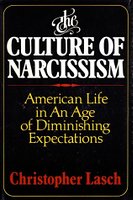

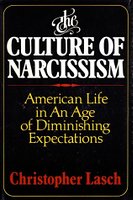

On Christopher Lasch's "The Culture of Narcissim," 1979.

On Christopher Lasch's "The Culture of Narcissim," 1979.

★『ナルシシズムの文化』は、文化史家ク リストファー・ラッシュによる1979年の著書で、20世紀のアメリカ文化における病的ナルシシズムの 常態化の根源と影響を心理、文化、芸術、歴史の総合を通して探求している。

| "The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations is a 1979 book by the cultural historian Christopher Lasch, in which the author explores the roots and ramifications of the normalizing of pathological narcissism in 20th-century American culture using psychological, cultural, artistic and historical synthesis.[1] For the mass-market edition published in September of the same year,[1] Lasch won the 1980 US National Book Award in the category Current Interest (paperback)." | 『ナルシシズムの文化』は、文化史家クリストファー・ラッシュによる 1979年の著書で、20世紀のアメリカ文化における病的ナルシシズムの常態化の根源と影響を心理、文化、芸術、歴史の総合を通して探求している。 同年9月に出版されたマスマーケット版で、ラッシュは1980年アメリカ国民書籍賞(Current Interest部門)を受賞(ペーパーバック)[1]する。 |

|

"Lasch proposes that since World War II, post-war America has produced a personality-type consistent with clinical definitions of "pathological narcissism". This pathology is not akin to everyday narcissism, a hedonistic egoism, but with clinical diagnosis of narcissistic personality disorder. For Lasch, "pathology represents a heightened version of normality."[3] He locates symptoms of this personality disorder in the radical political movements of the 1960s (such as the Weather Underground), as well as in the spiritual cults and movements of the 1970s, from est to Rolfing." - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Culture_of_Narcissism |

ラッシュによれば、第二次世界大戦後、戦後のアメリカでは、「病的ナル

シシズム」という臨床的な定義に合致する人格タイプが生み出されているという。この病理は、日常的なナルシシズム、快楽主義的なエゴイズムではなく、自己

愛性人格障害と臨床診断されるようなものである。ラッシュによれば、「病理は正常の高められたバージョンを表す」[3]。彼は、この人格障害の症状を、

1960年代の過激な政治運動(ウェザー・アンダーグラウンドなど)や、1970年代のエストからロルフィングまでの精神カルトや運動のなかに見いだす。 |

| Reaction, "An early response to The Culture of Narcissism commented that Lasch had identified the outcomes in American society of the decline of the family over the previous century. The book quickly became a bestseller and a talking point, being further propelled to success after Lasch notably visited Camp David to advise President Jimmy Carter for his "crisis of confidence" speech of 15 July 1979. Later editions include a new afterword, "The Culture of Narcissism Revisited".[4] Author Louis Menand argues that the book has been commonly misused by liberals and conservatives alike, who cited it for their own ideological agendas. Menand wrote: Lasch was not saying that things were better in the 1950s, as conservatives offended by countercultural permissiveness probably took him to be saying. He was not saying that things were better in the 1960s, as former activists disgusted by the 'me-ism' of the seventies are likely to have imagined. He was diagnosing a condition that he believed had originated in the nineteenth century.[5] Lasch attempted to correct many of these misapprehensions with The Minimal Self in 1984. Anthony Elliott writes that The Culture of Narcissism and The Minimal Self are Lasch's two best-known books.[6] " | 「『ナルシシズムの文化』に対する初期の反応は、ラシュが前世紀に起 こった家族の衰退がアメリカ社会にもたらした結果を明らかにしたと評するものであっ た。1979年7月15日のジミー・カーター大統領の「信頼の危機」演説のために、ラシュがキャンプ・デイヴィッドを訪れ、助言をしたこともあって、この 本は急速にベストセラーになり、話題となった。後の版では、新たに「ナルシシズムの文化再考」という後書きが加えられている[4]。 著者のルイ・メナンドは、この本がリベラル派と保守派によってよく誤用され、彼らは自分たちのイデオロギー的な目的のためにこの本を引用したと論じてい る。メナンドはこう書いている。 ラシュは、カウンターカルチャーの寛容さに怒った保守派がおそらく言っていると考えたように、1950年代のほうが物事がよかったと言っているのではな い。70年代の「ミーイズム」に嫌悪感を抱いた元活動家たちが想像したように、彼は1960年代の方がよかったとは言っていない。彼は19世紀に端を発す ると信じていた状態を診断していたのである[5]。 ラッシュは1984年に『最小限の自己』でこれらの誤解の多くを正そうとした。 アンソニー・エリオットは、『ナルシシズムの文化』と『最小限の自己』がラッシュの最もよく知られている2冊の本であると書いている[6]。」 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Culture_of_Narcissism |

|

| 1. The Culture of Narcissism at

Barnes & Noble provides the specific dates January 28 (first) and

September 21 (mass-market paperback). Retrieved March 9, 2012. 2. "National Book Awards – 1980". National Book Foundation. Retrieved 2012-03-09. There was a "Contemporary" or "Current" award category from 1972 to 1980. 3. The Culture of Narcissism, p. 38 4. Lasch, Christopher (May 17, 1991). The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0393348350. 5. Menand, 206 6. Elliott, Anthony (2002). Psychoanalytic Theory: An Introduction. Palgrave. p. 63. ISBN 0-333-91912-2. ++++++++++++ Menand, Louis. "American Studies." Farrar, Straus & Giroux: New York, 2002. |

1.

『ナルシシズムの文化』のバーンズ・アンド・ノーブルでの発売日は、1月28日(初版)と9月21日(大衆向けペーパーバック版)とされている。2012

年3月9日取得。 2. 「全米図書賞 – 1980年」。全米図書財団。2012年3月9日取得。 1972年から1980年までは「現代」または「最新」の賞カテゴリーが存在した。 3. 『ナルシシズムの文化』38ページ 4. クリストファー・ラッシュ (1991年5月17日). 『ナルシシズムの文化:期待が減少する時代におけるアメリカの生活』. W. W. ノートン社. ISBN 0393348350. 5. メナンド、206 6. エリオット、アンソニー(2002)。精神分析理論:入門。パルグレイブ。63 ページ。ISBN 0-333-91912-2。 ++++++++++++ メナンド、ルイス。「アメリカ研究」。ファラー、ストラウス&ギル:ニューヨーク、2002年。 |

| Some editions New York: Norton, 1979. ISBN 0-393-01177-1 New York: Warner Books, 1980. ISBN 0-446-97495-1 New York: Norton; Revised edition (May 1991). ISBN 978-0-393-30738-2 |

いくつかの版 ニューヨーク:ノートン社、1979年。ISBN 0-393-01177-1 ニューヨーク:ワーナーブックス、1980年。ISBN 0-446-97495-1 ニューヨーク:ノートン社;改訂版(1991年5月)。ISBN 978-0-393-30738-2 |

| The Age of Entitlement (2020) Narcissism § Cultural narcissism |

権利意識の時代(2020) ナルシシズム § 文化的なナルシシズム |

| a. From 1980 to 1983 in National

Book Award history there were dual awards for hardcover and paperback

books in many categories. Most of the paperback award-winners were

reprints, including this one, but its first edition was eligible only

in the same award year. |

a.

1980年から1983年にかけて、国民図書賞の歴史において、ハードカバーとペーパーバックの書籍が多くの部門で二重に受賞した。ペーパーバックの受賞

作の大半は再版本であり、本書もその一つであった。しかし初版は、同じ受賞年度にのみ対象となった. |

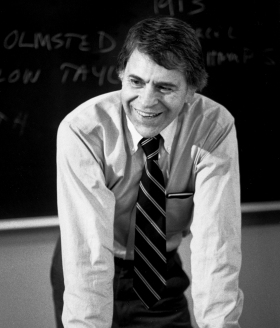

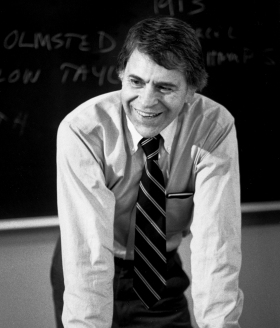

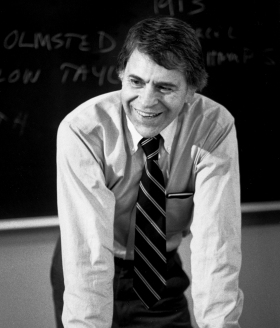

Christopher Lasch, 1932-1994.

