國学

Kokugaku

☆ 国学(旧字体:國學、新字体:国学)は、徳川時代に始まった学問運動であり、日本文献学および哲学の一派である。 国学の学者たちは、当時主流であった漢文、儒教、仏教のテキストの研究から、初期の日本の古典研究へと日本の学問の焦点を移すことに尽力した。[1]

| Kokugaku (Kyūjitai:

國學, Shinjitai: 国学; literally "national study") was an academic

movement, a school of Japanese philology and philosophy originating

during the Tokugawa period. Kokugaku scholars worked to refocus

Japanese scholarship away from the then-dominant study of Chinese,

Confucian, and Buddhist texts in favor of research into the early

Japanese classics.[1] |

国学(旧字体:國學、新字体:国学)は、徳川時代に始まった学問運動であり、日本文献学および哲学の一派である。 国学の学者たちは、当時主流であった漢文、儒教、仏教のテキストの研究から、初期の日本の古典研究へと日本の学問の焦点を移すことに尽力した。[1] |

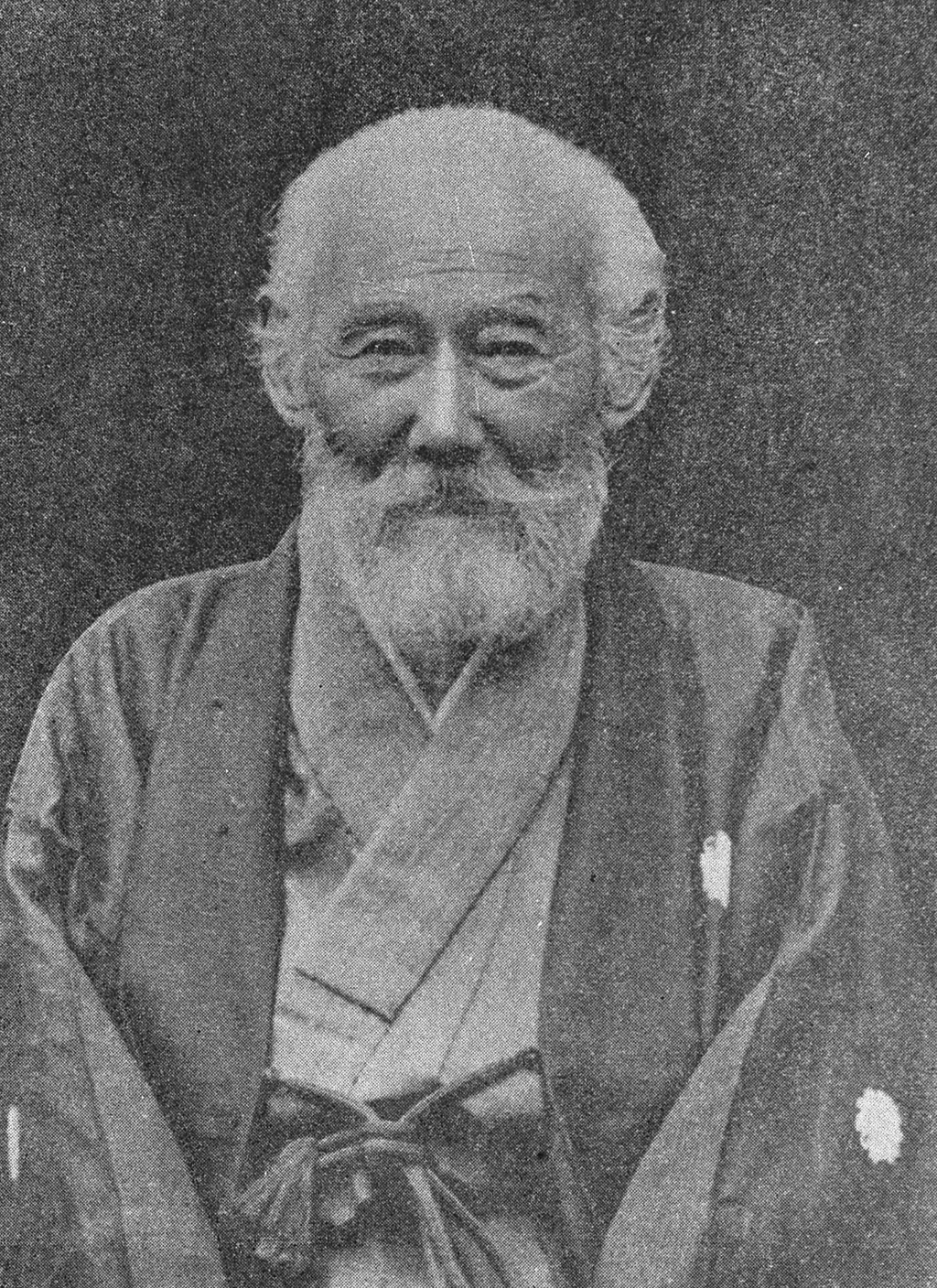

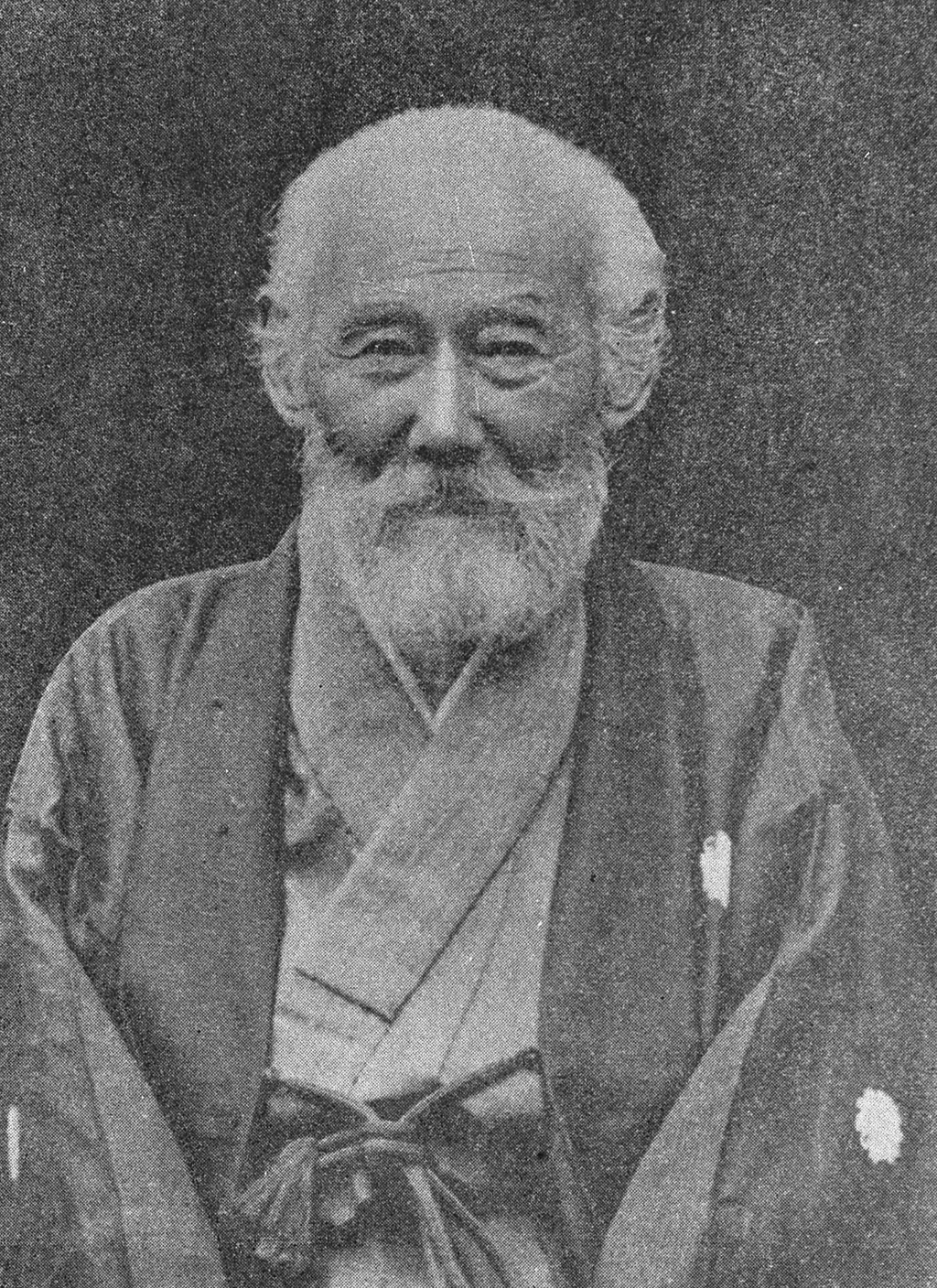

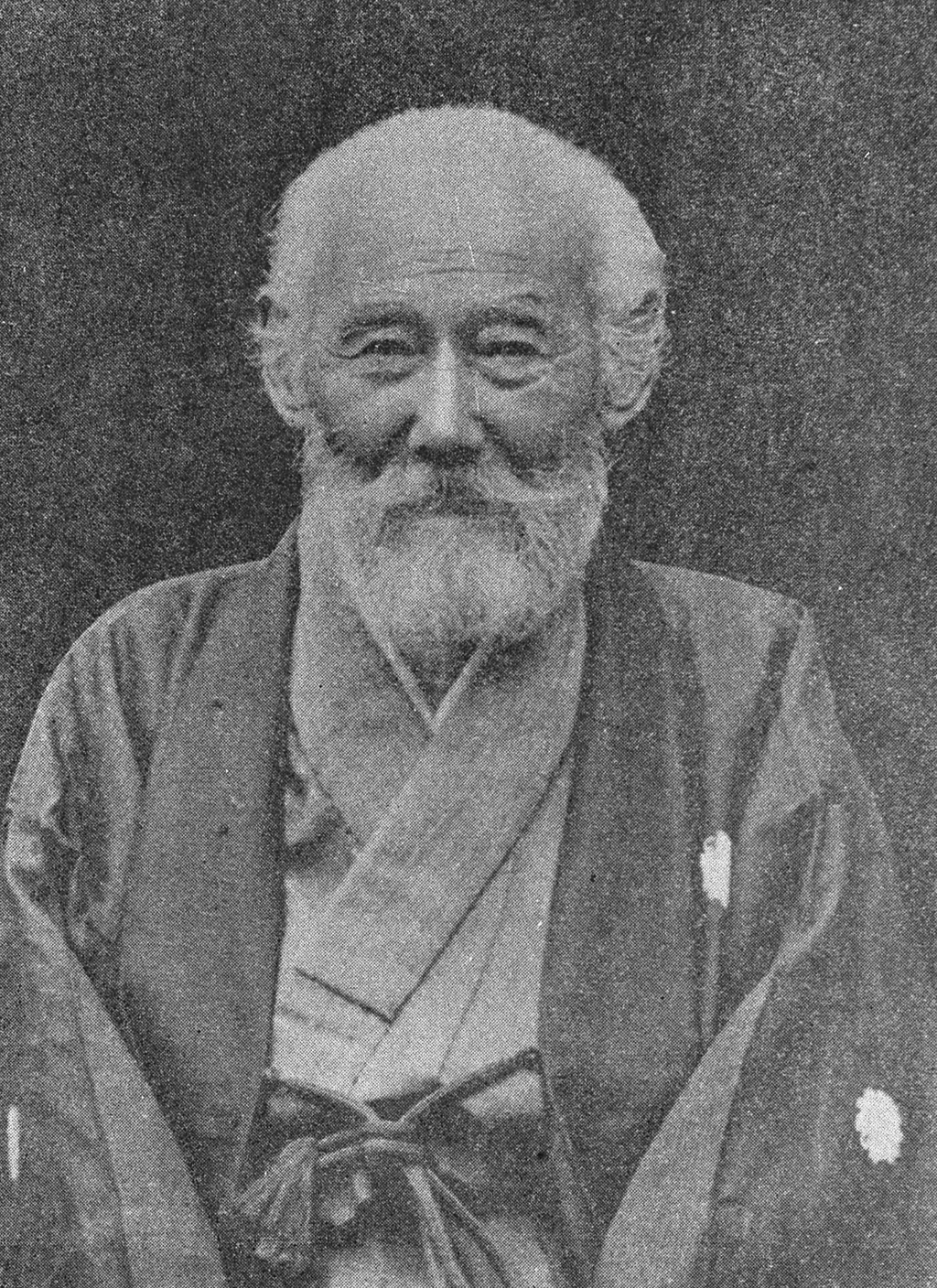

