モバイル・ヘルス

mHealth, mobile health

☆mHealth(m-healthまたはmhealthとも表記される)とは、モバイルヘルスの略語であり、モバイル機器によってサポートされる医療や公 衆衛生の実践に対して使用される用語である。この用語は、医療サービス、情報、データ収集のために、携帯電話、タブレットPC、PDA (Personal Digital Assistant)などのモバイル通信機器や、スマートウォッチなどのウェアラブル機器を使用することに関して、最も一般的に使用されている。mHealth分野は、eHealthのサブセグメントとして出現した、 mHealthアプリケーションには、コミュニティや臨床の健康データの収集、医療従事者、研究者、患者のためのヘルスケア情報の配信/共有、患者のバイ タルサインのリアルタイムモニタリング、(モバイル遠隔医療を介した)ケアの直接提供、医療従事者の訓練や協力におけるモバイル機器の使用が含まれる。

| mHealth

(also written as m-health or mhealth) is an abbreviation for mobile

health, a term used for the practice of medicine and public health

supported by mobile devices.[1] The term is most commonly used in

reference to using mobile communication devices, such as mobile phones,

tablet computers and personal digital assistants (PDAs), and wearable

devices such as smart watches, for health services, information, and

data collection.[2] The mHealth field has emerged as a sub-segment of

eHealth, the use of information and communication technology (ICT),

such as computers, mobile phones, communications satellite, patient

monitors, etc., for health services and information.[3] mHealth

applications include the use of mobile devices in collecting community

and clinical health data, delivery/sharing of healthcare information

for practitioners, researchers and patients, real-time monitoring of

patient vital signs, the direct provision of care (via mobile

telemedicine) as well as training and collaboration of health

workers.[4][5] In 2019, the global market for mHealth apps was estimated at US$17.92 billion, with a compound annual growth rate of 45% predicted from 2020 to 2027.[6] While mHealth has application for industrialized nations, the field has emerged in recent years as largely an application for developing countries, stemming from the rapid rise of mobile phone penetration in low-income nations. The field, then, largely emerges as a means of providing greater access to larger segments of a population in developing countries, as well as improving the capacity of health systems in such countries to provide quality healthcare.[7] Within the mHealth space, projects operate with a variety of objectives, including increased access to healthcare and health-related information (particularly for hard-to-reach populations); improved ability to diagnose and track diseases; timelier, more actionable public health information; and expanded access to ongoing medical education and training for health workers.[3][8] |

mHealth

(m-healthまたはmhealthとも表記される)とは、モバイルヘルスの略語であり、モバイル機器によってサポートされる医療や公衆衛生の実践に

対して使用される用語である[1]。この用語は、医療サービス、情報、データ収集のために、携帯電話、タブレットPC、PDA(Personal

Digital

Assistant)などのモバイル通信機器や、スマートウォッチなどのウェアラブル機器を使用することに関して、最も一般的に使用されている[2]。

[2] mHealth分野は、eHealthのサブセグメントとして出現した、

mHealthアプリケーションには、コミュニティや臨床の健康データの収集、医療従事者、研究者、患者のためのヘルスケア情報の配信/共有、患者のバイ

タルサインのリアルタイムモニタリング、(モバイル遠隔医療を介した)ケアの直接提供、医療従事者の訓練や協力におけるモバイル機器の使用が含まれる

[4][5]。 2019年、mHealthアプリの世界市場は179億2,000万米ドルと推定され、2020年から2027年までの年平均成長率は45%と予測された [6]。mHealthは先進国に応用されているが、この分野は近年、低所得国における携帯電話普及率の急速な上昇から、主に発展途上国向けのアプリケー ションとして出現している。mHealthの領域では、プロジェクトは、ヘルスケアや健康に関連する情報へのアクセスの増加(特に支援が届きにくい人々の ために)、病気の診断や追跡の能力の向上、よりタイムリーで実用的な公衆衛生情報、医療従事者のための継続的な医学教育やトレーニングへのアクセスの拡大 など、様々な目的で運営されている[3][8]。 |

Definitions Malaria Clinic in Tanzania helped by SMS for Life program that uses cell phones to efficiently deliver malaria vaccine mHealth broadly encompasses the use of mobile telecommunication and multimedia technologies as they are integrated within increasingly mobile and wireless health care delivery systems. The field broadly encompasses the use of mobile telecommunication and multimedia technologies in health care delivery. The term mHealth was coined by Robert Istepanian as use of "emerging mobile communications and network technologies for healthcare".[9][page needed] A definition used at the 2010 mHealth Summit of the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (FNIH) was "the delivery of healthcare services via mobile communication devices".[10] The GSM Association representing the worldwide mobile communications industry published a report on mHealth in 2010 describing a new vision for healthcare and identified ways in which mobile technology might play a role in innovating healthcare delivery systems and healthcare system cost management.[11] While there are some projects that are considered solely within the field of mHealth, the linkage between mHealth and eHealth is unquestionable. For example, an mHealth project that uses mobile phones to access data on HIV/AIDS rates would require an eHealth system in order to manage, store, and assess the data. Thus, eHealth projects many times operate as the backbone of mHealth projects.[3] In a similar vein, while not clearly bifurcated by such a definition, eHealth can largely be viewed as technology that supports the functions and delivery of healthcare, while mHealth rests largely on providing healthcare access.[10] Because mHealth is by definition based on mobile technology such as smartphones, healthcare, through information and delivery, can better reach areas, people, and/or healthcare practitioners with previously limited exposure to certain aspects of healthcare. The National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) has published a review of research on how mHealth and digital health technologies can help manage health conditions.[12] |

定義 携帯電話を使って効率的にマラリア・ワクチンを届けるSMS for Lifeプログラムにより、タンザニアのマラリア・クリニックが支援されている。 mHealthは、モバイル・テレコミュニケーションとマルチメディア・テクノロジーを、ますますモバイル化・ワイヤレス化する医療提供システムの中に統 合して利用することを広く包含している。この分野は、ヘルスケア提供におけるモバイル通信およびマルチメディア技術の使用を広く包含している。 mHealthという用語は、Robert Istepanianによって「ヘルスケアのための新たなモバイル通信およびネットワーク技術」の使用として造語された[9][要出典]。2010年の米 国国立衛生研究所財団(FNIH)のmHealthサミットで使用された定義は、「モバイル通信デバイスを介したヘルスケアサービスの提供」であった [10]。世界中のモバイル通信業界を代表するGSM協会は、2010年にヘルスケアのための新しいビジョンを記述したmHealthに関する報告書を発 表し、モバイル技術がヘルスケア提供システムとヘルスケアシステムのコスト管理の革新において役割を果たす可能性のある方法を特定した[11]。 mHealthの分野だけで考えられるプロジェクトもあるが、mHealthとeHealthの関連性は疑う余地がない。例えば、HIV/AIDSの感染 率に関するデータにアクセスするために携帯電話を使用するmHealthプロジェクトは、データを管理、保存、評価するためにeHealthシステムを必 要とする。このように、eHealthプロジェクトは、多くの場合、mHealthプロジェクトのバックボーンとして機能する[3]。 同様に、このような定義によって明確に二分されるわけではないが、eHealthは主にヘルスケアの機能と提供をサポートするテクノロジーとみなすことが でき、一方mHealthはヘルスケアへのアクセスを提供することに大きく依存している[10]。mHealthは定義上、スマートフォンなどのモバイル テクノロジーに基づいているため、ヘルスケアは、情報と配信を通じて、これまでヘルスケアの特定の側面に触れる機会が限られていた地域、人々、および/ま たは医療従事者によりよく到達することができる。ナショナリズム研究所(NIHR)は、mHealthとデジタルヘルス技術がどのように健康状態の管理に 役立つかに関する研究のレビューを発表している[12]。 |

| Medical uses mHealth apps are designed to support diagnostic procedures, to aid physician decision-making for treatments, and to advance disease-related education for physicians and people under treatment.[13] Mobile health has much potential in medicine and, if used in conjunction with human factors may improve access to care, the scope, and quality of health care services that can be provided. Some applications of mobile health may also improve the ability to improve accountability in healthcare and improve continuum of care by connecting interdisciplinary team members.[14] A dissemination strategy is required to drive potential users discover, download and use mHealth apps. mHealth apps can be disseminated via paid and unpaid marketing strategies using various communication channels. These channels include among others social media, e-mail, posters/flyers, radio and TV broadcasting.[15] mHealth is one aspect of eHealth that is pushing the limits of how to acquire, transport, store, process, and secure the raw and processed data to deliver meaningful results. mHealth offers the ability of remote individuals to participate in the health care value matrix, which may not have been possible in the past. Participation does not imply just consumption of health care services. In many cases remote users are valuable contributors to gather data regarding disease and public health concerns such as outdoor pollution, drugs and violence. While others exist, the 2009 UN Foundation and Vodafone Foundation[3] report presents seven application categories within the mHealth field:[7] Education and awareness Helpline Diagnostic and treatment support Communication and training for healthcare workers Disease and epidemic outbreak tracking Remote monitoring Remote data collection |

