制度的人種主義・体系的人種主義

【詳細解説編】システミック・レイシズム; Institutional racism, systemic racism 「アメリカ合衆国における制度的人種主義」はこちら

Ku Klux Klan members, on foot and horseback, by a cross erected in a field near Kingston, Ontario in 1927

☆制度的人種差別は体系的人種主義(システミック・レイシズム)とも呼ばれる。制度的人種差 別は、社会全体や組織全体に存在する政策や慣行であり、その結果、一部の人々が不当に有利になり、他の人々が人種に基づいて不当または有害な扱いを受け続 けることを支持するものと定義される。それは刑事司法、雇用、住宅、医療、教育、政治的代表などの分野における差別として現れる(→「アメリカ合衆国における制度的人種主義」)。

☆「人種」が非科学的な恣意区分であると承認することが「人種[区分]に基づく差別」を撤廃できるとは限らない.人種差別(人種主義)を行う側に科学とは無関係の意図的な権力の操作があるからだ.この意図的な区分がどのように自然主義的態度に直結するのかその論理を分析せねばならぬ.

| ★Institutional

racism, also known as systemic racism, is defined as policies and

practices that exist throughout a whole society or organization that

result in and support a continued unfair advantage to some people and

unfair or harmful treatment of others based on race. It manifests as

discrimination in areas such as criminal justice, employment, housing,

healthcare, education and political representation.[1] The term institutional racism was first coined in 1967 by Stokely Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton in Black Power: The Politics of Liberation.[2] Carmichael and Hamilton wrote in 1967 that, while individual racism is often identifiable because of its overt nature, institutional racism is less perceptible because of its "less overt, far more subtle" nature. Institutional racism "originates in the operation of established and respected forces in the society, and thus receives far less public condemnation than [individual racism]".[3] Institutional racism was defined by Sir William Macpherson in the UK's Lawrence report (1999) as: "The collective failure of an organisation to provide an appropriate and professional service to people because of their colour, culture, or ethnic origin. It can be seen or detected in processes, attitudes and behaviour that amount to discrimination through prejudice, ignorance, thoughtlessness, and racist stereotyping which disadvantage minority ethnic people."[4][5]  On Saturday 14 July 2018 a Stand Up To Racism rally was staged to oppose the gathering of a large number of far right demonstrators in London who were demanding the release of the extreme nationalist Tommy Robinson from prison where he had been jailed for contempt of court. |

制度的人種差別(システミック・レイシズム)とも呼ばれる制度的人種差

別は、社会全体や組織全体に存在する政策や慣行であり、その結果、一部の人々が不当に有利になり、他の人々が人種に基づいて不当または有害な扱いを受け続

けることを支持するものと定義される。それは刑事司法、雇用、住宅、医療、教育、政治的代表などの分野における差別として現れる[1]。 制度的人種差別という用語は、1967年にストークリー・カーマイケルとチャールズ・V・ハミルトンが『ブラック・パワー:解放の政治学』の中で初めて用 いたものである[2]。 カーマイケルとハミルトンは1967年に、個人的人種差別はそのあからさまな性質のためにしばしば識別可能であるが、制度的人種差別は「あからさまではな く、はるかに微妙な」性質のために知覚しにくいと書いている。制度的人種主義は「社会で確立され、尊敬されている勢力の運営に由来するものであり、した がって[個人的人種主義]よりも世間から非難されることははるかに少ない」[3]。 制度的人種主義は、イギリスのローレンス報告書(1999年)でウィリアム・マクファーソン卿によって次のように定義された: 「肌の色、文化、民族的出身を理由に、適切で専門的なサービスを人々に提供できない組織の集団的失敗。それは、少数民族の人々に不利益を与える偏見、無 知、無思慮、人種差別的なステレオタイプによる差別に相当するプロセス、態度、行動において見られたり、発見されたりする」[4][5]。  2018年7月14日(土)、極端な民族主義者であるトミー・ロビンソンが法廷侮辱罪で収監されていた刑務所からの釈放を要求する極右デモ隊がロンドンに多数集まったことに反対するため、Stand Up To Racism集会が開催された。 |

| Classification In the past, the term "racism" was often used interchangeably with "prejudice," forming an opinion of another person based on incomplete information. In the last quarter of the 20th Century, racism became associated with systems rather than individuals. In 1977, David Wellman in his book Portraits of White Racism, defined racism as "a system of advantage based on race," illustrating this definition through countless examples of white people supporting racist institutions while denying that they are prejudiced. White people can be nice to people of color while continuing to uphold systemic racism that benefits them, such as lending practices, well-funded schools, and job opportunities.[6] The concept of institutional racism re-emerged in political discourse in the mid and late 1990s, but has remained a contested concept.[7] Institutional racism is where race causes a different level of access to the goods, services, and opportunities of society.[8] Professor James M. Jones theorised three major types of racism: personally mediated, internalized, and institutionalized.[9] Personally mediated racism includes the deliberate specific social attitudes to racially prejudiced action (bigoted differential assumptions about abilities, motives, and the intentions of others according to their race), discrimination (the differential actions and behaviours towards others according to their race), stereotyping, commission, and omission (disrespect, suspicion, devaluation, and dehumanization). Internalized racism is the acceptance, by members of the racially stigmatized people, of negative perceptions about their own abilities and intrinsic worth, characterized by low self-esteem, and low esteem of others like them. This racism can be manifested through embracing "whiteness" (e.g. stratification by skin colour in non-white communities), self-devaluation (e.g., racial slurs, nicknames, rejection of ancestral culture, etc.), and resignation, helplessness and hopelessness (e.g., dropping out of school, failing to vote, engaging in health-risk practices, etc.).[10] Persistent negative stereotypes fuel institutional racism and influence interpersonal relations. Racial stereotyping contributes to patterns of racial residential segregation and redlining, and shapes views about crime, crime policy and welfare policy, especially if the contextual information is stereotype-consistent.[11] Institutional racism is distinguished from racial bigotry by the existence of systemic, institutionalized policies, practices and economic and political structures that place minority racial and ethnic groups at a disadvantage in relation to an institution's racial or ethnic majority. One example of the difference is public school budgets in the United States (including local levies and bonds) and the quality of teachers, which are often correlated with property values: Rich neighborhoods are more likely to be more "white" and to have better teachers and more money for education, even in public schools. Restrictive housing contracts and bank lending policies have also been listed as forms of institutional racism. Other examples sometimes described as institutional racism are racial profiling by security guards and police,[12] use of stereotyped racial caricatures, the under- and misrepresentation of certain racial groups in the mass media, and race-based barriers to gainful employment and professional advancement. Additionally, differential access to goods, services and opportunities of society can be included within the term "institutional racism", such as unpaved streets and roads, inherited socio-economic disadvantage and standardized tests (each ethnic group prepared for it differently; many are poorly prepared).[13] Some sociological[14] investigators distinguish between institutional racism and "structural racism" (sometimes referred to as "structured racialization").[15] The former focuses upon the norms and practices within an institution, and the latter upon the interactions among institutions, which interactions produce racialized outcomes against non-white people.[16] An important feature of structural racism is that it cannot be reduced to individual prejudice or to the single function of an institution.[17][citation needed] D. C. Matthew has argued in favor of "distinguishing between 'intrinsic institutional racism', which holds that institutions are racist in virtue of their constitutive features, and 'extrinsic institutional racism', which holds that institutions are racist in virtue of their negative effects."[18] |

分類 かつて「人種差別」という言葉は、不完全な情報に基づいて他人に対して意見を形成する「偏見」と同じ意味で使われることが多かった。20世紀の最後の4分 の1では、人種差別は個人というよりむしろシステムと関連づけられるようになった。1977年、デイヴィッド・ウェルマンは著書『白人差別の肖像』の中 で、人種差別を「人種に基づく優位のシステム」と定義し、白人が偏見を持っていることを否定しながら人種差別的な制度を支持している無数の例を通して、こ の定義を説明した。白人は有色人種に親切である一方で、融資慣行、資金が潤沢に提供される学校、雇用機会など、自分たちに利益をもたらす制度的人種差別を 支持し続けることができる[6]。制度的人種差別の概念は、1990年代半ばから後半にかけて政治的言説の中に再び登場したが、依然として論争が絶えない 概念である[7]。 制度的人種差別とは、人種によって社会の財、サービス、機会へのアクセスが異なるレベルになることである[8]。 ジェームズ・M・ジョーンズ教授は人種差別の3つの主要なタイプを理論化した:個人的媒介、内面化、制度化[9]。個人的媒介の人種差別には、人種的偏見 に基づく行動(人種による他者の能力、動機、意図についての偏見に満ちた差のある思い込み)、差別(人種による他者への差のある行動や振る舞い)、ステレ オタイプ、任務、不作為(軽蔑、猜疑、切り捨て、非人間化)に対する意図的な特定の社会的態度が含まれる。内面化された人種主義とは、人種的汚名を着せら れた人々が、自分自身の能力や本質的な価値について否定的な認識を受け入れることであり、低い自尊心や、自分と同じような他者に対する低い評価を特徴とす る。この人種差別は、「白人らしさ」の受容(例えば、非白人コミュニティにおける肌の色による階層化)、自己評価(例えば、人種的中傷、あだ名、先祖代々 の文化の拒絶など)、あきらめ、無力感、絶望感(例えば、退学、選挙に行かない、健康リスクの高い習慣に従事するなど)を通して現れることがある [10]。 根強い否定的な固定観念は、制度的人種差別に拍車をかけ、対人関係に影響を及ぼす。人種的ステレオタイプは、人種的居住分離や赤線引きのパターンに寄与 し、犯罪、犯罪政策、福祉政策についての見解を形成する。 制度的人種主義は、制度化された政策、慣行、経済的・政治的構造の存在によって人種的偏見と区別され、マイノリティの人種的・民族的集団を、ある機関のマ ジョリティの人種的・民族的集団との関係において不利な立場に置くものである。その違いの一例として、米国の公立学校予算(地方交付税や地方債を含む)や 教師の質が挙げられるが、これらはしばしば資産価値と相関関係にある: 裕福な地域は「白人」が多く、公立学校であってもより良い教師が多く、教育費も多い。制限的な住宅契約や銀行の融資政策も、制度的人種差別の一形態として 挙げられている。 その他、警備員や警察による人種プロファイリング、ステレオタイプ化された人種風刺画の使用[12]、マスメディアにおける特定の人種集団の過小評価や 誤った表現、有給の雇用や職業上の昇進に対する人種に基づく障壁などが、制度的人種主義と表現されることがある。さらに、舗装されていない道や道路、受け 継がれた社会経済的不利、標準化されたテスト(各民族グループはそれに対する準備が異なっており、多くの人々は準備不足である)など、社会の財やサービ ス、機会への差のあるアクセスも「制度的人種差別」という用語に含めることができる[13]。 社会学[14]の研究者の中には、制度的人種差別と「構造的人種差別」(「構造化された人種化」と呼ばれることもある)を区別する者もいる[15]。前者 は制度内の規範や慣行に焦点を当て、後者は制度間の相互作用に焦点を当て、その相互作用が非白人に対する人種化された結果を生み出している[16]。構造 的人種差別の重要な特徴は、それが個人の偏見や制度の単一の機能には還元できないということである[17][要出典]。 D. C.マシューは「制度がその構成的特徴によって人種差別的であるとする『内在的制度的人種主義』と、制度がその否定的効果によって人種差別的であるとする 『外在的制度的人種主義』とを区別する」ことを支持している[18]。 |