アメリカ社会の1970年代の文化批判といえる。

ソースティン・ヴェブレン(Thorstein Bunde

Veble, 1857-1929)の、The

Theory of the Leisure Class (1899)に比肩する、アメリカ文化批判. social critique

of 'conspicuous consumption' =顕示的/衒示的消費

"Conspicuous consumption is a term used to describe and explain the consumer practice of purchasing or using goods of a higher quality or in greater quantity than might be considered necessary in practical terms.[1] More specifically, it refers to the spending of money on or the acquiring of luxury goods and services in order to publicly (i.e., conspicuously) display the economic power of one's income or accumulated wealth. To the conspicuous consumer, such a public display of discretionary economic power is a means of either attaining or maintaining a given social status.[2][3]"-Conspicuous consumption.

顕示的/衒示的消費をうむメンタル・ストラクチャー;"The term was coined by Thorstein Veblen. The development of Veblen's sociology of conspicuous consumption has since produced the terms invidious consumption, the ostentatious consumption of goods to provoke the envy of other people; and conspicuous compassion, the deliberate use of charitable donations of money to enhance the social prestige of the donor with a display of superior socio-economic status.[4]"

クリストファー・ラッシュ(1932-1994)の「ナルシシズムの文化」は、ヴェブレンの「顕示的/衒示的消費」と異なり、その社会階層は、 より広がり、広く大衆文化に及んでいる。また、その前の世代のアドルノの「権威主義的パーソナリティ」とも異なり、外的権威への盲従ではなく、自己満足や 自己愛を満たすかたちで、消費社会が形成されているということだ。

| 1. アウェアネス・ムーブメントと自己の社会的侵入 | 1.1 歴史的時間感覚の欠如 |

|

| 1.2 セラピーの感覚 |

||

| 1.3 政治より内省へ |

||

| 1.4 告白と反告白 |

||

| 1.5 内面の空虚感 |

||

| 1.6 プライベーティズムについての進

歩的な批評 |

||

| 1.7 プライベーティズムについての批

評:リチャード・セネット(Richard Sennett, 1944-) のパブリック人間衰退論 |

||

| 2. 現代のナルシシズム的パーソナリティ |

2.1 人間の条件の隠喩としてのナルシ

シズム |

|

| 2.2 心理学と社会学 |

||

| 2.3 最近の臨床的文脈におけるナルシ

シズム |

||

| 2.4 ナルシシズムへの社会的影響 |

||

| 2.5 あきらめの世界観 |

||

| 3. さまざまな様式の変化:ホレーショ・アルジャーからハッピーな売

春婦へ |

3.1 労働倫理のオリジナルな意味 |

|

| 3.2 自己修養からイメージの改善を通

して自己の栄達へ |

||

| 3.3 業績の失墜 |

||

| 3.4 社会的サバイバルの技術 |

||

| 3.5 個人的礼賛 |

||

| 4. 偽りのセルフ・アウェアネスの陳腐な言葉——政治と日常生活のお

芝居 |

4.1 日用必需品の宣伝 |

|

| 4.2 真実と信頼性 |

||

| 4.3 広告と宣伝 |

||

| 4.4 スペクタクルとしての政治 |

||

| 4.5 街頭劇場としてのラディカリズム |

||

| 4.6 英雄崇拝とナショナリズム的な理

想化 |

||

| 4.7 ナルシシズムと不条理演劇 |

||

| 4.8 日常生活の演劇 |

||

| 4.9 ルーティンからの逃避としての皮

肉な冷静さ |

||

| 4.10 出口なし |

||

| 5. 墜ちたスポーツ |

5.1 遊びの精神〈対〉国民意識の高揚 |

|

| 5.2 ホイジンガのホモ・ルーデンス |

||

| 5.3 スポーツの批評 |

||

| 5.4 運動競技の堕落 |

||

| 5.5 帝国主義と奮闘努力の人生に対す

る信仰 |

||

| 5.6 集団への忠誠心と競争 |

||

| 5.7 官僚制とチームワーク |

||

| 5.8 スポーツとエンターテイメント産

業 |

||

| 5.9 逃避としてのレジャー |

||

| 6. 学校教育と新しい非識字 |

6.1 知力の麻痺 |

|

| 6.2 能力の低下 |

||

| 6.3 現代教育制度の歴史的起源 |

||

| 6.4 産業訓練からのマンパワーの選抜

まで |

||

| 6.5 アメリカナイゼーションから生活適応まで |

||

| 6.6 基礎教育と国家防衛のための教育 |

||

| 6.7 公民権運動と学校 |

||

| 6.7 文化多元主義と新しいパターナリズム |

||

| 6.8 マルチバーシティの台頭 |

||

| 6.9 文化的エリート主義とその批評家 |

||

| 6.10 日用品としての教育 |

||

| 7. 再生産の社会化と権威の崩壊 |

7.1 労働者の社会化 |

|

| 7.2 少年裁判所 |

||

| 7.3 親になるための教育 |

||

| 7.4 許容性の再考 |

||

| 7.5 信頼性への崇拝 |

||

| 7.6 諸機能の転移がもたらす心理的影響 |

||

| 7.7 ナルシシズム、統合失調症、そして家族 |

||

| 7.8 ナルシシズムと父親不在 |

||

| 7.9 権威の放棄と超自我の転換 |

||

| 7.10 その他の社会統制機関と家族との関係 |

||

| 7.11 オンザジョブの人間関係、家庭としての工場 |

||

| 8. フィーリングからの飛行:セックス戦争の社会心理 |

8.1 個人的関係がとるにたらぬものになったということ |

|

| 8.2 異性間の争い:その社会史 |

||

| 8.3 性革命 |

||

| 8.4 共に…… |

||

| 8.5 フェミニズムとセックス戦争の激化 |

||

| 8.6 適応という戦術 |

||

| 8.7 男のファンタジーにあらわれてくる去勢しようと迫る女たち |

||

| 8.8 社会主義体制下の男女 |

||

| 9. 生活革新への信仰も崩れた |

9.1 老年への不安 |

|

| 9.2 ナルシシズムと老齢 |

||

| 9.3 加齢の社会理論:計画的廃物化という成熟 |

||

| 9.4 延命:老化についての生物学的理論 |

||

| 10. 父親不在のパターナリズム |

10.1 ニューリッチとオールドリッチ |

|

| 10.2 支配階級としての経営エリートと専門家エリート |

||

| 10.3 進歩主義と新しいパターナリズムの台頭 |

||

| 10.4 福祉国家に対するリベラルな批評 |

||

| 10.5 官僚主義的依存とナルシシズム |

||

| 10.6 官僚主義への保守的批判 |

++

| Robert Christopher

Lasch (June 1, 1932 – February 14, 1994) was an American historian,

moralist and social critic who was a history professor at the

University of Rochester. He sought to use history to demonstrate what

he saw as the pervasiveness with which major institutions, public and

private, were eroding the competence and independence of families and

communities. Lasch strove to create a historically informed social

criticism that could teach Americans how to deal with rampant

consumerism, proletarianization, and what he famously labeled "the

culture of narcissism". His books, including The New Radicalism in America (1965), Haven in a Heartless World (1977), The Culture of Narcissism (1979), The True and Only Heaven (1991), and The Revolt of the Elites and the Betrayal of Democracy (published posthumously in 1996) were widely discussed and reviewed. The Culture of Narcissism became a surprise best-seller and won the National Book Award in the category Current Interest (paperback).[6][a] Lasch was always a critic of modern liberalism and a historian of liberalism's discontents, but over time, his political perspective evolved dramatically. In the 1960s, he was a neo-Marxist and acerbic critic of Cold War liberalism. During the 1970s, he supported certain aspects of cultural conservatism with a left-leaning critique of capitalism, and drew on Freud-influenced critical theory to diagnose the ongoing deterioration that he perceived in American culture and politics. His writings are sometimes denounced by feminists[7] and hailed by conservatives[8] for his apparent defense of a traditional conception of family life. He eventually concluded that an often unspoken, but pervasive, faith in "Progress" tended to make Americans resistant to many of his arguments. In his last major works he explored this theme in depth, suggesting that Americans had much to learn from the suppressed and misunderstood populist and artisan movements of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[9] |