医療用途 mHealthアプリは、診断手順をサポートし、治療に対する医師の意思決定を支援し、医師や治療を受けている人々に対する病気関連の教育を進めるように 設計されている[13]。モバイルヘルスは、医療において多くの可能性を秘めており、人的要因と組み合わせて使用されれば、ケアへのアクセス、提供できる ヘルスケアサービスの範囲と質を向上させる可能性がある。モバイルヘルスのいくつかのアプリケーションは、ヘルスケアにおけるアカウンタビリティを向上さ せる能力を改善し、学際的なチームメンバーをつなげることによってケアの継続性を改善する可能性もある[14]。潜在的なユーザーをmHealthアプリ を発見し、ダウンロードし、使用させるためには普及戦略が必要である。これらのチャネルには、特にソーシャルメディア、電子メール、ポスター/チラシ、ラ ジオ、テレビ放送が含まれる[15]。 mHealthは、意味のある結果を提供するために、生データと処理されたデータをどのように取得し、輸送し、保存し、処理し、確保するかの限界に挑戦し ているeHealthの一側面である。参加は、単にヘルスケアサービスの消費を意味するものではない。多くの場合、遠隔地の利用者は、屋外汚染、薬物、暴 力などの疾病や公衆衛生上の懸念に関するデータを収集する貴重な貢献者である。 他にも存在するが、2009年の国連財団とボーダフォン財団の報告書[3]は、mHealth分野における7つのアプリケーション・カテゴリーを提示している[7]。 教育と啓発 ヘルプライン 診断と治療のサポート 医療従事者のためのコミュニケーションとトレーニング 疾病と伝染病発生の追跡 遠隔モニタリング 遠隔データ収集 |

| Education and awareness Education and awareness programs within the mHealth field are largely about the spreading of mass information from source to recipient through short message services (SMS). In education and awareness applications, SMS messages are sent directly to users' phones to offer information about various subjects, including testing and treatment methods, availability of health services, and disease management. SMSs provide an advantage of being relatively unobtrusive, offering patients confidentiality in environments where disease (especially HIV/AIDS) is often taboo. Additionally, SMSs provide an avenue to reach far-reaching areas—such as rural areas—which may have limited access to public health information and education, health clinics, and a deficit of healthcare workers.[3][8] |

教育と啓発 mHealth分野での教育と啓発プログラムは、主にショートメッセージサービス(SMS)を通じて、発信元から受信者へ大量の情報を広めることである。 教育と啓蒙のアプリケーションでは、SMSメッセージがユーザーの携帯電話に直接送信され、検査や治療方法、医療サービスの利用可能性、疾病管理など、さ まざまなテーマに関する情報を提供する。SMSは比較的目立たないという利点があり、病気(特にHIV/AIDS)がタブー視されがちな環境において、患 者の秘密を守ることができる。さらに、SMSは、公衆衛生情報や教育、保健クリニックへのアクセスが制限され、医療従事者が不足している可能性のある農村 部など、広範囲に及ぶ地域に到達する手段を提供する[3][8]。 |

| Helpline Helpline typically consists of a specific phone number that any individual is able to call to gain access to a range of medical services. These include phone consultations, counseling, service complaints, and information on facilities, drugs, equipment, and/or available mobile health clinics.[3] |

ヘルプライン ヘルプラインは通常、特定の電話番号で構成され、個人が電話することで、さまざまな医療サービスを受けることができる。これには、電話相談、カウンセリング、サービスへの苦情、施設、医薬品、設備、および/または利用可能な移動診療所に関する情報などが含まれる[3]。 |

| Diagnostic support, treatment support, communication and training for healthcare workers Diagnostic and treatment support systems are typically designed to provide healthcare workers in remote areas advice about diagnosis and treatment of patients. While some projects may provide mobile phone applications—such as a step-by-step medical decision tree systems—to help healthcare workers diagnose, other projects provide direct diagnosis to patients themselves. In such cases, known as telemedicine, patients might take a photograph of a wound or illness and allow a remote physician to diagnose to help treat the medical problem. Both diagnosis and treatment support projects attempt to mitigate the cost and time of travel for patients located in remote areas.[3] mHealth projects within the communication and training for healthcare workers subset involve connecting healthcare workers to sources of information through their mobile phone. This involves connecting healthcare workers to other healthcare workers, medical institutions, ministries of health, or other houses of medical information. Such projects additionally involve using mobile phones to better organize and target in-person training. Improved communication projects attempt to increase knowledge transfer amongst healthcare workers and improve patient outcomes through such programs as patient referral processes.[3] For example, the systematic use of mobile instant messaging for the training and empowerment of health professionals has resulted in higher levels of clinical knowledge and fewer feelings of professional isolation.[16] |

医療従事者のための診断支援、治療支援、コミュニケーション、トレーニング 診断・治療支援システムは通常、遠隔地の医療従事者に患者の診断や治療に関するアドバイスを提供するために設計されている。医療従事者の診断を支援するた めに、段階的な医療判断ツリーシステムなどの携帯電話アプリケーションを提供するプロジェクトもあるが、患者自身に直接診断を提供するプロジェクトもあ る。遠隔医療として知られるこのようなケースでは、患者は傷や病気の写真を撮り、遠隔地の医師が診断して医療問題の治療に役立てることができる。診断と治 療の支援プロジェクトはどちらも、遠隔地にいる患者の移動にかかる費用と時間を軽減しようとするものである[3]。 医療従事者のためのコミュニケーションとトレーニングのサブセットに含まれるmHealthプロジェクトは、医療従事者を携帯電話を通じて情報源につなぐ ことを含む。これには、医療従事者を他の医療従事者、医療機関、保健省、またはその他の医療情報の発信源につなぐことが含まれる。このようなプロジェクト では、さらに、携帯電話を使って、対面での研修をよりよく組織化し、的を絞ったものにすることも含まれる。コミュニケーション改善プロジェクトでは、患者 紹介プロセスなどのプログラムを通じて、医療従事者間の知識の伝達を増加させ、患者の転帰を改善しようと試みられている[3]。例えば、医療従事者のト レーニングとエンパワーメントのためにモバイルインスタントメッセージを体系的に使用した結果、臨床知識のレベルが向上し、専門家としての孤立感が減少し た[16]。 |

| Disease surveillance, remote data collection, and epidemic outbreak tracking Projects within this area operate to utilize mobile phones' ability to collect and transmit data quickly, cheaply, and relatively efficiently. Data concerning the location and levels of specific diseases (such as malaria, HIV/AIDS, TB, Avian Flu) can help medical systems or ministries of health or other organizations identify outbreaks and better target medical resources to areas of greatest need. Such projects can be particularly useful during emergencies, in order to identify where the greatest medical needs are within a country[3] Policymakers and health providers at the national, district, and community level need accurate data in order to gauge the effectiveness of existing policies and programs and shape new ones. In the developing world, collecting field information is particularly difficult since many segments of the population are rarely able to visit a hospital, even in the case of severe illness. A lack of patient data creates an arduous environment in which policy makers can decide where and how to spend their (sometimes limited) resources. While some software within this area is specific to a particular content or area, other software can be adapted to any data collection purpose. |

疾病監視、遠隔データ収集、伝染病発生追跡 この分野のプロジェクトは、携帯電話の、迅速、安価、比較的効率的なデータ収集・送信能力を活用することを目的としている。特定の疾病(マラリア、 HIV/AIDS、結核、鳥インフルエンザなど)の発生場所と発生レベルに関するデータは、医療システム、保健省、その他の組織が発生を特定し、最も必要 とされる地域に医療資源をより的確に投入するのに役立つ。このようなプロジェクトは、国内で最も医療ニーズが高い場所を特定するために、緊急時に特に有用 である[3]。 国民、地区、地域レベルの政策立案者や医療提供者は、既存の政策やプログラムの有効性を評価し、新たな政策を立案するために、正確なデータを必要としてい る。発展途上国では、国民の多くが重症の場合でも病院を訪れることがほとんどないため、現場での情報収集は特に困難である。患者データの不足は、政策立案 者が(時には限られた)資源をどこにどのように使うかを決定する上で、困難な環境を作り出す。この分野のソフトウェアの中には、特定の内容や分野に特化し たものもあるが、その他のソフトウェアは、どのようなデータ収集目的にも適応できる。 |

| Treatment support and medication compliance for patients Remote monitoring and treatment support allows for greater involvement in the continued care of patients. Recent studies seem to show also the efficacy of inducing positive and negative affective states, using smart phones.[2] Within environments of limited resources and beds—and subsequently an 'outpatient' culture—remote monitoring allows healthcare workers to better track patient conditions, medication regimen adherence, and follow-up scheduling. Such projects can operate through either one- or two-way communications systems. Remote monitoring has been used particularly in the area of medication adherence for AIDS,[17][18] cardiovascular disease,[19][20] chronic lung disease,[20] diabetes,[21][3][22] antenatal mental health,[23] mild anxiety,[24] and tuberculosis.[17] Technical process evaluations have confirmed the feasibility of deploying dynamically tailored, SMS-based interventions designed to provide ongoing behavioral reinforcement for persons living with HIV.[25] among others. Specific mobile applications might also support adherence to taking medications.[26][27] In conclusion, the use of mobile phone technology (in combination with a web-based interface) in health care results in an increase in convenience and efficiency of data collection, transfer, storage and analysis management of data as compared with paper-based systems. Formal studies and preliminary project assessments demonstrate this improvement of efficiency of healthcare delivery by mobile technology.[28] Nevertheless, mHealth should not be considered as a panacea for healthcare.[29] Possible organizational issues include the ensuring of appropriate use and proper care of the handset, lost or stolen phones, and the important consideration of costs related to the purchase of equipment. There is therefore a difficulty in comparison in weighing up mHealth interventions against other priority and evidence-based interventions.[30] |

