国民解放のサパティスタ軍

Ejército Zapatista de

Liberación Nacional, EZLN

☆国

民解放のサパティスタ軍あるいはサパティスタ国民解放軍(スペイン語: Ejército Zapatista de Liberación

Nacional, EZLN)は、しばしばサパティスタ(ラテンアメリカスペイン語発音:

[sapaˈtistas])と呼ばれる。これは極左の政治的・武装組織であり、メキシコ最南端の州であるチアパス州において相当な領土を支配している。

[7][8][9] [10]

1994年以来、この組織は名目上メキシコ政府と戦争状態にある(ただし現時点では凍結状態の紛争と表現されることもある)。[11]

EZLNは市民抵抗の戦略を採用した。サパティスタの主力は主に農村部の先住民で構成されるが、都市部や国際的にも一部の支持者が存在する。EZLNの主

要なスポークスパーソンは、かつてサブコマンダンテ・マルコスとして知られた、現サブコマンダンテ・インスルヘンテ・ガレアーノである。

この組織名は、メキシコ革命期の南解放軍司令官であり農地改革革命家であったエミリアーノ・サパタに由来し、自らを彼の思想的継承者と見なしている。

EZLNのイデオロギーは、リバタリアン社会主義[3]、アナキスト[12]、マルクス主義[13]と特徴づけられ、解放の神学[14]に根ざしていると

されるが、サパティスタ自身は政治的分類を拒否している[15]。EZLNはより広範な反グローバリゼーション・反新自由主義社会運動と連携し、特に土地

を含む地域資源に対する先住民の支配を求めている。1994年の蜂起がメキシコ軍によって鎮圧されて以来、EZLNは軍事攻撃を控え、メキシコ国内外の支

持を集めようとする新たな戦略を採用している。

| The Zapatista Army

of National Liberation (Spanish: Ejército Zapatista de Liberación

Nacional, EZLN), often referred to as the Zapatistas (Latin American

Spanish pronunciation: [sapaˈtistas]), is a far-left political and

militant group that controls a substantial amount of territory in

Chiapas, the southernmost state of Mexico.[7][8][9][10] Since 1994, the group has been nominally at war with the Mexican state (although it may be described at this point as a frozen conflict).[11] The EZLN used a strategy of civil resistance. The Zapatistas' main body is made up of mostly rural indigenous people, but it includes some supporters in urban areas and internationally. The EZLN's main spokesperson is Subcomandante Insurgente Galeano, previously known as Subcomandante Marcos. The group takes its name from Emiliano Zapata, the agrarian revolutionary and commander of the Liberation Army of the South during the Mexican Revolution, and sees itself as his ideological heir. EZLN's ideology has been characterized as libertarian socialist,[3] anarchist,[12] or Marxist,[13] and having roots in liberation theology[14] although the Zapatistas have rejected[15] political classification. The EZLN aligns itself with the wider alter-globalization, anti-neoliberal social movement, seeking indigenous control over local resources, especially land. Since their 1994 uprising was countered by the Mexican Armed Forces, the EZLN has abstained from military offensives and adopted a new strategy that attempts to garner Mexican and international support. |

国民解放のサパティスタ軍あるいはサパティスタ国民解放軍(スペイン

語: Ejército

Zapatista de Liberación Nacional, EZLN)は、しばしばサパティスタ(ラテンアメリカスペイン語発音:

[sapaˈtistas])と呼ばれる。これは極左の政治的・武装組織であり、メキシコ最南端の州であるチアパス州において相当な領土を支配している。

[7][8][9] [10] 1994年以来、この組織は名目上メキシコ政府と戦争状態にある(ただし現時点では凍結状態の紛争と表現されることもある)。[11] EZLNは市民抵抗の戦略を採用した。サパティスタの主力は主に農村部の先住民で構成されるが、都市部や国際的にも一部の支持者が存在する。EZLNの主 要なスポークスパーソンは、かつてサブコマンダンテ・マルコスとして知られた、現サブコマンダンテ・インスルヘンテ・ガレアーノである。 この組織名は、メキシコ革命期の南解放軍司令官であり農地改革革命家であったエミリアーノ・サパタに由来し、自らを彼の思想的継承者と見なしている。 EZLNのイデオロギーは、リバタリアン社会主義[3]、アナキスト[12]、マルクス主義[13]と特徴づけられ、解放の神学[14]に根ざしていると されるが、サパティスタ自身は政治的分類を拒否している[15]。EZLNはより広範な反グローバリゼーション・反新自由主義社会運動と連携し、特に土地 を含む地域資源に対する先住民の支配を求めている。1994年の蜂起がメキシコ軍によって鎮圧されて以来、EZLNは軍事攻撃を控え、メキシコ国内外の支 持を集めようとする新たな戦略を採用している。 |

| Organization The Zapatistas describe themselves as a decentralized organization. The pseudonymous Subcomandante Marcos is widely considered its leader despite his claims that the group has no single leader. Political decisions are deliberated and decided in community assemblies. Military and organizational matters are decided by the Zapatista area elders who compose the General Command (Revolutionary Indigenous Clandestine Committee – General Command, or CCRI-CG).[16] |

組織 サパティスタは自らを分散型の組織と称している。偽名のサブコマンダンテ・マルコスは、グループに単独の指導者は存在しないと主張しているにもかかわら ず、広くその指導者と見なされている。政治的な決定は共同体集会において熟議され決定される。軍事および組織に関する事項は、総司令部(革命的先住民族秘 密委員会-総司令部、CCRI-CG)を構成するサパティスタ地域の長老たちによって決定される。[16] |

| Also known as

Zapatistas Leaders Subcomandante Insurgente Galeano, Subcomandante Insurgente Galeano, Delegado Cero (Delegate Zero), hasta 2014 Comandanta Ramona Subcomandante Elisa Subcomandante Moisés Foundation November 17, 1983 Dates of operation |

別名サパティスタ 指導者 副司令官ガレアーノ 司令官ラモナ 副司令官エリサ 副司令官モイセス 設立1983年11月17日 活動期間 |

| History Background The Chiapas region has been the scene of a succession of uprisings, including the "Caste War" or "Chamula Rebellion" (1867–1870) and the "Pajarito War" (1911).[17] The EZLN emerged during the government of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), which at the time had ruled Mexico for more than sixty years, in a dominant-party system. The situation led many young people to consider the legal channels of political participation closed and to bet on the formation of clandestine armed organizations to seek the overthrow of a regime that from their point of view was authoritarian, and thus improve the living conditions of the population. One of these organizations,[18] was known as the National Liberation Forces (FLN). The FLN were founded on August 6, 1969, by César Germán Yáñez Muñoz, in Monterrey, Nuevo León. According to Mario Arturo Acosta Chaparro, in his report Subversive movements in Mexico, "they had established their areas of operations in the states of Veracruz, Puebla, Tabasco, Nuevo León and Chiapas." In February 1974, a confrontation took place in San Miguel Nepantla [Wikidata], State of Mexico, between a unit of the Mexican Army, under the command of Mario Arturo Acosta Chaparro, and members of the FLN, some of whom died during combat, reportedly having been tortured.[19] As a consequence of this confrontation, the FLN lost its operational capacity. In the early 1980s, some of its militants decided to found a new organization. Thus, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) was founded on November 17, 1983, by non-indigenous members of the FLN from Mexico's urban north and by indigenous inhabitants of the remote Las Cañadas/Selva Lacandona regions in eastern Chiapas, by members of former rebel movements.[20] Some EZLN leaders have argued that the vanguardist and Marxist–Leninist orientation of the FLN failed to appeal to indigenous locals in Chiapas, leading former members of the FLN in the EZLN to ultimately opt for a libertarian socialist and neozapatista outlook.[21][22] Over the years, the group slowly grew, building on social relations among the indigenous base and making use of an organizational infrastructure created by peasant organizations and the Catholic Church (see Liberation theology).[23] In the 1970s, through the efforts of the Roman Catholic Diocese of San Cristóbal de Las Casas, most indigenous communities in the Lacandon forest were already politically active and had practice in dealing with governmental agencies and local officials.[20] Specifically in 1974 an indigenous conference brought indigenous peoples from across Chiapas together to discuss their conditions. Promoted and organized by the Catholic church, this event helped foster an indigenous political identity in the region.[24] In the 1980s, they joined with the Rural Collective Interest Association – "Unión de Uniones", (ARIC-UU).[20] However, disputes over strategy in the Chiapas would lead to the EZLN taking on over half of the ARIC-UU's membership in the early 1990s.[20] |

