Randomized controlled trial

ランダム化比較試験

Randomized controlled trial

●ランダム化比較試験

ランダム化

比較試験(ランダムかひかくしけん、RCT:randomized controlled

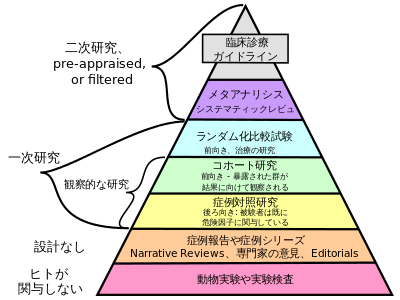

trial)とは、評価のバイアス(偏り)を避け、客観的に治療効果を評価することを目的とした研究試験の方法である[2]。根拠に基づく医療(EBM:

evidence-based

medicine)において、このランダム化比較試験を複数集め解析したメタアナリシスに次ぐ、根拠の質の高い研究手法である[2]。主に医療分野で用い

られているが、経済学においても取り入れられている[注釈 1][3]。無作為化比較試験

とも呼ばれている[4]。改善度に関する主観的評価を避けるための尺度であるエンドポイントを用いる、効果の差を計測するための治療していない偽薬などを

施した群を用意する、二重盲検法によって研究者がどちらが治療群かわからないようにし、治療群と対照群をランダムに割り当てるといった手法をとる[2]。

ランダム化

比較試験(ランダムかひかくしけん、RCT:randomized controlled

trial)とは、評価のバイアス(偏り)を避け、客観的に治療効果を評価することを目的とした研究試験の方法である[2]。根拠に基づく医療(EBM:

evidence-based

medicine)において、このランダム化比較試験を複数集め解析したメタアナリシスに次ぐ、根拠の質の高い研究手法である[2]。主に医療分野で用い

られているが、経済学においても取り入れられている[注釈 1][3]。無作為化比較試験

とも呼ばれている[4]。改善度に関する主観的評価を避けるための尺度であるエンドポイントを用いる、効果の差を計測するための治療していない偽薬などを

施した群を用意する、二重盲検法によって研究者がどちらが治療群かわからないようにし、治療群と対照群をランダムに割り当てるといった手法をとる[2]。

初のランダム化比較試験(RCT)は、イギリスにおいて、結核薬のストレプトマイシンが効く かどうかを調査するために、医学研究審議会(MRC:Medical Research Council)を代表してオースティン・ブラッドフォード・ヒル(英語版)らによって行われた[5]。結果は1948年に、英国医師会雑誌(BMJ: British Medical Journal)に掲載された[6]。差を知りたい介入以外の介入が等しくなければ、因果関係が正しく分からないという[7]、統計学者のロナルド・ フィッシャーによる統計理論が適用された[5]。 米国では、1962年に連邦食品・医薬品・化粧品法において薬剤の有効性の概念を設け、適切で十分に制御された2回の適切な対照を置いた臨床試験によって 有効性が示されれば、薬は承認されることとなった[8]。1990年代以降に普及した根拠に基づく医療における考え方では、RCTは、RCTを複数集め解 析したメタアナリシスに次ぐ、根拠の質の高い研究手法である[2]。

ランダム化比較試験は、主観的あるいは恣意的な評価のバイアス(偏り)を避けるために、以下 の点が揃っている[2]。 エンドポイント:改善度に関する尺度。改善度に関する主観的評価を避ける。 比較対照:治療を施した群と、偽薬あるいは比較のための治療を施した対照群。治療介入の効果を算出するため。対照群がない場合、何が要因なのかはっきりし ない。 ランダム化:母集団からのランダムな抽出や、治療群と対照群のランダムな割り当てを行う。効果が出そうな対照を選ぶことを避ける。 盲検化:研究者と被験者に、治療群と対照群がどちらであるかを分からないようにする。計測に主観が入らないようにする。 RCTによる効果検証・効果測定が一般に行われる以前では、いくつかの不合理な治療・投薬が存在していた。広く知られているのは、心筋梗塞の治療後に、予 防的にリドカイン(不整脈を防ぐ効果がある)の投薬が行われていた事例である。しかし、心筋梗塞後のリドカイン投薬群、非投薬群の追跡調査の結果、リドカ イン投与群でむしろ死亡率増加が認められたため、以後ははリドカインのルーチン投与は推奨されていない[9]。

社会科学におけるRCTでは、政策的課題に解を与えるための研究が行われ、2000年代以降 に増加している。学校の教育施策が学習に及ぼす影響、農業における新技術の影響、運転免許行政の不正、消費者金融市場のモラルハザードの影響、経済学理論 の検証などに使われている[10]。2019年には、バナジーとデュフロらのRCTを用いた研究がノーベル経済学賞を受賞したことで話題を呼んだ。

| A randomized

controlled trial (or randomized control trial;[2] RCT) is a form of

scientific experiment used to control factors not under direct

experimental control. Examples of RCTs are clinical trials that compare

the effects of drugs, surgical techniques, medical devices, diagnostic

procedures or other medical treatments. Participants who enroll in RCTs differ from one another in known and unknown ways that can influence study outcomes, and yet cannot be directly controlled. By randomly allocating participants among compared treatments, an RCT enables statistical control over these influences. Provided it is designed well, conducted properly, and enrolls enough participants, an RCT may achieve sufficient control over these confounding factors to deliver a useful comparison of the treatments studied. |

ランダム化比較試験(またはランダム化対照試験;[2]

RCT)とは、実験的に直接制御できない因子を制御するために用いられる科学実験の一形態である。RCTの例としては、薬物、手術手技、医療機器、診断手

順、その他の医療処置の効果を比較する臨床試験がある。 RCTに登録する参加者は、既知または未知の方法で互いに異なっており、それが試験結果に影響を及ぼす可能性があるが、直接制御することはできない。 RCTでは、参加者を比較した治療法群に無作為に割り当てることで、これらの影響を統計的にコントロールすることができる。RCTが適切にデザインされ、 適切に実施され、十分な参加者が登録されれば、RCTはこれらの交絡因子を十分にコントロールし、研究された治療法の有用な比較を行うことができる。 |

| Definition and examples An RCT in clinical research typically compares a proposed new treatment against an existing standard of care; these are then termed the 'experimental' and 'control' treatments, respectively. When no such generally accepted treatment is available, a placebo may be used in the control group so that participants are blinded to their treatment allocations. This blinding principle is ideally also extended as much as possible to other parties including researchers, technicians, data analysts, and evaluators. Effective blinding experimentally isolates the physiological effects of treatments from various psychological sources of bias. The randomness in the assignment of participants to treatments reduces selection bias and allocation bias, balancing both known and unknown prognostic factors, in the assignment of treatments.[3] Blinding reduces other forms of experimenter and subject biases. A well-blinded RCT is considered the gold standard for clinical trials. Blinded RCTs are commonly used to test the efficacy of medical interventions and may additionally provide information about adverse effects, such as drug reactions. A randomized controlled trial can provide compelling evidence that the study treatment causes an effect on human health.[4] The terms "RCT" and "randomized trial" are sometimes used synonymously, but the latter term omits mention of controls and can therefore describe studies that compare multiple treatment groups with each other in the absence of a control group.[5] Similarly, the initialism is sometimes expanded as "randomized clinical trial" or "randomized comparative trial", leading to ambiguity in the scientific literature.[6][7] Not all RCTs are randomized controlled trials (and some of them could never be, as in cases where controls would be impractical or unethical to use). The term randomized controlled clinical trial is an alternative term used in clinical research;[8] however, RCTs are also employed in other research areas, including many of the social sciences. |

