コナトゥス

Conatus

☆ バルーフ・スピノザの哲学において、コナトゥス (conatus; ラテン語で「 "effort; endeavor; impulse, inclination, tendency; undertaking; striving"」)とは、あるものが存在し続け、それ自体を高めようとする生得的な傾向のことである。これは心であった り、物質であったり、あるいはその両方の組み合わせであったりするが、汎神論的な自然観においては神の意志と結びつけられることが多い。コナトゥスは、生 物の本能的な生きようとする意志を指すこともあれば、運動や慣性に関するさまざまな形而上学的理論を指すこともある。今日では、古典力学が慣性力や運動量 保存といった概念を用いているため、技術的な意味でコナトゥスが使われることはほとんどない。

| In the philosophy of

Baruch Spinoza, conatus (/koʊˈneɪtəs/; wikt:conatus; Latin for "effort;

endeavor; impulse, inclination, tendency; undertaking; striving") is an

innate inclination of a thing to continue to exist and enhance itself.

This thing may be mind, matter, or a combination of both, and is often

associated with God's will in a pantheist view of nature. The conatus

may refer to the instinctive will to live of living organisms or to

various metaphysical theories of motion and inertia. Today, conatus is

rarely used in the technical sense, since classical mechanics uses

concepts such as inertia and conservation of momentum that have

superseded it. It has, however, been a notable influence on later

thinkers such as Arthur Schopenhauer and Friedrich Nietzsche. |

バルーフ・スピノザの哲学において、コナトゥス

(/koʊ↪Lmtəs/; wikt:conatus;

ラテン語で "effort; endeavor; impulse, inclination, tendency; undertaking;

