入植植民地主義としてのシオニズム

Zionism as settler colonialism

A

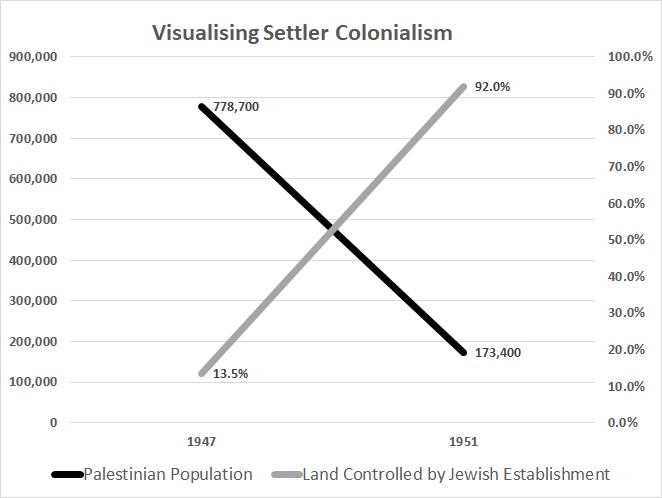

graph by Neve Gordon showing the population shift from 1947 to 1951 in

Israel–Palestine, plotted with the % of land controlled by what he

calls the "Jewish establishment".

☆入植植民地主義としてのシオニズム(Zionism as settler colonialism) について解説する。シオニズムは、その創設者や初期指導者、そして複数の学者によって、パレスチナ地域とイスラエル・パレスチナ紛争に関して、入植者によ る植民地主義の一形態と説明されてきた。 シオニズムの創設者や初期指導者たちは、自分たちが植民地化者であるという立場を認識し、それを詫びることもなかった。テオドール・ヘルツル、マックス・ ノルダウ、ゼエヴ・ジャボティンスキーといった初期の主要なシオニストの多くは、シオニズムを植民地化と表現した。入植者植民地主義のパラダイムは、後に パトリック・ウルフ、エドワード・サイード、ファイエズ・サイエグ、マキシム・ロディンソンといった様々な学者や人物によってシオニズムにも適用された。 この紛争に対する入植者植民地主義の枠組みは、1960年代のアフリカと中東の脱植民地化期に現れ、1990年代にはイスラエルとパレスチナの学者、特に 「新歴史家」たちによってイスラエルの学界で再浮上した。彼らはイスラエルの建国神話の一部を否定し、ナクバ(大災難)が現在も続いていると考えた。この 視点は、シオニズムがパレスチナ人の排除と同化プロセスを伴うものであり、アメリカやオーストラリアの建国に類似した他の入植者植民地主義の文脈と同様で あると主張する。 ベンニー・モリス、ユヴァル・シャニ、イラン・トロエンら、シオニズムを植民地主義と規定する見解への批判者は、シオニズムは伝統的な植民地主義の枠組み には当てはまらず、むしろ先住民族の帰還と自己決定の行為であると主張する。この議論は、イスラエル国家の建国とイスラエル・パレスチナ紛争に関する対立 する歴史的・政治的解釈をめぐる、より広範な緊張関係を反映している。

★イスラエル・パレスチナ紛争における先住民(Indigeneity in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict)の役割は、イスラエルのユダヤ人、パレスチナ人、あるいは双方が先住民と定義されるか否かに焦点を当てている。 21世紀に入り、多くのシオニストはユダヤ人がイスラエルの地の先住民であるとの見解を主張してきた。パレスチナ側の支持者はしばしば、パレスチナ人が占 領された先住民であり、シオニズムは入植者による植民地主義の一形態であるとの見解を主張する。一部の観察者は、ユダヤ人とパレスチナ人の双方を先住民族 と見なしている。国連はパレスチナ人を「パレスチナの先住民族」と呼んでいる。[1][2]

| The role of Indigeneity in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

centers on whether or not Israeli Jews, Palestinians, or both peoples

are to be defined as Indigenous peoples. During the 21st century, many

Zionists have advocated the view that Jews are the Indigenous people of

the Land of Israel. Advocates of the Palestinian cause often advocate

the view that Palestinians are an occupied Indigenous people and that

Zionism is a form of settler colonialism. Some observers consider both

Jews and Palestinians to be Indigenous. The United Nations has referred to Palestinians as the "indigenous people of Palestine".[1][2] |

イスラエル・パレスチナ紛争における先住民の役割は、イスラエルのユダ

ヤ人、パレスチナ人、あるいは双方が先住民と定義されるか否かに焦点を当てている。21世紀に入り、多くのシオニストはユダヤ人がイスラエルの地の先住民

であるとの見解を主張してきた。パレスチナ側の支持者はしばしば、パレスチナ人が占領された先住民であり、シオニズムは入植者による植民地主義の一形態で

あるとの見解を主張する。一部の観察者は、ユダヤ人とパレスチナ人の双方を先住民族と見なしている。 国連はパレスチナ人を「パレスチナの先住民族」と呼んでいる。[1][2] |

| Jews as indigenous Since the 1960s, it had become clear to Biblical Archaeologists and Bible critics, that the Israelites of whom the Jews and Samaritans emerged from, are in fact local Canaanites who didn't invade the Land of Israel as suggested by the Torah and Book of Joshua, but who have fled from the decaying Canaanite society of various city-states into safe havens in the hill country and developed a new lifestyle during the Iron Age.[3] Major Zionist organizations including the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), the American Jewish Committee, and the Israel Action Network of the Jewish Federations of North America have stated that Jews are Indigenous to the Land of Israel.[4][5] The International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs defines the Palestinian Bedouin as the Indigenous people of Palestine.[6][7] In 2015, a proposal titled "Recognition of the Jewish People as Indigenous to the Land of Israel" was submitted and approved by a 51% vote in favor at the World Zionist Congress. The bill's author stated that the bill rejects "the core anti-Israel accusation that Jews are foreign colonialists in the country and instead affirms that the Jewish people have indigenous rights to live in their ancestral home." The proposal was opposed by the liberal Zionist organization J Street, the Reform movement's ARZA, and the Conservative movement's Mercaz USA, among other organizations.[8] The New Zealand Jewish Council has stated that "Indigeneity and colonialism" are "not useful metaphors for Israel", citing Jewish presence in the land for thousands of years.[9] |

ユダヤ人は先住民族である 1960年代以降、聖書考古学者や聖書批評家たちは、ユダヤ人とサマリア人の起源であるイスラエル人が、トーラーやヨシュア記が示すようにイスラエルの地 へ侵入した異民族ではなく、鉄器時代に衰退するカナン諸都市国家から山岳地帯の安全な避難所へ逃れ、新たな生活様式を発展させた現地のカナン人であったこ とを明らかにした。[3] 反誹謗同盟(ADL)、アメリカ・ユダヤ人委員会、北米ユダヤ連盟のイスラエル行動ネットワークを含む主要なシオニスト組織は、ユダヤ人がイスラエルの地 に先住民族であると表明している。[4][5] 国際先住民族問題作業部会は、パレスチナのベドウィンをパレスチナの先住民と定義している。[6][7] 2015年、「ユダヤ民族をイスラエルの地の先住民族として認定する」と題する提案が世界シオニスト会議に提出され、賛成51%の賛成票で承認された。提 案者は「ユダヤ人がこの国における外来の植民者であるという反イスラエルの中核的非難を退け、代わりにユダヤ民族が祖先の故郷に居住する先住権を有するこ とを確認する」と述べた。この提案には、リベラル・シオニスト組織Jストリート、改革派運動のARZA、保守派運動のメルカズUSAなどの組織が反対し た。[8] ニュージーランド・ユダヤ人評議会は、ユダヤ人が数千年にわたりこの地に存在してきたことを挙げ、「先住性と植民地主義」は「イスラエルにとって有用な隠喩ではない」と表明している。[9] |

| Palestinians as indigenous The Native American and Indigenous Studies Association (NAISA) have stated that "[W]e strongly protest the illegal occupation of Palestinian lands and the legal structures of the Israeli state that systematically discriminate against Palestinians and other Indigenous peoples...We reaffirm this sentiment that recognizes the rights of Indigenous Palestinians when we demand an end to the illegal occupation of Palestinian lands and a free Palestine.[10] The author Gabor Maté has stated that Israel and Canada have shared colonial values as they are "both countries founded on the extirpation of Indigenous cultures and the displacement of Indigenous people".[11] |

パレスチナ人を先住民として ネイティブアメリカン・先住民研究協会(NAISA)は次のように表明している。「我々はパレスチナ領土の不法占領と、パレスチナ人及び他の先住民を体系 的に差別するイスラエル国家の法的構造に強く抗議する…パレスチナ領土の不法占領の終結と自由なパレスチナを要求するにあたり、我々は先住民であるパレス チナ人の権利を認めるこの意思を再確認する。」[10] 著者のガボール・マテは、イスラエルとカナダは「先住民の文化を根絶し、先住民を追放した上で建国された国々」である点で共通の植民地主義的価値観を共有していると述べている。[11] |

| Jews and Palestinians as indigenous Some organizations, including the ADL, have referred to both Jews and Palestinians as Indigenous to Israel/Palestine.[4] The Center for World Indigenous Studies considers both Jews and Palestinians to be Indigenous peoples of Israel/Palestine.[12] |

ユダヤ人とパレスチナ人は先住民である ADLを含むいくつかの組織は、ユダヤ人とパレスチナ人の双方をイスラエル/パレスチナの先住民と呼んでいる。[4] 世界先住民研究センターは、ユダヤ人とパレスチナ人の双方をイスラエル/パレスチナの先住民と見なしている。[12] |

| Criticism of indigeneity rhetoric AIJAC, the Australia/Israel & Jewish Affairs Council, has stated that "the claim Palestinians are indigenous in the same way Aboriginal Australians are indigenous is beyond ridiculous" and that "Jews are also not indigenous to the Land of Israel in the same prehistoric way that Aboriginal Australians are to Australia".[13] |

先住民族論への批判 オーストラリア・イスラエル・ユダヤ問題評議会(AIJAC)は「パレスチナ人がオーストラリア先住民と同じ意味で先住民族だという主張は馬鹿げている」 と述べ、「ユダヤ人もまた、オーストラリア先住民がオーストラリアに対して持つような先史時代的な意味で、イスラエルの地に対して先住民族ではない」と主 張している。[13] |

| Indigenous Coalition for Israel Native American–Jewish relations Origin of the Palestinians Zionism as settler colonialism |

