文化変容

acculturation,

Akkulturation

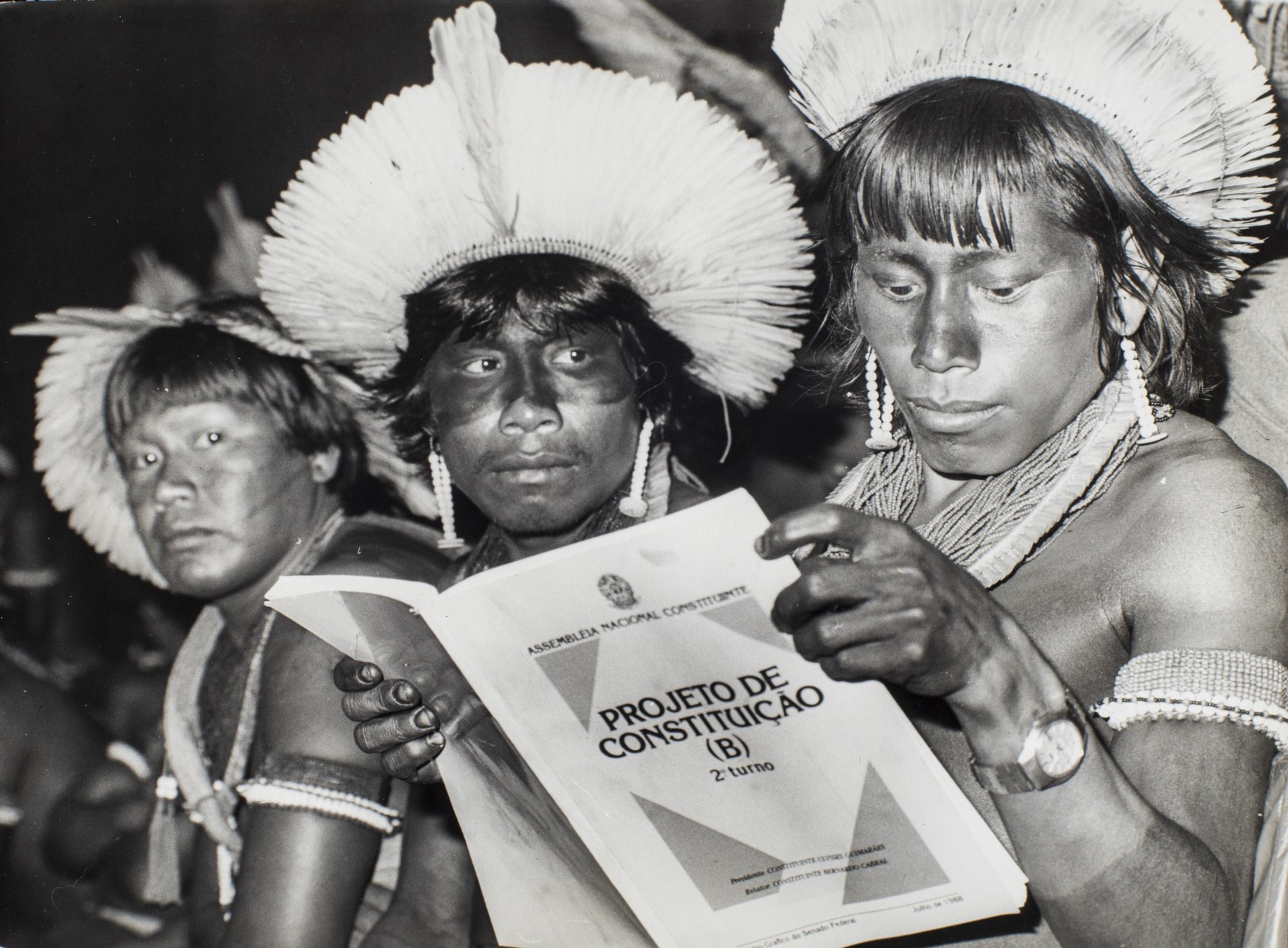

Indigene

Kayapos aus Brasilien (1988): Sichtbare Akkulturation.

☆文化変容(Acculturation)

とは、社会の主流文化に適応しながら2つの文化のバランスを取ることで生じる、社会的、心理的、文化的な変化のプロセスである。文化変容とは、個人が新し

い文化に置かれること、あるいは他の文化が誰かにもたらされることによって、新しい文化的環境を受け入れ、習得し、適応していく過程である。 [1]

異なる文化を持つ個人は、伝統などより一般的な文化の側面に参加することで、新しいより一般的な文化に自分自身を組み込もうとするが、同時に元々の文化的

価値観や伝統も維持しようとする。同化の影響は、主流文化の信奉者と、その文化に同化している人々の双方において、複数のレベルで確認することができる。

この集団レベルでは、同化はしばしば文化、宗教的慣習、保健医療、その他の社会制度の変化をもたらす。また、主流文化に触れる人々の食生活、服装、言語に

も大きな影響がある。

個人レベルでは、文化適応のプロセスとは、外国生まれの個人が、包括的なホスト文化の価値観、習慣、規範、文化的態度、行動様式を融合させる社会化プロセ

スを指す。このプロセスは、日常行動の変化だけでなく、心理的および身体的健康の多くの変化にも関連している。文化習得が第一文化学習のプロセスを説明す

るのに使われるように、文化適応は第二文化学習と考えることができる。

今日の社会で一般的に見られる通常の状況下では、文化同化のプロセスは通常、数世代にわたって長い時間をかけて起こる。文化同化のいくつかの事例では物理

的な力が作用し、より急速に起こることもあるが、それはプロセスの主な要素ではない。より一般的には、そのプロセスは社会的圧力や、より広く浸透している

ホスト文化への継続的な接触を通じて起こる。

| Akkulturation

(von lateinisch ad und cultura: „Hinzuführung zu einer Kultur“[1])

bezieht sich als weit gefasster Oberbegriff auf alle Anpassungsprozesse

von Personen oder sozialen Gruppen an eine Kultur in Hinsicht auf

Wertvorstellungen, Sitten, Brauchtum, Sprache, Religion, Technologie

und anderes. Der Begriff wird je nach Fachgebiet unterschiedlich

definiert, eine verbindliche Definition gibt es nicht. Im Wesentlichen

werden zwei unterschiedliche Begriffsbestimmungen in den

Sozialwissenschaften und demgegenüber in Psychologie und Pädagogik

verwendet. |

文化変容(ラ

テン語のadとculturaに由来する:「文化への参加」[1])とは、個人または社会集団が価値観、習慣、伝統、言語、宗教、技術、その他の側面にお

いて文化に適応するすべてのプロセスを指す広義の用語である。この用語は、研究分野によって定義が異なり、統一された定義はない。本質的には、社会科学と

対照的に心理学や教育では、2つの異なる定義が用いられている。 |

| Sozialwissenschaften Insbesondere in Anthropologie und Ethnologie werden die wechselseitigen Anpassungsprozesse bei der Begegnung zweier unterschiedlicher Kulturen als Akkulturation bezeichnet.[2] Dabei werden fremde geistige oder materielle Kulturgüter übernommen. Dieser Kulturwandel kann sowohl Einzelpersonen als auch ganze Gruppen betreffen. Der Ethnologe Richard Thurnwald beschrieb die Akkulturation als eine Form des sozialen Lernens. Er betonte dabei die Veränderung von Einstellungen und Verhalten sowie die Prägung der Persönlichkeit.[3] Akkulturation entsteht einerseits durch ungeregelte, defensive Kontakte, bei denen die Beteiligten vollkommen frei entscheiden, ob sie sich von einem Wandel wirtschaftliche Vorteile oder eine anderweitige Bereicherung versprechen. Es ist eine bewusste Auseinandersetzung mit den Eigenarten des Fremden im Vergleich mit der eigenen Kultur und der Bereitschaft zur Veränderung der eigenen Verhaltensweisen.[4] Der zweite Weg zur Akkulturation entsteht durch gezielte, offensive Maßnahmen der dominanteren Kultur (häufig mit der Absicht der Integration in das eigene Gesellschafts- und Wirtschaftssystem oder auch der vollständigen Assimilation der dominierten Kultur). Solche Maßnahmen werden mit mehr oder weniger Druck ausgeführt: entweder direkt durch Gewaltandrohung, Zwangserziehung, Erpressung u. ä. oder indirekt durch freiwillige Bildungsangebote, wirtschaftliche Anreize u. ä. Dabei sind die Vorbehalte oder Widerstände der Dominierten naturgemäß größer als bei der vollkommen freiwilligen Annäherung. Intensität, Richtung und Tempo des Akkulturationsprozesses hängen in erster Linie von der Motivation der dominierten Menschen ab: Je aktiver, bewusster und engagierter sie sich eigene Entwicklungsziele stecken, desto schneller, selbstbestimmter – und damit zumeist vorteilhafter – geht der Wandel vonstatten. Je passiver, unbewusster und gleichgültiger sie den Veränderungen gegenüber sind, desto langsamer und fremdbestimmter der Wandel. Politische Entwicklungsprogramme mit dem Ziel einer gelenkten Akkulturation lokaler Gemeinschaften scheitern häufig sowohl an der vorgenannten Eigendynamik der Dominierten (die entweder zu selbstständig oder zu ablehnend reagieren), als auch an den unkalkulierbaren Einflüssen anderer Akteure mit jeweils eigenen Interessen (Wirtschaftsunternehmen, Missionare, andere Staaten, supranationale Organisationen, Nichtregierungsorganisationen, Ethnologen, Touristen u. v. a.), die den Menschen fast immer diverse Alternativen bieten. In der öffentlichen Debatte wird die Akkulturation von „Stammesvölkern“ überwiegend mit negativen Begleiterscheinungen in Verbindung gebracht: kulturelle Entwurzelung und Zerfall der Gemeinschaften mit Apathie und Resignation, Werteverfall, Kriminalität, Generationenkonflikte, Alkoholismus, Drogenkonsum, Diskriminierung, wirtschaftliche Abhängigkeit uvm. Je größer die kulturellen Unterschiede und je aggressiver der Druck der dominanten Kultur, desto größer ist das Risiko für solch negative Entwicklungen.[2] Entscheidend für das Ausmaß der Akkulturation ist schlussendlich die Dauer und Intensität des Kontaktes. Eroberung und Kolonialismus sind dabei die extremsten Formen.[5]  Eine Familie der Schitsu'umsh-Indianer in ihrem Automobil (1916): Bildhafter Ausdruck von Akkulturation. Partielle Akkulturation gab und gibt es unter indigenen Völkern in mannigfacher Form bei sozialen Gruppen und Individuen. |

