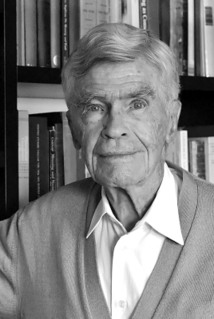

マリオ・ブンゲ

Mario

Bunge, 1919-2020

★マリオ・アウグスト・ブンゲ(September 21, 1919 - February 24, 2020)は、アルゼンチン・カナダの哲学者、物理学者である。科学的実在論、体系主義、唯物論、創発主義などを組み合わせた哲学的著作を残した。「正確 な哲学」を提唱し、実存主義、解釈学的、現象学的哲学、ポストモダニズムを批判した 偽科学に反対する意見で人気を博した。

| Mario

Augusto Bunge (/ˈbʊŋɡeɪ/;[3] Spanish: [ˈbuŋxe]; September 21, 1919 –

February 24, 2020) was an Argentine-Canadian philosopher and physicist.

His philosophical writings combined scientific realism, systemism,

materialism, emergentism, and other principles. He was an advocate of "exact philosophy"[1]: 211 and a critic of existentialist, hermeneutical, phenomenological philosophy, and postmodernism.[1]: 172 He was popularly known for his opinions against pseudoscience. |

マリ

オ・アウグスト・ブンゲ(/ˈɪ;[3] Spanish: [ˈɮ]; September 21, 1919 - February 24,

2020)は、アルゼンチン・カナダの哲学者、物理学者である。科学的実在論、体系主義、唯物論、創発主義などを組み合わせた哲学的著作を残した。 「正確な哲学」[1]: 211を提唱し、実存主義、解釈学的、現象学的哲学、ポストモダニズムを批判した[1]: 172 偽科学に反対する意見で人気を博した。 |

| Biography Bunge was born on September 21, 1919, in Florida Oeste, Buenos Aires, Argentina.[4]: 1 His mother, Marie Herminie Müser, was a German nurse who left Germany just before the beginning of World War I.[1]: 1–2 His father, Augusto Bunge, also of some German descent, was an Argentinian physician and socialist legislator.[1]: 1–2 Mario, who was the couple's only child, was raised without any religious education, and enjoyed a happy and stimulating childhood in the outskirts of Buenos Aires.[1]: 1–22 Bunge had four children: Carlos F. and Mario A. J. (with ex-wife Julia), and Eric R. and Silvia A., with his wife of over 60 years, the Argentinian mathematician Marta Cavallo.[1]: 5 Mario lived with Marta in Montreal since 1966, with one-year sabbaticals in other countries.[1]: 413 |

バイオグラフィー ブンゲは1919年9月21日、アルゼンチン・ブエノスアイレス市フロリダ・オエステで生まれた[4]: 1 母親のマリー・エルミニー・ミューザーはドイツ人の看護師で、第一次世界大戦が始まる直前にドイツを離れた[1]: 1-2 父アウグスト・ブンゲは、同じくドイツ系で、アルゼンチンの医師であり社会主義議員であった[1]: 1-2 夫婦の間に生まれた一人っ子のマリオは、宗教的な教育を受けずに育ち、ブエノスアイレス郊外で幸せで刺激的な子供時代を過ごした[1]: 1-22 ブンゲには4人の子供がいた: カルロス・F・Jとマリオ・A・J(前妻ジュリアとの間に)、エリック・Rとシルビア・Aは、60年以上連れ添った妻でアルゼンチン人数学者のマルタ・カ ヴァロとの間にできた[1]: 5 マリオは1966年からマルタとモントリオールで暮らし、1年間のサバティカル(研究休暇)で他の国に滞在した[1]: 413 |

