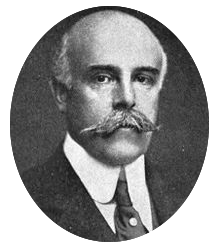

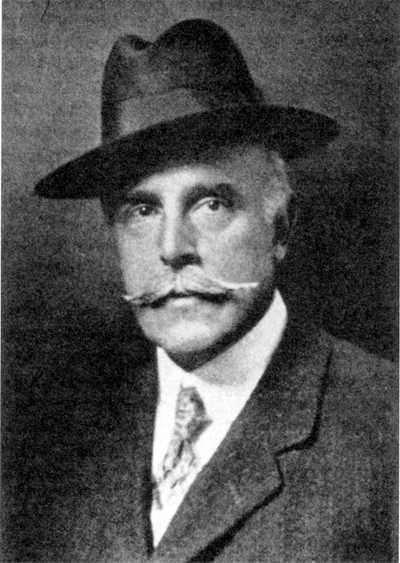

マディソン・グラント

Madison

Grant, 1865-1937

☆マディソン・グラント(Madison Grant;1865

年11月19日 -

1937年5月30日)は、アメリカの弁護士、動物学者、人類学者、作家であり、自然保護論者、優生学者、科学的人種差別論者として知られている。グラン

トは、自然保護における広範囲にわたる功績よりも、疑似科学的な「北欧人至上主義」の提唱者として知られている。「北欧人種」を優れているとする人種差別

主義の一形態である。[1][2]

白人至上主義の優生学者として、グラントは最も有名な人種差別主義の文献のひとつ『偉大なる人種の衰退』(1916年)の著者であり、米国における移民制

限法や反混血法の制定に積極的に関与した。自然保護論者としては、アメリカバイソンなどの種の保存に貢献したと評価されており[5]、ブロンクス動物園、

グレイシャー国立公園、デナリ国立公園の設立に協力し、セーブ・ザ・レッドウッド・リーグの共同設立者でもある。グラントは野生動物管理の分野を大きく発

展させた。[7]

| Madison Grant

(November 19, 1865 – May 30, 1937) was an American lawyer, zoologist,

anthropologist, and writer known for his work as a conservationist,

eugenicist, and advocate of scientific racism. Grant is less noted for

his far-reaching achievements in conservation than for his

pseudoscientific advocacy of Nordicism, a form of racism which views

the "Nordic race" as superior.[1][2] As a white supremacist eugenicist, Grant was the author of The Passing of the Great Race (1916), one of the most famous racist texts, and played an active role in crafting immigration restriction and anti-miscegenation laws in the United States.[3][4] As a conservationist, he is credited with the saving of species including the American bison,[5] helped create the Bronx Zoo, Glacier National Park, and Denali National Park, and co-founded the Save the Redwoods League.[6] Grant developed much of the discipline of wildlife management.[7] |

マディソン・グラント(1865年11月19日 -

1937年5月30日)は、アメリカの弁護士、動物学者、人類学者、作家であり、自然保護論者、優生学者、科学的人種差別論者として知られている。グラン

トは、自然保護における広範囲にわたる功績よりも、疑似科学的な「北欧人至上主義」の提唱者として知られている。「北欧人種」を優れているとする人種差別

主義の一形態である。[1][2] 白人至上主義の優生学者として、グラントは最も有名な人種差別主義の文献のひとつ『偉大なる人種の衰退』(1916年)の著者であり、米国における移民制 限法や反混血法の制定に積極的に関与した。自然保護論者としては、アメリカバイソンなどの種の保存に貢献したと評価されており[5]、ブロンクス動物園、 グレイシャー国立公園、デナリ国立公園の設立に協力し、セーブ・ザ・レッドウッド・リーグの共同設立者でもある。グラントは野生動物管理の分野を大きく発 展させた。[7] |

| Early life Grant was born in New York City, New York, the son of Gabriel Grant, a physician and American Civil War surgeon, and Caroline Manice. Madison Grant's mother was a descendant of Jessé de Forest, the Walloon Huguenot who in 1623 recruited the first band of colonists to settle in New Netherland, the Dutch Republic's territory on the American East Coast. On his father's side, Madison Grant's first American ancestor was Richard Treat, dean of Pitminster Church in England, who in 1630 was one of the first Puritan settlers of New England. Grant's forebears through Treat's line include Robert Treat (a colonial governor of New Jersey), Robert Treat Paine (a signer of the Declaration of Independence), Charles Grant (Madison Grant's grandfather, who served as an officer in the War of 1812), and Gabriel Grant (father of Madison), a prominent physician and the health commissioner of Newark, New Jersey.[8][9][10] Grant was a lifelong resident of New York City. Grant was the oldest of four siblings. The children's summers, and many of their weekends, were spent at Oatlands, the Long Island country estate built by their grandfather DeForest Manice in the 1830s.[11] As a child, he attended private schools and traveled Europe and the Middle East with his father. He attended Yale University, graduating early and with honors in 1887. He received a law degree from Columbia Law School, and practiced law after graduation; however, his interests were primarily those of a naturalist. He never married and had no children. He first achieved a political reputation when he and his brother, DeForest Grant, took part in the 1894 electoral campaign of New York mayor William Lafayette Strong. |