定義と例 臨床研究におけるRCTは、通常、提案された新治療 法と既存の標準治療とを比較するものであり、そ れぞれ「実験的」治療と「対照」治療と呼ばれる。このような一般に認められた治療法がない場合は、対照群にプラセボを使用し、参加者が治療割り付けについ て盲検化されるようにすることもある。この盲検化の原則は、研究者、技術者、データ分析者、評価者を含む他の関係者にも可能な限り適用されることが理想的 である。効果的な盲検化により、治療による生理学的効果を、様々な心理的バイアスの原因から実験的に分離することができる。 参加者の治療割り付けにおける無作為性は、治療割り付けにおける選択バイアスと割り付けバイアスを減少させ、既知の予後因子と未知の予後因子の両方のバラ ンスをとる[3]。 十分に盲検化されたRCTは臨床試験のゴールドスタンダードと考えられている。盲検化RCTは、医療介入の有効性を検証するために一般的に使用され、さら に薬物反応などの副作用に関する情報を提供することもある。ランダム化比較試験は、試験治療が人の健康に影響を及ぼすという説得力のある証拠を提供できる [4]。 RCT」と「無作為化試験」という用語は同義に用いられることがあるが、後者の用語は対照に関する言及を省略しているため、対照群が存在しない場合に複数 の治療群を互いに比較する研究を記述することができる。 [5]同様に、この頭字語は「ランダム化臨床試験」または「ランダム化比較試験」と拡大されることもあり、科学文献のあいまいさにつながっている[6] [7]。すべてのRCTがランダム化比較試験であるわけではない(対照群を用いることが非現実的または非倫理的な場合のように、決してそうなり得ないもの もある)。ランダム化比較臨床試験という用語は、臨床研究で使用される別の用語である[8]が、RCTは社会科学の多くを含む他の研究分野でも採用されて いる。 |

| History The first reported clinical trial was conducted by James Lind in 1747 to identify treatment for scurvy.[9] The first blind experiment was conducted by the French Royal Commission on Animal Magnetism in 1784 to investigate the claims of mesmerism. An early essay advocating the blinding of researchers came from Claude Bernard in the latter half of the 19th century.[vague] Bernard recommended that the observer of an experiment should not have knowledge of the hypothesis being tested. This suggestion contrasted starkly with the prevalent Enlightenment-era attitude that scientific observation can only be objectively valid when undertaken by a well-educated, informed scientist.[10] The first study recorded to have a blinded researcher was conducted in 1907 by W. H. R. Rivers and H. N. Webber to investigate the effects of caffeine.[11] Randomized experiments first appeared in psychology, where they were introduced by Charles Sanders Peirce and Joseph Jastrow in the 1880s,[12] and in education.[13][14][15] In the early 20th century, randomized experiments appeared in agriculture, due to Jerzy Neyman[16] and Ronald A. Fisher. Fisher's experimental research and his writings popularized randomized experiments.[17] The first published Randomized Controlled Trial in medicine appeared in the 1948 paper entitled "Streptomycin treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis", which described a Medical Research Council investigation.[18][19][20] One of the authors of that paper was Austin Bradford Hill, who is credited as having conceived the modern RCT.[21] Trial design was further influenced by the large-scale ISIS trials on heart attack treatments that were conducted in the 1980s.[22] By the late 20th century, RCTs were recognized as the standard method for "rational therapeutics" in medicine.[23] As of 2004, more than 150,000 RCTs were in the Cochrane Library.[21] To improve the reporting of RCTs in the medical literature, an international group of scientists and editors published Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) Statements in 1996, 2001 and 2010, and these have become widely accepted.[1][3] Randomization is the process of assigning trial subjects to treatment or control groups using an element of chance to determine the assignments in order to reduce the bias. |

歴史 最初に報告された臨床試験は、壊血病の治療法を特定するためにジェームズ・リンドが1747年に行ったものである[9]。最初の盲検実験は、1784年に フランスの動物磁気に関する王立委員会が催眠術の主張を調査するために行ったものである。研究者の盲検化を提唱した初期の論文は、19世紀後半のクロー ド・ベルナールによるものである[vague]。この提言は、科学的観察は十分な教育を受け、十分な情報を得た科学者によってのみ客観的に有効であるとい う啓蒙時代の一般的な態度とは対照的であった[10]。盲検化された研究者を用いた最初の研究は、1907年にW・H・R・リバーズとH・N・ウェバーが カフェインの効果を調査するために行ったと記録されている[11]。 ランダム化実験は、1880年代にチャールズ・サンダーズ・ピアースとジョセフ・ジャストローによって導入された心理学[12]や教育[13][14] [15]で最初に登場した。 20世紀初頭には、イエジー・ネイマン[16]とロナルド・A・フィッシャーによって、ランダム化実験が農業に登場した。フィッシャーの実験研究と彼の著 作はランダム化実験を普及させた[17]。 医学において最初に発表されたランダム化比較試験は、1948年に発表された「肺結核のストレプトマイシン治療(Streptomycin treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis)」と題された論文であり、Medical Research Councilの調査を記述したものであった[18][19][20]。その論文の著者の一人はオースティン・ブラッドフォード・ヒル(Austin Bradford Hill)であり、彼は近代的なRCTを考案したとされている[21]。 試験デザインは、1980年代に実施された心臓発作治療に関する大規模なISIS試験からさらに影響を受けた[22]。 20世紀後半には、RCTは医学における「合理的治療法」の標準的な方法として認識されるようになった [23] 。 [21] 医学文献におけるRCTの報告を改善するために、国際的な科学者と編集者のグループが1996年、2001年、2010年にConsolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) Statementsを発表し、これらは広く受け入れられている[1][3]。無作為化とは、バイアスを軽減するために、偶然の要素を用いて割り付けを決 定し、被験者を治療群または対照群に割り当てることである。 |

| Ethics Although the principle of clinical equipoise ("genuine uncertainty within the expert medical community... about the preferred treatment") common to clinical trials[24] has been applied to RCTs, the ethics of RCTs have special considerations. For one, it has been argued that equipoise itself is insufficient to justify RCTs.[25] For another, "collective equipoise" can conflict with a lack of personal equipoise (e.g., a personal belief that an intervention is effective).[26] Finally, Zelen's design, which has been used for some RCTs, randomizes subjects before they provide informed consent, which may be ethical for RCTs of screening and selected therapies, but is likely unethical "for most therapeutic trials."[27][28] Although subjects almost always provide informed consent for their participation in an RCT, studies since 1982 have documented that RCT subjects may believe that they are certain to receive treatment that is best for them personally; that is, they do not understand the difference between research and treatment.[29][30] Further research is necessary to determine the prevalence of and ways to address this "therapeutic misconception".[30] The RCT method variations may also create cultural effects that have not been well understood.[31] For example, patients with terminal illness may join trials in the hope of being cured, even when treatments are unlikely to be successful. Trial registration In 2004, the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) announced that all trials starting enrolment after July 1, 2005, must be registered prior to consideration for publication in one of the 12 member journals of the committee.[32] However, trial registration may still occur late or not at all.[33][34] Medical journals have been slow in adapting policies requiring mandatory clinical trial registration as a prerequisite for publication.[35] |

倫理 臨床試験に共通する臨床的均衡の原則(「望ましい治療法について...専門家である医学界における真の不確実性」)はRCTにも適用されているが [24]、RCTの倫理には特別な考慮事項がある。1つには、等質性そのものがRCTを正当化するには不十分であると主張されていることである[25]。 もう1つには、「集団的等質性」が個人的等質性(例えば、介入が有効であるという個人的信念)の欠如と相反する可能性があることである[26]。最後に、 いくつかのRCTに用いられているZelenのデザインは、被験者がインフォームドコンセントを提供する前に無作為化するものであり、スクリーニングや選 択された治療法のRCTでは倫理的であっても、「ほとんどの治療法の臨床試験では」非倫理的である可能性が高い[27][28]。 被験者はほとんどの場合、RCTへの参加についてインフォームド・コンセントを行うが、1982年以降の研究によると、RCTの被験者は、自分個人にとっ て最善の治療を確実に受けられると信じている可能性があり、つまり研究と治療の違いを理解していないことが報告されている[29][30]。この「治療上 の誤解」の蔓延状況と対処法を明らかにするためには、さらなる研究が必要である[30]。 例えば、末期患者の場合、治療が成功しそうにない場合でも、治ることを期待して試験に参加することがある。 臨床試験の登録 2004年、国際医学雑誌編集者委員会(ICMJE)は、2005年7月1日以降に登録が開始されるすべての臨床試験は、同委員会に加盟する12誌のいず れかに掲載を検討される前に登録されなければならないと発表した[32] 。 |

