メソアメリカ産品のイベリア社会への初期インパクト

Early impact of Mesoamerican goods in

Iberian society

☆メソアメリカ産品がイベリア社会に与えた初期の影響は、 ヨーロッパ社会、特にスペインとポルトガルに独特な影響を与えた。トウモロコシ、ジャガイモ、七面鳥、カボチャ、豆、トマトはすべて、既存のスペイン料理 やポルトガル料理のスタイルに取り入れられた。同様に重要だったのは、(旧世界ではすでに存在していたにもかかわらず)新世界でのコーヒーとサトウキビ栽 培の影響だった。食べ物による影響と並んで、新しい商品(タバコなど)の導入もイベリア社会の仕組みを変えた。これらの新世界の商品や食品が与えた影響 を、国家、経済、宗教制度、当時の文化に対する影響に基づいて分類することができる。16世紀初頭、外部団体(すなわち他のヨーロッパ諸国)がこれらの新 商品をスペインに依存するようになり、国家の権力と影響力が増大した。ポルトガルとスペインの両国の経済は、これらのアメリカ産品の取引によって、非常に 大きな力を持つようになった。)

| The early impact of Mesoamerican goods on Iberian society

had a unique effect on European societies, particularly in Spain and

Portugal. The introduction of American "miracle foods" was instrumental

in pulling the Iberian population out of the famine and hunger that was

common in the 16th century.[1] Maize (corn), potatoes, turkey, squash,

beans, and tomatoes were all incorporated into existing Spanish and

Portuguese cuisine styles. Equally important was the impact of coffee

and sugar cane growing in the New World (despite having already existed

in the Old World). Along with the impact from food, the introduction of

new goods (such as tobacco) also altered how Iberian society worked.