| Studies and career Bunge began his studies at the National University of La Plata, graduating with a PhD in physico-mathematical sciences in 1952.[5] He was professor of theoretical physics and philosophy, 1956–1966, first at La Plata then at University of Buenos Aires.[5] His international debut was at the 1956 Inter-American Philosophical Congress in Santiago, Chile. He was particularly noticed there by Willard Van Orman Quine, who called Bunge the star of the congress.[6] He was, until his retirement at age 90, the Frothingham Professor of Logic and Metaphysics at McGill University in Montreal, where he had been since 1966.[7][8][5] In a review of Bunge's 2016 memoirs, Between Two Worlds: Memoirs of a Philosopher-Scientist,[1] James Alcock saw in Bunge "a man of exceedingly high confidence who has lived his life guided by strong principles about truth, science, and justice" and one who is "[impatient] with muddy thinking".[9] He became a centenarian in September 2019. A Festschrift was published to mark the occasion, with essays by an international collection of scholars.[10] He died in Montreal, Canada, on February 24, 2020, at the age of 100.[11][12] |

研究・キャリア 1956年から1966年まで、ラプラタ大学、ブエノスアイレス大学で理論物理学と哲学の教授を務めた[5]。特にそこでウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン・ クィーンに注目され、彼はブンジを会議のスターと呼んだ[6]。 90歳で引退するまで、1966年からモントリオールのマギル大学のフロシングハム教授(論理学・形而上学)を務めた[7][8][5]。 ジェームズ・アルコックは、ブンゲの2016年の回顧録『Between Two Worlds: Memoirs of a Philosopher-Scientist』の書評で、ブンゲに「真理、科学、正義に関する強い原則に導かれて生きてきた、非常に高い自信を持つ人物」 であり、「泥臭い思考に(焦)」ある人だと見ている[9]。 2019年9月にセンテナリアンとなった。これを記念して、国際的な学者たちによるエッセイを収録したFestschriftが出版された[10]。 2020年2月24日、カナダのモントリオールで100歳で死去[11][12]。 |

| Politics Bunge defined himself as a left-wing liberal and democratic socialist, in the tradition of John Stuart Mill and José Ingenieros.[1]: 345–347 [13] He was a supporter of the Campaign for the Establishment of a United Nations Parliamentary Assembly, an organisation which advocates for democratic reform in the United Nations, and the creation of a more accountable international political system.[14]  José

Ingenieros

(born Giuseppe Ingegnieri, April 24, 1877 – October 31, 1925) was an

Argentine physician, pharmacist, positivist philosopher and essayist. José

Ingenieros

(born Giuseppe Ingegnieri, April 24, 1877 – October 31, 1925) was an

Argentine physician, pharmacist, positivist philosopher and essayist.He was born in Palermo (Italy), and graduated from the University of Buenos Aires School of Medicine in 1900. Ingenieros was philosophically influenced by Herbert Spencer and Auguste Comte, and wrote a very important philosophical and social work, "El hombre mediocre" (The Mediocre Man), in 1913. Ingenieros founded the Buenos Aires Institute of Criminology in 1907 and the Argentine Psychological Society in 1908; he was elected President of the Argentine Medical Association in 1909. Ingenieros married Eva Rutenberg, in Lausanne, in 1914. Appointed Assistant Dean of the School of Philosophy and Letters of his alma mater, he played a prominent role in the landmark University reform in Argentina, in 1918. He resigned his academic posts in 1919 to join Claridad, a communist organization, and in 1922, formed Unión Latinoamerica, a political action committee focused on anti-imperialism. He was an active Freemason since 1898.[1] He founded a monthly, Renovación, in 1925, but died in Buenos Aires later that year. |

ポリティクス ブンジは自らをジョン・スチュアート・ミルとホセ・インヘニエロスの伝統を受け継ぐ左翼の自由主義者、民主社会主義者であると定義した[1]: 345- 347 [13] 彼は、国連の民主的改革と、より説明責任のある国際政治システムの構築を提唱する組織、国連議会設立キャンペーンの支援者であった[14]。  ホセ・インヘニエロス[伊:ジュゼッペ・インヘニエリ](Joseppe

