補綴

prosthesis;ほてつ

補綴(ほてつ)とは、身体の欠損した部位の形態と機能を人工物で補うことをいう。欠損の部位でもっともよく使われるのが虫歯の詰め物や、義手義 足などであり、ドイツ語が外来語化して「プロテーゼ(Prothese)」と呼ばれる。補綴には、構造的な充填のほかに、欠損した部分がもとの機能を補綴 することがあるので、機能的な意味ももつ。体の表面に取り付け、機能的に補綴するものは人工物はエピテーゼと呼ばれる。

下記のものは、古代エジプトのミイラに発見された、足親指の義足部分である。

Mummies’

false toes helped ancient Egyptians walk , by University of

Manchester.

「シリコンベースの記憶増強の可能性はこれだけではない。「脳補綴(brain prosthesis)」と呼ばれる、脳の損傷部位に代わって働くチップも開発中である。脳卒中やてんかんの患者で使用可能になれば、正常な脳の増強にも 使われるようになるかもしれない。記憶障害の患者では海馬が損傷を受けていることが多い。新しい経験はまず海馬で処理されてから、脳の他の部分に記憶とし て貯蔵される。この海馬の役割をするチップ、つまり人工的な海馬、がラットで研究されているのだ。ラットの海馬を切片にし、電気刺激してインプットとアウ トプットとの関係を記録し、マッピングする。これをもとにモデルを作製し、チップ上に符号化して再現する。チップを脳の適当な場所に置き、損傷を受けた部 分をまたぐようにしてリード線で脳と結合する。これで、損傷部分に入ってくる情報がチップに送られ、チップからの情報は基本的に損傷部分をバイパスして正 常な部分に送られることになる。発想としては簡単そうだが、南カリフォルニア大学(USC)の研究者たちは、DARPA 、海軍研究事務所、米国国立科学財団から支援をうけ、完成するまでに10年聞を費やした。USC のチームは、ラットから取り出した海馬を用い生体外でこのシステムをテスト中である。ゆくゆくは、生きたサルにチップを移植して、記憶が関係する行動の変 化が起きるかどうかテストする予定だという」」(モレノ 2008:243-244)。

++++

| In medicine, a

prosthesis (pl.: prostheses; from Ancient Greek: πρόσθεσις, romanized:

prósthesis, lit. 'addition, application, attachment'),[1] or a

prosthetic implant,[2][3] is an artificial device that replaces a

missing body part, which may be lost through physical trauma, disease,

or a condition present at birth (congenital disorder). Prostheses are

intended to restore the normal functions of the missing body part.[4]

Amputee rehabilitation is primarily coordinated by a physiatrist as

part of an inter-disciplinary team consisting of physiatrists,

prosthetists, nurses, physical therapists, and occupational

therapists.[5] Prostheses can be created by hand or with computer-aided

design (CAD), a software interface that helps creators design and

analyze the creation with computer-generated 2-D and 3-D graphics as

well as analysis and optimization tools.[6] |

医学において、プロテーゼすなわち補綴(pl.:

prostheses、古代ギリシア語: πρόσθεσις、ローマ字表記:

prósthesis、lit. 追加、適用、装着」)[1]、または人工インプラント[2][3]は、身体的外傷、疾患、または生まれつきの状態(先天

性疾患)によって失われた身体の一部を補う人工装置である。義肢装具は、欠損した身体部位の正常な機能を回復させることを目的としている[4]。切断者の

リハビリテーションは、主にリハビリテーション医、義肢装具士、看護師、理学療法士、作業療法士からなる学際的チームの一員として、リハビリテーション医

がコーディネートする[5]。 |

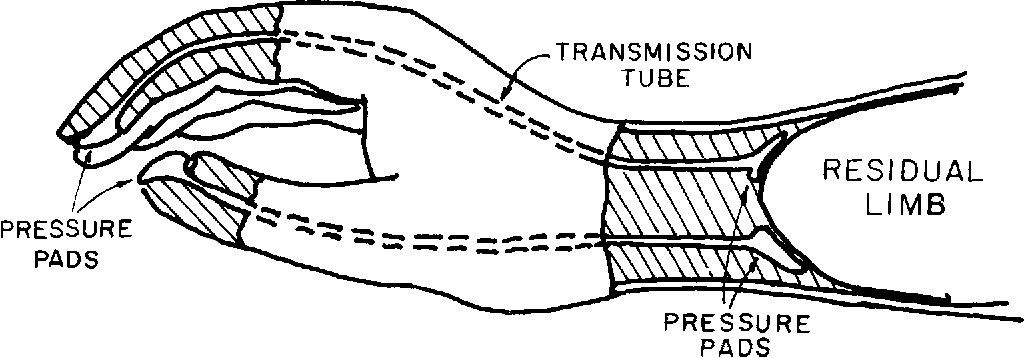

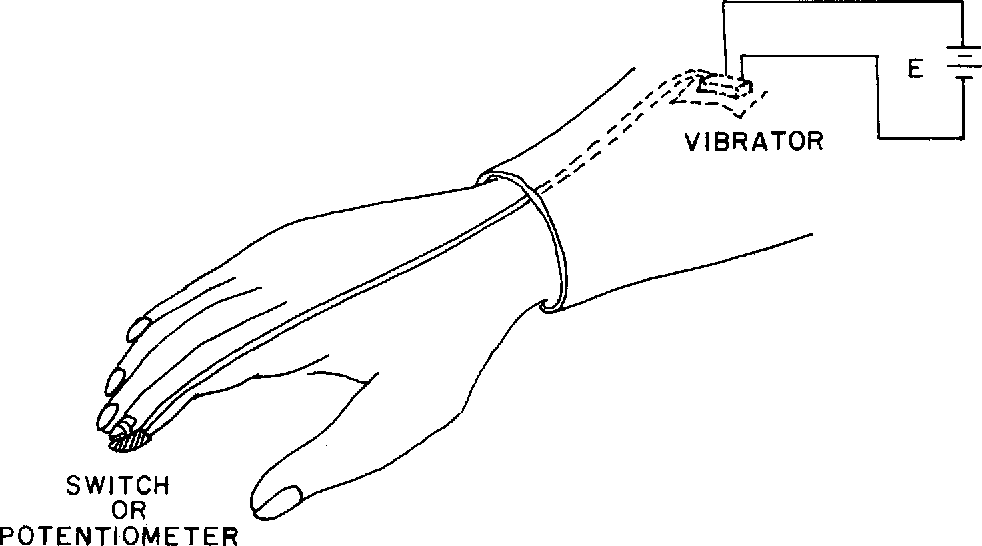

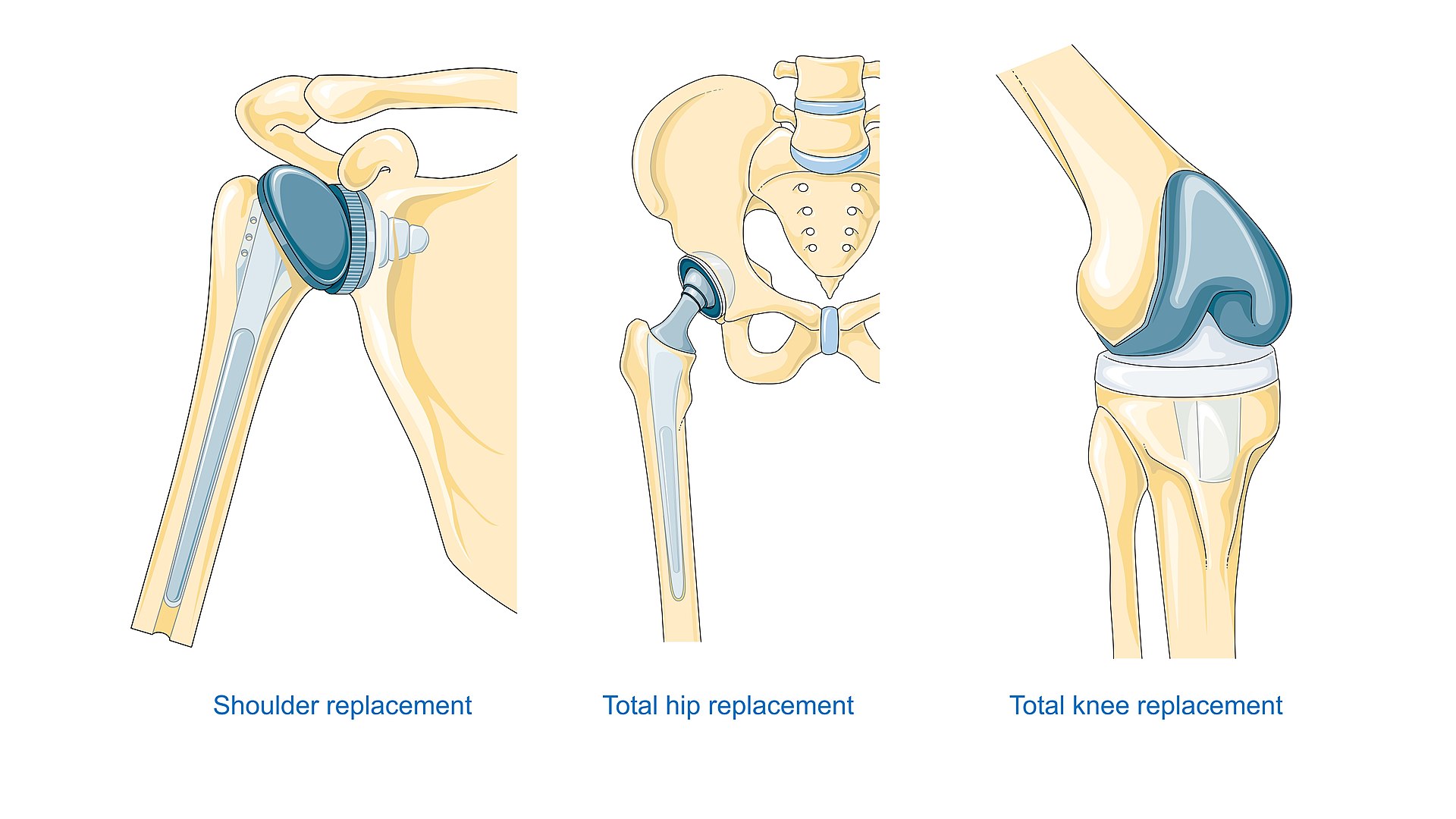

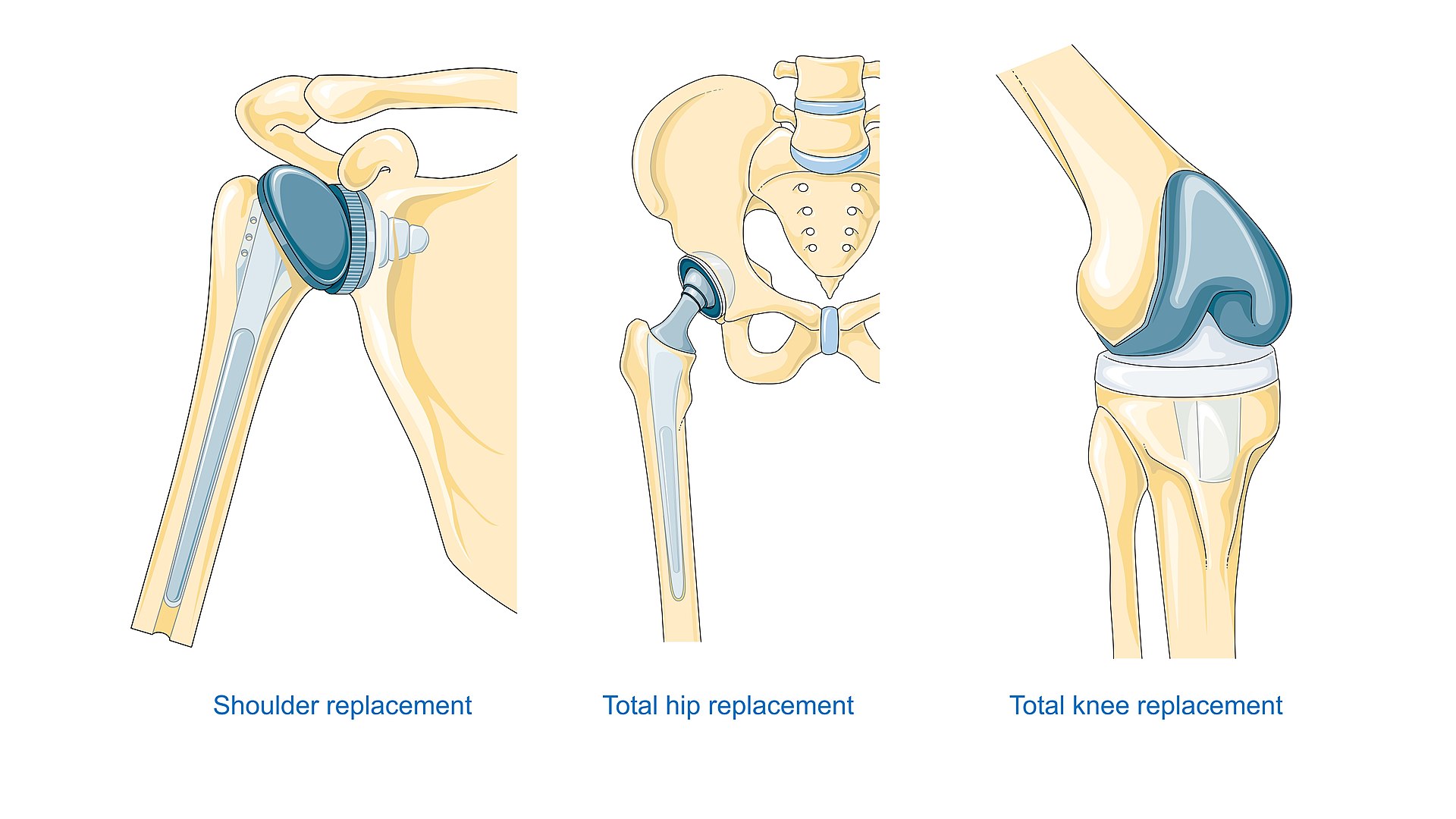

| Types A person's prosthesis should be designed and assembled according to the person's appearance and functional needs. For instance, a person may need a transradial prosthesis, but the person needs to choose between an aesthetic functional device, a myoelectric device, a body-powered device, or an activity specific device. The person's future goals and economical capabilities may help them choose between one or more devices. Craniofacial prostheses include intra-oral and extra-oral prostheses. Extra-oral prostheses are further divided into hemifacial, auricular (ear), nasal, orbital and ocular. Intra-oral prostheses include dental prostheses, such as dentures, obturators, and dental implants. Prostheses of the neck include larynx substitutes, trachea and upper esophageal replacements, Somato prostheses of the torso include breast prostheses which may be either single or bilateral, full breast devices or nipple prostheses. Penile prostheses are used to treat erectile dysfunction, correct penile deformity, perform phalloplasty procedures in cisgender men, and to build a new penis in female-to-male gender reassignment surgeries. Limb prostheses Limb prostheses include both upper- and lower-extremity prostheses. Upper-extremity prostheses are used at varying levels of amputation: forequarter, shoulder disarticulation, transhumeral prosthesis, elbow disarticulation, transradial prosthesis, wrist disarticulation, full hand, partial hand, finger, partial finger. A transradial prosthesis is an artificial limb that replaces an arm missing below the elbow.  An example of two upper-extremity prosthetics, one body-powered (right arm), and another myoelectric (left arm). Upper limb prostheses can be categorized in three main categories: Passive devices, Body Powered devices, and Externally Powered (myoelectric) devices. Passive devices can either be passive hands, mainly used for cosmetic purposes, or passive tools, mainly used for specific activities (e.g. leisure or vocational). An extensive overview and classification of passive devices can be found in a literature review by Maat et.al.[7] A passive device can be static, meaning the device has no movable parts, or it can be adjustable, meaning its configuration can be adjusted (e.g. adjustable hand opening). Despite the absence of active grasping, passive devices are very useful in bimanual tasks that require fixation or support of an object, or for gesticulation in social interaction. According to scientific data a third of the upper limb amputees worldwide use a passive prosthetic hand.[7] Body Powered or cable-operated limbs work by attaching a harness and cable around the opposite shoulder of the damaged arm. A recent body-powered approach has explored the utilization of the user's breathing to power and control the prosthetic hand to help eliminate actuation cable and harness.[8][9][10] The third category of available prosthetic devices comprises myoelectric arms. This particular class of devices distinguishes itself from the previous ones due to the inclusion of a battery system. This battery serves the dual purpose of providing energy for both actuation and sensing components. While actuation predominantly relies on motor or pneumatic systems,[11] a variety of solutions have been explored for capturing muscle activity, including techniques such as Electromyography, Sonomyography, Myokinetic, and others.[12][13][14] These methods function by detecting the minute electrical currents generated by contracted muscles during upper arm movement, typically employing electrodes or other suitable tools. Subsequently, these acquired signals are converted into gripping patterns or postures that the artificial hand will then execute. In the prosthetics industry, a trans-radial prosthetic arm is often referred to as a "BE" or below elbow prosthesis. Lower-extremity prostheses provide replacements at varying levels of amputation. These include hip disarticulation, transfemoral prosthesis, knee disarticulation, transtibial prosthesis, Syme's amputation, foot, partial foot, and toe. The two main subcategories of lower extremity prosthetic devices are trans-tibial (any amputation transecting the tibia bone or a congenital anomaly resulting in a tibial deficiency) and trans-femoral (any amputation transecting the femur bone or a congenital anomaly resulting in a femoral deficiency).[citation needed] A transfemoral prosthesis is an artificial limb that replaces a leg missing above the knee. Transfemoral amputees can have a very difficult time regaining normal movement. In general, a transfemoral amputee must use approximately 80% more energy to walk than a person with two whole legs.[15] This is due to the complexities in movement associated with the knee. In newer and more improved designs, hydraulics, carbon fiber, mechanical linkages, motors, computer microprocessors, and innovative combinations of these technologies are employed to give more control to the user. In the prosthetics industry, a trans-femoral prosthetic leg is often referred to as an "AK" or above the knee prosthesis. A transtibial prosthesis is an artificial limb that replaces a leg missing below the knee. A transtibial amputee is usually able to regain normal movement more readily than someone with a transfemoral amputation, due in large part to retaining the knee, which allows for easier movement. Lower extremity prosthetics describe artificially replaced limbs located at the hip level or lower. In the prosthetics industry, a trans-tibial prosthetic leg is often referred to as a "BK" or below the knee prosthesis. Prostheses are manufactured and fit by clinical Prosthetists. Prosthetists are healthcare professionals responsible for making, fitting, and adjusting prostheses and for lower limb prostheses will assess both gait and prosthetic alignment. Once a prosthesis has been fit and adjusted by a Prosthetist, a rehabilitation Physiotherapist (called Physical Therapist in America) will help teach a new prosthetic user to walk with a leg prosthesis. To do so, the physical therapist may provide verbal instructions and may also help guide the person using touch or tactile cues. This may be done in a clinic or home. There is some research suggesting that such training in the home may be more successful if the treatment includes the use of a treadmill.[16] Using a treadmill, along with the physical therapy treatment, helps the person to experience many of the challenges of walking with a prosthesis. In the United Kingdom, 75% of lower limb amputations are performed due to inadequate circulation (dysvascularity).[17] This condition is often associated with many other medical conditions (co-morbidities) including diabetes and heart disease that may make it a challenge to recover and use a prosthetic limb to regain mobility and independence.[17] For people who have inadequate circulation and have lost a lower limb, there is insufficient evidence due to a lack of research, to inform them regarding their choice of prosthetic rehabilitation approaches.[17]  Types of prosthesis used for replacing joints in the human body Lower extremity prostheses are often categorized by the level of amputation or after the name of a surgeon:[18][19] Transfemoral (Above-knee) Transtibial (Below-knee) Ankle disarticulation (more commonly known as Syme's amputation) Knee disarticulation Hip disarticulation Hemi-pelvictomy Partial foot amputations (Pirogoff, Talo-Navicular and Calcaneo-cuboid (Chopart), Tarso-metatarsal (Lisfranc), Trans-metatarsal, Metatarsal-phalangeal, Ray amputations, toe amputations).[19] Van Nes rotationplasty Prosthetic raw materials Prosthetic are made lightweight for better convenience for the amputee. Some of these materials include: Plastics: Polyethylene Polypropylene Acrylics Polyurethane Wood (early prosthetics) Rubber (early prosthetics) Lightweight metals: Titanium Aluminum Composites: Carbon fiber reinforced polymers[4] Wheeled prostheses have also been used extensively in the rehabilitation of injured domestic animals, including dogs, cats, pigs, rabbits, and turtles.[20] |

種類 義足は、その人の外見と機能的ニーズに応じて設計され、組み立てられなけれ ばならない。例えば、ある人が経橈骨義足を必要とする場合、審美的な機能装置、筋電装置、体動装置、または活動特異的な装置のいずれかを選択する必要があ る。その人の将来の目標や経済的な能力によって、1つ以上の装置から選択することができる。 顎顔面補綴には、口腔内補綴と口腔外補綴がある。口腔外義肢はさらに、半顔面義肢、耳介義肢、鼻腔義肢、眼窩義肢、眼球義肢に分けられる。口腔内補綴物には、義歯、咬合器、インプラントなどの歯科補綴物が含まれる。 頸部補綴には、喉頭補綴、気管補綴、上部食道補綴などがある、 胴体の人工肛門には、片側または両側の人工乳房、完全乳房装置、乳頭人工肛門などがある。 陰茎プロテーゼは、勃起不全の治療、陰茎変形の矯正、シスジェンダー男性の陰茎形成術、女性から男性への性別適合手術で新しい陰茎を作るために使用される。 義肢 義肢には上肢義肢と下肢義肢がある。 上肢義肢は、前四肢、肩関節離断術、経上腕義肢、肘関節離断術、経橈骨義肢、手関節離断術、全手、部分手、指、部分指など、さまざまな切断レベルで使用される。経橈骨人工関節は、肘から下が欠損した腕の代わりとなる義肢である。  2つの上肢義肢の例で、1つは体動式(右腕)、もう1つは筋電式(左腕)である。 上肢の義肢は主に3つのカテゴリーに分類される: 受動義肢装具、体動義肢装具、体外式義肢装具(筋電義肢)である。受動的な装置には、主に美容目的で使用される受動的な手と、主に特定の活動(レジャーや 職業など)に使用される受動的な道具がある。受動的デバイスの広範な概要と分類は、Maatらによる文献レビュー[7]に記載されている。受動的デバイス には、デバイスに可動部がないことを意味する静的なものと、デバイスの構成を調整できることを意味する調整可能なものがある(例:調整可能な手の開き)。 能動的な把持がないにもかかわらず、受動的な装置は、対象物の固定や支持を必要とする両手作業や、社会的相互作用における身振りに非常に有用である。科学 的データによると、世界中の上肢切断者の3分の1が受動的義手を使用している[7]。最近では、使用者の呼吸を利用して義手の動力と制御を行うことで、 ケーブルやハーネスを不要にするボディパワード・アプローチが研究されている。この特殊な義肢装具は、バッテリーシステムを搭載しているため、これまでの 義肢装具とは一線を画している。このバッテリーは、作動コンポーネントと感知コンポーネントの両方にエネルギーを供給するという2つの目的を果たす。作動 は主にモーターまたは空気圧システムに依存しているが[11]、筋活動を捕捉するために、筋電図、ソノミオグラフィ、筋運動学などの技術を含むさまざまな ソリューションが検討されてきた[12][13][14]。これらの方法は、通常、電極または他の適切なツールを使用して、上腕の運動中に収縮した筋肉に よって生成される微小電流を検出することによって機能する。その後、これらの取得された信号は、人工手が実行する把持パターンや姿勢に変換される。 義肢業界では、経橈骨義手はしばしば「BE」または肘下義手と呼ばれる。 下肢の義肢は、さまざまな切断レベルで代替品を提供する。これには、股関節切断、経大腿義足、膝関節切断、経脛骨義足、Syme切断、足部、部分足部、足 指が含まれる。下肢義肢装具の2つの主なサブカテゴリーは、経脛骨義肢(脛骨を切断する切断、または脛骨欠損をもたらす先天異常)と経大腿骨義肢(大腿骨 を切断する切断、または大腿骨欠損をもたらす先天異常)である[要出典]。 経大腿義足は、膝から上が欠損した脚の代わりとなる義肢である。経大腿切断者は、正常な動きを取り戻すのに非常に苦労する。一般に、大腿切断者は、両足が ある人よりも歩くのに約80%多くのエネルギーを使わなければならない[15]。これは、膝に関連する動きが複雑なためである。より新しく改良された設計 では、油圧、カーボンファイバー、機械的リンケージ、モーター、コンピュータ・マイクロプロセッサ、およびこれらの技術の革新的な組み合わせが採用され、 使用者がより制御できるようになっている。義肢業界では、経大腿義足は「AK」または膝上義足と呼ばれることが多い。 経脛義足は、膝から下が欠損した脚を補う義肢である。経脛骨切断者は通常、経大腿切断者よりも通常の動きを容易に取り戻すことができる。下肢義肢とは、人 工的に置換された手足のことで、腰の高さ以下に位置する。義肢業界では、経脛義足は「BK」または膝下義足と呼ばれることが多い。 義肢は臨床義肢装具士によって製造され、装着される。義肢装具士は、義肢の製作、フィッティング、調整を担当する医療専門家であり、下肢義肢の場合は歩行 と義肢のアライメントの両方を評価する。義肢装具士によって義肢が装着され調整されると、リハビリテーションの理学療法士(アメリカではPhysical Therapistと呼ばれる)が、新しい義肢装具使用者に義足での歩行を教える手助けをする。そのために、理学療法士は口頭で指示を与えたり、触診や触 覚の合図を使って誘導したりする。これは診療所または自宅で行われる。トレッドミルを使用することで、理学療法による治療と ともに、義足で歩行する際の多くの課題を経験することが できる。 英国では、下肢切断の75%が循環不全(dysvascularity)によるものである[17]。この状態は、糖尿病や心臓病など他の多くの病状(co -morbidities)と関連していることが多く、義肢を回復して使用し、運動能力や自立性を回復することが困難になる可能性がある[17]。循環不 全で下肢を失った人に対しては、研究が不足しているため、義肢リハビリテーションのアプローチの選択に関して情報を提供するための十分な証拠がない [17]。  人体の関節の置換に使用される義肢の種類 下肢の人工関節は、切断の程度や外科医の名前によって分類されることが多い。 経大腿(膝上) 経脛骨(膝から下) 足関節離断術(一般にSyme切断として知られている) 膝関節離断術 股関節離断術 半月板切断術 足の部分切断(ピロゴフ、タロ-ナビキュラーおよびカルカネオ-キューボイド(ショパール)、タルソ-中足骨(リスフラン)、経中足骨、中足骨-指節骨、レイ切断、足指切断)[19]。 ヴァン・ネス回旋形成術 補綴物の原材料 人工関節は、切断者の利便性を高めるために軽量化されている。これらの材料には次のようなものがある: プラスチック: ポリエチレン ポリプロピレン アクリル ポリウレタン 木材(初期の補綴物) ゴム(初期の義肢) 軽量金属 チタン アルミニウム 複合材料: 炭素繊維強化ポリマー[4]。 車輪付き義足は、犬、猫、豚、ウサギ、カメなどの負傷した家畜のリハビリにも広く使用されている[20]。 |