幼少期 グラントはニューヨーク州ニューヨーク市で、医師で南北戦争の軍医であったガブリエル・グラントとキャロライン・マニスの間に生まれた。マディソン・グラ ントの母親は、1623年にアメリカ東海岸のオランダ共和国領ニューネーデルラントへの入植者第1陣を募ったワロン人ユグノーのジェシー・ド・フォレスト の子孫であった。父方の祖先としては、1630年にニューイングランドに最初のピューリタン入植者の一人としてやってきた、イギリスのピトミンスター教会 の牧師長リチャード・トリートが最初である。Treatの系統を辿ると、ニュージャージー植民地の総督を務めたロバート・トリート(Robert Treat)、独立宣言署名者のロバート・トリート・ペイン(Robert Treat Paine)、1812年戦争で将校を務めたマディソン・グラントの祖父チャールズ・グラント(Charles Grant)、著名な医師でニュージャージー州ニューアークの衛生局長を務めたマディソンの父親ガブリエル・グラント(Gabriel Grant)がいる。[8][9][10] グラントは生涯ニューヨーク市に住んでいた。 グラントは4人兄弟の長男であった。子供時代の夏休みと週末の多くは、1830年代に祖父のデフォレスト・マニスがロングアイランドに建てた屋敷、オータ ンズで過ごした。[11] 子供の頃、私立学校に通い、父親とともにヨーロッパと中東を旅行した。エール大学に進学し、1887年に早期卒業で優等学位を取得した。コロンビア・ ロー・スクールで法務博士号を取得し、卒業後は弁護士として活動したが、彼の関心は主に自然科学者としてのものだった。彼は結婚せず、子供もいなかった。 1894年に兄のデフォレスト・グラントとともにニューヨーク市長ウィリアム・ラファイエット・ストロングの選挙キャンペーンに参加したことで、初めて政 治的な名声を得た。 |