イスラエル先住民連合 ネイティブアメリカンとユダヤ人の関係 パレスチナ人の起源 入植者植民地主義としてのシオニズム |

| References 1. "History & Background". United Nations. Retrieved 2025-10-10. 2. "The International Status of the Palestinian People". United Nations. Retrieved 2025-10-10. 3. 5/13 "The Bible's Buried Secrets" - Israelite Origins 4. "Responding to False Claims About Israel". American Jewish Committee. 2 August 2023. Retrieved 2025-10-10. 5. "Allegation: Israel is a Settler Colonialist Enterprise". Anti-Defamation League. Retrieved 2025-10-10. 6. "Indigenous peoples in Palestine". International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. Retrieved 2025-10-10. 7. "Jewish Voice for Peace's Stance on Zionism". Jewish Federation of Greater New Haven. Retrieved 2025-10-10. 8. "J Street says Jews not indigenous to Israel". Arutz Sheva. Retrieved 2025-10-10. 9. "Indigeneity and colonialism not useful metaphors for Israel". New Zealand Jewish Council. Retrieved 2025-10-10. 10. "NAISA Council Statement on Palestine". Native American and Indigenous Studies Association. Retrieved 2025-10-10. 11. "While some Indigenous people rally for Palestinians, others say it's not a struggle against colonialism". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 2025-10-10. 12. "Indigenous Israelis and Palestinians". Center for World Indigenous Studies. 27 September 2014. Retrieved 2025-10-10. 13. "Scribblings: The "Indigenous" Palestinians?". AIJAC. 2 July 2024. Retrieved 2025-10-10. |

参考文献 1. 「歴史と背景」. 国連. 2025年10月10日閲覧. 2. 「パレスチナ人民の国際的地位」. 国連. 2025年10月10日閲覧. 3. 5/13 「聖書に隠された秘密」 - イスラエル人の起源 4. 「イスラエルに関する虚偽の主張への対応」. アメリカ・ユダヤ人委員会。2023年8月2日。2025年10月10日閲覧。 5. 「主張:イスラエルは入植者による植民地主義的事業である」。反誹謗同盟。2025年10月10日閲覧。 6. 「パレスチナの先住民」。国際先住民族問題作業部会。2025年10月10日閲覧。 7. 「平和を求めるユダヤ人の声によるシオニズムへの立場」。グレーター・ニューヘイブン・ユダヤ連盟。2025年10月10日閲覧。 8. 「Jストリートはユダヤ人はイスラエルの先住民ではないと主張」。アルーツ・シェバ。2025年10月10日閲覧。 9. 「イスラエルにとって先住性と植民地主義は有用な隠喩ではない」 ニュージーランド・ユダヤ人評議会。2025年10月10日閲覧。 10. 「パレスチナに関するNAISA評議会声明」。ネイティブアメリカン・先住民研究協会。2025年10月10日閲覧。 11. 「一部の先住民はパレスチナ人を支持するが、他者は植民地主義との闘いではないと主張」。カナダ放送協会。2025年10月10日閲覧。 12. 「イスラエルとパレスチナの先住民」. 世界先住民研究センター. 2014年9月27日. 2025年10月10日閲覧. 13. 「雑記:『先住民』パレスチナ人?」. AIJAC. 2024年7月2日. 2025年10月10日閲覧. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indigeneity_in_the_Israeli-Palestinian_conflict |

★

| Zionism has been

described by its founders and early leaders, as well as by several

scholars, as a form of settler colonialism in relation to the region of

Palestine and the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Zionism's founders and early leaders were aware and unapologetic about their status as colonizers. Many early leading Zionists such as Theodor Herzl, Max Nordau, and Ze'ev Jabotinsky described Zionism as colonization. The paradigm of settler colonialism was also later applied to Zionism by various scholars and figures, including Patrick Wolfe, Edward Said, Fayez Sayegh and Maxime Rodinson. The settler colonial framework on the conflict emerged in the 1960s during the decolonization of Africa and the Middle East, and re-emerged in Israeli academia in the 1990s led by Israeli and Palestinian scholars, particularly the New Historians, who refuted some of Israel's foundational myths and considered the Nakba to be ongoing. This perspective contends that Zionism involves processes of elimination and assimilation of Palestinians, akin to other settler colonial contexts similar to the creation of the United States and Australia. Critics of the characterization of Zionism as settler colonialism, such as Benny Morris, Yuval Shany and Ilan Troen, argue that it does not fit traditional colonial frameworks, seeing Zionism instead as the repatriation of an indigenous population and an act of self-determination. This debate reflects broader tensions over competing historical and political narratives regarding the founding of the State of Israel and the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.  A graph by Neve Gordon showing the population shift from 1947 to 1951 in Israel–Palestine, plotted with the % of land controlled by what he calls the "Jewish establishment". |

シオニズムは、その創設者や初期指導者、そして複数の学者によって、パ

レスチナ地域とイスラエル・パレスチナ紛争に関して、入植者による植民地主義の一形態と説明されてきた。 シオニズムの創設者や初期指導者たちは、自分たちが植民地化者であるという立場を認識し、それを詫びることもなかった。テオドール・ヘルツル、マックス・ ノルダウ、ゼエヴ・ジャボティンスキーといった初期の主要なシオニストの多くは、シオニズムを植民地化と表現した。入植者植民地主義のパラダイムは、後に パトリック・ウルフ、エドワード・サイード、ファイエズ・サイエグ、マキシム・ロディンソンといった様々な学者や人物によってシオニズムにも適用された。 この紛争に対する入植者植民地主義の枠組みは、1960年代のアフリカと中東の脱植民地化期に現れ、1990年代にはイスラエルとパレスチナの学者、特に 「新歴史家」たちによってイスラエルの学界で再浮上した。彼らはイスラエルの建国神話の一部を否定し、ナクバ(大災難)が現在も続いていると考えた。この 視点は、シオニズムがパレスチナ人の排除と同化プロセスを伴うものであり、アメリカやオーストラリアの建国に類似した他の入植者植民地主義の文脈と同様で あると主張する。 ベンニー・モリス、ユヴァル・シャニ、イラン・トロエンら、シオニズムを植民地主義と規定する見解への批判者は、シオニズムは伝統的な植民地主義の枠組み には当てはまらず、むしろ先住民族の帰還と自己決定の行為であると主張する。この議論は、イスラエル国家の建国とイスラエル・パレスチナ紛争に関する対立 する歴史的・政治的解釈をめぐる、より広範な緊張関係を反映している。  ネヴェ・ゴードンによるグラフは、1947年から1951年にかけてのイスラエル・パレスチナにおける人口変動を示している。これは彼が「ユダヤ人支配層」と呼ぶ勢力が支配する土地の割合でプロットされている。 |

