient Matters. Charles E Tuttle reprint 1981. Edwards, Walter. 1998. "Mirrors to Japanese History", Archeology 51.3. Farris, William Wayne. 1998. Sacred Texts and Buried Treasures: Issues in the Historical Archaeology of Ancient Japan. University of Hawaiʻi Press. Hall, John Whitney. 1988. The Cambridge History of Japan: Volume 1, Ancient Japan. Cambridge University Press. Hérail, Francine (1986), Histoire du Japon – des origines à la fin de Meiji [History of Japan – from origins to the end of Meiji] (in French), Publications orientalistes de France. Hong, Wontack. 1994. Paekche of Korea and the Origin of Yamato Japan. Kudara International. Imamura. Keiji. 1996. Prehistoric Japan: New Perspectives on Insular East Asia. University of Hawaiʻi Press. Karlgren, Bernhard. 1957. Grammata Serica Recensa. Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities. Kidder, Jonathan Edward. 2007. Himiko and Japan's Elusive Chiefdom of Yamatai. University of Hawaiʻi Press. McCullough, Helen Craig. 1985. Brocade by Night: 'Kokin Wakashū' and the Court Style in Japanese Classical Poetry. Stanford University Press. Miller, Roy Andrew. 1967. The Japanese Language. University of Chicago Press. Miyake, Marc Hideo. 2003. Old Japanese: A Phonetic Reconstruction. Routledge Curzon. Philippi, Donald L. (tr.) 1968. Kojiki. University of Tokyo Press. Pulleyblank, EG. 1991. "Lexicon of Reconstructed Pronunciation in Early Middle Chinese, Late Middle Chinese, and Early Mandarin". UBC Press. Saeki, Arikiyo (2006), 邪馬台国論争 [Yamataikoku ronsō] (in Japanese), Iwanami, ISBN 4-00-430990-5. Goodrich, Carrington C, ed. (1951), Japan in the Chinese Dynastic Histories: Later Han Through Ming Dynasties, translated by Tsunoda, Ryusaku, South Pasadena, CA: PD & Ione Perkins. Wang Zhenping. 2005. Ambassadors from the Islands of Immortals: China-Japan Relations in the Han-Tang Period. University of Hawaiʻi Press. Hakkutsu sareta Nihon rett, 2010. Makimuku: were the huge buildings, neatly lined up, a palace? A discovery enlivens debate over the country Yamatai''. |

情報源 「奈良で卑弥呼女王の宮殿と思われる跡が発見される」、The Japan Times、2009年11月11日。 Aston, William G, tr. 1924. Nihongi: 最古の時代からAD697年までの日本書紀。2 vols. Charles E Tuttle reprint 1972. Baxter, William H. 1992. A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology. Mouton de Gruyter. Chamberlain, Basil Hall, tr. 1919. The Kojiki, Records of Ancient Matters. Charles E Tuttle 復刻 1981. Edwards, Walter. 1998. 日本史の鏡」『考古学』51.3. Farris, William Wayne. 1998. Sacred Texts and Buried Treasures: Issues in the Historical Archaeology of Ancient Japan. University of Hawaiʻi Press. Hall, John Whitney. 1988. ケンブリッジ日本史: 第1巻 古代日本. Cambridge University Press. Hérail, Francine (1986), Histoire du Japon - des origines à la fin de Meiji [日本の歴史-起源から明治の終わりまで] (in French), Publications orientalistes de France. Hong, Wontack. 1994. 韓国の百済と大和日本の起源. クダラ・インターナショナル. Imamura. 啓司. 1996. 先史時代の日本: 東アジア島嶼部の新たな展望. University of Hawaiʻi Press. Karlgren, Bernhard. 1957. Grammata Serica Recensa. Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities. Kidder, Jonathan Edward. 2007. Himiko and Japan's Elusive Chiefdom of Yamatai. University of Hawaiʻi Press. McCullough, Helen Craig. 1985. 日本古典詩歌における「古今和歌集」と宮廷風。Stanford University Press. Miller, Roy Andrew. 1967. The Japanese Language. シカゴ大学出版局。 三宅マーク秀雄. 2003. 古い日本語: A Phonetic Reconstruction. Routledge Curzon. Philippi, Donald L. (tr.) 1968. 古事記. 東京大学出版会。 Pulleyblank, EG. 1991. 「Lexicon of Reconstructed Pronunciation in Early Middle Chinese, Late Middle Chinese, and Early Mandarin」. UBC Press. 佐伯有清(2006)『邪馬台国論争』岩波書店、ISBN 4-00-430990-5. Goodrich, Carrington C, ed. (1951), Japan in the Chinese Dynastic Histories: グッドリッチ、キャリントン・C編(1951)『中国王朝史の中の日本-後漢から明代まで』角田龍作訳、サウス・パサデナ、カリフォルニア州: PD & Ione Perkins. 王振平. 2005. 仙人列島からの大使: 漢唐時代の中日関係. University of Hawaiʻi Press. 白骨されど日本rett, 2010. マキムク:整然と並ぶ巨大な建物は宮殿だったのか?発見で盛り上がる邪馬台国論争』。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yamatai |

|

| 邪馬台国(日本語ウィキペディア) |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