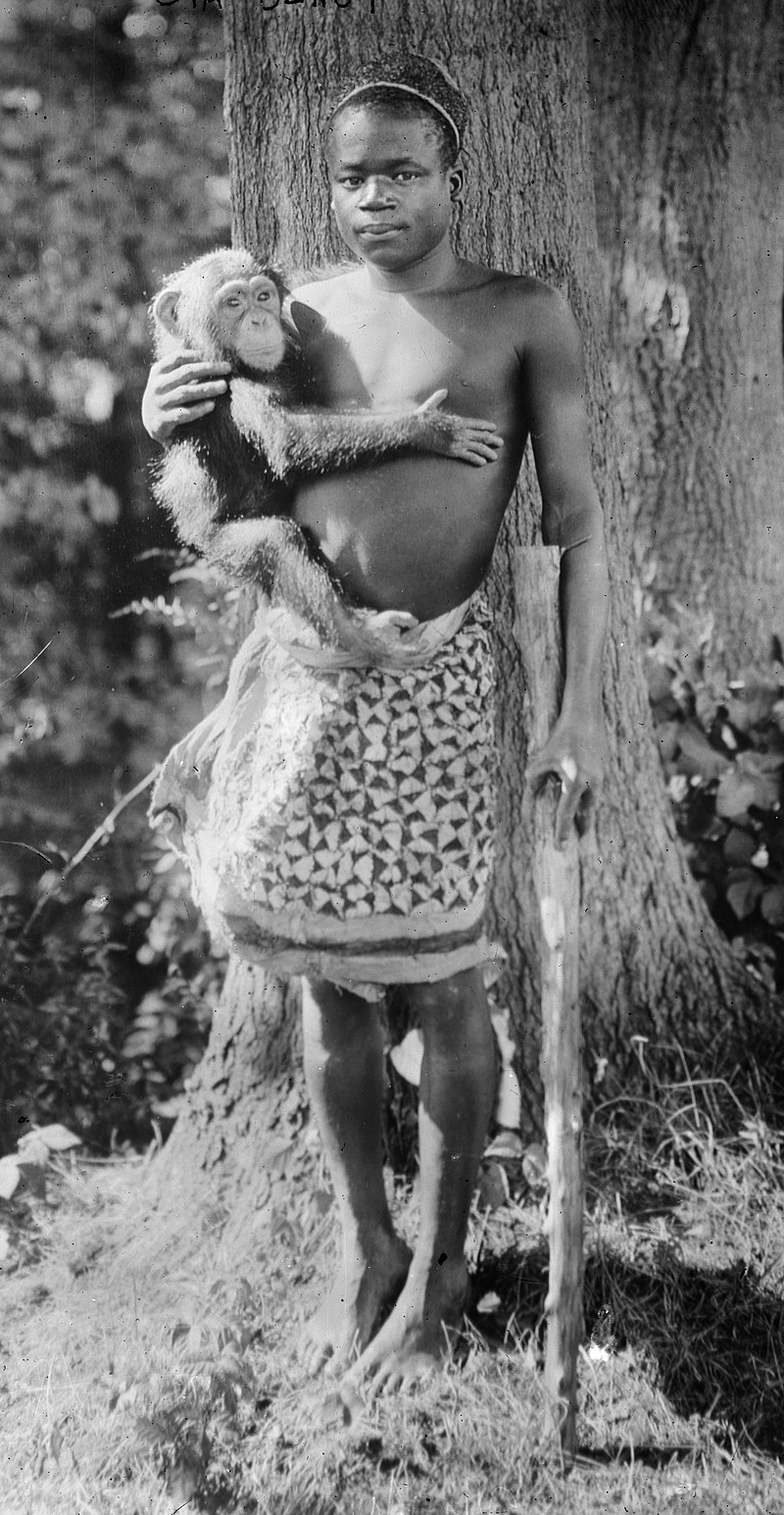

| Career and conservation efforts Thomas C. Leonard wrote that "Grant was a cofounder of the American environmental movement, a crusading conservationist who preserved the California redwoods; saved the American bison from extinction; fought for stricter gun control laws; helped create Glacier and Denali national parks; and worked to preserve whales, bald eagles, and pronghorn antelopes."[12] Grant was a friend of several U.S. presidents,[citation needed] including Theodore Roosevelt[1] and Herbert Hoover. He is credited with saving many species from extinction,[5] and co-founded the Save the Redwoods League with Frederick Russell Burnham, John C. Merriam, and Henry Fairfield Osborn in 1918. He is also credited with helping develop the first deer hunting laws in New York state, legislation which spread to other states as well over time.  Ota Benga was exhibited in the Monkey House of the Bronx Zoo, New York in 1906 He was also a developer of wildlife management; he believed its development to be harmonized with the concept of eugenics.[13] Grant helped to found the Bronx Zoo, build the Bronx River Parkway, save the American bison as an organizer of the American Bison Society, and helped to create Glacier National Park and Denali National Park. In 1906, as Secretary of the New York Zoological Society, he lobbied to put Ota Benga, a Congolese man from the Mbuti people (a tribe of "pygmies"), on display alongside apes at the Bronx Zoo.[3] Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, he served on the boards of many eugenic and philanthropic societies, including the board of trustees at the American Museum of Natural History, as director of the American Eugenics Society, vice president of the Immigration Restriction League, a founding member of the Galton Society, and one of the eight members of the International Committee of Eugenics. He was awarded the gold medal of the Society of Arts and Sciences in 1929. In 1931, the world's largest tree (in Dyerville, California) was dedicated to Grant, Merriam, and Osborn by the California State Board of Parks in recognition for their environmental efforts. A subspecies of caribou was named after Grant as well (Rangifer tarandus granti, also known as Grant's Caribou). He was an early member of the Boone and Crockett Club (a big game hunting organization) since 1893, and he mobilized its wealthy members to influence the government to conserve vast areas of land against encroaching industries.[14][15][16] He was the head of the New York Zoological Society from 1925 until his death.[17] Grant's campaigns for conservationism and eugenics were not unrelated: both assumed the need for various types of stewardship over their charges.[18] Grant was generally indifferent to forms of animal life that he did not regard as aristocratic, and assigned such a hierarchy to humans as well.[1] Historian Jonathan Spiro wrote, "Whereas wildlife managers felt that the survival of the species as a whole was more important than the lives of a few individuals, so Grant preached that the fate of the race outweighed that of a few particular humans who were 'of no value to the community'."[18] In Grant's mind, natural resources needed to be conserved for the "Nordic race" to the exclusion of other races. Grant viewed the Nordic race as he did any of his endangered species, and considered the modern industrial society as infringing just as much on its existence as it did on the redwoods.[citation needed] Like many eugenicists, Grant saw modern civilization as a violation of "survival of the fittest", whether it manifested itself in the over-logging of the forests, or the survival of the poor via welfare or charity.[4][19] In the words of The New Yorker, for figures such as Grant, "it was an unsettlingly short step from managing forests to managing the human gene pool".[1] |

キャリアと自然保護活動 トーマス・C・レオナードは、「グラントはアメリカの環境保護運動の共同創始者であり、カリフォルニアのセコイアを保護し、アメリカバイソンを絶滅から救 い、銃規制の強化を訴え、グレイシャー国立公園とデナリ国立公園の創設に尽力し、クジラ、ハクトウワシ、プロングホーンの保護に努めた」と書いている。 [12] グラントは、セオドア・ルーズベルト[1]やハーバート・フーヴァーを含む数人の米国大統領の友人であった。[要出典] 彼は多くの種を絶滅から救ったことで知られており[5]、1918年にはフレデリック・ラッセル・バーナム、ジョン・C・メリマン、ヘンリー・フェア フィールド・オズボーンとともにセーブ・ザ・レッドウッド・リーグを共同設立した。また、ニューヨーク州で初めてのシカ狩猟法の制定にも貢献した。この法 律は、その後他の州にも広がっていった。  1906年、オタ・ベンガはニューヨークのブロンクス動物園のサル館で展示された。 彼は野生動物管理の開発者でもあり、その開発は優生学の概念と調和していると考えていた。グラントはブロンクス動物園の創設、ブロンクス川パークウェイの 建設、アメリカバイソンの保護(アメリカバイソン協会の組織者として)、グレイシャー国立公園とデナリ国立公園の創設に尽力した。1906年、ニューヨー ク動物園協会の事務局長として、彼はブロンクス動物園でチンパンジーの隣に展示する目的で、ムブティ族(ピグミー族の一種族)出身のコンゴ人オタ・ベンガ を展示するよう働きかけた。 1920年代と1930年代を通じて、彼は優生学や慈善事業に関する多くの団体の役員を務め、アメリカ自然史博物館の評議員会、アメリカ優生学協会の理 事、移民制限連盟の副会長、ガルトン協会の創設メンバー、国際優生学委員会の8人のメンバーの1人などを歴任した。1929年には、科学芸術協会から金メ ダルを授与された。1931年には、カリフォルニア州ダイアビルにあった世界最大の樹木が、環境保護への貢献を称え、カリフォルニア州公園委員会によって グラント、メリアム、オズボーンの3人の名にちなんで命名された。カリブーの亜種にもグラントの名が付けられた(Rangifer tarandus granti、別名グラントカリブー)。彼は1893年より、ブーン・アンド・クロケット・クラブ(大型獣ハンティング組織)の初期のメンバーであり、そ の裕福な会員たちを動員して、産業の進出に対抗して広大な土地を保護するよう政府に影響を与えた。[14][15][16] 1925年から死去するまで、ニューヨーク動物園協会の会長を務めた。[17] グラントの自然保護と優生学のキャンペーンは無関係ではなかった。どちらも、自分たちの保護対象に対して、さまざまな種類の管理が必要であると想定してい た。[18] グラントは、自分が貴族階級とはみなさない動物たちの生命形態には概して無関心であり、そのようなヒエラルキーを人間にも当てはめていた。[1] 歴史家のジョナサン・スピロは、「野生生物管理者たちは、 種の全体としての生存が少数の個体の命よりも重要であると考える一方で、グラントは「社会にとって何の価値もない」少数の人間よりも人種の運命の方が重要 であると説いた」と書いている。[18] グラントの考えでは、他の人種を排除して「北方人種」のために天然資源を保護する必要があった。グラントは北欧人種を絶滅危惧種の一つとして捉え、現代の 産業社会がセコイアの木々と同様に北欧人種の存在を脅かしていると考えていた。[要出典] 多くの優生学者と同様に、グラントは現代文明が「適者生存」の原則に違反していると考えていた。それは森林の過剰伐採に現れる場合も、生活保護や慈善事業 を通じて貧困層の生存に現れる場合もあった。[4][19] 『ニューヨーカー』誌の表現を借りれば、グラントのような人物にとっては、「森林の管理から人間の遺伝子プールの管理への移行は、不安を覚えるほど短い一 歩だった」のである。[1] |

