方法論大全

All about Methodology

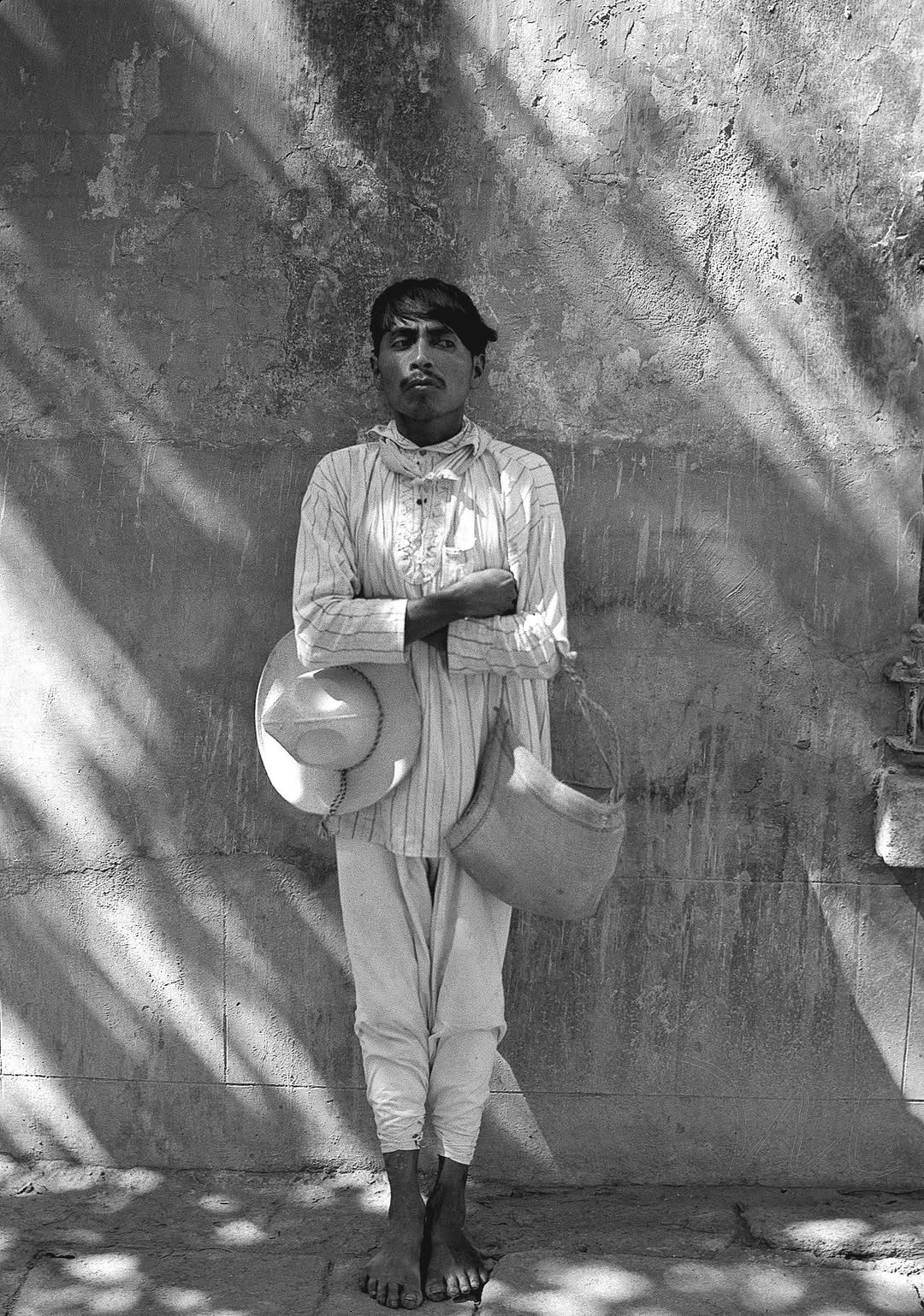

両サイドの写真はManuel Álvarez Bravo の作品

☆方法論(methodology) とは、最も一般的な意味で、研究手法の研究である。しかし、この用語は手法そのものや、関連する背景仮定についての哲学的議論を指すこともある。手法と は、知識の獲得や知識主張の検証といった特定の目標を達成するための構造化された手順である。通常、標本の選択、その標本からのデータ収集、データの解釈 といった様々な段階を含む。方法論の研究は、こうした過程の詳細な記述と分析に関わる。異なる方法を比較する評価的側面も含む。これにより、各方法の長所 短所や、どの研究目的に適用可能かが判断される。こうした記述と評価は、哲学的な背景前提に依存する。例としては、研究対象の現象をどう概念化するか、あ るいはそれらを支持・反証する証拠とは何かが挙げられる。最も広い意味で理解すれば、方法論はこうしたより抽象的な問題の議論も含む。 方法論は伝統的に定量的研究と定性的研究に分けられる。定量的研究は自然科学の主要な方法論である。精密な数値測定を用い、通常は将来の事象を予測する普 遍的法則の発見を目的とする。自然科学で支配的な方法論は科学的方法と呼ばれる。観察や仮説の立案といった段階を含む。さらに実験による仮説の検証、測定 値と予測結果の比較、発見の公表といった段階が続く。 質的研究は社会科学に特徴的で、正確な数値測定を重視しない。普遍的・予測可能な法則よりも、研究対象の現象の意味を深く理解することを主眼とする。社会 科学でよく用いられる手法には、調査、インタビュー、フォーカスグループ、ノミナルグループ技法がある。これらは標本サイズ、質問の種類、実施環境におい て互いに異なる。ここ数十年で、多くの社会科学者が定量的手法と定性的手法を組み合わせた混合手法研究を使い始めている。 方法論に関する議論の多くは、定量的アプローチが優れているか、特に社会領域に適用する際に適切かどうかという問題に関わる。一部の理論家は方法論という 学問分野そのものを否定する。例えば、方法は研究するものではなく使うべきものだから無意味だと主張する者もいる。また、研究者の自由や創造性を制限する ため有害だと考える者もいる。方法論研究者はこうした反論に対し、優れた方法論は研究者が効率的に信頼性の高い理論に到達する助けとなると主張して応じ る。方法の選択はしばしば重要である。同じ事実資料でも、方法によって異なる結論に至る可能性があるからだ。学際的研究の重要性が増し、効率的な協力を妨 げる障害が生じたことで、20世紀には方法論への関心が高まった。

| In

its most common sense, methodology is the study of research methods.

However, the term can also refer to the methods themselves or to the

philosophical discussion of associated background assumptions. A method

is a structured procedure for bringing about a certain goal, like

acquiring knowledge or verifying knowledge claims. This normally

involves various steps, like choosing a sample, collecting data from

this sample, and interpreting the data. The study of methods concerns a

detailed description and analysis of these processes. It includes

evaluative aspects by comparing different methods. This way, it is

assessed what advantages and disadvantages they have and for what

research goals they may be used. These descriptions and evaluations

depend on philosophical background assumptions. Examples are how to

conceptualize the studied phenomena and what constitutes evidence for

or against them. When understood in the widest sense, methodology also

includes the discussion of these more abstract issues. Methodologies are traditionally divided into quantitative and qualitative research. Quantitative research is the main methodology of the natural sciences. It uses precise numerical measurements. Its goal is usually to find universal laws used to make predictions about future events. The dominant methodology in the natural sciences is called the scientific method. It includes steps like observation and the formulation of a hypothesis. Further steps are to test the hypothesis using an experiment, to compare the measurements to the expected results, and to publish the findings. Qualitative research is more characteristic of the social sciences and gives less prominence to exact numerical measurements. It aims more at an in-depth understanding of the meaning of the studied phenomena and less at universal and predictive laws. Common methods found in the social sciences are surveys, interviews, focus groups, and the nominal group technique. They differ from each other concerning their sample size, the types of questions asked, and the general setting. In recent decades, many social scientists have started using mixed-methods research, which combines quantitative and qualitative methodologies. Many discussions in methodology concern the question of whether the quantitative approach is superior, especially whether it is adequate when applied to the social domain. A few theorists reject methodology as a discipline in general. For example, some argue that it is useless since methods should be used rather than studied. Others hold that it is harmful because it restricts the freedom and creativity of researchers. Methodologists often respond to these objections by claiming that a good methodology helps researchers arrive at reliable theories in an efficient way. The choice of method often matters since the same factual material can lead to different conclusions depending on one's method. Interest in methodology has risen in the 20th century due to the increased importance of interdisciplinary work and the obstacles hindering efficient cooperation. |

方法論とは、最も一般的な意味で、研究手法の研究である。しかし、この

用語は手法そのものや、関連する背景仮定についての哲学的議論を指すこともある。手法とは、知識の獲得や知識主張の検証といった特定の目標を達成するため

の構造化された手順である。通常、標本の選択、その標本からのデータ収集、データの解釈といった様々な段階を含む。方法論の研究は、こうした過程の詳細な

記述と分析に関わる。異なる方法を比較する評価的側面も含む。これにより、各方法の長所短所や、どの研究目的に適用可能かが判断される。こうした記述と評

価は、哲学的な背景前提に依存する。例としては、研究対象の現象をどう概念化するか、あるいはそれらを支持・反証する証拠とは何かが挙げられる。最も広い

意味で理解すれば、方法論はこうしたより抽象的な問題の議論も含む。 方法論は伝統的に定量的研究と定性的研究に分けられる。定量的研究は自然科学の主要な方法論である。精密な数値測定を用い、通常は将来の事象を予測する普 遍的法則の発見を目的とする。自然科学で支配的な方法論は科学的方法と呼ばれる。観察や仮説の立案といった段階を含む。さらに実験による仮説の検証、測定 値と予測結果の比較、発見の公表といった段階が続く。 質的研究は社会科学に特徴的で、正確な数値測定を重視しない。普遍的・予測可能な法則よりも、研究対象の現象の意味を深く理解することを主眼とする。社会 科学でよく用いられる手法には、調査、インタビュー、フォーカスグループ、ノミナルグループ技法がある。これらは標本サイズ、質問の種類、実施環境におい て互いに異なる。ここ数十年で、多くの社会科学者が定量的手法と定性的手法を組み合わせた混合手法研究を使い始めている。 方法論に関する議論の多くは、定量的アプローチが優れているか、特に社会領域に適用する際に適切かどうかという問題に関わる。一部の理論家は方法論という 学問分野そのものを否定する。例えば、方法は研究するものではなく使うべきものだから無意味だと主張する者もいる。また、研究者の自由や創造性を制限する ため有害だと考える者もいる。方法論研究者はこうした反論に対し、優れた方法論は研究者が効率的に信頼性の高い理論に到達する助けとなると主張して応じ る。方法の選択はしばしば重要である。同じ事実資料でも、方法によって異なる結論に至る可能性があるからだ。学際的研究の重要性が増し、効率的な協力を妨 げる障害が生じたことで、20世紀には方法論への関心が高まった。 |