Algeria The French political thinker Alexis de Tocqueville (1805–1859) supported colonization in general, and particularly the colonization of Algeria. In several speeches on France's foreign affairs, in two official reports presented to the National Assembly in March 1847 on behalf of an ad hoc commission, and in his voluminous correspondence, he repeatedly commented on and analyzed the issue. In short, Tocqueville developed a theoretical basis for French expansion in North Africa.[19] He even studied the Koran, sharply concluding that Islam was "the main cause of the decadence... of the Muslim world". His opinions are also instructive about the early years of the French conquest and how the colonial state was first set up and organized. Tocqueville emerged as an early advocate of "total domination" in Algeria and subsequent "devastation of the country".[20] On 31 January 1830, Charles X capturing Algiers made the French state thus begin what became institutional racism directed at the Kabyle, or Berbers, of Arab descent in North Africa. The Dey of Algiers had insulted the monarchy by slapping the French ambassador with a fly whisk, and the French used that pretext to invade and to put an end to piracy in the vicinity. The unofficial objective was to restore the prestige of the French crown and gain a foothold in North Africa, thereby preventing the British gaining advantage over France in the Mediterranean. The July Monarchy, which came to power in 1830, inherited that burden. The next ten years saw the indigenous population subjected to the might of the French army. By 1840, more conservative elements gained control of the government and dispatched General Thomas Bugeaud, the newly appointed governor of the colony, to Algeria, which marked the real start of the country's conquest. The methods employed were atrocious; the army deported villagers en masse, massacred the men and raped the women, took the children hostage, stole livestock and harvests and destroyed orchards. Tocqueville wrote, "I believe the laws of war entitle us to ravage the country and that we must do this, either by destroying crops at harvest time, or all the time by making rapid incursions, known as raids, the aim of which is to carry off men and flocks."[21] Tocqueville added: "In France I have often heard people I respect, but do not approve, deplore [the army] burning harvests, emptying granaries and seizing unarmed men, women and children. As I see it, these are unfortunate necessities that any people wishing to make war on the Arabs must accept."[22] He also advocated that "all political freedoms must be suspended in Algeria".[23] Marshal Bugeaud, who was the first governor-general and also headed the civil government, was rewarded by the King for the conquest and having instituted the systemic use of torture, and following a "scorched earth" policy against the Arab population. |

アルジェリア アレクシス・ド・トクヴィル フランスの政治思想家アレクシス・ド・トクヴィル(1805-1859)は、植民地化全般、特にアルジェリアの植民地化を支持した。フランスの外交問題に 関するいくつかの演説、1847年3月に特別委員会を代表して国民議会に提出した2つの公式報告書、そして膨大な書簡の中で、彼は繰り返しこの問題につい てコメントし、分析した。要するに、トクヴィルはフランスの北アフリカ進出の理論的基礎を築いたのである[19]。 彼はコーランまで研究し、イスラム教が「イスラム世界の...退廃の主な原因」であると鋭く結論づけた。彼の意見は、フランスによる征服の初期や、植民地 国家が最初にどのように設立され組織化されたかについても示唆に富んでいる。トクヴィルはアルジェリアにおける「完全な支配」とそれに続く「国の荒廃」の 初期の擁護者として登場した[20]。 1830年1月31日、アルジェを占領したシャルル10世はフランス国家を成立させ、北アフリカのアラブ系カビル人(ベルベル人)に対する制度的人種差別 を開始した。アルジェのデーがフランス大使をハエたたきでひっぱたいて王政を侮辱したため、フランスはこれを口実にアルジェに侵攻し、付近での海賊行為に 終止符を打った。非公式な目的は、フランス王家の威信を回復し、北アフリカに足場を築くことで、地中海でイギリスがフランスに対して優位に立つのを防ぐこ とだった。1830年に誕生した7月王政は、その重荷を引き継いだ。その後10年間、先住民はフランス軍の威力にさらされた。1840年になると、保守派 が政権を掌握し、新たに植民地総督に任命されたトマ・ブジョー将軍をアルジェリアに派遣した。軍隊は村人を集団で追放し、男性を虐殺し、女性をレイプし、 子供を人質にとり、家畜や収穫物を盗み、果樹園を破壊した。トクヴィルは、「私は、戦争法が我々にこの国を荒らす権利を与えており、収穫期に農作物を破壊 することによって、あるいは襲撃として知られる急速な侵入を常に行うことによって、これを行わなければならないと信じている。 トクヴィルはさらに、「フランスでは、私が尊敬する、しかし賛成はしない人々が、(軍隊が)収穫物を焼き、穀物庫を空にし、非武装の男、女、子供を捕らえ ることを嘆くのをしばしば耳にした。また、「アルジェリアではすべての政治的自由を停止しなければならない」とも主張した[23]。初代総督であり、民政 の責任者でもあったビュゴー元帥は、征服と組織的な拷問の実施、アラブ人に対する「焦土化」政策によって国王から褒賞を受けた。 |

| Land grab Once the conquest of Algiers was accomplished, soldier-politician Bertrand Clauzel and others formed a company to acquire agricultural land and, despite official discouragement, to subsidise its settlement by European farmers, which triggered a land rush. He became governor general in 1835 and used his office to make private investments in land by encouraging bureaucrats and army officers in his administration to do the same. The development created a vested interest in government officials for greater French involvement in Algeria. Merchants with influence in the government also saw profit in land speculation, which resulted in expanding the French occupation. Large agricultural tracts were carved out, and factories and businesses began exploiting cheap local labour and also benefited from laws and edicts that gave control to the French. The policy of limited occupation was formally abandoned in 1840 and replaced by one of complete control. By 1843, Tocqueville intended to protect and extend expropriation by the rule of law and so advocated setting up special courts, which were based on what he called "summary" procedure, to carry out a massive expropriation for the benefit of French and other European settlers. French and other European settlers could thus purchase land at attractive prices and live in villages, which the colonial government had equipped with fortifications, churches, schools and even fountains. Tocqueville's belief, which framed his writings and influenced state actions, was that the local people, who had been driven out by the army and robbed of their land by the judges, would gradually die out.[24][citation needed] The French colonial state, as he conceived it and as it took shape in Algeria, was a two-tiered organization, quite unlike the regime in Mainland France. It introduced two different political and legal systems that were based on racial, cultural and religious distinctions. According to Tocqueville, the system that should apply to the Colons would enable them alone to hold property and travel freely but would deprive them of any form of political freedom, which should be suspended in Algeria. "There should therefore be two quite distinct legislations in Africa, for there are two very separate communities. There is absolutely nothing to prevent us treating Europeans as if they were on their own, as the rules established for them will only ever apply to them".[25] Following the defeats of the resistance in the 1840s, colonisation continued apace. By 1848, Algeria was populated by 109,400 Europeans, only 42,274 of whom were French.[26] The leader of the Colons delegation, Auguste Warnier (1810–1875), succeeded in the 1870s in modifying or introducing legislation to facilitate the private transfer of land to settlers and continue Algeria's appropriation of land from the local population and distribution to settlers. Europeans held about 30% of the total arable land, including the bulk of the most fertile land and most of the areas under irrigation.[27] In 1881, the Code de l'Indigénat made the discrimination official by creating specific penalties for indigenes and by organising the seizure or appropriation of their lands.[28] By 1900, Europeans produced more than two-thirds of the value of output in agriculture and practically all of the agricultural exports. The colonial government imposed more and higher taxes on Muslims than on Europeans.[29] The Muslims, in addition to paying traditional taxes dating from before the French conquest, also paid new taxes from which the Colons were normally exempted. In 1909, for instance, Muslims, who made up almost 90% of the population but produced 20% of Algeria's income, paid 70% of direct taxes and 45% of the total taxes collected. Also, Colons controlled how the revenues would be spent and so their towns had handsome municipal buildings, paved streets lined with trees, fountains and statues, but Algerian villages and rural areas benefited little, if at all, from tax revenues.[30] In education The colonial regime proved severely detrimental to overall education for Muslims, who had previously relied on religious schools to learn reading, writing and religion. In 1843, the state appropriated the habus lands, the religious foundations that constituted the main source of income for religious institutions, including schools, but colonial officials refused to allocate enough money to maintain schools and mosques properly and to provide for enough teachers and religious leaders for the growing population. In 1892, more than five times as much was spent for the education of Europeans as for Muslims, who had five times as many children of school age. Because few Muslim teachers were trained, Muslim schools were largely staffed by French teachers. Even a state-operated madrasa often had French faculty members. Attempts to institute bilingual and bicultural schools, intended to bring Muslim and European children together in the classroom, were a conspicuous failure, and were rejected by both communities and phased out after 1870. According to one estimate, fewer than 5% of Algerian children attended any kind of school in 1870. As late as 1954, only one Muslim boy in five and one girl in sixteen received formal schooling.[31] Efforts were begun by 1890 to educate a small number of Muslims along with European students in the French school system as part of France's "civilising mission" in Algeria. The curriculum was entirely French and allowed no place for Arabic studies, which were deliberately downgraded even in Muslim schools. Within a generation, a class of well-educated, gallicized Muslims, the évolués (literally "evolved ones"), had been created. Enfranchisement Following its conquest of Ottoman Algeria in 1830, France maintained for well over a century its colonial rule in the territory that has been described as "quasi-apartheid".[32] The colonial law of 1865 allowed Arab and Berber Algerians to apply for French citizenship only if they abandoned their Muslim identity; Azzedine Haddour argues that it established "the formal structures of a political apartheid".[33] Camille Bonora-Waisman writes, "In contrast with the Moroccan and Tunisian protectorates", the "colonial apartheid society" was unique to Algeria.[34] Under the French Fourth Republic, Muslim Algerians were accorded the rights of citizenship, but the system of discrimination was maintained in more informal ways. Frederick Cooper writes that Muslim Algerians "were still marginalized in their own territory, notably the separate voter roles of 'French' civil status and of 'Muslim' civil status, to keep their hands on power."[34] The "internal system of apartheid" was met with considerable resistance by the Algerian Muslims affected by it, and it is cited as one of the causes of the 1954 insurrection. There was clearly nothing exceptional about the crimes committed by the French army and state in Algeria from 1955 to 1962. On the contrary, they were part of history repeating itself.[35] Following the views of Michel Foucault, the French historian Olivier Le Cour Grandmaison spoke of a "state racism" under the French Third Republic, a notable example being that the 1881 Indigenous Code applied in Algeria. Replying to the question "Isn't it excessive to talk about a state racism under the Third Republic?", he replied: "No, if we can recognize 'state racism' as the vote and implementation of discriminatory measures, grounded on a combination of racial, religious and cultural criteria, in those territories. The 1881 Indigenous Code is a monument of this genre! Considered by contemporary prestigious jurists as a 'juridical monstruosity', this code[36] planned special offenses and penalties for 'Arabs'. It was then extended to other territories of the empire. On one hand, a state of rule of law for a minority of French and Europeans located in the colonies. On the other hand, a permanent state of exception for the "indigenous" people. This situation lasted until 1945".[37] During a reform effort in 1947, the French created a bicameral legislature with one house for French citizens and another for Muslims, but it made a European's vote worth seven times a Muslim's vote.[38] Even the events of 1961 show that France had not changed its treatment of the Algerians over the years, as the police took up the institutional racism that the French state had made law in its treatment of Arabs who, as Frenchmen, had moved to Mainland France.[39] Paris massacre of 1961 Part of Algerian war Deaths 40/200+ Victims a demonstration of some 30,000 pro-National Liberation Front (FLN) Algerians Perpetrators Head of the Parisian police, Maurice Papon, the French National Police Further reading Original text: Library of Congress Country Study of Algeria Aussaresses, Paul. The Battle of the Casbah: Terrorism and Counter-Terrorism in Algeria, 1955–1957. (New York: Enigma Books, 2010) ISBN 978-1-929631-30-8. Bennoune, Mahfoud. The Making of Contemporary Algeria, 1830–1987 (Cambridge University Press, 2002) Gallois, William. A History of Violence in the Early Algerian Colony (2013), On French violence 1830–1847 online review Horne, Alistair. A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954–1962, (Viking Adult, 1978) Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina The Battle of Algiers The 1961 massacre was referenced in Caché, a 2005 film by Michael Haneke. The 2005 French television drama-documentary Nuit noire, 17 octobre 1961 explores in detail the events of the massacre. It follows the lives of several people and also shows some of the divisions within the Paris police, with some openly arguing for more violence while others tried to uphold the rule of law. Drowning by Bullets, a television documentary in the British Secret History series, first shown on 13 July 1992. |

