先住民社会におけるジェンダーギャップ

gender gap in indigenous society

☆先

住民社会におけるジェンダー格差は、植民地時代の影響に起因しており、女性がしばしば権力を握っていた伝統的な役割を崩壊させ、経済的不安、権利剥奪、脆

弱性の増大につながっている。不平等な賃金(例えば、オーストラリアではファーストネーションの女性は35%低い)、意思決定の制限、健康へのアクセスの

悪さ、無償の介護の不釣り合いな負担などがその顕著な例である。

| The gender gap in

indigenous societies stems from colonial impacts, disrupting

traditional roles where women often held power, leading to economic

insecurity, disenfranchisement, and increased vulnerability, marked by

unequal pay (e.g., 35% less for First Nations women in Australia),

limited decision-making, poor health access, and disproportionate

burdens of unpaid care, even as efforts to integrate gender

perspectives aim to restore equity and address these multifaceted

challenges. |

先住民社会におけるジェンダー格差は、植民地時代の影響に起因してお

り、女性がしばしば権力を握っていた伝統的な役割を崩壊させ、経済的不安、権利剥奪、脆弱性の増大につながっている。不平等な賃金(例えば、オーストラリ

アではファーストネーションの女性は35%低い)、意思決定の制限、健康へのアクセスの悪さ、無償の介護の不釣り合いな負担などがその顕著な例である。 |

| Key Aspects of the Gender Gap: |

ジェンダーギャップの主な側面: |

| Economic Disparity: Loss of traditional land rights and introduction of private property has dispossessed women, making them more susceptible to poverty and exploitation, facing significant pay gaps (like the 35% gap in Australia). | 経済格差:

伝統的な土地の権利を失い、私有財産が導入されたことで、女性は土地を奪われ、貧困や搾取を受けやすくなり、著しい賃金格差(オーストラリアでは35%の

格差がある)に直面している。 |

| Loss of Traditional Power: Colonialism eroded traditional systems where women's roles in resource management and home economies were respected, shifting power dynamics. | 伝統的権力の喪失:

植民地主義は、資源管理や家庭経済における女性の役割が尊重される伝統的なシステムを侵食し、パワー・ダイナミクスを変化させた。 |

| Care Burden: Indigenous women

carry heavier unpaid care responsibilities (children, elders), often

compounded by racism and lack of support, impacting their economic

participation. |

介護負担:

先住民女性はより重い無報酬の介護責任(子ども、年長者)を負っており、しばしば人種主義や支援の欠如が重なり、経済参加に影響を及ぼしている。 |

| Political Disenfranchisement:

Women often lack access to decision-making processes within communities

and broader governance, despite being crucial for development. |

政治的権利の剥奪:

女性は、開発にとって極めて重要であるにもかかわらず、コミュニティや広範な統治機構における意思決定プロセスへのアクセスがしばしば欠如している。 |

| Health & Basic Needs: Gaps persist in access to healthcare, sanitation, and clean water, with women facing particular challenges. | 健康と基本的ニーズ:

医療、衛生設備、清潔な水へのアクセスには格差があり、女性は特に困難に直面している。 |

| Intersectionality:

Discrimination based on ethnicity, race, and gender creates multiple

layers of oppression for indigenous women. |

交差性:

民族、人種、ジェンダーに基づく差別は、先住民女性にとって何重もの抑圧を生む。 |

| Underlying Causes: |

根本的な原因: |

| Colonization & External

Institutions: Imposition of patriarchal legal and economic systems by

outsiders undermined indigenous governance and women's traditional

rights. |

植民地化と外部制度:

部外者による家父長制的な法制度と経済制度の押し付けは、先住民の統治と女性の伝統的権利を弱体化させた。 |

| Economic Globalization: Weakened

traditional economies, increasing hardships, especially for women who

become heads of households due to male migration for work. |

経済のグローバル化:

伝統的な経済が弱体化し、特に男性の出稼ぎによって世帯主となった女性の苦労が増している。 |

| Pathways to Equality: |

平等への道: |

| Gender Perspective in

Development: Applying a gender lens to development strategies is

crucial for empowerment. |

開発におけるジェンダーの視点:

開発戦略にジェンダー・レンズを適用することは、エンパワーメントにとって極めて重要である。 |

| Restoring Traditional Knowledge: Revitalizing education and policies that incorporate indigenous histories and values, including female teachers, helps girls. | 伝統的知識を取り戻す:

女性教師を含め、先住民の歴史や価値観を取り入れた教育や政策を活性化させることは、少女たちを助けることになる。 |

| Strengthening

Self-Determination: Achieving self-determination for indigenous peoples

is essential for ensuring women's human rights. |

自己決定の強化 :先住民族の自決を実現することは、女性の人権を保障

するために不可欠である。 |

| Addressing Violence: Developing

justice systems within self-governance that effectively address

violence against indigenous women is a priority. |

暴力に対処する :

先住民女性に対する暴力に効果的に対処する司法制度を自治の中で発展させることが優先課題である。 |

★Topics: Gender roles among the Indigenous peoples of North America

Two

Spirit Society of Denver marches at PrideFest Denver, 2011

| Traditional gender

roles among Native American and First Nations peoples tend to vary

greatly by region and community. As with all Pre-Columbian era

societies, historical traditions may or may not reflect contemporary

attitudes. Gender roles exhibited by Indigenous communities have been

transformed in some aspects by Eurocentric, patriarchal norms and the

perpetration of systematic oppression.[1] In many communities, these

things are not discussed with outsiders.[citation needed] |

ナショナリズムの伝統的なジェンダーの役割は、地域やコミュニティに

よって大きく異なる傾向がある。すべての先コロンビア時代社会と同様に、歴史的伝統は現代の態度を反映している場合もあれば、反映していない場合もある。

先住民コミュニティが示すジェンダー役割は、ヨーロッパ中心主義的、家父長制的規範や組織的抑圧の蔓延によって変容してきた側面もある[1]。多くのコ

ミュニティでは、こうしたことは部外者と議論されることはない[要出典]。 |

| Apache Main article: Apache Traditional Apache gender roles have many of the same skills learned by both females and males. All children traditionally learn how to cook, follow tracks, skin leather, sew stitches, ride horses, and use weapons.[2] Typically, women gather vegetation such as fruits, roots, and seeds. Women often prepare the food. Men use weapons and tools to hunt animals such as buffalo.[3] It is expected that women do not participate in hunting,[4] but the role of mothers is important. A puberty rite ceremony for young girls is an important event.[4] Here the girl accepts her role as a woman and is blessed with a long life and fertility.[3][5] Apache people typically live in matrilocal households, where a married couple live with the wife's family.[6] |

