Lepers,

Nation-State, and Empress Dowager:

A Prolegomena to medical anthropology of bio-power governmentality

Mitsuho Ikeda and Hideaki Matsuoka,

Osaka University, Tokyo Medical and Dental University

After the Meiji Restoration in 1863, the Japanese modern state had started as constitutional monarchy with absolute power of the emperor. Under new constitution of 1947, the emperorship has turned from absolute monarchy to symbol of “the unity of the nation.”

This paper

examines the cultural and historical meaning of a“leprosy Tanka poet,”

Lai-Kajin, who was named as

Kaijin AKASHI (1901-1939). He had

participated in the nation-wide Tanka

creating movement represented in

series of books entitled “Shin-Manyō-Shu,”

published from 1937 to 1939.

The Tanka is artistic oral poem form in thirty-one syllables.

There was

nationwide social discrimination against leprosy (Hansen’s disease)

patients and their families. Under the colonial rules, there also was

empire-wide discrimination between people of Naichi, inner territory,

and Gaichi, from colonial

territories. The Japanese official language

policy had ambiguous aspects, e.g. there were coercive assimilation for

Japanization, Kōminka, and

also tolerance of bilingualism for colonized

people as second-class citizens. The oxymoronic Tanka movement might

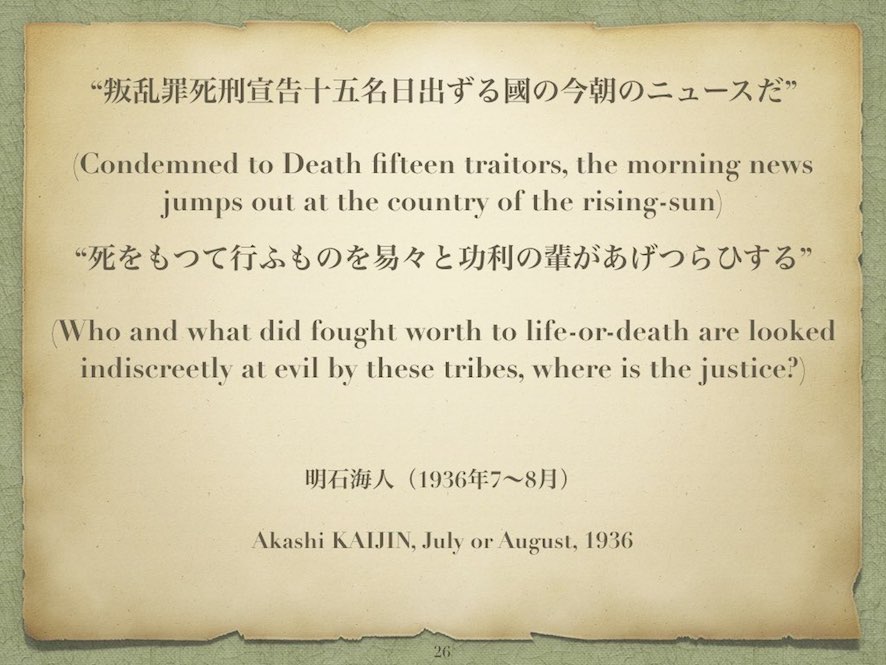

idealistically unify between these two categorical peoples and create

one national subject of the Empire of Japan through not romantically,

but existentialistically, poetic activities.

The Japanese

public health system had started as medical police (G:

Medizinischepolizei) and then has transformed as “national” public

health system for both militaristic conscription and maternal-children

health for “national” population growth policy. In this context the

public health for leprosy patients, had two sides of the same coin; (1)

paternalism in concentrated communities and (2) discriminative

“protection” expelled from public space, under the light of benevolence

of the Empress, later Dowager, TEIMEI (1884-1951). The absolute

segregation policy, the “No leprosy movement in each prefecture,”

Murai-Ken-Undō (1930s-1960s),

and “Search, intake, and segregation in

concentration communities,” Shūyō-Seisaku,

has continued until 1960s.

The legislation of forced “accommodation” has continued until 1996.

We also propose the interdisciplinary and inter-citizens studies on the relations between Hansen’s disease patients and the building of nation states in Asian countries; that means our long-range objective for the “Beyond Korea, beyond Japan, and beyond Anthropology.”

|

1 Lepers, Nation-State, and Empress Dowager: A Prolegomena to medical anthropology of bio-power governmentality Mitsuho Ikeda* and Hideaki Matsuoka** *Osaka University, **Tokyo Medical and Dental University *Corresponding author; tiocaima7n[at]gmail.com |

|

2 Korean folklore tradition on Leprosy |

|

3 Today's story line is mentioned below... |

|

4 Now let us cite the word “leprosy” from the Oxford English Dictionary, OED. The word came from medieval Latin, leprōsia. The first definition of leprosy is, “An infectious bacterial disease which slowly eats away the body, and forms shining white scales on the skin; common in mediaeval Europe.” We know that the word of “leper” has a bit of pejorative meaning of leprosy, as the OED says, a kind of slang abbreviated. We might use leper as a translation of Lai or Lai-Byō in Japanese with pejorative sense maintaining its severe discrimination against leprosy patients even now. This illness label has been changed to “Mr. Hansen’s disease” (Hansen-Shi-byō) later “Hansen’s disease” (Hansen-Byō) after 1970s. This is our tradition in which professionals publicly propose government to change from these kinds of pejorative words to the alternatives, but people know that this superficial politically correctness policy had been failed even though these pejorative words has not been disappeared and even though these maintained in our sentiments. In case of treating with strong social discriminatory terms, it is needless to say that we might keep these vocabularies orienting into certain social contexts. |

