旧ソ連邦における精神医学の濫用

Political abuse of psychiatry in the Soviet Union

☆

ソビエト連邦では、政治的反対や異議申し立てを精神医学的問題と解釈する根拠に基づき、精神医学が体系的に政治的に悪用された[1]。これは「異議申し立

ての精神病理学的メカニズム」と呼ばれた[2]。

レオニード・ブレジネフ書記長の指導下では、公然と公式教義に反する信念を表明した政治的反対者(ソビエトの反体制派)を無力化し社会から排除するために

精神医学が利用された。[4][5]

例えば「哲学的酩酊」という用語は、人民が国の共産主義指導者に反対し、マルクス・レーニン主義の創始者たち―カール・マルクス、フリードリヒ・エンゲル

ス、ウラジーミル・レーニン―の著作に言及することで批判の対象となった際に診断された精神障害に広く適用された。[6]

もう一つの一般的な疑似診断は「緩慢型統合失調症」であった。

スターリン時代の刑法典第58条の10「反ソビエト扇動」は、1958年に制定された新たなロシア・ソビエト連邦社会主義共和国刑法典において、第70条

「反ソビエト扇動及び宣伝」としてかなりの程度まで維持された。1967年には、より緩やかな法律である第190-1条「ソビエトの政治・社会制度を誹謗

する虚偽の捏造の流布」がロシア・ソビエト連邦社会主義共和国刑法に追加された。これらの法律は、アカデミー会員アンドレイ・スネジュネフスキーが開発し

た精神疾患診断システムと組み合わせて頻繁に適用された。これらが一体となって、非標準的な信念を容易に刑事犯罪と定義し、その後精神医学的診断の根拠と

する枠組みを確立したのである。[7]

| There was systematic

political abuse of psychiatry in the Soviet Union,[1] based on the

interpretation of political opposition or dissent as a psychiatric

problem.[2] It was called "psychopathological mechanisms" of dissent.[3] During the leadership of General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev, psychiatry was used to disable and remove from society political opponents (Soviet dissidents) who openly expressed beliefs that contradicted the official dogma.[4][5] The term "philosophical intoxication", for instance, was widely applied to the mental disorders diagnosed when people disagreed with the country's Communist leaders and, by referring to the writings of the Founding Fathers of Marxism–Leninism—Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, and Vladimir Lenin—made them the target of criticism.[6] Another common pseudo-diagnosis was "sluggish schizophrenia". Article 58-10 of the Stalin-era Criminal Code, "Anti-Soviet agitation", was to a considerable degree preserved in the new 1958 Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic Criminal Code as Article 70 "Anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda". In 1967, a weaker law, Article 190-1 "Dissemination of fabrications known to be false, which defame the Soviet political and social system", was added to the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic Criminal Code. These laws were frequently applied in conjunction with the system of diagnosis for mental illness, developed by academician Andrei Snezhnevsky. Together, they established a framework within which non-standard beliefs could easily be defined as a criminal offence and the basis, subsequently, for a psychiatric diagnosis.[7] |

ソビエト連邦では、政治的反対や異議申し立てを精神医学的問題と解釈す

る根拠に基づき、精神医学が体系的に政治的に悪用された[1]。これは「異議申し立ての精神病理学的メカニズム」と呼ばれた[2]。 レオニード・ブレジネフ書記長の指導下では、公然と公式教義に反する信念を表明した政治的反対者(ソビエトの反体制派)を無力化し社会から排除するために 精神医学が利用された。[4][5] 例えば「哲学的酩酊」という用語は、人民が国の共産主義指導者に反対し、マルクス・レーニン主義の創始者たち―カール・マルクス、フリードリヒ・エンゲル ス、ウラジーミル・レーニン―の著作に言及することで批判の対象となった際に診断された精神障害に広く適用された。[6] もう一つの一般的な疑似診断は「緩慢型統合失調症」であった。 スターリン時代の刑法典第58条の10「反ソビエト扇動」は、1958年に制定された新たなロシア・ソビエト連邦社会主義共和国刑法典において、第70条 「反ソビエト扇動及び宣伝」としてかなりの程度まで維持された。1967年には、より緩やかな法律である第190-1条「ソビエトの政治・社会制度を誹謗 する虚偽の捏造の流布」がロシア・ソビエト連邦社会主義共和国刑法に追加された。これらの法律は、アカデミー会員アンドレイ・スネジュネフスキーが開発し た精神疾患診断システムと組み合わせて頻繁に適用された。これらが一体となって、非標準的な信念を容易に刑事犯罪と定義し、その後精神医学的診断の根拠と する枠組みを確立したのである。[7] |

| Applying the diagnosis The "anti-Soviet" political behavior of some individuals – being outspoken in their opposition to the authorities, demonstrating for reform, and writing critical books – were defined simultaneously as criminal acts (e.g., a violation of Articles 70 or 190–1), symptoms of mental illness (e.g., "delusion of reformism"), and susceptible to a ready-made diagnosis (e.g., "sluggish schizophrenia").[8] Within the boundaries of the diagnostic category, the symptoms of pessimism, poor social adaptation and conflict with authorities were themselves sufficient for a formal diagnosis of "sluggish schizophrenia".[9] The psychiatric incarceration of certain individuals was prompted by their attempts to emigrate, to distribute or possess prohibited documents or books, to participate in civil rights protests and demonstrations, and become involved in forbidden religious activities.[10] In accordance with the doctrine of state atheism, the religious beliefs of prisoners, including those of well-educated former atheists who had become adherents of a religious faith, was considered to be a form of mental illness that required treatment.[11][12] The KGB routinely sent dissenters to psychiatrists for diagnosis, in order to discredit dissidence as the product of unhealthy minds and to avoid the embarrassment caused by public trials.[13] Highly classified government documents that became available after the dissolution of the Soviet Union confirm that the authorities consciously used psychiatry as a tool to suppress dissent.[14] According to the "Commentary" to the post-Soviet Russian Federation Law on Psychiatric Care, individuals forced to undergo treatment in Soviet psychiatric medical institutions were entitled to rehabilitation in accordance with the established procedure and could claim compensation. The Russian Federation acknowledged that before 1991 psychiatry had been used for political purposes and took responsibility for the victims of "political psychiatry."[15] The political abuse of psychiatry in Russia has continued, nevertheless, since the fall of the Soviet Union,[16] and human rights activists may still face the threat of a psychiatric diagnosis for their legitimate civic and political activities.[17] |

診断の適用 一部の個人の「反ソ連的」政治的行動――当局への反対を公然と表明し、改革を求めるデモを行い、批判的な書籍を執筆する行為――は、同時に犯罪行為(例: 第70条または第190条1項違反) 精神疾患の症状(「改革主義妄想」など)、そして既成の診断(「緩慢型統合失調症」など)の対象として同時に定義された。[8] 診断カテゴリーの範囲内では、悲観主義、社会的適応不良、当局との対立といった症状自体が、「緩慢型統合失調症」の形式的診断に十分であった。[9] 特定の個人に対する精神科収容は、国外移住の試み、禁止文書・書籍の配布・所持、市民権抗議活動やデモへの参加、禁じられた宗教活動への関与によって促さ れた。[10] 国家無神論の教義に従い、囚人の宗教的信念(宗教的信仰を奉じるようになった高学歴の元無神論者を含む)は、治療を要する精神疾患の一形態と見なされた。 [11][12] KGBは反体制派を精神科医に診断させることを常套手段とし、異議申し立てを不健全な精神の産物として信用を失墜させるとともに、公判による不名誉を回避 した。[13] ソ連崩壊後に公開された極秘政府文書は、当局が精神医学を意図的に反体制派弾圧の手段として利用したことを裏付けている。[14] ソ連崩壊後のロシア連邦精神医療法「解説」によれば、ソ連時代の精神医療施設で強制治療を受けた者は、定められた手続きに従い名誉回復を受ける権利があ り、賠償を請求できる。ロシア連邦は1991年以前、精神医学が政治的目的で利用されていたことを認め、「政治的精神医学」の犠牲者に対する責任を負っ た。[15] しかしながら、ソ連崩壊後もロシアにおける精神医学の政治的濫用は継続している[16]。人権活動家は、正当な市民的・政治的活動に対して精神医学的診断を下される脅威に依然として直面しうるのである[17]。 |

The Serbsky Central Research Institute for Forensic Psychiatry, also briefly called the Serbsky Institute (the part of its building in Moscow) |

セルブスキー法精神医学中央研究所、略してセルブスキー研究所とも呼ばれる(モスクワにあるその建物の一部) |

| Background Definitions Political abuse of psychiatry is the misuse of psychiatric diagnosis, detention and treatment for the purposes of obstructing the fundamental human rights of certain groups and individuals in a society.[18] It entails the exculpation and committal of citizens to psychiatric facilities based upon political rather than mental health-based criteria.[19] Many authors, including psychiatrists, also use the terms "Soviet political psychiatry"[20] or "punitive psychiatry" to refer to this phenomenon.[21] In his book Punitive Medicine (1979) Alexander Podrabinek defined the term "punitive medicine", which is identified with "punitive psychiatry," as "a tool in the struggle against dissidents who cannot be punished by legal means."[22] Punitive psychiatry is neither a discrete subject nor a psychiatric specialty but, rather, it is an emergency arising within many applied sciences in totalitarian countries where members of a profession may feel themselves compelled to serve the diktats of power.[23] Psychiatric confinement of sane people is uniformly considered a particularly pernicious form of repression[24] and Soviet punitive psychiatry was one of the key weapons of both illegal and legal repression.[25] As Vladimir Bukovsky and Semyon Gluzman wrote in their joint A Manual on Psychiatry for Dissenters, "the Soviet use of psychiatry as a punitive means is based upon the deliberate interpretation of dissent... as a psychiatric problem."[26] |

背景 定義 精神医学の政治的濫用とは、社会における特定の集団や個人の基本的人権を阻害する目的で、精神医学的診断・拘束・治療を誤用する行為である。[18] これは、精神健康に基づく基準ではなく政治的基準に基づいて、市民を精神医療施設へ送致し、その責任を免除することを伴う。[19] 多くの著者、精神科医を含む者も、この現象を指すために「ソビエト政治精神医学」[20] または「懲罰的精神医学」という用語を用いる。[21] アレクサンダー・ポドラビネクは著書『懲罰的医療』(1979年)において、「懲罰的精神医学」と同義の「懲罰的医療」を「法的手段では処罰できない反体 制派との闘争における手段」と定義した。懲罰的精神医学は独立した学問分野でも精神医学の専門分野でもない。むしろ全体主義国家において、専門職が権力の 恣意的な命令に従わざるを得ない状況下で、多くの応用科学分野に生じる緊急事態である[23]。正常な人々に対する精神科的拘禁は、特に有害な抑圧形態と して広く認識されている[24]。ソ連の懲罰的精神医学は、非合法・合法両方の抑圧における主要な武器の一つであった。[25] ウラジーミル・ブコフスキーとセミョン・グルズマンが共著『反体制派のための精神医学マニュアル』で述べたように、「ソ連が精神医学を懲罰的手段として用いるのは、反体制的行為を意図的に精神医学的問題と解釈する行為に基づいている」[26]。 |

| Mass repression in the Soviet Union Economic repression War communismCollectivizationDekulakizationSoviet famine of 1930–1933 UkraineKazakhstan Political repression Red TerrorPurges of the Communist PartyGreat PurgeGulagPunitive psychiatry Ideological repression Religion 1917–19211921–19281928–19411958–19641975–1987ChristianityIslamJudaismLegislationScienceCensorship ImagesArt Ethnic repression De-CossackizationNational operationsPopulation transfersRepressions of PolesUkrainian language suppression |