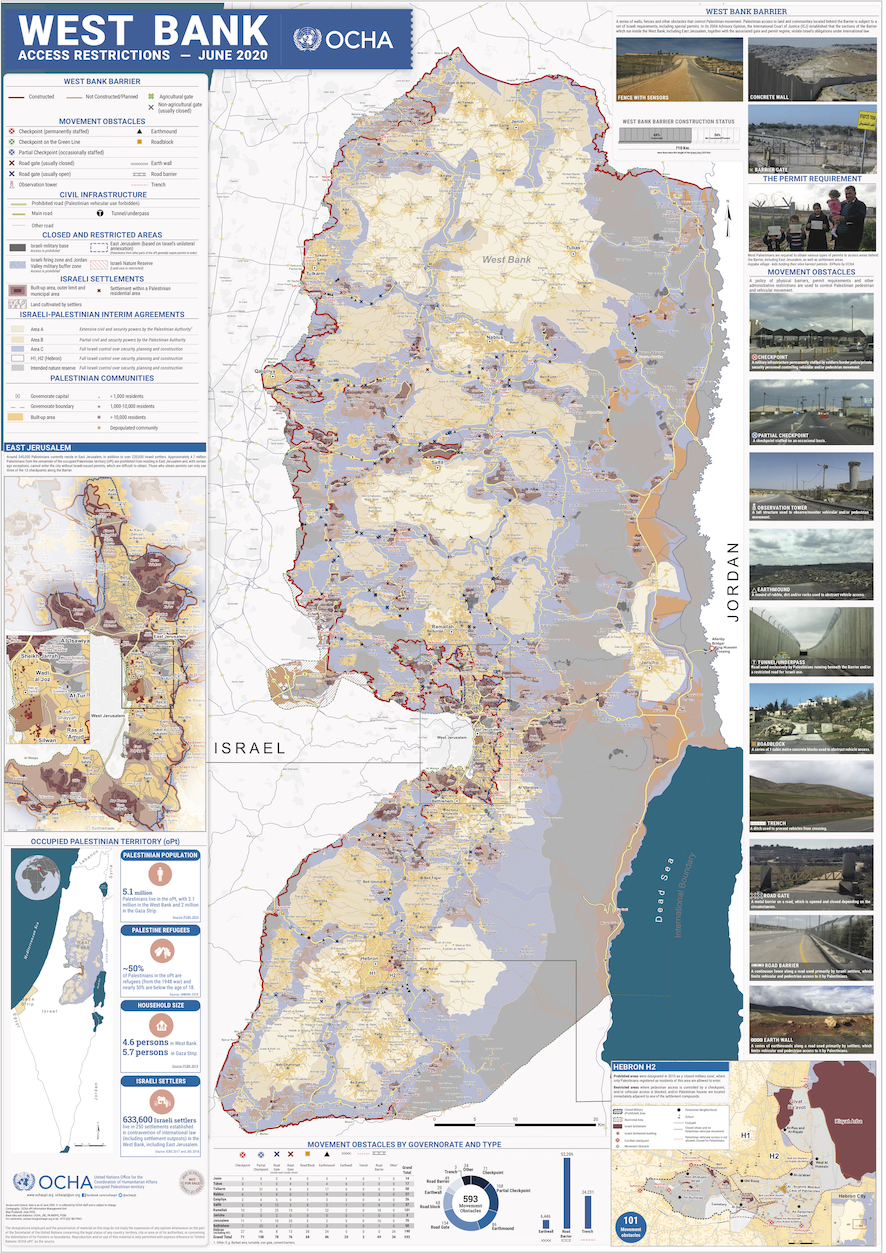

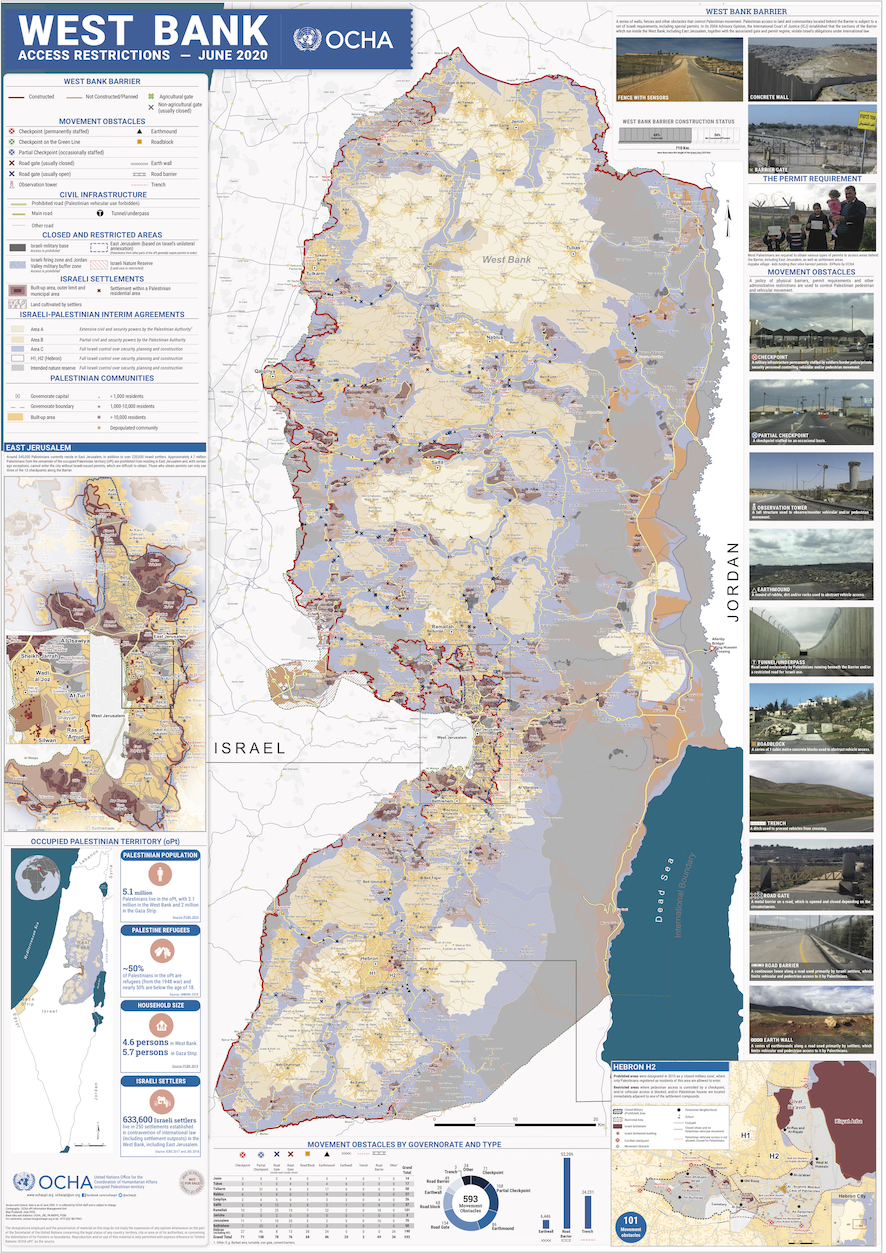

Concepts Map of Israeli settlements (magenta) in the occupied West Bank in 2020 Main article: Settler colonialism In Patrick Wolfe's model, in settler colonialism - in contrast to classical colonialism - the focus is on eliminating, rather than exploiting, the original inhabitants of a territory.[1] As theorized by Wolfe, settler colonialism is an ongoing "structure, not an event" aimed at replacing a native population.[2][3][4] Settler colonialism operates by processes including physical elimination of native inhabitants but also can encompass projects of assimilation, segregation, miscegenation, religious conversion, and incarceration.[5] Commentators, such as Daiva Stasiulis, Nira Yuval-Davis, and Joseph Massad have included Israel in their global analysis of settler societies.[6][7][8] Ancient Israel has also been analyzed as a case of settler colonialism.[9] |

概念 2020年時点の占領下ヨルダン川西岸地区におけるイスラエル入植地(マゼンタ色)の地図 主な記事: 入植者植民地主義 パトリック・ウルフのモデルによれば、入植者植民地主義は古典的植民地主義とは対照的に、領土の先住民を搾取するのではなく排除することに焦点を当てる。 [1] ウルフが理論化したように、入植者植民地主義は、先住民を置き換えることを目的とした、継続的な「出来事ではなく構造」である。[2][3][4] 入植者植民地主義は、先住民を物理的に排除するプロセスによって機能するが、同化、隔離、異人種間結婚、宗教的改宗、投獄などのプロジェクトも包含するこ とができる。[5] ダイヴァ・スタシウリス、ニラ・ユヴァル=デイヴィス、ジョセフ・マサドなどの評論家は、入植者社会に関する世界的な分析にイスラエルを含めている。 [6][7][8] 古代イスラエルも入植者植民地主義の事例として分析されている。[9] |

| Background Many of the fathers of Zionism themselves described it as colonisation, such as Vladimir Jabotinsky who said "Zionism is a colonization adventure".[10][11][12] Theodore Herzl, in a 1902 letter to Cecil Rhodes, described the Zionist project as "something colonial". Previously in 1896 he had spoken of "important experiments in colonization" happening in Palestine.[13][14][15] Max Nordau[16] in 1905 said, "Zionism rejects on principle all colonization on a small scale, and the idea of 'sneaking' into Palestine".[17] Major Zionist organizations central to Israel's foundation held colonial identity in their names or departments, such as Jewish Colonisation Association, the Jewish Colonial Trust, and The Jewish Agency's colonization department.[18][19] In 1905, some Jewish immigrants to the region promoted the idea of Hebrew labor, arguing that all Jewish-owned businesses should only employ Jews, to displace Arab workforce hired by the First Aliyah.[20] Zionist organizations acquired land under the restriction that it could never pass into non-Jewish ownership.[21] Later on, kibbutzim—collectivist, all-Jewish agricultural settlements—were developed to counter plantation economies relying on Jewish owners and Palestinian farmers. The kibbutz was also the prototype of Jewish-only settlements later established beyond Israel's pre-1967 borders.[21] In 1948, 750,000 Palestinians fled or were forcibly displaced from the area that became Israel, and 500 Palestinian villages, as well as Palestinian-inhabited urban areas, were destroyed.[22][23] Although considered by some Israelis to be a "brutal twist of fate, unexpected, undesired, unconsidered by the early [Zionist] pioneers", some historians have described the Nakba as a campaign of ethnic cleansing.[22] In the aftermath of the Nakba, Palestinian land was expropriated on a large scale and Palestinian citizens of Israel were encircled in specific areas.[24][25] In a 1956 speech, Israeli Chief of Staff Moshe Dayan stated in regards to Palestinian political violence: "Who are we that we should argue against their hatred? For eight years now, they sit in their refugee camps in Gaza and, before their very eyes we turn into our homestead the land and the villages in which they and their forefathers have lived. We are a generation of settlers, and without the steel helmet and the cannon we cannot plant a tree and build a home."[26][27] Arnon Degani argues that ending military rule over Israel's Palestinian citizens in 1966 shifted from colonial to settler-colonial governance.[28] After the Israeli capture of the Golan Heights in 1967, there was a nearly complete ethnic cleansing of the area, leaving only 6,404 Syrians out of about 128,000 who had lived there before the war. They had been forced out by campaigns of intimidation and forced removal, and those who tried to return were deported. After the Israeli capture of the West Bank, about 250,000 of 850,000 inhabitants fled or were expelled.[29] |

背景 シオニズムの創始者たちの多くは、自らそれを植民地化と表現した。例えばウラジーミル・ジャボティンスキーは「シオニズムは植民地化の冒険である」と述べ た。[10][11][12] テオドール・ヘルツルは1902年にセシル・ローズへの手紙で、シオニズム計画を「植民地的なもの」と表現した。それ以前の1896年には、パレスチナで 「重要な植民地化実験」が行われていると語っていた[13][14][15]。マックス・ノルダウ[16]は1905年に「シオニズムは小規模な植民地化 やパレスチナへの『潜入』という考えを原則的に拒否する」と述べた。[17] イスラエル建国の中核となった主要なシオニスト組織は、その名称や部門名に植民地主義的アイデンティティを保持していた。例えばユダヤ植民協会、ユダヤ植 民信託、ユダヤ機関の植民地化部門などである。[18][19] 1905年、この地域に移住した一部のユダヤ人はヘブライ労働の理念を推進し、ユダヤ人所有の企業は全てユダヤ人だけを雇用すべきだと主張した。これは第 一次アリヤーによって雇われたアラブ人労働力を置き換えるためであった。[20] シオニスト組織は、土地が非ユダヤ人の所有権に移転しないという制限付きで土地を取得した。[21] その後、ユダヤ人所有者とパレスチナ人農民に依存するプランテーション経済に対抗するため、集団主義的なユダヤ人だけの農業集落であるキブツが開発され た。キブツはまた、1967年以前のイスラエル国境の外に後に設立されたユダヤ人専用入植地の原型でもあった。[21] 1948年、75万人のパレスチナ人がイスラエルとなる地域から逃亡もしくは強制的に追放され、500のパレスチナ人村落およびパレスチナ人が居住する都 市部が破壊された。[22][23] 一部のイスラエル人からは「初期の[シオニスト]開拓者たちが予期せず、望まず、考慮もしていなかった残酷な運命の悪戯」と見なされることもあるが、一部 の歴史家はナクバを民族浄化の作戦と表現している。[22] ナクバの後、パレスチナ人の土地は大規模に収用され、イスラエルのパレスチナ人市民は特定の地域に囲い込まれた。[24] [25] 1956年の演説で、イスラエル軍の参謀総長モシェ・ダヤンはパレスチナ人の政治的暴力についてこう述べた。「我々など何者か。彼らの憎しみに異議を唱え る資格があろうか? 8年間、彼らはガザの難民キャンプに居座り、我々が彼らの目の前で、彼らとその祖先が暮らした土地や村々を我が家へと変えていくのを見ているのだ。我々は 開拓者の世代だ。鋼鉄のヘルメットと大砲なしでは、木を植えたり家を建てたりすることすらできないのだ。」[26] [27] アルノン・デガニは、1966年にイスラエルのパレスチナ人市民に対する軍事統治が終了したことで、統治形態が植民地支配から入植者植民地支配へと移行し たと論じている。[28] 1967年にイスラエルがゴラン高原を占領した後、同地域ではほぼ完全な民族浄化が行われ、戦前に約12万8千人が住んでいたシリア人のうち、わずか 6,404人だけが残り、残りは追放された。彼らは脅迫と強制移住作戦によって追い出され、帰還を試みた者は国外退去処分を受けた。イスラエルによるヨル ダン川西岸占領後、85万人の住民のうち約25万人が逃亡または追放された。[29] |