| Classifications By study design One way to classify RCTs is by study design. From most to least common in the healthcare literature, the major categories of RCT study designs are:[36] Parallel-group – each participant is randomly assigned to a group, and all the participants in the group receive (or do not receive) an intervention.[37][38] Crossover – over time, each participant receives (or does not receive) an intervention in a random sequence.[39][40] Cluster – pre-existing groups of participants (e.g., villages, schools) are randomly selected to receive (or not receive) an intervention.[41][42] Factorial – each participant is randomly assigned to a group that receives a particular combination of interventions or non-interventions (e.g., group 1 receives vitamin X and vitamin Y, group 2 receives vitamin X and placebo Y, group 3 receives placebo X and vitamin Y, and group 4 receives placebo X and placebo Y). An analysis of the 616 RCTs indexed in PubMed during December 2006 found that 78% were parallel-group trials, 16% were crossover, 2% were split-body, 2% were cluster, and 2% were factorial.[36] By outcome of interest (efficacy vs. effectiveness) Main article: Pragmatic clinical trial RCTs can be classified as "explanatory" or "pragmatic."[43] Explanatory RCTs test efficacy in a research setting with highly selected participants and under highly controlled conditions.[43] In contrast, pragmatic RCTs (pRCTs) test effectiveness in everyday practice with relatively unselected participants and under flexible conditions; in this way, pragmatic RCTs can "inform decisions about practice."[43] By hypothesis (superiority vs. noninferiority vs. equivalence) Another classification of RCTs categorizes them as "superiority trials", "noninferiority trials", and "equivalence trials", which differ in methodology and reporting.[44] Most RCTs are superiority trials, in which one intervention is hypothesized to be superior to another in a statistically significant way.[44] Some RCTs are noninferiority trials "to determine whether a new treatment is no worse than a reference treatment."[44] Other RCTs are equivalence trials in which the hypothesis is that two interventions are indistinguishable from each other.[44] |

分類 試験デザインによる分類 RCTを分類する一つの方法は、研究デザインによるものである。医療文献において最も一般的なものから最も一般的でないものまで、RCT研究デザインの主 な分類は以下の通りである: [36] 。 並行群-各参加者がランダムに群に割り付けられ、群内の参加者全員が介入を受ける(または受けない)[37][38]。 クロスオーバー-時間をかけて、各参加者が介入をランダムな順序で受ける(または受けない)[39][40]。 クラスター - 参加者の既存のグループ(村、学校など)が無作為に選択され、介入を受ける(または受けない)[41][42]。 ファクトリアル - 各参加者が介入または非介入の特定の組み合わせを受ける群に無作為に割り付けられる(例えば、第1群はビタミンXとビタミンY、第2群はビタミンXとプラ セボY、第3群はプラセボXとビタミンY、第4群はプラセボXとプラセボY)。 2006年12月にPubMedで索引付けされた616件のRCTを分析したところ、78%が並行群間試験、16%がクロスオーバー、2%がスプリットボ ディ、2%がクラスター、2%がファクトリアルであった[36]。 関心のある結果別(有効性 vs. 有効性) 主な記事 実用的臨床試験 RCTは「説明的」または「実用的」に分類される[43]。説明的RCTは、高度に選択された参加者を用い、高度に管理された条件下で、研究環境における 有効性を検証するものである[43]。対照的に、実用的RCT(pRCT)は、比較的非選択的な参加者を用い、柔軟な条件下で、日常診療における有効性を 検証するものである;このようにして、実用的RCTは「診療に関する決定に情報を提供する」ことができる[43]。 仮説別(優越性vs.非劣性vs.同等性) RCTのもう1つの分類では、RCTを「優越性試験」、「非劣性試験」、「同等性試験」に分類しており、方法論と報告方法が異なる[44]。ほとんどの RCTは優越性試験であり、ある介入が統計的に有意な方法で他の介入より優れているという仮説が立てられる。 [他のRCTは同等性試験であり、2つの介入は互いに区別できないという仮説が立てられる[44]。 |

| Randomization The advantages of proper randomization in RCTs include:[45] "It eliminates bias in treatment assignment," specifically selection bias and confounding. "It facilitates blinding (masking) of the identity of treatments from investigators, participants, and assessors." "It permits the use of probability theory to express the likelihood that any difference in outcome between treatment groups merely indicates chance." There are two processes involved in randomizing patients to different interventions. First is choosing a randomization procedure to generate an unpredictable sequence of allocations; this may be a simple random assignment of patients to any of the groups at equal probabilities, may be "restricted", or may be "adaptive." A second and more practical issue is allocation concealment, which refers to the stringent precautions taken to ensure that the group assignment of patients are not revealed prior to definitively allocating them to their respective groups. Non-random "systematic" methods of group assignment, such as alternating subjects between one group and the other, can cause "limitless contamination possibilities" and can cause a breach of allocation concealment.[46] However empirical evidence that adequate randomization changes outcomes relative to inadequate randomization has been difficult to detect.[47] Procedures The treatment allocation is the desired proportion of patients in each treatment arm. An ideal randomization procedure would achieve the following goals:[48] Maximize statistical power, especially in subgroup analyses. Generally, equal group sizes maximize statistical power, however, unequal groups sizes may be more powerful for some analyses (e.g., multiple comparisons of placebo versus several doses using Dunnett's procedure[49] ), and are sometimes desired for non-analytic reasons (e.g., patients may be more motivated to enroll if there is a higher chance of getting the test treatment, or regulatory agencies may require a minimum number of patients exposed to treatment).[50] Minimize selection bias. This may occur if investigators can consciously or unconsciously preferentially enroll patients between treatment arms. A good randomization procedure will be unpredictable so that investigators cannot guess the next subject's group assignment based on prior treatment assignments. The risk of selection bias is highest when previous treatment assignments are known (as in unblinded studies) or can be guessed (perhaps if a drug has distinctive side effects). Minimize allocation bias (or confounding). This may occur when covariates that affect the outcome are not equally distributed between treatment groups, and the treatment effect is confounded with the effect of the covariates (i.e., an "accidental bias"[45][51]). If the randomization procedure causes an imbalance in covariates related to the outcome across groups, estimates of effect may be biased if not adjusted for the covariates (which may be unmeasured and therefore impossible to adjust for). However, no single randomization procedure meets those goals in every circumstance, so researchers must select a procedure for a given study based on its advantages and disadvantages. Simple This is a commonly used and intuitive procedure, similar to "repeated fair coin-tossing."[45] Also known as "complete" or "unrestricted" randomization, it is robust against both selection and accidental biases. However, its main drawback is the possibility of imbalanced group sizes in small RCTs. It is therefore recommended only for RCTs with over 200 subjects.[52] Restricted To balance group sizes in smaller RCTs, some form of "restricted" randomization is recommended.[52] The major types of restricted randomization used in RCTs are: Permuted-block randomization or blocked randomization: a "block size" and "allocation ratio" (number of subjects in one group versus the other group) are specified, and subjects are allocated randomly within each block.[46] For example, a block size of 6 and an allocation ratio of 2:1 would lead to random assignment of 4 subjects to one group and 2 to the other. This type of randomization can be combined with "stratified randomization", for example by center in a multicenter trial, to "ensure good balance of participant characteristics in each group."[3] A special case of permuted-block randomization is random allocation, in which the entire sample is treated as one block.[46] The major disadvantage of permuted-block randomization is that even if the block sizes are large and randomly varied, the procedure can lead to selection bias.[48] Another disadvantage is that "proper" analysis of data from permuted-block-randomized RCTs requires stratification by blocks.[52] Adaptive biased-coin randomization methods (of which urn randomization is the most widely known type): In these relatively uncommon methods, the probability of being assigned to a group decreases if the group is overrepresented and increases if the group is underrepresented.[46] The methods are thought to be less affected by selection bias than permuted-block randomization.[52] Adaptive At least two types of "adaptive" randomization procedures have been used in RCTs, but much less frequently than simple or restricted randomization: Covariate-adaptive randomization, of which one type is minimization: The probability of being assigned to a group varies in order to minimize "covariate imbalance."[52] Minimization is reported to have "supporters and detractors"[46] because only the first subject's group assignment is truly chosen at random, the method does not necessarily eliminate bias on unknown factors.[3] Response-adaptive randomization, also known as outcome-adaptive randomization: The probability of being assigned to a group increases if the responses of the prior patients in the group were favorable.[52] Although arguments have been made that this approach is more ethical than other types of randomization when the probability that a treatment is effective or ineffective increases during the course of an RCT, ethicists have not yet studied the approach in detail.[53] Allocation concealment Main article: Allocation concealment "Allocation concealment" (defined as "the procedure for protecting the randomization process so that the treatment to be allocated is not known before the patient is entered into the study") is important in RCTs.[54] In practice, clinical investigators in RCTs often find it difficult to maintain impartiality. Stories abound of investigators holding up sealed envelopes to lights or ransacking offices to determine group assignments in order to dictate the assignment of their next patient.[46] Such practices introduce selection bias and confounders (both of which should be minimized by randomization), possibly distorting the results of the study.[46] Adequate allocation concealment should defeat patients and investigators from discovering treatment allocation once a study is underway and after the study has concluded. Treatment related side-effects or adverse events may be specific enough to reveal allocation to investigators or patients thereby introducing bias or influencing any subjective parameters collected by investigators or requested from subjects. Some standard methods of ensuring allocation concealment include sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes (SNOSE); sequentially numbered containers; pharmacy controlled randomization; and central randomization.[46] It is recommended that allocation concealment methods be included in an RCT's protocol, and that the allocation concealment methods should be reported in detail in a publication of an RCT's results; however, a 2005 study determined that most RCTs have unclear allocation concealment in their protocols, in their publications, or both.[55] On the other hand, a 2008 study of 146 meta-analyses concluded that the results of RCTs with inadequate or unclear allocation concealment tended to be biased toward beneficial effects only if the RCTs' outcomes were subjective as opposed to objective.[56] Sample size Main article: Sample size determination The number of treatment units (subjects or groups of subjects) assigned to control and treatment groups, affects an RCT's reliability. If the effect of the treatment is small, the number of treatment units in either group may be insufficient for rejecting the null hypothesis in the respective statistical test. The failure to reject the null hypothesis would imply that the treatment shows no statistically significant effect on the treated in a given test. But as the sample size increases, the same RCT may be able to demonstrate a significant effect of the treatment, even if this effect is small.[57] |

