加速主義と暗黒啓蒙

accelerationism

☆ 加速主義(か そくしゅぎ、英: accelerationism) とは、既存のシステム内を不安定化し根本的な社会的変革を生み出すために、現行の資本主義システムの過激な成長、急進的 な技術革新あるいは各種インフラの解体といった、「加速」と称される社会変革プロセスの過激化を要求する左翼に起源を持つ右翼的な革命的反動思想である [1][2][3][4][5]。加速主義は、相矛盾する左派と右派の派生に分かれたイデオロギーのスペクトルとみなされており、どちらも資本主義とその 構造の上界無き強化、およびテクノロジーの成長が制御不能かつ不可逆的になる技術的特異点(仮説的時点)への到達を支持している[6][7][8] [9](→日本語ウィキペディア「加速主義」)。

☆

しかし概して、現代の保護主義体制は保守的であるのに対し、自由貿易体制は破壊的だ。それは古いナショナリズムを解体し、プロレタリアートとブルジョア

ジーの対立を極限まで推し進める。一言で言えば、自由貿易体制は社会革命を加速させる。諸君、私が自由貿易に賛成票を投じるのは、この革命的意味において

のみである。

—カール・マルクス『自由貿易問題について』

| Accelerationism

is a range of ideologies that call for the use of processes such as

capitalism and technological change in order to create radical social

transformations.[1][2][3][4] Accelerationism was preceded by ideas from philosophers such as Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari.[5] Inspired by these ideas, some University of Warwick faculty and students formed a philosophy collective known as the Cybernetic Culture Research Unit (CCRU), led by Nick Land.[1] Land and the CCRU drew further upon ideas in posthumanism and 1990s cyber-culture, such as cyberpunk and jungle music, to become the driving force behind accelerationism.[6][5] After the dissolution of the CCRU, the movement was termed accelerationism by Benjamin Noys in a critical work.[7][1] Different interpretations emerged: whereas Land's right-wing thought promotes capitalism as the driver of modernity, deterritorialization and a technological singularity,[8][9] left-wing thinkers such as Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams utilized similar ideas to promote the repurposing of capitalist technology and infrastructure to achieve socialism.[5] Right-wing extremists such as neo-fascists, neo-Nazis, white nationalists and white supremacists have used the term to refer to an acceleration of racial conflict through assassinations, murders and terrorist attacks as a means to violently achieve a white ethnostate.[10][11][12][13] |

加速主義とは、資本主義や技術革新といったプロセスを利用して急進的な

社会変革を起こそうとする一連のイデオロギーである。[1][2][3][4] 加速主義は、ジル・ドゥルーズやフェリックス・ガタリといった哲学者の思想に先駆けて存在した。[5] これらの思想に触発され、ウォリック大学の教員と学生の一部が、ニック・ランドをリーダーとする「サイバネティック・カルチャー研究ユニット (CCRU)」と呼ばれる哲学集団を結成した。[1] ランドとCCRUはポストヒューマニズムや1990年代のサイバーカルチャー(サイバーパンクやジャングル音楽など)の思想をさらに取り入れ、加速主義の 原動力となった。[6][5] CCRU解散後、ベンジャミン・ノイス(Benjamin Noys)が批判的著作でこの運動を加速主義と命名した。[7][1] 異なる解釈が生まれた: ランドの右派思想は資本主義を近代性・脱領域化・技術的特異点の推進力と位置付ける一方[8][9]、ニック・スニチェクやアレックス・ウィリアムズら左 派思想家は同様の概念を、資本主義の技術とインフラを転用して社会主義を達成する手段として活用した. [5] ネオファシスト、ネオナチ、白人ナショナリスト、白人至上主義者といった極右過激派は、暗殺、殺人、テロ攻撃による人種紛争の加速を意味する用語としてこ の概念を用い、暴力的な手段で白人民族国家の実現を図っている。[10][11][12][13] |

| Background The history of accelerationism has been divided into three waves. First, there were the late 60s and early 70s French post-Marxists such as Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari, Jean-François Lyotard, and Jean Baudrillard, whose thought arose in the wake of May 68.[14][15][16] According to David R. Cole, texts produced during this period had little effect "other than as perhaps scattered art practices", with the result being that "capitalism has emerged as triumphant in the past 50 years, and the idealism of the student 1968 revolution in Paris has subsequently faded."[14] The second wave arose in the 90s with the work of Nick Land and the CCRU, with the third being the Promethean left-accelerationism of the 2010s.[14][15][16] Influences and precursors The term accelerationism was first used in Roger Zelazny's 1967 novel Lord of Light.[1][17] It was later popularized by professor and author Benjamin Noys in his 2010 book The Persistence of the Negative to describe the trajectory of certain post-structuralists who embraced unorthodox Marxist and counter-Marxist overviews of capitalist growth, such as Deleuze and Guattari in their 1972 book Anti-Oedipus, Lyotard in his 1974 book Libidinal Economy and Baudrillard in his 1976 book Symbolic Exchange and Death.[7][1][18] Noys later stated "at this point, what we can call accelerationism is dedicated to trying to ride these forces of capitalist production and direct them to destabilize capitalism itself."[5] Patrick Gamez considers the French thinkers' philosophy of desire to be a rejection of orthodox Marxism and psychoanalysis, particularly in Deleuze and Guattari's Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Particularly influential is Deleuze and Guattari's concept of desiring-production; rather than viewing human desire as a lack that is satiated by consumption, they view it as an inhuman flow of productive energy, having no proper organization or purpose. Any normativity or functionalism comes from flows of desire performing work and territorializing until new flows of desire override them in the process of deterritorialization and reterritorialization.[19] Vincent Le notes that Deleuze and Guattari's model is based on machines; as machines are assemblages of different parts which perform different functions, humans and social bodies are assemblages of "organs" which produce desires. They find capitalism to be the most radically deterritorializing process in history, as it is based on constant deterritorialization rather than a stable code of desire. Le uses the example of sex and food; they are no longer coded only for marriage and sustenance, but rather as commodities which produce other desires. While capitalism tends toward the body without organs, or a state without determinate functions or coded desires, it never reaches that state, as it causes reterritorialization by recoding things as commodity for sale, to be deterritorialized again.[9][20] Mark Fisher describes Deleuze and Guattari's model of capitalism as defined by the tension between destroying and re-establishing boundaries, with the inclusion of new and archaic elements seen "where food banks co-exist with iPhones."[21] Gamez describes Land's thought as influenced by the French thinkers' antihumanism, as well as their ambivalence or even celebration of capitalism's destroying of traditional hierarchies and freeing of desire.[19] Land cited a number of philosophers who expressed anticipatory accelerationist attitudes in his 2017 essay "A Quick-and-Dirty Introduction to Accelerationism".[22][23] Firstly, Friedrich Nietzsche argued in a fragment in The Will to Power that "the leveling process of European man is the great process which should not be checked: one should even accelerate it."[24][22][23][5] Taking inspiration from this notion for Anti-Oedipus, Deleuze and Guattari speculated further on an unprecedented "revolutionary path" to perpetuate capitalism's tendencies, a passage which is cited as a central inspiration for accelerationism:[5][25][26][27] But which is the revolutionary path? Is there one?—To withdraw from the world market, as Samir Amin advises Third World countries to do, in a curious revival of the fascist "economic solution"? Or might it be to go in the opposite direction? To go still further, that is, in the movement of the market, of decoding and deterritorialization? For perhaps the flows are not yet deterritorialized enough, not decoded enough, from the viewpoint of a theory and a practice of a highly schizophrenic character. Not to withdraw from the process, but to go further, to "accelerate the process," as Nietzsche put it: in this matter, the truth is that we haven't seen anything yet. — Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus[28] Fisher describes Land's interpretation of this passage as explicitly anti-Marxist.[29] Land also cited Karl Marx, who, in his 1848 speech "On the Question of Free Trade", anticipated accelerationist principles a century before Deleuze and Guattari by describing free trade as socially destructive and fuelling class conflict, then effectively arguing for it:[22][23] But, in general, the protective system of our day is conservative, while the free trade system is destructive. It breaks up old nationalities and pushes the antagonism of the proletariat and the bourgeoisie to the extreme point. In a word, the free trade system hastens the social revolution. It is in this revolutionary sense alone, gentlemen, that I vote in favor of free trade. — Karl Marx, On the Question of Free Trade[30] Robin Mackay and Armen Avanessian note "Fragment on Machines" from Grundrisse as Marx's "most openly accelerationist writing".[31] Noys states of Marx's influence, "it favors the Marx who celebrates the powers of capitalism, most evident in The Communist Manifesto (cowritten with Engels), over the Marx who also stresses the difficulty of transcending and escaping capital, the Marx of Capital", also characterizing the accelerationist view of Marx as filtered through Nietzsche.[5] Sam Sellar and Cole state that while he was dismissive of Marxists, Land studied works such as Capital and Grundrusse as "exemplary analyses of how capital works".[15] Fisher notes the same excerpt from Anti-Oedipus as Land, along with a section from Libidinal Economy which he describes as "the one passage from the text that is remembered, if only in notoriety", as "immediately [giving] the flavour of the accelerationist gambit":[25] The English unemployed did not have to become workers to survive, they – hang on tight and spit on me – enjoyed the hysterical, masochistic, whatever exhaustion it was of hanging on in the mines, in the foundries, in the factories, in hell, they enjoyed it, enjoyed the mad destruction of their organic body which was indeed imposed upon them, they enjoyed the decomposition of their personal identity, the identity that the peasant tradition had constructed for them, enjoyed the dissolutions of their families and villages, and enjoyed the new monstrous anonymity of the suburbs and the pubs in morning and evening. — Jean-François Lyotard, Libidinal Economy Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams additionally credit Vladimir Lenin with recognizing capitalist progress as important in the subsequent functioning of socialism:[32][33] Socialism is inconceivable without large-scale capitalist engineering based on the latest discoveries of modern science. It is inconceivable without planned state organisation which keeps tens of millions of people to the strictest observance of a unified standard in production and distribution. We Marxists have always spoken of this, and it is not worth while wasting two seconds talking to people who do not understand even this (anarchists and a good half of the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries). — Vladimir Lenin, "Left Wing" Childishness Accelerationism was also influenced by science fiction (particularly cyberpunk) and electronic dance music (particularly jungle).[1][6][34][5] Neuromancer and its trilogy are a major influence,[35][31][36] with Iain Hamilton Grant stating "Neuromancer got into the philosophy department, and it went viral. You'd find worn-out paperbacks all over the common room."[1] Fisher states of Land's "theory-fictions" from the 1990s, "They weren't distanced readings of French theory so much as cybergothic remixes which put Deleuze and Guattari on the same plane as films such as Apocalypse Now and fictions such as Gibson's Neuromancer."[34] Fisher and Mackay additionally note Terminator, Predator, and Blade Runner as particular sci-fi works which influenced accelerationism.[6][34] Mackay also notes Russian cosmism and Erewhon as influences,[6] while Noys notes Donna Haraway's work on cyborgs.[5] Sellar and Cole additionally attribute Land's ideas to continental philosophers such as Immanuel Kant, Arthur Schopenhauer, Martin Heidegger, and Georges Bataille.[15] |