| Definitions The term "methodology" is associated with a variety of meanings. In its most common usage, it refers either to a method, to the field of inquiry studying methods, or to philosophical discussions of background assumptions involved in these processes.[1][2][3] Some researchers distinguish methods from methodologies by holding that methods are modes of data collection while methodologies are more general research strategies that determine how to conduct a research project.[1][4] In this sense, methodologies include various theoretical commitments about the intended outcomes of the investigation.[5] As method The term "methodology" is sometimes used as a synonym for the term "method". A method is a way of reaching some predefined goal.[6][7][8] It is a planned and structured procedure for solving a theoretical or practical problem. In this regard, methods stand in contrast to free and unstructured approaches to problem-solving.[7] For example, descriptive statistics is a method of data analysis, radiocarbon dating is a method of determining the age of organic objects, sautéing is a method of cooking, and project-based learning is an educational method. The term "technique" is often used as a synonym both in the academic and the everyday discourse. Methods usually involve a clearly defined series of decisions and actions to be used under certain circumstances, usually expressable as a sequence of repeatable instructions. The goal of following the steps of a method is to bring about the result promised by it. In the context of inquiry, methods may be defined as systems of rules and procedures to discover regularities of nature, society, and thought.[6][7] In this sense, methodology can refer to procedures used to arrive at new knowledge or to techniques of verifying and falsifying pre-existing knowledge claims.[9] This encompasses various issues pertaining both to the collection of data and their analysis. Concerning the collection, it involves the problem of sampling and of how to go about the data collection itself, like surveys, interviews, or observation. There are also numerous methods of how the collected data can be analyzed using statistics or other ways of interpreting it to extract interesting conclusions.[10] As study of methods However, many theorists emphasize the differences between the terms "method" and "methodology".[1][7][2][11] In this regard, methodology may be defined as "the study or description of methods" or as "the analysis of the principles of methods, rules, and postulates employed by a discipline".[12][13] This study or analysis involves uncovering assumptions and practices associated with the different methods and a detailed description of research designs and hypothesis testing. It also includes evaluative aspects: forms of data collection, measurement strategies, and ways to analyze data are compared and their advantages and disadvantages relative to different research goals and situations are assessed. In this regard, methodology provides the skills, knowledge, and practical guidance needed to conduct scientific research in an efficient manner. It acts as a guideline for various decisions researchers need to take in the scientific process.[14][10] Methodology can be understood as the middle ground between concrete particular methods and the abstract and general issues discussed by the philosophy of science.[11][15] In this regard, methodology comes after formulating a research question and helps the researchers decide what methods to use in the process. For example, methodology should assist the researcher in deciding why one method of sampling is preferable to another in a particular case or which form of data analysis is likely to bring the best results. Methodology achieves this by explaining, evaluating and justifying methods. Just as there are different methods, there are also different methodologies. Different methodologies provide different approaches to how methods are evaluated and explained and may thus make different suggestions on what method to use in a particular case.[15][11] According to Aleksandr Georgievich Spirkin, "[a] methodology is a system of principles and general ways of organising and structuring theoretical and practical activity, and also the theory of this system".[16][17] Helen Kara defines methodology as "a contextual framework for research, a coherent and logical scheme based on views, beliefs, and values, that guides the choices researchers make".[18] Ginny E. Garcia and Dudley L. Poston understand methodology either as a complex body of rules and postulates guiding research or as the analysis of such rules and procedures. As a body of rules and postulates, a methodology defines the subject of analysis as well as the conceptual tools used by the analysis and the limits of the analysis. Research projects are usually governed by a structured procedure known as the research process. The goal of this process is given by a research question, which determines what kind of information one intends to acquire.[19][20] As discussion of background assumptions Some theorists prefer an even wider understanding of methodology that involves not just the description, comparison, and evaluation of methods but includes additionally more general philosophical issues. One reason for this wider approach is that discussions of when to use which method often take various background assumptions for granted, for example, concerning the goal and nature of research. These assumptions can at times play an important role concerning which method to choose and how to follow it.[14][11][21] For example, Thomas Kuhn argues in his The Structure of Scientific Revolutions that sciences operate within a framework or a paradigm that determines which questions are asked and what counts as good science. This concerns philosophical disagreements both about how to conceptualize the phenomena studied, what constitutes evidence for and against them, and what the general goal of researching them is.[14][22][23] So in this wider sense, methodology overlaps with philosophy by making these assumptions explicit and presenting arguments for and against them.[14] According to C. S. Herrman, a good methodology clarifies the structure of the data to be analyzed and helps the researchers see the phenomena in a new light. In this regard, a methodology is similar to a paradigm.[3][15] A similar view is defended by Spirkin, who holds that a central aspect of every methodology is the world view that comes with it.[16] The discussion of background assumptions can include metaphysical and ontological issues in cases where they have important implications for the proper research methodology. For example, a realist perspective considering the observed phenomena as an external and independent reality is often associated with an emphasis on empirical data collection and a more distanced and objective attitude. Idealists, on the other hand, hold that external reality is not fully independent of the mind and tend, therefore, to include more subjective tendencies in the research process as well.[5][24][25] For the quantitative approach, philosophical debates in methodology include the distinction between the inductive and the hypothetico-deductive interpretation of the scientific method. For qualitative research, many basic assumptions are tied to philosophical positions such as hermeneutics, pragmatism, Marxism, critical theory, and postmodernism.[14][26] According to Kuhn, an important factor in such debates is that the different paradigms are incommensurable. This means that there is no overarching framework to assess the conflicting theoretical and methodological assumptions. This critique puts into question various presumptions of the quantitative approach associated with scientific progress based on the steady accumulation of data.[14][22] Other discussions of abstract theoretical issues in the philosophy of science are also sometimes included.[6][9] This can involve questions like how and whether scientific research differs from fictional writing as well as whether research studies objective facts rather than constructing the phenomena it claims to study. In the latter sense, some methodologists have even claimed that the goal of science is less to represent a pre-existing reality and more to bring about some kind of social change in favor of repressed groups in society.[14] Related terms and issues Viknesh Andiappan and Yoke Kin Wan use the field of process systems engineering to distinguish the term "methodology" from the closely related terms "approach", "method", "procedure", and "technique".[27] On their view, "approach" is the most general term. It can be defined as "a way or direction used to address a problem based on a set of assumptions". An example is the difference between hierarchical approaches, which consider one task at a time in a hierarchical manner, and concurrent approaches, which consider them all simultaneously. Methodologies are a little more specific. They are general strategies needed to realize an approach and may be understood as guidelines for how to make choices. Often the term "framework" is used as a synonym. A method is a still more specific way of practically implementing the approach. Methodologies provide the guidelines that help researchers decide which method to follow. The method itself may be understood as a sequence of techniques. A technique is a step taken that can be observed and measured. Each technique has some immediate result. The whole sequence of steps is termed a "procedure".[27][28] A similar but less complex characterization is sometimes found in the field of language teaching, where the teaching process may be described through a three-level conceptualization based on "approach", "method", and "technique".[29] One question concerning the definition of methodology is whether it should be understood as a descriptive or a normative discipline. The key difference in this regard is whether methodology just provides a value-neutral description of methods or what scientists actually do. Many methodologists practice their craft in a normative sense, meaning that they express clear opinions about the advantages and disadvantages of different methods. In this regard, methodology is not just about what researchers actually do but about what they ought to do or how to perform good research.[14][8] |