無作為化 RCTにおける適切なランダム化の利点は以下のとおりである[45]。 「治療割り付けにおけるバイアス、特に選択バイアスと交絡を排除できる。 "治験責任医師、参加者、評価者から治療法の身元を盲検化(マスキング)することが容易になる"。 "治療群間の結果におけるいかなる差異も、単に偶然を示すだけである可能性を表現するために、確率論の使用を可能にする。" 患者を異なる介入に無作為に割り付けるには2つのプロセスがある。1つ目は、予測不可能な一連の割り付けを発生させるための無作為化手順の選択である;こ れは、等確率でいずれかの群に患者を割り付ける単純な無作為割り付けであったり、"制限的 "であったり、"適応的 "であったりする。第2のより実際的な問題は、割付の隠蔽であり、これは患者をそれぞれの群に決定的に割り付ける前に、患者の群割付が明らかにならないよ うにするためにとられる厳重な予防措置を指す。一方の群と他方の群との間で被験者を交互に割り当てるなど、無作為でない「系統的」な群割付け方法は、「汚 染の可能性が無限にある」ため、割付の隠蔽に違反する可能性がある[46]。 しかし、適切な無作為化が不適切な無作為化と比較して転帰を変化させるという経験的証拠を検出することは困難である[47]。 手順 治療割り付けは、各治療群における患者の望ましい割合である。 理想的なランダム化手順は以下の目標を達成する: [48] 。 特にサブグループ解析において統計的検出力を最大化する。一般的に、群サイズが等しいと統計的検出力が最大になるが、一部の解析(例えば、Dunnett の手順を用いたプラセボと複数用量の多重比較[49])では群サイズが等しくない方が強力な場合があり、解析以外の理由(例えば、試験治療を受ける可能性 が高い方が患者の登録意欲が高まる場合や、規制当局が治療に曝露される患者数の最小値を要求する場合など)で望まれる場合もある[50]。 選択バイアスの最小化。これは、治験責任医師が意識的または無意識的に、治療群間で患者を優先的に登録できる場合に発生する可能性がある。優れたランダム 化手順は、治験責任医師が以前の治療割り付けに基づいて次の被験者の群割り付けを推測できないように、予測不可能である。選択バイアスのリスクは、以前の 治療割り付けが分かっている場合(非盲検試験など)、または推測できる場合(薬剤に特徴的な副作用がある場合など)に最も高くなる。 割り付けバイアス(または交絡)を最小化する。これは、転帰に影響する共変量が治療群間で均等に分布しておらず、治療効果が共変量の効果と混同される(す なわち、「偶発的バイアス」[45][51])場合に発生する可能性がある。無作為化手順が群間で転帰に関連する共変量の不均衡を引き起こす場合、共変量 (測定されていないため調整が不可能な場合がある)について調整しなければ、効果の推定値に偏りが生じる可能性がある。 したがって、研究者はその長所と短所に基づいて、ある研究のために手順を選択しなければならない。 単純 これは一般的に使用されている直感的な手順で、「公平なコイン投げの繰り返し」に似ている[45]。「完全」または「無制限」無作為化としても知られ、選 択バイアスおよび偶発的バイアスの両方に対して頑健である。しかし、主な欠点は小規模のRCTでは群サイズが不均衡になる可能性があることである。した がって、被験者数が200人を超えるRCTにのみ推奨される[52]。 限定的 小規模のRCTで群サイズのバランスをとるには、何らかの「制限」ランダム化が推奨される[52]。RCTで用いられる制限ランダム化の主な種類は以下の とおりである: Permuted-block randomizationまたはblocked randomization:「ブロックサイズ」と「割付比」(一方の群対他方の群の被験者数)が指定され、各ブロック内で被験者がランダムに割付けられ る [46] 例えば、ブロックサイズ6、割付比2:1の場合、一方の群に4人、他方の群に2人の被験者がランダムに割付けられる。このタイプの無作為化は、「各群の参 加者の特性の良好なバランスを確保する」ために、多施設試験における施設別などの「層別無作為化」と組み合わせることができる[3]。 [46] パーミュートブロック無作為化の主な欠点は、ブロックサイズが大きくランダムに変化していても、この手順が選択バイアスにつながる可能性があることである [48] 。もう1つの欠点は、パーミュートブロック無作為化RCTからのデータの「適切な」分析にはブロックによる層別化が必要であることである[52]。 適応的バイアスコイン無作為化法(その中で壺型無作為化が最も広く知られているタイプ): これらの比較的まれな方法では、ある群に割り当てられる確率は、その群の割合が多い場合は減少し、その群の割合が少ない場合は増加する[46]。この方法 は、順列ブロック無作為化よりも選択バイアスの影響を受けにくいと考えられている[52]。 適応的 少なくとも2種類の「適応」ランダム化手順がRCTで使用されているが、単純ランダム化または制限ランダム化よりもはるかに頻度は低い: 共変量適応ランダム化で、その1つが最小化である: 最小化には「支持者と否定者」[46]がいることが報告されており、最初の被験者の群割り付けのみが本当にランダムに選択されるため、この方法では未知の 因子に関するバイアスが必ずしも排除されない[3]。 反応適応無作為化、結果適応無作為化としても知られる: RCTの過程で治療が有効または無効である確率が増加する場合、この方法は他のタイプの無作為化よりも倫理的であるという主張がなされているが、倫理学者 はまだこの方法を詳しく研究していない[53]。 割付の隠蔽 主な記事 割付隠蔽 「割付の隠蔽(allocation concealment)」(「患者が試験に参加する前に、割付される治療法がわからないように無作為化プロセスを保護する手順」と定義される)は、 RCTにおいて重要である[54]。実際には、RCTの治験責任医師は公平性を保つことが困難であることが多い。次の患者の割り付けを決定するために、密 封された封筒をライトにかざしたり、事務所を物色して群割り付けを決定したりする研究者の話があふれている[46]。このような行為は、選択バイアスと交 絡因子(いずれも無作為化によって最小化されるべきもの)をもたらし、研究結果を歪める可能性がある[46]。十分な割り付け隠蔽により、研究が進行中で あっても、研究終了後であっても、患者や研究者が治療割り付けを発見できないようにすべきである。治療に関連した副作用や有害事象は、治験責任医師や患者 に割り付けを明らかにするのに十分なほど特異的であり、それによってバイアスが生じたり、治験責任医師が収集した主観的パラメータや被験者から要求された パラメータに影響を及ぼす可能性がある。 割り付け隠蔽を確実にする標準的な方法には、連番を付けた不透明な密封封筒(SNOSE)、連番を付けた容器、薬局管理無作為化、および中央無作為化など がある [46] 。割り付け隠蔽方法をRCTのプロトコルに含めること、およびRCTの結果の公表において割り付け隠蔽方法を詳細に報告することが推奨されているが、 2005年の調査では、ほとんどのRCTでプロトコール、公表、またはその両方において割り付け隠蔽が不明確であることが明らかにされた。 [55] 一方、146件のメタアナリシスを対象とした2008年の研究では、割り付け隠蔽が不十分または不明確なRCTの結果は、RCTの結果が客観的なものでは なく主観的なものであった場合にのみ有益な効果に偏る傾向があると結論づけている [56] 。 サンプルサイズ 主な記事 サンプルサイズの決定 対照群と治療群に割り付けられた治療単位(被験者または被験者群)の数は、RCTの信頼性に影響する。治療の効果が小さい場合、どちらかの群の治療単位数 がそれぞれの統計検定で帰無仮説を棄却するには不十分な場合がある。帰無仮説を棄却できないということは、ある検定において、治療が被治療者に統計的に有 意な効果を示さないことを意味する。しかし、標本サイズが大きくなるにつれて、同じRCTが、たとえ効果が小さくても、治療の有意な効果を示すことができ るようになる可能性がある[57]。 |