ロ

バート・クリストファー・ラッシュ(1932年6月1日 -

1994年2月14日)は、アメリカの歴史学者、モラリスト、社会評論家で、ロチェスター大学の歴史学の教授を務めた。ロチェスター大学の歴史学教授を務

め、公的・私的な主要機関が家庭や地域社会の能力や独立性を損なっていることを歴史を使って明らかにしようとした。ラシュは、横行する消費主義、プロレタ

リア化、そして彼が有名に「ナルシシズムの文化」と呼ぶものにどう対処するかをアメリカ人に教えることができる、歴史に基づいた社会批判を生み出そうと努

力した。 彼の著書には、The New Radicalism in America (1965), Haven in a Heartless World (1977), The Culture of Narcissism (1979), The True and Only Heaven (1991) and The Revolt of the Elites and the Betrayal of Democracy (published in postphenced in 1996) などがあり、多くの論評と検討が行われた。ナルシシズムの文化』は驚きのベストセラーとなり、全米図書賞の時事問題部門(ペーパーバック)を受賞した [6][a]。 ラシュは常に近代自由主義の批判者であり、自由主義の不満の歴史家であったが、時とともにその政治的視点は劇的に進化した。1960年代には、新マルクス 主義者として冷戦時代のリベラリズムを痛烈に批判した。1970年代には、資本主義を左翼的に批判しながら文化的保守主義の一面を支持し、フロイトの影響 を受けた批評理論を用いて、アメリカの文化や政治に見られる継続的な劣化を診断している。彼の著作は、時にフェミニスト[7]から非難され、保守派[8] からは伝統的な家族生活の概念を明らかに擁護しているとして歓迎されている。 彼は最終的に、しばしば語られることのない、しかし浸透している「進歩」に対する信仰が、アメリカ人を彼の主張の多くに抵抗させる傾向があると結論づけま した。最後の主要な著作で彼はこのテーマを深く探求し、19世紀から20世紀初頭の抑圧され誤解されたポピュリストや職人運動からアメリカ人が学ぶべきこ とが多くあると示唆した[9]。 |

| Biography Born on June 1, 1932, in Omaha, Nebraska, Christopher Lasch came from a highly political family rooted in the left. His father, Robert Lasch, was a Rhodes Scholar and journalist who won a Pulitzer prize for editorials criticizing the Vietnam War while he was in St. Louis.[9][10] His mother, Zora Lasch (née Schaupp), who held a philosophy doctorate, worked as a social worker and teacher.[11][12][13] Lasch was active in the arts and letters early, publishing a neighborhood newspaper while in grade school, and writing the fully orchestrated "Rumpelstiltskin, Opera in D Major" at the age of thirteen.[9] |

略歴 1932年6月1日、ネブラスカ州オマハに生まれたクリストファー・ラッシュは、左派に根ざした政治色の強い家系に生まれた。父はローズ奨学生で、セント ルイス滞在中にベトナム戦争批判の社説でピューリッツァー賞を受賞したジャーナリスト[9][10]。 母はゾーラ・ラッシュ(旧姓シャウプ)で、哲学博士号を持ち、ソーシャルワーカーや教師として働いていた[11][12][13]。 ラシュは早くから芸術や文学に親しみ、小学校時代には近所の新聞を発行し、13歳で全編オーケストレーションの『ルンペルシュティルツキン、オペラ ニ長調』を作曲した[9]。 |

| Career Lasch earned a bachelor's degree in history from Harvard University, where he roomed with John Updike, and a master's degree in history and doctorate from Columbia University, where he worked with William Leuchtenburg.[14][15] Richard Hofstadter was also a significant influence. He contributed a Foreword to later editions of Hofstadter's The American Political Tradition and an article on Hofstadter in the New York Review of Books in 1973. He taught at the University of Iowa and then was a professor of history at the University of Rochester from 1970 until his death from cancer in 1994. Lasch also took a conspicuous public role. Russell Jacoby acknowledged this in writing that "I do not think any other historian of his generation moved as forcefully into the public arena".[12] In 1986 he appeared on Channel 4 television in discussion with Michael Ignatieff and Cornelius Castoriadis.[16] During the 1960s, Lasch identified as a socialist, but one who found influence not just in the writers of the time, such as C. Wright Mills, but also in earlier independent voices, such as Dwight Macdonald.[17] Lasch became further influenced by writers of the Frankfurt School and the early New Left Review and felt that "Marxism seemed indispensable to me".[18] During the 1970s, however, he became disenchanted with the Left's belief in progress—a theme treated later by his student David Noble—and increasingly identified this belief as the factor that explained the Left's failure to thrive despite the widespread discontent and conflict of the times. He was a professor of history at Northwestern University from 1966 to 1970.[19] At this point Lasch began to formulate what would become his signature style of social critique: a syncretic synthesis of Sigmund Freud and the strand of socially conservative thinking that remained deeply suspicious of capitalism and its effects on traditional institutions. Besides Leuchtenburg, Hofstadter, and Freud, Lasch was especially influenced by Orestes Brownson, Henry George, Lewis Mumford, Jacques Ellul, Reinhold Niebuhr, and Philip Rieff.[20] A notable group of graduate students worked with Lasch at the University of Rochester, Eugene Genovese, and, for a time, Herbert Gutman, including Leon Fink, Russell Jacoby, Bruce Levine, David Noble, Maurice Isserman, William Leach, Rochelle Gurstein, Kevin Mattson, and Catherine Tumber.[21] |

経歴 ハーバード大学で歴史学の学士号を取得し、ジョン・アップダイクと同室だった。コロンビア大学で歴史学の修士号と博士号を取得し、ウィリアム・ロイヒテン バーグと共同研究を行った[14][15] リチャード・ホフスタッターも大きな影響を与えた。ホフスタッターの『アメリカ政治の伝統』の後期版に序文を寄稿し、1973年には『ニューヨーク・レ ビュー・オブ・ブックス』にホフスタッターに関する記事を寄稿している。アイオワ大学で教鞭をとり、1970年から1994年に癌で亡くなるまで、ロチェ スター大学の歴史学の教授を務めた。ラッシュはまた、目立つ公的な役割を果たした。ラッセル・ジャコビーは「同世代の歴史家の中で、これほど力強く公の場 に出た者はいないと思う」と書いてこれを認めている[12]。 1986年にはチャンネル4のテレビに出演し、マイケル・イグナティエフやコーネリウス・カストリアディスと議論している[16]。 1960年代、ラッシュは社会主義者であると認識していたが、C・ライト・ミルズのような当時の作家だけでなく、ドワイト・マクドナルドのような初期の独 立した声にも影響を見出していた[17]。ラッシュはフランクフルト学派や初期の新左翼評論家の作家からさらに影響を受け、「マルクス主義は私にとって不 可欠に思えた」ことを感じている[18]。 [しかし、1970年代には、左翼の進歩に対する信念に幻滅し、このテーマは後に弟子のデヴィッド・ノーブルによって扱われ、この信念が時代の広範な不満 と対立にもかかわらず左翼が成功できなかった要因であると考えるようになる。1966年から1970年までノースウェスタン大学の歴史学の教授を務めてい た[19]。 この時点で、ラッシュは、ジークムント・フロイトと、資本主義とその伝統的制度への影響に深い疑念を抱き続ける社会的保守思想の一群との同調的統合とい う、彼の社会批判の特徴となるスタイルを打ち出し始めたのである。 ロイヒテンブルク、ホフスタッター、フロイトのほか、ラッシュはオレステス・ブラウンソン、ヘンリー・ジョージ、ルイス・マンフォード、ジャック・エルー ル、ラインホルド・ニーバー、フィリップ・リーフから特に影響を受けていた[20]。 [20] ロチェスター大学、ユージン・ジェノヴェーゼ、そして一時期はハーバート・グットマンで、レオン・フィンク、ラッセル・ジャコビー、ブルース・レビン、デ ヴィッド・ノーブル、モーリス・イッサーマン、ウィリアム・リーチ、ロシェル・ガースタイン、ケヴィン・マットソン、キャサリン・タンバなどの大学院生の グループがラッシュと共に仕事をしていた。[21]. |

| Personal Lasch married Nellie Commager, daughter of historian Henry Steele Commager, in 1956.[22] They had four children: Robert, Elizabeth, Catherine, and Christopher.[23] Death After seemingly successful cancer surgery in 1992, Lasch was diagnosed with metastatic cancer in 1993. Upon learning that it was unlikely to significantly prolong his life, he refused chemotherapy, observing that it would rob him of the energy he needed to continue writing and teaching. To one persistent specialist, he wrote: "I despise the cowardly clinging to life, purely for the sake of life, that seems so deeply ingrained in the American temperament."[9] He died at his home in Pittsford, New York on February 14, 1994, at age 61.[24] |