|

5 We have four objectives of this presentation; (I) To depict a history of leprosy patients as subjects under the Empire’s overwhelming bio-power, (II) Portraying equally significant poets and protagonists of three persons; Leper poet AKASHI Kaijin, Empress Dowager TEIMEI, and eldest Japanese-Korean Leper poet KIM Ha-il. And, (III) Characterizing the conjuncture and the articulation between literary art form and bio-politic, that made idealistically “Subject-Nation-Citizen” as a social illusion in all the territories of the Empire, and lastly we ask the question; (IV) Could illness sufferers become to be empire’s troubadour finally? Or Can subaltern-leper poet can narrate? |

|

6 |

|

7 After the Meiji Restoration in 1868, the Japanese modern state had started as constitutional monarchy with absolute power by the emperor [Meiji Constitution, proclamation in 1889, enacted in 1890]. Under new constitution of 1947, the emperorship has turned from absolute monarchy to political symbol of “the unity of the nation” until present time. The Japanese public health system had started as medical police (G: Johann Peter Frank’ term medizinischen Polizei) and then has transformed as “national” public health system for both military conscription and maternal-children health relating with “national” population growth policy. |

|

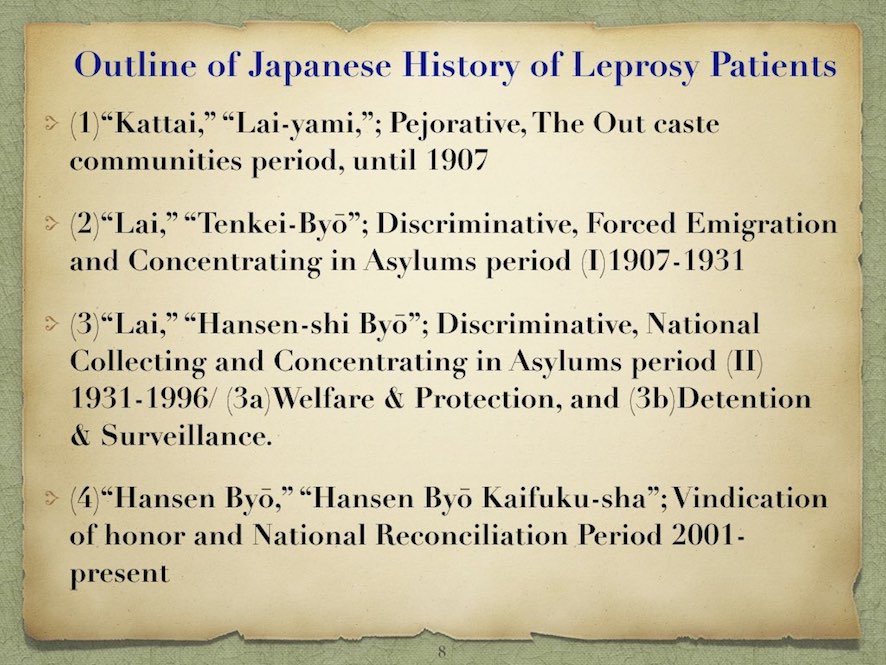

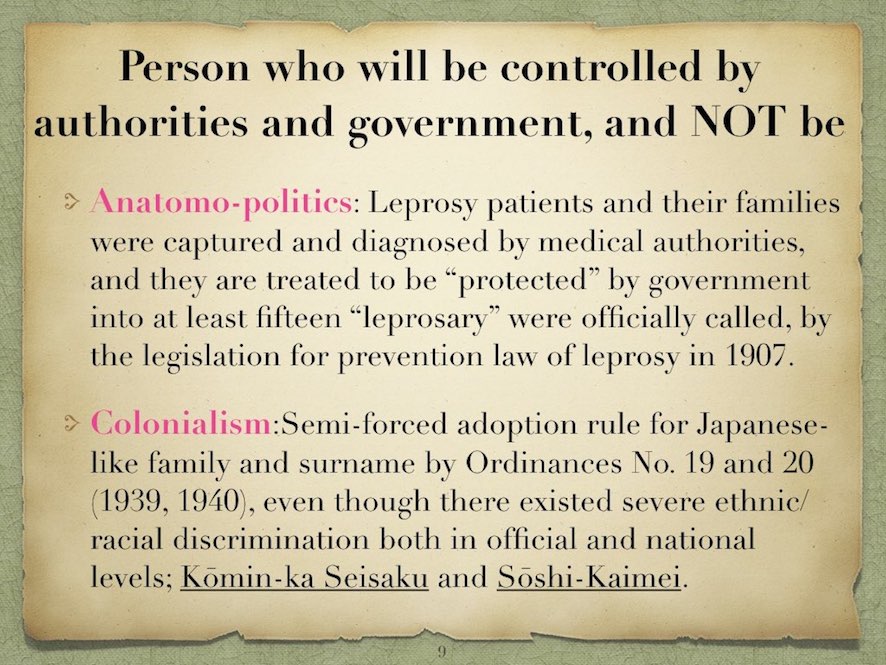

8 Let us depict a short history of leprosy patients as subjects under the Empire’s overwhelming bio-power. We just present brief history of how to be treated with leprosy patients. We can summarize four periods with disease nominations mentioned as follow. (1) “Kattai,” “Lai-yami,”; strong Pejorative, The period of outcaste communities, until 1907. (2) “Lai,” “Tenkei-Byō”; both Pejorative and Discriminative, Forced Emigration and Concentrating in Leprosaria period, 1907-1931. (3) “Lai,” “Hansen-shi Byō”; Discriminative, National policy of Collecting and Concentrating in Leprosaria period, 1931-1996. In this period the leprosy had been strongly medicalized by Japanese system of the medizinischen Polizei. In this context the public health policies for leprosy patients, had two sides of the same coin; on one side, (3-a) Welfare & Protection; under the paternalism in concentrated communities, “leprosariums” and, the other side, (3-b) Detention & Surveillance; they suffered from tenacious discriminative “protection” expelled from any kind of public space, under the light of benevolence agency, especially the Empress, later Dowager, TEIMEI. The absolute segregation policy, the “No leprosy movement in each prefecture,” Murai-Ken-Undō (1930s-1960s), and “Search, intake, and segregation in concentration communities,” Shūyō-Seisaku, has continued until 1960s. The legislation of forced “accommodation” has continued until 1996. (4) “Hansen Byō,” “Hansen Byō Kaifuku-sha”; the time of the Vindication of honor and National Reconciliation Period from 2001 to present. In the regime under the Japanese Empire’s bio-power domination, there existed the strict distinction between majorities and minorities, subjects of the mainland Japan and of the outside territories, normal and insane, and lastly non-infectious people and infectious people including the person who are suspected the infection with the bacteria. As following various legislation processes from 1906 to 1996 the leprosy patients and their families were captured and diagnosed by medical authorities, and they are treated to be “protected” by government into at least fifteen asylums (or leprosaria) in Japan and more in abroad colonies, “Leprosy, later Hansen’s disease sanatoriums,” (Hansen-Byō Ryōyō-sho) were officially called. |