History Tanimori Yoshiomi (1818 - 1911), a kokugaku scholar. What later became known as the kokugaku tradition began in the 17th and 18th centuries as kogaku ("ancient studies"), wagaku ("Japanese studies") or inishie manabi ("antiquity studies"), a term favored by Motoori Norinaga and his school. Drawing heavily from Shinto and Japan's ancient literature, the school looked back to a golden age of culture and society. They drew upon ancient Japanese poetry, predating the rise of medieval Japan's feudal orders in the mid-twelfth century, and other cultural achievements to show the emotion of Japan. One famous emotion appealed to by the kokugakusha is 'mono no aware'. The word kokugaku, coined to distinguish this school from kangaku ("Chinese studies"), was popularized by Hirata Atsutane in the 19th century. It has been translated as 'Native Studies' and represented a response to Sinocentric Neo-Confucian theories. Kokugaku scholars criticized the repressive moralizing of Confucian thinkers, and tried to re-establish Japanese culture before the influx of foreign modes of thought and behaviour. Eventually, the thinking of kokugaku scholars influenced the sonnō jōi philosophy and movement. It was this philosophy, amongst other things, that led to the eventual collapse of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1868 and the subsequent Meiji Restoration. |

歴史 国学者、谷森善臣(1818年~1911年)。 後に国学の伝統として知られるようになったものは、17世紀と18世紀に古学(「古代学」)、和学(「日本学」)、あるいは「いにしえ学」として始まっ た。これは本居宣長とその一派が好んで用いた用語である。神道や日本の古代文学から多くを引用し、文化や社会の黄金時代を振り返った。彼らは、12世紀半 ばの中世日本の封建制度の台頭に先立つ古代日本の詩歌や、その他の文化的功績を引用し、日本の情緒を表現した。国学者たちが訴えた有名な情緒のひとつに 「もののあわれ」がある。 国学という言葉は、漢学(「中国学」)と区別するために作られた造語で、19世紀に平田篤胤によって広められた。「国学」は「ネイティブ研究」と訳され、 中国中心主義の儒教理論への反発を表している。国学者たちは儒教思想家の抑圧的な道徳主義を批判し、外国の思考や行動様式が流入する前の日本文化を再構築 しようとした。 やがて、国学の思想は尊王攘夷思想と運動に影響を与えるようになった。この思想は、とりわけ1868年の徳川幕府の崩壊とそれに続く明治維新につながった。 |

| Tenets The kokugaku school held that the Japanese national character was naturally pure, and would reveal its inherent splendor once the foreign (Chinese) influences were removed. The "Chinese heart" was considered different from the "true heart" or "Japanese Heart". This true Japanese spirit needed to be revealed by removing a thousand years of Chinese learning.[2] It thus took an interest in philologically identifying the ancient, indigenous meanings of ancient Japanese texts; in turn, these ideas were synthesized with early Shinto and astronomy.[3] |