ソビエト連邦における 大規模な弾圧 経済的弾圧 戦時共産主義・集団化・デクラキゼーション・1930-1933年のソビエト飢饉・ウクライナ・カザフスタン 政治的弾圧 赤色テロ・共産党粛清・大粛清・グラグ・懲罰的精神医学 イデオロギー的弾圧 宗教 1917–1921年 1921–1928年 1928–1941年 1958–1964年 1975–1987年 キリスト教 イスラム教 ユダヤ教 立法 検閲 イメージ 芸術 民族的弾圧 脱コサック化 民族作戦 人口移住 ポーランド人弾圧 ウクライナ語弾圧 |

| An inherent capacity for abuse The diagnosis of mental disease can give the state license to detain persons against their will and insist upon therapy both in the interest of the detainee and in the broader interests of society.[27] In addition, receiving a psychiatric diagnosis can itself be regarded as oppressive.[28] In a monolithic state, psychiatry can be used to bypass standard legal procedures for establishing guilt or innocence and allow political incarceration without the ordinary odium attaching to such political trials.[27] In the period from the 1960s to 1986, the abuse of psychiatry for political purposes was reported to have been systematic in the Soviet Union and episodic in other Eastern European countries such as Romania, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia.[29] The practice of incarceration of political dissidents in mental hospitals in Eastern Europe and the former USSR damaged the credibility of psychiatric practice in these states and entailed strong condemnation from the international community.[30] Psychiatrists have been involved in human rights abuses in states across the world when the definitions of mental disease were expanded to include political disobedience.[31] As scholars have long argued, governmental and medical institutions have at times classified threats to authority during periods of political disturbance and instability as a form of mental disease.[32] In many countries, political prisoners are still sometimes confined and abused in mental institutions.[33] In the Soviet Union, dissidents were often confined in psychiatric wards commonly called psikhushkas.[34] Psikhushka is the Russian ironic diminutive for "psychiatric hospital".[35] One of the first penal psikhushkas was the Psychiatric Prison Hospital in the city of Kazan.[36] In 1939, it was transferred to the control of the NKVD (the secret police and precursor of the KGB) on the orders of Lavrentiy Beria, the head of the NKVD.[37] International human rights defenders such as Walter Reich have long recorded the methods by which Soviet psychiatrists in Psikhushka hospitals diagnosed schizophrenia in political dissenters.[32] Western scholars examined no aspect of Soviet psychiatry as thoroughly as its involvement in the social control of political dissenters.[38] |

虐待の潜在的可能性 精神疾患の診断は、国家に、被拘束者の意思に反して拘束し、治療を強制する権限を与える。これは被拘束者の利益と、より広範な社会の利益の両方のためとさ れる。[27] さらに、精神医学的診断を受けること自体が抑圧と見なされる場合もある。[28] 単一国家においては、精神医学が有罪無罪を確定する標準的な法的手続きを迂回する手段として利用され、通常の政治裁判に伴う嫌悪感なしに政治的投獄を可能 にする。[27] 1960年代から1986年にかけて、政治的目的のための精神医学の濫用は、ソビエト連邦では組織的に、ルーマニア、ハンガリー、チェコスロバキア、ユー ゴスラビアなどの他の東欧諸国では断続的に行われたと報告されている。[29] 東欧諸国や旧ソ連において政治的異議申し立て者を精神病院に収容する慣行は、これらの国家における精神医学の実践の信頼性を損ない、国際社会からの強い非 難を招いた。[30] 精神疾患の定義が政治的不服従を含むように拡大された際、世界中の国家で精神科医が人権侵害に関与してきた。[31] 学者が長年指摘してきたように、政府や医療機関は政治的混乱期に権威への脅威を精神疾患の一種として分類することがあった。[32] 多くの国では、政治犯が今も精神病院に収容され虐待される事例が存在する。[33] ソビエト連邦では、反体制派はしばしば「プシフシュカ」と呼ばれる精神科病棟に収容された。[34] プシフシュカとは「精神病院」を意味するロシア語の皮肉を込めた小辞である。[35] 最初の刑務所兼精神病院の一つがカザン市の精神科刑務所病院であった。[36] 1939年、NKVD長官ラヴレンチイ・ベリヤの命令により、NKVD(秘密警察、KGBの前身)の管理下に移管された。[37] ウォルター・ライヒら国際人権活動家は、精神病院のソ連精神科医が政治的異議申し立て者に統合失調症と診断した手法を長年記録してきた。[32] 西側学者たちがソ連精神医学のあらゆる側面を徹底的に検証した中で、政治的異議申し立て者の社会統制への関与ほど詳細に分析された分野は他にない。 [38] |

| Under Stalin, Khrushchev and Brezhnev As early as 1948, the Soviet secret service took an interest in this area of medicine.[39] One of those with overall responsibility for the Soviet secret police, pre-war Procurator General and State Prosecutor, the deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Andrey Vyshinsky, was the first to order the use of psychiatry as a tool of repression.[40] Russian psychiatrist Pyotr Gannushkin believed that in a class society, especially during the most severe class struggle, psychiatry was incapable of not being repressive.[41] A system of political abuse of psychiatry was developed at the end of Joseph Stalin's regime.[42] Punitive psychiatry was not simply an inheritance from the Stalin era, however, according to Alexander Etkind. The Gulag, or Chief Administration for Corrective Labor Camps, was an effective instrument of political repression. There was no compelling requirement to develop an alternative and more expensive psychiatric substitute.[43] The abuse of psychiatry was a natural product of the later Soviet era.[43] From the mid-1970s to the 1990s, the structure of the USSR mental health service conformed to the double standard in society, being represented by two distinct systems which co-existed peacefully for the most part, despite periodic conflicts between them: system one was that of punitive psychiatry. It directly served the authorities and those in power, and was headed by the Moscow Institute for Forensic Psychiatry named in honour of Vladimir Serbsky; system two was made up of elite, psychotherapeutically oriented clinics. It was headed by the Leningrad Psychoneurological Institute named in memory of Vladimir Bekhterev.[43] The hundreds of hospitals in the provinces combined elements of both systems.[43] If someone was mentally ill then, they were sent to psychiatric hospitals and confined there until they died.[44] If their mental health was uncertain but they were not constantly unwell, they and their kharakteristika [testimonial from employers, the Party and other Soviet institutions] were sent to a labour camp or to be shot.[44] When allusions to socialist legality started to be made, it was decided to prosecute such people.[44] Soon it became apparent that putting people who gave anti-Soviet speeches on trial only made matters worse for the regime. Such individuals were no longer tried in court. Instead they were given a psychiatric examination and declared insane.[44] |

スターリン、フルシチョフ、ブレジネフの時代 1948年という早い時期から、ソ連の秘密警察はこの医療分野に関心を示した[39]。戦前の検事総長兼国家検察官であり、外務次官を務めたアンドレイ・ ヴィシンスキーは、ソ連秘密警察の総責任者の一人として、精神医学を抑圧の手段として利用するよう最初に命じた人物である。[40] ロシアの精神科医ピョートル・ガヌシキンは、階級社会において、特に激しい階級闘争の時期には、精神医学が抑圧的でない状態を維持することは不可能だと考 えていた。[41] 精神医学の政治的悪用システムは、ヨシフ・スターリン体制の終盤に確立された。[42] しかしアレクサンドル・エトキンドによれば、懲罰的精神医学は単にスターリン時代の遺産ではなかった。強制労働収容所総局(グラグ)は政治的弾圧の有効な 手段であった。代替となるより高価な精神医学的手段を開発する強い必要性は存在しなかった。[43] 精神医学の濫用は、後期ソ連時代の自然な産物であった。[43] 1970年代半ばから1990年代にかけて、ソ連の精神健康サービスの構造は社会の二重基準に適合し、主に二つの異なるシステムによって表され、それらは 定期的な対立にもかかわらず、おおむね平和的に共存していた: 第一のシステムは懲罰的精神医学であった。これは直接的に権力者や支配層に奉仕し、ウラジーミル・セルブスキーの名を冠したモスクワ法医学精神医学研究所が主導した。 第二のシステムは、心理療法を志向するエリート診療所群で構成された。ウラジーミル・ベフテレフを記念して名付けられたレニングラード精神神経学研究所が主導した。[43] 地方の数百の病院は両システムの要素を併せ持っていた。[43] 当時、精神疾患を患う者は精神病院に送られ、死ぬまでそこに閉じ込められた。[44]精神状態が不安定だが常に病状が重いわけではない者は、その人物の 「特性証明書」(雇用主、党、その他のソ連機関による推薦状)と共に、強制労働収容所へ送られるか、銃殺された。[44] 社会主義的合法性への言及が始まると、こうした人々を起訴することが決定された。[44] 反ソ連的発言をした者を裁判にかけることが体制にとって事態を悪化させるだけだと、すぐに明らかになった。そうした個人はもはや法廷で裁かれなかった。代 わりに精神鑑定を受けさせられ、精神異常と宣告されたのである。[44] |

| The Joint Session, October 1951 Main article: Pavlovian session In the 1950s, the psychiatrists of the Soviet Union turned themselves into the medical arm of the Gulag State.[45] A precursor of later abuses in psychiatry in the Soviet Union, the "Joint Session" of the USSR Academy of Medical Sciences and the Board of the All-Union Neurological and Psychiatric Association took place from 10 to 15 October 1951. The event was dedicated, supposedly, to the great Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov, and alleged that several of the USSR's leading neuroscientists and psychiatrists of the time (among them Grunya Sukhareva, Vasily Gilyarovsky, Raisa Golant, Aleksandr Shmaryan, and Mikhail Gurevich) were guilty of practicing "anti-Pavlovian, anti-Marxist, idealistic [and] reactionary" science, and this was damaging to Soviet psychiatry.[46] During the Joint Session, these eminent psychiatrists, motivated by fear, had to publicly admit that their scientific positions were erroneous and they also had to promise to conform to "Pavlovian" doctrines.[46] These public declarations of obedience proved insufficient. In the closing speech, Andrei Snezhnevsky, the lead author of the Session's policy report, stated that the accused psychiatrists "have not disarmed themselves and continue to remain in the old anti-Pavlovian positions", thereby causing "grave damage to the Soviet psychiatric research and practice". The vice president of the USSR Academy of Medical Sciences accused them of "diligently worshipping the dirty source of American pseudo-science".[47] Those who articulated these accusations at the Joint Session – among them Irina Strelchuk, Vasily Banshchikov, Oleg Kerbikov, and Snezhnevsky – were distinguished by their careerist ambition and fear for their own positions.[46] Not surprisingly, many of them were promoted and appointed to leadership posts shortly after the session.[46] The Joint Session also had a negative impact on several leading Soviet academic neuroscientists, such as Pyotr Anokhin, Aleksey Speransky, Lina Stern, Ivan Beritashvili, and Leon Orbeli. They were labeled as anti-Pavlovians, anti-materialists and reactionaries and subsequently they were dismissed from their positions.[46] In addition to losing their laboratories some of these scientists were subjected to torture in prison.[46] The Moscow, Leningrad, Ukrainian, Georgian, and Armenian schools of neuroscience and neurophysiology were damaged for a period due to this loss of personnel.[46] The Joint Session ravaged productive research in neurosciences and psychiatry for years to come.[46] Pseudo-science took control.[46] Following a previous joint session of the USSR Academy of Sciences and the USSR Academy of Medical Sciences (28 June–4 July 1950) and the 10-15 October 1951 joint session of the Presidium of the Academy of Medical Sciences and the Board of the All-Union Society of Neuropathologists and Psychiatrists, Snezhnevky's school was given the leading role.[48] The 1950 decision to give monopoly over psychiatry to the Pavlovian school of Snezhnevsky was one of the crucial factors in the rise of political psychiatry.[49] The Soviet doctors, under the incentive of Snezhnevsky, devised a "Pavlovian theory of schizophrenia" and increasingly applied this diagnostic category to political dissidents.[50] |