|

9 Talking on assimilation for colonized people, the colonial government-general’s policy have two characteristics; inclusion and exclusion. For example, in Korean peninsula, we should remind that the semi-forced adoption rules for Japanese-like family and surname by the Ordinances No. 19 and 20 (1939, 1940). Sōshi-Kaimei, were administered by the colonial government-general even though there existed severe ethnic/racial discrimination both in official and ordinal levels; the “Policy for making Japanese subjects under the Emperor’s regime,”(Kōmin-ka Seisaku). On the one hand the colonial government excluded the minorities and patients from public space. And the government included all the useful person who could contribute the imperial pretext of bringing peace and prosperity to the “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” on the other. |

|

10 Now let us portraying three significant poets and protagonists; Leper poet AKASHI Kaijin, Empress Dowager TEIMEI, and eldest Japanese-Korean Leper poet KIM Ha-il. |

|

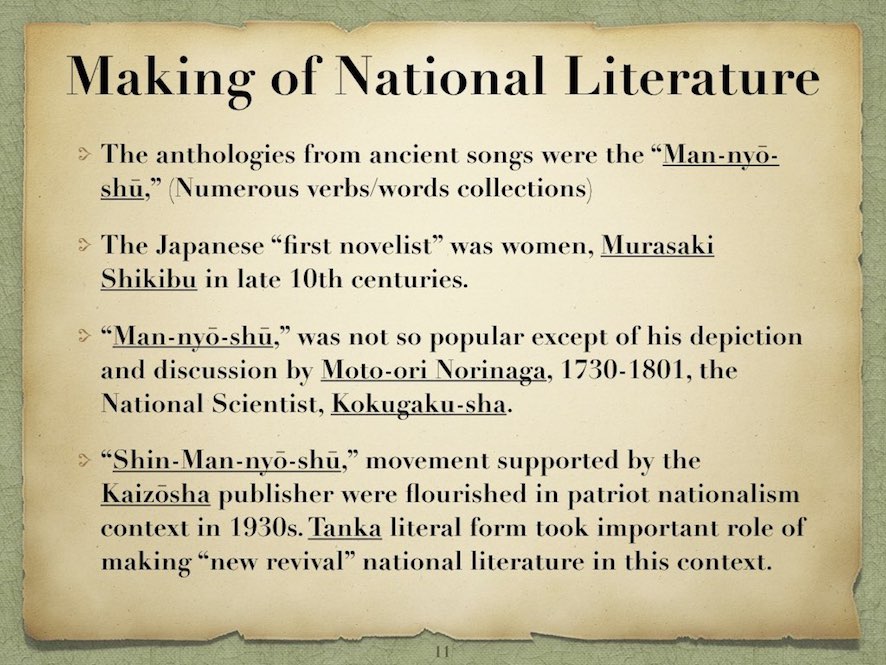

11 Now let us portraying three significant poets and protagonists; Leper poet AKASHI Kaijin, Empress Dowager TEIMEI, and eldest Japanese-Korean Leper poet KIM Ha-il. In late 1930s many Japanese were fascinated with national literature movement, for example making Tanka. The Tanka is traditional and artistic oral poem form in thirty-one syllables. The most ancient anthology of poetic songs of about over 4,500 poems by various kinds of people was called as the “Man-nyō-shū,” (lit. Collections of numerous verbs/words) from the late seventh century to late eighth century established hypothetically at least in 759. In modern times the Japanese intellectuals believed that the concept of Japanese nation had established at 12th and 16th century, but this is just from their retrospective imaginations or fantasies. After establish of this national discourse, they (public intellectuals in colonial time) intended the time of established Japan to redirect upstream to the Man-nyō-shū period, around eighth century. They said that all “the various kinds of people,” e.g. from peasants, vulgar folks, warriors to nobles, emperors or empresses were the same, all folks had participated in literary art work of making poems, the Man-nyō-shū, especially was represented as Tankas. They succeeded to made/fashion our “imagined community,” in Ben Anderson’s sense (1). After a thousand and hundred years later, the editing of the new project had been started to edit for the “Shin-Man-nyō-shū,” new version of the “Man-nyō-shū,” finally included in 26,783 poems by 6,675 authors. This was another revival movement which had evoked nationally “authentic Japanese spirits,” at that time new legislation for the National Mobilization Law, “Kokka Sōdōin Hō,” under the totalitarian regime in March 1938. (1) But the reality is not. “Man-nyō-shū,” was not so popular except of his depiction and discussion by Norinaga MOTO-ORI (1730-1801), a most famous National Scientist, Kokugaku-sha in the Edo period (1603-1868). Even though this is only a national myth, but nowadays we need to take courage in speaking the fact in public. |