個人的なこと 1956年に歴史学者ヘンリー・スティール・コメージャーの娘であるネリー・コメージャーと結婚した[22]。 二人の間には4人の子供がいた。ロバート、エリザベス、キャサリン、クリストファーである[23]。 死去 1992年に癌の手術が成功したかに見えたが、1993年に転移性の癌と診断された。1993年、転移性癌と診断され、化学療法による延命は難しいと判断 し、化学療法を拒否した。ある執拗な専門医に対して、「アメリカ人の気質に深く根付いていると思われる、純粋に生きるために生きるという臆病な執着を軽蔑 する」と書いている[9]。1994年2月14日にニューヨーク州ピッツフォードの自宅で61歳で死去した[24]。 |

| The New Radicalism in America Lasch's earliest argument, anticipated partly by Hofstadter's concern with the cycles of fragmentation among radical movements in the United States, was that American radicalism had at some point in the past become socially untenable. Members of "the Left" had abandoned their former commitments to economic justice and suspicion of power, to assume professionalized roles and to support commoditized lifestyles which hollowed out communities' self-sustaining ethics. His first major book, The New Radicalism in America: The Intellectual as a Social Type, published in 1965 (with a promotional blurb from Hofstadter), expressed those ideas in the form of a bracing critique of twentieth-century liberalism's efforts to accrue power and restructure society, while failing to follow up on the promise of the New Deal.[25] Most of his books, even the more strictly historical ones, include such sharp criticism of the priorities of alleged "radicals" who represented merely extreme formations of a rapacious capitalist ethos. His basic thesis about the family, which he first expressed in 1965 and explored for the rest of his career, was: When government was centralized and politics became national in scope, as they had to be to cope with the energies let loose by industrialism, and when public life became faceless and anonymous and society an amorphous democratic mass, the old system of paternalism (in the home and out of it) collapsed, even when its semblance survived intact. The patriarch, though he might still preside in splendor at the head of his board, had come to resemble an emissary from a government which had been silently overthrown. The mere theoretical recognition of his authority by his family could not alter the fact that the government which was the source of all his ambassadorial powers had ceased to exist.[26] |

アメリカにおける新しいラディカリズム ラシュの初期の主張は、アメリカにおけるラディカルな運動の断片化のサイクルに対するホフスタッターの懸念に先んじたもので、アメリカのラディカリズムが 過去のある時点で社会的に成り立たなくなったというものであった。左翼」のメンバーは、経済的正義や権力への疑念といったかつてのコミットメントを放棄 し、専門化した役割を担い、商品化されたライフスタイルを支持し、コミュニティの自立的な倫理を空洞化させたのである。彼の最初の主著は『アメリカの新し いラジカリズム』である。1965年に出版された(ホフスタッターの宣伝文句付き)『アメリカの新しいラジカリズム:社会的タイプとしての知識人』は、 20世紀のリベラリズムが権力を獲得し社会を再編しようとする一方で、ニューディールの約束を果たすことができなかったことに対する厳しい批判の形でこれ らの考えを表現している[25]。 彼の著書のほとんどは、より厳密に歴史的なものを含めて、強欲資本主義の倫理を単に極端に形成したものにしかならない「ラジカル」呼ばれる人々の優先事項 についての鋭い批判を含んでいる。 家族に関する彼の基本的なテーゼは、1965年に初めて表明され、その後の彼のキャリアにおいて探求されたものである。 政府が中央集権化され、政治が国家的な規模になったとき、それは産業主義が放つエネルギーに対処するためであり、公的生活が顔のない匿名的なものになり、 社会が不定形の民主的な塊になったとき、古い父権制は(家庭内外で)、その体裁がそのまま残っていても崩壊したのです」。家長は、まだ役員会の議長として 華麗に振る舞っているかもしれないが、静かに倒された政府からの使者のようなものであった。彼の家族によって彼の権威が理論的に認められただけでは、彼の 大使としての権限の源である政府が消滅してしまったという事実を変えることはできなかった[26]。 |

| The

Culture of Narcissism |

(このページ) |

| The True and Only Heaven Most explicitly in The True and Only Heaven, Lasch developed a critique of social change among the middle classes in the USA, explaining and seeking to counteract the fall of elements of "populism". He sought to rehabilitate this populist or producerist alternative tradition: "The tradition I am talking about ... tends to be skeptical of programs for the wholesale redemption of society ... It is very radically democratic and in that sense it clearly belongs on the Left. But on the other hand it has a good deal more respect for tradition than is common on the Left, and for religion too."[27] And said that: "...any movement that offers any real hope for the future will have to find much of its moral inspiration in the plebeian radicalism of the past and more generally in the indictment of progress, large-scale production and bureaucracy that was drawn up by a long line of moralists whose perceptions were shaped by the producers' view of the world."[28] |

真の天国と唯一の天国 The True and Only Heaven』では、アメリカの中産階級の社会変動に対する批判を展開し、「ポピュリズム」の要素の堕落を説明し、それに対抗することを試みている。彼 は、このポピュリズムあるいは生産者主義のオルタナティブな伝統を復興させようとしたのである。私が話している伝統は......社会の全面的な救済のた めのプログラムに懐疑的である傾向がある......」。私が話している伝統は、社会を全面的に救済するためのプログラムに懐疑的である傾向がありま す...それは非常に根本的に民主的で、その意味では明らかに左派に属します。しかし他方で、それは左派にありがちな伝統や、宗教に対してもかなりの敬意 を払っている」[27]と述べている。「未来に真の希望を与えるいかなる運動も、過去の平民的な急進主義に、より一般的には、生産者の世界観によってその 認識が形成された道徳主義者の長い列によって描かれた進歩、大規模生産、官僚主義の非難に、その道徳的霊感の多くを見つけなければならないだろう」 [28]と述べている。 |

| Critique of progressivism and

libertarianism By the 1980s, Lasch had poured scorn on the whole spectrum of contemporary mainstream American political thought, angering liberals with attacks on progressivism and feminism. He wrote that A feminist movement that respected the achievements of women in the past would not disparage housework, motherhood or unpaid civic and neighborly services. It would not make a paycheck the only symbol of accomplishment. ... It would insist that people need self-respecting honorable callings, not glamorous careers that carry high salaries but take them away from their families.[29] Journalist Susan Faludi dubbed him explicitly anti-feminist for his criticism of the abortion rights movement and opposition to divorce.[30] But Lasch viewed Ronald Reagan's conservatism as the antithesis of tradition and moral responsibility. Lasch was not generally sympathetic to the cause of what was then known as the New Right, particularly those elements of libertarianism most evident in its platform; he detested the encroachment of the capitalist marketplace into all aspects of American life. Lasch rejected the dominant political constellation that emerged in the wake of the New Deal in which economic centralization and social tolerance formed the foundations of American liberal ideals, while also rebuking the diametrically opposed synthetic conservative ideology fashioned by William F. Buckley Jr. and Russell Kirk. Lasch was also critical and at times dismissive toward his closest contemporary kin in social philosophy, communitarianism as elaborated by Amitai Etzioni. Only populism satisfied Lasch's criteria of economic justice (not necessarily equality, but minimizing class-based difference), participatory democracy, strong social cohesion and moral rigor; yet populism had made major mistakes during the New Deal and increasingly been co-opted by its enemies and ignored by its friends. For instance, he praised the early work and thought of Martin Luther King Jr. as exemplary of American populism; yet in Lasch's view, King fell short of this radical vision by embracing in the last few years of his life an essentially bureaucratic solution to ongoing racial stratification. He explained in one of his books The Minimal Self,[31] "it goes without saying that sexual equality in itself remains an eminently desirable objective ...". In Women and the Common Life,[32] Lasch clarified that urging women to abandon the household and forcing them into a position of economic dependence in the workplace, pointing out the importance of professional careers does not entail liberation, so long as these careers are governed by the requirements of corporate economy. |