アパッチ族 メイン記事: アパッチ族 伝統的なアパッチ族のジェンダー役割分担では、男女ともに多くの同じ技能を学ぶ。子供たちは伝統的に、料理、足跡の追跡、皮革の剥ぎ取り、縫い目、馬乗 り、武器の使用を学ぶ。[2] 通常、女性は果実、根、種子などの植物を採集する。女性はしばしば食物を調理する。男性は武器や道具を使ってバッファローなどの動物を狩る。[3] 女性が狩猟に参加しないことが期待されている[4]が、母親の役割は重要だ。少女のための思春期儀式は重要な行事である[4]。ここで少女は女性としての 役割を受け入れ、長寿と子宝に恵まれる[3][5]。アパッチ族は通常、妻の実家に夫婦が同居する母系居住形態で生活する[6]。 |

| Eastern Woodland societies Main article: Indigenous peoples of the Eastern Woodlands Eastern Woodland communities vary widely in whether they divide labor based on sex. In general, as in the Plains nations, women own the home while men's work may involve more travel.[7] Narragansett men in farming communities have traditionally helped clear the fields, cultivate the crops, and assist with the harvesting, whereas women hold authority in the home.[8] Among the Lenape, men and women have both participated in agriculture and hunting according to age and ability, although primary leadership in agriculture traditionally belongs to women, while men have generally held more responsibility in the area of hunting. Whether gained by hunting, fishing, or agriculture, older Lenape women take responsibility for community food distribution. Land management, whether used for hunting or agriculture, also is the traditional responsibility of Lenape women.[9] Historically, a number of social norms in Eastern Woodland communities demonstrate a balance of power held between women and men. Men and women have traditionally both had the final say over who they would end up marrying, though parents usually have a great deal of influence as well.[10] |

東部森林地帯の社会 詳細記事: 東部森林地帯の先住民 東部森林地帯の共同体は、性別に基づく分業の有無において大きく異なる。概して平原部族と同様に、女性は家庭を所有し、男性の仕事はより移動を伴う場合が ある。[7] ナラガンセット族の農業共同体では、男性は伝統的に畑の開墾、作物の栽培、収穫の補助を担い、女性は家庭内で権威を持つ。[8] レナペ族では、男女ともに年齢や能力に応じて農業と狩猟に参加してきた。ただし農業における主導権は伝統的に女性に属し、男性は狩猟分野でより大きな責任 を担ってきた。狩猟、漁労、農業のいずれで得たものであれ、年長のレナペ女性たちが共同体の食糧分配を担当する。狩猟用であれ農業用であれ、土地管理もま たレナペ女性の伝統的な責任である。[9] 歴史的に見て、東部森林地帯のコミュニティにおける多くの社会規範は、男女間の権力の均衡を示している。結婚相手については、男女双方に最終決定権があっ たが、親も通常大きな影響力を持っていた。[10] |

| Hopi Main article: Hopi The Hopi (in what is now the Hopi Reservation in northeastern Arizona) are traditionally both matriarchal and matrilineal,[11] with egalitarian roles in the community, and no sense of superiority or inferiority based on sex or gender.[12] Both women and men have traditionally participated in politics and community management,[13] although colonization has brought patriarchal influences that have seen changes in the traditional structures and formerly higher status of women.[14] However, even with these changes, matrilineal structures still remain, along with the central role of the mothers and grandmothers in the family, household, and clan structure.[15][16] |

ホピ族 メイン記事: ホピ族 ホピ族(現在のアリゾナ州北東部のホピ保留地)は伝統的に母系制かつ母系相続制であり[11]、共同体内で平等な役割を担い、性またはジェンダーに基づく 優劣の概念を持たない。[12] 男女ともに伝統的に政治や共同体運営に参加してきた[13]が、植民地化により父権的影響がもたらされ、伝統的構造や女性の従来の高位が変化した [14]。しかしこうした変化があっても、母系構造は依然として残り、家族・世帯・氏族構造における母や祖母の中心的役割も維持されている[15] [16]。 |

| Haudenosaunee/Iroquois Main article: Iroquois The Iroquois creation myth holds that before the world was created, there was a floating island in the sky upon which the Sky People lived. Among them, a pregnant Sky Woman who was going to give birth to twins. Her husband was angry to find out they were expecting twins, and pushed her off of the floating island where she landed on the back of a giant turtle which eventually grew and became the continent of North America, which the Sky Woman and her children then gave human life to.[17] This central myth, attributing the creation of the world to a woman rather than a man, is unique and informs the spiritual and philosophical importance of women within the Pre-Colonial Iroquois people. Pre-Colonialism, the Iroquois/Haudenosaunee Confederacy (the Onondaga, Mohawk, Seneca, Cayuga, Oneida and Tuscarora peoples) had a matriarchal socioeconomic and familial structure. Women owned their own property and belongings, and children were considered descendants in their mother's line rather than that of the father. Following his marriage, a man would move into the woman's family home where he and his future children would become members of the woman's clan.[18] In the case of parental separation or the death of the mother, children remained under the custody of the mother or the mother's surviving clan in the case of her death. Additionally, after marriage wives were empowered to divorce their husband by ordering him out of her household at any time, for any reason regardless of shared children or property.[19] In the 1600s, the Iroquois women carried out what is believed to be the first feminist rebellion in the United States.[20] Previously, Iroquois men bore the sole responsibility of deciding when to declare war against rival nations. Iroquois women, wanting a say in the declaration of war, boycotted sex and child-rearing. This was effective because women were believed to hold the secret to creating life, a greatly honored act. Additionally, since women grew and cultivated crops for their tribes, the women of the tribes restricted warriors’ access to food and clothing needed for battle. The rebellion was effective, and henceforth Iroquois women were granted the power to veto the tribe's engagement in warfare.[21] Pre-Colonial Iroquois women also exercised a high level of bodily autonomy. Womanhood was respected as sacred, and rape and other acts of violence against women were rare in indigenous societies. Further, women had total control over if, when, and how they desired to bear children.[22] Women, as heads of household, also had the authority to decide whether or not their children would go to war. Mothers alone held the power to force their children to fight in a war if they felt it served the community, or to forbid their children from fighting if they disapproved of the war, further solidifying women's power in military endeavors.[23] Further, women controlled the economy of their respective nations through growing and distributing food and other resources. Iroquois women were recognized for their agricultural contributions and creativity throughout the year in ceremonies, nearly all of which celebrated the land's fertility and crops, a primarily female domain.[24] While Iroquois did not practice land ownership in the same way as their colonial successors, the land was understood to be held by women. The Great Law of Peace of the Iroquois Confederacy, formed in the fifteenth century, dictated when an Iroquois woman used a patch of land either to live or for agriculture, it was respected as her property and if she were to move, another woman was free to use the land.[25] Additionally, women established and maintained the culture of their tribes by defining the political, social, and spiritual practices. Iroquois women were also responsible for nominating and regulating male sachems (chiefs) to ensure that they adequately fulfilled responsibilities to the nation.[26] Further, political power was shared among all members of the respective Nation, with women holding voting power alongside men.[27] Iroquois women and their power within their communities also inspired later post-colonial women's rights movements within the United States. The women's suffrage movement for white American movement began in Seneca Falls in 1848, part of the Iroquois Confederacy's territory.[28] Early leaders of the Women's suffrage movement, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Matilda Joslyn Gage specifically cited the equal rights of Iroquois women to participate in their government as inspiration for their movement. Further, they used Iroquois women as an example to dispute notions that the subordination of white women was not natural nor just, and used their society to demonstrate true democracy in action.[29] |

