Klezmer

(Yiddish: קלעזמער or כּלי־זמר) is an instrumental musical tradition of

the Ashkenazi Jews of Central and Eastern Europe. The essential

elements of the tradition include dance tunes, ritual melodies, and

virtuosic improvisations played for listening; these would have been

played at weddings and other social functions.[1][2] The musical

genre—also sometimes known by the earlier term freilach music (Yiddish:

פריילעך, romanized: freilach, "joyous, happy")—incorporated elements of

many other musical genres including Ottoman (especially Greek and

Romanian) music, Baroque music, German and Slavic folk dances, and

religious Jewish music.[3][4] As the music arrived in the United

States, it lost some of its traditional ritual elements and adopted

elements of American big band and popular music.[5][6] Among the

European-born klezmers who popularized the genre in the United States

in the 1910s and 1920s were Dave Tarras and Naftule Brandwein; they

were followed by American-born musicians such as Max Epstein, Sid

Beckerman and Ray Musiker.[7]

After the destruction of Jewish life in Eastern Europe during the

Holocaust, and a general fall in the popularity of klezmer music in the

United States, the music began to be popularized again in the late

1970s in the so-called Klezmer Revival.[8] During the 1980s and

onwards, musicians experimented with traditional and experimental forms

of the genre, releasing fusion albums combining the genre with jazz,

punk, and other styles.[9]

|

クレズマー(イディッシュ語:קלעזמערまたはכי-זמר)は、

中欧と東欧のアシュケナージ系ユダヤ人の器楽音楽の伝統である。この伝統の本質的な要素には、ダンス曲、儀式のメロディー、聴くために演奏されるヴィル

トゥオーゾ的な即興曲などが含まれ、これらは結婚式やその他の社交の場で演奏された。

[1][2]この音楽ジャンルは、それ以前はフライラッハ音楽(イディッシュ語: פריילעך、ローマ字表記:

freilach、「楽しい、幸福な」)と呼ばれることもあったが、オスマン帝国(特にギリシャとルーマニア)の音楽、バロック音楽、ドイツとスラヴの民

族舞踊、宗教的なユダヤ音楽など、他の多くの音楽ジャンルの要素を取り入れていた。

[1910年代から1920年代にかけてアメリカでこのジャンルを広めたヨーロッパ生まれのクレズマーの中には、デイブ・タラスとナフチュール・ブランド

ヴァインがいた。彼らに続いてマックス・エプスタイン、シド・ベッカーマン、レイ・ムジカーといったアメリカ生まれのミュージシャンが登場した[7]。

ホロコーストで東ヨーロッパのユダヤ人の生活が破壊され、アメリカにおけるクレズマー音楽の人気が全般的に低下した後、1970年代後半にいわゆるクレズ

マー・リバイバルと呼ばれる形で音楽が再び普及し始めた[8]。

1980年代以降、ミュージシャンたちはこのジャンルの伝統的かつ実験的な形態を実験的に取り入れ、このジャンルとジャズ、パンク、その他のスタイルを組

み合わせたフュージョン・アルバムをリリースした[9]。

|

Etymology

The term klezmer, as used in the Yiddish language, has a Hebrew

etymology: klei, meaning "tools, utensils or instruments of" and zemer,

"melody"; leading to k'lei zemer כְּלֵי זֶמֶר, meaning "musical

instruments".[10] This expression would have been familiar to literate

Jews across the diaspora, not only Ashkenazi Jews in Eastern

Europe.[11] Over time the usage of "klezmer" in a Yiddish context

evolved to describe musicians instead of their instruments, first in

Bohemia in the second half of the sixteenth century and then in Poland,

possibly as a response to the new status of the musicians who were at

that time forming professional guilds.[11] Previously the musician may

have been referred to as a lets (לץ) or other terms.[12][13] After the

term klezmer became the preferred term for these professional musicians

in Yiddish-speaking Eastern Europe, other types of musicians were more

commonly known as muziker or muzikant.

It was not until the late 20th century that the word "Klezmer" became a

commonly known English language term.[14] During that time, through

metonymy it came to refer not only to the musician but to the musical

genre they played, a meaning which it had not had in

Yiddish.[15][16][17] Early 20th century recording industry materials

and other writings had referred to it as Hebrew, Jewish, or Yiddish

dance music, or sometimes using the Yiddish term Freilech music

("Cheerful music").

Twentieth century Russian scholars sometimes used the term Klezmer;

Ivan Lipaev did not use it, but Moisei Beregovsky did when publishing

in Yiddish or Ukrainian.[11]

The first[citation needed] postwar recordings to use the term "klezmer"

to refer to the music were The Klezmorim's East Side Wedding and

Streets of Gold in 1977/78, followed by Andy Statman and Zev Feldman's

Jewish Klezmer Music in 1979.[citation needed]

|

語源

イディッシュ語で使われるクレズマーという言葉の語源はヘブライ語であり、kleiは「道具、道具、道具」、zemerは「旋律」を意味し、k'lei

zemer כּי ז מֶרは「楽器」を意味する。 [10]

この表現は、東欧のアシュケナージ系ユダヤ人だけでなく、ディアスポラ全域の識字力のあるユダヤ人に親しまれていたであろう。

[11]イディッシュ語の文脈における「クレズマー」の用法は、時が経つにつれて、楽器の代わりに音楽家を表現するようになった。

[11]以前は、音楽家はレット(לץ)または他の用語で呼ばれていたかもしれない[12][13]。クレズマーという用語がイディッシュ語を話す東ヨー

ロッパでこれらの職業音楽家を指す好ましい用語となった後、他のタイプの音楽家はより一般的にムジカーまたはムジカントと呼ばれるようになった。

クレズマー」という言葉が一般的に知られる英語用語になったのは20世紀後半になってからである[14]。その間に、メトニミーによって、ミュージシャン

だけでなく、彼らが演奏する音楽ジャンルを指すようになった。

イワン・リパーエフは使わなかったが、モイセイ・ベレゴフスキーはイディッシュ語やウクライナ語で出版する際に使っていた[11]。

戦後初めて[要出典]「クレズマー」という用語を使った録音は、1977/78年のザ・クレズモリムの『East Side

Wedding』と『Streets of Gold』であり、1979年のアンディ・スタットマンとゼヴ・フェルドマンの『Jewish

Klezmer Music』がそれに続く[要出典]。

|

Musical elements

Style

The traditional style of playing Klezmer music, including tone, typical

cadences, and ornamentation sets it apart from other genres.[18]

Although Klezmer music emerged out of a larger Eastern European Jewish

musical culture that included Jewish cantorial music, Hasidic Nigns,

and later Yiddish theatre music, it also borrowed from the surrounding

folk musics of Central and Eastern Europe and from cosmopolitan

European musical forms.[3][19] Therefore it evolved into an overall

style which has recognizable elements from all of those other genres.

Few klezmer musicians before the late nineteenth century had formal

musical training, but they inherited a rich tradition with its own

advanced musical techniques, each musician had their understanding of

how the style should be "correctly" performed.[20][18] The usage of

these ornaments was not random; the matters of "taste",

self-expression, variation and restraint were and remain important

elements of how to interpret the music.[18]

Klezmer musicians apply the overall style to available specific

techniques on each melodic instrument. They incorporate and elaborate

the vocal melodies of Jewish religious practice, including khazones,

davenen, and paraliturgical song, extending the range of human voice

into the musical expression possible on instruments.[21] Among those

stylistic elements that are considered typically "Jewish" in Klezmer

music are those which are shared with cantorial or Hasidic vocal

ornaments, including dreydlekh ("tear in the voice"; plural of

dreidel)[22][23] and imitations of sighing or laughing ("laughter

through tears").[24] Various Yiddish terms were used for these

vocal-like ornaments such as קרעכץ (Krekhts, "groan" or "moan"), קנײטש

(kneytsh, "wrinkle" or "fold"), and קװעטש (kvetsh, "pressure" or

"stress").[10] Other ornaments such as trills, grace notes,

appoggiaturas, glitshn (glissandos), tshoks (a kind of bent notes of

cackle-like sound), flageolets (string harmonics),[22][25] pedal notes,

mordents, slides and typical Klezmer cadences are also important to the

style.[18] In particular, the cadences which draw on religious Jewish

music identify a piece more strongly as a Klezmer tune, even if its

broader structure was borrowed from a non-Jewish source.[26][19]

Sometimes the term dreydlekh is used only for trills, while other use

it for all Klezmer ornaments. [27] Unlike in Classical music, vibrato

is used more sparingly, and is treated as another type of

ornament.[24][18]

In an article about Jewish music in Romania, Bob Cohen of Di Naye

Kapelye describes krekhts as "a sort of weeping or hiccoughing

combination of backwards slide and flick of the little finger high

above the base note, while the bow does, well, something – which aptly

imitates Jewish liturgical singing style." He also noted that the only

other place he has heard this particular ornamentation is in Turkish

music on the violin.[28] Yale Strom wrote that the use of dreydlekh by

American violinists gradually diminished since 1940s, but with the

klezmer revival on 1970, dreydlekh had become prominent again.[23]

The accompaniment style of the accompanist or orchestra could be fairly

impromptu, called צוהאַלטן (tsuhaltn, holding onto).[29]