土地の強奪 アルジェ征服が達成されると、軍人政治家のベルトラン・クラウゼルらが農地買収会社を設立し、公式の阻止にもかかわらず、ヨーロッパ人農民の入植を助成し た。1835年に総督に就任したクローゼルは、官僚や陸軍将校に同じことを奨励することで、総督職を利用して土地への私的投資を行った。その結果、政府高 官たちはアルジェリアへのフランスの関与を強めることになった。政府に影響力を持つ商人たちも土地投機で利益を得ようとし、結果としてフランスの占領を拡 大することになった。広大な農地が切り開かれ、工場や企業が現地の安い労働力を利用するようになり、フランスに支配権を与える法律や勅令の恩恵も受けるよ うになった。限定的な占領政策は1840年に正式に放棄され、完全な支配政策に取って代わられた。1843年まで、トクヴィルは収用を法の支配によって保 護し、拡大することを意図し、フランス人やその他のヨーロッパ人入植者の利益のために大規模な収用を実施するために、彼が「略式」と呼ぶ手続きに基づく特 別法廷の設置を提唱した。こうしてフランス人やその他のヨーロッパ人入植者は、魅力的な価格で土地を購入し、植民地政府が要塞、教会、学校、噴水まで備え た村に住むことができるようになった。トクヴィルの信念は、軍隊によって追い出され、裁判官によって土地を奪われた現地の人々が、次第に死に絶えるという ものであった[24][要出典]。 彼が構想し、アルジェリアで具体化したフランスの植民地国家は、フランス本土の体制とはまったく異なり、二層構造の組織であった。人種的、文化的、宗教的 区別に基づく2つの異なる政治・法制度が導入されたのである。トクヴィルによれば、コロン人に適用されるべき制度は、コロン人だけが財産を保有し、自由に 旅行することを可能にするが、アルジェリアでは停止されるべき政治的自由をいかなる形でも奪うものであった。「したがって、アフリカには2つの異なる法律 が存在するはずである。ヨーロッパ人のために確立された規則は彼らにしか適用されないのだから」[25]。 1840年代のレジスタンスの敗北後、植民地化は急速に進んだ。1848年までにアルジェリアには109,400人のヨーロッパ人が居住するようになり、 そのうちフランス人は42,274人に過ぎなかった[26]。コロン代表団のリーダーであったオーギュスト・ワルニエ(1810-1875)は、1870 年代に、入植者への土地の私的譲渡を容易にする法律の修正や導入に成功し、アルジェリアが地元住民から土地を収奪し、入植者に分配することを継続した。 1881年、Code de l'Indigénatは、土着民に対する具体的な罰則を設け、土地の差し押さえや没収を組織化することによって、差別を公式なものとした[28]。 1900年までに、ヨーロッパ人は農業生産額の3分の2以上を生産し、農産物輸出の実質的なすべてを生産した。植民地政府はヨーロッパ人よりもイスラム教 徒に対してより多く、より高い税金を課した[29]。イスラム教徒は、フランスによる征服以前からの伝統的な税金を支払うことに加えて、コロン人が通常免 除されていた新たな税金も支払った。例えば1909年、人口の90%近くを占めながらアルジェリアの収入の20%を生み出すイスラム教徒は、直接税の 70%、徴収された税全体の45%を支払っていた。また、コロンは税収の使い道を支配していたため、彼らの町には立派な市庁舎が建ち、舗装された街路樹が 立ち並び、噴水や彫像があったが、アルジェリアの村や農村地域は税収の恩恵をほとんど受けていなかった[30]。 教育 植民地体制は、それまで読み書きや宗教を学ぶために宗教学校に頼っていたイスラム教徒の教育全般に深刻な悪影響を及ぼした。1843年、国家は学校を含む 宗教施設の主な収入源であった宗教基金であるハブス(habus)の土地を割り当てたが、植民地当局者は学校やモスクを適切に維持し、増加する人口に十分 な教師や宗教指導者を賄うための十分な資金を割り当てることを拒否した。1892年には、ヨーロッパ人の教育費の5倍以上が、就学年齢の子供が5倍もいる イスラム教徒の教育費に費やされた。イスラム教の教師はほとんど養成されていなかったため、イスラム教の学校は主にフランス人教師によって運営されてい た。国営のマドラサでさえ、フランス人教員がいることが多かった。イスラム教徒とヨーロッパ人の子供たちを一緒に授業に参加させることを目的とした、バイ リンガルでバイカルチュラルな学校を設立しようとする試みは顕著な失敗であった。ある推計によれば、1870年当時、何らかの学校に通っていたアルジェリ ア人の子供は5%にも満たなかった。1954年の時点で、正式な学校教育を受けたイスラム教徒の少年は5人に1人、少女は16人に1人であった[31]。 1890年までに、フランスのアルジェリアにおける「文明化ミッション」の一環として、フランスの学校制度でヨーロッパ人生徒とともに少数のイスラム教徒 を教育する取り組みが始まった。カリキュラムはすべてフランス式で、アラビア語の学習は許されず、イスラム教の学校でもアラビア語の学習は意図的に格下げ された。一世代も経たないうちに、高学歴でガリシア人化したイスラム教徒、エヴォルーズ(文字通り「進化した者たち」)が生まれた。 フランチャイズ 1830年にオスマン帝国領アルジェリアを征服したフランスは、「準アパルトヘイト」と形容される植民地支配を1世紀以上にわたって続けた。 [32]1865年の植民地法では、アラブ人とベルベル人のアルジェリア人はイスラム教徒であることを放棄した場合のみフランス国籍を申請することができ た。アゼディーヌ・ハドゥールは、この法律が「政治的アパルトヘイトの形式的構造」を確立したと論じている。 フランス第四共和政の下で、ムスリムアルジェリア人は市民権を与えられたが、差別制度はより非公式な方法で維持された。フレデリック・クーパーは、イスラ ム教徒アルジェリア人は「自国の領土において依然として周縁化されており、特に『フランス人』市民権と『イスラム教徒』市民権という別々の有権者の役割を 担うことで、権力を手中に収めていた」と書いている[34]。この「アパルトヘイトの内部システム」は、その影響を受けたアルジェリアのイスラム教徒から かなりの抵抗を受け、1954年の反乱の原因の一つとして挙げられている。 1955年から1962年にかけてアルジェリアでフランス軍と国家が犯した犯罪には、明らかに例外的なものは何もなかった。それどころか、それらは繰り返 される歴史の一部であった[35]。 ミシェル・フーコーの見解に倣い、フランスの歴史家オリヴィエ・ル・クール・グランメゾンはフランス第三共和制下の「国家人種差別」について語った。第三 共和制下の国家的人種差別について語るのは行き過ぎではないか」という質問に対して、彼はこう答えた: 人種的、宗教的、文化的基準の組み合わせに基づく差別的措置の投票と実施として『国家的人種主義』を認めることができるのであれば、そうではない。 1881年の先住民法典は、このジャンルの記念碑である!この法典[36]は、「アラブ人」に対する特別な犯罪と刑罰を規定したもので、現代の著名な法学 者たちから「法学上の怪物」とみなされている。その後、この法典は帝国の他の領土にも拡大された。一方では、植民地にいる少数派のフランス人とヨーロッパ 人のための法治国家。他方、「先住民」にとっては恒久的な例外状態であった。この状況は1945年まで続いた」[37]。 1947年の改革努力の中で、フランスはフランス人のための議院とイスラム教徒のための議院を持つ二院制の議会を作ったが、ヨーロッパ人の一票はイスラム 教徒の一票の7倍の価値があった[38]。1961年の出来事でさえ、フランスが長年にわたってアルジェリア人に対する扱いを変えていなかったことを示し ており、警察はフランス人としてフランス本土に移住したアラブ人に対する扱いでフランス国家が法制化した制度的人種差別を取り上げた[39]。 1961年のパリの虐殺 アルジェリア戦争の一環 死者 40人/200人以上 犠牲者 親民族解放戦線(FLN)のアルジェリア人約30,000人のデモ 加害者 フランス国家警察のパリ警察署長モーリス・パポン 参考文献 原文 米国議会図書館アルジェリア国別研究 アウサレス、ポール カスバの戦い: The Battle of Casbah: Terrorism and Counter-Terrorism in Algeria, 1955-1957. (New York: Enigma Books, 2010) ISBN 978-1-929631-30-8. Bennoune, Mahfoud. The Making of Contemporary Algeria, 1830-1987 (Cambridge University Press, 2002). Gallois, William. A History of Violence in the Early Algerian Colony (2013), On French violence 1830-1847 オンラインレビュー Horne, Alistair. A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954-1962, (Viking Adult, 1978) モハメッド・ラクダル=ハミナ アルジェの戦い 1961年の大虐殺は、ミヒャエル・ハネケ監督の2005年の映画『Caché』で言及されている。 2005年のフランスのテレビドラマ・ドキュメンタリー『Nuit noire, 17 octobre 1961』では、この虐殺事件の詳細が描かれている。何人かの人物の人生を追うとともに、パリ警察内部の分裂の一端を描き、公然とさらなる暴力を主張する 者もいれば、法の支配を守ろうとする者もいた。 Drowning by Bullets(銃弾に溺れる)』は、1992年7月13日に初公開された英国秘史シリーズのテレビドキュメンタリー。 |