社会科学 特に人類学や民族学では、異なる2つの文化が出会った際に起こる相互適応プロセスを「文化変容」と呼ぶ。[2] このプロセスでは、外国の知的または物質的文化遺産が取り入れられる。この文化の変化は個人および集団全体に影響を与える可能性がある。 民族学者のリチャード・ターンワルドは、文化変容を社会学習の一形態と表現した。彼は、態度や行動の変化、および人格形成を強調した。[3] 一方、無秩序で防衛的な接触を通じて文化変容が起こる場合、参加者は変化から経済的利益やその他の恩恵を期待するかどうかを完全に自由に決定する。これ は、自文化と比較した外国の特異性に対する意識的な対峙であり、自らの行動パターンを変える意欲である。 文化変容を達成する2つ目の方法は、支配的文化による、対象を絞った攻撃的な手段である(支配的文化が被支配的文化を自国の社会経済システムに統合する、 あるいは完全に同化させる意図を持つ場合が多い)。こうした措置は、暴力の脅威、強制教育、恐喝などによる直接的な圧力、あるいは自主的な教育プログラム や経済的インセンティブなどによる間接的な圧力など、さまざまな程度の圧力によって実施される。当然ながら、被支配者の保留や抵抗は、完全に自主的なアプ ローチの場合よりも大きい。 文化変容プロセスの強度、方向性、速度は、被支配者の動機に主に依存する。被支配者がより積極的に、意識的に、献身的に自らの発展目標を設定すればするほ ど、変化はより速く、より自己決定され、したがって通常はより有利になる。被支配者が変化に対してより受動的で、無意識で、無関心であればあるほど、変化 は遅くなり、より外部から決定されることになる。 現地コミュニティの計画的な文化変容を目的とした政治開発プログラムは、前述の被支配者の勢い(過剰な自主性または過剰な否定的反応)により、しばしば失 敗に終わる。また、 独自の利害関係を持つ他のアクター(企業、宣教師、他国、超国家組織、非政府組織、民族学者、観光客など)による予測不可能な影響も挙げられる。これらの アクターは、ほぼ常に人々にさまざまな選択肢を提供している。 公共の議論では、「部族民」の文化同化は、否定的な副作用と関連付けられることが多い。すなわち、無関心や諦めによる文化的な根絶やコミュニティの崩壊、 価値観の低下、犯罪、世代間の対立、アルコール依存症、薬物使用、差別、経済的依存などである。文化的な違いが大きく、支配文化の圧力が強ければ強いほ ど、こうした否定的な展開のリスクも高まる。 結局のところ、接触の期間と強度が文化同化の程度を決定する。征服と植民地主義は、この最も極端な形態である。[5]  1916年、自動車に乗るシュティツムシュ族の家族:文化同化の鮮明な表現。社会集団や個人の中で、先住民の間では部分的な文化同化がさまざまな形で存在 し、現在も存在し続けている。 |