進歩主義・リバタリアニズムへの批判 1980年代に入ると、ラッシュは、進歩主義とフェミニズムに対する攻撃でリベラル派を怒らせ、現代アメリカの主流の政治思想の全領域に侮蔑を浴びせた。 彼はこう書いている。 過去の女性の功績を尊重するフェミニズム運動は、家事や母性、無報酬の市民活動や隣人への奉仕を軽んじることはない。給与を達成の唯一のシンボルとするこ ともないだろう。... それは人々が自尊心のある名誉ある職業を必要とすることを主張し、高い給料を持ちながら家族から引き離すような華やかなキャリアを持たないということであ る[29]。 また、ジャーナリストであるスーザン・ファルディは、中絶権運動への批判や離婚への反対から、彼を明白な反フェミニストと呼んだ[30]。 しかし、ラッシュはロナルド・レーガンの保守主義を伝統や道徳的責任に対するアンチテーゼとして見ている。また、当時、新右翼として知られていた団体、特 にその綱領に顕著なリバタリアニズムの要素に共感していたわけではなく、アメリカ生活のあらゆる側面に資本主義市場が侵入していくことを嫌悪していた。 ラシュは、経済的中央集権と社会的寛容をアメリカのリベラルな理想の基盤とするニューディール以降の支配的な政治体制を否定し、一方で、ウィリアム・F・ バックリー・ジュニアやラッセル・カークが作り上げた正反対の総合保守思想を非難している。また、エッツィオーニが提唱したコミュニタリアニズムにも批判 的で、時には否定的であった。ポピュリズムは、経済的公正(必ずしも平等ではないが、階級的格差を最小化する)、参加型民主主義、強固な社会的結束、道徳 的厳格さといったラシュの基準を満たすものだったが、ポピュリズムはニューディール時代に大きな過ちを犯し、次第に敵に利用され、友には無視されるように なった。例えば、キング牧師をアメリカのポピュリズムの模範とし、その思想と活動を賞賛しているが、キング牧師は晩年、人種差別を官僚主義的に解決しよう としたため、このような急進的なビジョンには程遠かったとラッシュは見ている。 彼は著書『最小限の自己』[31]のなかで、「それ自体、性的平等が依然として極めて望ましい目標であることは言うまでもない...」と説明している。女 性と共同生活』[32]においてラッシュは、女性に家庭を放棄するように促し、職場において経済的に依存する立場を強いること、専門職のキャリアの重要性 を指摘することは、これらのキャリアが企業経済の要件に支配されている限り、解放を伴わないことを明らかにしている。 |

| The Revolt of the Elites: And

the Betrayal of Democracy In his last months, he worked closely with his daughter Elisabeth to complete The Revolt of the Elites: And the Betrayal of Democracy, published in 1994, in which he "excoriated the new meritocratic class, a group that had achieved success through the upward-mobility of education and career and that increasingly came to be defined by rootlessness, cosmopolitanism, a thin sense of obligation, and diminishing reservoirs of patriotism," and "argued that this new class 'retained many of the vices of aristocracy without its virtues', lacking the sense of 'reciprocal obligation' that had been a feature of the old order."[33] Christopher Lasch analyzes[34] the widening gap between the top and bottom of the social composition in the United States. For him, our epoch is determined by a social phenomenon: the revolt of the elites, in reference to The Revolt of the Masses (1929) of the Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset. According to Lasch, the new elites, i.e. those who are in the top 20 percent in terms of income, through globalization which allows total mobility of capital, no longer live in the same world as their fellow-citizens. In this, they oppose the old bourgeoisie of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, which was constrained by its spatial stability to a minimum of rooting and civic obligations. Globalization, according to the historian, has turned elites into tourists in their own countries. The de-nationalization of society tends to produce a class who see themselves as "world citizens, but without accepting… any of the obligations that citizenship in a polity normally implies". Their ties to an international culture of work, leisure, information – make many of them deeply indifferent to the prospect of national decline. Instead of financing public services and the public treasury, new elites are investing their money in improving their voluntary ghettos: private schools in their residential neighborhoods, private police, garbage collection systems. They have "withdrawn from common life". Composed of those who control the international flows of capital and information, who preside over philanthropic foundations and institutions of higher education, they manage the instruments of cultural production and thus fix the terms of public debate. So, the political debate is limited mainly to the dominant classes and political ideologies lose all contact with the concerns of the ordinary citizen. The result of this is that no one has a likely solution to these problems and that there are furious ideological battles on related issues. However, they remain protected from the problems affecting the working classes: the decline of industrial activity, the resulting loss of employment, the decline of the middle class, increasing the number of the poor, the rising crime rate, growing drug trafficking, the urban crisis. In addition, he finalized his intentions for the essays to be included in Women and the Common Life: Love, Marriage, and Feminism, which was published, with his daughter's introduction, in 1997. |

エリートの反乱。そして、民主主義の裏切り 晩年は、娘のエリザベートと二人三脚で「エリートの反乱」を完成させた。そして、1994年に出版された『エリートの反乱:そして民主主義の裏切り』で は、「教育とキャリアという上昇志向によって成功を収め、次第に根無し草、国際主義、薄い義務感、愛国心の希薄さによって定義づけられるようになった新し い能力主義層を非難し、この新しい層が『その美徳なしに貴族の多くの悪を保持し』、古い秩序の特徴だった『相互義務感』を欠いていると主張」している [33][34] 。 "[33] クリストファー・ラッシュは、アメリカにおける社会構成の上位と下位の間の格差が広がっていることを分析している[34]。彼にとって我々の時代は、スペ インの哲学者であるホセ・オルテガ・イ・ガセットの『大衆の反乱』(1929年)を参照して、エリートの反乱という社会現象によって決定されるのである。 ラッシュによれば、新しいエリート、すなわち、資本の完全な流動性を可能にするグローバリゼーションによって、所得的に上位20パーセントに位置する人々 は、もはや同胞と同じ世界には住めなくなった。この点で、彼らは、空間的安定性によって最小限の根回しや市民的義務に制約されていた19世紀や20世紀の 古いブルジョアジーに対抗している。 歴史家によれば、グローバリゼーションは、エリートたちを自国への観光客に変えてしまった。社会の脱国家化は、自らを「世界市民」とみなす層を生み出す傾 向がある。しかし、「世界市民」でありながら、「政治における市民権」が通常意味する義務を一切受け入れない。仕事、レジャー、情報といった国際的な文化 との結びつきによって、彼らの多くは国の衰退という事態に深く無関心になる。新しいエリートたちは、公共サービスや国庫に資金を供給する代わりに、自分た ちの自主的なゲットーを改善するために資金を投入しているのだ。彼らは「庶民生活から撤退」したのだ。 資本と情報の国際的な流れをコントロールし、慈善財団や高等教育機関を主宰する人々で構成される彼らは、文化的生産の手段を管理し、その結果、公的議論の 条件を確定している。そのため、政治的な議論は主に支配階級に限られ、政治的なイデオロギーは一般市民の関心事との接点を失ってしまう。その結果、これら の問題に対する有力な解決策を誰も持たず、関連する問題で激しいイデオロギー論争が繰り広げられることになる。しかし、産業活動の衰退、それによる雇用の 喪失、中産階級の衰退、貧困層の増加、犯罪率の上昇、麻薬取引の拡大、都市の危機など、労働者階級に影響を及ぼす問題からは守られたままである。 また、『女たちとの共同生活』に収録するエッセイの意向を最終決定した。1997年、娘の紹介で出版された『愛と結婚とフェミニズム』に収録されるエッセ イの執筆意図を固めた。 |

| Books 1962: The American Liberals and the Russian Revolution. 1965: The New Radicalism in America 1889–1963: The Intellectual As a Social Type. 1969: The Agony of the American Left. 1973: The World of Nations. 1977: Haven in a Heartless World: The Family Besieged. 1979: The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations.[6] 1984: The Minimal Self: Psychic Survival in Troubled Times. 1991: The True and Only Heaven: Progress and Its Critics. 1994: The Revolt of the Elites: And the Betrayal of Democracy, W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 978-0-39331371-0 1997: Women and the Common Life: Love, Marriage, and Feminism. 2002: Plain Style: A Guide to Written English. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christopher_Lasch |

|

| Collective narcissism |

|

| In social psychology, collective

narcissism (or group narcissism)

is the tendency to exaggerate the positive image and importance of a

group to which one belongs.[1][2] The group may be defined by ideology,

race, political beliefs/stance, religion, sexual orientation, social

class, language, nationality, employment status, education level,

cultural values, or any other ingroup.[1][2] While the classic

definition of narcissism focuses on the individual, collective

narcissism extends this concept to similar excessively high opinions of

a person's social group, and suggests that a group can function as a

narcissistic entity.[1] Collective narcissism is related to ethnocentrism. While ethnocentrism is an assertion of the ingroup's supremacy, collective narcissism is a self-defensive tendency to invest unfulfilled self-entitlement into a belief about ingroup's uniqueness and greatness. Thus, the ingroup is expected to become a vehicle of actualisation of frustrated self-entitlement.[2] In addition, ethnocentrism primarily focuses on self-centeredness at an ethnic or cultural level, while collective narcissism is extended to any type of ingroup.[1][3] When applied to a national group, collective narcissism is similar to nationalism: a desire for national supremacy.[4] Collective narcissism is associated with intergroup hostility.[2] |

社

会心理学では、集団ナルシシズム(または集団ナルシシズム)とは、自分が属する集団の肯定的なイメージや重要性を誇張する傾向である[1][2]。

集団はイデオロギー、人種、政治信条/立場、宗教、性的指向、社会階級、言語、国籍、雇用形態、教育レベル、文化的価値観、またはその他のイングループで

定義されることがある。 [1][2]