One can categorize the impacts of these New World goods and foods based

on their influence over the state, the economy, religious institutions,

and the culture of the time. The power and influence of the state grew

as external entities (i.e. other European nations) became dependent on

Spain for these New Goods in the early 16th century. The economies of

both Portugal and Spain saw an enormous increase in power as a result

of trading these American goods. |

メ

ソアメリカ産品がイベリア社会に与えた初期の影響は、ヨーロッパ社会、特にスペインとポルトガルに独特な影響を与えた。トウモロコシ、ジャガイモ、七面

鳥、カボチャ、豆、トマトはすべて、既存のスペイン料理やポルトガル料理のスタイルに取り入れられた。同様に重要だったのは、(旧世界ではすでに存在して

いたにもかかわらず)新世界でのコーヒーとサトウキビ栽培の影響だった。食べ物による影響と並んで、新しい商品(タバコなど)の導入もイベリア社会の仕組

みを変えた。これらの新世界の商品や食品が与えた影響を、国家、経済、宗教制度、当時の文化に対する影響に基づいて分類することができる。16世紀初頭、

外部団体(すなわち他のヨーロッパ諸国)がこれらの新商品をスペインに依存するようになり、国家の権力と影響力が増大した。ポルトガルとスペインの両国の

経済は、これらのアメリカ産品の取引によって、非常に大きな力を持つようになった。 |

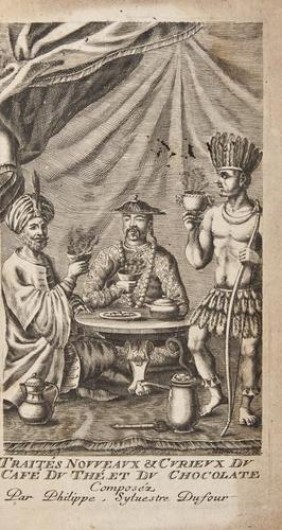

| Luxury goods and foods Several of the goods and foods brought to the Old World appealed to the lavish tastes of the upper classes. The difficulties involved in gaining this goods led them to go for higher prices and their elite status amongst the rich. Cocoa  "Traités nouveaux & curieux du café du thé et du chocolate", by Philippe Sylvestre Dufour, 1685. Chocolate was by far one of the most influential of the New World goods on Spanish, and later European, society. By the 1590s, chocolate had a significant presence in the Iberian Peninsula. The growing chocolate habit in Spain led to a cross-cultural transmission of tastes (such as vanilla, pepper, the color red, and a foamy froth similar to that found in chocolate). The taste for chocolate diffused in a bottom-up fashion as colonists and conquistadors encountered new native tastes. Spaniards in the Americas who initially encountered the chocolate liquid had mixed reactions, but a love for the new taste quickly spread into the Iberian Peninsula itself. The method in which chocolate's popularity spread changed by the time it had reached the peninsula. Cacao was necessary for chocolate, but it also served as a currency throughout Mesoamerica, which is evidence of its status as a precious good throughout the region. If a commoner were to drink it, it would be seen almost as bad as saying a bad prayer or omen. Chocolate began to form a relationship with the people it would be found at weddings or betrothals. The upper class in Spain would embrace this chocolate craving to the point where the lower classes sought to emulate them. For natives, chocolate was filled with religious meaning while it played the role of a drug for the Spanish. The distinction between how the two societies perceived the role of chocolate's use is interesting. Natives saw this liquid through the lens of religious meaning while the Spanish saw the economic and culinary benefits. By the 1620s, thousands of pounds of chocolate were imported to Spain annually. The components of European chocolate evolved over time as the Spanish sought to modify the formula to reflect available resources (such as adding sugar as a sweetener rather than honey). Chocolate started a lavish item in the diets of the Spanish nobility but eventually became an accessible commodity for all members of Spanish society. While the initial interest in chocolate for the Spanish was hampered by negative stigmas (i.e. that chocolate drinking was a form of idolatry), chocolate went on to become one of the most desired and influential goods from the New World.[2] Sugar While initially a crop of the Indian subcontinent, the cultivation of sugar in the New World had significant effects on Spanish society. New World sugar cultivation added to the growing power of the Spanish and Portuguese economies while also increasing the popularity of slave labor (which had severe impacts on African, American, and European societies). Sugar started off as a mark of social statues amongst the upper classes but gradually trickled down towards the lower classes. This desire for sugar reflected social reasons other than simply a biologically pleasing taste for the tongue.[2] Sociologist Pierre Bourdieu argues that subjective pleasures, such as a taste for sugar, reflect social constructs and often are determined by those in power.[3] Bourdeieu's argument certainly suggests that the popularity of sugar in Iberian society was a result of the perceived value placed on it by the upper classes whom held power. Coffee  Close-up of roasted coffee beans While initially an Ethiopian product, the cultivation of coffee in the New World increased its popularity amongst the European population substantially. The cultivation and spread of coffee into Europe was started in the 15th century in the Arab world.[4] The assimilation of chocolate into Spanish tastes paved the way for coffee as the new hot stimulant drink to gain popularity in Spain. Coffee imports even surpassed those of chocolate by the 18th century.[2] The desire for coffee, like that of chocolate, eventually spread to include all castes in Iberia. Coffee, along with chocolate and sugar, stimulated a growing taste for New World sweet goods. Tobacco  The earliest image of a man smoking, from Tabaco by Anthony Chute. As known more now than ever, tobacco had very addictive qualities. The insidious addictiveness of tobacco led to an increasingly prominent demand for the good in New World trade.[5] The plant was initially smoked by native tribes in the Americas for ceremonial purposes. It was believed to be a gift from the gods and was used primarily by religious leaders. The Spanish changed this dynamic of the crop when they began trading tobacco as a commodity. The demand for tobacco stimulated the Spanish and Portuguese trade networks as well as increased Iberian power in world trade. The tobacco trade dominated the economies of the south-eastern US up until the peak of cotton's popularity in world trade. Vanilla Vanilla, a flavoring derived from the orchids of the genus Vanilla, was first brought to Spain in the 1520s by Cortez following his conquest of the Aztec Empire.[6] The Aztecs had started cultivating the plant following their subjugation of the Totonec peoples of present-day Mexico. Vanilla quickly became popular as a sweetener in Spain and then the rest of Europe. Along with coffee and chocolate, sugar started a desire for sweet tastes from the New World. The crop eventually spread down to the rest of European society and has become and incredible common good in European society. One could even argue sugar had reached the status of a staple for Iberian and, in a broader sense, European society. |