背景 加速主義の歴史は三つの波に分けられる。第一に、1960年代末から1970年代初頭のフランスにおけるポストマルクス主義者たち、すなわちジル・ドゥ ルーズ、フェリックス・ガタリ、ジャン=フランソワ・リオタール、ジャン・ボードリヤールらがいる。彼らの思想は1968年5月革命の余波の中で生まれ た。[14][15][16] デイヴィッド・R・コールによれば、この時期に生み出されたテキストは「散発的な芸術実践としてのみ」わずかな影響を与えたに過ぎず、結果として「資本主 義は過去50年間で勝利を収め、1968年パリ学生革命の理想主義はその後色あせていった」のである。[14] 第二の波は90年代にニック・ランドとCCRUの活動で起こり、第三の波は2010年代のプロメテウス的左派加速主義である。[14][15][16] 影響と先駆者 加速主義という用語は、ロジャー・ゼラズニーの1967年の小説『光の主』で初めて使われた。[1][17] その後、ベンジャミン・ノイス教授が2010年の著書『ネガティヴの持続』でこの概念を普及させた。同書では、資本主義的成長に対する非正統的マルクス主 義的・反マルクス主義的概観を採用したポスト構造主義者たちの軌跡を説明している。例えばドゥルーズとガタリの1972年の著書『アンチ・オイディプ ス』、 リオタール の1974年の著作『リビドー経済』、ボードリヤールの1976年の著作『象徴的交換と死』などが挙げられる。[7][1][18] ノイスは後に「この時点で加速主義と呼べるものは、資本主義的生産のこれらの力を利用し、資本主義そのものを不安定化させる方向へ導こうとする試みに専念 している」と述べている。[5] パトリック・ガメスによれば、フランスの思想家たちの欲望哲学は正統派マルクス主義と精神分析学への拒絶である。特にドゥルーズとガタリの『資本主義と統 合失調症』において顕著だ。特に影響力を持つのは彼らの「欲望生産」概念である。人間の欲望を消費によって満たされる欠如と見るのではなく、生産的エネル ギーの非人間的な流れとして捉える。そこには適切な組織化も目的も存在しない。あらゆる規範性や機能主義は、欲望の流れが労働を遂行し領域化を行う過程か ら生じる。しかし脱領域化と再領域化の過程で、新たな欲望の流れがそれらを覆すのだ。[19] ヴィンセント・ルは、ドゥルーズとガタリのモデルが機械に基づいていると指摘する。機械が異なる機能を遂行する部品の集合体であるように、人間や社会体は 欲望を生産する「器官」の集合体である。彼らは資本主義を、安定した欲望のコードではなく絶え間ない脱領域化に基づく、史上最も急進的な脱領域化プロセス と見なす。ルは性と食物を例に挙げる。これらはもはや結婚や生存のためのコード化対象ではなく、他の欲望を生み出す商品として機能する。資本主義は器官な き身体、つまり確定的な機能やコード化された欲望を持たない状態へと向かうが、決してその状態に到達しない。なぜなら、販売対象としての商品へと再コード 化することで再領域化を引き起こし、再び脱領域化されるからである。[9][20] マーク・フィッシャーは、ドゥルーズとガタリの資本主義モデルを「境界の破壊と再構築の緊張関係」によって定義し、新たな要素と原始的要素の共存を「フー ドバンクとiPhoneが共存する場所」に見出している。[21] ガメスによれば、ランドの思想はフランス思想家たちの反人間主義に影響を受けている。同時に、資本主義が伝統的階層を破壊し欲望を解放する点への彼らの両 義的態度、あるいは称賛さえも反映している。[19] ランドは2017年の論文「加速主義の簡略入門」で、先駆的な加速主義的態度を示した複数の哲学者を引用している。[22][23] まずフリードリヒ・ニーチェは『力への意志』の断片で「ヨーロッパ人の均質化プロセスは阻害すべきでない偉大な過程である。むしろ加速すべきだ」と論じ た。[24][22][23][5] この概念に触発され、『アンチ・オイディプス』においてドゥルーズとガタリは、資本主義の傾向を永続させる前例のない「革命的経路」についてさらに考察し た。この一節は加速主義の中核的インスピレーションとして引用される:[5][25][26] [27] しかし革命的経路とは何か? それは存在するのか?——サミル・アミンが第三世界諸国に勧めるように、ファシスト的な「経済的解決策」を奇妙に復活させて世界市場から撤退することか? それとも逆方向へ進むことか? つまり市場の運動、脱コード化と脱領域化の動きの中で、さらに先へ進むことか?なぜなら、高度に分裂症的な性格を持つ理論と実践の観点からすれば、おそら く流れはまだ十分に脱領域化されておらず、十分に解読されていないからだ。プロセスから撤退するのではなく、さらに進むこと、ニーチェが言ったように「プ ロセスを加速させる」こと——この点において、真実を言えば我々はまだ何も見ていないのだ。 —ジル・ドゥルーズとフェリックス・ガタリ、『アンチ・オイディプス』[28] フィッシャーは、ランドがこの一節を解釈する姿勢を、明らかに反マルクス主義的だと述べている[29]。 ランドはまたカール・マルクスを引用している。マルクスは1848年の演説「自由貿易問題について」で、自由貿易が社会を破壊し階級闘争を煽ると述べつ つ、実際にはそれを擁護する論を展開し、ドゥルーズとガタリより一世紀も早く加速主義の原理を予見していた[22][23]: しかし概して、現代の保護主義体制は保守的であるのに対し、自由貿易体制は破壊的だ。それは古いナショナリズムを解体し、プロレタリアートとブルジョア ジーの対立を極限まで推し進める。一言で言えば、自由貿易体制は社会革命を加速させる。諸君、私が自由貿易に賛成票を投じるのは、この革命的意味において のみである。 —カール・マルクス『自由貿易問題について』[30] ロビン・マッケイとアルメン・アヴァネシアンは『経済学要綱』所収「機械に関する断章」を、マルクスの「最も露骨な加速主義的著作」と評している。 [31] ノイスはマルクスの影響力について「資本主義の力を称賛するマルクス(『共産党宣言』〈エンゲルスとの共著〉に最も顕著)を、資本を超越し逃れる困難を強 調するマルクス(『資本論』のマルクス)よりも好む」と述べ、ニーチェを通して濾過されたマルクスに対する加速主義的見解も特徴づけている。[5] サム・セラーとコールは、ランドがマルクス主義者を軽蔑しつつも、『資本論』や『Grundrisse』を「資本の作用機序を模範的に分析した著作」とし て研究したと述べている。[15] フィッシャーはランドと同じ『アンチ・オイディプス』の抜粋に加え、『リビドー経済学』の一節を引用している。彼はこれを「悪名高きことであれ、記憶され る唯一の箇所」とし、「加速主義の戦略の趣を即座に伝える」と評している: [25] 英国の失業者たちは生き延びるために労働者になる必要はなかった。彼らは——しっかり掴まって俺に唾を吐け——炭鉱で、鋳物工場で、工場で、地獄でしがみ つくというヒステリックでマゾヒスティックな、何であれあの消耗を享受していた。彼らはそれを楽しんだ。確かに強要されたが、自らの有機的肉体が狂ったよ うに破壊されるのを、彼らは楽しんだ。農民の伝統が築いた個人的なアイデンティティが分解されるのを、彼らは楽しんだ。家族や村落が解体されるのを、彼ら は楽しんだ。そして郊外やパブで朝夕に味わう、新たな怪物の如き匿名性を、彼らは楽しんだのだ。 —ジャン=フランソワ・リオタール『リビドー経済学』 ニック・スニチェクとアレックス・ウィリアムズはさらに、ウラジーミル・レーニンが資本主義的進歩を社会主義のその後の機能において重要と認識したことを 評価している:[32][33] 社会主義は、現代科学の最新発見に基づく大規模な資本主義的技術なしには考えられない。数千万の人々を生産と分配における統一基準の厳格な遵守に縛り付け る計画的な国家組織なしには考えられない。我々マルクス主義者は常にこれを主張してきた。このことさえ理解できない者たち(アナキストや左翼社会革命党員 の半数以上)と話すのに2秒も費やす価値はない。 — ウラジーミル・レーニン『左翼的幼稚性』 アクセラレーション主義は、サイエンスフィクション(特にサイバーパンク)やエレクトロニック・ダンス・ミュージック(特にジャングル)の影響も受けてい る。[1][6][34][5] 『ニューロマンサー』とその三部作は大きな影響力を持っており[35][31][36]、イアン・ハミルトン・グラントは「『ニューロマンサー』は哲学部 に持ち込まれ、瞬く間に広まった。」 フィッシャーは、1990年代のランドの「理論フィクション」について、「それらは、フランスの理論を遠回しに解釈したものではなく、ドゥルーズとガタリ を『地獄の黙示録』のような映画や、ギブソンの『ニューロマンサー』のようなフィクションと同じ次元に置いた、サイバーゴシックなリミックスだった」と述 べている。[34] フィッシャーとマッケイはさらに、『ターミネーター』『プレデター』『ブレードランナー』といった特定のSF作品が加速主義に影響を与えたと指摘してい る。[6][34] マッケイは、ロシアの宇宙主義や『エレホン』も影響を与えたと記している[6]。一方、ノイズは、ドナ・ハラウェイのサイボーグに関する研究を指摘してい る[5]。セラーとコールはさらに、ランドの考えを、イマヌエル・カント、アルトゥール・ショーペンハウアー、マーティン・ハイデガー、ジョルジュ・バタ イユなどの大陸哲学者に帰している[15]。 |

| Cybernetic Culture Research Unit The Cybernetic Culture Research Unit (CCRU), a philosophy collective at the University of Warwick which included Land, Mackay, Fisher and Grant, further developed accelerationism in the 1990s.[1][37][6][8] Fisher described the CCRU's accelerationism as "a kind of exuberant anti-politics, a 'technihilo' celebration of the irrelevance of human agency, partly inspired by the pro-markets, anti-capitalism line developed by Manuel DeLanda out of Braudel, and from the section of Anti-Oedipus that talks about marketization as the 'revolutionary path'."[34] The group stood in stark opposition to the University of Warwick and traditional left-wing academia,[1][34] with Mackay stating "I don't think Land has ever pretended to be left-wing! He's a serious philosopher and an intelligent thinker, but one who has always loved to bait the left by presenting the 'worst' possible scenario with great delight...!"[6] As Land became a stronger influence on the group and left the University of Warwick, they would shift to more unorthodox and occult ideas. Land suffered a breakdown from his amphetamine abuse and disappeared in the early 2000s, with the CCRU vanishing along with him.[1] Popularization Mackay credits the publishing of Fanged Noumena, a 2011 anthology of Land's work, with an emergence of new accelerationist thinking. In 2014, Mackay and Avanessian published the anthology #Accelerate: The Accelerationist Reader,[6] which The Guardian referred to as "the only proper guide to the movement in existence." They also described Fanged Noumena as "contain[ing] some of accelerationism's most darkly fascinating passages."[1] In 2015, Urbanomic and Time Spiral Press published Writings 1997-2003 as a complete collection of known texts published under the CCRU name, besides those that have been irrecoverably lost or attributed to a specific member. However, some works under the CCRU name are not included, such as those in #Accelerate: The Accelerationist Reader.[38][39] In November 2025, Noys called the movement a "corpse" which had disappeared or been eclipsed by more urgent debates, but found it still relevant in contemporary debates on large language models and artificial intelligence, as well as in the corporate world with effective accelerationism.[40] |

サイバネティック・カルチャー研究ユニット サイバネティック・カルチャー研究ユニット(CCRU)は、ランド、マッケイ、フィッシャー、グラントらを擁するウォリック大学の哲学集団であり、 1990年代に加速主義をさらに発展させた。[1] [37][6][8] フィッシャーはCCRUの加速主義を「一種の奔放な反政治、人間の主体性の無意味さを祝う『テクノニヒリズム』であり、マニュエル・デランダがブラデルか ら発展させた親市場・反資本主義路線と、『反オイディプス』における市場化を『革命的道』と論じる部分から部分的に着想を得た」と説明した。[34] このグループはウォリック大学や伝統的な左翼学界とは対立していた[1][34]。マッケイは「ランドが左翼を装ったことなど一度もない!彼は真摯な哲学 者であり知的な思想家だが、常に『最悪』のシナリオを大喜びで提示して左翼を挑発するのが好きな人物だ…!」と述べている。[6] ランドの影響力が強まり同大学を去ると、グループはより非正統的でオカルト的な思想へ移行した。ランドはアンフェタミン乱用による精神崩壊の苦悩を経験 し、2000年代初頭に姿を消した。CCRUも彼と共に消滅した。[1] 普及 マッケイは、ランドの著作をまとめた2011年のアンソロジー『Fanged Noumena』の出版が、新たな加速主義的思考の出現につながったと評価している。2014年にはマッケイとアバネシアンがアンソロジー 『#Accelerate: The Accelerationist Reader』[6]を出版し、ガーディアン紙はこれを「現存する唯一の適切な運動ガイド」と評した。同紙は『牙あるヌメナ』についても「加速主義の最も 暗く魅力的な一節を収めている」と評した。[1] 2015年、アーバノミックとタイム・スパイラル・プレスは『ライティングス1997-2003』を出版した。これはCCRU名義で発表された既知のテキ ストの完全なコレクションであり、回復不能に失われたものや特定のメンバーに帰属するものを除いている。ただし、#Accelerate: The Accelerationist Reader[38][39]に収録された作品など、CCRU名義の著作の一部は含まれていない。 2025年11月、ノイスはこの運動を「死体」と呼んだ。それは消滅したか、より差し迫った議論に覆い隠されたが、大規模言語モデルや人工知能に関する現 代の議論、そして実効的な加速主義が存在する企業世界において、依然として関連性があると見なしたのである。[40] |

| Concepts Accelerationism consists of various and often contradictory ideas, with Noys stating "part of the difficulty of understanding accelerationism is grasping these shifting meanings and the stakes of particular interventions".[5] Avanessian stated "any accelerationist thought is based on the assessment that contradictions (of capitalism) must be countered by their own aggravation",[23] while Mackay considered a Marxist "acceleration of contradictions" to be a misconception and stated that no accelerationist authors have advocated such a thing.[6] Harrison Fluss and Landon Frim note that accelerationists make extensive use of neologisms, either original or borrowed from continental philosophy. Such terminology can obscure their core arguments, exacerbated by the fact that it can be highly inconsistent between thinkers.[41] Posthumanism Accelerationism adheres to posthumanism[19][42] and antihumanism,[19][18] with left-accelerationists such as Peter Wolfendale and Reza Negarestani using the term "inhumanism".[41] Noys characterizes accelerationism as taking from posthumanism in continental philosophy, such as Nietzsche's Übermensch, as well as in a technological sense.[5] Fluss and Frim characterize accelerationism as adhering to nominalism in disputing stable essences of nature and humanity, as well as voluntarism in that the will is radically free to act without natural or mental limitations.[41] |