striving")とは、あるものが存在し続け、それ自体を高めようとする生得的な傾向のことである。これは心であった

り、物質であったり、あるいはその両方の組み合わせであったりするが、汎神論的な自然観においては神の意志と結びつけられることが多い。コナトゥスは、生

物の本能的な生きようとする意志を指すこともあれば、運動や慣性に関するさまざまな形而上学的理論を指すこともある。今日では、古典力学が慣性力や運動量

保存といった概念を用いているため、技術的な意味でコナトゥスが使われることはほとんどない。しかし、アルトゥール・ショーペンハウアーやフリードリヒ・

ニーチェのような後世の思想家には大きな影響を与えた。 |

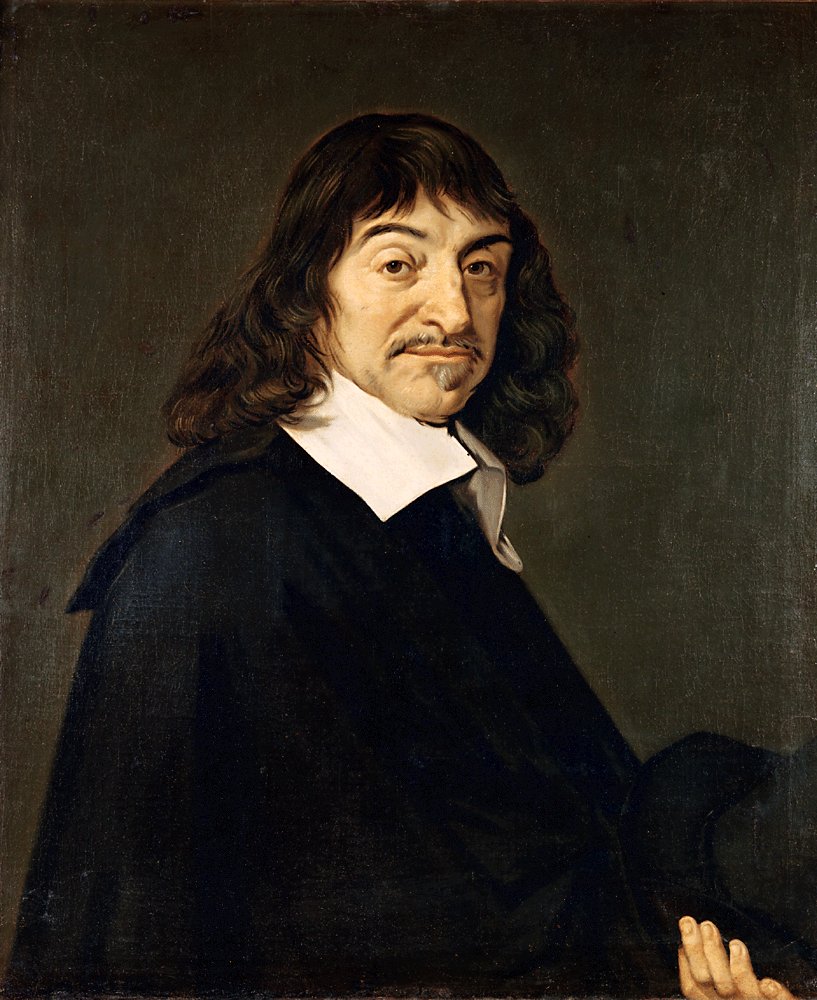

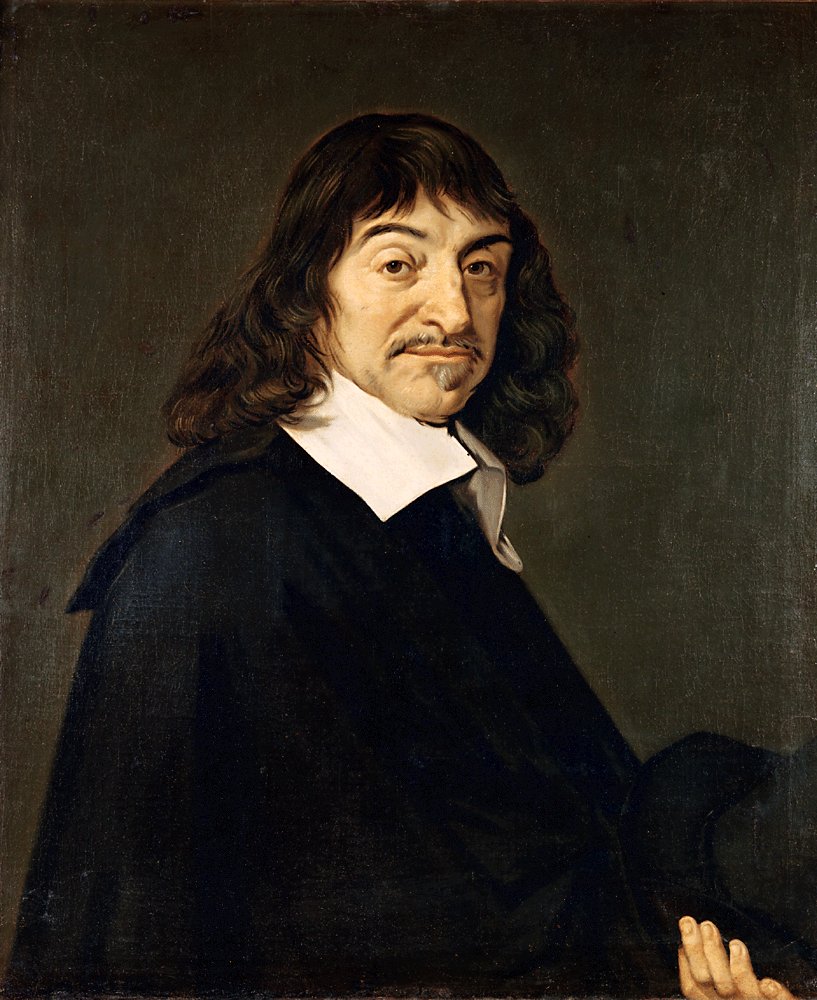

Definition and origin René Descartes used the term conatus in his mechanistic theory of