患者の治療サポートと服薬コンプライアンス 遠隔モニタリングと治療支援は、患者の継続的なケアに、より深く関与することを可能にする。最近の研究では、スマートフォンを使って肯定的・否定的な感情 状態を誘導する効果も示されているようだ[2]。リソースやベッド数が限られた環境、ひいては「外来患者」文化の中で、遠隔モニタリングは医療従事者が患 者の状態、投薬計画の遵守、フォローアップのスケジュールなどをよりよく追跡することを可能にする。このようなプロジェクトは、片方向または双方向の通信 システムを通じて行うことができる。遠隔モニタリングは、特にAIDS、[17][18]心血管系疾患、[19][20]慢性肺疾患、[20]糖尿病、 [21][3][22]妊産婦のメンタルヘルス、[23]軽度の不安症、[24]結核の服薬アドヒアランスの分野で利用されている[17]。技術的なプロ セス評価では、HIV感染者に継続的な行動強化を提供するように設計された、動的に調整されたSMSベースの介入を展開することの実現可能性が確認されて いる[25]。特定のモバイルアプリケーションは、服薬アドヒアランスを支援する可能性もある[26][27]。 結論として、ヘルスケアにおける携帯電話技術(ウェブベースのインターフェースとの組み合わせ)の使用は、紙ベースのシステムと比較して、データの収集、 転送、保存、分析管理の利便性と効率性の向上につながる。とはいえ、mHealthをヘルスケアの万能薬と考えるべきではない[29]。考えられる組織的 な問題としては、携帯電話の適切な使用と適切なケアの確保、携帯電話の紛失や盗難、機器の購入に関連するコストの重要な考慮事項などがある。したがって、 mHealthの介入を他の優先的でエビデンスに基づく介入と比較することは困難である[30]。 |

| Criticism and concerns The extensive practice of mhealth research has sparked criticism, for example on the proliferation of fragmented pilot studies in low- and middle-income countries, which is also referred to as "pilotitis."[31] The extent of un-coordinated pilot studies prompted for instance the Ugandan Director General Health Services Dr Jane Ruth Aceng in 2012 to issue a notice that, "in order to jointly ensure that all eHealth efforts are harmonized and coordinated, I am directing that ALL eHealth projects/Initiatives be put to halt."[32] The assumptions that justify mhealth initiatives have also been challenged in recent sociological research. For example, mobile phones have been argued to be less widely accessible and usable than is often portrayed in mhealth-related publications;[33] people integrate mobile phones into their health behavior without external intervention;[34] and the spread of mobile phones in low- and middle-income countries itself can create new forms of digital and healthcare exclusion, which mhealth interventions (using mobile phones as a platform) cannot overcome and potentially accentuate.[35] Mhealth has also been argued to alter the practice of healthcare and patient-physician relationships as well as how bodies and health are being represented.[36][37] Another widespread concern relates to privacy and data protection, for example in the context of electronic health records.[37][38] Studies looking into the perceptions and experiences of primary healthcare professionals using mheath have found that most health care professionals appreciated being connected to their colleagues, however some prefer face to face communication.[14] Some healthcare workers also felt that while reporting was improved and team members who require help or training could be more easily identified, some healthcare professionals did not feel comfortable being monitored continuously.[14] A proportion of healthcare professionals prefer paper reporting.[14] The use of mobile apps may sometimes lead to healthcare professionals spending more time performing additional tasks such as filling out electronic forms and may generate more workload in some cases.[14] Some healthcare professionals also do not feel comfortable with work-related contact from patients/clients outside of business hours (however some professionals did find this useful for emergencies).[14] Communicating with clients/patients while using a mobile device may need to be considered.[14] A decrease in eye contact and the potential to miss non-verbal cues due to concentrating on a screen while speaking with patients is a potential consideration.[14] |

批判と懸念 mhealth研究の広範な実践は、例えば中低所得国における断片的なパイロット研究の拡散に関する批判を巻き起こしており、これは「パイロット炎」とも 呼ばれている。 これは「パイロット炎」とも呼ばれている。[31] 調整されていないパイロット研究の程度は、例えば2012年にウガンダの保健サービス局長Jane Ruth Aceng博士に、「すべてのeヘルスへの取り組みが調和され調整されていることを共同で確実にするために、すべてのeヘルスプロジェクト/イニシアチブ を停止するよう指示する」という通達を出させた[32] 。例えば、携帯電話は、mhealth関連の出版物でよく描かれているほどには、広くアクセス可能でなく、使いやすいものではない、[33]人々は、外部 からの介入なしに、携帯電話を自分の健康行動に統合している、[34]中低所得国における携帯電話の普及そのものが、新たな形態のデジタル排除や医療排除 を生み出す可能性があり、mhealth介入(携帯電話をプラットフォームとして使用)は、それを克服することができず、強調する可能性がある、と主張さ れている。 [35] Mhealthはまた、ヘルスケアの実践や患者と医師の関係、さらには身体や健康がどのように表現されるかを変えるとも論じられている[36][37]。 もう一つの広く懸念される問題は、例えば電子カルテの文脈におけるプライバシーとデータ保護に関するものである[37][38]。 mheathを使用している一次医療従事者の認識と経験を調査した研究によると、ほとんどの医療従事者は同僚とつながっていることを評価しているが、対面 でのコミュニケーションを好む者もいることがわかった[14]。また、一部の医療従事者は、報告が改善され、支援やトレーニングが必要なチームメンバーを より簡単に特定できるようになったが、継続的に監視されることに抵抗を感じる医療従事者もいると感じている[14]。 [モバイルアプリの使用は、医療従事者が電子フォームへの記入などの追加タスクに多くの時間を費やすことにつながり、場合によっては仕事量が増える可能性 がある[14] 。 モバイル機器を使用しながらの顧客/患者とのコミュニケーションは、考慮する必要があるかもしれない[14]。患者と話している間、アイコンタクトの減少や、画面に集中することによる非言語的な合図を見逃す可能性は、潜在的な考慮事項である[14]。 |

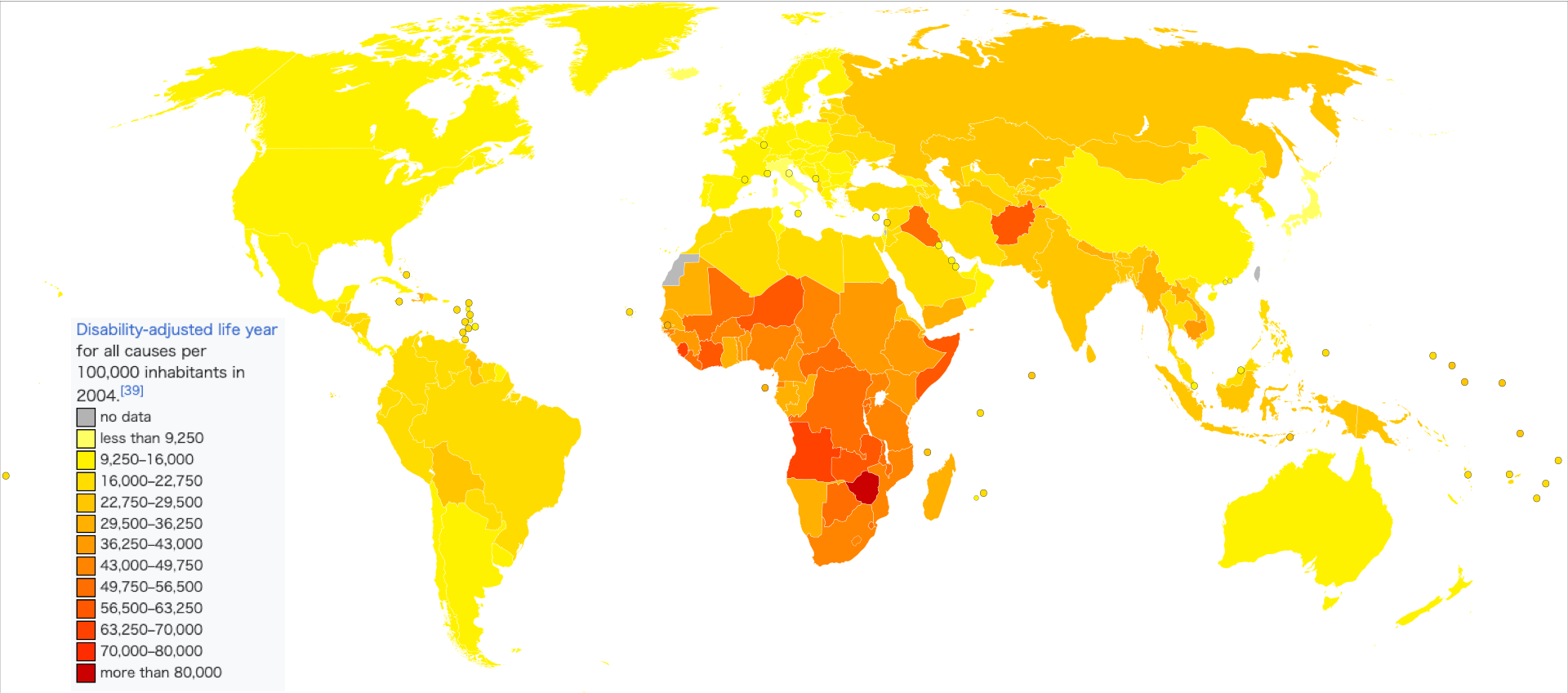

| Society and culture Healthcare in low- and middle-income countries  Disability-adjusted life year for all causes per 100,000 inhabitants in 2004.[39] no data less than 9,250 9,250–16,000 16,000–22,750 22,750–29,500 29,500–36,250 36,250–43,000 43,000–49,750 49,750–56,500 56,500–63,250 63,250–70,000 70,000–80,000 more than 80,000 Middle income and especially low-income countries face a plethora of constraints in their healthcare systems.[40] These countries face a severe lack of human and physical resources, as well as some of the largest burdens of disease, extreme poverty, and large population growth rates. Additionally, healthcare access to all reaches of society is generally low in these countries.[41] According to a World Health Organization (WHO) report from June 2011, higher-income countries show more mHealth activity than do lower-income countries (as consistent with eHealth trends in general). Countries in the European Region are currently the most active and those in the African Region the least active. The WHO report findings also included that mHealth is most easily incorporated into processes and services that historically use voice communication through conventional telephone networks. The report[42] was the result of a mHealth survey module designed by researchers at the Earth Institute's Center for Global Health and Economic Development,[43] Columbia University. The WHO notes an extreme deficit within the global healthcare workforce. The WHO notes critical healthcare workforce shortages in 57 countries—most of which are characterized as developing countries—and a global deficit of 2.4 million doctors, nurses, and midwives.[44] The WHO, in a study of the healthcare workforce in 12 countries of Africa, finds an average density of physicians, nurses and midwives per 1000 population of 0.64.[45] The density of the same metric is four times as high in the United States, at 2.6.[46] The burden of disease is additionally much higher in low- and middle-income countries than high-income countries. The burden of disease, measured in disability-adjusted life year (DALY), which can be thought of as a measurement of the gap between current health status and an ideal situation where everyone lives into old age, free of disease and disability, is about five times higher in Africa than in high-income countries.[47][page needed] In addition, low- and middle-income countries are forced to face the burdens of both extreme poverty and the growing incidence of chronic diseases, such as diabetes and heart disease, an effect of new-found (relative) affluence.[3] Considering poor infrastructure and low human resources, the WHO notes that the healthcare workforce in sub-Saharan Africa would need to be scaled up by as much as 140% to attain international health development targets such as those in the Millennium Declaration.[48] The WHO, in reference to the healthcare condition in sub-Saharan Africa, states: The problem is so serious that in many instances there is simply not enough human capacity even to absorb, deploy and efficiently use the substantial additional funds that are considered necessary to improve health in these countries.[48] Mobile technology has made a recent and rapid appearance into low- and middle-income nations.[49] While, in the mHealth field, mobile technology usually refers to mobile phone technology, the entrance of other technologies into these nations to facilitate healthcare are also discussed here. |