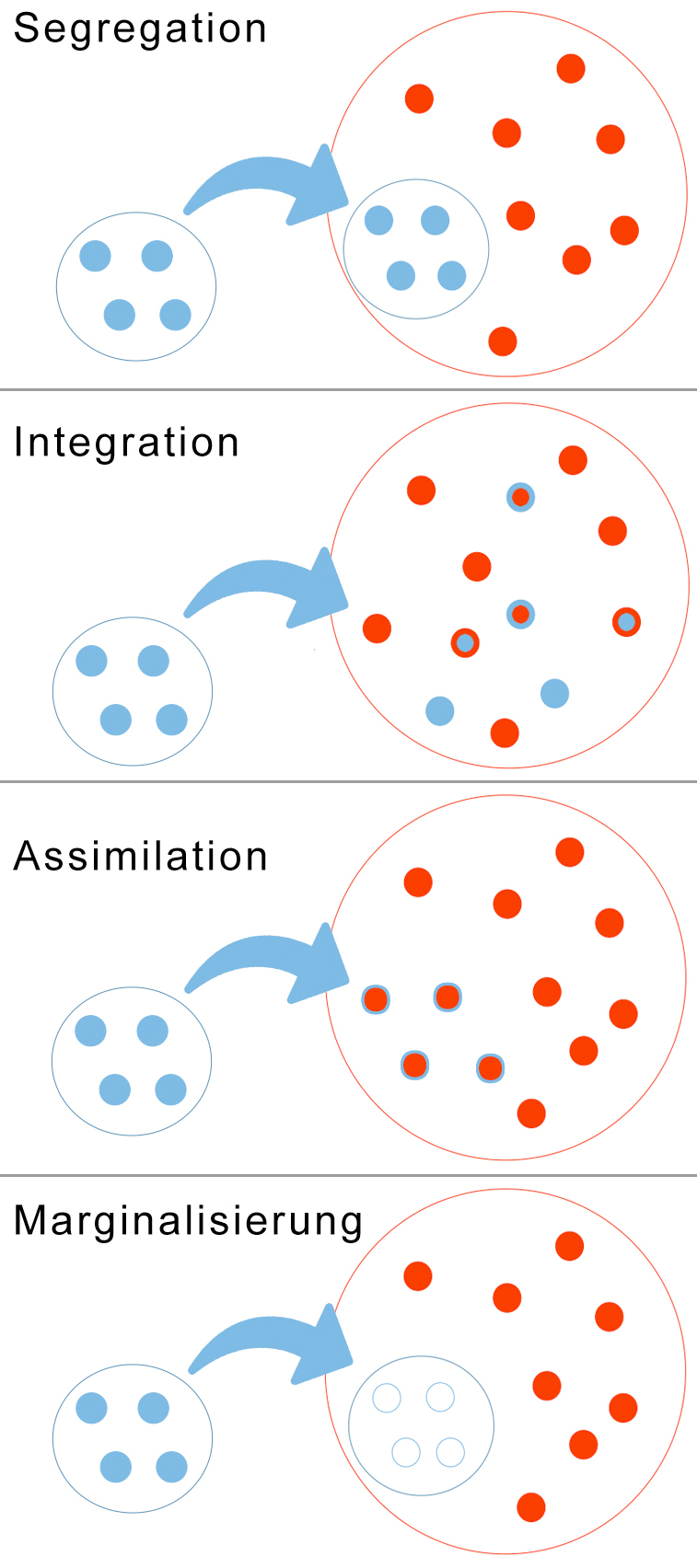

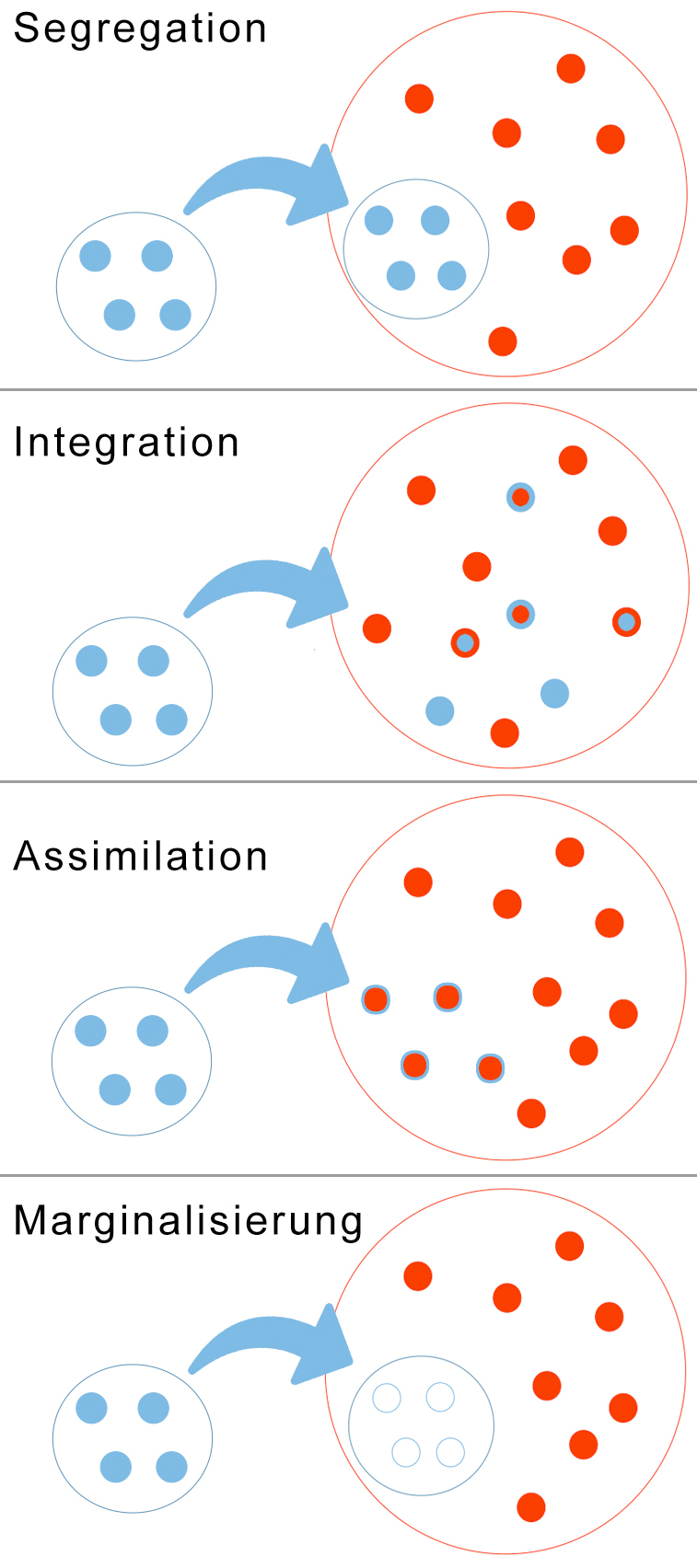

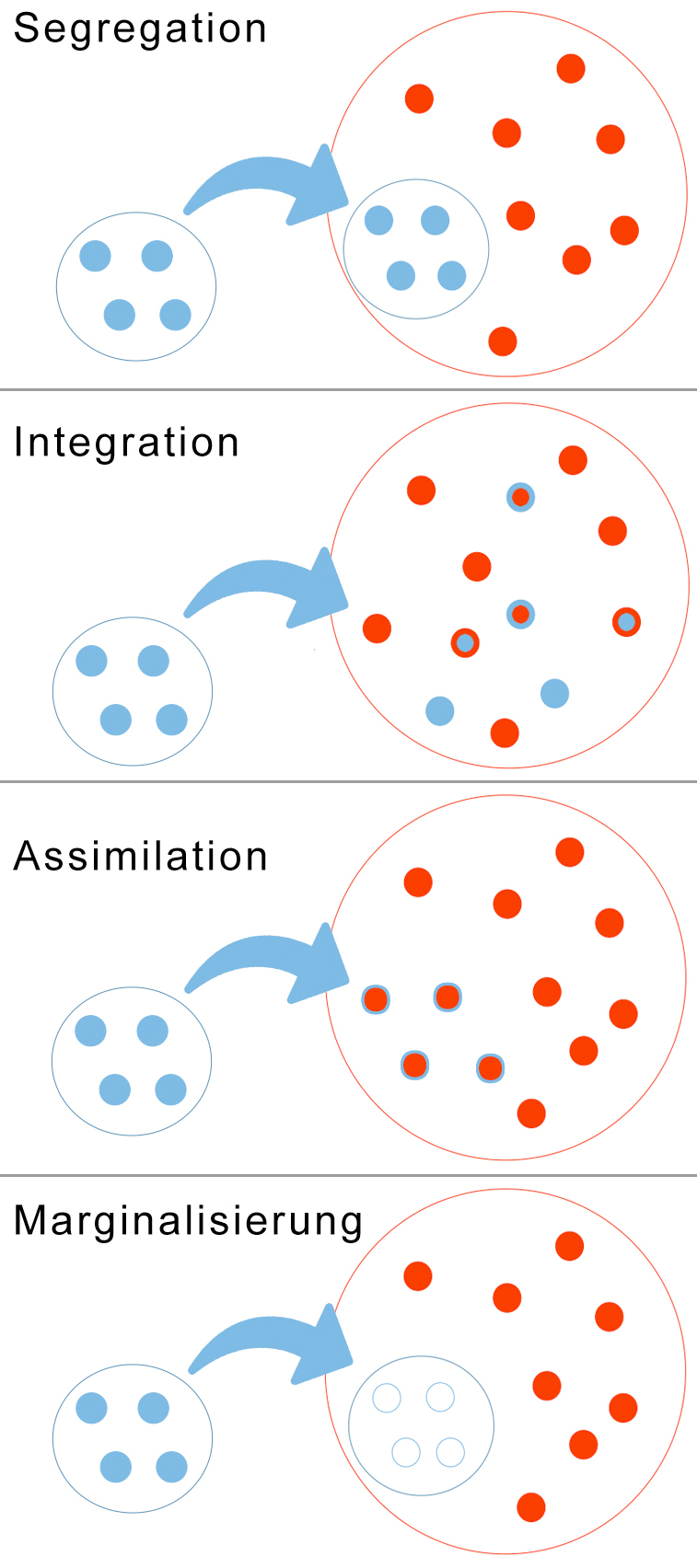

Formen der Akkulturation

(Migrationsforschung) Die vier Formen der Akkulturation (nach Berry) Siehe auch: John W. Berry#Berrys Modell der Akkulturationsstrategien John W. Berry betrachtet als Akkulturation den Anpassungsprozess von Migranten auf individueller oder auf Gruppenebene, die sich in einer anderen Kultur niederlassen als derjenigen, in der sie geboren wurden.[6] Er unterscheidet vier Strategien bzw. Formen der Akkulturation, je nachdem, ob die Zuwanderer bzw. ihre Gruppe die eigene Kultur beibehalten will/soll oder nicht und ob irgendeine Form des Kontaktes zwischen Zuwanderern und Aufnahmegesellschaft bestehen soll oder nicht.[7] Die Akkulturationsstrategien werden nicht immer frei gewählt, sondern sind auch ein Resultat von Umständen der Migration, der Zuwanderergruppe und der Aufnahmegesellschaft.[8] Segregation oder Separation: Beibehaltung der eigenen Kultur ohne Kontakt zur Aufnahmegesellschaft. Die Minderheit strebt eine weitgehende kulturelle Isolation an und lehnt die dominante Kultur ab oder wird von dieser abgelehnt. Integration: Beibehaltung von Elementen der eigenen Kultur mit Kontakt zur Aufnahmegesellschaft. Beide Gruppen streben nach Multikulturalität. Gegebenenfalls findet ebenfalls eine Beeinflussung der Aufnahmegesellschaft statt. Assimilation: Aufgabe der eigenen Kultur mit Kontakt zur Mehrheit. Der Prozess führt zur Verschmelzung mit der dominanten Kultur. Marginalisierung, auch Exklusion: Aufgabe der eigenen Kultur ohne Kontakt zur Mehrheit. Diese Form folgt häufig auf eine kulturelle oder ethnische Entwurzelung. Sozialpsychologie Ein ausgefeiltes Modell von Akkulturation hat der deutsch-amerikanische Sozialpsychologe Erik Erikson 1950 in seinem Buch Childhood and Society (Kindheit und Gesellschaft New York 1957) vorgelegt. Auch anhand eigener Feldforschung bei zwei US-Indianerstämmen entwickelte er ein aus acht Phasen bestehendes, Stufenmodell der psychosozialen Entwicklung, das die gesamte Lebensspanne umfasst. Schlüsselbegriffe dieses Konzeptes sind „Ich-Identität“ bzw. – bei misslungener Identitätsbildung – „Identitätsdiffusion“. Psychologische Folgen Die Phase der Akkulturation kann für die Psyche belastend sein. Kalervo Oberg spricht von Kulturschock, John W. Berry von Akkulturationsstress (accultrative stress).[9] Der Psychiater Wielant Machleidt hält den Stress nach erfolgter Migration für „seelisch extrem belastend und massiv unterschätzt“. Es komme durch die Migration zu einer Identitätskrise, die desto tiefgreifender sei, je fremder der Kulturraum ist. Zugleich fallen der Freundeskreis, die Arbeit und teils auch die Familie fort. Für ihn ist die Migration nach der Geburt („Geburt als Individuum“) und der Adoleszenz („Geburt als Erwachsener“) eine weitere Phase der Individuation („kulturelle Adoleszenz“ oder „Geburt als Weltbürger“). Die eigene Identität und das eigene Wertegefüge stehen dabei in Frage; es müsse neu ausgelotet werden, was das „Eigene“ und was das „Fremde“ ist.[10][11] Die Persönlichkeitsentwicklung, die dabei in Gang gesetzt wird, könne als eine Art Pubertät veranschaulicht werden. Ähnlich wie in der Pubertät komme es zu „großen Gefühlen und Affekten“ und „Omnipotenzphantasien“ ebenso wie zu „Schmerzen bei der Trennung von den psychischen und sozialen Räumen der Kindheit bzw. der Heimat“ und zu existenziellen Ängsten vor dem Scheitern. Dabei entstehe auch eine Verletzlichkeit – vor allem dann, wenn Diskriminierung, soziale Ausschließung und Isolation erlebt werden, könne sich eine chronisch erhöhte Stressbelastung ergeben. Die Phase der Akkulturation mündet ggf. in einen breiten Erfahrungshorizont bzw. in eine „Weltläufigkeit“ im Sinne einer mehrkulturellen Orientierung.[11] Siehe auch: Migrationssoziologie#Migration und Identität |

文化同化の形式(移民研究) ベリーによる文化同化の4つの形態 参照:ジョン・W・ベリー#ベリーの文化同化戦略モデル ジョン・W・ベリーは、文化同化とは、個人または集団レベルで、生まれ育った文化とは異なる文化に定住する移民の適応プロセスであると考える。6 彼は、移民またはその集団が望むか、望むべきか、あるいは望まないか、また 、移民と受入社会との間に何らかの接触があるかどうかによって区別している。[7] 文化同化戦略は、常に自由に選択されるものではなく、移民、移民グループ、受入社会の状況の結果でもある。[8] 隔離または分離:受入社会との接触なしに自らの文化を保持する。マイノリティは高度な文化的な孤立を達成しようとし、支配的文化を拒絶するか、あるいは支 配的文化から拒絶される。 統合:ホスト社会と接触しながら、自らの文化の要素を保持する。両グループは多文化主義を目指している。必要に応じて、ホスト社会も影響を受ける。 同化:マジョリティと接触しながら、自らの文化を放棄する。このプロセスは支配的文化との融合につながる。 疎外、排除:多数派と接触することなく、自らの文化を放棄すること。この形態は、文化的または民族的根絶にしばしば伴う。 社会心理学 洗練された文化適応のモデルは、ドイツ系アメリカ人の社会心理学者エリク・エリクソンが1950年に著書『Childhood and Society』(ニューヨーク、1957年)で発表した。彼は、2つのアメリカ・インディアン部族を対象とした独自の現地調査に基づき、生涯全体を網羅 する8段階の心理社会的発達モデルを開発した。この概念の主な概念は、「自我同一性」または(アイデンティティ形成に失敗した場合の)「アイデンティティ 拡散」である。 心理学的影響 文化適応の段階は精神にとってストレスとなる可能性がある。カルエロ・オベリはカルチャーショックについて、ジョン・W・ベリーは文化適応ストレスについ て述べている。9] 精神科医のヴィーラント・マクリートは、移住後に経験するストレスを「極めて精神的にストレスが大きく、過小評価されている」とみなしている。 彼は、移住はアイデンティティの危機につながり、その危機は文化環境が外国的なものであるほど深刻になる、と述べている。 同時に、友人関係や仕事、時には家族関係さえも失われる。彼にとって、出生後(「個としての誕生」)および思春期(「大人としての誕生」)の移住は、さら に個体化の段階(「文化的な思春期」または「世界市民としての誕生」)である。 自身のアイデンティティと価値体系が問われ、「自分自身」と「他者」を再検証する必要がある。[10][11] この過程で始まる人格形成は、一種の思春期として説明することができる。思春期と同様に、「強い感情や情動」、「全能感の空想」、そして「子供時代や家庭 という心理的・社会的空間からの分離による苦痛」や「失敗に対する実存的な不安」がある。また、これは脆弱性も生み出す。特に、差別、社会的排除、孤立な どを経験すると、慢性的なストレス負荷の増大につながる可能性がある。文化適応の段階では、多文化志向という意味での幅広い経験や「コスモポリタニズム」 につながる可能性がある。 参照:移民社会学#移民とアイデンティティ |