Historical repertoire

The repertoire of Klezmer musicians was very diverse and tied to

specific social functions and dances, especially of the traditional

wedding.[1][19] These melodies might have a non-Jewish origin, or have

been composed by a Klezmer, but only rarely are they attributed to a

specific composer.[30] Generally Klezmer music can be divided into two

broad categories: music for specific dances, and music for listening

(at the table, in processions, ceremonial, etc.)[30]

Dances

Freylekhs. The simplest and most widespread type of Klezmer dance tune

are those played in 2

4 and intended for group circle dances. Depending on the location this

basic dance may also have been called a Redl (circle), Hopke, Karahod

(round dance, literally the Belarusian translation of the Russian

khorovod), Dreydl, Rikudl, etc.[1][31][29][10]

Bulgar, or Bolgar, became the most popular Klezmer dance form in the

United States. Its origin is thought to be in Moldavia and with a deep

connection to the Sârbă genre there.[19]

Sher is a Contra dance in 2

4. Beregovsky, writing in the 1930s, noted that despite the dance being

very commonly played across a wide area, and that he suspected it had

its roots in an older German dance.[1] This dance continued to be known

in the United States even after other complex European Klezmer dances

had been forgotten.[32] In some regions the music of a Sher could be

interchangeable with a Freylekhs.[19]

Khosidl, or Khosid, named after Hasidic Jews, is a more dignified

embellished dance in 2

4 or 4

4. The dance steps can be performed in a circle or in a line.

Hora or Zhok (from the Romanian Joc) is a circle dance in 3

8. In the United States, it came to be one of the main dance types

after the Bulgar.[19]

Broygez-tants[30]

Kolomeike is a fast and catchy dance in 2

4 time, which originated in Ukraine, and is prominent in the folk music

of that country.

Skotshne is generally thought to be a more elaborate Freylekhs which

could be played either for dancing or listening.[1]

Nigun, a very broad term which can refer to melodies for listening,

singing or dancing.[10] Usually a mid-paced song in 2

4.

Waltzes were very popular, whether classical, Russian, or Polish. A

padespan was a sort of Russian/Spanish waltz known to klezmers.

Mazurka and polka, Polish and Czech dances, respectively, were often

played for both Jews and Gentiles.

Sirba – a Romanian dance in 2

2 or 2

4 (Romanian sârbă). It features hopping steps and short bursts of

running, accompanied by triplets in the melody.

Non-dance repertoire

The Doyne is a freeform instrumental form borrowed from the Romanian

shepherd's doina. Although there are many regional types of doina in

Romania and Moldova, the Jewish form is typically simpler, with a minor

key theme which is then repeated in a major key, followed by a

Freylekhs.[30] A Volekhl is a related genre.[10]

Tish-nign (table tune)[10]

Moralish, a type of Nigun, called Devekut in Hebrew, which inspires

spiritual arousal or a pious mood.[10][29]

A Vals (Waltz), pieces in 3

4 especially in the Hasidic context, may be slower than non-Jewish

waltzes and intended for listening while the wedding parties are seated

at their tables.[10]

Forms centering on bridal rituals, including Kale-bazetsn (seating of

the bride)

A Marsh (March) can be non-Jewish march melodies adapted into joyful

singing or playing contexts.[10]

Processional melodies, including Gas-nigunim (street tunes), Tsum tish

(to the table). According to Beregovski the Gas-nign was always in 3

4 time.[30]

The Taksim, whose name is borrowed from the Ottoman/Arab Taqsim is a

freeform fantasy on a particular motif, ornemented with trills,

roulades and so on; it usually ends with a Freylekhs.[30] By the

twentieth century it has mostly become obsolete and was replaced by the

doina.[33]

Fantazi or fantasy is a freeform song, traditionally played at Jewish

weddings to the guests as they dined. It resembles the fantasia of

"light" classical music.

A Terkisher is a type of virtuosic solo piece in 4

4 performed by leading klezmorim such as Dave Tarras and Naftule

Brandwein. There is no dance for this type of melody, rather it

references an Ottoman or "oriental" style, and melodies may incorporate

references to Greek Hasapiko into a Ashkenazic musical aesthetic.

Parting melodies played at the beginning or end of a wedding day, such

as the Zay gezunt (be healthy), Gas-nign, Dobriden (good day),

Dobranotsh or A gute nakht (good night) etc.[30][34] These types of

pieces were sometimes in 3

4 which may have given an air of dignity and seriousness.[35]

|

音楽的要素

スタイル

クレズマー音楽は、音色、典型的なカデンツ、装飾を含む伝統的な演奏スタイルによって、他のジャンルとは一線を画している[18]。クレズマー音楽は、ユ

ダヤ教のカントリー音楽、ハシディック・ニグンス、後のイディッシュ演劇音楽などを含む、より大きな東ヨーロッパのユダヤ人の音楽文化から生まれたが、中

欧・東欧の周辺の民族音楽や、コスモポリタンなヨーロッパの音楽形態からも借用した。

19世紀後半以前のクレズマー・ミュージシャンには、正式な音楽訓練を受けていた者はほとんどいなかったが、独自の高度な音楽技法を持つ豊かな伝統を受け

継いでおり、各ミュージシャンはこのスタイルをどのように「正しく」演奏すべきかを理解していた[20][18]。これらの装飾の使い方は無作為ではな

く、「好み」、自己表現、変化、抑制といった事柄が、音楽をどのように解釈するかという重要な要素であったし、今もそうである[18]。

クレズマー・ミュージシャンは、全体的なスタイルを各旋律楽器で利用可能な特定のテクニックに応用する。彼らは、カゾネ、ダヴェン、パラリトゥルガー・ソ

ングなど、ユダヤ教の宗教的実践の声楽的メロディーを取り入れ、精巧化し、人間の声の音域を楽器で可能な音楽表現に拡張している[21]。

[21]クレズマー音楽における典型的な「ユダヤ的」とされる様式的要素の中には、ドレイデルク(「声の涙」、ドレイデルの複数形)[22][23]やた

め息や笑い声の模倣(「涙を流して笑う」)など、カントリアやハシディズムの声楽的装飾と共通するものがある。

קרעו(Krekhts、「うめき声」)、קנײש(kneytsh、「しわ」または「折り目」)、קװעטש(kvetsh、「圧力」または「ストレ

ス」)など、様々なイディッシュ語の用語がこれらの声のような装飾に使用された[24]。

[10]その他、トリル、グレースノート、アポジャトゥーラ、グリットシュン(グリッサンド)、ツォック(キャッキャッというような音の一種の屈曲音)、

フラジオレット(弦楽器のハーモニクス)、[22][25]ペダルノート、モルデント、スライド、典型的なクレズマーのカデンツなどの装飾音もこのスタイ

ルにとって重要である。

[18]特に、宗教的なユダヤ音楽から引用されたカデンツは、たとえその幅広い構成が非ユダヤ的なソースから借用されたものであったとしても、楽曲をより

強くクレズマー曲として識別する。[クラシック音楽とは異なり、ヴィブラートの使用は控えめであり、装飾の一種として扱われる[24][18]。

ルーマニアのユダヤ音楽に関する記事の中で、Di Naye

Kapelyeのボブ・コーエンはクレヒトについて「弓が、まあ、何かをする間、基音より高い位置で小指の後方へのスライドとフリックを組み合わせた一種

の泣くような、あるいはしゃっくりをするような-これはユダヤ教の典礼歌唱スタイルを適切に模倣している」と述べている。彼はまた、この特殊な装飾を聴い

たことがあるのは、ヴァイオリンによるトルコ音楽だけだと述べている[28]。イェール・ストロームは、アメリカのヴァイオリニストによるドレイドレクの

使用は1940年代から徐々に減少していったが、1970年のクレズマー・リバイバルによって、ドレイドレクが再び目立つようになったと書いている

[23]。

伴奏者やオーケストラの伴奏スタイルはかなり即興的で、צוהאַÜן(tsuhaltn、持ちつ持たれつ)と呼ばれる[29]。

歴史的レパートリー

クレズマー・ミュージシャンのレパートリーは非常に多様であり、特に伝統的な結婚式のような特定の社会的行事や踊りと結びついていた[1][19]。これ

らのメロディーは非ユダヤ人に由来することもあれば、クレズマーによって作曲されたこともあるが、特定の作曲家に帰属することは稀である[30]。一般的

にクレズマー音楽は、特定の踊りのための音楽と、聴くための音楽(食卓、行列、儀式など)の2つに大別することができる[30]。

ダンス

フレイレク クレズマー・ダンス曲の中で最もシンプルで広く普及しているのは、グループ・サークル・ダンス用に2

4で演奏されるもので、グループでのサークルダンスのためのものである。場所によっては、この基本的なダンスはレドル(輪)、ホプケ、カラホド(円舞曲、

文字通りロシア語のホロヴォドのベラルーシ語訳)、ドレイドル、リクドルなどとも呼ばれていた[1][31][29][10]。

ブルガー(Bolgar)は、アメリカで最も人気のあるクレズマー・ダンスとなった。その起源はモルダヴィアで、同地のSârbăジャンルと深いつながり

があると考えられている[19]。

シャーは2

4.