ハウデノソーニー/イロコイ族 メイン記事:イロコイ族 イロコイ族の創造神話によれば、世界が創造される前、空には浮島があり、そこに天の民が住んでいた。その中に、双子を産む予定の妊娠した天の女がいた。夫 は双子を妊娠していると知り怒り、彼女を浮島から突き落とした。彼女は巨大な亀の背中に着地し、その亀は成長して北アメリカ大陸となった。天の女とその子 供たちは、この大陸に人間の命を与えたのである。[17] この中心的な神話は、世界の創造を男性ではなく女性に帰属させる点で独特であり、植民地化以前のイロコイ族社会における女性の精神的・哲学的重要性を示し ている。 植民地化以前、イロコイ/ハウデノソーニー連合(オノンダガ族、モホーク族、セネカ族、カイユーガ族、オナイダ族、タスカローラ族)は母系的な社会経済・ 家族構造を持っていた。女性は自身の財産と所有物を保有し、子供は父系ではなく母系の子孫とみなされた。男性は結婚後、女性の家族宅に移り住み、彼と将来 の子供たちは女性の氏族の一員となった[18]。親の別居や母親の死亡の場合、子供は母親の保護下に留まり、母親が死亡した場合は生存する母親の氏族が保 護を引き継いだ。さらに結婚後、妻はいつでも、いかなる理由でも、共有の子や財産に関係なく、夫を家から追い出すことで離婚する権利を持っていた。 [19] 1600年代、イロコイ族の女性たちはアメリカ合衆国初のフェミニスト反乱を起こしたとされる。[20] それまで、敵対する国民への宣戦布告の決定権はイロコイ族の男性だけが持っていた。戦争宣言への発言権を求めたイロコイ族の女性たちは、性行為と子育てを ボイコットした。これは効果的であった。なぜなら、生命を生み出す秘訣を女性が握っていると信じられており、それは非常に尊ばれる行為だったからだ。さら に、女性たちが部族のために作物を栽培していたため、部族の女性たちは戦士たちが戦闘に必要な食料や衣服を入手するのを制限した。この反乱は成功し、以後 イロコイ族の女性は部族の戦争参加を拒否する権限を与えられた。[21] 植民地時代以前のイロコイ族の女性は、身体に対する高い自律性も有していた。女性性は神聖なものとして尊重され、先住民族社会では女性に対する強姦やその 他の暴力行為は稀であった。さらに女性は、子を産むかどうか、いつ産むか、どのように産むかを完全に支配していた。[22] 家計の責任者としての女性は、子供を戦場に送るかどうかの決定権も有していた。母親だけが、戦争が共同体の利益になると判断すれば子供を戦場に強制的に送 り出す権限を持ち、戦争を不適切と考える場合は子供を戦場から遠ざける権限も持っていた。これにより、軍事活動における女性の権力はさらに強固なものと なった。[23] さらに女性は、食糧やその他の資源を栽培・分配することで、それぞれの国民の経済を支配していた。イロコイ族の女性は、年間を通じて行われる儀式のほぼ全 てで、土地の豊穣と収穫を称える農業への貢献と創造性が認められていた。これは主に女性の領域であった。[24] イロコイ族は植民地時代の後継者たちと同じ形で土地所有を実践していなかったが、土地は女性が保持していると理解されていた. 15世紀に成立したイロコイ連邦の「大平和法」は、イロコイ女性が居住地や農地として使用する土地は彼女の所有物として尊重され、彼女が移動した場合、他 の女性が自由にその土地を利用できると定めていた。[25] さらに、女性は政治的・社会的・精神的慣習を定義することで部族の文化を確立し維持した。イロコイ族の女性は、男性サチェム(首長)が国民への責任を適切 に果たすよう、その指名と統制も担っていた[26]。加えて、政治的権力は各部族の全構成員で共有され、女性は男性と同等の投票権を有していた。[27] イロコイ族の女性と、彼女たちがコミュニティ内で持つ権力は、後にアメリカ合衆国で起こった植民地時代後の女性権利運動にも影響を与えた。白人アメリカ人 による女性参政権運動は、1848年にイロコイ連邦の領土の一部であるセネカフォールズで始まった。[28] 婦人参政権運動の初期の指導者であるエリザベス・キャディ・スタントンとマチルダ・ジョスリン・ゲージは、イロコイ族の女性が政府に参加する平等な権利 を、彼らの運動のインスピレーションとして具体的に引用した。さらに、彼らは、白人女性の従属は自然でも公正でもないという概念に異議を唱える例としてイ ロコイ族の女性を挙げ、彼らの社会を、真の民主主義が実践されている例として示した。[29] |

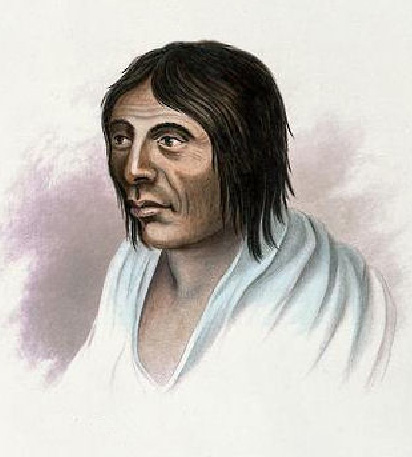

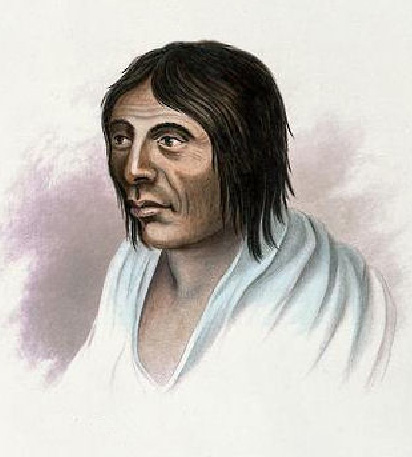

| Kalapuya Main article: Kalapuya  Kalapuya man of today's Willamette Valley, Oregon, USA; circa 1840, by Alfred Thomas Agate The Kalapuya had a patriarchal society consisting of bands or villages, usually led in social and political life by a male leader or group of leaders.[30] The primary leader was generally the man with the greatest wealth.[31] While female leaders did exist, it was more common for a woman to gain status in spiritual leadership. Kalapuya bands typically consisted of extended families of related men, their wives, and children.[31] Ceremonial leaders could be male or female, and spiritual power was regarded as more valuable than material wealth. As such, the spiritual leaders were often more influential than the political leaders.[32] Kalapuya males usually hunted while the women and young children gathered food and set up camps. As the vast majority of the Kalapuya diet consisted largely of gathered food, the women supplied most of the sustenance. Women were also in charge of food preparation, preservation, and storage.[33] The food hunted by men usually consisted of deer, elk, and fish from the rivers of the Willamette Valley, including salmon and eel. Plants gathered included wapato, tarweed seeds, hazelnuts, and especially camas. The camas bulbs were cooked by women into a cake-like bread which was considered valuable.[34] Women were involved in the community life and expressed their individual opinions.[33] When a man wanted to marry a woman, he had to pay a bride price to her father.[35] If a man slept with or raped another man's wife, he was required to pay the bride price to the husband. If he did not, he would be cut on the arm or face. If the man could pay the price, he could take the woman to be his wife.[36] There is a reference to gender variant people being accepted in Kalapuya culture. A Kalapuya spiritual person named Ci'mxin is recalled by John B. Hudson in his interviews from the Kalapuya Texts: They would say "He is a man (in body), he has changed to a woman (in dress and manner of life). But he is not a woman (in body). It is his spirit-power it is said that has told him, You become woman. You are always to wear your (woman's) dress just like women. That is the way you must always do."[37] After the arrival of Europeans to the Willamette Valley and the creation of the Grand Ronde Reservation and boarding schools such as Chemawa Indian School, children of the Kalapuya people were taught the typical gender roles of Europeans[vague].[38] |