Ingegnieri、1877年4月24日 - 1925年10月31日)は、アルゼンチンの医師、薬剤師、実証主義哲学者、エッセイストである。 ホセ・インヘニエロス[伊:ジュゼッペ・インヘニエリ](Joseppe

Ingegnieri、1877年4月24日 - 1925年10月31日)は、アルゼンチンの医師、薬剤師、実証主義哲学者、エッセイストである。パレルモ(イタリア)で生まれ、1900年にブエノスアイレ ス大学医学部を卒業した。ハーバート・スペンサーやオーギュスト・コントの影響を受け、1913年に哲学的・社会的に重要な著作「El hombre mediocre」(平凡な人間)を著す。1907年にブエノスアイレス犯罪学研究所、1908年にアルゼンチン心理学会を設立し、1909年にはアルゼ ンチン医師会会長に選出された。 1914年、ローザンヌでエバ・ルーテンベルグと結婚。母校 の哲学・文学部の副学部長に任命され、1918年にアルゼンチンで行われた画期的な大学改革で重要な役割を果たす。1919年に職を辞して共産主義団体ク ラリダに参加し、1922年には反帝国主義を掲げる政治活動団体ウニオン・ラティーノアメリカを結成。1898年からフリーメイソンとして活動していた [1]。1925年に月刊誌『レノバシオン』を創刊したが、同年末にブエノスアイレスで死去。 |

| Work Philosophy Bunge was a prolific intellectual, having written more than 400 papers and 80 books, notably his monumental Treatise on Basic Philosophy in eight volumes (1974–1989), a comprehensive and rigorous study of those philosophical aspects Bunge takes to be the core of modern philosophy: semantics, ontology, epistemology, philosophy of science and ethics.[5] In his Treatise, Bunge developed a comprehensive scientific outlook which he then applied to the various natural and social sciences. His work is based on global systemism, emergentism, rationalism, scientific realism, materialism and consequentialism.[15] Bunge repeatedly and explicitly denied being a logical positivist,[16] and wrote on metaphysics.[17] A variety of scientists and philosophers influenced his thought. Among those thinkers, Bunge explicitly acknowledged the direct influence of his own father, the Argentine physician Augusto Bunge, the Czech physicist Guido Beck, the Argentine mathematician Alberto González Domínguez, the Argentine mathematician, physicist and computer scientist Manuel Sadosky, the Italian sociologist and psychologist Gino Germani, the American sociologist Robert King Merton, and the French-Polish epistemologist Émile Meyerson.[1] Popularly, he is known for his remarks considering psychoanalysis as an example of pseudoscience.[18] He was critical of the ideas of well known scientists and philosophers such as Karl Popper, Richard Dawkins, Stephen Jay Gould, and Daniel Dennett.[9] Bunge appreciated some aspects of Popper's critical rationalism but found it insufficient as a comprehensive philosophy of science,[19] and instead formulated his own account of scientific realism.[20] John R. Wettersen, who defined "critical rationalism" more broadly than Popper's work, called Bunge's theory of science "a version of critical rationalism".[21] |

作品紹介 哲学 ブンゲは多作な知識人であり、400以上の論文と80以上の著書を書いた。特に、ブンゲが現代哲学の中核と考える哲学的側面(意味論、存在論、認識論、科 学哲学、倫理学)について包括的かつ厳密に研究した『基礎哲学論集』(全8巻、1974-1989)は重要なものである[5] 。 彼の仕事は、グローバル・システム主義、創発主義、合理主義、科学的実在論、唯物論、結果論に基づいている[15]。ブンゲは論理実証主義者であることを 繰り返し明確に否定し[16]、形而上学について書いている[17]。 ブンゲの思想に影響を与えたのは、さまざまな科学者や哲学者たちである。その中でもブンゲは、実父であるアルゼンチンの医師アウグスト・ブンゲ、チェコの 物理学者グイド・ベック、アルゼンチンの数学者アルベルト・ゴンサレス・ドミンゲス、アルゼンチンの数学者・物理学者・コンピュータ科学者マヌエル・サド スキー、イタリアの社会学者・心理学者ジノ・ゲルマニ、アメリカの社会学者ロバート・キング・マートン、フランス・ポーランド人の認識学者エミール・メイ ヤソンからの直接的な影響をはっきりと認めている[1]。 精神分析を疑似科学の一例とみなす発言で知られる[18]。カール・ポパー、リチャード・ドーキンス、スティーブン・ジェイ・グールド、ダニエル・デネッ トといった著名な科学者や哲学者の考え方に批判的であった[9]。 ポパーの批判的合理主義を評価しつつも、包括的な科学哲学としては不十分であると判断し[19]、代わりに独自の科学的実在論を打ち出した[20]。ポ パーの著作よりも広範に「批判的合理主義」を定義したジョン・R・ウェッターセンは、ブンゲの科学理論を「批判的合理主義のバージョン」と呼んだ [21]。 |