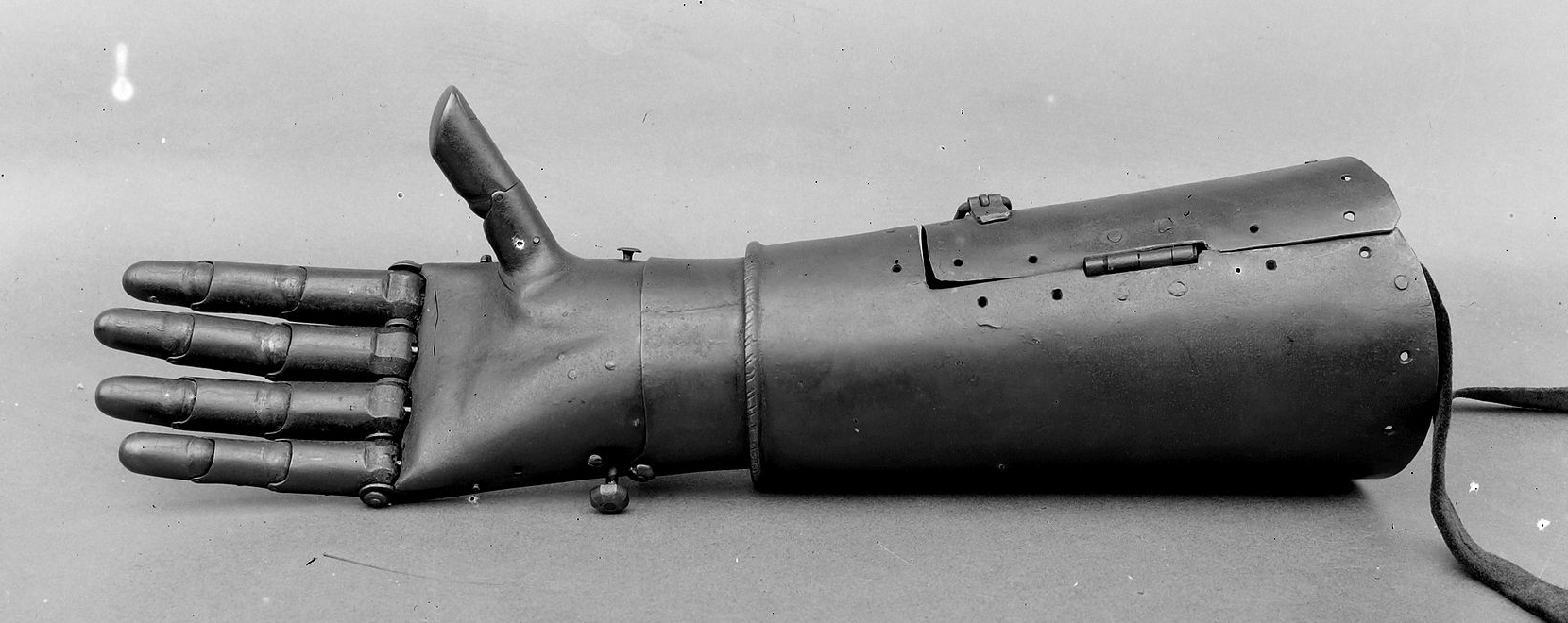

History Prosthetic toe from ancient Egypt Prosthetics originate from the ancient Near East circa 3000 BCE, with the earliest evidence of prosthetics appearing in ancient Egypt and Iran. The earliest recorded mention of eye prosthetics is from the Egyptian story of the Eye of Horus dates circa 3000 BC, which involves the left eye of Horus being plucked out and then restored by Thoth. Circa 3000-2800 BC, the earliest archaeological evidence of prosthetics is found in ancient Iran, where an eye prosthetic is found buried with a woman in Shahr-i Shōkhta. It was likely made of bitumen paste that was covered with a thin layer of gold.[21] The Egyptians were also early pioneers of foot prosthetics, as shown by the wooden toe found on a body from the New Kingdom circa 1000 BC.[22] Another early textual mention is found in South Asia circa 1200 BC, involving the warrior queen Vishpala in the Rigveda.[23] Roman bronze crowns have also been found, but their use could have been more aesthetic than medical.[24] An early mention of a prosthetic comes from the Greek historian Herodotus, who tells the story of Hegesistratus, a Greek diviner who cut off his own foot to escape his Spartan captors and replaced it with a wooden one.[25] Wood and metal prosthetics  The Capua leg (replica)  A wooden prosthetic leg from Shengjindian cemetery, circa 300 BCE, Turpan Museum. This is "the oldest functional leg prosthesis known to date".[26]  Iron prosthetic hand believed to have been owned by Götz von Berlichingen (1480–1562)  "Illustration of mechanical hand", c. 1564  Artificial iron hand believed to date from 1560 to 1600 Pliny the Elder also recorded the tale of a Roman general, Marcus Sergius, whose right hand was cut off while campaigning and had an iron hand made to hold his shield so that he could return to battle. A famous and quite refined[27] historical prosthetic arm was that of Götz von Berlichingen, made at the beginning of the 16th century. The first confirmed use of a prosthetic device, however, is from 950 to 710 BC. In 2000, research pathologists discovered a mummy from this period buried in the Egyptian necropolis near ancient Thebes that possessed an artificial big toe. This toe, consisting of wood and leather, exhibited evidence of use. When reproduced by bio-mechanical engineers in 2011, researchers discovered that this ancient prosthetic enabled its wearer to walk both barefoot and in Egyptian style sandals. Previously, the earliest discovered prosthetic was an artificial leg from Capua.[28] Around the same time, François de la Noue is also reported to have had an iron hand, as is, in the 17th century, René-Robert Cavalier de la Salle.[29] Henri de Tonti had a prosthetic hook for a hand. During the Middle Ages, prosthetics remained quite basic in form. Debilitated knights would be fitted with prosthetics so they could hold up a shield, grasp a lance or a sword, or stabilize a mounted warrior.[30] Only the wealthy could afford anything that would assist in daily life.[31] One notable prosthesis was that belonging to an Italian man, who scientists estimate replaced his amputated right hand with a knife.[32][33] Scientists investigating the skeleton, which was found in a Longobard cemetery in Povegliano Veronese, estimated that the man had lived sometime between the 6th and 8th centuries AD.[34][33] Materials found near the man's body suggest that the knife prosthesis was attached with a leather strap, which he repeatedly tightened with his teeth.[34] During the Renaissance, prosthetics developed with the use of iron, steel, copper, and wood. Functional prosthetics began to make an appearance in the 1500s.[35] Technology progress before the 20th century An Italian surgeon recorded the existence of an amputee who had an arm that allowed him to remove his hat, open his purse, and sign his name.[36] Improvement in amputation surgery and prosthetic design came at the hands of Ambroise Paré. Among his inventions was an above-knee device that was a kneeling peg leg and foot prosthesis with a fixed position, adjustable harness, and knee lock control. The functionality of his advancements showed how future prosthetics could develop. Other major improvements before the modern era: Pieter Verduyn – First non-locking below-knee (BK) prosthesis. James Potts – Prosthesis made of a wooden shank and socket, a steel knee joint and an articulated foot that was controlled by catgut tendons from the knee to the ankle. Came to be known as "Anglesey Leg" or "Selpho Leg". Sir James Syme – A new method of ankle amputation that did not involve amputating at the thigh. Benjamin Palmer – Improved upon the Selpho leg. Added an anterior spring and concealed tendons to simulate natural-looking movement. Dubois Parmlee – Created prosthetic with a suction socket, polycentric knee, and multi-articulated foot. Marcel Desoutter & Charles Desoutter – First aluminium prosthesis[37] Henry Heather Bigg, and his son Henry Robert Heather Bigg, won the Queen's command to provide "surgical appliances" to wounded soldiers after Crimea War. They developed arms that allowed a double arm amputee to crochet, and a hand that felt natural to others based on ivory, felt and leather.[38] At the end of World War II, the NAS (National Academy of Sciences) began to advocate better research and development of prosthetics. Through government funding, a research and development program was developed within the Army, Navy, Air Force, and the Veterans Administration. Lower extremity modern history  An artificial limbs factory in 1941 After the Second World War, a team at the University of California, Berkeley including James Foort and C.W. Radcliff helped to develop the quadrilateral socket by developing a jig fitting system for amputations above the knee. Socket technology for lower extremity limbs saw a further revolution during the 1980s when John Sabolich C.P.O., invented the Contoured Adducted Trochanteric-Controlled Alignment Method (CATCAM) socket, later to evolve into the Sabolich Socket. He followed the direction of Ivan Long and Ossur Christensen as they developed alternatives to the quadrilateral socket, which in turn followed the open ended plug socket, created from wood.[39] The advancement was due to the difference in the socket to patient contact model. Prior to this, sockets were made in the shape of a square shape with no specialized containment for muscular tissue. New designs thus help to lock in the bony anatomy, locking it into place and distributing the weight evenly over the existing limb as well as the musculature of the patient. Ischial containment is well known and used today by many prosthetist to help in patient care. Variations of the ischial containment socket thus exists and each socket is tailored to the specific needs of the patient. Others who contributed to socket development and changes over the years include Tim Staats, Chris Hoyt, and Frank Gottschalk. Gottschalk disputed the efficacy of the CAT-CAM socket- insisting the surgical procedure done by the amputation surgeon was most important to prepare the amputee for good use of a prosthesis of any type socket design.[40] The first microprocessor-controlled prosthetic knees became available in the early 1990s. The Intelligent Prosthesis was the first commercially available microprocessor-controlled prosthetic knee. It was released by Chas. A. Blatchford & Sons, Ltd., of Great Britain, in 1993 and made walking with the prosthesis feel and look more natural.[41] An improved version was released in 1995 by the name Intelligent Prosthesis Plus. Blatchford released another prosthesis, the Adaptive Prosthesis, in 1998. The Adaptive Prosthesis utilized hydraulic controls, pneumatic controls, and a microprocessor to provide the amputee with a gait that was more responsive to changes in walking speed. Cost analysis reveals that a sophisticated above-knee prosthesis will be about $1 million in 45 years, given only annual cost of living adjustments.[42] In 2019, a project under AT2030 was launched in which bespoke sockets are made using a thermoplastic, rather than through a plaster cast. This is faster to do and significantly less expensive. The sockets were called Amparo Confidence sockets.[43][44] Upper extremity modern history In 2005, DARPA started the Revolutionizing Prosthetics program.[45][46][47][48][49][50] Design trends moving forward There are many steps in the evolution of prosthetic design trends that are moving forward with time. Many design trends point to lighter, more durable, and flexible materials like carbon fiber, silicone, and advanced polymers. These not only make the prosthetic limb lighter and more durable but also allow it to mimic the look and feel of natural skin, providing users with a more comfortable and natural experience.[51] This new technology helps prosthetic users blend in with people with normal ligaments to reduce the stigmatism for people who wear prosthetics. Another trend points towards using bionics and myoelectric components in prosthetic design. These limbs utilize sensors to detect electrical signals from the user's residual muscles. The signals are then converted into motions, allowing users to control their prosthetic limbs using their own muscle contractions. This has greatly improved the range and fluidity of movements available to amputees, making tasks like grasping objects or walking naturally much more feasible.[51] Integration with AI is also on the forefront to the prosthetic design. AI-enabled prosthetic limbs can learn and adapt to the user's habits and preferences over time, ensuring optimal functionality. By analyzing the user's gait, grip, and other movements, these smart limbs can make real-time adjustments, providing smoother and more natural motions.[51] |

歴史 古代エジプトの義足 義肢装具の起源は紀元前3000年頃の古代近東であり、最も古い義肢装具の証拠は古代エジプトとイランにある。義眼に関する最古の記録は、紀元前3000 年頃のエジプトの「ホルスの目」の物語であり、ホルスの左目が摘出され、トトによって復元された。紀元前3000年から紀元前2800年頃、考古学的に最 も古い義眼の証拠が古代イランで発見され、シャールイショクタで女性と一緒に埋葬された義眼が見つかっている。紀元前1000年頃の新王国時代の遺体から 発見された木製のつま先が示すように、エジプト人もまた義足の初期のパイオニアであった[22]。紀元前1200年頃の南アジアでは、リグヴェーダに登場 する戦士の女王ヴィシュパラにまつわるもう一つの初期の文献が発見されている[23]。 ギリシャの歴史家ヘロドトスは、スパルタの捕虜から逃れるために自分の足を切り落とし、木製のものと取り替えたギリシャの占い師ヘゲシストラトゥスの物語を語っている[25]。 木と金属の義足  カプアの義足(レプリカ)  紀元前300年頃の聖金田墓地から出土した木製の義足(トルファン博物館蔵)。これは「現在知られている最古の機能的な義足」である[26]。  ゲッツ・フォン・ベルリッヒンゲン(1480年~1562年)が所有していたとされる鉄製の義手。  「機械の手のイラスト」1564年頃  1560年から1600年のものと思われる鉄の義手 長老プリニウスも、ローマの将軍マルクス・セルギウスが遠征中に右手を切断され、戦いに戻れるように盾を持つための鉄の手を作らせたという話を記録してい る。歴史的に有名で、かなり洗練された[27]義手は、16世紀初頭に作られたゲッツ・フォン・ベルリッヒンゲンのものである。しかし、義肢装具の使用が 最初に確認されたのは、紀元前950年から710年のことである。2000年、病理学者が古代テーベ近郊のエジプトのネクロポリスに埋葬されていたこの時 代のミイラを発見した。この外反母趾は木と革でできており、使用された形跡があった。2011年に生体力学エンジニアによって再現されたところ、研究者た ちはこの古代の義足が裸足でもエジプト式サンダルでも歩けることを発見した。それ以前に発見された最古の義足は、カプアの義足であった[28]。 同じ頃、フランソワ・ド・ラ・ヌエも鉄の手を持っていたとされ、17世紀にはルネ=ロベール・カヴァリエ・ド・ラ・サールが鉄の手を持っていた[29]。 中世には、義肢は極めて基本的な形であった。衰弱した騎士は、盾を支えたり、槍や剣を握ったり、騎乗した戦士を安定させたりするために義肢を装着した [30]。 ポヴェリアーノ・ヴェロネーゼのロンゴバルド家の墓地で発見されたこの骸骨を調査していた科学者たちは、この男が紀元後6世紀から8世紀の間に生きていたと推定している。 ルネサンス期には、鉄、鋼、銅、木材を使った義肢装具が発達した。機能的な義肢装具は1500年代に登場し始めた[35]。 20世紀以前の技術の進歩 イタリアの外科医が、帽子を脱ぎ、財布を開け、サインをすることができる腕を持つ切断者の存在を記録している[36]。アンブロワーズ・パレの手によっ て、切断手術と義肢装具のデザインが改善された。彼の発明のなかには、固定位置、調節可能なハーネス、膝ロック制御を備えた膝上開脚義足があった。彼の進 歩の機能性は、将来の義肢装具がどのように発展するかを示していた。 近代以前のその他の主な改良 Pieter Verduyn - 初の非ロック式膝下(BK)義足。 ジェームズ・ポッツ(James Potts) - 木製のシャンクとソケット、鋼鉄製の膝関節、膝から足首にかけての猫脚腱で制御される関節足部からなる義足。アングルシー・レッグ」または「セルフォ・レッグ」として知られるようになる。 サー・ジェームズ・サイム(Sir James Syme) - 大腿部を切断しない新しい足首切断法を考案。 ベンジャミン・パーマー - セルフォ脚を改良。自然な動きをシミュレートするため、前方にバネを追加し、腱を隠した。 デュボア・パルムリー - 吸引ソケット、多中心膝、多関節の足を持つ義足を作った。 Marcel Desoutter & Charles Desoutter - 最初のアルミニウム製義足[37]。 ヘンリー・ヘザー・ビッグとその息子ヘンリー・ロバート・ヘザー・ビッグは、クリミア戦争後、負傷兵に「外科器具」を提供するよう女王から命じられる。彼 らは、両腕切断者がかぎ針編みをすることができる腕と、象牙、フェルト、革をベースとした、他の人にとって自然に感じられる手を開発した[38]。 第二次世界大戦が終わると、NAS(全米科学アカデミー)は義肢装具の研究開発の向上を提唱し始めた。政府の資金援助により、陸軍、海軍、空軍、退役軍人局で研究開発プログラムが開発された。 下肢の近代史  1941年の義肢工場 第二次世界大戦後、カリフォルニア大学バークレー校のジェームズ・フォートとC.W.ラドクリフを含むチームが、膝上切断用の治具フィッティング・システ ムを開発し、四辺形ソケットの開発に貢献した。ジョン・サボリッチC.P.O.がContoured Adducted Trochanteric-Controlled Alignment Method (CATCAM)ソケットを発明し、後にサボリッチ・ソケットへと発展した。彼は、Ivan LongとOssur Christensenが開発した四辺形ソケットの代替品に倣い、木材から作られたオープンエンドプラグソケットに倣った。それ以前は、ソケットは四角形 に作られており、筋肉組織用の特別な収容部はなかった。そのため、新しい設計は、骨解剖学的構造をロックし、所定の位置に固定し、患者の筋組織だけでな く、既存の四肢にも体重を均等に分散させるのに役立っている。坐骨固定はよく知られており、今日、多くの義肢装具士が患者のケアに役立てている。このよう に、坐骨固定式ソケットには様々なバリエーションがあり、それぞれのソケットは患者の特定のニーズに合わせて作られている。長年にわたりソケットの開発と 改良に貢献した人物には、Tim Staats、Chris Hoyt、Frank Gottschalkなどがいる。Gottschalkは、CAT-CAMソケットの有効性に異議を唱えたが、切断外科医が行う外科的処置が、どのような タイプのソケットデザインであっても、切断者が人工関節を良好に使用できるように準備するために最も重要であると主張した[40]。 最初のマイクロプロセッサー制御の人工膝関節は1990年代初頭に発売された。インテリジェント人工膝関節は、市販された最初のマイクロプロセッサー制御 の人工膝関節である。これはChas. 1993年にイギリスのChas. A. Blatchford & Sons, Ltd.から発売され、義足を装着しての歩行がより自然に感じられるようになった[41]。ブラッチフォードは1998年に別の義足、アダプティブ・プロ テーゼを発売した。アダプティブ義足は、油圧制御、空気圧制御、マイクロプロセッサーを利用し、歩行速度の変化に反応しやすい歩容を切断者に提供した。コ スト分析によると、洗練された膝上義足は、毎年の生活費調整だけを考えると、45年後には約100万ドルになることが明らかになった[42]。 2019年には、AT2030のプロジェクトが開始され、石膏ギプスではなく、熱可塑性プラスチックを使ってオーダーメイドのソケットが作られる。これ は、より迅速に行うことができ、コストも大幅に削減できる。このソケットはアンパロ・コンフィデンス・ソケットと呼ばれている[43][44]。 上肢の現代史 2005年、DARPAはRevolutionizing Prostheticsプログラムを開始した[45][46][47][48][49][50]。 今後の設計動向 時代とともに前進する義肢装具のデザイントレンドの進化には多くのステップがある。多くの設計トレンドは、カーボンファイバー、シリコー ン、先端ポリマーなど、より軽量で耐久性に優れ、柔軟 性のある素材であることを指摘している。これらの素材は、義肢を軽量化し耐久性を向上させるだけでなく、自然な皮膚の外観や感触を模倣することを可能に し、ユーザーに快適で自然な体験を提供する。もうひとつのトレンドは、義肢のデザインにバイオニクスや筋電コンポーネントを使用することである。これらの 義肢は、ユーザーの残存筋肉からの電気信号を検出するセンサーを利用する。そして、その信号は動作に変換され、ユーザーは自分の筋肉の収縮を利用して義肢 をコントロールすることができる。これにより、切断者が利用できる動きの範囲と流動性が大幅に改善され、物を掴んだり、自然に歩いたりといった作業がより 実現しやすくなった[51]。AIを搭載した義肢は、時間の経過とともにユーザーの習慣や好みを学習・適応させ、最適な機能性を確保することができる。 ユーザーの歩行、握力、その他の動きを分析することで、これらのスマート義肢はリアルタイムで調整を行い、よりスムーズで自然な動きを提供することができ る[51]。 |

| Patient procedure A prosthesis is a functional replacement for an amputated or congenitally malformed or missing limb. Prosthetists are responsible for the prescription, design, and management of a prosthetic device. In most cases, the prosthetist begins by taking a plaster cast of the patient's affected limb. Lightweight, high-strength thermoplastics are custom-formed to this model of the patient. Cutting-edge materials such as carbon fiber, titanium and Kevlar provide strength and durability while making the new prosthesis lighter. More sophisticated prostheses are equipped with advanced electronics, providing additional stability and control.[52] |