| Psychologie und Pädagogik In Psychologie und Pädagogik versteht man unter Akkulturation das Hineinwachsen einer Person in ihr eigenes kulturelles Umfeld durch Erziehung. In der Regel bezieht sich der Begriff auf Heranwachsende in der Phase der Adoleszenz. Enkulturation bezeichnet hingegen die unbewusste ungesteuerte Sozialisation, besonders vor der Phase der Adoleszenz bei Heranwachsenden, z. B. bei Neugeborenen, Kleinkindern und Kindern. Erziehung und Akkulturation Die Akkulturation aus psychologischer Sicht vollzieht sich überwiegend durch Erziehung und teilweise auch durch ungeplantes Lernen. Die Erziehung in Familie oder Schule dient mitunter dazu, Heranwachsende mit den Regeln und Traditionen der eigenen Kultur vertraut zu machen, aber auch die Art der Erziehung wird unter diesem Kulturprozess gefasst. Jedes Kind und jeder Jugendliche macht immer auch Erfahrungen, z. B. in Gruppen Gleichaltriger, die sich den von Erwachsenen geplanten Erziehungsprozessen entziehen. Am Ende einer gelungenen Akkulturation ist der junge Mensch mit der eigenen Kultur vertraut, kennt ihre ungeschriebenen Gesetze und ist „gesellschaftsfähig“, sprich erwachsen. Akkulturation und Alkoholkonsum von Jugendlichen In einer 2016 erschienenen repräsentativen Studie bei 15-jährigen Jugendlichen mit familiärer Migrationsgeschichte in Deutschland zeigte sich, dass diejenigen, die die Wertvorstellungen ihrer Herkunftskultur beibehielten, mit einer geringeren Häufigkeit Rauschtrinken betrieben. Demgegenüber war die Wahrscheinlichkeit für regelmäßige Erfahrungen mit übermäßigem Alkoholkonsum bei den Jugendlichen höher, die stark zu einer Assimilation mit der deutschen Kultur tendierten. Auch bei Jugendlichen, deren Eltern eine starke Bindung zu den Traditionen des Herkunftslandes aufwiesen, war das Risiko für Rauschtrinken geringer.[12] |

心理学と教育 心理学と教育において、文化同化とは、教育を通じて個人が自身の文化的環境に成長する過程を意味すると理解されている。通常、この用語は思春期の段階にあ る青少年を指す。一方、エンカルチュレーションとは、特に思春期前の段階にある青少年、例えば新生児、幼児、児童における無意識で制御されていない社会化 を指す。 教育と文化変容 心理学的観点から見ると、文化変容は主に教育を通じて、またある程度は計画外の学習を通じて起こる。家庭や学校での教育は、とりわけ思春期の若者たちに自 分たちの文化の規則や伝統に慣れ親しませることを目的としているが、教育の種類もまたこの文化的なプロセスの一部であると理解されている。また、すべての 子供や思春期の若者たちは、例えば同年代の人々のグループなど、大人の計画した教育プロセスから外れた経験もしている。 順調な文化適応プロセスを経た結果、若者は自らの文化に精通し、その不文律を知り、「社会的に認められる」、すなわち大人になる。 若者の文化変容とアルコール消費 2016年に発表された、移住の家族歴を持つドイツの15歳を対象とした代表的な研究では、出身文化の価値観を維持している人々は、大量飲酒をする可能性 が低いことが示された。一方、ドイツ文化への同化傾向が強い若者ほど、過剰なアルコール摂取を定期的に経験する可能性が高かった。また、親が出身国の伝統 に強い愛着を持っている若者ほど、過剰飲酒のリスクも低かった。[12] |

| https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Akkulturation |

|

| Acculturation

is a process of social, psychological, and cultural change that stems

from the balancing of two cultures while adapting to the prevailing

culture of the society. Acculturation is a process in which an

individual adopts, acquires and adjusts to a new cultural environment

as a result of being placed into a new culture, or when another culture

is brought to someone.[1] Individuals of a differing culture try to

incorporate themselves into the new more prevalent culture by

participating in aspects of the more prevalent culture, such as their

traditions, but still hold onto their original cultural values and

traditions. The effects of acculturation can be seen at multiple levels

in both the devotee of the prevailing culture and those who are

assimilating into the culture.[2] At this group level, acculturation often results in changes to culture, religious practices, health care, and other social institutions. There are also significant ramifications on the food, clothing, and language of those becoming introduced to the overarching culture. At the individual level, the process of acculturation refers to the socialization process by which foreign-born individuals blend the values, customs, norms, cultural attitudes, and behaviors of the overarching host culture. This process has been linked to changes in daily behaviour, as well as numerous changes in psychological and physical well-being. As enculturation is used to describe the process of first-culture learning, acculturation can be thought of as second-culture learning. Under normal circumstances that are seen commonly in today's society, the process of acculturation normally occurs over a large span of time throughout a few generations. Physical force can be seen in some instances of acculturation, which can cause it to occur more rapidly, but it is not a main component of the process. More commonly, the process occurs through social pressure or constant exposure to the more prevalent host culture. Scholars in different disciplines have developed more than 100 different theories of acculturation,[3] but the concept of acculturation has only been studied scientifically since 1918.[3] As it has been approached at different times from the fields of psychology, anthropology, and sociology, numerous theories and definitions have emerged to describe elements of the acculturative process. Despite definitions and evidence that acculturation entails a two-way process of change, research and theory have primarily focused on the adjustments and adaptations made by minorities such as immigrants, refugees, and indigenous people in response to their contact with the dominant majority. Contemporary research has primarily focused on different strategies of acculturation, how variations in acculturation affect individuals, and interventions to make this process easier. |

文化変容とは、社会の主流文化に適応しながら2つの文化のバランスを取

ることで生じる、社会的、心理的、文化的な変化のプロセスである。文化変容とは、個人が新しい文化に置かれること、あるいは他の文化が誰かにもたらされる

ことによって、新しい文化的環境を受け入れ、習得し、適応していく過程である。[1]

異なる文化を持つ個人は、伝統などより一般的な文化の側面に参加することで、新しいより一般的な文化に自分自身を組み込もうとするが、同時に元々の文化的

価値観や伝統も維持しようとする。同化の影響は、主流文化の信奉者と、その文化に同化している人々の双方において、複数のレベルで確認することができる。 この集団レベルでは、同化はしばしば文化、宗教的慣習、保健医療、その他の社会制度の変化をもたらす。また、主流文化に触れる人々の食生活、服装、言語に も大きな影響がある。 個人レベルでは、文化適応のプロセスとは、外国生まれの個人が、包括的なホスト文化の価値観、習慣、規範、文化的態度、行動様式を融合させる社会化プロセ スを指す。このプロセスは、日常行動の変化だけでなく、心理的および身体的健康の多くの変化にも関連している。文化習得が第一文化学習のプロセスを説明す るのに使われるように、文化適応は第二文化学習と考えることができる。 今日の社会で一般的に見られる通常の状況下では、文化同化のプロセスは通常、数世代にわたって長い時間をかけて起こる。文化同化のいくつかの事例では物理 的な力が作用し、より急速に起こることもあるが、それはプロセスの主な要素ではない。より一般的には、そのプロセスは社会的圧力や、より広く浸透している ホスト文化への継続的な接触を通じて起こる。 異なる分野の学者たちは、100以上の異なる文化適応理論を開発しているが[3]、文化適応の概念が科学的に研究されるようになったのは1918年以降で ある。[3] 文化適応は心理学、人類学、社会学などの分野から異なる時期にアプローチされてきたため、文化適応プロセスの要素を説明する多数の理論や定義が生まれてい る。文化変容には双方向の変化プロセスが伴うという定義や証拠があるにもかかわらず、研究や理論は主に、支配的多数派との接触に対する移民、難民、先住民 などのマイノリティによる適応や順応に焦点を当ててきた。最近の研究では、主に異なる文化変容の戦略、文化変容の変化が個人に与える影響、このプロセスを 容易にする介入に焦点を当てている。 |

| Historical approaches The history of Western civilization, and in particular the histories of Europe and the United States, are largely defined by patterns of acculturation. One of the most notable forms of acculturation is imperialism, the most common progenitor of direct cultural change. Although these cultural changes may seem simple, the combined results are both robust and complex, impacting both groups and individuals from the original culture and the host culture. Anthropologists, historians, and sociologists have studied acculturation with dominance almost exclusively, primarily in the context of colonialism, as a result of the expansion of western European peoples throughout the world during the past five centuries.[4] The first psychological theory of acculturation was proposed in W.I. Thomas and Florian Znaniecki's 1918 study, The Polish Peasant in Europe and America. From studying Polish immigrants in Chicago, they illustrated three forms of acculturation corresponding to three personality types: Bohemian (adopting the host culture and abandoning their culture of origin), Philistine (failing to adopt the host culture but preserving their culture of origin), and creative-type (able to adapt to the host culture while preserving their culture of origin).[5] In 1936, Redfield, Linton, and Herskovits provided the first widely used definition of acculturation as: Those phenomena which result when groups of individuals having different cultures come into continuous first-hand contact, with subsequent changes in the original cultural patterns of either or both groups...under this definition acculturation is to be distinguished from...assimilation, which is at times a phase of acculturation.[6] Long before efforts toward racial and cultural integration in the United States arose, the common process was assimilation. In 1964, Milton Gordon's book Assimilation in American Life outlined seven stages of the assimilative process, setting the stage for literature on this topic. Later, Young Yun Kim authored a reiteration of Gordon's work, but argued cross-cultural adaptation as a multi-staged process. Kim's theory focused on the unitary nature of psychological and social processes and the reciprocal functional personal environment interdependence.[7] Although this view was the earliest to fuse micro-psychological and macro-social factors into an integrated theory, it is clearly focused on assimilation rather than racial or ethnic integration. In Kim's approach, assimilation is unilinear and the sojourner must conform to the majority group culture in order to be "communicatively competent." According to Gudykunst and Kim (2003)[8] the "cross-cultural adaptation process involves a continuous interplay of deculturation and acculturation that brings about change in strangers in the direction of assimilation, the highest degree of adaptation theoretically conceivable." This view has been heavily criticized, since the biological science definition of adaptation refers to the random mutation of new forms of life, not the convergence of a monoculture (Kramer, 2003). In contradistinction from Gudykunst and Kim's version of adaptive evolution, Eric M. Kramer developed his theory of Cultural Fusion (2011,[9] 2010,[10] 2000a,[11] 1997a,[10][12] 2000a,[11][13] 2011,[14] 2012[15]) maintaining clear, conceptual distinctions between assimilation, adaptation, and integration. According to Kramer, assimilation involves conformity to a pre-existing form. Kramer's (2000a, 2000b, 2000c, 2003, 2009, 2011) theory of Cultural Fusion, which is based on systems theory and hermeneutics, argues that it is impossible for a person to unlearn themselves and that by definition, "growth" is not a zero-sum process that requires the disillusion of one form for another to come into being but rather a process of learning new languages and cultural repertoires (ways of thinking, cooking, playing, working, worshiping, and so forth). In other words, Kramer argues that one need not unlearn a language to learn a new one, nor does one have to unlearn who one is to learn new ways of dancing, cooking, talking, and so forth. Unlike Gudykunst and Kim (2003), Kramer argues that this blending of language and culture results in cognitive complexity, or the ability to switch between cultural repertoires. To put Kramer's ideas simply, learning is growth rather than unlearning. |