カラプヤ 主な記事: カラプヤ  アメリカ合衆国オレゴン州ウィラメット渓谷の現代のカラプヤ人。1840年頃、アルフレッド・トーマス・エイゲート作 カラプヤ族は家父長制社会を形成し、通常は複数の集団や村落から成り、社会的・政治的な指導は男性指導者または指導者集団によって行われていた[30]。 主要な指導者は通常、最も富を持つ男であった。[31] 女性指導者も存在したが、女性が精神的指導者として地位を得る方が一般的であった。カラプヤの集団は通常、血縁関係にある男たちとその妻、子供たちからな る拡大家族で構成されていた。[31] 儀式の指導者は男女どちらでもあり、精神的力は物質的富よりも価値が高いとみなされていた。そのため、精神的指導者は政治的指導者よりも影響力を持つこと が多かった。[32] カラプヤ族の男性は通常狩猟を行い、女性と幼い子供たちは食物を採集しキャンプを設営した。カラプヤ族の食料の大部分は採集品で構成されていたため、女性 が大半の糧を供給していた。女性は食物の調理、保存、貯蔵も担当していた。[33] 男性が狩猟で得る食物は、ウィラメット渓谷の河川で獲れる鹿、ヘラジカ、魚(サケやウナギを含む)が主であった。採集された植物にはワパト、タールウィー ドの種子、ヘーゼルナッツ、特にカマスが含まれた。カマスの球根は女性によってケーキ状のパンに調理され、貴重なものとされた。[34] 女性は共同体の生活に関与し、個人の意見を表明した。[33] 男性が女性と結婚したい場合、その父親に花嫁代を支払わねばならなかった。[35] 男性が他人の妻と寝たり強姦したりした場合、その夫に花嫁代を支払う義務があった。支払わなければ、腕や顔を切りつけられた。代金を支払える場合、その女 性を妻として連れ去ることができた。[36] カラプヤ文化ではジェンダーの変容を許容していたという記述がある。ジョン・B・ハドソンは『カラプヤ文書』のインタビューで、Ci'mxinという名の カラプヤの霊能者をこう回想している: 彼らは言うだろう「彼は(肉体的には)男だ。しかし(服装や生活様式において)女へと変わった。だが(肉体的には)女ではない。彼の霊力こそが『お前は女 となれ』と命じたのだと伝えられている。お前は常に女のように(女性の)服を着るのだ。それが常なるべき姿だ」と告げたのだという。[37] ヨーロッパ人がウィラメット渓谷に到来し、グランド・ロンデ保留地やチェマワ・インディアン学校などの寄宿学校が設立された後、カラプヤ族の子どもたちは ヨーロッパ人の典型的なジェンダー役割を教え込まれた[曖昧]。[38] |

| Inuit Arvilingjuarmiut The Arvilingjuarmiut, also known as Netsilik, are Inuit who live mainly in Kugaaruk and Gjoa Haven, Nunavut, Canada. They follow the tradition of kipijuituq, which refers to instances where predominantly biologically male infants are raised as females. Often the decision for an infant to become Kipijuituq is left to the grandparents based on the reactions of the infant in the womb.[39] Children would later go on to choose their respective genders in their pubescent years once they have undergone a rite of passage that includes hunting animals.[39] Similar in concept is sipiniq from the Igloolik and Nunavik areas.[40] Aranu’tiq Aranu’tiq is a fluid category among the Chugach, an Alutiiq people from Alaska, that conforms to neither masculine nor feminine categories.[41] Gender expression is fluid and children typically dress in a combination of both masculine and feminine clothing.[41] Newborn babies are not regarded as new humans but rather as tarnina or inuusia which refers to their soul, personality, shade and are named after an older deceased relative as a way of reincarnation as the relationship between the child and others would go on to match those of the deceased.[42] |

イヌイット アルヴィリングジュアルミウト アルヴィリングジュアルミウトは、ネツィリックとも呼ばれるイヌイットの一派で、主にカナダのヌナブト準州にあるクガールクとジョア・ヘイブンに居住して いる。彼らはキピジュイトゥクという伝統に従っている。これは主に生物学的に男性である乳児が女性として育てられる事例を指す。キピジュイトクとなるかど うかの決定は、胎内での胎児の反応に基づいて祖父母に委ねられることが多い。[39] 子供たちは後に、動物狩りを含む通過儀礼を経た思春期に、それぞれがジェンダーを選択する。[39] 概念的に類似しているのは、イグルリック及びヌナヴィク地域におけるシピニクである。[40] アラヌティク アラヌティクは、アラスカのアリュート系民族チュガッチ族における流動的なカテゴリーであり、男性的・女性的のいずれのカテゴリーにも属さない。[41] ジェンダー表現は流動的で、子供たちは通常、男性的・女性的両方の衣服を組み合わせて着用する。[41] 新生児は新たな人間とは見なされず、むしろタルニナ(tarnina)またはイヌウシア(inuusia)と呼ばれる。これは彼らの魂、人格、影を指し、 死んだ年長の親族の名を継ぐことで転生を意味する。これにより、子供と他者との関係は死者の関係性を継承するのだ。[42] |

| Navajo Main article: Navajo Similar to other Indigenous cultures, Navajo girls participate in a rite of passage ceremony that is a celebration of the transformation into womanhood. This event is marked with new experiences and roles within the community. Described as Kinaaldá, the ritual takes place over four days, during the individual's first or second menstrual period. The reason for this is rooted deeply in Navajo supernatural beliefs and their creation myths.[43] The third gender role of nádleehi (meaning "one who is transformed" or "one who changes"), beyond contemporary Anglo-American definition limits of gender, is part of the Navajo Nation society, a "two-spirit" cultural role. The renowned 19th-century Navajo artist Hosteen Klah (1849–1896) is an example.[44][45][46] Navajo values emphasize the masculine and the feminine, despite the ritual being centered around feminine gender roles. Historically, it is recorded that Navajo cultures respected the autonomy of women and their equality to men in the tribe, in multiple spheres of life within their society. Contrarily, the primary discourse in Western society regarding girls' puberty is associated with discreteness, to be experienced privately for concern of shame and embarrassment regarding menstruation and bodily changes.[43] |