合同会議、1951年10月 主な記事:パブロフ式セッション 1950年代、ソビエト連邦の精神科医たちは自らを強制収容国家の医療部門へと変貌させた[45]。ソ連における精神医学の後の乱用の前兆となる「合同会 議」が、1951年10月10日から15日にかけてソ連医学アカデミーと全連邦神経精神医学協会理事会によって開催された。この行事は、表向きは偉大なロ シア生理学者イワン・パブロフに捧げられたもので、当時のソ連を代表する神経科学者・精神科医数名(グルニャ・スハレワ、ヴァシーリー・ギリャロフス キー、 ライサ・ゴラント、アレクサンドル・シュマリアン、ミハイル・グレヴィッチら)が「反パブロフ的、反マルクス主義的、観念論的[かつ]反動的」な科学を実 践した罪に問われ、これがソ連精神医学に損害を与えているとされた。[46] 合同会議において、これらの著名な精神科医たちは恐怖に駆られ、自らの科学的立場が誤りであったことを公に認めざるを得なかった。さらに彼らは「パブロフ 主義」の教義に従うことを約束させられた。[46] こうした公の服従宣言は不十分であった。閉会演説で、会議の政策報告書筆頭著者アンドレイ・スネシュネフスキーは、被告人精神科医らが「武装解除せず、旧 来の反パブロフ的立場に固執し続けている」と述べ、これが「ソ連精神医学研究と実践に深刻な損害をもたらしている」と断じた。ソ連医学アカデミー副会長は 彼らを「アメリカの疑似科学という汚れた源泉を熱心に崇拝している」と非難した。[47] 合同会議でこうした非難を表明した者たち―イリーナ・ストレルチュク、ヴァシーリー・バンシチョフ、オレグ・ケルビコフ、スネジュネフスキーら―は、出世 欲と自身の地位への恐怖によって特徴づけられていた。[46] 当然ながら、彼らの多くは会議直後に昇進し指導的地位に任命された。[46] 合同会議は、ピョートル・アノヒン、アレクセイ・スペランスキー、リナ・シュテルン、イワン・ベリタシュヴィリ、レオン・オルベリといったソ連の主要な神 経科学者たちにも悪影響を及ぼした。彼らは反パブロフ派、反唯物論者、反動分子とレッテルを貼られ、その後職を追われた。[46] 実験室を失っただけでなく、一部の科学者は獄中で拷問を受けた。[46] この人材の喪失により、モスクワ、レニングラード、ウクライナ、グルジア、アルメニアの各神経科学・神経生理学学派は一時的に打撃を受けた。[46] 合同会議はその後何年にもわたり、神経科学と精神医学における生産的な研究を荒廃させた。[46] 疑似科学が支配権を握った。[46] ソ連科学アカデミーとソ連医学アカデミーの合同会議(1950年6月28日~7月4日)、および医学アカデミー幹部会と全連邦神経病理学者・精神科医協会 の理事会による合同会議(1951年10月10日~15日)を経て、スネジュネフスキー学派が主導的役割を与えられた。[48] 1950年に精神医学の独占権をスネジュネフスキー率いるパブロフ学派に与えた決定は、政治精神医学台頭における決定的要因の一つであった。[49] ソ連の医師たちはスネジュネフスキーの主導で「統合失調症のパブロフ理論」を構築し、この診断カテゴリーを政治的異議申し立て者へ次第に適用していった。 [50] |

| "Sluggish schizophrenia" Main article: Sluggish schizophrenia The incarceration of free thinking healthy people in madhouses is spiritual murder, it is a variation of the gas chamber, even more cruel; the torture of the people being killed is more malicious and more prolonged. Like the gas chambers, these crimes will never be forgotten and those involved in them will be condemned for all time during their life and after their death."[51] (Alexander Solzhenitsyn) Psychiatric diagnoses such as the diagnosis of "sluggish schizophrenia" in political dissidents in the USSR were used for political purposes.[52] It was the diagnosis of "sluggish schizophrenia" that was most prominently used in cases of dissidents.[53] Sluggish schizophrenia as one of the new diagnostic categories was created to facilitate the stifling of dissidents and was a root of self-deception among psychiatrists to placate their consciences when the doctors acted as a tool of oppression in the name of a political system.[54] According to the Global Initiative on Psychiatry chief executive Robert van Voren, the political abuse of psychiatry in the USSR arose from the conception that people who opposed the Soviet regime were mentally sick since there was no other logical rationale why one would oppose the sociopolitical system considered the best in the world.[55] The diagnosis "sluggish schizophrenia", a longstanding concept further developed by the Moscow School of Psychiatry and particularly by its chief Snezhnevsky, furnished a very handy framework for explaining this behavior.[55] The weight of scholarly opinion holds that the psychiatrists who played the primary role in the development of this diagnostic concept were following directives from the Communist Party and the Soviet secret service, or KGB, and were well aware of the political uses to which it would be put. Nevertheless, for many Soviet psychiatrists "sluggish schizophrenia" appeared to be a logical explanation to apply to the behavior of critics of the regime who, in their opposition, seemed willing to jeopardize their happiness, family, and career for a reformist conviction or ideal that was so apparently divergent from the prevailing social and political orthodoxy.[55] Snezhnevsky, the most prominent theorist of Soviet psychiatry and director of the Institute of Psychiatry of the USSR Academy of Medical Sciences, developed a novel classification of mental disorders postulating an original set of diagnostic criteria.[9] A carefully crafted description of sluggish schizophrenia established that psychotic symptoms were non-essential for the diagnosis, but symptoms of psychopathy, hypochondria, depersonalization or anxiety were central to it.[9] Symptoms referred to as part of the "negative axis" included pessimism, poor social adaptation, and conflict with authorities, and were themselves sufficient for a formal diagnosis of "sluggish schizophrenia with scanty symptoms".[9] According to Snezhnevsky, patients with sluggish schizophrenia could present as quasi sane yet manifest minimal but clinically relevant personality changes which could remain unnoticed to the untrained eye.[9] Thereby patients with non-psychotic mental disorders, or even persons who were not mentally sick, could be easily labelled with the diagnosis of sluggish schizophrenia.[9] Along with paranoia, sluggish schizophrenia was the diagnosis most frequently used for the psychiatric incarceration of dissenters.[9] As per the theories of Snezhnevsky and his colleagues, schizophrenia was held to be much more prevalent than previously considered, for the illness might present with comparatively slight symptoms, and might only progress afterwards.[55] As a consequence, schizophrenia was diagnosed much more often in Moscow than in cities of other countries, as the World Health Organization Pilot Study on Schizophrenia reported in 1973.[55] The city with the highest prevalence of schizophrenia in the world was Moscow.[56] In particular, the scope was widened by sluggish schizophrenia because according to Snezhnevsky and his colleagues, patients with this diagnosis were capable of functioning almost normally in the social sense.[55] Their symptoms could be like those of a neurosis or could assume a paranoid character.[55] The patients with paranoid symptoms retained some insight into their condition but overestimated their own significance and could manifest grandiose ideas of reforming society.[55] Thereby, sluggish schizophrenia could have such symptoms as "reform delusions", "perseverance", and "struggle for the truth".[55] As Viktor Styazhkin reported, Snezhnevsky diagnosed a reformation delusion for every case when a patient "develops a new principle of human knowledge, drafts an academy of human happiness, and many other projects for the benefit of mankind".[57] In the 1960s and 1970s, theories, which contained ideas about reforming society and struggling for truth, and religious convictions were not referred to delusional paranoid disorders in practically all foreign classifications, but Soviet psychiatry, proceeding from ideological conceptions, referred critique of the political system and proposals to reform this system to the delusional construct.[58] Diagnostic approaches of conception of sluggish schizophrenia and paranoiac states with delusion of reformism were used only in the Soviet Union and several Eastern European countries.[59] On the covert orders of the KGB, thousands of social and political reformers—Soviet "dissidents"—were incarcerated in mental hospitals after being labelled with diagnoses of "sluggish schizophrenia", a disease fabricated by Snezhnevsky and "Moscow school" of psychiatry.[60] American psychiatrist Alan A. Stone stated that Western criticism of Soviet psychiatry aimed at Snezhnevsky personally, because he was essentially responsible for the Soviet concept of schizophrenia with a "sluggish type" manifestation by "reformerism" including other symptoms.[61] One can readily apply this diagnostic scheme to dissenters.[61] Snezhnevsky was long attacked in the West as an exemplar of psychiatric abuse in the USSR.[53] The leading critics implied that Snezhnevsky had designed the Soviet model of schizophrenia and this diagnosis to make political dissent into a mental disease.[62] He was charged with cynically developing a system of diagnosis which could be bent for political purposes, and he himself diagnosed or was involved in a series of famous dissident cases,[53] and, in dozens of cases, he personally signed a commission decision on legal insanity of mentally healthy dissidents including Vladimir Bukovsky, Natalya Gorbanevskaya, Leonid Plyushch, Mikola Plakhotnyuk,[63] and Pyotr Grigorenko.[64] |

「緩慢な統合失調症」 詳細記事: 緩慢な統合失調症 自由な思考を持つ健全な人々を精神病院に監禁することは、精神的殺害である。それはガス室の変種であり、さらに残酷だ。殺される人々の苦痛はより悪質で、 より長く続く。ガス室と同様に、これらの犯罪は決して忘れられることはなく、関与した者たちは生前も死後も永遠に非難されるだろう。」[51] (アレクサンドル・ソルジェニーツィン) ソ連における政治的異議申し立て者への「緩慢型統合失調症」診断のような精神医学的診断は、政治的目的のために利用された。[52] 反体制派の事例で最も顕著に使用されたのは「緩慢型統合失調症」の診断であった。[53] 新たな診断カテゴリーの一つとして創出された緩慢型統合失調症は、反体制派を封殺するための手段であり、政治体制の名の下に医師が抑圧の道具として行動す る際、精神科医たちの良心をなだめるための自己欺瞞の根源であった。[54] グローバル精神医学イニシアチブのロバート・ヴァン・ヴォレン代表によれば、ソ連における精神医学の政治的悪用は、ソ連体制に反対する人民は精神的に病ん でいるという概念から生じた。世界最高の社会政治体制とされたものに反対する論理的根拠が他に存在しないためである。[55] 「緩慢型統合失調症」という診断概念は、モスクワ精神医学派、特にその指導者スネジュネフスキーによって発展させた長年の概念であり、この行動を説明する 非常に便利な枠組みを提供した。[55] 学界の主流の見解によれば、この診断概念の発展に主導的役割を果たした精神科医たちは、共産党とソ連秘密警察(KGB)からの指示に従い、それが政治的に 利用されることを十分認識していた。とはいえ、多くのソ連精神科医にとって「鈍麻性統合失調症」は、体制批判者の行動を説明する論理的な枠組みに見えた。 彼らは改革主義的な信念や理想のために、幸福や家族、キャリアを危険に晒すことを厭わないように見えたからだ。その信念や理想は、当時の社会的・政治的正 統性とは明らかに乖離していたのである。[55] ソ連精神医学の最も著名な理論家であり、ソ連医学アカデミー精神医学研究所所長であったスネジュネフスキーは、独自の診断基準を提唱する精神障害の新分類 を開発した[9]。慎重に構築された「鈍麻性統合失調症」の記述は、精神病症状が診断に必須ではない一方、精神病質、心気症、自己疎外感、不安症状が核心 的であることを確立した。[9] 「陰性軸」の一部とされる症状には、悲観主義、社会的適応不良、権威との対立が含まれ、これらが「症状の乏しい緩慢型統合失調症」の正式診断に十分であっ た。[9] スネジュネフスキーによれば、緩慢型統合失調症患者は一見正常に見えるが、訓練を受けていない者には気づかれない、最小限ながら臨床的に重要な人格変化を 示すことがある。[9] これにより非精神病性精神障害患者、あるいは精神疾患を持たない人格さえも、緩慢型統合失調症と容易に診断される可能性があった。[9] 偏執症と並んで、緩慢型統合失調症は反体制派を精神科施設に収容する際に最も頻繁に用いられた診断名であった。[9] スネジュネフスキーらの理論によれば、統合失調症は従来考えられていたよりもはるかに蔓延しているとされた。なぜなら、この疾患は比較的軽微な症状で現 れ、その後進行する可能性があるからだ。[55] その結果、1973年に世界保健機関(WHO)が発表した統合失調症パイロット研究が報告したように、モスクワでは他国の都市よりもはるかに頻繁に統合失 調症が診断された。[55] 世界で最も統合失調症の罹患率が高かった都市はモスクワであった。[56] 特に、スネジュネフスキーらは、この診断を受けた患者は社会的な意味においてほぼ正常に機能し得るとしたため、緩慢型統合失調症によって診断範囲が拡大さ れた。[55] 彼らの症状は神経症に似たものとなることもあれば、妄想的な性格を帯びることもあった。[55] 妄想症状を持つ患者は自身の状態にある程度の自覚を持ちつつも、自己の重要性を過大評価し、社会改革という誇大妄想を示すことがあった。[55] したがって、緩慢型統合失調症には「改革妄想」「固執」「真実への闘争」といった症状が現れる可能性があった。[55] ヴィクトル・スチャージキンの報告によれば、スネシュネフスキーは「新たな人間認識原理を構築し、人類幸福アカデミーの構想を練り、その他人類の利益とな る数々の計画を立案する」患者全員に改革妄想と診断した。[57] 1960年代から1970年代にかけて、社会改革や真実のための闘争に関する思想、宗教的信念を含む理論は、ほぼ全ての外国の分類体系において妄想性パラ ノイア障害とは見なされなかった。しかしソ連精神医学は、イデオロギー的概念に基づき、政治体制への批判やその改革提案を妄想的構築物に帰した。[58] 停滞性統合失調症や改革妄想を伴う妄想状態という概念に基づく診断アプローチは、ソ連と東欧数カ国でのみ用いられた。[59] KGBの秘密指令により、数千人の社会・政治改革者——ソ連の「反体制派」——が「遅滞型統合失調症」という診断名で精神病院に収容された。この疾患はス ネシュネフスキーと「モスクワ学派」精神医学によって捏造されたものである。[60] 米国の精神科医アラン・A・ストーンは、西側諸国によるソ連精神医学への批判がスネシュネフスキー人格に向けられたのは、彼が「改革主義」を含むその他の 症状を伴う「緩慢型」の表出を特徴とするソ連の統合失調症概念の根本的責任者であったためだと述べた。[61] この診断体系は反体制派に容易に適用できる。[61] スネジュネフスキーは長らく西側で、ソ連における精神医学的虐待の典型例として攻撃されてきた。[53] 主な批判者たちは、スネジュネフスキーが政治的異議申し立てを精神疾患化するために、ソ連型統合失調症モデルとこの診断を設計したと示唆した。[62] 彼は政治的目的に都合よく歪められる診断体系を冷笑的に構築したとして非難され、自らも一連の著名な反体制派事件の診断に関与した[53]。さらに数十件 にわたり、ウラジーミル・ブコフスキー、ナターリヤ・ゴルバネフスカヤ、レオニード・プリュシッチの精神的に健康な dissidents の法律上の精神病の診断を、彼の人格 ミコラ・プラホトニュク[63]、ピョートル・グリゴレンコ[64]らを含む精神的に健全な反体制派の法的精神異常認定に関する委員会決定書に自ら署名し た。 |