| Nordicism See also: Nordicism  Title page of Grant's book The Passing of the Great Race (1916) This section relies excessively on references to primary sources. Please improve this section by adding secondary or tertiary sources. (October 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Grant was the author of the once much-read book The Passing of the Great Race[20] (1916), an elaborate work of racial hygiene attempting to explain the racial history of Europe. The most significant of Grant's concerns was with the changing "stock" of American immigration of the early 20th century (characterized by increased numbers of immigrants from Southern Europe and Eastern Europe, as opposed to Western Europe and Northern Europe), Passing of the Great Race was a "racial" interpretation of contemporary anthropology and history, stating race as the basic motor of civilization. Similar ideas were proposed by prehistorian Gustaf Kossinna in Germany. Grant promoted the idea of the "Nordic race",[19] a loosely defined biological-cultural grouping rooted in Scandinavia, as the key social group responsible for human development; thus the subtitle of the book was The racial basis of European history. As an avid eugenicist, Grant further advocated the separation, quarantine, and eventual collapse of "undesirable" traits and "worthless race types" from the human gene pool and the promotion, spread, and eventual restoration of desirable traits and "worthwhile race types" conducive to Nordic society.  "Present Distribution of the European Races" (1916)—Grant's map of the "Nordics" in red, the "Alpines" in green, and the "Mediterraneans" in yellow. He wrote, "A rigid system of selection through the elimination of those who are weak or unfit—in other words social failures—would solve the whole question in one hundred years, as well as enable us to get rid of the undesirables who crowd our jails, hospitals, and insane asylums. The individual himself can be nourished, educated and protected by the community during his lifetime, but the state through sterilization must see to it that his line stops with him, or else future generations will be cursed with an ever increasing load of misguided sentimentalism. This is a practical, merciful, and inevitable solution of the whole problem, and can be applied to an ever widening circle of social discards, beginning always with the criminal, the diseased, and the insane, and extending gradually to types which may be called weaklings rather than defectives, and perhaps ultimately to worthless race types."[21][excessive quote] Grant's work is considered one of the most influential and vociferous works of scientific racism and eugenics to come out of the United States. Stephen Jay Gould described The Passing of the Great Race as "the most influential tract of American scientific racism".[22] The Passing of the Great Race was published in multiple printings in the United States, and was translated into other languages, including German in 1925. By 1937, the book had sold 16,000 copies in the United States alone.[23][24][25] The book was embraced by proponents of the Nazi movement in Germany and was the first non-German book ordered to be reprinted by the Nazis when they took power. Adolf Hitler wrote to Grant, "The book is my Bible."[18][26] One of Grant's long-time opponents was the anthropologist Franz Boas. Grant disliked Boas and for several years tried to get him fired from his position at Columbia University.[27][28] Boas and Grant were involved in a bitter struggle for control over the discipline of anthropology in the United States, while they both served (along with others) on the National Research Council Committee on Anthropology after the First World War. Grant represented the "hereditarian" branch of physical anthropology at the time, despite his relatively amateur status, and was staunchly opposed to and by Boas himself (and the latter's students), who advocated cultural anthropology. Boas and his students eventually wrested control of the American Anthropological Association from Grant and his supporters, who had used it as a flagship organization for his brand of anthropology. In response, Grant, along with American eugenicist and biologist Charles B. Davenport, in 1918 founded the Galton Society as an alternative to Boas.[29] |