| Scholarly development [icon] This section needs expansion with: For proponents, please add specific quotes, works, and framings from relevant scholars. You can help by making an edit request. (July 2024) The settler colonial framework on the Palestinian struggle emerged in the 1960s during the decolonization of Africa and the Middle East, and re-emerged in Israeli academia in the 1990s led by Israeli and Palestinian scholars, particularly the New Historians, who refuted some of Israel's foundational myths and considered the Nakba to be ongoing.[15][30][31] This coincided with a shift from supporting a two-state solution to a one-state solution that constitutes a state for all citizens equally, which challenges the Jewish identity of Israel.[15] Proponents of the paradigm of Zionism as settler colonialism include Edward Said, Rashid Khalidi, Noam Chomsky, Ilan Pappé, Fayez Sayegh, Maxime Rodinson, George Jabbour [ar], Ibrahim Abu-Lughod, Baha Abu-Laban, Jamil Hilal [ar], Rosemary Sayigh, Amal Jamal and Ismail Raji al-Faruqi.[32][33][34][35][page needed] |

学術的発展 [icon] この節は拡充が必要である:支持論者については、関連する学者による具体的な引用、著作、枠組みを追加すること。編集依頼を行うことで貢献できる。(2024年7月) パレスチナ闘争に関する入植者植民地主義の枠組みは、1960年代のアフリカ・中東脱植民地化期に現れ、1990年代にイスラエルとパレスチナの学者、特 に新歴史家たちによってイスラエル学界で再浮上した。彼らはイスラエルの建国神話のいくつかを否定し、ナクバ(大災難)が現在も継続中であると見なした。 [15][30][31] これは、二国家解決案の支持から、全ての市民が平等に構成員となる単一国家解決案への転換と時期を同じくした。これはイスラエルのユダヤ的アイデンティ ティに疑問を投げかけるものである。[15] シオニズムを植民地主義と見なすパラダイムの支持者には、エドワード・サイード、ラシード・ハリディ、ノーム・チョムスキー、イラン・パッペ、ファイエ ズ・サイエグ、マキシム・ロディンソン、ジョージ・ジャブール[ar]、イブラヒム・アブ・ルゴド、バハ・アブ・ラバン、ジャミール・ヒラル[ar]、 ローズマリー・サイグ、アマル・ジャマル、イスマイル・ラジ・アル=ファルキらが含まれる。[32][33][34][35][ページ番号が必要] |

| 1960s One early analysis was that of Palestinian writer Fayez Sayegh in his 1965 essay "Zionist Colonialism in Palestine", which was unusual for the pre-1967 era in specifying Zionism as a form of settler colonialism.[36][37] Sayegh later drafted the UN's "Zionism is racism" resolution.[37] After Israel assumed control of the whole Mandatory Palestine in 1967, settler-colonial analyses became prominent among Palestinians.[38] Sayegh argues that Zionists originally formed a "settler-community" during the first fifteen years of Zionist colonization (1882-1897) before fulfilling what had been their aspiration from the outset: to form a "settler-state" (pp.2-3). For Sayegh, the "special character" of "Zionist colonization" distinguishing it from European colonization was three-fold: (1) the latter was driven "either by economic or by politico-imperialist motives: they had gone either in order to accumulate fortunes by means of privileged and protected exploitation of immense natural resources, or in order to prepare the ground for (or else aid and abet) the annexation of those coveted territories by imperial European governments", whereas Zionism was animated by the desire to attain nationhood; (2) other European settlers could co-exist with natives, but Zionism was incompatible with the continued existence of a native population; (3) other settlers were protected by their imperial metropole, while Zionism was at the mercy not only of local opposition but also Ottoman opposition. This third element, he argued, led the Zionists into alliance with British imperialism (pp.6-9).[39] In 1967, the French historian Maxime Rodinson published Israel: A Colonial Settler-State? (originally published in French). In it, he describes Europe as a whole as the metropole of Israeli settler colonialism.[40] Rodinson had probably read Sayigh’s work as his 1965 booklet had been translated into English and French.[41] |

1960年代 初期の分析の一つは、パレスチナ人作家ファイエズ・サイエグが1965年に発表した論文「パレスチナにおけるシオニスト植民地主義」である。これは 1967年以前の時代において、シオニズムを入植者植民地主義の一形態と特定した点で異例であった。[36][37] サイエグは後に国連の「シオニズムは人種差別である」決議案を起草した。[37] 1967年にイスラエルが委任統治領パレスチナ全域を掌握した後、入植者植民地主義の分析はパレスチナ人の間で顕著になった。[38] サイエグは、シオニストが当初の目標である「入植者国家」の形成に到達する前の15年間(1882-1897年)に、彼らは「入植者共同体」を形成したと 論じている(pp.2-3)。サエグによれば、「シオニスト植民地化」の「特殊性」は欧州植民地化と三つの点で異なる: (1) 後者は「経済的動機か政治的・帝国主義的動機に駆られていた。すなわち、特権的かつ保護された形で膨大な天然資源を搾取して富を蓄積するため、あるいは ヨーロッパ帝国政府によるそれらの領土併合の基盤を整える(もしくはそれを助長する)ために進出していた」のに対し、シオニズムは国家建設への願望によっ て推進されていた。(2) 他のヨーロッパ入植者は先住民と共存できたが、シオニズムは先住民の存続と両立し得なかった;(3) 他の入植者は帝国本国の保護下にあったが、シオニズムは現地の反対勢力だけでなくオスマン帝国の反対にも晒されていた。この第三の要素が、シオニストを英 国帝国主義との同盟へと導いたと彼は論じた(pp.6-9)。[39] 1967年、フランス人歴史家マキシム・ロディンソンは『イスラエル:植民地入植国家か?』(原題フランス語)を出版した。同書で彼は、ヨーロッパ全体を イスラエル入植植民地主義の母国と位置づけている[40]。ロディンソンはおそらくサイイグの著作を読んでいた。彼の1965年の小冊子は英語とフランス 語に翻訳されていたからだ[41]。 |

| 1980–2000 The "colonization perspective" emerged in the scholarship on Israeli history in the 1980s. This was associated with the New Historians movement in Israel, which focused on Israeli-Palestinian relations rather than only Jewish history and was willing to examine Zionist settlement's colonial character.[42] Alongside explicitly settler colonial analysis, other scholars of the 1980s and 1990s, such as Abdo and Yuval-Davis, argued that the "Zionist national project has been predicated on the destruction of the Palestinian one".[42] |

1980年から2000年 「植民地化という視点」は、1980年代のイスラエル史研究で登場した。これは、ユダヤ人の歴史だけでなく、イスラエルとパレスチナの関係に焦点を当て、 シオニストの入植の植民地的な性格を検証しようとした、イスラエルの「新歴史家」運動と関連していた。[42] 明確な入植者植民地主義の分析と並行して、アブドやユヴァル=デイヴィスといった1980年代から1990年代の他の学者たちは、「シオニストの国家建設 プロジェクトは、パレスチナ人の国家建設の破壊を前提としてきた」と主張した。[42] |

| 2000s Al-Faruqi described Zionism as a project aimed at "empty[ing] Palestine of its native inhabitants and to occupy their lands, farms, homes, and all movable properties," further characterizing it as "naked robbery by force of arms; of wanton, indiscriminate slaughter of men, women, and children; [and] of destruction of men's lives and properties."[43] According to the Israeli sociologist Uri Ram, the characterization of Zionism as colonial "is probably as old as the Zionist movement".[42] John Collins states that studies have "definitively established" that "the architects of Zionism were conscious and often unapologetic about their status as colonizers whose right to the land superseded that of Palestine's Arab inhabitants".[44] Other settler colonial projects did not lay out their plans for dispossessing and eliminating the inhabitants in detail and in advance.[45] According to Patrick Wolfe, Israel's settler colonialism manifests in immigration policies that promote unlimited immigration of Jews while denying family reunification for Palestinian citizens. Wolfe adds, "Despite Zionism's chronic addiction to territorial expansion, Israel's borders do not preclude the option of removal [of Palestinians] (in this connection, it is hardly surprising that a nation that has driven so many of its original inhabitants into the sand should express an abiding fear of itself being driven into the sea)."[46] Hussein Ibish argues that such zero-sum calls are "a gift that no occupying power and no colonizing settler movement deserves."[47] The peer-reviewed journal Settler Colonial Societies has published three special issues focused on Israel/Palestine.[48][49][clarification needed] Its editor Lorenzo Veracini, who describes Israel as a colonial state, states that Jewish settlers could only expel the British in 1948 because they had their own colonial relationships inside and outside Israel's new borders.[50] He suggests, however, that the possibility of an Israeli disengagement is always latent and that this colonial relationship could be severed if a one-state solution is reached which includes the "accommodation of a Palestinian Israeli autonomy within the institutions of the Israeli state".[51] Scholar Amal Jamal, of Tel Aviv University, has described Israel as the result of "a settler-colonial movement of Jewish immigrants", stating that Israel has continued to strengthen "exclusive Jewish control" of the land and its resources, while diminishing Palestinian rights and denying Palestinian self-determination.[52] According to Israeli academics Neve Gordon and Moriel Ram, the incompleteness versus completeness of ethnic cleansing in the territory occupied by Israel has affected the different forms that Israeli settler colonialism has taken in the West Bank versus the Golan Heights. For example, the few remaining Syrian Druze were offered Israeli citizenship in order to further the annexation of the area, while there was never an intention to incorporate West Bank Palestinians into the Israeli demos. Another example is the dual legal structure in the West Bank compared to the unitary Israeli law imposed in the Golan Heights.[53] |