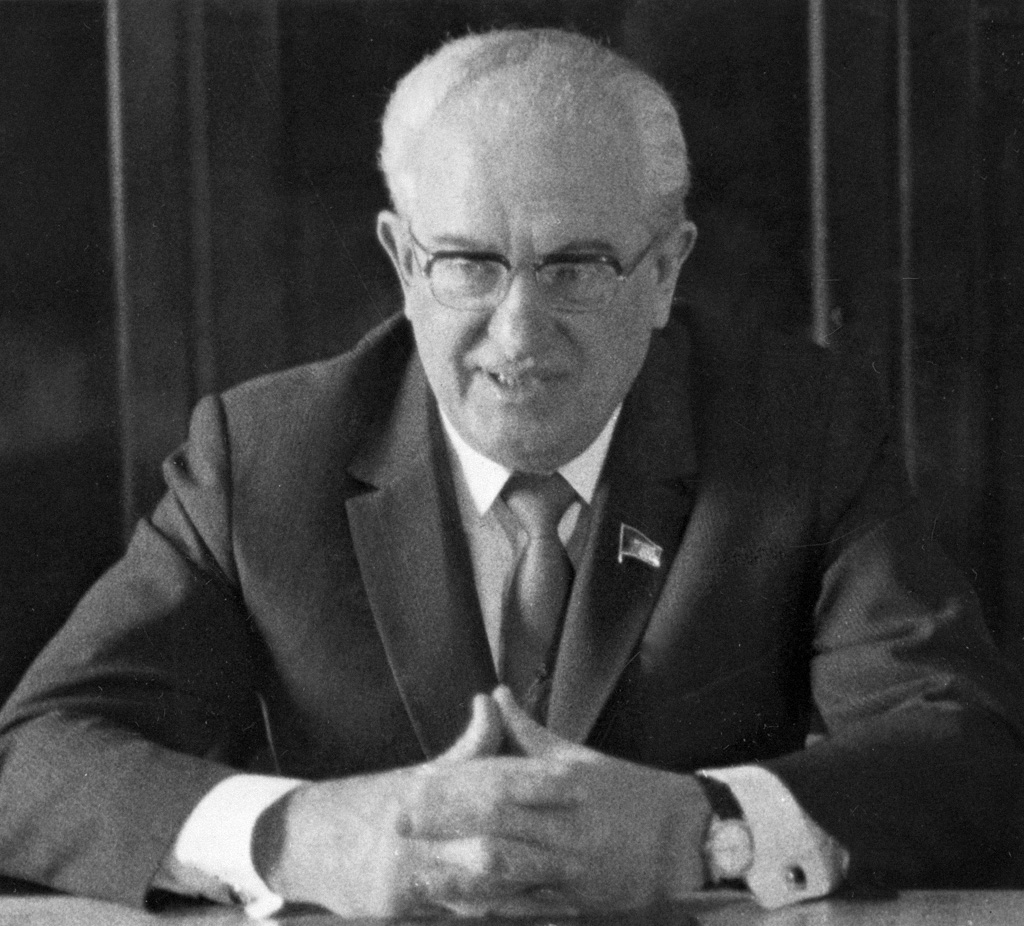

| Beginning of the trend toward mass abuse From Khrushchev to Andropov The campaign to declare political opponents mentally sick and to commit dissenters to mental hospitals began in the late 1950s and early 1960s.[39] As Vladimir Bukovsky commented on the emergence of the political abuse of psychiatry,[65] Nikita Khrushchev reckoned that it was impossible for people in a socialist society to have an anti-socialist consciousness. Whenever manifestations of dissidence could not be justified as a provocation of world imperialism or a legacy of the past, they were self-evidently the product of mental disease.[39] In a speech published in the Pravda daily newspaper on 24 May 1959, Khrushchev said: A crime is a deviation from generally recognized standards of behavior frequently caused by mental disorder. Can there be diseases, nervous disorders among certain people in a Communist society? Evidently yes. If that is so, then there will also be offences, which are characteristic of people with abnormal minds. Of those who might start calling for opposition to Communism on this basis, we can say that clearly their mental state is not normal.[39]  Yuri Andropov (1914–1984), a KGB Chairman and General Secretary of the CPSU The now available evidence supports the conclusion that the system of political abuse of psychiatry was carefully designed by the KGB to rid the USSR of undesirable elements.[66] According to several available documents and a message by a former general of the Fifth (dissident) Directorate of the Ukrainian KGB to Robert van Voren, political abuse of psychiatry as a systematic method of repression was developed by Yuri Andropov along with a selected group of associates.[67] Andropov was in charge of the wide-ranging deployment of psychiatric repression from the moment he was appointed to head the KGB.[68] He became KGB Chairman on 18 May 1967.[69] On 3 July 1967, he made a proposal to establish a Fifth Directorate (ideological counterintelligence) within the KGB to deal with internal political opposition to the Soviet regime.[70][71] The Directorate was set up at the end of July and took charge of KGB files on all Soviet dissidents, including Andrei Sakharov and Alexander Solzhenitsyn.[70] In 1968, KGB Chairman Andropov issued a departmental order "On the tasks of State security agencies in combating the ideological sabotage by the adversary", calling for the KGB to struggle against dissidents and their imperialist masters.[72] His aim was "the destruction of dissent in all its forms" and he insisted that the positions of the capitalist countries on human rights, and their criticisms of the Soviet Union and its own politics of human rights from these positions, was just one part of a wide-ranging imperialist plot to undermine the Soviet state's foundation.[72] Similar ideas can be found in the 1983 book Speeches and Writings by Andropov published when he had become General Secretary of the CPSU:[73] [w]hen analyzing the main trend in present-day bourgeois criticism of [Soviet] human rights policies one is bound to draw the conclusion that although this criticism is camouflaged with "concern" for freedom, democracy, and human rights, it is directed in fact against the socialist essence of Soviet society... |

大量虐待の潮流の始まり フルシチョフからアンドロポフへ 政治的反対者を精神病と宣言し、異論者を精神病院に収容する運動は1950年代末から1960年代初頭に始まった[39]。ウラジーミル・ブコフスキーが 政治的虐待としての精神医学の出現について述べたように[65]、 ニキータ・フルシチョフは、社会主義社会における反社会主義的意識を持つことが不可能だと考えた。反体制的な行動が世界帝国主義の挑発や過去の遺物として 正当化できない場合、それは明らかに精神疾患の産物であった[39]。1959年5月24日付プラウダ紙に掲載された演説で、フルシチョフは次のように述 べた: 犯罪とは、一般的に認められた行動規範からの逸脱であり、しばしば精神障害によって引き起こされる。共産主義社会において、特定の人民に疾病や神経障害が 存在しうるか?明らかに存在する。ならば、異常な精神状態を持つ者に特有の犯罪もまた存在するだろう。この根拠に基づき共産主義への反対を呼びかけ始める 者たちについては、彼らの精神状態が明らかに正常ではないと断言できる。[39]  ユーリ・アンドロポフ(1914–1984)、KGB議長兼ソ連共産党書記長 現在入手可能な証拠は、精神医学の政治的悪用システムが、ソ連から望ましくない要素を排除するためにKGBによって慎重に設計されたという結論を支持して いる。[66] 入手可能な複数の文書と、ウクライナKGB第五局(反体制派)の元将校がロバート・ヴァン・ヴォーレンに送ったメッセージによれば、抑圧の体系的手法とし ての精神医学の政治的悪用は、ユーリ・アンドロポフが選りすぐりの協力者グループと共に開発したものである。[67] アンドロポフはKGB長官に任命された瞬間から、精神医学的抑圧の広範な展開を担当していた。[68] 彼は1967年5月18日にKGB議長に就任した。[69] 1967年7月3日、ソ連体制に対する内部政治的反対勢力を扱うため、KGB内に第五局(イデオロギー対抗諜報)を設置する提案を行った。[70] [71] 同局は7月末に設置され、アンドレイ・サハロフやアレクサンドル・ソルジェニーツィンを含む全てのソ連反体制派に関するKGBのファイルを管理した。 [70] 1968年、KGB議長アンドロポフは「敵対勢力によるイデオロギー的破壊工作への国家保安機関の任務について」という部門指令を発令し、KGBが反体制 派とその帝国主義の主人に立ち向かうよう求めた。[72] 彼の目的は「あらゆる形態の異議申し立ての破壊」であり、資本主義諸国の人権に関する立場、およびそれらの立場からソ連とその人権政策に対する批判は、ソ 連国家の基盤を揺るがす広範な帝国主義的陰謀の一部に過ぎないと主張した。[72] 同様の思想は、アンドロポフがソ連共産党書記長に就任した際に刊行された1983年の著書『アンドロポフ演説・論文集』にも見られる:[73] [ソ連]人権政策に対する現代ブルジョア批判の主要な傾向を分析するとき、この批判は自由、民主主義、人権への「懸念」で偽装されているものの、実際にはソ連社会の本質である社会主義的性質を標的としているという結論に至らざるを得ない... |

| Implementation and the legal framework On 29 April 1969, Andropov submitted an elaborate plan to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union to set up a network of mental hospitals that would defend the "Soviet Government and the socialist order" from dissenters.[74] To persuade his fellow Politburo members of the risk posed by the mentally ill, Andropov circulated a report from the Krasnodar Region.[75] A secret resolution of the USSR Council of Ministers was adopted.[76] Andropov's proposal to use psychiatry for struggle against dissenters was adopted and implemented.[77] In 1929, the USSR had 70 psychiatric hospitals and 21,103 psychiatric beds. By 1935, this had increased to 102 psychiatric hospitals and 33,772 psychiatric beds, and by 1955 there were 200 psychiatric hospitals and 116,000 psychiatric beds in the Soviet Union.[78] The Soviet authorities built psychiatric hospitals at a rapid pace and increased the quantity of beds for patients with nervous and mental illnesses: between 1962 and 1974, the number of beds for psychiatric patients increased from 222,600 to 390,000.[79] Such an expansion in the number of psychiatric beds was expected to continue in the years up to 1980.[80] Throughout this period the dominant trend in Soviet psychiatry ran counter to the vigorous attempts in Western countries to treat as many as possible as out-patients rather than in-patients.[80] On 15 May 1969, a Soviet Government decree (No. 345–209) was issued "On measures for preventing dangerous behavior (acts) on the part of mentally ill persons."[81] This decree confirmed the practice of having undesirables hauled into detention by psychiatrists.[81] Soviet psychiatrists were told whom they should examine and were assured that they might detain these individuals with the help of the police or entrap them into coming to the hospital.[81] The psychiatrists thereby doubled as interrogators and as arresting officers.[81] Doctors fabricated a diagnosis requiring detention and no court decision was required for subjecting the individual to indefinite confinement in a psychiatric institution.[81] By the end of the 1950s, confinement to a psychiatric institution had become the most commonly used method of punishing leaders of the political opposition.[9] In the 1960s and 1970s, the trials of dissenters and their referral for "treatment" to the Special Psychiatric Hospitals under MVD control and oversight[82] came out into the open, and the world learned of a wave of "psychiatric terror" which was flatly denied by those in charge of the Serbsky Institute.[83] The bulk of psychiatric repression spans the period from the late 1960s to the early 1980s.[84] As CPSU General Secretary, from November 1982 to February 1984, Yury Andropov demonstrated little patience with domestic dissafection and continued the Brezhnev Era policy of confining dissenters in mental hospitals.[85] |