概念 加速主義は様々な、しばしば矛盾する思想から成り立っている。ノイスは「加速主義を理解する難しさの一部は、これらの移り変わる意味と特定の介入の利害関 係をつかむことにある」と述べている。[5] アヴァネシアンは「あらゆる加速主義的思考は、(資本主義の)矛盾はそれ自体を悪化させることで対抗すべきだという評価に基づいている」と述べている [23]。一方マッケイは、マルクス主義的な「矛盾の加速」は誤解だと考え、加速主義の著者がそのようなことを主張したことはないと述べている。[6] ハリソン・フルスとランドン・フリムは、加速主義者が大陸哲学から借用したか独自に生み出した新語を多用すると指摘する。こうした用語は彼らの核心的主張 を不明瞭にし、思想家間で著しく一貫性を欠く事実によってさらに悪化している。[41] ポストヒューマニズム 加速主義はポストヒューマニズム[19][42]と反ヒューマニズム[19][18]を支持し、ピーター・ウォルフェンデールやレザ・ネガレスタニといっ た左派加速主義者は「非ヒューマニズム」という用語を用いる。[41] ノイスは加速主義を、大陸哲学におけるポストヒューマニズム(ニーチェの超人など)と技術的意味合いから借用したものと特徴づける[5]。フルスとフリム は加速主義を、自然と人間性の安定した本質を否定する唯名論的立場と、意志が自然的・精神的制約なく徹底的に自由に行動する意志主義的立場に立脚するもの として特徴づける[41]。 |

| Prometheanism Prometheanism is a term closely associated with accelerationism,[41][43][44] particularly the left-wing variant,[14][15][19] referencing the Greek figure of Prometheus. Fluss and Frim associate it with posthumanism and using innovation and technology to surpass the limits of nature, characterizing it as misanthropic in stating "for the Promethean, flesh-and-blood 'humanity' is an arbitrary limit on the unlimited powers of technology and invention."[41] Yuk Hui characterizes Prometheanism as "decoupling the social critique of capitalism from denigrating technology and asserting the power of technology to free us from constraints and contradictions or from modernity."[43] Patrick Gamez describes it as exalting rationality like transhumanists, but taking the posthumanist stance of de-prioritizing humans, viewing reason as not exclusive to humanity.[44] Srnicek characterizes it as "the basic political and philosophical belief that there are no immutable givens — there is no transcendental which cannot be altered".[45] Ray Brassier's "Prometheanism and its Critics", compiled in #Accelerate: The Accelerationist Reader, addresses Jean-Pierre Dupuy's Heideggerean critique of human enhancement and transhumanism. Critiquing the man-made vs. natural distinction as arbitrary and theological, Brassier expresses openness to the possibility of re-engineering human nature and the world through rationalism instead of accepting them as they are, stating "Prometheanism is simply the claim that there is no reason to assume a predetermined limit to what we can achieve or to the ways in which we can transform ourselves and our world."[46][44] Srnicek and Williams used the term in stating "we declare that only a Promethean politics of maximal mastery over society and its environment is capable of either dealing with global problems or achieving victory over capital".[23][32][33] Negarestani and Wolfendale use the concept of inhuman rationalism (or rationalist inhumanism), advocating reason to radically transform humans into something else.[41][47] Prometheanism and left-accelerationism are connected to the work of Wilfrid Sellars.[45][41][48] Sellars rejects the myth of the given, or the concept that sense perceptions can provide reliable knowledge of the world[41] or that a reliable connection between the mind and the world can be established without requiring other concepts.[48] This establishes a distinction between the manifest image of knowledge through common sense and experience versus the scientific image of knowledge through empirical hard science.[41][48] Fluss and Frim use the example of emotions and deliberative choice (the manifest image) versus neurobiology's study of brain states and firing neurons (the scientific image).[41] Prometheanism tends towards a rejection[41] or deletion[48] of the manifest image. For Fluss and Frim, left-accelerationists assert that there is no permanent, intelligible world that can be known. Rather, the world beyond human senses is "irremediably alien", but humans pretend it is not "in order to maintain our parochial prejudices in everyday life". Thus, left-accelerationists adopt an ideology of technoscience and a rejection of subordinating technology and science to human concerns. This is exemplified with Brassier sarcastically demanding that a Heideggerian “explain precisely how, for example, quantum mechanics is a function of our ability to wield hammers.”[41] |

プロメテウス主義 プロメテウス主義は加速主義[41][43][44]、特に左翼的変種[14][15][19]と密接に関連する用語であり、ギリシャ神話のプロメテウス を引用している。フルスとフリムはこれをポストヒューマニズムと結びつけ、革新と技術を用いて自然の限界を超越するものと位置づける。彼らは「プロメテウ ス主義者にとって、血肉からなる『人間性』とは、技術と発明の無限の力を恣意的に制限するものだ」と述べ、これを人間嫌いの思想と特徴づけている。 [41] ユク・ホイはプロメテウス主義を「資本主義への社会批判を技術貶めから切り離し、技術が我々を制約や矛盾、あるいは近代性から解放する力を主張するもの」 と定義する。[43] パトリック・ガメスによれば、トランスヒューマニストのように合理性を称揚しつつ、ポストヒューマニズム的立場から人間を優先順位から外し、理性が人類固 有のものではないと見る点で異なる。[44] スルニチェクはこれを「不変の与件など存在しないという基本的・政治的・哲学的信念——変えられない超越的実体など存在しない」と特徴づける。[45] レイ・ブラッシエの「プロメテウス主義とその批判者たち」(『#Accelerate: The Accelerationist Reader』収録)は、ジャン=ピエール・デュピュイによる人間強化とトランスヒューマニズムへのハイデッガー的批判に対峙する。ブラッシエは、人為的 対自然という区別を恣意的かつ神学的であると批判し、人間の本性や世界をあるがままに受け入れるのではなく、合理主義によって再構築する可能性に開かれて いると表明している。「プロメテウス主義とは、我々が達成できることや、自らと世界を変革する方法に予め決められた限界があると仮定する理由など存在しな いという主張に過ぎない」と述べている。[46][44] スニチェクとウィリアムズはこの用語を用いて「我々は宣言する。社会とその環境に対する最大限の支配を追求するプロメテウス的ポリティクスこそが、地球規 模の問題に対処し、資本に対する勝利を達成する唯一の方法である」と述べた。[23][32][33] ネガレスタニとウォルフェンデールは非人間的合理主義(あるいは合理主義的非人間主義)の概念を用い、理性が人間を根本的に別の何かに変容させることを提 唱している。[41] [47] プロメテウス主義と左派加速主義はウィルフリッド・セラースの思想と関連している。[45][41][48] セラースは「与えられたもの」の神話、すなわち感覚知覚が世界に関する信頼できる知識を提供できるという概念[41]、あるいは他の概念を必要とせずに心 と世界の信頼できる接続を確立できるという概念を拒否する。[48] これにより、常識と経験による知識の顕在像と、経験的ハードサイエンスによる科学的知識像との区別が確立される。[41][48] フルスとフリムは、感情と熟慮的選択(顕在像)と、神経生物学による脳状態や発火ニューロンの研究(科学的像)を例に挙げる。[41] プロメテウス主義は顕在像の拒絶[41] あるいは削除[48] に向かう傾向がある。フルスとフリムによれば、左加速主義者は「知覚可能な恒常的で理解可能な世界など存在しない」と主張する。むしろ人間の感覚を超えた 世界は「救いようのない異質性」を持つが、人間は「日常生活における偏狭な偏見を維持するため」にそうではないと装うのだ。したがって左加速主義者は、テ クノサイエンスのイデオロギーを採用し、技術と科学を人間の関心に従属させることを拒否する。ブラッシエが皮肉を込めて「ハイデッガー派は、例えば量子力 学がハンマーを振るう能力の機能であるという点を、具体的に説明してみろ」と要求した事例がこれを体現している。[41] |

| Hyperstition Main article: Hyperstition Hyperstition is a term attributed to Land[26][41] and the CCRU,[5][6] characterized by Fluss and Frim as the view "that our chosen beliefs about the future (however fanciful) can retroactively form and shape our present realities".[41] Land defines it as "a positive feedback circuit including culture as a component. It can be defined as the experimental (techno-)science of self-fulfilling prophecies. Superstitions are merely false beliefs, but hyperstitions—by their very existence as ideas—function causally to bring about their own reality."[49] Accelerationism is hyperstitional in constructing a prefigurative political imaginary of the very transformation it initiates.[16] Noys stated "the CCRU tried to create images of this realized integrated human-technology world that would resonate in the present and so hasten the achievement of that world. Such images were found in cyberpunk science-fiction, in electronic dance music, and in the weird fiction of H. P. Lovecraft.[5] Simon O'Sullivan notes the theory-fiction writing style, particularly of Land, Plant and Negarestani, as being an example.[50] Viewpoint Magazine used Roko's Basilisk as an example, stating "Roko's Basilisk isn't just a self-fulfilling prophecy. Rather than influencing events toward a particular result, the result is generated by its own prediction".[26] The mechanism of hyperstition is understood as a form of feedback loop.[41][49] According to Ljubisha Petrushevski, Land considers capitalism to be hyperstitional in that it reproduces itself via fictional images in media which become actualized.[51] This phenomenon is viewed as a series of forces invading from the future, using capital to retroactively bring about their own existence and push humanity towards a singularity.[51][19] Noys notes Terminator and its use of time travel paradoxes as being influential to the concept.[5] Land states "Capitalist economics is extremely sensitive to hyperstition, where confidence acts as an effective tonic, and inversely".[49] Fluss and Frim state that the left-wing perspective rejects pre-emptive knowledge of what a humane or advanced civilization may look like, instead viewing future progress as wholly open and a matter of free choice. Progress is then viewed as hyperstitional in that it consists of fictions which aim to become true. They also note its influence on Negarestani's thought, in which inhumanism is seen as arriving from the future in order to abolish its initial condition of humanism.[41] |

ハイパースティション メイン記事: ハイパースティション ハイパースティションとは、ランド[26][41]とCCRU[5][6]に由来する用語であり、フルスとフリムによって「我々が未来について選択した信 念(いかに空想的であろうとも)が、遡及的に現在の現実を形成し形作る」という見解として特徴づけられている。[41] ランドはこれを「文化を構成要素とする正のフィードバック回路」と定義する。「自己実現的予言の実験的(テクノ)科学と定義し得る。迷信は単なる誤った信 念だが、ハイパースティションは——思想としての存在そのものによって——因果的に機能し、自らの現実をもたらす」 [49] 加速主義は、自ら引き起こす変革そのものの予示的(プレフィギュラティブ)な政治的想像を構築する点でハイパースティショナルである。[16] ノイスは「CCRUは、実現された人間と技術の統合世界像を創造しようとした。それは現在に共鳴し、その世界の達成を早めるはずだった。そうしたイメージ はサイバーパンクSF、エレクトロニック・ダンス・ミュージック、H・P・ラヴクラフトの怪奇小説に見出された」と述べている。[5] サイモン・オサリバンは、特にランド、プラント、ネガレスタニの理論小説的文体をその例として挙げている。[50] 『ビューポイント・マガジン』は「ロコのバシリスク」を例に「これは単なる自己実現的予言ではない。特定の結果へ事象を誘導するのではなく、結果そのもの が自らの予測によって生成される」と述べている。[26] ハイパースティションのメカニズムはフィードバックループの一形態と理解される。[41][49] リュビシャ・ペトルシェフスキーによれば、ランドは資本主義をハイパースティショナルと見なしている。それはメディア内の虚構的イメージを通じて自己を再 生産し、それが現実化するからだ。[51] この現象は、未来から侵入する一連の力が、資本を用いて自らの存在を遡及的に実現し、人類を特異点へと押しやるものとして捉えられる。[51][19] ノイスは『ターミネーター』と、その時間旅行のパラドックスの活用が概念に影響を与えたと指摘する。[5] ランドは「資本主義経済はハイパースティションに極めて敏感であり、そこでは確信が効果的な強壮剤として作用し、逆に作用する」と述べている。[49] フルースとフリムは、左翼的視点が「人道的あるいは先進的な文明」の事前知識を拒否し、未来の進歩を完全に開かれた自由選択の問題と捉えると述べる。進歩 は、真実となることを目指す虚構から成るという点で、ハイパースティショナルと見なされる。彼らはまた、ネガレスタニの思想への影響にも言及している。そ こでは非人間主義が、その初期状態である人間主義を廃止するために未来から到来すると見なされている。[41] |