歴史 背景 チアパス地方では、一連の反乱が起きてきた。例えば「カースト戦争」あるいは「チャムラ反乱」(1867年~1870年)や「パハリート戦争」(1911 年)などだ。[17] EZLNは、当時60年以上もメキシコを支配していた制度的革命党(PRI)の政権下で、支配政党体制の中で誕生した。この状況は多くの若者に、合法的な 政治参加の道は閉ざされていると考えさせ、自らの視点から権威主義的と見なした体制の打倒と、それによる民衆の生活条件の改善を求め、秘密武装組織の結成 に賭けるよう導いた。そうした組織の一つ[18]が、国民解放軍(FLN)として知られていた。FLNは1969年8月6日、セサル・ヘルマン・ヤニェ ス・ムニョスによってヌエボ・レオン州モンテレイで創設された。マリオ・アルトゥーロ・アコスタ・チャパロの報告書『メキシコの破壊活動運動』によれば、 「彼らはベラクルス州、プエブラ州、タバスコ州、ヌエボ・レオン州、チアパス州に活動拠点を確立していた」という。 1974年2月、メキシコ州サン・ミゲル・ネパントラ[Wikidata]で、マリオ・アルトゥーロ・アコスタ・チャパロ指揮下のメキシコ陸軍部隊と FLNメンバーとの間で衝突が発生した。戦闘中に死亡したFLNメンバーの一部は拷問を受けていたと伝えられている[19]。 この衝突の結果、FLNは作戦遂行能力を失った。1980年代初頭、一部の活動家が新たな組織の創設を決意した。こうして1983年11月17日、メキシ コ北部の都市部出身の非先住民FLNメンバーと、チアパス州東部遠隔地ラス・カニャダス/セルバ・ラカンドナ地域の先住民、そして旧反乱運動のメンバーに よって、サパティスタ民族解放軍(EZLN)が結成された。[20] EZLN指導者の中には、FLNの前衛主義的・マルクス・レーニン主義的指向がチアパス州の先住民に受け入れられなかったため、FLN出身者が最終的に自 由主義的社会主義と新サパティスタ思想を選択したと主張する者もいる。[21][22] 年月を経て、この組織は徐々に拡大した。先住民基盤層の社会的関係を発展させ、農民組織やカトリック教会(解放の神学参照)が構築した組織的基盤を活用し たのである。[23] 1970年代までに、サン・クリストバル・デ・ラス・カサス教区の尽力により、ラカンドン森林地域の先住民コミュニティの大半は既に政治的に活動的であ り、政府機関や地方当局者との対応経験を有していた。[20] 特に1974年には、チアパス州全域から先住民を集めた会議が開催され、彼らの状況について議論が行われた。カトリック教会が推進・主催したこのイベント は、地域における先住民の政治的アイデンティティの醸成に寄与した。[24] 1980年代には、彼らは農村共同利益組合連合(ARIC-UU)に参加した。[20] しかし、チアパス州における戦略をめぐる対立が原因で、1990年代初頭にはEZLNがARIC-UUの会員の半数以上を引き受けることになった。 [20] |

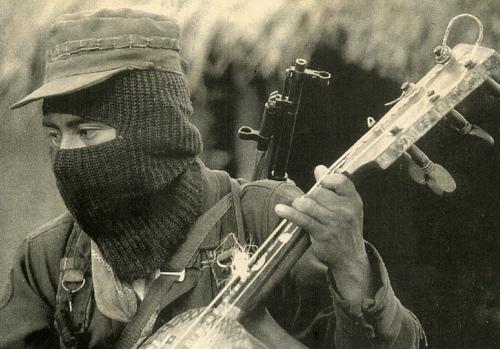

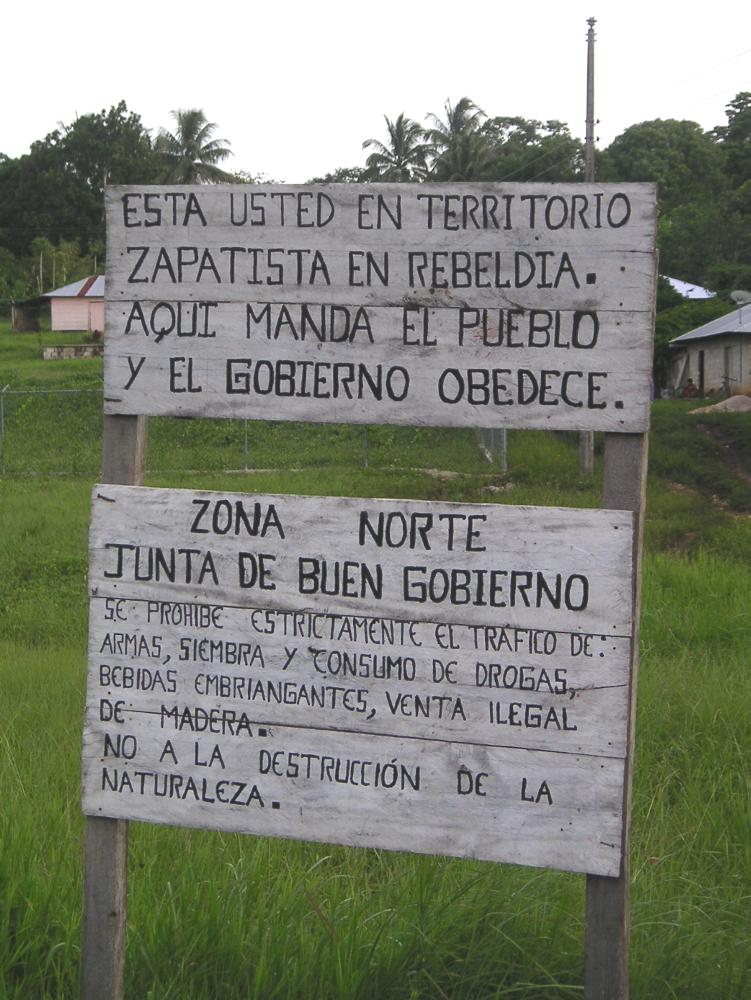

| 1990s See also: Zapatista uprising  Subcomandante Marcos surrounded by several commanders of the CCRI The Zapatista Army went public on January 1, 1994, releasing their declaration on the day the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) came into effect. On that day, they issued their First Declaration and Revolutionary Laws from the Lacandon Jungle. The declaration amounted to a declaration of war on the Mexican government, which they considered illegitimate. The EZLN stressed that it opted for armed struggle due to the lack of results that had been achieved through peaceful means of protest (such as sit-ins and marches).[25]  A sign indicating the entrance of Zapatista rebel territory. "You are in Zapatista territory in rebellion. Here the people command and the government obeys." Their initial goal was to instigate a revolution against the rise of neoliberalism[26] throughout Mexico, but since no such revolution occurred, they used their uprising as a platform to call attention to their movement to protest the signing of the NAFTA, which the EZLN believed would increase inequality in Chiapas.[27] Prior to the signing of NAFTA, however, dissent amongst indigenous peasants was already on the rise in 1992 with the amendment of Article 27 of the Constitution. The amendment called for the end of land reform and the regularizing of all landholdings, which ended land redistribution in Mexico.[28] The end of land distribution heralded the end of many communities that had been growing of the past decade, as they had been waiting for further distribution that was on an agrarian backlog according to the government.[28]  Zapatistan partisans. The Zapatistas hosted the Intercontinental Encounter for Humanity and Against Neoliberalism to help initiate a united platform for other anti-neoliberal groups.[26] The EZLN also called for greater democratization of the Mexican government, which had been controlled by the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (Institutional Revolutionary Party, also known as PRI) for 65 years, and for land reform mandated by the 1917 Constitution of Mexico, which had been repealed in 1991.[29] The Zapatistas had mentioned "independence" among their initial demands; however, it received little systematic treatment from the EZLN until the extensive contact between the Zapatistas and other indigenous organizations during the San Andrés negotiations and use of natural resources normally extracted from Chiapas. It also advocated for protection from violence and political inclusion of Chiapas's indigenous communities.[30] On January 1, 1994, an estimated 3,000 armed Zapatista insurgents seized six towns and cities in the Chiapas highlands. The Zapatistas soon retreated to the forest to avoid a federal military offensive.[31] "The EZLN listed a series of other demands that were a compendium of long-standing grievances of the indigenous communities of Chiapas, but also found echo in broad sectors of Mexican society outside of Chiapas: work, land, housing, food, healthcare, education, independence, liberty, democracy, justice, and peace."[30] Following a ceasefire on January 12, peace talks commenced later in the month between Catholic bishop Samuel Ruiz for the Zapatistas and former mayor of Mexico City, Manuel Camacho Solis, for the state.[32] |

1990年代 関連項目: サパティスタ蜂起  CCRIの複数の司令官に囲まれた副司令官マルコス サパティスタ軍は1994年1月1日、北米自由貿易協定(NAFTA)が発効した日に宣言を発表し、公に姿を現した。同日、彼らはラカンドン・ジャングル から「第一宣言」と「革命法」を発表した。この宣言は、彼らが非合法と見なしたメキシコ政府に対する宣戦布告に等しいものだった。EZLN(サパティスタ 民族解放軍)は、平和的抗議手段(座り込みやデモ行進など)では成果が得られなかったため、武力闘争を選択したと強調した[25]。  サパティスタ反乱地域の入口を示す標識。「ここは反乱中のサパティスタ領土だ。ここでは民衆が指揮し、政府が従う」 当初の目標はメキシコ全土に広がる新自由主義[26]への革命を煽ることだったが、そのような革命は起きなかったため、彼らは蜂起を足掛かりにNAFTA 調印への抗議運動を呼びかけた。EZLNはNAFTAがチアパス州の不平等を拡大すると考えていた。[27] しかしNAFTA調印以前から、1992年の憲法第27条改正により先住民農民の間で反発が高まっていた。この改正は土地改革の終結と全土地所有権の正規 化を求め、メキシコにおける土地再分配を終わらせたのである。[28] 土地分配の終焉は、過去10年間に成長してきた多くの共同体の終焉を告げた。政府によれば、それらは農業分野の未処理案件としてさらなる分配を待っていた 状態だったのだ。[28]  サパティスタの支持者たち。 サパティスタは「人類のための、新自由主義に反対する大陸間集会」を主催し、他の反新自由主義グループのための統一プラットフォームの構築を支援した。 [26] EZLNはまた、65年間にわたり制度的革命党(PRI)が支配してきたメキシコ政府の民主化強化と、1991年に廃止された1917年メキシコ憲法で定 められた土地改革の実施を要求した。[29] サパティスタは当初の要求に「独立」を含めていたが、サン・アンドレス交渉における他先住民族組織との広範な接触や、通常チアパス州から採取される天然資 源の利用を通じて、EZLNによる体系的な扱いはほとんどなかった。またチアパス州先住民族コミュニティの暴力からの保護と政治的包摂も主張した。 [30] 1994年1月1日、約3,000人の武装したサパティスタ反乱軍がチアパス高地の6つの町を占拠した。サパティスタは連邦軍の攻撃を避けるため、すぐに 森林地帯へ撤退した。[31] 「EZLNは一連の要求を掲げた。これらはチアパス先住民コミュニティの長年の不満をまとめたものだったが、チアパス以外のメキシコ社会広範な層にも共鳴 した。要求内容は労働、土地、住宅、食糧、医療、教育、独立、自由、民主主義、正義、平和であった。」[30] 1月12日の停戦後、同月下旬にはカトリック司教サミュエル・ルイス(サパティスタ側)と元メキシコシティ市長マヌエル・カマチョ・ソリス(州政府側)に よる和平交渉が始まった。[32] |