| Blinding Main article: Blinded experiment An RCT may be blinded, (also called "masked") by "procedures that prevent study participants, caregivers, or outcome assessors from knowing which intervention was received."[56] Unlike allocation concealment, blinding is sometimes inappropriate or impossible to perform in an RCT; for example, if an RCT involves a treatment in which active participation of the patient is necessary (e.g., physical therapy), participants cannot be blinded to the intervention. Traditionally, blinded RCTs have been classified as "single-blind", "double-blind", or "triple-blind"; however, in 2001 and 2006 two studies showed that these terms have different meanings for different people.[58][59] The 2010 CONSORT Statement specifies that authors and editors should not use the terms "single-blind", "double-blind", and "triple-blind"; instead, reports of blinded RCT should discuss "If done, who was blinded after assignment to interventions (for example, participants, care providers, those assessing outcomes) and how."[3] RCTs without blinding are referred to as "unblinded",[60] "open",[61] or (if the intervention is a medication) "open-label".[62] In 2008 a study concluded that the results of unblinded RCTs tended to be biased toward beneficial effects only if the RCTs' outcomes were subjective as opposed to objective;[56] for example, in an RCT of treatments for multiple sclerosis, unblinded neurologists (but not the blinded neurologists) felt that the treatments were beneficial.[63] In pragmatic RCTs, although the participants and providers are often unblinded, it is "still desirable and often possible to blind the assessor or obtain an objective source of data for evaluation of outcomes."[43] |

目隠し 主な記事 盲検化実験 RCTは、「研究参加者、介護者、結果評価者がどの介入を受けたかを知ることができないようにする手続き」によって盲検化(「マスク」とも呼ばれる)され ることがある[56]。割り付け隠蔽とは異なり、盲検化はRCTでは不適切であったり、実施できないことがある;例えば、RCTが患者の積極的な参加が必 要な治療(例えば、理学療法)を含む場合、参加者は介入について盲検化できない。 従来、盲検化されたRCTは「単盲検」、「二重盲検」、「三重盲検」に分類されてきたが、2001年と2006年の2つの研究により、これらの用語が人に よって異なる意味を持つことが示された。 [58][59] 2010年のCONSORT声明では、著者や編集者は「単盲検」、「二重盲検」、「三重盲検」という用語を使うべきではないと規定されている。その代わり に、盲検化されたRCTの報告では、「盲検化された場合、介入への割り付け後に盲検化されたのは誰か(例えば、参加者、ケア提供者、アウトカムを評価する 者)、どのように盲検化されたか」を議論すべきである[3]。 盲検化のないRCTは「非盲検」[60]、「オープン」[61]、または(介入が薬物療法の場合)「オープンラベル」[62]と呼ばれる。2008年のあ る研究では、非盲検RCTの結果が有益な効果に偏る傾向があるのは、RCTのアウトカムが客観的ではなく主観的であった場合に限られると結論づけている [56]。 [63] 実薬的RCTでは、参加者や提供者は盲検化されていないことが多いが、「評価者を盲検化するか、転帰を評価するための客観的なデータ源を得ることが望まし いし、しばしば可能である」[43]。 |

| Analysis of data The types of statistical methods used in RCTs depend on the characteristics of the data and include: For dichotomous (binary) outcome data, logistic regression (e.g., to predict sustained virological response after receipt of peginterferon alfa-2a for hepatitis C[64]) and other methods can be used. For continuous outcome data, analysis of covariance (e.g., for changes in blood lipid levels after receipt of atorvastatin after acute coronary syndrome[65]) tests the effects of predictor variables. For time-to-event outcome data that may be censored, survival analysis (e.g., Kaplan–Meier estimators and Cox proportional hazards models for time to coronary heart disease after receipt of hormone replacement therapy in menopause[66]) is appropriate. Regardless of the statistical methods used, important considerations in the analysis of RCT data include: Whether an RCT should be stopped early due to interim results. For example, RCTs may be stopped early if an intervention produces "larger than expected benefit or harm", or if "investigators find evidence of no important difference between experimental and control interventions."[3] The extent to which the groups can be analyzed exactly as they existed upon randomization (i.e., whether a so-called "intention-to-treat analysis" is used). A "pure" intention-to-treat analysis is "possible only when complete outcome data are available" for all randomized subjects;[67] when some outcome data are missing, options include analyzing only cases with known outcomes and using imputed data.[3] Nevertheless, the more that analyses can include all participants in the groups to which they were randomized, the less bias that an RCT will be subject to.[3] Whether subgroup analysis should be performed. These are "often discouraged" because multiple comparisons may produce false positive findings that cannot be confirmed by other studies.[3] |

データの解析 RCTで用いられる統計的手法の種類はデータの特徴によって異なり、以下のようなものがある: 二分法(バイナリー)の結果データに対しては、ロジスティック回帰(例えば、C型肝炎に対するペグインターフェロン アルファ-2a投与後の持続的ウイルス学的反応を予測するため[64])やその他の方法を用いることができる。 連続アウトカムデータの場合は、共分散分析(例えば、急性冠症候群後のアトルバスタチン投与後の血中脂質値の変化[65])で予測変数の効果を検定する。 打ち切られる可能性のある時間対事象の結果データには、生存分析(例えば、更年期にホルモン補充療法を受けた後の冠動脈性心疾患までの時間に対する Kaplan-Meier推定値およびCox比例ハザードモデル[66])が適切である。 使用する統計的手法にかかわらず、RCTデータの解析における重要な考慮事項は以下の通りである: RCTを中間結果のために早期に中止すべきかどうか。例えば、介入により「予想以上の有益性または有害性」が得られた場合、あるいは「研究者が実験的介入 と対照介入の間に重要な差がないという証拠を見つけた」場合、RCTは早期に中止されることがある[3]。 無作為化時に存在した群として正確に分析できる範囲(すなわち、いわゆる「intention-to-treat分析」が用いられているかどうか)。純粋 な」intention-to-treat解析は、無作為化された被験者全員について「完全な結果データが利用可能な場合にのみ可能」である[67];結 果データの一部が欠落している場合、既知の結果を有する症例のみを解析する、インプットデータを使用するなどの選択肢がある[3]。それでも、すべての参 加者を無作為化された群に含めることができればできるほど、RCTが受けるバイアスは少なくなる[3]。 サブグループ解析を実施すべきかどうか。多重比較は他の研究で確認できない偽陽性所見をもたらす可能性があるため、これらは「しばしば推奨されない」 [3]。 |