定義 「方法論」という言葉は様々な意味と結びついている。最も一般的な用法では、方法そのもの、方法を研究する学問分野、あるいはこれらの過程に関わる背景的 な前提についての哲学的議論を指す。[1][2][3] 一部の研究者は、方法をデータ収集の手段と定義し、方法論を研究プロジェクトの実施方法を決定するより一般的な研究戦略と区別する。[1][4] この意味で、方法論には調査の意図された成果に関する様々な理論的コミットメントが含まれる。[5] 方法として 「方法論」という用語は時に「方法」の同義語として用いられる。方法とは、あらかじめ定められた目標に到達する手段である。[6][7][8] 理論的または実践的問題を解決するための計画的かつ構造化された手順である。この点において、方法は自由で構造化されていない問題解決アプローチとは対照 的である。[7] 例えば、記述統計はデータ分析の方法であり、放射性炭素年代測定は有機物の年代を決定する方法であり、ソテーは調理の方法であり、プロジェクトベース学習 は教育の方法である。「技法」という用語は、学術的・日常的言説の両方でしばしば同義語として用いられる。方法論は通常、特定の状況下で用いられる明確に 定義された一連の決定と行動を含む。これは通常、反復可能な手順の連鎖として表現できる。方法論の手順に従う目的は、それが約束する結果をもたらすことに ある。探究の文脈では、方法とは自然・社会・思考の規則性を発見するための規則と手順の体系と定義される[6][7]。この意味で方法論とは、新たな知識 に到達するための手順、あるいは既存の知識主張を検証・反証する技法を指し得る[9]。これにはデータの収集と分析に関する様々な問題が含まれる。収集に 関しては、サンプリングの問題や、調査、インタビュー、観察といったデータ収集そのものの方法論が関わる。また、収集したデータを統計学やその他の解釈手 法を用いて分析し、興味深い結論を導き出す方法も数多く存在する。[10] 方法の研究として しかし、多くの理論家は「方法」と「方法論」という用語の違いを強調する。[1][7][2][11] この点において、方法論は「方法の研究または記述」あるいは「ある学問分野が用いる方法、規則、公理の原理の分析」と定義される。[12][13] この研究または分析には、異なる方法に関連する前提や実践の解明、研究設計や仮説検証の詳細な記述が含まれる。また評価的側面も含む:データ収集の形式、 測定戦略、データ分析手法を比較し、異なる研究目標や状況に対するそれらの長所・短所を評価する。この点において方法論は、科学的研究を効率的に遂行する ために必要な技能、知識、実践的指針を提供する。それは科学的な過程において研究者が下す様々な決定のための指針として機能する。[14][10] 方法論は、具体的な個別手法と科学哲学が扱う抽象的・普遍的問題の中間領域と理解できる。[11][15] この意味で方法論は研究課題の設定後に位置づけられ、研究者が過程で用いる手法を決定する助けとなる。例えば特定の事例において、あるサンプリング手法が 他より優れている理由や、どのデータ分析形式が最良の結果をもたらす可能性が高いかを研究者が判断する際、方法論は支援すべきである。方法論は、方法を説 明し、評価し、正当化することでこれを達成する。方法が様々であるように、方法論も様々である。異なる方法論は、方法の評価や説明に対する異なるアプロー チを提供し、したがって特定の事例においてどの方法を用いるべきかについて異なる提案を行う可能性がある。[15] [11] アレクサンドル・ゲオルギエヴィチ・スピルキンによれば、「方法論とは、理論的・実践的活動を組織化し構造化する原則と一般的な方法の体系、そしてこの体 系の理論である」[16][17]。ヘレン・カラは方法論を「研究のための文脈的枠組み、見解・信念・価値観に基づく首尾一貫した論理的計画であり、研究 者の選択を導くもの」と定義する。[18] ジニー・E・ガルシアとダドリー・L・ポストンは、方法論を研究を導く規則と仮定の複合体系、あるいはそうした規則と手順の分析のいずれかと理解してい る。規則と仮定の体系として、方法論は分析の対象、分析に用いられる概念的ツール、分析の限界を定義する。研究プロジェクトは通常、研究プロセスと呼ばれ る構造化された手順によって管理される。このプロセスの目標は研究課題によって与えられ、それはどのような情報を取得しようとするかを決定する。[19] [20] 背景となる前提についての議論 一部の理論家は、方法論をさらに広く捉えることを好む。それは単に方法の記述・比較・評価だけでなく、より一般的な哲学的問題も含む。この広いアプローチ を取る理由の一つは、どの方法をいつ使うかについての議論が、しばしば様々な背景前提を当然視していることだ。例えば、研究の目的や性質に関する前提であ る。これらの前提は、どの方法を選ぶか、またそれをどう進めるかに関して、時に重要な役割を果たすことがある。[14][11][21] 例えばトーマス・クーンは『科学革命の構造』において、科学は特定の枠組み(パラダイム)の中で機能し、それが問われるべき問題や優れた科学の基準を決定 すると論じている。これは研究対象の現象をどう概念化するか、その証拠と反証を何とするか、そして研究の一般的な目的は何かといった哲学的対立に関わる。 [14][22] [23] この広い意味において、方法論はこうした前提を明示し、それらに対する賛否両論を提示することで哲学と重なる。[14] C・S・ハーマンによれば、優れた方法論は分析対象データの構造を明確化し、研究者が現象を新たな視点で捉える手助けとなる。この点において、方法論はパ ラダイムと類似している。[3][15] スパークインも同様の見解を擁護しており、あらゆる方法論の中核的側面はそれに付随する世界観にあると主張している。[16] 背景となる前提条件の議論には、適切な研究方法論に重要な影響を及ぼす場合、形而上学的・存在論的問題が含まれることがある。例えば、観察された現象を外 部的で独立した現実と見なす現実主義的視点は、経験的データ収集の重視や、より距離を置いた客観的態度と結びつくことが多い。一方、理想主義者は外部現実 が精神から完全に独立していないと主張し、したがって研究過程においてより主観的な傾向を取り入れる傾向がある。[5][24] [25] 定量的アプローチにおいては、方法論に関する哲学的議論には、科学的方法の帰納的解釈と仮説演繹的解釈の区別が含まれる。定性的研究においては、多くの基 本前提が解釈学、実用主義、マルクス主義、批判理論、ポストモダニズムといった哲学的立場と結びついている。[14][26] クーンによれば、こうした議論における重要な要素は、異なるパラダイムが共約不可能なことだ。これは、対立する理論的・方法論的前提を評価する包括的枠組 みが存在しないことを意味する。この批判は、データの着実な蓄積に基づく科学的進歩と結びついた定量的アプローチの様々な前提を疑問視するものである。 [14][22] 科学哲学における抽象的な理論問題に関する他の議論も時折含まれることがある。[6][9] これには、科学的研究が虚構の記述とどのように、また実際に異なるのか、あるいは研究が主張する現象を構築するのではなく客観的事実を研究するのかといっ た問題が含まれる。後者の意味において、一部の方法論者は、科学の目的は既存の現実を表現することよりも、社会で抑圧された集団に有利な何らかの社会的変 化をもたらすことにあるとさえ主張している。[14] 関連用語と問題 ヴィクネシュ・アンディアッパンとヨック・キン・ワンは、プロセスシステム工学の分野を用いて、「方法論」という用語を、密接に関連する「アプローチ」 「方法」「手順」「技術」といった用語と区別している。[27] 彼らの見解では、「アプローチ」が最も一般的な用語である。「仮定の集合に基づいて問題に対処するために用いられる方法や方向性」と定義できる。例とし て、階層的アプローチ(タスクを階層的に一つずつ扱う)と並行的アプローチ(全てを同時に扱う)の違いが挙げられる。方法論はさらに具体的である。アプ ローチを実現するために必要な一般的な戦略であり、選択を行うための指針と理解できる。しばしば「枠組み」という用語が同義語として用いられる。手法は、 アプローチを実際に実施するためのさらに具体的な方法である。方法論は、研究者がどの手法を採用すべきかを決定する際に役立つ指針を提供する。手法自体 は、一連の技術と理解される。技術とは、観察・測定可能な実行ステップである。各技術には何らかの直接的な結果がある。ステップ全体の連鎖は「手順」と呼 ばれる。[27][28] 言語教育の分野では、これと類似するがより単純化された特徴付けが見られることがある。そこでは教授プロセスが「アプローチ」「方法」「技法」に基づく三 段階の概念化を通じて説明される。[29] 方法論の定義に関する一つの疑問は、それが記述的分野として理解されるべきか、規範的分野として理解されるべきかという点である。この点における核心的な 差異は、方法論が単に方法論や科学者が実際に行う行為を価値中立的に記述するものか否かである。多くの方法論研究者は規範的な意味でその技法を実践してお り、異なる方法論の長所短所について明確な見解を表明する。この観点から、方法論は研究者が実際に行う行為だけでなく、行うべき行為や優れた研究の実施方 法についても扱うのである。[14][8] |

| Types Theorists often distinguish various general types or approaches to methodology. The most influential classification contrasts quantitative and qualitative methodology.[4][30][19][16] Quantitative and qualitative Quantitative research is closely associated with the natural sciences. It is based on precise numerical measurements, which are then used to arrive at exact general laws. This precision is also reflected in the goal of making predictions that can later be verified by other researchers.[4][8] Examples of quantitative research include physicists at the Large Hadron Collider measuring the mass of newly created particles and positive psychologists conducting an online survey to determine the correlation between income and self-assessed well-being.[31] Qualitative research is characterized in various ways in the academic literature but there are very few precise definitions of the term. It is often used in contrast to quantitative research for forms of study that do not quantify their subject matter numerically.[32][30] However, the distinction between these two types is not always obvious and various theorists have argued that it should be understood as a continuum and not as a dichotomy.[33][34][35] A lot of qualitative research is concerned with some form of human experience or behavior, in which case it tends to focus on a few individuals and their in-depth understanding of the meaning of the studied phenomena.[4] Examples of the qualitative method are a market researcher conducting a focus group in order to learn how people react to a new product or a medical researcher performing an unstructured in-depth interview with a participant from a new experimental therapy to assess its potential benefits and drawbacks.[30] It is also used to improve quantitative research, such as informing data collection materials and questionnaire design.[36] Qualitative research is frequently employed in fields where the pre-existing knowledge is inadequate. This way, it is possible to get a first impression of the field and potential theories, thus paving the way for investigating the issue in further studies.[32][30] Quantitative methods dominate in the natural sciences but both methodologies are used in the social sciences.[4] Some social scientists focus mostly on one method while others try to investigate the same phenomenon using a variety of different methods.[4][16] It is central to both approaches how the group of individuals used for the data collection is selected. This process is known as sampling. It involves the selection of a subset of individuals or phenomena to be measured. Important in this regard is that the selected samples are representative of the whole population, i.e. that no significant biases were involved when choosing. If this is not the case, the data collected does not reflect what the population as a whole is like. This affects generalizations and predictions drawn from the biased data.[4][19] The number of individuals selected is called the sample size. For qualitative research, the sample size is usually rather small, while quantitative research tends to focus on big groups and collecting a lot of data. After the collection, the data needs to be analyzed and interpreted to arrive at interesting conclusions that pertain directly to the research question. This way, the wealth of information obtained is summarized and thus made more accessible to others. Especially in the case of quantitative research, this often involves the application of some form of statistics to make sense of the numerous individual measurements.[19][8] Many discussions in the history of methodology center around the quantitative methods used by the natural sciences. A central question in this regard is to what extent they can be applied to other fields, like the social sciences and history.[14] The success of the natural sciences was often seen as an indication of the superiority of the quantitative methodology and used as an argument to apply this approach to other fields as well.[14][37] However, this outlook has been put into question in the more recent methodological discourse. In this regard, it is often argued that the paradigm of the natural sciences is a one-sided development of reason, which is not equally well suited to all areas of inquiry.[10][14] The divide between quantitative and qualitative methods in the social sciences is one consequence of this criticism.[14] Which method is more appropriate often depends on the goal of the research. For example, quantitative methods usually excel for evaluating preconceived hypotheses that can be clearly formulated and measured. Qualitative methods, on the other hand, can be used to study complex individual issues, often with the goal of formulating new hypotheses. This is especially relevant when the existing knowledge of the subject is inadequate.[30] Important advantages of quantitative methods include precision and reliability. However, they have often difficulties in studying very complex phenomena that are commonly of interest to the social sciences. Additional problems can arise when the data is misinterpreted to defend conclusions that are not directly supported by the measurements themselves.[4] In recent decades, many researchers in the social sciences have started combining both methodologies. This is known as mixed-methods research. A central motivation for this is that the two approaches can complement each other in various ways: some issues are ignored or too difficult to study with one methodology and are better approached with the other. In other cases, both approaches are applied to the same issue to produce more comprehensive and well-rounded results.[4][38][39] Qualitative and quantitative research are often associated with different research paradigms and background assumptions. Qualitative researchers often use an interpretive or critical approach while quantitative researchers tend to prefer a positivistic approach. Important disagreements between these approaches concern the role of objectivity and hard empirical data as well as the research goal of predictive success rather than in-depth understanding or social change.[19][40][41] Others Various other classifications have been proposed. One distinguishes between substantive and formal methodologies. Substantive methodologies tend to focus on one specific area of inquiry. The findings are initially restricted to this specific field but may be transferrable to other areas of inquiry. Formal methodologies, on the other hand, are based on a variety of studies and try to arrive at more general principles applying to different fields. They may also give particular prominence to the analysis of the language of science and the formal structure of scientific explanation.[42][16][43] A closely related classification distinguishes between philosophical, general scientific, and special scientific methods.[16][44][17] One type of methodological outlook is called "proceduralism". According to it, the goal of methodology is to boil down the research process to a simple set of rules or a recipe that automatically leads to good research if followed precisely. However, it has been argued that, while this ideal may be acceptable for some forms of quantitative research, it fails for qualitative research. One argument for this position is based on the claim that research is not a technique but a craft that cannot be achieved by blindly following a method. In this regard, research depends on forms of creativity and improvisation to amount to good science.[14][45][46] Other types include inductive, deductive, and transcendental methods.[9] Inductive methods are common in the empirical sciences and proceed through inductive reasoning from many particular observations to arrive at general conclusions, often in the form of universal laws.[47] Deductive methods, also referred to as axiomatic methods, are often found in formal sciences, such as geometry. They start from a set of self-evident axioms or first principles and use deduction to infer interesting conclusions from these axioms.[48] Transcendental methods are common in Kantian and post-Kantian philosophy. They start with certain particular observations. It is then argued that the observed phenomena can only exist if their conditions of possibility are fulfilled. This way, the researcher may draw general psychological or metaphysical conclusions based on the claim that the phenomenon would not be observable otherwise.[49] |