1930年代に執筆したベレゴフスキーは、この踊りが広い地域で非常に一般的に演奏されているにもかかわらず、そのルーツは古いドイツの踊りにあるのでは

ないかと述べている[1]。

ホシドル(Khosidl)またはホシド(Khosid)は、ハシディック・ユダヤ人にちなんで命名されたもので、より威厳のある装飾が施された舞曲であ

る。

4または4

4. 踊りのステップは、輪になって踊ることも、一列に並んで踊ることもできる。

ホラ(Hora)またはゾック(Zhok)(ルーマニア語のジョック(Joc)に由来する)は、3人または4人で踊る円舞曲である。

8. アメリカでは、ブルガールに次いで主要なダンスの1つとなっている[19]。

ブロイゲズ・タンツ[30]。

コロメイケは2

4拍子で、ウクライナ発祥のもので、同国の民族音楽では著名である。

Skotshneは一般に、より精巧なFreylekhsであり、踊ったり聴いたりするために演奏されると考えられている[1]。

ニグン(Nigun)は、聴くため、歌うため、踊るためのメロディーを指す非常に広い用語である[10]。

4.

ワルツは、クラシック、ロシア、ポーランドを問わず非常に人気があった。パデスパンは、クレズマーの間で知られているロシア/スペインのワルツの一種であ

る。

マズルカとポルカは、それぞれポーランドとチェコの舞曲で、ユダヤ人と異邦人の両方でよく演奏された。

シルバ - ルーマニアのダンスで、2

2または2

4(ルーマニア語のsârbă)で踊る。3連符のメロディーを伴奏に、ホッピングステップや短距離走が特徴。

ダンス以外のレパートリー

ドインは、ルーマニアの羊飼いのドイナに由来する自由形式の器楽曲である。ルーマニアとモルドヴァには多くの地域的なタイプのドイナがあるが、ユダヤ人の

形式は一般的に単純であり、短調の主題が長調で繰り返され、その後にフレイレク(Freylekhs)が続く[30]。

Tish-nign(テーブル・チューン)[10]。

ヘブライ語でDevekutと呼ばれるNigunの一種であるMoralishは、精神的な興奮や敬虔な気分を鼓舞する[10][29]。

ヴァルス(ワルツ)、3番

4

特にハシディズムの文脈では、非ユダヤのワルツよりも遅く、結婚式のパーティーがテーブルに着いている間に聴くことを意図している場合がある[10]。

花嫁の着席(Kale-bazetsn)を含む花嫁の儀式を中心とした形式。

マーシュ(行進曲)は、ユダヤ教以外の行進曲の旋律を喜びの歌や演奏に転用したものである[10]。

Gas-nigunim(街頭曲)、Tsum tish(食卓へ)などの行進曲。ベレゴフスキによれば、ガスニグニムは常に3

4拍子であった[30]。

タクシム(Taksim)はオスマン・アラブのタクシム(Taqsim)から名前を借りたもので、特定のモチーフにトリルやルーラードなどで装飾を施した

自由曲の幻想曲である。

ファンタジ(Fantazi)またはファンタジー(Fantasy)は、ユダヤ人の結婚式で伝統的にゲストが食事をする際に演奏される自由曲である。軽

い」クラシック音楽のファンタジアに似ている。

テルキシャー(Terkisher)は、一流のクレズム奏者によって演奏される、独奏曲の一種である。

4拍子で、デイブ・タラスやナフチュール・ブランドヴァインといった一流のクレズモリムによって演奏される。このタイプの旋律には舞曲はなく、むしろオス

マン・トルコや「東洋的」なスタイルが参照され、旋律にはギリシャのハサピコへの言及がアシュケナージ風の音楽美学に組み込まれていることもある。

結婚式の始まりや終わりに演奏される別れのメロディーには、Zay

gezunt(健康であれ)、Gas-nign、Dobriden(良い一日を)、DobranotshやA gute

nakht(良い夜を)などがある[30][34]。

4で書かれることもあり、威厳と真剣さを与えていたと思われる[35]。

|

Orchestration

Klezmer music is an instrumental tradition, without much of a history

of songs or singing. In Eastern Europe, Klezmers did traditionally

accompany the vocal stylings of the Badchen (wedding entertainer),

although their performances were typically improvised couplets and the

calling of ceremonies rather than songs.[36][37] (The importance of the

Badchen gradually decreased by the twentieth century, although they

still continued in some traditions.[38])

As for the klezmer orchestra, its size and composition varied by time

and place. The Klezmer bands of the eighteenth and early nineteenth

century were small, with roughly three to five musicians playing

Woodwind or String instruments.[20] Another common configuration in

that era was similar to Hungarian bands today, typically a lead

violinist, second violin, cello, and Cimbalom.[39][40] In the

mid-nineteenth century, the Clarinet started to appear in those small

Klezmer ensembles as well.[41] By the last decades of the century, in

Ukraine, the orchestras had grown larger, averaging seven to twelve

members, and incorporating Brass instruments and up to twenty for a

prestigious occasion.[42][43] (However, for poor weddings a large

Klezmer ensemble might only send three or four of its junior

members.[42]) In these larger orchestras, on top of the core

instrumentation of strings and woodwinds, cornets, C clarinets,

trombones, a contrabass, a large Turkish drum, and several extra

violins.[30] The inclusion of Jews in tsarist army bands during the

19th century may also have led to the introduction of typical military

band instruments into klezmer. With such large orchestras, the music

was arranged so that the bandleader soloist could still be heard at key

moments.[44] In Galicia, and Belarus, the smaller string ensemble with

cimbalom remained the norm into the twentieth century.[45][30] American

Klezmer as it developed in dancehalls and wedding banquets of the early

twentieth century had a more complete orchestration not unlike those

used in popular orchestras of the time. They use a clarinet, saxophone,

or trumpet for the melody, and make great use of the trombone for

slides and other flourishes.

Jewish musicians of Rohatyn (west Ukraine)

The melody in Klezmer music is generally assigned to the lead violin,

although occasionally the flute and eventually clarinet.[30] The other

instrumentalists provide harmony, rhythm, and some counterpoint (the

latter usually coming from the second violin or viola). The clarinet

now often played the melody. Brass instruments—such as the French

valved cornet and keyed German trumpet—eventually inherited a

counter-voice role.[46] Modern klezmer instrumentation is more commonly

influenced by the instruments of the 19th century military bands than

the earlier orchestras.

Percussion in early 20th-century klezmer recordings was generally

minimal—no more than a wood block or snare drum. In Eastern Europe,

percussion was often provided by a drummer who played a frame drum, or

poyk, sometimes called baraban. A poyk is similar to a bass drum and

often has a cymbal or piece of metal mounted on top, which is struck by

a beater or a small cymbal strapped to the hand.