| Reporting of results The CONSORT 2010 Statement is "an evidence-based, minimum set of recommendations for reporting RCTs."[68] The CONSORT 2010 checklist contains 25 items (many with sub-items) focusing on "individually randomised, two group, parallel trials" which are the most common type of RCT.[1] For other RCT study designs, "CONSORT extensions" have been published, some examples are: Consort 2010 Statement: Extension to Cluster Randomised Trials[69] Consort 2010 Statement: Non-Pharmacologic Treatment Interventions[70][71] Relative importance and observational studies Two studies published in The New England Journal of Medicine in 2000 found that observational studies and RCTs overall produced similar results.[72][73] The authors of the 2000 findings questioned the belief that "observational studies should not be used for defining evidence-based medical care" and that RCTs' results are "evidence of the highest grade."[72][73] However, a 2001 study published in Journal of the American Medical Association concluded that "discrepancies beyond chance do occur and differences in estimated magnitude of treatment effect are very common" between observational studies and RCTs.[74] According to a 2014 Cochrane review, there is little evidence for significant effect differences between observational studies and randomized controlled trials, regardless of design, heterogeneity, or inclusion of studies of interventions that assessed drug effects.[75] Two other lines of reasoning question RCTs' contribution to scientific knowledge beyond other types of studies: If study designs are ranked by their potential for new discoveries, then anecdotal evidence would be at the top of the list, followed by observational studies, followed by RCTs.[76] RCTs may be unnecessary for treatments that have dramatic and rapid effects relative to the expected stable or progressively worse natural course of the condition treated.[77][78] One example is combination chemotherapy including cisplatin for metastatic testicular cancer, which increased the cure rate from 5% to 60% in a 1977 non-randomized study.[78][79] Interpretation of statistical results Like all statistical methods, RCTs are subject to both type I ("false positive") and type II ("false negative") statistical errors. Regarding Type I errors, a typical RCT will use 0.05 (i.e., 1 in 20) as the probability that the RCT will falsely find two equally effective treatments significantly different.[80] Regarding Type II errors, despite the publication of a 1978 paper noting that the sample sizes of many "negative" RCTs were too small to make definitive conclusions about the negative results,[81] by 2005-2006 a sizeable proportion of RCTs still had inaccurate or incompletely reported sample size calculations.[82] Peer review Peer review of results is an important part of the scientific method. Reviewers examine the study results for potential problems with design that could lead to unreliable results (for example by creating a systematic bias), evaluate the study in the context of related studies and other evidence, and evaluate whether the study can be reasonably considered to have proven its conclusions. To underscore the need for peer review and the danger of overgeneralizing conclusions, two Boston-area medical researchers performed a randomized controlled trial in which they randomly assigned either a parachute or an empty backpack to 23 volunteers who jumped from either a biplane or a helicopter. The study was able to accurately report that parachutes fail to reduce injury compared to empty backpacks. The key context that limited the general applicability of this conclusion was that the aircraft were parked on the ground, and participants had only jumped about two feet.[83] |

結果の報告 CONSORT 2010ステートメントは、「RCTを報告するためのエビデンスに基づく最小限の推奨事項」である[68]。CONSORT 2010チェックリストには、RCTの最も一般的なタイプである「個別無作為化二群間並行試験」に焦点を当てた25の項目(小項目多数)が含まれている [1]。 その他のRCT試験デザインについては、「CONSORTの拡張」が発表されており、その一例が以下の通りである: Consort2010ステートメント: クラスター無作為化試験への拡張[69]。 コンソーシア2010ステートメント: 非薬理学的治療介入[70][71]。 相対的重要性と観察研究 2000年にThe New England Journal of Medicine誌に発表された2つの研究では、観察研究とRCTは全体的に同様の結果を出していることが明らかにされた[72][73]。2000年の 調査結果の著者は、「観察研究はエビデンスに基づく医療を定義するために用いるべきではない」、RCTの結果は「最高ランクのエビデンス」であるという信 念に疑問を呈している。 「しかし、2001年のJournal of the American Medical Association誌に掲載された研究では、観察研究とRCTの間で「偶然を超えた食い違いが生じることがあり、治療効果の推定値の大きさに差が生じ ることは非常によくあることである」と結論づけている[74]。2014年のコクラン・レビューによると、デザイン、異質性、薬効を評価する介入研究を含 めるかどうかにかかわらず、観察研究とランダム化比較試験の間に有意な効果の差があるという証拠はほとんどない[75]。 他の2つの推論では、RCTが他のタイプの研究を超えて科学的知識に貢献することに疑問が呈されている: 研究デザインを新たな発見の可能性でランク付けした場合、逸話的証拠が最上位となり、観察研究、RCTの順となる[76]。 RCTは、治療された病態の自然経過が予想される安定したもの、または徐々に悪化するものに対して、劇的で迅速な効果を有する治療法には不要な場合があ る。77][78] 1つの例として、転移性精巣がんに対するシスプラチンを含む併用化学療法があり、1977年の非ランダム化試験において治癒率が5%から60%に増加した [78][79]。 統計結果の解釈 すべての統計的手法と同様に、RCTはI型(「偽陽性」)とII型(「偽陰性」)の統計的誤差の影響を受ける。タイプIの誤りについては、典型的なRCT では、2つの同等に有効な治療法が有意に異なると誤認される確率として0.05(すなわち20分の1)が用いられる[80]。タイプIIの誤りについて は、1978年に多くの「否定的」RCTのサンプルサイズが小さすぎて、否定的な結果について決定的な結論を出すことができないと指摘する論文が発表され たにもかかわらず[81]、2005年から2006年にかけても、かなりの割合のRCTでサンプルサイズの計算が不正確または不完全に報告されている [82]。 査読 結果の査読は科学的方法の重要な一部である。査読者は、信頼できない結果(例えば系統的なバイアスを生じさせるなど)につながる可能性のあるデザイン上の 問題がないか、関連する研究や他の証拠との関連において研究を評価し、研究がその結論を証明したと合理的に考えられるかどうかを評価する。ピアレビューの 必要性と、結論の過度な一般化の危険性を強調するために、ボストン地域の2人の医学研究者が、複葉機またはヘリコプターから飛び降りた23人のボランティ アに、パラシュートまたは空のバックパックのいずれかを無作為に割り当てるランダム化比較試験を行った。この研究では、パラシュートは空のリュックサック に比べて怪我を減らせないことを正確に報告することができた。この結論の一般的な適用可能性を制限した重要な背景は、航空機が地面に駐機しており、参加者 は約2フィートしかジャンプしていないことであった[83]。 |

| Advantages RCTs are considered to be the most reliable form of scientific evidence in the hierarchy of evidence that influences healthcare policy and practice because RCTs reduce spurious causality and bias. Results of RCTs may be combined in systematic reviews which are increasingly being used in the conduct of evidence-based practice. Some examples of scientific organizations' considering RCTs or systematic reviews of RCTs to be the highest-quality evidence available are: As of 1998, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia designated "Level I" evidence as that "obtained from a systematic review of all relevant randomised controlled trials" and "Level II" evidence as that "obtained from at least one properly designed randomised controlled trial."[84] Since at least 2001, in making clinical practice guideline recommendations the United States Preventive Services Task Force has considered both a study's design and its internal validity as indicators of its quality.[85] It has recognized "evidence obtained from at least one properly randomized controlled trial" with good internal validity (i.e., a rating of "I-good") as the highest quality evidence available to it.[85] The GRADE Working Group concluded in 2008 that "randomised trials without important limitations constitute high quality evidence."[86] For issues involving "Therapy/Prevention, Aetiology/Harm", the Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine as of 2011 defined "Level 1a" evidence as a systematic review of RCTs that are consistent with each other, and "Level 1b" evidence as an "individual RCT (with narrow Confidence Interval)."[87] Notable RCTs with unexpected results that contributed to changes in clinical practice include: After Food and Drug Administration approval, the antiarrhythmic agents flecainide and encainide came to market in 1986 and 1987 respectively.[88] The non-randomized studies concerning the drugs were characterized as "glowing",[89] and their sales increased to a combined total of approximately 165,000 prescriptions per month in early 1989.[88] In that year, however, a preliminary report of an RCT concluded that the two drugs increased mortality.[90] Sales of the drugs then decreased.[88] Prior to 2002, based on observational studies, it was routine for physicians to prescribe hormone replacement therapy for post-menopausal women to prevent myocardial infarction.[89] In 2002 and 2004, however, published RCTs from the Women's Health Initiative claimed that women taking hormone replacement therapy with estrogen plus progestin had a higher rate of myocardial infarctions than women on a placebo, and that estrogen-only hormone replacement therapy caused no reduction in the incidence of coronary heart disease.[66][91] Possible explanations for the discrepancy between the observational studies and the RCTs involved differences in methodology, in the hormone regimens used, and in the populations studied.[92][93] The use of hormone replacement therapy decreased after publication of the RCTs.[94] |