実施と法的枠組み 1969年4月29日、アンドロポフはソビエト連邦共産党中央委員会に対し、「ソビエト政府と社会主義秩序」を異議申し立て者から守るための精神病院ネッ トワーク設立に関する詳細な計画を提出した。[74] アンドロポフは精神疾患患者がもたらす危険性を政治局員に説得するため、クラスノダール地方からの報告書を回覧した。[75] ソ連閣僚会議の秘密決議が採択された。[76] 反体制派との闘争に精神医学を利用するというアンドロポフの提案は採択され、実施された。[77] 1929年、ソ連には70の精神病院と21,103床の精神科病床があった。1935年までに、これは102の精神病院と33,772床に増加し、 1955年までにソ連には200の精神病院と116,000床の精神科病床が存在した。[78] ソ連当局は精神病院を急速に建設し、神経疾患・精神疾患患者の病床数を増加させた。1962年から1974年の間に、精神科患者の病床数は222,600 床から390,000床に増加した。[79] このような精神科病床数の拡大は、1980年までの数年間も継続すると見込まれていた。[80] この期間を通じて、ソ連精神医学の主流傾向は、西側諸国で入院治療ではなく可能な限り外来治療を行うという活発な試みとは逆の方向を向いていた。[80] 1969年5月15日、ソ連政府は「精神疾患人格の危険な行動(行為)を防止するための措置について」の法令(第345-209号)を発布した。[81] この法令は、精神科医による「望ましくない者」の拘束収容を容認する慣行を正式に認めたものである。[81] ソ連の精神科医は、誰を診察すべきかを指示され、警察の協力を得てこれら個人を拘束するか、あるいは病院に来るよう仕向けることが保証されていた。 [81] こうして精神科医は尋問官と逮捕官の二重の役割を担った。[81] 医師は拘束を必要とする診断をでっち上げ、精神科施設への無期限収容に裁判所の決定は不要だった。[81] 1950年代末までに、精神科施設への収容は政治的反対派指導者を処罰する最も一般的な手段となった。[9] 1960年代から1970年代にかけ、反体制派の裁判と内務省(MVD)の管理下にある特別精神病院への「治療」送致[82]が公然化。セルブスキー研究 所の責任者らが全面否定した「精神医学的テロ」の波が世界に知られるようになった。[83] 精神医学的抑圧の大部分は1960年代後半から1980年代初頭にかけて行われた。[84] 1982年11月から1984年2月までソ連共産党書記長を務めたユーリ・アンドロポフは、国内の不満に対してほとんど忍耐を示さず、反体制派を精神病院 に収容するというブレジネフ時代の政策を継続した。[85] |

| Examination and hospitalization Political dissidents were usually charged under Articles 70 (agitation and propaganda against the Soviet state) and 190-1 (dissemination of false fabrications defaming the Soviet state and social system) of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic Criminal Code.[9] Forensic psychiatrists were asked to examine offenders whose mental state was considered abnormal by the investigating officers.[9] In almost every case, dissidents were examined at the Serbsky Central Research Institute for Forensic Psychiatry[86] in Moscow, where persons being prosecuted in court for committing political crimes were subjected to a forensic-psychiatric expert evaluation.[84] Once certified, the accused and convicted were sent for involuntary treatment to the Special Psychiatric Hospitals controlled by the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD) of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic.[84] The accused had no right of appeal.[9] The right was given to their relatives or other interested persons but they were not allowed to nominate psychiatrists to take part in the evaluation, because all psychiatrists were considered fully independent and equally credible before the law.[9] According to dissident poet Naum Korzhavin, the atmosphere at the Serbsky Institute in Moscow altered almost overnight when Daniil Lunts took over as head of the Fourth Department (otherwise known as the Political Department).[39] Previously, psychiatric departments were regarded as a 'refuge' against being dispatched to the Gulag. Now that policy altered.[39] The first reports of dissenters being hospitalized on non-medical grounds date from the early 1960s, not long after Georgy Morozov was appointed director of the Serbsky Institute.[39] Both Morozov and Lunts were personally involved in numerous well-known cases and were notorious abusers of psychiatry for political purposes.[39] Most prisoners, in Viktor Nekipelov's words, characterized Daniil Lunts as "no better than the criminal doctors who performed inhuman experiments on the prisoners in Nazi concentration camps."[87] A well-documented practice was the use of psychiatric hospitals as temporary prisons during the two or three weeks around the 7 November (October Revolution) Day and May Day celebrations, to isolate "socially dangerous" persons who otherwise might protest in public or manifest other deviant behavior.[88] |

診察と入院 政治的反体制派は通常、ロシア・ソビエト連邦社会主義共和国刑法第70条(ソビエト国家に対する扇動・宣伝)および第190条第1項(ソビエト国家及び社 会制度を誹謗する虚偽の捏造の流布)で起訴された[9]。捜査官が精神状態を異常と判断した被疑者については、法医学精神科医による診察が求められた [9]。 ほぼ全てのケースで、反体制派はモスクワのセルブスキー中央法医学精神医学研究所[86]で検査を受けた。同所では政治犯罪で起訴された人格に対し、法医 学的精神医学的鑑定が実施されていた[84]。鑑定結果が確定すると、被告及び有罪判決を受けた者は、ロシア・ソビエト連邦社会主義共和国内務省 (MVD)管轄の特別精神病院へ強制治療のため送致された。[84] 被告には上訴権は認められなかった。[9] その権利は親族やその他の利害関係者に与えられたが、評価に参加する精神科医を指名することは許されなかった。なぜなら、全ての精神科医は法の前で完全に独立しており、同等に信頼できるとみなされていたからである。[9] 反体制派詩人ナウム・コルジャヴィンによれば、ダニイル・ルンツが第四部(別名:政治部)の責任者に就任した際、モスクワのセルブスキー研究所の雰囲気は 一夜にして一変した。[39] それまでは、精神科病棟はグラーグ送りを免れる「避難所」と見なされていた。しかしこの方針は変わった。[39] 反体制派が医学的根拠なく入院させられた最初の報告は、セルブスキー研究所所長にゲオルギー・モロゾフが任命された直後の1960年代初頭に遡る。 [39] モロゾフもルンツも、数多くの著名な事例に直接関与し、政治的目的で精神医学を悪用した悪名高い人格であった。[39] ヴィクトル・ネキペロフの言葉を借りれば、ほとんどの囚人たちはダニイル・ルンツを「ナチス強制収容所で囚人に非人道的な実験を行った犯罪的医師たちと同 然」と評した。[87] よく記録されている慣行として、11月7日(十月革命記念日)とメーデーの祝祭日前後2~3週間、精神病院を仮設刑務所として利用し、「社会的に危険な」 人格を隔離する事例があった。そうしなければ、彼らは公の場で抗議したり、その他の逸脱行動を示したりする可能性があったからだ。[88] |

| Struggle against abuse Main article: Struggle against political abuse of psychiatry in the Soviet Union In the 1960s, a vigorous movement grew up protesting against abuse of psychiatry in the USSR.[89] Political abuse of psychiatry in the Soviet Union was denounced in the course of the Congresses of the World Psychiatric Association in Mexico City (1971), Hawaii (1977), Vienna (1983) and Athens (1989).[9] The campaign to terminate political abuse of psychiatry in the USSR was a key episode in the Cold War, inflicting irretrievable damage on the prestige of medicine in the Soviet Union.[60] |

虐待との闘い 主な記事:ソビエト連邦における精神医学の政治的悪用との闘い 1960年代、ソ連における精神医学の濫用に対する抗議運動が活発化した[89]。ソ連における精神医学の政治的濫用は、世界精神医学会総会(メキシコシ ティ1971年、ハワイ1977年、ウィーン1983年、アテネ1989年)において非難された。[9] ソ連における精神医学の政治的悪用を終わらせる運動は、冷戦における重要な局面であり、ソ連における医学の威信に回復不能な損害を与えた。[60] |

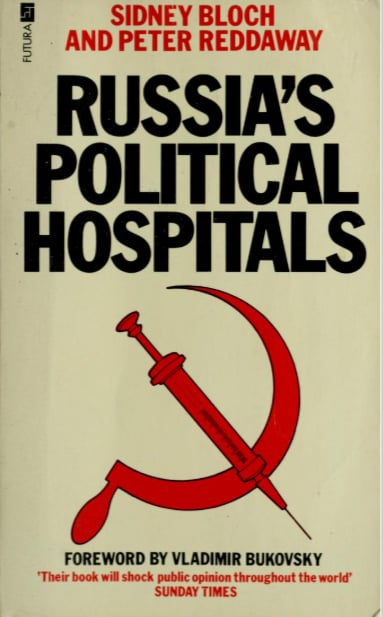

| Classification of the victims Main article: Cases of political abuse of psychiatry in the Soviet Union Upon analysis of over 200 well-authenticated cases covering the period 1962–1976, Sidney Bloch and Peter Reddaway developed a classification of the victims of Soviet psychiatric abuse. They were classified as:[90] 1.advocates of human rights or democratization; 2. nationalists; 3. would-be emigrants; 4. religious believers; 5. citizens inconvenient to the authorities. The advocates of human rights and democratization, according to Bloch and Reddaway, made up about half the dissidents repressed by means of psychiatry.[90] Nationalists made up about one-tenth of the dissident population dealt with psychiatrically.[91] Would-be emigrants constituted about one-fifth of dissidents victimized by means of psychiatry.[92] People detained only because of their religious activity made up about fifteen per cent of dissident-patients.[92] Citizens inconvenient to the authorities because of their "obdurate" complaints about bureaucratic excesses and abuses accounted for about five per cent of dissidents subject to psychiatric abuse.[93] |

被害者の分類 主な記事:ソビエト連邦における精神医学の政治的悪用事例 1962年から1976年までの期間をカバーする200件以上の確かな事例を分析した結果、シドニー・ブロックとピーター・レダウェイはソビエトの精神医学的虐待の被害者を分類した。彼らは次のように分類された:[90] 1.人権や民主化の擁護者 2. ナショナリスト 3. 国外移住希望者 4. 宗教信者 5. 当局にとって都合の悪い市民 ブロッホとレダウェイによれば、人権・民主化運動の支持者は、精神医学によって弾圧された反体制派の約半数を占めていた[90]。ナショナリストは精神医 学的処置を受けた反体制派人口の約1割を占めた。[91] 精神医学的手法で被害を受けた反体制派の約5分の1は移住希望者であった。[92] 宗教活動のみを理由に拘束された人民は反体制派患者の約15%を占めた。[92] 官僚の過剰行為や不正に対する「頑固な」苦情を理由に当局にとって厄介な市民は、精神医学的虐待を受けた反体制派の約5%を占めた。[93] |

| Incomplete figures In 1985, Peter Reddaway and Sidney Bloch provided documented data on some five hundred cases in their book Soviet Psychiatric Abuse.[94] True scale of repression On basis of the available data and materials accumulated in the archives of the International Association on the Political Use of Psychiatry, one can confidently conclude that thousands of dissenters were hospitalized for political reasons.[55] From 1994 to 1995, an investigative commission of Moscow psychiatrists explored the records of five prison psychiatric hospitals in Russia and discovered about two thousand cases of political abuse of psychiatry in these hospitals alone.[55] In 2004, Anatoly Prokopenko said he was surprised at the facts obtained by him from the official classified top secret documents by the Central Committee of the CPSU, by the KGB, and MVD.[95] According to his calculations based on what he found in the documents, about 15,000 people were confined for political crimes in the psychiatric prison hospitals under the control of the MVD.[95] In 2005, referring to the Archives of the CPSU Central Committee and the records of the three Special Psychiatrial Hospitals — Sychyovskaya, Leningrad and Chernyakhovsk hospitals — to which human rights activists gained access in 1991, Prokopenko concluded that psychiatry had been used as punitive measure against about 20,000 people for purely political reasons.[96] This was only a small part of the total picture, Prokopenko said. The data on the total number of people who had been held in all sixteen prison hospitals and in the 1,500 "open" psychiatric hospitals remains unknown because parts of the archives of the prison psychiatric hospitals and hospitals in general are classified and inaccessible.[96] The figure of fifteen or twenty thousand political prisoners in psychiatric hospitals run by the Soviet Ministry of Internal Affairs was first put forward by Prokopenko in the 1997 book Mad Psychiatry ("Безумная психиатрия"),[97] which was republished in 2005.[98] An indication of the extent of the political abuse of psychiatry in the USSR is provided by Semyon Gluzman's calculation that the percentage of "the mentally ill" among those accused of so-called anti-Soviet activities proved many times higher than among criminal offenders.[99][19] The attention paid to political prisoners by Soviet psychiatrists was more than 40 times greater than their attention to ordinary criminal offenders.[99] This derives from the following comparison: 1–2% of all the forensic psychiatric examinations carried out by the Serbsky Institute targeted those accused of anti-Soviet activities;[99][19] convicted dissidents in penal institutions made up 0.05% of the total number of convicts;[99][19] 1–2% is 40 times greater than 0.05%.[99][19] According to Viktor Luneyev, the struggle against dissent operated on many more layers than those registered in court sentences. We do not know how many the secret services kept under surveillance, held criminally liable, arrested, sent to psychiatric hospitals, or who were sacked from their jobs, and restricted in all kinds of other ways in the exercise of their rights.[100] No objective assessment of the total number of repressed persons is possible without fundamental analysis of archival documents.[101] The difficulty is that the required data are very diverse and are not to be found in a single archive.[101] They are scattered between the State Archive of the Russian Federation, the archive of the Russian Federation State Statistical Committee (Goskomstat), the archives of the RF Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD of Russia), the FSB of Russia, the RF General Prosecutor's Office, and the Russian Military and Historical Archive. Further documents are held in the archives of 83 constituent entities of the Russian Federation, in urban and regional archives, as well as in the archives of the former Soviet Republics, now the 11 independent countries of the Commonwealth of Independent States or the three Baltic States (Baltics).[101] |