| Philosophy of social sciences Bunge addressed issues of theory and method in the social sciences starting with his Treatise on Basic Philosophy and later in his career wrote two books entirely focused on the social sciences: Finding Philosophy in Social Science (1996) and Social Science under Debate: A Philosophical Perspective (1998). In these works he argued for an approach to the study of societies that he called systemism, an alternative to holism and individualism. He was an advocate for what he called mechanismic explanations and defended the view that social mechanisms are processes "in a concrete system, such that it is capable of bringing about or preventing some change in the system as a whole or in some of its subsystems".[22] |

社会科学の哲学 ブンゲは、『基礎哲学論』から社会科学の理論と方法の問題に取り組み、その後、社会科学に特化した2冊の本を書いた: 社会科学に哲学を見つける』(1996年)、『社会科学は議論される』(1998年): 社会科学における哲学の発見』(1996年)、『社会科学の議論:哲学的視点』(1998年)である。これらの著作で彼は、全体主義や個人主義に代わるシ ステム主義と呼ばれる社会研究へのアプローチを主張した。彼はメカニズム的説明と呼ばれるものの提唱者であり、社会的メカニズムとは「システム全体または そのサブシステムのいくつかにおいて何らかの変化をもたらす、または防ぐことができるような、具体的なシステムにおけるプロセス」であるという見解を擁護 した[22]。 |