患者の処置 義肢とは、切断された、あるいは先天的に奇形である、あるいは欠損した四肢を機能的に補うものである。義肢装具士は、義肢装具の処方、設計、管理を担当する。 ほとんどの場合、義肢装具士は患者の患肢の石膏模型を作ることから始める。軽量で強度の高い熱可塑性プラスチックが、この患者の模型に合わせて特注で成形 される。カーボンファイバー、チタン、ケブラーなどの最先端素材は、強度と耐久性を提供すると同時に、新しい義肢を軽量化する。より洗練された義足には高 度な電子機器が搭載され、さらなる安定性と制御性を提供する[52]。 |

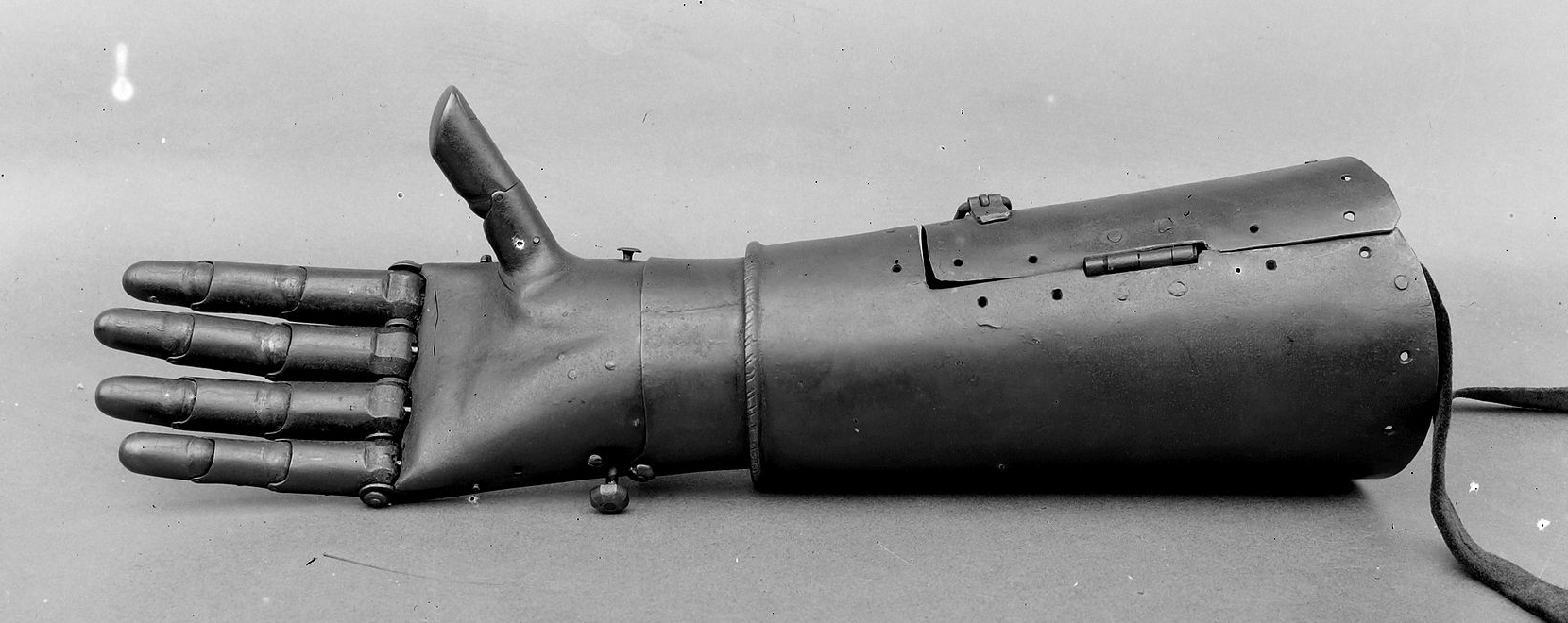

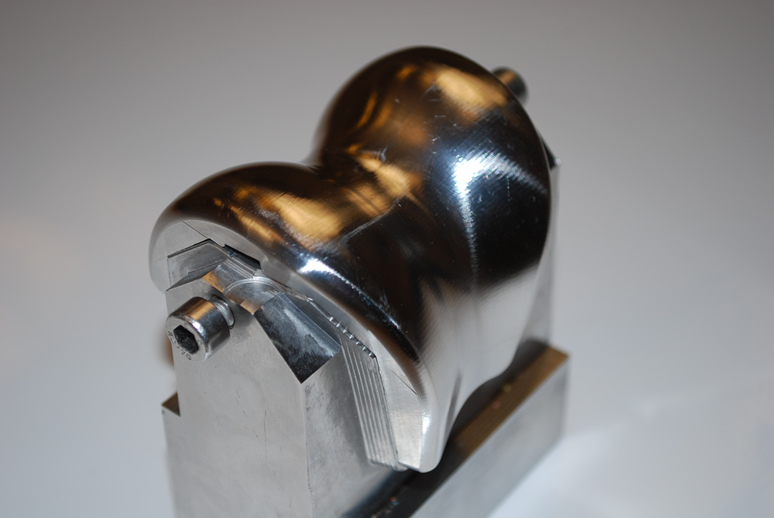

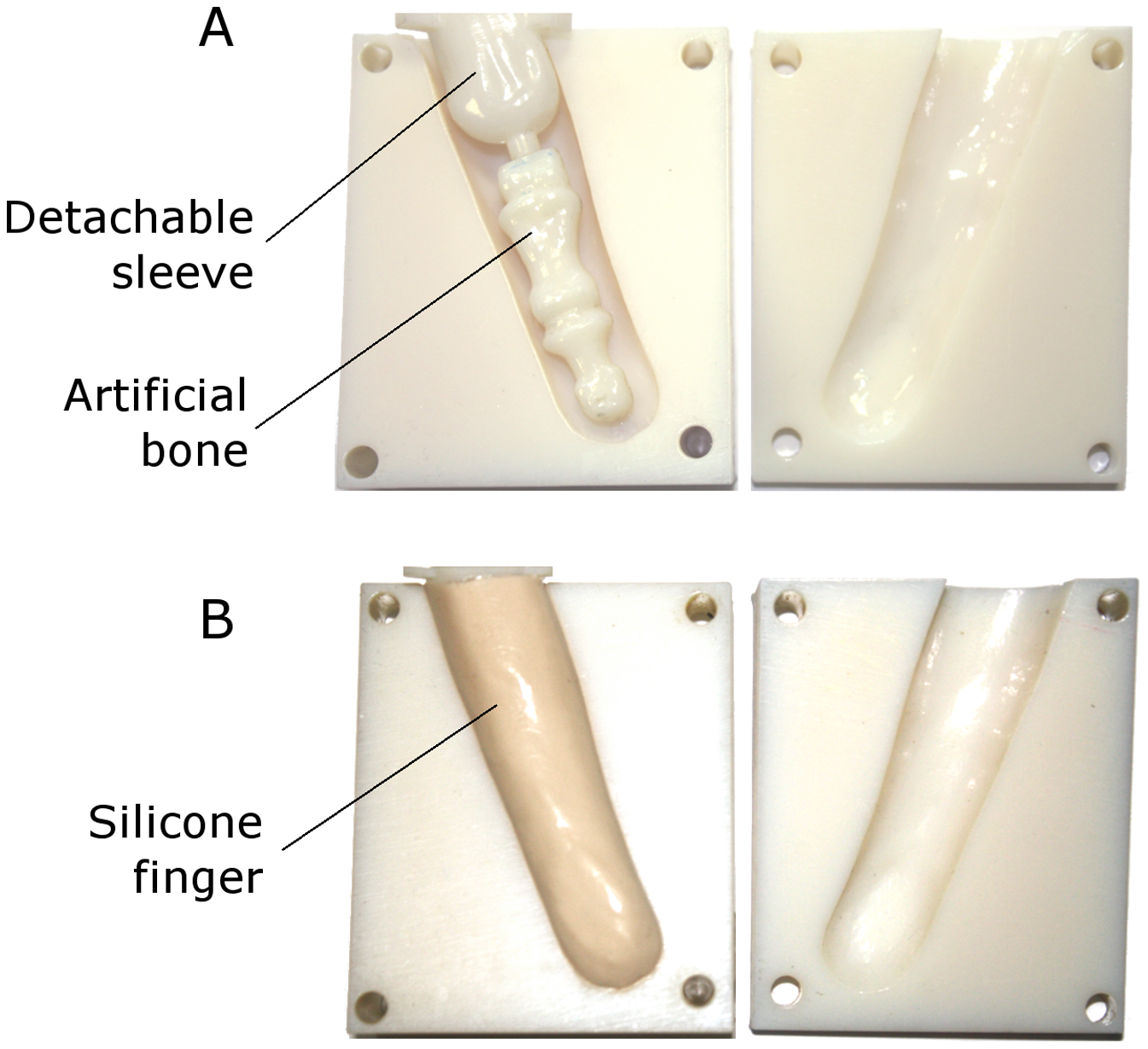

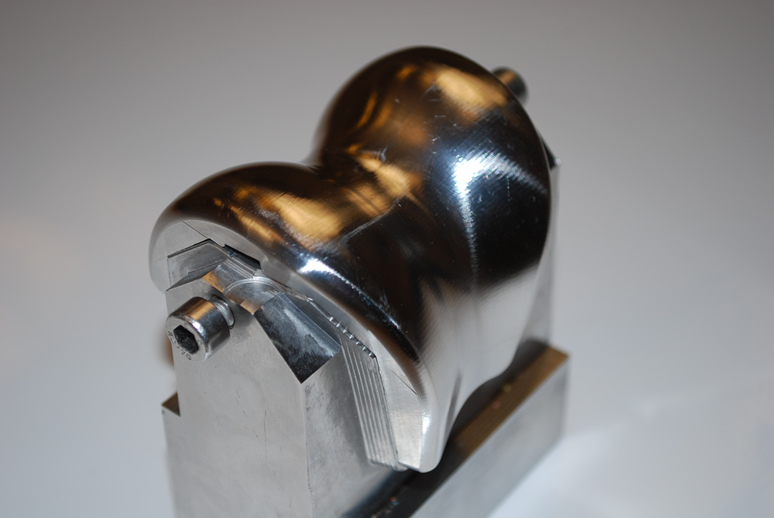

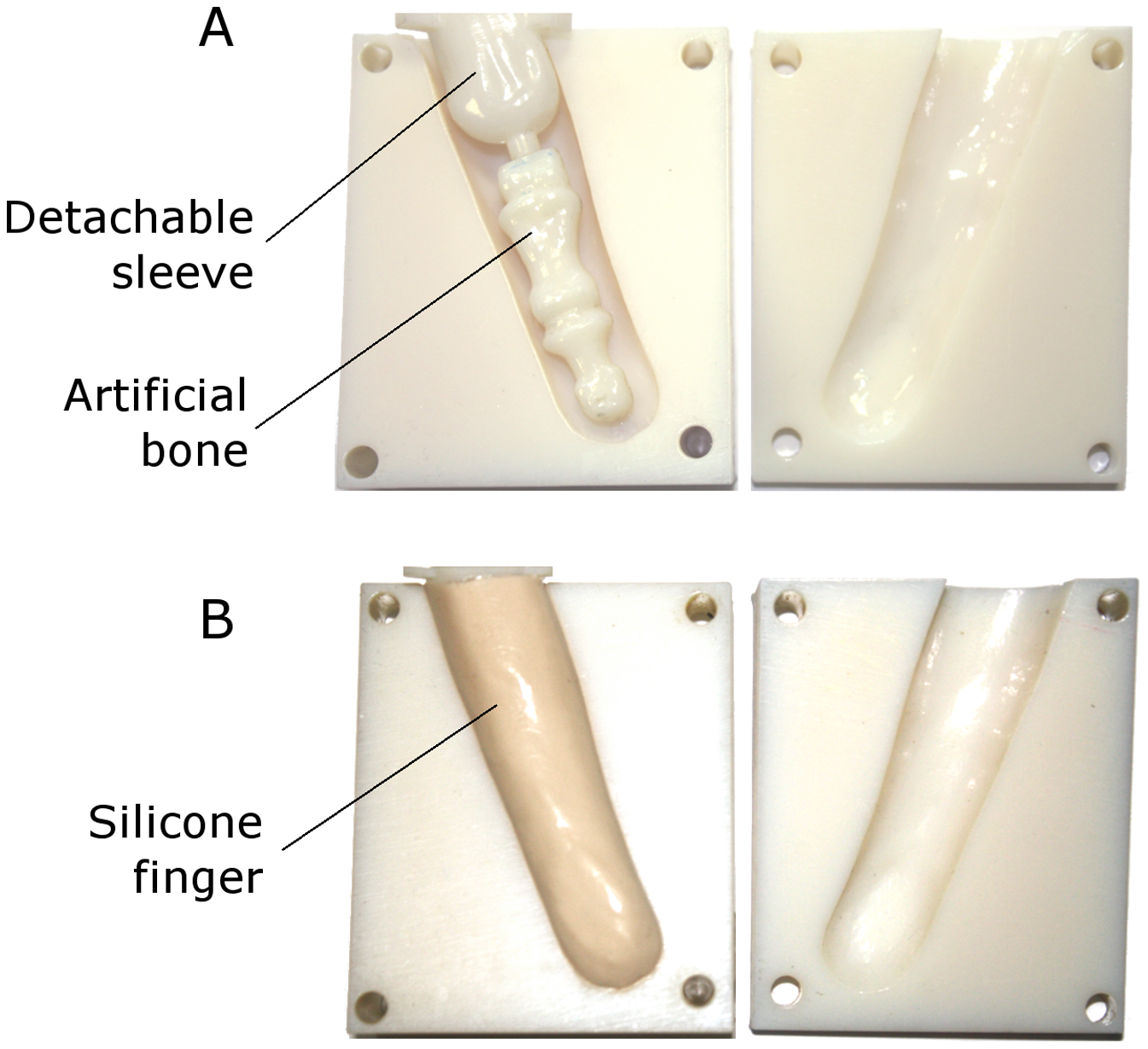

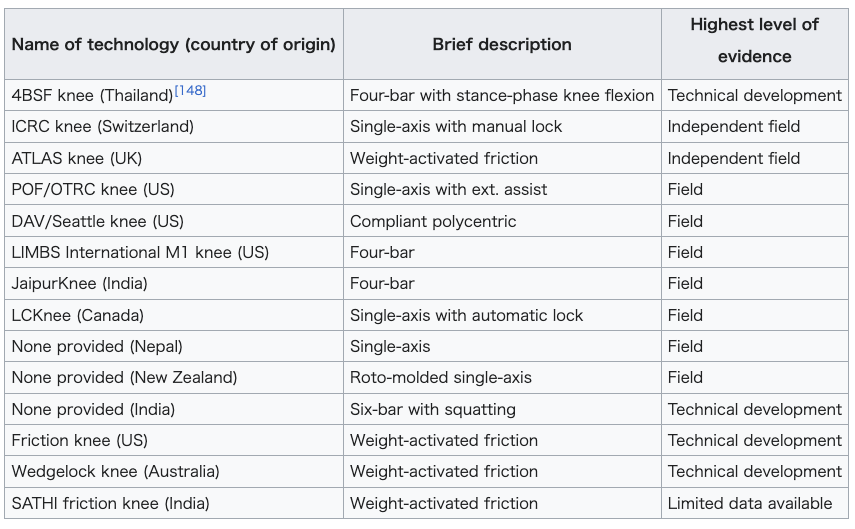

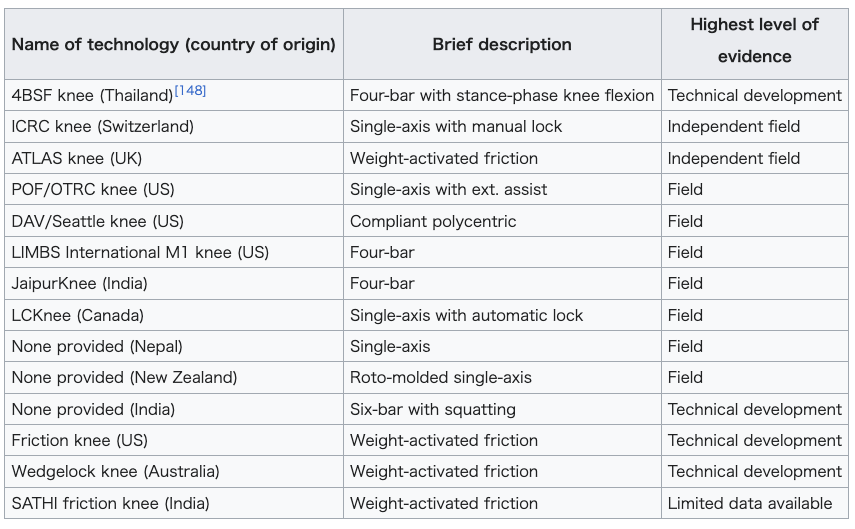

Current technology and manufacturing Knee prosthesis manufactured using WorkNC Computer Aided Manufacturing software Over the years, there have been advancements in artificial limbs. New plastics and other materials, such as carbon fiber, have allowed artificial limbs to be stronger and lighter, limiting the amount of extra energy necessary to operate the limb. This is especially important for trans-femoral amputees. Additional materials have allowed artificial limbs to look much more realistic, which is important to trans-radial and transhumeral amputees because they are more likely to have the artificial limb exposed.[53]  Manufacturing a prosthetic finger In addition to new materials, the use of electronics has become very common in artificial limbs. Myoelectric limbs, which control the limbs by converting muscle movements to electrical signals, have become much more common than cable operated limbs. Myoelectric signals are picked up by electrodes, the signal gets integrated and once it exceeds a certain threshold, the prosthetic limb control signal is triggered which is why inherently, all myoelectric controls lag. Conversely, cable control is immediate and physical, and through that offers a certain degree of direct force feedback that myoelectric control does not. Computers are also used extensively in the manufacturing of limbs. Computer Aided Design and Computer Aided Manufacturing are often used to assist in the design and manufacture of artificial limbs.[53][54] Most modern artificial limbs are attached to the residual limb (stump) of the amputee by belts and cuffs or by suction. The residual limb either directly fits into a socket on the prosthetic, or—more commonly today—a liner is used that then is fixed to the socket either by vacuum (suction sockets) or a pin lock. Liners are soft and by that, they can create a far better suction fit than hard sockets. Silicone liners can be obtained in standard sizes, mostly with a circular (round) cross section, but for any other residual limb shape, custom liners can be made. The socket is custom made to fit the residual limb and to distribute the forces of the artificial limb across the area of the residual limb (rather than just one small spot), which helps reduce wear on the residual limb. Production of prosthetic socket The production of a prosthetic socket begins with capturing the geometry of the residual limb, this process is called shape capture. The goal of this process is to create an accurate representation of the residual limb, which is critical to achieve good socket fit.[55] The custom socket is created by taking a plaster cast of the residual limb or, more commonly today, of the liner worn over their residual limb, and then making a mold from the plaster cast. The commonly used compound is called Plaster of Paris.[56] In recent years, various digital shape capture systems have been developed which can be input directly to a computer allowing for a more sophisticated design. In general, the shape capturing process begins with the digital acquisition of three-dimensional (3D) geometric data from the amputee's residual limb. Data are acquired with either a probe, laser scanner, structured light scanner, or a photographic-based 3D scanning system.[57] After shape capture, the second phase of the socket production is called rectification, which is the process of modifying the model of the residual limb by adding volume to bony prominence and potential pressure points and remove volume from load bearing area. This can be done manually by adding or removing plaster to the positive model, or virtually by manipulating the computerized model in the software.[58] Lastly, the fabrication of the prosthetic socket begins once the model has been rectified and finalized. The prosthetists would wrap the positive model with a semi-molten plastic sheet or carbon fiber coated with epoxy resin to construct the prosthetic socket.[55] For the computerized model, it can be 3D printed using a various of material with different flexibility and mechanical strength.[59] Optimal socket fit between the residual limb and socket is critical to the function and usage of the entire prosthesis. If the fit between the residual limb and socket attachment is too loose, this will reduce the area of contact between the residual limb and socket or liner, and increase pockets between residual limb skin and socket or liner. Pressure then is higher, which can be painful. Air pockets can allow sweat to accumulate that can soften the skin. Ultimately, this is a frequent cause for itchy skin rashes. Over time, this can lead to breakdown of the skin.[15] On the other hand, a very tight fit may excessively increase the interface pressures that may also lead to skin breakdown after prolonged use.[60] Artificial limbs are typically manufactured using the following steps:[53] Measurement of the residual limb Measurement of the body to determine the size required for the artificial limb Fitting of a silicone liner Creation of a model of the liner worn over the residual limb Formation of thermoplastic sheet around the model – This is then used to test the fit of the prosthetic Formation of permanent socket Formation of plastic parts of the artificial limb – Different methods are used, including vacuum forming and injection molding Creation of metal parts of the artificial limb using die casting Assembly of entire limb Body-powered arms Current technology allows body-powered arms to weigh around one-half to one-third of what a myoelectric arm does. Sockets Current body-powered arms contain sockets that are built from hard epoxy or carbon fiber. These sockets or "interfaces" can be made more comfortable by lining them with a softer, compressible foam material that provides padding for the bone prominences. A self-suspending or supra-condylar socket design is useful for those with short to mid-range below elbow absence. Longer limbs may require the use of a locking roll-on type inner liner or more complex harnessing to help augment suspension. Wrists Wrist units are either screw-on connectors featuring the UNF 1/2-20 thread (USA) or quick-release connector, of which there are different models. Voluntary opening and voluntary closing Two types of body-powered systems exist, voluntary opening "pull to open" and voluntary closing "pull to close". Virtually all "split hook" prostheses operate with a voluntary opening type system. More modern "prehensors" called GRIPS utilize voluntary closing systems. The differences are significant. Users of voluntary opening systems rely on elastic bands or springs for gripping force, while users of voluntary closing systems rely on their own body power and energy to create gripping force. Voluntary closing users can generate prehension forces equivalent to the normal hand, up to or exceeding one hundred pounds. Voluntary closing GRIPS require constant tension to grip, like a human hand, and in that property, they do come closer to matching human hand performance. Voluntary opening split hook users are limited to forces their rubber or springs can generate which usually is below 20 pounds. Feedback An additional difference exists in the biofeedback created that allows the user to "feel" what is being held. Voluntary opening systems once engaged provide the holding force so that they operate like a passive vice at the end of the arm. No gripping feedback is provided once the hook has closed around the object being held. Voluntary closing systems provide directly proportional control and biofeedback so that the user can feel how much force that they are applying. In 1997, the Colombian Prof. Álvaro Ríos Poveda, a researcher in bionics in Latin America, developed an upper limb and hand prosthesis with sensory feedback. This technology allows amputee patients to handle prosthetic hand systems in a more natural way.[61] A recent study showed that by stimulating the median and ulnar nerves, according to the information provided by the artificial sensors from a hand prosthesis, physiologically appropriate (near-natural) sensory information could be provided to an amputee. This feedback enabled the participant to effectively modulate the grasping force of the prosthesis with no visual or auditory feedback.[62] In February 2013, researchers from École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in Switzerland and the Scuola Superiore Sant'Anna in Italy, implanted electrodes into an amputee's arm, which gave the patient sensory feedback and allowed for real time control of the prosthetic.[63] With wires linked to nerves in his upper arm, the Danish patient was able to handle objects and instantly receive a sense of touch through the special artificial hand that was created by Silvestro Micera and researchers both in Switzerland and Italy.[64] In July 2019, this technology was expanded on even further by researchers from the University of Utah, led by Jacob George. The group of researchers implanted electrodes into the patient's arm to map out several sensory precepts. They would then stimulate each electrode to figure out how each sensory precept was triggered, then proceed to map the sensory information onto the prosthetic. This would allow the researchers to get a good approximation of the same kind of information that the patient would receive from their natural hand. Unfortunately, the arm is too expensive for the average user to acquire, however, Jacob mentioned that insurance companies could cover the costs of the prosthetic.[65] Terminal devices Terminal devices contain a range of hooks, prehensors, hands or other devices. Hooks Voluntary opening split hook systems are simple, convenient, light, robust, versatile and relatively affordable. A hook does not match a normal human hand for appearance or overall versatility, but its material tolerances can exceed and surpass the normal human hand for mechanical stress (one can even use a hook to slice open boxes or as a hammer whereas the same is not possible with a normal hand), for thermal stability (one can use a hook to grip items from boiling water, to turn meat on a grill, to hold a match until it has burned down completely) and for chemical hazards (as a metal hook withstands acids or lye, and does not react to solvents like a prosthetic glove or human skin). Hands  Actor Owen Wilson gripping the myoelectric prosthetic arm of a United States Marine Prosthetic hands are available in both voluntary opening and voluntary closing versions and because of their more complex mechanics and cosmetic glove covering require a relatively large activation force, which, depending on the type of harness used, may be uncomfortable.[66] A recent study by the Delft University of Technology, The Netherlands, showed that the development of mechanical prosthetic hands has been neglected during the past decades. The study showed that the pinch force level of most current mechanical hands is too low for practical use.[67] The best tested hand was a prosthetic hand developed around 1945. In 2017 however, a research has been started with bionic hands by Laura Hruby of the Medical University of Vienna.[68][69] A few open-hardware 3-D printable bionic hands have also become available.[70] Some companies are also producing robotic hands with integrated forearm, for fitting unto a patient's upper arm[71][72] and in 2020, at the Italian Institute of Technology (IIT), another robotic hand with integrated forearm (Soft Hand Pro) was developed.[73] Commercial providers and materials Hosmer and Otto Bock are major commercial hook providers. Mechanical hands are sold by Hosmer and Otto Bock as well; the Becker Hand is still manufactured by the Becker family. Prosthetic hands may be fitted with standard stock or custom-made cosmetic looking silicone gloves. But regular work gloves may be worn as well. Other terminal devices include the V2P Prehensor, a versatile robust gripper that allows customers to modify aspects of it, Texas Assist Devices (with a whole assortment of tools) and TRS that offers a range of terminal devices for sports. Cable harnesses can be built using aircraft steel cables, ball hinges, and self-lubricating cable sheaths. Some prosthetics have been designed specifically for use in salt water.[74] Lower-extremity prosthetics  A prosthetic leg worn by Ellie Cole Lower-extremity prosthetics describes artificially replaced limbs located at the hip level or lower. Concerning all ages Ephraim et al. (2003) found a worldwide estimate of all-cause lower-extremity amputations of 2.0–5.9 per 10,000 inhabitants. For birth prevalence rates of congenital limb deficiency they found an estimate between 3.5 and 7.1 cases per 10,000 births.[75] The two main subcategories of lower extremity prosthetic devices are trans-tibial (any amputation transecting the tibia bone or a congenital anomaly resulting in a tibial deficiency), and trans-femoral (any amputation transecting the femur bone or a congenital anomaly resulting in a femoral deficiency). In the prosthetic industry, a trans-tibial prosthetic leg is often referred to as a "BK" or below the knee prosthesis while the trans-femoral prosthetic leg is often referred to as an "AK" or above the knee prosthesis. Other, less prevalent lower extremity cases include the following: Hip disarticulations – This usually refers to when an amputee or congenitally challenged patient has either an amputation or anomaly at or in close proximity to the hip joint. Knee disarticulations – This usually refers to an amputation through the knee disarticulating the femur from the tibia. Symes – This is an ankle disarticulation while preserving the heel pad. Socket The socket serves as an interface between the residuum and the prosthesis, ideally allowing comfortable weight-bearing, movement control and proprioception.[76] Socket problems, such as discomfort and skin breakdown, are rated among the most important issues faced by lower-limb amputees.