北欧主義 関連項目:北欧主義  グラント著『偉大なる民族の消滅』(1916年)の表題ページ この節は、一次資料への言及に過度に依存している。 二次資料または三次資料を追加して、この節を改善してください。 (October 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) グラントは、かつて広く読まれた『偉大なる人種の消滅』[20](1916年)の著者であり、ヨーロッパの人種史を説明しようとする人種衛生学の精巧な作 品である。グラントの関心事の中で最も重要なものは、20世紀初頭のアメリカへの移民の「人種」の変化であった(南ヨーロッパと東ヨーロッパからの移民の 増加が特徴であり、西ヨーロッパと北ヨーロッパからの移民とは対照的であった)。『偉大なる人種の死』は、現代の人類学と歴史を「人種」の観点から解釈し たものであり、人種を文明の基本的な推進力としていた。 同様の考えは、ドイツの先史学者グスタフ・コシニャによっても提唱されていた。グラントは、スカンディナヴィアにルーツを持つ、生物学上・文化上のゆるや かな集団である「北欧人種」という考えを推進し、[19] 人類の発展を担う主要な社会集団として位置づけた。そのため、この本の副題は『ヨーロッパ史の民族学的基礎』とされた。熱心な優生学者であったグラント は、さらに、人間の遺伝子プールから「望ましくない」形質や「価値のない人種タイプ」を隔離し、隔離し、最終的に崩壊させ、望ましい形質や「価値のある人 種タイプ」を促進し、広め、最終的に北欧社会に適した「価値のある人種タイプ」を復元することを提唱した。  「ヨーロッパ人種の現在の分布」(1916年)—グラントによる「北欧人」を赤、「高山人」を緑、「地中海人」を黄色で示した地図。 彼は「弱者や不適格者、つまり社会的に不適格な人々を排除する厳格な選択システムがあれば、100年で問題はすべて解決し、刑務所や病院、精神病院に押し 寄せている望ましくない人々を排除することも可能になるだろう」と書いた。個々人は生涯にわたって地域社会によって養育され、教育を受け、保護されること ができるが、国家は断種によって、その血統がその個人で途絶えるようにしなければならない。さもなければ、将来の世代は、ますます増大する誤った感傷主義 の重荷に苦しめられることになるだろう。これは、この問題の現実的で慈悲深く、かつ不可避な解決策であり、常に犯罪者、病人、精神異常者から始まり、次第 に欠陥者というよりも弱者と呼ばれるタイプにまで広がり、最終的には価値のない人種タイプにまで広がる、社会から排除される人々の輪に適用できるものであ る。」[21][過剰引用] グラントの著作は、アメリカ合衆国から発信された科学人種主義および優生学の著作の中でも、最も影響力があり、声高なもののひとつとみなされている。ス ティーブン・ジェイ・グールドは『偉大なる人種の衰退』を「アメリカ科学人種主義の最も影響力のある論文」と評した。[22] 『偉大なる人種の衰退』はアメリカ合衆国で複数回にわたって再版され、1925年にはドイツ語を含む他の言語にも翻訳された。1937年までに、この本は アメリカ国内だけで16,000部が売れた。[23][24][25] この本はドイツのナチス運動の支持者たちに歓迎され、ナチスが政権を握った際に、ドイツ語以外の書籍として初めて増刷が命じられた。アドルフ・ヒトラーはグラントに「この本は私のバイブルだ」と手紙を書いた。[18][26] グラントの長年の反対者の一人は人類学者フランツ・ボアズであった。グラントはボアズを嫌悪し、数年にわたってコロンビア大学での彼の職を解くよう画策し た。[27][28] ボアズとグラントは、第一次世界大戦後に国家研究協議会人類学委員会(National Research Council Committee on Anthropology)の委員を務めていたが、その間、米国における人類学の分野をめぐって激しい主導権争いを繰り広げていた。 グラントは、当時、比較的新参者であったにもかかわらず、身体人類学の「遺伝的」分派を代表しており、文化人類学を提唱するボアズ(およびボアズの弟子た ち)と激しく対立していた。 ボアズとその弟子たちは、最終的にグラントとその支持者たちからアメリカ人類学会の主導権を奪い、グラントとその支持者たちは、自分たちの人類学の旗印と していた学会を手中に収めた。これに対し、グラントは、アメリカの優生学者であり生物学者でもあるチャールズ・B・ダベンポートとともに、1918年にボ アスの代替組織としてガルトン協会を設立した。[29] |

Immigration restriction Grant in the 1920s Grant advocated restricted immigration to the United States through limiting immigration from Eastern Europe and Southern Europe, as well as the complete end of immigration from East Asia. He also advocated efforts to purify the American population through selective breeding. He served as the vice president of the Immigration Restriction League from 1922 to his death. Acting as an expert on world racial data, Grant also provided statistics for the Immigration Act of 1924 to set the quotas on immigrants from certain European countries.[30] Even after passing the statute, Grant continued to be irked that even a smattering of non-Nordics were allowed to immigrate to the country each year. His support for anti-miscegenation laws was quoted in arguments for the Racial Integrity Act of 1924 in Virginia.[31][32] Though Grant was extremely influential in legislating his view of racial theory, he began to fall out of favor in the United States in the early 1930s. The declining interest in his work has been attributed both to the effects of the Great Depression, which resulted in a general backlash against Social Darwinism and related philosophies, and to the changing dynamics of racial issues in the United States during the interwar period. Rather than subdivide Europe into separate racial groups, the bi-racial (black vs. white) views of Grant's protegé Lothrop Stoddard became more dominant in the aftermath of the Great Migration of African-Americans from Southern States to Northern and Western ones (Guterl 2001).[citation needed] |