| Australia Further information: Racism in Australia, History of Australia, Indigenous Australians, and Reconciliation in Australia  Brisbane Anti-Racism Protest It is estimated that the population of Aboriginal peoples prior to the European colonisation of Australia (starting in 1788) was about 314,000.[40] It has also been estimated by ecologists that the land could have supported a population of a million people. By 1901, they had been reduced by two-thirds to 93,000. In 2011, First Nations Australians (including both Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islander people) comprised about 3% of the total population, at 661,000. When Captain Cook landed in Botany Bay in 1770, he was under orders not to plant the British flag and to defer to any native population, which was largely ignored.[unreliable source?][41] Land rights, stolen generations, and terra nullius Further information: Native title in Australia, Aboriginal land rights in Australia, and Stolen Generations Torres Strait Islander people are indigenous to the Torres Strait Islands, which are in the Torres Strait between the northernmost tip of Queensland and Papua New Guinea. Institutional racism had its early roots here due to interactions between these islanders, who had Melanesian origins and depended on the sea for sustenance and whose land rights were abrogated, and later the Australian Aboriginal peoples, whose children were removed from their families by Australian federal and state government agencies and church missions, under acts of their respective parliaments.[42][self-published source?] The removals occurred in the period between approximately 1909 and 1969, resulting in what later became known as the Stolen Generations. An example of the abandonment of mixed-race ("half-caste") children in the 1920s is given in a report by Walter Baldwin Spencer that many mixed-descent children born during construction of The Ghan railway were abandoned at early ages with no one to provide for them. This incident and others spurred the need for state action to provide for and protect such children.[43][unreliable source?] Both were official policy and were coded into law by various acts. They have both been rescinded and restitution for past wrongs addressed at the highest levels of government. The treatment of the First Nations Australians by the colonisers has been termed cultural genocide.[44] The earliest introduction of child removal to legislation is recorded in the Victorian Aboriginal Protection Act 1869.[45][self-published source?] The Central Board for the Protection of Aborigines had been advocating such powers since 1860, and the passage of the Act gave the colony of Victoria a wide suite of powers over Aboriginal and "half-caste" persons, including the forcible removal of children,[46] especially "at risk" girls.[47] By 1950, similar policies and legislation had been adopted by other states and territories, such as the Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act 1897 (Qld),[48] the Aborigines Ordinance 1918 (NT),[49] the Aborigines Act 1934 (SA)[50] and the 1936 Native Administration Act (WA). The child-removal legislation resulted in widespread removal of children from their parents and exercise of sundry guardianship powers by Protectors of Aborigines up to the age of 16 or 21. Policemen or other agents of the state were given the power to locate and transfer babies and children of mixed descent from their mothers or families or communities into institutions.[51][self-published source?] In these Australian states and territories, half-caste institutions (both government Aboriginal reserves and church-run mission stations) were established in the early decades of the 20th century for the reception of these separated children. Examples of such institutions include Moore River Native Settlement in Western Australia, Doomadgee Aboriginal Mission in Queensland, Ebenezer Mission in Victoria and Wellington Valley Mission in New South Wales. In 1911, the Chief Protector of Aborigines in South Australia, William Garnet South, reportedly "lobbied for the power to remove Aboriginal children without a court hearing because the courts sometimes refused to accept that the children were neglected or destitute". South argued that "all children of mixed descent should be treated as neglected". His lobbying reportedly played a part in the enactment of the Aborigines Act 1911; this made him the legal guardian of every Aboriginal child in South Australia, including so-called "half-castes". Bringing Them Home,[52] a report on the status of the mixed race stated "... the physical infrastructure of missions, government institutions and children's homes was often very poor and resources were insufficient to improve them or to keep the children adequately clothed, fed, and sheltered". In reality, during this period, removal of the mixed-race children was related to the fact that most were offspring of domestic servants working on pastoral farms,[53][self-published source?] and their removal allowed the mothers to continue working as help on the farm while at the same time removing the whites from responsibility for fathering them and from social stigma for having mixed-race children visible in the home.[54] Also, when they were left alone on the farm they became targets of the men who contributed to the rise in the population of mixed-race children.[55][self-published source?] The institutional racism was government policy gone awry, one that allowed babies to be taken from their mothers at birth, and this continued for most of the 20th century. That it was policy and kept secret for over 60 years is a mystery that no agency has solved to date.[56][self-published source?] In the 1930s, the Northern Territory Protector of Natives, Cecil Cook, perceived the continuing rise in numbers of "half-caste" children as a problem. His proposed solution was: "Generally by the fifth and invariably by the sixth generation, all native characteristics of the Australian Aborigine are eradicated. The problem of our half-castes will quickly be eliminated by the complete disappearance of the black race, and the swift submergence of their progeny in the white". He did suggest at one point that they be all sterilised.[57] Similarly, the Chief Protector of Aborigines in Western Australia, A. O. Neville, wrote in an article for The West Australian in 1930: "Eliminate in future the full-blood and the white and one common blend will remain. Eliminate the full-blood and permit the white admixture and eventually, the race will become white".[58] Official policy then concentrated on removing all black people from the population,[59] to the extent that the full-blooded Aboriginal people were hunted to extinguish them from society,[60] and those of mixed race would be assimilated with the white race so that in a few generations they too would become white.[61][self-published source?] By 1900, the recorded First Nations Australian population had declined to approximately 93,000. Western Australia and Queensland specifically excluded Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people from the electoral rolls. The Commonwealth Franchise Act 1902 excluded "Aboriginal natives of Australia, Asia, Africa and Pacific Islands except for New Zealand" from voting unless they were on the roll before 1901.[62] Land rights returned In 1981, a land rights conference was held at James Cook University, where Eddie Mabo,[63] a Torres Strait Islander, made a speech to the audience in which he explained the land inheritance system on Murray Island.[64] The significance of this in terms of Australian common law doctrine was taken note of by one of the attendees, a lawyer, who suggested there should be a test case to claim land rights through the court system.[65] Ten years later, five months after Eddie Mabo died, on 3 June 1992, the High Court announced its historic decision, namely overturning the legal doctrine of terra nullius, which was the term applied by the British relating to the continent of Australia – "empty land".[66] Public interest in the Mabo case had the side effect of throwing the media spotlight on all issues related to Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders in Australia, and most notably the Stolen Generations. The social impacts of forced removal have been measured and found to be quite severe. Although the stated aim of the "resocialisation" program was to improve the integration of Aboriginal people into modern society, a study conducted in Melbourne and cited in the official report found that there was no tangible improvement in the social position of "removed" Aboriginal people as compared to "non-removed", particularly in the areas of employment and post-secondary education.[67] Most notably, the study indicated that removed Aboriginal people were actually less likely to have completed a secondary education, three times as likely to have acquired a police record and were twice as likely to use illicit drugs.[68] The only notable advantage "removed" Aboriginal people possessed was a higher average income, which the report noted was most likely due to the increased urbanisation of removed individuals, and hence greater access to welfare payments than for Aboriginal people living in remote communities.[69] First Nations health and employment Further information: Closing the Gap and First Nations Australians' health In his 2008 address to the houses of parliament apologising for the treatment of the First Nations population, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd made a plea to the health services regarding the disparate treatment in health services. He noted the widening gap between the treatment of First Nations and non-Indigenous Australians, and committed the government to a strategy called "Closing the Gap", admitting to past institutional racism in health services that shortened the life expectancy of the Aboriginal people. Committees that followed up on this outlined broad categories to redress the inequities in life expectancy, educational opportunities and employment.[70] The Australian government also allocated funding to redress the past discrimination. First Nations Australians visit their general practitioners (GPs) and are hospitalised for diabetes, circulatory disease, musculoskeletal conditions, respiratory and kidney disease, mental, ear and eye problems and behavioural problems yet are less likely than non-Indigenous Australians to visit the GP, use a private doctor, or apply for residence in an old age facility. Childhood mortality rates, the gap in educational achievement and lack of employment opportunities were made goals that in a generation should halve the gap. A national "Close the Gap" day was announced for March of each year by the Human Rights Commission.[71] In 2011, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare reported that life expectancy had increased since 2008 by 11.5 years for women and 9.7 years for men along with a significant decrease in infant mortality, but it was still 2.5 times higher than for the non-indigenous population. Much of the health woes of the First Nations Australians could be traced to the availability of transport. In remote communities, the report cited 71% of the population in those remote Fist Nations communities lacked access to public transport, and 78% of the communities were more than 80 kilometres (50 miles) from the nearest hospital. Although English was the official language of Australia, many First Nations Australians did not speak it as a primary language, and the lack of printed materials that were translated into the Australian Aboriginal languages and the non-availability of translators formed a barrier to adequate health care for Aboriginal people. By 2015, most of the funding promised to achieve the goals of "Closing the Gap" had been cut, and the national group[72] monitoring the conditions of the First Nations population was not optimistic that the promises of 2008 will be kept.[73] In 2012, the group complained that institutional racism and overt discrimination continued to be issues, and that, in some sectors of government, the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples was being treated as an aspirational rather that a binding document.[74] |