利点 RCTは偽の因果関係やバイアスを減らすことができるため、医療政策や実践に影響を与えるエビデンスの階層において、最も信頼性の高い科学的エビデンスで あると考えられている。RCTの結果はシステマティックレビューにまとめられることがあり、エビデンスに基づく診療の実施に用いられることが多くなってき ている。RCTまたはRCTのシステマティックレビューを利用可能な最も質の高いエビデンスとみなしている科学団体の例をいくつか挙げる: 1998年の時点で、オーストラリア国立保健医療研究評議会は、「レベルⅠ」のエビデンスを「関連するすべてのランダム化比較試験のシステマティックレ ビューから得られたもの」、「レベルⅡ」のエビデンスを「少なくとも1つの適切にデザインされたランダム化比較試験から得られたもの」と指定している [84]。 少なくとも2001年以降、米国予防医療作業部会は、臨床実践ガイドラインの推奨を行う際に、研究のデザインとその内部妥当性の両方をその質の指標として 考慮している[85]。同部会は、内部妥当性が良好な(すなわち、評価が「I-good」の)「少なくとも1件の適切なランダム化比較試験から得られたエ ビデンス」を、利用可能な最高質のエビデンスとして認めている[85]。 GRADE作業部会は2008年に、「重要な制限のない無作為化試験は、質の高いエビデンスとなる」と結論づけた[86]。 Therapy/Prevention, Aetiology/Harm (治療/予防、病因/害)」に関わる問題については、2011年時点のOxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicineは、「レベル1a」のエビデンスを互いに矛盾のないRCTのシステマティックレビューと定義し、「レベル1b」のエビデンスを「個別の RCT(狭い信頼区間あり)」と定義している[87]。 臨床実践の変更に貢献した予想外の結果を示した著名なRCTには、以下のものがある: 食品医薬品局の承認後、抗不整脈薬であるフレカイニドとエンカイニドはそれぞれ1986年と1987年に市販された [88] 。これらの薬剤に関する非ランダム化試験は「白熱した」ものとされ [89] 、その売上は1989年初めには合計で1ヵ月あたり約16万5,000処方まで増加した [88] 。 2002年以前は、観察研究に基づいて、医師が心筋梗塞を予防するために閉経後の女性にホルモン補充療法を処方することは日常的であった[89]。しか し、2002年と2004年に、Women's Health Initiativeから発表されたRCTでは、エストロゲンとプロゲスチンを併用したホルモン補充療法を受けている女性は、プラセボを服用している女性 よりも心筋梗塞の発症率が高く、エストロゲンのみのホルモン補充療法では冠動脈性心疾患の発症率は低下しなかったと主張された。 [66] [91] 観察研究とRCTとの間の食い違いの説明として考えられるのは、方法論、使用されたホルモンレジメン、および研究された集団の違いであった[92] [93] ホルモン補充療法の使用は、RCTの発表後に減少した[94]。 |

| Disadvantages Many papers discuss the disadvantages of RCTs.[77][95][96] Among the most frequently cited drawbacks are: Time and costs RCTs can be expensive;[96] one study found 28 Phase III RCTs funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke prior to 2000 with a total cost of US$335 million,[97] for a mean cost of US$12 million per RCT. Nevertheless, the return on investment of RCTs may be high, in that the same study projected that the 28 RCTs produced a "net benefit to society at 10-years" of 46 times the cost of the trials program, based on evaluating a quality-adjusted life year as equal to the prevailing mean per capita gross domestic product.[97] The conduct of an RCT takes several years until being published; thus, data is restricted from the medical community for long years and may be of less relevance at time of publication.[98] It is costly to maintain RCTs for the years or decades that would be ideal for evaluating some interventions.[77][96] Interventions to prevent events that occur only infrequently (e.g., sudden infant death syndrome) and uncommon adverse outcomes (e.g., a rare side effect of a drug) would require RCTs with extremely large sample sizes and may, therefore, best be assessed by observational studies.[77] Due to the costs of running RCTs, these usually only inspect one variable or very few variables, rarely reflecting the full picture of a complicated medical situation; whereas the case report, for example, can detail many aspects of the patient's medical situation (e.g. patient history, physical examination, diagnosis, psychosocial aspects, follow up).[98] Conflict of interest dangers A 2011 study done to disclose possible conflicts of interests in underlying research studies used for medical meta-analyses reviewed 29 meta-analyses and found that conflicts of interests in the studies underlying the meta-analyses were rarely disclosed. The 29 meta-analyses included 11 from general medicine journals; 15 from specialty medicine journals, and 3 from the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. The 29 meta-analyses reviewed an aggregate of 509 randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Of these, 318 RCTs reported funding sources with 219 (69%) industry funded. 132 of the 509 RCTs reported author conflict of interest disclosures, with 91 studies (69%) disclosing industry financial ties with one or more authors. The information was, however, seldom reflected in the meta-analyses. Only two (7%) reported RCT funding sources and none reported RCT author-industry ties. The authors concluded "without acknowledgment of COI due to industry funding or author industry financial ties from RCTs included in meta-analyses, readers' understanding and appraisal of the evidence from the meta-analysis may be compromised."[99] Some RCTs are fully or partly funded by the health care industry (e.g., the pharmaceutical industry) as opposed to government, nonprofit, or other sources. A systematic review published in 2003 found four 1986–2002 articles comparing industry-sponsored and nonindustry-sponsored RCTs, and in all the articles there was a correlation of industry sponsorship and positive study outcome.[100] A 2004 study of 1999–2001 RCTs published in leading medical and surgical journals determined that industry-funded RCTs "are more likely to be associated with statistically significant pro-industry findings."[101] These results have been mirrored in trials in surgery, where although industry funding did not affect the rate of trial discontinuation it was however associated with a lower odds of publication for completed trials.[102] One possible reason for the pro-industry results in industry-funded published RCTs is publication bias.[101] Other authors have cited the differing goals of academic and industry sponsored research as contributing to the difference. Commercial sponsors may be more focused on performing trials of drugs that have already shown promise in early stage trials, and on replicating previous positive results to fulfill regulatory requirements for drug approval.[103] Ethics If a disruptive innovation in medical technology is developed, it may be difficult to test this ethically in an RCT if it becomes "obvious" that the control subjects have poorer outcomes—either due to other foregoing testing, or within the initial phase of the RCT itself. Ethically it may be necessary to abort the RCT prematurely, and getting ethics approval (and patient agreement) to withhold the innovation from the control group in future RCT's may not be feasible. Historical control trials (HCT) exploit the data of previous RCTs to reduce the sample size; however, these approaches are controversial in the scientific community and must be handled with care.[104] |

欠点 多くの論文がRCTの欠点について論じている[77][95][96]。最も頻繁に挙げられる欠点は以下の通りである: 時間と費用 ある研究では、2000年以前に国立神経障害・脳卒中研究所が資金提供した28件の第Ⅲ相RCTが見つかり、その総費用は3億3,500万米ドル [97]、RCT1件当たりの平均費用は1,200万米ドルであった。とはいえ、RCTの投資対効果は高い可能性があり、同調査では、28のRCTが、一 人当たり国内総生産の平均値と等しい質調整生存年を評価した上で、試験プログラムの費用の46倍の「10年後の社会への正味利益」をもたらしたと予測して いる[97]。 RCTの実施は公表されるまでに数年を要するため、データは長い年月に わたって医学界から制限され、公表時には関連性が低くなっている可能性がある [98] 。 いくつかの介入を評価するのに理想的である数年から数十年にわたってRCTを維持するにはコストがかかる[77][96]。 発生頻度の低い事象(乳幼児突然死症候群など)やまれな有害転帰(薬剤のまれな副作用など)を予防するための介入には、非常に大きなサンプルサイズを持つ RCTが必要であり、したがって観察研究によって評価するのが最善であろう[77]。 RCTの実施にはコストがかかるため、これらの研究では通常1つの変数またはごく少数の変数のみを調査し、複雑な医学的状況の全体像を反映することはほと んどない;一方、例えば症例報告では、患者の医学的状況の多くの側面(例えば、患者の病歴、身体診察、診断、心理社会的側面、フォローアップ)を詳述する ことができる[98]。 利益相反の危険 医学的メタアナリシスに使用される基礎研究における利益相反の可能性を開示するために行われた2011年の研究では、29のメタアナリシスが検討され、メ タアナリシスの基礎となる研究における利益相反が開示されることはほとんどないことが判明した。29のメタアナリシスには、一般医学雑誌から11、専門医 学雑誌から15、Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviewsから3が含まれていた。29のメタアナリシスは、合計509のランダム化比較試験(RCT)をレビューした。このうち318件のRCTが資 金源を報告しており、219件(69%)が産業界からの資金提供を受けていた。509件のRCTのうち132件が著者の利益相反の開示を報告しており、 91件(69%)が1人以上の著者と産業界との金銭的関係を開示していた。しかし、この情報がメタ解析に反映されることはほとんどなかった。RCTの資金 源を報告したのはわずか2件(7%)であり、RCTの著者と企業との関係を報告したものはなかった。著者らは、「メタアナリシスに含まれるRCTから業界 からの資金提供や著者の業界との金銭的関係によるCOIを認めなければ、メタアナリシスから得られたエビデンスの読者の理解と評価が損なわれる可能性があ る」と結論づけている[99]。 RCTの中には、政府、非営利団体、その他の資金源とは対照的に、医療業界(例、製薬業界)から全面的または部分的に資金提供を受けているものもある。 2003年に発表されたシステマティックレビューでは、1986年から2002年の4つの論文で、産業界がスポンサーとなったRCTとそうでないRCTを 比較しており、すべての論文で産業界がスポンサーとなったことと肯定的な研究結果との相関がみられた[100]。2004年に主要な医学・外科学雑誌に掲 載された1999年から2001年のRCTを対象とした研究では、産業界が資金提供したRCTは「統計的に有意な産業界寄りの所見と関連する可能性が高 い」と判定されている。 「このような結果は外科の試験でも同様であり、産業界からの資金提供は試験の中止率には影響しないものの、完了した試験の出版確率の低下と関連していた [102]。 産業界から資金提供を受けて出版されたRCTの結果が産業界寄りである理由として、出版バイアスが考えられる[101]。商業スポンサーは、初期段階の試 験で既に有望性が示されている医薬品の試験を実施することや、医薬品承認のための規制要件を満たすために過去の良好な結果を再現することに重点を置いてい る可能性がある[103]。 倫理 医療技術における破壊的革新が開発された場合、対照被験者の転帰がより不良であることが「明らか」になった場合、RCTで倫理的に検証することが困難な場 合がある。倫理的には、RCTを早期に中止する必要があるかもしれず、将来のRCTで対照群から技術革新を差し控える倫理的承認(および患者の同意)を得 ることは、実行不可能かもしれない。 歴史的対照試験(HCT)は、過去のRCTのデータを利用し てサンプル数を減らすものであるが、このような手法は科学界で 論争を呼んでおり、取り扱いには注意が必要である[104]。 |