歴史的なアプローチ 西洋文明の歴史、特にヨーロッパと米国の歴史は、文化変容のパターンによってほぼ定義されている。 文化変容の最も顕著な形態のひとつが帝国主義であり、直接的な文化変容の最も一般的な原因である。これらの文化変容は単純に見えるかもしれないが、その複 合的な結果は強固かつ複雑であり、元の文化と受入文化の両方のグループと個人に影響を与える。人類学者、歴史家、社会学者は、過去5世紀にわたって西欧諸 民族が世界中に広がった結果、植民地主義の文脈を中心に、ほぼ独占的に文化変容を研究してきた。 文化変容に関する最初の心理学理論は、W.I. トーマスとフローリアン・ザナシェツキが1918年に発表した研究『ヨーロッパとアメリカのポーランド人農民』で提唱された。シカゴのポーランド系移民を 研究した彼らは、3つの人格タイプに対応する3つの文化変容の形を明らかにした。ボヘミアン(受入文化を取り入れ、出身文化を放棄する)、フィルシテ人 (受入文化を取り入れず、出身文化を保持する)、創造的タイプ(受入文化に適応し、出身文化を保持する)の3つである。[5] 1936年、レッドフィールド、リントン、ハーコビッツは、広く使用されるようになった最初の文化変容の定義を提示した。 異なる文化を持つ個人の集団が継続的に直接的な接触を持つことで生じる現象であり、その後のどちらか一方または両方の集団の元々の文化パターンの変化を伴 う。この定義では、同化とは区別されるべきである。同化は、時に文化変容の一形態である。 米国で人種や文化の統合に向けた取り組みが生まれるはるか以前は、一般的なプロセスは同化であった。1964年、ミルトン・ゴードン(Milton Gordon)著『アメリカ生活における同化(Assimilation in American Life)』では、同化のプロセスを7つの段階に分けて概説し、このトピックに関する文献の基礎を築いた。その後、ヤング・ユン・キム(Young Yun Kim)がゴードンの研究を再び取り上げたが、異文化適応を多段階のプロセスとして論じた。キムの理論は、心理的および社会的プロセスの単一性と、相互に 機能する人格環境の相互依存に焦点を当てている。[7] この見解は、ミクロ心理学的およびマクロ社会的要因を統合した理論に融合させた最も初期のものであるが、人種的または民族的統合よりも同化に焦点を当てて いることは明らかである。キムのアプローチでは、同化は単線的であり、滞在者は「コミュニケーション能力」を発揮するために、多数派グループの文化に適合 しなければならない。グディクンストとキム(2003年)[8]によると、「異文化適応プロセスには脱文化と文化適応の継続的な相互作用が含まれ、見知ら ぬ人々に同化の方向への変化をもたらす。これは理論上考えられる適応の最高度である」という。生物科学における適応の定義は、単一文化の収束ではなく、新 しい生命形態のランダムな突然変異を指すため、この見解は強く批判されている(クレイマー、2003年)。 グディクンストとキムの適応進化論とは対照的に、エリック・M・クレイマーは「文化融合」理論を展開した(2011年、[9] 2010年、[10] 2000年a、[11] 1 1997a,[10][12] 2000a,[11][13] 2011,[14] 2012[15])は、同化、適応、統合の概念を明確に区別している。クレイマーによると、同化とは既存の形式への適合を意味する。クレイマー (2000a、2000b、2000c、2003、2009、2011)の文化融合理論は、システム理論と解釈学を基盤としており、 人格を脱構築することは不可能であり、「成長」とは、ある形が幻滅されて別の形が生まれるというゼロサム的なプロセスではなく、むしろ新しい言語や文化レ パートリー(思考法、料理、遊び、仕事、礼拝など)を学ぶプロセスであると定義する。つまり、クレイマーは、新しい言語を学ぶために既存の言語を捨て去る 必要はないし、新しい踊りや料理、話し方などを学ぶために自分自身を捨て去る必要もないと主張している。グディクンストとキム(2003年)とは異なり、 クレイマーは、言語と文化の融合は認知の複雑性、つまり文化レパートリーの切り替え能力につながると主張している。クレイマーの考え方を簡単に言えば、学 習とは、既存の知識を捨て去ることではなく、成長することである。 |

| Conceptual models Theory of Dimensional Accrual and Dissociation Although numerous models of acculturation exist, the most complete models take into consideration the changes occurring at the group and individual levels of both interacting groups.[16] To understand acculturation at the group level, one must first look at the nature of both cultures before coming into contact with one another. A useful approach is Eric Kramer's[17] theory of Dimensional Accrual and Dissociation (DAD). Two fundamental premises in Kramer's DAD theory are the concepts of hermeneutics and semiotics, which infer that identity, meaning, communication, and learning all depend on differences or variance. According to this view, total assimilation would result in a monoculture void of personal identity, meaning, and communication.[18] Kramer's DAD theory also utilizes concepts from several scholars, most notably Jean Gebser and Lewis Mumford, to synthesize explanations of widely observed cultural expressions and differences. Kramer's theory identifies three communication styles (idolic, symbolic, or signalic) in order to explain cultural differences. It is important to note that in this theory, no single mode of communication is inherently superior, and no final solution to intercultural conflict is suggested. Instead, Kramer puts forth three integrated theories: the theory Dimensional Accrual and Dissociation, the Cultural Fusion Theory[19] and the Cultural Churning Theory.[20] For instance, according to Kramer's DAD theory, a statue of a god in an idolic community is god, and stealing it is a highly punishable offense.[21] For example, many people in India believe that statues of the god Ganesh – to take such a statue/god from its temple is more than theft, it is blasphemy. Idolic reality involves strong emotional identification, where a holy relic does not simply symbolize the sacred, it is sacred. By contrast, a Christian crucifix follows a symbolic nature, where it represents a symbol of God. Lastly, the signalic modality is far less emotional and increasingly dissociated. Kramer refers to changes in each culture due to acculturation as co-evolution.[22] Kramer also addresses what he calls the qualities of out vectors which address the nature in which the former and new cultures make contact.[23] Kramer uses the phrase "interaction potential" to refer to differences in individual or group acculturative processes. For example, the process of acculturation is markedly different if one is entering the host as an immigrant or as a refugee. Moreover, this idea encapsulates the importance of how receptive a host culture is to the newcomer, how easy is it for the newcomer to interact with and get to know the host, and how this interaction affects both the newcomer and the host. |

概念モデル 次元蓄積と解離の理論 文化変容に関する数多くのモデルが存在するが、最も完全なモデルは、相互作用する両グループのグループレベルと個人レベルで起こる変化を考慮に入れてい る。[16] グループレベルでの文化変容を理解するには、まず、互いに接触する前の両文化の性質を考慮する必要がある。有用なアプローチとして、エリック・クレイマー (Eric Kramer)[17]の次元蓄積と解離(DAD)理論がある。クレイマーのDAD理論における2つの基本的前提は、解釈学と記号論の概念であり、アイデ ンティティ、意味、コミュニケーション、学習はすべて、相違または差異に依存するというものである。この見解によると、完全な同化は、人格、意味、コミュ ニケーションを欠いた単一文化を生み出すことになる。[18] また、クレイマーのDAD理論は、広く観察される文化表現と相違点の説明を統合するために、複数の学者、特にジャン・ゲプサーとルイス・マンフォードの概 念も利用している。 クレイマーの理論では、文化の違いを説明するにあたり、3つのコミュニケーション・スタイル(偶像的、象徴的、または信号的)を特定している。この理論で は、コミュニケーションの単一の様式が本質的に優れているという考え方はなく、異文化間の対立に対する最終的な解決策も提示されていない点に留意すべきで ある。その代わりに、クレイマーは3つの統合理論を提示している。次元の蓄積と解離理論、文化融合理論[19]、文化撹拌理論[20]である。 例えば、クレイマーのDAD理論によると、偶像崇拝のコミュニティにおける神の像は神そのものであり、それを盗むことは厳しく罰せられるべき犯罪である。 [21] 例えば、インドでは多くの人々がガネーシャ神の像を信奉しており、その像を寺院から持ち出すことは窃盗以上の冒涜行為である。偶像崇拝には強い感情的な同 一化が伴い、聖遺物は単に神聖なものを象徴するのではなく、神聖そのものである。それに対して、キリスト教の十字架は象徴的な性質に従い、神の象徴を表し ている。最後に、信号的な様態は感情性がはるかに少なく、ますます解離していく。 クレイマーは、文化変容による各文化の変化を共進化と呼んでいる。[22] クレイマーはまた、新旧の文化が接触する性質について、彼がベクトルの性質と呼ぶものについても言及している。[23] クレイマーは、個人または集団の文化変容プロセスにおける相違について、「相互作用の可能性」という表現を用いている。例えば、移民として、あるいは難民 としてホスト社会に参入する場合、文化適応のプロセスは著しく異なる。さらに、この考え方は、ホスト文化が新参者に対してどれほど寛容であるか、新参者が ホストと交流し、ホストを知るのがどれほど容易であるか、そして、この交流が新参者とホストの両方にどのような影響を与えるか、という点の重要性を要約し ている。 |