ナバホ族 メイン記事: ナバホ族 他の先住民族文化と同様に、ナバホ族の少女は成人式に相当する儀礼に参加する。これは女性への変容を祝うものであり、コミュニティ内での新たな経験と役割 の始まりを意味する。キナールダと呼ばれるこの儀礼は、個人の初潮または二回目の月経期間中に四日間にわたって行われる。その理由はナバホ族の超自然的な 信仰と創造神話に深く根ざしている。[43] 現代の英米におけるジェンダーの定義の枠を超えた第三のジェンダー役割「ナドリーヒ」(「変容した者」または「変化する者」を意味する)は、ナバホ国民社 会の一部であり、「二つの精霊」という文化的役割である。19世紀の著名なナバホ族芸術家ホスティーン・クラ(1849–1896)がその例である。 [44][45] [46] ナバホの価値観は、儀礼が女性的なジェンダーを中心としているにもかかわらず、男性性と女性性を重視する。歴史的に、ナバホ文化は女性の自律性と、部族内 における男性との平等を、社会の様々な生活領域で尊重していたと記録されている。これとは対照的に、西洋社会における少女の思春期に関する主要な言説は、 月経や身体的変化に伴う羞恥心や気まずさを懸念し、私的に経験すべきものとして、秘匿性に関連付けられている。[43] |

| Nez Perce Main article: Nez Perce people During the early colonial period, Nez Perce communities tended to have specific gender roles. Men were responsible for the production of equipment used for hunting, fishing, and protection of their communities, as well as the performance of these activities. Men made up the governing bodies of villages which were composed of a council and headman.[47][48][49] Nez Perce women in the early contact period were responsible for maintaining the household which included the production of utilitarian tools for the home. The harvest of medicinal plants was the responsibility of the women in the community due to their extensive knowledge. Edibles were harvested by both women and children. Women also regularly participated in politics, but due to their responsibilities to their families and medicine gatherings, they did not hold office.[47][48][49] Critical knowledge regarding culture and tradition was passed down by all the elders of the community.[47][48][49] |

ネズパース族 主な記事: ネズパース族 植民地時代の初期、ネズパース族の共同体には明確なジェンダー役割が存在した。男性は狩猟、漁労、共同体防衛に用いる道具の製作と、それらの活動の実行を 担った。村落の統治機関は評議会と首長で構成され、男性がこれを占めていた。[47][48] [49] 接触初期のネズパース族の女性は、家庭の維持管理を担当した。これには家庭用の実用的な道具の製作も含まれた。薬用植物の採取は、女性たちが豊富な知識を 持っていたため、コミュニティ内の女性の責任であった。食用の植物は女性と子供の両方が採取した。女性は政治にも定期的に参加したが、家族への責任や薬草 採取のため、役職には就かなかった。[47][48][49] 文化と伝統に関する重要な知識は、コミュニティの長老たち全員によって受け継がれた。[47][48][49] |

| Ojibwe Main article: Ojibwe Historically, most Ojibwe cultures believe that men and women are usually suited to specific tasks.[50] Hunting is usually a men's task, and first-kill feasts are held as an honour for hunters.[50] The gathering of wild plants is more often a women's occupation; however, these tasks often overlapped, with men and women working on the same project but with different duties.[50] Despite hunting itself being more commonly a male task, women also participate by building lodges, processing hides into apparel, and drying meat. In contemporary Ojibwe culture, all community members participate in this work, regardless of gender.[50] Wild rice (Ojibwe: manoomin) harvesting is done by all community members,[51] though often women will knock the rice grains into the canoe while men paddle and steer the canoe through the reeds.[51] For Ojibwe women, the wild rice harvest can be especially significant as it has traditionally been a chance to express their autonomy:[52] The wild rice harvest was the most visible expression of women's autonomy in Ojibwe society. Binding rice was an important economic activity for female workers, who within their communities expressed prior claims to rice and a legal right to use wild rice beds in rivers and lakes through this practice. Ojibwe ideas about property were not invested in patriarchy, as in European legal traditions. Therefore, when early travelers and settlers observed Indigenous women working, it would have involved a paradigm shift for them to appreciate that for the Ojibwe, water was a gendered space where women's ceremonial responsibility for water derives from these related legal traditions and economic practices. — Brenda J. Child, Holding Our World Together, p. 25 While the Ojibwe continue to harvest wild rice by canoe, both men and women now take turns knocking rice grains.[50] Both Ojibwe men and women create beadwork and music, and maintain the traditions of storytelling and traditional medicine.[51] In regards to clothing, Ojibwe women have historically worn hide dresses with leggings and moccasins, while men would wear leggings and breechcloths.[51] After trading with European settlers became more frequent, the Ojibwe began to adopt characteristics of European dress.[51] |

オジブウェ族 メイン記事: オジブウェ族 歴史的に、ほとんどのオジブウェ文化では、男性と女性は通常、特定の任務に適していると信じられている。[50] 狩猟は通常男性の任務であり、最初の獲物を祝う宴が狩猟者の栄誉として行われる。[50] 野生の植物の採取はより頻繁に女性の仕事であった。しかし、これらの仕事はしばしば重なり合い、男女が同じプロジェクトに取り組むが、異なる役割を担って いた。[50] 狩猟そのものはより一般的に男性の任務であったにもかかわらず、女性も小屋の建設、皮を衣服に加工すること、肉の乾燥といった形で参加した。現代のオジブ ウェ文化では、ジェンダーに関係なく、すべてのコミュニティメンバーがこの仕事に参加する。[50] ワイルドライス(オジブウェ語:マヌーミン)の収穫は共同体全員で行う[51]。ただし、葦原を漕ぎ進むカヌーを男性が操縦する間、女性が米粒をカヌーに 叩き落とす役割を担うことが多い[51]。オジブウェの女性にとってワイルドライス収穫は特に重要であり、伝統的に自律性を示す機会となってきた: [52] ワイルドライスの収穫は、オジブウェ社会における女性の自律性が最も顕著に表れる場であった。稲を束ねる作業は女性労働者にとって重要な経済活動であり、 この慣行を通じて彼女たちはコミュニティ内で稲への優先的な権利を主張し、河川や湖のワイルドライス生育地を利用する法的権利を行使していた。オジブウェ の財産観は、ヨーロッパの法伝統のような家父長制に根ざしていなかった。したがって、初期の旅行者や入植者が先住民の女性の労働を目撃した際、オジブウェ にとって水がジェンダー化された空間であり、女性の儀式における水への責任がこうした法的伝統と経済的慣行に由来することを理解するには、彼らの認識の転 換が必要だったのだ。 — ブレンダ・J・チャイルド『私たちの世界をつなぎとめる』p.25 オジブウェ族は今もカヌーで野生米を収穫するが、米粒を叩き落とす作業は男女が交代で行うようになった。[50] オジブウェ族の男女は共にビーズ細工や音楽を創作し、語り継ぎの伝統や伝統医療を守っている。[51] 衣服に関しては、オジブウェ族の女性は歴史的に皮のドレスにレギンスとモカシンを、男性はレギンスとブリーチクロスを着用してきた。[51] ヨーロッパ人入植者との交易が頻繁になるにつれ、オジブウェ族はヨーロッパ風の服装の特徴を取り入れ始めた。[51] |

| Osage Main article: Osage Nation |

オセージ族 主な記事: オセージ国民 |

| Sioux Main article: Sioux The Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota peoples, in addition to some other Siouan-speaking people like the Omaha and Ponca, are patriarchal or patrilineal and have historically had highly defined gender roles.[53][54] In such tribes, hereditary leadership would pass through the male line, while children are considered to belong to the father and his clan. If a woman marries outside the tribe, she is no longer considered to be part of it, and her children would share the ethnicity and culture of their father.[54] In the 19th century, the men customarily harvested wild rice whereas women harvested all other grain (among the Dakota or Santee).[55] The winkte are a social category in Lakota culture, of male people who adopt the clothing, work, and mannerisms that Lakota culture usually considers feminine.[56] Usually, winkte are homosexual, and sometimes the word is also used for gay men who are not in any other way gender-variant.[56] |