社会と文化 中低所得国の医療  2004年における人口10万人当たりの全死因による障害調整生存年[39]。 データなし 9,250人未満 9,250-16,000 16,000-22,750 22,750-29,500 29,500-36,250 36,250-43,000 43,000-49,750 49,750-56,500 56,500-63,250 63,250-70,000 70,000-80,000 80,000人以上 中所得国、特に低所得国は、医療制度において多くの制約に直面 している[40]。これらの国々は、人的・物的資源の深刻な不足に加え、疾病 負担が最も大きく、極度の貧困、人口増加率が高いという問題を抱えている。さらに、これらの国々では、社会のあらゆる層への医療アクセスは一般的に低い [41]。 2011年6月の世界保健機関(WHO)の報告書によると、高所得国は低所得国よりもmHealth活動を示している(一般的なeHealthの傾向と一 致している)。現在、ヨーロッパ地域の国々が最も活発で、アフリカ地域の国々が最も不活発である。WHOの報告書の調査結果には、mHealthは、歴史 的に従来の電話ネットワークを通じた音声通信を使用しているプロセスやサービスに最も容易に組み込まれることも含まれている。この報告書[42]は、地球 研究所のグローバルヘルス・経済開発センター(コロンビア大学[43])の研究者によって設計されたmHealth調査モジュールの結果であった。 WHOは、世界の医療労働力の極端な不足を指摘している。WHOは、57カ国(そのほとんどが発展途上国である)において深刻な医療労働力不足に陥ってお り、世界全体で240万人の医師、看護師、助産師が不足していると指摘している[44]。WHOは、アフリカの12カ国における医療労働力の調査におい て、人口1000人あたりの医師、看護師、助産師の平均密度が0.64であることを明らかにしている[45]。 疾病負担はさらに、高所得国よりも低・中所得国の方がはるかに高い。障害調整生存年(DALY:Disability-Adjusted Life Year)で測定される疾病負担は、現在の健康状態と、すべての人が老後まで病気や障害のない理想的な状態とのギャップの測定と考えることができるが、ア フリカでは高所得国の約5倍も高い[47][要出典]。さらに、低・中所得国は、極度の貧困と、新たに発見された(相対的な)豊かさの影響である糖尿病や 心臓病などの慢性疾患の罹患率の増加の両方の負担に直面せざるを得ない[3]。 貧弱なインフラと低い人的資源を考慮すると、WHOは、ミレニアム宣言のような国際的な保健開発目標を達成するためには、サハラ以南のアフリカの保健医療労働力を140%も拡大する必要があると指摘している[48]。 WHOは、サハラ以南のアフリカの医療状況について、次のように述べている: この問題は非常に深刻であり、多くの場合、これらの国々で保健を改善するために必要と考えられている多額の追加資金を吸収し、配備し、効率的に使用するための人的能力さえも、単に不足しているのである[48]」と述べている。 mHealthの分野では、モバイルテクノロジーは通常携帯電話技術を指すが [49] 、ヘルスケアを促進するためにこれらの国民に他の技術が入り込んでいることについても、ここでは議論する。 |

| Health and development The link between health and development can be found in three of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), as set forth by the United Nations Millennium Declaration in 2000. The MDGs that specifically address health include reducing child mortality; improving maternal health; combating HIV and AIDS, malaria, and other diseases; and increasing access to safe drinking water.[50] A progress report published in 2006 indicates that childhood immunization and deliveries by skilled birth attendants are on the rise, while many regions continue to struggle to achieve reductions in the prevalence of the diseases of poverty including malaria, HIV and AIDS and tuberculosis.[51] |

健康と開発 健康と開発との関連は、2000年のナショナリズム・ミレニアム宣言で定め られたミレニアム開発目標(MDGs)のうち3つの目標に見られる。2006年に発表された進捗報告書によると、小児期の予防接種と熟練産婆による分娩は 増加傾向にあるが、マラリア、HIV/エイズ、結核を含む貧困の疾病の蔓延の減少を達成するために、多くの地域で苦闘が続いている[51]。 |

| Healthcare in developed countries In developed countries, healthcare systems have different policies and goals in relation to the personal and population health care goals. In the US and EU many patients and consumers use their cell phones and tablets to access health information and look for healthcare services. In parallel the number of mHealth applications grew significantly in the last years. Clinicians use mobile devices to access patient information and other databases and resources. Physicians also use mobile devices as an streamlined tool for exchanging patient information, for educational purposes, and as a tool for decision support. [52] |

先進国の医療 先進国では、医療制度は個人と集団のヘルスケア目標に関して異なる政策と目標を掲げている。 米国やEUでは、多くの患者や消費者が携帯電話やタブレットを使って健康情報にアクセスし、医療サービスを探している。これと並行して、mHealthアプリケーションの数はここ数年で著しく増加した。 臨床医は、患者情報やその他のデータベースやリソースにアクセスするためにモバイル機器を使用している。 医師はまた、患者情報を交換するための合理的なツールとして、教育目的のために、そして意思決定支援のためのツールとしてモバイル機器を使用している。[52] |

| Technology and market Basic SMS functions and real-time voice communication serve as the backbone and the current most common use of mobile phone technology. The broad range of potential benefits to the health sector that the simple functions of mobile phones can provide should not be understated.[53] The appeal of mobile communication technologies is that they enable communication in motion, allowing individuals to contact each other irrespective of time and place.[54][55] This is particularly beneficial for work in remote areas where the mobile phone, and now increasingly wireless infrastructure, is able to reach more people, faster. As a result of such technological advances, the capacity for improved access to information and two-way communication becomes more available at the point of need. |

技術と市場 基本的なSMS機能とリアルタイムの音声コミュニケーションは、携帯電話技術のバックボーンであり、現在最も一般的な利用法である。携帯電話のシンプルな機能が保健分野にもたらす潜在的なメリットの広範さは、過小評価されるべきではない[53]。 移動体通信技術の魅力は、移動中のコミュニケーションを可能にし、時間や場所に関係なく個人同士が連絡を取り合えるようにすることである[54] [55]。これは、携帯電話、そして現在ではますます無線インフラが普及しているため、より多くの人に、より早く連絡を取ることができる遠隔地での活動に 特に有益である。このような技術的進歩の結果、情報へのアクセス向上と双方向通信の能力が、必要な時点でより利用しやすくなる。 |