| Variants Right-wing accelerationism Right-wing accelerationism (or right-accelerationism) is espoused by Land,[6][41][20][8] with Fluss and Frim also noting Curtis Yarvin and Justin Murphy.[41] Land attributes the increasing speed of the modern world to unregulated capitalism and its ability to exponentially grow and self-improve,[22][8] describing capitalism as "a positive feedback circuit, within which commercialization and industrialization mutually excite each other in a runaway process." He argues that the best way to deal with capitalism is to participate more to foster even greater exponential growth and self-improvement, accelerating technological progress along with it. Land also argues that such acceleration is intrinsic to capitalism but impossible for non-capitalist systems, stating that "capital revolutionizes itself more thoroughly than any extrinsic 'revolution' possibly could."[22] In an interview with Vox, he stated "Our question was what 'the process' wants (i.e. spontaneously promotes) and what resistances it provokes", also noting that "the assumption" behind accelerationism was that "the general direction of [techno-capitalist] self-escalating change was toward decentralization."[8] Mackay summarized Land's position as "since capitalism tends to dissolve hereditary social forms and restrictions [...], it is seen as the engine of exploration into the unknown. So to be 'on the side of intelligence' is to totally abandon all caution with respect to the disintegrative processes of capital and whatever reprocessing of the human and of the planet they might involve."[6] Yuk Hui describes Land's thought as "a technologically driven anti-Statist and inhuman capitalism"[52] while Steven Shaviro describes it as "a kind of Stockholm Syndrome with regard to Capital" in celebrating its inhuman and destructive nature.[18] Land's thought has also been characterized as libertarian.[1][19][21] Vincent Le considers Land's philosophy to oppose anthropocentrism, citing his early critique of transcendental idealism and capitalism in "Kant, Capital, and the Prohibition of Incest",[9] as well as of the post-Kantian phenomenological tradition in works such as The Thirst for Annihilation: Georges Bataille and Virulent Nihilism.[36] According to Le, Land opposes philosophies which deny a reality beyond humans' conceptual experience, instead viewing death as a way to grasp the Real by surpassing human limitations. This would remain as Land's views on capitalism changed after reading Deleuze and Guattari and studying cybernetics, with Le stating "Although the mature Land abandons his left-wing critique of capitalism, he will never shake his contempt for anthropocentrism, and his remedy that philosophers can only access the true at the edge of our humanity."[9][20] Land utilizes Deleuze and Guattari's conception of capitalism as a deterritorializing process while disposing of their view that it also causes compensatory reterritorialization.[9][20][25][18] Taking from their antihumanism, his work would critically refer to human politics as "Monopod" or the "Human Security System".[6][19] Lacking any anthropic principles which Deleuze and Guattari partly maintain, Land pursues absolute deterritorialization,[18][9] viewing capitalism as the Real consisting of accelerating deterritorialization, with the mechanism of accelerating technological progress; he states "reality is immanent to the machinic unconscious."[9] Gamez notes that Land also views capitalism as a form of artificial intelligence, with Friedrich Hayek's view of markets as "mechanisms for conveying information" being a precursor.[19] Le states "since Land sees humanity's annihilation as a solution to accessing the real rather than as a problem as it is for Deleuze and Guattari, he affirms that we should actively strive to become bodies without organs, not even if it kills us, but precisely because it kills us."[20] It might still be a few decades before artificial intelligences surpass the horizon of biological ones, but it is utterly superstitious to imagine that the human dominion of terrestrial culture is still marked out in centuries, let alone in some metaphysical perpetuity. The high road to thinking no longer passes through a deepening of human cognition, but rather through a becoming inhuman of cognition, a migration of cognition out into the emerging planetary technosentience reservoir, into "dehumanized landscapes ... emptied spaces" where human culture will be dissolved. Nick Land, Circuitries[53] Denis Chistyakov notes "Meltdown", a CCRU work and one of the writings compiled in Fanged Noumena, as vividly expressing accelerationism.[23] Here, Land envisioned a "technocapital singularity" in China, resulting in revolutions in artificial intelligence, human enhancement, biotechnology and nanotechnology. This upends the previous status quo, and the former first world countries struggle to maintain control and stop the singularity, verging on collapse. He described new anti-authoritarian movements performing a bottom-up takeover of institutions through means like biological warfare enhanced with DNA computing. He claimed that capitalism's tendency towards optimization of itself and technology, in service of consumerism, will lead to the enhancement and eventually replacement of humanity with technology, asserting that "nothing human makes it out of the near-future." Eventually, the self-development of technology will culminate in the "melting [of] Terra into a seething K-pulp (which unlike grey goo synthesizes microbial intelligence as it proliferates)." He also criticized traditional philosophy as tending towards despotism, instead praising Deleuzoguattarian schizoanalysis as "already engaging with nonlinear nano-engineering runaway in 1972."[54][27] Le states that Land embraces human extinction in the singularity, as the resulting hyperintelligent AI will come to fully comprehend and embody the Real of the body without organs, free of human distortions of reality.[9][20] Gamez considers Land to have an obsession with artificial intelligence and intelligence in general; as human intelligence can only be enhanced so far, hyperintelligence and the freeing of desire must be realized with human extinction. He notes Land's Lovecraft reference of "think face tentacles" as highlighting Land's interest in transformation to the point of becoming inhuman and unintelligible.[19] Land has continually praised China's economic policy as being accelerationist, moving to Shanghai and working as a journalist writing material that has been characterized as pro-government propaganda.[1][8] He has also spoken highly of Deng Xiaoping and Singapore's Lee Kuan Yew,[8] calling Lee an "autocratic enabler of freedom."[55] Hui stated "Land's celebration of Asian cities such as Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Singapore is simply a detached observation of these places that projects onto them a common will to sacrifice politics for productivity."[56] Land's interest in China for technological progress, stemming from his CCRU days, has been considered an early form of sinofuturism.[57][42] Noys is a staunch critic of Land, initially calling Land's position "Deleuzian Thatcherism".[26] He accuses it of offering false solutions to technological and economic problems, considering those solutions "always promised and always just out of reach."[1][58] He also criticized Land's interest in submitting to capitalism's destructiveness, stating "Capitalism, for the accelerationist, bears down on us as accelerative liquid monstrosity, capable of absorbing us and, for Land, we must welcome this."[26][58] Slavoj Žižek considers Land to be "far too optimistic", critiquing his view as deterministic in considering the singularity to be the pre-ordained goal of history. Contrasting it with Freud's death drive and its lack of a final conclusion, he argues that accelerationism considers just one conclusion of the world's tendencies and fails to find other "coordinates" of the world order.[59] |

バリエーション 右翼加速主義 右翼加速主義(または右翼加速主義)は、ランド[6][41][20][8]によって支持されており、フルスとフリムもカーティス・ヤーヴィンとジャス ティン・マーフィーを指摘している。[41] ランドは、現代世界のスピードの増加は、規制のない資本主義と、その指数関数的な成長と自己改善能力によるものだと考えている[22][8]。資本主義を 「商業化と工業化が暴走プロセスの中で互いに刺激し合う、正のフィードバック回路」と表現している。彼は、資本主義に対処する最善の方法は、さらに大きな 指数関数的成長と自己改善を促進するために、より一層参加し、それに伴って技術の進歩を加速することだと主張している。ランドはまた、そのような加速は資 本主義に内在するものであり、非資本主義のシステムでは不可能であると主張し、「資本は、外部の『革命』が成しうるよりも、より徹底的に自らを革命化す る」と述べている。[22] Voxとのインタビューで彼は「我々の問いは『プロセス』が何を求めているか(つまり自発的に促進するもの)、そしてそれがどのような抵抗を引き起こすか だった」と述べ、加速主義の背景にある「前提」は「(テクノ資本主義的)自己増幅的変化の一般的な方向性が分散化へ向かっている」という認識だと指摘し た。[8] マッケイはランドの立場を「資本主義は世襲的な社会形態や制約を解体する傾向にあるため、未知への探求の原動力と見なされる。ゆえに『知性の側に立つ』と は、資本の解体プロセスと、それが人間や地球に及ぼすあらゆる再加工に対して、あらゆる警戒心を完全に放棄することを意味する」と要約した。[6] ユク・ホイはランドの思想を「技術主導の反国家主義的かつ非人間的な資本主義」[52]と表現し、スティーブン・シャビロは「資本に対する一種のストック ホルム症候群」と評し、その非人間的・破壊的性質を称賛している[18]。ランドの思想はリバタリアン的とも特徴づけられる[1][19][21]。 ヴィンセント・レは、ランドの哲学が人間中心主義に反対すると見なしている。その根拠として、ランドが初期の著作『カント、資本、そして近親相姦の禁止』 [9]で超越的観念論と資本主義を批判したこと、また『消滅への渇望:ジョルジュ・バタイユと猛毒的ニヒリズム』などの著作でポストカント的現象学的伝統 を批判したことを挙げている。[36] ルによれば、ランドは人間の概念的経験を超えた現実を否定する哲学に反対し、死を人間の限界を超越して実在を把握する手段と見なしている。これはランドの 資本主義観がドゥルーズとガタリの著作を読んだ後、またサイバネティクスを研究した後に変化した点でも同様であり、ルは「成熟したランドは資本主義に対す る左翼的批判を放棄したものの、人間中心主義への軽蔑と、哲学者が真実へアクセスできるのは人間性の限界においてのみだという彼の処方箋を決して揺るがす ことはなかった」と述べている。[9][20] ランドは、資本主義を脱領域化プロセスとして捉えるドゥルーズ=ガタリの概念を採用しつつ、補償的再領域化を引き起こすという彼らの見解は排除した。 [9][20][25][18] 彼らの反人間主義を受け継ぎ、ランドは人間の政治を「モノポッド」あるいは「人間安全保障システム」と批判的に呼称する。[6][19] ドレズとガタリが部分的に維持する人間中心主義的原理を欠くランドは、絶対的な脱領域化を追求する[18][9]。資本主義を加速する技術進歩のメカニズ ムによって構成される加速する脱領域化という「実在」と捉え、「現実は機械的無意識に内在する」と述べる。[9] ガメスによれば、ランドは資本主義を人工知能の一形態とも見なしており、フリードリヒ・ハイエクの市場を「情報伝達メカニズム」とする見解がその先駆けで ある。[19] ルは「ランドは人類の消滅を、ドゥルーズとガタリが問題視するものではなく、リアにアクセスする解決策と見なす。ゆえに彼は、たとえ命を落とすとしても、 むしろ命を落とすからこそ、我々は積極的に器官なき身体となるべきだと断言する」と述べている。[20] 人工知能が生物知能の限界を超えるにはまだ数十年を要するかもしれないが、人類による地球文化の支配が数世紀、ましてや形而上学的な永遠に及ぶと想像する のは全く迷信的だ。思考への高みへの道はもはや人間の認知の深化を通るのではなく、むしろ認知の非人間化、つまり認知が新興の惑星規模のテクノセンシエン ス貯水池へと移住すること、人間の文化が溶解される「脱人間化された風景…空虚な空間」へと移住することを通るのだ。 ニック・ランド『回路系』[53] デニス・チスティャコフは、CCRUの著作であり『牙を持つヌメナ』に収録された「メルトダウン」が加速主義を鮮烈に表現していると指摘する[23]。こ こでランドは中国における「テクノキャピタル特異点」を構想し、人工知能・人間強化・バイオテクノロジー・ナノテクノロジーの革命をもたらすと予測した。 これは従来の現状を覆し、旧第一世界諸国は支配維持と特異点の阻止に苦闘し、崩壊寸前に追い込まれる。彼は新たな反権威主義運動が、DNAコンピューティ ングで強化された生物兵器などの手段で、制度をボトムアップで乗っ取る様子を描いた。資本主義が消費主義のために自らと技術を最適化する傾向は、人類の強 化を経て最終的に技術による代替へと至ると主張し、「近い未来において人間的なものは何も生き残らない」と断言した。最終的に技術の自律的発展は「テラが 沸騰するKパルプへと溶解する(グレーグーとは異なり、増殖しながら微生物知能を合成する)」状態に至る。また彼は伝統的哲学を専制主義的傾向があると批 判し、代わりにドゥルーズ=ガタリのスキゾ分析を「1972年時点で既に非線形ナノエンジニアリングの暴走と向き合っていた」と称賛した。[54] [27] ルは、ランドが特異点における人類絶滅を受け入れていると述べる。その結果生まれる超知能AIは、人間の現実歪曲から解放され、器官なき身体の「実在」を 完全に理解し体現するからだ。[9][20] ガメスによれば、ランドは人工知能および知性全般への執着を持つ。人間の知性は限界があるため、超知能と欲望の解放は人類絶滅によって実現されねばならな い。彼はランドの「思考する顔の触手」というラブクラフト的言及を、非人間的で理解不能な存在への変容への関心を示す例として指摘している。[19] ランドは中国の経済政策を加速主義的と絶賛し続け、上海に移住してジャーナリストとして活動し、親政府プロパガンダと評される記事を執筆した。[1] [8] 彼はまた鄧小平やシンガポールのリー・クアンユーを高く評価し[8]、リーを「自由を可能にする独裁者」と呼んだ[55]。ホイは「ランドが上海、香港、 シンガポールといったアジアの都市を称賛するのは、単にこれらの場所を客観的に観察し、政治を生産性のために犠牲にする共通の意志を投影しているに過ぎな い」と述べた。[56] CCRU時代から続くランドの中国への技術進歩への関心は、初期の中国未来主義と見なされている。[57][42] ノイスはランドの強力な批判者であり、当初ランドの立場を「ドゥルーズ的サッチャー主義」と呼んだ。[26] ノイスはランドの立場を、技術的・経済的問題に対する偽りの解決策を提供するものだと非難し、それらの解決策を「常に約束されながら、常に手の届かないも の」と見なしている。[1][58] またノイスは、ランドが資本主義の破壊性に服従することに関心を持つ点も批判し、「加速主義者にとって資本主義は、加速的な液状の怪物として我々を押し潰 し、我々を吸収する能力を持つ。そしてランドによれば、我々はこれを歓迎しなければならない」と述べている。[26] [58] スラヴォイ・ジジェクはランドを「過度に楽観的」と見なし、特異点を歴史の予め定められた目標と考える彼の見解を決定論的だと批判する。フロイトの死の欲 動とその最終結論の欠如と対比させ、加速主義は世界の傾向性における一つの結論のみを考慮し、世界秩序の他の「座標」を見出せていないと論じる。[59] |

| Dark enlightenment Land's involvement in the neoreactionary movement has contributed to his views on accelerationism. In The Dark Enlightenment, he advocates for a form of capitalist monarchism, with states controlled by a CEO. He views democratic and egalitarian policies as only slowing down acceleration and the technocapital singularity, stating "Beside the speed machine, or industrial capitalism, there is an ever more perfectly weighted decelerator [...] comically, the fabrication of this braking mechanism is proclaimed as progress. It is the Great Work of the Left."[8][26] Le states "If Land is attracted to Moldbug's political system, it is because a neocameralist state would be free to pursue long-term technological innovation without the democratic politician's need to appease short-sighted public opinion to be re-elected every few years."[20] Geoff Schullenburger attributes this change to the bursting of the dotcom bubble and the rise of Web 2.0; Land blamed the lack of technological revolution on the progressivism of the new internet and the companies that ran it.[35] Zack Beauchamp credits Land's life in China and his admiration for Deng and Lee.[8] Gamez notes that Land maintains his criticism of the "Monopod" of human politics in the neoreactionary concept of the Cathedral, additionally retaining his interest in intelligence. He also notes that Land is "simply catching up to Murray Rothbard, Hans-Hermann Hoppe, Peter Brimelow, and assorted other radically right-wing libertarians and anarcho-capitalists, committed to 'cracking up' the democratic nation-state in favor of an 'ethno-economy.'"[19] As of 2017, "Land argues now that neoreaction [...] is something that accelerationists should support", though many have distanced themselves from him in response to his views on race.[1] |