信条 国学者たちは、日本国民の性格は生まれつき純粋であり、外来(中国)の影響を取り除けば、その本質的な素晴らしさが明らかになると考えた。「中国人の心」 は「真の心」や「日本人の心」とは異なるものと見なされた。この真の日本精神は、千年にわたる中国学問の除去によって明らかにされる必要があった。[2] したがって、古代の日本語のテキストの古代の土着の意味を文献学的に特定することに関心を抱くようになった。そして、これらの考えは初期の神道と天文学と が統合された。[3] |

| Influence The term kokugaku was used liberally by early modern Japanese to refer to the "national learning" of each of the world's nations. This usage was adopted into Chinese, where it is still in use today (C: guoxue).[4] The Chinese also adopted the kokugaku term "national essence" (J: kokusui, C: 国粹 guocui).[5] According to scholar of religion Jason Ānanda Josephson, kokugaku played a role in the consolidation of State Shinto in the Meiji era. It promoted a unified, scientifically grounded and politically powerful vision of Shinto against Buddhism, Christianity, and Japanese folk religions, many of which were named "superstitions."[6] |

影響 国学者という用語は、近世の日本人が世界の各国の「国民学」を指して自由に使用していた。この用法は中国語にも取り入れられ、現在でも使用されている (C: 国学)。[4] 中国人は「国民の本質」(J: 国体、C: 国粹 guocui)という国学者の用語も取り入れた。[5] 宗教学者のジェイソン・アナンダ・ジョセフソンによると、国学者たちは明治時代における国家神道の強化に一役買った。神道を仏教、キリスト教、日本の民間 信仰(その多くは「迷信」と呼ばれた)に対して、統一された、科学的根拠のある、政治的に強力なビジョンとして推進したのである。[6] |

| Shimogawa Keichū Hanawa Hokiichi Hagiwara Hiromichi Todoroki Buhē [ja] Hirata Atsutane Hayashi Ōen Kada no Azumamaro Kamo no Mabuchi Katori Nahiko [ja] Motoori Norinaga Motoori Ōhira Motoori Haruniwa Tanaka Ōhide Matsuo Taseko [ja] Shimazaki Masaki Tsunoda Tadayuki Nakane Kōtei Yamakuni Hyōbu Ueda Akinari Date Munehiro Fujitani Mitsue [ja] Tachibana Moribe [ja] Kume Kunitake Hasuda Zenmei Hirao Rosen Fujimoto Tesseki |

下川家忠 塙保己一 萩原弘道 轟布平 平田篤胤 林復然 嘉田阿津佐麻呂 賀茂真淵 香取直彦 本居宣長 本居大平 本居春庭 田中大英 松尾為聡 島崎藤樹 角田忠之 中根幸亭 山国兵部 上田秋成 伊達宗広 藤谷光恵 立花森平 久米邦武 蓮田善明 平生釟 藤本鉄石 |

| Soga–Mononobe

conflict, the juncture at which Buddhism supplanted Shinto as the

religious foundation of the Japanese state — an event bitterly resented

by the kokugakusha Magokoro, a fundamental concept of kokugaku Ukehi, a prehistoric practice promoted by a number of kokugakusha Mitogaku, a philosophy ideologically related to kokugaku Ishihara Shiko'o Guido von List, European analogue advocating a similar revival of prehistoric religion |