ナルシシズムの古典的な定義は個人に焦点を当てていますが、集団的ナルシシズムはこの概念を人の社会的集団に対する同様の過剰な高評価に拡張し、集団がナ

ルシシズム的存在として機能することを示唆しています[1]。 集団的ナルシシズムはエスノセントリズムと関連している。民族中心主義がイングルー プの優位性を主張するのに対し、集団的ナルシシズムは満たされ ない自己充足感をイングループの独自性や偉大さについての信念 に投資する自己防衛的な傾向である。また、エスノセントリズムは主に民族的・文化的なレベルでの自己中心性に焦点を当てるが、集団的ナルシシズムはあらゆ るタイプのイングループに拡大される[1][3]。 国家集団に適用される場合、集団的ナルシシズムはナショナリズムに似ている:国家至上主義への欲求である[4]。 集団的ナルシシズムは集団間敵意と関連している[2]。 |

| Development of the concept In Sigmund Freud's 1922 study Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego, he noted how every little canton looks down upon the others with contempt,[5] as an instance of what would later to be termed Freud's theory of collective narcissism.[6] Wilhelm Reich and Isaiah Berlin explored what the latter called the rise of modern national narcissism: the self-adoration of peoples.[7] "Group narcissism" is described in a 1973 book entitled The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness by psychologist Erich Fromm.[8] In the 1990s, Pierre Bourdieu wrote of a sort of collective narcissism affecting intellectual groups, inclining them to turn a complacent gaze on themselves.[9] Noting how people's desire to see their own groups as better than other groups can lead to intergroup bias, Henri Tajfel approached the same phenomena in the seventies and eighties, so as to create social identity theory, which argues that people's motivation to obtain positive self-esteem from their group memberships is one driving-force behind in-group bias.[10] The term "collective narcissism" was highlighted anew by researcher Agnieszka Golec de Zavala[11][1][2][12][13] who created the Collective Narcissism Scale[1] and developed research on intergroup and political consequences of collective narcissism. People who score high on the Collective Narcissists Scale agree that their group's importance and worth are not sufficiently recognised by others and that their group deserves special treatment. They insist that their group must obtain special recognition and respect. The Scale was modelled on the Narcissistic Personality Inventory. However, collective and individual narcissism are modestly correlated. Only collective narcissism predicts intergroup behaviours and attitudes. Collective narcissism is related to vulnerable narcissism (individual narcissism manifesting as distrustful and neurotic interpersonal style), and grandiose narcissism (individual narcissism manifesting as exceedingly self-aggrandising interpersonal style) and to low self-esteem.[11][14] This is in line with the theorising of Theodore Adorno who proposed that collective narcissism motivated support for the Nazi politics in Germany and was a response to undermined sense of self-worth.[15] |

概念の発展 ジークムント・フロイトは1922年の研究「集団心理と自我の分析」の中で、後にフロイトの集団ナルシシズム理論と呼ばれることになる事例として、どの小 さなカントン??も他を軽蔑して見下していることを指摘している[5]。 ヴィルヘルム・ライヒとアイザイヤ・バーリンは後者が近代国家ナルシシズムと呼ぶものの増加、つまり民族の自己崇拝を研究した[6]。 7] 「集団ナルシシズム」は心理学者エーリッヒ・フロムが1973年に出版した「人間破壊の解剖学」で説明されている[8] 1990年代、ピエール・ブルデューは知的集団に影響を与える一種の集団ナルシシズムについて書き、彼らが自分自身に自己満足の視線を向けるよう傾けてい ることを指摘している[9]。 9] 1970年代から80年代にかけてアンリ・ターフェル(Henri Tajfel)が同じ現象にアプローチし、集団に属していることで肯定的な自尊心を得たいという人々の動機が集団内バイアスの1つの原動力になると主張す る社会アイデンティティ理論を作り上げた[10]。 [集団的ナルシシズムという言葉は研究者のアニエスカ・ゴレック・デ・ザヴァラ[11][1][2][12][13]によって新たに強調され、集団的ナル シシズム尺度[1]を作成して集団的ナルシシズムの集団間および政治的結果に関する研究を発展させている。集団的ナルシシズム尺度で高得点を得た人々は、 自分たちの集団の重要性や価値が他者から十分に認識されておらず、自分たちの集団は特別な扱いを受けるに値するということに同意する。彼らは自分たちのグ ループが特別な認識と尊敬を得なければならないと主張する。 この尺度は、Narcissistic Personality Inventoryをモデルとしている。しかし、集団的ナルシシズムと個人的ナルシシズムの相関は緩やかである。集団的ナルシシズムのみが集団間の行動や 態度を予測する。集団的自己愛は脆弱な自己愛(不信感と神経症的な対人関係スタイルとして現れる個人の自己愛)、および壮大な自己愛(非常に自己顕示的な 対人関係スタイルとして現れる個人の自己愛)、および低い自尊心と関連している[11][14]。これは、ドイツのナチの政治に対する支援を動機づけ、自 己価値の感覚が損なわれたことに対する応答であるとしたセオドア・アドルノの理論付けと一致するものであった[15]。 |

| Characteristics and consequences Collective narcissism is characterized by the members of a group holding an inflated view of their ingroup which requires constant external validation.[16] Collective narcissism can be exhibited by an individual on behalf of any social group or by a group as a whole. Research participants found that they could apply statements of the Collective Narcissism Scale to various groups: national, ethnic, religious, ideological, political, students of the same university, fans of the same football team, professional groups and organizations[1] Collectively narcissistic groups require external validation, just as individual narcissists do.[17] Organizations and groups who exhibit this behavior typically try to protect their identities through rewarding group-building behavior (this is positive reinforcement).[17] Collective narcissism predicts retaliatory hostility to past, present, actual and imagined offences to the ingroup and negative attitudes towards groups perceived as threatening.[2][12] It predicts constantly feeling threatened in intergroup situations that require a stretch of imagination to be perceived as insulting or threatening. For example, in Turkey, collective narcissists felt humiliated by the Turkish wait to be admitted to the European Union. After a transgression as petty as a joke made by a Polish celebrity about the country's government, Polish collective narcissists threatened physical punishment and openly rejoiced in the misfortunes of the "offender".[12] Collective narcissism predicts conspiracy thinking about secretive malevolent actions of outgroups.[18] |

特徴および結果 集団的ナルシシズムは集団のメンバーが常に外部からの検証を必要とする自分たちのイングループに対する膨張した見解を持つことによって特徴づけられる [16]。集団的ナルシシズムはあらゆる社会集団を代表する個人または集団全体によって示されることがある。研究参加者は集団的ナルシシズム尺度のステー トメントを国家、民族、宗教、イデオロギー、政治、同じ大学の学生、同じサッカーチームのファン、プロのグループや組織など様々なグループに適用できるこ とがわかった[1] 集団的ナルシシズム的グループは個人のナルシストと同じように外的検証を必要とします。この行動を示す組織やグループは通常、グループ構築行動を報いる (これは正の強化)ことによりアイデンティティを保護しようとします[17] 。 集団的ナルシシズムは過去、現在、実際の、そして想像上のイングル ープへの攻撃に対する報復的敵意や脅威と認識されるグループ に対する否定的態度を予測する。 2][12] それは侮辱や脅威として認識されるには想像力の拡張を 必要とするグループ間状況において常に脅威を感じている ことを予測するものである。例えば、トルコでは、集団的ナルシストはトルコのEU加盟を待つことで、屈辱を感じていた。ポーランドの有名人が自国の政府に 対して行ったジョークのような些細な違反の後、ポーランドの集団的ナルシストは体罰を脅し、公然と「違反者」の不幸を喜んだ。 集団的ナルシズムはアウトグループの秘密の悪意ある行動に関する陰謀論を予測する[12]。 |