| Selected publications 1959. Causality: The Place of the Causal Principle in Modern Science. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. (Fourth edition, New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 2009.) 1960. La ciencia, su método y su filosofía. Buenos Aires: Eudeba. (In French: La science, sa méthode et sa philosophie. Paris: Vigdor, 2001, ISBN 2910243907.) 1962. Intuition and Science. Prentice-Hall. (In French: Intuition et raison. Paris: Vigdor, 2001, ISBN 2910243893.) 1963. The Myth of Simplicity: Problems of Scientific Philosophy. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. 1967. Scientific Research: Strategy and Philosophy. Volume 1: The Search for System. Volume 2: The Search for Truth. Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag. Revised and reprinted as Philosophy of Science, 2 Vols. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction, 1998. 1967. Foundations of Physics. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag. 1973. Method, Model, and Matter. Dordrecht: Reidel. 1973. Philosophy of Physics. Dordrecht: Reidel. 1977. "Emergence and the Mind", Neuroscience 2(4), 501–509. 1980. The Mind-Body Problem. Oxford: Pergamon. 1981. Scientific Materialism. Dordrecht: Reidel. 1983. "Demarcating Science from Pseudoscience", Fundamenta Scientiae 3: 369–388. 1984. "What is Pseudoscience?", The Skeptical Inquirer 9: 36–46. 1987. Philosophy of Psychology (with Rubén Ardila). New York: Springer. 1987. "Why Parapsychology Cannot Become a Science", Behavioral and Brain Sciences 10: 576–577. 1988. Ciencia y desarrollo. Buenos Aires: Siglo Veinte. 1974–89. Treatise on Basic Philosophy:[26] 8 volumes in 9 parts: I: Semantics I: Sense and Reference. Dordrecht: Reidel, 1974. II: Semantics II: Interpretation and Truth. Dordrecht: Reidel, 1974. III: Ontology I: The Furniture of the World. Dordrecht: Reidel, 1977. IV: Ontology II: A World of Systems. Dordrecht: Reidel, 1979. V: Epistemology and Methodology I: Exploring the World. Dordrecht: Reidel, 1983. VI: Epistemology and Methodology II: Understanding the World. Dordrecht: Reidel, 1983. VII: Epistemology and Methodology III: Philosophy of Science and Technology: Part I. Formal and Physical Sciences. Dordrecht: Reidel, 1985. Part II. Life Science, Social Science and Technology. Dordrecht: Reidel, 1985. VIII: Ethics: the Good and the Right. Dordrecht: D. Reidel, 1989. 1996. Finding Philosophy in Social Science. New Haven: Yale University Press. 1996. "Is Religious Education Compatible with Science Education?" (with Martin Mahner), Science & Education 5(2), 101–123. 1997. Foundations of Biophilosophy (with Martin Mahner). New York: Springer. 1997. "Mechanism and Explanation", Philosophy of the Social Sciences 27(4), 410–465. 1998. Dictionary of Philosophy. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books. 1998. Elogio de la curiosidad. Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana. 1998. Social Science under Debate: A Philosophical Perspective. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. 1999. The Sociology–Philosophy Connection. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction. 2001. Philosophy in Crisis: The Need for Reconstruction. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books. 2001. Scientific Realism: Selected Essays of Mario Bunge. Edited by Martin Mahner. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books. 2003. Emergence and Convergence: Qualitative Novelty and the Unity of Knowledge. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. 2004. "How Does It Work? The Search for Explanatory Mechanisms", Philosophy of the Social Sciences 34(2), 182–210. 2004. Über die Natur der Dinge. Materialismus und Wissenschaft (with Martin Mahner). Stuttgart: S. Hirzel Verlag. 2006. Chasing Reality: Strife over Realism. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. 2009. Political Philosophy: Fact, Fiction, and Vision. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction. 2010. Matter and Mind: A Philosophical Inquiry. New York: Springer. 2012. Evaluating Philosophies. New York: Springer. 2012. "Does Quantum Physics Refute Realism, Materialism and Determinism?", Science & Education 21(10): 1601–1610. 2013. Medical Philosophy: Conceptual Issues in Medicine. New Jersey: World Scientific Publishing Company. 2016. Between Two Worlds: Memoirs of a Philosopher–Scientist. New York: Springer. 2017. Doing Science: In the Light of Philosophy. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Company. 2018. From a Scientific Point of View: Reasoning and Evidence Beat Improvisation across Fields. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars. |