|

オーケストレーション

クレズマー音楽は器楽の伝統であり、歌や歌の歴史はあまりない。東ヨーロッパでは、クレズマーは伝統的にバドヒェン(結婚式のエンターテイナー)のヴォー

カルを伴奏していたが、彼らのパフォーマンスは歌というよりは即興の連詩や儀式の呼びかけが一般的であった[36][37](バドヒェンの重要性は20世

紀までに徐々に低下したが、いくつかの伝統ではまだ続いている[38])。

クレズマー楽団に関しては、その規模や編成は時代や場所によって異なっていた。18世紀から19世紀初頭にかけてのクレズマー楽団は小規模で、木管楽器ま

たは弦楽器を演奏するおよそ3人から5人の音楽家で構成されていた[20]。その時代のもうひとつの一般的な構成は、今日のハンガリーの楽団に似ており、

典型的にはリード・ヴァイオリン奏者、セカンド・ヴァイオリン、チェロ、チンバロムであった[39][40]。

[39][40]19世紀半ばになると、クラリネットがそれらの小規模なクレズマー・アンサンブルにも登場するようになった[41]。

今世紀最後の数十年までには、ウクライナではオーケストラの規模が大きくなり、平均7人から12人のメンバーで構成されるようになり、金管楽器が組み込ま

れ、名誉ある機会には20人にまでなった。

[42][43](ただし、貧しい結婚式の場合、大規模なクレズマー・アンサンブルは3、4人のジュニア・メンバーしか派遣しないこともあった

[42])。これらの大規模なオーケストラでは、弦楽器と木管楽器という中核となる楽器の他に、コルネット、Cクラリネット、トロンボーン、コントラバ

ス、大きなトルコ太鼓、そして数人の追加ヴァイオリンが演奏された[30]。19世紀にツァーリスト軍の楽団にユダヤ人が参加したことも、典型的な軍楽隊

の楽器をクレズマーに導入することにつながったと考えられる。ガリシアやベラルーシでは、20世紀に入ってもシンバロムを伴う小規模な弦楽合奏が主流で

あった[44]。

20世紀初頭のダンスホールや結婚披露宴で発展したアメリカのクレズマーは、当時のポピュラー・オーケストラで使われていたものとは異なり、より完全な編

成を持っていた。メロディーにはクラリネット、サクソフォン、トランペットを使い、スライドやその他の華やかな演出にはトロンボーンを多用する。

ロハティン(ウクライナ西部)のユダヤ人音楽家たち

クレズマー音楽の旋律は一般的にリード・ヴァイオリンに割り当てられるが、時にはフルート、最終的にはクラリネットが担当することもある[30]。クラリ

ネットが旋律を担当することも多くなった。金管楽器(フランスのバルブ付きコルネットやキーの付いたドイツのトランペットなど)は、最終的にカウンター

ヴォイスの役割を受け継いだ[46]。現代のクレズマー楽器の編成は、初期のオーケストラよりも19世紀の軍楽隊の楽器の影響を受けていることが多い。

20世紀初頭のクレズマー録音におけるパーカッションは、一般的にウッド・ブロックやスネア・ドラム以上の最小限のものであった。東ヨーロッパでは、パー

カッションはフレームドラム(ポイク、バラバンとも呼ばれる)を演奏するドラマーが担当することが多かった。ポイクはバスドラムに似ており、上部にシンバ

ルや金属片が取り付けられていることが多く、ビーターや手にはめた小さなシンバルで叩く。

|

Melodic modes

Western, Cantorial, and Ottoman music terminology

Klezmer music is a genre that developed partly in the Western musical

tradition but also in the Ottoman Empire, and is primarily an oral

tradition which does not have a well-established literature to explain

its modes and modal progression.[47][48] But, as with other types of

Ashkenazic Jewish music, it has a complex system of modes which were

used in its compositions.[10][49] Many of its melodies do not fit well

in the major and minor terminology used in Western music, nor is the

music systematically microtonal in the way that Middle Eastern music

is.[47] Nusach terminology, as developed for Cantorial music in the

nineteenth century, is often used instead, and indeed many Klezmer

compositions draw heavily on religious music.[34] But it also

incorporates elements of Baroque and Eastern European folk musics,

making description based only on religious terminology

incomplete.[26][29][50] Still, since the Klezmer revival of the 1970s,

the terms for Jewish prayer modes are the most common to describe the

those used in klezmer.[51] The terms used in Yiddish for these modes

include Nusach (נוסח); shteyger (שטײגער), "manner, mode of life" which

describes the typical melodic character, important notes and scale; and

gust (גוסט), a word meaning "taste" which was commonly used by Moisei

Beregovsky.[29][30][48]

Beregovsky, who was writing in the Stalinist era and was constrained by

having to downplay Klezmer's religious aspects, did not use the

terminology of Synagogue modes, except in some early work in 1929.

Instead, he relied on German-inspired musical terminology of major,

minor, and "other" modes, which he described in technical

terms.[30][52] In his 1940s works he noted that the majority of the

klezmer repertoire seemed to be in a minor key, whether Natural minor

or others, that around a quarter of the material was in Freygish, and

that around a fifth of the repertoire was in a Major key.[30]

Another set of terminology sometimes used to describe klezmer music is

that of the Makams used in Ottoman and other Middle Eastern

music.[51][53] This approach dates back to Idelsohn in the early

twentieth century, who was very familiar with Middle Eastern music, and

has been developed in the past decade by Joshua

Horowitz.[54][50][51][47]

Finally, some Klezmer music, and especially those composed in the

United States from the mid-twentieth century onwards, may not be

composed with these traditional modes, but rather built around

chords.[26]

|

旋律モード

西洋音楽、カントリア音楽、オスマン音楽の用語

クレズマー音楽は、部分的には西洋音楽の伝統の中で発展したが、オスマン帝国でも発展したジャンルであり、主に口承による伝統であるため、そのモードと

モード進行を説明する確立された文献はない[47][48]。しかし、他のタイプのアシュケナージ系ユダヤ音楽と同様に、その作曲に使用されたモードの複

雑なシステムを持っている。

[10][49]そのメロディの多くは、西洋音楽で使用される長調や短調の用語にはうまく当てはまらず、また中東音楽のように体系的な微分音でもない。

[しかし、バロック音楽や東欧の民族音楽の要素も取り入れているため、宗教用語だけによる説明は不完全である[26][29][50]。それでも、

1970年代のクレズマー・リバイバル以降、クレズマーで使用されるものを説明する際には、ユダヤ教の祈りのモードの用語が最も一般的となっている。

[51]これらのモードを表すイディッシュ語の用語には、ヌザッハ(נוס)、シュタイガー(שטײגער)、典型的な旋律の特徴、重要な音符、音階を表

す「作法、生活様式」などがある; ガスト(גוס)は「味」を意味する言葉で、モイセイ・ベレゴフスキーがよく使っていた。 [29][30][48]

ベレゴフスキーはスターリン主義の時代に作曲をしており、クレズマーの宗教的な側面を軽視しなければならないという制約を受けていたため、1929年の初

期の作品を除いてシナゴーグ・モードの用語は使わなかった。1940年代の作品において彼は、クレズマーのレパートリーの大部分は自然短調かその他の短調

であるようであり、およそ4分の1がフライギッシュ調であり、およそ5分の1が長調であると述べている[30]。

クレズマー音楽を説明するのに使われることがあるもうひとつの用語集は、オスマン・トルコやその他の中東音楽で使われるマカムのものである[51]

[53]。このアプローチは、中東音楽に精通していた20世紀初頭のアイデルゾーンにさかのぼり、過去10年間ではジョシュア・ホロヴィッツによって発展

してきた[54][50][51][47]。

最後に、いくつかのクレズマー音楽、特に20世紀半ば以降にアメリカで作曲された音楽は、これらの伝統的なモードで作曲されておらず、むしろ和音を中心に

構築されている場合がある[26]。

|

Description Description

Because there is no agreed-upon, complete system for describing modes

in Klezmer music, this list is imperfect and may conflate concepts

which some scholars view as separate.[49][54] Another problem in

listing these terms as simple eight-note (octatonic) scales is that it

makes it harder to see how Klezmer melodic structures can work as

five-note pentachords, how parts of different modes typically interact,

and what the cultural significance of a given mode might be in a

traditional Klezmer context.[47][48]

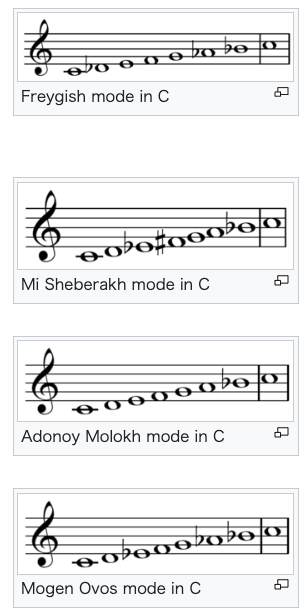

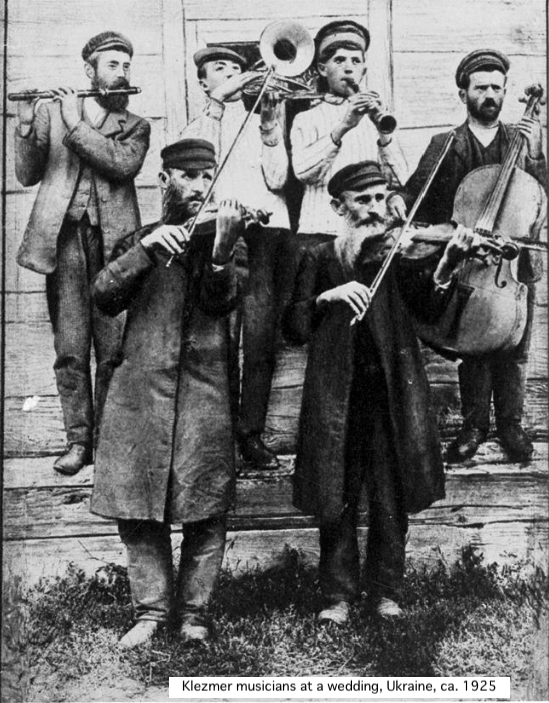

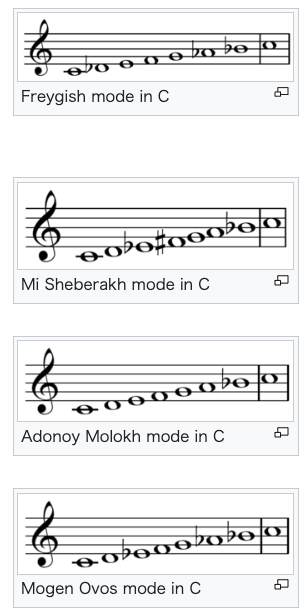

Freygish mode in C

Freygish, Ahavo Rabboh, or Phrygian dominant scale resembles the

Phrygian mode, having a flat second but also a permanent raised

third.[55] It is among the most common modes in Klezmer and is closely

identified with Jewish identity; Beregovsky estimated that roughly a

quarter of the Klezmer music he had collected was in Freygish.[30][47]

Among the most well-known pieces composed in this mode are Hava Nagila

and Ma yofus. It is comparable to the Maqam Hijaz found in Arabic

music.[47]

Mi Sheberakh mode in C

Mi Sheberakh, Av HaRachamim, "altered Dorian" or Ukrainian Dorian scale

is a minor mode which has a raised fourth.[55] It is sometimes compared

to Nikriz Makamı. It is closely related to Freygish since they share

the same pitch intervals.[47] This mode is often encountered in Doynes

and other Klezmer forms with connections to Romanian or Ukrainian music.