不完全な数字 1985年、ピーター・レダウェイとシドニー・ブロックは著書『ソビエト精神医学の虐待』において、約500件の事例に関する記録データを提供した[94]。 抑圧の真の規模 国際精神医学政治利用協会のアーカイブに蓄積された入手可能なデータと資料に基づき、数千人の反体制派が政治的理由で入院させられたと確信を持って結論づ けられる[55]。1994年から1995年にかけて、モスクワの精神科医による調査委員会がロシア国内の5つの刑務所精神科病院の記録を調査し、これら の病院だけで約2000件の精神医学の政治的悪用事例を発見した。[55] 2004年、アナトリー・プロコペンコは、ソ連共産党中央委員会、KGB、内務省(MVD)の公式極秘文書から得た事実に対し驚いたと述べた。[95] 文書から得た情報に基づく彼の試算によれば、内務省管轄下の精神科刑務病院には政治犯罪者として約15,000人が収容されていた。[95] 2005年、プロコペンコは1991年に人権活動家がアクセスしたソ連共産党中央委員会公文書館及び3つの特別精神病院(シチョフスカヤ病院、レニング ラード病院、チェルニャホフスク病院)の記録を参照し、純粋に政治的理由から約2万人が懲罰手段として精神医学を利用されたと結論付けた。[96] プロコペンコによれば、これは全体像のごく一部に過ぎない。全16の刑務所病院と1,500の「開放型」精神病院に収容された総数のデータは、刑務所精神 病院および一般病院の記録の一部が機密扱いされアクセス不能なため、依然として不明である。[96] ソ連内務省が運営する精神病院に収容された政治犯が1万5千から2万人という数字は、プロコペンコが1997年の著書『狂気の精神医学』 (Безумная психиатрия)[97]で初めて提示したもので、2005年に再版された[98]。 ソ連における精神医学の政治的悪用規模を示す指標として、セミョン・グルズマンの計算がある。いわゆる反ソビエト活動で告発された者における「精神病患 者」の割合は、一般犯罪者よりも数倍高かった[99][19]。ソ連の精神科医が政治犯に注いだ注意力は、一般犯罪者に対するそれの40倍以上であった [99]。これは以下の比較から導かれる:セルブスキー研究所が実施した全法医学精神鑑定のうち、反ソビエト活動容疑者を対象としたものは1~2%であっ た[99][19]。刑務施設における有罪判決を受けた反体制派は、全受刑者の0.05%を占めていた[99][19]。1~2%は0.05%の40倍で ある[99]。[19] ヴィクトル・ルネエフによれば、反体制派への弾圧は裁判記録に表れたものよりもはるかに多層的に行われていた。秘密警察が監視下に置いた者、刑事責任を問 われた者、逮捕された者、精神病院に送られた者、職を解かれた者、その他あらゆる方法で権利行使を制限された抑圧された人格の数は不明である[100]。 抑圧された人格の総数を客観的に評価するには、公文書記録の根本的な分析が不可欠だ[101]。問題は、必要なデータが非常に多様であり、単一の公文書館 には存在しないことだ[101]。それらはロシア連邦国家公文書館、ロシア連邦国家統計委員会(ゴスコムスタット)公文書館、ロシア連邦内務省(ロシア MVD)公文書館、ロシア連邦保安庁(FSB)、ロシア連邦検察庁、ロシア軍事歴史公文書館に分散している。さらに、ロシア連邦を構成する83の主体(共 和国・自治共和国・地方自治体)の公文書館、都市・地域の公文書館、そして旧ソビエト連邦構成共和国(現在の独立国家共同体(CIS)加盟11カ国および バルト三国)の公文書館にも関連文書が保管されている。[101] |

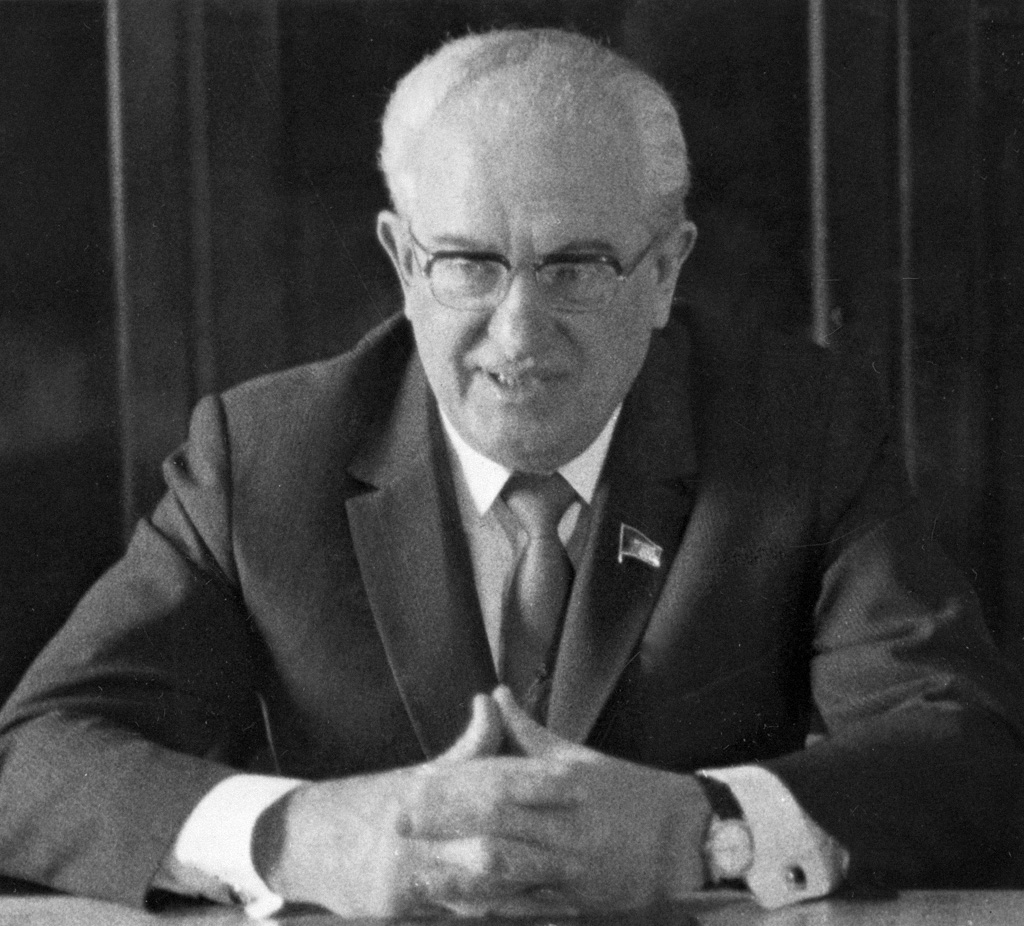

| Concealment of the data According to Russian psychiatrist Emmanuil Gushansky, the scale of psychiatric abuses in the past, the use of psychiatric doctrines by the totalitarian state have been thoroughly concealed.[102] The archives of the Soviet Ministries of Internal Affairs (MVD) and Health (USSR Health Ministry), and of the Serbsky Institute for Forensic Psychiatry, which between them hold evidence about the expansion of psychiatry and the regulations governing that expansion, remain totally closed to researchers, says Gushansky.[102] Dan Healey shares his opinion that the abuses of Soviet psychiatry under Stalin and, even more dramatically, in the 1960s to 1980s remain under-researched: the contents of the main archives are still classified and inaccessible.[103] Hundreds of files on people who underwent forensic psychiatric examinations at the Serbsky Institute during Stalin's time are on the shelves of the highly classified archive in its basement[104] where Gluzman saw them in 1989.[105] All are marked by numbers without names or surnames, and any biographical data they contain[104] is unresearched and inaccessible to researchers.[105] Anatoly Sobchak, the former Mayor of Saint Petersburg, wrote: The scale of the application of methods of repressive psychiatry in the USSR is testified by inexorable figures and facts. A commission of the top Party leadership headed by Alexei Kosygin reached a decision in 1978 to build 80 psychiatric hospitals and 8 special psychiatric institutions in addition to those already in existence. Their construction was to be completed by 1990. They were to be built in Krasnoyarsk, Khabarovsk, Kemerovo, Kuibyshev, Novosibirsk, and other parts of the Soviet Union. In the course of the changes that the country underwent in 1988, five prison hospitals were transferred from the MVD to the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Health, while another five were closed down. There was a hurried covering of tracks through the mass rehabilitation of patients, some of whom were mentally disabled (in one and the same year no less than 800,000 patients were removed from the psychiatric registry). In Leningrad alone 60,000 people with a diagnosis of mental illness were released and rehabilitated in 1991 and 1992. In 1978, 4.5 million people throughout the USSR were registered as psychiatric patients. This was equivalent to the population of many civilized countries.[106] In Ukraine, a study of the origins of the political abuse of psychiatry was conducted for five years on the basis of the State archives.[107] A total of 60 people were again examined.[107] All were citizens of Ukraine, convicted of political crimes and hospitalized on the territory of Ukraine. Not one of them, it turned out, was in need of any psychiatric treatment.[107]  Alexander Yakovlev (1923–2005), the head of the Commission for Rehabilitation of the Victims of Political Repression From 1993 to 1995, a presidential decree on measures to prevent future abuse of psychiatry was being drafted at the Commission for Rehabilitation of the Victims of Political Repression.[108] For this purpose, Anatoly Prokopenko selected suitable archival documents and, at the request of Vladimir Naumov, the head of research and publications at the commission, Emmanuil Gushansky drew up the report.[108] It correlated the archival data presented to Gushansky with materials received during his visits, conducted jointly with the commission of the Independent Psychiatric Association of Russia, to several strict-regime psychiatric hospitals (former Special Hospitals under MVD control).[108] When the materials for discussion in the Commission for Rehabilitation of the Victims of Political Repression were ready, however, the work came to a standstill.[108] The documents failed to reach the head of the Commission Alexander Yakovlev.[108] The report on political abuse of psychiatry prepared at the request of the commission by Gushansky with the aid of Prokopenko lay unclaimed and even the Independent Psychiatric Journal (Nezavisimiy Psikhiatricheskiy Zhurnal)[102] would not publish it. The Moscow Research Center for Human Rights headed by Boris Altshuler and Alexey Smirnov and the Independent Psychiatric Association of Russia whose president is Yuri Savenko were asked by Gushansky to publish the materials and archival documents on punitive psychiatry but showed no interest in doing so.[108] Publishing such documents is dictated by present-day needs and by how far it is feared that psychiatry could again be abused for non-medical purposes.[109] In its 2000 report, the Commission for Rehabilitation of the Victims of Political Repression included only the following four phrases about the political abuse of psychiatry:[110] The Commission has also considered such a complex, socially relevant issue, as the use of psychiatry for political purposes. The collected documents and materials allow us to say that the extrajudicial procedure of admission to psychiatric hospitals was used for compulsory hospitalization of persons whose behavior was viewed by the authorities as "suspicious" from the political point of view. According to the incomplete data, hundreds of thousands of people have been illegally placed to psychiatric institutions of the country over the years of Soviet power. The rehabilitation of these people was limited, at best, to their removal from the registry of psychiatric patients and usually remains so today, due to gaps in the legislation. In the 1988 and 1989, about two million people were removed from the psychiatric registry at the request of Western psychiatrists. It was one of their conditions for the re-admission of Soviet psychiatrists to the World Psychiatric Association.[111] Yury Savenko has provided different figures in different publications: about one million,[112] up to one and a half million,[113] about one and a half million people removed from the psychiatric registry.[114] Mikhail Buyanov provided the figure of over two million people removed from the psychiatric registry.[115] |