類型 理論家はしばしば方法論に対する様々な一般的な類型やアプローチを区別する。最も影響力のある分類は、定量的方法論と定性的方法論を対比させるものである。[4][30][19][16] 定量的と定性的 定量的研究は自然科学と密接に関連している。それは精密な数値測定に基づいており、それらは正確な一般法則に到達するために用いられる。この精密さは、後 に他の研究者によって検証可能な予測を行うという目標にも反映されている。[4][8] 定量的研究の例としては、大型ハドロン衝突型加速器で新生成粒子の質量を測定する物理学者や、収入と自己評価による幸福度の相関関係を調べるオンライン調 査を実施するポジティブ心理学者が挙げられる。[31] 質的研究は学術文献で様々な特徴が挙げられるが、この用語の厳密な定義はほとんど存在しない。対象を数値化しない研究形態を指す場合、しばしば量的研究と 対比して用いられる。[32][30] しかし両者の区別は必ずしも明確ではなく、様々な理論家がこれを二分法ではなく連続体として理解すべきだと主張している。[33][34][35] 多くの質的研究は、何らかの形態の人間の経験や行動に関心を寄せている。その場合、少数の個人と、彼らが研究対象の現象の意味について持つ深い理解に焦点 を当てる傾向がある。[4] 質的手法の例としては、新製品に対する人々の反応を学ぶためにフォーカスグループを実施する市場調査員や、新たな実験的治療法の潜在的な利点と欠点を評価 するために、その参加者に対して非構造化の詳細なインタビューを行う医学研究者が挙げられる。[30] また、データ収集資料や質問票設計の指針となるなど、定量的研究の改善にも用いられる。[36] 定性的研究は、既存の知識が不十分な分野で頻繁に採用される。これにより、当該分野や潜在的な理論の第一印象を得ることが可能となり、さらなる研究で問題 を調査する道筋が整うのである。[32][30] 自然科学では定量的手法が主流だが、社会科学では両手法が併用される。[4] 社会科学者の中には主に一方の手法に注力する者もいれば、多様な手法を用いて同一現象を調査しようとする者もいる。[4][16] データ収集対象となる個人群の選定方法は、両アプローチにおいて核心的である。この過程はサンプリングと呼ばれ、測定対象となる個人や現象のサブセットを 選択する作業を含む。この点で重要なのは、選ばれた標本が母集団全体を代表していること、つまり選択時に重大な偏りが生じていないことだ。そうでない場 合、収集されたデータは母集団全体の様相を反映しない。これは偏ったデータから導かれる一般化や予測に影響を与える。[4][19] 選ばれた個人の数は標本サイズと呼ばれる。質的調査では標本サイズは通常かなり小さいが、量的調査では大規模な集団に焦点を当て、大量のデータを収集する 傾向がある。収集後、データは分析・解釈され、研究課題に直接関連する興味深い結論を導き出す必要がある。これにより得られた豊富な情報は要約され、他者 にとってより理解しやすくなる。特に量的調査の場合、多数の個別測定値を理解するために何らかの統計手法を適用することが多い。[19][8] 方法論の歴史における多くの議論は、自然科学が用いる定量的手法を中心に展開してきた。この点で核心的な問いは、こうした手法が社会科学や歴史学といった 他の分野にどの程度適用可能かということだ。[14] 自然科学の成功は往々にして定量的手法の優位性を示すものと見なされ、このアプローチを他分野にも適用すべき根拠として用いられてきた。[14][37] しかし、この見方は近年の方法論的言説において疑問視されている。この点に関して、自然科学のパラダイムは理性の片寄った発展であり、あらゆる研究領域に 等しく適しているわけではないと主張されることが多い。[10][14] 社会科学における定量的手法と定性的手法の分断は、この批判の結果の一つである。[14] どちらの方法が適切かは、研究の目的によって決まることが多い。例えば、定量的手法は、明確に定式化・測定可能な事前仮説の評価に優れている。一方、定性 的手法は、新たな仮説の構築を目的として、複雑な個別問題の研究に用いられる。これは、対象分野の既存知識が不十分な場合に特に重要だ。[30] 定量的手法の重要な利点には、精度と信頼性がある。しかし、社会科学が関心を寄せるような非常に複雑な現象を研究する際には、しばしば困難を伴う。さら に、測定結果自体によって直接裏付けられていない結論を擁護するためにデータが誤って解釈される場合、追加の問題が生じうる。[4] ここ数十年、社会科学の研究者の多くは両方の方法論を組み合わせるようになった。これは混合手法研究として知られている。この主な動機は、二つのアプロー チが様々な形で互いを補完し得る点にある。ある問題は一方の方法論では無視されたり研究が困難であったりし、他方の方法論で取り組む方が適している。また 別のケースでは、同じ問題に両方のアプローチを適用し、より包括的でバランスの取れた結果を得るのである。[4][38][39] 質的調査と量的調査は、しばしば異なる研究パラダイムや背景にある前提と結びつけられる。質的調査研究者は解釈的または批判的アプローチを用いることが多 いのに対し、量的調査研究者は実証主義的アプローチを好む傾向がある。これらのアプローチ間の重要な相違点は、客観性と厳密な実証データの役割、そして研 究目標が深い理解や社会変革ではなく予測の成功にあることにある。[19][40] [41] その他 様々な他の分類が提案されている。一つは実質的方法論と形式的方法論の区別である。実質的方法論は特定の研究領域に焦点を当てる傾向がある。その知見は当 初この特定分野に限定されるが、他の研究領域へ転用可能である場合もある。一方、形式的方法論は多様な研究に基づいており、異なる分野に適用可能なより一 般的な原理の確立を目指す。また、科学言語の分析や科学的説明の形式的構造の分析を特に重視する場合もある。[42][16][43] これと密接に関連する分類では、哲学的方法、一般的科学的方法、特殊科学的方法が区別される。[16][44] [17] 方法論的見解の一種に「手続き主義」と呼ばれるものがある。これによれば、方法論の目的は研究プロセスを単純な規則の集合、あるいは正確に守れば自動的に 優れた研究につながるレシピに還元することである。しかし、この理想は一部の定量的研究には適用可能でも、質的研究には通用しないという反論がある。この 立場を支持する一つの論拠は、研究は技術ではなく、方法を盲目的に従うだけでは達成できない職人技であるという主張に基づいている。この点において、研究 は優れた科学となるためには創造性や即興性といった形態に依存するのだ。[14][45][46] その他の類型には、帰納法、演繹法、超越的方法がある。[9] 帰納的方法は経験科学で一般的であり、多くの個別観察から帰納的推論を経て、普遍法則の形で一般結論に到達する。[47] 演繹的方法(公理的方法とも呼ばれる)は幾何学などの形式科学でよく見られる。自明な公理や第一原理の集合から出発し、演繹を用いてこれらの公理から興味 深い結論を導出する。[48] 超越的方法はカント哲学およびポストカント哲学で一般的である。特定の観察から出発し、観察された現象はその可能性条件が満たされて初めて存在し得ると論 じる。こうして研究者は、現象がそうでなければ観察不可能だという主張に基づき、一般的な心理学的あるいは形而上学的結論を導き出すことができる。 [49] |

| Importance It has been argued that a proper understanding of methodology is important for various issues in the field of research. They include both the problem of conducting efficient and reliable research as well as being able to validate knowledge claims by others.[3] Method is often seen as one of the main factors of scientific progress. This is especially true for the natural sciences where the developments of experimental methods in the 16th and 17th century are often seen as the driving force behind the success and prominence of the natural sciences.[14] In some cases, the choice of methodology may have a severe impact on a research project. The reason is that very different and sometimes even opposite conclusions may follow from the same factual material based on the chosen methodology.[16] Aleksandr Georgievich Spirkin argues that methodology, when understood in a wide sense, is of great importance since the world presents us with innumerable entities and relations between them.[16] Methods are needed to simplify this complexity and find a way of mastering it. On the theoretical side, this concerns ways of forming true beliefs and solving problems. On the practical side, this concerns skills of influencing nature and dealing with each other. These different methods are usually passed down from one generation to the next. Spirkin holds that the interest in methodology on a more abstract level arose in attempts to formalize these techniques to improve them as well as to make it easier to use them and pass them on. In the field of research, for example, the goal of this process is to find reliable means to acquire knowledge in contrast to mere opinions acquired by unreliable means. In this regard, "methodology is a way of obtaining and building up ... knowledge".[16][44] Various theorists have observed that the interest in methodology has risen significantly in the 20th century.[16][14] This increased interest is reflected not just in academic publications on the subject but also in the institutionalized establishment of training programs focusing specifically on methodology.[14] This phenomenon can be interpreted in different ways. Some see it as a positive indication of the topic's theoretical and practical importance. Others interpret this interest in methodology as an excessive preoccupation that draws time and energy away from doing research on concrete subjects by applying the methods instead of researching them. This ambiguous attitude towards methodology is sometimes even exemplified in the same person. Max Weber, for example, criticized the focus on methodology during his time while making significant contributions to it himself.[14][50] Spirkin believes that one important reason for this development is that contemporary society faces many global problems. These problems cannot be solved by a single researcher or a single discipline but are in need of collaborative efforts from many fields. Such interdisciplinary undertakings profit a lot from methodological advances, both concerning the ability to understand the methods of the respective fields and in relation to developing more homogeneous methods equally used by all of them.[16][51] |