贅沢品と食品 旧世界にもたらされたいくつかの商品や食品は、上流階級の贅沢な嗜好に訴えた。これらの商品を手に入れるには困難が伴うため、彼らはより高価なものを求め、富裕層の中でのエリートとしての地位を獲得した。 ココア  Philippe Sylvestre Dufour著 "Traités nouveaux & curieux du café du thé et du chocolate", 1685. チョコレートは、新世界の商品の中でも、スペイン社会、後のヨーロッパ社会に最も大きな影響を与えた商品のひとつである。1590年代には、チョコレート はイベリア半島で大きな存在感を示していた。スペインではチョコレートの習慣が広まり、嗜好品(バニラ、胡椒、赤い色、チョコレートに似た泡立ちなど)が 異文化間で伝播した。チョコレートの嗜好は、植民者や征服者が新たな先住民の嗜好に出会うことによって、ボトムアップ式に広まっていった。最初にチョコ レート液に出会ったアメリカ大陸のスペイン人は、複雑な反応を示したが、新しい味に対する愛情は、すぐにイベリア半島そのものに広がった。チョコレートの 人気が広まる方法は、半島に到達するまでに変化した。カカオはチョコレートに必要なものであったが、メソアメリカ全土で通貨の役割も果たしていた。平民が それを飲むと、悪い祈りや前兆を口にするのと同じくらい悪いこととみなされた。チョコレートは、結婚式や婚約の席で見かけるようになり、人々と関係を結ぶ ようになった。スペインの上流階級はこのチョコレートの渇望を受け入れ、下層階級はそれを模倣しようとした。原住民にとってチョコレートは宗教的な意味を 持つものであったが、スペイン人にとっては麻薬の役割を果たしていた。2つの社会がチョコレートの役割をどのように認識していたかの違いは興味深い。原住 民は宗教的な意味というレンズを通してこの液体を見たのに対し、スペイン人は経済的、料理的な利益を見たのである。1620年代には、年間何千ポンドもの チョコレートがスペインに輸入されていた。ヨーロッパのチョコレートの成分は、スペイン人が利用可能な資源(蜂蜜ではなく砂糖を甘味料として加えるなど) を反映させるために配合を変更しようとしたため、時間の経過とともに進化した。チョコレートは当初、スペイン貴族の贅沢品であったが、やがてスペイン社会 のすべての人々にとって身近な商品となった。スペイン人のチョコレートに対する最初の関心は、否定的な汚名(すなわち、チョコレートを飲むことは偶像崇拝 の一形態であるということ)によって妨げられたが、チョコレートはその後、新世界から最も望まれ、影響力のある商品のひとつとなった[2]。 砂糖 当初はインド亜大陸の作物であったが、新世界での砂糖栽培はスペイン社会に大きな影響を与えた。新世界での砂糖栽培は、スペインとポルトガルの経済力を高 めると同時に、奴隷労働(これはアフリカ、アメリカ、ヨーロッパ社会に深刻な影響を与えた)の人気を高めた。砂糖は上流階級の間で社会的地位を示す印とし て始まったが、次第に下層階級にも浸透していった。社会学者ピエール・ブルデューは、砂糖への味覚のような主観的な快楽は社会的な構成を反映し、しばしば 権力者によって決定されると論じている[3]。ブルデューの議論は、イベリア社会における砂糖の人気は、権力を握る上流階級が砂糖に価値を見出した結果で あることを確かに示唆している。 コーヒー  焙煎したコーヒー豆のアップ コーヒーは当初エチオピアの産物であったが、新大陸で栽培されるようになると、ヨーロッパの人々の間で人気が高まった。コーヒーのヨーロッパへの栽培と普 及は、15世紀にアラブ世界で始まった[4]。チョコレートのスペイン嗜好への同化は、スペインで新しいホットな刺激飲料としてコーヒーが人気を得る道を 開いた。コーヒーの輸入量は、18世紀にはチョコレートの輸入量を上回った[2]。コーヒーへの欲求は、チョコレートと同様、やがてイベリア半島のあらゆ るカーストへと広がっていった。コーヒーは、チョコレートや砂糖とともに、新世界の甘いものへの嗜好を刺激した。 タバコ  アンソニー・シュート作『Tabaco』より、タバコを吸う男性の最古の画像。 今でこそ知られているように、タバコには中毒性があった。タバコの陰湿な中毒性は、新世界の交易におけるタバコの需要を増大させた[5]。それは神々から の贈り物であると信じられており、主に宗教指導者によって使用されていた。スペイン人がタバコを商品として取引し始めたことで、この作物のダイナミズムが 変化した。タバコの需要はスペインとポルトガルの貿易網を刺激し、世界貿易におけるイベリア人の力を増大させた。世界貿易における綿花の人気がピークに達 するまで、タバコ貿易はアメリカ南東部の経済を支配した。 バニラ バニラはバニラ属のランから採れる香料で、1520年代にアステカ帝国を征服したコルテスによって初めてスペインに持ち込まれた[6]。 バニラは瞬く間にスペイン、そしてヨーロッパの他の国々で甘味料として普及した。コーヒーやチョコレートとともに、砂糖は新世界の甘い味への欲求を刺激し た。この作物はやがてヨーロッパ社会の他の地域にも広まり、ヨーロッパ社会では信じられないほどの共通財となった。砂糖はイベリア人にとって、そして広い 意味ではヨーロッパ社会にとって、主食の地位に達したとさえ言える。 |

| Staples Several foods that came from the New World rapidly became staples in Europe. Examples of European dependence on Mesoamerican foods can be found in Ireland with the potato and in Italy with the tomato. Maize  Variegated maize ears Columbus encountered and noted the cultivation of maize on all of his voyages.[7] The Aztecs and Mayans of Central America had long cultivated several forms of the crop before its introduction into Europe. Traders and merchants brought corn back to Europe in the 16th century where, due to its ability to grow in diverse regions, the crop spread rapidly in popularity. Maize became a pivotal crop in the Turkish Empire and the Balkans by the mid 16th century. Maize became a necessity for the growing Ottoman armies and was noted for its productive harvests. The fact that corn had reached the Ottoman Empire by the mid-16th century certainly suggests it was a prevalent crop in both Spain and Portugal at the time. Squash The native populations of the Americas had long relied on squash, along with corn and beans, as prime staples for their peoples. The Spanish who brought this crop back to Europe found similar practical use in the crop and adopted it as a staple. Squash was known in the Turkish Empire by 1539.[7] This could have possibly been the result of goods brought from expelled Spanish Jews and Muslims. If this is true, then it raises an interesting question about how the expulsion of Jews and Muslims from the Iberian Peninsula altered the rest of the Old World. Jews and Muslims leaving the peninsula would bring with them goods, customs, and traditions from Spain to their new homes. This certainly could have been the reason why squash had reached the Ottomans in the early 16th century. Beans While beans have long been around in Europe and Asia. Common, lima, and sieva beans are a few of the new types of beans that were introduced to Europe following Columbus's initial voyages. Natives had long recognized the protein-rich benefits of beans. The Spanish were quick to adopt the new beans into their diets. Tomatoes Tomatoes had long been popular in South America where the native peoples of Peru grew and traded them. Cortez's conquests in the 16th century resulted in the crops introduction into Spain and then Europe. The crop grew well in Mediterranean soils and quickly grew in popularity. The first discovered cookbook with tomato recipes was published in Naples in 1692.[8]: 17 Culinary historian Alan Davidson argues that the tomato and potato were initially treated with suspicion due to their similarity to the poisonous belladonna plant.[9] This explains why Spanish society was initially slow to incorporate the tomato into their diet (relative to the initial popularity of other foods, such as chocolate and maize). Turkey Spaniards had encountered domesticated turkeys in Panama in 1502.[7] These turkeys were part of a pre-existing land trade route throughout Central and South America carried out by various native peoples. The Spanish then brought the turkey back to Spain where it became a popular new type of meat eaten by the masses. New peppers Columbus had recorded at least two new types of peppers following his first voyage. Spain, following Columbus's initial encounter, gradually incorporate these new peppers into their diets and spread them throughout Europe. The spread of peppers in the Old World was dependent on pre-existing trade networks through Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Near East. The Portuguese and Ottomans were more influential in the diffusion of the Mesoamerican food complex across Europe than the Spanish (who introduced the crops in the first place). By 1543, the first European illustrations of peppers were published in a German herbal.[7] Peppers from the New World began to replace the pre-existing peppers from Africa and Asia. Potato  Russet potatoes with sprouts The tuberous crop known as the potato originated in the southern region of Peru.[10] The potato served as the principal staple crop for the Inca Empire and was met with similar popularity in the Spanish Empire. Spanish armies and workers adopted the crop as a staple because of the relative ease associated with its production. Peasants also adopted the crop as the 16th century progressed. The potato continued to spread rapidly throughout Europe where, by the 19th century, it had replaced the turnip and rutabaga as the principal food staples.[11] |