|

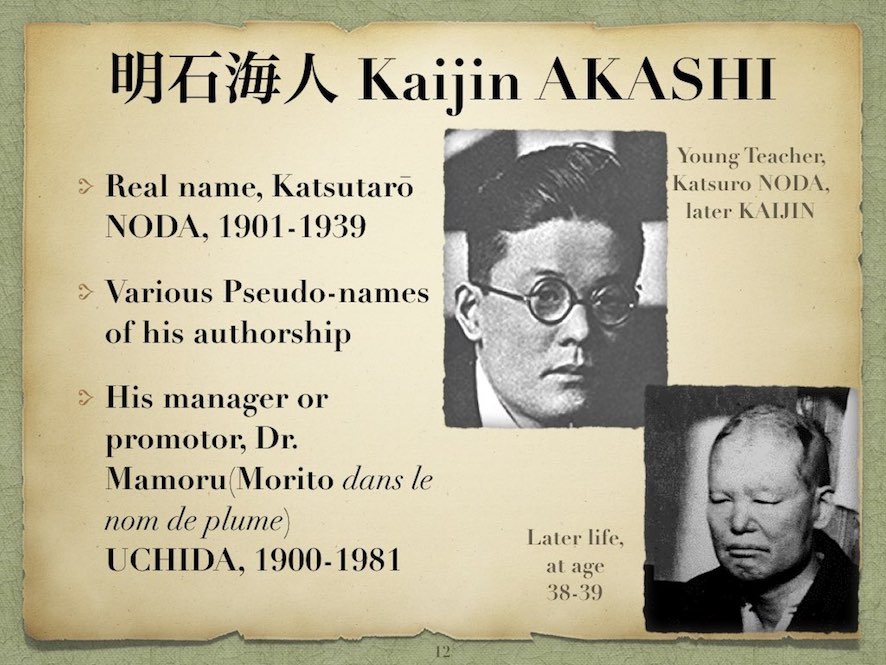

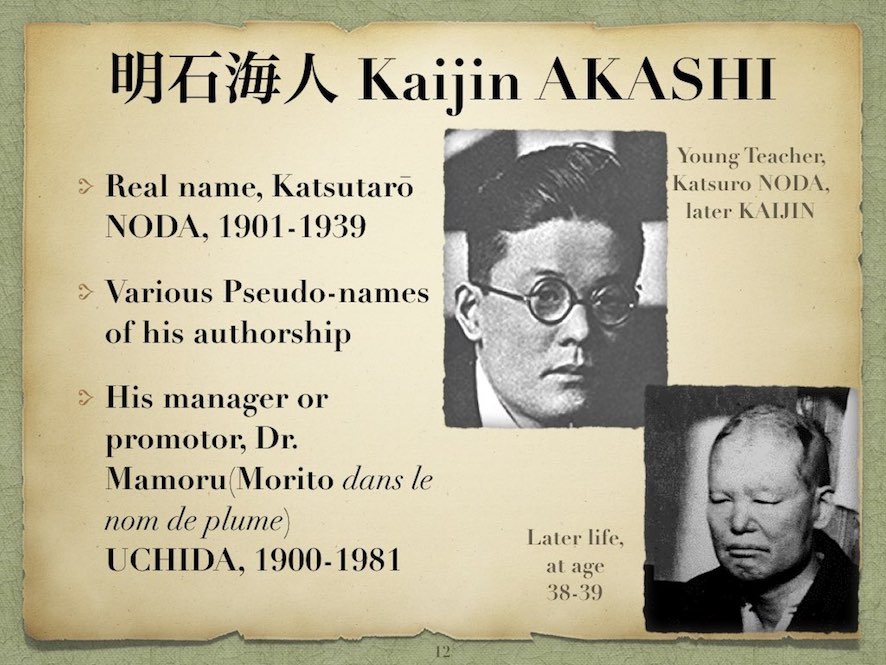

12 When the first volume of Shin-Man-nyō-shū had been published from January 1938, eleven poems of Kaijin AKASHI were collected in this volume according Japanese alphabetical order A-I-U-E-O of authors names. This was the first incident of the discover of Lai-Kajin, leprosy poet, among Japanese outside leprosarium. His real name was NODA Katsutarō, 1901-1939 with had had various pseudo-names of his authorship. His real name has not been known in public until 1980 or later. Almost of the artists in leprosaria had pseudo-names because they wanted to be free from social discrimination by accounting with their identities and their families. Kaijin had a good fellow who was also his doctor in charge. His name is Dr. Uchida Mamoru, one year younger. |