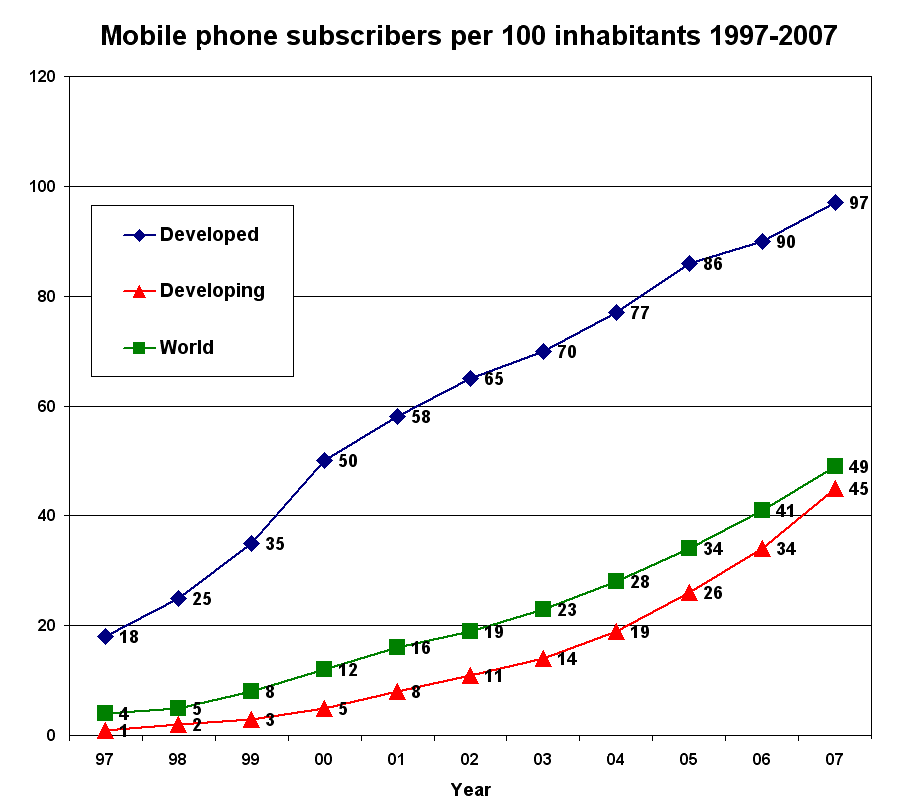

Mobile phones Mobile phone subscribers per 100 inhabitants 1997–2007 With the global mobile phone penetration rate drastically increasing over the last decade, mobile phones have made a recent and rapid entrance into many parts of the low- and middle-income world. Improvements in telecommunications technology infrastructure, reduced costs of mobile handsets, and a general increase in non-food expenditure have influenced this trend. Low- and middle-income countries are utilizing mobile phones as "leapfrog technology" (see leapfrogging). That is, mobile phones have allowed many developing countries, even those with relatively poor infrastructure, to bypass 20th century fixed-line technology and jump to modern mobile technology.[56] The number of global mobile phone subscribers in 2007 was estimated at 3.1 billion of an estimated global population of 6.6 billion (47%).[57] These figures are expected to grow to 4.5 billion by 2012, or a 64.7% mobile penetration rate. The greatest growth is expected in Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. In many countries, the number of mobile phone subscribers has bypassed the number of fixed-line telephones; this is particularly true in developing countries.[58] Globally, there were 4.1 billion mobile phones in use in December 2008. See List of countries by number of mobile phones in use. While mobile phone penetration rates are on the rise, globally, the growth within countries is not generally evenly distributed. In India, for example, while mobile penetration rates have increased markedly, by far the greatest growth rates are found in urban areas. Mobile penetration, in September 2008, was 66% in urban areas, while only 9.4% in rural areas. The all India average was 28.2% at the same time.[59] So, while mobile phones may have the potential to provide greater healthcare access to a larger portion of a population, there are certainly within-country equity issues to consider. Mobile phones are spreading because the cost of mobile technology deployment is dropping and people are, on average, getting wealthier in low- and middle-income nations.[60] Vendors, such as Nokia, are developing cheaper infrastructure technologies (CDMA) and cheaper phones (sub $50–100, such as Sun's Java phone). Non-food consumption expenditure is increasing in many parts of the developing world, as disposable income rises, causing a rapid increase in spending on new technology, such as mobile phones. In India, for example, consumers have become and continue to become wealthier. Consumers are shifting their expenditure from necessity to discretionary. For example, on average, 56% of Indian consumers' consumption went towards food in 1995, compared to 42% in 2005. The number is expected to drop to 34% by 2015. That being said, although total share of consumption has declined, total consumption of food and beverages increased 82% from 1985 to 2005, while per-capita consumption of food and beverages increased 24%. Indian consumers are getting wealthier and they are spending more and more, with a greater ability to spend on new technologies.[61] |

携帯電話 人口100人当たりの携帯電話加入者数 1997-2007 世界の携帯電話普及率が過去10年間で劇的に上昇したことで、携帯電話は低・中所得国の多くの地域で最近急速に普及した。通信技術インフラの改善、携帯電 話端末の低価格化、非食品支出の全般的な増加が、この傾向に影響を及ぼしている。中低所得国は、携帯電話を「リープフロッグ・テクノロジー」(リープフ ロッグを参照)として活用している。つまり、携帯電話によって、インフラが比較的貧弱な発展途上国であっても、20 世紀的な固定回線技術を回避して、近代的なモバイル技術にジャンプすることができるようになったのである[56]。 2007年の世界の携帯電話加入者数は、世界人口66億人(47%)のうち31億人と推定された[57]。この数字は、2012年までに45億人(携帯電 話普及率64.7%)に成長すると予想されている。最大の成長が見込まれるのは、アジア、中東、アフリカである。多くの国で、携帯電話の加入者数は固定電 話の加入者数を上回っている。携帯電話使用台数別国別リストを参照のこと。 携帯電話の普及率は世界的に上昇傾向にあるが、各国内の伸びは概して均等ではない。たとえばインドでは、携帯電話の普及率は著しく上昇しているが、伸び率 が圧倒的に高いのは都市部である。2008年9月のモバイル普及率は、都市部で66%だったのに対し、農村部ではわずか9.4%だった。インド全土の平均 は、同時期で28.2%であった[59]。したがって、携帯電話は、より多くの人口に、より大きな医療アクセスを提供する可能性を秘めているかもしれない が、考慮すべき国内公平性の問題があることは確かである。 ノキアなどのベンダーは、より安価なインフラ技術(CDMA)やより安価な携帯電話(サンの Java 携帯電話など、50~100 ドル未満)を開発している。可処分所得の上昇に伴い、発展途上国の多くの地域で非食品消費支出が増加しており、携帯電話な どの新技術への支出が急速に増加している。たとえばインドでは、消費者が豊かになり、今後も豊かになり続けるだろう。消費者の支出は必需品から自由裁量へ とシフトしている。例えば、インディアンの消費者の消費の平均は、1995年には56%が食料品であったが、2005年には42%であった。2015年に は34%まで落ち込むと予想されている。とはいえ、消費の総シェアは低下しているものの、食品・飲料の総消費量は1985年から2005年にかけて82% 増加し、一人当たりの食品・飲料消費量は24%増加している。インディアンの消費者は裕福になりつつあり、新しい技術に費やす能力も高まり、ますます消費 するようになっている[61]。 |

| Smartphones From the first quarter of 2015 through the first quarter of 2021, 107,033 mHealth apps in the health and fitness category were available via the Apple Store and Google Play, an increase of 11.37% from the previous quarter.[6] More advanced mobile phone technologies are enabling the potential for further healthcare delivery. Smartphone technologies are now in the hands of a large number of physicians and other healthcare workers in low- and middle-income countries. Although far from ubiquitous, the spread of smartphone technologies opens up doors for mHealth projects such as technology-based diagnosis support, remote diagnostics and telemedicine, preprogrammed daily self-assessment prompts, video or audio clips,[62] web browsing, GPS navigation, access to web-based patient information, post-visit patient surveillance, and decentralized health management information systems (HMIS). While uptake of smartphone technology by the medical field has grown in low- and middle-income countries, it is worth noting that the capabilities of mobile phones in low- and middle-income countries has not reached the sophistication of those in high-income countries. The infrastructure that enables web browsing, GPS navigation, and email through smartphones is not as well developed in much of the low- and middle-income countries.[53] Increased availability and efficiency in both voice and data-transfer systems in addition to rapid deployment of wireless infrastructure will likely accelerate the deployment of mobile-enabled health systems and services throughout the world.[63] |

スマートフォン 2015年第1四半期から2021年第1四半期までに、健康とフィットネスカテゴリーの107,033のmHealthアプリがApple StoreとGoogle Playを通じて利用可能となり、前四半期から11.37%増加した[6]。より高度な携帯電話技術は、さらなるヘルスケア提供の可能性を可能にしてい る。スマートフォンの技術は現在、低・中所得国の多くの医師やその他の医療従事者の手に渡っている。ユビキタスには程遠いものの、スマートフォン技術の普 及は、技術ベースの診断支援、遠隔診断や遠隔医療、あらかじめプログラムされた毎日の自己評価プロンプト、ビデオやオーディオクリップ、[62]ウェブブ ラウジング、GPSナビゲーション、ウェブベースの患者情報へのアクセス、訪問後の患者サーベイランス、分散型健康管理情報システム(HMIS)などの mHealthプロジェクトに門戸を開く。 低・中所得国では、医療分野でのスマートフォン技術の利用が拡大しているが、低・中所得国の携帯電話の機能は、高所得国の携帯電話のような洗練されたもの には達していないことは注目に値する。スマートフォンによるウェブ閲覧、GPSナビゲーション、電子メールを可能にするインフラは、低・中所得国の多くで はそれほど発達していない[53]。無線インフラの急速な展開に加えて、音声およびデータ転送システムの両方における可用性と効率性が向上すれば、モバイ ル対応の医療システムやサービスの展開が世界中で加速する可能性が高い[63]。 |

| Other technologies Beyond mobile phones, wireless-enabled laptops and specialized health-related software applications are currently being developed, tested, and marketed for use in the mHealth field. Many of these technologies, while having some application to low- and middle-income nations, are developing primarily in high-income countries. However, with broad advocacy campaigns for free and open source software (FOSS), applications are beginning to be tailored for and make inroads in low- and middle-income countries.[7] Some other mHealth technologies include:[1] Patient monitoring devices Mobile telemedicine/telecare devices Microcomputers Data collection software Mobile Operating System Technology Mobile applications (e.g., gamified/social wellness solutions) Chatterbots |

その他のテクノロジー 携帯電話以外にも、ワイヤレス対応のノートパソコンや特殊な健康関連ソフトウェア・アプリケーションが、mHealth分野で使用するために現在開発、テ スト、販売されている。これらの技術の多くは、低・中所得国民にもある程度適用できるものの、主に高所得国で発展している。しかし、フリーでオープンな ソース・ソフトウェア(FOSS)のための広範なアドボカシー・キャンペーンにより、アプリケーションは低・中所得国向けに調整され、進出し始めている [7]。 その他のmHealth技術には、以下のようなものがある[1]。 患者モニタリング・デバイス モバイル遠隔医療/遠隔介護機器 マイクロコンピュータ データ収集ソフトウェア モバイルオペレーティングシステム技術 モバイル・アプリケーション(ゲーミフィケーション/ソーシャル・ウェルネス・ソリューションなど) チャターボット |

| Mobile device operating system technology Technologies relate to the operating systems that orchestrate mobile device hardware while maintaining confidentiality, integrity and availability are required to build trust. This may foster greater adoption of mHealth technologies and services, by exploiting lower cost multi purpose mobile devices such as tablets, PCs, and smartphones. Operating systems that control these emerging classes of devices include Google's Android, Apple's iPhone OS, Microsoft's Windows Mobile, and RIM's BlackBerry OS. Operating systems must be agile and evolve to effectively balance and deliver the desired level of service to an application and end user, while managing display real estate, power consumption and security posture. With advances in capabilities such as integrating voice, video and Web 2.0 collaboration tools into mobile devices, significant benefits can be achieved in the delivery of health care services. New sensor technologies[64] such as HD video and audio capabilities, accelerometers, GPS, ambient light detectors, barometers and gyroscopes[65] can enhance the methods of describing and studying cases, close to the patient or consumer of the health care service. This could include diagnosis, education, treatment and monitoring. |