スー族 メイン記事: スー族 ラコタ族、ダコタ族、ナコタ族、およびオマハ族やポンカ族などの他のスー語族を話す民族は、父系社会であり、歴史的に明確なジェンダー役割分担を持ってい た。[53][54] こうした部族では、世襲の指導権は男子系を通じて継承され、子供は父親とその氏族に属すると見なされる。女性が部族外と結婚した場合、彼女はもはや部族の 一員とは見なされず、その子供は父親の民族性と文化を共有する。[54] 19世紀には、男性は慣習的に野生米を収穫し、女性はその他の穀物を全て収穫した(ダコタ族またはサンティー族において)。[55] ウィンクテはラコタ文化における社会的カテゴリーであり、男性でありながらラコタ文化が通常女性的と見なす服装、仕事、振る舞いを採用する者たちを指す。 [56] 通常、ウィンクテは同性愛者であり、時にはこの言葉は他の点でジェンダー自認が異なるわけではないゲイ男性に対しても用いられる。[56] |

| Native Americans in the United

States – Gender roles Indigenous feminism Matriarchy (the Native Americans subsection) Missing and murdered Indigenous women Native American feminism Patriarchy Sexual victimization of Native American women Two-Spirit |

アメリカ先住民 – ジェンダー役割 先住民フェミニズム 母系社会(アメリカ先住民のサブセクション) 行方不明及び殺害された先住民女性 アメリカ先住民フェミニズム 父権制 アメリカ先住民女性への性的被害 ツー・スピリット |

| References 1. Liddell, Jessica L.; McKinley, Catherine E.; Knipp, Hannah; Scarnato, Jenn Miller (August 2021). "'She's the Center of My Life, the One That Keeps My Heart Open': Roles and Expectations of Native American Women". Affilia. 36 (3): 357–375. doi:10.1177/0886109920954409. ISSN 0886-1099. PMC 8276874. PMID 34267418. 2. 100 Native Americans Who Shaped American History, Juettner, 2007. 3. "Our Culture". Official Website of the Mescalero Apache Tribe. Retrieved 2021-11-06. 4. Opler, Morris (1996). An Apache Life-way: The Economic, Social, and Religious Institutions of the Chiricahua Indian. Bison Books. ISBN 0803286104. 5. Markstrom, Carol (2008). Empowerment of North American Indian Girls : Ritual Expressions at Puberty. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-3257-0. 6. Wightman, Abigail. "Honoring Kin: Gender, Kinship, and the Economy of Plains Apache Identity". Shareok. 7. James Ax tell, The Indian Peoples of Eastern America: A Documentary History of the Sexes, New York, Oxford University Press, 1981, 107–110 8. James Ax tell, The Indian Peoples of Eastern America: A Documentary History of the Sexes, New York, Oxford University Press, 1981, 123 9. Gun log Fur, A Nation of Women: Gender and Colonial Encounters Among the Delaware Indians, Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009, 87 10. James Axtell, The Indian Peoples of Eastern America: A Documentary History of the Sexes, New York, Oxford University Press, 1981, 74–75 11. Schlegel, Alice, Hopi Gender Ideology of Female Superiority, in Quarterly Journal of Ideology: "A Critique of the Conventional Wisdom", vol. VIII, no. 4, 1984, p. 44 and see pp. 44–52 (essay based partly on "seventeen years of fieldwork among the Hopi", per p. 44 n. 1) (author of Dep't of Anthropology, Univ. of Ariz., Tucson). 12. LeBow, Diana, Rethinking Matriliny Among the Hopi, op. cit., p. [8]. 13. LeBow, Diana, Rethinking Matriliny Among the Hopi, op. cit., p. 18. 14. Schlegel, Alice, Hopi Gender Ideology of Female Superiority, op. cit., p. 44 n. 1. 15. Schlegel, Alice, Hopi Gender Ideology of Female Superiority, op. cit., p. 45. 16. Schlegel, Alice, Hopi Gender Ideology of Female Superiority, op. cit., p. 50. 17. "Creation Myths -- Iroquois Creation Myth". www.cs.williams.edu. Retrieved 2025-03-07. 18. "Iroquois Woman". web.pdx.edu. Retrieved 2025-03-07. 19. Baskin, Cyndy (1982-01-01). "Women in Iroquois Society". Canadian Woman Studies/les cahiers de la femme. ISSN 0713-3235. 20. "Iroquois women gain power to veto wars, 1600s | Global Nonviolent Action Database". nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu. Retrieved 2025-03-07. 21. "Iroquois women gain power to veto wars, 1600s | Global Nonviolent Action Database". nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu. Retrieved 2025-03-07. 22. Baskin, Cyndy (1982-01-01). "Women in Iroquois Society". Canadian Woman Studies/les cahiers de la femme. ISSN 0713-3235. 23. "Exhibit in Seneca Falls shows how Iroquois women influenced early feminists | Cornell Chronicle". news.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2025-03-07. 24. Baskin, Cyndy (1982-01-01). "Women in Iroquois Society". Canadian Woman Studies/les cahiers de la femme. ISSN 0713-3235. 25. Baskin, Cyndy (1982-01-01). "Women in Iroquois Society". Canadian Woman Studies/les cahiers de la femme. ISSN 0713-3235. 26. "Iroquois Woman". web.pdx.edu. Retrieved 2025-03-07. 27. "Exhibit in Seneca Falls shows how Iroquois women influenced early feminists | Cornell Chronicle". news.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2025-03-07. 28. "Exhibit in Seneca Falls shows how Iroquois women influenced early feminists | Cornell Chronicle". news.