|

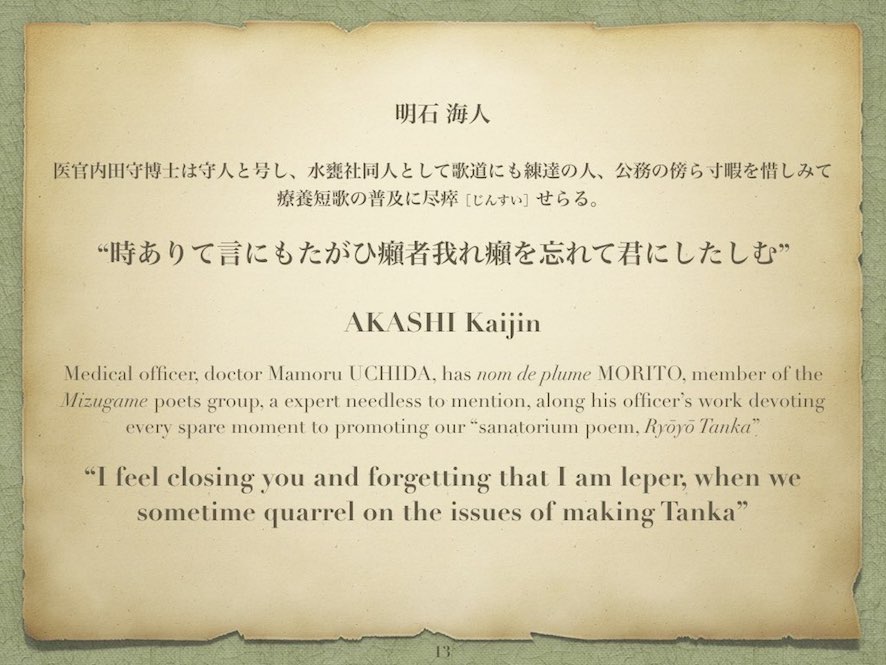

13 In Kaijin’s best seller book, entitled “Hakubō,” (lit. sketch with black carbon lines), there appears his anthem for “Morito” Uchida, also innocent pen name (nom de plume), referring our presentation slide #13. |

|

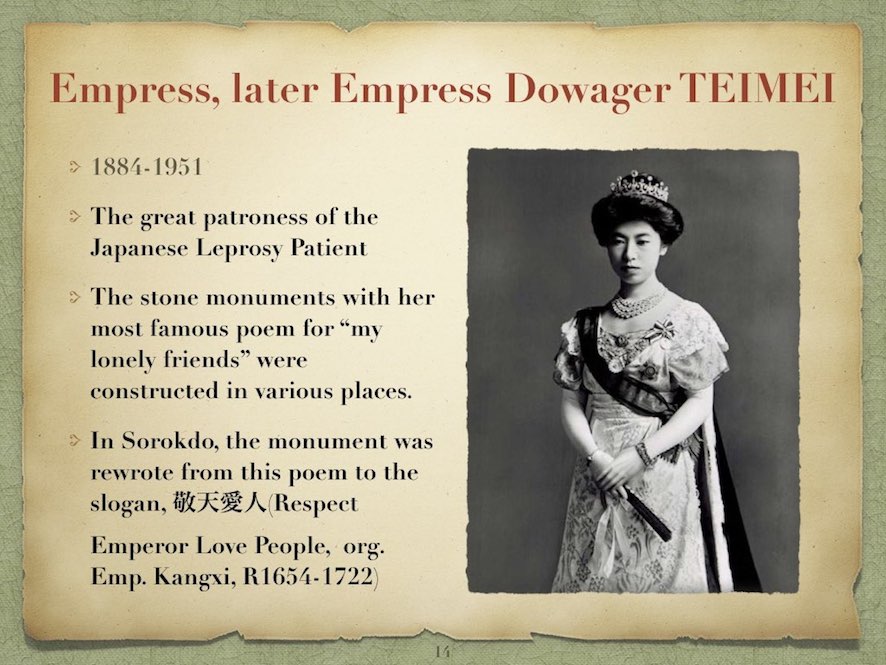

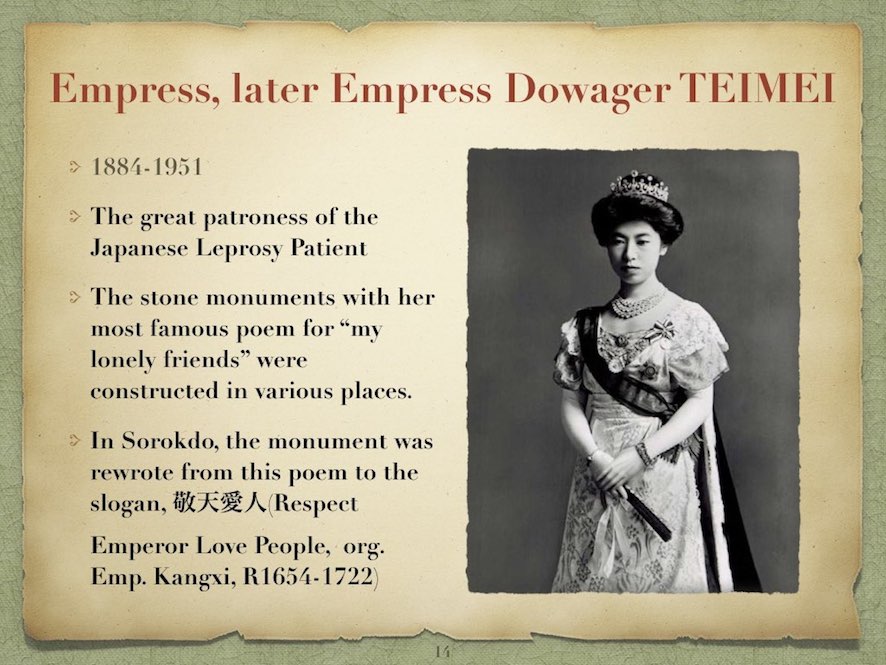

14 In next we will introduce Empress, later Empress Dowager TEIMEI Setsuko, 1884-1951. She was the great patroness for the Japanese Leprosy Patients in modern history (2). The stone monuments with her most famous poem for “my lonely friends” were constructed in various places, with explaining short prose, “for comforting leprosy patients,” poem says, “Instead of me, please go comfort my lonely friends. " (#14, and also #15) . (2) Empress Kōmyō, 701-760, was the most famous empress who had promoted to build the Hiden-In (Welfare facility) for poor and miserable people and the Seyaku-In (Herbarium) for patients, and also who had the legend that after she had sacked pus from a leprosy patient, the patient have metamorphosed to the Akshobhya, a Buddhist deity. Even now her legend is very influential, that is the reason why the naming of the National Sanatorium Oku- Kōmyō -En, in Okayama, Japan, was. |