Fourfold models The four essential (paradigm) forms of acculturation The fourfold model is a bilinear model that categorizes acculturation strategies along two dimensions. The first dimension concerns the retention or rejection of an individual's minority or native culture (i.e. "Is it considered to be of value to maintain one's identity and characteristics?"), whereas the second dimension concerns the adoption or rejection of the dominant group or host culture. ("Is it considered to be of value to maintain relationships with the larger society?") From this, four acculturation strategies emerge.[24] Assimilation occurs when individuals adopt the cultural norms of a dominant or host culture, over their original culture. Sometimes it is forced by governments. Separation occurs when individuals reject the dominant or host culture in favor of preserving their culture of origin. Separation is often facilitated by immigration to ethnic enclaves. Integration occurs when individuals can adopt the cultural norms of the dominant or host culture while maintaining their culture of origin. Integration leads to, and is often synonymous with biculturalism. Marginalization occurs when individuals reject both their culture of origin and the dominant host culture. Studies suggest that individuals' respective acculturation strategy can differ between their private and public life spheres.[25] For instance, an individual may reject the values and norms of the dominant culture in their private life (separation), whereas they might adapt to the dominant culture in public parts of their life (i.e., integration or assimilation). |

4つのモデル 文化適応の4つの本質的な(パラダイム)形態 4つのモデルは、2つの次元に沿って文化適応戦略を分類する双一次モデルである。第1の次元は、個人の少数派文化または母国文化の保持または拒絶に関係す る(すなわち、「アイデンティティと特性を維持することが価値あることと考えられているか」)。一方、第2の次元は、支配的集団またはホスト文化の採用ま たは拒絶に関係する。(「より大きな社会との関係を維持することは価値があると考えられているか」) これにより、4つの文化適応戦略が浮かび上がる。[24] 同化は、個人が元々の文化よりも支配文化または受容文化 の文化規範を採用する際に起こる。時には政府によって強制されることもある。 分離は、個人が元々の文化を維持することを優先し、支配 文化または受容文化を拒絶する際に起こる。分離は、しばしば民族的な孤立地域への移住によって促進される。 統合は、個人が元々の文化を維持しながら、支配文化また は受容文化の文化規範を採用できる場合に起こる。統合は、二文化主義につながり、しばしば二文化主義と同義である。 疎外は、個人が出身文化と支配的な受入文化の両方を拒絶 した場合に起こる。 研究によると、個人の文化適応戦略は、私生活と公生活の間で異なる可能性がある。例えば、個人は私生活では支配的文化の価値観や規範を拒絶するかもしれな いが(分離)、公生活では支配的文化に適応するかもしれない(すなわち、統合または同化)。 |

| Predictors of acculturation

strategies The fourfold models used to describe individual attitudes of immigrants parallel models used to describe group expectations of the larger society and how groups should acculturate.[26] In a melting pot society, in which a harmonious and homogenous culture is promoted, assimilation is the endorsed acculturation strategy. In segregationist societies, in which humans are separated into racial, ethnic and/or religious groups in daily life, a separation acculturation strategy is endorsed. In a multiculturalist society, in which multiple cultures are accepted and appreciated, individuals are encouraged to adopt an integrationist approach to acculturation. In societies where cultural exclusion is promoted, individuals often adopt marginalization strategies of acculturation. Attitudes towards acculturation, and thus the range of acculturation strategies available, have not been consistent over time. For example, for most of American history, policies and attitudes have been based around established ethnic hierarchies with an expectation of one-way assimilation for predominantly White European immigrants.[27] Although the notion of cultural pluralism has existed since the early 20th century, the recognition and promotion of multiculturalism did not become prominent in America until the 1980s. Separatism can still be seen today in autonomous religious communities such as the Amish and the Hutterites. Immediate environment also impacts the availability, advantage, and selection of different acculturation strategies. As individuals immigrate to unequal segments of society, immigrants to areas lower on economic and ethnic hierarchies may encounter limited social mobility and membership to a disadvantaged community.[28] It can be explained by the theory of Segmented Assimilation, which is used to describe the situation when immigrants individuals or groups assimilate to the culture of different segments of the society of the host country. The outcome of whether entering the upper class, middle class, or lower class is largely determined by the socioeconomic status of the last generation.[29][30] On a broad scale study, involving immigrants in 13 immigration-receiving countries, the experience of discrimination was positively related to the maintenance of the immigrants' ethnic culture.[31] In other words, immigrants that maintain their cultural practices and values are more likely to be discriminated against than those whom abandon their culture. Further research has also identified that the acculturation strategies and experiences of immigrants can be significantly influenced by the acculturation preferences of the members of the host society.[32] The degree of intergroup and interethnic contact has also been shown to influence acculturation preferences between groups,[33] support for multilingual and multicultural maintenance of minority groups,[34] and openness towards multiculturalism.[35] Enhancing understanding of out-groups, nurturing empathy, fostering community, minimizing social distance and prejudice, and shaping positive intentions and behaviors contribute to improved interethnic and intercultural relations through intergroup contact. Most individuals show variation in both their ideal and chosen acculturation strategies across different domains of their lives. For example, among immigrants, it is often easier and more desired to acculturate to their host society's attitudes towards politics and government, than it is to acculturate to new attitudes about religion, principles, values, and customs.[36] |

文化適応戦略の予測因子 移民の個々の態度を説明するのに使用される4つのモデルは、より大きな社会に対するグループの期待と、グループがどのように文化適応すべきかを説明するの に使用されるモデルと一致する。[26] 調和のとれた均質な文化が促進される「るつぼ社会」では、同化が推奨される文化適応戦略である。人種、民族、宗教などのグループに日常生活で分離されてい る分離主義社会では、分離文化戦略が推奨される。複数の文化が受け入れられ、尊重される多文化主義社会では、個人は統合主義的な文化適応アプローチを採用 することが推奨される。文化排除が推奨される社会では、個人はしばしば疎外文化戦略を採用する。 文化同化に対する態度、そしてそれゆえに利用可能な文化同化戦略の範囲は、時代によって一貫したものではない。例えば、米国の歴史の大半において、政策や 態度は、主に白人のヨーロッパからの移民に対する一方的な同化を期待する形で、確立された民族階層を基盤としていた。[27] 文化多元主義の概念は20世紀初頭から存在していたが、多文化主義の認識と推進が米国で注目されるようになったのは1980年代になってからである。今日 でも、アーミッシュやフッター派のような宗教的自治共同体では分離主義が見られる。また、個人の置かれた環境も、異なる文化適応戦略の利用可能性、利点、 選択に影響を与える。個人が社会の不平等なセグメントに移民する場合、経済的および民族的階層が低い地域への移民は、限定的な社会移動性や不利なコミュニ ティへの所属に直面する可能性がある。[28] これは、セグメンテッド・アサイレーション(Segmented Assimilation)理論によって説明できる。この理論は、移民の個人またはグループが、受入国の社会の異なるセグメントの文化に同化する状況を説 明する際に使用される。上流階級、中流階級、下流階級のいずれに属するかの結果は、主として直近の世代の社会経済的地位によって決定される。 13の移民受入国における移民を対象とした大規模な調査では、差別経験は移民の民族文化の維持と正の相関関係にあることが分かった。言い換えれば、文化的 な慣習や価値観を維持する移民は、文化を放棄する移民よりも差別を受けやすいということである。さらに研究を重ねた結果、移民の文化適応戦略や経験は、受 入社会の構成員の文化適応の好みによって大きく影響を受けることが明らかになっている。[32] 集団間および民族間の接触の度合いも、集団間の文化適応の好みに影響を与えることが示されている。[33] また、 少数派グループの多言語・多文化維持への支持[34]、そして多文化主義への開放性[35]にも影響することが示されている。 アウトグループへの理解を深め、共感を育み、コミュニティを育成し、社会的距離や偏見を最小限に抑え、ポジティブな意図や行動を形成することは、グループ 間の接触を通じて、異民族間および異文化間の関係の改善に貢献する。 ほとんどの個人は、生活の異なる領域において、理想とする文化適応戦略と実際に選択する文化適応戦略の両方に違いを見せている。例えば、移民の場合、宗 教、原則、価値観、慣習に関する新しい態度に適応するよりも、政治や政府に対するホスト社会の態度に適応する方が、より容易で望ましいことが多い。 [36] |