重要性 方法論を正しく理解することは、研究分野の様々な問題にとって重要であると論じられてきた。その中には、効率的で信頼性の高い研究を行うという問題と、他 者による知識の主張を検証することができるという問題の両方が含まれる[3]。方法論はしばしば科学の進歩の主な要因の1つと見なされる。これは特に自然 科学に当てはまり、16~17世紀 における実験手法の発展が、自然科学の成功と隆盛の原動力にな ったとみなされることが多い。その理由は、選択した方法論に基づき、同じ事実の材料から全く異なる、時には正反対の結論が導き出されることがあるからであ る[16]。 アレクサンドル・ゲオルギエヴィチ・スピルキンは、世界は無数の実体やそれらの間の関係を私たちに提示しているため、広い意味で理解する場合、方法論は非 常に重要であると主張している[16]。理論的な側面では、これは真の信念を形成し、問題を解決する方法に関するものである。実践的な面では、自然に影響 を与えたり、互いに対処したりする技術に関係する。これらの異なる方法は通常、世代から世代へと受け継がれていく。スピルキンは、より抽象的なレベルでの 方法論への関心は、これらの技法を形式化し、より使いやすく、より継承しやすくすることで向上させようとする試みから生まれたと考えている。例えば研究の 分野では、信頼できない手段で得た単なる意見とは対照的に、知識を得るための信頼できる手段を見つけることがこのプロセスの目的である。この点において、 「方法論とは・・・知識を獲得し、構築するための方法」である[16][44]。 様々な理論家が、方法論への関心が20世紀に著しく高まったことを観察している[16][14]。 この関心の高まりは、このテーマに関する学術的な出版物だけでなく、特に方法論に焦点を当てた研修プログラムの制度化された確立にも反映されている [14]。ある者は、このトピックが理論的、実践的に重要であることを示す肯定的な兆候であるとみなす。また、この方法論への関心を、研究する代わりに方 法を適用することで、具体的なテーマに関する研究を行うことから時間とエネルギーを引き離す、過剰な偏執と解釈する人もいる。このような方法論に対する曖 昧な態度は、時に同一人格の中でさえ例証される。例えばマックス・ウェーバーは、彼自身が方法論に多大な貢献をしながらも、彼の時代の方法論への注力を批 判していた[14][50] 。これらの問題は、一人の研究者や単一の学問分野では解決できず、多くの分野からの協力的な取り組みが必要である。このような学際的な取り組みは、各分野 の手法を理解する能力に関しても、すべての分野で等しく使用されるより均質な手法を開発することに関しても、方法論の進歩から多くの利益を得ている [16][51]。 |

| Criticism Most criticism of methodology is directed at one specific form or understanding of it. In such cases, one particular methodological theory is rejected but not methodology at large when understood as a field of research comprising many different theories.[14][10] In this regard, many objections to methodology focus on the quantitative approach, specifically when it is treated as the only viable approach.[14][37] Nonetheless, there are also more fundamental criticisms of methodology in general. They are often based on the idea that there is little value to abstract discussions of methods and the reasons cited for and against them. In this regard, it may be argued that what matters is the correct employment of methods and not their meticulous study. Sigmund Freud, for example, compared methodologists to "people who clean their glasses so thoroughly that they never have time to look through them".[14][52] According to C. Wright Mills, the practice of methodology often degenerates into a "fetishism of method and technique".[14][53] Some even hold that methodological reflection is not just a waste of time but actually has negative side effects. Such an argument may be defended by analogy to other skills that work best when the agent focuses only on employing them. In this regard, reflection may interfere with the process and lead to avoidable mistakes.[54] According to an example by Gilbert Ryle, "[w]e run, as a rule, worse, not better, if we think a lot about our feet".[55][54] A less severe version of this criticism does not reject methodology per se but denies its importance and rejects an intense focus on it. In this regard, methodology has still a limited and subordinate utility but becomes a diversion or even counterproductive by hindering practice when given too much emphasis.[56] Another line of criticism concerns more the general and abstract nature of methodology. It states that the discussion of methods is only useful in concrete and particular cases but not concerning abstract guidelines governing many or all cases. Some anti-methodologists reject methodology based on the claim that researchers need freedom to do their work effectively. But this freedom may be constrained and stifled by "inflexible and inappropriate guidelines". For example, according to Kerry Chamberlain, a good interpretation needs creativity to be provocative and insightful, which is prohibited by a strictly codified approach. Chamberlain uses the neologism "methodolatry" to refer to this alleged overemphasis on methodology.[56][14] Similar arguments are given in Paul Feyerabend's book "Against Method".[57][14] However, these criticisms of methodology in general are not always accepted. Many methodologists defend their craft by pointing out how the efficiency and reliability of research can be improved through a proper understanding of methodology.[14][10] A criticism of more specific forms of methodology is found in the works of the sociologist Howard S. Becker. He is quite critical of methodologists based on the claim that they usually act as advocates of one particular method usually associated with quantitative research.[10] An often-cited quotation in this regard is that "[m]ethodology is too important to be left to methodologists".[58][10][14] Alan Bryman has rejected this negative outlook on methodology. He holds that Becker's criticism can be avoided by understanding methodology as an inclusive inquiry into all kinds of methods and not as a mere doctrine for converting non-believers to one's preferred method.[10] |

批判 方法論に対する批評のほとんどは、ある特定の形式や理解に向けられたものである。そのような場合、ある特定の方法論的理論は否定されるが、多くの異なる理 論からなる研究分野として理解される場合、方法論全体は否定されない[14][10]。この点で、方法論に対する多くの反論は、特にそれが唯一の有効なア プローチとして扱われる場合、量的アプローチに焦点を当てている[14][37]。それらはしばしば、方法論やそれに対する賛否の理由についての抽象的な 議論にはほとんど価値がないという考えに基づいている。この点に関して、重要なのは方法を正しく用いることであり、その綿密な研究ではないと主張すること ができる。例えばジークムント・フロイトは方法論者を「眼鏡を覗く暇がないほど徹底的に眼鏡を掃除する人々」[14][52]に例えている。C・ライト・ ミルズによれば、方法論の実践はしばしば「方法と技術のフェティシズム」[14][53]に堕落する。 方法論的反省は時間の無駄であるばかりでなく、実際に負の副作用をもたらすと主張する者さえいる。このような議論は、エージェントがそのスキルの使用にの み集中するときに最良に機能する他のスキルとの類推によって擁護されるかもしれない。ギルバート・ライルの例によれば、「私たちは、自分の足についてたく さん考えるならば、原則として、より良く走るのではなく、より悪く走る」[55][54]。この点において、方法論は依然として限定的で従属的な有用性を 有しているが、あまりに強調されすぎると、練習の妨げとなり、陽動となるか、あるいは逆効果とさえなる[56]。 もう一つの批判は、方法論のより一般的で抽象的な性質に関するものである。それは、方法論の議論は具体的で個別主義的なケースにおいてのみ有用であり、多 くの、あるいはすべてのケースを支配する抽象的なガイドラインに関するものではないとしている。反方法論者の中には、研究者が効果的に仕事をするためには 自由が必要だという主張に基づいて、方法論を否定する者もいる。しかし、この自由は「融通の利かない不適切なガイドライン」によって制約を受け、阻害され る可能性がある。例えば、ケリー・チェンバレンによれば、優れた解釈には挑発的で洞察に満ちた創造性が必要だが、これは厳格に成文化されたアプローチでは 禁止されている。チェンバレンは「メソドーラトリー(methodolatry)」という新語を用いて、この方法論偏重の主張について言及している [56][14]。同様の主張はポール・ファイヤアーベントの著書『方法論に抗して』にも示されている[57][14]。 しかしながら、方法論一般に対するこれらの批判は常に受け入れられているわけではない。多くの方法論者は、方法論の適切な理解によって研究の効率性と信頼性をいかに向上させることができるかを指摘することによって、自分たちの技術を擁護している[14][10]。 方法論のより具体的な形態に対する批判は、社会学者ハワード・S・ベッカーの著作に見られる。この点に関してよく引用されるのは、「方法論は方法論者に任 せるには重要すぎる」[58][10][14]というものである。彼は、方法論をあらゆる種類の方法に対する包括的な探究として理解することによって、ま た信者でない人々を自分の好む方法に改宗させるための単なる教義として理解することによって、ベッカーの批判を回避することができると主張している [10]。 |

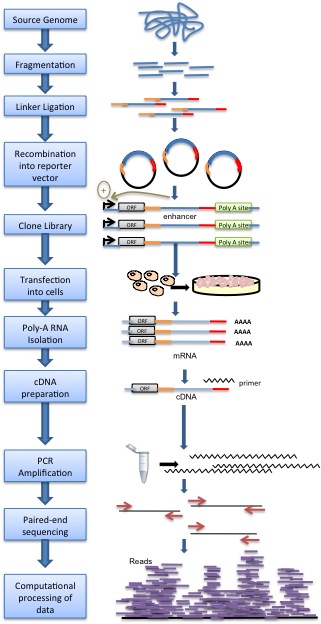

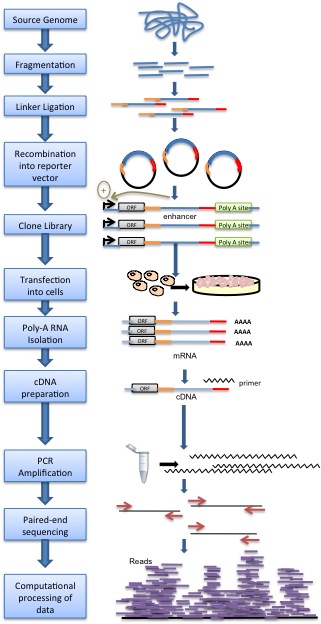

| In different fields Part of the importance of methodology is reflected in the number of fields to which it is relevant. They include the natural sciences and the social sciences as well as philosophy and mathematics.[54][8][19] Natural sciences  The methodology underlying a type of DNA sequencing The dominant methodology in the natural sciences (like astronomy, biology, chemistry, geoscience, and physics) is called the scientific method.[8][59] Its main cognitive aim is usually seen as the creation of knowledge, but various closely related aims have also been proposed, like understanding, explanation, or predictive success. Strictly speaking, there is no one single scientific method. In this regard, the expression "scientific method" refers not to one specific procedure but to different general or abstract methodological aspects characteristic of all the aforementioned fields. Important features are that the problem is formulated in a clear manner and that the evidence presented for or against a theory is public, reliable, and replicable. The last point is important so that other researchers are able to repeat the experiments to confirm or disconfirm the initial study.[8][60][61] For this reason, various factors and variables of the situation often have to be controlled to avoid distorting influences and to ensure that subsequent measurements by other researchers yield the same results.[14] The scientific method is a quantitative approach that aims at obtaining numerical data. This data is often described using mathematical formulas. The goal is usually to arrive at some universal generalizations that apply not just to the artificial situation of the experiment but to the world at large. Some data can only be acquired using advanced measurement instruments. In cases where the data is very complex, it is often necessary to employ sophisticated statistical techniques to draw conclusions from it.[8][60][61] The scientific method is often broken down into several steps. In a typical case, the procedure starts with regular observation and the collection of information. These findings then lead the scientist to formulate a hypothesis describing and explaining the observed phenomena. The next step consists in conducting an experiment designed for this specific hypothesis. The actual results of the experiment are then compared to the expected results based on one's hypothesis. The findings may then be interpreted and published, either as a confirmation or disconfirmation of the initial hypothesis.[60][8][61] Two central aspects of the scientific method are observation and experimentation.[8] This distinction is based on the idea that experimentation involves some form of manipulation or intervention.[62][63][64][4] This way, the studied phenomena are actively created or shaped. For example, a biologist inserting viral DNA into a bacterium is engaged in a form of experimentation. Pure observation, on the other hand, involves studying independent entities in a passive manner. This is the case, for example, when astronomers observe the orbits of astronomical objects far away.[65] Observation played the main role in ancient science. The scientific revolution in the 16th and 17th century affected a paradigm change that gave a much more central role to experimentation in the scientific methodology.[62][8] This is sometimes expressed by stating that modern science actively "puts questions to nature".[65] While the distinction is usually clear in the paradigmatic cases, there are also many intermediate cases where it is not obvious whether they should be characterized as observation or as experimentation.[65][62] A central discussion in this field concerns the distinction between the inductive and the hypothetico-deductive methodology. The core disagreement between these two approaches concerns their understanding of the confirmation of scientific theories. The inductive approach holds that a theory is confirmed or supported by all its positive instances, i.e. by all the observations that exemplify it.[66][67][68] For example, the observations of many white swans confirm the universal hypothesis that "all swans are white".[69][70] The hypothetico-deductive approach, on the other hand, focuses not on positive instances but on deductive consequences of the theory.[69][70][71][72] This way, the researcher uses deduction before conducting an experiment to infer what observations they expect.[73][8] These expectations are then compared to the observations they actually make. This approach often takes a negative form based on falsification. In this regard, positive instances do not confirm a hypothesis but negative instances disconfirm it. Positive indications that the hypothesis is true are only given indirectly if many attempts to find counterexamples have failed.[74] A cornerstone of this approach is the null hypothesis, which assumes that there is no connection (see causality) between whatever is being observed. It is up to the researcher to do all they can to disprove their own hypothesis through relevant methods or techniques, documented in a clear and replicable process. If they fail to do so, it can be concluded that the null hypothesis is false, which provides support for their own hypothesis about the relation between the observed phenomena.[75] |