モバイル・デバイスのオペレーティング・システム技術 信頼性を構築するためには、機密性、完全性、可用性を維持しながら、モバイルデバイスのハードウェアをオーケストレーションするオペレーティングシステム に関する技術が必要である。これは、タブレット、PC、スマートフォンのような低コストの多目的モバイルデバイスを利用することで、mHealth技術と サービスのより大きな採用を促進する可能性がある。これらの新興クラスのデバイスを制御するオペレーティングシステムには、Googleの Android、AppleのiPhone OS、MicrosoftのWindows Mobile、およびRIMのBlackBerry OSが含まれる。 オペレーティング・システムは、ディスプレイ面積、消費電力、セキュリティ態勢を管理しながら、アプリケーションとエンド・ユーザーに望ましいレベルの サービスを効果的にバランスさせて提供するために、機敏に進化しなければならない。音声、ビデオ、Web 2.0コラボレーション・ツールをモバイル・デバイスに統合するような機能の進歩により、ヘルスケア・サービスの提供において大きな利益を達成することが できる。HDビデオやオーディオ機能、加速度計、GPS、環境光検出器、気圧計、ジャイロスコープ[65]などの新しいセンサー技術[64]は、ヘルスケ アサービスの患者や消費者の近くで、症例の説明や研究の方法を強化することができる。これには、診断、教育、治療、モニタリングが含まれる。 |

| Air quality sensing technologies Environmental conditions have a significant impact on public health. Per the World Health Organization, outdoor air pollution accounts for about 1.4% of total mortality.[66] Utilizing Participatory sensing technologies in mobile telephone, public health research can exploit the wide penetration of mobile devices to collect air measurements,[65] which can be utilized to assess the impact of pollution. Projects such as the Urban Atmospheres are utilizing embedded technologies in mobile phones to acquire real time conditions from millions of users mobile phones. By aggregating this data, public health policy shall be able to craft initiatives to mitigate the risk associated with outdoor air pollution. |

大気質センシング技術 環境条件は公衆衛生に大きな影響を与える。世界保健機関(WHO)によると、屋外の大気汚染は総死亡率の約1.4%を占めている[66]。携帯電話の参加 型センシング技術を活用することで、公衆衛生研究は、大気測定を収集するための携帯端末の幅広い普及率を利用することができ[65]、汚染の影響を評価す るために活用することができる。Urban Atmospheresのようなプロジェクトでは、携帯電話の組み込み技術を利用して、何百万人ものユーザーの携帯電話からリアルタイムの状況を取得して いる。このデータを集約することで、公衆衛生政策が、屋外の大気汚染に関連するリスクを軽減するためのイニシアチブを立案することができるようになる。 |

| Data Data has become an especially important aspect of mHealth. Data collection requires both the collection device (mobile phones, computer, or portable device) and the software that houses the information. Data is primarily focused on visualizing static text but can also extend to interactive decision support algorithms, other visual image information, and also communication capabilities through the integration of e-mail and SMS features. Integrating use of GIS and GPS with mobile technologies adds a geographical mapping component that is able to "tag" voice and data communication to a particular location or series of locations.[67] These combined capabilities have been used for emergency health services as well as for disease surveillance, health facilities and services mapping, and other health-related data collection.[68][69][70][71] |

データ データは、mHealthの特に重要な側面となっている。データ収集には、収集デバイス(携帯電話、コンピュータ、またはポータブルデバイス)と情報を格 納するソフトウェアの両方が必要である。データは主に静的なテキストを視覚化することに重点を置いているが、インタラクティブな意思決定支援アルゴリズ ム、その他の視覚的な画像情報、また電子メールやSMS機能の統合によるコミュニケーション機能にも拡張することができる。GISとGPSをモバイル技術 と統合することで、特定の場所や一連の場所に音声やデータ通信を「タグ付け」することができる地理的マッピング・コンポーネントが追加される[67]。こ れらの複合機能は、緊急保健サービスだけでなく、疾病サーベイランス、保健施設やサービスのマッピング、その他の保健関連データ収集にも利用されている [68][69][70][71]。 |

| History The motivation behind the development of the mHealth field arises from two factors. The first factor concerns the myriad constraints felt by healthcare systems of developing nations. These constraints include high population growth, a high burden of disease prevalence,[47] low health care workforce, large numbers of rural inhabitants, and limited financial resources to support healthcare infrastructure and health information systems. The second factor is the recent rapid rise in mobile phone penetration in developing countries to large segments of the healthcare workforce, as well as the population of a country as a whole.[57] With greater access to mobile phones to all segments of a country, including rural areas, the potential of lowering information and transaction costs in order to deliver healthcare improves. The combination of these two factors has motivated much discussion of how greater access to mobile phone technology can be leveraged to mitigate the numerous pressures faced by developing countries' healthcare systems. mHealth has a rich research history starting in the early 2000s and has since transformed healthcare delivery and patient engagement. The evolution of mHealth can be traced through significant milestones and initiatives: |

歴史 mHealth分野の発展の背景には、2つの要因がある。第一の要因は、発展途上国の医療制度が感じている無数の制約に関するものである。これらの制約に は、高い人口増加、高い疾病負担率、低い医療労働力[47]、多数の農村住民、医療インフラと医療情報システムを支える限られた財源が含まれる。2つ目の 要因は、発展途上国において、医療従事者の大部分や国全体の人口に携帯電話が急速に普及していることである[57]。農村部を含む国のあらゆる層が携帯電 話にアクセスできるようになれば、医療を提供するための情報コストや取引コストを削減できる可能性が高まる。 これら2つの要因が組み合わさることで、携帯電話技術へのアクセス拡大が、発展途上国の医療制度が直面する数々の圧力を緩和するためにどのように活用できるかについて、多くの議論がなされるようになった。 mHealthは、2000年代初頭に始まった豊かな研究の歴史があり、それ以来、医療提供と患者エンゲージメントを変革してきた。mHealthの進化は、重要なマイルストーンとイニシアチブを通してたどることができる: |

| Timeline of key events This section contains promotional content. Please help improve it by removing promotional language and inappropriate external links, and by adding encyclopedic text written from a neutral point of view. (December 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Early 2000s – Emergence of mHealth research Research initiatives exploring the potential of mobile devices in healthcare settings began to surface. Academic institutions and technology companies started investigating the feasibility of using mobile phones for health-related purposes.[72] 2006 – The Genes, Environment, and Health Initiative (GEI) The GEI program was launched, emphasizing prospective cohort studies. This program laid the groundwork for understanding the interplay between genetics, the environment, and health outcomes.[73][74][75] 2007 – Technological advancements A critical year with the introduction of the first iPhone, marking the beginning of the smartphone era that would significantly impact mHealth.[76] 2008 – WHO mHealth Summit The World Health Organization (WHO) organized a summit that recognized the potential of mobile technology in improving global healthcare access, marking a significant milestone in mHealth advocacy.[77] 2009 – Launch of mHealth Alliance The United Nations Foundation established the mHealth Alliance, focusing on leveraging mobile technology to improve health outcomes, especially in developing countries.[78] 2010 – Pioneering mHealth projects Several groundbreaking mHealth projects were initiated worldwide, including programs for remote patient monitoring, disease management, health education via SMS, and mobile apps for healthcare professionals.[79] mHealth Training Institute (mHTI) The first NIH mHealth Training Institute was held at UCLA to serve as an incubator for developing transdisciplinary scientists capable of co-creating mHealth solutions for complex healthcare problems. The week-long workshop is grounded in a team science model that emphasizes both information transaction and relationship development in the advancement of transdisciplinary mHealth teams capable of impactful healthcare solutions.[80] 2011 – The mHealth Evidence Workshop A collaborative effort involving NSF, NIH, RWJF, and McKesson Foundation, explored mobile health technology evaluation to outline an approach to evidence generation in the field of mHealth that would ensure research is conducted on a rigorous empirical and theoretic foundation.[81] Open mHealth Open mHealth architecture was introduced, fostering innovation in healthcare through facilitating access and harmonization of digital health data from disparate sources using a global community of developers and health tech decision-makers to make sense of that digital health data through an open interoperability standard.[82][83] 2012 – mHealth app revolution The proliferation of smartphone apps dedicated to health and fitness catalyzed the mHealth revolution, allowing users to track fitness, monitor vitals, access medical information, and engage in telemedicine.[84] Smart Health and Wellbeing (SHB) As a follow-up to the mHealth Evidence Workshop, NSF launched the Smart Health and Wellbeing program to address fundamental technical and scientific issues that would support the much-needed transformation of healthcare from reactive and hospital-centered to preventive, proactive, evidence-based, person-centered, and focused on wellbeing rather than disease.[85] ASSIST Engineering Research Center (ERC) NSF and NIH initiated a joint research program specifically focusing on mHealth, following up on the insights gained from the mHealth Evidence Workshop. The Engineering Research Center ASSIST ERC at NC State University was established to further mHealth research by developing leading-edge systems for high-value applications such as healthcare and IoT by integrating fundamental advances in energy harvesting, low-power electronics, and sensors with a focus on usability and actionable data.[86] 2013 – Wearable technology Around this time, Fitbit (originally Healthy Metrics Research, Inc.) also emerged, pioneering wearable health technology.[87] 2014 – The Big Data To Knowledge (BD2K) Initiative The NIH BD2K Centers of Excellence program provided a significant boost to mHealth research, leading to 12 research centers, like the Mobile Data To Knowledge (MD2K)[88] headquartered at the University of Memphis and Stanford's Center for Mobility Data Integration to Insight (Mobilize),[89] to facilitate studies and innovation in the field.[90] 2015 – Advancements in wearable technology Wearable devices, such as smartwatches and fitness trackers, have become more sophisticated, enabling continuous health monitoring, activity tracking, and integration with mobile health apps.[91][92] All of Us mHealth gained prominence in the All of Us program, a precision medicine initiative aiming to collect health data from diverse populations.[93] The launch of smartwatches, particularly the Apple Watch,[94] further emphasized the integration of wearables and health tracking. 'mHealthHUB The mHealthHUB is launched as a virtual forum where technologists, researchers, and clinicians connect, learn, share, and innovate on mHealth tools to transform healthcare. Focused on creating an innovation ecosystem that fosters the collaborative team science essential for mHealth and data science innovations, the site becomes a collaboratory "watering hole" for the mHealth research community.[95] 2017 – NSF Center for Underserved Populations The NSF established the Engineering Research Center for Precise Advanced Technologies and Health Systems for Underserved Populations, emphasizing the integration of engineering research and education with technological innovation to transform national prosperity, health, and security.[96] Research and development expansion Pharmaceutical companies, tech giants, and healthcare institutions increased their investment in mHealth R&D, exploring AI-driven health apps, remote diagnostics, and personalized medicine.[97][98] 2020 – Biomedical Technology Resource Centers (BTRCs) Novel mHealth research centers funded by NIH spring from the remnants of the BD2K initiative. mHealth-focused P41 awards for new centers, like the mHealth Center for Discovery, Optimization, and Translation of Temporally-Precise Interventions (mDOT Center)[99] headquartered at the University of Memphis and Stanford's Mobilize Center,[100] were established to focus on innovative biomedical technologies for healthcare.[101] During the COVID-19 pandemic The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the adoption of mHealth solutions for remote consultations, contact tracing apps, telehealth services, and remote patient monitoring to maintain healthcare access during lockdowns.[102][103][104] Present – Ongoing research and integration Current research focuses on AI-driven diagnostics, blockchain for secure health data management, machine learning for predictive analytics, and the integration of mHealth into mainstream healthcare systems.[105][106] |