主食 新大陸からもたらされたいくつかの食品は、ヨーロッパで急速に主食となった。ヨーロッパがメソアメリカの食品に依存した例は、アイルランドのジャガイモやイタリアのトマトに見られる。 トウモロコシ  多彩なトウモロコシの穂 コロンブスはすべての航海でトウモロコシの栽培に遭遇し、その栽培について言及している[7]。中央アメリカのアステカ人とマヤ人は、ヨーロッパにトウモ ロコシが導入される以前から、いくつかの形態のトウモロコシを栽培していた。16世紀には、商人や商人がトウモロコシをヨーロッパに持ち帰り、多様な地域 で栽培できることから、トウモロコシは急速に普及した。トウモロコシは、16世紀半ばまでにトルコ帝国とバルカン半島で極めて重要な作物となった。トウモ ロコシは成長するオスマン帝国軍の必需品となり、その生産性の高さで注目された。16世紀半ばまでにトウモロコシがオスマン帝国に到達していたという事実 は、当時のスペインとポルトガルの両方でトウモロコシが普及していたことを示唆している。 カボチャ アメリカ大陸の先住民は、トウモロコシや豆類とともにカボチャを主食としていた。この作物をヨーロッパに持ち帰ったスペイン人は、この作物に同様の実用性 を見出し、主食として採用した。カボチャは1539年までにトルコ帝国でも知られるようになった。もしこれが本当なら、イベリア半島から追放されたユダヤ 人とイスラム教徒が旧世界の他の地域にどのような変化をもたらしたかについて、興味深い問題を提起することになる。イベリア半島を去ったユダヤ人とイスラ ム教徒は、スペインからの商品、習慣、伝統を新天地に持ち込むことになる。16世紀初頭にオスマン・トルコにスカッシュが伝わったのも、確かにこれが理由 だったかもしれない。 豆 豆の歴史は古く、ヨーロッパでもアジアでも食べられてきた。コモン・ビーンズ、リマ・ビーンズ、シーバ・ビーンズは、コロンブスの最初の航海後にヨーロッ パに持ち込まれた新しい種類の豆の一部である。原住民は、豆のタンパク質が豊富な利点を長い間認識していた。スペイン人は、この新しい豆をすぐに食生活に 取り入れた。 トマト トマトは南米ペルーで古くから親しまれていた。16世紀のコルテスの征服により、トマトはスペイン、そしてヨーロッパに導入された。この作物は地中海の土 壌でよく育ち、急速に人気が高まった。トマトのレシピが掲載された最初の料理本は、1692年にナポリで出版された[8]: 17 料理史家のアラン・デヴィッドソンは、トマトとジャガイモは当初、ベラドンナという有毒植物に似ていることから、疑いの目で扱われていたと主張している [9]。 このことから、スペイン社会が当初、トマトを食生活に取り入れるのに時間がかかったことが説明できる(チョコレートやトウモロコシなど、他の食品の当初の 人気と比較すると)。 トルコ スペイン人は1502年にパナマで家畜化された七面鳥に遭遇した[7]。この七面鳥は、様々な先住民によって中南米全域に渡って行われていた陸上交易ルー トの一部であった。その後、スペイン人は七面鳥をスペインに持ち帰り、大衆が食べる新しいタイプの肉として人気を博した。 新しいトウガラシ コロンブスは最初の航海の後、少なくとも2種類の新しいトウガラシを記録していた。スペインは、コロンブスの最初の出会いに続いて、これらの新しいトウガ ラシを徐々に食生活に取り入れ、ヨーロッパ全土に広めた。旧世界におけるトウガラシの普及は、ヨーロッパ、アフリカ、アジア、近東を結ぶ既存の貿易ネット ワークに依存していた。ポルトガル人とオスマン・トルコ人は、(最初に作物を導入した)スペイン人よりも、メソアメリカの食品複合体のヨーロッパ全土への 普及に大きな影響力を持った。1543年までには、ヨーロッパ初のトウガラシの図版がドイツの薬草に掲載された[7]。新大陸産のトウガラシが、アフリカ やアジア産の既存のトウガラシに取って代わり始めた。 ジャガイモ  新芽のついたラセットポテト ジャガイモとして知られる塊茎作物はペルー南部が原産地である[10]。ジャガイモはインカ帝国の主要な主食作物であり、スペイン帝国でも同様の人気を博 した。スペインの軍隊と労働者は、その生産に関連する比較的容易なことから、主食としてこの作物を採用した。16世紀に入ると、農民もこの作物を採用し た。ジャガイモはヨーロッパ全土に急速に普及し続け、19世紀にはカブとルタバガに代わって主食となった[11]。 |