2000年代 アル・ファルキは、シオニズムを「パレスチナの先住民を追い出し、彼らの土地、農場、家、そしてすべての動産を占領する」ことを目的とした計画と表現し、 さらに「武器による露骨な強奪、男性、女性、子供たちに対する無差別で無差別な虐殺、そして人々の生命と財産の破壊」と特徴づけた[43]。 イスラエルの社会学者ウリ・ラムによれば、シオニズムを植民地主義と特徴づける見解は「おそらくシオニズム運動と同じくらい古い」ものである[42]。 ジョン・コリンズは、研究によって「シオニズムの設計者たちは、パレスチナのアラブ住民よりも土地に対する権利が優先される植民者としての自らの立場を認 識しており、しばしばそれをまったく恥じていなかった」ことが「決定的に立証された」と述べている。[44] 他の入植者による植民地化プロジェクトは、住民を追い出し、排除する計画を事前に詳細に策定することはなかった。[45] パトリック・ウルフによれば、イスラエルの入植者による植民地主義は、ユダヤ人の無制限の移民を促進する一方で、パレスチナ人市民の家族再統合を否定する 移民政策に表れている。ウルフはさらにこう付け加える。「シオニズムが領土拡張に慢性的に依存しているにもかかわらず、イスラエルの国境は(パレスチナ人 の)排除という選択肢を排除していない(この点に関して、これほど多くの元住民を砂漠へ追いやった国家が、自らも海へ追いやられることへの根強い恐怖を表 明するのは、まったく驚くに当たらない)。」[46] フセイン・イビシュは、こうしたゼロサム的な要求は「いかなる占領勢力も、いかなる入植者による植民地化運動も受けるに値しない贈り物だ」と論じている。[47] 査読付き学術誌『Settler Colonial Societies』はイスラエル/パレスチナに焦点を当てた特集号を三回刊行している[48][49][説明が必要]。編集者ロレンツォ・ヴェラチーニ はイスラエルを植民地国家と位置付け、ユダヤ人入植者が1948年に英国を追放できたのは、彼らがイスラエル新国境の内外で独自の植民地関係を構築してい たからだと述べている。[50] しかし彼は、イスラエルの離脱可能性は常に潜在しており、単一国家解決が達成されればこの植民地関係は断ち切られる可能性があると示唆している。その解決 には「イスラエル国家の制度内におけるパレスチナ系イスラエル人の自治の受け入れ」が含まれる。[51] テルアビブ大学のアマル・ジャマル教授は、イスラエルを「ユダヤ人移民による入植者植民地運動」の結果と位置付け、同国が土地と資源に対する「排他的なユ ダヤ人支配」を強化し続ける一方で、パレスチナ人の権利を縮小し、パレスチナ人の自己決定権を否定し続けていると述べている。[52] イスラエル人学者ネヴェ・ゴードンとモリエル・ラムによれば、イスラエル占領地域における民族浄化の「不完全性」と「完全性」の差異が、ヨルダン川西岸地 区とゴラン高原でイスラエル入植者植民地主義が取る形態の違いに影響を与えている。例えば、同地域併合を推進するため、残存する少数のシリア系ドルーズ教 徒にはイスラエル国籍が提供された。一方、ヨルダン川西岸地区のパレスチナ人をイスラエル国民(デモス)に組み入れる意図は全くなかった。別の例として、 ヨルダン川西岸地区における二重の法体系が挙げられる。これはゴラン高原に適用される単一のイスラエル法とは対照的である。[53] |

| 2010s–2020s Salamanca et al. state that Israeli practices have often been studied as distinct but related phenomena, and that the settler-colonial paradigm is an opportunity to understand them together. As examples of settler colonial phenomena they include "aerial and maritime bombardment, massacre and invasion, home demolitions, land theft, identity card confiscation, racist laws and loyalty tests, the wall, the siege on Gaza, cultural appropriation, dependence on willing (or unwilling) native collaboration regarding security arrangements".[54] Anthropologist Anne de Jong says that early Zionists promoted a narrative of binary conflict between two competing groups with equally valid claims in order to deflect criticisms of settler colonialism.[55] In 2013, historian Lorenzo Veracini argued that settler colonialism has been successful in Israel proper but unsuccessful in the territories occupied in 1967.[56] Historian Rashid Khalidi argues that all other settler-colonial wars in the twentieth century ended in defeat for colonists, making Palestine an exception: "Israel has been extremely successful in forcibly establishing itself as a colonial reality in a post-colonial age".[57] Although settler colonialism is an empirical framework, it is associated with favoring a one-state solution.[58] Rachel Busbridge argues that settler colonialism is "a coherent and legible frame" and "a far more accurate portrayal of the conflict than the picture of Palestinian criminality and Israeli victimhood that has conventionally been painted".[59] She also argues that settler colonial analysis is limited, especially when it comes to the question of decolonization.[60] Historian Nur Masalha says, "The Palestinians share common experiences with other indigenous peoples who have had their narrative denied, their material culture destroyed and their histories erased or reinvented by European white settlers and colonisers."[61] This paradigm has gained significant traction among left-leaning activists at universities.[62][63][64] Palestinian-American historian Rashid Khalidi states that settler-colonial projects are usually "extensions of the people and of the sovereignty of the mother country", whereas Zionism is an independent "national movement" whose means were nevertheless "explicitly settler-colonial".[65][66] Elia Zureik's Israel's Colonial Project in Palestine: Brutal Pursuit, updates his earlier work on colonialism and Palestine and applies Michel Foucault's work on biopolitics to colonialism, arguing that racism plays a central role and that surveillance becomes a tool of governance. It also analyses the dispossession of indigenous people and population transfer, including sociological, historical and postcolonial studies into an examination of the Zionist project in Palestine.[67] Sánchez and Pita argue that Israeli settler colonialism has had far more severe effects on the indigenous Palestinian population than the discriminations suffered by the Spanish and Mexican populations in the Southwest of the United States in the wake of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo which ended the Mexican–American War.[68] Most scholars who have addressed Israeli settler colonialism have not discussed the Golan Heights.[53] Sociologist Areej Sabbagh-Khoury suggests that "in tracing the settler colonial paradigm ... Israeli critical sociology, albeit groundbreaking, has suffered from a myopia engendered through hegemony."[69] She states that "until recently, most Israeli academics engaged in discussing the nature of the state ignored its settler colonial components", and that scholarship conducted "within a settler colonial framework" has not been given serious attention in Israeli critical academia, "perhaps due to the general disavowal of the colonial framework among Israeli scholars."[69] Hebrew graffiti spray-painted on a home in a-Sawiyah, Nablus District by Zionist settlers in 2018 reads "Kill or deport." |

2010年代–2020年代 サラマンカらは、イスラエルの行為はしばしば別個だが関連する現象として研究されてきたと述べ、入植者植民地主義のパラダイムがそれらを一体として理解す る機会だと指摘する。入植者植民地主義的現象の例として、彼らは「空爆と海上爆撃、虐殺と侵略、家屋破壊、土地強奪、身分証明書没収、人種差別的法律と忠 誠心テスト、分離壁、ガザ包囲、文化的収奪、治安対策における自発的(あるいは非自発的)な現地協力への依存」を挙げている。[54] 人類学者アン・デ・ジョンは、初期シオニストが植民地主義への批判をかわすため、同等に正当な主張を持つ二つの対立集団間の二項対立という物語を推進した と述べる。[55] 2013年、歴史家ロレンツォ・ヴェラチーニは、入植者植民地主義はイスラエル本国では成功したが、1967年に占領した地域では失敗したと論じた。 [56] 歴史家ラシード・ハリディは、20世紀の他の全ての入植者植民地戦争は植民者側の敗北で終わったと指摘し、パレスチナが例外であると主張する。「イスラエ ルは、ポスト植民地時代において、自らを植民地的現実として強制的に確立することに極めて成功した」。[57] 入植者植民地主義は経験的枠組みであるが、一国家解決案を支持する傾向と結びついている。[58] レイチェル・バスブリッジは、入植者植民地主義が「首尾一貫した明瞭な枠組み」であり、「従来描かれてきたパレスチナ人の犯罪性とイスラエルの被害者像よ りも、紛争をはるかに正確に描写するもの」だと論じている。[59] 彼女はまた、入植者植民地主義分析には限界があると主張する。特に脱植民地化の問題に関してはそうだ。[60] 歴史家ヌール・マサルハは言う。「パレスチナ人は、自らの物語を否定され、物質文化を破壊され、歴史を消し去られたり改竄されたりした他の先住民族と共通 の経験を持つ。その加害者はヨーロッパの白人入植者および植民地支配者である。」[61] このパラダイムは大学内の左派系活動家の間で大きな支持を得ている。[62][63][64] パレスチナ系アメリカ人歴史家ラシード・ハリディは、入植者植民地主義プロジェクトは通常「母国の国民と主権の延長」であるのに対し、シオニズムは独立し た「国民運動」でありながら、その手段は「明らかに植民地主義的」であったと述べている。[65][66] エリア・ズレイクの『パレスチナにおけるイスラエルの植民地化プロジェクト:残忍な追求』は、植民地主義とパレスチナに関する彼の以前の研究を更新し、ミ シェル・フーコーの生命政治に関する研究を植民地主義に適用し、人種差別が中心的な役割を果たし、監視が統治の手段になると主張している。また、パレスチ ナにおけるシオニズムのプロジェクトを検証するために、社会学的、歴史的、ポストコロニアル研究を含む、先住民族の収奪と人口移動を分析している。 [67] サンチェスとピタは、イスラエルの入植者による植民地主義は、米墨戦争を終結させたグアダルーペ・イダルゴ条約の締結後に米国南西部でスペイン系およびメ キシコ系住民が被った差別よりも、パレスチナ先住民に対してはるかに深刻な影響を与えたと主張している。[68] イスラエルの入植者による植民地主義について論じた学者のほとんどは、ゴラン高原については論じていない。[53] 社会学者アリー・サバ・クーリーは、「入植者植民地主義のパラダイムを追跡する上で... イスラエルの批判社会学は、画期的であるにもかかわらず、覇権によって生み出された近視眼に悩まされてきた」と示唆している。[69] 彼女は「最近まで、国家の本質を論じるイスラエルの学者の大半はその入植者植民地主義的要素を無視してきた」と述べ、また「入植者植民地主義の枠組みの中 で」行われた研究は、イスラエルの批判的学界において真剣な注目を払われてこなかったと指摘する。その理由は「おそらくイスラエルの学者たちの間で植民地 主義的枠組みが一般的に否定されてきたためである」と。[69] 2018年、[ヨルダン川西岸]ナブラス地区ア・サウィヤの住宅にシオニスト入植者がスプレーで落書きしたヘブライ語は「殺すか追放せよ」と記されている。 |