Military offensive Subcomandante Marcos of EZLN during the Earth Color March See also: 1995 Zapatista Crisis Arrest-warrants were made for Marcos, Javier Elorriaga Berdegue, Silvia Fernández Hernández, Jorge Santiago, Fernando Yanez, German Vicente and other Zapatistas. At that point, in the Lacandon Jungle, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation was under military siege by the Mexican Army. Javier Elorriaga was captured on February 9, 1995, by forces from a military garrison at Gabina Velázquez in the town of Las Margaritas, and was later taken to the Cerro Hueco prison in Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas.[33] The PGR threatened the San Cristóbal de Las Casas's Catholic Bishop, Samuel Ruiz García, with arrest. Claiming that they helped conceal the Zapatistas' guerrilla uprising, although their activities had been reported years before in Proceso, a Mexican leftist magazine. It is likely however that the Mexican Government knew about the uprising but failed to act.[34][35][36] This adversely impacted Holy See–Mexico relations.[37] In response to the siege of the EZLN, Esteban Moctezuma, the interior minister, submitted his resignation to President Zedillo, which Zedillo refused to accept. Influenced by Moctezuma's protest, President Zedillo abandoned the military offensive in favor of a diplomatic approach. The Mexican army eased its operation in Chiapas, allowing Marcos to escape the military perimeter in the Lacandon Jungle.[38] Responding to the change of conditions, friends of the EZLN along with Subcomandante Marcos prepared a report for under-Secretary of the Interior Luis Maldonado Venegas; the Secretary of the Interior Esteban Moctezuma; and then President Zedillo.[39] The document stressed Marcos' pacifist inclinations and his desire to avoid a bloody war. The document also said that the marginalized groups and the radical left that existed in Mexico supported the Zapatista movement. It also stressed that Marcos maintained an open negotiating track. |

軍事攻撃 地球色の行進におけるEZLNのマルコス副司令官 関連項目:1995年サパティスタ危機 マルコス、ハビエル・エロリアガ・ベルデゲ、シルビア・フェルナンデス・エルナンデス、ホルヘ・サンティアゴ、フェルナンド・ヤネス、ゲルマン・ビセンテ らサパティスタに対する逮捕令状が発令された。当時、ラカンドン・ジャングルでは、サパティスタ民族解放軍がメキシコ軍による軍事包囲下に置かれていた。 ハビエル・エロリアガは1995年2月9日、ラス・マルガリータス町のガビーナ・ベラスケス駐屯地部隊に捕らえられ、後にチアパス州トゥストラ・グティエ レスのセロ・ウエコ刑務所に移送された[33]。 PGR(連邦検察庁)はサン・クリストバル・デ・ラス・カサス司教サミュエル・ルイス・ガルシアを逮捕すると脅した。サパティスタのゲリラ蜂起を隠蔽した としてだが、その活動は数年前にメキシコの左派雑誌『プロセソ』で既に報じられていた。しかし実際にはメキシコ政府は蜂起を把握しながら行動を起こさな かった可能性が高い[34][35][36]。これはローマ教皇庁とメキシコの関係に悪影響を与えた。[37] EZLN包囲作戦への抗議として、エステバン・モクテズマ内務大臣はセディージョ大統領に辞表を提出したが、大統領は受理を拒否した。モクテズマの抗議に 影響されたセディージョ大統領は、軍事作戦を放棄し外交的アプローチを選択した。メキシコ軍はチアパス州での作戦を緩和し、マルコスがラカンドン・ジャン グル内の軍事包囲網から脱出することを許した。[38] 状況の変化を受けて、EZLNの支持者たちは副司令官マルコスと共に、内務次官ルイス・マルドナド・ベネガス、内務大臣エステバン・モクテズマ、そして当 時のセディージョ大統領宛ての報告書を作成した。この文書はマルコスの平和主義的傾向と流血の戦争回避の意思を強調した。またメキシコ国内の境界化された 集団や急進左派がサパティスタ運動を支持していることも記した。さらにマルコスが交渉の道を常に開いていることも強調していた。 |

| 2000s In April 2000, Vicente Fox, the presidential candidate for the opposition National Action Party (PAN), sent a new proposal for dialogue to Subcomandante Marcos, without obtaining a response. In May, a group of civilians attacked two indigenous people from the autonomous municipality of Polhó, Chiapas. Members of the Federal Police were sent to guarantee the security of the area. The Zapatista coordinators and several non-governmental organizations described it as "a clear provocation to the EZLN."[40] Vicente Fox was elected president in 2001 (the first non-PRI president of Mexico in over 70 years) and, as one of his first actions, urged the EZLN to enter into dialogue with the federal government. However, the EZLN insisted that it would not return to peace negotiations with the government until seven military positions were closed. Fox subsequently made the decision to withdraw the army from the conflict zone, so all the military located in Chiapas began to leave the area. Following this gesture, Subcomandante Marcos agreed to initiate dialogue with the Vicente Fox government, but shortly thereafter demanded conditions for peace; especially, that the federal government disarm the PRI paramilitary groups in the area.[41] The Zapatistas marched on Mexico City to pressure the Mexican Congress and formed the Zapatista Information Center, through which information would be exchanged about the trip of the guerrilla delegation to Mexico City, and mobilizations would be articulated to demand compliance with the conditions of the EZLN for dialogue. Although Fox had stated earlier that he could end the conflict "in fifteen minutes",[42] the EZLN rejected the agreement and created 32 new "autonomous municipalities" in Chiapas. They would then unilaterally implement their demands without government support, although they had some funding from international organizations. On June 28, 2005, the Zapatistas presented the Sixth Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle[43] declaring their principles and vision for Mexico and the world. This declaration reiterated the support for the indigenous peoples, who make up roughly one-third of the population of Chiapas, and extended the cause to include "all the exploited and dispossessed of Mexico". It also expressed the movement's sympathy to the international alter-globalization movement and supported leftists governments in Cuba, Bolivia, Ecuador, and elsewhere, with whom they felt there was common cause.  Comandanta Ramona On May 3–4, 2006, a series of demonstrations protested the forcible removal of irregular flower vendors from a lot in Texcoco for the construction of a Walmart branch. The protests turned violent when state police and the Federal Preventive Police bused in some 5,000 agents to San Salvador Atenco and the surrounding communities. A local organization called the People's Front in Defense of the Land, which adheres to the Sixth Declaration, called in support from other regional and national adherent organizations. "Delegate Zero" and his "Other Campaign" were at the time in nearby Mexico City, having just organized May Day events there, and quickly arrived at the scene. The following days were marked by violence, with some 216 arrests, over 30 rape and sexual abuse accusations against the police, five deportations, and one casualty, a 14-year-old boy named Javier Cortes shot by a policeman.[44] A 20-year-old UNAM economics student, Alexis Benhumea, died on the morning of June 7, 2006, after being in a coma caused by a blow to the head from a tear-gas grenade launched by police.[45] Most of the resistance organizing was done by the EZLN and Sixth Declaration adherents, and Delegate Zero stated that the "Other Campaign" tour would be temporarily halted until all prisoners were released.[46][47] In late 2006 and early 2007, the Zapatistas (through Subcomandante Marcos), along with other indigenous peoples of the Americas, announced the Intercontinental Indigenous Encounter. They invited indigenous people from throughout the Americas and the rest of the world to gather on October 11–14, 2007, near Guaymas, Sonora. The declaration for the conference designated this date because of "515 years since the invasion of ancient Indigenous territories and the onslaught of the war of conquest, spoils and capitalist exploitation". Comandante David said in an interview, "The object of this meeting is to meet one another and to come to know one another's pains and sufferings. It is to share our experiences, because each tribe is different."[48] The Third Encuentro of the Zapatistas People with the People of the World was held from December 28, 2007, through January 1, 2008.[49] In mid-January 2009, Marcos made a speech on behalf of the Zapatistas in which he supported the resistance of the Palestinians as "the Israeli government's heavily trained and armed military continues its march of death and destruction". He described the actions of the Israeli government as a "classic military war of conquest". He said, "The Palestinian people will also resist and survive and continue struggling and will continue to have sympathy from below for their cause."[50] |