主要イベント年表 このセクションには宣伝的な内容が含まれている。宣伝文句や不適切な外部リンクを削除し、中立的な視点から書かれた百科事典的な文章を追加することで、このセクションの改善にご協力いただきたい。(2023年12月)(このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) 2000年代前半 - mHealth研究の出現 医療現場におけるモバイル機器の可能性を探る研究イニシアチブが表面化し始めた。学術機関やテクノロジー企業は、健康関連の目的で携帯電話を使用することの実現可能性を調査し始めた[72]。 2006年 - 遺伝子・環境・健康イニシアチブ(GEI) GEIプログラムが開始され、前向きコホート研究が重視された。このプログラムにより、遺伝、環境、健康転帰の相互作用を理解するための基礎が築かれた[73][74][75]。 2007年-技術的進歩 最初のiPhoneが登場し、mHealthに大きな影響を与えるスマートフォン時代の幕開けとなった重要な年である[76]。 2008 - WHO mHealthサミット 世界保健機関(WHO)は、世界的な医療アクセスの改善におけるモバイルテクノロジーの可能性を認識したサミットを開催し、mHealthの提唱における重要なマイルストーンとなった[77]。 2009年 - mHealthアライアンスの立ち上げ ナショナリズム財団は、mHealthアライアンスを設立し、特に発展途上国において、モバイルテクノロジーを活用して保健の成果を改善することに焦点を当てた[78]。 2010 - 先駆的なmHealthプロジェクト 患者の遠隔モニタリング、疾病管理、SMSを介した健康教育、医療専門家のためのモバイルアプリなどのプログラムを含む、いくつかの画期的なmHealthプロジェクトが世界中で開始された[79]。 mHealthトレーニング研究所(mHTI) 最初のNIH mHealth Training Instituteは、複雑なヘルスケア問題に対するmHealthソリューションを共創できる学際的科学者を育成するためのインキュベーターとして、 UCLAで開催された。この1週間のワークショップは、インパクトのあるヘルスケアソリューションを提供できる学際的なmHealthチームの育成におい て、情報交換と関係構築の両方に重点を置いたチーム科学モデルに基づいている[80]。 2011 - mHealthエビデンスワークショップ NSF、NIH、RWJF、McKesson Foundationが参加した共同作業で、研究が厳密な経験的・理論的基盤の上で実施されることを保証する、mHealth分野におけるエビデンス生成 のアプローチを概説するために、モバイルヘルス技術の評価を探求した[81]。 オープンmHealth オープンmHealthアーキテクチャが導入され、オープンな相互運用性標準を通じてデジタルヘルスデータの意味を理解するために、開発者と医療技術の意 思決定者のグローバルコミュニティを使用して、異種ソースからのデジタルヘルスデータへのアクセスと調和を促進することを通じて、ヘルスケアにおけるイノ ベーションを促進した[82][83]。 2012 - mHealthアプリ革命 健康とフィットネスに特化したスマートフォンアプリの普及は、mHealth革命の触媒となり、ユーザーはフィットネスを追跡し、バイタルをモニターし、医療情報にアクセスし、遠隔医療に従事することができるようになった[84]。 スマートヘルス&ウェルビーイング(SHB) mHealthエビデンス・ワークショップのフォローアップとして、NSFはスマートヘルス&ウェルビーイング・プログラムを立ち上げ、ヘルスケアの、反 応的で病院中心のものから、予防的で、プロアクティブで、エビデンスに基づき、個人中心で、病気よりもウェルビーイングに焦点を当てたものへの転換をサ ポートする、基本的な技術的・科学的問題に取り組んだ[85]。 ASSIST工学研究センター(ERC) NSFとNIHは、mHealthエビデンス・ワークショップから得られた洞察に続いて、特にmHealthに焦点を当てた共同研究プログラムを開始し た。NC州立大学の工学研究センターASSIST ERCは、使いやすさと実用的なデータに焦点を当て、エネルギーハーベスティング、低電力エレクトロニクス、センサーにおける基本的な進歩を統合すること によって、ヘルスケアやIoTなどの高価値アプリケーションのための最先端のシステムを開発することによって、mHealth研究を促進するために設立さ れた[86]。 2013 - ウェアラブル技術 この頃、Fitbit(当初はHealthy Metrics Research, Inc.)も登場し、ウェアラブルヘルス技術の先駆者となった[87]。 2014年 - ビッグデータから知識へ(BD2K)イニシアティブ NIH BD2K Centers of Excellenceプログラムは、mHealth研究に大きな後押しを与え、メンフィス大学に本部を置くMobile Data To Knowledge(MD2K)[88]やスタンフォードのCenter for Mobility Data Integration to Insight(Mobilize)[89]のような12の研究センターを導き、この分野での研究とイノベーションを促進した[90]。 2015年 - ウェアラブル技術の進歩 スマートウォッチやフィットネストラッカーなどのウェアラブルデバイスがより洗練され、継続的な健康モニタリング、活動追跡、モバイルヘルスアプリとの統合が可能になった[91][92]。 私たちのすべて mHealthは、多様な集団から健康データを収集することを目的とした精密医療イニシアティブであるAll of Usプログラムで注目を集めた[93]。 スマートウォッチ、特にApple Watch[94]の発売は、ウェアラブルと健康追跡の統合をさらに強調した。 mHealthHUB」について mHealthHUBは、技術者、研究者、臨床医がヘルスケアを変革するためのmHealthツールについてつながり、学び、共有し、革新する仮想フォー ラムとして発足した。mHealthとデータ・サイエンスのイノベーションに不可欠な共同チーム・サイエンスを育成するイノベーション・エコシステムの創 造に焦点を当て、このサイトはmHealth研究コミュニティのための共同研究「水飲み場」となる[95]。 2017年 - NSFのUnderserved Populationsのためのセンター NSFは、「Engineering Research Center for Precise Advanced Technologies and Health Systems for Underserved Populations」を設立し、工学研究と教育と技術革新の統合を重視し、国民の繁栄、健康、安全保障を変革することを目指す[96]。 研究開発の拡大 製薬会社、ハイテク大手、医療機関は、mHealthの研究開発への投資を拡大し、AIを活用した健康アプリ、遠隔診断、個別化医療を模索した[97][98]。 2020 - バイオメディカル・テクノロジー・リソース・センター(BTRC) メンフィス大学に本部を置くmHealth Center for Discovery, Optimization, and Translation of Temporally-Precise Interventions(mDOT Center)[99]やスタンフォードのMobilize Center[100]のような、新しいセンターのためのmHealthに焦点を当てたP41賞が、ヘルスケアのための革新的な生物医学技術に焦点を当て るために設立された[101]。 COVID-19パンデミック時 COVID-19のパンデミックは、閉鎖中の医療アクセスを維持するための遠隔診察、連絡先追跡アプリ、遠隔医療サービス、遠隔患者モニタリングのためのmHealthソリューションの採用を加速させた[102][103][104]。 現在-進行中の研究と統合 現在の研究は、AI主導の診断、安全な健康データ管理のためのブロックチェーン、予測分析のための機械学習、そして主流のヘルスケアシステムへのmHealthの統合に焦点を当てている[105][106]。 |

| Research Emerging trends and areas of interest: Emergency response systems (e.g., road traffic accidents, emergency obstetric care). Human resources coordination, management, and supervision. Mobile synchronous (voice) and asynchronous (SMS) telemedicine diagnostic and decision support to remote clinicians.[107] Clinician-focused, evidence-based formulary, database and decision support information available at the point of care.[107] Pharmaceutical supply chain integrity and patient safety systems (e.g. Sproxil and mPedigree).[108] Clinical care and remote patient monitoring[citation needed] Health extension services. Inpatient monitoring.[109] Health services monitoring and reporting. Health-related mLearning for the general public. Public health services, for example, tobacco cessation[110] Mental health promotion[111][24] and illness prevention[112] Training and continuing professional development for health care workers.[113] Health promotion and community mobilization. Support of long-term conditions, for example medication reminders and diabetes self-management.[114][115] Peer-to-peer personal health management for telemedicine.[116] Patient participation and social mobilisation for infectious disease prevention (e.g. Participatient).[117][118] Surgical follow-up, such as for major joint arthroplasty patients.[119] Mobile social media for global health personnel;[4] for example, the capacity to facilitate professional connectedness, and to empower health workforce.[120] According to the Vodafone Group Foundation on February 13, 2008,[full citation needed] a partnership for emergency communications was created between the group and United Nations Foundation. Such partnership will increase the effectiveness of the information and communications technology response to major emergencies and disasters around the world. |