motion. René Descartes used the term conatus in his mechanistic theory of

motion.The Latin cōnātus comes from the verb cōnor, which is usually translated into English as, to endeavor; used as an abstract noun, conatus is an innate inclination of a thing to continue to exist and enhance itself. Although the term is most central to Spinoza's philosophy, many other early modern philosophers including René Descartes, Gottfried Leibniz, and Thomas Hobbes made significant contributions, each developing the term differently.[1] Whereas the medieval Scholastic philosophers such as Jean Buridan developed a notion of impetus as a mysterious intrinsic property of things,[2] René Descartes (1596–1650) developed a more modern, mechanistic concept of motion which he called the conatus.[3] For Descartes, in contrast to Buridan, motion and rest are properties of the interactions of matter according to eternally fixed mechanical laws, not dispositions and intentions, nor as inherent properties or forces of things, but rather as a unifying, external characteristic of the physical universe itself.[4] Descartes specifies two varieties of the conatus: conatus a centro,[b] or a theory of gravity and conatus recedendi[c] which represents centrifugal forces.[5] Descartes, in developing his First Law of Nature, also invokes the idea of a conatus se movendi, or "conatus of self-preservation", a generalization of the principle of inertia, which was formalized by Isaac Newton and made into the first of his three Laws of Motion fifty years after the death of Descartes."[6] Thomas Hobbes criticized previous definitions of conatus for failing to explain the origin of motion, defining conatus to be the infinitesimal unit at the beginning of motion: an inclination in a specified direction.[7] Furthermore, Hobbes uses conatus to describe cognition functions in the mind,[8] describing emotion as the beginning of motion and the will as the sum of all emotions, which forms the conatus of a body and its physical manifestation is the perceived "will to survive".[1] In a notion similar that of Hobbes, Gottfried Leibniz differentiates between the conatus of the body and soul,[9] primarily focusing however on the concept of a conatus of body in developing the principles of integral calculus to explain Zeno's paradoxes of motion.[10] Leibniz later defines the term monadic conatus, as the state of change through which his monads perpetually advance.[11] This conatus is a sort of instantaneous or virtual motion that all things possess, even when they are static. Motion, meanwhile, is just the summation of all the conatuses that a thing has, along with the interactions of things. By summing an infinity of such conatuses (i.e., what is now called integration), Leibniz could measure the effect of a continuous force.[12] |

定義と由来 ルネ・デカルトは機械論的運動論において、コナトゥス(conatus)という言葉を使った。 ルネ・デカルトは機械論的運動論において、コナトゥス(conatus)という言葉を使った。ラテン語のcōnātusは動詞cōnorに由来し、通常英語では「努力する」と訳される。抽象名詞として使用されるconatusは、物事が存在し続 け、それ自体を高めようとする生得的な傾向である。この用語はスピノザの哲学において最も中心的なものであるが、ルネ・デカルト、ゴットフリート・ライプ ニッツ、トマス・ホッブズなど他の多くの近世哲学者も重要な貢献をしており、それぞれが異なる形でこの用語を発展させている[1]。 ジャン・ビュリダンのような中世のスコラ哲学者たちが物事の神秘的な本質的性質としての原動力の概念を発展させたのに対して[2]、ルネ・デカルト (1596-1650)はより近代的で機械論的な運動の概念を発展させ、それを彼はコナトゥスと呼んだ。 [デカルトにとって、ビュリダンとは対照的に、運動と静止は永遠に固定された機械的法則に従った物質の相互作用の特性であり、気質や意図ではなく、物事の 固有の性質や力でもなく、むしろ物理的宇宙そのものの統一的で外的な特性であった。 [デカルトはコナトゥスについて、コナトゥス・ア・セントロ(conatus a centro)[b]、すなわち重力の理論と、コナトゥス・レセデンディ(conatus recedendi)[c]、すなわち遠心力の理論の2種類を規定している。 [これはアイザック・ニュートンによって定式化され、デカルトの死から50年後に彼の3つの運動法則のうちの最初の法則となった。 トマス・ホッブズは運動の起源を説明できていないとして、それまでのコナトゥスの定義を批判し、コナトゥスを運動の始まりにおける無限小の単位、すなわち 指定された方向への傾きであると定義した[7]。さらにホッブズはコナトゥスを用いて心における認識機能を説明しており[8]、情動を運動の始まりとし て、意志をすべての感情の総和として記述しており、それが身体のコナトゥスを形成し、その物理的な表れが知覚された「生存しようとする意志」であると述べ ている。 [ライプニッツはホッブズと類似した概念において、肉体と魂のコナトゥスを区別しており[9]、ゼノンの運動のパラドックスを説明するために積分学の原理 を発展させる際に、主として肉体のコナトゥスの概念に焦点を当てた[10]。ライプニッツは後に、モナドが永続的に進む変化の状態としてモナド的コナトゥ スという言葉を定義している[11]。このコナトゥスは、静止しているときでさえも、すべての事物が持つ、ある種の瞬間的な、あるいは仮想的な運動であ る。一方、運動とは、事物の相互作用とともに、事物が持つすべてのコナトゥスの総和にすぎない。ライプニッツは、このようなコナトゥスの無限大を合計する こと(すなわち、現在では積分と呼ばれていること)によって、連続的な力の効果を測定することができた[12]。 |