[77] Shank and connectors This part creates distance and support between the knee-joint and the foot (in case of an upper-leg prosthesis) or between the socket and the foot. The type of connectors that are used between the shank and the knee/foot determines whether the prosthesis is modular or not. Modular means that the angle and the displacement of the foot in respect to the socket can be changed after fitting. In developing countries prosthesis mostly are non-modular, in order to reduce cost. When considering children modularity of angle and height is important because of their average growth of 1.9 cm annually.[78] Foot Providing contact to the ground, the foot provides shock absorption and stability during stance.[79] Additionally it influences gait biomechanics by its shape and stiffness. This is because the trajectory of the center of pressure (COP) and the angle of the ground reaction forces is determined by the shape and stiffness of the foot and needs to match the subject's build in order to produce a normal gait pattern.[80] Andrysek (2010) found 16 different types of feet, with greatly varying results concerning durability and biomechanics. The main problem found in current feet is durability, endurance ranging from 16 to 32 months[81] These results are for adults and will probably be worse for children due to higher activity levels and scale effects. Evidence comparing different types of feet and ankle prosthetic devices is not strong enough to determine if one mechanism of ankle/foot is superior to another.[82] When deciding on a device, the cost of the device, a person's functional need, and the availability of a particular device should be considered.[82] Knee joint In case of a trans-femoral (above knee) amputation, there also is a need for a complex connector providing articulation, allowing flexion during swing-phase but not during stance. As its purpose is to replace the knee, the prosthetic knee joint is the most critical component of the prosthesis for trans-femoral amputees. The function of the good prosthetic knee joint is to mimic the function of the normal knee, such as providing structural support and stability during stance phase but able to flex in a controllable manner during swing phase. Hence it allows users to have a smooth and energy efficient gait and minimize the impact of amputation.[83] The prosthetic knee is connected to the prosthetic foot by the shank, which is usually made of an aluminum or graphite tube. One of the most important aspect of a prosthetic knee joint would be its stance-phase control mechanism. The function of stance-phase control is to prevent the leg from buckling when the limb is loaded during weight acceptance. This ensures the stability of the knee in order to support the single limb support task of stance phase and provides a smooth transition to the swing phase. Stance phase control can be achieved in several ways including the mechanical locks,[84] relative alignment of prosthetic components,[85] weight activated friction control,[85] and polycentric mechanisms.[86] Microprocessor control To mimic the knee's functionality during gait, microprocessor-controlled knee joints have been developed that control the flexion of the knee. Some examples are Otto Bock's C-leg, introduced in 1997, Ossur's Rheo Knee, released in 2005, the Power Knee by Ossur, introduced in 2006, the Plié Knee from Freedom Innovations and DAW Industries' Self Learning Knee (SLK).[87] The idea was originally developed by Kelly James, a Canadian engineer, at the University of Alberta.[88] A microprocessor is used to interpret and analyze signals from knee-angle sensors and moment sensors. The microprocessor receives signals from its sensors to determine the type of motion being employed by the amputee. Most microprocessor controlled knee-joints are powered by a battery housed inside the prosthesis. The sensory signals computed by the microprocessor are used to control the resistance generated by hydraulic cylinders in the knee-joint. Small valves control the amount of hydraulic fluid that can pass into and out of the cylinder, thus regulating the extension and compression of a piston connected to the upper section of the knee.[42] The main advantage of a microprocessor-controlled prosthesis is a closer approximation to an amputee's natural gait. Some allow amputees to walk near walking speed or run. Variations in speed are also possible and are taken into account by sensors and communicated to the microprocessor, which adjusts to these changes accordingly. It also enables the amputees to walk downstairs with a step-over-step approach, rather than the one step at a time approach used with mechanical knees.[89] There is some research suggesting that people with microprocessor-controlled prostheses report greater satisfaction and improvement in functionality, residual limb health, and safety.[90] People may be able to perform everyday activities at greater speeds, even while multitasking, and reduce their risk of falls.[90] However, some have some significant drawbacks that impair its use. They can be susceptible to water damage and thus great care must be taken to ensure that the prosthesis remains dry.[91] Myoelectric A myoelectric prosthesis uses the electrical tension generated every time a muscle contracts, as information. This tension can be captured from voluntarily contracted muscles by electrodes applied on the skin to control the movements of the prosthesis, such as elbow flexion/extension, wrist supination/pronation (rotation) or opening/closing of the fingers. A prosthesis of this type utilizes the residual neuromuscular system of the human body to control the functions of an electric powered prosthetic hand, wrist, elbow or foot.[92] This is different from an electric switch prosthesis, which requires straps and/or cables actuated by body movements to actuate or operate switches that control the movements of the prosthesis. There is no clear evidence concluding that myoelectric upper extremity prostheses function better than body-powered prostheses.[93] Advantages to using a myoelectric upper extremity prosthesis include the potential for improvement in cosmetic appeal (this type of prosthesis may have a more natural look), may be better for light everyday activities, and may be beneficial for people experiencing phantom limb pain.[93] When compared to a body-powered prosthesis, a myoelectric prosthesis may not be as durable, may have a longer training time, may require more adjustments, may need more maintenance, and does not provide feedback to the user.[93] Prof. Alvaro Ríos Poveda has been working for several years on a non-invasive and affordable solution to this feedback problem. He considers that: "Prosthetic limbs that can be controlled with thought hold great promise for the amputee, but without sensorial feedback from the signals returning to the brain, it can be difficult to achieve the level of control necessary to perform precise movements. When connecting the sense of touch from a mechanical hand directly to the brain, prosthetics can restore the function of the amputated limb in an almost natural-feeling way." He presented the first Myoelectric prosthetic hand with sensory feedback at the XVIII World Congress on Medical Physics and Biomedical Engineering, 1997, held in Nice, France.[94][95] The USSR was the first to develop a myoelectric arm in 1958,[96] while the first myoelectric arm became commercial in 1964 by the Central Prosthetic Research Institute of the USSR, and distributed by the Hangar Limb Factory of the UK.[97][98] Robotic prostheses Brain control of 3D prosthetic arm movement (hitting targets). This movie(nothing) was recorded when the participant controlled the 3D movement of a prosthetic arm to hit physical targets in a research lab. Main articles: Neural prosthetics and Powered exoskeleton § Current products (powered exoskeletons) Further information: Robotics § Touch, 3-D printing, and Open-source hardware Robots can be used to generate objective measures of patient's impairment and therapy outcome, assist in diagnosis, customize therapies based on patient's motor abilities, and assure compliance with treatment regimens and maintain patient's records. It is shown in many studies that there is a significant improvement in upper limb motor function after stroke using robotics for upper limb rehabilitation.[99] In order for a robotic prosthetic limb to work, it must have several components to integrate it into the body's function: Biosensors detect signals from the user's nervous or muscular systems. It then relays this information to a microcontroller located inside the device, and processes feedback from the limb and actuator, e.g., position or force, and sends it to the controller. Examples include surface electrodes that detect electrical activity on the skin, needle electrodes implanted in muscle, or solid-state electrode arrays with nerves growing through them. One type of these biosensors are employed in myoelectric prostheses. A device known as the controller is connected to the user's nerve and muscular systems and the device itself. It sends intention commands from the user to the actuators of the device and interprets feedback from the mechanical and biosensors to the user. The controller is also responsible for the monitoring and control of the movements of the device. An actuator mimics the actions of a muscle in producing force and movement. Examples include a motor that aids or replaces original muscle tissue. Targeted muscle reinnervation (TMR) is a technique in which motor nerves, which previously controlled muscles on an amputated limb, are surgically rerouted such that they reinnervate a small region of a large, intact muscle, such as the pectoralis major. As a result, when a patient thinks about moving the thumb of their missing hand, a small area of muscle on their chest will contract instead. By placing sensors over the reinnervated muscle, these contractions can be made to control the movement of an appropriate part of the robotic prosthesis.[100][101] A variant of this technique is called targeted sensory reinnervation (TSR). This procedure is similar to TMR, except that sensory nerves are surgically rerouted to skin on the chest, rather than motor nerves rerouted to muscle. Recently, robotic limbs have improved in their ability to take signals from the human brain and translate those signals into motion in the artificial limb. DARPA, the Pentagon's research division, is working to make even more advancements in this area. Their desire is to create an artificial limb that ties directly into the nervous system.[102] Robotic arms Advancements in the processors used in myoelectric arms have allowed developers to make gains in fine-tuned control of the prosthetic. The Boston Digital Arm is a recent artificial limb that has taken advantage of these more advanced processors. The arm allows movement in five axes and allows the arm to be programmed for a more customized feel. Recently the I-LIMB Hand, invented in Edinburgh, Scotland, by David Gow has become the first commercially available hand prosthesis with five individually powered digits. The hand also possesses a manually rotatable thumb which is operated passively by the user and allows the hand to grip in precision, power, and key grip modes.[103] Another neural prosthetic is Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory Proto 1. Besides the Proto 1, the university also finished the Proto 2 in 2010.[104] Early in 2013, Max Ortiz Catalan and Rickard Brånemark of the Chalmers University of Technology, and Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Sweden, succeeded in making the first robotic arm which is mind-controlled and can be permanently attached to the body (using osseointegration).[105][106][107] An approach that is very useful is called arm rotation which is common for unilateral amputees which is an amputation that affects only one side of the body; and also essential for bilateral amputees, a person who is missing or has had amputated either both arms or legs, to carry out activities of daily living. This involves inserting a small permanent magnet into the distal end of the residual bone of subjects with upper limb amputations. When a subject rotates the residual arm, the magnet will rotate with the residual bone, causing a change in magnetic field distribution.[108] EEG (electroencephalogram) signals, detected using small flat metal discs attached to the scalp, essentially decoding human brain activity used for physical movement, is used to control the robotic limbs. This allows the user to control the part directly.[109] Robotic transtibial prostheses The research of robotic legs has made some advancement over time, allowing exact movement and control. Researchers at the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago announced in September 2013 that they have developed a robotic leg that translates neural impulses from the user's thigh muscles into movement, which is the first prosthetic leg to do so. It is currently in testing.[110] Hugh Herr, head of the biomechatronics group at MIT's Media Lab developed a robotic transtibial leg (PowerFoot BiOM).[111][112] The Icelandic company Össur has also created a robotic transtibial leg with motorized ankle that moves through algorithms and sensors that automatically adjust the angle of the foot during different points in its wearer's stride. Also there are brain-controlled bionic legs that allow an individual to move his limbs with a wireless transmitter.[113] Prosthesis design The main goal of a robotic prosthesis is to provide active actuation during gait to improve the biomechanics of gait, including, among other things, stability, symmetry, or energy expenditure for amputees.[114] There are several powered prosthetic legs currently on the market, including fully powered legs, in which actuators directly drive the joints, and semi-active legs, which use small amounts of energy and a small actuator to change the mechanical properties of the leg but do not inject net positive energy into gait. Specific examples include The emPOWER from BionX, the Proprio Foot from Ossur, and the Elan Foot from Endolite.[115][116][117] Various research groups have also experimented with robotic legs over the last decade.[118] Central issues being researched include designing the behavior of the device during stance and swing phases, recognizing the current ambulation task, and various mechanical design problems such as robustness, weight, battery-life/efficiency, and noise-level. However, scientists from Stanford University and Seoul National University has developed artificial nerves system that will help prosthetic limbs feel.[119] This synthetic nerve system enables prosthetic limbs sense braille, feel the sense of touch and respond to the environment.[120][121] Use of recycled materials Prosthetics are being made from recycled plastic bottles and lids around the world.[122][123][124][125][126] |