Adonoy Molokh mode in C

Adonoy Molokh or Adoyshem Molokh a synagogue mode with a flatted

seventh.[29] It is sometimes called the "Jewish major".[54] It has some

similarities to the Mixolydian mode.[55]

Mogen Ovos mode in C

Mogen Ovos is a synagogue mode which resembles the Western Natural

minor.[29] In klezmer music, it is often found in greeting and parting

pieces, as well as dance tunes.[47] It has some similarities to the

Bayati maqam used in Arabic and Turkish music.

Yishtabakh resembles Mogen Ovos and Freygish. It is a variant of the

Mogen Ovos scale that frequently flattens the second and fifth

degrees.[56]

|

説明 説明

クレズマー音楽におけるモードを記述するための合意された完全なシステムは存在しないため、このリストは不完全であり、一部の学者は別個のものとして捉え

ている概念を混同している可能性がある[49][54]。これらの用語を単純な8音(オクタトニック)音階として列挙することのもう一つの問題は、クレズ

マーの旋律構造が5音のペンタコードとしてどのように機能するのか、異なるモードの部分が一般的にどのように相互作用するのか、伝統的なクレズマーの文脈

において与えられたモードの文化的意義がどのようなものなのかがわかりにくくなることである[47][48]。

C調フレイギッシュ・モード

ベレゴフスキーは、彼が収集したクレズマー音楽のおよそ4分の1がフライギッシュ・モードであると推定している[30][47]。このモードで作曲された

最も有名な曲の中には、Hava NagilaとMa yofusがある。アラブ音楽に見られるマッカム・ヒジャーズに匹敵する[47]。

ミ・シェベラフ・モード(C調

ミ・シェベラフ(Av

HaRachamim)、「変化ドリアン」、またはウクライナ・ドリアン・スケールは、4thが上がったマイナー・モードである[55]。このモードはド

インズや、ルーマニアやウクライナの音楽とつながりのある他のクレズマー様式にしばしば見られる。

アドノイ・モローク・モード(C調

Adonoy MolokhまたはAdoyshem Molokhは、7thがフラットになったシナゴーグ・モード[29]。

ハ調モーゲンオヴォスモード

クレズマー音楽では、挨拶や別れの曲、ダンス曲でよく使われる[47]。アラビア音楽やトルコ音楽で使われるバヤティ・マカームと類似点がある。

YishtabakhはMogen

OvosやFreygishに似ている。これはモゲン・オヴォスの音階の変形であり、2度と5度を頻繁に平坦化する[56]。

|

History

Europe

Development of the genre

The Bible has several descriptions of orchestras and Levites making

music, but after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, many

Rabbis discouraged musical instruments.[57] Therefore, while there may

have been Jewish musicians in different times and places since then,

the "Klezmer" arose much more recently.[58] The earliest written record

of the use of the word was identified by Isaac Rivkind [he] as being in

a Jewish council meeting from Krakow in 1595.[59][60] They may have

existed even earlier in Prague, as references to them have been found

as early as 1511 and 1533.[61] It was in the 1600s that the situation

of Jewish musicians in Poland improved, as they gained the right to

form Guilds (Khevre), and therefore to set their own fees, hire

Christians, and so on.[62] Therefore over time this new form of

professional musician developed new forms of music and elaborated this

tradition across a wide area of Eastern European Jewish life. The rise

of Hasidic Judaism in the late-eighteenth century and onwards also

contributed to the development of klezmer, due to their emphasis on

dancing and wordless melodies as a component of Jewish practice.[17]

Medieval Jewish wedding procession (date unknown)

The Eastern European klezmer profession (1700–1930s)

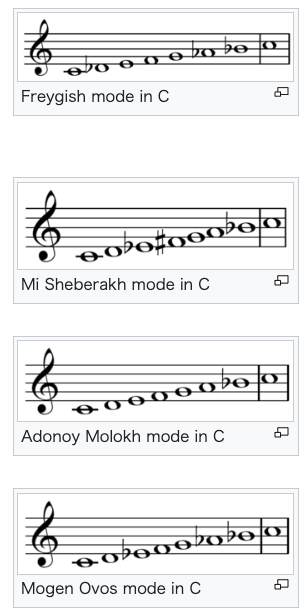

Portrait of Pedotser (A. M. Kholodenko), nineteenth century klezmer

virtuoso

The nineteenth century also saw the rise of a number of klezmer violin

virtuosos who combined the techniques of classical violinists such as

Ivan Khandoshkin and of Bessarabian folk violinists, and who composed

dance and display pieces that became widespread even after the

composers were gone.[63] Among these figures were Aron-Moyshe

Kholodenko "Pedotser", Yosef Drucker "Stempenyu", Alter Goyzman "Alter

Chudnover" and Josef Gusikov.[64][65][66][67]

Unlike in the United States, where there was a robust Klezmer recording

industry, there was relatively less recorded in Europe in the early

twentieth century. The majority of European recordings of Jewish music

consisted of Cantorial and Yiddish Theatre music, with only a few dozen

known to exist of Klezmer music.[68] These include violin pieces by

artists such as Oscar Zehngut, H. Steiner, Leon Ahl, and Josef

Solinski; flute pieces by S. Kosch, and ensemble recordings by Belf's

Romanian Orchestra, the Russian-Jewish Orchestra, Jewish Wedding

Orchestra, and Titunshnayder's Orchestra.[68][69]

Klezmer in the late Russian empire and Soviet era

The loosening of restrictions on Jews in the Russian Empire, and their

newfound access to academic and conservatory training, created a class

of scholars who began to reexamine and evaluate klezmer using modern

techniques.[30] Abraham Zevi Idelsohn was one such figure, who sought

to find an ancient Middle Eastern origin for Jewish music in the

diaspora.[70] There was also new interest in collecting and studying

Jewish music and folklore, including Yiddish songs, folk tales, and

instrumental music. An early expedition was by Joel Engel, who

collected folk melodies in his birthplace of Berdyansk in 1900. The

first figure to collect large amounts of klezmer music was Susman

Kiselgof, who made several expeditions to the Pale of Settlement from

1907 to 1915.[71] He was soon followed by other scholars such as Moisei

Beregovsky and Sofia Magid, Soviet scholars of Yiddish and klezmer

music.[72][30] Most of the materials collected in those expeditions are

now held by the Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine.[73]

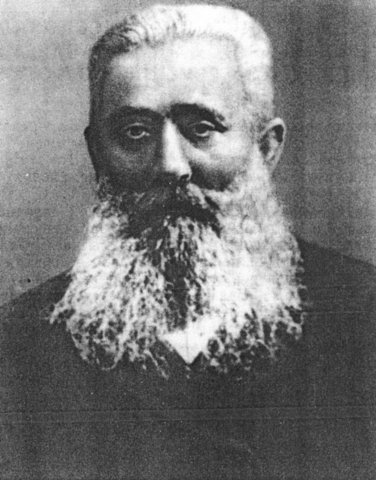

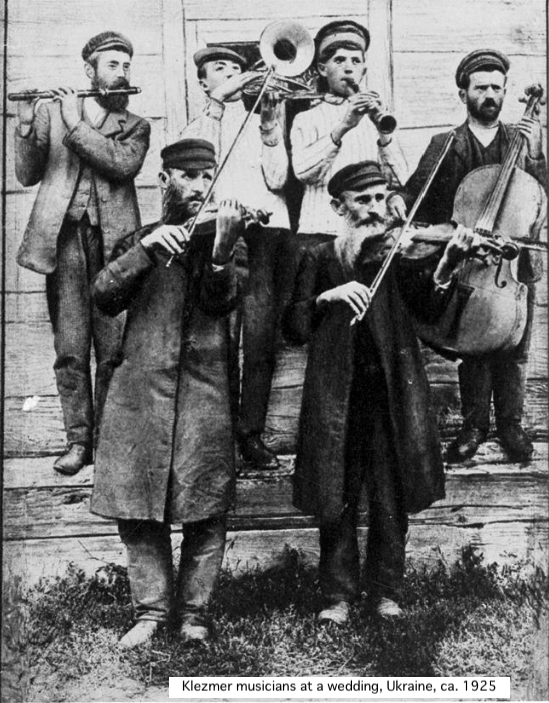

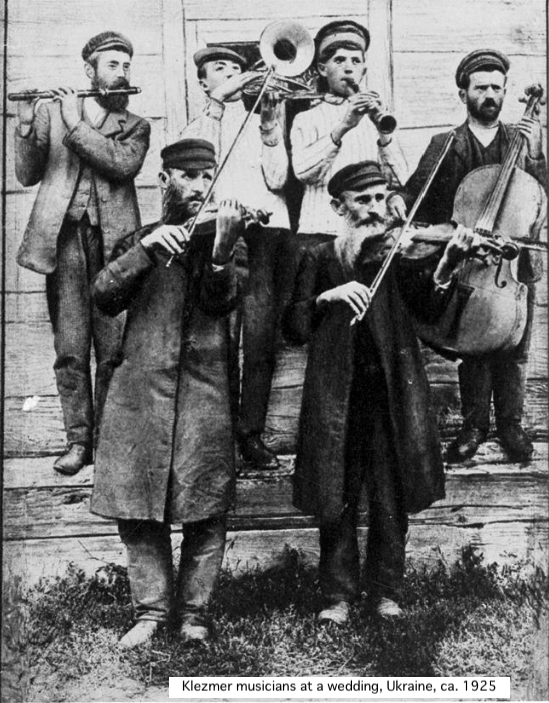

Klezmer musicians at a wedding, Ukraine, ca. 1925

Beregovsky, writing in the late 1930s, lamented how little scholars

knew about the range of playing technique and social context of

Klezmers from past eras, except for the late nineteenth century which

could be investigated through elderly musicians who still remembered

it.[1]

Jewish music in the Soviet Union, and the continued use of Klezmer

music, went through several phases of official support or censorship.