| Acculturative stress The large flux of migrants around the world has sparked scholarly interest in acculturation, and how it can specifically affect health by altering levels of stress, access to health resources, and attitudes towards health.[37][38][39] The effects of acculturation on physical health is thought to be a major factor in the immigrant paradox, which argues that first generation immigrants tend to have better health outcomes than non-immigrants.[37] Although this term has been popularized, most of the academic literature supports the opposite conclusion, or that immigrants have poorer health outcomes than their host culture counterparts.[37] One prominent explanation for the negative health behaviors and outcomes (e.g. substance use, low birth weight) associated with the acculturation process is the acculturative stress theory.[40] Acculturative stress refers to the stress response of immigrants in response to their experiences of acculturation.[38][37][31] Stressors can include but are not limited to the pressures of learning a new language, maintaining one's native language, balancing differing cultural values, and brokering between native and host differences in acceptable social behaviors. Acculturative stress can manifest in many ways, including but not limited to anxiety,[41] depression, substance abuse, and other forms of mental and physical maladaptation.[42][43] Stress caused by acculturation has been heavily documented in phenomenological research on the acculturation of a large variety of immigrants.[44] This research has shown that acculturation is a "fatiguing experience requiring a constant stream of bodily energy," and is both an "individual and familial endeavor" involving "enduring loneliness caused by seemingly insurmountable language barriers".[41] One important distinction when it comes to risk for acculturative stress is degree of willingness, or migration status, which can differ greatly if one enters a country as a voluntary immigrant, refugee, asylum seeker, or sojourner. According to several studies,[24][16][26][45] voluntary migrants experience roughly 50% less acculturative stress than refugees, making this an important distinction.[43] According to Schwartz (2010), there are four main categories of migrants: Voluntary immigrants: those that leave their country of origin to find employment, economic opportunity, advanced education, marriage, or to reunite with family members that have already immigrated. Refugees: those who have been involuntarily displaced by persecution, war, or natural disasters. Asylum seekers: those who willingly leave their native country to flee persecution or violence. Sojourners: those who relocate to a new country on a time-limited basis and for a specific purpose. It is important to note that this group fully intends to return to their native country. This type of entry distinction is important, but acculturative stress can also vary significantly within and between ethnic groups. Much of the scholarly work on this topic has focused on Asian and Latino/a immigrants, however, more research is needed on the effects of acculturative stress on other ethnic immigrant groups. Among U.S. Latinos, higher levels of adoption of the American host culture has been associated with negative effects on health behaviors and outcomes, such as increased risk for depression and discrimination, and increased risk for low self-esteem.[46][38] Other studies have found greater levels of acculturation are associated with greater sleep problems.[47][48] However, some individuals also report "finding relief and protection in relationships" and "feeling worse and then feeling better about oneself with increased competencies" during the acculturative process. Again, these differences can be attributed to the age of the immigrant, the manner in which an immigrant exited their home country, and how the immigrant is received by both the original and host cultures.[49] Recent research has compared the acculturative processes of documented Mexican-American immigrants and undocumented Mexican-American immigrants and found significant differences in their experiences and levels of acculturative stress.[39][50] Both groups of Mexican-American immigrants faced similar risks for depression and discrimination from the host (Americans), but the undocumented group of Mexican-American immigrants also faced discrimination, hostility, and exclusion by their own ethnic group (Mexicans) because of their unauthorized legal status. These studies highlight the complexities of acculturative stress, the degree of variability in health outcomes, and the need for specificity over generalizations when discussing potential or actual health outcomes. Researchers recently uncovered another layer of complications in this field, where survey data has either combined several ethnic groups together or has labeled an ethnic group incorrectly. When these generalizations occur, nuances and subtleties about a person or group's experience of acculturation or acculturative stress can be diluted or lost. For example, much of the scholarly literature on this topic uses U.S. Census data. The Census incorrectly labels Arab-Americans as Caucasian or "White".[37] By doing so, this data set omits many factors about the Muslim Arab-American migrant experience, including but not limited to acculturation and acculturative stress. This is of particular importance after the events of September 11, 2001, since Muslim Arab-Americans have faced increased prejudice and discrimination, leaving this religious ethnic community with an increased risk of acculturative stress.[37] Research focusing on the adolescent Muslim Arab American experience of acculturation has also found that youth who experience acculturative stress during the identity formation process are at a higher risk for low self-esteem, anxiety, and depression.[37] Some researchers argue that education, social support, hopefulness about employment opportunities, financial resources, family cohesion, maintenance of traditional cultural values, and high socioeconomic status (SES) serve as protections or mediators against acculturative stress. Previous work shows that limited education, low SES, and underemployment all increase acculturative stress.[43][39][24][3][26] Since this field of research is rapidly growing, more research is needed to better understand how certain subgroups are differentially impacted, how stereotypes and biases have influenced former research questions about acculturative stress, and the ways in which acculturative stress can be effectively mediated. |

文化適応ストレス 世界中で移民が大量に発生していることから、学術界では文化適応に注目が集まり、それが具体的にどのようにしてストレスレベル、保健医療へのアクセス、健 康に対する態度を変化させることで健康に影響を与えるのかが研究されている。[37][38][39] 文化適応が身体的健康に与える影響は、 移民パラドックスの主要な要因であると考えられており、移民の第一世代は非移民よりも健康状態が良い傾向にあると主張している。[37] この用語は一般化されているが、学術文献のほとんどは、移民は受入文化の同世代の人々よりも健康状態が悪いという逆の結論を支持している。[37] 文化適応プロセスに伴う否定的な健康行動や結果(薬物使用、低出生体重児など)の主な説明として、文化適応ストレス理論が挙げられる。文化適応ストレスと は、移民が文化適応の経験から受けるストレス反応を指す。。ストレス要因には、新しい言語の習得、母国語の維持、異なる文化の価値観のバランス、受入国と 母国の社会行動の相違の仲介などがあるが、これらに限定されるものではない。文化適応ストレスは、不安[41]、うつ病、薬物乱用、その他の精神的・肉体 的不適応[42][43]など、さまざまな形で現れる可能性がある。文化適応によるストレスは、 。この研究では、文化適応は「絶え間なく体力を消耗する疲労体験」であり、「乗り越えられないように見える言語の壁によって生じる孤独感に耐える」という 「個人および家族の努力」であることが示されている。 文化適応ストレスのリスクに関して重要な区別として、自発性、すなわち移民の地位が挙げられる。自発的な移民、難民、亡命希望者、短期滞在者としてある国 に入国した場合、その自発性の度合いは大きく異なる可能性がある。複数の研究によると[24][16][26][45]、自発的な移民は難民よりもおよそ 50%文化適応ストレスが少ないことが分かっており、これは重要な違いである。Schwartz(2010年)によると、移民は主に4つのカテゴリーに分 類される。 自発的移民:出身国を離れ、就職、経済的機会、高度な教育、結婚、またはすでに移民している家族との再会を目的とする人々。 難民:迫害、戦争、自然災害により、不本意ながら移住を余儀なくされた人々。 亡命希望者:迫害や暴力から逃れるために自らの意思で母国を離れる人々。 短期滞在者:期限付きで特定の目的のために新しい国に移住する人々。このグループは、母国に完全に帰国する意思があることに留意すべきである。 この種の入国区分は重要であるが、文化適応ストレスは、民族グループ内およびグループ間で大きく異なる可能性もある。このテーマに関する学術研究の多くは アジア系およびラテン系移民に焦点を当てているが、他の移民グループに対する文化適応ストレスの影響については、さらに研究が必要である。米国のラテン系 住民の間では、米国のホスト文化の受容度が高いと、うつ病や差別のリスクが高まり、自尊心が低下するなど、保健行動や保健結果に悪影響を及ぼすことが分 かっている。[46][38] 他の研究では、 高いレベルの文化適応は、より深刻な睡眠障害と関連していることが分かっている。[47][48] しかし、一部の個人は、文化適応の過程において「人間関係に安堵と保護を見出す」ことや、「気分が悪くなった後、能力が向上して自分自身についてより良く 感じる」ことを報告している。これらの違いは、移民の年齢、移民が自国を離れた方法、移民が母国文化と受入文化の両方からどのように受け入れられているか によって説明できる。[49] 最近の研究では、合法的に移住したメキシコ系アメリカ人と不法入国したメキシコ系アメリカ人の文化適応プロセスを比較し、 経験や文化適応ストレスのレベルに大きな違いがあることが分かった。[39][50] メキシコ系アメリカ人移民の両グループは、ホスト(アメリカ人)からの抑うつや差別という同様のリスクに直面していたが、不法滞在のメキシコ系アメリカ人 移民グループは、不法滞在という法的地位の理由から、自らの民族グループ(メキシコ人)からも差別、敵意、排除に直面していた。これらの研究は、文化適応 ストレスの複雑性、保健結果の変動の程度、および潜在的なまたは実際の保健結果を論じる際の一般化に対する特異性の必要性を浮き彫りにしている。 最近、研究者たちはこの分野におけるさらなる複雑性を明らかにした。調査データが複数の民族グループをまとめていたり、民族グループを誤って分類していた りしたのである。このような一般化が行われると、個人またはグループの文化適応または文化適応ストレスの経験に関する微妙なニュアンスや微妙さが希薄化し たり、失われたりする可能性がある。例えば、このテーマに関する学術文献の多くは米国国勢調査のデータを使用している。国勢調査では、アラブ系アメリカ人 を白人または「ホワイト」と誤って分類している。[37] このように分類することで、このデータセットでは、アラブ系ムスリム系アメリカ人の移民経験に関する多くの要因が除外されている。これには、文化同化や文 化同化ストレスなど、さまざまな要因が含まれる。これは、2001年9月11日の事件以降、特に重要である。なぜなら、ムスリム系アラブ系アメリカ人は偏 見や差別をより多く受けるようになり、この宗教的民族的コミュニティは文化適応ストレスのリスクが高まっているからである。[37] 思春期のムスリム系アラブ系アメリカ人の文化適応に関する研究では、アイデンティティ形成の過程で文化適応ストレスを経験した若者は、自尊心の低さ、不 安、うつ病のリスクが高いことも分かっている。[37] 一部の研究者は、教育、社会的支援、雇用機会への期待、経済的資源、家族の結束、伝統的文化価値の維持、高い社会経済的地位(SES)が、文化適応ストレ スに対する防御策または緩衝剤として機能すると主張している。これまでの研究では、限定的な教育、低い社会経済的地位、不完全雇用はすべて文化適応ストレ スを増大させることが示されている。[43][39][24][3][26] この研究分野は急速に成長しているため、特定のサブグループがどのように異なる影響を受けるか、ステレオタイプや偏見が文化適応ストレスに関する過去の研 究課題にどのような影響を与えたか、文化適応ストレスを効果的に緩和する方法について、より理解を深めるためのさらなる研究が必要である。 |

| Other outcomes Culture When individuals of a certain culture are exposed to another culture (host) that is primarily more present in the area that they live, some aspects of the host culture will likely be taken and blended within aspects of the original culture of the individuals. In situations of continuous contact, cultures have exchanged and blended foods, music, dances, clothing, tools, and technologies. This kind of cultural exchange can be related to selective acculturation that refers to the process of maintaining cultural content by researching those individuals' language use, religious belief, and family norms.[51] Cultural exchange can either occur naturally through extended contact, or more quickly though cultural appropriation or cultural imperialism. Cultural appropriation is the adoption of some specific elements of one culture by members a different cultural group. It can include the introduction of forms of dress or personal adornment, music and art, religion, language, or behavior.[52] These elements are typically imported into the existing culture, and may have wildly different meanings or lack the subtleties of their original cultural context. Because of this, cultural appropriation for monetary gain is typically viewed negatively, and has sometimes been called "cultural theft". Cultural imperialism is the practice of promoting the culture or language of one nation in another, usually occurring in situations in which assimilation is the dominant strategy of acculturation.[53] Cultural imperialism can take the form of an active, formal policy or a general attitude regarding cultural superiority. |