現在の技術と製造 WorkNC Computer Aided Manufacturingソフトウェアを使用して製造された人工膝関節 長年にわたり、義肢は進歩してきた。新しいプラスチックや炭素繊維などの素材により、義肢はより強く、より軽くなり、義肢を操作するのに必要な余分なエネ ルギーの量を抑えることができるようになった。これは特に経大腿切断者にとって重要である。このことは、義肢が露出する可能性が高い経橈骨・経上腕切断者 にとって重要である[53]。  義指の製造 新素材に加え、電子機器の使用も義肢では非常に一般的になっている。筋肉の動きを電気信号に変換して手足を制御する筋電義肢は、ケーブルで操作する義肢よ りもはるかに一般的になっている。筋電信号は電極で拾われ、信号は統合され、ある閾値を超えると義肢の制御信号がトリガーされる。逆に、ケーブル制御は即 時的で物理的であり、筋電制御にはないある程度の直接的な力のフィードバックが得られる。コンピューターは手足の製造にも広く使われている。コンピュータ 支援設計とコンピュータ支援製造は、義肢の設計と製造を支援するためにしばしば使用される[53][54]。 現代のほとんどの義肢は、切断者の残存肢(切り株)にベルトやカフス、または吸引によって取り付けられている。残存肢は義肢装具のソケットに直接はめ込む か、より一般的にはライナーが使用され、ライナーは真空(吸引ソケット)またはピンロックによってソケットに固定される。ライナーは柔らかいので、硬いソ ケットよりもはるかに優れた吸引フィットが得られる。シリコーン製ライナーは、標準的なサイズ、主に断面が円形(ラウンド)のものを入手できるが、その他 の残存肢の形状であれば、特注のライナーを作ることができる。ソケットは、残存肢にフィットするようにカスタムメイドされ、義肢の力を残存肢の領域全体に 分散させる(1つの小さな場所だけでなく)ため、残存肢の摩耗を軽減するのに役立つ。 義足ソケットの製作 義足ソケットの製作は、残存肢の形状をキャプチャすることから始まる。このプロセスの目的は、残存肢を正確に表現することであり、これは良好なソケット フィットを達成するために非常に重要である。[55] カスタムソケットは、残存肢の石膏模型、または今日より一般的には残存肢の上に装着するライナーの石膏模型を採取し、その石膏模型から型を作成することに よって作成される。近年では、コンピュータに直接入力できるさまざまなデジタル形状キャプチャシステムが開発され、より高度な設計が可能になっている [56]。一般に、形状キャプチャープロセスは、切断者の残存肢から3次元(3D)形状データをデジタルで取得することから始まる。データ取得には、プ ローブ、レーザースキャナー、構造化光スキャナー、写真ベースの3Dスキャンシステムのいずれかを使用する[57]。 これは、骨隆起や潜在的な圧迫点に体積を追加したり、荷重を受ける部分から体積を削除したりして、残存肢のモデルを修正するプロセスである。この作業は、 ポジティ ブモデルに石膏を追加したり削除したりすることで手作業で行うことも、コンピュータ化されたモデルをソフトウ ェアで操作することでバーチャルに行うこともできる[58]。義肢装具士は、半溶融プラスチックシートやカーボンファイバーにエポキシ樹脂をコーティング したもので陽性モデルを包み、義肢ソケットを製作する[55]。 残存肢とソケットの最適な適合は、義肢全体の機能と使用にとって極めて重要である。残存肢とソケットアタッチメント間のフィッ トが緩すぎると、残存肢とソケットまたはライナ ーとの接触面積が減少し、残存肢の皮膚とソケットま たはライナーとの間のポケットが増加する。そうなると圧力が高くなり、痛みを伴うことがある。エアポケットに汗がたまり、皮膚が柔らかくなることもある。 最終的には、これがかゆみを伴う皮疹の原因となることが多い。一方、非常にタイトな装着は、界面圧を過度に増加させ、長期間の使用後に皮膚の破壊につなが る可能性がある [15] 。 義肢は通常、以下の手順で製造される [53] 。 残存肢の測定 義肢に必要なサイズを決定するための身体の測定 シリコン製ライナーの装着 残存肢に装着するライナーのモデルを作成する。 模型の周囲に熱可塑性シートを形成 - これを用いて義肢の適合性をテストする。 永久ソケットの形成 義肢のプラスチック部品の形成 - 真空成形や射出成形など、さまざまな方法が用いられる。 ダイカストで義肢の金属部品を作る。 義肢全体の組み立て 体動力アーム 現在の技術では、体動力アームは筋電アームの2分の1から3分の1程度の重さしかない。 ソケット 現在の体動アームには、硬質エポキシやカーボンファイバーで作られたソケットがある。これらのソケットや「インターフェイス」は、骨隆起にパッドを提供す る、より柔らかく圧縮可能な発泡素材で裏打ちすることによって、より快適にすることができる。自己懸垂型ソケットや顆上型ソケットは、肘から下が短いか中 程度の人に有用である。手足が長い場合は、ロック式のロールオンタイプのインナーライナーを使用するか、より複雑なハーネスを使用してサスペンションを補 強する必要がある。 手首 手首のユニットは、UNF1/2-20ネジ(米国)を使用したスクリューオン・コネクターか、クイックリリース・コネクターのどちらかで、さまざまなモデルがある。 任意開閉 体動式システムには、「引っ張って開く」随意開閉式と「引っ張って閉じる」随意閉止式の2種類がある。事実上すべての「スプリット・フック」義足は、随意開閉式システムで作動する。 GRIPSと呼ばれる最新の 「prehensors 」は、随意的閉鎖システムを利用している。この違いは大きい。ボランタリー・オープニング・システムのユーザーは、グリップ力を弾性バンドやバネに頼るの に対し、ボランタリー・クローズド・システムのユーザーは、グリップ力を生み出すために自分の身体の力とエネルギーに頼る。 ボランタリー・クロージング・システムの使用者は、通常の手と同等、最大で100ポンドを超えるプレヒニオン力を発生させることができる。ボランタリー・ クロージング・グリップは、人間の手のようにグリップを握るために一定の張力を必要とし、その性質上、人間の手の性能に近づく。ボランタリー・オープン・ スプリット・フックのユーザーは、ゴムやスプリングが発生させることができる力に制限があり、それは通常20ポンド以下である。 フィードバック さらなる違いは、使用者が握られているものを「感じる」ことを可能にするバイオフィードバックにある。ボランタリー・オープニング・システムは、一旦噛み 合わされると、腕の先で受動的な万力のように動作するように保持力を提供する。フックが保持されている物体の周りを閉じた後は、把持のフィードバックは提 供されない。ボランタリー・クロージング・システムは、直接比例制御とバイオフィードバックを提供するため、ユーザーは自分がどれだけの力を加えているか を感じることができる。 1997年、ラテンアメリカのバイオニクス研究者であるコロンビアのアルバロ・リオス・ポベダ教授は、感覚フィードバック付きの上肢と手の義肢を開発した。この技術により、切断患者はより自然な方法で義手システムを扱うことができるようになった[61]。 最近の研究では、義手の人工センサーから得られる情報に従って正中神経と尺骨神経を刺激することで、生理学的に適切な(自然に近い)感覚情報を切断者に提 供できることが示された。このフィードバックにより、参加者は視覚的・聴覚的フィードバックがなくても、義手の把持力を効果的に調節することができた [62]。 2013年2月、スイスのローザンヌ工科大学とイタリアのサンタンナ工科大学の研究者たちは、切断患者の腕に電極を埋め込み、患者に感覚フィードバックを 与え、義手をリアルタイムで制御できるようにした[63]。上腕の神経につながったワイヤーによって、デンマークの患者は、シルベストロ・ミセラとスイス とイタリアの研究者たちによって作られた特殊な義手を通して、物を扱い、触覚を瞬時に受け取ることができた[64]。 2019年7月、ジェイコブ・ジョージ率いるユタ大学の研究者たちによって、この技術はさらに拡張された。この研究者グループは、患者の腕に電極を埋め込 み、いくつかの感覚知覚をマッピングした。そして、各電極を刺激して各感覚がどのように引き起こされるかを調べ、その感覚情報を義肢にマッピングしてい く。こうすることで、研究者たちは、患者が自然の手から受け取るのと同じような情報の近似値を得ることができる。残念ながら、このアームは一般ユーザーが 手にするには高価すぎるが、ジェイコブ氏は、保険会社が義手の費用を負担してくれる可能性があると述べている[65]。 ターミナル・デバイス ターミナル・デバイスには、さまざまなフック、プレヘンサ、手、その他のデバイスが含まれる。 フック ボランタリー・オープン・スプリット・フック・システムは、シンプルで、便利で、軽く、頑丈で、汎用性があり、比較的手頃な価格である。 フックは、外観や全体的な汎用性では通常の人間の手には及ばないが、その材料公差は、機械的応力では通常の人間の手を上回り、上回ることができる(通常の 手では不可能な、箱を切り開くためやハンマーとしてフックを使用することさえできる)、 熱的安定性(沸騰したお湯の中のものをつかむ、グリルで肉を焼く、完全に燃え尽きるまでマッチを持つ、といった使い方ができる)、化学的危険性(金属製の フックは酸や灰汁に耐え、義手や人間の皮膚のように溶剤に反応しない)。 手  米国海兵隊員の筋電義手を握る俳優オーウェン・ウィルソン 義手には、随意的に開くタイプと随意的に閉じるタイプの両方があるが、より複雑な機構と化粧用手袋のカバーのため、比較的大きな作動力が必要であり、使用 するハーネスの種類によっては、不快に感じることがある[66]。オランダのデルフト工科大学の最近の研究によると、機械式義手の開発は過去数十年間、軽 視されてきた。この研究では、現在のほとんどの機械式義手の挟む力のレベルは、実用化には低すぎることが示された[67]。最もテストされた義手は、 1945年頃に開発された義手であった。しかし2017年、ウィーン医科大学のLaura Hrubyによってバイオニックハンドの研究が開始された[68][69]。いくつかのオープンハードウェアの3Dプリント可能なバイオニックハンドも利 用可能になっている[70]。 商業プロバイダーと素材 ホスマー社とオットーボック社は、主要な市販フック・メーカーである。ベッカー・ハンドは現在もベッカー家によって製造されている。義手には、標準的な純 正品または特注の化粧用シリコン手袋を装着することができる。しかし、通常の作業用手袋を着用することもできる。その他の端末装置には、多用途の堅牢なグ リッパーであり、顧客がその一部を変更することができるV2P Prehensor、テキサス・アシスト・デバイス(ツールの全種類あり)、スポーツ用の端末装置を提供するTRSなどがある。ケーブルハーネスは、航空 機用スチールケーブル、ボールヒンジ、自己潤滑性ケーブルシースを使って作ることができる。海水での使用に特化して設計された義肢装具もある [74] 。 下肢義足  エリー・コールが着用した義足 下肢義足とは、人工的に置換された手足のうち、腰の高さ以下に位置するものを指す。Ephraimら(2003)は、全年齢を対象として、人口1万人当た り2.0~5.9人が下肢切断の全原因であると推定している。先天性四肢欠損症の出生時有病率については、1万出生あたり3.5~7.1例と推定されてい る[75]。 下肢義肢装具の2つの主なサブカテゴリーは、経脛骨(脛骨を切断する切断、または脛骨欠損をもたらす先天異常)と経大腿骨(大腿骨を切断する切断、または 大腿骨欠損をもたらす先天異常)である。義肢業界では、経脛義足は「BK」または膝下義足と呼ばれることが多く、経大腿義足は「AK」または膝上義足と呼 ばれることが多い。 その他、下肢の症例としては、以下のようなものがある: 股関節脱臼-これは通常、切断患者または先天性障害患者が、股関節またはその近傍に切断または異常がある場合を指す。 膝関節離断-これは通常、膝を切断して大腿骨と脛骨を離断することを指す。 Symes(サイムス)-これは、踵パッドを温存したまま足首を切断するものである。 ソケット ソケットは、残遺体と人工関節の間のインターフェースとして機能し、理想的には快適な体重負荷、動作制御、プロプリオセプションを可能にする[76]。不快感や皮膚破壊などのソケットの問題は、下肢切断者が直面する最も重要な問題のひとつと評価されている[77]。 シャンクとコネクター この部分は、膝関節と足部(上肢義足の場合)またはソケットと足部との間に距離と支持を作り出す。シャンクと膝/足の間に使用されるコネクターの種類に よって、義足がモジュール式かそうでないかが決まる。モジュラー式とは、装着後にソケットに対する足の角度や変位を変えられることを意味する。発展途上国 では、コスト削減のため、ほとんどの義足が非モジュラーである。小児の場合、年平均1.9cm成長するため、角度と高さのモジュール性が重要である [78]。 足部 地面に接する足は、立脚時に衝撃吸収と安定性を提供する[79]。