オーストラリア さらに詳しい情報 オーストラリアの人種差別、オーストラリアの歴史、オーストラリア先住民、オーストラリアの和解  ブリスベン反人種主義デモ ヨーロッパ人によるオーストラリア植民地化(1788年開始)以前のアボリジニの人口は、約31万4,000人と推定されている[40]。また、生態学者 は、この土地が100万人の人口を養うことができたと推定している。1901年までに、その数は3分の2の93,000人にまで減少した。2011年に は、ファースト・ネーションズ・オーストラリア人(オーストラリア先住民アボリジニとトレス海峡諸島民の両方を含む)の人口は661,000人で、全人口 の約3%を占めている。1770年にキャプテン・クックがボタニー湾に上陸した際、英国旗を立てるな、先住民に従えという命令を受けていたが、それはほと んど無視された。 土地の権利、奪われた世代、テラ・ヌリウス さらなる情報 オーストラリアの先住民の権利、オーストラリアのアボリジニの土地の権利、盗まれた世代 トレス海峡諸島の先住民は、クイーンズランド州最北端とパプアニューギニアの間のトレス海峡にあるトレス海峡諸島の先住民である。メラネシア人を起源と し、糧を海に依存し、土地の権利を剥奪されたこれらの島民と、後にオーストラリアのアボリジニとの間の相互作用により、制度的人種差別が早くからこの地に 根を下ろした。1920年代における混血児(「ハーフカースト」)の遺棄の例は、ウォルター・ボールドウィン・スペンサーによる報告書に示されており、 ギャン鉄道の建設中に生まれた混血児の多くが、養育する者のいないまま幼少期に遺棄されたという。この事件や他の事件によって、そのような子供たちを養 育・保護するための国家的措置の必要性が高まった[43][信頼できない情報源?]。どちらも撤回され、過去の過ちに対する賠償が政府の最高レベルで取り 組まれている。 植民地支配者によるオーストラリア先住民の扱いは、文化的ジェノサイド(大量虐殺)と呼ばれている[44]。 1869年に制定されたビクトリア州アボリジニ保護法(The Victorian Aboriginal Protection Act)[45][自費出版?][45][自費出版?] アボリジニ保護中央委員会(Central Board for the Protection of Aborigines)は、1860年からこのような権限を提唱しており、同法の成立によってビクトリア植民地は、アボリジニや「ハーフカースト」の人々 に対する幅広い権限一式を与えられた。 [1950年までに、同様の政策や法律が他の州や準州でも採用されるようになった。例えば、1897年アボリジニ保護・アヘン販売制限法(QLD) [48]、1918年アボリジニ条例(NT)[49]、1934年アボリジニ法(SA)[50]、1936年先住民管理法(WA)などである。) 子供の連れ去りに関する法律は、子供を親から連れ去り、16歳または21歳までのアボリジニー保護官による様々な後見権限を行使する結果となった。警察官 や州のその他の代理人には、母親や家族、地域社会から赤ん坊や混血児の居場所を突き止め、施設に移す権限が与えられた[51][自費出版][51][自費 出版?] こうしたオーストラリアの州や準州では、20世紀初頭の数十年間、こうした引き離された子供たちを受け入れるために、ハーフカーストの施設(政府のアボリ ジニ保護区と教会が運営する伝道所の両方)が設立された。こうした施設の例としては、西オーストラリア州のムーア・リバー先住民入植地、クイーンズランド 州のドゥーマジー・アボリジニ・ミッション、ビクトリア州のエベネザー・ミッション、ニューサウスウェールズ州のウェリントン・バレー・ミッションなどが あります。 1911年、南オーストラリア州のアボリジニ主任保護官ウィリアム・ガーネット・サウス(William Garnet South)は、「アボリジニの子供たちがネグレクト(育児放棄)や貧困状態にあることを裁判所が認めないことがあるため、法廷審理なしでアボリジニの子 供たちを連れ去る権限を与えるよう働きかけた」と伝えられている。サウスは「混血の子供はすべてネグレクトとして扱われるべきだ」と主張した。彼のロビー 活動は、1911年のアボリジニ法制定に一役買ったと伝えられている。これにより彼は、いわゆる「ハーフ・キャスト」を含む、南オーストラリア州のすべて のアボリジニの子供の法的後見人となった。混血の現状に関する報告書『Bringing Them Home』[52]には、「......伝道所、政府の施設、児童養護施設の物理的な基盤は非常に貧弱であることが多く、それらを改善したり、子供たちに 十分な衣服、食事、保護を与え続けたりするには資源が不足していた」と記されている。 現実には、この時期、混血児の排除は、そのほとんどが牧畜農場で働く家事使用人の子供であったという事実と関連していた[53][自費出版? [55][自費出版?] 制度的な人種差別は、政府の政策が失敗したものであり、出生時に赤ん坊を母親から引き離すことを許したものであり、これは20世紀の大部分にわたって続い た。それが政策であり、60年以上も秘密にされていたことは、今日までどの機関も解明していない謎である[56][自費出版ソース?] 1930年代、ノーザン・テリトリーの先住民保護官セシル・クックは、「ハーフカースト」の子供の数が増え続けていることを問題視した。彼が提案した解決 策は 「一般的に5世代目、そして必ず6世代目までには、オーストラリア原住民の特徴はすべて根絶される。黒人種族が完全に消滅し、その子孫が速やかに白人の中 に沈むことによって、ハーフカーストの問題はすぐに解消されるだろう」というものだった。彼はあるとき、彼ら全員を不妊化することを提案した[57]。 同様に、西オーストラリア州のアボリジニー主任保護官であったA・O・ネビルは、1930年に『ウェスト・オーストラリアン』紙に寄稿した記事で次のよう に述べている: 「将来、純血と白人を排除すれば、共通の混血が残るだろう。全血を排除して白人の混血を認めれば、最終的には白人になる」[58]。 その後、公式の政策はすべての黒人を人口から排除することに集中し[59]、完全な血を持つアボリジニは社会から抹殺するために狩猟され[60]、混血の 人々は白人と同化され、数世代後には彼らも白人となるようにされた[61][自費出版][61]。 1900年までに、記録されているオーストラリアの先住民の人口は約93,000人まで減少していた。 西オーストラリア州とクイーンズランド州は、アボリジニとトレス海峡諸島民を選挙人名簿から明確に除外していた。1902年に制定された連邦選挙権法は、 1901年以前に選挙人名簿に登録されていない限り、「ニュージーランドを除くオーストラリア、アジア、アフリカ、太平洋諸島の先住民」を選挙権から除外 した[62]。 土地の権利返還 1981年、ジェームス・クック大学で土地の権利に関する会議が開催され、トレス海峡諸島民のエディ・マボ[63]が聴衆を前にスピーチを行い、マレー島 の土地相続制度について説明した[64]。 [65]それから10年後、エディ・マーボが亡くなってから5ヵ月後の1992年6月3日、高等法院は歴史的な判決を発表した。すなわち、英国がオースト ラリア大陸に適用していたテラ・ヌリアス(terra nullius)の法理、すなわち「何もない土地」を覆すというものであった[66]。 マボ事件に対する世間の関心は、オーストラリアのアボリジニとトレス海峡諸島民に関するあらゆる問題、とりわけ「盗まれた世代」にメディアのスポットライ トを当てるという副次的効果をもたらした。強制連行による社会的影響は測定され、かなり深刻であることが判明している。再社会化」プログラムの目的は、ア ボリジニの現代社会への統合を改善することであったが、メルボルンで実施され、公式報告書に引用された調査によると、「連れ去られた」アボリジニの社会的 地位は、「連れ去られていない」アボリジニの社会的地位と比較して、特に雇用と中等後教育の分野において、目に見える改善は見られなかった[67]。 最も注目すべきは、「連れ去られた」アボリジニの人々は、中等教育を修了している可能性が低く、警察沙汰になる可能性が3倍高く、違法薬物を使用する可能 性が2倍高いということであった[68]。 ファースト・ネーションの健康と雇用 さらに詳しい情報 格差是正とオーストラリア先住民の健康 ケビン・ラッド首相は、2008年の議会演説の中で、ファーストネーション住民の扱いについて謝罪し、医療サービスにおける格差について訴えた。ラッド首 相は、先住民族と非先住民族との待遇格差が拡大していることを指摘し、政府は「格差の是正(Closing the Gap)」と呼ばれる戦略に取り組み、保健サービスにおける過去の制度的人種差別が先住民族の平均余命を縮めていたことを認めた。これに続く委員会では、 平均余命、教育機会、雇用における不公平を是正するための大まかなカテゴリーが概説された[70]。オーストラリア政府もまた、過去の差別を是正するため の資金を割り当てた。オーストラリア先住民は、糖尿病、循環器疾患、筋骨格系疾患、呼吸器疾患、腎臓疾患、精神疾患、耳疾患、眼疾患、行動上の問題で一般 開業医(GP)を受診し、入院しているが、GPを受診したり、私立医を利用したり、高齢者施設に入居を申請したりする割合は、非先住民よりも低い。小児死 亡率、教育達成の格差、雇用機会の欠如は、一世代で格差を半減させるべき目標として掲げられた。人権委員会は、毎年3月に全国的な「格差をなくす日 (Close the Gap)」を設けることを発表した[71]。 2011年、オーストラリア保健福祉研究所(Australian Institute of Health and Welfare)は、2008年以降、平均寿命が女性で11.5年、男性で9.7年延び、乳児死亡率が大幅に減少したと報告したが、それでも非先住民の 2.5倍であった。オーストラリア先住民の健康上の悩みの多くは、交通手段の確保に起因している。報告書によると、遠隔地のコミュニティでは、人口の 71%が公共交通機関を利用できず、78%が最寄りの病院から80キロ(50マイル)以上離れていた。英語はオーストラリアの公用語であったが、多くの先 住民族は英語を母国語としておらず、アボリジニの言語に翻訳された印刷物の不足や翻訳者の不足は、アボリジニが適切な医療を受ける上での障壁となってい た。2015年までに、「格差是正」の目標を達成するために約束された資金のほとんどが削減され、先住民の状況を監視している全国的なグループ[72] は、2008年の約束が守られることを楽観視していなかった[73]。2012年、同グループは、制度的な人種差別とあからさまな差別が引き続き問題であ り、政府の一部の部門では、先住民の権利に関する国連宣言が拘束力のある文書ではなく、願望として扱われていると訴えた[74]。 |