2000年代 2000年4月、野党・国民行動党(PAN)の大統領候補ビセンテ・フォックスは、副司令官マルコスに新たな対話提案を送ったが、返答は得られなかった。 5月には、民間人グループがチアパス州ポルホ自治自治体の先住民2人を襲撃した。連邦警察隊員が地域の安全確保のために派遣された。サパティスタの調整役 と複数の非政府組織はこれを「EZLNに対する明らかな挑発」と評した。[40] ビセンテ・フォックスは2001年に大統領に選出された(70年以上ぶりの非PRI(革命制度党)出身大統領)。就任後早々に、EZLNに対し連邦政府と の対話に入るよう促した。しかしEZLNは、7つの軍事拠点が閉鎖されるまで政府との和平交渉には戻らないと主張した。これを受けフォックスは紛争地域か らの軍撤退を決定し、チアパス州に駐留する全軍が撤退を開始した。この姿勢を受け、副司令官マルコスはビセンテ・フォックス政権との対話開始に同意した が、直後に和平条件を要求。特に連邦政府が同地域のPRI準軍事組織を武装解除することを求めた。[41] サパティスタ勢力はメキシコシティへ進軍し、メキシコ議会に圧力をかけた。同時に「サパティスタ情報センター」を設立し、ゲリラ代表団のメキシコシティ訪 問に関する情報交換や、EZLNの対話条件履行を求める動員活動の調整を行った。フォックスは以前「15分で紛争を終結させられる」と発言していたが [42]、EZLNは合意を拒否し、チアパス州に32の新たな「自治自治体」を創設した。政府の支援なしに一方的に要求を実施する方針で、国際機関からの 資金援助は一部あったものの、政府の支援は得られなかった。 2005年6月28日、サパティスタは『ラカンドン密林第六宣言』を発表し、メキシコと世界に対する自らの理念と展望を表明した。この宣言は、チアパス州 人口の約3分の1を占める先住民への支持を再確認するとともに、その大義を「メキシコの全ての搾取され、剥奪された者たち」へと拡大した。また、国際的な 反グローバリゼーション運動への共感を表明し、キューバ、ボリビア、エクアドルなど、共通の目的があると見なした左派政権を支持した。  コマンダンタ・ラモナ 2006年5月3日から4日にかけて、テスココの土地でウォルマート支店建設のため不法な花売り業者を強制排除したことに抗議する一連のデモが行われた。 抗議活動は、州警察と連邦予防警察がサン・サルバドル・アテンコ及び周辺地域に約5,000人の警官をバスで投入したことで暴力的となった。第六宣言を支 持する地元組織「土地防衛人民戦線」は、他の地域・全国レベルの支持組織に支援を要請した。当時、メキシコシティ近郊でメーデー行事を主催したばかりの 「ゼロ代表」とその「もうひとつの運動」は、直ちに現場に駆けつけた。その後数日間は暴力事件が相次ぎ、約216名が逮捕され、警察に対する30件以上の 強姦・性的虐待の告発、5件の国外退去処分、そして警察官に射殺された14歳の少年ハビエル・コルテスという犠牲者が出た。[44] 2006年6月7日朝、メキシコ国立自治大学(UNAM)経済学部生のアレクシス・ベンフメア(20歳)が死亡した。警察が発射した催涙ガス弾が頭部に直 撃し、昏睡状態に陥った後のことである。[45] 抵抗運動の組織化の大半はEZLNと第六宣言支持者によって行われ、ゼロ代表は「もうひとつの運動」ツアーを全囚人の解放まで一時停止すると表明した。 [46] [47] 2006年末から2007年初頭にかけ、サパティスタ(副司令官マルコスを通じて)は他のアメリカ先住民と共に「大陸間先住民集会」を宣言した。彼らは 2007年10月11日から14日にかけて、ソノラ州グアイマス近郊にアメリカ大陸及び世界中の先住民を集結させるよう呼びかけた。会議宣言はこの日付を 選んだ理由として「先住民族の古来の領土への侵略、征服戦争・略奪・資本主義的搾取の開始から515年」を挙げた。コマンダンテ・ダビドはインタビューで 「この集会の目的は互いに会い、互いの痛みや苦悩を理解し合うことだ。各部族は異なるため、経験を共有するためである」と述べた。[48] 第三回サパティスタ人民と世界の人々の集いは、2007年12月28日から2008年1月1日にかけて開催された。[49] 2009年1月中旬、マルコスはサパティスタを代表して演説を行い、「イスラエル政府の高度に訓練され武装した軍隊が死と破壊の行進を続けている」とし て、パレスチナ人の抵抗を支持した。彼はイスラエル政府の行動を「典型的な軍事的征服戦争」と表現した。彼は「パレスチナ人民もまた抵抗し、生き残り、闘 争を続け、彼らの大義に対して下からの共感を得続けるだろう」と述べた。[50] |

2010s A Zapatista point towards Palenque, 2010 On December 21, 2012, tens of thousands of EZLN supporters marched silently through five cities in the state of Chiapas: Ocosingo, Las Margaritas, Palenque, Altamirano and San Cristóbal. Hours after the march, a communiqué from the CCRI-CG was released in the form of a poem, signed by the Subcomandante Marcos.[51] This mobilization, which included the participation of around 40,000 Zapatistas, was the largest since the 1994 uprising. Of this number, La Jornada estimated that half would have marched through the streets of San Cristóbal de las Casas, 7,000 in Las Margaritas and 8,000 in Palenque; for its part El País calculated that San Cristóbal would have seen the concentration of some 10,000 participants.[52][53] Beyond the number of people, the silence with which they marched and the lack of an opening or closing speech were the elements that marked this action. The poet and journalist Hermann Bellinghausen, specialist in coverage of the movement, ended his chronicle in this way:[54] Able to "appear" suddenly, the rebellious indigenous "disappeared" as neatly and silently as they had arrived in this city at dawn that, two decades after the EZLN's traumatic uprising here on the new year of 1994, received them with care and curiosity, without any expression of rejection. Under the arches of the mayor's office, which today suspended its activities, dozens of Ocosinguenses gathered to photograph with cell phones and cameras the spectacular concentration of hooded people who filled the park like a game of Tetris, advancing between the planters with an order that seemed choreographed, to get the platform installed quickly from early on, raise their fist and say, quietly, "here we are, once again".[52] The Zapatistas invited the world to a three-day fiesta to celebrate ten years of Zapatista autonomy in August 2013 in the five caracoles of Chiapas. They expected 1,500 international activists to attend the event, titled the Little School of Liberty.[55][56] In June 2015, the EZLN reported that there was aggression against indigenous people in El Rosario, Chiapas; The report, signed by Subcomandante Moisés, indicated that the attack occurred that same month and year. In addition, there was a complaint by the Las Abejas Civil Society Organization that stated that an indigenous Tzotzil person was assassinated on June 23 on 2015.[57] In 2016, at the National Indigenous Congress, the EZLN agreed to select a candidate to represent them in the 2018 Mexican general election. This decision broke the Zapatista's two-decade tradition of rejecting Mexican electoral politics. In May 2017, María de Jesús Patricio Martínez, a woman of Mexican and Nahua heritage, was selected to stand,[58][59] but she was unable to gather the 866,000 signatures required to appear on the ballot.[60] At the end of August 2019, Subcomandante Insurgente Galeano announced the expansion of EZLN into 11 more districts.[61] In response, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador stated that this expansion was welcome, provided it was done without violence.[62] |

2010年代 2010年、パレンケに向かう箇所でのサパティスタによる検問所 2012年12月21日、数万人のEZLN支持者がチアパス州の5都市——オコシンゴ、ラス・マルガリータス、パレンケ、アルタミラノ、サン・クリストバ ル——を静かに行進した。行進の数時間後、CCRI-CG(先住民族共同体評議会)からの声明が詩の形で発表され、サブコマンダンテ・マルコスが署名した [51]。約4万人のサパティスタが参加したこの動員は、1994年の蜂起以来最大規模であった。このうち『ラ・ホルナダ』紙は、半数がサン・クリストバ ル・デ・ラス・カサス市街を行進し、7,000人がラス・マルガリータス、8,000人がパレンケに参加したと推定した。一方『エル・パイス』紙は、サ ン・クリストバルに約10,000人の参加者が集結したと算出した[52]。[53] 人数以上に、この行動を特徴づけたのは、彼らが沈黙のうちに行進したことと、開会・閉会の演説がなかったことだ。この運動の報道を専門とする詩人・ジャー ナリストのヘルマン・ベリングハウゼンは、自身の記録をこう締めくくった: [54] 突然「現れた」反乱の先住民たちは、夜明けにこの街に現れた時と同じように、整然と静かに「消えた」。1994年の新年、EZLN(民族解放軍)によるこ の地での衝撃的な蜂起から20年が経った今、街は拒絶の意思を示すことなく、彼らを気遣いと好奇心をもって迎えたのである。市役所のアーチの下では、その 日は業務を停止していたが、数十人のオコシンゴの住民が集まり、携帯電話やカメラで、公園をテトリスのように埋め尽くす覆面集団の壮観な集結を撮影した。 彼らは植栽の間を、まるで振り付けされたかのような秩序で進み、早朝から素早く演壇を設置し、拳を掲げて静かに言った。「我々はここにいる。再び」と。 [52] 2013年8月、サパティスタは世界に対し、チアパス州の五つのカラコル(集落)でサパティスタ自治10周年を祝う三日間の祭典へ招待した。彼らは「自由 の小学校」と題されたこのイベントに1,500人の国際活動家が参加すると予想していた。[55][56] 2015年6月、EZLNはチアパス州エル・ロサリオにおける先住民への攻撃を報告した。副司令官モイセス署名による報告書は、攻撃が同年同月に発生した ことを示していた。加えて、市民団体ラス・アベハスは、2015年6月23日にツォツィル族の先住民人格が殺害されたと訴えた。[57] 2016年、全国先住民会議においてEZLNは、2018年メキシコ総選挙に自派代表候補を擁立することを合意した。この決定は、メキシコ選挙政治を拒絶 してきたサパティスタの20年にわたる伝統を破るものだった。2017年5月、メキシコ系ナワ族の女性マリア・デ・ヘスス・パトリシオ・マルティネスが立 候補者に選出された[58]。[59] しかし彼女は、立候補に必要な86万6千の署名を集めることができなかった。[60] 2019年8月末、反乱軍副司令官ガレアノは、EZLNがさらに11の地区へ拡大することを発表した。[61] これに対し、アンドレス・マヌエル・ロペス・オブラドール大統領は、暴力を行使せずに実施される限り、この拡大を歓迎すると述べた。[62] |