|

15 (Repeat) In next we will introduce Empress, later Empress Dowager TEIMEI Setsuko, 1884-1951. She was the great patroness for the Japanese Leprosy Patients in modern history . The stone monuments with her most famous poem for “my lonely friends” were constructed in various places, with explaining short prose, “for comforting leprosy patients,” poem says, “Instead of me, please go comfort my lonely friends. " (#14, and also #15) . (3) (3) Even though she was a naïve or innocent empress, but one of the stone monument with the same poem in the Sorokdo island, Jeollanam-do, South Korea, was stripped and rewrote as Kei-Ten-Ai-Jin (lit. Respect Sovereign and Love People) after the Korean national liberation August 15,1945 |

|

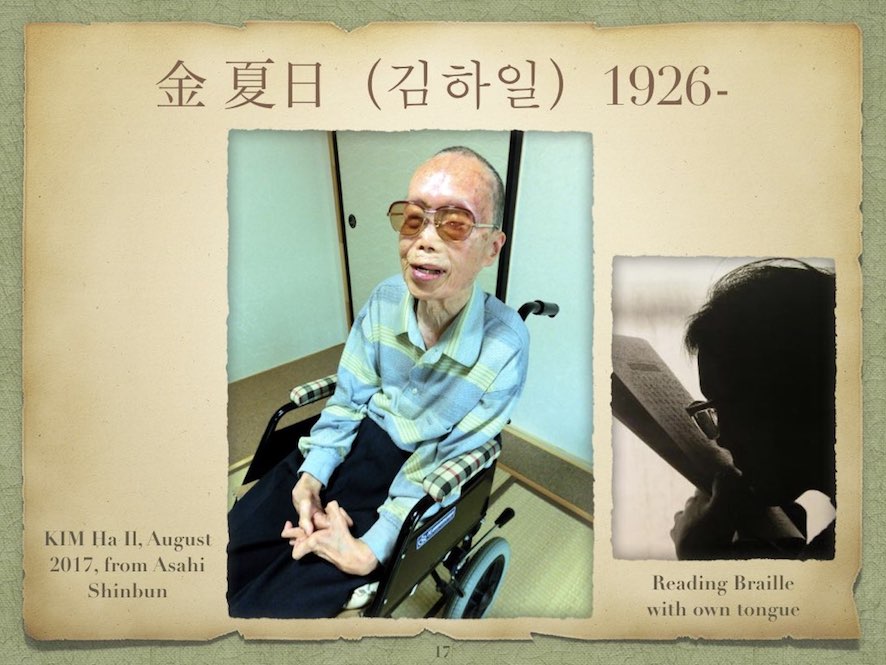

16 And now we are introducing the poet is a Japanese-Korean Ex-Leprosy Tanka Poets, who are called as “KIM Ha-il,” born in 1926. We can say that he is the testimony in-between Hansen’s disease patient in leprosarium and colonized discriminative racism even in postcolonial time including the present. Through reading his poems we can ask if we still in colonial time between Korea and Japan or in postcolonial period when our relationship has drastically change after 1945. His double identities were labelled both as Zainichi-Kajin (Japanese-Korean poet) and Hansen-Byō-Kajin (Leprosy poet). |

|

17 In present time it seems that there exists a backrush to imperial history among a part of Japanese. We call them this shameless racists, “Heito-no-hito-tachi,” (people who hate foreigners without modesty) (4). The Japanese liberal minded anthropologists have feeling of troublesome by the people with hate speech against Koreans. In actual many Japanese-Koreans have adopted Japanese names because of free from racial/ethnic discrimination for long time. So the nominal Korean identities are hidden. (4) They are emerging with visible neo-Nazi like costume from mid-2000s, most famous example is the Zai-Toku-Kai, (orig. lit., Association of Citizens against the Special Privileges of the Zainichi) against both Japanese-Korean and Korean-in-Japan, the Zainichi-Korean. |