| Critiques of the framework Scholarly Rejections German philosopher Ingo Elbe argues that applying the settler colonialism paradigm to Zionism "leads to a lack of sensitivity for the specific nature of Zionism" by reducing it to a form of white settler colonialism.[70] He notes that such critiques often ignore key historical realities: that Jews "have always resided in the area that was named 'Palestine' by the Romans," that they maintained "a special cultural connection to Eretz Israel," and that Zionism's "civilizing mission... was primarily directed at the Jewish people itself." Elbe emphasizes that European Jews did not migrate from a colonial metropole but were "looking for a safe haven from their systematic antisemitic marginalization and eventual extermination," while Jews from Arab countries also fled persecution.[70] Israeli historian S. Ilan Troen suggests that Zionism was the repatriation of a long displaced indigenous population to their historic homeland, and that Zionism does not fit the framework of a settler society as it "was not part of the process of imperial expansion in search of power and markets".[71] With his wife Carol Troen, a former applied linguist at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Troen writes that the concept of Palestinian indigeneity is a recent addition to the "linguistic arsenal of lawfare" used to deny Israel's legitimacy. They suggest this frames Israel as inherently settler colonial and as "reprehensible in its exploitation of the indigenous".[72] Some critics highlight ideas such as the putative non-exploitation of indigenous labor by Zionists as a reason not to consider it a colonial movement.[73] Historian Benny Morris suggests that Zionism does not meet the definition of colonialism since it did not involve "an imperial power acquiring political control over another country, settling it with its sons, and exploiting it economically".[74][better source needed] Historian Tom Segev states that "colonialism is irrelevant to the Zionist experience" because most Jewish immigrants came as refugees, and Zionists did not seek to "dominate the local population".[62] Journalist Roger Cohen and law scholar Yuval Shany, describe the Israeli–Palestinian conflict as one between two indigenous groups.[63][undue weight? – discuss] Shany argues that labelling Israel's establishment as a colonial enterprise is "a significant category error".[63] He says that Israel cannot be considered colonialist because it was not an "imposed power" and its creation "was endorsed by the United Nations". Cohen states that Israel's "very diverse, multihued society" includes many Jews who fled persecution in the Middle East and Europe, and who had no metropole they could flee to, unlike most settler colonial societies.[63] Some scholars have stated the lack of an imperial power to benefit from exploiting the region, means a colonial paradigm does not apply.[74] Other scholars have stated that Israel's external supporters, either private organizations or various states (such as the United Kingdom, France, Germany,[75] Australia,[23] or the United States), may function as a metropole (defined as the homeland of a colonial empire).[73] |

枠組みへの批判 学術的反論 ドイツの哲学者インゴ・エルベは、シオニズムに植民地主義のパラダイムを適用することは、それを白人入植者植民地主義の一形態に還元することで「シオニズ ムの特異性に対する感受性の欠如を招く」と論じている。[70] 彼は、こうした批判がしばしば重要な歴史的現実を無視していると指摘する。すなわち、ユダヤ人は「ローマ人によって『パレスチナ』と名付けられた地域に常 に居住していた」こと、彼らが「エレツ・イスラエル(聖地)との特別な文化的結びつき」を維持していたこと、そしてシオニズムの「文明化使命...は主に ユダヤ民族自身に向けられていた」ことである。エルベは、ヨーロッパのユダヤ人が植民地支配母国から移住したのではなく、「組織的な反ユダヤ主義による疎 外と最終的な絶滅から逃れる安全な避難所を求めていた」と強調する。またアラブ諸国出身のユダヤ人も迫害から逃れてきたのである。[70] イスラエルの歴史家S・イラン・トロエンは、シオニズムは長く追放された先住民族の歴史的故郷への帰還であり、「権力と市場を求める帝国的拡張のプロセス の一部ではなかった」ため、入植者社会の枠組みには当てはまらないと示唆している。[71] トロエンは妻のキャロル・トロエン(元ネゲヴ・ベン=グリオン大学応用言語学者)と共に、パレスチナ先住性という概念はイスラエルの正当性を否定するため に用いられる「法廷戦術の言語的武器庫」への近年の追加要素だと記している。彼らはこれがイスラエルを本質的に入植者植民地主義的であり、「先住民の搾取 において非難に値する」ものとして位置づけると示唆している。[72] 一部の批判者は、シオニストによる先住民労働力の搾取がなかったとされる点などを根拠に、これを植民地運動と見なすべきでないとする。[73] 歴史家ベニー・モリスは、シオニズムは「帝国主義的権力が他国を政治的に支配し、自国民を移住させ、経済的に搾取する」という植民地主義の定義に該当しな いと指摘する。[74][より良い出典が必要] 歴史家トム・セゲフは「植民地主義はシオニズムの経験とは無関係だ」と述べている。その理由は、ユダヤ人移民の大半が難民として来訪したこと、またシオニ ストが「現地住民を支配しようとはしなかった」ことにある。[62] ジャーナリストのロジャー・コーエンと法学者のユバル・シャニは、イスラエル・パレスチナ紛争を二つの先住民族間の対立と描写している。[63][過度な 強調? – 議論] シャニは、イスラエル建国を植民地事業とレッテル貼ることは「重大なカテゴリー誤り」だと主張する。[63] 彼は、イスラエルは「強制された権力」ではなく、その建国が「国連によって承認された」ため、植民地主義とは見なせないと言う。コーエンは、イスラエルの 「非常に多様で多色的な社会」には、中東やヨーロッパでの迫害から逃れた多くのユダヤ人が含まれており、彼らはほとんどの入植者植民地社会とは異なり、逃 れることのできる母国を持たなかったと述べている。[63] 一部の学者は、地域搾取の利益を得る帝国主義勢力が存在しないため、植民地主義の枠組みは適用されないと主張している。[74] 他の学者は、イスラエルの外部支援者(民間組織や英国、フランス、ドイツ[75]、オーストラリア[23]、米国などの国家)が、植民地帝国の母国と定義 される「母国」として機能し得ると述べている。[73] |

| Reception among Jews and Israelis The portrayal of Zionism as settler colonialism is strongly rejected by most Zionists and Israeli Jews, and is perceived either as an attack on the legitimacy of Israel, a form of antisemitism, or historically inaccurate.[76][71][77] |

ユダヤ人とイスラエル人における受容 シオニズムを植民地主義として描く見解は、大多数のシオニストやイスラエル人ユダヤ人によって強く拒否されている。これはイスラエルの正当性への攻撃、反ユダヤ主義の一形態、あるいは歴史的に不正確であると見なされている。[76][71][77] |

| Activistic use According to The Economist, the Palestinian diaspora has sought to reframe the Israeli-Palestinian conflict from "a clash between two national movements" to "a generational liberation struggle against 'settler colonialism'".[78] This paradigm has gained significant traction among left-leaning activists at universities.[62][63][64] Sociology professor Jeffrey C. Alexander refers to colonialism as "the go-to term for total pollution" of Israel's legitimacy.[63] According to scholar Bernard D. Goldstein, "The accusation of 'settler colonialism' is increasingly used to attack Israel and justify its destruction."[79] |

活動的な使用 エコノミスト誌によると、パレスチナ人ディアスポラは、イスラエル・パレスチナ紛争を「二つの国民運動間の衝突」から「『入植者による植民地主義』に対す る世代を超えた解放闘争」へと再定義しようとしている[78]。このパラダイムは、大学における左派活動家の間で大きな支持を得ている[62][63]。 [64] 社会学教授のジェフリー・C・アレクサンダーは、植民地主義をイスラエルの正当性を「完全に汚染する」ための「頼りになる用語」と呼んでいる。[63] 学者バーナード・D・ゴールドスタインによれば、「『入植者による植民地主義』という非難は、イスラエルを攻撃し、その破壊を正当化するためにますます多用されている」という。[79] |

| Anabaptist settler colonialism Indigeneity in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict |

「再洗礼派の入植者による植民地主義」は「入植植民地主義」を参照 イスラエル・パレスチナ紛争における先住性 |

| Sources al-Faruqi, Ismail Raji (2003) [1980]. Islam and the Problem of Israel. Kuala Lumpur: The Other Press. ISBN 983954134X. Anonymous (2021). "Palestine Between German Memory Politics and (De-)Colonial Thought". Journal of Genocide Research. 23 (3): 374–382. doi:10.1080/14623528.2020.1847852. S2CID 236962242. Behar, Moshe (2020). "Competing Marxisms, Cessation of (Settler) Colonialism, and the One-state Solution in Israel-Palestine". The Arab and Jewish Questions. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-2315-5299-8. Busbridge, Rachel (2018). "Israel-Palestine and the Settler Colonial 'Turn': From Interpretation to Decolonization". Theory, Culture & Society. 35 (1): 91–115. doi:10.1177/0263276416688544. S2CID 151793639. Collins, John (2011). "A Dream Deterred: Palestine from Total War to Total Peace". In Bateman, Fiona; Pilkington, Lionel (eds.). Studies in Settler Colonialism: Politics, Identity and Culture. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 169–185. doi:10.1057/9780230306288_12. ISBN 978-0-2303-0628-8. Retrieved 16 October 2024. and as subsequent work (Finkelstein 1995; Massad 2005; Pappe 2006; Said 1992; Shafir 1989) has definitively established, the architects of Zionism were conscious and often unapologetic about their status as colonizers Degani, Arnon Yehuda (2015). "The decline and fall of the Israeli Military Government, 1948–1966: a case of settler-colonial consolidation?". Settler Colonial Studies. 5 (1): 84–99. doi:10.1080/2201473X.2014.905236. S2CID 159868363. de Jong, Anne (2018). "Zionist hegemony, the settler colonial conquest of Palestine and the problem with conflict: a critical genealogy of the notion of binary conflict". Settler Colonial Studies. 8 (3): 364–383. doi:10.1080/2201473X.2017.1321171. S2CID 151592376. Gordon, Neve; Ram, Moriel (2016). "Ethnic cleansing and the formation of settler colonial geographies" (PDF). Political Geography. 53: 20–29. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2016.01.010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2022. Jamal, Amal (2017). "Neo-Zionism and Palestine: The Unveiling of Settler-Colonial Practices in Mainstream Zionism". Journal of Holy Land and Palestine Studies. 16 (1): 47–78. doi:10.3366/hlps.2017.0152. ISSN 2054-1988. Masalha, Nur (9 February 2012). The Palestine Nakba: Decolonising History, Narrating the Subaltern, Reclaiming Memory. Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-8481-3970-1. Sabbagh-Khoury, Areej (2022). "Tracing Settler Colonialism: A Genealogy of a Paradigm in the Sociology of Knowledge Production in Israel". Politics & Society. 50 (1): 44–83. doi:10.1177/0032329221999906. S2CID 233635930. Salamanca, Omar Jabary; Qato, Mezna; Rabie, Kareem; Samour, Sobhi (2012). "Past is Present: Settler Colonialism in Palestine". Settler Colonial Studies. 2 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1080/2201473X.2012.10648823. hdl:1854/LU-4141856. ISSN 2201-473X. S2CID 162682469. Sayegh, Fayez (2012). "Zionist Colonialism in Palestine (1965)". Settler Colonial Studies. 2 (1): 206–225. doi:10.1080/2201473X.2012.10648833. hdl:1959.3/357351. S2CID 161123773. Svirsky, Marcelo (2021). "The Reproduction of Settler Colonialism in Palestine". Journal of Perpetrator Research. 4 (1). doi:10.21039/jpr.4.1.79. S2CID 234839359. Sánchez, Rosaura; Pita, Beatrice (December 2014). "Rethinking Settler Colonialism:1848/1948: Two Watershed Moments" (PDF). American Quarterly. 66 (4): 1039–1055. doi:10.1353/aq.2014.0065. S2CID 145691918. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 May 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022. Veracini, Lorenzo (2013). "The Other Shift: Settler Colonialism, Israel, and the Occupation". Journal of Palestine Studies. 42 (2): 26–42. doi:10.1525/jps.2013.42.2.26. hdl:1959.3/316461. Wolfe, Patrick (2006). "Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native". Journal of Genocide Research. 8 (4): 387–409. doi:10.1080/14623520601056240. S2CID 143873621. |