| 2020s The EZLN has made opposition to mega-infrastructure projects in the region a major priority.[63][64] In 2020, it announced the Journey for Life and in 2021, Zapatistas visited various activist groups in Europe.[65][66] In November 2023, the EZLN announced the dissolution of the Rebel Zapatista Autonomous Municipalities due to growing violence in the region.[67] Later that month, they announced the reorganisation of the MAREZ into thousands of "Local Autonomous Governments" (GAL) which form area-wide "Zapatista Autonomous Government Collectives" (CGAZ) and zone-wide "Assemblies of Collectives of Zapatista Autonomous Governments" (ACGAZ).[68] In June 2025, the EZLN said "The National Indigenous Congress and the Zapatista Army of National Liberation condemn the police violence with which our Ñhöñhö brothers and sisters Estela Hernández, Sergio Chávez, Jesús Torres, Leonardo García, and Martín Álvarez, along with two others whose identities we have not been able to establish, were arrested and tortured. Their bodies were the center of the hatred and racism that characterize Mauricio Kuri's government in Querétaro, just as the dispossession and destruction emanating from the Mexican state and its institutions are centered on our Mother Earth and among the indigenous peoples."[69] On August 4 2025, during the Meeting of Resistances and Rebellions "Some Parts of the Whole", held at the Caracol IV of Morelia, in the municipality of Altamirano, the EZLN condemned the current genocide in Gaza, calling for international solidarity, calling the current campaign a "systematic aggression against the Palestinian people," representing an extreme expression of the destruction the capitalist system wreaks in other parts of the world.[70][71] |

2020年代 EZLNは、この地域における巨大インフラプロジェクトへの反対を主要な優先課題としている。[63][64] 2020年には「命の旅」を発表し、2021年にはサパティスタが欧州の様々な活動家グループを訪問した。[65][66] 2023年11月、EZLNは地域における暴力の激化を理由に、反乱サパティスタ自治自治体の解散を発表した。[67] 同月下旬、MAREZを再編し、数千の「地域自治政府」(GAL)を設置すると発表した。これらは地域全体の「サパティスタ自治政府集団」(CGAZ) と、ゾーン全体の「サパティスタ自治政府集団連合」(ACGAZ)を形成する。[68] 2025年6月、EZLNは「全国先住民会議とサパティスタ民族解放軍は、警察による暴力行為を非難する。その暴力により、我々の兄弟姉妹であるニョニョ のエステラ・エルナンデス、セルヒオ・チャベス、ヘスス・トレス、レオナルド・ガルシア、マルティン・アルバレス、および身元が確認できていない他の2名 が逮捕され、拷問を受けたのだ。彼らの身体は、ケレタロ州のマウリシオ・クリ政権を特徴づける憎悪と人種主義の的となった。同様に、メキシコ国家とその機 関から発せられる収奪と破壊は、我々の母なる大地と先住民を標的としている。」[69] 2025年8月4日、アルタミラノ郡モレリアにあるカラコルIVで開催された「抵抗と反乱の集会 「全体の一部」会議において、EZLNはガザにおける現在のジェノサイドを非難し、国際的な連帯を呼びかけた。彼らは現在の作戦を「パレスチナ人民に対す る組織的な攻撃」と位置づけ、資本主義体制が世界の他の地域で引き起こす破壊の極限的な表現であると述べた。[70][71] |

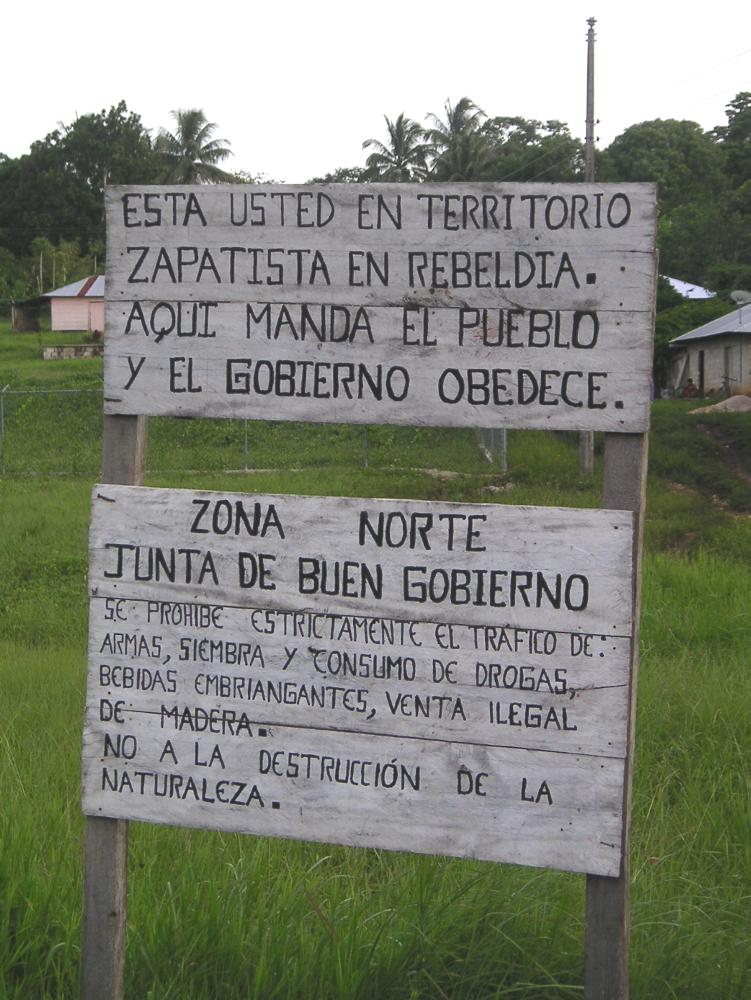

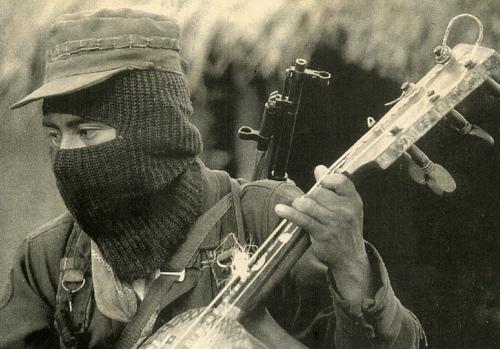

Ideology Federal Highway 307, Chiapas. The top sign reads, in Spanish, "You are in Zapatista rebel territory. Here the people command and the government obeys." Bottom sign: "North Zone. Council of Good Government. Trafficking of weapons, planting of drugs, drug use, alcoholic beverages, and illegal selling of wood are strictly prohibited. No to the destruction of nature."  A member of the Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional, playing a guitarrón in Chiapas, Mexico The neo-Zapatistas did not proclaim adherence to a specific political ideology beyond left-wing politics. The ideology of the Zapatista movement, Neozapatismo, synthesizes Mayan tradition with elements of libertarian socialism,[72] anarchism,[12] Catholic liberation theology[73] and Marxism.[13][74] Some authors also draw parallels between neozapatismo and autonomism, while others argue it can be better defined as semi-anarchist.[75] The historical influence of Mexican anarchists and various Latin American socialists is apparent in Neozapatismo. The positions of Subcomandante Marcos add a Marxist[76] element to the movement. A Zapatista slogan is in harmony with the concept of mutual aid: "Everything for everyone. Nothing for us" (Para todos todo, para nosotros nada). The EZLN opposes economic globalization, arguing that it severely and negatively affects the peasant life of its indigenous support base and oppresses people worldwide. The signing of NAFTA also resulted in the removal of Article 27, Section VII, from the Mexican Constitution, which had guaranteed land reparations to indigenous groups throughout Mexico through collective land tenure.[77] |

イデオロギー チアパス州、連邦道307号線。 上部の看板にはスペイン語でこう書かれている。「ここはサパティスタ反乱軍の支配地域だ。ここでは民衆が命令し、政府が従う」 下部の看板:「北部地区。善政評議会。武器の密輸、麻薬栽培、薬物使用、酒類、違法な木材販売は厳禁。自然破壊に反対」  メキシコ・チアパス州でギターロンを演奏するサパティスタ民族解放軍(Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional)の隊員 新サパティスタ派は左翼政治を超えた特定の政治イデオロギーへの帰属を宣言しなかった。サパティスタ運動のイデオロギーであるネオサパティズモは、マヤの 伝統と自由社会主義[72]、アナキズム[12]、カトリック解放の神学[73]、マルクス主義[13]の要素を統合している。[74] 一部の著者はネオサパティズモと自治主義の類似性を指摘する一方、他者は半無政府主義として定義する方が適切だと主張する[75]。メキシコ無政府主義者 や様々なラテンアメリカ社会主義者の歴史的影響はネオサパティズモに顕著に見られる。サブコマンダンテ・マルコスの立場は運動にマルクス主義的要素を加え る[76]。サパティスタのスローガンは相互扶助の概念と調和している: 「万人のために全てを。我々のために何も」(Para todos todo, para nosotros nada)。 EZLNは経済的グローバリゼーションに反対し、それが先住民支持基盤の農民生活を深刻に損ない、世界中の人々を抑圧すると主張する。NAFTAの調印は また、集団所有権を通じてメキシコ全土の先住民集団に土地補償を保証していたメキシコ憲法第27条第VII項の削除をもたらした[77]。 |

| Postcolonialism Postcolonialism scholars have argued that the Zapatistas' response to the introduction of NAFTA in 1994 may have reflected a shift in perception taking place in societies that have experienced colonialism.[78] The Zapatistas have used organizations like the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) to raise awareness for their rebellion and indigenous rights, and what they claim is the Mexican government's lack of respect for the country's impoverished and marginalized populations.[79] Appealing to the ECOSOC and other non-governmental bodies may have allowed the Zapatistas to establish a sense of autonomy by redefining their identities both as indigenous people and as citizens of Mexico.[80] |