| Other influential goods The influence of goods and foods from the Americas spread into other aspects of Iberian life aside from playing lavish and staple roles. Cotton Cotton was originally cultivated by the inhabitants of the Indus Valley. While Europe had contact with the crop before the discovery of the New World, its use and popularity increased dramatically following the incorporation of cotton plantations on newly quired American lands. Columbus encountered woven cotton fabrics in Nicaragua and Honduras during his fourth voyages.[7] While cotton's spread into Europe was gradual, it came to revolutionize fabric production in the Old World. This crop, along with many others in the Americas, led to an increasing demand for slave labor. Cotton would reach the peak of its cultivation during the Industrial Revolution in Europe. Rubber Rubber was originally cultivated by the Olmec people of Mesoamerica. This was usually done by draining the sap from rubber trees. Rubber did not have an early noticeable impact on the Iberian people. The fact that the Pará rubber tree initially only grew in the Amazon Rainforest. It would not be until the 19th century that the tree was able to be grown in a non-Brazilian area. Flow of knowledge While not necessarily a good, the flow of knowledge from the New World that came with the introduction of new foods had an enormous influence on Iberian and European society. The knowledge on how to cultivate new foods was essential in the early spread of Mesoamerican goods into Iberian society. It is reasonable to assume that the influx of knowledge added new professions to Iberian society while changing the way pre-existing professions operated, especially in regards to agriculture. |

その他の影響力のある商品 アメリカ大陸からの商品や食品の影響は、贅沢品や主食としての役割以外にも、イベリア人の生活の他の側面にも広がっていった。 綿花 綿花はもともとインダス渓谷の住民によって栽培されていた。ヨーロッパは新大陸発見以前から綿花と接触していたが、新たに開拓されたアメリカの土地に綿花 プランテーションが組み込まれたことで、その使用と人気は飛躍的に高まった。コロンブスは4回目の航海中にニカラグアとホンジュラスで綿織物に出会った [7]。ヨーロッパへの綿花の普及は緩やかなものであったが、綿花は旧世界の織物生産に革命をもたらした。この作物は、アメリカ大陸の他の多くの作物とと もに、奴隷労働の需要を増大させた。綿花は、ヨーロッパの産業革命期に栽培のピークを迎えることになる。 ゴム ゴムはもともとメソアメリカのオルメカ人によって栽培されていた。これは通常、ゴムの木から樹液を抜くことによって行われた。ゴムは、イベリア半島の人々 には早くから目立った影響を与えなかった。パラゴムの木は当初、アマゾンの熱帯雨林にしか生えていなかったからだ。この木がブラジル以外の地域で栽培され るようになったのは、19世紀になってからである。 知識の流れ 必ずしも良いことではないが、新しい食べ物の伝来とともにもたらされた新大陸からの知識の流れは、イベリア社会とヨーロッパ社会に多大な影響を与えた。新 しい食品の栽培方法に関する知識は、メソアメリカの商品がイベリア社会に早くから広まる上で不可欠なものであった。知識の流入は、イベリア社会に新たな職 業を加える一方で、特に農業に関して、既存の職業の運営方法を変えたと考えるのが妥当である。 |