The officially-supported Soviet Jewish musical culture of 1920s

involved works based on or satirizing traditional melodies and themes,

whereas those of the 1930s were often "Russian" cultural works

translated into a Yiddish context.[74] After 1948, Soviet Jewish

culture entered a phase of repression, meaning that Jewish music

concerts, whether tied to Hebrew, Yiddish, or instrumental Klezmer were

no longer allowed to be performed. [75] Moisei Beregovsky's academic

work was shut down in 1949 and he was arrested and deported to Siberia

in 1951.[76][77] The repression was eased in the mid-1950s as some

Jewish and Yiddish performances were allowed to return to the stage

once again.[78] However, the main venue for Klezmer has always been

traditional community events, weddings, and not the concert stage or

academic institute; those traditional venues were repressed along with

Jewish culture in general, according to anti-religious Soviet

policy.[79]

|

歴史

ヨーロッパ

ジャンルの発展

聖書にはオーケストラやレビ人が音楽を演奏している描写がいくつかあるが、CE70年の第二神殿破壊後、多くのラビは楽器を推奨しなかった[57]。

そのため、それ以降も様々な時代や場所でユダヤ人音楽家が存在していた可能性があるが、「クレズマー」が生まれたのはずっと最近のことである[58]。

この言葉が使用された最古の文献記録は、1595年にクラクフで行われたユダヤ人評議会の記録であるとアイザック・リブキンド[彼]によって確認されてい

る。

[ポーランドにおけるユダヤ人音楽家の状況が改善されたのは1600年代であり、彼らはギルド(Khevre)を結成する権利を獲得し、その結果、独自の

報酬を設定したり、クリスチャンを雇ったりすることができるようになった[62]。18世紀後半以降のハシディック・ユダヤ教の台頭も、ユダヤ教の慣習の

要素として踊りと言葉のない旋律を重視していたため、クレズマーの発展に貢献した[17]。

中世ユダヤ人の結婚式の行列(年代不明)

東欧のクレズマー職業(1700~1930年代)

ペドツァー(A.M.ホロデンコ)の肖像(19世紀のクレズマー・ヴィルトゥオーゾ)

19世紀には、イワン・カンドシキン(Ivan

Khandoshkin)のようなクラシックのヴァイオリニストとベッサラビアの民俗ヴァイオリニストのテクニックを組み合わせたクレズマー・ヴァイオリ

ンのヴィルトゥオーゾが数多く台頭した。

[これらの人物の中には、アロン=モイシェ・ホロデンコ「ペドツェル」、ヨセフ・ドラッカー「ステンペンユー」、アルター・ゴイズマン「アルター・チュド

ノヴァー」、ヨセフ・グシコフがいた[64][65][66][67]。

強固なクレズマー録音産業があったアメリカとは異なり、20世紀初頭のヨーロッパでは比較的録音が少なかった。ヨーロッパで録音されたユダヤ音楽の大半

は、カントリー音楽とイディッシュ・シアター音楽であり、クレズマー音楽の録音は数十曲しか存在しないことが知られている[68]。

ロシア帝国末期とソビエト時代のクレズマー

ロシア帝国におけるユダヤ人に対する規制が緩和され、彼らが新たに学問や音楽院での訓練を受けられるようになったことで、現代的なテクニックを用いてクレ

ズマーを再検討し、評価し始める一群の学者が生まれた[30]。アブラハム・ゼヴィ・イデルゾーン(Abraham Zevi

Idelsohn)はそのような人物の一人であり、ディアスポラにおけるユダヤ音楽の起源を古代中東に求めようとした[70]。初期の探検はジョエル・エ

ンゲル(Joel

Engel)によるもので、彼は1900年に生まれ故郷のベルジャンスクで民俗旋律を収集した。大量のクレズマー音楽を収集した最初の人物はススマン・キ

ゼルゴフであり、彼は1907年から1915年にかけて居住区に何度か遠征した[71]。彼はすぐに、イディッシュ語とクレズマー音楽のソビエト人学者で

あるモイセイ・ベレゴフスキーやソフィア・マギドといった他の学者たちによって追随された[72][30]。

結婚式でのクレズマー音楽家たち、ウクライナ、1925年頃

1930年代後半に執筆したベレゴフスキーは、過去の時代のクレズマーの演奏技術の幅や社会的背景について、学者がほとんど知らないことを嘆いていた。

ソビエト連邦におけるユダヤ音楽、そしてクレズマー音楽の継続的な使用は、公式支援や検閲のいくつかの段階を経た。1920年代に公式に支援されたソビエ

トのユダヤ音楽文化は、伝統的なメロディやテーマに基づいた作品や風刺的な作品を含んでいたのに対し、1930年代のものはしばしばイディッシュ語の文脈

に翻訳された「ロシア」文化的な作品であった[74]。1948年以降、ソビエトのユダヤ文化は弾圧の段階に入り、ヘブライ語、イディッシュ語、または器

楽的なクレズマーに関係なく、ユダヤ音楽のコンサートはもはや演奏することを許されなかった。[75]モイセイ・ベレゴフスキーの学問的研究は1949年

に閉鎖され、彼は逮捕され、1951年にシベリアに強制送還された[76][77]。

1950年代半ばには弾圧が緩和され、ユダヤ人とイディッシュ人の演奏の一部が再びステージに戻ることが許された[78]。

しかし、クレズマーの主な場は常に伝統的なコミュニティのイベントや結婚式であり、コンサートのステージや学術機関ではなかった。それらの伝統的な場は、

反宗教的なソ連の政策に従って、ユダヤ人文化全般とともに弾圧された[79]。

|

United States

Early American klezmer (1880s–1910s)

The first klezmers to arrive in the United States followed the first

large waves of Eastern European Jewish immigration which began after

1880, establishing themselves mainly in large cities like New York,

Philadelphia and Boston.[17] Klezmers—often younger members of klezmer

families, or less established musicians—started to arrive from the

Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Romania and Austria-Hungary.[80] Some of

them found work in restaurants, dance halls, union rallies, wine

cellars, and other modern venues in places like New York's Lower East

Side.[81][82] But the major source of income for klezmer musicians

seems to have remained weddings and Simchas, as in Europe.[83] Those

early generations of klezmers are much more poorly documented than

those working in the 1910s and 1920s; many never recorded or published

music, although some are remembered through family or community

history, such as the Lemish klezmer family of Iași, Romania who arrived

in Philadelphia in the 1880s and established a klezmer dynasty

there.[84][83]

Big band klezmer orchestras (1910s–1920s)

Max Leibowitz orchestra from 1921

The vitality of the Jewish music industry in major American cities

attracted ever more klezmers from Europe in the 1910s. This coincided

with the development of the recording industry, which recorded a number

of these klezmer orchestras. By the time of the First World War, the

industry turned its attention to ethnic dance music and a number of

bandleaders were hired by record companies such as Edison Records,

Emerson Records, Okeh Records, and the Victor Recording Company to

record 78 rpm discs.[85] The first of these was Abe Elenkrig, a barber

and cornet player from a klezmer family in Ukraine whose 1913 recording

Fon der Choope (From the Wedding) has been recognized by the Library of

Congress.[86][87][88]

Among the European-born klezmers recording during that decade were some

from the Ukrainian territory of the Russian Empire (Abe Elenkrig, Dave

Tarras, Shloimke Beckerman, Joseph Frankel, and Israel J. Hochman),

some from Austro-Hungarian Galicia (Naftule Brandwein, Harry Kandel and

Berish Katz), and some from Romania (Abe Schwartz, Max Leibowitz, Max

Yankowitz, Joseph Moskowitz).[89][90][91][92]

The mid 1920s also saw a number of popular novelty "Klezmer" groups

which performed on the radio or Vaudeville stages. These included

Joseph Cherniavsky's Yiddish-American Jazz Band, whose members would

dress as parodies of Cossacks or Hasidim.[93] Another such group was

the Boibriker Kapelle, which performed on the radio and in concerts

trying to recreate a nostalgic, old-fashioned Galician Klezmer

sound.[94] With the passing of the Immigration Act of 1924 which

greatly restricted Jewish immigration from Europe, and then the onset

of the Great Depression by 1930, the market for Yiddish and klezmer

recordings in the United States saw a steep decline, which essentially

ended the recording career of many of the popular bandleaders of the

1910s and 1920s, and made the Large klezmer orchestra less viable.[95]

Celebrity clarinetists

Along with the rise of klezmer "big bands" in the 1910s and 1920s, a

handful of Jewish clarinet players who had led those bands became

celebrities in their own right, with a legacy that lasted into

subsequent decades. The most popular among these were Naftule

Brandwein, Dave Tarras, and Shloimke Beckerman.[96][97][98]

Klezmer revival

In the mid-to-late 1970s there was a klezmer revival in the United

States and Europe, led by Giora Feidman, The Klezmorim, Zev Feldman,

Andy Statman, and the Klezmer Conservatory Band. They drew their

repertoire from recordings and surviving musicians of U.S. klezmer.[99]

In particular, clarinetists such as Dave Tarras and Max Epstein became

mentors to this new generation of klezmer musicians.[100] In 1985,

Henry Sapoznik and Adrienne Cooper founded KlezKamp to teach klezmer

and other Yiddish music.[101]

Elane Hoffman Watts, klezmer drummer, in 2007

The 1980s saw a second wave of revival, as interest grew in more

traditionally inspired performances with string instruments, largely

with non-Jews of the United States and Germany. Musicians began to

track down older European klezmer, by listening to recordings, finding

transcriptions, and making field recordings of the few klezmorim left

in Eastern Europe. Key performers in this style are Joel Rubin,

Budowitz, Khevrisa, Di Naye Kapelye, Yale Strom, The Chicago Klezmer

Ensemble, The Maxwell Street Klezmer Band, the violinists Alicia

Svigals, Steven Greenman,[102] Cookie Segelstein and Elie Rosenblatt,

flutist Adrianne Greenbaum, and tsimbl player Pete Rushefsky. Bands

like Brave Old World, Hot Pstromi and The Klezmatics also emerged

during this period.