さらに、足の形状や硬さによって歩行バイオメカニクスに影響を与える。これは、圧力中心 (COP)の軌跡と地面反力の角度が足の形状と硬さによって決定されるためであり、正常な歩行パターンを生み出すためには被験者の体格に合っている必要が ある[80]。現在の足に見られる主な問題は耐久性で、耐久性は16ヶ月から32ヶ月の範囲である[81]。これらの結果は成人を対象としたものであり、 活動レベルが高いことやスケール効果により、おそらく子供の方が悪化するだろう。様々なタイプの足部・足関節補装具を比較したエビデンスは、足部・足関節 のメカニズ ムの1つが他のものよりも優れているかどうかを判断するには十分ではない。装具を決定する際には、装具の費用、その人の機能的必要性、特定の装具の入手可 能性を考慮する必要がある [82] 。 膝関節 経大腿(膝上)切断の場合にも、関節可動域を提供する複雑なコネク タが必要であり、遊脚期には屈曲が可能だが立脚期には不可能である。人工膝関節は膝の代わりをすることが目的であるため、経大腿切断者にとって最も重要な コンポーネントである。優れた人工膝関節の機能は、立脚相では構造的な支持と安定性を提供し、遊脚相では制御可能な方法で屈曲できるなど、正常な膝の機能 を模倣することである。そのため、利用者はスムーズでエネルギー効率の高い歩行をすることができ、切断の影響を最小限に抑えることができる[83]。義膝 はシャンクによって義足に接続されており、シャンクは通常アルミニウムまたはグラファイトチューブで作られている。 義膝関節の最も重要な側面のひとつは、立脚相制御機構であろう。立脚相制御の機能は、体重受容時に四肢に負荷がかかったときに脚が座屈するのを防ぐことで ある。これにより、立脚相の片脚支持タスクをサポートするための膝の安定性が確保され、遊脚相へのスムーズな移行が可能になる。立脚相の制御は、メカニカ ルロック[84]、義足コンポーネントの相対アライメント[85]、体重作動摩擦制御[85]、ポリセントリック機構[86]など、いくつかの方法で実現 することができる。 マイクロプロセッサー制御 歩行時の膝の機能を模倣するために、膝の屈曲を制御するマイクロプロセッサー制御の膝継手が開発されている。1997年に発表されたオットー・ボック社の C-leg、2005年に発表されたオスル社のRheo Knee、2006年に発表されたオスル社のPower Knee、フリーダム・イノベーションズ社のPlié Knee、DAWインダストリーズ社のSelf Learning Knee(SLK)などがその例である[87]。 このアイデアは、カナダのエンジニアであるケリー・ジェームズがアルバータ大学で開発したものである[88]。 マイクロプロセッサーは、膝角度センサーとモーメントセンサーからの信号を解釈・分析するために使用される。マイクロプロセッサーはセンサーからの信号を 受信し、切断者の動作の種類を判断する。ほとんどのマイクロプロセッサー制御の膝継手は、義足に内蔵されたバッテリーから電力を供給される。 マイクロプロセッサーが計算した感覚信号は、膝継手内の油圧シリンダーが発生させる抵抗を制御するために使われる。小さなバルブがシリンダーに出入りする作動液の量を制御することで、膝の上部に接続されたピストンの伸長と圧縮が調節される[42]。 マイクロプロセッサー制御義足の主な利点は、切断者の自然な歩行に近いことである。切断者が歩行速度に近い速度で歩いたり、走ったりできるものもある。速 度の変化も可能で、センサーによって考慮され、マイクロプロセッサーに伝達される。マイクロプロセッサー制御の義足を装着した人は、機能性、残存肢の健康 状態、安全性において、より高い満足度と改善を報告していることを示唆する研究もある[90]。 しかし、その使用を損なう重大な欠点もある。水濡れに弱いため、義足が濡れないように細心の注意を払う必要がある。 筋電義足 筋電義足は、筋肉が収縮するたびに発生する電気的張力を情報として利用する。この張力は、肘の屈曲/伸展、手首の上転/前転(回旋)、指の開閉などの義肢 の動きを制御するために、皮膚に貼った電極によって、自発的に収縮した筋肉から取り込むことができる。このタイプの義肢は、電動義手、手首、肘、または足 の機能を制御するために、人体の残存神経筋系を利用する[92]。これは、義肢の動きを制御するスイッチを作動または操作するために、身体の動きによって 作動するストラップおよび/またはケーブルを必要とする電動スイッチ義肢とは異なる。筋電式上肢義足の方が体動式義足よりも機能が優れていると結論付ける 明確な証拠はない。筋電式上肢義足を使用する利点としては、美容的な魅力が向上する可能性があること(このタイプの義足はより自然な外観になる可能性があ る)、軽度の日常動作に適している可能性があること、幻肢痛を経験している人に有益である可能性があることなどが挙げられる。 [筋電義足は、体動式義足と比較すると、耐久性に劣り、訓練時間が長く、調整が必要で、メンテナンスが必要で、使用者へのフィードバックがない可能性があ る[93]。 Alvaro Ríos Poveda教授は、このフィードバックの問題に対する非侵襲的で手頃な価格の解決策に数年間取り組んできた。彼は次のように考えている: 「思考によってコントロールできる義肢は、切断者にとって大きな可能性を秘めているが、脳に戻る信号からのパフォーマティビティ・フィードバックがなけれ ば、正確な動作を行うために必要なレベルのコントロールを達成することは難しい。機械的な手から脳に直接触覚を接続することで、義肢装具は切断された手足 の機能を、ほとんど自然な感覚で回復させることができる」。彼は、1997年にフランスのニースで開催された第18回世界医学物理学・生体医工学会議にお いて、感覚フィードバックを備えた最初の筋電義手を発表した[94][95]。 ソビエト連邦は1958年に筋電義手を開発した最初の国であり[96]、1964年にはソビエト連邦中央義肢研究所によって最初の筋電義手が実用化され、イギリスのHangar Limb Factoryによって販売された[97][98]。 ロボット義肢 3D義手の動きの脳制御(目標にぶつかる)。この動画(なし)は、研究室において、被験者が義手の3次元的な動きを制御し、物理的な標的に命中させる様子を記録したものである。 主な記事 ニューラル義肢装具および動力式外骨格§現在の製品(動力式外骨格) さらに詳しい情報 ロボット工学§タッチ、3Dプリンティング、オープンソースハードウェア ロボットは、患者の障害や治療結果の客観的測定値の作成、診断の補助、患者の運動能力に基づいた治療法のカスタマイズ、治療計画の遵守の保証、患者の記録 の管理などに使用することができる。上肢のリハビリテーションにロボット工学を用いると、脳卒中後の上肢運動機能に有意な改善が見られることが、多くの研 究で示されている[99]。ロボット義肢が機能するためには、それを身体の機能に統合するためのいくつかのコンポーネントが必要である: バイオセンサーは、使用者の神経系や筋肉系からの信号を検出する。バイオセンサーは、ユーザーの神経系や筋肉系からの信号を検出し、その情報を装置内部の マイクロコントローラーに伝え、義肢やアクチュエーターからのフィードバック(位置や力など)を処理してコントローラーに送る。例えば、皮膚上の電気的活 動を検出する表面電極、筋肉に埋め込まれた針電極、神経が通って成長する固体電極アレイなどがある。こうしたバイオセンサーの一種が筋電義肢に採用されて いる。 コントローラーと呼ばれる装置が、ユーザーの神経系と筋肉系、そして装置自体に接続されている。コントローラーは、ユーザーから装置のアクチュエーターに 意図的な命令を送り、機械的センサーやバイオセンサーからのフィードバックを解釈してユーザーに伝える。コントローラーは、装置の動きの監視と制御も担当 する。 アクチュエータは、力と動きを生み出す筋肉の働きを模倣する。例えば、元の筋組織を補助したり、その代わりとなるモーターなどがある。 標的筋再神経支配(TMR)とは、切断された四肢の筋肉を以前は支配していた運動神経を外科的に迂回させ、大胸筋のような無傷の大きな筋肉の小さな領域に 再神経支配させる技術である。その結果、患者が失った手の親指を動かそうと思うと、代わりに胸の筋肉の小さな領域が収縮する。再神経支配された筋肉にセン サーを配置することで、この収縮をロボット義肢の適切な部位の動きを制御することができる[100][101]。 この手技の変種として、標的感覚再神経支配(TSR)がある。この手技はTMRと似ているが、運動神経を筋肉に迂回させるのではなく、感覚神経を胸部の皮 膚に外科的に迂回させる点が異なる。最近では、人間の脳から信号を受け取り、その信号を義肢の動きに変換するロボット義肢の能力が向上している。国防総省 の研究部門であるDARPAは、この分野でさらなる進歩を遂げようとしている。彼らの望みは、神経系に直接結びつく義肢を作ることである[102]。 ロボットアーム 筋電アームに使用されるプロセッサの進歩により、開発者は義肢を細かく制御できるようになった。ボストン・デジタル・アームは、このようなより高度なプロ セッサを利用した最近の義肢である。このアームは5軸の動きを可能にし、よりカスタマイズされた感触のためにアームをプログラムすることができる。最近で は、スコットランドのエジンバラでデビッド・ゴウが発明したI-LIMBハンドが、5本の指を個別に動かせる初の市販義手となった。このハンドは、ユー ザーが受動的に操作する手動で回転可能な親指も備えており、精密、パワー、キーグリップの各モードで握ることができる[103]。 もうひとつの神経義手は、ジョンズ・ホプキンス大学応用物理学研究所のProto 1である。Proto 1の他に、同大学は2010年にProto 2も完成させている[104]。2013年初頭、スウェーデンのチャルマース工科大学およびサハーグレンスカ大学病院のマックス・オルティス・カタランと リカード・ブローネマルクは、マインドコントロールが可能で、(オッセオインテグレーションを使用して)身体に永久的に取り付けることができる初のロボッ トアームの製作に成功した[105][106][107]。 非常に有用なアプローチは、アームローテーションと呼ばれるもので、身体の片側のみに影響を及ぼす切断である片側切断者に一般的である。これは、上肢を切 断した被験者の残存骨の遠位端に小さな永久磁石を挿入するものである。被験者が残存腕を回転させると、磁石が残存骨とともに回転し、磁場分布の変化を引き 起こす[108]。EEG(脳波)信号は、頭皮に取り付けた小さな平らな金属ディスクを使って検出され、基本的に身体運動に使用される人間の脳活動を解読 し、ロボット手足の制御に使用される。これにより、ユーザーはその部分を直接操作することができる[109]。 ロボット義足 ロボット義足の研究は、正確な動作と制御を可能にすることで、時間の経過とともに進歩してきた。 シカゴ・リハビリテーション研究所の研究者は2013年9月、使用者の大腿部の筋肉からの神経インパルスを動きに変換するロボット脚を開発したと発表した。現在テスト中である[110]。 マサチューセッツ工科大学メディアラボのバイオメカトロニクス・グループ長であるヒュー・ハー氏は、ロボット義足(PowerFoot BiOM)を開発した[111][112]。 アイスランドのÖssur社も、足首がモーターで動くロボット義足を作っている。この義足は、アルゴリズムとセンサーによって動き、装着者の歩幅のさまざ まなポイントで足の角度を自動的に調整する。また、ワイヤレス送信機で個人の手足を動かすことができる脳制御のバイオニック・レッグもある[113]。 義足の設計 ロボット義足の主な目的は、歩行中に能動的な作動を与え、特に切断者の安定性、対称性、エネルギー消費など、歩行のバイオメカニクスを改善することであ る。現在市販されている義足には、アクチュエータが直接関節を駆動する完全動力義足や、少量のエネルギーと小型アクチュエータを使用して脚の機械的特性を 変化させるが、歩行に正味の正のエネルギーを注入しない半能動義足など、いくつかの動力義足がある。具体的な例としては、BionX社のemPOWER、 Ossur社のProprio Foot、Endolite社のElan Footなどがある[115][116][117]。また、過去10年間にわたり、さまざまな研究グループがロボット脚の実験を行ってきた[118]。研 究されている中心的な課題としては、立脚期と遊脚期におけるデバイスの動作設計、現在の歩行課題の認識、堅牢性、重量、バッテリー寿命/効率、騒音レベル などのさまざまな機械設計上の問題などがある。しかし、スタンフォード大学とソウル大学の科学者は、義肢の感覚を助ける人工神経システムを開発した [119]。この人工神経システムは、義肢が点字を感じ、触覚を感じ、環境に反応することを可能にする[120][121]。 リサイクル素材の使用 世界中でペットボトルや蓋をリサイクルして義肢が作られている[122][123][124][125][126]。 |