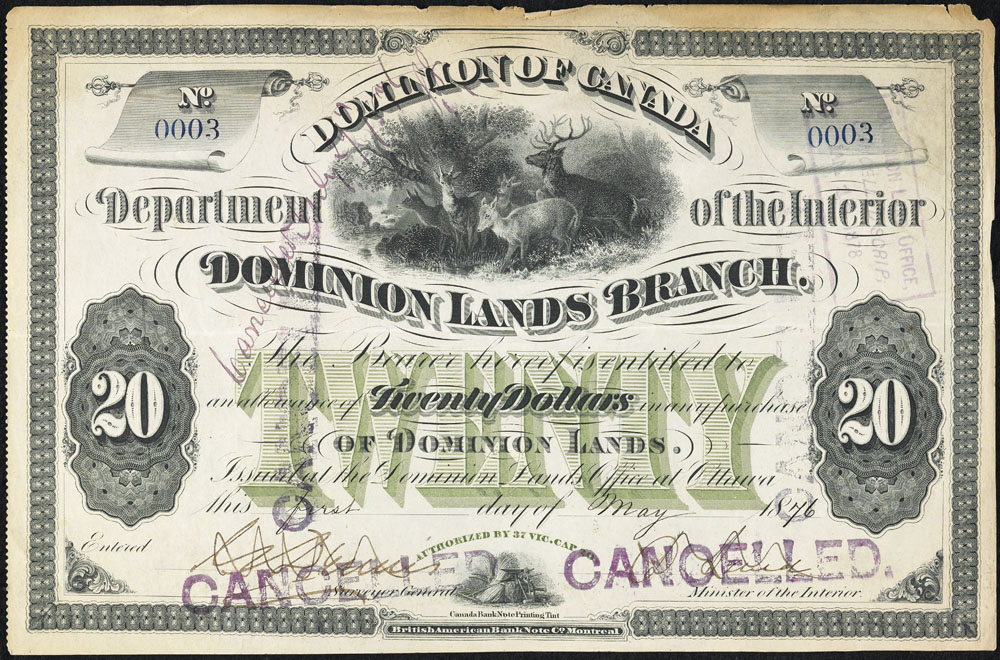

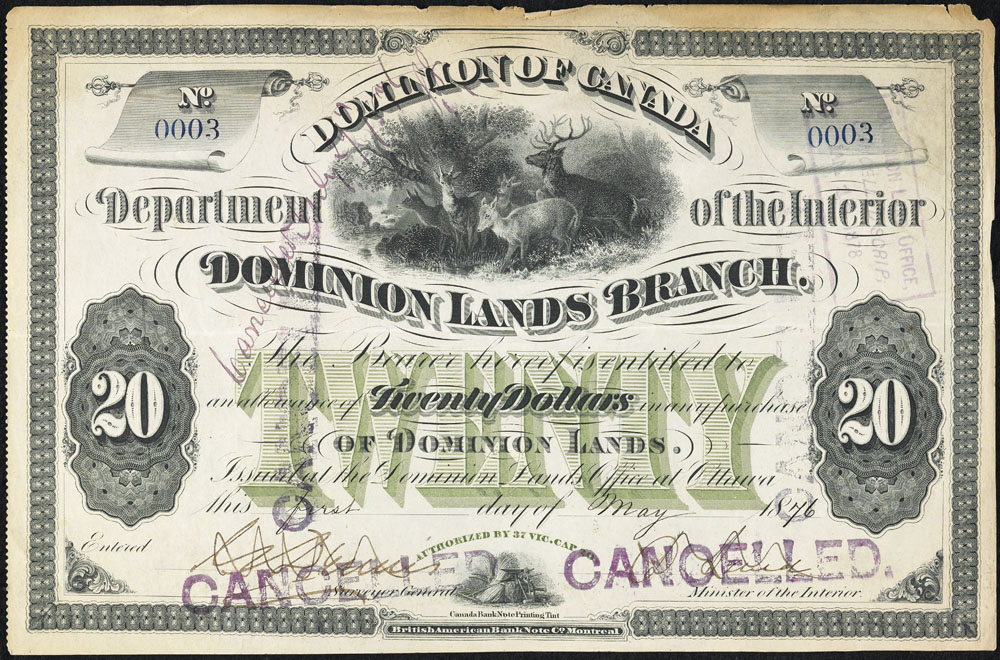

| Canada Indigenous Canadians The living standard of indigenous peoples in Canada falls far short of those of the non-indigenous, and they, along with other 'visible minorities' remain, as a group, the poorest in Canada.[16][75] There continue to be barriers to gaining equality with other Canadians of European ancestry. The life expectancy of First Nations people is lower; they have fewer high school graduates, much higher unemployment rates, nearly double the number of infant deaths and significantly greater contact with law enforcement. Their incomes are lower, they enjoy fewer promotions in the workplace and as a group, the younger members are more likely to work reduced hours or weeks each year.[75] Many in Europe during the 19th century (as reflected in the Imperial Report of the Select Committee on Aborigines),[76] supported the goal put forth by colonial imperialists of 'civilizing' the Native populations. This led to an emphasis on the acquisition of Aboriginal lands in exchange for the putative benefits of European society and their associated Christian religions. British control of Canada (the Crown) began when they exercised jurisdiction over the first nations and it was by Royal Proclamation that the first piece of legislation the British government passed over First Nations citizens assumed control of their lives. It gave recognition to the Indians tribes as First Nations living under Crown protection.[citation needed] It was after the treaty of Paris in 1763, whereby France ceded all claims in present-day Canada to Britain, that King George III of Great Britain issued a Royal Proclamation specifying how the Indigenous in the crown colony were to be treated. It is the most significant pieces of legislation regarding the Crown's relationship with Aboriginal people. This Royal Proclamation recognized Indian owned lands and reserved to them all use as their hunting grounds. It also established the process by which the Crown could purchase their lands, and also laid out basic principles to guide the Crown when making treaties with the First Nations. The Proclamation made Indian lands transferred by treaty to be Crown property, and stated that indigenous title is a collective or communal rather than a private right so that individuals have no claim to lands where they lived and hunted long prior to European colonization.[77] Indian Acts In 1867, the British North America Act made land reserved for Indians a Crown responsibility. In 1876 the first of many Indian Acts passed, each successive one leeched more from the rights of the indigenous as was stated in the first. The sundry revised Indian Acts (22 times by 2002) solidified the position of Natives as wards of the state, and Indian agents were given discretionary power to control almost every aspect of the lives of the indigenous.[78] It then became necessary to have permission from an Indian agent if Native people wanted to sell crops they had grown and harvested, or wear traditional clothes off the reserves. The Indian Act was also used to deny Indians the right to vote until 1960, and they could not sit on juries.[79] In 1885, General Middleton after defeating the Metis rebellion[80][81] introduced the Pass System in western Canada, under which Natives could not leave their reserves without first obtaining a pass from their farming instructors permitting them to do so.[82] While the Indian Act did not give him such powers, and no other legislation allowed the Department of Indian Affairs to institute such a system,[82] and it was known by crown lawyers to be illegal as early as 1892, the Pass System remained in place and was enforced until the early 1930s. As Natives were not permitted at that time to become lawyers, they could not fight it in the courts.[83] Thus was institutional racism externalized as official policy. When Aboriginals began to press for recognition of their rights and to complain of corruption and abuses of power within the Indian department, the Act was amended to make it an offence for an Aboriginal person to retain a lawyer for the purpose of advancing any claims against the crown.[84] Métis Main article: Métis people (Canada) Unlike the effect of those Indian treaties in the North-West, which established the reserves for the Indigenous, the protection of Métis lands was not secured by the scrip policy instituted in the 1870s,[85] whereby the crown exchanged a scrip[86] in exchange for a fixed (160–240 acres)[87] grant of land to those of mixed heritage.[88]  Minnesota Historical Society Location No. HD2.3 r7 Negative No. 10222 "Mixed blood (Indian and French) fur trader" ca. 1870 Although Section 3 of the 1883 Dominion Lands Act set out this limitation, this was the first mention in the orders-in-council confining the jurisdiction of scrip commissions to ceded Indian territory. However, a reference was first made in 1886 in a draft letter of instructions to Goulet from Burgess. In most cases, the scrip policy did not consider Métis ways of life, did not guarantee their land rights, and did not facilitate any economic or lifestyle transition.[89] Metis land scrip Metis scrip issued to "half-breeds", 1894  Most Métis were illiterate and did not know the value of the scrip, and in most cases sold them for instant gratification due to economic need to speculators who undervalued the paper. Needless to say, the process by which they applied for their land was made deliberately arduous.[90] There was no legislation binding scrip land to the Métis who applied for them, Instead, Métis scrip lands could be sold to anyone, hence alienating any Aboriginal title that may have been vested in those lands. Despite the evident detriment to the Métis, speculation was rampant and done in collusion with the distribution of scrip. While this does not necessarily preclude a malicious intent by the federal government to consciously 'cheat' the Métis, it illustrates their apathy towards the welfare of the Métis, their long-term interests, and the recognition of their Aboriginal title. But the point of the policy was to settle land in the North-West with agriculturalists, not keep a land reserve for the Métis. Scrip, then, was a major undertaking in Canadian history, and its importance as both an Aboriginal policy and a land policy should not be overlooked as it was an institutional 'policy' that discriminated against ethnic indigenous to their continued detriment.[91] Enfranchisement Until 1951, the various Indian Acts defined a 'person' as "an individual other than an Indian", and all indigenous peoples were considered wards of the state. Legally, the Crown devised a system of enfranchisement whereby an indigenous person could become a "person" in Canadian law. Indigenous people could gain the right to vote and become Canadian citizens, "persons" under the law, by voluntarily assimilating into European/Canadian society.[92][93] It was hoped that indigenous peoples would renounce their native heritage and culture and embrace the 'benefits' of civilized society. Indeed, from the 1920s to the 1940s, some Natives did give up their status to receive the right to go to school, vote or drink. However, voluntary enfranchisement proved a failure when few natives took advantage.[94] In 1920, a law was passed to authorize enfranchisement without consent, and many Aboriginal peoples were involuntarily enfranchised. Natives automatically lost their Indian status under this policy and also if they became professionals such as doctors or ministers, or even if they obtained university degrees, and with it, they lost their right to reside on the reserves. The enfranchisement requirements particularly discriminated against Native women, specifying in Section 12 (1)(b) of the Indian Act that an Indian status woman marrying a non-Indian man would lose her status as an Indian, as would her children. In contrast non-Indian women marrying Indian men would gain Indian status.[95] Duncan Campbell Scott, the Deputy Superintendent of Indian Affairs, neatly expressed the sentiment of the day in 1920: "Our object is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic, and there is no Indian question and no Indian Department" This aspect of enfranchisement was addressed by passage of Bill C-31 in 1985,[96] where the discriminatory clause of the Indian Act was removed, and Canada officially gave up the goal of enfranchising Natives. Residential schools Main article: Canadian Indian residential school system In the 19th and 20th centuries, the Canadian federal government's Indian Affairs Department officially encouraged the growth of the Indian residential school system as an agent in a wider policy of assimilating Native Canadians into European-Canadian society. This policy was enforced with the support of various Christian churches, which ran many of the schools. Over the course of the system's existence, approximately 30% of Aboriginal children, roughly some 150,000, were placed in residential schools nationally, with the last school closing in 1996. There has long been controversy about the conditions experienced by students in the residential schools. While day schools for First Nations, Metis and Inuit children always far outnumbered residential schools, a new consensus emerged in the early 21st century that the latter schools did significant harm to Aboriginal children who attended them by removing them from their families, depriving them of their ancestral languages, undergoing forced sterilization for some students, and by exposing many of them to physical and sexual abuse by staff members, and other students, and dis-enfranchising them forcibly.[97] With the goal of civilizing and Christianizing Aboriginal populations, a system of 'industrial schools' was developed in the 19th century that combined academic studies with "more practical matters" and schools for Natives began to appear in the 1840s. From 1879 onward, these schools were modelled after the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, whose motto was "Kill the Indian in him and save the man".[98][self-published source?] It was felt that the most effective weapon for "killing the Indian" in them was to remove children from their Native supports and so Native children were taken away from their homes, their parent, their families, friends and communities.