In the 1990s, musicians from the San Francisco Bay Area helped further

interest in klezmer music by taking it into new territory. Groups such

as the New Klezmer Trio inspired a new wave of bands merging klezmer

with other forms of music, such as John Zorn's Masada and Bar Kokhba,

Naftule's Dream, Don Byron's Mickey Katz project and violinist Daniel

Hoffman's klezmer/jazz/Middle-Eastern fusion band Davka.[99] The New

Orleans Klezmer All-Stars[103] also formed in 1991 with a mixture of

New Orleans funk, jazz, and klezmer styles.

Starting in 2008, "The Other Europeans" project, funded by several EU

cultural institutions,[104] spent a year doing intensive field research

in the region of Moldavia under the leadership of Alan Bern and scholar

Zev Feldman. They wanted to explore klezmer and lăutari roots, and fuse

the music of the two "other European" groups. The resulting band now

performs internationally.

A separate klezmer tradition had developed in Israel in the 20th

century. Clarinetists Moshe Berlin and Avrum Leib Burstein are known

exponents of the klezmer style in Israel. To preserve and promote

klezmer music in Israel, Burstein founded the Jerusalem Klezmer

Association, which has become a center for learning and performance of

Klezmer music in the country.[105]

Since the late 1980s, an annual Klezmer festival is held every summer

in Safed, in the north of Israel.[106][107]

|

アメリカ

初期のアメリカ・クレズマー(1880年代~1910年代)

アメリカに最初に到着したクレズマーたちは、1880年以降に始まった東欧系ユダヤ人移民の最初の大きな波に従って、主にニューヨーク、フィラデルフィ

ア、ボストンなどの大都市に定着した[17]。クレズマーたちは、しばしばクレズマー一家の若いメンバーや、それほど確立していない音楽家であったが、ロ

シア帝国、ルーマニア王国、オーストリア=ハンガリーから到着し始めた[80]。

[しかし、クレズマー・ミュージシャンの主な収入源は、ヨーロッパと同様に結婚式やシムチャであったようである[83]。これらの初期の世代のクレズマー

は、1910年代や1920年代に活動したクレズマーよりもはるかに記録が乏しく、多くは録音や音楽出版をすることはなかったが、1880年代にフィラデ

ルフィアに到着し、そこでクレズマー王朝を築いたルーマニアのイアシュイのレミシュ・クレズマー一家のように、家族やコミュニティの歴史を通して記憶され

ている者もいる[84][83]。

ビッグバンドのクレズマー・オーケストラ(1910年代~1920年代)

1921年のマックス・ライボヴィッツ楽団

アメリカの主要都市におけるユダヤ人音楽産業の活力は、1910年代にヨーロッパからますます多くのクレズマーを惹きつけた。これはレコーディング産業の

発展と重なり、これらのクレズマー・オーケストラは数多くレコーディングされた。第一次世界大戦の頃になると、レコード産業は民族舞踊音楽に注目するよう

になり、エジソンレコード、エマーソンレコード、オケレコード、ビクターレコーディングカンパニーなどのレコード会社に雇われ、78回転ディスクを録音す

るバンドリーダーたちが数多く現れた[85]。

この10年間に録音されたヨーロッパ生まれのクレズマーの中には、ロシア帝国のウクライナ領出身の者(エイブ・エレンクリグ、デイヴ・タラス、シュロイム

ケ・ベッカーマン、ジョセフ・フランケル、イスラエル・J・ホッフマン)、オーストリア=ハンガリーのガリシア出身の者(ナフチュール・ブランドヴァイ

ン、ハリー・カンデル、ベリッシュ・カッツ)、ルーマニア出身の者(エイブ・シュワルツ、マックス・ライボヴィッツ、マックス・ヤンコヴィッツ、ジョセ

フ・モスコヴィッツ)がいた[89][90][91][92]。

1920年代半ばには、ラジオやヴォードヴィルのステージで演奏する人気のある斬新な「クレズマー」グループも数多く登場した。ジョセフ・チェルニアフス

キーのイディッシュ・アメリカン・ジャズ・バンドもそのひとつで、メンバーはコサックやハシディムのパロディに扮していた[93]。

[94]ヨーロッパからのユダヤ人移民を大幅に制限した1924年の移民法の成立、そして1930年までの世界恐慌の勃発により、アメリカにおけるイ

ディッシュ語とクレズマー音楽のレコーディング市場は急落し、1910年代と1920年代の人気バンドリーダーたちのレコーディングキャリアは実質的に終

わりを告げ、大規模なクレズマー・オーケストラは存続できなくなった[95]。

有名クラリネット奏者

1910年代から1920年代にかけてのクレズマー「ビッグバンド」の台頭とともに、それらのバンドを率いていた一握りのユダヤ人クラリネット奏者は、そ

れ自体が有名人となり、その後数十年にわたってその名声が続いた。その中で最も人気があったのは、ナフチュール・ブランドヴァイン、デイヴ・タラス、シュ

ロイムケ・ベッカーマンであった[96][97][98]。

クレズマー・リバイバル

1970年代半ばから後半にかけて、アメリカやヨーロッパでクレズマー・リバイバルが起こり、ジオラ・ファイドマン、ザ・クレズモリム、ゼヴ・フェルドマ

ン、アンディ・スタットマン、クレズマー・コンサーヴァトリー・バンドなどが主導した。特に、デイヴ・タラスやマックス・エプスタインといったクラリネッ

ト奏者は、この新世代のクレズマー・ミュージシャンの指導者となった[100]。

1985年、ヘンリー・サポズニクとアドリアン・クーパーは、クレズマーやその他のイディッシュ音楽を教えるためにクレズカンプを設立した[101]。

2007年、エレーン・ホフマン・ワッツ(クレズマー・ドラム奏者)

1980年代には第二次復興の波が押し寄せ、弦楽器を使ったより伝統的な演奏への関心が高まり、主にアメリカやドイツの非ユダヤ人の間で演奏されるように

なった。ミュージシャンたちは、録音を聴いたり、トランスクリプションを探したり、東欧に残る数少ないクレズモリムのフィールド・レコーディングをしたり

して、古いヨーロッパのクレズマーを探し始めた。このスタイルの主要な演奏家は、ジョエル・ルービン、ブドウィッツ、ケヴリサ、ディ・ネー・カペリ、エー

ル・ストローム、シカゴ・クレズマー・アンサンブル、マックスウェル・ストリート・クレズマー・バンド、ヴァイオリニストのアリシア・スヴィガルス、ス

ティーブン・グリーンマン[102]、クッキー・セゲルスタイン、エリー・ローゼンブラット、フルート奏者のエイドリアンヌ・グリーンバウム、ツィンブル

奏者のピート・ルシェフスキーなどである。ブレイブ・オールド・ワールド、ホット・プストロミ、クレズマティックスなどのバンドもこの時期に登場した。

1990年代には、サンフランシスコ・ベイエリアのミュージシャンたちが、クレズマー音楽を新たな領域へと発展させ、クレズマー音楽への関心をさらに高め

ることに貢献した。ニュー・クレズマー・トリオのようなグループは、ジョン・ゾーンのマサダ・アンド・バー・コクバ、ナフチュールズ・ドリーム、ドン・バ

イロンのミッキー・カッツ・プロジェクト、ヴァイオリニスト、ダニエル・ホフマンのクレズマー/ジャズ/中近東フュージョン・バンド、ダブカなど、クレズ

マーと他の音楽形態を融合させたバンドの新しい波に影響を与えた[99]。

2008年からは、複数のEU文化機関が資金を提供する「The Other

Europeans」プロジェクト[104]が、アラン・バーンと学者ゼヴ・フェルドマンの指導のもと、モルダヴィア地方で1年間集中的な現地調査を行っ

た。彼らはクレズマーとラウタリのルーツを探求し、2つの「他のヨーロッパ」グループの音楽を融合させようと考えた。こうして生まれたバンドは現在、国際

的な演奏活動を行っている。

イスラエルでは20世紀、クレズマーとは別の伝統が発展していた。クラリネット奏者のモシェ・バーリンとアブラム・レイプ・ブルスタインは、イスラエルに

おけるクレズマー・スタイルの代表者として知られている。イスラエルにおけるクレズマー音楽の保存と普及のため、バースタインはエルサレム・クレズマー協

会を設立し、同協会はイスラエルにおけるクレズマー音楽の学習と演奏の中心となっている[105]。

1980年代後半からは、毎年夏にイスラエル北部のサフェドでクレズマー・フェスティバルが開催されている[106][107]。

|

Popular culture

In music

While traditional performances may have been on the decline, many

Jewish composers who had mainstream success, such as Leonard Bernstein

and Aaron Copland, continued to be influenced by the klezmeric idioms

heard during their youth (as Gustav Mahler had been). George Gershwin

was familiar with klezmer music, and the opening clarinet glissando of

Rhapsody in Blue suggests this influence, although the composer did not

compose klezmer directly.[108] Some clarinet stylings of swing jazz

bandleaders Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw can be interpreted as having

been derived from klezmer, as can the "freilach swing" playing of other

Jewish artists of the period such as trumpeter Ziggy Elman.