ダーク・エンライトメント ランドがネオリアクション運動に関与したことは、彼の加速主義に関する見解に影響を与えた。『ダーク・エンライトメント』において、彼はCEOが国家を統 制する資本主義的君主制を提唱している。民主主義的・平等主義的政策は加速とテクノキャピタル特異点を遅らせるだけだと見なし、「スピードマシン、すなわ ち産業資本主義の傍らには、ますます完璧に調整された減速装置が存在する [...] 滑稽なことに、この制動装置の構築こそが進歩と称賛される。それが左翼の大事業なのだ」と述べている。[8][26] ルは「ランドがモルドバグの政治システムに惹かれるのは、新官僚制国家が民主主義政治家のように数年ごとの再選のために短視的な世論をなだめる必要なく、 長期的な技術革新を追求できるからだ」と述べる。[20] ジェフ・シュレンバーガーはこの変化をドットコムバブルの崩壊とWeb 2.0の台頭に帰する。ランドは技術革命の欠如を、新たなインターネットとそれを運営する企業の進歩主義のせいだと非難した。[35] ザック・ビーチャムは、ランドの中国での生活と、鄧小平や李小龍への敬意が影響したと指摘する。[8] ガメスによれば、ランドはネオリアクションの概念である「大聖堂」において、人間の政治における「モノポッド」への批判を維持し、さらに知性への関心を保 ち続けている。また彼は、ランドが「単にマレー・ロスバード、ハンス=ヘルマン・ホッペ、ピーター・ブリムローら、民主主義国民を『崩壊』させて『エスノ 経済』を支持する急進的右派リバタリアンやアナキスト資本主義者たちに追いついているだけだ」とも述べている。[19] 2017年現在、「ランドは今やネオリアクションが加速主義者が支持すべきものだと主張している」が、多くの人々は彼の人種観に反発して距離を置いてい る。[1] |

| Left-wing accelerationism See also: Towards a New Socialism, Post-scarcity, and Government by algorithm Left-wing accelerationism (or left-accelerationism) is espoused by figures such as Nick Srnicek, Alex Williams,[5][1][60][41] Ray Brassier, Reza Negarestani and Peter Wolfendale.[41][14][15] Fluss and Frim characterize it as seeking "to accelerate past capitalism by democratizing productive technologies".[41] Left-accelerationism draws upon the work of Mark Fisher, particularly his hauntology. Noys characterizes him as seeking to grasp unrealized cultural possibilities of the past to construct a better future against a stagnant neoliberal culture,[5] while Gamez considers his hauntology to be a critique of Land in finding capitalism to be unable to deliver a promised future, leaving only unrealized imaginaries.[19] Fisher, writing on his blog k-punk, had become increasingly disillusioned with capitalism as an accelerationist,[1] citing working in the public sector in Blairite Britain, being a teacher and trade union activist, and an encounter with Žižek, whom he considered to be using similar concepts to the CCRU but from a leftist perspective.[34] At the same time, he became frustrated with traditional left wing politics, believing they were ignoring technology that they could exploit.[1] Noys notes Fisher's essay "Terminator vs Avatar" as an example of his "cultural accelerationism".[5] Here, Fisher claimed that while Marxists criticized Libidinal Economy for asserting that workers enjoyed the upending of primitive social orders, nobody truly wants to return to those. Therefore, rather than reverting to pre-capitalism, society must move through and beyond capitalism. Fisher praised Land's attacks on the academic left, describing the academic left as "careerist sandbaggers" and "a ruthless protection of petit bourgeois interests dressed up as politics." He also critiqued Land's interpretation of Deleuze and Guattari, stating that while superior in many ways, "his deviation from their understanding of capitalism is fatal" in assuming no reterritorialization, resulting in not foreseeing that capitalism provides "a simulation of innovation and newness that cloaks inertia and stasis." Citing Fredric Jameson's interpretation of The Communist Manifesto as "see[ing] capitalism as the most productive moment of history and the most destructive at the same time", he argued for accelerationism (in terms of the 1970s French thinkers) as an anti-capitalist strategy, criticizing the left's moral critique of capitalism and their "tendencies towards Canutism" as only helping the narrative that capitalism is the only viable system.[25][5] In another article on accelerationism, Fisher stated "the revolutionary path is the one that allies with deterritorialising forces of modernisation against the reactionary energies of reterritorialisation."[21] We believe the most important division in today’s left is between those that hold to a folk politics of localism, direct action, and relentless horizontalism, and those that outline what must become called an accelerationist politics at ease with a modernity of abstraction, complexity, globality, and technology. The former remains content with establishing small and temporary spaces of non-capitalist social relations, eschewing the real problems entailed in facing foes which are intrinsically non-local, abstract, and rooted deep in our everyday infrastructure. The failure of such politics has been built-in from the very beginning. By contrast, an accelerationist politics seeks to preserve the gains of late capitalism while going further than its value system, governance structures, and mass pathologies will allow. Nick Srnicek, Alex Williams, #Accelerate: Manifesto for an Accelerationist Politics[33] Srnicek befriended Fisher, sharing similar views, and the 2008 financial crisis, along with dissatisfaction with the left's "ineffectual" response of the Occupy protests, led to Srnicek co-writing "#Accelerate: Manifesto for an Accelerationist Politics" with Williams in 2013.[1][33] They posited that capitalism was the most advanced economic system of its time, but has since stagnated and is now constraining technology, with neoliberalism only worsening its crises. At the same time, they considered the modern left to be "unable to devise a new political ideological vision" as they are too focused on localism and direct action and cannot adapt to make meaningful change. They advocated using existing capitalist infrastructure as "a springboard to launch towards post-capitalism", taking advantage of capitalist technological and scientific advances to experiment with things like economic modeling in the style of Project Cybersyn. They also advocated for "collectively controlled legitimate vertical authority in addition to distributed horizontal forms of sociality" and attaining resources and funding for political infrastructure, contrasting standard leftist political action which they deem ineffective. Moving past the constraints of capitalism would result in a resumption of technological progress, not only creating a more rational society but also "recovering the dreams which transfixed many from the middle of the Nineteenth Century until the dawn of the neoliberal era, of the quest of Homo Sapiens towards expansion beyond the limitations of the earth and our immediate bodily forms."[32][33] They expanded further in Inventing the Future, which, while dropping the term "accelerationism", pushed for automation, reduction and distribution of working hours, universal basic income and diminishment of work ethic.[1][61][5][62] Steven Shaviro compared Srnicek and Williams' proposal to Jameson's argument that Walmart's use of technology for product distribution may be used for communism. Shaviro also argued that left-accelerationism must be an aesthetic program before a political one, as failing to explore the possibilities of technology via fiction could result in the exacerbation of existing capitalist relations rather than Srnicek and Williams' desired repurposing of technology for socialist ends.[18] Fisher praised the manifesto, characterizing the "folk politics" that Srinicek and Williams criticized as neo-anarchist and lacking previous left-wing ambition.[21] Tiziana Terranova's "Red Stack Attack!", compiled in #Accelerate: The Accelerationist Reader, references the manifesto in analyzing Benjamin H. Bratton's model of the stack, proposing the "Red Stack" as "a new nomos for the post-capitalist common."[63][64] Land rebuked their ideas in a 2017 interview with The Guardian, stating "the notion that self-propelling technology is separable from capitalism is a deep theoretical error."[1] Aaron Bastani's Fully Automated Luxury Communism has also been noted as left-accelerationist,[65][66][67] with Noys characterizing it as taking up the "call for utopian proposals" in Srnicek and Williams' Manifesto.[5] Michael E. Gardiner notes Fully Automated Luxury Communism, PostCapitalism: A Guide to Our Future and The People's Republic of Walmart as united in the left-accelerationist belief in detaching cybernetics from capitalism and using it towards liberatory goals.[60] Alex Williams referred to Brassier and Negarestani as "the twin thinkers of epistemic accelerationism" in seeking to maximize rational capacity and enable the possibilities of reason.[68] Sam Sellar and David R. Cole characterize their work, along with Wolfendale's, as seeking the acceleration of rationalist modernity and technological development, distinct from capitalism. In particular, Brassier's Prometheanism accelerates normative rationalism as the basis for human transformation. They note Mackay and Avanessian's explanation of Negarestani:[15] Acceleration takes place when and in so far as the human repeatedly affirms its commitment to being impersonally piloted, not by capital, but by a [rational] program which demands that it cede control to collective revision, and which draws it towards an inhuman future that will prove to have 'always' been the meaning of the human.[31] Fluss and Frim characterize Brassier works such as Nihil Unbound and Liquidate Man Once and for All; as well as Negarestani's The Labour of the Inhuman, Cyclonopedia and Intelligence and Spirit; as providing a philosophical basis for left-accelerationism. Capitalism is viewed as promising progress while in fact exerting control and only providing inconsequential progress in the form of commodities to purchase. This requires biopower and a conservative view of the human, with inhumanism being viewed as a revolutionary force which promotes the constant upgrading and redefining of humanity. However, Fluss and Frim criticize this for discarding individual human welfare in favor of a larger system of constant technological revision, mirroring Land and making room for human subjugation rather than revolution; they state "It requires no special prescience to see that the 'liquidation of the human' is a prelude to the 'liquidation of human beings.'"[41] Noys posits a tension between left-accelerationism's liberatory tones and the reactionary and elitist tones of its influences such as Nietzsche, stating "the risk of a technocratic elitism becomes evident, as well as the risk we will lose the agency we have gained by aiming to join with the chaotic flux of material and technological forces."[5] |