異なる分野で 方法論の重要性の一部は、それが関連する分野の多さに反映されている。哲学や数学だけでなく、自然科学や社会科学も含まれる[54][8][19]。 自然科学  DNA配列決定の一種の基礎となる方法論 自然科学(天文学、生物学、化学、地球科学、物理学など)における支配的な方法論は科学的方法と呼ばれる[8][59]。その主な認識目的は通常、知識の 創造とみなされるが、理解、説明、予測的成功など、密接に関連する様々な目的も提案されている。厳密に言えば、単一の科学的方法は存在しない。この点で、 「科学的方法」という表現は、特定の手順を指すのではなく、前述のすべての分野に特徴的な、異なる一般的または抽象的な方法論的側面を指す。重要な特徴 は、問題が明確な方法で定式化されていることと、理論に対する賛否を示す証拠が公開されており、信頼性が高く、再現可能であることである。最後の点は、他 の研究者が最初の研究を確 認または反証するために実験を繰り返すことができるよう にするために重要である[8][60][61]。このため、歪曲的な影 響を避け、他の研究者によるその後の測定が同じ結果をもたら すことを確実にするために、状況の様々な要因や変数を制御しな ければならないことが多い[14]。このデータは、しばしば数式を用いて記述される。その目的は通常、実験の人工的な状況だけでなく、世界全体に適用され る普遍的な一般化に到達することである。データによっては、高度な測定機器を用いなければ得られないものもある。データが非常に複雑な場合、そこから結論 を導き出すためには、高度な統計的手法を用いる必要があることが多い[8][60][61]。 科学的方法は多くの場合、いくつかのステップに分けられる。典型的な場合、その手順は、定期的な観察と情報の収集から始まる。そしてこれらの知見から、科 学者は観察された現象を説明し、説明する仮説を立てる。次のステップは、この特定の仮説のために設計された実験を実施することである。実際の実験結果は、 仮説に基づいて予想される結果と比較される。そして、得られた知見を解釈し、最初の仮説の確認または反証として発表することができる[60][8] [61]。 この区別は、実験は何らかの操作や介入を伴うという考えに基づいている[62][63][64][4] 。例えば、生物学者が細菌にウイルスDNAを挿入することは、一種の実験である。一方、純粋観察では、独立した実体を受動的に研究する。例えば、天文学者 が遠く離れた天体の軌道を観測する場合がそうである。16世紀から17世紀にかけての科学革命は、科学的方法論において実験にはるかに中心的な役割を与え るパラダイム転換に影響を与えた[62][8]。このことは、近代科学が積極的に「自然に疑問を投げかける」[65]と述べることによって表現されること がある。 この分野における中心的な議論は、帰納的方法論と仮説演繹的方法論の区別に関するものである。これら2つのアプローチの間の意見の相違の核心は、科学的理 論の確証に関する理解に関するものである。帰納的アプローチは、理論はそのすべての肯定的事例、すなわちそれを例証するすべての観察によって確認または支 持されるとする。[69][70]一方、仮説演繹的アプローチは、肯定的な事例ではなく、理論の演繹的帰結に焦点を当てる。このアプローチは、改竄に基づ く否定的な形をとることが多い。この点で、肯定的な事例は仮説を確証しないが、否定的な事例は仮説を反証する。仮説が真であるという肯定的な兆候は、反例 を見つけようとする多くの試みが失敗した場合にのみ間接的に与えられる[74]。このアプローチの基礎となるのは帰無仮説であり、観察されるものの間には 何の関連もない(因果関係を参照)と仮定する。研究者は、明確で再現可能なプロセスで文書化された、関連する手法や技法を通じて、自らの仮説を反証するた めにできる限りのことをする。もしそれができなければ、帰無仮説は偽であると結論づけることができ、観察された現象間の関係性に関する自らの仮説を支持す ることになる[75]。 |

| Social sciences See also: Historical method Significantly more methodological variety is found in the social sciences, where both quantitative and qualitative approaches are used. They employ various forms of data collection, such as surveys, interviews, focus groups, and the nominal group technique.[4][30][19][76] Surveys belong to quantitative research and usually involve some form of questionnaire given to a large group of individuals. It is paramount that the questions are easily understandable by the participants since the answers might not have much value otherwise. Surveys normally restrict themselves to closed questions in order to avoid various problems that come with the interpretation of answers to open questions. They contrast in this regard to interviews, which put more emphasis on the individual participant and often involve open questions. Structured interviews are planned in advance and have a fixed set of questions given to each individual. They contrast with unstructured interviews, which are closer to a free-flow conversation and require more improvisation on the side of the interviewer for finding interesting and relevant questions. Semi-structured interviews constitute a middle ground: they include both predetermined questions and questions not planned in advance.[4][77][78] Structured interviews make it easier to compare the responses of the different participants and to draw general conclusions. However, they also limit what may be discovered and thus constrain the investigation in many ways.[4][30] Depending on the type and depth of the interview, this method belongs either to quantitative or to qualitative research.[30][4] The terms research conversation[79] and muddy interview[80] have been used to describe interviews conducted in informal settings which may not occur purely for the purposes of data collection. Some researcher employ the go-along method by conducting interviews while they and the participants navigate through and engage with their environment.[81] Focus groups are a qualitative research method often used in market research. They constitute a form of group interview involving a small number of demographically similar people. Researchers can use this method to collect data based on the interactions and responses of the participants. The interview often starts by asking the participants about their opinions on the topic under investigation, which may, in turn, lead to a free exchange in which the group members express and discuss their personal views. An important advantage of focus groups is that they can provide insight into how ideas and understanding operate in a cultural context. However, it is usually difficult to use these insights to discern more general patterns true for a wider public.[4][30][82] One advantage of focus groups is that they can help the researcher identify a wide range of distinct perspectives on the issue in a short time. The group interaction may also help clarify and expand interesting contributions. One disadvantage is due to the moderator's personality and group effects, which may influence the opinions stated by the participants.[30] When applied to cross-cultural settings, cultural and linguistic adaptations and group composition considerations are important to encourage greater participation in the group discussion.[36] The nominal group technique is similar to focus groups with a few important differences. The group often consists of experts in the field in question. The group size is similar but the interaction between the participants is more structured. The goal is to determine how much agreement there is among the experts on the different issues. The initial responses are often given in written form by each participant without a prior conversation between them. In this manner, group effects potentially influencing the expressed opinions are minimized. In later steps, the different responses and comments may be discussed and compared to each other by the group as a whole.[30][83][84] Most of these forms of data collection involve some type of observation. Observation can take place either in a natural setting, i.e. the field, or in a controlled setting such as a laboratory. Controlled settings carry with them the risk of distorting the results due to their artificiality. Their advantage lies in precisely controlling the relevant factors, which can help make the observations more reliable and repeatable. Non-participatory observation involves a distanced or external approach. In this case, the researcher focuses on describing and recording the observed phenomena without causing or changing them, in contrast to participatory observation.[4][85][86] An important methodological debate in the field of social sciences concerns the question of whether they deal with hard, objective, and value-neutral facts, as the natural sciences do. Positivists agree with this characterization, in contrast to interpretive and critical perspectives on the social sciences.[19][87][41] According to William Neumann, positivism can be defined as "an organized method for combining deductive logic with precise empirical observations of individual behavior in order to discover and confirm a set of probabilistic causal laws that can be used to predict general patterns of human activity". This view is rejected by interpretivists. Max Weber, for example, argues that the method of the natural sciences is inadequate for the social sciences. Instead, more importance is placed on meaning and how people create and maintain their social worlds. The critical methodology in social science is associated with Karl Marx and Sigmund Freud. It is based on the assumption that many of the phenomena studied using the other approaches are mere distortions or surface illusions. It seeks to uncover deeper structures of the material world hidden behind these distortions. This approach is often guided by the goal of helping people effect social changes and improvements.[19][87][41] |