出典 アル=ファルキ、イスマイル・ラジ(2003年)[1980年]。『イスラムとイスラエル問題』。クアラルンプール:ザ・アザー・プレス。ISBN 983954134X。 匿名 (2021). 「ドイツの記憶政治と(脱)植民地主義思想の狭間にあるパレスチナ」. 『ジェノサイド研究ジャーナル』. 23 (3): 374–382. doi:10.1080/14623528.2020.1847852. S2CID 236962242. ベハール、モーシェ(2020)。「競合するマルクス主義、(入植者)植民地主義の終結、そしてイスラエル・パレスチナにおける一国家解決」。『アラブとユダヤの問題』。コロンビア大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-2315-5299-8。 バスブリッジ、レイチェル(2018)。「イスラエル・パレスチナと入植者による植民地化の『転換』:解釈から脱植民地化へ」。『理論、文化、社会』。 35 (1): 91–115. doi:10.1177/0263276416688544. S2CID 151793639. コリンズ、ジョン (2011). 「阻まれた夢:全面戦争から全面平和へのパレスチナ」. フィオナ・ベイトマン、ライオネル・ピルキントン (編). 『入植者植民地主義の研究:政治、アイデンティティ、文化』. ロンドン:パームグレイブ・マクミラン UK. pp. 169–185. doi:10.1057/9780230306288_12。ISBN 978-0-2303-0628-8。2024年10月16日取得。そして、その後の研究(Finkelstein 1995; Massad 2005; Pappe 2006; Said 1992; シャフィール 1989)が明らかにしたように、シオニズムの設計者たちは自らの植民者としての立場を自覚しており、しばしばそれを躊躇なく認めていた。 デガニ、アルノン・イェフダ(2015)。「イスラエル軍事政府の衰退と崩壊、1948–1966:入植者植民地主義の定着事例か?」。『入植者植民地主 義研究』。5 (1): 84–99. doi:10.1080/2201473X.2014.905236. S2CID 159868363. デ・ジョン、アン(2018)。「シオニストの覇権、パレスチナの入植者植民地主義的征服、そして紛争の問題:二項対立的紛争概念の批判的系譜」 . Settler Colonial Studies. 8 (3): 364–383. doi:10.1080/2201473X.2017.1321171. S2CID 151592376. Gordon, Neve; Ram, Moriel (2016). 「民族浄化と入植者植民地地理の形成」 (PDF). 政治地理学. 53: 20–29. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2016.01.010. 2021年5月13日時点のオリジナル (PDF) からアーカイブ. 2022年6月10日閲覧. ジャマル、アマル (2017). 「新シオニズムとパレスチナ:主流シオニズムにおける入植者植民地主義的実践の暴露」. 『聖地とパレスチナ研究ジャーナル』. 16 (1): 47–78. doi:10.3366/hlps.2017.0152. ISSN 2054-1988. マサルハ、ヌール(2012年2月9日)。『パレスチナ・ナクバ:脱植民地化の歴史、被抑圧者の物語、記憶の回復』。ゼッド・ブックス。ISBN 978-1-8481-3970-1。 サバグ=クーリ、アリージ(2022年)。「入植者植民地主義の辿り:イスラエルにおける知識生産の社会学におけるパラダイムの系譜」。『政治と社会』 50巻1号:44–83頁。doi:10.1177/0032329221999906。S2CID 233635930。 サラマンカ、オマル・ジャバリー;カト、メズナ;ラビー、カリーム;サムーア、ソブヒ(2012)。「過去は現在である:パレスチナにおける入植者植民地 主義」。『入植者植民地研究』2巻1号:1–8頁。doi:10.1080/2201473X.2012.10648823。hdl:1854/LU- 4141856. ISSN 2201-473X. S2CID 162682469. サエグ、ファイエズ(2012)。「パレスチナにおけるシオニスト植民地主義(1965年)」。『入植者植民地研究』2巻1号:206–225頁。 doi:10.1080/2201473X.2012.10648833. hdl:1959.3/357351. S2CID 161123773. Svirsky, Marcelo (2021). 「パレスチナにおける入植者植民地主義の再現」. 加害者研究ジャーナル。4 (1)。doi:10.21039/jpr.4.1.79。S2CID 234839359。 サンチェス、ロサウラ、ピタ、ベアトリス(2014年12月)。「入植者植民地主義の再考:1848年/1948年:2つの分水嶺」 (PDF). American Quarterly. 66 (4): 1039–1055. doi:10.1353/aq.2014.0065. S2CID 145691918. 2022年5月17日にオリジナルからアーカイブ (PDF)。2022年4月29日に取得。 ベラチーニ、ロレンツォ (2013). 「もうひとつの転換:入植者植民地主義、イスラエル、そして占領」. 『パレスチナ研究ジャーナル』. 42 (2): 26–42. doi:10.1525/jps.2013.42.2.26. hdl:1959.3/316461. ウルフ、パトリック(2006)。「入植者植民地主義と先住民の排除」。『ジェノサイド研究ジャーナル』。8(4): 387–409。doi:10.1080/14623520601056240。S2CID 143873621。 |

| Further reading Ascone, Laura (2024). "Colonialism Analogies". Decoding Antisemitism. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-49238-9_30. ISBN 978-3-031-49237-2. Barker, Adam J. (2012). "Locating Settler Colonialism". Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History. 13 (3). Johns Hopkins University Press. doi:10.1353/cch.2012.0035. S2CID 162637674. Degani, Arnon (2016). "From Republic to Empire: Israel and the Palestinians after 1948". The Routledge Handbook of the History of Settler Colonialism. Routledge. pp. 353–. ISBN 978-1-1348-2847-0. Hassan, Salah D. (2011). "Displaced Nations: Israeli Settlers and Palestinian Refugees". Studies in Settler Colonialism: Politics, Identity and Culture. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 186–203. ISBN 978-0-2303-0628-8. Kaiser, Max (2022). Jewish Antifascism and the False Promise of Settler Colonialism. Springer International Publishing. ISBN 978-3-0311-0122-9. Khalidi, Rashid (2020). The Hundred Years' War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917–2017. Metropolitan Books. ISBN 978-1-6277-9854-9. Makdisi, Saree (2011). "Zionism Then and Now". Studies in Settler Colonialism: Politics, Identity and Culture. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 237–256. ISBN 978-0-2303-0628-8. Omer, Atalia (2025). "Turning Palestine into a Terra Nullius : On Amalek and "Miracles"". Journal of Genocide Research: 1–22. doi:10.1080/14623528.2025.2504737. Popperl, Simone (2018). "Geologies of Erasure: Sinkholes, Science, and Settler Colonialism at the Dead Sea". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 50 (3): 427–448. doi:10.1017/S002074381800082X. S2CID 165365500. Rouhana, Nadim (22 May 2025). "Mowing the Lawn: Lethal Metaphors in Israeli National Security Culture Pre-7 October". Journal of Genocide Research: 1–22. doi:10.1080/14623528.2025.2506162. Shafir, G. (2018). "From Overt to Veiled Segregation: Israel's Palestinian Arab Citizens in the Galilee". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 50 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1017/S0020743817000915. S2CID 166029058. Strawson (2019). "Colonialism". Israel Studies. 24 (2): 33. doi:10.2979/israelstudies.24.2.03. JSTOR 10.2979/israelstudies.24.2.03. Retrieved 3 August 2025. Todorova, Teodora (2021). Decolonial Solidarity in Palestine-Israel: Settler Colonialism and Resistance from Within. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-7869-9642-8. Wolfe, Patrick (2016). Traces of History: Elementary Structures of Race. Verso Books. ISBN 978-1-7816-8917-2. |