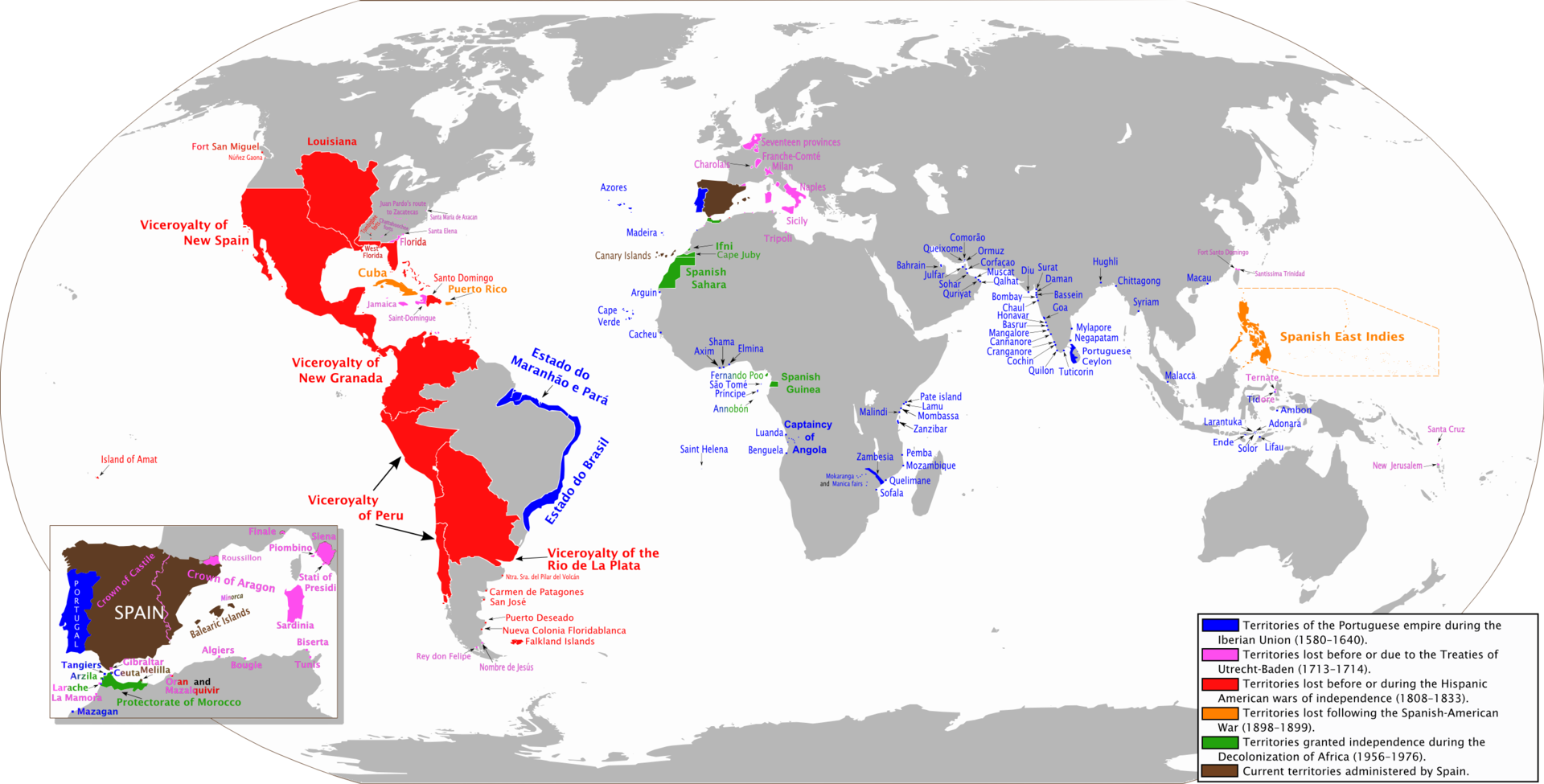

| Non-social consequences The influx of new goods and foods into 16th-century Spain and Portugal had significant effects on other aspects of Iberian history besides merely the society. Economic impact  Spanish Currency Spain and Portugal, having been the first two European nations to begin trading New World goods, developed impressive economies as a result of their control over the trade of American goods and foods in the early 16th century. Cravings for New World stimulants such as coffee and sugar may have motivated people to work harder to obtain money to supply these new habits. Along with this, the accessory implements that were necessary for many of these new goods (such as tobaccos and coffee) led to a new professions aimed at manufacturing clay pipes, snuffboxes, porcelain chocolate pots etc.[2] The Spanish and Portuguese capitalized upon every opportunity to extract revenue back to their empires; utilizing forced labor. When the Pope banned the use of forced labor by the natives, Spanish and Portuguese entrepreneurs turned to the African Slavery. The demand for New World goods, such as chocolate, led to an enormous growth in the transatlantic slave trade during the 16th and 17th centuries. The slave trade had devastating effects on the societies of several African nations. The Spanish crown applied the tactic of extraction to keep cost at ultimate low, which led to political corruption in their colonies and back at home. Patch summarizes it as, “an entire commercial system based on government official came into existence.”[12] Spain extractive method of its colonies would soon be problematic and outdated, as new global players would become involved in the Americas. The Spanish colonial system and economic dependency for raw materials would hinder Spain's commercial markets. Spain would place less emphasis on their colonies in North America due to its lack of mineral wealth and would use them to as buffers to protect ports and other colonies further south. Weber highlights the flaw when stating, “The economic malaise that affected Spain’s North American colonies reflected the weakness of the Spanish economy itself, built traditionally on the exportation of raw materials and the importation of manufactured goods.”[13] Spanish economy back at home, spiraling with inflation, would become dependent upon foreign imports and manufactured goods. The significant amount of silver brought back to Spain and Portugal created inflation in Europe. For Spain, the period is referred to as Spanish price revolution. the Spanish inflation had raised domestic manufactures and made them uncompetitive. Spain's colonial agenda of extraction would lead to its inability to supply its colonies and subjects at home. Weber builds upon the Spanish inability to capitalize commercial markets when stating, “The cost of transportation plus profits for numerous middlemen and additional internal custom duties (alcabalas) along the way drove the price of some items to many time their Verecruz or Mexico City value by the time they reached the frontier.”[14] The crown's inability to establish efficient trading route and placement of high tariffs would discourage merchants and traders from legitimate business practices. Spain's colonies in the Americas would soon suffer as merchants and traders would turn to other forms of trade. Weber summarizes it when stating, “For suppliers and consumers alike, such artificially high prices made smuggling so attractive that perhaps two-thirds of all commerce throughout the Spanish empire consisted of illegal trade, much of it with foreigner… it increased as English and French merchants grew more numerous and proximate.”