[99] The 1876 Indian Act gave the federal government responsibility for Native education and by 1910 residential schools dominated the Native education policy. The government provided funding to religious groups such as the Catholic, Anglican, United Church and Presbyterian churches to undertake Native education. By 1920, attendance by natives was made compulsory and there were 74 residential schools operating nationwide. Following the ideas of Sifton and others like him, the academic goals of these schools were "dumbed down". As Duncan Campbell Scott stated at the time, they did not want students that were "made too smart for the Indian villages":[100] "To this end the curriculum in residential schools has been simplified and the practical instruction given is such as may be immediately of use to the pupil when he returns to the reserve after leaving school." The funding the government provided was generally insufficient and often the schools ran themselves as "self-sufficient businesses", where 'student workers' were removed from class to do the laundry, heat the building, or perform farm work. Dormitories were often poorly heated and overcrowded, and the food was less than adequately nutritious. A 1907 report, commissioned by Indian Affairs, found that in 15 prairie schools there was a death rate of 24%.[101] Indeed, a deputy superintendent general of Indian Affairs at the time commented: "It is quite within the mark to say that fifty percent of the children who passed through these schools did not benefit from the education which they had received therein." While the death rate did decline in later years, death would remain a part of the residential school tradition. The author of that report to the BNA, Dr. P.H. Bryce, was later removed and in 1922 published a pamphlet[102] that came close to calling the governments indifference to the conditions of the Indians in the schools 'manslaughter'.[101] Anthropologists Steckley and Cummins note that the endemic abuses – emotional, physical, and sexual – for which the system is now well known for "might readily qualify as the single-worst thing that Europeans did to Natives in Canada".[103] Punishments were often brutal and cruel, sometimes even life-threatening or life-ending. Pins were sometimes stuck in children's tongues for speaking their Native languages, sick children were made to eat their vomit, and semi-formal inspections of children's genitalia were carried out.[104] The term Sixties Scoop (or Canada Scoops) refers to the Canadian practice, beginning in the 1960s and continuing until the late 1980s, of taking ("scooping up") children of Aboriginal peoples in Canada from their families for placing in foster homes or adoption. Most residential schools closed in the 1970s, with the last one closing in 1996. Criminal and civil suits against the government and the churches began in the late 1980s and shortly thereafter the last residential school closed. By 2002, the number of lawsuits had passed 10,000. In the 1990s, beginning with the United Church, the churches that ran the residential schools began to issue formal apologies. In 1998, the Canadian government issued the Statement of Reconciliation,[105] and committed $350 million in support of a community-based healing strategy to address the healing needs of individuals, families and communities arising from the legacy of physical and sexual abuse at residential schools. The money was used to launch the Aboriginal Healing Foundation.[106] Starting in the 1990s, the government started a number of initiatives to address the effects of the Indian residential school. In March 1998, the government made a Statement of Reconciliation and established the Aboriginal Healing Foundation. In the fall of 2003, the Alternative Dispute Resolution process was launched, which was a process outside of court providing compensation and psychological support for former students of residential schools who were physically or sexually abused or were in situations of wrongful confinement. On 11 June 2008, Prime Minister Stephen Harper issued a formal apology on behalf of the sitting Cabinet and in front of an audience of Aboriginal delegates. A Truth and Reconciliation Commission ran from 2008 through to 2015 to document past wrongdoing in the hope of resolving conflict left over from the past.[107] The final report concluded that the school system amounted to cultural genocide.[108] Contemporary situation Main article: Analysis of Western European colonialism and colonization The overt institutional racism of the past has clearly had a profoundly devastating and lasting effect on visible minorities and Aboriginal communities throughout Canada.[109] European cultural norms have imposed themselves on Native populations in Canada, and Aboriginal communities continue to struggle with foreign systems of governance, justice, education, and livelihood. Visible Minorities struggle with education, employment and negative contact with the legal system across Canada.[110] Perhaps most palpable is the dysfunction and familial devastation caused by residential schools. Hutchins states;[103][self-published source?] "Many of those who attended residential schools have been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, suffering from such symptoms as panic attacks, insomnia, and uncontrollable or unexplainable anger.[111] Many also suffer from alcohol or drug abuse, sexual inadequacy or addiction, the inability to form intimate relationships, and eating disorders. Three generations of Native parents lost out on learning important parenting skills usually passed on from parent to child in caring and nurturing home environments,[112] and the abuse suffered by students of residential schools has begun a distressing cycle of abuse within many Native communities." The lasting legacy of residential schools is but only one facet of the problem.[113] The Hutchins report continues: "Aboriginal children continue to struggle with mainstream education in Canada. For some Indian students, English remains a second language, and many lack parents with sufficient education themselves to support them. Moreover, schooling in Canada is based on an English written tradition, which is different from the oral traditions of the Native communities.[114] For others, it is simply that they are ostracised for their 'otherness'; their manners, their attitudes, their speech, or a hundred other things which mark them out as different. "Aboriginal populations continue to suffer from poor health. They have seven years less life expectancy than the overall Canadian population and almost twice as many infant deaths. While Canada as a nation routinely ranks in the top three on the United Nations Human Development Index,[115] its on-reserve Aboriginal population, if scored as a nation, would rank a distant and shocking sixty-third." As Perry Bellegarde National Chief, Assembly of First Nations, points out, racism in Canada today is, for the most part, a covert operation.[116] Its central and most distinguishing tenet is the vigour with which it is consistently denied.[117] There are many who argue that Canada's endeavors in the field of human rights and its stance against racism have only resulted in a "more politically correct population who have learnt to better conceal their prejudices".[118] In effect, the argument is that racism in Canada is not being eliminated, but rather is becoming more covert, more rational, and perhaps more deeply imbedded in our institutions. That racism is alive is evidenced by the recent referendum in British Columbia by which the provincial government is asking the white majority to decide on a mandate for negotiating treaties with the Indian minority.[119] The results of the referendum will be binding,[120] the government having legislatively committed itself to act on these principles if more than 50% of those voting reply in the same way. Moreover, although it has been revised many times, "the Indian Act remains legislation which singles out a segment of society based on race". Under it, the civil rights of First Nations peoples are "dealt with in a different manner than the civil rights of the rest of Canadian citizens".[103]  Joyce Echaquan, on the lake shore, 1999 The Aboriginal Justice Inquiry in Manitoba,[121] the Donald Marshall Inquiry in Nova Scotia,[122] the Cawsey Report in Alberta[123] and the Royal Commission of Aboriginal People all agree,[124] as far as Aboriginal people are concerned, racism in Canadian society continues institutionally, systematically, and individually. In 2020, after the death of Joyce Echaquan, the Prime Minister of Canada, Justin Trudeau, recognized a case of systemic racism. In 2022, Pope Francis visited Canada for a week-long tour called a “pilgrimage of penance.”[125] Vatican officials called the trip a “penitential pilgrimage”. The Pope was welcomed in Edmonton, where he apologized for Indigenous abuse which took place in the 20th century at Catholic-run residential schools, which have since closed.[126] During his stay, he met with Indigenous groups to address the scandal of the residential schools.[127] “I am sorry,” The Pope said, and asked forgiveness for the church and church members in “projects of cultural destruction and forced assimilation” and the systematic abuse and erasure of indigenous culture in the country’s residential schools.[128] Anti-Chinese immigration laws The Canadian government passed the Chinese Immigration Act of 1885, levying a $50 head tax upon all Chinese people immigrating to Canada. When the 1885 act failed to deter Chinese immigration, the Canadian government then passed the Chinese Immigration Act, 1900, increasing the head tax to $100, and, upon that act failing, passed the Chinese Immigration Act, 1904, increasing the head tax (landing fee) to $500, equivalent to $8,000 in 2003[129] – when compared to the head tax – Right of Landing Fee and Right of Permanent Residence Fee – of $975 per person, paid by new immigrants in 1995–2005 decade, which then was reduced to $490 in 2006.[130] The Chinese Immigration Act, 1923, better known as the "Chinese Exclusion Act", replaced prohibitive fees with a ban on ethnic Chinese immigrating to Canada – excepting merchants, diplomats, students, and "special circumstance" cases. The Chinese who entered Canada before 1923 had to register with the local authorities and could leave Canada only for two years or less. Since the Exclusion Act went into effect on 1 July 1923, Chinese-Canadians referred to Canada Day (Dominion Day) as "Humiliation Day",[131] refusing to celebrate it until the Act's repeal in 1947.[132] Black Canadians  Ku Klux Klan members, on foot and horseback, by a cross erected in a field near Kingston, Ontario in 1927 There are records of slavery in some areas of British North America, which later became Canada, dating from the 17th century. The majority of these slaves were Aboriginal,[133] and United Empire Loyalists brought slaves with them after leaving the United States. |