蘇我・物部氏の対立、仏教が神道に取って代わり、日本の国家の宗教的基盤となった転換期 — 国学者たちから激しい非難を受けた出来事 国学者の根本概念である「まごころ」 国学者の多くが推進した先史時代の慣習「うけひ」 国学と思想的に関連する哲学「みとがく」 石原志公男 ヨーロッパにおける同様の先史宗教復興を提唱した人物、グイド・フォン・リスト |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kokugaku |

|

| The Kokugaku (Native Japan Studies) School First published Fri Nov 16, 2018; substantive revision Mon Jun 21, 2021 In its broadest sense, kokugaku has been used to refer to scholarship that takes Japan as its focus instead of China. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, however, it came to refer more narrowly to the effort to discern a native Way distinct from Buddhism and Confucianism within Japan’s most ancient writings, and to the attendant effort to resurrect that Way in the present. Most scholars agree on the major leaders of these studies during the Tokugawa period, with Motoori Norinaga (1730–1801) thought to be its greatest intellectual and Hirata Atsutane (1776–1843) its most effective popularizer. Motoori Norinaga saw the roots of the discipline in Keichū’s (1640–1701) use of historical linguistics to analyze the eighth-century collection of poems called Man’yōshū, whereas Atsutane found it in the Japanese-studies academic efforts of Kada no Azumamaro (1669–1736). Both included Kamo no Mabuchi (1697–1769) in their list of founders. In any case, after Hirata Atsutane, the lineage of Kokugaku’s leaders became more complex as the new Meiji state used Kokugaku notions of racial identity and cultural superiority to mobilize support for Japan’s nationalist ideology and purported international destiny. After 1945 such notions of racial identity and cultural superiority were briefly considered taboo and replaced by less toxic arguments regarding Japanese uniqueness, though these too have morphed yet again into the broad category of Nihonjinron, “theories of Japaneseness” which is a major strain within contemporary Japanese popular culture. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/kokugaku-school/ |

国学(日本固有の学問) 初出 2018年11月16日(金)、大幅改訂 2021年6月21日(月 広義では、国学とは中国ではなく日本を研究対象とする学問を指す。しかし、18世紀から19世紀にかけては、より狭義に解釈されるようになり、仏教や儒教 とは異なる日本古来の道を、日本最古の文献から見出し、その道を現代に復活させようとする試みを指すようになった。徳川時代におけるこれらの研究の主な指 導者については、ほとんどの学者が同意しており、本居宣長(1730~1801)が最も偉大な思想家であり、平田篤胤(1776~1843)が最も効果的 な普及者であったと考えられている。 本居宣長は、8世紀の歌集『万葉集』を歴史言語学的に分析した契沖(1640-1701)にその学問のルーツを見出し、一方、平田篤胤は、賀田亜曾麻呂 (1669-1736)の日本学の学術的取り組みにそのルーツを見出した。両者とも、その創始者リストに鴨長明(1697~1769)を含めていた。いず れにしても、平田篤胤以降、国学者の系譜はより複雑になり、明治新政府は国学者の民族アイデンティティや文化優越性の概念を利用して、日本の民族主義的イ デオロギーと国際的使命への支持を動員した。1945年以降、このような人種的アイデンティティや文化的優越性に関する考え方は一時的にタブー視され、よ り無害な「日本独自性」論に取って代わられたが、それもまた「日本人論」というより幅広いカテゴリーに変容し、現代の日本の大衆文化の主要な潮流となって いる。 |