さらに読む アスコネ、ローラ(2024)。「植民地主義の類推」。反ユダヤ主義の解読。シャム:スプリンガー・ネイチャー・スイス。doi:10.1007/978-3-031-49238-9_30。ISBN 978-3-031-49237-2。 バーカー、アダム J. (2012). 「入植者による植民地主義の位置付け」. 『植民地主義と植民地史』. 13 (3). ジョンズ・ホプキンズ大学出版局. doi:10.1353/cch.2012.0035. S2CID 162637674. デガニ、アーノン (2016). 「共和国から帝国へ:1948 年以降のイスラエルとパレスチナ人」. 『入植者植民地主義の歴史に関するラウトレッジ・ハンドブック』. ラウトレッジ. pp. 353–. ISBN 978-1-1348-2847-0. ハッサン、サラ D. (2011). 「追放された国家:イスラエル人入植者とパレスチナ難民」. 『入植者植民地主義の研究:政治、アイデンティティ、文化』. パルグレイブ・マクミラン UK. pp. 186–203. ISBN 978-0-2303-0628-8. カイザー、マックス(2022)。ユダヤ人の反ファシズムと入植者植民地主義の誤った約束。スプリンガー・インターナショナル・パブリッシング。ISBN 978-3-0311-0122-9。 ハリディ、ラシッド(2020)。パレスチナに対する百年戦争:入植者植民地主義と抵抗の歴史、1917年~2017年。メトロポリタン・ブックス刊。ISBN 978-1-6277-9854-9。 マクディシ、サリー(2011)。「シオニズムの過去と現在」。『入植者植民地主義の研究:政治、アイデンティティ、文化』。パルグレイブ・マクミランUK刊。pp. 237–256。ISBN 978-0-2303-0628-8。 オマー、アタリア(2025)。「パレスチナを無主地(テラ・ヌリウス)へ変える:アマレクと『奇跡』について」。『ジェノサイド研究ジャーナル』:1–22頁。doi:10.1080/14623528.2025.2504737。 ポッペル、シモーネ(2018)。「消去の地質学:死海の陥没穴、科学、入植者植民地主義」『国際中東研究ジャーナル』50巻3号:427–448頁。doi:10.1017/S002074381800082X。S2CID 165365500。 ルーハナ、ナディム(2025年5月22日)。「芝刈り:10月7日以前のイスラエル国家安全保障文化における致命的な比喩」。『ジェノサイド研究ジャーナル』:1–22頁。doi:10.1080/14623528.2025.2506162。 シャフィール、G. (2018). 「露骨な隔離から隠された隔離へ:ガリラヤにおけるイスラエルのパレスチナ系アラブ市民」. 中東研究国際ジャーナル. 50 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1017/S0020743817000915. S2CID 166029058. ストローソン (2019). 「植民地主義」. 『イスラエル研究』. 24 (2): 33. doi:10.2979/israelstudies.24.2.03. JSTOR 10.2979/israelstudies.24.2.03. 2025年8月3日取得. トドロヴァ, テオドラ (2021). 『パレスチナ・イスラエルにおける脱植民地連帯:内部からの入植者植民地主義と抵抗』. ブルームズベリー出版. ISBN 978-1-7869-9642-8. ウルフ、パトリック (2016). 『歴史の痕跡:人種の初歩的構造』. ヴァーソ・ブックス. ISBN 978-1-7816-8917-2. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zionism_as_settler_colonialism |

☆サロゲート・コロニアリズム(Surrogate colonialism)

| Surrogate colonialism

is a term used most notably by anthropologist Scott Atran in his essay

"The Surrogate Colonization of Palestine 1917–1939"[1] to describe a

type of colonization project whereby a foreign power encourages and

provides support for a settlement project of a non-native group over

land occupied by an indigenous people. For Atran, the mission of

Ashkenazi Zionism in Palestine is a form of "surrogate colonialism"

because it was forged based on a strategic consensus with the ruling

British Empire. The surrogate colonialism, Atran further notes, is one

of the major contributing factors to the Balfour Declaration, which

encouraged and legitimized Zionist settlement in Mandatory Palestine.

Sociologist Ran Greenstein claims both Zionist settlement in Palestine

and White settlement in South Africa are examples of surrogate

colonization since in both, most of settlers did not come from the

ranks of the principal colonizing power of the time: the British Empire

in the case of Palestine and the Dutch Empire, later the British

Empire, in the case of South Africa.[2] |

代理植民地主義とは、人類学者スコット・アトランが論文『パレスチナの 代理植民地化 1917–1939』[1]で用いた用語であり、外国勢力が先住民族が占拠する土地において非先住民集団の入植計画を奨励し支援する植民地化プロジェクト の一形態を指す。アトランによれば、パレスチナにおけるアシュケナージ・シオニズムの使命は「代理植民地主義」の一形態である。なぜならそれは支配的な大 英帝国との戦略的合意に基づいて形成されたからだ。さらにアトランは、代理植民地主義がバルフォア宣言の主要な要因の一つであると指摘する。同宣言は委任 統治領パレスチナにおけるシオニスト入植を奨励し正当化した。社会学者ラン・グリーンスタインは、パレスチナにおけるシオニスト入植と南アフリカにおける 白人入植の両方が代理植民地化の事例だと主張する。なぜなら、いずれの場合も入植者の大半は当時の主要植民勢力(パレスチナでは大英帝国、南アフリカでは オランダ帝国→後に大英帝国)の出身者ではなかったからだ。[2] |

| In other academic and

non-academic settings, the term has been more loosely adopted and used

figuratively to describe different forms of indirect domination,

especially in post-colonial context. For example, it has been used to

refer to the compliance of native rulers with the dominance of foreign

power. For example, Geoff Kiangi uses it to describe African wars

fought by African leaders but instigated from former colonial

masters.[3] In his analysis of Arab regimes in the Middle East, Dr.

Mohammad Manzoor Alam claims that even so-called "rejectionist" rulers,

who openly declared hostility to Western dominance, were in fact

exemplifying "surrogate" or "internal" colonialism since they were

silently compliant with Western rule.[4] Similarly, Editor of the

Indian Defence Review, Bharat Verma, blamed the Chinese government for

treating Pakistan “as an extension of its war machine and a surrogate

colony”.[5] |

他の学術的・非学術的文脈では、この用語はより緩やかに採用され、特に

ポストコロニアルな文脈において、様々な形態の間接的支配を比喩的に描写するために用いられてきた。例えば、現地の支配者が外国勢力の支配に従うことを指

すために用いられることがある。例えば、ジェフ・キアンジは、アフリカの指導者によって戦われたが、元植民地支配者によって扇動されたアフリカの戦争を説

明するためにこの用語を使用している。[3]

中東のアラブ政権を分析したモハンマド・マンズール・アラム博士は、西洋支配への敵意を公言した「拒否主義」の支配者たちでさえ、実際には西洋の支配に

黙って従っていたため、「代理」あるいは「内部」植民地主義の典型例であったと主張している。[4]

同様に、インド国防レビュー誌の編集者バーラト・ヴァルマは、中国政府がパキスタンを「自国の戦争機械の延長線上にあり、代理植民地として扱っている」と

非難した。[5] |

| "Surrogate Colonism" has also

been used to describe neocolonialism. In a 1983 speech at the United

Nations Conference on Trade and Development in Belgrade, Indian Prime

Minister Indira Gandhi stated: |

「代理植民地主義」は新植民地主義を表す言葉としても使われてきた。1983年、ベオグラードで開催された国連貿易開発会議での演説で、インドのインディラ・ガンディー首相はこう述べた。 |

| "I am a soul in agony. As one

who feels passionately about freedom, I cannot but be alarmed at the

continuing pushing domination, the new methods and forms of

colonialism. This is all the more pernicious because less obvious and

recognizable. Except for a few places, the visible presence of foreign

rule has gone. We are free to run our affairs and yet, are we not bound

by a new type, a surrogate colonialism? How else shall we describe the

power of and the pressure exerted through the monopoly control of

capital; the withholding of superior technology; the political use of

grain; the manipulation of information, so subtle and subliminal in

influencing minds and attitudes? Is it not time for us to pause from

our daily concerns to ponder over the new dependency? Instead of

reacting, should we the developing not think of acting on our own?"[6] |

私は苦しむ魂だ。自由を熱烈に求める者として、継続する支配の押し付

け、植民地主義の新たな手法や形態に警戒せざるを得ない。これはより悪質だ。なぜなら、より目立たず、認識しにくいからだ。ごく一部の地域を除き、外国支

配の顕在的な存在は消えた。我々は自由に事を運べる。だが、新たな形態の、代理植民地主義に縛られてはいないか?資本の独占的支配を通じて発揮される力と

圧力、優れた技術の提供拒否、穀物の政治的利用、情報操作――これらは人々の思考や態度を、いかに巧妙かつ潜在的に影響しているか。我々は日々の懸念から

一歩離れ、この新たな依存関係を深く考える時ではないか。反応する代わりに、発展途上国である我々は自ら行動を起こすべきではないのか?」[6] |

| 1. Atran, Scott (November 1989).

"The Surrogate Colonization of Palestine 1917-1939" (PDF). American

Ethnologist. 16 (4): 719–744. doi:10.1525/ae.1989.16.4.02a00070. S2CID

130148053. 2. Greenstein, Ran (1995). Genealogies of Conflict: Class, Identity and State in Israel/Palestine and in South Africa. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England. 3. Kiangi, Geoff; Adesida, Olugbenga; Oteh, Arunma, eds. (2001). "Africa: Problems, Challenges, and the Basis for Hope". African Voices. The Nordic Africa Institute: 67–83. 4. Alam, Mohammad. "Whither the Arab Spring?". Institute of Objective Studies. Retrieved 9 January 2012. 5. Verma, Bharat. "If Pakistan Splinters". Indian Defence Review. Retrieved 9 January 2012. 6. Gandhi, Shrimati Indira (8 June 1983). "Peace and development" (PDF). United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. p. 8. Retrieved 30 August 2016. |

1.

アトラン、スコット(1989年11月)。「パレスチナの代理植民地化 1917-1939」 (PDF)。アメリカ民族誌学者。16 (4):

719–744。doi:10.1525/ae.1989.16.4.02a00070. S2CID 130148053. 2. グリーンスタイン、ラン(1995年)。『紛争の系譜:イスラエル/パレスチナと南アフリカにおける階級、アイデンティティ、国家』ニューハンプシャー州ハノーバー:ニューイングランド大学出版局。 3. キアンギ、ジェフ、アデシダ、オルグベンガ、オテ、アルンマ編(2001)。「アフリカ:問題、課題、そして希望の基礎」。アフリカの声。北欧アフリカ研究所:67-83。 4. アラム、モハンマド。「アラブの春はどこへ行くのか?」。客観研究研究所。2012年1月9日取得。 5. バーラト・ヴァーマ。「パキスタンが分裂した場合」。インド防衛レビュー。2012年1月9日取得。 6. ガンディー、シュリマティ・インディラ(1983年6月8日)。「平和と開発」(PDF)。国連貿易開発会議。8ページ。2016年8月30日取得。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Surrogate_colonialism |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099