研究 新たな傾向と関心分野 緊急対応システム(交通事故、緊急産科医療など)。 人的資源の調整、管理、監督。 遠隔地の臨床医に対するモバイル同期(音声)および非同期(SMS)遠隔医療診断・意思決定支援[107]。 臨床医に焦点を当てた、エビデンスに基づく処方、データベース及び意思決定支援情報を、診療の時点で利用できるようにする[107]。 医薬品サプライチェーンの完全性と患者安全性システム(SproxilやmPedigreeなど)[108]。 臨床ケアと遠隔患者モニタリング[要出典]。 医療普及サービス。 入院患者のモニタリング[109]。 医療サービスのモニタリングと報告。 一般市民を対象とした健康関連のmLearning。 公衆衛生サービス、例えばタバコの禁煙[110]。 メンタルヘルス促進[111][24]および疾病予防[112]。 医療従事者に対する研修と継続的専門能力開発[113]。 健康増進と地域社会の動員。 長期疾患の支援、例えば服薬リマインダーや糖尿病の自己管理[114][115]。 遠隔医療のためのピアツーピアの個人健康管理[116]。 感染症予防のための患者参加と社会動員(例:パーティシペーション)[117][118]。 人工関節置換術患者などの手術フォローアップ[119]。 グローバル・ヘルス担当者のためのモバイル・ソーシャル・メディア[4]。例えば、専門家同士のつながりを促進し、保健医療従事者に力を与える能力[120]。 2008年2月13日付のボーダフォングループ財団によると[要出典]、ボーダフォングループと国連財団との間で緊急通信のためのパートナーシップが構築 された。このようなパートナーシップは、世界中の大規模な緊急事態や災害に対する情報通信技術による対応の有効性を高めるものである。 |

| Health informatics Health 2.0 Open source software packages for mHealth Telehealth Healthcare workforce information systems(HRHIS) Telemedicine service providers |

健康情報学 健康2.0 mHealthのためのオープンソースソフトウェアパッケージ(下で説明) テレヘルス 医療従事者情報システム 遠隔医療サービスプロバイダー |

| Asangansi, Ime; Braa, Kristin

(2010). Safran, C.; Reti, S.; Marin, H.F. (eds.). The emergence of

mobile-supported national health information systems in developing

countries. MEDINFO 2010. Studies in health technology and informatics.

Vol. 160. IOS Press. pp. 540–544. doi:10.3233/978-1-60750-588-4-540.

ISBN 978-1-60750-588-4. PMID 20841745. Open access icon Brown, David (30 November 2007). "Globally, Deaths From Measles Drop Sharply". World. The Washington Post. Retrieved 2010-08-14. Describes role of EpiSurveyor mobile data collection software in contributing to the highly successful fight against measles mortality. "The doctor in your pocket". The Economist. 15 September 2005. Giuffrida, Antonio; El-Wahab, Shireen; Anta, Rafael (February 2009). Mobile Health: The potential of mobile telephony to bring health care to the majority (Report). Inter-American Development Bank. Huang, Anpeng; Chen, Chao; Bian, Kaigui; et al. (March 2014). "WE-CARE: An Intelligent Mobile Telecardiology System to Enable mHealth Applications". IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics. 18 (2): 693–702. doi:10.1109/jbhi.2013.2279136. PMID 24608067. S2CID 14856105. Huang, Anpeng. "Worldwide Gallery for Mobile Health". Archived from the original on 2014-10-20. "JMIR mHealth and uHealth". JMIR mHealth and uHealth. JMIR Publications. ISSN 2291-5222. Open access icon Peer-reviewed journal on mHealth and uHealth (ubiquitous health) Kaplan, Warren A. (23 May 2006). "Can the ubiquitous power of mobile phones be used to improve health outcomes in developing countries?". Globalization and Health. 2: 9. doi:10.1186/1744-8603-2-9. PMC 1524730. PMID 16719925. Open access icon Mechael, Patricia N. (Winter 2009). "The Case for mHealth in Developing Countries". Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization. 4 (1): 103–118. doi:10.1162/itgg.2009.4.1.103. Mechael, Patricia N.; Sloninsky, Daniela (August 2008). Towards the Development of an mHealth Strategy: A Literature Review (PDF) (Working Document). New York: Earth Institute at Columbia University. "Mobile Medical Applications". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Olmeda, Christopher J. (2000). Information Technology in Systems of Care. Delfin Press. ISBN 978-0-9821442-0-6. Saran, Cliff (3 April 2008). "Technology plays crucial role in vaccination distribution". Computer Weekly. TechTarget. Retrieved 2010-08-14. Discusses use of handheld electronic data collection in managing public health data and activities. Shackleton, Sally-Jean (May 2007). Rapid Assessment of Cell Phones for Development (Report). Implemented by Women'sNet. UNICEF South Africa. Tal, Amir; Torous, John, eds. (September 2017). "Special Issue: Digital and Mobile Mental Health". Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 40 (3). ISBN 978-1-4338-9119-9. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Division for Public Administration and Development Management (2007). Mobile Applications on Health and Learning (PDF) (Report). Compendium of ICT Applications on Electronic Government. Vol. 1. United Nations. ST/ESA/PAD/SER.E/113. Reitebuch, Lukas (2022). Mobile Health Applications. Springer. ISBN 978-3-662-66253-3. "A world of witnesses". The Economist. 10 April 2008. Retrieved 2017-10-26. Discusses use of EpiSurveyor software in public health monitoring in Africa. |

Asangansi, Ime; Braa, Kristin

(2010). Safran, C.; Reti, S.; Marin, H.F. (eds.).

開発途上国におけるモバイル対応国民健康情報システムの出現。MEDINFO 2010. 医療技術と情報学の研究。第160巻。IOS Press.

540-544頁. doi:10.3233/978-1-60750-588-4-540. ISBN 978-1-60750-588-4.

PMID 20841745. オープンアクセスアイコン Brown, David (30 November 2007). 「世界的に、麻疹による死亡者数は急激に減少している」. World. The Washington Post. 2010-08-14を参照。EpiSurveyorモバイルデータ収集ソフトウェアが、麻疹死亡率との戦いで大成功を収めたことに貢献した。 「The Economist. The Economist. 15 September 2005. Giuffrida, Antonio; El-Wahab, Shireen; Anta, Rafael (February 2009). モバイルヘルス: Mobile Health: The potential of mobile telephony to bring health care to the majority (Report). 米州開発銀行。 Huang, Anpeng; Chen, Chao; Bian, Kaigui; et al. 「WE-CARE: WE-CARE: An Intelligent Mobile Telecardiology System to Enable mHealth Applications」. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics. 18 (2): 693–702. doi:10.1109/jbhi.2013.2279136. PMID 24608067. s2cid 14856105. Huang, Anpeng. 「Worldwide Gallery for Mobile Health」. Archived from the original on 2014-10-20. 「JMIR mHealth and uHealth」. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. JMIR Publications. ISSN 2291-5222。オープンアクセスアイコン mHealth and uHealth(ユビキタスヘルス)に関する査読付き学術誌。 Kaplan, Warren A. (23 May 2006). 「携帯電話のユビキタスパワーは、発展途上国における健康アウトカムの改善に利用できるか?」. Globalization and Health. 2: 9. doi:10.1186/1744-8603-2-9. PMC 1524730. PMID 16719925. オープンアクセスアイコン Mechael, Patricia N. (Winter 2009). 「The Case for mHealth in Developing Countries」. Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization. 4 (1): 103–118. doi:10.1162/itgg.2009.4.1.103. Mechael, Patricia N.; Sloninsky, Daniela (August 2008). mHealth戦略の策定に向けて: A Literature Review (PDF) (Working Document). ニューヨーク: コロンビア大学地球研究所。 「モバイル医療アプリケーション」. 米国食品医薬品局. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Olmeda, Christopher J. (2000). Information Technology in Systems of Care. Delfin Press. ISBN 978-0-9821442-0-6. Saran, Cliff (3 April 2008). 「予防接種の配布にテクノロジーが重要な役割を果たす」. Computer Weekly. TechTarget. 2010-08-14を参照。公衆衛生データと活動の管理における携帯型電子データ収集の使用について述べている。 Shackleton, Sally-Jean (May 2007). 開発のための携帯電話の迅速評価(報告書)。Women'sNetが実施。UNICEF South Africa. Tal, Amir; Torous, John, eds. (September 2017). 「特集: デジタルとモバイルのメンタルヘルス」. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 40 (3). ISBN 978-1-4338-9119-9. 国連経済社会局行政開発管理部 (2007). 健康と学習に関するモバイルアプリケーション(PDF)(報告書)。電子政府に関するICTアプリケーション大要。第1巻。Vol.1. 国民。st/esa/pad/ser.e/113. Reitebuch, Lukas (2022). モバイルヘルスアプリケーション。Springer. ISBN 978-3-662-66253-3. 「目撃者の世界」. The Economist. 10 April 2008. 2017-10-26を参照。アフリカの公衆衛生モニタリングにおけるEpiSurveyorソフトウェアの使用について論じる。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MHealth |

****

| Mobile devices Source:[58] OpenAPS is a set of development tools and documentation to support a DIY implementation of an artificial pancreas for people with Type 1 Diabetes. Common setups include the interfacing of CGMs, Insulin Pumps, and Raspberry Pi devices. It is released under the MIT license, but compatible medical devices are proprietary.[59] Ushahidi allows people to submit crisis information through text messaging using a mobile phone, email or web form. Displays information in map view. It is released under the GNU Affero General Public License, but some libraries use different licenses.[60] |

モバイル機器 出典:[58] OpenAPSは、1型糖尿病患者のための人工膵臓のDIY実装をサポートする開発ツールとドキュメントのセットである。一般的なセットアップには、 CGM、インスリンポンプ、Raspberry Piデバイスのインターフェイスが含まれる。MITライセンスの下でリリースされているが、互換性のある医療機器はプロプライエタリである[59]。 Ushahidiでは、携帯電話、電子メール、ウェブフォームを使ったテキストメッセージで危機情報を送信できる。情報はマップビューで表示される。 GNU Affero General Public Licenseでリリースされているが、一部のライブラリは異なるライセンスを使用している[60]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_open-source_health_software#Mobile_devices |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099