社会科学 こちらも参照のこと: 歴史的方法 社会科学では、方法論の多様性が著しく、量的アプローチと質的アプローチの両方が用いられている。調査、インタビュー、フォーカス・グループ、唯名論手法 など、様々なデータ収集形態が採用されている[4][30][19][76]。調査は量的調査に属し、通常、大人数の個人を対象に何らかの形式のアンケー トを実施する。参加者が理解しやすい質問であることが最も重要であり、そうでなければ回答の価値があまりない可能性があるからである。オープンな質問に対 する回答の解釈に伴う様々な問題を避けるため、調査は通常、クローズドな質問に限定される。この点で、参加者個人に重点を置き、多くの場合オープン・クエ スチョンを含むインタビューとは対照的である。構造化インタビューは、事前に計画され、各個人に与えられる質問のセットが決まっている。非構造化インタ ビューとは対照的で、自由な会話に近く、興味深く適切な質問を見つけるために、インタビュアー側の即興性が求められる。半構造化インタビューはその中間を なすもので、あらかじめ決められた質問と、あらかじめ計画されていない質問の両方が含まれる[4][77][78]。構造化インタビューは、異なる参加者 の回答を比較しやすくし、一般的な結論を導きやすくする。しかし、構造化されたインタビューは、発見される可能性のあるものを制限するため、多くの点で調 査を制約することにもなる[4][30]。インタビューの種類や深さによって、この方法は量的研究にも質的研究にも属する[30][4]。研究者の中に は、自分自身と参加者が環境を移動し、その環境に関わりながらインタビューを実施するゴー・アロング法[81]を採用する者もいる。 フォーカスグループは、市場調査でよく用いられる質的調査手法である。少人数の人口統計学的に類似した人民が参加するグループインタビューの一種である。 研究者はこの方法を用いて、参加者の相互作用や反応に基づいてデータを収集することができる。インタビューは、調査中のトピックに関する意見を参加者に尋 ねることから始まることが多く、その結果、グループのメンバーが個人的な意見を述べたり議論したりする自由な交流が生まれることもある。フォーカス・グ ループの重要な利点は、文化的背景の中で考えや理解がどのように作用するかを洞察できることである。しかし、これらの洞察を用いて、より広い一般大衆に当 てはまるより一般的なパターンを見分けることは通常困難である[4][30][82]。フォーカス・グループの利点の1つは、調査者が短時間で問題に対す る幅広い明確な視点を特定できることである。また、グループの相互作用は、興味深い貢献を明確にし、拡大するのに役立つかもしれない。欠点の1つは、司会 者の人格と集団効果によるもので、参加者が述べた意見に影響を与える可能性がある[30]。異文化の設定に適用する場合は、文化的・言語的適応と集団構成 への配慮が、集団討論への参加を促すために重要である[36]。 唯名論グループ技法はフォーカス・グループと似ているが、いくつかの重要な違いがある。グループは多くの場合、問題の分野の専門家で構成される。グループ の規模は似ているが、参加者間の相互作用はより構造化されている。その目的は、さまざまな問題に関して専門家の間でどの程度一致しているかを判断すること である。最初の回答は、参加者間で事前に会話することなく、各自が書面で行うことが多い。こうすることで、表明された意見に影響を及ぼす可能性のある集団 の影響を最小限に抑えることができる。後の段階では、異なる回答やコメントをグループ全体で議論し、互いに比較することができる[30][83] [84]。 これらのデータ収集形態のほとんどは、ある種の観察を伴う。観察は、自然環境、すなわち野外で行われる場合と、実験室のような管理された環境で行われる場 合がある。管理された環境では、人工的であるために結果が歪められる危険性がある。その利点は、関連要因を正確にコントロールすることにあり、観察の信頼 性と再現性を高めるのに役立つ。非参加型観察は、距離を置いた、または外部からのアプローチを伴う。この場合、研究者は、参加型観察とは対照的に、観察さ れた現象を引き起こしたり変化させたりすることなく、観察された現象を記述し記録することに集中する[4][85][86]。 社会科学の分野における重要な方法論的論争は、自然科学がそうであるように、社会科学が、確固とした、客観的で、価値中立的な事実を扱うかどうかという問 題に関するものである。ウィリアム・ノイマンによれば、実証主義は「人間の活動の一般的なパターンを予測するために使用することができる確率論的な因果法 則のセットを発見し、確認するために、演繹的な論理と個人の行動の正確な経験的観察を組み合わせるための組織的な方法」と定義することができる[19] [87][41]。この見解は、解釈主義者によって否定されている。例えばマックス・ウェーバーは、自然科学の手法は社会科学には不適切であると主張して いる。その代わりに、意味や、人々がどのように社会世界を創造し、維持しているかが重視される。社会科学における批判的方法論は、カール・マルクスやジー クムント・フロイトに関連している。他のアプローチを用いて研究された現象の多くは、単なる歪曲や表面的な錯覚に過ぎないという前提に基づいている。こう した歪みの背後に隠された物質世界のより深い構造を明らかにしようとするものである。このアプローチはしばしば、人々が社会の変化や改善をもたらすのを助 けるという目標によって導かれる[19][87][41]。 |

| Philosophy Main article: Philosophical methodology Philosophical methodology is the metaphilosophical field of inquiry studying the methods used in philosophy. These methods structure how philosophers conduct their research, acquire knowledge, and select between competing theories.[88][54][89] It concerns both descriptive issues of what methods have been used by philosophers in the past and normative issues of which methods should be used. Many philosophers emphasize that these methods differ significantly from the methods found in the natural sciences in that they usually do not rely on experimental data obtained through measuring equipment.[90][91][92] Which method one follows can have wide implications for how philosophical theories are constructed, what theses are defended, and what arguments are cited in favor or against.[54][93][94] In this regard, many philosophical disagreements have their source in methodological disagreements. Historically, the discovery of new methods, like methodological skepticism and the phenomenological method, has had important impacts on the philosophical discourse.[95][89][54] A great variety of methods has been employed throughout the history of philosophy: Methodological skepticism gives special importance to the role of systematic doubt. This way, philosophers try to discover absolutely certain first principles that are indubitable.[96] The geometric method starts from such first principles and employs deductive reasoning to construct a comprehensive philosophical system based on them.[97][98] Phenomenology gives particular importance to how things appear to be. It consists in suspending one's judgments about whether these things actually exist in the external world. This technique is known as epoché and can be used to study appearances independent of assumptions about their causes.[99][89] The method of conceptual analysis came to particular prominence with the advent of analytic philosophy. It studies concepts by breaking them down into their most fundamental constituents to clarify their meaning.[100][101][102] Common sense philosophy uses common and widely accepted beliefs as a philosophical tool. They are used to draw interesting conclusions. This is often employed in a negative sense to discredit radical philosophical positions that go against common sense.[92][103][104] Ordinary language philosophy has a very similar method: it approaches philosophical questions by looking at how the corresponding terms are used in ordinary language.[89][105][106] Many methods in philosophy rely on some form of intuition. They are used, for example, to evaluate thought experiments, which involve imagining situations to assess their possible consequences in order to confirm or refute philosophical theories.[107][108][100] The method of reflective equilibrium tries to form a coherent perspective by examining and reevaluating all the relevant beliefs and intuitions.[95][109][110] Pragmatists focus on the practical consequences of philosophical theories to assess whether they are true or false.[111][112] Experimental philosophy is a recently developed approach that uses the methodology of social psychology and the cognitive sciences for gathering empirical evidence and justifying philosophical claims.[113][114] |

哲学 主な記事 哲学的方法論 哲学方法論とは、哲学において用いられる方法を研究する形而上学的な探究分野である。哲学方法論は、哲学者がどのように研究を行い、知識を獲得し、競合す る理論を選択するのかを構造化するものである[88][54][89]。哲学方法論は、哲学者が過去にどのような方法を用いてきたかという記述的な問題 と、どのような方法を用いるべきかという規範的な問題の両方に関わっている。多くの哲学者は、これらの方法が自然科学に見られる方法と大きく異なるのは、 通常、測定機器を通じて得られる実験データに依拠しない点であると強調している[90][91][92]。どの方法に従うかは、哲学理論がどのように構築 されるか、どのようなテーゼが擁護されるか、どのような論拠が賛成・反対を問わず引用されるか[54][93][94]に広く影響を及ぼす可能性がある。 歴史的に見て、方法論的懐疑主義や現象学的方法のような新しい方法の発見は哲学的言説に重要な影響を与えてきた[95][89][54]。 哲学の歴史を通じて、多種多様な方法が採用されてきた: 方法論的懐疑主義は、体系的な疑いの役割を特に重要視する。方法論的懐疑主義は、体系的な疑いの役割を特に重要視している。この方法によって、哲学者たちは証明不可能な絶対的に確かな第一原理を発見しようとする[96]。 幾何学的方法はそのような第一原理から出発し、それに基づいて包括的な哲学体系を構築するために演繹的推論を用いる[97][98]。 現象学は物事がどのように見えるかを個別主義的に重視する。それは、これらの事物が実際に外界に存在するかどうかについての判断を保留することにある。こ の技法はエポケーとして知られており、その原因についての仮定から独立して出現を研究するために使用することができる[99][89]。 概念分析の方法は、分析哲学の出現によって個別主義的に注目されるようになった。それは概念を最も基本的な構成要素に分解してその意味を明らかにすることによって研究するものである[100][101][102]。 常識哲学は、一般的で広く受け入れられている信念を哲学的ツールとして使用する。それらは興味深い結論を導き出すために使われる。これは常識に反する急進的な哲学的立場を貶めるために否定的な意味で用いられることが多い[92][103][104]。 通常の言語哲学も非常によく似た方法を持っており、対応する用語が通常の言語でどのように使用されているかを見ることによって哲学的な問いにアプローチする[89][105][106]。 哲学における多くの方法は、ある種の直観に依存している。例えば、哲学的理論を確認したり反駁したりするために、状況を想像して起こりうる結果を評価する思考実験の評価に用いられる[107][108][100]。 反省的平衡の方法は、関連するすべての信念や直観を検討し再評価することによって、首尾一貫した視点を形成しようとするものである[95][109][110]。 プラグマティストは、哲学的理論が真か偽かを評価するために、哲学的理論の実践的結果に焦点を当てる[111][112]。 実験哲学は、経験的証拠を収集し、哲学的主張を正当化するために社会心理学や認知科学の方法論を用いる最近開発されたアプローチである[113][114]。 |

| Mathematics See also: Philosophy of mathematics § Logic and rigor In the field of mathematics, various methods can be distinguished, such as synthetic, analytic, deductive, inductive, and heuristic methods. For example, the difference between synthetic and analytic methods is that the former start from the known and proceed to the unknown while the latter seek to find a path from the unknown to the known. Geometry textbooks often proceed using the synthetic method. They start by listing known definitions and axioms and proceed by taking inferential steps, one at a time, until the solution to the initial problem is found. An important advantage of the synthetic method is its clear and short logical exposition. One disadvantage is that it is usually not obvious in the beginning that the steps taken lead to the intended conclusion. This may then come as a surprise to the reader since it is not explained how the mathematician knew in the beginning which steps to take. The analytic method often reflects better how mathematicians actually make their discoveries. For this reason, it is often seen as the better method for teaching mathematics. It starts with the intended conclusion and tries to find another formula from which it can be deduced. It then goes on to apply the same process to this new formula until it has traced back all the way to already proven theorems. The difference between the two methods concerns primarily how mathematicians think and present their proofs. The two are equivalent in the sense that the same proof may be presented either way.[115][116][117] |

数学 も参照のこと: 数学の哲学 § 論理と厳密性 数学の分野では、合成的方法、分析的方法、演繹的方法、帰納的方法、発見的方法など、さまざまな方法を区別することができる。例えば、構成的手法と分析的 手法の違いは、前者が既知から出発して未知へと進むのに対し、後者は未知から既知への道筋を見つけようとする点である。幾何学の教科書は、多くの場合、構 成的手法を使っている。既知の定義や公理を列挙することから始め、最初の問題の解が見つかるまで、推論的なステップを一つずつ踏んでいく。構成的方法の重 要な利点は、明確で短い論理的説明である。不利な点としては、そのステップが意図した結論につながるかどうかが、はじめのうちは明らかでないことが通常で ある。数学者がどのようなステップを踏むべきかを最初にどうやって知ったのかが説明されないので、このことは読者を驚かせることになる。分析的方法は、数 学者が実際にどのように発見をしたかをよく反映している。そのため、数学を教えるには解析的方法の方が良いと思われがちである。解析的方法は、意図した結 論から出発し、その結論を導くことができる別の定式を見つけようとする。そして、すでに証明されている定理まで遡るまで、この新しい定式に同じプロセスを 適用していく。この2つの方法の違いは、主に数学者の考え方と証明の見せ方に関わる。同じ証明をどちらの方法で提示してもよいという意味で,この2つは等 価である[115][116][117]. |

| Statistics Main article: Statistics Statistics investigates the analysis, interpretation, and presentation of data. It plays a central role in many forms of quantitative research that have to deal with the data of many observations and measurements. In such cases, data analysis is used to cleanse, transform, and model the data to arrive at practically useful conclusions. There are numerous methods of data analysis. They are usually divided into descriptive statistics and inferential statistics. Descriptive statistics restricts itself to the data at hand. It tries to summarize the most salient features and present them in insightful ways. This can happen, for example, by visualizing its distribution or by calculating indices such as the mean or the standard deviation. Inferential statistics, on the other hand, uses this data based on a sample to draw inferences about the population at large. That can take the form of making generalizations and predictions or by assessing the probability of a concrete hypothesis.[118][119][120] |