In Spinoza's philosophy In Spinoza's philosophyMain article: Philosophy of Baruch Spinoza Conatus is a central theme in the philosophy of Benedict de Spinoza (1632–1677), which is derived from principles that Hobbes and Descartes developed.[13] Contrary to most philosophers of his time, Spinoza rejects the dualistic assumption that mind, intentionality, ethics, and freedom are to be treated as things separate from the natural world of physical objects and events.[14] One significant change he makes to Hobbes' theory is his belief that the conatus ad motum, (conatus to motion), is not mental, but material.[8] Spinoza also uses conatus to refer to rudimentary concepts of inertia, as Descartes had earlier.[1] According to Spinoza, "each thing, as far as it lies in itself, strives to persevere in its being" (Ethics, part 3, prop. 6). Since a thing cannot be destroyed without the action of external forces, motion and rest, too, exist indefinitely until disturbed.[15] His goal is to provide a unified explanation of all these things within a naturalistic framework, man and nature must be unified under a consistent set of laws; God and nature are one, and there is no free will. For example, an action is free, for Spinoza, only if it arises from the essence and conatus of an entity. However, an action can still be free in the sense that it is not constrained or otherwise subject to external forces.[16] Human beings are thus an integral part of nature.[15] Spinoza explains seemingly irregular human behaviour as really natural and rational and motivated by this principle of the conatus.[15] Some have argued that the conatus consists of happiness and the perpetual drive toward perfection.[17] Conversely, a person is saddened by anything that opposes his conatus. Others have associated desire, a primary affect, with the conatus principle of Spinoza. Desire is then controlled by the other affects, pleasure and pain, and thus the conatus strives towards that which causes joy and avoids that which produces pain.[8] |