移民制限 1920年代のグラント グラントは、東ヨーロッパや南ヨーロッパからの移民を制限し、東アジアからの移民を完全に禁止することで、米国への移民を制限することを提唱した。また、 人種改良を通じて米国の人口を純粋化する取り組みも提唱した。1922年から死去するまで、移民制限連盟の副会長を務めた。また、グラントは世界の民族に 関する専門家の立場から、1924年の移民法に、特定のヨーロッパ諸国からの移民の割り当て数を定めるための統計情報を提供した。[30] 法律が成立した後も、グラントは毎年北欧人以外の移民が少数でも入国することを不愉快に思っていた。混血防止法への彼の支持は、バージニア州における 1924年の人種純血法の議論の中で引用された。 グラントは人種理論に関する自身の見解を立法化する上で非常に大きな影響力を持っていたが、1930年代初頭にはアメリカ国内での人気を失い始めていた。 彼の著作への関心が薄れたのは、世界恐慌の影響により社会ダーウィニズムや関連する哲学に対する反発が一般的に広まったことと、戦間期のアメリカ国内にお ける人種問題の力学が変化したことの両方が原因である。ヨーロッパを別々の人種グループに細分化するのではなく、グラントの弟子であったロスロップ・ス トッダードの二元論(黒人対白人)の見方が、南部から北部および西部へのアフリカ系アメリカ人の大移動の余波の中でより支配的になった(Guterl 2001)。[要出典] |

| Legacy According to historian of economics Thomas C. Leonard: "Prominent American eugenicists, including movement leaders Charles Davenport and Madison Grant, were conservatives. They identified fitness with social and economic position, and they also were hard hereditarians, dubious of the Lamarckian inheritance clung to by progressives. But as eugenicists, these conservatives were not classical liberals. Like all eugenicists, they were illiberal. Conservatives do not object to state coercion so long as it is used for what they regard as the right purposes, and these men were happy to trample on individual rights to obtain the greater good of improved hereditary health.... Historians invariably style Madison Grant a conservative, because he was a blueblood clubman from a patrician family, and his best- known work, The Passing of the Great Race, is a museum piece of scientific racism. But Grant's eugenic ideas originated from a corner of the conservative impulse intimately connected to Progressivism: conservation."[33] Leonard wrote that Grant also opposed war, had doubts about imperialism, and supported birth control.[34] Leonard's view that eugenicists such as Grant were conservatives is an outlier, however. Writer Jonah Goldberg has noted that "eugenics lay at the heart of the progressive enterprise" and was embraced by almost all early progressives, from Margaret Sanger to H.G. Wells and John Maynard Keynes.[35] Likewise, Thomas Sowell has noted that most leading eugenicists were firmly ensconced within progressive intellectual circles, where the desire for the government to take strong action to protect the gene pool went hand-in-hand with other statist views, including opposition to free-market capitalism.[36] Similarly, historian Edwin Black has stated that the eugenic crusade was "created in the publications and academic research rooms of the Carnegie Institution, verified by the research grants of the Rockefeller Foundation, validated by leading scholars from the best Ivy League universities, and financed by the special efforts of the Harriman railroad fortune."[37] From this perspective, it is perfectly understandable that Madison Grant—a graduate of elite Ivy League universities and a strong advocate for various progressive causes of the day—would also be a eugenicist. Grant became a part of popular culture in 1920s America, especially in New York. Grant's conservationism and fascination with zoological natural history made him influential among the New York elite, who agreed with his cause, most notably Theodore Roosevelt. Author F. Scott Fitzgerald featured a reference to Grant in The Great Gatsby. Tom Buchanan, a fatuous Long Island aristocrat married to Daisy, was reading a book called The Rise of the Colored Empires by "this man Goddard", blending Grant's Passing of the Great Race and his colleague Lothrop Stoddard's The Rising Tide of Color Against White World Supremacy.[citation needed] Grant left no offspring when he died in 1937 of nephritis. Several hundred people attended Grant's funeral,[18] and he was buried in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Tarrytown, New York. He left a bequest of $25,000 to the New York Zoological Society to create "The Grant Endowment Fund for the Protection of Wild Life", $5,000 to the American Museum of Natural History, and another $5,000 to the Boone and Crockett Club.[citation needed] Relatives destroyed his personal papers and correspondence after his death.[38] California State Parks removed Grant's Marker at Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park in June 2021. California State Parks removed Grant's Marker at Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park in June 2021. At the postwar Nuremberg Trials, three pages of excerpts from Grant's Passing of the Great Race were introduced into evidence by the defense of Karl Brandt, Hitler's personal physician and head of the Nazi euthanasia program, in order to justify the population policies of the Third Reich, or at least indicate that they were not ideologically unique to Nazi Germany.[39] Grant's works of scientific racism have been cited to demonstrate that many of the genocidal and eugenic ideas associated with the Third Reich did not arise specifically in Germany, and in fact that many of them had origins in other countries, including the United States.[40] As such, because of Grant's well-connected and influential friends, he is often used to illustrate the strain of race-based eugenic thinking in the United States, which had some influence until the Second World War. Because of the use made of Grant's eugenics work by the policy-makers of Nazi Germany, his work as a conservationist has been somewhat ignored and obscured, as many organizations with which he was once associated (such as the Sierra Club) wanted to minimize their association with him.[18] His racial theories, which were popularized in the 1920s, are today seen as discredited.[41][42] The work of Franz Boas and his students, Ruth Benedict and Margaret Mead, demonstrated that there were no inferior or superior races.[42]  On June 15, 2021, California State Parks removed a memorial to Madison Grant from Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park placed in the park in 1948. The monument's removal is part of a broader effort in California Parks to address outdated exhibits and interpretations related to the founders of Save the Redwoods. In spring 2022, California State Parks will install a new interpretive panel, co-written with academic scholars, that tells a fuller story about Grant, his conservation legacy, and his central role in the eugenics movement.[43][44] |