ポストコロニアル主義 ポストコロニアル主義の研究者たちは、1994年のNAFTA導入に対するサパティスタの反応は、植民地主義を経験した社会で起きている認識の変化を反映 している可能性があると主張している。[78] サパティスタは国連経済社会理事会(ECOSOC)などの組織を利用し、自らの反乱と先住民族の権利、そしてメキシコ政府が国内の貧困層や周縁化された人 々を軽視していると主張する現状への認識を高めてきた。[79] ECOSOCやその他の非政府機関に訴えることで、サパティスタは自らのアイデンティティを先住民として、またメキシコ市民として再定義し、自律性の感覚 を確立できた可能性がある。[80] |

| Religion One of the most important tenets of Zapatista ideology was liberation theology, with the Bishop of Chiapas Samuel Ruiz being considered the key figure.[81] The Zapatista movement is outwardly secular, and does not have an official religion. However, the overarching Zapatista movement has been influenced by liberation theology and its proponents. The organization established early on that it "has no ties with any Catholic religious authorities nor authorities of any other creed."[82] Local Catholic clergy was catalytic for the formation of neo-Zapatistas in Chiapas, given the strong position that the Church enjoyed within local indigenous communities. Indigenous catechists that taught liberation theology proved essential in organising the local population, and gave the aura of legitimacy to movements hitherto considered too dangerous or radical. The activity of Catholic socialist catechists in the region allowed FLN to make inroads with local villages and start cooperating with Catholic association Slop (Tzeltal name for 'root'), whose primary aim was organizing indigenous resistance. Cooperation of FLN with local Catholic activists then gave birth to zapatista EZLN.[83] In the decades preceding the 1994 uprising, the Roman Catholic Diocese of San Cristóbal de Las Casas, guided by the Bishop Samuel Ruiz Garcia, developed a cadre of indigenous catechists.[73] In practice, these liberationist Christian catechists promoted political awareness, established organizational structures, and helped raise progressive sentiment among indigenous communities in Chiapas.[84] The organization of these catechists and events such as the 1974 Indigenous Congress laid much of the ideological and often organizational groundwork for the EZLN to unite many indigenous communities under a banner of liberation. Further, many of these indigenous catechists later joined and organized within the EZLN.[85] Anthropologists Duncan Earle and Jeanne Simonelli assert that the liberationist Catholicism spread by the aforementioned catechists which emphasized helping the poor and addressing material conditions in tandem with spiritual ones brought many indigenous Catholics into the Zapatista Movement.[86] Beyond just the Zapatistas, the blossoming indigenous resistance and identity of the late 20th century saw a broader indigenous movement based in indigenous liberationist Christianity.[87] One such group in the broader movement is Las Abejas, an ecumenical Christian organization. Supported, but not controlled by the Diocese of San Cristobal, Las Abejas is dedicated to nonviolence, but shares sympathies and solidarity for the aims of the Zapatistas.[88] Due to their ties to the Zapatistas, 45 Las Abejas members were killed in the Acteal Massacre in 1997.[89] Once EZLN rebelled in 1994, the Catholic Church was accused of inciting the rebellion; this accusation was confirmed by Zapatistas, who credited local catechists with persuading local indigenous population to participate in the uprising.[90] The Zapatista movement was therefore described as one that combines Marxism with traditional, Catholic spirituality.[91] Because of its commitment to Catholicism, the EZLN was able to rally even conservative Catholics behind its socialist cause.[92] |

宗教 サパティスタイデオロギーの最も重要な教義の一つは解放の神学であり、チアパス州司教サミュエル・ルイスがその中心人物と見なされていた。[81] サパティスタ運動は表向きは世俗的であり、公式の宗教は持たない。しかし、包括的なサパティスタ運動は解放の神学とその提唱者たちから影響を受けてきた。 この組織は早い段階で、「カトリックの宗教当局やその他の信条の当局とは一切関係がない」と表明していた[82]。 地元のカトリック聖職者は、教会が地元の先住民コミュニティ内で強い影響力を持っていたことを考えると、チアパス州におけるネオ・サパティスタの形成に重 要な役割を果たした。解放の神学を教えた先住民のカテキスタは、地元住民を組織化する上で欠かせない存在となり、それまで危険すぎる、あるいは過激すぎる と考えられていた運動に正当性を与えた。この地域におけるカトリック社会主義の教理教師たちの活動により、FLN は地元の村々に浸透し、先住民による抵抗運動の組織化を主な目的とするカトリック団体 Slop(ツェルタル語で「根」を意味する)との協力関係を築き始めた。FLN と地元のカトリック活動家たちの協力により、サパティスタ EZLN が誕生したのである。[83] 1994年の蜂起に先立つ数十年間、サン・クリストバル・デ・ラス・カサス教区は、サミュエル・ルイス・ガルシア司教の指導のもと、先住民カテキスタの幹 部育成に取り組んだ[73]。実際には、これらの解放主義的なキリスト教の教理教師たちは、政治的意識を高め、組織構造を確立し、チアパス州の先住民コ ミュニティの間で進歩的な感情を高めることに貢献した。[84] これらの教理教師たちの組織や、1974年の先住民会議などのイベントは、EZLN が多くの先住民コミュニティを解放の旗印の下に結束させるための、イデオロギー的、そして多くの場合組織的な基礎の多くを築いた。さらに、これらの先住民 教理教師の多くは、後に EZLN に加入し、その内部で組織化した。[85] 人類学者のダンカン・アールとジャンヌ・シモネリは、前述のカテキスタたちが広めた解放主義カトリックが、貧しい人々を助け、精神的条件と並行して物質的 条件に取り組むことを強調したことで、多くの先住民カトリック教徒をサパティスタ運動に引き入れたと主張している。[86] サパティスタたちを超えて、20世紀後半に花開いた先住民の抵抗とアイデンティティは、先住民解放主義キリスト教に基づくより広範な先住民運動を生み出し た。[87] この広範な運動における一例が、エキュメニカルなキリスト教組織「ラス・アベハス」である。サン・クリストバル教区から支援は受けるが支配は受けないこの 組織は非暴力に徹しつつ、サパティスタの目標への共感と連帯を表明している。[88] サパティスタとの繋がりゆえに、1997年のアクテアル虐殺ではラス・アベハスのメンバー45名が殺害された。[89] 1994年にEZLNが反乱を起こすと、カトリック教会は反乱を扇動したとして非難された。この非難はサパティスタたちによって裏付けられ、彼らは地元の 教理教師が先住民を説得して蜂起に参加させたとしている。[90] したがってサパティスタ運動は、マルクス主義と伝統的なカトリック的霊性を融合させたものと評された。[91] カトリックへの忠誠心ゆえに、EZLNは保守的なカトリック信徒さえも社会主義的大義の下に結集させることができた。[92] |

Communications Sign of the entering Zapatista autonomous territory: North Zone Junta (Meeting) of Good Governance. Strictly prohibited: The trafficking of arms, planting and consumption of drugs, intoxicating drinks, illegal sale of wood. No to the destruction of nature. Zapata lives, the fight continues... You are in Zapatista territory in Rebellion. Here the people rule, the government obeys. The Zapatistas initially focused on the news media as a weak point of the Mexican federal government and turned the Chiapas war from a military impossibility to an informational guerrilla movement. From 1994 to 1996, the Zapatistas enjoyed favorable news coverage from national and international media, particularly via Subcomandante Marcos as its spokesperson.[93] Marcos and the Zapatistas would issue hundreds of missives, hold encuentros (mass meetings), give numerous interviews, meet high-profile public and literary figures including Oliver Stone, Naomi Klein, Gael García Bernal, Danielle Mitterrand, Régis Debray, John Berger, Eduardo Galeano, Gabriel García Márquez, José Saramago and Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, participate in symposia and colloquia, deliver speeches, host visits by thousands of national and international activists, and participate in two marches that toured much of the country.[94] Media organizations from North and South America, as well as from many European and several Asian nations, have granted press coverage to the movement and its spokesperson. The EZLN's writings have been translated into at least 14 different languages and Marcos, according to journalist Jorge Alonso, had by 2016 been the subject of "over 10,000 citations".[95] As EZLN external communications dissipated after 1994, their mainstream coverage similarly decreased, particularly as spokesperson Subcomandante Marcos became critical of the media in 1996 and 1997.[96] The Zapatistas' communication strategy evolved to incorporate mythopoetic techniques, blending Indigenous storytelling traditions with political messaging and magical realism. This approach allowed the Zapatistas to transcend the constraints of standard Spanish prose, which they viewed as embedded with colonial and hegemonic biases. By employing mythopoetics—a style characterized by metaphorical narratives, allegories, and cultural symbolism—they effectively communicated Mesoamerican philosophical tenets while broadening their appeal to both local and international audiences.[97] |