スピノザの哲学 スピノザの哲学主な記事 スピノザの哲学 ホッブズとデカルトが発展させた原理から派生したベネディクト・デ・スピノザ(1632-1677)の哲学において、コナトゥスは中心的なテーマである [13]。スピノザは同時代のほとんどの哲学者とは異なり、心、意図性、倫理、自由が物理的な物や出来事からなる自然界とは別のものとして扱われるべきで あるという二元論的な仮定を否定している。 [14]ホッブズの理論に対して彼が行った重要な変更の一つは、コナトゥス・アド・モトゥム(運動に対するコナトゥス)は精神的なものではなく、物質的な ものであるという彼の信念である[8]。スピノザはまた、コナトゥスを、デカルトが以前に持っていたような慣性の初歩的な概念に言及するために用いている [1]。スピノザによれば、「それぞれの事物は、それ自体の中にある限り、その存在にとどまろうと努める」(『倫理学』第3部、小論6)。スピノザの目標 は、自然主義的な枠組みの中でこれらすべての物事について統一的な説明を提供することであり、人間と自然は一貫した一連の法則の下で統一されなければなら ず、神と自然は一体であり、自由意志は存在しない。例えば、スピノザにとって、ある行為が自由であるのは、それがある実体の本質とコナトゥスから生じる場 合だけである。スピノザは、一見不規則に見える人間の行動を、実に自然で合理的なものであり、このコナトゥスの原理によって動機づけられたものであると説 明している[15]。コナトゥスは幸福と完璧に向かう永続的な衝動からなると主張する者もいる[17]。また、第一次感情である欲望をスピノザのコナトゥ スの原理と関連付ける者もいる。そして欲望は他の情動である快楽と苦痛によって制御され、その結果コナトゥスは喜びをもたらすものに向かって努力し、苦痛 をもたらすものを避けるのである[8]。 |

| Later usages and related concepts After the development of classical mechanics, the concept of a conatus, in the sense used by philosophers other than Spinoza,[8] an intrinsic property of all physical bodies, was largely superseded by the principles of inertia and conservation of momentum. Similarly, Conatus recendendi became centrifugal force, and conatus a centro became gravity.[5] However, Giambattista Vico, inspired by Neoplatonism, explicitly rejected the principle of inertia and the laws of motion of the new physics. For him, conatus was the essence of human society,[18] and also, in a more traditional, hylozoistic sense, as the generating power of movement which pervades all of nature,[19] which was composed neither of atoms, as in the dominant view, nor of extension, as in Descartes, but of metaphysical points animated by a conatus principle provoked by God.[20] Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860) developed a principle notably similar to that of Spinoza's conatus.[1][21] This principle, Wille zum Leben, or of a "Will to Live", described the specific phenomenon of an organism's self-preservation instinct.[22] Schopenhauer qualified this, however, by suggesting that the Will to Live is not limited in duration, but rather, "the will wills absolutely and for all time", across generations.[23] Rejecting the primacy of Schopenhauer's Will to Live, Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) developed a separate principle the Will to Power, which comes out of a rejection of such notions of self-preservation.[24] In systems theory, the Spinozistic conception of a conatus has been related to modern theories of autopoiesis in biological systems.[25] However, the scope of the idea is definitely narrower today, being explained in terms of chemistry and neurology where, before, it was a matter of metaphysics and theurgy.[26] |

その後の用法と関連概念 古典力学の発展後、スピノザ以外の哲学者によって使用された意味でのコナトゥスの概念、すなわちすべての物体に内在する性質[8]は、慣性および運動量保 存の原理によってほとんど取って代わられた。同様に、Conatus recendendiは遠心力となり、Conatus a centroは重力となった[5]。しかし、新プラトン主義に触発されたジャンバッティスタ・ヴィーコは、新物理学の慣性原理と運動法則を明確に否定し た。彼にとっては、コナトゥスは人間社会の本質であり[18]、また、より伝統的な、ヒロイゾ的な意味では、自然のすべてに浸透している運動の生成力であ り[19]、それは支配的な見解のような原子でも、デカルトのような延長でもなく、神によって引き起こされたコナトゥスの原理によって運動する形而上学的 な点から構成されていた。 [20] アルトゥール・ショーペンハウアー(1788-1860)は、スピノザのコナトゥスの原理とよく似た原理を開発した。 [しかし、ショーペンハウアーは、「生きる意志」は期間限定的なものではなく、世代を超えて「意志は絶対的かつ永遠に意志し続ける」ものであることを示唆 し、これを修飾した[23]。フリードリヒ・ニーチェ(1844-1900)は、ショーペンハウアーの「生きる意志」の優位性を否定し、そのような自己保 存の概念の否定から生まれた「力への意志」という別の原理を開発した。 [システム理論においては、スピノザ的なコナトゥスの概念は生物学的システムにおけるオートポイエーシスの現代的な理論に関連している[25]。しかし、 その考え方の範囲は今日では確実に狭くなっており、以前は形而上学や神学の問題であったのに対して、化学や神経学の観点から説明されている[26]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conatus |