| Attachment to the body Most prostheses can be attached to the exterior of the body in a non-permanent way. Some others however can be attached in a permanent way. One such example are exoprostheses (see below). Direct bone attachment and osseointegration Main article: Osseointegration Osseointegration is a method of attaching the artificial limb to the body. This method is also sometimes referred to as exoprosthesis (attaching an artificial limb to the bone), or endo-exoprosthesis. The stump and socket method can cause significant pain in the amputee, which is why the direct bone attachment has been explored extensively. The method works by inserting a titanium bolt into the bone at the end of the stump. After several months the bone attaches itself to the titanium bolt and an abutment is attached to the titanium bolt. The abutment extends out of the stump and the (removable) artificial limb is then attached to the abutment. Some of the benefits of this method include the following: Better muscle control of the prosthetic. The ability to wear the prosthetic for an extended period of time; with the stump and socket method this is not possible. The ability for transfemoral amputees to drive a car. The main disadvantage of this method is that amputees with the direct bone attachment cannot have large impacts on the limb, such as those experienced during jogging, because of the potential for the bone to break.[15] |

身体への装着 ほとんどの人工関節は、非永久的な方法で身体の外側に取り付けることができる。しかし、永久的な方法で装着できるものもある。その一例が人工関節外装(下記参照)である。 直接的な骨結合とオッセオインテグレーション 主な記事 オッセオインテグレーション オッセオインテグレーションは、義肢を身体に装着する方法である。この方法は、エキソプロテーゼ(義肢を骨に取り付ける)、またはエンドエキソプロテーゼとも呼ばれることがある。 切り株とソケットを用いる方法は、切断者に大きな痛みを引き起こす可能性があるため、骨に直接取り付ける方法が広く研究されている。この方法は、切り株の 先端の骨にチタン製のボルトを挿入することで機能する。数ヵ月後、骨はチタンボルトにくっつき、アバットメントがチタンボルトに取り付けられる。アバット メントは切り株から伸び、(取り外し可能な)義肢がアバットメントに取り付けられる。この方法の利点には、以下のようなものがある: 義肢の筋肉のコントロールが向上する。 義肢を長期間装着できる。スタンプ・ソケット法ではこのようなことは不可能である。 経大腿切断者が自動車を運転できるようになる。 この方法の主な欠点は、骨が折れる可能性があるため、骨直接結合の切断者は、ジョギング時のような大きな衝撃を四肢に与えることができないことである [15] 。 |

| Cosmesis Cosmetic prosthesis has long been used to disguise injuries and disfigurements. With advances in modern technology, cosmesis, the creation of lifelike limbs made from silicone or PVC, has been made possible.[127] Such prosthetics, including artificial hands, can now be designed to simulate the appearance of real hands, complete with freckles, veins, hair, fingerprints and even tattoos. Custom-made cosmeses are generally more expensive (costing thousands of U.S. dollars, depending on the level of detail), while standard cosmeses come premade in a variety of sizes, although they are often not as realistic as their custom-made counterparts. Another option is the custom-made silicone cover, which can be made to match a person's skin tone but not details such as freckles or wrinkles. Cosmeses are attached to the body in any number of ways, using an adhesive, suction, form-fitting, stretchable skin, or a skin sleeve. |

コスメシス 美容義肢は、長い間、怪我や醜状を目立たなくするために用いられてきた。現代の技術の進歩により、シリコーンやポリ塩化ビニールで作られた本物そっくりの 手足を作るコスメシス(cosmesis)が可能になった[127]。義手を含むこのような義肢は、現在では、そばかす、静脈、髪、指紋、タトゥーまで、 本物の手の外観をシミュレートするようにデザインすることができる。カスタムメイドの義手は一般に高価である(細部のレベルにもよるが、数千米ドルもす る)。一方、標準的な義手は、さまざまなサイズのものがあらかじめ用意されているが、カスタムメイドのものほどリアルではないことが多い。もうひとつの選 択肢は、オーダーメイドのシリコンカバーで、これはその人の肌の色に合わせて作ることができるが、そばかすやしわなどの細部は作れない。コスメは、接着 剤、吸引、体にフィットした伸縮性のある皮膚、皮膚スリーブなど、さまざまな方法で体に装着される。 |

| Cognition Main article: Neuroprosthetics Unlike neuromotor prostheses, neurocognitive prostheses would sense or modulate neural function in order to physically reconstitute or augment cognitive processes such as executive function, attention, language, and memory. No neurocognitive prostheses are currently available but the development of implantable neurocognitive brain-computer interfaces has been proposed to help treat conditions such as stroke, traumatic brain injury, cerebral palsy, autism, and Alzheimer's disease.[128] The recent field of Assistive Technology for Cognition concerns the development of technologies to augment human cognition. Scheduling devices such as Neuropage remind users with memory impairments when to perform certain activities, such as visiting the doctor. Micro-prompting devices such as PEAT, AbleLink and Guide have been used to aid users with memory and executive function problems perform activities of daily living. |

認知 主な記事 ニューロプロステティクス 神経運動義足とは異なり、神経認知義足は、実行機能、注意、言語、記憶などの認知プロセスを物理的に再構成または増強するために、神経機能を感知または調 節する。現在利用可能な神経認知義肢はないが、脳卒中、外傷性脳損傷、脳性麻痺、自閉症、アルツハイマー病などの治療に役立つ、埋め込み可能な神経認知ブ レイン・コンピュータ・インターフェイスの開発が提案されている。Neuropageのようなスケジューリング・デバイスは、記憶障害のある利用者に、医 者に行くなどの特定の活動をいつ行うべきかを思い出させる。PEAT、AbleLink、Guideなどのマイクロプロンプティングデバイスは、記憶や実 行機能に問題のある利用者が日常生活活動を行うのを支援するために使用されている。 |

| Prosthetic enhancement Further information: Powered exoskeleton § Research Sgt. Jerrod Fields works out at the U.S. Olympic Training Center in Chula Vista, California. In addition to the standard artificial limb for everyday use, many amputees or congenital patients have special limbs and devices to aid in the participation of sports and recreational activities. Within science fiction, and, more recently, within the scientific community, there has been consideration given to using advanced prostheses to replace healthy body parts with artificial mechanisms and systems to improve function. The morality and desirability of such technologies are being debated by transhumanists, other ethicists, and others in general.[129][130][131][132] Body parts such as legs, arms, hands, feet, and others can be replaced. The first experiment with a healthy individual appears to have been that by the British scientist Kevin Warwick. In 2002, an implant was interfaced directly into Warwick's nervous system. The electrode array, which contained around a hundred electrodes, was placed in the median nerve. The signals produced were detailed enough that a robot arm was able to mimic the actions of Warwick's own arm and provide a form of touch feedback again via the implant.[133] The DEKA company of Dean Kamen developed the "Luke arm", an advanced nerve-controlled prosthetic. Clinical trials began in 2008,[134] with FDA approval in 2014 and commercial manufacturing by the Universal Instruments Corporation expected in 2017. The price offered at retail by Mobius Bionics is expected to be around $100,000.[135] Further research in April 2019, there have been improvements towards prosthetic function and comfort of 3D-printed personalized wearable systems. Instead of manual integration after printing, integrating electronic sensors at the intersection between a prosthetic and the wearer's tissue can gather information such as pressure across wearer's tissue, that can help improve further iteration of these types of prosthetic.[136] Oscar Pistorius In early 2008, Oscar Pistorius, the "Blade Runner" of South Africa, was briefly ruled ineligible to compete in the 2008 Summer Olympics because his transtibial prosthesis limbs were said to give him an unfair advantage over runners who had ankles. One researcher found that his limbs used twenty-five percent less energy than those of a non-disabled runner moving at the same speed. This ruling was overturned on appeal, with the appellate court stating that the overall set of advantages and disadvantages of Pistorius' limbs had not been considered. Pistorius did not qualify for the South African team for the Olympics, but went on to sweep the 2008 Summer Paralympics, and has been ruled eligible to qualify for any future Olympics.[citation needed] He qualified for the 2011 World Championship in South Korea and reached the semi-final where he ended last timewise, he was 14th in the first round, his personal best at 400m would have given him 5th place in the finals. At the 2012 Summer Olympics in London, Pistorius became the first amputee runner to compete at an Olympic Games.[137] He ran in the 400 metres race semi-finals,[138][139][140] and the 4 × 400 metres relay race finals.[141] He also competed in 5 events in the 2012 Summer Paralympics in London.[142] |

補綴強化さらに詳しい情報動力式外骨格§研究 カリフォルニア州チュラビスタの米国オリンピック・トレーニングセンターでトレーニングに励むジェロッド・フィールズ軍曹。 日常生活で使用する標準的な義肢に加えて、切断者や先天性患者の多くは、スポーツやレクリエーション活動への参加を補助するための特殊な手足や器具を持っている。 SFの世界では、そして最近では科学界でも、機能を向上させるために、健康な身体の一部を人工的な機構やシステムで置き換える高度な義肢の使用が検討され ている。このような技術の道徳性や望ましさは、トランスヒューマニストや他の倫理学者、その他一般によって議論されている[129][130][131] [132]。脚、腕、手、足などの身体の一部を置き換えることができる。 健康な個人を使った最初の実験は、イギリスの科学者ケヴィン・ワーウィックによるものだったようだ。2002年、ワーウィックの神経系にインプラントが直 接埋め込まれた。約100個の電極を含む電極アレイが正中神経に設置された。生成された信号は十分に詳細で、ロボットアームがワーウィック自身の腕の動作 を模倣し、インプラントを介して再びタッチフィードバックの形を提供することができた[133]。 ディーン・カーメンのDEKA社は、先進的な神経制御義肢である「ルーク・アーム」を開発した。2008年に臨床試験が開始され[134]、2014年に FDAの認可が下り、2017年にはユニバーサル・インスツルメンツ社による商業生産が予定されている。メビウス・バイオニクス社が小売で提供する価格は 約10万ドルになると予想されている[135]。 2019年4月のさらなる研究では、3Dプリントされたパーソナライズされたウェアラブルシステムの補綴機能と快適性に向けた改善があった。プリント後に 手作業で統合する代わりに、義肢装具と装着者の組織との交差点に電子センサーを統合することで、装着者の組織全体の圧力などの情報を収集することができ、 この種の義肢装具のさらなる反復の改善に役立てることができる[136]。 オスカー・ピストリウス 2008年初頭、南アフリカの 「ブレードランナー 」であるオスカー・ピストリウスは、2008年夏季オリンピックに出場する資格がないとの裁定を短期間下されたが、その理由は、彼の人工脛骨の手足が、足 首のあるランナーよりも不当に有利であると言われていたからである。ある研究者は、彼の手足が同じスピードで動く障害者でないランナーよりも25%少ない エネルギーを消費することを発見した。この判決は控訴審で覆され、控訴裁判所はピストリウスの手足の長所と短所を総合的に考慮していないと述べた。 ピストリウスはオリンピックの南アフリカ代表には選ばれなかったが、2008年夏季パラリンピックで優勝を果たし、今後のオリンピックに出場する資格を得 た。2012年夏季ロンドンオリンピックでは、ピストリウスはオリンピックに出場した最初の切断ランナーとなった[137]。彼は400メートルレースの 準決勝[138][139][140]と4×400メートルリレーレースの決勝に出場した[141]。 |