[14] Religious impact The abundance of meat in Spanish America led to the use of animal fats over olive oil in cooking. Pope Pius III, in recognition of the meat basis for their diet, granted a thirty-year exemption from fasting for the colonists. This led to a further reliance on meat in the Spanish American diet and persisted to be a common occurrence in the cuisine following the thirty-year mark.[1] Similarly, the Catholic restriction on meat on Fridays led to new innovations in cuisine using newly discovered American foodstuffs. State impact  An anachronous map showing areas pertaining to the Spanish Empire at various times over a period exceeding 400 years. Despite the mutual trade exclusion that existed between Spain and Portugal in the early 16th century, Portuguese merchants still acquired goods from the Spanish. This led to a Portuguese dominance on the pepper trade within Europe. The Portuguese trade with the New World flourished despite the Treaty of Tordesillas due to illicit trade and Spanish permission to Portuguese merchants to bring African slaves and other trade goods into the colonies.[7] This obvious disregard towards sanctions on trade didn't signify inherent disloyalty, but was a necessity for those whose livelihoods depended on such trade. The trade underground trade between Spain and Portugal was heightened by the African slave trade and became well established as mutually beneficial crops (such as maize, grains, squash, and beans were traded between the nations). Venice, Genoa, and Florence (among other Old World nations) depended on Iberians for New world goods in the early 16th century.[7] If not for the incorporation of American "miracle foods", Europe may have not pulled out of its 16th-century cycles of hunger and starvation.[1] The dependence on Spain and Portugal for New World goods perpetuated their colonization throughout the world. This, in turn, led to Spain and Portugal becoming the two leading world powers in the 16th and 17th centuries. The enormous wealth being extracted from the Americas and poured into the Spanish society would lead to corruption at home and in the colonies. Corruption and accumulation of vast resources at the top of the food chain had some ripple effects throughout the core countries. Corruption ran high from the top of the system, beginning from the crown in Spain and spread throughout the colonies. Royals, elites, government officials, and merchants grew significantly wealthy in a short period of time. Patch points out that, “State played a leading role in capital accumulation under colonialism. “Corruption” was therefore an integral and necessary part of the state system.”[12] Government officials played a key role in the system in which they helped mobilize and invest capital, channeled the surplus away from the producers, and then split the profits with their merchant partners. Merchant status increased as corruption increased, playing a key role in spreading different commodities and ideas. One recorded instances of corruption occurred when the Crown needed revenue such as in times of war. The Sale of Magistracies began in the 1670s, when the government of the last Habsburg king, Charles II, introduced the measure in a desperate attempt to tap all possible sources of revenue.[12] Technically not sold but a post was usually granted to worthy subject who had performed monetary service for the king. Corruption ran high as the sale of a post became more commonly sold then given away. Cultural impact By the late 1630s, it was increasingly common to find depictions of chocolate accouterments in still life paintings.[2] |