|

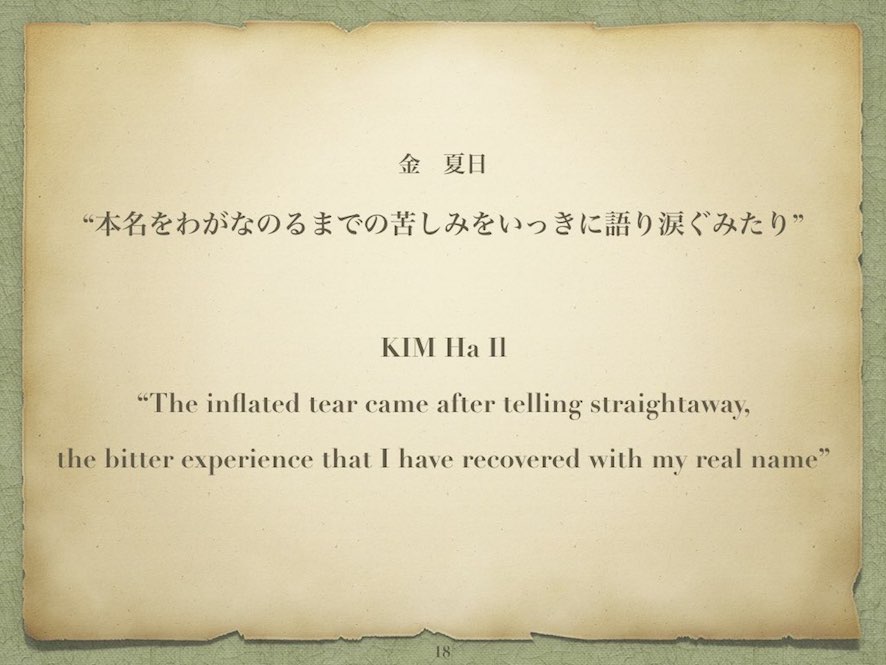

18 One of poems relating KIM’s own bitter experience camouflaging with using Japanese-like pseudo name is today presented in slide #18(“The inflated tear came after telling straightaway, the bitter experience that I have recovered my real name” )(5). This is the second inquiry asking if we are able to be free of the “concept of culture”, that means one nation strictly might assign with one culture. We can paraphrase this inquiry as following next, “Can we, anthropologists and their collaborators, become to be post-colonial trans-nationalities?” (5) Nominating themselves by their own names or alias is very important agenda in our paper. Remind Sōshi-Kaimei, semi-forced adoption rules for Japanese-like family and surname by the Ordinances No. 19 and 20 (1939, 1940) of the colonial government-general in the pollical current on the “Policy for making Japanese subjects under the Emperor’s regime,”(Kōmin-ka Seisaku). After the Korean Independence, the racism against Korean people in Japan have come back. So many Korean people use her/his alias in front of Japanese or Japanese-like audience to avoid from racial discrimination as alternative option beside of real name usage. The continuing usage of alias or disclosure of her/his real name is still big issue for Korean-Japanese or Korean in Japan who have rights of the Special Permanent Residency in Japan, Tokubetsu-Eijū-Ken. To compare with usage of alias of leprosarium residents, it is very similar condition that we can observe. But leprosarium residents use alias because of rebirth of their identities in closed leprosarium environment. They want to use alias for obscuring their own identities not to disclose through communication with outside world. Both leper poet and non-leper poet use pen name (nom de plume) according historical tradition of making Tanka. By these reasons there are complicated alias usages by leper-poets in Japan. |

|

19 Now we are going to characterize the conjuncture and the articulation between literary arts form and bio-politics, that made idealistically “Subject-Nation-Citizen” as a social illusion in all the territories of the Empire. Our hypothesis is to say that the empire and her nation had been building citizenship through the promoting for empire-wide literal movement of making Tanka. We think that making Tanka had been very important role to foster Japanese subject of “our emperor” at least before end of the imperial power structure. Let us scrutinize how to become idealistically a Japanese “Subject-Nation-Citizen.” First was to respect for “our emperor,” the symbol of absolute power. There was not social contract but obedience without thinking. We can see Japanese imperial subjects under the “protection” by the emperor with absolute governor; For example, the Constitution of the Empire of Japan, C.E.J., says, “Japanese subjects may present petitions, by observing the proper forms of respect, and by complying with the rules specially provided for the same.” Article 30.C.E.J. |

|

20 In this context, even though the successes of military occupation later colonial dominations by the civilians, the Japanese imperialists had failed to assimilation policy including abroad subjects. Under the colonial rules, there also was empire-wide discrimination between people of Naichi, inner territory, and of Gaichi, from colonial territories (6). The Japanese official language policy had ambiguous aspects, e.g. there were coercive assimilation for Japanization, Kōminka, and also tolerance for usage of mother tongue or bilingualism or toward the colonized people as second-class citizens treated. We repeat again that under the national movement of making Tanka as citizens’ ordinary ritual, “every” subject could become a member of the empire as imagined community. Many soldiers enrolled from both inner territory and colonial territories, and even Kamikaze fighters also composed farewell Tanka poem in end of the Pacific War (1944-1945). For the people of colonized territories composing Tanka could explore the horizon where any kind of discriminations might be disappeared not eternally but fleetingly, not actually but virtually. This type of contradictory Tanka movement might idealistically unify between these two categorical peoples and create one national subject of the Empire of Japan through not romantically, but existentialistically, poetic activities like AKASHI Kaijin. (6) The Japanese Empire government used to say the nation as an innocent child of the emperor, Ten-nō no Sekishi. But this slogan had encountered with the contradiction between racial pedigree of inner territory (Naichi) and forced-occupied colonial citizen of foreign territory (Gaichi). |

|

21 Tanka in making process is also the communicative vehicle, good to think, feel, and criticize. Tanka in reading process can also be explored horizon where any kind of social sphere might be in their actuality. Non-leprosy patrons including medical doctors, celebrate authors, and literary professionals, did also compose Tanka. They said that the leprosy patient’s making Tanka activities were categorized as “Leper literary or Leper Genre,” (Lai Bungaku/Bungei). Now we can discuss their Liberation from what? The raison d’être of this genre, leper literary or leper genre, has been always contested as representing antagonistic two attitudes; On one hand, “Yes,” Pros, there cannot divide between their experience and their opera, Lai-Bungaku, leprosy literature really exists. On the other hand, “No,” Cons, making and maintaining this genre should be real representation and reproduction for the reaffirmation of social discrimination. |

|

22 They think that a genuine literature, Jun-Bungaku exists, there is no difference between Lai-Bungaku and J Jun-Bungaku because the both would be included in literal activity a whole. We now confront the third inquiry as following question; Do the cultural anthropologist depict only the works that he/she is academically or topically interested in or not? The anthro-tribes sometimes tend not to see the artist’s ontological issue in historical context but to see what they want to see are, tribes-themselves per se. Our answer will be mentioned after the presenting of last episode between AKASHI Kajin and his editor MAEKAWA Samio. |

|

23 The trouble incident had occurred in September 1936. |

|

24 |

|

25 The trouble incident had occurred in September 1936. Kaijin had heard the news that had noticed the execution by death for fifteen young traitors by the military court authority in July 12,1936. They had attempted coup d’état in Empire of Japan on February 26 the same year. Kaijin subscribed two poems criticizing court authority for at “Nihon-Kajin” magazine organized by Samio MAEKAWA, who was one of famous propagandistic poets of the nationalism. Maekawa was willing to accept two poems by his national ideology. Kaijin’s two poems say, the first; “Condemned to Death fifteen traitors, the morning news jumps out at the country of the rising-sun,” and the second, “Who and what did fought worth to life-or-death are looked indiscreetly at evil by these tribes, where is the justice?” But finally the magazine had banned to publish by the military authority. Kaijin wrote apologizing to MAEKAWA that he was worth to be sacrificed because he was a “wretched cripple”(Hai-jin) as leaper. But Leper Kaijin could not be become a scapegoat instead of chief editor, MAEKAWA. |