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2025-03-07. 29. "Exhibit in Seneca Falls shows how Iroquois women influenced early feminists | Cornell Chronicle". news.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2025-03-07. 30. Prescott, Cynthia Culver. “Gender and Generation on the Far Western Frontier.” Google Books, Google, 2007 31. Juntunen, Dasch, and Rogers, The World of the Kalapuya, p. 17. 32. Juntunen, Dasch, and Rogers, The World of the Kalapuya, p. 19. 33. Juntunen, Dasch, and Rogers, The World of the Kalapuya, p. 20. 34. Kramer, Stephanie. “Camas Bulbs, the Kalapuya, and Gender: Exploring Evidence of Plant Food Intensification in the Willamette Valley of Oregon.” University of Oregon Scholars Bank, University of Oregon, June 2000, 35. Jacobs, Melville (1945). Kalapuya Texts. Seattle: The University of Washington. pp. 45–46. 36. Jacobs, Melville (1945). Kalapuya Texts. Seattle: The University of Washington. p. 44. 37. Jacobs, Melville (1945). Kalapuya Texts. Seattle: The University of Washington. pp. 48–49. 38. Juntunen, Dasch, and Rogers, The World of the Kalapuya, p. 111. 39. Stewart, Henry, "Kipijuituq in Netsilik Society", Many Faces of Gender, University of Calgary Press, pp. 13–26, doi:10.2307/j.ctv6cfrqv.6, ISBN 978-1-55238-397-1, retrieved 2021-02-26 40. Issenman, Betty Kobayashi (1997). Sinews of Survival: the Living Legacy of Inuit Clothing. Vancouver: UBC Press. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-7748-5641-6. OCLC 923445644. 41. Bernard Saladin d'Anglure; Peter Frost; Claude Lévi-Strauss. Inuit Stories of Being and Rebirth: Gender, shamanism, and the third sex. ISBN 978-0-88755-559-6. OCLC 1125818726. 42. Lisa Frink; Rita S. Shepard; Gregory A. Reinhardt (2002). Many Faces of Gender: Roles and Relationships through time in Indigenous northern communities. University Press of Colorado. ISBN 0-87081-677-2. OCLC 49795560. 43. Markstrom, Carol A.; Iborra, Alejandro (December 2003). "Adolescent Identity Formation and Rites of Passage: The Navajo Kinaalda Ceremony for Girls". Journal of Research on Adolescence. 13 (4): 399–425. doi:10.1046/j.1532-7795.2003.01304001.x. ISSN 1050-8392. 44. Franc Johnson Newcomb (1980-06). Hosteen Klah: Navaho Medicine Man and Sand Painter. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-1008-2. 45. Lapahie, Harrison, Jr. Hosteen Klah (Sir Left Handed). Lapahie.com. 2001 (retrieved 19 Oct 2009) 46. Berlo, Janet C. and Ruth B. Phillips. Native North American Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-284218-3 . p. 34 47. "Gender Roles" at the Nez Perce Museum, United States Department of the Interior, Parks Service; accessed 5 48. Colombi, Benedict J. "Salmon and the Adaptive Capacity of Nimiipuu (Nez Perce) Culture to Cope with Change" in the American Indian Quarterly, Vol. 36, No. 1 (Winter 2012), pp. 75–97. University of Nebraska Press; accessed 5 April 2016 49. "History of CTUIR Archived 2016-03-27 at the Wayback Machine" at Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation; accessed 5 April 2016 50. Buffalohead, Priscilla (1983). "Farmers, Warriors, Traders: A Fresh Look at Ojibway Women" (PDF). Minnesota History. 48: 236–244. 51. St. Louis County Historical Society (SLCHS). "Lake Superior Ojibwe Gallery" (PDF). 1854 Treaty Authority. Retrieved February 26, 2021. 52. Child, Brenda J. (2013). Holding our world together : Ojibwe women and the survival of community. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-312159-6. OCLC 795167052. 53. Medicine, Beatrice (1985). "Child Socialization among Native Americans: The Lakota (Sioux) in Cultural Context". Wíčazo Ša Review. 1 (2): 23–28. doi:10.2307/1409119. JSTOR 1409119. 54. Melvin Randolph Gilmore, "The True Logan Fontenelle", Publications of the Nebraska State Historical Society, Vol. 19, edited by Albert Watkins, Nebraska State Historical Society, 1919, p. 64, at GenNet, accessed August 25, 2011 55. Jonathan Periam, Home and Farm Manual, 1884, likely citing USDA brief on "Wild Rice". 56. Medicine, Beatrice (2002). "Directions in Gender Research in American Indian Societies: Two Spirits and Other Categories by Beatrice Medicine". Online Readings in Psychology and Culture (Unit 3, Chapter 2). W. J. Lonner, D. L. Dinnel, S. A. Hayes, & D. N. Sattler (Eds.). Center for Cross-Cultural Research, Western Washington University. Archived from the original on 2003-03-30. Retrieved 2015-07-07. |