主な著作 1959. 『因果性:現代科学における因果原理の位置づけ』ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局。(第4版、ニューブランズウィック:トランザクション出版社、2009年) 1960. 『科学、その方法と哲学』ブエノスアイレス:エウデバ。(フランス語版:La science, sa méthode et sa philosophie. パリ:ヴィグドル、2001年、ISBN 2910243907) 1962. 『直観と科学』プレンティス・ホール社。(仏訳:Intuition et raison. パリ:ヴィグドル、2001年、ISBN 2910243893) 1963. 単純性の神話:科学哲学の問題。ニュージャージー州イングルウッドクリフス:プレンティス・ホール。 1967. 科学研究:戦略と哲学。第1巻:体系の探求。第2巻:真実の探求。ベルリン、ニューヨーク:シュプリンガー・ヴェルラッグ。改訂版として『科学哲学』全2巻で再版。ニュージャージー州ニューブランズウィック:トランザクション、1998年。 1967. 『物理学の基礎』ベルリン、ハイデルベルク、ニューヨーク:シュプリンガー・ヴェルラッグ。 1973. 『方法、モデル、物質』ドルドレヒト:ライデル。 1973. 『物理学の哲学』ドルドレヒト:ライデル。 1977. 「創発と心」『ニューロサイエンス』2(4)、501–509頁。 1980. 『心身問題』. オックスフォード: パーガモン. 1981. 『科学的唯物論』. ドルドレヒト: ライデル. 1983. 「科学と疑似科学の境界線」, 『科学の基礎』3: 369–388. 1984. 「疑似科学とは何か」、『懐疑的探求者』9: 36–46. 1987. 『心理学哲学』(ルベン・アルディラとの共著)。ニューヨーク:シュプリンガー。 1987. 「超心理学が科学になれない理由」、『行動と脳科学』10: 576–577. 1988. 『科学と発展』. ブエノスアイレス: シグロ・ベインテ. 1974–89. 『基礎哲学論』: [26] 9部構成の8巻: I: 意味論I: 意味と参照. ドルドレヒト: ライデル, 1974. II: 意味論II: 解釈と真理. ドルドレヒト: ライデル, 1974. III:存在論 I:世界の家具。ドルドレヒト:ライデル社、1977年。 IV:存在論 II:システムの世界。ドルドレヒト:ライデル社、1979年。 V:認識論と方法論 I:世界を探求する。ドルドレヒト:ライデル社、1983年。 VI: 認識論と方法論 II: 世界を理解する。ドルドレヒト: ライデル社、1983年。 VII: 認識論と方法論 III: 科学技術哲学: 第I部 形式科学と物理科学。ドルドレヒト: ライデル社、1985年。第II部 生命科学、社会科学と技術。ドルドレヒト: ライデル社、1985年。 VIII:倫理:善と正義。ドルドレヒト:D. ライデル、1989年。 1996年。社会科学における哲学の発見。ニューヘイブン:イェール大学出版局。 1996年。「宗教教育は科学教育と両立するか?」(マーティン・マーナーとの共著)、Science & Education 5(2)、101–123。 1997年。生物哲学の基礎(マーティン・マーナーと共著)。ニューヨーク:シュプリンガー。 1997年。「メカニズムと説明」、社会科学哲学 27(4)、410–465。 1998年。哲学辞典。ニューヨーク州アマースト:プロメテウス・ブックス。 1998年。好奇心への賛辞。ブエノスアイレス:エディトリアル・スダメリカーナ。 1998年。議論中の社会科学:哲学的視点。トロント:トロント大学出版局。 1999年。社会学と哲学のつながり。ニュージャージー州ニューブランズウィック:トランザクション。 2001年。危機にある哲学:再構築の必要性。ニューヨーク州アマースト:プロメテウス・ブックス。 2001年。科学的現実主義:マリオ・ブンゲの選集。マーティン・マーナー編。ニューヨーク州アマースト:プロメテウス・ブックス。 2003年。創発と収束:質的新規性と知識の統一。トロント:トロント大学出版局。 2004年。「それはどのように機能するのか?説明メカニズムの探求」、社会科学哲学 34(2)、182–210。 2004年。Über die Natur der Dinge. Materialismus und Wissenschaft(マーティン・マーナーとの共著)。シュトゥットガルト:S. Hirzel Verlag。 2006年。Chasing Reality: Strife over Realism. トロント:トロント大学出版局。 2009年。Political Philosophy: Fact, Fiction, and Vision. ニュージャージー州ニューブランズウィック:Transaction。 2010年。物質と精神:哲学的探求。ニューヨーク:Springer。 2012年。哲学の評価。ニューヨーク:Springer。 2012年。「量子物理学は現実主義、唯物論、決定論を否定するのか?」、Science & Education 21(10): 1601–1610。 2013年。医学哲学:医学における概念的問題。ニュージャージー州:ワールド・サイエンティフィック出版。 2016. 二つの世界の間:哲学者・科学者の回想録。ニューヨーク:スプリンガー。 2017. 科学を実践する:哲学の光のもとで。シンガポール:ワールド・サイエンティフィック出版。 2018. 科学的観点から:あらゆる分野において、推論と証拠は即興を凌駕する。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ・スカラーズ。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mario_Bunge |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099