遺産 経済史家のトーマス・C・レナードは次のように述べている。「著名なアメリカの優生学者、運動のリーダーであるチャールズ・ダベンポートやマディソン・グ ラントを含む人々は保守派であった。彼らは適性を社会的・経済的地位と同一視し、また、進歩派が固執するラマルク説の遺伝を疑う強硬な遺伝論者でもあっ た。しかし、優生学者としての彼らは古典的自由主義者ではなかった。他の優生学者と同様に、彼らは不寛容であった。保守派は、それが彼らが正しいと考える 目的のために用いられる限り、国家による強制に異議を唱えることはない。そして、彼らは遺伝的健康の改善という大義のために個人の権利を踏みにじることを 厭わなかった。歴史家たちは、マディソン・グラントを保守派とみなす。なぜなら、彼は貴族階級の家柄の生まれで、社交界の名士であり、彼の最も有名な著書 『偉大なる人種の衰退』は科学人種主義の博物館に展示されるべき作品だからだ。しかし、グラントの優生学的な考え方は、進歩主義と密接に結びついた保守的 な衝動の片隅から生まれたものであり、それは「保全」であった。 レナードは、グラントは戦争にも反対し、帝国主義にも疑問を抱き、避妊も支持していたと書いている。 しかし、グラントのような優生学者は保守派であるというレナードの見解は例外である。作家ジョナ・ゴールドバーグは、「優生学は進歩主義の事業の中心に位 置しており」、マーガレット・サンガーからH.G.ウェルズ、ジョン・メイナード・ケインズに至るまで、初期の進歩主義者のほぼ全員に受け入れられていた と指摘している。[35] 同様に、トーマス・ソウェルは、優生学者のほとんどが、進歩的な知識人のサークルにしっかりと根を下ろしていたと指摘している。遺伝子プールを守るために 政府が強力な措置を取ることを望む声は、自由市場資本主義への反対など、他の国家主義的な見解と歩調を合わせていた。[36] 同様に、歴史家のエドウィン・ブラックは、優生学運動は「カーネギー協会の出版物や学術研究室で生み出され、 ロックフェラー財団の研究助成金によって検証され、アイビーリーグの一流大学を代表する学者たちによって支持され、ハリマン鉄道財閥の特別な努力によって 資金提供された」と述べている。[37] この観点から見ると、エリート校であるアイビーリーグの卒業生であり、当時のさまざまな進歩的な運動の強力な支持者であったマディソン・グラントが優生学 者であったとしても、まったく理解できる。 グラントは1920年代のアメリカ、特にニューヨークで大衆文化の一部となった。グラントの自然保護主義と動物学上の博物学への関心は、彼の主張に賛同す るニューヨークのエリート層、特にセオドア・ルーズベルト大統領に影響を与えた。作家のF・スコット・フィッツジェラルドは『華麗なるギャッツビー』の中 でグラントについて言及している。デイジーと結婚した愚鈍なロングアイランドの貴族トム・ブキャナンは、「この男ゴダード」の著書『有色人帝国の興隆』を 読み、グラントの『偉大なる人種の滅亡』と、同僚のロスロップ・ストッダードの著書『白人世界支配に対する有色人種の満ち来る潮流』を混ぜ合わせていた。 グラントは1937年に腎炎で死去した際、子孫を残さなかった。数百人がグラントの葬儀に参列し[18]、彼はニューヨーク州タリータウンのスリーピー・ ホロウ墓地に埋葬された。彼は、野生生物保護のためのグラント基金を創設するために2万5000ドルをニューヨーク動物学協会に、5000ドルをアメリカ 自然史博物館に、さらに5000ドルをブーン・アンド・クロケット・クラブに遺贈した。[要出典] 彼の死後、親族が彼の個人資料や書簡を破棄した。[38] カリフォルニア州立公園局は2021年6月、プレリークリーク・レッドウッド州立公園のグラントの記念碑を撤去した。 カリフォルニア州立公園局は2021年6月、プレリークリーク・レッドウッド州立公園のグラントの記念碑を撤去した。 戦後のニュルンベルク裁判では、第三帝国の人口政策を正当化するため、あるいは少なくともそれがナチス・ドイツに特有のイデオロギーではないことを示すた めに、ヒトラーの個人医師でありナチスの安楽死計画の責任者であったカール・ブラントの弁護側によって、『グレート・レースの通過』からの抜粋3ページ分 が証拠として提出された。 グラントの科学的人種主義の著作は、第三帝国に関連する大量虐殺や優生学の考え方の多くがドイツで特別に生じたものではなく、実際にはその多くがアメリカ 合衆国を含む他の国々で生まれたものであることを示すために引用されてきた 。そのため、グラントの有力な友人たちの影響力により、第二次世界大戦まで米国に少なからず影響を与えていた人種に基づく優生学的な考え方を説明する際 に、グラントがよく引き合いに出される。ナチス・ドイツの政策立案者たちがグラントの優生学的研究を利用したため、彼の自然保護活動家としての業績はほと んど顧みられることなく、また、かつて彼と関わりを持っていた多くの組織(シエラ・クラブなど)が、彼との関わりを最小限に留めようとしたため、彼の業績 はほとんど顧みられることなく、また、隠蔽されてしまった。 。1920年代に広まった彼の人種理論は、今日では否定されていると見なされている。[41][42] フランツ・ボアズと彼の学生であるルース・ベネディクトとマーガレット・ミードの研究は、劣った人種や優れた人種は存在しないことを証明した。[42]  2021年6月15日、カリフォルニア州立公園局は、1948年にプレリークリーク・レッドウッド州立公園に設置されたマディソン・グラントの記念碑を撤 去した。この記念碑の撤去は、セーブ・ザ・レッドウッドの創設者に関する時代遅れの展示や解釈に対処するための、カリフォルニア州立公園局のより広範な取 り組みの一環である。2022年春には、学術研究者との共同執筆による新たな解説パネルがカリフォルニア州立公園に設置され、グラント、彼の自然保護の遺 産、優生学運動における彼の中心的役割について、より詳細な説明がなされる予定である。[43][44] |