左翼加速主義 関連項目: 新たな社会主義へ、ポストスカーシティ、アルゴリズムによる統治 左翼加速主義(または左派加速主義)は、ニック・スニチェク、アレックス・ウィリアムズ[5][1][60][41]、レイ・ブラッシエ、レザ・ネガレス タニ、ピーター・ウォルフェンデールらによって提唱されている。[41][14][15] フルスとフリムはこれを「生産技術を民主化することで資本主義を加速的に超越しようとする」ものと特徴づける。[41] 左派加速主義はマーク・フィッシャーの著作、特に彼の「ハウントロジー=憑在論」に依拠している。ノイスは、彼を停滞した新自由主義文化に対抗し、より良 い未来を構築するために過去の未実現の文化的可能性を把握しようとする者と特徴づける[5]。一方ガメスはそのハウントロジー=憑在論を、資本主義が約束 された未来を実現できず未実現の想像のみを残すというランド批判と見なす。[19] フィッシャーは自身のブログ「k-punk」で、加速主義者として資本主義への幻滅を深めていた[1]。ブレア政権下の英国で公共部門に勤め、教師兼労働 組合活動家として活動した経験、そしてCCRUと類似概念を左派的視点から用いると考えたジジェクとの邂逅が背景にある。[34] 同時に彼は伝統的な左翼政治にも苛立ちを覚えた。彼らが活用可能な技術を無視していると考えたからだ。[1] ノイスはフィッシャーの論文「ターミネーター対アバター」を彼の「文化的加速主義」の例として挙げている。[5] ここでフィッシャーは、マルクス主義者が『リビドー経済学』を「労働者が原始的社会秩序の転覆を享受している」と主張した点を批判した一方で、誰も本当に それらに戻りたいとは思っていないと主張した。したがって社会は前資本主義へ回帰するのではなく、資本主義を貫通して超越しなければならない。フィッ シャーはランドの学界左派への攻撃を称賛し、彼らを「出世主義の妨害者」であり「政治を装った小ブルジョワ的利害の冷酷な保護」と評した。またランドの ドゥルーズとガタリ解釈を批判し、多くの点で優れているものの「資本主義理解における逸脱が致命的」だと指摘した。再領土化を想定しないため、資本主義が 「停滞と不変を覆い隠す革新と新しさのシミュレーション」を提供することを予見できなかったと論じた。フレデリック・ジェイムソンの『共産党宣言』解釈を 引用し、「資本主義を歴史上最も生産的であると同時に最も破壊的な瞬間と見なす」と指摘した上で、 彼は(1970年代のフランス思想家たちの観点から)加速主義を反資本主義戦略として主張し、左派の資本主義に対する道徳的批判や「カヌ主義的傾向」は、 資本主義が唯一実行可能なシステムだという物語を助長するだけだと批判した。[25][5] 別の加速主義論考でフィッシャーは「革命的道筋とは、再領土化の反動的エネルギーに対抗する近代化の脱領土化勢力と連帯する道である」と述べた。[21] 我々は、今日の左翼における最も重要な分断は、地方主義・直接行動・徹底した水平主義という民衆政治を堅持する者と、抽象性・複雑性・グローバル性・技術 という近代性に安住する加速主義政治(こう呼ぶべきもの)を提唱する者との間にあると考える。前者は、非資本主義的社会関係の小さな一時的な空間を確立す ることに満足し、本質的に非ローカルで抽象的、かつ我々の日常インフラに深く根ざした敵対者と対峙する際に伴う真の問題を回避する。このような政治の失敗 は最初から組み込まれていた。対照的に、加速主義的政治は、後期資本主義の成果を維持しつつ、その価値体系、統治構造、大衆病理が許容する範囲を超えてい くことを目指す。 ニック・スニチェク、アレックス・ウィリアムズ『#Accelerate:加速主義政治マニフェスト』[33] スニチェクはフィッシャーと親交を深め、同様の見解を共有した。2008年の金融危機と、オキュパイ運動における左派の「非効果的な」対応への不満が重な り、スニチェクは2013年にウィリアムズと共同で『#加速:加速主義政治のためのマニフェスト』を執筆した。[1][33] 彼らは資本主義が当時最も進んだ経済システムであったが、その後は停滞し、今や技術を制約していると主張した。新自由主義はその危機を悪化させるだけだ と。同時に、現代の左派は「新たな政治的イデオロギー的ビジョンを考案できない」と考えた。左派は地域主義や直接行動に過度に集中し、意味ある変化をもた らす適応ができないからだ。彼らは既存の資本主義的インフラを「ポスト資本主義へ飛躍するための踏み台」として活用し、資本主義の技術的・科学的進歩を利 用してプロジェクト・サイバーシンのような経済モデルの実験を行うことを提唱した。また「分散型の水平的社会形態に加え、集団的に管理された正当な垂直的 権威」を主張し、政治的インフラのための資源と資金の獲得を訴えた。これは彼らが非効率とみなす標準的な左翼的政治行動とは対照的である。資本主義の制約 を乗り越えることで技術進歩が再開され、より合理的な社会が創出されるだけでなく、「19世紀半ばから新自由主義時代の夜明けまで多くの人々を魅了した 夢、すなわちホモ・サピエンスが地球の限界と肉体の制約を超越して拡大を目指す探求」が回復されるとした。[32][33] 彼らは『未来を発明する』でさらに展開した。ここでは「加速主義」という用語は使わなかったが、自動化、労働時間の削減と分配、ベーシックインカム、労働 倫理の弱体化を推進した。[1][61][5][62] スティーブン・シャビロは、スニチェクとウィリアムズの提案を、ウォルマートの製品流通技術が共産主義に転用可能だとするジェイムソンの主張と比較した。 シャビロはさらに、左派加速主義は政治的プログラム以前に美的プログラムでなければならないと論じた。なぜなら、フィクションを通じて技術の可能性を探求 しないことは、スニチェクとウィリアムズが望む社会主義的目的のための技術転用ではなく、既存の資本主義的関係の悪化を招く恐れがあるからだ。[18] フィッシャーはこの宣言を称賛し、スニチェクとウィリアムズが批判した「フォーク・ポリティクス」を新アナキスト的であり、従来の左翼的野心を欠いている と特徴づけた。[21] ティツィアーナ・テラノーヴァの『レッド・スタック攻撃!』は『#Accelerate: The Accelerationist Reader』に収録され、ベンジャミン・H・ブラットンのスタック理論を分析する中で本マニフェストを参照し、「レッド・スタック」を「ポスト資本主義 的コモンズの新たなノモス」として提唱した。[63][64] ランドは2017年のガーディアン紙インタビューで彼らの考えを非難し、「自律的に推進する技術が資本主義から分離可能だという考えは、根本的な理論的誤 りだ」と述べた。[1] アーロン・バスタニの『完全自動化による贅沢共産主義』も左派加速主義として注目されている。[65] [66][67] ノイスはこれをスニチェクとウィリアムズの『マニフェスト』における「ユートピア的提案の要請」を継承するものだと特徴づけた。[5] マイケル・E・ガーディナーは『完全自動化贅沢共産主義』『ポスト資本主義:我々の未来へのガイド』『ウォルマート人民共和国』が、サイバネティクスを資 本主義から切り離し解放的目標へ活用するという左派加速主義的信念で結ばれていると指摘する。[60] アレックス・ウィリアムズは、理性能力の最大化と理性の可能性の実現を追求するブラッシエとネガレスタニを「認識論的加速主義の双子の思想家」と呼んだ [68]。サム・セラとデイヴィッド・R・コールは、彼らの著作をウォルフェンデールのものと併せて、資本主義とは異なる合理主義的近代性と技術発展の加 速を追求するものとして特徴づけている。特にブラッシエのプロメテウス主義は、人間変革の基盤として規範的合理主義を加速させる。彼らはマッケイとアヴァ ネシアンによるネガレスタニの解釈を指摘する: [15] 加速は、人間が繰り返し、資本ではなく[理性的な]プログラムによって非人格的に操縦されることを受け入れるとき、そしてその範囲において起こる。このプ ログラムは、人間が集団的修正への統制権を譲渡することを要求し、人間を非人間的な未来へと引き寄せる。その未来は、結局のところ『常に』人間の意味で あったと証明されるだろう。[31] フルスとフリムは、ブラッシエの『解き放たれた虚無』『人間を完全に清算せよ』といった著作、ならびにネガレスタニの『非人間的労働』『サイクロノペディ ア』『知性と精神』を、左派加速主義の哲学的基盤を提供するものと位置づけている。資本主義は進歩を約束しながら、実際には支配を強め、購入可能な商品と いう形での取るに足らない進歩しか提供しない。これはバイオパワーと人間に対する保守的な見解を必要とし、非人間主義は人間性の絶え間ないアップグレード と再定義を促進する革命的力と見なされる。しかしフルスとフリムは、この思想が個人の福祉を犠牲にして技術的改変の巨大システムを優先する点、ランドを反 映しつつ革命ではなく人間の隷属を許容する点を批判する。「『人間の清算』が『人類の清算』の前奏曲であることは、特別な予見力を要さずとも明らかだ」と 彼らは述べる。[41] ノイスは、左派加速主義の解放的トーンと、ニーチェなどの影響源が持つ反動的・エリート主義的トーンとの間に緊張関係があると指摘し、「技術官僚的エリー ト主義の危険性が明らかになるだけでなく、物質的・技術的力の混沌とした流動と融合しようとする過程で獲得した主体性を失う危険性も明らかになる」と述べ ている。[5] |

| Xenofeminism Feminist collective Laboria Cuboniks advocated for the use of technology for gender abolition in "Xenofeminism: A Politics for Alienation", which has been characterized as a form of left-accelerationism.[69][60][41][5] Noys states "The relationship to accelerationism is not direct or discussed in detail, but certainly similar points of reference are shared in a rupture with naturalism and an integration of technology as a site of liberation".[5] Fluss and Frim state "Xenofeminists seek to undermine what they perceive as the basis for essentialism itself: Nature." They note that xenofeminists criticize the sex-gender distinction as still taking biological sex to be natural and immutable, instead rejecting the givenness of biological sex as well.[41] |

ゼノフェミニズム フェミニスト集団ラボリア・クボニクスは「ゼノフェミニズム:疎外のための政治」において、ジェンダー廃止のための技術利用を提唱した。これは左派加速主 義の一形態と特徴づけられている。[69][60][41][5] ノイスは「加速主義との関係は直接的でも詳細に論じられてもいないが、自然主義との決別と解放の場としての技術統合という点で確かに共通の参照点が存在す る」と述べている。[5] フルスとフリムは「ゼノフェミニストたちは、本質主義そのものの基盤と見なすもの、すなわち『自然』を弱体化させようとしている」と指摘する。彼らは、ゼ ノフェミニストが性(sex)とジェンダーの区別を批判している点に言及している。その批判は、生物学的性が依然として自然で不変のものと見なされている 点に向けられており、生物学的性の与えられた性質そのものをも拒否しているのだ。[41] |

| Effective accelerationism Effective accelerationism (abbreviated to e/acc) takes influence from effective altruism, a movement to maximize good by calculating what actions provide the greatest overall/global good and prioritizing those rather than focusing on personal interest/proximity. Proponents advocate for unrestricted technological progress "at all costs", believing that artificial general intelligence will solve universal human problems like poverty, war and climate change, while deceleration and stagnation of technology is a greater risk than any posed by AI. This contrasts with effective altruism (referred to as longtermism to distinguish from e/acc), which tends to consider uncontrolled AI to be the greater existential risk and advocates for government regulation and careful alignment.[70][71] Other views In a critique, Italian Marxist Franco Berardi considered acceleration "the essential feature of capitalist growth" and characterized accelerationism as "point[ing] out the contradictory implications of the process of intensification, emphasizing in particular the instability that acceleration brings into the capitalist system." However, he also stated "my answer to the question of whether acceleration marks a final collapse of power is quite simply: no. Because the power of capital is not based on stability." He posited that the "accelerationist hypothesis" is based on two assumptions: that accelerating production cycles make capitalism unstable, and that potentialities within capitalism will necessarily deploy themselves. He criticized the first by stating "capitalism is resilient because it does not need rational government, only automatic governance"; and the second by arguing that while the possibility exists, it is not guaranteed to happen as it can still be slowed or stopped.[72] In The Question Concerning Technology in China, Yuk Hui critiqued accelerationism, particularly Ray Brassier's "Prometheanism and its Critics", stating "if such a response to technology and capitalism is applied globally, [...] it risks perpetuating a more subtle form of colonialism." He argues that accelerationism's Prometheanism tries to promote Prometheus as a universal technological figure despite other cultures having different myths and relations to technology.[43] Further critiquing Westernization, globalization and the loss of non-Western technological thought, he has also referred to Deng Xiaoping as "the world's greatest accelerationist" due to his economic reforms, considering them an acceleration of the modernization process which started in the aftermath of the Opium Wars and intensified with the Cultural Revolution.[56] Aria Dean articulated a position of "Blacceleration" as a "necessary alternative to right and left accelerationism". Synthesizing racial capitalism with accelerationism, she argued that accelerationism is intrinsically tied to the black experience through capitalism's relationship to slavery, particularly the treatment of slaves as both inhuman capital and human, which is not accounted for in other accelerationist analyses of capitalism. This challenges the accelerationist distinction made between human and capital, in turn challenging their rejection of humanism in favor of an inhuman subject since black people have historically been treated as such a subject; she states "to speak of transversing or travestying humanism in favor of inhuman capital without recognizing the way in which the black is nothing other than the historical inevitability of this transgression—and has been for some time—circularly reinforces the white humanism these thinkers seeks [sic] to disavow."[73] Fluss and Frim state that it emphasizes "the historical exclusion of black people from white humanist discourses, and the historical process whereby capitalism has engendered the 'black nonsubject.'"[41] |