データの隠蔽 ロシアの精神科医エマニュエル・グシャンスキーによれば、過去における精神医学的虐待の規模、全体主義国家による精神医学的教義の活用は徹底的に隠蔽され てきた。[102] ソ連内務省(MVD)と健康省(ソ連健康省)、そしてセルブスキー法精神医学研究所のアーカイブは、精神医学の拡大とその拡大を規制する規則に関する証拠 を保持しているが、研究者には完全に閉鎖されたままであるとグシャンスキーは述べる。[102] ダン・ヒーリーは、スターリン時代のソ連精神医学における虐待、そしてさらに劇的な1960年代から1980年代の虐待が、依然として研究不足であるとの 見解を共有している。主要なアーカイブの内容は依然として機密扱いであり、アクセス不能である。[103] スターリン時代にセルブスキー研究所で法医学的精神鑑定を受けた数百人のファイルは、同研究所地下の極秘アーカイブの書架に保管されている[104]。グ ルズマンは1989年にこれを目撃した[105]。全てのファイルには氏名のない番号が記されており、含まれる経歴データ[104]は未調査で研究者には アクセス不能だ。[105] 元サンクトペテルブルク市長アナトリー・ソブチャクは記している: ソ連における抑圧的精神医学手法の適用規模は、容赦ない数字と事実によって証明されている。アレクセイ・コスイギン率いる党最高指導部委員会は1978 年、既存施設に加え80の精神病院と8つの特別精神科施設を建設する決定を下した。建設は1990年までに完了する予定だった。建設予定地はクラスノヤル スク、ハバロフスク、ケメロヴォ、クイビシェフ、ノヴォシビルスクなどソ連各地に及んだ。1988年に国が経験した変革の過程で、5つの刑務所病院が内務 省から健康省の管轄に移管され、さらに別の5つが閉鎖された。患者たちの大量更生を通じて、足跡を急いで隠蔽する動きがあった。その中には精神障害者が含 まれていた(同じ年だけで80万人もの患者が精神科登録簿から削除された)。レニングラード市だけでも、1991年から1992年にかけて精神疾患の診断 を受けた6万人が釈放され更生された。1978年時点で、ソ連全土で450万人が精神科患者として登録されていた。これは多くの文明国の人民に相当する数 字である。[106] ウクライナでは、国家公文書館を基に、精神医学の政治的悪用に関する起源調査が5年間実施された。[107] 計60の人民が再審査を受けた。[107] 全員がウクライナ市民で、政治犯罪で有罪判決を受けウクライナ国内で入院していた。結果として、精神科治療を必要とする者は一人もいなかった。[107]  政治弾圧被害者復権委員会委員長 アレクサンドル・ヤコヴレーフ(1923–2005) 1993年から1995年にかけ、政治弾圧被害者復権委員会では精神医学の将来的な濫用防止策に関する大統領令の草案作成が進められた。[108] このためアナトリー・プロコペンコが適切な公文書を選定し、委員会の研究出版部長ウラジーミル・ナウモフの要請によりエマヌイル・グシャンスキーが報告書 を作成した。[108] 報告書は、グシャンスキーに提示された公文書データを、ロシア独立精神医学協会委員会と共同で実施した数か所の厳重管理精神病院(旧内務省管轄特別病院) 視察で入手した資料と照合したものだった。[108] しかし、政治弾圧被害者復権委員会での審議資料が整った時点で、作業は停滞した。[108] 文書は委員会の長であるアレクサンドル・ヤコブレフに届かなかった。[108] 委員会からの依頼でグシャンスキーがプロコペンコの協力を得て作成した精神医学の政治的悪用に関する報告書は放置されたままとなり、独立精神医学ジャーナ ル(Nezavisimiy Psikhiatricheskiy Zhurnal)[102]でさえもこれを掲載しなかった。ボリス・アルチュラーとアレクセイ・スミルノフが率いるモスクワ人権研究センター、およびユー リ・サヴェンコが会長を務めるロシア独立精神医学協会は、グシャンスキーから懲罰的精神医学に関する資料と公文書を公開するよう要請されたが、全く関心を 示さなかった。[108] このような文書の公開は、現代の必要性と、精神医学が再び非医療目的で悪用される恐れがどれほど大きいかによって決定される。[109] 政治弾圧被害者復権委員会は2000年の報告書において、精神医学の政治的悪用について以下の4つの記述のみを掲載した。[110] 委員会はまた、精神医学の政治的目的への利用という複雑で社会的に重要な問題も検討した。収集された文書と資料から、司法手続きを経ない精神病院への入院 手続きが、当局によって政治的に「疑わしい」と見なされた人格の強制入院に利用されていたと断言できる。不完全なデータによれば、ソビエト政権下において 数十万人が国内の精神医療機関に違法に収容された。これらの人々の名誉回復は、せいぜい精神科患者登録簿からの削除に留まり、法制度の欠陥ゆえに今日なお その状態が続いている。 1988年と1989年には、西側精神科医の要請により約200万人が精神科登録簿から削除された。これはソ連精神科医が世界精神医学会に再加盟するため の条件の一つであった。[111] ユーリー・サヴェンコは異なる出版物で異なる数字を提示している:約100万人[112]、最大150万人[113]、約150万人が精神科登録から削除 された[114]。ミハイル・ブヤノフは200万人以上が精神科登録から削除されたという数字を提示した[115]。 |

| Theoretical analysis In 1990, Psychiatric Bulletin of the Royal College of Psychiatrists published the article "Compulsion in psychiatry: blessing or curse?" by Russian psychiatrist Anatoly Koryagin. It contains analysis of the abuse of psychiatry and eight arguments by which the existence of a system of political abuse of psychiatry in the USSR can easily be demonstrated. As Koryagin wrote, in a dictatorial State with a totalitarian regime, such as the USSR, the laws have at all times served not the purpose of self-regulation of the life of society but have been one of the major levers by which to manipulate the behavior of subjects. Every Soviet citizen has constantly been straight considered state property and been regarded not as the aim, but as a means to achieve the rulers' objectives. From the perspective of state pragmatism, a mentally sick person was regarded as a burden to society, using up the state's material means without recompense and not producing anything, and even potentially capable of inflicting harm. Therefore, the Soviet State never considered it reasonable to pass special legislative acts protecting the material and legal part of the patients' life. It was only instructions of the legal and medical departments that stipulated certain rules of handling the mentally sick and imposing different sanctions on them. A person with a mental disorder was automatically divested of all rights and depended entirely on the psychiatrists' will. Practically anybody could undergo psychiatric examination on the most senseless grounds and the issued diagnosis turned him into a person without rights. It was this lack of legal rights and guarantees that advantaged a system of repressive psychiatry in the country.[116] According to American psychiatrist Oleg Lapshin, Russia until 1993 did not have any specific legislation in the field of mental health except uncoordinated instructions and articles of laws in criminal and administrative law, orders of the USSR Ministry of Health. In the Soviet Union, any psychiatric patient could be hospitalized by request of his headman, relatives or instructions of a district psychiatrist. In this case, patient's consent or dissent mattered not. The duration of treatment in a psychiatric hospital also depended entirely on the psychiatrist. All of that made the abuse of psychiatry possible to suppress those who opposed the political regime, and that created the vicious practice of ignoring the rights of the mentally ill.[117] According to Yuri Savenko, the president of the Independent Psychiatric Association of Russia (the IPA), punitive psychiatry arises on the basis of the interference of three main factors:[118] 1. The ideologizing of science, its breakaway from the achievements of world psychiatry, the party orientation of Soviet forensic psychiatry. 2. The lack of legal basis. 3. The total nationalization of mental health service. Their interaction system is principally sociological: the presence of the Penal Code article on slandering the state system inevitably results in sending a certain percentage of citizens to forensic psychiatric examination.[23] Thus, it is not psychiatry itself that is punitive, but the totalitarian state uses psychiatry for punitive purposes with ease.[23] According to Larry Gostin, the root cause of the problem was the State itself.[119] The definition of danger was radically extended by the Soviet criminal system to cover "political" as well as customary physical types of "danger".[119] As Bloch and Reddaway note, there are no objective reliable criteria to determine whether the person's behavior will be dangerous, and approaches to the definition of dangerousness greatly differ among psychiatrists.[120] Richard Bonnie, a professor of law and medicine at the University of Virginia School of Law, mentioned the deformed nature of the Soviet psychiatric profession as one of the explanations for why it was so easily bent toward the repressive objectives of the state, and pointed out the importance of a civil society and, in particular, independent professional organizations separate and apart from the state as one of the most substantial lessons from the period.[121] According to Norman Sartorius, a former president of the World Psychiatric Association, political abuse of psychiatry in the former Soviet Union was facilitated by the fact that the national classification included categories that could be employed to label dissenters, who could then be forcibly incarcerated and kept in psychiatric hospitals for "treatment".[122] Darrel Regier, vice-chair of the DSM-5 task force, has a similar opinion that the political abuse of psychiatry in the USSR was sustained by the existence of a classification developed in the Soviet Union and used to organize psychiatric treatment and care.[123] In this classification, there were categories with diagnoses that could be given to political dissenters and led to the harmful involuntary medication.[123] According to Moscow psychiatrist Alexander Danilin, the so-called "nosological" approach in the Moscow psychiatric school established by Snezhnevsky boils down to the ability to make the only diagnosis, schizophrenia; psychiatry is not science but such a system of opinions and people by the thousands are falling victims to these opinions—millions of lives were crippled by virtue of the concept "sluggish schizophrenia" introduced some time once by an academician Snezhnevsky, whom Danilin called a state criminal.[124] St Petersburg academic psychiatrist professor Yuri Nuller notes that the concept of Snezhnevsky's school allowed psychiatrists to consider, for example, schizoid psychopathy and even schizoid character traits as early, delayed in their development, stages of the inevitable progredient process, rather than as personality traits inherent to the individual, the dynamics of which might depend on various external factors.[125] The same also applied to a number of other personality disorders.[125] It entailed the extremely broadened diagnostics of sluggish (neurosis-like, psychopathy-like) schizophrenia.[125] Despite a number of its controversial premises and in line with the traditions of then Soviet science, Snezhnevsky's hypothesis has immediately acquired the status of dogma which was later overcome in other disciplines but firmly stuck in psychiatry.[126] Snezhnevsky's concept, with its dogmatism, proved to be psychologically comfortable for many psychiatrists, relieving them from doubt when making a diagnosis.[126] That carried a great danger: any deviation from a norm evaluated by a doctor could be regarded as an early phase of schizophrenia, with all ensuing consequences.[126] It resulted in the broad opportunity for voluntary and involuntary abuses of psychiatry.[126] However, Snezhnevsky did not take civil and scientific courage to reconsider his concept which clearly reached a deadlock.[126] According to American psychiatrist Walter Reich, the misdiagnoses of dissidents resulted from some characteristics of Soviet psychiatry that were distortions of standard psychiatric logic, theory, and practice.[53] |