| In social science Due to the recent emergence of RCTs in social science, the use of RCTs in social sciences is a contested issue. Some writers from a medical or health background have argued that existing research in a range of social science disciplines lacks rigour, and should be improved by greater use of randomized control trials. Transport science Researchers in transport science argue that public spending on programmes such as school travel plans could not be justified unless their efficacy is demonstrated by randomized controlled trials.[105] Graham-Rowe and colleagues[106] reviewed 77 evaluations of transport interventions found in the literature, categorising them into 5 "quality levels". They concluded that most of the studies were of low quality and advocated the use of randomized controlled trials wherever possible in future transport research. Dr. Steve Melia[107] took issue with these conclusions, arguing that claims about the advantages of RCTs, in establishing causality and avoiding bias, have been exaggerated. He proposed the following eight criteria for the use of RCTs in contexts where interventions must change human behaviour to be effective: The intervention: Has not been applied to all members of a unique group of people (e.g. the population of a whole country, all employees of a unique organisation etc.) Is applied in a context or setting similar to that which applies to the control group Can be isolated from other activities—and the purpose of the study is to assess this isolated effect Has a short timescale between its implementation and maturity of its effects And the causal mechanisms: Are either known to the researchers, or else all possible alternatives can be tested Do not involve significant feedback mechanisms between the intervention group and external environments Have a stable and predictable relationship to exogenous factors Would act in the same way if the control group and intervention group were reversed Criminology A 2005 review found 83 randomized experiments in criminology published in 1982–2004, compared with only 35 published in 1957–1981.[108] The authors classified the studies they found into five categories: "policing", "prevention", "corrections", "court", and "community".[108] Focusing only on offending behavior programs, Hollin (2008) argued that RCTs may be difficult to implement (e.g., if an RCT required "passing sentences that would randomly assign offenders to programmes") and therefore that experiments with quasi-experimental design are still necessary.[109] Education RCTs have been used in evaluating a number of educational interventions. Between 1980 and 2016, over 1,000 reports of RCTs have been published.[110] For example, a 2009 study randomized 260 elementary school teachers' classrooms to receive or not receive a program of behavioral screening, classroom intervention, and parent training, and then measured the behavioral and academic performance of their students.[111] Another 2009 study randomized classrooms for 678 first-grade children to receive a classroom-centered intervention, a parent-centered intervention, or no intervention, and then followed their academic outcomes through age 19.[112] |

社会科学におけるRCT 社会科学におけるRCTの最近の出現により、社会科学におけるRCTの使用は論争の的となっている。医学や保健学出身の著者の中には、様々な社会科学分野 における既存の研究は厳密性に欠けており、ランダム化比較試験をより活用することによって改善されるべきであると主張する者もいる。 交通科学 交通科学の研究者は、ランダム化比較試験によってその有効性が実証されない限り、学校旅行計画のようなプログラムへの公的支出は正当化されないと主張して いる[105]。 Graham-Roweと同僚[106]は、文献で見つかった交通介入の77の評価をレビューし、それらを5つの「質レベル」に分類した。彼らは、ほとん どの研究は質が低いと結論づけ、今後の交通研究では可能な限りランダム化比較試験を使用することを提唱した。 スティーブ・メリア博士[107]は、これらの結論に異議を唱え、因果関係を立証しバイアスを回避するというRCTの利点に関する主張が誇張されていると 主張した。彼は、介入が効果的であるために人間の行動を変えなければならない文脈において、RCTを使用するための以下の8つの基準を提案した: 介入: 介入は、ある特定の集団の全構成員(例:国全体の人口、ある特定の組織の全従業員など)には適用されていない。 対照群に適用されるのと同様の文脈や設定で適用される。 他の活動から切り離すことができ、研究の目的はこの切り離された効果を評価することである。 実施から効果発現までの期間が短い。 因果関係のメカニズムが 研究者が知っているか、あるいは可能性のある代替案をすべてテストできる。 介入グループと外部環境との間に重要なフィードバック・メカニズムが含まれていない。 外生因子との関係が安定していて予測可能である。 対照群と介入群を逆にしても同じように作用する。 犯罪学 2005年のレビューでは、1982~2004年に発表された犯罪学におけるランダム化実験が83件見つかったのに対し、1957~1981年に発表され たものはわずか35件であった[108]: 「Hollin(2008)は、犯罪行動プログラムのみに焦点を当て、RCTの実施は困難である可能性があり(例えば、RCTが「犯罪者をプログラムに無 作為に割り当てるような判決を下す」ことを必要とする場合)、したがって準実験的デザインによる実験が依然として必要であると主張している[109]。 教育 RCTは多くの教育的介入の評価に用いられてきた。1980年から2016年の間に、1,000件を超えるRCTの報告が公表されている[110]。例え ば、2009年の研究では、260人の小学校教師の教室を、行動スクリーニング、教室介入、保護者トレーニングのプログラムを受ける群と受けない群に無作 為に割り付け、その後、生徒の行動と学業成績を測定した[111]。また、2009年の別の研究では、678人の小学1年生の児童の教室を、教室中心の介 入を受ける群、保護者中心の介入を受ける群、介入を受けない群に無作為に割り付け、その後、19歳まで学業成績を追跡した[112]。 |

| Criticism A 2018 review of the 10 most cited randomised controlled trials noted poor distribution of background traits, difficulties with blinding, and discussed other assumptions and biases inherent in randomised controlled trials. These include the "unique time period assessment bias", the "background traits remain constant assumption", the "average treatment effects limitation", the "simple treatment at the individual level limitation", the "all preconditions are fully met assumption", the "quantitative variable limitation" and the "placebo only or conventional treatment only limitation".[113] |

批判 2018年に最も引用された10件の無作為化比較試験のレビューでは、背景形質の分布の乏しさ、盲検化の困難さが指摘され、無作為化比較試験に内在するそ の他の仮定やバイアスについて議論されている。これらには、「特異的期間評価バイアス」、「背景形質が一定である仮定」、「平均治療効果の限界」、「個人 レベルでの単純治療の限界」、「すべての前提条件が完全に満たされている仮定」、「量的変数の限界」、「プラセボのみまたは従来治療のみの限界」などが含 まれる[113]。 |

| Drug development Hypothesis testing Impact evaluation Jadad scale Pipeline planning Royal Commission on Animal Magnetism Statistical inference |

薬の開発 仮説検定 影響評価 Jadad尺度 パイプライン計画 動物磁気の王立委員会 統計的推論 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Randomized_controlled_trial |

文献

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