At the same time, non-Jewish composers were also turning to klezmer for

a prolific source of fascinating thematic material. Dmitri Shostakovich

in particular admired klezmer music for embracing both the ecstasy and

the despair of human life, and quoted several melodies in his chamber

masterpieces, the Piano Quintet in G minor, op. 57 (1940), the Piano

Trio No. 2 in E minor, op. 67 (1944), and the String Quartet No. 8 in C

minor, op. 110 (1960).

The compositions of Israeli-born composer Ofer Ben-Amots incorporate

aspects of klezmer music, most notably his 2006 composition Klezmer

Concerto. The piece is for klezmer clarinet (written for Jewish

clarinetist David Krakauer),[109] string orchestra, harp and

percussion.[110]

In visual art

Issachar

Ber Ryback - Wedding Ceremony Issachar

Ber Ryback - Wedding Ceremony

The figure of the klezmer, as a romantic symbol of nineteenth century

Jewish life, appeared in the art of a number of twentieth century

Jewish artists such as Anatoli Lvovich Kaplan, Issachar Ber Ryback,

Marc Chagall, and Chaim Goldberg. Kaplan, making his art in the Soviet

Union, was quite taken by the romantic images of the Klezmer in

literature, and in particular in Sholem Aleichem's Stempenyu, and

depicted them in rich detail.[111]

In film

Yidl Mitn Fidl (1936), directed by Joseph Green

Fiddler on the Roof (1971), directed by Norman Jewison

Les Aventures de Rabbi Jacob (1973), directed by Gérard Oury

Jewish Soul Music: The Art of Giora Feidman (1980), directed by Uri

Barbash

A Jumpin' Night in the Garden of Eden (1988), directed by Michal Goldman

Fiddlers on the Hoof (1989), directed by Simon Broughton

The Last Klezmer: Leopold Kozlowski: His Life and Music (1994),

directed by Yale Strom

Beyond Silence (1996), about a Klezmer-playing clarinettist, directed

by Charlotte Link

A Tickle in the Heart (1996), directed by Stefan Schwietert[112]

Itzhak Perlman: In the Fiddler's House (1996), aired 29 June 1996 on

Great Performances (PBS/WNET television series)

L'homme est une femme comme les autres (1998, directed by Jean-Jacques

Zilbermann with soundtrack by Giora Feidman)

Dummy (2002), directed by Greg Pritikin

Klezmer on Fish Street (2003), directed by Yale Strom

Le Tango des Rashevski (2003) directed by Sam Garbarski

Klezmer in Germany (2007), directed by Kryzstof Zanussi and C. Goldie

A Great Day on Eldridge Street (2008), directed by Yale Strom

The "Socalled" Movie (2010), directed by Garry Beitel

In literature

In Jewish literature, the klezmer was often represented as a romantic

and somewhat unsavory figure.[113] However, in nineteenth century works

by writers such as Mendele Mocher Sforim and Sholem Aleichem they were

also portrayed as great artists and virtuosos who delighted the

masses.[30] Klezmers also appeared in non-Jewish Eastern European

literature, such as in the epic poem Pan Tadeusz, which depicted a

character named Jankiel Cymbalist, or in the short stories of Leopold

von Sacher-Masoch.[12] In George Eliot's Daniel Deronda (1876), the

German Jewish music teacher is named Herr Julius Klesmer.[114] The

novel was later adapted into a Yiddish musical by Avram Goldfaden

titled Ben Ami (1908).[115]

|

大衆文化

音楽

伝統的な演奏は衰退していったかもしれないが、レナード・バーンスタインやアーロン・コープランドなど、メインストリームで成功を収めたユダヤ人作曲家の

多くは、(グスタフ・マーラーがそうであったように)少年時代に耳にしたクレズマー音楽のイディオムの影響を受け続けていた。ジョージ・ガーシュウィンは

クレズマー音楽に精通しており、『ラプソディー・イン・ブルー』の冒頭のクラリネットのグリッサンドはその影響を示唆しているが、作曲家が直接クレズマー

を作曲したわけではない[108]。同じ頃、ユダヤ人以外の作曲家たちもクレズマーに注目し、魅力的な主題の材料を多量に求めていた。特にドミトリー・

ショスタコーヴィチは、人間の生の恍惚と絶望の両方を包含するクレズマー音楽を賞賛し、彼の室内楽の傑作であるピアノ五重奏曲ト短調op.57(1940

年)、ピアノ三重奏曲第2番ホ短調op.67(1944年)、弦楽四重奏曲第8番ハ短調op.110(1960年)にいくつかのメロディーを引用してい

る。

イスラエル出身の作曲家オフェル・ベン=アモッツの作品には、クレズマー音楽の側面が取り入れられており、特に2006年に作曲したクレズマー協奏曲が有

名である。この作品はクレズマー・クラリネット(ユダヤ人クラリネット奏者デヴィッド・クラカウアーのために書かれた)、弦楽オーケストラ[109]、

ハープ、打楽器のためのものである[110]。

視覚芸術

Issachar

Ber Ryback - 結婚式 Issachar

Ber Ryback - 結婚式

19世紀のユダヤ人生活のロマンティックな象徴としてのクレズマーの姿は、アナトリ・ルボヴィッチ・カプラン、イッサハル・ベル・ライバック、マルク・

シャガール、チャイム・ゴールドベルクといった20世紀のユダヤ人芸術家の芸術にも登場した。ソビエト連邦で芸術を制作していたカプランは、文学、特に

ショーレム・アレイチェムの『Stempenyu』に登場するクレズマーのロマンチックなイメージに強く惹かれ、それらを詳細に描いた[111]。

映画では

Yidl Mitn Fidl』(1936年)ジョセフ・グリーン監督屋根の上のバイオリン弾き』(1971年)ノーマン・ジュイソン監督

ラビ・ヤコブの冒険』(1973年)ジェラール・ウリー監督

ジューイッシュ・ソウル・ミュージック ジオラ・フェイドマンの芸術』(1980)監督:ウリ・バーバシュ

A Jumpin' Night in the Garden of Eden(1988)、ミハエル・ゴールドマン監督

フィドラーズ・オン・ザ・フーフ』(1989)監督:サイモン・ブロートン最後のクレズマー Leopold Kozlowski: His Life

and Music』(1994)監督:エール・ストローム

ビヨンド・サイレンス』(1996)クラズマー奏者のクラリネット奏者を描く、シャーロット・リンク監督作品。

A Tickle in the Heart』(1996)、ステファン・シュヴィエタート監督[112]。

Itzhak Perlman: In the Fiddler's House』(1996年)、1996年6月29日にGreat

Performances(PBS/WNETのテレビシリーズ)で放映。

L'homme est une femme comme les

autres』(1998年、監督:ジャン=ジャック・ジルベルマン、サウンドトラック:ジオラ・フェイドマン)

ダミー』(2002年、グレッグ・プリティキン監督

魚通りのクレズマー(2003)監督:イェール・ストロム

ル・タンゴ・デ・ラシェフスキー』(2003)監督:サム・ガルバルスキー

ドイツのクレズマー』(2007)監督:クリシュトフ・ザヌッシ、C・ゴールディ

エルドリッジ通りの素敵な一日』(2008)監督:エール・ストローム

映画『ソコールド』(2010)監督:ギャリー・バイテル

文学

ユダヤ文学では、クレズマーはしばしばロマンチックで、やや悪趣味な人物として描かれた[113]。しかし、メンデレ・モッシャー・スフォリムやショーレ

ム・アレイチェムなどの作家による19世紀の作品では、彼らは大衆を喜ばせる偉大な芸術家、名人としても描かれた。

[例えば、ヤンキエル・シンバリストという人物を描いた叙事詩『パン・タデウシュ』やレオポルト・フォン・ザッハー=マゾッホの短編小説などである

[12]。ジョージ・エリオットの『ダニエル・デロンダ』(1876年)では、ドイツ系ユダヤ人の音楽教師はユリウス・クレスマーという名前であった

[114]。

|

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Klezmer

|

|

|

|

Description

Description

Issachar

Ber Ryback - Wedding Ceremony

Issachar

Ber Ryback - Wedding Ceremony

☆

☆