| Collective vs. individual There are several connections, and intricate relationships between collective and individual narcissism, or between individual narcissism stemming from group identities or activities, however no single relationship between groups and individuals is conclusive or universally applicable. In some cases, collective narcissism is an individual's idealization of the ingroup to which they belong,[20] while in another the idealization of the group takes place at a more group-level, rather than an instillation within each individual member of the group.[1] In some cases, one might project the idealization of himself onto his group,[21] while in another case, the development of individual-narcissism might stem from being associated with a prestigious, accomplished, or extraordinary group.[1][22] An example of the first case listed above is that of national identity. One might feel a great sense of love and respect for one's nation, flag, people, city, or governmental systems as a result of a collectively narcissistic perspective.[20] It must be remembered that these feelings are not explicitly the result of collective narcissism, and that collective narcissism is not explicitly the cause of patriotism, or any other group-identifying expression. However, glorification of one's group (such as a nation) can be seen in some cases as a manifestation of collective narcissism.[20] In the case where the idealization of self is projected onto ones group, group-level narcissism tends to be less binding than in other cases.[21] Typically in this situation the individual—already individually narcissistic—uses a group to enhance his own self-perceived quality, and by identifying positively with the group and actively building it up, the narcissist is enhancing simultaneously both his own self-worth, and his group's worth.[21] However, because the link tends to be weaker, individual narcissists seeking to raise themselves up through a group will typically dissociate themselves from a group they feel is damaging to their image, or that is not improving proportionally to the amount of support they are investing in the group.[21] Involvement in one's group has also been shown to be a factor in the level of collective narcissism exhibited by members of a group. Typically a more involved member of a group is more likely to exhibit a higher opinion of the group.[23] This results from an increased affinity for the group as one becomes more involved, as well as a sense of investment or contribution to the success of the group.[23] Also, another perspective asserts that individual narcissism is related to collective narcissism exhibited by individual group members.[3] Personal narcissists, seeing their group as a defining extension of themselves, will defend their group (collective narcissism) more avidly than a non-narcissist, to preserve their own perceived social standing along with their group's.[3] In this vein, a problem is presented; for while an individual narcissist will be heroic in defending his or her ingroup during intergroup conflicts, he or she may be a larger burden on the ingroup in intragroup situations by demanding admiration, and exhibiting more selfish behavior on the intragroup level—individual narcissism.[3] Conversely, another relationship between collective narcissism and the individual can be established with individuals who have a low or damaged ego investing their image in the well-being of their group, which bears strong resemblance to the "ideal-hungry" followers in the charismatic leader-follower relationship.[1][24] As discussed, these ego-damaged group-investors seek solace in belonging to a group;[24] however, a strong charismatic leader is not always requisite for someone weak to feel strength by building up a narcissistic opinion of their own group.[21] |

集団と個人の関係 集団的自己愛と個人的自己愛、または集団のアイデンティティや活動から生じる個人的自己愛にはいくつかの関連性や複雑な関係があるが、集団と個人の間の単 一の関係は決定的ではなく、普遍的に適用できるものではない。あるケースでは、集団的ナルシシズムは個人が所属する集団の理想化であり[20]、別のケー スでは集団の理想化は集団の個々のメンバーの中に植え付けられるというよりも、より集団レベルで行われる[1]。 あるケースでは、自分の理想化をその集団に投影するかもしれないし[21]、別のケースでは個人ナルシシの発達は名声、実績、または並外れた集団との関連 から生じるかもしれない[1][22]。 上記の最初のケースの例としては、ナショナル・アイデンティティのことが挙げられる。集団的ナルシシズムの視点の結果として、人は自分の国家、国旗、国 民、都市、または政府システムに対して大きな愛と敬意を感じるかもしれない[20]。これらの感情は明示的に集団的ナルシシズムの結果ではなく、集団的ナ ルシシズムは愛国主義や他の集団同一化表現の原因ではないことを忘れてはいけない。しかしながら、(国家などの)自分の集団を美化することは、場合によっ ては集団的ナルシシズムの現れと見ることができる[20]。 自己の理想化が集団に投影される場合、集団レベルのナルシシズムは他の場合よりも拘束力が弱い傾向がある[21]。一般的にこの状況では個人-すでに個人 的にナルシスト-は自分の自己認識の質を高めるために集団を利用し、集団と積極的に同一化して集団を活発に盛り上げることによって、ナルシストは自分の自 己価値と集団の価値の両方を同時に高めているのです。 [21]しかし、リンクが弱くなる傾向があるため、グループを通して自分を高めようとする個人のナルシストは一般的に自分のイメージにダメージを与えてい ると感じるグループや、グループに投資しているサポートの量に比例して向上しないグループから自分を切り離すだろう[21]。 集団への関与もまた、集団のメンバーが示す集団的自己愛 のレベルの要因であることが示されている。また、別の観点では個人のナルシシズムが集団の個々のメンバーが示す集団的ナルシシズムに関連していると主張し ている[23]。 個人的なナルシシストはグループを自分自身の延長とみなし、非ナルシストよりも熱心にグループ(集団的ナルシシズム)を擁護し、グループと一緒に自分自身 の認識された社会的地位を維持しようとする[3]。 [3] この脈絡で問題が提示される;個人のナルシストは集団間の葛藤の中で彼または彼女のイングループを守るために英雄的になるが、彼または彼女は賞賛を要求す ることによって集団内の状況でイングループにより大きな負担となり、集団内のレベル-個人のナルシズムでより自分勝手な振る舞いを示すかもしれないからで ある[3]。 逆に、集団的ナルシシズムと個人の間の別の関係は、自我が低いか損傷している個人が自分のイメージを集団の幸福に投資することで成立し、これはカリスマ的 リーダー・フォロワーの関係における「理想を求める」フォロワーと強く類似している[1][24]。 [1][24]議論されたように、これらの自我が損傷した集団投資家は集団に属することで慰めを求める[24]。しかし、自分の集団に対するナルシス ティックな意見を構築することで力を感じる弱い人間にとって強いカリスマ的指導者は必ずしも必要なものではない[21]。 |

| The charismatic leader-follower

relationship Another sub-concept encompassed by collective narcissism is that of the "Charismatic Leader-Follower Relationship" theorized by political psychologist Jerrold Post.[24] Post takes the view that collective narcissism is exhibited as a collection of individual narcissists, and discusses how this type of relationship emerges when a narcissistic charismatic leader, appeals to narcissistic "ideal-hungry" followers.[24] An important characteristic of the leader follower-relationship are the manifestations of narcissism by both the leader and follower of a group.[24] Within this relationship there are two categories of narcissists: the mirror-hungry narcissist, and the ideal-hungry narcissist—the leader and the followers respectively.[24] The mirror-hungry personality typically seeks a continuous flow of admiration and respect from his followers. Conversely, the ideal-hungry narcissist takes comfort in the charisma and confidence of his mirror-hungry leader. The relationship is somewhat symbiotic; for while the followers provide the continuous admiration needed by the mirror-hungry leader, the leader's charisma provides the followers with the sense of security and purpose that their ideal-hungry narcissism seeks.[24] Fundamentally both the leader and the followers exhibit strong collectively narcissistic sentiments—both parties are seeking greater justification and reason to love their group as much as possible.[1][24] Perhaps the most significant example of this phenomenon would be that of Nazi Germany.[24] Adolf Hitler's charisma and polarizing speeches satisfied the German people's hunger for a strong leader.[24] Hitler's speeches were characterized by their emphasis on "strength"—referring to Germany—and "weakness"—referring to the Jewish people.[25] Some have even described Hitler's speeches as "hypnotic"—even to non-German speakers[24]—and his rallies as "watching hypnosis on large scale".[24] Hitler's charisma convinced the German people to believe that they were not weak, and that by destroying the perceived weakness from among them (the Jews), they would be enhancing their own strength—satisfying their ideal-hungry desire for strength, and pleasing their mirror-hungry charismatic leader.[24] |

カリスマ的指導者とフォロワーの関係 集団的ナルシズムによって包含されるもう一つの下位概念は政治心理学者であるジェロルド・ポストによって理論化された「カリスマ的リーダー-フォロワー関 係」のそれである[24]。ポストは集団的ナルシズムが個々のナルシストの集合として示されるという見解をとり、ナルシスト的カリスマリーダー、ナルシス ト的「理想を求める」フォロワーに訴えるときこのタイプの関係がいかに出現するのかを論じている[24]。 リーダー・フォロワー関係の重要な特徴は、グループのリーダーとフォロワーの両方によるナルシズムの発現である[24]。この関係の中でナルシストの2つ のカテゴリがあります:鏡に飢えたナルシスト、そして理想に飢えたナルシスト、それぞれリーダーとフォロワーです[24]。逆に、理想に飢えたナルシスト は鏡に飢えた指導者のカリスマ性と自信に安らぎを感じる。この関係はやや共生的で、鏡に飢えたリーダーが必要とする継続的な賞賛をフォロワーが提供する一 方で、リーダーのカリスマ性は、彼らの理想に飢えたナルシシズムが求める安心感と目的意識をフォロワーに与える[24]。根本的にリーダーとフォロワーの 両方が強い集団的ナルシスト感情を示す-両者は、できるだけ自分のグループを愛するための大きな正当化理由と根拠を求めている[1][24]。 おそらくこの現象の最も重要な例はナチスドイツのものであろう[24] アドルフ・ヒトラーのカリスマ性と極論的な演説は、ドイツ国民の強いリーダーへの飢餓感を満たした[24] ヒトラーの演説は、ドイツを指す「強さ」とユダヤ人を指す「弱さ」を強調していることが特徴であった[25]。 [ヒトラーの演説を「催眠術のようだ」と評する者もおり[24]、彼の集会を「大規模な催眠術を見る」と評する者もいる[24]。ヒトラーのカリスマ性 は、ドイツ国民に自分たちは弱くない、自分たちの中から弱いと思われているもの(ユダヤ人)を破壊することによって、自分自身の力を高める-理想に燃える 強者の欲求を満たし、ミラーハングのカリスマの指導者に喜んでもらうことができると思わせるものであった[24]。 |