参考文献 1. リデル、ジェシカ・L.;マッキンリー、キャサリン・E.;ニップ、ハンナ;スカルナート、ジェン・ミラー(2021年8月)。「『彼女は私の人生の中心 であり、私の心を開き続ける存在だ』:ネイティブアメリカン女性の役割と期待」。『アフィリア』36巻3号:357–375頁。doi: 10.1177/0886109920954409. ISSN 0886-1099. PMC 8276874. PMID 34267418. 2. 『アメリカ史を形作った100人のネイティブアメリカン』、Juettner、2007年。 3. 「我々の文化」. メスカレロ・アパッチ族公式ウェブサイト. 2021年11月6日閲覧. 4. オプラー, モリス (1996). 『アパッチの生活様式: チリカワ・インディアンの経済・社会・宗教制度』. バイソン・ブックス. ISBN 0803286104. 5. マークストロム、キャロル(2008)。『北米インディアン少女のエンパワーメント:思春期における儀礼表現』。ネブラスカ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-8032-3257-0。 6. ワイトマン、アビゲイル。「血縁を尊ぶ:ジェンダー、親族関係、そして平原アパッチのアイデンティティの経済」。Shareok。 7. ジェームズ・アクステル著『東アメリカ先住民:性別の記録史』ニューヨーク、オックスフォード大学出版局、1981年、107–110頁 8. ジェームズ・アクステル『東アメリカ先住民:両性の記録史』ニューヨーク、オックスフォード大学出版局、1981年、123頁 9. ガン・ログ・ファー『女たちの国民:デラウェア族におけるジェンダーと植民地時代の出会い』フィラデルフィア、ペンシルベニア大学出版局、2009年、 87頁 10. ジェームズ・アクステル『東アメリカ先住民:両性の史料史』ニューヨーク、オックスフォード大学出版局、1981年、74–75頁 11. アリス・シュレーゲル「ホピ族の女性優位性に関するジェンダー観」『イデオロギー季刊誌: 「通説への批判」掲載、第VIII巻第4号、1984年、44頁。また44–52頁参照(44頁注1によれば「ホピ族における17年間の現地調査」を一部 基にした論文)。(著者はアリゾナ大学人類学部、ツーソン校所属)。 12. LeBow, Diana, 『ホピ族における母系制の再考』, 前掲書, p. [8]. 13. LeBow, Diana, 『ホピ族における母系制の再考』, 前掲書, p. 18. 14. シュレーゲル、アリス『ホピ族の女性優位性に関するジェンダーイデオロギー』前掲書、44頁注1。 15. シュレーゲル、アリス『ホピ族の女性優位性に関するジェンダーイデオロギー』前掲書、45頁。 16. シュレーゲル、アリス『ホピ族の女性優位性に関するジェンダーイデオロギー』前掲書、50頁。 17. 「創造神話 -- イロコイ族の創造神話」. www.cs.williams.edu. 2025年3月7日閲覧. 18. 「イロコイ族の女性」. web.pdx.edu. 2025年3月7日閲覧. 19. バスキン, シンディ (1982-01-01). 「イロコイ社会における女性」. Canadian Woman Studies/les cahiers de la femme. ISSN 0713-3235. 20. 「イロコイの女性が戦争拒否権を獲得、1600年代 | グローバル非暴力行動データベース」. nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu. 2025年3月7日取得. 21. 「イロコイ族の女性が戦争拒否権を獲得、1600年代|グローバル非暴力行動データベース」. nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu. 2025-03-07 取得. 22. バスキン、シンディ (1982-01-01). 「イロコイ社会における女性」. Canadian Woman Studies/les cahiers de la femme. ISSN 0713-3235. 23. 「セネカフォールズでの展示が示す、イロコイ族の女性が初期フェミニストに与えた影響 | Cornell Chronicle」. news.cornell.edu. 2025-03-07 参照. 24. Baskin, Cyndy (1982-01-01). 「イロコイ社会における女性」. カナダ女性研究/女性研究誌. ISSN 0713-3235. 25. バスキン, シンディ (1982-01-01). 「イロコイ社会における女性」. カナダ女性研究/女性研究誌. ISSN 0713-3235. 26. 「イロコイ族の女性」. web.pdx.edu. 2025年3月7日閲覧. 27. 「セネカフォールズの展示が示す、イロコイ族女性が初期フェミニストに与えた影響 | コーネル・クロニクル」. news.cornell.edu. 2025年3月7日閲覧. 28. 「セネカフォールズ展覧会、イロコイ族女性が初期フェミニストに与えた影響を提示 | コーネル・クロニクル」. news.cornell.edu. 2025年3月7日閲覧. 29. 「セネカフォールズ展覧会、イロコイ族女性が初期フェミニストに与えた影響を提示 | コーネル・クロニクル」. news.cornell.edu. 2025年3月7日閲覧. 30. プレスコット、シンシア・カルバー。「西部辺境におけるジェンダーと世代」Google Books、Google、2007年 31. ユンテネン、ダッシュ、ロジャース『カラプヤ族の世界』p. 17。 32. ユンテネン、ダッシュ、ロジャース『カラプヤ族の世界』p. 19。 33. ユンテネン、ダッシュ、ロジャース共著『カラプヤ族の世界』p. 20. 34. クレイマー、ステファニー「カマス球根、カラプヤ族、そしてジェンダー:オレゴン州ウィラメット渓谷における植物性食糧集約化の証拠を探る」オレゴン大学 学術データベース、オレゴン大学、2000年6月、 35. ジェイコブズ、メルヴィル(1945年)。『カラプヤ文書』シアトル:ワシントン大学出版局、45-46頁。 36. ジェイコブズ、メルヴィル(1945)。『カラプヤ文書』。シアトル:ワシントン大学出版局、44頁。 37. ジェイコブズ、メルヴィル(1945)。『カラプヤ文書』。シアトル:ワシントン大学出版局、48-49頁。 38. ユントゥネン、ダッシュ、ロジャース著『カラプヤ族の世界』111頁。 39. スチュワート、ヘンリー「ネツィリック社会におけるキピジュイトゥク」『ジェンダーの多様な顔』カルガリー大学出版局、13–26頁、doi: 10.2307/j.ctv6cfrqv.6、 ISBN 978-1-55238-397-1, 2021年2月26日取得 40. イッセンマン, ベティ・コバヤシ (1997). 『生存の筋: イヌイット衣類の生き続ける遺産』. バンクーバー: UBC出版. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-7748-5641-6. OCLC 923445644. 41. ベルナール・サラディン・ダンギュール; ピーター・フロスト; クロード・レヴィ=ストロース. 『イヌイットの生成と再生の物語:ジェンダー、シャーマニズム、第三の性』. ISBN 978-0-88755-559-6. OCLC 1125818726. 42. リサ・フリンク、リタ・S・シェパード、グレゴリー・A・ラインハート(2002年)。『ジェンダーの多様な顔:先住民北部コミュニティにおける時代を超 えた役割と関係性』。コロラド大学出版局。ISBN 0-87081-677-2。OCLC 49795560。 43. マークストロム、キャロル・A、イボラ、アレハンドロ (2003年12月)。「思春期のアイデンティティ形成と通過儀礼:少女のためのナバホ族キナルダ儀式」。『Journal of Research on Adolescence』。13巻4号:399–425頁。doi:10.1046/j.1532-7795.2003.01304001.x。ISSN 1050-8392. 44. フラン・ジョンソン・ニューカム (1980-06). 『ホスティーン・クラ:ナバホ族の呪術師であり砂絵師』. オクラホマ大学出版局. ISBN 0-8061-1008-2. 45. ラパヒー・ハリソン・ジュニア『ホスティーン・クラ(サー・レフトハンドド)』Lapahie.com. 2001年(2009年10月19日アクセス) 46. バーロ・ジャネットC.、ルースB.フィリップス共著『北米先住民芸術』オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局、ISBN 978-0-19-284218-3. p. 34 47. 「ジェンダー役割」ネズパース博物館、米国内務省公園局;2016年4月5日アクセス48. コロンビ、ベネディクト・J. 「サーモンと変化への適応能力:ニミイプー(ネズパース)文化の事例」『アメリカン・インディアン・クォータリー』第36巻第1号(2012年冬号)、 pp. 75–97. ネブラスカ大学出版局; 2016年4月5日アクセス 49. 「CTUIRの歴史 Archived 2016-03-27 at the Wayback Machine」ウマティラ・インディアン居留地連合部族; 2016年4月5日アクセス 50. バッファローヘッド、プリシラ (1983). 「農民、戦士、商人:オジブウェイ女性への新たな視点」(PDF). ミネソタ歴史. 48: 236–244. 51. セントルイス郡歴史協会 (SLCHS). 「スペリオル湖オジブウェ・ギャラリー」(PDF). 1854年条約権限機関. 2021年2月26日閲覧。 52. チャイルド、ブレンダ・J. (2013). 『私たちの世界をつなぎとめる:オジブウェの女性と共同体の存続』. ペンギンブックス. ISBN 978-0-14-312159-6. OCLC 795167052. 53. メディシン、ベアトリス(1985年)。「ネイティブアメリカンにおける児童社会化:文化的文脈におけるラコタ(スー族)」。『ウィチャゾ・シャー・レ ビュー』1巻2号:23–28頁。doi:10.2307/1409119。JSTOR 1409119。 54. メルビン・ランドルフ・ギルモア、「真のローガン・フォンテネル」、『ネブラスカ州歴史協会刊行物』第19巻、アルバート・ワトキンス編、ネブラスカ州歴 史協会、1919年、64頁、GenNetにて、2011年8月25日アクセス 55. ジョナサン・ペリアム、『家庭と農場の手引書』、1884年、おそらく米国農務省の「野生米」に関する報告書を引用。 56. メディシン、ベアトリス(2002)。「アメリカ先住民社会におけるジェンダー研究の方向性:ベアトリス・メディシンによる『二つの魂』とその他のカテゴ リー」。『心理学と文化のオンライン読本』(第3ユニット第2章)。W. J. ロンナー、D. L. ディネル、S. A. ヘイズ、D. N. サトラー(編)。ウェスタン・ワシントン大学 異文化研究センター。2003年3月30日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ。2015年7月7日に閲覧。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gender_roles_among_the_Indigenous_peoples_of_North_America |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099