その他の結果 文化 ある文化に属する個人が、主に彼らが住む地域でより多く存在する別の文化(ホスト)にさらされると、ホスト文化のいくつかの側面が、おそらくその個人の元 々の文化の側面に取り入れられ、融合されることになるだろう。継続的な接触がある状況では、文化は食料、音楽、ダンス、衣類、道具、技術を交換し、融合し てきた。このような文化交流は、個人の言語使用、宗教的信念、家族の規範を調査することで文化的内容を維持するプロセスを指す選択的同化と関連付けること ができる。[51] 文化交流は、長期にわたる接触を通じて自然に発生する場合もあれば、文化の流用や文化帝国主義を通じてより迅速に発生する場合もある。 文化の流用とは、異なる文化集団のメンバーが、ある特定の文化の要素を取り入れることである。服装や装飾品、音楽や芸術、宗教、言語、行動様式などの形式 の導入が含まれる場合がある。[52] これらの要素は通常、既存の文化に輸入されるが、その意味は大きく異なったり、元の文化的な文脈の繊細さが欠けている場合がある。このため、金銭的利益を 目的とした文化の流用は一般的に否定的に捉えられ、「文化の窃盗」と呼ばれることもある。 文化帝国主義とは、ある国民の文化や言語を別の国民に広める行為であり、通常は同化が文化適応の主要な戦略である状況で発生する。[53] 文化帝国主義は、文化の優越性を主張する積極的な公式政策や一般的な態度として現れることがある。 |

| Language Further information: Language shift In some instances, acculturation results in the adoption of another country's language, which is then modified over time to become a new, distinct, language. For example, Hanzi, the written language of Chinese language, has been adapted and modified by other nearby cultures, including: Japan (as kanji), Korea (as hanja), and Vietnam (as chữ Hán). Jews, often living as ethnic minorities, developed distinct languages derived from the common languages of the countries in which they lived (for example, Yiddish from High German and Ladino from Old Spanish). Another common effect of acculturation on language is the formation of pidgin languages. Pidgin is a mixed language that has developed to help communication between members of different cultures in contact, usually occurring in situations of trade or colonialism.[54] For example, Pidgin English is a simplified form of English mixed with some of the language of another culture. Some pidgin languages can develop into creole languages, which are spoken as a first language. Language plays a pivotal role in cultural heritage, serving as both a foundation for group identity and a means for transmitting culture in situations of contact between languages.[55] Language acculturation strategies, attitudes and identities can also influence the sociolinguistic development of languages in bi/multilingual contexts.[56][57][58] |

言語 さらに詳しい情報:言語の変化 場合によっては、文化同化の結果、他国の言語が採用され、それが時間をかけて変化し、新しい独特の言語となる。例えば、中国語の表記言語である漢字は、日 本(漢字)、韓国(漢字)、ベトナム(チュ・ハン)など、近隣の他の文化によって適応され、変化してきた。ユダヤ人は、しばしば少数民族として生活してお り、彼らが住む国の共通語から派生した独特の言語を発達させてきた(例えば、イディッシュ語は高地ドイツ語から、ラディーノ語は旧スペイン語から派生して いる)。言語に対する文化同化のもう一つの一般的な影響は、ピジン言語の形成である。ピジンとは、異なる文化を持つ人々の接触の際に、コミュニケーション を助けるために発展した混合言語であり、通常は貿易や植民地主義の状況で発生する。[54] 例えば、ピジン英語は、英語を簡素化し、他の文化の言語を混ぜ合わせたものである。ピジン言語の中には、第一言語として話されるクレオール言語へと発展す るものもある。 言語は文化遺産において極めて重要な役割を果たしており、集団のアイデンティティの基盤となり、言語間の接触状況における文化伝達の手段ともなる。 [55] 言語の文化適応戦略、態度、アイデンティティは、二言語/多言語の状況における言語の社会言語学的な発展にも影響を与える可能性がある。[56][57] [58] |

| Food Food habits and food consumption are affected by acculturation on different levels. Research has indicated that food habits are discreet and practiced privately, and change occurs slowly. Consumption of new food items is affected by the availability of native ingredients, convenience, and cost; therefore, an immediate change is likely to occur.[59] Aspects of food acculturation include the preparation, presentation, and consumption of food. Different cultures have different ways in which they prepare, serve, and eat their food. When exposed to another culture for an extended period of time, individuals tend to take aspects of the "host" culture's food customs and implement them with their own. In cases such as these, acculturation is heavily influenced by general food knowledge, or knowing the unique kinds of food different cultures traditionally have, the media, and social interaction. It allows for different cultures to be exposed to one another, causing some aspects to intertwine and also become more acceptable to the individuals of each of the respective cultures.[60] |

食 食習慣や食消費は、異なるレベルで文化適応の影響を受ける。研究では、食習慣は慎重に、かつ個人的に行われるものであり、変化はゆっくりと起こることを示 している。新しい食品の消費は、地元の食材の入手可能性、利便性、コストに影響されるため、即時の変化が起こる可能性が高い。[59] 食文化の適応の側面には、食品の調理、盛り付け、消費が含まれる。異なる文化では、料理の調理法、盛り付け、食べ方が異なる。ある文化に長期間にわたって 触れると、個人は「ホスト」文化の食習慣の一部を取り入れ、それを自分の食習慣に取り入れる傾向がある。このような場合、文化変容は一般的な食に関する知 識、すなわち異なる文化が伝統的に持つ独特な種類の食品、メディア、社会的交流に大きく影響される。異なる文化がお互いに影響し合うことで、いくつかの側 面が絡み合い、それぞれの文化の個人にとってより受け入れやすくなる。[60] |

| Controversies and debate Definitions Anthropologists have made a semantic distinction between group and individual levels of acculturation. In such instances, the term transculturation is used to define individual foreign-origin acculturation, and occurs on a smaller scale with less visible impact. Scholars making this distinction use the term "acculturation" only to address large-scale cultural transactions. Acculturation, then, is the process by which migrants gain new information and insight about the norms and values of their culture and adapt their behaviors to the host culture.[61] Recommended models Research for long assumed that the integrationist model of acculturation leads to the most favorable psychological outcomes[62] and marginalization to the least favorable,[31] despite some early criticism.[3][63] Although a correlational meta-analysis of the acculturation literature[64] and a large-scale study led by John W. Berry (2006) found that integration correlated with better psychological and sociocultural adaptation,[65] recent longitudinal meta-analyses find no support for a meaningful causal relationship.[66] Critically, given the high heterogeneity in effect, the association between integration and adaptation can be expected to be negative almost 30% of the time.[67] Typological approach Several theorists have stated that the fourfold models of acculturation are too simplistic to have predictive validity.[45] Some common criticisms of such models include the fact that individuals don't often fall neatly into any of the four categories, and that there is very little evidence for the applied existence of the marginalization acculturation strategy.[63][68] In addition, the bi-directionality of acculturation means that whenever two groups are engaged in cultural exchange, there are 16 permutations of acculturation strategies possible (e.g. an integrationist individual within an assimilationist host culture).[3] According to the research, another critic of the fourfold of acculturation is that the people are less likely to cultivate a self-perception but either not assimilate other cultures or continuing the heritage cultures.Rethinking the Concept of Acculturation - PMC The interactive acculturation model represents one proposed alternative to the typological approach by attempting to explain the acculturation process within a framework of state policies and the dynamic interplay of host community and immigrant acculturation orientations. Studying a Causal Process With Correlational Data Acculturation, which focuses on the processes of cultural change, is inherently concerned with causal relationships. However, a significant limitation of the field is that nearly all existing research has been correlational in nature, making it impossible to infer causality.[69] Therefore, major notions such as the integration hypothesis studied in hundreds of studies still lack solid empirical support.[66] Calls have been made to address this issue by considering acculturation from a developmental, longitudinal perspective.[70][71][72] |

論争と討論 定義 人類学者は、集団レベルと個人レベルの文化変容を意味論的に区別している。このような場合、個人レベルの外国起源の文化変容を定義するために「トランスカ ルチャー」という用語が使用され、より小規模で目立たない影響を伴う。この区別を行う学者は、「文化変容」という用語を大規模な文化取引のみに使用する。 つまり、文化変容とは、移民が自らの文化の規範や価値観に関する新たな情報や洞察を得て、自らの行動をホスト文化に適応させるプロセスである。 推奨されるモデル 初期の批判はあったものの、長年にわたって研究では、文化適応の統合モデルが最も好ましい心理的結果につながり[62]、疎外が最も好ましくない結果につ ながるとされてきた[31]。文化適応に関する文献の相関関係のメタ分析[64]や、ジョン・W・ベリー(John W. Berry)が主導した大規模な研究( (2006) による大規模な研究では、統合が心理的および社会文化的な適応と相関していることが判明したが[65]、最近の縦断的メタ分析では、有意な因果関係は認め られなかった[66]。 重要なのは、効果に高い異質性があることを考えると、統合と適応の関連性はほぼ30%の確率で負になることが予想されることだ[67]。 類型論的アプローチ いくつかの理論では、4つの文化適応モデルは単純化されすぎており、予測妥当性がないと述べている。[45] このようなモデルに対する一般的な批判としては、個人が4つのカテゴリーのいずれかにきれいに当てはまることはあまりないという事実や、疎外文化適応戦略 が実際に存在する証拠がほとんどないということが挙げられる。[63][68] さらに、文化同化の双方向性は、2つのグループが文化交換を行う場合、16通りの文化同化戦略の組み合わせが可能であることを意味する(例えば、同化主義 のホスト文化における統合主義の個人)。研究によると、文化同化の4つの側面に対するもう一つの批判は、 自己認識を育む可能性が低く、他文化に同化することも、伝統文化を継承することもできない。文化変容の概念を再考する - PMC 相互文化変容モデルは、国家政策の枠組みと、受入コミュニティと移民の文化変容志向の動的な相互作用の中で文化変容プロセスを説明しようとする試みであ り、類型論的アプローチに対する代替案のひとつである。 相関データを用いた因果プロセスの研究 文化変容のプロセスに焦点を当てる文化変容は、本質的に因果関係に関わるものである。しかし、この分野における大きな問題は、既存の研究のほとんどが相関 関係を調べるものであり、因果関係を推論することが不可能であることである。[69] したがって、何百もの研究で検討されてきた統合仮説のような主要な概念は、依然として確固とした実証的裏付けに欠けている。[66] この問題に対処するために、発達的・経時的な視点から文化変容を考察することが求められている。[70][71][72] |

| Naturalization Acclimatization Socialization Deculturalization Globalization Nationalization Acculturation gap Educational anthropology Ethnocentrism Cultural relativism Cultural conflict Inculturation Cultural competence Language shift Westernization Cultural identity Linguistic imperialism Intercultural communication Fusion music Fusion cuisine |

帰化 順化 社会化 脱文化化 グローバル化 国民化 文化変容ギャップ 教育人類学 自民族中心主義 文化的相対主義 文化の衝突 文化内化 文化の適応能力 言語シフト 西洋化 文化アイデンティティ 言語帝国主義 異文化コミュニケーション フュージョン音楽 フュージョン料理 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acculturation |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099