|

| In the philosophy of mind,[1] and in psychology, conation

refers to the ability to apply intellectual energy to a task to achieve

its completion or reach a solution.[2] Conation may be distinguished

from other mental phenomena, particularly cognition, and sensation,[1]

and has been described as "neglected" in comparison with these

phenomena. It may overlap to some extent with the concept of

motivation, but "the ability to focus and maintain persistent effort"

has been seen as more pertinent to conation.[2] Definitions Merriam-Webster's online dictionary defines conation as "an inclination (as an instinct or drive) to act purposefully".[3] The word comes from the Latin words conari (to try) and conatio (an attempt).[4] Hannah et al. define "moral conation" as "the capacity to generate responsibility and motivation to take moral action in the face of adversity and persevere through challenges".[5] History Edwin Boring included a review of the history of the concept in his History of Experimental Psychology, published in 1929, referring to James Ward's typology of cognition, conation, and feeling,[2] and to conation as George Stout's "famous doctrine". The division of the mind into cognition, conation (or desire), and feeling was also described by Immanuel Kant.[6] However, Norman Schur more recently included the word "conation" among his 1000 most challenging (or oft-forgotten or unknown) words in the English language.[7] For George Berkeley in his essay De Motu, it was a term to be avoided, because "we do not rightly understand" its meaning.[8] Research Neuropsychology researchers Ralph M. Reitan and Deborah Wolfson looked at the performance of specific tasks which were "judged to require conative ability" in a research study published in 2000 and surmised that "conation, which has been a neglected dimension of behavior in neuropsychological assessment, may be the missing link between cognitive ability and prediction of performance capabilities in everyday life".[2] See also Attentional control Conatus Determination https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conation |

心

の哲学[1]や心理学において、コネーション(conation)とは、知的エネルギーを課題に適用し、その完了や解決に到達する能力のことである

[2]。コネーションは、他の精神現象、特に認知や感覚[1]と区別されることがあり、これらの現象と比較して「軽視されている」と表現されてきた。それ

は動機づけの概念とある程度重なるかもしれないが、「持続的な努力に集中し、それを維持する能力」はコネーションにより適切であると考えられてきた

[2]。 定義 メリアム・ウェブスターのオンライン辞書は、コネイションを「目的を持って行動しようとする(本能や衝動としての)傾き」と定義している[3]。この言葉 はラテン語のconari(試みる)とconatio(試み)に由来する[4]。ハンナらは「道徳的コネイション」を「逆境に直面したときに道徳的行動を とる責任と動機を生み出し、困難を忍耐強く乗り越える能力」と定義している[5]。 歴史 エドウィン・ボーリングは、1929年に出版された『実験心理学史』の中で、この概念の歴史を概説しており、ジェームズ・ウォードの認知、コネーション、 フィーリングの類型論[2]、ジョージ・スタウトの「有名な教義」としてのコネーションに言及している。しかし、ノーマン・シュアーはより最近、 「conation」という単語を彼の1000の最も挑戦的な(あるいはしばしば忘れられた、あるいは知られていない)英語の単語の中に含めている [7]。 ジョージ・バークレーは彼のエッセイ「De Motu」の中で、「conation」はその意味を「正しく理解していない」ため、避けるべき用語であると述べている[8]。 研究 神経心理学の研究者であるラルフ・M・レイタンとデボラ・ウルフソンは、2000年に発表された研究において、「コネイション能力を必要とすると判断され た」特定のタスクのパフォーマンスを調査し、「神経心理学的評価において行動の軽視されてきたコネイションは、認知能力と日常生活におけるパフォーマンス 能力の予測との間に欠けているリンクかもしれない」と推測している[2]。 以下も参照。 注意制御 コナトゥス 決定 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