効果的加速主義 効果的加速主義(略称e/acc)は、効果的利他主義の影響を受けている。効果的利他主義とは、個人的な利益や身近な問題に焦点を当てるのではなく、全体 的・地球規模で最大の善をもたらす行動を計算し、それらを優先することで善を最大化しようとする運動である。支持者は「いかなる代償を払っても」技術進歩 を無制限に推進すべきだと主張する。人工汎用知能(AGI)が貧困・戦争・気候変動といった普遍的人類問題を解決すると信じ、技術の減速や停滞こそがAI がもたらすリスクよりも重大な脅威だと考える。これは効果的利他主義(e/accと区別するため長期主義と呼称)とは対照的である。後者は制御不能なAI を最大の存亡リスクと見なし、政府規制と慎重な調整を提唱する。[70][71] その他の見解 イタリアのマルクス主義者フランコ・ベラルディは批判の中で、加速主義を「資本主義的成長の本質的特徴」と位置付け、「加速主義は強化プロセスの矛盾した 含意を指摘し、特に加速が資本主義システムにもたらす不安定性を強調する」と特徴づけた。しかし彼は同時に「加速が権力の最終的崩壊を示すかという問いへ の私の答えは、単純にノーだ。なぜなら資本の力は安定性に基づかないからだ」とも述べている。彼は「加速主義仮説」が二つの前提に基づくと主張した:生産 サイクルの加速が資本主義を不安定化させること、そして資本主義内部の潜在性が必然的に展開されることである。前者を「資本主義は合理的統治を必要とせ ず、自動的統治のみで耐性を持つ」と批判し、後者については「可能性は存在するが、遅延や停止の可能性もあり、必ずしも実現する保証はない」と論じた。 [72] 『中国における技術に関する問い』において、ユク・ホイは加速主義、特にレイ・ブラッシエの「プロメテウス主義とその批判者たち」を批判し、「技術と資本 主義へのこのような対応が世界的に適用されれば、[...]より微妙な形の植民地主義を永続させる危険性がある」と述べた。彼は、加速主義のプロメテウス 主義が、他の文化が異なる神話や技術との関係を持つにもかかわらず、プロメテウスを普遍的な技術的象徴として推進しようとしていると主張する。[43] 西洋化、グローバル化、非西洋的技術思想の喪失をさらに批判し、彼は鄧小平を「世界最大の加速主義者」と呼んだ。その経済改革はアヘン戦争の余波で始まり 文化大革命で激化した近代化プロセスの加速と見なされるからだ。[56] アリア・ディーンは「右派・左派アクセラレーション主義への必要不可欠な代替案」として「ブラックセレーション」の立場を明確にした。人種的資本主義と加 速主義を統合し、資本主義と奴隷制の関係、特に奴隷が非人間的資本かつ人間として扱われた点(他の資本主義分析では考慮されない)を通じて、加速主義が本 質的に黒人体験と結びついていると論じた。これは加速主義が人間と資本を区別する点に異議を唱え、ひいては非人間的主体を支持してヒューマニズムを拒否す る姿勢に疑問を投げかける。なぜなら黒人は歴史的にそのような主体として扱われてきたからだ。彼女は「非人間的資本を優先してヒューマニズムを横断したり 歪めたりすると言いつつ、黒人がこの越境の歴史的必然性に他ならず(そして長い間そうであった)という点を認識しないことは、これらの思想家が否定しよう とする白人ヒューマニズムを循環的に強化する」と述べている。[73] フルスとフリムは、これが「黒人が白人人間主義的言説から歴史的に排除されてきたこと、そして資本主義が『黒人の非主体』を生み出した歴史的過程」を強調 すると述べている。[41] |

| Alternative uses of the term Since accelerationism was coined in 2010, the term has taken on several new meanings. The term has been used to advocate for making capitalism as destructive as possible in order to cause a revolution against it.[74][26][2] Fisher considered this a misunderstanding of left-accelerationism, with such misunderstandings being the reason Srnicek and Williams dropped the term for Inventing The Future.[21] Several commentators have also used the label accelerationist to describe a controversial political strategy articulated by Slavoj Žižek.[75] An often-cited example of this is Žižek's assertion in a November 2016 interview with Channel 4 News that, were he an American citizen, he would vote for U.S. president Donald Trump, despite his dislike of Trump, as the candidate more likely to disrupt the political status quo in that country.[76] Richard Coyne characterized his strategy as seeking to "shock the country and revive the left."[77] Chinese dissidents have referred to Chinese leader Xi Jinping as "Accelerator-in-Chief" (referencing state media calling Deng Xiaoping "Architect-in-Chief of Reform and Opening"), believing that Xi's authoritarianism is hastening the demise of the Chinese Communist Party and that, because it is beyond saving, they should allow it to destroy itself in order to create a better future.[78] In relation to far-right terrorism Since the late 2010s, international networks of neo-fascists, neo-Nazis, white nationalists and white supremacists have increasingly used the term accelerationism to refer to right-wing extremist goals, namely an "acceleration" of racial conflict through violent means such as assassinations, murders, terrorist attacks and eventual societal collapse to achieve the building of a white ethnostate.[11][12][13] The New York Times held far-right accelerationism as detrimental to public safety.[79] The inspiration for this distinct variation is occasionally cited as American Nazi Party and National Socialist Liberation Front member James Mason's newsletter Siege, where he argued for sabotage, mass killings and assassinations of high-profile targets to destabilize and destroy the current society, seen as a system upholding a Jewish and multicultural New World Order.[11] His works were republished and popularized by the Iron March forum and Atomwaffen Division, right-wing extremist organizations strongly connected to various terrorist attacks, murders and assaults.[11][80][81][82] Far-right accelerationists have also been known to attack critical infrastructure, particularly the power grid, attempting to cause a collapse of the system or believing that 5G was causing COVID-19. Some have encouraged the promotion of 5G conspiracy theories as easier than convincing potential recruits that the Holocaust never happened.[83][84] According to the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), which tracks hate groups and files class action lawsuits against discriminatory organizations and entities, "on the case of white supremacists, the accelerationist set sees modern society as irredeemable and believe it should be pushed to collapse so a fascist society built on ethnonationalism can take its place. What defines white supremacist accelerationists is their belief that violence is the only way to pursue their political goals."[82] Brenton Harrison Tarrant, the perpetrator of the 15 March 2019 Christchurch mosque shootings that killed 51 people and injured 49 others, strongly encouraged right-wing accelerationism in a section of his manifesto titled Destabilization and Accelerationism: Tactics. Tarrant's manifesto influenced John Timothy Earnest, the perpetrator of both the 24 March 2019 Escondido mosque fire at Dar-ul-Arqam Mosque in Escondido, California, and the 27 April 2019 Poway synagogue shooting which resulted in one dead and three injured.[8] Patrick Crusius, the perpetrator of the 3 August 2019 El Paso Walmart shooting that killed 23 people and injured 23 others was influenced by Tarrant as well.[8] Tarrant and Earnest, in turn, influenced Juraj Krajčík, the perpetrator of the 2022 Bratislava shooting that left dead two patrons of a gay bar.[85][11][8] Zack Beauchamp pointed to Land's shift towards neoreactionarism, along with the neoreactionary movement crossing paths with the alt-right as another fringe right wing internet movement, as the likely connection point between far-right racial accelerationism and the term for Land's otherwise unrelated technocapitalist ideas. They cited a 2018 Southern Poverty Law Center investigation which found users on the neo-Nazi blog The Right Stuff who cited neoreactionarism as an influence.[8] Land himself became interested in the Atomwaffen-affiliated theistic Satanist organization Order of Nine Angles (ONA) which adheres to the ideology of Neo-Nazi terrorist accelerationism, describing the ONA's works as "highly-recommended" in a blog post.[86] Since the 2010s, the political ideology and religious worldview of the Order of Nine Angles, supposedly founded by the British neo-Nazi leader David Myatt in 1974,[11] have increasingly influenced militant neo-fascist and neo-Nazi insurgent groups associated with right-wing extremist and white supremacist international networks,[11] most notably the Iron March forum.[11] |

用語の代替用法 加速主義が2010年に提唱されて以来、この用語はいくつかの新たな意味を獲得してきた。資本主義を可能な限り破壊的にし、それに対する革命を引き起こす ことを提唱するために用いられてきたのである。[74][26][2] フィッシャーはこれを左派加速主義に対する誤解と見なし、こうした誤解こそがスニチェクとウィリアムズが『未来を発明する』においてこの用語を放棄した理 由だと考えた。[21] また、複数の評論家が、スラヴォイ・ジジェクが提唱する物議を醸す政治戦略を表すために「加速主義者」というレッテルを使用している。[75] この例としてよく引用されるのは、2016年11月のチャンネル4ニュースのインタビューで、ジジェクが「もし自分がアメリカ市民だったら、トランプを 嫌っているにもかかわらず、アメリカの現状を打破する可能性が高い候補者として、ドナルド・トランプ大統領に投票するだろう」と述べたことだ。[76] リチャード・コインは、この戦略を「国に衝撃を与え、左翼を復活させる」ことを目指したものだと評している。[77] 中国の反体制派は、中国の指導者である習近平を「最高加速者」(国営メディアが鄧小平を「改革開放の最高設計者」と呼んだことにちなんで)と呼んでいる。 彼らは、習の権威主義が中国共産党の終焉を早めており、もはや救いようがないため、より良い未来を築くために、共産党が自らを破壊することを許すべきだと 考えているのだ。[78] 極右テロリズムとの関係 2010年代後半以降、ネオファシスト、ネオナチ、白人ナショナリスト、白人至上主義者からなる国際ネットワークは、右派過激派の目標を指す言葉として 「加速主義」を頻繁に用いるようになった。具体的には、暗殺、殺人、テロ攻撃といった暴力手段による人種紛争の「加速」、そして最終的な社会崩壊を通じて 白人民族国家の建設を達成することを意味する。[11] [12][13] ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙は、極右加速主義が公共の安全を損なうと指摘した。[79] この特異な変種の起源として、アメリカ・ナチ党および国家社会主義解放戦線メンバーであるジェームズ・メイソンのニュースレター『包囲』が時折引用され る。同書では、ユダヤ系かつ多文化的な新世界秩序を支える体制と見なされる現行社会を不安定化・破壊するため、破壊工作、大量殺戮、重要人物暗殺を主張し ていた。[11] 彼の著作は、数々のテロ攻撃・殺人・暴行事件と深く関わる極右組織「アイアン・マーチ」フォーラム及び「アトムヴァッフェン・ディヴィジョン」によって再 出版され普及した。[11][80][81][82] 極右加速主義者は重要インフラ、特に電力網への攻撃も行っており、システムの崩壊を引き起こそうとするか、5GがCOVID-19を引き起こしていると信 じている。ホロコーストが起きなかったと新入りに信じ込ませるより、5G陰謀論を広める方が簡単だと主張する者もいる。[83][84] ヘイトグループを追跡し差別的組織・団体に対する集団訴訟を提起する南部貧困法律センター(SPLC)によれば、「白人至上主義者の場合、加速主義者集団 は現代社会を救いようのないものと見なし、民族国家主義に基づくファシスト社会が取って代わるよう、崩壊へと追い込むべきだと信じている。白人至上主義加 速主義者を特徴づけるのは、暴力こそが彼らの政治目標を達成する唯一の方法だという信念だ。」[82] 2019年3月15日に51人を殺害、49人に負傷を負わせたクライストチャーチ・モスク銃乱射事件の犯人ブレントン・ハリソン・タラントは、自身のマニ フェスト「不安定化と加速主義:戦術」と題した部分で、右派の加速主義を強く推奨していた。タラントの宣言書は、2019年3月24日にカリフォルニア州 エスコンディードのダル・アル・アルカム・モスクで発生したモスク放火事件と、2019年4月27日に1名の死者・3名の負傷者を出したパウエイ・シナ ゴーグ銃撃事件の両方の実行犯であるジョン・ティモシー・アーネストに影響を与えた。[8] 2019年8月3日にエルパソのウォルマートで発生した銃乱射事件(死者23名、負傷者23名)の犯人パトリック・クルーシャスもまた、タラントの影響を 受けていた。[8] タラントとアーネストはさらに、2022年にブラチスラバでゲイバーの客2名を殺害した銃乱射事件の犯人ユライ・クライチクに影響を与えた。[85] [11][8] ザック・ビーチャムは、ランドのネオリアクション主義への移行と、ネオリアクション運動が別の極右インターネット運動であるオルタナ右翼と交差した点を、 極右人種加速主義とランドのそれ以外の技術資本主義思想を結びつける可能性のある接点として指摘した。彼らは2018年の南部貧困法律センター調査を引用 し、ネオナチ系ブログ「ザ・ライト・スタッフ」のユーザーがネオリアクション主義を影響源として言及していた事実を指摘した。ランド自身は、ネオナチ系テ ロリスト加速主義のイデオロギーを奉じるアトムヴァッフェン関連の神学的サタニスト組織「九角の秩序(ONA)」に関心を示し、ブログ記事でONAの著作 を「強く推奨する」と評した。[86] 2010年代以降、1974年に英国のネオナチ指導者デイヴィッド・マイアットが創設したとされるナイン・アングルズ教団の政治イデオロギーと宗教的世界 観は、右翼過激派や白人至上主義の国際ネットワークに関連する過激なネオファシスト・ネオナチ反乱組織、特にアイアン・マーチ・フォーラムにおいて、ます ます影響力を強めている。 |

| Accelerating Change Creative destruction – Concept in economics Christian Identity – Revolutionary violence Ecofascism – Association with violence Futures studies Great Acceleration – Proposed geologic epoch Non-simultaneity – Concept of uneven temporal development in the writings of Ernst Bloch and Marxist theories Speculative realism – Movement in contemporary Continental-inspired philosophy Strategy of tension – Political policy encouraging violent struggle Terrorgram – Network of neo-fascist Telegram channels Time–space compression – Idea in space–time |

加速する変化 創造的破壊 – 経済学における概念 キリスト教アイデンティティ – 革命的暴力 エコファシズム – 暴力との関連性 未来学 グレート・アクセラレーション – 提案された地質時代 非同時性 – エルンスト・ブロッホやマルクス主義理論における不均等な時間的発展の概念 思弁的リアリズム – 現代の大陸哲学に影響を受けた運動 緊張戦略 – 暴力闘争を助長する政治政策 テログラム – 新ファシスト系テレグラムチャンネルのネットワーク 時空間圧縮 – 時空間における概念 |

| References |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Accelerationism |

|

★

日本語ウィキペディア

| 加速主義(か

そくしゅぎ、英:

accelerationism)とは、既存のシステム内を不安定化し根本的な社会的変革を生み出すために、現行の資本主義システムの過激な成長、急進的

な技術革新あるいは各種インフラの解体といった、「加速」と称される社会変革プロセスの過激化を要求する左翼に起源を持つ右翼的な革命的反動思想である

[1][2][3][4][5]。加速主義は、相矛盾する左派と右派の派生に分かれたイデオロギーのスペクトルとみなされており、どちらも資本主義とその

構造の上界無き強化、およびテクノロジーの成長が制御不能かつ不可逆的になる技術的特異点(仮説的時点)への到達を支持している[6][7][8]