| Works The Caribou. New York: Office of the New York Zoological Society, 1902. "Moose". New York: Report of the Forest, Fish, Game Commission, 1903. The Origin and Relationship of the Large Mammals of North America. New York: Office of the New York Zoological Society, 1904. The Rocky Mountain Goat. Office of the New York Zoological Society, 1905. The Passing of the Great Race; or, The Racial Basis of European History. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1916. New ed., rev. and Amplified, with a New Preface by Henry Fairfield Osborn. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1918 Rev. ed., with a Documentary Supplement, and a Preface by Henry Fairfield Osborn. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1921. Fourth rev. ed., with a Documentary Supplement, and a Preface by Henry Fairfield Osborn. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1936. Saving the Redwoods; an Account of the Movement During 1919 to Preserve the Redwoods of California. New York: Zoological Society, 1919.[45] Early History of Glacier National Park, Montana. Washington: Govt. print. off., 1919. The Conquest of a Continent; or, The Expansion of Races in America, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1933. Selected articles "The Depletion of American Forests", Century Magazine, Vol. XLVIII, No. 1, May 1894. "The Vanishing Moose, and their Extermination in the Adirondacks", Century Magazine, Vol. XLVII, 1894. "A Canadian Moose Hunt". In: Theodore Roosevelt (ed.), Hunting in Many Lands. New York: Forest and Stream Publishing Company, 1895. "The Future of Our Fauna", Zoological Society Bulletin, No. 34, June 1909. "History of the Zoological Society", Zoological Society Bulletin, Decennial Number, No. 37, January 1910. "Condition of Wild Life in Alaska". In: Hunting at High Altitudes. New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1913. "Wild Life Protection", Zoological Society Bulletin, Vol. XIX, No. 1, January 1916. "The Passing of the Great Race", Geographical Review, Vol. 2, No. 5, Nov., 1916. "The Physical Basis of Race", Journal of the National Institute of Social Sciences, Vol. III, January 1917. "Discussion of Article on Democracy and Heredity", The Journal of Heredity, Vol. X, No. 4, April, 1919. "Restriction of Immigration: Racial Aspects", Journal of the National Institute of Social Sciences, Vol. VII, August 1921. "Racial Transformation of America", The North American Review, March 1924. "America for the Americans", The Forum, September 1925. |

作品 カリブー。ニューヨーク:ニューヨーク動物学会事務局、1902年。 「ヘラジカ」。ニューヨーク:森林・魚類・狩猟委員会報告書、1903年。 北米の大型哺乳類の起源と関係。ニューヨーク:ニューヨーク動物学会事務局、1904年。 ロッキー山山羊。ニューヨーク動物園協会事務局、1905年。 偉大なる人種の消滅、あるいはヨーロッパ史における人種的基盤。ニューヨーク:チャールズ・スクリブナーズ・サンズ、1916年。 ヘンリー・フェアフィールド・オズボーンによる新序文付きの改訂新版、増補版。ニューヨーク:チャールズ・スクリブナーズ・サンズ、1918年 改訂版、ドキュメンタリー付録、ヘンリー・フェアフィールド・オズボーンによる序文。ニューヨーク:チャールズ・スクリブナーズ・サンズ、1921年。 第4版改訂版、ドキュメンタリー付録、ヘンリー・フェアフィールド・オズボーンによる序文。ニューヨーク:チャールズ・スクリブナーズ・サンズ、1936年。 セイブ・ザ・レッドウッド:1919年のカリフォルニアのレッドウッド保護運動の記録。ニューヨーク:動物園協会、1919年。[45] モンタナ州グレイシャー国立公園の初期の歴史。ワシントン:政府印刷局、1919年。 大陸の征服、またはアメリカにおける人種の拡張、チャールズ・スクリブナーズ・サンズ、1933年。 選択された記事 「アメリカの森林の枯渇」、『センチュリー』誌、第48巻、第1号、1894年5月。 「消えゆくヘラジカ、そしてアディロンダックにおける根絶」、『センチュリー』誌、第47巻、1894年。 「カナダのヘラジカ狩り」。セオドア・ルーズベルト編、『多くの土地での狩猟』。ニューヨーク:フォレスト・アンド・ストリーム出版、1895年。 「我々の動物相の未来」、動物学会会報、第34号、1909年6月。 「動物学会の歴史」、動物学会会報、10年記念号、第37号、1910年1月。 「アラスカにおける野生生物の現状」。『高地での狩猟』、ニューヨーク:Harper & Brothers、1913年。 「野生生物の保護」、『動物園協会会報』第19巻第1号、1916年1月。 「偉大なる人種の消滅」、『地理的レビュー』第2巻第5号、1916年11月。 「人種の身体的基礎」、『国立社会科学研究所ジャーナル』第3巻、1917年1月。 「民主主義と遺伝に関する論文についての議論」、The Journal of Heredity、第10巻、第4号、1919年4月。 「移民制限:人種的側面」、Journal of the National Institute of Social Sciences、第7巻、1921年8月。 「アメリカの人種的変容」、The North American Review、1924年3月。 「アメリカ人のためのアメリカ」、フォーラム、1925年9月。 |

| Eugenics in the United States Institutional racism Henry Fairfield Osborn Racism |

米国における優生学 制度的レイシズム ヘンリー・フェアフィールド・オズボーン レイシズム |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Madison_Grant |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099