理論的分析 1990年、英国王立精神医学会誌『Psychiatric Bulletin』はロシア人精神科医アナトリー・コリャギンの論文「精神医学における強制:祝福か呪いか?」を掲載した。そこには精神医学の濫用に関す る分析と、ソ連において精神医学が政治的濫用のシステムとして存在していたことを容易に立証できる八つの論拠が含まれている。コリャギンが記したように、 ソ連のような全体主義体制の独裁国家では、法律は常に社会生活の自律的調整を目的とするものではなく、被支配者の行動を操作する主要な手段の一つであっ た。あらゆるソ連市民は常に国家の所有物と見なされ、目的ではなく支配者の目標達成のための手段とみなされていた。国家の実利主義の観点から、精神疾患の 人格は社会にとって負担と見なされた。国家の物質的資源を無償で消費し、何ら生産せず、むしろ危害を加える可能性すら秘めている存在だった。したがってソ 連国家は、患者の物質的・法的生存権を保護する特別立法を制定することを合理的な措置とは決して考えなかった。精神疾患の患者に対する対応規則や異なる制 裁を定めたのは、司法部門と医療部門の指示に過ぎなかった。精神障害者は自動的に全ての権利を剥奪され、精神科医の意思に完全に依存する状態に置かれた。 事実上、いかなる者も最も理不尽な理由で精神鑑定を受けさせられ、下された診断によって権利のない人格へと変貌した。この法的権利と保障の欠如こそが、国 内における抑圧的な精神医療制度を有利に働かせたのである。[116] アメリカの精神科医オレグ・ラップシンによれば、1993年までのロシアには、精神健康分野における具体的な法律が存在せず、刑事法や行政法における不整 合な指示や条文、ソ連保健省の命令のみが頼りだった。ソ連では、精神科患者は、その責任者、親族、あるいは地区精神科医の指示によって入院させることがで きた。この場合、患者の同意や反対は全く問題とされなかった。精神科病院での治療期間も、完全に精神科医の裁量に委ねられていた。こうした状況が、政治体 制に反対する者を抑圧するための精神医学の濫用を可能にし、精神疾患を持つ者の権利を無視する悪しき慣行を生み出したのである。[117] ロシア独立精神医学協会(IPA)会長ユーリ・サヴェンコによれば、懲罰的精神医学は主に三つの要因が絡み合って発生する:[118] 1. 科学のイデオロギー化、世界精神医学の成果からの断絶、ソ連法医学精神医学の党指向性。 2. 法的根拠の欠如。 3. 精神健康サービスの完全なナショナリズム化。 これらの相互作用システムは本質的に社会学的である:国家体制を誹謗する刑法条項の存在は、必然的に一定割合の市民を法医学的精神鑑定に送り込む結果をも たらす。[23] したがって、懲罰的なのは精神医学そのものではなく、全体主義国家が精神医学を懲罰目的に容易に利用しているのだ。[23] ラリー・ゴスティンによれば、問題の根本原因は国家そのものにあった[119]。ソ連の刑事制度は「危険性」の定義を大幅に拡大し、従来の身体的危険に加 え「政治的」危険も包含した[119]。ブロッホとレダウェイが指摘するように、人格の行動が危険となるか否かを判断する客観的かつ信頼できる基準は存在 せず、危険性の定義に対する精神科医の解釈は大きく異なる。[120] バージニア大学ロースクールの法学・医学教授リチャード・ボニーは、ソ連の精神医学が国家の抑圧的目的に容易に利用された理由の一つとして、その変質した 性質を挙げた。彼はこの時代から得られる最も重要な教訓の一つとして、市民社会、特に国家から独立した専門職組織の重要性を指摘している。[121] 世界精神医学会元会長ノーマン・サルトリウスによれば、旧ソ連における精神医学の政治的悪用は、国民分類体系に異議申し立て者をレッテル貼りし、強制的に 精神病院に収容して「治療」名目で拘束できるカテゴリーが含まれていた事実によって助長された。[122] DSM-5作業部会の副議長であるダレル・レジアーも同様の見解を持ち、ソ連における精神医学の政治的悪用は、ソ連で開発され精神科治療・ケアの基盤とし て用いられた分類体系の存在によって支えられていたと指摘している。[123] この分類体系には、政治的異議申し立て者に付与可能な診断カテゴリーが存在し、有害な強制投薬につながったのである。[123] モスクワ精神科医アレクサンドル・ダニリンによれば、スネジュネフスキーが確立したモスクワ精神医学派のいわゆる「病理学的」アプローチは、唯一の診断で ある統合失調症を下す能力に帰着する。精神医学は科学ではなく、こうした意見体系に過ぎず、何千人もの人々という犠牲者がいる。ダニリンが国家犯罪者と呼 んだスネシュネフスキーという学者がかつて導入した「遅発性統合失調症」という概念によって、何百万もの人生が台無しにされたのである。[124] サンクトペテルブルクの学術精神科医ユーリ・ヌラー教授は、スネシュネフスキー学派の概念により、精神科医は例えば分裂病質性精神障害や分裂病質的人格特 性さえも、個人の固有の人格としてではなく、様々な外的要因に依存する可能性のある動態を持つものではなく、必然的な進行過程の初期段階、発達が遅れた段 階として捉えることが可能になったと指摘している[125]。同様の考え方は他の多くの人格障害にも適用された[125]。これにより、鈍重な(神経症 様・精神病質様)統合失調症の診断範囲が極端に拡大された[125]。数多くの論争を呼ぶ前提にもかかわらず、当時のソ連科学の伝統に沿って、スネジュネ フスキーの仮説は即座に教条的地位を獲得した。この教条は後に他の分野では克服されたが、精神医学においては頑なに定着した。[126] スネジュネフスキーの概念は、その教条性ゆえに多くの精神科医にとって心理的に都合が良く、診断時の疑念を解消した。[126] これは重大な危険を伴った。医師が評価した規範からの逸脱は、すべて統合失調症の初期段階と見なされ、それに伴うあらゆる結果を招きかねなかったのであ る。[126] その結果、精神医学が自発的・非自発的に乱用される余地が広く生まれた。[126] しかしスネシュネフスキーは、明らかに行き詰まりを見せていた自身の概念を再考する市民的・科学的勇気を持ち合わせていなかった。[126] アメリカの精神科医ウォルター・ライヒによれば、反体制派への誤診は、標準的な精神医学の論理・理論・実践を歪めたソ連精神医学の特性に起因していた。[53] |

| According to Semyon Gluzman,

abuse of psychiatry to suppress dissent is based on condition of

psychiatry in a totalitarian state.[19] Psychiatric paradigm of a

totalitarian state is culpable for its expansion into spheres which are

not initially those of psychiatric competence.[19] Psychiatry as a

social institution, formed and functioning in the totalitarian state,

is incapable of not being totalitarian.[19] Such psychiatry is forced

to serve the two differently directed principles: care and treatment of

mentally ill citizens, on the one hand, and psychiatric repression of

people showing political or ideological dissent, on the other hand.[19]

In the conditions of the totalitarian state, independent-minded

psychiatrists appeared and may again appear, but these few people

cannot change the situation in which thousands of others, who were

brought up on incorrect pseudoscientific concepts and fear of the

state, will sincerely believe that the uninhibited, free thinking of a

citizen is a symptom of madness.[19] Gluzman specifies the following

six premises for the unintentional participation of doctors in

abuses:[19] 1. The specificity, in the totalitarian state, of the psychiatric paradigm tightly sealed from foreign influences. 2. The lack of legal conscience in most citizens including doctors. 3. Disregard for fundamental human rights on the part of the lawmaker and law enforcement agencies. 4. Declaratory nature or the absence of legislative acts that regulate providing psychiatric care in the country. The USSR, for example, adopted such an act only in 1988. 5. The absolute state paternalism of totalitarian regimes, which naturally gives rise to the dominance of the archaic paternalistic ethical concept in medical practice. Professional consciousness of the doctor is based on the almost absolute right to make decisions without the patient's consent (i.e. there is disregard for the principle of informed consent to treatment or withdrawal from it). 6. The fact, in psychiatric hospitals, of frustratingly bad conditions, which refer primarily to the poverty of health care and inevitably lead to the dehumanization of the personnel including doctors. Gluzman says that there, of course, may be a different approach to the issue expressed by Michel Foucault.[127] According to Michael Perlin, Foucault in his book Madness and Civilization documented the history of using institutional psychiatry as a political tool, researched the expanded use of the public hospitals in the 17th century in France and came to the conclusion that "confinement [was an] answer to an economic crisis... reduction of wages, unemployment, scarcity of coin" and, by the 18th century, the psychiatric hospitals satisfied "the indissociably economic and moral demand for confinement."[128] In 1977, British psychiatrist David Cooper asked Foucault the same question which Claude Bourdet had formerly asked Viktor Fainberg during a press conference given by Fainberg and Leonid Plyushch: when the USSR has the whole penitentiary and police apparatus, which could take charge of anybody, and which is perfect in itself, why do they use psychiatry? Foucault answered it was not a question of a distortion of the use of psychiatry but that was its fundamental project.[129] In the discussion Confinement, Psychiatry, Prison, Foucault states the cooperation of psychiatrists with the KGB in the Soviet Union was not abuse of medicine, but an evident case and "condensation" of psychiatry's "inheritance", an "intensification, the ossification of a kinship structure that has never ceased to function."[130] Foucault believed that the abuse of psychiatry in the USSR of the 1960s was a logical extension of the invasion of psychiatry into the legal system.[131] In the discussion with Jean Laplanche and Robert Badinter, Foucault says that criminologists of the 1880—1900s started speaking surprisingly modern language: "The crime cannot be, for the criminal, but an abnormal, disturbed behavior. If he upsets society, it's because he himself is upset".[132] This led to the twofold conclusions.[132] First, "the judicial apparatus is no longer useful." The judges, as men of law, understand such complex, alien legal issues, purely psychological matters no better than the criminal. So commissions of psychiatrists and physicians should be substituted for the judicial apparatus.[132] And in this vein, concrete projects were proposed.[132] Second, "We must certainly treat this individual who is dangerous only because he is sick. But, at the same time, we must protect society against him."[132] Hence comes the idea of mental isolation with a mixed function: therapeutic and prophylactic.[132] In the 1900s, these projects have given rise to very lively responses from European judicial and political bodies.[133] However, they found a wide field of applications when the Soviet Union became one of the most common but by no means exceptional cases.[133] According to American psychiatrist Jonas Robitscher, psychiatry has been playing a part in controlling deviant behavior for three hundred years.[134] Vagrants, "originals," eccentrics, and homeless wanderers who did little harm but were vexatious to the society they lived in were, and sometimes still are, confined to psychiatric hospitals or deprived of their legal rights.[134] Some critics of psychiatry consider the practice as a political use of psychiatry and regard psychiatry as promoting timeserving.[134] As Vladimir Bukovsky and Semyon Gluzman point out, it is difficult for the average Soviet psychiatrist to understand the dissident's poor adjustment to Soviet society.[135] This view of dissidence has nothing surprising about it—conformity reigned in Soviet consciousness; a public intolerance of non-conformist behavior always penetrated Soviet culture; and the threshold for deviance from custom was similarly low.[135] An example of the low threshold is a point of Donetsk psychiatrist Valentine Pekhterev, who argues that psychiatrists speak of the necessity of adapting oneself to society, estimate the level of man's social functioning, his ability to adequately test the reality and so forth.[136] In Pekhterev's words, these speeches hit point-blank on the dissidents and revolutionaries, because all of them are poorly functioning in society, are hardly adapting to it either initially or after increasing requirements.[136] They turn their inability to adapt themselves to society into the view that the company breaks step and only they know how to help the company restructure itself.[136] The dissidents regard the cases of personal maladjustment as a proof of public ill-being.[136] The more such cases, the easier it is to present their personal ill-being as public one.[136] They bite the society's hand that feed them only because they are not given a right place in society.[136] Unlike the dissidents, the psychiatrists destroy the hardly formed defense attitude in the dissidents by regarding "public well-being" as personal one.[136] The psychiatrists extract teeth from the dissidents, stating that they should not bite the feeding hand of society only because the tiny group of the dissidents feel bad being at their place.[136] The psychiatrists claim the need to treat not society but the dissidents and seek to improve society by preserving and improving the mental health of its members.[136] After reading the book Institute of Fools by Viktor Nekipelov, Pekhterev concluded that allegations against the psychiatrists sounded from the lips of a negligible but vociferous part of inmates who when surfeiting themselves with cakes pretended to be sufferers.[136] According to the response by Robert van Voren, Pekhterev in his article condescendingly argues that the Serbsky Institute was not so bad place and that Nekipelov exaggerates and slanders it, but Pekhterev, by doing so, misses the main point: living conditions in the Serbsky Institute were not bad, those who passed through psychiatric examination there were in a certain sense "on holiday" in comparison with the living conditions of the Gulag; and all the same, everyone was aware that the Serbsky Institute was more than the "gates of hell" from where people were sent to specialized psychiatric hospitals in Chernyakhovsk, Dnepropetrovsk, Kazan, Blagoveshchensk, and that is not all.[137] Their life was transformed to unimaginable horror with daily tortures by forced administration of drugs, beatings and other forms of punishment.[137] Many went crazy, could not endure what was happening to them, some even died during the "treatment" (for example, a miner from Donetsk Alexey Nikitin).[137] Many books and memoirs are written about the life in the psychiatric Gulag and every time when reading them a shiver seizes us.[137] The Soviet psychiatric terror in its brutality and targeting the mentally ill as the most vulnerable group of society had nothing on the Nazi euthanasia programs.[138] The punishment by placement in a mental hospital was as effective as imprisonment in Mordovian concentration camps in breaking persons psychologically and physically.[138] The recent history of the USSR should be given a wide publicity to immunize society against possible repetitions of the Soviet practice of political abuse of psychiatry.[138] The issue remains highly relevant.[138] |

セミョン・グルズマンによれば、異議を封じるための精神医学の濫用は、

全体主義国家における精神医学の状況を基盤としている[19]。全体主義国家の精神医学的パラダイムは、当初精神医学の専門領域ではなかった分野への拡大

に責任を負う[19]。全体主義国家において形成され機能する社会制度としての精神医学は、全体主義的でない状態を維持することが不可能である。[19]

このような精神医学は、二つの異なる原理に奉仕することを強いられる。一方では精神疾患を持つ市民のケアと治療、他方では政治的・思想的異議を示す人々に

対する精神医学的抑圧である。[19]

全体主義国家の条件下では、独立した精神科医が現れ、再び現れる可能性もある。しかし、こうした少数の人々では、誤った疑似科学的概念と国家への恐怖で

育った何千人もの他の者たちが、市民の抑制されない自由な思考が狂気の症状だと心から信じる状況を変えることはできない。[19]グルズマンは、医師が意