|

26 (repeat) The trouble incident had occurred in September 1936. Kaijin had heard the news that had noticed the execution by death for fifteen young traitors by the military court authority in July 12,1936. They had attempted coup d’état in Empire of Japan on February 26 the same year. Kaijin subscribed two poems criticizing court authority for at “Nihon-Kajin” magazine organized by Samio MAEKAWA, who was one of famous propagandistic poets of the nationalism. Maekawa was willing to accept two poems by his national ideology. Kaijin’s two poems say, the first; “Condemned to Death fifteen traitors, the morning news jumps out at the country of the rising-sun,” and the second, “Who and what did fought worth to life-or-death are looked indiscreetly at evil by these tribes, where is the justice?” But finally the magazine had banned to publish by the military authority. Kaijin wrote apologizing to MAEKAWA that he was worth to be sacrificed because he was a “wretched cripple”(Hai-jin) as leaper. But Leper Kaijin could not be become a scapegoat instead of chief editor, MAEKAWA. |

|

27 (repeat) The trouble incident had occurred in September 1936. Kaijin had heard the news that had noticed the execution by death for fifteen young traitors by the military court authority in July 12,1936. They had attempted coup d’état in Empire of Japan on February 26 the same year. Kaijin subscribed two poems criticizing court authority for at “Nihon-Kajin” magazine organized by Samio MAEKAWA, who was one of famous propagandistic poets of the nationalism. Maekawa was willing to accept two poems by his national ideology. Kaijin’s two poems say, the first; “Condemned to Death fifteen traitors, the morning news jumps out at the country of the rising-sun,” and the second, “Who and what did fought worth to life-or-death are looked indiscreetly at evil by these tribes, where is the justice?” But finally the magazine had banned to publish by the military authority. Kaijin wrote apologizing to MAEKAWA that he was worth to be sacrificed because he was a “wretched cripple”(Hai-jin) as leaper. But Leper Kaijin could not be become a scapegoat instead of chief editor, MAEKAWA. |

|

28 Now the time we conclude that the lepers could neither become to be empire’s healers nor to be comrades. In the leprosarium they have been continued to be still objects like still-life under the gaze of “paternalism wrapped in humanism” until 2001 (Ikeda 2010). After that time they still have been struggling with the court battle for their families’ restoration of symbolic repatriation against social discrimination; the struggle against their negative public memories. We can still remind or déjà vu the message of Spivak’s paper, “Can the Subaltern Speak?” even though we are able to hear their talks (of the ex-patients of leprosy) in the fellowship meetings nowadays. We can paraphrase this question as “Can the subaltern-leper poet narrate instead of our voice?” (7) (7) Even though I, especially one of authors, Ikeda myself, speak ultra-broken English, I never have been frustrated with usage of my non-mother tongue. I remind one episode narrating in YouTube by Slovenian Philosopher Slavoj Žižek that I heard about one year ago. He said that his friends of the Indian outcast the Dalit had abandoned their own language and culture because that their language and culture was always visible maker of racial discrimination. Is this abnormal or crazy choice of abandoning their own cultural heritage? My answer anthropologically is “no,” because our unwillingness to say “no” comes from the premise in which we think that any people should have rights of own culture and language. This is a wrong fetishism ideology on culture and language that brings us to back to before age of enlightenment, back to before of the age of the Port-Royal Grammar. In this case the most important issue is not to conserve to the Dalit culture but to liberate now the people from racial discrimination even though abandoning their own culture. In similar I want to liberate myself to discuss with our Korean colleagues or comrades on this argument. I do not mind not to speak Korean or Japanese for pursuing our common agenda. |

|

29 We have started our research project in less than a year, but we have discovered many pitfalls that was covered and camouflaged by paternalism wrapped in humanism. We have comprehended that we need more the cooperation on the relations between Hansen’s disease ex-patients and medical anthropologists in Asian countries; that means our message for long-range objective for the main title of the 60th anniversaries of the Korean Society of Cultural Anthropology, “Beyond Korea, [we would like to add] beyond Japan, and beyond Anthropology.” (Repeat) (7) Even though I, especially one of authors, Ikeda myself, speak ultra-broken English, I never have been frustrated with usage of my non-mother tongue. I remind one episode narrating in YouTube by Slovenian Philosopher Slavoj Žižek that I heard about one year ago. He said that his friends of the Indian outcast the Dalit had abandoned their own language and culture because that their language and culture was always visible maker of racial discrimination. Is this abnormal or crazy choice of abandoning their own cultural heritage? My answer anthropologically is “no,” because our unwillingness to say “no” comes from the premise in which we think that any people should have rights of own culture and language. This is a wrong fetishism ideology on culture and language that brings us to back to before age of enlightenment, back to before of the age of the Port-Royal Grammar. In this case the most important issue is not to conserve to the Dalit culture but to liberate now the people from racial discrimination even though abandoning their own culture. In similar I want to liberate myself to discuss with our Korean colleagues or comrades on this argument. I do not mind not to speak Korean or Japanese for pursuing our common agenda. In this case, the Dalit people can cut the connection between racism against them and their own language as liberation from discrimination in general. Refer to Jean-Paul Sartre's attitude before the emergence of Negritude movement. |

Credit

Link

Bibliography

Other informations

Máscara coreano para danza folklorica que se representa el paciente con lepra, Collection of the National Museum of Etnnology, Suita, Japan

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099