| Intergroup aggression Collective narcissism has been shown to be a factor in intergroup aggression and bias.[1] Primary components of collectively narcissistic intergroup relations involve aggression against outgroups with which collective narcissistic perceive as threatening.[26][1][2][12][27] Collective narcissism helps to explain unreasonable manifestations of retaliation between groups. A narcissistic group is more sensitive to perceived criticism exhibited by outgroups, and is therefore more likely to retaliate.[28] Collective narcissism is also related to negativity between groups who share a history of distressing experiences. The members of a narcissistic ingroup are likely to assume threats or negativity towards their ingroup where threats or negativity were not necessarily implied or exhibited.[1][2][12] It is thought that this heightened sensitivity to negative feelings towards the ingroup is a result of underlying doubts about the greatness of the ingroup held by its members.[24] Similar to other elements of collective narcissism, intergroup aggression related to collective narcissism draws parallels with its individually narcissistic counterparts. An individual narcissist might react aggressively in the presence of humiliation, irritation, or anything threatening to his self-image.[29] Likewise, a collective narcissist, or a collectively narcissistic group might react aggressively when the image of the group is in jeopardy, or when the group is collectively humiliated.[1] A study conducted among 6 to 9 year-olds by Judith Griffiths indicated that ingroups and outgroups among these children functioned relatively identical to other known collectively narcissistic groups in terms of intergroup aggression. The study noted that children generally had a significantly higher opinion of their ingroup than of surrounding outgroups, and that such ingroups indirectly or directly exhibited aggression on surrounding outgroups.[30] |

集団間攻撃性 集団的自己愛は集団間攻撃と偏見の要因であることが示されている[1]。集団的自己愛的な集団間関係の主要な構成要素は集団的自己愛者が脅威として認識す るアウトグループに対する攻撃を伴う[26][1][2][12][27] 集団的自己愛は集団間の報復の理不尽な発現を説明するのに役立っている。集団的自己愛はまた苦痛を伴う経験の歴史を共有する集団間の否定的な態度に関連し ている。自己愛的な内集団の成員は脅威や否定性が必ずしも暗示されたり示されたりしなかった内集団に対して脅威や否定性を想定しやすい[1][2] [12]。内集団に対する否定的感情に対するこの感度の高さは、その成員が持つ内集団の偉大さに対する根底の疑念の結果であると考えられている[24]。 集団的ナルシシズムの他の要素と同様に、集団的ナルシシズムに関連する集団間攻撃性は個人的ナルシシズムの対応するものと類似性を示す。個人のナルシスト は屈辱、苛立ち、または彼の自己イメージを脅かすものの存在下で攻撃的に反応するかもしれない[29]。同様に集団ナルシスト、または集団ナルシスト集団 は集団のイメージが危ういとき、または集団が集団的に屈辱を受けたとき攻撃的に反応するかもしれない[1]。 ジュディス・グリフィスが6歳から9歳を対象に行った研究では、これらの子どもたちのイングループとアウトグループは、集団間攻撃性という点では他の既知 の集団的自己愛性集団と比較的同じ機能をもっていることが示された。研究では、一般的に子どもは周囲のアウトグループよりも自分のイングループに対して有 意に高い評価を持ち、そのようなイングループは周囲のアウトグループに対して間接的または直接的に攻撃性を示すことが指摘された[30]。 |

| Ethnocentrism Collective narcissism and ethnocentrism are closely related; they can be positively correlated and often shown to be coexistent, but they are independent in that either can exist without the presence of the other.[3] In a study conducted by Boris Bizumic, some ethnocentrism was shown to be an expression of group-level narcissism.[3] It was noted, however, that not all manifestations of ethnocentrism are narcissistically based, and conversely, not all cases of group-level narcissism are by any means ethnocentric.[3] It has been suggested that ethnocentrism – when pertaining to discrimination or aggression based on the self-love of one's group; or, in other words, based on exclusion from one's self-perceived superior group – is an expression of collective narcissism.[1] In this sense, it might be said that collective narcissism overlaps with ethnocentrism, depending on given definitions and the breadth of their acceptance. |

エスノセントリズム 集団的ナルシシズムとエスノセントリズムは密接に関連しており、正の相関を持ち、しばしば共存することが示されるが、どちらかが他方の存在なしに存在する ことができるという点で独立したものである[3]。 [3] ボリス・ビズミックが行った研究では、一部のエスノセントリズムは集団レベルのナルシシズムの表現であることが示された[3]。しかし、エスノセントリズ ムのすべての発現がナルシシズムに基づいているわけではなく、逆に集団レベルのナルシシズムのすべてのケースが決してエスノセントリックではないことが言 及された[3]。 エスノセントリズムとは、自分の集団に対する自己愛に基づく差別や攻撃、言い換えれば、自分が優位と考える集団からの排除に基づく差別や攻撃であり、集団 的ナルシシズムの表れであると指摘されている。その意味で、集団的ナルシシズムは、与えられた定義とその受容の幅によっては、エスノセントリズムと重なる と言えるかもしれない。 |

| In the world In general, collective narcissism is most strongly manifested in groups that are "self-relevant", like religions, nationality, or ethnicity.[21] As discussed earlier, phenomena such as national identity (nationality) and Nazi Germany (ethnicity and nationality) are manifestations of collective narcissism among groups that critically define the people who belong to them. In addition to this, a group's extant collective narcissism is likely to be exacerbated during conflict and aggression.[1] And in terms of cultural effects, cultures that place an emphasis on the individual are apparently more likely to see manifestations of perceived individual greatness projected onto social ingroups within that culture.[1] And finally, narcissistic groups are not restricted to any one homogenous composition of collective or individually collective or individual narcissists.[3] A quote from Hitler almost ideally sums the actual nature of collective narcissism as it is realistically manifested, and might be found reminiscent of almost every idea presented here: "My group is better and more important than other groups, but still is not worthy of me".[3] Although, this is inconsistent with the interpretation given to collective narcissism by Golec de Zavala and colleagues. Those authors suggest collective narcissists invest their vulnerable self-worth in the exaggerated image of their group and therefore cannot distance themselves from the group through which they achieve self-importance[11][14] |

世界において 一般的に集団的ナルシシズムは宗教、国籍、民族のような「自己関連性」を持つ集団において最も強く現れる[21]。先に述べたように、ナショナルアイデン ティティ(国籍)やナチスドイツ(民族・国籍)などの現象は、そこに属する人々を批判的に定義する集団における集団的ナルシシズムの現れであるといえるで しょう。 また、文化的な影響として、個人を重視する文化では、個人の偉大さがその文化内の社会集団に投影されることが多いようである[1]。 [そして最後に、ナルシスト集団は集団的または個人的なナルシストの均質な構成に制限されない[3] ヒトラーの引用は現実的に現れる集団的ナルシズムの実際の性質をほぼ理想的に要約しており、ここで紹介するほぼすべてのアイデアを連想させることが分かる かもしれない。「自分の集団は他の集団よりも優れていて重要だが、それでも自分にはふさわしくない」[3]。しかし、これはゴーレック・デ・ザヴァラらが 集団的ナルシシズムに与えた解釈と矛盾している。それらの著者は集団的ナルシストが自分の脆弱な自己価値を自分たちの集団の誇張されたイメージに投資し、 それゆえ彼らが自己重要性を獲得する集団から距離を置くことができないことを示唆した[11][14]。 |

| American exceptionalism Cabal Clique Collectivism and individualism Cronyism Cult Elitism Exceptionalism Emotional contagion Gang Gender narcissism Group dynamics Group emotion Groupthink Hubris and group pride Marking your own homework Mobbing Narcissism of small differences Nepotism Old boy network Peer pressure Social group Social identity approach Social projection Supremacism |

アメリカ例外主義 陰謀団 派閥 集団主義と個人主義 縁故主義 カルト エリート主義 例外主義 感情の伝染 ギャング 性差ナルシシズム 集団力学 集団感情 集団思考 傲慢と集団的誇り 自己採点 集団いじめ 些細な差異のナルシシズム 縁故主義 オールドボーイネットワーク 仲間からの圧力 社会的集団 社会的アイデンティティ理論 社会的投影 優越主義 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Collective_narcissism |

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1997-2099

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099