統計 主な記事 統計学 統計学はデータの分析、解釈、表示について研究する。多くの観察や測定のデータを扱わなければならない多くの形式の定量的研究で中心的な役割を果たす。こ のような場合、データ分析は、データを浄化、変換、モデル化し、実用的に有用な結論を得るために用いられる。データ分析には数多くの方法がある。それらは 通常、記述統計と推測統計に分けられる。記述統計は手元のデータに限定する。最も顕著な特徴を要約し、それを洞察に満ちた方法で示そうとする。これは例え ば、分布を視覚化したり、平均や標準偏差のような指標を計算することで実現できる。一方、推測統計学は、標本に基づくこのデータを使って、母集団全体につ いての推論を行う。一般化や予測を行ったり、具体的な仮説の確率を評価したりする形をとることができる[118][119][120]。 |

| Pedagogy Main article: Pedagogy Pedagogy can be defined as the study or science of teaching methods.[121][122] In this regard, it is the methodology of education: it investigates the methods and practices that can be applied to fulfill the aims of education.[123][122][1] These aims include the transmission of knowledge as well as fostering skills and character traits.[123][124] Its main focus is on teaching methods in the context of regular schools. But in its widest sense, it encompasses all forms of education, both inside and outside schools.[125] In this wide sense, pedagogy is concerned with "any conscious activity by one person designed to enhance learning in another".[121] The teaching happening this way is a process taking place between two parties: teachers and learners. Pedagogy investigates how the teacher can help the learner undergo experiences that promote their understanding of the subject matter in question.[123][122] Various influential pedagogical theories have been proposed. Mental-discipline theories were already common in ancient Greek and state that the main goal of teaching is to train intellectual capacities. They are usually based on a certain ideal of the capacities, attitudes, and values possessed by educated people. According to naturalistic theories, there is an inborn natural tendency in children to develop in a certain way. For them, pedagogy is about how to help this process happen by ensuring that the required external conditions are set up.[123][122] Herbartianism identifies five essential components of teaching: preparation, presentation, association, generalization, and application. They correspond to different phases of the educational process: getting ready for it, showing new ideas, bringing these ideas in relation to known ideas, understanding the general principle behind their instances, and putting what one has learned into practice.[126] Learning theories focus primarily on how learning takes place and formulate the proper methods of teaching based on these insights.[127] One of them is apperception or association theory, which understands the mind primarily in terms of associations between ideas and experiences. On this view, the mind is initially a blank slate. Learning is a form of developing the mind by helping it establish the right associations. Behaviorism is a more externally oriented learning theory. It identifies learning with classical conditioning, in which the learner's behavior is shaped by presenting them with a stimulus with the goal of evoking and solidifying the desired response pattern to this stimulus.[123][122][127] The choice of which specific method is best to use depends on various factors, such as the subject matter and the learner's age.[123][122] Interest and curiosity on the side of the student are among the key factors of learning success. This means that one important aspect of the chosen teaching method is to ensure that these motivational forces are maintained, through intrinsic or extrinsic motivation.[123] Many forms of education also include regular assessment of the learner's progress, for example, in the form of tests. This helps to ensure that the teaching process is successful and to make adjustments to the chosen method if necessary.[123] |

教育学 主な記事 教育学 教育学は教育の方法論であり、教育の目的を達成するために適用される方法と実践を研究するものである[123][122][1]。その目的には、知識の伝 達だけでなく、技能や性格の育成も含まれる[123][124]。しかし、最も広い意味では、学校の内外を問わず、あらゆる形態の教育を包含している [125]。この広い意味において、教育学は「ある人格による、他の人格の学習を高めるための意識的な活動」[121]に関係している。教育学は、教師が どのように学習者が問題の主題の理解を促進するような経験をするのを助けることができるかを研究している[123][122]。 様々な影響力のある教育学理論が提案されてきた。精神修養理論は古代ギリシアではすでに一般的であり、教えることの主な目的は知的能力を訓練することであ ると述べている。それらは通常、教育を受けた人々が持つ能力、態度、価値観のある理想に基づいている。自然主義理論によれば、子どもには先天的に一定の発 達を遂げる自然な傾向があるとされる。彼らにとっての教育学とは、必要な外的条件が整うようにすることで、このプロセスが起こるのをいかに助けるかという ことである。学習理論は、学習がどのように行われるかに主眼を置いており、これらの洞察に基づいて適切な教授法を策定している[127]。この見解では、 心は最初は白紙の状態である。学習とは、正しい連想を確立させることによって心を発達させることである。行動主義は、より外的志向の学習理論である。学習 は古典的条件づけと同一視され、この条件づけでは、学習者の行動は、この刺激に対する望ましい反応パターンを喚起し、定着させることを目的として、学習者 に刺激を提示することによって形成される[123][122][127]。 具体的にどのような方法を用いるのが最適であるかは、主体性や学習者の年齢など、さまざまな要因によって異なる[123][122]。つまり、内発的動機 づけや外発的動機づけによって、こうした動機づけの力が維持されるようにすることが、選択された教育方法の重要な側面のひとつである。これは、教育過程が うまくいっていることを確認し、必要に応じて選択した方法を調整するのに役立つ[123]。 |

| Related concepts Methodology has several related concepts, such as paradigm and algorithm. In the context of science, a paradigm is a conceptual worldview. It consists of a number of basic concepts and general theories, that determine how the studied phenomena are to be conceptualized and which scientific methods are considered reliable for studying them.[128][22] Various theorists emphasize similar aspects of methodologies, for example, that they shape the general outlook on the studied phenomena and help the researcher see them in a new light.[3][15][16] In computer science, an algorithm is a procedure or methodology to reach the solution of a problem with a finite number of steps. Each step has to be precisely defined so it can be carried out in an unambiguous manner for each application.[129][130] For example, the Euclidean algorithm is an algorithm that solves the problem of finding the greatest common divisor of two integers. It is based on simple steps like comparing the two numbers and subtracting one from the other.[131] |

関連概念 方法論には、パラダイムやアルゴリズムなど、いくつかの関連概念がある。科学の文脈では、パラダイムとは概念的な世界観のことである。様々な理論家が方法 論の類似した側面を強調しており、例えば、方法論は研究される現象に対する一般的な見通しを形成し、研究者が新しい光で現象を見るのを助けると述べている [3][15][16]。 コンピュータサイエンスにおいてアルゴリズムとは、有限のステップ数で問題解決に到達するための手順や方法論のことである。例えば、ユークリッド・アルゴ リズム は、2つの整数の最大公約数を求める問題を解くアルゴリズムである。これは、2つの数を比較し、一方から他方を引くといった単純なステップに基づいている [131]。 |

| Paradigm – Set of distinct concepts or thought patterns Ethnomethodology Philosophical methodology Political methodology Scientific method Software development process Survey methodology |

パラダイム - 明確な概念や思考パターンの集合 エスノメソドロジー 哲学的方法論 政治的方法論 科学的方法論 ソフトウェア開発プロセス 調査方法論 |

| Further reading Berg, Bruce L., 2009, Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences. Seventh Edition. Boston MA: Pearson Education Inc. Creswell, J. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications. Creswell, J. (2003). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications. Franklin, M.I. (2012). Understanding Research: Coping with the Quantitative-Qualitative Divide. London and New York: Routledge. Guba, E. and Lincoln, Y. (1989). Fourth Generation Evaluation. Newbury Park, California: Sage Publications. Herrman, C. S. (2009). "Fundamentals of Methodology", a series of papers On the Social Science Research Network (SSRN), online. Howell, K. E. (2013) Introduction to the Philosophy of Methodology. London, UK: Sage Publications. Ndira, E. Alana, Slater, T. and Bucknam, A. (2011). Action Research for Business, Nonprofit, and Public Administration - A Tool for Complex Times. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Joubish, Farooq Dr. (2009). Educational Research Department of Education, Federal Urdu University, Karachi, Pakistan Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research & evaluation methods (3rd edition). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications. Silverman, David (Ed). (2011). Qualitative Research: Issues of Theory, Method and Practice, Third Edition. London, Thousand Oaks, New Delhi, Singapore: Sage Publications Soeters, Joseph; Shields, Patricia and Rietjens, Sebastiaan. 2014. Handbook of Research Methods in Military Studies New York: Routledge. Ioannidis, J. P. (2005). "Why Most Published Research Findings Are False". PLOS Medicine. 2 (8): e124. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124. PMC 1182327. PMID 16060722. |

さらに読む Berg, Bruce L., 2009, 『社会科学のための質的研究法』. 第7版。Boston MA: Pearson Education Inc. Creswell, J. (1998). 質的調査と研究デザイン: 5つの伝統の中から選ぶ。カリフォルニア州サウザンド・オークス: Sage Publications. Creswell, J. (2003). 研究デザイン: 質的、量的、混血のアプローチ。カリフォルニア州サウザンド・オークス: Sage Publications. Franklin, M.I. (2012). 研究を理解する: Understanding Research: Coping with the Quantitative-Qualitative Divide. London and New York: Routledge. Guba, E. and Lincoln, Y. (1989). Fourth Generation Evaluation. カリフォルニア州ニューベリーパーク: Sage Publications. Herrman, C. S. (2009). Social Science Research Network (SSRN)のオンライン論文シリーズ「Fundamentals of Methodology」。 Howell, K. E. (2013) Introduction to the Philosophy of Methodology. London, UK: Sage Publications. Ndira, E. Alana, Slater, T. and Bucknam, A. (2011). Action Research for Business, Nonprofit, and Public Administration - A Tool for Complex Times. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Joubish, Farooq Dr. (2009). パキスタン、カラチの連邦ウルドゥー大学教育学部教育研究学科。 Patton, M. Q. (2002). 質的調査と評価方法(第3版). カリフォルニア州サウザンド・オークス: Sage Publications. Silverman, David (Ed). (2011). 質的研究: Theory, Method and Practice, Third Edition. ロンドン、サウザンド・オークス、ニューデリー、シンガポール: Sage Publications Soeters, Joseph; Shields, Patricia and Rietjens, Sebastiaan. 2014. Handbook of Research Methods in Military Studies New York: Routledge. Ioannidis, J. P. (2005). 「Why Most Published Research Findings Are False". PLOS Medicine. 2 (8): e124. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124. PMC 1182327. PMID 16060722. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Methodology |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Mexican, 1902–2002の作品

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