[9]。 現代の加速主義的哲学の一部は、広範囲にわたる社会変革の可能性を抑制する相反する傾向を克服することを目的として、脱領土化(英語版)の力を特定し、そ れを深め、急進化することを目的としたジル・ドゥルーズとフェリックス・ガタリの脱領土化の理論に依拠している[10]。ジャン・ボードリヤールの「致命 的戦略」や、イギリスの哲学者で後の暗黒啓蒙の論者であるニック・ランドによって発明された理論体系も加速主義に大きな影響を与えている[1]。 ニック・ ランドの体系は「加速」のプロセスを構成する社会的、経済的、文化的、リビード的な力を分析し、それを促進することを目的としている[11]。 【加速主義】「資本主義の矛盾を徹底的に加速させることで新たな社会秩序を生み出す」 を中核とする政治思想。テクノロジーと資本の暴走を肯定的に解釈する点に特徴。  |

|

| 概要 この用語は元々極左に起源を持ちその中で利用されていたが、本来の加速主義とは明確に区別された形で、ネオファシスト、ネオナチ、白人ナショナリスト、白 人至上主義者といった極右によって使用されるようになり、暴力的意味合いを増した。極右においての「加速」は、白人エスノステートを暴力的に達成する手段 であり、暗殺、殺人、テロ攻撃などによる人種対立の「加速」を意味している[12][13][14][15]。 「加速」は主に産業経済にコミットする政治戦略だが、最近では道徳と人工知能に関する議論でも用いられる。ホイ・ユクとLouis Moreleは、「加速」と「シンギュラリティ仮説」を検討している[16]。 James Brusseauは、人工知能イノベーションによって引き起こされる道徳的ジレンマが、テクノロジーの制限や遅延によってではなく、さらなるイノベーショ ンによって解決されるというイノベーションの倫理としての「加速」について論じている[17]。効果的加速主義 (e/acc) として知られる運動は、「どんな犠牲を払ってでも」技術を進歩させることを主張している[18]。 日本においては、加速主義がマルクス主義の革命理論などと混同されてきた。資本主義を深化させることは自己破壊的な傾向を早め、最終的にはその崩壊につな がるという信念を一般的に指す言葉として、通常は侮蔑語として用いられる[19][20]。すなわち、テクノロジーの諸手段を介して資本主義の「プロセス を加速せよ」、そしてこの加速を通じて「未来」へ、資本主義それ自体の「外 (the Outside)」へと脱出せよというメッセージとして認識されている。 かつて、ニック・ランドなど主流派の加速主義を指す際に、右派加速主義という表現が用いられていた[21]が、現在では加速主義とは本質的に右派的な思想 であるため、用いられなくなりつつある。また、無条件的加速主義は、右派、左派と並ぶ第三勢力のようにして日本では紹介されてきたが[21]、今日では単 なる(右派)加速主義のサブセットとみなされることが多くなっている。このことから現在の思想における加速主義は、(右派)加速主義と左翼(左派)加速主 義の二つに大別される。 思想的系譜 マルクスの「資本論」:資本主義の自己崩壊理論 ドゥルーズ=ガタリ:『アンチ・オイディプス』の「脱コード化」概念 SF的想像力:イーファン・モリス「加速主義宣言」(2013) 批判的視点 技術決定論的偏向:社会関係の変革を軽視 新自由主義との親和性:市場原理の過剰拡大を助長 倫理的危険性:現存する弱者犠牲を正当化 日本文脈での展開 プラットフォーム資本主義批判:宇野常寛らによる「ゼロ年代の想像力」との接合 ポスト働き方改革:AI導入加速が労働疎外を深化させる矛盾 補足 加速主義は現代デジタル資本主義のパラドクス(例:自動化が失業を生むがUBI議論を喚起)を考える上で重要な視座を提供する。ただしその実践には、技術 の民主的統制という課題が常に付随する。 |

|

| 背景 1848年の「自由貿易問題についての演説」と題する演説におけるカール・マルクスを含め、多くの哲学者が明らかに加速主義的態度を表明している。 しかし、総じて、今日の保護貿易制度は保守的である一方で、自由貿易制度は破壊的です。自由貿易制度は古い国民を解体し、プロレタリアートとブルジョア ジー間の敵対心を極限まで押し進めます。一言で言えば、自由貿易制度は社会革命を促進するのです。この革命的な意味においてのみ、みなさん、私は自由貿易 を支持して投票するのです[22]。 同様に、フリードリヒ・ニーチェも次のように述べている。「ヨーロッパ人の平準化プロセスは、咎められるべきではない素晴らしいプロセスだ。これはむしろ 加速されるべきである…」[23]。この言明はしばしば、ドゥルーズ=ガタリにならって、「プロセスを加速する」命令だと解釈される[24]。 |

|

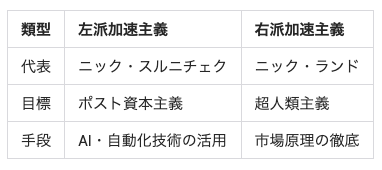

| 現代の加速主義 著名な理論家の一人に、「加速主義の父」[25]とも呼ばれている右派加速主義者のニック・ランド(Nick Land)がいる[26]。1995年から2003年にかけてウォーリック大学の非公式研究ユニットとして活動したサイバネティック文化研究ユニット (Cybernetic Culture Research Unit, CCRU)[27]には、ランドも加盟していたが、これが左派と右派両方の加速主義思想における重要な先祖と考えられている[28]。 現代の著名な左派加速主義者には、インターネット上で発表した「加速派政治宣言(Manifesto for an Accelerationist Politics)」[29]の著者であるニック・スルニチェク(Nick Srnicek)とアレックス・ウィリアムズ(Alex Williams)、そして「ゼノフェミニズム:疎外の政治学(Xenofeminism: A Politics for Alienation)」を書いたラボリア・クーボニクス(Laboria Cuboniks)コレクティブが含まれる[30]。 アレックス・ウィリアムスとニック・スルニチェク(Alex Williams and Nick Srnicek)によるマニフェストが現在公開されている。 #ACCELERATE MANIFESTO for an Accelerationist Politics 加速主義的な論調のもと、ポール・メイソン(Paul Mason)は著書『ポスト資本主義:未来へのガイド(PostCapitalism: A Guide to our Future)』において、資本主義の後の未来について思弁を試みた。彼は次のように宣言する。「500年前の封建主義の終焉とともに、資本主義のポスト 資本主義への置き換えは外的衝撃によって加速され、新しい種類の人間の出現によって形作られるだろう。そしてこの動きはすでに始まっている」。共同生産 (collaborative production)の台頭が、結果的に資本主義の自壊を促進すると彼は考えている。 ベンジャミン・H・ブラットン(Benjamin H. Bratton)の著書『スタック:ソフトウェアと主権について(The Stack:On Software and Sovereignty)』も加速主義に関連している。彼は同書にて、情報技術インフラストラクチャが現代の政治地理学をどのように弱体化させるかに焦点 を当て、オープンエンドの「デザインブリーフ」を提案している。ティツィアナ・テラノヴァ(Tiziana Terranova)の「赤いスタックの攻撃!(Red Stack Attack!)」[31]はブラットンのスタックモデルと左派加速主義をリンクしている。 |

|

| 他の用法 「加速主義」という語が2010年に造語されて以来、幾つかの新しい用法が加えられた。とりわけ、極右過激主義やテロ組織[32]が、この語を煽情的に取 り上げている。評論家には、スロベニア人のフロイト=マルクス主義者である哲学者、スラヴォイ・ジジェクの論争を生んだ政治戦略の議論にレッテルを貼るた めに使う人物も存在する[33][34]。しばしば引用される例として、2016年11月のチャンネル4ニュースでのインタビューで、ジジェクが、「仮に 自分がアメリカ人だとしたら、ドナルド・トランプ大統領に投票しただろう。何故ならば、最もアメリカ政治の現状を破壊してくれそうだからだ」と主張したこ とに対して使われている[35]。第1次トランプ政権で首席戦略官を務めたスティーブン・バノンは、第2次トランプ政権で「影の大統領」とも評されたテッ ク右派実業家・発明家のイーロン・マスクをアメリカに破壊的な影響をもたらす「トップクラスの加速主義者」と批判している[36]。 |

|

| 極右「加速主義」テロリズム 元来の哲学的、理論的関心にもかかわらず、2010年代後期以来、ネオファシストや、ネオナチ、白人ナショナリズム、白人至上主義などの国際的ネットワー クの中で、「加速主義」が使われることが増加してきた。彼らは、「加速主義」を「極右過激主義の目標」として引用している。つまり、白人エスノステートを 建設するために、例えば、暗殺、殺人、テロ攻撃、最終的な社会の破壊などといった、暴力的手段を用いて行う人種間闘争を志向することを意味して「加速主 義」を引用しているということが知られている[37][38][39]。 |

|

| 「加速主義」団体 アトムヴァッフェン・ディビジョン[40] ザ・ベース[41] Combat 18[42][43][44] マンソン・ファミリー[45][46] 北欧抵抗運動[47][48][49] Order of Nine Angles[50] ロシア帝国運動[51] |

|

| 書籍 Land, Nick (2011). Brassier, Ray; Mackay, Robin. eds. Fanged Noumena. Urbanomic. ISBN 9780955308789 Mackay, Robin, ed (2014). #ACCELERATE: The Accelerationist Reader. Urbanomic. ISBN 9780957529557 Noys, Benjamin (2013). Malign Velocities: Accelerationism and Capitalism. Zero Books. ISBN 9781782793007 Srnicek, Nick; Williams, Alex (2015). Inventing the Future. Postcapitalism and a World without Work. Verso Books. ISBN 9781784780982 ポール・メイソン『ポストキャピタリズム-資本主義以後の世界』(佐々とも訳)、東洋経済新報社、2017年 マーク・フィッシャー『資本主義リアリズム』セバスチャン・ブロイ+河南瑠莉訳、堀之内出版、2018年 マーク・フィッシャー『ポスト資本主義の欲望』大橋完太郎訳、左右社、2022年 『現代思想』2019年6月号 特集「加速主義」、青土社 ニック・スルニチェク+アレックス・ウィリアムズ「加速派政治宣言」、水嶋一憲+渡邉雄介訳、『現代思想 2018年1月号 特集=現代思想の総展望 2018』、青土社、2017年 木澤佐登志『ニック・ランドと新反動主義 現代世界を覆う〈ダーク〉な思想』、星海社新書、2019年 ニック・ランド『暗黒の啓蒙書』(五井健太郎訳)、講談社、2020年 アーロン・バスターニ(英語版)『ラグジュアリーコミュニズム』(橋本智弘訳)、堀之内出版、2021年 ニック・ランド『絶滅への渇望:ジョルジュ・バタイユと伝染性ニヒリズム』(五井健太郎訳)、河出書房新社、2022年 ニック・スルニチェク『プラットフォーム資本主義』大橋完太郎+居村匠訳、人文書院、2022年 |

|

| 文 Brassier, Ray (2014年2月13日). “Wandering Abstraction”. Mute. 2019年4月3日閲覧。 Brennan, Eugene (12 August 2013). “"Debate is Idiot Distraction": Accelerationism and the Politics of the Internet”. 3:AM Magazine. Land, Nick.“Meltdown”. 2012年4月8日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2013年12月10日閲覧。 . Moreno, Gean (2012). “Notes on the Inorganic, Part I: Accelerations”. E-flux 2019年4月3日閲覧。. Negri, Antonio (2014). “Reflections on the "Manifesto for an Accelerationist Politics"”. E-flux. オリジナルの2015-02-05時点におけるアーカイブ。 2015年2月5日閲覧。. Pasquinelli, Matteo (2014年6月9日). “The Labour of Abstraction: Theses on Marxism and Accelerationism”. 2019年4月3日閲覧。 Power, Nina (2015). “Decapitalism, Left Scarcity, and the State”. Fillip 2019年4月3日閲覧。. Wark, McKenzie (2013年). “#Celerity: A Critique of the Manifesto for an Accelerationist Politics”. 2019年4月3日閲覧。 “#ACCELERATE MANIFESTO for an Accelerationist Politics”. Critical Legal Thinking (2013年5月14日). 2019年4月3日閲覧。 Wolfendale, Peter (2014年). “So, Accelerationism, what's all that about?”. Dialectical Insurgency. 2019年4月3日閲覧。 『現代思想43のキーワード』2019年5月臨時増刊号、青土社「加速主義」仲山ひふみ “樋口恭介【備忘】加速主義覚え書き.2019”. 2019年6月6日閲覧。[リンク切れ] |

|

| https://x.gd/4Usf9 |

|

★ ニック・ランド

| Nick Land (born 14

March 1962) is an English philosopher best known for popularising the

ideology of accelerationism.[2] His work has been tied to the

development of speculative realism,[3][4] and departs from the formal

conventions of academic writing, incorporating unorthodox and esoteric

influences.[5] Much of his writing was anthologized in the 2011