通信 サパティスタ自治地域進入の標識:北部善政評議会。厳禁事項:武器の密輸、麻薬の栽培・消費、酒類、違法な木材販売。自然破壊に反対。 サパタは生きている、闘いは続く… お前は反乱中のサパティスタ領土にいる。ここでは民衆が統治し、政府は従う。 サパティスタは当初、メキシコ連邦政府の弱点として報道機関に焦点を当て、チアパス戦争を軍事的に不可能なものから情報ゲリラ運動へと転換させた。 1994年から1996年にかけ、サパティスタは国内外のメディアから好意的な報道を得た。特にスポークスマンである副司令官マルコスを通じてである [93]。マルコスとサパティスタは数百通の書簡を発表し、エンクエントロ(大集会)を開催し、数多くのインタビューに応じ、オリバー・ストーン、ナオ ミ・クライン、 ガエル・ガルシア・ベルナル、ダニエル・ミッテラン、レジス・ドブレ、ジョン・バーガー、エドゥアルド・ガレアーノ、ガブリエル・ガルシア・マルケス、 ジョゼ・サラマーゴ、マヌエル・バスケス・モンタルバンといった著名な公人や文筆家と面会し、シンポジウムやコロキウムに参加し、演説を行い、国内外の活 動家数千人の訪問を受け入れ、国内の大半を巡った二つの行進に参加した。[94] 北米・南米をはじめ、欧州の国民やアジアの国民のメディア組織が、この運動とそのスポークスパーソンを取材対象としてきた。EZLNの文書は少なくとも 14言語に翻訳され、ジャーナリストのホルヘ・アロンソによれば、マルコスは2016年までに「1万件以上の引用」の対象となっていた。[95] 1994年以降、EZLNの対外的な発信が減退すると、主流メディアの報道も同様に減少した。特にスポークスマンである副司令官マルコスが1996年と 1997年にメディアを批判したことが影響している。[96] サパティスタのコミュニケーション戦略は、神話詩的手法を組み込む形で進化した。先住民の物語伝承の伝統と政治的メッセージ、そして呪術的リアリズムを融 合させたのである。この手法により、サパティスタは植民地主義的・覇権主義的偏見が内在すると見なした標準スペイン語散文の制約を超越できた。隠喩的叙 述・寓意・文化的象徴を特徴とする神話詩的表現を採用することで、彼らはメソアメリカの哲学的原理を効果的に伝達しつつ、国内外の聴衆への訴求力を拡大し たのである。[97] |

| Horizontal autonomy and

indigenous leadership See also: Rebel Zapatista Autonomous Municipalities Zapatista communities build and maintain their own health, education, and sustainable agro-ecological systems, promote equitable gender relations via Women's Revolutionary Law, and build international solidarity through outreach and political communication, in addition to their focus on building "a world where many worlds fit". The Zapatista struggle re-gained international attention in May 2 of 2014 with the death of teacher and education promoter José Luis Solís López a.k.a. "Teacher Galeano" (a self chosen name honoring anti-capitalist author Eduardo Galeano),[98] who was murdered in an attack on a Zapatista school and health clinic led by local paramilitaries of the Central Independiente de Obreros Agrícolas y Campesinos Histórica,[99] (Historical Independent Central of Agricultural Workers and Peasants, CIOAC-H).[100][101] In the weeks that followed, thousands of Zapatistas and national and international sympathizers mobilized and gathered to honor Galeano. This event also saw the unofficial spokesperson of the Zapatistas, Subcomandante Marcos, announce that he would be stepping down.[102][103] |

水平的自治と先住民族のリーダーシップ 関連項目:反乱サパティスタ自治自治体 サパティスタ共同体は、自らの健康・教育・持続可能な農業生態系を構築・維持し、「女性の革命法」を通じて公平な男女関係を促進し、国際連帯を構築する。 これに加え、「多くの世界が共存する世界」の構築に注力している。サパティスタの闘争は、2014年5月2日に教師であり教育推進者であったホセ・ルイ ス・ソリス・ロペス(通称「教師ガレアーノ」)が死亡したことで、再び国際的な注目を集めた。[98] ザパタ派の学校と健康センターへの襲撃で殺害されたことで、再び国際的な注目を集めた。この襲撃は、農業労働者・農民歴史的独立中央(CIOAC-H) [99] の地元準軍事組織が主導したものである。[100][101] その後数週間で、数千人のサパティスタと国民および国際的な支持者が動員され、ガレアノを偲ぶ集会が開かれた。この集会で、サパティスタの非公式スポーク スマンである副司令官マルコスは、自身の退任を発表した。[102][103] |

Legacy Rage Against the Machine performs with the Zapatista flag in the background The Zapatistas continued to control the Chiapas area through the late 2010s, with around 300,000 people across 55 municipalities. These poor communities run and train their own civic programs (education, health, government, justice) autonomously, with little interference from the Mexican government.[104] The 1994 uprising has led to broader interest in the area, also known as Zapatourismo. Stores in San Cristóbal capitalize on revolutionary chic, selling balaclavas, music, and shirt souvenirs.[104] Subcomandante Marcos's image and signature balaclava and pipe are widely appropriated in the tourism industry, similar to the iconic status of Che Guevara.[104][105] Visitors cannot tour the villages but can attempt to visit the caracol administrative centers, subject to the approval of a reception committee.[104] Marcos's fame had subsided by the early 2020s.[105] American rock bands have voiced support for the Zapatistas. Rage Against the Machine released three songs in support of the EZLN, including "People of the Sun" (1996).[106] The extreme metal band Brujeria is also known for their support of the Zapatistas.[107] The EZLN invited supporters to Chiapas for two days of celebration in honor of their 30th anniversary in 2023.[105] |

レガシー レイジ・アゲインスト・ザ・マシーンはサパティスタ旗を背景に演奏した サパティスタは2010年代後半まで、55の自治体でおよそ30万人の住民を擁し、チアパス地域を支配し続けた。これらの貧しいコミュニティは、メキシコ 政府の干渉をほとんど受けずに、独自の市民プログラム(教育、健康、行政、司法)を自律的に運営し訓練している。[104] 1994年の蜂起は「サパティスモ観光」として知られる地域への関心拡大をもたらした。サン・クリストバルの店舗は革命的な流行を取り入れ、バラクラバ、 音楽、シャツの土産品を販売している。[104]副司令官マルコスのイメージと特徴的なバラクラバ、パイプは観光産業で広く流用され、チェ・ゲバラの象徴 的地位と同様である。[104][105] 訪問者は村々を観光できないが、受け入れ委員会の承認を得ればカラコル行政センターへの訪問を試みることができる。[104] マルコスの名声は2020年代初頭までに衰えた。[105] アメリカのロックバンドはサパティスタへの支持を表明している。レイジ・アゲインスト・ザ・マシーンはEZLN支援のため「太陽の人々」(1996年)を 含む3曲をリリースした。[106] エクストリームメタルバンドのブルヘリアもサパティスタ支援で知られる。[107] EZLNは2023年、結成30周年を記念する2日間の祝賀行事のため支持者をチアパス州に招待した。[105] |

| Subcomandante

Elisa Comandanta Esther Capitán Insurgente Marcos, previously known as Subcomandante Marcos Comandanta Ramona |

副司令官エリサ 司令官エスター 反乱軍大尉マルコス(旧称:副司令官マルコス) 司令官ラモナ |

| A Place Called Chiapas, a

documentary on the Zapatistas and Subcomandante Marcos Index of Mexico-related articles Indigenous movements in the Americas Movement for Peace with Justice and Dignity Zapatismo Zapatista coffee cooperatives Women in the EZLN |

『チアパスという場所』―サパティスタとサブコマンダンテ・マルコスに

関するドキュメンタリー メキシコ関連記事の目次 アメリカ大陸の先住民運動 正義と尊厳を伴う平和のための運動 サパティズム サパティスタのコーヒー協同組合 EZLN(サパティスタ民族解放軍)の女性たち |

| References |

|

| Bibliography Ferron, Benjamin (2019). "A Heretical Accumulation of International Capital: The Zapatista Activists' Media Networks". In Pertierra, Anna Cristina; Salazar, Juan Francisco (eds.). Media Cultures in Latin America: Key Concepts and New Debates. New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780429425127. ISBN 978-0-429-42512-7. Gunderson, Christopher (2013). The provocative cocktail: Intellectual origins of the Zapatista uprising, 1960–1994 (PhD). City University of New York. ProQuest 1430904296. Henck, Nick (2019). Subcomandante Marcos: Global Rebel Icon. Black Rose Books. ISBN 978-1-55164-706-7. O'Neil, Patrick H.; Fields, Karl; Share, Don (2006). Cases in Comparative Politics (2nd ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-92943-4. Seward, Ruhiya Kristine Kathryn (2012). Fusing Identities and Mobilizing Resistance in Chiapas and Mexico, 1994-2009 (PhD). The New School for Social Research. |

参考文献 フェロン、ベンジャミン(2019)。「異端的な国際資本の蓄積:サパティスタ活動家のメディアネットワーク」。ペルティエラ、アンナ・クリスティーナ; サラザール、フアン・フランシスコ(編)。『ラテンアメリカのメディア文化:主要概念と新たな議論』。ニューヨーク:ラウトリッジ。doi: 10.4324/9780429425127. ISBN 978-0-429-42512-7. ガンダーソン、クリストファー(2013年)。挑発的なカクテル:サパティスタ蜂起の知的起源、1960–1994年(博士論文)。ニューヨーク市立大 学。ProQuest 1430904296. ヘンク、ニック(2019)。『副司令官マルコス:世界的な反逆の象徴』。ブラック・ローズ・ブックス。ISBN 978-1-55164-706-7。 オニール、パトリック・H.;フィールズ、カール;シェア、ドン(2006)。『比較政治学の事例研究(第2版)』。ニューヨーク:W. W. ノートン社。ISBN 0-393-92943-4。 Seward, Ruhiya Kristine Kathryn (2012). 『チアパスとメキシコにおけるアイデンティティの融合と抵抗の動員、1994-2009年』(博士論文)。ザ・ニュー・スクール・フォー・ソーシャル・リ サーチ。 |