谷

森 善臣(たにもり よしおみ、文化14年12月28日(1818年2月3日) -

1911年(明治44年)11月16日)は、幕末から明治時代にかけての国学者。陵墓・南朝史・皇室系譜の研究に業績を残した。本姓は平氏、初名は松彦だ

が、28歳の時に種松(種万都・種梥とも)へ改名。通称は二郎・外記。菫壺・靖斎とも号した。 谷

森 善臣(たにもり よしおみ、文化14年12月28日(1818年2月3日) -

1911年(明治44年)11月16日)は、幕末から明治時代にかけての国学者。陵墓・南朝史・皇室系譜の研究に業績を残した。本姓は平氏、初名は松彦だ

が、28歳の時に種松(種万都・種梥とも)へ改名。通称は二郎・外記。菫壺・靖斎とも号した。経歴 京都の三条西家侍臣の家に生まれる。幼時から鋭敏で書をよくし、やがて伴信友の門に入って国学や歌道を学んだ。勤王の志が篤く、山陵(→天皇陵?) の荒廃を嘆いて畿内各地の陵墓を踏査し、嘉永4年(1851年)『諸陵徴』を、安政2年(1855年)『諸陵説』を著す。同5年(1858年)6月から学 習院学問所にて和書御会の講師を務める。文久2年(1862年)山陵奉行・戸田忠至の下で平塚瓢斎・北浦定政らと山陵修補御用掛嘱託となり、陵墓の修築に 加えてその考証・比定作業にも従事。同3年(1863年)1月、篤志によって正六位下内舎人兼大和介に叙任され、7月には『諸陵徴』『諸陵説』両書につき 孝明天皇から恩賞を賜っている。慶応3年(1867年)10月、『山陵考』を幕府へ献上し、翌月諸陵助に任じられた。 明治元年(1868年)2月、神祇事務局判事となるが、間もなく制度事務局権判事へ改任。明治2年(1869年)4月、昌平学校へ出仕して皇学館一等教授 となり、5月より国史考閲御用掛・教導局御用掛を兼ね、7月に大学中博士に任じられる。明治3年(1870年)、正七位に叙された後、同4年(1871 年)4月に御系図取調御用掛、1875年(明治8年)4月に修史局修撰となったが、この頃よりしばらく新政府組織とは距離を置き、南朝史・国語学分野へ研 究対象を広げて著作活動に専念している。 やがて陵墓研究に対する多大な功績が認められ、1893年(明治26年)10月に従五位、さらに1897年(明治30年)4月に従四位へ特進。1898年 (明治31年)1月に御陵墓取調事務嘱託、1904年(明治37年)5月に帝国年表調査委員となり、皇室系譜の調査や歴代天皇の確定に寄与する。1906 年(明治39年)5月、特旨をもって正四位に叙され、晩年まで精力的に活動した。 1911年(明治44年)11月16日卒去、享年95。墓所は雑司ヶ谷霊園(東京都豊島区)にある。 主な著作としては、上で挙げたものの他、『帝皇略譜』・『南山小譜』・『藺笠のしづく』・『神武天皇御陵考』・『柏原山陵考』・『新葉集歌人履歴』・『声 韻図考』・『五十音図纂』・『語鑑言語経緯』・『嵯峨野の露』・『大塔宮護良親王二王子小伝』など、枚挙にいとまがない。しかし、それらを収める草稿類 『谷森靖斎藁草』・『谷森靖斎翁雑稿』・『谷森靖斎史論雑纂』などが全て谷森家にあり、1932年(昭和7年)次男・健男により宮内省図書寮へ献納された 経緯からか、現在までに公刊されたものはわずかで、そのため善臣の学問的業績は学界でもあまり知られていないという事情にある。ただ、善臣の蒐集・校訂し た典籍類は「谷森本」として『国史大系』の底本に利用されており、その卓抜な考証がわが国の歴史学に与えた影響は極めて大きい。 親族 谷森真男 - 善臣の長男で、内閣大書記官・元老院議官・香川県知事などを歴任した官僚。 谷森饒男 - 善臣の孫にして、健男の長男。検非違使を研究した歴史学者として知られる。 参考文献 林恵一 「谷森善臣著作年譜抄」(『書陵部紀要』第23号 宮内庁書陵部、1971年11月、NCID AN00118722) 堀田啓一 「谷森善臣の山陵研究」(森浩一編 『考古学の先覚者たち』 中央公論社、1985年、ISBN 9784120013935) 柳雄太郎 「谷森善臣」(『国史大辞典 第9巻』 吉川弘文館、1988年、ISBN 9784642005098) 上田長生 「幕末期の陵墓考証とその『政治化』 ―谷森善臣と疋田棟隆―」(『幕末維新期の陵墓と社会』 思文閣出版、2012年、ISBN 9784784216048) |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