社会以外の影響 16世紀のスペインとポルトガルに流入した新しい商品や食品は、単に社会だけでなく、イベリア史の他の側面にも大きな影響を与えた。 経済的影響  スペインの通貨 スペインとポルトガルは、新世界の商品貿易を始めた最初のヨーロッパ2カ国であり、16世紀初頭にアメリカの商品と食品の貿易を支配した結果、印象的な経 済を発展させた。コーヒーや砂糖のような新世界の刺激物への渇望が、こうした新しい習慣を供給するための資金を得るために、人々をより懸命に働かせる動機 になったのかもしれない。これとともに、これらの新しい商品の多く(タバコやコーヒーなど)に必要だった付属器具は、土管、嗅ぎたばこ入れ、磁器のチョコ レートポットなどを製造することを目的とした新しい職業につながった[2]。 スペインとポルトガルは、強制労働を利用することで、自分たちの帝国に収益を還元するあらゆる機会を利用した。ローマ教皇が原住民による強制労働の使用を 禁止すると、スペインとポルトガルの企業家たちはアフリカの奴隷制度に目を向けた。チョコレートのような新世界の商品への需要が、16世紀から17世紀に かけての大西洋横断奴隷貿易の巨大な成長につながった。奴隷貿易はアフリカ諸国の社会に壊滅的な影響を与えた。スペイン王室は、究極的にコストを低く抑え るために、奴隷の引き抜きという戦術をとった。パッチは、「政府の役人に基づいた商業システム全体が存在するようになった」と要約している[12]。スペ インの植民地抽出法は、新しいグローバルプレーヤーがアメリカ大陸に関与するようになると、すぐに問題となり、時代遅れになる。スペインの植民地システム と原材料への経済的依存は、スペインの商業市場を阻害することになる。スペインは鉱物資源に乏しい北米の植民地をあまり重視せず、より南の港や他の植民地 を守るための緩衝材として利用するようになる。ウェーバーは、「スペインの北アメリカ植民地に影響を及ぼした経済的不調は、伝統的に原材料の輸出と製造品 の輸入で成り立ってきたスペイン経済そのものの弱点を反映していた」[13]と述べ、その欠陥を強調している。スペインとポルトガルに持ち帰られた大量の 銀は、ヨーロッパにインフレをもたらした。スペインにとって、この時期はスペイン価格革命と呼ばれている。スペインのインフレは国内製造業を引き上げ、競 争力を失わせた。スペインの植民地政策である採掘は、自国の植民地や臣民への供給能力を失わせることになった。ウェーバーは、「輸送費に加え、多数の仲買 人の利益、さらに途中の内国関税(alcabalas)が、辺境に到着するまでに、いくつかの品目の価格をヴェレクルズやメキシコシティの価格の何倍にも 押し上げた」と述べている[14]。効率的な交易ルートを確立できず、高い関税を課した王室は、商人や貿易商の合法的な商行為を思いとどまらせた。スペイ ンのアメリカ大陸の植民地は、商人や貿易商が他の貿易形態に目を向けるようになり、すぐに苦境に立たされることになる。ウェーバーは、「供給者にとっても 消費者にとっても、このような人為的に高く設定された価格が密貿易を魅力的なものにし、スペイン帝国全体の商業のおそらく3分の2が違法な貿易で構成さ れ、その多くが外国人とのものであった。 宗教的影響 スペイン領アメリカでは肉が豊富だったため、料理にはオリーブオイルよりも動物性油脂が使われるようになった。ローマ教皇ピウス3世は、彼らの食生活が肉 食中心であったことを認め、植民者たちに30年間の断食免除を与えた。同様に、カトリックが金曜日に肉を制限したことで、新しく発見されたアメリカの食材 を使った料理に新たな革新が生まれた。 国家による影響  時代錯誤(=時代を貫いた)の地図で、400年以上にわたって様々な時期にスペイン帝国に属していた地域を示している。 16世紀初頭にスペインとポルトガルの間に存在した相互貿易排除にもかかわらず、ポルトガル商人は依然としてスペインから商品を入手していた。その結果、 ヨーロッパにおける胡椒貿易はポルトガルの優位に立った。トルデシリャス条約にもかかわらずポルトガルの新大陸貿易が盛んになったのは、不法貿易と、ポル トガル商人がアフリカ人奴隷やその他の貿易品を植民地に持ち込むことをスペインが許可したためである[7]。このような貿易に対する制裁に対する明らかな 無視は、本質的な不誠実を意味するものではなく、そのような貿易によって生計を立てていた人々にとっては必要なことであった。スペインとポルトガルの地下 貿易はアフリカの奴隷貿易によって盛んになり、相互に有益な作物(トウモロコシ、穀物、カボチャ、豆など)が国家間で取引されるようになった。ヴェネツィ ア、ジェノヴァ、フィレンツェ(他の旧世界諸国を含む)は、16世紀初頭、新世界の商品をイベリア人に依存していた[7]。もしアメリカの「奇跡の食品」 が取り入れられていなければ、ヨーロッパは16世紀の飢餓と飢餓のサイクルから抜け出せなかったかもしれない。その結果、スペインとポルトガルは16世紀 から17世紀にかけて世界をリードする2大国となった。 アメリカ大陸から引き出された莫大な富はスペイン社会に注ぎ込まれ、国内と植民地の腐敗を招くことになる。食物連鎖の頂点における腐敗と莫大な資源の蓄積 は、中核国全体にいくつかの波及効果をもたらした。腐敗はスペイン王室から始まり、植民地全体に広がった。王族、エリート、政府高官、商人たちは短期間で 著しく裕福になった。パッチは、「植民地主義下の資本蓄積において、国家が主導的な役割を果たした」と指摘する。したがって、"腐敗 "は国家システムに不可欠で必要な部分であった」[12]。政府高官は、資本を動員し投資するのを助け、余剰を生産者から引き離し、商人パートナーと利益 を分配するというシステムにおいて重要な役割を果たした。腐敗が進むにつれて商人の地位は高まり、さまざまな商品や思想を広める上で重要な役割を果たし た。記録されている腐敗の事例のひとつは、戦争時など王室が歳入を必要としたときに起こったものである。1670年代、ハプスブルク家最後の国王シャルル 2世の政府が、可能な限りの歳入源を掘り起こそうと必死の試みで導入したこの措置によって、司法権の売却が始まった[12]。技術的には売却されたわけで はないが、通常、国王のために金銭的な奉仕をした立派な臣下には、その地位が与えられた。ポストの売却が一般的になり、その後譲渡されるようになったた め、汚職が蔓延した。 文化的影響 1630年代後半になると、静物画にチョコレートの装飾品が描かれることが多くなった[2]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Early_impact_of_Mesoamerican_goods_in_Iberian_society |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