| Further reading Castellanos, L. (2007). México Armado: 1943-1981. Epilogue and chronology by Alejandro Jiménez Martín del Campo. México: Biblioteca ERA. 383 pp. ISBN 968-411-695-0 ISBN 978-968-411-695-5 Conant, J. (2010). A Poetics of Resistance: The Revolutionary Public Relations of the Zapatista Insurgency. Oakland: AK Press. ISBN 978-1-849350-00-6. (Ed.) Ponce de Leon, J. (2001). Our Word Is Our Weapon: Selected Writings, Subcomandante Marcos. New York: Seven Stories Press. ISBN 1-58322-036-4. Ferron, Benjamin; Neveu, Érik (2015). La communication internationale du zapatisme, 1994-2006 [The international communication of Zapatismo, 1994-2006] (in French). Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes. ISBN 978-2-7535-4021-7. Dylan Eldredge Fitzwater, The Zapatista Institutions of Autonomy and their Social Implications, 2021 Hackbarth, Kurt; Mooers, Colin (September 9, 2019). "The Zapatista Revolution Is Not Over". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. Henao, Sebastián Granda (2022). "'El pueblo manda y el gobierno obedece': Decolonising Politics and Constructing Worlds in the Everyday through Zapatista Autonomy". In Márquez Duarte, Fernando David; Espinoza Valle, Victor Alejandro (eds.). Decolonizing Politics and Theories from the Abya Yala. Bristol, England: E-International Relations. pp. 172–191. ISBN 978-1-910814-62-8. OCLC 1376407615. Patrick & Ballesteros Corona, Carolina (1998). Cuninghame, "The Zapatistas and Autonomy", Capital & Class, No. 66, Autumn, pp 12–22. Gottesdiener, Laura (January 23, 2014). "A Glimpse Into the Zapatista Movement, Two Decades Later". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. The Zapatista Reader edited by Tom Hayden 2002 A wide sampling of notable writing on the subject. ISBN 9781560253358 Khasnabish, Alex (2010). Zapatistas: Rebellion from the Grassroots to the Global. London and New York: Zed Books. ISBN 978-1848132085. Klein, Hilary. (2015) Compañeras: Zapatista Women's Stories. Seven Stories Press. ISBN 978-1-60980-587-6 (Eds.) Holloway, John and Peláez, Eloína (1998). Zapatista! Reinventing Revolution in Mexico. London: Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0745311777. McKinley, James C. Jr. (January 6, 2006). "The Zapatista's Return: A Masked Marxist on the Stump". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Mentinis, Mihalis (2006). Zapatistas: The Chiapas Revolt and what it means for Radical Politics. London: Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0745324869. Muñoz Ramírez, Gloria (2008). The Fire and the Word: A History of the Zapatista Movement. San Francisco: City Lights Publishers. ISBN 978-0872864887. Rider, Nick (March 12, 2009). "Visiting the Zapatistas". New Statesman. Retrieved April 18, 2021. Ross, John (1995). Rebellion from the Roots: Indian Uprising in Chiapas. Monroe, ME.: Common Courage Press. ISBN 978-1567510430. Ross, John (2000). The War Against Oblivion: the Zapatista Chronicles 1994–2000. Monroe, ME: Common Courage Press. ISBN 978-1567511741. Ross, John (2006). ¡Zapatistas! Making Another World Possible: Chronicles of Resistance 2000–2006. New York: Nation Books. ISBN 978-1560258742. Subcomandante Marcos (2016). Critical Thought in the Face of the Capitalist Hydra. Durham, NC: Paperboat Press. ISBN 978-0979799327. Subcomandante Marcos (2018). The Zapatistas' Dignified Rage: Final Public Speeches of Subcommander Marcos. Nick Henck (ed.) and Henry Gales (trans.). Chico, CA.: AK Press. ISBN 978-1849352925. Theodoros Karyotis, Ioanna-Maria Maravelidi, Yavor Tarinski (2022). Asking questions with the Zapatistas. Reflections from Greece on our Civilizational Impasse. Editor: Matthew Little, Publisher: Transnational Institute of Social Ecology. Oikonomakis, Leonidas (2019). Political Strategies and Social Movements in Latin America: The Zapatistas and Bolivian Cocaleros. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-3-319-90203-6. Collier, George A. (2008). Basta!: Land and the Zapatista Rebellion in Chiapas (3rd ed.). Food First Books. ISBN 978-0-935028-97-3. Harvey, Neil (1998). The Chiapas Rebellion: The Struggle for Land and Democracy. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-2238-2. |

追加文献(さらに読む) カステジャノス、L.(2007)。『武装したメキシコ:1943-1981』。エピローグと年表はアレハンドロ・ヒメネス・マルティン・デル・カンポに よる。メキシコ:ビブリオテカ・エラ。383頁。ISBN 968-411-695-0 ISBN 978-968-411-695-5 コナント、J.(2010)。『抵抗の詩学:サパティスタ反乱の革命的広報活動』。オークランド:AKプレス。ISBN 978-1-849350-00-6。 (編)ポンセ・デ・レオン、J.(2001)。『我々の言葉は我々の武器:サブコマンダンテ・マルコス選集』。ニューヨーク:セブン・ストーリーズ・プレ ス。ISBN 1-58322-036-4。 フェロン、ベンジャミン;ヌヴー、エリック(2015)。『ザパティズムの国際的コミュニケーション、1994-2006』(フランス語)。レンヌ:プレ ス・ユニヴェルシテール・ド・レンヌ。ISBN 978-2-7535-4021-7。 ディラン・エルドレッジ・フィッツウォーター『サパティスタ自治機構とその社会的含意』2021年 ハックバース、カート;ムーアズ、コリン(2019年9月9日)。「サパティスタ革命は終わっていない」『ザ・ネイション』ISSN 0027-8378. エナオ、セバスティアン・グランダ(2022)。「『民衆が命じ、政府は従う』:サパティスタ自治を通じた日常における脱植民地化政治と世界の構築」マル ケス・ドゥアルテ、フェルナンド・ダビッド;エスピノサ・バレ、ビクトル・アレハンドロ(編)。『アビア・ヤラからの脱植民地化政治と理論』. イギリス・ブリストル: E-International Relations. pp. 172–191. ISBN 978-1-910814-62-8. OCLC 1376407615. パトリック&バレステロス・コロナ、カロリナ (1998). カニンガム、「サパティスタと自治」、『資本と階級』第66号、秋号、12–22頁。 ゴットスディナー、ローラ(2014年1月23日)。「サパティスタ運動を垣間見る、20年後の今」。『ザ・ネイション』。ISSN 0027-8378。 サパティスタ派読本 トム・ヘイデン編 2002年 主題に関する著名な著作の幅広い抜粋。ISBN 9781560253358 ハスナビッシュ、アレックス(2010年)。『サパティスタ派:草の根から世界へ広がる反乱』。ロンドン・ニューヨーク:ゼッドブックス。ISBN 978-1848132085。 クライン、ヒラリー(2015)『コンパニェラス:サパティスタ女性たちの物語』セブン・ストーリーズ・プレス刊。ISBN 978-1-60980-587-6 (編)ホロウェイ、ジョンとペラエス、エロイナ(1998)。『サパティスタ!メキシコにおける革命の再発明』ロンドン:プルート・プレス刊。ISBN 978-0745311777。 マッキンリー、ジェームズ・C・ジュニア(2006年1月6日)。「サパティスタの帰還:演説台に立つ仮面のマルクス主義者」。ニューヨーク・タイムズ。 ISSN 0362-4331。 メンティニス、ミハリス(2006)。『サパティスタ:チアパス蜂起と急進的政治への示唆』ロンドン:プルート・プレス。ISBN 978-0745324869。 ムニョス・ラミレス、グロリア(2008)。『炎と言葉:サパティスタ運動の歴史』サンフランシスコ:シティ・ライツ出版社。ISBN 978-0872864887。 ライダー、ニック(2009年3月12日)。「サパティスタを訪問して」。ニュー・ステーツマン。2021年4月18日取得。 ロス、ジョン(1995)。『根源からの反乱:チアパスにおける先住民蜂起』。メイン州モンロー:コモン・カレッジ・プレス。ISBN 978-1567510430。 ロス、ジョン(2000年)。『忘却との戦い:サパティスタ年代記 1994–2000』。メイン州モンロー:コモン・カレッジ・プレス。ISBN 978-1567511741。 ロス、ジョン(2006)。『サパティスタたち! 別の世界を可能にする:抵抗の記録 2000–2006』。ニューヨーク:国民・ブックス。ISBN 978-1560258742。 副司令官マルコス(2016)。『資本主義のヒドラに直面する批判的思考』。ノースカロライナ州ダーラム:ペーパーボート・プレス。ISBN 978-0979799327。 副司令官マルコス(2018)。『サパティスタの尊厳ある怒り:副司令官マルコスの最後の公的演説』。ニック・ヘンク(編)、ヘンリー・ゲイルズ(訳)。 カリフォルニア州チコ:AKプレス。ISBN 978-1849352925。 テオドロス・カリオティス、イオアンナ=マリア・マラヴェリディ、ヤヴォル・タリンスキ(2022)。『サパティスタと共に問う。文明の行き詰まりに関す るギリシャからの考察』。編集:マシュー・リトル、出版社:トランスナショナル社会生態学研究所。 オイコノマキス、レオニダス(2019)。『ラテンアメリカにおける政治戦略と社会運動:サパティスタとボリビアのコカ栽培者たち』。パルグレイブ・マク ミラン。ISBN 978-3-319-90203-6。 コリアー、ジョージ・A.(2008)。『もういい!:チアパスにおける土地とサパティスタ反乱(第3版)』フード・ファースト・ブックス。ISBN 978-0-935028-97-3。 ハーヴェイ、ニール(1998)。『チアパス反乱:土地と民主主義のための闘い』。デューク大学出版局。ISBN 0-8223-2238-2。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zapatista_Army_of_National_Liberation |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099