カナダ カナダ先住民 カナダにおける先住民の生活水準は、非先住民の生活水準にはるかに及ばず、他の「目に見える少数民族」とともに、集団としてカナダで最も貧しいままである [16][75]。ヨーロッパ系の祖先を持つ他のカナダ人と平等を得るには、依然として障壁がある。ファースト・ネーションズの人々の平均寿命は短く、高 校卒業者の数は少なく、失業率ははるかに高く、乳児死亡者数はほぼ2倍で、法執行機関との接触はかなり多い。彼らの所得は低く、職場での昇進も少なく、集 団として、若いメンバーほど年間労働時間や労働週間が短縮される傾向にある[75]。 19世紀のヨーロッパでは(アボリジニーに関する特別委員会の帝国報告書に反映されているように)、先住民を「文明化」するという植民地帝国主義者の掲げ る目標を支持する者が多かった[76]。このため、ヨーロッパ社会とそれに関連するキリスト教宗教の恩恵と引き換えにアボリジニの土地を獲得することが重 視されるようになった。イギリス(王室)によるカナダの支配は、彼らが先住民族に対する管轄権を行使したときに始まり、イギリス政府が先住民族市民の生活 管理を前提とした最初の法案を通過させたのは、勅令によるものだった。これは、インディアン部族を王室の保護下で生活するファーストネーションとして承認 するものであった[要出典]。 イギリス国王ジョージ3世が勅令を発布し、王権植民地の先住民をどのように扱うべきかを規定したのは、フランスが現在のカナダにおけるすべての領有権をイ ギリスに割譲した1763年のパリ条約の後であった。これは王室とアボリジニの関係に関する最も重要な法律である。この勅令は、インディアンの所有地を認 め、彼らの狩猟場としてすべての使用を確保しました。また、王室が彼らの土地を購入する手続きを定め、さらに王室が先住民族と条約を結ぶ際の指針となる基 本原則を定めました。この布告では、条約によって譲渡されたインディアンの土地は王室の所有物とされ、先住民の所有権は私的権利ではなく、集団的または共 同体的なものであり、ヨーロッパ人の植民地化以前から彼らが生活し狩猟を行っていた土地に対して個人が権利を主張することはできないとされた[77]。 インディアン法 1867年、英領北アメリカ法はインディアンのために確保された土地を王室の責任とした。1876年、多くのインディアン法の最初のものが成立し、その都 度、最初のものに記載された先住民の権利からさらに多くのものが搾取された。そして、先住民が栽培し収穫した作物を販売したり、保護区外で伝統的な衣服を 着用したりするには、インディアン諜報員の許可が必要となった[78]。インディアン法はまた、1960年までインディアンに選挙権を与えず、陪審員にも なれなかった[79]。 1885年、メティ族の反乱を打ち破ったミドルトン将軍[80][81]は、カナダ西部にパス制度を導入し、この制度では、先住民は、まず耕作指導員から 許可されたパスを取得しなければ、保護区を離れることができなかった[82]。インディアン法はミドルトン将軍にそのような権限を与えておらず、他のいか なる法律もインディアン局がこのような制度を導入することを認めておらず[82]、1892年の時点で違法であることが王室の弁護士によって知られていた が、パス制度は1930年代初頭まで実施された。当時原住民は弁護士になることを認められていなかったため、法廷で争うことはできなかった[83]。こう して制度的人種差別は公式の政策として外在化した。 アボリジニが自分たちの権利の承認を求め、インディアン省内の腐敗や権力の乱用を訴えるようになると、この法律は改正され、アボリジニが王室に対する請求 を進める目的で弁護士を雇うことは犯罪とされた[84]。 メティス 主な記事 メティス人(カナダ) 先住民のための保護区を設立した北西部のインディアン条約の効果とは異なり、メティスの土地の保護は、1870年代に制定されたスクリップ政策[85]に よって確保されることはなかった。この政策では、王室は、混血の遺産を持つ者に一定の土地(160~240エーカー)[87]を与える代わりにスクリップ [86]を交換した[88]。  ミネソタ歴史協会所蔵No.HD2.3 r7 ネガNo.10222 「混血(インディアンとフランス人)毛皮商人」1870年頃 1883年ドミニオンランド法第3条はこの制限を定めていたが、スクリップ委員会の管轄権を割譲されたインディアン領土に限定する参事会命令で言及された のはこれが初めてであった。しかし、この言及は1886年、バージェスからグーレへの指示書草案で初めてなされた。ほとんどの場合、スクリップ政策はメ ティの生活様式を考慮せず、彼らの土地の権利を保証せず、経済や生活様式の移行を促進するものではなかった[89]。 メティスの土地スクリップ  1894年、「混血」に発行されたメティスのスクリップ ほとんどのメティスは読み書きができず、スクリップの価値を知らず、ほとんどの場合、経済的な必要性から、紙を過小評価する投機家に即座に売ることができ た。言うまでもないことだが、彼らが土地を申請する手続きは意図的に困難なものにされていた[90]。 その代わり、メティスの土地は誰にでも売ることができ、その結果、その土地に帰属していたかもしれないアボリジニの権原を剥奪することになった。メティス にとって明らかに不利益であるにもかかわらず、スクリップの配布と結託した投機が横行した。このことは、連邦政府が意識的にメティ族を「だます」という悪 意があったことを必ずしも否定するものではないが、メティスの福祉や長期的な利益、そしてアボリジニの権利の承認に対して無関心であったことを物語ってい る。しかし、この政策の要諦は、北西部の土地を農業従事者に定住させることであり、メティスのための土地保留地を維持することではなかった。スクリップ は、カナダ史における一大事業であり、アボリジニ政策として、また土地政策としてのその重要性は、先住民族を差別し、彼らの継続的な不利益をもたらす制度 的な「政策」であったという点で、見過ごすことはできない[91]。 フランチャイズ 1951年まで、様々なインディアン法は「人」を「インディアン以外の個人」と定義し、すべての先住民は国家の被後見人とみなされていた。法律上、王室は 先住民がカナダ法における「人」になるための権利付与制度を考案した。先住民は自発的にヨーロッパ/カナダ社会に同化することで選挙権を獲得し、カナダ市 民、法の下の「人」となることができた[92][93]。 先住民が土着の遺産や文化を放棄し、文明社会の「恩恵」を受け入れることが期待されたのである。実際、1920年代から1940年代にかけて、学校に通う 権利、投票権、飲酒権を得るために身分を捨てる先住民もいた。しかし、自発的な権利付与は、それを利用する原住民がほとんどいなかったことから、失敗に終 わったことが証明された[94]。 1920年、同意なしでの権利付与を認める法律が可決され、多くのアボリジニが強制的に権利付与された。原住民はこの政策のもとで自動的にインディアンの 地位を失い、また医師や牧師などの専門職に就いたり、大学の学位を取得したりすると、それとともに保護区に居住する権利も失った。 特にインディアンの女性に対する差別は強く、インディアン法第12条(1)(b)において、インディアンの身分の女性が非インディアンの男性と結婚する と、インディアンとしての身分を失い、その子供も失うと規定されていた。対照的に、インディアンでない女性がインディアンの男性と結婚すると、インディア ンの身分を得ることになる[95]。 1920年、インディアン問題副総監であったダンカン・キャンベル・スコットは、当時の心情を端的に表している: 「私たちの目的は、カナダで政治に吸収されなかったインディアンが一人もいなくなり、インディアンの問題もインディアン省もなくなるまで続けることであ る」 この権利付与の側面は、1985年の法案C-31の可決によって対処され[96]、インディアン法の差別条項が削除され、カナダは公式に先住民の権利付与 という目標を放棄した。 住民学校 主な記事 カナダ・インディアン居住学校制度 19世紀から20世紀にかけて、カナダ連邦政府のインディアン局は、カナダ先住民をヨーロッパ系カナダ人の社会に同化させるという広範な政策の一環とし て、インディアン居住学校制度の発展を公式に奨励した。この政策は、多くの学校を運営するさまざまなキリスト教会の支援によって実施された。この制度が存 続している間、アボリジニの子供たちの約30%、およそ15万人が全国的にレジデンシャル・スクールに入れられ、1996年に最後の学校が閉鎖されまし た。入所学校で生徒が経験した環境については、長い間論争があった。ファースト・ネーションズ、メティス、イヌイットの子供たちのためのデイ・スクール は、常にレジデンシャル・スクールの数をはるかに上回っていたが、21世紀初頭には、後者の学校が、家族から引き離し、先祖伝来の言語を奪い、一部の生徒 には強制不妊手術を施し、多くの生徒を職員や他の生徒による身体的・性的虐待にさらし、強制的に権利を剥奪することによって、そこに通うアボリジニの子供 たちに大きな害を与えたという新たなコンセンサスが生まれた[97]。 アボリジニの文明化とキリスト教化を目的として、19世紀には学問と「より実践的な事柄」を組み合わせた「産業学校」のシステムが開発され、1840年代 には先住民のための学校が現れ始めた。1879年以降、これらの学校はペンシルバニア州のカーライルインディアンスクールをモデルとしており、そのモッ トーは「彼の中のインディアンを殺し、人間を救う」であった[98][自費出版?] 彼らの中の「インディアンを殺す」ための最も効果的な武器は、子どもたちを先住民のサポートから引き離すことであると考えられていたため、先住民の子ども たちは家や親、家族、友人、地域社会から連れ去られた[99]。 1876年のインディアン法は先住民の教育に対する責任を連邦政府に与え、1910年までにはレジデンシャルスクールが先住民の教育政策を支配するように なった。政府はカトリック教会、英国国教会、合同教会、長老派教会などの宗教団体に資金を提供し、先住民の教育に取り組ませた。1920年までに先住民の 出席は義務化され、全国で74の寄宿学校が運営されるようになった。シフトンや彼のような人々の考えに従い、これらの学校の学問的目標は「おぼろげ」なも のとなった。ダンカン・キャンベル・スコットが当時述べていたように、「インディアンの村では頭が良すぎる」生徒を望まなかったのである[100]。「こ の目的のために、レジデンシャルスクールのカリキュラムは簡略化され、実践的な指導は、生徒が学校を出て保護区に戻ったときにすぐに役立つようなものと なっている。 政府が提供する資金は一般に不十分で、学校はしばしば「自給自足のビジネス」として運営され、「学生労働者」は洗濯や暖房、農作業のために授業から外され た。寮は暖房が行き届かず、過密状態であることが多く、食事は栄養価が十分とは言えなかった。1907年にインディアン局が委託した報告書によると、15 の草原の学校で24%の死亡率があった[101]: 「これらの学校を通過した子供たちの50パーセントは、そこで受けた教育から利益を得られなかったと言うのは、かなり的を射ている。後年、死亡率は減少し たものの、死はレジデンシャル・スクールの伝統の一部であり続けた。BNAへのその報告書の著者であるP.H.ブライス博士は後に解任され、1922年に は、学校におけるインディアンの状況に対する政府の無関心を「過失致死」と呼ぶに近い小冊子[102]を出版した[101]。 人類学者のステックリーとカミンズは、この制度が現在よく知られているように、感情的、身体的、性的といった常習的な虐待は、「ヨーロッパ人がカナダで先 住民に行った唯一最悪のこととして容易に認められるかもしれない」[103]と指摘している。先住民の言語を話した子どもたちの舌にピンが刺さったり、病 気の子どもたちが吐いたものを食べさせられたり、子どもたちの性器の半公式的な検査が行われたりしたこともあった[104]。 シックスティーズ・スクープ(またはカナダ・スクープ)という言葉は、1960年代に始まり1980年代後半まで続いた、カナダのアボリジニの子どもたち を里親や養子縁組のために家族から引き離す(「すくい上げる」)カナダの慣習を指す。 ほとんどの収容施設は1970年代に閉鎖され、最後の収容施設は1996年に閉鎖された。政府と教会に対する刑事訴訟と民事訴訟は1980年代後半に始ま り、その後まもなく最後の収容学校が閉鎖された。2002年までに訴訟件数は10,000件を超えた。1990年代に入ると、合同教会を皮切りに、レジデ ンシャル・スクールを運営していた教会が正式な謝罪を表明し始めた。1998年、カナダ政府は「和解の声明」[105]を発表し、レジデンシャル・スクー ルでの身体的・性的虐待の遺産から生じる個人、家族、コミュニティの癒しのニーズに取り組むため、コミュニティを基盤とした癒し戦略の支援に3億 5,000万ドルを拠出することを約束した。この資金はアボリジニ・ヒーリング財団の設立に使われた[106]。 1990年代から、政府はインディアン・レジデンシャル・スクールの影響に対処するために多くのイニシアチブを開始した。1998年3月、政府は和解声明 を発表し、アボリジナル・ヒーリング財団を設立。2003年秋には裁判外紛争解決手続き(Alternative Dispute Resolution process)が開始され、身体的・性的虐待を受けたり、不当な監禁状態にあった元寮制学校の生徒たちに補償金と精神的サポートを提供する裁判外の手続 きとなった。2008年6月11日、スティーブン・ハーパー首相は現内閣を代表し、アボリジニ代表の聴衆の前で正式な謝罪を表明した。真相究明委員会は 2008年から2015年まで、過去に残された対立を解決するために過去の不正行為を記録するために開催された[107]。最終報告書は、学校制度は文化 的虐殺に相当すると結論づけた[108]。 現代の状況 主な記事 西欧の植民地主義と植民地化の分析 過去のあからさまな制度的人種差別は、カナダ全土の目に見えるマイノリティとアボリジニ・コミュニティに壊滅的かつ永続的な影響を与えたことは明らかであ る[109]。ヨーロッパの文化的規範がカナダの先住民に押し付けられ、アボリジニ・コミュニティは統治、司法、教育、生活に関する外国の制度と闘い続け ている。目に見えるマイノリティは、カナダ全土で教育、雇用、法制度との否定的な接触に苦しんでいる[110]。 おそらく最も顕著なのは、レジデンシャル・スクールが引き起こした機能不全と家族の荒廃であろう。ハッチンズは次のように述べている[103][自費出 版?]。「収容所学校に通った人々の多くは心的外傷後ストレス障害と診断され、パニック発作、不眠症、制御不能または説明不能な怒りなどの症状に苦しんで いる。ネイティブの親たちは3世代にわたって、通常は親から子へと受け継がれる重要な育児スキルを、思いやりと養育に満ちた家庭環境で学ぶ機会を失い [112]、寄宿学校の生徒たちが受けた虐待は、多くのネイティブ・コミュニティで悲惨な虐待の連鎖を始めている。収容学校の永続的な遺産は、問題の一面 に過ぎない[113]。 ハッチンス報告書はこう続けている: 「アボリジニの子供たちは、カナダの主流教育で苦労し続けている。一部のインディアンの生徒にとって、英語は依然として第二言語であり、多くの生徒には、 彼らを支援する十分な教育を受けた親がいない。さらに、カナダの学校教育は、ネイティブ・コミュニティの口承伝統とは異なる、英語の文字による伝統に基づ いている[114] 。「アボリジニの人々は、依然として不健康に苦しんでいる。アボリジニの平均寿命はカナダの全人口より7年短く、乳幼児死亡数はカナダのほぼ2倍である。 国家としてのカナダは、国連の人間開発指数[115]で常に上位3位にランクされているが、保護区内のアボリジニ人口は、国家として採点された場合、遠く 離れた衝撃的な63位である。 ペリー・ベルガード(カナダ先住民協会全国会長)が指摘するように、今日のカナダにおける人種差別は、その大部分が秘密裏に行われている[116]。 [117]人権の分野でのカナダの努力と人種差別に対する姿勢は、「偏見をよりうまく隠すことを学んだ、より政治的に正しい人々」[118]をもたらした にすぎないと主張する者も多い。事実上、カナダにおける人種差別は解消されつつあるのではなく、むしろより隠密に、より理性的に、そしておそらくより深く 制度に埋め込まれつつあるという主張である。 この住民投票の結果は拘束力を持ち[120]、投票者の50%以上が同じ回答をした場合、政府はこの原則に基づいて行動することを立法的に約束した。さら に、何度も改正されてはいるが、「インディアン法は依然として、人種に基づいて社会の一部を特別視する法律」である。この法律の下で、先住民の市民権は 「他のカナダ市民の市民権とは異なる方法で扱われている」[103]。  ジョイス・エチャカン、湖畔にて、1999年 マニトバ州のアボリジナル・ジャスティス調査[121]、ノヴァ・スコシア州のドナルド・マーシャル調査[122]、アルバータ州のコーシー報告書 [123]、そしてアボリジニ王立委員会はすべて、アボリジニに関する限り、カナダ社会における人種差別は制度的、組織的、そして個人的に続いている [124]と認めている。 2020年、ジョイス・エチャカンの死後、カナダのジャスティン・トルドー首相は組織的人種差別の事例を認めた。 2022年、教皇フランシスコは「悔悛の巡礼」と呼ばれる1週間のツアーでカナダを訪れた[125]。教皇はエドモントンで歓迎され、20世紀にカトリッ クが運営し、現在は閉鎖されている居住学校で行われた先住民虐待について謝罪した[126]。滞在中、教皇は居住学校のスキャンダルを取り上げるために先 住民グループと面会した[127]。 反中国移民法 カナダ政府は1885年に中国移民法を制定し、カナダに移民するすべての中国人に50ドルの頭税を課した。1885年の法律が中国人移民の抑止に失敗する と、カナダ政府は次に1900年の中国移民法を成立させ、頭税を100ドルに引き上げ、この法律が失敗すると、1904年の中国移民法を成立させ、頭税 (上陸料)を500ドルに引き上げ、2003年には8,000ドルに相当した[129]-1995年から2005年の10年間に新規移民が支払った一人当 たり975ドルの頭税(上陸料と永住権料)と比較すると、2006年には490ドルに引き下げられた[130]。 1923年に制定された中国移民法(Chinese Immigration Act, 1923)は、「中国人排斥法」として知られ、商人、外交官、学生、および「特別な事情」のあるケースを除き、中国人のカナダへの移民を禁止し、禁止料金 に取って代わった。1923年以前にカナダに入国した中国人は、地元当局に登録しなければならず、2年以内に限りカナダを離れることができた。排外法が 1923年7月1日に施行されて以来、中国系カナダ人はカナダ・デー(ドミニオン・デー)を「屈辱の日」と呼び[131]、1947年に同法が廃止される まで祝うことを拒否していた[132]。 黒人カナダ人  1927年、オンタリオ州キングストン近郊の野原に建てられた十字架のそばで、徒歩と馬に乗ったクー・クラックス・クランのメンバーたち。 後にカナダとなる英領北アメリカの一部の地域では、17世紀からの奴隷制度の記録がある。これらの奴隷の大半はアボリジニであり[133]、ユナイテッ ド・エンパイア・ロイヤリストはアメリカを離れた後に奴隷を連れてきた。 |